Title: The Boy Fortune Hunters in Egypt

Author: L. Frank Baum

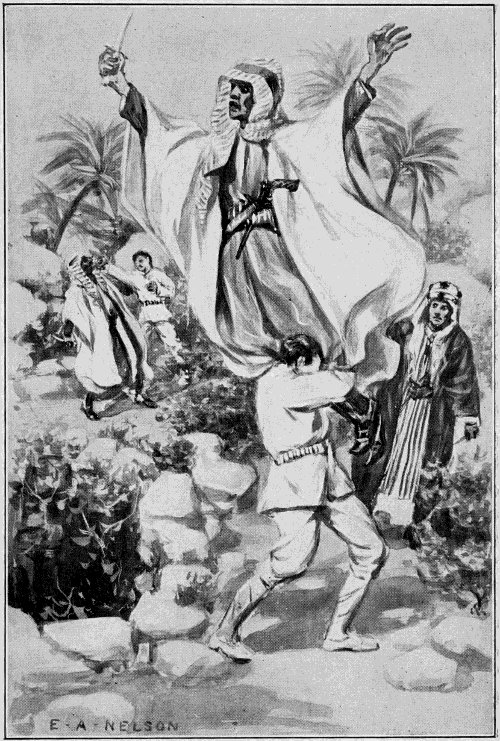

Illustrator: Emile A. Nelson

Release date: October 29, 2017 [eBook #55845]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Mary Glenn Krause, MFR, Stephen Hutcheson, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/boyfortunehunter00aker |

Ships of the desert.

By

FLOYD AKERS

Author of

“The Boy Fortune Hunters In Panama,” etc.

CHICAGO

THE REILLY & BRITTON CO.

CHICAGO

Cloth 12 mos. Splendidly Illustrated.

Price 60 cents each.

Copyright 1908

by

THE REILLY & BRITTON CO.

I was standing on the deck of the Seagull, looking over the rail and peering into the moonlight that flooded the bay where we lay at anchor, when the soft dip of an oar caught my ear.

It was the softest dip in the world, stealthy as that of an Indian, and in the silence that reigned aboard ship I stood motionless, listening for a repetition of the sound.

It came presently—the mere rustle of the drops as they slid off the oar’s blade—and a small boat stole from the shadows astern and crept to our side.

I glanced along the rail and saw, a few paces away, the dim form of the watch, alert and vigilant; but the man knew I was there, and forbore to hail the mysterious craft below.

At a snail’s pace the boat glided along our side until it was just beneath me, when I could see a blot in the moonlight that resembled a human form. Then a voice, so gentle that it scarce rose above the breeze, called out:

“Ahoy, mate!”

Now I ought to explain that all this was surprising; we were a simple, honest American merchant ship, lying in home waters and without an element of mystery in our entire outfit. On the neighboring shore of the harbor could be seen the skids from which the Seagull had been launched a month before, and every man and boy in Chelsea knew our history nearly as well as we did ourselves.

But our midnight visitor had chosen to steal upon us in a manner as unaccountable as it was mysterious, and his hail I left unanswered while I walked to the landing steps and descended them until I stood upon the platform that hung just over the boat.

And now I perceived that the tub—for it was little else—was more than half full of water, and that the gunwale rode scarce an inch above the smooth surface of the bay. The miserable thing was waterlogged and about to sink, yet its occupant sat half submerged in his little pool, as quiet and unconcerned as if no danger threatened.

“What’s up?” I demanded, speaking rather sternly.

The form half rose, the tub tipped and filled, and with a gentle splash both disappeared from view and left me staring at the eddies. I was about to call for help when the form bobbed up again and a hand shot out and grasped a rope dangling from the landing stage. I leaned over to assist, and the fellow scrambled up the line with remarkable agility until I was able to seize his collar and drag him, limp and dripping, to a place beside me.

At this time I was just eighteen years of age and, I must confess, not so large in size as I longed to be; but the slender, bent form of the youth whom I had rescued was even of less stature than my own. As he faced me in the moonlight and gave a gasp to clear the water from his throat, I noted the thin, pinched features and the pair of large, dark eyes that gazed with pleading earnestness into my own.

“For Heaven’s sake, what are you up to?” I asked, impatiently; “and how came you to be afloat in that miserable tub? It’s a wonder you didn’t sink long before you reached our side.”

“So it is,” he replied in a low voice. “Are you—are you Sam Steele, sir?”

“Yes.”

“Ah! I hoped it would be you. Can I go aboard, sir? I want to talk to you.”

I could not well have refused, unless I consigned the fellow to the waters of the bay again. Moreover, there was a touching and eager appeal in the lad’s tones that I could not resist. I turned and climbed to the deck, and he followed me as silently as a shadow. Then, leaning against the rail, I inquired somewhat testily:

“Couldn’t you wait until morning to pay me a visit? And hadn’t you enough sense to know that old dinghy wouldn’t float?”

“But it did float, sir, until I got here; and that answered my purpose very well,” he replied. “I had to come at night to keep from being discovered and recaptured.”

“Oh! You’re a criminal, then. Eh?”

“In a way, sir. I’m an escaped cabin-boy.”

That made me laugh. I began to understand, and the knowledge served to relieve the strain and dissolve the uncanny effect of the incident. An escaped cabin-boy! Well, that was nothing very wonderful.

“Here, come to my room and get some dry togs,” I said, turning abruptly to the gangway. The lad followed and we passed silently through the after-cabin, past the door of Uncle Naboth’s quarters—whence issued a series of stentorian snores—and so into my own spacious stateroom, where I lighted a lamp and carefully closed the door.

“Now, then,” I exclaimed, pulling some of my old clothes from a locker, “slip on this toggery at once, so your teeth will stop chattering.”

He discarded his dripping garments and replaced them with my dry flannel shirt and blue trousers, my thick socks and low shoes. I picked up his own ragged clothes and with a snort of contempt for their bedraggled and threadbare condition tossed them out of the window into the sea.

“Oh!” he exclaimed, and clutched at his breast.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“Nothing. I thought at first you had thrown away mother’s picture; but it’s here, all right,” and he patted his breast tenderly.

“Hungry?” I inquired.

“Yes, sir.” He gave a shiver, as if he had just remembered this condition; and I brought some biscuits and a tin of sardines from my cupboard and placed them before him.

The boy ate ravenously, washing down the food with a draught of water from the bottle in the rack. I waited for him to finish before I questioned him. Then, motioning him to a seat on my bunk, for he seemed weak and still trembled a bit, I said:

“Now, tell me your story.”

“I’m a Texan,” he replied, slowly, “and used to live in Galveston. My folks are dead and an uncle took care of me until a year ago, when he was shot in a riot. I didn’t mind that; he was never very good to me; but when he was gone I had no home at all. So I shipped as a cabin-boy aboard the Gonzales, a tobacco sloop plying between Galveston and Key West, for I always loved the sea and this was the best berth I could get. The Captain, Jose Marrow, is half Mexican and the cruelest man in the world. He whipped me when he was drunk, and abused and cuffed me when sober, and many a time I hoped he would kill me instead of keeping up the tortures I suffered. Finally he came up here with a cargo, and day before yesterday, just as he had unloaded and was about to sail again, he sent me ashore on an errand. Of course I skipped. I ran along the bay and hid in a lumber shed, from the top of which I could watch the Gonzales. She didn’t sail, because old Marrow was bound to have me back, I guess; so I had to lay low, and all the time I was sure he’d find me in the end and get me back. The sloop’s in the bay yet, sir, only about a quarter of a mile away.”

“Well?”

“Well, last evening a couple of men came to sort some of the timbers, and I lay hid on top the pile and listened to their talk. They spoke of the Seagull, and how it was to sail far away into the Mediterranean, and was the best built ship that ever left this port.”

“That’s true enough, my lad.”

“And they said Cap’n Steele was the best man to work for in the merchant service, and his son, Sam Steele—that’s you, sir—was bound to make as good a sailor as his dad, and had been in some queer adventures already, and was sure to find more of them before he was much older.”

I had to smile at that evident “taffy,” and my smile left the boy embarrassed. He hesitated a moment, and then continued:

“To a poor devil like me, sir, such a tale made me believe this ship a floating paradise. I’ve heard of captains who are not as cruel as old Marrow; so when the men had gone I decided to get to you in some way and beg you to take me aboard. You see, the Mexican is waiting to hunt me down, and I’d die sooner than go back to his terrible ship. If you’ll take me with you, Mr. Steele, I’ll be faithful and true, and work like a nigger for you. If you won’t, why, just say the word, and I’ll jump overboard again.”

