Cover was created by the transcriber and was placed in the public domain.

Title: A Text-book of Diseases of Women

Author: Charles B. Penrose

Release date: June 26, 2017 [eBook #54982]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by deaurider, Wayne Hammond and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

1

2

3

Cover was created by the transcriber and was placed in the public domain.

With 225 Illustrations

With 225 Illustrations

SIXTH EDITION, REVISED

SIXTH EDITION, REVISED4

Set up, electrotyped, printed, and copyrighted July, 1897. Revised, reprinted,

and recopyrighted May, 1898. Reprinted December, 1899. Revised,

reprinted, and recopyrighted December, 1900. Revised, reprinted,

and recopyrighted July, 1901. Reprinted January, 1902.

Revised, reprinted, and recopyrighted, June, 1904.

Reprinted August, 1905. Revised, reprinted,

and recopyrighted March, 1908.

Copyright, 1908, by W. B. Saunders Company.

Copyright, 1908, by W. B. Saunders Company.

PRINTED IN AMERICA

PRINTED IN AMERICA

PRESS OF

PRESS OF

W. B. SAUNDERS COMPANY

PHILADELPHIA

5

I have carefully revised this book for the sixth edition, and have made those changes and additions that have been rendered necessary by the increase of our knowledge of gynecology.

1720 Spruce Street, Philadelphia.

March, 1908.

6

7

I have written this book for the medical student. I have attempted to present the best teaching of modern gynecology, untrammelled by antiquated theories or methods of treatment. I have, in most instances, recommended but one plan of treatment for each disease, hoping in this way to avoid confusing the student or the physician who consults the book for practical guidance. I have, as a rule, omitted all facts of anatomy, physiology, and pathology which may be found in the general text-books upon these subjects. Such facts have been mentioned in detail only when it seemed important for the elucidation of the subject, or when there were certain points in the pathology that were peculiar to the diseases under consideration. I am indebted to Dr. H. D. Beyea for several pathological drawings, and to Dr. Wm. R. Nicholson for the preparation of the Index.

8

9

15

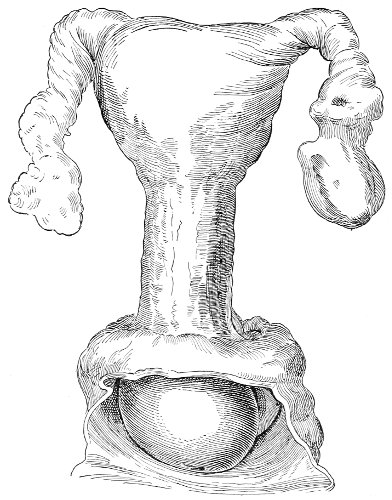

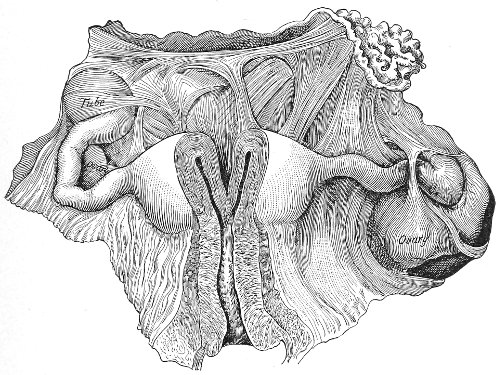

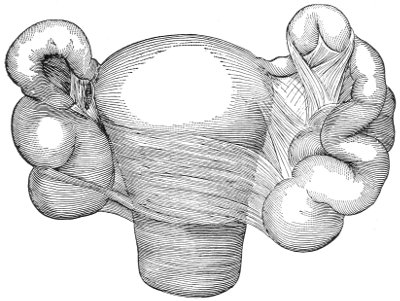

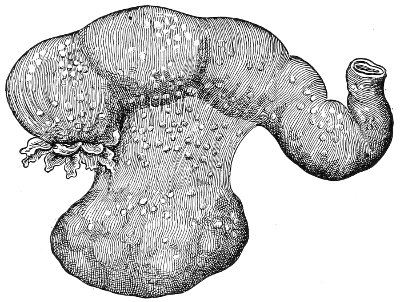

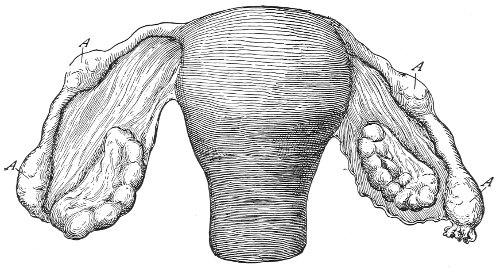

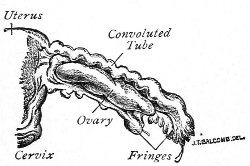

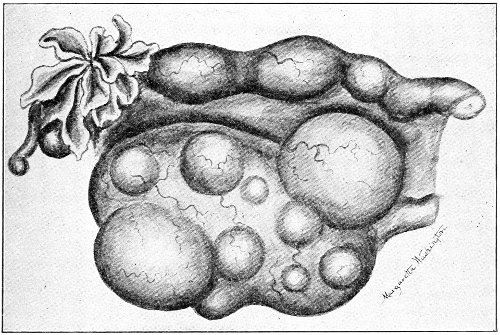

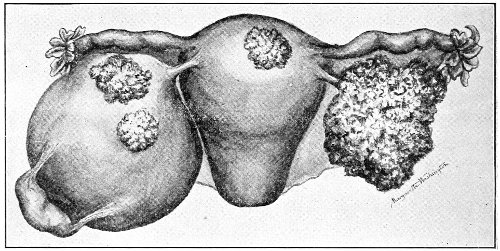

Gynecology is the study of diseases peculiar to women. As woman possesses organs which man has not, and as the parts—physiological and social—that she plays in life differ from those played by man, we should expect to find her afflicted with a certain number of diseases, peculiar to her, which are dependent upon her anatomy, physiology, and mode of life. Such diseases occur in barbarous as well as in civilized women; and similar diseases, peculiar to the female, occur in the lower animals. Thus, in the cow and the mare we find tumors of the vagina, prolapse of the vagina and uterus, fibroid tumors, sarcoma and cancer of the uterus, and some forms of ovarian cysts. Cysts of the tubes and the ovaries are exceedingly common in old mares; cats and goats are similarly affected.

From a pathological point of view, however, the civilized woman unfortunately differs from her barbarous sister, and from the female of the lower animals, in many important particulars. She is more liable to the pathological conditions which, more or less, all females have in common. These conditions appear in a more severe form, and are followed by more disastrous results, in the civilized than in the barbarous state.

The female among the lower animals and among 16 savages seems to be about equal in proportionate strength and physical endurance to the male, though in size and in gross muscular strength she may be his inferior. Her subordinate position is often due not so much to any difference in strength as to the fact that the male possesses weapons—as the horns of the deer—with which nature has not endowed the female; and though she is liable to more diseases than the male, yet her relative position does not seem to be materially altered by this fact. The bitch is as enduring as the dog. The female grizzly is as ferocious and as dangerous as the male. The mare is as fast as the horse. The squaw among the American Indians can lift and carry burdens which the lazy buck would not attempt.

How different it is with the civilized woman, as we know her in this country! The average healthy woman in this country is very much inferior in physical strength and endurance to the average man, and this inferiority is tremendously increased when she becomes sick from any of the diseases to which her sex is liable.

The increased liability of the civilized woman to disease is in a large measure due to her poor physique. But this is not all.

The causes of many of the diseases with which the gynecologist has to deal cannot be traced so easily.

Fibroid tumors of the uterus, which are so common among the colored women of this country, are said by Tait to be unknown among their African cousins, who are removed by but a few generations.

The most common causes of diseases of women are injuries received during parturition; sepsis; venereal diseases; errors of development; improper mode of life and clothing during the period of development; neglect during menstruation; and celibacy.

The results of the injuries received during parturition are most numerous. They may appear immediately, a short time after labor, or at some remote period. The disabilities attending laceration through the sphincter 17 ani or a recto-vaginal or vesico-vaginal fistula appear before the mother leaves her bed. The suffering from a laceration of the cervix, a subinvolution of the uterus, or a retrodisplacement may not be felt for some weeks or months after labor; while the still more remote result, the development of cancer, may not appear for many years, though it can be positively traced to the lesion in the cervix as the primary cause.

Septic infection of the genital tract kills or makes invalids of many women. The infection occurs at the time of a miscarriage or of a normal labor, or it may be acquired from the dirty instruments or the dirty hands of a physician. It is not a cause of disease among civilized women alone, but occurs among barbarous and semi-barbarous races.

Venereal disease, especially gonorrhea, has been said to be the most common cause of disease among women. The disease extends from the external genitals through the uterus and Fallopian tubes, causing sterility, chronic invalidism, and death from peritonitis.

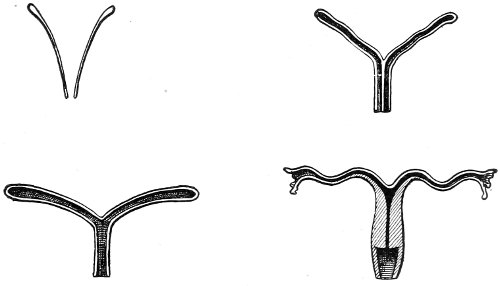

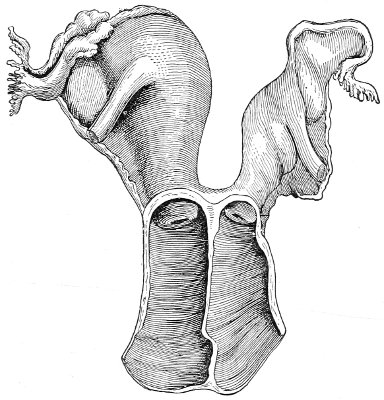

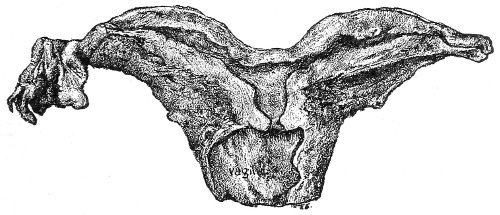

Errors of development are frequent causes of disease and suffering among women. Atresia of the vagina or of the cervix uteri, by causing retention of the uterine discharges, produces most serious pathological conditions. Arrested development of the whole or of part of the uterus is a common cause of disease.

Improper clothing and an improper mode of life during the period of development are most fertile sources of diseases of women. Clothing which contracts the waist, as well as clothing which, though not unduly tight in the inactive state, yet interferes with abdominal respiration during activity, is most injurious. Such clothing diminishes the capacity of inspiration by restricting abdominal expansion, and thus crowds down the pelvic organs toward the pelvic floor; and the continuous support to the abdominal walls diminishes their natural muscular strength and places the woman in a condition predisposing to the various displacements of the uterus. 18

An improper mode of life, irregular hours for sleeping and eating, insufficient exercise, and lack of fresh air and sun, resulting in poor muscular development, seem to predispose the woman, as the man, to a variety of pathological conditions; but as the reproductive apparatus in woman is more delicately organized, and as, during the period of active life, this is really her chief part, it more especially suffers as a result of any general systemic derangement.

Neglect during menstruation, especially in the young girl, is a frequent cause of subsequent suffering. The effect of menstruation upon the whole system is remarkable. The nervous, vascular, and digestive systems all share in the menstrual function. The usual work of the girl at school or other employment should be altered to suit the altered conditions of her body at the menstrual period. Long school hours and close mental application or active exercise are too often continued at this time.

Celibacy is an unnatural state and a common cause of disease. Certain forms of fibroid tumors of the uterus are more common in single than in married women, and more common in sterile than in childbearing women. And the painful cirrhotic ovaries of the old maid are the result of the unceasing menstrual congestions never relieved by pregnancy and lactation. 19

In order to make a complete gynecological examination, we must examine the abdomen, the external organs of generation, and the pelvic structures.

Examination of the Abdomen.—In order to make a perfectly satisfactory examination of the abdomen, the woman should be in bed, with all clothing removed except the undershirt and the night-dress, which should be drawn well up above the costal margin. Examination made with any constricting clothing about the waist or about the lower thorax is most unsatisfactory.

The abdomen is examined by inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation.

The woman should lie flat upon her back, and the abdomen should be thoroughly exposed. We can then determine by inspection the presence of dilated veins or of lineæ albicantes, the general size and form of the abdomen, the occurrence of any abdominal movement, and the presence of any asymmetry in the abdominal contour, such as would be made by the bulge of a tumor or the displacement of an abdominal organ. The shape of the abdomen, even though symmetrical, is often diagnostic of certain intra-abdominal conditions. Thus, an abdominal enlargement that is due merely to fat presents a different contour from the enlargement caused by tympanitic distention of the intestine. The enlargement due to ascites, or free fluid in the peritoneum, differs in contour from that caused by an encysted collection of fluid.

It should be remembered that lineæ albicantes are not always the result of pregnancy, but that they may have 20 been caused by distention of the abdomen from some other cause.

Palpation.—We can determine most by palpation of the abdomen. The examiner should always remember that it is most important to secure the patient’s confidence, and to proceed so gently, slowly, and gradually in performing palpation that no voluntary or reflex contraction of the abdominal muscles may impede his manipulations.

In cases in which there is a sore or tender spot within the abdomen the contraction of the recti muscles may be altogether involuntary, persisting even when the patient is anesthetized. We see this in the rigid right rectus muscle of appendicitis. The hands should be warmed, and palpation should be performed with both hands. A certain amount of gentle stroking or massage of the abdomen will secure the patient’s confidence by making her feel that she will not be hurt by any sudden violent pressure, and will also prevent reflex contraction of the muscles. By proceeding in this way, slowly, the examiner can palpate the whole of the abdominal surface, exploring first the structures lying most anterior, and then, pressing the fingers more deeply, he can examine the more posterior structures.

Fluctuation in an encysted fluid accumulation is generally readily determined. While one hand is placed against one side of the fluid mass and the opposite side is percussed by the fingers of the other hand, the wave of fluctuation is easily felt. Sometimes a thrill or a false wave of fluctuation is observed in the subcutaneous fat of obese women. This disturbing element may, however, be eliminated by an assistant pressing the ulnar edge of his hand in the median line upon the abdominal surface, thus stopping the fat wave of fluctuation.

Special organs in the abdomen sometimes require special methods of examination. It is very often necessary for the gynecologist to examine the kidneys, because many women have movable or floating kidneys, and the 21 nervous, gastric, and abdominal symptoms may be due to this condition. The presence of a floating kidney may often be determined by inspection; the presence of a movable kidney, however, must be determined by palpation. This should be performed with the woman in the sitting, or standing, erect posture; or sitting upon the edge of a chair, with the body inclined somewhat forward and the hands upon the knees; or lying upon a bed, on the side opposite the kidney that is being examined. One hand should be placed over the lumbar muscles; the other hand should be placed upon the anterior abdominal wall immediately below the costal margin, and should be pressed backward. If the kidney lies below its normal position, it may in this way be brought between the two hands, and can be felt to glide upward as the hands are pressed together. In case a movable kidney cannot readily be found, because it may have returned to its normal position, it may often be brought down again if the woman is made to cough.

In a thin woman the vermiform appendix may sometimes be felt through the abdominal wall; and in cases of pain and inflammation in the right iliac region it is sometimes important to determine whether or not the trouble has started in the vermiform appendix or in the Fallopian tube. In order to palpate the vermiform appendix the examiner should stand upon the right side of the woman, who is lying upon her back, and should place the tips of the fingers of the right hand at about the junction of the upper and middle thirds of a line drawn from the middle of Poupart’s ligament to the umbilicus. By pressing backward firmly and gently, pulsations of the right common iliac artery may be felt; and then by drawing the hand directly outward it will pass over the different structures in this region lying between the palpating hand and the posterior abdominal wall. The appendix may often be felt, especially if it is indurated by inflammation.

Percussion of the abdomen should be performed with 22 the woman in the dorsal position; though, if the examiner suspects the presence of free fluid in the peritoneum, or ascites, much may be learned by percussing in different positions and noting the accompanying changes in the percussion-note.

Percussion should then be performed with the woman upon her back, upon the right side, upon the left side, sitting up, and upon the hands and knees. An encysted fluid accumulation will give practically the same result in percussion in all positions, while free fluid will gravitate to the most dependent portion.

Auscultation of the abdomen is best performed with the stethoscope. By it we may hear fetal heart-sounds, uterine souffle, placental bruit, peritoneal friction sounds, and the peristaltic sounds of the intestinal tract. All of these sounds are of importance, and the presence or absence of any of them may have an important bearing upon the diagnosis of the case.

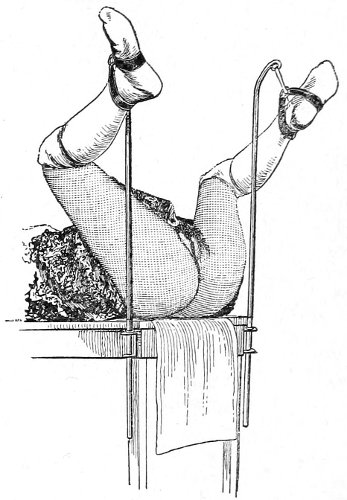

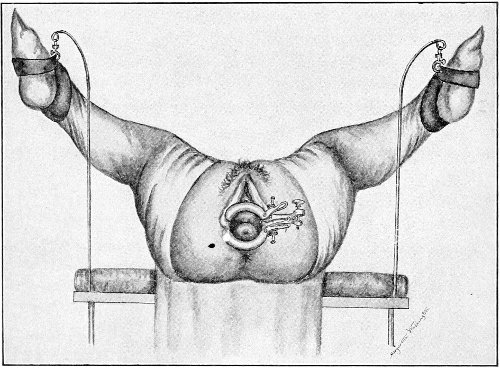

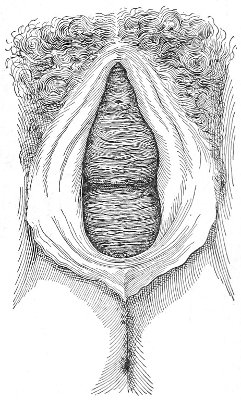

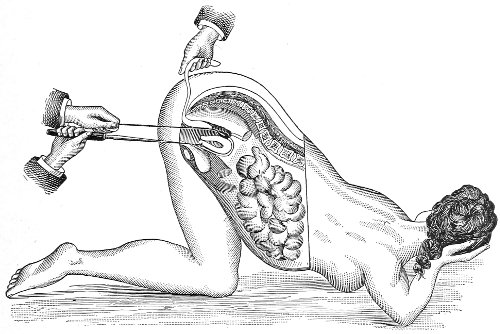

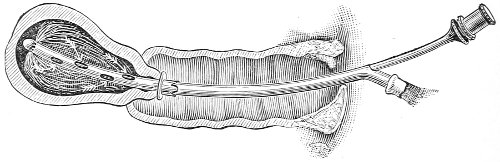

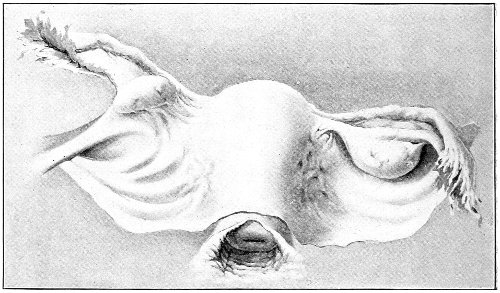

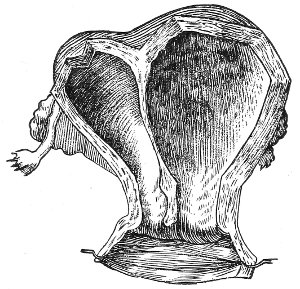

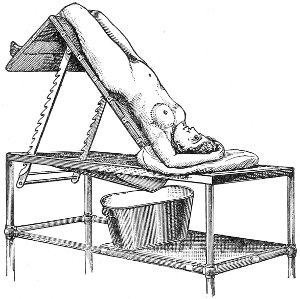

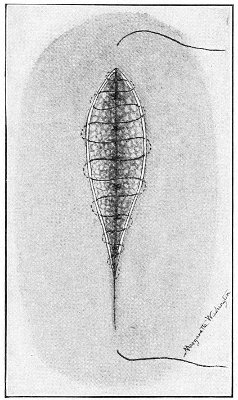

Examination of External Genitals and Pelvic Structures.—To examine the external organs of generation and the pelvic viscera the woman should be placed upon a table. In some cases the physician may be obliged, for want of proper facilities or on account of the physical condition of the patient, to make his examination upon a bed. Such an examination, however, is never so satisfactory or so thorough as the examination made with the woman upon the examining-table. A great number of gynecological tables have been introduced. The one which seems to the writer the best, on account of its simplicity and the perfect relaxation of the abdominal muscles furnished by it, is shown in the accompanying illustration (Fig. 1). It is a plain wooden table, at the foot of which are attached the upright supports for holding the stirrups for the feet, such as have been devised by Dr. Edebohls. By this arrangement the feet and legs are supported without any effort on the part of the woman; when the buttocks are drawn well down to the foot of the table there is a certain amount of flexion 23 of the pelvis upon the trunk, and the most complete attainable relaxation of the abdominal muscles is secured.

