Emancipated! v

Title: Revolted Woman: Past, present, and to come

Author: Charles G. Harper

Release date: December 19, 2018 [eBook #58496]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Wayne Hammond and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

i

ii

iii

iv

LONDON:

Printed by Strangeways and Sons,

Tower St., Cambridge Circus, W.C.

vii

viii

ix

It might have been supposed, having in mind her first and most stupendous faux pas, that Woman would be content to sit, for all time, humbly under correction, satisfied with her lot until the crack of doom, when man and woman shall be no more; when heaven and earth shall pass away, and pale humanity come to judgment.

But it is essentially feminine, and womanlike (and therefore of necessity illogical) that she should be forgetful of the primeval curse which Mother Eve brought upon the race, and that she should, instead of going in sackcloth and ashes for her ancestor’s disobedience, seek instead, not only to be the equal of man, but, in her foremost advocates—the strenuous and ungenerous females who periodically crucify the male sex in sexual novels written under manly pseudonyms—aspire to rule him, while as yet she has no efficient control over her own hysterical being. x

Humanity is condemned by the First Woman’s disobedience to earn a precarious livelihood by the sweat of its brow. All the toil and trouble of this work-a-day world proceed from her sex; and yet the cant of ‘Woman’s Mission’ fills the air, and the New Woman is promised us as some sort of a pedagogue who shall teach the ‘Child-Man’ how to toddle in the paths of virtue and content. How absurd it all is, when the women who write these things pander to the depraved palate which gained Holywell Street a living and an unenviable notoriety years ago; when they obtain three-fourths of their readers from their fellow-women who read their productions hopeful of indecency, and conceive themselves cheated if they do not find it. Let us, however, do these women writers, or ‘Literary Ladies,’ as they have labelled themselves—margarine masquerading as ‘best fresh’—the justice to acknowledge that they do not halt half-way on the road to viciousness, though to reach their goal they wade knee-deep in abominations. Here, indeed, they are no cheats, and it remains the unlikeliest sequel that you close their pages and yet do not find Holywell Street outdone.

Consider: If morals are to be called into question, xi can it be disputed that, as compared with Woman, Man is the moral creature, and has ever been, from the time of Potiphar’s wife, up to the present?

Woman is the irresponsible creature who cannot reason nor follow an argument to its just conclusion—who cannot control her own emotions, nor rid herself of superstition. What question more pertinent, then, to ask than this: If mankind is to be led by the New Woman, is she, first of all, sure of the path?

| I. | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| WOMAN UP TO DATE | 1 |

| II. | |

| THE DRESS REFORMERS | 28 |

| III. | |

| WOMAN IN ART, LITERATURE, POLITICS, AND SOCIAL POLITY | 45 |

| IV. | |

| SOME OLD-TIME TERMAGANTS AND ILL-MADE MATCHES OF CELEBRATED MEN | 61 |

| V. | |

| DOMESTIC STRIFE | 109 |

| VI. | |

| WOMEN IN MEN’S EMPLOYMENTS | 130 |

xiv

xv

xvi

1

REVOLTED WOMAN

‘Certain Women also made us astonished.’—Luke, xxiv. 22.

She is upon us, the Emancipated Woman. Privileges once the exclusive rights of Man are now accorded her without question, and, clad in Rational Dress, she is preparing to leap the few remaining barriers of convention. Her last advances have been swift and undisguised, and she feels her position at length strong enough to warrant the proclamation that she does not merely claim equal rights with man, but intends to rule 2 him. Such symbols of independence as latch-keys and loose language are already hers; she may smoke—and does; and if she does not presently begin to wear trousers upon the streets—what some decently ambiguous writer calls bifurcated continuations!—we shall assume that the only reason for the abstention will be that womankind are, generally speaking, knock-kneed, and are unwilling to discover the fact to a censorious world which has a singular prejudice in favour of symmetrical legs.

Society has been ringing lately with the writings and doings of the pioneers of the New Woman, who forget that Woman’s Mission is Submission; but although the present complexion of affairs seems to have come about so suddenly, the fact should not be blinked that in reality it is but the inevitable outcome, in this age of toleration and laissez faire, of the Bloomerite agitation, the Women’s Rights frenzy, the Girl of the Period furore, and the Divided Skirt craze, which have attracted public attention at different times, ranging from over forty years ago to the present day.

Several apparently praiseworthy or harmless movements that have attracted the fickle enthusiasm of women during this same period have really been byways of this movement of emancipation. Thus, we have had the almost wholly admirable enthusiasm for the Hospital Nurse’s career; the (already much-abused) profession of Lady Journalist; the Woman 3 Doctor; the Female Detective; the Lady Members of the School Board; and the (it must be allowed) most gracious and becoming office of Lady Guardian of the Poor.

Side by side, again, with these, are the altogether minor and trivial affectations of Lady Cricketers, the absurd propositions for New Amazons, or Women Warriors, who apparently are not sufficiently well read in classic lore to know what the strict following of the Amazons’ practice implied; nor can they reck aught of the origin of the Caryatides.

Again, the Political Woman is coming to the front, and though she may not yet vote, she takes the part of the busybody in Parliamentary Elections, and already sits on Electioneering Committees.

In this connexion, it should not readily be forgotten that Mrs. Brand earned her husband the somewhat humiliating reputation of having been sung into Parliament by his wife at the last election for Wisbech, and thus gave the coming profession of Women Politicians another push forward. The dull agricultural labourers of that constituency gave votes for vocal exercises on improvised platforms in village school-rooms, nor thought of aught but pleasing the lady who could sing them either into tears with the cheap sentimentality of Auld Robin Grey, melt them with the poignant pathos of ‘Way down the Swanee River’, or excite their laughter over the equally ready humour of the latest soi-disant 4 ‘comic’ song from the London Halls. Think upon the most musical, most melancholy prospect thus opened out before our prophetic gaze! What matter whether you be Whig or Tory, Liberal or Conservative, Rotten-Tim-Healeyite, or a member of Mr. Justin MacCarthy’s tea-party, so long as your wife can win the rustics’ applause by her singing of such provocations to tears or laughter as The Banks of Allan Water or Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay, or whatever may be the current successor of that vulgar chant?

But the so-called ‘New Purity’ movement, and novel evangels of that description, most do occupy the attention of the modern woman who is in want of an occupation.

We smile when we read of the proceedings of Mrs. Josephine Butler and her following of barren women who are the protagonists of the New Purity; for woman has ever been the immoral sex, from the time of Potiphar’s wife to these days when the Divorce Courts are at once the hardest worked in the Royal Courts of Justice, and the scenes of the most frantic struggles on the part of indelicate women, who, armed with opera-glasses and seated in the most favourable positions on Bench or among counsel, gloat over what should be the most repellent details in this constant public washing of dirty private linen, and survey the co-respondents with delighted satisfaction. The intensity of the joy shown by those 5 who are fortunate enough to obtain a seat in court on a more than usually loathsome occasion is only equalled at the other extreme by the poignancy of regret exhibited by those unhappy ladies who have been unsuccessful in their scheming to secure places.

And, again, the reclamation of corrupt women, if not impossible, is rarely successful, for ‘woman is at heart a rake,’ and, as Ouida says, who has, one might surmise, unique opportunities of knowing, she is generally ‘corrupt because she likes it.’ Thus, throughout the whole range of history, Pagan or Christian, courtesans have never been to seek. They have, these filles de joie, always succeeded in attracting to themselves wealth and genius, luxury and intellect; and through their paramount influence, Society at the present day is corrupt to extremity. The Evangelists of the New Purity, who hold that the innate viciousness of man is the cause of woman’s subjection and inferiority, can have no reading nor any knowledge of the world’s history while they continue to proclaim their views; or else they know themselves, even as they preach, for hypocrites. For woman has ever been the active cause of sin, from the Fall to the present time, and doubtless will so continue until the end. It is not always, as they would have you believe, from necessity that the virtuous woman turns her back upon virtue, but very frequently from choice and a delight in sin and wrong-doing. How then 6 shall the New Purity arise from the Old Corruption?

‘Who can find a virtuous woman?’ asks Solomon (Prov. xxxi. 10), and goes on to say that her price is far above rubies: doubtless for the same reason that rubies are so highly valued—because they are so scarce.

