Title: Our Home and Personal Duty

Author: Jane Eayre Fryer

Illustrator: Edna A. Cook

Release date: December 3, 2016 [eBook #53653]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Emmy, MFR and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

In these vital tasks of acquiring a broader view of human possibilities the common school must have a large part. I urge that teachers and other school officers increase materially the time and attention devoted to instruction bearing directly on the problems of community and national life.—Woodrow Wilson.

The notion of what constitutes adequate civics teaching in our schools is rapidly changing. The older idea was based on the theory that children were not citizens—that only adults were citizens. Therefore, civics teaching was usually deferred to the eighth grade, or last year of the grammar school, and then was mostly confined to a memorizing of the federal constitution, with brief comments on each clause. Today we recognize that even young children are citizens, just as much as adults are, and that what is wanted is not training for citizenship but training in citizenship. Moreover, we believe that the “good citizen” is one who is good for something in all the relationships of life.

Accordingly, a beginning is being made with the early school years, where an indispensable foundation is laid through a training in “morals and manners.” This sounds rather old-fashioned, but nothing has been discovered to take its place. Obedience, cleanliness, orderliness, courtesy, helpfulness, punctuality, truthfulness, care of property, fair play, thoroughness, honesty, respect, courage, self-control, perseverance, thrift, kindness to animals, “safety first”—these are the fundamental civic virtues which make for good citizenship in the years to come. Of course, the object is to establish right habits of thought and action, and this takes time and patience and sympathy; but the end in view justifies the effort. The boy or girl who has become habitually orderly and courteous and helpful and punctual and truthful, and who has acquired[iv] a fair degree of courageous self-control, is likely to become a citizen of whom any community may well be proud.

The best results are found to be secured through stories, poems, songs, games, and the dramatization of the stories found in books or told by the teacher. This last is of great value, for it sets up a sort of brief life-experience for the child that leaves a more lasting impression than would the story by itself. Most of the stories told in this reader, emphasizing certain of the civic virtues enumerated above, will be found to lend themselves admirably to simple dramatization by the pupils, the children’s imagination supplying all deficiencies in costumes, scenery, and stage settings. Moreover, the questions following the text will help the teacher to “point the moral” without detracting in the slightest degree from the interest of the story.

The basis for good citizenship having been laid through habit-formation in the civic virtues, the next step is for the children to learn how these virtues are being embodied in the people round about them who are serving them and their families. The baker, the milkman, the grocer, the dressmaker, the shoemaker, the carpenter, the plumber, the painter, the physician, the druggist, the nurse—these are the community servants who come closest to the life-experience of the children.

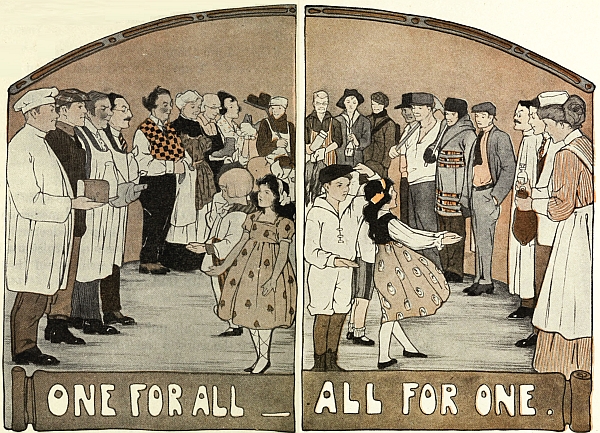

How dependent each member of a community—especially an urban community—is on all the rest, and how important it is that each shall contribute what he can to the community’s welfare, are illustrated by the stories of the Duwell family. Here a typical though somewhat ideal American[v] family is shown in its everyday relations, as a constant recipient of the services rendered by those community agents who supply the fundamental need of food, clothing, shelter, and medical attendance. The children in the class will learn, with the Duwell children, both the actual services that are rendered and the family’s complete dependence on those services. Moreover, they will acquire the splendid working ideals of interdependence and coöperation. And, finally, they will discover that the adult citizens who are rendering them these services are embodying the very civic virtues in which they themselves have been so carefully trained.

The pupils are now ready to follow the services rendered by public servants such as the policeman, the fireman, the street cleaner, the ashes and garbage collector, the mail carrier; and by those who furnish water, gas, electricity, the telephone, the trolley, etc.; and these are presented in civics readers that follow this one. The civic virtues previously considered are again found exemplified to a marked degree; and the threefold idea of dependence, interdependence, and coöperation through community agencies finds ample illustration.

But it is not enough for the pupils to stop with finding out what the community is doing for them. The essential thing in this citizenship-training is for the young citizens to find out what they can do to help things along. Civic activities are suggested both in the stories, poems, etc., in these books, and in the suggestive questions at the close of each chapter.

Like all texts or other helps in education, these civics readers cannot teach themselves or take the place of a live teacher. But it is believed that they can be of great assistance to sympathetic, civically minded instructors of youth who feel that the training of our children in the ideals and practices of good citizenship is the most imperative duty and at the same time the highest privilege that can come to any teacher.

