Title: The Charm of Scandinavia

Author: Francis E. Clark

Sydney Clark

Release date: May 6, 2018 [eBook #57106]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/charmofscandinav00clarrich |

THE CHARM OF SCANDINAVIA

THE CHARM

OF SCANDINAVIA

BY

FRANCIS E. CLARK

AND

SYDNEY A. CLARK

ILLUSTRATED

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1918

Copyright, 1914,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

DEDICATED TO

JUDICIA

F. E. C.

S. A. C.

While this book is largely based upon personal observation in the countries described, the authors have taken pains to consult many recent and some older authors who have written about Scandinavia, that they might become familiar with the history and customs of the countries which a traveler could not otherwise so readily understand.

Among these authorities may be mentioned Paul Du Chaillu’s work on “The Viking Age”; Boyesen’s “History of Norway” in the “Story of the Nations” series, a most excellent and informing book, as interesting as it is accurate; Goodman’s “The Best Tour in Norway”; F. M. Butlin’s recent valuable book, “Among the Danes”; “Swedish Life in Town and Country,” by Oscar G. von Heidenstam; Emil Svenson, Holger Rosman, Gunnar Anderson, and C. G. Lawins, who have combined to write a handbook about Sweden’s history, industries, social systems, art, etc.

We should like to acknowledge especial indebtedness to a book by Hon. W. W. Thomas, entitled “Sweden and the Swedes.” No American has written so sympathetically about the Swedes from a long and intimate knowledge of them as Mr. Thomas, who as Consul, United States Minister, and private citizen has spent nearly half a century among them. This book, like[viii] Ernest Young’s admirable volume on Finland, has been used chiefly, as have the other authorities, to confirm, modify, or correct our own impressions.

Since this book is the result of more than one journey throughout the length and breadth of Scandinavia, the dates appended to the different letters do not necessarily refer to the time they were written, but rather to the season and the part of the country described.

In all essential particulars the book is a record of the actual experiences that brought the authors under the spell of Scandinavia. They hope this story of the sturdy, liberty-loving peoples may impart to the reader something of the same charm.

F. E. C.

S. A. C.

(An introduction which the authors, earnestly but with becoming modesty, ask their readers to peruse, that the scheme of the book may be understood.)

Phillips and Aylmer had engagements which required them to take long journeys in Sweden and Norway, Denmark and Finland, and a friendly discussion arose as to the relative beauties and merits of these countries. Aylmer upheld the charms of Norway and Denmark with youthful vehemence, and Phillips, with equal vigor, asserted the superiority of Sweden and Finland. Judicia, to whom they appealed, suggested that each one, while on his journey, write her full and interesting accounts of the things in Scandinavia that charmed them most, and she would then render her decision. But, the letters written, she begged the question by proposing that the letters be published, and each reader decide for himself. The writers agreed, and “The Charm of Scandinavia” is the result.

