Title: Heroines of the Modern Stage

Author: Forrest Izard

Release date: July 31, 2018 [eBook #57611]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Charlie Howard and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

MODERN HEROINES SERIES

EDITED BY WARREN DUNHAM FOSTER

MODERN HEROINES SERIES

EDITED BY WARREN DUNHAM FOSTER

Now Ready

Heroines of Modern Progress

Heroines of Modern Religion

Heroines of the Modern Stage

Each volume 12mo cloth

Illustrated $1.50

HEROINES OF

THE MODERN STAGE

BY

FORREST IZARD

ILLUSTRATED

New York

STURGIS & WALTON

COMPANY

1915

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1915, by

STURGIS & WALTON COMPANY

Set up and electrotyped. Published November, 1915

v

The following pages give some account of those actresses who stand out today as the most interesting to an English-speaking reader. The Continental actresses included are those who gained international reputations and belonged to the English and American stage almost as much as to their own.

All actresses have been modern, in a sense, for the acting of female rôles by women is distinctly a latter-day touch in that ancient institution, the theatre.1 Thus a book on modern actresses might range from Elizabeth Barry to Mrs. Fiske. But while many volumes already exist that serve well to keep alive the names of the dead-and-gone heroines,2 biographies of actresses whom we of today have seen, are, in general, insufficient or inaccessible. That is true even of such notable women as Sarah Bernhardt, Ada Rehan and Mrs. Fiske; while accounts in English of such Continental actressesvi as Duse and Réjane are altogether lacking. The author hopes that in these chapters he has done something toward making better known the careers of those actresses and of others who present themselves either in vivid recollection or in the light of present day achievement. The concluding chapter deals briefly with a number of American actresses of the present, who, although not rising in all cases to the eminence or popularity attained by those to whom separate chapters are given, yet have made some distinct contribution to our stage.

The author’s thanks are due to Mr. Edwin F. Edgett for the loan of material; to Mr. John Bouvé Clapp and to Mr. Robert Gould Shaw for the use of the originals from which some of the illustrations were made; and, for assistance of many kinds, to the editor of the series.

Boston, Massachusetts,

October, 1915.

F. I.

xi

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | v | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I | Sarah Bernhardt | 3 |