When the woman has been placed in this position the examiner should investigate thoroughly, and in order, the following structures: The anus, the perineum, the labia majora, the nymphæ, the fourchette, the orifices of the ducts of the vulvo-vaginal glands, the hymen or its remains, the vestibule and the small glands of the vestibule, the external urinary meatus, and the clitoris.

To determine any pathological condition of these structures it is necessary that the physician should be familiar with the appearance in the normal woman, and to gain such essential knowledge we should avail ourselves of every opportunity offered to make a critical examination of the external genitals of women, going over all the different structures in order.

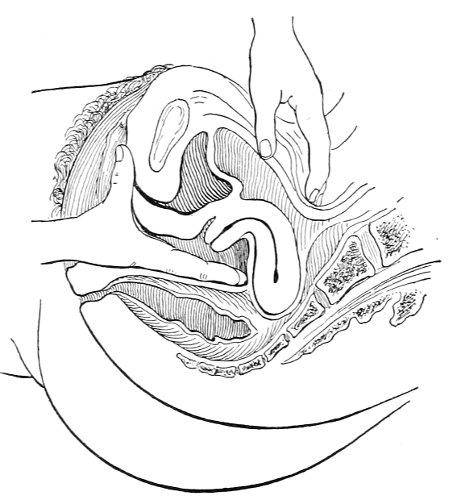

Fig. 1.—Woman in the dorsal position with feet supported in Edebohls’ stirrups.

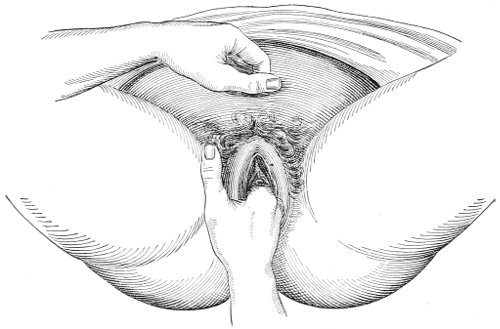

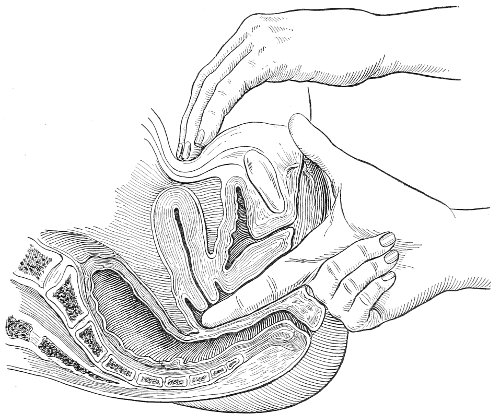

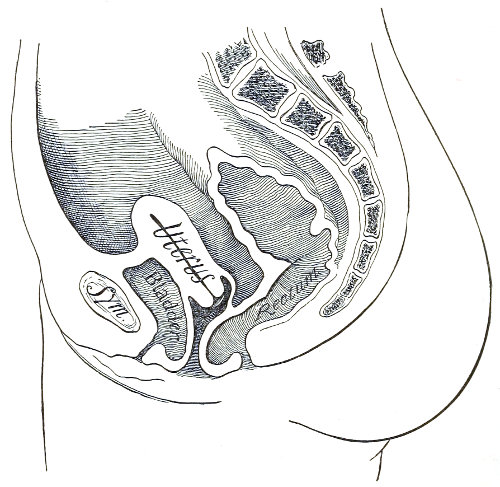

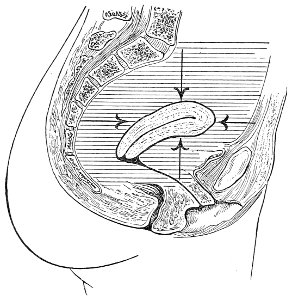

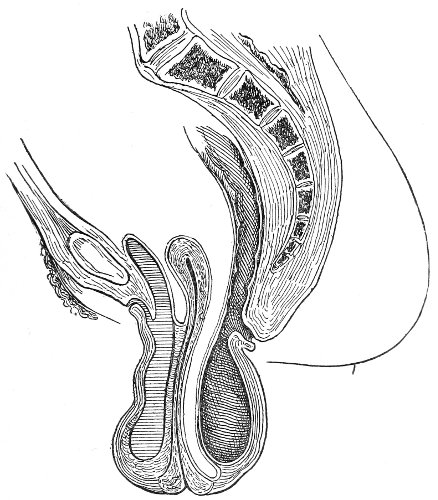

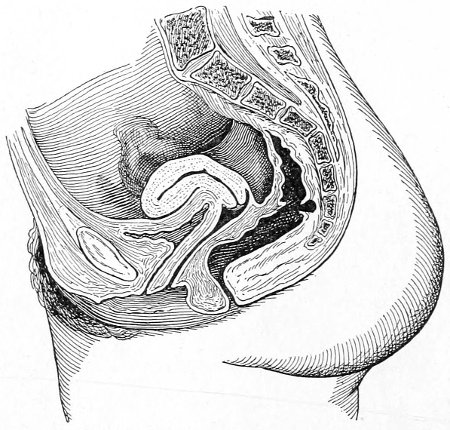

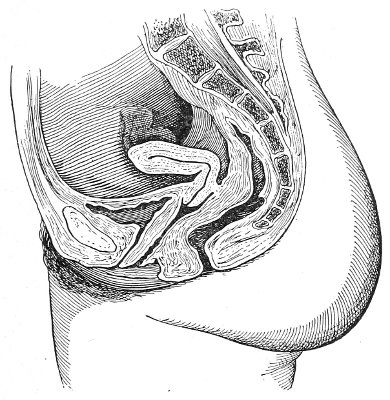

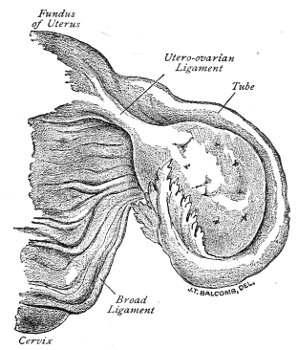

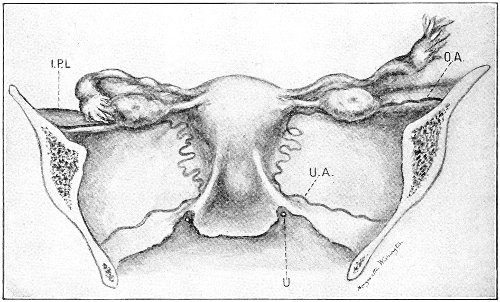

Vaginal and Bimanual Examination.—Having examined and noted the condition of the external genitals, the physician should next proceed to examine the vagina. The index finger of the right or the left hand should be gently introduced into the vagina. The condition of the vaginal walls, and the direction, consistency, form, etc. of the vaginal cervix, may be determined. The shape and size of the os uteri should be noted. The ulnar edge and the tips of the fingers of the other hand should then be placed upon the abdomen, immediately above the symphysis pubis, and gently pressed backward and downward toward the vaginal finger 24 (Fig. 2). In this way the various pelvic organs, the uterus, Fallopian tubes, ovaries, and ureters, may be palpated between the two hands, and their position, size, shape, and consistency may be determined. Such an examination is, of course, made much more easily in a thin woman than in a fat one. A thin woman a few weeks after labor may be examined most easily, on account of the relaxation of the abdominal and vaginal walls.

Fig. 2.—Bimanual examination.

This is called the bimanual method of examination, and the student will find that as he acquires practice in this method he will gradually depend less upon examination by the uterine sound and the speculum, and will rely altogether upon his sense of touch, his ability to palpate.

It matters not which hand be used in making the vaginal examination. It will, however, be found that the hand that is used the more frequently will become the more proficient.

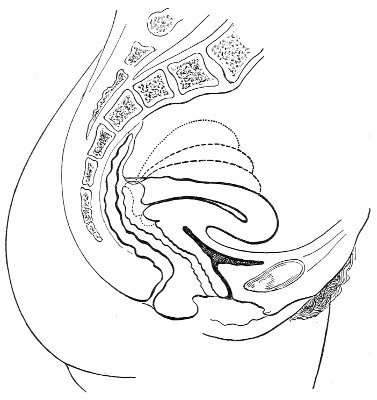

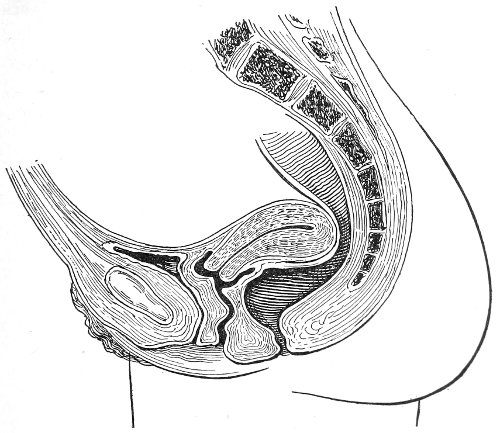

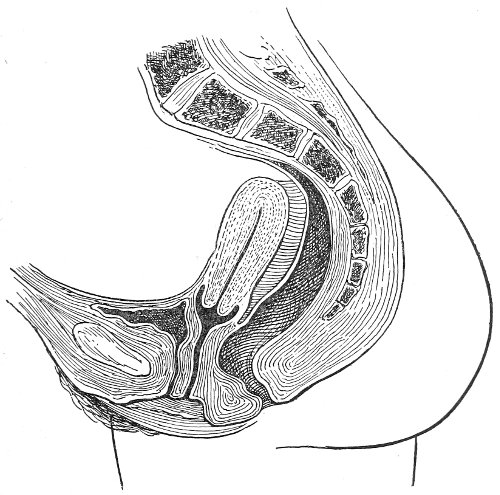

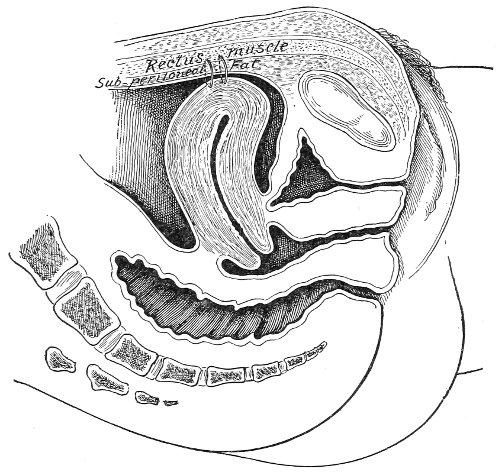

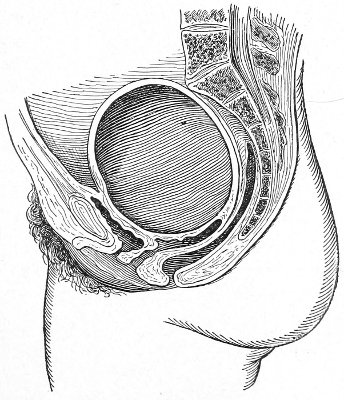

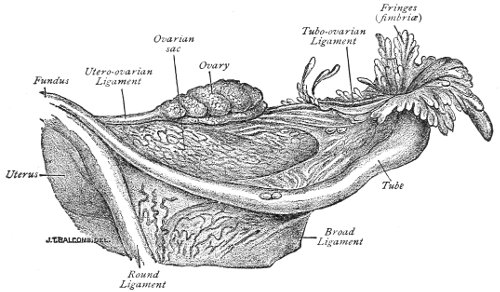

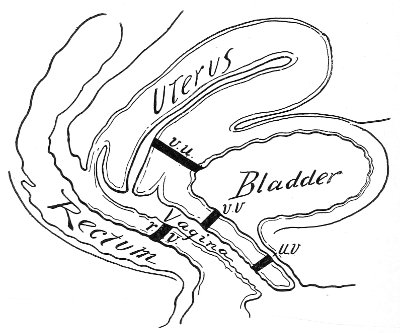

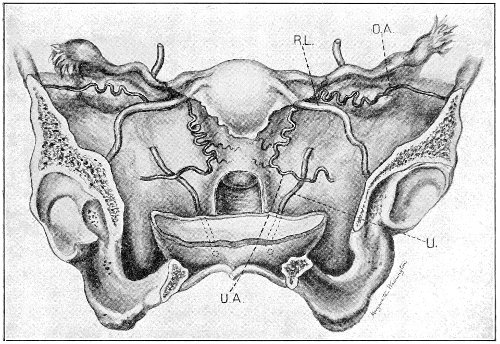

In making the bimanual examination the structures 25 should be palpated methodically in order. The vaginal finger notes the condition of the cervix uteri. If the fundus be in the normal position, the uterus can then be taken between the abdominal hand (upon the fundus) and the vaginal finger (upon the cervix) (Fig. 3). The shape, size, mobility, and consistency are noted. The vaginal finger is then passed anteriorly and laterally toward either uterine cornu, while the abdominal fingers pass over to the posterior aspect of the same cornu. The ovarian ligament and the proximal end of the Fallopian tube may thus be felt. Passing farther outward, the whole of the tube and the ovary may be examined. The same procedure is then applied to the opposite side.

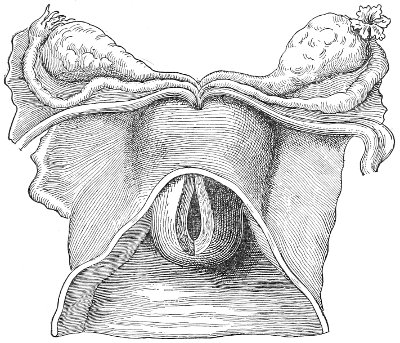

Fig. 3.—Bimanual examination; median sagittal section of the pelvis.

The condition of the ureters may be determined by placing the vaginal finger in either lateral vaginal fornix and drawing it outward and forward, when these structures will pass over the end of the finger. When the 26 ureters are indurated by inflammation they can be plainly felt.

By the method of examination here advised the physician will always make a visual examination before making a digital one. There are several advantages derived from this procedure. In the first place, no examination of a woman is thorough unless a careful visual examination of the external genitals has been made. The discovery of discharges and of lesions of the external genitals may throw much light upon the condition found higher up in the pelvis. Again, the examiner protects himself. A great many unfortunate cases of syphilis have been acquired by physicians from a primary sore upon the examining finger. A preliminary visual examination enables one to guard against this danger. The primary sore occurs upon the end of the examining finger or upon the web between the index and middle fingers—the part of the hand that is pressed against the fourchette.

The hands of the physician should, of course, be surgically clean before making an examination, and the grease or oil which is used as a lubricant should be clean. The hands should always be washed, after separating the parts to make the visual examination, before the finger is thrust into the vessel containing the lubricant. It is best to place a small portion of the lubricant on a plate or a saucer for each individual patient, and thus avoid the danger of contaminating the rest. Carbolized oil, borated vaseline or cosmoline, and a thick sterile solution of soap are good lubricants. Neutral green soap diluted with boiled water to the consistency of thin jelly is a very agreeable lubricant which may easily be washed from the hands and the vagina.

If practicable, the woman should receive a vaginal douche of bichloride-of-mercury solution, 1:4000, and the vulva should be washed, before making a bimanual examination. The examiner should always clean the external genitals of all discharges before introducing the vaginal finger. In this way we avoid the danger of 27 carrying septic material from the external genitals to the upper portion of the genital tract. This preliminary cleansing is not desirable before the external genitals have been examined; for much may be learned from observation of the discharges which bathe or escape from the various structures. If practicable, a cleansing vaginal douche of bichloride-of-mercury solution should be administered after the bimanual examination.

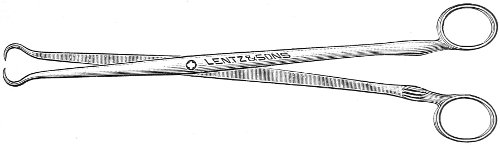

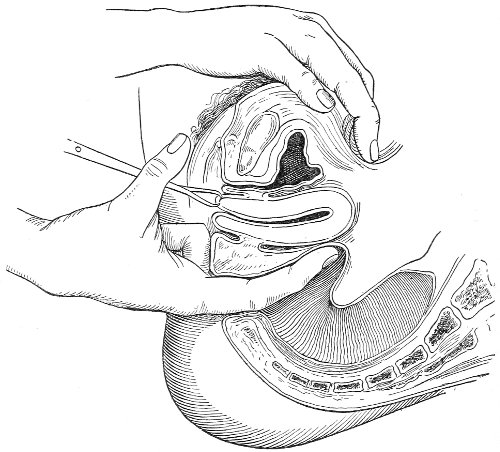

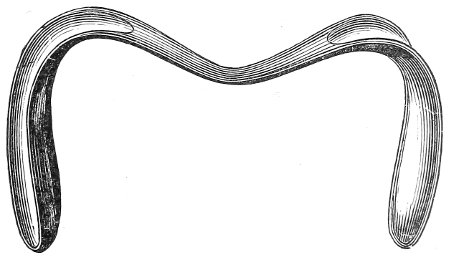

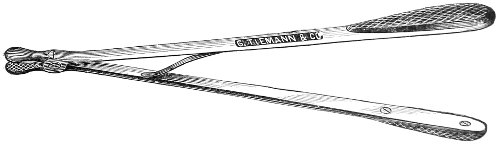

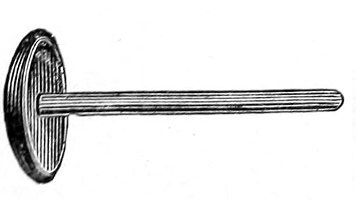

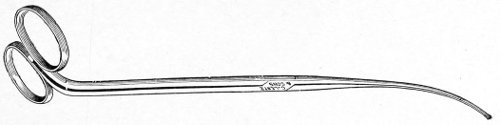

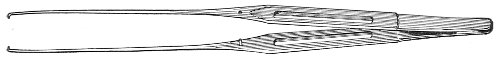

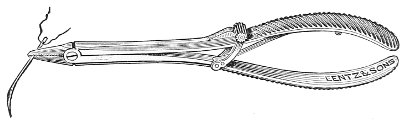

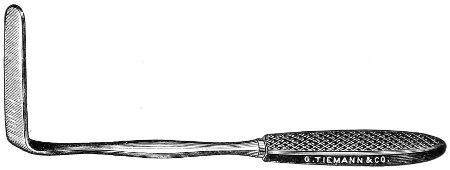

Fig. 4.—Double tenaculum.

