Title: The Boy Inventors and the Vanishing Gun

Author: Richard Bonner

Illustrator: Charles L. Wrenn

Release date: June 11, 2018 [eBook #57305]

Most recently updated: June 25, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank

E-text prepared by Roger Frank

Jack Chadwick stepped from the door of the shed where he and Tom Jesson, his cousin—and, like Jack, about seventeen years old—had been busy all the morning getting the Flying Road Racer back into shape, after that wonderful craft’s adventurous cruise along the Gulf Coast of Mexico.

“Almost eleven o’clock,” said Jack, and, thrusting his hand into the breast pocket of his khaki working shirt, he drew out a rather crumpled bit of yellow paper.

“What time did Mr. Pythias Peregrine say he’d be here?” inquired Tom, who, like Jack, was attired in a business-like costume of khaki, topped off with an automobile cap.

Jack, who had been busy perusing the telegraphic message inscribed on the bit of yellow paper, read it aloud.

“‘Jack Chadwick, High Towers, Nestorville, Mass.:

“‘Can I see you about noon on Thursday next? Wish to talk over a new invention with you and your father. Wire if you can see me at that time and I will call on you.

“Wonder what he can want?” mused Professor Chadwick’s son, in a speculative tone. “Pythias Peregrine is one of the best-known inventors in the country. I guess we all ought to feel honored by his wanting to consult with us, Tom.”

“You bet we ought. Wonder what sort of a man he is. I suppose he’ll be inclined to look down upon us as a couple of kids when he does see us. But—hello, Jack!” he broke off suddenly—“what’s that off there in the sky—over there to the northwest?”

“That speck yonder? It looks like—yes, by ginger, it is—it’s an aëroplane of some sort!”

“That’s what.”

A sudden idea struck Tom.

“Say, Jack, don’t you recall reading about Mr. Peregrine and his aëroplane Red Hawk?”

“Yes, I do, very well indeed. He captured the Jordan Meritt speed and long-distance cup with it.”

“That’s right, and I’m willing to bet the hole out of a doughnut that that is the Red Hawk approaching right now. Pokeville is sixty miles off in that direction, and what more natural than that Mr. Peregrine should take an up-to-date way of paying his call?”

“I do believe you’re right, Tom,” said Jack. “Let’s go in and spruce up a bit, and then we’ll come out and meet him.”

In the rear of the work shed, which housed the Flying Road Racer, was a washroom, and to this the boys hastened to remove some of the grime of their morning’s work. While they are thus engaged, and the aëroplane is winging its way rapidly toward High Towers, it is a good time to tell something about the two lads and their adventures.

As readers of the first volume of this series—“The Boy Inventors’ Wireless Triumph”—are aware, Jack Chadwick was the wide-awake, good-looking son of a man well known for his achievements in science. The name of Chester Chadwick was one of the best known in the world along the lines of his chosen field of endeavor. Tom Jesson, almost as bright a lad as his chum and cousin, was, like Jack, motherless. His father, Jasper Jesson—Mr. Chadwick’s brother-in-law—lived at High Towers, the remainder of which establishment was composed of Mrs. Jarley, a motherly old housekeeper, two under servants, and Jupe, a colored man-of-all-work about the place.

High Towers, Professor Chadwick’s estate, was, as we already know from the address on Mr. Peregrine’s telegram, located near the village of Nestorville, not far from Boston. It was a fine old place, and consisted of a big, rambling house set in the midst of oaks and elms with broad lawns and fields stretching on every side. But the most interesting features of the place were a big lake and a group of sheds, workshops and laboratories in which Professor Chadwick and his son and nephew worked over their inventions.

For Jack and Tom were more like chums to Professor Chadwick than son and nephew. Together the three had devised the Flying Road Racer, the Chadwick gas gun, and many other remarkable devices. From his patents Professor Chadwick had amassed a considerable fortune, thus disproving the popular idea that inventors are, of necessity, shiftless or needy.

The present story opens on a day not long after the three, together with Mr. Jesson, had returned from an adventurous trip in the neighborhood of the semi-savage country of Yucatan. As readers of “The Boy Inventors’ Wireless Triumph” know, Jack and Tom, accompanied by Jupe, had been despatched mysteriously to Lone Island, a desolate spot of land off the mouth of the Rio Grande. Here they had awaited a wireless message from Professor Chadwick, who was cruising on a chartered steam yacht, the Sea King. At last the eagerly expected message came, and the boys set out on a gasolene motor boat to find the Sea King, which, the message had informed them, was disabled.

They found her, and also discovered that she was in peculiar trouble. The rascally governor of the province of Yucatan, off which she lay, had, so they learned, imprisoned Professor Chadwick, Mr. Jesson and some sailors. The boys found that the Sea King carried on board the Flying Road Racer—of which more anon—and they determined to utilize this craft of the land and air in the work of rescue.

How Tom was re-united to his father, the explorer who had been given up as lost in the wilderness of Yucatan for many years, cannot be told in detail here; nor can we go into the surprising incident of the three colored gems contained in a silver casket which caused a lot of trouble for the boys and the others. But all came out well, and wireless played a considerable part in getting the party out of many dilemmas.

It will also be recalled by readers of the volume whose contents we have lightly sketched, that the Flying Road Racer—the aerial auto—had been badly damaged, so far as her raising apparatus was concerned, when she was blown to sea in a hurricane, during which those on board narrowly escaped with their lives. Since their return to High Towers, the boys had been engaged in refitting the craft on new principles, and Professor Chadwick had been busy in Washington in connection with some patents. Mr. Jesson had interested himself in scientific farming, and, at the very moment that the boys had hastened into the shed to make swift preparations to receive what they believed to be Mr. Peregrine’s Red Hawk, he was busy in a corn patch with Jupe, the colored man.

Jack had just given a hasty dab with the brush and comb to his hair, and Tom’s face was still buried in a towel when from the rear of the shed where the corn patch was came the sound of angry and alarmed voices.

“Hyar, you, wha’ fo’ yo’ don’ look out? Wha’ fo’ yo’ mean come floppin’ lak an ole buzzard inter dis yar cohn patch—huh?”

Then, in milder tones:

“My dear sir, I beg of you, be careful. This corn is a particular kind. If you alight here you’ll ruin several hills of it.”

“That’s Jupe and Uncle Jasper,” exclaimed Jack, throwing down the brush and comb and rushing out; “wonder what’s up?”

Tom hastily followed his cousin.

“Sounds as if somebody’s trying to spoil dad’s corn patch,” he murmured, as he ran.

As they rounded the corner of the Flying Road Racer’s shed, the boys came on an astonishing sight—if anything can be called astonishing in this century of marvels.

Above Mr. Jesson’s corn, of which he was justly proud, hovered a beautifully finished monoplane with bright red planes. Its propeller was buzzing like an angry bee—or rather like a dragon-fly, which it resembled with its long tail and bright gossamer wings.

In the air ship was seated a small, rather stout figure, whose countenance was almost hidden by goggles and a black leather skull cap pierced with holes. As this brilliant apparition of the skies swooped over the corn, so low that it almost mowed the feathery heads of the topmost stalks, Jupe made angry passes at it with his hoe.

Mr. Jesson, less strenuous but equally alarmed for his corn, had his arms raised imploringly.

“Yo’ jes git out of hyar, or I gib yo’ one wid dis yar hoe!” Jupe was exclaiming angrily, as the boys came on the scene.

“Why, I—bless my soul—I won’t hurt you,” came reassuringly in sharp, nervous tones from the occupant of the red aëroplane, which, the boys had already guessed, was the Red Hawk, and their visitor, Mr. Peregrine. “I merely dropped to inquire if this is High Towers?”

“Ya’as, dis am High Towers, an’ we got ’nough sky schooners ’roun’ hyar now widout you drappin’ in on our cohn patch,” angrily cried Jupe.

“Jupe! Jupe!” shouted Jack, “be more respectful. That’s Mr. Peregrine!”

“Don’t cahr ef he is Jerry Green,” grunted Jupe, “he don’ wan’ ter fustigate dis yar cohn patch wid dat red bug oh hisn.”

“Don’t be alarmed—won’t hurt it—very sorry—watch!”

With these jerky sentences, the occupant of the monoplane pulled a lever and turned a wheel on the side of the body of his machine. Instantly it rose, as gracefully as a butterfly, skimmed above the corn patch, circled around the boys’ astonished heads, and then dropped lightly in front of the shed which housed its ponderous rival of the skies.

As it came to a standstill the boys ran up to greet its operator, who, although he appeared rather fat and podgy, had already leaped nimbly to the ground.

“This is Mr. Pythias Peregrine?” inquired Jack politely.

“My name—glad to see you—dropped in, as it were—how do you do?—quite well?—glad to hear it.”

“Mah goodness,” exploded Jupe, leaning on his hoe and scratching his woolly head, “dat dar Jerry Green talks lak he had a package of firecrackers in him tummy.”

