1

2

HOME

UNIVERSITY

LIBRARY

OF

MODERN KNOWLEDGE

Editors:

HERBERT FISHER, M.A., F.B.A., LL.D.

Prof. GILBERT MURRAY, D.Litt.,

LL.D., F.B.A.

Prof. J. ARTHUR THOMSON, M.A.,

LL.D.

Prof. WILLIAM T. BREWSTER, M.A.

(Columbia University, U.S.A.)

LONDON

WILLIAMS AND NORGATE

3

THE ALPS

BY

ARNOLD LUNN

LONDON

WILLIAMS AND NORGATE

4

First printed July 1914

5

PREFACE

For the early chapters of this book I have

consulted, amongst other authorities, the books

mentioned in the bibliography on pp. 251-254.

It would, however, be ungracious if I

failed to acknowledge my indebtedness to

that most readable of historians, Mr. Gribble,

and to his books, The Early Mountaineers

(Fisher Unwin) and The Story of Alpine

Climbing (Nelson). Mr. Gribble and his publisher,

Mr. Unwin, have kindly allowed me to

quote passages translated from the works of

the pioneers. Two friends, experts in the

practice and history of mountaineering, have

read the proofs and helped me with numerous

suggestions.

7

8

CONTENTS

Volumes bearing upon the subject, already published

in the library, are—

7. Modern Geography. By Dr. Marion Newbigin.

(Illustrated.)

36. Climate and Weather. By Prof. H. N. Dickson.

(Illustrated.)

88. The Growth of Europe. By Prof. Grenville Cole.

(Illustrated.)

9

THE ALPS

CHAPTER I

THE MEDIÆVAL ATTITUDE

Rousseau is usually credited with the discovery

that mountains are not intrinsically

hideous. Long before his day, isolated men

had loved the mountains, but these men were

eccentrics. They founded no school; and

Rousseau was certainly the first to popularise

mountains and to transform the cult of hill

worship into a fashionable creed. None the

less, we must guard against the error of supposing

that mountain love was confined to

the few men who have left behind them

literary evidence of their good taste. Mountains

have changed very little since man

became articulate, and the retina of the

human eye has changed even less. The

beauty of outline that stirs us to-day was

implicit in the hills “that shed their burial

sheets about the march of Hannibal.” It

10

seems reasonable to suppose that a few men

in every age have derived a certain pleasure,

if not from Alpine travel at least from the

distant view of the snows.

The literature of the Ancient World contains

little that bears upon our subject. The

literature of the Jews is exceptional in this

respect. This is the more to their credit, as

the mountains of Judæa, south of the beautiful

Lebanon range, are shapeless and uninteresting.

Deuteronomy, the Psalms, Job, and

Isaiah contain mountain passages of great

beauty. The Old Testament is, however, far

richer in mountain praise than the New

Testament. Christ retired more than once

to the mountains; but the authors of the

four Gospels content themselves with recording

the bare fact that certain spiritual

crises took place on mountain-tops. There is

not a single indication in all the gospels that

Nazareth is set on a hill overlooking one of

the fairest mountain prospects in all Judæa,

not a single tribute to the beauty of Galilee

girdled by the outlying hills of Hermon.

The Greeks lived in a land of mountains

far lovelier than Palestine’s characterless

heights. But the Jews showed genuine if

spasmodic appreciation for their native

ranges, whereas the Greeks, if their literature

does them justice, cared little or nothing for

11

their mountains. The note of fear and

dread, pleasantly rare in Jewish literature, is

never long absent from Greek references to

the mountains. Of course, the Greeks gave

Olympus to their gods, but as Mr. Norman

Young remarks in a very able essay on The

Mountains in Greek Poetry, it was necessary

that the gods should look down on mankind;

and, as they could not be strung up

in mid-air, the obvious thing was to put them

on a mountain-top. Perhaps we may concede

that the Greeks paid a delicate compliment

to Parnassus, the Home of the Muses;

and certainly they chose for their temples

the high ground of their cities. As one

wanders through the olives and asphodels,

one feels that the Greeks chose for their

dwellings and temples those rising grounds

which afforded the noblest prospect of the

neighbouring hills. Only the cynic would

contend that they did this in order to escape

the atmosphere of the marshes.

The Romans were disgustingly practical.

They regarded the Alps as an inconvenient

barrier to conquest and commerce. Virgil

shows an occasional trace of a deeper feeling,

and Horace paused between draughts of

Falernian wine to admire the snows on

Soracte, which lent contrast to the comfort

of a well-ordered life.

12

Mr. Freshfield has shown that the Chinese

had a more genuine feeling for mountains;

and Mr. Weston has explained the ancient

cult of high places among the Japanese,

perhaps the most consistent mountain worshippers

in the world. The Japanese pilgrims,

clad in white, make the ascent to the shrines

which are built on the summits of their sacred

mountains, and then withdraw to a secluded

spot for further worship. For centuries, they

have paid official tribute to the inspiration of

high places.

But what of the Alps? Did the men who

lived within sight of the Swiss mountains

regard them with indifference and contempt?

This was, perhaps, the general attitude, but

there is some evidence that a love for mountains

was not quite so uncommon in the

Middle Ages as is usually supposed.

Before attempting to summarise this evidence,

let us try to realise the Alps as they

presented themselves to the first explorers.

The difficulties of Alpine exploration, as that

term is now understood, would have proved

quite as formidable as those which now confront

the Himalayan explorer. In spite of

this, glacier passes were crossed in the earliest

times, and even the Romans seemed to have

ventured across the Théodule, judging by

the coins which have been found on the top

13

of that great glacier highway. In addition

to the physical difficulties of Alpine travel,

we must recognise the mental handicap of

our ancestors. Danger no longer haunts the

highways and road-passes of the Alps. Wild

beasts and robber bands no longer threaten

the visitor to Grindelwald. Of the numerous

“inconveniences of travel” cited by an early

visitor to the Alps, we need now only fear

“the wonderful cunning of Innkeepers.”

Stilled are the voices that were once supposed

to speak in the thunder and the avalanche.

The dragons that used to wing their way

across the ravines of the central chain have

joined the Dodo and “the men that eat the

flesh of serpents and hiss as serpents do.”

Danger, a luxury to the modern, formed part

of the routine of mediæval life. Our ancestors

had no need to play at peril; and, lest we

lightly assume that the modern mountaineer

is a braver man than those who shuddered

on the St. Bernard, let us remember that our

ancestors accepted with grave composure a

daily portion of inevitable risks. Modern life

is so secure that we are forced to the Alps

in search of contrast. When our ancestors

needed contrast, they joined a monastery.

Must we assume that danger blinded them

to the beauty of the Alps? The mountains

themselves have not changed. The modern

14

mountaineer sees, from the windows of the

Berne express, a picture whose colours have

not faded in the march of Time. The bar of

silver that thrusts itself above the distant

foothills, as the train swings out of the

wooded fortress of the Jura, casts the same

challenge across the long shadows of the uplands.

The peaks are a little older, but the

vision that lights the world for us shone with

the same steadfast radiance across the plains

of long ago. Must we believe that our

adventurous forefathers could find nothing

but fear in the snows of the great divide?

Dangers which have not yet vanished menaced

their journey, but the white gleam of the

distant snows was no less beautiful in the

days when it shone as a beacon light to

guide the adventurous through the great

barrier down the warmth of Italian lowlands.

An age which could face the great adventure

of the Crusades for an idea, or more often for

the sheer lust of romantic wandering, was not

an age easily daunted by peril and discomfort.

May we not hope that many a mute, inglorious

mountain-lover lifted his eyes across

the fields and rivers near Basle or Constance,

and found some hint of elusive beauty in the

vision that still remains a mystery, even for

those who have explored the once trackless

snows?

