![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: Lucerne

Author: G. Flemwell

Release date: July 2, 2018 [eBook #57435]

Most recently updated: January 24, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

Author of “Alpine Flowers and Gardens”

“The Flower Fields of Alpine Switzerland”

&c.

| Beautiful Switzerland | ||

| ——— | ||

| In this series have already appeared: | ||

| LUCERNE | | | CHAMONIX |

| VILLARS AND CHAMPÉRY | ||

| LAUSANNE | ||

| Painted and Described by | ||

| G. FLEMWELL | ||

| ——— | ||

| Other volumes in preparation | ||

There is good warrant for turning directly to Lucerne and to the lake which lies in the midst of the four Forest Cantons when making, or renewing, acquaintance with Switzerland; and there should be no question of thereby slighting other famed districts of this favoured land. Almost invariably it is best to go straight to the heart of things, and the Vierwaldstätter-See, or Lake of the Four Forest Cantons—commonly known to us as the Lake of Lucerne—is held to be, both geographically and historically, at the very heart of Switzerland. There is, too, the additional assurance that no other district in the whole of the {6}twenty-two Cantons which go to the making of the Confederation can offer a more admirable, a more ideal introduction to the fascinating wonders and delights of Swiss scenery. In spite of our being in the heart of the country, we are, as it were, upon the frontier of a Promised Land, one flowing as literally as may be with milk and honey—and glaciers; we are, that is to say, at the portal by which we may as lief best enter the domain of the Swiss Alps. For if we except Pilatus, that gaunt, tormented rock-mass standing in severe isolation upon the threshold of the city, Lucerne is relatively modest and restrained as regards its immediate scenery; but away on the horizon which bounds the waters of the Lake is the long snowy array of majestic Alps, and we may soon reach by boat and rail the giants of Schwyz, Uri, Unterwalden and the Bernese Oberland. The steamboats alone will transport us, through graduated scenic grandeur, to the great cliffs and snow-covered crags of Uri, romantic birthplace of the Swiss Republic.

However, there is no occasion to become restive at the prospect; Lucerne itself is the most charming of preludes and points d’appui for all that lies afield. Particularly is this so if opportunity allows us to be here in the spring of the year, with the fruit trees all a-flower and the grey-towered Musegg ramparts deep set in a rosy-white haze; and with the fields all a-wave with blue, white, and gold, and the lakeside{7} promenade laden with the myriad flower-spikes of the horse-chestnut trees. Spring is earlier here—some ten days earlier in May—than away at the very feet of the Alps. We may well be content, then, to remain awhile amid such vernal freshness, studying the life and history of the town of the “wooden storks’ nests”, and revelling on the quay in the Alpine panorama framed by the soft blue sky and blue-green waters—a panorama which is never more delightful than at this season of the year, never even in autumn when October clears the atmosphere, robes the near hills in fire, deepens the blue colouring of distant rock and forest, and spreads a new white drapery upon the higher peaks.

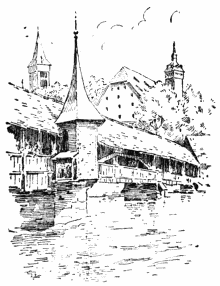

To those who knew this town, say, five-and-twenty years ago, and who have not revisited it until to-day, how many are the changes which they will meet, and with what mixed feelings will they meet these changes! The past twenty-five years have meant astonishing developments for almost every quarter of Switzerland. Cities have burst their bounds and have spread far along the countryside; villages have grown into towns, and from nothing, or perhaps from a single old-time chalet, great groups of hotels and their dependencies have sprung up upon the mountains. And Lucerne certainly has been no laggard in this movement. Twenty-five years ago the sign and symbol of the{8} city was a stolid, stunted tower set in water beside a long, roofed, wooden bridge running slantwise across a river, with tapering twin steeples beyond. But nowadays the place would be unrecognizable without an airship floating above vast Palace hotels which all but obscure the twin steeples and cause the aged Kapell-Brücke and its faithful companion, the Wasserturm, to look as two quaint old country folk come into town to see the sights, and who remain coyly by the See-Brücke on the outskirts, so to speak, of all the splendid modern hustle—two dear, simple, reticent old things in their old-world garb, despite the efforts of the authorities to bring them abreast of the times by festooning them about with many strings of electric lights. We have to be thankful that these and other intensely individual relics of the past weathered the rage for demolition that appears to have reigned in the town during the middle of the nineteenth century. Something of what this rage was like can be gathered from Professor Weingartner’s pictures which line the walls of Muth’s Beer Restaurant in the Alpen-Strasse. Here, whilst sampling the Schweinswürstl, a speciality of the house, we can study the presentment of at least a dozen old gates and towers which were pulled down between the years 1832 and 1870. That the remaining nine Musegg towers, the two wooden bridges

and the Water Tower escaped this onslaught would seem to have been a miracle of good luck. At any rate, the townspeople of to-day must surely look upon it in some such light. For a new spirit now rules in this direction—a spirit of conservatism, even of rehabilitation—and what of the antique past remains is dear and safe, and what can be done to reinstate or reconstruct that which was lost, or in danger of being lost, in the fresco and iron-work decorated house-fronts is rapidly being done. Art is in the ascendancy to-day in Lucerne, and Hans Holbein’s heart would be rejoiced could he but return to the quarters he frequented in 1516 before he journeyed, in 1526, to the Court of England. I do not think that the townspeople would go so far as Rodin, the great French sculptor, and say, “Une seule chose est utile au monde: l’Art!” (for there is the hotel business, and however artistically inclined the Lucerneois may be, they are eminently practical); but it is quite evident that to-day they would never accept without amendment Plato’s scheme for a republic in which Art was ignored.

In some of its aspects Lucerne is reminiscent of both Nuremberg and Venice: of the former in its ancient towers, its beaten ironwork and its frescoed houses; and of the latter in its river and lakeside life and architecture, especially looking from the Schwei{10}zerhof Quay to the finely domed railway station across the water, or again at night-time when many-tinted reflected lights dance upon the flood, and row-boats, with the oarsmen poised much as in Venetian gondolas, move stealthily athwart the velvet shadows. All this, however, is merely reminiscent; Lucerne is substantially herself—“Lucerna, the Shining One”, quick with an individual beauty in which orderliness, dignity, and self-respect are prominent qualities. And because these traits in her character are so manifest, certain lapses in good taste and the fitness of things are apt to be the more keenly regretted. Go down along the right side of the Reuss river, past the Kapell-Brücke with its 154 paintings of ancient local history and legend filling the beam-spaces beneath the roof, past the befrescoed Gasthaus zu Pfistern, past the Flower and Fruit Market in the old Rathaus arcades, past the Hotel Balances and its history-telling façade, across the Wine Market containing a fifteenth-century fountain dedicated to St. Maurice—who, with St. Leodegar, is co-patron of the town—down to the Mühlen-Platz, and there you will find stark modernism, in the shape of ramshackle baths and uncompromising factory workshops, right beside one of the chief and most picturesque relics of Old Lucerne—the fourteenth-century wooden Spreuer-Brücke, with its quaint shrine and paintings of the{11} Dance of Death, sung of by the poet Longfellow. But perhaps a more brazen example of this intrusiveness is to be seen by passing over the bridge and standing at the nearest corner of the Zeughaus. From this point there is what is probably the most perfect ensemble of varied mediaeval architecture to be found in the town—the old bridge and its quaint, rosy-red shrine in the foreground, spanning the green and rapidly flowing Reuss, and backed by the Musegg towers and ramparts and the bulky monastic building whose deep roof is pierced by a triple line of windows. It is a nearly perfect glimpse of the past, and that it is not entirely perfect is due to a bald modern villa set high against the rampart walls. This brazen-faced building is wellnigh as incongruous, perched up there beneath the unique and precious Mannlithurm, whose warrior sentinel, hand upon sword, watches over the town, as is the Alhambra Labyrinth, with its “interesting Oriental groups and palm-groves”, in the Glacier Garden.

