Title: The Vicar of Morwenstow: Being a Life of Robert Stephen Hawker, M.A.

Author: S. Baring-Gould

Release date: April 2, 2018 [eBook #56899]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by David Edwards, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/vicarofmorwensto00bariiala |

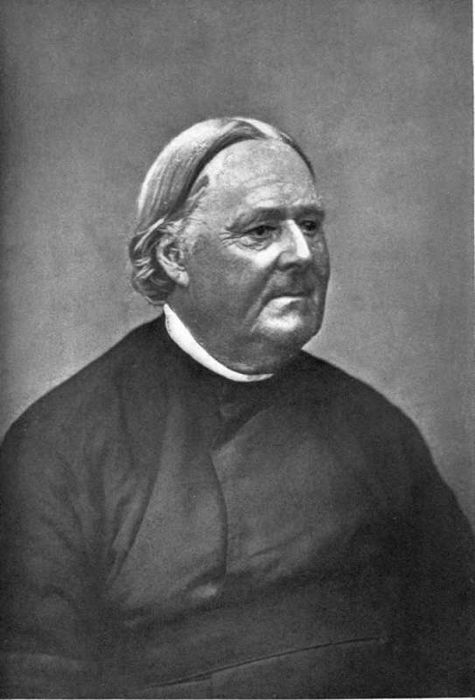

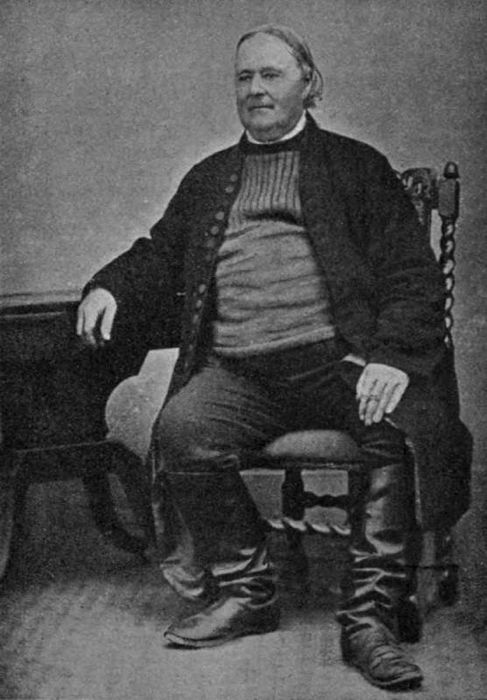

ROBERT STEPHEN HAWKER

Homme étrange, original et supérieur, mais qui, dès l’enfance, portait en soi un germe de folie, et qui à la fin devint fou tout à fait; esprit admirable et mal équilibré, en qui les sensations, les émotions et les images étaient trop fortes; à la fois aveugle et perspicace, véritable poëte et poëte malade, qui au lieu des choses, voyait ses rêves, vivait dans un roman et mourut sous le cauchemar qu’il s’était forgé; incapable de se maîtriser et de se conduire, prenant ses résolutions pour des actes, ses velléités pour des résolutions, et le rôle qu’il se donnait pour le caractère qu’il croyait avoir; en tout disproportionné au train courant du monde, se heurtant, se blessant, se salissant à toutes les bornes du chemin; ayant commis des extravagances, des injustices, et néanmoins gardant jusqu’au bout la sensibilité délicate et profonde, l’humanité, l’attendrissement, le don des larmes, la faculté d’aimer, la passion de la justice, le sentiment religieux, l’enthousiasme, comme autant de racines vivaces où fermente toujours la séve généreuse pendant que la tige et les rameaux avortent, se déforment ou se flétrissent sous l’inclémence de l’air.—H. Taine.

| Birth of Mr. Hawker—Dr. Hawker of Charles Church—The Amended Hymn—Robert S. Hawker runs away from School—Boyish Pranks—At Cheltenham—Publishes his Tendrils—At Oxford—Marries—The Stowe Ghost—Robert Hawker and Mr. Jeune at Boscastle—The Mazed Pigs—Nanny Heale and the Potatoes—Records of the Western Shore—The Bude Mermaid—Takes his Degree—Comes with his Wife to Morwenstow | 1 |

| Ordination—The Black Pig “Gyp”—Writes to the Bishop—His Father appointed to Stratton—He is given Morwenstow—The Waldron Lantern—St. Morwenna—The Children of Brychan—St. Modwenna of Burton-on-Trent—The North Cornish Coast—Tintagel—Stowe—Sir Bevil Grenville—Mr. Hawker’s Discovery of the Grenville Letters—Those that remain—Antony Payne the Giant—Letters of Lady Grace—Of Lord Lansdown—Cornish Dramatic Power—Mr. Hicks of Bodmin | 20 |

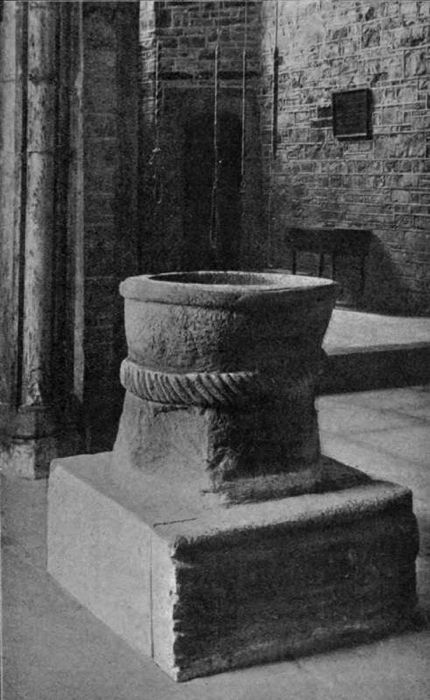

| Description of Morwenstow—The Anerithmon Gelasma—Source of the Tamar—Tonacombe—Morwenstow Church—Norman Chevron Moulding—Chancel—Altar—Shooting Rubbish—The Manning Bed—The Yellow Poncho—The Vicarage—Mr. Tom Knight—The Stag Robin Hood—Visitors—Silent Tower of Bottreaux—The Pet of Boscastle | 47 |

| Mr. Hawker’s Politics—Election of 1857—His Zeal for the Labourers—“The Poor Man and his Parish Church”—Letter to a Landlord—Death of his Man Tape—Kindness to the Poor—Verses over his Door—Reckless Charity—Hospitality—A Breakdown—His Eccentric Dress—The Devil and his Barn—His Ecclesiastical Vestments—Ceremonial—The Nine Cats—The Church Garden—Kindness to Animals—The Rooks and Jackdaws—The Well of St. John—Letter to a Young Man entering the University | 78 |

| The Inhabitants of Morwenstow in 1834—Cruel Coppinger—Whips the Parson of Kilkhampton—Gives Tom Tape a Ride—Tristam Pentire—Parminter and his Dog Satan—The Gauger’s Pocket—Wrecking—The Wrecker and the Ravens—The Loss of the Margaret Quail—The Wreck of the Ben Coolan—“A Croon on Hennacliff”—Letters concerning Wrecks—The Donkeys and the Copper Ore—The Ship Morwenna—Flotsam and Jetsam—Wrecks on 14th Nov., 1875—Bodies in Poundstock Church—The Loss of the Caledonia—The Wreck of the Phœnix and of the Alonzo | 105 |

| Wellcombe—Mr. Hawker Postman to Wellcombe—The Miss Kitties—Advertisement of Roger Giles—Superstitions—The Evil Eye—The Spiritual Ether—The Vicar’s Pigs Bewitched—Horse killed by a Witch—He finds a lost Hen—A Lecture against Witchcraft—Its Failure—An Encounter with the Pixies—Curious Picture of a Pixie Revel—The Fairy-Ring—Antony Cleverdon and the Mermaids | 148 |

| Condition of the Church last Century—Parson Radford—The Death of a Pluralist—Opposition Mr. Hawker met with—The Bryanites—Hunting the Devil—Bill Martin’s Prayer-meeting—Mr. Pengelly and the Candle-end—Cheated by a Tramp—Mr. Hawker and the Dissenters—Mr. B——’s Pew—A Special Providence over the Church—His Prayer when threatened with the Loss of St. John’s Well—Objection to Hysterical Religion—Mr. Vincent’s Hat—Regard felt for him by old Pupils—“He did not Appreciate Me”—Modryb Marya—A Parable—A Carol—Love of Children—Angels—A Sermon, “Here am I” | 167 |

| The Vicar of Morwenstow as a Poet—His Epigrams—The “Carol of the Pruss”—“Down with the Church”—The “Quest of the Sangreal”—Editions of his Poems—Ballads—The “Song of the Western Men”—The “Cornish Mother’s Lament”—“A Thought”—Churchyards | 202 |

| Restoration of Morwenstow Church—The Shingle Roof—The First Ruridecanal Synod—The Weekly Offertory—Correspondence with Mr. Walter—On Alms—Harvest Thanksgiving—The School—Mr. Hawker belonged to no Party—His Eastern Proclivities—Theological Ideas—Baptism—Original Sin—The Eucharist—His Preaching—Some Sermons | 218 |

| The First Mrs. Hawker—Her Influence over her Husband—Anxiety about her Health—His Fits of Depression—Letter on the Death of Sir Thomas Acland—Reads Novels to his Wife—His Visions—Mysticism—Death of his Wife—Unhappy Condition—Burning of his Papers—Meets with his Second Wife—The Unburied Dead—Birth of his Child—Ruinous Condition of his Church—Goes to London—Resumes Opium-eating—Sickness—Goes to Boscastle—To Plymouth—His Death and Funeral—Conclusion | 241 |

| FOOTNOTES | xxx |

Birth of Mr. Hawker—Dr. Hawker of Charles Church—The Amended Hymn—Robert S. Hawker runs away from School—Boyish Pranks—At Cheltenham—Publishes his Tendrils—At Oxford—Marries—The Stowe Ghost—Robert Hawker and Mr. Jeune at Boscastle—The Mazed Pigs—Nanny Heale and the Potatoes—Records of the Western Shore—The Bude Mermaid—Takes his Degree—Comes with his Wife to Morwenstow.