15

Those who have tried to discover the

mediæval attitude have too often merely

generalised from detached expressions of

horror. Passages of praise have been treated

as exceptional. The Monk Bremble and the

Bishop Berkeley have had their say, unchallenged

by equally good evidence for the

defence. Let us remember that plenty of

modern travellers might show an equally

pronounced distaste for mountains. For the

defence, we might quote the words of an old

traveller borrowed in Coryat’s Crudities, a

book which appeared in 1611: “What, I

pray you, is more pleasant, more delectable,

and more acceptable unto a man than to

behold the height of hilles, as it were the very

Atlantes of heauen? to admire Hercules his

pillers? to see the mountaines Taurus and

Caucasus? to view the hill Olympus, the seat

of Jupiter? to pass over the Alpes that were

broken by Annibals Vinegar? to climb up

the Apennine promontory of Italy? from

the hill Ida to behold the rising of the

Sunne before the Sunne appears? to visit

Parnassus and Helicon, the most celebrated

seates of the Muses? Neither indeed is there

any hill or hillocke, which doth not containe

in it the most sweete memory of worthy

matters.”

There is the genuine ring about this. It is

16

the modern spirit without the modern affectations.

Nor is this case exceptional. In the

following chapter we shall sketch the story

of the early Alpine explorers, and we shall

quote many passages instinct with the real

love for the hills.

Are we not entitled to believe that Gesner,

Marti, and Petrarch are characteristic of

one phase of mediæval sentiment, just as

Bremble is characteristic of another? There

is abundant evidence to show that the habit

of visiting and admiring mountain scenery

had become fashionable before the close of

the sixteenth century. Simler tells us that

foreigners came from all lands to marvel at

the mountains, and excuses a certain lack of

interest among his compatriots on the ground

that they are surfeited with a too close knowledge

of the Alps. Marti, of whom we shall

speak at greater length, tells us that he found

on the summit of the Stockhorn the Greek

inscription cut in a stone which may be

rendered: “The love of mountains is best.”

And then there is the evidence of art. Conventional

criticism of mountain art often

revolves in a circle: “The mediæval man

detested mountains, and when he painted a

mountain he did so by way of contrast to set

off the beauty of the plains.” Or again:

“Mediæval man only painted mountains as

17

types of all that is terrible in Nature. Therefore,

mediæval man detested mountains.”

Let us try to approach the work of these

early craftsmen with no preconceived notions

as to their sentiments. The canvases still

remain as they were painted. What do they

teach us? It is not difficult to discriminate

between those who used mountains to point

a contrast, and those who lingered with

devotion on the beauty of the hills. When we

find a man painting mountains loosely and

carelessly, we may assume that he was not

over fond of his subject. Jan von Scorel’s

grotesque rocks show nothing but equally

grotesque fear. Hans Altdorfer’s elaborate

and careful work proves that he was at least

interested in mountains, and had cleared his

mind of conventional terror. Roughly, we

may say that, where the foreground shows

good and the mountain background shows

bad workmanship, the artist cared nothing for

hills, and only threw them in by way of

gloomy contrast. But such pictures are not

the general rule.

Let us take a very early mountain painting

that dates from 1444. It is something of a

shock to find the Salève and Mont Blanc as

the background to a New Testament scene.

How is the background used? Konrad Witz,

the painter, has chosen for his theme the

18

miraculous draught of fishes. If he had

borrowed a mountain background for the

Temptation, the Betrayal, the Agony, or the

Crucifixion, we might contend that the mountains

were introduced to accentuate the

gloom. But there is no suggestion of fear

or sorrow in the peaceful calm that followed

the storm of Calvary. The mountains in

the distance are the hills as we know them.

There is no reason to think that they are

intended as a contrast to the restful foreground.

Rather, they seem to complete and

round off the happy serenity of the picture.

Let us consider the mountain work of a

greater man than Witz. We may be thankful

that Providence created this barrier of hills

between the deep earnestness of the North

and the tolerance of Italy, for to this we

owe some of the best mountain-scapes of

the Middle Ages. There is romance in the

thought of Albrecht Dürer crossing the

Brenner on his way to the Venetian lagoons

that he loved so well. Did Dürer regard

this journey with loathing? Were the great

Alps no more than an obstacle on the road

to the coast where the Adriatic breaks “in

a warm bay ’mid green Illyrian hills.” Did

he echo the pious cry of that old Monk who

could only pray to be delivered from “this

place of torment,” or did he rather linger

19

with loving memory on the wealth of inspiring

suggestion gathered in those adventurous

journeys? Contrast is the essence

of Art, and Dürer was too great a man to

miss the rugged appeal of untamed cliffs,

because he could fathom so easily the gentler

charm of German fields and Italian waters.

You will find in these mountain woodcuts the

whole essence of the lovable German romance,

that peculiar note of “snugness” due to the

contrast of frowning rock and some “gemütlich”

Black Forest châlet. Hans Andersen,

though a Dane, caught this note; and in

Dürer’s work there is the same appealing

romance that makes the “Ice Maiden” the

most lovable of Alpine stories. One can

almost see Rudy marching gallantly up the

long road in Dürer’s “Das Grosse Glück,” or

returning with the eaglets stolen from their

perilous nest in the cliffs that shadow the

“Heimsuch.” Those who pretend that Dürer

introduced mountains as a background of

gloom have no sense for atmosphere nor for

anything else. For Dürer, the mountains

were the home of old romance.

Turn from Dürer to Da Vinci, and you will

find another note. Da Vinci was, as we shall

see, a climber, and this gives the dominant

note to his great study of storm and thunder

among the peaks, to be seen at Windsor

20

Castle. His mountain rambles have given

him that feeling of worship, tempered by awe,

which even the Climbers’ Guides have not

banished. But this book is not a treatise on

mountain Art—a fascinating subject; and we

must content ourselves with the statement

that painters of all ages have found in the

mountains the love which is more powerful

than fear. Those who doubt this may examine

at leisure the mountain work of Brueghel,

Titian, or Mantegna. There are many other

witnesses. At the beginning of the sixteenth

century, Hans Leu had looked upon the hills

and found them good, and Altdorfer had

shown not only a passionate enthusiasm for

mountains, but a knowledge of their anatomy

far ahead of his age. Wolf Huber, ten years

his junior, carried on the torch, and passed

it to Lautensack, who recaptured the peculiar

note of German romance of which Dürer is

the first and the greatest apostle. It would

be easy to trace the apostolic succession to

Segantini, and to prove that he is the heir

to a tradition nearly six hundred years old.

But enough has been said. We have adduced

a few instances which bear upon the contention

that, just as the mountains of the

Middle Ages were much the same as the

mountains of to-day, so also among the men

of those times, as among the men of to-day,

21

there were those who hated and those who

loved the heights. No doubt the lovers of

mountain scenery were in the minority; but

they existed in far larger numbers than is

sometimes supposed.

22

CHAPTER II

THE PIONEERS

Within the compass of this book, we

cannot narrate the history of Alpine passes,

though the subject is intensely interesting,

but we must not omit all mention of the

great classic traverse of the Alps. We should

read of Hannibal’s memorable journey not

in Livy, nor even in Bohn, but in that vigorous

sixteenth-century translation which owes its

charm and force even more to Philemon

Holland the translator than to Livy.

Livy, or rather Holland, begins with

Hannibal’s sentiments on “seeing near at

hand the height of those hills ... the horses

singed with cold ... the people with long

shagd haire.” Hannibal and his army were

much depressed, but, none the less, they

advanced under a fierce guerilla attack from

the natives, who “slipt away at night, every

one to his owne harbour.” Then follows a

fine description of the difficulties of the pass.

