Title: The Chautauquan, Vol. 05, December 1884, No. 3

Author: Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle

Chautauqua Institution

Editor: Theodore L. Flood

Release date: August 3, 2017 [eBook #55250]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

A MONTHLY MAGAZINE DEVOTED TO THE PROMOTION OF TRUE CULTURE. ORGAN OF THE CHAUTAUQUA LITERARY AND SCIENTIFIC CIRCLE.

Vol. V. DECEMBER, 1884. No. 3.

President, Lewis Miller, Akron, Ohio. Superintendent of Instruction, Rev. J. H. Vincent, D.D., New Haven, Conn. Counselors, Rev. Lyman Abbott, D.D.; Rev. J. M. Gibson, D.D.; Bishop H. W. Warren, D.D.; Prof. W. C. Wilkinson, D.D. Office Secretary, Miss Kate F. Kimball, Plainfield, N. J. General Secretary, Albert M. Martin, Pittsburgh, Pa.

| REQUIRED READING FOR DECEMBER | |

| What English Is | 123 |

| Sunday Readings | |

| [December 7] | 127 |

| [December 14] | 127 |

| [December 21] | 128 |

| [December 28] | 128 |

| Glimpses of Ancient Greek Life | |

| III.—Greek Private Life | 129 |

| Greek Mythology | |

| Chapter III. | 131 |

| Temperance Teachings of Science; or, the Poison Problem | |

| Chapter III.—Physiological Effects of the Poison Habit | 134 |

| Studies in Kitchen Science and Art | |

| III.—Barley, Oats, Rice and Buckwheat | 137 |

| The Cereals | 139 |

| Home Studies in Chemistry and Physics | |

| III.—Chemistry of Air | 141 |

| The Laureate Poets | 144 |

| The Spell of the Halcyon | 146 |

| Christmas Dangers and Christmas Hints | 147 |

| Do Animals Feign Death? | 150 |

| The War Department | 151 |

| Milton as the Poets’ Poet | 154 |

| Geography of the Heavens for December | 155 |

| The Liberal Upheaval in Norway | 157 |

| How to Help the C. L. S. C. | 158 |

| Outline of Required Readings | 160 |

| Programs for Local Circle Work | 160 |

| How to Organize a Local Circle | 161 |

| The Local Circle | 162 |

| Local Circles | 163 |

| The C. L. S. C. Classes | 167 |

| Questions and Answers | 168 |

| The Chautauqua University | 170 |

| Editor’s Outlook | 171 |

| Editor’s Note-Book | 174 |

| C. L. S. C. Notes on Required Readings for December | 176 |

| Notes on Required Readings in “The Chautauquan” | 178 |

| People’s Christmas Vesper and Praise Service | 180 |

| Talk About Books | 181 |

| Special Notes | 182 |

BY RICHARD GRANT WHITE.

In the course of our two foregoing articles we followed the advance of the great Aryan or Indo-European race, to which we belong, from its original seat in Central Asia, which it began to leave more than four thousand years ago, until we found it in possession of India, Persia, and all of Europe. We considered briefly and incidentally the fact that within the last two hundred and fifty years this Asiatic race has taken absolute possession of the greater part of the continent of North America. We saw that speech was the bond and the token of the now vast and vague, but once narrow and compact, unity of this powerful race, which was brought into existence to conquer, to rule, and to humanize the world. Of the numerous languages which have sprung from the Aryan stem, English is the youngest. Compared in age with any other language of that stock, we may almost say with any existing language of any stock, it is like a new born babe in the presence of hoary eld. Only eight hundred years ago it was unknown. True, its rudiments and much of its substance then existed; but so it might be said that they existed in a certain degree four thousand years ago, as we saw in our last article. Yet again, more than four hundred years passed away before modern English was born. It was not until about the beginning of the sixteenth century that the language of Spenser, of Shakspere, of the Bible, of Bunyan, of Milton, of Goldsmith, Burke, Irving, Hawthorne, and Thackeray, came fully into existence as the recognized established speech of the English race.

Since that time the changes it has undergone have been trivial and unimportant. Like the languages of all other highly civilized peoples, it has received many additions, but its essential character has not changed; its structure has been modified so slightly that the change is perceptible only on the closest examination; its syntactical construction has remained unshaken. The prose of Spenser and Shakspere and the correspondence of the educated men of their day is as easily understood by an unlettered English speaking man of our day as the prose of Sir Arthur Helps or the more intelligible passages in the daily newspapers. During that time, indeed, there have been changes of style in writing English, which are more or less distinctive of periods. A reader of moderate experience and discrimination can soon tell whether a page that is put before him was written in the Elizabethan period, in that of the Restoration (Charles II.), in that of Queen Anne, or that of Victoria. But the differences by which his judgment would be guided are differences of tone, of manner, of “the way of putting things,” of certain tricks of expression, and are without any relations whatever to the “grammar,” or to the essential character of language. The presence of words not in use at one period, but which came into use at another, is an important means of such a discrimination. But, in the first place, the introduction of new words does not modify the essential character of a language; and in the next we are not now considering a criticism which goes so far as to examine the history of the English vocabulary.

This modern English, which is the youngest, is also the greatest language ever spoken. A man may be supposed, not unreasonably, to be prejudiced in favor of his mother tongue; but the judgment that declares in favor of English against all other languages, even Greek, needs neither motive nor support from prejudice. The two facts, that the English language is the vehicle and the medium of a literature unequaled by that produced in any other known tongue, and that it is becoming the common intermediary and most widely diffused speech of the world, show that it possesses in the highest degree the two essential elements of a great and complete language—adaptation to man’s highest and to his homeliest needs in expression. There is no other known language in which “King Lear,” “Hamlet,” “Antony and Cleopatra,” the Falstaff scenes in “King Henry the Fourth,” “The Pilgrim’s Progress,” “Paradise Lost,” the Roger de Coverley papers of the “Spectator,” “The Elegy in a Country Churchyard,” “The Vicar of Wakefield” and “She Stoops to Conquer,” “The School for Scandal,” “Waverley,” “The Antiquary” and “The Fortunes of Nigel,” “Childe Harold” and “Don Juan,” “The Pickwick Papers,” “Henry Esmond,” “Adam Bede” and “Romola,” “In Memoriam” and “Sir Galahad,” “The Earthly Paradise,” “Child Roland” and “The Scarlet Letter” could all have been written. No other language is at once grand enough and simple enough, strong enough and flexible enough, lofty enough and homely enough to be the natural, fitting and complete utterance of the literature of which these are the typical productions, and to be,[124] moreover, at the same time perfectly adapted to the needs of the jurist, the politician, the man of business, and the mariner. I remember that once on the St. Lawrence, on the way to Quebec, as the steamer came to a landing, the French officer on the “bridge” screamed an order to the engineer, “Arretez donc, Alphonse! arretez donc!”[1] and that then I recollected that the day before on the British steamer in which I left Montreal, the English officer in just the same situation had quietly said, in his strong, firm voice, “Hold hard!” and that I then thought not only how much more effective those two syllables were as a phrase of nautical command, but that they might be used by an English poet in a passage of grand and strong emotion. English has no words which are too great or too little, too fine or too homely to be used when need requires. English words change their character and their expression according to their connection and the manner in which they are uttered.

English owes its supremacy first, to the vigorous vitality of its germ and the clean robustness of its stem; next, to the rich and infinitely varied word-growth, which this trunk supports and nourishes. All languages are more or less composite, but of all languages English is most composite. It has been largely and richly grafted. It is, of all languages, the most complex in substance, and the simplest in structure. This simplicity of structure enables the uneducated man—Bunyan, for example—to use it with correctness and force, while the vast variety of its substance adapts it to all the needs of poet and philosopher. Let us see how such a language came into existence, and what it is.