“Can you swim?”

“No.”

I thought a moment.

“What’s your name?” I asked, finally.

“Joe Herring.”

“Well, Joe, you’re asking something unusual, I must say. I’m not the captain of the Seagull, but merely purser, or to be more exact the secretary to Mr. Perkins, the supercargo. I own a share in the ship, to be sure, and purchased it with money I made myself; but that fact doesn’t count when we’re at sea, and Captain Steele is the last man in the world to harbor a runaway member of the crew of a friendly ship. Indeed, your old master came aboard us this morning, to inquire about you, and I heard my father say that if he set eyes on you anywhere he’d let Captain Marrow know. As he never breaks his word this promise is to be depended upon. Do you see, now, what a fix you’re in?”

“I do, sir.”

His voice was low and despondent and he seemed to shrink back in his seat into an attitude hopeless and helpless.

I looked at the boy more closely, and the appeal in his pinched features, that had struck me at the first glance on the landing stage, became more impressive than ever.

“How old are you, Joe?”

“Fifteen, sir.”

He was tall, but miserably thin. His brown hair, now wet and clinging about his face, curled naturally and was thick and of fine texture, while his dark eyes were handsome enough to be set in the face of a girl. This, with a certain manly dignity that shone through his pitiful expression, decided me to befriend the lad, and I had an inspiration even in that first hour of meeting that Joe Herring would prove a loyal follower and a faithful friend.

“We sail at ten o’clock, and it’s now past midnight,” I remarked, thoughtfully.

“Yes, sir; I’ll go any time you say.”

“But you can’t swim, Joe.”

“Never mind. Don’t let me be a bother to you. You’ll want to turn in,” casting a wistful look around my pleasant room, “and so I’ll find my way on deck and you needn’t give me another thought.”

“Very good,” said I, nodding. “I think I’ll turn in this minute.”

He rose up, slowly.

“Just climb into that upper berth, Joe, and go to sleep. There’ll be work for you tomorrow, and you’ll need to get rested.”

He stared into my smiling face a moment with a startled look that soon became radiant. Then he broke down and cried like a baby.

“Here, no snivelling!” I growled, savagely. “Pile into that berth; but see you get your shoes off, first.”

He obeyed, still blubbering but evidently struggling to restrain his sobs. Indeed, his privations of the past two days, half starved and hunted like a dog, had completely unnerved the poor fellow. When he had tumbled into the berth I locked the door, put out the light, and rolled myself in my own blanket.

A few moments later I heard Joe stirring. He leaned over the edge of the bunk and murmured:

“God bless you, Sam Steele! I’ll never forget, sir, the way you——”

“Oh, shut up and go to sleep, Joe,” I cried. “You’ve kept me awake long enough already.”

“Yes, sir.” And after that he was silent.

Those who were present at the launching of our beautiful new Seagull were unanimous in declaring her the trimmest, daintiest, most graceful craft that had ever yet floated in the waters of old Chelsea bay. Her color was pure white, her brass work brilliant as gold. She was yacht built, on the lines of the fast express boats, and no expense had been spared in her construction or fittings.

My father, Captain Steele, one of the ablest and best known sailors on the Atlantic coast, had personally supervised the building of the Seagull and watched every step of progress and inspected every bit of timber, steel, or brass, so that nothing might be slighted in any way. She was one hundred and eighty-seven feet in length, with a thirty-six foot beam and a depth of twenty-one feet, and her net tonnage was close to fourteen hundred. We had her schooner rigged, because Captain Steele believed in sailing and had designed his ship for a merchantman of the highest class, but of the old school.

Uncle Naboth and I, who were also part owners of the ship—the firm being Steele, Perkins & Steele—had begged earnestly to convert her into a modern steamer; but my father angrily resented the suggestion.

“Her name’s the Seagull,” he declared, “an’ a seagull without wings ’ud be a doggone jack-rabbit; so wings she mus’ have, my lads, ef Dick Steele’s goin’ to sail her.”

We had really put a fortune into the craft, and Uncle Naboth—a shrewd old trader who marked the world as it moved and tried to keep pace with it—was as anxious to have the ship modern in every respect as I was. So we stood stubbornly side by side and argued with the Captain until he finally granted a partial concession to our wishes and consented to our installing an auxiliary equipment of a screw propeller driven by powerful engines, with the express understanding that they must only be used in case of emergency.

“It’s a rank waste o’ money, an’ takes up vallyble room,” he growled; “but ef so be you ain’t satisfied with decent spars an’ riggin,’ why, git your blarsted ol’ machinery aboard—an’ be hanged to ye both!”

This consent was obtained soon after my return from Panama, but Uncle Naboth and I had ordered the engines months previously, having been determined to install them from the day the Seagull was first planned; so no time was lost in getting them placed.

You will know the Seagull more intimately as my story progresses, so I will avoid a detailed description of it just now, merely adding that the ship was at once the envy and admiration of all beholders and the pride and joy of her three owners.

My father had sailed for forty years and had at one time lost his right leg in a shipwreck, so that he stumped around with a cork substitute. But he was as energetic and active as in his youth, and his vast experience fully justified his reputation as one of the ablest and shrewdest seamen in the merchant service. Indeed, Captain Steele was universally known and respected, and I had good reason to be proud of the bluff old salt who owned me as his son. He had prejudices, it is true, acquired through many strange adventures at sea and in foreign parts; but his heart was simple and frank as that of a child, and we who knew him best and loved him well had little fear of his stubborn temperament.

Naboth Perkins, my dead mother’s brother, was also a remarkable man in his way. He knew the sea as well as did my father, but prided himself on the fact that he “couldn’t navigate a ferry-boat,” having always sailed as supercargo and devoted his talents to trading. He had been one of my earliest and most faithful friends, and although I was still a mere boy at the time the Seagull was launched, I had encountered some unusual adventures in company with quaint, honest Uncle Naboth, and won certain bits of prize money that had proved the foundation of our fortunes.

These prize-winnings, converted into hard cash, had furnished the funds for building our new ship, in which we purposed beginning a conservative, staid career as American merchantmen, leaving adventures behind us and confining ourselves to carrying from port to port such merchandise as might be consigned to our care. You will hear how well our modest intention was fulfilled.

The huge proportions and staunch construction of the Seagull would enable her to sail in any known sea with perfect safety, and long before she was completed we were besieged with proposals from shippers anxious to secure our services.

Uncle Naboth, who handled all such matters for our firm, finally contracted with a big Germantown manufacturer of “Oriental” rugs to carry a load of bales to Syria, consigned to merchants there who would distribute them throughout Persia, Turkey and Egypt, to be sold to American and European tourists and carried to their homes as treasures of Oriental looms.

It was not so much the liberal payment we received as the fact that the long voyage to the Syrian port would give us an opportunity of testing the performances of the Seagull that induced Mr. Perkins to accept the contract and undertake the lengthy voyage.

“If she skims the Atlantic an’ the Mediterranean all right,” said he, “the boat’ll weather any sea on earth; so we may as well find out at the start what she’s good for. ’Sides that, we’re gittin’ a thunderin’ price fer cartin’ them rags to Syria, an’ so the deal seems a good one all ’round.”

My father gravely approved the transaction. He also was eager to test the powers of our beautiful new ship, and this would not be his first voyage to the Orient, by any means. So the papers were made out and signed and as soon as our last fittings and furnishings were installed and our crew aboard we were to voyage down the coast in sunny September weather and anchor in the Chesapeake, there to load our cargo.

Our ship’s company had been carefully selected, for the fame of my father’s new vessel and the popularity of the Captain himself attracted to us the best seamen available; so we had the satisfaction of signing a splendid company of experienced men. In addition to these sailors we shipped a first and second engineer, clever young fellows that became instantly unpopular with my father, who glared at the poor “mechanics” as if he considered them interlopers, if not rank traitors. Some of the seamen, it was arranged, would act as stokers if the engines were called into requisition, so with the addition of a couple of oilers who were also carpenter’s assistants we were satisfied we might at any time steam or sail, as the occasion demanded.

I am sure Captain Steele had already acknowledged in his heart that we were justified in equipping the Seagull with engines, since any old salt fully realizes the horror of being becalmed and knows the loss such a misfortune is sure to entail in time, wages, and grub. But he would not admit it. Instead, he persisted in playing the part of a much injured and greatly scandalized seaman. It would be time enough to “take water” when the value of the propeller was fully proved.