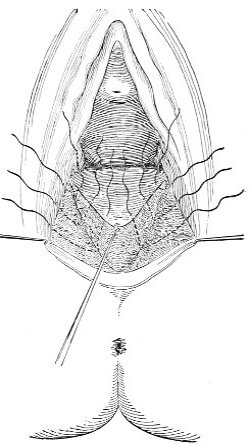

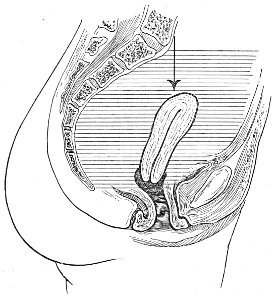

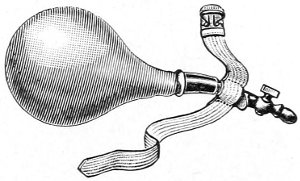

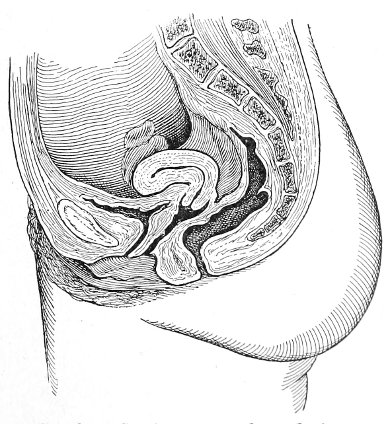

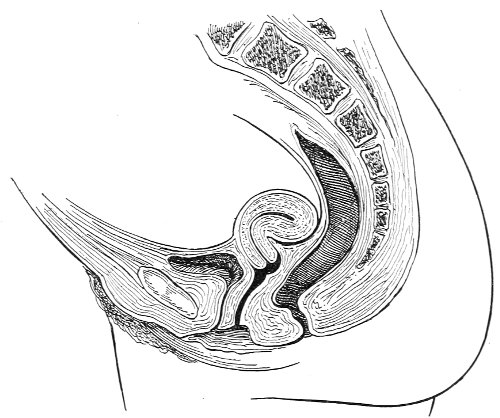

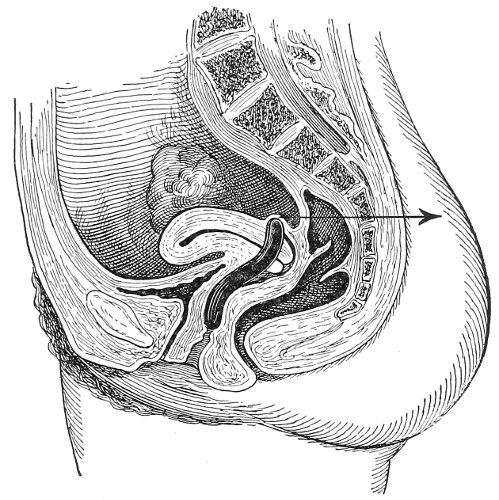

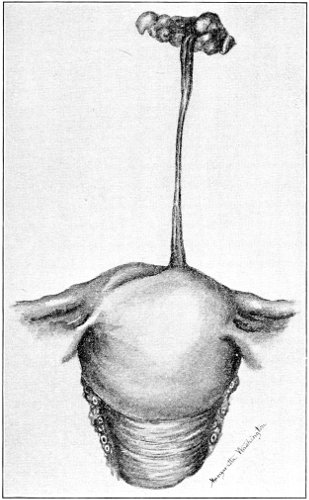

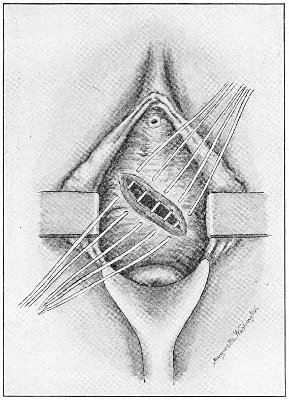

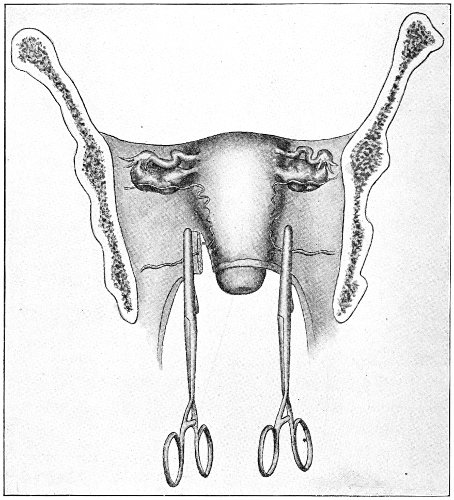

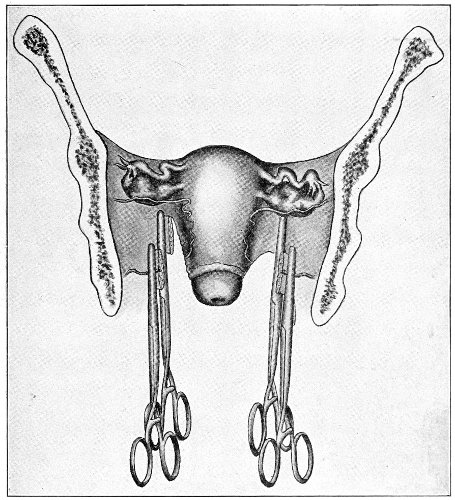

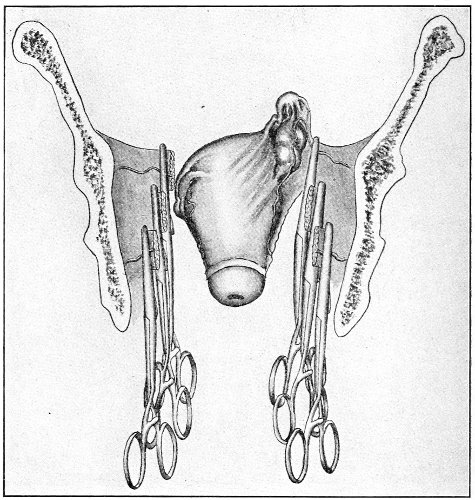

The examination of the uterus and other pelvic structures is often facilitated by dragging the uterus downward with a tenaculum while the vaginal or the bimanual examination is being made. Sensation in the cervix is so slight that little or no pain is experienced in this procedure. The anterior or posterior lip of the cervix is caught with the single or the double tenaculum (Fig. 4), guided along the vaginal finger or introduced through the speculum, and the uterus is drawn down by an assistant in case the bimanual examination is being made, or by the external hand of the examiner in case a simple vaginal examination is made. When this is done the utero-sacral ligaments are made tense, and can be felt like two cords extending from the sides of the cervix outward and backward to the pelvic wall. The posterior surface of the uterus can be palpated often as high up as the fundus. The method is especially useful when the examination is made by the rectum, and in this way the whole posterior surface and the fundus of the uterus may be palpated (Fig. 5).

The contraindications to a vaginal examination are 28 virginity, the presence of a hymen, and any acute inflammatory or painful condition of the vulva or vagina. None of these conditions, however, forbid an examination if an exact diagnosis is essential to the proper treatment of the case, and can be made only in this way. It may be that in these cases a rectal examination will be sufficient for diagnosis.

Fig. 5.—Bimanual examination with one finger in the rectum. The uterus is drawn down with the double tenaculum.

Rectal examination of the pelvic structures is made in a way similar to that already described for the vaginal examination. Bimanual examination may be made by palpating the various organs between the rectal finger and the abdominal hand.

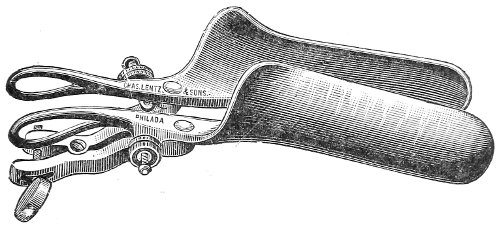

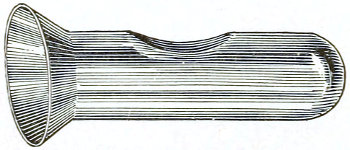

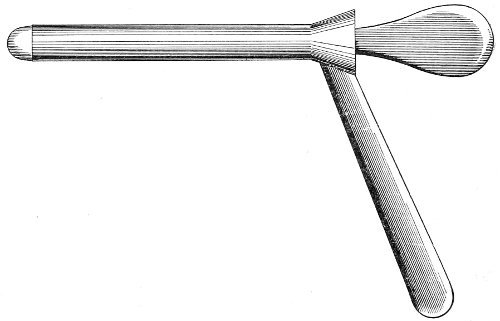

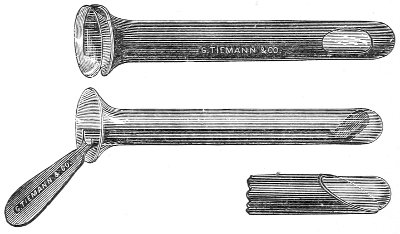

The Vaginal Speculum.—The speculum is an instrument through which a visual examination is made of the vagina, the external os uteri, and the vaginal cervix. A 29 great number of specula have been invented. At the present day the best two instruments of this class are the bivalve speculum, such as Goodell’s (Fig. 6), and the duck-bill speculum (Fig. 7), or perineal retractor, invented by Sims.

Fig. 6.—Goodell’s speculum.

Fig. 7.—Sims’ speculum.

Fig. 8.—Sims’ depressor for the anterior vaginal wall.

The bivalve speculum is introduced with the woman upon her back, in the dorso-sacral position already described. The vulva and the vagina should be cleaned. The speculum should be warmed by placing it in hot water, and should then be lubricated with the soap solution or with vaseline. It should be introduced with the blades closed and the plane of the blades lying not exactly 30 in the median sagittal plane of the body, but inclined at a small acute angle to this plane, one edge of the speculum being directed toward either vaginal sulcus. The instrument is passed into the vagina toward the position in which, by a previous digital examination, the vaginal cervix had been found to lie. The instrument is then turned with the handles toward either thigh, so that the blades become parallel to the anterior and posterior vaginal walls, in order that, when separated, they will open the vaginal slit. The handles are brought together and the blades opened. When the vaginal cervix comes well into view the blades are fixed in place by the screws (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.—Goodell’s speculum in position.

In some cases, where the cervix points well forward or well backward, it may be readily brought into view through the speculum by catching it with a tenaculum.

By means of the bivalve speculum we are able to make a partial inspection of the vaginal walls, an imperfect inspection of the vaginal vault, and a good inspection of the vaginal cervix and the external os. Applications 31 can be made to the cervix, but none of the minor operations of gynecology can be performed through this speculum.

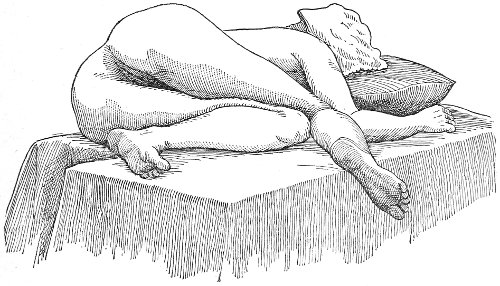

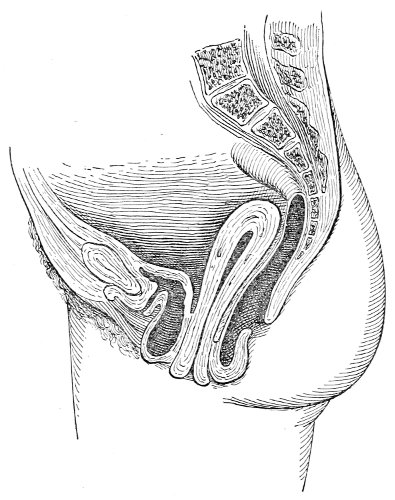

The Sims speculum enables us to make the most thorough inspection of the vagina, the vaginal vault, and the vaginal cervix. The Sims speculum is merely a hook or retractor for the perineum, and may be introduced with the woman in the dorsal position, the Sims position, or the genu-pectoral position. If the Sims speculum is introduced in the dorso-sacral position, it is necessary to hold forward the anterior vaginal wall in order to obtain a view of the cervix.

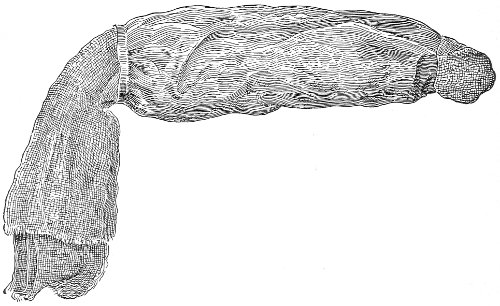

Fig. 10.—The Sims position.

The Sims position, which is also called the latero-abdominal position, is shown in Fig. 10. The woman is placed on the bed or table upon her left side. The side of the face is upon the pillow; the left arm is behind the back, so that the left breast rests upon the table. The thighs are flexed upon the abdomen at an angle of about 90° to the trunk. The right thigh is more flexed than the left, so that the right knee may touch the table above the left knee. The legs are flexed on the thighs. In this position there is a tendency for the intestines, following the force of gravity, to fall from the pelvis, 32 and for the uterus and other pelvic viscera to be drawn up. When the perineum is retracted with the blade of the Sims speculum, air will enter the vagina and the vaginal slit will become distended (Fig. 11). To facilitate inspection of the cervix it is usually necessary also to push forward the anterior abdominal wall by some kind of depressor, such as the one shown in Fig. 8.

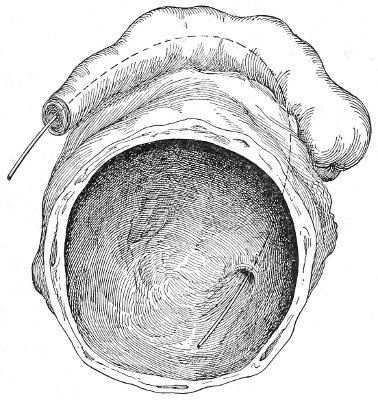

Fig. 11.—The cervix uteri exposed with the Sims speculum.

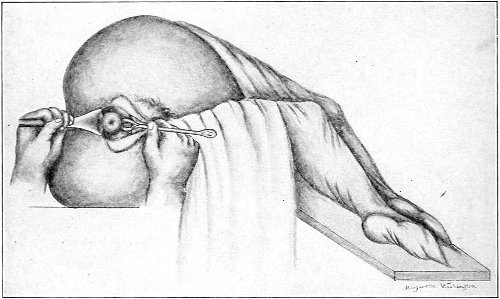

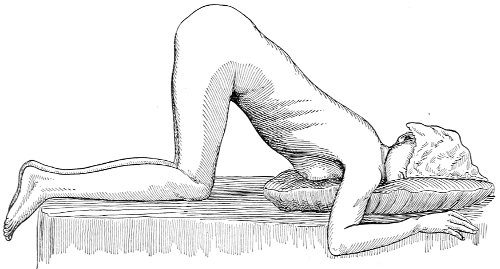

Fig. 12.—The knee-chest position.

The genu-pectoral position or the knee-chest position is shown in Fig. 12. The side of the face is upon the pillow; the breast is upon the table; the thighs are vertical. In 33 this position the intestines fall from the pelvis, and the other pelvic viscera are drawn upward by the force of gravity. If the anus is opened, air rushes in and distends the rectum. If the perineum is retracted, air enters and distends the vagina. If the urethra is opened, the bladder is likewise distended. The position is the most useful one for inspection of the rectum, vagina and vaginal cervix, and the bladder.

The Sims speculum, with the woman in the dorsal, the Sims, or the knee-chest position, is the most useful instrument by which to expose the cervix uteri for any of the minor operations of gynecology. The manipulations of the operator are not hampered by working between metal walls.

Examination of the Rectum.—If the woman is placed in the knee-chest position, a most satisfactory inspection of the whole of the rectum may be made. The woman should be placed in this position with the buttocks before a good light, and the posterior margin of the anus should be retracted by the small blade of a Sims speculum; the rectum will immediately become distended with air and the rectal walls will be well exposed. Or the rectal specula (Figs. 13, 14) may be used. In employing the longer of these instruments it is best to use light reflected from a head-mirror or thrown directly from an electric head-light into the speculum.

|

|

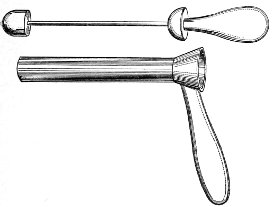

Fig. 13.—Rectal speculum, large size. |

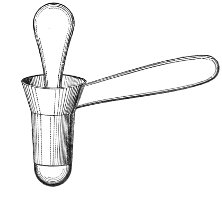

Fig. 14.—Rectal speculum, small size. |

The instrument should always be introduced for the 34 first two inches with the obturator in place. The obturator should then be withdrawn and the speculum pushed farther in, the operator watching and guiding its course around the rectal valves or folds of mucous membrane, so as to prevent injury to the walls of the rectum. Anesthesia is not necessary for this procedure.

Examination of the Bladder.—It will readily be understood that all the hollow viscera are much more easily examined when their walls are separated by distention with air than when the walls are collapsed. The bladder is most readily examined in this way. The woman should be placed in the knee-chest position, or in the dorsal position with the hips elevated above the abdomen. In either position the intestines fall from the pelvis, and when the urethra is opened air enters and distends the bladder. This distention is most certainly accomplished in the knee-chest position. In women who are not very fat, however, the extreme dorso-sacral position is equally good. The details of this method of examination are described on a later page.

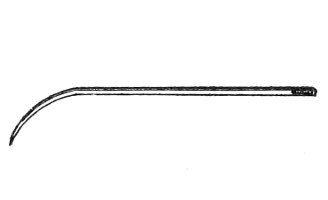

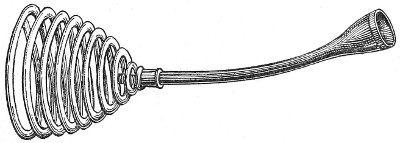

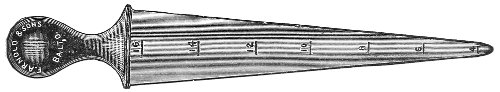

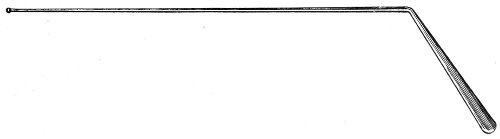

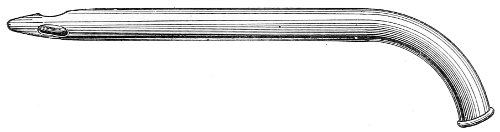

The uterine sound is an instrument by which the length of the uterine cavity may be determined (Fig. 15). The sound, which is a large surgical probe, somewhat curved to adapt itself to the normal shape of the uterine axis, is made of pliable metal, so that the curvature may be changed readily to suit any case. The sound is graduated, and at a position of 2½ inches from the tip is a small elevation marking the length of the normal uterine cavity.

Fig. 15.—Uterine sound.

The uterine sound was at one time used a great deal to determine the length and direction of the uterus, and 35 perhaps to assist in determining the character of the uterine contents or of the endometrium. With our present methods of examination, however, the sound is of but little if any use. The size and direction of the uterus can in nearly all cases be determined by bimanual examination. The use of the uterine sound is by no means free from danger. Many cases of septic endometritis and salpingitis have been caused by it, and the physician has often unintentionally committed an abortion by passing the sound in a pregnant woman. The uterine sound should never be used in a routine way. It should never be used unless one expects to determine with it something that cannot be determined by simpler methods of examination.

The most thorough aseptic precautions should be observed when the sound is introduced. The vulva, vagina, and cervix should be cleaned and the sound should be sterilized. The sound should never be introduced if there is any suspicion of pregnancy.