| II | Helena Modjeska | 52 |

| III | Ellen Terry | 93 |

| IV | Gabrielle Réjane | 126 |

| V | Eleonora Duse | 171 |

| VI | Ada Rehan | 203 |

| VII | Mary Anderson | 230 |

| VIII | Mrs. Fiske | 265 |

| IX | Julia Marlowe | 299 |

| X | Maude Adams | 324 |

| XI | Some American Actresses of Today | 347 |

| Appendix | 368 | |

| Bibliography | 377 | |

| Index | 381 |

xiii

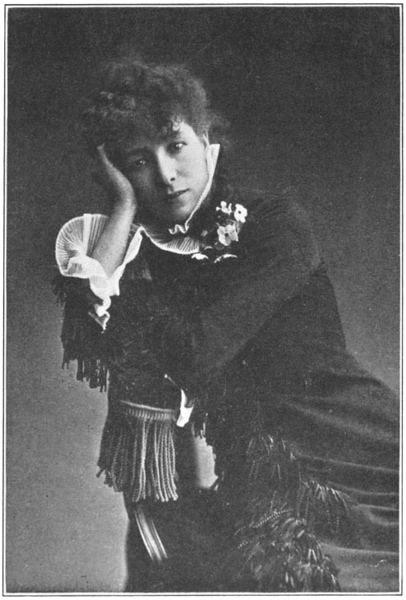

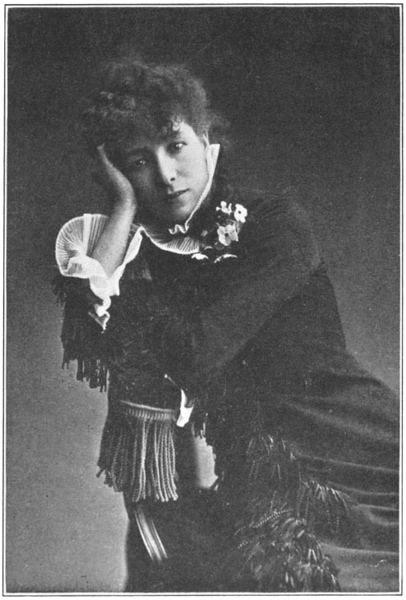

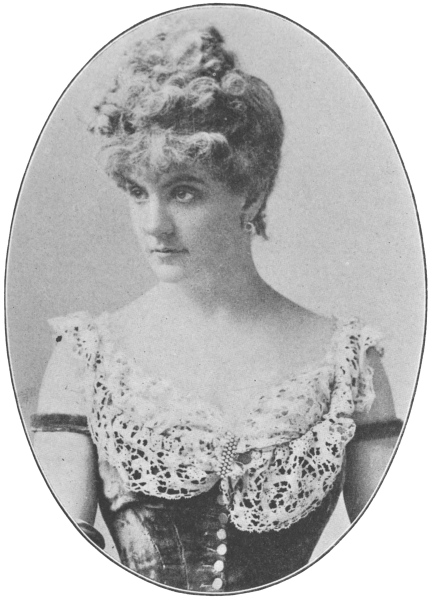

| Sarah Bernhardt | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

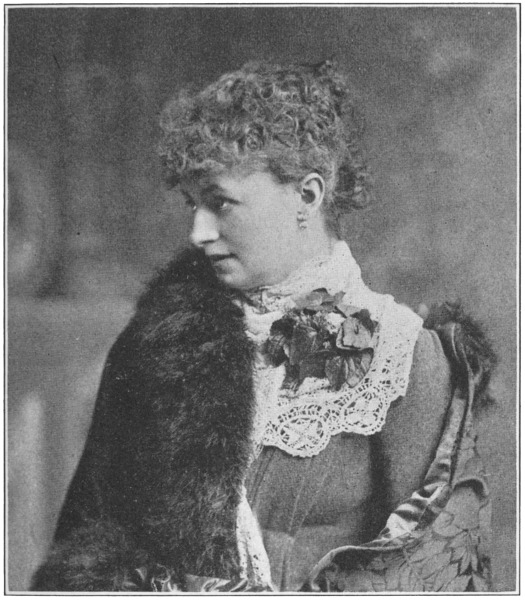

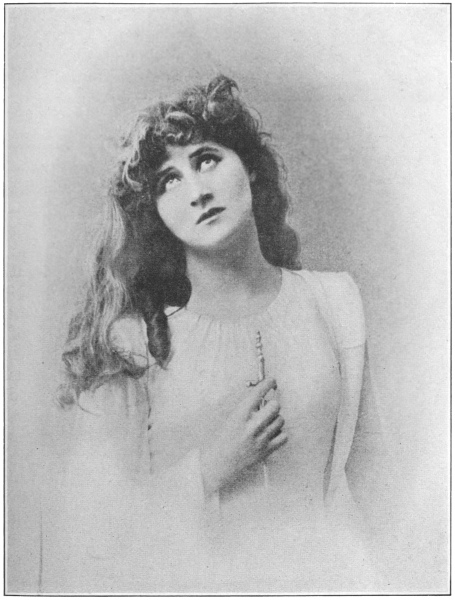

| Helena Modjeska | 52 |

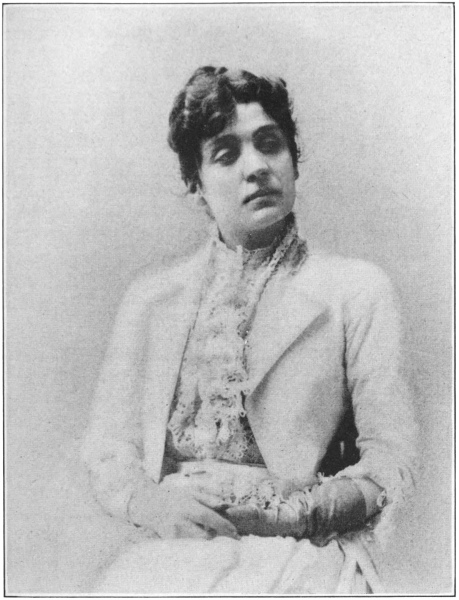

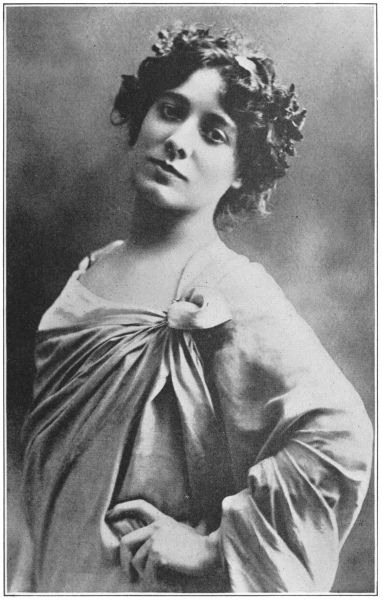

| Ellen Terry | 92 |

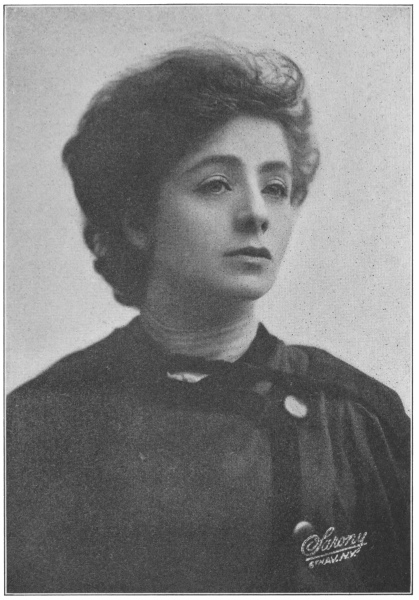

| Gabrielle Réjane | 126 |

| Eleonora Duse | 170 |

| Ada Rehan | 202 |

| Mary Anderson | 230 |

| Mrs. Fiske | 264 |

| Julia Marlowe | 298 |

| Maude Adams | 324 |

3

“Sarah-Bernhardt, Officier d’Académie, artiste dramatique, directrice du théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt, professeur au Conservatoire;” so run the rapid phrases of the French “Who’s Who.” And, it might have added: “personality extraordinary, and woman of mystery.”

“The impetuous feminine hand that wields scepter, thyrsus, dagger, fan, sword, bauble, banner, sculptor’s chisel and horsewhip—it is overwhelming.” Thus the poet Rostand epitomized “the divine Sarah.” Her career, he said, gives one the vertigo—it is one of the marvels of the nineteenth century. And he might have added, of the twentieth, for Bernhardt, who began her stage career at the time of our Civil War, was only recently, at an amazing age, to be seen on the stage of London and Paris. There are many who think, with William Winter,3 that she has been merely “an accomplished4 executant, an experienced, expert imitator, within somewhat narrow limits, of the operations of human passion and human suffering.” The fact remains, the woman has been a genius of work and achievement, “the Lady of Energy,” who has fairly earned the title of great actress. It is difficult to think of any woman the light of whose fame has carried to the ends of the earth in quite the same way. To be sure it has not always been from the lamp of pure genius. There have been self-advertising, scandal, extravagant eccentricity, to swell the general effect, but back of all this has been the worker.4

5 She was born in Paris, at 265 Rue St. Honoré, October 23, 1844.5 Her blood is a mingling of French and Dutch-Jewish. Her real name is Rosine Bernard, and she was the eleventh of fourteen children. Of her father6 hardly anything can be learned. Sarah herself says that when she was still a mere baby he had gone to China, but why he went there she had no idea. Her mother was, by birth, a Dutch Jewess, by sympathy a Frenchwoman, by habit a cosmopolitan; “a wandering beauty of Israel,” forever traveling. As much because there was no home, therefore, as because the French have a custom of banishing infants from the household, Sarah spent her childhood in the care of a foster-mother, first in the Breton country, near Quimperlé (where she fell in the fireplace and was badly burned), then at Neuilly, near Paris. Her mother came seldom to see her, though there seems to have been affection, at least on the child’s side. It was a lonely childhood—made worse by the high-strung, sensitive nature that was Sarah’s from the beginning.6

When Sarah was seven she was sent away to boarding school at Auteuil, where she says she spent two comparatively happy years. Her mysterious father then sent orders that she was to be transferred to a convent. “The idea that7 I was to be ordered about without any regard to my own wishes or inclinations put me into an indescribable rage. I rolled about on the ground, uttering the most heartrending cries. I yelled out all kinds of reproaches, blaming mamma, my aunts, and Mme. Fressard for not finding some way to keep me with her. The struggle lasted two hours, and while I was being dressed I escaped twice into the garden and attempted to climb the trees and throw myself into the pond, in which there was more mud than water. Finally, when I was completely exhausted and subdued, I was taken off sobbing in my aunt’s carriage.”7

At the Augustinian convent at Grandchamp, Versailles, she was baptized and confirmed a Christian. She became extravagantly pious and conceived a passionate adoration of the Virgin. Nevertheless, she was fractious and was more than once expelled.8

8 When she left the convent Sarah was a capricious, sensitive, religious girl, who must indeed have constituted a problem for her mother. Sarah, strangely enough, was herself strongly inclined to be a nun. But her mother, who was a woman of the world and of means, had other plans and provided as “finishing governess” for Sarah a Mlle. de Brabander. One day, when she was fifteen, her fate was decided for her. At a family council her own ambition to be a nun was voted down and the decision was: “Send her to the Conservatoire.” Sarah had never even heard of the famous school for actors of the government theatres. That same evening she was taken to the theatre for the first time—the Théâtre Français. Brittanicus and Amphitrion moved her profoundly, and she left the theatre weeping, as much for the sudden shattering of her cherished plan as from the effects of the plays.

Thus she began her studies at the Conservatoire (1860) with no love for the career chosen for her.9 She was no beauty;—she was decidedly9 thin, had kinky hair, and a pale face. But she worked hard. Her extraordinary nervous energy and her intelligence had their effect and when she left the Conservatoire she had won two second prizes.10 The discernment of some of the judges11 saw in her something of the artist she was to be, and she immediately had a call to the company of the Comédie Française. With the signing of her contract came her resolve, that if the stage were to be her working place, she would throw herself into her task with all her soul. “Quand-même,”—in spite of all,—was already her motto,—she would, in the face of any obstacle, win a place for herself.12

Though with wonderful success she has been busily pursuing that object from that day to10 this, the beginnings of her career were not promising. Her début (1862) in Racine’s Iphigénie created no particular comment. She remembers, however, that on that occasion, when she lifted her long and extraordinarily thin arms, for the sacrifice, the audience laughed.13 Other parts fell to her, but she did not long remain at the House of Molière. As other managers were later to learn, Sarah cared little for agreements and contracts.

The occasion of her first desertion of the Comédie was trivial enough. Here at the great national theatre she expected to remain always, but one day her sister trod on the gown of Mme. Nathalie, another actress of the company, “old, spiteful and surly,” who in petty anger shoved the girl aside. Sarah promptly responded by boxing the ears of her elder colleague. Neither would apologize, and the quickly achieved result was that the younger actress retired.

She remained away from the Comédie Française for ten years, and it was during this time that she laid the foundation of her fame. Brief engagements at the Gymnase14 and the Porte11 St. Martin were followed by an opportunity to join the company at the Odéon. MM. Chilly and Duquesnel were the managers. The latter was young, kind to Sarah, and discerning of her talents. As for Chilly, he was less enthusiastic: “M. Duquesnel is responsible for you. I should not upon any account have engaged you.”

“And if you had been alone, monsieur,” she answered, “I should not have signed, so we are quits.”

Mlle. Bernhardt’s career—once she had launched herself upon it—divides naturally into three periods: the six years (1866–1872) at the Odéon, the playhouse of the Latin Quarter, “the theatre,” she says, “that I have loved most”; another term (1872–1880) at the Française; and her long career since, during which she has been her own mistress, accepting engagements where it pleased her, managing theatres of her own, and traveling over all the world.

Her first taste of success came when she played Zacharie in Athalie, soon after she went to the Odéon. It fell to her to recite the choruses, and the “voix d’or” won its first triumph. She was now twenty-two. For four years, with plentiful interludes of temper and temperament, she had been striving for success. Now, at the Odéon, she worked and worked hard. “I was always ready to take any one’s place at a moment’s notice, for I knew all the rôles.” Chilly, who at first could see only her12 thinness15 and not her ability, was brought round to Duquesnel’s view of her. “I used to think,” she says again, “of my few months at the Comédie Française. The little world I had known there had been stiff, scandal-mongering, and jealous. At the Odéon I was very happy. We thought of nothing but putting on plays, and we rehearsed morning, afternoon, and at all hours, and I liked that very much.”16

At the Odéon Sarah soon became the favorite of the students of the Quartier. Rather to the disgust of the older patrons of the house, the students were indiscriminate in their appreciation of the young actress, and applauded her indifferent work equally with her successes.

For successes she now began to have. With difficulty M. Chilly was induced to consent to the production of Coppée’s one-act play Le Passant. But so successful was it that it not13 only ran for a hundred nights, but Bernhardt and the beautiful Mlle. Agar played it for Napoleon and Eugénie at the Tuileries. In Kean, by Dumas, she was, by all accounts, admirable.17

George Sand came to the Odéon for the rehearsals of her play L’Autre. Of her Bernhardt says: “Mme. George Sand was a sweet charming creature, extremely timid. She did not talk much but smoked all the time.”