Mr. Peregrine, having alighted from his Red Hawk, removed his helmet and goggles and mopped his forehead vigorously—for the day was warm, it being about the middle of August. The removal of his headpiece revealed him as a round-faced, good-natured looking man, with a rosy complexion and deep-set, twinkling blue eyes. Having taken off his goggles, he replaced them by a pair of big horn-rimmed spectacles, which, somehow, gave him an odd resemblance to an amiable bull-frog. Indeed, his explosive way of talking was very much at variance with his rotund figure and appearance of “easy-goingness.”

“Naturally want to know what I came to see you about? Of course. Father at home?—No. Recollect you said in your telegram he was in Washington. Very warm, isn’t it?—It is.”

“I got on the long-distance telephone as soon as I received your message,” rejoined Jack, finding it rather hard to keep a straight face as Mr. Peregrine rapidly “popped” out the above sentences. “He said he recalled you very well as an old scientific friend, and that anything that we could do to aid you we were to do. Both my Cousin Tom and myself will be very glad to help in any way you may require. By the way,” as Mr. Jesson came up, “this is my uncle, and Tom’s father, Mr. Jasper Jesson.”

“Jasper Jesson, eh? Noted explorer?—Yes. Lost in Yucatan?—You were. Did I read about it in the papers?—I did. Columns of it. Was it interesting?—Very. Glad to meet you, sir. Glad to meet you.”

He and Mr. Jesson shook hands cordially. Mr. Jesson expressed his surprise at the manner in which Mr. Peregrine had been able to handle his Red Hawk when the corn patch was threatened.

The inventor from Pokeville waved his hand airily.

“Was there ever any need for you to be alarmed?—None at all, my dear sir, none at all. Very simple—Red Hawk, fine little air craft.— Fast?—Very.—Your corn in danger?—Never for a moment.—Sorry I alarmed you, though.”

The somewhat eccentric man went on to tell how he had set out from Pokeville an hour before, and had winged his way to High Towers in fast time. He had used the lake, which lay at the foot of the hill on which they stood talking, as his guide. From above it was visible at a distance of several miles.

“You spoke in your telegram of wishing to see us in regard ito some invention?” hinted Jack, at this juncture.

“Did I?—Of course I did,” sputtered out Mr. Peregrine, using his customary way of expressing himself. “A most interesting thing, too. Well, the fact is, that I’m at a standstill.—Invention won’t work—heard a lot of you boys—thought I’d get you to help me out.—Pay well—very grateful.”

“So far as the last feature is concerned, don’t mention it,” said Jack, “if we can help you out at all, Mr. Peregrine, it will give us great pleasure. But what is this invention of yours?”

Mr. Peregrine cocked his head on one side and paused a short time before answering. At length he spoke.

“It’s a vanishing gun,” he said, forgetting for once to add another explosive sentence.

“A vanishing gun!” gasped the boys, while Mr. Jesson looked astonished and Jupe muttered: “Wha’ de matter wid dis yar Jerry Green and his perishing gun?”

“Yes, a vanishing motor gun,” repeated the inventor—“working on it for the government. Big thing—designed for defense against aëroplanes—having lot of trouble, though—need help—will you come?”

“Why—why,” said Jack, in some perplexity, “I think we might; but, Mr. Peregrine, can’t you explain a little more in detail?”

“Impossible now—hard to tell about gun intelligently till you can see and examine it. Why not come over to-morrow?—Not long trip—soon show you gun—like to have your opinion on it, anyway.—Lot depends on it—government offers big prize for successful one.”

“I think you can quite well go. Jack,” said Mr. Jesson, “Jupe, here, and I can look after the place till you get back. I know your father would like you to help Mr. Peregrine.”

“Then it’s settled,” declared Jack, who was equally anxious to see Mr. Peregrine’s invention, “we’ll be over as early as possible.”

“Many thanks,” said the inventor warmly, looking really relieved, “with you to help, I’m sure we can get it to work all right. One thing more—your Flying Road Racer—may I look at it?”

“Surely,” rejoined Jack, “it’s in this shed. Come in, Mr. Peregrine. Mind that step. There, that’s the Flying Road Racer!”

Jack’s face flushed proudly as he indicated what looked like an ordinary automobile, with a silvery aluminum body shaped like a cigar and a propeller at one end. A framework rose above the body, which was fitted with comfortably padded seats. On this framework was a neatly folded mass of material of a lightish yellow shade.

“But how can it fly?—Don’t see any wings—planes—anything,” asked Mr. Peregrine, much puzzled. He had expected to see, from the newspaper accounts he had read of the wonderful craft, a sort of monstrous flying machine. Instead, he beheld only an odd-shaped automobile of great size, with some fabric folded on the top of the framework like a giant bolt of cloth.

“You see that folded mass on the top,” explained Jack, smiling at the inventor’s perplexity; “well, that’s the gas envelope by which we fly. When we wish to make an ascent we put water in the gas tank and the moisture causes the radolite crystals to expand into vapor. When this is done we turn the gas into the bag by twisting this valve.”

He indicated a brass tap on the dashboard, which bore, also, a number of instruments and lubricating devices, besides this and other valves.

“Well, the bag is so folded that it expands without trouble as the gas rushes in. When ready to fly, we connect the engines with that propeller instead of with the ordinary auto transmission. And then we——”

“But—but—but——” exclaimed the inventor eagerly, “how do you keep your machine on the ground while the bag is filling?”

“Easily,” smiled Jack. “I invented a form of anchor like a mushroom type. One of these is cast out on each side. The harder the Flying Road Racer tugs the deeper the edge of these anchors is embedded in the earth. When we wish to rise we pull ‘trip-lines’ attached to each anchor and—up we go!”

“Wonderful!” exclaimed Mr. Peregrine. “Wouldn’t I like a ride in your machine some day?—I would.”

“You shall certainly have one,” rejoined Jack, “both on the road and in the air.”

Mr. Peregrine was pressed to remain to the noon-day meal, but he refused, saying that he must return to his home in time to put the vanishing gun in shape for the boys’ visit the next day.

“Can I promise you a surprise?” were his last words, as he started the Red Hawk skyward, “I think I can.—Good-bye.”

Whirr-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-r-r! The Red Hawk leaped skyward, bearing its lone navigator swiftly aloft. In ten minutes it was a dot, and finally was obliterated altogether.

“Well, what do you think of him?” asked Tom, as they turned away and began to walk toward the house.

“That he is an eccentric man, but very clever,” rejoined Jack. “I’m quite anxious to see this wonderful gun of his.”

“So am I,” said Tom, with equal eagerness, “if he has invented one that will shoot straight upward on an absolutely vertical line, he has a marvelous invention. Several inventors have been at work on the problem of getting out a gun that will really be effective against aëroplanes, but none has yet been found.”

“Well, I hope we can give Mr. Peregrine some good suggestions,” said Jack, as they reached the house and Mrs. Jarley announced that lunch was ready.

On returning to the Flying Road Racer’s shed that afternoon, the lads’ ears were saluted by a buzzing, roaring sound that they instantly recognized.

“Somebody’s started up the motor!” exclaimed Jack, in a voice in which anger mingled with astonishment.

“That’s right,” echoed Tom indignantly, “wonder who on earth it can be?”

“Come on, let’s hurry up and find out,” and Jack started on a run for the shed.

As he reached the door, clouds of blue smoke met him. The vapor almost choked him. Whoever was tampering with the motor had neglected to pay much attention to the lubricating devices, with the result that the fumes of burning oil filled the air.

“Oh, hello, Jack Chadwick. I—you see—I thought you wouldn’t mind me looking at your machine,” exclaimed a lad of about Jack’s own age, as the indignant young inventor burst into the shed with Tom close on his heels.

The lad who spoke was a rather thick-set youth, with a pronounced squint in his eyes which did not improve his mean and crafty face. Beside him was another boy, a little younger, dressed in a loud gray suit with a bright colored necktie. He was smoking a cigarette.

“Say, you Sam Taylor, put that thing out,” cried Jack, as he entered the shed and took in the scene before him.

“Oh, I suppose you are one of those sissies who get sick when they smoke,” sneered Sam Taylor, in an aggravating tone.

“I’ve never tried it, so I don’t know,” snapped Jack, “but if you want to ruin your health you’d better do it elsewhere than in this shed. And you, Zack Baker,” he went on, turning to the other lad, “what are you doing in here? You might have waited till you were invited.”

In the meantime Tom had stopped the motor and was draining the flooded engine.

“No need to get so mad,” retorted Zack, “as I told you, we thought we’d just drop in and see how the thing worked.”

“Yes, and you might have ruined it,” snapped out Tom indignantly. “I like your nerve in marching in here without speaking to us.”

“Oh, well, don’t get so cross about it. No harm done,” struck in Sam Taylor, who had prudently thrown away his cigarette; “what’s the use of getting all worked up over it?”

