Title: The Bitter Cry of the Children

Author: John Spargo

Author of introduction, etc.: Robert Hunter

Release date: May 9, 2018 [eBook #57125]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Bryan Ness and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

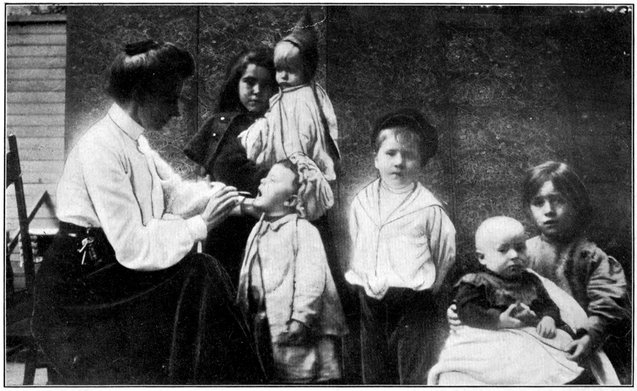

A TYPICAL SCENE

The matron of a Day Nursery examining a child’s throat. The two “Little Mothers” are typical.

I count myself fortunate in having had a hand in bringing this remarkable and invaluable volume into existence. Quite incidentally in my book Poverty I made an estimate of the number of underfed children in New York City. If our experts or our general reading public had been at all familiar with the subject, my estimate would probably have passed without comment, and, in any case, it would not have been considered unreasonable. But the public did not seem to realize that this was merely another way of stating the volume of distress, and, consequently, for several days the newspapers throughout the country discussed the statement and in some instances severely criticised it. One prominent charitable organization, thinking that my estimate referred to starving children, undertook, without delay, to provide meals for the children. In the midst of the excitement Mr. Spargo kindly volunteered to investigate the facts at first hand. His inquiry was so searching and impartial and the data he gathered so interesting and valuable that I urged him to put his material in some permanent form. The following admirable study of this problem is the result of that suggestion.

viiiI am safe in saying that this book is a truly powerful one, destined, I believe, to become a mighty factor in awakening all classes of our people to the necessity of undertaking measures to remedy the conditions which exist. The appeal of adults in poverty is an old appeal, so old indeed that we have become in a measure hardened to its pathos and insensitive to its tragedy. But this book represents the cry of the child in distress, and it will touch every human heart and even arouse to action the stolid and apathetic. The originality of the book lies in the mass of proof which the author brings before the reader showing that it is not alone, as most of our charitable experts believe, the misery of the neglected or the actively maltreated child that should receive attention. Even more important is the misery of that one whose whole future is darkened and perhaps blasted by reason of the fact that during his early years of helplessness he has not received those elements of nutritious food which are necessary to a wholesome physical life.

Few of us sufficiently realize the powerful effect upon life of adequate nutritious food. Few of us ever think of how much it is responsible for our physical and mental advancement or what a force it has been in forwarding our civilized life. Mr. Spargo does not attempt in this book to make us realize how much the more favored classes owe to the ixfact that they have been able to obtain proper nutrition. His effort here is to show the fearful devastating effect upon a certain portion of our population of an inadequate and improper food supply. He shows the relation of the lack of food to poverty. The child of poverty is brought before us. His weaknesses, his mental and physical inferiority, his failure, his sickness, his death, are shown in their relation to improper and inadequate food. He first proves to our satisfaction that this child of misery is born into the world with powerful potentialities, and he then shows, with tragic power, how the lack of proper food during infancy makes it inevitable that this child become, if he lives at all, an incompetent, physical weakling. It is perhaps unnecessary to point out that the problem of poverty is largely summed up in the fate of this child, and when the author deals with this subject he is in reality treating of poverty in the germ.

There have been many books written about the children of the poor, but, in my opinion, none of them give us so impressive a statement as is contained here of the most important and powerful cause of poverty. Among many reasons which may be found for the existence of distress, the author has taken one which seems to be more fundamental than the others. But, while this is true, there is no dogmatic treatment of the problem, for the author realizes that the xcauses of poverty in this country of abundance are numerous. Indeed, wherever one looks, one may see conditions which are fertile in producing it. Students of the poor find some of these causes in the conditions surrounding the poor. Students of finance and of modern industry find causes of poverty in the methods and constitution of this portion of our society. The causes, therefore, of poverty cannot be gone into fully in any partial study of modern society. It is even maintained, and not without reason, that if all men were sober, competent, and industrious, there would be no less poverty in the world. But however that may be, one thing is certain, and that is that as the race as a whole could not have advanced beyond savagery without a fortuitous provision of material necessities, so it is not possible for the children of the poor to overcome their poverty until they are assured in their childhood of the physical necessities of life. We should have no civilization to-day, our entire race would still be a wild horde of brutalized savages, but for the meat and milk diet or the grain diet assured to our earliest forefathers. And it should not be forgotten that as this is true of the life of the race, so is it true of that portion of our community which lives in poverty unable to procure proper food to give its children. This is the great fundamental fact which lies at the base of the problem of poverty and which xiis the theme of this book. It is a fact which should be best known to the men and women who work in the field of our philanthropies, and yet it must be said that it is a fact which has heretofore been almost entirely ignored by this class of workers.

For this reason I welcome this volume. I am convinced that it will mark the beginning of an epoch of deeper study and of sounder philanthropy. I look to see in the near future some effort made to establish a standard of physical well-being for the children. I expect to see the community insisting that some provision shall be made whereby every child born into the world will receive sufficient food to enable him to possess enough vitality to overcome unnecessary and preventable disease and to grow into a manhood physically capable of satisfactorily competing in industrial or intellectual pursuits. I do not believe that this is a dream impossible of realization. About a hundred years ago our forefathers decided that there should be a universal standard of literacy. To bring this about the following generations of men established a free school system which was meant to assure to every child a certain minimum of education. If that can be done for the mind, the other thing can be done for the body. And when it is done for the body, we shall make another striking advance in civilization not unlike that recorded in the history of mankind when the free xiipeople of this American continent established a system of free and universal education.

If such a momentous thing should follow the publication of this book, and similar studies which will without doubt subsequently be made, its publication would indeed mark an epoch. But, of course, it must be said that before any far-reaching result can come, the general public must be acquainted with the conditions which exist. It is for this reason that I hope Mr. Spargo’s book will be read by hundreds of thousands of people, and that it will awaken in them a determination to respond wisely and justly to the bitter cry of the children of the poor.

The purpose of this volume is to state the problem of poverty as it affects childhood. Years of careful study and investigation have convinced me that the evils inflicted upon children by poverty are responsible for many of the worst features of that hideous phantasmagoria of hunger, disease, vice, crime, and despair which we call the Social Problem. I have tried to visualize some of the principal phases of the problem—the measure in which poverty is responsible for the excessive infantile disease and mortality; the tragedy and folly of attempting to educate the hungry, ill-fed school child; the terrible burdens borne by the working child in our modern industrial system.

In the main the book is frankly based upon personal experience and observation. It is essentially a record of what I have myself felt and seen. But I have freely availed myself of the experience and writings of others, as reference to the book itself will show. I have tried to be impartial and unbiassed in my researches, and have not “winnowed the facts till only the pleasing ones remained.” At times, indeed, I have found it necessary, while writing xivthis book, to abandon ideas which I had held and promulgated for years. That is an experience not uncommon to those who submit opinions formed as a result of general observation to strict scientific scrutiny. I had long believed and had promulgated the opinion that the great mass of the children of the poor were blighted before they were born. The evidence given before the British Interdepartmental Committee, by recognized leaders of the medical profession in England, pointed to a fundamentally different view. According to that evidence, the number of children born healthy and strong is not greater among the well-to-do classes than among the very poorest. The testimony seemed so conclusive, and the corroboration received from many obstetrical experts in this country was so general, that I was forced to abandon as untenable the theory of antenatal degeneration.

In view of the foregoing, I need hardly say that I do not claim any originality for the view that Nature starts all her children, rich and poor, physically equal, and that each generation gets practically a fresh start, unhampered by the diseased and degenerate past.[A] The tremendous sociological significance of this truth—if truth it be—will, I think, be generally recognized. Readers of Ruskin’s Fors Clavigera will remember the story of the dressmaker xvwith a broken thigh, who was told by the doctors in St. Thomas’s Hospital, London, that her bones were in all probability brittle because her mother’s grandfather had been employed in the manufacture of sulphur. If this theory of antenatal degeneration is wrong, and we have not to reckon with grandfathers and great-grandfathers, the solution of the problem of arresting and repairing the deterioration of the race is made so much easier. It may be thought by some readers that I have accepted the brighter, more hopeful view too readily, and with too much confidence. I can only say that I have read all the available evidence upon the other side, and found myself at last obliged to accept the brighter view. I cannot but feel that the actual experience of obstetricians dealing with thousands of natural human births every year is far more valuable and conclusive than any number of artificial experiments upon guinea pigs, mice, or other animals.

The part of the book devoted to the discussion of remedial measures will probably attract more criticism than any other. I expect, and am prepared for, criticism from those, on the one hand, who will accuse me of being too radical and revolutionary, and, on the other hand, those who will say I have ignored almost all radical measures. I have purposely refrained from considering any of the far-reaching speculations of the “schools,” and confined myself xvientirely to those measures which have been tried in various places with sufficient success to warrant their general adoption, and which do not involve any revolutionary change in our social system. I have tried, in other words, to formulate a programme of practical measures, all of which have been subjected to the test of experience.

A word of personal explanation may not be out of place here. I have been privileged to know something of the leisure and luxury of wealth, and more of the toil and hardship of poverty. When I write of hunger I write of what I have experienced—not the enviable hunger of health, but the sickening hunger of destitution. So, too, when I write of child labor. I know that nothing I have written of the toil of little boys and girls, terrible as it may seem to some readers, approaches the real truth in its horror. I have not tried to write a sensational book, but to present a careful and candid statement of facts which seem to me to be of vital social significance.

As far as possible, I have freely acknowledged my indebtedness to other writers, either in the text or in the list of authorities at the end of the book. It was, however, impossible thus to acknowledge all the help received from so many willing friends in this and other countries. Hundreds of school principals and teachers, physicians, nurses, settlement workers, public officials, and others, in this country xviiand in Europe, have aided me. It is impossible to name them all, and I can only hope that they will find themselves rewarded, in a measure, by the work to which they have contributed so much.