The trade of courtesan has always been numerous and powerful, and has been constantly recruited from every class. Vanity, of course, is the great inducement; love of dress and power, and greed of notoriety, are other compelling forces; and a joy in outraging all decency and propriety, of defying conventions of respectability and religion, is answerable for the rest.

This kind of woman makes all mankind her prey, and has no generous instincts whatever. Everything ministers to her vanity and lavish waste. It is a matter of notoriety that men of light and leading are drawn after her all-conquering chariot, and that in three out of every four plays she is the heroine.

She is cruel as the grave, heartless as a stone, and extravagant beyond measure. Her kind have utterly wasted the patrimony of thousands of dupes, and having reduced them to beggary the most abject and forlorn, have sought fresh victims of their insatiable greed.

They have ruined kingdoms, like the mistresses of Louis XIV. and XV. of France; they have brought shame and dishonour upon nations, like 7 the dissolute women of Charles the Second’s court, who toyed with his wantons at Whitehall while the Dutch guns thundered off Tilbury; they have risen, like Madame de Pompadour, to a height from which they looked down upon diplomatists of the Great Powers of Europe—and scorned them; and the blood shed during many sanguinary wars has been shed at their behest. Courtesans have married into the peerage of England, and, indeed, some of the oldest titles—not to say the bluest blood—of the three kingdoms derive from the king’s women: Nell Gwynne, whose offspring became Duke of Saint Albans; Louise de Querouaille, created Duchess of Portsmouth; Barbara Palmer, made Duchess of Cleveland; and others. Lais and Phryne belong not to one period, but to all eras alike; Aspasias and Fredegondas are of all countries and of every class.

But ‘pretty Fanny’s ways’ are many and diverse. It may be that she is incapacitated or restrained from living as full and as free a life as she could wish. Very well: then she becomes a New Puritan, whose self-appointed functions are to those privy cupboards in which repellent skeletons are concealed; to the social sewers; and, in fine, to all those places where she can gratify the morbid curiosity which actuates the New Puritanical mind, rather than the hope of, or belief in, achieving anything for the benefit of the race.

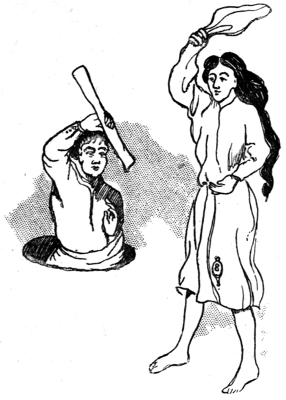

If she has no wish to become a New Puritan, 8 there be many other modern fads in which she may fulfil a part. She may, as a New Traveller, show us the glory of the New Travel, in the manner of that greatly daring lady, the intrepid Mrs. French-Sheldon, who, travelling at the heels of the masculine explorers of African wilds (carried luxuriously in a litter, accompanied with cases of champagne and a large escort of Zanzibari porters), went forth to study the untutored savage in his native wilds. But when the untutored presented themselves before this up-to-date traveller unclothed as well as unread, that very properly-tutored lady screamed, and distributed loin-cloths to these happy and yet unabashed primitives. She delivered an address before the British Association on her return from that unnecessary and futile expedition, in which she tickled the sensibilities of the assembled savants by describing how she kept her hundred and thirty Zanzibari coolies in order with a whip. She told the members of the Association that ‘she went into Africa with all delicacy and womanliness.’ Possibly; but judging her out of her own mouth, she must have left a goodly portion of those qualities behind her in the Dark Continent.

Other women travellers—of the type of Miss Dowie, for instance—are more unconventional, if less adventurous. She, a true exemplar of the women who would forget their sex—and make others forget it—if they could, climbed the Karpathian mountains in search of a little cheap 9 notoriety, clad in knickerbockers, jacket, and waistcoat, and redolent of tobacco from the smoking of cigarettes. Her adventures added nothing to the gaiety of readers, nor to the world’s store of science; but we were the richer by one more spectacular extravaganza.

This is that somewhat repellent type, the mannish woman, who is not content to charm man by the grace and sweetness of her femininity, but must aspire to be a poor copy of himself. The type is common nowadays, and the individuals of it have gone through several phases of their singular craze. These are they who walk with the guns of a shooting party; who tramp the stubble and arouse the ill-humours of that creature of wrath and impatience, the sportsman who is eager for a drive at the birds. These women, not dismayed by the butchery of the battue, look on, and even carry a gun themselves; but they are the nuisances of the party, and flush covey after covey by showing themselves to the wary birds when they should be crouching down beside some windy hedge, in a moist and clammy October ditch.

‘Let us be unconventional, or we die!’ is the unspoken, yet very evident, aspiration of the Modern Woman; and, really, the efforts made in the direction of the unconventional are so uniformly extravagant that we almost, from sheer weariness and disgust, begin to wish she had gone some way toward adopting the alternative. 10

The New Woman will know naught of convention, nor submission. Her advocates do not hail from Altruria; they are aggressive, and devoured with a zeal for domination, in revolt from the ‘centuries of slavery’ to which, according to themselves, they have been compelled by Man. ‘Man,’ shrieks one, ‘is always in mischief or in bed.’ But she will have this changed; not, indeed, in the present generation of vipers, which is stubborn and stiff-necked in its wicked ways; but she will see, and urges her fellow-women to see also, that proper principles are spanked into the coming generations. Considering, however, that the nursery has ever been the woman’s peculiar province, surely the blame, if blame there be, must rest with her for the past and present faulty upbringing of the race. If ‘proper principles’ have not already had their part in the education of man, surely that must be owing solely to woman’s flagrant dereliction of duty.

Instances, neither few nor far between, may be urged of wives and mothers, possibly also sisters and maiden aunts, who have raised men to action and dragged them from a disgraceful sloth to an honourable industry. True, indeed, it were an altogether unjustifiable heresy to deny their influence and its beneficent effects; but to use it as an argument for placing women on an equality with men would be a non sequitur of the most absurd description. The influence wielded by those good women was so powerful for good because they were true 11 to themselves and their sex; because they were, in a word, so womanly. The influence of the New Woman upon the man is, and shall be, nil, because the spirit of antagonism between the sexes is being aroused by her pretensions, and comradeship becomes impossible when woman and man fight for supremacy.

Women’s advocates come and go like summer flies, provoking to wrath by their insistent buzzing, but, when caught and examined, proving to be insignificant enough. They have their little day, and cease to be. Who, for instance, now remembers Mrs. Mona Caird, that unconventional person who floated into publicity on the ‘Marriage a Failure’ correspondence of the Daily Telegraph, some few years ago, and, in the heyday of her notoriety, wrote and published that weak and ineffectual novel, The Wing of Azrael? Other women, more advanced in shamelessness, have taken her place, and capped the freedom of her views with outlooks of greater licence.

And so the game proceeds: each woman daring a little further than her fellow-adventurer into the muddy depths of free selection; of freedom in contracting marriages and licence in dissolving them; each newcomer shocking the sensibilities of women readers with delightful thrills from the impropriety, expressed or implied, that runs through her pages as inevitably as the watermark runs through ‘laid’ paper. 12

It is amusing to note that, following the lead of the late lamented George Eliot, the greater number of these women writers of sexual novels scribble under manly pseudonyms. What, then! doth divinity after all hedge a man so nearly that to masquerade as a ‘John Oliver Hobbes,’ or a ‘George Egerton,’ is to draw an admiring crowd of women worshippers where, as plain Miss or Mrs., your immortal writings would fall flat? What a deplorable cacoëthes imprimendi this is, to be sure, that seizes upon the palpitating authoresses of Yellow Asters, Dancing Fawns, or Heavenly Twins; and how depraved the taste for indelicate innuendo and theories of licence that renders these books popular!

This manner of thing destroys all the respect for home life upon which English society was, until late years, so broadly based, and domesticity in consequence is become an old-fashioned virtue among women. They are only the older generation of matrons who practise it now, and when their race is run, and the New Woman shall have become sole mistress, the sweet domesticity of the Englishman’s home will have vanished.

