Title: The Irish Penny Journal, Vol. 1 No. 40, April 3, 1841

Author: Various

Release date: July 23, 2017 [eBook #55181]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brownfox and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by JSTOR www.jstor.org)

| Number 40. | SATURDAY, APRIL 3, 1841. | Volume I. |

The following Sunday morning, Rose paid an early visit to her patient, for, as it was the day of young Dandy’s christening, her presence was considered indispensable. There is, besides, something in the appearance and bearing of a midwife upon those occasions which diffuses a spirit of buoyancy and light-heartedness not only through the immediate family, but also through all who may happen to participate in the ceremony, or partake of the good cheer. In many instances it is known that the very presence of a medical attendant communicates such a cheerful confidence to his patient, as, independently of any prescription, is felt to be a manifest relief. So is it with the midwife; with this difference, that she exercises a greater and more comical latitude of consolation than the doctor, although it must be admitted that the one generally falls woefully short of that conventional dress with which we cover nudity of expression. No doubt many of her very choicest stock jokes, to carry on the metaphor, are a little too fashionably dressed to pass current out of the sphere in which they are used; but be this as it may, they are so traditional in character, and so humorous in conception, that we never knew the veriest prude to feel offended, or the morosest temperament to maintain its sourness, at their recital. Not that she is at all gross or unwomanly in any thing she may say, but there is generally in her apothegms a passing touch of fancy—a quick but terse vivacity of insinuation, at once so full of fun and sprightliness, and that truth which all know but few like to acknowledge, that we defy any one not irretrievably gone in some incurable melancholy to resist her humour. The moment she was seen approaching the house, every one in it felt an immediate elevation of spirits, with the exception of Mrs Keho herself, who knew that wherever Rose had the arrangement of the bill of fare, there was sure[Pg 314] to be what the Irish call “full an’ plinty”—“lashins an’ lavins”—a fact which made her groan in spirit at the bare contemplation of such waste and extravagance. She was indeed a woman of a very un-Irish heart—so sharp in her temper and so penurious in soul, that one would imagine her veins were filled with vinegar instead of blood.

“Banaght Dheah in shoh” (the blessing of God be here), Rose exclaimed on entering.

“Banaght Dheah agus Murra ghuid” (the blessing of God and the Virgin on you), replied Corny, “an’ you’re welcome, Rose ahagur.”

“I know that, Corny. Well, how are we?—how is my son?”

“Begarra, thrivin’ like a pair o’ throopers.”

“Thank God for it! Hav’n’t we a good right to be grateful to him any way? An’ is my little man to be christened to-day?”

“Indeed he is—the gossips will be here presently, an’ so will her mother. But, Rose, dear, will you take the ordherin’ of the aitin’ an’ drinkin’ part of it?—you’re betther up to these things than we are, an’ so you ought, of coorse. Let there be no want of any thing; an’ if there’s an overplush, sorra may care; there’ll be poor mouths enough about the door for whatever’s left. So, you see, keep never mindin’ any hint she may give you—you know she’s a little o’ the closest; but no matther. Let there, as I said, be enough an’ to spare.”

“Throth, there spoke your father’s son, Corny; all the ould dacency’s not dead yet, any how. Well, I’ll do my best. But she’s not fit to be up, you know, an’ of coorse can’t disturb us.” The expression of her eye could not be misunderstood as she uttered this. “I see,” said Corny—“devil a betther, if you manage that, all’s right.”

“An’ now I must go in, till I see how she an’ my son’s gettin’ an: that’s always my first start; bekase you know, Corny, honey, that their health goes afore every thing.”

Having thus undertaken the task required of her, she passed into the bedroom of Mrs Keho, whom she found determined to be up, in order, as she said, to be at the head of her own table.

“Well, alanna, if you must, you must; but in the name of goodness I wash my hands out of the business teetotally. Dshk, dshk, dshk! Oh, wurra! to think of a woman in your state risin’ to sit at her own table! That I may never, if I’ll see it, or be about the place at all. If you take your life by your own wilfulness, why, God forgive you; but it mustn’t be while I’m here. But since you’re bent on it, why, give me the child, an’ afore I go, any how, I may as well dress it, poor thing! The heavens pity it—my little man—eh?—where was it?—cheep—that’s it, a ducky; stretch away. Aye stretchin’ an’ thrivin’ an, my son! Oh, thin, wurra! Mrs Keho, but it’s you that ought to ax God’s pardon for goin’ to do what might lave that darlin’ o’ the world an orphan, may be. Arrah be the vestments, if I can have patience wid you. May God pity you, my child. If anything happened your mother, what ’ud become of you, and what ’ud become of your poor father this day? Dshk, dshk, dshk!” These latter sounds, exclamations of surprise and regret, were produced by striking the tongue against that part of the inward gum which covers the roots of the teeth.

“Indeed, Rose,” replied her patient, in her sharp, shrill, quick voice, “I’m able enough to get up; if I don’t, we’ll be harrished. Corny’s a fool, an’ it’ll be only rap an’ rive wid every one in the place.”

“Wait, ma’am, if you plaise. Where’s his little barrow? Ay, I have it. Wait, ma’am, if you plaise, till I get the child dressed, an’ I’ll soon take myself out o’ this. Heaven presarve us! I have seen the like o’ this afore—ay have I—where it was as clear as crystal that there was something over them—ay, over them that took their own way as you’re doin’.”

“But if I don’t get up”——

“Oh, by all manes, ma’am—by all manes. I suppose you have a laise o’ your life, that’s all. It’s what I wish I could get.”

“An’ must I stay here in bed all day, an’ me able to rise, an’ sich wilful waste as will go an too?”

“Remember you’re warned. This is your first baby, God bless it, an’ spare you both. But, Mrs Keho, does it stand to raison that you’re as good a judge of these things as a woman like me, that it’s my business? I ax you that, ma’am.”

This poser in fact settled the question, not only by the reasonable force of the conclusion to be derived from it, but by the cool authoritative manner in which it was put.

“Well,” said the other, “in that case, I suppose, I must give in. You ought to know best.”

“Thank you kindly, ma’am; have you found it out at last? No, but you ought to put your two hands under my feet for preventin’ you from doin’ what you intinded. That I may never sup sorrow, but it was as much as your life was worth. Compose yourself; I’ll see that there’s no waste, and that’s enough. Here, hould my son—why, thin, isn’t he the beauty o’ the world, now that he has got his little dress upon him?—till I pin up this apron across the windy; the light’s too strong for you. There now: the light’s apt to give one a headache when it comes in full bint upon the eyes that way. Come, alanna, come an now, till I show you to your father an’ them all. Wurra, thin, Mrs Keho, darlin’,” (this was said in a low confidential whisper, and in a playful wheedling tone which baffles all description), “wurra, thin, Mrs Keho, darlin’, but it’s he that’s the proud man, the proud Corny, this day. Rise your head a little—aisy—there now, that’ll do—one kiss to my son, now, before he laives his mammy, he says, for a weeny while, till he pays his little respects to his daddy an’ to all his friends, he says, an’ thin he’ll come back to mammy agin—to his own little bottle, he says.”

