Title: Reports Relating to the Sanitary Condition of the City of London

Author: John Simon

Release date: April 28, 2017 [eBook #54622]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Harry Lamé and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

BY

LONDON:

JOHN W. PARKER AND SON, WEST STRAND.

MDCCCLIV.

LONDON:

SAVILL AND EDWARDS, PRINTERS, CHANDOS STREET,

COVENT GARDEN.

[iii]

TO

LOUIS MICHAEL SIMON,

OF THE STOCK EXCHANGE, LONDON, AND OF

THE PARAGON, BLACKHEATH,

I DEDICATE THIS REPRINT OF MY REPORTS:

LOOKING

LESS TO WHAT LITTLE INTRINSIC MERIT THEY MAY HAVE,

THAN TO THE YEARS OF ANXIOUS LABOUR THEY REPRESENT:

DEEMING IT FIT TO ASSOCIATE

MY FATHER’S NAME

WITH A RECORD OF ENDEAVOURS TO DO MY DUTY:

BECAUSE IN THIS HE HAS BEEN MY BEST EXAMPLE;

AND

BECAUSE I COUNT IT THE HAPPIEST INFLUENCE IN MY LOT,

THAT, BOUND TO HIM BY EVERY TIE OF GRATEFUL AFFECTION,

I HAVE LIKEWISE BEEN ABLE, FROM MY EARLIEST CHILDHOOD

TILL NOW—THE EVENING OF HIS LIFE,

TO REGARD HIM WITH UNQUALIFIED AND INCREASING RESPECT.

[v]

| Page | |

|---|---|

| Dedication | iii |

| Preface | vii |

| First Annual Report | 1 |

| Further Remarks on Water-supply | 72 |

| Second Annual Report | 77 |

| Third Annual Report | 177 |

| Fourth Annual Report | 211 |

| Fifth Annual Report | 213 |

| Appendix of Tables Illustrating the Sanitary Condition of the City of London. | 264 |

| Report on City Burial-Grounds | 280 |

| Report on Extramural Interments | 285 |

[vii]

The following Reports, officially addressed to the Commissioners of Sewers of the City of London, were originally printed only for the use of the Corporation; and although, to my very great pleasure, they have been extensively circulated through the medium of the daily press, there has continued so frequent an application for separate copies that the surplus-stock at Guildhall has long been exhausted. Under these circumstances—believing the Reports may have some future interest, as belonging to an important educational period in the matters to which they refer, I have requested the Commission to allow their collective reprint and publication; and this indulgence having been kindly accorded me, I have gathered into the present volume all my Annual Reports, together with a special Report suggesting arrangements for extramural burial.

From the nature of the work, I have not considered myself at liberty to make those extensive alterations of text which usually belong to a second edition. I have restricted myself to a few verbal[viii] corrections, and to rectifying or omitting some unimportant paragraph, here or there, in case its matter has been more fully or more correctly stated in parts of a subsequent Report. Frequently, where I have wished to explain or qualify passages in the text, I have added foot-notes; but these are distinguished as interpolations by the mark—J. S., 1854.

My Reports lay no claim to the merit of scientific discovery. Rather, they deal with things already notorious to Science; and, in writing them, my hopes have tended chiefly towards winning for such doctrines more general and more practical reception. It has seemed to me no unworthy object, that, confining myself often to almost indisputable topics—to truths bordering on truism, I should labour to make trite knowledge bear fruit in common application.

Nor in any degree do they profess to be cyclopædic in the subject of Preventive Medicine; for it is but a small part of this science that hitherto is recognised by the law; and that—so far as the metropolis is concerned, scarcely beyond the confines of the City. It would have been an idle sort of industry, to say much of places or of matters foreign to the jurisdiction of those whom I officially addressed.

In re-publishing documents which proclaim extreme[ix] sanitary evils, as affecting the City, I think it right to draw attention to the dates of the several Reports, and to state that for the last five years many of these evils have been undergoing progressive diminution, of late at a rapid and increasing rate; while, at their worst, they represented only what I fear must be considered the present average condition of our urban population.

This national prevalence of sanitary neglect is a very grievous fact; and though I pretend to no official concern in anything beyond the City boundaries, I cannot forego the present opportunity of saying a few words to bespeak for it the reader’s attention. I would beg any educated person to consider what are the conditions in which alone animal life can thrive; to learn, by personal inspection, how far these conditions are realised for the masses of our population; and to form for himself a conscientious judgment as to the need for great, if even almost revolutionary, reforms. Let any such person devote an hour to visiting some very poor neighbourhood in the metropolis, or in almost any of our large towns. Let him breathe its air, taste its water, eat its bread. Let him think of human life struggling there for years. Let him fancy what it would be to himself to live there, in that beastly degradation of stink, fed with such bread, drinking such water. Let him enter[x] some house there at hazard, and—heeding where he treads, follow the guidance of his outraged nose, to the yard (if there be one) or the cellar. Let him talk to the inmates: let him hear what is thought of the bone-boiler next door, or the slaughter-house behind; what of the sewer-grating before the door; what of the Irish basket-makers upstairs—twelve in a room, who came in after the hopping, and got fever; what of the artisan’s dead body, stretched on his widow’s one bed, beside her living children.

Let him, if he have a heart for the duties of manhood and patriotism, gravely reflect whether such sickening evils, as an hour’s inquiry will have shown him, ought to be the habit of our labouring population: whether the Legislature, which his voice helps to constitute, is doing all that might be done to palliate these wrongs; whether it be not a jarring discord in the civilisation we boast—a worse than pagan savageness in the Christianity we profess, that such things continue, in the midst of us, scandalously neglected; and that the interests of human life, except against wilful violence, are almost uncared for by the law.

And let not the inquirer too easily admit what will be urged by less earnest persons as their pretext for inaction—that such evils are inalienable from poverty. Let him, in visiting those homes[xi] of our labouring population, inquire into the actual rent paid for them—dog-holes as they are; and studying the financial experience of Model Dormitories and Model Lodgings, let him reckon what that rent can purchase. He will soon have misgivings as to dirt being cheap in the market, and cleanliness unattainably expensive.

Yet what if it be so? Shift the title of the grievance—is the fact less insufferable? If there be citizens so destitute, that they can afford to live only where they must straightway die—renting the twentieth straw-heap in some lightless fever-bin, or squatting amid rotten soakage, or breathing from the cesspool and the sewer; so destitute that they can buy no water—that milk and bread must be impoverished to meet their means of purchase—that the drugs sold them for sickness must be rubbish or poison; surely no civilised community dare avert itself from the care of this abject orphanage. And—ruat cœlum, let the principle be followed whithersoever it may lead, that Christian society leaves none of its children helpless. If such and such conditions of food or dwelling are absolutely inconsistent with healthy life, what more final test of pauperism can there be, or what clearer right to public succour, than that the subject’s pecuniary means fall short of providing him other conditions than those? It may[xii] be that competition has screwed down the rate of wages below what will purchase indispensable food and wholesome lodgment. Of this, as fact, I am no judge; but to its meaning, if fact, I can speak. All labour below that mark is masked pauperism. Whatever the employer saves is gained at the public expense. When, under such circumstances, the labourer or his wife or child spends an occasional month or two in the hospital, that some fever-infection may work itself out, or that the impending loss of an eye or a limb may be averted by animal[1] food; or when he gets various aid from his Board of Guardians, in all sorts of preventable illness, and eventually for the expenses of interment, it is the public that, too late for the man’s health or independence, pays the arrears of wage which should have hindered this suffering and sorrow.

[1] Twenty years’ daily experience of hospital surgery enables me to say, from personal knowledge, that our wards and out-patient rooms are never free from painful illustrations of the effects of insufficient nutrition—cases, in fact, of chronic starvation-disease among the poor; such disease as Magendie imitated, in his celebrated experiments, by feeding animals on an exclusively non-azotised diet.

Probably on no point of political economy is there more general concurrence of opinion, than against any legislative interference with the price of labour. But I would venture to submit, for the[xiii] consideration of abler judges than myself, that before wages can safely be left to find their own level in the struggles of an unrestricted competition, the law should be rendered absolute and available in safeguards for the ignorant poor—first, against those deteriorations of staple food which enable the retailer to disguise starvation to his customers by apparent cheapenings of bulk; secondly, against those conditions of lodgment which are inconsistent with decency and health.