Ned Britton was Captain’s Mate, of course. Ned had sailed with my father for years; he had also sailed two exciting voyages with Uncle Naboth and me, and we all admired and respected this strong, gallant fellow as much as we had come to trust in his ability.

Two other curious characters were established fixtures of any craft that the firm of Steele, Perkins & Steele might own. These were two stalwart black men named Nux and Bryonia, South Sea Islanders whom Uncle Naboth had rescued from death years before and attached to his service. Since then they had become my own trusted friends, and more than once had I owed my life to their intelligence and faithfulness. Bryonia, or Bry, as we called him, was a famous cook, and always had charge of our ship’s galley. With Bry aboard we were never in want of a substantial, well cooked meal; for, as Uncle Naboth was wont to declare: “Thet Bry could take a rope’s end an’ a bit o’ tarpaulin an’ make a Paris tubble-de-hoot out’n ’em.”

Nux was cabin steward and looked after our comforts aft with a deftness and skill that were wholly admirable. These blacks were both of them shrewd, loyal, and brave, and we knew we might always depend upon their fidelity.

On the morning following my adoption of Joe Herring I left the runaway locked up in my stateroom and went on deck to watch the final preparations for our departure. A fair breeze swept down the bay, so at ten o’clock we hoisted anchor, spread our main and foresails and, slowly gathering way, the Seagull slipped through the water on her maiden trip amid the shouts of hundreds who stood on the shore to watch and bid us God speed.

We fired a shot from our small howitzer as a parting salute to our friends, dipped our pennants in gallant fashion, showed our heels, and sped away so swiftly that the harbor was soon left far behind.

We passed the old Gonzales soon after leaving our anchorage. It was still waiting to recapture its absconding cabin-boy, though why Captain Marrow should attach so much importance to the youth I could not then understand.

As soon as we were well at sea I liberated Joe and told him he was to be my special servant and assistant, but must also help Nux to look after the cabin during his spare time—which was likely to be plentiful enough. Knowing that the sooner I established the lad’s footing aboard the easier it would be for us both, I sent him on an errand that would take him past my father’s station on the deck. His sharp eye encountered the boy at once, as I had expected, and he promptly roared out an order for him to halt.

Joe stopped and saluted respectfully. He was looking cheery and bright this morning; indeed, a different boy from the one I had pulled from the sinking dinghy the night before. Life bore a new aspect for Joe and his heart was light as a feather. He looked honest and wholesome enough in the fresh blue suit I had given him, and he had been duly warned that his only remaining danger lay in not winning the countenance of the skipper.

“Who are you? ’N’ where ’n’ thunder’d you come from?” demanded Captain Steele.

“Joe Herring, sir. Master Sam’s assistant, sir,” answered the boy, in his quiet tones.

“Assistant! Bungs an’ barnacles! Assistant to Sam! What doin’? Loafin’ an’ a-killin’ time?”

“I beg to refer you to Master Sam, sir,” was the composed answer, although from where I watched the scene I could see that Joe was badly frightened.

“What Sam needs is suthin’ to do, more ’n a grub-devourin’ assistant,” pursued my father, sternly. “Look here; did my son lug you aboard?”

“He did, sir,” replied Joe, truthfully.

“Send him to me, then,” ordered my father.

I stepped forward at once, saluting the Captain with my usual deference. When we were at sea I had been taught to put by the fact that this was my father, bearing in mind only the immediate fact that he was my commander. Still, in my capacity as secretary to Uncle Naboth I was in a measure independent of ship’s discipline.

“What tricks are you up to now, Sam?” demanded the Captain, scowling at me.

“Father, this boy was the runaway from the Gonzales, whom Captain Marrow has been seeking so earnestly. He was so abused by the dirty Mexican that he would rather die than return to his slavery. So he threw himself on my mercy, and knowing he would surely be retaken if I left him ashore, I brought the lad with us. Don’t blame him, sir. I’ll take all the responsibility.”

The Captain stared at me a moment.

“See that you do, then,” he grumbled. “Sam, it’s a illegal an’ unperfessional act to harbor a runaway.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Usually no good ever comes of it.”

“He’s an honest lad, sir.”

The Captain eyed him closely.

“It’s no affair o’ mine,” he muttered, half turning away. “The boy belongs now to the Perkins outfit, mind you. I’ll have no runaways ner stowaways in my crew.”

I knew then the battle was won, and that my father would refuse to surrender Joe to his old captain under any circumstances. The “Perkins outfit,” so sneeringly referred to, meant Uncle Naboth and myself, and although it was evident the mission of the Seagull was dependent on the “Perkins outfit” to manage and arrange its commerce in a profitable manner, it pleased my father to denominate us landlubbers and consider us of “no ’count” in the sailing of the ship.

Uncle Naboth wasn’t aboard yet. He had gone by rail some days before to Philadelphia to attend to the business of our cargo, and it was not until we anchored in the placid waters of the Chesapeake that my uncle appeared, smiling and cheery as ever.

Mr. Perkins was short and stout, with a round, chubby face, smoothly shaven, and a circle of iron-gray locks around his bald head. His eyes were small, light blue and twinkling; his expression simple and childlike; his speech inelegant and with a humorous twist that rendered him an agreeable companion. But as a trader Naboth Perkins was famed far and wide; his shrewdness was proverbial; his talent for bargaining fairly marvelous; his honesty undisputed. I have heard merchants say it was a pleasure to pay Mr. Perkins his demands, even though they could procure the same service elsewhere at less cost. For he was square as a die, faithful to the smallest detail, and his word was absolutely to be relied upon. The little old gentleman was known as a money-maker, and had been the partner of my father, his brother-in-law, for many years.

Such a character could not fail to be eccentric, and Uncle Naboth’s ways were at time puzzling; but I knew he was devoted to me, since he had proved this quality many times; and I naturally regarded my whimsical uncle with great affection.

When Mr. Perkins came aboard he announced that the bales of rugs were all on the dock and ready to load without delay. I was much interested in our queer cargo, for it seemed strange to me that Americans should ship “Oriental” rugs to the Orient, to be purchased there by Americans and brought back home again. But Uncle Naboth, who had been through the mills at Germantown, explained the matter very clearly.

“You see,” he said, “there ain’t enough genooine Oriental rugs left to supply the demand, now thet they’ve got to be sich a fad with rich people. When the Orient was fust diskivered there was a good many rugs there, but it had took years to make each one of ’em, an’ some was so old they had holes wore in ’em; but that made ’em the more vallyble ’cause it proved they was antiques. They picked ’em up fast, an’ the Orientals was glad to sell ’em an’ say nothin’. Ev’ry tourist thet goes to the East wants to buy rugs to send home, an’ he’ll pay ’most any price that’s asked fer rare ol’ patterns an’ dim, washed-out colors. Ef there’s a few holes, badly mended, so much the better, fer they proves the rugs is old. So the clever Easterners an’ the cleverer Yankees hit on a scheme to supply the demand, an’ here in Germantown they makes thousands of rare ol’ Oriental rugs every year. They buy a few genooine ones to copy the patterns from, an’ they weave ’em by machinery. Then the new rugs is put into a machine that beats dust an’ dirt into ’em an’ beats it out again, till the new, fresh colors gits old an’ faded. After this they’re run through a rubbin’ machine that wears ’em down some an’ makes a few holes, here an’ there; an’ then the menders take ’em an’ darn the holes. In about a day’s time one o’ them rugs goes through about as much wear an’ tear by machinery as it would get in centuries of use; an’ fer my part I can’t tell the diff’rence atween a genooine Oriental an’ a imitation one. We’ve got a whole cargo to take to Syria, an’ in a few months they’ll mostly come back agin, an’ be laid on the floors of our millionaires. Queer traffic, ain’t it, Sam? But if you stops to think, there’s been enough Oriental rugs carted out’n the Orient, in the last hundred years, to carpet most of Asia an’ Africa with; so it stands to reason they ain’t all the real thing. If it wasn’t fer Yankee ingenooity an’ Oriental trickery the supply’d been exhausted years ago, an’ our people’d hev to carpet their floors with honest, fresh rugs instead o’ these machine worn imitations. That would break their hearts, wouldn’t it?”

But Uncle Naboth had arranged also to carry another queer line of merchandise on our voyage, consisting of several large cases consigned by a Connecticut manufacturer. These contained imitations of ancient Egyptian scarabs (a sort of mud beetle considered sacred by the old sun-worshippers), and a collection of funeral figures, tiny household gods and other articles supposed to be found only in the tombs of the primitive kings and nobles of Egypt.