Young Corny soon went the rounds of the whole family, from his father down to the little herd-boy who followed and took care of the cattle. Many were the jokes which passed between the youngsters on this occasion—jokes which have been registered by such personages as Rose, almost in every family in the kingdom, for centuries, and with which most of the Irish people are too intimately and thoroughly acquainted to render it necessary for us to repeat them here.

Rose now addressed herself to the task of preparing breakfast, which, in honour of the happy event, was nothing less than “tay, white bread, and Boxty,” with a glass of poteen to sharpen the appetite. As Boxty, however, is a description of bread not generally known to our readers, we shall give them a sketch of the manner in which this Irish luxury is made. A basket of the best potatoes is got, which are washed and peeled raw; then is procured a tin grater, on which they are grated; the water is then shired off them, and the macerated mass is put into a clean sheet, or table-cloth, or bolster-cover. This is caught at each end by two strong men, who twist it in opposite directions until the contortions drive up the substance into the middle of the sheet, &c.; this of course expels the water also; but lest the twisting should be insufficient for that purpose, it is placed, like a cheese-cake, under a heavy weight, until it is properly dried. They then knead it into cakes, and bake it on a pan or griddle; and when eaten with butter, we can assure our readers that it is quite delicious.

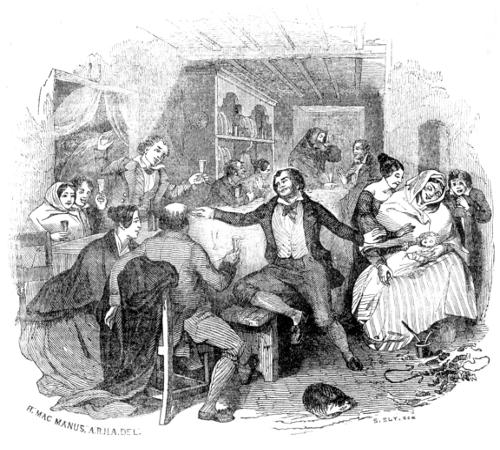

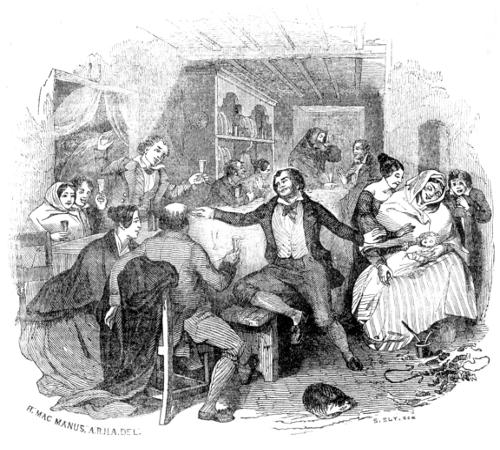

The hour was now about nine o’clock, and the company asked to the christening began to assemble. The gossips or sponsors were four in number; two of them wealthy friends of the family that had never been married, and the two others a simple country pair, who were anxious to follow in the matrimonial steps of Corny and his wife. The rest were, as usual, neighbours, relatives, and cleaveens, to the amount of sixteen or eighteen persons, men, women, and children, all dressed in their best apparel, and disposed to mirth and friendship. Along with the rest was Bob M’Cann, the fool, who by the way could smell out a good dinner with as keen a nostril as the wisest man in the parish could boast of, and who on such occasions carried turf and water in quantities that indicated the supernatural strength of a Scotch brownie rather than that of a human being. Bob’s qualities, however, were well proportioned to each other, for, truth to say, his appetite was equal to his strength, and his cunning to either.

Corny and Mrs Moan were in great spirits, and indeed we might predicate as much of all who were present. Not a soul entered the house who was not brought up by Corny to an out-shot room, as a private mark of his friendship, and treated to an underhand glass of as good poteen “as ever went down the red lane,” to use a phrase common among the people. Nothing upon an occasion naturally pleasant gives conversation a more cheerful impulse than this; and the consequence was, that in a short time the scene was animated and mirthful to an unusual degree.

Breakfast at length commenced in due form. Two bottles of whisky were placed upon the table, and the first thing done was to administer a glass to each guest.

“Come, neighbours,” said Corny, “we must dhrink the[Pg 315] good woman’s health before we ate, especially as it’s the first time, any how.”

“To be sure they will, achora, an’ why not? An’ if it’s the first time, Corny, it won’t be the—— Musha! you’re welcome, Mrs ——! an’ jist in time too”—this she said, addressing his mother-in-law, who then entered. “Look at this swaddy, Mrs ——; my soul to happiness, but he’s fit to be the son of a lord. Eh, a pet? Where was my darlin’? Corny, let me dip my finger in the whisky till I rub his gums wid it. That’s my bully! Oh, the heavens love it, see how it puts the little mouth about lookin’ for it agin. Throth you’ll have the spunk in you yet, acushla, an’ it’s a credit to the Kehos you’ll be, if you’re spared, as you will, plaise the heavens!”

“Well, Corny,” said one of the gossips, “here’s a speedy uprise an’ a sudden recovery to the good woman, an’ the little sthranger’s health, an’ God bless the baker that gives thirteen to the dozen, any how!”

“Ay, ay, Paddy Rafferty, you’ll have your joke any way; an’, throth, you’re welcome to it, Paddy; if you weren’t, it isn’t standin’ for young Corny you’d be to-day.”

“Thrue enough,” said Rose, “an’, by the dickens, Paddy isn’t the boy to be long under an obligation to any one. Eh, Paddy, did I help you there, avick? Aisy, childre; you’ll smother my son if you crush about him that way.” This was addressed to some of the youngsters, who were pressing round to look at and touch the infant.

“It won’t be my fault if I do, Rose,” said Paddy, slyly eyeing Peggy Betagh, then betrothed to him, who sat opposite, her dark eyes flashing with repressed humour and affection. Deafness, however, is sometimes a very convenient malady to young ladies, for Peggy immediately commenced a series of playful attentions to the unconscious infant, which were just sufficient to excuse her from noticing this allusion to their marriage. Rose looked at her, then nodded comically to Paddy, shutting both her eyes by way of a wink, adding aloud, “Throth you’ll be the happy boy, Paddy; an’ woe betide you if you aren’t the sweetest end of a honeycomb to her. Take care an’ don’t bring me upon you. Well, Peggy, never mind, alanna; who has a betther right to his joke than the dacent boy that’s—aisy, childre: saints above! but ye’ll smother the child, so you will.—Where did I get him, Dinney? sure I brought him as a present to Mrs Keho; I never come but I bring a purty little babby along wid me—than the dacent boy, dear, that’s soon to be your lovin’ husband? Arrah, take your glass, acushla; the sorrabarm it’ll do you.”

