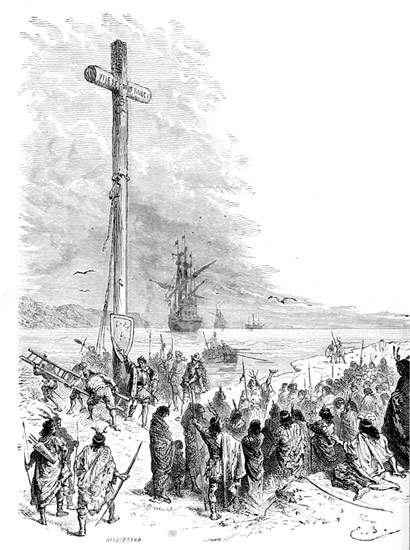

CARTIER TAKING POSSESSION FOR FRANCE.

Title: The Making of the Great West, 1512-1883

Author: Samuel Adams Drake

Release date: July 17, 2018 [eBook #57528]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent hyphenation and spelling in the original document have been preserved. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

Footnote 1 in the section "DEATH AND BURIAL OF DE SOTO" is missing.

There are two [7] anchors for Footnote 7 in the section "SWORD AND GOWN IN CALIFORNIA".

There are two [3] anchors for Footnote 3 in the section "THE LOST COLONY: ST. LOUIS OF TEXAS". The second appears to be a printer's error.

No map was identified in the text showing the Santa Fé and Oregon trails.

No section was found referring to the "Edmunds Bill".

The following alternate spellings were identified and retained:

BY

SAMUEL ADAMS DRAKE

WITH MANY ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

London

GIBBINGS & COMPANY, Ltd.

18 BURY STREET, W.C.

1894

Copyright, 1887, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS.

Presswork by Berwick & Smith, Boston, U.S.A.

"Time's noblest offspring is the last."

This history is intended to meet, so far as it may, the want for brief, compact, and handy manuals of the beginnings of our country.

Although primarily designed for young people, the fact has not been overlooked that the same want exists among adult readers, to whom an intelligent view of the subject, in a little space, is nowhere accessible.

For the purpose in hand, the simplest language consistent with clearness has been made use of, though I have never hesitated to employ the right word, whenever I could command it, even if it were of more than three syllables.

As in the "Making of New England," "this book aims to occupy a place between the larger and lesser histories,—to so condense the exhaustive narrative as to give it greater vitality, or so extend what the narrow limits of the school-history often leave obscure as to supply the deficiency. Thus, when teachers have a particular topic before them, it is intended that a chapter on the same subject be read to fill out the bare outlines of the common-school text-book.

"To this end the plan has been to treat each topic as a unit, to be worked out to a clear understanding of its objects viii and results before passing to another topic. And in furtherance of this method, each subject has its own descriptive notes, maps, plans and pictorial illustration, so that all may contribute to a thorough knowledge of the matter in hand. The several topics readily fall into groups that have an apparent or underlying connection, which is clearly brought out."

In this volume, I have followed up to its legitimate ending the work done by the three great rival powers of modern times in civilizing our continent. I have tried to make it the worthy, if modest, exponent of a great theme. The story grows to absorbing interest, as the great achievement of the age,—of the Anglo-Saxon overcoming the Latin race, as one great wave overwhelms another with resistless force.

Under the title of "The Great West," the present volume deals mostly with the section lying beyond the Mississippi. Another is proposed, in which the central portion of the Union will be treated. The completed series, it is hoped, will present something like a national portrait of the American people. ix

