“‘WE ARE UNDER WAY AT LAST.’”

Title: A Year in a Yawl

Author: Russell Doubleday

Release date: March 20, 2018 [eBook #56792]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from images made available by the HathiTrust

Digital Library.)

“‘WE ARE UNDER WAY AT LAST.’”

“Saw the Great Cakes of Ice go Racing by”

Taking Soundings.—“... Frank Shouted, ‘Three Fathoms!’”

Fish they Caught in the Gulf of Mexico

On the Gulf Coast.—“Graceful Palms and Sturdy Live Oaks”

“The Moon Broke from the Clouds and Silvered the Crescent Sea”

John Gomez’s Cabin.—“A ... Cottage Thatched with Palm Branches”

“The Tall, Straight Shaft of the Cape Fear Light”

Beaufort, North Carolina.—Poplar Trees Bent Over by the Wind

A “Bugeye.”—“Flew by Like the Shadow of a Swiftly Moving Cloud”

On the “Raging Canal.”—“‘Step Lively’ Once More Got Going”

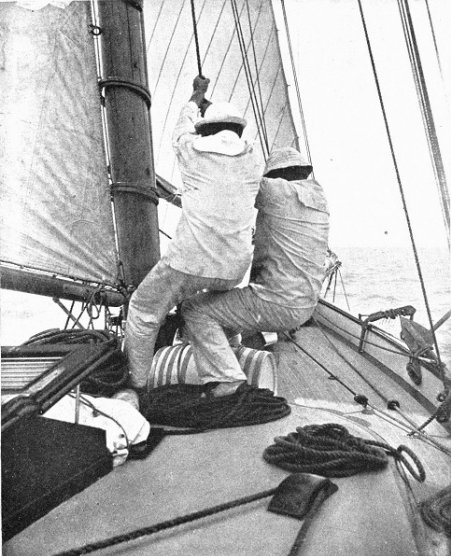

Swaying on the Halliards.—“The Sails were Hoisted”

“The ‘Gazelle’ Raced with the Flying Spray into Port”

Acknowledgments are due to Mr. Thos. A. Hine, Mr. Clinton P. Townsend, and Miss Katherine R. Constant for the use of the photographs printed in this book.

In the shadow of a big apple tree four boys lay on the grass studying a map of the United States. One of the group was talking vehemently and pointing out a route of some sort with a stubby carpenter’s pencil; the other three were watching with eager interest.

“That sounds all right,” said one of the four as he rose to lean on his elbow, “but you can’t do it with a little boat like yours. I don’t believe you could do it anyway, Ken.”

“Well, I couldn’t do it in a steam-yacht,” the boy with the pencil returned, “for obvious reasons. But I can and will make that trip.”

“I admire your pluck, Ken,” the third boy exclaimed. “It took considerable gumption to plan and build a craft like yours alone; but I don’t believe you’d bring your boat through whole.”

Again they bent down to the map, and the three listened while Kenneth Ransom went over the route again.

“Yes, it looks all right on the map,” Clyde Morrow broke in; “but you don’t realize that the couple of inches of Illinois River from Chicago to the Mississippi, for instance, is a couple of hundred miles.”

“Of course it’s a big undertaking, but think of the fun. You fellows like to sail on the Lake, and we have been through some pretty tough squalls, and had some mighty pleasant times, too. Sailing on the Lake is good sport, and exciting, too, for a while, but the cruising I propose to do makes Lake sailing tame. Think of the places we shall see, the fishing we shall do! Think of sailing on the warm Gulf of Mexico in January, cruising around the thousands of tropical islands, then up the Atlantic coast when it is most apt to be calm, stopping whenever there is anything worth stopping for. Just think of the cities we can visit—St. Louis, Vicksburg, Memphis, New Orleans, Mobile, Jacksonville, Hampton Roads, Philadelphia, New York, and—” He stopped for sheer loss of breath.

“Why, it’s the chance of a lifetime. I’ve set my heart on it, and I’m going. Who’ll go with me?”

Kenneth had talked eagerly, so full of his subject that he could hardly get the words out fast enough. Now he stopped and waited to see if his friends would take fire from his enthusiasm.

For an instant all three boys were silent. The thought of the adventure to be had tingled in their veins.

“I’ll go!” suddenly exclaimed Arthur Morrow, who had hitherto been comparatively calm, jumping to his feet to shake Ransom’s hand. Almost at the same moment, Clyde, his cousin, and Frank Chauvet grabbed Kenneth and shouted, “I, too,” in unison.

“Good!” was Ransom’s only comment as he extricated himself from the grasp of his impetuous friends. But his face was shining, and his eyes said what his voice for a minute could not express.

Kenneth had been at work on a boat for some time when the foregoing conversation took place. He had planned her himself, plotting out her lines with great care and with all the enthusiasm of a boy who has the means at last to carry out a long-cherished idea.

She was to be thirty feet over all, twenty-two feet on the water-line, nine feet wide, and three feet draught with her centre-board up. His idea was to make her yawl-rigged and as strong and staunch as good material and careful workmanship could ensure.

For a workshop he had to be content with a woodshed at the back of his father’s house, a good three-fourths of a mile from the Lake shore of St. Joseph, Michigan.

Fortunately, he was able to get some extra fine white oak, well seasoned, from a nearby mill; and though it was tough and tried the temper of his home-made tools, this very toughness and hardness stood the young ship-builder and his crew in good stead later.

He built a steaming-box to bend the ribs and planking of his boat out of rough lumber, and made an old stove, with a section of big pipe plugged up at both ends, serve as a boiler to make the steam. Thus equipped, he began the work unaided of building a thirty-foot yacht in which to cruise around on Lake Michigan and the waters tributary to it. With great labor and care the keel was steamed, bent, and laid on the blocks; then one by one the ribs were put in place. It was slow work, but it was extremely interesting to this young naval architect and ship-builder, and as his boat grew his ideas enlarged. To be a naval architect had been his ambition ever since he had left high school. To become a designer and builder of ships was his aim in life, and as he worked alone at his little ship, he wondered how he was going to get the experience that would be needed to design vessels for various uses and differing conditions. About lake craft he knew something, but of ocean and river vessels he was entirely ignorant. He made up his mind that he must see and study the different kind of craft in their native waters.

One day, as he was working on the planking of his boat, the inspiration came to him. He had pulled the plank out of the long steam-box, hot, damp, and more or less pliable, and with great labor made it fast to the cut-water with a hand vise. As he bent the plank from rib to rib he secured it until it was in place and followed the designed curve. He stood a minute facing the bow to see if the curve was true. It really began to look like a boat and less like a skeleton.

“This is going to be a pretty smart craft,” he said to himself as he eyed his work lovingly. “She’ll be strong and handy, roomy and seaworthy, and fit to go most anywhere.”

“By Jove!” he said aloud, slapping his knee by way of emphasis, and sitting down suddenly.

“Why not?” The idea was so bold that he hardly dared to think of it. Sail to the ocean in a craft only thirty feet long? Impossible; but why? He could hardly wait to secure the plank permanently, he was so anxious to look at a map and see if there was a possible route to the salt sea that his vessel could follow.

The rest of that day was spent in studying maps, and for a good part of the night Kenneth and his father discussed it.

“Yes, it is possible,” Mr. Ransom said at length; “but I doubt if it has ever been done before, and certainly never by so small a boat.”

“But, father,” the boy pleaded, “can I go? You know what I want to do and why I want to go. It would mean a whole lot to me; it would be experience I can get in no other way.”

“Yes, boy, you can go if the mother can spare you,” the elder reluctantly consented; “but don’t set your heart on it till I talk to her. Good night.”

“Well, if they won’t let me go,” the boy said, as he blew out the lamp, “I’ll miss the chance of my life; but I think they will,” and he went to bed.

It was late the next morning when the boat felt the touch of her designer’s hand, for there was much talking to be done, much to be explained, and the boy found it hard to convince his mother that it was to his advantage; that it was almost necessary, in fact, for him to go on this hazardous trip.

“We can go!” he almost shouted, partly to his boat, partly to relieve his feelings, “and we’ll do it, too.” The boy’s eyes travelled over every line and curve of his creation with a pride that was tempered with concern, for much depended on the staunchness and sea-worthiness of his handiwork.