The poor elephants “were ever readie and

anone to run upon their noses”—a phrase

23

which evokes a tremendous picture—“and

the snow being once with the gate of so many

people and beasts upon it fretted and thawed,

they were fain to go upon the bare yce underneeth

and in the slabberie snow-broth as it

relented and melted about their heeles.” A

great rock hindered the descent; Hannibal

set it on fire and “powred thereon strong

vinegar for to calcine and dissolve it,” a

device unknown to modern mountaineers.

The passage ends with a delightful picture

of the army’s relief on reaching “the dales

and lower grounds which have some little

banks lying to the sunne, and rivers withall

neere unto the woods, yea and places more

meet and beseeming for men to inhabit.”

Experts are divided as to what pass was

actually crossed by Hannibal. Even the Col

de Géant has been suggested by a romantic

critic; it is certainly stimulating to picture

Hannibal’s elephants in the Géant ice-fall.

Probably the Little St. Bernard, or the Mont

Genèvre, is the most plausible solution. So

much for the great traverse.

Some twenty-five glacier passes had been

actually crossed before the close of the

sixteenth century, a fact which bears out

our contention that in the Middle Ages a

good deal more was known about the craft

of mountaineering than is generally supposed.

24

There is, however, this distinctive difference

between passes and peaks. A man may

cross a pass because it is the most convenient

route from one valley to another. He may

cross it though he is thoroughly unhappy

until he reaches his destination, and it would

be just as plausible to argue from his journey

a love of mountains as to deduce a passion

for the sea in every sea-sick traveller across

the Channel. But a man will not climb a

mountain unless he derives some interest

from the actual ascent. Passes may be

crossed in the way of business. Mountains

will only be climbed for the joy of the climb.

The Roche Melon, near Susa, was the first

Alpine peak of any consequence to be climbed.

This mountain rises to a height of 11,600 feet.

It was long believed to be the highest mountain

in Savoy. On one side there is a small

glacier; but the climb can be effected without

crossing snow. It was climbed during the

Dark Ages by a knight, Rotario of Asti, who

deposited a bronze tryptych on the summit

where a chapel still remains. Once a year

the tryptych is carried to the summit, and

Mass is heard in the chapel. There is a

description of an attempt on this peak in the

Chronicle of Novalessa, which dates back to

the first half of the eleventh century. King

Romulus is said to have deposited treasure on

25

26

the mountain. The whole Alpine history of

this peak is vague, but it is certain that the

peak was climbed at a very early period, and

that a chapel was erected on the summit before

Villamont’s ascent in 1588. The climb

presents no difficulties, but it was found discreet

to remove the statue of the Virgin, as

pilgrims seem to have lost their lives in

attempting to reach it. The pilgrimages did

not cease even after the statue had been

placed in Susa.

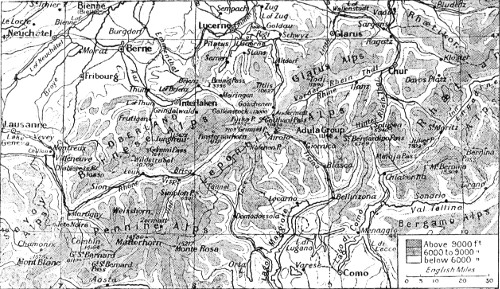

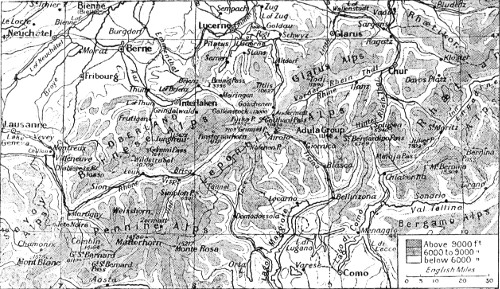

Bartholomew, Edin

Another early ascent must be recorded,

though the climb was a very modest achievement.

Mont Ventoux, in Provence, is only

some 6430 feet above the sea, and to-day

there is an hôtel on the summit. None the

less, it deserves a niche in Alpine history, for

its ascent is coupled with the great name of

the poet Petrarch. Mr. Gribble calls Petrarch

the first of the sentimental mountaineers.

Certainly, he was one of the first mountaineers

whose recorded sentiments are very much

ahead of his age. The ascent took place on

April 26, 1335, and Petrarch described it

in a letter written to his confessor. He

confesses that he cherished for years the

ambition to ascend Mont Ventoux, and

seized the first chance of a companion to

carry through this undertaking. He makes

the customary statement as to the extreme

27

difficulty of the ascent, and introduces a

shepherd who warns him from the undertaking.

There are some very human touches

in the story of the climb. While his brother

was seeking short cuts, Petrarch tried to

advance on more level ground, an excuse for

his laziness which cost him dear, for the

others had made considerable progress while

he was still wandering in the gullies of the

mountain. He began to find, like many

modern mountaineers, that “human ingenuity

was not a match for the nature of

things, and that it was impossible to gain

heights by moving downwards.” He successfully

completed the ascent, and the climb

filled him with enthusiasm. The reader

should study the fine translation of his letter

by Mr. Reeve, quoted in The Early Mountaineers.

Petrarch caught the romance of

heights. The spirit that breathes through

every line of his letter is worthy of the poet.

Petrarch is not the only great name that

links the Renaissance to the birth of mountaineering.

That versatile genius, Leonardo

da Vinci, carried his scientific explorations

into the mountains. We have already mentioned

his great picture of storm and thunder

among the hills, one of the few mementos

that have survived from his Alpine journeys.

His journey took place towards the end of

28

the fifteenth century. Little is known of

it, though the following passage from his

works has provoked much comment. The

translation is due to Mrs. Bell: “And this

may be seen, as I saw it, by any one going up

Monboso, a peak of the Alps which divide

France from Italy. The base of this mountain

gives birth to the four rivers which flow

in four different directions through the whole

of Europe. And no mountain has its base

at so great a height as this, which lifts itself

above almost all the clouds; and snow

seldom falls there, but only hail in the summer

when the clouds are highest. And this hail

lies (unmelted) there, so that, if it were not

for the absorption of the rising and falling

clouds, which does not happen more than

twice in an age, an enormous mass of ice

would be piled up there by the layers of hail;

and in the middle of July I found it very

considerable, and I saw the sky above me

quite dark; and the sun as it fell on the

mountain was far brighter here than in the

plains below, because a smaller extent of

atmosphere lay between the summit of the

mountain and the sun.”

We need not summarise the arguments

that identify Monboso either with Monte

Rosa or Monte Viso. The weight of evidence

inclines to the former alternative, though, of

29

course, nobody supposes that Da Vinci

actually reached the summit of Monte Rosa.

There is good ground, however, for believing

that he explored the lower slopes; and it is

just possible that he may have got as far as

the rocks above the Col d’Ollen, where, according

to Mr. Freshfield, the inscription “A.T.M.,

1615” has been found cut into the crags at

a height of 10,000 feet. In this connection

it is interesting to note that the name “Monboso”

has been found in place of Monte Rosa

in maps, as late as 1740.1

We now come to the first undisputed ascent

of a mountain, still considered a difficult

rock climb. The year that saw the discovery

of America is a great date in the history

of mountaineering. In 1492, Charles VII of

France passed through Dauphiny, and was

much impressed by the appearance of Mont

Aiguille, a rocky peak near Grenoble that

was then called Mont Inaccessible. This

mountain is only some seven thousand feet

in height; but it is a genuine rock climb, and

is still considered difficult, so much so that

the French Alpine Club have paid it the

doubtful compliment of iron cables in the

more sensational passages. Charles VII was

struck by the appearance of the mountain,

30

and ordered his Chamberlain de Beaupré to

make the ascent. Beaupré, by the aid of

“subtle means and engines,” scaled the peak,

had Mass said on the top, and caused three

crosses to be erected on the summit. It was

a remarkable ascent, and was not repeated

till 1834.

