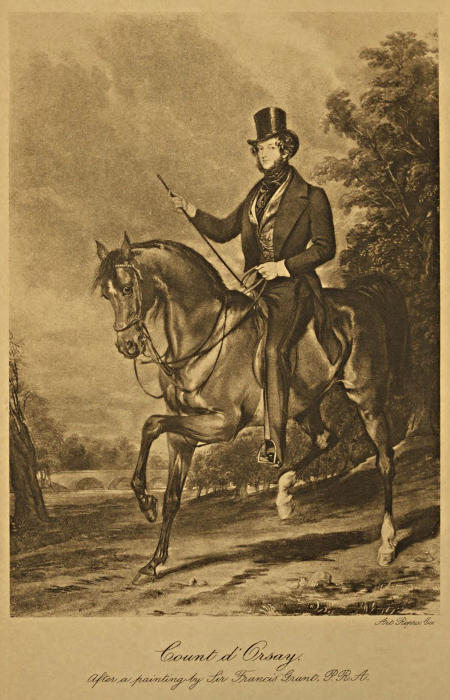

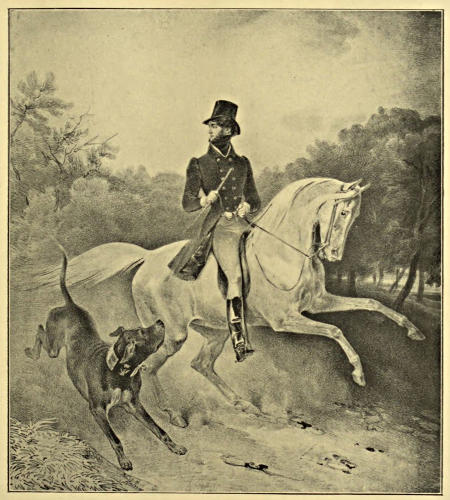

Art Repro. Co.

Count d’Orsay

After a painting by Sir Francis Grant, P.R.A.

Title: D'Orsay; or, The complete dandy

Author: W. Teignmouth Shore

Release date: February 16, 2018 [eBook #56581]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Clarity and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet

Archive/Canadian Libraries)

D’Orsay

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

A Soul’s Awakening [Crown 8vo, 6s.

Times.—“Mr Teignmouth Shore has captured our sympathy for his characters in an unusual degree.”

Morning Post.—“A charming and pathetic melody.… A tenderness that is infinitely moving.”

Punch.—“Powerful and pathetic. This truly charming story.”

Above All Things [Crown 8vo, 6s.

Daily Telegraph.—“All small investors in a hurry to make much out of little should read this novel, for it puts plainly and precisely before them some of the methods by which a swindler may, with seemingly virtuous intentions, appropriate, with perfect safety, other people’s money.”

Yorkshire Post.—“The people of his fiction play their parts so naturally and so simply that we sympathise almost as humanly with their troubles and joys as we might with those of our personal friends.”

Bookman.—“Delicate and unobtrusive art.”

Creatures of Clay

Recently published.] [Crown 8vo, 6s.

JOHN LONG, LIMITED, LONDON

Art Repro. Co.

Count d’Orsay

After a painting by Sir Francis Grant, P.R.A.

D’ORSAY

OR

The Complete Dandy

By

W. Teignmouth Shore

WITH PHOTOGRAVURE AND SIXTEEN OTHER PORTRAITS

London

John Long, Limited

Norris Street, Haymarket

(All Rights Reserved)