| Page | |

| PART I | |

| Phillips Writes of Sweden and Finland | 1 |

| PART II | |

| Aylmer Writes of Norway and Denmark | 175 |

| The Old Borgund Stave-kirke | Frontispiece |

| Facing Page | |

| Map of Scandinavia | 1 |

| Skikjoring, a Highly Enjoyable Sport | 8 |

| Skate Sailing, a Favorite Sport in Sweden | 8 |

| The Royal Palace, Stockholm | 16 |

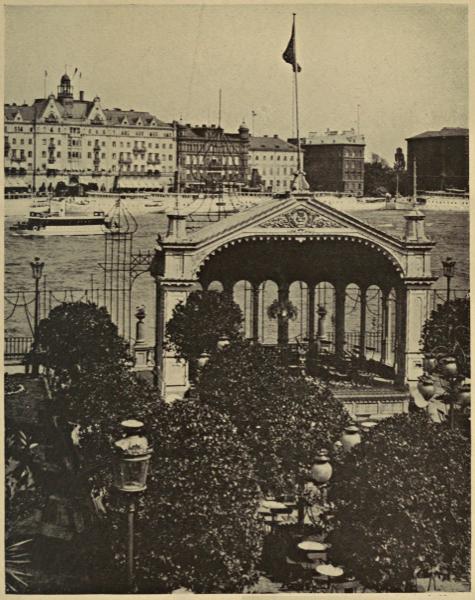

| Tea House on Banks of Mälar | 20 |

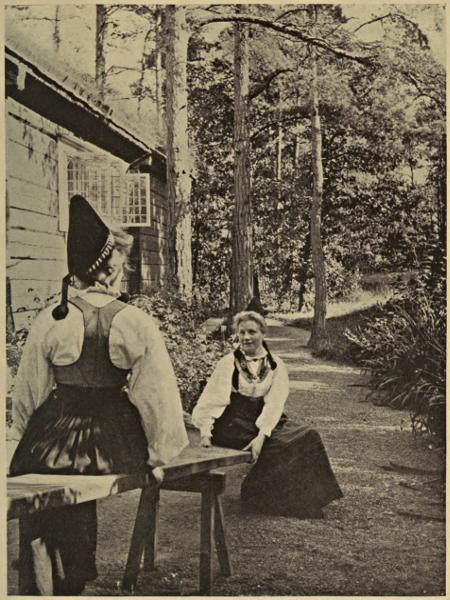

| Some Girls of Dalecarlia | 34 |

| Where Gustavus Adolphus Rests among Hard-Won Battle Flags | 42 |

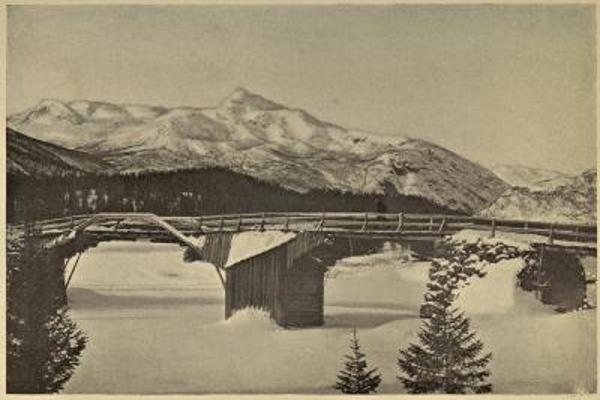

| A Typical Swedish Landscape in Winter | 46 |

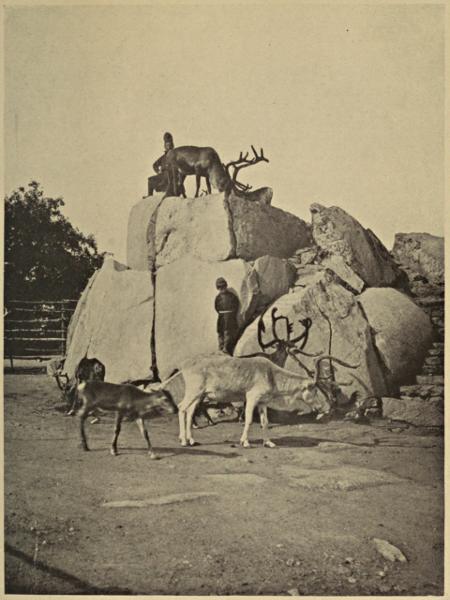

| Reindeer and Lapps from North Sweden | 66 |

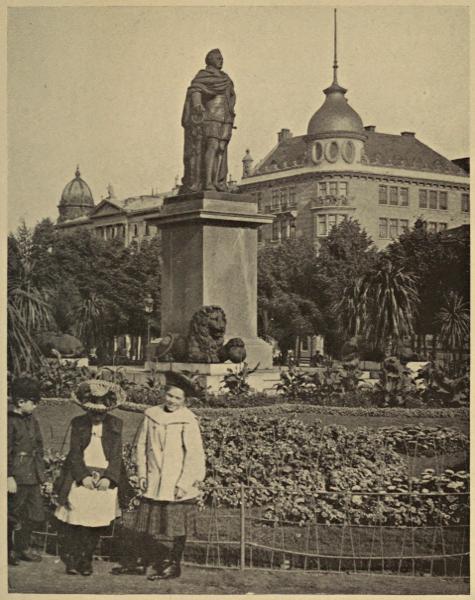

| Lion-Guarded Statue of Charles XIII, in King’s Garden, Stockholm | 74 |

| The Castle at Upsala | 86 |

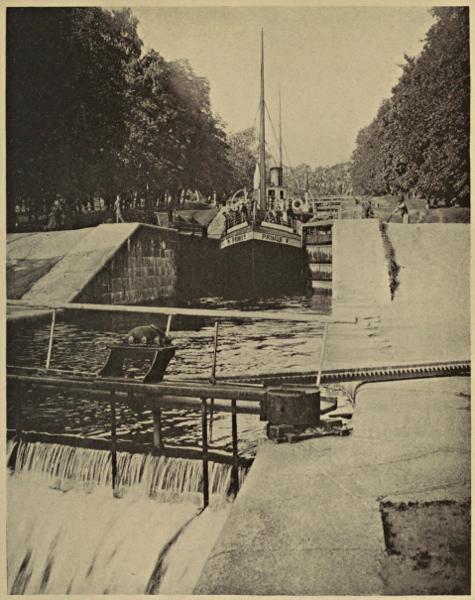

| The Locks, Borenshult, Göta Canal | 96 |

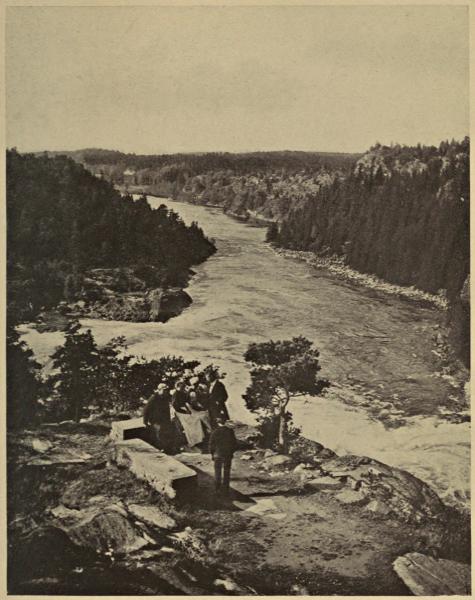

| The Gorge of the Göta at Trölhatten | 100 |

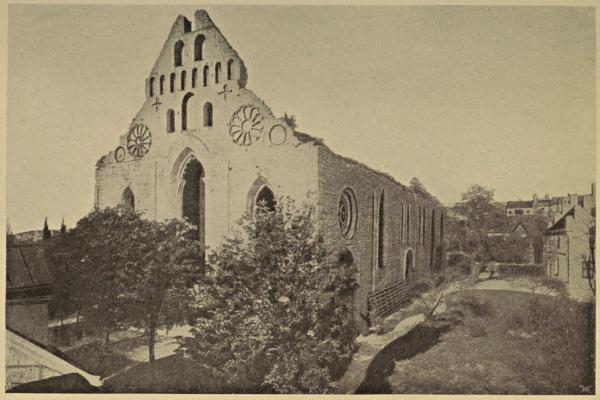

| Ruins of St. Nikolaus Cathedral, Visby, Gotland | 110 |

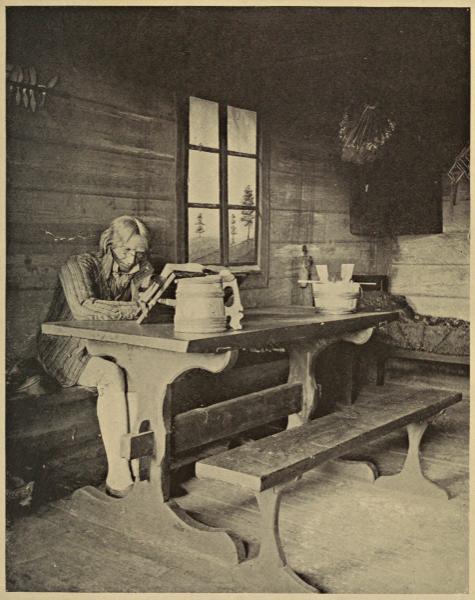

| Interior of a Finnish Cottage | 136 |

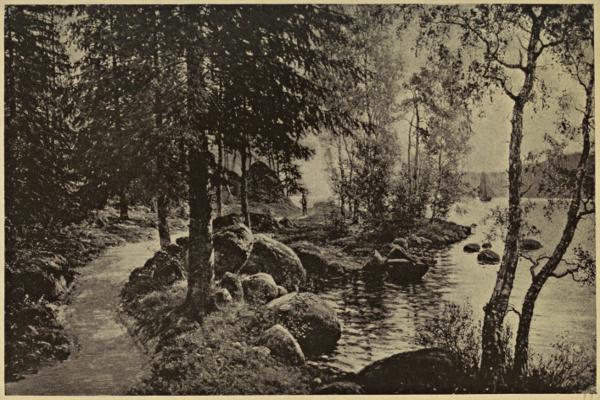

| In Finnish Lakeland | 144 |

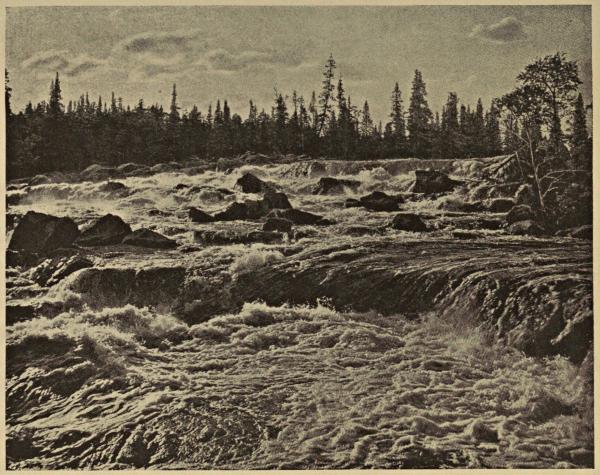

| In Eastern Finland | 150 |

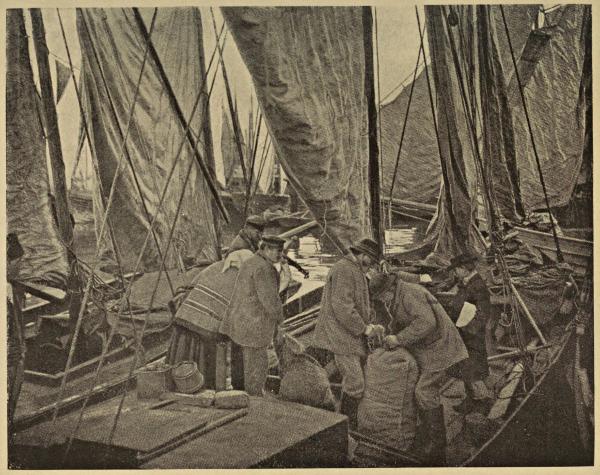

| Fish Harbor, Helsingfors | 164 |

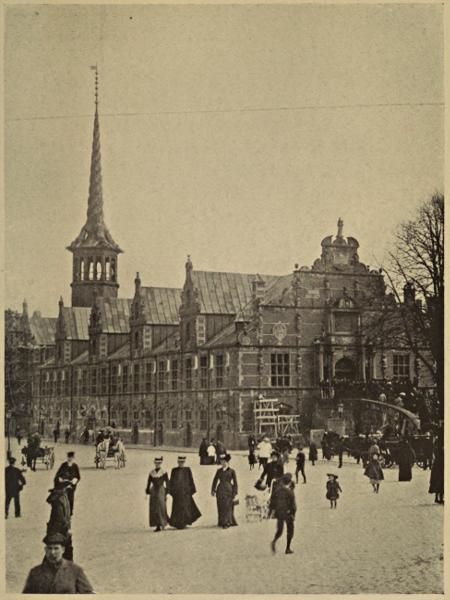

| Copenhagen Exchange | 182 |

| Watch Parade in Amalienborg Square | 196 |

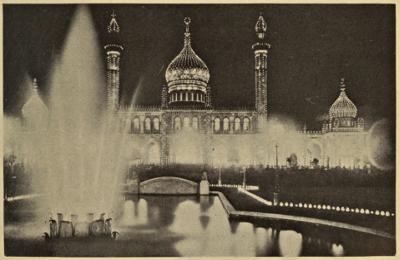

| [xiv]The Splendor of Tivoli on a Gala Night in Summer | 196 |

| Frederiksborg Castle, Copenhagen | 208 |

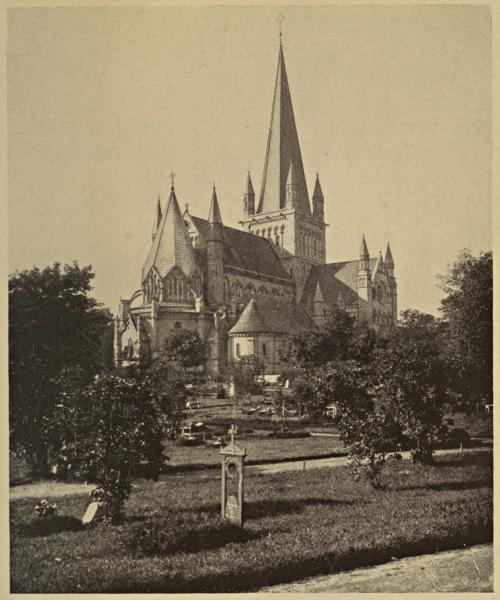

| Trondhjem Cathedral | 250 |

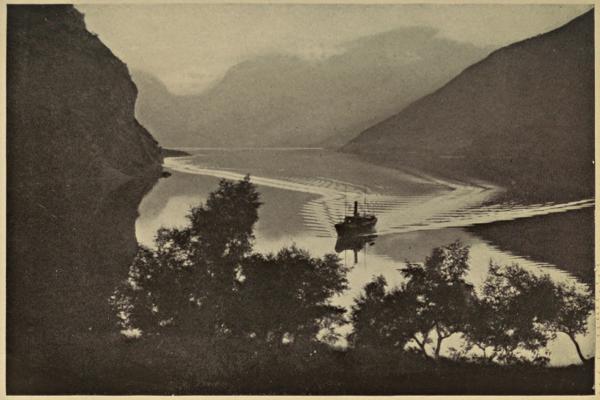

| On the Sognefjord | 256 |

| Ski Jumping | 260 |

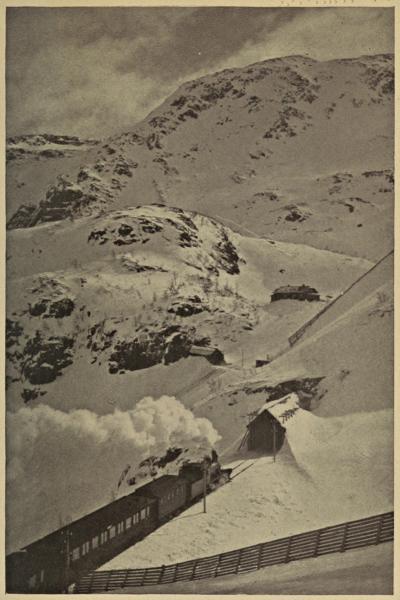

| The Railroad between Bergen and Christiania | 268 |

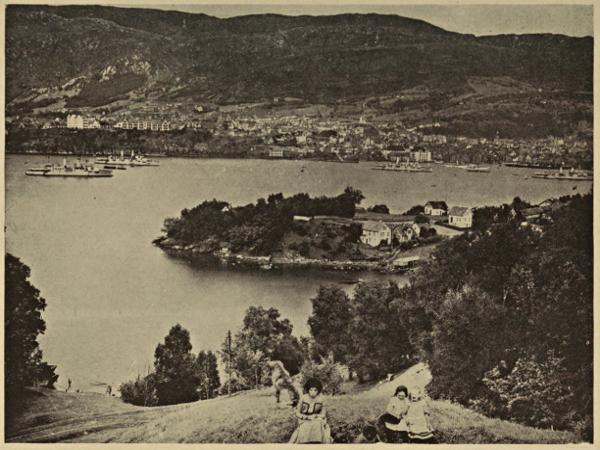

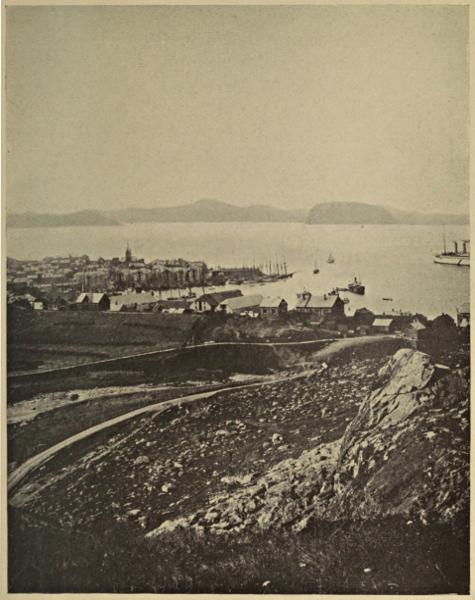

| Bergen, Northeast from Laksevaag | 278 |

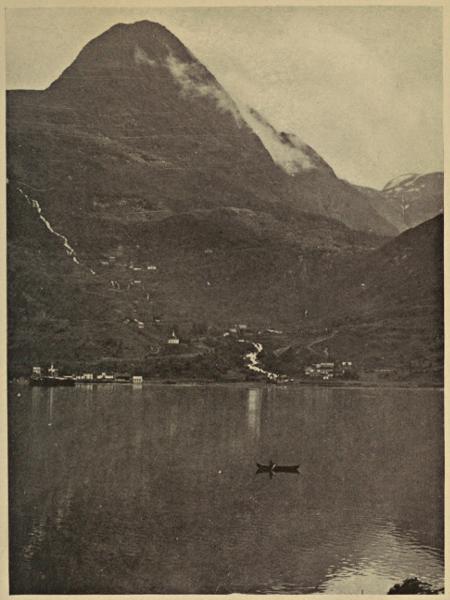

| Across the Glassy Geirangerfjord | 286 |

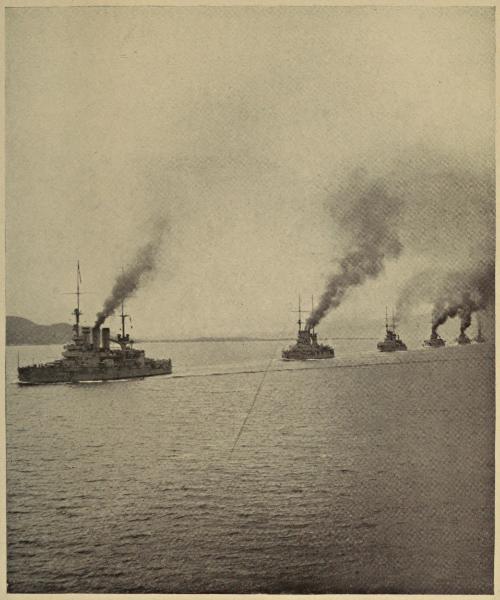

| German Battleships in Norwegian Waters | 292 |

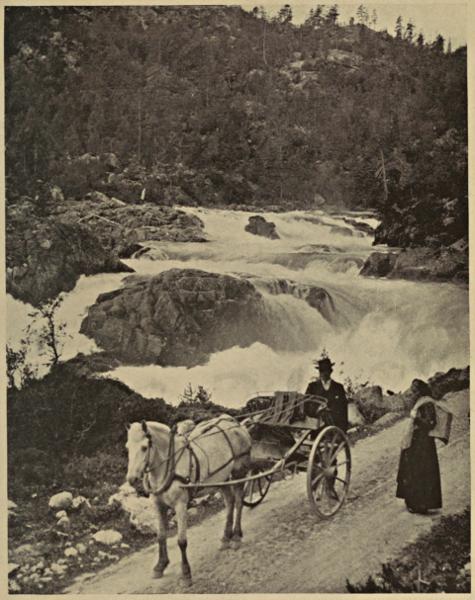

| A Stolkjaerre | 296 |

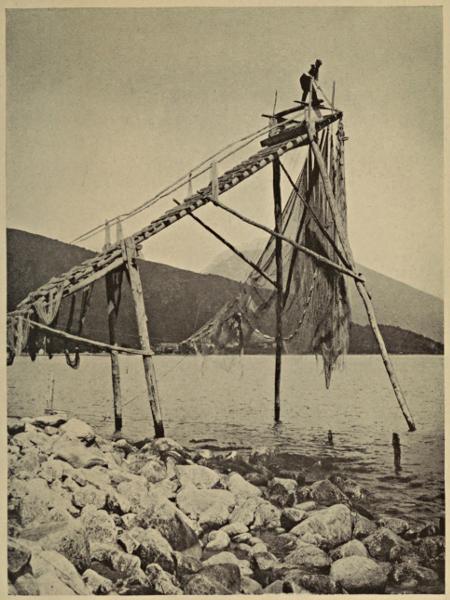

| Fishermen Arranging their Nets at Balestrand on the Sognefjord | 300 |

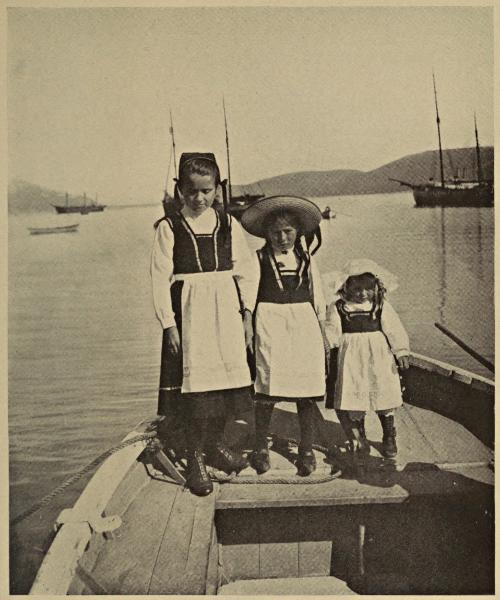

| Three Little Belles of the Arctic at Tromsö | 304 |

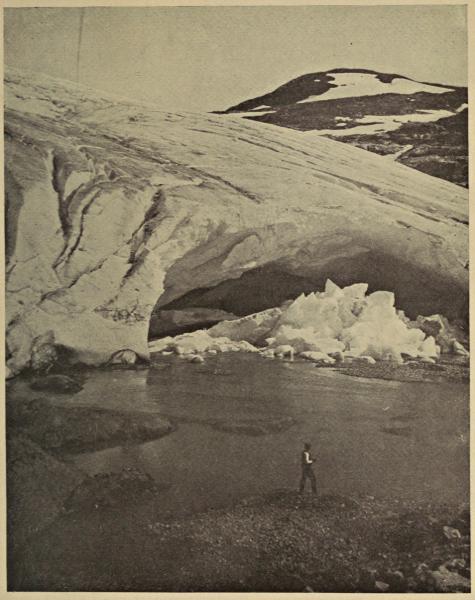

| The Hardanger Glacier and Rembesdal Lake | 308 |

| View from Hammerfest | 310 |

Transcriber’s note: The map is clickable for a larger version.

NORWAY, SWEDEN AND DENMARK

COPYRIGHT, 1914, BY

THE J. N. MATTHEWS CO., BUFFALO, N. Y.

In which Phillips descants on his route to Scandinavia from Berlin; on the gastronomic delights of a Swedish railway restaurant; on the lavish comfort and economy as well as the safety of travel in Sweden; on the quiet charms of the scenery in southern Sweden, as well as on the well-earned social position and independence of the Swedish farmer.

Stockholm, January 1.

My dear Judicia,

You have brought this upon yourself, you know, for it was your proposition that Aylmer and I should try to make you feel the charm of Scandinavia as we have felt it. But do not suppose that we are going to enter upon a contest of wits in order to make our respective countries shine upon the written page, or that we are going to indulge in high-flown descriptions. We shall try to tell you of things as we see them; of the peasant in his low-thatched roof, who is as interesting as the king in his palace. We may not even think it beneath our dignity to tell you of the Smörgåsbörd, and of the different kinds of cheese of many colors which grace the breakfast table, for all these different, homely, commonplace things enter into the spell of Scandinavia.

As you know, we started on this long northern journey at Berlin. This trip has been robbed of all its terrors, since keen competition has compelled the railway and steamboat companies to exchange the little Dampfschiff, little bigger than tugboats, which used to connect Germany with Scandinavia, for great ferry steamers, which take within their capacious maws whole railway trains, so that now we can go to sleep in Berlin, in a very comfortable sofwagn, and wake up the next morning on Swedish soil, with no consciousness of the fact that in the middle of the night we had a four hours’ voyage across a bit of blue sea which is often as stormy as the broad Atlantic itself.