For the New Woman is not womanly, except in the physiological sense, and there she cannot help herself. She will inevitably be the mother of the coming generation, but beyond that function imposed upon her by Nature, she is not feminine. She is rather what Mr. Frederic Harrison describes as the ‘advanced woman who wants to be abortive 13 man,’ and she holds the fallacy that what man may do woman may do also—and more!

Directly a woman marries, she considers that she has full licence; although, goodness knows! the unmarried girls of to-day are latitudinarian enough, and do, unreproved, things that thirty years ago would have branded them with an ineffaceable mark of shame.

The pretty girl of to-day, who has earned her right to wear a wedding-ring, has no sooner returned from her honeymoon than she sets out upon a campaign of conquests. Smart men, who hate to be bored with the unmarried girl, before whom they must be either silent or discreet, hang around the young matron at garden parties and dances, or flirt shamefully in the semi-rusticity of the country house or shooting-box, and discuss with her the latest veiled obscenity of Mr. Oscar Wilde’s, or enlarge upon the ethics of a second Mrs. Tanqueray with an unblushing frankness that argues long acquaintance with and study of these putrescent topics. The young matron has full licence at this day, and the divorce courts afford some faint inkling of how she uses it. She aspires to be the boon companion of the men; she plays billiards with the manly cue, and not infrequently she can give the average male billiard-player points, and then beat him.

It seems but a few years since when women who smoked cigarettes were voted fast: to-day, the smoking-room of the country house is not sacred to 14 the male sex, and the ‘good stories’ of that sometime exclusively masculine retreat are now not alone the property of the men. She has not annexed the cigar and the pipe yet—not because she lacks the will, but her physique is not yet equal to them; but she can roll a cigarette, can take or offer a light with the most practised and inveterate smoker who ever bought a packet of Bird’s Eye or Honey Dew, and she wears—think of it, O Mrs. Grundy, if, indeed, you are not dead!—a smoking-jacket.

At the more ‘advanced’ houses, amongst the ‘smartest’ sets, the women do not retire to the drawing-room at the conclusion of dinner—they sit with the men, not infrequently; and if the usual not over-Puritanical talk that was wont to follow upon the ladies’ withdrawal is not indulged in so openly, at least the conversation is sufficiently unconventional.

Slang and swearing are the commonest—in two senses—accompaniments and underlinings of the smart woman’s speech: any little disappointment that would have been ‘annoying’ to her mother is to the modern and up-to-date woman a ‘condemned nuisance,’ if not more than that; and ‘damns’ fall as readily from her lips as the mild ‘dear me!’ of a generation ago. For the first cause of this unlovely change we must look to the theatre and music-hall stages, whose women have in some few instances married the eldest sons of peers, and have succeeded to titles upon their husbands’ heirship being fulfilled. 15 Their husbands’ titles have given them rank and precedence, whose mothers toiled at the wash-tub in some public laundry, or disputed not unsuccessfully with the most foul-mouthed of Irish viragoes on the filthy stairs of some rotten tenement in the purlieus of Saint Giles’s. The symmetry of their legs and the voluptuousness of their persons captivated the callow youths who night by night occupied the front rows of the stalls at the Gaiety Theatre, and who—under the well-known nickname of ‘Johnnies’—fed the Sacred Lamp of Burlesque with a stream of half-guineas. These heirs to wealth and hereditary honours kept the chorus-girls and skipping-rope dancers in broughams and villas ornées in the classic Cyprian suburb of St. John’s Wood, and, when they were more than usually foolish, married them.

Society is become, through them, quite demimondaine, and it is not uncommon to have pointed out to you in the Row titled women who have notoriously been under the protection of more than one man before they, by some lucky or unlucky chance, caught their coronets. Nearly all Society is free to-day to these whited sepulchres; only the Queen’s Court—that last bulwark of virtue and decency—holds out against them. Elsewhere they are more than tolerated; it is scarcely too much to say that they are admired by fin-de-siècle womanhood, who are notoriously and obviously Jesuitical. If the adaptation of their outrés manners is proof enough of admiration, then you shall find sufficient 16 warranty for this statement, for the slangy girl or young married woman is rather the rule than the exception in this year of grace, and their manners are arrived at that complexion which would make their grandmothers turn in their graves, could that cold clay become sentient again for the smallest space of time.

This decay of decency began with the advent of that loathsome amalgam of vanity and reckless extravagance in dress and speech, the Professional Beauty, whose profession first became recognised about the year 1879. You will not find that ‘profession’ entered under ‘Trades’ in the Post-Office Directory; but if logic ruled the world, then the shameless women whose photographs for years filled the shop-windows of town would find their trade recognised on the same commercial standing with any one of the thousand and one ways of getting a living shown in that volume. They would be on precisely the same moral level with the quasi milliners of London, had necessity brought about their flaunting pervasion of Society, but, seeing that merely the love of admiration and notoriety induced their careers, it is difficult to find a depth sufficiently deep for them.

But indignation is apt to melt into a scornful pity when we see the Professional Beauty of sixteen years ago, who left her husband for the questionable admiration of great Personages and the envy of London Society, a faded and struggling woman of 17 the world, who, without a shred of histrionic ability, has taken to the stage, relying upon the magnificence of her diamonds and the abandon of her dress for an applause which had never been hers for her acting or her elocution. A just resentment fades into melancholy commiseration for a woman like this, who has sunk so low that scandal can no longer harm her; who essays the rôle of ‘beauty’ when her years are rapidly totting up to fifty.

These are the tawdry careers which, appealing to woman’s innate love of admiration, bid her go and do likewise. The contempt with which all right-thinking men regard the spotted and fly-blown records of the Professional Beauties is hidden from them by the glare of publicity, and vanity still bids them adventure out from the home before the eye of the world.

One does not find the New Women justified of their sex, for cosmetics have no commerce with common sense, and high heels are not conducive to lofty thinking; rouge, violet powder, tight-lacing, or an inordinate love of jewellery, are not earnest of brain-power; and yet these are the commonest adjuncts to, or characteristics of, a woman’s life.

The sight of many diamonds at Kimberley impressed Lord Randolph Churchill mightily awhile ago, and the contemplation of those glittering objects of feminine adornment led to the historic pronouncement that ‘whatever may have been the origin of man,’ he is ‘coldly convinced that womankind 18 are descended from monkeys.’ However that may be, certain it is that imitation is, equally with the simians, her forte. Men originate almost everything; even the fashions are set and controlled by M. Worth, and women follow his lead, both dressmakers and clients.

And Woman is a consistent and inveterate poseur, from the time of her leaving the cradle, through girlhood, young-womanhood, and matron-hood, to her last gasp. That tale of the old lady, dying from extreme age and decay of nature, who had her face rouged over against the arrival of her doctor, so that she should receive him to the best effect as she lay on her death-bed, is characteristic of her sex. Vanity, thy name is woman!

Could we but see her without her ‘side’! But we cannot. All the world’s a stage to her, and all the time she plays a part with an ineffable artistry of diplomacy beyond the understanding of a Richelieu or a Machiavelli. A statesman can frequently anticipate the ruses of a rival diplomat and thus check his schemes—because, being men, they both reason from a given point and can understand very accurately the workings of each other’s minds; but how shall one understand woman or predicate her actions when she does not understand herself or her fellow-feminines, and acts on the moment upon unreasoned impulse and pure caprice?

You may point to this and that feminine figure which has made an equable and logical course 19 throughout her career, and exclaim triumphantly, ‘Here is the natural woman, without guile or self-consciousness: a logical and close-reasoning creature.’ Well, you are welcome to your opinion, pious, or derived from what shall seem to you as evidence sufficient for your contention. Hold it, nor inquire more narrowly, nor seek proselytes to your faith. The natural woman? My dear sir, how should your matter-of-fact and obvious nature distinguish the excellently-fashioned and well-assumed mask from the natural face? Summum ars—— you know the rest. Ponder it, nor prate glibly of natures, good sir!

Conceive of the dreadfully unreal puppets the novelists have created and labelled with feminine names. How the machinery creaks and rattles when the puppets move! With what unreal stagger they pace the stage, and how deep below contempt is the unlikeness to womankind of their ways and words.