First Published in 1911

| PAGE | ||

| I. | Jocund Youth | 15 |

| II. | She | 24 |

| III. | Mars and Venus | 35 |

| IV. | The Primrose Path | 42 |

| V. | Byron | 48 |

| VI. | Pilgrims of Love | 53 |

| VII. | Marriage | 65 |

| VIII. | Rome | 76 |

| IX. | Paris | 81 |

| X. | A Solemn Undertaking | 92 |

| XI. | Seamore Place | 100 |

| XII. | Handsome is— | 116 |

| XIII. | A London Salon | 135 |

| XIV. | Round the Town | 145 |

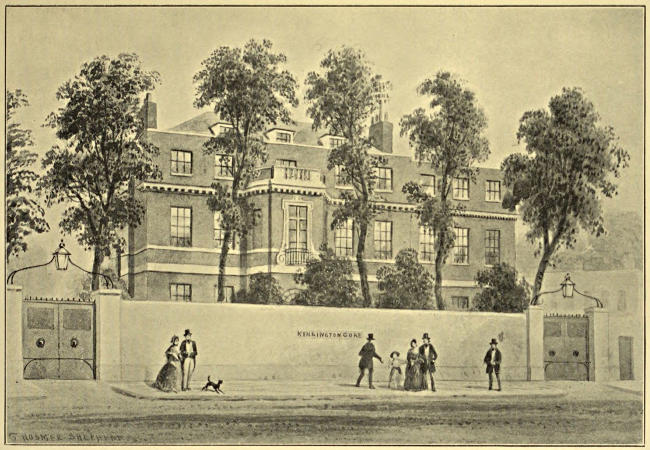

| XV. | Gore House | 157 |

| XVI. | Stars | 172 |

| XVII. | Company | 174 |

| XVIII. | More Friends | 189 |

| XIX. | Nap | 195 |

| XX. | W. S. L. | 216 |

| XXI. | The Artist | 225 |

| [vi]XXII. | Letters | 235 |

| XXIII. | Exchequer Bonds | 245 |

| XXIV. | Sundry Festivities | 255 |

| XXV. | Sunset | 270 |

| XXVI. | The End of Gore House | 280 |

| XXVII. | Paris for the Last Time | 284 |

| XXVIII. | D’Orsay in Decline | 289 |

| XXIX. | Death | 302 |

| XXX. | What Was He? | 311 |

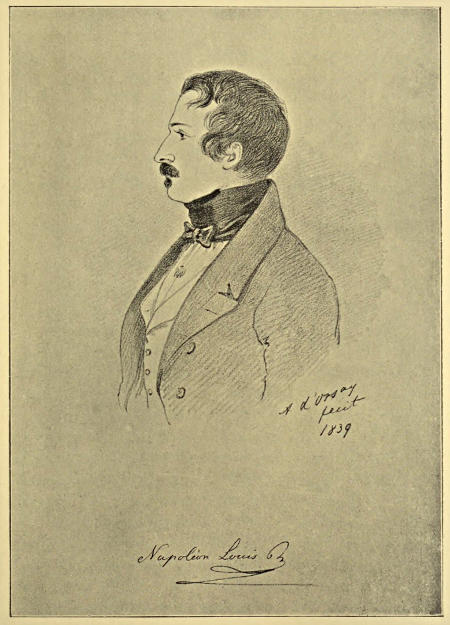

| Count d’Orsay | Frontispiece |

| After a Painting by Sir Francis Grant, P.R.A. | |

| FACING PAGE | |

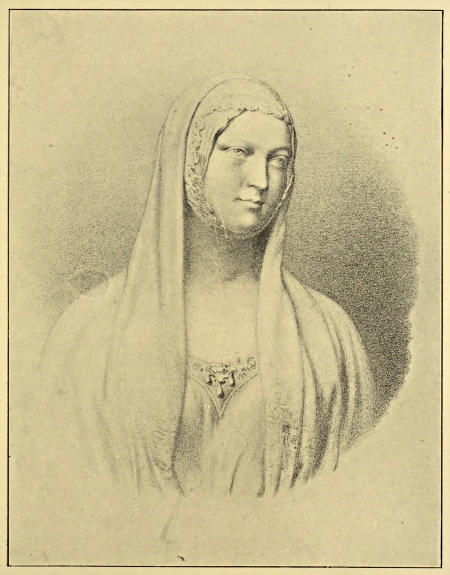

| Lady Blessington | 28 |

| From a Water-colour Drawing by A. E. Chalon, R.A. | |

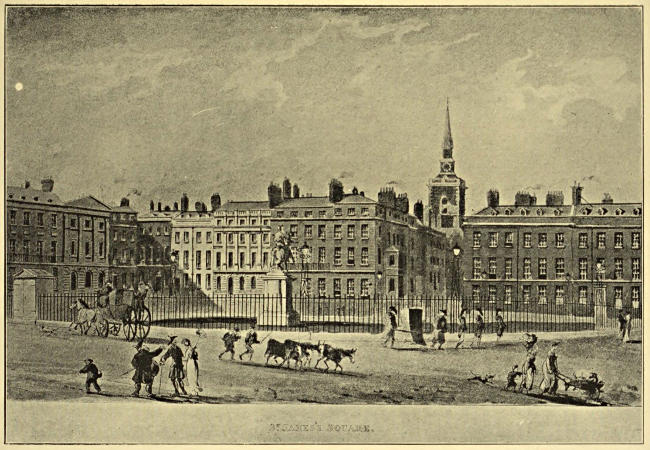

| St James’s Square in 1812 | 36 |

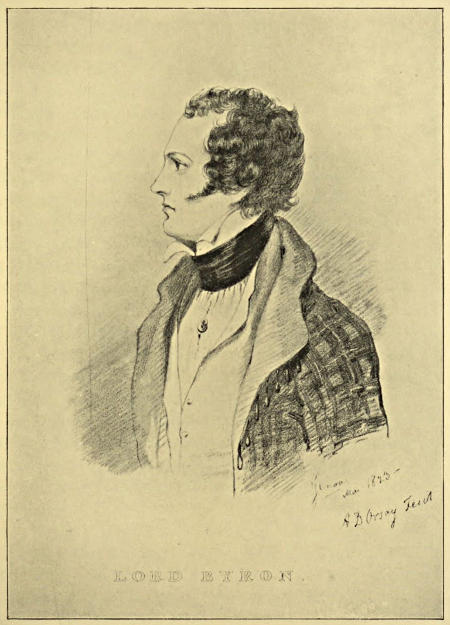

| Lord Byron | 50 |

| By D’Orsay. | |

| D’Orsay, 1830 | 96 |

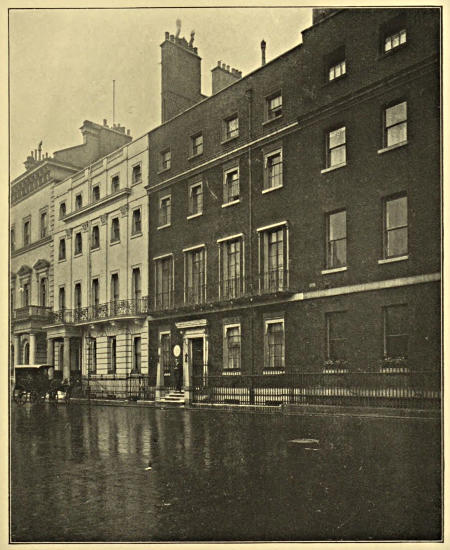

| 10 St James’s Square | 100 |

| Seamore Place | 114 |

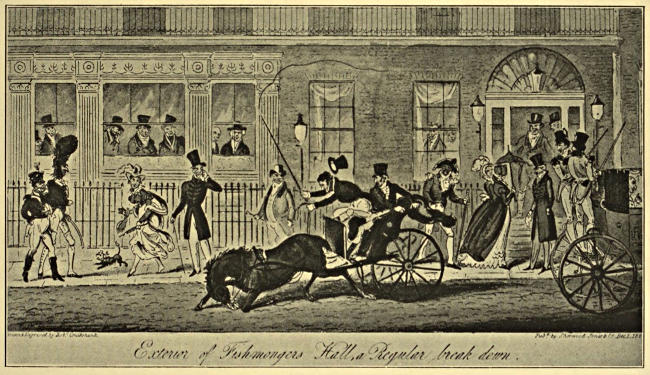

| Crockford’s | 150 |

| Gore House | 160 |

| From a Water-colour Drawing by T. H. Shepherd. | |

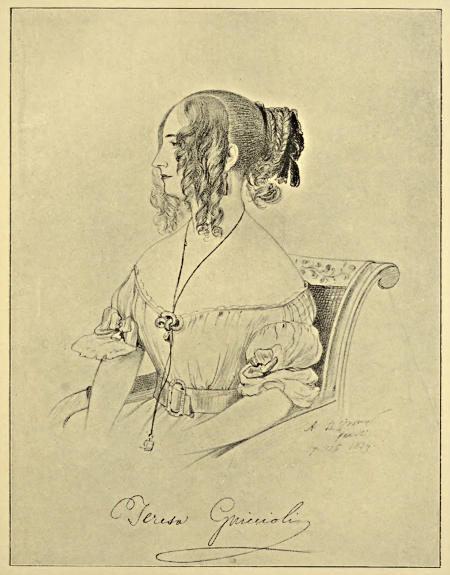

| The Countess Guiccioli | 164 |

| By D’Orsay. | |

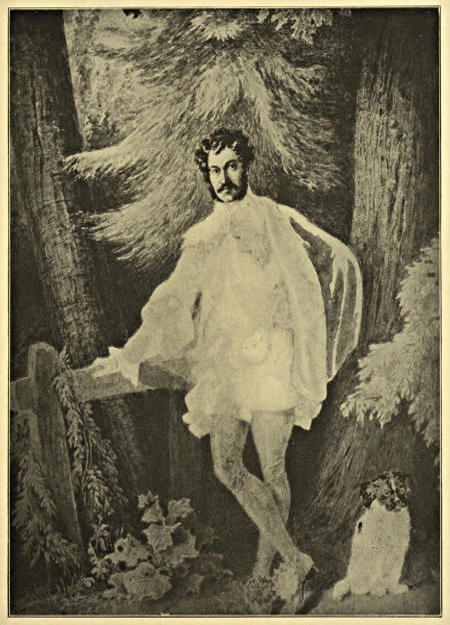

| Edward, First Baron Lytton | 176 |

| From a Painting by A. E. Chalon, R.A. | |

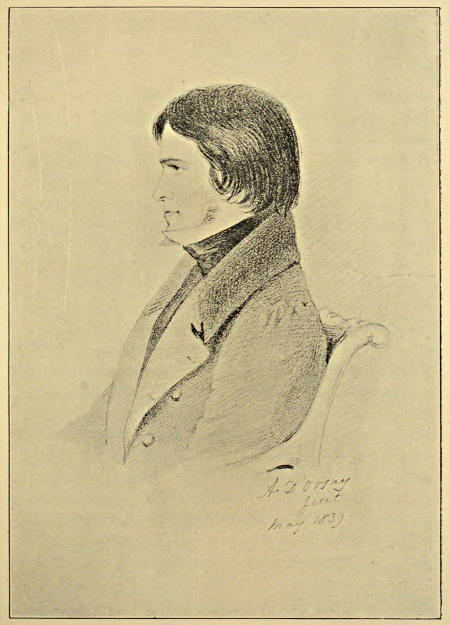

| Carlyle in 1839 | 188 |

| By D’Orsay. | |

| Napoleon III. | 206 |

| By D’Orsay. | |

| Lady Blessington | 234 |

| From the Bust by D’Orsay. | |

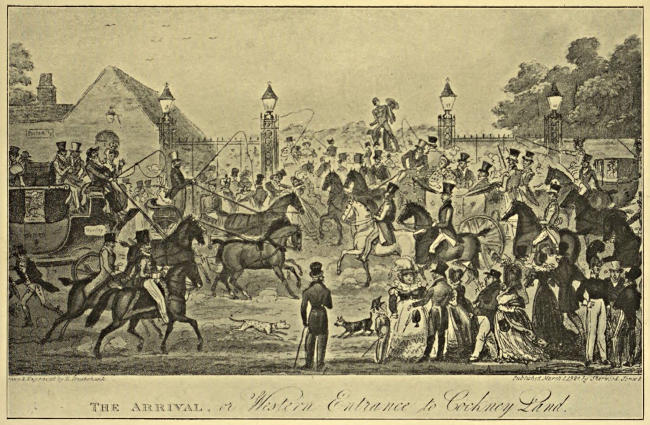

| Hyde Park Corner in 1824 | 250 |

| Garden View of Gore House | 280 |

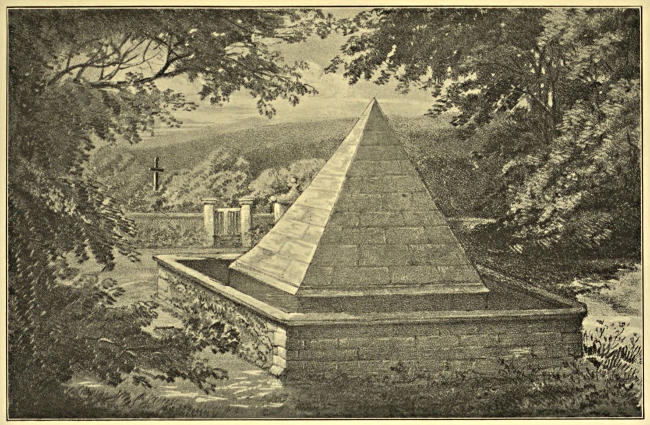

| Mausoleum of Lady Blessington | 288 |

| From a Photograph by D’Orsay. |

What a delightful fellow is your complete dandy. No mere clothes’ prop he, the coat does not make the dandy; no mere flâneur in fine garments; far more than that is our true dandy.

Though there is not any authority for making the statement, we do not think that we are wrong in asserting that on the day when Adam first complained to Eve that she had not cut his fig-leaf breeches according to the latest fashion dandyism was born. It is not dead yet, only moribund, palsied, shaking and decrepit with old age, blown upon by an over-practical world of money-spinners and money-spenders. Joy seems to have become a thing of which it is necessary to go in pursuit; in the golden days of the dandies it was a good comrade which came almost without hailing to those who desired its company. A real dandy would wither and wilt in a world where joy is so much of a stranger as it is now to most folk.

It is curious that there does not exist any history of the Rise, Decline and Fall of Dandyism, a subject fit for the pen of Gibbon. But the reason is, that to write it with anything[x] approaching to accuracy and completeness, or with sufficient sympathy and insight, would stagger the painstaking pedantry of a German philosopher and tax the wit and wisdom of George Meredith. Perhaps some day the University of Oxford or of Cambridge, when it has finished trifling with ponderous records of kings and queens, of statesmen and soldiers, of men of science and of writers of books, will gather together a happy band of scholars and men of the world, and will issue to us a joint-stock history of Dandyism. Reform is in the University air; let us hope. Might not the Academic authorities go even further with profit to themselves and to the nation? Ought they not to found and well endow a Chair of Dandyism? Should there not be a Professor of Dandyism to teach the young idea how to distinguish between dress and mere clothes? Between those two there is as great a gulf fixed as between the gentle art of the gourmet and the mere feeding of the gourmand. To teach also the art of living and the history of dandies and of dandyism? In these prosaic days we are only too ready to learn how to obtain the means of living without acquiring also a knowledge of how to use those means to good purpose. The Universities should likewise institute scholarships of dandyism, to encourage the study of dandyism in our Public and Board Schools, in both of which it is so grossly neglected. These scholarships must not[xi] be of meagre twenties and thirties of pounds, but of several hundreds per annum, so as to enable the scholar to practise the arts that he studies. We commend this outlet for money to millionaires of a practical turn of mind. The future happiness of our race depends upon its dandyism.

The dandy has played a conspicuous part upon the stage of history: Alcibiades, Marc Antony, Buckingham, Claude Duval, Benjamin Disraeli prove the truth of this statement. It would be a nice point to decide how far their dandyism was part and parcel of their equipment for attaining greatness. At one period of English history the whole population of the country was divided between dandies and anti-dandies, Cavaliers and Puritans, the former dandified in dress, religion, methods of fighting and in morals. They were great dandies those martial Cavaliers, and so were a few of their successors, who flirted and frivoled at Whitehall under Charles II.