The people which spoke the English language when it assumed its modern form, had made it. This may seem to be the sort of truth which is triteness; but it is not so. The people which speaks a language generally does make it; but not always, as we shall see. The people who made the English language, and who made England, were of that part of the great Aryan family which had taken possession of the northwestern part of Europe—that which lies around the southern and western part of the Baltic Sea. It is commonly said that the English are a very composite and heterogeneous people. In a narrow sense this is true, but in a large and really significant sense it is quite untrue. In his welcome to the Danish princess Alexandra, when she arrived in England to become Princess of Wales, the poet laureate prettily availed himself of the minor truth, to sing

The English race is, and for more than five hundred years has been compounded of Saxons (Angles, Saxons and Jutes), Danes and Normans. But these three peoples were of such close kindred that, in Launcelot Gobbo’s phrase, they were “cater cousins.”[A] They were all Goths; the Danes and the Normans were both Scandinavians; and the Saxons, the Angles, and particularly the Jutes, although they were Low German tribes (the term Low German meaning merely inhabitants of the lower parts of Germany near the sea) were, because of their origin, and also of their neighborhood to the others, so like them in blood and in speech that the difference was rather superficial than essential.

These Jutes, Angles and Saxons, continuing the armed Aryan progress westward, went to Britain in companies of hundreds and thousands, and fighting their way from the shore inland at various points, and continually reinforced from their hive on the continent, in the course of about one hundred and fifty years they obtained complete possession of the island, from the Tweed to the Channel, excepting only the mountainous part at the west, now called Wales. They seem not to have mingled with the conquered Britains, who it will be remembered were Celts, but to have wholly displaced them, to have swept the land clean of them, except in Wales, the Highlands of Scotland, and a small remnant in Cornwall, the extreme southwestern point of the island. They carried with them their Scandinavian-tinged Low German speech (called for convenience Anglo-Saxon), which became the language of the country whose name their presence and possession changed from Britain to Angle-land, Engel-land, England. But when they had established themselves they were not left undisturbed. The Danes poured in upon them at the north, and soon getting foot-hold, they in their turn attempted the conquest of the whole island. They succeeded so nearly that they not only obtained possession of the northern part of the England of that day, but of the government; and three Danish kings[B] ruled the land at London. They did not, however, like the Anglo-Saxons, destroy their predecessors; partly from lack of strength to accomplish such a destruction, and partly, it would seem, from affinities of race and habits of life. Danes and Anglo-Saxons mingled; although the former were chiefly confined to the northern part of the country. One result of this conquest and intermingling was a modification of the speech of the country, particularly at the north. It received a strong Scandinavian infusion, the alterative influence of which has been recognized more and more by philologists as they have studied the structure and history of the English language. It should be said here, and perhaps should have been said before, that the name Dane had in these early times a large and loose signification. It was applied, without much discrimination, to any people that lived in the Scandinavian country—Norway and Sweden as well as Denmark.

Alfred, that first great Englishman, who, if not the only good English king, has been approached neither in ability nor worth by any of his successors to this day, is generally thought of as having conquered the Danes and extinguished their power in England; but erroneously. The Danes were worsted by him; but the Danish settlers in England were not ousted, nor could they be, for they had become a part of the people; the Danish influence upon English life was not much minished. It was within the quarter of a century following Alfred’s death that the Danish king Sweyne levied an annual tribute of £36,000 upon England, and that Danes were called Lord Danes. Forty-two years after Alfred, the Danish Canute, son of Sweyne, was crowned king of England; and the Danish pretensions to the rule of England were not wholly abandoned until the occurrence of an event which had little less influence upon the language of England than upon its fortunes. Edward the Confessor, the last of the royal line of ancient England, was little more than king in name and state. The country was really ruled by a council of six great earls, Danes and English, who partitioned the control of the country among themselves. The Anglo-Saxons had invaded Britain, and had conquered the Celtic Britons and removed them from the soil; the Scandinavian Danes had invaded England, and partly conquered the Anglo-Saxons (now called Englishmen), but had not destroyed their near kinsmen, and the two people had mingled. And now, in the eleventh century (1066), the Normans invaded England and conquered its Dano-Anglo-Saxon people in their turn. Harold, who claimed and obtained the throne, on the death of Edward the Confessor, as his heir, but not as his descendant or lineal successor, was himself half Dane, his father having been Earl of Kent, his mother Gytha, a Danish noblewoman. The influence of the Scandinavian element on the character and the language of modern England was very great, and until of late has been underrated.

The conquest of England by the Normans, and the division of it into sixty thousand knight’s fees, distributed mostly among the followers of the Norman duke, who were thus with their families and followers scattered widely over the country,[125] was the cause of one of the most remarkable phenomena in the history of language—the introduction of Norman-French as an element of English speech. Some French or Romance words had come into England before, because of neighborhood and of affectation of foreign refinement, and a few Latin words had crept in under favor of the clergy; but now Norman-French was distributed all through the island as the speech not only of the holders of the sixty thousand knight’s fees, but of all their followers, and a considerable number of their tenants, to say nothing of their adulatory imitators, or of the Norman clergy who accompanied them to bless and to share their conquest.

Now who were the Normans, and what was this Norman-French which they introduced into England? The Normans were simply North-men from the great Scandinavian peninsula now divided into Norway and Sweden. They were pirates and robbers. Bold and bloody on sea and land, they had been for two or three centuries the scourge and the terror of Southern Europe. The people on the continent called them simply “North-men,” the people of England “East-men,” (the name being determined, it will be seen, by the relative position of those who gave it), and sometimes, as has been said before, “Danes.” These sea rovers and raiders effected settlements in various parts of Europe, but their most important lodgement, the only one with which we have now any concern, was in France, which they invaded on the south of the Seine, between that river and the Loire. Here in the course of less than a hundred years they had established themselves so firmly that in the year 912, Charles, the Frankish king, recognized and enfeoffed[2] the Viking Rollo, as first Duke of Normandy; Rollo acknowledging Charles as his over-lord, and receiving baptism—for the Normans were now, as the Anglo-Saxons had been until about A. D. 600, pagans. These Gothic Norsemen did not make the language that they soon came to speak. Conquerors and rulers although they were, they adopted the language of the country and the people which they had conquered, and spoke it with slight Gothic modification. This was the Norman-French which, only one hundred and fifty years after they were well settled in the country which they had seized, and which was called from them “Terra North manorum,”[3] or Normandy, they took into England.

This French language (Norman or other) was like many other things wrongly named. It was not the speech of the Franks or French, a German tribe, who in the fifth century conquered the country, and from whom it came to have its name. What, then, was it? We must turn back a moment.