In the midst of her term at the Odéon came an astonishing episode in Bernhardt’s career—her activities during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. The theatres were of course closed, but it was not in her nature to sit still and do nothing. Therefore she sent her young son18 out of the city, and in the fall of 1870, after her own severe illness, proceeded to establish an army hospital in the foyers of the Odéon, with herself as its working head. With an executive ability and a zeal characteristic but none the less remarkable, she not only organized its14 commissariat, and kept all the records and accounts, but herself acted as one of the nurses. The section of her autobiography that deals with the siege of Paris and with her journey through the enemy’s country to Hombourg and back that she might bring home her family, will afford some future historian a graphic impression of one of the saddest days in the history of Paris.

When the Odéon reopened, in the fall of 1871, Sarcey, the great critic, said of Sarah, who played (in Jean-Marie) a young Breton girl: “No one could be more innocently poetic than this young lady. She will become a great comédienne, and she is already an admirable artist. Everything she does has a special savor of its own. It is impossible to say whether she is pretty. She is thin, and her expression is sad, but she has queenly grace, charm, and the inexpressible je ne sais quoi. She is an artist by nature, and an incomparable one. There is no one like her at the Comédie Française.”

At the end of 1871 Victor Hugo, who had been practically an exile during the Empire, came back to France. His return, as it proved, meant another turning point in Sarah’s life, for when the Odéon decided to produce his Ruy Blas, she was selected, after a good deal of bickering, as the Queen. Hugo she found, despite her strong previous prejudice against him, “charming, so witty and refined, and so gallant.”19

15 The play was produced on January 26, 1872. That night, in Bernhardt’s own words, “rent asunder the thin veil which still made my future hazy, and I felt that I was destined for celebrity. Until that day I had remained the students’ little Fairy. I became then the elect of the Public.” Hugo himself, on his knee, kissed her hands and thanked her. M. Sarcey, who from the beginning was Bernhardt’s staunchest admirer among the critics, praised her warmly: “No rôle was ever better adapted to Mlle. Bernhardt’s talents. She possesses the gift of resigned and patient dignity. Her diction is so wonderfully clear and distinct that not a syllable is missed.”

The Comédie Française now made overtures for her return to its fold. Bernhardt at once16 accepted, which was wretchedly unfair to the Odéon, for she owed much to Duquesnel. When in 1866 he persuaded Chilly to take her on, she was comparatively unknown; now, in 1872, she was rapidly becoming the talk of Paris. Her contract with the Odéon had yet a year to run, but Sarah demanded, as the condition of her remaining, an advance in the stipulated salary.20 Chilly indignantly refused; so Mlle. Bernhardt hurried away to the Comédie and forthwith signed her new contract. The Odéon brought an action against her and she had to pay a forfeit of six thousand francs.

This sudden change of scene is but one instance of the directness, not to say unscrupulousness, of Bernhardt’s methods in advancing herself. “Quand-même” it was to be, at any cost. If she had merely followed her inclinations, however, she would probably have remained at the Odéon, for she has often protested the attraction for her of the scene of her first triumphs. The Comédie, on the other hand, had never this appeal to her. As is easily understood, her imperiousness and willfulness made her feel less at home at the more staid Comédie. The other members of her company, with a few exceptions, were unfriendly and jealous. Moreover she made almost a failure in her début (in Mlle. de Belle-Isle), but this was due not to stage-fright, as Sarcey guessed, but to her anxiety on seeing her mother, suddenly17 taken ill, leave the theatre. Sarcey loyally championed her early efforts, though he was often keenly critical also: “I fear,” he wrote (apropos of Dalila), “that the management has made a mistake in already giving Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt leading parts. I do not know whether she will ever be able to fill them, but she certainly cannot do so at present. She is wanting in power and breadth of conception. She impersonates soft and gentle characters admirably, but her failings become manifest when the whole burden of the piece rests on her fair shoulders.” Other critics, particularly Paul de Saint-Victor, were consistently hostile. She had in the company envious rivals who inspired attacks on her, and she clashed frequently with M. Perrin, the director of the theatre. With that indomitable persistence that is her finest trait, however, she kept right on, and won her way to genuine achievement. As Aricie in Phèdre she made a secondary part notable. Thus Sarcey: “There can be no doubt about it now. All the opposition to Mlle. Bernhardt must yield to facts. She simply delighted the public. The beautiful verses allotted to Aricie were never better delivered. Her voice is genuine music. There was a continuous thrill of pleasure among the entire audience.”

That she had thoroughly arrived was soon to be proved and re-proved. Zaïre21 was followed18 by Phèdre herself, Berthe in La Fille de Roland, Doña Sol in Hernani, Monime in Mithridate, and revivals of Ruy Blas and Le Sphinx, each a personal triumph for the actress who was so rapidly filling the eye of Paris.22

For Sarah Bernhardt had by now succeeded in making herself, if not a universally acknowledged artist, at least a real Parisian celebrity.19 It was not a reputation confined to the actress per se. Designedly or not, Sarah set the tongues of Paris (and shortly of all Europe) wagging by a continuous exhibition of eccentricity that amounts to a tradition. To mention only what seem to be well authenticated manifestations of her caprice: She kept a pearwood coffin at the foot of her bed, slept in it and learned her parts in it. It is to be the veritable coffin of her last resting place.23 She kept as a further reminder of her mortality a complete human skeleton in her bedroom. Years before she had a tortoise as a household pet. She named it Chrysogère and had a shell of gold, set with topazes, fitted to its back. Now she was keeping two Russian greyhounds, a poodle, a bulldog, a terrier, a leveret, a monkey, three cats, a parrot, and several other birds. Later she had lions, and an alligator! She made ascents in a captive balloon at the Exhibition and once in a balloon that was not captive.24 Perrin was outraged by this caprice and tried to fine her for “traveling without leave.” She wrote for the newspapers. She scorned the fashions. She dabbled in painting and sculpture, and, particularly with her chisel, her efforts were, if not noteworthy, at least respectable. Indeed, a group sculpture won an honorable mention in the Salon of 1876, though20 there were plenty to deny that it was really her work. Her studiolike apartment was the rendezvous of all artistic Paris.

In 1879 her poetic, restrained, and generally admirable impersonation of Doña Sol in Hernani brought her general homage. On the night of the one-hundredth performance Victor Hugo presided at a banquet in her honor, and M. Sarcey, in behalf of her “many admiring friends,” presented to her a necklace of diamonds.

When it was proposed, in 1879, that the Comédie Française company go to London, Sarah refused to go along unless she be made Associate “à parte entière.”25 Her proposal was rejected, and at a meeting of the Committee M. Got represented the feeling that prevailed among the directors of the theatre by crying: “Well, let her stay away! She is a regular nuisance!” Sarah finally gave in, however, and in reward was made “Sociétaire à parte entière.”26

21 On the first evening at the Gaiety, Bernhardt was to make her bow to England in the second act of Phèdre. Just before she went on she had one of her occasional bad attacks of stage fright, and could not remember her lines. “When I began my part,” she wrote, “as I had lost my self-possession, I started on rather too high a note, and when once in full swing I could not get lower again; I simply could not stop. I suffered, I wept, I implored, I cried out, and it was all real. My suffering was horrible.” The Telegraph next morning said: “Clearly Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt exerted every nerve and fiber and her passion grew with the excitement of the spectators, for when after a recall that could not be resisted the curtain drew up, Mr. Mounet-Sully was seen supporting the exhausted figure of the actress, who had won her triumph only after tremendous physical exertion, and triumph it was, however short and sudden.”

An American writer—probably Henry James—said at this time in the Nation: “It would require some ingenuity to give an idea of the intensity, the ecstasy, the insanity, as some people would say, of curiosity and enthusiasm provoked by Mlle. Bernhardt.... She is not, to my sense, a celebrity because she is an artist. She is a celebrity because, apparently, she desires, with an intensity that has rarely been22 equaled, to be one, and because all ends are alike to her.... She has compassed her ends with a completeness which makes of her a sort of fantastically impertinent victrix poised upon a perfect pyramid of ruins—the ruins of a hundred British prejudices and proprieties.... The trade of a celebrity, pure and simple, had been invented, I think, before she came to London; if it had not been, it is certain that she would have discovered it. She has in a supreme degree what the French call the génie de la réclame—the advertising genius; she may, indeed, be called the muse of the newspaper.”

But trouble was brewing, and the irrepressible Sarah was soon making difficulties for her confrères. She insisted on her right to give performances before private audiences on the nights she was not appearing with the company. Perrin had flown into a rage when he first heard of these performances, for it was the Comédie’s chief grievance against her that she would not rest. There came a day in London when Sarah sent word she was too tired to appear. A Saturday audience had to be dismissed at the last moment; it was too late to change the bill. A great commotion ensued among the company and in the Paris press. So many and varied were the attacks on her that she was on the point of resignation. She had brought to London a number of her sculptures and paintings and gave an exhibition, selling a few pieces, and entertaining at the gallery reception a23 group of aristocrats and celebrities—Gladstone and Leighton among them. She made a trip to Liverpool to buy more lions, and came back with a chetah, a wolf, and a half dozen chameleons to add to her menagerie. The members of the company thought she was ruining the dignity of “Molière’s House”; and all manner of stories were told. “It was said,” she wrote, “that for a shilling anyone might see me dressed as a man; that I smoked huge cigars leaning on the balcony of my house; that at the various receptions when I gave one-act plays, I took my maid with me for the dialogue; that I practiced fencing in my garden, dressed as a pierrot in white, and that when taking boxing lessons I had broken two teeth for my unfortunate professor.” These stories were only less dreadful than the tales told in Paris: that she had thrown a live kitten into the fire, and poisoned two monkeys with her own hands!