The literature of dandyism is varied, vast and interesting, but space forbids our doing more than briefly alluding to two of its lighter branches in English letters. The drama—or rather the comedy—of dandyism holds a very high place in the history of the British Stage. Lyly, the Euphuist, was a literary dandy of the first water, and his euphuism the height of dandyism in literary style. Shakespeare in Love’s Labour Lost has given us a whole[xii] comedy of dandyism, and in Mercutio a portrait of the complete Elizabethan dandy. But the comedy of dandyism was at its zenith in the days of Charles II. Congreve and Wycherley were its high priests, who preached through the mouths of their brilliant puppets the gospel of joy which the Court so ably practised. We have in The School for Scandal another bright flash of dandyism, though Charles Surface has too much heart for a true and perfect dandy.

In fiction we have many striking examples of dandiacal literature, notably Vivian Grey and Pelham, both written by dandies.

Dandies vary in kind as well as in degree, there being some who play at dandyism in the days of their youth, such for example as Disraeli; others who are pinchbeck dandies, falling into the slough of overdressing, such for example as Charles Dickens, who was a mere colourist in garments. There are the born dandies, Brummel, D’Orsay, George Bernard Shaw for examples, the last of whom was born at least 200 years behind his time; he would have been delightful at the Court of Charles the Merry. It is not necessary to be in the fashion to achieve the dignity of dandyism; G. B. S. sets the fashion himself and is the only one who can follow it.

The psychology of the dandy has been much misunderstood, probably because it has been so little studied. What dandies have done has been told to us in many a biography, but what[xiii] they have been—upon that point silence reigns almost supreme. Yet the mind of the complete dandy is well worth plumbing. Those who know him not will perchance advance the theory that a man possessed of a mind cannot be a dandy; as a matter of fact the reverse is the truth; he must possess mind, but not a heart.

Even so profound a philosopher and student of human nature—the two are seldom found in conjunction, which accounts for the inefficacy of most philosophy—as Professor Teufelsdröckh of Weissnichtwo has defined a dandy as “a Clothes-wearing Man, a Man whose trade, office and existence consists in the wearing of Clothes. Every faculty of his soul, spirit, purse and person is heroically consecrated to this one object, the wearing of clothes wisely and well: so that others dress to live, he lives to dress.”

Which proves that though undoubtedly German philosophers know most things in Heaven and on Earth they do not know all, though they themselves would never make this admission. Teufelsdröckh’s definition of a dandy is preposterously incomplete, showing that he did not possess insight into the heart and soul of dandyism. He perceived the clothes, but not the man.

The proper wearing of proper clothes is but part of the whole duty of a dandy-man. A complete dandy is dandified in all his modes of life; his sense of honour and his conceptions of morality are dandified; he is an epicure in[xiv] all the arts of fine living, in all forms of fashionable and expensive amusement, in all luxurious accomplishments. He must be endowed with wit, or at least gifted with a tongue of sprightliness sufficient to pass muster as witty. He must be perfect in the amiable art of polite conversation and expert in the language of love. He must own “the courtier’s, soldier’s, scholar’s eye, tongue, sword”; he must be “the glass of fashion and the mould of form, the observed of all observers.”

How far did D’Orsay fulfil these requirements? It is the aim of the following pages to answer that question.

It is the habit of historians to pay little heed to the childhood and the training of the kings, conquerors, statesmen and the other big folk whose achievements they record and whose characters they seldom fathom or portray. But perhaps they are right just as perhaps sometimes they are accurate. It is easier to judge correctly and with understanding the boy and what really were the influences that affected his development, when we know the performances of his maturity, than it is to trace in the child the father of the man. By what the man was we may know what the boy had been. Which brings us to this point, that we need not very deeply regret that the records of D’Orsay’s early years are but scanty. Such as they are they suffice to give us all that we require—a fugitive glimpse here and there of a childhood as great in promise as the manhood was in performance.

Gédéon Gaspard Alfred de Grimaud, Count d’Orsay and du Saint-Empire, Prince of Dandies, was born upon the 4th of September, in the year 1801. Whether or not he came into the world under the influence of a lucky star we can find no record; upon that point each of us may draw[16] his own conclusion in accordance with his judgment of D’Orsay’s career and character.

He sprang from a noble and distinguished family, his father Albert, Count d’Orsay, being a soldier of the Empire and accepted as one of the handsomest men of his day, Napoleon saying of him that he was “aussi brave que beau.” It has been written of the son, “Il est le fils d’un général de nos armées héroiques, aussi célèbre par sa beauté que par ses faits d’armes.” Alfred inherited his father’s good looks and his accomplishment with the sword.

Writing in 1828, Lady Blessington says: “General d’Orsay, known from his youth as Le Beau d’Orsay, still justifies the appellation, for he is the handsomest man of his age that I have ever beheld…;” and Lady Blessington was an experienced judge of manly beauty.

His mother, a beautiful woman, was Eléanore, Baroness de Franquemont, a daughter of the King of Würtemberg by his marriage with Madame Crawford, also needless to say a beautiful woman; also apparently dowered handsomely with wit and worldly wisdom. Her marriage with the King who, it has been neatly said, “baptised with French names his dogs, his castles and his bastards,” was of course a left-handed affair, and on his right-handedly marrying within his own rank, she retired in dudgeon to France. Later she married an Irishman of large means, a Mr O’Sullivan, with whom she resided for some time in India, surviving him and dying at the advanced age of eighty-four,[17] full of youthfulness and ardour. The grandson inherited her accomplishment in love.

So alluring, indeed, were her charms, that on her return from the East one of her many admirers presented her with a bottle of otto of Roses, outdone in sweetness by the following Mooreish compliment:—

The fragrance of the otto has long departed but that of the compliment remains. A pretty compliment deserves to attain immortality.

When in Paris in 1828 Lady Blessington was upon terms of intimacy with the D’Orsays, and was greatly impressed by la belle Sullivan, or, as she preferred to be called, Madame Crawford. She visited her in a charming hôtel, “entre Cour et Jardin”; and decided that she was the most “exquisite person of her age” that she had ever seen. She was then in her eightieth year, but we are told that she did not look more than fifty-five, and was full of good-humour and vivacity. “Scrupulously exact in her person, and dressed with the utmost care as well as good taste, she gives me a notion of the appearance which the celebrated Ninon de l’Enclos must have presented at the same age, and has much of the charm of manner said to have belonged to that remarkable woman.”

There is considerable mystery about this good lady’s career.

It was a foregone conclusion that a woman of this style would dote upon and do her best endeavour to spoil a bright, handsome boy such as was her grandson Alfred. Being an only son, an elder brother having died in infancy, the child was made much of on all sides. His good looks, his smartness, even his early developed taste for extravagant luxuries, charmed his accomplished grandmother, whom when later on he entered the army we find presenting him with a magnificent service of plate, which brought upon him more ridicule than envy from his brother officers.

In 1815 Paris was in a ferment of excitements and entertainments, all the great men and many of the great ladies of Europe were there gathered together—where the spoil is there shall the vultures be gathered together. Young D’Orsay, mere lad though he was, came very much to the front; even thus early his immaculate dress was noticeable; his spirited English hunter and his superb horsemanship attracted attention. Though he probably did not particularly relish the occurrence, he was presented to the Duke of Wellington. A great meeting this, the conqueror of the men of France and the future conqueror of the women of England.

Lord William Pitt Lennox, himself only sixteen, relates that he met D’Orsay in Paris in 1814, and he goes on to state that “in the hours of recreation, he showed me all the sights of the ‘City of Frivolity,’ as Paris has been not inaptly named.” Pretty good for two such mere lads!

“One of our first visits was to the Café des[19] Milles Colonnes, which was, at the period I write of, the most attractive café in Paris. Large as it was, it was scarcely capable of containing the vast crowds who besieged it every evening, to admire its saloons decorated with unprecedented magnificence.…

“Wellington had a private box at the Théâtre Français, which D’Orsay and myself constantly occupied to witness the splendid acting of Talma, Madame Georges, Mademoiselle Duchesnois in tragedy, and of that daughter of Nature, Mademoiselle Mars, in comedy.…

“Upon witnessing Perlet in Le Comédien d’Etampes, D’Orsay said—

“‘Is not Perlet superlative?’”

In another of his numerous voluminous and often highly entertaining memoirs, Lord William writes of this same visit to Paris:—

“One youth attracted great attention that day”—it was a royal hunt in the Bois de Boulogne—“from his handsome appearance, his gentlemanlike bearing, his faultless dress and the splendid English hunter he was mounted upon. This was Count Alfred d’Orsay, afterwards so well known in London society. De Grammont,[1] who some few years after married his sister, had sent him from England a first-rate Leicestershire hunter, whose fine shape, simple saddle and bridle contrasted favourably with the heavy animals and smart caparisons then in fashion with the Parisian Nimrods.

“The Count was presented to Wellington[20] and his staff, and from that moment he became a constant guest at the Hôtel Borghese.…”

Of another hunt, or rather of the return from it, we read:—

“Nothing occurred during the day’s sport to merit any particular comment; perhaps the most amusing part of it was our ‘lark’ home across the country, when myself, Fremantle, and other attachés of the English Embassy, led some half dozen Frenchmen a rather stiffish line of stone walls and brooks. Among the latter was D’Orsay, who, albeit unaccustomed to go ‘across country,’ was always in the ‘first flight,’ making up by hard riding whatever he may have lacked in judgment; he afterwards lived to be an excellent sportsman and a good rider to hounds.”

As became the son of his father, though scarcely fitting in the grandson of a king, D’Orsay was ever a staunch Bonapartist, feeling the full strength of the glamour of Napoleon. But the Emperor and the Empire vanished in cannon smoke; the Bourbons occupied rather uncomfortably the throne of France, and D’Orsay, much against the grain, entered the King’s garde-du-corps. But so ardent was his devotion to Bonapartism, that when the new monarch made his state entry into his capital, the lad refused to be a witness of his triumph, would not add his voice to the general acclamation, and indulged in the luxury of tears in a back room.