It will be remembered that the column of Aryan immigration after entering Europe at its southeastern corner, divided; one division, the Celto-Græco-Italic, following the northern shore of the Mediterranean, taking possession of the country there, then pushing up northward to the country once called Gaul, now France, and finally crossing the English Channel and taking possession of Britain and Ireland. This column of immigrants founded, among other states, one which is hitherto the grandest, most influential fact in the history of the world—Rome, the city, the republic, and finally the empire of Rome; the influence of which upon the world has now, after more than two thousand years, not passed away; for the Roman Catholic Church, ecclesiastically supreme because it was the Church of Rome, is still one of the great powers of the earth. The Celtic peoples in Gaul were conquered by the great Cæsar half a century before the Christian era. The Romans were wise conquerors; they made the people whom they conquered Romans. The Celts of Gaul, during centuries of Roman rule lost almost all their native habits and customs, among them their mother tongue. They had Roman customs and laws and they gradually adopted the Roman language—the Latin. As might be expected, however, they did not speak pure Latin. The very people of Rome did not speak pure Latin, if by that we mean the Latin of Cicero’s orations, and the poems of Horace and of Virgil. That was a literary language. The popular Latin was speech much less formal and artificial. But the Celts of Gaul (or France) spoke this popular Latin much debased, and somewhat intermixed with Celticisms. The degradation of this form of Latin went on until the country was successfully invaded by German tribes in the fifth century. These Franks and Burgundians, being fewer than the Celto-Roman people whom they conquered, and inferior in civilization, gradually adopted their language, which, however, they broke up and simplified, by ridding it of case endings and tense signs; doing this for mere convenience sake; they had not the time or the patience to learn all the Latinish inflections. When about four hundred years of Frankish rule and influence and intermarriage had elapsed, it was discovered that the language of the people had become so greatly unlike Latin that it was practically another tongue. Wherefore it was decreed in the year 813 by the Council of Tours that the bishops should address their clergy and people in the Romance tongue, which was the name given to this popular modification of the old Roman (Latin) speech. This the Frank kings and courtiers, who had continued to speak German, were soon obliged to adopt; and after the division of Charlemagne’s empire, in the year 843, German was restricted to the country beyond and just about the Rhine. The Romance tongue, spoken to the westward, was rapidly modified by degradation of forms, and by intermixture of Teutonic words, until it became about the eleventh century, what is known as Old French. It was a debased form of this Old French which the Scandinavian North-men, or Normans, adopted, and finally carried into England, not only as the court language, but to spread it all over the country. This, then, is the strange phenomenon in language which is consequent upon the Norman conquest of England; that a Gothic people conquering and uniting themselves with another Gothic people, took into the conquered country, not a Gothic, but a Romance tongue. When the Norman conquerors spread themselves over all England, accompanied by their followers of various ranks (for it is an absurdly erroneous notion that all the Normans that went to England were nobles, or even knights), they took there no race of foreign blood. To the Dano-Anglo-Saxon English stock, they merely added more of the Danish element. But most strangely, the language brought in by this victorious body of near kinsmen was the most foreign that could have been found west of the Caucasus.

At first, with the pride of conquerors, the Normans in England spoke their own, or rather their adopted tongue. Norman-French was the language of the court, of the law-courts, of “society.” English was “vulgar.” This went on for some generations. The condition of things in this respect could not, however, remain unchanged. Two tongues can not be spoken by people in constant intercourse with each other without both being more or less affected by the contact. This happened. The English (called Anglo-Saxon or Old English) and the Norman-French were each modified by the other; they interchanged words and idioms; each dovetailing itself into the other, until about the year 1350, when it was discovered that the distinction of Norman and Englishman had practically passed away, and that the conqueror, yielding to the steady, gradual influence of the people and the country he had conquered, had himself become an Englishman. English had become the speech of the whole people, and thereafter English was by decree the language of all public documents, proclamations, and the like, the language of the court, and of “society.”

Of the English, however, which thus came into vogue, it must be remembered, first, that it did not prevail in the same form among all the people, but only among the superior classes and the middle classes of the best condition; that even among them it was spoken and written with much variation; and that[126] as to the rustic people, they spoke almost as many dialects of the Old English as there were shires in England. Second, that this English of 1350 was so unlike both the Old English of Alfred’s day, four hundred years before, that he would not have been able to read it without much study, and that it was equally unlike the English of Queen Anne, four hundred years later.

The introduction of the Norman-French element into the English language was a gain, the value of which, in the enrichment of our tongue, and in its increased adaptability to the wants of a highly civilized people can not be overestimated. The Old English (or Anglo-Saxon) was a strong, manly speech, and not without a certain homely charm and simple sweetness. It was direct, too, and seemed (but perhaps merely seemed) to be the speech of an honest people. It was however, rude, inflexible, limited in its vocabulary, and incapable of expressing fine distinctions of thought. In all these respects it was so profited, so endowed, so broadened, so suppled and so refined by its union with the Romance vocabulary which was largely grafted upon it, that it blossomed almost into another language; quite another if its capacities are considered. An examination of the more particular nature of these changes, which have direct connection with the practical use of the language, must be postponed until our next article.

To this two-elemented language, a language composed of two stocks so different as the Gothic and the Latin, and yet strangely spoken by a people wholly Gothic and largely Scandinavian in blood, there came now, or began to come, an addition which was destined to affect its character greatly, and without which it would not be the matchless language that it is. This addition was not an addition of substance, but of spirit, not of matter but of manner. It came to the English language because of the bold and independent spirit of the English race in politics and in religion. It came through the translation of the Bible into the English tongue. This brought into the English language, alone among all the languages of the Indo-European race, not a foreign element indeed, but the informing spirit of a great literature written in a tongue so radically unlike all Aryan speech that the existence of the two would seem wholly incompatible with the theory of evolution, and to imply two independent creations of man; at least two independent creations of language. Yet these two languages or families of languages, the Aryan and the Semitic, seem to have come into existence in neighboring countries. As our Aryan forefathers, in their earlier movements, and before their first division, passed between the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf, they skirted the northern borders of the great peninsula of Arabia, into which none of them, not even those who turned southward, seem to have attempted to penetrate. This peninsula was at that time, we may be sure, although there is neither evidence of the fact nor testimony to it, occupied by the Semitic race; a race of great power and peculiar genius, which has had an influence upon the world hardly less than that of the Aryan peoples. Why the Aryans did not attempt the conquest and possession of Arabia, we do not know. But it is to be remembered that they were then comparatively small in numbers; and the Semitic race is one at once so warlike and so sagacious, that the conquest would have been one of the utmost difficulty, even if it were practicable; and moreover, that the country is not an inviting one to strangers.

The great function of the Semitic race in the world seems to have been the conception and the promulgation of the idea of the One Spiritual God. This idea, to which the race still holds, spread itself with an all-controlling influence over the civilized globe. It is the corner stone of the Christian and the Mohammedan religions. The Semitic race, of which the Hebrews are a family, has, or had, among its other gifts, the gift of sublime, intense, and imaginative utterance in prose and in poetry. In this respect it is without rival among all the peoples who have or who have had a literature. To these qualities it adds that of a direct simplicity, which in pathos (if with art, with an art so hidden as to leave not even the suggestion of consciousness), attains the power both of the ideal and the real, and never descends so low as sentiment. Of fancy, the Hebrew writers (for it is they whom we are now considering) exhibit none; less it would seem because of the nature of their themes, than because fancifulness was foreign to their intensity and loftiness of soul. The writings forming the most important part of the early Hebrew sacred literature form also, as we all know, that Old Testament which fills the largest part of the Bible—that is, the Book which has been for more than fifteen hundred years held sacred by all christendom.

This sacred Book—which, even if it did not contain the revelation of the idea of the One Eternal and Almighty God, and of his dealings with them who deemed themselves his chosen people, and the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth and of the great apostle to the Gentiles, would yet be the most remarkable collection of writings known in literature—it has been the policy of the church of Rome to keep from the people. Its translation into the vulgar tongue, and its distribution among the people at large, have always by that church been most earnestly discouraged, and even, until a comparatively late date, forbidden. It is remarkable that its earliest translations were into languages of Gothic peoples. Bishop Ulphilas’s translation of the Gospels and a small part of the Old Testament into the Mæso-Gothic language, in the fourth century, has already been mentioned. About three centuries later an Anglo-Saxon translation of the Gospels was made; and there is evidence, as we are assured by Bosworth,[C] in the rubrics[4] that portions of them were constantly read in Anglo-Saxon churches. But these versions did little to bring the Bible before the eyes of the people at large; and besides, they were, as we have seen, confined to a very small part of that book. The Old Testament remained to all intents and purposes in an unknown tongue until the dawn of the Reformation in England. Wycliffe and his followers translated the whole of the Bible about 1380; and from that time, notwithstanding bulls, and anathemas, and persecutions, this book of books, The Book, became the possession of the whole English people.