As a matter of fact, it is probable that Sarah was finding irksome the restrictions of the Comédie, was ambitious to earn more money and, as anxious for her exit from the company as were her jealous confrères, was only waiting for a chance to sever her contract. But contracts with the Française are not lightly broken. As Coquelin had told her: “When one has the good fortune and the honor of belonging to the Comédie Française one must remain there until the end of one’s career.” She had to watch her chance shrewdly.

Again returned to Paris, the company of the24 Comédie revived, on April 17, 1880, Augier’s L’Aventurière. From whatever cause—pique at being assigned a part she disliked in a play she detested, a temporary suspension of her usual power, or, as she says herself, illness that prevented proper study of her part,—she failed rather miserably. Even the usually indulgent Sarcey said: “Her Clorinde was absolutely colorless”; and the other critics, to a man, wrote scathing reviews. Sarah saw her chance, as she thought, and determined that this would be her last performance at the Comédie. The morning after the fiasco she wrote to Perrin:

“Monsieur l’Administrateur:

“You made me play before I was ready. You gave me only eight stage rehearsals, and there were only three full rehearsals of the piece. I could not make up my mind to appear under such conditions, but you insisted upon it. What I foresaw has come to pass, and the result of the performance has even gone beyond what I expected. One critic actually charges me with playing Virginie in L’Assommoir instead of L’Aventurière! May Emile Augier and Zola absolve me! It is my first rebuff at the Comédie, and it shall be my last. I warned you at the dress rehearsal. You have gone too far. I now keep my word. When you receive this letter I shall have left Paris. Be good enough, Monsieur l’Administrateur, to accept my resignation as from this moment.

Apr. 18, 1880. Sarah Bernhardt.”

An immense commotion at once arose, as if some tremendous political upheaval had occurred.25 Sarah took train and disappeared in the country, just as on a similar occasion, years before, she had suddenly gone off to Spain. The press, her fellow players, and the author of the play all poured upon her head a shower of abuse. M. Sarcey prophesied: “She had better not deceive herself. Her success will not be lasting. She is not one of those artistes who can bear the whole weight of a piece on their own shoulders, and who require no assistance to hold the public attention.”27 The Comédie took legal action against her, and a few months later, when the suit was tried, Sarah was formally deprived of her standing as sociétaire, of her portion of the reserve fund, amounting to more than eight thousand dollars, and in addition had to pay the Française damages of twenty thousand dollars. She hadn’t the money, but she soon earned it, on her first American tour.

So ended, for good and all, Bernhardt’s connection with the government theatres; so abruptly did she turn a corner in her remarkable career. From her retirement Sarah announced, absurdly enough, that she would renounce the stage, and live by painting and sculpture, for these, she said, brought her thirty thousand francs ($6,000) a year. As a matter of fact, within two weeks she signed a26 contract with Henry E. Abbey, who post-haste crossed the ocean for the purpose, to go to America. His English agent, Jarrett, had long been importuning her to go. Now she was glad to accept.28

Sarah’s wanderings now began—those wanderings that have carried her up and down the world, made her name familiar everywhere, brought her riches and (in William Winter’s sonorous phrase) “such adulation and advocacy as have seldom been awarded to even the authentic benefactors of human society.” First she played a month in London, giving the pieces she was preparing for the American tour, and scoring a tremendous success, artistic, financial and social. A newspaper writer said at this time: “It has been said here that English society is not so eager this season to make her a social goddess as it was last; but it would hardly be possible for a woman to be more thoroughly besieged than is Sarah—that is the name by which people generally fondly call her. To see her is almost as difficult as to see the Queen—I dare say for people not connected with the artistic world even more so. Sarah lives very comfortably—even luxuriously—and entertains lavishly. It seems to me that the only lack of attention that she could possibly complain of is that the Queen has not yet left her card, and that is a complaint she must share with many people.”

27 To her amazement the Paris critics followed her to London, and praised her extravagantly. Sarcey personally tried to induce her to return to Paris, and M. Perrin sent Got, the doyen of the Comédie, on the same errand. Sarah refused; she was enjoying her freedom and her large earnings. She went to Belgium and then to Denmark. At Copenhagen she brought a storm about her ears by a gratuitous affront to the German Ambassador to Denmark, Baron Magnus. At a dinner in her honor he gallantly proposed a health to “la belle France.” Sarah was at once on her feet, in a theatrical mood, mindful of the smarts that lingered from the war of 1870–1871, and much impressed with her own importance. “I suppose, Monsieur l’Embassadeur de Prusse,” she cried, “you mean the whole of France.” This obvious reference to Alsace-Lorraine put the amiable Baron to confusion, broke up the dinner, threw consternation into the French diplomats on duty in Copenhagen, and enraged Bismarck. It is only fair to say that Sarah was genuinely sorry for her impetuous “break.”

Before sailing for America, Sarah was prevailed upon to undertake a month’s provincial tour in France—something she had never done. She appeared in Nantes, Bordeaux, Toulouse, Lyons and Geneva. Everywhere enthusiasm for her ran high. “Medals bearing her image and superscription, Sarah Bernhardt bracelets and collars, photographs and biographies were sold in the streets. At Lyons the Khedive’s28 son unsuccessfully offered £80 for a stage-box.”29

On October 16, 1880, Mlle. Bernhardt sailed for New York. On November 8, at Booth’s Theatre, she made her first appearance in America in Adrienne Lecouvreur, which, with much success, she had added to her repertoire since leaving the Comédie.30 Her triumph was immediate. She had been told that New York would receive her coldly. At the end of the play, however, “there was quite a manifestation and everyone was deeply moved,” while after the play a large crowd serenaded and cheered before her hotel. Sarah had been put on her mettle, and, as always, she did her best in the face of possible opposition. And these ovations repeated themselves in each city, both in the United States and in Canada.

The Bishop of Montreal took it upon himself to condemn Bernhardt, her company, her plays, the authors and French literature in general. As if in reply to his utterances, the public flocked to see Sarah. As is usual with such strictures, the Bishop had given the best possible29 advertising31 and each night Sarah’s sleigh was dragged by cheering men.

Wherever she went, her astute managers saw to it that the Bernhardtian advertising tradition was maintained: She went to Menlo Park to call on Thomas A. Edison; at Boston she visited a captive live whale in the harbor, and stood (and fell!) upon its back; in Canada she visited a tribe of Iroquois; at Montreal she ventured on the ice in the St. Lawrence and put her life in peril; visiting the Colt factory at Springfield, Massachusetts, she fired off some newly invented cannon;—“it amused me very much without procuring me any emotion,” she wrote; at Chicago she witnessed the slaughtering of pigs at the stock-yards; in St. Louis her jewelry was exhibited in a store window; at Niagara she again endangered her life by getting herself into an awkward place on the ice bridge below the falls.

Her object was accomplished, at all events. She had won in America a new fame and a much needed fortune. She had earned more than one hundred and eighty thousand dollars. She was now able to pay her debt to the Française, and had a comfortable sum left. And her return to France was a veritable return from Elba. Her vessel was met by scores of small boats, gay with welcoming flags, and the wharves held30 thousands of people shouting: “Vive Sarah Bernhardt!” Her first performance in France of La Dame aux Camélias, at Havre in May, 1881, was “a perfect triumph.”

It is startling to reflect that a woman who thus reached the zenith of her career a generation ago is still a working actress. What a triumph for the frail physique and the dauntless will! It is worth while to get a picture of her at about the time of her American tour, when she was thirty-six years old. A correspondent who visited her in London wrote: “I never was more agreeably disappointed in the appearance of a person than when Sarah smilingly and merrily tripped into the room. She looked infinitely fresher, brighter and prettier than I had ever seen her on the stage. Her photographs are perfect caricatures—every one of them. They give no idea of those wonderfully clear, translucent, great blue eyes, with their now soft and melting and now keen and penetrating glance; of her fresh and fair complexion, which on the stage is hidden under a horrid mask of thick paint; of her beautiful light blond hair, which lacks just a shade of being golden and is curled in the most graceful fashion; of her tender and sensitive mouth, the slightest motion of which is full of character and expression. I had never considered her pretty. I now, after a most careful and painstaking inspection, decidedly thought her so. She was charmingly dressed, too, and her thinness of person, which is so generally marked,31 but which she ridicules herself, was most artistically disguised. The waves of lace and ruffles which fell about her neck appeared to hide a bust worthy of Diana herself.”