For the nearest approach to an adequate portrayal of the feminine character, commend me to the women of Mr. Thomas Hardy’s novels, whose mental gyrations are set forth with a touch of inspiration: Bathsheba Everdene, Tess, Viviette, and the uncertain heroine of The Trumpet Major. Their speech has the convincing timbre of their sex; their walk is the true gait, not the masculine tramp that echoes through the pages of most men’s novels; and how truly like nature their tongues say ‘No,’ when their hearts throb ‘Yes, yes!’ 20

They live, these women and girls—they breathe and palpitate with the full tide of life, and no other living novelist can so inform his feminine creations with reality.

But turn to the academic heroines of Mr. Besant. If they were not presented with the subtle suavity of his literary style, I do not know how we could endure the paragons of virtue and learning who occupy the foremost place in book after book that owns him author.

Phillis, in The Golden Butterfly, came as a novelty, but the type perpetuated in each succeeding novel—now as Armorel Rosevean in Armorel of Lyonesse; again, as Angela Messenger in All Sorts and Conditions of Men, and so onwards—is both monotonous and earnest of a poverty of imagination. They would seem to be frankly unreal: an acknowledged Besantine convention—analogous to that early Christian art by which representations of saints, with attendant aureoles, and posing in impossible attitudes, were shown, not as portraitures, but as religious abstractions. These maidens are all sweet and severely proper; as learned as professors and as didactic as lecturers, and they have haloes heavy with gilding. ‘I cannot,’ cries the novelist, in effect, ‘show you the living woman. Consider: how unforeseen her contradictory attitudes and consistent inconsistency.’ And this, after all, is wisdom: to portray your ideal of the sweet girl graduate; to sketch woman as she 21 might be, rather than to fashion an inadequate presentment of woman as she is.

She will have to develop very greatly before she becomes the equal of man, either in mind or muscle; and she will have to slough some singular feminine characteristics if her incursions into masculine walks of life are to be continued. At present she carries her purse in her hand along the most crowded streets, at the imminent risk of its being snatched away. Ask her why she does this, and she will tell you that she has no pockets, or that they are difficult to reach, or else that they are too easily reached by pickpockets. It never occurs to her that the devising of new pockets comes within the range of the dressmaker’s craft. Not that it matters much; for the purse-snatcher obtains little result for his pains, and, beyond some postage-stamps, half a dozen visiting-cards, a packet of needles, and a few coppers, his enterprise usually goes unrewarded.

Woman does not date her correspondence. She has no ‘views’ on the subject; she simply forgets. Sometimes, indeed, she will head her letters with the day of the week; but, as the weeks slip by, a letter written on any ‘Wednesday’ becomes rather vague in date.

Also, it is notorious that the gist of a woman’s letter, the real reason of its being written, appears in a postscript.

Again, it surely does not behove the New Woman to throng the streets in front of the 22 establishments of Mr. Peter Robinson or Madame Louise, in admiring ecstasies over novel cuts and colours, bows and bonnets, and all the feminine accoutrements of fashion. Conceive of men crowding the tailors’ and the haberdashers’ in like manner, and taking equal delight in ‘shopping!’ This last occupation, or rather pastime, of women is a certain sign of mental inferiority. A woman will spend a whole day ‘shopping’—that is to say, in the inspection of goods she does not want and has no intention of buying—and will return home when day is done and count her time well and profitably spent. ‘Shopping,’ as apart from any idea of purchasing, is a recognised form of feminine recreation, as tradesfolk know to their cost. Happy the shopkeeper whose trade does not lend itself to ‘shopping,’ but wretched is he where the vice is rampant. For woman is pitiless and exacting, impervious either to criticism, sarcasm, irony, or innuendo, on occasion; and the more logical the man with whom she contends, so much the more baffling is she to him. So, short of plain and possibly offensive speech (for none so readily or more causelessly offended than your ‘shopper’), the unhappy victims of this mania have no redress, but must continue to heap their counters with bales of cloth and rolls of silk for due examination, and must exhibit a Christian patience and forbearance when the ‘shopper’ departs without purchasing or apologising. 23

No mere man could do this, for such assurance could only proceed from the opposite sex.

A perusal of the advertisement sheets which form the bulk of women’s newspapers and magazines makes for disillusionment and depression; and you would need but little excuse if, after a course of these appeals to feminine love of adornment, you rose from it with a settled conviction that Woman is a Work of Art, padded here, pinched in there, painted, dyed, and carefully made up in every particular. He was, indeed, a philosopher worthy the name (or perhaps it was a more than usually candid woman!) who said that none of the consolations of religion or any pious ecstasies could equal the profound and solemn joy which accompanies a woman’s conviction of her being well dressed and the envy of her fellows.

Here, indeed, is another striking difference between the sexes. A man is happiest when circumstances permit him to don the old clothes which for years have been his only wear in leisure hours: he would wear them while out and about on his business did the convenances permit—so easy and comfortable is the old hat; so well adapted by long use is the old jacket to the form; so easy the bagged and misshapen trousers. But, alas! this may not be, for the world judges a man by his appearance, and it simply does not pay to appear in public otherwise than ‘well dressed.’ For dukes and millionaires ’tis another matter; they can afford to be ‘shabby’ and 24 comfortable, and certainly, whether they manage to attain comfort or not, they generally contrive to appear ill-dressed and dowdy.

Woman is altogether different from and inferior to man: narrow-chested, wide-hipped, ill-proportioned, and endowed with a lesser quantity of brains than the male sex. She will, when sufficiently open to conviction, allow that, mentally, she is not so well equipped as man, but gives herself away altogether in insisting upon the ‘instinct’ that takes the place of reason in her sex; thereby tacitly placing herself on a level with other creatures—like the dog or cat—who act upon ‘instinct’ rather than upon reasoning powers. ‘A woman’s reason’ is a notoriously inadequate mental process; and, having once arrived at a conviction or a determination on any subject, it is of no use attempting to argue her out of it. That is widely acknowledged by the popular saying that ‘it is useless to argue with a woman’

These qualifications, limitations, or defects, as you may variously call them, according to your leanings, explain in great measure the reason why the Liberal and Radical parties in politics hesitate to give women the Parliamentary franchise. Party wirepullers are well aware, putting on one side the small but noisy section of unsexed females who 25 clamour to be in the forefront of all political and social revolutions, that the great majority of women are, by nature and tradition, Tories of the most thorough-going type. They know, also, how hopeless it would be to drive new convictions into their heads, and so, being reasoning creatures, they have hitherto declined to extend the franchise to the sex which would at once swamp their parties throughout the country. The Conservative party, on the other hand, have for some time recognised how useful the women would be in furthering their principles and putting a needful skid upon the wheels of Radical ‘movements;’ and they have voted in favour of Woman Suffrage when that question has come up for discussion from time to time. The wonderful success of the Primrose League, due almost entirely to the personal initiative and enthusiasm of the Dames, opened the eyes of the party to the value of woman as a factor in politics, and if ever she obtains her vote the reform will be the work of the Conservatives. Thus do party needs negative convictions on either side of the House; for what, indeed, are convictions when weighed in the balance against self-interest?

It is a notorious fact among artists and physiologists that the Perfect Woman is of more rare occurrence than the Perfect Man; that it is a matter of extreme difficulty to find a woman whose body is symmetrical and well knit in all its parts. A painter of the nude works, of necessity, 26 from several models, selecting one for her shapely arms, another for her neck, and so on; and so the final work of art in sculpture or painting is always eclectic, and never a portraiture of one woman.

And yet man has always been ready to do battle for her, and to dare death and the Devil himself for her favour. She has, too, continually presumed upon her influence, like the fair lady in the days of chivalry, who threw her glove among the lions of an arena and boasted that her knight would retrieve it for her sake. She did not overrate his courage, but she strained his devotion beyond its strength; for, leaping among the wild beasts, the brave man picked up the glove, and, coming back from the jaws of death, flung it in the woman’s face.

But will men dare the death and slit one another’s weasands for the possession of the New Woman as they have done for the women of the past? I think not. The contempt and incredulity of one sex for the judgment and discrimination of the other, which is chiefly a modern growth induced by woman’s arrogance, is not compatible with suit and service; and, in truth, the enmity between man and woman, shadowed forth in Genesis, is having another lease of life, owing to the fatuous females who cry to-day upon the house-tops.