I take this opportunity, however, of expressing my sincere thanks to Mr. Robert Hunter; to Mr. Owen R. Lovejoy, of the National Child Labor Committee; to Dr. George W. Goler, of Rochester, N.Y.; to Dr. S. E. Getty, of St. John’s Riverside Hospital, Yonkers, N.Y.; to Dr. Louis Lichtschein, of New York City; to Dr. George W. Galvin, of Boston, Mass.; and to Professor G. Stanley Hall, of Clark University, for many valuable suggestions and criticisms. To Mr. Fernando Linderberg, of Copenhagen; to his Excellency, Baron Mayor des Planches, the Italian Ambassador at Washington; and to Professor Emile Vinck, of Brussels, I am indebted for assistance in securing valuable reports which would otherwise have been inaccessible. I am also indebted to my colleague, Miss C. E. A. Carman, of Prospect House; and especially to Mr. W. J. Ghent for his expert assistance in preparing the book for the press. Finally, I am indebted to my wife, whose practical knowledge of factory conditions, especially as they relate to women and children, has been of immense service to me.

A. For the necessary qualifications of this broad generalization see the illustrative material in Appendix C, I.

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | vii | |

| Preface | xiii | |

| I. | The Blighting of the Babies | 1 |

| II. | The School Child | 57 |

| III. | The Working Child | 125 |

| IV. | Remedial Measures | 218 |

| V. | Blossoms and Babies | 263 |

| Appendices: | ||

| A. How Foreign Municipalities Feed their School Children | 271 | |

| B. Report on the Vercelli System of School Meals | 288 | |

| C. Miscellaneous | 291 | |

| Notes and Authorities | 307 | |

| Index | 325 | |

| 1. | A Typical Scene | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

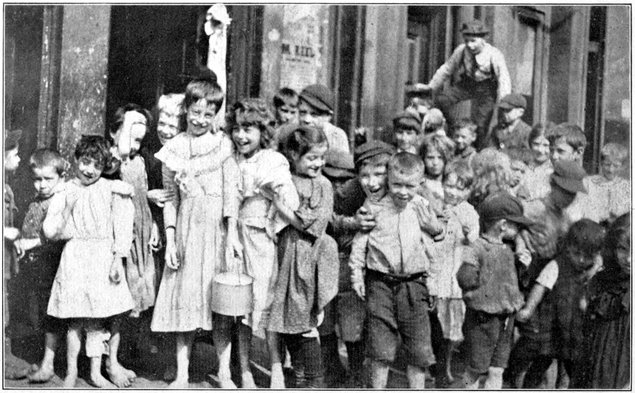

| 2. | Three “Little Mothers” and their Charges | 1 |

| 3. | Group of “Lung Block” Children | 5 |

| 4. | Rachitic Types | 12 |

| 5. | Babies whose Mothers Work | 16 |

| 6. | Police Station used as a “Clean Milk” Depot | 35 |

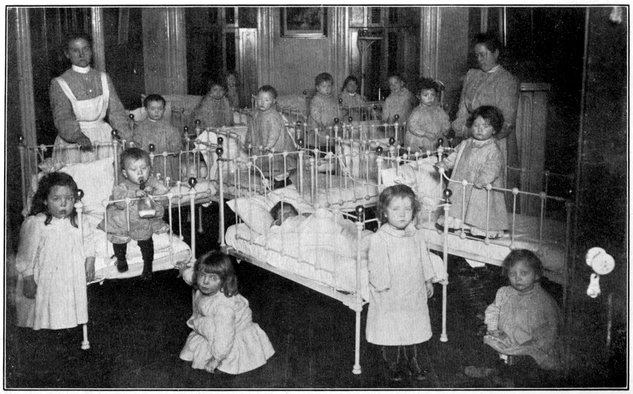

| 7. | Babies of a New York Day Nursery | 39 |

| 8. | Group of Children whose Mothers are employed away from their Homes | 42 |

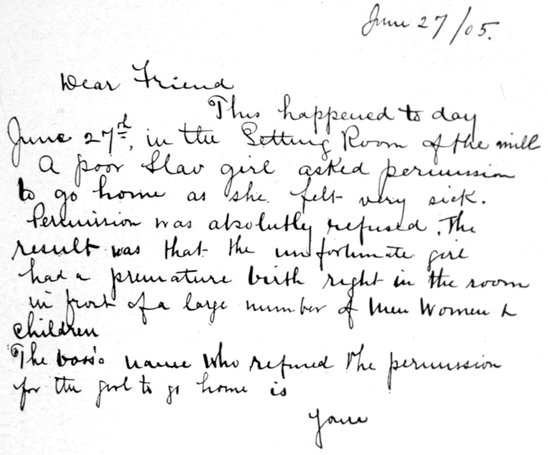

| 9. | A Sample Report (facsimile letter) | 46 |

| 10. | Babies whose Mothers work cared for in a Crèche | 53 |

| 11. | A “Lung Block” Child in a Tragically Suggestive Position | 60 |