| GROUP I.—THREE RIVAL CIVILIZATIONS. | |

| I. The Spaniards. | |

| PAGE | |

| An Historic Era | 1 |

| De Soto's Discovery of the Mississippi | 10 |

| Death and Burial of De Soto | 18 |

| The Indians of Florida | 20 |

| How New Mexico came to be Explored | 28 |

| "The Marvellous Country" | 39 |

| Folk Lore of the Pueblos | 45 |

| Last Days of Charles V. and Philip II. | 53 |

| Sword and Gown in California | 55 |

| II. The French. | |

| Prelude | 67 |

| Westward by the Great Inland Waterways | 71 |

| The Situation in A.D. 1672 | 80 |

| Count Frontenac | 84 |

| Joliet and Marquette | 85 |

| The Man La Salle | 93 |

| La Salle, Prince of Explorers | 99 |

| Discovery of the Upper Mississippi | 105 |

| The Lost Colony: St. Louis of Texas | 109 |

| Iberville founds Louisiana | 118 |

| France wins the Prize | 123 |

| Louis XIV. | 130 |

| III. The English. | |

| The Bleak North-west Coast | 132 |

| Hudson's Bay to the South Sea | 136 |

| The Russians in Alaska | 140 |

| England on the Pacific | 143 |

| Queen Elizabeth | 147 |

| Interlude. | |

| What Jonathan Carver aimed to do in 1766 | 149 |

| John Ledyard's Idea | 153 |

| A Yankee Ship discovers the Columbia River | 156 |

| The West at the Opening of the Century | 162 |

| GROUP II.—BIRTH OF THE AMERICAN IDEA. | |

| I. America for Americans. | |

| Acquisition of Louisiana | 171 |

| A Glance at our Purchase | 175 |

| II. The Pathfinders. | |

| Lewis and Clarke ascend the Missouri | 184 |

| They cross the Continent | 191 |

| Pike explores the Arkansas Valley | 198 |

| New Mexico in 1807 | 205 |

| Gold in Colorado.—A Trapper's Story | 208 |

| The Flag in Oregon | 211 |

| Louisiana admitted 1812 | 214 x |

| III. The Oregon Trail. | |

| The Trapper, Backwoodsman, and Emigrant | 215 |

| Long explores the Platte Valley | 219 |

| Missouri and the Compromise of 1821 | 223 |

| Arkansas admitted 1836 | 227 |

| Thomas H. Benton's Idea | 227 |

| With the Vanguard to Oregon | 233 |

| Texas admitted | 241 |

| Interlude. | |

| New Political Ideas | 246 |

| Iowa admitted | 248 |

| The War with Mexico | 248 |

| Conquest of New Mexico | 251 |

| Taking of California | 256 |

| The Mormons in Utah | 264 |

| GROUP III.—GOLD IN CALIFORNIA, AND WHAT IT LED TO. | |

| I. The Great Emigration. | |

| El Dorado found at last | 271 |

| Swarming through the Golden Gate | 276 |

| The California Pioneers | 279 |

| California a Free State | 285 |

| Arizona | 288 |

| II. The Contest for Free Soil. | |

| The Kansas-Nebraska Struggle | 290 |

| Kansas the Battle-ground | 295 |

| The Battle fought and won | 299 |

| Two Free States admitted | 307 |

| III. The Crown of the Continent. | |

| Gold in Colorado, and the Rush there | 308 |

| The Pacific Railroads | 315 |

| Kansas, Nevada, Nebraska, and Colorado admitted | 320 |

| The Recent States | 322 |

| The Work of Eighty Years | 326 |

| PAGE | |

| Taking Possession for France | Frontispiece |

| Spanish Arms | 1 |

| Ship of the Sixteenth Century | 2 |

| Isabella of Spain | 3 |

| Medal of Charles V. | 5 |

| Ponce de Leon | 6 |

| Balboa discovering the Pacific | 8 |

| French Map of 1542. From Jomard | 10 |

| De Soto | 11 |

| Soldier of 1585 | 12 |

| Cuban Bloodhound | 14 |

| Departure of the Spaniards | 16 |

| Burial of De Soto | 19 |

| Florida Warrior | 21 |

| Palisaded Town | 23 |

| A Florida Indian's Cabin | 24 |

| Making a Canoe | 25 |

| A Chieftain's Grave | 26 |

| Processional Fans | 27 |

| Rock Inscriptions, New Mexico | 29 |

| Map, New Mexico. Route of Spanish Invaders | 31 |

| Junction of the Gila and Colorado | 34 |

| Organ Mountains | 36 |

| El Paso del Norte | 38 |

| A Pueblo Restored | 41 |

| Acoma | 43 |

| Casa Grande, Gila Valley | 44 |

| Ruins of Pecos | 47 |

| Cereus Gigantea | 49 |

| Pueblo Idols | 50 |

| Hieroglyphics, Gila Valley | 51 |

| Map, California Coast | 55 |

| Sir Francis Drake | 57 |

| Drake sails away | 58 |

| Old Map showing Drake's Port | 60 |

| Carmel Mission Church | 61 |

| Spanish Map of 1787, showing Missions, Presidios, and Routes | 63 |

| Map from Arcano del Mare, 1647 | 64 |

| Ships of the Sixteenth Century | 68 |

| A Wood Ranger | 70 |

| Champlain | 72 |

| A Portage | 73 |

| Totem of the Foxes | 76 |

| French Costumes | 77 |

| Fox River | 78 |

| Louis XIV. | 82 |

| Marquette's Map | 86 |

| Wild Rice | 87 |

| Totem of the Illinois | 89 |

| War Canoe, from Lahontan | 90 |

| The Calumet | 91 |

| La Salle | 94 |

| Map showing La Salle's Explorations | 95 |

| Wampum Belt | 102 |

| Sioux Chief | 107 |

| Sioux Totem | 108 |

| Sugar Plant | 120 |

| Map showing Delta of the Mississippi and Adjacent Coast | 122 |

| Bienville | 124 |

| French Soldiers | 126 |

| New Orleans, 1719 | 129 |

| Abandoned Hut, North-west Coast | 133 |

| Hudson's Bay Company's House, London | 135 |

| Hudson's Bay Sled, loaded | 136 |

| Indian Mask, West Coast | 139 |

| Seals, St. Paul's Island | 140 |

| Russian Church, Alaska | 141 |

| Snow Spectacles, Alaska | 144 xii |

| Indian Carving | 144 |

| Indian Grave, North-west Coast | 155 |

| Queen Elizabeth | 148 |

| Falls of St. Anthony | 151 |

| Indian Burial Scaffold | 152 |

| Map, Mouth of Columbia River | 157 |

| Medal, Ships Columbia and Washington | 159 |

| An Oregon Belle | 161 |

| A Flat-Boat | 164 |

| On the Lower Mississippi | 167 |

| A Louisiana Sugar-Plantation | 176 |

| French Settlements: Germ of St. Louis | 177 |

| Old Convent, New Orleans | 179 |

| Map, St. Louis and Vicinity | 180 |

| Chouteau's Pond, St. Louis | 181 |

| Rock Towers near Dubuque | 182 |

| Mountain Goat, or Big-horn | 185 |

| Indians moving Camp | 186 |

| A Mandan | 188 |

| Mandan Skin Boats | 190 |

| Gate of the Rocky Mountains | 193 |

| Catching Salmon, Columbia River | 196 |

| Map illustrating Lieut. Pike's Explorations | 199 |

| Indian Burial-place | 200 |

| Pike's Peak | 202 |

| The Yucca-tree; Spanish Bayonet | 205 |

| Church, Santa Fé, with Fort Marcy | 207 |

| An Emigrant's Camp | 217 |

| Map illustrating Long's Explorations | 220 |

| Prairie-dog Village | 221 |

| Digging in the River for Water | 222 |

| Statue of Benton | 229 |

| Fort Laramie | 235 |

| Amole, or Soap-plant | 237 |

| San Antonio | 242 |

| The Alamo | 244 |

| Samuel Houston | 245 |

| Mexican Cart | 249 |

| Mexican Arastra, for grinding Ores | 250 |

| Pueblo Woman grinding Corn | 253 |

| Boy and Donkeys | 254 |

| Pueblo of Taos | 255 |

| Big Tree | 257 |

| Map showing States and Territories acquired from Mexico | 259 |

| California Indians and Tule Hut | 260 |

| El Capitan, Yosemite | 262 |

| Salt-Lake City and Tabernacle | 265 |

| Sutter's Mill | 272 |

| Two Miners | 274 |

| The Golden Gate | 276 |

| Chinese Laundryman | 277 |

| A Father | 280 |

| Mount Shasta | 281 |

| On the Oregon Trail | 282 |

| San Francisco in 1849 | 283 |

| Early Coin | 284 |

| Hydraulic Mining | 286 |

| Chicken-Vender | 287 |

| Mission San Xavier del Bac, near Tucson | 289 |

| Stephen A. Douglas | 291 |

| A Squatter's Improvements | 296 |

| Street, Kansas City, 1857 | 297 |

| Lawrence, Kansas | 298 |

| The Ferry, Lawrence, Kansas | 300 |

| A Squatter moving his Claim | 301 |

| Mud Fort, Lawrence | 303 |

| John Brown | 304 |

| John Brown's Cabin | 305 |

| Gate, Garden of the Gods | 309 |

| Humors of the Road | 310 |

| Denver in 1859 | 311 |

| Overland Stage—in Camp | 311 |

| Going in | 312 |

| Coming Out | 312 |

| Office of "Rocky-Mountain News," Denver | 312 |

| Colorado City, 1859 | 313 |

| Quartz Stamping-Mill | 314 |

| Quaker Gun at Stage Station | 315 |

| Pony Express and Overland Stage | 317 |

| Track-laying, Pacific Railroad | 319 |

| Reaping-Machine | 327 |

"True History, henceforth charged with the education of the People, will study the successive movements of humanity."—Victor Hugo. 1

"And from America the golden fleece

That yearly stuffs old Philip's treasury."

Marlowe's Faustus.

The story we have to tell was the problem of the sixteenth century, and is no less the marvel of the nineteenth. Put in the simplest possible form, the riddle to be solved in every palace of Christendom was, "How is the discovery of a new world going to affect mankind?"

To make the whole story clear, from beginning to end, calls for an effort to first put ourselves in relation with that remote time,—its thought, its interests, its aims and civilization. Let us try to do this now, at this time, when from our standpoint of achieved success we may calmly look back over the field, and see clearly the causes which have led up to it in orderly succession.

In the very beginning we see three rival civilizations. We see different nations, each of which is putting forth efforts to grasp dominion in, or stamp its own civilization 2 upon, the New World in despite of the other. We see civilization apparently engaged in defeating its own ends. Naturally, then, our first interest centres in the combatants themselves. Who and what are these Old World gladiators, who, in making choice of the New for their arena, have stripped for the encounter?

Great affairs were engaging the attention of the civilized world, so great that nearly all Europe was up in arms. It was the era of unsettled conditions,—of old jealousies and animosities revived, of new opportunities and new adjustments created by them. But among the nations of Europe power was very differently distributed from what we see it to-day. Spain, not England, was acknowledged mistress of the seas. Not yet had England wrested that proud title from her ancient rival in the greatest naval battle of the century. Drake and Frobisher had not been born. Hawkins was a lad, strolling about the quays of his native seaport. Who, then, should dispute with Spain dominion of the seas? 3

The royal standard of Spain had indeed floated very far at sea. Columbus had borne it even in sight of the shores of Mexico; but, though he had given to Spain a new world, he, the man of his century, did not succeed in finding his long-sought strait to India, and so had died without seeing the one great purpose of his life accomplished.

Yet Columbus, so to speak, was a lever of Archimedes,[1] for with the greatness of his idea he had moved both the Old World and the New. The Old was thrown into commotion because of his discoveries and what they implied to mankind, the New thrilled with the new life that stirred in her bosom. Spain at once stepped forward into the front rank of nations. How strange and striking are the events that have flowed from this one idea working in one man's brain! And where, in all the history of the world, shall we look for their equal?

By the time Columbus had returned to Spain, the Portuguese mariner, Diaz, had also discovered the Cape of Good Hope. Upon this these two proud and powerful nations, Spain and Portugal, agreed to divide between themselves all the unknown lands and seas to the east and to the west of a meridian line which 4 should be drawn from pole to pole, one hundred and seventy leagues west of the Azores. All other nations were thus to be excluded from the New World.[2]

Having first secured a solid foothold in the Antilles,[3] through Columbus and his discoveries, Spain early threw out her expeditions into Florida (1512) and Mexico (1519). The one was the logical result of the other, for St. Domingo and Cuba now assumed distinct importance, as stations, whence it was easy to move forward upon new schemes of conquest. In the harbors of these islands the Spaniards could refit their ships or recruit their crews after the long ocean voyage from Europe. Cuba, especially, became an arsenal of the highest military importance, which Spain took great pains to strengthen.

So at the very outset, Spain held this great advantage over her competitors. She possessed a naval station conveniently situated for making descents upon the adjacent coasts, which none of them was able to secure for themselves.