Other contemporary accounts show that those who visited her at her studio found her clad in a gray or white flannel suit of masculine garments,—jacket, trousers, necktie and all, “looking something like a thirteen-year-old boy.” Though Sarah performed wonders in the way of self-advertising, more than one observer has noticed that she had a certain natural dignity that was not altogether inconsistent with a rather rollicking playfulness. “Her words are those of a lady,” wrote one, “and her enunciation, though rapid, beautifully distinct.” She has always been eminently hospitable.

In the engaging phrase of one of her biographers,32 “Marriage was the only eccentricity that Sarah had not yet perpetrated.” In the spring of 1882 she remedied this deficiency by marrying a member of her company, a Greek named Damala, or, as he was known on the stage, Daria. Sarah had been proceeding up and down Europe (always patriotically excepting Germany), playing in France, Holland, Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Russia, Italy, Austria and Spain, everywhere with immense success.33 In the midst of this tour, quite unexpectedly32 (April, 1882), came the announcement of the marriage. In order to have the ceremony performed in London, she had traveled from Naples, and then returned to Spain to resume the tour.34 It was the talk of the day that the reason for Sarah’s sudden marriage and for the selection of London as the scene of the ceremony, was not only her passing infatuation for Damala, but also a wish to propitiate English Puritanism. For a tour of England and Scotland soon followed. The marriage was not a huge success, however. It lasted not more than a year.

The mere statement of Bernhardt’s wanderings is sufficiently astonishing and is one proof of her wonderful vitality. In 1886, a tour that lasted more than a year took her to Mexico, Brazil, Chile, the Argentine,35 the United States and Canada. Two years later she acted in Constantinople, Cairo and Alexandria, besides most of the European countries. In the early part of 1891 she left Europe for two years and played not only in North and South America, but this time as far afield as Australia. Sarah has been a cosmopolitan figure, if there ever was one. As the land of readily won dollars, the United States has naturally been much favored; for beginning in 1880, Bernhardt has33 made no less than nine tours in America.36

Like a number of actors of the other sex, but almost alone among actresses, Bernhardt has dabbled in the management of theatres. Soon after her first American tour, she assumed control of the Ambigu in Paris. If she had acted in her own theatre (as later she did) her business venture might have succeeded. As it was, she was acting Fédora at the Vaudeville, and later, with only moderate success, in Holland34 and Belgium. The Ambigu languished. In the meantime, Sarah had spent all her money. Finding herself in straits, she auctioned her jewels, and realized handsomely on them. It was an event in Paris, and the sale produced no less than thirty-five thousand dollars.

Her next venture in management was more successful. In 1883, on behalf of her son, she bought a partnership in the Porte St. Martin, and produced Frou-Frou there for the first time in Paris. Her régime at this house was interrupted by the long tour begun in 1886, but continued, under the prosperity shed by her own presence, until 1893, when she bought the Renaissance. Since that day she has owned her own theatre, until 1899 at the Renaissance, and since then at the more commodious Théâtre Sarah-Bernhardt, her renaming of the Théâtre des Nations.

When Bernhardt went to America for the first time she had in her company an actress named Marie Colombier. For reasons that are difficult to determine, this woman conceived a passionate hatred of Sarah and on her return to France prepared, or had prepared for her,37 a thinly disguised pseudo-biography of Bernhardt which sold in enormous numbers under the name Les Memoires de Sarah Barnum. This pamphlet subjected Bernhardt to miscellaneous35 ridicule and abuse. Although on the whole false, parts of it may have been true enough to penetrate the armor against gossip that Sarah schooled herself to wear. At any rate, she was furiously angry. When the book had been in circulation long enough to give her action its proper background and advertising value, Bernhardt one day turned up at Mme. Colombier’s apartment, accompanied by her son and M. Jean Richepin, and armed with a horsewhip. The party forced themselves in, and Sarah, great actress, proceeded to chase her detractor about the place, beating her soundly with the whip. A similar incident occurred at Rio de Janeiro in 1886. Mme. Noirmont, a member of the company, one day “went for” Sarah with strong language and the flat of her hand. Sarah was at first content with the woman’s arrest, but one evening, between the acts, her desire for revenge got the better of her, and Mme. Noirmont was, in her turn, thoroughly horsewhipped. The cause of these (at the time) world famous ructions, which are now important only—if at all—as shedding light on Sarah’s frail humanity, has always remained shrouded in mystery.

Further proof that the “divine Sarah” was after all very human was furnished in 1907 when she published a volume of reminiscences.38 William Winter’s estimate of this book is characteristic;36 it contains, he says: “some passages of interest, but, as a whole, it is diffuse, flamboyant, and artificial,—an eccentric contribution to theatrical annals, mottled over by affectation, egregious vanity, and the pervasive insincerity of an inveterate self-exploiter.” It would be juster to say that the book shows in many places a more likable woman than the eccentric celebrity was supposed to be, and that it contains but few passages that are not of interest. At any rate, it shows Sarah to be, after all, in many respects like us commonplace people.

Whatever hostility she may have met in her earlier days, Bernhardt long ago won the unqualified homage of her countrymen. To them she became a cherished national institution, the great actress of her time. “The great and only Sarah” is the phrase of the once scoffing Sarcey. “I am not quite sure,” wrote Lemaître in 1894, “whether Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt can say ‘How do you do?’ like any ordinary mortal. To be herself she must be extraordinary, and then she is incomparable.” “You cannot praise her for reciting poetry well,” said M. Theodore de Banville, a poet learned in metres and rhythms; “she is the muse of poetry itself. A secret instinct moves her. She recites poetry as the nightingale sings, as the wind sighs, and as the water murmurs.”

“Her acting is the summit of art,”—again Sarcey—“our grandfathers used to speak with emotion of Talma and Mlle. Mars. I never saw37 either the one or the other, and I have barely any recollection of Rachel, but I do not believe that anything more original and more perfect than Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt’s Phèdre has ever been seen in any theatre.”

To take this view of Sarah one must, perhaps, be a Frenchman. The Sarcey of America, William Winter, certainly could not take it. With what may be termed the utilitarian Puritanism that seeks in the theatre to be “benefited, cheered, encouraged, ennobled, instructed, or even rationally entertained,” he could see in Bernhardt’s art only an exhibition of morbid eccentricity. Mr. Winter, here as elsewhere, has been made intolerant of much in the institution he has served and honored by his insistence on “intrinsic grandeur” in its characters. He is always looking for “the woman essentially good and noble,” whereas the modern drama has as one of its most cherished prerogatives its right to portray mixed characters,—often women whose “essential goodness” is mingled with much human frailty.

Fairly enough, however, according to his lights, does Mr. Winter specify and define Bernhardt’s peculiar merits: “They are, in brief, the ability to elicit complete and decisive dramatic effect from situations of horror, terror, vehement passion, and mental anguish; neatness in the adjustment of manifold details; evenly sustained continuity; ability to show a woman who seeks to cause physical infatuation and who generally can succeed in doing so; a38 woman in whom vanity, cruelty, selfishness, and animal propensity are supreme; a woman of formidable, sometimes dangerous, sometimes terrible mental force.”

Not all of Madame Bernhardt’s impersonations, however, fall within Mr. Winter’s proscribed class. She has at times shown a startling propensity for breaking into new and strange fields. Her Jeanne d’Arc (1890), a genuine success, was certainly not a “morbid eccentric.” “It is impossible to make Hamlet Parisian,” but, in 1899, Sarah played Hamlet, to the satisfaction of the French at least. “She never did anything finer,” said Rostand. “She makes one understand Hamlet, and understand him beyond the possibility of a doubt.”39 A year later she was playing Reichstadt, the son of Napoleon, in L’Aiglon, an impersonation that even Mr. Winter admitted “was one of beautiful symmetry.” And of recent years Sarah has threatened—though as yet she has not accomplished—the acting of Mephistopheles in Faust.

When Bernhardt was in London in 1895, George Bernard Shaw was in the midst of his career as the dramatic critic of the Saturday Review, serving a three-year term of what he called his slavery to the theatre. He observed Sarah with none too sympathetic eyes, but what39 he said shows, under his purposefully irritating exterior, the shrewd critical insight that makes the “Dramatic Opinions and Essays” one of the soundest books of theatrical comment, as well as one of the most readable:

“Madame Bernhardt has the charm of a jolly maturity, rather spoilt and petulant, perhaps, but always ready with a sunshine-through-the-clouds smile if only she is made much of. Her dresses and diamonds, if not exactly splendid, are at least splendacious; her figure, far too scantily upholstered in the old days, is at its best; and her complexion shows that she has not studied modern art in vain.... She is beautiful with the beauty of her school, and entirely inhuman and incredible. But the incredibility is pardonable, because, though it is all the greatest nonsense, nobody believing in it, the actress herself least of all, it is so artful, so clever, so well recognized a part of the business, and carried off with such a genial air, that it is impossible not to accept it with good-humor. One feels, when the heroine bursts on the scene, a dazzling vision of beauty, that instead of imposing on you, she adds to her own piquancy by looking you straight in the face, and saying, in effect: ‘Now who would ever suppose that I am a grandmother?’ That, of course, is irresistible; and one is not sorry to have been coaxed to relax one’s notions of the dignity of art when she gets to serious business and shows how ably she does her work. The coaxing suits well with the childishly egotistical character of40 her acting, which is not the art of making you think more highly or feel more deeply, but the art of making you admire her, pity her, champion her, weep with her, laugh at her jokes, follow her fortunes breathlessly, and applaud her wildly when the curtain falls. It is the art of finding out all your weaknesses and practicing on them—cajoling you, harrowing you, exciting you—on the whole, fooling you. And it is always Sarah Bernhardt in her own capacity who does this to you. The dress, the title of the play, the order of the words may vary; but the woman is always the same. She does not enter into the leading character: she substitutes herself for it.”