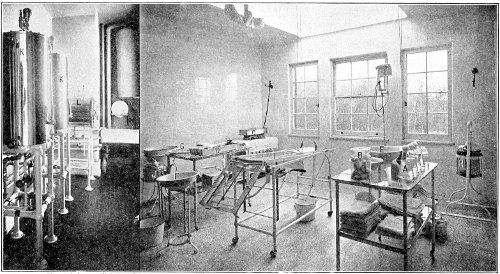

ANTISEPSIS—In all examinations the physician should observe every precaution to avoid carrying infection from one patient to another. All instruments used in the examination should be thoroughly cleansed with soap and warm water, and then boiled for five minutes in a 1-per cent. solution of carbonate of soda. 36

Vulvitis.—Vulvitis, or inflammation of the vulva, is not a common disease. The vulva is composed of several parts which are anatomically distinct, and, though all these parts are usually involved in an acute attack of inflammation of the vulva, yet the symptoms of the disease and the pathological appearance depend to a great extent upon the structures which are principally affected. The labia majora, the nymphæ, the vestibule with its mucous crypts or glands, the clitoris, the external urinary meatus, and the ducts of Bartholin’s glands may all be involved in the inflammation. The sebaceous glands of the labia may be especially involved, producing a form of sebaceous acne which has been called follicular vulvitis. Inguinal adenitis may accompany vulvitis.

The appearance of the parts is that characteristic of inflammation of the skin and mucous membrane in any other part of the body. The mucous membrane becomes red and swollen; the labia may become edematous; an abundant purulent discharge covers the parts, and unless cleanliness is practised the irritation from the discharge spreads to the inner aspects of the thighs, the perineum, and the anal region.

The patient suffers with local pain, which is increased by walking and by the passage or contact of urine.

The usual cause of vulvitis is gonorrhea. The condition is sometimes secondary to other diseases. It may be caused by the irritation from the discharges of a vesico-vaginal or recto-vaginal fistula, from a cancer of the cervix or in some forms of endometritis. Girls and 37 women who are unclean may be attacked by vulvitis as a result of irritation from decomposed smegma, sweat, urine, etc. The oxyuris, or thread-worm, may enter the vulva from the rectum and cause, in unclean children, sufficient irritation to produce inflammation. Vulvitis from uncleanliness is most likely to occur in hot weather after prolonged exercise. It not infrequently attacks children, especially those of a strumous diathesis, whose hygienic surroundings are poor. In such cases the suspicions of the parents may demand a medico-legal examination; and it is of importance to remember that vulvitis of this kind is not rare, and is not due to violation or contagion. Vulvitis in little girls may be also due to gonorrhea, independently of violation. This is the cause of epidemics of vulvitis and vaginitis in girls crowded in houses, hospitals, or asylums. The disease is spread by contamination from towels or bed-clothing.

The essential points of treatment to observe in the acute stage of vulvitis are rest in the recumbent posture and perfect cleanliness. The labia should be separated and the parts frequently bathed and cleaned with warm water. Various local washes or applications are of use. A warm solution of boracic acid (ʒj to a pint of water), the dilute solution of the subacetate of lead, or a solution of bichloride of mercury (1:5000) may be used.

If the disease is of gonorrheal origin, the parts should be painted once or twice a day with a 2 per cent. solution of nitrate of silver, applied after the discharges have been gently washed away.

As the disease subsides the inflammation may be found to persist in the crypts of the vestibule, the urinary meatus, and the ducts of Bartholin’s glands. It is very important that all remains of the inflammation, especially if it be of septic or gonorrheal origin, should be eradicated before the woman is discharged from treatment. The presence of any focus of inflammation, even though latent, is a constant source of danger to the woman; for septic organisms or material may be carried from the external 38 genitals to the higher parts of the genital tract, as the uterus and Fallopian tubes, with the most disastrous results.

Sometimes a small drop of pus will be observed escaping from one of the small glands or crypts of the vestibule, about the urinary meatus, after the inflammation has disappeared in other parts of the vulva. In this case the gland should be punctured with a fine cautery-point or a fine wooden probe or point saturated with pure carbolic acid or other caustic.

If the disease persists in the external meatus or urethra, it must be treated by the local applications appropriate for urethritis.

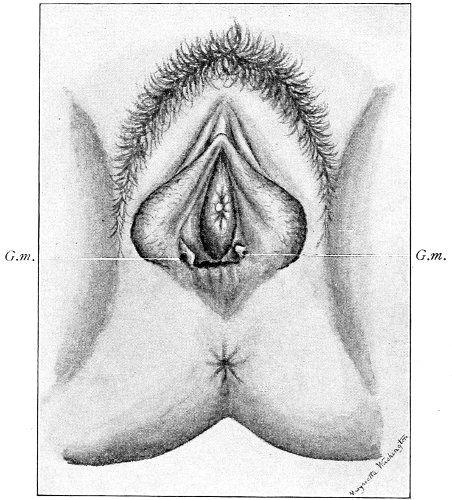

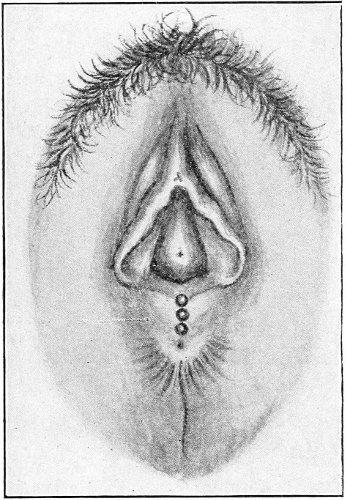

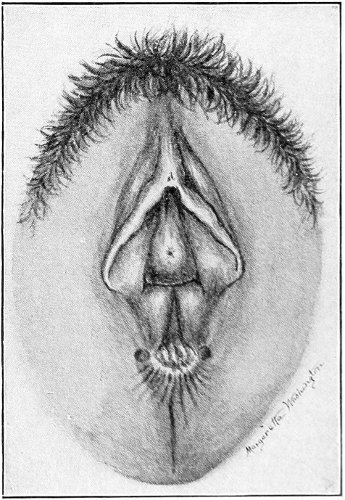

Fig. 16.—Appearance of the external genitals in a woman with gonorrhea: G. m., gonorrheal macula situated at the base of a vaginal caruncle.

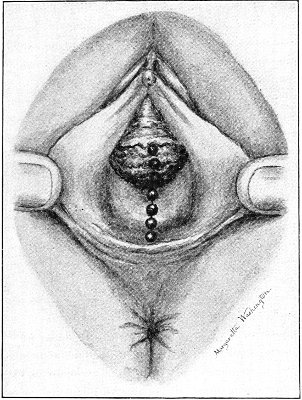

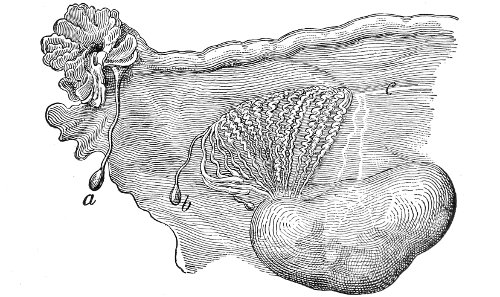

Inflammation of the Vulvo-vaginal Glands.—The vulvo-vaginal glands are two in number. They are about the size of a bean, and are situated deeply on the inner aspect of the labia majora, where they may be felt in thin women. The duct of the gland is about one 39 inch in length, and opens immediately in front of the hymen, about the middle of the side of the ostium vaginæ. In cases of vulvitis the duct of the gland usually becomes inflamed, and the inflammation may extend to the gland, producing abscess of the vulvo-vaginal gland.

Inflammation of the duct and the gland may also occur independently of vulvitis, from direct septic or gonorrheal infection.

Suppuration of the duct may be demonstrated by pressing over the course of the duct, when a drop of pus will escape from the opening. In such cases the orifice of the duct is usually surrounded by a red areola, resembling a flea-bite, which has been called the gonorrheal macula (Fig. 16). This macula persists long after all other traces of inflammation about the vulva and vagina have disappeared, and after all frank suppuration in the duct has subsided. Its presence indicates at least the probability of previous gonorrheal infection.

When the duct of the gland alone is the seat of inflammation, it should be laid open with fine scissors or knife, and the tract thoroughly cauterized with the nitrate-of-silver stick, pure carbolic acid, or a solution of chloride of zinc (2 per cent.).

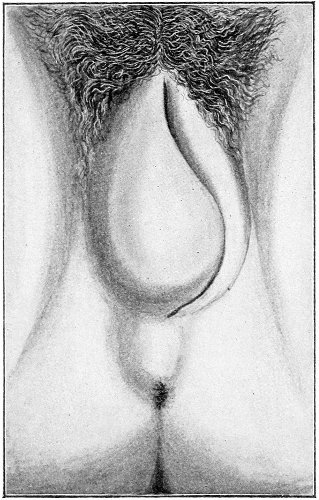

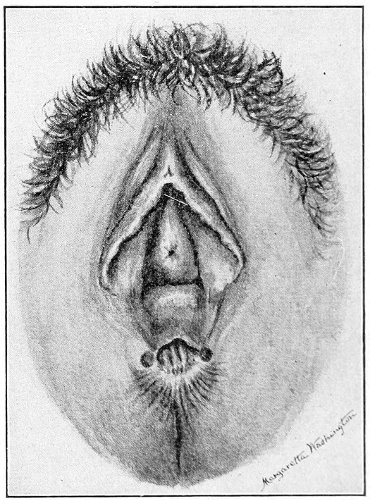

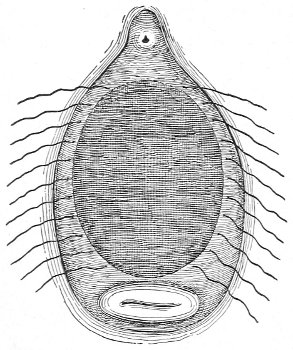

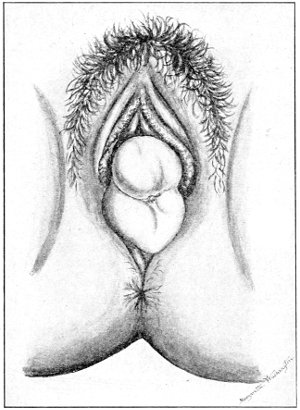

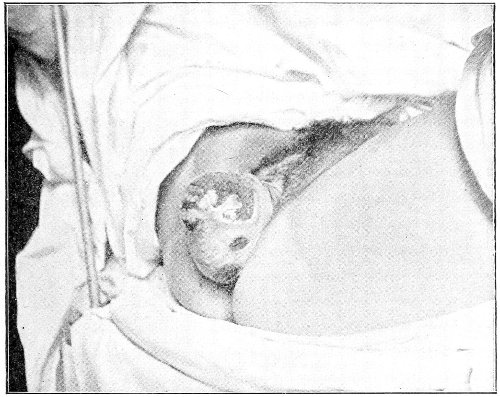

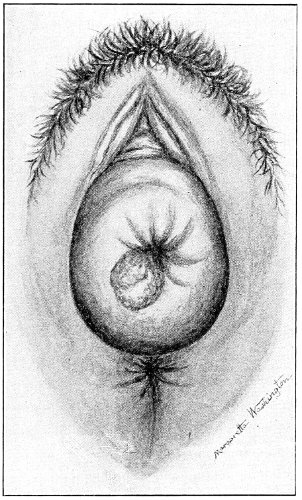

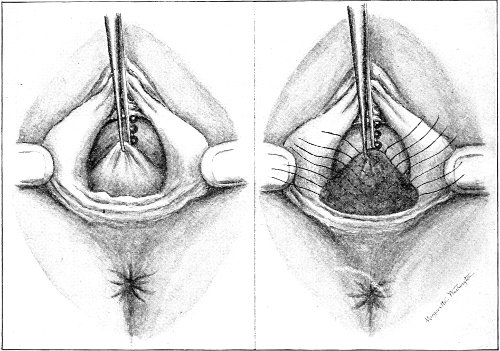

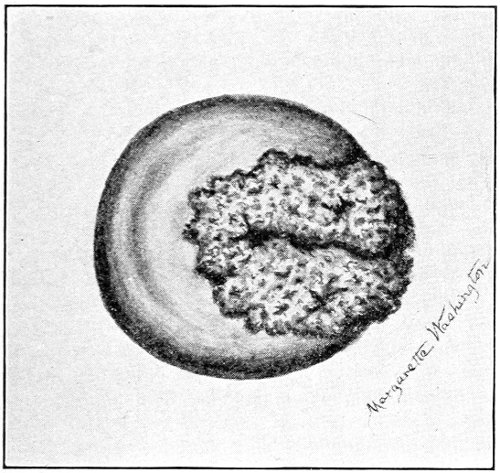

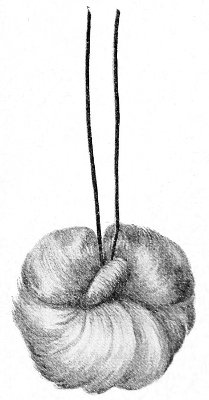

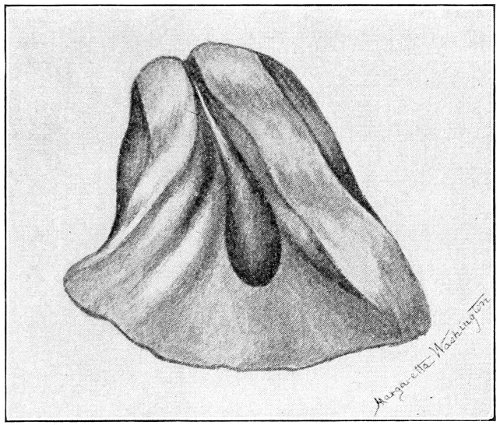

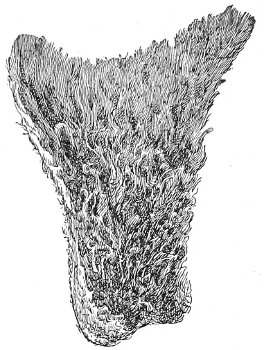

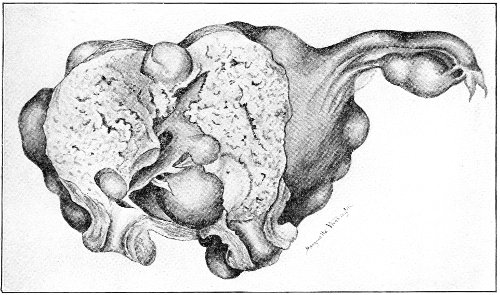

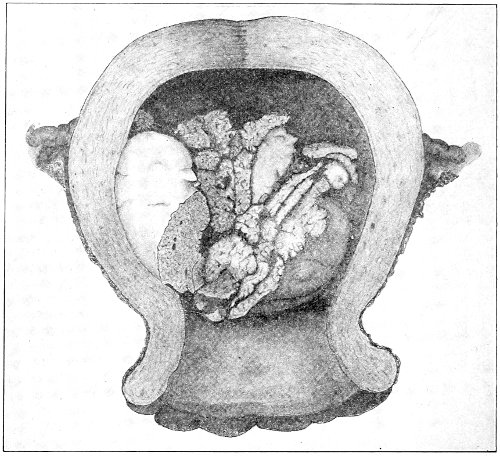

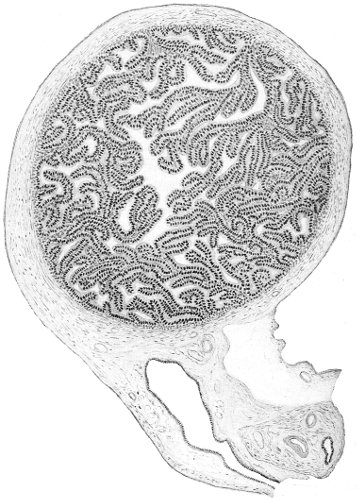

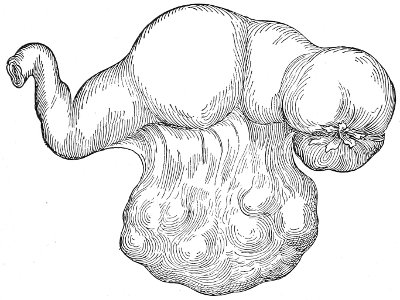

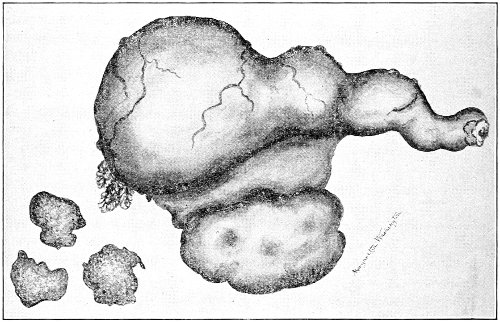

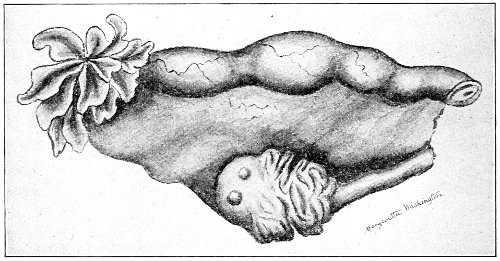

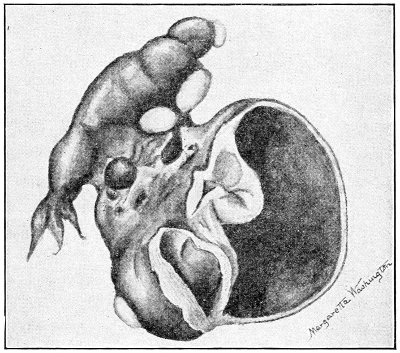

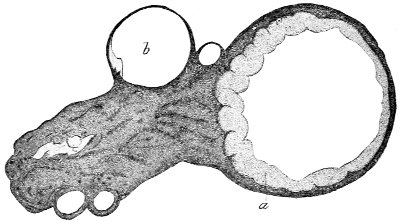

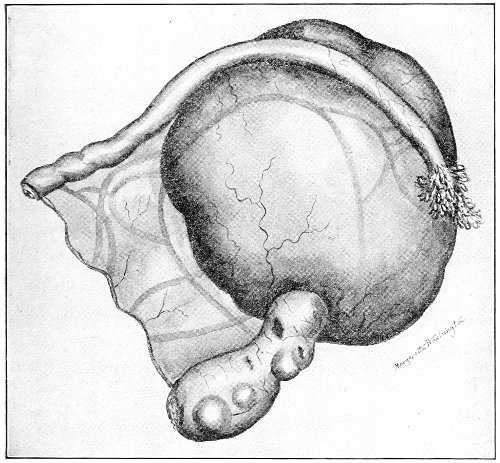

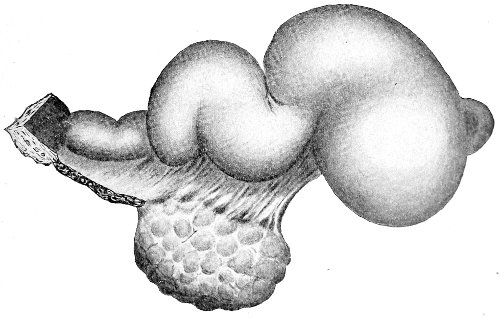

Suppuration of the vulvo-vaginal gland is accompanied by marked swelling and peripheral edema. The swelling may extend to the anus, and is of characteristic shape (Fig. 17). The pain is always severe. Fluctuation is first apparent on the inner surface of the labium majus. If the condition is not treated, one or more fistulous openings appear below the orifice of the duct, and the pus is discharged. The condition then becomes chronic. The fistulous openings persist. Acute inflammation disappears from the gland, leaving it in a condition of hypertrophic induration. A thin, milky or greenish, purulent fluid may be pressed out of the duct or the fistulous openings. Infection from this discharge may be communicated to man, or may ascend the genital 40 tract, producing inflammation of the endometrium or of the Fallopian tubes.

Fig. 17.—Abscess of right vulvo-vaginal gland.

In abscess of the vulvo-vaginal gland a free incision should immediately be made into the labium at the junction of the skin and the mucous membrane. The interior should be wiped out with pure carbolic acid and the cavity packed with gauze. If the disease is first seen in the chronic stage, after the abscess has evacuated itself, the only method of cure is to excise, with curved scissors, the whole of the indurated gland, the duct, and the fistulous tracts. The wound may be left open and packed, or it may be closed immediately with buried catgut sutures.

