Footnotes have been collected at the end of each chapter, and are

linked for ease of reference.

There was a short list of corrections to certain dates provided by the printer.

This version retains that table, but has made the suggested corrections.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

I

A HISTORY

OF THE

COLDSTREAM GUARDS.

II

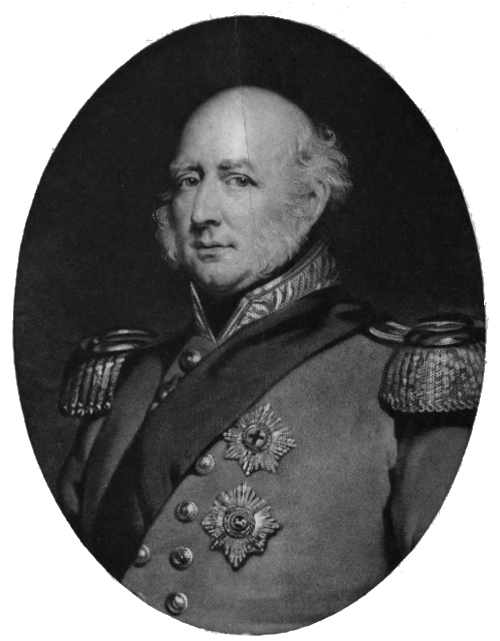

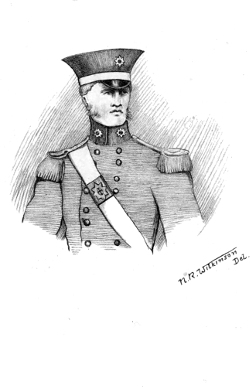

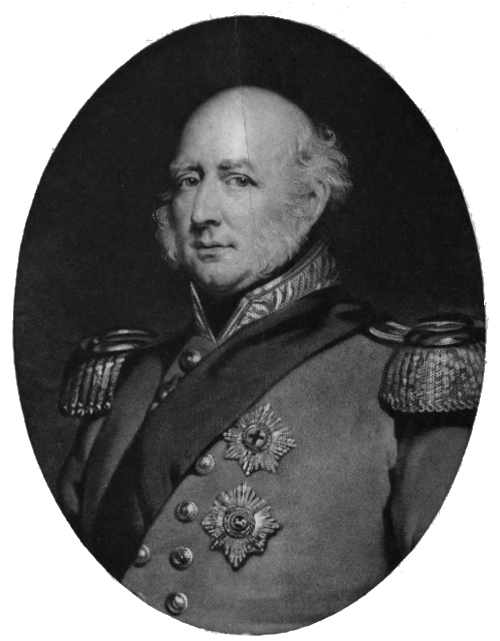

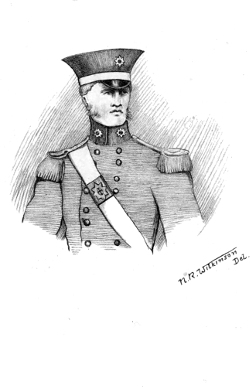

Field Marshal H.R.H. Adolphus Frederick, Duke of Cambridge K.G., G.C.B., G.C.H.,

Colonel Coldstream Guards 1805-1850.

FROM A PRINT IN THE POSSESSION OF THE REGIMENT.

A

HISTORY

OF THE

COLDSTREAM GUARDS,

From 1815 to 1895.

BY

LT. Col. Ross-of-Bladensburg, C.B.

LATE

Coldstream Guards.

Illustrated by

Lieut. Nevile R. Wilkinson,

Coldstream Guards.

London,

A.D. Innes & Co.

1896.

THIS HISTORY

OF

HER MAJESTY'S COLDSTREAM REGIMENT OF FOOT GUARDS,

FROM THE YEAR 1815 TO 1885,

IS, BY MOST GRACIOUS PERMISSION,

HUMBLY DEDICATED TO

HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN-EMPRESS

vii

PREFACE.

The following pages are a continuation of Colonel MacKinnon’s

Origin and Services of the Coldstream Guards, from the victory of

Waterloo down to the year 1885. They have been compiled with

great care and much labour, and the reader will, I trust, feel

justified in adding, with accuracy and marked ability.

The first few chapters deal with events that took place in

France, after Waterloo, including the military occupation of the

North-Eastern frontier by the Allies, up to the year 1818.

The period onwards to the Crimean War, although containing

but few accounts of interest concerning the career of the Regiment,

is valuable as continuing, to a considerable extent, the history of

events in Europe so far as that is consistent with the subject of

the present volume.

There is reference, nevertheless, to the part taken by the

Regiment in the suppression of the Canadian rebellion.

From the date, however, of 1854, the subject assumes a different

character, and is of absorbing interest to every Officer and man

associated with the Coldstream Guards.

The events connected with that campaign have been carefully

selected from thoroughly authentic sources; they are recorded in

no spirit of vainglory or self-sufficiency, but as a true and faithful

tale of the share which the Regiment took in that eventful war,—illustrating,

as it does, acts of gallantry, a noble and uncomplaining

endurance of difficulties and hardships, and a strict performance of

duty under very trying circumstances.

The accuracy of the record of the more recent Egyptian campaigns

is of special value, from the fact of the author of this work

having himself taken an active part in one of them.

The perusal of these records will be accompanied by the conviction

which exists in the minds of all of us, that those who

replace their gallant predecessors will, when their turn comes,

deserve equally well of their country.

FREDK. STEPHENSON, General,

Colonel, Coldstream Guards.

1896.

viii

AUTHOR'S NOTE.

I beg to return sincere thanks to the many members of the Coldstream

Guards, past and present, who have helped me to compile the volume I

now venture to issue to the public; and to assure them that, but for

their assistance, it would have been far less worthy of their acceptance

than even it is at the present time. It is not possible for me, in the short

space at my disposal, to mention all by name to whom I am indebted in

this respect. But I should fail in my duty did I not, at least, express my

gratitude to General Sir Frederick Stephenson, G.C.B., and to General

Hon. Sir Percy Feilding, K.C.B., for the interest they have shown in my

work, and for the trouble they have taken to enable me to carry it out.

Major Vesey Dawson was indefatigable in compiling all that concerns

the Nulli Secundus Club. Captain Shute prepared an Appendix on the

Coldstream Hospital. Mr. Sutton spared no pains in supplying information

which the Regimental Orderly Room affords; and Mr. Studd

arranged materials that required considerable labour. Major Goulburn,

Grenadier Guards, moreover, lent me the interesting Crimean Diary of

the late Colonel Tower; and Colonel Malleson kindly looked through the

proofs, and made many valuable suggestions.

I also offer my acknowledgments to Messrs. Blackwood and Sons,

and to Messrs. Seeley and Co., for their courteous permission to use the

maps in Mr. Kinglake’s Invasion of the Crimea and in Sir E. Hamley’s

War in the Crimea .

Lastly, I must express the pleasure it gives me that my work is illustrated

by so able and accomplished an artist as Mr. Wilkinson.

It only now remains for me to explain that as Colonel MacKinnon’s

Origin and Services of the Coldstream Guards does not contain illustrations

of uniforms worn by the Regiment during the many generations of its existence,

we preferred to give representations, not of the familiar figures of

this century, but of those that are less known. Thus, though the following

pages only describe events from the year 1815 to 1885, the plates generally

refer to a more remote period of the history of the Regiment.

John Ross-of-Bladensburg,

Lt.-Colonel.

October, 1896.

ix

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. |

| |

| THE CAPITULATION OF PARIS. |

| |

| |

PAGE |

| |

| Flight of Napoleon from the field of Waterloo—Reaction in Paris—Napoleon’s abdication—Surrender to Captain Maitland—Provisional Government set up in France—Advance of the Allies from Waterloo—Operations of Marshal Grouchy—Allies hope to cut the enemy off from Paris—Blücher’s energy to secure that object—Unsuccessful efforts of the Provisional Government to obtain a suspension of hostilities—The Allies before Paris—The Prussians move round to the south of the city—Co-operation of Wellington—Capitulation of the capital, July 3rd—Advance of Austrians and Russians—“Waterloo men”—The “Wellington pension”—Rank of Lieutenant granted to Ensigns of the Brigade of Guards—The soldier’s small account-book introduced into the British army |

1 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER II. |

| |

| MILITARY OCCUPATION OF FRANCE. |

| |

| Termination of the war—Difficulties of the situation—The Allies occupy Paris—Dissolution of the Provisional Government—Entry of Louis XVIII. into the capital—New French Government formed—Blücher and the Pont de Jena—Arrival of the Allied Sovereigns—Reviews in France—Paris in the hands of the Allies—Treatment of the French by the Prussians; by the British—The wreck of the French Imperial forces disbanded—Life in Paris—The Louvre stripped of its treasures of art—Prosecution of Imperialist leaders—Labedoyère, Ney, Lavalette—Peace of Paris, November 20th |