Columbus died in 1506; Ferdinand, King of Spain, whose name by the accident of time is linked in with that of Columbus, had also died; and now Charles, who shortly was crowned Emperor of Germany, began his most eventful reign. The period it covers is one of the most momentous in modern history, and as great occasions commonly bring forth great men, so those monarchs who then ruled over the peoples of Europe were worthy of the time in which they lived. Charles was himself one of the greatest of these monarchs. Francis I. of France was another; Henry VIII. of England another. Hence we have felt justified in saying, as we did at the beginning of this chapter, that our 5 starting-point was fixed in an historic era; for every thing betokened that as between such men as these were the struggle was to be a contest of giants.

During this reign the conquests of Mexico and Peru took place. During this reign Spain was raised to such a height of greatness as had never before been known in her history. Europe looked on in wonder to see these grand schemes of conquest being carried on three thousand miles away, while Spain's powerful neighbors were kept in awe at home. The English poet Dryden, who wrote a play upon the conquest of Mexico, makes Cortez and Montezuma hold the following dialogue, Cortez offering peace or war:—

Mont. Whence, or from whom dost thou these offers bring?

Cortez. From Charles the Fifth, the world's most potent king.

Other nations would gladly have shared the riches of the New World with the conquerors, but Spain haughtily warned away intruders, meaning to keep the prize for herself alone. 6

It was then that Francis I. demanded to be shown that clause in the will of Adam disinheriting him in the New World. But Spain was too formidable to be attacked on the seas. On the land, the two great rivals met at Pavia, where the pride of France was laid so low that after the battle was over, Francis wrote to his mother the memorable words, so often made use of in like emergencies, "Madam, all is lost except honor."

The pre-eminent grandeur of Spain, at this period, shines out all the clearer by comparison with the inferior attitude of England, not only as a military power, but in respect of peaceful achievement. By the light Spain carried in the van of discovery other nations moved forward, but at a distance indicating their respect for the dictator of European politics.

It is worth our remembering that in the efforts made to obtain a foothold upon the mainland, or terra firma,[4] as the Spaniards then called it, the territory of the United States may claim precedence in the order of time. Before Cortez landed in Mexico, Ponce de Leon had discovered and named Florida. Therefore Florida was the first portion of the North-American continent to receive the baptism of a Christian name.[5]

Although, under this name of Florida, Spain first 7 claimed every thing in North America, it was the great central region lying about the tropics to which her explorers first turned their attention.

Cortez landed on the Gulf Coast, unfurled his banner of "blood and gold," set fire to his ships,[6] to let his followers know that for him and them there was no retreat, and marched on into the heart of Mexico. Two initial points are thus fixed from which to continue the story of Spanish domination in the New World, Florida and Mexico.

Then again, having at last found their way across the Isthmus of Darien to the South Sea[7] (1513), the Spaniards in a measure ceased from their persistent and useless search for an open water-way to India. Cortez presently hewed out another road, with the sword, across Mexico, to this great western ocean. His achievement was quickly followed up by Ulloa (1539), Cabrillo (1542), and other Spanish navigators, who were sent by Cortez or the Viceroy to extend discovery up the coast. They coasted the Gulf of California, first called the Vermilion Sea, and sailed beyond it, as high as 30° North latitude.

So thanks to Cortez, Spain had secured the much-coveted way to India at last. Yet when he came home to his native country, the king demanded of those about him who Cortez was. "I am a man," said the conqueror of Mexico, "who has gained your majesty more provinces than your father left you towns."

Supreme on land and sea, Spain pushed on her conquests abroad without hinderance. If such deeds as hers had so irritated the self-love of a rival prince, how must they have stirred the blood of all those daring spirits by whom Charles was surrounded, and who 9 burned to distinguish themselves in the service of their liege lord and sovereign. In America, men said the making of a new empire had begun. If that were so, it meant that men of energy, ambition and capacity, the kind of men on whom fortune waits to bestow her choicest favors, should seek her there.

But Mexico and Peru were already won. When, therefore, the Spaniards began to look about them for new worlds to conquer, their eyes fell upon Florida. It is true that all those who had set forth upon this errand met with nothing but disaster.[8] A spell seemed hanging over this land of flowers. The Spaniards had indeed, with much pomp, planted a cross, strangely proclaiming themselves masters of the country; yet, without power to hold a foot of ground, this cross stood a monument to their failures, as its inscription seemed an epitaph to their presumption.

[1] Lever of Archimedes. The saying attributed to this celebrated mathematician of ancient times, that if they would give him a fulcrum for his lever he would move the world, is often employed in one or another sense as a figure of speech.

[2] Pope Alexander VI. confirmed the act of partition by a special decree, called a bull.

[3] Antilles, an early name of the West Indies.

[4] Terra Firma, literally meaning firm land; a name first used by the Spaniards to distinguish the American continent, or that part first discovered, from the West India Islands.

[5] Christian Name, from its discovery on Easter Sunday, Pascha Floridum—Flowery Easter.

[6] Burning One's Ships has passed into a proverb often used to illustrate some act of extraordinary hardihood, by which one puts it out of his power to draw back from an undertaking. Cortez only followed the example of the Emperor Julian in ancient Rome, and of William the Conqueror in England.

[7] South Sea. The Pacific Ocean was so first called.

[8] Disaster befell the attempt of Narvaez upon Florida in 1528. Look it up.

"One may buy gold at too dear a price."—Spanish.

If we look at the earliest Spanish maps on which the Gulf of Mexico is laid down, not only do we find the delta of a great river put in the place where we would expect to see, on our maps of to-day, the Mississippi making its triumphal entry into the sea, but the map-makers have even given it a name—Rio del Espiritu Santo—meaning, in their language, the River of the Holy Ghost.

That this knowledge ought not to detract from the work of subsequent explorers is quite clear to our minds, because the charts themselves show that only the coast line[2] had been examined when these results were put 11 upon parchment. The explorers had indeed found a river, and made a note of it, but had passed on their way without so much as suspecting that the muddy waters they saw flowing out of the land before them drained a continent. Had they made this important discovery, we cannot doubt their readiness to have profited by it in making their third invasion of Florida. So the discovery, if it can be called one, had no practical value for those who made it, and the country remained a sealed book as before. We cannot wonder at this because La Salle subsequently failed to find the river when actually searching for it, though he had seen it before.

With 600 men, both horse and foot, thoroughly equipped and ably led, Hernando de Soto[3] set sail from Havana in May, and landed on the Florida coast on Whitsunday[4] of the year 1539.

De Soto did not burn his ships, like Cortes, but sent them back to Havana to await his further orders. These Spaniards had come, not as peaceful colonists, looking for homes and a welcome among the owners of the soil, but as soldiers bent only upon conquest. De Soto, as we have seen, had brought an army with him. Its camp was pitched in military order. It moved at the trumpet's 12 martial sound. Two hundred horsemen carrying lances and long swords marched in the van. With them rode the Adelantado, his standard-bearer and suite. Behind these squadrons marched the men of all arms—cross-bowmen, arquebusmen, calivermen, pikemen, pages and squires, who attached themselves to the officers in De Soto's train—then came the baggage with its camp-guard of grooms and serving-men: and last of all, another strong body of infantry solidly closed the rear of the advancing column, so that whether in camp or on the march, it was always ready to fight. In effect, De Soto entered Florida sword in hand, declaring all who should oppose him enemies.

De Soto enforced an iron discipline, never failing, 13 like a good soldier, himself to set an example of obedience to the orders published for the conduct of his army. In following his fortunes, it is well to keep the fact firmly in mind that De Soto was embarked in a campaign for conquest only.

Toward the unoffending natives of the country the invaders used force first, conciliation afterwards. As in Mexico and Peru, so here they meant to crush out all opposition,—to thoroughly subjugate the country to their arms. De Soto had served under Pizarro, and had shown himself an apt pupil of a cruel master. The Indians were held to have no rights whatever, or at least none that white men were bound to respect. Meaning to make slaves of them, the Spaniards had brought bloodhounds to hunt them down, chains with iron collars to keep them from running away, and wherever the army went these poor wretches were led along in its train, like so many wild beasts, by their cruel masters. On the march they were loaded down with burdens. When the Spaniards halted, the captives would throw themselves upon the ground like tired dogs. When hungry they ate what was thrown to the dogs. So far as known, Hernando de Soto was the first to introduce slavery,[5] in its worst form, into the country of Florida, and in this manner did this Christian soldier of a Christian prince set up the first government by white men begun in any part of the territory of the United States.