But if I have addressed myself to this objection, partly because—to the very limited extent in which it starts from a true premiss, it deserves reply; and partly because I wish emphatically to declare my conviction, that such evils as I denounce are not the more to be tolerated for their rising in unwilling Pauperism, rather than in willing Filth; yet I doubt whether poverty be so important an element in the case as some people imagine. And although I have referred especially to a poor neighbourhood—because here it is that knowledge and personal refinement will have least power to compensate for the insufficiencies of public law; yet I have no hesitation in saying that sanitary mismanagement spreads very appreciable evils high in the middle ranks of society; and from some of the consequences, so far as I am aware, no station can call itself exempt.

[xiv]

The fact is, as I have said, that, except against wilful violence, life is practically very little cared for by the law. Fragments of legislation there are, indeed, in all directions: enough to establish precedents—enough to testify some half-conscious possession of a principle; but, for usefulness, little beyond this. The statutes tell that now and then, there has reached to high places the wail of physical suffering. They tell that our law-makers, to the tether of a very scanty knowledge, have, not unwillingly, moved to the redress of some clamorous wrong. But—tested by any scientific standard of what should be the completeness of sanitary legislation; or tested by any personal endeavour to procure the legal correction of gross and glaring evils; their insufficiencies, I do not hesitate to say, constitute a national scandal, and, perhaps in respect of their consequences, something not far removed from a national sin.

In respect of houses—here and there, under local Acts of Parliament, exist sanitary powers, generally of a most defective kind; pretending often to enforce amendments of drainage and water-supply; sometimes to provide for the cleansing of filthy and unwholesome tenements; in a few cases to prevent over-crowding; very rarely to ensure stringent measures against houses certified to be unfit for human habitation. Occasionally—but[xv] a few lines would exhaust the list, an application of the Public Health Act, or some really efficient local Act, has put it within reach of the authorities to do all that is needful under certain of these heads. But I know of no such town that would bear strict examination as to its possession of legal powers to fulfil, what I presume must be the principle contemplated by the law—that no house should be let for hire unless presenting the conditions indispensable for health, or be hired for more occupants than it can decently and wholesomely accommodate.[2] However this[xvi] may be expressed, and in whatever laws embodied, local or general, I will venture to say that no Government should suffer a town, either to be without the means of enforcing this principle, or, having such means, to shirk their exercise. Our Constitution may properly concede that local representative authorities shall have their option whether, for sanitary purposes, to fall under a general law, or to have Local Improvement Acts of their own; but, in the present state of knowledge, it certainly seems incontestable that one or other of these alternatives should be compulsory, and that all Local[xvii] Improvement Acts should be required, in their sanitary clauses, to come up to the standard of the Public Health Act of the time, whatever it may be.

[2] In addition to the ordinary powers—given, for instance, in the Public Health or City Sewers Act, for abating accumulated nuisances and for enforcing wholesome constructional arrangements; a principal requirement of all bodies having jurisdiction for the public health is, that there should be vested in them some authority, enabling them to regulate, in the spirit of the Common Lodging House Act, all houses which are liable to be thronged by a dangerous excess of low population. Almost invariably such houses are of the class technically known as ‘tenement-houses,’ i. e., houses divided into several tenements or holdings; whereof each—though very often consisting but of a single small room, receives its inmates without any available restriction as to their sex or number, and without regard to the accommodation requisite for cleanliness, decency, and health. The inhabitants of such houses, especially where of the lower order of Irish, constantly lapse into the most brutal filthiness of habits, and live in almost incredible conditions of dirt, over-crowding, and disease. See sections of the following Reports, beginning severally at pages 44, 146, and 195. Powers for dealing with these evils might be given to Local Boards of Health, most usefully, I think, in some such form as the following: 1) that—in respect of any house occupied by more than one family, if it be situate in any court, alley, or other place having no carriage-way, and be not assessed to the poor-rate at a higher rental than £...... per annum; or if in it any occupied holding consist of only one room, provided the rent of such room do not exceed the sum of ......shillings per week, or if in it there reside, or within three months previous have resided, any person receiving parochial relief, medically or otherwise; on the certificate of a duly authorized medical officer, that any such house, or part thereof, is habitually in a filthy condition, or that from over-crowding or defective ventilation the health of its inmates is endangered, or that there has prevailed in it undue sickness or mortality of an epidemic or infectious kind; the Local Board may call upon its owner to register it in a book kept for this purpose; and in respect of all houses thus registered, the Local Board may make rules for periodical washing, cleansing, and limewhiting, and for the regular removal of all dust or refuse-matter, may fix the number of tenements into which it shall be lawful to divide any such house, or the total number of inmates who may at one time be received therein, may require its better ventilation by the construction of additional windows or louvres, and may from time to time make such other regulations and orders as they shall judge necessary for the maintenance of health and decency; and may recover from the owner or lessee of any such house penalties for neglect of any legal requisitions, rules, and orders, as aforesaid: 2) that—on the certificate of a duly authorised medical officer, that the condition of any house or room is such as to render probable the rise or the spread of infectious and dangerous disease among its inmates, the Local Board may cause the owner or lessee of such house to be summoned before a magistrate; who, after due hearing, or in default of the owner’s or lessee’s appearance, may order the house, or any part of it, to be evacuated of all tenants within such time as he shall judge fit, and not again to be tenanted till after licence from the Local Board given on the certificate of their medical officer that its causes of unhealthiness are abated; and the magistrate may enforce penalties for non-compliance with his order, as aforesaid: 3) that—after an Order in Council bringing into action the extraordinary clauses of the Nuisances Removal Act, the Local Board, on receiving the certificate of their medical officer that any house, or part of house, is in such condition as to be imminently dangerous to the lives of its inmates in respect of the prevailing epidemic, or any similar disease, may issue a peremptory order for its evacuation, and may recover, from the owner or lessee to whom such order is addressed, penalties for every day during which, or part of which, after such order, the house, or any part thereof, continues to be tenanted; nor, under like penalties, shall it be lawful, except after written licence from the Local Board, given as aforesaid, to allow such house to be re-occupied.

Under circumstances like those just adverted to, may be found traces of enactment against offensive and injurious trades. Unregulated slaughtering throughout all London, except the City, tallow-melting in St. Paul’s church-yard, bone-boiling beside Lambeth Palace, may serve to illustrate the[xviii] completeness and efficiency of these laws—even in our metropolitan area. Here we greatly lack some competent authority, on the part of the Government, to investigate all circumstances connected with such establishments, generally; to suggest laws for their prospective restriction, as to places wherein they may lawfully settle; and to frame regulations—enforceable by any Local Board of Health, for ensuring that all available measures be employed to mitigate their nuisance. Considering the circumstances under which many of these establishments have existed, no one can entertain a thought, that—even for the public health, they should be liable to the tyranny of an unconditional displacement. But if there existed—as undoubtedly there should exist, some skilled tribunal, competent to speak on the subject; then, I will venture to say, it might be quite in accordance with our English sense of liberty, that—after a certain condemnatory verdict by this tribunal, it should be open to the Local Board of Health to procure their expulsion, on payment of whatever compensation an ordinary jury might award.

Again, with factories; thanks to Lord Shaftesbury’s indefatigable benevolence, the law has appointed an inspection of certain establishments, a restriction of their hours of labour, and some care against the dangers of unboxed machinery.[xix] And with mining also the law has interfered, chiefly as to the ventilation of mines; but hitherto so ineffectively that, while I write, the coal-miners are remonstrating with the Legislature on the thousand lives per annum still sacrificed through the insufficient protection accorded them. If there be meaning in this legislation—if it imply any principle, the meaning and the principle require to be developed into a general law, that every establishment employing labour be liable to inspection and regulation in regard of whatever acts and conditions are detrimental or hazardous to life. If factory-children are cared for, lest they be over-worked; and miners, lest they be stifled; so, for those who labour with copper, mercury, arsenic, and lead, let us care, lest they be poisoned! for grinders, lest their lungs be fretted into consumption! for match-makers, lest their jaws be rotted from them by phosphorus! And here let it again be noticed, as in the class of cases last spoken of, how greatly wanted is some skilled tribunal, to form part of any lawful machinery which might ensure that, in these and similar instances, no precautions necessary to life are withheld through ignorance or parsimony.

