Title: Port Arthur

a monster heroism

Author: Richard Barry

Release date: November 23, 2017 [eBook #56038]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by John Campbell and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Some minor changes are noted at the end of the book.

PORT ARTHUR

BY

RICHARD BARRY

Illustrations from Photographs

taken on the field by the Author

NEW YORK

MOFFAT, YARD & COMPANY

1905

Copyright, 1905, by

Moffat, Yard & Company

Published April, 1905

TO

FREMONT OLDER

Grateful acknowledgment of permission to reprint some of the articles and photographs which enter, with additional new material, into the redaction of this volume is made to the Century Magazine, Everybody’s Magazine, Collier’s Weekly, the Saturday Evening Post, the Scientific American, the London Fortnightly Review and Westminster Gazette, the Paris L’Illustration and Le Monde Illustre, and the London Illustrated News, Black and White, Sphere and Graphic, in which journals they in part originally appeared. The reproduction of the frontispiece in oils by Mazzanovich, redrawn from Mr. Barry’s snapshot on the field, is here made by courtesy of Everybody’s Magazine.

CONTENTS | |

| PREFACE | |

| PAGE | |

| The Siege at a Glance | 15 |

| INTRODUCTORY | |

| The Investment, Siege, and Capture of Port Arthur | 17 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The City of Silence | 33 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Invisible Army | 40 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Two Pictures of War—A Glance Back | 67 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Japanese Kitchener | 81 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Camp | 108 |

| [8] CHAPTER VI | |

| 203-Meter Hill | 118 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| A Son of the Soil | 142 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Bloody Angle | 152 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| A Battle in the Storm | 164 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The Cremation of a General | 183 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The General’s Pet | 191 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Courting Death Under the Forts | 198 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| From Kitten to Tiger | 211 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Scientific Fanatics | 234 |

| [9] CHAPTER XV | |

| Japan’s Grand Old Man | 253 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| The Cost of Taking Port Arthur | 276 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| A Contemporary Epic | 289 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| The New Siege Warfare | 316 |

| EPILOGUE | |

| The Downfall | 339 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | |

| OPPOSITE PAGE | |

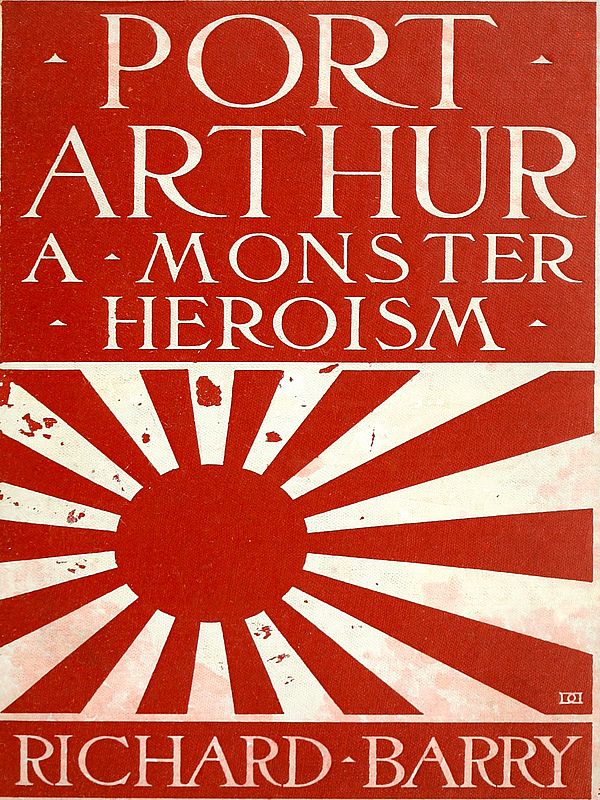

| Going into Action. From a Painting by Massanovich. Out from the maize, on a dog trot, springs a battalion, across the terraces, over the stubble, these Scientific Fanatics press on, up the Griddle of Death | Frontispiece |

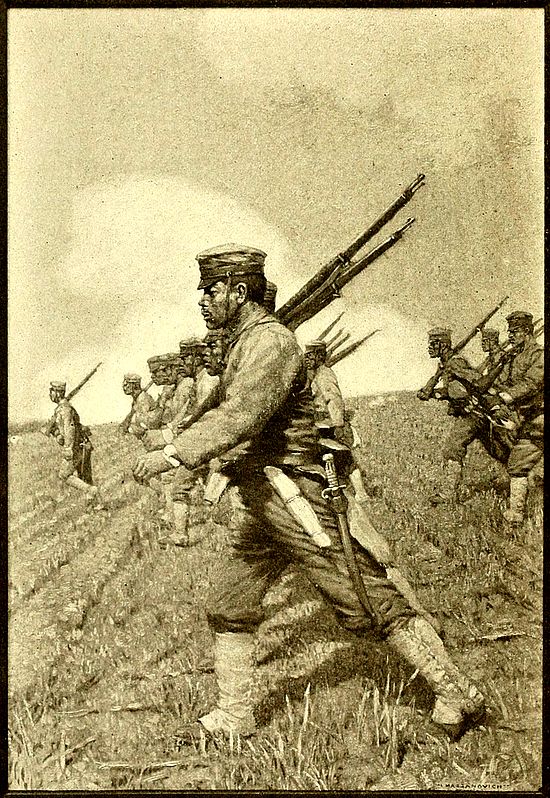

| Richard Barry and Frederick Villiers. They were mess-mates during the siege. Mr. Villiers, the veteran war artist of seventeen campaigns, was dean of the War Correspondents at Port Arthur. The photograph shows them before their Dalny home | 34 |

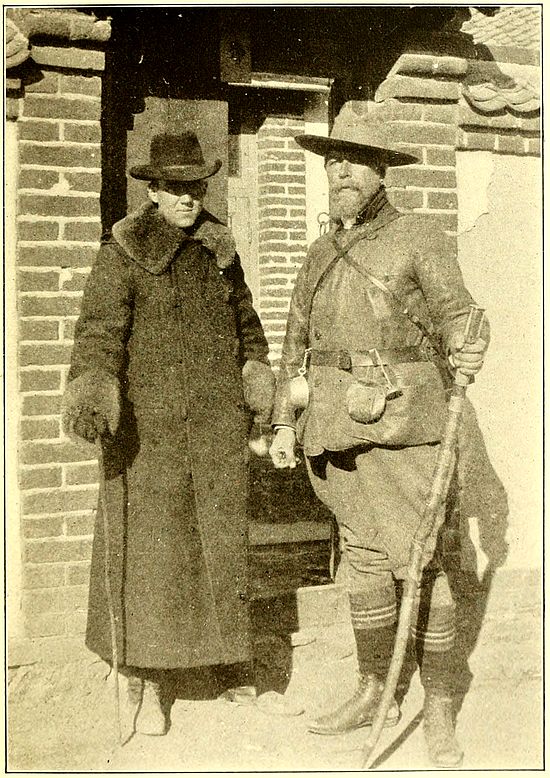

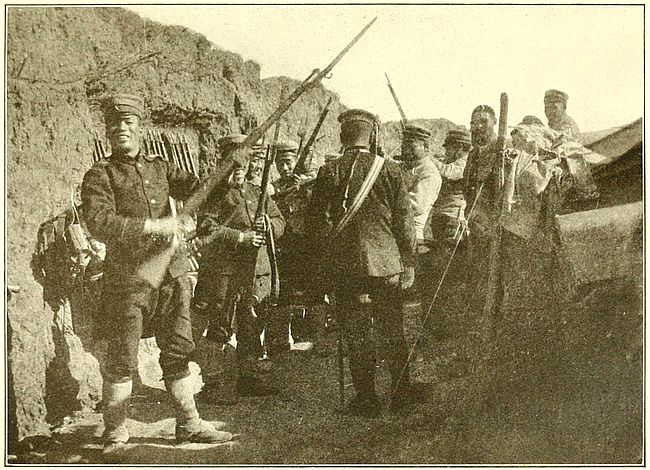

| Starting for Port Arthur. Reserve regiment leaving Dalny for the firing line, eighteen miles away | 46 |

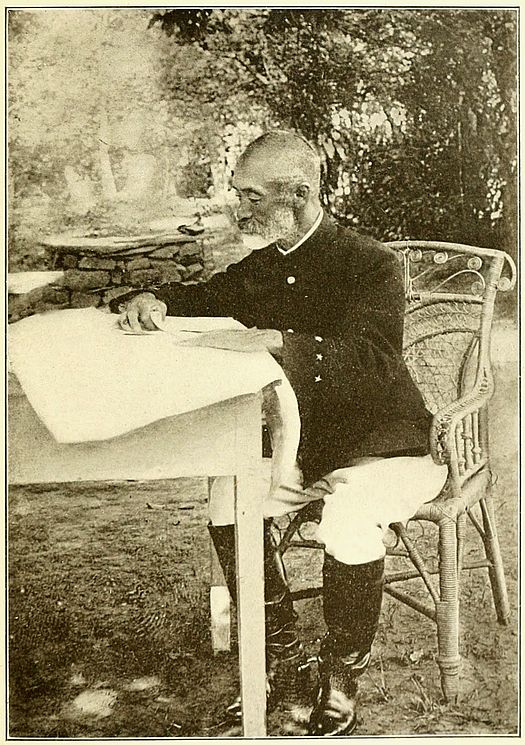

| General Baron Nogi, Commander of the Third Imperial Japanese Army, studying the Defenses of Port Arthur in his Manchurian Garden in the Willow Tree Village | 62 |

