Title: The Boy Fortune Hunters in the South Seas

Author: L. Frank Baum

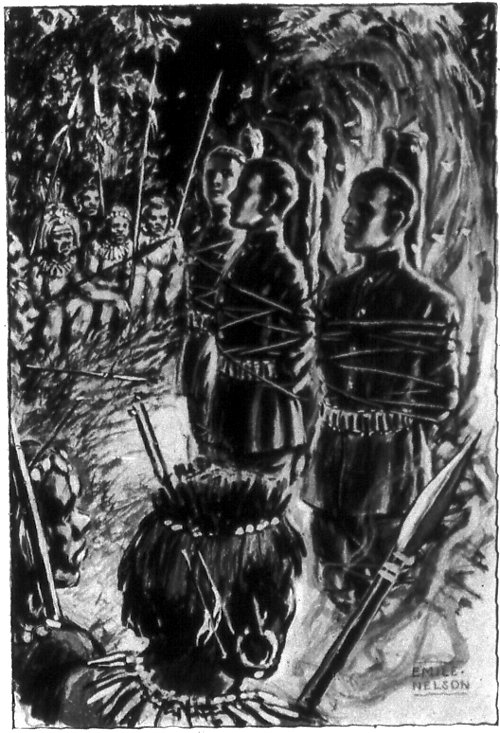

Illustrator: Emile A. Nelson

Release date: October 17, 2017 [eBook #55763]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mary Glenn Krause, MFR, Stephen Hutcheson,

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University

of South Florida and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By

FLOYD AKERS

Author of

The Boy Fortune Hunters in Alaska,

The Boy Fortune Hunters in Panama,

The Boy Fortune Hunters in Egypt,

The Boy Fortune Hunters in China,

and The Boy Fortune Hunters in Yucatan

PUBLISHERS

THE REILLY & BRITTON CO.

CHICAGO

Copyright, 1911

By

The Reilly & Britton Co.

“There’s one thing certain,” said my uncle, Naboth Perkins, banging his fist on the table for emphasis. “If we don’t manage get a cargo in ten days we’ll up anchor an’ quit this bloomin’ island.”

My father the skipper, leaning back in his easy-chair with his legs—one of them cork—stretched upon the table and his pipe in his mouth, nodded assent as he replied:

“Very good.”

“Here it is five weeks since we finished unloadin’ that machinery,” went on Uncle Naboth, “an’ since then the Seagull’s been floatin’ like a swan in the waters o’ Port Phillip an’ lettin’ the barnacles nip her. There ain’t a shipper in Melbourne as’ll give us an ounce o’ cargo; an’ why? Jest because we’re American an’ float the Stars an’ Stripes—that’s why. There’s a deep-seated conspiracy agin American shipping in Australia, an’ what little truck they’ve got to send to America goes in British ships or it don’t go at all.”

Again Captain Steele nodded.

“S’pose we try Adelaide,” suggested big Ned Britton, our first mate.

“That’s jest as bad,” declared Uncle Naboth. “It’s an off season, they say; but the fact is, Australia sends mighty little to the United States, an’ those that ship anything prefer English bottoms to ours. Everything’s been contracted for months ahead, and the only chance the Seagull has of going home freighted is to grab some emergency deal—where time counts—an’ load an’ skip before any Britisher comes into port.”

“Well?” said my father, inquiringly.

“Well, that’s what we’ve been waitin’ for, an’ I’m gettin’ desprit tired o’ the job. So now I’ll give these folks jest ten days to rustle up a cargo for us, an’ if they don’t do it, away we goes in ballast.”

I laughed at his earnestness.

“Why, Uncle Naboth, it won’t hurt us to go home without freight,” said I. “In fact, we’ll make better time, and for my part I see no use in waiting ten days longer for such a ghostly chance.”

“Don’t be foolish, Sam,” returned my uncle, impatiently. “Boys never have any business instincts, anyhow. It’s our business to carry cargoes, so to make the long voyage back home light-waisted is a howlin’ shame—that’s what it is!”

“We were paid so much for the cargo we brought that we can well afford to run home in ballast,” I remarked.

“There you go—jest like a boy. You’ve got a fat bank account, Sam Steele; an’ so hev I; an’ so’s the Cap’n, your father. An’ we three own the Seagull an’ can do as we blame please with her. But business is business, as Shylock says to the lawyers. We’re runnin’ this schooner to make money—not one way, but both ways—an’ our business is to see that every league she travels counts in dollars an’ cents. Nice merchantmen we’d be to float off home in ballast, jest ’cause we got a big lump fer bringin’ a load of farm machinery here; wouldn’t we, now?”

“Oh, I don’t object to your trying for a cargo, Uncle Naboth. That’s your part of the business, and if any man could make a contract you can do so; but I see no use in getting annoyed or worried in case we find it impossible to secure a consignment of freight.”

Uncle Naboth smiled grimly.

“I ain’t worried, Sam,” he said more mildly. “I’m only tellin’ you an’ the Cap’n what my sentiments is.”

We were seated in our pleasant sitting-room at the Radley Arms, one of the cosiest inns I ever stopped at. It was a place much patronized by mariners of the better class and Mrs. Wimp, our landlady, was certainly a wonderful cook. Joe Herring, my chum and a lad who, although only about my own age, served as second mate of the Seagull, had aroused my uncle to speech by remarking that as far as he was concerned he wouldn’t mind boarding all winter at the Radley Arms. But Joe was a silent fellow, as was my father Captain Steele, and having evoked the above tirade he said nothing further. Uncle Naboth had a perfect right to issue his ultimatum concerning our freight, being supercargo and part owner, and as our recent voyages had been fairly prosperous and we were already amply paid for our present trip to Australia we were all in a mood to take things philosophically.

I think Ned Britton, the mate, was the most uneasy of our party, but that was because he disliked the land and was only comfortable when afloat. Ned even now lived on shipboard and kept everything taut and in running order, while my father, Uncle Naboth and I had rooms at Mrs. Wimp’s admirable inn. I am free to confess that I like a bit of land loafing now and then, while poor Ned is never happy unless he knows the water is sliding under the keel.

Joe and I had ransacked sleepy old Melbourne pretty well by this time and had enjoyed every day of the five weeks we had been ashore. There wasn’t a great deal of excitement in town, but we managed to have a good time and to keep amused. Our little group had sat in silent meditation for a few moments following my uncle’s last remark, when Mrs. Wimp stuck her head in the door and said:

“’Ow’d yer loike to see a gent as wants to see yer?”

We looked at one another inquiringly.

“Who is it?” demanded Uncle Naboth.

“’E didn’t say.”

“Didn’t say what, Mrs. Wimp?”

“Didn’t say ’oo ’e were.”

“Did he say who he wanted to see?”

“No sir.”

“Then never mind. Tell him to call again, Mrs. Wimp,” I ventured to say, amused at the landlady’s noncommittal manner.

“No, no!” exclaimed my uncle. “It may be somethin’ about a cargo. Who did he ask for, Mrs. Wimp?”

“’E jus’ dropped in an’ said: ‘Is the Seagull people stoppin’ ’ere?’ ‘They is,’ says I. ‘Then I wants to see ’em,’ says ’e. So I comes up to see if it’s agreeable.”

“It is, Mrs. Wimp,” asserted Uncle Naboth. “Be kind enough to show the gentleman up.”

Thereat Mrs. Wimp withdrew her head and closed the door. My father filled his pipe anew and relighted it. Joe looked thoughtfully out of the window into the alley below. I turned over a newspaper that lay upon the table, while Ned and my uncle indulged in a few remarks about the repairs recently made to the ship’s engines. Not one of us realized that the next few minutes were destined to alter the trend of all our lives.

Then came the visitor. He silently opened the door, closed it swiftly behind him and stood with his back to it shrewdly eyeing us each one in turn.

The man’s stature was quite short and he was of slight build. His hair, coarse in texture, sprinkled with gray and cropped close, stood straight up on his forehead like a scrubbing brush. His eyes were black and piercing in expression; his nose rather too fat; his chin square and firm; his face long and lean, and his skin of the dusky olive hue peculiar to natives of southern climes. His apparel was magnificent. The velvet coat had gold buttons; he sported a loud checked vest of purple and orange, and his cravat was a broad bow of soft white ribbon with gold fringe at the edges.

At once I began speculating whether he was a vaudeville actor or a circus barker; but either idea was dispelled when I noticed his diamonds. These were enormous, and had a luster that defied imitation. His shirt buttons were diamonds as big around as my little finger nail; he had another monster in the center of his bow tie and his fingers fairly glittered with gems of the same character. Every link of a huge watch guard was set with diamonds, and his cuff buttons were evidently worth a small fortune.