Special thanks are due to Doctor J. Lynn Barnard of the Philadelphia School of Pedagogy, for valuable suggestions and helpful criticism in the making of this reader; also to Miss Isabel Jean Galbraith, a demonstration teacher of the Philadelphia School of Pedagogy, for assistance in preparing the questions on the lessons.

For kind permission to use stories and other material, thanks are due to the following: The Ohio Humane Society for “Little Lost Pup,” by Arthur Guiterman; Mrs. Huntington Smith, President Animal Rescue League of Boston, for “The Grocer’s Horse,” and to her publishers, Ginn and Company; Mary Craige Yarrow for “Poor Little Jocko”; Houghton Mifflin Company for “Baking the Johnny-cake”; The American Humane Education Society for selection by George T. Angell; and to the Red Cross Magazine for several photographs.

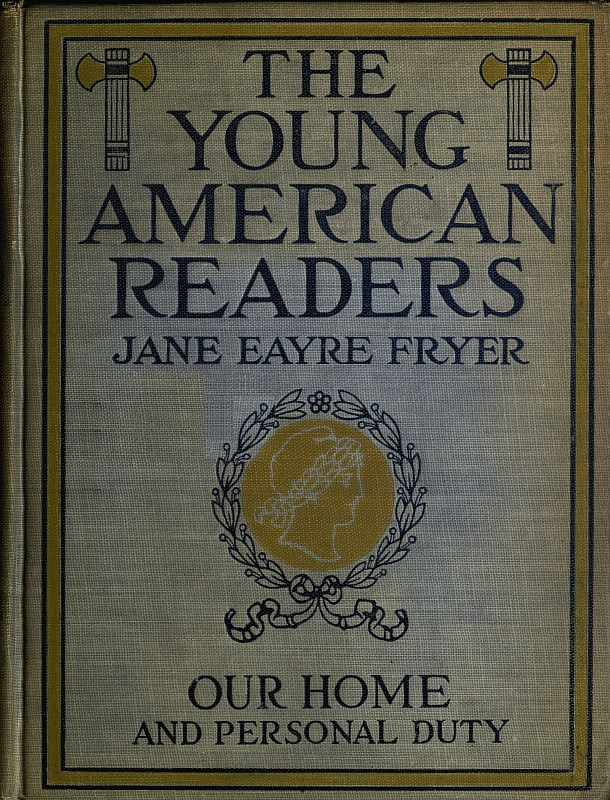

A bird’s-eye view of the plan of the young american readers

It may be said that a child’s life and experience move forward in ever widening circles, beginning with the closest intimate home relations, and broadening out into knowledge of community, of city, and finally of national life.

A glance at the above diagram will show the working plan of the Young American Readers. This plan follows the natural growth and development of the child’s mind, and aims by teaching the civic virtues and simplest community relations to lay the foundations of good citizenship. See Outline of Work on page 231.

| PART I | |

| CIVIC VIRTUES | |

| Stories Teaching Thoroughness, Honesty, Respect, Patriotism, Kindness to Animals. | |