“I’m not worked up,” replied Jack, with a flushed and angry face, “but I don’t want you fellows prying about here.”

“Don’t be alarmed. We won’t steal your precious invention,” said Sam, in his sneering tones. “Come on, Zack, we’ve seen all we wanted to see, anyhow.”

“Yes, come on,” said Zack, with a rather uncomfortable look on his face, “we know better than to stay where we are not wanted. Anyhow, I’ve got something that will surprise you fellows. I’ll bet it’ll beat you at flying, even if you do get Mr. Peregrine to help you out.”

With this remark, which he considered quite crushing, Zack swung out of the shed, followed by his pasty-faced companion. Once outside they made their way to the front gate of High Towers and mounted their bicycles, on which they had ridden out from the village for the purpose, as we have seen, of examining the invention of Jack Chadwick and his cousin.

“Wonder how they knew anything about Mr. Peregrine?” said Jack, when he had thoroughly examined the Flying Road Racer and found that it was undamaged.

“Oh, Zack’s folks used to live near Pokeville,” rejoined Tom, “and as for their knowing that he had called on us, I reckon he and Sam saw the Red Hawk flying over and guessed at its destination.”

“That must be it,” said Jack, picking up a wrench and tightening a bolt on the Flying Road Racer’s frame, “but they’re the very last chaps I want snooping round here trying to find out how the Flying Road Racer works.”

“Which reminds me,” said Tom, “that Zack spoke of some invention of his that would surprise us. Wonder what it can be?”

“I’ve no idea,” began Jack, and then broke off suddenly, “yes, by ginger, I have, though; I do recall hearing, last time I was in Nestorville, that he and Sam were working on some sort of mechanical flyer.”

“Gee whiz! I’d like to see it,” laughed Tom. “I’ll bet it can’t fly any more than an old bullfrog.”

“I’m not bothering about it one way or the other,” rejoined Jack, “and now, as the machine is all fixed up, what do you say if we try it out on a trial spin?”

“The very thing,” said Tom, “it’ll feel good to be riding in it again. Wait till I run up to the house and get the dust coats, and I’ll be with you.”

While Tom was gone Jack started up the engine and ran the odd-looking air-and-land machine out of the shed. With its heavy uprights and the big folds of the empty gas bag on top, the Flying Road Racer looked even odder when outside than it had within its shelter. But that, despite its cumbersome appearance, it was capable of good speed, was soon shown when the boys had swung down the driveway and out upon the smooth road leading to Nestorville.

“Going into the village?” asked Tom, noting the direction in which his cousin was driving.

“Yes. I want to get some copper wire and some bolts. After that we can take a spin out into the country.”

As he spoke Jack pressed the accelerator, and the rather ponderous car leaped forward like a scared wild thing. The dust rose about it in clouds, for the weather had been hot and dry for some time. But the road was straight and Jack did not decrease the speed. Instead, it rather increased as they flew along.

They had crossed a bridge on the outskirts of Nestorville and were still proceeding at a good pace, when something came into sight which caused Jack to slow down. It was a cloud of dust, but so thick that it effectually concealed whatever was causing it.

“Another auto coming, I guess,” conjectured Tom.

Jack shook his head.

“I don’t think so,” he said, “it’s coming too slowly for that. Maybe a flock of sheep or—Jiminy crickets!”

Out of the dust cloud, which a vagrant puff of wind swept aside, had suddenly emerged a most curious looking object. It resembled nothing so much as a large bee or horse-fly. But it was of metal, and of quite a size. In a series of extraordinary leaps and bounds, zigzagging from one side of the road to the other, it advanced toward the astonished boys.

“What on earth is it?” gasped Tom, as Jack slowed down the auto to a crawl.

“It’s Zack’s flying machine. That’s what it is,” exclaimed Jack, “ho! ho! ho! If that isn’t a crazy-looking machine!”

Indeed, the object now coming toward them with wobbly leaps and hops, was a most curious-looking affair. Its metal wings flopped up and down with great speed, and underneath it could be seen a sort of legs, with wheels on them in place of toes or feet. In between the wings sat Zack, with an alarmed look on his face. In the road behind him was a small runabout auto in which sat Sam Taylor, encouraging him. But Zack paid no attention. In fact, it was taking all his energies to manage his odd machine.

“Well, whatever else it will do, it won’t fly,” declared Tom, “and you’d better look out for it, Jack. I don’t believe he has it under control.” Indeed it didn’t appear so. Zack could now be seen striving with levers and wheels, and the motor of the odd machine gave out a continuous volley of sharp reports.

“Stick to it, Zack!” called out Sam encouragingly from his auto, in which he slowly followed the wild evolutions of Zack’s mechanical bug— for so it could, with propriety, be called. But Zack paid no attention to him. Instead, he began shouting to Jack:

“Pull out of the road! Pull out of the road! I can’t control it.”

Jack maneuvered the Flying Road Racer till its outside wheels overhung a ditch at the side of the road. He had just completed this move when Zack’s machine, its wings beating faster than ever, actually left the ground and soared into the air.

“Hooray! That’s it, Zack! You’re flying!” shouted Sam enthusiastically, although it is doubtful if he would have cared to change places with his crony.

But although Zack had begun to soar, his flight soon ended. At a height of about four feet from the ground the machine wobbled and then crashed to earth. Zack strove in vain to stop it as it drove, snorting and popping, full at the Flying Road Racer, which Jack could not steer further off the road.

“Look out!” cried Jack, “you’ll be into us. You’ll——”

The sentence was never completed. As Jack uttered it, Zack gave a wild yell and tried to jump out of his uncontrollable invention. The next instant the machine, its wings flapping and its motor buzzing furiously, struck the front of the Flying Road Racer a glancing blow and then turned completely over, burying its luckless inventor in a ruin of twisted rods and bent wings.

“Good gracious! He’s killed!” cried Jack, in horrified tones.

“If he is it will be your fault,” shouted Sam, shaking his fist at the two Boy Inventors; “you did it on purpose.”

“Did what on purpose?” demanded Jack rather angrily, climbing out of the car to the ground.

“Why, got in my way and made me lose control of my flying machine,” struck in a new voice.

It was that of Zack, who, at the same moment, crawled out from under the ruins of his queer invention.

He was scratched and shaken, but not injured, as could be readily seen when he stood up.

“I hope you are not badly hurt, Zack,” said Jack, in a mild tone.

Zack’s face was crimson with anger and mortification.

“It’s all your fault!” he roared. “I’ll get even on you. You just see if I don’t.”

“Don’t talk nonsense,” said Tom quietly, “it had nothing to do with us. I guess your machine was no good. That’s what the trouble was.”

“Oh, it was, was it?” sputtered Zack furiously, regarding the remnants of his craft, “well, you just mind your own business. If it hadn’t been for you coming along and spying on me—”

“Spying on you! Well, I like that!” cried Tom, unable to suppress his indignation. “Who was in our shed this morning looking around to see what you could see?”

“Pshaw! A whole lot you could show me,” sneered Zack.

“Or me, either,” struck in Sam, who had descended from his runabout and stood beside Zack. “I tell you what,” he went on, doubling up his fists, “I’ve a good mind to—to—”

“Well, to what?” said Jack, waxing indignant in his turn.

“To sue you for damages or something. Zack and I were partners in that machine, and now it’s all smashed.”

“That was because you expected too much of it,” said Jack quietly. “It was impossible for it to fly, anyway. You have been working on the wrong principle.”

“You mind your own business, Mister Know-it-all,” yelled Zack furiously. “I guess you aren’t the only fellows around here who can invent anything. By rights, I ought to make you pay for the damage you’ve done.”

“Well, just hark at that,” cried Tom, “as if we had anything to do with your old tin hornet collapsing. You were foolish ever to get into it.” Zack could control his fury no longer. He gave a sudden step forward and aimed a vicious blow at Tom. The latter had no wish to get into a fight with Zack, so contented himself with stepping aside. Not landing his blow as he had expected, had the effect of almost throwing Zack from his feet. He saved himself from a tumble only by an effort.

“Look out!” laughed Jack, “you’ll have another tumble if you aren’t careful, Zack.”

“Oh, you make me tired,” grunted the infuriated lad. But he turned away and tried no further hostilities.

“If you want us to, we’ll tow your machine back to town,” volunteered Jack, who felt that there was, perhaps, some excuse for Zack’s anger; “we’re going that way.”

“Then go on, and be quick about it,” shouted Sam furiously. “I guess I can tow the machine in just as well as you fellows.”

“Oh, all right. If that’s the way you feel about it, we’ll be getting on,” said Jack. As he spoke he climbed back into the Flying Road Racer, followed by Tom. He backed the machine away from the wreck and noted, at the same time, that the engine hood had been slightly dented by the impact. But the motor itself was not affected and buzzed away in a lively fashion.