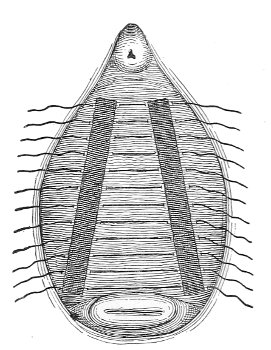

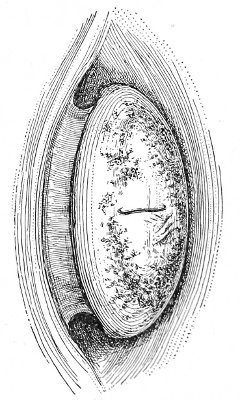

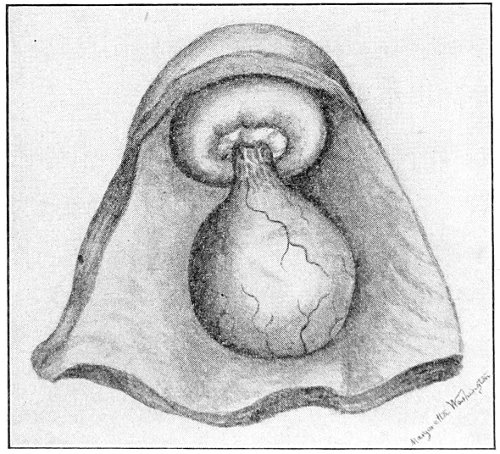

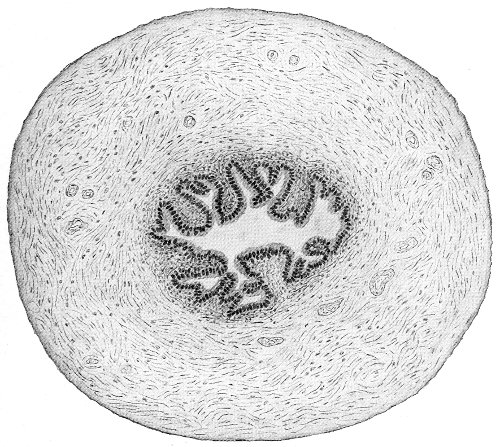

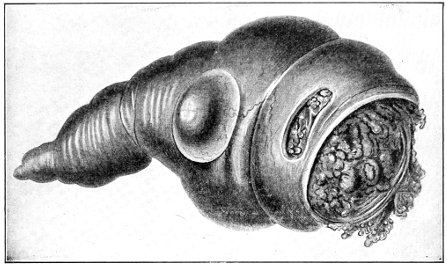

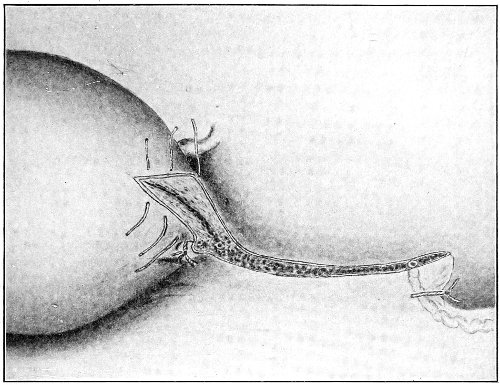

Cysts of the Vulvo-vaginal Glands.—Cysts may 41 occur in the duct of the vulvo-vaginal gland or in the gland itself. Cysts of the duct are small—about the size of a chestnut. They are situated superficially, lying immediately under the mucous membrane of the vagina at the base of the labium minus.

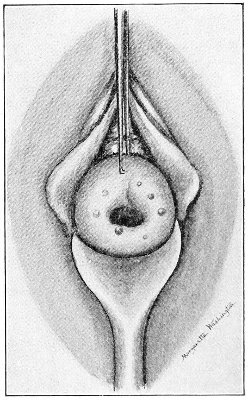

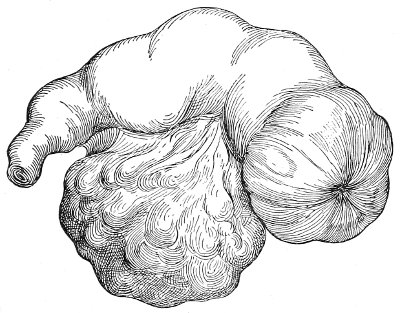

Fig. 18.—Cyst of the right vulvo-vaginal gland (Hirst).

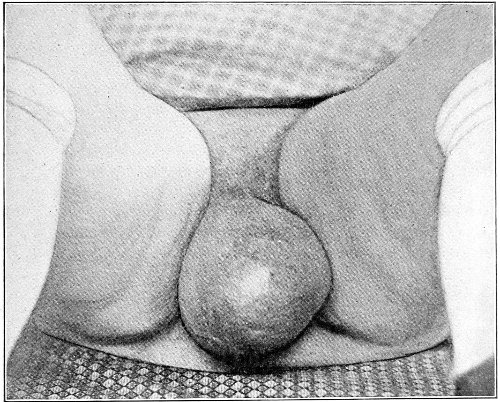

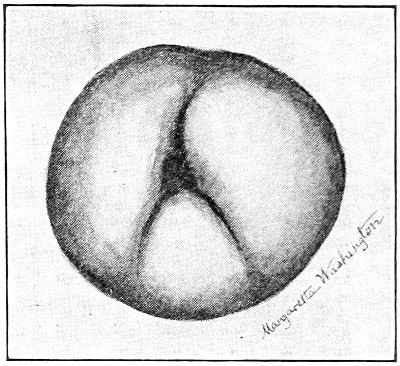

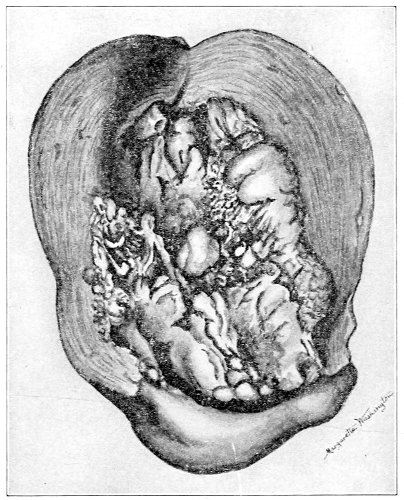

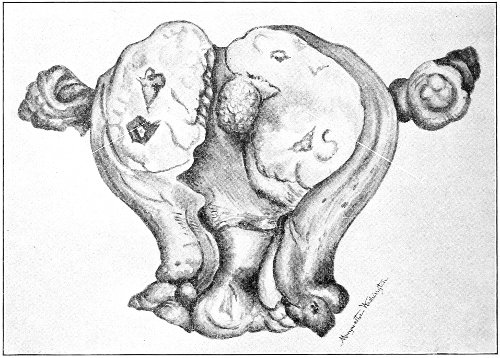

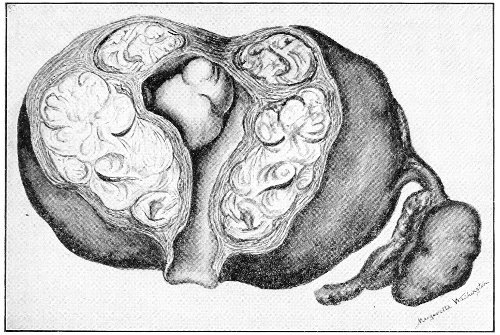

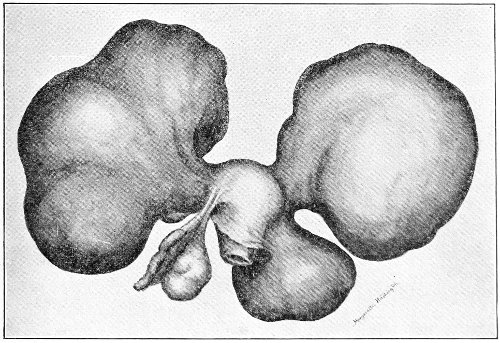

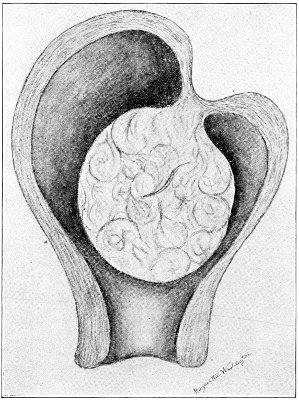

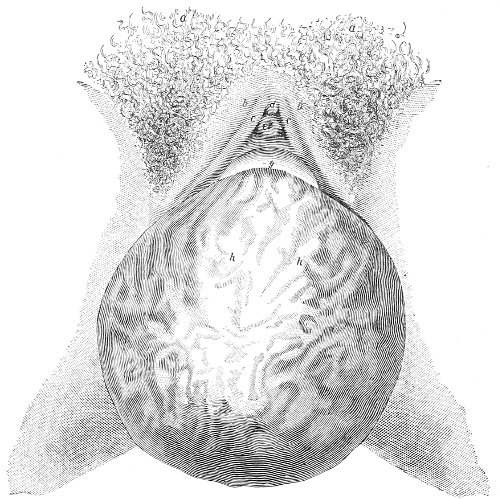

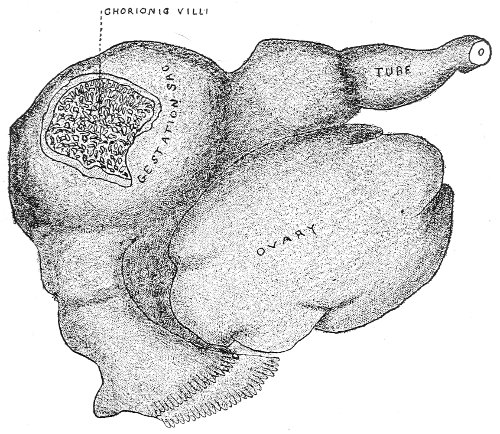

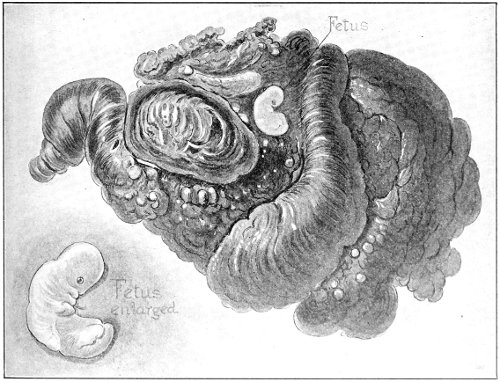

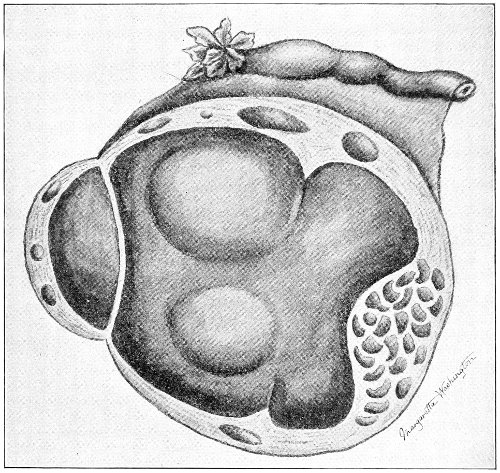

Cysts of the gland may be unilocular if formed at the expense of a single lobule of the gland, or multilocular if several lobules enter into their formation. These cysts may attain the size of the fetal head (Fig. 18).

Cysts of the gland or of the duct are formed by retention of the cyst-contents. The retention is due to occlusion of the duct, usually the result of inflammation. In some cases the duct remains pervious, and the retention is due to the altered character of the secretion of the gland, which becomes too viscous to pass, except under unusual pressure, along the duct.

These cysts contain clear yellow or chocolate-colored 42 fluid. The diagnosis of cyst of the vulvo-vaginal gland is usually not difficult. If we are in doubt in regard to the fluid character of the tumor, this may be determined with the exploring-needle.

Inguinal hernia, hydrocele of the canal of Nuck, cysts of the round ligament, and sacculated cysts of old hernial sacs may be mistaken for cysts of the vulvo-vaginal glands. In such cases, however, the tumor lies more in the upper and outer part of the labium majus, and extends to, and may be connected with, the external inguinal ring.

Cysts of the vulvo-vaginal glands should be treated by free incision and packing, or by extirpation. If the sac is emptied by the aspirator or by a small incision, it will refill. The best method is to extirpate the cyst. In case there has been no inflammatory action binding the cyst to surrounding structures, extirpation without rupture is easy. If rupture occurs, the cyst-wall may be dissected off with the knife or removed with the curved scissors. The wound may be immediately closed with deep and superficial sutures.

Pruritus Vulvæ.—Pruritus vulvæ, or itching of the vulva, may be due to a great variety of causes. Eruptions of the vulva, such as eczema, cause itching. Irritation from the discharge of vaginitis, metritis, cancer of the cervix or body of the uterus, the presence in children of the thread-worm, the irritation from diabetic urine, or trophic lesions of the nerves due to diabetes, may result in pruritus. Some of the pathological conditions of the uterus, tubes, and ovaries may produce reflex irritation of the nerves of the vulva, and cause itching, in a manner similar to that in which vesical calculus causes itching of the glans penis.

The congestion of the external genitals that accompanies pregnancy may also produce pruritus.

There are some cases of pruritus vulvæ, however, in which no physical cause for the intolerable itching can be discovered, and in which minute examination of the affected portions of skin or mucous membrane demonstrates 43 no pathological change. Such cases are called idiopathic.

The itching may be so severe that the woman cannot refrain from scratching and rubbing the parts on all occasions. She becomes debarred from the society of her friends, and seeks relief in anodynes and hypnotics. The continual scratching increases the irritation of the vulva, and an eczematous eruption may result, which produces an irritating discharge that spreads the irritation to other parts of the body with which it may come in contact.

The itching of pruritus may extend into the vagina, to the skin of the abdomen, to the inner aspect of the thighs, and to the anus.

In the treatment of pruritus it is first of importance to discover, if possible, the cause of the itching. Any vaginal or uterine discharge should be investigated. Discharge from the uterus can be eliminated as a cause by placing against the external os a pledget of cotton, frequently renewed, to absorb the discharge before it reaches the vulva, or the parts may be kept clean by frequent douches. In children the stools should be examined for the thread-worm. The urine should always be examined. Diabetes is a frequent cause of pruritus vulvæ in old women. Any pathological condition of the uterus, Fallopian tubes, and ovaries should be treated before we can eliminate this as a possible cause of pruritus.

In the cases of so-called idiopathic pruritus in which no local lesion can be discovered attention should be directed to the general nutrition of the patient. As in pruritus ani, the gouty diathesis may cause the disease. Alcoholic drinks, rich food, fish and shell-fish, may assist in its production.

Treatment.—A great variety of local applications have been used for the relief of pruritus. In case of diabetes the urine should, as much as possible, be kept from contact with the parts, which should be thoroughly dried after urinating, and dusted with a powder consisting 44 of equal parts of subnitrate of bismuth and prepared chalk.

The following local applications are useful in pruritus:

| Bichloride of mercury, | gr. ½; | ||

| Emulsion of bitter almonds, | ℥j, | ||

| applied twice a day. | |||

A powder of 1 grain of morphine to 2 grains of prepared chalk, applied twice a day.

| ℞. | Tinct. opii, | ||

| Tinct. iodi, | |||

| Tinct. aconit., | āā. | ʒv; | |

| Acid, carbolic., | ʒj, | ||

| applied once or twice in the twenty-four hours. | |||

An ethereal solution of iodoform sprayed into the folds of the vulva with an atomizer.

Cauterization with pure carbolic acid.

In pruritus of gouty origin an ointment, composed of 15 grains of calomel to 1 dram of cerate, will often relieve or cure the local condition. A small quantity should be rubbed over the itching area at bed-time. Often one or two applications give immediate relief. If the condition does not quickly improve it is useless to continue this treatment. The danger of salivation from its prolonged use should be remembered.

In cases which have resisted all local applications the affected areas of mucous membrane have been excised. Even this method, however, does not promise certain cure. It should be tried, however, when the pruritus is localized and has resisted the milder forms of treatment.

Kraurosis Vulvæ.—Kraurosis vulvæ is a very rare disease, of chronic inflammatory nature, affecting the vulva. The disease is characterized by cutaneous atrophy, with very marked shrinking and contraction of 45 the vaginal orifice. The lesions may be unilateral or circumscribed, but usually the tissues of the labia majora, the nymphæ, and the area surrounding the clitoris and urinary meatus are more or less involved. The cause of the disease has not as yet been determined. It has been observed at every age after puberty, in the nulliparæ as well as the multiparæ, and in the parturient woman. It must be differentiated from pruritus and the atrophic changes which take place after the physiological and induced menopause.

The first symptoms noticed by the patient are usually those of pruritus—an intense itching and burning about the vulva. In some cases the affected tissue early becomes excessively hyperplastic. The mucous membrane and the skin of the vulva are often discolored, small red spots appearing, which are sensitive to touch. Later a peculiar shrinking of the superficial tissue takes place, and the diseased surfaces become dry and whitened. The nymphæ gradually disappear, fusing with the labia majora; and the mucous membrane and skin become shiny and drawn smoothly over the shrunken clitoris. Cracks or fissures appear on the dry surfaces. A sensation of drawing and shrinking of the vulva is now usually experienced. The vaginal orifice gradually narrows and contracts, until frequently the little finger can scarcely be introduced. When this last condition of atrophy is reached, the pathological process is arrested, the subjective sensations of shrinking pass away, and the symptoms resembling pruritus are no longer experienced. The shrunken and contracted vaginal orifice, however, persists and is never spontaneously restored.

Treatment.—Palliative treatment by local applications may be tried, or a cure may be attempted by operation. The palliative treatment is simply directed toward the relief of the subjective symptoms, which at times are exceedingly painful. Pure carbolic acid or a solution of cocaine applied locally, or pure nitrate of silver applications frequently repeated, afford temporary relief. Cloths 46 wrung out of hot water and placed over the vulva also lessen the suffering. A solution of the neutral acetate of lead in glycerin, on cotton placed between the labia, is recommended. Forced dilatation of the vaginal orifice under ether has been practised with good result. The most satisfactory treatment is complete excision of the diseased tissue. Unless all affected tissue is removed, the disease may return.

Varicose Tumors of the Vulva.—Varicose tumors of the vulva are usually the result of pregnancy. They may, however, accompany any form of pelvic or abdominal tumor, the pressure of which interferes with the venous circulation of the pelvis. The varicose condition usually affects the labia majora. It varies from a mere increase in size of the veins of the vulva to a varicose tumor the size of the fetal head. The condition, being secondary, usually disappears with the removal of the exciting cause. The labia may be supported with a compress and a bandage.

Hematoma of the Vulva.—Hematoma of the vulva is due to the subcutaneous rupture of a vein. Blows, kicks, or falls cause this condition. It is usually produced by rupture of a varicose vein during pregnancy or labor.

The affected labium is purple in color and may reach the size of a fetal head. When the hematoma is small the vagina should be kept as clean and aseptic as possible, and a light compress should be applied. Absorption usually takes place. If the collection of blood is large or if it has become infected, a free incision should be made into the labium, the clots should be turned out, and the cavity thoroughly washed and packed with gauze.

Papilloma.—Papillomata or warts of the vulva are not uncommon. They may occur singly, scattered over the vulva and the neighboring skin, and extending up the vagina as far as the cervix uteri, or they may occur in large cauliflower-like masses. They are pink or purplish in color. They often exude a bloody, offensive discharge, 47 which is capable of exciting a similar condition by contact. Papilloma is usually the result of gonorrhea or syphilis. It may, however, be caused by irritation from filth or by the leucorrhea of pregnancy.

The treatment of papilloma is by excision. The small warts should be picked up with forceps and clipped off with curved scissors. Every one should be removed or the condition may recur. In the case of large papillomatous tumors the wound of excision should be closed with continuous sutures. Pregnancy is no contraindication to excision of papillomata.

The vulva may be the seat of epithelioma, lupus, sarcoma, fibroma, fibromyoma, myxoma, lipoma, or enchondroma. These tumors present the same characteristics and demand the same surgical treatment as in other parts of the body.