| Thoroughness | |

| PAGE | |

| The Little Prairie Dogs and Old Mr. Wolf | 3 |

| Don’t Give Up, Phœbe Cary | 8 |

| The Bridge of the Shallow Pier | 9 |

| The Thoughtful Boy | 16 |

| Grandfather’s Story | 17 |

| Honesty | |

| Honest Abe | 23 |

| I. The Broken Buck-horn | 23 |

| II. The Rain-soaked Book | 24 |

| III. The Young Storekeeper | 26 |

| Dry Rain and the Hatchet | 28 |

| I. How Dry Rain Got His Name | 28 |

| II. Dry Rain Goes Trading | 29 |

| The Seven Cranberries | 32 |

| The Donkey’s Tail | 36 |

| [x]Hurting a Good Friend | 39 |

| Respect | |

| A School Without a Teacher | 42 |

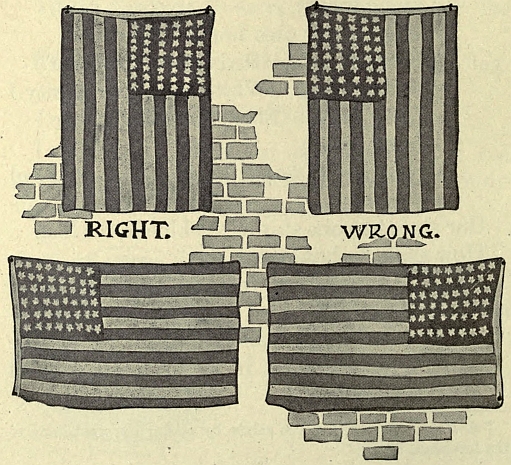

| Our Flag | 47 |

| Scout’s Pledge | 48 |

| My Gift | 49 |

| Flag Day | 49 |

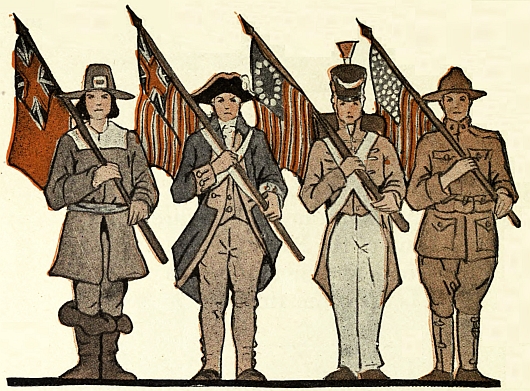

| How Our Flag Developed | 52 |

| The Flag of the U. S. A. | 54 |

| The American Flag, Joseph Rodman Drake | 55 |

| Kindness to Animals | |

| The True Story of Cheesey | 56 |

| I. The Dog and the Policeman | 56 |

| II. The Policeman’s Story | 57 |

| III. Cheesey’s Christmas Presents | 58 |

| The Chained Dog | 60 |

| Little Lost Pup, Arthur Guiterman | 62 |

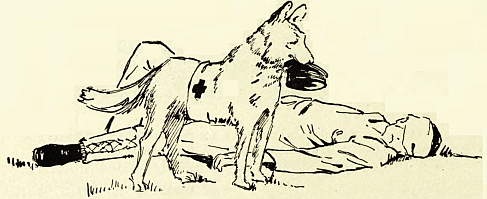

| Picture of Red Cross Army Dogs | 64 |

| The Hunting Party | 66 |

| The Lost Kitty, Ella Wheeler Wilcox | 67 |

| My Peculiar Kitty | 68 |

| Poor Little Jocko | 69 |

| Robin Redbreast | 74 |

| Who Killed Cock Robin? | 75 |

| My Friend, Mr. Robin | 77 |

| If All the Birds Should Die, George T. Angell | 78 |

| Furry | 80 |

| The Grocer’s Horse (adapted), Mrs. Huntington Smith | 83 |

| I. The Careless Driver | 83 |

| II. What Happened in the Barn | 86 |

| A Letter from a Horse | 88 |