“The Egyptian gov’ment,” explained Uncle Naboth, “won’t let any more genooine relics be taken out’n the country, ’cause they wants ’em all fer the Cairo Museum; so the Yankees hev come to the front agin, an’ made mud relics by the bushel, so’s the eager tourists can buy what they wants to bring home an’ prove they’ve been there. These cases o’ goods is consigned to merchants in Luxor, a little town up the Nile, an’ I’ve agreed to run over to Alexandria, after we’ve unloaded our Syrian rugs, an’ dump the rubbish on the dock there. There ain’t many cases of it, but the profits is so big that we get well paid for the job.”

“But how did these wares get to Philadelphia from Connecticut?” asked my father.

“Oh, I’ve been correspondin’ with ol’ Ackley, the Yankee that makes ’em, fer some time,” said my uncle, “but I couldn’t tell how much room the rugs would take up until I got here. When I found I could stow the Egyptian rubbish, I telegraphed to Ackley an’ the consignment got here by freight yesterday. But that ain’t the worst of it, partners.”

“What is the worst?” I inquired.

“Why, the Yankee manufacturer has sent me his beloved son, with a letter askin’ me to carry him with us to Egypt, so’s he can study the country an’ find out what ancient relics they need supplied in large quantities, an’ collect from the dealers fer this first batch.”

“We don’t take passengers,” said my father, sharply.

“So I said; but the young duffer is here, an’ won’t take no fer an answer. He says he’s willin to pay fer his passage, an’ his dad wants him to keep an eye on them precious modern antiquities as we’re to carry. So I’ve put the case up to you, an’ you can decide it.”

“It’s none o’ my business, Naboth,” said my father, turning away with a frown; “I don’t like passengers, but you an’ Sam can do as you please. Only, if you take him, keep him out o’ my way.”

Uncle winked at me, and I knew the passenger would be booked.

Work of loading the cargo progressed rapidly, and in two days the bales of rugs were all aboard and carefully stowed in our dry and ample hold. Then the Yankee antiques for Egypt appeared for loading, and with them came a youth whose appearance caused me to smile involuntarily.

“Archibald Ackley, Jr., Middletown, Conn.,” his cards read. He was a stocky, well built fellow about seventeen years of age, although he evidently wished to appear much older. He had sharp gray eyes, lanky hair of light tow color, immense hands and feet, a swaggering gait, and a style of dress gay enough to rival the plumage of a bird-of-paradise.

Archibald’s features might have been handsome originally, but a swiftly pitched base-ball had once ruthlessly pushed his generous nose against his left cheek, and there it had remained.

The youth sported a heavy watchchain that was palpably plated, a big “diamond” on his cravat that perhaps came from the famous “Barrios mines,” of New York, and his fingers were loaded with rings of vast proportions set with doubtful gems. It may be Mr. Ackley, Jr., imagined himself an exquisite, and sought to impress people by a display of wealth that may have cost him or his father several dollars; but, as I said, my first glimpse of his gorgeous person caused me to smile—an impertinence I quickly tried to repress.

Mr. Perkins and I considered carefully the young man’s request for a passage to Egypt, and as we had ample accommodations we decided to take him along; but when he came for his answer and I caught sight of him for the first time, I almost regretted our decision.

Uncle Naboth, however, seemed not to be disagreeably impressed. He shook the boy’s hand—it was a “flipper,” all right—with cordial greeting and said to him:

“Very good, Archie, my lad; we’ve talked it over an’ you can go ’long ef so be you want to. But remember this is a merchantman, an’ no passenger ship, an’ make up your mind to abide by Cap’n Steele’s rules an’ reggleations.”

“That’s fair,” said the boy, evidently pleased. “I’m not likely to bother any one. All I want is a berth to sleep in and three square meals a day. How’s the feed?”

“Why, we have hearty appetites, ourselves, my lad, an’ there’s no call for you to starve as I knows on,” with a wink at me. “You’ll eat at our table an’ have the best the ship affords.”

“That’s what I want,” said Archie, nodding his bullet head; “there’s nothing too good for me. What’s the price for the passage?”

I told him.

“That’s a pretty steep figure,” he rejoined, uneasily. “I can take an ocean liner for about the same cost.”

“It is your privilege, sir,” I said, stiffly. “We don’t want passengers; so we don’t want you. But Mr. Perkins is disposed to accommodate you because your father is one of our shippers. Go or stay, as you like; but make up your mind quickly, for we sail at seven.”

He scowled first at me and then at uncle; but presently he grinned.

“I haven’t a choice,” said he, carelessly. “Pop’s paying the shot, for he wants me to keep an eye on the scarabs and things and see the goods safe landed and the money collected for them. They’re shipped to a lot of dirty Arabs who can’t be trusted. So here’s your money, and I’ll mail the receipt for the passage to Pop before we skate away, so he’ll know it’s you who are robbing him instead of me.”

I felt like punching the cad’s nose, but Uncle Naboth laughed good naturedly and nodded approval.

“That’s businesslike an’ to the point,” said he. “Take the money, Sam, and give our passenger the proper receipt.”

I did so, and Archibald Ackley, Jr., stalked away down the dock to fetch his baggage from the hotel.

To my surprise the Gonzales made the harbor that afternoon and anchored alongside us. I promptly hid the trembling Joe in my cabin and locked him up; it proved a wise action because Captain Marrow lost no time in boarding us and asking for an interview with Captain Steele.

This made me nervous, for I knew my father would not lie under any circumstances, and I dreaded the result of the ugly Mexican’s visit. So I stood beside my father to make every possible endeavor to save my protege from recapture.

“Cap’n Steele, sir, where’s my cabin-boy?” asked Marrow, gruffly, as he came up and touched his cap.

My father looked him over with grave attention.

“Cap’n Marrow,” he replied, sternly, “where’s that calf that broke out’n my ten-acre lot three year ago come next Sunday?”

Marrow muttered a curse and glared at us evilly.

“I happen to know, Steele, that my boy Joe, who was tryin’ to vamoose, stole a rotten dinghy an’ rowed out to the Seagull the night afore you sailed. Ain’t thet so?”

“Mebbe,” said my father.

“Then I demand him in the name o’ the law, an’ I’ll hold you here in the bay till you give me back the stolen goods,” continued Marrow, savagely.

“Ned,” said my father, turning quietly to his brawny mate, “show Cap’n Marrow over the side, an’ if he’s too slow in goin’, toss him overboard.”

“Aye, aye, sir,” returned Ned, pleasantly.

“I’ll hev the law, remember! You can’t sail from the harbor till you’ve given up my property!” roared the exasperated Mexican.

“Mebbe,” repeated my father, again, as he turned indifferently away.

But I saw trouble brewing and resolved to head it off.

“Captain Marrow,” I said, politely, with a motion to Ned to delay his intention, for the mate’s hand was lifted to seize the fellow in his terrible grip, “please allow me to explain this case. A boy—perhaps it was your runaway—did indeed board us at Chelsea, as you say; but my father, Captain Steele, did not discover his presence until we were at sea. Then we were obliged to carry him on here, where he was put upon the dock. I assure you I saw him bolt for the land as fast as he could go.”

This was true in fact, as I had sent Joe on an errand. I did not relate, of course, that the boy had quickly returned, but my tale seemed to impress Marrow and explain why Captain Steele had so recklessly sneered at his demands, as if wilfully defying the marine law. “If you make haste, sir,” I continued, very courteously, “you may still be able to lay hands on the boy, who I am sure has no money to take him any distance from Philadelphia.”

Marrow looked at me shrewdly.

“Did Joe say anything about me, or about money?” he asked.

“Not a word, sir,” answering the last question. “But I advise you to make haste. And you must forgive Captain Steele for his abrupt answers, caused by what he considered the insolence of your demand and the knowledge that you are in the wrong in threatening to hold his ship. You know, sir, it would cost you heavily to do this, when the court found you were unable to prove your case.”

This argument decided the man. He swore a nasty oath and stamped his foot in futile rage; but he at once left the ship to be rowed ashore, and that was the last we saw of him.

Still I wondered at his interest in the miserable, half starved boy he had so wickedly abused; and I wondered at his strange question about money. There must be some mystery about Joe.

At seven o’clock, all being snugly stowed and the last of our fresh provisions taken aboard, we hoisted anchor and headed out toward the mouth of the bay. Our passenger had settled himself in a spare cabin an hour before, having brought with him two huge “telescopes” that appeared to contain all his belongings.