Mr. Romanes wants us to ‘give her the apple, and let us see what comes of it.’ Heaven forbid: let her pluck it if she has the courage and the power, but let us not earn our own condemnation 27 by inviting her to do so. He is of opinion that ‘the days are past when any enlightened man ought seriously to suppose that, in now again reaching forth her hand to eat of the tree of knowledge, woman is preparing for the human race a second Fall.’ There may be two opinions on this head. Women may occasionally surpass in learning the Senior Wrangler of as good a year as was ever known; they may exercise their brains and their muscles to their utmost tension; but let them not in those cases exercise the natural function of woman and bring children into the world. For nature, which never contemplated the production of a learned or a muscular woman, will be revenged upon her offspring, and the New Woman, if a mother at all, will be the mother of a New Man, as different, indeed, from the present race as possible, but how different the clamorous females of to-day cannot suspect, or surely they would at once renounce the platform and their prospects of the tribune

But it is not to be supposed that even the prospect of peopling the world with stunted and hydrocephalic children will deter the modern woman from her path, even though her modernity lead to the degradation and ultimate extinction of the race. She will raise the old, half-humorous query once more: ‘Why trouble about posterity; what has posterity done for us?’ and thus go her triumphant gait heedless of the second and greater Fall she is preparing for mankind. 28

‘I do not like the fashion of your garments—you will say, they are Persian attire, but let them be changed.’—King Lear.

Modern dress-reform crusades have ever been allied with womanly revolts against man’s authority. They proceeded originally from that fount of vulgarity, that never-failing source of offence—America. In the United States, that ineffable land of wooden nutmegs and timber hams, of strange religions, of jerrymandering and unscrupulous log-rollery, the Prophet Bloomer first arose, and, discarding the feminine skirt, stood forth, unashamed and blatant, in trousers! The wrath of the Bloomers (as the followers of the Prophet were 29 termed) was calculated to disestablish at once and for ever the skirts and frocks, the gowns and miscellaneous feminine fripperies, that had obtained throughout the centuries; and they conceived that with the abolishment of skirts the long-sustained supremacy of man was also to disappear, even as the walls of Jericho fell before the trumpet-sound of the Lord’s own people. For these enthusiasts were no cooing doves, but rather shrieking cats, and they were both abusive and overweening. No more should ‘tempestuous petticoats’ inspire a Herrick to dainty verse, but the woman of the immediate future should move majestically through the wondering continents of the Old World and the New with mannish strides in place of the feminine mincing gait induced by clinging draperies. Away Erato and your sister Muses—if, indeed, your susceptibilities would have allowed your remaining to behold the spectacle! For really, that must have been a ‘sight for sore eyes’— to adopt the expression of the period—the too-convincing vision of a middle-aged woman, proof against ridicule, consumed with all seriousness and an ineffable zeal for converting all and sundry to her peculiar views in the matter of a becoming and convenient attire. And never was prophet less justified of his country than the Bloomer seer of hers; for nakedness, even to undraped piano-legs, was then a reproach in the country of the Stars and Stripes, where legs are not legs, an’t please you, but ‘extremities’ or ‘limbs;’ 30 where trousers are neither more than ‘pantaloons’ nor less than ‘continuations.’ In that Land of Freedom, where one would have outraged all modesty by the merest mention of legs or feet—these last indispensable adjuncts being generally known as ‘pedal extremities’—it surely was illogical in the highest degree that women should wear a species of trouser, and thereby proclaim the indelicate(!) fact to all the world of their possession of legs. Truly Pudicitia is as American a goddess as Mammon is a god!

For the Bloomer costume was nothing else but a travesty of male attire. Aggressiveness is inseparable, it would seem, from all new ideas, and the minor prophets of Bloomerism were aggressive enough, in all conscience. They were not content with wearing the breeches in the literal sense: they sought to convert all womankind to their faith by the writing of pamphlets and the making of speeches on public platforms. Mrs. Ann Bloomer was their fount of inspiration. She it was who introduced the craze to America in 1849. Two years later it had crossed the herring-pond, and that Annus Mirabilis, the year of the Great Exhibition, witnessed a few of its enthusiasts—beldams in breeches—clad in this hybrid garb, walking in London streets. But women refused to be converted in any large numbers, and only a few more than usually impudent females went so far as to back their views by wearing the badges of the cult in public. 31

But although so few Englishwomen were converted to the new dress, and though fewer still had the courage to wear it, the Bloomer agitation was largely noticed in the papers and by the satirists of the time. It was noticed, indeed, in a manner entirely disproportioned to its real import, and the humorous papers, the ballad-mongers, and innumerable private witlings, had their fling at the follies of these early dress-reformers. The Bloomers—unlovely name!—held meetings in London, attended, it must be owned, by crowds of ribald unbelievers; and they even went to the length of holding a ‘Bloomer Ball,’ a grotesque idea hailed with delight by a roaring crowd which assembled ‘after the ball,’ and showed its prejudices by hooting the ridiculous women who had come attired in jackets and trousers like those of the Turk. No Turk, indeed, so unspeakable as they. But the crowd did not stop at this point. They had brought dead cats, decayed cabbages, rotten eggs, and all imaginable articles of offence with which to point their wit, and they used them freely, not only upon the women, but also upon the men who accompanied them. For discrimination was not easy between the sexes in the badly lit streets, when both wore breeches, and at a time when men went generally clean-shaven; and so the rightfully breeched were as despitefully used as the usurpers of man’s distinctive dress.

And so Bloomerism languished awhile and presently died out, but not before a vast amount had 32 been written and printed in its praise or abuse. The satirical effusions which owe their origin to this mania are none of them remarkable for reticence or delicacy. Indeed, the subject did not allow of this last quality, and the broad-sheet verses issued from the purlieus of Drury Lane by the successors of Catnach are, some of them, very frank. Perhaps the best and most quotable is the broad-sheet, I’ll be a Bloomer. The writer, not a literary man by any means, starts off at score, and his first verses, if models neither of taste, rhyme, nor rhythm, are vigorous. It is when the inspiration runs dry, and he relies upon a slogging industry with which to eke out his broad-sheet, that exhaustion becomes evident.

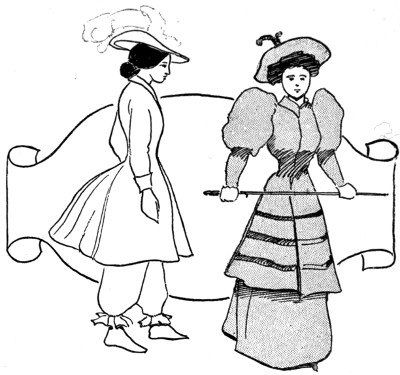

THE BLOOMER

COSTUME, 1851.

Punch had, among other Bloomer skits, the following rather good example:—

The Bloomer agitation was but the beginning of a series of crazes for the reform of women’s dress, and the ‘Girl of the Period’ furore succeeded it, after an interval of several years. True, the Girl of the Period was scarcely a dress-reformer, but her dress and manners were sufficiently pronounced, and certainly her vulgarity could not have been surpassed by the most fat and blowzy Bloomer that ever held forth upon a public platform.

To Mrs. Lynn Linton belongs the honour of having discovered the Girl, and she communicated her discovery to the Saturday Review in 1868. This it was that gave some point to the saying that the Girl of the Period was but the Girl of a Periodical.

And certainly the vulgarity of the Girl of the Period was extremely pronounced. It was a vulgarity that showed itself in bustles and paniers; the ‘Grecian Bend;’ skirts frilled and flounced and hung about with ridiculous festoons, and short enough to display her intolerable Balmoral boots. An absurdly inadequate ‘Rink’ hat rendered her chignon all the 39 more obvious, and ——. But enough! The Man of the Period was her equal in absurdity. He cultivated a hateful affectation of lassitude and indifference; he affected a peculiarly odious drawl, and he taxed his mind with an effort to sustain a constantly nil admirari attitude toward things the most admirable and happenings the most startling. He wore the most ridiculous fashion of whiskers, compared with which the perennial ‘mutton-chop’ and the bearded chin and clean-shaven upper lip of the Dissenter or typical grocer are things of beauty and a satisfaction to the æsthetic sense.