| 12. | A Typical “Little Mother” | 72 |

| 13. | A Cosmopolitan Group of “Fresh Air Fund” Children | 94 |

| 14. | “Fresh Air Fund” Children enjoying Life in the Country | 117 |

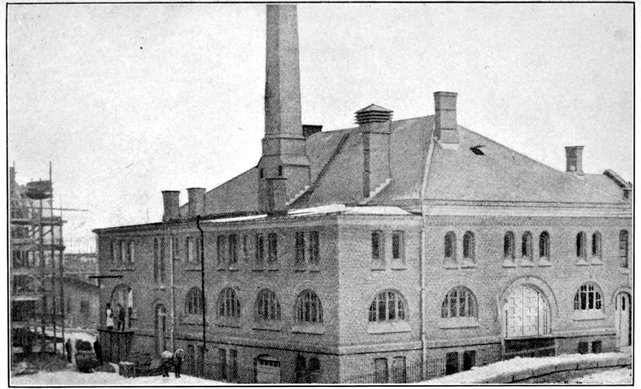

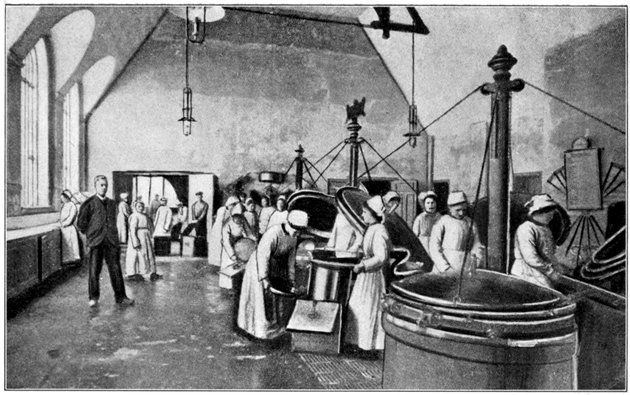

| 15. | Communal School Kitchen, Christiania, Norway | 124 |

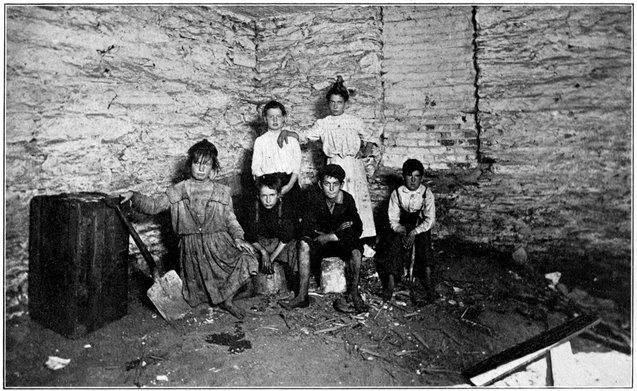

| 16. | New York Cellar Prisoners | 133 |

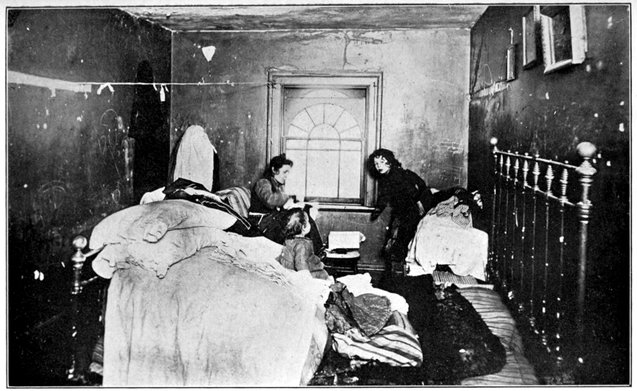

| 17. | Little Tenement Toilers | 140 |

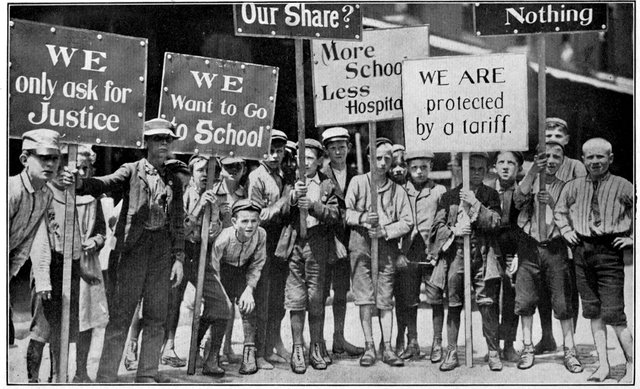

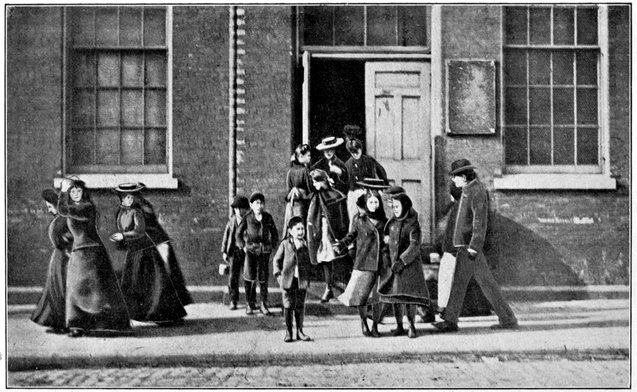

| 18. | Juvenile Textile Workers on Strike | 147 |

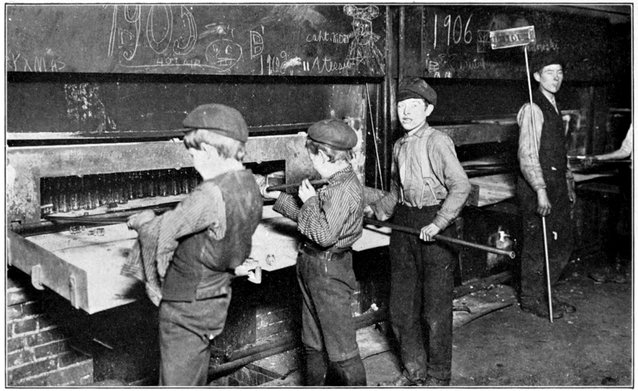

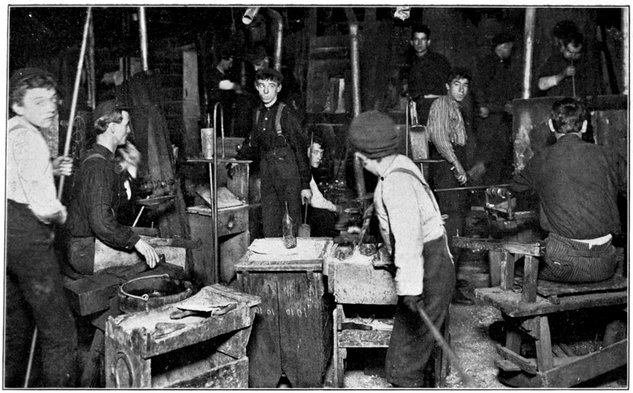

| 19. | Night Shift in a Glass Factory | 158 |

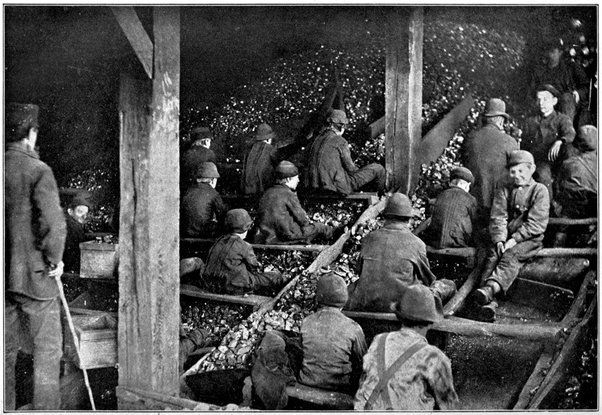

| 20. | Breaker Boys at Work | 165 |

| 21. | Home “Finishers”: A Consumptive Mother and her Two Children at Work | 172 |

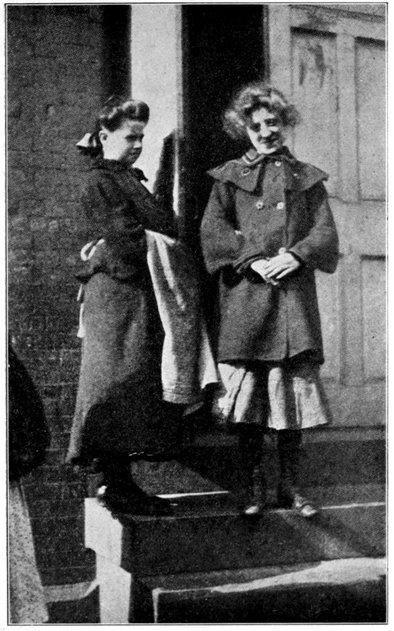

| 22. | Silk Mill Girls after Two Years of Factory Life | 184 |

| 23. | A “Kindergarten” Tobacco Factory in Philadelphia | 197 |

| 24. | A Glass Factory by Night | 204 |

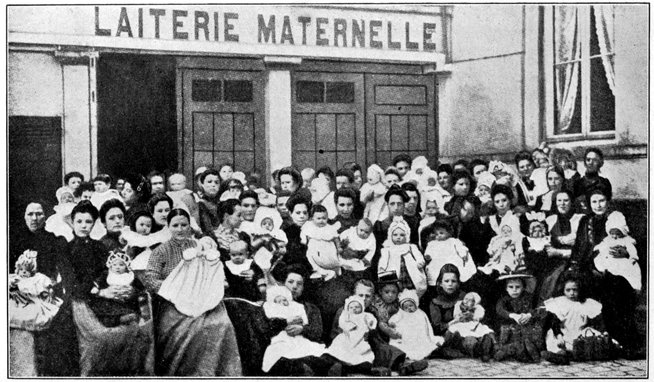

| xxii25. | A Free Infants’ Milk Depot (Municipal), Brussels | 225 |

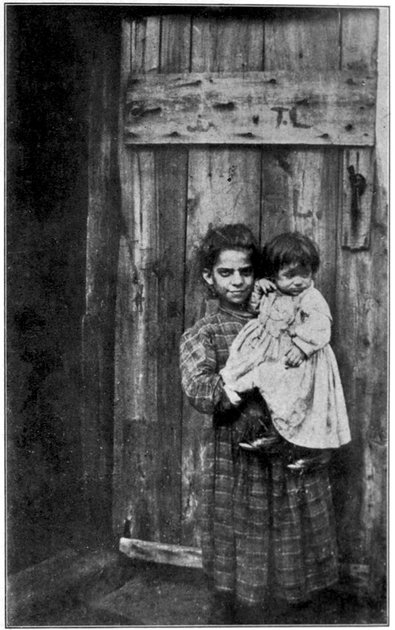

| 26. | A Group of Working Mothers | 231 |

| 27. | A “Clean Milk” Distribution Centre in a Baker’s Shop | 234 |

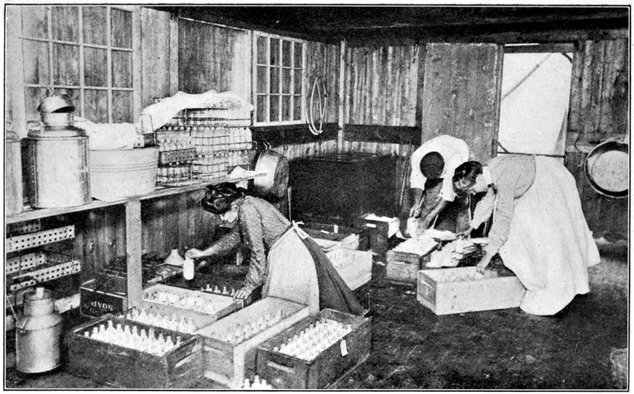

| 28. | Packing Bottles of “Clean Milk” in Ice | 240 |

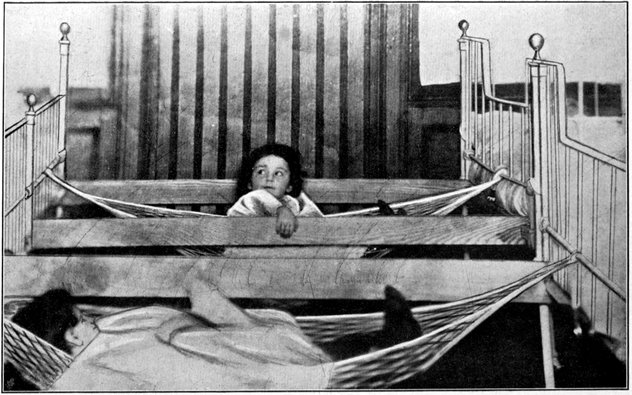

| 29. | “A Makeshift”: Hammocks swung between the Cots in an Overcrowded Day Nursery | 245 |

| 30. | Interior of the Communal School Kitchen, Christiania | 252 |

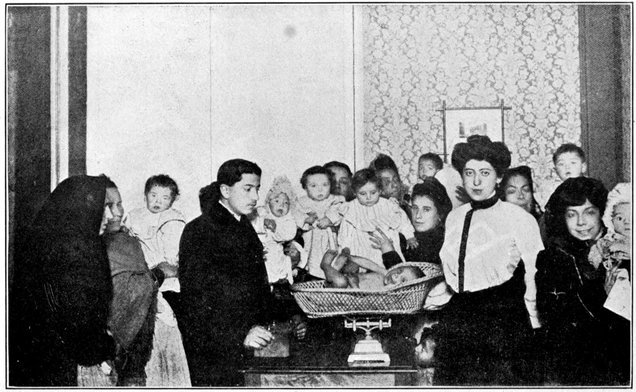

| 31. | Weighing Babies at the Gota de Leche, Madrid | 257 |

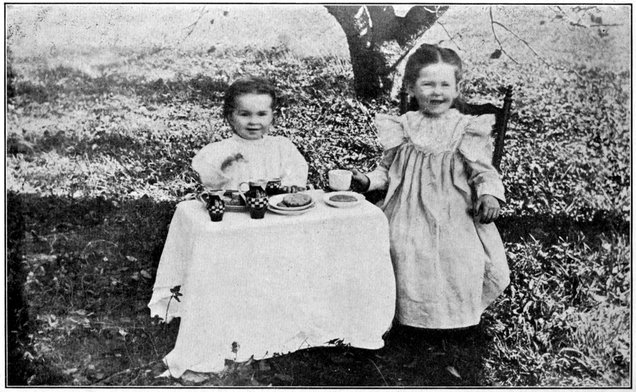

| 32. | Five o’Clock Tea in the Country | 261 |

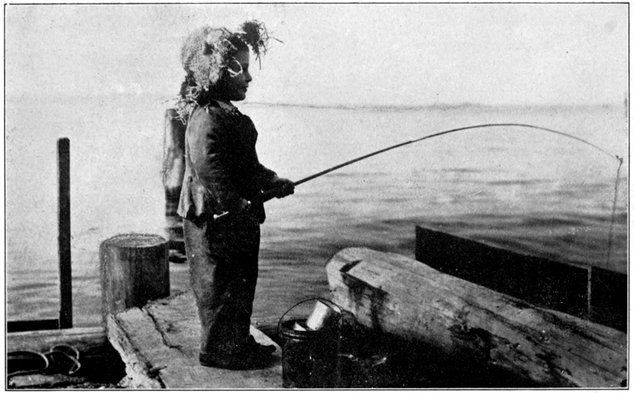

| 33. | A Little Fisherman | 268 |

Note.—I am indebted to Miss Marjory Hall of New York for the pictures of day nurseries and crèches; to Dr. G. W. Goler of Rochester, N.Y., for permission to use several illustrations of his work; to the Rev. Peter Roberts for the excellent illustration, “Breaker Boys at Work”; and to the Pennsylvania Child Labor Committee for several other illustrations of working children.—J. S.