As soon as he had the Flying Road Racer clear of the wreckage, Jack set his lever ahead and the big machine moved off, no further words being exchanged between the cousins and the two boys, who now, clearly enough, chose to regard Jack and Tom as their enemies. As the Flying Racer glided away, Sam, yielding to a sudden impulse of fury, stooped down. He picked up a stone and hurled it with all his might at the two occupants of the land-and-air machine.

Had it struck the mark for which it was intended, the consequences might have been serious. But it whizzed harmlessly by Jack’s ear, avoiding him by a fraction of an inch.

“The coward,” cried Tom wrathfully; “shall we go back and give them a good pummeling?”

Jack shook his head.

“No, leave them alone,” he said. “After all, I’m afraid we didn’t appear to be very sorry over the wreck of that contrivance of Zack’s. He had a right to feel mad, I guess.”

“He was a chump for ever thinking that that thing could fly,” was Tom’s angry contribution to the conversation. He looked back and saw Sam standing in the middle of the road shaking a fist at the retreating Road Racer. Zack was bending over the wreckage examining it with care. The next instant a turn in the winding turnpike shut out the scene from view. But that encounter might have had serious results for our two young heroes in the immediate future, although, at the time, they troubled their minds little over it.

Left alone, Zack and Sam managed to attach the wreck of the “flying” machine to Sam’s auto. Then they set out to tow it back to town on its landing wheels. But they took a roundabout way. Neither of them wanted to display their failure to the prying eyes of the villagers. Fortunately for their plans, Zack’s home was on the outskirts of Nestorville, in which settlement his father had a large store. Sam lived in the town itself, and was the only son of indulgent parents—too indulgent, people said, for old Lem Taylor, who was a banker, grudged his son nothing. The runabout car had been a birthday gift to him a few weeks before, and Zack and he, who were inseparables, had done a lot of riding in it since.

As for Zack, he was more or less the tool of Sam, who had a good deal more evil in his nature than had his crony. The rivalry between Zack and Jack Chadwick and Tom Jesson dated back to the days before the two latter went to Yucatan. At school Zack had tried out several inventions which had been failures. Like many other boys—and men—the success of Jack and Tom had embittered him against them to a degree. Then, too, since their return from their wonderful experiences in the tropics, they had become prominent figures in the village, quite eclipsing himself and Sam.

Zack had hoped that his flying machine would aid in restoring him to his former importance; but now that it was wrecked, this hope was gone. In fact, he dreaded coming in for a lot of joking on that score, for he had been free in his boasts about its marvelous qualities. Altogether, then, neither he nor Sam felt in a very pleasant frame of mind as they towed the debris of the “Flying Hornet”—as Zack had thought of christening his machine—back to his home.

“I’ll bet those kids will tell everybody in town about the smash-up, and we’ll get well laughed at,” grumbled Sam, as he cautiously drove along.

“Bother it all, I guess that’s right,” rejoined Zack. “Just like our luck that they came along when they did. However, I got some ideas from our inspection of their Flying Racer when I looked her over, and we’ll rebuild the Hornet as soon as possible.”

“That’s the way to talk,” said Sam approvingly; “by the way, I wonder what Mr. Peregrine was doing at their home this morning?”

“Looks to me as if some new invention was under way,” hazarded Zack; “wonder what it can be now?”

“I’d like to find out. If only we could, maybe we could get even on them some way for ordering us out of their shed. If we don’t look out those kids will be running this town.”

“That’s what. Tell you what we’ll do—we’ll take a run over to Pokeville in your machine to-morrow, Sam. I know where Mr. Peregrine’s house is. We’ll look around some and see what we can find out. I’m not going to let those kids get ahead of me again if I can help it.”

“Nor I, either,” agreed Sam; “conceited young ninnies! If we can only find out what they are up to with Mr. Peregrine, maybe we’ll find a way.”

It may be as well to say here, as these boys leave our story for the present, that like most bullies, they were cowards, too, and when they heard nothing in town to indicate that Jack and Tom had told of their mishap, they decided to allow all their threats to stand as “bluff,” and to let well enough alone for the immediate future, at least so far as the Boy Inventors were concerned.

Jack and Tom sped along on their way to Nestorville pleasantly enough, but just as they were entering the little town there came a sudden ominous cracking sound from the rear of the machine.

“Something’s smashed!” exclaimed Tom, as Jack quickly brought the car to a standstill.

“That’s right,” agreed Jack; “just get out and see what it is, will you, Tom?”

But Tom was already out of the machine. Down on his knees in the dust he got, and soon found out what had happened.

“A stay rod has parted,” he announced; “it’s that one we welded. I guess we didn’t use heat enough.”

“Glad it’s nothing worse,” rejoined Jack; “we’ll make a stop at the blacksmith’s and get it rewelded; he has a machine for that purpose.”

“Wonder how long that will take?” questioned Tom, who had given a glance up at the sky.

“Oh, hardly any time at all. Why?”

“See those black clouds in the north. Looks as if we were in for a storm. The air feels heavy, too.”

“Well, a heavy rainstorm will do a lot of good and won’t hurt us. The whole country’s as dry as an old bone.”

“That’s what. But I was thinking of that stretch of clay road on our way back. If much rain falls that will be as sticky as a tub full of glue.”

“Oh, we’ll be back long before the storm breaks,” said Jack confidently.

But the welding job took a little longer than they thought it would, and as they set out on their return journey the sky was as black as a slate, and little sharp puffs of wind were driving the dust in whirling “devils” through the streets. As they rolled away from the blacksmith’s shop, one or two large drops pattered down on the folded gas envelope above their heads.

The boys didn’t bother about this, however, and sped along while the rain fell faster and faster. At last they reached the stretch of clay road, which was about two miles from their home.

“Have to put on full power,” decided Jack, turning on more of the radolite gas. The motor puffed and snorted as the Flying Road Racer labored through the heavy blue clay, but it didn’t stall and, considering the nature of the going, good speed was made.

But if they succeeded in avoiding being stalled, others were not so fortunate; As they came puffing around a bend in the heavy, sticky road, they saw, through the rain, that a big yellow touring car was stuck in the middle of the highway, and all the efforts of the two men operating were unavailing to force it through the mire.

As the Flying Road Racer came chugging through the mud, one of the men looked around and hailed the boys. His was a somewhat heavy-set figure, muffled in a red rubber rain coat. From under his goggles there streamed an immense red beard. His companion, so far as the boys could see, was slighter of figure and dark, with a small moustache almost hiding a thin-lipped mouth.

“Hey, you kids,” hailed the red-bearded one, in a deep, rather rough voice, “get us out of this, will you?”

“What’s the trouble?” asked Jack, slowing up. Although he was not best pleased at the other’s sharp mode of address, he felt that it was his duty to do what he could to aid two fellow motorists in distress.

“You can see what the trouble is, can’t you?” exclaimed the black-moustached man; “we’re stalled, stuck, in this infernal clay.”

“Got a rope?” asked Jack; “we’ll try and give you a tow out of it. We’re likely to get stuck ourselves, though.”

“Not much danger of that, with such a car as yours,” responded the red-bearded man, fumbling in the tool box of his car in search of a rope, such as most autos carry nowadays for just such emergencies. He finally found it, and came toward the boys’ car, which Jack had stopped. But the engine was still turning over rather rapidly.

“That’s a powerful motor you have there,” said the stranger, placing one foot on the running board and speaking in a rather patronizing tone, which didn’t much appeal to either of the boys; “what make of car is that?”

“It’s our own invention,” responded Tom quickly, rather too quickly, in fact, for the red-bearded man responded instantly, and with a curious inflection in his tones:

“Oh, is that so? I shouldn’t wonder, now, if you two are the Boy Inventors the papers have printed so much about. And this is the Flying Road Racer, eh? Umph! How does it work?”

“That’s rather a secret for the present,” said Jack, who resented the man’s dictatorial tone and inquisitive manner; “anyhow, if we are going to haul you out of this, we’d better start now before the road gets soaked any more.”

“Oh, all right. No offence meant,” answered the red-bearded man, and immediately busied himself attaching one end of the rope to the rear axle of the boys’ car. Then Jack moved ahead, and the other end of the tow line was made fast to the stalled auto.

This done the men got into their car, the red-bearded man taking the wheel.

“Now, then!” he shouted, as he turned on his power.

Jack did the same, and after a minute of indecision the Flying Road Racer began to move ahead, dragging the yellow car after it. In a few minutes both autos were safely through the heavy, sticky clay, and on the hard road beyond.

“Thanks,” said the red-bearded autoist, as the yellow car gained solid ground, “and now you can do us another favor if you don’t mind. Are we on the right road to Pokeville?”

Jack nodded.

“Straight ahead till you come to a place called Smith’s Corners,” he said; “you cross a bridge beyond that and then turn to the right.”

“Know anybody in Pokeville?” asked the black-moustached man; “ever hear of a Mr. Pythias Peregrine?”