Against adulterations of food, here and there, obsolete powers exist, for our ancestors had an eye to these things; but, practically, they are of no[xx] avail. If we, who are educated, habitually submit to have copper in our preserves, red-lead in our cayenne, alum in our bread, pigments in our tea, and ineffable nastinesses in our fish-sauce, what can we expect of the poor? Can they use[3] galactometers? Can they test their pickles with ammonia? Can they discover the tricks by which bread is made dropsical[4], or otherwise deteriorated in value, even faster than they can cheapen it in price? Without entering on details of what might be the best organisation against such things, I may certainly assume it as greatly a desideratum, that local authorities should uniformly have power to deal with these frauds (as, of course, with every sale of decayed and corrupted food) and that they should be enabled to employ skilled officers, for detecting at least every adulteration of bread and every poisonous admixture in condiments and the like.

[3] The proverbial dilutions of milk are not its only deteriorations. Cows are so ill kept in London, and in consequence so often sickly, that milk suffers—sometimes by mere impoverishment, sometimes by much graver derangements. If there were instituted a proper Inspection of Provisions, one function of its officers should be to visit cow-houses, and to prevent the distribution of milk thus damaged or infected. I suspect that a sanitary reform of these establishments would make a sensible difference to the nursery-population of the metropolis.

[4] A chief artifice in the cheapening of bread is to increase its weight by various means which render it retentive of water. The other usual frauds consist in the employment of inferior flours—either not cereal, or damaged and partially deglutinised.

[xxi]

In some respects this sort of protection is even more necessary, as well as more deficient, in regard to the falsification of drugs. The College of Physicians and the Apothecaries’ Company are supposed to exercise supervision in the matter; so that at least its necessity is recognised by the law. The security thus afforded is, in practice, null. It is notorious in my profession that there are not many simple drugs, and still fewer compound preparations, on the standard strength of which we can reckon. It is notorious that some important medicines are so often falsified in the market, and others so often mis-made in the laboratory, that we are robbed of all certainty in their employment. Iodide of potassium—an invaluable specific, may be shammed to half its weight with the carbonate of potash. Scammony, one of our best purgatives, is rare without chalk or starch, weakening it, perhaps, to half the intention of the giver. Cod-liver oil may have come from seals or from olives. The two or three drops of prussic acid that we would give for a dose may be nearly twice as strong at one chemist’s as at another’s. The quantity of laudanum equivalent to a grain of opium being, theoretically, 19 minims; we may practically find this grain, it is said, in 4.5 minims, or in 34.5. And my colleague, Dr. R. D. Thomson, who has much experience in these matters, tells me that of[xxii] calamine—not indeed an important agent, but still an article of our pharmacopœia—purporting daily to be sold at every druggist’s shop, there has not for years, he believes, existed a specimen in the market.[5]

[5] Dr. Thomson tells me that he has known white precipitate of mercury sold in hundred-weights as calomel, and in one case (he believes by accident or ignorance) as trisnitrate of bismuth. In my text I have endeavoured to adduce such illustrations as I suppose to be most notorious; but I may refer the reader to various interesting papers published, through the last two or three years, in the Lancet (Analytical Sanitary Commission) from one of which I quote the astounding instance, given above, of variations in the strength of laudanum. Mr. Thomas Taylor, of Vere Street, informs me that, whereas an ounce of laudanum should contain about four grains of morphia, he finds the actual quantity varying in different specimens from two grains to six; and that in two specimens of solid opium, outwardly alike and supposed to be of equal quality, he has found the per centage of morphia to vary from 31⁄2 to 10. It requires little instruction in medicine to appreciate these facts.

Again, with the promiscuous sale of poisons, what incredible laxity of government! One poison, indeed, has its one law. Arsenic may not be sold otherwise than coloured, nor except with full registration of the sale, and in the presence of a witness known to both buyer and vender. Admirable, so far as it goes! but why should arsenic alone receive this dab of legislation? Is the principle right, that means of murder and suicide should be rendered difficult of access for criminal purposes? Does any one question it? Then, why[xxiii] not legislate equally against all poisons?—against oxalic acid and opium, ergot and savin, prussic acid, corrosive sublimate, strychnine?

Nor can our past legislators be more boastful of their labours for the medical profession—either for its scientific interests, or for the public protection against ignorance and quackery.[6] Nearly two dozen corporate bodies within the United Kingdom are said to grant licences for medical practice; and I hardly know whether it lessens or aggravates this confusion, that such licences are in many cases partial; that one licentiate may practise north of the Tweed, but nowise to the south; that one may practise in London, another only seven miles beyond it. Not that the licence seems much to matter! for innumerable poachers in all directions trespass on what the law purports to sell as a secured preserve for qualified practitioners: their encroachments are made with almost certain impunity;[xxiv] and—as for the titles of the Profession, any impostor may style himself doctor or surgeon at his will. Even where licences are held, conveying identical titles, they imply neither equal privileges (as I have said) nor even uniform education. The law has troubled itself little as to the terms on which they shall be granted; and the qualifications exacted from candidates—the conditions preliminary to their becoming eligible for licence, vary in so remarkable a degree among the many corporate bodies which are fountains of this honour, that the credentials conferred have really little meaning, apart from a context which the public is unable to supply. It is charged against particular institutions, that their degrees and licences are attained with a very inglorious facility; and when it is recollected that the issuing of such testimonials is a source—sometimes a chief source—of income to the corporations which grant them, it will be felt that at least there must exist great danger of this reproach being sometimes deserved. If a national title to practise medicine is to be granted by several Boards, and if yet the tenure of that title is to determine public confidence in favour of its holder, it would seem indispensable that some guarantee should be given for these several licences representing equal qualifications—some guarantee that the holder in each case possesses professional[xxv] knowledge, and has enjoyed professional opportunities, at least above some uniform standard recognised as a minimum qualification by all the diplomatising bodies. Indispensable, however, as this may seem, years of endeavour have failed to attain it. What is called medical reform has been agitated longer than I can remember; and more than one minister has been willing to legislate for its promotion. Unfortunately the very magnitude of the evils has delayed their cure. With the constitution I have described—a system of conflicting jurisdictions, of licences without titles, and titles without licences, how could we escape internal dissension? how escape the antagonism, perhaps the jealousies, of rival corporations and of different professional classes? Home-Secretaries have had little leisure to fathom these things to the bottom. Unexamined and unadjudicated by any competent authority, such influences have bewildered public judgment, made statesmen regard us with despair, postponed legislative correction, and maintained us in a state of anarchy and confusion, best to be appreciated when we compare with our own the organisation and government of the legal profession.

[6] Legislative passiveness towards scientific medicine is not the only evil we have to complain of. Surely, in selling Letters Patent for the protection of quack-medicines—in seeming to sanction and authenticate whatever lies their proprietor may post upon the wall, the State demeans itself into complicity with fraud, and soils its fingers with something fouler than the Vespasian tax. It illustrates the curious forgetfulness shewn towards medicine by the Legislature, that this immoral practice of giving patents for pretended cures of disease should have been allowed to continue—as of course it must have continued, solely by oversight, till past the middle of the nineteenth century.

And be it noted, how this reacts upon the State. So completely is our government dissevered from Science in general, and, most of all, from the sciences[xxvi] relating to Life, that, on such subjects, there exists not for state-purposes anything like a tribunal of appeal. The Legislature recognises no Medical Authority. Occasionally this fact stands out in painful conspicuousness, and brings most injurious results. In contested cases requiring scientific testimony—before Parliamentary Committees, for instance, and in a variety of legal proceedings,—instead of the Court having satisfactory power of referring particular questions to skilled impartial adjudicators, the uniform practice is, that scientific men are retained on opposite sides, to support partisan interests. The advantages, such as they are, which belong to this system, might, I believe, easily be obtained under altered arrangements: the disadvantages are glaring. It might be invidious to refer to illustrations of their reality: but it is of course impossible to doubt of the working of this system, that, in so far as it makes each witness feel himself engaged to maintain the views of his employer, it tends towards a moral prostitution and subornation of science. In the interests of truth, it would surely seem desirable that scientific evidence should be tendered, so far as may be, in a judicial spirit towards the suit; either that the technical point should be referred to a technical jury, or that the technical witness should be summoned at the Court’s discretion, should be examined[xxvii] in-chief by the Court, and should be subject only to such cross-examination as may procure the most complete statement of his knowledge on the matter in hand.

