London. Henry Colburn, 1846.

Title: Memoirs of the Reign of King George the Second, Volume 1 (of 3)

Author: Horace Walpole

Editor: Baron Henry Richard Vassall Holland

Release date: April 21, 2018 [eBook #57016]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MWS, John Campbell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of each chapter.

The Appendix has sections marked B to K; there is no section A, and no section J.

As the Editor notes in his Preface, “Some, though very few, coarse expressions, have been suppressed by the Editor, and the vacant spaces filled up by [3 or 4] asterisks.” A few names have been editorially omitted; these are sometimes indicated by —— and sometimes by ****.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

MEMOIRS

OF THE REIGN OF

KING GEORGE THE SECOND.

BY

HORACE WALPOLE,

YOUNGEST SON OF SIR ROBERT WALPOLE, EARL OF ORFORD.

EDITED, FROM THE ORIGINAL MSS.

WITH A PREFACE AND NOTES,

BY THE LATE

LORD HOLLAND.

Second Edition, Revised.

WITH THE ORIGINAL MOTTOES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

HENRY COLBURN, PUBLISHER,

GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET.

1847.

The work now submitted to the public is printed from a Manuscript of the late Horace Walpole, Earl of Orford.

Among the papers found at Strawberry Hill, after the death of Lord Orford, was the following Memorandum, wrapped in an envelope, on which was written, “Not to be opened till after my Will.”

“In my Library at Strawberry Hill are two wainscot chests or boxes, the larger marked with an A, the lesser with a B. I desire, that as soon as I am dead, my Executor and Executrix will cord up strongly and seal the larger box, marked A, and deliver it to the Honourable Hugh Conway Seymour, to be kept by him unopened and unsealed till the eldest son of Lady Waldegrave, or whichever of her sons, being Earl of Waldegrave, shall attain the age of twenty-five years; when the said chest,[vi] with whatever it contains, shall be delivered to him for his own. And I beg that the Honourable Hugh Conway Seymour, when he shall receive the said chest, will give a promise in writing, signed by him, to Lady Waldegrave, that he or his Representatives will deliver the said chest unopened and unsealed, by my Executor and Executrix, to the first son of Lady Waldegrave who shall attain the age of twenty-five years. The key of the said chest is in one of the cupboards of the Green Closet, within the Blue Breakfast Room, at Strawberry Hill, and that key, I desire, may be delivered to Laura, Lady Waldegrave, to be kept by her till her son shall receive the chest.

(Signed) “Hor. Walpole, Earl of Orford.

“August 19, 1796.”

In obedience to these directions, the box described in the preceding Memorandum was corded and sealed with the seals of the Honourable Mrs. Damer and the late Lord Frederick Campbell, the Executrix and Executor of Lord Orford, and by them delivered to the late Lord Hugh Seymour, by whose Representatives it was given up, unopened and unsealed, to the present Earl of Waldegrave, when he attained the age of twenty-five. On examining the[vii] box, it was found to contain a number of manuscript volumes and other papers, among which were the Memoirs now published.

Though no directions were left by Lord Orford for the publication of these Memoirs, there can be little doubt of his intention that they should one day or other be communicated to the world. Innumerable passages in the Memoirs show they were written for the public. The precautions of the Author to preserve them for a certain number of years from inspection, are a proof, not of his intention that they should remain always in the private hands of his family, but of his fears lest, if divulged, they might be published prematurely; and the term fixed for opening the chest seems to mark the distance of time when he thought they might be made public without impropriety. Ten years have elapsed since that period, and more than sixty years since the last of the historical events he commemorates in this work.[1] No man is now alive whose character or conduct is the subject of praise or censure in these Memoirs.

The printed correspondence of Lord Orford contains allusions to this work. In a letter written in[viii] 1752,[2] he informs Mr. Montagu, that “his Memoirs of last year are quite finished,” but that he means to “add some pages of notes that will not want anecdotes;” and in answer to that gentleman,[3] who had threatened him in jest with a Messenger from the Secretary’s Office to seize his papers, after a ludicrous account of the alarm into which he had been thrown by the actual arrival of a King’s Messenger at his door, he adds, “however, I have buried the Memoirs under the oak in my garden, where they are to be found a thousand years hence, and taken, perhaps, for a Runic history in rhyme.”

The Postscript, printed in this edition at the end of the Preface, but annexed by the Author to his Memoirs of the year 1751, evidently implies, that what he had then written was destined for publication. It is addressed in the usual style of an author to his reader, and contains an answer to objections that might be made to him. In this answer or apology for his work he justifies the freedom of his strictures on public men, vindicates the impartiality of his characters and narrative, claims the merit of care and fidelity in his reports of parliamentary proceedings, and explains the sources of information from which he derived his knowledge [ix]of the many private anecdotes and transactions he relates.

In the beginning of his Memoirs of 1752, he again speaks of his work as one ultimately destined for the public. “I sit down,” he says, “to resume a task, for which I fear Posterity will condemn the Author, at the same time that they feel their curiosity gratified.”

Many other passages might be quoted that imply he wrote for Posterity, with an intention that at some future time his work should be given to the public. “These sheets,” he remarks, “were less intended for a history of war than for civil annals. Whatever tends to a knowledge of the characters of remarkable persons, of the manners of the age, and of its political intrigues, comes properly within my plan. I am more attentive to deserve the thanks of Posterity than their admiration.”—“I am no historian,” he observes in another place; “I write casual memoirs, I draw characters, I preserve anecdotes, which my superiors, the historians of Britain, may enchase into their mighty annals, or pass over at pleasure.”—“To be read for a few years is immortality enough for such a writer as me.”—“Posterity, this is an impartial picture.”

At the conclusion of his Memoirs of 1758, where[x] the Author makes a pause in his work, and seems uncertain whether he should ever resume it or not, he again addresses himself to his readers in the style of an author looking forward to publication. If he should ever continue his work, he warns his readers “not to expect so much intelligence and information in any of the subsequent pages as may have appeared in the preceding.”—“During the former period,” he goes on to observe, “I lived in the centre of business, was intimately acquainted with many of the chief actors, was eager in politics, indefatigable in heaping up knowledge and materials for my work. Now, detached from these busy scenes, with many political connexions dropped or dissolved, indifferent to events, and indolent, I shall have fewer opportunities of informing myself or others.”

He then proceeds to give a character of himself, and to “lay open to his readers his nearest sentiments.” He acknowledges some enmities and resentments, confesses that he has been injured by some, and treated by others with ingratitude, but assures his readers, as he probably thought himself, that he has written without bias or partiality, “that affection and veneration for truth and justice have preponderated above all other considerations,”[xi] and that when he has expressed himself of particular men with a severity that may appear objectionable, it was “the unamiableness of the characters he blames that imprinted the dislikes,” to which he pleads guilty. Can it be supposed, he asks, that “he would sacrifice the integrity of these Memoirs, his favourite labour, to a little revenge that he shall never taste?” Whatever may be thought of the soundness of this reasoning, and whatever opinion may be formed of the impartiality of his work, it seems impossible that anything short of a positive injunction to commit his Memoirs to the Press could have conveyed a stronger indication of the intention and desire of the Author, that, at some future period after his decease, this his favourite labour should be communicated to the public.

The extraordinary pains taken by Lord Orford to correct and improve his Memoirs, and prepare them for publication, afford no less convincing proof of his intentions in the legacy of his work. The whole of the Memoirs now published have been written over twice, and the early part three times. The first sketches or foul copies of the work are in his own hand-writing; then follows what he calls the corrected and transcribed copy, which is also[xii] written by himself; and this third or last copy, extending to the end of 1755, is written by his secretary or amanuensis, Mr. Kirkgate, with some corrections by himself, and the notes on the blank pages, opposite to the fair copy, entirely in his own hand. This last copy was bound into two regular volumes, with etchings from designs furnished by Bentley and Muntz, to serve as a frontispiece to the whole work, and as head-pieces for each chapter, explanations of which were subjoined at the end.

So much for the authenticity of the present work, and obvious intention of the Author that after a sufficient lapse of years it should be published. Of the Author himself, so well known by his numerous publications, little need be said, except to give the dates of his entrance into Parliament, and of his retirement from public life, with some few observations on his political character and connexions.