24 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER III. |

| |

| OCCUPATION OF FRENCH FORTRESSES. |

| |

| xOrganization of the Allied army of occupation, under the supreme command of the Duke of Wellington—Return of the remainder to their respective countries—Instructions of the Allied Courts to Wellington—Convention relating to the occupation, attached to the Treaty of Paris—Positions assigned to each contingent on the north-eastern frontier of France—March from Paris to Cambrai—Military precautions—Camps of instruction and field exercises—Reduction of the army of occupation—Difficulties with the French—Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle—Evacuation of France—The Guards Brigade leave Cambrai, after nearly three years' stay there, and embark at Calais—Valedictory Orders—The Coldstream sent to Chatham—Conclusion of military service in French territory |

48 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER IV. |

| |

| FIRST PART OF THE LONG EUROPEAN PEACE. |

| |

| Distress in England after the war—Reductions in the Army and Navy—Stations of the Brigade—French Eagles captured, deposited in the Chapel Royal, Whitehall—Reforms in interior economy—Death of George III., and Accession of George IV.—Cato Street Conspiracy—Trial of Queen Caroline—Coronation of George IV.—Guards in Dublin—Distress in 1826—Death of the Duke of York—Changes in uniform—Death of George IV.; succeeded by William IV.—Political agitation at home, revolution abroad; the Reform Act—Coronation of William IV.—First appearance of cholera—Death of the King, and Accession of Her Majesty Queen Victoria—Changes and reforms introduced during the reign of William IV. |

72 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER V. |

| |

| SECOND PART OF THE LONG EUROPEAN PEACE. |

| |

| Beginning of the reign of Queen Victoria—Troops during Parliamentary elections—Coronation of the Queen—Fire at the Tower of London, 1841—Rebellion in Canada—Two Guards Battalions sent there, 1838, of which one the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards—Return home, 1842—Visit of the Russian Tsar Nicholas I. to England—European revolution—Bi-centenary celebration of the formation of the Coldstream Guards, 1850—Death of the Colonel of the Regiment, H.R.H. the Duke of Cambridge; succeeded by General the Earl of Strafford—Exhibition in London—Death of the Duke of Wellington—Changes and reforms up to 1854—Camp at Chobham |

103 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER VI. |

| |

| BEGINNING OF THE WAR IN THE EAST. |

| |

| xiPosition of Russia in Europe—State of the Continent in 1853—British alliance with France—The Tsar’s quarrel with Turkey—Commencement of hostilities on the Danube—-The affair of Sinope—How it drew England and France into the war—Three Battalions of the Brigade of Guards ordered on foreign service—Concentration of the Allies in the Mediterranean—Guards Brigade at Malta—Thence to Scutari—Want of transport—The Allies moved to Varna—Good feeling between the British and French troops—Course of the war on the Danube—Siege of Silistria—Retreat of the Russians into Bessarabia—Intervention of Austria—The Allies in Bulgaria-Sickness among the troops—Return to Varna—Preparations for the invasion of the Crimea—The organization and strength of the Allies |

130 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| |

| THE INVASION OF THE CRIMEA. |

| |

| Small results gained by the Allies—Sudden determination to attack Sevastopol—Russian position in the Trans-Caucasian provinces—Conditions under which the Crimea was invaded—The allied Armada sails from Varna to Eupatoria—Landing effected at “Old Fort”—The move to Sevastopol; the order of march—The enemy on the Alma river, opposes the advance of the Allies—Description of the field of battle; strength and position of the enemy—Commencement of the battle of the Alma—Advance of the Light and the Second Divisions—Deployment of the First Division—Advance of the Guards and Highland Brigades—Defeat of the Russians—No pursuit—Losses—Bravery and steadiness of the British troops—The Allies lose valuable time after the battle—Arriving at last before their objective, Sevastopol, they refuse to attack it—General description of Sevastopol |

156 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

| |

| BEFORE SEVASTOPOL. |

| |

| Predicament in which the Allies found themselves—Flank march round Sevastopol—Occupation of Balaklava by the British and of Kamiesh Bay by the French—The Allies refuse to assault Sevastopol; they prefer to bombard it—Depression of the Russians, who fear a prompt assault—Description of the defences round the south side of Sevastopol; successful efforts of the enemy to strengthen them—Description of the upland of the Chersonese, occupied by the Allies; their position and labours—First bombardment and its results—No attack; a regular siege inevitable—Draft of Officers and men to the Coldstream arrive in the Crimea—Establishment of the Regiment—Russian reinforcements begin to arrive—Battle of Balaklava; Cavalry charges—Sortie of the Russians against the British right flank; its failure |

180 |

| |

| |

| xiiCHAPTER IX. |

| |

| THE BATTLE OF INKERMAN. |

| |

| Large Russian reinforcements reach the Crimea—Position and strength of the enemy; of the Allies—Description of the field of Inkerman—Commencement of the battle, 5th of November—The progress of the first part of the fight—The Guards Brigade advance to the scene of action—The struggle round the Sandbag battery—Arrival of the Fourth Division under General Cathcart—The manœuvre of the latter, and its failure—The arrival of the French—Successes of the British artillery—Repulse of the Russian attack; the retreat of the enemy; there is no pursuit—Operations of the garrison of Sevastopol and of the Russian force in the Tchernaya Valley during the day—Great losses incurred on both sides—Reaction among the soldiery after the battle |

204 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER X. |

| |

| THE WINTER OF 1854-55 IN THE CRIMEA. |

| |

| Prostration of both sides after the battle of Inkerman—Sevastopol not to be taken in 1854—Tardy arrangements to enable the army to remain in the Crimea during the winter—Violent hurricane of the 14th of November; stores scattered and destroyed—The winter begins in earnest—How the Government at home attended to the wants of the army at the seat of war—Absence of a road between the base at Balaklava and the front—Miserable plight to which the army was reduced—Indignation in England, and the measures taken to relieve the troops—Admirable manner in which the misfortunes were borne by the British soldiers—Operations on both sides during the winter—The Turks occupy Eupatoria; successful action fought there—The Guards Brigade sent to Balaklava |

231 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XI. |

| |

| THE FALL OF SEVASTOPOL. |

| |

| Stay of the Brigade at Balaklava—Improvement in the condition of the men—Return of the Guards to the front, June 16th—Changed aspect of affairs before Sevastopol—Review of events during the time spent at Balaklava—Second bombardment—Interference by Napoleon III. in the course of the war; operations paralysed—General Canrobert resigns, and is succeeded by General Pélissier—Energy displayed by the latter—Third bombardment—Fourth bombardment; assault of Sevastopol—Its failure—Death of Lord Raglan; succeeded by General Simpson—Siege operations continued—Battle of the Tchernaya—Fifth bombardment—Sixth bombardment; second assault—The Malakoff is captured—Fall of the south side of Sevastopol—The Russians evacuate the town, and retreat to the north side—State in which the Allies found Sevastopol |

249 |

| |

| |

| xiiiCHAPTER XII. |

| |

| THE END OF THE RUSSIAN WAR. |

| |

| Home events during the war—Sympathy of Her Majesty with her Crimean soldiers—Badges of distinction added to the Colours—Inactivity of the Allies after the fall of Sevastopol—Expeditions against the Russian coast—Sir W. Codrington succeeds Sir J. Simpson as Commander of the Forces—The winter of 1855-56—Negotiations for a peace, which is concluded, March 30th—Events after the cessation of hostilities—A British cemetery in the Crimea—Embarkation and return home—The Crimean Guards Brigade at Aldershot; visit of Her Majesty the Queen—Move to London, and cordial reception there—Distribution of the Victoria Cross—Summary of events connected with the war—Losses—Appointment of H.R.H. the Duke of Cambridge as Commander-in-Chief, and of Major-General Lord Rokeby to command the Brigade of Guards |

267 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XIII. |

| |

| A PERIOD OF WAR, 1856-1871. |

| |

| Reductions after the war—Comparison between the situations in Europe, in 1815 and in 1856—Fresh troubles and complications imminent—Many wars and disturbances—Scientific instruction introduced into the army—Practical training of the troops carried out—The material comfort of the soldier attended to—Military activity in England in 1859—The Earl of Strafford succeeded by General Lord Clyde—Death of H.R.H. the Prince Consort—Misunderstanding with the United States of America—Chelsea barracks completed—Marriage of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales—Death of Lord Clyde; succeeded by General Sir W. Gomm—The Brigade of Guards Recruit Establishment—Public duties in London—Fenian troubles in Ireland; the 1st and 2nd Battalions succeed each other there; the Clerkenwell outrage—Reforms in the armament of the British infantry |