Robert Stephen Hawker was born at Stoke Damerel on 3rd December, 1804, and was baptised there in the parish church. His father, Mr. Jacob Stephen Hawker, was at that time a medical man, practising at Plymouth. He afterwards was ordained to Altarnun, and spent thirty years as curate and then vicar of Stratton in Cornwall, where he died in 1845. Mr. J. S. Hawker was the son of the famous Dr. Hawker, incumbent of Charles Church in Plymouth, author of Morning and Evening Portions, a man as remarkable for his abilities as he was for his piety.

Young Robert was committed to his grandfather to be educated. The doctor, after the death of his wife, lived in Plymouth with his daughter, a widow, Mrs. Hodgson, at whose expense Robert was educated.

The profuse generosity, the deep religiousness, and the eccentricity of the doctor, had their effect on the boy, and traced in his opening mind and forming character deep lines, which were never effaced. Dr. Hawker had a heart always open to appeals of poverty, and in his kindness he believed every story of distress which was told him, and hastened to relieve it without inquiring closely whether it were true or not; nor did he stop to consider whether his own pocket could afford the generosity to which his heart prompted him. His wife, as long as she lived, found it a difficult matter to keep house. In winter, if he came across a poor family without sufficient coverings on their beds, he would speed home, pull the blankets off his own bed, and run with them over his arm to the house where they were needed.

He had an immense following of pious ladies, who were sometimes troublesome to him. “I see what it is,” said the doctor in one of his sermons: “you ladies think to reach heaven by hanging on to my coat-tails. I will trounce you all: I will wear a spencer.”

In Charles Church the evening service always closed with the singing of the hymn, “Lord, dismiss us with Thy blessing,” composed by Dr. Hawker himself. His grandson did not know the authorship of the hymn: he came to the doctor one day with a paper in his hand, and said: “Grandfather, I don’t altogether like that hymn, ‘Lord, dismiss us with Thy blessing’: I think it might be improved in metre and language, and would be better if made somewhat longer”.

“Oh, indeed!” said Dr. Hawker, getting red; “and pray, Robert, what emendations commend themselves to your precocious wisdom?”

“This is my improved version,” said the boy, and read as follows:—

“Now, listen to the old version, grandfather:—

“This one is crude and flat; don’t you think so, grandfather?”

“Crude and flat, sir! Young puppy, it is mine! I wrote that hymn.”

“Oh! I beg your pardon, grandfather; I did not know that: it is a very nice hymn indeed; but—but grace is a bad rhyme for peace, and one naturally wishes to put grease in its place. Your hymn may be good”—and, as he went out of the door—“but mine is better.”

Robert was sent to a boarding-school by his grandfather; where, I do not know, nor does it much matter, for he stayed there only one night. He arrived in the evening, and was delivered over by the doctor to a very godly but close-fisted master. Robert did not approve of being sent supperless to bed, still less did he approve of the bed and bedroom in which he was placed.

Next morning the dominie was shaving at his window, when he saw his pupil, with his portmanteau on his back, striding across the lawn, with reckless indifference to the flower-beds, singing at the top of his voice, “Lord, dismiss us with Thy blessing.” He shouted after him from the window, but Robert was deaf. The boy flung his portmanteau over the hedge, jumped after it, and was seen no more at that school.

He was then put with the Rev. Mr. Laffer, at Liskeard. Mr. Laffer was the son of a yeoman at Altarnun: he afterwards became incumbent of St. Gennys. At this time he was head master of the Liskeard Grammar School. There Robert Hawker was happy. He spent his holidays either with his father at Stratton, or with his grandfather and aunt at Plymouth. At Stratton he was the torment of an old fellow who kept a shop in High Street, where he sold groceries, crockery and drapery. One day he slipped into the house when the old man was out, and found a piece of mutton roasting before the fire. Robert took it off the crook, hung it up in the shop, and placed a bundle of dips before the fire, to roast in its place.

He would dive into the shop, catch hold of the end of thread that curled out of the tin in which the shopkeeper kept the ball of twine with which he tied up his parcels, and race with it in his hand down the street, then up a lane and down another, till he had uncoiled it all, and laced Stratton in a cobweb of twine, tripping up people as they went along the streets. The old fellow had not the wits to cut the thread, but held on like grim death to the tin, whilst the ball bounced and uncoiled within it, swearing at the plague of a boy, and wishing him “back to skule again.”

“I doan’t care whether I ring the bells on the king’s birthday,” said the parish clerk, another victim of the boy’s pranks; “but if I never touch the ropes again, I’ll give a peal when Robert goes to skule, and leaves Stratton folks in peace.”

As may well be believed, the mischievous, high-spirited boy played tricks on his brothers and sisters. The clerk was accustomed to read in church, “I am an alien unto my mother’s children,” pronouncing “alien” as “a lion.” “Ah!” said Mrs. Hawker, “that means Robert: he is verily a lion unto his mother’s children.”

“I do not know how it is,” said his brother one day: “when I go out with Robert nutting, he gets all the nuts; and when I go out rabbiting, he gets all the rabbits; and when we go out fishing together, he catches all the fish.”

“Come with me fishing to-morrow, Claud,” said Robert, “and see if you don’t have luck.”

Next day he surreptitiously fastened a red herring to his brother’s hook, playing on his brother the trick Cleopatra had played on Anthony; and, when it was drawn out of the water, “There!” exclaimed Robert, “you are twice as lucky as I am. My fish are all raw; and yours is ready cleaned, smoked and salted.”

The old vicarage at Stratton is now pulled down: it stood at the east end of the chancel, and the garden has been thrown into the burial-ground.

At Stratton he got one night into the stable of the surgeon, hogged the mane, and painted the coat of his horse like a zebra with white and black oil paint. Then he sent a message to the doctor, as if from a great house at a distance, requiring his immediate attendance. The doctor was obliged to saddle and gallop off the horse in the condition in which he found it, thinking that there was not time for him to stay till the coat was cleaned of paint.

His pranks at Plymouth led at last to his grandfather refusing to have him any longer in his house.

Robert held in aversion the good pious ladies, who swarmed round the doctor. It was the time of sedan-chairs; and trains of old spinsters and dowagers were wont to fill the street in their boxes between bearers, on the occasion of missionary teas, Dorcas meetings, and private expositions of the Word. Robert used to open the house door, and make a sign to the bearers to stop. A row of a dozen or more sedans were thus arrested in the street. Then the boy would go to each sedan in order, open the window, and, thrusting his head in, kiss the fair but venerable occupant, and then start back in mock dismay, exclaiming: “A thousand pardons! I thought you were my mother. I am sorry. How could I have made such a mistake, you are so much older?”

Sometimes, with the gravest face, he would tell the bearers that the lady was to be conveyed to the Dockyard, or the Arsenal, or to the Hoe; and she would find herself deposited among anchors and ropes, or cannon-balls, or on the windy height overlooking the bay, instead of at the doctor’s door.

Two old ladies, spinster sisters, Robert believed were setting their caps at the doctor, then a widower. He took an inveterate dislike to them, and their insinuating, oily manner with his grandfather; and he worried them out of Plymouth.

He did it thus. One day he called on a certain leading physician in Plymouth, and told him that Miss Hephzibah Jenkins had slipped on a piece of orange peel, broken her leg, and needed his instant attention. He arrived out of breath with running, very red; and, it being known that the Misses Jenkins were intimate friends of Dr. Hawker, the physician went off at once to the lady, with splints and bandages.

Next day another medical man was sent to see Miss Sidonia Jenkins. Every day a fresh surgeon or physician arrived to bind up legs and arms and heads, or revive the ladies from extreme prostration, pleurisy, inflammation of the lungs, heart-complaint, etc., till every medical man in Plymouth, Stonehouse and Devonport had been to the house of the spinsters. When these were exhausted, an undertaker was sent to measure the old ladies for their coffins; and next day a hearse drew up at their door to convey them to their graves, which had been dug according to order in the St. Andrew’s churchyard.

This was more than the ladies could bear. They shut up the house and left Plymouth. But this was also the end of Robert’s stay with his grandfather. The good doctor had endured a great deal, but he would not put up with this; and Robert was sent to Stratton, to his father.

When the boy left school at Liskeard, he was articled to a lawyer, Mr. Jacobson, at Plymouth, a wealthy man in good practice, first cousin to his mother; but this sort of profession did not at all approve itself to Robert’s taste, and he remained with Mr. Jacobson a few months only. Whether he then turned his thoughts towards going into holy orders, cannot be told; but he persuaded his aunt, Mrs. Hodgson, to send him to Cheltenham Grammar School.