Where a more tolerant judgment would proclaim Sarah’s inalterable romanticism, Mr. Shaw, whose passion for truth and realism leave him little room for the sort of truth and reality there may be in the romantic, sees only the tricks of her trade: “Every year Madame Bernhardt comes to us with a new play, in which she kills somebody with any weapon from a hairpin to a hatchet; intones a great deal of dialogue as a sample of what is called ‘the golden voice,’ to the great delight of our curates, who all produce more or less golden voices by exactly the same trick; goes through her well-known feat of tearing a passion to tatters at the end of the second or fourth act, according to the length of the piece; serves out a ration of the celebrated smile; and between whiles gets through any ordinary acting that may be necessary in a thoroughly41 businesslike and competent fashion. This routine constitutes a permanent exhibition, which is refurnished every year with fresh scenery, fresh dialogue, and a fresh author, whilst remaining itself invariable. Still, there are real parts in Madame Bernhardt’s repertory which date from the days before the traveling show was opened; and she is far too clever a woman, and too well endowed with stage instinct, not to rise, in an off-handed, experimental sort of way, to the more obvious points in such an irresistible new part as Magda.” On the whole, Shaw is something less than fair to Sarah. But one cannot deny him an appreciative chortle when he speaks of her “dragging from sea to sea her Armada of transports.”

On December 9, 1896, there was held a fête in Paris in honor of Bernhardt—the most striking in a long line of similar occasions. It was felt that her position as queen of the stage deserved a public recognition. It was carried through with Gallic enthusiasm. Sardou presided at a mid-day banquet attended by Coppée, Lemaître, Theuriet, Lavedan, Coquelin, Charpentier, Rostand, and a host of others from the literary and artistic world of Paris. Sardou hailed her as the acknowledged sovereign of dramatic art, and bore testimony not only to her acting, but also to “the benevolence, the charity, and the exquisite kindness of the woman.” When Sarah had responded with a few words of thanks, there was a great demonstration, emotionally enthusiastic and Gallic.42 Later in the day, at the Renaissance, the ceremonies were continued. Sarah gave the third act of Phèdre and the fourth act of Rome Vaincue. She gave her best efforts and her hearers were much moved. Huret records that all his neighbors in the audience were weeping. Then, five poets, François Coppée, Edmond Harancourt, Catulle Mendès, André Theuriet and Edmond Rostand, advanced in turn, each to read a sonnet in Sarah’s honor. When Rostand’s—the last and best—was finished, she was seen to tremble and to stand weeping in their midst. “No spectacle could be finer,” says Huret, “than this woman, whose unconquerable energy had withstood the struggles and difficulties of a thirty-years’ career, standing overwhelmed and vanquished by the power of a few lines of poetry.”

Whether or not she was a divinely ennobled and beneficent artist, this trait of “unconquerable energy” is undeniably a marvel. For instance, in January, 1906, when she was sixty-one, she appeared in Boston. In the twenty-six hours between half-past eight on Friday evening and half-past ten on Saturday evening she acted Fédora, Phèdre, and Cesarine in Dumas’s La Femme de Claude, each a long, exacting and, one would think, exhausting rôle. At the end of the third play, however, Bernhardt had her artistic resources and her strength as fully under her command as at the beginning. And she had been forty-four years on the stage. This was but an incident of a43 widely extended tour, a sample of what she had been doing all her life.

In February, 1907, she was made a professor at the Conservatoire, partly in an attempt to make her eligible for the cross of the Legion of Honor. This was an honor that Sarah had long desired, and, it must be said, deserved. Her service to her country as a herald of its language and art—to say nothing of that during 1870—has been inestimably greater than that of many who have received the honor. But in France an actress is still without social position, and the social conservatism of Paris officialdom always prevailed in the face of Sarah’s champions. For no actress, merely as an actress, had ever been admitted to the Legion. In January, 1914, however, it was announced throughout the world that Mme. Bernhardt had received the long-coveted decoration. The usual objections and traditions had been interposed, but President Poincaire himself cut the red tape. In March the formal presentation occurred. L’Université des Annales organized the ceremony. Government officials, actors and actresses, poets, playwrights and a throng of the notabilities of Paris gathered to do Madame Sarah honor. The Minister of Fine Arts, on behalf of the Government, presented the decoration and made a formal speech in which he summed up her services as patriot and as a missionary of the French language. Verses by Rostand and other poets were read, music composed for the occasion was played, artists advanced and44 heaped flowers at Bernhardt’s feet, and then came forward twelve actors and actresses, each representing a famous character in Bernhardt’s repertoire, and speaking lines from the original plays. The whole became a sonnet in dialogue. Finally Bernhardt herself ended the very French but very sincere occasion by an eloquent and tender speech of thanks.

About this time a photograph found its way into the American newspapers. It showed Madame Sarah with the glittering cross of the Legion pinned to her dress. Seated on her lap and gazing at the decoration is Madame Sarah’s great-grandchild.

We have mentioned Mr. Winter’s wholesale repudiation of the plays in which Bernhardt attained her eminence. Without subscribing to the total depravity of such plays and of Bernhardt’s influence, one can freely admit that her appeal fell below the supremest heights of drama, and that her field was, after all, a narrow one. There were natural causes for this narrowness. It was imposed by her personality. She partakes to the fullest extent of that variation of the French character that is predominatingly sensual, yet regards its sensuality as a kind of spirituality. Again, her technical equipment as an actress included a voice of such richness and variety of effect, and a power of gesture and pose so naturally adapted to the grand style, that her tendency was for the florid and rhetorical. Thus the idealistic or poetic play, on the one hand, and the frankly45 naturalistic on the other, were beyond her province. The result has been, most notably, a succession of plays by Sardou—Fédora, Théodora, La Tosca, Cléopâtre, Gismonda, Zoraya, in which the author “accepting her limitations, harped time and time again upon the same notes. His heroines are creatures all alike compounded of Bernhardtesque attributes—feline in their endearments, tigerish in their passions of love and hate. As stage figures they represent the boldest prose of the emotions, expressed with a rhetoric that is flawless, but still rhetoric.”40

So much for the main note. In a career so astonishingly long and successful there have been, of course, others. We have seen how, in46 L’Aiglon, Hamlet, and Jeanne d’Arc she boldly went outside her usual field. Even within it there have been of course many moments of winning appeal or great power. To none other than Mr. Winter did her Frou-Frou appear pure-spirited, “an exquisite texture ... of childlike womanhood,”41 and as Floria Tosca “Bernhardt’s acting ... was magnificent,—for it created the effect of perfect illusion”; it will “be remembered with a shuddering sense of horror as long as anything is remembered of her achievement.... Of its kind it was absolutely perfect art.” In La Femme X he found her art consummate. Her Marguérite Gauthier in La Dame aux Camélias did much to give that heroine genuine and compelling appeal to the purer emotions, her Phèdre has its moments of genuine nobility. And though it may be true that, in the main, she worked in those strata of the drama that are of “little benefit to humanity,” the sheer extent and strength of her influence bear witness that much in her work found a response in the minds and sympathies of two generations of people.

She is, after all, unique, whatever the loftiness of her message; for the intensity of her47 power, the span of time over which she has exercised it and the universality of her fame combine to write a chapter that stands alone in theatrical annals.

To the body of Bernhardtian legend has now been added the legend of the leg. This time it is an authentic legend, and one that adds greatly to Sarah’s merited fame for courage and will.

In February, 1915, she wrote to Mme. Jane Catulle Mendès:

“My Dear: As you perhaps have learned, they are going to cut off my leg Monday. They should have done so last Sunday, but it seems I was not sufficiently prepared for that first performance. The principal artist, my right leg, had not learned its rôle. It has now learned it, and it will be charming.”

There is a long story of patiently endured suffering back of that lightly phrased note. In 1912 she made a visit to America, playing—as before and since in London—in the vaudeville theatres short scenes from her former successes. There were circumstances in her acting that puzzled the beholders. She would take a fixed position and maintain it for long periods. When she moved across the stage, it was usually with another’s support. Such hamperings to her acting were commonly put down to her advanced age, or sometimes to rheumatism. As a matter of fact, Sarah had for ten years48 suffered from osteoarthritis—chronic inflammation of the articulation of her right knee. The trouble manifested itself first at Montevideo, and was there temporarily and inadequately treated. From that time, at first intermittently and then continuously, the knee brought her pain that she endured with fortitude and without curtailment of her work. As time went on, she gradually modified the business of her parts, and even had plays written to suit her limitations,—as in Le Procès de Jeanne d’Arc, in which she stood in court all during one act and in another remained seated at the side of her bed.

