Title: The Irish Penny Journal, Vol. 1 No. 35, February 27, 1841

Author: Various

Release date: June 5, 2017 [eBook #54852]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brownfox and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by JSTOR www.jstor.org)

| Number 35. | SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 1841. | Volume I. |

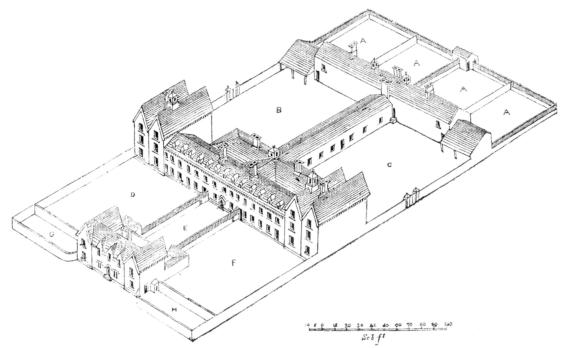

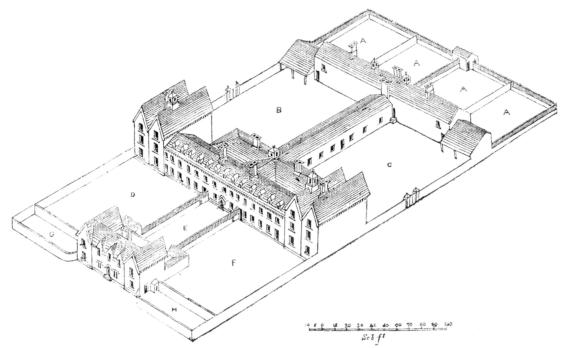

The entrance front building, forming a distinct structure, is placed about 150 feet in advance of the main building, and consists of one door (above the ground), on which the Board-room and clerk’s office are placed; underneath these are the waiting-hall, in which applicants for relief are received, and a room for a porter, who has charge of the paupers on their admission, for the purpose of seeing that they are washed, cleaned, and clothed in the workhouse dress; he is therefore placed near the probationary wards. Distinct wards are also provided for vagrants receiving temporary relief. This arrangement of the probationary and vagrant wards secures the vicinity of the body of the house from the risk of infection from persons previous to their being examined and declared free from disease.

The main building is separated from the entrance front by a courtyard and garden, which divide the two front yards for the boys and girls; the centre of the main building contains the master’s house, which is placed immediately among all classes, and from which ready access is had to any of the rooms; the kitchen offices are close under the master and matron’s inspection, as well as the several stores.

The wash-house and kitchen offices are placed in a situation distinct from the paupers in the yards, and none but those immediately employed in them have access thereto; on each side the master’s house are placed the rooms for children, who have separate staircases, used also by the master and matron; the extreme wings contain on the ground floor rooms for the old and infirm people, and some accommodation also for the able-bodied, which class, however, being employed (the women in the wash-house, &c., and the men at a mill, in breaking stones, or other useful occupation,) the same extent of day room is not requisite. The chapel and dining hall answers three purposes, inasmuch as it also serves, by means of a double partition, for day rooms for able-bodied men and women, should occasion require it. The situation of this building as a dining-hall is, from its central position, best suited for all classes, and is most convenient as regards the serving the food from the kitchen; the two rooms for boys and girls will also serve the purpose of a chapel, if required.

The Infirmary is placed at the back of the building, occupying a position distinct from the wards of the house, and sufficiently convenient for the supply of food from the kitchen offices without entailing the necessity of a separate establishment.

Wards are placed on each end of the infirmary buildings for idiots, epileptics, and lunatics, in which cells are provided for those for whom occasional restraint is unavoidable, or whose habits render distinct accommodation necessary.

The arrangement of the building is made with true regard to ventilation. At each end, in the centre of the building, a large hall, containing a superficial area of 425 feet, is carried up to the roof of the house, on which is constructed a large ventilator, containing windows hung on centres, and moveable with a line, to admit any circulation or change of air required. The several rooms throughout are arranged to open at once into the landing of the stone stairs, which are carried up in this space. The several doors have semicircular arches above them to be opened as occasion may require; and which, without producing any strong current, would always effect an extensive ventilation during the occupation of the rooms. The usual manner of ventilating the common sleeping rooms, is by placing the windows on each side of the room, which are very useful, but chiefly so after the paupers have left the apartment. The windows throughout are constructed with the upper part hinged, and to fall inside, which allows them to be opened during rainy weather.

Cast-iron air-gratings are to be inserted in small flues formed in the walls, and fixed a few inches above the floors, for obtaining, when required, an admission of external air.

When we call to mind the interminable discussions which only a few years ago were usual in every society, as to the necessity, or advantages, or practicability, of a poor-law system in Ireland, and then transfer our attention to the actual progress which has been made in carrying into effect a certain, defined, and enacted arrangement, it is something like escaping from a dark, close wood, in which there was neither path nor direction, into an open country, with the bright canopy of heaven above, and our desired destination, or the sure road conducting to it, plainly in view.

To devise, and, much more, to bring into operation, a legalized system of poor relief suited to the wants and circumstances[Pg 274] of Ireland, will, when duly considered, appear to have been a truly great and formidable undertaking. Innumerable plans had been set forth from time to time for this purpose, anterior to the act passed among the first of her present Majesty’s reign; but it may well be questioned if there was any one of them which would not on trial have proved to be a complete failure. Into that speculation, however, we have no occasion to enter at present, as there is now a law, having its machinery already so near to completion, that it must be in full effect at no distant day throughout the whole country, to the provisions and execution of which it will be at once more interesting and more profitable to direct our attention.

We may confidently attribute whatever facilities have been found to attend the practical introduction of the law into Ireland, to the fact that its management was entrusted in the first instance to a Commission; that the Commissioners were men already perfectly conversant with the subject, and that they were invested with sufficient powers to accomplish the object. No better machinery could have been devised, and we shall soon be enabled to perceive that it has not disappointed the expectations to which it might fairly have given rise.

The first great object which presented itself for consideration, in connection with the act of Parliament, may be supposed to have been the division of the country into suitable districts for the administration of the system. It required a new series of boundaries for its own provisions and purposes, as the proposed relief was to be afforded territorially, according to none of the existing divisions, either parochial, baronial, or by counties. The Commissioners were empowered to “unite such and so many townlands as they might think fit to be a Union for the relief of the destitute poor;” and the subject was one that evidently demanded the most serious examination.

The principle of forming the Unions was that which the Commissioners had previously adopted in England, namely, that the Union should consist of a market-town as a centre, and the district of country surrounding and depending on it, and extending to about ten miles round it in all directions. The size of Unions was indeed a subject which caused a good deal of anxious consideration. People, generally speaking, were at first desirous of having smaller Unions—not taking into account, that by increasing the number of Unions, more expense would be incurred, as the larger the Union, the smaller is the establishment charge in proportion. However, the Commissioners, guided by local facilities, formed Unions of townlands already combined by social affinities as well as geographical position, and have thus exceeded the number at first estimated on a theoretical scale. The number declared up to the 25th of March last is 104, and 26 more, it is supposed, will comprise the whole of Ireland, and constitute the entire.