“Bedad, I’m afeard, Mrs Moan. What if it ’ud get into my head, an’ me’s to stand for my little godson? No, bad scran to me if I could—faix, a glass ’ud be too many for me.”

“It’s not more than half tilled, dear; but there’s sense in what the girl says, Dandy, so don’t press it an her.”

In the brief space allotted to us we could not possibly give any thing like a full and correct picture of the happiness and hilarity which prevailed at the breakfast in question. When it was over, they all prepared to go to the parish chapel, which was distant at least a couple of miles, the midwife staying at home to see that all the necessary preparations were made for dinner. As they were departing, Rose took the Dandy aside, and addressed him thus:

“Now, Dandy, when you see the priest, tell him that it is your wish, above all things, ‘that he should christen it against the fairies.’ If you say that, it’s enough. And, Peggy, achora, come here. You’re not carryin’ that child right, alanna; but you’ll know betther yet, plaise goodness. No, avillish, don’t keep its little head so closely covered wid your cloak; the day’s a burnin’ day, glory be to God, an’ the Lord guard my child; sure the least thing in the world, where there’s too much hait, ’ud smother my darlin’. Keep its head out farther, and just shade its little face that way from the sun. Och, will I ever forget the Sunday whin poor Molly M’Guigan wint to take Pat Feasthalagh’s child from under her cloak to be christened, the poor infant was a corpse; an’ only that the Lord put it into my head to have it privately christened, the father an’ mother’s hearts would break. Glory be to God! Mrs Duggan, if the child gets cross, dear, or misses any thing, act the mother by him, the little man. Eh, alanna! where was it? Where was my duck o’ diamonds—my little Con Roe? My own sweety little ace o’ hearts—eh, alanna! Well, God keep it, till I see it again, the jewel!”

Well, the child was baptized by the name of his father, and the persons assembled, after their return from chapel, lounged about Corny’s house, or took little strolls in the neighbourhood, until the hour of dinner. This of course was much more convivial, and ten times more vociferous, than the breakfast, cheerful as that meal was. At dinner they had a dish, which we believe is, like the Boxty, peculiarly Irish in its composition: we mean what is called sthilk. This consists of potatoes and beans pounded up together in such a manner that the beans are not broken, and on this account the potatoes are well champed before the beans are put into them. This is dished in a large bowl, and a hole made in the middle of it, into which a miscaun or roll of butter is thrust, and then covered up until it is melted. After this, every one takes a spoon and digs away with his utmost vigour, dipping every morsel into the well of butter in the middle, before he puts it into his mouth. Indeed, from the strong competition which goes forward, and the rapid motion of each right hand, no spectator could be mistaken in ascribing the motive of their proceedings to the principle of the old proverb, devil take the hindmost. Sthilk differs from another dish made of potatoes in much the same way, called colcannon. If there were beans, for instance, in colcannon, it would be sthilk. This practice of many persons eating out of the same dish, though Irish, and not cleanly, is of very old antiquity. Christ himself mentions it at the Last Supper. Let us hope, however, that, like the old custom which once prevailed in Ireland, of several persons drinking at meals out of the same mether, the usage we speak of will soon be replaced by one of more cleanliness and individual comfort.

After dinner the whisky began to go round, for in these days punch was a luxury almost unknown to the class we are writing of. In fact, nobody there knew how to make it but the midwife, who wisely kept the secret to herself, aware that if the whisky were presented to them in such a palatable shape, they would not know when to stop, and she herself might fall short of the snug bottle that is usually kept as a treat for those visits which she continues to pay during the convalescence of her patients.

“Come, Rose,” said Corny, who was beginning to soften fast, “it’s your turn now to thry a glass of what never seen wather.” “I’ll take the glass, Dandy—deed will I—but the thruth is, I never dhrink it hard. No, but I’ll jist take a drop o’ hot wather an’ a grain o’ sugar, an’ scald it; that an’ as much carraway seeds us will lie upon a sixpence does me good; for, God help me, the stomach isn’t at all sthrong wid me, in regard of bein’ up so much at night, an’ deprived of my nathural rest.”

“Rose,” said one of them, “is it thrue that you war called out one night, an’ brought blindfoulded to some grand lady belongin’ to the quality?”

“Wait, avick, till I make a drop o’ wan-grace[1] for the misthress, poor thing; an’, Corny, I’ll jist throuble you for about a thimbleful o’ spirits to take the smell o’ the wather off it. The poor creature, she’s a little weak still, an’ indeed it’s wonderful how she stood it out; but, my dear, God’s good to his own, an’ fits the back to the burden, praise be to his name!”

She then proceeded to scald the drop of spirits for herself, or, in other words, to mix a good tumbler of ladies’ punch, making it, as the phrase goes, hot, strong, and sweet—not forgetting the carraways, to give it a flavour. This being accomplished, she made the wan-grace for Mrs Keho, still throwing in a word now and then to sustain her part in the conversation, which was now rising fast into mirth, laughter, and clamour.

“Well, but, Rose, about the lady of quality, will you tell us that?”

“Oh, many a thing happened me as well worth tellin’, if you go to that; but I’ll tell it to you, childre, for sure the curiosity’s nathural to yez. Why, I was one night at home an’ asleep, an’ I hears a horse’s foot gallopin’ for the bare life up to the door. I immediately put my head out, an’ the horseman says, ‘Are you Mrs Moan?’

‘That’s the name that’s an me, your honour,’ says myself.