We are not concerned with exploration

beyond the Alps, and we have therefore

omitted Peter III’s attempt on Pic Canigou

in the Pyrenees, and the attempt on the

Pic du Midi in 1588; but we cannot on the

ground of irrelevance pass over a remarkable

ascent in 1521. Cortez is our authority.

Under his order, a band of Spaniards ascended

Popocatapetl, a Mexican volcano which

reaches the respectable height of 17,850 feet.

These daring climbers brought back quantities

of sulphur which the army needed for its

gunpowder.

The Stockhorn is a modest peak some

seven thousand feet in height. Simler tells us

that its ascent was a commonplace achievement.

Marti, as we have seen in the previous

chapter, found numberless inscriptions cut

into the summit stones by visitors, enthusiastic

in their appreciation of mountain

scenery, and its ascent by Müller, a Berne

professor, in 1536, is only remarkable for the

joyous poem in hexameters which records his

31

delight in all the accompaniments of a mountain

expedition. Müller has the true feelings

for the simpler pleasures of picnicing on the

heights. Everything delights him, from the

humble fare washed down with a draught

from a mountain stream, to the primitive joy

of hurling big rocks down a mountain side.

The last confession endears him to all who

have practised this simple, if dangerous,

amusement.

The early history of Pilatus, another low-lying

mountain, is much more eventful than

the annals of the Stockhorn. It is closely

bound up with the Pilate legend, which was

firmly believed till a Lucerne pastor gave it

the final quietus in 1585. Pontius Pilate,

according to this story, was condemned by

the Emperor Tiberius, who decreed that he

should be put to death in the most shameful

possible manner. Hearing this, Pilate very

sensibly committed suicide. Tiberius concealed

his chagrin, and philosophically remarked

that a man whose own hand had not

spared him had most certainly died the most

shameful of deaths. Pilate’s body was attached

to a stone and flung into the Tiber,

where it caused a succession of terrible

storms. The Romans decided to remove it,

and the body was conveyed to Vienne as a

mark of contempt for the people of that

32

place. It was flung into the Rhone, and did

its best to maintain its reputation. We need

not follow this troublesome corpse through

its subsequent wanderings. It was finally

hurled into a little marshy lake, near the

summit of Pilatus. Here Pilate’s behaviour

was tolerable enough, though he resented

indiscriminate stone-throwing into the lake

by evoking terrible storms, and once a year

he escaped from the waters, and sat clothed

in a scarlet robe on a rock near by. Anybody

luckless enough to see him on these occasions

died within the twelve-month.

So much for the story, which was firmly

believed by the good citizens of Lucerne.

Access to the lake was forbidden, unless the

visitor was accompanied by a respectable

burgher, pledged to veto any practices that

Pilate might construe as a slight. In 1307,

six clergymen were imprisoned for having

attempted an ascent without observing the

local regulations. It is even said that climbers

were occasionally put to death for breaking

these stringent by-laws. None the less,

ascents occasionally took place. Duke Ulrich

of Württemberg climbed the mountain in 1518,

and a professor of Vienna, by name Joachim

von Watt, ascended the mountain in order

to investigate the legend, which he seems to

have believed after a show of doubt. Finally,

33

in 1585, Pastor John Müller of Lucerne,

accompanied by a few courageous sceptics,

visited the lake. In their presence, he threw

stones into the haunted lake, and shouted

“Pilate wirf aus dein Kath.” As his taunts

produced no effect, judgment was given by

default, and the legend, which had sent

earlier sceptics into gaol, was laughed out of

existence.

Thirty years before this defiant demonstration,

the mountain had been ascended by the

most remarkable of the early mountaineers.

Conrad Gesner was a professor at the ancient

University of Zürich. Though not the first

to make climbing a regular practice, he was

the pioneer of mountain literature. He never

encountered serious difficulties. His mountaineering

was confined to those lower heights

which provide the modern with a training

walk. But he had the authentic outlook of

the mountaineer. His love for mountains was

more genuine than that of many a modern

wielder of the ice-axe and rope. A letter

has been preserved, in which he records his

resolution “to climb mountains, or at all

events to climb one mountain every year.”

We have no detailed record of his climbs,

but luckily his account of an ascent of Pilatus

still survives, a most sincere tribute to the

simple pleasures of the heights. It is a

34

relief to turn to it after wading through more

recent Alpine literature. Gesner’s writing is

subjective. It records the impress of simple

emotions on an unsophisticated mind. He

finds a naïve joy in all the elemental things

that make up a mountain walk, the cool

breezes plying on heated limbs, the sun’s

genial warmth, the contrasts of outline, colour,

and height, the unending variety, so that

“in one day you wander through the four

seasons of the year, Spring, Summer, Autumn

and Winter.” He explains that every sense

is delighted, the sense of hearing is gratified

by the witty conversation of friends, “by the

songs of the birds, and even by the stillness

of the waste.” He adds, in a very modern

note, that the mountaineer is freed from the

noisy tumult of the city, and that in the

“profound abiding silence one catches echoes

of the harmony of celestial spheres.” There

is more in the same key. He anticipates the

most enduring reward of the mountaineer,

and his words might serve as the motto for

a mountain book of to-day: “Jucundum erit

postea meminisse laborum atque periculorum,

juvabit hæc animo revolvere et narrare

amicis.” Toil and danger are sweet to recall,

every mountaineer loves “to revolve these

in his mind and to tell them to his friends.”

Moreover, contrast is the essence of our enjoyment

35

and “the very delight of rest is intensified

when it follows hard labour.” And

then Gesner turns with a burst of scorn to his

imaginary opponent. “But, say you, we

lack feather beds and mattresses and pillows.

Oh, frail and effeminate man! Hay shall

take the place of these luxuries. It is soft,

it is fragrant. It is blended from healthy

grass and flower, and as you sleep respiration

will be sweeter and healthier than ever. Your

pillow shall be of hay. Your mattress shall

be of hay. A blanket of hay shall be thrown

across your body.” That is the kind of thing

an enthusiastic mountaineer might have

written about the club-huts in the old days

before the hay gave place to mattresses. Nor

does Gesner spoil his rhapsody by the inevitable

joke about certain denizens of the

hay.

There follows an eloquent description of

the ascent and an analysis of the Pilate

legend. Thirty years were to pass before

Pastor Müller finally disposed of the myth,

but Gesner is clearly sceptical, and concludes

with the robust assertion that, even if evil

spirits exist, they are “impotent to harm the

faithful who worship the one heavenly light,

and Christ the Sun of Justice.” A bold

challenge to the superstitions of the age, a

challenge worthy of the man. Conrad Gesner

36

was born out of due season; and, though he

does not seem to have crossed the snow line,

he was a mountaineer in the best sense of the

term. As we read his work, we seem to hear

the voice of a friend. Across the years we

catch the accents of a true member of our

great fraternity. We leave him with regret,

with a wish that we could meet him on some

mountain path, and gossip for a while on

mountains and mountaineers.

But Gesner was not, as is sometimes

assumed, alone in this sentiment for the hills.

In the first chapter we have spoken of Marti,

a professor at Berne, and a close friend of

Gesner. The credit for discovering him belongs,

I think, to Mr. Freshfield, who quotes

some fine passages from Marti’s writings.

Marti looks out from the terrace at Berne on

that prospect which no true mountain lover

can behold without emotion, and exclaims:

“These are the mountains which form our

pleasure and delight when we gaze at them

from the highest parts of our city, and admire

their mighty peaks and broken crags that

threaten to fall at any moment. Who, then,

would not admire, love, willingly visit, explore,

and climb places of this sort? I should

assuredly call those who are not attracted by

them dolts, stupid dull fishes, and slow

tortoises.... I am never happier than on

37

the mountain crests, and there are no wanderings

dearer to one than those on the

mountains.”