292 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XIV. |

| |

| ARMY REFORM, 1871-85. |

| |

| xivEffect produced in England by the military successes of Prussia—Short service and the reserve system introduced—Abolition of army purchase—Abolition of the double rank in the Foot Guards—Substitution of the rank of Sub-Lieutenant for that of Ensign or Cornet—Manœuvres and summer drills—Changes in the drill-book—Illness and recovery of H.R.H. the Prince of Wales—Death of Surgeon-Major Wyatt, and of Field-Marshal Sir W. Gomm—General Sir W. Codrington appointed Colonel of the Coldstream Guards—Death of Captains Hon. R. Campbell and R. Barton—Company training—Pirbright Camp established—Medical service in the Brigade—Change in the establishment of the Regiment—Death of Sir W. Codrington, and appointment of General Sir Thomas Steele as Colonel—Troubles in Ireland—Alarm in London—The Royal Military Chapel |

319 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XV. |

| |

| THE WAR IN EGYPT, 1882. |

| |

| Origin of the war—Emancipation of Egypt from Turkish rule; introduction of European control—Deposition of Ismail Pasha—Tewfik becomes Khedive—Military revolts—Disorganization of the country—Joint action of the English and French; its failure—Naval demonstration—Bombardment of the forts of Alexandria—The French withdraw and leave Great Britain to act alone—British troops sent to Egypt—The Suez Canal seized—Base of operations established at Ismailia—Action of Tel el-Makhuta—Clearing the communications—Actions at Kassassin, August 28th and September 7th—Character of the Egyptian army—Night march on Tel el-Kebir—The enemy is overwhelmed, September 13th—Pursuit; losses—End of the war—Return of the Coldstream to England |

350 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XVI. |

| |

| FIRST PART OF THE WAR IN THE SUDAN, 1884-85—EXPEDITION |

| UP THE NILE. |

| |

| General description of the possessions of the Khedive in 1882—Rebellion in the Sudan; rapid rise of the Mahdi—Policy of the British Government—General Gordon sent to Khartum; he is cut off and besieged there—General Lord Wolseley goes to Egypt—Formation of a Camel Corps, of which the Guards compose a Regiment—Problem how to effect the rescue of Gordon—The Nile route selected—Advance to Korti—News from General Gordon—Two columns advance from Korti: one across the Bayuda Desert, the other up the river—Battles of Abu Klea and Abu Kru—The Nile reached near Metemmeh—Sir C. Wilson’s effort to proceed to Khartum—Death of General Gordon—Change of plan entailed by this event—Battle of Kirbekan—Retrograde movement of both columns—Troops placed in summer quarters |

372 |

| |

| |

| CHAPTER XVII. |

| |

| SECOND PART OF THE WAR IN THE SUDAN, 1884-85—SUAKIN CAMPAIGN. |

| |

| xvReasons for the expedition to Suakin—Departure of the Coldstream—Orders to Lieut.-General Sir G. Graham—Position of the enemy—Advance against Hashin—Engagement at Tofrek—Attack on a convoy, escorted by the Coldstream and Royal Marines—Advance to Tamai—Construction of the railway—Attack on T'Hakul—Abrupt end of the campaign—The Coldstream proceed to Alexandria, and thence to Cyprus—Evacuation of the Sudan; how the Mahdi took advantage of it; how the Dongolese were treated—Position taken up south of Wady Halfa—Defeat of the Arabs at Ginnis—Return of the Guards Camel regiment—Return of the Coldstream from Cyprus—Honourable distinctions added to the Colours—Officers of the Regiment in December, 1885 |

393 |

| APPENDIX I. |

| |

| 1. |

Despatch of M.-Gen. Sir John Byng To H.R.H. the Duke of York, on the Battle of Waterloo, Nivelles, June 19, 1815 |

413 |

| 2. |

General Orders, Nivelles, June 20, 1815 |

414 |

| 3. |

Proclamation of the Duke of Wellington to the French People, Malplaquet, June 22, 1815 |

415 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX II. |

| |

| 1. |

General Order, Paris, October 28, 1815 |

416 |

| 2. |

Orders for Billeting the British Troops in France, October 29, 1815 |

416 |

| 3. |

Alarm Posts of British Divisions in France, October 30, 1815 |

418 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX III. |

| |

| Orders for a British Contingent to occupy French Fortresses, November 9, 1815 |

418 |

| |

| APPENDIX IV. |

| |

| Distribution of the British Contingent in France, April 10, 1816 |

421 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX V. |

| |

| Short Account of the Band of the Coldstream Guards |

424 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX VI. |

| |

| 1. |

Farewell Order to the Allied Army of Occupation in France, November 10, 1818 |

426 |

| 2. |

Farewell Order to the British Contingent, Cambrai, November 10, 1818 |

427 |

| 3. |

General Order, Paris, December 1, 1818 |

427 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX VII. |

| |

| Coldstream Guards Hospital |

428 |

| |

| |

| xviAPPENDIX VIII. |

| |

| The Nulli Secundus Club; and List of Members from its Formation, 1783, to 1896 |

429 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX IX. |

| |

| General Order, Constantinople, April 30, 1854 |

436 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX X. |

| |

| Death of Field-marshal Lord Raglan, G.C.B. |

437 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX XI. |

| |

| Ages and previous Occupations of the Non-commissioned Officers and Men of the 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards, and Drafts sent to the East, engaged in the War with Russia |

439 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX XII. |

| |

| 1. |

Return of the Numbers Killed in the Crimea |

440 |

| |

| 2. |

Return of the Numbers Wounded in the Crimea, Dead, Invalided, etc. |

440 |

| 3. |

Deaths in the 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards by months during the War with Russia |

441 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX XIII. |

| |

| The Victoria Cross |

442 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX XIV. |

| |

| 1. |

The British Forces employed in the Egyptian Campaign, 1882 |

444 |

| 2. |

Extracts from General Orders issued after the Battle of Tel el-Kebir |

446 |

| 3. |

Extract of Report on Army Signalling in Egypt, 1882 |

447 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX XV. |

| |

| Stations occupied by the Coldstream Guards, 1833-1885[1] |

448 |

| |

| |

| APPENDIX XVI. |

| |

| 1. |

Coldstream Roll[2] |

458 |

| 2. |

Commanding Officers of the Coldstream Guards, from 1650 to 1896 |

478 |

| 3. |

Regimental Staff Officers[2] |

482 |

| 4. |

Warrant Officers |

485 |

xvii

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| |

PAGE |

| |

| Field-Marshal H.R.H. Adolphus Frederick Duke of Cambridge, K.G. |

Frontispiece |

| Pikeman, 1669; Drum Major, 1670; Grenadier Company, 1670 |

To face 18 |

| Sergeant, 1658; Drummer, 1658 |

” 36 |

| Musqueteer, 1650 |

” 66 |

| Musketeer, 1669 |

” 86 |

| Officer temp. James II. |

” 102 |

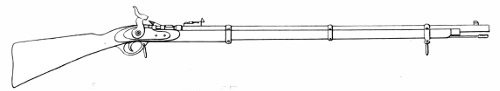

| Muskets and Rifles from 1830 to 1890 |

” 126 |

| Private, 1742 |

” 230 |

| Colours, 1669, 1684, 1685 |

” 248 |

| Colours of the Colonel, Lieut-Colonel, and Majors, 1750, and the Queen’s Colour, 1893 |

” 266 |

| Drummer, 1745 |

” 286 |

| Sergeant, 1775; Officer, 1795 |

” 300 |

| Officer, 1839; Officer, 1849 |

” 318 |

| Officer, 1849; Private’s Undress Cap, 1850 |

” 342 |

| Sergeant Drummer, 1895 |

” 392 |

xviii

MAPS.

| |

PAGE |

| 1. Sketch Map to illustrate the British Occupation of France from 1815 to 1810 |