The most important subject which demanded attention was the construction of a governing power for each Union, in conformity with the terms and intention of the act of Parliament. It was to consist of a Board of Guardians, one-third being resident magistrates, and the remainder freely elected by the rate-payers. The Commissioners were authorised to fix the number for each Union, and they were of opinion that a number of elected Guardians, varying from 16 to 24, would be best calculated for carrying out the provisions of the act. These, with the addition of one-third, composed of the local magistrates, who are Guardians ex officio, would, it was calculated, give to each Union a Board of from 21 to 32 members, which would be sufficient for deliberation, and yet not so numerous as to impede efficient action. With regard to the actual elections, now numerous, which have taken place, the Commissioners in their last Report express their regret that much excitement and discordant feeling should have been exhibited in some instances; but at the same time they declare their belief, that, as a general result, efficient Boards of Guardians have been constituted.

The third important object which demanded attention, was the procuring of suitable workhouses for the several Unions. The Commissioners were of opinion that one central workhouse, of a size sufficient for the whole of the Union, would be best; but for the sake of hastening the practical benefits of the act, and to save expense as much as possible, they were disposed to avail themselves of existing buildings nearly central, capable of being converted into workhouses, if obtainable. Their expectations on this head, however, were very far from being realized. It seems certain that the opinion originally formed as to the excess of barrack accommodation in Ireland was unfounded, there being in fact no more than the exigencies of the public service require; and of barracks, eventually, they obtained but one, situate in the town of Fermoy, which is now in process of conversion into a workhouse for that Union. In other Unions, old houses and other buildings were carefully surveyed; but in no one instance, says Mr Wilkinson, the intelligent and skilful architect of the Commissioners, have premises of this kind been found eligible in point of economy or convenience of arrangement, the sums asked in nearly every instance having been far beyond the value for the purpose of conversion. As a general result, the only old buildings which have been actually converted, or are now in process of conversion, into workhouses, are, in Dublin, the House of Industry for the North Union, and the Foundling Hospital for the South; in Fermoy the barrack already mentioned; and the House of Industry in Clonmel.

The number of new buildings contracted for, and in progress, was in March last 64; the notices for contracts since published amount to 50; so that building arrangements remain to be made for only 16 Unions.

In the appendix to the last Annual Report of the Commissioners there is a tabular statement, showing at one view the number and names of the Unions which have been declared up to April last—the area in statute acres, and population of each—the number of Guardians respectively—with other particulars, including indeed every thing necessary to afford satisfactory information on the subject; and, but that it would occupy a great deal of space, we would gladly transfer it to our columns.

Having thus briefly noticed the three leading points indispensably preliminary to the working of the poor-law, namely, 1st, the Unions, or districts within which each local administration is to be comprised; 2dly, the Guardians, or local administrators of the law; and, 3dly, the Workhouses or buildings designed for the reception of the destitute poor, it only remains to add a few observations relative to certain topics on which there has been a good deal of discussion, and concerning which a clear opinion has not yet been arrived at by many.

In the first place, there has been much misconception as to the true nature of the work which the act of Parliament devolved upon the Commissioners of Poor-Laws. That such is the case, is evident from the many applications which have been made to them from time to time to afford relief in different districts under various circumstances of distress, as though the Commissioners possessed any general powers for this purpose. The applications were not indeed at all surprising. “Hunger,” saith the proverb, “will break through stone walls;” and it was not to be expected that those who witnessed and deeply sympathised with numerous and touching instances of extreme destitution would be very nice in scanning the phraseology or exact intendments of an act of Parliament. However, in reality the Commissioners had no power to act in any manner different from that which the legislative chart, if we may use the phrase, had prescribed to them. Their mission was to fulfil the great work of founding and bringing into operation an extensive system of poor relief, not to distribute a bounty, or immediately to afford relief in any specific case of distress, however urgent. Their task was formidable and onerous; and if the accomplishment of it has appeared to some to have been tedious in its course, it may well be asked, wherein has there been a failure of any means necessary to the end, or by what better means could the work have been made to advance more speedily and more securely to completion, than by those which have been employed? The law, it may be said, has as yet been brought to bear on the wants of the poor only in the Unions of Cork and Dublin. True; but for this the law itself, or that process which it made imperative in order to effect the essential and solid purposes which it had in view, is alone answerable.

Unions, Guardians, Workhouses, and Assessment, must, by the terms of the act, in every instance precede relief. By the 41st section it is enacted, “That when the Commissioners shall have declared the workhouse of any Union to be fit for the reception of destitute poor, and not before, it shall be lawful for the Guardians, with the approbation of the Commissioners, to take order for relieving and setting to work therein destitute poor persons.” Thus it appears that until a workhouse[Pg 275] be provided, the practical benefits of the act cannot be obtained.

It may be premature at present to speak of the interior economy of the workhouse, but we may shortly refer to the leading views put forth by the Commissioners on the subject. They disapprove, then, we collect in the first place, of more land being occupied in connection with the house than may be sufficient for the purpose of a garden, or than can be conveniently managed by the boys, or the aged and infirm men. Employment for the able-bodied is to be provided within the workhouse, to which they are to be strictly confined so long as they remain dependent on the Union for support. This, in the opinion of the Commissioners, given in their Fifth Annual Report, “Should be of such a nature as to be irksome, and to awaken or increase a dislike to remain in the workhouse, for which purpose corn-mills will probably be found, as in England, to be the most effective. With the aged and infirm the case is somewhat different: they should all be employed, but their employment need not partake so much of the character of a test: and with the children the test is altogether inapplicable; so long as they remain in the workhouse, they should be taught and trained to become useful members of the community; and for this purpose an acre or two of garden ground, in which the boys may work and acquire habits of industry, as well as skill and strength for manual labour, will be found extremely useful.”

With regard to diet, they observe in their Sixth Report, that, as a general rule, it is unquestionably desirable that the workhouse diet should be, on the whole, inferior to that of the labouring classes of the surrounding district; yet that it is not on this circumstance alone, or even in any very great degree, that the efficiency of the workhouse depends. On the contrary, say they, “We are satisfied that the diet, clothing, bedding, and other merely physical comforts, may in the workhouse be better than in the neighbouring cottages, and yet that none but the really destitute poor will seek for admission into the workhouse, provided that order and discipline be strictly maintained therein. It is in truth the regularity, order, strict enforcement of cleanliness, constant occupation, the preservation of decency and decorum, and exclusion of all the irregular habits and tempting excitements of life, on which reliance must mainly be placed for deterring individuals, not actually and unavoidably destitute, from seeking refuge within the workhouse, and not upon the absence of mere physical comforts. This is the view by which the legislature appears to have been governed in adopting the general principles of the Irish poor relief act; and to this view we consider it to be essential that the dietaries and the other regulations of the workhouse should conform.”