Small cysts have been found in the labia majora and minora, the vestibule, the hymen, and the clitoris.

Elephantiasis.—True elephantiasis of the vulva (elephantiasis Arabum), due to the presence of the Filaria sanguinis hominis, is a rare disease in this climate. The disease occurs especially in Barbadoes. It may affect the labia and the clitoris. The hypertrophied labia may attain the size of the adult head.

The treatment of this condition is excision of the affected structures.

There is a syphilitic form of hypertrophy or elephantiasis of the vulva which is not uncommon in this country. The labia minora and majora may be transformed into enormous flap-like folds. Though at first free from ulceration, this may subsequently result from chafing. Warty growths may cover the hypertrophied labia, the perineum, and the buttocks. The disease usually affects both labia, though it may be confined to one.

This manifestation of syphilis does not yield readily to constitutional or local medicinal treatment. Many cases prove to be incurable by medicine. Antisyphilitic treatment 48 should always be tried at first, and if this fails, the hypertrophied structures should be excised with the knife.

If, in such cases, there is any doubt in regard to diagnosis between syphilis and cancer, a small portion of tissue should be excised and submitted to microscopic examination.

Adhesions of the Clitoris.—Adhesions between the glans of the clitoris and the prepuce or hood which covers it are exceedingly common. Usually no trouble whatever is caused by these adhesions, unless an accumulation of smegma takes place, or irritation is produced by the presence of a concretion.

In case of any irritation about the genitals, the prepuce and clitoris should always be carefully examined. In fact, a careful examination of the clitoris should form a routine part of all examinations of the external genitals.

When trouble arises from the presence of adhesions, the prepuce should be drawn back and the adhesions freed with a blunt probe. A 20 per cent. solution of cocaine should be applied to the clitoris for ten minutes previous to the operation. The whole corona and the sulcus back of the corona should be exposed. The raw surface should be covered with vaseline, and the patient should abstain from walking as long as pain is caused by it. The prepuce should be drawn back and vaseline applied every day for two weeks, to prevent the formation of adhesions. 49

Inflammation of the Vagina.—Acute inflammation of the vagina is not a very common affection. Primary inflammation confined to the vagina alone is unusual. The disease in most cases is secondary to vulvitis, urethritis, or endo-cervicitis. The causes of vulvitis (which have already been considered) are also the causes of vaginitis. It is of importance to remember that the disease may occur in children as a result of the same factors which produce vulvitis.

The exanthemata, as measles and scarlet fever, may cause vaginitis as part of the general involvement of the skin and mucous membrane which occurs in these diseases. The most usual cause is gonorrhea.

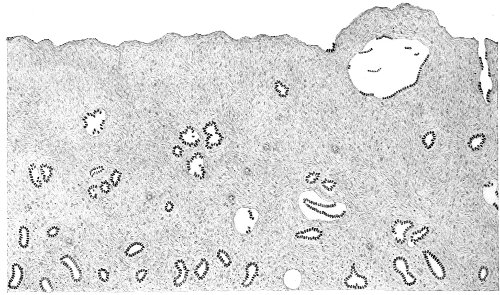

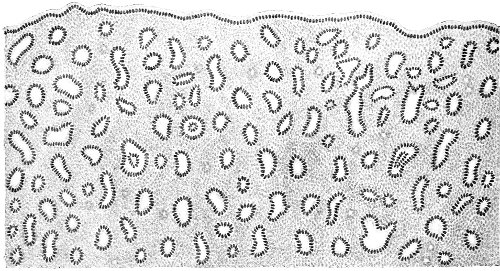

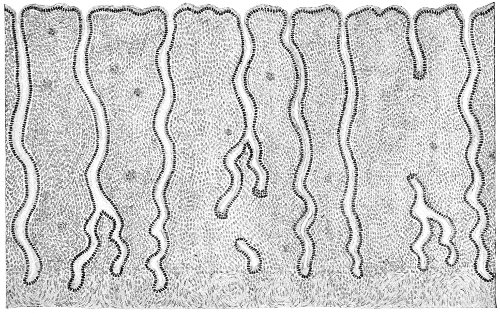

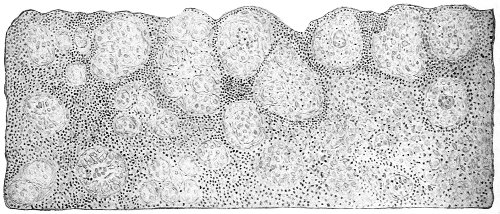

Several varieties of acute vaginitis may be recognized—the simple, the granular, the senile, and the emphysematous. It is unusual to find the entire surface of the vagina involved. The disease is confined to areas or patches separated by healthy tissue.

In simple vaginitis the inflamed membrane remains smooth.

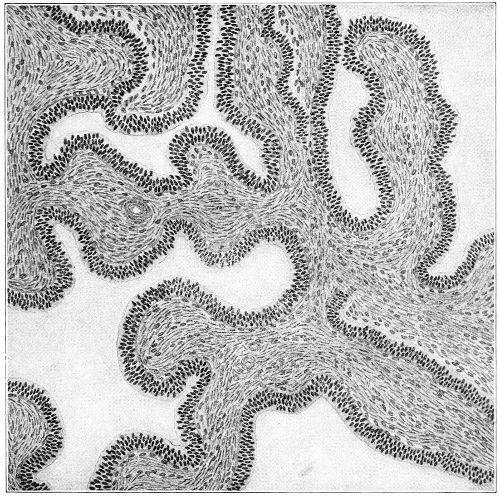

In granular vaginitis, which is the variety usually seen, the papillæ are infiltrated with small cells, and are much enlarged, so that the inflamed surface has a granular appearance.

Senile vaginitis is due to infection of portions of the vaginal mucous membrane that have lost their epithelium as a result of the atrophic changes of old age. This disease occurs in patches of various size, sometimes presenting the character of ecchymosis; in other cases the 50 patches have altogether lost the epithelium, and permanent adhesions may take place between areas which are brought in contact. This form of vaginitis has also been called adhesive vaginitis. It is said that a similar condition may occur in children.

The emphysematous form of vaginitis occurs in pregnancy. The vaginal walls are swollen and crepitating. The gas is contained in the meshes of the connective tissue.

Acute vaginitis is accompanied by dull pain and a sense of fulness in the pelvis. The discomfort is increased by standing, walking, defecation, and urination. There is a free discharge of serum or pus, which may be tinged with blood. The character of the discharge depends upon the variety and the period of the disease. Inspection, which can best be made through the Sims speculum, with the woman in the Sims or knee-chest position, shows the characteristic lesions of inflammation of the mucous membrane.

Acute vaginitis, if neglected, may pass into the chronic form. It usually lingers in the upper part of the vagina, in the fornices, especially in vaginitis of gonorrheal origin. By careful inspection we find here one or more granular patches of inflammation, which cause a vaginal discharge from which man may be infected, and from which infection of the upper portion of the genital tract, the uterus, and the Fallopian tubes may be derived.

Treatment.—Vaginitis, especially of the gonorrheal form, should be treated vigorously, and treatment should be continued until all traces of inflammation have disappeared. Inflammation of any part of the lower portion of the genital tract may have the most disastrous consequences if it extends to the uterus and the Fallopian tubes.

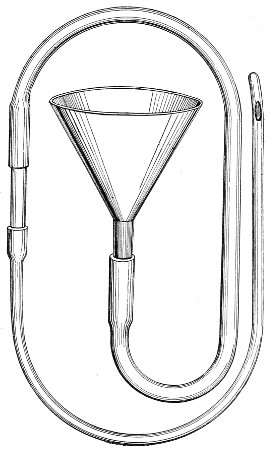

The woman should be kept as quiet as possible. The bowels should be moved freely with saline purgatives. She should take, three times in twenty-four hours, lying upon her back, a vaginal douche of one gallon of a boracic-acid 51 solution (ʒj to the pint). The temperature of the solution should be about 110° F.

If the disease be of gonorrheal origin, a warm bichloride solution (1:5000) should be used in the same way.

After the acute symptoms have subsided local applications should be made, in addition to the douches. The woman should be placed in the knee-chest position, and the vagina should be thoroughly exposed with the Sims speculum. If necessary, the vaginal surface should be gently cleaned with warm water and cotton. A 4 per cent. solution of cocaine may be applied to the vagina if there is much pain. Then the entire vaginal surface should be painted with a solution of bichloride of mercury (1:1000). These applications should be made daily until the disease is cured. The vaginal douches should be continued at the same time.

In the chronic form of the disease and in senile vaginitis the local patches of inflammation should be painted once a day with a solution of nitrate of silver, 5 to 10 per cent., or stronger if the condition does not yield. The senile form of vaginitis, being dependent upon a general condition, is often impossible to cure. We can sometimes relieve the discomfort by applying boracic-acid ointment (ʒj to ℥j) to the vagina. The application of pure carbolic acid to the inflamed patches sometimes does good.

Urethritis usually accompanies a gonorrheal vaginitis, and demands coincident treatment.

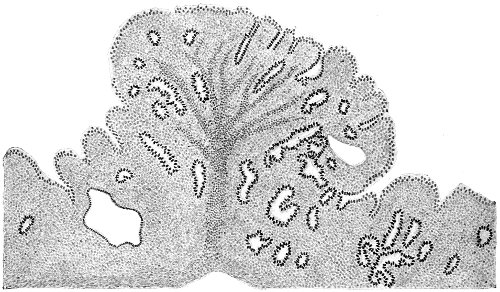

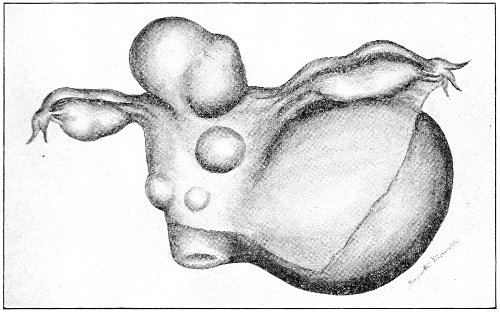

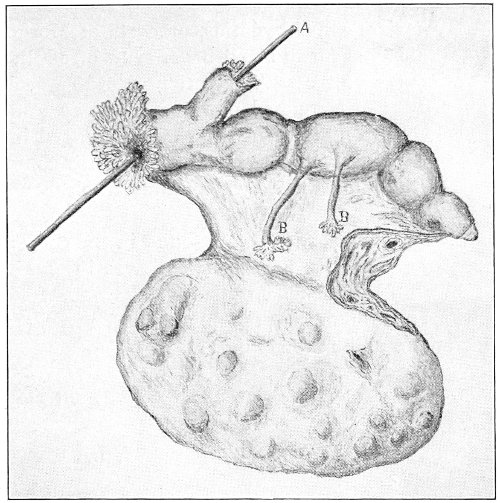

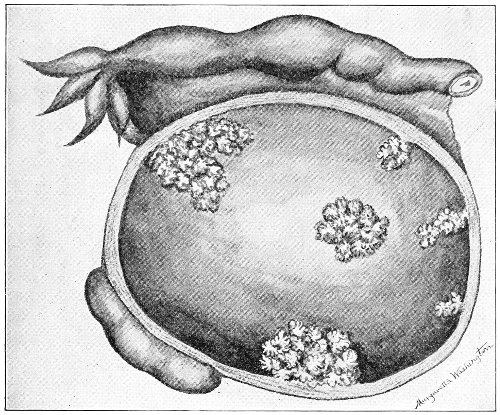

Tumors of the Vagina.—Vaginal Cysts.—Well-defined cysts are sometimes found in the vaginal walls. They occur at all ages from childhood to old age.

Vaginal cysts are usually single. They vary in size from that of a pea to that of a fetal head. The vaginal mucous membrane covers the free surface of the cyst, and may either be movable over it or may be much attenuated and closely incorporated with the cyst-wall. Vaginal cysts may be sessile or more or less pedunculated. The internal surface of the cyst is usually covered with 52 cylindrical epithelium, which is sometimes ciliated. The contents vary in consistency and color. They are often viscid, transparent, and of a pale yellow tint. They may contain pus or altered blood.

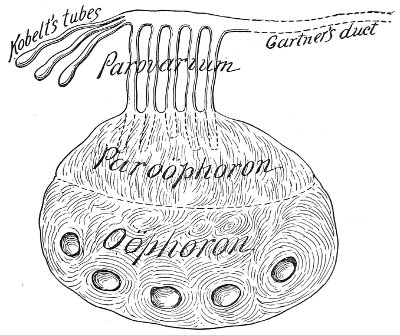

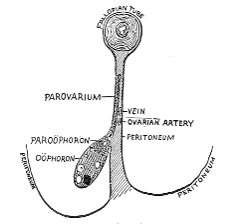

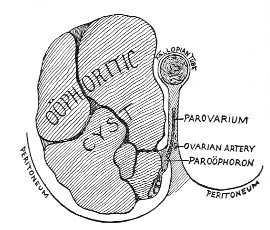

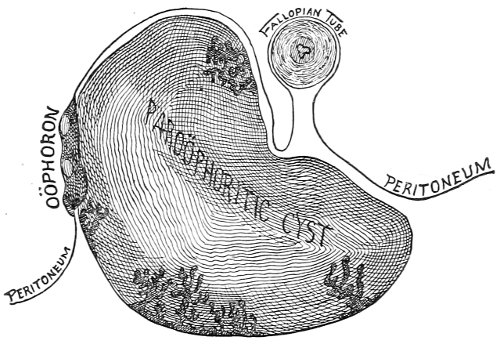

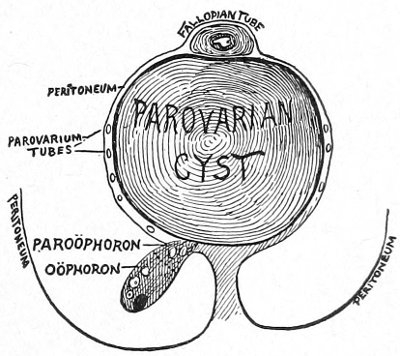

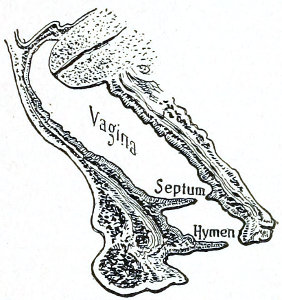

The origin of vaginal cysts has been much disputed. It is probable that they arise from the remains of the Wolffian canal—the canal of Gärtner. In the embryo the transverse or longitudinal tubule of the parovarium extends to the side of the uterus and thence down the side of the vagina to the urethral orifice. It persists in this condition in some of the lower animals—the sow and the cow—and may also persist as a closed tube in woman. In such cases it may become distended and form the vaginal cyst.

The treatment of vaginal cyst is removal. If the tumor be situated near the vulva, it may be extirpated by careful dissection. If this operation be deemed impracticable, partial excision of the cyst should be practised. The tumor should be seized with a tenaculum, opened by the scissors, and part of the wall, with the overlying mucous membrane, should be excised. The interior of the cyst should then be packed with gauze.

Fibroid Tumors of the Vagina.—Fibroid tumors sometimes occur in the vagina. They are usually found in the upper part of the anterior wall. They are sometimes adherent to the urethra. They are usually of small size, but may attain a diameter of six inches. The treatment of such tumors is removal.

Cancer and sarcoma may attack the vagina, though these diseases as primary conditions are very rare. When possible, complete removal should be done.

Atresia of the Vagina.—Severe puerperal infection or mechanical injury, followed by extensive destruction of the tissues of the vagina, may result in a cicatricial narrowing or complete closure or atresia of the vaginal canal.

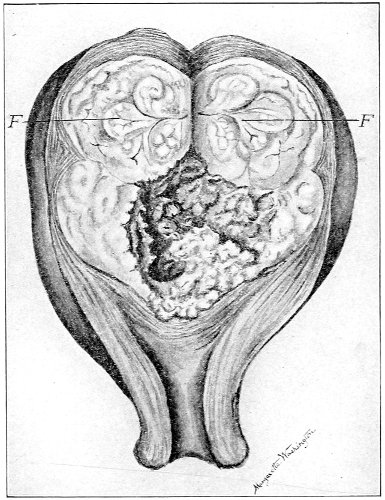

The symptoms of this condition are due to retention of the uterine discharges. There is no discharge of 53 menstrual blood from the vagina. Attacks of pain occur periodically at the menstrual periods. A cystic tumor, which may be felt by rectal examination, is present. The tumor consists of the distended portion of the vaginal canal (hematocolpos), and sometimes of the distended cervical canal and body of the uterus. The contents of the hematocolpos are usually sterile, although they may become purulent (pyocolpos).

The diagnosis is readily made by vaginal and rectal examination.

Treatment consists in incision and excision of the vaginal septum and the suture of the vaginal mucous membrane above to that below the obstruction. In very severe cases it is difficult to maintain the patulous condition of the vaginal canal on account of subsequent cicatricial contraction. In such cases the repeated passage of vaginal bougies or the transplantation of mucous membrane has been resorted to.

Vaginismus.—The term “vaginismus” has been applied to a condition characterized by a spasmodic contraction of the muscles which close the vaginal orifice. The muscular spasm occurs reflexly when penetration of the vagina is attempted, as at coitus or a digital examination. The condition is due to dread of pain, and is usually the result of some painful local lesion, such as a urethral caruncle, fissures or sores of the vulva or anus, etc.; or it may be due to some painful condition of the tubes and ovaries. Similar contraction is observed in the sphincters of the anus when there is present a painful anal lesion.

Vaginismus has been said to occur in neurotic and hysteric women in whom there was no discoverable local lesion.

Treatment consists in the removal of any local cause of pain or irritation.

If the reflex spasm of the muscles persists when coitus is attempted, notwithstanding the removal or the absence 54 of any discoverable local cause, operative measures have been advised.

Under anesthesia the vaginal entrance has been stretched by means of large dilators or the fingers, or the fibers of the sphincter vaginæ have been cut on each side of the fourchette and a glass or vulcanite tube of suitable size has then been placed in the vagina and retained for two or three weeks by a perineal pad and T-bandage.

Vaginismus is a very rare condition. Operative treatment, except that which may be required for the removal of some local cause of irritation, is rarely, if ever, necessary.

Coccygodynia.—Coccygodynia is a rare affection characterized by pain in the coccyx and surrounding structures. The pain is caused by pressure, as in sitting, or by any movement involving the muscles attached to the coccyx. The disease is usually caused by traumatism, and in most cases is due to injuries to the coccyx in labor, as a result of which the bone is fractured or dislocated, and becomes fixed in an abnormal position. Sometimes osteitis or necrosis develops. In the unusual cases, in which no structural changes are detected, the condition may be due to rheumatism. Coccygodynia is very rarely found in men.

The diagnosis may be made by introducing the index finger in the rectum and palpating the anterior and lateral surfaces of the coccyx, and by moving the bone between the finger in the rectum and the thumb placed in the crease of the nates. The mobility, deformity, and tenderness may be readily determined. If a local lesion is found, and the symptoms have not yielded within a reasonable time to expectant treatment, removal of the coccyx by operation is indicated. The coccyx is exposed by a median incision, the bone is separated from its muscular and tendinous attachments, and is removed at the sacrococcygeal articulation with scalpel or scissors. If 55 the articulation is ankylosed, it may be necessary to use the chain-saw. The wound is drained with a few strands of silkworm-gut and closed with interrupted sutures.