To face 54 |

| 2. Black Sea and surrounding Country |

” 149 |

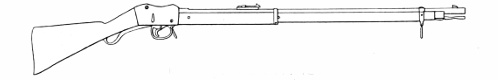

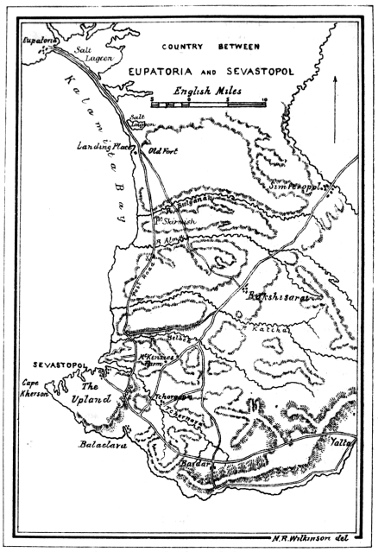

| 3. Country between Eupatoria and Sevastopol |

” 165 |

| 4. Battle of the Alma |

” 174 |

| 5. Sketch Map of Country near Sevastopol |

” 182 |

| 6. Sevastopol |

” 194 |

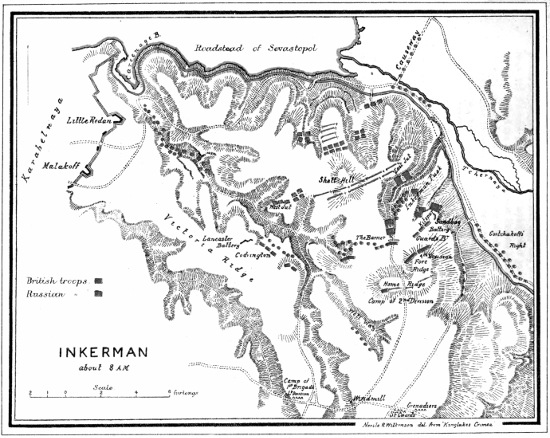

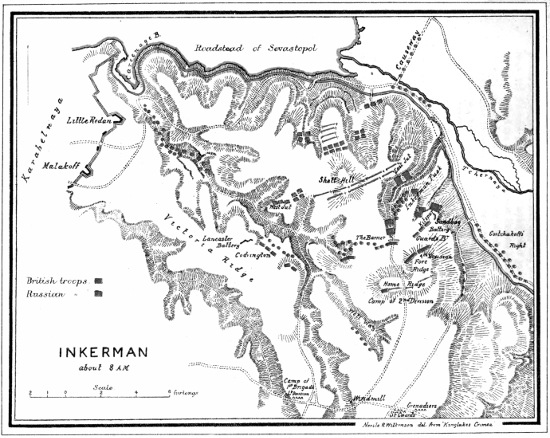

| 7. Battle of Inkerman |

” 216 |

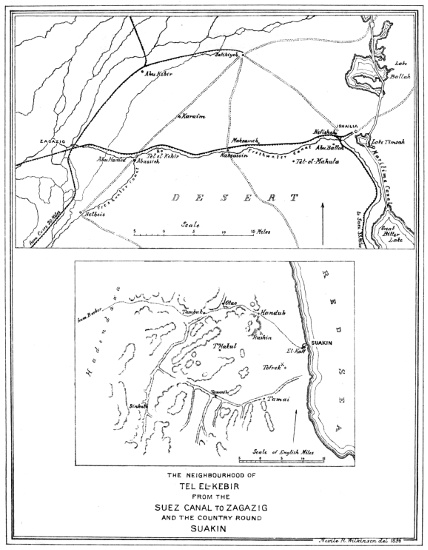

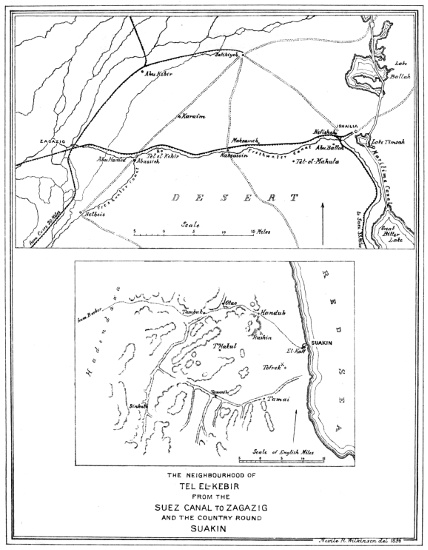

| 8. The Neighbourhood of Tel el-Kebir from the Suez Canal to Zagazig and the Country round Suakin |

” 360 |

| 9. Sketch Maps to illustrate Egyptian and Sudan Expeditions, 1882-1885 |

” 379 |

CORRIGENDA.

| Page |

86, |

line |

31, |

for “May 25th” read “May 27th.” |

| ” |

90, |

” |

13, |

for “May 15, 1829” read “May 16, 1829.” |

| ” |

118, |

” |

12, |

for “November 13th” read “November 9th.” |

xix

INTRODUCTION.

The central figure in Europe, during the first fifteen years of this

century, was the Emperor Napoleon, the great military leader, who,

having restored order in France—violently disturbed by the terror,

anarchy, and confusion of the Revolution that broke out in 1789,—succeeded

in ruling that country, and in imposing his arbitrary will

upon its people. A master of the science of war, and gifted with

the genius that makes a man supreme in the field of battle, he

organized the military qualities of his subjects, who, under his

guidance, invaded their neighbours, destroyed their institutions,

and overran Europe from one end to the other. One opponent only

remained unsubdued, and that was England; and so strong was

her resistance to this modern Attila, that she succeeded not only in

breaking his power, but in adding also to her own importance and

influence in the world.

Napoleon, though a General of the first order,—whose campaigns

will always commend themselves to the student of the art of war,—was

less remarkable for his knowledge of that other science which

makes a man a statesman. He lived by the sword, and he perished

by the sword. He destroyed the prosperity of the people he subdued,

but he could not cement a friendship with them. His object

was war and only war, and he reaped its reward—military fame;

but he did not use the absolute power he wielded, for the advantage

of France, nor was he able to establish his name among the greatest

and most enlightened rulers of mankind.

xxAfter a period of victory, he exhausted the resources of his

country, and then there was formed against him a coalition of

European Princes, who gradually closed their forces around him

with ever tightening grasp, and pursued him to the heart of his

Empire. At last, he was defeated and undone, and acknowledged

his impotence to carry on any longer the mighty struggle in which

he had been engaged (1814). Europe then restored the Bourbons as

Kings of France, and determined that Napoleon should be expelled

therefrom, and interned in the island of Elba,—an Emperor of a

very narrow dominion, and a Monarch only in name. But scarcely

had he been there a year, when he broke loose. Landing in

France, he made the King (Louis XVIII.) fly from Paris; and,

amid the acclamations of the people, he once more re-established

himself upon the throne (March, 1815).

The Allied Sovereigns now combined to drive this disturber of

the peace from France, and took immediate steps to invade that

country again. In June, two of the Powers had their forces in

Belgium,—the British and their immediate allies (the Dutch,

Hanoverians, etc.), under the Duke of Wellington; and the Prussians,

under Marshal Blücher. The rest were still east of the Rhine.

Perceiving that his antagonists were not yet able to move forward

together against him, the French Emperor resolved to strike the

first blow, by advancing northwards and by attacking Wellington and

Blücher. Accordingly, he left Paris on the 12th of June, and on the

16th he fought the battles of Ligny, where he defeated the Prussians

and drove them off the field, and of Quatre-Bras, from which place

the British, though they held their ground, eventually fell back

slowly towards Waterloo. Giving orders to Marshal Grouchy,

who was placed at the head of a considerable force, to pursue

Blücher, and to prevent him from forming a junction with Wellington,

Napoleon advanced, and attacked the British at Waterloo

(June 18th). Here the most decisive battle of the present age took

place. Stubbornly did the British troops maintain their position;

while Blücher, rallying his forces, and leaving behind only a small

xxicorps to contain Grouchy, marched with the remainder to the field

of Waterloo. The French were now enveloped, and completely

and irretrievably defeated.

There was a Guards Division at the battle of Waterloo,

commanded by Lieutenant-General Sir George Cooke, formed of

two Brigades. The 1st Guards Brigade (Major-General P. Maitland)

was composed of the 2nd and 3rd First (now Grenadier)

Guards; and the 2nd Guards Brigade (Major-General Sir John

Byng) of the 2nd Coldstream and the 2nd Third (now Scots) Guards.

Sir George Cooke being severely wounded during the course of the

day, the command of the Guards Division devolved upon Sir

John Byng.

1THE HISTORY

OF

THE COLDSTREAM GUARDS.

1815-1885.

CHAPTER I.

THE CAPITULATION OF PARIS.

Flight of Napoleon from the field of Waterloo—Reaction in Paris—Napoleon’s abdication—Surrender

to Captain Maitland—Provisional Government set up in France—Advance

of the Allies from Waterloo—Operations of Marshal Grouchy—Allies hope

to cut the enemy off from Paris—Blücher’s energy to secure that object—Unsuccessful

efforts of the Provisional Government to obtain a suspension of hostilities—The

Allies before Paris—The Prussians move round to the south of the city—Cooperation

of Wellington—Capitulation of the capital, July 3rd—Advance of Austrians

and Russians—“Waterloo men”—The “Wellington pension”—Rank of Lieutenant

granted to Ensigns of the Brigade of Guards—The soldier’s small account-book

introduced into the British army.

The battle of Waterloo broke the power of Napoleon for ever. So

confident of victory had that great soldier been, that he did not

even make any preparations for retreat, and hence, when he was

defeated, a terrible rout ensued. The wreck of the French army,

blocking the only road which was available, hurried from the scene

of disaster in a confused mass of fugitives. The Prussians, who

were comparatively fresh, took up the pursuit, and relentlessly

they pressed it home, driving the enemy back, increasing his

panic, and completing his misfortunes. Through the whole night of

the 18th-19th of June, a fierce and active pursuit was maintained;

2while the British troops, exhausted by the labours and anxieties

of the day, bivouacked as they stood, on the bloody but glorious

field of victory.