The Spaniards were seeking for the gold which they believed the country contained. At the first landing, a Spaniard,[6] who had lived twelve years among the Florida Indians, was brought by them into the camp among his friends. The first thing De Soto asked this 14 man was whether he knew of any gold or silver in the country. When he frankly said that he did not, his countrymen would not believe him. The Indians, when questioned, pointed to the mountains, where gold is, indeed, found to this day. Though he did not believe him, De Soto took the rescued man along with him as his interpreter.

It was said, and by many believed, that somewhere in Florida stood a golden city, ruled over by a king or high priest who was sprinkled from head to foot with gold-dust instead of powder. This story was quite enough to excite the cupidity of the Spaniards, who grew warm when speaking of this city as the El Dorado,[7] or city of the Gilded One.

Such fables would not now be listened to by sensible 15 people, but in the time we are writing of they were firmly believed in, not only by the poor and ignorant, but by the greatest princes in Christendom, as well. No doubt they helped to fill De Soto's ranks. Lord Bacon tells us that in all superstitions wise men follow fools, and as this was a superstitious age, we can readily believe him. The great, the prolific, the true mines of the country, the cultivation of the soil, was not thought of by these soldiers of fortune who followed De Soto into Florida.

This ill-starred expedition is memorable rather for its misfortunes than because of any service it has rendered to civilization. Most graphically are these shadowed forth in the death and burial of De Soto himself, and in that sense they will stand for all time on the page of history as a memorial to what men will dare and suffer for greed of gold. In any other cause the expedition would be worthy an epic.

Although composed of the best soldiers in the world, with a valiant and skilful captain for its leader, the little army became so hopelessly entangled, so utterly lost in the primeval wildernesses, that to this day it has never been possible to trace out the true course of that fatal march.[8] Wherever he could hear of gold, thither De Soto led his weary and footsore battalions. When baffled on one side, he turned with rare perseverance to another. And though they were being wasted in daily combats, though famine and disease followed them step by step through swamp and everglade, over mountains and rivers, still, with wondrous fatuity, De Soto pushed ever on. Like an enchantress his El Dorado had lured him on to his destruction.

For about two years De Soto and his companions 16 wholly passed from the knowledge of men. A miserable remnant of this once gallant band then made their way to the coast, not indeed as conquerors, but as fugitives.[9]

Just where these years were passed is not clear. Long ago time obliterated all traces of the invaders' march. So the clew is lost. Yet we do know that one day in May, 1541, two years after its first landing, the army halted on the banks of an unknown river almost half a league broad. One of the soldiers says of it, that if a man stood still on the other side it could not be discerned whether he was a man or no. The river was of great depth, and of a strong tide which bore 17 along with it continually many great trees. All doubt vanishes. This could be no other than the "Father of Waters" itself.

[1] Mississippi River first mentioned (Indian). The name is variously spelled by early writers. "Father of Waters," or "Great Father of Waters," is the accepted meaning. Most probably the Espiritu Santo of the earliest known Spanish map of Florida (1521), of Sebastian Cabot's (1544); and St. Esprit of the one given in the text, though the Mobile may be meant. De Soto's people seem first to have called it Rio Grande or Great River. This disaster brought exploration in this quarter to a full stop for forty years, when it was resumed by the French, of whose efforts we shall presently speak. The river then appears on a map of the explorer Louis Joliet (1674) under its present name, though there spelled "Messasipi." From this time the name superseded all others.

[2] Gulf Coast of Florida is laid down with tolerable accuracy on a map of 1513 (Ptolemy, Venice). Garay examined it in 1518. By 1530 (Ptolemy, Basle) the Gulf Coast had obtained quite accurate delineation. The Gulf, itself, being the highway for ships bound to Mexico and Yucatan, was well known to Spanish sailors. Erelong it became an exclusively Spanish sea on which no other flag was allowed.

[3] Hernando de Soto is described by one of his followers as "a stern man of few words, who, though he liked to know and sift the opinions of other men, always did what he liked himself, and so all men did condescend unto his will."—Rel. Portugall.

[4] Whitsunday, or Whitsuntide, a festival of the Christian Church commemorating the descent of the Holy Ghost upon the apostles.

[5] Slavery, a certain type, it is true, existed among the Indians of this continent, who held their captives in semi-servitude, though the condition was totally different, in that the captive was considered eligible for adoption into the family and tribe of his master. Among the Indians the question of social equality had nothing to do with their policy toward their prisoners, or such as refused to become incorporated with themselves.

[6] A Spaniard who came with Narvaez to Florida, named Juan (John) Ortiz.

[7] El Dorado. Bear this name in mind. We shall meet with it again.

[8] That Fatal March. The one clew to the route De Soto took in his wanderings up and down what are now the Gulf States, is found in the names of various Indian nations whose countries he traversed. Thus the names Apalache, Coça (Coosa), Tuscaluca (Tuscaloosa), and Chicaça (Chicasaw) are so many landmarks. But no precise data remain from which to lay down, with reasonable accuracy, a journey which extended over at least eight or ten states, covered thousands of miles, and occupied years in making. De Soto's crossing place is placed on Pownall's (Eng.) official map of 1755 at or near Osier Point, on the east bank, now corresponding with the north-west corner of the State of Mississippi and De Soto County. On a map of 1775, it is fixed on the thirty-fourth parallel, some distance below the ancient village of the Arkansas, or "Handsome Men."

[9] As Fugitives, De Soto's followers, under command of Moscoso, his successor, built themselves boats, in which they descended the Mississippi to the coast, finally reaching Tampico, in Mexico, "whereat the viceroy greatly wondered."

"By a Portugall of the Company."

"The Gouernour felt in himselfe that the houre approached, wherein he was to leaue this present life, and called for the Kings Officers, Captaines and principall persons. Hee named Luys de Moscoso de Aluarado his Captaine generall. And presently he was sworne by all that were present, and elected for Gouernour. The next day, being the one and twentieth of May, 1542, departed out of this life, the valorous, virtuous, and valiant Captaine, Don Fernando de Soto, Gouernour of Cuba, and Adelantado of Florida: whom fortune aduanced, as it vseth to doe others, that he might have the higher fall.[1] Hee departed in such a place, and at such a time, as in his sicknesse he had but little comfort: and the danger wherein all his people were of perishing in that countrie, which appeared before their eyes, was cause sufficient, why euery one of them had neede of comfort, and why they did not visite nor accompanie him as they ought to have done. Luys de Moscoso determined to conceale his death from the Indians, because Ferdinando de Soto had made them beleeue, that the Christians were immortall; and also because they tooke him to be hardy, wise, and valiant: and if they should knowe that hee was dead, they would be bold to set upon the Christians, though they liued peaceably by them.

"As soon as he was dead, Luys de Moscoso commanded to put him secretly in an house, where he remayned three dayes: and remouing him from thence, commanded him to be buried in the night at one of the 19 gates of the towne within the wall. And as the Indians had seene him sick, and missed him, so did they suspect what might be. And passing by the place where he was buried, seeing the earth moued, they looked and spake one to another. Luys de Mososco vnderstanding of it, commanded him to be taken up by night, and to cast a great deale of sand into the Mantles, wherein he was winded vp, wherein he was carried in a canoa, and throwne into the midst of the riuer. The Cacique of Guachoya inquired of him, demanding what was become of his brother and lord, the Gouernour: Luys de Moscoso told him, that he was gone to Heauen, as many other times he did: and because he was to stay there certaine dayes, he had left him in his place. The Cacique thought with himselfe that he was dead; and commanded two young and well proportioned Indians to be brought thither; and said, 20 that the vse of that countrie was, when any Lord died, to kill Indians, to waite vpon him, and serue him by the way: and for that purpose by his commandement were those come thither: and prayed Luys de Moscoso to command them to be beheaded, that they might attend and serue his Lord and brother. Luys de Moscoso told him, that the Gouernour was not dead, but gone to Heauen, and that of his owne Christian Souldiers, he had taken such as he needed to serue him, and prayed him to command those Indians to be loosed, and not to vse any such bad custome from thenceforth."

Indian High Priest. "Old prophecies foretell our fall at hand.

When bearded men in floating castles land,

I fear it is of dire portent."—Dryden's Indian Emperor.