“The inventor?” inquired Jack:

“That’s our man—I mean I’ve often heard of him,” said the red-bearded one; “I reckon now he’s got quite a place there. Lots of servants and all that?”

“I’m sure I don’t know,” rejoined Jack, wondering what interest the two men could have in the eccentric inventor.

“Well, don’t you know anything about his habits? Does he live near his workshops?”

“As I said before, I don’t really know much about Mr. Peregrine,” replied Jack, wondering more and more what could be the object of all these questions.

“Then you haven’t heard anything about a new invention of his? Something he is designing for the government?”

It was on the tip of Jack’s tongue to say that they were going over to Pokeville the very next day in connection with this identical thing; but some instinct checked him. He could not have told why for the life of him, but somehow he mistrusted these two men in the yellow auto. So in reply he merely shook his head.

“Well, we’ve got to be getting on,” said the red-bearded one, as the rain came down harder than ever; “many thanks for your help, and good-bye.”

“Good-bye,” responded both boys, and the yellow auto chugged off down the road through the rain.

A minute later Jack started his machine, and whizzed along after them. But badly as the yellow auto had behaved in the mud, it proved a flyer on the road. It maintained its lead, its occupants from time to time turning their heads and looking back at the two lads in the Flying Road Racer. As the boys turned into the gate of High Towers the yellow car was still speeding through the downpour, as if it were on very urgent business indeed.

“What do you think of those chaps?” asked Tom, as they sped up the driveway.

“I hardly know what to say,” said Jack; “they may be just two tourists going through the country, as they implied, or they may be—something quite different. I don’t know why, but I didn’t half like that red-whiskered chap.”

“Nor did I,” was the prompt rejoinder.

“Why?”

“Oh, just like you, I don’t know why. But there was something about both of them that gave me the idea that they are not all that they seemed to be.”

“Same here. They must have had some object, too, in making all those inquiries about Mr. Peregrine. I wonder what it could be?”

“Hasn’t it occurred to you that a man like him, the possessor of a valuable invention, might have some rivals who would like to find out just along what lines he has been working?”

“It certainly has,” rejoined Jack, as he ran the Flying Road Racer into its shed. “I won’t forget to tell Mr. Peregrine about our encounter when we see him to-morrow.”

“That’s a good idea,” assented Tom.

It rained in torrents all that night; but by dawn the sky had cleared, and a bright sun shone warmly. But everywhere about High Towers were plentiful evidences of the abundance of the downpour. The brook that fed the lake was swollen to a torrent, the lake itself had risen some feet, and its waters, usually clear, were muddy and discolored.

The boys were astir early, making ready for their trip to Pokeville. Jupe was set to work with the hose cleaning the body of the Flying Road Racer, while the boys made some adjustments to the machinery. So fast did they work that by the time breakfast was announced they were ready to start.

“I think I will come with you,” announced Mr. Jesson at the last moment. “I’d like to see Mr. Peregrine’s workshops and laboratories, and although he appears to be a trifle eccentric he is a very likable man.”

“I wonder what you’d have said if he’d lighted in your corn patch,” said Tom, with a grin.

This reminded Mr. Jesson that he ought to see how his corn had withstood the rainstorm, and he hastened off to do this, while the boys got the car out of its shed. Among other adjustments the boys had made that morning, was one involving a change of the gas envelope for a new type which they had invented. Mr. Jesson, on his return from his corn, which he announced was unharmed, noticed the change, the former gas bag having been of a yellow hue. The one the boys had folded on top of the framework that morning was quite black in color.

“Another invention?” inquired Tom’s father, indicating the bag.

“Well, not exactly an invention,” replied Jack, “more of an adaptation. You know that the difficulty in making sustained flights in a dirigible has always been evaporation or the condensation of the gas. This bag is made of a rubber cloth which is interwoven with steel wires and coated with a peculiar air-tight varnish. It makes a very strong fabric, and almost does away with the danger of the bag bursting under the expansion of radolite gas at high altitudes.

“Another feature of it is a small ‘subdivision’ as it were, of its interior. In other words, there is a small balloon or envelope inside the main one. This smaller bag is filled with ordinary air. Now then, when we reach a great height and want to keep on going higher, we pump this ordinary air out of the smaller ‘balloonet’ and the machine rises. At least that’s what we expect it to do. You can see; that by alternately pumping it full or emptying it, we will have—or hope to have—a craft that will always maintain an even keel without danger.”

“That sounds like a great idea,” said Mr. Jesson, “but you haven’t tested it out yet?”

“No, but we hope to have an opportunity to do so before long,” said Jack; “and now, uncle, if you are ready we’ll start. The roads are heavy, and I guess we won’t be able to make very good time.”

“Well, why not fly over?”

“We may have to,” was the rejoinder, “but I don’t want to use the gas-making tank or generator again till it has had a thorough cleaning.”

Jupe, to his unspeakable disgust, was left behind, and stood waving a good-bye to the party as they skimmed off. The road to Pokeville was a fairly good one, and they were able to make about thirty miles an hour over it.

At this rate of going it was not long before they rolled through the little cross-roads settlement of Smith’s Corners, beyond which was the bridge, of which they had informed the two automobilists the previous evening. Jack was sending the auto ahead at a good rate down the hill that led to the bridge, when all at once he noticed a sign nailed to a tree at one side of the road:

Jack jammed on the brakes, bringing the heavy car to a stop.

“What are you going to do now?” asked Mr. Jesson, who, as well as Tom, had noticed the sign.

“Why, it strikes me that this is a mighty good time to test out that new gas bag,” announced Jack, with a quizzical look on his face.

“By ginger! You’re right,” agreed Tom; “let’s get busy at once.”

“I hope it works as well as the old one did down in Yucatan,” said Mr. Jesson.

“I hope so,” rejoined Jack.

He bent over the valve which admitted gas to the folded envelope, and Tom, at the same time, adjusted the generator so that the radolite crystals would begin to make the volatile vapor on which they depended to rise from the earth. A hissing sound presently ensued, and the indicator on the gauge showed that all was ready to fill the gas bag.

As the gas rushed into its container, the folds started to round out, and in fifteen minutes the bag began to assume its cylindrical shape. Before the machine became too buoyant, however, Jack and Tom secured it to the ground by the anchors, the “trip-lines” of which were led on board. Then the work of filling went on, and soon the Flying Road Racer—a “Road Racer” no longer—was tugging at her bonds.

“All right,” announced Jack, after a while, and they prepared to “cast off.”

But just as they were about to pull on the triplines and release the anchors, there was a sudden commotion on the road behind them. They looked around and saw a farmer approaching in a small wagon drawn by a dilapidated-looking mule. The mule was careering about, and evidently objected to coming closer to the weird-looking structure—half auto, half flying machine—that was drawn up in the road in front of it.

“Whoa, thar, you obstreperous critter!” shouted the farmer, getting out and hitching his refractory animal.

This done, he came rapidly toward the boys and their—to him—extraordinary machine.

“Waal, what under ther sun be this yar contraption?” he demanded, gazing curiously at the big balloon bag which was swaying and tugging at its bonds.

“It’s a sort of flying machine,” rejoined Jack, repressing an inclination to laugh; “didn’t you ever see one before?”

“Ya’as, I seen one at ther country fair, but it warn’t nuthin’ like this yar.”

“If you’ll wait a minute you’ll see us fly,” said Jack; but the former didn’t seem to hear him.

The countryman’s eyes were riveted on the notice concerning the bridge.

“Gosh all hemlock!” he exclaimed, in a vexed tone, “if that ain’t jes’ ther peskiest kind er luck. I suppose ther crick has swolled frum ther rain an’ ther old bridge has busted at last. Consarn it all!”

“Isn’t there any other bridge?” asked Mr. Jesson.

“Ya’as, but it’s ’bout a mile further daown, and a roundabout way ter git thar, and I’m in a hurry. Yer see Betsy Jane is mighty sick, and I’m goin’ arter ther doctor.”

“Where does he live?” asked Jack, imagining that Betsy Jane must be the farmer’s wife.

“’Cross ther crick a piece. Consarn it, what am I goin’ ter do?”

“Tell you what,” said Tom, “we’ll take you over in our machine, and bring you and the doctor back. You can leave the mule tied here.”

“What, me ride in thet contraption? Not but what it’s mighty good of ye ter offer it—but——”

“If it’s safe for us, it ought to be safe enough for you,” remarked Mr. Jesson.

“By heck! Thet’s so. Waal, since you’re so kind, I dunno if I care ef I do. By gum! won’t ther folks stare when I tell ’em I’ve rid in er airyoplane?”

“But this isn’t an aëroplane,” objected Tom, who was a stickler for facts, “it’s a dirigible.”

“Don’t keer ef it’s digestible er not, so long as yer daon’t spill me aout,” was the rejoinder.

“Oh, you’ll find it digestible all right,” chuckled Jack, “come on. Climb in, Mister——”

“Hank Appleyard is my name, mister.”