The boy had great abilities, and a passionate love of books, but wanted application. He read a great deal, but his reading was desultory. He was, however, a good classic scholar. To mathematics he took a positive dislike, and never could master a proposition in Euclid. At Cheltenham he wrote some poems, and published them in a little book entitled Tendrils, by Reuben. They appeared in 1821, when he was seventeen years old.

From Cheltenham, Robert S. Hawker went to Oxford, 1823, and entered at Pembroke; but his father was only a poor curate, and unable to maintain him at the university. Robert was determined to finish his course there. He could not command the purse of his aunt, Mrs. Hodgson, who was dead; and when he retired to Stratton for his long vacation in 1824, his father told him that it was impossible for him to send him back to the university.

But Robert Hawker had made up his mind that finish his career at college he would. The difficulty was got over in a manner somewhat novel.

There lived at Whitstone, near Holsworthy, four Miss I’ans, daughters of Colonel I’ans. They had been left with an annuity of £200 apiece, as well as lands and a handsome place. At the time when Mr. Jacob Hawker announced to his son that a return to Oxford was impossible, the four ladies were at Efford, near Bude, an old manor house leased from Sir Thomas Acland. Directly that Robert Hawker learnt his father’s decision, without waiting to put on his hat, he ran from Stratton to Bude, arrived hot and blown at Efford, and proposed to Miss Charlotte I’ans to become his wife. The lady was then aged forty-one, one year older than his mother; she was his godmother, and had taught him his letters.

Miss Charlotte I’ans accepted him; and they were married in November, when he was twenty. Robert S. Hawker and his wife spent their honeymoon at Morwenstow, in Combe Cottage. During that time he was visited by Sir William Call and his brother George. They dined with him, and told ghost-stories. Sir William professed his utter disbelief in spectral appearances, in spite of the most convincing, properly authenticated cases adduced by Mr. Hawker. It was late when the two gentlemen rose to leave. Their course lay down the steep hill by old Stowe. The moment that they were gone Robert got a sheet and an old iron spoon which he had dug up in the garden, and which bore on it the date 1702. He slipped a tinder-box and a bottle of choice brandy, which had belonged to Colonel I’ans, into his pocket, and ran by a short cut to a spot where the road was overshadowed by trees, at the bottom of the Stowe hill, which he knew the two young men must pass. He had time to throw the sheet over himself, strike a light, fill the great iron spoon with salt and brandy, and ignite it, before Sir William and his brother came up.

In the dense darkness of the wood, beside the road, they suddenly saw a ghastly figure, illumined by a lambent blue flame which danced in the air before it. They stood rooted to the spot, petrified with fear. Slowly the apparition stole towards them. They were too frightened to cry out and run. Suddenly, with an unearthly howl, the spectre plunged something metallic into the breast of Sir William Call’s yellow nankeen waistcoat, the livid flame fell around him in drops, and all vanished.

When he came to himself Sir William found an iron spoon in his bosom. He and his brother, much alarmed, and not knowing what to think of what they had seen, returned to Combe. They knocked at the door. Hawker put his head with nightcap on out of the bedroom-window and asked who were disturbing his rest. They begged to be admitted: they had something of importance to communicate. He came down stairs in a dressing-gown, and introduced them to his parlour. There the iron spoon was examined. “It is very ancient,” said Sir William: “the date on it is 1702—just the time when Stowe was pulled down.”

“It smells very strong of brandy,” said George Call.

Robert Hawker’s twinkling eye and twitching mouth revealed the rest.

“’Pon my word,” said Sir William Call, “you nearly killed me; and, what is more serious, nearly made me believe in spirits.”

“Ah!” added Robert dryly, “you probably did believe in them when they ran in a river of flame over your yellow nankeen waistcoat.”

The marriage with Charlotte I’ans took place on 6th November, 1824. On Hawker’s return to Oxford with his wife after the Christmas vacation (and he took her there, riding behind him on a pillion), he was obliged, on account of being married, to migrate from Pembroke to Magdalen Hall. About this time he made acquaintance with Jeune and Jacobson, the former afterwards Bishop of Peterborough, the latter Bishop of Chester. Jeune, and afterwards Jacobson, came down into Cornwall to pay him a visit in the long vacation of 1825; and Mr. Jeune acted as groomsman at the marriage of Miss Hawker to Mr. Kingdon. It was on the occasion of this visit of Mr. Jeune to Robert Hawker that they went over together to Boscastle, and there performed the prank described in Footprints of Former Men in Cornwall. The two young men put up in the little inn of Joan Treworgy, entitled The Ship. The inn still exists; but it is rebuilt, and has become more magnificent in its accommodation and charges.

“We proceeded to confer about beds for the night, and, not without misgivings, inquired if she could supply a couple of those indispensable places of repose. A demur ensued. All the gentry in the town, she declared, were accustomed to sleep two in a bed; and the officers that travelled the country, and stopped at her house, would mostly do the same: but, however, if we commanded two beds for only two people, two we must have; only, although they were both in the same room, we must certainly pay for two, and sixpence apiece was her regular price. We assented, and then went on to entreat that we might dine. She graciously agreed; but to all questions as to our fare her sole response was, ‘Meat—meat and taties. Some call ’em,’ she added, in a scornful tone, ‘purtaties; but we always says taties here.’ The specific differences between beef, mutton, veal, etc., seemed to be utterly or artfully ignored; and to every frenzied inquiry her calm, inexorable reply was, ‘Meat—nice wholesome meat and taties.’

“In due time we sat down in that happy ignorance as to the nature of our viands which a French cook is said to desire; and, although we both made a not unsatisfactory meal, it is a wretched truth that by no effort could we ascertain what it was that was roasted for us that day by widow Treworgy, and which we consumed. Was it a piece of Boscastle baby? as I suggested to my companion. The question caused him to rush out to inquire again; but he came back baffled and shouting, ‘Meat and taties.’ There was not a vestige of bone, nor any outline that could identify the joint; and the not unsavoury taste was something like tender veal. It was not till years afterwards that light was thrown on our mysterious dinner that day by a passage which I accidently turned up in an ancient history of Cornwall. Therein I read, ‘that the silly people of Bouscastle and Boussiney do catch in the summer seas divers young soyles (seals), which, doubtful if they be fish or flesh, conynge housewives will nevertheless roast, and do make thereof savory meat.’”

Very early next morning, before any one else was awake, Hawker and Jeune left the inn, and, going to all the pig-sties of the place, released their occupants. They then stole back to their beds.

“We fastened the door, and listened for results. The outcries and yells were fearful. By-and-by human voices began to mingle with the tumult: there were shouts of inquiry and surprise, then sounds of expostulation and entreaty, and again ‘a storm of hate and wrath and wakening fear.’ At last the tumult reached the ears of our hostess, Joan Treworgy. We heard her puff and blow, and call for Jim. At last, after waiting a prudent time, we thought it best to call aloud for shaving-water, and to inquire with astonishment into the cause of that horrible disturbance which had roused us from our morning sleep. This brought the widow in hot haste to our door. ‘Why, they do say, captain,’ was her doleful response, ‘that all the pegs up-town have a-rebelled, and they’ve a-been, and let one the wother out, and they be all a-gwain to sea, hug-a-mug, bang!’”

Some years after, when Mr. Jeune was Dean of Magdalen Hall, Mr. Hawker went up to take his M.A. degree. The dean on that occasion was, according to custom, leading a gentleman-commoner of the same college, a very corpulent man, to the vice-chancellor, to present him for his degree, with a Latin speech. Hawker was waiting his turn. The place was crowded, and the fat gentleman-commoner was got with difficulty through the throng to the place. Hawker leaned towards the dean as he was leading and endeavouring to guide this unwieldy candidate, who hung back, and got hitched in the crowd, and said in a low tone:—

“Why, your peg’s surely mazed, maister.”

When the crowd gave way, and the dean reached the vice-chancellor’s chair, he was in spasms of uncontrollable laughter.

At Oxford Mr. Robert Hawker made acquaintance with Macbride, afterwards head of the college; and the friendship lasted through life.

In after years, when Jeune, Jacobson and Macbride were heads of colleges, Robert S. Hawker went up to Oxford in his cassock and gown. The cassock was then not worn, as it sometimes is now, except by heads of colleges and professors. Mr. Hawker was therefore singular in his cassock. He was outside St. Mary’s one day, with Drs. Jeune, Jacobson and Macbride, when a friend, looking at him in his gown and cassock, said: “Why, Hawker, one would think you wanted to be taken for a head.”

“About the last thing I should like to be taken for, as heads go,” was his ready reply, with a roguish glance at his three companions.

Mr. Hawker has related another of his mischievous tricks when an undergraduate. There was a poor old woman named Nanny Heale, who passed for a witch. Her cottage was an old decayed hut, roofed with turf. One night Robert Hawker got on the roof, and looking down the chimney, saw her crouching over her turf fire, watching with dim eyes an iron crock, or round vessel, filled with potatoes, that were simmering in the heat. This utensil was suspended by its swing handle to an iron bar that went across the chimney. Hawker let a rope, with an iron hook at the end, slowly and noiselessly down the chimney, and, unnoted by poor Nanny’s blinking sight, caught the handle of the caldron; and it, with its mealy contents, began to ascend the chimney slowly and majestically.