De Soto's invasion of Florida is, we think, most memorable for what it has preserved touching the manners and customs of the Indians with whom the Spaniards dealt in such evil sort. In this light only has it historic value. Though incomplete as to details it is our earliest portrait of this singular people, as they existed a full century before New England was settled, and so marks a definite limit of history whence to date that knowledge from.

Yet when we shall have gone so far back in the history of this primitive race as the beginning of the sixteenth century, nothing is found in their manners, customs or traditions, as they have come down to us, which would go to confirm the theory that the ancestors of these people were more civilized than themselves. 21 The little they seem to have known about it belongs to the very infancy of art, not to its growth out of lower conditions. These Indians knew how to make beads of the pearl oyster. So did those of New England know how to make shell wampum. The Florida Indians could weave cloth of the fibre of wild hemp and dye it prettily; they could tan, dress, and decorate deerskins; had found out how to mould rude earthen vessels and bake them in the sun. In some of these things they certainly surpassed their brethren of New England, though their arms and implements are quite like those used farther north. Then inasmuch as all the tools they had to work with were of the rudest sort, being shaped out of stone or bone, so the making of most things cost them a great deal of time and labor, and hence the mechanical arts in use among them were such only as spring from the first and most pressing wants of a people, as is everywhere the case in the history of primitive man.[1]

It must be borne in mind that what we are told about these Florida Indians is written by their enemies. Therefore, when their courage is praised, we feel that they must have deserved it. Perhaps what most astonishes us about the narratives themselves is the cold-blooded 22 way in which they recount the slaughter made of these Indians, who seem hardly to have been considered in the light of human beings.

It would seem as if the ill-repute of the Spaniards must have gone before them, for upon nearing the Florida shore the invaders saw smokes everywhere curling above it, which they soon found were lighted for the purpose of warning the inhabitants to be on their guard.

The first Indians met with were instantly set upon by De Soto's horsemen, who had nearly killed John Ortiz before they discovered him to be a Christian like themselves. Though in doubt what the landing of so many white men could mean, these Indians were loyally bringing Ortiz as a peace-offering to the Spanish camp. It is worth while to remember this, since on the part of the Spaniards the first act was one of violence and intimidation.

Therefore, whenever the Spaniards approached an Indian town, the inhabitants fled from it in terror; and so in order to procure guides to lead them, or porters to carry the baggage, while on the march, De Soto found himself obliged to seize by force such Indians as his own men could lay hands upon. On these he put chains and caused them to bear the burdens of his soldiers. If possible, a chief was kidnapped to be held a hostage for the good conduct of his tribe. No Spaniard was therefore safe outside his encampment.[2]

Again, the Spaniards plundered the villages they entered of whatever they stood in need, just the same as if they were in a conquered country. If they wanted corn they took it; if they found any thing of value they helped themselves, without making any show of paying for it. In consequence, the exasperated 23 Indians everywhere obstructed De Soto's march so far as it lay in their power to do so; and on the other hand, in proportion to the resistance he met with, De Soto treated the natives with greater or less severity. We know these Indians therefore, for men of courage, since in defence of their homes and liberties they could fight with naked breasts against men in armor, and with bows and arrows against fire-arms.[3]

So that by the time De Soto arrived at the Mississippi, he had lost over a hundred men and most of his horses.

What such treatment would be likely to lead to is easily foreseen. Most surely it sowed the seeds of future hostility to the white man broadcast. His cruelty became a tradition. The Indian has a long memory and is by nature revengeful. From having looked upon the whites as gods, gifted with all good and beneficent things, the Indian quickly perceived them to be a cruel people filled with avarice, and bent on destroying 24 him. His worst enemies could do no more. And thus the two races met each other in the New World.

We should not omit to mention here one of the strangest things that fell out in the whole course of the expedition. When the Spaniards came to the town of Quizaquiz, where they made some stay, Indians flocked there from distant villages in order to see for themselves what manner of people had come among them; for they said it had been foretold them by their fathers' fathers that men with white faces should come and subdue them, and now they believed the prophecy had come true.

In appearance, the Indian villages and towns we're everywhere much the same. The houses were little round cabins, built of wooden palings, sometimes thatched with palm leaves, sometimes with canes or reeds laid on the roof in the manner of tiles. The better to resist the fierce Gulf winds, they were built low on the ground. In the colder climates, the walls would be smeared over with clay. The only difference to be perceived between the cabins of the common sort and the dwellings of the chief men was that they were larger and more roomy residences, with sometimes a gallery built out over the front, under which the family could sit in the heat of the day.

Every little knot of cabins would have one or more 25 corn-cribs close beside it. This was a loft or granary set up in the air on poles, exactly in the manner now practised by the whites, and for the like purpose of storing up maize or Indian corn which was universally cultivated. Only for the supplies of maize everywhere found, both the Spaniards and their horses would soon have starved, as corn[4] became their only article of food, and ofttimes they had to go hungry for want of it.

Men and women wore mantles woven either of the bark of trees or of a wild sort of hemp which the Indians knew how to dress properly for the purpose. They also understood the art of tanning and dyeing such skins as were obtained in the chase, which they also made up into garments. Two of these mantles made a woman's usual dress. One was worn about them, hanging from the waist down, like a petticoat or gown, the other would be thrown over the left shoulder with the right arm bared, after the manner of the Egyptians. 26 The warriors wore only this last mantle, which allowed them free use of the right arm in drawing forth an arrow from the quiver, or in bending the bow. When dressed up in his head-gear of feathers, and wearing his ornamented mantle flung across his shoulder, bow in hand, and carrying his well-filled quiver at his back, the Indian warrior made no unpicturesque figure, even beside the heavily-armed white man, for he was of a well-proportioned and muscular build, with good features, an eye like the eagle's, and a bearing which told of the manhood throbbing beneath his dusky skin.

The Indians of Florida worshipped both a god of good and evil. They also made sacrifice to both spirits alike. In some places they worshipped and sacrificed to the sun as the great life-giving principle; in others they had a curious custom when any great lord died, of sacrificing living persons to appease or comfort his spirit with the offering of these other spirits who were to serve him and bear him company in the happy hunting-grounds.

Some tribes kept their dead unburied for a certain time in a rude sort of pantheon, or temple, dedicated to their gods.[5] Over this a strict watch was kept to guard against the intrusion of evil spirits who were supposed to lie in wait, in the form of some prowling beast of prey. This custom sprung from a belief that the spirits of the dead revisited their mortal bodies at times.

Besides maize, pumpkins, beans, and melons, whatever 27 natural fruits the country produced the Indian lived on. He hunted and fished. The summer was his season of plenty, the winter one of want, sometimes of distress, but in the semi-tropical region, bordering upon the Gulf, his wants were fewer and more easily supplied, and hence, as a rule, life was freer from hardship than in more northern climes.

The stronger nations made war upon the weaker, but treaties were duly respected. The vanquished were compelled to pay tribute to the conquerors or join themselves with some stronger tribe than their own. The languages differed so much with different nations, that De Soto found he must have a new interpreter for every new nation he visited; nevertheless the Indians quickly learned to speak the Spanish tongue. In public the people behaved with great propriety, showed respect for their rulers, and often confounded De Soto, who pretended to supernatural powers, by the shrewdness of their replies. For instance, when the Spaniard gave out that he was the child of the sun, a Natchez chief promptly bid him dry up the river, and he would believe him. In some places the Indians greeted the Spaniards with songs and music. Their instruments were reeds hung with tinkling balls of gold or silver. When the chieftain, or 28 cacique, went abroad in state, men walked by his side carrying screens elegantly made of the bright plumage of birds. These were borne at the end of a long staff.

The Spaniards found the fertile parts of the country everywhere crowded with towns, and very populous. But they did not find the gold[6] they coveted so much. They called the Indians a people ignorant of all the blessings of civilization, but to their honor be it also said, they were free from the vices by which it is accompanied and degraded.

[1] Primitive Man. All the articles named as being found in common use among the Florida Indians have been taken from the burial mounds which exist in the States of Ohio, Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Wisconsin, etc. And all are more or less referred to as so many evidences of an extinct civilization.

[2] Narvaez pursued the same policy, and met with like treatment.

[3] Fire-arms of that period were very clumsy weapons indeed. The arquebus was a short hand-gun, the caliver longer, and with the help of a slow-match could be fired from a rest. Only a certain proportion of the infantry were thus armed; the rest carried pikes.