However, it will not do to be too critical. Rather should we give thanks for the strong directing hand which in the main the town now holds upon Progress, that arch-egoist with no eyes but for itself. There are times when it is no easy matter to reconcile the old with the new: to say where antiquity shall rule for art and sentiment’s sake, and where it shall{12} give way, tears or no tears, before the utilities of the present. Nor is it less difficult to give an unprejudiced and far-sighted judgment upon the actual truth, and, therefore, upon the actual merit and value of beauty and ugliness. It is such a personal matter—personal so largely to the time being. We must not imagine that the chimney-pot hat will be for all time cherished as respectable, though we may expect some wailing and remonstrance when its call to go arrives. So, possibly, even probably, here in this town the old inhabitants of 400 years ago, when every house was of wood, were heard to carp and grumble—may even have risen in protest—when Jacob von Hertenstein built for himself the first stone dwelling and had it painted gaily with pictures by young Hans Holbein, thus setting a fashion which eventually not only ousted the “storks’ nests”, but set up something for whose preservation we now clamour, although at the same time we incline to rave against some of its recent offspring, the Palace hotels. Thus, if we are not careful, do we find ourselves caught in a tangle of inconsistencies. Apt to think, like the cicerone of Chichester Cathedral, that “nothing later than the fourteenth century is of much value”, we should be wary lest posterity has cause to deride us. We are enthusiastic children where temporary custom and passing bias are concerned,{13} and what to us is horrible to-day is often splendid to-morrow.

On the other hand, there is a strong tendency, perhaps a kind of bravado, which aims at showing that we are no longer overawed by the past as were our ancestors; that we live very much in the present, with one eye on the immediate future, and that we do not so much say “Let the dead bury their dead” as “Let us at once bury all that is moribund”. In short, an egotistical irreverence stalks abroad with regard to the past, as well as an exorbitant sentimentality, and our pressing necessity is to beware of both and to keep in the middle of the road. Now this is just the happy and wise position which Lucerne seems to occupy at present. The merest feather will show which way the wind is blowing, and in the current edition of the Official Guidebook there is no trace of the phrase employed in an earlier edition: “In a town where the present is so beautiful, we may well let the past be forgotten”. Beautiful most certainly the town is to-day, and that is partly because the beauty of its past is not forgotten.

History is boiled down and compressed into tabloid form in another guidebook. “In olden times,” it hurriedly tells us, “there stood upon the banks of the Reuss a little village of fishermen, for which the founding of the convent of St. Leodegar, about the{14} year 735, became the first event of importance. The little place grew up by and by into a town, and the time came when it was strong enough to lay its hands upon the trade of the lake. Later on, when the peasantry of the inner cantons concluded that alliance, out of which in time the Swiss confederacy was to rise, Lucerne did not hesitate to join them, so that from the year 1332 the history of the Confederacy has been also that of Lucerne.” That is all very true as far as it goes; food in the form of a tabloid is never quite satisfactory. But probably the majority of visitors will be content with this high essence, not caring to dive deeper into antecedent waters to fish up Lacustrians, Alemanni, King Pepin, the Abbot of Murbach, or the Dukes of Hapsburg. There are, however, certain tit-bits of history—or are they of legend?—which are always palatable, and among these is a story meriting a place by the side of that recounted of Tell and his son. It dates from 1362, from the time, that is to say, when the hold of Austria upon Lucerne was weakening under the contagious example set the townspeople by their neighbours of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden. Things had reached such a pass that the partisans of Austria had had to leave the town, and the Bailiff of Rothenbourg, Governor of the district, was vowing vengeance and plotting with certain traitors among the Swiss

to retake the town by night and put the townspeople to the sword. After dark, on 29th June, a little boy, Pierre Hohdorf, who had been bathing in the lake and had fallen asleep on the shore, was awakened by the stealthy tread of armed men creeping warily towards a cave beneath the Abbey of the Tailors. Recognizing the Governor among the number, and knowing well the bad blood existing between the Austrians and the townspeople, Pierre Hohdorf, under cover of the reeds, followed these men to their meeting-place, but was surprised by a newcomer, taken by this latter into the cave, denounced as a spy, and threatened with instant death. The boy could only confess that he had fallen asleep after his bath, had been awakened by footsteps, and had become curious to know what was the matter. This was not considered a satisfactory explanation by his captors; a dagger was already uplifted above his breast, when the Governor intervened, caused little Pierre to swear that he would never reveal to a living soul anything of what he had seen or heard, and then allowed him to go free. The boy made his way in all haste to the town and to the Abbey of the Butchers, where he saw that lights were still burning. Entering the building and going to the hall where numbers of citizens were talking and drinking, Pierre went straight up to the big stove and thus addressed it:{16}—“O stove, you are not a living soul; I may therefore tell you what I have just seen and heard without breaking the oath which the Austrians have forced me to take”. He then went on to tell the stove the whole of his adventure. At first the men thought it was just a child’s prank; but they soon pricked up their ears, realized the seriousness of what they were hearing, buckled on their swords, shouldered their battle-axes, hurried out into the streets, and awaited the coming of the Austrians and traitors. As one o’clock struck, the enemy stole out from the Abbey of the Tailors, were quickly confronted and after a fierce struggle were either killed or routed, the arch-traitor, Jean de Malters, together with the Governor, saving their lives in flight.

But Lucerne suffers somewhat from the brilliant history of her near neighbours, her precursors in Swiss freedom. William Tell and his famous companions monopolize so much of the atmosphere that the average visitor is probably satisfied if he supplements a knowledge of their exploits with what he can pick up casually in his strolls around the town.[1] In this way, if he finds himself in the Pfistergasse and notices the ancient three-storied building known as “von Moos’s Haus”, he will come into contact with Ruskin,{17} who made of it one of his exquisitely careful drawings; in this way, at the Gütsch, he will learn how Queen Victoria loved the alleys midst the stately pines; in this way he will hear of Richard Wagner’s erstwhile residence for some six prolific years at Tribschen, the country house nestling among Teutonic-looking poplar trees on the promontory not far beyond the airship station, and of how the great man was wont to wend his way of an afternoon to Dubeli’s Café in the Fürren Gasse, where he smoked his pipe and in all probability sought inspiration for Die Meistersinger, the Siegfried Götterdämmerung, and the Siegfried-Idyll, and perhaps discussed philosophy with Nietzche, who was a frequent visitor to Tribschen in those friendly days before he discovered that the great composer was merely a “clever rattlesnake”. In this way, too, the visitor will hear of the droll doings of Fridli an der Halden, popularly known as Bruder Fritschi, who flourished in the fifteenth century and founded a merry festival which, in the shape of the Fritschi Procession, is still kept up at carnival-time. Many tales are told of this worthy. He seems to have been a prime favourite, not only in Lucerne, but far afield, being on several occasions held captive in some distant town.

“The news reached Lucerne”, we are told, “that Fritschi was being detained at Basle, whereupon the burgomaster and council{18} of the former town at once declared war, announcing that within eight days they would appear in force before Basle and demand the release of the prisoner. They received the reply that their appearance was eagerly looked for, and that the greater the number of the enemy, the better pleased the Basle folk would be. The expedition really took place. Several hundred of the men of Lucerne, with the two burgomasters and eighteen councillors at their head, marched to Basle, where they were received by the burgomaster and council and a host of citizens in martial attire. Brother Fritschi welcomed his fellow-townsmen from a window of one of the best houses, and several days were spent in feasting and revelry.”

The lighter side of warfare, this, and without doubt a welcome interlude in what were seriously stirring times. Frivolous history, do you call it? Is, then, serious history a record only of long faces, and a reserve

Is not a merry smile a thing of great gravity in the world’s economy, and may not a hearty laugh be as potent as a bloody battle? Why, at a time when kings and their peoples slept booted and spurred, jesters were paid to break the horrid spell with laughter. True, the world called, and still calls, these merrymakers “fools”, but the sooner a foolish world recasts its mode of thinking in these matters, the sooner will it realize how low and odious is its recognized god of {19}war. Lucerne holds excellent and moving proof of this in the Museggstrasse, where stands the International Museum of War and Peace, founded by the Russian, Johann von Bloch. In this Museum there are things which, although they represent what have long been looked upon as among the noblest elements in serious history, come as a dreadful and a useful shock to such as pin their faith to the vaunted advance in intellectuality, humanity, and civilization of this present age.

