Title: The Boy Travellers in the Far East, Part Fourth

Author: Thomas Wallace Knox

Release date: February 6, 2019 [eBook #58837]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

AUTHOR OF

"THE YOUNG NIMRODS" "CAMP-FIRE AND COTTON-FIELD" "OVERLAND THROUGH ASIA"

"UNDERGROUND" "JOHN" "HOW TO TRAVEL" ETC.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1882, by

HARPER & BROTHERS,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

All rights reserved.

The favorable reception, by press and public, accorded to "The Boy Travellers in the Far East" is the author's excuse for venturing to prepare a volume upon Egypt and the Holy Land. He is well aware that those countries have been the favorite theme of authors since the days of Herodotus and Strabo, and many books have been written concerning them. While he could not expect to say much that is new, he hopes the form in which his work is presented will not be found altogether ancient.

The author has twice visited Egypt, and has made the tour of Palestine and Syria. The experiences of Frank and Fred in their journeyings were mainly those of the writer of this book in the winter of 1873-'74, and in the spring of 1878. He has endeavored to give a faithful description of Egypt and the Holy Land as they appear to-day, and during the preparation of this volume he has sent to those countries to obtain the latest information concerning the roads, modes of travel, and other things that may have undergone changes since his last journey in the Levant.

In addition to using his own notes and observations, made on the spot, he has consulted many previous and some subsequent travellers, and has examined numerous books relating to the subjects on which he has written. It has been his effort to embody a description of the Egypt of old with that of the present, and to picture the lands of the Bible as they have appeared through many centuries down to our own time. If it shall be found that he has made a book which combines amusement and instruction for the youth of our land, he will feel that his labor has not been in vain.

Many of the works consulted in the preparation of this book are mentioned in its pages. To some authors he is indebted for illustrations as well as for descriptive or historical matter, the publishers having kindly allowed the use of engravings from their previous publications. Among the works which deserve acknowledgment are "The Ancient Egyptians," by Sir Gardner Wilkinson; "The Modern Egyptians," by Edward William Lane; the translation of "The Arabian Nights' Entertainments," by the same author; "From Egypt to Palestine," by Dr. S. C. Bartlett; "The Land and the Book," by Dr. W. M. Thomson; "Boat Life in Egypt," and "Tent Life in Syria," by William C. Prime, LL.D.; "The Khedive's Egypt," by Edwin De Leon; "The Desert of the Exodus," by Professor E. H. Palmer; "Dr. Olin's Travels in the East;" "Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid," by Piazzi Smith; and "The Land of Moab," by Dr. H. B. Tristram. The author is indebted to Lieutenant-commander Gorringe for information concerning Egyptian obelisks, and regrets that want of space prevented the use of the full account of the removal of "Cleopatra's Needle" from Alexandria to New York.

With this explanation of his reasons for writing "The Boy Travellers in Egypt and the Holy Land," the author submits the result of his labors to those who have already accompanied Frank and Fred in their wanderings in Asia, and to such new readers as may desire to peruse it. He trusts the former will continue, and the latter make, an acquaintance that will prove neither unpleasant nor without instruction.

P.S.—This volume was written and in type previous to July, 1882. Consequently the revolt of Arabi Pasha and the important events that followed could not be included in the narrative of the "Boy Travellers."

T. W. K.

| CHAPTER I. | From Bombay to Suez.—The Red Sea, Mecca, and Mount Sinai. |

| CHAPTER II. | Suez.—Where the Israelites Crossed the Red Sea.—The Suez Canal. |

| CHAPTER III. | From Suez to Cairo.—Through the Land of Goshen. |

| CHAPTER IV. | Street Scenes in Cairo. |

| CHAPTER V. | A Ramble Through the Bazaars of Cairo. |

| CHAPTER VI. | Mosques, Dervishes, and Schools.—Education in Egypt. |

| CHAPTER VII. | The Citadel.—The Tombs of the Caliphs.—The Nilometer.—The Rosetta Stone. |

| CHAPTER VIII. | Wonders of the Egyptian Museum of Antiquities. |

| CHAPTER IX. | The Pyramids of Gizeh and Sakkara.—Memphis and the Apis Mausoleum. |

| CHAPTER X. | An Oriental Bath.—Egyptian Weddings and Funerals. |

| CHAPTER XI. | Ascending the Nile.—Sights and Scenes on the River. |

| CHAPTER XII. | Sugar Plantations and Mills.—Snake-charmers.—Sights at Beni-Hassan. |

| CHAPTER XIII. | Sioot, the Ancient Lycopolis.—Scenes on the River. |

| CHAPTER XIV. | Girgeh and Keneh.—The Temples of Abydus and Denderah.—An Egyptian Dance. |

| CHAPTER XV. | Arrival at Luxor.—The Great Temple of Karnak. |

| CHAPTER XVI. | The Rameseum, Medinet Aboo, and the Vocal Memnon. |

| CHAPTER XVII. | The Tombs of the Kings.—Recent Discoveries of Royal Mummies. |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | Harem Life in the East.—From Luxor to Assouan. |

| CHAPTER XIX. | A Camel Journey.—The Island of Philæ, and the First Cataract of the Nile. |

| CHAPTER XX. | From Assouan to Alexandria.—Farewell to Egypt. |

| CHAPTER XXI. | Voyage from Egypt to Palestine.—Journey from Jaffa to Ramleh. |

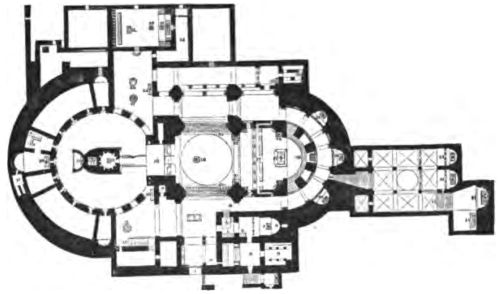

| CHAPTER XXII. | From Ramleh to Jerusalem.—The Church of the Holy Sepulchre. |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | In and Around Jerusalem. |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | From Jerusalem to Bethlehem.—Church and Grotto of the Nativity. |

| CHAPTER XXV. | From Bethlehem to Mar Saba and the Dead Sea. |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | From the Dead Sea to the Jordan, Jericho, and Jerusalem.—The Valley of the Jordan. |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | From Jerusalem to Nabulus.—Historic Places on the Route. |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | From Nabulus to Nazareth, Samaria, Jenin, and the Plain of Esdraelon. |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | Ascent of Mount Tabor.—Around and on the Sea of Galilee. |

| CHAPTER XXX. | From Galilee to Damascus.—A Ride Through Dan and Banias. |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | Sights and Scenes in Damascus. |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | Damascus to Beyroot.—The Ruins of Baalbec.—Farewell. |

"Here we are in port again!" said Fred Bronson, as the anchor fell from the bow of the steamer and the chain rattled through the hawse-hole.

"Three cheers for ourselves!" said Frank Bassett in reply. "We have had a splendid voyage, and here is a new country for us to visit."

"And one of the most interesting in the world," remarked the Doctor, who came on deck just in time to catch the words of the youth.

"Egypt is the oldest country of which we have a definite history, and there is no other land that contains so many monuments of its former greatness."

Their conversation was cut short by the captain, who came to tell them that they would soon be able to go on shore, as the Quarantine[Pg 14] boat was approaching, and they could leave immediately after the formalities were over.

When we last heard from our friends they were about leaving Bombay under "sealed orders." When the steamer was fairly outside of the beautiful harbor of that city, and the passengers were bidding farewell to Colaba Light-house, Dr. Bronson called the youths to his side and told them their destination.

"We are going," said he, "to Egypt, and thence to the Holy Land. The steamer will carry us across the Indian Ocean to the Straits of Bab-el-mandeb, and then through these straits into the Red Sea; then we continue our voyage to Suez, where we land and travel by rail to Cairo."

One of the boys asked how long it would take them to go from Bombay to Suez.

"About ten days," was the reply. "The distance is three thousand miles, in round numbers, and I believe we are not to stop anywhere on the way."