Nanny, thoroughly aroused by this unnatural proceeding of her old iron vessel, peered despairingly after it, and shouted at the top of her voice:—

“Massy ’pon my sinful soul! art gawn off—taties and all?”

The vessel was quietly grasped, and carried down in hot haste, and planted upright outside the cottage door. A knock, given on purpose, summoned the inmate, who hurried out, and stumbled over, as she afterwards interpreted the event, her penitent crock.

“So, then,” was her joyful greeting,—“so, then! theer’t come back to holt, then! Ay, ’tis a-cold out o’ doors.”

Good came out of evil: for her story, which she rehearsed again and again, with all the energy and persuasion of truth, reached the ears of the parochial authorities; and they, thinking that old Nanny’s wits had failed her, gave an additional shilling a week to her allowance.

Hawker’s vacations were spent at Whitstone, or at Ivy Cottage, near Bude. At Whitstone he built himself a bark shanty in the wood, and set up a life-sized carved wooden figure, which he had procured in Oxford, at the door, to keep it. The figure he called “Moses.” It has long since disappeared.

In this hut he was wont to read. His meals were brought out there to him. His intervals of work were spent in composing ballads on Cornish legends, afterwards published at Oxford in his Records of the Western Shore, 1832. They have all been reprinted in later editions of his poems. One of these, his “Song of the Western Men,” was adapted to the really ancient burden:—

These verses have so much of the antique flavour, that Sir Walter Scott, in one of his prefaces to a later edition of the Border Minstrelsy, refers to them as a “remarkable example of the lingering of the true ballad spirit in a remote district”; and Mr. Hawker possessed a letter from Lord Macaulay in which he admitted that, until undeceived by the writer, he had always supposed the whole song to be of the time of the Bishops’ trial.

At Ivy Cottage he had formed for himself a perch on the edge of the cliff, where he could be alone with his books, his thoughts, and, as he would say with solemnity, “with God.”

Perhaps few thought then how deep were the religious impressions in the joyous heart, full of exuberant spirits, of the young Oxford student. All people knew of him was, that he was remarkable for his beauty, for his brightness of manner, his overflowing merriment, and love of playing tricks. But there was a deep undercurrent of religious feeling setting steadily in one direction, which was the main governing stream of his life. Gradually this emerges into sight, and becomes recognised. Then it was known to few except his wife and her sisters.

Of this period of his life, it is chiefly his many jests which have lingered on in the recollection of his friends and relations.

One absurd hoax that he played on the superstitious people of Bude must not be omitted.

At full moon in the July of 1825 or 1826, he swam or rowed out to a rock at some little distance from the shore, plaited seaweed into a wig, which he threw over his head, so that it hung in lank streamers half-way down his back, enveloped his legs in an oilskin wrap, and, otherwise naked, sat on the rock, flashing the moonbeams about from a hand-mirror, and sang and screamed till attention was arrested. Some people passing along the cliff heard and saw him, and ran into Bude, saying that a mermaid with a fish’s tail was sitting on a rock, combing her hair, and singing.

A number of people ran out on the rocks and along the beach, and listened awestruck to the singing and disconsolate wailing of the mermaid. Presently she dived off the rock, and disappeared.

Next night crowds of people assembled to look out for the mermaid; and in due time she reappeared, and sent the moon flashing in their faces from her glass. Telescopes were brought to bear on her; but she sang on unmoved, braiding her tresses, and uttering remarkable sounds, unlike the singing of mortal throats which have been practised in do-re-mi.

This went on for several nights; the crowd growing greater, people arriving from Stratton, Kilkhampton, and all the villages round, till Robert Hawker got very hoarse with his nightly singing, and rather tired of sitting so long in the cold. He therefore wound up the performance one night with an unmistakable “God save the King,” then plunged into the waves, and the mermaid never again revisited the “sounding shores of Bude.”

Miss Fanny I’ans was a late riser. Her brother-in-law, to break her of this bad habit, was wont to throw open her window early in the morning, and turn in a troop of setters, whose barking, yelping and frantic efforts to get out of the room again, effectually banished sleep from the eyes of the fair but somewhat aged occupant.

Efford Farm had been sub-let to a farmer, who broke the lease by ploughing up and growing crops on land which it had been stipulated should be kept in grass.

Sir Thomas Acland behaved with great generosity in the matter. He might have reclaimed the farm without making compensation to the ladies; but he allowed them £300 a year as long as they lived, took the farm away, and re-leased it to a more trusty tenant.

Mr. Robert Stephen Hawker obtained the Newdegate in 1827:[1] he took his degree of B.A. in 1828, and then went with his wife to Morwenstow, a place for which even then he had contracted a peculiar love, and there read for holy orders.

Ordination—The Black Pig, “Gyp”—Writes to the Bishop—His Father appointed to Stratton—He is given Morwenstow—The Waddon Lantern—St. Morwenna—The Children of Brychan—St. Modwenna of Burton-on-Trent—The North Cornish Coast—Tintagel—Stowe—Sir Bevil Grenville—Mr. Hawker’s discovery of the Grenville Letters—Those that remain—Antony Payne the Giant—Letters of Lady Grace—Of Lord Lansdown—Cornish Dramatic Power—Mr. Hicks of Bodmin.

Robert Stephen Hawker was ordained deacon in 1829, when he was twenty-five years old, by the Bishop of Exeter, to the curacy of North Tamerton, of which the Rev. Mr. Kingdon was non-resident incumbent. He threw two cottages into one, and added a veranda and rooms, and made himself a comfortable house, which he called Trebarrow. He was ordained priest in 1831, by the Bishop of Bath and Wells. He took his M.A. degree in 1836. He had a favourite rough pony which he rode, and a black pig of Berkshire breed, well cared for, washed and curry-combed, which ran beside him when he went out for walks and paid visits. Indeed, the pig followed him into ladies’ drawing-rooms, not always to their satisfaction. The pig was called Gyp, and was intelligent and obedient. If Mr. Hawker saw that those whom he visited were annoyed at the intrusion of the pig, he would order it forth; and the black creature slunk out of the door with its tail out of curl.

It was whilst Mr. Hawker was at Tamerton that Henry Phillpotts was appointed Bishop of Exeter. There was some unpleasant feeling aroused in the diocese at the mode of his appointment; and the bishop sent a pastoral letter to his clergy to state his intentions and explain away what caused unpleasantness. Mr. Hawker wrote the bishop an answer of such a nature that it began a friendship which subsisted between them till the death of Dr. Phillpotts. Whilst Mr. Hawker was curate of Tamerton, on one or two occasions the friends of the labouring dead requested that the burial hour might be that at which the deceased was accustomed “to leave work.” The request touched his poetical instinct, and he wrote the lines:—

In 1834 died the non-resident vicar of Stratton, and the Bishop of Exeter offered to obtain the living for Mr. Robert Stephen Hawker; but he refused it, as his father was curate of Stratton, and he felt how unbecoming it would be for him to assume the position of vicar where his father had been, and still was, curate. In his letter to the bishop he urged his father’s long service at Stratton; and Dr. Phillpotts, at his request, obtained the presentation for Mr. Jacob Stephen Hawker to the vicarage of Stratton.

The very next piece of preferment that fell vacant was Morwenstow, whose vicar, the Rev. Mr. Young, died in 1834. Mr. Young had been non-resident, and had lived at Torrington, the parish being served by a succession of curates, some of them also non-resident. The vicarage house, which stood west of the tower near a gate out of the churchyard, was let to the clerk, and inhabited by him and his wife. The first curate was Mr. Badcock, who lived at Week St. Mary, some fourteen miles distant. He rode over for Sunday duty. Next came a M. Savant, a Frenchman ordained deacon in the English Church, but never priest. He was a dapper dandy, very careful of his ecclesiastical costume, in knee-breeches and black silk stockings. He lodged at Marsland. Parson Davis of Kilkhampton came over to Morwenstow to celebrate the holy communion. The Frenchman was succeeded by Mr. Bryant, who lived at Flexbury, in the parish of Poughill; the next to him was Mr. Thomas, a man who ingratiated himself with the farmers—a cheery person, fond of a good story, and interested in husbandry, “but not much of the clerical in him,” as an old Morwenstow man describes him. Whilst Mr. Thomas was curate, the vicar, Parson Young, died. A petition from the farmers and householders of Morwenstow to the bishop was got up, to request him to appoint Mr. Thomas. The curate, so runs the tale, went to Exeter to present the paper with their signatures, and urge his claims in person.

“My lord,” said he, “the Dissenters have all signed the petition: they are all in favour of me. Not one has declined to attach his name; even the Wesleyan minister wishes to see me vicar of Morwenstow.”

“Then, my good sir,” said Dr. Phillpotts, “it is very clear that you are not the man for me. I wish you a good-morning.” And he wrote off to Robert Stephen Hawker, offering him the incumbency of Morwenstow.

There was probably not a living in the whole diocese, perhaps not one in England, which could have been more acceptable to Mr. Hawker. As his sister tells me, “Robert always loved Morwenstow: from a boy he loved it, and, when he could, went to live there.”

He at once accepted the preferment, and went into residence. There had not been a resident vicar since the Rev. Oliver Rose[*],[2] who lived at Eastaway, in the parish. This Rev. Oliver Rose had a brother-in-law, Mr. Edward Waddon of Stanbury; and the cronies used to meet and dine alternately at each other’s house. As they grew merry over their port, the old gentlemen uproariously applauded any novel joke or story by rattling their glasses on the table. Having laughed at each other’s venerable anecdotes for the last twenty years, the introduction of a new tale or witticism was hailed with the utmost enthusiasm. This enthusiasm reached such a pitch, that, in their applause of each other’s sallies, they occasionally broke their wine-glasses.