[4] Corn. The Indians' corn-mill was a smooth round hole worn in the rock. A stone pestle was used. The coarse meal mixed with water or tallow, or both, was then wrapped in leaves, and baked in hot ashes.

[5] Burial Places. Upon finding one of these receptacles for the dead, a Franciscan of Narvaez' company, who declared the practice idolatrous, caused all the bodies to be burnt, thereby much incensing the natives.

[6] Gold. Hearing the Spaniards always asking for gold, the natives shrewdly made use of it to rid themselves of these unwelcome visitors, by sending them farther and farther away. In reality the Indians had almost none of the precious metals, but the finding of a few trinkets among them seems to have dazzled De Soto's eyes.

"Northward, beyond the mountains we will go,

Where rocks lie covered with eternal snow."

In the disasters of Narvaez and De Soto, the movement from the side of Florida towards the West had met with an untimely check. But, strangely enough, it made progress in another quarter through these very misfortunes. 29

For while De Soto was vainly seeking for gold on that side, his countrymen were bestirring themselves in the same business in a quite different direction, as we shall see.

At this time it was Don Antonio de Mendoza who was the emperor's viceroy in Mexico. Now Mendoza aimed to gain distinction with his sovereign by being the first who should discover and make known to the world, all the unexplored region lying north of Mexico, which was accounted as rich as any yet known to the Spaniards. Most of all, perhaps, Mendoza wished to find the land's end in that northern direction, as by doing so he would complete the work of putting a girdle round the continent, and gain the glory of it for himself.

Various efforts were making to do this both by land and sea.[1] And curiously enough these efforts came from the West. 30

For the purpose in hand Mendoza had with him in Mexico two or three survivors[2] of Narvaez' expedition, who, in the most wonderful manner, had made their way overland through the unknown regions of the North, from Florida into Mexico. These men told the viceroy, Mendoza, that the natives who dwelt among the mountains to the north were a very rich people, who lived in great cities and had gold and silver in abundance. Mendoza also held captive some Indians whose homes were in that far-away country, which he was now meditating how to conquer.

Yet two important obstacles met Mendoza at the start. In the first place, the unknown country, which the Spaniards vaguely knew by the name of Cibola,[3] could be reached only through mountain defiles, so rugged and inaccessible that men questioned whether it could be reached at all. Nature had admirably adapted it for defence. Clearly, then, a few resolute men might easily defend their country against a host, and the Spaniards having reason to expect the most determined resistance found a twofold hinderance in their way.

The second obstacle, the Spaniards had created for themselves, by making slaves of all natives taken in arms. Rather than be slaves the Indians had fled into the mountain fastnesses. As their fear of the Spaniards was very great, these fugitives secreted themselves in the most inaccessible places, choosing rather to live like wild beasts than be branded like cattle with hot irons, and nursing their hatred of their oppressors. Not venturing to come down into the open valleys where they would be at the mercy of their conquerors, these unhappy people lived in caves, or in stone dwellings perched high among the rocks, where they could 32 at least breathe the air of liberty unmolested. Those who formerly lived in the valleys had also fled to the mountains when they heard of the Spaniards' coming. So the Spaniards would have to contend not only with nature, but with a brave and a hostile people, if they attempted to subdue them.

Considering that great difficulties are often overcome or results accomplished by simple means, the viceroy took a poor barefooted friar[4] from his cell, gave him one of Narvaez' men for a guide, and with a few natives of the country sent him out to explore the unknown wilds. Upon reaching Culiacan, which was the most northerly place the Spaniards had made their way to, the captive Indians were sent ahead with messages of peace and good-will to the distrustful natives, who took good care to keep out of the way.

These promises of peace induced a great many of the natives to come down from the mountains; and once there they were easily won over with gifts and kind words, and in gratitude for the promise not to capture and enslave them as they had done, told the Spaniards to go and come as freely as they chose. The natives were then sent home to spread the news among their brethren.

The way being thus opened, the friar and his party set forth by one route, while still another party, led by Vasquez de Coronado,[5] went forward by a different one, on the same errand. Of the two parties, that of the friar alone succeeded in penetrating far into the country, and the information he brought back now reads more like a story from the Arabian Nights than the sober record of one already well versed in the country and people, such as Mendoza says he believed Father Marco to be. Yet the father is thought to have reached 33 Cibola, or Zuñi, which was the object of his journey, when the murder of his negro guide caused him to hasten back with all speed to the Spanish settlements.

So these attempts, as well as a second made by Coronado in the following year, were fruitless in every thing except the formal act of taking possession of the country, and the acquisition of some imperfect geographical knowledge about the valleys of the Colorado,[6] the Gila,[7] and the Rio Grande del Norte.[8] About all we can say of them is that the explorers went through the country.

As in Florida, so here a long period of inaction followed these failures. In both cases the Spaniards had come and seen, but not conquered. The Mississippi flowed on untroubled to the sea, the heart of the continent still kept its secret fast locked in the bosom of its hills. But we know now that the gold and silver the Spaniards craved so much to possess were there waiting for the more successful explorers.

It is forty years before we again hear of any serious effort made to search out the secrets of this land of mystery. The Church then took the matter in hand. It was wisely decided that the best way to conquer the people was to convert them. Accordingly two pious Franciscans set out from the Spanish settlements in New Biscay[9] on this errand. This time they penetrated into the country by the valley of the Rio Grande, under protection of a few soldiers, who, after conducting the fathers to a remote part of this valley, left them to pursue their pious work alone, and themselves returned to New Biscay. Hearing nothing from these missionaries, those who had sent them fitted out an expedition in the following year—1582—to go in search of them. 34 This rescuing party brought back a more exact knowledge of the country and people than had so far been obtained through all the many explorers put together.

In proportion as they advanced up the Rio Grande, these explorers found everywhere very populous towns. The people lived well and contentedly. Some were found who had even kept the faith taught them by Christians,[10] long ago, but in general they worshipped idols in temples built for the purpose. In the natives themselves the Spaniards remarked a wide difference. Some went almost naked, and lived in poor hovels of mud covered with straw thatch. Others, again, would be clothed in skins, and live in houses four stories high. 35 Often the natives showed the Spaniards cotton mantles skilfully woven in stripes of white and blue, of their own making and dyeing, which were much admired. It seemed for the most part a land of thrift and plenty, for the towns were populous beyond any thing the Spaniards had ever dreamed of. And the farther north the explorers went, the better the condition of the people became. Finding themselves in a land much like Old Mexico, in respect of its mountains, rivers, and forests, the explorers gave it the name of New Mexico.

One of the greatest towns visited, called Acoma,[11] contained above six thousand persons. It was built upon the level top of a high cliff, with no other way of access to it than by steps hewn out of the solid rock which formed the cliff. The sight of this place made the Spaniards wonder not a little at the skill and foresight shown in planning and building these natural fortresses, which nothing but famine could conquer. All the water was kept in cisterns. But this was not all the aptitude these people showed in overcoming obstacles or supplying needs. Their cornfields lay at some distance from the town. In this country it hardly ever rains. So the want of rain to make the corn grow was supplied by digging ditches to bring the water from a neighboring stream into the fields. We therefore see how conditions of soil and climate had taught the Indians the uses of irrigation.[12]

Turning out of the valley of the Rio Grande, to the west, the explorers at length came to the province of Zuñi, where many Spanish crosses were found standing just as Coronado had left them forty years before. Here our Spaniards heard of a very great lake, situated at a great distance, where a people dwelt who wore bracelets 36 and earrings of gold. Part of the company were desirous of going thither at once, but the rest wished to return into New Biscay in order to give an account of all they had seen and heard. So only the leader with a few men went forward, meeting everywhere good treatment from the natives, who in one place, we are told, showered down meal before the Spaniards, for their horses to tread upon, feasting and caressing their strange visitors as long as they remained among them.

These explorers returned to Old Mexico in July, 1583, by the valley of the Pecos,[13] to which stream they gave the name of River of Oxen, because they saw great herds of bison[14] feeding all along its course. 37

Out of these discoveries and reports came new attempts to plant a colony on the Rio Grande. Nothing prospered, however, until 1598, when Juan de Oñate[15] invaded New Mexico at the head of a force meant to thoroughly subdue and permanently hold it. Oñate was named governor under the viceroy. These Spaniards established themselves on the Rio Grande, not far from where Santa Fé now is. Most of the village Indians submitted themselves to the Spaniards, whose authority over them was, at best, little more than nominal, though the roving tribes, the fierce Apaches and warlike Navajoes, never forgot their hereditary hatred to the Spaniards, with whom they kept up an incessant warfare.