His inherited instincts and his education gave him a taste for all the fine arts of life, and Nature endowed him with exceptionally good looks. An[21] upstanding man he became, over six feet in stature; broad-shouldered and slim-waisted; hands and feet of unusual beauty; long, curly, dark chestnut hair; forehead high and wide; lips rather full; eyes large, and light hazel in colour. Though there was something almost femininely soft about his beauty he was nowise effeminate; in fact, he was a superb athlete, and highly skilled in almost every form of manly exercise and sport. We are told that he was a wit; a capital companion at all hours of the day and night; a quite capable amateur artist, who, as is the way of amateurs, received assistance from his professional friends, and—which is unusual at any rate among amateurs in art if not in sport—took pay for his work. In short, he was a very highly-gifted and accomplished young man.

D’Orsay was born in an age when the atmosphere was electric with adventure; when nobodies rapidly became somebodies, and many who had been brought up to consider themselves very considerable somebodies were shocked at being told that in truth they were nobodies, or at best but the thin shadows of great names. It was an age when even the discomforts of a throne were not an unreasonable aspiration for the most humbly born. With his beauty of face and figure, fascinating manners and high family influence, young D’Orsay must have looked upon the world as a fine fat oyster which he could easily open and from which he could pluck the pearl of success. He possessed a winning tongue that would have made him a great diplomat; the[22] daring and skill at arms that would have stood him in good stead as a soldier of fortune; a power of raising money in most desperate straits that would have rendered him an unrivalled minister of finance. From all these roads to distinction he turned aside; he was born to a greater fate; his was the genius of a complete dandy. Few great men have been able so justly to appraise their abilities; still fewer to attain so surely their ambition.

During his short service in the army he proved himself a good officer and made himself popular with his men by looking to their comfort and welfare. Naturally he assumed the lead in all the gaieties of the garrison town, the assemblies, the dances, the dinners, the promenadings, but how petty they must have been to him, and how often he must have wistfully repined for Paris. He could not play his great part on so circumscribed a stage and with so poor a company of players. But if he could not find sufficient social sport, he could fight, and did. On one occasion the cause of the duel was noteworthy. It happened only a few days after he had joined his regiment that at mess one of his brother officers made use of an offensive expression in connection with the name of the Blessed Virgin. D’Orsay, as became a devout Catholic gentleman, expostulated. The offence was offensively repeated, upon which D’Orsay, evidently feeling that a verbal retort would not suffice to meet the gravity of the occasion, threw a plateful of spinach in the face of the transgressor. Thereupon a challenge and a duel fought that evening upon the town ramparts.[23] With what result? Alas, as so often upon important affairs, history holds her tongue. The historic muse is an arrant jade, who chatters unceasingly upon matters of no moment, and is silent upon points concerning which we thirst for information. That is one of the ways of women.

On the occasion of a later duel, D’Orsay remarked to his second before the encounter:—

“You know, my dear friend, I am not on a par with my antagonist; he is a very ugly fellow, and if I wound him in the face he won’t look much the worse for it; but on my side it ought to be agreed that he should not aim higher than my chest, for if my face should be spoiled ce serait vraiment dommage.”

A dandy with a damaged nose or deprived of one eye would be a figure of fun.

From remote ancestors D’Orsay inherited the spirit of chivalry, setting woman upon a lofty pedestal and then asking her to step down and make love to him. He was always ready to rescue a woman—not merely a beauty—in distress, of which a fine example is an event which befell while he was living out of barracks in apartments, which were kept by a widow, who had one son and two daughters. The son was a muscular young man of robust temper, and attracted—or rather distracted—one day by the sounds of tumult rising from below, D’Orsay hastened downstairs to find this youth employed in bullying his mother. The blood of D’Orsay was inflamed; the dandy thrashed the lout, promising still heavier punishment should occasion arise.

Even the ardent D’Orsay, while he was thus preparing himself for his life-work and laying the foundation upon which he was to raise so superb a fame, could not in the hours of his highest inspiration have dreamed that Fate was deciding his future in the person of a lovely Irish peeress, the cynosure of London society. Such, in fact, was the case. In the year 1821 he visited England and met with the woman who held his fortunes in her beautiful arms.

Margaret, or as she preferred to be called, and when a lady expresses a preference that should suffice, Marguerite Power was born at Knockbrit, near Clonmel, on the 1st of September 1789, being the third of the six children of Edmund Power, a Tipperary squireen of extravagant propensities and of a violent temper and overbearing tyranny which rendered him a curse to his family. He was a good-looking, swaggering fellow, with a showy air, fond of fine clothes, fine wine, fine horses, and various other fine things, indulgence in which his income did not justify. His were a handsome set of children: the two sons, Michael and Robert, attained the army rank of captain; Marguerite—and two sisters, Ellen and Mary Anne; the eldest child died young. Of a quieter disposition than her brothers and sisters, Marguerite as a child[25] was rather weak and ailing, sensitive and reflective. At that time of her life her beauty was not obvious; indeed few then seem to have realised that there was any charm in the soft, round, clear-complexioned face, with its pretty dimples and large, grey eyes shielded by long, drooping lashes. Her voice was low, soft, caressing; her movements unstudiedly graceful. A dreamy child, who lived in fancy-land; strange to her comrades, who awarded her little else than ridicule and misunderstanding.

In 1796 the Powers moved into Clonmel, which change was welcomed by all the family save Marguerite, who looked forward to it with a foreboding that was only too fully fulfilled. In some ways this move wrought good for the child, awakening her to the realities of life, arousing an interest in the ways and doings of the society into which she was thrown; her health improved, and with it her spirits, both mental and physical.

Her father’s pecuniary affairs now went rapidly from worse to much worse, and his adventures in politics rendered him highly unpopular with those of his own rank and station. He was a hospitable soul in his reckless, feckless way while he had a penny to spend, and often when he had not, filling his house with guests, many of whom were military men, and emptying his purse.

When only fifteen years old Marguerite began to go out into society, as did her sister Ellen, her junior by more than a year. The rackety society of a small, Irish garrison town can scarcely have been wholesome for a young, impressionable girl, and to its influence may be attributed the development[26] in Lady Blessington’s character of many evil traits which healthful surroundings and judicious restraint might have held in check. The two graceful, pretty children quickly became popular.

Among the familiar guests at the father’s house in 1804 were two officers of the 47th Regiment of Foot, then stationed in Clonmel, Captain Murray and Captain Maurice St Leger Farmer, the latter a man of considerable means, which was quite sufficient in Power’s eyes to make him an excellent match for Marguerite, to whom both the officers were paying attention. Though Farmer was young, good-looking, plausible, the child’s fancy turned toward his rival, who wooed and would have won her had a fair field been granted him. He warned Marguerite that Farmer had proposed for her hand to her father, the news coming to her entirely unexpected, most unwelcome, difficult to credit. But in a few days the information was proved conclusively to be true, her father informing her that Farmer had approached him in the matter, and that he had given his cordial consent to his addresses. Marguerite was dismayed, at first stunned. She fully understood the strong inducements which the prospect of her marriage with Farmer had for a man in her father’s embarrassed circumstances, and knew only too well from bitter experience how intolerant he was of opposition to any of his whims or wishes, and how little weight the desires of any of his children bore with him. From her mother she expected some sympathy, but to her dismay received[27] scant consideration for her plea to be spared, her unwillingness being counted the romantic notion of a child too young to be able to form a right judgment of the advantages offered by this proposed marriage. Tears and entreaties availed not, and the child was married to a man whom she held in detestation and in fear.

That the outcome of this inhuman mating was misery is not wonderful; there was not in it any possibility of happiness. The one a very turbulent man who, though not actually insane, was subject to paroxysms of rage that were terrifying; the other a child not yet sixteen years of age, with a nature very sensitive, impressionable, and with that intense longing for love, sympathy and understanding so common among Irish women and men. We know what Marguerite Power did become; it is idle to conjecture what she might have been had not this abominable marriage been thrust upon her.

From her own account, which seems trustworthy, we learn that her husband treated his child-wife outrageously, not even refraining from physical violence. Her arms were meanly pinched till black and blue; her face struck. When he went abroad, not infrequently he would lock her into her room, sometimes leaving her for hours without nourishment.

Three months after their marriage Farmer was ordered to rejoin his regiment at Kildare, and his wife took the bold, determined step of refusing to go with him. A separation being arranged, Marguerite returned to her father’s house, where she received a welcome the reverse of kind. Home was made utterly distasteful to her, and sympathy—the[28] one thing that might have saved her—was withheld by her father and mother. It was given to her from an alien quarter, and she accepted the “protection” offered to her by Captain Thomas Jenkins of the 11th Light Dragoons, a Hampshire man of considerable property. The astonishing thing is that she acted on the advice given to her by Major, afterwards Sir Edward Blakeney, her supposed friend and well-wisher. Meanwhile Farmer had gone out to India in the East India Company’s service.

When Lord Mountjoy, better known as Lord Blessington, first met with the fascinating Marguerite is not quite clear, but in all probability he did so in or about 1804, when serving as Lieutenant-Colonel of the Tyrone Militia when stationed at Clonmel.

Blessington plays a considerable and mysterious part in the life of D’Orsay. His father, the Right Hon. Luke Gardiner, was born in the year 1745, and did his duty by his country and possibly by his conscience in various ways. He married the daughter of a Scotch baronet, who presented him with several daughters and two sons, one of these latter dying in infancy, the other, Charles John, entering the world on July 19, 1782. He was educated at Eton and at Christ Church, Oxford, and succeeded his father in the titles of Viscount and Baron Mountjoy in 1798. In 1809 he was elected, upon what qualifications it is difficult to imagine, a representative peer of Ireland, and in 1816 was created Earl of Blessington. In this same year we hear of his visiting Marguerite in Manchester Square, London.