The fire in his makeshift furnace was soon roaring, and it was not long before the ring of the hatchet and adze filled the little shop as the boy went to work with new zest. Luncheon was a vexatious interruption, for he begrudged the time spent in eating. The yawl took shape plank by plank; and as she grew her builder planned ways and means, figured out places to stow provisions, water, spare tackle, rigging, and all the other hundred and one things that would be required for a long voyage. His imagination played a large part, too, and he sailed wonderful seas, through terrific storms, and along beautiful coasts—dreams, many of which, improbable as they were, came true, for adventures innumerable and utterly unexpected were to be encountered.

“By Jove!” he said aloud one day after he had had a particularly hard tussle with a plank that had to be both bent and twisted into position. “This is almost too much for me alone; and I can’t sail around to the Atlantic by myself. Whom shall I get to go with me?”

He leaned up against the workbench to think. The yawl, almost fully planked, now stood up higher than the builder’s head. The newly placed timber still steamed and gave out an odor dear to the wood-worker. There was no sound except the hiss of steam in the steam-box. Suddenly the door of the shed opened and three heads appeared.

“Hello, Ken, what are you doing? Holy smoke! look at that; isn’t she a beauty?” Frank Chauvet didn’t even stop to take breath between his sentences.

“Hullo, you chaps. Come in,” returned Ken, making a place for them on the bench. “The very fellows I want to see,” he said to himself. “What do you think of my boat? Look out, Arthur, you’ll sit on that adze if you don’t be careful. You’ve got to look before you sit in this shop.”

The third boy was meanwhile walking around the boat, inspecting her critically, feeling the wood, measuring the thickness of the timbers, and eying the shape with an approving glance.

“Say, Ken, where are you going to take her? Arctic regions? She’s built strong enough to go around the Horn.” Clyde Morrow looked up at his friend inquiringly. “Ken, did you do all this yourself? She’s great, simply great!”

“Yep—sure—you knew I was building a boat. Why didn’t you come around before?” Then, before they had time to answer, he went on, “Clyde, you said she was strong enough to go around the Horn; she’s got to be strong enough to make a journey almost as long and quite as trying.” He paused a minute and eyed his friends one after the other. Frank and Arthur were sitting side by side on the workbench. Clyde was leaning against the boat, Ransom himself faced them, half leaning, half sitting on a large block of iron that served as an anvil.

“What do you think about cruising to the Atlantic and back in that boat?” Kenneth pointed to the yawl. “Circumnavigating the Eastern half of the United States, in other words.”

“What!” cried Arthur and the other two boys. “You’re crazy!” Clyde added.

“No, I’m not; it can be done and I’m going to try to do it.” Kenneth spoke confidently and with a smile at his friends’ incredulity.

“Wake up, old man,” said Frank with a laugh; “that’s a nice dream, but you’re likely to fall out of bed.”

“Listen; I’ve studied this thing out and it can be done. Wait a minute,” he interrupted himself to say as Clyde opened his mouth to speak. “You know what I want to be and what I want to do, and there is no way of seeing all kinds of boats and experiencing all kinds of weather and conditions of water and climate except by seeing and experiencing them.” He laughed at the lame finish of his sentence. “The best and most thorough way of doing it, it seems to me, is to go in a small boat that you have built yourself and see everything at first-hand. What a cruise it will be! I wish I could go to-morrow.”

“What! do you really mean to go?” said Frank. “Why, you’re clean daft, Ken.”

“Not on your life,” answered Ransom sturdily. “Look here.”

He reached down a well-thumbed atlas from a shelf and led the way out of doors and under the apple tree. Then spreading it out, he began to explain what was in his mind.

“You shall be my mate, Arthur,” said Kenneth, who from that time his friends were apt to call Cap. “You spoke first, but to show that there is no partiality, Frank shall be navigator and Clyde chief-quartermaster.”

“No, I’d rather be the crew,” Frank protested; “that would be more exclusive and less responsible.”

“I’ll vote to be cook: then I’ll have you all in my power,” and Clyde pointed exultingly at the other three.

“Well, none of you can be anything for a good while yet. Come and look at the boat.” All four started toward the shop. “I tell you what, you can all be ship-carpenters, shipwrights, riggers, fitters, caulkers, and generally hard hustlers for a couple of months before we graduate to our high positions,” and Ransom led on to their “Argo.”

After going over the plans of the boat together, and talking of all the pleasures and dangers in prospect, the four separated; Frank, Arthur, and Clyde going to tell their people and ask their permission to join the expedition, an ordeal which they dreaded with all their hearts. Kenneth lingered a while to think over the happy outcome of his afternoon’s talk, and to plan anew his building, for from now on he had efficient assistants. He felt for the first time that his would be a great responsibility; for if anything happened to any of his friends he would be to blame.

The thoughtful mood soon wore off, however, and when he locked up the shop, and went into the house, he was radiant with pleasure.

“Father! Arthur, Clyde, and Frank said that they would go with me.” Kenneth burst into the room with his news.

“That’s good,” was his father’s reply. “If the Morrows and Chauvets will let their sons go, that is, of course——”

“But you will speak a good word for me, won’t you, father?” Kenneth smiled at him confidently.

“Ye-e-es, if you think you must go.” The elder Ransom looked at his son rather sadly.

“Why, of course. I thought that it was all settled. Is anything the matter? What is it?” Kenneth was excited and worried; the possibility of a final refusal from his father had never occurred to him.

“Wait a minute, son.” Mr. Ransom pulled his boy down on the arm of his big leather easy chair. “The fact is, your mother and I have been talking over this projected cruise of yours, and—though you may not realize it—it is hard for us to have you, our youngest and last, go away upon so long and dangerous a trip.” He stopped for a moment and looked into the boy’s fast saddening face. “We promised that you should go, and go you shall, if you insist, but you are pretty young to undertake such a journey, and your mother and I thought that you might give it up for a while. We knew that you would be disappointed”—the father held up his hand to check the words which were just ready to pour out of the boy’s mouth—“and so we thought that we would try to make it up to you in some other way. If you will be willing to give up your project for a while, at least, your mother and I have decided to deed over this house and place to you, and your assigns, forever,” and he smiled at the legal phrase.

“Give me the house and grounds if I don’t go? Father, what can I say? I thank you awfully, but I would like to think it over a bit before I answer. It is rather sudden.” The boy grabbed his father’s hand, and then went upstairs to his own room.

He was touched, and very grateful, but grievously disappointed. He had set his heart on the trip, had persuaded his friends to go with him, and now he must give it all up. What seemed hardest of all, was that he would have to tell his companions that the whole thing was off. The photographs of boats that lined the walls of the room, and the plan of his own boat, laid out on the table, seemed a mockery to him. “Well, I won’t take the house any way,” he said to himself. “If they want me to stay as badly as that, I won’t go, of course; but——”

A minute or two later he came into the room where his father and mother were sitting reading.

“I’ll stay,” he said, standing before them. “I didn’t know you wanted me to, so much; but I can’t take the house; I don’t want to be paid to stay—but you’re terribly good to me.”

It was hard to give up gracefully, and he dropped rather dejectedly into a chair.

“By George, mother!” Mr. Ransom said to his wife, “that boy is the right sort, and I think that we ought not to spoil his chance. I vote we let him go.”

Kenneth looked eagerly at his mother. She said nothing, but he read plainly in her face that though she feared to let him take the voyage, she would not refuse his wish.

He could not say a word; but he had to go out, unlock the door of his shop, and tell his boat confidentially what bricks his father and mother were. He just had to tell something.

The next morning the other three boys came with long faces and disgruntled tempers. Their parents, one and all, were against the trip, and declared that Kenneth’s father and mother were crazy to let him go on such a journey.

Kenneth said nothing of his experience of the night before, but felt absolutely sure now of his parents’ backing and encouragement.

“Don’t you give up like that, fellows,” he said cheerfully, slapping his mate-to-be on his shoulder, to stir him up. “If you don’t have confidence yourself, how can you expect other people to believe in you and the success of the trip?”

“But—” began Frank.

“Bear a hand with this stick, will you?” Kenneth interrupted.

“Arthur, open that trap at the end of the steam-box, please. That’s it—in she goes!” With a will, Frank and Kenneth pushed the long plank into the box.