With this expedition came a number of Franciscan missionaries who, as soon as a town was gained over, established a mission for the conversion of the natives. In 1601 Santa Fé was founded and made the capital. In thirty years more the Catholic clergy had established as many as fifty missions which gave religious instruction to ninety towns and villages.

New Mexico had now reached her period of greatest prosperity under Spanish rule. For fifty years more the country rather stood still than made progress. The Spaniards were too overbearing, and the old hostility too deep, for peace to endure. Then, the system of bondage which the Spaniards brought with them from Old Mexico, and most unwisely put in practice here, bore its usual bitter fruit. Determined to be slaves no longer, in 1680 the native New Mexicans rose in a body, and drove the invaders out of the country with great slaughter. Upon the frontier of Old Mexico the fugitives halted, and then founded El Paso del Norte, 38 which they considered the gateway to New Mexico, and so named it. It took the Spaniards twelve years to recover from this blow. By that time little was left to show they had ever been masters of New Mexico. But a new invasion took place, concerning which few details remain, though we do know it resulted in a permanent conquest before the end of the century.

As far back as 1687 Father Kino had founded a mission on the skirt of the country lying round the head of the Gulf of California, to which the Spaniards gave the name of Pimeria.[16] It will be noticed that once again they were following up the traces of Father Marco and Coronado. When the Spaniards took courage after this defeat, and again entered New Mexico, Kino (1693) founded other missions in the Gila country which in time grew to be connecting links between New Mexico and California, in what is now Arizona.[17]

[1] By Land and Sea. As rivals, both Cortez and Mendoza strove to be beforehand with each other. Cortez despatched Ulloa from Acapulco, northward, July, 1539. Alarcon, sailing by Mendoza's order in 1540, goes to the head of the Gulf of California, and so finds the Colorado River, while a land force, under Coronado, marched north to act in concert with Alarcon.

[2] Survivors of Narvaez' Expedition (Florida, 1528). The chief among these was Alvar Nuñez, sometimes called Cabeça de Vaca (literally cow's head), who had been treasurer to the expedition of Narvaez.

[3] Cibola. The Zuñi country of our own day. Supposed to be derived from Cibolo, the Mexican bull, and therefore applied to the country of the bison. Cibola is on an English map of 1652 in my possession. Zuñi is thirty miles south of Fort Wingate.

[4] Poor Barefooted Friar was Marco de Niza (Mark of Nice), a friar of the Franciscan order. For a long time his story was doubted. It is, in fact, an exaggerated account of what is, clearly, a true occurrence.

[5] Vasquez de Coronado. (See note 1.)

[6] Colorado (Co-lor-ah´-doe) Spanish, meaning ruddy or red. First called Tizon, meaning a firebrand.

[7] Gila, pronounced Hee'la.

[8] Rio Grande del Norte, Spanish, Great River of the North. Usually called, simply, Rio Grande.

[9] New Biscay. Northernmost province of Mexico, capital Chihuahua (Shee´wah´wah).

[10] By Christians. Cabeça de Vaca and his companions.

[11] Acoma, one of the seven cities of Cibola; forty-five miles south of old Fort Wingate.

[12] Irrigation. Without it, it would hardly be possible to raise crops in New Mexico to-day.

[13] Valley of Pecos. East of, and parallel with that of the Rio Grande.

[14] Bison. Cabeça de Vaca is the first to mention this animal. One is said to have been kept as a show in Montezuma's garden, where the Spaniards saw it for the first time. See note 3.

[15] Juan de Oñate. Hopeless confusion exists concerning the proper date of this invasion.

[16] Pimeria essentially corresponds with Arizona. It took this name from the Pimos Indians of the Gulf.

[17] Arizona, or Arizuma, a name given by the Spaniards to denote the mineral wealth of Pimeria, where silver and gold were said to exist in virgin masses. Silver ores were, in fact, discovered by the Spaniards at an early day. Originally part of Senora (Sonora), Old Mexico.

"Antiquity here lives, speaks, and cries out to the traveller, Sta, viator."—V. Hugo, The Rhine.

Mention has been made of the towns which the Spaniards came to in the course of their marchings up and down the country. Men had told them, in all soberness, that far away in the north-west seven flourishing 40 cities,[1] wondrous great and rich, lay hid among the mountains. We remember that their first expeditions were planned to reach these seven cities. Now, when, at last, the Spaniards did come to them, these wonderful cities proved to be large, but not rich, full of people, though by no means such as the white men expected to see there.

Though sorely vexed to think they had come so far to find so little, the Spaniards were very much astonished by the appearance of these cities, the like of which they had never seen before. So these cities hid away among desert mountains were long remembered and often talked about.

But these cities were not cities at all, as the term is now understood. Instead of many houses spread out over much ground, the builders plainly aimed at putting a great many people into a little space. Yet the cities they built were neither simply walled towns, nor simply fortresses, but a skilful combination of both.

In the open plain they commonly consisted of one great structure either enclosed by a high wall, or else so built round it that wall and building were one.

On the other hand, if the pueblo[2] stood upon a height, the houses would be built all in blocks, and have streets running through them, though in other respects the manner of building was everywhere the same.

In either case, this style of architecture made them look less like the peaceful abodes of peaceful men, than the strongholds of a warlike and predatory race, whence the inmates might sally forth upon their weaker neighbors, just as the lords of feudal times did from the rock-built castles of the Rhine. It is plain they had grown up out of the necessity for defence, as every 41 thing else was sacrificed to its demands, and we know that necessity is the mother of invention.

The single great house, in which all the inhabitants lived together, is perhaps the most curious. Let us suppose this to be a three-story building, parted off into from sixty to a hundred little rooms, with something like a thousand people living in it. Could the outer wall be taken away, the whole edifice would look like a monstrous honeycomb, and in fact the pueblo was nothing else than a human hive, as we shall presently see.

Now the city of Acoma is one of those which are built upon a height. The builders chose the flat top of a barren sandstone cliff, containing about ten acres, 42 which rises about three hundred feet above the plain. In New Mexico such table-lands are called mesas, from mesa, the Spanish word meaning table. Therefore, while no one knows its age, or history, all agree that Acoma must go far back into the past. Acoma was so strongly built that to-day it looks hardly different from what it did when the Spaniards first saw it, perched on the top of its rock, in 1582.

We see then in the builders of Acoma a people gifted with a much higher order of intelligence than the Red Indian, who is always found living in huts, or hovels, of the rudest possible kind. The wild Indian always carries his house about with him, and so is ever ready, at a moment's notice, to

"Fold his tent, like the Arabs,

And as silently steal away."

The sedentary Indian sometimes patterned his after the burrowing animals, like the beaver, and sometimes after the birds of the air, like the sparrow.

Now to describe Acoma itself. It consists of ranges of massive buildings rising in successive tiers from the ground. The second story is set a little back from the first, and the third a little back from the second, so leaving a space in front of each range of buildings for the inhabitants or sentinels to walk about in, in peaceful times, or send down missiles upon the heads of their enemies in time of war. By running up the outer wall of each story, for a few feet higher than this platform, the builders made what is called a parapet in military phrase, meant for the protection of the defenders. There were no doors or windows except in the topmost tier. Acoma, then, was a castle built upon a rock. 43

It would seem that only birds of the air or creeping things could gain admittance to such a place. Indeed, there was no other way for the inhabitants themselves to enter their dwellings except by climbing up ladders set against the outer walls of the building for the purpose. In this manner one could climb to the first platform, then to the second, but could not get in till he came to the roof, through which he descended by a trap door into his own quarters.

The whole collection of buildings being divided by partition walls into several blocks, each containing sixty or seventy houses, is, practically, the apartment hotel of to-day. The material commonly used was adobe,[3] or bricks dried and hardened in the sun. Such a building could not be set on fire or its walls battered down with any missiles known to its time.

We see then that the Pueblo Indians must have had enemies whom they feared,—enemies at once aggressive, 44 warlike, and probably much more numerous than themselves. How well they were able to meet these conditions, their houses show us to this day.