‘Dress yourself thin,’ says he, ‘for you’re sadly wanted; dress yourself and mount behind me, for there’s not a moment to be lost!’ At the same time I forgot to say that his hat was tied about his face in sich a way that I couldn’t catch a glimpse of it. Well, my dear, we didn’t let the grass grow undher our feet for about a mile or so. ‘Now,’ says he, ‘you must allow yourself to be blindfoulded, an’ it’s useless to oppose[Pg 316] it, for it must be done. There’s the character, may be the life, of a great lady at stake; so be quiet till I cover your eyes, or,’ says he, lettin’ out a great oath, ‘it’ll be worse for you. I’m a desperate man;’ an’, sure enough, I could feel the heart of him beatin’ undher his ribs, as if it would burst in pieces. Well, my dears, what could I do in the hands of a man that was strong and desperate. ‘So,’ says I, ‘cover my eyes in welcome; only, for the lady’s sake, make no delay.’ Wid that he dashed his spurs into the poor horse, an’ he foamin’ an’ smokin’ like a lime-kiln already. Any way, in about half an hour I found myself in a grand bedroom; an’ jist as I was put into the door, he whishpers me to bring the child to him in the next room, as soon as it would be born. Well, sure I did so, afther lavin’ the mother in a fair way. But what ’ud you have of it?—the first thing I see, lyin’ an the table, was a purse of money an’ a case o’ pistols. Whin I looked at him, I thought the devil, Lord guard us! was in his face, he looked so black and terrible about the brows. ‘Now, my good woman,’ says he, ‘so far you’ve acted well, but there’s more to be done yet. Take your choice of these two,’ says he, ‘this purse, or the contents o’ one o’ these pistols, as your reward. You must murdher the child upon the spot.’ ‘In the name of God an’ his Mother, be you man or devil, I defy you,’ says I; ‘no innocent blood ’ll ever be shed by these hands.’ ‘I’ll give you ten minutes,’ says he, ‘to put an end to that brat there;’ an’ wid that he cocked one o’ the pistols. My dears, I had nothin’ for it but to say in to myself a pather an’ ave as fast as I could, for I thought it was all over wid me. However, glory be to God! the prayers gave me great stringth, an’ I spoke stoutly. ‘Whin the king of Jerusalem,’ says I—‘an’ he was a greater man than ever you’ll be—whin the king of Jerusalem ordhered the midwives of Aigyp to put Moses to death, they wouldn’t do it, and God preserved them in spite of him, king though he was,’ says I; ‘an’ from that day to this it was never known that a midwife took away the life of the babe she aided into the world—No, an’ I’m not goin’ to be the first that’ll do it.’ ‘The time is out,’ says he, puttin’ the pistol to my ear, ‘but I’ll give you one minute more.’ ‘Let me go to my knees first,’ says I; ‘an’ now may God have mercy on my sowl, for, bad as I am, I’m willin’ to die, sooner than commit murdher an the innocent.’ He gave a start as I spoke, an’ threw the pistol down. ‘Ay,’ said he, ‘an the innocent—an the innocent—that is thrue! But you are an extraordinary woman: you have saved that child’s life, and previnted me from committing two great crimes, for it was my intintion to murder you afther you had murdered it.’ I thin, by his ordhers, brought the poor child to its mother, and whin I came back to the room, ‘Take that purse,’ says he, ‘an’ keep it as a reward for your honesty.’ ‘Wid the help o’ God,’ says I, ‘a penny of it will never come into my company, so it’s no use to ax me.’ ‘Well,’ says he, ‘afore you lave this, you must swear not to mintion to a livin’ sowl what has happened this night, for a year and a day.’ It didn’t signify to me whether I mintioned it or not; so being jack-indifferent about it, I tuck the oath, and kept it. He thin bound my eyes agin, hoisted me up behind him, an’ in a short time left me at home. Indeed, I wasn’t betther o’ the start it tuck out o’ me for as good as six weeks afther!”

The company now began to grow musical; several songs were sung; and when the evening got farther advanced, a neighbouring fiddler was sent for, and the little party had a dance in the barn, to which they adjourned lest the noise might disturb Mrs Keho, had they held it in the dwelling-house. Before this occurred, however, the “midwife’s glass” went the round of the gossips, each of whom drank her health, and dropped some silver, at the same time, into the bottom of it. It was then returned to her, and with a smiling face she gave the following toast:—“Health to the parent stock! So long as it thrives, there will always be branches! Corny Keho, long life an’ good health to you an’ yours! May your son live to see himself as happy as his father! Youngsters, here’s that you may follow a good example! The company’s health in general I wish; an’, Paddy Rafferty, that you may never have a blind child but you’ll have a lame one to lead it!—ha! ha! ha! What’s the world widout a joke? I must see the good woman an’ my little son afore I go; but as I won’t follow yez to the barn, I’ll bid yez good night, neighbours, an’ the blessin’ of Rose Moan be among yez!”

And so also do we take leave of our old friend Rose Moan, the Irish Midwife, who we understand took her last leave of the world only about a twelvemonth ago.

[1] A wan-grace is a kind of small gruel or meal tea sweetened with sugar.

Before steam and all the other facilities for travel had made us so well acquainted with the productions of remote parts of the earth as we are at present, every traveller on his return astonished his auditors or the readers of his works with accounts of monsters which existed only as the creations of his ingenuity, and to give importance to his discoveries. One out of many which could be produced, and which, as they may afford innocent amusement, we purpose from time to time to bring under the notice of the readers of the Penny Journal, we lately met with in an account of Struy’s Travels through Russia, Tartary, &c., in the seventeenth century. The object of wonder was in this case the Scythian or Tartarian lamb, a creature which, it was stated, sprang from the ground like a plant, and, restrained to the spot on which it was produced, devoured every vegetable production within its reach, and was itself in turn eaten by the wolves of the country. This singular production has since been found to be nothing more than a plant of the fern tribe, the Aspedium barometz, found occasionally in arid plains, where scarcely any other vegetable production can exist; it rises like many others of the tree ferns with a rugged or shaggy stem; and the plant having decayed or been uprooted by any accident, it is not impossible that by means of a storm or otherwise it might be found supported on its feet, namely, the stumps of the leaves; but that it pastured on other plants, or was mistaken by the wolves for a lamb, although speculations which the wonder-seeking traveller might be tempted to indulge in, it need hardly be said are ornamental additions introduced to suit the taste of the narrator, and to pander to that love of the marvellous which prevailed in the age in which he lived. The following is his account of this wonderful plant-animal:—

“On the western side of the Volga there is an elevated salt plain of great extent, but wholly uncultivated and uninhabited. On this plain (which furnishes all the neighbouring countries with salt) grows the boranez, or bornitch. This wonderful plant has the shape and appearance of a lamb, with feet, head, and tail distinctly formed. Boranez, in the language of Muscovy, signifies a little lamb. Its skin is covered with very white down, as soft as silk. The Tartars and Muscovites esteem it highly, and preserve it with great care in their houses, where I have seen many such lambs. The sailor who gave me one of those precious plants found it in a wood, and had its skin made into an under-waistcoat. I learned at Astrican from those who were best acquainted with the subject, that the lamb grows upon a stalk about three feet high, that the part by which it is sustained is a kind of navel, and that it turns itself round, and bends down to reach the herbage which serves it for food. They also said that it dries up and pines away when the grass fails. To this I objected, that the languor and occasional withering might be natural to it, as plants are accustomed to fade at certain times. To this they replied, that they had also once thought so, but that numerous experiments had proved the contrary to be the fact, such as cutting away, or by other means corrupting or destroying the grass all around it; after which they assured me that it fell into a languishing state and decayed insensibly. These persons also added, that the wolves are very fond of these vegetable lambs, and devour them with avidity, because they resemble in taste the animals whose name they bear, and that in fact they have bones, blood, and flesh, and hence they are called zoophytes, or plant-animals. Many other things I was likewise told, which might, however, appear scarcely probable to such as have not seen them.”