In Lucerne there is much excuse for pensiveness upon this subject. I know no town where the problem of Peace and War presents itself more suggestively. Not that Lucerne is a hotbed of that militarism which is apt to think of Peace as “sweet poison for the age’s tooth”; for excepting a subdued rattle of arms from the barracks near the Spreuer-Brücke, and an occasional drilling of recruits in the recesses of the Gütsch woods, little or nothing is seen here of the actual cult of warfare. Peace pervades Lucerne, and War is evident upon all hands as an irresistibly suggestive reminiscence. There could be no more appropriate home for the Bloch Museum. Fritschi is the town’s hero, not for the part he played in the Burgundian Wars, but for his drolleries; a sham castle-fortress stands picturesquely by the steamboat quay; the Glacier Garden, witness of neolithic man’s grim struggles as far back, possibly, as 700,000 years, is{20} now a sylvan resort of pleasure-seeking tourists; and the soft-blue distant Alps of Uri and Unterwalden send to the town subdued echoes of past tyranny and revolt. On every hand is all that could be wished for from peace; and warfare, in the form of battlements and towers, sits crumbling upon the Musegg slopes—swords turned into ploughshares, the past’s frowning exigencies left to serve the present’s decorative sense and purpose. Truly the Bloch Museum has found a fitting home, and for long years may this fitness endure, spreading wide its virtues to the four corners of the globe and inspiring men to live up to that high level which, in their quiet moments, they so persistently claim for modern civilization.

And yet, because something finer is expected of the present than of the past there is no right rhyme or reason for heaping wholesale abuse upon the latter’s crudely drastic ways. We may quite well admit how much of actual beauty arises from previous horrors. As, surely, few can visit Lucerne’s unique Glacier Garden without being impressed with the fact of how much the loveliness and grandeur of the town’s surrounding scenery is indebted to that dismal and terrific epoch, of which these giants’ cauldrons, mills and mill-stones are the witnesses, so, surely, few can stroll up to the Drei Linden, or through the cathedral-like pine woods of the Gütsch to Sonnenberg, and survey

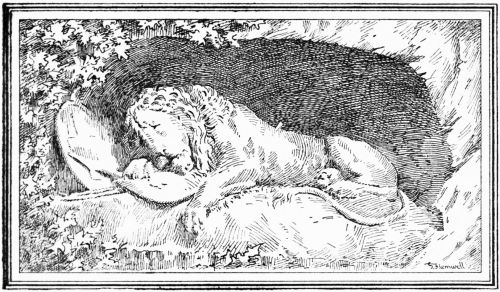

the lovely reaches of the Lake and the blue borderline of the Alps beyond without feeling the enormous and quiet benefits which to-day are enjoyed because of the sanguinary struggles of a bygone age. Nor, surely, can many stand by the shady water pool and gaze at the rock-cliff wherein is sculptured Thorwaldsen’s famous masterpiece and not be sensible of how large a debt is laid upon to-day’s tranquillity by such past incidents which in a sense were so ugly and so vicious. “Honour to you, brave men”, says Carlyle with stirring eloquence, referring to this same monument in honour of the 800 officers and men of the Swiss Guard, slain at the Tuileries in defending Louis XVI, very many of whom were natives of Lucerne and district (which was noted for its so-called mercenaries)—

“Honour to you, brave men; honourable pity, through long times! Not martyrs were ye; and yet almost more. He was no King of yours, this Louis; and he forsook you like a King of shreds and patches; ye were but sold to him for some poor sixpence a-day; yet would ye work for your wages, keep your plighted word. The work now was to die; and ye did it. Honour to you, O Kinsmen; and may the old Deutsch Biederkeit and Tapferkeit, and valour which is Worth and Truth, be they Swiss, be they Saxon, fail in no age! Not bastards; true-born were these men: sons of the men of Sempach, of Murten, who knelt, but not to thee, O Burgundy! Let the traveller, as he passes through Lucerne, turn aside to look at their monumental Lion; not for Thorwaldsen’s sake alone. Hewn out of living rock, the Figure rests there, by the still Lake-waters, in lullaby of{22} distant-tinkling rance-des-vaches, the granite Mountains dumbly keeping watch all round; and, though inanimate, speaks.”

Yes, it speaks. Aye, and the mountains speak, the Lake speaks, the whole wide landscape speaks—speaks of all we owe to the violent deaths of such as these. And if to-day this land breathes freedom throughout every pore; if to-day she attracts all wanderers by her beauty, how shall we deny that it is due to a convulsed and tortured past?

But in admitting this, our deep sense of gratitude to bygone men and days, is such gratitude to bespeak our resolve to follow closely their example? Are we to despair of freedom and beauty being maintained, even accentuated, by other and more refined methods? Why should we? Why should not this very freedom, this very beauty be the instrument of our secure regeneration? In view of the hundreds of thousands of travellers who come to Switzerland (it is deputed that 300,000 yearly visit Lucerne alone), who fall under the beneficent spell of her life and landscape, and who return to their hearths and homes with ineffaceable souvenirs—in view of all this precious and increasing influence, it seems impossible that history can so far repeat itself as to soil afresh the Alps with battle-carnage. Walk along the lake-front amid the gathering shades of night, when the gulls have gone to slumber, leaving the duck and coot alone to seek{23} their supper from the passer-by, and when the lights flash out from the great hotels on the heights of Pilatus, the Stanserhorn, the Bürgenstock and the Rigi. Can you help believing, when you gaze over at those far-off constellations of electric lights, that men are now living in closer and truer communion with all that is ennobling in Nature? can you help believing that, although men may drag luxury with them to the summits of the Alps—although they there must have their billiard and their music room, and eat their evening’s dinner in full dress, yet are they inevitably influenced for good in their ideals, and in the practical assertion of their ideals, by the air, the flowers, the snow-capped peaks and rolling glaciers around them, and the wondrous lake-land panorama spread out low about their feet?{24}

To call the Lake of the Four Forest Cantons the Lake of Lucerne is as correct locally as to call Lac Leman the Lake of Geneva; and it meets with as much sympathy among the inhabitants. The Lake of Lucerne is really but a modest portion of the whole, and the whole is so delightfully irregular in form as almost to be three lakes, if not four. The form of the Lake is sometimes likened to that of a cross, but this, as any map will show, is a reckless definition, and has far less warrant than the profile of Pilate’s face which some find in the outline of Mount Pilatus, or the lion couchant which some see in the combined outline of the two Mythen when viewed from Brunnen. As a matter of fact, the Lake’s form is too eccentric to resemble anything but what it is—a series of bays. And, speaking strictly, the Lake of Lucerne is just one of these bays.

Where fascination and charm are so great and abundant, where places of historical and natural interest are so many and famous, it is not easy to decide what to see first; and yet, I suppose, comparatively{25} few visitors hesitate to make a bee-line for the Rigi. By right of conquest the Rigi holds a prime place among the attractions of the district. Thanks to sunrise, thanks to Mark Twain, to Tartarin, and a host of others, thanks also to the fact of the railway to its summit being the first of its kind in the field, the Rigi’s fame is as great as, if not greater than, that of Tell’s Chapel on the Bay of Uri. Certainly it is greater than that of Pilatus—though whether it is deservedly so is another matter. So famous is it, that writers, carried far upon the wave-crest of enthusiasm, have not shrunk from acclaiming it “Queen of the Mountains”—a valuation which gives one furiously to think how uncommonly crowded with royalties is this stanch republic. But whatever may be thought of the Rigi as a monarch among mountains, it is, in any case, a Mecca among mountains. Its summit, the Kulm, is deservedly popular, not only for the intrinsic beauty of the vast panorama of Alp, valley, lake, and plain, but also because it is an eminently suitable spot from which to comprehend something of the rugged, tumbled country whose stern exigencies upon life have bred that simple, direct, and nobly independent spirit which broke the might of Austria and of Burgundy and wrung—indeed, still wrings—respect from all enemies of Freedom.