“Very well, then, Mr. Appleyard. Put your foot on that step. That’s it. Now then. Are you all right?”

“By bean poles! This is as comfortable as my parlor cheer ter hum,” remarked Mr. Appleyard, with a tug at his gray goatee, as he sank into the softly cushioned tonneau.

He lay back luxuriantly, and drew out a small and very dirty corncob pipe. Before the boys could observe what he was doing he struck a match. At the sound of the lucifer Jack, who was preparing to “up anchor,” turned like a flash. In a jiffy he had grasped the astonished farmer’s wrist and sent both pipe and match flying into the road.

“Dum gast it all! What did yer do thet fer?” expostulated the indignant agriculturist.

“Because that bag above us holds fifty thousand cubic feet of inflammable gas, and we don’t want to go up before we get ready,” snapped out Jack.

The farmer turned pale.

“By gum, an’ I wuz goin’ ter take a smoke! Say, young fellers, I guess I’ll—”

He was preparing to clamber out, but Jack shoved him back in his seat.

“Sit where you are and hold tight,” he exclaimed. “All right, Tom! Heave away! Ah! Up they come! We’re off!”

“Hey, let me out! Let me out! By gosh, this is too dem rich fer my blood! I——”

Farmer Appleyard, pale and trembling, peered over the side of the tonneau and then sank back with a gasp. The earth lay several score of feet beneath him, and the distance was rapidly increasing. The buoyant gas which filled the container, as if it had been an immense black rugby football, had raised the Flying Road Racer so swiftly that it had seemed literally to “flash” upward.

Below was spread the panorama of the countryside, patches of woods, fields, fenced pastures, and farmhouses. From that height they could see quite plainly the ruined bridge and the angry, turbulent waters of the swollen current that had washed it away. All at once the boys’ passengers had a fresh shock. Jack connected the engine with the propeller, and the Flying Road Racer began to forge ahead. Tom, simultaneously, released the clutch that held the rudder rigid while the Flying Road Racer was merely a land vehicle.

Soon they were flying above the swollen stream, and looking back they could see the road by which they had come, and the farmer’s mule kicking and plunging furiously at its halter rope.

“Poor Balaam! I misdoubt he’ll ever git over, this,” breathed Farmer Appleyard.

“Where is the doctor’s house? Can you see it?” demanded Jack presently.

“Yes. It’s that thar white place with the two big spruces in front. My, won’t he be astonished when he sees me comin’ ter summon him by ther sky route!”

“Is your wife very ill?” asked Tom, as Jack headed the Flying Road Racer for the house indicated by the farmer.

“Eh, young feller? My wife! Waal, she’s as well as I be, I guess.”

“But—but you said she was sick,” exclaimed Tom, wondering if the novel air ride had turned their passenger’s brain.

“What, I said my wife was sick?” demanded the farmer incredulously.

“Why, of course you did, and that you were going for the doctor.”

“Waal, so I am. Fer Dr. Bates, the best horse doctor round here.”

“A horse doctor!” gasped Tom, “but what about Betsy Jane, your——”

“Old gray mare. Ther pesky critter had ther colic, and——”

But a roar of laughter from Jack and Mr. Jesson, who had listened to the conversation, interrupted him. They were still laughing over their comical mistake when Jack brought the Flying Road Racer to the ground in a pasture at the back of Dr. Bates’ house. Sure enough, a sign on the front porch, which they had glimpsed as they descended, said:

And pretty soon out came Dr. Bates himself, his round red face a comical mixture of alarm and amazement at this unexpected apparition of the skies. Explanations were soon made, and the “vet” prevailed upon to return in the air ship to the spot where Farmer Appleyard had left his mule, the farmer promising to drive the horse doctor back by the lower bridge.

“Well,” laughed Jack, as, after bidding farewell to the grateful farmer and the wondering horse doctor, they took the air once more, “I’ll bet that’s the first time an air ship has been used to convey a horse doctor.”

Tom made a queer noise in response.

“What’s the matter?” asked Jack.

“I’m giving a ‘horse laugh’ over Betsy Jane,” rejoined Tom, in high good humor over their adventure.

It was decided after a brief consultation not to deflate the gas bag and drop to earth, but to fly straight on to Pokeville. Jack knew the direction in a general way, and kept the Flying Road Racer headed for a white steeple which appeared on the distant horizon. He believed that this marked the site of the village they were in quest of.

The trip with the farmer had delayed them somewhat, and it was almost eleven o’clock as they drew near the little town for which Jack was aiming. As they got close to it a cluster of white tents with a crowd of people about them could be seen on the outskirts of the place. Gay flags hung above the canvas structures, and even at the height that the air travelers were—about five hundred feet—they could hear the sounds of music.

“It’s a circus!” cried Tom.

“So it is,” said Mr. Jesson, “and look—what is that?—surely a balloon they are sending up!”

Sure enough, as he spoke the boys became aware of a huge, dirty-looking sphere with black smoke rolling from its narrow mouth. It was still tied to the ground apparently, but even as they watched there came the sharp report of a saluting cannon. Instantly the balloon was released from the earth, and shot rapidly skyward, reeling and careening. The manner of its inflation was plainly, judging by the smoke from its mouth, by hot air. The balloon, in fact, formed a part of the free show given by the circus to draw the crowds, and was a common enough feature of small traveling shows.

“Look, there’s somebody swinging below it!” shouted Jack suddenly.

The figure he indicated was a small one, and as they drew closer they could see that it wore red tights gaily spangled. It was suspended from the hot-air balloon by a trapeze, and held on by gripping the ropes on either side of its insecure seat. Under the trapeze hung an object not unlike an immense umbrella closed up. This, the boys knew, was a parachute, and that as soon as the balloon had risen to a sufficient height, the aëronaut would cut the parachute loose and fall by it to the ground.

“Phew!” exclaimed Tom, “I’d hate to do a parachute jump like that.”

“Yes,” said Mr. Jesson, “I was reading only the other day of a parachute jumper whose parachute failed to open. He fell more than a thousand feet to the earth and was dashed to bits.”

“Let’s go closer to the hot-air balloon and watch him when he cuts loose,” suggested Jack.

The others agreed, and the Flying Road Racer was headed for the hot-air balloon, which was rising rapidly. But the Boy Inventors’ dirigible craft had no difficulty in keeping up with it. Soon they were quite close to it, and sweeping around the great pear-shaped bag in big circles. And now they observed something that they had not seen before.

The aëronaut was a boy of not more than twelve years old. His face was white and pinched, and he looked terrified. As the balloon swung higher, there was borne upward from below repeated pistol shots.

“That’s the signal for him to cut loose,” exclaimed Tom. “I know. I’ve seen lots of ascents like this one.”

“Well, why doesn’t he?” demanded Jack.

“For a very good reason,” said Mr. Jesson, who had been observing the young aëronaut closely; “he’s scared to death.”

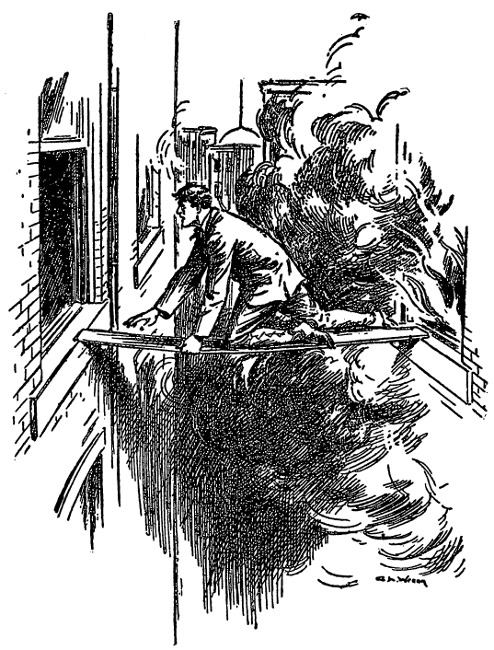

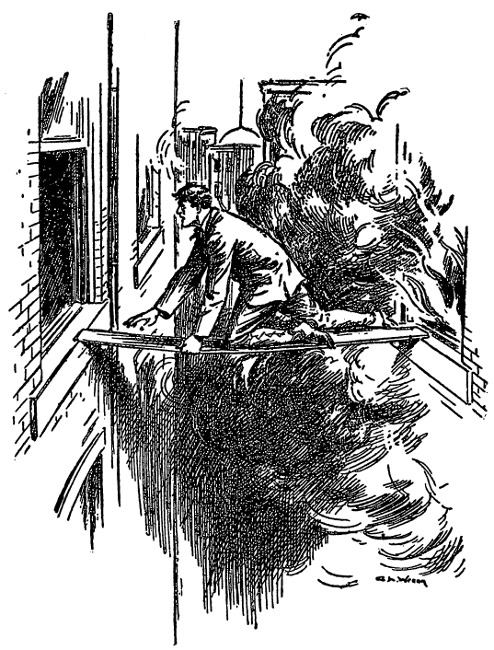

The boys, observing the spangled air traveler more carefully, now perceived that Mr. Jesson was correct. The little fellow turned a pitiable face toward them. What made his situation worse was that the hot air in the balloon was evaporating, and if he did not jump quickly it would be too late. Jack shouted words to that effect to the lad. But the panic-stricken boy only clung tighter to the ropes of his trapeze, and shook his head pitifully. It seemed as if he dared not look downward at the empty void between himself and the earth.