| PAGES | ||

|---|---|---|

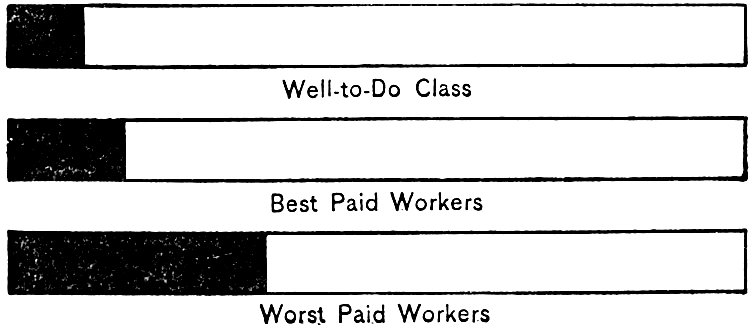

| 1. | Diagram showing Relative Death-rates per 100,000 Persons in Different Classes | 6 |

| 2. | Table showing Number of Deaths in United States and England and Wales, at Different Ages | 12 |

| 3. | Table showing Infantile Mortality from Eleven Given Causes and the Estimated Influence of Poverty thereon | 21 |

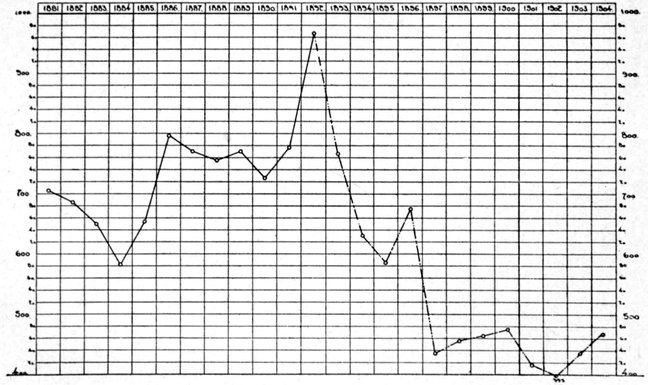

| 4. | Diagram showing the Infantile Death-rate of Rochester, N.Y., and the Influence thereon of a Pure Milk Supply | 22 |

| 5. | Schedule relating to Five Families in which the Mothers are employed away from their Homes | 40–41 |

| 6. | Schedule showing Dietary of Children in Six Families | 93 |

| 7. | Table showing Comparative Height, Weight, and Chest Girth of English Boys according to Social Class | 97 |

| 8. | Occupations of Juvenile Delinquents in Six Large Cities | 188 |

| 9. | Occupations of Juvenile Delinquents in Six Towns of less than 100,000 Inhabitants | 189 |

| 10. | Table showing Reasons for the Employment of 213 Children | 212, 213 |

THREE “LITTLE MOTHERS” AND THEIR CHARGES

The burden and blight of poverty fall most heavily upon the child. No more responsible for its poverty than for its birth, the helplessness and innocence of the victim add infinite horror to its suffering, for the centuries have not made tolerable the idea that the weakness or wrongdoing of its parents or others should be expiated by the suffering of the child. Poverty, the poverty of civilized man, which is everywhere coexistent with unbounded wealth and luxury, is always ugly, repellent, and terrible either to see or to experience; but when it assails the cradle it assumes its most hideous form. Underfed, or badly fed, neglected, badly housed, and improperly clad, the child of poverty is terribly handicapped at the very start; it has not an even chance 2to begin life with. While still in its cradle a yoke is laid upon its after years, and it is doomed either to die in infancy, or, worse still, to live and grow up puny, weak, both in body and in mind, inefficient and unfitted for the battle of life. And it is the consciousness of this, the knowledge that poverty in childhood blights the whole of life, which makes it the most appalling of all the phases of the poverty problem.

Biologically, the first years of life are supremely important. They are the foundation years; and just as the stability of a building must depend largely upon the skill and care with which its foundations are laid, so life and character depend in large measure upon the years of childhood and the care bestowed upon them. For millions of children the whole of life is conditioned by the first few years. The period of infancy is a time of extreme plasticity. Proper care and nutrition at this period of life are of vital importance, for the evils arising from neglect, insufficient food, or food that is unsuitable, can never be wholly remedied. “The problem of the child is the problem of the race,”[1] and more and more emphatically science declares that almost all the problems of physical, mental, and moral degeneracy originate with the child. The physician traces the weakness and disease of the adult to defective nutrition in early childhood; the penologist traces moral 3perversion to the same cause; the pedagogue finds the same explanation for his failures. Thanks to the many notable investigations made in recent years, especially in European countries, sociological science is being revolutionized. Hitherto we have not studied the great and pressing problems of pauperism and criminology from the child-end; we have concerned ourselves almost entirely with results while ignoring causes. The new spirit aims at prevention.

To the child as to the adult the principal evils of poverty are material ones,—lack of nourishing food, of suitable clothing, and of healthy home surroundings. These are the fundamental evils from which all others arise. The younger children are spared the anxiety, shame, and despair felt by their parents and by their older brothers and sisters, but they suffer terribly from neglect when, as so often happens, their mothers are forced to abandon the most important functions of motherhood to become wage-earners. The cry of a child for food which its mother is powerless to give it is the most awful cry the ages have known. Even the sound of battle, the mingled shrieks of wounded man and beast, and the roar of guns, cannot vie with it in horror. Yet that cry goes up incessantly: in the world’s richest cities the child’s hunger-cry rises above the din of the mart. Fortunate indeed is the child whose lips have never uttered that cry, who has never gone breakfastless 4to play or supperless to bed. For periods of destitution come sooner or later to a majority of the proletarian class. Practically all the unskilled laborers and hundreds of thousands engaged in the skilled trades are so entirely dependent upon their weekly wages, that a month’s sickness or unemployment brings them to hunger and temporary dependence. Not long ago, in the course of an address before the members of a labor union, I asked all those present who had ever had to go hungry, or to see their children hungry, as a result of sickness, accident, or unemployment to raise their hands. No less than one hundred and eighty-four hands were raised out of a total attendance of two hundred and nineteen present, yet these were all skilled workers protected in a measure by their organization.

A GROUP OF “LUNG BLOCK” CHILDREN

The white symbol of a child’s death hangs on a door in the background.

It is not, however, the occasional hunger, the loss of a few meals now and then in such periods of distress, that is of most importance; it is the chronic underfeeding day after day, month after month, year after year. Even where lack of all food is rarely or never experienced, there is often chronic underfeeding. There may be food sufficient as to quantity, but qualitatively poor and almost wholly lacking in nutritive value, and such is the tragic fate of those dependent upon it that they do not even know that they are underfed in the most literal sense of the word. They live and struggle and go down to their 5graves without realizing the fact of their disinheritance. A plant uprooted and left lying upon the ground withers quickly and dies; planted in dry, lifeless, arid soil it would wither and die, too, less quickly perhaps but as surely. It dies when there is no soil about its roots and it dies when there is soil in abundance, but no nourishing qualities in the soil. As the plant is, so is the life of a child; where there is no food, starvation is swift, mercifully swift, and complete; when there is only poor food lacking in nutritive qualities starvation is partial, slower, and less merciful. The thousands of rickety infants to be seen in all our large cities and towns, the anæmic, languid-looking children one sees everywhere in working-class districts, and the striking contrast presented by the appearance of the children of the well-to-do bear eloquent witness to the widespread prevalence of underfeeding.

Poverty and Death are grim companions. Wherever there is much poverty the death-rate is high and rises higher with every rise of the tide of want and misery. In London, Bethnal Green’s death-rate is nearly double that of Belgravia;[2] in Paris, the poverty-stricken district of Ménilmontant has a death-rate twice as high as that of the Elysée;[3] in Chicago, the death-rate varies from about twelve per thousand in the wards where the well-to-do reside to thirty-seven per thousand in the tenement wards.[4] The ill-developed 6bodies of the poor, underfed and overburdened with toil, have not the powers of resistance to disease possessed by the bodies of the more fortunate. As fire rages most fiercely and with greatest devastation among the ill-built, crowded tenements, so do the fierce flames of disease consume most readily the ill-built, fragile bodies which the tenements shelter. As we ascend the social scale the span of life lengthens and the death-rate gradually diminishes, the death-rate of the poorest class of workers being three and a half times as great as that of the well-to-do. It is estimated that among 10,000,000 persons of the latter class the annual deaths do not number more than 100,000, among the best paid of the working-class the number is not less than 150,000, while among the poorest workers the number is at least 350,000.[5] The following diagram illustrates these figures clearly and needs no further comment:—

DIAGRAM

Showing Relative Death-rates per 100,000 Persons in Different Classes.

7This difference in the death-rates of the various social classes is even more strongly marked in the case of infants. Mortality in the first year of life differs enormously according to the circumstances of the parents and the amount of intelligent care bestowed upon the infants. In Boston’s “Back Bay” district the death-rate at all ages last year was 13.45 per thousand as compared with 18.45 in the Thirteenth Ward, which is a typical working-class district, and of the total number of deaths the percentage under one year was 9.44 in the former as against 25.21 in the latter. Wolf, in his classic studies based upon the vital statistics of Erfurt for a period of twenty years, found that for every 1000 children born in working-class families 505 died in the first year; among the middle classes 173, and among the higher classes only 89. Of every 1000 illegitimate children registered—almost entirely of the poorer classes—352 died before the end of the first year.[6] Dr. Charles R. Drysdale, Senior Physician of the Metropolitan Free Hospital, London, declared some years ago that the death-rate of infants among the rich was not more than 8 per cent, while among the very poor it was often as high as 40 per cent.[7] Dr. Playfair says that 18 per cent of the children of the upper classes, 36 per cent of the tradesman class, and 55 per cent of those of the working-class die under the age of five years.[8]

8And yet the experts say that the baby of the tenement is born physically equal to the baby of the mansion.[9] For countless years men have sung of the Democracy of Death, but it is only recently that science has brought us the more inspiring message of the Democracy of Birth. It is not only in the tomb that we are equal, where there is neither rich nor poor, bond nor free, but also in the womb of our mothers. At birth class distinctions are unknown. For long the hope-crushing thought of prenatal hunger, the thought that the mother’s hunger was shared by the unborn child, and that poverty began its blighting work on the child even before its birth, held us in its thrall. The thought that past generations have innocently conspired against the well-being of the child of to-day, and that this generation in its turn conspires against the child of the future, is surcharged with the pessimism which mocks every ideal and stifles every hope born in the soul. Nothing more horrible ever cast its shadow over the hearts of those who would labor for the world’s redemption from poverty than this spectre of prenatal privation and inherited debility. But science comes to dispel the gloom and bid us hope. Over and over again it was stated before the Interdepartmental Committee by the leading obstetrical authorities of the English medical profession that the proportion of children born 9healthy and strong is not greater among the rich than among the poor.[10] The differences appear after birth. Wise, patient Mother Nature provides with each succeeding generation opportunity to overcome the evils of ages of ignorance and wrong, with each generation the world starts afresh and unhampered, physically, at least, by the dead past.