The time was passed pleasantly enough on the steamer. The weather was so warm that the passengers preferred the deck to the stifling cabins, and the majority of them slept there every night, and lounged there during the day. The boys passed their time in reading about the countries they were to visit, writing letters to friends at home, and completing the journal of their travels. In the evenings they talked about what they had seen, and hoped that the story of their wanderings would prove interesting to their school-mates in America, and to other youths of their age.[1]

Soon after entering the Red Sea they passed the island of Perim, a barren stretch of rock and sand, crowned with a signal station, from which the English flag was flying. As they were looking at the island, and thinking what a dreary place it must be to live in, one of the passengers told the boys an amusing story of how the English obtained possession of it.

"Of course you are aware," said he, "that the English have a military post at Aden, a rocky peninsula on the shore of Arabia, about a hundred and twenty miles from the entrance of the Red Sea. They bought it from the Sultan of that part of Arabia in 1839 by first taking possession, and then telling him he could name his price, and they would[Pg 15] give him what they thought best, as they were determined to stay. Aden is a very important station for England, as it lies conveniently between Europe and Asia, and has a fine harbor. The mail steamers stop there for coal, and the government always keeps a garrison in the fort. It is one of the hottest and most unhealthy places in the world, and there is a saying among the British officers that an order to go to Aden is very much like being condemned to be shot.

"Soon after the Suez Canal was begun the French thought they needed a port somewhere near Aden, and in 1857 they sent a ship-of-war to obtain one. The ship touched at Aden for provisions, and the captain was invited to dine with the general who commanded at the fort. During dinner he became very talkative, and finally told the general that his government had sent him to take possession of Perim, at the entrance of the Red Sea.

"Perim was a barren island, as you see, and belonged to nobody; and the English had never thought it was worth holding, though they occupied it from 1799 to 1801. As soon as the French captain had stated his business in that locality the general wrote a few words on a slip of paper, which he handed to a servant to carry to the chief of staff. Then he kept his visitor at table till a late hour, prevailed on him to sleep on shore that night, and not be in a hurry to get away the next morning.

"The French ship left during the forenoon and steamed for Perim. And you may imagine that captain's astonishment when he saw a dozen men on the summit of the island fixing a pole in the ground. As soon as it was in place they flung out the English flag from its top, and greeted it with three cheers. In the little note he wrote at the dinner-table the general had ordered a small steamer to start immediately for Perim and take possession in the name of the Queen, and his orders were obeyed. The French captain was dismissed from the navy for being too free with his tongue, and the English have 'hung on' to Perim ever since."

The Doctor joined them as the story of the occupation of Perim was concluded. There was a laugh over the shrewdness of the English officer and the discomfiture of the French one, and then the conversation turned to the Red Sea.

"It may properly be called an inlet of the Indian Ocean," said the Doctor, "as it is long and narrow, and has more the characteristics of an inlet than of a sea. It is about fourteen hundred miles long, and varies from twenty to two hundred miles in width; it contains many shoals[Pg 16] and quicksands, so that its navigation is dangerous, and requires careful pilotage. At the upper or northern extremity it is divided into two branches by the peninsula of Mount Sinai; the western branch is called the Gulf of Suez, and is about one hundred and eighty miles long, by twenty broad. This gulf was formerly more difficult of navigation than the Red Sea proper, but recently the Egyptian government has established a line of beacons and light-houses along its whole length, so that the pilots can easily find their way by day or at night."

One of the boys asked why the body of water in question was called the Red Sea.

The Doctor explained that the origin of the name was unknown, as it had been called the Red Sea since the time of Herodotus and other early writers. It is referred to in the Hebrew Scriptures as Yam Suph, the Sea of Weeds, in consequence of the profusion of weeds in its waters. These weeds have a reddish color; the barren hills that enclose the sea have a strong tinge of red, especially at the hours of sunset and sunrise, and the coral reefs that stretch in every direction and make navigation dangerous are often of a vermilion tint. "You will see all these things as you proceed," he continued, "and by the time you are at Suez you will have no difficulty in understanding why this body of water is called the Red Sea."

The boys found it as he had predicted, and the temperature for the first two days after passing Perim led Frank to suggest that the name might be made more descriptive of its character if it were called the Red-hot Sea. The thermometer stood at 101° in the cabin, and was only a little lower on deck; the heat was enervating in the extreme, and there was no way of escaping it; but on the third day the wind began to blow from the north, and there was a change in the situation. Thin garments were exchanged for thick ones, and the passengers, who had been almost faint with the heat, were beginning to shiver in their overcoats.

"A change of this sort is unusual," said the gentleman who had told them of the seizure of Perim, "but when it does come it is very grateful. Only in January or February is the Red Sea anything but hot; the winds blow from the sandy desert, or from the region of the equator, and sometimes it seems as though you were in a furnace. From December to March the thermometer averages 76°, from thence to May it is 87°, and through the four or five months that follow it is often 100°. I have frequently seen it 110° in the cabin of a steamer, and on one occasion, when the simoom was blowing from the desert, it was 132°.[Pg 17] Steamers going north when the south wind is blowing find themselves running just with the wind, so that they seem to be in a dead calm; in such cases they sometimes turn around every ten or twelve hours and run a few miles in the other direction, so as to let the wind blow through the ship and ventilate it as much as possible. The firemen are Arabs and negroes, accustomed all their lives to great heat, but on almost every voyage some of them find the temperature of the engine-room too severe, and die of suffocation."

Our friends passed by Jeddah, the port of Mecca, and from the deck of the steamer the white walls and towers of the town were distinctly visible. Frank and Fred would have been delighted to land at Jeddah and make a pilgrimage to Mecca, but the Doctor told them the journey was out of the question, as no Christian is allowed to enter the sacred city of the Moslems, and the few who had ever accomplished the feat had done so at great personal risk.

"The first European who ever went there was Burckhardt, in 1814," said Dr. Bronson. "He prepared himself for his travels by studying the Arabic language, and went in the disguise of an Arab merchant, under the name of Sheikh Ibrahim ibn Abdallah. Then he travelled[Pg 18] through Syria, Asia Minor, and Egypt for several years, and became thoroughly familiar with the customs of the people, so that he was able to pass himself successfully as a learned Moslem. Captain Burton went to Mecca in 1852, and since his time the city has been visited by Maltzan, Palgrave, and two or three others. Captain Burton followed the example of Burckhardt and wore the Arab dress; he spoke the language fluently, but in spite of this his disguise was penetrated while he was returning to Jeddah, and he was obliged to flee from his companions and travel all night away from the road till he reached the protection of the seaport."

"What would have happened if he had been found out?" Frank inquired.

"The mob of fanatical Moslems would have killed him," was the reply. "They would have considered it an insult to their religion for him to enter their sacred city—the birthplace of the founder of their religion—and he would have been stoned or otherwise put to death. Some Europeans who have gone to Mecca have never returned, and nothing was ever heard of them. It is supposed they were discovered and murdered."

"What barbarians!" exclaimed Fred.

"Yes," replied the Doctor; "but if you speak to any of them about it, they will possibly reply that Christian people have put to death those who did not believe in their religion. They might quote a good many occurrences in various parts of Europe in the past five hundred years, and could even remind us that the Puritans, in New England, hanged three men and one woman, and put many others in prison, for the offence of being Quakers. Religious intolerance, even at this day, is not entirely confined to the Moslems."

Frank asked what could be seen at Mecca, and whether the place was really worth visiting.

"As to that," the Doctor answered, "tastes might differ. Mecca is said to be a well-built city, seventy miles from Jeddah, with a population of about fifty thousand. The most interesting edifice in the place is the 'Caaba,' or Shrine, which stands in the centre of a large square, and has at one corner the famous 'Black Stone,' which the Moslems believe was brought from heaven by the angels. Burckhardt thought it was only a piece of lava; but Captain Burton believes it is an aerolite, of an oval shape, and about seven feet long. The pilgrims walk seven times around the Caaba, repeating their prayers at every step, and they begin their walk by prostrating themselves in front of the Black Stone[Pg 19] and kissing it. The consequence is that it is worn smooth, as the number of pilgrims going annually to Mecca is not less than two hundred thousand. The pilgrimage is completed with the ascent of Mount Arafat, twelve miles east of Mecca; and when a Moslem returns from his journey he is permitted to wear a green turban for the rest of his life. The pilgrimage is an easier matter than it used to be, as there are steamers running from Suez and other points to carry the pilgrims to Jeddah, and from there they can easily accomplish their journey to Mecca and return in a couple of weeks."