With these general views no reflecting person will, we should think, be disposed to quarrel.

A good deal of discussion has taken place as to the regulation which prohibits strangers, and particularly reporters of the press, from attending the meetings of Guardians. However, we in Ireland have nothing specially to complain of in this respect, as the same rule exists in England, and has not been attended there by any public inconvenience. The question properly is, why the rule should be different here? The Guardians, it must be understood, are under no obligation of secrecy. They are quite at liberty to note, report, and publish at their own discretion; the rule merely excludes strangers, and of course reporters who are not Guardians, from the Board. The Commissioners in their Sixth Report very truly say that “the presence of strangers would be a restraint upon the deliberations of the Guardians; while the knowledge that their proceedings were to be published would certainly conduce to debate and display, and obstruct the dispatch of business. A desire for popularity would be awakened, and individual Guardians would too probably be led to address themselves to the passions of their hearers, or to party or sectarian feelings prevalent without doors, rather than to the sober disposal of the business in hand. Prejudices would be excited, passions inflamed, personalities would arise, and the most respectable members of the Board, who, from their property, position, and habits of business, would be best entitled and best fitted to take part in and guide its proceedings, would be borne down by clamour, or wearied by lengthened discussion, if not finally compelled to abandon their post.”

It was no easy matter to have brought this great work of a statutable poor relief to its present advanced state, without exciting stronger feelings of opposing party than any which fortunately have yet been elicited; but it may well be doubted if things would go on in the same quiet and businesslike manner if Guardian meetings were to be open to the public; and if there be any evil connected with the exclusion complained of, we may safely conjecture, at least, that it is the lesser of two—less than that which would arise from the jarrings and discord of party on a subject which, above any other, calls for unanimity, and should awaken only the feelings of a common benevolence and patriotism.

We may now advert, in the last place, to the ameliorations in our social condition which may be expected to arise when the new system shall have been put fully in operation. In the first place, a reproach will be wiped away from our country, which certainly existed against it so long as it could be said that no law existed in it for the relief of the poor. Destitution will then be provided for, and mendicancy will be without excuse. It is true that there is no direct provision in the act for the restraint of beggary, but a legalised provision for the destitute is indirectly a law against it, and must operate most powerfully as such. When people are taxed to maintain the poor, they naturally become unwilling to open their purse-strings, unless with great reluctance, at the solicitation of mendicants; the trade of mendicancy declines; and those who would still cling to it are forced, if of the class of the able-bodied, to apply themselves to some means of profitable industry, or to resort to the workhouse for subsistence. The Poor-Relief Act is thus, indirectly, a law against mendicancy, and in this point of view is calculated to work most beneficially, and greatly to alter the face of things in Ireland.

But it is also a law of positive economy to the country. The support of the destitute not being abandoned to casual charity, but conducted systematically by persons appointed to bestow their exclusive attention to it, and all rateable parties being under a legal obligation to contribute in due proportion to their circumstances, there cannot be a doubt that a less expenditure will suffice under such management for the maintenance of the really destitute than if the work were left to mere voluntary benevolence, and no means existed of compelling all classes fairly to share the burden among them.

Many persons have felt a terror at the idea of the taxation they supposed they should have to suffer under a poor-law; but the great probability, nay, almost the certainty of the matter, is, that it will be a considerable saving to them. The present rate in Dublin is 1s. in the pound for the year, on a very moderate valuation, and much more than half the rate is borne by landlords.[1] This, however, appears to be beyond the intention of the law as to town property, for which inordinate rents are not usually obtained; but the result is within the control of the Guardians, who may revise the valuation whenever they propose to levy a new rate.

The expense of the relief, even under higher rates, would be less, far less, on those who have hitherto supported the poor, than the outlay which they have annually made for that object; and now they will have the satisfaction of knowing that what they give is given to the destitute poor; that all is well applied, none misspent, and every part so economized in distribution, that the sum contributed relieves a greater number of poor than the larger sum formerly given in alms.

It must also be considered, that the poorer classes subsisting by labour will be relieved by the workhouses from the continual encroachments of beggars on their scanty meals, and the still more scanty means of lodging possessed by them.[Pg 276] Let the opponent of such a provision for the poor—if any reflecting person in the country can on public grounds be opposed to it—let him, we say, contemplate the hard lot of the labouring classes, compelled by the importunities of beggars not only to give up a considerable share of the food actually insufficient for themselves, but also to divide their beds or their children’s beds with persons of the lowest habits, and thus see their families deprived of food, of rest, health, and morality; while a large number of the wealthy classes remained listless and inaccessible within their closed doors, or were exercising their better feelings in a distant land.

We do not accuse the wealthy members of society, as a class, with indifference to the wants of the poor: we but refer to a contrast between their security against the intrusion of mendicants, and the defenceless state of the labouring classes—a contrast which doubtless must have been ever present to the mind of the poor working man: and we do this to show how much the wealthy will gain by a law which provides safe means for its application in relieving poverty.

The expense, then, which we are now incurring, is not a new charge, but a wise and equitable distribution of one heretofore borne by portions of the community in very disproportionate shares, without having any tendency to obviate the mendicancy by which it was created, but, on the contrary, having a direct tendency to foster and increase that most demoralizing of all the conditions in life.

Be the expense what it may, it cannot tend to induce a more extensive reliance on the public provision than mendicancy has encouraged: nay, we maintain, that when the law shall have been for a short time in full and general operation, the number of unemployed and dependent poor will gradually decline. But expectation must have a little patience: the machinery for sustaining in orderly and decent comfort upwards of one hundred thousand human beings, cannot be created otherwise than by a very gradual process. This is not a clime in which men and families can be encamped: when they are to be lodged, durable structures must be provided, and for this work much time is necessary. We are sure that no time has been lost; nay, we regard the progress made as among the most accelerated public labours of this or any other country.

In the mean time, the law is not without working out much good for the labouring classes. Workmen of every grade have been busily employed in the construction of workhouses since the spring of 1839, for which object government has advanced upwards of a million of money, free of interest, for ten years after the commencement of relief in each Union.

We are, however, reasoning without having an argument opposed to us; for any thing like argument against the law we have not heard. In Dublin it is merely complained, that although houses are open and rates levied, the mendicants still throng the streets. But it is not shown that any thing like the same number of apparently deserving objects of relief are to be seen; they on the contrary are in the workhouses, maintained by the rates; and were it not for the poor children whom the mendicants drag along with them, the imposture would soon be stopped by its own want of success.

The policy of the law contemplates the repression of beggary and vagrancy, and all those disorders and crimes which accompany or have their origin in those habits—the encouragement of a more productive industry—the more universal recognition of the identity of interest amongst all classes affected by the law—and with the cordial co-operation of all the intelligent classes of society which it has hitherto received, and will probably receive yet further hereafter—there cannot be a doubt but that the law, when in full operation, will realize all this, and more.