I did not let Joe out of his confinement until about midnight, and when from the swish of the water against our sides I knew we had reached the open sea.

It is useless to relate the unimportant incidents of our voyage to Gibraltar and up the Mediterranean. The Seagull behaved beautifully in both good and bad weather, amply fulfilling our most ardent expectations. It is true the voyage was unnecessarily long, since with our powerful engines we could have cut down our time to less than one-half; but we were obliged to concede this to Captain Steele’s prejudice in favor of sailing, and the breeze held so steady and persistent that we cut the waves like a clipper and made a most remarkable sailing record for the voyage.

It was not until we passed Sicily that the Seagull was required to prove her staunchness. The waves at the lower end of the Mediterranean were wilder than any I had ever before encountered, but our beauty rode them like a swan and never a seam spread nor a beam so much as creaked.

The voyage, however, served to make us better acquainted with both our boy passenger and my boy assistant—the rich man’s son and the runaway Joseph—though this acquaintance was not ripened without some interesting experiences.

A more willing or grateful follower no one could have than Joe Herring. The kindly treatment accorded him was in such sharp contrast to the dog’s life he had led aboard the Gonzales that he was anxious to show his appreciation on every possible occasion. His dark eyes followed me affectionately wherever I went, and he would leap quickly to anticipate my every order. Also he liked to serve Uncle Naboth and my father, and proved so considerate of their wishes and comforts that he soon won their hearts completely. Nor was Joe so frail as he seemed at first glance. His muscles were hard as iron and on occasion his thin frame developed remarkable strength. This he proved conclusively within the first week of the voyage, as you shall hear.

Our young passenger, whose imposing name we had quickly shortened to plain “Archie,” seemed likely to cause us unsuspected trouble. He at once developed two bad habits. The first was to sit on deck, lolling in a folding deck chair he had brought aboard, and play distressing tunes upon a harmonica—which he termed a “mouth-organ.” The lad must have had a most powerful inherent love for music to enable him to listen to his own awful strains; but it was clear his musical talent was not developed, or at least not properly educated to any artistic degree.

The first morning out the Captain, forced to listen to this “music,” scowled and muttered under his breath but forbore to interfere with the passenger’s evident enjoyment of his own performance. The second morning he yelled at Archie to “shut up!” but the boy calmly disregarded the order. The third morning my father stumped over to where I sat and ordered me to take away Archie’s “blamed ol’ jew’s-harp” and fling it overboard.

I had myself been considerably annoyed by the wretched music, so I obeyed so far as to stroll over to our passenger and ask him to kindly discontinue his performance.

He looked up resentfully.

“This is the passenger’s deck, ain’t it?” he demanded.

“We have no passenger’s deck; but we allow you to sit here,” I replied.

“Then leave me alone, and mind your own business,” he retorted. “I’m a free born American citizen, and I’ve paid my passage and can do as I please.”

“But you can’t annoy everybody with that beastly music while you’re aboard the Seagull,” I answered, rather nettled at his attitude. “We also have rights, sir, and they must be considered.”

“I’ve paid for mine,” he said. “You get out, Sam Steele. I know what I’m doing,” and he commenced to play again.

I looked at him reflectively. Just how to handle such a situation puzzled me. But Joe stood just behind and had heard all. With a bound of amazing quickness he was upon the unprepared Archie, seized the mouth-organ from his grasp and flung the instrument of torture far over the side.

“Beg your pardon, sir, I’m sure,” he said, with a grin.

Archie whistled softly and looked his assailant over. He rose slowly from his chair and, still whistling, began to unbutton his coat and take it off. He folded it neatly, laid it in the chair, removed his linen cuffs and placed them beside his coat, and proceeded deliberately to roll up his sleeves.

The youth’s intentions were so obvious that I was about to order Joe to go below, as his slight figure seemed no match for the burly Archie, when a pleading look in the boy’s eyes restrained me.

Uncle Naboth and Ned Britton, who had been promenading the deck near, had noted the incident and now paused to see its outcome. Some of the sailors also were interested, from their distant posts, while my father stood on the bridge and looked at our little group with an amused smile lighting his rugged face.

Altogether it would not do to retreat in face of the coming fray, or to interfere with the logical outcome of Joe’s rash act. The Yankee boy’s face was white and set, and his soft whistle only rendered his bull-headed determination to exact revenge the more impressive.

Having rolled up his sleeves, doubled his great fists and swung his arms once or twice to ease his muscles, Archie advanced steadily upon poor Joe, who stood listlessly with his hands thrust in his coat pockets and his head and shoulders bent slightly forward, in his accustomed pose.

“That mouth-organ cost two dollars,” said Archie, grimly, “and you don’t look as if you’re worth two cents. So I’ll just take it out o’ your hide, my son, to teach you a lesson.”

With that he paused and swung his right fist upward, and Joe, roused to action at last, gave a sudden bound. My eye could scarcely follow him as he leapt at Archie, embracing him and clinging to his antagonist like a vise. To my astonishment, the bulky Yankee swung around, tottered and fell heavily upon his back, with Joe kneeling triumphant upon his breast.

We all gave an admiring cheer, for we could not help it, and at the sound Joe arose and stood in his place again, meekly as before.

Archie got up more slowly, feeling the back of his head, which had whacked against the deck. He made a sudden rush and a lunge with his fist that might have settled Joe had he not dodged and closed again on his adversary with the same lightning tactics he had at first employed. They fell in a heap, and although Archie tried to keep Joe hugged to his breast the latter slid away like an eel and a moment after was on his feet and had assumed his careless, waiting pose.

When the Yankee got up this time he was again softly whistling. Without a glance at his late antagonist he deliberately rolled down his sleeves, attached his cuffs and resumed his coat. Then he walked over to Joe and with a smile that showed more good nature than chagrin he held out his bulky hand.

“Shake, sonny,” said he. “You’re good stuff, and I forgive you everything. Let’s be chums, Joe. If I could have landed on your jaw I’d have mashed you like a turnip; but you wouldn’t let me, and so I’m bound to give in gracefully.”

That speech was the best thing the boy had done, and my original dislike for him began to evaporate. Joe shook the proffered hand cordially, and my father, who had come down to join our group, gave Archie an admiring buffet on the shoulder and said: “You’ll do, my lad.”

But after all Joe was the hero of the occasion, and we all loved him for the clever and skillful fight he had put up. Archie was an expert boxer, as we afterward discovered, but Joe’s talent for wrestling gave him a decided advantage in a rough-and-tumble encounter.

At luncheon we were all in a hearty good humor, but imagine my dismay to hear shortly afterward the strains of a mouth-organ coming from the deck! I ran up at once, and there sat Master Archie in his chair, blowing furiously into an instrument fully three inches longer than the one Joe had tossed overboard.

I laughed; I could not help it; and even my father’s face wore an amused smile. Joe looked at me inquiringly, but I shook my head and retreated to my cabin. Such a queer condition of mutiny deserved careful thought.

But, as I said, Archie had another bad habit. He smoked cigarettes in his stateroom, which was against our most positive rules. The first time we observed from the deck thin smoke curling through the open window of Archie’s cabin, a hasty investigation was made and the cause speedily discovered. The boy was lying in his berth, reading a novel and coolly puffing his cigarette.

Uncle Naboth sent for the passenger and gravely informed him he’d have to quit smoking cigarettes in his cabin.

“On deck it don’t matter so much,” added my uncle, “though a decent pipe is a more manly smoke, to my notion. But we’ve put a furtun’ into our new ship, an’ can’t afford to take chances of burnin’ her up on the first voyage. Cigarettes are dangerous. If you throw a lighted stub into a corner we may go up in smoke and perhaps lose many vallyble human lives. So we can’t allow it, young man. Smoke yer paper cigars on deck, ef ye want to; but don’t light another in yer cabin.”

Archie made no promise. He listened to my uncle’s lecture, and walked away without a word.

An hour later I saw smoke coming through the window again, and peering through the aperture discovered Archie lying in his bunk, calmly smoking. The boy was exasperatingly stubborn. I called black Nux and gave him an order. With a pleased grin the South Sea Islander brought a length of fire hose, attached it to a plug in the sruppers and carried the nozzle to Archie’s window. Presently we heard a yell as the powerful stream struck the smoker and completely deluged him. He leapt from his berth, only to be struck full in the face by the water from the hose, which sent him reeling against the door. I shut off the water, and Nux, kneeling at the low window, looked down on the discomfitted Archie and exclaimed:

“Goodness sake, Mars Ackley! were dat on’y you-uns? Thought it were a fire, sure thing. Beg pard’n, Mars Ackley!”