Frank asked how far it was from Mecca to Medina, the place where Mohammed died and was buried.

"Medina is about two hundred and fifty miles north of Mecca," said[Pg 20] the Doctor, "and is only a third the size of the latter city. It is next to Mecca in sanctity, and a great many pilgrims go there every year. The tomb of the Prophet is in a large mosque, in the centre of the city, and there is an old story that the coffin of Mohammed is suspended in the air by invisible threads hanging from heaven. Captain Burton visited Medina, and reports that the Moslems have no knowledge of the story, and say it must have been invented by a Christian. The tomb is in one side of the building, but no one is allowed to look upon it, not even a Moslem; the most that can be seen is the curtain surrounding it, and even that must be observed through an aperture in a wooden screen. The custodians say that any person who looks on the tomb of the Prophet would be instantly blinded by a flood of holy light."

So much for the two holiest places in the eyes of the Moslems. Frank and Fred concluded that they did not care to go to Mecca and Medina, and the former instanced the old fable of a fox who despised the grapes which were inaccessible, and denounced them as too sour to be eaten.

As they entered the Gulf of Suez the attention of the boys was[Pg 21] directed to Mount Sinai, and they readily understood, from the barrenness and desolation of the scene, why it was called "Mount Sinai in the Wilderness." With a powerful telescope not a sign of vegetation was anywhere visible.

It was late in the forenoon of a pleasant day when the ship came to anchor, as we have described in our opening lines. The Quarantine doctor came on board, and was soon convinced that no reason existed why the passengers, who chose to do so, might not go on shore. Doctor Bronson and his young friends bargained with a boatman to carry them and their baggage to the steps of the Hotel de Suez for a rupee each. The town, with the hotel, was about two miles from the anchorage, and the breeze carried them swiftly over the intervening stretch of water. Half a dozen steamers lay at the anchorage, waiting for their turn to pass the Canal; and a dozen or more native craft, in addition to the foreign ships, made the harbor of Suez appear quite picturesque. The rocky hills behind the town, and the low slopes of the opposite shore, glistened in the bright sunlight; but the almost total absence of verdure in the landscape rendered the picture the reverse of beautiful. Not a tree nor a blade of grass can be seen on the African side of the Gulf,[Pg 22] while on the opposite shore the verdure-seeking eye is only caught by the oasis at the Wells of Moses, where a few palm-trees bid defiance to the shifting sands of the desert.

Suez appeared to our friends a straggling collection of flat-roofed houses and whitewashed walls, where the sea terminates and the desert begins. Before the construction of the Canal it was little better than an Arab village, with less than two thousand inhabitants; at present it is a town of ten or twelve thousand people, the majority of whom are supported, directly or indirectly, by the Canal or the railway. There has been a town of some sort at this point for more than three thousand years, but it has never been of much importance, commercially or otherwise. The situation in the midst of desert hills, and more especially the[Pg 23] absence of fresh water, have been the drawbacks to its prosperity. There is little to be seen in its shops, and for that little the prices demanded are exorbitant. Few travellers remain more than a day at Suez, and the great majority are ready to leave an hour or two after their arrival.

Frank and Fred were impatient to see the Suez Canal, which enables ships to pass between the Red and Mediterranean Seas. In going from the anchorage to the town they passed near the southern end of the Canal, and from the veranda of the hotel they could see steamers passing apparently through the sandy desert, as the position where they stood concealed the water from sight. As soon as they had secured their rooms at the hotel, they started out with the Doctor to make a practical acquaintance with the great channel from sea to sea.

There was a swarm of guides and donkey-drivers at the door of the hotel, so that they had no difficulty in finding their way. At the suggestion of the Doctor they followed the pier, nearly two miles in length, which leads from the south part of the town to the harbor; the water is very shallow near Suez, and this pier was built so that the railway trains could be taken along side the steamers, and thus facilitate the transfer of passengers and freight. The pier is about fifty feet wide, and has a solid foundation of artificial stone sunk deep into the sand. At the end of the pier are several docks and quays belonging to the Canal and railway companies, and there is a large basin, called Port Ibrahim, capable of containing many ships at once. The Canal Company's repair-shops and warehouses stand on artificial ground, which was made by dredging the sand and piling it into the space between the pier and the land, and Frank thought that not less than fifty acres had thus been enclosed.

A line of stakes and buoys extended a considerable distance out into the head of the Gulf, and the Doctor explained that, in consequence of the shallowness near the land, the Suez Canal began more than a mile from the shore. The sand-bar is visible at low tide, and when the wind blows from the north a large area is quite uncovered. A channel was dredged for the passage of ships, and the dredging-machines are frequently in use to remove the sand which blows from the desert or is swept into the channel by the currents.

At the end of the long pier is a light-house; and while our friends stood there and contemplated the scene before them, the Doctor reminded the boys that in all probability they were in sight of the spot where the hosts of Pharaoh were drowned after the Israelites had crossed over in safety.

"That is very interesting," said Frank; "but is this really the place?"

"We cannot be absolutely certain of that," was the reply, "as there are different opinions on the subject. But it was in this neighborhood certainly, and some of those who have made a careful study of the matter say that the crossing was probably within a mile of this very spot."

The eyes of the boys opened to their fullest width at this announcement, and they listened intently to the Doctor's remarks on the passage of the Israelites through the Red Sea.

"You will remember," said the Doctor, "that the Bible account tells us how the Lord caused a strong wind to blow from the north, which swept away the waters and allowed the Israelites to pass over the bed of the sea. After they had crossed, and the hosts of Pharaoh pursued them, the wind changed, the waters returned, and the army of the Egyptian ruler was drowned in the waves. The rise of the tide at this place is from three to six feet, and the sand-bank is only slightly covered when the tide is out; now, when the wind blows from the north with great force the water is[Pg 26] driven away, and parts of the sand-bank are exposed. On the other hand, when a strong wind blows from the south, the water is forced upon the sand-bank, and the tide, joined to this wind, will make a depth of six or seven feet where a few hours before the ground was dry. This is the testimony of many persons who have made careful observations of the Gulf of Suez, and the miracle described in the Bible is in exact accordance with the natural conditions that exist to-day.

"One modern writer on this subject says he has known a strong north-east wind to lay the ford dry, and be followed by a south-west wind that rendered the passage impossible even for camels. M. De Lesseps, the projector of the Suez Canal, says he has seen the northern end of the sea blown almost dry, while the next day the waters were driven far up on the land. In 1799 Napoleon Bonaparte and his staff came near being drowned here in a sudden change of wind, and fatal accidents occur once in a while from the same cause. On the map prepared by the officers of the maritime canal to show the difference between high and low water, you will see that the conditions are just as I have stated them.

"Some writers believe," the Doctor continued, "that the sea was farther inland three thousand years ago, and that the crossing was made about ten miles farther north than where we now stand. There is some difficulty in locating all the places named in the biblical story of the exodus, and it would be too much to expect all the critics to agree on the subject. The weight of opinion is in favor of Suez as the crossing-place of the Israelites, and so we will believe we are at the scene of the deliverance of the captives and the destruction of the hosts of Pharaoh. It is a mistake to suppose that Pharaoh was himself drowned in the Red Sea; it was only his army that suffered destruction."