“A few more of those, and the body of the boat will be complete. But there’s a lot more to be done, and we’ve got to keep at it.” Ransom stopped, went to a far corner, and poked among some old boards; he finally picked out one, and showed it to the boys.

“I move that we make this our motto. All those in favor will signify as much by saying ‘aye.’”

Four “aye’s” rang out vigorously.

“Contrary minded will signify by saying ‘no.’

“It is moved and carried, that this shall be our motto, and we’ll nail our colors to the—the—woodshed.”

“Hear! Hear!” laughed the three at the end of Ken’s speech; but when he nailed up the board bearing this motto in clear letters:

there was a cheer that cleared the air amazingly, and chased away the gloom that had bid fair to settle over the company.

“I believe that my father will be able to convince your people that our trip is feasible,” said Kenneth from his place on top of a ladder. “Anyhow, let’s get to work. For ‘keeping everlastingly at it brings success.’” Soon all the noises the young shipbuilders made seemed to voice that motto.

It was a long time before the three got permission to go, but their evident determination, and their continual “keeping at it,” aided by Mr. Ransom’s support, finally brought success. All this time the four worked like beavers. The planking was completed, the cabin laid out and built, the deck laid, and the cockpit floored.

“Well, I’ll be jiggered!” Kenneth exclaimed one day. “I never thought—how are we going to get her down to the water?”

Immediately the noise of hammer and saw, the dull clap of wood, and the sharp ring of iron ceased, and all four stood open-mouthed, speechless.

“Why, it’s a good three-quarters of a mile to the nearest water,” gasped Frank.

“And think of that hill down to the ravine between,” added Clyde.

“She must weigh three tons,” wailed Arthur.

“Oh, I guess Johnson, the house mover, will do it,” Kenneth suggested. “Let’s go and see him.” But Johnson wanted a prohibitive price for moving the boat to the launching ways, so the crew decided to tackle the job themselves.

Then the trouble began. The sides of the shop had to come down to allow the yawl to be moved out, and a truck had to be built that would safely bear the great weight.

Despite all, however, the boat was finally loaded, and under the eyes of all the townspeople who could get away from their work, the first stage of their journey began.

All went well for a time. A sturdy team was hitched to the wheeled truck, and the progress over the first part of the smooth, level road was easy. Passers-by were apt to quote passages about “sailing the raging meadows,” and about young tars who preferred to do their sailing ashore. But Ransom and his friends were good-natured and too busy to heed anything but the overland trip of their precious craft.

When the brink of the hill leading down to the ravine was reached, the team was stopped and a consultation was held. The slope was almost thirty degrees, and a bridge at the bottom had to be passed slowly, or the great weight might go through the planking.

“Make her fast to that tree,” suggested Arthur, “with a block and fall, and pay out gradually till she gets to the bottom; then reverse the operation and make fast in front, hitch the team to the line and haul up.”

“Great head, Art! We’ll do it.” And Ken started back to the shop for the block and fall.

The road curved just before descending to the ravine, and a big tree grew in the bend. A line made fast to it would lead straight down. It was most advantageously placed. A sling was put around the tree, and another was run about the boat herself just below the rail. To each of these a block was attached. The captain went over each rope carefully to see that all was right, tight, and strong. Frank drove the horses, which were to back with all their might; Clyde watched the boat herself; while Kenneth and Arthur tended the line, and stood prepared to pay out slowly.

“Let her go; slowly now, e-e-e-asy!” yelled Ransom to Frank with the team.

Kenneth and Arthur took in the slack, and braced against the strain. The horses began to move slowly and the truck slid gradually over the crest of the hill; the line tightened and the blocks clucked sleepily under the strain.

“Go e-e-e-asy!” yelled Ransom.

The truck was going faster; he and Arthur could hardly hold it back.

“Easy there; pull up, Frank.” The horses were straining back with all their might, but the weight of the boat was pushing them on faster than they wanted to go.

“Stop, Frank! She’s running away!”

But there was no stopping her from before—the horses were fairly off their feet. The running line was beginning to burn Kenneth’s and Arthur’s hands. She was running away, sure enough, and to certain destruction if she was not stopped at once.

Frank’s face was pale and anxious as he shouted and strained back on the reins, trying to stop his team; Clyde, utterly impotent, ran from side to side, looking in vain for a stick or log with which to check the wheels. Kenneth and Arthur clung desperately to the line, which, in spite of all, they could not control.

The speed of the boat was certainly growing faster and faster every second. The work of months and the means of a glorious trip was going to destruction.

“Here, Arthur, quick! I’ll try to hold, while you take a double turn round that other tree—quick—quick!” cried Kenneth, his anxiety almost taking away his voice for the moment.

Arthur turned to obey. “Quick—for the love of Moses, quick!”

Just in time, Arthur got the turns round the tree, for Kenneth could not stand the strain on his hands longer and he dropped the rope. His weight off the restraining line, the truck almost pushed the horses over on their heads. But the slack was taken up in a minute, and though the line creaked ominously under the strain, and stood as taut as a harp string, it held; the truck slackened speed.

“Kick me round the block, will you, Arthur, for a chump,” Ransom said as he came up to his friend, bandaging his blistered hands with his handkerchief as he spoke. “To let a weight like that go without taking a turn, was about the most foolish thing that I ever did. Let her go, easy, now.”

The other three boys said nothing for a while, but when the bottom of the hill was reached all were rather limp.

To drag the boat out of the valley was about as difficult as letting her down into it, and it consumed the balance of the daylight. The close of the second day saw the boat resting on the launching ways, and the boys were triumphant.

“If the rest of our journey is as slow as this,” Arthur remarked as he put on his coat to go home, “we’ll be ancient mariners before we cover the 6,000 miles.”

The following day the boat was launched, and as she nodded her acknowledgments to the pretty girl who had just named her “Gazelle,” it was evident to all that the title fitted her like the coat of white paint that glistened on her sides.

The hearts of Captain Kenneth and his friends glowed within them when they saw the boat at which they had labored so steadily floating in her natural element as gracefully and daintily as if she had been born in it.

When their friends had gone, the four sat in the cosey cabin and congratulated each other by looks and handclasps rather than words. They felt that they were fairly started, now that their craft was afloat; but it was two good long months before she was ready to take her trial trip; and two weeks beyond that before all was ready to start in earnest. Rigging and final finishing took much time, and the placing of the necessary stores seemed an endless job.

“Well, boys,” Ransom said, as the other three came aboard on the morning of October 27, 1898, “this is the day that we say good-by to old St. Joe.”

“Grab my bag, will you, Ken?” came by way of answer from Arthur. “Look out! If you dump the buttons from my sewing kit, I’ll have your heart’s blood.”

“...THE BOAT WAS LAUNCHED.”

“Don’t you worry. I’ll be careful enough,” was Ransom’s answer. “I’ll have occasion to borrow before long.”

And so they laughed and chatted, and put on a brave front in order to conceal the slight uneasiness that lingered persistently in the background of all their thoughts.

It was three o’clock before complete arrangements were made, and all hands were right glad that there was so much to do. Home was inexpressibly dear to those four boys, and though they looked forward to their trip with real enthusiasm, when the parting really came they found it a good deal of a wrench.

The wind was coming out of the north in a business-like way, and the sea it banked up was not of the sort to tempt the fair-weather sailor.

“All ready, boys?” sang out Captain Ransom from his place at the tiller.

“All ready!” was the answer.

“Arthur, stand by to tend the jib sheet; Frank, stand at the halliards; Clyde, go forward, yank up the mud-hook and cat it. I’ll tend the mizzen.”

The boys jumped to do his bidding. The windlass creaked and the yawl began to eat up the anchor cable.

“She’s broke!” came the cry from forward as the anchor gave up its last hold on Michigan soil for many a long day.

“Haul up your jib, Clyde. Now, Arthur, in with your sheet.” Ransom at the same time hauled in the mizzen a little, and shifted the helm.

The boat gathered headway slowly, then gained in speed till she was bounding over the rollers bravely.

“We are under way at last,” Ransom half sighed; but the sigh changed to a thrill of pure delight as he felt his boat slipping along under him; felt her answer to his touch on the tiller, as an intelligent horse responds to the hand on his bridle-rein.

The graceful craft heeled over to the freshening breeze till she showed a little of the dark green of her underbody. The way she moved along surprised and delighted the people on shore almost as much as it did her captain and crew.