We are concerned here only with the effect of this momentous work upon the English language. It was great and peculiar. Wycliffe’s English version was followed in 1535 by Coverdale’s, which was afterward republished with revision, by Taverner’s, and by others, including the famous Genevan Bible[5], of which fifty editions were published in England within thirty years. These versions were mostly revisions, each “translator” availing himself, of course, of the text of his predecessors. Finally, in 1611, there was made what is known as the “authorized,” or King James I. version, which has since that time been, next to their common blood and common speech, the strongest bond of unity for the English race. But between the making of Wycliffe’s translation in 1380 and the middle of the sixteenth century, the Bible had taken strong hold of the English people. It sank into their hearts; it lifted their souls; its modes of thought became their modes of thought; its phrases, their household words. When Puritanism appeared, and strangely relied upon the Old Testament as its armory of theological warfare, the thoughts and the words of the prophets, priests and kings of Israel were the daily intellectual food of no inconsiderable part of the common people, and the air of all England was vocal with the phraseology of Job, of David, of Isaiah, and of Ezekiel. The effect of this upon the English mode of thought and expression was great and lasting; enduring even to this day. Its value was inestimable. By reason of it English diction acquired a simplicity, a strength, a directness, a largeness of style, a capacity of grandeur[127] and of pathos, a richness and variety which it otherwise would not have acquired, and which has not been attained by the language of any other people. The spirit of Hebrew literature was transfused into the English mind to such a degree as to modify its mode of thought and of utterance. This took place because the diffusion of the Bible happened just at the time when the language was in a state of transition, and modern English was in course of formation. Had it not occurred until afterward, as was the case with other European peoples, it would have been too late to produce this effect. The English of Shakspere, of Milton, of Bunyan, and their great successors would not have existed but for the translation and diffusion of the Bible among the English people.

This, then, English is: a sturdy Gothic stem, largely and deeply grafted with Romanic scions, and permeated with the spirit of Hebrew sublimity and passion. These are the source elements of the supremacy of the youngest language of the Aryan stock. It unites all the powers and possibilities of its congeners, and adds to them those of the speech of the only other race that has felt and uttered the highest aspirations of humanity, and largely swayed the course of man’s progress through his unknown future.

[A] Quarter cousins. The Merchant of Venice; Act ii, Sc. 2.

[B] Omitting Sweyne, who was proclaimed king, but whose possession of the throne was brief, and whose regal authority was not fully established or recognized.

[C] See the preface to his edition of the Gothic and Anglo-Saxon Gospels with the versions of Wycliffe and Tyndall. London: 1865.

SELECTED BY CHANCELLOR J. H. VINCENT, D.D.

But by what means can a mortal man, the creature of a day form any idea of eternity? What can we find within the compass of nature to illustrate it by? With what comparison shall we compare it?… What are any temporal things, placed in comparison with those that are eternal? What is the duration of the long-lived oak, of the ancient castle, of Trajan’s pillar,[1] of Pompey’s amphitheater?[2] What is the antiquity of the Tuscan urns,[3] though probably older than the foundations of Rome; yea, of the pyramids of Egypt, suppose they have remained upward of three thousand years; when laid in the balance with eternity? It vanishes into nothing. Nay, what is the duration of “the everlasting hills,” figuratively so called, which have remained ever since the general deluge, if not from the foundation of the world, in comparison of eternity? No more than an insignificant cipher. Go farther yet; consider the duration, from the creation of the first-born son of God, of Michael, the archangel, in particular, to the hour when he shall be commissioned to sound his trumpet, and to utter his mighty voice through the vault of heaven, “Arise ye dead and come to judgment!” Is it not a moment, a point, a nothing, in comparison of unfathomable eternity?… In order to illustrate this, a late author has repeated that striking thought of St. Cyprian:[4] Suppose there were a ball of sand, as large as the globe of earth; suppose a grain of this sand were to be annihilated, reduced to nothing, in a thousand years; yet that whole space of duration, wherein this ball would be annihilating at the rate of one grain in a thousand years, would bear infinitely less proportion to eternity, duration without end, than a single grain would bear to all the mass!

To infix this important point the more deeply in your mind, consider another comparison: Suppose the ocean to be so enlarged as to include all the space between the earth and the starry heavens. Suppose a drop of water to be annihilated once in a thousand years; yet that whole space of duration, wherein this ocean would be annihilating at the rate of one drop in a thousand years, would be infinitely less in proportion to eternity than one drop of water to that whole ocean. See the spirits of the righteous that are already praising God in a happy eternity! We are ready to say, “How short will it appear to those who drink of the rivers of pleasure at God’s right hand!” We are ready to cry out:

But this is only speaking after the manner of men; for the measures of long and short are only applicable to time, which admits of bounds, and not to unbounded duration. This rolls on (according to our low conceptions) with unutterable, inconceivable swiftness; if one would not rather say, it does not roll or move at all, but is one still, immovable ocean. For the inhabitants of heaven “rest not day and night,” but continually cry, “Holy, holy, holy, is the Lord, the God, the Almighty, who was, and who is, and who is to come!” And when millions of ages are elapsed, their eternity is but just begun.… What then is he, how foolish, how mad, in how unutterable a degree of distraction, who, seeming to have the understanding of a man, deliberately prefers temporal things to eternal? Who (allowing that absurd, impossible supposition that wickedness is happiness—a supposition utterly contrary to all reason, as well as to matter of fact) prefers the happiness of a day, say a thousand years, to the happiness of eternity, in comparison of which, a thousand ages are infinitely less than a year, a day, a moment?—Wesley’s Sermons.

There are some thoughts which, however old, are always new, either because they are so broad that we never learn them thoroughly, or because they are so intensely practical that their interest is always fresh.… Now, among such thoughts we may reckon that which all children know—that God loves every one of us with a special love. It is one of the commonest thoughts in religion, and yet so amazing that when we come to look steadily at it we come nigh to not believing it. God does not look at us merely in the mass and multitude. As we shall stand single and alone before his judgment seat, so do we stand, so have we always stood, single and alone before the eye of his boundless love. This is what each man has to believe of himself. From all eternity God determined to create me, not simply a fresh man, not simply the son of my parents, a new inhabitant of my native country, an additional soul to do the work of the nineteenth century. But he resolved to create me such as I am, the me by which I am myself, the me by which other people know me, a different me from any that have ever been created hitherto, and from any that will be created hereafter. Unnumbered possible creatures which God saw when he chose me, he left to remain in their nothingness. They might have worshiped him a thousand times better than I shall ever worship him. They might have been higher, holier, and more interesting. But there was some nameless thing about me which he preferred. His love fastened on something special in me. It was just me, with my individual peculiarities, the size, shape, fashion, and way of my particular, single, unmated soul, which in the calmness of his eternal predilection drew him to create me.…

Must I not infer, then, also, that in the sight of God I stand in some peculiar relation to the whole of his great world? I clearly belong to a plan, and have a place to fill, and a work to do, all which are special; and only my specialty, my particular me, can fill this place or do this work. This is obvious,[128] and yet it is overwhelming also. I almost sink under the weight of the thought. It seems to bring God so very near.… I come in sight of the most overshadowing responsibilities. Responsibility is the definition of life. It is the inseparable characteristic of my position as a creature. I am constantly moving, constantly acting. I move impulsively and I work negligently. What, then, becomes of my special place and of my special work? From this point of view life looks very serious. Surely we must trust God with a huge confidence, or we shall be frightened into going and burying our talent in the earth!

Now, what is it about us which was the prime object of God’s love when he chose us for creation? It can not be put into words. It is just all that which makes us ourselves, and distinguishes us from all other selves, whether created or possible. It was precisely our particularity which God so tenderly and intensely loved. The sweetness of this thought is almost unbearable. I draw in my breath as if to convince myself that I am alive, I lay my hand on my heart to feel its beating. First I smile, and then I weep. I hardly know what to do with myself, I am so delightfully entangled in the meshes of divine love. This specialty of God’s love startles me more and more, the longer I familiarize myself with it. I am obliged to make acts of faith in God, acts of faith in all his different perfections, but the greatest act of faith in this specialty of his love of me, of such as I am, such as I know myself to be, even such as he knows me to be. Deeper and perpetually deeper, taller and perpetually taller, the shadow of my responsibilities is cast upon me. But it is not a dark shadow, not depressing, but inspiring; sobering, but not paralyzing. I see plainly that my love of God must be as special as God’s love of me. I must love him out of my special place, love him through my special work; and what is that place, and what is that work? Is not this precisely the question of questions?—Faber.