In the Spring of 1914, while she was playing in Liège, she gave the afflicted knee a slight sprain. Upon this, the trouble became acute. She remained, first at her house on Belle Isle, and later at Andernos, now Arcachon, with the knee in a fixed plaster cast. The pain was reduced; Mme. Sarah could paint and could work on her memoirs, and her general health was excellent; but here she was with her career cut off! When the surgeons, hoping to replace the cast with some apparatus that would permit her to walk, found that instead the knee would have to be kept unmoved for an indefinite time, Sarah took matters into her own hands, and ordered the offending member removed. It was better, she said, in a letter to Maurice Barres, “to be mutilated than to remain impotent.”

On February 22, 1915, at Bordeaux, in her seventy-first year, Mme. Bernhardt’s right leg49 was amputated above the knee. “While the hospital attendants were preparing for the operation,” said a dispatch from her bedside, “the actress conversed volubly with her doctors: ‘Work is my life. So soon as I can be fitted with an artificial leg, I shall resume the stage and all my good spirits shall be restored. I hope again to be able to use all that force of art which now upholds me and which will sustain me until beyond the grave,’”—a speech, as Philip Hale said, “worthy of one of Plutarch’s men.” Surgeons and nurses present at the operation were deeply impressed by the calm courage with which she faced the operation.42

Even in the midst of the horrors and anxieties of universal war, Bernhardt’s ordeal challenged world-wide sympathy. Portraits and eulogies appeared in every paper. For a week or more, until it became certain that the operation had been successful, bulletins on her condition were printed daily. Queen Victoria of Spain, the aged Eugénie, M. Deschanel, president of the Chamber of Deputies, Edmond Rostand—these were only a few of those, both proud and humble, whose messages poured in upon her from all quarters. Alexandra, Queen-mother of Great Britain, sent word of the “sympathy which all England shares for the greatest artist in the world.” After the operation,50 Mme. Bernhardt said that she was to “live again. Already I am free from suffering, happy and full of courage, and now I am going to get well quickly. I shall retake my place in the world.”

This announcement was sufficiently astounding. The remarkable woman then followed it with another,—that she would make a new tour in America, this time not in the vaudeville theatres (where interest in her was before not overwhelming), but in the regular theatres, where she would offer a number of plays in which she has not yet been seen on this side of the Atlantic.

Thus does Bernhardt remain vividly alive to the last. M. Jules Lemaître once said that he admired her because of the unknown he felt to be in her. “She might go into a nunnery, discover the North Pole, be inoculated with rabies, assassinate an emperor, or marry a negro king, and I should never be surprised at anything she did. She is more alive and more incomprehensible by herself than a thousand other human beings.”

Thus it may be that she will again rally about her on the stage of Paris the loyal affection that went out to her in the hospital. It is an open secret that for half a dozen years the allegiance of her Paris public has not always been unflagging. She is indubitably old, and her affliction was imperfectly understood. And yet, when her latest play, Jeanne Doré, by Tristan Bernard, was produced in December, 1913, a51 flash of the old enthusiasm broke out again and one correspondent described the occasion as “easily the most brilliant first night of the Paris season so far.” The part, moreover, was an exacting emotional one. In it Madame Sarah seems again to have shown her great power.

52

The acting of Madame Modjeska is still remembered vividly by American and English theatregoers, yet its beginnings lie as far away in time as the sixties and as distant in place as Poland. She was born on October 12, 1840, in Cracow, the old Polish capital, now the second city of Galitzia, or Austrian Poland. Twenty-five years before, by the agreement of Russia, Prussia, and Austria, it had been proclaimed a free city. In the year when Modjeska was six, however, Austria, greedy then as now, broke her pledge and annexed the city. The Poles were always a passionately patriotic people, and did not submit calmly. Discontent grew to open revolt, but the hopes of the Cracovians were crushed by the bombardment of the city by the Austrians in 1848.

Thus the little Helcia43 was born in tragic times, and as a little girl saw scenes of terror and bloodshed. Her mother’s house was struck by the cannon shot, and she saw men and children killed before her very door. The horrors of those days were vividly impressed upon her memory and were perhaps not without their effect upon the nature of the future actress.

Her father, Michael Opid, born in the Carpathian53 mountains, and a teacher in the high school in Cracow, was a simple-hearted, lovable man, something of a scholar and a great lover of music. He was extremely fond of children. His own girls and boys and those of his neighbors would gather about him in the evening, listening to the folk lore of the mountaineers, Polish legends, and tales from the Iliad. When Helcia, years later, herself studied Homer, those winter evenings and their stories were vividly recalled. But Michael Opid’s chief delight was music. He played several instruments, the flute especially well. His melodies appealed almost too strongly to the sensitive little Helcia, who during plaintive passages in the music would burst into wails and cries. Singers and musicians were frequent visitors at the Opid house, and in its atmosphere there was thus an artistic element, which undoubtedly had some influence in determining the career of Helcia. Her father died when she was seven, of consumption, induced by exposure while seeking his drowned brother’s body. When he knew he was dangerously ill, he returned to his native mountains to die.

It had been the second marriage of Madame Opid. She had been Madame Benda, and having altogether ten children to care for, she could give by no means exclusive attention to any one of them, even had she known that that one was to be a great actress. The children were well cared for so far as their bodily wants54 were concerned, but their personalities were left to themselves to develop. For Helcia this was not altogether unfortunate, for her imagination, stirred by history-making events and by the songs and poems of which she was so fond, had free rein. She did not care much for the society of other children, and was not popular with them. She was a little dreamer, almost painfully bashful, living much in a world of her imagination, and fond of going to church. She would steal away alone to the Dominican chapel, where she would lie face down on the floor, in the manner of the peasant women, arms outstretched, kissing the floor and praying for a miracle or a glimpse of an angel or a saint.

Her first schooling was in the house of a friend of her mother’s, a woman with two well-educated daughters who taught the little Helcia, by the time she was seven, to read with ease. She fed her imagination with all the books she could find at hand. In school she liked her Polish history, her French and her grammar.

When Helcia was seven, she was taken to the theatre for the first time. The play was The Daughter of the Regiment, and was followed by a ballet The Siren of Dniestr, in which little Josephine Hofmann (to be Josef Hofmann’s aunt) dressed as a butterfly, hovered about in the air. Helcia was entranced; to her it was all a dream of joy come true.44 She went to bed55 that night with a high fever, and for weeks afterward she practiced the butterfly dance, watching her shadow on the wall, much to the amusement of her small brothers. But theatricals became the family pastime. Helcia’s three older brothers were enthusiastic. They rigged up a stage at home, with the help of some other boys formed a little company, and every month gave performances for admiring friends. They excluded the girls, and played all the women’s parts themselves. The home theatre was probably of great influence in the lives of its members, for two of the boys, besides Helcia and her sister, subsequently went on the stage.

In 1850, when Helcia was in her tenth year, Cracow was burned. The conflagration lasted ten days, and a large part of the city was destroyed. Madame Opid up to this time had been a woman of some property. Her first husband had left her a small estate which she had managed skillfully. Her two houses were now destroyed, her insurance had lapsed ten days before, and she was practically ruined. Here was more misfortune to impress the growing Helcia, to make her, for her years, unusually sensitive and thoughtful. After a few days of almost vagabondage, the family was given temporary quarters in a friend’s house. There Helcia, left much to herself, spent her time56 reading her Life of St. Genevieve, a treasured volume which she rescued in the moment of peril. At length installed in a newly hired house, Madame Opid sent Helcia and her little sister Josephine as day pupils to St. John’s convent, and supplemented the teachings of the sisters with lessons at home in music and dancing.

It was at this time, when Helena was ten, that she first met Gustave Modrzejewski,45 who was later to be her husband. He was twenty years her senior. He was a friend of the family and taught the children German, the hated language of the oppressor.

When Helena was twelve, her half-brothers Joseph and Felix Benda had gone away to be actors on the professional stage. To relieve the quiet at home she and her brother Adolphe Opid, who was then fifteen, wrote a play, a one-act tragedy. The scene was laid in Greece, and the acting required the death of Adolphe, and an impassioned scene of grief by Helena when with a sob she threw herself over her dead lover’s body. She drew from the sympathetic servants and her great-aunt Theresa genuine tears, but her practical mother was unmoved, thought Helena over-excited and forbade further theatricals.