Out from the shelter of the river’s headland she flew to the lake itself, which still heaved a reminder of the terrific storm of a few days ago.

A line of handkerchiefs waved from the bluff, and here and there a vivid bit of color showed a private signal that told of some special watcher.

It was these signals that the boys looked for with particular eagerness and answered with frantic zeal. They told of loving and anxious hearts—anxious, but proud of boys who had the courage to undertake such a journey.

The “Gazelle” sped on until she came abreast of the life-saving station on the end of the long pier. The station’s cannon boomed out its hail of God-speed and good luck, and the boys lowered the ensign from the peak three times in answer. It was the last audible message. Minute by minute, the shore grew dimmer and dimmer; the handkerchief signals faded; even the brave bits of color steadfastly waving were lost to view.

The “Gazelle” and her crew were at last outward bound.

It was a quiet group of boys that stood in the cockpit of the “Gazelle,” and watched the shores of their native town fade from view. They had persevered in their scheme in spite of discouragement from their elders and ridicule from their companions. They had undertaken a seemingly impossible thing. What would the outcome be?

It was well that the young adventurers could not foresee what the future had in store for them, for stouter hearts even than theirs might have hesitated at the prospect.

As it was, none of them had forgotten that “Keeping Everlastingly at it Brings Success,” and all four meant to follow that motto to the end.

“Clyde!” Ransom suddenly interrupted the reverie into which they had fallen. “I think I once heard you say that you would like to be cook. Now’s your chance. Go ahead and be it.”

“My, what a memory you have!” the other answered, with a wry face. “But wait until you try some of my cooking, then the smile will travel my way. I’m sorry for you.” And Clyde disappeared down the companionway.

The storm which had just passed left the surface of the Lake very uneasy, and the little yacht was tossed from the crest of one huge wave to another like a chip; but she bore the rough usage splendidly, and hardly shipped water at all; the spray which her sharp spoon bow dashed up as she flew into the white caps was all the wetting her deck showed.

“Say,” came a muffled voice from below, “I’ll mutiny if some one doesn’t come down and hold the things on the stove. The coffee-pot is trying to jump into the saucepan’s lap. Hello! On deck there! Come down and sit on the—” The owner of the voice showed a very red and wrathful face at the foot of the ladder. Frank went below at once, and soon the sound of voices mingled with that of clattering tins and chinking pottery. Then the odor of steaming coffee and frying bacon came through the half-closed companionway. Kenneth and his mate began to lose interest in the set of the sails, the curve of the rail, and the angry look of the water. Frequent glances, thrown at the opening from which such satisfying aromas penetrated, betrayed the direction in which their thoughts had strayed.

“All hands below to supper,” was the welcome cry. “Except the skipper, who will stay on deck and steer, I suppose.”

So the cook got even.

The table, hinged to either side of the centre-board trunk, bore a goodly store of “shore grub.” The ship’s stove was steaming away in the galley, way forward almost under the deck. On either side of the cabin the bunks were ranged; good, wide bunks with generous cushions. They served as beds by night and couches by day, the bedding being rolled up under the deck and concealed by curtains. Under each bunk was a wide chest or locker, and, besides, a row of drawers was built forward, so that each member of the crew had ample room wherein to stow his belongings. A man-o’-warsman would be at a loss to know what to do with so much space.

The cabin was fourteen feet long, nine feet wide at the widest part, and six feet high. Any member of the crew could stand upright without fear of his upper story.

The skipper saw all this in his mind’s eye as he fondled the tiller (a boat’s most sensitive, sympathetic spot) and watched the sails puffing to the breath of the breeze. He grew hungrier every minute, but every minute the wind grew stronger and the waves higher, so that his interest in the behavior of his boat returned and increased, until he forgot about the complainings of his stomach altogether. The “Gazelle” seemed to know that her maker’s eye was upon her, for she showed off in brave style. She rose on the waves as lightly as a cork, and swept along at a surprising rate of speed.

Frank and Arthur soon came climbing up on deck, and then Ransom had his turn below. In spite of Clyde’s protestations, he was no mean cook, and if “the proof of the pudding lies in the eating,” the crew were certainly satisfied with their first meal aboard.

“How are we going to work this thing?” said Arthur, as Ransom’s head appeared above the hatch coaming. “We certainly won’t get in to Chicago before morning.”

“We’ll divide up the night into regular watches. Four on, four off. See?” explained Kenneth.

“But who’s who?” queried Clyde, from the foot of the companionway ladder.

“Arthur and I will be the starboard watch, you and Frank will be the port. That satisfactory?”

“Sure,” the other three responded.

“Well, suppose the port watch goes on duty for the second dog watch—from six to eight—while the starboard watch does the dishes?”

“I never heard of a starboard watch washing dishes,” said Frank. “But I think they could not be better employed.”

Kenneth and Arthur went below and began to “wrestle” pots and dishes, while Frank and Clyde sailed the boat.

The yacht rolled a good deal, and the amateur dishwashers found it difficult to keep the water in the dish pan. But if the yawl pitched, it was not unduly, and she always recovered herself easily. Her poise was well-nigh perfect.

Though the off-and-on plan was carried out, there was little sleep for either watch—the experience was too new—and when Chicago was reached late the next morning, all hands were glad to lay up for a while and rest. They considered that the trip had now fairly begun, inasmuch as people had predicted that the “Gazelle” would never cross even the Lake in safety. The boys took advantage of city prices and bought all sorts of things and stowed them aboard the yacht. There was enough stuff aboard to stock a small store for a year, yet the yawl did not seem to be overburdened.

“Hear ye’r goin’ through to ther canal?” It was the evening of the second day when a burly, bearded chap shouted this in a fog-horn voice to Arthur. “Want a tow through, Cap?”

“Here, Ken, is a fellow who wants to tow us to the canal,” Arthur shouted down the open hatch to Ransom.

They did want a tow, and the agreement was soon made, so the tugboat man departed content.

The following afternoon a little tubby, snub-nosed, paintless tug steamed up, and the boys recognized their tugboat man in the pilot house.

“Hello, Cap!” was his greeting. “Ready?”

“Hello, Captain!” Ransom responded. “All ready. Give us a line.”

The hawser was hauled aboard and made fast to the capstan bitts forward, and soon the yacht was on her way once more.

All of the boys had seen the Chicago River before, but never had any of them come so close to the shipping. There were whalebacks for freight, and whalebacks for passengers, steamboats, Great Lake, grain, and passenger steamers, little tugs towing barges ten times their size; sailing craft of all kinds. It was bewildering, and how the little tug ever found a way through the labyrinth was a marvel. All went well, however, though the boys held their breaths whenever there was a particularly close shave, and so were almost continually in a state of suspended animation.

It seemed as if miles of craft of various kinds had been passed, when they came up to an enormous grain steamer which was fast aground. She was surrounded by a mob of puffing tugs, which had been working since the day before to get her off. The steamer and her escorts took up most of the stream, but a narrow lane remained open at one side just wide enough to allow the tug and the “Gazelle” to pass through. There was barely room between the towering sides of the great freighter and the heavily timbered side of the river-bulkhead, but there seemed to be no danger that the great vessel would get off and fill up the narrow passageway. The boys, therefore, told their tug to go on.

The tug entered the open lane and puffed steadily ahead, the yacht following a hundred feet behind. The towboat passed on, and the “Gazelle” came abreast of the freighter’s stern. It overshadowed the small craft just as a tall office building would dwarf a news-stand beside it. The four boys gazed at her great iron sides in admiration and wonder; they could almost touch it.

“I wonder will they ever get her off!” exclaimed Arthur. “She looks as if she was built on to the bottom.”

“Say, Ken, look!” It was Frank who grabbed Ransom’s arm and pointed to the great ship’s counter. “Isn’t she moving now?”

She certainly was. The freighter’s stern was swinging round; slowly at first, but gaining in speed every moment. The tug was going ahead, and the iron sides were closing down on the little yacht irresistibly. It was a horrible trap which the tug, by reason of the long tow-line, had escaped. The boys realized their danger, and shouted to the captain of the tug. He immediately rang for full speed ahead. It was a grim race to escape destruction.