Operation should not be advised hastily. The painful symptoms are not always relieved by it. Operation should not be performed unless bony deformity or other distinct lesion is found. 56

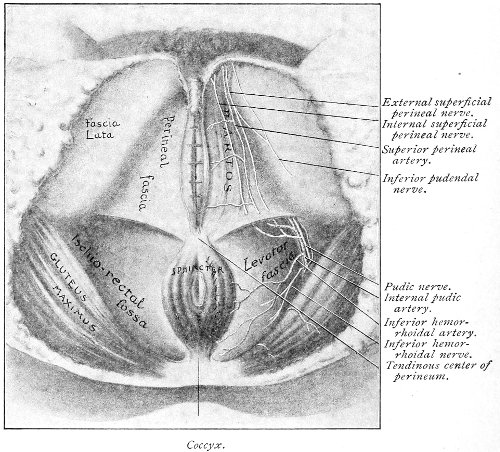

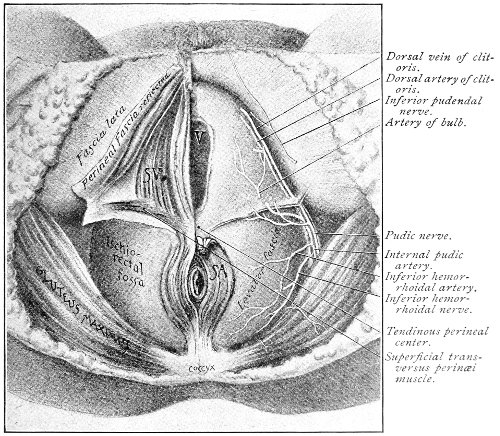

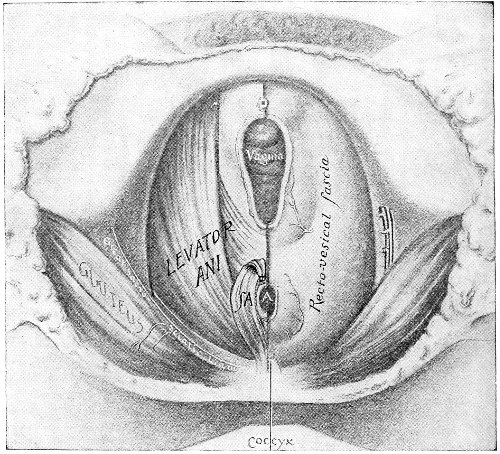

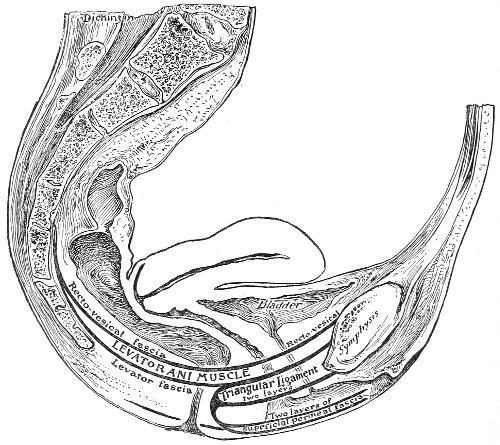

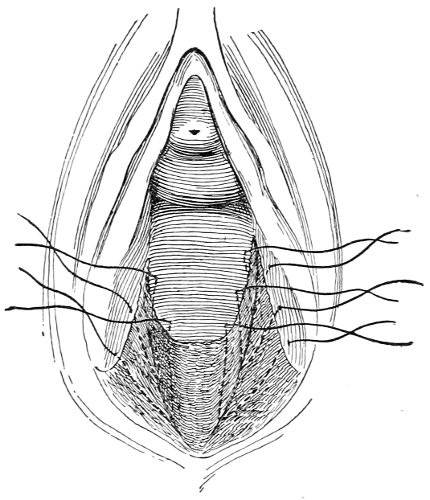

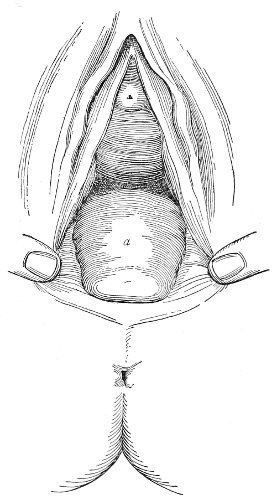

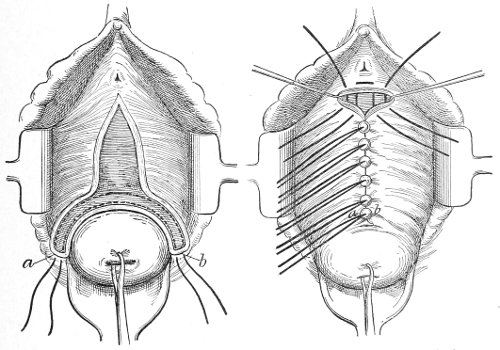

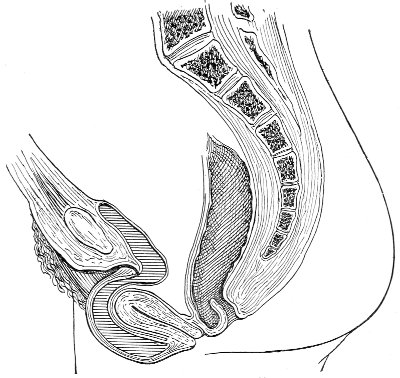

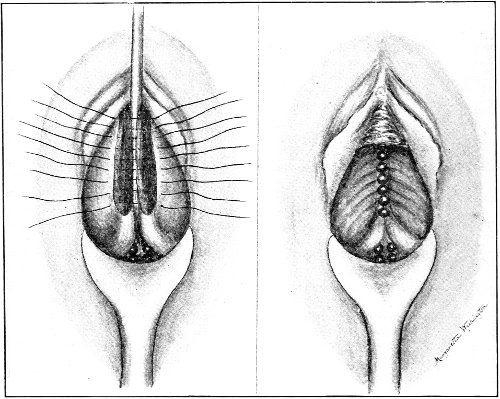

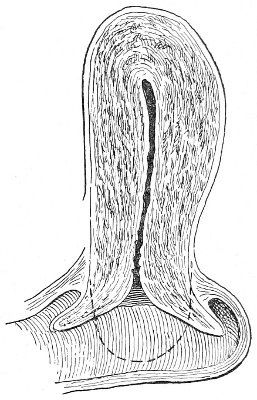

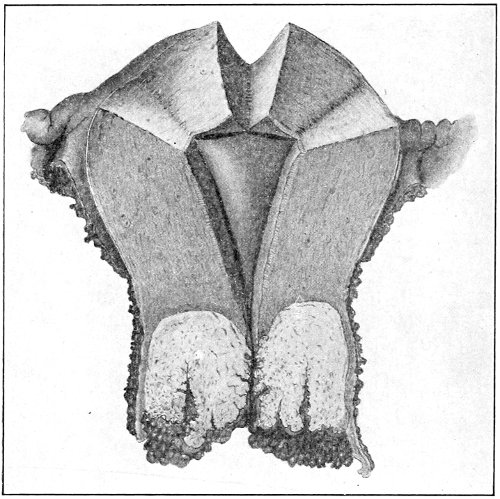

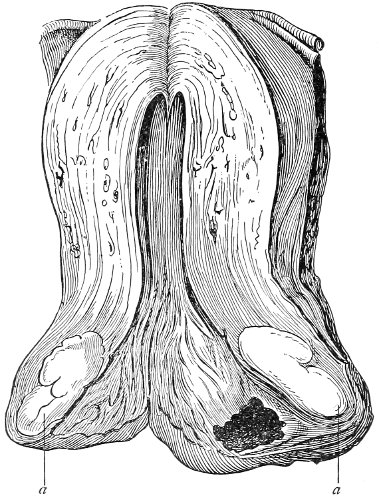

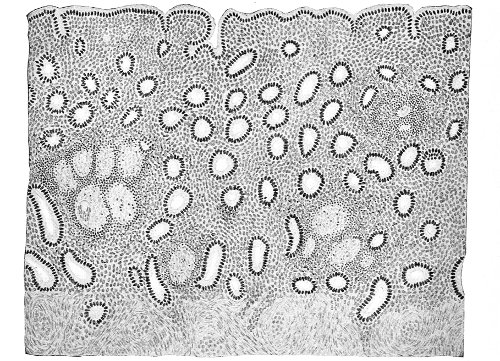

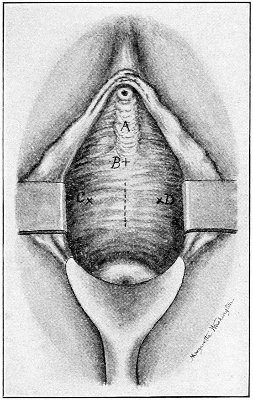

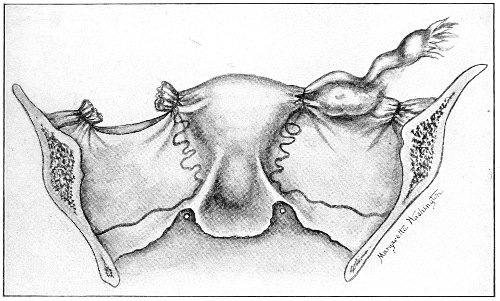

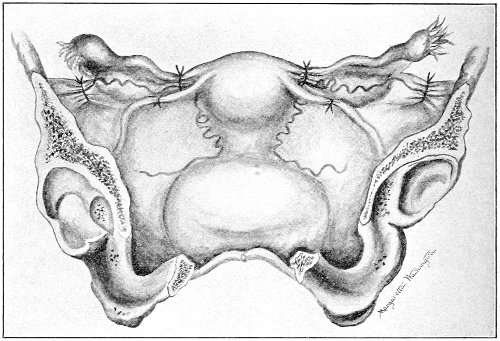

An accurate knowledge of the anatomy and mechanism of the female perineum is essential to an understanding of the nature and treatment of injuries to this structure. The anatomical structures lying between the anus behind and the symphysis pubis in front are those that most directly interest the gynecologist. Proceeding from 57 below upward, we find the following structures lying in superimposed planes: the skin, the superficial fascia, the deep layer of the superficial fascia, the transversus perinæi and the sphincter vaginæ muscles, the anterior layer of the triangular ligament, the posterior layer of the triangular ligament, the levator ani muscle (Fig. 19).

Fig. 18, A.—Superficial structures of the female perineum (Weisse).

Fig. 19.—Dissection of female perineum: on the left side the perineal muscles are exposed by the reflection of the perineal fascia; on the right side the muscles and the superficial layer of the triangular ligament have been removed, thereby exposing the deep layer of the ligament. S. V., Sphincter vaginæ muscle.

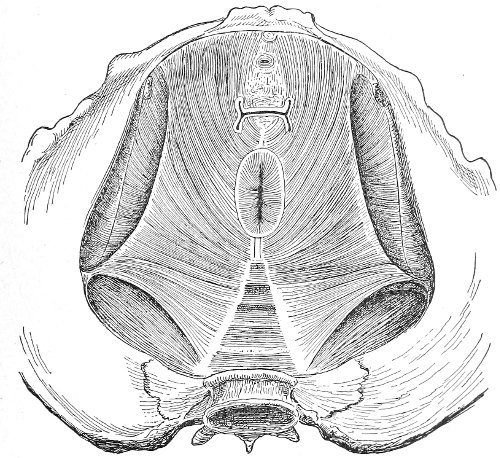

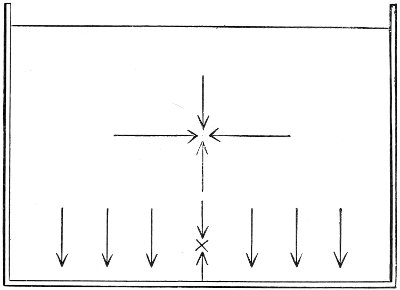

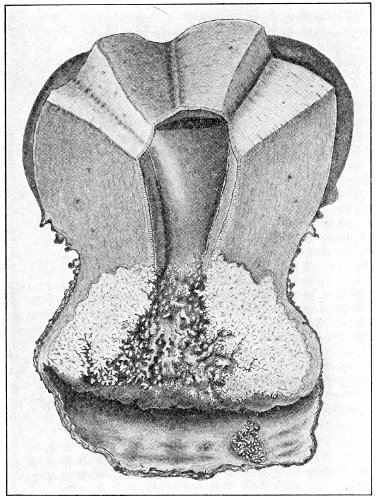

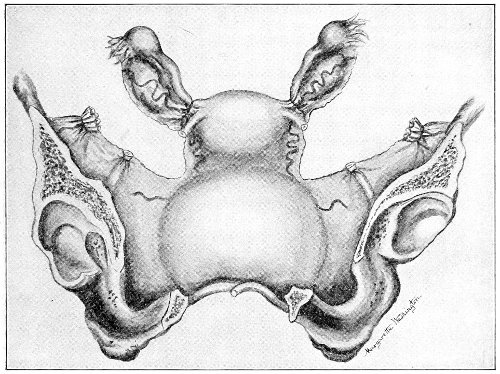

The vagina passes through these structures. They surround and support the ostium vaginæ as the fascia and muscles surround and support the opening of the rectum or the anus. The muscles and fasciæ are attached in the median line between the anus and the vagina, and therefore this part of the body, which is called the perineum, is supported or maintained in its 58 proper position by these various structures. The transversus perinæi arises from the ramus of the ischium and is inserted in the perineum. The bulbo-cavernosus, or sphincter vaginæ, arises in the perineum and is inserted in and about the clitoris. The inner fibers of the levator ani arise from the symphysis pubis and are inserted in the perineum and the lower part of the vagina (Fig. 20). When these muscles contract, their action, therefore, is to draw the perineum upward and forward. At the same time the anus is drawn upward and forward, and so also is the posterior margin of the ostium vaginæ and the lower portion of the posterior vaginal wall.

Fig. 20.—Dissection of female perineum, showing the deeper structures after removal of the levator and sphincter ani muscles.

The vagina has no circular sphincter like the anus, but 59 the vaginal month is kept closed by the action of the transversus perinæi, sphincter vaginæ, and levator ani muscles, which draw the perineum forward, and thus keep the posterior vaginal wall in apposition with the anterior wall.

Fig. 21.—Muscular floor of the pelvis seen from above.

This sling of muscles and fascia, which surrounds and supports the opening of the vagina, may readily be felt in the nulliparous woman by introducing the finger in the vagina and pressing backward and outward toward the ischio-rectal fossa. We then feel plainly, immediately within the ostium vaginæ, a firm resisting band of tissue, apparently about half an inch broad, embracing the posterior portion of the lower vagina. This band is formed by the inner edges of the various muscles and planes of fascia that have been described.

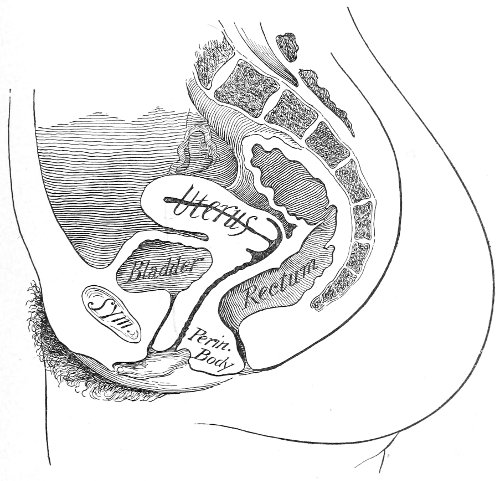

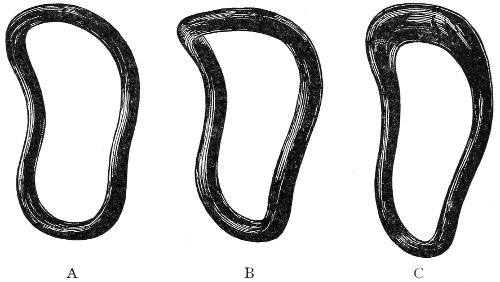

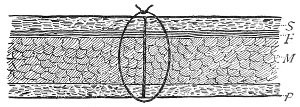

Fig. 22.—Sagittal section showing relations of the several layers of fascia within the pelvic floor (Dickinson).

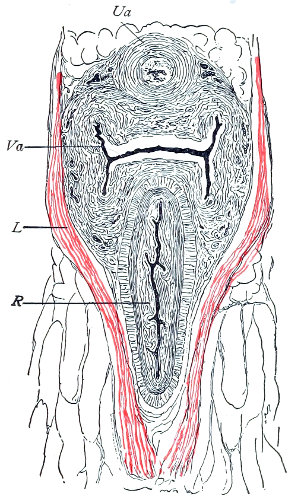

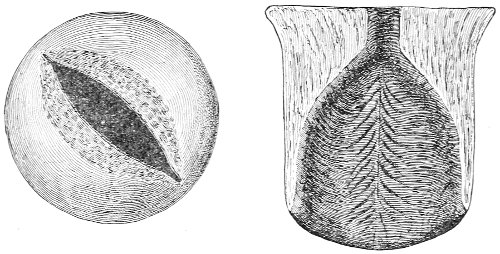

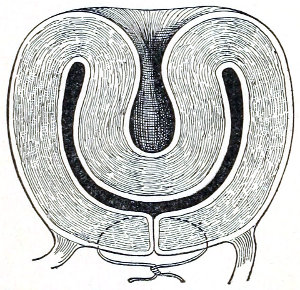

The vagina extends, as a transverse slit in the pelvic floor, upward and backward, approximately in the direction 60 of a line drawn from the ostium vaginæ to the fifth sacral vertebra. It is approximately parallel with the conjugate of the brim, so that when the woman is erect the long axis of the vagina is inclined at an angle of 60° to the horizon. The vagina is not a vertical open tube: it is a slit in the pelvic floor, in health always closed by the accurate apposition of the anterior and posterior walls (Fig. 21). The anterior vaginal wall is about 2½ inches long in a vertical mesial line. The posterior vaginal wall is about 3½ inches long. The vaginal walls are triangular in shape, being broader above than below. The shape of the normal vagina at the pelvic outlet is shown by Fig. 23. The section here shows the vaginal 61 slit of the shape of the letter H. The portions of the slit extending backward and somewhat outward are called the vaginal sulci or furrows. They are directions of diminished resistance in which tears are liable to occur.

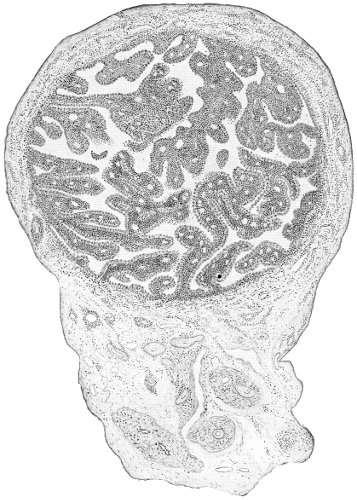

Fig. 23.—Section illustrating the characteristic form of the vaginal cleft (Henle): Ua, urethra; Va, vagina; L, levator ani; R, rectum.] 62

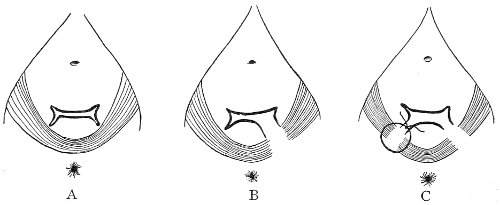

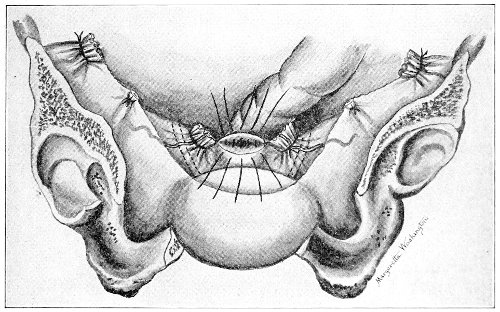

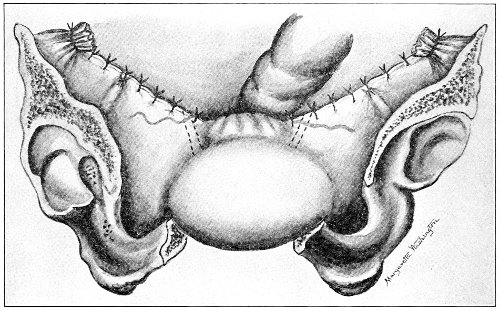

The injuries to the perineum that may result from childbirth are classified according to the position or the direction and extent of the laceration. They are as follows: slight median tear; median tear involving the sphincter ani; tear in one or both of the vaginal sulci; subcutaneous laceration of the muscles and fascia.