Having said so much on the defects and the wrongs of our existing sanitary condition, perhaps I may venture to speak of the almost obvious remedy. ‘Almost obvious’ I say; for surely no one will doubt that this great subject should be dealt with by comprehensive and scientific legislation; and I hardly see how otherwise, than that it should be submitted in its entirety to some single department of the executive, as a sole charge; that there should be some tangible head, responsible—not only for the enforcement of existing laws, such as they are or may become, but likewise for their progress from time to time to the level of contemporary science, for their completion where fragmentary, for their harmonisation where discordant.

If—as is rumoured, the approaching re-constitution of the General Board of Health is (after the pattern of the Poor-law Board) to give it a Parliamentary President, that member of the Government ought to be open to challenge in respect of every matter relating to health. What, for this purpose, might be the best subordinate arrangements of such a Board, it would take a volume to discuss. But at least as regards its constituted[xxviii] head, sitting in Parliament, his department should be, in the widest sense, to care for the physical necessities of human life. Whether skilled coadjutors be appointed for him or not; engineers—lawyers—chemists—pathologists; whether he be, as it were, the foreman of this special jury, or, according to the more usual precedent of our public affairs, collect advice on his own responsibility, and speak without quotation of other authority than himself, his voice, unless the thing is to be a sham, must represent all these knowledges.

The people, through its representatives, must be able to arraign him wherever human life is insufficiently cared for.

He must be able to justify or to exterminate adulterations of food; to shew that alum ought to be in our loaves, or to banish it for ever; to shew that copper is wholesome for dessert, or to give us our olives and greengages without it; to shew that red-lead is an estimable condiment, or to divert it from our pepper-pots and curries.

Similarly with drugs and poisons—the alternatives of life and death—a minister of Public Health would, I presume, be responsible for whatever evils arise in their unlicensed and unregulated sale. He would hardly dare to acquiesce in our present defencelessness against fraud and ignorance; in doses being sold—critical doses, for the strength of[xxix] which we, who prescribe them, cannot answer within a margin of cent. per cent.; or in pennyworths of poison being handed across the counter as nonchalantly as cakes of soap.[7] Surely, before he had been six months in office, he would have procured some enactment to remedy this long neglect of the legislature, by providing that the druggist’s trade be exercised only after some test of fitness, and in subjection to certain regulations.

[7] Without referring to what may be considered rare—the sale of poison for the purposes of intended homicide, I may remind the reader of the very dreadful facts collected by the Commissioners on Trades and Manufactures, as to the immense sales of opium in our principal manufacturing towns, for the purpose of quieting—and with the effect of killing, children, while their poor mothers are absent from home in their several occupations.

Within his province, likewise, it would fall to be cognisant of all that relates to the constitution of the Medical Profession. The difficulties which have baffled successive Home-Secretaries might soon find their solution in the less divided attention which he could bring to their study. Amid conflicting opinions and an apparent scramble for power, he would soon distinguish where might be the strife of jealousy and covetousness, where a truthful zeal for the honour and efficiency of medicine. I think he could not be long in curing our more scandalous anomalies. Probably—unless human bowels require other doctoring in London[xxx] than in Manchester, he would manage that a doctor there should be a doctor also here; that no licence for the partial practice of medicine should be recognised—no licence admitting a man to do in Edinburgh what it would be a misdemeanour for him to do in Greenwich. And obviously, in order to this—since a professional diploma is the only criterion by which the public can measure the competence of those who seek their patronage, he would see that, as far as may be, the various licensing bodies exact from their candidates equal and sufficient qualifications; that the diploma entitling a man to call himself Surgeon or Physician, Accoucheur or Apothecary, mean the same thing—imply the same education, whether it be got in Scotland, Ireland, or England; and that any falsification of such diploma, or any unauthorised assumption of the title which implies its possession, be promptly punishable at law.[8]

[8] This check at least seems indispensable, for the reason above given, that a professional diploma is the only criterion by which the public can measure professional competence; and for the validity of such a criterion, it therefore, I think, becomes the duty of a government, on behalf of the public, to provide. For anything beyond this (except in one particular case) the matter might take its natural course. No law can supersede a necessity for common sense in the subject; and medicine, I think, requires no protection. Let my neighbour, by all means, if he desire it, send for a green-grocer to reduce his dislocation or assuage his gout! and let him take the consequences of his folly, in a spoilt limb or in a hair’s breadth escape with his life. Only—let the green-grocer be punishable, if he seek this office under false pretences, calling himself by any title which implies a professional qualification. And, for what harm he may do—let him of course (as would, if necessary, the presidents of our colleges) be prepared to abide before judge and jury his trial for malpractice. But, in strict adhesion to the principle I have professed, that protection is wanted, not for the profession, but for the public, I would suggest one exception to what otherwise might be universal free-trade in medicine. I refer to the case of druggists; who, whenever the Legislature may awake to the necessity of regulating their trade, ought, I think, to be expressly prohibited from the treatment of disease. To an immense majority of our population—to all the under-educated classes, the druggist’s shop appears an emporium for medical skill, as well as for medical appliances. They probably have some vague overestimate of our art of healing, and think perhaps that the several bottles on the shelf correspond to the several ailments they can specifically cure. They ask for something “good for a dropsy,” or “good for a wasting,” or “good for a palpitation;” not knowing how much skill may be requisite to interpret the symptom; not knowing that, to our highest skill, there is no medicine thus indiscriminately, or even generally, “good.” At present almost universally, druggists, with no medical qualification, are tampering more or less with serious medical responsibilities; and the mischief thus occasioned—especially among the poorer classes, is a matter of notoriety, on which persons engaged in hospital practice would be competent and tolerably impartial witnesses. It is because this evil arises in the almost inevitable ignorance of those who chiefly suffer from it, that, in accordance with the principle above suggested, I think it deserves consideration from the Legislature.

[xxxi]

Into the hands of this new minister—advised, perhaps, for such purposes by some permanent commission[9] of skilled person, would devolve the[xxxii] guardianship of public health against combined commercial interests, or incompetent administration. He would provide securities for excluding sulphur from our gas, and animalcules from our water. He would come into relation with all Local Improvement Boards, in respect of the sanitary purposes of their existence. To him we should look, to settle at least for all practical purposes the polemics of drainage and water-supply; to form opinions which might guide Parliament, whether street sewers really require to be avenues for men, whether hard water really be good enough for all ordinary purposes, whether cisternage really be indispensable to an urban water-supply.

[9] There are many instances in my mind, some already adverted to, where the existence of a standing jury for scientific—especially for sanitary, purposes might be of great utility. It is an organisation which prevails extensively in France, under the name of Conseils de Salubrité; forming, in most of the large towns there, a constant board of reference for the municipality, in respect of sanitary regulations. Mutatis mutandis, it might become invaluable as an English institution, in respect of many matters touched upon in this sketch; and perhaps with some division of duties, into such as would best belong to a General Board of the kind, and such as might properly be vested in Local Boards. To determine the indispensable conditions of healthy lodgment; to examine the influence of trades and occupations, and to devise the regulations they may require, for the neighbourhood’s sake, or for their operatives’; to supervise the sale of food and drugs; to be cognisant of medical matters; would seem, either locally or generally, to require the co-operations of several skilled persons. But, though I have spoken of such, as indispensable jurors for these subjects, I do not forget that other interests than those of life may need to be consulted. For the fair representation of these, the lay faculty of educated common-sense will fulfil an inestimable usefulness, if it may be there to mediate between science, which is sometimes crotchety, and trade, which is sometimes selfish.

[xxxiii]

Organisations against epidemic diseases—questions of quarantine—laws for vaccination, and the like, would obviously lie within his province; and thither, perhaps, also his colleagues might be glad to transfer many of those medical questions which now belong to other departments of the executive—the sanitary regulation of emigrant ships, the ventilation of mines, the medical inspection of factories and prisons, the insecurities of railway traffic, et hoc genus omne.