Faster the tug churned on, but nearer and nearer came that terrible iron wall, until it bumped against the yawl’s white sides. Both yacht and freighter were edged in to the spiles of the bulkhead until there was but three feet of open water between. Men on the freighter, ashore, and on nearby vessels saw the danger. They shouted words of encouragement and warning; but even as they did it, they knew that it was of no avail. Nearer and nearer the fearful iron wall approached, inexorably. The boys saw that the boat was doomed to certain destruction, and perhaps death lay in wait for them, but they could do nothing.

They were being drawn into the very jaws of the trap, and the crew looked at the smooth sides of the freighter for a foothold or a hanging rope that they might cling to, and then to the slimy bulkhead. Each had picked out a place for himself to spring for when the time should come. Suddenly the movement of the great ship’s stern stopped. She quivered a moment and was still. She had grounded just in time, and the “Gazelle” slipped through with not three feet to spare.

The shout that went up from the onlookers was like the sudden escape of long pent-up steam—it was a glad cry of relief, and the boys echoed it in spirit, but could do nothing but wave their caps in answer.

It had been a narrow escape, and the crew of the “Gazelle” were thankful enough to come out of it alive. To the shouts of the onlookers, however, they waved their caps airily, as if it was an everyday matter to escape from the jaws of death.

After this all went well. The tug and its light tow made such good time that the entrance lock to the Illinois and Michigan Canal was reached by nine o’clock. All hands turned in except Ransom, who was to take the first four-hour watch. But, from time to time during the night, various members of the crew waked with a feeling that there was a house crushing them. Whether this was caused by the experience with the ship, or the pancakes which Clyde constructed for supper, this chronicler does not pretend to state.

Early the following morning, the boys paid their canal fees, and passed through the lock.

“How long is this canal, Ken?” Frank asked, after they had tied up in the basin.

“Ninety-six or seven miles, I think,” he answered.

“Walking good?” was Clyde’s question. “I don’t see a crowd of tug men crying like hackmen at a depot, ‘Tug, sir.’ ‘Tow, sir.’ ‘Take you through quick, sir!’”

“You’re right,” said Kenneth, with a smile. “It’s pretty late for shipping, I hear; but perhaps that steam freighter that we heard was coming through will give us a lift. Let’s wait a while and see.”

They did, and the freighter good-naturedly gave them a tow all the afternoon. But good things, like everything else, have an ending, and the following morning found them towless.

A good half of this ninety-six mile canal the boys towed their boat by hand—they were their own mules, as Arthur expressed it. Two towed, and two stayed aboard, steered, and tended ship. The starboard and port watches took turns.

The hunting along the way was good, and many a plump duck tried the carving abilities of the cook and tickled the palate of the passengers.

Seven days of towing by hand, and friendly helps from passing steamers, brought them to La Salle, the end of the canal and the Illinois River.

Letters from home reached them here, and gladdened their hearts mightily. It was one of the consolations of this trip that every few days they received word from home, and were able to send messages to the anxious ones who were left behind.

Though the boys were somewhat footsore from their unaccustomed walking and their amphibious journeying, they were gaining weight steadily, and would have made splendid “after” pictures for a tonic advertisement.

The night on which they reached La Salle was cold, and, after getting their letters, the four friends made all ship-shape on deck, and then went below, closing the hatch behind them. After a rousing supper, to which, needless to say, they did full justice, the table was cleared, dishes put away, and in a twinkling the place was turned into a reading saloon or a lounging room. The swinging lamp shed a soft glow on the warm coloring of the cherry woodwork and cushioned bunks. The light on the table was ample, and the boys set out to answer the pile of letters they had received. It was a great temptation to tell hair-raising tales of every little happening that they had met with, but from the first it was agreed that the pleasant things alone should be detailed at any length. For a time, the scratching of pens on paper was the only sound, other than the comfortable, subdued creak of the throat of the main boom on the mast, which made itself heard as a passing gust struck the yawl. Presently, however, one of the pens stopped scratching, and its owner added a new element to the soft sounds—that of heavy breathing and an unmistakable snore. Soon all but Ransom were stretched out on their bunks, fully clothed but sound asleep. He still struggled to write, keeping awake by force of fist in eye. He, too, was almost dozing, the gust had passed, and the boom was quiet, the low hum of the lamp was the only sound to be heard.

Thump, thump! The thud of something heavy jarred the four out of their doze with a start. Then a scraping sound followed, and a couple of thumps at their very feet. It was startling, and Ransom scrambled to his feet and, followed by his three companions, who, half asleep as they were, looked about with dismayed faces, rushed on deck, expecting to find themselves on shore and in imminent danger. But, instead, they found a comfortable old log, with some branches clinging to it, that had floated down stream and had merely knocked off some of the “Gazelle’s” white paint in passing.

“That’s one on us,” laughed Kenneth in a relieved manner. “Let’s turn in.”

When the boys got up the next morning, they found a layer of snow on deck, and a thin skin of ice on the still water. It was high time to be on their way, so they shipped their mast again, bent on the sails, and set up the rigging in a hurry, and the following day were well on their way down the river towards the Mississippi.

The Illinois River is broad and shallow, and in order to keep enough water in the stream to float the grain boats down to the great river, enormous darns are built at intervals. A lock at each dam allows the vessels to drop to the lower level. Leading to each lock is a canal a hundred yards or so long.

The “Gazelle” made good way down the river, but each dam was approached with much care. A tack missed, the boat would in all probability go to her destruction.

They had but three more dams to pass, and were sailing along with a beautiful breeze across stream to their starboard hand. Several hundred yards above the lock, Arthur blew a lusty blast on the horn to notify the gatekeeper of their approach. Again he blew, and at last they saw the man come out of his house and begin to work the levers that opened the enormous gates. The “Gazelle” swept on, straight as an arrow, for the gate, every stitch drawing, her forefoot fairly spurning the water, and the small boat—“His Nibs”—bobbing gaily behind.

The yacht was sailing faster than they realized, and suddenly the boys saw that they would reach the gate before it was opened wide enough to admit them. There was but one thing to do. With a warning shout of “hard-a-lee,” Kenneth bore down on the tiller, the other boys hauled in the sheets, and in a minute the boat was heading out and up the stream. It was quick work, but for a time all seemed well. Then the wind slackened and a swift current caught them. The boat began to drift down stream toward the dam. To the alarmed boys the current seemed as swift as a mill race. It was carrying them at a terrific rate straight for the dam and to what seemed must be certain death. Now they could see the ugly heads of the logs sticking out of the water at the brink of the falls, and jagged stones which turned the stream to foam in a hundred places.

Still the wind lagged, and the current increased in speed. The boys looked from one to the other. Each knew that nothing could be done, but instinctively they hoped that something would intervene to save them. But what could save them now? With pallid faces and hearts that beat fast, they agreed to stick to each other and the ship.

Still the stream ran on and the breeze lagged. The line of white that defined the edge of the falls could now be distinctly seen, and the roar of the water drowned all other sounds. They began to give up hope. It seemed as if nothing could help them—surely nothing could.

Ransom was watching the bit of bunting—the fly—at the mainmast head. He saw it straighten out and begin to snap.

“Boys!” he exclaimed, “there’s a chance yet. Look!”

Even as he spoke, a puff of wind struck them, the sails rounded out, and the backward speed of the yacht slackened. Inch by inch, she began to gain on the current. Her crew felt as if they were pushing her along; their nerves and muscles were tense. Soon they saw that they were making real headway. If the wind held they would be safe yet. It was a gallant fight that the spruce “Gazelle” made—a fight for her life and the lives of her crew, and still the wind held strong and true. She gained.

At last it was safe to come about. “Hard-a-lee,” sang out the steersman cheerfully, as he headed the boat up into the wind. The “Gazelle” paused a moment in apparent indecision, her headsails flapping, then around she came and headed straight for the now widely open gates.

Though the adventure with the dam shook the young sailors’ nerves somewhat, still it served to give them increased confidence in their boat. Distinctly, a craft that behaved so well under such trying circumstances was worth sticking to, they argued, and not unreasonably.

When the boys saw how little shipping there was moving, they realized that winter was coming apace, and that if they were to enjoy the balmy South without a spell of Arctic journeying no time must be lost. A skin of ice on the water was now a common occurrence, and it took a considerable amount of courage to crawl out from under the warm blankets and go on deck to wash o’ mornings.