From the point where this conversation took place they went to the Waghorn Quay, just beyond. It was named in honor of Lieutenant Waghorn,[Pg 27] who devoted several years to the establishment of the so-called "overland route" between England and India. Through his exertions the line of the Peninsular and Oriental steamers was established, and the mails between England and India were regularly carried through Egypt, instead of taking the tedious voyage around the Cape of Good Hope. He died in London in poverty in 1850; since his death the importance of his services has been recognized, and a statue to his memory stands on the quay which bears his name. At his suggestion the name of "overland route" was given to this line of travel between England and India, though the land journey is only two hundred and fifty miles, to distinguish it from the "sea route" around the Cape of Good Hope.

From Waghorn Quay it was only a short distance to the Canal, and as they reached its bank a large steamer was just entering on its way to the Mediterranean. Frank observed that she was moving very slowly, and asked the Doctor why she did not put on full steam and go ahead.

"That would be against the rules of the Canal Company," was the reply. "If the steamers should go at full speed they would destroy the Canal in a short time; the 'wash' or wake they would create would break down the banks and bring the sand tumbling into the water. They must not steam above four miles an hour, except in places where the Canal widens into lakes, and even there they cannot go at full speed."

"Then there are lakes in the Canal, are there?" Fred inquired.

"I'll explain that by-and-by," the Doctor responded. "Meantime look across the head of the Gulf and see that spot of green which stands out so distinctly among the sands."

The boys looked in the direction indicated and saw an irregular patch of verdure, on which the white walls of several houses made a sharp contrast to the green of the grass and the palm-trees that waved above them.

"That spot," said the Doctor, "is known as 'Ayoon Moosa,' or 'The Wells of Moses.' It is an oasis, where several wells or springs have existed for thousands of years, and it is supposed that the Israelites halted there and made a camp after their deliverance from Egypt. As the pursuing army of Pharaoh had been destroyed before their eyes, they were out of danger and in no hurry to move on. The place has borne the name of 'The Wells of Moses' from time immemorial; there is a tradition that the largest of them was opened by the divining-rod of the great leader of the Hebrews in their escape from captivity, and is identical with Marah, described in Exodus, xv. 23. The wells are pools of water fed by springs which bubble in their centre; the water in all of them is too[Pg 28] brackish to be agreeable to the taste, but the camels drink it readily, and the spot is an important halting place for caravans going to or from the desert."

The Doctor farther explained that Suez was formerly supplied with water from these wells, which was brought in goat-skins and casks on the backs of camels. The springs are seven or eight miles from Suez in a direct line, and the easiest way of reaching them is by a sail or row boat to the landing place, about two miles from the oasis. Since the opening of the fresh-water canal in 1863 this business of supplying the city has ceased, and the water is principally used for irrigating the gardens in the oasis. Most of the fresh vegetables eaten in Suez are grown around the springs, and there is a hotel there, with a fairly good restaurant attached[Pg 29] to it. The residents of Suez make frequent excursions to the Wells of Moses, and almost any day a group of camels may be seen kneeling around the principal springs.

Our friends returned along the quay to Suez, and strolled through some of the streets of the town. There was not much to be seen, as the shops are neither numerous nor well stocked, and evidently are not blessed with an enormous business. They visited a mosque, where they were obliged to take off their shoes, according to the custom of the East, before they could pass the door-way; the custodian supplied them with slippers, so that they were not required to walk around in their stockinged feet. When you go on a sight-seeing tour in an Egyptian city, it is well to carry your own slippers along, or intrust them to your guide, as the Moslems are rigid enforcers of the rule prohibiting you to wear your boots inside a mosque.

The principal attraction in the mosque was a group to whom a mollah, or priest, was delivering a lecture. The speaker stood in a high pulpit which was reached by a small ladder, and his hearers stood below him or squatted on the floor. What he said was unintelligible to our friends, as he was speaking in Arabic, which was to them an unknown tongue. The audience was apparently interested in his remarks, and paid no attention to the strangers except to scowl at them. In some of the mosques of the East Christians are not admitted; this was the rule half a century ago, but at present it is very generally broken down, and the hated infidel may visit the mosques of the principal cities of Egypt and Turkey, provided he pays for the privilege.

They returned to the hotel in season for dinner. The evening was passed in the house, and the party went to bed in good season, as they were to leave at eight o'clock in the morning for Cairo. They were at the station in due time for departure, and found the train was composed of carriages after the English pattern, in charge of a native conductor who spoke French. By judiciously presenting him with a rupee they secured a compartment to themselves.

While they were waiting for the train to move on the Doctor told the boys about the "overland route" through Egypt.

"The route that was established by Lieutenant Waghorn was by steamship from England to Alexandria, and thence by river steamboats along the Nile to Cairo. From Cairo, ninety miles, to Suez the road was directly through the desert, and passengers were carried in small omnibuses, drawn by horses, which were changed at stations ten or fifteen miles apart. Water for supplying these stations was carried from the Nile and kept in tanks, and it was a matter of heavy expense to maintain the stations. The omnibus road was succeeded by the railway, opened in 1857, and the water for the locomotives was carried by the trains, as there was not a drop to be had along the route. This railway was abandoned and the track torn up after the construction of the Canal, as the expense of maintaining it was very great. In addition to the cost of carrying water was that of keeping the track clear of sand, which was drifted by the wind exactly as snow is drifted in the Northern States of America, and sometimes the working of the road was suspended for several days by the sand-drifts. The present railway follows the banks of the Maritime Canal as far as Ismailia, and thence it goes along the Fresh-Water Canal, of which I will tell you.

"The idea of a canal to connect the Mediterranean and Red Seas is by no means a modern one."

"Yes," said Frank, "I have read somewhere that the first Napoleon in 1799 thought of making a canal between the two seas, and his engineers surveyed the route for it."

"You are quite right," responded the Doctor, "but there was a canal long before the time of Napoleon, or rather there have been several canals."

"Several canals!" exclaimed Frank. "Not several canals at once?"

"Hardly that," said the Doctor, with a smile; "but at different times there have been canals between the two seas. They differ from the present one in one respect: the maritime Canal of to-day runs from one sea to the other, and is filled with salt-water, while the old canals connected[Pg 31] the Nile with the Red Sea, and were constantly filled with fresh-water. The Fresh-Water Canal of to-day follows the line of one of the old canals, and in several places the ancient bed was excavated and the ancient walls were made useful, though they were sadly out of repair."

One of the boys asked how old these walls were, to be in such a bad condition.

"We cannot say exactly how old they are," was the reply, "and a hundred years or so in our guessing will make no difference. According to some authorities, one of the rulers of ancient Egypt, Rameses II., conceived and carried out the idea of joining the two seas by means of the Nile and a canal, but there is no evidence that the work was accomplished in his time. The first canal of which we have any positive history was made by Pharaoh Necho I. about 600 b.c., or nearly twenty-five hundred years ago. It tapped the Nile at Bubastis, near Zagazig, and followed the line of the present Fresh-Water Canal to the head of the Bitter Lake. The Red Sea then extended to the Bitter Lake, and the shallow places were dredged out sufficient to allow the passage of the small craft that were in use in those days. The canal is said to have been sixty-two Roman miles long, or fifty-seven English ones, which agrees with the surveys of the modern engineers.

"This canal does not seem to have been used sufficiently to keep it from being filled by the drifting sand, as it was altogether closed a hundred years later, when it was re-opened by Darius; the latter made a salt-water canal about ten miles long near the south end of the Bitter Lake, to connect it with the Red Sea. Traces of this work were found when the Fresh-Water Canal was made, and for some distance the old track was followed. Under the arrangement of the canals of Necho and Darius, ships sailed up the Nile to Bubastis, and passed along the canal to the[Pg 32] Bitter Lake, where their cargoes were transferred to Red Sea vessels. About 300 b.c. Ptolemy Philadelphus caused the two canals to be cleared out, and connected them by a lock, so that ships could pass from the fresh to the salt water, or vice versa.