This fashion was the ‘Piccadilly-weeper’ variety of adornment, known at this day—chiefly owing to Sothern’s impersonation of a contemporary lisping fop—as the ‘Dundreary.’ This creature was a fitting mate to the Girl of the Period. He married her, and the most obvious results are the ‘Gaiety-Johnnies,’ the ‘mashers,’ and the ‘chappies’ of to-day, whose retreating chins and foreheads afford subjects for the sad contemplation of philosophers—to whom we will leave them.

As for their female offspring, they are, doubtless, the ‘Lotties and Totties’ of Mrs. Lynn Linton’s loathing, who smoke cigarettes and ape the dress and deportment of the ladies of the Alhambra or the Empire promenades.

It is at once singular and amusing to notice how surely all women’s dress-reform agitations move in the same groove—that of a more or less close 40 imitation of man’s attire. Even fashions which are not ostensible ‘reforms’ have a decided tendency to make for masculinity. The girls who, some few years since, cut their hair short—like the boys; who wore bowler hats, shirt-fronts, men’s collars and neckties; who carried walking-sticks, or that extraordinary combination of walking-stick and sunshade known facetiously as a ‘husband-beater;’ who affected tailor-made frocks, donned man-like jackets, and adopted a masculine gait, were not accredited reformers with a Mission, but they showed, excellently well, the spirit of the age, and if they were wanting in thoroughness, why, Lady Harberton, with her ‘divided skirts,’ was a very Strafford for thoroughness in her particular line.

Divided skirts were introduced to the notice of the public some ten years ago by Viscountess Harberton and a Society of Dress Reformers, calling themselves, possibly on lucus a non lucendo principles, first a ‘National’ Society, and at a later period arrogating the title of ‘Rational.’ It may seem matter for ridicule that an obscure coterie of grandams should adopt such a grandiose title as the first, or that they should, by using the ‘Rational’ epithet, be convicted of allowing the inference that they considered every woman irrational who did not adhere to their principles; but, like all ‘reformers,’ they were without humour and consumed with a deadly earnestness. They (unlike the rest of the world) saw nothing for laughter in the public discussions 41 42 43 which they initiated, by which they sought to show that corsets were not only useless but harmful, and that the petticoat might advantageously be discarded for trousers worn underneath an ordinary skirt, somewhat after the fashion that obtains in riding costumes.

THE RATIONAL

DRESS.

But, for all the pother anent divided skirts, they did not catch on; and a newer rival, another variety of ‘Rational Dress,’ now rules the field, the camp, the grove, but more especially the road. For the popular and widespread pastime of cycling has given this newest craze a very much better chance than ever the Bloomer heresy or the original Divided Skirt frenzy obtained; and it is not too much to say that, if the cycle had not been so democratic a plaything, this latest experiment in dress reform would have been but little heard of. Rational Dress, as seen on the flying females who pedal down the roads to-day, is only Bloomerism with a difference. That is to say, the legs are clothed in roomy knickerbockers down to the knees, and encased in cloth gaiters for the rest, buttoned down to the ankles. These in place of the Turk-like trousers, tied round the ankles and finished off with frills, of over forty years ago. As for the attenuated skirts of the Prophet Bloomer, Rational Dress replaces them with a species of frantic frock-coat, spreading as to its ample skirts, but tightened round the waist. A ‘Robin Hood’ hat, even as in the bygone years, crowns this confection; and, 44 really, the parallels between old-time schismatics and the modern revolting daughters are wonderfully close. Everything recurs in this world in cycles of longer or shorter duration. The whirligig of time may be uncertain in its revolutions, but it performs the allotted round at last; and so surely as yesterday’s sun will reappear to-morrow, as certainly will the crinolines, the chignons, and the Bloomer vagaries of yester-year recur. You may call the recurrent fashions by newer names, but, by any name they take, they remain practically the same. The farthingale of Queen Bess’s time is the crinoline of the Middle Victorian period, and ‘came in’ once more as the ‘full skirt’ of some seasons since. The chignon is resurrected as the ‘Brighton Bun,’ and is as objectionable in its reincarnation as it was in its previous existence; and we have already seen that Rational Dress, Divided Skirts, and the Bloomer costume are but different titles for one fad. The very latest development is not pretty: but there! ’tis ‘pretty Fanny’s way,’ and so an end to all discussion. 45

In these days, when women begin to talk of their Work with all the zeal and religious fervour that characterises the attitude of the savage towards his fetish, it behoves us to inquire what that Work may be which arouses so much enthusiasm and is the cause of the cool insolence which is becoming more and more the note of the New Woman. A very little inquiry soon convinces the seeker after the true inwardness of modern fads and fancies that Woman’s Work—so to spell it in capitals, in the manner dear to the hearts of the unsexed men and women who reckon Adam a humbug and Eve the most despitefully-entreated of her adorable sex—has nothing to do with the up-bringing of children or the management of the home. Those traditional duties are nothing less, if you please, than the slavery which man’s tyranny has imposed upon the physically weaker sex, and are not worthy of sharing the aristocratic prominence of capital letters which the desultory following of arts 46 and sciences has arrogated. Modern doctrinaires preach heresies which would make miserable that very strong man, St. Paul, who constantly enjoined woman to silence and submission. Place aux dames is the century-end watchword, in a sense very different from the distinguished consideration which the dames of years bygone received. Place aux dames is all very well, as some one has somewhere said—but then, dames in their place, which, with all possible deference to the femininely-influenced philosophers of to-day, is not in politics, nor in any arts or sciences whatever.

Those who so blithely advocate the throwing open of the professions to woman, and invite her to work with them, side by side, in works of practical philanthropy, base their arguments on false premises. They assume, at starting, that womankind has been throughout the centuries in an arrested condition. Her mental and bodily growth has, they say, been retarded by cunningly-devised restrictions; she has not been permitted to develop or to reach maturity—she is, in short, according to these views, undeveloped man, rather than a separate and fully developed sex. Those views are, of course, merely fallacies of the most unstable kind. Woman’s place and functions have been definitely fixed for her by nature, and those functions and that place are to be the handmaid of man (or the handmatron if you like it better), and to be the mother of his children; and her place is the home. Her physical 47 and mental limitations are subtly contrived by nature to keep woman in the home and engrossed in domestic matters; and, really, if abuse is needed at all, man does not deserve it, but to nature belongs the epithet of tyrant, if an owner must be found for the unenviable distinction.

Woman is essentially narrow-minded and individualistic. Her time has ever been fleeted in working for the individual, and the community would be badly off at this day had not the State been thoroughly masculine for a time that goes back beyond the historians into the regions of myths and fairy tales. Small brains cannot engender great thoughts; which is but another way of saying that woman’s brain is less than man’s. It is only recently that woman has organized her forces at all, and she would not have done so, even now, had she not a plentiful lack of anything to occupy her thoughts withal in these days of the subdivision of labour and of extended luxury. And so, with plenty of time to spare, she begins to ask if there is nothing that becomes her better than the ‘suckling of fools and the chronicling of small beer.’ But although Carlyle said in his wrath that men and women were mostly fools, yet there be children nourished with nature’s food who have developed a certain force of intellect; and as for the chronicles of small beer, gossip and scandal-mongering have never been compulsory in women, but only unwelcome features of their nature. Idleness, 48 luxury, and the supreme consideration with which even the most foolish feminine manifestations have been received, have always been fruitful sources of mischief, and this by-past consideration has favoured the development of vanity and the growth of the feminine Ego to its present proportions.