This passage tends to prove that mountain

appreciation had already become a commonplace

with cultured men. Had Marti’s views

been exceptional, he would have assumed a

certain air of defence. He would explain

precisely why he found pleasure in such unexpected

places. He would attempt to justify

his paradoxical position. Instead, he boldly

assumes that every right-minded man loves

mountains; and he confounds his opponents

by a vigorous choice of unpleasant alternatives.

Josias Simler was a mountaineer of a very

different type. To him belongs the credit of

compiling the first treatise on the art of

Alpine travel. Though he introduces no

personal reminiscences, his work is so free

from current superstition that he must have

been something of a climber; but, though a

climber, he did not share Gesner’s enthusiasm

for the hills. For, though he seems to have

crossed glacier passes, whereas Gesner confined

himself to the lower mountains, yet the note

of enthusiasm is lacking. His horror of

narrow paths, bordering on precipices, is

typical of the age; and if he ventured across

a pass he must have done so in the way of

business. There is, as we have already

38

pointed out, a marked difference between

passes and mountains. A merchant with a

holy horror of mountains may be forced to

cross a pass in the way of business, but a man

will only climb a mountain for the fun of the

thing. It is clear that Simler could only see

in mountains a sense of inconvenient barriers

to commerce, but as a practical man he set

out to codify the existing knowledge. Gesner’s

mountain work is subjective; it is the literature

of emotion; he is less concerned with the

mountain in itself, than with the mountain

as it strikes the individual observer. Simler,

on the other hand, is the forerunner of the

objective school. He must delight those

who postulate that all Alpine literature should

be the record of positive facts. The personal

note is utterly lacking. Like Gesner, he was

a professor at Zürich. Unlike Gesner, he was

an embodiment of the academic tradition

that is more concerned with fact than with

emotion. None the less, his work was a very

valuable contribution, as it summarised existing

knowledge on the art of mountain travel.

His information is singularly free from error.

He seems to have understood the use of the

rope, alpenstocks, crampons, dark spectacles,

and the use of paper as a protection against

cold. It is strange that crampons, which

were used in Simler’s days, were only reintroduced

39

into general practice within the last

decades, whilst the uncanny warmth of paper

is still unknown to many mountaineers. His

description of glacier perils, due to concealed

crevasses, is accurate, and his analysis of

avalanches contains much that is true. We

are left with the conviction that snow- and

ice-craft is an old science, though originally

applied by merchants rather than pure

explorers.

We quoted Simler, in the first chapter, in

support of our contention that foreigners

came in great numbers to see and rejoice in

the beauty of the Alps. But, though Simler

proves that passes were often crossed in the

way of business, and that mountains were

often visited in search of beauty, he himself

was no mountain lover.

It is a relief to turn to Scheuchzer, who is a

living personality. Like Gesner and Simler,

he was a professor at Zürich, and, like them,

he was interested in mountains. There the

resemblance ceases. He had none of Gesner’s

fine sentiment for the hills. He did not share

Simler’s passion for scientific knowledge. He

was a very poor mountaineer, and, though he

trudged up a few hills, he heartily disliked

the toil of the ascent: “Anhelosæ quidem

sunt scansiones montium”—an honest, but

scarcely inspiring, comment on mountain

40

travel. Honesty, bordering on the naïve, is,

indeed, the keynote of our good professor’s

confessions. Since his time, many ascents

have failed for the same causes that prevented

Scheuchzer reaching the summit of

Pilatus, but few mountaineers are candid

enough to attribute their failure to “bodily

weariness and the distance still to be accomplished.”

Scheuchzer must be given credit

for being, in many ways, ahead of his age.

He protested vigorously against the cruel

punishments in force against witches. He

was the first to formulate a theory of glacier

motion which, though erroneous, was by no

means absurd. As a scientist, he did good

work in popularising Newton’s theories. He

published the first map of Switzerland with

any claims to accuracy. His greatest scientific

work on dragons is dedicated to the English

Royal Society, and though Scheuchzer’s

dragons provoke a smile, we should remember

that several members of that learned society

subscribed to publish his researches on those

fabulous creatures.

With his odd mixture of credulity and

common sense, Scheuchzer often recalls

another genial historian of vulgar errors.

Like Sir Thomas Browne, he could never

dismiss a picturesque legend without a pang.

He gives the more blatant absurdities their

41

quietus with the same gentle and reluctant

touch: “That the sea is the sweat of the

earth, that the serpent before the fall went

erect like man ... being neither consonant

unto reason nor corresponding unto experiment,

are unto us no axioms.” Thus Browne,

and it is with the same tearful and chastened

scepticism that Scheuchzer parts with the more

outrageous “axioms” in his wonderful collection.

But he retained enough to make his

work amusing. Like Browne, he made it a

rule to believe half that he was told. But on

the subject of dragons he has no mental

reservations. Their existence is proved by

the number of caves that are admirably suited

to the needs of the domestic dragon, and by

the fact that the Museum, at Lucerne, contains

an undoubted dragon stone. Such

stones are rare, which is not surprising owing

to the extreme difficulty of obtaining a genuine

unimpaired specimen. You must first catch

your dragon asleep, and then cut the stone

out of his head. Should the dragon awake the

value of the stone will disappear. Scheuchzer

refrains from discouraging collectors by hinting

at even more unpleasant possibilities. But

then there is no need to awaken the dragon.

Scatter soporific herbs around him, and help

them out by recognised incantations, and the

stone should be removed without arousing

42

the dragon. In spite of these anæsthetics,

Scheuchzer admits that the process demands

a courageous and skilled operator, and perhaps

it is lucky that this particular stone was

casually dropped by a passing dragon. It is

obviously genuine, for, if the peasant who had

picked it up had been dishonest, he would

never have hit on so obvious and unimaginative

a tale. He would have told some really

striking story, such as that the stone had

come from the far Indies. Besides, the stone

not only cures hæmorrhages (quite commonplace

stones will cure hæmorrhages), but

also dysentery and plague. As to dragons,

Scheuchzer is even more convincing. He has

examined (on oath) scores of witnesses who

had observed dragons at first hand. We need

not linger to cross-examine these honest folk.

Their dragons are highly coloured, and lack

nothing but uniformity. Each new dragon

that flies into Scheuchzer’s net is gravely

classified. Some dragons have feet, others

have wings. Some have scales. Scheuchzer

is a little puzzled whether dragons with a

crest constitute a class of their own, or

whether the crest distinguished the male from

the female. Each dragon is thus neatly

ticketed into place and referred to the sworn

deposition of some vir quidam probus.

But the dragons had had their day.

43

Scheuchzer ushers in the eighteenth century.

Let us take leave of him with a friendly smile.

He is no abstraction, but a very human soul.

We forget the scientist, though his more

serious discoveries were not without value.

We remember only the worthy professor,

panting up his laborious hills in search of

quaint knowledge, discovering with simple

joy that Gemmi is derived from “gemitus”

a groan, quod non nisi crebris gemitibus

superetur. No doubt the needy fraternity

soon discovered his amiable weakness. An

unending procession must have found their

way to his door, only too anxious to supply

him with dragons of wonderful and fearful

construction. Hence, the infinite variety

of these creatures. When we think of

Scheuchzer, we somehow picture the poor old

gentleman, laboriously rearranging his data,

on the sworn deposition of some clarissimus

homo, what time the latter was bartering in

the nearest tavern the price of a dragon for

that good cheer in which most of Scheuchzer’s

fauna first saw the light of day.

44

CHAPTER III

THE OPENING UP OF THE ALPS

The climbs, so far chronicled, have been

modest achievements and do not include a

genuine snow-peak, for the Roche Melon has

permanent snow on one side only. We have

seen that many snow passes were in regular

use from the earliest times; but genuine Alpine

climbing may be said to begin with the ascent

of the Titlis. According to Mr. Gribble, this

was climbed by a monk of Engleberg, in 1739.