However, with all due respect for Her Majesty,{26} I see no reason why her illustrious presence, though it dominate the Bay of Küssnacht, should so overwhelm the rights and reputation of that Bay. In course of sequence, and moving, as is seemly, with the orbit of the sun, the Bay of Küssnacht should come first upon the programme. But there stands the Rigi, clothed in such bright repute that the Bay which laves its northern base is, as far as tourists are concerned, comparatively neglected. Little else do many see of its beauty-spots than the tiny gleaming-white shrine to St. Nicholas, the fishermen’s patron saint, set picturesquely upon one of the isolated rocks of Meggen; and this only as the steamer passes on its way across to the royal presence at Vitznau. And yet this Bay possesses a very charming individuality. There is little that is wild and rugged about it, if the bold escarpments of the Rigi be excepted. Handsome châteaux—particularly Neu-Habsburg, standing by the ruins of an ancient seat of the Dukes of Hapsburg—and country houses, orchards, and rich farm-pastures claim its shores. The verdure of field and tree touches the water’s edge and merges in a velvet-rich reflection of itself. Happy prosperity is the keynote of this Bay: “Earth is here so kind, that just tickle her with a hoe and she laughs with a harvest”—welcome complement to the wild, weird shores of Uri. Moreover, at the end of the Bay is Küssnacht,

as quaint and picturesque a town as there is in the Lake’s whole district (despite the bold intrusion of “Auto Benzin” and “Afternoontea” by the side of ancient heraldic decorations). Here Goethe stopped in 1797, at the Gasthaus zum Engel, containing the ancient Rathsaal, dating from 1424; here, too, a little way back from the town, is the Hollow Way, which figures so prominently in Schiller’s William Tell; and here, crowning a steep wooded knoll near by, are the last remnants of Gessler’s sinister stronghold in whose dungeon Tell was to have been incarcerated—

The ruins of this castle, composed largely of the Rigi’s pudding-stone, are not in themselves impressive to-day, except in their associations with the tragic past—associations strikingly symbolized by the bold erect clumps of Atropa, the venomous Belladonna, so suggestively established amid the crumbling debris. But the site is a fascinating and beautiful one with the shady stream, the old water-mill and farmsteads below, and glimpses of the Lake between the trees. It is especially lovely in autumn when the beeches are a-fire, and one wonders then if Longfellow, who knew Lucerne and neighbourhood, was here or hereabouts inspired to write—

“Magnificent Autumn! He comes not like a pilgrim, clad in russet weeds. He comes not like a hermit, clad in gray. But he comes like a warrior, with the stain of blood upon his brazen mail.”

For the Bay of Küssnacht is a revelation of what the dying year can achieve in colour-splendour.

The peculiar geography of the Lake has happily done much to guard natural beauties and rural simplicities against certain of man’s customary attacks. Only at four points upon its shores has the Federal Railway found it convenient to break the peace. Communication is thus in large part by the more fitting and picturesque service of steamboats. Unless, therefore, we go round, via Küssnacht, to Arth-Goldau on the eastern side of the Rigi and thence take the mountain-line to the summit, it is by steamboat that we must reach Weggis or Vitznau, from whence to make the ascent of the Monarch. Weggis, with its big old chocolate-coloured chalets seated upon full-green slopes, and its luxuriance of fig trees sweeping the water-line, was, before the mountain-railway at Vitznau came into existence in 1871, the starting-point for reaching the Rigi’s heights; even to-day the many who prefer pedestrianism use this route, though Vitznau has become the crowded centre. In whatever else she may have suffered from this change, Weggis has lost nothing in beauty and repose by Vitznau being the dumping-ground for some 120,000{29} tourists annually. But let it not be thought that Vitznau has no charming moments, particularly in the spring and autumn, when the ruddy conglomerate crags of the Rigi soar above woods and orchards radiant with colour, and thin mists lend increasing fascination to the “Pearl of the Lake”—the abrupt, cliff-like mass of the Bürgenstock rising from the opposite shore, at all times an arresting feature of the lake-side scenery despite its comparatively modest proportions.

As for the Rigi and the ascent thereof, what more can be said than countless pens have told already? Enthusiasm—easily and plentifully acquired in such splendid surroundings—has dubbed it “without a rival on the face of the earth”. Can I say more? Less, perhaps; but surely never more! However, an abundant rapture is excusable. Language is poor to explain the lavish beauty that Nature has assembled in the panorama which unfolds itself as the train moves upwards; superlative exclamation is wellnigh bound to creep into the expression of even the coldest of temperaments. When, beyond a foreground in which trees and chalets are so out of the perpendicular as to appear as though toppling over into the abyss below, the giant Alps of the Bernese Oberland slowly rise above the peaks of Unterwalden, and the distant Jura mountains come into view upon the horizon far be{30}yond Lucerne, lying map-like by the softly iridescent Lake, whose complex contours gradually reveal themselves from Alpnachstad to Küssnacht and from Buochs to Kehrsiten—when this wide-flung landscape, bathed in slight blue-purple haze, is steadily disclosed before the eager gaze of the tourist, whose imagination has been already whipped into liveliness by all that he has read and heard, small wonder if language is driven to hyperbole. And as the train creeps up and up, over steep slopes covered with bracken-fern and stately yellow Gentian; up and up, over rocky chasm and flower-filled pasture, till at last, at some 6000 feet, the summit-station of the Kulm is reached and the tourist steps out, and finds himself dominating an Alpine landscape over which his eye can roam for miles in all directions, then certainly may he be excused if his emotion runs riot with his gift of weighty utterance.

“There are some descriptions”, wrote Alexandre Dumas, the elder, about this very prospect, “which the pen cannot give, some pictures which the brush cannot render; one has to appeal to those who have seen them and content oneself with saying that there is no more magnificent spectacle in the world than this panorama of which one is the centre, and which embraces 3 mountain chains, 22 lakes, 17 towns, 40 villages, and 70 glaciers spread over a circumference of 250 miles. It is not merely a magnificent view, a splendid panorama, it is a phantasmagoria.”

Here, at all events, distance lends enchantment to the view. Details are blurred for the time being, for{31} the brain at first has no use for them. Large, unified impressions monopolize the senses; inquisitiveness and criticism are swamped by acute though vague emotion, and we are content to gaze at the vast expanse of lovely shaded colour rather than at any formal object. But after a while, when the senses have drunk deeply of these first impressions, enquiry, that dream-destroying faculty, asserts itself; out come sundry maps and guidebooks, topography is to the front, history is probed, and away to Memory’s secret treasury flies our unambitious entrancement, only to invade us afresh in later quiet moments at home. George Borrow, in the very characteristic Introduction to his Wild Wales, considers that “scenery soon palls unless it is associated with remarkable events, and the names of remarkable men”. Possibly this opinion is upon all-fours with that other expressed by Mason, one of Horace Walpole’s friends:—

Be this as it may—and both opinions are at least debatable—the scenery here, around the Rigi, is so bound up with remarkable events and remarkable men that, willy-nilly, some sort of acquaintance has to be made with them.{32}

Among the twenty-two lakes which go to the making of this wondrous panorama are at least two that we shall hear of when we come into closer contact with William Tell and his momentous age. Away to the left of the Rossberg, and beyond and above the Lake of Zug, is the little Aegeri-See, upon whose shores the epoch-marking battle of Morgarten was fought in 1315, some seven years after the secret banding together of the men of Schwyz, Uri, and Unterwalden to throw off the tyrannic yoke of Austria. The trouble, which had been brewing through many years of oppression, came to a head when the men of Schwyz attacked and pillaged the Abbey of Einsiedeln (to the east of the Lake of Aegeri, and still a famous place of pilgrimage), taking the monks prisoners, because the Abbot, under a deed of gift from the Austrian Emperor, claimed the mountain pastures of Schwyz for his cattle. Austria determined to crush this revolt, and on November 15, 1315, the Duke Leopold I raised an army 20,000 strong and marched upon Schwyz.

“The Austrians”, says Alexandre Daguet, in his little primer used in Swiss schools, “were so sure of victory that they had with them carts full of rope with which to bind their prisoners. A noble of the neighbourhood, Henri de Hünenberg, warned the Confederates of the danger which menaced them, and 1300 armed peasants at once posted themselves upon the heights dominating the Lake of Aegeri. The Austrian army climbed laboriously the mountain path, when suddenly blocks of rock were hurled upon

them from the heights, causing frightful disorder in their ranks. Others of the Confederates then attacked the Austrians with clubs and halebards, slaughtering such as were not drowned in the lake. A crowd of nobles bit the dust, and the Duke himself only narrowly escaped death, arriving pâle et effaré the same evening at Winterthour.”

This battle was the young Confederation’s baptism of blood, and on the following 19th of December the secret pact made on the Rütli in 1307 was publicly confirmed at Brunnen.

The Lake of Sempach, too, upon whose shores, in 1386, another heroic victory was won from Austria, can be seen in the direction of Basle.

“The Swiss, to the number of 1400, knelt in prayer, then flung themselves upon the enemy. But in vain did they strive against the wall of pikes. Sixty of their number already lay bathed in their own blood, and in another moment the little army would have been enveloped by the enemy. Suddenly a man of Unterwalden, Arnold von Winkelried, cried aloud to them: ‘Confederates, I will open a way for you; take care of my wife and children’. Then, throwing himself upon the enemy’s pikes, he gathered in his arms as many of these as possible, and fell, opening a breach in the Austrian ranks, through which the Confederates rushed. The Austrians resisted furiously. The Duke Leopold himself fought with great bravery, but he was killed by a man of Schwyz.”