The appearance of this small but gorgeous individual in our dingy sitting-room produced an incongruous effect. The air was fogged with tobacco smoke; my father still lazily rested his legs across the table-top; the rest of us lounged in unconventional attitudes. However, being Americans we were more astonished than impressed by the vision that burst upon us and did not rise nor alter our positions in any way.

“Which it is the gentleman who the ship Seagull owns?” demanded the stranger, mixing his English in his agitation, although he spoke it very clearly for a foreigner.

Uncle Naboth became our spokesman.

“There are three owners,” said he.

“Ah! where they are?”

“All in this room,” replied my uncle.

“Excellent!” exclaimed our visitor, evidently pleased. He glanced around him, drew a chair to the table and sat down. My father moved his wooden leg a bit to give the stranger more room.

“What is price?” he inquired, looking at Mr. Perkins, whom he faced.

“Price for what, sir?”

“Ship,” said the man.

“Oh, you want to buy the ship?” gasped my uncle, fairly staggered by the suggestion.

“If you please, if you like; if it is rais—rais—raison—a—ble.”

Uncle Naboth stared at him. My father coolly filled his pipe again. The man’s quick eye caught Joe and I exchanging smiling glances, and he frowned slightly.

“At what price you hold your ship?” he persisted, turning again to my uncle.

“My dear sir,” was the perplexed reply, “we’ve never figured on selling the Seagull. We built it to keep—to have for our own use. We’re seamen, and it’s our home. If you’d ask us offhand what we’d sell our ears for, we’d know just as well what to answer.”

The man nodded, looking thoughtful.

“What the ship cost?” he asked.

“Something over two hundred thousand dollars.”

“United State America dollars?”

“Of course.”

Our visitor drew an envelope from his pocket; laid it on the table and scribbled some figures upon the back.

“Ver’ well,” he said, presently; “I take him at two hunder thousan’ dollar, American.”

“But—”

“It is bargain. What your terms?”

“Cash!” snapped Uncle Naboth, laughing at the man’s obstinacy.

The diamond-bedecked man leaned his elbow on the table and his head on his hand in a reflective pose. Then he straightened up and nodded his head vigorously.

“Why not?” he exclaimed. “Of course it must the cash be. You will know, sir, that a gentleman does not carry two hunder’ thousan’ dollar about his person, and although I have had more than that sum on deposit in Bank of Melbourne, it have been expend in recent purchases. However, nevertheless, in spite of, I may say, I have ample fund in Bogota. I will make you draft on my bank there, and you may sail with me in my ship and collect the money in gold when we arrive. That is cash payment, Señor; is not?”

“Bogota!” remarked my uncle, by this time thoroughly bewildered. “That is a long way off.”

“Merely across Pacific,” said the other easily. “There is direct route to it through the South Seas.”

My father nodded in confirmation of this statement. He knew his charts by heart.

“Sir,” said Uncle Naboth, sitting up and heaving a deep sigh, “I have not the honor of knowing who the blazes you are.”

The stranger cast a stealthy glance around the room. Then he leaned forward and said in a low voice:

“I am Jiminez.”

This impressive statement failed to enlighten my uncle.

“Jiminez who?” he inquired.

For an instant the man seemed offended. Then he smiled condescendingly.

“To be sure!” he replied. “You are of United State and have no interest in South American affairs. It is natural you have ignorance regarding our politics. In Bogota the name of De Jiminez stands for reform; and reform stands for—” He hesitated.

“What?” asked my uncle.

“Revolution!”

“That’s only nat’ral,” observed Mr. Perkins complacently. “I hear revolutions are your reg’lar diet down in South America. If there didn’t happen to be a revolution on tap your people wouldn’t know what to do with themselves.”

Señor de Jiminez frowned at this.

“We will not politic discuss, if you please,” he rejoined stiffly. “We will discuss ship.”

“We don’t want to sell,” said my uncle positively.

De Jiminez looked at him speculatively.

“I tell you with frankness, I must have ship,” said he.

“What for?”

“I will tell you that—but in more privacy,” with a wave of his hand toward our interested group.

“Oh, these are all Seagull men,” announced Uncle Naboth. “I’ll introduce you, Mr. Yim—Him—Jim—”

“Jiminez.” He pronounced it “He-ma-noth” now, in Spanish fashion.

“This is Captain Steele, our skipper and part owner,” continued my uncle. “This young man is Sam Steele, his son, and also part owner. Sam is purser and assistant supercargo of the Seagull. I’m supercargo, the third owner, and uncle to Sam an’ brother-in-law to the Cap’n. Is that all clear to you?”

De Jiminez bowed.

“Here is Ned Britton, our first mate; and also Joe Herring, our second mate. Both are trusted comrades and always know as much as we know. So what you say, stranger, is as private before these people as if you spoke to but one of us. Therefore, fire ahead.”

The man considered a moment; then he said slowly:

“You must know there are spies upon me here in Melbourne, as there are everywhere, whichever I go; so I cannot too careful be. You ask me why I want ship. I answer: to carry supplies of war to Colombia—arms and ammunition for the Cause—all of which I have successful purchase here in Australia.”

“Oh; you’re going to start something, are you?” inquired Uncle Naboth.

“It is already start, sir,” was the dignified response. “I am to complete the revolution. As you do not understan’ ver’ well, I will the explanation make that my country is rule by a bad president—a dictator—an autocrat! We call ourselves republic, Señor Americaine; but see! we are not now a republic; we are under despotism. My belove people are all slave to tyrant, who heeds no law but his own evil desire. Is it not my duty to break his power—to free my country?”

“Perhaps,” answered Mr. Perkins, his calmness in sharp contrast to the other’s agitation. “But I can’t see as it’s any of our bread-and-butter. It’s your country, sir, but you must remember it’s not ours; and to tell you the cold fact, we don’t propose to sell the Seagull.”

At this Señor de Jiminez looked a bit worried. But the little Spaniard was game, and did not give up easily.

“I must have ship!” he asserted. “I am rich—have much money entrusted to me for the Cause—my estate is ver’ large. The best families of Colombia are all with me; now and always, whatever I do. See, Señor; it was my ancestor who discover South America! who discover the River Orinoco! who was first governor of my country under the Queen of Spain! Yes, yes. I am descend direct from the great navigator Gonzalo Quesada de Jiminez, of whom you read in history.”

“I congratulate you,” said Uncle Naboth dryly.

“I have here in Melbourne congregate the means to carry on the war, which is now languish for want of arms and ammunition. It is all ready to send to Bogota. Therefore, you see, I must really have ship.”

“But why buy one?” asked my uncle. “Why not send your stuff as freight?”

“Impossible!” exclaimed the other. “You are United State. Well, United State forbid any merchant ship to carry arms to friendly state for starting revolution. If I hire you to do so I get you in trouble, and myself in trouble. I want no quarrel with United State, for when I am myself President of Colombia I must stand well with other powers. So it is same with every nation. I cannot hire a ship. I must buy one and take responsibility myself.”

This frank and friendly explanation led me to regard the flashy little man more kindly than before. I had been busy thinking, knowing that Uncle Naboth had set his heart on making some money on the return voyage. So, during the pause that followed the speech of Señor de Jiminez, I turned the matter over in my mind and said:

“Tell me, sir, what you propose doing with the ship after you get to Colombia with it?”

He stared at me a moment.

“It is of little use then,” said he, “unless I could put some cannon on board and use him for gunboat.”

“Have you ever been aboard the Seagull?” I continued.

He shook his head.

“I have inquire about every ship now in Port Phillip,” he said. “Not one is available but yours that is big enough to carry my cargo—all others are owned in foreign lands and cannot be bought. But I see your ship, and it look like a good ship; I inquire and am told by my friends here it is famous for speed and safety.”

“It is all that,” agreed my uncle heartily.

“We have a couple of guns on board already,” I continued; “for sometimes we sail in seas where it is necessary for us to protect ourselves. But as a matter of fact the Seagull would make a poor gunboat, because she has no protective armor. So it seems all you could use her for would be to carry your revolutionary supplies to Colombia and land them secretly.”

“That is all that I require!” he said quickly, giving me a keen look.

“Sam,” said my uncle, “you’re goin’ to make a durn fool of yourself; I kin see it in your eye!”

By this time all eyes were upon my face, and realizing that I was about to suggest a bold undertaking I was a little embarrassed how to continue.