Mr. Coolidge, on the other hand, states that

it was ascended by four peasants, in 1744.

In any case, the ascent was an isolated feat

which gave no direct stimulus to Alpine

climbing, and Mr. Gribble is correct in dating

the continuous history of Alpine climbing

from the discovery of Chamounix, in 1741.

This famous valley had, of course, a history

of its own before that date; but its existence

was only made known, to a wider world, by

the visit of a group of young Englishmen,

towards the middle of the eighteenth century.

In 1741, Geneva was enlivened by a vigorous

45

colony of young Britons. Of these, William

Windham was a famous athlete, known on

his return to London as “Boxing Windham.”

While at Geneva, he seems, despite the presence

of his “respectable perceptor,” Mr.

Benjamin Stillingfleet, the grandson of the

theologian, to have amused himself pretty

thoroughly. The archives record that he

was fined for assault and kindred offences.

When these simple joys began to pall he

decided to go to Chamounix in search of

adventure.

His party consisted of himself, Lord Haddington,

Dr. Pococke, the Oriental traveller,

and others. They visited Chamounix, and

climbed the Montanvert with a large brigade

of guides. The ascent to the Montanvert

was not quite so simple as it is to-day, a fact

which accounts for Windham’s highly coloured

description. Windham published his account

of the journey and his reflections on glaciers,

in the Journal Helvetique of Neuchâtel, and

later in London. It attracted considerable

attention and focussed the eyes of the curious

on the unknown valley of Chamounix. Among

others, Peter Martel, an engineer of Geneva,

was inspired to repeat the visit. Like Windham,

he climbed the Montanvert and descended

on to the Mer de Glace; and, like

Windham, he published an account of the

46

journey and certain reflections on glaciers and

glacier motion. His story is well worth reading,

and the curious in such matters should

turn either to Mr. Gribble’s Early Mountaineers,

or to Mr. Matthews’ The Annals of Mont

Blanc, where they will find Windham’s and

Martel’s letters set forth in full.

Martel’s letter and his map of Chamounix

were printed together with Windham’s narrative,

and were largely responsible for popularising

Chamounix. Those who wished to earn

a reputation for enterprise could hardly do

so without a visit to the glaciers of Chamounix.

Dr. John Moore, father of Sir John Moore,

who accompanied the Duke of Hamilton on

the grand tour, tells us that “one could

hardly mention anything curious or singular

without being told by some of those travellers,

with an air of cool contempt: ‘Dear Sir, that

is pretty well, but take my word for it, it is

nothing to the glaciers of Savoy.’” The

Duc de la Rochefoucauld considered that

the honour of his nation demanded that he

should visit the glaciers, to prove that the

English were not alone in the possession of

courage.

More important, in this connection, than

Dr. Moore or the duke is the great name of

De Saussure. De Saussure belonged to an

old French family that had been driven out

47

of France during the Huguenot persecutions.

They emigrated to Geneva, where De Saussure

was born. His mother had Spartan views on

education; and from his earlier years the child

was taught to suffer the privations due to

physical ills and the inclemency of the season.

As a result of this adventurous training, De

Saussure was irresistibly drawn to the mountains.

He visited Chamounix in 1760, and

was immediately struck by the possibility

of ascending Mont Blanc. He does not seem

to have cherished any ambition to make the

first ascent in person. He was content to

follow when once the way had been found;

and he offered a reward to the pioneer, and

promised to recompense any peasant who

should lose a day’s work in trying to find the

way to the summit of Mont Blanc. The

reward was not claimed for many years, but,

meanwhile, De Saussure never missed a chance

of climbing a mountain. He climbed Ætna,

and made a series of excursions in various

parts of the Alps. When his wife complained,

he indited a robust letter which every married

mountaineer should keep up his sleeve for

ready quotation.

“In this valley, which I had not previously

visited,” he writes, “I have made observations

of the greatest importance, surpassing

my highest hopes; but that is not what you

48

care about. You would sooner—God forgive

me for saying so—see me growing fat like a

friar, and snoring every day in the chimney

corner, after a big dinner, than that I should

achieve immortal fame by the most sublime

discoveries at the cost of reducing my weight

by a few ounces and spending a few weeks

away from you. If, then, I continue to take

these journeys, in spite of the annoyance they

cause you, the reason is that I feel myself

pledged in honour to go on with them, and

that I think it necessary to extend my knowledge

on this subject and make my works as

nearly perfect as possible. I say to myself:

‘Just as an officer goes out to assault a fortress

when the order is given, and just as a

merchant goes to market on market-day, so

must I go to the mountains when there are

observations to be made.’”

De Saussure was partly responsible for the

great renaissance of mountain travel that

began at Geneva in 1760. A group of enthusiastic

mountaineers instituted a series of

determined assaults on the unconquered snows.

Of these, one of the most remarkable was

Jean-Andre de Luc.

De Luc was born at Geneva, in 1727. His

father was a watchmaker, but De Luc’s life

was cast on more ambitious lines. He began

as a diplomatist, but gravitated insensibly to

49

science. He invented the hygrometer, and

was elected a member of the Royal Societies

of London, Dublin, and Göttingen. Charlotte,

the wife of George III, appointed him her

reader; and he died at Windsor, having

attained the ripe age of ninety. He was a

scientific, rather than a sentimental, mountaineer;

his principal occupation was to

discover the temperature at which water

would boil at various altitudes. His chief

claim to notice is that he made the first

ascent of the Buet.

The Buet is familiar to all who know

Chamounix. It rises to the height of 10,291

feet. Its summit is a broad plateau, glacier-capped.

Those who have travelled to Italy

by the Simplon may, perhaps, recall the

broad-topped mountain that seems to block

up the western end of the Rhone valley, for

the Buet is a conspicuous feature on the line,

between Sion and Brigue. It is not a difficult

mountain, in the modern sense of the term;

but, to climbers who knew little of the nature

of snow and glacier, it must have presented

quite a formidable appearance. De Luc made

several attempts before he was finally successful

on September 22, 1770. His description

of the view from the summit is a fine piece

of writing. Familiarity had not staled the

glory of such moments; and men might still

50

write, as they felt, without fear that their

readers would be bored by emotions that had

lost their novelty.

Before leaving, De Luc observed that the

party were standing on a cornice. A cornice

is a crest of windblown snow overhanging a

precipice. As the crest often appears perfectly

continuous with the snow on solid

foundation, cornices have been responsible

for many fatal accidents. De Luc’s party

naturally beat a hurried retreat; but “having

gathered, by reflection, that the addition of

our own weight to this prodigious mass which

had supported itself for ages counted for

absolutely nothing, and could not possibly

break it loose, we laid aside our fears and

went back to the terrible terrace.” A little

science is a dangerous thing; and it was a

mere chance that the first ascent of the Buet

is not notorious for a terrible accident. It

makes one’s blood run cold to read of the

calm contempt with which De Luc treated the

cornice. Each member of the party took it

in turn to advance to the edge and look over

on to the cliff below supported as to his coattails

by the rest of the party.

De Luc made a second ascent of the Buet,

two years later; but it was not until 1779

that a snow peak was again conquered. In

that year Murith, the Prior of the St. Bernard

51

Hospice, climbed the Velan, the broad-topped

peak which is so conspicuous a feature from

the St. Bernard. It is a very respectable

mountain rising to a height of 12,353 feet.

Murith, besides being an ecclesiastic, was

something of a scientist, and his botanical

handbook to the Valais is not without merit.

It is to Bourrit, of whom we shall speak

later, that we owe the written account of the

climb, based on information which Bourrit

had at first hand from M. Murith.