Therefore, the stops along the Illinois River were cut as short as possible, and only the difficulties of navigating a strange stream prevented them from sailing at night. As it was, not a few risks that would otherwise have been carefully avoided were taken in order to gain time.

At Beardstown, Illinois, they came to two fine bridges across the stream, but built too low to allow of even the “Gazelle’s” short spar passing underneath.

The yacht was sweeping along at a merry pace, wind astern, and current aiding. Frank, who was doing lookout duty forward, caught sight of the up-stream bridge first, and blew a long, unmelodious note on the ship’s fog horn.

“What do you think of that for nerve?” shouted Frank to his companions in the cockpit aft. “Here we are, four chaps in a thirty-foot toy boat, blowing a horn to make a thousand-ton bridge make an opening for us.”

“Yes, we’re little, I know, but oh, my!” Arthur answered. “Just give them another blow. They are fearful slow. Guess they don’t know we’re in a hurry.”

The yacht sped on at a splendid gait, and the draw opened none too soon, for the “Gazelle” slid through before the great span had stopped swinging round. She made a gallant sight, her mainsail and jigger spread out wide wing and wing and rounded out like the cheeks of Boreas, her round, spoon bow slipped over rather than cut through the water, and the easy lines of her stern left but little wake behind. “His Nibs,” towing behind, made enough fuss, however, to supply several boats many times its size. It fairly strutted along in its importance.

The pedestrians on the footpath forgot in their interest to be impatient at the delay caused by the opening of the bridge, and watched the yacht flying along, more like a live creature than a thing of mere wood and canvas.

A few hundred yards below, another bridge spanned the stream, and Frank, still forward, blew another long, open sesame blast. In answer, the draw began to move; so slowly, however, that the crew were troubled. It seemed as if it would never open in time to let them through. But the boys figured that the draw moved faster than they realized, and that the space was wider than it seemed. They therefore held on their course, and the “Gazelle,” appearing to understand that she was watched, fairly outdid herself. Her crew became exhilarated, and watched with flushed cheeks and shining eyes the water as it rushed past. “Great Scott, look at that!” suddenly Frank shouted. “Come about, for Heaven’s sake!” The other three looked where he pointed, and saw that the draw had stopped moving and that it would be impossible to go through the narrow opening. The men on the bridge, seeing the danger—it was growing each second so terribly imminent—worked desperately to set the machinery which turned the bridge going.

The boat was within seventy-five feet of the low trusses that would undoubtedly shatter its spars to kindling wood and tear the sails to rags, and still the “Gazelle” flew along, joyously careless of all save the buoyancy of the moment. She was sailing down the right side of the river in order to follow the motion of the draw, which was from left to right. The pier which supported the middle span was in midstream—a massive stone structure with a prow like the ram of a battleship; planned, in fact, to break up and separate the ice.

“Come about, Ken, quick, or you’ll carry away your stick,” Frank waved his arms and pointed frantically to the bridge.

Ransom paused a minute and measured the distance between his craft and the bridge, glanced at the stone pier and hesitated. He was pale, but outwardly calm. At last he put the tiller over to port, and the gallant little craft swung round on her heel like a dancer—her pace slackened; but the current and wind still carried her onward nearer and nearer the bridge, her momentum spinning her round until she was headed straight for the beak of the stone pier, jutting out wicked and green with river slime. On she went, her crew watching breathlessly to see if she would come round and tack into the wind in time. Yes, she would! No; no; yes! Half a dozen times in as many seconds the chances changed, but still she swept on.

Suddenly, with a bump that threw all four boys prone on the deck, she struck the pier, and as they lay half dazed, she slid up the inclined stone, greased, as it was, with slime, until the forward part of her underbody was clear out of water and her stern deep in. With a jar, the motion ceased, and then she began to slide backward. Deeper and deeper went her stern, until it seemed as if she would dive backward. At last, she slid off altogether, and turned round into the wind by the impact with the pier, and began to pay off on the other tack. Ransom jumped up and seized the tiller, amazed and delighted that the boat still held together, and that he and his companions were uninjured. The draw now commenced to swing again, and Ransom, watching it over his shoulder, saw it open wider and wider till the channel was clear. Then he put the boat about again, and she sailed calmly through the gap; Arthur at the main sheet, Clyde tending the jib, and Frank forward as before.

A prolonged cheer rose from the men on the draw, and a faint shout came down the wind from the people on the other bridge.

Cheer on, if the gallant little ship was not racked to pieces and strained beyond repair.

“Arthur, get below and sound the pump,” said Ransom, anxiously. The mate flew down the companionway, and the boys on deck soon heard the suction of the pump and the swish of the stream thrown in the centre-board trunk. It was a time of suspense until the sucking sound was heard that betokened that she was dry. The good Michigan white oak held true, and beyond some slackened stays and a broken turnbuckle, the yacht was uninjured.

“By George, boys!” exclaimed Arthur, as he came from below, “she’s the stuff! You can’t hurt her. She’s as sound as can be—not a seam started.”

From here on, the Illinois was plain sailing. Wafted by favoring winds and a swift current, the “Gazelle” made fast time and reached the Mississippi on Thanksgiving Day.

“Boys,” said Ransom, as he came up from examining the charts, “if we have luck to-day, we’ll be sailing on the Mississippi.”

“A mighty good way to celebrate the day,” suggested the mate.

“I wonder what it looks like,” Clyde speculated.

“Oh! I think it’s very broad, and very muddy, with low banks covered with colored people singing songs to a banjo.” This was Arthur’s contribution.

“No, I think that we’ll find the banks lined with wood piles; with here and there a plantation landing——”

“And boats, great flat-bottomed things,” Frank interrupted Clyde to say; “with tall chimneys instead of stacks belching rolls of black smoke.”

“You fellows have been reading Mark Twain, and think you know it all,” Kenneth remarked from his place at the tiller. “But where do you suppose we are now? Look around.”

The boys had been so busy making up an imaginary river, that they did not notice when they passed a low point and entered into what appeared to be a wider part of the stream.

“Why, you don’t know the Mississippi when you see it. Let’s give three cheers for it,” cried the captain.

“Hip-Hip, Hurrah!” The cheers rang out together, with a will.

“Now, three more for the boat.”

Again they rang out—undignified, perhaps, but fitting, in that they voiced the thanksgiving which all four of the crew felt, but could not express in words.

As the sun sank, turning the brown waters of the mighty river to crimson and gold, the “Gazelle” dropped her anchor in a little cove and rested, while her crew partook of mallard duck, shot during the day—their Thanksgiving dinner.

“People said we wouldn’t be able to cross the Lake safely, eh?” said Frank, exultingly; “and here we are anchored to the bottom of the Mississippi. We’re the people.”

“Going to take on a pilot, Ken?” suggested Arthur.

“Sure!” returned the captain. “Who will give up his berth to him?”

“Oh, I guess we can get along without one,” Arthur interposed hastily. “Clyde, give me some more duck.”

“This mallard is all right, Clyde,” remarked Kenneth rather thoughtfully. “But I confess I’d swap it for a home-made pumpkin pie.”

“Now, drop that, Ken,” said Clyde, “I object to your invidious comparisons. It isn’t a square deal to call to mind home feasts on Thanksgiving night anyway.”

After dinner they all went on deck and looked for a long time on the mighty river, about which they had heard and read so much, but which none of them had seen before. The river that was to carry them to the salt water, which, in spite of the 1,300 odd miles that lay between it and them, seemed nearer now that they were on the direct course. It appeared an easy thing for them to float down that great stream, and let the resistless current carry them down to the Gulf.

The four turned in elated; a feeling that was tempered, however, by the thought that they were far from home, and were widening the distance between them and it at a rapidly increasing pace. Had they foreseen what was before them on this steadily flowing, almost quiet stream, they would have slept even less quietly.

Early morning saw them busy washing down decks, airing the bedding, etc., while a savory odor rose on the quiet air. As soon as this fragrance spread itself, it might be noticed that the crew accelerated their motions, the brooms and brushes were plied with greater zeal, the sails were raised to dry them with greater vigor, and, in fact, all the morning chores were hastened with tell-tale rapidity.

But before any one got any breakfast—unless it was a surreptitious bite taken by the cook himself—the anchor was tripped, the jib hauled up, all the sail sheeted home and the run to St. Louis begun.