Lady Blessington

(From a Water-Colour Drawing by A. E. Chalon, R.A.)

[TO FACE PAGE 28

As far as wealth was concerned Blessington certainly was granted a fine start in life, but it may well be doubted if he were well endowed or endowed at all with brains of any value, though we are informed by a lukewarm but still possibly too warm biographer that he was “possessed of some talents.” Let us hope so; but if so, he contrived with great skill to bury them. We do hear of him speaking in the House of Lords in support of a motion for a vote of thanks to Lord Wellington, and as a specimen of his eloquence we quote:—

“No general was better skilled in war, none more enlightened than Lord Viscount Wellington. The choice of a position at Talavera reflected lustre on his talents; the victory was as brilliant and as glorious as any on record. It was entitled to the unanimous approbation of their lordships, and the eternal gratitude of Spain and of this country.”

It is also recorded that his lordship spoke but seldom, which may be counted to him for a saving grace.

He seems to have been more at home in the green-room than in the neighbourhood of the woolsack. He was very wealthy, very prodigal, vastly futile. Byron relates of him:—“Mountjoy … seems very good-natured, but is much tamed since I recollect him in all the glory of gems and snuff-boxes, and uniforms and theatricals, sitting to Strolling, the painter, to be depicted as one of the heroes of Agincourt.”

In another portrait he appears as Achilles, dragging at his chariot-tail the body of Hector, a friend “sitting” for the corpse. Physically he was[30] vigorous; a tall, bright-looking man; a capital companion, when only good spirits and a strong head unadorned with brain-sauce were called for.

In 1808, or 1809, Blessington—then mere Mountjoy—fell in with a very charming and well-favoured lady named Brown, but there were “some difficulties in the way of the resolution he had formed of marrying the lady, but the obstacles were removed.” The obstacle was the mere trifle of her already being possessed of if not blessed with a husband, Major Brown, who, however, discreetly and considerately departed this life in 1812, thus enabling Blessington to legalise the lady’s position in his establishment, the outcome of his connection with her having already been that she had borne him two children, Charles John and Emilie Rosalie. This lady subsequently presented him with two further pledges of her fond affection, Lady Harriet Anne Frances Gardiner, born in 1812, and Luke Wellington, afterwards by courtesy Viscount Mountjoy, born in 1814. On the 9th of September of this same year she died.

Blessington was gifted with a penchant for losing his heart to ladies possessed of “obstacles” in the way of his complete happiness, for, as has been noted, he was in 1816 vice Jenkins befriending Marguerite Farmer. Again fortune smiled on his desires, Farmer dying of injuries received during a drunken frolic in October 1817. On 16th February of the following year his widow became Lady Blessington, she then being in her twenty-ninth, he in his thirty-seventh, year.

Her beauty had ripened into something near[31] akin to perfection, a bright and radiant spirit shining through the physical tenement. Hers was a vivid, compelling loveliness, supported by a vivacious good humour. Her figure, though somewhat tending toward over-fullness, was moulded on exquisite lines and of almost perfect proportions; her movements still graceful and free, as they had been when she was a child; her face—now pensively lovely, now suddenly illuminated with a joyous fancy that first expressed itself in her sparkling eyes; pouting lips; a clear, sweet-toned voice; the merriest of merry laughs. In sober truth, a very fascinating woman.

This wild Irish girl, for certainly she had been a leetle wild, had climbed high up the social ladder. Without any other fortune than her face and her winsome ways she had won a peer for her lord, who if not highly endowed with ability possessed fortune in abundance, which for the purposes of her contentment was even more to be desired.

The fond pair paid a visit to my lord’s estate in County Tyrone, and also to Dublin, where the appearance of my lady created no small stir. From the first day of their marriage Blessington exhibited a sumptuous extravagance in providing luxuries for Lady Blessington, who herself records:—“The only complaint I ever have to make of his taste, is its too great splendour; a proof of which he gave me when I went to Mountjoy Forest on my marriage, and found my private sitting-room hung with crimson Genoa silk velvet, trimmed with gold bullion fringe, and all the furniture of equal richness—a richness that[32] was only suited to a state-room in a palace,” or to any other room seldom used or seen.

The wilds of Ireland, however, were not a fitting stage for one so ambitious to charm as was Lady Blessington, so after a short sojourn in Tyrone she and her husband returned to London, where they took up their residence at 10 St James’ Square, a house that had been dignified by the occupancy of Chatham and was to be by that of Gladstone.

Lady Blessington was as blest as was to be the Duke of Leeds’ bride, of whom the rhyme ran:—

The mansion was fitted and furnished in a style that only great wealth could afford or ill taste admire.

Lady Blessington with her “gorgeous charms” set the one-half of London society raving about her beauty and her extravagance; the other half avoided the company of a lady with so speckled a past.

There were at that time two great salons in London: the one at Holland House to which wit, beauty and respectability resorted; the second being at Lady Blessington’s house, to which only wit and beauty were attracted. Among the constant visitors to the latter may be named Canning, Castlereagh, who lived a few doors off; Brougham, Jekyll, Rogers, Moore,[33] Kemble, Mathews the elder, Lawrence, Wilkie. Moore records a visit paid by him in May 1822, accompanied by Washington Irving. He speaks of Lady Blessington as growing “very absurd.”

“I have felt very melancholy and ill all this day,” she said.

“Why is that?” Moore asked, doubtless with becoming sympathy in his voice and manner.

“Don’t you know?”

“No.”

“It is the anniversary of my poor Napoleon’s death.”

Joseph Jekyll, who was well known in society as a wit and teller of good stories and to his family as a writer of capital letters, was born in 1754, dying in 1837. It is quite startling to find him writing casually in 1829 of having talked with “Dr” Goldsmith; how close this brings long past times; there are those alive who met D’Orsay, who in turn knew Jekyll, who talked with Goldsmith. Jerdan speaks of Jekyll as having “a somewhat Voltaire-like countenance, and a flexible person and agreeable voice.”

He was a great hand at dining-out, though it distressed him to meet other old folk, whom he unkindly dubbed “Methusalems.”

In November 1821, he writes: “London still dreary enough; but I have dinners with judges and lawyers—nay, yesterday with the divine bit of blue, Lady Blessington and her comical Earl. I made love and Mathews (the elder) was invited to make faces.”

And in the February of the succeeding year, he records another visit to St James’ Square:—

“London is by no means yet a desert. Lately we had a grand dinner at Lord Blessington’s, who has transmogrified Sir T. Heathcote’s ground floor into a vast apartment, and bedizened it with black and gold like an enormous coffin. We had the Speaker, Lord Thanet, Sir T. Lawrence.…” etc.

In June 1822 we find Blessington in quite unexpected company and engaged upon matters that would scarcely have seemed likely to appeal to him. On the first of that month a meeting was held of the British and Foreign Philanthropic Society, of which the object was “to carry into effect measures for the permanent relief of the labouring classes, by communities for mutual interest and co-operation, in which, by means of education, example and employment, they will be gradually withdrawn from the evils induced by ignorance, bad habits, poverty and want of employment.” Robert Owen was the moving spirit of the Society, and the membership was highly distinguished, including among other unforgotten names those of Brougham, John Galt and Sir James Graham. At a meeting at Freemasons’ Hall, Blessington was entrusted with the reading of a report by the committee, in which it was recommended that communities should be established on Owen’s wildly visionary plan. The meeting was enthusiastic, much money was promised, and—history does not record anything further of the Society.

In France—a youthful son of Mars; in England—Venus at her zenith.

D’Orsay paid his first visit to London in 1821, as the guest of the Duc de Guiche, to whom his sister, Ida, was married. De Guiche, son of the Duc de Grammont, had been one of the many “emigrants” of high family who had sought and had found in England shelter from the tempest of the Revolution, and had shown his gratitude for hospitality received by serving in the 10th Hussars during the Peninsular War.

Landor, writing some twenty years later, says: “The Duc de Guiche is the handsomest man I ever saw. What poor animals other men seem in the presence of him and D’Orsay. He is also full of fun, of anecdote, of spirit and of information.”

Gronow describes him as speaking English perfectly, and as “quiet in manner, and a most chivalrous, high-minded and honourable man. His complexion was very dark, with crisp black hair curling close to his small, well-shaped head. His features were regular and somewhat aquiline; his eyes, large, dark and beautiful; and his manner, voice, and smile were considered by the fair sex to be perfectly irresistible”; concluding,[36] “the most perfect gentleman I ever met with in any country.”

So we may take it that D’Orsay did not feel that he was visiting a land with which he had not any tie of sympathy.

His sister Ida was a year older than himself, or, to put it more gallantly, a year less young, and bore to him a strong likeness in appearance but not in disposition—fortunately for her husband. Her good looks were supported by good sense.

William Archer Shee describes the Duchesse de Guiche as “a blonde, with blue eyes, fair hair, a majestic figure, an exquisite complexion.…”

In those golden days the adornment of a handsome person with ultra-fashionable clothes did not qualify a man as a dandy. Much more was demanded. It was, therefore, no small feather in D’Orsay’s cap that he came to London an unknown young man, was seen, and by his very rivals at once acknowledged as a conqueror. His youth, his handsome face, his debonairness, his wit, were irresistible. Everywhere, even at Holland House, he made a good impression. He rode in Hyde Park perfectly “turned out,” the admired of those who were accustomed to receive, not to give, admiration. At a ball at the French Embassy where all the lights of fashionable society shone in a brilliant galaxy, he was a centre of attraction “with his usual escort of dandies.”

St James’s Square in 1812

[TO FACE PAGE 36

At the Blessingtons’ he was a favoured guest. Gronow, discreetly naming no names, writes of the “unfortunate circumstances which entangled the Count as with a fatal web from early youth”;[37] surely a poorly prosaic way of describing the romantic love of a young man for a beautiful woman only twelve years his senior?