Napoleon, stupefied by the unexpected result of the battle,

forced his way through the surging mass of his now disorganized

troops to Quatre-Bras, and as he went along, he had ever increasing

evidence of the catastrophe that had overwhelmed him.

He sent a message to Grouchy, announced his defeat, but gave

the Marshal no orders. He then rode to Charleroi, and, almost

unattended, pushed on to Philippeville, where he made his first

effort to repair his broken fortunes. He ordered Marshal Soult

to rally the débris of his forces at Laon; he despatched a letter

to General Rapp, who was in command on the German frontier,

and to General Lamarque, engaged in La Vendée, with orders to

march to Paris; and he was sanguine enough to declare that he

could reorganize a sufficient force to cover the capital, and to give

time for the concentration of a much larger army, wherewith to

renew the war and to save France from the invasion that

threatened her.[3] But he was far from being reassured. He could

scarcely deny even to himself that the end of his career had at

last come in earnest, and that the stupendous ascendency which

he exercised over his countrymen had disappeared now and for

ever. Once before had he been obliged to acknowledge himself

vanquished, and the glamour of invincibility no longer surrounded

his person. He had engaged in a desperate undertaking. The

whole of Europe was arming against him, and was determined to

put him down. His first bold venture to try and beat the Allies

in detail had signally failed. The armies of Great Britain and of

Prussia had hopelessly crushed the flower of his forces. He had

henceforward to reckon with Austria and Russia, and with a

formidable coalition flushed with victory. His countrymen never

forgave a military leader who had suffered a disaster in the field.

He knew that his prestige was weakened, that the influence which

his name inspired was shaken, that his resources were at an end,

and that his enemies were gathering about him from every quarter.

Tormented by these gloomy thoughts, he pursued his journey,

and reached Philippeville; and there he snatched a few hours

repose. But the fear of the Prussians haunted his followers, and

3he was hurried on, still in a state of indecision.[4] The momentous

question had now to be faced, and immediately decided. What

was Napoleon to do? Should he remain in the field in command

of his troops, rally the shattered remnants of the grand army, and

cover Paris, or should he fly to the capital, assert his authority

there, and trust to the magic of his name to retain his supremacy

over France? His own desire was to stay among his men, and

to abide the result at the head of an army, devoted to his person

and to his interests. Had he done so, his fate would have been

less humiliating than it eventually proved to be. But his failing

health, and the shock he had experienced, paralysed the active

energies of the man, and, dreading a revolution in the seat of

government, he agreed, against his better judgment, to start at

once for Paris. He reached his destination early on the 21st,

exhausted and shaken both in body and mind.

Paris was struck dumb by this event. On the 18th, the guns

of the Invalides thundered a salute in honour of the battle of

Ligny, and on the two following days the details of the French

victory over the Prussians were published in glowing colours; but

towards the evening of the 20th, the news of trouble began to

leak out, and on the morrow the Emperor arrived at the Elysée

palace attended only by a few of his personal Staff. “Dans le

premier moment on refusa à croire; ce fut ensuite une anxiété

cruelle; puis une morne stupeur.”[5] And now at length the fatal

news was fully realized, and spread like wildfire through the

excited people, and all knew for certain that the army of Napoleon

had been annihilated, that his military genius had played him

false, and that the catastrophe was at once complete and irretrievable.

Then the weakness of the Emperor’s power began to show

itself, and the instability of the foundation upon which he had

constructed his Imperial system became apparent. France, who

drained her resources freely to serve her passion for glory, now

spurned the defeated hero who had made her glorious. His rule,

though it pandered to her vanity, did not rest upon the true

affections of the people; and his want of success at the critical

moment was an unpardonable offence, to be atoned only by

4abdication. Enemies created everywhere by his arbitrary will,

by his reckless policy, and by the jealousy his brilliant genius

inspired, now saw their opportunity to revenge themselves, and

they arose to crush him. Alone in Paris, without an army,

he was almost a prisoner in the hands of his foes, where he

could not hope to recover from the disaster which had overwhelmed

him, or employ his talents for the military protection of

the country. The Chambers took the control of public affairs;

and Napoleon, prostrated by recent events, and unable to

resolve upon any definite course of action, acquiesced sullenly

in allowing the reins of government to be snatched from his

hands. He was forced to await the decision of a special

Council of State that was summoned to settle the future

of the Emperor and the policy to be pursued by the nation.

Lafayette, who was named member of the Council, and was its

leading spirit, insisted that the defence of the country should

not be the only question discussed, but that negotiations for

the restoration of peace should be also proceeded with; and

he succeeded in carrying a resolution, to the effect that,

as the Allies had signified their determination not to treat

with Napoleon, the two Chambers should themselves nominate

negotiators, who were, under their authority alone, to come to

terms with the conquerors.[6] It was a revolution; and it was

nearly complete on the morning of the 22nd. In the divided

councils of the Emperor, Lafayette gained a great advantage, and

giving voice to the one thought that filled all minds in that

moment of anguish, he resolved that Napoleon’s deposition should

forthwith, and at all hazards, be carried into immediate execution.

A struggle—a one-sided struggle—took place between the

Emperor and the Chambers. The former could only rely upon his

previous military prestige and upon the halo of influence that still

might be supposed to surround his name; but he did nothing to

rouse himself out of the lethargy that oppressed his moral

faculties. The latter, representing the reactionary and Republican

parties, were tired of Napoleon and of his greatness. They

regarded him as the sole obstacle to peace, and as a fallen leader

who must be swept away in the interests of the country. So fickle

were the French to the man they received as their ruler in defiance

of Europe four months before, and who had been their unquestioned

5master for nearly fifteen years, and so intent were they to be rid

of him, that they only granted him—and that with difficulty—but

one short hour to make up his mind to vacate his throne; in

default, he was to be discrowned by force. Napoleon was indignant,

but he did not resist. “I have not returned from Elba,” he

said, “to deluge Paris with blood;”[7] and, fearing to provoke a

civil war, he accepted the inevitable, and abdicated in favour of

his son within thirty-six hours of his arrival in the capital.

And yet his overweening pride was still thirsting for power, and

this act of renunciation was neither tendered nor accepted in good

faith. Napoleon II., as he was called, was a child, and was in

Austria, and the Emperor still clung to the delusive hope that he

might be re-installed in the power he had lost, though he could

only wield it in the name of his son. On the other hand, the

Chambers, fearing to drive their antagonist to extremes, and dreading

above all things a revival of his wonted energy, agreed to an

equivocal recognition of Napoleon II. In this way they also

satisfied the cravings of the army for Imperialism; but the assent

was a mere fictitious one, which was intended to have no meaning

and which had no result. The Empire was indeed doomed, its

founder dishonoured, and his dynasty destroyed. It was a wretched

end to a glorious career, not even redeemed by that fortitude and

personal dignity which mark the fall of the truly great. This

final downfall is without parallel in history, and the weakness of

human nature and the vanity of man’s personal ambition stand

out prominently, as the main features of the drama. The last

scene was approaching, and may be described in a few words.

The moment Napoleon abdicated, he ceased to be a factor in

the great events that followed. He was even an obstacle in the

way of those who had usurped his place, and was treated with a

contumely he had little deserved at the hands of flatterers, who,

having basked in his smiles, had now constituted themselves the

arbiters of his lot. Driven almost with indignity to the suburban

retreat of La Malmaison, where his personality could not affect

the Parisians, he still dreamt of power, but did nothing to grasp

it. At last he was obliged to fly to the coast before the Allies,

who were approaching the capital. Despairing of making good

his escape, and feeling keenly the humiliation of his position,

should capture await him in the land where for so long he had

6been the idol, he yielded himself a prisoner to Captain Maitland,

who commanded H.M.S. Bellerophon—stationed near Rochfort to

intercept the Imperial fugitive,—as to the representative of “the

most powerful, the most constant, and the most generous” of

his enemies (July 15th). This is the last of Napoleon, and henceforward

he lived and died a captive in the island of St. Helena,

hated by his gaolers, forgotten by his country, and forsaken by his

kindred.

“But where is he, the modern, mightier far,

Who, born no king, made monarchs draw his car;

The new Sesostris, whose unharness’d kings,

Freed from the bit, believe themselves with wings,

And spurn the dust o’er which they crawl’d of late,

Chain’d to the chariot of the chieftain’s state?

Yes! where is he, the champion and the child

Of all that’s great or little, wise or wild?

Whose game was empires, and whose stake was thrones?

Whose table earth—whose dice were human bones?

Behold the grand result in yon lone isle,

And as thy nature urges, weep or smile.”