And herein lies the greatest hope of the race; we are not handicapped from the start; we can begin with the child of to-day to make certain a brighter and nobler to-morrow as though there had never been a yesterday of woe and wrong.[B]

In England the high infantile mortality has occasioned much alarm and called forth much agitation. There is a world of pathos and rebuke in the grim truth that the knowledge that it is becoming increasingly difficult to get suitable recruits for the army and navy has stirred the nation in a way that the fate of the children themselves and their inability to become good and useful citizens could not do.[11] 10Alarmed by the decline of its industrial and commercial supremacy, and the physical inferiority of its soldiers so manifest in the South African war, a most rigorous investigation of the causes of physical deterioration has been made, with the result that on all sides it is agreed that poverty in childhood is the main cause. Greater attention than ever before has been directed to the excessive mortality of infants and young children. Of a total of 587,830 deaths in England and Wales in 1900 no less than 142,912, or more than 24 per cent of the whole, were infants under one year, and 35.76 per cent were under five years of age. That this death-rate is excessive and that the excess is due to essentially preventable causes is admitted, many of the leading medical authorities contending that under proper social conditions it might be reduced by at least one-half. If that be true, and there is no good reason for doubting it, the present death-rate means that more than 70,000 little baby lives are needlessly sacrificed each year.

No figures can adequately represent the meaning of this phase of the problem which has been so picturesquely named “race suicide.” Only by gathering them all into one vast throng would it be possible to conceive vividly the immensity of this annual slaughter of the babies of a Christian land. If some awful great child plague came and swept away every 11child under a year old in the states of Massachusetts, Idaho, and New Mexico, not a babe escaping, the loss would be less than those that are believed to be needlessly lost each year in England and Wales. Or, to put it in another form, the total number of these infants believed to have died from causes essentially preventable in the year 1900 was greater than the total number of infants of the same age living in the following six states,—Connecticut, Maine, Delaware, Florida, Colorado, and Idaho. Even if the estimate of the sacrifice be regarded as being excessive, and we reduce it by half, it still remains an awful sum.

Unfortunately, there is no reason to suppose that the infantile death-rate in the United States is nearly so far below that of England as is generally supposed. The general death-rate is given in the census returns as 16.3 per thousand, or about two per thousand less than in England. But owing to a variety of causes, chief of which is the defective system of registration in several states, these figures are not very reliable, and it is generally agreed that the mortality for the whole country cannot be less than for the “Registration Area,” 17.8 per thousand. Similarly, the difference in the infantile death-rate of the two countries is much less than the following crude figures contained in the census reports appear at first to indicate:—

| 12 | |||

| United States | England and Wales | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths at all ages, | 1,039,094 | Deaths at all ages, | 587,830 |

| Deaths under 1 year, | 199,325 | Deaths under 1 year, | 142,912 |

| Deaths under 5 years, | 317,532 | Deaths under 5 years, | 209,960 |

In the English returns the death of every child having had a separate existence is counted, even though it lived only a few seconds, but in this country there is no uniform rule in this respect. In Chicago, for instance, “no account is taken of deaths occurring within twenty-four hours after birth,”[12] and in Philadelphia a similar custom prevailed until 1904.[13] Such facts seriously vitiate comparisons of the infantile death-rates of the two countries which are based upon the crude statistics of census returns.

But while the difference is much less than the figures given would indicate, it is still safe to assume that the infantile death-rate is lower in this country than in England. Such a condition might reasonably be expected for numerous reasons. We have a larger rural population with a higher economic status; new virile blood is being constantly infused by the immigration of the strongest and most aggressive elements of the population of other lands; our people, especially our women, are more temperate. All these factors would tend naturally to a lower death-rate at all ages, but especially of infants.

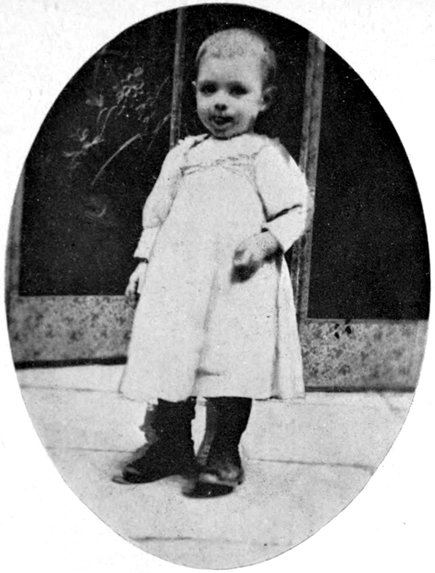

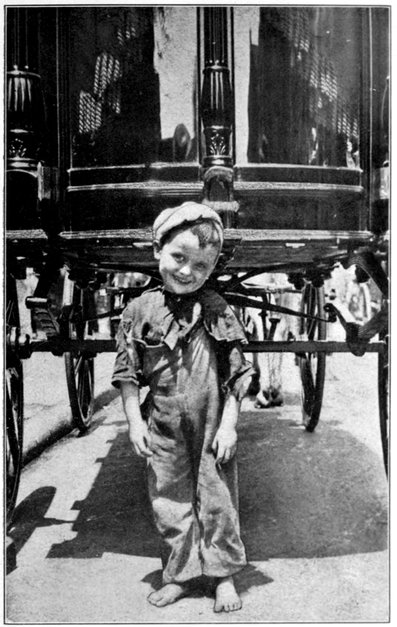

Danny’s Best Smile

Rickety, Ill fed, and Neglected

13That with all these favorable conditions our infantile mortality should so nearly approximate that of England, that of every thousand deaths 307.8 should be of children under five years of age—according to the crude figures of the census, more if a correct registration upon the same basis as the English figures could be had—is a matter of grave national concern. If we make an arbitrary allowance of 20 per cent, to account for the slight improvement shown by the death-rates and for other differences, and regard 30 per cent of the infantile death-rate as being due to socially preventable causes, instead of 50 per cent, as in the case of England, we have an appalling total of more than 95,000 unnecessary deaths in a single year.

And of these “socially preventable” causes there can be no doubt that the various phases of poverty represent fully 85 per cent, giving an annual sacrifice to poverty of practically 80,000 baby lives. If some modern Herod had caused the death of every male child under twelve months of age in the state of New York in the year 1900, not a single child escaping, the number thus brutally slaughtered would have been practically identical with this sacrifice. Poverty is the Herod of modern civilization, and Justice the warning angel calling upon society to “arise and take the young child” out of the reach of the monster’s wrath.

If our vital statistics were specially designed to that end, they could not hide the relation of poverty to disease and death more effectually than they do now. It is impossible to tell from any of the elaborate tables compiled by the census authorities what proportion of the total number of infant deaths were due to defective nutrition or other conditions primarily associated with poverty. No one who has studied the question doubts that the proportion is very great, but it is impossible to present the matter statistically, except in the form of a crude estimate. There is much of value in our great collections of statistics, but the most vital facts of all are rarely included in them.

In the great dispensary a little girl of tender years stands holding up a baby not yet able to walk. She is a “little mother,” that most pathetic of all poverty’s victims, her childhood taken away and the burden of womanly cares thrust upon her. “Please, doctor, do somethin’ fer baby!” she pleads. Baby is sick unto death, but she does not realize it. Its breath comes in short, wheezy gasps; its skin burns, and its little eyes glow with the brightness that doctors and nurses dread. One glance is all the doctor needs; in that brief glance he sees the ill-shaped head and the bent and twisted legs that tell 15of rickets. Helpless, with the pathetically perfunctory manner long grown familiar to him he gives the child some soothing medicine for her tiny charge’s bronchial trouble and enters another case of “bronchitis” upon the register. “And if it wasn’t bronchitis, ’twould be something else, and death soon, anyhow,” he says. Death does come soon, the white symbol of its presence hangs upon the street door of the crowded tenement, and to the long death-roll of the nation another victim of bronchitis is added—one of the eleven thousand so registered under five years of age. The record gives no hint that back of the bronchitis was rickets and back of the rickets poverty and hunger. But the doctor knows—he knows that little Tad’s case is typical of thousands who are statistically recorded as dying from bronchitis or some other specific disease when the real cause, the inducing cause of the disease, is malnutrition. Even as the Great White Plague recruits its victims from the haunts of poverty, so bronchitis preys there and gathers most of its victims from the ranks of the children whose lives are spent either in the foul and stuffy atmosphere of overcrowded and ill-ventilated homes, or on the streets, underfed, imperfectly clad, and exposed to all sorts of weather.

For nearly half a century rachitis, or “rickets,” has been known as the disease of the children of the 16poor. It has been so called ever since Sir William Jenner noticed that after the first two births, the children of the poor began to get rickety, and careful investigation showed that the cause was poverty, the mothers being generally too poor to get proper nourishment while nursing them.[14] It is perhaps the commonest disease from which children of the working-classes suffer. A large proportion of the children in the public schools and on the streets of the poorest quarters of our cities, and a majority of those treated at the dispensaries or admitted into the children’s hospitals, are unmistakably victims of this disease. One sees them everywhere in the poor neighborhoods. The misshapen heads and the legs bent and twisted awry are unmistakable signs, and the scanty clothing covers pitiful little “pigeon-breasts.” The small chests are narrowed and flattened from side to side, and the breast-bones are forced unnaturally forward and outward. Tens of thousands of children suffer from this disease, which is due almost wholly to poor and inadequate food. Here again statistical records hide and imprison the soul of truth, failing to yield the faintest idea of the ravages of this disease. The number of deaths credited to it in 1900 was only 351 for the whole of the United States, whereas 10,000 would not have been too high a figure.

BABIES WHOSE MOTHERS WORK—THEY ARE CARED FOR IN A DAY NURSERY

Seldom, if ever, fatal by itself, rickets is indirectly 17responsible for a tremendous quota of the infantile death-rate.[15] In epidemics of such infectious diseases as measles, whooping-cough, and others, the rickety child falls an easy victim. In these diseases, as well as in bronchitis, pneumonia, convulsions, diarrhœa, and many other disorders, the mortality is far higher among rickety children than among others. Nor do the evils of rachitis cease with childhood, but in later life they are unquestionably important and severe. There is no escape for the victim even though the storms of childhood be successfully weathered, but like some cruel, relentless Nemesis the consequences pursue the adult. The weakening of the constitution in infancy through poverty and underfeeding cannot be remedied, and epilepsy and tuberculosis find easy prey among those whose childhood had laid upon it the curse of poverty in the form of rickets.