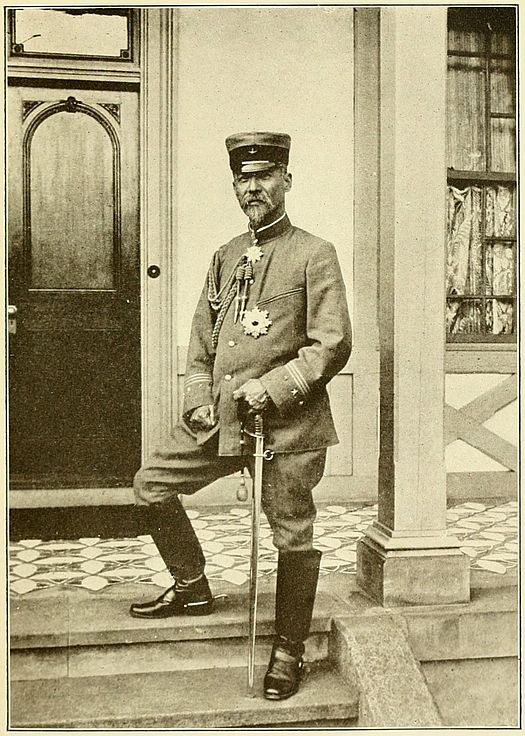

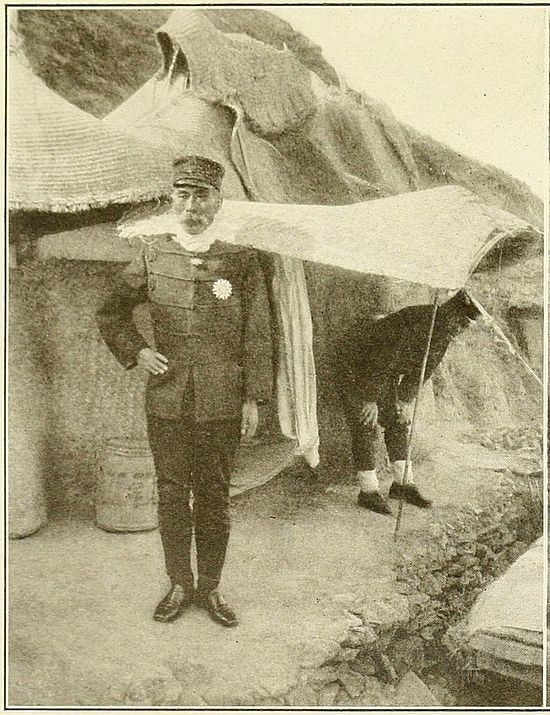

| General Baron Kodama, Chief of the Japanese Staff, standing on his door step | 84 |

| Bo-o-om! Discharge of the Japanese 11-inch mortar during the Grand Bombardment of October 29th. This gun stood a mile and a half from Port Arthur and is shown firing into the Two Dragon Redoubt. The vibration made a clear photograph impossible | 112 |

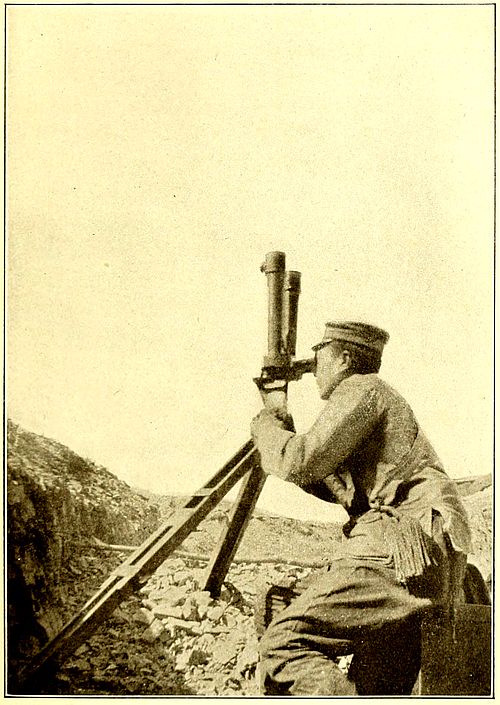

| The Hyposcope. Lieutenant Oda looking from 203-Meter Hill through the hyposcope at the Russian fleet in the new harbor at Port Arthur | 120 |

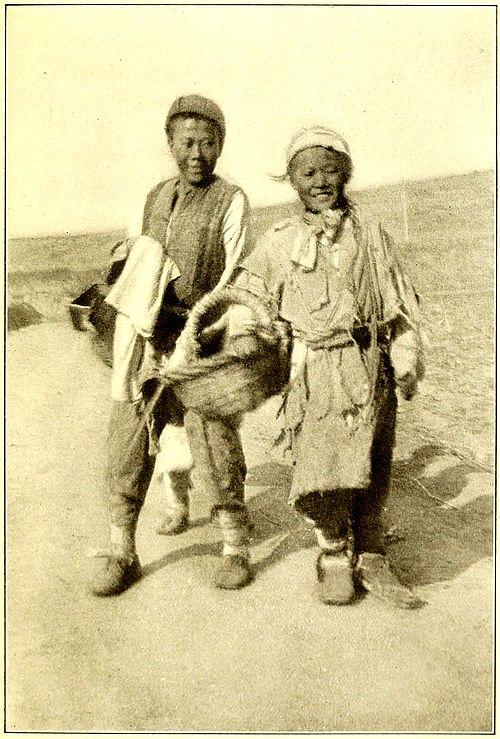

| [12] Orphans. Driven from home by shells which killed their father and mother, these brothers tramped from camp to camp selling eggs | 148 |

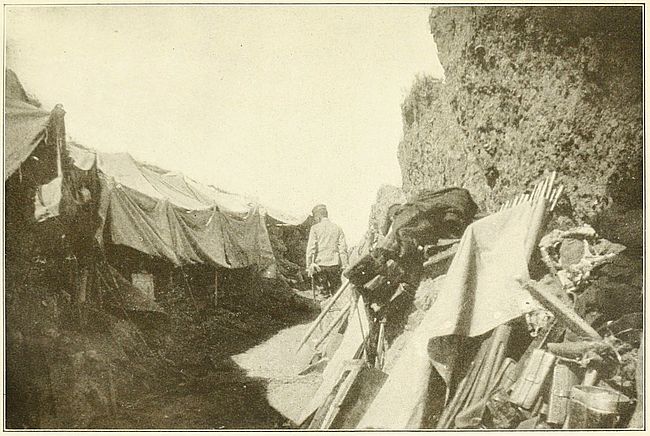

| Human Barnacles. Clinging to the bases of the forts, like barnacles to a ship, these sturdy Japanese existed in wretched quarters throughout the summer, autumn and half the winter | 160 |

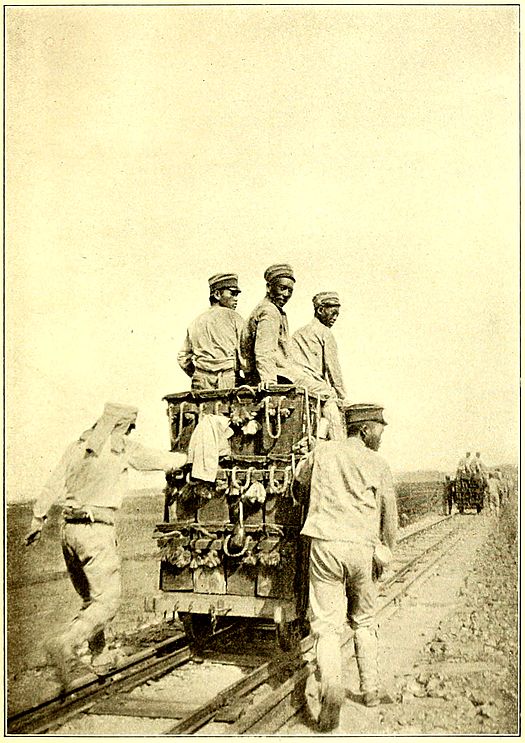

| Ammunition for the Front | 180 |

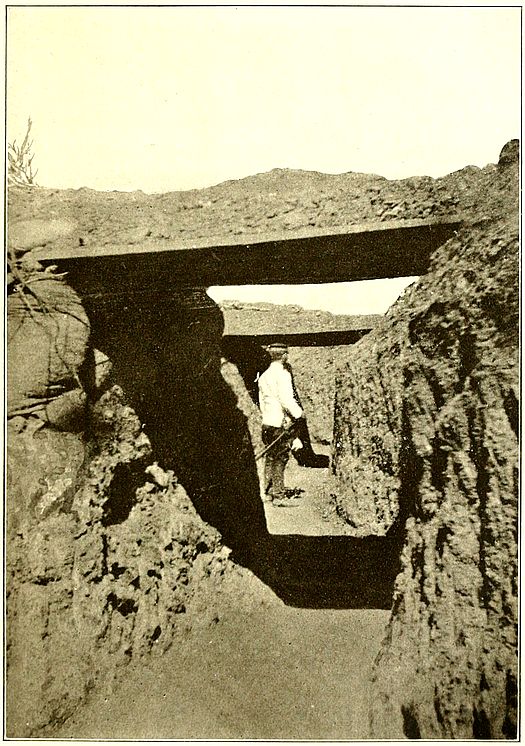

| How They Got in. Eighteen miles of these terminal trenches were dug through the plain before the Russian forts | 202 |

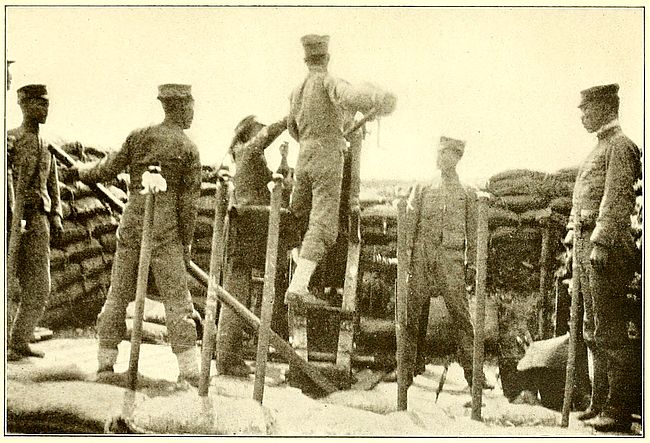

| The Last Word. The officer is giving last instructions to his men before the Grand Assault of September 21st. This photograph was taken in the front Parallel, 300 yards from the Cock’s Comb Fort | 222 |

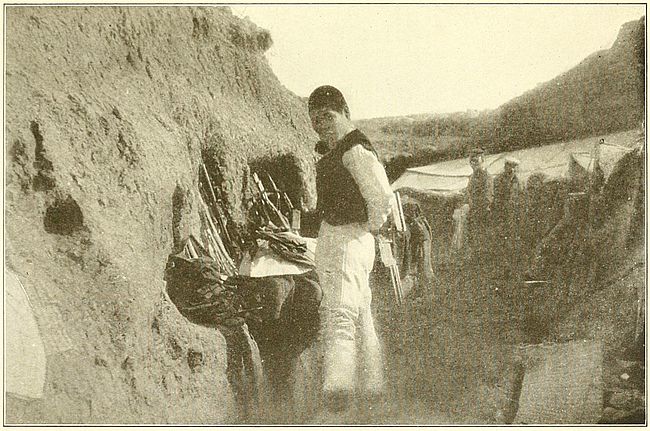

| Preparing for Death. A superstition holds that the Japanese soldier who dies dirty finds no place among the Shinto shades; so, before going into action, every soldier changes his linen, as this one is doing | 241 |