[8]

The overthrow of her great military hero brought no satisfaction

or relief to France. She needed a chief to direct, and a policy

to shape her actions; but at the most critical moment, when the

Allies were thundering at her gates, she deliberately deprived

herself of the one, and had not thought of the other. Napoleon

was rejected; but who was to take his place, and who was to

safeguard her interests? The noisy demagogues had effectively

stirred up a revolution, and had deposed the only soldier who

could have stood between her and the victorious enemy. Their

momentary success was complete; but they left nothing except

chaos behind them, and their work was folly because it was

destructive. It is true, they did conceive some hope that they

could rear up a Republic or a Constitutional Monarchy upon the

ruins of the Imperial system, and none for a moment believed

that the unconditional restoration of the Royal Family was imminent.

The “obstacle to peace” was removed; but the peace that

France desired was denied her, and she was not to be allowed to

have a voice in shaping her own destinies. The Allies were

masters of the situation; and they were as intent upon taking

7ample securities against the people who had for so long scourged

Europe, as against the man who had led them on to plunder

Christendom. The man was gone, but the people remained; and

in their eagerness to repudiate him, they forgot that they too had

some account to render to the conquerors.[9]

A Provisional Government was set up in Paris on the evening

of the 22nd of June, composed of five persons, among whom was

Fouché, Duc d'Otranto, late Minister of Police under Napoleon,

and one of his bitterest enemies. He had the address to be

named President, and in the anarchy produced by the panic which

the crisis created, he alone preserved his faculties unimpaired.

Seizing the supreme control of the State during the moment of

interregnum, he became dictator, and the sole and irresponsible

advocate of his country’s cause. A Republican by conviction, a

regicide, and holding to the extravagant tenets which were

enunciated in 1789, he was far more keenly alive to his own

immediate interests than to his avowed principles; and perceiving

clearly that his credit and reward could best be secured by obliging

France to accept—even against her will—a Bourbon régime, he

devoted his great talents and his incomparable powers of intrigue

to bring about the unconditional restoration of King Louis. His

treachery was deeply resented by the nation, but what could they

do? Napoleon had been abandoned, and there was no one to

replace him,—none to form a patriotic administration, none to give

effect to the national aspirations of the people, none to cope with

the difficulties that had arisen, none to secure those terms which

a proud and vigorous race had a right to expect, even when

overwhelmed by adversity. In the universal prostration which

succeeded the battle of Waterloo, Fouché, “one of the most hateful

among the hateful tribunes of the Terror,”[10] reigned in France, an

autocrat, hated by all, feared by all, and obeyed by all.[11]

While these events were taking place in Paris, the victorious

Allies were advancing towards that city, there to reap the fruits

of their success, to restore the peace of Europe, and to impose

their will upon the now distracted country that lay at their mercy.

After the battle there was a meeting between the Duke of

8Wellington and Marshal Blücher, at which operations for the

immediate future were decided. The former engaged to advance

the following day, and returned for the night to his head-quarters

at Waterloo; the latter agreed to pursue the enemy without delay,

and to endeavour to cut off Grouchy. He then went to Genappe,

and, on the 20th, his advanced troops were in French territory.

Early on the 19th, the army commanded by Wellington left their

bivouacs, the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards starting from the

farm of Hougomont, which they had held—in conjunction with

the 2nd Battalion of the Third Guards, and with the light

companies of the First Guards (2nd and 3rd Battalions)—with

such credit to themselves. They reached Nivelles that evening,

where Major-General Sir John Byng wrote his despatch on the

battle, and on the stubborn contest that centred round Hougomont.[12]

On the 20th, the Guards Division reached Binche, and on that

day the Duke of Wellington issued a General Order, which not

only conveyed his thanks to the army under his command,

for their conduct in the decisive action on the 18th, but which

also warned the troops of the absolute necessity of treating the

inhabitants of France as a friendly people.[13] This admonition

of the rules which prevail in war time among civilized nations,

was not indeed needed by the seasoned troops of British origin,

who had been trained in the humane usages invariably adopted by

England, to respect the liberties and the property of the people

over whose lands war has to be waged. It was rather addressed

to the Anglo-allies (Dutch, Belgians, and Germans), to enforce

the maxim that hostilities are not conducted against the population,

and that ill treatment of peasants only exasperates the

enemy, and does nothing to secure his final subjugation. It is to

be remarked that this policy was not followed by the Prussians,

with the result that the latter never gained the good will of the

French, while the British, on the contrary, were looked upon by

that proud and sensitive people with respect, and almost without

distrust.

On the morning of the 22nd of June, Wellington was at

Malplaquet, the scene of one of Marlborough’s greatest triumphs

over the same enemy. Before leaving, he issued a proclamation

in French to the people whose territories were then entered by the

9British troops, to the effect that the invaders had come to deliver

them from the iron yoke that oppressed them; and that the

population would be well treated by the army, provided they did

not join the cause of the “Usurper” (Napoleon), who had been

“pronounced to be the enemy of the human race, with whom neither

peace nor truce could be made.”[14] Neither in this effort to conciliate

the population did Prince Blücher follow the example of his

colleague; on the contrary he displayed resentment against the

natives of a country whose military genius had, in the past, humbled

in the dust the pride of his own nation. It was perhaps natural

that he should assume this attitude when the provocation which

the Prussians received is taken into account, but it was not

calculated to reassure the French in their despair, nor to reconcile

them to the restoration of the Royal Family.

In order to give a general view of the whole military situation,

it will now be necessary to refer briefly to the incidents of the

war that took place close to Waterloo, on the day of the battle,

where Marshal Grouchy was struggling with Blücher’s rear-guard.

On the 18th he was at Wavre, with 32,000 men, of whom 5000

were cavalry; and there he was held in check during the whole

day by Thieleman’s Prussian Corps, only 15,000 strong. It was not

until evening that he turned the right of the Prussians, when at

length he opened a road for his troops, whereon to advance to the

main body of the French army, known to be somewhere near

Waterloo. As it was then too late to continue the action, Grouchy

hoped next day to complete the victory he had achieved, ere he

pushed forward to join his chief. On the morning of the 19th he

received no tidings from the Emperor, and he believed that all was

well; but Thieleman, though he was not informed of the full

details of the disaster to which the French had been subjected,

heard that a great battle had been fought, and that they were

defeated; so he, too, determined to attack Grouchy in the morning.

A battle consequently took place on the 19th, in which the

Prussians, though they contested the ground inch by inch, were

forced to fall back towards Louvain by the superiority of the masses

they engaged. At the very moment of victory, Grouchy received

the message which Napoleon had sent him from Quatre-Bras,

announcing the total destruction of the French army, and thus

revealing to him the full extent of the danger in which he was

10placed. Perceiving at once the necessity that his corps should be

saved from the general wreck, he determined to retreat through

Namur upon Givet, and began to move without delay. General

Pirch I., having been detached from the main Prussian army on

the evening of the 18th to intercept him, joined Thieleman,

who also advanced as soon as he perceived that he was no longer

being pursued by the corps which had defeated him. Both Prussian

Generals endeavoured to arrest the enemy, but they failed to do so;

and Grouchy, who marched with great rapidity and resolution, ably

seconded by the valour of his subordinate Generals, reached Givet

on the 21st, and entered French territory in safety. He was then

ordered to join Marshal Soult, who was attempting to rally the

broken fragments of the main army at Laon. This occurred on

the fatal 22nd, the same day that Napoleon, coerced by the political

leaders in Paris, closed his public career, and signed his abdication

of the French throne in favour of his son.

Grouchy’s corps was the only one that, having taken part in

the campaign in Belgium, remained intact. The main French

army had been panic-stricken at Waterloo, and a large mass of

those who survived the battle fled straight to Paris, or deserted

their standards, and were nowhere to be found; many flung away

their arms, and dispersed to their homes. The disruption of the

great army was complete, and the defeat signal and decided

beyond all former precedent. The co-operation of the greater

bulk of Napoleon's forces in subsequent military events was

impossible, and little resistance was to be apprehended from these

men. But there was a remnant of true soldiers still available, who,

seeking their Colours, concentrated some 20,000 strong near

Philippeville. On the 22nd they were at Laon, and about that

time the French could dispose of some 50,000 men for the defence

of the northern frontier.frontier. The situation was a desperate one, and

would have been fatal even to Napoleon himself in the full vigour

of his military genius; but the position was all the more impossible,

since the Saxons, the Austrians, and the Russians were by this time

upon the eastern frontier of France, and were ready to advance in

a concentrated and concentric march upon the capital.

On the 22nd of June, Wellington reached Le Cateau Cambresis.

He had three divisions at Bavay, and four echeloned along the

road to Le Cateau—the Guards Division being at Gommignie.