As Grantley Berkeley puts it: “The young Count made a most favourable impression where-ever he appeared; but nowhere did it pierce so deep or so lasting as in the heart of his charming hostess of the magnificent conversaziones, soirées, dinners, balls, breakfasts and suppers, that followed each other in rapid succession in that brilliant mansion in St James’ Square.”

Grantley Berkeley also says: “At his first visit to England, he was pre-eminently handsome; and, as he dressed fashionably, was thoroughly accomplished, and gifted with superior intelligence, he became a favourite with both sexes. He had the reputation of being a lady-killer … and his pure classical features, his accomplishments, and irreproachable get-up, were sure to be the centre of attraction, whether in the Park or dining-room.”

Then of later times: “He used to ride pretty well to hounds, and joined the hunting men at Melton; but his style was rather that of the riding-school than of the hunting-field.…

“In dress he was more to the front; indeed, the name of D’Orsay was attached by tailors to any kind of raiment, till Vestris tried to turn the Count into ridicule. Application was made to his tailor for a coat made exactly after the Count’s pattern. The man sent notice of it to his patron, asking whether he should supply the order, and the answer being in the affirmative,[38] the garment was made and sent home. No doubt D’Orsay imagined that some enthusiastic admirer had in this way sought to testify his appreciation; but, on going to the Olympic Theatre to witness a new piece, he had the gratification of seeing his coat worn by Liston as a burlesque of himself.” This “take-off” did not please D’Orsay, who withdrew his patronage from the Olympic and appeared no more in the green-room which he had been wont to frequent. But the town, which had caught wind of the joke, was delighted, and roared with merriment.

Is there a hidden reference to D’Orsay’s visit and possibly even to Lady Blessington in these lines from “Don Juan”?

At a later date we find Byron describing the Count to Tom Moore as one “who has all the air of a cupidon déchainé, and is one of the few specimens I have ever seen of our ideal of a Frenchman before the Revolution.”

Also at that later date (1823), when he met D’Orsay at Genoa with the Blessingtons, Byron was lent by Blessington a journal which the Count[39] had written during this first visit of his to London. When returning it, he writes, on 5th April:—

“My Dear Lord,—How is your gout? or rather how are you? I return the Count d’Orsay’s journal, which is a very extraordinary production, and of a most melancholy truth in all that regards high life in England. I know, or knew personally, most of the personages and societies which he describes; and after reading his remarks, have the sensation fresh upon me as if I had seen them yesterday. I would, however, plead in behalf of some few exceptions, which I will mention by and bye. The most singular thing is, how he should have penetrated not the facts, but the mystery of English ennui, at two-and-twenty.[2] I was about the same age when I made the same discovery, in almost precisely the same circles—for there is scarcely a person whom I did not see nightly or daily, and was acquainted more or less intimately with most of them—but I never could have discovered it so well, Il faut être Français to effect this. But he ought also to have seen the country during the hunting season, with ‘a select party of distinguished guests,’ as the papers term it. He ought to have seen the gentlemen after dinner (on the hunting days), and the soirée ensuing thereupon—and the women looking as if they had hunted, or rather been hunted; and I could have wished that he had been at a dinner in town, which I recollect at Lord[40] Cowper’s—small, but select, and composed of the most amusing people.… Altogether, your friend’s journal is a very formidable production. Alas! our dearly-beloved countrymen have only discovered that they are tired, and not that they are tiresome; and I suspect that the communication of the latter unpleasant verity will not be better received than truths usually are. I have read the whole with great attention and instruction—I am too good a patriot to say pleasure—at least I won’t say so, whatever I may think.… I beg that you will thank the young philosopher.…”

A few days later—how pleasing it is to find one great writer openly admiring another and a younger!—Byron writes to D’Orsay himself:—

“My Dear Count d’Orsay (if you will permit me to address you so familiarly)—you should be content with writing in your own language, like Grammont, and succeeding in London as nobody has succeeded since the days of Charles the Second, and the records of Antonio Hamilton, without deviating into our barbarous language—which you understand and write, however, much better than it deserves. ‘My approbation,’ as you are pleased to term it, was very sincere, but perhaps not very impartial; for, though I love my country, I do not love my countrymen—at least, such as they now are. And besides the seduction of talent and wit in your work, I fear that to me there was the attraction of vengeance. I have seen and felt much of what you have described so well …[41] the portraits are so like that I cannot but admire the painter no less than his performance. But I am sorry for you; for if you are so well acquainted with life at your age, what will become of you when the illusion is still more dissipated?”

It is much to be regretted that this vivacious journal has never seen the light of publicity; there must have been considerable interest in a piece of writing which so greatly attracted and excited the admiration of Byron; but even more important, its pages would have helped to the understanding of D’Orsay and have brought us closer to him in these his young days. Further, a view of English society at that date by a candid Frenchman must have been highly entertaining. D’Orsay, apparently having changed his mind with regard to persons and things, or fearing that the publication of so scathing an indictment might savour of ingratitude toward those who had entertained him with kindness, consigned to the flames this “very formidable production” of his ebullient days of youth. Another account is that it was destroyed by his sister.

In 1822 D’Orsay tore himself away from the enchantments of London and bade farewell to the beautiful enchantress of St James’ Square.

In November 1822, D’Orsay again met Lady Blessington.

Apparently it was at Blessington’s express desire that the house in St James’ Square was shut up; its glories were dimmed with holland sheetings; the mirrors that had reflected so much of youth and love and beauty were covered; the windows that had so often shone with hospitable lights were shuttered and barred. On 25th August a start was made on a Continental tour. Blessington was satiated with the turmoil of pleasures that London afforded, satiety held him in its bitter grasp. He had exhausted the wild joys of the life of a man about town; he was still thirsty for enjoyment, but the accustomed draughts no longer quenched his thirst. It was bluntly said by one that he was “prematurely impaired in mental energies.” Whether that were or were not the case, judging by his conduct during the remainder of his life he must have lost all sense of honour and of social decency.

To the party of two a third member was added in the person of Lady Blessington’s youngest sister, Mary Anne Power, a woman pretty in a less full-blown style than her sister,[43] which caused her to be likened to a primrose set beside a peach blossom. Lady Blessington, who for herself preferred Marguerite to Margaret, renamed her sister Marianne. In 1831 Marianne married the Comte de St Marsault, but the union was disastrously unhappy. The Comte was an aged gentleman of ancient lineage, and his wintriness blighted the poor primrose.

The tourists travelled in great style by Dover, Calais, Rouen, St Germain-en-Laye, and so on to Paris. At St Germain Lady Blessington’s thoughts naturally turned toward the unhallowed fortunes of the La Pompadour and du Barry. She pondered over the curious fact that decency does in social estimation take from vice half its sting, and over the coarseness displayed by Louis XV. in choosing his mistresses from outside the ranks of the ladies of his Court, rendering the refinement of Louis XIV. virtuous by contrast. She very truly says—and what better judge could we wish for upon such a point than she?—“A true morality would be disposed to consider the courtly splendour attached to the loves of Louis XIV. as the more demoralising example of the two, from being the less disgusting.”

In Paris they halted for some days, meeting among other distinguished men with the volatile Tom Moore, whom Lady Blessington hits off with the singular felicity and simplicity of language that distinguishes her literary style. She found him to be of “a happy temperament, that conveys the idea of having never lived out[44] of sunshine, and his conversation reminds one of the evolutions of some bird of gorgeous plumage, each varied hue of which becomes visible as he carelessly sports in the air.”

Lady Blessington’s birthday, September 1st, was celebrated during this visit to Paris, and she tells us that after a woman has passed the age of thirty the recurrence of birthdays is not a matter for congratulation, concluding with the striking remark: “Youth is like health, we never value the possession of either until they have begun to decline.”

From Paris they went on to Switzerland. Their travelling equipage not unnaturally aroused the wonderment of the onlookers who assembled to witness their departure. Travelling carriages and a baggage wagon—a fourgon—piled high with imperials and packages of all sizes; the courier, as important in his mien as a commander of an army corps, bustling here, bustling there; lady’s maid busily packing; valets and footmen staggering and grumbling under heavy trunks. Lady Blessington heard a Frenchman under her window exclaim: “How strange those English are! One would suppose that instead of a single family, a regiment at least were about to move!”

Move at last the regiment did, though not without dire struggling. They are off! Amid a tornado of expostulations and exhortations; off along the straight, dusty roads to Switzerland. Further we need not accompany them. For us the centre of interest lies at Valence, on the Rhone, where D’Orsay was with his regiment[45] under orders to march with the Duc d’Angoulême over the Pyrenees. But to war’s alarms D’Orsay was now deaf. He heard above the din of trumpet and of drum the call of love, and answered to it. He resigned his commission. For at the hotel where was established the regimental mess the Blessingtons arrived on November 15th; the romance of love eclipsed the romance of war.

From this point onward there can be little doubt as to D’Orsay’s position as regards Lady Blessington, but as concerns Blessington everything grows more and more extraordinary, and more and more discreditable to the blind or easy-going husband. Charles Greville says that Blessington was really fond of the fascinating young Frenchman. He looked on him as a charming, happy comrade. It was at his persuasion that D’Orsay threw up his commission, Blessington making “a formal promise to the Count’s family that he should be provided for.” At any rate such provision was made later on. Greville adds that D’Orsay’s early connection with Lady Blessington was a mystery; certainly it was so as far as concerns the behaviour of the lady’s husband. D’Orsay’s conduct is explicable in two ways: either infatuation for a beautiful woman blinded him to his real interests and rendered him unable to count the cost of the course he now decided to pursue, or he preferred to that of the soldier the dolce far niente life of a dependent loafer. Possibly, however, the two motives mingled.