| [xi]A Plea for the Horse | 89 |

| PART II | |

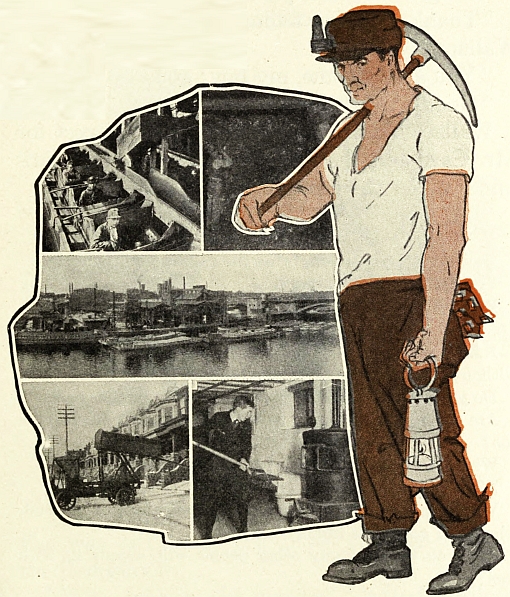

| COMMUNITY OCCUPATIONS | |

| Stories about People Who Minister to Our Daily Needs. | |

| People Who Provide Us with Food | |

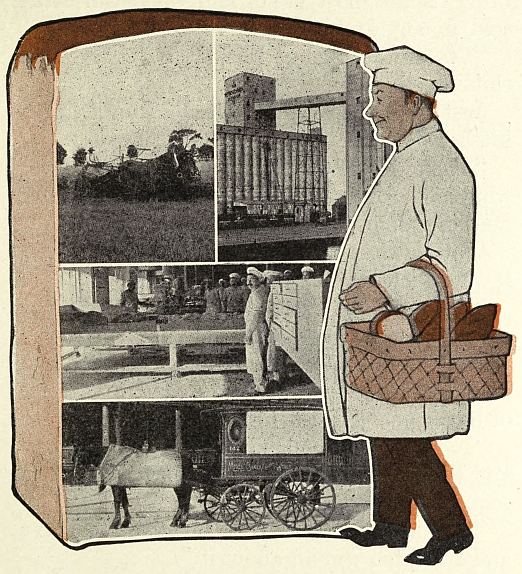

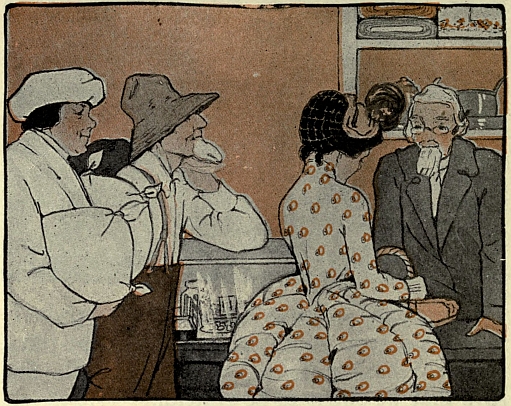

| The Baker | 95 |

| I. An Early Call | 95 |

| II. The Staff of Life | 99 |

| III. A Visit to the Bakery | 101 |

| IV. Where the Wheat Comes From | 107 |

| Baking the Johnny-cake | 111 |

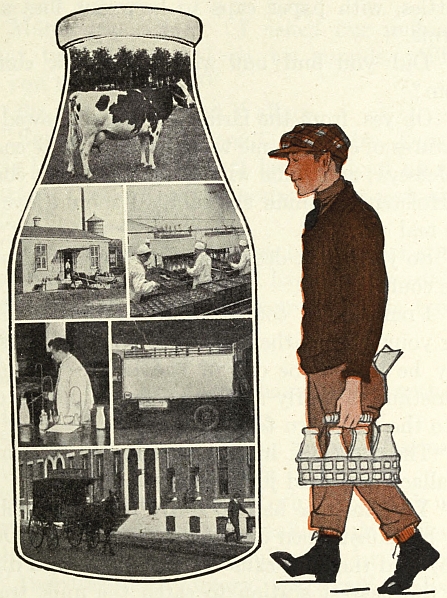

| The Milkman | 115 |

| I. Before the Sun Rises | 115 |

| II. Milk, from Farm to Family | 119 |

| The Grocer | 122 |

| I. The Old-time Grocer | 122 |

| II. The Modern Grocer | 125 |

| People Who Help Clothe Us | |

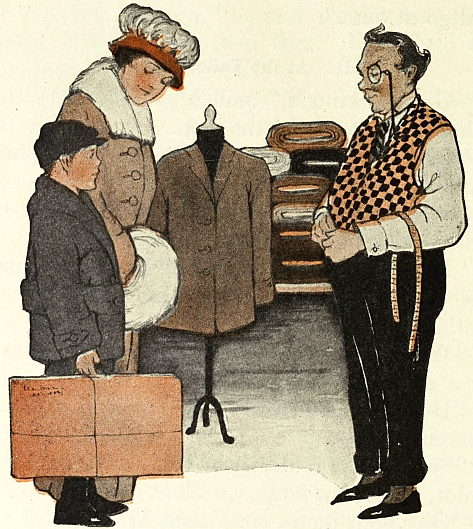

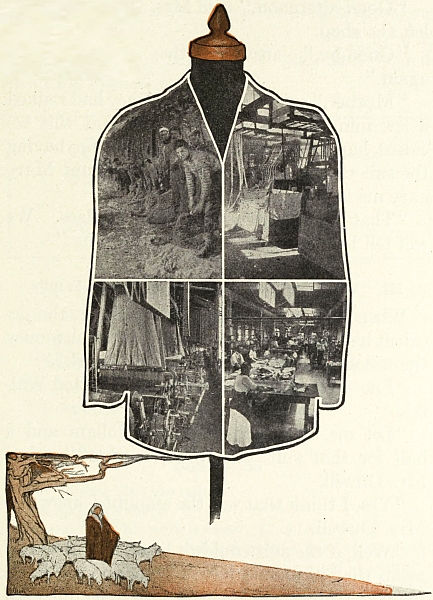

| The Tailor | 127 |

| I. The Accident | 127 |

| II. At the Tailor Shop | 129 |

| III. What the Tailor Saved the Duwell Family | 132 |

| The Dressmaker | 134 |

| I. An Invitation to a Party | 134 |

| II. A Disappointment | 136 |

| III. At the Dressmaker’s | 137 |

| IV. The Party | 142 |

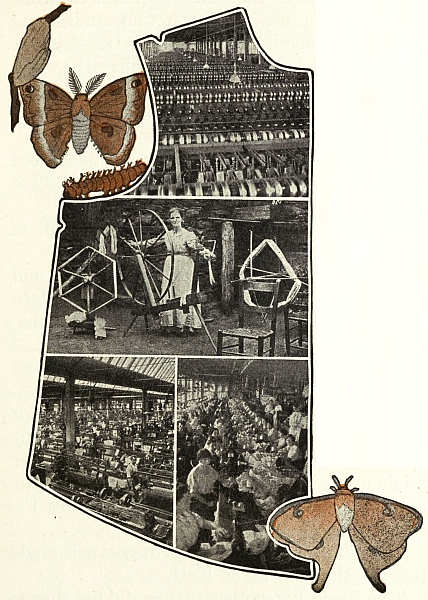

| [xii]The Silk Dress | 144 |

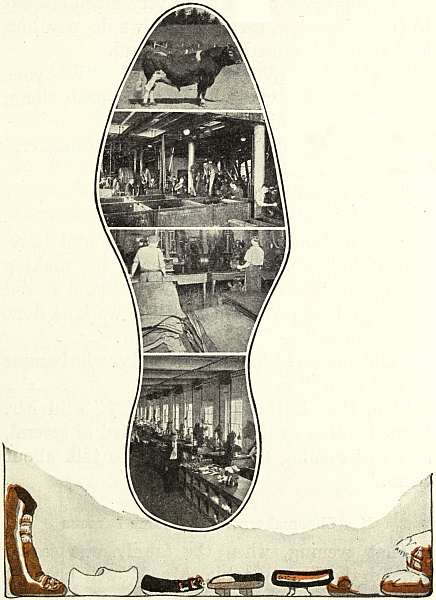

| The Shoemaker | 145 |

| I. The Worn Shoes | 145 |

| II. Shoemakers Who Became Famous | 150 |

| III. At the Shoemaker’s Shop | 152 |

| People Who Supply Us with Shelter | |

| The Carpenter | 154 |

| I. A Trip into the Country | 154 |

| II. The Sawmill | 158 |

| III. The Carpenter | 161 |

| IV. The Wolf’s Den | 163 |

| V. The Cave Dwellers | 165 |

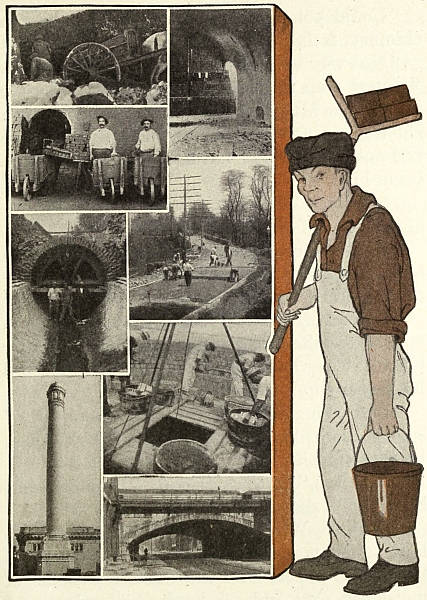

| The Bricklayer | 168 |

| I. The Fallen Chimney | 168 |