You remember that I wrote you about a former journey across this same bit of water during an equinoctial gale, how our boat was tossed about like a cork, how the port was stove in, and I was washed out of my bunk. Well, last night I was reminded of that former journey by contrast, for I never knew when we were trundled aboard ship at Sassnitz, or when we were trundled on to dry land again at Trelleborg. I was sorry to cross the island of Rügen in the night, for this bit of wind-swept, sea-washed land will always be associated for us with “Elizabeth” and her adventures, though to be sure her German garden was not on Rügen, but on the mainland near by.

However, if I did not know when we passed from Germany to Sweden, it was very evident that we were in a different country when the window curtain was raised in the morning, and the porter informed me[3] deferentially, in his musical Swedish voice, that “caffe and Smörbröd” would be served in the compartment if I wished. Everything is different here. This little four hours’ voyage in the middle of the night seems to have put a wide ocean between the experiences of to-day and yesterday. The brick houses are exchanged for wooden ones. The pine trees which abound in the sandy wastes north of Berlin have been exchanged for graceful white birches, sprinkled with spruce and fir. Instead of the gutturals of the south we hear the open, flowing vowels of the north. Even the signs with which the railway stations are so abundantly plastered that one has difficulty in finding their names, are different from those in Germany, and our attention is called to wholly different brands of beer, whisky, and margarine.

One thing you will rejoice in, I am sure, Judicia, and that is, that I am assured by every responsible authority that railway accidents are almost unknown in Sweden, or at least that the risk is quite infinitesimal. It is said that even in America, which has such an evil reputation for railway smashups, you can travel by rail on the average a distance one hundred and fifty-six times around the world without getting a scratch. I wonder how many thousands of times one would have to travel twenty-five thousand miles in Sweden before the train would run off the track or bump into another train. One would think that the railway accident insurance companies in Sweden would get very little business.

I concluded not to accept the porter’s kind invitation[4] to “caffe and Smörbröd,” for I wanted to indulge at the first opportunity in a genuine Swedish railway restaurant. Think of anticipating with pleasure a railway restaurant breakfast in America or England!

I waited for breakfast until we reached Alfvesta, well on toward noon, and then made the most of the twenty-five minutes generously allowed for refreshments. “Can this be a railway restaurant?” a stranger would say to himself. Here is a bountifully filled table covered with all sorts of viands, fish, flesh, and fowl, and good red herring besides. And around this tempting table a number of gentlemen, hats and overcoats laid aside, are wandering nonchalantly, as though they had the whole day at their disposal; picking up here a ball of golden butter and there a delicate morsel of cheese; from another dish a sardine, or a slice of tongue or cold roast beef, or possibly some appetizing salad. If you would do in Sweden as the Swedes do and not declare your foreign extraction, you, too, will wander around this table in a most careless and casual way, and, when you have heaped your plate with the fat of the land, and spread a piece of crisp rye flatbread thick with fresh and fragrant butter, when you have poured out a cup of delicious coffee reduced to exactly the right shade of amber by abundant cream, then you take your spoil to a side table near by and try to feel as much at leisure in eating it as your Swedish fellow passengers appear to be.

But this is only the beginning. This is just to whet the appetite for what is to come. I counted twenty-seven[5] different dishes on the Smörgåsbörd table from which one might choose; or one might take something from each of the twenty-seven if he so desired. Then comes the real meal: fish and potatoes, meat and vegetables of several different kinds, salad, puddings, and cheese—and to all of these viands you help yourself. No officious waiter hovers over you, impatient for your order and eager to snatch away your plate before the last mouthful is finished, an eagerness only equaled by his rapacious desire for the expected tip. No, the only official in the room is the modest young lady who sits at a table in the far corner, and who seems to take no notice of your coming and going. If you get up a dozen times to help yourself from either end of the table; if you pour out half a dozen cups of coffee, or indulge in a quart of milk from the capacious pitchers, it seems to be no concern of hers. Her only duty is to sit behind the table and take your money when you get through, and a very small amount she takes at that.