Horace Walpole, afterwards Earl of Orford, was third son of the celebrated Sir Robert Walpole. He was born on the 5th of October, 1717, and brought into Parliament in 1741, for the borough of Callington. At the general election in 1747, he was returned a second time for the same borough; and in 1754 he came into Parliament for Castle[xiii] Rising. On the death of his uncle, Lord Walpole, of Wolterton, in 1757, he accepted the Chiltern Hundreds, in order to succeed his cousin, become Lord Walpole, in the representation of Lynn Regis, “the Corporation of which had such reverence for his father’s memory, that they would not bear distant relations while he had sons living.”[4] At the general election for 1761, he was again returned for Lynn without opposition; but being threatened with a contested election, and heartily tired of politics, from which he had in a great measure withdrawn after the accession of his friends to office in 1765, he voluntarily retired from Parliament in 1768. In 1791 he succeeded his nephew as Earl of Orford, and died on the 2nd of March, 1797, in the eightieth year of his age.

The House of Commons, in which Mr. Walpole first sat, was the one that overturned his father’s Administration. In the very first week of the session, the Minister was left in a minority. He still, however, kept his place, and so nearly were parties balanced, that for two months he maintained, with alternate victories and reverses, a contest with his adversaries. At length, secretly betrayed by some of his colleagues, who had entered into private engagements[xiv] with his enemies, and defeated in an election question, which had been made a trial of strength between Ministry and Opposition, he retired from office, and became Earl of Orford.

His son Horace, though exempt from ambition, was roused by his father’s danger, and, while the struggle lasted, took a lively interest in all that passed. In his letters, he gives an entertaining and not uncandid account of the Debates that took place, and communicates freely to his Correspondent the hopes and fears, the good and bad success of his party; his anticipations of their strength in the different questions as they arose, are followed by his explanations of their failures, as far as he could account for them at the time; the desertion and falling off of their friends are stigmatized as they occurred, with the severity such conduct deserved; and when Sir Robert was compelled to resign, his son records with satisfaction the successful efforts used to secure him from the vengeance of his enemies, by disuniting the parties coalesced against him, and rendering them odious to the public, and hostile to one another.

But, though assiduous in his attendance on Parliament during this period, and sincerely anxious for his father, Mr. Walpole, who had no turn for[xv] public speaking, once and once only addressed the House. It was on a motion of Lord Limerick, seconded by Sir John St. Aubin, to appoint a Committee of Inquiry into the conduct of Robert, Earl of Orford, during the last ten years of his Administration.[5] A similar motion to inquire generally into the conduct of affairs at home and abroad for the last twenty, had been made and rejected a fortnight before.[6] The selection of this occasion for his maiden speech, did credit to the judgment and feelings of Mr. Walpole; and, though there is little force in his arguments against the motion, there is modesty, right feeling, and some happiness, both of thought and expression, in what he said. The speech, as he delivered it, is preserved in his Correspondence; and as it has no sort of resemblance to the speech published in his name by the London Magazine, and since reprinted in the Parliamentary History, we subjoin it for the satisfaction of our readers. The report of it, given by Mr. Walpole himself the day after it was made, is as follows:—

“Mr. Speaker,

“I have always thought, Sir, that incapacity and inexperience must prejudice the cause they undertake to defend; and it has been diffidence of myself, [xvi]not distrust of the cause, that has hitherto made me so silent upon a point on which I ought to have appeared so zealous.

“While the attempts for this inquiry were made in general terms, I should have thought it presumption in me to stand up and defend measures in which so many abler men have been engaged, and which, consequently, they could so much better support: but when the attack grows more personal, it grows my duty to oppose it more particularly; lest I be suspected of an ingratitude, which my heart disdains. But I think, Sir, I cannot be suspected of that, unless my not having abilities to defend my father can be construed into a desire not to defend him.

“My experience, Sir, is very small; I have never been conversant in business and politics, and have sat a very short time in this House. With so slight a fund, I must mistrust my power to serve him, especially as in the short time I have sat here, I have seen that not his own knowledge, innocence, and eloquence, have been able to protect him against a powerful and determined party. I have seen, since his retirement, that he has many great and noble friends, who have been able to protect him from farther violence. But, Sir, when no repulses[xvii] can calm the clamour against him, no motives should sway his friends from openly undertaking his defence. When the King has conferred rewards on his services; when the Parliament has refused its assent to any inquiries of complaint against him, it is but maintaining the King’s and our own honour to reject this Motion, for the repeating which, however, I cannot think the authors to blame, as I suppose, now they have turned him out, they are willing to inquire whether they had any reason to do so.

“I shall say no more, Sir, but leave the material part of this defence to the impartiality, candour, and credit of men who are no ways dependent on him. He has already found that defence, Sir, and I hope he always will. It is to their authority I trust; and to me it is the strongest proof of innocence, that for twenty years together no crime could be solemnly alleged against him; and, since his dismission, he has seen a majority rise up to defend his character, in that very House of Commons in which a majority had overturned his power. As, therefore, Sir, I must think him innocent, I must stand up to protect him from injustice—had he been accused, I should not have given the House this trouble; but I think, Sir, that the precedent of what[xviii] was done upon this question a few days ago, sufficient reason, if I had no other, for me to give my negative now.”

This speech of a son, in defence of his father, appears to have been well received by the House. Mr. Pitt, who was at that time one of the most violent against Lord Orford, said in reply, “How very commendable it was in Mr. Walpole to have made the above speech, which must have made an impression on the House; but, if it was becoming in him to remember that he was the child of the accused, the House ought to remember, too, that they are the children of their country.” “It was a great compliment from him,” adds Mr. Walpole, “and very artful, too.” The Motion was carried by a majority of 252 to 245. Nothing was made of the inquiry.

For many years after the fall of Lord Orford, Mr. Walpole took an active part in all the political intrigues and dissensions of the times. Though he had not been treated, as he frequently hints, with any great kindness or indulgence by his father, he was indignant at the persecution against him, and appears to have been warmly and affectionately attached to his memory. In his private correspondence,[xix] he continually alludes to the mild and prudent policy of Sir Robert, and contrasts it with the violence and rashness of succeeding Ministers; and, as he advanced in life, these impressions became stronger, and recur more frequently in his writings. His political connexions were originally with his father’s friends; and for many years he appears to have indulged in sentiments of bitter hostility towards his enemies. When any of them were guilty of tergiversations, either in their public conduct or political friendships, he never fails in his correspondence to mark their perfidy and inconsistencies, and seems to enjoy with delight their apostasy and disgrace. But after a certain time he became less inimical to their persons, though to the end of his life he never ceased to blame their persecution of his father, which, indeed, many of them subsequently acknowledged to have been unmerited and unjust.

At the time when these Memoirs commence, the resentments he retained on his father’s account were directed less against the enemies who had openly opposed, than against the friends who had secretly betrayed and deserted him. He appears, for instance, to have been reconciled very speedily to Lord Granville, and ultimately to have become a[xx] warm admirer of Mr. Pitt. But against the Pelhams and Lord Hardwicke, whom he repeatedly and unequivocally charges with treachery to his father, his resentment was implacable.[7] In the early part of his public life, his chief political friends appear to have been Mr. Winnington and Mr. Fox. For the former, who died in 1746, his admiration was unbounded.

In his Memoirs, indeed, where in no instance but one he ever confers praise unmixed with censure, he bestows on Mr. Winnington the character of being one “whom it was impossible to hate or to trust;” and, in a subsequent passage, he describes him “as perniciously witty, affecting an honesty in avowing whatever was dishonourable.” But, in[xxi] his private correspondence, written immediately after the sudden and melancholy death of Mr. Winnington,[8] he calls him one of the first men in England, and adds, “I was familiarly acquainted with him, loved and admired him, for he had great good-nature, and a quickness of wit most peculiar to himself; and for his public talents he has left nobody equal to him, as before nobody was superior to him but my father.”

With Mr. Fox he appears to have lived on the most confidential terms, till that gentleman accepted the Seals in 1755 under the Duke of Newcastle. Mr. Walpole, whose inveteracy to the Pelhams was unabated, could not pardon in his father’s friend, a connexion with the man whom he regarded as the chief traitor in the accomplishment of his father’s ruin. The step too was taken without consulting him. This added to his indignation; and from that time, though he continued in habits of intimacy with Mr. Fox, he became cold to his interests, and, by his own account, was, on one important occasion, active and successful in traversing his designs.