Living remote from the whites, these people, like those of Old Zuñi, have kept more of their primitive manners, and live more as their fathers did, than those do who inhabit the pueblos of the Rio Grande, where they have been longer in contact with Europeans. Forty years ago they knew only a few Spanish words, which they had learned when Spaniards held their country. In a remarkable manner, the people have kept their own tongue and nationality free from foreign taint. From this fact we are led to think them much the same people that they were long, long ago.

There are other buildings in the country of the Gila, called Casas Grandes,[4] or Great Houses, which are quite different from those described in this chapter, but were apparently built for a similar purpose of defence.

[1] Seven Cities. See preceding chapter.

[2] Pueblo, Spanish for town or village.

[3] Adobe, Spanish. The same material is much used throughout New Mexico, Arizona, California, Utah, and Colorado.

[4] Casas Grandes, or Casas Montezumas. Lieut. Emory, U.S.A., thus describes one seen on the Gila: "About the noon halt a large building was seen on the left. It was the remains of a three-story mud house, sixty feet square, and pierced for doors and windows. The walls were four feet thick. The whole interior of the building had been burned out and much defaced." Casa Grande is on a map of 1720; is on the Gila.

While professing Christianity, the Pueblo Indians have mostly kept some part of the idolatrous faith of their fathers. Thus the two have become curiously blended in their worship. We often see the crucifix, or pictures of the Virgin hanging on the walls of their dwellings, but neither the coming of the whites, nor the zeal of missionaries could wholly eradicate the deeply grounded foundations of their ancient religion. The little we know about this belief, in its purity, comes to us chiefly in the form of legendary lore, although since the Zuñi have been studied[1] with this object we have a much clearer conception of it than ever before.

By this uncertain light we find it to be a religion of symbols and mysteries, primarily founded upon the wondrous workings of nature for man's needs, and so embodying philosophy growing out of her varied phenomena. Therefore sun, moon, and stars, earth, sky, and sea, and all plants, animals, and men were supposed to bear a certain mystical relation to each other in the plan of the universe. Instead of one all-supreme being, the Zuñi worshipped many gods each of whom 46 was supposed to possess some special attribute or power. Some were higher, some lower down in the scale of power.

The phenomena of nature, being more mysterious, were thought to be more closely related to the higher gods. If there was drought in the land, the priests prayed for rain from the housetops, as the Prophet Elijah did in the wilderness. Each year, in the month of June, they went up to the top of the highest mountain, which they called the "Mother of Rain," to perform some secret ceremony touching the coming harvest. And because rain seldom falls in this country, they made earnest supplication to water, as a beneficent spirit, who ascended and descended the heavens in their sight, and to the sun as the twin deity in whom lay the power of life and death,—to ripen the harvest or wither all living things away into dust.

Like the ancient Egyptians, of whom they constantly remind us, the Zuñi believed animals possessed certain mystic powers, not belonging to man, so investing them with a sacred character. Beasts of prey were supposed to have magic power over other animals, hence the bear stood higher in the Zuñi mythology than the deer or antelope. The Indians call this magic power medicine, but the Zuñi gave it form to his own mind—the substance of a thing unseen—by making a stone image of the particular animal he had chosen for his medicine, which he carried with him to war or the chase as a charm of highest virtue. We call this fetich-worship.

Each pueblo had one or more close, underground cells[2] in which certain mysterious rites, connected, it is believed, with the worship of the people, were solemnized. We are told that, at Pecos, the priests kept 47 watch night and day over a sacred fire, which was never suffered to go out for a single moment, for fear some calamity would instantly happen to the tribe. It is also said that when Pecos was assaulted and sacked by a hostile tribe, the priests kept their charge over the sacred fire while the tumult of battle raged about them. And when, at length, the tribe itself had nearly died out, the survivors took the sacred fire with them to another people, beyond the mountains, where it is kept burning as the symbol of an ever-living faith.

Another legend goes on to say that an enormous serpent was kept in a den in the temple of Pecos to which on certain occasions living men were thrown as a sacrifice. Both legends would seem to point to Pecos as a holy place, from which the priests gave out instruction 48 to the people, as of old they did from the temples of the heathen gods.

The tradition of the origin of the Zuñi, as told by Mr. Cushing, is almost identical with that held by the Mandans of the Upper Missouri. Each says the race sprung from the earth itself, or rather that the first peoples lived in darkness and misery in the bowels of the earth, until at length they were led forth into the light of day by two spirits sent from heaven for their deliverance, as the Zuñi say, or by discovering a way out for themselves, as the Mandans say.[3]

A tradition of the Pimos[4] Indians makes a beautiful goddess the founder of their race. It says that in times long past a woman of matchless beauty resided among the mountains near this place. All the men admired and paid court to her. She received the tributes of their devotion, grain, skins, etc., but gave no favors in return. Her virtue and her determination to remain secluded were equally firm. There came a drought which threatened the world with famine. In their distress the people applied to her, and she gave them corn from her stock, and the supply seemed endless. Her goodness was unbounded. One day as she was lying asleep a drop of rain fell upon her and produced conception. A son was the issue, who was the founder of the race that built these structures.

But Montezuma[5] is the patriarch, or tutelary genius, whom all the Indians of New Mexico look to as their coming deliverer.

One tradition runs that Montezuma was a poor shepherd who tended sheep in the mountains. One day an eagle came to keep him company. After a time the eagle would run before Montezuma, and extend its 49 wings, as if inviting him to seat himself on its back. When at last Montezuma did so, the eagle instantly spread its wings and flew away with him to Mexico where Montezuma founded a great people.

Ever since then the Indians have constantly watched for the second coming of Montezuma, and thenceforth the eagle was held sacred, and has become a symbol among them. He is to come, they say, in the morning, at sunrise, so at that hour people may be seen on the housetops looking earnestly toward the east, while chanting their morning prayers, for like the followers of Mahomet, these people chant hymns upon the housetops. Although beautiful and melodious these chants are described as being inexpressibly sad and mournful.

In person the people are well formed and noble looking. They are honest among themselves, hospitable to strangers, and unlike nomads, are wholly devoted to caring for their crops and flocks. They own many sheep. They raise corn, wheat, barley and fruit. One pueblo raises corn and fruit, another is noted for its pottery, while a third is known for its skill in weaving. 50

But after all, these Pueblo Indians are only barbarians of a little higher type than common. Whenever we look closely into their habits and manners, we are struck with the resemblances existing among the whole family of native tribes. If we assume them to have known a higher civilization they have degenerated. If we do not so assume, the observation of three centuries shows them to have come to a standstill long, long ago.

Pueblo Customs. When the harvest time comes the people abandon their villages in order to go and live among their fields, the better to watch over them while the harvest is being gathered in.

Grain is threshed by first spreading it out upon a dirt floor made as hard as possible, and then letting horses tread it out with their hoofs. It is then winnowed in the wind.

The woman, who is grinding, kneels down before a trough with her stone placed before her in the manner of a laundress's wash-board. Over this stone she rubs another as if scrubbing clothes. The primitive corn-mill is simply a large concave stone into which another stone is made to fit, so as to crush the grain by pressure of the hand.

The unfermented dough is rolled out thin so that after baking it may be put up in rolls, like paper. It 51 is then the color of a hornet's nest, which indeed it resembles. Ovens, for baking, are kept on the housetops.

The processes of spinning and weaving, than which nothing could be more primitive, are thus described by Lieut. Emory, as he saw it done on the Gila, in 1846.

"A woman was seated on the ground under one of the cotton sheds. Her left leg was turned under with the sole of the foot upward. Between her great toe and the next a spindle, about eighteen inches long, with a single fly, was put. Ever and anon she gave it a dexterous twist, and at its end a coarse cotton thread would be drawn out. This was their spinning machine. Led on by this primitive display, I asked for their loom, pointing first to the thread, and then to the blanket girded about the woman's loins. A fellow who was stretched out in the dust, sunning himself, rose lazily up, and untied a bundle which I had supposed to be his bow and arrows. This little package, with four stakes in the ground, was the loom. He stretched his cloth and began the process of weaving."

But these self-taught weavers were behind their brethren of the pueblos, whose loom was of a more improved pattern. One end of the frame of sticks, on which the warp was stretched, would be fastened to the floor, and the other to a rafter overhead. The weaver sat before this frame, rapidly moving the shuttle in her hand to and fro, and so forming the woof.

Pottery was in common use among them as far back as we have any account of the Pueblo Indians. Jars for carrying and 52 holding water were always articles of prime necessity, though baskets of wicker-work were sometimes woven water-tight for the purpose.