If you have “put a knife to your throat,” and have contented yourself with coffee and cakes, the charge will be fifty öre, or thirteen and a half cents. If you have helped yourself, however liberally, only from the cold dishes, the Smörgåsbörd, the charge will be seventy-five öre, or twenty cents, while even the most extravagant meal, where everything hot and cold is sampled, would be but two kronor, or a trifle over fifty cents.

I shall not tell you, Judicia, how much I paid for that particular breakfast, for I know that your first remark[6] would be: “All that in twenty-five minutes, and you a Fletcherite!”

What strikes the uninitiated traveler with wonder and amaze on reaching Sweden is the lavishness of everything and its cheapness. On this table in Alfvesta, for instance, there were great mounds of butter nearly a foot high, instead of the little minute dabs that we see on most continental tables, with which you are supposed to merely smear your bread. The big joints of beef, the great legs of mutton, the bright silver pudding dishes of capacious size, all seem to say to the tourist: “Help yourself, and don’t be stingy.” But elegance is not sacrificed to abundance. Everything is neat and clean. The silver is polished to the last degree. The glasses are crystal clear. You do not have to scrub your plate with your napkin, as is the custom at some continental hotels, and the cooking is as delicious as the food is abundant.

Am I dwelling too long upon these merely temporal and gastronomic features of Sweden? Do you remind me that the charm of a country does not depend upon what we shall eat or what we shall drink? I reply that the first thing for a traveler, like an army, to consider, is the base of supplies. What famous general was that who made the immortal remark that every army marched upon its stomach? Why is not that equally true of a traveler?

But though the dinner table is one of the initial experiences in Sweden, it does not often need to be described. Ex uno disce omnes, and from this one meal[7] you may learn what to expect from Trelleborg on the south to Riksgränsen, some twelve hundred miles farther north, the Dan and Beersheba of Sweden. At every stopping-place, large or small, which the railway time-table kindly marks with a diminutive knife and fork, to show that the needs of the inner man are here met, you will find just such lavish, well-cooked, moderate-priced refreshments. Indeed the favorite English phrase, “cheap and nahsty”, has no equivalent in Swedish, for there is no such thing known. Cheapness does not imply poor quality or slatternly service.

You are reminded of this fact even before you leave Berlin, for a sleeping-car berth which costs more than twelve marks, something over three dollars on the south side of Berlin, costs for a longer distance on the north side, since most of the journey is to be in Sweden, less than six marks, or not quite one half as much, while the compartments are even more comfortable and better fitted. Yes, dear Judicia, Scandinavia is the country for you and me to travel in as well as for the very few other Americans, who, according to European notions, are not millionaires.

When I took my seat again after breakfast at Alfvesta, in the comfortable second-class compartment, we were soon flying, as rapidly as Swedish trains ever fly, which is rarely more than thirty miles an hour, through the heart of southern Sweden, and I had time to refresh my memory concerning this great Scandinavian peninsula, which, as some people think, hangs like a huge icicle from the roof of the world. The icicle idea, however, is[8] entirely erroneous, so far at least as the southern part of Sweden and Norway go. The average temperature is about that of Washington, though it is cooler in summer; and very often in the neighborhood of the west coast, where the Gulf Stream, that mighty wizard of the Atlantic, does its work, there is little snow or ice from one year’s end to another.

This southern section of Sweden is called Gothland, or, literally, the Land of the Gota or Goths, a name which we always couple with the Vandals. Indeed, one of the titles by which the King of Sweden is still addressed at his coronation is “Lord of the Goths and Vandals.” Truly these old Goths and Vandals were the “scourge of God”, as Attila their leader was called, when they sailed away in their great viking ships, carrying their conquests as far as the Pillars of Hercules, and founding colonies and kingdoms along all the shores of Europe, and even across the Mediterranean, in Africa.

Scandinavia, when judged by its square miles, is certainly no mean country. Sweden alone, which claims a little more than half of the great peninsula, is as large as France or Germany, and half as large again as all Great Britain. If we should compare Sweden with some of our own more familiar boundaries, we should see that it is a little larger than California, and not unlike that Golden State in its geographical outlines. We should see also that it is about three times as large as all New England, and more than three times as large as Illinois.

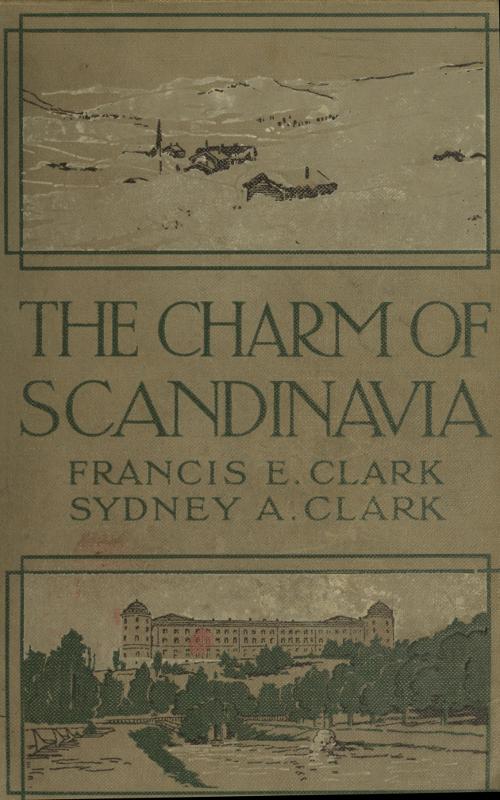

Skikjoring, a Highly Enjoyable Sport.

Skate Sailing, a Favorite Sport in Sweden.

Before I finish this journey I shall have a realizing sense of Sweden’s long-drawn-out provinces, for it takes[9] nearly sixty hours of continuous railway travel to go even as far north as the railway will carry us.

Gothland in the south, Svealand in the center, and Norrland in the north are the three great divisions of Sweden, the latter larger than the other two put together.

From the car window I see many charming sights, even in this wintry season. Indeed I am not sure that Sweden is not quite as lovely in winter as in summer. The red farmhouses, half buried in snow (for the winter is more severe now that we are getting away from the coast); the great stacks of hay that enable the patient cows to chew the cud contentedly through the long winter days; the splendid forests of white birch, the most graceful tree that grows; the ice-locked lakes, and the rushing streamlets that are making their way to the Baltic—all these combine to give us a landscape which is charming in the extreme.

I suppose that Aylmer will surfeit you with eloquent descriptions of far-reaching fjords, mighty mountains, and abysmal cañons when he comes to write about his beloved Norway, but I am sure he will find nothing more peacefully lovely and harmonious than the farmlands of southern and central Sweden. These are the lands, too, which raise not only grass and turnips and sugar beets, but a grand crop of men and women, who are the very backbone of the Swedish commonwealth. More than eighty-five per cent of the land is owned and farmed by its proprietors, and mostly small proprietors at that. Absentee landlordism is little known. A[10] country whose people thus have their roots in the soil has little fear from anarchists and revolutionists.

These peasant proprietors, as they are called, are by no means the dense yokels with which we associate the word “peasant” in many parts of Europe. The peasants of Sweden are simply farmers, and not always small farmers at that, for they sometimes own hundreds of acres. They are farmers who enjoy the daily newspapers and the monthly magazines, whose children all go to school, and who can aspire to the university for their sons and daughters, if they so elect. They are farmers who hold the balance of power among the law-makers of Sweden, and who always have a hundred or more of their own number in the Riksdag, some of whom are among the best orators and debaters in the Assembly. They know that no important piece of legislation to which they are opposed can ever be enacted in Sweden, and they are as proud as the nobility itself of their ancient history, and more tenacious of their ancient privileges.

Honorable W. W. Thomas, for many years the American Minister to Sweden and Norway, and who has written entertainingly concerning the people of the country, which he came to consider his adopted land, tells a good story that illustrates the independence of the Swedish peasant. It is worth quoting to you, as the train rushes by hundreds of just such peasant homes.

“Clad in homespun, and driving a rough farm wagon, this peasant pulled up at a post station in the west of[11] Sweden. There were but two horses left in the stable, and these he immediately ordered to be harnessed into his wagon. Just as they were being hitched up, there rattled into the courtyard in great style the grand equipage of the Governor of the Province, with coachman and footman in livery. Learning the state of affairs, and wishing to avoid a long and weary delay, the coachman ordered these two horses to be taken from the peasant’s cart and harnessed into the Governor’s carriage, but the peasant stoutly refused to allow this to be done.

“‘What,’ said the Governor, ‘do you refuse to permit those horses to be harnessed into my carriage?’

“‘Yes, I do,’ said the peasant.

“‘And do you know who I am,’ quoth the Governor, somewhat in a rage; ‘I am the Governor of this Province; a Knight of the Royal Order of the North Star, and one of the chamberlains of his Majesty the King.’

“‘Oh ho,’ said the peasant, ‘and do you, sir, know who I am?’

“He said this in such a bold and defiant manner that the Governor was somewhat taken aback. He began to think that the fellow might be some great personage after all, some prince perhaps, traveling in disguise.

“‘No,’ said he in an irresolute voice, ‘I do not know who you are. Who are you?’

“‘Well,’ replied the peasant, walking up to him and looking him firmly in the eye, ‘I’ll tell you who I am—I am the man that ordered those horses!’

“After this there was nothing more to be said. The[12] peasant quietly drove away on his journey, and the Governor waited until such time as he could legally procure fresh means of locomotion.”

As I said, I thought of this characteristic story of peasant independence as my train sped by many a comfortable farmhouse, whose occupants, I have no doubt, would defy the authority of the governor, or of the king himself, if he should attempt to trample upon their rights.

But we are now drawing near to Sweden’s capital, and perhaps you will think that this letter is quite long enough for my first promised installment concerning the charms of Sweden.

Faithfully yours,

Phillips.

In which Phillips lauds Stockholm as the most beautiful of European cities; tells the tragic story of the royal palace; remarks casually upon the superabundance of telephones, for which Stockholm is famous; describes the Riksdag and the medieval ceremony of opening Parliament, and comments briefly on the relations of Church and State in Sweden.

Stockholm, January 3.

My dear Judicia,

When last I wrote you, if I remember rightly, I was just approaching Stockholm, after the six-hundred-mile journey from Berlin. It was quite dark, and for that I was not sorry, for Stockholm is so brilliantly lighted that it is almost as beautiful by night as by day. As we approached, the many quays, from which scores of little steamers are constantly darting to and fro, were all picked out by globes of electric light. Old Stockholm, climbing the hill to the left, looked like a constellation of stars in the bright heavens, and the occasional glimpses of broad streets which one gets as he approaches the central station were flooded with the soft glow of the incandescent burners. Nevertheless, beautiful as was the night scene, I was quite impatient for the morning light to reveal the glories of the most beautiful capital of Europe, which I remembered so well, but was none the less anxious to see again.