M.

Method of making Tar at Archangel.—They dig a hole in the ground, of sufficient size, some two or three fathoms deep, and little more than half way down they make a platform of wood, and thereon heap earth about a foot deep, except in the middle, where a hole is left in the form of a tunnel. They then fill the pit with fir billets piled up from the platform, and rising about a fathom or more above ground, which part they wall about with turf and clay to keep in the fire. They command the fire by quenching: for which use they make a lixivium of the ashes of fir. When all is ready, they set fire a-top, and keep the wood burning, but very leisurely, till it has sunk within a foot or two of the partition; and then they heave out the fire as fast as it is possible; for if it once laid hold of the tar which is settled down into the lower pit, it blows all up forthwith. These tar-pits take up[Pg 317] a great deal of trouble, and many men to tend them during the time of their burning, that the fire may descend even and leisurely, whereby the tar may have time to soak out of the wood, and settle down into the pit. As it comes from the wood it is pure tar, but in the pit it mixes with water, which issues from the wood also; therefore it is afterwards clarified.—Life of Sir Dudley North.

Aurora Borealis.—According to Crantz, the Greenlanders hold the northern lights for a game of tennis, or for a dance of departed souls; and this opinion is not a whit more irrational than the superstition of the oriental nations, the Greeks and Romans, and all the unenlightened people of the middle ages, who, in the aurora borealis, and other fiery meteors, saw fighting armies, flaming swords, chariots and spears, battles and blood, and even thought that they heard the clashing of arms and the sound of martial music. In the rainbow the ancient inhabitants of the north discovered a bridge from earth to heaven, and called it the bridge of the gods, which was watched by a dog, whom no art could elude, and whose auditory faculty was such, that he could hear the grass grow or the wool on the sheep’s back; the Kamschatkadales make of it a new garment for their aërial spirits, edged with fringes of red-coloured seal-skin, and leather thongs of various gaudy dyes.

“Primus ordo sanctissimus; secundus ordo sanctior; tertius sanctus. Primus sicut sol ardescit; secundus sicut luna; tertius sicut stellæ.”—See the ancient catalogue of the three classes of Irish saints, as published by Usher and Lanigan.

In my last paper I endeavoured to show how exceedingly absurd and unfounded was the notion of the Abbé Dubois and Denon, that the serpent-charmers of India were and are a set of juggling impostors, who practise on the credulity of the vulgar, and vainly set forward pretensions to an art which has no actual existence, and which, consequently, possesses no legitimate claims on the attention of the philosophic inquirer. I now wish to bring all that I would observe upon this very curious subject to a conclusion. I acknowledge my inability to furnish my readers with a thorough explanation of the means by which these wonders are performed, but I think I may be able, at all events, to suggest such hints as may place them on the direct path to the attainment of the knowledge they desire; after which, nothing will be necessary but some degree of research and perseverance to afford them a complete gratification of their wishes.

It is evident, that whatever may be the supplementary means employed in serpent-charming, music is necessary to its accomplishment. I should not be satisfied on this point were it merely dependent upon the assertions of the jugglers themselves, as in such case it might not unnaturally be set down as a mere external cloak for some more important secret which the performers did not wish to be discovered; and for this reason I made the observation in my first article on this subject, that the precise importance of the music in these operations was not as yet entirely apparent. I wish it to be understood, however, that although the degree of importance in which music should be held as an adjunct to the charming of snakes, or as a primary part of the process, has not as yet been ascertained by those who have investigated or endeavoured to investigate the business, and published the results of their inquiries, I for my part am fully satisfied on the subject. To return, however, to our more immediate matter of discussion.

Many have conceived that serpent-charming depends in the first instance upon the snakes being previously deprived of their fangs, and thus rendered innocuous. This opinion I have already demonstrated as palpably erroneous. Others, again, hold that the jugglers possess a power, by eating certain herbs, or chewing the leaves or roots of certain plants, of rendering themselves proof against animal poisons. In order to render themselves perfectly secure, it is said that their practice is to chew the herbs, to inoculate various parts of their body with the juice, and even bathe themselves in water in which these herbs have been steeped. It is supposed that the bodies of the charmers thus become not merely proof against the most deadly poison should they chance to be bitten, but that those thus prepared exhale from their persons an odour which produces a benumbing or stupifying effect upon the reptiles, and renders them an easy capture. Whether or not it be true that such is the case, we know that the Psylli not merely profess the power of charming snakes, but also that of curing by spells, and the application of certain herbs, such as have been bitten by them. We are informed by the historian and biographer Plutarch, that Cato in his march through the desert took with him many of those persons called Psylli (then a distinct tribe, though at the present day that name is applied indiscriminately to all professing the art of serpent-charming) to suck out the poison from the wounds of any of his soldiers that might chance to be bitten by any of the numerous venomous serpents which infested his route. The powers of the Psylli were then always attributed to magic, and the performers themselves took care to confirm that opinion by accompanying the application of remedies to their patients with muttered spells or elaborately wrought and imposing incantations. This is a testimony respecting the ancient repute in which charmers were held, not lightly to be rejected.

While some travellers are too sceptical, I have likewise to complain that others are too credulous. For instance, while Dubois and Denon scout the idea of serpents being charmed at all, Bruce asserts, and that from minute personal observation, that all the blacks of Sennaar are completely armed by nature against the bite of either scorpion or viper. “They will,” says he, “take their horned snakes (there the most common and one of the most fatal of the viper tribe) in their hands at all times, put them in their bosoms, and throw them at one[Pg 318] another as children will balls or apples, during which sport the serpents are seldom irritated to bite, or if they do, no mischief results from the wound.” Of course it must be evident that Bruce in this instance ascribed rather too much to the bounty of nature, and forgot how far art might have aided in producing the appearance which astonished him.

Don Pedro D’Orbies Y. Vargas, who published in the year 1791 the result of a series of investigations he instituted to ascertain the secret on which serpent-charming depended, informs us that it is also extensively practised by the natives of South America, and that they produce the wished-for end by means of a certain plant named the quacho-mithy, so designated from its having been first observed to have been resorted to by the serpent-hawk, or, as the bird is sometimes styled, the “quacho-mithy,” and by it sucked, preparatory to its encounters with the poisonous reptiles which it fought with and destroyed for its prey. Taking the hint from the naturally and instinctively instructed bird, the Indians chewed the plant thus discovered, and inoculated and washed their bodies with its juice, rubbing it into punctures made in their breasts, hands, and feet; and, thus prepared, they dreaded not the bite of the most venomous snake. Don Pedro himself, and the domestics of his household, used after these simple precautions to venture into the thickest woods and the most dangerous meadows, and fearlessly seize in their hands the largest and most poisonous serpents; the creatures seemed as if under the influence of a sort of charm or fascination, and very rarely attempted to bite; and at any rate, even if they did, no evil consequence resulted from the wound beyond the temporary inconvenience produced by the laceration of the flesh by the animals’ teeth.