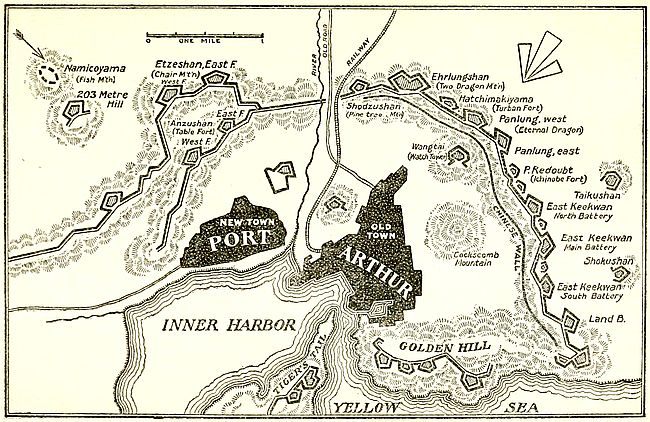

| A map of Port Arthur. Showing the defenses and the direction of the Japanese attack | 281 |

| Home. The shack, 800 yards from the firing line, occupied for three months by the fighting General Oshima, Commander of the Ninth Division | 290 |

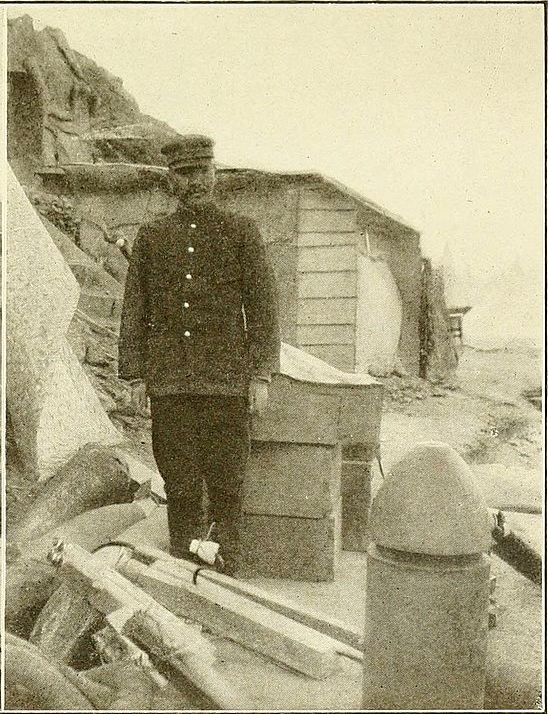

| Plunder. Showing Adjutant Hori, Secretary to General Oshima, standing near plunder taken from the captured Turban Fort | 290 |

| In action. Loading a 4.7 gun of the ordinary field artillery during the assault of September 20th | 312 |

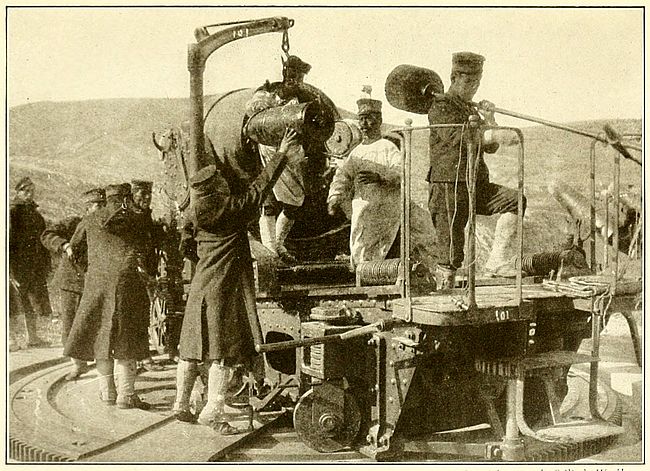

| The Osacca Babe. Loading the 11-inch coast defense mortar during the general bombardment of October 29th, two miles from Port Arthur | 332 |

Cloud girt among her mountains,

Nippon, in wrath as of old,

Unleashes her young warrior;

Lo, the world’s champion behold!

He comes abysmal as chaos,

A boy with the smile of a girl,

Tumbles his man with a handshake,

And spits him up with a twirl.

Nourished on rice and a dewdrop,

He fans him to sleep with a star,

Believing the fathers of Nippon

Created things as they are.

So up and across the short ocean

He sails to the land of can’t,

To keep up the name of his fathers

And smash down the things that shan’t.

Ah! What a freshet of glory

When into the noisy fray

Against a shaggy old giant

Comes this youth asmile and gay!

The sea attack on Port Arthur began on February 9th, 1904, at noon. The land isolation occurred on May 26th, when the Second Army, under General Oku, took Nanshan Hill. Four grand series of Russian defenses from Nanshan down the peninsula were then taken by the Japanese. The capture of Taikushan on August 9th, of Shokushan two days later, and of Takasakiyama the following day, drove the Russians into their permanent works. The real siege of Port Arthur began, thus, on August 12th, and continued for four months and nineteen days.

The failure of the first grand assault, continuing seven days from August 19th, forced Nogi and his army to go slowly about the terrific job of digging a way into the fortress. In the following four months there occurred six more grand assaults, the periods between them being occupied in mining, sapping, and engineering.[16] What was known as the second assault was made from September 19th to 25th; the third from October 29th to November 1st; the fourth from November 28th to 30th; the fifth from December 4th to 9th; the sixth from December 18th to 20th; the final assault from December 28th to 31st. The morning of January 1st, 1905, General Stoessel, the Russian commander, asked for terms of capitulation, and the following day these terms were submitted and ratified.

The grand strategy of the Japanese operations was simple. It comprehended one brief design: to demonstrate on the west, where 203-Meter Hill is, while the infantry and the heavy ordnance smashed the Russian right center, where are located the principal Russian forts, Keekwan (Cock’s Comb), Ehrlung (Two Dragons), and Panlung (Eternal Dragon). Four and a half months of sapping, mining, bombarding, and hand-to-hand fighting, than which history holds no record of more desperate contest, won the forts of the Cock’s Comb and the Two Dragons for the Japanese. The fall of the Two Dragons on December 31st brought Stoessel to his knees.

In all the long history of military exploits, there is not one that can compare, in point of difficulties surmounted, with the reduction of Port Arthur. That this fortress should have been taken by assault entitles the Japanese operations to rank with the finest work done by any army in any age; that it should have been taken in five months from the day on which the investment was completed (the day on which the Russians were driven into their permanent works) is an exploit which has never been approached. For Port Arthur’s defenses had been laid out on the most modern plan. Nature, moreover, has cast the topographical features of the place on lines that are admirably suited to defense. The harbor is surrounded by two approximately concentric ranges of hills, the crests of which are broken by a series of successive[18] conical elevations. The engineers took the suggestion thus offered, and ran two concentric lines of fortification around the city, building massive masonry forts on the highest summits, and connecting them by continuous defensive works. The inner line of the forts lay at an average distance of one mile from the city, and constituted the main line of permanent defense; the outer line, at an average distance of a mile and a half from Port Arthur. Beyond these again were the semi-permanent defenses. The positions of the various forts were chosen in such a relation to each other that they were mutually supporting—that is to say, if any one were captured by the enemy, it could not be held because it was dominated by the fire from the neighboring forts; and, indeed, it often happened that the Japanese seized positions from which they were driven in this way.

In the majority of cases the slope of the hills was very steep, and what was even worse for the Japanese, smooth and free from cover; so that if an attempt were made to rush the works, a charge would have to be made over a broad glacis, swept by the shrapnel, machine gun, and[19] rifle fire of the defenders. Once across the danger zone, the attack was confronted by the massive masonry parapets of the fort, over which the survivors, cut down to a mere handful, would be powerless to force an entrance.

The defense of Port Arthur, however, did not stop at the outer line of fortifications, but extended no less than eighteen miles to the northward, to a point where the peninsula on which Port Arthur is situated narrows to a width of three miles. Here a range of conical hills, not unlike some of those at Port Arthur, reaches from sea to sea; and these had been ringed with intrenchments for troops and masked (or hidden) emplacements for artillery. Between Nanshan and Port Arthur the Russians had built four more lines of intrenchments, reaching from sea to sea, all very strong and admirably suited for defense. Now it must be borne in mind that all this wonderful net-work of fortifications, strong by nature of the ground, strong by virtue of the great skill and care with which it had been built, was distinguished from all other previous defensive works by the fact that in this fortress, for the first time, were utilized all those[20] terrible agencies of war which the rapid advance of science in the past quarter of a century has rendered available. Among these we may mention rapid-fire guns, machine guns, smokeless powder, artillery of high velocity and great range, high explosive shells, the magazine rifle, the telescopic sight giving marvelous accuracy of fire, the range-finder giving instantaneously the exact distance of the enemy, the searchlight, the telegraph and the telephone, starlight bombs, barbed-wire entanglements, and a dozen other inventions, all of which were deemed sufficient, when applied to such stupendous fortifications as those of Port Arthur, to render them absolutely impregnable.

The Russians believed them to be so—certainly the indomitable Stoessel did. And well he might; for there was no record in history of any race of fighters, at least in modern times, that could face such death-dealing weapons, and not melt away so swiftly before their fury as to be swept away in defeat.

But a new type of fighter has arisen, as the sequel was to tell.

On February 8, 1904, the first blow fell upon[21] Port Arthur in that famous night attack by the torpedo boats. On February 9th occurred the engagement between the remnant of the Russian fleet and the Japanese fleet under Admiral Togo which ended in the Russian retreat into the harbor and the closing of Port Arthur by sea.

On May 26th the Japanese Second Army, which had been landed at Petsewo Bay, attacked the first line of defense at Nanshan, eighteen miles north of Port Arthur, and gave an inkling of the mettle of the Japanese troops by capturing the position in a frontal attack. The Japanese pushed on to Port Arthur and there followed, in quick succession, a series of bloody struggles at the successive lines of defense in which the Japanese would not be denied. The fiercest fight took place at the capture of a double height, Kenshan and Weuteughshan, which Stoessel re-attacked vainly for three days, losing three times as many men as were lost originally in the attempt to hold the position.

On May 29th Dalny was occupied, and became the base of the besieging army. A railway runs from Dalny for three miles to a junction with the main line from the north to Port Arthur.

On August 9th to 11th the outlying semi-permanent works Taikushan and Shokushan, lying about three and one-half miles from Port Arthur, were taken, and the Russians driven in to their permanent positions.

The army detailed for the capture of Port Arthur was 60,000 strong; Stoessel at the date of the battle of Nanshan probably had 35,000 men.

Encouraged by their uninterrupted success in capturing Russian intrenchments by dashing frontal attack, the Japanese, particularly after their brilliant success of August 9th to 11th, believed that they could storm the main defenses in like manner. They hurled themselves against the Russian right center in a furious attack upon the line of forts stretching from the railway around the easterly side of the town to the sea. For seven days they battled furiously. But the wave of conquest that had flowed over four lines of defense, broke utterly against the fifth; and after a continuous struggle, carried on day and night, beneath sunlight, moon, and searchlight, they retired completely baffled, with an awful casualty list of 25,000 men.