He was, in truth, during the whole of his public life, too much under the guidance of personal feelings[xxii] and resentments, and too apt to sacrifice his friendships to his aversions; and as the latter were often excited by trivial and accidental causes, his political conduct, though unexceptionable on the score of interest or ambition, was fluctuating and uncertain, and his judgment of men variable and capricious. The affair of Admiral Byng, in which he took a part that does credit to his feelings and humanity, completed his estrangement from Mr. Fox. He animadverts with great severity on the cruelty of obstructing an irregular application for mercy with the view of embarrassing an Administration. The questionable conduct of Mr. Fox on that occasion seems to have deserved some such censure; but Mr. Walpole betrays his own partiality by the comparative tenderness with which he treats the Ministers themselves. They had it in their power to save Admiral Byng, and justice as well as humanity required them to exert it if they thought him either injured or innocent. Yet they chose to sign the warrant for his execution rather than incur the odium with the King or the public of insisting on his pardon.

About the time of his separation from Mr. Fox, Mr. Walpole appears to have lost the influence he had acquired over the Duke of Bedford through[xxiii] the intervention of Mr. Rigby; and during the latter part of these Memoirs, detached from all political intimacies, he seems to have had no better means of information than might have been possessed by any other industrious and attentive member of the House of Commons.

On the merits of the present work it would be improper to enlarge in this place. That it contains much curious and original information will not be disputed. The intimacy which the Author enjoyed with many of the chief personages of the times, and what he calls, “his propensity to faction,” made him acquainted with the most secret intrigues and negotiations of parties; and where his resentments did not cloud his judgment, his indifference to the common objects of ambition rendered him an impartial spectator of their quarrels and accommodations. The period of which he treats was not distinguished by splendid virtues or great vices, by extraordinary events or great revolutions; but it is a part of our history little known to us, and not undeserving our curiosity, as it forms the transition from the expiring struggles of Jacobitism to the more important contests that have since engaged, and still occupy our attention.

The account of Parliamentary Debates in these[xxiv] Memoirs would alone be a valuable addition to our history. No one is ignorant, that from the fall of Sir Robert Walpole to the American war, our reports of the proceedings in Parliament are more barren and unsatisfactory than at any period since the reign of James the First. For the last ten years of George the Second, Mr. Walpole has supplied that deficiency in a manner equally entertaining and instructive. His method was to make notes of each speaker’s argument during the Debate, and frequently to take down his expressions. He afterwards wrote out the speeches at greater length, and described the impression they made on the House. The anecdotes interspersed in the work are numerous, and, from the veracity of the Author, when they are founded on his personal knowledge, they may always be received as authentic. When derived from others, or from the common rumour of the day, he gives his authority for them, and enables his readers to judge of the credibility they deserve.

To his portraits it will be objected, that in general they incline to severity, and though he professed, and probably intended the strictest impartiality in his delineations of character, it cannot be denied that they are sometimes heightened by[xxv] friendship, and more frequently discoloured by resentment; and on many occasions it is evident, that they are dictated by the conduct of the persons he describes in the last occurrence that brought them before his eyes, rather than by a steady and comprehensive view of their merits and defects. His observations on the Cavendishes may be taken as an illustration of this remark. He seldom mentions the two Dukes of Devonshire, who flourished in his time, without some sneer or malignant reflection. The truth was, that notwithstanding his Whiggism, he held all the members of that family in detestation, on account of the part they had taken against him on his breach with his uncle Lord Walpole. Yet, within a few years after the conclusion of these Memoirs, when William, fourth Duke of Devonshire, had bequeathed five thousand pounds to his friend Mr. Conway, in approbation of his public conduct, he uses the following exaggerated expressions in speaking of the legacy.

“You might despise,” he writes to Mr. Conway,[9] “the acquisition of five thousand pounds simply; but when that sum is a public testimonial to your virtue, and bequeathed by a man so virtuous, it is worth a million. Who says virtue is not rewarded[xxvi] in this world? It is rewarded by virtue, and persecuted by the bad: can greater honour be paid to it?”

There are, indeed, few persons in his Memoirs, of whom he does not vary his opinion in the course of his work. Marshal Conway, the Pelhams, and Lord Hardwicke, are almost the only exceptions. He always speaks of Marshal Conway with affection and respect; of Mr. Pelham with dislike; of Lord Hardwicke with hatred; and of the Duke of Newcastle with contempt and aversion. Of other persons mentioned in his book, there is scarcely any strong expression of commendation or censure, which in some subsequent passage he does not qualify, soften, or contradict. It is a proof, however, of his fairness, at least of his desire to give his readers the impression he formed at the time of the personages and transactions he describes, that even when he changed his opinion, he allowed his original account to remain, leaving it to be effaced in the minds of others, as it was not unfrequently in his own, by subsequent reflections and events. In some instances, but rarely, he subjoins a note correcting his first impression: more frequently he only intimates to his readers his change of sentiment by the difference of his language with respect[xxvii] to the person he had before described. In his Memoirs of 1752, for example, he characterizes Lord George Sackville as a man “of distinguished bravery,” and that passage he has left as originally written, though after the battle of Minden he appears to have had more than doubts of Lord George’s courage. He was, in truth, as he says of himself, a bitter, but placable enemy, a warm, but (one instance only excepted) an inconstant friend.

It remains only to say a few words of the labours of the Editor. He has added some notes marked (E), and in some very few instances added or altered a word for the sake of delicacy or perspicuity. On such occasions the word added, or substituted, is printed between brackets of this shape [ ].

The spelling of the manuscript is peculiar, and different from that in ordinary use. It was the intention of the editor to have followed this orthography in the printed book, knowing it was the result of system and affectation, and not of accident or carelessness. He has accordingly retained it in the title of the book, and in words of unfrequent recurrence; but, finding such vicious and affected orthography disfigured the text, and fearing it might perplex on perusal, he determined in common[xxviii] words to revert to the usual and approved mode of spelling. The word to-morrow, for instance, which Lord Orford always writes to-morow, he has printed in the usual manner.

With respect to omissions, it is right to inform the reader, that one gross, indelicate, and ill-authenticated story had been cut out by Lord Waldegrave before the manuscript was delivered to the Editor; but he is assured the Author himself acknowledged that the facts related in it rested on no authority but mere rumour. Some, though very few, coarse expressions, have been suppressed by the Editor, and the vacant spaces filled up by asterisks; and two or three passages, affecting the private characters of private persons, and nowise connected with any political event, or illustrative of any great public character, have been omitted. Sarcasms on mere bodily infirmity, in which the Author was too apt to indulge, have in some instances been expunged; and where private amours were mentioned in the notes or appendix, the name of the lady has been seldom printed at length, unless the story was already known, or intimately connected with some event of importance, to the elucidation of which it was indispensable. Such liberties would be still more necessary if the remaining[xxix] historical works of Lord Orford were ever to see the light. They have been very sparingly used on the present occasion, and appeared to be warranted by the consideration, that, though the work had been obviously written for publication, it was left without directions how to dispose of it, and entirely at the discretion of those by whose authority it is now given to the public. Greater freedom might perhaps have been taken, without prejudice to the Author, or to his Memoirs. But the Editor was unwilling to omit any fact or anecdote, that had a direct or indirect tendency to illustrate the causes, or trace the progress of any political change or public event. The few omissions made are entirely of a private nature, and, in general, regard persons comparatively insignificant.

The Author had himself affixed an Appendix to the work. Some of his notes, which were of an inconvenient length, have been transferred to that part of the book, and some articles have been added by the Editor. The latter are marked with asterisks, and are for the most part taken from notes and compilations of Lord Orford himself, or of some contemporary pen.

[1] The reader will bear in mind, that some years have elapsed since this was written.

[2] June 6th, 1752.

[3] July 20th, 1752.

[4] Correspondence, Feb. 13th, 1757.

[5] March 23rd, 1742.

[6] March 9th, 1742.

[7] A story of the private intrigues of the Duke of Newcastle with Lord Carteret, during Sir Robert Walpole’s Administration, is told by Lord Orford in his Common Place Book. When Lord Hervey was to be made Privy Seal (in 1740), the Duke of Newcastle, to prevent the appointment, obtained Lord Carteret’s consent to accept the office, and moved at Council, that it should be offered to him. Sir Robert said he did not know whether Lord Carteret (who was then in Opposition) would take the place. The Duke said he would answer for him. Sir Robert replied, “I always suspected you had been dabbling there, now I know it; but if you make such bargains, I don’t think myself obliged to keep them.” Lord Hervey had the office.

[8] Correspondence, April 25, 1746.

[9] Letter to Mr. Conway, October 13, 1764.