Though violent persecution is not an event, under the present circumstances of the Christian profession in this country, within the range of probability, yet serious and faithful opposition may be expected. Vigorous attempts will be made to deprive you of your crown, at one time by an assault on your doctrinal, at another by efforts to corrupt your practical, principles. A strong current will set in from the world to obstruct your progress, swelled by the confluence of false opinions, corrupt customs, ensnaring examples, and all the elements of vice, error and impiety, which are leagued in a perpetual confederacy against God and his Christ. Your faith will often be beset, not merely by the avowed patrons of error, but by such as “hold the truth in unrighteousness;” who, never having experienced the renovating power of divine truth, will be among the first and foremost to ridicule and oppose its genuine influence. While you live like the world, you may with impunity think with the church, but let the doctrines you profess descend from the head to the heart, and produce there the contrition, the humility, the purity, the separation from the world which distinguish the new creature, that world will be armed against you. “They think it strange that ye run not to the same excess of riot, speaking evil of you.” In order to stand your ground, it will be requisite for you to “quit yourselves like men, and be strong.” Aware that he is everywhere and at all times surrounded with danger, the life of a Christian is a life of habitual watchfulness; in solitude, in company; at home, abroad; in repose and in action; in a state of suffering, or a state of enjoyment; in the shade of privacy, or in the glare of publicity. Aware of his incessant liability to be ensnared, he feels it incumbent on him to watch. The melancholy history of the falls of Noah, of David, and of Peter, is adapted and designed to teach us this lesson.

An opportunity may present itself, perhaps, in your future course, of growing suddenly rich, of making at least a considerable accession to your property; but it involves the sacrifice of principle, the adoption of some crooked and sinister policy, some palpable violation of the golden rule; or, to put it in the most favorable light, such an immersion of your mind in the cares and business of the world as will leave no leisure for retirement, no opportunity for “exercising yourself unto godliness,” no space for calm meditation and the serious perusal of the Scriptures. Are you prepared in such a conjuncture to reject the temptation; or are you resolved at all events to make haste to get rich, though it may plunge you into the utmost spiritual danger? “Count the cost;” for with such a determination you can not be Christ’s disciple.

By the supposition with which we set out, you have solemnly renounced the indulgence of sinful pleasures. But recollect that sin will return to the charge, she will renew her solicitations a thousand and a thousand times; she will sparkle in your eyes, she will address her honeyed accents to your ears, she will assume every variety of form, and will deck herself with a nameless variety of meretricious embellishments and charms, if haply in some one unguarded moment she may entangle you in those “fleshly lusts which war against the soul.” “Count the cost.” Are you prepared to shut your eyes, to close your ears, and to persist in a firm, everlasting denial?—Robert Hall.

God delights in our temptations, and yet hates them; he delights in them when they drive us to prayer; he hates them when they drive us to despair. The Psalm says: “An humble and contrite heart is an acceptable sacrifice to God,” etc. Therefore, when it goes well with you, sing and praise God with a hymn; goes it evil, that is, does temptation come, then pray; “For the soul has pleasure in him;” and that which follows is better: “and in them that hope in his goodness.” … He that feels himself weak in faith, let him always have a desire to be strong therein, for that is a nourishment which God relishes in us.

The weak in faith also belong to the kingdom of Christ; otherwise the Lord would not have said to Peter, “Strengthen thy brethren,” Luke xxii; and Romans xiv: “Receive the weak in faith;” also I. Th., v: “Comfort the feeble minded, support the weak.” If the weak in faith did not belong to Christ, where, then, would the apostles have been whom the Lord oftentimes … reproved because of their unbelief?

Upright and faithful Christians ever think they are not faithful, nor believe as they ought; and therefore they constantly strive, wrestle, and are diligent to keep and to increase faith, as good workmen always see that something is wanting in their workmanship. But the botchers think that nothing is wanting in what they do, but that everything is well and complete.

Christ desires nothing more of us than that we speak of him. But thou wilt say, If I speak or preach of him, then the word freezes upon my lips. O! regard not that, but hear what Christ says: “Ask and it shall be given unto you,” etc.; and “I am with him in trouble; I will deliver him and bring him to honor,” etc.

When we are found true in our vocation and calling, then have we reaped honor sufficient, though not on this earth, yet in that to come; there we shall be crowned with the unchangeable crown of honor “which is laid up for us.” Here on earth we must seek for no honor, for it is written, “Woe unto you when men shall bless you.” We belong not to this life, but to another far better. The world loves that which is its own; we must content ourselves with that which it bestows upon us, scoffing, flouting, contempt. I am sometimes glad that my scholars and friends are pleased to give me such wages; I desire neither honor nor crown here on earth, but I will have compensation from God, the just Judge, in heaven.—Luther’s Table-Talk.

Selected from J. P. Mahaffy’s “Old Greek Life.”

While the citizen prized above all things his liberty and his rights as a member of the state—a feeling which produced in many cases a citizen democracy—this principle was unknown within the household, in which he was a despot, ruling absolutely the inferior members, who had no legal grades except as distinguished into free and slaves. The laws were very cautious about interfering with his rights, and he was permitted to exercise much injustice and cruelty without being punished. If in such a case he was murdered by his dependants, the whole household of slaves was put to death, unless the culprit was detected. Nor could a household exist (except perhaps in Sparta) without the master. If he died, his widow became again the ward of her father or eldest brother, or son; and so strongly was this sometimes felt that men on their deathbeds betrothed their wives to friends who were likely to treat them and their orphan children with kindness. Of course clever women and servants often practically had their own way, and ruled their lord or master; but the theory of the Greek home was nevertheless always that of an absolute monarchy, if not a despotism.

There were two distinct styles of female dress prevalent. The first was the Dorian, which was noted for its simplicity. Unmarried girls at Sparta often wore but a single light garment, chiton,[1] fastened with clasps down the sides—a dress much criticized by their neighbors. Over this was the Doric peplos,[1] fastened on the shoulders with clasps, and leaving the arms bare. The Ionians wore a long linen chiton with sleeves, which reached down to the ground, and over it a large flowing wrapper, himation,[2] fastened with a girdle, worn high or low according to fashion. As a general rule, unmarried women confined their hairdressing to mere artistic arrangement of the hair itself, while married women wore bands, fillets, nets, and coronets. Dyeing the hair was not uncommon, and the fashionable color was auburn, or reddish fair hair. Women’s shoes were very carefully made, and they carried fans and parasols, as may be seen in the terra-cotta figures so common in our museums. Both sexes wore rings, but in addition the women wore earrings, armlets, and ankle-rings, generally of gold. These were the ornaments against which lawgivers made enactments, and which were forbidden or discouraged in days of trouble or poverty. The ornaments of one rich lady are spoken of as worth 50 minæ (about $975), a very large sum in those days. The ordinary color of women’s dress was white, but saffron cloaks, and even flowered patterns, are mentioned.