The company was now complete and each member of it apparently entirely content. They moved on to Orange, and on November 20th reached Avignon, at which place a considerable stay was made. Avignon! Petrarch and Laura! Lady Blessington and Count d’Orsay! Glory almost overwhelming for any one town. The battlemented walls; the ancient bridge; the swift stream of the Rhone; the storied palace of the Pope; and the famous fountain of Vaucluse, given to fame by Petrarch; a proper setting for the love of Alfred and of Marguerite.

They stayed at the Hôtel de l’Europe, a comfortable hostelry, an inn which many years before had been the scene of an incident which formed the groundwork of the comedy of The Deaf Lover. It was now the scene of incidents which might well have supplied the materials for a comedy of The Blind Husband: or, There are None so Short-sighted as those who Won’t See!

There was gaiety and society at Avignon, much social coming and going, dinners, dances, receptions and routs. The Duc and Duchesse de Caderousse Grammont, who resided in a château close to the town, were doubtless delighted to see their young connection the Count, and to welcome his friends. Lady Blessington enjoyed herself immensely, and it is interesting to know that her refined taste was charmed by the decorum of French dancing:—

“The waltz in France,” she writes, “loses its objectionable familiarity by the manner in which it is performed. The gentleman does not clasp[47] his fair partner round the waist with a freedom repugnant to the modesty and destructive to the ceinture of the lady; but so arranges it, that he assists her movements, without incommoding her delicacy or her drapery. In short, they manage these matters better in France than with us;[3] and though no advocate for this exotic dance, I must admit that, executed as I have seen it, it could not offend the most fastidious eye.”

Lady Blessington was, as we know, an authority upon “objectionable familiarity.” What would this fastidious dame have thought of the shocking indelicacy of modern ball-room romps? Would “kitchen” Lancers have appealed favourably to her? Would her approbation have honoured the graceful cake-walk? But we must not linger over such nice inquiries; we must not lose ourselves in the maze of might-have-beens, but must move on to fact, Southward ho! To Italy, the land of Love and Olives.

Genoa was reached on the last day of March 1823, and Lady Blessington, as also doubtless D’Orsay, because of the sweet sympathy between two hearts that beat as one, was enraptured with the beautiful situation of the town, in her Journal breaking forth into descriptive matter which must be the envy of every conscientious journalist. Their entrance was made by night, and they found lodging at the Alberga del la Villa, a house situated upon the sea front, bedecked with marble balconies and the rooms adorned with a plenitude of gilding that brought comfort to the simple heart of Lady Blessington. But it was not by matters so material as its beauties or the comforts of its inns that her soul was really touched. To be in Genoa was to be in the same place as Byron, of whom the very morrow might bring the sight. The only fly in the honey was that the poet might still be fat, as, alack, Tom Moore had reported him to be when at Venice. An imperfect peer is sad enough; but an obese poet—Oh, fie!

On April first, auspicious date, the fair inspirer of poems met with the writer of them, the vision being not entrancing but disappointing to the eager lady. What it was to the poet we[49] do not know, though there are, indeed, quite firm grounds for surmising that Byron was not entirely pleased by the invasion of the privacy which he so jealously guarded, by the intrusion upon his retirement of the Blessingtons even when accompanied by D’Orsay.

Ingenuity was practised in order to secure admission. The day selected for the drive out to Albano was rainy, a circumstance which it was calculated would compel even the most curmudgeonly of poets to offer hospitality and shelter. The event proved the soundness of the calculation. The carriage drew up to the gates of the Casa Saluzzo; the two gentlemen alighted, sent in their names, were admitted, were cordially welcomed. Outside in the downpour sat the two pretty ladies. We know not what emotion, if any, agitated Marianne Power; but who can doubt that painful anxiety and doubt fluttered in the bosom of her sister? Would Byron, or would Byron not? To be admitted or not to be admitted? Of what count were all the charms of Genoa, what weighed all the joys of illicit love, if she could not gain admission to the presence of the poet whose conversation—and her own—she was destined to record?

Slowly the minutes passed. Then at last came relief. Byron had learned that the ladies were at his gates; breathless, hatless, he ran out.

“You must have thought me,” he gasped, “quite as ill-bred and sauvage as fame reports in having permitted your ladyship to remain a[50] quarter of an hour at my door: but my old friend Lord Blessington is to blame, for I only heard a minute ago that it was so highly honoured. I shall not think you do not pardon (sic) this apparent rudeness, unless you enter my abode—which I entreat you will do.”

So the lady reports his speech, the which is precisely the manner in which Byron would have expressed himself—more or less.

Lady Blessington was quite easily mollified, granting the pardon so gracefully sought, accepting his assisting hand, and, crossing the courtyard, passed into the vestibule. Before them bowed the uniformed chasseur and other obsequious attendants, all showing in their faces the surprise they felt at their master displaying so much cordiality in his reception of the visitors.

The whole account in her Journal gives promise of the eminence to which Lady Blessington afterward attained as a writer of fiction.

Lady Blessington was disappointed in Byron as Oscar Wilde was by the Atlantic and Mr Bernard Shaw is by the world. He did not reach the ideal she had framed of the author of Childe Harold and Manfred. He was a jovial, vivacious, even flippant man of the world. His brow should have been gloomy with sardonic melancholy, and his eyes shadowed by a hidden grief which not even love or the loveliness of Lady Blessington could assuage. But, alas, for the evanescence of ideals!

Lord Byron

(By D’Orsay)

[TO FACE PAGE 50

Of this meeting we also have Byron’s version. He writes to Moore:—

“Miladi seems highly literary, to which and your honour’s acquaintance with the family, I attribute the pleasure of having seen them. She is also very pretty, even in a morning,—a species of beauty on which the sun of Italy does not shine so frequently as the chandelier. Certainly English women wear better than their Continental neighbours of the same sex.”

Accounts differ as to whether Byron did or did not extend familiar friendship to the Blessingtons; it really does not much matter—if at all. But it is of importance to know that he fell before the charms of the irresistible D’Orsay. Indeed so blinded was he with admiration that he not only discovered the young Frenchman to be “clever, original, unpretending,” but also stated that “he affected to be nothing that he was not.” We fancy D’Orsay would not have counted an accusation of modesty as a compliment. In such a man, properly conscious of his gifts, modesty can only be a mockery. Mock modesty is to the true what mock is to real turtle—an insolent imitation. D’Orsay was above all things candid, when there existed no valid reason for being otherwise.

While at Genoa D’Orsay drew Byron’s portrait, which afterward formed the frontispiece to Lady Blessington’s Conversations of Lord Byron, which is quite the most realistic and skilful of her ladyship’s works of fiction. The poet gave the painter a ring, a souvenir not to be worn for it was too large. It was made of lava, “and so far adapted to the fire of his years and[52] character,” so Byron wrote to Lady Blessington, through whose hand he conveyed the gift, perchance deeming that by so doing he would enhance its value.

Byron’s yacht, the Bolivar, was purchased by Blessington for £300, having cost many times that sum. The vessel was fitted in the most sumptuous manner; soft cushions, alluring couches, marble baths, every extravagance that the heart of a woman could conceive or the purse of man pay for; suitable surroundings for our modern Antony and Cleopatra.

“The Pilgrims from St James’ Square” travelled onward through Florence to Rome, from which latter city they were driven in haste by the heat and the fear of malaria; so to Naples where they arrived on July 17th. It was from the hill above the Campo Santo that they gained their first view of the town where they were to spend so many happy hours. On the brow of the eminence the postilions pulled up the horses, so that the travellers might at their leisure survey the wonderful panorama; the towers, the steeples, the domes, the palaces, the multitude of gardens, the blue waters of the famous Bay; Vesuvius outlined against the spotless sky; from behind the Isle of Capri the sun sending up broad shafts of light; directly below them the high walls and the solemn cedars of the city of the dead.

At the hotel Gran Bretagna, facing the sea, they secured comfortable quarters commanding a fine view over the Bay, which enchanted Lady Blessington. But it was quickly decided that a less noisy abode was desirable, and after a prolonged house-hunting the Palazzo Belvedere at Vomero was engaged. Before they could move into it English comforts had to be superimposed upon Italian magnificence, much to the amazement of the Prince and Princess Belvedere, who[54] had not found their home lacking in anything material. Blessington must have been born with the bump of extravagance highly developed, and Lady Blessington did not do anything to depress it. The gardens of the Palazzo were superb and delightful the views they commanded. So in these luxurious surroundings the toil-worn travellers settled down to contentment—though the heat was intense.

Of the rooms we may note that the salon was a spacious apartment, of which the four corners were turned into so many independent territories, of which one was occupied by Lady Blessington’s paper-strewn table, and another by D’Orsay’s, artistically untidy; the others were allotted to Marianne Power and to young Charles Mathews. Blessington had his own private sanctum, in which he busied himself with literary and artistic enterprises, all of which were still-born, except a novel, concerning which Jekyll gives this advice: “Don’t read Lord Blessington’s Reginald de Vavasour … duller than death.”

How charming a morning spent in that salon in that charming company: the Lady of the House, romantic and tender; D’Orsay, debonair and gracious; Marianne, pretty, never in the way, never out of it when her company was wanted; and gay, young Charles Mathews intent upon his drawings. To them enter, upon occasion fitting or otherwise, the Lord of the House, too full of his own affairs to heed the affair that was going on before his eyes, or heedless of it, who can say which; now bestowing[55] a caress upon his adoring wife, now casting a heavy jest to his young protégé, the Count; now summoning Mathews to come into his room and discuss the plans for the superb home that he was going to build in Ireland, but which remained a castle in the air.