"Four hundred years later (about 200 a.d.), according to some writers, a new canal was made, tapping the Nile near Cairo, and connecting with the old one, which was again cleared out and made navigable. Another canal, partly new and partly old, is attributed to the seventh century, and still another to the eleventh century; since that time there has been nothing of the sort till the Maritime Canal Company found it necessary, in 1861, to supply the laborers on their great work with fresh-water. They cleared out the old canal in some places, and dug a new one in others as far as the Bitter Lake; afterward they prolonged it to Suez, which it reached in 1863, and at the same time they laid a line of iron pipes from Ismailia to Port Said, on the Mediterranean. It would have been impossible to make and maintain the Maritime Canal without a supply of fresh-water, and thus the work of the Egyptians of twenty-five hundred years ago became of practical use in our day.

"Look on this map," said the Doctor, as he drew one from his pocket and handed it to the youths, "and you will see the various points I have[Pg 33] indicated, together with the line of the Maritime Canal, and of the Fresh-Water Canal which supplies this part of Egypt with water."

Several minutes were passed in the study of the map. Before it was finished the train started, and in a short time our friends were busily contemplating the strange scene presented from the windows of their carriage.

The railway followed very nearly the bank of the Fresh-Water Canal, which varied from twenty to fifty feet in width, and appeared to be five or six feet deep. Beyond it was the Maritime Canal, a narrow channel, where steamers were slowly making their way, the distances between them being regulated by the pilots, so as to give the least possible chance of collision. Considering the number of steamers passing through the Canal, the number of accidents is very small. Frank could not understand how steamers could meet and pass each other, till the Doctor explained that there were "turnouts" every few miles, where a steamer proceeding in one direction could wait till another had gone by, in the same way that railway-trains pass each other by means of "sidings." Then there was plenty of space in Lake Timsah and the Bitter Lake, not only for ships to move, but to anchor in case of any derangement of their machinery.

From the information derived from the Doctor, and from the books and papers which he supplied, Frank and Fred made up the following account of the Suez Canal for the benefit of their friends at home:

"The Canal is one hundred miles long, from Suez, on the Red Sea, to Port Said, on the Mediterranean. Advantage was taken of depressions in the desert below the level of the sea, and when the water was let in, these depressions were filled up and became lakes (Timsah and Bitter Lakes), as you see on the map. There were thirty miles of these depressions; and then there was a marsh or swamp (thirty miles across), called Lake Menzaleh, which was covered during the flood of the Nile, and only needed a channel to be dug or dredged sufficiently deep for the passage of ships. The first spadeful of earth was dug by Ferdinand de Lesseps at Port Said on the 25th of April, 1868, and the completed Canal was opened for the passage of ships on the 16th of November, 1869. About forty steamers entered it at Port Said on that day, anchored in Lake Timsah for the night, and passed to the Red Sea on the 17th. M. de Lesseps projected the Canal while he was serving in Egypt as French Consul, and it was through his great energy and perseverance that the plan was finally carried out. The Canal was distinctively a French enterprise, and was opposed by England, but as soon as it was completed the English Government[Pg 34] saw its great importance, and bought a large amount of stock that had hitherto been held by the Egyptian Government.

"The line of the Canal where digging was necessary was through sand, but in many places it was packed very hard, so that pickaxes were needed to break it up. Much of the sand was removed by native laborers with shovels and baskets; but after the first two years it was necessary to substitute machinery for hand labor. Excavating and dredging machines driven by steam were put in operation, and the work was pushed along very rapidly; the channel through Lake Menzaleh was made by floating dredges equipped with long spouts that deposited the sand two or three hundred feet from where they were at work, and the dry cuttings at higher points were made by similar excavators mounted on wheels. At one place, just south of Lake Timsah, there was a bed of solid rock, where it was necessary to do a great deal of blasting, and the last blast in this rock was made only a few hours before the opening of the Canal.

"The cost of the work was nearly $100,000,000, of which about

one-third[Pg 35]

[Pg 36] was paid by Egypt, under the mistaken impression that the

Canal would be beneficial to the country. The Khedive, or Viceroy of

Egypt, spent nearly $10,000,000 on the festivities at the opening of the

Canal, and this foolish outlay is one of the causes of the present

bankruptcy of the country. Palaces and theatres were built for this

occasion, roads were opened that were of no use afterward, and an

enormous amount of money was spent for fireworks, music, banquets, and

presents of various kinds to all the guests. The Empress of France was

present at the opening of the Canal, and distinguished persons from all

parts of the world were invited and entertained in princely style.

"In 1870, the first year the Canal was in operation, 486 vessels passed through it; in the next year the number was 765, and it steadily increased till it became 1264 vessels in 1874, 1457 in 1876, and 2026 in 1880. More than two-thirds of the entire number of ships passing the Canal are English, and in some years they have been fully three-fourths, while the French are less than one-thirteenth of the total number. France, which expected much from the Canal, has realized very little; while England, which opposed its construction, has reaped nearly all the benefit therefrom.[2]

"By the original charter the company was allowed to charge ten francs (two dollars) a ton on the measurement of each ship going through the Canal, and ten francs for each passenger. The revenue, after deducting the expenses of operating, amounts to about five per cent. on the capital of the company, and the officers think it will be seven or eight per cent. before many years.

"The following figures show the dimensions of the Canal:

| Feet | |

| Width at water-line, where the banks are low | 328 |

| Width at water-line in deep cuttings, where the banks are high | 190 |

| Width at bottom of the Canal | 72 |

| Depth of water in the Canal | 26 |

"The scenery on the Canal is not particularly interesting, as one soon gets tired of looking at the desert, with its apparently endless stretch of sand. At Ismailia and Kantara there has been an attempt at cultivation, and there are some pretty gardens which have been created since the opening of the Fresh-Water Canal, and are kept up by irrigation. But nearly all the rest is a waste, especially on the last twenty-seven miles, through Lake Menzaleh to Port Said. If you make this ride on one of the small steamers maintained by the Canal Company you find that one mile is exactly like any other, and you are soon glad enough to seek the cabin and go to sleep.

"Here are some figures showing the saving in distances (in nautical miles) by the Canal:"

| Via Cape of Good Hope. | Via Canal. | Saving. | |

| England to Bombay | 10,860 | 6020 | 4840 |

| New York to Bombay | 11,520 | 7920 | 3600 |

| St. Petersburg to Bombay | 11,610 | 6770 | 4840 |

| Marseilles to Bombay | 10,560 | 4620 | 5940 |

There is little to relieve the monotony of the desert between Suez and Ismailia beyond the view of the two canals, and the ships and boats moving on their waters. Occasionally a line of camels may be seen walking with a dignified pace, or halted for the adjustment of their loads, or for some other purpose. In every direction there is nothing but the desert, either stretching out into a plain or rising in mountains, on which not a particle of verdure is visible. Under the bright sun of the Egyptian sky the sands glittered and sparkled till the light they reflected became painful to the eyes of the observers. The prudent Doctor had bought some veils in the bazaar of Suez, and now brought them from the recesses of his satchel for the use of the delighted boys as well as for his own.

The color of the desert mountains on the southern horizon varied[Pg 39] from white to yellow and purple, and from yellow and purple back again to white. Frank said that some of them seemed to be composed of amethysts and garnets, mixed and melted together in a gigantic crucible. The Doctor told him he was not the first to make such a description, as the idea had occurred to previous travellers, some of whom thought the mountains were composed of all kinds of precious stones mingled with glass. The dazzling appearance of these elevations had led many persons to explore them in search of gems; but of all these explorers none had ever found the fortune he sought.

As they approached Ismailia there were signs of vegetation on the banks of the Fresh-Water Canal, and near the town they came to some pretty gardens which have been created since the opening of the Canal. While the works of the Canal were in progress Ismailia was an active town, with a considerable population, but at present many of its buildings are unoccupied, and there is a general appearance of desolation. There are a few cottages near the banks of Lake Timsah, and of late years the town has obtained popularity with some of the European residents of Cairo, who go there for the sake of the salt-water bathing. The air is clear and dry, the water is of the deep blue of the united seas, and is generally of an agreeable temperature, while it has the smoothness of an inland lake, and is not popular with sharks or any other disagreeable inhabitants of tropical waters. The current created by the changes of the tide between the two seas is sufficient to keep the water from becoming stagnant, but is not strong enough to interfere with navigation or disturb the bather.