On September 1st the Japanese, finding that they could not take Port Arthur by assault, settled down to reduce it by an engineering siege. This latter was carried on by means of “sapping and mining,” supported by heavy bombardment, its object being to shake the defense by terrific artillery fire, blow up the parapets and other defenses by subterranean mines, and capture the fortress by fierce assaults delivered from concealed trenches close to the fortifications. Sapping and mining may be described as a method of attack by tunneling. The Japanese found that they could not get into the forts by a rush above ground, so they determined to burrow in below ground. The main attack was directed against the line of forts to the east of the city, or the Russian right center. The first operation was to cut a deep trench, not less than six feet in depth and a dozen or more feet in width, roughly parallel with the line of forts, and at a distance of about 1,000 yards therefrom. From this trench three lines of zigzag trenches were dug in the direction of the principal forts of Ehrlung, Keekwan, and Panlung. These trenches were about six feet deep (deep enough[24] to hide the sappers from view) and eight feet wide (wide enough to allow the troops to march to the assault four abreast). The zigzag consisted of an alternate approach and parallel, the former extending diagonally toward the fortification, the latter parallel with it. The angle of the diagonal approaches was always carefully mapped out by the engineers, and was so laid with reference to the enemy’s forts that it could neither be seen nor reached by shell fire. The digging was done chiefly at night, and the soil was carried back through the excavated trenches in gabions and on stretchers, and dumped out of sight of the enemy. As the parallels were advanced across the valley or level spaces, they were roofed at intervals, with planks covered with soil and grass, so that as the Russians looked out toward the ravine in which the army was supposed to be encamped, there was nothing to indicate that the enemy was cutting a series of covered roadways, right up to the base of the forts themselves. Of course in many cases the trenches were located, and desperate night sorties were made in the endeavor to break up the work. But it went remorselessly forward.[25] When the foot of the fortified slopes was reached, a second great parallel, extending around the whole face of the fortified eastern front, was cut—this latter for the purpose of assembling the troops for the final dash upon the forts. From this parallel the Japanese cut tunnels straight through the hills until they found themselves immediately below the massive parapets of such forts as they wished to reach. Here cross tunnels were cut, parallel with the walls and immediately below them, in which tons of dynamite were placed and the wires laid ready for the great explosion—much of this being done, it must be remembered, entirely unknown to the Russians, secure in their great fortifications overhead. The work of the sappers and miners was now complete.

It must not be supposed that while this slow work was being carried on, the garrison at Port Arthur, or the city itself, or even the fleet in the harbor, was being left in peace, or had any respite from the harassments of the siege. For as soon as the investment was complete, the Japanese erected hidden batteries in various carefully-selected positions, until they had no less[26] than 300 guns trained against the city. All the furious assaults that failed so disastrously were preceded by bombardments, the like of which had never been witnessed in the history of the world. These batteries consisted of regular siege guns of from 5 inches to 6 inches caliber, a large number of naval guns of 4.7-inch and 6-inch caliber, and the regular field ordnance of the three divisions and two independent brigades composing the Third Imperial Army.

By far the most formidable pieces used in the bombardment, however, were the powerful 11-inch mortars, which were mounted in batteries of from two to four in various positions behind the ranges of hills which effectually screened the Japanese from Russian observation. The pieces are the Japanese latest type of coast-defense mortars, such as are used along the Straits of Shimoneseki and about the Bay of Yezo. They were brought by sea to Dalny, carried by railroad for a distance of fifteen miles to the end of the track, and from thence were hauled by hand over special tracks laid direct to the emplacements. In some cases, indeed, the guns were dragged on rollers through the sand, as many[27] as 800 men being required to haul a single mortar; for the mortar barrels, without the carriage, weigh eight tons apiece. This task was accomplished under fire, in rainy weather, and in the night, to the accompaniment of bursting shrapnel and other discouragements which would have daunted a less dauntless race. Even when the selected site of the batteries was reached, every one of the eighteen mortars had to be placed upon a concrete foundation eight feet in depth and eighteen feet in diameter. In each case an excavation had to be dug, the concrete prepared and rammed into place, the heavy foundation plates, traversing racks, and the massive gun carriage, weighing much more than the gun itself, erected and adjusted, and the whole of the heavy and costly piece put together with the greatest nicety. All through the long months in which the sappers and miners were cutting their trenches, the engineers were putting in place these huge mortars, which were not originally intended, be it remembered, for such field operations as these; but were designed for permanent sea-coast fortifications around the harbors of Japan.

The mortar itself has a bore of 28 centimeters, or 11 inches. The shells are designed to burst on contact. They are loaded with a high explosive designed by the Japanese Dr. Shimose, and corresponding in its terrific bursting effects to the English lyddite, the French melinite, and our own maximite. Each shell weighs 500 pounds. Its cost is $175, and the cost of each discharge, including that of the impelling power, is about $400. During the heavy bombardments, each gun was fired once every eight minutes, and as the grand bombardment lasted in every case about four hours, the cost for these mortar batteries alone must have been over $200,000, and for the whole of the batteries, including naval guns, machine guns, etc., the cost of each bombardment was approximately half a million dollars. The 11-inch mortar has a maximum range, with a moderate degree of elevation, of seven or eight miles; but as none of these batteries were more than three miles distant from the point of attack, they were fired at angles of as great as sixty degrees, the huge shells hurtling high into the heavens, passing over two ranges of hills, and falling like thunderbolts[29] out of the blue sky, vertically upon the devoted city.

But if the batteries were located behind hills that entirely shut out the object of attack from view, how, it will be asked, could the guns be aimed with such accuracy, to sink, as they did, a whole fleet of warships, one by one? It was in this way: For the attack of stationary objects such as forts, docks, buildings, ships at anchor, etc., the artillery officers were provided with a map of the whole area of bombardment, which was laid out in squares, each square having its own number. The Japanese having, at the close of the Chinese war, been in possession of Port Arthur themselves, and having possessed during the past few years an excellent bureau of intelligence, knew the exact location of every building or object of importance in and around the city. Consequently, when the artillery officers were directed to attack a building in a certain square, or a particular fort, they knew exactly what angle of elevation to give their gun, and how far to traverse it, so as to cause the shell to fall with mathematical accuracy upon the particular object to be hit.

The attack upon the warships, however, was another proposition, for they could be, and were, shifted, from time to time. To make sure of hitting them, it was necessary to have some direct line of vision. The Japanese knew that such a line of vision could be obtained from the top of a hill to the west of the city known as 203-Meter Hill—the Russians knew it, too. Hence that awful struggle for possession of this hill, which cost so many thousands of lives. The Japanese won the position. When they had taken it, they placed observers provided with the hyposcope—a telescope that enables the observer to observe the surrounding country with out exposing himself above the surrounding parapet—upon the summit, in suitable positions, and held the hill with sufficient force to prevent its being retaken. The batteries were then trained at the individual warships, and the effects of the shells was telephoned from 203-Meter Hill to the various batteries, and the errors corrected, according as they were long, short, or wide, until the huge shells commenced to drop with unerring accuracy down through the decks and out through the bottom of the doomed warships.[31] The ships tried to escape observation by hiding on the outside of the harbor behind the Tiger’s Tail hills, and in a cove behind Golden Hill; but there was no escape, and ultimately every ship of the squadron was sunk.

That was the beginning of the end. The 11-inch batteries when directed at the forts tore gaping holes in the parapets, and according to the testimony of General Stoessel, they were simply irresistible. One by one, after furious bombardments, the walls of the great forts were blown up by the explosion of the subterranean mines that had been laid by the sappers and miners, and the Japanese massed in readiness for the attack in the inner parallels swept in through the wide gaps thus formed, and seized the fortifications, from which, a few months before, they had been swept back in terrible and crushing defeat.

PORT ARTHUR

Dalny, August 3d: Guns have blown their thunder to us distantly all the afternoon. The sounds boom a low thud with monotonous distinctness. Lounging on the taffrail of a small cargo steamer in Dalny Bay they strike those of us who are innocent of war, who have never felt the thrill, the halt and the plunge of battle as tame; almost without interest. In a California cottage, a summer’s night, a mile from the seashore I have listened before now to the surf climb up and lay down upon the beach with the same heavy lust.

This sound has in it, too, something of nature’s immanence and majesty; an elemental force of decay and a primal grandeur of progress. Yet[34] it is ominously deadly. The sky above is a perfect azure, the sea below a perfect turquoise, the town beyond a haze of tranquil ocher. We are lying among warships, but they are silent. Beyond us a troopship is unloading a thousand conscripts for the trenches, but they are silent. The city of Dalny is beautiful—and silent. Silence everywhere. Then comes that boom—silence—boom—boom—boom! The captain steps up and speaks a few words. We begin to realize that we are listening to siege guns pounding the life out of a doomed city. The captain waves an arm toward a point of land to be seen faintly through a glass. Only half a day’s walk that way and beyond—to the southeast—lies Port Arthur.

We are ten. Yesterday there landed here eight military observers—four British, one Spaniard, one German, one Chilean and one American. These eighteen have been assigned by the Japanese Government to the army now operating against Port Arthur. The eighteen are the only Occidentals who will see the siege.

Four days ago we left Moji in a transport steamer, the Oyomaru. The ship’s name tells[35] of the trip—“The prosperous ocean ship.” We might have come across a millpond so placid was our journey. Yesterday afternoon we sighted a line of sand piles and verdure-covered rocks rising out of the ocean. We were about to steam past when a flash of sunlight, like a gay salute from a boy’s pocket mirror, struck our bow. It was the heliograph. The Oyomaru put to port and slid in under the lee of the islands. As we came up an old gray battleship veered on her anchor to give us room and as we turned her bows we floated in among the fleet, dragging at its chains, steam up, waiting to dash at the word to Port Arthur, four miles away.

We were at the Elliot Islands, inhabited by fisher folk and seized by the Japanese for a naval base. Around us lay the silence of death, though twenty men-of-war were within gun shot. Only the spiral upshoot of smoke from fifty stacks and the heave and push of tide-driven fighting craft gave evidence of the tensity we were in. From the highest hill a thin shaft, like a straw in the wind, cut against the sunset. There lay the wireless-telegraph station to which[36] are flashed signals from the torpedo craft and cruisers guarding the mouth of Port Arthur.

At dawn we left the fleet, silent, with that lazy curl of smoke uplifting its ragged fringe. On for five hours we came at ten knots until we rounded a cape and turned into Talienwan Bay. In the farther curve, as a pebble in a sling, lay Dalny.