Woman never becomes more than an ineffectual amateur in all the careers she enters. Her practice in art and literature inevitably debases art and letters, for she is a copyist at most. In literature she never originates, but appropriates and assimilates men’s thoughts, and in the transcription of those thoughts seldom rises above the use of clichés. But the Modern Woman desires most ardently to enter those spheres of mental and technical activity, undeterred by any disheartening doubts of her fitness for letters or government, of her capacity for organizing or originating. She points triumphantly for confirmation of her sex’s endowments to the lives and works of the George Eliots, the Harriet Martineaus, the Elizabeth Frys, the Angelica Kauffmanns, or the women of the French political salons; but she does not stop to consider that those distinguished women succeeded not because, but in spite of, their sex, and that few of the women who have made what the world terms successful careers had any of the more gracious feminine characteristics beyond their merely physiological attributes. Many of them were unsexed creatures whose womanhood was an accident of their birth. 49

The rush of women into the artistic and literary professions has always had a singularly ill effect upon technique, for the woman’s mind is normally incapable of rising to an appreciation of the possibilities of any medium. They have not even a glimmering perception of style, and would as cheerfully (if not, indeed, with greater readiness) acclaim Dagonet a poet as they would the Swan of Avon, although the gulf that divides Shakespeare from Mr. G. R. Sims is not only one formed by lapse of the centuries: to them the works of Miss Braddon appear as the ultimate expression of the passions, and they would as readily label a painting by Velasquez ‘nice’ as they would call the productions of Mr. Dudley Hardy ‘awfully jolly.’ Subject rather than execution wins their admiration, and the nerveless handling of a painting whose subject appeals to their imagination wins their praise while the highest attainments of technique are disregarded. For them does Mr. W. P. Frith paint the Derby Day and So Clean; for their delight are the ‘dog and dolly’ pictures of Mr. Burton Barber, the Can ’oo Talk? the ‘peep-bo’ and ‘pussy-cat’ stories in paint contrived; and for their ultimate satisfaction are they reproduced as coloured supplements in the summer and Christmas numbers of the illustrated papers.

You may count distinguished women artists upon the fingers of your hands, with some fingers to spare, and some of these achieved their fame by reason of 50 their womanhood, rather than the excellence of their art. Angelica Kauffmann is a notable example. She attained the unique position of a female Royal Academician through Reynolds’s infatuation: she painted portraits and classical compositions innumerable, but the portraits are poor and her classicism the most futile and emasculate. Literature, too—although more women have made reputations with the pen than the brush—can show but a very small proportion of feminine genius; and (although the ultimate verdict of the critics may yet depose these) Charlotte Brontë, Fanny Burney, and George Eliot are the most outstanding names in this department. These few names compare with an intolerable deal of mediocrity, cosseted and sheltered from the adverse winds of criticism in its little day; but yet so constitutionally weak that it has withered and died out of all knowledge. The women who, like George Eliot, and her modern successor, Mrs. Humphry Ward, adventure into ethical novels, are too excruciatingly serious and possessed with too solemn a conviction of their infallibility for much patient endurance; and really, when one remembers the spectacle of G. H. Lewis truckling to the critics, intriguing for favourable reviews, and endeavouring to stultify editors for the sake of his George Eliot, in order that no breath of adverse criticism and no wholesome wind from the outer world should come to dispel her colossal conceit, we obtain a curious peep into the methods by which the feminine Ego 51 is nourished. But the spectacle is no less pitiful than strange.

It is not often, however, that women writers present us with philosophical treatises in the guise of novels. Their high-water mark of workmanship is the Family Herald type of story-telling, even as crystoleum-painting and macramé-work exhaust the energies and imagination of the majority of women ‘art’ workers. What, also, is to say of the lady-novelists’ heroes, of god-like grace and the mental attributes of the complete prig? What but that if we collate the masculine characters of even the better-known, and presumably less foolish, feminine novels, we shall find woman’s ideal in man to be the sybaritic Guardsman, the loathly, languorous Apollos who recline on ‘divans,’ smoke impossibly fragrant cigarettes, gossip about their affaires du c[oe]ur, and wave ‘jewelled fingers’—repellent combinations of braggart, prig, and knight-errant, with the thews and sinews of a Samson and the morals of a mudlark.

Philanthropy is a field upon which the modern woman enters with an enthusiasm that, unfortunately, is very much greater than her sense. Her care is for the individual, and she it is who encourages indiscriminate almsgiving, but cannot understand the practical philanthropy which compels men to work for a wage, or organizes vast schemes of relief works. Her whole nature is individualistic, and we would not have it otherwise, for it has, in many 52 instances of womanly women, made homes happy and comfortable, and nerved men in the larger philanthropy which succours without pauperising thousands. But she has no business outside the home.

Philanthropy, of sorts, we have always with us, and the undeserving need never lack shelter and support in a disgraceful idleness while the tender-hearted or the hysterical amateur relieving-officers are permitted to make fools of themselves, and rogues and vagabonds of the lazy wastrels who will never do an honest day’s work so long as a subsistence is to be got by begging. The fashionable occupation of ‘slumming’ made many more paupers than it relieved, and the ‘Darkest England’ cry of Mr. William Booth, whom foolish folk call by the title of ‘General’ he arrogates, is the most notorious exhibition of sentimentalism in recent years. That appeal to the charitable and pitiful folks of England was, like the Salvation Army itself, engineered by the late Mrs. Catherine Booth, and it captured many thousands of pounds wherewith to succour the unfit, the criminal, the unwashed; the very scum and dregs of the race whom merciless Nature, cruel to be kind, had doomed to early extinction. But mouthing and tearful sentimentality has interfered with beneficent natural processes, and the depraved and ineffectual are helped to a longer term of existence, that they may transmit their bodily and mental diseases to another generation, and so foul 53 the blood and stunt the growth of the nation in years to come.

Science, anthropology, and economics have no meaning for the femininely-influenced founders of Salvation Army doss-houses: the body politic—society, in the larger sense—national life, are phrases that convey no meaning to the sobbing philanthropists to whom the welfare of the dosser is a creed and Darwinian theories rank blasphemy.

The tendency of sentimental philanthropy is to relieve all alike from the consequences of their misdeeds, and to preserve the worst and the unfittest, and to enable the worst to compete at an advantage with the best, and to freely propagate its rickety kind. Philanthropy of this pernicious sort is essentially sentimental and feminine.

But the most disastrous interference, up to the present, of sentimental fanatics—women and femininely-influenced men—has been their successful campaign against those beneficent Acts of Parliament, the Contagious Diseases Acts, framed from time to time for the protection of Her Majesty’s forces of the Army and Navy.

Those Acts, applied to the garrison towns and the dockyard towns of Aldershot, Chatham, Plymouth, Dover, Canterbury, Windsor, Southampton, and others, provided for the registration and compulsory periodical medical examination of the public women who infest the streets of those places. Horrible diseases, spread by these abandoned 54 creatures, decimated the regiments and the crews of the ships that put in at their ports; and thus, through them, the blood of future generations was poisoned and contaminated. The women whose depravity and disease spread foul disorders among not only the soldiers and sailors, but also amongst the civil populations of these garrison towns, were free, before the application of the C. D. Acts, to ply their trade no matter what might be their bodily condition; but the operation of those measures, at first providing for voluntary inspection and examination, and afterwards making those precautions compulsory, rendered it a criminal offence for a woman registered by the police to have intercourse with men while knowing that she was suffering from disease. Such an offence, or the offence of not presenting themselves at the examining officer’s station at the fortnightly period prescribed by the Acts, rendered women of this class liable to imprisonment. If at these examinations a woman was found to be healthy, a certificate was given her; if the medical officer certified her to be diseased, she was taken by compulsion to hospital, and detained there until recovery.

Plymouth, Aldershot, and Chatham, in especial, were in a shocking condition before the Acts came into force; but during the years in which they were administered by the police, a diminution of disease by more than one-half was seen in the Army and Navy, and the registration of the women led to 55 a very great falling-off of the numbers who obtained so shameful a living. Evidence given before the Royal Commission upon the Contagious Diseases Acts in 1872 proved this beyond question, and also proved that these women not only had no objection to the medical examinations, but regarded them and the hospitals as very great benefits.

The shocking revelations as to the social condition of Plymouth, Devonport, and Stonehouse, afforded by the evidence of the police, cannot be more than hinted at in this place. It is sufficient to say that over 2000 women were put upon the registers, either as occasionally or habitually living a loose life, and that all classes were to be found in these documents, but especially girls employed behind the counters of shops during the day. The police seem everywhere to have been conscientious in the execution of their duty, and to have performed ungrateful and delicate tasks with great discretion. The registers were private and strictly confidential official documents, and both the medical examinations and the police visits to suspected houses were conducted with all possible secrecy, the police in the latter case being plain-clothes men, and not readily to be identified by the public.