At this battle the town of Lucerne lost its famous burgomaster, Petermann von Gundoldingen, whose frescoed house still stands in the Seidenhof Strasse. The coat of mail which Duke Leopold wore at Sempach is kept in the Museum at the old Rathaus at{34} Lucerne, together with several banners taken from the Austrians.

To the south of the Lake of Zug, and lying beneath the precipitous masses of the two Mythen, is the little Lowerz-See with the tiny Isle of Schwanau, seeming like a mere boat upon its surface. This lake, also, has its part in history. King Ludwig of Bavaria, Wagner’s far-sighted if eccentric patron, sojourned for a time upon the Isle of Schwanau; so also did Goethe. But history goes back further than this: back again to the tyrannical Austrian governors, one of whom had his castle on the island. And history (or is it legend?—hereabouts the line is often not well marked between the two) tells of how this Governor “was smitten with the charms of three beautiful but virtuous sisters, living in the neighbourhood of Arth”, and of how these three sisters, to escape his importunities, “fled to the pathless wilds of the Rigi”. Here, near a spring of water, they built themselves “a little hut of bark” and settled down to live, until one summer night some herdsmen noticed “three bright lights hovering over the wooded rocks”, and, following these lights, they reached the little hut where they discovered the three good sisters wrapped in their last long sleep. The spot, near the Rigi-Kaltbad Hotel, is still famous as the Schwesternborn, and its waters are noted for their healing properties.{35}

Between the Lakes of Zug and Lowerz rises the Rossberg, from whose side, on September 2, 1806, descended the terrible fall of rock which destroyed the town of Goldau. Ruskin speaks of it in Modern Painters, and Lord Avebury, in The Scenery of Switzerland, gives the following brief account:—

“The railway from Lucerne to Brunnen passes the scene of the remarkable rockfall of Goldau. The line runs between immense masses of puddingstone, and the scar on the Rossberg from which they fell is well seen on the left. The mountain consists of hard beds of sandstone and conglomerate, sloping towards the valley, and resting on soft argillaceous layers. During the wet season of 1806 these became soaked with water, and being thus loosened, thousands of tons of the solid upper layers suddenly slipped down and swept across the valley, covering a square mile of fertile ground to a depth, it is estimated, in some places of 200 feet. The residents in the neighbourhood heard loud cracking and grating sounds, and suddenly, about 2 o’clock in the afternoon, the valley seemed shrouded in a cloud of dust, and when this cleared away the whole aspect of the place was changed. The valley was blocked up by immense masses of rocks and rubbish, Goldau and three other villages were buried beneath the debris, and part of the Lake of Lowerz was filled up. More than 450 people were killed.”

In September, 1881, a similar catastrophe overtook the village of Elm, in Canton Glarus (somewhat to the right of the Glärnisch, and almost in a direct line with Brunnen, looking from the Rigi), when the Plattenbergkopf fell: 10,000,000 cubic metres of rock. Sir Martin Conway, in The Alps from End to End, has a long and vivid description of this mountain-fall and of all the horrors which it entailed.{36}

Enough! It would take volumes to hold all of moment that could be told in connection with this panorama. But what of the Rigi itself? Well, it serves what has become peculiarly its purpose—a nesting-place for innumerable hotels and their parasitic incongruities, and a platform from which thousands upon thousands witness the sunrise. Except, then, in its remoter parts and around about its base it is so trampled on by hosts of feet that the early spring crocus and the late autumn gentians are almost alone among the lovely flowers to have a peaceful, profitable time. Ask the Swiss Heimatschutz—the Society for the Protection of Natural Beauty—what it thinks of the present state of the Rigi, the Stanserhorn, and Mount Pilatus; it will give an answer couched in no mixed terms. One of the most patent and painful paradoxes of our age is, that our appreciation destroys so much of that which we appreciate. Inconsequence links its arm in that of the holiday-maker. Hence the call for the Eastern Labyrinth in the Glacier Garden at Lucerne, and the extraordinary number of bead-necklace and bracelet shops crowded together in that quarter of the town. True, on the Rigi “the questionable melody of the Alpine horn” echoes through the early morning darkness, and chamois finds a place upon the hotel menu—goat being inadmissible at such an altitude; but are there

not also the bazaars full of Brummagem trinkets and what not?—strange, mysterious effect of Alpine air upon the human system!

From the Rigi it is well to turn to Mount Pilatus. The experience will be in but small measure a repetition; for Pilatus has marked individuality. Although Alpnachstad, the starting-point of the Pilatus Railway, is one of the few places on the Lake which may be reached by rail from Lucerne, not many people, I imagine, avail themselves of this means of transit. To take the train, as being quicker than the steamboat, is a false economy; in Switzerland less haste means wider experience and finer views. The tree-clothed cliff of the Bürgenstock is never seen to greater advantage than when the boat heads for Kehrsiten, after leaving Kastanienbaum (where, by the way, it is said that the first horse-chestnut trees on the Lake were planted); nor is Pilatus ever more picturesque than when seen from the quay-side at Stansstad. But more than this—for those who invariably see dignity and beauty in man’s labours, and who think that “ugliness means failure of some kind”—there is, from Kehrsiten, an admirable view of the open ironwork shaft of the electric lift which decorates the lovely Hammetschwand; and after passing the swing bridge which gives entrance to the Alpnacher-See, there are the Cement Works of Rotzloch, where{38} the gorge, the trees, the whole hillside are as though dressed for some bal poudre—even the piermaster.

It was in late October when I was last upon Pilatus. Fog ruled the roast about Lucerne; a fog so dense, though white, that the steamboats moved with the utmost caution, feeling their way as much by incessant interchange of bell-signals with the shore as by the compass. That the beech woods were ablaze with autumn’s waning energy was known, but little besides grey, ghostlike objects could be seen as the train started with a jerk upon its strenuous journey. Nor was there anything but fog and phantoms for some twenty minutes or more. Then slowly the fog lightened, the phantoms took on the form of trees, grew warmer in tint, still warmer and still clearer, until the golden, red-brown woods, purpled in part by distance, became revealed, all wreathed about with trails of veil-like mist. Before the lower, rock-strewn pastures of the Matt-Alp were reached, every vestige of the fog was left lying compact below, and the train was labouring upwards towards a radiant, cloudless sky. The Alps, of course, are rich in such experience as this, but I can remember nothing that ever more nearly realized my conception of fairyland. Indeed, if it were not like saying that a lovely hothouse orchid is so natural as to seem to be made of wax, I would declare that the piercing of the fog{39}zone that day on the autumn-tinted sides of Mt. Pilatus resembled nothing so much as the grand transformation scene of our Christmas-time theatres, when gauze veil after gauze veil is slowly rolled away, and from grey, then tinted mystery emerges brilliant, spotless colour.

What a wonderful journey this railway provides! If any proof were needed of the high eminence of Swiss engineers and of the indomitable spirit and resource which the Alps breed in their children, here assuredly it is. Beasts, plants, birds, and insects are not alone to feel the influence of Alpine circumstance upon character; hare and saxifrage, ptarmigan and fritillary are not the only pupils trained in Nature’s Alpine school. Man, in common with the chamois and the edelweiss, the eagle and the erebia, owes priceless capacity to the life imposed by high-flung precipice and pasture. Nursed in all the rigour and beneficence accompanying contact with high altitudes, he develops much of that amazing efficiency, that impelling adaptiveness which is so admired in “Alpines”. The will to master the worst and to enjoy the best is never more alert than in the dweller among mountains. And this fact is borne in upon the imagination as the train climbs panting up the face of the Eselwand, in every way the culminating labour of its journey. Here the track has been carved upon a{40} sheer precipice, and it makes one dizzy to think of the workmen’s initial efforts to gain a foothold. Some idea of the resource and nerve that must have been required can be gathered by standing upon the Kulm Station platform and turning to gaze down the way the train came up; or, better still, on the rocks beyond the hotel and facing the Esel’s fearsome cliff to which the line so desperately clings; for from this vantage-ground the Titlis and the Alps of Uri, Unterwalden, and the Grisons rise beyond and between the Esel and the Matthorn, giving terrible depth to the gaunt masses of these latter, and thus suggesting the magnitude of the task performed by the railway builders.