There is another subject respecting which I should reluctantly forego the present opportunity of saying something. To the philosopher, perhaps, any partial sanitary legislation—even for a metropolis, may seem of low importance, as compared with our commanding need that the general legislation of the country be imbued with deeper sympathies for life. Yet London is almost a nation in itself; and the good which might be effected by its sanitary regeneration would, even as example, be of universal influence. Now, at this moment, there seems a chance—such a chance as may not soon recur—for gaining a first step towards this consummation. The re-construction of the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers, on the principle of local representation, affords extraordinary facilities for providing London, at length, with an efficient sanitary government. For, while any administration[xxxiv] for this purpose would require to be entrusted with very extensive and very stringent powers, it seems probable that such authority might by the public be willingly conceded to a body constituted, in great part, of persons representing local interests. The jurisdiction required would be substantially such as is already vested in the City Commissioners of Sewers, for the sanitary control of the city; the concession of which—because to a representative body—was never any matter of municipal dispute. In so vast a government as that of the metropolis, Local Boards of Health for its various sections would seem indispensable; it is presumed that these boards[10] would be represented in the general Commission; which, in conjunction with them, and including certain skilled assessors, might constitute a complete sanitary organisation, consultative and executive.

[10] It would seem premature to discuss what might be the best constitution of such Local Boards for the metropolis; but it will appear to the reader, on a moment’s reflection, that there would be no difficulty in finding materials for their organisation. If, according to suggestions lately ventilated, municipal institutions should be given to the parts of London hitherto without them; these new corporations would probably have sanitary functions allotted them, and might readily become Local Boards of Health under such a constitution as I have sketched. If, on the other hand, our present non-municipal system were to be continued, probably our several Boards of Guardians might seem specially proper to act as Local Boards of Health; first, as being elected representative bodies, already invested with certain authority of the kind—as, for instance, under the Nuisances Removal Act; secondly, because various of their officers would be almost indispensable parts of any sanitary machinery. Indeed, my experience of such matters suggests it to me as not unimportant, that, under any arrangement which may be made, the jurisdiction of Local Boards of Health should, at least in area, be conterminous with Poor Law Unions; so that those who administer sanitary affairs—affairs which are always chiefly relative to the poor—may, as far as possible, in their several districts, come into relation with single sets of Poor Law officers.

I have one word more to say about the Reports. They have been received by the public with such[xxxv] remarkable indulgence and favour, that I feel some anxiety lest I may seem to have plumed myself with other feathers than my own. Let me, therefore, at least in part, confess my debts.

Before my first enlistment in the service of public health, others had fought this great cause with rare courage and devotion; establishing its main principles in a manner to require no corroboration, and to admit little immediate increase. The true patriarchs of the cause in this country are the present working members of the General Board of Health. The constitution of my city appointment is quite independent of this Board; but I should be acting an unworthy part if I refrained from acknowledging, that, in innumerable instances, I have gathered most valuable knowledge from the Board’s official publications, and that, in personal intercourse with its members and officers, I have had abundant reason to be grateful for information invariably given with that frank kindness which belongs[xxxvi] to brotherhood in science, and to sympathy for common objects.

I must likewise acknowledge constant obligations to the courtesy of the Registrar-General, and express with how much pleasure and instruction I have studied the works of his inestimable office. Especially I would offer my tribute of respect to Dr. Farr’s learning and industry, as well as to that capacity for generalisation which the world has long recognised in his eloquent and thoughtful writings.

And, though this be not the place to boast of private friendships, I may venture to say that there are few topics relating to sanitary medicine that I have not enjoyed the advantage of discussing with men who have given genius, inquiry, and reflection to their development.

Thank God! the number of persons capable of apprehending the cause, and ready to take interest in its promotion, is now daily on the increase. If some minister of Public Health could take his seat in the House of Commons—some minister knowing his subject and feeling it, I believe he would find no lack of sympathy and co-operation. The world abounds with admirable wishes and intentions, that vaguely miscarry for want of guidance. How many men can get no farther in their psalm of life than the question, in quo corriget. To such—not masters of the subject, but willing and eager to be its servants, an official leader might be[xxxvii] everything: for in great causes like this, where the scandal of continued wrong burns in each man’s conscience, the instincts of justice thirst for satisfaction. What can we do or give—how shall we speak or vote, to lessen these dreadful miseries of sanitary neglect—is, at this moment, I believe, the fervent inquiry of innumerable minds, waiting, as it were for the word of command, to act.

How much of this generous earnestness towards the cause exists in society—how much desire to grasp any reasonable opportunity of good has lately happened to fall under my notice. Last winter, when the signs of the times were making us fear that Cholera would presently again be epidemic in London, it was remembered that, in the greater part of the metropolis, nothing whatever had been done since the last invasion to give immunity against the returning disease. It was remembered—too late, how indescribably dreadful a thing is the epidemic prevalence of sudden death. And the poor were thought of—in their unprotectedness, their filth, their ignorance. Among the persons thus aroused, was a gentleman whom I reluctantly leave unnamed; saying of him only, that, from a distinguished position in official life, he had retired to literary enjoyments, amid which he bears the imputation of many unacknowledged writings which charm and instruct the public. When the rumours of the pestilence began, he too heard[xxxviii] and read and became aghast. The notion that ‘in a skilful, helpful, Christian country nothing should be done’ against these impending dangers—that the poor should be left ‘defenceless, huddled together in some dismal district, not more helpful than women’—was felt by him, he wrote, ‘deeply as a disgrace;’ and he pleaded that, ‘on a great and pressing occasion, it remains for the thoughtful, the rich, and the benevolent, to try and do these needful things for the people.’[11] Let us, he urged, endeavour to meet this shameful reproach; let us combine voluntary charitable assistance for extemporaneous sanitary measures, rapid, though partial; let us get a hundred thousand pounds and do what we can in aid of local authorities in the poorest districts—in Bethnal Green, in Shoreditch. Eventually this plan was abandoned, at least for the time. There was argued against it, that prompt legislation might do more good, with less exoneration of local responsibility. Whether rightly or wrongly, the latter view was acted on; and in accordance with it, the gentleman first adverted to (waving his own hopes and wishes in the matter) took active part in framing suggestions,[12] which Lord Palmerston[xxxix] had expressed himself willing to accept, for modifying the laws of Nuisance and Disease-Prevention to a form more suitable for the apprehended emergency. But, in the meantime, what had happened? The author of the plan, as it were at a moment’s notice, had seemed to draw round himself half the intellectual and moral strength of the metropolis. Himself setting aside the literary ambition of his life, he found others ready to meet him with their several self-sacrifices. Over-worked men of science and of business, who afford no time to relaxation; favourites of society, who might have been suspected of mere shuddering at distasteful subjects; men of high laborious rank in Church and State; poets; heads of professions; minds that guide the tastes and morals of the country, or feed its imagination; not least, the invalid from his distant wintering-place; men, in short, immersed in all kinds and grades of occupation, were either bodily present at the deliberations referred to, or were writing about the plan in terms of warm interest, anxious to promote whatever usefulness could be shown them. About the means there was discussion—about the object, none; nor lukewarmness. All were competing, by gifts of time and labour, to snatch some opportunity of serving this neglected cause.

[11] I quote from a pamphlet printed by him for private circulation. It was entitled ‘Health-Fund for London; some Thoughts for next Summer: by Friends in Council.’

[12] These have since been laid before the House of Lords, on the motion, I think, of Lord Harrowby, who took much interest in the subject.

Such—to return to my text—such, I am deeply assured, would be the spirit which a minister of[xl] Public Health would find abundantly on his side in Parliamentary discussion, and in the Press. There is no attachment to the incongruities I have sketched as belonging to our abortion of a sanitary system. Still less is there any want of feeling for the poor—any reluctance to raise their state and better their circumstances—any unconsciousness that these things are great solemn duties. On the contrary, everywhere there is the conviction that something must be done; everywhere a waiting for authority to say what. But, the trumpet giving an uncertain sound, who can prepare himself to battle? Knowledge, and method, and comprehensiveness, are wanted—the precise, definite, categorical impulses of a Parliamentary leader, who can recognise principles and stick to them.

And for such a minister, what a career! It would be idleness to speak of the blessings he could diffuse, the anguish he could relieve, the gratitude and glory he could earn. A heathen can tell him this. Homines enim ad Deos nullâ re propius accedunt quam salutem hominibus dando. Nihil habet nec fortuna tua majus quam ut possis, nec natura tua melius quam ut velis, conservare quam plurimos.