Sailing on the Mississippi seemed an easy thing. It was broad and deep and smooth. Indeed, the boys were congratulating themselves on the ease with which they had conquered the terrible “Father of Waters,” Mississippi, when there was a crash in the cabin and a terrible bump from below. Frank jumped down the companionway with a single leap, and found the centre-board bobbing up and down in its trunk, and the ship’s best china cup lying in fragments on the floor. It was resting on the top of the trunk, the centre-board had struck a sand bar, had bobbed up and knocked the cup to flinders.

Their overconfidence was gone in a minute, and soon they were paying the customary tribute to that always uncertain stream—heaving the lead and taking soundings.

The “Gazelle” got over the bar all right, but the lesson was not forgotten.

The second day after leaving the mouth of the Illinois River they passed under the great Eads Bridge and anchored a little below St. Louis.

“Who’s going ashore?” Clyde looked around from one to the other of his companions. “I think it is our turn. The starboard watch ought to have a loaf once in a while, you know.”

“Not by a jugful! Hasn’t the port watch been at the helm all day?” Arthur was more vehement than it was necessary he should be.

“Well, we did all the dirty work; cooked the meals and washed the dishes.” Frank was getting interested.

“Here, here, let’s quit this squabbling. We all have worked hard, and we all want to go ashore, and each has an equal right, but some of us must stay.” Ransom realized that quarrelling would spoil the trip quicker than anything else.

The three stood in an attitude that said as plainly as words: “What are you going to do about it?”

“Leave it to these.” Kenneth showed four ends of rope yarn sticking out of his closed hand. “These yarns are of different lengths. The two that get the shortest will have to stay aboard—the lucky two who pull the longest can go ashore. See?”

“It goes,” the three answered.

The upshot of it was that Clyde and Frank went ashore, and the other two remained to keep ship and do chores.

It was late when “the liberty party” returned with pockets bulging with letters and papers, with heads full of the things they had seen, and tongues aching to tell of them; and last, but not least, with able-bodied appetites and stomachs ready for the meal which the “left-behinders” had prepared.

It would be hard to tell whether the tongues or the knives and forks won the race, but certainly both did valiant service. By way of compensation, the starboarders washed the dishes, while the port did the heavy looking on. Soon things were cleared away, and the hinged table was lined with boys reading letters.

“Look at this,” said Kenneth, after a time of quiet, broken only by the crackle of stiff paper. “I had hoped that this would show up about this time. We need it in our business.”

It was a check for $125, and was expected to last them many weeks. The money that Kenneth had saved for this trip had been left in his father’s hands, to be forwarded from time to time as needed, and almost every cent of the little hoard had its particular use.

“Well, don’t be proud,” exclaimed Arthur, “you are not the only one,” and he flourished a money order.

Frank, too, produced one.

“We are bloated bondholders,” the captain said smiling. “But we won’t spend it on riotous living now, or we’ll have to eat and drink Mississippi River water later.”

Arthur was under the weather next day, so Ransom went ashore alone, taking the precious check and money orders with him. He rather despaired of finding any one who would identify him so that he could cash the check; but as luck would have it, he met an acquaintance on the street who made him all right with the bank officials at once. John Brisbane was a pleasant fellow and knew the city thoroughly. He towed Ransom round the town and showed him most of the sights, and even introduced him to some Mississippi pilots. They listened to his tale of what he and the crew had done and intended still to do with polite incredulity for a while, but finally concluding that he was telling them a “tall story,” they began to jeer openly.

“That’s right,” Ransom protested earnestly, a little vexed but still smiling. “We are planning to go around the Eastern United States, and we’ll do it, too.”

After the river men saw that he was in earnest, and that he really intended to put the trip through, they began to tell him things about the river: where to look for this bar, how to avoid that eddy, and where deep water ran round the other bend. Indeed, they gave him so much information about the Mississippi between St. Louis and New Orleans that he was bewildered, and felt as if he were waking up from a dream wherein some one was reading a guide-book of the river, while another called off the soundings of the charts.

When he finally bid good-by to the pilots Ransom felt thankful to get away with his reason intact.

Then John Brisbane showed him the Post Office, and after bidding him good-bye and good luck, went off.

Ransom found that he had barely time to cash his money orders, and feared that when he got on the end of the long line in the crowded waiting-room the window would be closed before he got to it.

One by one the people stepped up to the narrow window and held what seemed to be long conversations with the official behind the glass. First it was a woman with a baby, which had to be held by some one else while the mother signed her name, the baby meanwhile objecting vigorously; then a man with a lot of bundles, which he was constantly dropping and as often picking up, delayed the line; and then one thing and another until Ransom, who watched the hands of the big clock approach nearer and nearer four o’clock, fingered his money orders nervously and grew nearly frantic with apprehension.

At last he reached the window and got his money just in time. He put it in the inside pocket of his coat and buttoned it up, but pulled it open again when he went over to the stamp window to buy stamps for the crew and for himself. The crowd was unaccountably thick, and he wondered at it, as a man was pushed against him so heavily that he grunted. The stamps once bought, he rushed out to buy some greatly needed supplies for the ship’s larder.

“It’s lucky I got that money,” he said to himself, as he opened the door of a grocery shop. “We would have about starved to death if it had not come.”

“How much is it?” Ken asked of the grocery man when the goods had been selected.

“Three forty-eight,” was the reply.

Ransom went into his vest pocket, where he usually carried a small amount of money for everyday purposes, and pulled up two quarters, a nickel and two pennies.

“Fifty-seven cents,” he laughed, while the grocery man watched him narrowly.

“Well, it is lucky that check came. What we should have done without it, I don’t know.” He reached for his inside pocket as he spoke. “But it did, so it’s all right. How much did you——”

He stopped in the middle of the sentence—the pocket was empty! He ran his hand way down in—empty. He turned the pocket inside out—not a thing in it. Then he felt each pocket in turn rapidly, then carefully—no money. The grocery man began putting away the things which Kenneth had bought. Ransom did not notice him, but kept up his frantic search—no result. He stopped to think. The perspiration stood in drops on his brow, and a leaden weight had settled down on his heart as he realized that he had been robbed of over a hundred dollars of his earnings; every cent of which was needed to carry him through. He felt sure that his pocket had been picked at the Post Office. Then the thought came to him with crushing force that he had lost the money of the other boys, and that he would have to make it up out of what was left of his small hoard at home.

“Perhaps I dropped it,” he thought to himself, and he rushed back to the Post Office to see.

He searched the big room desperately, and was so evidently troubled that the watchman asked him what he was looking for.

“I lost some money here; have you seen anything of it? I will pay a reward.”

The man looked at him incredulously, and then laughed in his face.

“Found any money? I guess not! Why, there’s been a thousand people in this room to-day. Found any money? Just listen to that!” He broke into a laugh again, and turned his back on the distracted boy.

Kenneth wandered aimlessly out into the corridor, every nerve racking with agony. As he walked along, he saw among a lot of names, titles of departments and court rooms, “U.S. Marshal.”

“I guess I’ll ask him; he ought to know if there are pickpockets around here, and he may help me,” and suiting the action to the word, Ransom made for the room.

The assistant marshal, a small, keen-eyed, albeit kindly man, was just closing the office when the boy burst in.

“I have lost some money,” Ransom began right away. “Stolen out of my pocket, I think.”

“When?”—the question came out like a pistol shot.

“This afternoon, when I——”

“Where?” the other interrupted in the same sharp way. He acted as if he was specially interested.

“Down-stairs, in the money order and stamp room.” Ransom was getting even more excited—the other’s manner was catching.

“Describe it.”

Ransom paused to think a minute, and then began slowly as the denominations of the bills came to him.

“One twenty, eight tens, four fives, two twos and a dollar bill—then,” and he paused again, “there was besides two fives and five twos and three fives.”

As he spoke, the marshal began fingering the combination of the safe, his back to Kenneth; but the boy was so engrossed that he did not notice what he was doing.

“Well, you’ve got a good memory, youngster, here’s the money.” As he spoke, the marshal turned and handed out a bunch of bills and some letters.

“What!” the boy exclaimed amazed, his cheeks flushing, and his breath coming in quick gasps as he dropped into a chair. “Oh!”

“Your name is Kenneth, you said?” The official was smiling. “Well, I am going to name my youngest Kenneth, so that he will always come out on top—congratulate you.”