Besides this, other troops were employed against Le Quesnoi

11and Valenciennes, which were occupied by men of the Garde

Nationale. Blücher was at Catillon-sur-Sambre with his troops in

the vicinity, including Thieleman, who had returned from the

pursuit of Grouchy, but excluding Pirch I., who was ordered to

remain in rear for the purpose of reducing the fortresses which

defended the French frontier. The Prussians were also at that

time blockading Landrecies and Maubeuge—also garrisoned by

local levies, from whom little resistance was to be expected. The

Anglo-Prussian Allies halted on the 23rd, for the purpose of

collecting their stragglers, and of bringing up ammunition; and

thereby a much-needed rest was afforded to men who, for more

than eight days, had been constantly and actively occupied in the

arduous labours of the war. During the halt the two Generals,

Wellington and Blücher, met to decide how a united advance

could best be made upon Paris. As a result of this conference, it

was agreed that the Allies should not pursue the enemy directly,

but, covered by the Oise, push along the right bank of that river,

upon Compiègne and Creil, so as to turn his left, and if possible,

cut him off from Paris,—the movement to be masked by the Prussian

cavalry, whose presence, it was hoped, would induce the French to

retard their retreat.[15] Wellington, moreover, anxious that the

moral effect of the battle of Waterloo should be fully reaped, and

that Napoleon should have no time to recover from the disaster,

hastened the arrival of King Louis into French territory, offering

to secure Cambrai as his residence until Paris should be captured.

Hearing, also, that that fortress was imperfectly guarded, he sent

Sir Charles Colville forward with a detachment to seize it (June

23rd). The attack was successful, in so far that the town was

taken with little loss; but the citadel held out until the 25th, when

the Governor capitulated to the King. His Majesty by this time

reached the British head-quarters, and he temporarily established

his Court in Cambrai.

On the 24th the combined armies continued their advance.

The British pushed on two brigades towards Cambrai, but otherwise

only altered their position slightly, as they were waiting for

their pontoon train. The Prussians, however, moved forward,

taking Guise and St. Ouentin. During the day, intelligence was

received of Napoleon’s abdication, but the news was at first

12discredited. Later, it became confirmed; but both Commanders

determined that terms of peace could only be signed at Paris,

and they rejected all overtures made to them by the Provisional

Government to arrest their march upon the capital. On the 25th

of June, the British head-quarters were at Joncourt, the Coldstream

Guards being at Le Cateau.

Blücher, on the other hand, hearing that the French had not been

deceived by the cavalry demonstration made in the direction of

Laon, now came to the conclusion that they were hastening towards

Paris; he therefore determined to secure the passages over the Oise,

and he pushed on to these points with the utmost rapidity. A

squadron entered Compiègne in the evening of the 26th, and early

the following day a Prussian brigade supported it, just in time to prevent

this place from falling into the hands of the enemy; for Grouchy,

who had superseded Soult, ordered D'Erlon to occupy the bridge

with the remnants of his Corps, about 4000 strong. D'Erlon, finding

the Prussians in position, cannonaded it, and very soon afterwards

retired, unpursued by the Prussians, who were too much exhausted

to advance; so that it was mid-day before the advantage gained

could be pressed home. These operations were connected with

the movements of other Prussian columns, one of which also succeeded

in capturing the bridge of Creil just before the French

arrived there. Brushing the enemy away, the invaders continued

to march to Senlis, where D'Erlon was met and driven off the

straight line of his retreat. The bridge of St. Maxence was found

partially destroyed, and the river had to be crossed in boats, but

that of Verberie was taken. By the evening of the 27th, Blücher’s

advanced troops were on the left of Grouchy, intercepting the

road to Paris, and with every hope of being able to prevent him

from reaching the capital before the Prussians.[16] At dawn of

the 28th, a small force under Pirch II. came into collision with

the enemy near Villers-Cotterets, and, being greatly outnumbered

at that point, they were in some danger of being overpowered.

The French, however, were in no condition to fight; they had

lost heart, and many were deserting their Colours. Being disorganized

by their reverses, and by the fear that Blücher’s energy

inspired, they now allowed Pirch to get away unhurt. The latter

had succeeded by his manœuvre to delay them, so that during the

day they were repeatedly attacked with considerable loss, and most

13of them were forced to turn to their left to cross the river Marne,

and so reach Paris by a circuitous route. By the evening of the 28th,

the Prussians had not only captured sixteen guns and four thousand

prisoners, forced the French from their true line of retreat, and

increased the terror and confusion which prevailed among them,

but they also succeeded in following some few detachments of

the enemy, who had been enabled to fly straight to Paris. In

this manner their advanced posts were within five miles of the

capital, near Le Bourget and Stains, where they carried panic and

dismay into the heart of the city.[17] Blücher established his head-quarters

at Senlis.

During this vigorous pursuit, the Anglo-allies were also

advancing southwards. On the 26th, Sir John Byng assaulted

the fortress of Peronne with the 1st Guards Brigade, who

carried the outworks by storm with little loss, soon after which

the town capitulated. The British head-quarters were at Vermand

and the army in the vicinity, advanced cavalry patrols having

penetrated as far as Roye. The Coldstream Guards halted at

Coulaincourt. Next day the army crossed the river Somme at

Willecourt; the Duke was at Nesle, and Roye was occupied. On

the 28th, the British right was near St. Just, and Montdidier was

occupied; the left was in rear of La Tulle, where the roads meet

that run from Compiègne and Roye; the reserve reached the

latter place, and the Guards Division was at Conchy, where the

rest of the First Army-Corps was posted.

The rapid approach of the invaders upon Paris made it plain

to the Provisional Government that they had no power to arrest

the progress of the Allies for a single moment; and although the

north side of the city was secured by a line of fortified works,

sufficiently strong to resist a coup de main, yet the wreck of

Napoleon’s army had not reached the capital, and time was

imperatively required to bring them there and to organize some

defence. An armistice was once more sought on the 27th, and

again on the 28th, in the despairing hope that the Government

might be allowed some breathing-time in which to consider their

position, and make some show of resistance, in order to save

France the humiliation which was clearly in store for her. But

the allied Commanders were inexorable, and, refusing all such

negotiations, they pursued their operations with the same activity

14as in the past. Wellington indeed frankly told the Commissioners

who approached him on behalf of the Provisional Government,

that he—

“must see some steps taken to re-establish a government in France which

should afford the Allies some chance of peace” before he could sanction

a suspension of hostilities; that he personally “conceived the best security

for Europe was the restoration of the King, and that the establishment of

any other government than the King’s in France must inevitably lead to

new and endless wars;” and he concluded by these words: “That, in my

opinion, Europe had no hope of peace if any person excepting the King

were called to the throne of France; that any person so called must be

considered an usurper, whatever his rank and quality; that he must act

as an usurper, and must endeavour to turn the attention of the country

from the defects of his title towards war and foreign conquests; that the

Powers of Europe must, in such a case, guard themselves against this evil;

and that I could only assure them” (the Commissioners) “that, unless

otherwise ordered by my Government, I would exert any influence I might

possess over the Allied Sovereigns to induce them to insist upon securities

for the preservation of peace, besides the treaty itself, if such an arrangement

as they had stated were adopted”—viz., any arrangement whereby

a prince, other than the King, were called to the throne of France.[18]

On the 29th, Blücher pressed on towards Paris, and reconnoitred

the defences thrown round the northern side of the city. The

remnants of the great army which had been shattered at Waterloo

also entered the capital on that day, and the French mustered

some 80,000 to 90,000 men there—troops from the provincial

depôts and from the country having been called for the defence

of the seat of government, and as many discharged veterans

as could be collected having been assembled in a special corps

some 17,000 strong. Besides this, there was plenty of artillery

available, and about 30,000 of the Garde Nationale; but on the

latter no great reliance could be placed. Marshal Davoût, Prince

d'Eckmühl, was appointed Commander-in-chief. The British

forces were still in rear, and occupied positions between Gournay

and St. Maxence, the Guards Division being near St. Martin

Longeau. At dawn, on the 30th of June, the advanced French

post at Aubervilliers was attacked by the 4th Prussian Corps

under Bülow, and the enemy was driven back, and pursued as far

as the canal in rear of that village; but it became evident that to

dislodge him from that line, a more serious effort would be necessary.

15The Duke of Wellington having proceeded to Blücher’s head-quarters

during the night of the 29th-30th, a conference was held as

to the future operations to be pursued. It was then agreed to

move the Prussians to their right, to take advantage of the capture

of the bridge of St. Germains which had already been effected, and

to extend the investment of the capital round the west and south

of the city, threatening to cut it off from those provinces that

furnished it with supplies. The British army at the same time

was to move into the posts which their allies had taken up

north of the city, and to mask the defences which the enemy

had erected there. During the night of the 29th-30th and the following

day, these operations were carried out, the 4th Prussian

Corps covering the movement until the British arrived. In the

evening, the latter were about Louvres, twelve miles away from

Paris; the Guards Division being at La Chapelle. The two Prussian

Corps, under Thieleman and Ziethen, were close to St. Germain;

while two regiments of Hussars, under Lieut.-Colonel von Sohr,

having been thrown forward, bivouacked at Marley, on the road

to Versailles. During the day, Bülow’s Corps had been engaged,

as we have seen. On the 1st of July he began to move off,

and in the afternoon he was relieved by the advanced British

forces, who took his place; the Guards Division were at Le

Bourget and the forest of Bondy, five miles from the capital.