Upper Grosvenor Street,

May 15th, 1854.

[1]

REPORTS

RELATING TO

THE SANITARY CONDITION

OF THE

CITY OF LONDON.

TO THE HON. THE COMMISSIONERS OF SEWERS OF THE CITY OF LONDON.

November 6th, 1849.

Gentlemen,

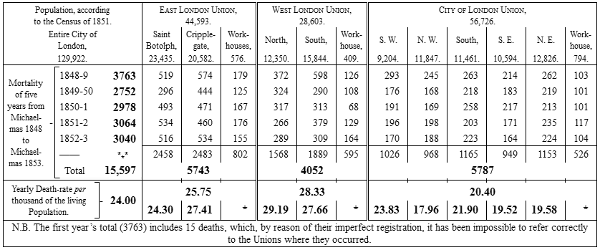

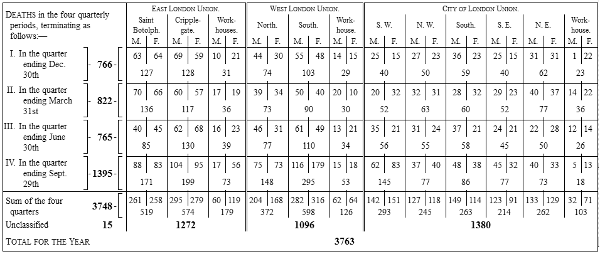

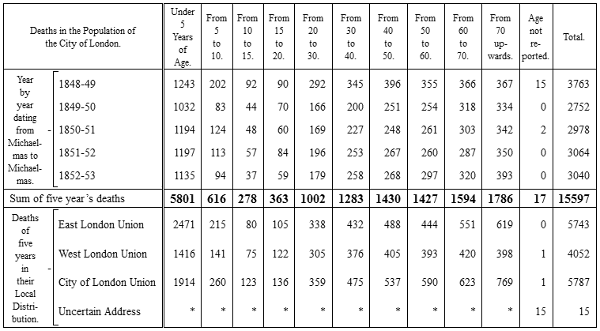

During the 52 weeks dating from October 1st, 1848, to September 29th, 1849, there died of the population of the City of London 3763 persons.

The rate of mortality, estimated from these data for a population of 125,500, would be about the proportion of 30 deaths to every thousand living persons.[13]

[13] The Census of 1851, compared with that of 1841, would lead me to believe that in 1848-9 the population of the City must have been about 129,000. With this correction, the death-rate would have been about 29·16 per thousand.—J. S., 1854.

The lowest suburban mortality recorded in the fifth volume of the Registrar-General’s Reports, for the year then under estimation, gave a rate of 11 in the thousand; and we might perhaps be justified in adopting that rate as a minimum for the purpose of sanitary comparison.

[2]

According to this standard (undoubtedly a very superior one) it would appear that, during the last year, death has prevailed in the City of London with nearly three times its recognised minimum of severity.

But, to avoid all sources of fallacy, I will allow a very ample margin to this estimate; I will take 15 per thousand as a fair standard of mortality, and will assume that last year’s deaths in the City have amounted to only double their normal proportion.

Probably no one contends that the lower rate of mortality, as illustrated at Dulwich or Sydenham, indicates an over-healthy condition of the locality to which it refers. Probably no one argues that human life, in those healthier districts, is prolonged beyond enviable limits. Surely, on the contrary, every one who can measure the large amount of misery and destitution which results from a high rate of mortality, will think it most desirable that, by every means within the scope of sanitary science, exertion should be made to reduce the higher rate to the level of the lower.

Therefore, Gentlemen, I venture to assure myself, that I shall but have anticipated the wishes of this Hon. Court, in preparing for your consideration a statement of those circumstances, which apparently conspire to determine the larger mortality of the City of London.

In order to prevent any misapprehension of my remarks, I think it well to observe that, in commenting on this mortality, I purposely avoid instituting any comparison between it and the mortality of those urban districts which immediately adjoin us: for the object of my comparison is not to illustrate how, by similar or worse circumstances, an equally great mortality may have been procured elsewhere;[3] but rather to suggest how, by other and better sanitary arrangements here, our present high mortality may be diminished.

Indeed, while I speak of the causes of that high mortality which distinguishes the City of London from the healthier sub-districts I have cited, it will be obvious that many of my observations do not apply to the City of London exclusively, but admit of equal application to various other central districts of the metropolis;—relating, in fact, generally to the characteristic evils of all urban residences.

With those other districts I have nothing to do; but I wish it to be understood, that in describing the City as healthy or unhealthy, I am not comparing it with Holborn, or Whitechapel, or Bermondsey, or other urban localities, where—whatever the relative badness of the places, the scale of comparison would be essentially vicious, and the results of comparison worthless. It is my object to test the salubrity of the City by comparison with a superior standard, in order that some definite aim may appear, towards which to direct the endeavours of sanitary improvement.

Starting, then, from our Registrars’ Returns, I invite you to inquire with me, how it has come to pass that within the City of London there have died in the last year twice as many persons as it seems necessary that there should die; and whence has arisen the apparent anomaly, that here—in the very focus of civilization, where the resources of curative medicine are greatest, and all the appliances of charitable relief most effectual, still, notwithstanding these advantages, there has passed away irrevocably during the year so undue a proportion of human life.

[4]

Let it not be imagined that the word cholera is a sufficient answer to these questions, or that its mention can supersede the necessity for sanitary investigation. Let it, on the contrary, be observed that the epidemic which has visited us, extends its ravages only to localities previously and otherwise hostile to life; so that, while all regions of the globe in succession are shadowed by its dark transit, the healthiest districts of each region remain utterly unharmed in presence of the pestilence. Compare, for instance, the cholera mortality in a healthy suburban sub-district with that of an unhealthy urban one. Dulwich and the parish of St. Ann’s, Blackfriars, in the City of London, are probably nearly equal in population: in the former, there was not a single death from cholera; in the latter, the deaths from this cause alone were at the rate of twenty-five to every thousand of the population. Dulwich is one of the healthiest sub-districts within the bills of mortality; St. Ann’s belongs to one of the unhealthiest sub-districts of the City of London; and the cholera visited each in proportion to its ordinary healthiness.

Such is the general rule; and accordingly I would suggest to you that the presence of epidemic cholera, instead of serving to explain away the local inequalities of mortality, does, in fact, only constitute a most important additional testimony to the salubrity or insalubrity of a district, and renders more evident any disparity of condition which may previously have been overlooked. The frightful phenomenon of a periodic pestilence belongs only to defective sanitary arrangements; and, in comparing one local death-rate with another, it is requisite to remember that, in addition to the ordinary redundance of deaths which marks an unhealthy district, there is a tendency from time to time to[5] the recurrence of epidemic pestilence, which visits all unhealthy districts disproportionately, and renders their annual excess of mortality still more egregious and glaring.