To those who wish for an exemplification of the favourable working of the law, we recommend the perusal of a little work lately published under the title of “Benevola,” in which the English and Irish systems of relief are well contrasted, and the tendency of the Irish provision is ingeniously exemplified. To those who will not be satisfied without a practical exemplification, we can only recommend patience; but we will say—Do not in the mean time forget the cost and other deplorable evils of Irish mendicancy.

F.

[1] As the principle on which the tenant is entitled to make deductions from rent, on account of the poor rate, is not clearly understood by many, the following explanation is given:—

This tax being imposed on the annual value of each tenement, say a rate of 5d. on £50, £60, or whatever the valuation may amount to, the tenant is to deduct one-half of the rate, say 2½d., from every pound in the year’s rent. The rate is imposed for a year; it may happen that no further rate will be necessary in the year, or it may occur that three or four rates will be necessary; still each rate is for the year, and is either the whole amount required or an instalment. In any event it is levied on a year’s value; and landlords are to allow their tenants one half of each rate of 5d., 6d., or whatever it may be, out of every pound in THE YEAR’S rent, when receiving either a half year’s, quarter’s, month’s, or week’s gale.

Suppose the annual value is £50, the rent being also £50, the rate of 5d. will amount to £1. 0s. 10d., and in paying a half year’s rent of £25, the tenant must deduct fifty times 2½d., or 10s. 5d., being half the tax paid.

If the year’s rent be greater than the annual value, the tenant will deduct more than half the amount of the tax. Thus, a rate of 5d. on an annual value of £50, being, as already stated, £1. 0s. 10d., if the annual rent be £80, the tenant will deduct from the first gale falling due after the rate is declared by the Guardians, eighty times 2½d. or 16s. 8d. On the other hand, if the annual rent be less than the value, say £40, the deduction will be only forty times 2½d., or 8s. 4d.

The tenant and landlord become liable to the rate at the same moment; therefore a rate declared in April 1840 attaches to rent then accruing, but not to a gale previously due.

The study of natural history is one which, independent of the charm it possesses to the inquisitive and contemplative mind, in affording food for the cultivation of the highest qualities of the intellect, is also beneficial in a moral point of view, as it insensibly brings the cultivator of it to contemplate the power and goodness of his Creator. It leads his thoughts from the petty affairs of life, and, making him look with admiration and a feeling of love on every manifestation of the Divine power which surrounds him, instils into his mind one of the strongest principles of action desired by the Almighty—a feeling of universal benevolence.

There cannot be a better illustration of this latter effect which I have mentioned the study of natural history produces on the mind, than that afforded us by the history of the birth and after life of the insect I have headed this article with—“the Gadfly.” Strange and wonderful though the transformations be to which the butterfly and many other individuals of the insect world are subject, those of this little creature far surpass them all.

Many of my readers are well acquainted with that fly which in the latter part of summer is seen to be so annoying to the horse, buzzing about him, and every now and then dashing itself with some degree of violence against his sides and legs. This motion, to all appearance, is without design; but a closer study of the habits of the insect will show that, far from being the effect of chance, it is one of paramount importance to the existence of the fly, as on it depends the continuation of its species.

If attentively observed, it will be found that it is the female of this fly alone who resorts to this peculiar motion; this she does to deposit her eggs in the hair of the horse, to which they at once become attached by a gelatinous fluid surrounding them; by this mucus they are enabled to retain their hold for a few days, during which time they are fitted[Pg 277] to be hatched, and the slightest touch will liberate a little worm they contain. The horse, in resorting to the common practice of licking himself, breaks the egg, and the small worm contained in it adhering to the tongue of the animal, is conveyed with the food into the stomach; there it clings by means of hooks placed at either side of its mouth, and its hold is so tenacious that it will be broken before it can be detached. Here, in this strange abode, changing as it were its nature in becoming a parasite, it remains for the whole of the winter, feeding on the mucus of the stomach. At the end of the ensuing spring, having reached its full perfection in this secondary state, led by that instinct which regulates all the animated creation, from man to a monad, it detaches itself from the cuticular coat, and is carried into the vilous portion of the stomach with the food, passes out of it with the chyme, and is at length evacuated with the feces. The larva or maggot, now a second time changing its nature, seeks shelter in the ground, and after some time becomes a chrysalis; in that helpless state it lies for some weeks, when, bursting from its deathlike sleep, it wakes into life and activity in the form of a perfect fly.

There is hardly a parallel to this wonderful chain of causes and effects, and effects and causes, to be met with in all the varied and mysterious workings of nature; scarcely one which exhibits so many acts apparently so unconnected with the ultimate results.

V.

Jack Rivers should have been a gentleman. His family, his property, his early education, entitled him to that dignity. Jack was not a gentleman; with perverted views of ambition he spurned the distinction, and gloried in the well-merited title of knave. Many loftier and nobler minds have been reduced to even a lower point of moral degradation by early indulgence in gross licentious habits. Such was not the case with Jack. Immoderate sensual gratification ranked not in the catalogue of his crimes. He was no toper; was a married man at twenty, and a faithful husband all his life. Yet, Jack was an acknowledged, nay, more, a professed knave, though neither a lover of money nor a spendthrift. Shakspeare it is said, ransacked all nature, and left almost no character untouched; yet neither in his historical portraits, the etchings of his own times, nor his prophetic creations, has he given us a picture that at all resembled Snap Rivers, the faithfully expressive soubriquet assumed by our hero. Nature, whimsical nature, must have been in her drollest mood—must have been actually studying the picturesque when she cast his nativity. He certainly was a model for an artist in that line, for he stood six feet six inches by military standard, was extremely slender, rejoiced in the possession of a hatchet face ornamented with the most splendid Roman nose imaginable, illumined by two small ferret eyes, squinting fiercely inwards, which gave to his countenance the most sinister expression possible. Quite aware of the value of these natural advantages, Jack’s genius and striking taste in dress added considerably to their effect. It was his invariable custom through life to wrap his outer man in a long blue cloak, a garment little used in his day. Summer and winter, a pair of blue rib-and-fur woollen stockings encased his spindle legs, gartered above the knee beneath a pair of gun-mouthed unmentionables; a red nightcap ever maintained its conspicuous place on his elevated poll, while an immense fire-shovel or clerical hat gave a finish to his unique and matchless appearance. He possessed one other accomplishment: he was afflicted—poh!—blessed with a most inveterate stammer in his speech: a word in speaking he could not utter without the most frightful contortion of countenance, and unintelligible splutter, splutter, splutter. Yet, no one of his attributes did he turn to such beneficial effect as this; for when he either wished to gain time, or baffle an opponent, forth came a torrent of manting sounds in all their horrific grandeur, and he who could quell the feelings of pity could rarely resist the ready propensity to laugh at the ludicrous exhibition; so Jack was generally successful. But, notwithstanding this great natural defect, whenever he pleased he could make himself well understood, by falling back upon a species of recitative, or musical method of speaking, peculiar to himself, and always commencing with a loud “ho! ho!” which gave timely warning to all his acquaintances that he was about to favour them with his own sentiments in his own style. One circumstance of his early life must be mentioned, as it may have given a bent to his mind in after years. At the early age of seventeen he had deserted his respectable and happy home, and found himself a private in a dragoon regiment. The act broke his father’s heart. So, having spent three years in that admirable school of morality, Jack purchased out, and returned to his young wife, as well as to the possession of a snug £400 a-year, which fell into his hands by hereditary descent.