Charles James Mathews, who was born December 26th, 1803, was in his early years destined for the Church, but his exuberant high spirits scarcely foreshadowed success in that walk of life. Having evinced a decided taste for architecture, he was articled to Augustus Pugin, whose office he entered in 1819. Charles James was a lively lad, quick of wit and ready of tongue, a well-read young fellow, too. In August, 1823, the elder Mathews received a letter from Blessington, who had returned from Italy and with whom he had long been intimately acquainted, expressing his intention to build a house at Mountjoy Forest and to give the younger Mathews “an opportunity of making his début as an architect.” So off to the North of Ireland went Charles James, and for a couple of months lived a very jolly life with his “noble patron.” The plans for the new house were approved, but it was considered necessary to consult Lady Blessington before any final decisions were arrived at, and, eventually, the whole scheme was shelved. Young Mathews was invited by Blessington to accompany him on his return to Italy, and—says Mathews—“on the twenty-first of September, 1823, eyes were wiped and handkerchiefs waved, as, comfortably ensconced in the[56] well-laden travelling carriage, four post-horses rattled us away from St James’ Square.”

So it will be seen that kindly Blessington left Marguerite and Alfred to take care of each other this summer time, with Marianne to play gooseberry. Expeditions here, there and everywhere, were the order of the day; drives along the coast, or in the evening down into Naples, to the Chiaja thronged with carriages. There were many English then resident in Naples, among them Sir William Gell, whom D’Orsay once described as “Le brave Gell, protecteur-général des humbugs.” He was evidently a bit of a “character”; a man of learning, withal, who wrote of the topography of Troy and the antiquities of Ithaca; chamberlain to the eccentric Queen Caroline, in whose favour he gave his evidence; an authority on Pompeii—and an amiable man. Mathews speaks of him as “Dear, old, kind, gay Sir William Gell, who, while wheeling himself about the room in his chair, for he was unable to walk a step without help, alternately kept his friends on the broad grin with his whimsical sallies” and talked archæological “shop”; “his hand was as big as a leg of mutton and covered with chalkstones”; nevertheless he could draw with admirable precision.

Greville tells of him, some years later, as living in “his eggshell of a house and pretty garden, which he planted himself ten years ago, and calls it the Boschetto Gellio.” Moore speaks of him as “still a coxcomb, but rather amusing.”

He was a man of sound humour; he could[57] make fun out of his own misfortunes, as in this letter written from Rome in 1824: “I am sitting in my garden, under the shade of my own vines and figs, my dear Lady Blessington, where I have been looking at the people gathering the grapes, which are to produce six barrels of what I suspect will prove very bad wine; and all this sounds very well, till I tell you that I am positively sitting in a wheelbarrow, which I found the only means of conveying my crazy person into the garden. Don’t laugh, Miss Power.”

He was not always respectful to his royal mistress, for he accuses her of being capable of saying, “O trumpery! O Moses!”

Lady Blessington was indeed fortunate in the guides who chaperoned her on her visits to the many interesting places around Naples; Uwins, the painter, escorted her to picture-galleries and museums; so did Westmacott, the sculptor; Herschel, afterward Sir John, accompanied her to the Observatory; Sir William Gell was her cicerone at Pompeii, and to D’Orsay fell the honour of everywhere being by her side.

Pompeii inspired Lady Blessington to verse—

The house-party was once again complete when Blessington and Mathews arrived in November.

Young Mathews fancied he had dropped into Paradise, and gives a glowing description of his environment: “The Palazzo Belvedere, situated about a mile and a half from the town on the heights of Vomero, overlooking the city, and the beautiful turquoise-coloured bay dotted with latine sails, with Vesuvius on the left, the island of Capri on the right, and the lovely coast of Sorrento stretched out in front, presented an enchanting scene. The house was the perfection of an Italian palace, with its exquisite frescoes, marble arcades, and succession of terraces one beneath the other, adorned with hanging groves of orange-trees and pomegranates, shaking their odours among festoons of vines and luxuriant creepers, affording agreeable shade from the noontide sun, made brighter by the brilliant parterres of glowing flowers, while refreshing fountains plashed in every direction among statues and vases innumerable.”

Among the company Mathews found one of about his own age, with whom he struck up a firm friendship; D’Orsay was naturally a fascinating companion and exemplar for any young man of parts. Enthusiasm glows in the following description: “Count d’Orsay … I have no hesitation in asserting was the beau-idéal of manly dignity and grace. He had not yet assumed the marked peculiarities of dress and deportment which the sophistications of London life subsequently developed. He was the model of all that could be conceived of noble demeanour and youthful candour; handsome beyond all[59] question; accomplished to the last degree; highly educated, and of great literary acquirements; with a gaiety of heart and cheerfulness of mind that spread happiness on all around him. His conversation was brilliant and engaging, as well as clever and instructive. He was moreover the best fencer, dancer, swimmer, runner, dresser; the best shot, the best horseman, the best draughtsman of his age.” There are some touches of exaggeration here, but it is valuable as the impression made upon a shrewd youth of the world.

He notes, too, that D’Orsay spoke English in the prettiest manner; maybe with a touch of Marguerite’s brogue.

Mathews has given us a description of the routine of life at the Palazzo Belvedere:—“In the morning we generally rise from our beds, couches, floors, or whatever we happen to have been reposing upon the night before, and those who have morning gowns or slippers put them on as soon as they are up. We then commence the ceremony of washing, which is longer or shorter in its duration, according to the taste of the persons who use it. You will be glad to know that from the moment Lady Blessington awakes she takes exactly one hour and a half to the time she makes her appearance, when we usually breakfast; this prescience is remarkably agreeable, as one can always calculate thus upon the probable time of our breakfasting; there is sometimes a difference of five or six minutes, but seldom more. This meal taking place latish in the day, I always[60] have a premature breakfast in my own room the instant I am up, which prevents my feeling that hunger so natural to the human frame from fasting. After our collation, if it be fine we set off to see sights, walks, palaces, monasteries, views, galleries of pictures, antiquities, and all that sort of thing; if rainy, we set to our drawing, writing, reading, billiards, fencing, and everything in the world.… In the evening each person arranges himself (and herself) at his table and follows his own concerns till about ten o’clock, when we sometimes play whist, sometimes talk, and are always delightful! About half-past eleven we retire with our flat candlesticks in our hands.… At dinner Lady B. takes the head of the table, Lord B. on her left, Count d’Orsay on her right, and I at the bottom. We have generally for the first service a joint and five entrées; for the second, a rôti and five entrées, including sweet things. The name of our present cook is Raffelle, and a very good one when he likes.”

A heated but brief quarrel between D’Orsay and Mathews gives us a glimpse of the former’s hot temper. The two had become constant comrades, fencing, shooting, swimming, riding, drawing together.

Blessington had formed the habit of boring the party by insisting on their accompanying him on sailing trips aboard the Bolivar, his purchase from Byron, which expeditions had more than once culminated in their being becalmed for hours and overwhelmed with heat[61] and ennui. One sultry morning when Blessington suggested a sail, they with one consent began to make excuses, good and bad: the ladies were afraid of the sun; D’Orsay said a blunt “No,” and Mathews was anxious to complete a sketch. To which last Lord Blessington remarked—

“As you please. I only hope you will really carry out your intention; for even your friend Count d’Orsay says that you carry your sketch-book with you everywhere, but that you never bring back anything in it.”

Possibly there was an element of truth in the criticism; at any rate it struck home.

It was apparently a somewhat sulky party that went a-driving that afternoon; two charming women and two ill-humoured young men. Suddenly, without any further provocation, Mathews burst out—

“I have to thank you, Count d’Orsay, for the high character you have given me to Lord Blessington, with regard to my diligence.”

“Comment?” responded D’Orsay.

“I should have been more gratified had you mentioned to me, instead of to his lordship, anything you might have—”

“Vous êtes un mauvais blagueur, par Dieu, la plus grande bête et blagueur que j’ai jamais rencontré, et la première fois que vous me parlez comme ça, je vous casserai la tête et je vous jetterai par la fenêtre.”

Indubitably ill-temper, of which we know not the cause, had made the Count forget his[62] manners; Mathews rightly kept silent, reserving the continuation of the quarrel for a future and more proper occasion, and Lady Blessington aided him by the rebuke—

“Count d’Orsay, I beg you to remember I am present, and that such language is not exactly what I should have expected before me.”

But the fiery Frenchman was not to be suppressed and answered hotly.

In the evening Mathews received a note from D’Orsay, repeating the offence in almost more offensive terms. Of course, a duel was the order of the day; Mathews wrote demanding satisfaction or an apology; of which former he was promptly promised all he might desire to have. Mathews found his friend Madden willing to act as his second, but Blessington very naturally, as host of both the parties, refused to act for the Count. But Madden was a diplomatist, and despatched to D’Orsay what his principal terms a “very coolly written” letter, which called forth the following:—

“Mon Cher Mr Madden,—Je suis très loin d’être fâché que Mr Mathews vous ait choisi pour son témoin, ma seule crainte eut été qu’il en choisît un autre.

“Je suis aussi très loin d’être offensé d’un de vos avis. Lorsque j’estime quelqu’un, son opinion est toujours bien reçue.

“L’affaire, comme vous savez, est très simple dans le principe. On me fit la question si Mathews avait dessiné à Caprée; je dis que non, mais qu’il emportoit toujours ses crayons et son[63] album pour ne rien faire—que cela étoit dommage avec ses grandes dispositions. Lord Blessington n’as pas eu le courage de lui représenter sans y mêler mon nom, et Mathews a pris la chose avec moi sur un ton si haut que j’ai été obligé de la rabaisser, après lui avoir exprimé que ce n’étoit que par intérêt pour lui que j’avois fait cette représentation. Il à continué sur le même ton; je lui dis alors que la première fois qu’il prendroit un ton semblable avec moi je le jetterois hors de la voiture et lui casserois la tête. J e vous répète mot pour mot cette altercation. La seule différence que j’ai fait entre lui et un autre, c’est que je n’ai fait que dire ce que j’aurois fait certainement vis-à-vis d’un autre qui prendroit ce ton avec moi. Si j’ai accompagné mon projet d’avenir de mots offensants et inconvenants, j’en suis aussi fâché pour lui que pour moi, car c’est me manquer à moi-même que d’user des mots trop violents.