Murith started on August 30, 1779, with

“two hardy hunters,” two thermometers, a

barometer, and a spirit-level. They slept a

night on the way, and proceeded to attack

the mountain from the Glacier du Proz. The

hardy hunters lost their nerve, and tried to

dissuade M. Murith from the attempt; but

the gallant Prior replied: “Fear nothing;

wherever there is danger I will go in front.”

They encountered numerous difficulties,

amongst others a wall of ice which Murith

climbed by hacking steps and hand-holds

with a pointed hammer. One of the hardy

huntsmen then followed; his companion had

long since disappeared.

They reached the summit without further

difficulty, and their impressions of the view

are recorded by Bourrit in an eloquent passage

which recalls De Luc on the Buet, and once

52

more proves that the early mountaineers were

fully alive to the glory of mountain tops—

“A spectacle, no less amazing than magnificent,

offered itself to their gaze. The sky

seemed to be a black cloth enveloping the

earth at a distance from it. The sun shining

in it made its darkness all the more conspicuous.

Down below their outlook extended

over an enormous area, bristling with rocky

peaks and cut by dark valleys. Mont Blanc

rose like a sloping pyramid and its lofty head

appeared to dominate all the Alps as one

saw it towering above them. An imposing

stillness, a majestic silence, produced an

indescribable impression upon the mind. The

noise of the avalanches, reiterated by the

echoes, seemed to be the only thing that

marked the march of time. Raised, so to

say, above the head of Nature, they saw the

mountains split asunder, and send the fragments

rolling to their feet, and the rivers

rising below them in places where inactive

Nature seemed upon the point of death—though

in truth it is there that she gathers

strength to carry life and fertility throughout

the world.”

It is curious in this connection to notice

the part played by the Church in the early

53

history of mountaineering. This is not surprising.

The local curé lived in the shadow

of the great peaks that dominated his valley.

He was more cultured than the peasants of

his parish; he was more alive to the spiritual

appeal of the high places, and he naturally

took a leading part in the assaults on his

native mountains. The Titlis and Monte

Leone were first climbed by local monks.

The prior of the St. Bernard made, as we have

seen, a remarkable conquest of a great local

peak; and five years later M. Clément, the

curé of Champery, reached the summit of

the Dent du Midi, that great battlement of

rock which forms a background to the eastern

end of Lake Geneva. Bourrit, as we shall

see, was an ecclesiastic with a great love for

the snows. Father Placidus à Spescha was

the pioneer of the Tödi; and local priests played

their part in the early attempts on the Matterhorn

from Italy. “One man, one mountain”

was the rule of many an early pioneer; but

Murith’s love of the snows was not exhausted

by this ascent of the Velan. He had already

explored the Valsorey glacier with Saussure,

and the Otemma glacier with Bourrit. A few

years after his conquest of the Velan he

turned his attention to the fine wall of

cliffs that binds in the Orny glacier on the

south.

54

Bourrit, who wrote up Murith’s notes on

the Velan, was one of the most remarkable

of this group of pioneers. He was a whole-hearted

enthusiast, and the first man who

devoted the most active years of his life to

mountaineering. He wins our affection by

the readiness with which he gave others due

credit for their achievements, a generous

characteristic which did not, however, survive

the supreme test—Paccard’s triumph on

Mont Blanc. Mountaineers at the end of the

eighteenth century formed a close freemasonry

less concerned with individual achievement

than with the furthering of common

knowledge. We have seen, for instance, that

De Saussure cared little who made the first

ascent of Mont Blanc provided that the way

was opened up for future explorers. Bourrit’s

actual record of achievement was small. His

exploration was attended with little success.

His best performance was the discovery, or

rediscovery of the Col de Géant. His great

ambition, the ascent of Mont Blanc, failed.

Fatigue, or mountain sickness, or bad weather,

spoiled his more ambitious climbs. But this

matters little. He found his niche in Alpine

history rather as a writer than as a mountaineer.

He popularised the Alps. He was

the first systematic writer of Alpine books, a

fact which earned him the title, “Historian

55

of the Alps,” a title of which he was inordinately

proud. Best of all, in an age when

mountain appreciation was somewhat rare, he

marked himself out by an unbounded enthusiasm

for the hills.

He was born in 1735, and in one of his

memoirs he describes the moment when he

first heard the call of the Alps: “It was from

the summit of the Voirons that the view of

the Alps kindled my desire to become acquainted

with them. No one could give me

any information about them except that they

were the accursed mountains, frightful to look

upon and uninhabited.” Bourrit began life

as a miniature painter. A good many of his

Alpine water colours have survived. Though

they cannot challenge serious comparison

with the mountain masterpieces of the sixteenth

and seventeenth centuries, they are

not without a certain merit. But Bourrit

would not have become famous had he not

deserted the brush for the pen. When the

Alps claimed him, he gave up miniatures, and

accepted an appointment as Precentor of

Geneva Cathedral, a position which allowed

him great leisure for climbing. He used to

climb in the summer, and write up his journeys

in the winter. He soon compiled a formidable

list of books, and was hailed throughout

Europe as the Historian of the Alps. There

56

was no absurd modesty about Bourrit. He

accepted the position with serene dignity.

His house, he tells us, is “embellished with

beautiful acacias, planned for the comfort

and convenience of strangers who do not

wish to leave Geneva without visiting the

Historian of the Alps.” He tells us that

Prince Henry of Prussia, acting on the advice

of Frederick the Great, honoured him with a

visit. Bourrit, in fact, received recognition

in many distinguished quarters. The Princess

Louise of Prussia sent him an engraving to

recall “a woman whom you have to some

extent taught to share your lofty sentiments.”

Bourrit was always popular with the ladies,

and no climber has shown a more generous

appreciation for the sex. “The sex is very

beautiful here,” became, as Mr. Gribble tells

us, “a formula with him as soon as he began

writing and continued a formula after he had

passed his threescore years and ten.”

We have said that Bourrit’s actual record

as a climber is rather disappointing. We

may forget this, and remember only his

whole-hearted devotion to the mountains.

Even Gesner, Petrarch, and Marti seem

balanced and cold when they set their tributes

besides Bourrit’s large enthusiasm. Bourrit

did not carry a barometer with him on his

travels. He did not feel the need to justify

57

his wanderings by collecting a mass of scientific

data. Nor did he assume that a mountain

tour should be written up as a mere guide-book

record of times and route. He is

supremely concerned with the ennobling effect

of mountain scenery on the human mind.

“At Chamounix,” he writes, “I have seen

persons of every party in the state, who

imagined that they loathed each other, nevertheless

treating one another with courtesy,

and even walking together. Returning to

Geneva, and encountering the reproaches of

their various friends, they merely answered

in their defence, ‘Go, as we have gone, to

the Montanvert, and take our share of the

pure air that is to be breathed there; look

thence at the unfamiliar beauties of Nature;

contemplate from that terrace the greatness

of natural objects and the littleness of man;

and you will no longer be astonished that

Nature has enabled us to subdue our passions.’

It is, in fact, the mountains that many men

have to thank for their reconciliation with

their fellows, and with the human race; and

it is there that the rulers of the world and the

heads of the nations ought to hold their

meetings. Raised thus above the arena of

passions and petty interests, and placed more

immediately under the influence of Divine

inspiration, one would see them descend from

58

these mountains, each like a new Moses

bringing with them codes of law based upon

equity and justice.”

This is fine writing with a vengeance, just

as Ruskin’s greatest passages are fine writing.

Before we take our leave of Bourrit, let us see

the precentor of the cathedral exhorting a

company of guides with sacerdotal dignity.