| II. The Bricklayer | 172 |

| III. After School | 173 |

| The Plumber, the Plasterer, the Painter | 176 |

| I. A Visit to a Little Town | 176 |

| II. At Home | 178 |

| III. The New Kitchen | 179 |

| People Who Supply Us with Fuel | |

| The Coal Man and the Miner | 181 |

| I. Black Diamonds | 181 |

| II. In a Coal Mine | 183 |

| People Who Care for Our Health | |

| The Dentist | 187 |

| I. Why Ruth was Afraid | 187 |

| [xiii]II. At the Dentist’s | 190 |

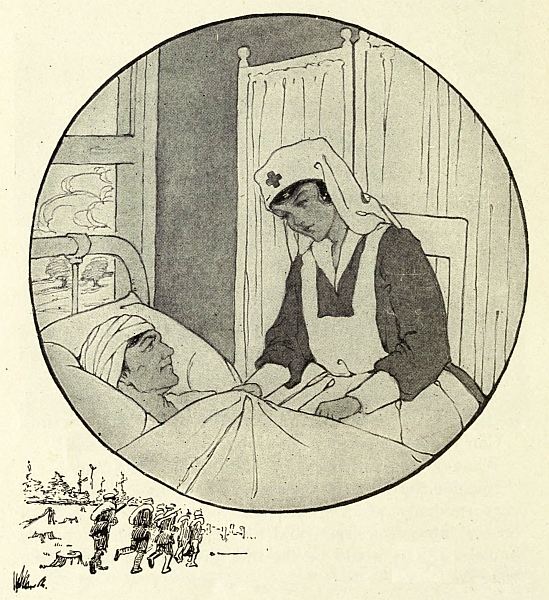

| The Druggist, the Nurse, and the Doctor | 192 |

| I. The Sick Baby | 192 |

| II. The Druggist | 194 |

| III. The Trained Nurse | 196 |

| IV. The Doctor, a Hero | 199 |

| One for All and All for One (a play) | 201 |

| PART III | |

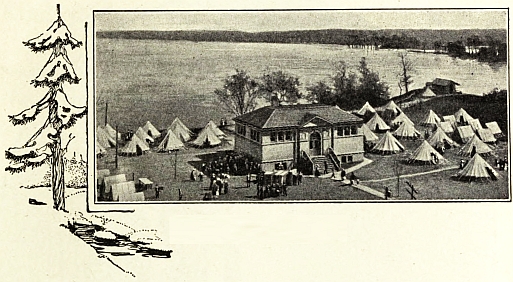

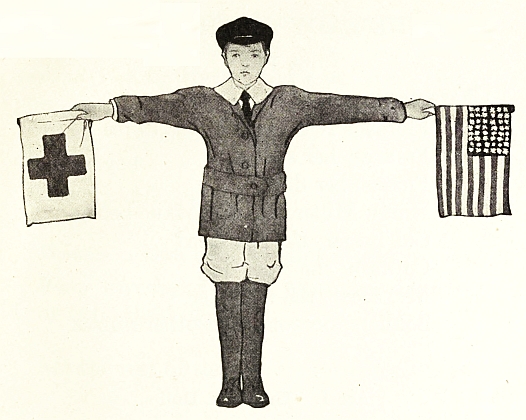

| THE AMERICAN RED CROSS | |

| Junior Membership and School Activities. | |

| The Junior Red Cross | 209 |

| The President’s Proclamation | 210 |

| The American Red Cross in Times of Peace | 211 |

| The American Red Cross in Times of War | 215 |

| Before the Days of the Red Cross | 215 |

| Florence Nightingale | 216 |

| How the Red Cross Came to Be | 219 |

| How I Can Help the Red Cross | 222 |

| The Lady of the Lamp (a play) | 224 |

| Act I. The Sick Doll | 224 |

| Act II. Good Old Cap | 225 |

| Act III. The Lady of the Lamp | 227 |

| You and I and All of Us | 228 |

Stories Teaching Thoroughness, Honesty,

Respect, Patriotism, Kindness to

Animals

These stories also teach, incidentally, the co-ordinate virtues of obedience, cleanliness, orderliness, courtesy, helpfulness, punctuality, truthfulness, care of property, and fair play.