“Drop on the parachute!” shouted Tom; “if you don’t, the balloon will fall with you!”

As his cousin spoke, Jack maneuvered the Flying Road Racer yet closer to the hot-air balloon. Big wrinkles now appeared in the bag of the circus balloon, and it began to sag downward more rapidly.

“Great ginger! That kid is paralyzed by fright!” exclaimed Tom, his own face pale; “what are we going to do?”

“Save him if we can,” breathed Jack, “but how?”

“Can’t you get alongside that balloon and take him off?” interrogated Mr. Jesson.

“It will be fearfully risky.”

“True; but we can’t let him be dashed to earth without attempting to save him.”

“I have it,” exclaimed Tom; “I’ll get out the light grappling iron. I’ll throw it and try to entangle it in the parachute. Then we can pull the balloon alongside and get that boy off.”

“A capital idea,” said Mr. Jesson; “how close can you get, Jack?”

“I’ll come as close as I dare,” was the reply. Below—far, far below—the crowd, with upturned faces, watched the maneuvering of the great air craft. This was indeed a spectacle they hadn’t bargained for. The tension was too great for speech. A death-like silence hung over the throng.

Behind one of the white tents two men stood, also gazing upward. But there was no pity nor suspense on their faces. Instead, they cast furious glances at the drama of the skies being unfolded before them.

“I told you that kid would lose his nerve!” snarled out one of them, a heavy-set man in a loud checked suit, in whose bright red necktie an imitation diamond, as big as a walnut, glistened.

His companion slashed at his high boots with a whip he held in his hand.

“I’ll fix him for this,” he growled, “and I’d like to fix those pesky butters-in on board that dirigible, too.”

In the meantime, the dirigible, under Jack’s skillful handling, had been maneuvered quite close to the hot-air balloon. Tom, with the light grapple in one hand, and its attached rope in the other, stood ready to make a cast.

“Now!” shouted Jack suddenly, as the gas envelope of the Flying Road Racer almost bumped against the flabby bag of the hot-air balloon. The grapple whizzed through the air, and so skillfully had it been thrown, that its flukes caught and became entangled in the pendent parachute under the trapeze, to which clung the terrified boy.

“Haul in!” shouted Jack, and Tom and Mr. Jesson belayed heartily on the rope. As the trapeze swung alongside the body of the dirigible, Tom reached out and seized the lad. The little fellow had partially recovered his nerve and was able to help himself, and in a moment more he was safe on board the Flying Road Racer.

What a cheer came up from below! The crowd had seen a unique rescue in mid-air—a triumph of the wonderful resource and achievement of the twentieth century—and it went wild. Hats were thrown up and women sobbed and laughed in the same breath.

As for the young air navigators, they were the coolest people in that neighborhood. Tom cut the balloon loose, and it went sagging and wallowing off, dropping in a field a short time later. In the meantime, Jack began to send the Flying Road Racer earthward, using the depression planes in doing so.

The boy they had rescued speedily found his tongue, and when he did he told them a story that made them flush with indignation. He had been hired out to the circus, he said, by his father some years before. From that time on his life had been one of misery. Urged on by the ringmaster’s whip, he had learned to ride bareback and do some other tricks, but this had been his first trip aloft. The way in which he shuddered as he spoke of it, showed that only the utmost cruelty could have prevailed on him to make an ascent on the hot-air balloon.

The regular parachute jumper had been injured—disabled for life—by a fall at the last “stand” the circus had played. As the boy, who said his name was Ralph Ingersoll, was light and active, he had been ordered to take the parachute performer’s place, by the brutal men to whose care he had been consigned. Terrified by threats of a terrific beating, the boy had consented, with what results we know.

“Oh! If it hadn’t been for you, I would have been killed,” he exclaimed, clasping his hands and gazing gratefully at his rescuers.

“Never mind, Ralph,” said Mr. Jesson, whose indignation had been aroused by the lad’s recital, “we’ll see what we can do to stop any further ill treatment of you.”

“Oh, then you are going to take me back to the circus!” cried the boy, a look of real terror coming over his thin, pale face.

“Well, for the present, yes,” said Mr. Jesson, “but we will have your case investigated, and the law——”

“No law will save me if you take me back,” cried the boy, crouching in a spasm of fear, “they’ll kill me—beat me to death, or do away with me in some way before you can save me.” As he spoke, the Flying Road Racer reached the ground, and the crowd came rushing and surging about it. Through the press, the two men who had so angrily watched the Boy Inventors’ plucky rescue came shoving their way. A look of black rage was on both their faces.

“Now, then,” shouted the man with the whip, as he pushed his way to the side of the Flying Road Racer, “what’s all this mean? What right had you to interfere with this lad?”

“The right that everyone has to save a human life,” rejoined Mr. Jesson firmly, standing between the angry man and the boy, who crouched behind his protector in an agony of fear.

“Oh, that’s all very fine; but you spoiled our show. Come on now, Ralph, you young sneak. I’m going to fix you for getting cold feet.”

“Hold on a minute,” said Mr. Jesson calmly. “It’s evident to me from this boy’s story that you have treated him brutally. You could be proceeded against for the way you have abused him.”

“None of your business, is it, Mister Smart Alec?” demanded the man with the red necktie and the diamond. “I’m Josh Sawdon, the boss of this show, and I demand that boy. He was given us by his father to train.”

“That’s right,” declared his companion, with a vicious crack of his whip, “and we are going to do it, too. Come on, mister, give us that boy.”

“Have you got any papers to prove your right to him?” asked Mr. Jesson calmly.

“No, we ain’t,” sneered Sawdon, “at least, we ain’t got none to show you. Come on, now—give us that boy, or——”

“Well, or what?”

Mr. Jesson stared calmly at the man, who had stepped threateningly toward him. Sawdon stopped short. Something in the direct look of the bronzed explorer checked him.

“I am satisfied that you have no right to this lad,” said Mr. Jesson, in calm, even tones. “I am even better satisfied that you have used him shamefully. Therefore, we will take him under our protection till the matter can come up in the courts.”

“Hooray!” yelled the crowd, whose sympathies were plainly with the aerial party.

Sawdon sprang forward furiously. Behind him came the man with the whip. He “clubbed” his weapon and aimed a vicious blow at Mr. Jesson’s head. But Tom caught the descending wrist in a steel grip. He gave it a quick wrench, and with an “ouch!” of pain the fellow dropped the whip.

In the meantime Sawdon set up a shout for his assistants. In a moment a score of canvasmen and performers came running from every side, armed with tent pegs. The crowd scattered right and left before the attackers.

“We’ll have to get out of this quick,” exclaimed Mr. Jesson, in a low voice to Jack.

The boy nodded. At the same instant he started the propeller. Up shot the Flying Road Racer like a stone out of a sling. Sawdon, who had just sprung at its side, was flung over in a heap, with his companion of the whip on top of him. As the big machine rose a roar of rage went up from the circus hands. But they could do nothing but shake their fists.

Suddenly Tom bethought himself of something which they had forgotten in the excitement. Putting his head over the edge of the car he shouted downward to the crowd:

“Is this Pokeville?”

“Naw, this is Westerlo!” was yelled back from below; “Pokeville’s six miles to the west.”

Jack changed his course, and before long they came in sight of a small town, which really proved to be Pokeville. They descended in the village, much to the alarm of some of the inhabitants, and inquired the way to Mr. Peregrine’s home.

A handsome structure with a pillared portico, standing on a hill about a mile off, was pointed out to them as the home of the inventor.

“No use flying there,” decided Jack; “we’ll take to automobiling again.”

Accordingly, the Flying Road Racer’s gas envelope was deflated, and once more “an auto,” she sped off toward Mr. Peregrine’s house. As they left the village, a car coming in the opposite direction almost crashed into them as it rounded a corner. It was going fast, but not too fast for Jack and Tom to see that it was a yellow vehicle, and that one of its passengers had a big red beard. It was the same car that they had pulled out of the mud the previous evening, whose occupants had been so curious about Mr. Peregrine and his habits.

Jack was conscious of a vague sense of uneasiness at the presence of these mysterious men in Pokeville.

During the trip from Westerlo to Pokeville the case of Ralph Ingersoll had been discussed in all its bearings, and it had been decided that, for the present at any rate, he was to make his home with the boys. Ralph appeared a bright little fellow, and his evident fear of being sent to some institution decided Mr. Jesson not to carry out his first intention.