A large part of the superiority of Pilatus over the Rigi lies in its magnificent foreground: invaluable adjunct to the panorama. A vast, unbroken horizon is well for a time, but it is all of a piece, and its very immensity becomes wearisome. Humanity is more at home with partially hidden views. To have everything simultaneously discovered is, for many subtle but important reasons, to impose a limit upon interest. A certain amount of interruption gives durability to pleasure. Delightful combinations are present, and the eye can rest reposefully upon portions which in themselves are perfect pictures. In this manner, then, Pilatus is more attractive than either the Rigi or the Stanserhorn. The panorama itself may be much the{41} same from all three of these eminences, but from Pilatus it is enhanced by the mighty foreground. All about the summit are wild, weird places of fascination, and this was particularly so during those late autumnal days, with the dense, billowy sea of fog below, covering the whole Lake, stretching away over the plain towards the Jura, straggling up the valleys towards Engelberg and the Brünig Pass, and leaving such prominences as the Rigi, the Bürgenstock, and the Stanserhorn like islands floating on a scarcely moving ocean. The huge, abrupt escarpments of Pilatus looked the more impressive for the purple shadows which they threw upon this milk-white sea; and the choughs, circling and whistling about the crags, lent just that eerie note which has been so fruitful of legend in the past.

For fiery dragons once had their lairs upon these heights. Renward Cysart, town clerk of Lucerne in the sixteenth century, says so; and he tells of how they were often seen flying backwards and forwards between Pilatus and the Rigi. One day, he avers, a cooper from Lucerne, while climbing Pilatus, missed his footing, fell into a cavern, and on coming to his senses, found himself confronted with “two large, terrible, and monstrous dragons”, which, however, did him no harm, but allowed him to live with them until the return of summer, when he, clinging to the tail of one of his delightful hosts, was landed in a safe place, from{42} whence he reached home and recounted his adventure, which recountal was handed down through several generations until it came to Master Cysart who, therefore, vouches for its accuracy, though regretting “that the day, year, and name have, through carelessness, passed into forgetfulness”. Dragons were common objects of the Alps in those and previous days. The country between Stans and Kernwald (well seen from Pilatus) was ravaged, about the year 1240, by an enormous specimen, which was slain by one Winkelried, an ancestor of the hero of Sempach. Legend usually has relative truth at the back of it, and although we may feel inclined to dismiss dragons and their doings as unalloyed fabrications of primitive, superstitious minds, yet certain authorities hold that the dragon was a species of enormous serpent formerly inhabiting some parts of the Alps, but now extinct there.

Pilatus is said to obtain its name from what is perhaps the most important of the host of legends connected with the mountain. Although there has been an attempt to derive Pilatus from pileatus, meaning “hatted” (in reference to the “hat” or hood of cloud which so frequently sits upon the summit), the more probable derivation seems to be from the one-time belief that Pontius Pilate’s remains were buried in a lake near the summit of the mountain. According to this legend, Pontius Pilate committed

suicide in prison in Rome, and his body was thrown into the Tiber, when at once a terrific, devastating storm arose. The body was therefore taken out, conveyed to Vienne, in France, and thrown into the Rhone, here again causing disturbance. It was then transferred to Lausanne, but a further repetition of its untoward behaviour caused it to be banished to the little lake upon Mount Pilatus. Here it remained benign so long as the lake was in no way interfered with. If, however, anything was thrown into the water, “the lightnings flashed, the thunder rolled, and desolation broke over the land”. The town council of Lucerne therefore felt called upon to forbid all persons to approach the Lake, and it is related how at least one wretched man was executed for disobedience. But

“by degrees the belief in the supernatural powers of the old Roman began to decay,” says J. Hardmeyer, in his little work upon this mountain, “and at last, in 1585, a certain Johannes Muller, rector of Lucerne, brought about its complete overthrow. With numerous companions he made his way to the lake on Mount Pilatus, boldly challenged the evil spirit to show his might, threw stones into the water, and made some of his people wade about in it, and behold, neither storm nor tempest followed, not a wave rose, and the skies remained as serene as before. This was the death-blow to the legend of Pontius Pilate and his evil deeds. The council of Lucerne went still further: they had the mountain lake drained off, so that nothing remained of it but a small morass, where a little water still collects after the melting of the snows, but soon disappears.”

Thus perishes Romance before the onward march of prosaic understanding!{44}

Andermatt and Engelberg are the two really Alpine villages which one usually connects with Lucerne. Andermatt is rather remote, being away up in the mountains beyond Göeschenen; but the journey to Engelberg is no more than that to the summit of Pilatus. From Stansstad, with its sturdy, grey old tower upon the water’s edge—a tower built soon after the banding together of the Forest Cantons, and last used in the desperate struggle against the French in 1798—there is an electric railway. The line passes over the orchard-covered plain to Stans, the capital of Nidwalden and the birthplace of Arnold von Winkelried, whose monument is in the marketplace, and whose ancient farmstead still exists amid flowery fields beyond the town; then on past Wolfenschiessen, known to history in connection with the Austrian Governor of that name killed hereabouts by the woodman Baumgartner for insulting his wife—a deed which appears to have done much to mature the defensive alliance of 1307 between the three Cantons; and so on to Grafenort, where the engine is changed and the line commences its steep{45} ascent to Engelberg. Through a forest, wherein the hart’s-tongue fern luxuriates, the train advances, crossing and re-crossing the winding carriage-road. Here and there through the trees to the right of the line are glimpses of towering cliffs with waterfalls tumbling wildly over the rugged sides and falling into the gorge below, where foams and froths the Engelberger Aa on its way to the Lake at Buochs. The ascent is not a long one. Soon the forest is replaced by rapid flower-strewn slopes, and the near presence of impressive mountains. Then the valley somewhat broadens, and through almost flat pastures the train quickly reaches the village, its big hotels and spick-and-span prosperity.

Engelberg has all the airs and graces which two crowded seasons can give. It is as popular in winter as in summer, and is organized accordingly. But with the exception of its famous monastery, there is little that is old and picturesque about it. As the local guidebook says—and says seemingly with pride and glee—: “Favoured by a great fire in the autumn of 1887, the witnesses of modern civilization have become predominant”—an expression of sentiment which is apt to make one think of Thoreau’s caustic remark about man placing his hoof among the stars. However, although “the splendid hotel buildings tower gigantically above the country cottages of former{46} times”, and the fine old timbered dwelling of the tailor stands an heroic interval in the midst of shop-fronts decorated in the best art shades of paint, yet something has been spared of the peasants’ old-time costumes—the women’s quaint silver hair-shields and bejewelled silver-gilt necklaces, and the men’s elaborately embroidered blouses. Nor have the blessings of fire and civilization suppressed the lovely mountain flowers which carpet the pastures outside the hotel-zone. Here, from the early spring crocus and soldanella to the late autumn crocus and willow-gentian, there is a rich round of floral delight. Rock, Alp, and forest are alike gay with colour, and many a botanical treasure haunts the district. Perhaps the best season for appreciating this side of Engelberg’s charm is spring and early summer. The near fields and slopes are then wearing their finest dress. Where, erstwhile, the sportsleute revelled on ski, the vernal gentian and yellow violet are in radiant masses, and where the luge ran merrily but a few weeks previously, the geranium and globe-flower are ablaze. And for this bright and wild abundance there is a wonderfully effective background of stately mountains. The rugged Engelberg, the fretted Spannorts, and the giant Titlis of such distinctive form, all abundantly clothed in snow at this season, make as admirable a setting for these slopes and fields of

early flowers as could be well desired. Later on, when the Surenen Pass, the Trübsee, the Joch Pass, and the Engstlenalp can be comfortably reached, the wealth of Alpine anemone, deep-blue monkshood, blue-and-white columbine, steel-blue thistle, and a host of other treasures carry the Feast of Flora to the very verge of the eternal snows.

It was the pastures of the Surenen which gave birth to the legend of the famous Bull of Uri—the bull whose head figures on Uri’s armorial shield. A shepherd becoming inordinately attached to a lamb, baptized it into the Christian Church; whereupon the lamb developed into a monster and slew the shepherd. The monster continued to be such a scourge upon these pastures that the inhabitants of Uri trained a pure white bull especially to do battle with it. In the combat which ensued, the monster was slain, but the bull was so grievously wounded that it died soon after. One of the bull’s horns became the famous battlehorn of the men of Uri, striking panic into the hearts of their enemies whenever it was sounded.