After the boy changed his drenched clothing for dry he came on deck and stalked around in silent anger while Nux went to the cabin and cleared it of the water and wet bedding. I wondered if the lesson would be effective, but could not judge a nature that was so unlike any I had ever before encountered.

Bye-and-bye Archie calmed down sufficiently to drop into his deck chair and begin playing his mouth-organ. He wailed out the most distressing attempts at tunes for an entire hour, eyeing defiantly any who chanced to look toward him; but we took care not to pay the slightest attention to his impertinence. Joe came to me once with a pleading look in his eye, but I shook my head sternly. The sailors were evidently amused by our little comedy forward, for I could see them exchanging smiles now and then when a screech more blood-curdling than usual came from the mouth-organ.

Archie tired himself out in time and went below. He closed and locked his window and began again to smoke in his cabin. In half an hour the smoke was so thick in the little room that we could see nothing but its gray clouds through the thick pane.

The set frown upon my father’s face told me trouble was brewing for our passenger, but as yet the Captain forbore to interfere. Uncle Naboth came to me indignant and angry and demanded to know what should be done to the “young pig” whose actions were so insolent and annoying.

“Let me think,” I replied, gravely. “We must certainly conquer young Ackley in some way, even if we have to toss him overboard; but I hope it will not come to that.”

“Then think quick an’ to the point, Sam,” rejoined my uncle; “for I’m jest achin’ to wollop the fool wi’ a cat-o’-nine-tails.”

At dinner Archie joined our table, silent but with a sneering and triumphant look upon his face. He was not handsome at any time, but just now his damaged face was positively disagreeable to behold. It occurred to me that the trouble with the young fellow was that he had not been taught to obey, and doubtless he imagined we were his enemies because we were endeavoring to prevent him from doing exactly what he wanted to. His idea of being a “free-born American citizen” was to be able to override the rights and privileges of others, and the sooner he got that notion out of his head the better it would be for him.

Archie was a deliberate eater and remained at the table with a sort of bravado because we took not the slightest notice of him. So I left him finishing his meal when I went on deck.

A few minutes afterward, however, he came bounding up the companionway with a white face and rushed up to where Uncle Naboth and I were standing.

“I’ve been robbed!” he cried, shaking his big fist at me. “My cabin’s been entered by a thief, and I’ll have the law on you all if you don’t restore my property!”

“What have you lost?” I inquired.

“You know well enough, Sam Steele. I’ve lost all my cigarettes—ev’ry box of ’em!—and my four mouth-organs, too. They picked the lock on my door, and opened my telescopes, and stole my property.”

“How’s this, Sam?” inquired Uncle Naboth, his eyes twinkling.

“I don’t know, sir,” I answered, greatly surprised. “There are no duplicate keys to the cabin doors, and Ackley had his in his pocket, I suppose.”

“They picked the lock, I tell you, and the locks on both my traveling cases,” declared the boy, in a rage; “and you must be a fine bunch of practiced thieves, because they were all locked again after the goods were stolen.”

“How about your window?” I asked.

“I left it bolted on the inside. No one could enter that way.”

“Did you lose anything except the cigarettes and the mouth-organs?” I continued, beginning to be greatly amused.

“No; but those things are my property, and you or your people have stolen them. Look here, Sam Steele,” he added, coming close and shaking his fist threateningly; “either you return my property in double quick time or I’ll take it out of your hide. Just make your choice, for I mean business.”

I think he saw that I was not afraid of him, but I chose to ignore his challenge. I was neither as clever a wrestler as Joe Herring nor as expert with my fists as Archie Ackley; so it would be folly for me to undertake a personal encounter. But I said, quietly enough:

“You are getting insolent, my lad, and insolence I will not stand for. Unless you control your temper I will order you to the ship’s lockup, and there you shall stay until we drop anchor again.”

He gazed into my face long and steadily, and then began to whistle softly as he turned and walked away. But a few moments later he returned and said:

“Who’s going to make good my loss?”

“Send me your bill,” replied Uncle Naboth. “I’ll pay it.”

“I think Joe stole the things,” continued Archie.

I called Joe to us.

“Did you enter Ackley’s cabin and take his cigarettes and mouth-organs?” Uncle Naboth inquired.

“No,” said Joe, looking at Archie and laughing at his angry expression.

“Do you know who did it?” persisted my Uncle.

“No,” said Joe, again.

“He’s lying!” cried Archie, indignantly.

“Are you lying, Joe?” I asked, gently.

“Yes, sir,” returned Joe, touching his cap.

“Then tell the truth,” said I.

“I won’t, sir,” replied the boy, firmly. “If you question me, I’m bound to lie; so it will be better to let me alone.”

This answer surprised and annoyed me, but Uncle Naboth laughed aloud, and to my astonishment Archie frankly joined him, without a trace of his recent ill-nature.

“Just as I thought,” he observed. “You’re a slick one, Joe.”

“I try to do my duty,” answered Joe, modestly.

“Bring me your bill, young feller,” said Uncle Naboth, “and I’ll cash it in a jiffy—an’ with joy, too. I don’t see jest how Joe managed the affair, but he’s saved us all a lot of trouble, an’ I’m much obleeged to him, fer my part.” And the old gentleman walked away with a cheerful nod.

“Uncle’s right,” I said to Archie. “You wouldn’t be reasonable, you know, and we were simply obliged to maintain our ship’s discipline. So, if your offending goods hadn’t been abstracted so cleverly, there would have been open war by another day and our side was the strongest.”

Archie nodded forgivingly toward Joe.

“Perhaps it was best,” he admitted, with more generosity than I had expected from him. “You see, Steele, I won’t be bulldozed or browbeaten by a lot of cheap skates who happen to own a ship, for I’m an independent American citizen. So I had to hold out as long as I could.”

“You were wrong in that,” I remarked.

“Right or wrong, I’ll hold my own.”

“That’s a bad philosophy, Archie. When you took passage aboard this ship you made yourself subject to our rules and regulations, and in all honesty you’re bound to abide by them. A true American shows his independence best by upholding the laws of his country.”

“That’s rot,” growled Archie, but Joe and I both laughed at him because he could find nothing better to say. When he returned to his deck chair the passenger’s face bore its normal expression of placid good nature. It was evident he prided himself on the fact that he had not “given in” of his own accord, and perhaps he was glad that the force of circumstances alone had conquered his stubborn temper.

After that we had little trouble with Archie Ackley, although in many ways the stubborn nature of the boy was unpleasantly evident. In his better moods he was an agreeable companion, but neither Joe nor I, the only two other boys aboard, sought his society more than was necessary. My uncle and the Captain both declared there was a heap of good in the lad, and a few such lessons as the one he had received would make a man of him.

Joe I found a treasure in many ways, and always a faithful friend. Since that first night when he had come aboard he had nothing to tell of his past history or experiences; but his nature was quick and observant and I could see he had picked up somewhere a considerable fund of worldly knowledge which he could draw upon as occasion offered.

My father, Uncle Naboth, and I were all three delighted with the Seagull’s sailing performances, though secretly I longed to discover how she would behave under steam, since her propeller had never been in use since the day it was given a brief trial test in Chelsea Bay. Tomlinson, the engineer, assured me we could make from sixteen to eighteen knots when the engines were working, and the man was naturally as impatient as I was to test their full powers. Still, we realized that we must wait, and Captain Steele was so delighted with the superb sailing qualities of the ship that even I had not the heart to suggest supplanting his white wings with black smoke from our funnels.

In due time we crossed the stormy Mediterranean and reached in safety our Syrian port, where we unloaded the rugs and delivered them in good condition to the consignees. We sailed along the coast, past Port Said, and finally came to the Bay of Alexandria, where we were to unload Ackley’s cases of “modern antiques” and get rid of our passenger.

It was a new experience to me to find myself on the historic shores of Egypt, anchored before the famous city founded by Alexander the Great. I begged Uncle Naboth to take me ashore; overhearing my request Archie Ackley invited us all—with an air of great condescension—to dine with him at the Royal Khedivial Hotel.

My father refused. He was too fond of the Seagull to leave her alone in a foreign port; but Ned Britton took his place, and the four of us—Archie, Uncle Naboth, the Mate and I—followed by our faithful blacks, Nux and Bryonia, disembarked on the quay and walked up the long, foreign-looking streets to the big hotel.

It was a queer sensation to find ourselves moving amidst a throng of long-robed turbaned Arabs; fez-topped Turks, with Frenchmen, and Syrians; gray-bearded, stooping Jews; blind beggars; red-coated English soldiers, and shrinking, veiled Moslem women.