“For our part, sir,” said I, addressing Señor de Jiminez and keeping my gaze averted from the others, “it is our intention to sail for America presently, and we would like to carry a good paying cargo with us. So it strikes me we ought to find a way to get together. Have you spent all your funds here in purchases, or have you some left?”

He figured on the envelope again—eagerly now, for his quick brain had already grasped my forthcoming proposition.

“I have still in bank here equal to nine thousan’ dollar United State money,” said he.

“Very well,” I rejoined. “Now suppose you purchase from us the Seagull for two hundred thousand dollars, and pay down nine thousand in cash, agreeing to resell the ship to us as soon as we are free of the cargo for the sum of one hundred and ninety-one thousand dollars, accepting your own draft, which you are to give us, in full payment. In that way the thing might be arranged.”

He had brightened up wonderfully during my speech and was about to reply when Uncle Naboth, who had been shaking his head discontentedly, broke in with:

“No, Sam, it won’t do. It ain’t enough by half. Your scheme is jest a makeshift an’ I kin see where we might get into a peck o’ trouble aidin’ an’ abettin’ a rebellion agin a friendly country. Moreover, you don’t take into account the fact that we’ve got to operate the ship across the South Seas, an’ the salaries an’ wages fer such a long voyage amounts to considerable.”

I have respect for Uncle Naboth’s judgment, so was rather crestfallen at his disapproval. But Señor de Jiminez, who was alert to every phase of the argument, said quickly:

“It is true. Nine thousan’ dollar is too much for an ordinary voyage, and too little for such voyage as I propose. I will pay fifteen thousan’ dollar.”

“You haven’t the cash,” remarked my uncle, “and revolutions are uncertain things.”

Jiminez took time to muse over the problem, evidently considering his dilemma from every viewpoint. Then he began to shed his diamonds. He took out his jeweled cuff buttons, his studs, pin and watch guard, and laid them on the table.

“Here,” said he, “are twenty thousan’ dollar worth of jewels—the finest and purest diamonds in all the world. I offer them as security. You take my nine thousan’ dollar in gold, and my personal note for six thousan’, which I pay as soon as in Colombia we land. If I do not, you keep the diamonds, which bring you much more in your own country. You see, gentlemen, I trust you. You are honest, but you make a hard bargain—hard for the man who must use you in spite of difficulty. But I have no complaint. I am in emergency; I must pay liberally to accomplish my great purpose. So then, what is result? Do I purchase the ship as Señor Sam Steele he describe?”

Uncle Naboth hesitated and looked at my father, who had listened with his usual composure to all this but said not a word. Now he removed his pipe, cleared his throat and said:

“I’m agree’ble. Colombia ain’t so blame much out’n our way, Naboth. An’ the pay’s lib’ral enough.”

“What do you think, Ned?” asked my uncle.

“The Cap’n’s said it,” answered the mate, briefly.

“Joe?”

Joe started and looked around at being thus appealed to. He was only a boy; but Uncle Naboth knew from experience that Joe never spoke without thinking and that his thoughts were fairly logical ones.

“The deal looks all right on the face of it, sir,” said he. “But before you sign a contract I’d know something more of this gentleman and his prospects of landing his arms in safety, so we can get away from Colombia without a fight. Let Sam find out all he can about this revolution and its justice, and get posted thoroughly. Then, if it still seems a safe proposition, go ahead, for the terms are fair enough.”

“Of course,” answered Uncle Naboth, “we don’t mean to jump before we look. Other things bein’ equal an’ satisfaction guaranteed, I’ll say to you, Mr. Jim—Yim—Jiminez, that I b’lieve we can strike a bargain.”

The little man’s face had seemed careworn as he listened intently to this exchange of ideas. Evidently he was desperately anxious to get the Seagull to deliver his contraband goods. But he offered no objection to Joe’s cautious suggestion. Instead he turned to me, after a little thought, and said:

“Time is with me very precious. I must get to Bogota as soon as possible—to the patriots awaiting me. So to satisfy your doubts I will quickly try. It is my request, Señor Sam, that you accompany me to my hotel, and the evening spend in my society—you and your friend Señor Joe. Then to-morrow morning we will sign the papers and begin to load at once the ship. Do you then accept my hospitality?”

I turned to Uncle Naboth.

“Do you think you can trust Joe and me?” I asked.

“Guess so,” he responded. “Your jedgment’s as good as mine in this deal, which is a gamble anyway you put it. Go with Mr. Jiminez, if you like, and find out all he’ll let you. Mostly about him, though; nobody knows anything about a revolution.”

“Very well, Uncle,” I answered. Then I turned to the Colombian. “Sir,” said I, “we cordially accept your invitation. You seem fair and just in your dealings and for the present, at least, I’m glad to have formed your acquaintance. Keep your diamonds until we ask for the security. As you sail in our company you may as well wear them until circumstances require us to demand them of you.”

He bowed and restored the gems to their former places. Then he rose and took his hat.

“You will return with me to my apartments?”

“If you desire it,” said I.

“Then, Señors, I am at your service.”

Joe quietly left his seat, saying: “I’ll be ready in a jiffy, Sam,” and started for his room—a room we shared together. After a moment’s hesitation I followed him.

“What are you going to do?” I asked.

“Slick up a bit and pack my toothbrush. Didn’t you hear De Jiminez speak of his ‘apartments’ at the hotel? And we’re to stay all night it seems.”

“True enough,” I exclaimed. “We must look decent, old man,” and I quickly changed my clothing and threw into a small grip such articles as I thought might be needed. Joe was ready before me, and I saw him quietly slip a revolver into his hip pocket; so I did the same, smiling at the incongruity of going armed to make a semisocial visit.

We found Señor de Jiminez slightly impatient when we returned to the sitting-room, so we merely said good-bye to our friends and followed him out to the street. The Radley Arms was situated in a retired and very quiet district, and our exit seemed entirely unobserved except by our curious landlady. A sleepy beggar was sitting on the corner, and before him the Colombian paused and said in a calm tone:

“What will your report be, then? That I have visited the Radley Arms? Well, let me give you help. I had friends there—these young gentlemen—who are returning with me to my hotel. You will find us there this evening and until morning. Will such information assist you, my good spy?”

The beggar grinned and replied:

“You’re a rare one, De Jiminez. But don’t blame me; I’m only earnin’ my grub.”

“I know,” said the other, gravely. “You do the dirty work for my countryman, the chief spy. But I do not care; you are both powerless to injure me, or to interfere with my plans.”

Then he walked on, and a short distance down the street hailed a cab that was rolling by. We three entered the vehicle and were driven directly into the busiest section of the city.

“The driver of this cab,” remarked De Jiminez, “is also a spy; and if you could behind us see you would find the beggar riding with us.”

“They seem to keep good track of you, Señor,” said Joe.

“I do not mind,” answered the man. “If my arrangement with you succeeds I shall be able to get away from here before my enemies can interfere.”

It was already growing late in the day and the streets were lighted as we entered the main thoroughfares. Our host seemed lost in thought and few remarks were exchanged between us during the long ride.

Finally we drew up before an imposing looking edifice which I quickly recognized as the Hotel Markham, quite the swellest public house in all Melbourne. It cost one a lot to stop at such a place I well knew, but reflected that Señor de Jiminez, if important enough to conduct a revolution, might be expected to live in decent style—especially if the “patriots” paid his expenses.

I suppose it would be becomingly modest to admit right here that Joe and I were rather young to be sent on such an errand. Perhaps Señor de Jiminez recognized this fact even more fully than we did. But in justice to ourselves I must add that we were boys of more than ordinary experience, our adventures on many voyages having taught us to think quickly, act coolly and carefully consider every motive presented to us. Predisposed as I was in favor of this queer Colombian, who interested me because he was playing a desperate game and had the nerve to play it well, I had no intention of deceiving myself or allowing him to deceive me in regard to his standing and responsibility. It was my business to find out all I could about the man, and I fully intended to keep my eyes and ears wide open.

The first thing I noticed as we entered the hotel was the respectful deference paid our conductor by the servants, who seemed eager to wait upon him. The manager came from his little booth with a smile and bow for Señor de Jiminez and promptly assigned Joe and me to a large room which he said was connected with the “suite” of our host. De Jiminez himself conducted us to this room, a very luxurious chamber, and then excused himself, saying:

“You will wish to prepare for dinner and I must the same do also. When you are ready, be kind to come into my apartments, Number 18, which is the first door at your left. Have you necessaries in everything?”