The reader has now seen these Memoirs; and though some who know mankind, and the various follies, faults and virtues, that are blended in our imperfect natures, may smile with me at this free relation of what I have seen and known, yet I am aware that more will be offended at the liberty I have taken in painting men as they are; and that many, from private connexions of party and family, will dislike meeting such unflattered portraits of their heroes or their relations. Yet this, I fear, must always be the case in any history written impartially by an eye witness: and eye witnesses have been generally allowed the properest historians. Indeed, the editor of Chalon’s History of France was of a different opinion, and lamented that Thuanus, who has obliged the world with so complete and so ample a history of his own times, should[xxx] have confined himself to write nothing but what passed in his own time, and comme sous ses propres yeux.[11]

Thus much I shall premise: if I had intended a romance, I would not have chosen real personages for the actors in it; few men can sit for patterns of perfect virtue. If I had intended a satire, I would not have amassed so many facts, which, if not true, would only tend to discredit the Author, not those he may censure. Yet councils and transactions, not persons, are what I anywhere mean[12] to blame. The celebrated Bayle has indeed offered a notable excuse for all who may offend on the severer side. “The perfection of a history,” says he,[13] “is, when it displeases all sects and all nations, this being a proof that the author neither flatters nor spares any of them, and tells the truth to all parties.” A latitude this, in which I am not at all desirous of being comprehended; nor very reconcileable [xxxi]with a notion of history which he has laid down in another place.[14] There he says, “As the sacred history was not the work of a particular person, but of a set of men, who had received from God a special commission to write; in like manner, civil history ought to be drawn up by none but persons appointed by the State for that purpose.”

Unless State writers could be inspired, too, I fear history would become the most useless of all studies. One knows pretty well what sort of directions, what sort of information would be given from a Secretary’s office; how much veracity would be found, even if the highest in the historical commission were a Bishop Sprat. It is not easy to conceive how Bayle, who thought it his duty to collect and publish every scandalous anecdote from the most obsolete libels, should at last have prescribed a method of writing history, which reduces it to the very essence of a gazette; a kind of authorized composition which the most partial bigots to a Court have piqued themselves upon exposing. Roger North, the voluminous squabbler in defence of the most unjustifiable excesses of Charles the Second’s Administration, has drawn[15] the following [xxxii]picture of State Historians. “It was hard to varnish over the unaccountable advancement of this noble Lord without aid of the Gazetteer—but the historian has made sure of a lofty character of his Lordship, by taking it from the Court. We may observe in his book in most years a catalogue of preferments, with dates and remarks, which latter, by the secretarian touches, show out of what shop he had them; and certainly the most unfit for history of any, because they are for the most part not intended for truth but flourish; and what have Court compliments to do with history?” Here I beg leave to rest this part of my apology; and proceed to answer other objections, which I foresee will be made to me.

For the facts, such as were not public, I received chiefly from my father and Mr. Fox, both men of veracity; and some from communication with the Duke of Bedford at the very time they were in agitation. I am content to rest their authenticity on the sincerity of such men; at the same time I beg it may be remembered, that I never assert anything positively unless from very good authority; and it may be observed, that where I am not certain, I always say, it was said, it was believed, it was supposed, or use some such phrase. The speeches,[xxxiii] I can affirm, nay, of every one of them, to be still more authentic, as I took notes at the time, and have delivered the arguments just as I heard them; never conceiving how it can be proper in a real history to compose orations, as very probably counsels were not taken in consequence of those arguments which the Author supplies; and by that means his reasoning is not only fictitious, but misleads the reader. I do not pretend by this to assert, that parliamentary determinations are taken in consequence of any arguments the Parliament hears; I only pretend to deliver the arguments that were thought proper to be given, and thought proper to be taken.

It will perhaps be thought that some of the characters are drawn in too unfavourable a light. It has been the mode to make this objection to an honest Author, Bishop Burnet, though he only did what Tacitus, the Cardinal de Retz, and other most approved historians taught him to do, that is, speak the truth. If I have thought such authorities sufficient, I have at least acted with this farther caution, that I have endeavoured to illustrate, as far as I could, my assertions by facts, and given instances of effects naturally flowing from the qualities I ascribe to my actors. If, after all, many of the[xxxiv] characters are bad, let it be remembered, that the scenes I describe passed in the highest life, the soil the Vices like:[16] and whoever expects to read a detail of such revolutions as these brought about by heroes and philosophers, would expect—what? why, transactions that never would have happened if the actors had been virtuous.

But to appease such scrupulous readers—here are no assassins, no poisoners, no Neros, Borgias, Catilines, Richards of York! Here are the foibles of an age, no very bad one; treacherous Ministers, mock Patriots, complaisant Parliaments, fallible Princes. So far from being desirous of writing up to the severe dignity of Roman historians, I am glad I have an opportunity of saying no worse—yet if I had, I should have used it.

Another objection which I foresee will be made to me, is, that I may have prejudices on my father’s account. I can answer this honestly in a word: all who know me, know, that I had no such prejudice to him himself, as blinded me to his failings, which I have faithfully mentioned in my character of him. If more is necessary, let me add, his friends are spared no more than his enemies; and all the good[xxxv] I know of the latter I have faithfully told. Still more; have I concealed my father’s own failings? I can extend this defence still farther. Some of my nearest friends are often mentioned in these Memoirs, and their failings I think as little concealed as those of any other persons. Some whom I have little reason to love, are the fairest characters in the book. Indeed, if I can call myself to any account for heightening characters, it is on the favourable side; I was so apprehensive of being thought partial, that I was almost willing to invent a Lord Falkland.

With more reason I can avow myself guilty of the last objection, I apprehend, and that is, having inserted too many trifling circumstances. Yet, as this is but the annal of a single year, events which would die away to nothing in a large body of history, are here material; and what was a stronger reason with me, the least important tend to illustrate either the character of the persons or the times. The objection will particularly have weight against the notes; I do not doubt but some anecdotes in them will be thought very trifling; it is plain, I thought them so myself, by not inserting them in the body of the work. I have nothing to say for them, but that they are trifles relating to considerable people;[xxxvi] and such all curious persons have ever loved to read. Are not such trifles valued, if relating to any reign of 150 years ago? If this book should live so long, these too may become acceptable; if it does not, they will want no excuse. If I might, without being thought to censure so inimitable an author, I would remark that Voltaire, who in his Siècle de Louis XIV. prescribes the drawing only the great outlines of history, is as circumstantial as any chronicler, when he feels himself among facts and seasons that passed under his own knowledge.

If it is any satisfaction to my readers to assist them in censuring the Author, I may say that I have spared the most inconsiderable person in the book as little as the demigods: obliquely it is true, for my own character could have very little to do directly in this Work: but I have censured very freely some measures, for which I voted, particularly the transactions about Mr. Murray, which I must confess were carried on with an intemperate rashness very ill-becoming Parliament or justice. Among these measures I must not have involved the rigorous clauses in the Mutiny Bill, or the præmunire clause in the Regency Bill, for none of which, I thank God, I ever voted!

When I said I foresaw no other objections, let me[xxxvii] be understood to mean objections to faults that I might have avoided, such as want of sincerity, partiality, &c.: I hope I have cleared myself from them. As to the composition, I fear faults enough will appear in it: I would excuse them too if I could: but if imputations must lie upon my memory, let my character as a writer be the scape-goat to bear my offences!

[11] See the Preface to the first volume of L’Histoire de France. Paris, 1720.

[12] As personal enmity undoubtedly operates on every man’s mind more or less, I have, in a subsequent part of these Memoirs, specified the persons whom I did not love, that so much may be abated in the characters I have given of them, as are not corroborated by facts.

[13] Vide Gen. Dict. vol. 10, p. 426.

[14] Vide Gen. Dict. vol. 10, p. 336.

[15] Vide his Examen, part i. chap. 2, p. 33.

[16] The soil the Virtues like.—Pope.