The vicar of Morwenstow, when Mr. Waddon snapped off the foot of his glass, would put the foot and a fragment in his pocket, and treasure it; for each wine-glass broken was to him a testimony to the brilliancy of his jokes, and also a reminder to him of them for future use.

In time he had accumulated a considerable number of broken wine-glasses, and he had them fitted together to form an enormous lantern; and thenceforth, when he went to dine at Stanbury, this testimony to his triumphs was borne lighted before him.

The lantern fell into the hands of Mr. Hawker, and he presented it to the lineal descendant of Mr. E. Waddon, as a family relic. It is still in existence, and duly honoured. It is of oak, with the fragments of wine-glasses let in with great ingenuity in the patterns of keys, hearts, etc., about the roof, the sides being composed of the circular feet of the glasses.

On looking at the map of Cornwall, one is surprised to see it studded with the names of saints, of whom one knows nothing, and these names of a peculiarly un-English sound. The fact is, that Cornwall was, like Ireland, a land of saints in the fifth and sixth centuries. These were either native Cornish, or were Irish or Welsh saints who migrated thither to seek on the desolate moors or wild, uninhabited coasts of Cornwall, solitary places, where they might live to God, and fight demons, like the hermits of Egypt. Cornwall was the Thebaid of the Welsh.

Little or nothing is known of the vast majority of these saints. They have left their names and their cells and holy-wells behind them, but nothing more.

The legends of a few local saints survive, but of very few. Such is that of St. Melor “with the golden hand,” probably some old British deity who has bequeathed his myth to an historical personage. St. Padarn, St. Cadoc, St. Petrock, have their histories well known, as they belong to Wales. But there are other saints, emigrants from Wales, who settled on the north-west coast, of whom but little is known.

What little can be collected concerning St. Morwenna, who had her cell at Morwenstow, I proceed to give.

In the fifth century there lived in Brecknock an Irish invader, Brychan by name, who died in 450. According to Welsh accounts, he had twenty-four sons and twenty-five daughters, in all forty-nine children. Statements, however, vary, of which this is the largest. The smallest number attributed to him is twenty-four; and, as his grandchildren may have been included in the longer list, this may account for the discrepancy. He is said to have had three wives—Ewrbrawst, Rhybrawst and Peresgri—though it is not said that they were living at the same time. The fact seems to have been that all the Hy Brychan or family are regarded as brothers and sisters.

The names of the sons and daughters and grandchildren of Brychan are given in the Cognacio Brychani, and in the Bonnedd-y-Saint; and a critical examination of the lists is given by Dr. Rees in his Essay on the Welsh Saints. In the “Young Woman’s Window” at St. Neots, near Liskeard, in Cornwall, is fifteenth-century glass, which represents Brychan with his offspring, twenty-four in number, all of whom have been confessors or martyrs in Devon and Cornwall. The following are named: 1. St. John, or Ive, who gave his name to the Church of St. Ive; 2. Endelient, who gave his name to Endelion; 3. Menfre, to St. Miniver; 4. Teth, to St. Teath; 5. Mabina, to St. Mabyn; 6. Merewenna, to Marham Church near Bude; 7. Wenna, to St. Wenn; 8. Yse, to St. Issey; 9. Morwenna, to Morwenstow; 10. Cleder, to St. Clether; 11. Kerie, to Egloskerry; 12. Helic, to Egloshayle; 13. Adwen, to Advent; 14. Lanent, to Lelant. Leland, in his Itinerary, adds Nectan, Dilic, Wensenna, Wessen, Juliana,[4] Wymp, Wenheder, Jona, Kananc, and Kerhender.

A few, but not many of these can be identified with those attributed to Brychan by the Welsh genealogists. Morwenna is most probably the Welsh Mwynen, in Latin Monyina, daughter of Brynach Wyddel by Corth, one of the daughters of Brychan; and her sisters Gwennan and Gwenlliu are probably the Wenna and Wenheder of Leland’s list.

St. Morwenna was therefore apparently the granddaughter of Brychan. Her father, Brynach Wyddel, is the St. Branock of Braunton near Ilfracombe. He also founded churches in Carmarthen and Pembroke.

In Cornwall, as in Wales, churches were called after the saints who founded cells there. Morwenna, we may safely conclude, like so many of her brothers, sisters, cousins, uncles and aunts, migrated to Cornwall. St. Nectan, who may have been her brother, and who certainly was a near relation, established himself, we may conjecture, at St. Neighton’s Kieve, at which time probably Morwenna had her cell at Marham Church. St. Nectan afterwards established himself on Hartland Point from which, in clear weather, and before a storm, the distant coast of his native Wales was visible; and perhaps at the same time Morwenna erected her cell on the cliff above the Atlantic, which has since borne her name. There she died. Leland, in his Collectanea, quoting an ancient MS. book of places where the bodies of saints rest, says that St. Morwenna lies at Morwenstow: “In villa, quæ Modwenstow dicitur, S. Mudwenna quiescit.”

It will be seen from this extract that Leland confounded Morwenna with Modwenna; and Mr. Hawker, following Leland and Butler, did the same. In the year before he died I had a correspondence with him on this point.

There exists a late life of St. Modwenna by one Concubran, an Irish writer of the end of the thirteenth and beginning of the fourteenth century. There is also an Irish life of a Monynna of Newry, in Ireland, who received the veil from the hands of St. Patrick, and died about A.D. 518.

Concubran had this life, and knowing of the fame of the saintly abbess Modwenna of Burton-on-Trent, he supposed the two saints were the same, and wove the Irish legend of Monynna with the English life of Modwenna, and made out of them a life which is a tissue of anachronisms. He represents St. Modwenna as contemporary with Pope Cœlestine I. (423-432), St. Patrick (died 465), St. Ibar (died 500), St. Columba (died 597), St. Kevin (died 618), and King Alfrid of Northumbria (died 705).

St. Modwenna, or Moninna, founded a convent at Fochard Brighde, near Faugher, in the county of Louth, about the year 630; and 150 virgins placed themselves under her rule. But one night, an uproarious wedding having disturbed the rest and fluttered the hearts of her nuns, and threatened to turn their heads, Modwenna deemed it prudent to remove the excitable damsels to some more remote spot, where no weddings took place, nor convivial songs were heard; and she pitched upon Killsleve-Cuilin, in the county of Armagh, where she erected a monastery. One of her maidens was named Athea, another Orbile. She had a brother, a holy abbot, named Ronan.

In Concubran’s Life of St. Modwenna, we are told that about this time Alfrid, son of the King of England, came to Ireland. This is certainly Alfrid, the illegitimate son of Oswy, who, on the accession of Egfrid (A.D. 670), fled to Ireland, and remained there studying, as Bede tells us, for some while. The Irish king, according to Concubran, was Conall. But this is a mistake. Conall, nephew of Donald II., reigned from 642 to 658. Seachnach was king in 670, but was killed the following year, and was succeeded by Finnachta, who reigned till 695. When Alfrid was about to return to Northumbria, the Irish king wanted to make him a present, but, having nothing in his treasury, bade a kinsman go and rob some church or convent, and give the spoils to the Northumbrian prince. The noble fell on all the lands of the convent of Moninna, and pillaged them and the church. Then the saint, with great boldness, took ship, crossed over to England, went to Northumbria, and found the Prince Alfrid at Whitby (A.D. 685), and demanded redress. The king—for Alfrid was now on the throne—promised to repay all, and placed Moninna in the famous double monastery of Whitby founded by St. Hilda in 658. His own sister, Elfleda, was there; and he committed her to St. Modwenna, to be instructed by her in the way of life. Elfleda was then aged thirty-one. Three years after she succeeded to the place of St. Hilda, and was second Abbess of Whitby. Then St. Modwenna returned to Ireland, and visited her foundations there. After a while she made a pilgrimage to Rome, and in passing through England founded a religious house at Burton-on-Trent, and left in it some of her nuns. I need not follow her history farther.

Concubran tells some odd stories of St. Modwenna. One day she and her nuns went to visit St. Bridget—regardless, be it remembered, of the gap of two centuries which intervened. A girl in the company took an onion away with her lest she should be hungry on the road. On reaching the Liffey, the river was found to be too swollen to be crossed. “There is something wrong,” said Modwenna: “let us examine our consciences and cast away the accursed thing.”

“The accursed thing is this onion,” said the maiden, producing the bulb.

“Take it back to Bridget,” said Modwenna; and, when the onion had been restored, the Liffey subsided.

Bridget sent a silver chalice to Modwenna. She threw it into the river, and the waves washed it to its destination.

One night Modwenna said to her assembled nuns: “My sisters, we must all cleanse our consciences, for our prayers stick in the roof of the chapel, and cannot break out.”

Then one of the nuns said: “It is my fault. I complained to a knight of my acquaintance of the cold I felt; and he told me I was too scantily clothed. He was moved to such pity of me, that he gave me some warm lamb’s-wool underclothing, and I have that on now.” The garment was removed and destroyed; and the prayers got out of the roof and flew to heaven.[5]

One night, shortly before her death, before the grey dawn broke, a couple of lay sisters came to her cell. As they approached, they saw two silver swans rise in the air, and sail away. They immediately concluded that these were angels come to bear off the soul of the abbess.