We assured him we were amply provided for and he left us with a courteous bow. There wasn’t much for us to do, except to wash and brush ourselves and examine the rich furnishings of the place. Neither Joe nor I was an utter stranger to luxurious living, although our ordinary quarters were commonplace enough and our mode of life extremely simple. We have seen palaces of great magnificence, and therefore the handsome room assigned us did not impress us as much as it interested us.

We whiled away half or three-quarters of an hour in order not to crowd our host too closely, and then we knocked at the door of room Number 18.

A servant in private livery admitted us to a spacious drawing-room and Señor de Jiminez, arrayed in a regulation dress suit, in which he appeared far more imposing than in the flashy attire he had before worn, advanced quickly to greet us. At a center table sat an aged, pleasant faced lady and crouching in a chair by the fireplace was a youth of about my own age, who bore so strong a facial resemblance to De Jiminez that it needed no shrewdness to guess he was his son.

Our host led us first to the lady.

“Young gentlemen,” said he, as with profound deference he bowed before her, “I have the honor to present my mother, Señora de Jiminez.”

She smiled graciously and extended her hands to us.

“It is unfortune,” he added, “that she is not with your English language familiar.”

“Oh, but I speak Spanish—a little,” said I; for I had learned it during a sojourn in Panama. Then I told the lady I was glad to meet her, speaking in her own tongue, and she bade me welcome.

De Jiminez seemed pleased. He next led me to the young fellow by the fire, who had not risen nor even glanced toward us, but seemed tremendously interested in his own thoughts. These could not have been very pleasant, judging from the somber expression of his face.

“My son Alfonso,” said our host, introducing us. “Alfonso, I present Mr. Steele and Mr. Herring, two young American gentlemen I have recently met.”

The boy looked up quickly.

“Not of the Seagull!” he exclaimed in English.

“Yes.”

“Then—” he began eagerly; but his father stopped him with a gesture.

“I am making consideration of a proposition they have made to me,” he observed with dignity.

“Perhaps, Alfonso, we may sail back to Colombia in the Seagull.”

The boy’s eyes glistened. They were dark and restless eyes, very like those of his parent. He rose from his chair and shook hands with us with an appearance of cordiality. We now saw he was remarkably short of stature. Although he was sixteen the crown of his head scarcely reached to my shoulder. But he assumed the airs and dress of a man and I noticed he possessed his father’s inordinate love for jewelry.

“Would you prefer in the hotel restaurant to dine, or in our private salon?” inquired the elder De Jiminez.

“It is unimportant to us, sir,” I returned. “Do not alter your usual custom on our account, I beg of you.”

“Then,” said he, “I will order service in the salon.” He seemed relieved and went to consult his servant.

Meantime young Alfonso looked at us curiously.

“You do not own the Seagull, I suppose,” he remarked.

“Why not?” I asked with a smile.

“It’s a fine ship. I’ve been over to look at it this afternoon—”

“Oh; you have!”

“Yes. They would not let me go aboard, but I saw all I wished to. It is swift and trim—what is called ‘yacht built.’ It can sail or go by steam. Your crew looks like a good one.”

“That is all true, sir,” I agreed, amused at his observations.

“And you young fellows own it?”

“I don’t,” said Joe. “I’m second mate, that’s all. But Mr. Steele here is one-third owner, with his father and uncle owning the other two-thirds.”

Alfonso looked at me intently.

“Have you sold it to my father?” he asked in a low voice.

“Not yet,” said I, laughing. “But, as Señor de Jiminez told you, we are considering the matter.”

“You know why we want it?”

“‘We’?” I repeated. “Are you also a conspirator—pardon me, a patriot—then?”

“I am a De Jiminez,” he returned proudly. “After my father I am entitled to rule over Colombia.”

“To rule? That savors of monarchy. I thought Colombia is a republic.”

“You are quite right. It is a republic—as Mexico is; as Venezuela and Costa Rica are. But the president has great power. Is not Diaz equal to a king?”

“I am not very well posted on South American or Mexican politics,” I replied evasively. “But from what your father said I imagine there is already a president in Colombia.”

He gave a frown at this, amusingly like his father’s frown. Then his face cleared and he said:

“Permit me to explain. The family of De Jiminez has controlled Colombian politics ever since my great ancestor discovered the country and called it New Grenada. But a few years ago, while my father was traveling in Europe, the opposition obtained control and still has the presidency. The important and wealthy class, however, resented the usurpation, and even before my father alarmed at the situation hurried back home, a revolution had begun. I say a revolution, because the opposition had firmly established themselves. We are really attempting a restoration of the rightful party to its former power.”

“In our own republic,” I said thoughtfully, “the votes of the majority rule. Why do you not resort to the ballot instead of to arms?”

“I have visited your country,” he said. “The conditions there are different. In Colombia we have a small class of wealthy and influential people and a horde of vulgar laborers who are little more than slaves. They have small intelligence, no education, and work for a bare living. My father tried to establish a school system that would enable them to rise above such conditions. They would not send their children to the schools. Then he tried to force them by law—compulsory education you know, copied from your own and other countries—but they rebelled at this and the opposition made capital out of their resentment. The result was the overthrow of the De Jiminez party as I have stated.”

This seemed to put a new aspect on the revolution. I began to approve the action of the De Jiminez party and to sympathize with their “cause.”

“Has your father many followers in Colombia?” I asked.

“The intelligent class is of course with him; small in numbers but controlling the wealth of the country. We ourselves are coffee planters and bankers, and we employ several hundred laborers who will do whatever we may direct—and do it willingly. Many of the families in sympathy with us can also control their servants; but we have found great difficulty in securing arms and ammunition for them. We have organized and drilled several regiments—I have drilled our own men myself—but they cannot fight without weapons. That is why we are so eager to ship our cargo of arms to Colombia.”

The elder De Jiminez had returned in time to hear the conclusion of this speech, and he nodded approval. It seemed to me that the little fellow really talked remarkably well. He spoke better English than his father and expressed himself in well chosen language. It at once occurred to me why Joe and I had been invited here. The young De Jiminez was a rabid partisan of “the Cause” and his clever father imagined that an enthusiastic boy would be more apt to impress boys of his own age than his senior might impress men. The thought put me somewhat on my guard and made me inquire into things more carefully.

“Australia seems a queer place to obtain a cargo of arms,” I remarked. “There are no factories here I believe.”

“No,” said our host, “the arms I purchased came from England consigned to a local firm. We could not purchase direct for it would result in international complications; but we have many friends here in Australia. It is a favorite resort for exiles from my country, and that is why I arranged the purchase here. But come; dinner is served and I hope you have good appetites.”

He gave his arm to his old mother, who was remarkably active for her years, and led the way to a connecting room where the dinner was served. It was a fine spread, and Joe and I did full justice to the many courses.

Afterward we returned to the drawing-room, where the old lady read a Spanish periodical while we chatted in English concerning Colombian affairs and the revolution.

I learned that the De Jiminez family was considered among the wealthiest of the republic. Our host conducted an important banking business in Bogota and had extensive coffee plantations in the foothills. He was not directly known as the leader of the revolutionists, but would be chosen the new president by the insurgents if they succeeded in overturning the present government. Yet De Jiminez was scarcely safe in his own country just at present and intended to land in a secret cove on the coast and transport his cargo of arms inland to one of the rendezvous of the revolutionists.

Young Alfonso was as ardent a partisan as his father. He was tremendously ambitious and it seemed his father encouraged this, telling his son many times that the future of his country would some day be dependent upon the boy’s ability and courage and that he must uphold the honorable name of De Jiminez.

Their assumed importance was of course amusing to me, who looked upon their seven by nine country with tolerant disdain; but to them Colombia and the revolution were the most tremendous things in the world. And, after all they were simple, kindly people, honestly inclined and desirous of improving the conditions in their native land if this “tempest in a teapot” resulted in their favor. I had already decided that we would be justified in concluding the deal with Señor de Jiminez when a diversion was created by the arrival of visitors.

The servant ushered two ladies into the room. One was a beautiful woman of middle age and the other a tall, slim girl who was evidently her daughter. Both were exquisitely dressed and impressed me as persons of importance even before I noticed the extreme courtesy with which our host greeted them.

Introductions followed. The elder lady was Señora de Alcantara of Bogota, and the younger her daughter Lucia. At once Madam inquired in an eager tone:

“Well, De Jiminez, have you succeeded in getting a ship?”