At fourteen Helena finished the highest grade at the convent. This was the end of her formal schooling, but she at once began a strenuous57 and varied course of reading. She began with the Polish poets, of whom there are several proudly cherished by their countrymen. It was the family’s pleasant custom, fostered by the well-read Mr. Modrzejewski, to read aloud in the winter evenings. In this way Helena learned of Scott, Dickens, Dumas, George Sand, and many another. She had neglected her German, and it was to stimulate an interest in the disliked language that Mr. Modrzejewski proposed that she be taken to see a German play. She was immensely excited, for it was seven years since she had been to the theatre. The play was Schiller’s Kabale und Liebe. She entered the theatre in a state of awe, she sat through the performance in spellbound fascination, and the next morning with the help of a dictionary began reading Schiller in German. Schiller became for the time an overwhelming enthusiasm with her. She imagined herself in love with him, and placed before her in her room his statuette, as a kind of idol. Such extravagances as this, and the religious period that preceded it, would have indicated to a discerning eye a promisingly responsive and emotional nature. To those about her, however, even to her mother, she was only a moody and at times excitable child whose enthusiasm was to be repressed and whose future was doubtful. She helped with the family work, as all did in this time of stress, but she was living apart in a world of poetry, of vague and ardent dreams.

58 She was now taken to the theatre occasionally. Felix Benda had become one of the popular actors of the local theatre. One day, when Helena was about sixteen, he overheard her reciting to her sister. Surprised and pleased, he took her next day to the house of one of the leading actresses of the company, who as an artist of experience could judge of the young girl’s chances of success on the stage. All this came very suddenly. Helena had not seriously thought of a stage career. The hearing was a trying ordeal, for she was terribly frightened. After giving Helena a lesson or two, the actress was discouraging. She advised Madame Opid to keep the young girl at home rather than allow her to become a mediocre actress. For a while Helcia’s budding ambitions were crushed.

Madame Opid, for one, was not disappointed. The family was not so well off as it was before the fire and to Helcia fell a large share of the housework. But she studied and read and thought, with unsettled mind and changing purpose. At one time she thought she would try to achieve fame as a writer; again, at her mother’s wish, she studied furiously with a teacher’s examination in mind; again, to become a nun seemed the only thing worth while. But shortly there came a rude shock to all these plans. Fritz Devrient, a German actor of great talent, played Hamlet in Cracow, and Helena was taken to see him. She had heard of Shakespeare, but had never seen or read any59 of his plays. The effect on her was overwhelming. Shakespeare became her master then and there, and she never deserted him. She spent a sleepless night, and the longing to be an actress returned with redoubled strength. She greedily read the plays of Shakespeare in Polish translations, and his bust speedily replaced that of Schiller. The family friend, Gustave Modrzejewski, to her great delight seconded her in her renewed ambition, recommended that she study for the German stage as offering a wider field than the Polish, and arranged for lessons from an excellent actor, Herr Axtman. Indeed, his interest extended further, for when Helcia was seventeen he urged that their marriage, which had come to be an understood thing, take place at once. She had seen much of him; they had read together Goethe and Lessing and the northern sagas; he was her guardian and the kindly counselor of the family; and she looked on him, a man more than twice her age, with real affection; and so they were married at once.

After Helena had taken the name which she was to make so famous, there followed a few quiet years during which her ambitions lay in abeyance. When she was twenty her son Rudolphe was born. The little family, and Madame Opid as well, moved to Bochnia, a little town in Austrian Poland. Here it was that, owing to the circumstance that Bochnia possessed salt mines, Mme. Modjeska had her first opportunity to appear on a real stage. Some60 of the miners had been killed in an accident. It occurred to the Modjeskis to give, for the benefit of the bereaved families, some amateur theatricals. They met a friend, a dancing master named Loboiko, who obtained a hall, hastily built some scenery and acted as leading man of the company. There were but three others—a young man who was the dancing master’s pupil, Helena as leading lady, and Josephine, her younger sister. Stasia, their nine-year-old niece, was prompter. The plays were two pieces now forgotten—The White Camelia, in one act, in which Helena was a countess, and The Prima-Donna, in which she was an Italian peasant girl who became an actress. Delighted as she was to realize her cherished ambition to appear on the stage before an actual audience, when the bell rang for the rise of the curtain she was thoroughly frightened. Before she went on she could not think of her lines, and she fairly shook with nervousness. Yet once on the stage her words came to her and she found herself, much to her surprise, quite at her ease. The dignitaries and the country gentlemen of the district and the townspeople all turned out for the performance, and for the two others that followed it, in unexpectedly large numbers. Madame Modjeska’s acting, at this her first opportunity for showing it, attracted attention. An actor and stage manager from Warsaw, who happened to be in Bochnia and saw her act, asked her how long she had been on the stage,—an amusing and pleasing question,—and61 urged her to turn her eyes toward Warsaw. Such men do not pay empty compliments, and Helena’s confidence now took new hold. The prospect of going to Warsaw drove from her mind any idea of becoming a German actress. It was Warsaw and the Imperial Theatre, or die!

Such was the modest beginning of a career. Mr. Modjeski, so far from objecting to his young wife’s being an actress, saw in the new turn of affairs a chance to retrieve the family fortunes and to get a living for them all. A license for a traveling company was obtained from Cracow, Mr. Modjeski constituted himself manager, and the little band of players, travelling in a peasant’s wagon, went on to New Sandec.46 Here the company was gradually enlarged until it had nineteen members, and here they stayed all summer. Helena was from the beginning their star. She and her comrades were but strolling players, living in poorly furnished quarters and eating frugal meals. She had but two dresses, one black for tragedy, the other white for comedy. Yet she was happy as never before or perhaps since. Long afterward she thrilled with the recollection of the enthusiasm and joy of those early days. To live in her own world of youth and eager beginnings62 and at the same time in the imaginary world of her heroines, was a happiness that outweighed all lack of comforts.

For more than a year the company traveled about in Austrian Poland. It was during this period that the Polish insurrection of 1863 was brewing. The oppression under which Russian Poland suffered found sympathy in Galitzia and indeed the entire Polish people was in mourning. Every one, at least in the towns, wore black, for the wearing of colors was practically forbidden by public feeling. Yet people contrived to go to the theatre, and “The New Sandec Combination,” as it was called, prospered. Their Polish historical pieces roused the patriotism of their audiences and did their share in maintaining the spirit of the people in the face of the Russian outrages.

Madame Modjeska was the favorite of the provincial public to which her company addressed itself. The popular demand for her was such that the audiences fell off when she was not in the cast, and she consequently was forced to appear constantly. When her daughter was born47 she had finished acting her part in a five act tragedy only two hours before; and in ten days she was again appearing. The company grew in size and improved in quality, and their repertoire was enlarged to include such plays as Schiller’s Die Räuber and Sheridan’s The School for Scandal.

This year and a half of “barnstorming” was63 invaluable experience for Modjeska. It gave her confidence and technique, and, finally, recognition. One of the managers of the endowed theatre of Lemberg48 had seen and liked her acting. In the autumn of 1862 the Modjeskis retired from the strolling company, and after a few probationary performances Helena, then twenty-two, was enrolled a member of the resident company at Lemberg. With her first opportunity to play on a well-equipped stage, with good actors, and before a city audience, she felt that she had made a distinct step upward. She played a wide variety of characters, ranging from great ladies to pages, ingénues, and the soubrette parts in operetta. She profited by the example and the friendly advice of Madame Ashberger, who was the leading lady, but the younger women of the company were jealous of the upstart newcomer with the pretty face. They influenced the management to give Modjeska only small parts, and this, with the insufficiency of the salary, so discouraged her that after a year at Lemberg she and her husband returned to try their fortunes again in the provinces.

Mr. Modjeski established in the town of Czerniowce a stock company that was largely a family affair. Joseph and Felix Benda, Helena’s half-brothers, her sister’s husband and Josephine herself, all were members, while Simon Benda led the orchestra. There were more than twenty actors altogether, some of64 whom afterwards became famous in Poland. The two years at Czerniowce Modjeska filled with hard work. 1863 marked the crisis in the affairs of unhappy Poland. The Galitzians were only less stirred by the tyranny and bloodshed in Russian Poland than their kinsfolk, the victims. Excitement and patriotic feeling ran high and troops were being raised everywhere; yet throughout this troublous period the theatres prospered. As for Modjeska, with admirable energy and ambition she studied and worked. So far she had not played in tragedy. On a visit to Vienna, a brief vacation she took to see a bit of the world with Mr. Modjeski, a manager before whom she tried her powers in a scene from Marie Stuart advised her to cultivate her voice and her German before essaying the more serious rôles. Accordingly she practiced faithfully in the midst of a busy career at the theatre. She had attained a considerable reputation in Galitzia, and, as before, appeared constantly, not only in the company’s home town but in towns about the province. She was happy in her work, but her health was suffering, and for a while consumption threatened her. Other troubles soon came. In 1865 her two year old daughter died, and soon afterwards other misfortunes, of a domestic nature, ended in her separation from her husband, whom she never saw again.

Moving now to her birthplace, Cracow, with her mother, her little son and her brother Felix, she was soon a member of the company at the65 old theatre where she had been taken, years before, to see the plays that had so greatly excited her.