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| A. D. | PAGE | |

| 1751. | State of ministry | 1 |

| King’s return to England | 3 | |

| Removal of Lord Harrington | ib. | |

| Transactions between Spain and the South Sea Company | 6 | |

| Proceedings in Parliament | 8 | |

| Affair of the Queries | 9 | |

| Mr. Pitt’s opposition for eight thousand seamen | 12 | |

| The Westminster Election and Petition | 13 | |

| History of Mr. Alexander Murray | 17 | |

| Debate on Naval Establishment | ib. | |

| Quarrel of Pitt and Hampden | 18 | |

| Debate on Westminster Petition, and Breach of Privilege | 19 | |

| Anecdote of Speaker Onslow in 1742 | 21 | |

| Mr. Murray and Breach of Privilege | 22 | |

| Sir William Yonge | ib. | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| 1751. | Debate on Army | 25 |

| Westminster Petition—Breach of Privilege | 26 | |

| Quarrel of Lord Coke and the Speaker | 28 | |

| [xl] Murray’s Behaviour in House of Commons | 29 | |

| Debate and Proceedings on Murray’s Contempt | 30 | |

| Murray Imprisoned | 31 | |

| Staff Opposed | ib. | |

| Westminster Petitions withdrawn | 32 | |

| Report from Murray | ib. | |

| Petition from Gibson | ib. | |

| Ways and Means | ib. | |

| Sir John Cotton | 33 | |

| Report on Murray’s Case | 34 | |

| Mutiny Bill | 35 | |

| Lord Egmont | 35 | |

| Mutiny Bill | 38 | |

| Colonel Lyttelton | ib. | |

| Colonel Townshend | 39 | |

| Colonel Conway | 41 | |

| Sir Henry Erskine | ib. | |

| Charge against General Anstruther | 42 | |

| Committee for the Suppression of Vice | 44 | |

| General Naturalization Bill | 45 | |

| Gin Bill | ib. | |

| Subsidy to Bavaria | 49 | |

| Reformation of the Calendar | 51 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| Petition from a Minorchese | 58 | |

| Oswald | 59 | |

| State of Parties | 60 | |

| Naturalization Bill | 61 | |

| Affairs of Nova Scotia | 62 | |

| South Sea Company | 63 | |

| Debate on Nova Scotia | ib. | |

| Sir Henry Erskine’s Charge against General Anstruther | ib. | |

| Bishop Secker | 65 | |

| [xli] Gin Act | 67 | |

| Charge against Anstruther | 68 | |

| Prince of Wales ill | ib. | |

| Council held at Bedford House | ib. | |

| Gin Act | 70 | |

| Death of the Prince of Wales | 72 | |

| Conduct and Character of Frederick Prince of Wales | ib. | |

| Sensation produced by his Death | 78 | |

| On the King | ib. | |

| On the Country | 79 | |

| Changes in Prince George’s Family | ib. | |

| Addresses of Condolence | 80 | |

| Meeting at Lord Egmont’s | 81 | |

| A Council | ib. | |

| France and Germany | ib. | |

| King and Princess Dowager | 83 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| 1751. | Indulgence to Murray Revoked | 86 |

| Changes in young Prince’s Establishment | ib. | |

| Bubb Doddington | 87 | |

| Chief Justice Willes | 89 | |

| Dr. Lee | 90 | |

| Promotions and Resignations | 91 | |

| Naturalization Bill | 92 | |

| Pitt | ib. | |

| Fox | 94 | |

| Address of Condolence | ib. | |

| New Appointments | ib. | |

| Anstruther’s Affair | 95 | |

| Breach of Privilege | ib. | |

| Further New Appointments | 96 | |

| Lord Middlesex | ib. | |

| [xlii] Duke of Cumberland | 98 | |

| Pelhams Espouse the Interests of Princess Dowager | 104 | |

| Resentment of Duke of Cumberland | 105 | |

| Duties on Gin | 106 | |

| Anstruther’s Cause | ib. | |

| Anstruther’s Cause dropped | 113 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| 1751. | Prince of Wales Created | 114 |

| Regency Bill | ib. | |

| Murray’s Case in the King’s Bench | 115 | |

| Regency Bill | 116 | |

| William Pulteney, Lord Bath | 118 | |

| Character of Speaker Onslow | 129 | |

| Horace Walpole | 140 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| King’s Conversation on Regency Bill | 157 | |

| Lord Hardwick | 158 | |

| Pelhams determine to Remove Duke of Bedford and Lord Sandwich | 161 | |

| Duke of Newcastle | 162 | |

| Mr. Pelham | 166 | |

| Character of Lord Granville | 168 | |

| His former Administration | 169 | |

| His former Dismissal, and other Events of 1745 | 170 | |

| History of the Resignations of 1745, and some Subsequent Transactions | 172 | |

| Winnington | 174 | |

| Resigners Restored to Office | 175 | |

| Character of George II. | ib. | |

| Lady Suffolk | 177 | |

| Duke of Grafton | 180 | |

| [xliii] Princess Emily | 182 | |

| Pelhams not in Favour | 183 | |

| Duke of Newcastle determines to Remove his Colleagues | 185 | |

| Duke of Bedford | 186 | |

| Lord Sandwich | ib. | |

| Pelhams foment Family Disputes | 188 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| 1751. | Change of the Ministry | 190 |

| Mr. Legge | ib. | |

| Duke of Bedford has an Audience | 193 | |

| He declines Office, but with marks of Favour | ib. | |

| Further Appointments | 194 | |

| Lord Anson | ib. | |

| Duke of Devonshire and Lord Hartington | 195 | |

| Whigs Satisfied | 196 | |

| Lord Holderness | 198 | |

| Parliament Prorogued | 200 | |

| Murray Released | 201 | |

| Discovery of Lyttelton’s Letter | 202 | |

| Foreign Affairs | 203 | |

| Marquis de Mirepoix | ib. | |

| Sir Charles Hanbury Williams | 205 | |

| Death of the Prince of Orange | 206 | |

| Princess of Orange | 207 | |

| Parliament | 208 | |

| Debates on Privilege | ib. | |

| Vote of Seamen | 211 | |

| The Duke’s Illness | 212 | |

| Vote of Army Estimates and Debates | 213 | |

| Affairs of France | 216 | |

| Debate on Land Tax | 218 | |

| Death of Lord Bolingbroke | 220 | |

| [xliv] Walpole and Bolingbroke | 225 | |

| New Appointments | 226 | |

| Death of the Queen of Denmark | 227 | |

| Cessation of Opposition | 228 | |

| Parallel between Walpole and Pelham | 229 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| 1752. | Reflections of Author on his Work | 237 |

| State of Parties | 239 | |

| Treaty with Saxony | 240 | |

| Parliament | 241 | |

| Duke of Bedford opposes the Saxon Treaty | 242 | |

| Debates in Commons on the Saxon Treaty | 243 | |

| In Lords | 244 | |

| Bill for Commuting Capital Punishments dropped | 256 | |

| History of the Purchase of Scotch Forfeited Estates | ib. | |

| Debates on Scotch Forfeiture Bill | 257 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| The Scotch Bill in Lords | 262 | |

| Session Ended | 275 | |

| Character of Archibald Duke of Argyle | ib. | |

| King goes to Hanover | 278 | |

| History of the Factions in Ireland | ib. | |

| Divisions in the Tutorhood of the Prince of Wales | 283 | |

| Account of the Pretender’s Family and Court | 284 | |

| German Alliances unlucky | 288 | |

| Dissensions in Prince of Wales’s Household | 289 | |

| New Governor Appointed | 291 | |

| Lord Waldegrave, Governor | ib. | |

| Dr. Thomas, Preceptor | 292 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| 1753. | Debates in Parliament | 293 |

| [xlv] Affair of the Stoppage on the Silesian Loan | 295 | |

| Public Paper on Silesian Loan | 297 | |

| The Pretended Memorial | 298 | |

| History of Lord Ravensworth and Fawcett | 303 | |

| Debate on Nova Scotia | 307 | |

| Fawcett’s Testimony | 307 | |

| Proceedings in Lords on Fawcett’s Testimony | 310 | |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| Seizure of Dr. Cameron | 333 | |