Once upon a time, three fat little prairie dogs lived together in a nice deep burrow, where they were quite safe and warm and snug.

These little prairie dogs had very queer names. One was Jump, another was Bump, and another was Thump.

Well, they lived very happily together until one day Jump said, “I believe I would rather live up on top of the ground than in this burrow.”

“I believe I would, too,” said Bump.

“I believe I would!” said Thump. “I’ll tell you what we can do! Let us each build a house!”

“Let us!” cried Jump and Bump, and away they all scampered up out of the burrow.

Each one ran in a different direction to hunt for something to use in building a house.

Jump gathered some straws.

“These will do,” he thought. “I shall not bother to look for anything else. Besides, they are very light and easy to carry.”

So Jump built a little straw house.

Bump gathered some sticks.

“These will make a nice house. They are quite good enough,” he said.

So Bump built a little stick house.

Thump saw the straw and the sticks, but thought he might find something better.

Pretty soon he came to a pile of stones.

“My, what a fine strong house they would make!” he thought. “They are heavy to move, but I will try to use them.”

So he carried and carried and worked and worked, but finally he had a stone house.

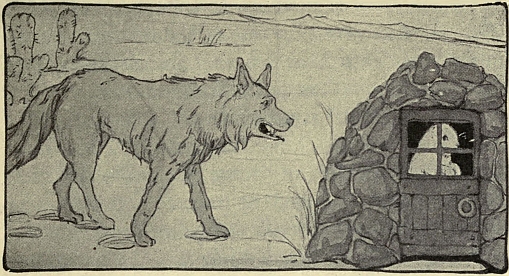

The next morning when old Mr. Prairie Wolf awoke and stretched himself, he saw the three little houses in the distance.

“What can they be?” wondered old Mr. Wolf.[5] “Maybe I can get breakfast over there.” So he started toward them.

The first house he came to was the straw one.

He peeped in the window and saw little Jump.

He knocked on the door. “Mr. Jump, let me come in,” said he.

“Oh, no, by my bark—bark—bark! you cannot come in,” barked little Jump, pushing with all his might against the door with his little paws.

“Then I’ll blow your house over with one big breath!” growled old Mr. Prairie Wolf.

So he blew one mighty breath, and blew the house over, and ate up poor little Jump.

On his way home, old Mr. Wolf stopped to look in the window of the little stick house. He saw little Bump.

“My, what a good breakfast I shall have to-morrow!” he thought to himself.

The next morning he came early and knocked on the door of the little stick house.

“Mr. Bump, Mr. Bump,” said he, “let me come in.”

“Oh, no, by my bark—bark—bark! you cannot come in,” barked little Bump, standing on his hind legs with his back braced against the door.

“Then I’ll throw your house over with one blow of my paw,” growled old Mr. Prairie Wolf.

And he did, and ate up poor little Bump.

On his way home, he stopped to look in the window of the little stone house.

Thump sat by the fireplace toasting his feet.

“My, my!” chuckled old Mr. Wolf, smacking his lips, “he is the fattest one of all. What a fine breakfast I shall have to-morrow!”

The next morning he came earlier than ever, and knocked on the door of the little stone house.

“Mr. Thump, let me come in,” said he.

“All right,” called little Thump, “when my feet get warm.”

So old Mr. Prairie Wolf sat down to wait.

By and by, old Mr. Wolf knocked on the door again. “Aren’t your feet warm yet, Mr. Thump?” he growled.

“Only one,” called Thump; “you will have to wait until the other one is warm.”

So old Mr. Wolf sat down to wait.

After a few minutes had passed, he knocked on the door again.

“Isn’t your other foot warm yet, Mr. Thump?” he growled.

“Yes,” called Thump, “but the first one is cold now.”

“See here, Mr. Thump,” growled old Mr. Wolf, “do you intend to keep me waiting all day while you warm first one foot and then the other? I am tired of such foolishness. I want my breakfast. Open the door, or I’ll knock your house over!”

“Oh, all right,” barked little Thump, “and while you are doing it, I shall eat my breakfast.”

That made old Mr. Prairie Wolf very angry, and he kicked at the little stone house with all his might; but little Thump knew he could not move a stone.

After a long while the noise stopped, and little Thump peeped out of the window. He saw old Mr. Wolf limping painfully off; and that was the way he always remembered him, for he never never saw him again.

This story, which is built on the framework of the old classic, “The Three Pigs,” lends itself readily to dramatization. Let the four characters take their parts as they remember the story. By no means have them memorize the words.

Which little prairie dog worked hardest to build his house?

The others had an easy time, didn’t they?

But which one was happiest in the end? Why?

Once upon a time, a mother loved her little boy so well that she made the mistake of offending one of his good fairies. This was the fairy of carefulness.

The mother made the mistake of trying to do everything for her little son. She even put his toys away when he was tired of playing.