Her body was laid at Burton-on-Trent, and was long an object of pilgrimage. But the fact that for a short while St. Modwenna instructed the sister of Alfrid, “son of the King of England,” has led some writers into strange mistakes. Capgrave supposes him to be Alfred the Great, son of Ethelwolf, and that the sister was Edith of Polesworth, who died in 954. And Dugdale followed Capgrave. Mr. Hawker, following Alban Butler, who accepted the account of Dugdale and Capgrave, made the blunder greater by fusing St. Morwenna of Cornwall, who, as has been shown, lived in the fifth century, with Modwenna, who lived at the end of the seventh century, and made her the instructress of St. Edith of Polesworth, who died in the tenth century, in the year 954. And Modwenna, as has been stated, was confounded by Concubran with Monynna of Newry, who died at the beginning of the sixth century.

On unravelling this tangle in 1874, I wrote to Mr. Hawker of Morwenstow, and told him that the east window of his church represented Morwenna of Cornwall teaching Edith of Polesworth, and that it was an anachronism and mistake altogether, as it was not Edith who was educated by the saintly Modwenna, and the abbess Modwenna was not the virgin Morwenna. I told him also that St. Modwenna was buried at Burton-on-Trent.

I received this answer:—

“What! Morwenna not lie in the holy place at Morwenstow! Of that you will never persuade me—no, never. I know that she lies there. I have seen her, and she has told me as much; and at her feet ere long I hope to lay my old bones.”

In the little glen of Morwenstow, 350 feet above the Atlantic, St. Morwenna had her cell, and gave origin to the church and parish of Morwenstow. As she lay a-dying, says a legend according to Hawker, her brother Nectan came to her from Hartland.

“Raise me in thy arms, brother,” she said, “that my eyes may rest on my native Wales.” And so she died on Morwenstow cliff, looking out across the Severn Sea to the faint blue line of the Welsh mountains. St. Nectan had a cell at Wellcombe, as also at Hartland, for both of these churches bear his name.

The coast from Tintagel to Hartland is almost unrivalled for grandeur. The restless Atlantic is ever thundering on this iron-walled coast. The roar can be heard ten miles inland; flakes of foam are picked up after a storm at Holsworthy. To me, when staying three miles inland, it has seemed the roar of a hungry caged beast, ravening at its bars for food.

The swell comes unbroken from Labrador, to hurl itself against this coast, and to be shivered into foam on its iron cuirass.

“Twice,” said a friend who dwelt near this coast, “twice in the sixteen years that I have spent here has the sea been calm enough to reflect a passing sail.”

This Atlantic has none of the tameness of the German Ocean, that plays on the low flat shores of Essex; none of the witchery of the green crystal that breaks over the white sands of Babbicombe and Torquay: it is emphatically “the cruel sea,” fierce, insatiate, hungering for human lives and stately vessels, that it may cast them up mumbled and mangled after having robbed them of life and treasure.

It is a rainy coast. It is said in Devon, and the same is true here:—

The moist air from the ocean condenses over the land, and envelops it in fine fog or rain. But when the sky is clear, with only floating clouds drifting along it, the sunlight and shadows that fall over the landscape through the vaporous air are exquisite in their delicacy of colour; the sun-gleams soft as primrose, the shadows pure cobalt, tenderly laid on as the bloom on the cheek of a plum.

As the tall cliffs on this wild coast lose themselves in mist, so does history, which attaches itself to many a spot along it, stand indistinct and weird in its veil of legend. Kings and saints of whom little authentic is known, whose very dates are uncertain, have given their names to castle and crag and church.

Tintagel Rock is crowned with the ruins of the stronghold of Duke Gorlois, whose wife became the mother of the renowned Arthur, by Uther Pendragon. We have the tale in Geoffry of Monmouth. There, in the home of the shrieking sea-mews, Arthur uttered his first feeble cries. It is a scene well suited to be the cradle of the hero of British myth—a tremendous crag standing out of the sea, which has bored a tunnel through it, and races in and clashes in subterranean passages under the crumbling walls which sheltered Arthur.

The crag is cut off from the mainland by a chasm once spanned by a drawbridge, but now widened by storm so as to threaten to convert Tintagel into an island.

Near Boscastle rises Pentargon, “Arthur’s Head,” a noble black sheer precipice, forming one horn of a little bay into which a waterfall plunges from a green combe.

But there are other names besides those of Arthur, Uther Pendragon, Morwenna, Juliot and Nectan, which are associated with this coast.

At Stowe, in the parish of Kilkhampton, adjoining Morwenstow, lived Sir Bevil Grenville, the Bayard of old Cornwall, “sans peur et sans reproche,” who fought and conquered at Stratton, and fell at Lansdown. Sir Bevil nearly ruined himself for the cause of his king, Charles I.

One of Mr. Hawker’s most spirited ballads is—

One day, if indeed we may trust the story, Mrs. Hawker, the first wife of the vicar of Morwenstow, when lunching at Stowe in the farmhouse, noticed that a letter in old handwriting was wrapped round the mutton-bone that was brought on the table. Moved by curiosity, she took the paper off, and showed it to Mr. Hawker. On examination it was found that the letter bore the signature of Sir Bevil Grenville. Mr. Hawker at once instituted inquiries, and found a large chest full of letters of different members of the Grenville family in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. He at once communicated with Lord Carteret, owner of Stowe, and the papers were removed; but by some unfortunate accident they were lost. The only ones saved were a packet extracted from the chest by Mr. Davies, rector of Kilkhampton, previous to their being sent away from Stowe. These were copied by Miss Manning of Eastaway, in Morwenstow; and her transcript, together with some of her originals—I fear not all—is now in the possession of Ezekiel Rous, Esq., of Bideford.[6]

In his Footprints of Former Men, Mr. Hawker has printed a letter from Antony Payne, the gigantic serving-man of Sir Bevil, written after the battle of Lansdown, to Lady Grace Grenville, giving an account of the death of her husband. This was probably one of the letters in the collection found by Mr. Hawker, and so sadly lost.

This Antony Payne was a remarkable man. He measured seven feet two inches without his shoes when aged twenty-one, when he was taken into the establishment at Stowe. He afterwards added two inches to his height. It is said that one Christmas Eve the fire languished in the hall at Stowe. A boy with an ass had been sent to the woods for logs, but had loitered on his way. Lady Grace lost patience. Then Antony started in quest of the dilatory lad, and re-entered the hall shortly after, bearing the loaded animal on his back. He threw down his burden at the hearth-side, shouting, “Ass and fardel! Ass and fardel for my lady’s Yule!”

On another occasion he rode into Stratton with Sir Bevil. An uproar proceeded from the little inn-yard, and Sir Bevil bade his giant find out what was the cause of the disturbance. Antony speedily returned with a man under each arm, whom he had arrested in the act of fighting.

“Here are the kittens,” said the giant; and he held them under his arms whilst his master chastised them with his riding-whip.

After the battle of Stamford Hill, Sir Bevil returned for the night to Stowe; but his giant remained with some other soldiers to bury the dead. He had caused trenches to be dug to hold ten bodies side by side, and in these trenches he and his followers deposited the slain. On one occasion they had laid nine corpses in their places; and Payne was bringing another, tucked under his arm like one of the “kittens,” when all at once the supposed dead man began to kick and plead for life. “Surely you won’t bury me, Mr. Payne, before I am dead?”—“I tell thee, man,” was the grim reply, “our trench was dug for ten, and there’s nine in it already: thou must take thy place.”—“But I bean’t dead, I say; I haven’t done living yet: be massyful, Mr. Payne; don’t ye hurry a poor fellow into the earth before his time.”—“I won’t hurry thee: thou canst die at thy leisure.” Payne’s purpose was, however, kinder than his speech. He carried the suppliant to his own cottage, and left him to the care of his wife. The man lived, and his descendants are among the principal inhabitants of Stratton at this day.

I make no apology for transcribing from the original letters a very few of the most interesting and touching, some for whose escape we cannot feel too thankful. The following beautiful letter is from Lady Grace Grenville to her husband.

The superscription is:—

For my best Friend, Sir Bevill Grenvile.