“It looks like Greece; the Piraeus with Marathon in the distance,” said Frederic Villiers. I thought of another place; San Diego Bay with Point Loma curving a crescent out of the Pacific.

The Russians came here to stay; that is plain. We can see miles of brick buildings, some five stories high. The great brick chimney of an electric light plant towers above the city. The public buildings, hospitals, schools and railroad station are as fine as those of Los Angeles. Costly villas with spacious grounds, coolie covered, stretch back under the hillsides. A zoological garden of several dozen acres can be seen off at the left. There are miles of new wharves cemented and built with stone. Two piers strike out four hundred yards into the harbor,[37] locked down by solid masonry. A breakwater half a mile long stretches at our stern.

Ten years ago could the Romanoff seated in the Winter Palace at Petersburg, placing a finger on the map of western Asia, as he said: “Let there be a Russian city here;”—could he possibly have foreseen to-day?—the Russians gone, half of the magnificent city burned, the safe and beautiful harbor filled with Japanese transports and men-of-war, the railway held for a Japanese line of advance and Russian prestige on the Manchurian littoral smashed like a rotten egg!

This afternoon we have found how desperate the silence is. For mere movement after three days on shipboard and five months solitary confinement in Tokyo we asked to launch the ship’s boat and row about the harbor. The captain assented. Eight of us got in and started off among the transports. Next to us was a hospital ship painted white with a green stripe running across her middle like an abdominal bandage round an invalid. “Looks as enticing as a cocktail before dinner,” said one of the boys. It did have a cool glance that must be grateful[38] to a wounded man just in from the battlefield. We but turned her bows when we ran into a warship—a gunboat of the third class. She was in black, with red stripes about her portholes and stanchions. The gun carriages were outlined in red—stuff put on to keep off rust. Just beyond the gunboat lay a torpedo destroyer—the most devilish craft that floats—long, thin, low, with four thick funnels above engines like a bull’s lungs.

As we passed the gunboat a bugle piped “to quarters” and several officers turned their glasses on us. But on we went, gay with the freedom of the lark, and stretching our ship-bound muscles against the buffeting of the choppy sea. Yonder lay the torpedo boats and brother destroyers and beyond an armored cruiser of the second class. The cruiser piped “to quarters” and more glasses were leveled on us.

About this time the coxswain turned her nose to the Oyomaru, but before we got there the ship’s sampan glided alongside, the mate in her alive, jabbering Nipponese and gesticulating toward the ship. We hurried back.

As we climbed on board Villiers yelled: “You’ve spoiled it now. You’ll never see Port Arthur.”

Then we found we had created a sensation—this strange boat manned by eight foreigners, appearing in broad afternoon in the harbor of the nearest naval base to the scene of the fleet’s activities. Two warships had prepared to fire on us at word of command and signaling from the fleet to the shore had only found that it was “supposed” we were “neutral allies,” but that officially we could not be recognized. The captain was reprimanded and we were told to keep close to the ship until released. Tokyo had said nothing of us to Dalny. To-morrow we will be released. But we will not again go about the harbor. We will go on shore. We will have ears and eyes, but no legs or tongues.

Ho-o-zan, (the Phœnix Mountain) three miles from and looking into Port Arthur, Sept. 14th: Here we are with the Third Imperial Army waiting for Russia’s downfall in the Far East. With her fleet gone, Russia’s sea power has vanished. With Kuropatkin smashed it will be another year before she can have a great army in the field. So now there remains only impregnable Port Arthur to say that Russia but eight months ago held all Manchuria.

Ten of us are privileged to follow the fortunes of the army of investment. We alone of eighty-four war correspondents who entered the field are here to record the details of a siege that promises to go down in history with Plevna and Sebastopol. At the present time I may tell you only of how the army lives and works, and what sensations engulf one in the midst of this elemental[41] contest at the apex of a world, where two civilizations are in life and death throes.

Impregnable is the word for the line of forts confronting us. Military authorities innumerable have predicted it would never be taken from a white soldiery, although Japan ten years ago did take it, in a single day of fierce assault, from the weakly armed and poorly trained Chinese. But through seven years Russia has been preparing for what she faces to-day—a great army of veteran troops from a warlike nation, equipped for scientific fighting and officered by men trained in the best schools in the world. She has repaired and rebuilt the old Chinese Wall till it lies across the back of the city, from sea to sea, a buttress of protection and menace, plentifully loopholed for rifles and hung at intervals, like huge fobs on a gigantic chain, with forts. Every natural elevation is commanded by a battery, and every weak depression built up for similar defense. Six miles from sea to sea, convex into the valley, and cutting off the apex of the Liaotung peninsula as a conical cake might be cut by a spoon, lies this bristling line. Looking at it, and what confronts it from above,[42] this appears as grand a battlefield as the mind can conceive.

The mere names of some of the forts bring gleams of the situation. To our right, in the center, lie Anzushan and Etzeshan, the Chair and Table Mountains. Some giant might hang his legs over Anzushan and sup from Etzeshan, but were he built in proportion he would be nearly two thousand feet high, for they rise from the valley precipitously half that distance. It was here, the key to the center, that the Japanese pierced the line ten years ago, but they have tried no such move this time; a different foe confronts them now. Far beyond the Chair and Table Mountains, the key to the outer, we see Golden Mount, the key to the inner defenses, at once a sea and land fort. It shines glorious and confident in the sunlight, the model of a conventionally built fortification, rising square and solid from the hills, buttressed with sod and sand bags and parapeted on a bevel.

After all the outer seventeen forts have fallen and after that terrible Chinese Wall has been pierced, there still remains Golden Mount, the Tiger’s Tail and Liaotishan. Just below Golden[43] Mount, to be seen only from a certain angle in the valley in front of us, lie the shattered remnant of the Russian fleet—three gray old battleships, four tarnished cruisers and a half dozen torpedo boats, smashed and done by Togo’s fleet, whose smoke curls irregularly over the sky line as it tugs warily there on perpetual watch, a watch uninterrupted for seven months, in which the monotony has been varied by three great naval battles.

To the right of Golden Mount and still below it lies the new town of Port Arthur built by the Russians. Hid behind a hill is the old town of frame houses. There is not a living thing to be seen on the streets, lying in plain view through a strong glass, as though in miniature on the palm of your hand. It is unharmed and spotless, seemingly in fresh paint. Four sticks piercing the sky line tell of the wireless telegraph station. To the right a huge crane can be seen sticking up to indicate the dock yards and a patch of blue, landlocked water, the west harbor. Nearest us the arsenal and railroad shops are plain. Then comes the railroad mockingly deserted in the sunlight. Then a high embankment[44] shuts the view, but we know that under the embankment nestles a series of barracks. Far out on the plain, between the two armies, and between us on the mountain and the Russian forts, two miles off, a lone factory chimney up-slants to the blue; though bursting shells have been thick about there it is unharmed, and, so far as we can see, Port Arthur is unharmed. So far the Japanese have not shelled it at all. But we are told the navy has wrecked the Russian quarter. The army scorns to destroy the city which now lies at the mercy of its siege guns, just as it scorns to starve out the beleaguered garrison. It is a civilized game the Japanese are playing, one of strategy and force.

Far down in the plain called the Mariner’s, or the Shuishiying Valley, a little to the left and back of the lone chimney, is a great fort known as the Two Dragons, a most difficult place to take because of its long approaches. It is the advance guard of the Russian line; only eight hundred yards from the Japanese trenches. Far out to the right, resting on the northern arm of Pigeon Bay, is a bald-headed peak some eight hundred feet high. This is Liaotishan, the extreme[45] left of the Russian position. Behind the town are great peaks, the highest hereabouts, and on them, in the early morning, four brass cannons can be seen glittering. They are thought to be dummy cannon, for they have not yet spoken.

To the left of the town, with its Golden Mount, begin the really great forts, scenes of carnage destined for history’s brightest page, and about which have taken place the battles I am about to describe. The Eternal Dragon and the three batteries of the Cock’s Comb are the essential. Far behind this Eternal Dragon and the wall, a few hundred yards from the sea, is a wooded driveway, leading to a mountain called Wangtai, or “the watch tower.” Up this, of an afternoon, a carriage can sometimes be seen drawn by white horses. Prisoners tell us it is General Stoessel’s carriage and that he thus goes to his headquarters. Why is he not fired upon? Because he is out of close rifle range and the Japanese never waste a shell on a single man or on even a group.

Occasionally we can see men moving a heavy gun about, or walking in squads through the[46] town. The Japanese wait to concentrate their fire; they never harass the enemy. On the contrary, the Russians, now when they should hoard every shell, waste hundreds each day. They will fling a six-inch screamer at a mule or an umbrella, and no part of the Japanese rear is safe, though distances are so great that the chances of being hit are one in a thousand.

All is quiet except that now and then a Russian shell whizzes. The sound can no longer be called the “boom of cannon,” so savage and rending is the detonation of these mighty modern charges. To hear one explode even half a mile off sets every fiber of the body in action, so angry is the report. Infantry popping can be heard, oftenest in the night, as the outposts come together, or the sentries chaff each other by showing dummy heads or arms. But over beyond that ragged line we know that twenty thousand men, driven into a corner—and what a corner it is!—are fighting like rats in a hole, that they are of the same blood that defeated Napoleon when on the defense a century ago, the same that half a century ago stubbornly contested Sebastopol, the same that a quarter of a[47] century ago, at appalling loss of life, reduced the marvelous Plevna. They sit thus hunted, at bay, well ammunitioned and provisioned, determined to sell every ounce of blood dearly.

To take Port Arthur seems impossible. It takes men drunk with victory and strong in ancient might to dare the task. It is only looking at what the Japanese have already taken that makes one have faith in their ability to do what they are now trying; otherwise, looking across at that six-mile line, one would say as he might have said of the ridges lying behind us: human energy and prowess cannot force them; only madmen would attempt it. But the Japanese have already forced at least five positions, seemingly as difficult as Port Arthur. First, they took Nanshan, which was even worse than this, for the approaches were gradual for two miles, while here precipitous heights and deep ravines give shelter. Nanshan the Japanese took in a single desperate day; Kenzan, where they had to climb hand over hand, they scaled in a night; Witozan, where they broke in over parapets built on rocks seven hundred feet above the sea,[48] they reduced at high noon; Anshirey, where the road climbs up a spiral for a mile, and is raked at every yard, they enfiladed and took in two days; and Taikushan, a saddle of malachite and granite straddling the main road to Port Arthur, they shelled out in thirty-six hours. Thus it is we have faith that some morning the world will wake to hear that the Rising Sun flies over Port Arthur, which the military experts of the Powers have declared impregnable.