He put out his hand, and Kenneth, half dazed with his unexpected good fortune, grasped it with both his. In his gratitude he felt the uselessness of words; and though he tried on all the different ones he could think of that would apply to the situation, not one of them seemed adequate.

“How did it happen?” his curiosity made him ask at last.

“Oh, I saw a fellow in a dark corner looking over something,” the marshal explained, “and I did not just like his looks; he must have been a green hand to be looking at his graft in the open like that; so I went up to him and asked him if he had found something. The fellow looked up, saw my uniform, and got a case of cold feet right away. ‘Yes,’ he said, half scared, ‘I found this by the money order window.’ All the same, he still held onto the wad—he hated to give it up—so I remarked, quiet like, ‘I guess you found it in somebody’s pocket.’ Well, I got the roll quick enough then, and put it in the safe; but I never expected the owner would run it to earth as quickly as you did.”

Kenneth thanked him again, and gave him a bill from the roll which he was holding.

The marshal had to finally cut off his torrent of thanks with a short, “Young man, this office closed an hour ago.”

Ransom from the door shouted an invitation to visit the yacht, and then went back to the grocery man and made him do up the things he had ordered before with elaborate care; he paid his three dollars and forty-eight cents and went off, the most thankful boy in town.

Though Kenneth was elated enough when he left the centre of the city and started for the river front, his heart sank within him when he caught sight of the water. The swift current was carrying great pieces of ice, which gleamed white against the dark stream. The ice cakes were close together, and as the boy thought of the scant three-eighths of an inch thickness of “His Nibs’s” sides, He despaired of reaching the yacht anchored on the other shore.

“But what shall I do?” he asked himself. “The boys haven’t any boat, and I’ve got the eatables.”

It seemed hard that he should fall from one nerve-racking experience into another, with scarcely a breathing space between times.

For the next five minutes or so he studied the surface of the water, hoping that a time would come when the ice ran less thick; but he realized that each minute of waiting was precious daylight lost. Running down the sloping bank of the levee, he tumbled his bundles into the frail little boat, unmoored her, and pushed out between two monster river steamboats.

For a minute he paused to pull himself together, saw that all was snug on board, settled his cap more firmly on his head, and prepared for the struggle to come.

Then out from the shelter of the huge boats he shot—nerves tense, eyes alert; “His Nibs” was on its best behavior, and obeyed its master’s slightest touch, as if it understood the desperate situation. The rowboat was short, and so could spin around like a top on occasion.

The river seemed bent on destroying the boy and his little craft. It hurled great chunks of sharp-edged ice at him in quick succession, but he always succeeded in dodging them somehow. Twisting this way and that, now up stream, now down, he made his way painfully over toward the “Gazelle,” lying so peacefully at anchor in the little cove near the other shore. A warning shout told the three boys that the captain they were so anxious about was returning, and they rushed on deck to greet him. It was well they did so, for he had hardly strength enough to throw them “His Nibs’s” painter and climb aboard.

“Boys,” said Ransom, after he had told of his adventures, “St. Louis is a nice city, but let’s get out. It’s hoodooed for me.”

In spite of Ransom’s determination to leave St. Louis at once, however, it was several days before the ice permitted them to move from their anchorage. Many friends had been made in the meantime, and nothing unpleasant occurred, so that it was with a feeling of regret rather than of joy that the voyagers finally pulled up the mud hook and began in earnest the sail down the Mississippi.

The newspapers had found out that the “Gazelle” and her crew were in port, and many of the inhabitants knew about and were interested in the little craft and her youthful sailors.

The channel followed the city side of the river, and as the “Gazelle” got under way the steamboats lining the levee, bow in, stern out, gave her a rousing salute on whistles of varying tones. People on deck waved their hands and shouted “Good luck!” and a “God speed!”

The ice was still very much in evidence, and kept the steersman busy on the lookout; but Kenneth managed in spite of that to enjoy the attention which they received.

“St. Louis is not so bad a place, after all,” he declared with a change of heart.

The ice gave the youngsters a great deal of trouble. It was necessary to keep on the watch continually, and to luff or tack every little while to avoid slamming into a jagged-edged piece. The channel was very crooked, and crossed continually from one side of the stream to the other. The “Father of Waters” had a decided mind of his own, and no matter how carefully and laboriously a straight channel was dredged, he was quite likely to abandon it and make a new one.

The boys found the course a continual puzzle, and fairly gasped when they thought of the 1,200 miles of it still before them. But though the experience was trying, it was valuable, and especially so to Ransom, who learned just what a boat can do under numerous and ever varying circumstances. It was the most intimate sort of experience; their very existence depending upon surmounting each difficulty in turn.

The first afternoon’s run was thirty-eight miles, which, considering the many delays on account of ice, the “crossings” and their unfamiliarity with the river’s peculiarities, the boys thought very good. It was a rather trying sail, however, and all hands were glad when a snug little bend opened up—deep enough to give shelter to the yacht.

All four of the boys were by this time well-seasoned sailors. They had had some hard knocks, had been through many close shaves, knew what it was to be cold, hungry, and tired; but as time went on they had become closer and closer friends. They learned to put up with each other’s little peculiarities, and shook down into a harmonious ship’s company—a cheerful atmosphere prevailed that promised final success, and was not only an inspiration to themselves but to all who saw it. Their solid friendship was to be sorely tested. Just how solid it was, was shortly to be proved in a most unexpected manner.

Each had his special duties to perform, and as the voyage grew in length each became more and more proficient. This was especially true of the cook, Clyde. Not that he was a poor one at the start, for he had shipped with the recommendation that in ten minutes he could cook a meal that the four could not eat in ten days. This was a little far-fetched, however, for the “rules and regulations” very plainly stated that any one who could not satisfy his appetite in five hours would be obliged to wait until the next meal. Nevertheless, the cook was very modest, and explained his improvement by saying that it was due to his becoming familiar with his quarters. In proof of which, lie showed some pancakes which were not only round but also flat. In the beginning, owing to the listing of the vessel under the pressure of the wind on her sails, the batter would run to one side of the pan, and the pancakes were often quite able to stand alone on end.

None of the boys could handle a needle very deftly at first, but they soon became very good seamsters. They even progressed so far in the art that they began to openly boast of their skill. Frank returned one night from a hunting trip ashore with a number of ducks and a shy look about him which his companions were at a loss to account for, until they discovered an unbecomingly big tear in his trousers. After supper he tackled the gap with a big needle and a couple of yards of linen thread. He wanted to have it good and strong, he explained.

Frank did not bother to take his trousers off, but began to sew the rent baseball-seam fashion, and though the result was not elegant as regards mere looks, he certainly accomplished his object, and he was justly proud of his achievement.

“Any of you fellows want any sewing done?” he remarked airily, as he sawed off the end of the thread. “I am going to paint on the mainsail, in beautiful, gilt script letters, ‘Monsieur Chauvet, Modes,’ and rig you fellows up in natty sailor uniforms to ferry my customers over to me.”

“Well, I don’t know,” Arthur remarked (he had been busy writing while Frank was embroidering); “I can sew (lo) a little, myself; listen.”

He dodged a pillow, a spool, a ball of tarred twine and a book, and then began the following:

“For the sake of the song we’ll forgive the pun, if you never let it occur again,” said Ransom judicially.

It was late when they turned in that night, and Ransom was just on the verge of dozing off when he heard a great rustling in Frank’s bunk across the cabin. Clyde and Arthur were asleep, so Ransom whispered, “What’s the matter, old man?”

“Oh, Ken, I’m in trouble.” There was a kind of gurgle in his voice that stilled the captain’s anxiety. “If ever I get toploftical, you just pipe up a song about a fellow that sewed his outer clothes to his underclothes.” Then followed a savage, ripping sound, which bespoke a tragedy, and all was still again.

In spite of their best efforts, it seemed as if the elements were against the young voyagers. One day a heavy mist fell, and made the following of the channel nothing more nor less than a game of blindman’s buff, with the fun excluded, and a few sand bars, rocks and snags thrown in to make it interesting. Another day the snow fell so heavily that they had to tie up, the channel marks being obscured. Here they went ashore and visited the town of Herculaneum, a mining village, where Arthur and Kenneth took in the lead-smelting furnaces, while Frank and Clyde stayed aboard.