After a brief halt at the station the train moved off in the direction of Cairo, and for an hour or more the views from the windows of the railway-carriage were remarkable in their character. On one side of the train the naked desert filled the picture, with its endless stretch of sand; on the other the gardens on the banks of the Fresh-Water Canal were marvels of luxuriance. The richest soil in the world lay side by side with the most desolate, and our friends agreed that they had never seen so marked a contrast during a ride on a railway train. The Doctor explained that the abundant vegetation was due to the wonderful fertilizing power of the Nile water, and said it was no wonder that the ancient Egyptians worshipped the river, and attributed all their wealth and prosperity to its influence.

At Zagazig the train stopped an hour or more for dinner, and there was a change of carriages for the passengers destined for Cairo. Zagazig is the junction of the lines for Cairo and Alexandria, and since the opening[Pg 40] of the railway the town has become of considerable importance. A great deal of cotton is raised in the vicinity, and in some years not less than fifty thousand tons of that article are sent from the station. The country around here is very fertile, and is said to be the Goshen of the Bible. The ruins of the ancient town of Bubastis are about a mile from Zagazig, but they are so slight as to be unworthy a visit. Bubastis was an important place two thousand years ago, and was famous for a festival to which more than half a million pilgrims went every year.

For the remaining fifty-two miles from Zagazig to Cairo the route lay through a fertile country, and only occasional glimpses were afforded of the desert. Boats and barges were moving on the Canal, some of them carrying the local products of the country to Cairo or Ismailia, while[Pg 41] others were laden with coal and other foreign importations which find a market among the Egyptians. The boys were interested in the processes of irrigating the lands, and eagerly listened to the Doctor's explanation of the matter. Before reaching Zagazig they had seen some men at work dipping water by means of buckets suspended from poles, and emptying it into basins formed by excavations on the banks; they were told that this apparatus for hoisting water was called a "shadoof," and had been in use from the most ancient days of Egypt.

"The simplest form of shadoof," said the Doctor, "is the one you are looking at. It consists of two posts of wood or sun-dried mud, supporting a horizontal bar, on which the pole suspending the bucket is balanced in the centre. A lump of mud on one end of the pole balances the weight of the bucket on the other, and enables the man who operates it to lift his burden with ease. The bucket is made of rushes woven so tightly as to hold water, and at the same time be as light as possible, and it is dipped and raised with great rapidity. Water is lifted from six to eight feet by the shadoof. If a higher elevation is needed, a second and even a third or a fourth may be used; on the upper part of the Nile I have seen half a dozen of them in operation on a series of steps, one above the other.

"You will see representations of the shadoof on the walls of the temples and tombs of Egypt, and the conclusion is certain that the form has not changed in the least in three thousand years. When the Nile is at its height there is no need of anything of the sort, as the water flows all[Pg 42] over the land, and the entire country is inundated. As soon as the river falls it is necessary to raise water by artificial means, as the growing plants in the fields would soon perish under the hot sun of Egypt without a supply of moisture. Then the shadoof comes in play, and the more the river descends the greater is the number demanded. In some parts of the country the sakkieh is used in place of the shadoof, and the result is the same."

Fred wished to know the difference between the shadoof and the sakkieh.

"The sakkieh," said the Doctor, "is a wheel operated by a beast of burden—a horse, camel, mule, donkey, or ox. The animal walks in a circle, and turns a horizontal wheel which has cogs connected with an upright wheel, bearing a circle of earthen buckets on its rim. These buckets dip in water as the wheel turns; their mouths are then brought uppermost, and they raise the water and pour it into a trough. Where the water must be raised to a great height from a well, or from the side of a perpendicular bank, two wheels[Pg 43] are used, one at the spot where the animal walks, and the other at the surface of the water. A stout band or rope passes over the wheels, and to this band buckets are attached to lift the water. I have seen water raised fifty or sixty feet by this process, the ox or mule walking patiently for hours, until it was his turn to be relieved."

While the Doctor was talking the train passed a sakkieh, which was being turned by a pair of oxen driven by a small boy. The boys observed that the eyes of the animals were blindfolded by means of a piece of cloth drawn over their heads, and they naturally wished to know the reason of it.

"It is the custom of the country," was the reply. "The animals are believed to work better when their attention is not drawn to things around them, and they are less likely to be frightened if anything unusual happens in their neighborhood. This is particularly the case with the native buffalo and with the mule, and the practice of blindfolding the latter animal is not unknown in our own country. On the Western plains and among the Rocky Mountains it is the custom to throw a blanket over the head of a pack-mule when he is being saddled and is about to receive his burden. He stands perfectly quiet during the whole operation; while, if he were not temporarily deprived of sight, he would be very restive, and perhaps would break away from his driver, and scatter things around him very miscellaneously."

Just beyond the sakkieh they saw a man driving a pair of bullocks in front of a plough, and as the implement was lifted from the ground in turning they had an opportunity of seeing how it was made.

"It is nothing but a wooden point," said Frank, "like the end of a small log or stake."

"Yes," echoed Fred, "and there is only one handle for the man to grasp. Wonder what he would think of our two-handled ploughs of iron in America!"

"He would probably decline to use it," the Doctor responded, "as he needs one hand for managing his goad, and could not understand how he could control a goad and an American plough unless nature had equipped him with three hands."

"That the plough is the same here to-day that it was three thousand years ago, we have proof in the pictures of agriculture on the walls of the tombs at Thebes. The ancient implement is identical with the modern one, the propelling force is the same, and the principal difference we can see is in the costume of the ploughman."

"The plough only scratches the earth," said Fred; "and if the soil was not very rich they would soon find out they needed something that would stir up the ground a little deeper."

"Sometimes," said the Doctor, "you will see several ploughs following each other in the same furrow. The object is to accomplish by this repeated ploughing what we do by a single operation."

Close by the field where the man was ploughing another was planting grain or something of the sort, and another a little farther on was cutting some green stalks that looked like our Indian-corn. The Doctor explained that the stalks were probably intended for feed for cattle, and that the article in question was known as "doora" among the natives, and was a close relative of the corn grown in America.

"But how funny," said Frank, "that they should be ploughing, planting, and reaping, all in sight of each other!"

"That is one of the peculiarities of the country," said the Doctor, with a smile. "You must remember that they do not have cold and frost, as we do, and the operations of agriculture go on through the whole year."

"All the year, from January to January again?" said Fred.

"Yes," was the reply, "though some attention must be paid to the change of seasons in order to get the best crops. From two to five crops, according to the article planted, can be raised in the course of the year, provided always that there is a constant supply of water for irrigating the fields. When a crop is ready for gathering it is harvested, and the ground is immediately ploughed and planted again."

As if to emphasize what the Doctor was saying, the train carried them past a thrashing-floor where the scriptural process of "treading out the corn" was going on. There was a floor of earth, which had been packed very hard and made smooth as possible, and on this floor the pair of oxen were walking in a circle and dragging a sort of sled, with rollers between the runners, on which a man was perched in a high chair. The straw[Pg 45] which had been deprived of its grain was heaped in the centre of the circle, ready for removal; the Doctor explained that the grain was separated from the chaff by throwing it in the air when the wind was blowing, and such a thing as a winnowing-machine was practically unknown in Egypt.

Attempts have been made to introduce modern implements and machinery for agricultural purposes, but they have generally failed. The Khedive expended a large amount of money for the latest improvements in farming; he had a large farm near Cairo, on which the purchases were placed, but it was soon found that the implements were unpopular with the natives, and they were abandoned. They lay for some years in one of the sheds of the establishment, and were finally sold as old iron.