Constituted as his mind then was, his principles soon began to develope themselves, and to afford a strong contrast to those which had governed the actions of his father. That he shortly became dreaded by all his neighbours, may be admitted; that he would and did overreach every man with whom he had business transactions, was an admitted fact, because it was his own proud boast; and when checked by his friends for those admissions, he would boldly reply, “Ho! ho! woo-ood you have me tit-tit-too put my lil-lighted ca-handle under a bu-hushal?” But that he was hated, or even disrespected in consequence of his acts, has no foundation in reality. There was nothing mean or grovelling about his knavery—all was above-board, done in clear day-light. There was nothing selfish or avaricious about him; the glory of the deed was all he aimed at, for every body knew he would prefer gaining a pound by open imposition, to the receipt of ten by honourable means. He never used a soothing phrase to human being. He seemed to court the hostility of his species, yet that would not come; for notwithstanding his profane and coarse salutations, he had a humane heart, and a short time sufficed to unmask it. The poor never went hungry from his door, and a distressed acquaintance had a certain resource while there was a penny in the purse of Snap Rivers. He was as welcome to his cash as to his bitterest malediction, and that was ever ready for either friend or foe. But the insolent great man, or the would-be important, who aped a dignity to which he had no fair claim, was the object of his deep immitigable hate; with such he could hold no terms; and did such ever cross his path, he would plot for months till he would circumvent him in some shape. Did ever Shakspeare light on such a character? Yet, notwithstanding all these seeming contradictions, a single trait has not been here placed to his account that was not in a degree beyond description truly his.

On one occasion Jack was invited to an evening party in the house of his brother-in-law, a plain honest man, an extensive farmer, wealthy and respectable, in every point the very antithesis of his eccentric relative. The district was remarkable for the peace and harmony which prevailed throughout its entire population. Party strife and sectarian animosity were here totally unknown, while intermarriages among all sects cemented a union and fostered a spirit of Christian charity and forbearance, which, while it ameliorated the heart and breathed peace around it, shed also a lustre on the humble community beyond the dignity which vain pomp confers on the fleeting distinctions which gorgeous wealth creates.

But Jack was an invited guest; so was his own amiable minister, the virtuous and respected Protestant rector, Mr B——; so was Dr D——, a pretty tolerable wag; and so was the Rev. Mr K——, the parish priest, between whom and the rector there existed a sincere unfeigned friendship. The priest had studied in France; was a man of high attainments, polished manners, possessed a vast fund of sparkling wit, with as ready and as happy an expression as ever distinguished man; but his brilliant qualities were ever under the control of strict decorum, and, further, restrained by a lofty sense of that dignity which should inhedge the minister of religion. He was consequently an especial favourite with all classes, and an honoured guest at every social board. No man revered him more than Snap Rivers, and none was more anxious, or better knew how, to draw out his conversational powers.

The party was all assembled with the exception of our hero, and as his presence and pungent remarks always contributed to the hilarity of his friends, the kind-hearted host was not half satisfied with his absence. “What the devil’s keeping Jack?” had just escaped from Mr Anderson’s tongue, as the door opened, and the head and shoulders of Snap Rivers made their welcome appearance. When he had fairly entered the room, he raised himself to his full height, stared deliberately around him, pulled off his hat with some attempt at grace, and exclaimed in his own fashion, “Ho! ho! a goo-hoodly company, by Ju-hupiter! Ho! ho! the bla-hack-coats!”[Pg 278] Then casting up his eyes in the most fervent manner, he added—

“From daw-hocters and praw-hoctors, lil-lawyers and cla-hargymen, good Lord deliver us!”

“Early in the attack, Mr Rivers,” said the priest.

“Ho! ho! Mr Lil-long-tongue, sure you nee-heedn’t care; you’re always prepared. I wo-wo-wish your brother co-co-corbie there would bib-bib-bib-borrow some of your chin-whack.”

“Listen to him noo,” said the host; “he’s begun, an’ the diel would na stop his tongue; we’ll a’ get a wipe in our turn.”

“Never mind,” said the rector. “Mr Rivers, I am happy to perceive, is charitably inclined to-night. He wishes to increase my usefulness for the benefit of his neighbours, as he never condescends to occupy his seat in church.”

“And never will, Mr Modesty, till you think fit to change your tune.”

“Pray inform me how I shall accommodate myself to your taste, Mr Rivers.”

“There are tit-two mim-methods open to you. Either you shall pra-hactise what you pre-heach, or pre-heach what you pra-hactise!”

“You are pleased to speak in riddles, Mr Rivers; be kind enough to explain.”

“Ho! ho! tha-hat is mim-more than I intended. Fu-hoo men blame me for con-ce-ling my thoughts. But I shall try to be clear. You pre-heach cha-harity, and you pra-hactise rir-rir-robbery. Ho! ho! but you are a saint! Now, I am a knave; and how lies the difference? In my fif-favour to be sure, for I give the world fif-fair play—every body knows my cha-haracter.”

“Your character is generally known,” interposed the priest; “and, as you admire candour, allow me to add, as generally execrated.”

“And what is that yoo-hoore affair, Mr Law-long-tongue. Why meddle in other men’s fif-fif-feuds?”

“You mistake, Mr Rivers; he who interrupts the harmony of society is accountable to every member. You have rudely burst the bounds of decorum to-night; you have unfeelingly assailed a mild and amiable gentleman; your charge is as unjust as your manner is coarse and vulgar, and both are as execrable as any thing, save the malice that prompted the attack.”

“Ho! ho! I might as well have rir-roused a hive of hornets. You black-coats fight among you-yourselves like cat and dog, but you will not allow others to interfere with the claw-hoth, I perceive.”

“The deevil stop your tongue, but it’s gleg the nicht, Jack Rivers,” said the host; “can you no gie us peace?—sure nae ither man would insult the rector.”

“Ho! ho! but you’re in a wonderful pucker, Mr Numskull. Let the rector defend himself.”

“Mr B—— is too gentle a character to manage you,” said the priest.

“Your greatest enemy wo-on’t brand you with that crime,” replied Rivers, “for you ride rough-shod over all that come in your way.”