Besides, Jack and Tom had argued that the lad would be useful to them around their inventions, and they needed an assistant, anyway. So, to Ralph’s great joy, matters were arranged as described above. But Mr. Jesson warned Ralph that, in the event of the circus people proving a legal right to him, he might have to be returned to them. This idea; however, proved so disquieting to the lad that the kind-hearted explorer forebore to press it.

Ralph declared that he had no knowledge of his parents, but that he had been placed with the circus men at an early age. Thus all that he could recall of his past was misery and privation.

As they turned into Mr. Peregrine’s grounds, the inventor himself came toward them. Even at a distance they could see that he was perturbed and excited. His face was flushed, and as soon as he got within speaking distance he began to talk, almost more explosively than usual.

“My stars! I’m glad you’ve come!” he exclaimed. “Queer doings—strange men—frightened them off—but afraid they’ve seen more than I want ’em to.”

“Jump in and tell us about it as we drive to the house,” said Mr. Jesson; “we, too, have had some odd adventures on our way here.”

Just then Mr. Peregrine caught sight of Ralph Ingersoll, who still wore his gaudy tights.

“Bless my soul—what’s this?—circus—bing-bang—through a hoop—whoop-la!” he exclaimed.

“Not exactly,” said Mr. Jesson, with a smile at the inventor’s rapid-fire speech; “but I’ll explain later on. First tell us about the strange men. Possibly we can throw some light on the matter. The boys told me about encountering two men on the road last night, who asked about you, and whom we saw again just now.”

“One of them with a red beard—long one—other chap had black moustache—eh?”

“Yes, that describes the fellows as accurately as we could size them up for their goggles,” struck in Jack, who meanwhile had started the machine again. He drove it up to the front door of Mr. Peregrine’s home, and when they had all alighted a man was detailed to take it to the barn. Within they found a good lunch awaiting them, and Mrs. Peregrine came to meet them with a smile of ready welcome.

As all the passengers were rather grimy, they first had a good wash, and Ralph was provided with a suit which had belonged to Mr. Peregrine’s son, now a lad of nineteen and away at college. During the meal Mr. Peregrine described how, on visiting the shed which housed his invention that morning, he had surprised a strange man with a red beard peeping through a window at it.

“I must tell you,” he continued, “that a powerful syndicate has tried to purchase my invention; but I have refused to sell. Since that time I have been harassed in many ways, and I am afraid that this is their latest move against me.”

When Mr. Peregrine was very much in earnest he dropped his odd way of talking, and there was no doubt but that he was very serious now. His wife, too, looked troubled. Clearly his enemies were powerful, and determined enough to cause the inventor considerable alarm.

“But surely your invention is patented, and you have nothing to fear on the score of their stealing your ideas?” asked Mr. Jesson.

“That’s just it,” said the inventor, with a troubled look; “I have taken no steps in the matter of a patent yet, as I feared a leak somewhere. These people who are after my vanishing gun are aware of this, too, as they have spies in Washington.”

“Well, that does make the matter serious,” agreed Mr. Jesson, and then, as Mrs. Peregrine looked rather alarmed, the subject was changed.

After lunch Mr. Peregrine asked if they would care to see his invention and try to ascertain what the trouble was with it.

“We can’t look it over too soon for me,” exclaimed Jack.

“I do hope you’ll be able to suggest something that will get me over the sticking point,” responded Mr. Peregrine, as the party donned their hats and, following him, made their way to the shed where stood the gun of which so much was expected.

The boys could hardly restrain their curiosity while Mr. Peregrine unlocked the door of the shed, which was furnished with quite an elaborate system of protection. Besides the heavy locks of a novel variety, it was fitted with a burglar alarm connecting with the house.

The door being opened, the boys saw a strange-looking piece of apparatus. Imagine a dull gray-colored submarine boat on wheels of solid steel with wide tires, and you have something of an idea of what they gazed upon. The cigar-shaped body of this odd vehicle was apparently of steel with riveted plates, and about twelve or thirteen feet in length. “Amidships,” so to speak, was a low sort of hood, pierced with slits. From the top of this projected a slender rod of steel tubing with a small, square, boxlike terminal on its top.

“But where does the gun part of it come in?” asked Jack, much mystified.

Mr. Peregrine smiled, and then, motioning to them to come closer, he indicated, what they had not before noticed, a break in the continuity of the “shell” of his invention. This was in the form of a band, completely encircling the diameter of the fore part of the machine. In two places in this band, at opposite points, appeared round openings.

“There,” said the inventor, pointing to this band and the two holes, “is the vital part of my invention. You see those holes?—yes—well, they are the muzzles of my vanishing guns.”

The group about the inventor nodded; but as yet they had only a very vague idea of the details of this strange invention.

“That slender shaft of tubing rising from the conning tower,” said Mr. Peregrine, who in his enthusiasm had lost his jerky manner of talking, “is nothing more nor less than a periscope; you know what that is, I presume.”

“A device which will show whatever is occurring outside, while the operator of the machine to which it is attached remains hidden,” said Jack.

“Correct. But this is an improved periscope. It gives the operator of the ‘gun carriage’ a wide view of the sky in every direction. But to explain my invention more fully I must invite you inside.”

So saying, the inventor opened a door in the side of the steel structure, which they had not previously noticed. Taking Jack by the arm, he gave him a half shove into the interior of the steel cigar.

As the space within was small, Mr. Peregrine explained that he would have to show the points of his invention to one of them at a time. When Jack was inside the inventor closed the door and, turning a switch, caused a flood of light to illuminate the interior of the wheeled cylinder. Jack found that they were standing within the conning tower. Through the slits he could see out into the shed, but his attention was speedily distracted by Mr. Peregrine.

The inventor indicated a seat, and invited Jack to occupy it. The boy was informed that he was seated in the operator’s position. In front of him was a sort of desk with a white top. This was divided into squares. The inventor explained that the white surface represented the expanse of sky commanded by the periscope.

“The instant an aëroplane is seen to enter one of those squares, each of which, as you see, is numbered,” he explained, “I press one of these buttons which are correspondingly marked.”

He reached up to a sort of switchboard above the periscope desk, and pressed one of the numbered buttons on it. A whirring sound followed.

“What’s that?” demanded Jack.

“That noise is caused by the cylindrical band which you observed on the fore part of the machine,” said Mr. Peregrine; “two guns, controlled by electricity, are set in that band. By pressing this button one of them is automatically aimed at the square of sky which the periscope shows is occupied by a supposedly hostile aëroplane.”

Jack nodded. It was plain to him that the band which they had noticed revolved on an axis, and that the muzzles of the ‘vanishing gun’ revolved with it.

“The guns fire explosive shells,” went on the inventor, “and when they burst in mid-air they do damage extending over a wide area. This is an essential feature of the machine, for of course it would be impossible, actually, to hit an aëroplane fair and square except by chance.”

After showing Jack several more unique features of his strange invention, Mr. Peregrine took the boy “forward” into the gun chamber. Jack then saw just how each gun’s magazine of six shells was worked, and how the steel cases on the walls were especially designed for reserve ammunition. The boy could not help feeling the warmest admiration for the inventive genius that the eccentric designer of this queer, modern implement of warfare had displayed.

“But it seems to me that you have solved every problem in connection with this invention, Mr. Peregrine,” said Jack, after he had inspected the storage batteries and engine, designed to supply motive power to the vehicle which housed the vanishing guns.

“Yes,” rejoined the inventor, with a return to his odd, jerky manner, “everything solved—all complete—guns work—everything all right—but won’t go.”

“Won’t go?” questioned Jack wonderingly, “how do you mean?”

“What I say—can’t get it to move—wheels won’t go round.”

The inventor went on to explain that, although he had solved almost all the problems in connection with his wonderful device, one of the most important was still unmastered—namely, the means of locomotion for his invention. To be of any use at all in the field, it must be able to move, and move fast.

Now, although the inventor had provided a gasolene engine of considerable power, still he had not, up to date, been able to make the wheels revolve. Till he could do this, therefore, his invention must be considered a failure.

“It’s this that I wanted you to help me out on, Jack Chadwick,” he said, after he had jerkily explained his trouble; “can you do it?”

Jack looked rather dubious.

“Your machine is so enormously heavy,” he said, “that I’m afraid it is going to be a difficult matter.”

“Not so heavy as it looks,” responded the inventor, tapping the plates; “these are not steel, as you may think, but a mixture of vanadium and aluminum. The machine is practically bomb-proof. Any explosive dropped from an aëroplane would have to be more deadly than any at present known to do it much harm.”

Jack inspected the driving motor, a six-cylinder affair located behind a bulkhead, which cut it off from the conning tower, although the motor controls and the steering apparatus led into that compartment. The young inventor made a thorough and careful examination of the motor, and of the means by which it was geared to the driving shaft.