“The most beautiful capital in Europe!” did I hear[14] you say, Judicia, with a suspicion of skepticism in your rising inflection? “Have you forgotten Paris, and Rome, and Budapest, and Vienna? Are you not somewhat carried away by your desire to make out a good case for Sweden?” No, I cannot plead guilty to any of these charges, which I am sure are lurking in your mind, for ever since my first visit, years ago, I have considered Stockholm, for beauty of situation, for freshness and vigor, and (though this might be disputed) a certain originality of architecture, not only in the first rank of cities, but the first in the first rank. To be sure, it is not as large as many another city, but bigness is not beauty. It has not the picture galleries of Florence, or the antiquities of London, or the palaces of Paris, but it has charms all its own, which, in my opinion, weave about it a spell which no other city possesses.

The morning light did not dissipate the impressions of the evening before, nor the happy memories of the past, for I found that Stockholm had improved in its architecture since my last visit, though its glorious situation can never be improved.

Through half a dozen different channels the waters of the great lake Mälar rush to join the Baltic, for, though the lake is only eighteen inches above the sea, so great is the volume of water that it is always pressing through the narrow channels in swirls and eddies, and it dances forward with an eager joy that gives one a sense of marvelous life and abounding vigor and seems to impart its character to the whole city. Around the city on one side are the stern, fir-clad promontories,[15] the great lake and the black forests to the west, and one can seem to step from the heart of nature’s wilds into the heart of the most advanced civilization. Out toward the Baltic on the east is an archipelago forty miles in length, dotted with islands and headlands, smiling and peaceful in summer, ice-bound and storm-lashed in the winter, but equally beautiful in January or June.

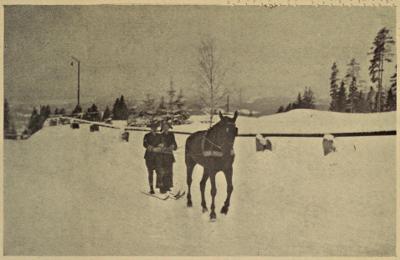

The first building that strikes the eye is naturally the royal palace, which, I must say, to republican eyes, looks square and somber and lacking in ornamentation, but which connoisseurs in palaces say is one of the most beautiful in Europe.

Do you remember my writing you some years ago about my interview with good King Oscar in this old palace? After waiting in the public reception room for a little while I was announced by the lord chamberlain and stepped into a little room leading off the large reception hall, and there, all alone, stood a very tall and very handsome man in a light blue military uniform, with two or three jeweled decorations on his breast. This was Oscar II, by the grace of God, King of Sweden and Norway, of the Goths and Vandals. He bowed and smiled with a most winning and gracious expression, and, coming forward, took me by the hand and led me to a seat on one side of a small table, on the other side of which he seated himself. I do not think it was the glamour of royalty that dazzled my eyes when I wrote of his winning smile. Many others have spoken of his charm of manner, and he was noted as being the most[16] courtly, affable, and gracious monarch that sat upon any throne of Europe.

But alas, the good king has died since my last visit to Stockholm, his later years being embittered by the partition of his kingdom, when Norway decided to set up a king of her own. But though kings may come and kings may go, the grim old palace which has harbored all the rulers of Sweden for eight hundred years still stands on the banks of the tumultuous Mälar.

When the palace was rebuilt, or restored, some two hundred and twenty years ago, it was the scene of a most tragic event. In 1692 Charles XI decided that it was time to remodel the old home of the Swedish kings, which had already stood upon that spot for six centuries. He commanded Tessin, a great architect, who has left his impress upon Stockholm and all Sweden, to rebuild the palace. Accordingly the architect traveled in Italy and France and England to make a study of the best palaces he could find. When his plans were completed, he showed them to Louis XIV of France, who was so much pleased with them that he commanded his ambassador to Sweden to congratulate Charles XI “on this beautiful edifice he was proposing to erect.”

Copyright by Underwood & Underwood, N. Y.

The Royal Palace, Stockholm.

But Charles XI never lived to see the plans carried out. He died after the work had been well begun, and when the scaffoldings surrounded the palace on every side. The work of reconstruction was of course interrupted while the king’s body was lying in state, but just before the funeral procession moved out of the palace a fire broke out, and the whole edifice was destroyed, save[17] the great walls, which are standing to this day. With extreme difficulty the king’s body was saved and carried into the royal stables, where his grandson, a lad fifteen years of age, who was destined to become Charles XII, one of the most famous kings of Sweden, had taken refuge.

A picture in the National Museum makes the scene live over again: the old queen, frightened by the double catastrophe; the boy king, helping his frightened grandmother down the steps, while the tongues of fire leap out at them from behind; the courtiers in hot haste carrying the coffin of the old king, while the little princesses look on with childish interest, scarcely realizing the gravity of the situation.

Again the great architect had to go to work on his task, so sadly interrupted. For thirty years it was pursued, during the days of Sweden’s greatest poverty, and only in 1754, nearly sixty years after Tessin began his work of rebuilding, was it completed, and nearly thirty years after the death of the master builder.

The palace has at least the merit of commodiousness, for we are told that “when King Oscar celebrated his Jubilee in 1897, all his guests, including more than twenty princes and half as many princesses, belonging to all the thrones of Europe, were lodged there with their numerous suites.”

But your republican soul, Judicia, will be more interested in some of the other buildings of Stockholm, perhaps even in the hideous excrescence which towers up above the roofs of the houses, and which shows us where[18] the telephone exchange is situated, to which ten thousand wires, more or less (I did not count them), converge. I should think, however, that it would require at least ten thousand wires to satisfy the rapacious demands of the Stockholmers for telephone service. Every hotel room, even in the modest hostelries, has one, and most of them have two telephones, a city telephone and a long-distance one.

In every little park and open space are two telephone booths, for long and short distances. Stockholm, with a population about the twentieth part of greater London, has nearly twice as many telephones as the British metropolis, and the service is always prompt, cheap, and obliging.

Then there is the great Lift, a conspicuous feature of Old Stockholm, which hoists passengers in a jiffy from the level of the Baltic to the heights of the old town. That, too, would interest you, Judicia, for I remember your strenuous objections to hill-climbing.

To turn from structures, useful but hideous, to one more beautiful, and, shall I say, less useful? there is the Riksdag, a modern building of very handsome and generous proportions, where the law-makers of Sweden assemble, and where, I suppose, rival parties fire hot shot at one another as freely as they do in Washington or London. Every year the Swedish parliament meets in the middle of January and closes its sessions on the fifteenth of May, and this is the one place which the king may not enter, as one of the guardians of the Riksdag proudly informed me. Both houses of Parliament[19] go to him, but he may not return to them. At the opening of Parliament, the legislators assemble in the palace, where the king addresses them, and the medieval ceremony connected with this function is worth telling you about.

After prayers and a special sermon in the cathedral relating to the duties of legislation (a religious custom that reminds us of the old Election Day Sermon of the good State of Massachusetts, a custom now unhappily abolished), the members of the upper and lower houses march into a great hall in the palace, the speakers of the two houses leading the way, and take their seats on either side of the throne. This throne is of solid silver, on a raised platform, and on either side of it are seats for the princes and members of the royal family. The queen and princesses sit in the gallery, surrounded by members of the court. “All sorts and conditions of men are represented—bishops and country clergymen, provincial governors and landed noblemen, freehold peasants, rural schoolmasters, university dons, and industrial kings.”

We are reminded of the past history of Sweden by the uniforms of the military guards, some of whom are in the costume of Charles XII, and others in that of Gustavus III. The courtiers are arrayed in gorgeous uniforms, and their breasts blaze with their many decorations. After the guard and the gentlemen-in-waiting come the princes, in the march to the throne room, and last of all the king himself. He seats himself upon the throne and commences his address, which always begins[20] with the words, “Good Sirs and Swedish Men” and ends with his assurance of good will to all.

The presidents of the two houses respond to the speech of the king. The heads of the departments read their reports and present their budgets. Then, the stately ceremony being over, the gorgeous procession files out in the same order in which it came in, and the two houses proceed to the Parliament Building to begin the work of the new session.

If the fad that prevailed among our novelists a few years ago in finding titles for their stories should ever reach Sweden, I am sure that there would be a novel called “The Man from Dalecarlia,” for he is certainly the most picturesque figure in the Riksdag. In the midst of the sober, black coats and white shirt fronts and patent-leather shoes and top hats, he stands out like a very bird of paradise in his navy blue coat, trimmed with red piping, bright red waistcoat, knee breeches tied with heavy tassels, and bright shoe-buckles. He might have stepped into the Riksdag out of the century before last. But I am glad he has not discarded his national costume, and, whenever I see a Dalecarlian girl on the street in her bright striped apron and piquant cap (and these girls often seek service in Stockholm), I am again grateful for the bit of color which they bring into the gray, wintry streets.

Copyright by Underwood & Underwood, N. Y.

Tea House on Banks of Mälar. In the distance, the Grand Hotel, Stockholm.

Most of the Swedes are decidedly conventional in their costume in these days, and you see more shiny beavers and Prince Albert coats than you would in the streets of London, though it cannot be said that Swedes[21] despise brilliant uniforms on state occasions. At such times the diplomatic representatives of the United States look like crows in a flock of peacocks.

While I am writing you about the government and the court, let me tell you a few words about the church, for Church and State are very closely connected in Sweden. To be sure, there are many free churches—Independent (or Congregational), Baptist, and Methodist—but the prevailing religion, to which I suppose three fourths of the people in the country adhere, is the State Lutheran Church. There are some exceedingly fine churches in Stockholm, though, considering the size of the city, it strikes a visitor that there are surprisingly few. Some of the parishes are very large, and contain twenty or thirty thousand nominal adherents. The Church of the Knights is perhaps the most interesting one, where many of the kings of Sweden, even down to our own time, are buried.

The parish priest is appointed by the king, or consistory, at least nominally, and is paid out of the taxes. Yet there is a good degree of self-government in the churches, for the parish elects the boards of administration of church affairs, and even votes on ministerial candidates. Each candidate has to preach a trial sermon before the congregation, while the king, if it is a royal benefice, as many of the churches are, appoints one of the three candidates who receive the highest number of votes, usually appointing the one who is the candidate of the majority.

It must be even a more trying thing to “candidate”[22] in Sweden than in America, for here it is frankly admitted that the preacher and his sermon are on trial, and there is no polite fiction about an exchange with a brother minister, with a suggestion that the health of the candidate’s wife requires a change of parishes.

I had it in mind, Judicia, to tell you in this letter about certain things less lofty than affairs of Church and State, but must reserve the story for another epistle.

Faithfully yours,

Phillips.

In which Phillips suggests that Stockholm should be called the “Automatic City”; describes the queer statistical animals, called “unified cattle”; extracts some interesting facts from the census; does not consider the stores or the bathtubs beneath his notice; treats of the effective temperance legislation of Sweden, and tells why a fire is so rare an excitement in Stockholm.

Stockholm, January 7.