An epidemic of measles spreads over the great city. Silently and mysteriously it enters and, unseen, touches a single child in the street or the school, and the result is as the touch of the blazing torch to dry stubble and straw; only it is not stubble but the nation’s heart, its future citizenry, that is attacked. From child to child, home to home, street to street, the epidemic spreads; mansion and tenement are alike stricken, and the city is engaged in a fierce battle against the foe which assails its children. 18In the tenement districts doctors and nurses hurry through the sun-scorched streets and wearily climb the long flights of stairs hour after hour, day after day; in the districts where the rich live, doctors drive in their carriages to the mansions, and nurses tread noiselessly in and out of the sick rooms. Rich and poor alike struggle against the foe, but it is only in the homes of the poor that there is no hope in the struggle; only there that the doctors can say no comforting words of assurance. When the battle is over and the victims are numbered, there is rejoicing in the mansion and bitter, poignant sorrow in the tenement. For poor children are practically the only ones ever to die from measles. Nature starts all her children equally, rich and poor, but the evil conditions of poverty create and foster vast inequalities of opportunity to live and flourish.

Dr. Henry Ashby, an eminent authority upon children’s diseases, says: “In healthy children among the well-to-do class the mortality (from measles) is practically nil, in the tubercular and wasted children to be found in workhouses, hospitals, and among the lower classes, the mortality is enormous, no disease more certainly being attended with a fatal result. William Squires places it in crowded wards at 20 to 30 per cent of those attacked. Among dispensary patients the mortality generally amounts to 9 or 10 per cent. In our own dispensary, during the six 19years, 1880–1885, 1395 cases were treated with 128 deaths, making a mortality of 9 per cent. Of the fatal cases 73 per cent were under two years of age and 9 per cent under six months of age.”[16]

These are terrible words coming as they do from a great physician and teacher of physicians. Upon any less authority one would scarcely dare quote them, so terrible are they. They mean that practically the whole 8645 infant deaths recorded from measles in the United States in the year 1900 were due to poverty—to the measureless inequality of opportunity to live and grow which human ignorance and greed have made. Moreover, the full significance of this impressive statement will not be realized if we think only of its relation to one disease. The same might be said of many other diseases of childhood which blight and destroy the lives of babies as mercilessly as the sharp frosts blight and kill the first tender blossoms of spring. The same writer says: “It may be taken for granted that no healthy infants suffer from convulsions; those who do are either rickety or the children of neurotic parents.”[17] And there were no less than 14,288 infant deaths from convulsions in the United States in the census year. It would probably be a considerable underestimate to regard 10,000 of these deaths, or 70 per cent of the whole, as due to poverty.

It is not my intention to attempt the impossible 20task of sifting the death returns so as to measure the sum of infantile mortality due to poverty. These figures and the table which follows are not introduced for that purpose; I have taken only a few of the diseases more conspicuously associated with defective nutrition and other conditions comprehended by the term poverty, and, supported by a strong body of medical testimony, made certain more or less arbitrary allowances for poverty’s influence upon the sum of mortality from each cause. Some of the estimates may perhaps be criticised as being too high,—no man knows,—but I am convinced that upon the whole the table is a conservative one. No competent judge will dispute the statement that some of the estimates are very low, and when it is remembered that only a few of the many causes of infantile mortality are included and that there are many others not enumerated in which poverty plays an important part, I think it can safely be said that in this country, the richest and greatest country in the world’s history, poverty is responsible for at least 80,000 infant lives every year—more than two hundred every day in the year, more than eight lives each hour, day by day, night by night throughout the year. It is impossible for us to realize fully the immensity of this annual sacrifice of baby lives. Think what it means in five years—in a decade—in a quarter of a century.

| 21 | |||

| Table showing Infantile Mortality from Eleven Given Causes and the Estimated Influence of Poverty thereon | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | No. of Deaths under Five Years | Est. Per Cent Due to Bad Conditions | Est. No. of Deaths Due to Bad Conditions—Poverty |

| Measles | 8,465 | 85 | 7,195 |

| Inanition | 10,687 | 90 | 9,618 |

| Convulsions | 14,288 | 70 | 10,000 |

| Consumption | 4,454 | 60 | 2,648 |

| Pneumonia | 37,206 | 45 | 14,340 |

| Bronchitis | 10,900 | 50 | 5,450 |

| Croup | 10,897 | 45 | 4,900 |

| Debility and Atrophy | 12,130 | 75 | 9,397 |

| Cholera Infantum | 25,563 | 45 | 11,502 |

| Diarrhœa | 3,962 | 45 | 1,782 |

| Cholera Morbus | 3,180 | 45 | 1,431 |

| 151,732 | 51.57 | 78,263 | |

There are doubtless many persons, lay and medical, who will think that the foregoing figures exaggerate the evil. But I would remind them that I have only ascribed 30 per cent of the infantile death-rate to “socially preventable causes,” and only 85 per cent of that number to poverty in the broadest sense of that word.[C] I have purposely set my estimate 22much lower than I am convinced it should be. All the facts point irresistibly to the conclusion that even 50 per cent would be a conservative estimate.

In connection with the New York Foundling Asylum on Randall’s Island, it was decided some few years ago to introduce the Straus system of Pasteurizing the milk given to the babies. The year before the system was introduced there were 1181 babies in the asylum, of which number 524, or 44.36 per cent, died. In the year following, during which the system was in operation, the number of children was 1284 and the number of deaths only 255, or 19.80 per cent. In other words, there were 8.03 per cent more children and 48.66 per cent fewer deaths.[18]

Even more important is the testimony furnished by the Municipal “Clean Milk” depots of Rochester, New York. Some years ago the Health Officer, Dr. George W. Goler, called the attention of the city authorities to the high infantile mortality occurring over a period of several years during the months of July and August. After thorough investigation it was fairly established that impure milk was one very important reason for this high death-rate among children under five years of age. Accordingly the Pasteurization system was introduced. Depots were opened in the poorest parts of the city and placed in charge of trained nurses. After three years it was decided that instead of Pasteurizing the milk obtained from all sorts of places, with all its contained bacteria and dirt, a central depot on a farm should be established and all energies should be devoted to the insuring of a pure, clean, and wholesome supply by keeping dirt and germs out of the milk and sterilizing all bottles and utensils. Strict control is also exercised in this way over the farmer with whom the contract for supplying the milk is made.

23Some idea of the important effects of this scientific attention by the Board of Health to the staple diet of the vast majority of children may be gathered from the following figures, which do not, however, tell the whole story. In the months of July and August during the eight years, 1889–1896, prior to the establishment of the Municipal Milk Stations, there were 1744 deaths under five years of age from all causes; in the same months during eight following years, 1897–1904, there were only 864 deaths under five years of age from all causes, a decrease of 50.46 per cent, despite a progressive increase of population.[19] It can hardly be questioned, I think, that these figures suggest that my estimate is altogether conservative.

The yearly loss of these priceless baby lives does not, however, represent the full measure of the awful cost of the poverty which surrounds the cradle. It is not only that 75,000 or 80,000 die, but that as many more of those who survive are irreparably 24weakened and injured. Not graves alone but hospitals and prisons are filled with the victims of childhood poverty. They who survive go to school, but are weak, nervous, dull, and backward in their studies. Discouraged, they become morose and defiant, and soon find their way into the “reformatories,” for truancy or other juvenile delinquencies. Later they fill the prisons, for the ranks of the vagrant and the criminal are recruited from the truant and juvenile offender. Or if happily they do not become vicious, they fail in the struggle for existence, the relentless competition of the crowded labor mart, and sink into the abysmal depths of pauperism. Weakened and impaired by the privations of their early years, they cannot resist the attacks of disease, and constant sickness brings them to the lowest level of that condition which the French call la misère.

However interesting and sociologically valuable such an analysis might be, the separation of the different features of poverty so as to determine their relative influence upon the sum of mortality and sickness is manifestly impossible. We cannot say that bad housing accounts for so many deaths, poor clothing for so many, and hunger for so many more. These and other evils are regularly associated in cases of poverty, the underfed being almost invariably 25poorly clad, and housed in the least healthy homes. We cannot regard them as distinct problems; they are only different phases of the same problem of poverty,—a problem which does not lend itself to dissection at the hands of the investigator. Still, notwithstanding that for many years all efforts to reduce the rate of mortality among infants have dealt only with questions of bad housing and of unhygienic conditions in general,—on the assumption that these are the most important factors making for a high rate of infant mortality,—it is now generally admitted that, important as they are in themselves, these are relatively unimportant factors in the infant death-rate. “Sanitary conditions do not make any real difference at all,” and “It is food and food alone,” was the testimony of Dr. Vincent before the British Interdepartmental Committee,[20] and he was supported by some of the most eminent of his colleagues in that position. That the evils of underfeeding are intensified when there is an unhygienic environment is true, but it is equally true that defect in the diet is the prime and essential cause of an excessive prevalence of infantile diseases and of a high death-rate.

Perhaps no part of the population of our great cities suffers so much upon the whole from overcrowding and bad housing as the poorest class of Jews, yet the mortality of infants among them is 26much less than among the poor of other nationalities, as, for instance, among the Irish and the Italians. Dr. S. A. Knopf, one of our foremost authorities upon the subject of tuberculosis, places underfeeding and improper feeding first, and bad housing and insanitary conditions in general second as factors in the causation of children’s diseases. In Birmingham, England, an elaborate study of the vital statistics of nineteen years showed that there had been a large decrease in the general death-rate, due, apparently, to no other cause than the extensive sanitary improvements made in that period, but the rate of infantile mortality remained absolutely unchanged. The average general death-rate for the nine years, 1873–1881, was 23.5 per thousand; in the ten years, 1882–1891, it was only 20.6. But the infantile death-rate was not affected, and remained at 169 per thousand during both periods. There had been a reduction of 12 per cent in the general death-rate, while that for infants showed no reduction. Had this been decreased in like degree, the infantile mortality would have fallen from 169 to 148 per thousand.[21]

Extensive inquiries in the various children’s hospitals and dispensaries in New York, and among physicians of large practice in the poorer quarters of several cities, point with striking unanimity to the same general conclusion. The Superintendents of six large dispensaries, at which more than 25,000 27children are treated annually, were asked what proportion of the cases treated could be ascribed, on a conservative estimate, primarily to inadequate nutrition, and the average of their replies was 45 per cent.