On this day the enemy gained an advantage over the Prussians—the

only one of the campaign, except the delusive victory

at Ligny,—for the cavalry brigade under von Sohr, ordered to

reconnoitre round the southern suburbs, proceeding too far away

from its supports, was attacked, and, though the men defended

themselves bravely, they were cut to pieces. This transient success,

however, produced no effect upon the main result, and was but a

passing incident in the drama now soon to close. Next day, the

2nd, Blücher continued his march round Paris; and his troops,

under Ziethen, came into collision with the enemy near Sèvres,

who was driven back to Issy, and, later in the evening, into the

town. Thieleman pushed forward advanced troops to Chatillon;

and the reserve, under Bülow, was near Versailles. The British

remained in the positions on the north front of the capital, sending

detachments across the Seine, which occupied the villages of

Asnières, Courbevoie, and Suresnes, to keep up communications

with the Prussians. On the 3rd, Vandamme made an attempt to

16drive Ziethen’s troops out of Issy, and a battle took place, which,

lasting about four hours, ended disastrously for the French, who

were repulsed, and forced to take refuge within the barriers of the

city. This effort was the end of the operations, and no more

fighting took place, for the Provisional Government, holding that

the defence of Paris was not practicable against the victorious

Allies, now agreed to treat for a capitulation.

A great change had by this time come over public feeling in

Paris, and this was mainly the work of Fouché. France, left

without a chief in the moment of her abasement, fell into the

hands of Napoleon’s ex-Minister of Police. Once installed in

power, he issued a proclamation to the people he was deliberately

deluding (June 24th). It held out extravagant hopes that, under

his guidance, France would at last be contented with an honourable

peace. It was a dishonest proclamation, for it made

impossible promises; and yet, in the national degradation which

marked the crisis, the people had perforce to obey the man, who,

while in secret correspondence with the Allies for the restoration

of the King, told them—

“After twenty-five years of political tempests, the moment has arrived

when everything wise and sublime that has been conceived respecting

social institutions may be perfected in yours. Let reason and genius

speak, and from whatever side their voices may proceed, they shall be

heard.... Who is the man, that, born on the soil of France, whatever

may be his party or political opinions, will not range himself under the

national standard, to defend the independence of his country! Armies

may be in part destroyed, but the experience of all ages and of all nations

proves that a brave people, combating for justice and liberty, cannot be

vanquished. The Emperor, in abdicating, has offered himself a sacrifice.

The members of the Government devote themselves to the due execution

of the authority with which they have been invested by your representatives.”[19]

Nor was it long before Fouché gained sufficient influence over

Davoût to make it clear to him that the Empire had come to an

end, and that the only solution possible out of the impasse in

which France had become involved, was submission to the will

of the conquerors and the restoration of the Bourbons. Once

gained over, the Marshal did not hesitate to obey, and efforts to

ensure the defence of the capital were undertaken with deliberate

17half-hearted vigour.[20] The Parisians were rapidly becoming

indifferent to their fate; they cared not who was to rule them,

provided they were allowed to live in peace. The era of glory

had afforded them some satisfaction, but it had its drawbacks,

and late events had brought these to a crisis; therefore they were

glad to welcome the strongest, and to have done with conquests.

The Chambers, also, had exhausted all their energies in destroying

the man whose military genius might have served the country at

this terrible juncture. They succeeded admirably in their design;

and now they devoted themselves to academical studies, and busied

themselves in discussing a new constitution, quite oblivious of the

fact that their labours must be fruitless. All sections of the nation

were easily dealt with by Fouché; and even the army, devoted to

their late incomparable leader, soon submitted to his will.

Besides the efforts already made to obtain a suspension of

hostilities from the allied Commanders, Marshal Davoût approached

them on the 30th of June, but again unsuccessfully. On the same

day, he also joined in a protest addressed to the Chambers against

the return of the Bourbons—a protest intended, perhaps, rather to

satisfy the susceptibilities of the army than for any other purpose.

The Chambers, in their reply, alluded to their proposed constitution;

and stated that, while they were prepared to accept whatever

dynasty the Allies might insist on fixing upon the throne, they

were convinced that the accession of the new Monarch could only

become an accomplished fact, when he had agreed to the conditions

they meant to impose upon his prerogative. They “will never,”

they said, “acknowledge as legitimate Chief of the State him who,

on ascending the throne, shall refuse to acknowledge the rights of

the nation, and to consecrate them by a solemn compact.”[21]

But neither the Chambers nor the army were to determine the

fate of the country; for Fouché, alone among Frenchmen, was

possessed of power, and he only had any voice in shaping its

policy in this crisis. Wellington, anxious above all things that

Paris should submit without further bloodshed, consented, on the 2nd

of July, to a suspension of hostilities, on the basis of the evacuation

of the capital by the army. But he was not altogether master of

the situation, for Marshal Blücher, to whom he was so greatly

indebted for his victory over the enemy, had different ideas, and

wished to humble the French in a manner that would have been

18impolitic as well as hostile to the best interests of a stable peace.

It required, therefore, all the Duke’s tact to make him understand,

that the best way to end the war, was to accept a capitulation,

and to give up all ideas of incurring the responsibility of taking

so large a city as Paris by force of arms. Blücher, fortunately,

had some respect for the good sense of his colleague, and agreed

to these views, and, on the 3rd, he consented to treat. Thereupon

hostilities ceased abruptly, while Vandamme was being driven back,

in the manner that has been already described, near Issy.[22]

Commissioners met on the 3rd, at the Palace of Saint-Cloud,

and speedily agreed to a Military Convention, which stipulated the

following conditions:—

(1) The army to evacuate Paris within three days, and to take

up a position in rear of the Loire, the movement to be complete

within eight days; (2) St. Denis, St. Ouen, Clichy, and Neuilly

to be given up to the Allies on the 4th, Montmartre on the 5th,

and, on the 6th, all barriers, giving access into the city, to be placed

in the power of the Allies; (3) Order to be maintained in Paris

by the Garde Nationale, and by the municipal Gens d’armerie;

(4) The actual authorities to be respected “so long as they shall

exist;” (5) Private and public property, except that which relates

to war, to be respected, and all individuals to enjoy their rights

and liberties, “without being disturbed or called to account, either

as to the situations which they hold, or may have held, or as to

their conduct or political opinions;” (6) The capital to be furnished

with supplies.[23]

These stipulations, ratified by the British and Prussian

Commanders, were carried out by the French with scrupulous

fidelity. In spite of the violence of the troops, whose enthusiasm

for the Imperial system had scarcely abated, the army, 70,000

men and 200 guns, marched towards the Loire on the 4th, under

Marshal Davoût.[24] The Chambers continued their sittings, still

intent upon their proposed constitution. On the 7th, the Allies

determined to enter Paris, heralding the re-instatement of

Louis XVIII., the Bourbon king.

GRENADIER COMPANY 1670. DRUM MAJOR 1670. PIKEMAN 1669.

N. R. Wilkinson del. A. D. Innes &Co London Mintern Bros Chromo.

19During this time the Germans, Austrians, and Russians were

advancing to the capital, and, although the war was practically concluded

by the Military Convention just signed, yet it languished for

a few months longer in some of the provinces. The North-German

Corps (26,000 men), formed of contingents brought together by

the petty Princes, was occupied in the beginning of July, in reducing

some of the French fortresses on the north-east frontier. The

Austrian army, under Prince Schwartzenburg, including Saxons

and South Germans, and amounting to more than 250,000 men,

had its advanced troops between the Seine and the Marne, near

La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, on the 10th of July. The Russians, under

Marshal Barclay de Tolly (nearly 170,000 men), were at Paris

and in its vicinity by the middle of July. A combined Austro-Sardinian

army (60,000) was in the south-east of France, and

completed, during that month, the subjugation of the districts in

that quarter.[25]

Besides the various expressions of thanks to the gallant army

that destroyed the power of Napoleon at Waterloo, to which

allusion has already been made, letters were published in General

Orders, July 2nd, from the Commander-in-Chief, H.R.H. the

Duke of York, and from the Secretary of State for the Colonies

and for War, Earl Bathurst, conveying the admiration felt at the

conduct of the troops.[26] On the 5th, the resolutions of thanks

passed by the House of Lords and by the House of Commons

were published in General Orders;[27] and, on the 17th, those of the

Common Council of the City of London (dated July 7th) were

communicated to the troops in the same manner.

Towards the end of July it was determined, in recognition of

the “conspicuous valour” displayed by the army “in the late

glorious victory,” to grant: (1) increase to the pensions allowed to

Officers for wounds, according as they might be promoted in the

service; (2) to all Subalterns in the Infantry of the Line and in the