The sight of the ploughs, shadoofs, thrashing-machines, and other aids of agriculture naturally led to a conversation on the products of Egypt. The boys learned that two kinds of corn were grown there—doora, which they had seen, and millet, which has a single ear on the top of a stalk. Egyptian wheat has been famous for many centuries, and is still cultivated, though to a less extent than formerly, as much of the ground once devoted to wheat is now given up to cotton. Coffee is grown in some localities, and so are indigo and sugar; there is a goodly variety of beans, peas, lentils, and the like, and watermelons, onions, and cucumbers are easily raised. The tobacco crop is of considerable value; grapes are abundant, and there are many fruits, including dates, figs, apricots, oranges, peaches, lemons, bananas, and olives. The methods of agriculture are very primitive, and in many instances slovenly; and if a thousand English or American farmers could be sent to Egypt to instruct the natives in the use of foreign implements, and teach them to till their farms on the Western plan, the value of Egyptian products would be doubled. But, to make the plan successful, it would be necessary to devise some means of compelling the natives to use the methods and machines that the strangers would bring among them, and this would be a difficult task.

The train halted several times, and finally came to Kallioob station, where it united with the direct line from Cairo to Alexandria. "Now," said the Doctor, "keep a sharp lookout on the right-hand side of the carriage and tell me what you see."

In a few minutes Frank gave a shout of delight, and called out,

"There they are—the Pyramids! the Pyramids!"

Fred saw them almost at the same moment, and joined his cousin in a cheer for the Pyramids, of which he had read and heard so much.

There they were, pushing their sharp summits into the western sky,[Pg 47] to which the sun was declining, for it was now late in the afternoon. Clearly defined, they rose above the horizon like a cluster of hills from the edge of a plain; and as our friends came nearer and nearer the Pyramids seemed to rise higher and higher, till it was difficult to believe that they were the work of human hands, and were only a few hundred feet in height. In a little while the attention of the youths was drawn to the minarets of the Mosque of Mohammed Ali and the high walls of the Citadel, on the summit of the hill that overlooks and commands the city of Cairo. Their glances turned from pyramids to mosque, and from mosque back again to pyramids, and from the sharp outline of the Mokattam Hills to the glistening sands of the Western Desert. Near by were the rich fields of the Valley of the Nile, and now and then the shining water of the old river was revealed through openings among the fringe of palms; the mud-built villages of the Egyptians passed as in a panorama, the white walls of the houses of Cairo took the place of the more primitive structures, groups of men and camels, and other beasts of burden, were seen wending their way to the great city or returning from it. The population grew more dense, the houses and gardens assumed a more substantial appearance, roads gave way to streets, and gardens to blocks of houses, and all too soon for our excited travellers the train rolled into the station at Cairo, and the journey to the wonderful City of the Caliphs had been accomplished.

From the sentimental to the practical the transition was instantaneous. Hardly had the train halted before the carriages were surrounded by a crowd of hotel runners, dragomen, guides, and other of the numerous horde that live upon the stranger within the gates. Doctor Bronson had telegraphed to the Hotel du Nil to send a carriage and a guide to meet his party at the station; the guide was there with a card from the manager of the hotel, and at once took charge of the strangers and their baggage, and showed the way to the waiting carriage. Frank said he should advise all his friends on their first visit to Cairo to follow the Doctor's example, and thus save themselves a struggle with the unruly crowd and a vast amount of annoyance. The worst feature of a journey in Egypt is the necessity of a constant fight with the great swarm of cormorants that infest all public places where travellers are likely to go; many a journey that would have been enjoyable with this evil removed has been completely spoiled by its presence.

From the moment when you touch Egyptian soil till the moment when you leave it there is little rest from the appeals of the beggar, and the demands, often insolent, of those who force themselves and their services upon you. The word "backsheesh" (a present) is dinned into your ears from morning till night; it is with you in your dreams, and if your digestion is bad you will have visions of howling Arabs who beset you for money, and will not be satisfied. Giving does no good; in fact it is worse than not giving at all, as the suppliant generally appeals for more; and if he does not do so he is sure to give the hint to others who[Pg 49] swarm about you, and refuse to go away. If you hire a donkey or a carriage, and give the driver double his fare, in order to satisfy him, you find you have done a very unwise thing. His demand increases, a crowd of his fellows gather around, all talking at once, and there is an effort to convince you that you have not given half enough. Not unfrequently your clothes are torn in the struggle, and if you escape without loss of money or temper you are very fortunate.

The railway-station at Cairo is an excellent place to study the character of the natives, and to learn their views regarding the money of others, and the best modes of transferring it to their own pockets.

From the station our friends drove through the new part of Cairo, where the broad streets and rows of fine buildings were a disappointment to the youths, who had expected to see quite the reverse.

"Don't be impatient," said the Doctor, "we shall come to the narrow streets by-and-by. This part of Cairo is quite modern, and was constructed principally under Ismail Pacha a few years ago. He had a fancy for making a city on the plan of Paris or Vienna, and giving it the appearance of the Occident instead of the Orient. In place of the narrow and sometimes crooked streets of the East he caused broad avenues to be laid out and tall buildings to be erected. The new city was to stand side by side with the old one, and for a time it seemed as though the Eastern characteristics of Cairo would be blotted out. But the money to carry on the improvements could not be had, and the new part of Cairo has an unhappy and half desolate appearance. The natives preferred the old ways, and there was not a sufficient influx of foreigners to populate the new city. It had grown rapidly for a few years, but suddenly its growth was suspended, and here it has been ever since."

They passed several public and private buildings that would have done honor to any European city, and if it had not been for the natives walking in the streets, riding on donkeys, or now and then conducting a stately camel, they might easily have believed themselves far away from Egypt. Suddenly the scene changed; they passed the new theatre, where Ismail Pacha delighted to listen to European operas performed by European companies; they crossed the triangle known as the Square of Ibrahim Pacha, and containing a bronze statue of that fiery ruler; and by a transition like that of the change in a fairy spectacle, they were in one of the crowded and shaded streets of the City of the Caliphs. They had entered the "Mooskee," one of the widest and most frequented streets of the part of Cairo that has not succumbed to Western innovations, and retains enough of its Eastern character to remain unpaved.

The speed of their carriage was reduced, and a boy who had been riding at the side of the driver jumped down, and ran ahead shouting to clear the way. The boys thought they were travelling in fine style to have a footman to precede them, but the Doctor told them it was the custom of the country to have a runner, called a "syce," to go before every carriage, and clear the way for it. The syce carried a stick as the badge of his office, and when he was in the employ of an official he had no hesitation in striking right and left among those who were in the way.[Pg 51] High officials and other dignitaries employed two of these runners, who kept step side by side, and were generally noticeable by the neatness of their dress. No matter how fast the horses go the syce will keep ahead of them, and he does not seem at all fatigued after a run that would take the breath out of an American.

They met other carriages; they met camels and donkeys with riders on their backs, or bearing burdens of merchandise, and they passed through crowds of people, in which there were many natives and some Europeans. The balconies of the houses projected over the street, and in some places almost excluded the sunlight, while their windows were so arranged that a person within was entirely concealed from the view of those without. The boys observed that the carving on the windows revealed a vast amount of patience on the part of the workmen that executed it, and they wondered if all the windows of Cairo were like those they were passing. Some of the walls were cracked and broken, as though threatening to fall; but the windows appeared so firmly fixed in their places that they would stay where they were when the rest of the building had tumbled.

While they were engrossed with the strange sights and sounds around them, the carriage halted at the head of a narrow lane, and our three friends descended to walk to the hotel.

Frank and Fred were up in good season on the morning after their arrival in Cairo. While waiting for breakfast they read the description of the city, and familiarized themselves with some of the most important points of its history, which they afterward wrote down to make sure of remembering them. Here is what they found:

"The city known as 'Cairo' (Ky-ro) to Europeans is called Masr-el-Kaherah by the Arabs, the word Kaherah meaning 'victorious.' It was founded about the end of the tenth century by a Moslem general who had been sent from Tunis to invade Egypt; he signalled his victory by building a city not far from Fostat; the latter is called Masr-el-Ateekah, or Old Cairo, and was formerly the capital; but the new city grew so fast that it became the capital very soon after it was founded. It has gone through a good many sieges, and had a prominent place in the history of the Crusades; the great Moslem conqueror, Yoosef Salah-ed-Deen (known to us as Saladin), built strong walls around Cairo, and founded the citadel on the hill at the southern end. The city is about two miles broad by three in length, and stands on a plain overlooked by the range of the Mokattam Hills; the new quarter of Ismaileeyah was recently added, and when that is included, the Cairo of to-day will be nearly twice the extent of the city of fifty years ago. Cairo was the city of the Caliphs, or Moslem rulers, down to 1517; from that time till it was captured by the French, in 1798, it was the chief city of the Turkish province of Egypt. The French held it three years, when it was captured by the Turks and English; ten years later Mohammed Ali became an almost independent ruler of the country, and from his time to the present Egypt has been ruled by his family, who pay an annual tribute to Turkey, and are required to do in certain things as they are ordered by the Sultan. Cairo is still the capital of Egypt; the Viceroy or Khedive lives there except during the hottest part of summer, when he goes to Alexandria, where he has a palace.