In Homeric days we find the old barbarous custom still surviving of buying a girl from her father for a wife, and this was commonly done, unless the father himself offered her as a compliment. The father, however, usually gave her an outfit from the price he received for her. In case of a separation this outfit came back to the father, but he was also obliged to restore the price he had received for his daughter. She does not appear to have had any legal rights whatever. In later days the custom of paying money was reversed, and the husband received with his wife a dowry, which was regarded as common property with his own, so long as she lived with him. In case of separation or divorce, this dowry had to be repaid to her father, and at Athens 18 per cent. was charged upon it in case of delay in repayment. In many states, to marry a second wife during the life of the first was against the practice, and probably the law, of the Greeks, but concubinage was tolerated and even recognized by them, though a married woman had at Athens a right to bring an action for general ill-treatment against her husband, in which she was obliged to appear and give evidence in person. The dowry seems to have been partly intended as a useful obstacle to divorce, which required its repayment, but we find that heiresses made themselves troublesome by their airs of importance, and this is referred to in Greek literature, in which men are frequently advised not to marry above them in wealth or connections. As all citizens were considered equal in birth, and as marriages with aliens were illegal and void, we do not hear of advice to young men not to marry beneath them. To marry a poor citizen girl was always considered a good deed, and is commended as such.

When a child was born in the house, it was usual in Attica, and probably elsewhere also, to hang a wreath of olive in case of a boy, a fillet of wool in case of a girl, over the door. This served as an announcement to friends and neighbors. Greek law permitted the parents absolutely to dispose of it as their property, and there was no provision against exposing it, which was often done in the case of girls, in order to avoid expense. These exposed children if found and brought up, became the slaves of the finder. But on the other hand, the laws showed special favor to the parents of large families. If a child was not exposed, there followed on the fifth day a solemn purification of all the people in the house, and on the seventh a sacrifice, when the relations assembled and the child was named generally after parents and grandparents, sometimes by reason of special wants or fancies—in fact, on the same principles which we follow in christening our children. There is no evidence until the later Macedonian times that birthday feasts were held yearly: and Epicurus’ direction that his should be kept after his death was thought very peculiar. Children of rich people were often nursed by hired nurses—an employment to which respectable Athenian citizens were reduced in the hard times at the end of the Peloponnesian war. But a Lacedæmonian nurse was specially valued, and often bought at a great price among prisoners, as they were famed for bringing up the child without swaddling-clothes, and making him hardy and courageous. The Greeks used cradles for children as we do, and gave them honey as we do sugar, and the nurses represented on the vases are distinguished by a peculiar kerchief on the head, as they often are in our day by a cap or national costume.

As might be expected, the inventive genius of the Greeks showed itself in the constructing of all manner of toys, and children devised for themselves perhaps all the games now known and many more beside. Aristotle says you must provide them with toys, or they will break things in the house, and the older philosopher Archytas[3] was celebrated for inventing the child’s rattle. Plato also complains of the perpetual roaring of younger, and the mischievousness of older children. We may infer from these things that the Greek boys were fully as troublesome as our own. They had balls, hoops, swings, hobbyhorses, and dice, with dolls for the girls, and various animals of wood and earthenware, like the contents of our Noah’s arks. They played hide and seek, blind man’s buff, French and English, hunt the slipper, the Italian morra,[4] and many other games which the scholiasts and Germans have in vain endeavored to explain. But for grown people, we do not find many games, properly speaking, played for the game’s sake, like our cricket. There was very simple ball playing, and, of course, gambling with dice.

As for the girls of the house, they were brought up to see and hear as little as possible. They only went out upon a few[130] state occasions, and knew how to work wool and weave, as well as to cook. We may fairly infer that the great majority of them could not read or write. The boys, on the contrary, were subjected to the most careful education, and on no point did the Greek lawgivers and philosophers spend more care than in the proper training, both physical and mental, of their citizens. The discipline was severe, and they were constantly watched and repressed, nor were they allowed to frequent the crowded market-place. Corporal punishment was commonly applied to them, and the quality most esteemed in boys was a blushing shyness and modesty, hardly equaled by the girls of our time. Nevertheless, Plato speaks of the younger boys as the most sharpwitted, insubordinate, and unmanageable of animals.

It does not seem that the office of schoolmaster was thought very honorable, except of course in Sparta, where he was a sort of minister of education. It was, as with us, a matter of private speculation, but controlled by police regulations that the school should open and close with sunrise and sunset and that no grown men should be allowed to go in and loiter there. The infant-school teachers, who merely taught children their letters, were of a low class in society, sometimes even teaching in the open air, like the old hedge schoolmasters in Ireland. The more advanced teaching of reading and writing was done by the grammar teacher, whose house was called, like that of philosophers and rhetoricians, a school,[5] a place of leisure. For the physical and the æsthetic side we have still to mention the trainer and the teacher of music, the former of whom taught in the palæstra[6] the exercises and sports afterward carried on by the full-grown citizens in the gymnasia, which were a feature in all Greek towns. The teachers of riper youth stood in social position above the mere teachers of letters, but beneath the professors of rhetoric and philosophy (sophists). These latter performed the functions of college tutors at our universities, and completed the literary side of Greek education. The fees paid to the various teachers were in proportion to their social importance. Some of the sophists made great fortunes, and exacted very high fees; the mere schoolmasters are spoken of as receiving a miserable pittance.

The Greeks never thought of making foreign languages a matter of study, and contented themselves with learning to read and write their own. In so doing the schoolmasters used as text books the works of celebrated epic or elegiac poets, above all Homer, and then the proverbial philosophy of Hesiod, Solon, Phocylides,[7] and others, so that the Greek boy read the great classics of his language at an early age. He was required to learn much of them by heart,[8] especially when books were scarce; and his teacher pointed out the moral lessons either professedly or accidentally contained in these poets. Thus they stood in the place of our Bible and hymns in education. All this was grammar, which with music and gymnastics made up the general education of the Greeks. It excluded the elementary arithmetic of our “three R’s,” and included what they do not, a gentlemanly cultivation in music and field sports. It is very doubtful whether swimming was included, though Herodotus speaks of the Greeks generally as being able to swim. There is, however, evidence that from the fourth century B. C. onwards both elementary geometry and arithmetic, and also drawing, were ordinarily taught.

As regards music, every Greek boy (like modern young ladies) either had or was supposed to have a musical ear, and he was accordingly taught either the harp or the flute, and with it singing. Here again the lyric poems of the greatest poets were taught him, and the Greek music always laid the greatest stress on the words. Aristotle and others complain that amateurs were spending too much time on the practicing of difficult music, and we know from the musical treatises preserved to us that the Greeks thought and taught a great deal more about musical theory and the laws of sound than we do. The Greek tunes preserved are not pleasing, but we know that they used the strictest and most subtle principles in tuning instruments, and understood harmony and discord as well as we do. Great Athenians, like Cimon, were often able to sing and accompany themselves on the harp, or lyre as we should rather call it. The Greeks laid great stress on the moral effects of music, especially as regards the performer, and were very severe in their censure of certain styles of music. They distinguished their scales as modes, and are said to have put far greater stress on keys than we do, calling some manly and warlike (Dorian), others weak and effeminate, or even immoral (Mixo-Lydian). The modern Chinese have the same beliefs about the moral effects of music. The Greeks had their keynote in the middle of the scale, and used chiefly the minor scale of our music. They had different names and signs for the notes of the various octaves which they used, and also different signs for vocal and for instrumental music.

Among the various exercises taught were those in fashion at the public contests in the games—throwing the discus, running, and wrestling, and those of use in war—throwing the dart, managing the sword and shield, and riding. Boxing was not highly esteemed, and seems not to have been properly understood by the Greeks, who would have had no chance against an English prize-fighter. The severest contest was the pancration, where the combatants, who were naked and unarmed, were allowed to use any violence they liked to overcome their adversary. It was therefore a combination of boxing, wrestling and kicking, with occasional biting and gouging by way of additional resource. We hear of a wonderful jumping feat by Phayllus of Croton, who leaped forty-four feet; but as he probably jumped down-hill, and used artificial aids, we can not be sure that it was more than can be done now-a-days. The Spartans specially forbade boxing and the pancration, because the vanquished was obliged to confess his defeat and feel ashamed; and they did not tolerate professional trainers. All the special exercises for developing muscle practiced in our gymnasia seem to have been known, and they were all practiced naked, as being sunburnt was highly valued. The Greeks smeared themselves first with oil and then with sand before their exercises, and cleaned themselves with a scraper or strigil, or in later days by taking a bath.