My ever Dearest,—I have received yours from Salisbury, and am glad to hear you came so farr well, with poore Jack. Ye shall be sure of my prairs, which is the best service I can doe you. I canott perceave whither you had receaved mine by Tom, or no, but I believe by this time you have mett that and another since by the post. Truly I have been out of frame ever since you went, not with a cough, but in another kinde, much indisposd. However, I have striven with it, and was at Church last Sunday, but not the former. I have been vexed with diverse demands made of money than I could satisfie, but I instantly paid what you sent, and have intreated Mr. Rous his patience a while longer, as you directed. It grieves me to think how chargeable your family is, considering your occasion. It hath this many yeares troubled me to think to what passe it must come at last, if it run on after this course. How many times what hath appeared hopefull, and yet proved contrary in the conclusion, hath befalen us, I am loth to urge, because tis farr from my desire to disturbe your thoughts; but this sore is not to be curd with silence, or patience either, and while you are loth to discourse or thinke of that you can take little comfort to see how bad it is, and I was unwilling to strike on that string which sounds harsh in your eare (the matter still grows worse, though). I can never putt it out of my thoughts, and that makes me often times seeme dreaming to you, when you expect I should sometimes observe more complement with my frends, or be more active in matters of curiousity in our House, which doubtlesse you would have been better pleasd with had I been capable to have performd it, and I believe though I had a naturall dullnes in me, it would never so much have appeard to my prejudice, but twas increasd by a continuance of sundry disasters, which I still mett with, yet never till this yeare, but I had some strength to encounter them, and truly now I am soe cleane overcome, as tis in vaine to deny a truth. It seems to me now tis high time to be sensible that God is displeased, having had many sad remembrances in our estate and childrene late, yet God spard us in our children long, and when I strive to follow your advice in moderating my grieffe (which I praise God) I have thus farr been able to doe as not to repine at God’s will, though I have a tender sence of griefe which hangs on me still, and I think it as dangerous and improper to forgett it, for I cannott but think it was a neer touched correction, sent from God to check me for my many neglects of my duty to God. It was the tenth and last plague God smote the Egyptians with, the death of their first borne, before he utterly destroyed them, they persisting in their disobedience notwithstanding all their former punishments. This apprehension makes me both tremble and humbly beseech Him to withdraw His punishments from us, and to give us grace to know and amend whatever is amisse. Now I have powrd out my sad thoughts which in your absence doth most oppresse me, and tis my weakness hardly to be able to say thus much unto you, how brimfull soever my heart be, though oftentimes I heartely wish I could open my heart truly unto you when tis overchargd. But the least thought it may not be pleasing to you will at all times restraine me. Consider me rightly, I beseech you, and excuse, I pray, the liberty I take with my pen in this kinde. And now at last I must thanke you for wishing me to lay aside all feare, and depend on the Almighty, who can only helpe us; for His mercy I daily pray, and your welfare, and our poore boys; so I conclude, and am ever your faithfully and only

Grace Grenvile.

Stow, Nov. 23, 1641.

I sent yours to Mr. Prust, but this from him came after mine was gone last weeke. Ching is gone to Cheddar. I looke for Bawden, but as yet is not come. Sir Rob. Bassett is dead.

I heard from my cosen Grace Weekes, who writes that Mr. Luttrell says if you and he could meete the liking between the young people, he will not stand for money you shall finde. Parson Weekes wishes you would call with him, and that he might entice you to take the castle in your way downe. She sayes they enquire in the most courteous manner that can be imagind. Deare love, thinke how to farther this what you can.

The following is an earlier letter by many years, written when Grace was a wife of six years’ standing.

Sweet Mr. Grenvile,—I cannott let Mr. Oliver passe without a line, though it be only to give you thankes for yours, which I have receaved. I will in all things observe your directions as neer as I can, and because I have not time to say much now I will write againe to-morrow ... [something torn away], and think you shall receave advertizment concerning us much as you desyre. I cannot say I am well, neither have I bin so since I saw you, but, however, I will pray for your health, and good successe in all businesses, and pray be so kinde as to love her who takes no comfort in anything but you, and will remayne yours ever and only

Grace Grenvile.

Fryday Night, Nov. 13, 1629.

The superscription of this letter is:—

“To my ever dearest and best Friend, Mr. Bevill Grenvile, at the Rainbow, in Fleet Street.”

Lady Grace was the daughter of Sir George Smith of Exeter, Kt.: she was born in 1598, and married Sir Bevil Grenville in 1620. He died in 1643, on the battlefield of Lansdown, near Bath; and she followed him to the grave in 1647. Her portrait is at Haynes, “ætatis suæ 36, 1634”. One of Sir Bevil is in the possession of Lord John Thynne; another with date 1636, “ætatis suæ 40,” is in the possession of Rev. W. W. Martyn of Tonacombe, in Morwenstow.

There are other letters of the Grenvilles in the bundle from which I have selected these. One from John Grenville to his brother, giving a curious picture of London life in the seventeenth century, narrating how he quarrelled with a certain barber Wells, and came very nigh to pulling off noses;[7] one from Jane, wife of John Grenville, Earl of Bath, to her husband “for thy deare selfe,” beginning, “My deare Heart,” and telling how:—

I am now without any man in the house, my father being gone, and Jacke is drunk all day and leyes out of nights, and if I do but tell him of it he will be gone presantly; therefore, for God’s sake, make haste up, for I am so parpetually ill that I am not fit to bee anny longgar left in this condission. My poore motther hath now so much bisnese that I do not knowe how long she will be abble to tary with mee, and if that should happen, which God forbid it should at any time, much more now, what dost thou thinke I should do? I want the things thou prommysed to send me very much, which, being to long to put in a lettar, I have geven my brother a not of. My deare, consider how nere I am my time, and many women comming this yeare before thar time.... Thou mayst now thinke how impassiontly I am till I see thee agane, thinking every day a hondared yeare; my affecksion being so gret that I wounder how I have stayd till the outmoust time. I will saye no more now, hopping to see thee every day, but that I am, and ever will bee, thy most affectionate and faithful wife and sarvant,

Jane Grenvile.

Thy babe bayrs thy blessing.

This letter is dated only June 17, without year. It is always pleasant to meet with the beating of a warm human heart. A third letter I venture to transcribe here, from George Lord Lansdown,[8] grandson of Sir Bevil, to his nephew, Bevil Grenville.

Dear Nephew,—I approve very well of your resolution of dedicating yourself to the service of God. You could not chuse a better master, provided you have so sufficiently searched your heart and examined your reins, as to be persuaded you can serve Him well. In so doing, you may secure to yourself many blessings in this world, as well as sure hope in the next.

There is one thing which I perceive you have not yet thoroughly purged yourself from; which is, flattery. You have bestowed so much of it upon me in your last letter, that I hope you have no more left, and that you meant it only to take your leave of such flights, which, however well meant, oftener put a man out of countenance than oblige him. You are now to be a searcher after truth, and I shall hereafter take it more kindly to be justly reproved by you than to be undeservedly complimented.

I would not have you misunderstand me, as if I recommended to you a sour Presbyterian severity. That is yet more to be avoided: advice, like physick, must be so sweetned and prepared as to be made palatable, or Nature may be apt to revolt against it.

Be always sincere, but at the same time be always polite. Be humble without descending from your character, and reprove and correct without ofending good manners. To be a Cynick is as bad as to be a Sycophant: you are not to lay aside the gentleman with the sword, nor put on the gown to hide your birth and good breeding, but to adorn it.

Such has been the malice of the wicked, that pride, avarice, and ambition have been charged upon the Clergy in all ages, in all countrys, and equally in all religions. What they are most obliged to combat against in the pulpits they are most accused of encouraging in their conduct. Let your example confirm your doctrine, and let no man ever have it in his power to reproach you with practising contrary to what you preach.

You had an unckle, the late Dean of Durham,[9] whose memory I shall ever revere. Make him your example. Sanctity sat so easy, so unaffected, and so gracefull upon him, that in him we beheld the very beauty of Holiness. He was as chearful as familiar, as condescending in his conversation, as he was strict, regular, and exemplary in his piety; as well-bred and accomplished as a courtier, and as reverend and venerable as an Apostle; he was indeed Apostolical in everything, for he left all to follow his Lord and Master. May you resemble him; may he revive in you; may his spirit descend upon you, as Elijah’s on Elisha; and may the great God of heaven, in guiding, directing, and strengthening your pious resolutions, pour down the choicest of his blessings upon you!

Lansdown.

The old house at Stowe was converted into farm buildings, and a new red brick mansion, square, containing a court in the middle, was built in 1660 by John, Earl of Bath. He died in 1701; and his son, Charles, shot himself accidentally when going from London to Kilkhampton to his father’s funeral, leaving a son, William Henry, third Earl of Bath, seven years of age when his father died. Thus, as was said, at the same time there were three Earls of Bath above ground. William Henry died at the age of seventeen, in 1711; and then the Grenville property was divided between the sisters of Charles, second Earl of Bath—Jane, who married Sir William Gower, ancestor of the Dukes of Sutherland; and Grace, who at the age of eight married George, afterwards first Lord Carteret, then aged eleven.

The letters of this little pair to one another, when the husband was at school and she at Haynes, exist in the possession of Lord John Thynne.

Stowe House was pulled down. Within the memory of one man, grass grew and was mown in the meadow where sprang up Stowe House, and grew and was mown in the meadow where Stowe had been.

A few crumbling walls only mark the site of the old home of the Grenvilles.[10]

The Cornish people in former days were passionately fond of theatrical performances. In numerous parts of Cornwall there exist green dells or depressions in the surface of the ground, situated generally on a moor. These depressions have been assisted by the hand of man to form rude theatres: the slopes were terraced for seats, and on fine summer days, at the “revels” of the locality, were occupied by crowds of spectators, whilst village actors performed on the turf stage.[11] Originally the pieces acted were sacred, curious mysteries, of which specimens remain, relating to the creation, or the legendary history of St. Meriadoc, or the passion of the Saviour, the prototypes of the Ammergau Passions-spiel. These in later times gave way to secular pieces, not always very choice in subject, and with the broadest of jokes in the speeches of the performers; not worse, perhaps, than are to be found in Shakspeare, and which were tolerated in the days of Elizabeth. These dramatical performances were in full vigour when Wesley preached in Cornwall. He seized on these rude green theatres, and harangued from their turfy platforms to wondering and agitated crowds, which thronged the grassy slopes.