“What a mess of foreigners,” cried Archie, and Uncle Naboth, with a laugh, reminded him that we were the foreigners and this curiously mixed crowd, the natives.

We dined in sumptuous style at the handsome hotel, for Archie proved a liberal host and feasted us royally. It was late at night when we retraced our steps toward the quay; but the streets of the city were still thronged with people, many of whom were sitting at little tables placed on the sidewalks, where they smoked and drank Turkish coffee and chatted together in a very babel of tongues.

As we left the heart of Alexandria and drew near to the water-front the streets became more deserted and the lights were fewer and dimmer. There were still straggling groups here and there, and suddenly, as we turned a corner, we observed a commotion just ahead of us and heard a terrified voice cry out:

“Help—Americans—help!”

Ned Britton gave a bound and was in the thick of the melée at once. Archie was only a step behind him and I saw his big fists swinging right and left in fast and furious fashion, while Joe ducked his head and tossed a tall Arab over his shoulder with marvelous ease. Nux and Bryonia took a hand, and while none of our party was armed, the free use of their terrible fists wrought such havoc among the long-gowned Arabs that the result of the skirmish was not long in doubt. Like a mist they faded away and escaped into the night, leaving a little man wriggling and moaning upon the ground as if in deathly agony. I held fast to my left arm, which had been slashed by a knife and was bleeding profusely, while I stared around in surprise at our easy victory. Uncle Naboth had not taken part in the fray, but now appeared seated calmly upon the prostrate form of the Arab whom Joe had vanquished, and his two hundred and odd pounds rendered the prisoner fairly secure.

Our blacks raised the little man to his feet, where he ceased squirming but stood weakly leaning against Nux and trembling like a leaf.

“Are you hurt, sir?” asked Ned.

The stranger shook his head. It was so dark in this spot that we could not distinguish his features very clearly.

“I—I think not,” he gasped. “But they nearly had me, that time. If you hadn’t come up as you did, I—I——”

He broke off abruptly and leaned over to peer at the Arab Uncle Naboth was sitting upon.

“That’s him! That’s Abdul Hashim himself! Kill him—kill him quick, some one!” he yelled, in a sudden frenzy.

The cry seemed to rouse the Arab to life. Like an eel he twisted, and Uncle Naboth slid off his back and bumped upon the sidewalk. The next moment we Americans were alone, for Abdul Hashim had saved his bacon by vanishing instantly.

“Oh, why—why did you let him go?” wailed the little man, covering his face with his hands. “He’ll get me again, some day—he’s sure to get me again!”

“Never mind that,” said Ned, gruffly, for we were all disgusted at this exhibition of the fellow’s unmanly weakness. “You can thank God you’re out of his clutches this time.”

“I do, sir—I do, indeed!” was the reply. “But don’t leave me just now, I beg of you.”

We looked at Uncle Naboth for advice. Bry had slit my sleeve with his pocketknife and was binding a handkerchief tightly around my wound, for he was something of a surgeon as well as a cook.

“We’re going aboard our ship,” said my uncle, shortly. “You’re welcome to come along, my man, an’ stay till mornin’.”

The stranger accepted the invitation with alacrity and we started again for the quay, which was reached without farther incident. Our boat was waiting and we were soon rowed where the Seagull was anchored and climbed aboard.

Under the clear light of the cabin lamp we looked at the person we had rescued with natural curiosity, to find a slender man, with stooping shoulders, a red Van Dyke beard, bald head and small eyes covered with big spectacles. He was about forty years of age, wore European clothes somewhat threadbare and faded in color, and his general appearance was one of seedy respectability.

“Gentlemen,” said he, sitting in an easy chair and facing the attentive group before him, “I am Professor Peter Pericles Van Dorn, of the University of Milwaukee.”

I had never heard of such a university; but then, Milwaukee is a good way inland. Neither had any of us before heard the name so unctuously announced; though we were too polite to say so, and merely nodded.

“It will please me,” continued the Professor, “to be informed of your station and the business that has brought you to Egypt.”

My uncle laughed and looked at me quizzically, as if inviting me to satisfy the stranger. Captain Steele scowled, resenting the implied impertinence. The only others present were Archie and Ned Britton.

I told Van Dorn we were a merchant ship from Boston, and had casually touched at the port of Alexandria to unload some wares belonging to Mr. Ackley, who was going to ship his property to Luxor and deliver it to merchants there.

“What sort of wares?” demanded the stranger.

“Scarabs, funeral figures, and copies of antique jewelry,” replied Archie, a bit uneasily.

“The curse of the country,” snapped the little man, scornfully. “There ought to be a law to prevent such rubbish being shipped into Egypt—except,” pausing to continue with a touch of bitterness, “that there are too many laws in this beastly country already.”

“The poor tourists must have scarabs to take home with them,” said Archie, with a grin. “About fifteen thousand travelers come to Egypt every year, and your Khedive won’t let any genuine scarabs leave Egypt.”

“Don’t call him my Khedive, sir!” cried the little professor. “I detest—I hate the government here, and everything connected with it. But you are not interested in that. Gentlemen,” assuming a pompous tone, “I am glad to meet you. You have arrived in the very nick of time to save me from assassination, or at least from utter failure in my great work. I am sure it was an All-wise Providence that directed you to stop at Alexandria.”

“Disguised as old Ackley’s mud scarabs,” added my uncle, dryly.

“And what are your future plans?” inquired the Professor, eagerly.

“To return to America at once,” I replied.

“No! A thousand times no!” shouted little Van Dorn, banging his fist on the table, “I charter you from this minute. I engage this ship—at your own price—to transport me and my treasure to New York!”

“Treasure!” we exclaimed, incredulously.

The Professor glanced around and lowered his voice.

“The greatest treasure, gentlemen, that has ever been discovered in Egypt. I have found the place where the priests of Karnak and Luxor hid their vast wealth at the invasion of Cambyses the Persian.”

He paused impressively. My father looked at his watch and Uncle Naboth yawned. For myself, I should have liked to hear more, but my wound was paining me and Bry awaited my coming to dress it properly. So I said to our guest:

“If you please, Professor, we will hear your story in the morning. It is now late, and we are all longing for our berths. So we will bid you good-night and wish you pleasant dreams.”

He glared at me indignantly.

“Can you sleep after what I have told you?” he demanded.

“I hope so, sir,” I replied, and turned away to call Joe to show the man to his room. He made no farther protest, but going away and looking rather thoughtful.

Bry found that the knife had merely inflicted a flesh wound on my arm, and promised it would give me little trouble. The bleeding had stopped, so my black surgeon washed the cut thoroughly, bandaged and plastered it quite professionally, and sent me to bed to sleep soundly until morning.

Really, I forgot all about the Professor, who looked the part of a savant much better than he acted it, it seemed to me.

At breakfast Professor Van Dorn was silent and preöccupied, and as soon as the meal was over asked for a private interview with the person in authority aboard the Seagull. We went to the Captain’s room, a large cabin where all could be comfortably seated. None of us had much confidence in the stranger’s romantic assertions of the night before, but we were all curious to know what tale the man had to relate, and were disposed to listen. Archie’s eyes bunged out so far from his round face that I took pity on the boy and asked him to join us. Ned Britton came, too, for he had been present at Van Dorn’s rescue and we trusted him implicitly.

When we were seated and the Professor had assured himself we could not be overheard, he at once asked permission to relate the business that had brought him to Egypt and the strange experiences he had encountered here. We told him to fire away and we would hear his story.

“Gentlemen,” said he, “you must know that I hold the honorable chair of Egyptology in my university. Since my youth I have studied arduously the history of this most ancient people, from whom sprung the modern civilization of which we boast today.” He spoke pedantically, and I began to think he might be a real professor, after all. “To perfect my studies my college generously sent me here, three years ago, and soon after my arrival I became acquainted with Professor John Lovelace, whose famous works on ancient Egypt you have doubtless read.”

We had not read them, but we let the assertion pass.

“Over here,” continued the narrator, “he was usually called Lovelace Pasha, but he was not entitled to the distinction except in the imagination of the natives, who had a high respect for his intelligence and industry. At the time we met Lovelace he was searching diligently but secretly for a vast treasure, and he took me into his confidence and engaged me to assist him. You must know that in the sixth century before Christ Egypt was at its height of wealth and greatness; and the most important treasures were at that time in the possession of the priests of the great temple of Karnak. They consisted of wonderful gems, countless jewels and ornaments of gold and silver and, above all, a library of papyrus rolls relating the history of Egypt during that now unknown period between the sixth and twelfth dynasties.