| King of France’s Amours | 334 | |

| The Marriage Bill | 336 | |

| Mr. C. Townshend, and Mr. H. Conway | 341 | |

| Debates on the Marriage Bill in Lords | 346 | |

| Dissensions caused by the Marriage Bill | 350 | |

| Execution of Dr. Cameron | 353 | |

| Continuation of the Troubles in Ireland | 354 | |

| Seats in Parliament offered to Government | 355 | |

| Ireland | 356 | |

| The Jew Bill | 357 | |

| Debates on the Jew Bill | 358 | |

| Ireland | 362 | |

| Debate on the Proposal to Repeal the Plantation Act | 364 | |

| Irish Affairs continued | 367 | |

| 1754. | Ireland | 368 |

| Motion to Repeal Bribery Oath | 369 | |

| Parliament | ib. | |

| Death of Mr. Pelham | 370 | |

| CHAPTER XII. | ||

| Motives for continuing this Work | 372 | |

| Solemnity not necessary in Memoirs | 374 | |

| Flattery the Vice of Historians | 375 | |

| [xlvi] Author’s Apprehensions for the Constitution | 376 | |

| Author’s Political Principles | 377 | |

| Embarrassments on Death of Mr. Pelham | 378 | |

| Agitations on choice of Successor in the Ministry | 379 | |

| Appointment and Disappointment of Mr. Fox | 381 | |

| Mr. Fox has an Audience | 386 | |

| Duke of Newcastle sole Minister | 387 | |

| New Disposition of Employments | ib. | |

| New Appointments | 388 | |

| Sir Thomas Robinson | ib. | |

| Affairs in Ireland | 389 | |

| New Parliament | 391 | |

| Duke of Newcastle slights Mr. Legge | ib. | |

| Origin of the War | 392 | |

| Remarks on America | 395 | |

| Spain | 398 | |

| Defeat of Major Washington | 399 | |

| Consultations on War | 400 | |

| Law-suit about Richmond New Park | 401 | |

| Debates on Address | 403 | |

| Prince of Hesse turns Papist | 405 | |

| Disturbances in the New Parliament | 406 | |

| Elections | ib. | |

| Debates on Election Petitions | 407 | |

| Army Estimates | 410 | |

| Debates on Army Estimates | 411 | |

| Breach between Sir George Lyttelton and Mr. Pitt | 414 | |

| State of Ministry and Parties | 417 | |

| Projected Changes in Ministry | 418 | |

| Fox made Cabinet-Counsellor | 420 | |

| Debate on Mutiny Bill | ib. | |

| Charles Townshend’s Attack on Lord Egmont | 421 | |

| Deaths of Lord Gower and Lord Albemarle | 422 | |

| ——— | ||

| Appendix | 427 | |

| VOL. I. | ||

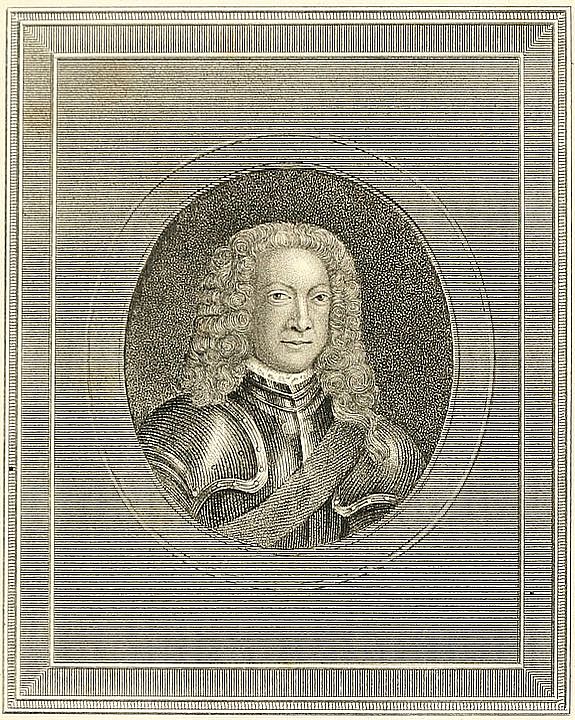

| George II. | Frontispiece. | |

| Mr. Pelham | p. 378 | |

| VOL. II. | ||

| Mr. Fox | Frontispiece. | |

| Duke of Bedford | 270 | |

| VOL. III. | ||

| Mr. Pitt | Frontispiece. | |

| Duke of Newcastle | 182 |

MEMOIRS

OF THE REIGN OF

KING GEORGE THE SECOND.

An nescis, Mî Filî, quantillâ Prudentiâ regitur Orbis?

Chancellor Oxenstiern to his Son.

State of the Ministry at the commencement of the year 1751—The Duke of Newcastle disagrees with the Duke of Bedford—Lord Sandwich’s subserviency to the Duke of Cumberland—Mr. Pelham adopts his brother’s jealousies—Removal of Lord Harrington on the King’s return to England—Some account of his career—Conclusion of the Spanish war—Meeting of Parliament—Mr. Pitt’s recantations—Circulation of a political paper, called “Constitutional Queries,” brought before the notice of Parliament—Motion for providing eight thousand seamen—The Westminster Election and Petition—Speeches of Lord Trentham and Mr. Fox—Debate on the Naval establishment—Quarrel of Pitt and Hampden—Breach of privilege—Anecdote of Onslow.

It had been much expected that on the King’s return from Hanover several changes would be made in the Ministry. The Duke of Newcastle had, for some time before his attending the King thither, disagreed with the other Secretary of State, the Duke of Bedford, not only because he had brought the latter into[2] the Ministry (his incessant motive of jealousy,) nor from the impetuosity of the Duke of Bedford’s temper, but from the intimate connexions that Lord Sandwich had contracted with the Duke.[17] Lord Sandwich had been hoisted to the head of the Admiralty by the weight of the Duke of Bedford, into whose affection he had worked himself by intrigues, cricket-matches, and acting plays, and whom he had almost persuaded to resign the Seals in his favour. There had been a time when he had almost obtained the Duke of Newcastle’s concurrence; and if he could have balanced himself between the Duke and the Duke of Newcastle, one may, without wronging the delicacy of his political character, suspect that he would have dropped the Duke of Bedford’s confidence. But a blind devotion to the Duke’s inclinations, which he studied in all the negotiations[18] of the war and the peace, protracting the one to flatter his command, and hurrying on the other when no part of Flanders was left for the Duke’s army, and himself was impatient to come over to advance his interest in the Cabinet, this had embroiled him with the Duke of Newcastle, and consequently cemented his old attachments.

Mr. Pelham had, according to his manner, tried to soothe where his brother provoked, been convinced by trifles that his brother’s jealousy was solidly grounded, adopted his resentments, and promoted them. While the Court was at Hanover, Lord Sandwich had drawn a great concourse of the young men of fashion to Huntingdon races, and then carried them to Woburn to cricket-matches made there for the entertainment of the Duke. These dangerous practices opened Mr. Pelham’s eyes; and a love affair between one of his [relations] and a younger brother[19] of the Duchess of Bedford fixed his aversion to that family. At this period the Duke of Richmond[20] died, who besides the Duchess and his own dignity, loved the Duke of Newcastle—the only man who ever did. The Pelhams immediately offered the Mastership of the Horse to the Duke of Bedford, which he would have accepted, had they left him the nomination of Lord Sandwich for his successor.

The King came over: but though the brothers were resolved to disagree with their associates in the Ministry, they could not resolve to remove them; none of the great offices were filled up but the Lieutenancy of Ireland, from which Lord Harrington[21] was removed [4]in the most unworthy manner. He had raised himself from a younger brother’s fortune to the first posts in the Government, without either the talent of speaking in Parliament, or any interest there. He had steered through all the difficulties of the Court and changes of Ministry, with great dexterity, till, in the year 1746, notwithstanding all his personal obligations to the King, he was the first man who broke into his closet at the head of those insulting and disloyal resignations that were calculated and set on foot by the Pelhams, in the very heat of the rebellion, to force their master, by a general desertion of his servants, to abandon[5] Lord Granville, whom he was recalling into the Ministry. The King had brooded over this ingratitude, not with much hope of revenging it, but as he sometimes resented such indignities enough to mention them, the Pelhams sacrificed Lord Harrington to their master, astonished at their complaisance, in order to bargain for other victims on his part, which they would have forced, not purchased, if there had been any price necessary but their own ingratitude. Lord Harrington was removed, and the Lieutenancy of Ireland again heaped on the Duke of Dorset, then President of the Council.

January 10.—The South Sea Company having consented to receive the hundred thousand pounds on the new treaty with Spain in lieu of all their demands, thought they had a title to some favour with the King, and accordingly came to a resolution to address him, to be pleased to continue their Governor, and to take into his consideration the state of the Company. To this message they received an answer in general terms. They addressed again for one more particular: they were told in very harsh phrase, that the King had obtained for them from the Crown of Spain all that was possible to be obtained.

This was the conclusion of the Spanish war; fomented (to overturn Sir Robert Walpole) by Lord Granville, who had neglected it for a French war; by Lord Sandwich, who made a peace that stipulated for no one of the conditions for which it was undertaken; by Pitt, who ridiculed and condemned his own orations for it, and who declared for a peace on any terms; and by the Duke of Newcastle, who betrayed all the claims of the merchants and the South Sea Company, when he had got power, to get more power by sacrificing them to the interests of Germany and the Electorate. As there never was[8] a greater bloom of virtue and patriotism than at that period, if posterity should again see as fair a show, it will be taught to expect as little fruit.