The Cornish people became Methodists, and play-going became sinful. The doom of these dramas was sealed when the place of their performances was turned into an arena for revivals. The camp-meeting supplanted the drama.

But, though these plays are things of the past, the dramatic instinct survives among the Cornish people. There is scarce a parish in which some are not to be found who are actors by nature. For telling a story, with power of speech, expression and gesture, they have not their equals in England among un-professionals.

One of the most brilliant raconteurs of our times was Mr. Hicks, Mayor of Bodmin.

Some years ago a member sauntering into the Cosmopolitan Club would find a ring of listeners gathered about a chair. In that ring he would recognise the faces of Thackeray, Dickens, and other literary celebrities, wiping away the tears which streamed from their eyes between each explosion of laughter. He would ask, in surprise, what was the attraction.

“Only the little fat Cornishman from Bodmin telling a story.”[12]

His tales were works of art, wrought out with admirable skill, every point sharpened, every detail considered, and the whole told with such expression and action as could not be surpassed. His “Rabbit and Onions” has been essayed by many since his voice has been hushed; but the copies are pale, and the outlines blurred.

The subject of this memoir had inherited the Cornish love of story-telling, and the power of telling stories with dramatic force. But he had not the skill of Mr. Hicks in telling a long story, and keeping his hearers thrilling throughout the recital, breathless lest they should lose a word. Mr. Hawker contented himself with brief anecdotes, but those he told to perfection.

I shall, in the course of my narrative, give a specimen or two of stories told by common Cornish peasants. Alas, that I cannot reproduce the twinkling eye, the droll working countenances, and the agitated hands, all assistants in the story-telling!

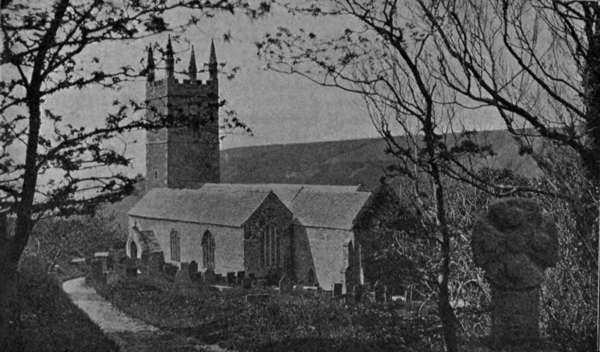

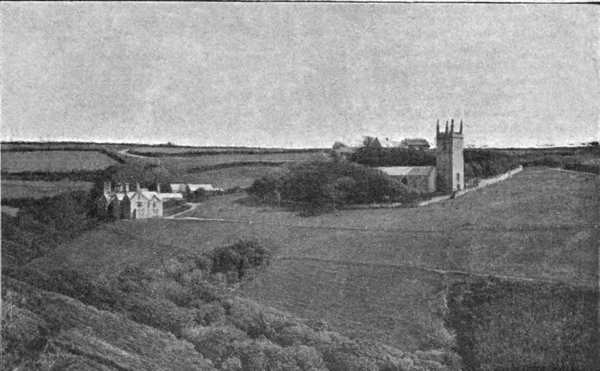

Description of Morwenstow—The Anerithmon Gelasma—Source of the Tamar—Tonacombe—Morwenstow Church—Norman Chevron-Moulding—Chancel—Altar—Shooting Rubbish—The Manning Bed—The Yellow Poncho—The Vicarage—Mr. Tom Knight—The Stag, Robin Hood—Visitors—The Silent Tower of Bottreaux—The Pet of Boscastle.

A writer in The Standard gives this description of Morwenstow: “No railway has as yet come near Morwenstow, and none will probably ever approach it nearer than Bude. The coast is iron-bound. Strangely contorted schists and sandstones stretch away northward in an almost unbroken line of rocky wall to the point of Hartland; and to the south-west a bulwark of cliffs, of very similar character, extends to and beyond Tintagel, whose rude walls are sometimes seen projected against the sunset in the far distance. The coast scenery is of the grandest description, with its spires of splintered rock, its ledges of green turf, inaccessible, but tempting from the rare plants which nestle in the crevices, its seal-haunted caverns, its wild birds (among which the red-legged chough can hardly be reckoned any longer, so much has it of late years lessened in numbers),[13] the miles of sparkling blue sea over which the eye ranges from the summits ablaze and fragrant with furze and heather; and here and there the little coves of yellow sand, bound in by towering blackened walls, haunts which seem specially designed for the sea-elves—

“Even in bright weather, and in summer—in spite of the beauty and quiet of the scene, and in spite, too, of the long, deep valleys, filled with wood, which, in the parish of Morwenstow especially, descend quite to the sea, and give an impression of extreme stillness and seclusion—no one can wander along the summit of the cliffs without a consciousness that he is looking on a giant, at rest indeed for a time, but more full of strength and more really terrible than any of the Cormorans or the Goemagots who have left their footprints and their strongholds on the hills of Cornwall. The sea and the coast here are, in truth, pitiless; and, before the construction of the haven at Bude, a vessel had no chance whatever of escape which approached within a certain distance of the rocks. Such a shipwreck as is described in Galt’s story of The Entail—when persons standing on the cliff, without the smallest power to help, could see the vessel driven onward, could watch every motion on its deck, and at last see it dashed to pieces close under their feet—has more than once been observed from the coast of Morwenstow by Mr. Hawker himself. No winter passes without much loss of life. The little churchyards along the coast are filled with sad records; and in that of Morwenstow the crews of many a tall vessel have been laid to rest by the care of the vicar himself, who organised a special band of searchers for employment after a great storm.”[14]

The road to Morwenstow from civilisation passes between narrow hedges, every bush on which is bent from the sea. Not a tree is visible. The whole country, doubtless, a century ago was moor and fen. At Chapel is a plantation; but every tree crouches shrivelled, and turns its arms imploringly inland. The leaves are burnt and sear soon after they have expanded.

The glorious blue Atlantic is before one, with only Lundy Isle breaking the continuity of the horizon line. In very clear weather, and before a storm, far away in faintest blue, the Welsh coast can be seen to the north-west.

Suddenly the road dips down a combe; and Morwenstow tower, grey-stoned, pinnacled, stands up against the blue ocean, with a grove of stunted sycamores on the north of the church. Some way below, deep down in the glen, are seen the roofs and fantastic chimneys of the vicarage. The quaint lyche-gate and ruined cottage beside it, the venerable church, the steep slopes of the hills blazing with gorse or red with heather, and the background of sparkling blue sea half-way up the sky—from such a height above the shore is it looked upon—form a picture, once seen, never to be forgotten.

The bottom of the glen is filled with wood, stunted, indeed, but pleasant to see after the treeless desolation of the high land around.

A path leads from church and vicarage upon Morwenstow cliffs. On the other side of the combe rises Hennacliffe to the height of 450 feet above the sea, a magnificent face of splintered and contorted schist, with alternating friable slaty beds.

Half-way down Morwenstow cliff, only to be reached by a narrow and scarcely distinguishable path, is the well of St. Morwenna. Mr. Hawker repaired it; but about twenty years ago the spring worked itself a way through another stratum of slate, and sprang out of the sheer cliff some feet lower down, and falls in a miniature cascade, a silver thread of water, over a ledge of schist into the sea.

On a green spot, across which now run cart-tracks, in the side of the glen, stood originally, according to Mr. Hawker, a chapel to St. Morwenna, visited by those who sought her sacred well. The green patch forms a rough parallelogram, and bears faint traces of having been levelled out of the slope. No stone remains on another of the ancient chapel.

From the cliff an unrivalled view can be had of the Atlantic, from Lundy Isle to Padstow point. Tintagel Rock, with its ancient castle, stands out boldly, as the horn of a vast sweep against glittering water, lit by a passing gleam behind. Gulls, rooks, choughs, wheel and scream around the crag, now fluttering a little way above the head, and then diving down towards the sea, which roars and foams several hundreds of feet below.

The beach is inaccessible save at one point, where a path has been cut down the side of a steep gorse-covered slope, and through slides of ruined slate rock, to a bay, into which the Tonacombe Brook precipitates itself in a broken fall of foam.

The little coves with blue-grey floors wreathed with sea-foam; the splintered and contorted rock; the curved strata, which here bend over like exposed ribs of a mighty mammoth; the sharp skerries that run out into the sea to torment it into eddies of froth and spray—are of rare wildness and beauty.

It is impossible to stand on these cliffs, and not cite the ἀνήριθμον γέλασμα, παμμῆτόρ τε γῆ of the poet.

If this were quoted in the ears of the vicar of Morwenstow, he would stop, lay his hand on one’s arm and say—

“How do you translate that?”

“‘The many-twinkling smile of ocean.’”

“I thought so. So does every one else. But it is wrong,” with emphasis—“utterly wrong. Listen to me. Prometheus is bound, held backwards, with brazen fetters binding him to the rock. He cannot see the waters, cannot note their smiles. He gazes up into the sky above him. But he hears. Notice how Æschylus describes the sounds that reach his ears, not the sights. Above, indeed, is the ‘divine æther’; he is looking into that, and he hears the fanning of the ’swift-winged breezes,’ and the murmur and splash of the ‘fountains of rivers’; and then comes the passage which I translate, ‘The loud laugh of ocean waves.’”