“I think so,” he replied, glancing at me a bit doubtfully. “The only thing still to be settled is the matter of terms. I have not much money left to satisfy the owners, who have no confidence in their being able to collect when we arrive at Colombia. But I hope it can yet be arranged in a satisfactory manner.”

“I also hope so,” she returned, “for I am anxious to travel home in your company.”

“You!” he exclaimed in unfeigned astonishment.

“Yes. I have just received letters of absolute pardon from the government. I am free to return to my home in Bogota whenever I please.”

“You surprise me, Señora,” he said, evidently disturbed by the news. Then he took the lady aside, and while they were conversing privately Alfonso said to us:

“De Alcantara, her husband, was the first leader of the revolution, and was killed in battle two years ago. His wife and daughter fled to Australia and their estates were confiscated. This is indeed surprising news; but I think the government wishes to placate the wealthy classes by this lenient action.”

Señor de Jiminez returned to our group smiling and content. I overheard Madam de Alcantara say in Spanish to Madam de Jiminez. “Never, under any circumstances, will I abandon the Cause. I shall return to my estates, because here I am an exile and dependent upon our friends for maintenance. There I may intrigue to advance the revolution, although I am warned against mixing in politics if I accept the government’s amnesty.”

“The Cause is sacred to us all,” was the calm reply.

Lucia de Alcantara was at once monopolized by Alfonso, who deserted us to pay the young girl marked attention. She did not appear to resent this; neither did she respond with much enthusiasm. She was really a beautiful girl, not more than fifteen or sixteen years of age, and her slender, willowy form towered so far above the undersized Alfonso that I remarked to Joe, aside: “That certainly is the long and short of it old man, isn’t it?”

“I suppose there will be accommodations in the Seagull for the ladies?” inquired Señor de Jiminez.

“Yes,” said I; “they might be made fairly comfortable.”

He said no more then, but presently sat down to a quiet game of bezique with Madam de Alcantara, leaving Alfonso to entertain us as well as Lucia. We found that the girl spoke English, and she became so interested in our accounts of the United States that she fairly ignored the youthful Colombian to question us about our country, our ship, and the chances of our sailing together across the South Seas.

It was quite late when they left, Alfonso and his father both escorting their guests to the carriage, and on their return Joe and I pleaded fatigue and retired to our rooms.

“Well, Joe,” I said, when we were alone, “what do you think now?”

“Mighty pretty girl,” he returned musingly.

“But about the business deal?”

“Oh, that,” he responded, waking up, “I’m in favor of it, taking it all around. We get well paid and run no especial chances except when we land the goods. We’ve done harder things than that, Sam, for less money; so it needn’t bother us much. You see the Alcantaras can have the for’ard cabin and—”

“Bother the Alcantaras!” I exclaimed impatiently. “You’re usually opposed to passengers, Joe.”

“I know; but they’re anxious to get home and Lucia said—”

“‘Lucia!’”

“Isn’t that her name?” he demanded.

“I believe it is.”

“She’s a clever sort of a girl. Usually, Sam, girls are dubs; but this Spanish creature has lots of ‘go’ to her and won’t make bad company on the voyage.”

I let him alone, then, and went to bed. Joe Herring was a silent fellow at ordinary times, but if I had let him ramble on about this girl I am sure he’d have kept me awake half the night. It didn’t strike me there was anything remarkable about her either.

Our report seemed to satisfy my uncle and my father when we returned to the Radley Arms at ten o’clock the next morning. At twelve Señor de Jiminez appeared in his checked vest and diamonds and signed the contract, paying us nine thousand dollars in gold and giving us a draft on his own bank in Bogota for six thousand. We also secured papers granting us the right to repurchase the Seagull by returning the notes we accepted for the sale price, which notes we believed not worth the paper they were written on. Then, all business details being completed and the ship formally turned over to its new owner, the early afternoon saw us all aboard the Seagull engaged in stowing the cases of arms and ammunition which had already begun to arrive. De Jiminez did not intend to waste any time, that was certain, and one dray after another brought our freight to the lighter, which transferred it to the ship.

The boxes were of all sizes and shapes, being labeled in big black letters “Machinery.” They were consigned to the coffee plantation of De Jiminez. There were a lot of them and they were tremendously heavy things; but we stowed them in the hold as rapidly as they arrived and two days sufficed to get the entire cargo aboard.

On the evening of the second day our passengers boarded us. There were five of them including the elder De Jiminez, his mother and son, and Madam de Alcantara and her daughter. They were accompanied by trunks and bandboxes galore; enough to make my father grunt disdainfully and Uncle Naboth look glum. I think none of us—except perhaps our erratic second mate, Joe—was greatly delighted at the prospect of female passengers on a long voyage; but we had made our bargain and must abide by it.

De Jiminez had bustled around all day getting the ship’s papers in shape and preparing for the voyage, while young Alfonso, whom Uncle Naboth had promptly dubbed “Little Jim,” attended to the loading of the boxes with the coolness and care of a veteran. They couldn’t wait a moment after the last case of arms was aboard. Bill Brace, the engineer, had steam up long ahead of time; so at dusk we hoisted anchor and slowly steamed out of Port Phillip into the calm blue waters of the South Pacific. If any government spies watched De Jiminez depart he was indifferent to them, and they were now powerless to interfere with his plans.

The comfort of our passengers depended wholly upon two men of our crew whom I have not yet had the opportunity of introducing to you. Our own personal comfort had depended upon them for years, so I am justified in making the above statement. They were gigantic blacks; not negroes of the African type, but straight-haired ebony fellows who were natives of some island in these very seas where we were now sailing. Their names were Nux and Bryonia, and one was our steward and the other our cook—fairly entitled, indeed, to be called our “chef.”

Concerning these curious names there is a serio-comic story which I will briefly relate.

A number of years ago, while Uncle Naboth Perkins was sailing an old tub he and my father jointly owned on a voyage from New Zealand to San Francisco, he encountered somewhere in the South Seas a native canoe drifting upon the waves. It seemed at first to be vacant, but as it passed close to the lee of the slow-going sailing vessel the seamen noticed something lying flat in the bottom of the dugout. They threw a grappling hook and drew the little boat alongside, when they discovered two black men lying bound hand and foot and senseless from lack of food and water. How many days they had drifted about in that condition no one could tell, least of all the poor victims. Being hoisted aboard the bodies were laid side by side upon the deck and Uncle Naboth, who was the only excuse for a physician there was aboard, examined them and found that both were still alive. But the condition of the poor fellows was exceedingly precarious. Had they not possessed such stalwart frames and splendid constitutions they would have been dead long before.

So Uncle Naboth brought out the ship’s medicine chest and found it rather shy of restoratives. Aside from calomel and quinine, neither of which seemed appropriate for the case, the only remedies the chest contained were two bottles of homeopathic pills—one of nux vomica and the other of bryonia.

My uncle pondered a time between these unknown medicines and decided to give one black the nux and the other the bryonia, hoping thus to save at least one of the disabled castaways. So a course of treatment began. Both were liberally fed brandy and water and one was given six pills of nux vomica and the other six pills of bryonia, the doses being administered every hour. Mr. Perkins became intensely interested in the results, and that no mistake might be made he labeled one black boy “Nux” and the other “Bryonia.” “Nux” regained consciousness first, and while the amateur physician was regretting that he had not fed them both the same dope “Bryonia” opened his eyes to the world again.

I have always suspected the brandy and water really did the job, but Uncle Naboth was so proud of his medical skill that he will never admit that possibility.

“It’s a doctor’s duty to guess,” he has said more than once referring to this occasion, “an’ I managed to guess right because I only had two medicines an’ both of ’em was recommended to kill or cure. The dog-gone little sugar pills must ’a’ had extract o’ magic in ’em; that’s what I think.”

Anyhow, Nux and Bryonia got well and regained their strength, and more grateful fellows never lived. Neither could understand a word of English, while their own language was a puzzle to all the crew; but they were quick to observe and ready to undertake any work that lay at hand.

Not knowing where to drop the castaways, nor wishing to delay the voyage because of two black men, my uncle decided to carry them along with him, and their intelligence and devotion so won him that before the voyage ended he prized Nux and Bryonia more than all the rest of the crew put together. They gradually picked up a word of English here and there until they were able to make themselves understood, and in time they learned to speak it fluently. But they had never a word to say of their experiences or past life and we really knew little about their antecedents.

The following year we had another ship in which I sailed my first voyage with Uncle Naboth, and Nux and Bryonia watched over me so faithfully—saving my life on one important occasion—that I learned to regard them both very highly and a friendship was formed between us that time has only strengthened. So of course when we built our fine new ship the Seagull, Nux and Bry became fixtures in it as much as we were ourselves, and I must admit that no owners ever had more faithful or capable servants.