The same gentleman to whom I was indebted for the anecdote of the encounter with the cobra de capella, mentioned in a preceding paper, informed me that he had detected a snake-charmer in the act of chewing and inoculating himself with some plant, the name or character of which he could not however ascertain, though he offered the juggler a considerable sum for the information. One of the leaves of this plant, and the only one he saw, he states to have been of a long and narrow form, with the sides indented or scolloped, somewhat like those of our own common dandelion.

Now, it appears to me by no means difficult of deduction from the facts brought forward in this and the preceding papers on the same subject, that the secret of the snake-charmers is dependent upon two ingredients, viz, in the first place the employment of an antidote which will not only mollify the effects of the reptiles’ venom, should the experimenters happen to be bitten, but, from some peculiar odour which it emits, stupify or intoxicate the snake, and indispose it from violence, inclining it rather to appreciate the melody with which they are treating it, and luxuriate in hearing of their fife; and, in the second place, the sounds of music which the whole class of reptiles appear more or less to be sensible of, and which will induce the serpents to quit their holes when they come within the sphere of the influence of the intoxicating odour, and, abandoning themselves to its effects, fall into a state of temporary oblivion, and are taken captive. We ourselves are well acquainted with several substances which are capable of producing upon such creatures as we are conversant with in these islands, effects no less astonishing than those produced upon the snakes by the charmers of India or South America. It is, for instance, a very common thing, and an experiment I have not only often seen tried, but have tried myself dozens of times, and that with success, to charm trout, perch, or roach, with assafœtida. If you sprinkle this substance, finely powdered, upon the surface of the water, you will presently see the fish crowding to the spot; and even if you rub your hands well with it, and, gradually approaching the water, gently immerse them in it, you will ere long find the fish attracted towards you, and, losing their natural timidity, actually permit themselves to be taken. Many have imagined that it was upon the use of a certain drug that the wonderful power possessed and successfully exerted by Sullivan, the whisperer, depended; but for my part I think the circumstance of Sullivan’s son having been unable to produce similar effects, although instructed by his father in the mystery, is sufficient to show that Sullivan’s trick depended upon some means less certain in operation than the mere employment of a drug would be, and in which mechanical dexterity and personal bearing occupied places of no mean importance.

Rat-catchers used formerly to employ certain drugs, or combinations of them, to collect these vermin into one place, and thus destroy them wholesale, or to entice them into the trap; and it has been pretended by some worthy members of this ancient and mystic calling, that they are possessed of secrets by which they can, if they please, draw away all the rats from any premises on which they may be employed. I have, however, sought after the most talented living professors of rat-catching, and I cannot say I have ever witnessed miracles equal to that. I have, however, seen a trap placed in a cellar haunted by rats, and left there all night, filled next morning with these vermin to the number of thirty, and surrounded by a host of others, who actually could not enter from want of room! I have seen a tame white rat smeared with a certain composition, let loose in a vault, and in less than half an hour return, followed by at least half a dozen others, who appeared so enamoured of the white-coloured decoy, or of some scent that hung about him, that they suffered themselves to be taken alive in the rat-catcher’s hand, and never so much as offer to bite. I purchased this secret from an old rat-catcher, and have much pleasure in communicating it to the public, and more especially to the discriminating patrons of the Irish Penny Journal. It consists of the following simple preparation:—

| Powdered assafœtida | 2 grains. |

| Essential oil of rhodium | 3 drachms. |

| Essential oil of lavender | 1 scruple. |

| Oil of aniseed | 1 drachm. |

Let the assafœtida be first well triturated with the aniseed, then add the oil of rhodium, still continuing to rub the material well up together in a mortar, after which add the oil of lavender, and cork up the mixture in a close bottle until required. The method of employing this receipt is very simple, and consists merely in smearing the decoy rat with it, in mixing a few drops of it with a little flour or starch, and employing the paste thus formed as a bait for the trap; and if you anoint your hands with this mixture, you may put them into a cage full of rats without the slightest danger of a bite. I have done so repeatedly myself, and never got bitten unless when I had prepared the composition improperly, or displayed timidity in proceeding to handle the animals—a defect of demeanour which appears capable of counteracting the working of the charm.

The liking which rats exhibit for the perfume produced by the above simple composition is truly wonderful, but will be readily admitted, even while as yet its efficacy remains untested, by any person who has witnessed the passion exhibited by cats for valerian, or of dogs for galbanum, and after much consideration and attentive observation I have come to the conclusion that the effects produced by different substances upon these animals have a common origin, viz., in the peculiar odour calling into play the sexual appetite, and that too in a more than commonly energetic manner; of course I only mean to apply this latter observation to the case of dogs, rats, and cats. I have no intention of thus seeking to explain away the effect produced upon serpents or fishes by certain odours, accompanied by music; indeed, in these instances I should rather ascribe the effects produced to a sort of intoxicating, fascinating influence, bearing no distant resemblance to the power exercised towards other animals by many of the serpent tribe themselves. The fascination of the rattle-snake, for example, seems in a great measure to depend upon the agency of a certain intoxicating odour which the reptile has the power of producing at pleasure. In support of this opinion I may adduce the testimony of Major A. Gordon, who thus explains the fascination of serpents in a paper read before the New York Historical Society. He adduced various facts in support of his opinions, and amongst the rest mentions a negro, who could by smell alone discover a rattle-snake when in the exercise of this power, at the distance of two hundred feet, and who, following such indications, never failed of finding some poor animal drawn within its vortex, and in vain struggling with the irresistible influence. By no means remotely allied to charming and fascination would appear to be that mysterious and as yet doubtful power, animal magnetism, a subject on which I shall not dilate, as it hardly falls within the limits indicated by the heading of this paper, which has now run to a length considerably greater than I contemplated at starting; and consequently I think it time to take my leave, trusting I have at least given a clue to the great secret on which depends the magical influence of the serpent-charmer.

H. D. R.

Our readers may remember a very simple experiment, but pregnant with important results, which we described in our former article: namely, if an onion plant, exposed to day light, be laid horizontally on the ground, the extremities of the stem and roots will in the course of a few hours turn themselves in their natural directions, the one upwards and the other downwards; if a similar plant be placed in a dark cellar, to which no light has access, the same things will take place; but that which happens in a few hours in the one instance, will require as many days in the other. From this experiment we were led to conclude that in the production of the proper directions of stems and roots, two classes of causes operate, namely, the light; and, secondly, some other principle distinct from light. Our former article was devoted to the explanation of the manner in which light causes stems to ascend, and roots to descend; we shall now endeavour to investigate that other principle, less powerful, but more universal, which shares in the production of the same phenomena.