"The word 'Khedive' comes from the Persian language, and means 'ruler' or 'prince.' It was adopted by Ismail Pacha, and continued by his successor; the English word which is nearest in meaning to Khedive is 'Viceroy,' and the head of the Egyptian government is generally called the Viceroy by Europeans. He should be addressed as 'Your Highness.'

"Some of the most interesting stories of the 'Arabian Nights' Entertainments' are laid in Cairo, and the reader of those anecdotes will learn from them a great deal of the manners of the times when they were written. We are told that the translation by Edward William Lane is the best. Lane was an Englishman, who was a long time in Cairo. He learned the language of the people, wore their dress, and lived among them, and he wrote a book called 'The Modern Egyptians,' which describes[Pg 54] the manners and customs of the inhabitants of Cairo better than any other work. When we are in doubt concerning anything, we shall consult 'The Modern Egyptians' for what we want. Lane's translation of the 'Arabian Nights' occupied several years of his time, and was mostly made while he lived in Cairo. We have read some of these stories, and find them very interesting, and often envy Aladdin, with his wonderful lamp and his magic couch, and would very much like to sit down with Sinbad the Sailor and listen to the account of his adventures.

"There are so many things in Cairo which we want to see that we will not try to make out a list in advance. We have engaged a guide to show us around, and shall trust to him for a day or two. At the end of that time we hope to know something about the city, and be able to go around alone."

Every evening, while the boys were in Cairo, was devoted to the journal of their experiences during the day. They have allowed us to copy from it, and we can thus find out where they went and what they did. As there were so many things to describe the labor was divided, and while Frank was busy over one thing, Fred occupied himself with another. Let us see what they did:

"It is the custom to ride on donkeys when going about Cairo, as many of the streets are so narrow that you cannot pass through them with carriages. We had the best we could secure, and very nice they were under the saddle, but we soon learned that it required some skill to ride them. The guide rode ahead, and we noticed that he did not put his feet in the[Pg 55] stirrups as we did; while we were wondering the meaning of it, Frank's donkey stumbled and fell forward, and Frank went sprawling in the dust over the animal's head.

"We all laughed (Frank did not laugh quite as loud as the rest, but he did the best he could), and so did the people in the street where the accident happened. Frank was up in an instant, and so was the donkey; and when we were off again the guide said that the donkey had a habit of stumbling and going down in a heap. If you have your feet in the stirrups when he goes down, you can't help being thrown over the animal's head; but if you ride as the guide does, your feet come on the ground when the donkey falls, and you walk gracefully forward a few steps till the boy brings your animal up for you to mount again.

"We immediately began learning to ride with our feet free, and an hour's practice made us all right.

"The donkeys all have names, generally those that have been given to them by travellers. We have had 'Dan Tucker,' 'Prince of Wales,' 'Chicken Hash,' and 'Pinafore,' and in the lot that stands in front of the hotel there are 'General Grant,' 'Stanley,' 'New York,' and 'Mince Pie.' They are black, white, gray, and a few other colors, and sometimes the boys decorate them with hair-dye and paint so that they look very funny. The donkey-boys are sharp little fellows, though sometimes they keep at the business after they have become men. They generally speak a little English; there are two at our hotel that speak it very well, and know the city perfectly, so that when we take them along we have very little need of a guide. They will run all day as fast as the donkey can, sometimes holding him by the bridle, but generally close behind, ready to prod or strike him if he does not go fast enough.

"The saddle is a curious sort of thing, as it has a great hump in front instead of a pommel, and there is not the least support to the back any more than in an English riding-pad. They explain the peculiarity of the saddle by saying that the donkey's shoulders are lower than his back, and the hump keeps you from sliding forward.

"About the best thing we have yet seen in Cairo is the people in the streets. They are so odd in their dress, and they have so many curious customs, that our attention is drawn to them all the time. We can't say how many varieties of peddlers there are, but certainly more than we ever saw in any other place, not excepting Tokio or Canton, or any of the cities of India. We will try to describe some of them.

"Here is an old woman with a crate like a flat basket, which she[Pg 56] carries on her head. It is filled with little articles of jewellery, and she goes around in the harems and in the baths frequented by women, as they are her best customers. The guide says her whole stock is not worth a hundred francs, and if she makes a franc a day at her business she thinks she is doing well.

"There are women who sell vegetables, fruits, and sweetmeats, which they carry in the same way as the one we have just described. They are wrapped from head to foot in long cloaks or outer dresses, and they generally follow the custom of the country and keep their faces covered. The oldest of them are not so particular as the others, and we are told that the custom of wearing the veil is not so universal as it was twenty or thirty years ago.

"There is no change of fashion among the women of Egypt. They wear the same kind of garments from one year to another, and as all are veiled, except among the very poorest classes, they all look alike. Every lady, when she goes out, covers her face with the yashmak or veil, so that only her eyes are visible; her body is wrapped in a black mantle which reaches the ground, and, though she looks at you as if she knew you, it is impossible to penetrate her disguise. We are told that when the European ladies residing here wish to call on each other, and have nobody to escort them, they put on the native dress, and go along the streets without the least fear that anybody will know them.

"The wives of the high officials have adopted some of the fashions of Europe in the way of dress; they wear boots instead of slippers, and have their dresses cut in the Paris style, and they wear a great deal of jewellery mounted by Parisian jewellers. Their hats or bonnets are of European form; but they cling to the veil, and never go out-of-doors without it, though they often have it so thin that their features can be seen quite distinctly. We have seen some of them riding in their carriages,[Pg 57] and if they had been friends of ours we think we should have recognized them through their thin veils.

"How much we wish we could understand the language of the country! Doctor Bronson says the peddlers on the streets have a curious way of calling out their wares, quite unlike that of the same class in other countries. For instance, the water-carrier has a goat-skin on his back filled with water, and as he goes along he rattles a couple of brass cups together, and cries out, 'Oh ye thirsty! oh ye thirsty!' A moment after he repeats the call, and says, 'God will reward me!' And sometimes he says, 'Blessed is the water of the Nile!' Those who drink the water he offers usually give him a small piece of money, but if they give nothing he makes no demand, and moves on repeating his cry.

"The seller of lemons shouts, 'God will make them light, oh lemons!' meaning that God will lighten the baskets containing the lemons. The orange peddler says, 'Sweet as honey, oh oranges!' And the seller of roasted melon-seeds says, 'Comforter of those in distress, oh melon-seeds!' Behind him comes a man selling flowers of the henna-plant, and his cry is, 'Odors of Paradise, oh flowers of henna!' The rose-merchant says, 'The rose is a thorn—it bloomed from the sweat of the Prophet!' We could make a long list of these street cries, but have given you enough to show what they are.

"Every few steps we meet women carrying jars of water on their heads.

Many of the houses are supplied in this primitive way, and the

employment of carrying water supports a great many people in this

strange city of the East. Of late years pipes have been introduced, and

an aqueduct brings water from[Pg 58]

[Pg 59] the Nile, so that the occupation of the

bearer has been somewhat diminished. But the public fountain still

exists, and the people gather there as they did in the days of the

Bible. Every mosque has a fountain in the centre of its court-yard, not

so much for supplying water for those who wish to carry it away as to

furnish an opportunity for the faithful to wash their hands before

saying their prayers. Some of these fountains are large, and protected