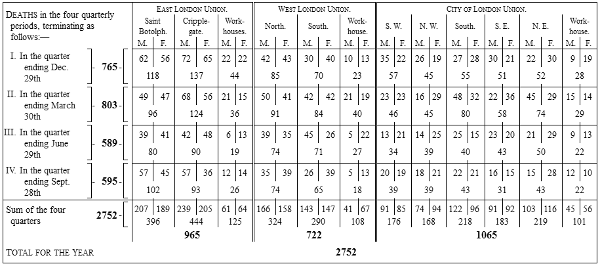

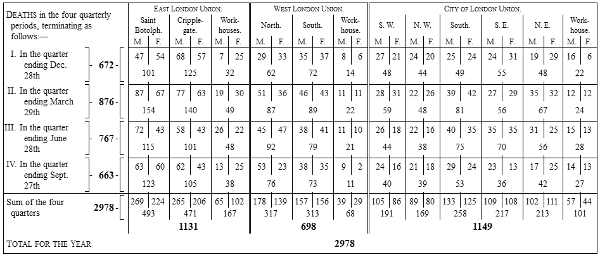

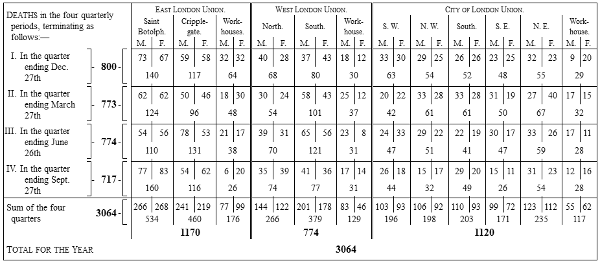

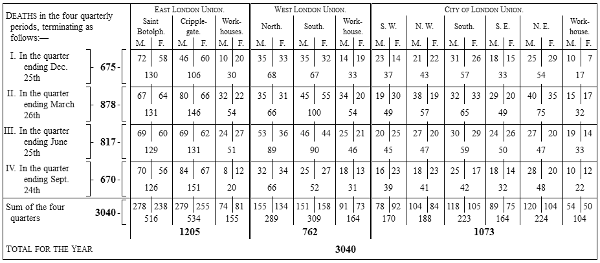

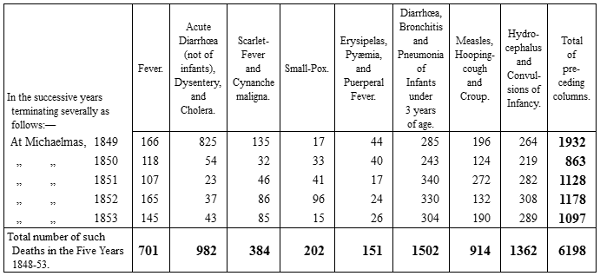

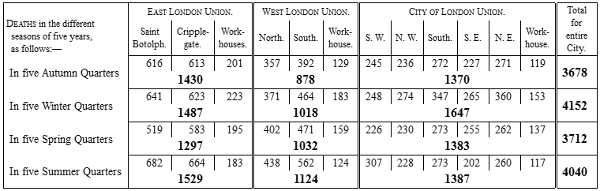

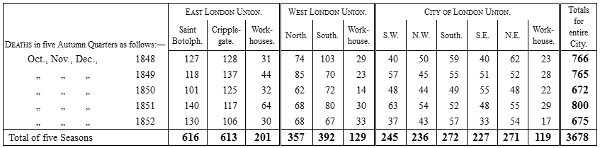

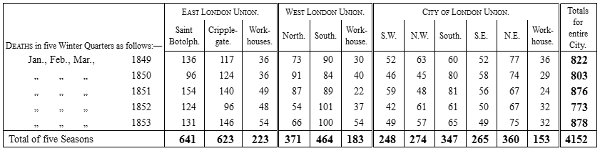

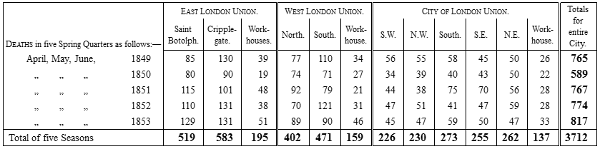

As materials which may aid you to estimate the sanitary defects of the City, I subjoin two tables[14] illustrating the relative mortality of the several sub-districts. The first of these tables indicates numerically the local distribution of the year’s deaths, and gives their proportion to the population of each district and sub-district. The second relates particularly to the last quarter, and illustrates the pressure of the epidemic. The two together furnish a synoptical view of the several rates of mortality, as calculated for the entire City, for the Unions separately, for the sub-districts separately; and for the last quarter of the year separately. In the tedious process of constructing these tables, I have been careful to avoid every source of inaccuracy, and believe that they present you with a true measure of the health of the City during the past year.

[14] I have not reprinted these tables quite as here described. The local distribution of the 3763 deaths of the year is given in the Appendix, No. III.; and the sub-district death-rates of the year, as nearly as I can get them, in a note overleaf, page 6. The high mortality of this summer quarter (in which 1395 persons died) will be best appreciated by the reader in referring to Appendix, No. XIV.; where it can be compared with the mortality of similar periods of time in the four other years there accounted for.—J. S., 1854.

From these comparative tables it will be observed, that the high mortality of the population does not affect the entire City equally; that, in some of its portions, the rate of death approaches the minimum standard much more nearly than in others; that in those districts where the[6] general rate is best, the temporary aggravation from epidemic causes has likewise been least; and that our aggregate City rate, either for ordinary times or for a period of epidemic disease, is compounded from the joint result of several very different proportions. Reference to the Registrar-General’s tables will enable any one to see that the ordinary rate of mortality for the West London Union is a fourth higher than the rate for the City of London Union, while the rate for the East London Union bears a still higher proportion; and these very different rates are, as it were, merged in the one aggregate rate, struck for the whole City, as comprising the three unions referred to. It will be obvious, therefore, that many parts of the City are much healthier than this aggregate rate would signify, while others are much unhealthier. In regard of last year, for instance, the aggregate rate of mortality was (as I have stated) 30 per thousand of the general population of the City: but if this rate be analysed by examination of the sub-district mortality, it will be seen that in one sub-district the rate of death stood nearly as low as 20; that in another sub-district of the same union it rose to 36, and in a third sub-district (of another union) to within a small fraction of 40.[15]

[15] On account of changes of population shown by the subsequent Census, these figures would require correction. The death-rates per thousand in the several sub-districts were probably about as follows, viz.:—

| EAST LONDON UNION. | W. L. UNION. | CITY OF LONDON UNION. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Botolph. | Cripplegate. | North. | South. | S. W. | N. W. | South. | S. E. | N. E. |

| 261⁄2 | 32 | 34 | 41 | 38 | 22 | 24 | 212⁄3 | 22 |

J. S., 1854.

If it were possible to furnish you with statistics derived[7] from a still smaller sub-division of each district, these points would be infinitely more manifest. In some limited localities of the City you would probably find an approximation to the average mortality of suburban districts; while in other spots, if they were isolated for your contemplation, you would see houses, courts, and streets where the habitual proportion of deaths is far beyond the heaviest pestilence-rate known for any metropolitan district aggregately—localities, indeed, where the habitual rate of death is more appalling than any which such averages can enable you to conceive.

These facts are quite unquestionable, and I have felt it my duty to bring them under your notice as pointedly and impressively as I can; feeling assured, as I do, that so soon as you are cognisant of them, every motive of humanity, no less than of economical prudence, must engage you to investigate with me, whether or not there may lie within your reach any adoptable measures for lessening this large expenditure of human life, and for relieving its attendant misery. It is, therefore, with the deepest feeling of responsibility that I proceed to fulfil the main object of my First Annual Report, by tracing these effects to their causes, and by explaining to you, from a year’s observation and experience, what seem to me the chief influences prevailing against life within the City of London.

My remarks for this purpose will fall under the following heads, viz.:—

In treating of these topics, I shall not pretend to bring before you all the details on which my opinions are founded, or to enumerate under each head those infinite individual instances which require sanitary correction. It is my wish at this time to submit to you only such general considerations as may show you the largeness of the subject, its various ramifications, and its pressing importance; and it is my hope that these considerations may suffice to convince you of the necessity which exists in the City of London for some effective and permanent sanitary organisation.

[9]

I. It is not in my power to lay before you any numerical statement of the proportion of drained to undrained houses. From such information as I possess, I may venture to speak of imperfect house-drainage as having been a general evil in all the poorer districts of the City; and the latest intelligence on the subject leads me to consider this great evil as but very partially removed. So far as I can calculate from very imperfect materials, I should conjecture that some thousands of houses within the City still have cesspools connected with them. It requires little medical knowledge to understand that animals will scarcely thrive in an atmosphere of their own decomposing excrements; yet such, strictly and literally speaking, is the air which a very large proportion of the inhabitants of the City are condemned to breathe. Sometimes, happily for the inmates, the cesspool in which their ordure accumulates, lies at some small distance from the basement-area of the house, occupying the subsoil of an adjoining yard, or if the privy be a public one, of some open space exterior to the private premises. But in a very large number of cases, it lies actually within the four walls of the inhabited house; the latter reared over it, as a bell-glass over the beak of a retort, receiving and[10] sucking up incessantly the unspeakable abomination of its volatile contents. In some such instances, where the basement story of the house is tenanted, the cesspool lies—perhaps merely boarded over—close beneath the feet of a family of human beings, whom it surrounds uninterruptedly, whether they wake or sleep, with its fetid pollution and poison.