One is irresistibly reminded of Japan, where

mountaineering and sacrificial rites go hand

in hand—

“The Historian of the Alps, in rendering

them this justice in the presence of a great

throng of people, seized the opportunity

of exhorting the new guides to observe the

virtues proper to their state in life. ‘Put

yourselves,’ he said to them, ‘in the place of

the strangers, who come from the most distant

lands to admire the marvels of Nature under

these wild and savage aspects; and justify the

confidence which they repose in you. You

have learnt the great part which these magnificent

objects of our contemplation play in

the organisation of the world; and, in pointing

out their various phenomena to their astonished

eyes, you will rejoice to see people raise

their thoughts to the omnipotence of the

Great Being who created them.’ The speaker

was profoundly moved by the ideas with

59

which the subject inspired him, and it was

impossible for his listeners not to share in his

emotion.”

Let us remember that Bourrit put his

doctrine into practice. He has told us that

he found men of diverse creeds reconciled

beneath the shadow of Mont Blanc. Bourrit

himself was a mountaineer first, and an

ecclesiastic second. Perhaps he was no

worse as a Protestant precentor because the

mountains had taught him their eternal

lessons of tolerance and serene indifference

to the petty issues which loom so large beneath

the shadow of the cathedral. Catholic

or Protestant it was all the same to our good

precentor, provided the man loved the hills.

Prior Murith was his friend; and every

Catholic mountaineer should be grateful to

his memory, for he persuaded one of their

archbishops to dispense climbers from the

obligation of fasting in Lent.

60

CHAPTER IV

THE STORY OF MONT BLANC

The history of Mont Blanc has been made

the subject of an excellent monograph, and

the reader who wishes to supplement the

brief sketch which is all that we can attempt

should buy The Annals of Mont Blanc, by

Mr. C. E. Mathews. We have already seen

that De Saussure offered a reward in 1760 to

any peasant who could find a way to the

summit of Mont Blanc. In the quarter-of-a-century

that followed, several attempts were

made. Amongst others, Bourrit tried on two

occasions to prove the accessibility of Mont

Blanc. Bourrit himself never reached a

greater height than 10,000 feet; but some

of his companions attained the very respectable

altitude of 14,300 feet. De Saussure

attacked the mountain without success in

1785, leaving the stage ready for the entrance

of the most theatrical of mountaineers.

Jacques Balmat, the hero of Mont Blanc,

impresses himself upon the imagination as

no other climber of the day. He owes his

61

62

fame mainly, of course, to his great triumph,

but also, not a little, to the fact that he was

interviewed by Alexandre Dumas the Elder,

who immortalised him in Impressions de

Voyage. For the moment, we shall not

bother to criticise its accuracy. We know

that Balmat reached the summit of Mont

Blanc; and that outstanding fact is about

the only positive contribution to the story

which has not been riddled with destructive

criticism. The story should be read in the

original, though Dumas’ vigorous French loses

little in Mr. Gribble’s spirited translation

from which I shall borrow.

| A |

Summit |

of |

Mont Blanc |

| B |

” |

” |

Dôme du Gouter |

| C |

” |

” |

Aiguille du Gouter |

| D |

” |

” |

Aiguille de Bianossay |

| E |

” |

” |

Mont Maudit |

| E′ |

” |

” |

Mont Blanc du Tacul |

| F |

” |

” |

Aiguille du Midi |

| G |

Grand Mulets |

| H |

Grand Plateau |

| L |

Les Bosses du Dromadaire |

| M |

Glacier des Bossons |

| N |

Glacier de Taconnaz |

Dumas visited Chamounix in 1883. Balmat

was then a veteran, and, of course, the great

person of the valley. Dumas lost no time in

making his acquaintance. We see them sitting

together over a bottle of wine, and we

can picture for ourselves the subtle art with

which the great interviewer drew out the old

guide. But Balmat shall tell his own story—

“H’m. Let me see. It was in 1786. I

was five-and-twenty; that makes me seventy-two

to-day. What a fellow I was! With the

devil’s own calves and hell’s own stomach.

I could have gone three days without bite or

sup. I had to do so once when I got lost on

the Buet. I just munched a little snow, and

63

that was all. And from time to time I looked

across at Mont Blanc saying, ‘Say what you

like, my beauty, and do what you like. Some

day I shall climb you.’”

Balmat then tells us how he persuaded his

wife that he was on his way to collect crystals.

He climbed steadily throughout the day, and

night found him on a great snowfield somewhere

near the Grand Plateau. The situation

was sufficiently serious. To be benighted on

Mont Blanc is a fate which would terrify a

modern climber, even if he were one of a large

party. Balmat was alone, and the mental

strain of a night alone on a glacier can only

be understood by those who have felt the

uncanny terror that often attacks the solitary

wanderer even in the daytime. Fortunately,

Balmat does not seem to have been bothered

with nerves. His fears expressed themselves

in tangible shape.

“Presently the moon rose pale and encircled

by clouds, which hid it altogether at about

eleven o’clock. At the same time a rascally

mist came on from the Aiguille du Gouter,

which had no sooner reached me than it began

to spit snow in my face. Then I wrapped my

head in my handkerchief, and said: ‘Fire

away. You’re not hurting me.’ At every

64

instant I heard the falling avalanches making

a noise like thunder. The glaciers split, and

at every split I felt the mountain move. I

was neither hungry nor thirsty; and I had an

extraordinary headache which took me at

the crown of the skull, and worked its way

down to the eyelids. All this time, the mist

never lifted. My breath had frozen on my

handkerchief; the snow had made my clothes

wet; I felt as if I were naked. Then I redoubled

the rapidity of my movements, and

began to sing, in order to drive away the

foolish thoughts that came into my head. My

voice was lost in the snow; no echo answered

me. I held my tongue, and was afraid. At

two o’clock the sky paled towards the east.

With the first beams of day, I felt my courage

coming back to me. The sun rose, battling

with the clouds which covered the mountain

top; my hope was that it would scatter them;

but at about four o’clock the clouds got

denser, and I recognised that it would be

impossible for me just then to go any further.”

He spent a second night on the mountain,

which was, on the whole, more comfortable

than the first, as he passed it on the rocks of

the Montagne de la Côte. Before he returned

home, Balmat planned a way to the summit.

And now comes the most amazing part of the

65

story. He had no sooner returned home than

he met three men starting off for the mountain.

A modern mountaineer, who had spent two

nights, alone, high up on Mont Blanc, would

consider himself lucky to reach Chamounix

alive; once there, he would go straight to bed

for some twenty-four hours. But Balmat was

built of iron. He calmly proposed to accompany

his friends; and, having changed his

stockings, he started out again for the great

mountain, on which he had spent the previous

two nights. The party consisted of François

Paccard, Joseph Carrier, and Jean Michel

Tournier. They slept on the mountain; and

next morning they were joined by two other

guides, Pierre Balmat and Marie Couttet.

They did not get very far, and soon turned

back—all save Balmat. Balmat, who seems

to have positively enjoyed his nights on the

glacier, stayed behind.

“I laid my knapsack on the snow, drew

my handkerchief over my face like a curtain,

and made the best preparations that I could

for passing a night like the previous one.

However, as I was about two thousand feet

higher, the cold was more intense; a fine

powdery snow froze me; I felt a heaviness

and an irresistible desire to sleep; thoughts,

sad as death, came into my mind, and I knew

66

well that these sad thoughts and this desire

to sleep were a bad sign, and that if I had

the misfortune to close my eyes I should

never open them again. From the place

where I was, I saw, ten thousand feet below

me, the lights of Chamounix, where my comrades

were warm and tranquil by their firesides

or in their beds. I said to myself:

‘Perhaps there is not a man among them

who gives a thought to me. Or, if there

is one of them who thinks of Balmat, no

doubt he pokes his fire into a blaze, or draws

his blanket over his ears, saying, ‘That ass of

a Jacques is wearing out his shoe leather.

Courage, Balmat!’”

Balmat may have been a braggart, but it

is sometimes forgotten by his critics that he

had something to brag about. Even if he