Legend also hangs about the Engelberg; for it was upon those rocky heights that Conrad von Seldenbüren heard angels singing, St. Cecilia with her lute being amongst the number. This so impressed the good man that he there and then (in the year 1120) founded the monastery which stands to this day,{48} and, until 1798, ruled the valley. Great for centuries as a centre of literature and science, it still retains its prestige as an educational institution. The building contains much of high interest—the great library of over 20,000 books and manuscripts, and the Sacristy full of precious relics of the past—but access to these is difficult for visitors. As for the natives of Engelberg, for the most part they practise the breeding of cattle and the weaving of silk, both industries being fostered by the Monastery, itself owning a herd of mouse-coloured cows with tuneful silver bells. The natives have retained much of their engaging individuality. Sturdy children of a sturdy race, many of them are quite typical descendants of what one imagines Tell’s strong, strenuous age to have been.

In leaving Engelberg, unless the Surenen Pass be crossed into Uri, and so down to the Lake near Flüelen, the best way is to branch off at Stans and touch the Lake at Buochs. From Buochs, where farms and orchards form the prevailing note, the steamboat passes, by way of Beckenried and its big old walnut tree, to Gersau at the southern foot of the Rigi. Until the end of the eighteenth century this village, prosperous-looking nowadays with its big hotels along the quay-side promenade, was a fullblown republic on its own account; but to-day its independence is merged in that of the Canton Schwyz.{49} There is a lovely walk from here to Brunnen; loveliest perhaps in spring when the rosy, black-pointed heather (Erica carnea) decks the rocks through which in part the road is cut. Not far along this road is the chapel of Kindlimord nestling among pines on the steep and rocky shore of a tiny deep-green bay. It is said that here a strolling fiddler murdered his child who cried to him for food, and that this romantically situated little chapel was built in expiation of the deed.

On the farther shore of the Lake, almost opposite Kindlimord, and below the woods of Seelisberg, is Treib, the most ancient and picturesque of houses in all this district. Rich in colour and quaint design, and possessing its own little harbour, it stands quite alone amid the beech woods which here sweep down to the water. It is a perfect bijou picture from the distant past: something for a showcase in some sheltering museum, rather than for such buffeting storm-winds and waves as recently overthrew its stone breakwater. Built in 1243, it did service as the first Federal Palace, the Assembly of the three Cantons, Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden, having been held here in 1291. It then became the Guild House of the boatmen of the Four Cantons. At that time roads were scarce, communication was mostly by water, and Treib was correspondingly important. The interior{50} of the house is redolent of old-world associations: the small bottle-glass windows, the massive old stoves, the fine wooden ceilings, the quaintly carved chairs, the aged pewter plates, the genealogical tree dating from 1360, and the fourteenth-century clocks, one of which is entirely of wood—but absolutely unheeding of Greenwich time. Treib is indeed a refreshing place to linger in after the almost omnipresence of the great hotels. But the past is impossible as a permanency. Modern hoteldom holds its own—and more than its own. At Brunnen, whither the boat transports us, Treib is just a sideshow—something to patronize in fine weather as a poor and utterly antiquated relation.

Brunnen owes the spoiling of its site to the magnificent prospect to be enjoyed from thence of the Bay of Uri. Hotels innumerable, to the right and to the left, crowding upon quay, perching upon cliff and soaring above forest; but the prospect of the Bay of Uri remains—at once Brunnen’s making and undoing. From the very nature of things this invasion was inevitable. It was inevitable that the touring world and his wife should wish for ample accommodation at such a view-point. Nor is forgiveness difficult if one but turns one’s face towards the Uri-Rothstock. Brushes and pens without number have essayed to depict this prospect, to translate its beauty and magnificence, to catch its ceaseless, changeful charm; and brushes and

pens without number have necessarily failed in the attempt. Something only of its fascinating phases and ensemble can at most be given. As a whole it is too elusive, too consummate: too surely out of reach of human dexterity in either paint or words. Even if it had but one mood, one fixed mood upon which contemplation could feed indefinitely, a description of it must needs be inadequate; but as it is—well, description falls far short of what is felt. Seen through the soft-gold haze of spring, or through actinic summer sunshine, or through the warm mists of autumn, or through winter’s steely breath, there is such ever-shifting light and shade, such incessant recomposing of the picture, and always such mystery in parts and such subtlety over all, that here, at any rate, one knows that one’s inner consciousness is more than a match for one’s powers of formal expression. A restless repose suffuses the whole landscape; its moods are unified though everchanging. The Lake reflects the mountains, and the mountains reflect the Lake; for the Lake—to use Canon Rawnsley’s simile—“is as many-minded as a beautiful woman”, and so, also, are the mountains.

And this elusive yet striking quality of beauty is no particular possession of the mere distant view from Brunnen; it is just as evident upon near inspection. From Tellsplatte or from Flüelen, from Isleton or from{52} the Rütli, or from any open spot upon the whole length of the wonderful Axenstrasse, “this temple of wild harmony” has all the charming variety and mystery of lovely woman. The close intimacy of severe and towering crags (as at Sisikon and Isleton) does nothing to dispel it; rather is it accentuated by the presence of something so rudely definite. Whether it be where the bare precipice plunges headlong to the Lake (as at the Teufelsmünster, near Flüelen), or whether it be where the beech woods run down to meet the waters (as at the Rütli and round about the Schillerstein), sublimity, which in part is mystery, is never wanting. Always there are heights, or snows, or distances over which the thin air plays in endless moods of light and shade. The Bay of Uri is indeed a wonder-spot in which to roam and float and dream. Well might the water-sprite in Gerhart Hauptmann’s The Sunken Bell have drawn his inspiration from men and women to be found wandering here entranced; well might these scenes by Uri’s waters have given him the insight to exclaim:—

For amid scenes like these man knows that he is more than mortal; amid scenes like these he discerns that{53} elusiveness in himself which is akin to the elusiveness around him; amid scenes like these his own inexpressible subtleties are alive to the inexpressible subtleties of Nature, and his fairy self goes out in intimate communion with the fairy world.

Men may well continue to write of the Bay of Uri; just as they may well continue to write of beautiful woman. Will they ever have finished writing about either? will they ever have said all that can be said? It is one of the extraordinary things about the Bay of Uri that romance should be doubled in its every corner. Much in history has had a most prosaic background, but here, in Uri, Nature and History have combined to lift events into the very forefront of romantic fascination. No story of the heroic past is more universally known than that of William Tell and the founding of the Swiss Confederation; and it is probably safe to say that this universality is due in no small measure to the magnificent natural setting for that story. One indeed wonders if Goethe, had he never visited these waters and been enthralled by their surroundings, would have been moved to recommend his friend Schiller to dramatize this story. One, moreover, wonders if Schiller ever would have achieved the famous thing he did if he had not been able to place his drama amid the scenery of this Bay. One’s questioning may go further still, and one may even{54} wonder if the superb scenery has not played an important part in welding the story with the very religion of the Swiss people. History and Nature seem here to be made for each other, and it does not necessarily require a Swiss to feel the thrill which each lends to the other.

Here, briefly, is the story. Around the year 1240 the Austrian Empire was the dominant power in these parts. The Canton of Unterwalden was governed by the Empire; whereas the Cantons of Uri and of Schwyz governed themselves, but were under the protection of, and owed service to the Empire. Little by little the Hapsburg dynasty endeavoured to absorb the whole country surrounding the Lake. Governors were set up in the three Cantons, tyranny developed, and to meet this process of absorption, Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden, in 1307, entered into a solemn alliance (the original document, drawn up afterwards, still exists in the archives of Schwyz). This, then, broadly stated, was the setting of the stage upon which William Tell and his companions played their famous parts. These actors emerge, so to speak, from the wings to the dull mutterings of popular exasperation. The Governors are treating the people as the merest serfs. Wolfenschiessen, Governor of Unterwalden, has been killed by the outraged Baumgartner of Altzellen; a dungeon-castle is being built at Altdorf, in Uri, to{55} overawe the people; Arnold of Melchthal’s old father has had his eyes put out and his estate confiscated because his son has chastised one of the Governor’s impudent servants; and Governor Gessler has vowed vengeance upon Werner Stauffacher of Steinen in Schwyz, because the latter is a landed proprietor, and has built himself too fine a house. Walter Fürst (Tell’s father-in-law) of Canton Uri, Werner Stauffacher of Canton Schwyz, and Arnold von Melchtal of Canton Unterwalden, each bringing with them ten men, meet at night on the Rütli—a steep, grass-covered clearing made in the beech woods almost opposite Brunnen—and pledge themselves, in the name of their respective Cantons, to resist all attempts at annexation by Austria. Governor Gessler, hearing rumours of this revolt, sets his hat upon a pole at Altdorf and orders all and sundry to bow down to it.