“Nothing gives me greater pleasure, I admit, when I meet such characters as you; for history furnishes no likeness of you, and among living men we would seek in vain for your fellow.”

“Ho! ho! your French politeness is less polished than stringent to-night, I think. I don’t admire it much. I would rather see your native talent in its native Irish dress. Out with the sentiments of your heart, plainly, man, and at once say, ‘Out of h——, Rivers, you’re matchless.’”

“Oh no, I cannot profit by your advice. I felt my own want of ability, and therefore left the picture to be dashed off by an abler hand. The truthfulness of your sketch no person will venture to dispute.”

The laugh was against Jack, and he bore the punishment with good temper, collecting himself, however, for a renewal of hostilities. After tea, as was the custom on such occasions, the ladies and such of the young men as preferred female society withdrew to another apartment, while the majority of the elderly gentlemen, including the clergymen, the doctor, and Snap Rivers, collected round the host to enjoy the comforts of the bottle; and as the steam began to rise, the hilarity of the party got up in proportion. After various gay sallies, Rivers said,

“Well, Master Galen, how goes trade now? You-oo and the se-hexton are se-heldom idle, I believe.”

“Always doing a little,” said the good-natured doctor, “but nothing worth notice. Any snaps with yourself of late, my conscientious friend?”

“Good, doctor, good; seldom at a loss for a sly hit. A-a-and to tell you the truth, I have mere trifles to boast of since I diddled the fellows in the pa-harish of Billy.”

“I am not aware of the circumstance; pray what was it?” said the doctor.

“Lil-lil-let our brilliant host tell you; he was a witness to the transaction,” said Rivers; “besides, unfortunately, my tongue was not made by the same craftsman that manufactured my brains.”

“How happy for your neighbours!” said the priest; “could your tongue give ready expression to the subtle plottings of your skull, we would be deluged with a torrent of knavery. But, Mr Anderson, do favour us with the story.”

“By my conscience, then, it will do but little credit to Jack, in any honest man’s mind; but if you will hae it, then you must hae it. About three months ago there was a property to be sold by public cant in B——ls, and, to be sure, the devil drives it to Jack’s ears. Weel! the lease was a perpetuity, very valuable, and fifty pun’ o’ a deposit was to be paid doon on the nail. Very weel, he comes owre and engages me to gang alang wi’ him to buy the place. But on the morning of the sale when I called on him, what was my surprise to see him dressed up in a rabbitman’s coat, tied roun’ wi’ a strae rope, a hat owre the red nightcap, no worth thrippence, wi’ breeks, shoes, and stockings that would disgrace a beggarman. Weel, in spite o’ a’ I could say, aff he starts in that fashion, and you’ll grant a bonny figure he cut among respectable men; but diel hait he cared; for while the folk was gathering, he sets himsel up on a kind o’ a counter, and begins beating wi’ his heels, and glancing roun’ him like a monkey, and jabbering the purest nonsense. I actually thought I would hae drapped through the earth wi’ perfect shame, though I was a little relieved when I saw he was set down for an idiot, and heard the gentlemen freely crack their jokes on him. Weel, the auction commenced, and when twa or three bids were gi’en, he looks up at the cant-master so innocently, and says, in his ain style, ‘Ho, ho, may I gie a bid?’ ‘To be sure, my fine fellow,’ says the man, laughing doon at him; ‘bid up, and nae doot ye’ll get the property.’ The bidding was up to £150. ‘£200,’ cries Jack, the roars o’ the company. ‘£250,’ says another. ‘£300,’ says Jack, and he skellied up at the cant-master in such a fashion as nae living man could stand. You could hae tied the hail gathering wi’ a strae, while Jack kept glowering about and whistling, and beating time to the tune wi’ his heels.”

“And what tune did he whistle?” said the doctor.

“The diel a mair or less nor ‘the Rogue’s March,’” said the narrator. “But when the roars had subsided, the cant-master, to humour the joke, takes up Jack’s bid, and he says, ‘Three hundred pounds once—three hundred pounds twice—three hundred pounds, three—three—three—all done?—three times!’ and down, in fine, he knocks a property worth three thousand, adding, ‘The place is yours, my man.’ ‘Yes, by my sowl,’ says Jack, springing off the counter, ‘the place is mine;’ and pulling a bag out of a side pocket, and placing it on the table, he added, ‘And there’s your required deposit for you!’ But he may tell the rest himsel.”

“And what followed, Mr Rivers?” said the doctor.

“Wha-hat followed! Why, you-oo would have thought the fellow was stuck, or af-flicted with my own impediment; but after some attempts he stammered out, ‘Oh, every person knows I was only in jest.’ ‘Ho! ho! my boy,’ said I, ‘but every person here shall know that I ne-ever was more in earnest. If I be a fool, my money’s no fool. Ho! ho! gentlemen, you enjoyed your jokes at my expense; but it’s an old saying, he may laugh that wins; the tables a-a-are turned, and it’s my time now, I presume.’”

“And, Mr Anderson,” said the doctor, “did all present quietly submit to the imposition?”

“Why, to tell the truth, every sowl in the place was dumfoundered, and stared at each other like as mony idiots. The cant-master made some new objection about ruining him, but Jack very glibly replied, ‘The sale is good and lawful. After more than three bids, the property was knocked down to me. The terms have been duly complied with, the deposit tendered before witnesses, and here is the remainder of the purchase money at your service when the deeds are perfected. I grant you were more merry than wise on this occasion;[Pg 279] and if you wish to know whom you have to deal with, it may be sufficient to inform you that I am Snap Rivers of the Doaghs; you have likely heard the name before;’ and out he marched as cool as a cucumber.”

The rector knew less of his parishioner than did the rest of the party; he therefore listened in amazement to the relation; but when the host had concluded, as if to assure himself that he was not dreaming, he said, “And, Mr Anderson, did all this really occur?”

“I’faith I assure you it did.”

“And is it possible that you could lend yourself to so nefarious and disreputable a transaction?”

“It’s no the first time Jack has made a tool o’ me,” said the simple-minded host: “he inveigled me there just to make a witness o’ me. I was innocently led into the affair; but besides what you have heard, I have neither more nor less to do with it.”

“And do you really intend to retain the property, Mr Rivers?” warmly inquired the indignant rector.

“Do I intend to retain it! Lord, how simple you would appear! Ho! ho! retain it! to be sure I will, and a very good thing it is, let me tell you.”

“Well, sir, under these circumstances it is my duty to be plain: you and I can have no further acquaintance,” said the rector.

Snap appeared surprised, and with a vacant stare, or at least a well-feigned look of simplicity, he modestly inquired, “And why, may I ask, shoo-oo-ood you cut my acquaintance?”

“The reason is plain,” said the rector; “you are in possession of a property surreptitiously obtained. You have deeply injured the proprietor, ruined the auctioneer, and instead of feeling remorse, you glory in the nefarious deed.”