If the flower stalk of the common dandelion be split vertically into a number of portions, each of these will be seen, spontaneously, to curl outwards; the same tendency must be familiar to every one in celery dressed for the table; if the root of the dandelion be split vertically into two or more parts, these will likewise be found to curve, but in a contrary direction from those of the stem; they will curl inwards. We thus find that all the portions of stem placed round the central axis have a natural tendency to curl outwards; while all the portions of root round the central axis have a tendency to curl inwards. The stem may be therefore considered as consisting of a number of springs placed round a central axis, and all endeavouring to burst away from each other; while the root, in a like manner, may be regarded as composed of a number of springs placed round a central axis, and all pressing against each other. These natural tendencies are overcome, in the living plant, by the mutual cohesion of these parts or springs; but when this cohesion is removed by the knife, their influence becomes acknowledged.

Now, if we imagine a number of springs, all of equal strength, and either dragging away from each other or pressing together, it will be easily understood that in such cases perfect equilibrium should result: for, of two springs pulling in opposite directions, for either to overcome, it is necessary that one should be the more powerful; and the same applies to springs pressing against each other. As long, therefore, as a stem consists of a number of equal springs, all endeavouring to burst away from each other, its direction will be in a straight line; and as long as a root is composed of equal springs pressing towards each other, its direction, likewise, will be straight.

If a stem or root be placed for a certain length of time in a horizontal position, the peculiar tendency to curvation of its parts will become modified. If a stem which has been thus treated be split along its axis, the part which, while it was in a horizontal position, was superior, will have its tendency to curl outwards increased; while that which was under the same circumstances inferior, will have its tendency to curl outwards diminished. If a root be placed, during a certain period, horizontally, and then split along its axis, the superior portion will be found to have its tendency to curl inwards increased, while the inferior portion will have the same tendency diminished. A horizontal position is therefore found to increase the peculiar tendencies to curvation of the superior parts of stems and roots, and to lessen those of the inferior half.

Now, we have already ascertained that while equal springs either pull against or press towards each other, equilibrium is obtained; but if from any cause the springs become unequal, the greater power may be expected to overcome the less. When a stem or root has been kept for some time horizontally, the upper half has its elastic power increased, while the spring of the most depending portion has become diminished; we have therefore now springs of unequal power placed round a central axis, the superior being rendered more energetic, while their antagonists have become weakened; it is reasonable, therefore, to expect that the respective directions of roots and stems under such circumstances should be obedient to the excess of elasticity which the upper half has acquired over the lower; in other words, these stems and roots ought to direct themselves in accordance with the natural tendencies of the superior springs which enter into the structure of these organs. Now, the superior springs of the stems have a natural tendency to curl outwards, or when placed horizontally, upwards; and the superior half of the root has an equally natural tendency to curl inwards, or, when placed horizontally, downwards. Need we be surprised, therefore, if in obedience to these more powerful springs the stems and roots of vegetables shall (as experience shows us they will do) curve, after having been placed for some time in a horizontal position, the former upward and the latter downward?

Let us now endeavour to explain the causes which produce these peculiar and different tendencies to curvation of stems and roots, and for this purpose it will be necessary for us to premise, that the fleshy substance which constitutes the basis of vegetable structure is composed of a multitude of little vesicles or cells, each perfectly distinct in itself, and merely adhering by its external surface with those surrounding it, while it contains a thick syrupy liquid; these cells, although pressed to a certain extent against each other, are not so closely approached as to obliterate completely the spaces existing between them, so that little passages, called intercellular passages, continue to remain, during the life of the plant, between the cells through which the ascending sap rises in its passage to the buds. This ascending sap is not so viscid a liquid as that contained in the cells: thus, the syrupy contents of the latter must, according to the principle of endosmose described in a previous article, absorb into the cells the ascending sap, in a way similar to that whereby syrup placed in a bladder, immersed in a basin of water, will attract the latter liquid through the membrane, until the bladder be filled. While the sap continues to ascend, therefore, the cells must necessarily continue swollen in proportion to their size.

If we examine the relative size of the cells in stems and roots, we will meet with a remarkable phenomenon: in stems the largest cells are situated towards the centre; but on the contrary, in roots, the largest cells are placed near the circumference. Now, we have ascertained in the preceding paragraph that all the cells have a tendency to swell in proportion to their size: it follows that the central cells of stems and the circumferential cells of roots possess the greatest tendency to swell. The centre of a stem has therefore greater elasticity than the circumference, while the circumference of a root has greater elasticity than the centre. When this elasticity in either case is permitted to exert itself by means of a vertical section, it causes each half of the stem to curl outwards, and each half of the root to curl inwards. If the influence of endosmose be acknowledged, the explanation is perfect.

But it may be said, what proof have we that endosmose operates in these cases? An experiment instituted by Dutrochet, and repeated by the writer of this article, sufficiently demonstrates its influence. A plant of dandelion was immersed in syrup, and after a certain time the root and stalk were severally split in a vertical direction: the tendencies to incurvation of these organs were now seen to be completely changed from what they are under ordinary circumstances; the parts of the stalk curled inwards, those of the root outwards: this was exactly what might be expected, if we suppose endosmose to be the cause of these phenomena; placed in syrup, this thick fluid attracted liquid out of the cells, which consequently shrunk in place of expanding; and the larger cells contracting more than the smaller, the former elasticities became reversed.

It remains to be seen why it is that when roots and stems are planted for some time in a horizontal position, the proper elasticities of the superior parts become increased, while those of the inferior become diminished. These phenomena can be explained by recollecting that the ascending sap is a heterogeneous fluid, composed of mucilage and syrup, mixed with light water and carbonic acid, which have been drawn up unchanged from the extremities of the roots, and are destined to escape, or undergo decomposition in the leaves. It is not difficult to imagine that this heterogeneous fluid contained in the intercellular passages should be subjected to the influence of gravity; if this be admitted, we can then understand how in a horizontal root or stem the heavier and more viscid portion of the sap should descend into the inferior half, and the lighter ascend between the cells of the superior half; endosmose will take place in proportion to the difference[Pg 320] of density between the liquid in the intercellular passages and that contained in the cells; therefore it will take place more energetically in the superior half, where is the lighter fluid; and as the elasticity depends upon the energy of endosmose, the upper portion will, according to its nature, curve with greater force, while the elasticity of the lower part will be lessened. This explanation acquires increased weight from the fact that the specific gravity of the most depending portions of stems and roots growing horizontally in the dark, is greater than that of the upper.