Bitter as the contest is, war has not touched the bowels of the land. Looking into the plain behind me I can see a score of busy and peaceful villages serene in a sea of golden harvest. Maize and buckwheat, beans and millet, cabbage and barley alternate green and russet over the meadows. Springless bullock carts, ancient as Jerusalem, helped by tiny donkeys and naked children, painfully garner the grain. Women sing in low monotones at the primitive stone mills where blindfolded donkeys travel all day in a circle, grinding out the seed and flour. Lines of coolies wend through the footpaths, spring-kneed with huge weights on limber poles. Shells at the rate of four or five an hour drop[49] into this great area, separated from the field of battle by a range of mountains, plowing up a hill, shattering a house, tearing a road, killing a donkey, wounding a coolie, but of no great damage. No one minds. The harvest goes on. The glorious, golden September continues. The women sing, the naked children play, the tiny donkeys labor.

It is the plain in front, under the Cock’s Comb and the Golden Mount, guarded by the Two Dragons that has desolate quiet. There the maize is untouched and the heavy heads of the millet fall from sheer weight, while the cabbages are crushed by infantry passing in the night. Fires have blackened the villages, the Manchurians have fled, and in ragged lines from sea to sea the two armies hold their hostile trenches, from which, through the twenty-four hours, goes up the intermittent ping and pop of rifle bullets.

What of the army? You cannot see it; much less can you hear it. An army of a hundred thousand men is here, around us, among us, but we do not know it, we can hardly guess it. Little would one think, were it not for the firing, that[50] so much as a company were idling along that plain. A machine gun rattles, a low, deep boom comes from the sea; the forts reply, a flash streaks the air, we see a puff of smoke, then a cloud of earth is thrown up; finally, after a long while, as we are about to turn away, the angry shriek of a shell comes over and we hear it burst a thousand yards below in the valley. Only our ears tell us that war is on. The Japanese are as invisible as the Russians. It will take days and weeks to spy out the labyrinthine ways of this great army as it toils among the hills, into the valley and up the ravines, mounting its guns, and digging its way up to the parapets, where its units will cling, like barnacles to a ship, until the monstrous hulk founders.

But getting down into the rear plain, traveling the road, taking a different one each day, passing among the villages and through the hills, one begins to realize that the country is honeycombed by grim activity. Back and forth, from the front to Cho-ray-che, a railroad station halfway from Port Arthur to Dalny, travel lines of transport. Each line has from one to five dozen light wagons drawn by single small[51] shaggy horses, each guided by a small dust-visaged soldier.

“There is the strength of our army,” said an officer to me one day as a company of them passed, grimed, heated, menial. They are the flower of Japanese youth, clerks, professional men, students, exiled on rice and pickled plums, getting none of the glory of war. They are the unnamed and unknown but all-powerful commissary.

As the transport passes in, loaded with bags of rice, there comes out another line, this time of coolies, paired, and well burdened with human freight. They are bearing the wounded, in bamboo stretchers that do not jolt the piteously shattered frames, to the railroad station, whence they go by train to Dalny, thence by hospital ship to Japan. Every day comes this dribble of wounded, some days only a score, but after a battle the ways are thick with them—hundreds, thousands.

Occasionally, but very seldom, a battalion or a regiment of infantry will be seen moving in, with compact lines, knapsacks on back, bearing rifles with the barrel holes brass covered. The[52] other night over by the western sea I suddenly came upon a troop of cavalry racing along the sands in the sunset. They rode their horses well, considering that the Japanese is not a horseman. Each had an extra mount. They frolicked like plainsmen till the coves rang. I had not seen so much gayety before in all the Japanese army. But what can cavalry do at a siege?

For the sublime we need not go to the firing line where men risk their lives and lose them. At the front of our mountain lies a deep rutted road, at the end of which, hid well among the hills, is the hole for a concrete gun-emplacement, redoubted with sandbags, the glacis slippery with shale. Along this road as the sun sinks we see what looks like a gigantic snake, its tail pulling an ugly head slowly backward, its dust-covered belly squirming laboriously. Descending we find a cable thick as a man’s thigh stretched between two long lines of men, each of whom has hold and is pulling that ugly head—a siege gun—nose and breech clap-boarded, and wallowing, without its carriage, on wooden rollers. We count the men—300. Men alone can do the work, for they alone can move in[53] unison, quietly, at the word of command. There is no noise. The commands cannot be heard five hundred yards away. The three hundred bend their backs as one and the Pride of Osacca bunts her nose through the dust a rod nearer emplacement. They toil there a week to get that monster into position, pygmies moving a power that will rend the mountains, as tradition has it that Hendrick Hudson and his crew moved the ships’ cannon into the Catskills for the eternal generation of Knickerbocker thunder. To look upon that gun, helpless but disputatious in the hands of the three hundred, to realize that a week hence its bulk, into which one of these naked Manchurian children can easily creep, will toss five hundred weight of shell five miles through the air into one of those Russian forts where it will shatter the skill, labor, and life of an Empire—ah, that is sublime! Is it not also terrible?

The same scientific skill with which the gun is handled is seen throughout the army. Even after a battle, in the disorder of regiments, the search for the wounded, the burial of the dead, there is no confusion. All moves quietly and[54] quickly. No officer swears, for the simple reason that the Japanese language hasn’t the words. Only the interpreters, who know English, swear. They, however, can be excused; they handle the correspondents, to whom they can’t speak, as the soldiers do to the Russians, with lead. You read of “the confusion and bustle of an army” and “the terrors of war.” There is no confusion, no terror here. No shrieks, no shouts, no hurrying. Once, as a regiment, after losing half its men, scaled the top parapet of one of those lower forts across the way, it gave out three rapid “Banzais.” Just that triple cry in the early dawn, from troops drunk with victory and mad with fatigue, is about the only evidence I have that the army possesses nerves. It rings in my ears yet and will always ring there—a wild shriek of samurai exultation floating out of the mist of the valley above the voice of rifle and cannon. “The officers lost control for a few minutes, but not for long,” explained a certain general to me later, apologetically. He didn’t countenance such enthusiasm. War is business here—the most superb game of chess ever played upon the chequered board of the world.

One thing that relieves the situation of much of the evident hurry that once made war picturesque is the absence of the orderly. The mounted officer, riding for life, dispatch in breast-pocket or saddle bag, from the general to his brigadiers and his colonels, is food for reminiscence. The telephone rang his knell. This is the first time in history that the field telephone has come successfully into extensive active use. General Nogi can sit in his headquarters, four miles from Port Arthur, and speak with every battery and every regiment lying within sight of the doomed forts. Little bands of uniformed men, carrying bamboo poles and light wire frames on transport carts, and armed with saws and shovels, have intersected the peninsula with lines of instantaneous communication. It is the twentieth century. Yet, as I walked over the hills near the headquarters of the commander of artillery yesterday, I saw, hanging from one of the bamboo poles and all along a wire leading from it to the artillery commander’s tent, strips of white cotton cloth called “goheis.” You can see the same before all the Shinto shrines in Japan. They are offerings[56] of supplication to the spirits of the fathers. Some simple linesman, garbed in khaki and wearing an electric belt, not content with telephonic training, would thus guard his general. “Oh, ye who have watched over Japan, in peril and in safety, from the age of Jimmu, even to the present day,” he cries, “now, in a foreign land, faithfully guard this, our talisman and signal!”

I have said there are no sounds in the Japanese army. But there are—a few. At night, from far back on the rear plain, comes the monosyllabic sound of singing, several companies in unison, interspersed with light laughter—nothing hilarious, nothing loud, only an overflow of happy spirit into the night—never in the daytime, always at night. The song is a long one by Fukishima, a Major-General now in the north with Marshal Oyama, with a refrain: “Nippon Caarte, Nippon Caarte; Rosen Marke-te.” (Russia defeated is, Japan victorious.) The laughter comes from the game they play, something like our fox and geese, an innocent sport with nothing rough about it. Of late the Osacca band has been here, playing for the[57] generals at luncheon and for the convalescents in the field hospitals, but very quiet music—The Geisha, some Misereres, waltzes from Wang, and Sir Arthur Sullivan’s tunes. They avoid the military, the dramatic, and the inspiriting. The music is taken to soothe, just as their surgeons use opium when necessary. How different from the Russian, of whom each regiment has a band busy every day with the pomp and circumstance of conflict! One day, a week before we came here, the Russians made a sortie into the plain, parading for several hundred yards in front of the Two Dragons. That was before the lines were as closely drawn as they are now and the Japanese looked with amusement on the show-off. At the head marched two bands, brassing a brilliant march. Then came the colors flashing in the sun. The officers were dashingly decorated, and the troops wore colored caps. It was a rare treat for the Japanese, for they had never seen anything such as that in their own army. Like a boy bewildered at the gay plumage of a bird he might not otherwise catch, the simple and curious Japanese let the foe vaingloriously march back into the town. So here[58] they sit, playing children’s games, to the chamber music of women, as gentle as girls—but you should see them fight!

The transport camps are sheltered by mountains so high and steep that Russian shells cannot be fired at an angle to drop in behind them. Through one of these nooks I came one morning, unable to find the main road, and pushed among the horses. As I emerged at the farther end a soldier rushed at me with a bayonet and slashed at my legs. The bayonet was sheathed and I had a stout stick, so no damage was done. I soon explained who I was. He sullenly let me pass and his comrades began chaffing him. Some officers across the ravine also laughed. I thought they were laughing at me. Almost any human nature laughs at the foreigner. That was the first evidence of violence and the first evidence of rudeness I had seen in the Japanese soldier. I passed the day off in the regiment and, as night fell, came back through the horses, where I went without comment. Round a corner, out of sight of the camp I suddenly came upon the same soldier apparently waiting to see me. I grasped my stick[59] tightly, but he was weaponless, and advanced smiling, cigarette box in hand. He wanted to apologize and be friends. His comrades had been laughing at him, not at me, and had taunted him till he felt so ashamed of himself that unless I smoked with him and returned for some tea he would never stand right with them again. We had the tea and the whole mess joined in. That was a private soldier—a hostler. The courtesy of the officers is embarrassing, it is so continuous and exacting. Everywhere, from general to private, it is real and delightful, especially toward an American. I have heard many say that it is only a crust, that underneath the Japanese is a devil and a dastard. But a very nice crust. Let us enjoy it; as to the pie underneath, let the Russians testify.

For the essence of courtesy and thoughtfulness there is General Nogi. James Ricalton and I went to call on him two days ago. He spent half an hour with us at his headquarters in the village of Luchufong, which is Chinese for Willow Tree Apartment. It is one of the prettiest villages in the great plain, on the edge of a brook, fringing the zone of fire. Everything[60] shows seclusion and quiet, though there is located the brain that directs these gigantic operations, the girth of which Nogi alone comprehends. “Do you understand the situation?” I asked weeks ago of Frederic Villiers, the veteran English war artist, survivor of seventeen campaigns, present ten years ago at the other fall of Port Arthur, and dean of the war correspondents.