The servants of the house were of course slaves, with the exception of some field-laborers, and of nurses in times of depression and distress, when some free women went out for hire. To these cases we may add the cook, who was not an inmate of the house before the Macedonian time, but was hired for the day when wanted for a dinner party. All the rest were slaves, and were very numerous in every respectable household. The principal sorts of servants were as follows: There was a general steward; a butler who had charge of the store-room and cellar; a marketing slave; a porter; baking and cooking slaves for preparing the daily meals; an attendant upon the master in his walks, and this was an indispensable servant; a nurse, an escort for the children; and a lady’s maid. In richer houses there was also a groom or mule-boy. This list shows a subdivision of labor more like the habits of our East-Indian families than those of ordinary households in England. If faithful, slaves were often made free, especially by the will of their master on his death-bed, but they did not become citizens. They remained in the position of resident aliens under the patronage of their former master or his representatives.

In proportion as the free population of Greece diminished the freeing of slaves became more and more common, until it actually appears to have been the leading feature in the life of the small towns. Thousands of inscriptions recording this setting free of individual slaves are still found, and on so many various stones, even tombstones, that it almost appears as if material for recording had failed them by reason of the quantity of these documents. The same increase of liberation was[131] a leading feature in the Roman empire, but there the freedman obtained the right and position of a citizen, which was not the case in Greece. The most enlightened moralists of both countries exhorted benevolence toward slaves, and the frequent freeing of them as the duty of humane masters, but none of these writers ever dreamt of the total abolishing of slavery, which they all held to be an institution ordained by nature. This seems also the view of the early Christian writers, who nowhere condemn the principle of slavery as such.

In the oldest times the dead were buried in their own ground, and close beside the house they had occupied. Afterward the burying of the dead within the walls of cities was forbidden except in the case of great public benefactors, who were worshiped as heroes and had a shrine set over them. The rest were buried in the fairest and most populous suburb, generally along both sides of the high road, as at Athens and at Syracuse, where their tombs and the inscriptions occupied the attention of everyone that passed by. The oldest and rudest monuments placed over the tomb were great mounds of earth, then these mounds came to be surrounded by a circle of great stones; afterward chambers were cut underground in the earth or rock, and family vaults established. Handsome monuments in marble, richly painted and covered with sculpture, were set up over the spot. These monuments sometimes attained a size almost as great as a temple. The scenes sculptured on the marble were from the life and occupation of the deceased, more often parting scenes, where they were represented taking leave of their family and friends, nor do we possess any more beautiful and touching remains of Greek life than some of these tombs. In the chamber of the dead many little presents, terra-cotta figures, trinkets and vases were placed, nay, in early times favorite animals, and even slaves or captives were sacrificed in order to be with him; for the Greeks believed that though the parting with the dead was for ever, he still continued to exist, and to interest himself in human affairs and in pursuits like those of living men. The crowded suburbs where the tombs were placed were generally ornamented with trees and flowers, and were a favorite resort of the citizens. The dead bodies of executed criminals were either given back to their relations or, in extreme cases, cast into a special place, generally some natural ravine or valley hidden from view and ordinary thoroughfare. Here the executioner dwelt, who was generally a public slave. This place was called barathrum[9] at Athens, and Ceadas[10] at Sparta.

The earliest and most natural form of idolatry was the worship of the heavenly bodies, and especially the sun, whose splendor, light, heat, and salutary influence upon all nature were regarded as the supernatural and independent powers of a deity. Hence the ancient myths ascribed personality, and intelligent activity, to the god of day, whom they worshiped under the name of Phœbus Apollo. They, however, attached to the history and worship of Apollo many things not connected with his original character as the source of light.

Delphi was a principal place of their religious solemnities, and from an early day the site of a temple dedicated to Apollo. The first was destroyed by fire; but in the time of the Pisistratidæ a much more gorgeous one was built, and, through a long period of their national history, was a center of potent influences that did much to fashion the character of the people. Its wealth became immense, and was computed at ten thousand talents. In the neighborhood of Delphi the Pythian games were celebrated in the third year of every Olympiad, and in honor of Apollo’s victory over the terrible Pythian serpent. On these occasions the celebrated Amphictyonic Council, whose sessions were usually held at Thermopylæ, met at Delphi, and the grave senators had the oversight of the games, prescribed rules for the contestants, and directed in the distribution of prizes.

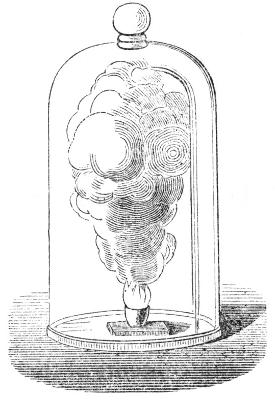

The shrine of the god at Delos, his birthplace, was also greatly renowned. It was situated at the foot of Mount Cynthus, but the whole island was sacred. The same divinity had beside a great number of less celebrated temples and shrines, not only in Greece, but also in Asia Minor, and wherever Greek colonies were extended. The rites observed in these sacred places were, in general, more seemly than the ceremonial of their worship paid to some other of their gods, and may be counted among the educational forces that improved the social and political condition of the commonwealth. He granted them a prophetic dispensation, and the responses given by his oracles raised their hopes, or, if unfavorable, caused alarm. The supposed medium of the communications, a priestess, who ministered at the altar, was esteemed an important personage. The inspiration, when the conditions were favorable, often induced what seemed an ecstatic state of mind, bordering on madness, causing strange contortions of countenance, and incoherent utterances, understood by none except those who claimed to be inspired as interpreters, and even their rendering of the responses was often in enigmas, or terms of such double meaning as admitted an explanation in accordance with the events that followed. The convulsions of the priestess were, perhaps, real, but possibly brought on partly by the chewing of laurel leaves, and partly by gaseous vapors that issued from a cleft in the rock, beneath the sacred tripod.

The concept or image of this god Apollo, as expressed by both poets and artists, was their highest ideal of human excellence and beauty; a tall, majestic body, of exquisite symmetry, and having the vigor of immortal youth. Some of his statues, still extant, are described as marvels of excellence in their line, and those who can not have access to the originals will find copies more or less perfect, in almost any considerable collection having specimens of ancient art. One of the most celebrated of all ancient statues, on account of the completeness of the sculptor’s work, is the “Apollo Belvidere.” It was found at Antium in 1503, purchased, and placed in a part of the Vatican[1] called Belvidere. In proportions and altitude it is a noble figure; naked, or but slightly clad, and in every feature suggestive of the highest perfection of art. It seems to represent the great archer just after discharging his arrow at the Python, and shows his manly satisfaction and assurance of victory.

The legendary history of this god, whose worship was much celebrated by both Greeks and Romans, recites, among other things of interest, the memorable circumstances of his friendship for Hyacinthus, and his great love for Daphne. The legends will not lose all their interest, though it will be impossible to print them entire.

Hyacinthus was a beautiful youth of noble parentage, for whom the great Apollo manifested ardent friendship. He accompanied him in his sports, led the dogs when he went to hunt, followed him in his excursions on the mountains, and for him neglected his lyre and his arrows. As they one day played quoits together, Apollo heaving aloft the heavy discus,[2] with his great strength sent it high and far. Hyacinthus watched its flight through the air, and, excited with the sport ran to seize it, eager, in turn, to make his throw. Alas! in its rebound from the earth, it struck him a fatal blow. Apollo, pale and anxious, sustained the fainting youth, and sought, in vain, to heal the mortal wound. As some fair lily, whose[132] stalk has been broken, turns its limp flowers toward the earth, the head of the dying boy, too heavy for its shattered support, fell over on his shoulder; and the friendly god, lamenting deeply, said: “O hapless youth! thou diest, robbed of a life so pleasant, and I the cause. But thou shalt be immortal still. My lyre shall celebrate our love; and as a beautiful, fragrant flower, thou shalt dwell with me forever; the inscriptions on thy leaves[3] shall proclaim my sorrow.” Even as he spoke the blood that stained the grass disappeared, and a hyacinth, of hues more beautiful than Tyrian purple, sprang from the spot, and shed its sweet fragrance there. “Beloved, though dead, thou shalt still live; and, with every returning spring the flowers that henceforth bear thy name shall revive the memory of thy virtues, and of thy sudden departure to the home of the immortals.”