But we have stronger arguments in favour of the supposition that gravity is essentially connected with the several directions of stems and roots. These directions take place naturally in the “line of gravity,” that is, parallel to a line drawn from the centre of the mass towards the centre of the earth; at the same time it is to be remarked, that although roots grow in the direction of gravity, that is, towards the centre of the earth, stems grow in exactly the opposite way. An experiment made by Mr Knight has been repeated by different philosophers, to determine whether these directions of stems and roots bear to other physical laws the same relation they do to gravity. Seeds permitted to germinate in wet moss were attached to the circumference of a wheel made to revolve constantly in a vertical manner; under these circumstances the roots grew outwards, away from the circumference of the wheel, and the stems towards its centre; the roots were thus found to obey the centrifugal force, and the stems the centripetal; but while the wheel revolved vertically, gravity and the centrifugal force were operating in the same direction. It was necessary to cause them to act in different directions, and for this purpose the wheel was made to revolve horizontally: in this case the centrifugal force acted at right angles to the line of gravity, and it was accordingly found, in obedience to the law of the composition of forces, that the roots no longer grew towards the centre of the earth, nor towards the circumference of the wheel, but in a plane between these two forces; and the angle which they formed with the line of gravity could be rendered more or less acute by increasing or diminishing the velocity with which the wheel rotated. It was thus made evident that roots and stems were influenced by physical laws, although growing in opposite directions.

We have thus shown why roots grow downwards and stems towards the heavens: in the dark these things arise through the influence of gravity controlling endosmose, and thus producing the proper incurvations of the parts of stems and roots. Under the influence of light the same phenomena more energetically arise from the agency of this element over vegetable growth.

J. A.

Beauty in spectacles is like Cupid in knee breeches, or the Graces with pocket handkerchiefs—an excrescence of refinement; an innovation of the ideas which spiritualize woman into a goddess; a philosophical blossom of the “march of mind.” Beauty in spectacles! and has it come to this? Burke said that the age of chivalry was past, and publishers say that the age of poetry has followed it; powder and periwigs destroyed the one, and spectacles have gone far to annihilate the other. Think of the queen of beauty of some tournament—thanks to my Lord Eglintoun for making such words familiar to us—looking on the encountering knights through a patent pair of spectacles!—picture to yourself a beautiful and romantic young lady parting from her lover, taking the “first long lingering kiss of love,” as pretty Miss Pardoe terms it, and just imagine the figure the spectacles would cut in such an encounter; think of Mary Queen of Scots, Lady Jane Grey, Scott’s “Jewess,” or Shakspeare’s “Lady Macbeth,” with such appendages! I think of a heroine in a novel taking off her spectacles to shed “salt tears” for her lover’s absence, or in the emotion of a distressing juncture throwing herself at the feet of some obdurate tyrant, breaking the lenses of her “sight preservers;” think of all this, and judge of the effect which spectacles, as an ornament, have upon romance. Beauty has three stages—the coy, the dignified, and the intellectual. The first exists until about twenty, the second until twenty-five, and the last until beauty has made unto itself wings and flown away. It is in this last stage that women wear spectacles. The symptoms of spectacles begin at an early age. The young Miss has a primness, a staidness, and a miniature severity of aspect, at variance from her years. They never seem young; there is no freshness of heart in them: they become women faster than other girls, and become old faster than other women; they are remarkable for thin lips, sharp noses, and white artificial teeth. They are walking strictures upon human life—bleak visions of philosophy in petticoats—daughters, not it would seem of love, but of Fellows of the Royal Society! They are fond of phrenology and meetings of scientific associations. They like a good pew in church, and write long letters to their unfortunate “friends in the country.” They are generally spinsters, or, if married, motherless. No young wife with “six small children” ever wore spectacles. They go a good deal into company, where they are seen seated on sofas talking to ladies older than themselves, or turning over the leaves of a book, and with interesting abstraction poring over it. They dance quadrilles, but never waltz. Heaven and earth! think of a pair of spectacles whirling in a waltz. They have a genius for the “scholastic profession,” and frequently exercise it as amateurs “never eat suppers;” and are, many of them, members of the Horticultural Society. The lady with the spectacles! Half a century ago this would have been understood to refer to some one stricken in years, but now-a-days infirmity of eye-sight has been raised to the rank of a charm. The moment spectacles become really useful they are abandoned; it is the harmonious combination of youth and short-sightedness which gives beauty to the guise. Intense interest is expected to be felt towards her, who, still young and lovely, abandons the frivolities of her sex for the calm secluded pleasures of intellect. This is the point our heroines aim at. But we have done with them. They may be very good in their way, but their ways are not as our ways. Flirts, coquettes, prudes, and a host of other orders into which the sex are classified, have their failings, but they, at least, are women; while the “lady with the spectacles” seems hardly a daughter of Eve, but a mysterious being; a new creation, come into the world to gladden the lovers of modern science, and patronise the house of Solomons and Co.—Court Gazette.

Marriage.—It is the happiest and most virtuous state of society, in which the husband and wife set out early together, make their property together, and with perfect sympathy of soul graduate all their expenses, plans, calculations and desires, with reference to their present means, and to their future and common interest. Nothing delights me more than to enter the neat little tenement of the young couple, who within perhaps two or three years, without any resources but their own knowledge or industry, have joined heart and hand, and engage to share together the responsibilities, duties, interests, trials, and pleasures of life. The industrious wife is cheerfully employing her own hands in domestic duties, putting her house in order, or mending her husband’s clothes, or preparing the dinner, whilst, perhaps, the little darling sits prattling upon the floor, or lies sleeping in the cradle—and everything seems preparing to welcome the happiest of husbands and the best of fathers, when he shall come from his toil to enjoy the sweets of his little paradise. This is the true domestic pleasure, the “only bliss that survived the fall.” Health, contentment, love, abundance, and bright prospects, are all here. But it has become a prevalent sentiment, that a man must acquire his fortune before he marries—that the wife must have no sympathy, nor share with him in the pursuit of it, in which most of the pleasure truly consists; and the young married people must set out with as large and expensive an establishment as is becoming those who have been wedded for 20 years. This is very unhappy. It fills the community with bachelors, who are waiting to make their fortunes, endangering virtue and promoting vice—it destroys the true economy and design of the domestic institution, and it promotes idleness and inefficiency among females, who are expecting to be taken up by a fortune, and passively sustained, without any care or concern on their part—and thus many a wife becomes, as a gentleman once remarked, not a “help-mate,” but a “help-eat.”—Winslow.

Printed and published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron, at the Office of the General Advertiser. No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin.—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; Slocombe and Simms, Leeds; J. Menzies, Prince’s Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.