In one case the Registrar in a cursory examination of the register for a single day pointed out eleven cases out of a total of seventeen, due almost beyond question entirely to undernutrition.

The Superintendent of the New York Babies’ Hospital, Miss Marianna Wheeler, kindly copied from the admission book particulars of sixteen consecutive cases. The list shows malnutrition as the most prominent feature of 75 per cent of the cases. Miss Wheeler says: “The large majority of our cases are similar to these given; in fact, if I kept on right down the admission book, would find the same facts in case after case.”

As in all human problems, ignorance plays an important rôle in this great problem of childhood’s suffering and misery. The tragedy of the infant’s position is its helplessness; not only must it suffer on account of the misfortunes of its parents, but it must suffer from their vices and from their ignorance as well. Nurses, sick visitors, dispensary doctors, and those in charge of babies’ hospitals tell pitiful stories of almost incredible ignorance of which babies are the victims. A child was given cabbage by its mother 28when it was three weeks old; another, seven weeks old, was fed for several days in succession on sausage and bread with pickles! Both died of gastritis, victims of ignorance. In another New York tenement home a baby less than nine weeks old was fed on sardines with vinegar and bread by its mother. Even more pathetic is the case of the baby, barely six weeks old, found by a district nurse in Boston in the family clothes-basket which formed its cradle, sucking a long strip of salt, greasy bacon and with a bottle containing beer by its side. Though rescued from immediate death, this child will probably never recover wholly from the severe intestinal disorder induced by the ignorance of its mother. Yet, after all, it is doubtful whether the beer and bacon were worse for it than many of the patent “infant foods” of the cheaper kinds commonly given in good faith to the children of the poor. If medical opinion goes for anything, many of these “foods” are little better than slow poisons.[22] Tennyson’s awful charge is still true, that:—

Nor is the work of this spirit of murder confined to the concoction of “patent foods” which are in reality patent poisons. The adulteration of milk with formaldehyde and other base adulterants is responsible for a great deal of infant mortality, and its 29ravages are chiefly confined to the poor. It is little short of alarming that in New York City, out of 3970 samples of milk taken from dealers for analysis during 1902, no less than 2095, or 52.77 per cent, should have been found to be adulterated.[23] Mr. Nathan Straus, the philanthropist whose Pasteurized milk depots have saved many thousands of baby lives during the past twelve years, has not hesitated to call this adulteration by its proper name, child-murder. He says:—

“If I should hire Madison Square Garden and announce that at eight o’clock on a certain evening I would publicly strangle a child, what excitement there would be!

“If I walked out into the ring to carry out my threat, a thousand men would stop me and kill me—and everybody would applaud them for doing so.

“But every day children are actually murdered by neglect or by poisonous milk. The murders are as real as the murder would be if I should choke a child to death before the eyes of a crowd.

“It is hard to interest the people in what they don’t see.”[24]

Ignorance is indeed a grave and important phase of the problem, and the most difficult of all to deal with. Education is the remedy, of course, but how shall we accomplish it? It is not easy to educate after the natural days of education are passed. Mrs. 30Havelock Ellis has advocated “a noviciate for marriage,” a period of probation and of preparation and equipment for marriage and maternity.[25] But such a proposal is too far removed from the sphere of practicality to have more than an academic interest at present. Simply worded letters to mothers upon the care and feeding of their infants, supplemented by personal visits from well-trained women visitors, would help, as similar methods have helped, in the campaign against tuberculosis. Many foreign municipalities have adopted this plan, notably Huddersfield, England, and several American cities have followed their example with marked success. There should be no great difficulty about its adoption generally. One great obstacle to be overcome is the resentment of the mothers whom it is most necessary to reach, as many of those engaged in philanthropic work know all too well. One poor woman, whose little child was ailing, became very irate when a lady visitor ventured to offer her some advice concerning the child’s clothing and food, and soundly berated her would-be adviser. “You talk to me about how to look after my baby!” she cried. “Why, I guess I know more about it than you do. I’ve buried nine already!” It is not the naïve humor of the poor woman’s wrath that is most significant, but the grim, tragic pathos back of it. Those four words, “I’ve buried nine already!” tell more eloquently 31than could a hundred learned essays or polished orations the vastness of civilization’s failure. For, surely, we may not regard it as anything but failure so long as women who have borne eleven children into the world, as had this one, can say, “I’ve buried nine already!”

But circular letters and lady visitors will not solve the problem of maternal ignorance; such methods can only skim the surface of the evil. This ignorance on the part of mothers, of which the babies are victims, is deeply rooted in the soil of those economic conditions which constitute poverty in the broadest sense of the term, though there may be no destitution or absolute want. It is not poverty in the narrow sense of a lack of the material necessities of life, but rather a condition in which these are obtainable only by the concentrated effort of all members of the family able to contribute anything and to the exclusion of all else in life. Young girls who go to work in shops and factories as soon as they are old enough to obtain employment frequently continue working up to within a few days of marriage, and not infrequently return to work for some time after marriage. Especially is this true of girls employed in mills and factories; their male acquaintances are for the most part fellow-workers, and marriages between them are numerous. Where many women are employed men’s wages are, as a consequence, 32almost invariably low, with the result that after marriage it is as necessary that the woman should work as it was before.

When the years which under more favored conditions would have been spent at home in preparation for the duties of wifehood and motherhood are spent behind the counter, at the bench, or amid the whirl of machinery in the factory, it is scarcely to be wondered at that the knowledge of domestic economy is scant among them, and that so many utterly fail as wives and mothers. Deprived of the opportunities of helping their mothers with the housework and cooking and the care of the younger children, marriage finds them ill-equipped; too often they are slaves to the frying-pan, or to the stores where cooked food may be bought in small quantities. Bad cooking, extravagance, and mismanagement are incidental to our modern industrial conditions.

But there is a great deal of improper feeding of infants which, apparently due to ignorance, is in reality due to other causes, and the same is true of what appears to be neglect. In every large city there are hundreds of married women and mothers who must work to keep the family income up to the level of sufficiency for the maintenance of its members. According to the census of 1900 there were 769,477 33married women “gainfully employed” in the United States, but there is every reason to believe that the actual number was much greater, for it is a well-known fact that married women, especially in factories, often represent themselves as being single, for the reason, possibly, that it is considered more or less of a disgrace to have to continue working after marriage. Moreover, it is certain that many thousands of women who work irregularly, a day or two a week, or, as in many cases, only at intervals during the sickness or unemployment of their husbands, were omitted. A million would probably be well within the mark as an estimate of the number of married women workers, the census figures notwithstanding. These working mothers may be conveniently divided into two classes, the home workers, such as dressmakers, “finishers” employed in the clothing trades, and many others; and the many thousands who are employed away from their homes in cigar-making, cap-making, the textile industries, laundry work, and a score of other occupations including domestic service.

The proportion of married women having small children is probably larger among those employed in the home industries than in those which are carried on outside of the homes. Out of 748 female home “finishers” in New York, for instance, 658 were married and 557 had from one to seven children 34each.[26] The percentage could hardly equal that in the outside industries. While there are exceptional cases, as a rule no married woman, especially if she has young children, will go out to work unless forced to do so by sheer necessity. Dr. Annie S. Daniel, in a most interesting study of the conditions in 515 families where the wives worked as finishers, found that no less than 448, or 86.78 per cent of the whole, were obliged to work by reason of poverty arising from low wages, frequent unemployment, or sickness of their husbands. Of the other 67 cases, 45 of the women were widows, 15 had been deserted, and 7 had husbands who were intemperate and shiftless. Of all causes low wages was the most common, the average weekly income of the men being only $3.81. The average of the combined weekly earnings of man and wife was $4.85, and rent, which averaged $8.99 per month, absorbed almost one-half of this. In addition to the earnings of the men and women, there were other smaller sources of income, such as children’s wages and money received from lodgers, which brought the average income per family of 4½ persons up to $5.69 per week.[27]

POLICE STATION USED AS A “CLEAN MILK” DEPOT, ROCHESTER, N.Y.

Nothing could be further from the truth than the comfortable delusion under which so many excellent people live, that so long as the work is done at home the children will not be neglected nor suffer. While it is doubtless true that home employment of the 35mother is somewhat less disadvantageous to the child than if she were employed away from home,—though more injurious from the point of view of the mother herself,—the fact is that such employment is in every way prejudicial to the child. Even if the joint income of both parents raises the family above want, the conditions under which that income is earned must involve serious neglect of the child. The mother is taken away from her household duties and the care of her children; her time is given an economic value which makes it too precious to be spent upon anything but the most important thing of all,—provision for their material needs. She has no time for cooking and little for eating; the children must shift for themselves.

Thus the employment of the mother is responsible for numerous evils of underfeeding, improper feeding, and neglect. She works from early morn till night, pausing only twice or thrice a day to snatch a hasty meal of bread and coffee with the children. Her pay varies with the kind of work she does, from one-and-a-half to ten cents an hour. Ordinarily she will work from twelve to fourteen hours daily, but sometimes, when the work has to be finished and delivered by a fixed time, she may work sixteen, eighteen, or even twenty hours at a stretch. And then there are the “waiting days” when work is slack, and hunger, or the fear of hunger, weighs 36heavily upon her and crushes her down. Hard is her lot, for when she works there is food, but little time for eating and none for cooking or the care of her children; when there is no work there is time enough, but little food.

In Brooklyn, in a rear tenement in the heart of that huge labyrinth of bricks and mortar near the Great Bridge, such a mother lives and struggles against poverty and the Great White Plague. She is an American, born of American parents, and her husband is also native-born but of Scotch parentage. He is a laborer and when at work earns $1.75 per day, but partly owing to frequently recurring sickness and partly also to the difficulty of obtaining employment, it is doubtful whether his wages average $6 a week the year through. Of six children born only two are living, their ages being seven years and two-and-a-half years respectively. Both are rickety and weak and stunted in appearance. As she sat upon her bed sewing, only pausing to cough when the plague seemed to choke her, she told her story: “It’s awful,” she said, “but I must work else we shall get nothing to eat and be turned into the street besides. I have no time for anything but work. I must work, work, work, and work. Often we go to our beds as we left them when I haven’t time or strength to shake them up, and Joe, my husband, is too tired or sick to do it. Cooking? 37Oh, I cook nothing, for I haven’t time; I must work. I send the little girl out to the store across the way and she gets what she can,—crackers, cake, cheese, anything she can get—and I’m thankful if I can only make some fresh tea.” Neither of this woman’s two little children has ever known the experience of being decently fed, and their weak, rickety bodies tell the results. From a bare account of their diet it might be inferred that the mother must be ignorant or neglectful, but she is, on the contrary, a most intelligent woman and devoted to her children. Under better conditions she would perhaps have been a model housewife and mother, but it is not within the possibilities of her toil-worn, hunger-wasted body to be these and at the same time a wage-earner. So, without attempting to minimize the part which ignorance plays, it is well to emphasize the fact, so often lost sight of and forgotten, that what appears to be ignorance or neglect is very frequently only poverty in one of its many disguises.