“Ho! ho! is that the way the land lies? Why, man, did not I purchase it at a public sale? and was I not the highest bidder? If the auction was ill managed on their parts, am I to blame?”

“These arguments,” replied the rector, “might satisfy a Jew, but have no force on the Christian mind. You have no moral right. It is true, the law of the land may protect you, yet still you retain that to which in justice you have not even a shadow of claim.”

“Well, I am rejoiced to hear these noble sentiments from you, Mr Rector, although your high tone smacks a little of prudery. I trust you will cherish them; and if you do, what the devil, I ask, will become of your tithes, to which you have less claim than I have to the property? I gave something for it, yoo-oo give nothing at all for them; and yet you have the confounded impudence to rebuke me for one solitary act of knavery, while you practise the same trick on hundreds yearly.”

The rector vouchsafed no reply, but retired to the ladies, disgusted with the hardened villany of his ribald parishioner, who laughed in triumph at the clergyman’s discomfiture; and turning to the priest, he said,

“Well, Master Glib-tongue, what do you think of the affair? Did not I badger Mr Modesty in prime style? I think he will not readily volunteer his infernal impudence again, after such a lesson.”

“I know, Snap,” said the priest, “you are a consummate scoundrel. You have treated a most amiable man with unfeeling rudeness, and you deserve the reprobation of every right-thinking mind. Your legal swindling is bad, but your unblushing advocacy of the principle is worse; and if any thing still more flagrant can be conceived, your base and savage retort upon your own pastor is the very climax of your heartless villany.”

“Ho! ho! Mr Bladderchops, you have taken up the cudgels, with a vengeance. But you should remember the proverb, ‘Come into court with clean hands.’ What are you better than Mr Modesty? You don’t take the tithes, simply because you can’t get them. You don’t rob by act of parliament, but you wheedle the money out of some, and frighten it out of others, with the magic of your priestcraft.”

Mr Anderson was in agony, and interposing said, “I think, Jack, if you had any decency or feeling for me, you wouldn’t insult a clergyman at my table. You might be satisfied with driving one out of the room.”

“Ho! ho! Mr Numskull, but you’re thin in the skin! You have a wonderful leaning towards the corbies; you might fairly volunteer to defend the rector, but I beg you to let the priest answer for himself.”

“And were I to answer according to your merits, a horsewhip would afford the fitting reply. Respect for my own character forbids that appeal, and protects your insolence. Yet you go not unchastised. The cupidity of your heart, like every other crime, engenders its own punishment; and though you appear to glory in acts which shock the feelings of all other men, yet, despite your coarse ribaldry, there is an avenger within your own breast, which with scorpion venom stings you to madness, and will never cease its gnawings till penitence, a very unlikely consummation, pour its healing balm on ulcers scared and encrusted by the fires of iniquity!”

“Ho! ho! how very familiar you black-coats are with horrors! How very glibly you can ‘talk of hell where devils dwell, and thunder out damnation.’ Now, I think you priests should be more modest. It would serve your interests better to merely consign us to purgatory.”

“Your own acts, Rivers, determine such cases.”

“Ho! ho! I am aware of that; but, notwithstanding, cannot a little bit of clerical hocus-pocus serve us on a pinch?”

“The habitually profane have little to hope for either from God or man; they sneer at blessings mercifully offered, and too frequently die in their sins.”

“Then, under all these circumstances I think it as wise to have nothing to do with your purgatory.”

“I wish it may not lie your fate to go farther and fare worse.”

“Well, the devil couldn’t bandy compliments with you, Mr K——; so I think, brother Bill, you had better push about the jorum. The priest has too much tongue for me to-night, and there’s no moving his temper. But wait a bit: if I don’t gage him to his heart’s content, the first public place I meet him in, my name’s not Snap Rivers.” The party separated good friends, and the priest paid no attention to the threat. A month had elapsed, and Mr K—— having business in the nearest town, found himself on the market-day perusing a placard, announcing the exhibition of a large beautiful milk-white bullock, said to be a ton weight. In the midst of his reading the priest was surprised to hear himself called by name. “Ho! ho! Mr K——, come hither!” His eye followed in the direction of the sounds, and at about a perch distant he beheld Rivers, dressed as usual in his long blue cloak, gun-mouthed breeches, blue rib-and-fur stockings, his red nightcap and fire-shovel hat—as ludicrous a figure, “take him for all and all,” as ever stood in a market.

“Ho! ho! Mr K——, come hither,” and the priest, not unwillingly, obeyed the summons. The meeting occurred just in the market-place. The little square was thronged to excess. The anxiety of business sat upon every countenance, and hundreds, passing hither and thither in the ardent pursuit of their own affairs, might have passed their most intimate friend without recognition; so true it is that the contemplative man is never more in solitude than in the midst of a crowd. But the first salutations over, Rivers entered eagerly into conversation with the priest, on topics of mutual interest; with not unwarrantable familiarity he laid his hand on his shoulder, continued to talk earnestly, insinuated his finger into a button-hole, without, apparent motive caught him by the collar, then grasped it firmly; and that done, to his victim’s consternation he pulled off his fire-shovel hat, left the red nightcap uncovered, and with much vigour brandishing the chapeau, began to call an auction. The market-people deemed him mad. The priest felt no desire to be disposed of by public sale, but Snap laboured most earnestly in his new vocation.

“Ho, ho! oh yes! oh yes! hear ye! hear ye!”

And the people did hear, and did flock around the pair. The priest’s feelings may be fancied more readily than pourtrayed. He at once saw his tormentor’s aim; he knew that violence would only serve to increase the awkwardness of his position, and with much presence of mind he resolved quietly to baffle, and if possible to turn the table upon Rivers. The crowd rushed rapidly to the centre of attraction. Mr K—— remained apparently unconcerned, and Snap was the object of every eye, as he continued vociferously to bawl, “Hear ye! hear ye! oh yes! oh yes!” The gaping spectators were lost in wonderment. No one could either divine the cause of the uproar or explain the strange conduct of the man in the cloak. At length the priest, seizing the favourable moment, pulled off his hat, and with a serene look and respectful tone thus addressed the assembly—

“Ladies and gentlemen, I have the honour of informing[Pg 280] you that Mr John Rivers of the Doaghs, this long gentleman at my shoulder with the blue cloak and red nightcap, purposes in his present remarkable dress to ride ‘the white bullock’ three times round the market this day for your amusement; the performance to begin precisely at 12 o’clock.”

Three thundering cheers announced the delight of the crowd, while Rivers, baffled, disappointed, astonished, perfectly dumfoundered, slackened his gripe, fell back a few steps, and stared most fixedly at the placid countenance of the priest; he gaped and struggled for utterance; the muscles of his face played in wild commotion. He solemnly raised his hands and eyes in the attitude of prayer, and at last was enabled to bawl, or rather half sing, “All that ever you did upon me was but a flea-bite to this. So, to make up matters, you shall dine with Yellow Peg and me to-morrow; you are the only man that ever could say he was more than a match for Snap Rivers.”