My dear Judicia,

You know how our American cities often strain themselves to find an appropriate name or nickname by which they shall be known among their sister municipalities. Stockholm is certainly the “Queen City of the North,” and is deserving of any other high-flown title you have a mind to give her. But if we descend to more prosaic designations, we might well call it the “Automatic City.” Nowhere in the world can you drop a penny in the slot and get so much back for it as you can in Stockholm.

The automobile, which abounds everywhere, is an automatic machine which registers in its taximeter the distance run, and thus avoids all disputes with the chauffeur. The telephones, whose little green pagodas dot the city in every direction, are also penny-in-the-slot affairs, and you can talk, as I think I have already told you, with any town on the map of Scandinavia for a very reasonable sum.

But when it comes time for frokost (breakfast), or middag (dinner), then the automat is very much in evidence. It seems at first to the traveler that the keeping of automat restaurants is the chief business in Stockholm, for we find one at almost every corner. Drop a ten öre piece in the slot, and, according to your choice of viands, a glass of milk, a cup of tea or coffee, a cheese sandwich, a sausage, or a boiled egg drops out of the spout. Or, if you wish a more extravagant meal, twenty-five öre (about seven cents) will give you your choice of a dozen hot dishes. One writer with a sense of humor speaks of such establishments as I have described as the “rich man’s automat,” but he is not far from wrong when you compare this establishment with the little wooden buildings which you see in the market squares and along the docks of Stockholm, for this is the automat reduced to its lowest terms for cheapness and simplicity. There is no apparent opening in this wooden box, but a shelf runs around it, and large cups are chained to it, with a tap in the wall at every few feet. Inside is a tank of hot milk. The marketmen drop a five öre piece (a trifle over a cent) into the slot, and out runs nearly a pint of rich, hot milk. No wonder that there are enough cattle to give every man, woman, and child in Sweden on the average one milch cow, or else the “poor man’s automat” could never be maintained at any such figures.

The process of arithmetic, however, by which this milch cow is allotted to every man, woman, and child, is interesting and peculiar, since for the purpose of comparative[25] statistics the Swedish Bureau has invented fictitious animals called “unified cattle.” This is explained by Mr. Sundbarg in his Swedish Land and Folk as follows: The milch cow is the unit, and all other animals the multiples. For instance, a horse is equal to a cow and a third; a sheep is reckoned as a tenth of a cow; a goat as only a twelfth of a cow, while it takes four pigs to make a cow. I cannot for the life of me see why a pig should be worth two and a half sheep; can you? A reindeer is only worth a fifth of a cow, which seems to me altogether too small a value to put upon these indispensable animals of snowland.

Well, the result is that in the last census which is available to me Sweden possessed something over five millions of these composite animals called “unified cattle,” and, as I before told you, every mother’s son and daughter in Sweden, on the average, possesses one milch cow, or it may be three quarters of a horse, ten sheep, twelve goats, four pigs, or five and a half reindeer. If I were a Swede I think I would choose to have my share in reindeer.

While we are dealing with statistics, Judicia, let us have it out and squeeze the census dry of interesting facts and be done with it. How many wealthy persons do you suppose there are among the five and a half millions of Swedes who have not yet crossed the Atlantic to seek a home in the New World? Well, if at your leisure you can find out what 13.75 per cent of five and a half millions is you will know exactly the number of people that can be called “wealthy.” It would not be[26] far from seven hundred thousand. Then in “easy” circumstances we find sixty-seven per cent of the people, or about three and a half millions. In “straightened” circumstances there are rather more than could be called wealthy, while we find that there are only about three per cent of the people who are in genuine poverty and have to receive help from the State or from their richer neighbors.

I think these statistics speak exceedingly well, for the Swedes. Agur’s prayer, “Give me neither poverty nor riches; feed me with food convenient for me,” seems to have been answered for them. Even those in wealthy circumstances are not so enormously rich that they are in danger of losing heaven by such a burden of wealth as would prevent the camel from passing through the eye of the needle.

Since I have told you how many cows, how many fractions of a pig or of a reindeer every Swede possesses, you may also be glad to know that if all the land were divided up evenly every old grandam and every baby in the cradle would have twenty and a half acres. Only two and a quarter acres of these are under cultivation, but he would have nearly ten acres of woodland, which would surely furnish him with enough fuel, while his seven and a half acres of uncultivated land would furnish plenty of pasturage for his cow, or his three-quarters of a horse.

Speaking of fuel, I must launch into a mild eulogy of these Swedish stoves. Even Aylmer will admit that they are better than the air-tight, iron monstrosities[27] which they have in Norway, and in America too, for that matter, where “central heating” has not replaced them. These Swedish stoves are much like the German porcelain heaters, only they are built on a more generous scale. They occupy a whole corner of the room, and often extend from floor to ceiling. Usually they are of white porcelain, though often other colored tiles are used, and sometimes they are highly ornamented with cupids or dragons, or like allegorical animals.

In the morning, quite early, the pretty chambermaid makes a fire of short birch sticks, filling the firebox up to the top. Then the drafts must be left open until all the gases and smoke have escaped, which have such a tortuous course to travel through the many pipes concealed within the porcelain that gradually they heat the great white monument through and through. When the birch is reduced to living coals, the dampers are shut off; the heat is thus retained, and a genial warmth is given out for the rest of the day. Even at night the tilings of the stove are quite warm, and you seldom want more than one “heating” in the course of the twenty-four hours, except in the most extreme weather.

After this little excursion into stoveland, let me return for a moment to our fascinating statistics. It is said that the Swedes are the longest-lived people in the world, and within a hundred years they have reduced the death rate nearly one half. I wonder if this low death rate is not due in part to their cleanly habits. I suppose the fresh, northern mountain air, crisp and frosty in the winter, and the out-of-door life which a[28] people largely agricultural live has much to do with it, but I am also inclined to think that their love of the prosaic bathtub is partly responsible, for I suppose that the Scandinavians, with the exception of the Japanese, and perhaps the Finns, are the cleanliest people in the world.

I have seen a funny picture which represents a school bath. It is a photograph, too. Here is a big school bathroom with a dozen tubs shaped like washtubs setting on the floor, each one occupied by a sturdy little youngster of some ten summers. Each one is industriously scrubbing the back of his next neighbor, while he is immersed up to his middle in the warm water. Over each boy’s head is a shower bath, and if friendly competition does not make the back of each of those boys immaculate I do not know how cleanliness can be achieved.

However much the school tub may have to do with the longevity of the Swede, I know that the blue ribboners would ascribe the increasing span of his years to the temperance law which the last parliamentary half-century has seen enacted and enforced. Sweden once had the sad reputation of being the most drunken country in Europe, and no wonder, for in 1775 Gustavus III made liquor selling and liquor making a State monopoly, and much revenue was derived from intoxicating fluids. The heaviest drinker was the greatest benefactor of the State, for he was thus adding with every dram to the public revenues. Tea and coffee were shut out of the country by the laws, lest some poor toper should prefer[29] them. Beer even was unknown, and wine was rare and costly.

Who do you think was the first man to protest against this wholesale drunkard making? It was no other than Linnæus, the gentle botanist, to whom the world is indebted for naming more plants than Adam ever named. He tried to convince the people of the awful effects of alcoholism upon the national life. After about a decade and a half the government became ashamed of itself and abolished its monopoly. But then things went from bad to worse, for the making and selling of liquor became absolutely free. Everybody who had a little grain made it into whisky. Every large farm had its distillery, and to make drunkards became, not the business of the State, but of everybody who wished to make money.

Thus things went on for some forty years, when the Neal Dow, or more properly the Father Matthew of Sweden, came to the front. This was Canon Wieselgren, who in 1830 began to write and lecture against this awful national evil, and at last, aided by famous men of science, who made exhaustive studies of alcoholism, he brought about a complete and blessed reform in the liquor laws. The tax on whisky was raised so high that private individuals could neither make nor sell it. Local option was allowed, and many communities forbade altogether the sale of liquor. At last the famous Gothenburg system was adopted, and “the monopoly of the manufacture and sale of spirits was given to a company which is allowed to make only a fair rate of interest out[30] of the capital employed, and must hand over the surplus to the community, to be used in the support of such institutions as may tend to diminish the consumption of liquor and combat drunkenness.” The company is guaranteed five per cent on its capital should the sale fall below a certain minimum. This system has the great advantage that it precludes all desire on the part of the company and its retail sellers to increase the sale of drink, as the interest on the capital employed is secured and is not liable to be increased by a larger output.

There are various other regulations which are of interest to all in our country, since the liquor problem is always a burning question. The retail seller must provide food as well as drink, and is not allowed to sell liquor without food, and then only in a small glass to each customer. Youths under eighteen years of age cannot buy, and the retail shops must close at six o’clock. The profits that are made by the company must be used in providing rooms, free libraries, lectures, sports, and games, and it is said that the visitors to the seven reading rooms thus provided in Gothenburg reach half a million every year. Now Sweden and Norway are the most temperate countries in Europe. A drunken man is a rara avis. Crime has diminished in like proportion, as is to be expected.

Let me tell you of one more Swedish phenomenon before I close this letter. During all this visit to Stockholm, and in my previous visits as well, I have never seen a fire engine go tearing through the streets, though[31] one could hardly live for a day in Boston or New York without such an excitement. And yet they have fire engines and horses ready harnessed day and night in Stockholm, and men sleeping in their boots ready to drop down through a hole in the floor on to their seat on the fire engine at any moment. One would think that the men would get tired of waiting for an event that so seldom happens, and that the horses would die for lack of exercise, as they undoubtedly would if they had to wait for a fire to give them a good run.

Do you want to know, Judicia, why the excitement of a fire is so rare in Stockholm? I will tell you, as my friend, Mr. Thomas, the ex-Minister to Sweden, has told me. “Once a year, if you live here, two gentlemen will call on you with book and pencil in hand and carefully examine every stove in your rooms. They also examine all the flues and chimneys. They are officers of the municipality, and the patriarchal government of Stockholm wishes to see that there is no danger of your burning yourself up.”

If they find that your chimneys are foul, a little boy with a sooty face, with white teeth and eyeballs shining through the grime, will wait on you. He will have a rope wound around his neck, with an iron hook on the end, and you must let him go down your chimney and clean out all the soot and cinders. You must also comply with twelve regulations when you build your house, which relate to the material for the walls and the roof, the construction of the cellar, etc., and the house must not be more than sixty-eight feet high. If you think[32] these regulations are too severe, they will at least reduce the size of your insurance bill, for $1.25 will insure your house for $2500 for a year; that is, the premium is a twentieth of one per cent—less than a quarter part of what it would be in America. For $17.50 you may insure your house forever for $1000. If it stands for two hundred years you will never have to pay another cent; so you see there are some advantages, even if there are some annoyances, in a paternal government.

I know your aversion to statistics, my dear Judicia, and in spite of their proverbial dullness it does seem to me rather necessary for one who would feel the deepest charm of Sweden to know something about the characteristics of the Swedes and their comparative standing in matters material and moral with the other nations of Europe. But since, in an early letter, these matters have been disposed of, I can promise you in my next something to which your romantic soul will respond more generously.