William Tell, among others, refuses to bow the knee, and is condemned by Gessler to shoot an apple from off his (Tell’s) son’s head:—

Tell comes successfully through the ordeal, but has a second arrow hidden in his tunic. The Governor sees it and forces Tell to confess{56}—

Gessler thereupon has Tell seized and bound, and declares:—

A violent storm springs up; the bark is likely to be wrecked. Gessler, in fear and trembling for his own safety, and knowing Tell to be an adept steersman, has him released and orders him to take the helm. Tell directs the bark to the Axenberg, springs upon a little shelf of rock and,

escapes up the wooded cliff. Making for Küssnacht, Tell awaits the Governor in the Hollow Way and shoots him through the heart.

Of course, critics have arisen, who attempt the destruction of this story. Some would not account themselves progressive if they did not try to annihilate the

past, or turn it upside down, or inside out. Bacon was Shakespeare; Homer was a crowd of at least twenty scribes; a Welshman, and not Columbus, discovered America; and Bonivard, the Prisoner of Chillon, was an out-and-out scamp. So would some deal with Tell. They would treat him as the lake on Mount Pilatus was treated—they would throw stones at him, scoff at his simple, heroic virtue, and drain him even of his existence. Listen to what Baedeker, in his guide to Switzerland, has to say of “the romantic but unfounded tradition of William Tell”:

“The legend of the national hero of Switzerland, as well as the story of the expulsion of the Austrian bailiffs in 1308, is destitute of historical foundation. No trace of such a person is to be found in the work of John of Winterthur (Vitoduranus, 1349), or that of Conrad Justinger of Bern (1420), the earliest Swiss historians. Mention is made of him for the first time in the Sarner Chronik of 1470, and the myth was subsequently embellished by Ægidius Tschudi of Glarus (d. 1542), and still more by Johann von Müller (d. 1809), while Schiller’s famous play has finally secured to the hero a world-wide celebrity. Similar traditions are met with among various northern nations, such as the Danes and Icelanders.”

Does not such reading as this appear to damage the scenery of Uri’s Bay? It seems at least but poor service to render to the tourist—this killing of half of the district’s wild romance. Those who cling to the stout, red little volume as to a dear and trusted friend, must nevertheless feel something like a pang of regret as they climb up through the beech wood{58} to the green slope and the old chalet of the Rütli and drink water from the three famous springs; nor can they be unconscious of a certain feeling of loss as they walk by the bushes of mountain honeysuckle along the path to the little chapel on the Tellsplatte and gaze through the ironwork screen at the fine mural pictures of this outrageous but glorious myth. Tradition is a hard thing to kick against.

Sentiment, however, is of no use for confounding the critics. But let the Baedeker-beridden tourist take heart; there is evidence, after all, not only that Tell may have lived, but that he may have done something to earn his reputation. William Peter, in the Appendix to his English translation of Schiller’s play, voices this evidence. Among other points in favour of the substantial veracity of tradition, he gives two facts of special hopefulness:—

“The many old German Songs and Romances in which he (Tell) is celebrated, and which are so remarkable for their ancient dialect and simplicity as to leave little doubt either of their own authenticity or of the truth of the deeds which they commemorate”;

and

“The creation of three Chapels (one of them—viz. at the Tell’s plat—in 1388, only 24 years after Tell’s death, and when there were 114 persons present in the Landsgemeinde of Uri who had personally known him)”.

He further states that

“The last of Tell’s posterity—a female named Verena—died in 1720. The male branch had become extinct in 1684, by the Death of John Martin Tell of Attinghausen. Tell (the famous Tell) resided at, and was Mayor of Bürglen, which is not half an hour’s walk from the village of Attinghausen. He lived for many years after the events celebrated in Schiller’s Play, performed his part at the battles of Morgarten and Laupen in 1315 and 1339, and perished, in 1354, in his generous attempt to rescue a child from the overflowing waters of the Schächen (the mountain torrent which flows through Bürglen and into the Reuss at Attinghausen).”

Moreover, there is the proved importance of tradition, as such. Something can and must be said for it. That certain episodes, accepted as fact, do not appear in written contemporary history, is not in itself safe proof of the falsity of those episodes. Just because no mention is made of Tell in the White Book of Sarnen, this is small reason for denouncing the hero as a mere replica of Toko, principal actor in an old Danish legend. The truthfulness of traditions handed down from generation to generation by word of mouth has frequently startled those who have set out to refute them. The tradition of the Flood, current among many widely separated and obscure peoples, has been proved by geology to be quite worthy of credence. A rolling stone may gather much moss; but the essential thing, the stone, is beneath the richly-tinted covering.

So, let critic and historian do their worst to damage William Tell; he will escape them as surely as he{60} escaped Gessler. His name and deeds, be they fact or be they fiction, are so much part and parcel of the scenery, that nothing save a devastating convulsion of Nature can possibly bring them to naught. Landmarks must be obliterated, the whole landscape must be radically changed, if Tell is to sink into oblivion. As things are, go where you will around the Lake, he and his age are bound to assert themselves. Even the elements will combine to bring him to your mind. Walk from Brunnen along the magnificent Axenstrasse hewn by the Government from the rock-cliffs of the Axenberg as a strategic route; stroll on amid the red-barked pines, the rocks aglow with tufts of rosy Erinus alpinus, or with the rosy springtime heather, or the blood-red summer cranesbill, while Orange Tip, or White Admiral and Purple Emperor butterflies flit from flower to flower or from sun-patch to sun-patch along the road; stroll on to the wayside clearing where stands a stone memorial to the artist, Henry Telbin, who fell from this spot whilst sketching in 1860; sit here amongst the bright wild sunflowers[2] and gaze down the sheer rocks to the sparkling blue-green waters partly flooded in golden light, and take note of how calm and peaceful all is as the gay-awninged row-boats and the curiously ungainly steam cargo-barges steal about the surface. Now mark that

faint, distant rumbling, and look up towards the snows of the Uri-Rothstock. A storm is brewing beyond Göeschenen and among the Bernese Alps. You say that it is nothing; that it is a very long way off? Wait awhile! Mark that filmy wisp of cloud, sprung suddenly from nowhere, wreathing itself slowly about the Teufelsmünster’s cliff; mark, too, how the blue sky has changed to grey behind the snows, and how the snows themselves have turned a sullen white. “Cat’s-paws” are playing erratically upon the water; the mountains are growing harder in colour; heavy vapours are filling the gorges, and the pines about you are whispering mysteriously among themselves. Do you notice how all the row-boats are hastening towards Brunnen, and how the gulls are screaming? Black clouds are rolling up over the Seelisberg hotels; white horses are visible upon the Lake, and the Uri-Rothstock now looks quite forbidding. Do you hear that dull roaring? No, it is not thunder; it is the wind as it approaches. The pines above you are warning you. The snows have disappeared in darkness; Isleton is blotted out, and the Rütli can scarcely be seen for drifting cloud-bursts. The scene is now a chaos of cold indigo steeped in greyness. The wind is rushing on you with a whistling howl, and hurling hail at you. Forked lightning, piercing the murk, stabs at the seething waters, and the thunder rattles and booms{62} and rolls interminably. Where all but a brief while ago was crystal-bright and tranquil, at present is dull-grey pandemonium.

And as the electric tongues flash zigzag across the gloom, you fancy that you catch sight of a storm-tossed barque of ancient form, and that you hear above the screeching wind the scream of fear-struck Gessler, imploring Tell to take the helm. For it was some such storm as this to which Tell owed his freedom and his life. Critics point to the convenient suddenness of the two storms which find a place in Schiller’s play; they call them specimens of poetic licence. But this is not necessarily the case. From the very configuration of the Bay of Uri it is a deadly storm-trap. Ah, it can smile and look winsome enough when it pleases—and this, to our great good, is more than often; but it is subject to surprisingly sudden fits of rage, when it is as fearsome as, and perhaps more treacherous than, many a hurricane-ridden ocean.

The storm has passed as quickly as it came, and butterflies and flowers are in their element once more. If possible, the Bay is the lovelier for its rude half-hour of stress. It can be grand in tempest and foul weather; but that which fits it best is the rule and realm of sunshine. Thus, in hard-won peace and grimly conceived beauty, may we appropriately take leave of the Lake of the Forest Cantons.{63}