17th.—The Parliament met. The King acquainted the Houses with the new treaties concluded with Spain for terminating our differences, and with Bavaria for securing the peace of the Empire (by the meditated election of the Archduke Joseph for King of the Romans, was understood). The Address was moved in the House of Lords by the Earl of Northumberland[22] and the Lord Archer; and in the Commons by Horace Walpole[23] (son of the late Earl of Orford) and Mr. Probyn. Lord Egmont opposed the Address, on the approbation it gave to the treaties, and the subsidies it promised to pay, and proposed leaving out many of the paragraphs. The House sat till near eight; the speakers against the Address were Mr. Henley, Mr. Bathurst, Sir John Cotton, Mr. Vyner, Mr. Martin, Mr. Doddington, Mr. Potter, and Dr. Lee; for it, Mr. W. Pitt, Mr. Pelham, Sir J. Barnard, General Oglethorpe, Horace Walpole senior, and Mr. Fox. Mr. William Pitt recanted his having seconded the famous question for the no search in the last Parliament; said it was a mad and foolish motion, and that he was since grown ten [9]years older and wiser: made a great panegyric on the Duke of Newcastle’s German Negotiations of this summer, and said he was himself so far from wishing to lessen the House of Commons, that whatever little existence he had in this country, it was owing to the House of Commons. These recantations of his former conduct were almost all he had left to make. On his first promotion he had declared against secret committees, and offered profuse incense to the manes and friends of Sir Robert Walpole. He now exploded his own conduct in contributing to kindle the Spanish war, and hymned that Hanoverian adulation in the Duke of Newcastle, which he had so stigmatized in Lord Granville. Indeed, the Duke of Newcastle had no sooner conquered his apprehensions of crossing the sea, than he adopted all Lord Granville’s intrepidity in negotiation. The Address was carried by 203 to 74.

The morning the Parliament met, great numbers of treasonable papers were dispersed by the Penny Post, and by being dropped into the areas of houses, called “Constitutional Queries,”[24] levelled chiefly at the Duke, whom they compared to Richard III. As it was the great measure of the Prince’s Opposition to attack his brother, the Jacobites bore but half the suspicion of being authors of this libel.

On the 22nd the Duke of Marlborough[25] moved in the House of Lords to have the Queries burnt by the hangman, which was agreed to, and they communicated their resolution to the Commons at a conference in the Painted Chamber. Sir John Strange, Master of the Rolls, in a lamentable discussion, seconded by the Attorney-General, Rider, moved to concur with the Lords. Sir Francis Dashwood, after much disclaiming of Jacobitism, objected to the word false in the resolution, as he thought some of the charges in the Queries not ungrounded, particularly in the complaint against alarm-posts, and the dismission of old officers, an instance of which he quoted in the person of his uncle, the Earl of Westmoreland, who had been removed seventeen years before, and under the administration of Sir Robert Walpole. General Handasyde, a blundering commander on the Prince’s side, spoke strongly against the Queries; and Colonel Richard Lyttelton, with a greater command of absurdity, spoke to the same points as Sir Francis Dashwood; like him, disclaimed Jacobitism, and wished that “even a worse punishment than burning could be found out for the paper;” told a long story of Colonel George Townshend’s having been refused leave to stay in Norfolk, “though he was cultivating the Whig interest;” and an alarming history of the Duke’s having placed two Sentinels to guard the[11] ruins of Haddock’s Bagnio and the Rummer Tavern at Charing-cross, which had been burnt down; and then ran into a detail of the abuse on the King about the Hanover troops in the year 1744, when his own relations and friends had been at the head of the Opposition.

Mr. Pelham answered in a very fine speech, and said, he had a new reason for condemning this paper, as he saw it already had had part of its intended effects, in catching honest minds. Lord Egmont made an extremely fine and artful speech, “That in general he disliked such methods of proceeding against libels, for two reasons; that he did not approve of Parliament taking the business of the law upon them, and because such notice only tended to spread the libel more; but that the present was of so evil a nature, that no censure could be too severe, especially as it was calculated to sow division between two brothers of the Blood Royal, where he was persuaded and hoped there was no such thing: that if there were any grounds for the accusations in the paper, he should choose a more proper day to inquire into them, and would; that as to the case of the Hanover troops,[26] he did not know why, as the same Ministry[12] continued, that satire was left so unpunished, this so condemned; or why the author of this was so sought after, the authors of the other so promoted.” The resolution was agreed to, nemine contradicente, and an Address presented to the King, to desire him to take effectual means to discover the author, printers, and publishers of the Queries, which were burnt on the 22nd.

The same day, Lord Barrington[27] moved that the number of seamen should be but eight thousand for the present year. Nugent, Lord Egmont, Potter, and the Opposition, declared for the old number of ten thousand, on a supposition that the view of the Ministry was to erect the land army into our principal force. W. Pitt, who, with his faction, was renewing his connexions with the Prince of Wales, as it was afterwards discovered, and impatient to be Secretary of State, which he expected to carry, as he had his other preferments, by storm; and the competition between him and Fox, the principal favourite of the Duke, breaking out more and more, said (without previously acquainting Mr. Pelham with his intention) that if the motion had been made for ten thousand, he should have preferred the greater number. Potter immediately moved for them, and Pitt agreed with him. Mr. Pelham seemed to acquiesce; but when the question was put, Lord Hartington, a favourite by descent of the old Whigs, to[13] show Pitt that he would not be followed by them if he deserted Mr. Pelham, divided the House, and the eight thousand were voted by 167 to 107; only Pitt, Lyttelton, the three Grenvilles, Colonel Conway, and eight more, going over to the minority.

On the 28th, Mr. Cooke, a pompous Jacobite, and Member for Middlesex, presented a long petition from several of the Electors of Westminster against Lord Trentham. This election and scrutiny had taken up above five months of the last year. The resentment of the Jacobites against Lord Gower for deserting their principles had appeared in the strongest colours, on the necessity of his son being rechosen, after being nominated into the Admiralty. They had fomented a strong spirit against Lord Trentham, on his declining to present a petition to the King in favour of a young fellow[28] hanged for a riot; and on his countenancing a troop of French players[29] in the little [14]theatre in the Haymarket. Lord Egmont, who was intriguing to recover his interest in Westminster, had set up a puppet, one Sir George Vandeput; and the Pelhams were suspected of not discouraging the opposition. On Lord Trentham’s success, a petition had been framed in such treasonable terms, that Mr. Cooke himself waved undertaking it, and this new one was drawn up: Sir John Cotton opposed the party’s petitioning at all, but did not prevail. Both Mr. Cooke and the petition severely abused the High Bailiff (whose practice, as a lawyer, the Jacobites totally destroyed), and who, as Mr. Cooke said, had attempted to violate the maiden and uncorrupted city of Westminster.

Lord Trentham,[30] who had never spoken in Parliament before, replied with great manliness and sense, and spirit, reflecting on the rancour shown to[15] him and his family, and asserting that the opposition to him had been supported by perjury and by subscriptions, so much condemned and discountenanced by the Opposition, when raised to maintain the King on the Throne during the last Rebellion. In answer to the censure on the High Bailiff, he produced and read a letter from Mr. Cooke to the High Bailiff, while he was believed in their interest, couched in the strongest terms of approbation of his conduct and integrity. This was received with a loud and continued shout. It was long before Mr. Cooke could get an opportunity of replying, and longer before he had anything to reply. He reflected on Lord Trentham’s not telling him of this letter, and justified it. Lord Egmont talked of his own obligations to Westminster, called Mr. Cooke’s letter honest flattery, to encourage a man to do his duty; and said that the opposition to Lord Trentham was the sense of the nation, expressed against the Administration.

Mr. Fox replied with great wit and abilities, and proved that of all men in England Lord Egmont had least obligation to Westminster, which had rejected him at the last general election, and exposed the doctrine of honest flattery, which was only given, when the person it was given to was thought honest, by acting as his flatterer desired. Mr. Fox was apt to take occasion of attacking Lord Egmont, the champion against the Duke, and because, after Mr. Fox had managed and carried through his contested election, Lord Egmont had not given one vote with the Court.[16] Mr. Cooke moved to hear the petition that day fortnight; Lord Trentham for the morrow se’nnight, which was agreed to. Lord Duplin then moved to call in the High Bailiff to give the House an account how he had executed the orders which he received last February of expediting the scrutiny as much as possible. He came, pleaded many obstructions, and being asked why he had not complained, said, he had feared being taxed with putting an end to the scrutiny.