After the boy grew older and went to school, she did many of his lessons for him. His daily[10] marks in arithmetic were good, for much of his work was done by his mother at home. Of course his teacher did not know this for the boy copied his mother’s work.

Now, just as you would expect, this made the boy very careless. But he was really a bright boy, and even though he did not do well, he managed to pass his examinations.

“If you would only be more careful,” his teachers would say, “you would have the highest marks.”

When his mother saw his reports, she would say: “Oh, isn’t this too bad, son; I know you will have better marks next time.”

So, when the boy became a man he did everything in the same careless manner, forgetting that other people would not excuse him as his mother had done.

Now the good fairy of carefulness was very much offended at the way in which the mother spoiled her little son. So she said to herself, “I must, I must teach that boy a lesson!”

When he was little, this boy was very fond of playing at building bridges. After he was grown up, he became a builder of real bridges.

At first, he built only small bridges over the brooks and little streams, but one day an order was given him to build an important bridge over a large river.

Just as you might guess, this pleased the man very much, and he was glad to begin the work at once.

Soon his men were busy, putting in the piers for the new bridge, and he was hurrying them as fast as he could, in order to get the bridge built on time.

Every day he sat in a rowboat calling to his men. They were about to begin work on the middle pier when the foreman of the workers came to him.

“Mr. Builder,” he said, “I think we shall have to wait for more material if we go down to the right depth for this pier.”

“Nonsense, man,” said the builder, “we have no time to wait. There is a pretty good bottom under that place. Don’t go so deep. Get along with the material you have.”

“But, sir,—” began the man.

“Do as I tell you,” ordered the builder.

“All right, sir,” replied the foreman; “you may order that done, but one of the other men will have to do the job.”

“Very well,” was the angry reply of the builder, “Jim Nevermind will take your place.”

The foreman slowly drew on his jacket. “Somebody will pay for such carelessness,” he muttered. “I hope it will not be—” but the rest of the sentence was drowned by the orders of the new foreman.

In a very short time the bridge was finished and the inspector came to look it over.

“It looks all right,” he said. “Are you sure the piers are sound? I haven’t time to examine them, but I know that a man who has built as many bridges as you, would make them right.”

“I am glad you are pleased, sir,” replied the builder.

“You have certainly made record time,” continued the inspector, “and I shall carry back a good report.”

“Thank you very much,” said the builder; but his pleasure was somewhat spoiled because of the shallow pier.

“It is all nonsense,” he thought, “to be so particular; besides, the current in that river is so slow that there is no danger.” And it seemed true, for three years later, the bridge appeared[13] to be as firm and strong as when it was first built.

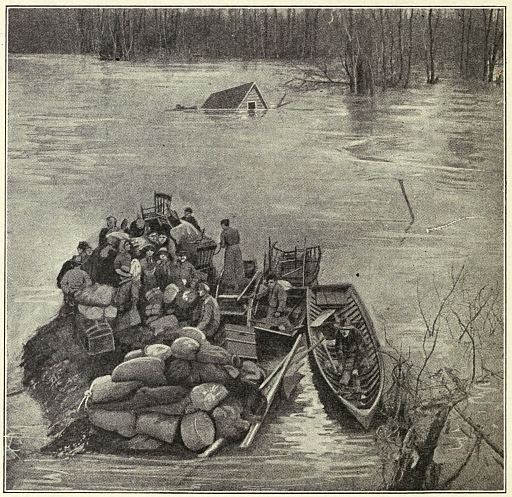

But one day in the early part of the fourth year there came a great flood. The slow-moving current became a raging torrent, sweeping everything in its way and blocking large timbers and trees against the bridge.

It so happened that a party of young people were riding along in a big hay wagon drawn by four beautiful bay horses. When they came to the bridge the driver stopped.

“Shall we cross?” he asked.

“Oh, yes,” the children shouted, “it will be fun.”

“It looks safe enough,” said one of the two grown people who were with them. So with a “Gee-up, boys,” to the horses, the driver started across the bridge.

Just—ah, you know, don’t you? Just as they reached the middle pier, there came a creak and a rumble, a moment’s swaying, and a crash. The bridge had caved in, and the hay wagon, full of terror-stricken children, together with the frightened horses, was swept into the water.

“Don’t jump!” shouted the driver to the[14] children, trying to guide the swimming horses shoreward; but that was impossible.

For a full minute, which seemed like hours, they were swept onward. Then,—maybe the good fairy of carefulness had planned it—they rested on a little island the top of which was just covered with water.

The white-faced driver counted the children, “All here! Thank God!” he said.

The little folks cried and hugged each other, and called aloud for their mothers and fathers.

They had to stay there all night, cold and frightened and hungry. That was dreadful enough, but it was nothing compared with the fear that the water might rise higher still.

But slowly and steadily it went down, and by early morning all of the little island was uncovered. All the party were then quickly rescued with boats.

The builder started, as the heading in the evening paper caught his eye—“Terrible Bridge Accident—Who is to Blame?”

“Why, why, it’s the bridge of the shallow pier!” he exclaimed. “People will find out that I am the one to blame!”

“Shall I run away?” he wondered, and sat for hours with his head in his hands.