Bryonia was the taller of the two, although both were stalwart fellows, and perhaps he was a bit more shrewd and active than Nux. He became our cook, learning the art with amazing rapidity, and I am positive that no ship’s cook ever lived who was his superior. Nux, a jolly good-natured fellow who was strong as an ox, was our steward and cared for the after cabin perfectly. They did other tasks when occasion required, and the two have accompanied me in more than one hair-raising adventure, proving themselves plucky, intelligent and true to the bone. Somehow we had all come to depend greatly upon our black South Sea Islanders, and they in turn were very fond of us—especially of Uncle Naboth and myself.

It so happened that this was the first voyage since they were picked up that had taken us to the South Seas. We had been to Alaska, to Panama, to Egypt, China and Yucatan, but the fortune of commerce now led us for the first time into the South Pacific. When first we headed for Australia I had said to them:

“Well, boys, you’re going somewhere near your native land on this voyage.”

They exchanged a quick glance but said nothing in reply. They seemed neither overjoyed nor sorry, but accepted this journey with the same calm philosophy they had the others. In mentioning the incident to Uncle Naboth he said:

“I don’t see why our going through the South Seas should make any difference to them. Why, Sam, the South Pacific has a million little islands in it, none of which amounts to a row of pins. Nux and Bry were natives of one of these dinky islands an’ I guess they had a hard, wild life of it judging from the condition they was in when I found ’em. My pickin’ ’em up was great luck for the pair an’ no mistake. They’re civilized Injuns, now, an’ their life on shipboard is luxury compared to what they used to have. Besides we’ve treated ’em well an’ they’ve grown fond of us; I doubt if we landed plump on their native island they’d ever leave the ship an’ go back to their old life.”

“I should hope not!” I exclaimed. “How old do you think they are, Uncle Naboth? Whenever I ask them they shake their heads and say they do not know.”

“Perhaps they don’t; many of the savage races never keep track of their age; they think it’s bad luck to count the years. But I should judge these fellows are about twenty-five years old. Nux may be a little older, but not much.”

Perhaps it was natural that these native islanders should be a source of much curiosity to Alfonso de Jiminez and Lucia de Alcantara. They were accustomed to seeing dark-skinned races, and in Australia one meets Borneans, Samoans, the East India and native Malay tribes, Philippinos, Japs and Chinese; but such handsome and dignified blacks as Nux and Bryonia were different, indeed, and I have often thought the desert Moors the nearest approach to them of any people I have ever seen.

Our islanders wore neat uniforms of gray and gold, which rendered their appearance the more striking. They would never accept money for their service, saying they owed their lives and happiness to us and could never repay us. Moreover they declared they had no use for money. But they delighted in their uniforms, so we kept them well supplied and they wore them at all times.

The addition of five passengers to our complement did not phase Bry in the least. On the contrary it gave him a chance to cook some of the delicious dishes for which he was famous among ourselves, and so to extend his reputation. Nux had more extra work than his comrade, looking after the cabins and serving the meals; but he had a great capacity for work and made no complaint whatever.

Captain Steele had been a mariner all his life and was no stranger to the South Seas; but this course from Melbourne to the coast of Colombia, while not unknown to the charts, was strange to him and he had to put in a lot of study before he got his lines properly marked and knew exactly where to travel.

“Ye see, Sam,” he said to me one evening as I sat in his cabin watching him figure, “it would be all plain sailin’ if it warn’t fer them measley little islands—hundreds of ’em the chart shows, an’ there’s indycations of hundreds more that ain’t been located. If we get a hair’s breadth off our course we’ll have to do a good bit of dodgin’. The spots on the chart marked islands means a lot of rocks in plain English, an’ rocks won’t do the Seagull any good if we happen to bump agin ’em.”

“Isn’t there a way to avoid most of the islands?” I asked.

“Not that anyone knows of. The South Seas is spotted with ’em most everywheres an’ it’s better to keep in your reg’lar course, where you know your soundin’s, than to try findin’ a clearer track over to Colombia.”

“Let’s see,” I said, tracing the chart with my finger; “our course lies directly through the Low Archipelago. What a lot of islands there are! But there seems to be plenty of room between them.”

“Certainly,” agreed my father. “Give us weather like this an’ we’ll dodge every rock in our way.”

I understood what he meant. The weather is treacherous in these seas near the equator, and it would be bad for us to encounter a storm among the rocky shoals of the islands. Just now the weather was magnificent and the sea as smooth as glass. Our engines were in fine working order and we made sufficient speed to satisfy even the restless new “owner,” Señor de Jiminez.

A piano was in the main cabin and Lucia played and sang very agreeably. Her songs were mostly those dreamy Spanish things with melody enough to haunt you long afterward, and Joe especially listened with eagerness to every note, although “Little Jim” was always on hand to turn the music. Joe couldn’t do that, not being able to read a note and he was often on duty besides; but Lucia knew he appreciated her music and whether our boy mate was in the cabin or tramping the deck overhead she played to please him more than she did Alfonso.

Now that all the hurly-burly of stowing the cargo and getting under way was over, our passengers settled down to enjoy the voyage, and it was then that the peculiar traits in their various characters became noticeable. I admit that we are all peculiar in one way or another, as some clever student of human nature has observed and recorded before my time. Perhaps, therefore, our new acquaintances were no more odd in their ways than the ordinary run of humanity.

Madam de Jiminez was as placid and contented as the day was long. She required little amusement and was no bother at all. Madam de Alcantara, on the contrary, proved fussy and exacting. She led poor Nux a dog’s life, waiting on her whims, and her daughter had no easy time of it either. Lucia was very dutiful and obedient and ran at once when summoned by her mother—which was every fifteen minutes on a fair average. Yet the Señora was quite gracious to all about her and never lost her temper or said unkind things. Being as beautiful as she was gracious we had not the heart to blame her. I believe her fussiness was a nervous affliction and that the lady really had a kindly nature. Lucia was devoted to her and tenderly loved her.

This girl, the third of our female passengers, was always bright and cheery and the life of the party. She accepted Alfonso’s marked attentions with absolute indifference. Being accustomed to them she evidently considered them characteristic of the boy and to be borne with patience while in his society. Joe pleased her better; but she was not the least bit a flirt and had no thought as yet of falling in love with anyone. Her feeling for Joe was one of good comradeship.

Little Jim would have been a very decent fellow could he have modified his airs of importance and curbed his excessive vanity. He was really a bright, clever boy, and the son of a man somewhat distinguished in his own country. But the youth’s patronizing manner was intolerable, and one evening when he had joined Joe and me and we were leaning over the rail together I was obliged to “call him down” in no gentle manner.

“I don’t mind associating with you here where there is no formality, you know,” he said; “but if you ever come to Bogota you must not expect me to be quite so free with you.”

“If ever we come to Bogota,” I remarked, “we are liable to find you in jail or in hiding among the mountains. These petty South American revolutions take queer turns sometimes and are liable to become dangerous.”

“Petty!” he exclaimed. “Petty revolutions!”

“That is certainly what they are,” I returned. “Your country is so small and insignificant that we seldom hear of it in the big world; and your revolution is so absurdly unimportant that we never hear of it at all.”

“But you will!” he cried. “When we have won and my father is made president the world will ring with our victory.”

“Nonsense,” said I. “The newspapers in the United States will give it about an inch of space, and the people who read that inch will wonder where on earth Colombia is.”

He seemed nettled at this, and a little crestfallen.

“That inch of publicity,” I continued, “you will perhaps get in case you win. But if you lose you remain unnoticed. There are lots of Central and South American republics, and plenty of revolutions in them at all times. To be frank with you, Alfonso, the people of more important nations are weary of reading about them.”

He hardly knew what to reply, but his humiliation was of short duration. After strutting up and down the deck a few turns he rejoined us and said:

“You may sneer at Colombia—and at her great revolution—but you cannot sneer at the family of De Jiminez. We are very ancient.”

“You are, indeed,” I assented. “You have had a great many ancestors; but they are mostly dead, are they not?”

“How far back can you trace your descent?” he asked.

“As far as my father. Those before him we’ve lost track of. They are also dead, and therefore of no importance to us just now.”

“The family of De Jiminez,” he stated proudly, “is very wealthy.”

“Why mention so common a thing?” I responded. “There are thousands of big fortunes in the world. Joe Herring, who stands there beside you and is our second mate, is a millionaire; yet he lacks distinction on that account because there happen to be so many other millionaires in the world.”