Now, here is a removable cause of death. These gases, which so many thousands of persons are daily inhaling, do not, it is true, in their diluted condition, suddenly extinguish life; but, though different in concentration, they are identically the same in nature with that confined sewer-gas which, on a recent occasion, at Pimlico, killed those who were exposed to it with the rapidity of a lightning stroke. In their diluted state, as they rise from so many cesspools, and taint the atmosphere of so many houses, they form a climate the most congenial for the multiplication of epidemic disorders, and operate beyond all known influences of their class in impairing the chances of life.

It may be taken as an axiom for the purposes of sanitary improvement, that every individual cesspool is hurtful to its vicinage; and it may hence be inferred how great an injury is done to the public health by their existence in such numbers, that parts of the City might be described as having a cesspool-city excavated beneath it.

I beg most earnestly to press on the consideration of your Hon. Court, the extreme importance of proceeding with all convenient speed to alter this very faulty construction, and to substitute for it an arrangement compatible with the health of the population.

[11]

While addressing you on this subject, and while congratulating your Hon. Court on the fact, that public attention is so much directed to a matter in which your exertions are certain to effect large and salutary reform, I cannot refrain from expressing a wish, that more accurate knowledge prevailed among the public as to the history and jurisdiction of the nuisance in question. It seems constantly to be forgotten, that your responsibility in the matter dates but from last January. The cesspool-nuisance has been the slow growth of other less enlightened ages, not in the City merely, but in the whole metropolis, and in all other towns in England. The extreme injury which it inflicts on the health of the population, and the vital necessity of abating that injury, are points which only began to claim attention in this country about ten years ago; and which have since but very slowly been forcing their way (chiefly through the indomitable zeal and perseverance of Mr. Chadwick) into that share of notice which they deserve. House-drainage with effective water-supply, are the remedies which can alone avail; and it is only during the present year that authority to enforce these measures has been vested by the Legislature in any public bodies whatsoever.

Before the month of January last, when your increased jurisdiction was established, it appears to me that, for the existence of cesspools in the City, you had no more responsibility than for the original site of the metropolis, or for the architecture of Westminster Abbey.

During the last ten months, however, the care of effective house-drainage has rested solely and entirely with your Hon. Court; for two of those ten months, I thought[12] it desirable, on account of the epidemic, that no considerable disturbance of the soil should take place in the construction of new works; in the remaining eight months, two miles of new sewer were formed, and 900 houses were drained for the first time.

If the house-drainage of the City had depended for its completion, even since that time, solely on the labours of this Commission, no doubt it would have proceeded at a far quicker pace. How effectively your Hon. Court had prepared for the best application of your increased powers, is sufficiently evinced in the 45 miles of sewerage, ramifying through all the districts of your jurisdiction, ready at every point to receive the streams of private drainage, and leaving to the owners of house-property (with few exceptions) no excuse for their non-performance of these necessary works. I believe the extent of public sewerage within the City to be quite unparalleled, and to furnish facilities of the rarest kind for the abolition of cesspools, and for the establishment of an improved system of house drainage. But, Gentlemen, while you have exerted yourselves to the utmost in the application of your increased authority, and have directed your staff of officers, from first to last, to proceed with all possible despatch in enforcing sanitary improvement in the matter now under consideration, the intentions of your Court and the industry of its officers have been in a great measure frustrated by the passive resistance of landlords. Delays and subterfuges have been had recourse to by the owners of house-property, in order to avoid compliance with the injunctions of the Commission; and the temporary interruption of works, which occurred in August[13] and September, prevented these evasions from being dealt with as otherwise they would have been.

Now, however, the course is again open. For some weeks your Hon. Court has directed that all works of drainage and sewerage shall proceed; many are already in progress; and I can see no reason why, within a year from the present time, the number of cesspools and of undrained houses within the City of London should not be reduced to a very small proportion.

Everything, however, in this respect will depend on the spirit of thoroughness with which the Act of Parliament is enforced; and I would strongly recommend, in all cases of non-drainage or other non-compliance with the terms of notice, that no indulgence whatever should be conceded to landlords beyond the time specified in the notification of the Court; that no difference should be recognised between a ‘notice’ and ‘a peremptory notice;’ that all notices should be ‘peremptory;’ and that, a certain period for performance having been allowed to the landlord, on the very day of that period’s expiration, the work, if undone, should be given over for completion by the workmen of the Commissioners of Sewers, in accordance with the 61st clause of the Act of Parliament. In favour of the adoption of this principle, I can adduce no stronger argument than my conviction, that its non-adoption would insure a sacrifice of human life, in exact proportion to the procrastination allowed; and that, too, in a matter where henceforth your responsibility is undivided and your power absolute.

In order to give efficiency to whatever improvements of[14] house-drainage may be instituted, the present system of water-supply will require to undergo very extensive modifications; for at present in the poorer tenements, even where some show of house-drainage is made, the arrangements are constantly rendered inoperative from insufficiency or absence of water. To this matter, however, I shall presently revert.

Another most important desideratum in connexion with the sewerage of the City is that, if possible, some more perfect system of trapping should be devised, or that, in some way or other, the sewers should be ventilated effectively and inoffensively.[16] At present there are frequent complaints of offensive exhalation from gratings in the open ways of the City; and it will be obvious to your Hon. Court, that all which I have urged on the subject of cesspool-exhalations must apply equally to those which are emitted from sewers. The impediments to effective trapping are almost insuperable; but I believe that when the water-supply of the City is very largely increased, washing the drains amply and incessantly, the evil complained of will undergo a sensible diminution.

In further connexion with my present subject, I would also solicit attention to the fact that the sanitary purposes of drainage are but imperfectly achieved, where the outfall of sewerage is into a tidal river passing through the heart of a densely peopled metropolis. I should be stepping[15] beyond my province, if I were to say much respecting the schemes now before the public for dealing with the difficulty to which I here refer, inasmuch as those schemes involve questions of engineering and machinery, on which I am incompetent to form an opinion. But I can have no hesitation in stating it as a matter greatly to be desired in the City of London, that the noble river which ebbs and flows beneath its dwellings should cease to be the drainpool of our vast metropolis; and that the immeasurable filth which now pollutes the stream should be intercepted in its course, and be conveyed to some distant destination, where instead of breeding sickness and mortality, it might become a source of agricultural increase and national wealth.[17]

I would venture, likewise, to express an opinion that the City of London is peculiarly interested in the accomplishment of this great public work, not only on general grounds relating to the conservancy of the river, but likewise and especially on sanitary grounds, by reason of the large bank-side population, subjects of the City, who now, instead of deriving advantage from their nearness to the stream, are constantly disgusted and injured by its misuse.

While the consideration of this most important measure is pending, I would invite attention to some circumstances, by which even the present evil is needlessly aggravated.

In the first place the sewers are of defective length, so that during the ebb of the tide their contents, as they escape, are suffered to flow in a stream of some length[16] across the mud of the retreating river. The stream, together with the mud which it saturates, and the open mouth of the sewer, evolve copious and offensive exhalations, and I would recommend that measures be taken for abatement of the nuisance. This purpose, as concerns the sewer, would be fulfilled by the addition, in each instance, of a sufficient length of brick or cast-iron work, to prolong the canal beyond low water mark; but the great extent of mud which is left uncovered at each tide, and which during the present pollution of the river is a source of extreme nuisance and of disease, constitutes an evil for which no remedy can be found till the stream shall be narrowed and embanked.

Meanwhile, the complaints which reached the Committee of Health during the summer, together with the results of my own inspection, lead me to believe that the several small docks which lie along the City bank of the river from the Tower to the Temple, fulfil little really useful purpose; that they are to a great extent used as laystalls for their vicinage; that copious deposits and accumulations of filth take place in them; that they are a nuisance and injury, except to the very few who are interested in their maintenance; and that it would be of public advantage that they should be filled up.

[17]

II. I am sure that I do not exaggerate the sanitary importance of water, when I affirm that its unrestricted supply is the first essential of decency, of comfort, and of health; that no civilization of the poorer classes can exist without it; and that any limitation to its use in the metropolis is a barrier, which must maintain thousands in a state of the most unwholesome filth and degradation.