“At this time, when the Egyptians had grown as proud and insolent as they were wealthy, that terrible Persian, Cambyses, invaded the country with a conquering host and steadily advanced up the Nile toward Karnak and Thebes, laying waste the country as he came and despoiling the temples of their wealth. The legends say that the priests of Karnak, terror stricken, threw all their treasure into the Sacred Lake which adjoins their temple, in order to keep it from falling into the hands of the invader; and, as the lake is bottomless, the treasure has never yet been recovered.

“Now, sirs, Professor Lovelace, a shrewd and far-seeing man, doubted the truth of this story. It was an undeniable fact that the great treasure of Karnak was hidden somewhere by the priests, and that Cambyses put all the holy men to the sword because they would not reveal their secret. Also it is historical that the treasure has not since been discovered, and that the conqueror was unable to lay hands upon it after all his efforts to do so. During the centuries that have passed the Sacred Lake has been dragged many times, with the hope of finding the immense wealth of Karnak; but it is now known that the quicksands at the bottom of the lake would have swallowed it up instantly, so naturally all these attempts have proved absolute failures.

“My friend Lovelace, pondering on this queer story, came to believe that the wily priests had never thrown their treasure into the lake at all. No one knew better than they that to place it there was to lose it forever; furthermore, the most valuable part of the treasure consisted of the historic papyri—the bark rolls on which the ancient Egyptians inscribed their records. To place these in water would be to destroy them; thus the falsity of the tale was evident. It was clear, my friend decided, that the priests had hidden the treasure somewhere in the desert, near Karnak, where the shifting sands would leave no evidence of the place to betray it to the keen eyes of the Persian. But they spread the report that it had been cast into the lake, so if any traitor might be among the people the truth would not be revealed.

“Since Cambyses put every priest of Karnak to death, in his unreasoning anger, there was none to recover the treasure when the Persian was gone home again, from which Professor Lovelace conjectured that it still lay secure in its original hiding-place.

“But where was that hiding place? That was the question to be solved. For years he sought in the desert without success but with rare patience, and at just about the time I arrived in Egypt he obtained a clue to guide him.

“On one of the ruined temple walls, hidden away in an unimportant corner, is carved a diagram which to an ordinary observer appeared to mean nothing at all. But Lovelace studied it and came to the conclusion that the diagram described the spot where the treasure was hidden. There was a picture of a high arch, called in Egypt a pylon; and through this picture, from one corner diagonally across to another corner, a line was chiseled. This line extended far beyond the pylon, past a group of three pictured palm trees, and then ended in a cross. Do you follow me, gentlemen?” with an eager, nervous glance into our faces.

Uncle Naboth nodded, but he looked bewildered. Archie’s face wore a perfectly blank expression. My father was smoking placidly and looking out of the cabin window. Said I:

“We are not very familiar with Egyptian history, Professor; but I think we catch the drift of your story. Pay out the cable, sir, and we’ll grasp what we can of it.”

He seemed relieved, saying:

“Very well, my boy. Egyptian history is very fascinating, but this is neither the time nor the place for me to instruct you in it. Still, it is necessary that you understand something of the importance of the proposition I am going to make you, and I will be as clear as possible in my descriptions. The arch, or pylon, referred to in the picture, had three square towers, to distinguish it from many others, and after searching long among the ruins of Karnak, which cover many acres, Lovelace Pasha and I found one which, though partly demolished, still had one of the characteristic towers left, with traces of the others. Taking these as our guide we drew an imaginary line from corner to corner, as in the diagram, and taking our compass we started out to follow this imaginary line across the desert. Three miles away we found, to our great joy, the group of palms, very ancient, without doubt, but still standing, and near to these was a small oasis watered by a tiny spring.

“The question now remaining was, how far beyond the three palms was the point marked on the diagram by the cross—the point where the treasure had been buried? We were obliged to work very cautiously, for at this oasis lived a small but fierce tribe of desert Arabs having for their sheik, or ruler, one Abdul Hashim—the same devil who nearly murdered me last night. The Arabs were curious to know what we were after, for they are great thieves and often steal the contents of an ancient tomb after some lucky excavator has discovered it. So we kept our secret from them, until finally they became so angry that they would have driven us away from their neighborhood had not Professor Lovelace secured an order from the Khedive granting him the privilege of excavating and exploring in certain sections of the desert for relics of Egypt’s ancient civilization. The Khedive will always grant these licenses, permitting the explorer to work at his own expense in the interests of science; but when a discovery has been made the laws oblige us to give or sell everything to the National Museum at Cairo, where they pay only the most insignificant prices because there is no other legal way in which one may dispose of ancient treasure or relics.

“But that absurd law did not concern us at the time; what we were eager for was to discover the hidden treasure of Karnak, and to avoid the hostile Arabs we worked mostly during the clear moonlit nights, when all the tribe were asleep. We had sand-augers made, with which we burrowed into the sand to the foundation of rock underneath, striving to find some obstruction to indicate where the treasure was buried. By means of our compass we were enabled to follow a straight line, and we worked slowly and carefully for a distance of five miles beyond the oasis, and then back again, without any definite result. Sometimes we would strike an obstruction and dig down only to find a point of rock or a loose boulder, and the task seemed to me, after a few months, to be endless and impracticable. But Lovelace would not give up. He was positive he was on the right track, and when I declared I had had enough of the job and was going back to Cairo, he became suspicious of me, and threatened to kill me if I deserted him.

“This was my first suspicion that his mind had become unbalanced.

“‘You know too much, Van Dorn, to be permitted to go away and blab my secrets to others,’ he said. I assured him I should keep a closed mouth, but the fellow was so crazy over his idea that he would not trust me. He was a big man, determined and masterful, and I had to obey him whether I wanted to or not. I stuck to the search, though I became afraid of my companion.

“Well, sirs, not to bother you with details which are to you unimportant, I will say that finally, after more than two years of patient search, we chanced upon the treasure. My auger one day stuck in the sand and could not be withdrawn. Digging down we found that the point had plunged into a bronze ring and become fast. Lovelace gave a howl of joy at sight of the ring, for he knew then that our search was ended.

“It was after midnight, with bright stars shining down to light us as we worked. We cleared away the sand to the depth of more than four feet, and found the ring, duly attached to a large block of granite that rested on the rock foundation.”

“Is there a layer of rock under the desert sands, then?” I inquired.

“Yes; in this section of the country,” was the answer. “Archeologists will tell you that originally the earth was covered by a vast table-land of solid rock such as we now call sandstone. The erosion of wind and weather caused bits of this rock to crumble. The simoons caught them and whirled them around, breaking off other particles of rock and crumbling them into sand. As ages passed the sand increased in volume, until now the desert is covered with it to a depth of from two to six feet, and sometimes even more. Often the winds blow this sand into billows, leaving the bare table-land of rock to be seen stretching for miles and miles.

“But to return to my story. The block of granite was heavy, measuring three by six feet on the surface and being more than two feet in thickness. Three bronze rings were imbedded in it, but pry and lift as we would we could not budge the huge stone an inch. It was evident that we must have help, so we covered up the stone again, marked the spot carefully, and went back to the Arab village.

“Next morning Lovelace bargained with the sheik, Abdul Hashim, for the use of two of his men to assist us. Also we were obliged to send to Luxor for four stout staves to use as levers. You may well imagine that all this excited the wonder of the Arabs, and I doubted if Lovelace would be able to keep his secret from them. However, he appeared to attach no importance to this danger, and the next evening we set out for our buried stone, accompanied by our assistants bearing the oaken staves. We quickly dug away the sand and cleared the stone, and then we four used the levers together and by straining our muscles to the utmost managed to lift the huge slab of granite until it stood on edge.

“Underneath was a rock cavity, carefully chiseled out by hand, and at first we saw only a mass of dried reeds brought from the Nile bank. Removing these we came upon heavy layers of rotted cloth, of the kind that was once used in Egypt for wrapping mummies. But after this padding was dragged away the treasure became visible and Lovelace’s hands shook with excitement while he examined it. First there were many rolls of papyrus, carefully swathed in bandages; then several Canopic jars of pure gold, each containing quarts of wonderful pearls, rubies and emeralds; and finally a vast collection of wrought jewelry, gold and silver ornaments, some packed in rude wooden boxes which were old and falling to decay and others scattered loosely over them and filling every crevice.