He turned and stared at Joe by the light of the swinging lantern.

“You a millionaire!” he exclaimed.

“Perhaps a little better than that,” admitted Joe, quietly. “I’m a seaman and pretty nearly a man.”

“But you have money—a million?”

“My agent says it’s getting to be nearly twice that; it grows so tremendously while I’m away.”

“Then why do you sail in a ship as second mate?”

“Mainly because I love the life, and secondly because I love Sam, here,” returned Joe gravely. “The adventure and companionship give me more pleasure than to pose in a big city as a rich young kid. As a matter of fact the money is a nuisance to me.”

“Why don’t you buy a ship of your own and hire Sam to sail with you?” asked Little Jim.

“Hire Sam! Why Sam is worth more of that dreadful money than I am. I’m sure he could buy the De Jiminez estates with the bank thrown in and still be rich.”

The statement dazed Alfonso.

“Is it true? Is it possible?” he asked. “Or are you joking?”

“It is true,” said Joe. “The surprising thing is that you have not heard of the Seagull and its adventures before this. The ship has made several fortunes for its owners, and in the United States and Europe it is famous. But I suppose that inasmuch as we hear little of the Colombians they hear little of us.”

Alfonso did not try to patronize us so extensively after this conversation, but he patronized others and I was sorry he could not remedy so great a defect in his character. His father was just as important in his way, but not so officious. A passion for display in dress and jewelry possessed the elder De Jiminez and he spent most of his spare time in changing his clothes, appearing before us in a succession of dazzling costumes that made us fairly gasp for breath. He had other jewels beside the diamonds. Sometimes he wore rubies, and sometimes emeralds; but he was never as proud as when sporting his glittering assortment of diamonds. I think he imagined their sparkle rendered him personally admirable and the envy of all beholders, and the poor man never knew we callous Americans were laughing at him.

Señor de Jiminez was very happy to have succeeded at last in accomplishing his great mission. The arms and munitions of war had been secured with great difficulty and after many disappointments. Best of all, a ship had been chartered to carry the stores to Colombia. With such reinforcements the languishing revolution would receive new impetus—sufficient, he fondly hoped, to render it successful.

Our fine weather held for five days. Then, just as we were approaching the dangerous district Captain Steele had spoken of to me, the sky lowered, a stiff breeze came out of the northwest and the waves began to pile up as only the waves of the South Pacific can.

By night it was blowing a gale; but our passengers, with the exception of Lucia and Alfonso, had taken to their berths long before this. The Seagull behaves beautifully in a storm. An ordinary gale does not disturb her coolness in the least. She merely tosses her head, takes the bit in her teeth, so to speak, and prances a trifle instead of gliding.

But this was no ordinary storm. We who had experienced all sorts of weather in our voyages were soon forced to admit that fact. The wind veered every hour or so; it blew steadily for a time and then came in gusts—“pushes,” Uncle Naboth called them—that were exceedingly trying to both the ship and crew. We would no sooner find our sea legs on one slant of the deck when over she flopped and we had to seek a new angle to cling to. The waves were tremendous and the wind seized their curling edges and scattered them in foamy spray over the ship. The sky became black as ink; the gale roared and shrieked with maddening intensity; yet we bore it all stolidly enough for a time, confident of the staunchness of our bark and the skill of her captain.

My father had put on his pea-jacket and helmet at the beginning of the storm and kept his station on deck sturdily. He assured us he knew exactly where we were and that we had a clear sea ahead of us; but when the Seagull began to swerve here and there, driven by the irresistible power of the gale, even he became bewildered and uncertain of his bearings.

All that night the ship fought bravely. It kept up the fight throughout the long succeeding day. Perhaps it was because all hands were weary that the ship seemed to head into the storm of the second night with less than her usual energy and spirit.

Drenched to the skin I crept along the deck to where my father stood. I am no seaman and have no business on deck at such a time, but I will own that for the first time in my experience at sea I had become nervous, and I wanted the captain to reassure me.

I found him near the bow, clinging to the rail and trying to peer into the night. He was dripping with spray and had to wipe his eyes every few moments to enable him to see at all.

“How’s everything, father?” I asked, my mouth to his ear.

He shook his head.

“All right if we don’t bump something,” he managed to say when a brief lull came. “We’ve veered an’ sliced an’ slipped around so much that I don’t just know where we’re at; ’cept we’re way off our course.”

That was bad; very bad. We hadn’t sighted an island since the storm began, but that was no evidence we were not near a group of them. There was a fairly good searchlight aboard the ship, and it was now being worked every minute from the lookout; but it couldn’t do more on a night like this than warn us of any near by danger.

“Go back!” roared my father in my ear. “Go to bed an’ save your strength. You may need it afore long.”

That was the most fearful speech I ever heard him utter. Nothing had ever disturbed his supreme confidence before. I crept away heartsick and awed, and managed to get safely below, where I found Uncle Naboth smoking his pipe in the main cabin.

“Where yer been, Sam?” he inquired.

“Talking to father.”

“What does he say?”

“We’ve lost our bearings and the sea is full of islands. The ship is all right, you know. It’s only the water that’s dangerous.”

He gave a grunt and looked thoughtful.

“I’ve seen gales, ’n’ gales,” he remarked presently. “Usually they’re respectable critters an’ you know what to expect of ’em. But this sort of a jugglin’ wind beats all figgerin’. Fer me, Sam, I fall back on our luck. It’s stayed by us so far, an’ I don’t see no reason fer it to change front. Eh?”

“I agree with you, Uncle,” I replied, and was about to add another optimistic remark when in rushed—or tumbled, rather—Señor de Jiminez, his face white and his teeth chattering. He had shed his gorgeous raiment and was attired merely in a dark brown bath robe.

“Tell me,” he said, steadying himself by the table as the ship lurched to leeward, “is there—can there be—any danger?”

“Danger of what?” I asked, not knowing just how to reply to him.

“To the cargo—to the arms!” he gasped in choking tones. Then I saw he was not frightened about the safety of the people, or even the ship, but was exercised solely on account of those precious arms.

“Why, if we go down, the cargo goes with us,” I returned, smiling in spite of the gravity of the situation. “But I imagine we’ll all float long enough to—”

The Seagull lurched the other way as a great wave caught her, and while we clung to the furniture for support there came a sharp crack and the ship staggered and keeled well over.

She lay there a long time, trembling slightly. I could hear the waves dash against her with the force of a trip hammer. The door of the stateroom opposite flew open and Madam de Alcantara came rolling into the cabin and landed at my feet. I managed to seize her and drag her to a chair beside me; but she clung round my neck sobbing and crying out:

“What is it? Oh, what is it? Are we sinking? Is all lost?” This in Spanish was quite impressive.

“Be calm, Madam,” I replied, noticing that she was robed in a charming dressing gown and had not been injured by her dash across the cabin floor. “There’s nothing serious the matter, you may be sure.”

I was not really confident of this. Never had I known the Seagull to behave in such a manner before. She rolled terribly, and the waves were dealing her sides thundering blows, one after another.

Uncle Naboth was endeavoring to gain the door to get on deck when Joe came in, water running from his slicker in floods and his face covered with grease and grime.

“What’s up, old man?” I demanded.

“Screw snapped and tore away the rudder,” said Joe. “I was in the engine-room when it happened. It sent the wheels whirling, I can tell you, before we could shut down.”

“Then we’re now drifting?”

He nodded.

“If there was any chance at all we could ship a new rudder. That would serve to keep us straight, anyhow, and we could use the sails as soon as the wind moderates. But the gale’s as crazy as a bedbug, and I can’t see that anything can be done just now.”

“Nothing but wait,” said I. “Where’s father?”

“Trying to lash a rudder to the stern; but it’s hopeless.”

“And Ned?”

“Ned’s with him, of course. I wanted to help but they ordered me below.”

By this time all of our passengers had gathered in the cabin listening to Joe’s dismal report. Nux was there, too, tying Madam de Jiminez fast in a big chair so she would not fall out and then tendering his services wherever they were needed.

For a wonder the ship became a bit steadier now that she was absolutely helpless. She got into the trough of the sea where the wind did not buffet her so badly, and although the waves washed over her constantly she was so tight and staunch that she shed the water like a duck. I do not remember ever to have passed a more uneasy hour than the one that followed the cracking of the screw and the loss of our rudder. Had it not been for the women it is likely I would have regarded our predicament in the light of an adventure, and been excited and elated over the danger. But the presence of our female passengers altered the case entirely and rendered it far more serious.