“No,” said he, “I was at Plevna with the Russians, but that was jackstraws to this game of go. I know nothing of go. Ask the military attachés.” In turn I asked the different military attachés—the German, French, English, Chilean, Spanish, Swedish, and finally the young lieutenant here for the United States. They all understood all about Port Arthur, but the trouble was, no two knew it the same. So I went back to Villiers. “Nogi is the only man that knows,” said he; “Nogi alone can tell you how the batteries are placed, how the divisions and regiments are to be deployed and played, what forts are the keys, what Russian batteries the weakest, the reserve force, the commissary and hospital supplies.”

So, naturally, coming to meet such a man we must have some awe, some curiosity and some respect for the master strategist, commander of the army which drove the Russians down the peninsula and which holds it now in a death trap. We expected to meet a man of iron, for Nogi is the General whose eldest son, a lieutenant in the Second Army, was killed at Nanshan; who has under his command a second son, a lieutenant, and who wrote home after the first disaster: “Hold the funeral rites until Hoten and I return, when you can bury three at once.”

The General received us in his garden. He was at a small table, under a willow, working with a magnifying glass over a map. He wore an undress blue uniform with the three stars and three stripes of a full general on the sleeve—no other decoration, though once before I had seen him wearing the first class order of the Rising Sun. His parchment-crinkled face, brown like chocolate with a summer’s torrid suns, beamed kindly on us. His smile and manner were fatherly. It was impossible to think that any complicated problem troubled his mind. A resemblance[62] in facial contour to General Sherman arrested us. Lying near, in his hammock, was a French novel. He reads both French and English, but does not trust himself to speak in either. Miki Yamaguchi, Professor of languages in the Nobles School, Tokyo, for seven years resident in America, and graduate of the Wabash college, was the interpreter.

“Look after your bodies,” the General said after greeting us. “I was out to the firing line the other day and came back with a touch of dysentery, so take warning. I do not want any of you to be sick. At the first sign of danger consult our surgeons. We have good surgeons.”

“We are of little account, General,” said Ricalton, “but it is a very serious thing for a man on whom the world’s eyes are centered to have dysentery.”

The General smiled. “I am quite well now,” he said; “but how old are you?” he asked, looking at Ricalton’s gray hairs. They compared ages. Ricalton proved to be three years the older.

From Stereograph, Copyright 1904, by Underwood & Underwood, New York

GENERAL BARON NOGI“The command of the army, then, belongs to me,” said Ricalton. “I’m your senior.”

“Ah,” said the General, “but then I should[63] have to do your work and I fear I could not do it as well as you do.”

That night a huge hamper came to Ricalton’s tent in charge of the headquarters orderly. It contained three huge bunches of Malaga grapes, half a dozen Bartlett pears, a peck of fine snow apples, and bore a card reading: “The General sends his compliments to his senior in command.”

“He is a great man,” said Ricalton, “who can so notice, in the midst of colossal labors, a passing old photographer.”

But, as Nogi goes, so go the other generals, and so goes the army. Villiers and I went yesterday to call on a certain Lieutenant-General who commands the most important third of the forces. His division has borne the brunt of the fighting, and he doesn’t live as Nogi does, on the edge of the zone of fire, but close under the guns within a mile of the Russian forts, so close that in his lookout two of his staff officers were recently killed. His home is a dugout in the side of a mountain. It is large enough for him to lie down in and turn over. He had a heavy white blanket, a rubber pillow to be inflated[64] with lung power, a fan, an officer’s trunk that carries sixty pounds, and a small lantern of oiled silk—this was his furniture, his complete outfit. On a peg hung his sword, and outside, on the ground, lay his boots. Some member of his staff had fixed up an iron bedstead and a water bowl, but they were lying off at the side of the dugout, untouched. He came to meet us in a thin pair of rubber slippers, his uniform a bit worn, the string on his breast, where the order of the Rising Sun is usually worn, barren, his eyes kindly, his manner fatherly and his hospitality generous; he spread a lunch bountiful as Nogi’s.

“I know the Russians,” said Villiers that night. “I was with them all through the Russo-Turkish War. I remember Skoboleff, their great cavalry leader, a magnificent type of man, a soldier to the ground, but fiery, emotional, vivacious, vain, fond of orders, jewels, wine and women, looking on war as a lark, dashing and brilliant, the scourge of Europe! He was not this type of man—a scientific chap, sober, full of business to the chin, no lugs to him, and as unemotional as a fish. Kuropatkin was Skoboleff’s[65] Chief of Staff and you see what these fellows have done with him. The day of cynical dash and reckless valor has gone by in war, my boy. We are living in an age of modesty and gentleness, of science and concentration; Japan is the master.”

We lay under the searchlights, which were turning the night valley into a noontide halo, as Villiers spoke. Every light came from the Russian side, which lay wary and restless beyond us. From the Japanese side came no light, no sound. All was secrecy and silence. Yet we knew those hills were alive with toiling brown figures, that a ten-mile line of rifle pits was guarded at every rod by a sleepless soldier watching for the Rising Sun and that the tents of those Generals blinked unceasingly with the steady glow of the oiled silk lanterns, quivering cabalistically with ideographs.

As I looked upon swaying and heavy searchlights, I could think only of the Indian cobra and his mortal enemy, the mongoose. Silently, rolled in a ball, alert for a fatal spring, the little mongoose watches, and the hooded cobra swings ponderously, more nervous with[66] each move. All other enemies he can crush; none other he fears; his body is murderous, his fangs deadly, his stealthy glide noiseless and sure. How well he knows his power! Despot of the jungle, why should he fear? And yet, since the world dawned his tribe has done well to avoid the mongoose.

Steadily swings the cobra; viciously he lunges. Now look! In the folds of the cobra’s neck those incisive teeth, those death-dealing claws! With the fury of whirlwinds lashes the cobra. With eternal calm cling the teeth and claws. Hour after hour goes the unequal struggle. The huge coils relax, the great head falls. Then the beady eyes twinkle. The mongoose slips off in the darkness; prone lies the cobra. Who sheds tears?

Tokyo, June 1st:—Who pays for the war? Here are a few telling one another that they are the bankers. It is at a Sunday concert in the fifth city of the world, a wilderness of sheds flimsy over two million human beings. In the midst rise vast acres of country solitude and rest. A tangle of cryptomeria and fir shade puzzled paths winding through furse of elderberry and hawthorn. Haze and vista spread away past hills and forests, past hothouses and lawns of firm packed earth. A lake dimples a vale, as a smile the cheek of a lovely woman, and its pebbly bed reflects the laughter of the sun. About it fluttering flags, new and gay, festoon the sentiment of all nations, one—Russia—excepted. Thousands, tens of thousands, dot the paths, are merry with the lake, instill from the greenery a quiet joy. Hundreds of voices, atune with instruments,[68] filter the fragrant air with music. Beyond the fence is squalor so dense three sen a month pays for a dwelling; here is leisure so luxurious the senses float in dreams. In a corner a moldy Diabutsu, the calm of Nirvana on his face, nods on a leaf of lotus; “out of the slime itself spotless the lotus grows.”

Tokyo is beautiful—brunette and beautiful. This first day of June she has risen past the cherry blossom, past the wistaria, through the freshness of spring to the full radiance of summer. Pink, like the fleece of clouds in the sky, and heliotrope, like the first flush of sunrise, are past. Now green, rich and deep from a soil of winnowed sustenance, mantles her in Oriental splendor—a splendor simple and elegant with the wealth of the east, shadowy and sunny with the blow of Japan. It folds her about with the assuring clasp of a lover, and she responds with the shy, voluptuous acceptance of a maid o’erwon.

This is a summer of content, a dream of gayety, of insouciance. A million babies gurgle with the baby glory of it. A million mothers coo and coddle at the eternal freshness of it. But[69] here, to-day, in this wilderness of terraced garden, in this bouquet of smiling East, have assembled the daintiest mothers in the land—the peeresses. The son of one is a major-general. Others have captains, colonels, aides-de-camp to tug their heartstrings with fear, to inflate their pulses with pride. Have we not penetrated to the very viscera of war’s nature when we find the mothers of its heroes thus assembled?

One of these mothers, a Princess, passes. Should she buy that delicate lace and lingerie, so charming with all that’s feminine, from boxes labeled and graded, she would choose misses’ sizes, so tiny is she. A toy of a woman, demure and pretty; yet put up by the finest of Parisian makers. The dotted mulle of her veil sweeps slightly away, scallop-like, from a face thin with aristocratic aquilinity. Behind that face, with wax complexion and eyes of bead-like purity, scintillates a mind bred on intellectual fashions. She speaks with the cultured English of Vassar. She knows Omar Khayyam as well as any. The major-general is her son. Beside her walks another son, his gold-rimmed spectacles completing a fine picture of esthetic[70] pride. His silk tie is the envy of every Japanese not bred abroad, for his clothes are from Piccadilly. The garden is full of these and such as these. They are giving a concert for the relief fund.

The music! It is the choicest that the sensuous imagination of man has built out of rules and dreams. “William Tell” thunders its diapason from the hid footholds of the earth. The audacious march of Leroul spits out its song of triumph. “America” murmurs a swelling hymn. A Weber overture sparkles, ascends, leaping crags, whirling diaphanous gayety through cloud and shadow.

Then a Japanese aria, weird with the rapt genius of the land, molten with Malay poise, floats a mystery of ancient longing through the broad day’s haze. It weaves through fir and cryptomeria, assaults the hearts of thousands, and, triumphant, storms the heavens; is lost in the faint sky, a sky blue with the dreaminess Whistler would have etched in immortal phantasy.

The Relief Fund gets fifty sen apiece from these peeresses with Piccadilly sons, brothered[71] by major-generals. And all other manner of folk, down to the little sister, carrying on her back a future soldier of the emperor, daughter of a rice cleaner in a three-sen dwelling beyond the gate, thus while the pleasant hours away.

On the heights of Tokyo they are paying for the war.

Here are the heights of Nanshan on the 27th of May. It is 5.20 o’clock in the morning and seas of sunlight are hid in a fog across Korea Bay. The fog lifts, and as the day bursts in along the whole line the banner of the Rising Sun is planted on the Russian ramparts of Kinchow. Since midnight the artillery of the third division has been hammering from the right, off toward Talienwan. At intervals the infantry of the first and fourth divisions charge from the front whence they have been advancing for two days. It is the second army of 60,000 Japanese and the investment of Port Arthur has begun. The railway has long been cut. Now Kinchow is taken and the Russians are helter-skelter Dalnyward.