H. H.

After dining with Caviglia, dear A——, to continue my yarn, we started by moonlight for the Pyramid, in company with the Genius Loci, and duly provided with candles for exploration. I must premise that Caviglia, whose extraordinary discoveries you are doubtless well acquainted with, has just been set to work again by Colonel Vyse, Mr Sloane, and Colonel Campbell, our Consul-General at Cairo. He is at present attempting to make further discoveries in the Great Pyramid; and as soon as he gets a firman from the Pasha, intends to attack the others.

The shape of this Pyramid has been compared to “four equilateral triangles on a square basis, mutually inclining towards each other till they meet in a point.” Lincoln’s-Inn Fields, the area of which corresponds to its base, wholly filled up with an edifice higher by a third than St Paul’s, may give some idea of its dimensions.

The entrance is on the northern face of the Pyramid, on the sixteenth step, though you can ride up to it, such immense mounds of fallen stones have accumulated at the base. A long low passage, most beautifully cut and polished, runs downwards above 260 feet at an angle of twenty-seven degrees, to a large hall sixty feet long, directly under the centre of the Pyramid, cut out of rock, and never, it would appear, finished. This was discovered by Caviglia; the passage before this time was supposed to end about half way down, being blocked up with stones at the point where another passage meets it, running upwards at the same angle of 27, and by which you might mount in a direct line to the grand gallery, and from that to the king’s chamber, where stands the sarcophagus, nearly in the centre of the pile, were it not for three or four blocks of granite that have been slid down from above, in order to stop it up.

By climbing through a passage, formed, as it is supposed, by the Caliph Mamoun, you wind round these blocks of granite into the passage, so that, with the exception of ten or twelve feet, you do in fact follow the original line of ascent. We descended by it. Close to the opening of this passage on the grand gallery is the mouth of a well about 200 feet deep, by which we ascended from the neighbourhood of the great lower hall. Two or three persons had descended it before Caviglia’s time, but he cleared it out to the full depth that his predecessors had reached, and believing it went still deeper, hearing a hollow sound as he stamped on the bottom, he attempted to excavate there, but was obliged to desist on account of the excessive heat, which neither he nor the Arabs could stand.

Think what his delight must have been, when in the course of clearing the passage which I mentioned to you leads directly from the great lower hall, smelling a strong smell of sulphur; and remembering he had burnt some in the well to purify the air, he dug in that direction, and found a passage leading right into the bottom of the well, where the ropes, pick-axes, &c., &c., were lying that he had left there in despair, on abandoning the idea of further excavation in that direction as hopeless.

Up this well, as I said, we climbed, holding a rope, and fixing our feet in holes cut in the stone; the upper part of the ascent was very difficult, and bats in numbers came tumbling down on us; but at last we landed safely in the grand gallery, a noble nondescript of an apartment, very lofty, narrowing towards the roof, and most beautifully chiselled; it ends towards the south in a staircase, if I may so term an inclined plane, with notches cut in the surface for the feet to hold by; the ascent is perilous, the stone being as polished and slippery as glass; before ascending, however, we proceeded by another beautifully worked passage, cut directly under the staircase to a handsome room called the queen’s chamber. Returning to the gallery, we mounted the inclined plane to the king’s chamber, directly over the queen’s. The passage to leading to it was defended by a portcullis now destroyed, but you see the grooves it fell into. His majesty’s chamber is a noble apartment, cased with enormous slabs of granite, twenty feet high; nine similar ones (seven large and two half-sized) form the ceiling.

At the west end stands the sarcophagus, which rings, when struck, like a bell. From the north and south sides respectively of this room branch two small oblong-square passages, like air-holes, cut through the granite slabs, and slanting upwards—the first for eighty feet in a zigzag direction, the other for one hundred and twenty.

It is Caviglia’s present object to discover whither these lead. Being unable to pierce the granite, he has begun cutting sideways into the limestone at the point where the granite casing of the chamber ends has reached the northern passage at the point where it is continued through the limestone, and is cutting a large one below it, so that the former runs like a groove in the roof of the latter, and he has only to follow it as a guide, and cut away till he readies the denouement. “Now,” says Caviglia, “I will show you how I hope to find out where the southern passage leads to.”

Returning to the landing-place at the top of the grand staircase, we mounted a ricketty ladder to the narrow passage that leads to Davison’s chamber, so named after the English consul at Algiers, who discovered it seventy years ago; it is directly above the king’s chamber, the ceiling of the one forming, it would appear, the floor of the other. The ceiling of Davison’s chamber consists of eight stones, beautifully worked; and this ceiling, which is so low that you can only sit cross-legged under it, Caviglia believes to be the floor of another large room above it, which he is now trying to discover. To this room he concludes the little passage leads that branches from the south side of the king’s chamber. He has accordingly dug down the calcareous stone at the farther end of Davison’s chamber, in hopes of meeting it; once found, it will probably lead him to the place he is in quest of.—Lord Lindsay’s Letters from the East.

John Philpot Curran.—Mr Curran happening to cross-examine one of those persons known in Ireland by the significant description of half-gentlemen, found it necessary to ask a question as to his knowledge of the Irish tongue, which, though perfectly familiar to him, the witness affected not to understand, whilst he at the same time spoke extremely bad English. “I see, sir, how it is: you are more ashamed of knowing your own language than of not knowing any other.”

A barrister entered the hall with his wig very much awry, and of which not at all apprised, he was obliged to endure from almost every observer some remark on its appearance, till at last, addressing himself to Mr Curran, he asked him, “Do you see any thing ridiculous in this wig?” The answer instantly was, “Nothing but the head.”

Bills of indictment had been sent up to a grand jury, in the finding of which Mr Curran was interested. After delay and much hesitation, one of the grand jurors came into court to explain to the judge the grounds and reasons why it was ignored. Mr Curran, very much vexed by the stupidity of this person, said “You, sir, can have no objection to write upon the back of the bill ignoramus, for self and fellow-jurors; it will then be a true bill.”

Mr Hoare’s countenance was grave and solemn, with an expression like one of those statues of the Brutus head. He seldom smiled; and if he smiled, he smiled in such a sort as seemed to have rebuked the spirit that could smile at all. Mr Curran once observing a beam of joy to enliven his face, remarked, “Whenever I see smiles on Hoare’s countenance, I think they are like tin clasps on an oaken coffin.”

Printed and published every Saturday by Gunn and Cameron, at the Office of the General Advertiser, No. 6, Church Lane, College Green, Dublin.—Agents:—R. Groombridge, Panyer Alley, Paternoster Row, London; Simms and Dinham, Exchange Street, Manchester; C. Davies, North John Street, Liverpool; Slocombe and Simms, Leeds; Fraser and Crawford, George Street, Edinburgh; and David Robertson, Trongate, Glasgow.