Lord Trentham then desired he might be asked, if he remembered any threats used to him. Lord Egmont objected to the question, and the High Bailiff was ordered to withdraw. A long debate ensued, though Mr. Fox proposed to put the question in these less definite words, “how he had been obstructed.” At last it was proposed that the Speaker should decide, whether, supposing the High Bailiff accused any person, they could be heard to their defence, consistently with the orders of the House, before hearing the merits of the petition. The oracle was dumb—at last being pressed, it said, “I wish, without using many words, I could persuade gentlemen to go upon some other matter.” Lord Trentham finding the Speaker against him, and the Ministry and one or two of the old Whigs inclined to give it up, gave it up with grace and propriety. But the young Whigs, headed by Lord Coke, grew very riotous, and though the Speaker declared still more fully against them, they divided the House, and carried it by 204 to 106 to call in the High Bailiff, who, returning to the bar,[17] charged Crowle, Sir George Vandeput’s Counsel, with triumphing in having protracted the scrutiny, and with calling the orders of the House brutum fulmen. Being further questioned, he said he had been scandalously abused; had received papers threatening his life; had been charged with running away to Holland; had been pursued into the vestry after declaring the majority for Lord Trentham; had been stoned there, and that one gentleman at the head of the mob had asked them, if nobody had courage enough to knock the dog down, and that he ought to be killed. Being asked who this was, he named Mr. Alexander Murray, brother of Lord Elibank; both such active Jacobites, that if the Pretender had succeeded, they could have produced many witnesses to testify their zeal for him; both so cautious, that no witnesses of actual treason could be produced by the Government against them: the very sort of Jacobitism that has kept the cause alive, and kept it from succeeding. Mr. Murray, with Crowle and one Gibson, an upholsterer, were ordered to attend on the Thursday following with the High Bailiff, to have his charge made out.

29th.—The report for the eight thousand seamen was made from the committee, and debated again till past eight at night, when it was agreed to by 189 to 106. Mr. W. Pitt spoke with great affectation of concern for differing with Mr. Pelham, protested he had not known it was his measure (which Mr. Pelham made many signs of not allowing), and that it was his[18] fear of Jacobitism which had made him differ on this only point with those with whom he was determined to lead his life. He called the fleet our standing army, the army a little body of military spirit, so improved by discipline, that that discipline alone was worth five thousand men; made great panegyrics on Mr. Pelham (so did Lyttleton and George Grenville), and concluded with saying, “I do not believe the majority of this House like eight thousand better than ten.”

The times were changed! Men who remembered how Sir Robert Walpole’s fears of the Pretender and his Spithead expeditions were ridiculed by his opponents, admired Mr. Pitt’s humility and conviction, who was erecting a new opposition on those arguments.

He was attacked by Hampden, who had every attribute of a buffoon but cowardice, and none of the qualifications of his renowned ancestor but courage. He drew a burlesque picture of Pitt and Lyttleton under the titles of Oratory and Solemnity, and painted in the most comic colours what mischiefs rhetoric had brought upon the nation, and what emoluments to Pitt. Pitt flamed into a rage, and nodded menaces of highest import to Hampden, who retorted them, undaunted, with a droll voice that was naturally hoarse and inarticulate. Mr. Pelham interposed, and, according to his custom, defended Pitt, who had deserted him; gave up Hampden, who had supported him. It was not unusual for Pitt to mix the hero with the orator; he had once blended those characters[19] very successfully, when, having been engaged to make up a quarrel between his friend Hume Campbell[31] and Lord Home, in which the former had kissed the rod, Pitt within very few days treated the House with bullying the Scotch declaimer. On the present occasion, the Speaker insisted on the two champions promising to proceed no farther, with which Punch first, and then Alexander the Great, complied.

31st.—Mr. Crowle appeared with the High Bailiff at the bar of the House, and owned the words charged on him, but endeavoured to prove that the protraction was meant for the benefit of his client; and that the brutum fulmen was applied to those who urged him with the orders of the House impertinently. He showed great deference and submission to the House. It was then debated till six o’clock, whether any witnesses should be called in against him, and carried by 204 to 138, that there should. Three were called, who proved the words. Lord Hartington, (whose head being filled with the important behaviour of the Cavendishes and Russels at the Revolution, was determined that it should be the fault of the times, not his, if his conduct did not always figure equally[20] with theirs in solemnity), moved, with a pomp of tragic tenderness, and was seconded by Lord Coke, who abused the independent electors, “that Mr. Crowle had wilfully protracted the scrutiny, and showed contempt of the House.”

This was opposed;[32] the lawyers pleaded in earnest for their brother, and the Ministry were inclined to give it up, till Lord Egmont made a furious speech for Crowle, and called the Whigs the Rump of their old party. Mr. Fox took this up warmly in an exceedingly fine speech of spirit and ridicule, and concluded with telling Lord Egmont, that though he intended to have interceded for Crowle (who had interest at Windsor, where Fox was chosen), he must now be for this resolution; but yet should show compassion for Mr. Crowle, if it were only on his having such a friend. The House divided at eleven at night, and the resolution passed by 181 to 129. Lord Hartington then offered to the House to[21] take Mr. Crowle into custody, or to reprimand him immediately; the latter of which was chosen for him by Mr. Fox, and he was reprimanded on his knees by the Speaker. As he rose from the ground,[33] he wiped his knees, and said, “it was the dirtiest house he had ever been in.”

The Whigs took pleasure in copying the precedents,[34] that had been set them at the famous Westminster Election, in 1742; and the Speaker had the satisfaction both times of executing the vengeance of either party, and indulging his own dignity. On the former occasion, his speech to the kneeling Justices was so long and severe, that the morning it was printed, Sir Charles Hanbury Williams complained to him of the printer’s having made a grievous mistake—“Where?—how? I examined the proof sheet myself!” Sir Charles replied, “in the conclusion he makes you say, more might have been said; to be sure you wrote it, less might have been said.”

The King on these votes commended the young men, and said to the Duke of Newcastle before the Duke [22]of Bedford, “they are not like those puppies who are always changing their minds. Those are your Pitts and your Grenvilles, whom you have cried up to me so much! You know I never liked them.”

February 1.—Mr. Murray appeared at the bar of the House of Commons, and heard the High Bailiff’s charge. He asserted his innocence; said he should deny nothing that was true; that much was false; smiled when he was taxed of having called Lord Trentham and the High Bailiff rascals, and desired Counsel, which, after a debate of two hours, was granted to him, and a respite till the Wednesday following, upon condition of his being taken into custody, and giving bail for his appearance. Gibson, the upholsterer, was then brought to the bar, witnesses for and against him heard, and the words proved, though some members[35] of the House, who had been present at the conclusion of the scrutiny, did not hear him speak them. Sir William Yonge moved a resolution of his guilt, which was carried by 214 to 63, and he was committed to Newgate.

Sir William Yonge[36] was still employed in any [23]government causes where the Ministry wanted to inflict punishments and avoid odium—their method of acquiring merit! His vivacity and parts, whatever the cause was, made him shine, and he was always content with the lustre that accompanied fame, without thinking of what was reflected from rewarded fame—a convenient ambition to Ministers, who had few such disinterested combatants! Sir Robert Walpole always said of him, “that nothing but Yonge’s character[37] could keep down his parts, and nothing but his parts support his character.”

[17] William, second son of George the Second, Commander of the army in Flanders, and Duke of Cumberland. He was, by an affectation of adopting French usages, called emphatically “The Duke,” during the latter years of George the Second and the beginning of the reign of George the Third.—E.

[18] Lord Sandwich had been Plenipotentiary at the Conference at Breda in 1747, and concluded the Peace at Aix-la-Chapelle in 1749.

[19] Richard Levison Gower.

[20] The second son of that name, Knight of the Garter and Master of the Horse, died Aug. 8, 1750, aged 49.

[21] Yesterday morning (Dec. 8, 1756), died at his house in the Stable-yard, St. James’s, the Right Hon. William Stanhope, Earl of Harrington, a General of his Majesty’s Forces, a Governor of the Charter-house, a Fellow of the Royal Society, and one of the Lords of his Majesty’s Most Honourable Privy Council.

His Lordship served in the reign of Queen Anne in Spain, being Captain of a Company, with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, in the third regiment of Guards; and in the end of the year 1710 was constituted Colonel of a regiment of Foot.

On the accession of his late Majesty he was appointed Colonel of a regiment of Dragoons, and returned to Parliament for the town of Derby; and in 1715 was made Colonel of a regiment of Horse. On the 19th of August, 1717, he was appointed Envoy Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to the King of Spain.