Here, then, is the theater, scene of such sublime[72] assault and conquest as the eye of history has not looked upon since Grant stood on Orchard Knob and watched his thin blue line scale Missionary Ridge; the hill of Nanshan, key to the advance on Port Arthur. Turned in its lock Nanshan confronts the Japanese, impregnable, ghastly grim in the fresh sunlight. We may well pause to inspect the position. It rises, formidable, the height of a church steeple, from a narrow plain. The edges of this plain dip sheer down a hundred feet of slippery rock to the two bays—Talienwan and Kinchow. From bay to bay is scarce three miles. From Nanshan we may see, through a glass, the bay of Kinchow. Riding on it are four of the enemy’s gunboats. Their shells are flying over our heads. They have not yet found the range. To the left in Talienwan, a Russian gunboat, guarding four transports, is enfilading the third Japanese Division and supporting a regiment of its own men flanking the base of the hill. The hill has been cleared of underbrush and terraced, divided into four intervals and on these intervals trenches built. One hundred and ten cannon are there manned. At the bottom are[73] barbed-wire fences, Spanish trocha, not like the fences of a cow pasture, but dovetailed and doubled so that if a man breaks through one he stumbles into the oblique, bloody arms of another.

This the Japanese are to assault before noon. There is no timber, only a few bushes and rock the size of a bull’s head, hard things to wade through, but no defense. They must cross the open plain, 500 yards, in full range of those one hundred and ten cannon, smash the barbed wire, climb the terraced plateaus where they will be picked off like rabbits in a shooting gallery, assault the trenches and finally take the heights. To take one trench seems heroic achievement, four an impossibility. Impossible but for one thing—orders. The navy was ordered at the outset of the war “to exterminate” the Russian fleet, this Second Army went out to “take Port Arthur.” And they obey orders—these Japanese. So why contemplate that to attempt that Hill of Nanshan is folly, to take it madness?

The Russians wait. All is silence—the awed hush preceding carnage, terror, death. Waiting they sing, not light tunes heard so bright and[74] gay on the heights of Tokyo to-day; chansons of France, Italy’s peerless compositions, America’s solemn new-born hymn or Japan’s flute note weird and penetrating. From deep bass throats and barytones majestic rolls organ music of fierce, wild grandeur, as through some vast forest aisle the harmonies of winds and woods and waves unite in mighty pæans, celebrating to the august fastnesses glories yet fresh to man. Schools, traditions, customs civilized have not touched the fiber of that central gauntness, shining up through the spirit of the singers, like dreamland on a tragedian’s afterglow. Siberia with all its wildness, with all its immensity, where aback the mammoth wallowed; the Caucasus tossing aloft primeval ecstasy the long slant of the steppes, and Russia, bold, defiant, revengeful; all rolled in one, are in that note. The clothes of the men are heavy, ungainly, ill-made, nothing serviceable but the boots, which are well adapted for running away. The faces—sodden with ignorance and vice—reflect only stolid endurance; no initiative, no individuality. Only through the song shines the soul.

The singing ceases. There is a dreadful[75] hush. It is eleven o’clock. Off toward Kinchow, which is hid by a fringe of low fir trees, something is moving. Soon hunchbacked dabs can be seen bobbing across the furze, leaping over the stones, pausing, searching, then onward dashing. The firing begins. Two machine guns—only ten of the one hundred and ten are quick-firers—lead off. You can easily tell them. The sound is little, like the popping of a dozen beer bottles in quick succession. Then silence. The strip of cartridges is torn aside, another inserted, again a dozen pops. So it goes until the ten are brought into action and there is no intermission. Flicks of dust are kicked up by the shells, most falling short, a few passing on through the trees. One of the bobbing dabs falls, the rest press on. Now the gunners are getting the range; the shells pick off more hunchbacks.

But there is no stop. This is not reconnoisance; it is battle. The skirmishers deployed and well up, now the main line advances. Out from the trees on a dog-trot springs a battalion. It is going to try that griddle of death. The men dash valiantly on, agile fellows, intense as[76] fanatics. Now the hundred field cannon come into play. Most are Chinese of ancient date, some are modern, rim-firing. Smoke fills the plain. It is difficult to see. The torrent of lead is on. Snatched through the noise of firing you can hear great cries; they grow spasmodic, then cease. The firing slows. Soon only the automatic pops are heard. The smoke drifts off. The foremost man is there on the wire, gutted. He hangs, a frightful mass, limp on the barbs. Here and there a poor fellow is crawling, as you have seen some worm trodden on vainly seek its hole. Not a man of the battalion has survived. A thousand brave, faithful soldiers are gone. So this is civilized warfare!

Yes. They now see it was folly to attempt the hill of Nanshan. So they open up with artillery, a whole regiment of it, infinitely superior to the sixty antiquated cannon, the forty Canet pieces and the ten quick-firers. For an hour they rain that leaden taunt back at dubious Nanshan, who austerely barks out a thin reply, coughs a wheezy growl and ceases. Meanwhile the thousands in leash, battle inflamed, recall that the dead battalion are Osacca men,[77] and, being merchants from the Japanese Chicago, had been hailed as cowards by sons of samurai. A company of Osaccans went down, stuck, like pigs, in the Kinshu Maru. But after Nanshan the pork packers of Osacca will hold their heads decently high with the boldest.

Toward three o’clock the second advance is ordered. Half the third division and a part of the first, nearly 15,000 men, close in. They get across the plain, dropping a few hundreds, and smash the wire. Drunkenly dizzy, flaring with the lust of battle, the vanguard tears clothes, limbs, and tosses on the treacherous barbs.

They have no scissors, no choppers, no axes. Worse, they have no time. They keep on at the fence, gashing shins, stripped of impediments, down to the instincts and passions, all discipline gone, every vestige of civilization lost. Now they are through, half-naked, savage, yelling, even Japanese stoicism gone. Up to the very muzzles of the first entrenchment they surge, waver and break like the dash of angry waves against a rock-bound coast. It seems no tide or wind can melt that precipitous front. But only seems. A rest, a terrible breathing spell, the[78] slow, wounded gasp of an animal in pain, and again the intrepid Japanese lash their haggard forms against that low trench. Glory! They win! The Rising Sun glares in the afternoon as it greeted the sun of that morning above Kinchow.

Yet only a quarter of the battle is won. Another rest. Another assault. Again and again they go up. Nine times they hammer away, muskets to jowl, heads down like bulls in the ring, with one thought; nay! not a thought, an instinct—to win or die.

The officers are picked off by sharpshooters, as flies are flicked from a molasses jug. Two colonels are killed, the list of done captains swells. Then, through the haze, commanding the first division, looms a prince of the blood, the general whose peeress-mother is but this afternoon smiling serene on Tokyo heights. He below Kinchow, smoke-stained, grimed with death, hears the artillery report that ammunition is about gone, but one round left and Nanshan still Russian. Defeat stares Prince-General in the face. Retreat, disgrace seems right ahead. And orders were to “take Port Arthur.”[79] Smiling, he tells the gunners to wait. “Charge again,” he says.

So up they go, for the tenth and last time. At the top more civilized warfare. Spottsylvania Court House was no more savage. Japanese bayonets clash with Russian sabers. Bayonets struck from hands they grasp knives carried suicidally in belts. Thus, hand to hand, they grapple, sweat, bleed, shout, expire. The veneer of centuries sloughed, as a snake his cast-off skin, they spit and chew, claw and grip as their forefathers beyond the memory of man.

The Prince-General waits, ready to fire his last round, and retreat, hopeless. It has been a desperate fight—yes, reckless, unparalleled. If lost he loses nobly. “Are you through, General?” his aide asks. “I have just begun my part of the fighting,” he answers. His name is Fushimi—remember it. As he speaks a weak cry goes up—weak because even victory cannot rouse spirits so terribly taxed.

It was a bloody sun going down in Korea Bay that night, but it saw its rising counterpart flaunting above Nanshan, while the Russians[80] were making use of the best part of their apparel, sprinting towards the Tiger’s Tail.

The cost! The fleeing ones left five hundred corpses in the four trenches. The others paid seven times that price—killed and wounded—to turn across the page of the world’s warfare that word Nanshan, in company with two others, perhaps above them—Balaklava and Missionary Ridge.

Now who pays for this war?

Headquarters, Third Imperial Army, Before Port Arthur, Oct. 12th:

“Goddama’s here!”

“Who?”

“General Goddam—what’s his name?”

“Kodama?”

“That’s it. Who is he? They couldn’t do more for the Emperor—special train, guard mounted, and all that. He came while I was in the staff tent—a mite of a fellow in a huge coat.”

Thus Villiers two weeks ago announced the advent to the army of the Chief of the General Staff. Who is he? The soldiers know, for they have a verse in their interminable war song:

“On with Nippon, down with Russia

Is the badge of our belief;

The Son of Heaven sends us saké,

And Kodama sends us beef!”

But who is he? A poor, unlettered samurai of the famous Censhu clan who to-day, at fifty-two years of age, rules Japan and guides her armies. Many will dispute this. They will tell you that the illustrious Mutsuhito, member of the oldest dynasty in the world, rules Japan. They believe that the Marshal Marquis Oyama and the Marshal Marquis Yamagata, veteran spirits, great warriors, shrewd in counsel, valorous in conflict, guide their armies. They forget, perhaps they do not know, that Gentaro Kodama, whose rank is that of Lieutenant-General, his title Baron, his position Assistant Chief of the General Staff, thinks while the others sleep and works while the others eat; that the “illustrious ones” may “guide” and “rule.” People seldom know the boss behind the President, the power behind the throne, or the advisor at the general’s ear.

Most public men in Japan will tell you that Kodama is an unsafe person of second-rate capacity. That is what the Directorate said of Napoleon, it is what Halleck and his staff said of Grant, it is what the Crown Prince said of Von Moltke. They will tell you that his charge[83] of the commissary and transport in the China war was an accident. That is what the Directorate said of Napoleon after Egypt, what Halleck said of Grant after Donelson and Henry, what the Crown Prince said of Von Moltke before the Franco-Prussian war.

The public men sent Kodama to Formosa to get rid of him, as Napoleon was sent to Italy, as Grant was sent to Pittsburg Landing, as Von Moltke was shipped from Metz. Kodama went and raised Formosa from savagery to commerce and prosperity. He could have been Prime Minister. “No,” he said. “I would rather pull strings than be one of the strings to be pulled. Russia is peeking up over the border. Let us prepare. Give me a desk in the War Office.”

The public men shook hands, grateful that the unsafe upstart was out of the way. Only soldiers and seers foresee war. Kodama is not a seer. The public men reveled in peace and wondered occasionally that Kodama should bury himself in that dry hole of a war office. They were grateful because the unsafe upstart kept out of the way.