Faithfully yours,

Phillips.

Wherein Phillips tells of the many beautiful excursions from Stockholm, and soon takes Judicia into the heart of Dalecarlia, noted for the fertility of its soil and the bright costumes of its maidens. He also rehearses the romantic story of Gustavus Vasa, involving the treacherous cruelty of Christian II and the many hairbreadth escapes of Gustavus, until he roused the Swedes to fight for and win their freedom.

Mora, Dalecarlia, January 10.

My Dear Judicia,

I told you in a former letter, did I not, about the pretty maidens from Dalecarlia whom one often meets in their bright costumes on the streets of Stockholm, as well as the “Member from Dalecarlia,” who relieves the solemn monotony of the Riksdag with his ancient provincial costume. Attracted by these brilliant birds of passage, I am going to take you to-day to the very heart of Dalecarlia, where they live, for it is the most interesting province in all Sweden.

Stockholm has the distinct advantage, not only of being a most interesting city in itself, but of being a center from which you can easily make excursions to any part of Scandinavia, east or west, or north or south; and, believe me, in whichever direction you start you will have no regrets that you did not take some other excursion, for each one has its own peculiar fascination.

A story is told of a young English couple who came[34] to Stockholm for their honeymoon. They thought a week would be sufficient to exhaust the attractions of the city and its environs. Without guide or guide book they started out one morning, taking one of the little steamers, not knowing or caring whither they went or where they would bring up. So delighted were they with this trip that the next day they took another, and the next still another, and so on every day for three months they made a different excursion over the waterways of Sweden, coming back to Stockholm every night; and even then they had not exhausted the possible trips. Indeed there are more than two hundred of these little steamers that ply through the canals and the lakes, and along the Baltic coast. One of the delights of Sweden is its infinite variety.

If it were summer time we would take one of these little steamers along the coast directly north to Gafle; but at this time of year it is more convenient to take the comfortable train, which in a few hours will land us in the very heart of Dalecarlia, or Dalarne, as the Swedes usually call it.

Copyright by Underwood & Underwood, N. Y.

Some Girls of Dalecarlia.

The province has many attractions. Smiling valleys, which one can see even under their blanket of snow must be abundantly productive, are frequently crossed by strong rivers rushing to the Baltic. The Dal especially is a splendid stream, while Lake Siljan, a great sheet of water in the very heart of the province, with peaceful shores sloping gently back from its blue waters on every side, adds the last touch to the sylvan scene. I am writing of it as it is in summer, but I am always in doubt[35] whether these Swedish landscapes are more beautiful in white or green.

The quaint costumes of the Dalecarlians, as you can imagine, add immensely to the interest of the country. It is the only province of Sweden, so far as I know, that retains its ancient dress and glories in it. In some parts each parish has its own peculiar costume, and, as is natural and appropriate, the ladies are far brighter in plumage than the men.

As you know, I am not good at describing a lady’s dress. How often have you upbraided me for not being able to tell you what the bride wore? Let me then borrow the description of a connoisseur in these matters: “Bright bits of color were the maidens we met along the road. The skirts of their dresses were of some dark-blue stuff, except in front. Here, from the waist down, for the space that would be covered by an ample apron, the dress was white, black, yellow, red, and green, in transverse bars about two inches wide. Each bar was divided throughout its entire length by a narrow rib or backbone of red, and these gaudy stripes repeated themselves down to the feet. The waist of these dresses was very low, not much more than a broad belt, and above this swelled out their white chemise, covering the bust and arms, and surmounted with a narrow lace collar around the neck. Outside the collar was a gaudy kerchief, caught together on the breast by a round silver brooch with three pendants. On their heads was a black helmet of thick cloth, with a narrow red rib in the seams. The helmet rose to a point on top, and came[36] low down in the neck behind, where depended two black bands ending in red, woolly globes that played about their shoulders. Under the helmet might be seen the edge of a white kerchief bound about their brows, and beneath the kerchief escaped floods of golden ringlets that waved above bright blue eyes and adown brown, ruddy cheeks. In cold weather the maids and the matrons also wear a short jacket of snowy sheepskin with the wool inside.”

But the greatest charm to me about Dalecarlia is not in the lovely pastoral scenery, or even in the bright costumes and brighter faces of its maidens, but in its noble, soul-stirring history, for here is where Sweden’s Independence Day dawned, and to the devout Swede every foot of the province is sacred soil.

To get fully into this tonicky, patriotic atmosphere we must go around the great lake to Mora, on its northwestern shore. Then we will walk a mile out into the country, for you will not mind a little walk through the snow on a beautiful crisp morning like this, until we come to a square, stone building, which is peculiar in having a large door but no windows. The custodian, who lives near by, unlocks the massive door, and we find on entering that what we have come to see is all underground.

Opening a trapdoor in the center of the building, our guide precedes us down half a dozen steps until we stand on the floor of a small cellar, less than ten feet square and perhaps seven feet high. Here was enacted the homely scene which was the turning point in[37] Sweden’s history. The cackling geese that saved Rome, the spider that inspired Bruce to another heroic effort for Scotland’s freedom, were not more necessary to the story of these nations than was Margit, wife of Tomte Matts Larsson, who placed a big tubful of Christmas beer which she had been brewing over this trapdoor so that the bloodthirsty Danes, who were eagerly searching for Gustavus Vasa, never suspected that he was hidden in the cellar beneath.

But in order to understand the full significance of this rude cellar and the importance to the history of Sweden of Margit’s ready wit, we must go back to Stockholm in imagination and transport ourselves by the same ready means of conveyance back nearly four hundred years to the later months of 1520, when Christian II of Denmark, who was a Christian only in name, was crowned king of Sweden in the Church of St. Nikolaus at Stockholm.

Christian had been provoked by the opposition of the leading Swedes to the union of their country with Denmark and with their attempt to set up a king of their own. At last he determined to crush out all opposition, and with a great army he ravaged the country, conquered the provinces one after the other, and, as we have seen, was at last crowned king in Stockholm.

He appeared to be on especially good terms with the nobles of the country that he had conquered, and invited them all, together with the chief men of Stockholm and the most distinguished ecclesiastics of the country, to the great festivities connected with his coronation.[38] Suddenly, and mightily to their amazement, they all found themselves arrested and thrown into various dungeons on the charge of treason to the king. The city was put in a state of siege. The muzzles of big guns threatened the people at every street corner. But the prisoners were not kept long in suspense. Soon the gates of the palace, in whose dungeons they were confined, were flung open and, surrounded by soldiers and assassins, they were marched to a central square.

First Bishop Matthias was brought forth. “As he knelt with hands pressed together and uplifted as in prayer, his own brother and his chancellor sprang forward to take a last farewell. But at that very moment the headsman swung his broadsword. The bishop’s head fell and rolled on the ground toward his friends, while his blood spurted from the headless trunk.”

One by one the other victims followed—twelve senators, three mayors, and fourteen of the councilors of Stockholm—until, before the sun set on that black Thursday, November 8, 1520, eighty-two of Sweden’s best and noblest men had paid the penalty of their love of freedom and their hatred of tyranny. This was but the beginning. Other outrages followed. The noble ladies of Sweden were carried off to Copenhagen and there thrown into dungeons. This massacre is called in history “Stockholm’s Blood Bath.”

The unchristian Christian by this massacre seems to have merely whetted his appetite for blood, for on his return to Denmark the next month he glutted his insane[39] desire for the lives of his best people by many another murder.

A touching story is told of such a scene in Jönköping. He beheaded Lindorn Rabbing and his two little boys, eight and six years of age. The elder son was first decapitated. “When the younger saw the flowing blood which dyed his brother’s clothes, he said to the headsman, ‘Dear Man, don’t let my shirt get all bloody like brother’s, for mother will whip me if you do.’ The childish prattle touched the heart of even the grim headsman. Flinging away his sword, he cried: ‘Sooner shall my own shirt be stained with blood than I make bloody yours, my boy.’ But the barbarous king beckoned to a more hardened butcher, who first cut off the head of the lad, and then that of the executioner who had shown mercy.”

Do you wonder, Judicia, that the hearts of the Swedes were mad with grief and anger? Yet they seemed utterly cowed, stunned, so terrible were their disasters, and it appeared impossible that help should arise from any quarter.

But Sweden’s darkest day was just before its dawn, and the one who was to accomplish her deliverance from tyrants forever was a young man four and twenty years of age. His father, Erik Johansson, was one of the noblemen whose blood reddened the streets of Stockholm on that awful November day, while his mother and sisters were carried off to languish in the dungeons of Copenhagen. Just as the ax was about to strike its fatal blow, a messenger came in hot haste from the king offering pardon to Erik Johansson, but he would not accept it[40] from such a monster, and he cried out: “My comrades are honorable gentlemen. I will, in God’s name, die the death with them.”

His son, Gustavus, had also been summoned to Stockholm by the king; but he suspected mischief, for he had already been a wanderer for two years in the wilds of Sweden to escape Christian’s wrath, so he did not obey the order. When he heard of the massacre, he at once fled from his hiding-place on the banks of Lake Mälar and sought refuge in Dalecarlia. Here he adopted the costume of the country as a disguise. He put on a homespun suit of clothes. He cut his hair squarely around his ears, and with a round hat, and an ax over his shoulder he started out to arouse the Swedish people to make one more last stand for liberty.

Here in beautiful Dalecarlia he had innumerable adventures. I should have to write a volume if I attempted to tell them all. On one occasion he was let down from a second-story window of a farmhouse by a long towel held by Barbro Stigsdotter, a noble Swedish woman whose husband had taken the side of the king. She deserves a place beside our own Barbara Frietchie, and I wish I were another Whittier to immortalize her. When her dastardly husband returned with twenty Danish soldiers to arrest the young nobleman, Gustavus was nowhere to be found, and we are told that Arendt Persson never forgave his wife this deed.

Another good story is told about Gustavus at Isala not far away. Here the hunted fugitive was warming himself in the little hut of Sven Elfsson, while Sven’s[41] wife was baking bread. Just at this unlucky moment the Danish spies who were searching for him broke into the hut. But with rare presence of mind and noble patriotism, with which Swedish women seem to have been preëminently endowed, she struck him smartly on the shoulder with the long wooden shovel with which she was accustomed to pull her loaves out of the oven, at the same time shouting in a peremptory voice: “What are you standing here and gaping at? Have you never seen folks before? Out with you into the barn!”

The Danish soldiers could not believe that a peasant woman would treat a scion of the nobility like that, and concluded that after all he was not the man they were looking for. Sven himself seems to have been as patriotic as his wife, for when the soldiers had retired for a little he covered Gustavus up deep in a load of straw and drove him out farther into the forest. But the suspicious soldiers could not be so easily put off their scent, and, suspecting that there might be somebody or something of importance under the straw, they stuck their spears into it over and over again. At last, satisfied that there was nothing there, they rode on.