As a contributory cause of excessive mortality and sickness among young children, the employment of mothers away from their homes is even more important. There is no longer any serious dispute upon that point, though twenty-five years ago it was the subject of a good deal of vigorous controversy 38on both sides of the Atlantic.[28] Professor Jevons thoroughly established his claim that the employment of mothers and the ensuing neglect of their infants is a serious cause of infantile mortality and disease. So important did he consider the question to be that he strenuously advocated the enactment of legislation forbidding the employment of mothers until their youngest children were at least three years old.[29] When one who is familiar with the facts considers all that the employment of mothers involves, it is difficult to imagine how its evil effects upon the children could ever have been questioned. In too many cases the toil continues through the most critical periods of pregnancy; the infants are weaned early in order that the mother may return to her employment, and placed in charge of some other person—often a mere child, inexperienced and ignorant. These “little mothers” have been much praised and idealized until we have become prone to forget that their very existence is a great social menace and crime. It is true that many of them show a wonderful amount of courage and precocity in dealing with the babies intrusted to their care. But in praising these qualities we must not forget that they are still children, necessarily unfitted for the responsibilities thus placed upon them. Moreover, they themselves are the victims of a great social crime when their childhood is taken away and the cares of life which belong to grown men and women are thrust upon them.

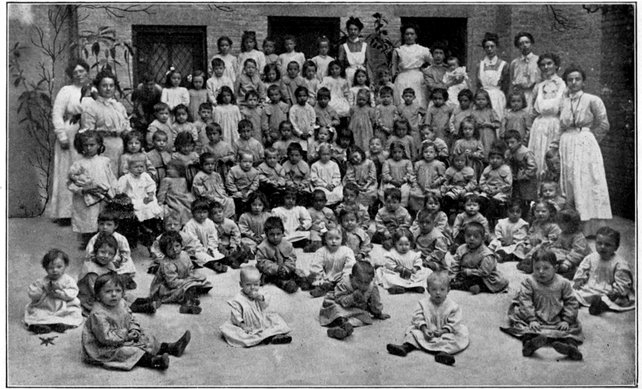

BABIES OF A NEW YORK DAY NURSERY

The mothers of all these babies work away from their homes.

39In a personal letter to the writer, Mr. Roscoe Doble, Clerk to the Health Board of Lawrence, Massachusetts, says: “Relative to the high infantile mortality, I can only say that ignorance in the preparation of food, illy ventilated tenements, and, in many cases, unavoidable neglect occasioned by the mothers being obliged to work away from the homes, often leaving their babies in the care of other children, seem to be the prime factors in the high mortality among children.” Similar testimony has been given by physicians and nurses wherever I have made inquiries, indicating a general consensus of opinion among experts upon the subject. A striking instance of the ignorance of these little girls to whom infants are intrusted was observed in Hamilton Fish Park when one of them gave a baby, apparently not more than four or five months old, soda water, banana, ice cream, and chewed cracker—all inside of twenty minutes.

In several factory towns I made careful investigations of the home conditions of a number of families where the mothers were employed away from their homes, noting particularly the rates of infantile mortality among them. The following typical schedule relates to five cases noted in the course of a single day in one of the small towns of New York:—

| Name | Age | Average Weekly Earnings | Husband’s Work, Wages, etc. | Total number of Children Born | No. of Children having Died | No. of Children now Alive | Nationality of the Parents | Age of Youngest Child | How Children are cared for while Mother Works | General Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mrs. M. | 43 | $7.00 | Mill laborer. Wages $9.00 week but is often sick. Drinks heavily. | 5 | 5 | Mother, Irish; Father, Scotch. | All five died under 18 months of age; three of them under 6 months. All the children were cared for by other children while mother worked. Three died of convulsions, two of diarrhœa. | |||

| Mrs. K. | 38 | $6.50 | Laborer. Often unemployed. Average wage the year round not more than $7.00 a week. | 7 | 5 | 2 | Mother, Irish American; Father, Swede. | 10 months. | By girl, aged 9 years. | All five that died were under 12 months of age. Two of them died of convulsions, one of acute gastritis, two of measles. The baby is a puny little thing. |

| 41Mrs. C. | 34 | $7.00 | Deserted wife. | 6 | 4 | 2 | Mother, German; Father, Austrian. | 18 months. | By oldest girl, aged 9 years. | One child was scalded to death while mother was at work; one died of convulsions and two of bronchitis. |

| Mrs. S. | 29 | $6.00 | Sick two years and unable to work. Was a laborer formerly. | 6 | 3 | 3 | Mother English; Father, American. | 2 years. | By father and girl of 7 years. | The first two children and the last born are alive; the third, fourth, and fifth are dead, each of them dying within the first year. Mother says they were poor, puny babies. Causes Of death: Debility, 2; convulsions, 1. |

| Mrs. H. | 41 | $6.00 | Dead 6 months. Was a laborer, often sick and unemployed. Widow does not think he earned $6.00 a week the year round. | 8 | 5 | 3 | Mother, American; Father (deceased), French-Canadian. | 20 months. | By oldest girl, 11 years old. | The first two and the eighth born are alive; the five intervening are dead. Four of these died within the first year. Causes of death: Debility, 2; intestinal dyspepsia, 2; bronchitis, 1. |

42It will be observed that out of a total of 32 children born only 10 were alive at the time of the inquiry, and that of the number dead no less than 18 were under one year of age, the cause of death in most cases being associated with neglect and defective diet. Of the ten children surviving, six were decidedly weak, and the mothers said that they were “generally sick” and that somehow it seemed as if they “took” every sort of disease, a well-known condition of the undernourished child.

In the same town the case of a poor Hungarian mother was brought to my attention by one perfectly familiar with all the details, a witness of unassailable veracity. This poor Hungarian child-wife and mother was barely fifteen when her baby was born, but she had been working fully three years in the mill. When the child was born the father disappeared. “He was afraid he could never pay the cost,” the wife said in his defence. On the ninth day after her confinement she returned to her work, leaving the baby in charge of a girl nine years old.

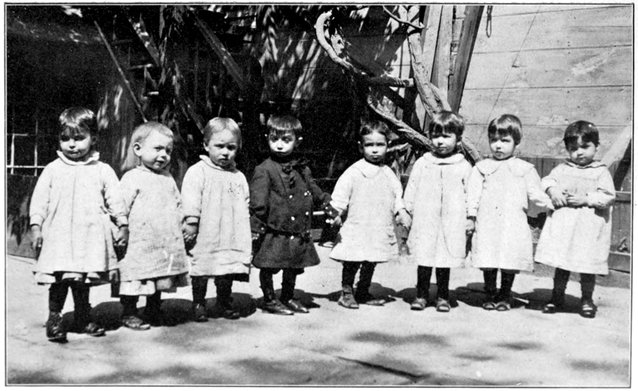

A GROUP OF CHILDREN WHOSE MOTHERS ARE EMPLOYED AWAY FROM THEIR HOMES

Upon the day the baby was two weeks old, word came to the mother while at work that it had been taken suddenly ill and imploring her to return to it at once. Terrified, she sought the foreman of her department and begged to be allowed to go home. “Ma chil seek! Ma chil die!” she cried. But the foreman needed her and scowled; they were “rushed” 43in the winding-room. And so he refused to grant her the permission she sought—refused with foul objurgations. Heartbroken, she went to another, superior, foreman and in broken English begged to be allowed to go to her sick babe. “Ma chil seek! Ma chil die!” she cried incessantly. This foreman also refused at first to let her go. Perhaps it was because he thought of his own daughter that he relented at last and gave her permission to go home—permission to give a mother’s care to the child born of her travail! Eye-witnesses say that she sank down upon her knees and, with hysterical gratitude, kissed the foreman’s rough, dirty hands. “You good man! You good man!” she shrieked, then fled from the mill with frenzied haste.

But when she reached her little tenement home in “Hunk’s town” the baby was already dead, and there was only a lifeless form for her to clasp in her arms. The life of an infant child is too frail a thing, and too uncertain, to permit us to say that a mother’s care would have sufficed to save that babe. But the doctor said neglect was the cause of death, and the poor mother has moaned daily these many months, “If I no work, ma chil die not. I work an’ kill ma chil!”

Thirty-five years ago Paris was besieged by Germany’s vast army. For months the war raged with terrible cost to invader and invaded; industry was paralyzed and factories were closed down, with the 44result that there was the most frightful poverty due to unemployment. But, because the mothers were forced to stay at home, and were thus enabled to give their children their personal care and attention instead of trusting them to the “little mothers,” the mortality of infants decreased by 40 per cent. No other explanation of that striking fact, so far as I am aware, has ever been attempted.[30] Very similar was the effect upon the infantile death-rate during the great cotton famine in Lancashire as a result of the prolonged unemployment of so many hundreds of mothers. Notwithstanding the immense increase in poverty, the fact that the mothers could personally care for their infants more than compensated for it and lowered the rate of mortality in a most striking manner.[31] These examples of a profound social fact are sufficient for our present purpose, though, were it necessary, they might be indefinitely multiplied.

Perhaps the employment of mothers too close to the time of childbirth, both before and after, is almost as important as the subsequent neglect and intrusting of children to the tender mercies of ignorant and irresponsible caretakers. Élie Reclus tells us that among savages it is the universal custom to exempt their women from toil during stated periods prior to and following childbirth,[32] and in most 45countries legislation has been enacted forbidding the employment of women within a certain given period from the birth of a child. In Switzerland the employment of mothers is prohibited for two months before confinement and the same period afterwards.[33] At present the English law forbids the employment of a mother within four weeks after she has given birth to a child, and the trend of public opinion seems to be in favor of the extension of the period of exemption to the standard set by the Swiss law.[34] So far as I am aware there exists no legislation of this kind in the United States, in which respect we stand alone among the great nations, and behind the savage of all lands and ages.