We were a glum lot, if I may except Uncle Naboth, who still strove to smoke his pipe and remain philosophic. Alfonso was calm and endeavored to comfort his father by saying that as long as we floated the arms were safe. Lucia devoted herself to her mother with a coolness that was admirable, and Madam de Jiminez was as quiet and contented as ever, not making any sort of a fuss and proving her courage in a way that quite won us all. I do not know just what hysterics are; but if they’re a sort of a wild fit that induces one to run amuck, then Madam de Alcantara had them—and had them badly. She screeched, and kicked and howled and wailed that she was too young to die; although for that matter she hadn’t the advantage of many of us, and I don’t see that youth has any special show in a South Sea gale, anyhow.

At the end of an hour my father came stumping in on his wooden leg, looking haggard and weary.

“Brandy, Sam!” he said, tumbling into a chair.

I brought him the bottle and a glass and he took a good swig.

“Bry can’t make coffee. The galley’s washed out,” continued the captain. And then he drew his hand across his forehead with a gesture that I well knew, and that always betokened perturbation of an unusual sort.

“Did you fail to ship the rudder?” I asked.

“’Tain’t that, Sam. There wasn’t much chance, anyhow. But Billy Burke an’ Dick Leavenworth is washed away—gone—done for!”

My heart gave a thump of dismay. Two of our finest seamen lost; fellows I had earnestly respected and admired. It was the first fatality our crew had ever experienced, so no wonder my father was broken-hearted over it. I remembered that Leavenworth had a family, and the thought made me shudder.

“The ship will the storm stand, and be all good—will it not?” asked De Jiminez, by this time thoroughly unstrung and despairing. There was something almost pitiful in the question—hoping against hope—and of course Captain Steele lied to reassure him.

“The Seagull’s all right,” he asserted. “She’ll stand a much worse knockin’ around than this, an’ be none the worse for it. You’d better all go to bed an’ try to sleep. If only we had a clear sea I’d turn in myself.”

“But it is said we are drifting, Captain! A propeller we have not; a rudder we have not! We have no defense against the sea—we are impotent—helpless!” wailed De Jiminez.

“Why, yes; that’s a fact,” admitted the captain. “We’re jest like a chip, floatin’ whichever way the wind blows. But you never heard of a chip sinkin’, did you?”

“N—no,” was the doubting reply.

“What do you mean by saying there’s not a clear sea?” asked young Alfonso.

“Study yer jogerfy,” said my father gruffly. “You’ll find the South Seas specked with islands everywheres. I don’t jest know where we are at this minute, but I’ll gamble there’s islands not far away.”

“Oh. Then if the ship happens to break up we can easily get to land, and perhaps save the cargo,” remarked Little Jim complacently.

My father stared at him, muttered some inaudible remark and rose to return to the deck.

“Must you go?” I asked.

“It’s my place, Sam,” said he.

“But you’ll be careful?” I never said such a thing to him before, but I had poor Dick and Billy Burke in my mind—cautious fellows, both of them—and my father had a wooden leg.

“I’ll lash myself to the riggin’ when I get to it,” he returned, and disappeared up the companionway.

We sat in dismal silence for a time. The wind seemed to be abating, but the waves continued their mad rolling as vigorously as ever. Finally Madam de Jiminez expressed a wish to return to her stateroom. Nux understood Spanish, for our blacks were marvels at acquiring languages and could speak half a dozen tongues; so the steward assisted the old lady to her berth and made her as comfortable as possible. After a long argument Lucia prevailed upon her mother to go to bed, and the moaning, despairing woman was led to her room. Perhaps inspired by this example Uncle Naboth decided to “turn in,” but the two De Jiminez stuck it out and remained all night in the cabin, deploring their hard luck in choicest Spanish. As much to escape their moody companionship as anything else I went to my own room and lay down upon the bunk without removing my clothing. It was then about three o’clock, and although the motion of the vessel had greatly moderated I found it no easy task to stay in my berth. Being at the mercy of the waves the Seagull performed some queer antics, and once or twice I wondered if she wouldn’t “turn turtle,” so far over did the waves keel her. But, queerly enough, we get used to anything in time, and as I was much exhausted I finally fell into a doze, and then into a deep slumber.

Joe wakened me at early dawn, laying a wet, clammy hand in mine and jerking me to a sitting position.

“Get up, Sam!” he said. “Something’s going to happen pretty quick.”

“Are we leaking?” I asked as I tumbled from the berth.

“Yes; but that isn’t it. Come on deck; and step lively while you’ve got the chance.”

He rushed away with the words and I followed him closely.

The sky was gray and overcast, and although it was so early there was light enough to observe distinctly our surroundings. The waves were simply gigantic and the disabled Seagull was like a fisherman’s bob in their grasp. The cargo had not shifted, fortunately, owing to its being so heavy and so carefully stowed, so we kept on our keel as well as the sea would allow us. I found nothing terrifying in the view from the deck until my eye caught sight of a dark object looming ahead, which I instantly recognized as the rocky shore of an island. The waves were bearing us rapidly toward it, and we were helpless to resist.

“See there! and there!” cried Joe, pointing to right and left.

I saw. Rocks were everywhere, on all sides of us. We were right in the heart of a group of South Sea islands—what group, we had no idea. My father’s stern, set face showed from the poop; the sailors stood motionless at the rail. The two De Jiminez, father and son, clung together and stared with blanched faces at the threatening coast.

There was scarcely any wind, as we were partially sheltered in this location. A wind might possibly have saved us; but as it was, and in our crippled condition, there was absolutely no hope.

Uncle Naboth stumbled toward us and said to Joe:

“Call the passengers. Get ’em all on deck an’ see that there are plenty of life preservers. Ned’s getting the boats ready to launch.”

I went with Joe, for there was nothing I could do on deck. Madam de Alcantara began to scream again, but she was not slow in grabbing her jewels and gaining the deck, where she collapsed at once and sobbed like a baby. We got the old lady up easily, and she was as cheerful as anyone could be under such trying circumstances. I had Lucia search for all the cloaks and warm clothing she could lay hands on and Joe and I brought up a lot of blankets; for the air was chilly, even in this tropical clime, and I knew we would all be soaked if we managed to get ashore in the boats.

Bryonia provided a lot of food for us—tinned meats, biscuits and various edibles that might be eaten uncooked—and had the forethought to add some utensils for cooking, as well. A keg of fresh water was deposited in each of the boats. By this time the grim island ahead was very near, and Captain Steele shouted his orders to have the boats lowered.

We put the women into the first, while it still swung at the davits, and Ned Britton, cool as a cucumber, picked a crew to man it. He watched his chance and dropped the longboat neatly on the crest of a high wave, casting loose as the ship rolled heavily in the opposite direction. A little cheer arose from our men as they saw Ned’s boat floating safely, and at once Joe began loading the gig. The two De Jiminez and Uncle Naboth were with this lot; but Joe was not so fortunate as Ned had been. He dropped the boat all right into the gulf between two big waves, but a line got tangled, somehow, and in a jiffy the gig was over and her occupants struggling frantically in the water. The boatswain dropped the third boat quick as a flash, got free from the ship and began picking up the swimmers. Ned also came to the rescue, at the peril of capsizing his own frail craft, and he drew Little Jim aboard as the boy was sinking for the third time. His father was hauled in by a boat hook wielded by the sturdy boatswain, and fortunately Uncle Naboth was spilled so close to the side that he was able to seize a rope and hold fast until rescued. Not a life was lost and the third boat, the cutter, carried its double load easily.

There remained to us but one more boat to launch, and I went to my father and said:

“Come, sir; there’s nothing to be gained by waiting.”

He shook his head.

“Get aboard, Sam,” said he, “and take all the men that’s left with you. I’m goin’ to stay here.”

“But that is folly!” I cried. “It’s a useless sacrifice, father. You can’t help the poor Seagull by staying.”

“It’s my ship—part o’ her, anyhow—an’ I’ll stay by her like she’s always stayed by me,” he returned obstinately.

I was in despair and for a moment knew not what to do. Turning half around I found the two big blacks, Nux and Bryonia, standing just behind me. The remaining sailors were already in the boat, looking anxiously towards us.

I caught Bry’s eye and there was an inquiring look in it that could not be misunderstood.

“Take him, boys!” I exclaimed, and at the word the two promptly caught my father up and bore him kicking and struggling to the boat, where they dumped him on the bottom and then sat upon him.