But soon drops of blood began to trickle through the straw upon the white snow, and in order to allay the suspicions of the Danes, who might come up with him at any moment, Sven gashed his horse’s leg, that they might suppose that the blood came from the animal and not from anything concealed in his sledge. At Isala to-day we see the barn of good Sven Elfsson, and just in front of it a monument telling of Gustavus’ hairbreadth[42] escape. Fortunately the wounds received by him under the straw were not serious, and after many days and many adventures he reached Lake Siljan and the little village of Mora, where we first saw him concealed in Larsson’s cellar, over whose door good Margit had put her tub of Christmas beer.

Christmas Day came at last in the sad year of 1520, as it has in many a glad year since for the people of Sweden, and the Dalecarlians flocked to the church at Mora. After the church service, as they streamed along the road to their homes, a young man of noble mien suddenly mounted a heap of snow by the roadside and in burning words, made eloquent and forceful not only by his bitter indignation but by his terrible sufferings as well, he rehearsed the perfidy and cruelty of the Danes, and urged the Swedes to assert their rights as free men and save their country.

But the people were tired of fighting and overawed by the savage Christian and his myrmidons, and they begged him to leave them in peace. The poor young nobleman had exhausted his resources; he had fired his last shot, and so in despair of arousing the people to fight for freedom, since in Dalarne of all the provinces he expected to find the spirit of liberty not quite dead, he fastened his long skis on his feet, took a staff in his hand, and disappeared into the forest.

Copyright by Underwood & Underwood, N. Y.

Where Gustavus Adolphus Rests among Hard-Won Battle Flags.

Day after day he made his solitary way through the woods and over the snow fields, for he knew that the spies of Denmark were on his track. He had almost approached the borders of Norway, where he intended to[43] seek an asylum, when he heard a sound of approaching runners, and then the glad cry, which must have sounded like music in his ears: “Come back, Gustav; we of Dalecarlia have repented. We will fight for Fatherland if you will lead us.” We can imagine how gladly he responded and how eagerly he returned with the two ski-runners to Mora. Here the people elected him “lord and chieftain over Dalarne and the whole realm of Sweden.”

As a snowball grows in size as it rolls down the hill until it becomes an irresistible avalanche, so the peasants of Sweden gathered around Gustavus, sixteen at first, then two hundred. In a month there were four hundred, and he had won his first victory at Kopparberget. There he spoiled the Egyptians and divided the spoil among his followers, which of course did not diminish his popularity. Soon the four hundred grew to fifteen hundred, and the hundreds became thousands.

But the Danes were not to give up without a struggle. Six thousand men were sent out against the patriots, who had now mustered five thousand men to oppose them on the banks of the river Dal, on the edge of the province nearest to Stockholm. The Danes were mightily surprised when told that the Swedes were so determined to win that they would live on water and bread made from the bark of trees. One of their commanders cried out: “A people who eat wood and drink water, the devil himself cannot subdue, much less any other.”

The Danes were utterly defeated, their morale very likely being affected by these terrible stories of the wood-eating[44] Dalecarlians. Some of them were driven into the river and drowned, and the rest flew helter-skelter, broken and defeated, back to their headquarters. Of course the war was not entirely over, but the young hero knew no defeat, and finally, on June 23, 1523, on Midsummer’s Eve, which is a holiday in Sweden second only to Christmas, Gustavus Vasa, who had been unanimously elected king by the Riksdag, rode triumphantly into his nation’s capital.

He showed his religious character by going first to the cathedral, where he kneeled before the high altar and returned thanks to Almighty God; and here in my story I may well leave the man who freed his country from the Danish yoke—the George Washington of Sweden.

You are such a stanch patriot, Judicia, and such a hater of tyrants, dead or alive, that I know I need not apologize for writing somewhat at length of this glorious period in Swedish history.

Faithfully yours,

Phillips.

Wherein are described the glories of an Arctic winter; the comfort of traveling beyond the polar circle (with a brief philological excursion); the inexpressible beauties of the “European Lady of the Snows”; the unique railway station of Polcirkeln, and the regions beyond.

Kiruna, Lapland, January 15.

My dear Judicia,

I wonder if you remember how I wrote you some years ago about a journey I made toward the arctic circle in midwinter, and how enraptured I was with the still, cold days, the wonderful frosty rime on every bush and fence rail, and the dawn and twilight glories of the low-running Arctic sun.

Well, finding myself in Sweden again in winter, I resolved to push my explorations a little farther toward the North Pole and to enjoy once more, if possible, one of the most delightful experiences of my life. The former journey was made about the middle of February, if I remember rightly, and certain engagements obliged me to turn my face southward before I had nearly reached the “farthest north” which I longed for. This time I resolved that I would not be robbed of a single zero joy, but would, if possible, catch the sun napping; that is, that I would get beyond that degree of latitude where for days at a time he never shows his face above[46] the rim of the horizon, and where the mild-mannered moon almost rivals his power at midday.

In order to do this, and to find the sun hibernating, I had to leave Stockholm early in January, for, though he goes to bed in many parts of Lapland late in November, he rises and shakes out his golden locks before the middle of January, unless you go to the most northern point of Scandinavia, and then you get out of Swedish Lapland into Norway. So you see I had no time to lose, if I would catch the sun in bed, and must leave other charms of Sweden in winter as well as in summer for later letters.

To go far beyond the arctic circle in winter is not much to brag about in Sweden, for you can make the journey quite as comfortably as you can go from New York to Chicago, and the distance, by the way, from Stockholm to Kiruna is about the same.

Do not suppose, however, that we have any “Twentieth Century Limited” in this part of the world. The Lapland flier takes about thirty-eight hours to make the distance, but one need have no fear of dashing into another flier at the rate of fifty miles an hour, for the Lapland express runs only three times a week in either direction.

A Typical Swedish Landscape in Winter.

Though the speed is not hair-raising, the accommodations are all that could be desired. Only second and third-class cars are run on most of the roads of Sweden, though, by a polite fiction, you can buy a first-class ticket if you insist upon it. If you are “a fool, a lord, or an American,” you may possibly do so, in which case[47] you will pay the combined fare of a second and third-class ticket. The guard will put you in a second-class compartment just the same as those of your fellow travelers and paste up on the window the words “First Class.” It is said that at the same time he sticks his tongue in his cheek and winks derisively at the brakeman.

I cannot vouch for this fact, for I have never bought a first-class ticket in Sweden, and I never should, even if I had money “beyond the dreams of avarice,” as the novelist would say. For the second-class compartments are entirely comfortable, upholstered in bright plush, with double windows and ample heat, which each traveler can turn on or off for himself, a little table on which to put your books and writing materials, a carafe of fresh water, which is changed several times a day, and a crystal-clear tumbler. What more can you ask? To be sure your privacy is more likely to be invaded than if you are a “first-class” snob, and you may sometimes have as many as three other people in your compartments, which easily accommodates six. But to see the people and hear them, even if you cannot understand their tongue, is part of the joy of traveling, and the Swedish language is so musical with its sing-song rhythm that it never grates upon the ear, and if one is disposed for a nap it will quite lull him to sleep.

My friend, ex-Minister Thomas, has so admirably described one inevitable and absolutely unique Swedish expression that I think I must quote for you his sprightly account of it. “Should you ever hear two persons talking in a foreign tongue,” he says, “and are in doubt[48] as to what nation they belong, just listen. If one or the other does not say ‘ja så,’ within two minutes, it is proof positive they are not Swedes. There is the ‘ja så’ (pronounced ya so) expressing assent to the views you are imparting, ‘just so’; the ‘ja så’ of approval and admiration, with a bow and a smile; the ‘ja så’ of astonishment, wonder, and surprise at the awful tale you are unfolding. Now the Swede’s eyes and mouth become circles of amazement, and he draws out his reply, ‘ja so-o-o-o-o-o-o!’ There is the hesitating ‘ja så’ of doubt; the abrupt ‘ja så, ja så!’ twice repeated, which politely informs you that your friend does not believe a word you are saying; the ‘ja så’ sarcastic, insinuating, and derogatory; the fierce ‘ja så’ of denial; the enraged ‘ja så,’ as satisfactory as swearing; the threatening ‘ja så,’ fully equivalent to ‘I’ll punch your head’; and the pleasant, purring, pussycat ‘ja så,’ chiefly used by the fair—a sort of flute obligato accompaniment to your discourse, which shows that she is listening and pleased, and encourages you to continue. And other ‘ja sås’ there be, too numerous for mention. I am inclined to think there is not an emotion of the human soul that the Swedes cannot express by ‘ja så,’ but the accent and intonation are different in every case. Each feeling has its own peculiar ‘ja så,’ and there be as many, at least, as there are smells in Cologne, which number, the most highly educated nostrils give, if I mistake not, as seventy-three.”

Some other phrases in Swedish are almost equally useful, and if we should hear a fellow traveler say[49] lagom over and over again we would know that somebody or something was “just about right,” though we might not be able to determine from the context whether he was referring to the scenery, to his wife’s disposition, or to the frokost which he enjoyed at the last railway station.

Another very useful Swedish word, which it is a pity we cannot introduce into our English vocabulary, is syskon. This is a collective noun, referring to brothers and sisters alike and embracing all of them that belong to one family. As “parents” refers to both father and mother, so syskon means all the brothers and sisters of the family.

However, if I keep on with this rambling philological discussion I shall not get you to Kiruna, my dear Judicia, even within the thirty-eight hours which the Swedish time-table allows. I must tell you though that, since this is a journey of two nights and parts of two days, the “lying down” accommodations are quite as important as those for sitting up. But for five crowns additional, or about $1.30, you can secure a comfortable berth, nicely made up in your compartment, with clean linen.

The black porter with his whisk brush is not at all in evidence, for there is no dust in these trains, at least in winter time, and the white porter who makes up your bed, who is, I suspect, also a brakeman, is never seen except night and morning, when he makes and unmakes it. When you alight you never hear the familiar phrase, “Brush you off, sah?” and you have to search for your[50] bed-maker if you desire to slip a kroner into his hand—a piece of superogatory generosity which quite surprises him.

Something over an hour after leaving Stockholm on our journey north we came to the famous old university city of Upsala, but I could not stop here if I wished to see the Midday Moon, and shall have to go back at some future day in order to tell you about this most interesting historic town in Sweden, the burial place of Gustavus Vasa and the depository of one of the world’s chief philological treasures, the Codex Argenteus.

The Lapland express leaves Stockholm at 6.30 in the evening, which at this time of the year is several hours after dark, and it was not until the next morning, between nine and ten o’clock, that the landscape became visible; yet the first signs of dawn come wonderfully early in these northern latitudes, considering how near we are to the land of perpetual night. By eight o’clock in the morning one has a suspicion that the sun is somewhere far, far below the horizon. By nine o’clock the suspicion deepens into a certainty, and by ten o’clock on your side of the arctic circle, where I found myself early on the morning after leaving Stockholm, the tiniest rim of the sun may be seen peering above the horizon, as though uncertain whether it were worth while to go the rest of the way or not.