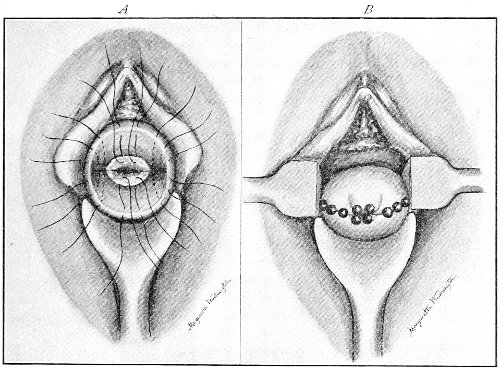

All these injuries demand operative treatment. The operation for the repair of injuries to the perineum is called perineorrhaphy. It is called immediate or primary, intermediate, and secondary perineorrhaphy, according to the time after the receipt of the injury at which the operation is performed. The primary operation is done during the first twenty-four hours. The primary operation should always be performed. A careful inspection of the perineum and the posterior vaginal wall should always be made after labor, and any laceration should be repaired within twenty-four hours. The advantages of the primary operation are many. The parts are usually so numb that it is not necessary to administer an anesthetic. No denudation is necessary, and therefore no tissue need be sacrificed. The woman is spared the pain and discomfort of granulation and cicatrization.

The bad results that follow neglect of the primary operation are very numerous, and will be studied hereafter. The injured muscles retract, and, being functionally useless, undergo atrophy, and when finally repaired never possess their former strength. Involution in the vagina and the uterus may be arrested, and all the disasters incident to subinvolution may appear. Vaginal and uterine prolapse occur; the natural supports of the 63 vagina and uterus become stretched, and, though afterward the perineum may be restored, yet it may be found impossible to retain the uterus in its proper position. It is always good surgery to repair an injury as soon as possible.

When practicable, a certain amount of preparation of the patient should be made before the operation of perineorrhaphy. This is most easily effected before the intermediate and secondary operations. The vagina and the vulva should be sterilized, and the intestinal tract should be emptied. Thorough evacuation of the bowels is most important when the sphincter ani has been injured, because it is desirable, after operation for this lesion, that the bowels should not be moved for five or six days. A saline purgative should be administered on an empty stomach about five hours before the operation, and a rectal injection of soap and water should be administered about one hour before the operation. Whatever purgative be employed, it should be administered at such a time that its action shall have ceased by the time of the operation. If this precaution is not observed, there may be a discharge of feces that will infect the wound and interfere with the manipulations.

For operation upon the perineum the woman should be placed in the dorso-sacral position (Fig. 1, page 23).

The intermediate operation is performed during the granulation period—ten days or two weeks after labor. At this time the raw surfaces are covered with granulation-tissue and bathed with pus. The edges of the wound and the surrounding tissue may be hard and swollen from infiltration with inflammatory products. In the intermediate operation it is necessary to administer an anesthetic or to anesthetize the parts locally with a 10 per cent. solution of cocaine.

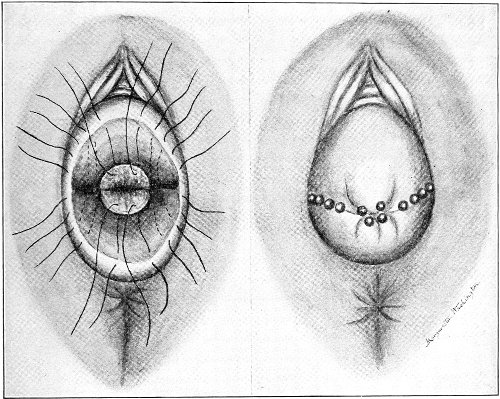

All cicatricial tissue, granulation-tissue, and rough edges should be scraped away with the knife, the scissors, or the curet. The raw surfaces should be thoroughly 64 washed with a 50 per cent. solution of peroxide of hydrogen and a 1:1000 solution of bichloride of mercury. The sutures should then be introduced.

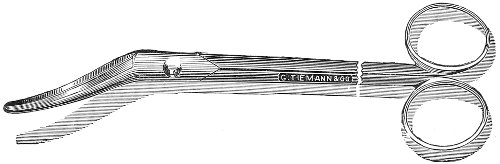

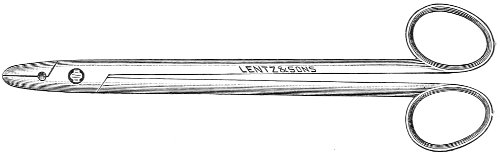

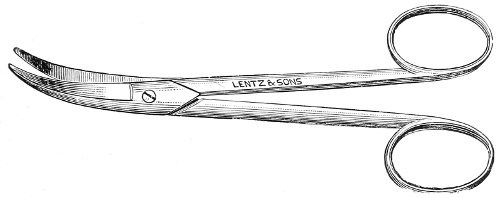

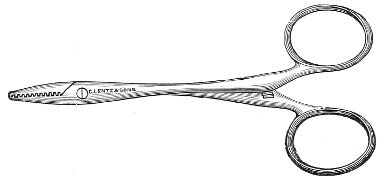

Fig. 24.—Emmet’s perineal scissors.

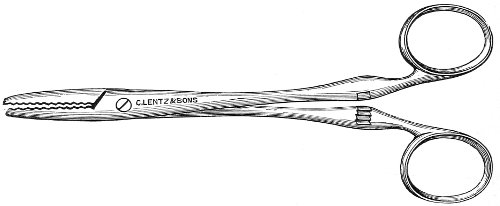

Fig. 25.—Curved scissors for denuding.

Fig. 26.—Tenacula for plastic operations.

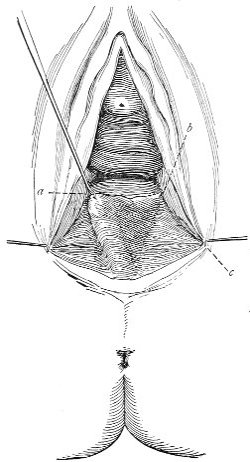

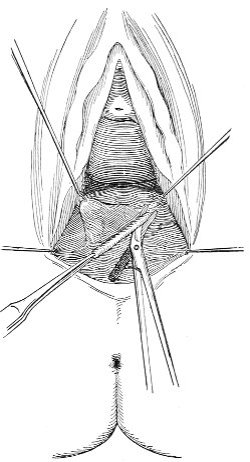

The secondary operation is performed at any time after cicatrization has occurred—often many years after the receipt of the injury. This operation is at present one of the commonest in gynecology, because the injury is not detected, is neglected, or is improperly repaired after labor. In the secondary operation an anesthetic is necessary. The mucous membrane must be removed or denuded on the posterior wall and about the mouth of the vagina, in order that the lacerated structures may be brought again in apposition. The denudation is best made by means of scissors curved on the flat (Figs. 24 and 25).

The strip of mucous membrane to be removed is picked up with a tenaculum (Fig. 26) or with tissue forceps 65 (Fig. 27); the scissors are placed with the blades parallel to the surface to be denuded, and the strip is cut away evenly, in one piece if possible. A similar contiguous strip is removed, and so on until the necessary surface is bare. Sponges in holders (Fig. 28) or continuous irrigation may be used to remove blood.

Fig. 27.—Tissue-forceps.

Fig. 28.—Sponge-holder.

For all operations on the perineum round-pointed needles curved at the tip should be used (Fig. 29). The tissues are always sufficiently soft for the passage of such a needle. A needle with a cutting edge is unnecessary and may increase the bleeding.

The needle may be held in any kind of needle-holder preferred. The Emmet needle-holder (Fig. 30) is very convenient.

Fig. 29.—Emmet’s perineal needle.

Fig. 30.—Emmet’s needle-holder.

The point of the needle should be guided and held by the tenaculum. The tenaculum must always be held in a plane parallel with the plane of the needle-holder; otherwise the needle-point may escape from the embrace of the tenaculum. 66

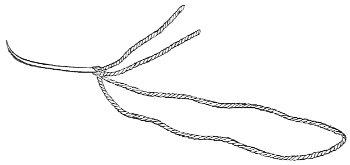

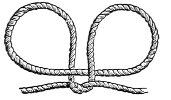

Silver wire and silkworm gut are the best sutures in the operation of perineorrhaphy.

The suture is conveniently attached to the needle by means of a silk carrier (Fig. 31).

Fig. 31.—Perineal needle with silk carrier.

Fig. 32.—Shot-compressor.

The sutures may be fastened by passing the ends through a perforated shot which is slipped down to the line of union and compressed by the shot-compressor (Fig. 32). All blood should be carefully removed from the surfaces that are brought together. The sutures should only be sufficiently tense to produce accurate apposition. A light gauze drain should be introduced in the vagina, and should be removed in forty-eight hours. Afterward one vaginal douche of about a quart of warm bichloride solution (1:2000) should be administered every day. After the douche the labia should be separated and the vagina carefully dried by cotton held in dressing-forceps. Except in those cases in which the sphincter ani is involved, the bowels may be moved on the second or third day. The woman should stay in bed for two weeks, at the end of which time the sutures should be removed. 67 She should avoid heavy lifting, long standing, and bicycle- or horseback-riding for two months after the operation. Constipation should always be avoided. Coitus may be resumed six weeks after operation.

The special forms of operation will be discussed in the consideration of the varieties of perineal injury.

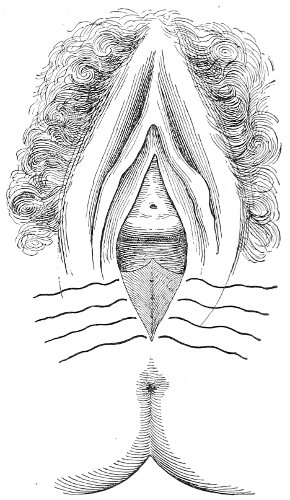

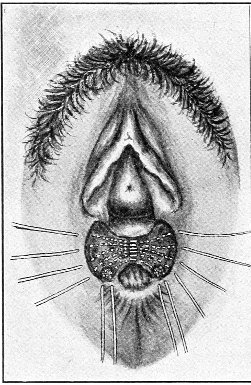

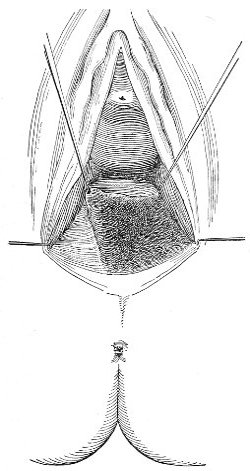

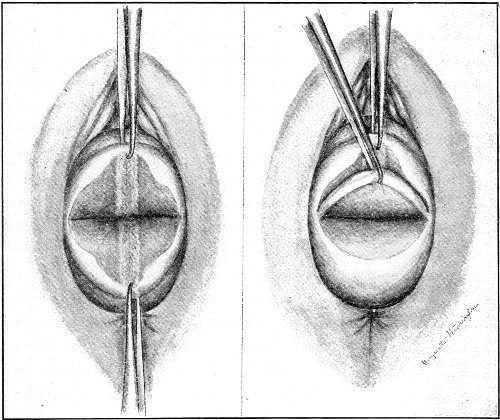

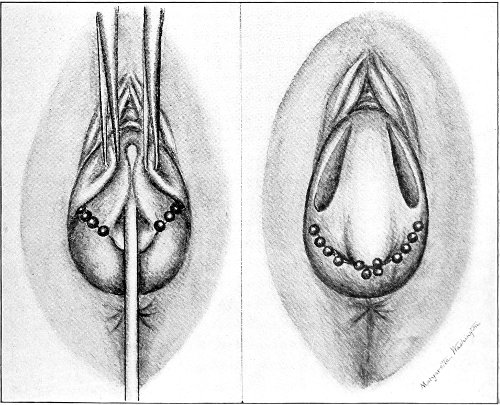

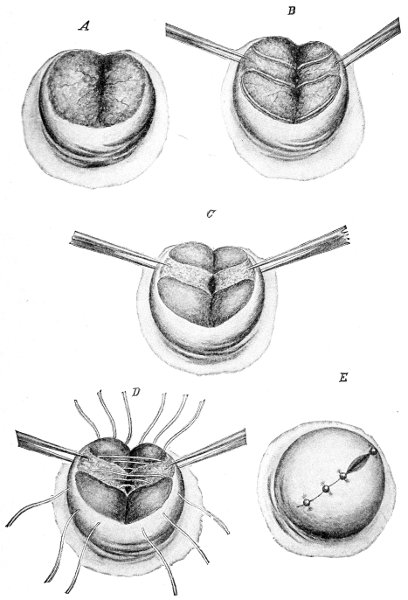

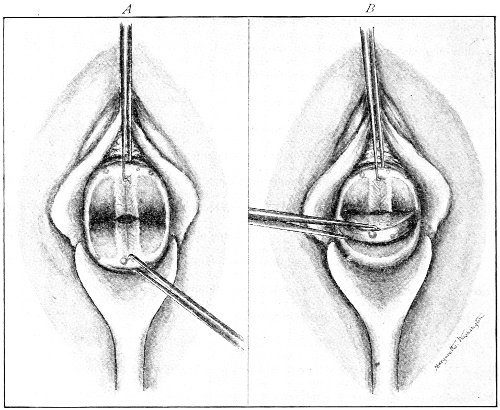

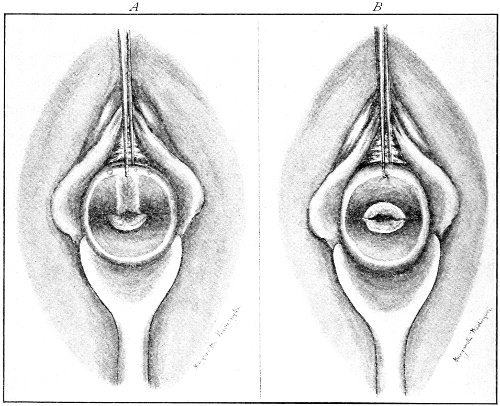

Slight Median laceration of the Perineum.—In this injury the tear takes place through the fourchette. Posteriorly it may extend as far as the sphincter ani muscle. Upward it may extend for an inch up the posterior vaginal wall. The appearance of this tear is shown in Fig. 33. It will be noted that, as this tear takes place in the median line, none of the muscles that support the perineum are involved, nor are the planes of fascia injured. The perineum is slightly split, and the insertions and origins of the muscles and the fascia are slightly separated. The supporting structures of the perineum and the pelvic floor are, however, uninjured.

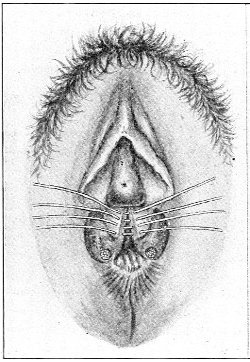

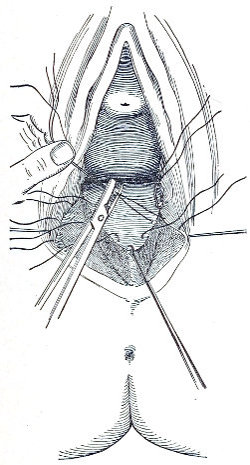

Fig. 33.—Recent slight median laceration of the perineum: sutures introduced.

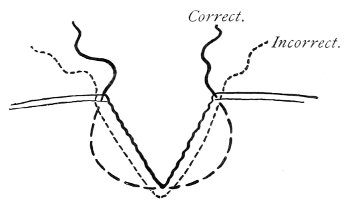

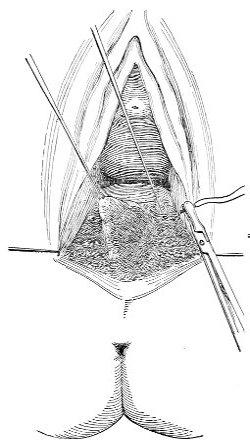

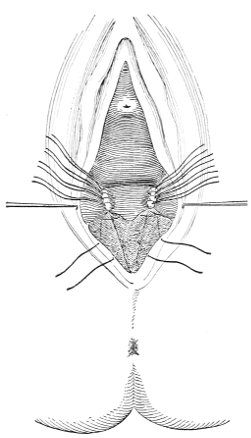

If this tear is detected after labor, it should be closed by the immediate operation. A slight tear involving chiefly the cutaneous aspect of the perineum should be closed by three or four sutures introduced from the outside, as in Fig. 33. The needle should be introduced about a quarter of an inch from the edge of the wound. It should not be passed parallel with the plane of the lacerated surface, but should be swept outward and then inward toward the 68 angle at the bottom of the tear (Fig. 34). It may either emerge at the angle and be re-introduced, or it may be passed directly through to the skin-margin on the opposite side of the wound. If the suture is passed in this way, there will be perfect apposition throughout the whole surface of laceration. If the sutures are improperly passed, there may result only apposition of the skin-edges.

Fig. 34.—Diagram representing the correct and the incorrect method of passing the suture for closure of slight perineal laceration.

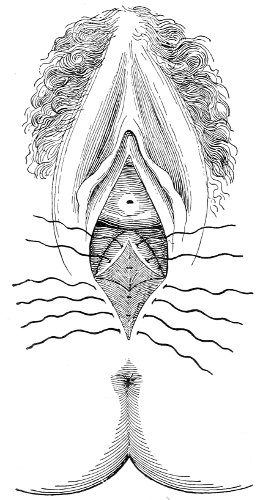

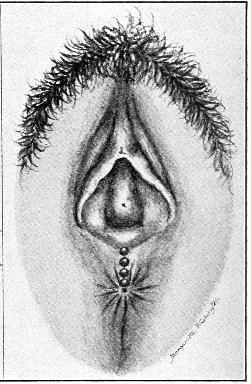

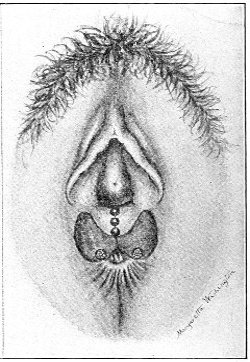

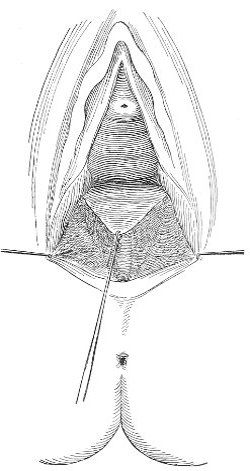

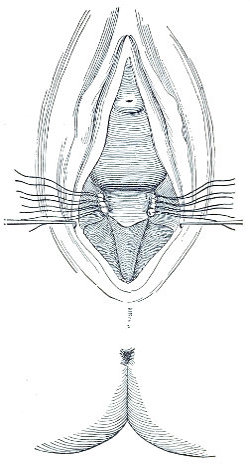

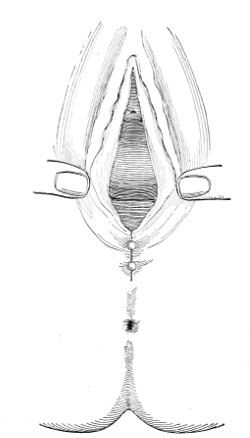

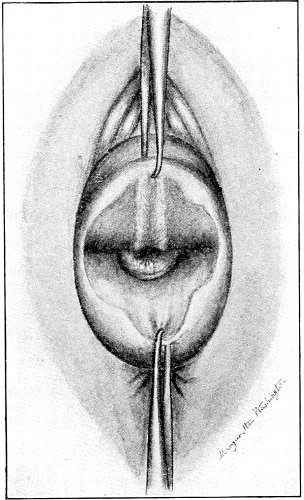

If the laceration extends up the posterior vaginal wall, two sets of sutures must be introduced—one on the vaginal aspect of the tear, and one on the skin aspect (Fig. 35).

Fig. 35.—Recent slight median laceration of the perineum extending up the posterior vaginal wall: sutures introduced on the vaginal and cutaneous aspects.

The secondary operation of perineorrhaphy is not indicated in slight median lacerations of the perineum that may have been neglected at the time of labor, as the integrity of the pelvic floor is practically unaffected by them.