Apollo and Daphne.—The beautiful Daphne (dawn) was Apollo’s first love. This was nature, if the myth is interpreted astronomically. The sun pursues the dawn that flees before his brighter effulgence. But in this love affair, Cupid, as he is wont, becomes an exciting cause, and with his arrow pierced the lover’s heart. It was on this wise: Apollo once, exulting in his own recent victory over the monster Python, saw the rogue, Cupid, playing with his bow, and called to him saying: “What have you to do with such warlike weapons? Leave them for hands more worthy of them, and, child as you are, do not meddle with my arms.”

The taunting words vexed the son of Venus, and, to avenge himself he resolved that even the conquering Apollo should feel the keen point of his little dart, and confess a wound that would be difficult to heal. So he quickly drew from his quiver two arrows of different make and metal, one to excite love, the other to repel it. With the latter, a blunt, leaden shaft, he struck the nymph Daphne, daughter of the river god Peneus. The other he thrust through the heart of Apollo, who, thus smitten, forgot his victories, and was at once seized with passionate love for the beautiful nymph, while she, delighting in woodland sports and the pleasures of the chase, had no desire to leave them. Her father wished to see her wedded, but now, more than ever, she hated the thought of marriage, and, blushing, earnestly besought her sire, saying: “Dearest father, grant me this favor, that I may always remain a maiden, like the fleet huntress Artemis.”

He consented, but at the same time, in praise of her rare beauty, said: “Child, your own face will forbid it.” Apollo dearly loved her and longed to claim her as his own, but his suit was in vain. She had no love to answer his, and turned from him. Stung by her indifference, yet enthralled by her charms, he followed, but her flight was swifter than the wind, and she delayed not a moment at his entreaties. “Stay,” he cried, “daughter of Peneus, stay. Do not fly from me as a lamb from the wolf, or a dove from the hawk. I am not a foe. For love I pursue thee; and the fear that you may suffer injury in your rapid flight makes me miserable. You know me not. I am not a clown to be avoided and despised. Jupiter is my father, and gives me to know the present and future. They reverence me at Delphi and Tenedos as the god of prophecy, of song, and of the lyre. I carry weapons. At the twang of my bow the arrow flies true to its mark. But Cupid’s darts have pierced me, and the distress of heart is insupportable. I know the virtue of all the healing plants, and minister to others, but myself suffer this malady that no medicine can cure. Pity, and—” … The nymph continued her flight, and left his plea half uttered. But even as she fled, her airy robe and unbound hair flung loose on the wind, she charmed him yet more. Impatient that his suit did not prevail, he quickened his speed, and the distance between them grew less. She eluded his grasp only as a panting hare escapes from the open jaws of the hound.

So flew Apollo and Daphne; he on wings of love, she on wings of fear. The very breath of the more powerful pursuer reaches her delicate person; her strength fails, and, ready to sink, she cries to her father: “Help me, Peneus! Let the earth open to receive me, or change my form that has brought me into this trouble!” She spoke, and, at his will, the metamorphose was instant. A tender bark enclosed her form; her limbs became branches, her hair leaves; her feet were rooted in the ground, and her head became a symmetrical tree top, graceful to look upon, but retaining nothing of its former self save its beauty. Apollo stood amazed. He embraced with his arms the still palpitating, shrinking trunk, and lavished many kisses on the delicate branches that shrank from his lips. “You shall, assuredly, be my tree; and I will wear you for my crown. With you will I decorate my harp and my quiver. Conquerors shall weave from your branches wreaths to adorn their brows; and, as immortality is mine, you, too, shall be always green, and your leaf shall suffer no decay.” The nymph, thence a beautiful laurel tree, bowed her head in acknowledgment, and the god was content.

This story of Apollo has been variously interpreted, and is often alluded to by the poets.

Waller applies it to the case of one whose love songs, though they did not soften the heart of his mistress, yet won for the poet widespread fame.

Phæton’s Ride.—The ocean nymph Clymene[4] bore to the god of day a son, they named Phæton (gleaming). Once when he boasted his celestial origin Ephaphos, a son of Jupiter, disputed his claim, alleging that he was puffed up with pride in a false father. The indignant Phæton reported the insult to his mother, who, with a solemn oath and imprecation, reassured him of his heavenly origin, and added: “The land whence the sun rises lies next to ours; go and inquire for yourself. See if he will not own you as his son.” The youth heard with delight, and full of pride and hope hastened to the palace of his sire, who received him kindly, and from whom he obtained an unwary oath that, in proof of his fatherhood, he would grant him whatever he asked. The ambitious Phæton immediately demanded permission to prove his pedigree, and confound his adversary, by taking his father’s seat, with leave, for one day, to guide the solar chariot in its course through the heavens. Phœbus, aware of the danger of any such attempt, would gladly have recalled his word, and persuaded the rash youth from his wild purpose. “This, my son, is far too perilous an undertaking, and quite unsuited to thy powers. These fiery horses would despise the guidance of Jupiter himself, were he to take the reins; how, then, can a mortal hand restrain them? Thou knowest not the perils of the way. In the freshness of the early morning the panting coursers scarce can climb that steep ascent; at noonday the downward glance to the far rolling sea, and the green earth lying at so vast a depth is hazardous even for a god. Canst thou, then, yet so young, resist the rapid movement of the whirling heavens, or endure the blinding brilliancy of those flaming orbs? That monstrous ‘Lion,’ the ‘Scorpion,’ and the ‘Crab,’ will surely terrify thee. The famed ‘Archer’ and the raging ‘Bear’ will threaten destruction. In the later hours the course descends rapidly, and requires most steady driving. Any charioteer, unused to the road, and the team, would be plunged headlong, or, deviating from the course, be swept away by the force that bears all else along, swift as the lightning. Forego that rash design. Look now on what the world contains, and ask some other boon. Ask it, and fear no refusal. Yet you shall have this, if you persist. The oath was sworn, and must be kept. Will you not be advised, and choose more wisely?”

But the self-confident youth, heedless of his father’s counsel, and despising the warning, would, at any risk, gratify his foolish ambition. He demanded the immediate fulfillment of the promise, and prevailed.

And now the purple gates of the East were unfolded, and from within the palace there breathed celestial fragrance. The stars and waning moon gradually disappeared; and, at Phœbus’ command, the swift Hours led forth from their stalls the prancing steeds and attached them to the golden chariot, their harness sparkling with gems, and the yoke gleaming all over with diamonds of exceeding brilliance. The daring youth gazed in admiration too eager for the coveted pleasure. Phœbus bathed his face with a powerful unguent that made him capable of enduring awhile the terrible heat, and placing a radiant circlet on his brow, that made him seem the very god of light, gave such instructions as were necessary. “Spare the whip, and hold tight the reins; my steeds need no urging; the labor is to guide and hold them in; you are not to take what seems the direct road, but turn off to the left; keep within the middle zone, that the skies and the earth may each receive their due share of light and heat; go not too high, lest you burn the dwellings of Ouranos; nor yet too low, or you will set the earth on fire; the middle course is safest and best; night is passing through the western gates, and the chariot can delay no longer; go, if you must, but, if you will, tarry in safety where you are, and allow me, as I have been wont, to light and heat the world.” The too eager youth, hearing but little, sprang to the lofty seat, grasped the reins with boundless delight, standing erect, and pouring out thanks for his opportunity.