And yet, in spite of the very evident benefits derived from the Acts and deposed to before the Commission by such unimpeachable authorities as the foremost medical officers of the Army and Navy, commanding officers, clergymen of the Established 56 Church, Wesleyan ministers, the entire medical and nursing staffs of hospitals, and the police authorities themselves, these Acts were repealed, in submission to the outcries of the ‘mules and barren women,’ who, headed by the rancorous Mrs. Josephine Butler and the gushing sentimentalists from the religio-radical benches of the House of Commons, called public meetings, and shrieked and raved upon platforms throughout the country: a chorus of shocked spinsters and ‘pure’ men, whose advocacy of what they called, forsooth, ‘the liberty of the subject’ and the abolition of what they falsely termed the ‘State licensing of vice,’ has resulted in a liberty accorded these women to spread disease far and wide.

The nation, the men of Army and Navy, have reason abundant to curse the sentimental women, the maiden aunts, the religieuses, the gorgons of a mistaken propriety and a peculiarly harmful prudery, whose interference with affairs which they were not competent to direct has wrought such untoward results.

This is what a writer says in the Westminster Review: ‘The struggle for the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts was an ordeal such as men have never been obliged to undergo. It involved not merely that women should speak at public meetings, which was a great innovation, but that they should discuss the most painful of all subjects, upon which, up to that time, even men had not 57 dared to open their mouths. Yet so nobly did the women bear their part all through those terrible years of trial, that they raised a spirit of indignation which swept away the Acts, but never, by word or deed, did they deservedly incur reproach themselves.’

Rubbish, every word of it! The women who spoke upon these painful subjects were under no compulsion, legal or moral, to initiate or take part in the frenzy of wrong-headed emotion, which was exhibited upon public platforms to the dismay and disgust of all right-thinking men and women. It cannot be conceded that the subject was painful to these persons, nor can the statement be allowed to go unchallenged that they did not deserve reproach. Reproach of the most bitter kind was and is deserved by the prejudiced persons who distorted facts and gladly relied upon any hearsay evidence that would seem to square with their theories, and even refused to admit the weight of incontrovertible statistics produced against their rash and windy statements. The examinations of Mrs. Josephine Butler1 and of those two ridiculous persons, the Unitarian pastor from Southampton and his wife, 58 Mr. and Mrs. Kell, are damning indictments of their good faith and good sense. These are types of women and womanish men who take delight in the investigation of pruriency, whose noses are in every cesspool and their hands in the nearest muck-heap. 59 Their kind stop at nothing in the way of unfounded statements, and are greedy of rumour rather than of accredited facts. Want of acquaintance with, or experience of, the subjects they dogmatise upon deterred them as little then as now from case-hardened obstinacy; and perhaps no one cut such a sorry figure before the Commission as that illogical and contradictory person, the late John Stuart Mill, the femininely-influenced author of the nowadays somewhat discredited Subjection of Women. ‘His chief ground for objection to the system’ (of the C. D. Acts) ‘was on the score of the infringement of personal liberty’ (i.e., the liberty to spread loathsome diseases); ‘but he considered it also objectionable for the Government to provide securities against the consequences of immorality. It is a different thing to remedy the consequences after they occur’—as who should say, in the manner of the proverb, Lock the stable door when the horse has been stolen.

This sham philosopher and political economist of ill-argued theories, who is to-day honoured by an uncomfortable and ungainly statue on the Victoria Embankment, forgot that England has not achieved her greatness by the study or practice of morality: and shall we fall thus late in the day by a Quixotic observance of it?

The sooner the statue of this woman’s advocate is cast into the Thames, or melted down, the better.

Woman’s influence and interference in these 60 matters have proved an unmixed evil. It would be hopeless, however, to convince her of error: as well might one attempt to hustle an elephant.

Political women are, fortunately, rare in England. A Duchess of Devonshire, a Lady Palmerston, and the politico-social Dames of the Primrose League, these are all the chiefest and most readily-cited female politicians: and their interest was, and is, not so much in the success or defeat of this party or the other as in the return of their favoured candidate or the failure of a pet aversion. Politics have no real meaning for women: their natures do not permit of their comprehension of national and international questions. What does Empire signify to woman if her little world is distracted? and what is a revolted province to her as against a broken plate?

The Fates preserve us from Female Suffrage; for give women votes and patriotism is swamped by the only women who would care to exercise the privilege of voting: the clamorous New Woman, all crotchets, fads and Radical nostrums for the regeneration of the parish and the benevolent treatment of subjugated races in an Empire won by the sword and retained by might.

61

The ‘strong-minded woman,’ as the phrase goes, we have always with us nowadays; and as this species of strength of mind seems really to be a violent and uncertain temper, there can be little doubt but that the strong-minded woman has always been more frequent than welcome. Certainly shrewishness and termagancy have been too evident throughout the ages, from the days of Xanthippe to the present time. That much we know from the lives—or shall we say, under the painful circumstances, the ‘existences?’—of public men who have been cursed with scolding wives. But what Asmodeus shall unveil the private conjugal tyrannies, the hectorings, and the curtain-lectures that make miserable the undistinguished lives of men of no importance for good or evil in the State? How many women, in fine, ‘wear the breeches’ through the ‘strength of mind’ which may be justly defined as readiness of that impassioned invective which in its turn may be reduced (like a vulgar fraction) to its 62 lowest common denominator of ‘nagging.’ Not a pretty word, is it? And it is a practice even less pretty than that cross-grained definition would warrant. We cannot, however, lift the veil that hides the domestic infelicities of the lieges, but must be content to recount the troubles and oppressions that have befallen historic Caudles, who bulk a great deal larger in the history of England than they did, in their own homes, to their wives.

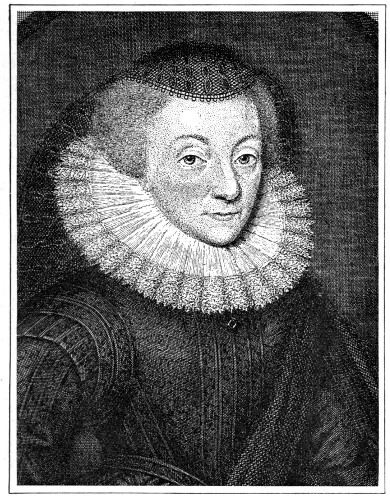

Sir Edward Coke, the great law officer of James the First’s reign—the revered ‘Coke upon Lyttleton’ of the law-student—was little enough of an authority in his own household after he had married his second wife, herself a widow—the ‘relict,’ in fact, of Sir William Newport-Hatton. He married her but a few months after his wife’s death, privately and in haste; probably urged to such an indecent speed by the necessity of forestalling the Lord Keeper Bacon in the lady’s affections. But he had not been wise in his haste; for affection—for him, at least—she had none. She had probably buried all her kindly feelings in the grave with Sir William Hatton, for she would never be known as Lady Coke, but always as Lady Hatton, and, in truth, she led that distinguished and bitter lawyer the life of a dog. One wonders, indeed, why she married him at all, who was old enough to be her father. It was not ambition, for she was by birth a Cecil and daughter of the second Lord Burleigh; nor the want of money, nor the need of a protector, for she was very well 63 able to take care of herself, as Sir Edward presently discovered, and she was sufficiently wealthy. They quarrelled incessantly—about property, about the marriage of their daughter, about anything and everything. Sir Edward Coke was only suffered to enter her house in London by the back door, and she plundered his residence in the country. She sent her daughter away to Oatlands to prevent a marriage with Sir John Villiers, which Sir Edward was pressing forward; and he, ‘with his sonne and ten or eleven servants, weaponed in violent manner,’ repaired thither, broke open the door, and took her away. Lady Hatton intrigued at Court against the distracted Coke, who was already in disfavour at St. James’s, and procured an interference by the Star Chamber, which condemned his ‘most notorious riot;’ but Coke eventually gained the upper hand in this matter at least, and the girl was married to the man of his choice. This did not end the enmity. For years they contended together until death parted them. But she survived him by ten years.