Suddenly he threw back his shoulders and said aloud, “No, I will not run away. I will stay and do what I can to make the bridge right and never neglect my duty again!”

Do you wonder that the good fairy of carefulness, and thoroughness, smiled and whispered, “I wish he could have learned his lesson more easily!”

The careless little boy had a very easy time both at home and at school, didn’t he?

But, what kind of man did he grow to be?

It did not seem as if just one shallow pier would matter, did it?

But if he had been honest and thorough in his work when he was little, do you think he would have been content to be paid for such a carelessly built bridge?

How do you suppose he felt when he heard about the accident?

Can you remember some time when you felt like being careless, but decided to do your very best?

Charles was fastening the lid on a box of Christmas presents which his little brothers were going to send to their cousins.

“If I were you, I’d put another nail on each side,” said grandfather.

“Oh, I think these will hold,” Charles replied, giving the box a little shake. “There are three, on each side.”

“Four would be better,” grandfather said.

“Oh, grandpa, don’t you think three will do?” asked the boy. “I—I haven’t any more.”

“So that is the trouble,” said the old gentleman, laughing. “Very well, here is some money. When you get back from the store I will tell you how the history of a whole great nation was changed for want of a few horseshoe nails!”

“A few horseshoe nails!” exclaimed Charles. “Is it true, grandpa?”

“It is true,” answered grandfather. “Now hurry up if you want to hear how it came about.”

“Oh, thank you!” Charles cried, as he started out of the door.

He was so delighted with the promise of one of grandfather’s stories that he was back in less time than if he had gone for candy!

“Well done!” grandfather greeted him. “Now sit down, and while you get your breath, I will tell you the story.

“Many, many years ago, when King Richard was ruler of England, he owned a beautiful horse which he rode whenever he went into battle.

“One day word came that Henry, the Earl of Richmond, was on his way to attack the king’s men.

“King Richard ordered his favorite horse[19] brought to him, and turned to talk to the officers of his army.

“Now the groom who had charge of the king’s horses suddenly noticed that this horse needed shoeing.

“So he hurried to the nearest smithy.

“‘Shoe this horse quickly,’ he said to the blacksmith. ‘His Majesty has called for him. The enemy is near!’

“The blacksmith worked with all his might, and soon had four horseshoes ready.

“When he had nailed on two shoes, he found he had not nails enough for the other two. Suddenly the bugles sounded.

“‘Hurry!’ cried the groom. ‘The soldiers are gathering!’

“‘Shall I make more nails?’ asked the blacksmith.

“‘How many have you?’ asked the groom.

“‘I have only eight,’ replied the smith. ‘It would not take very long to hammer out eight more.’

“‘You will have to make eight do,’ said the groom.

“‘If you could only wait a little while,’ urged the smith, working away.

“‘I suppose I might,—but it would be a[20] risk! Won’t four nails hold a horseshoe?’

“‘Well, that depends on how hard the horse is ridden,’ answered the blacksmith, driving the last of the eight nails in place.

“The horse reached the king in good time, for it took quite a long while for the officers to make their plans.

“Soon King Richard was riding among his men, cheering them on in the battle.

“‘No other horse could carry a man as surely and swiftly,’ whispered the king, patting the horse’s neck.

“He had not noticed that the horse had lost one shoe. Onward he urged him over a rocky hill. Another shoe flew off.

“Suddenly the horse stumbled and fell, and the king was thrown to the ground.

“Before he could rise, the horse, although lamed, had struggled to his feet and galloped away, dreadfully frightened.

“Then the king shouted, ‘A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!’

“But there was no horse for him. When his men had seen him thrown, they had all turned and fled.

“And so the battle was lost, and King Richard was killed, and the history of the great nation of England was changed, for Henry, Earl of Richmond, became king.”

“And all for the want of a few horseshoe nails!”, finished Charles, as grandfather stopped speaking. “I will put two more nails into each side of the box lid, grandpa!”

“While you are doing that, I will teach you a few lines that I learned when I was a boy,” said grandfather. “Try to remember them.”

How might the battle have ended if the groom had waited until the blacksmith had put the right number of nails in the horse’s shoes?

Which do you think King Richard would rather have lost—a little time or his kingdom?

How do you suppose the groom and the blacksmith felt when they learned the result of the battle?

Do you know any careless people?

What do you think of them?

Can you remember ever doing something carelessly in order to finish more quickly?

Tell about it.

What is worth doing at all is worth doing well.

Go to the ant, thou sluggard; consider her ways, and be wise.

As a boy, Abraham Lincoln was known as “Honest Abe.” Like other boys he sometimes did wrong, but never did he try to hide his wrongdoing. He was always ready to own up and tell the truth. So his neighbors called him “Honest Abe.”

In this way he was like young George Washington. The American people are fond of that kind of boy. That is one of the reasons why Lincoln and Washington were each twice elected President of the United States.

When he was fourteen years old, young Abraham[24] attended a log cabin school during the winter.

Nailed to one of the logs in the schoolhouse was a large buck’s head, high above the children’s reach.

A hunter had shot a deer in the forest, and presented the head, when mounted, to the school. It had two unusually fine horns.

One day the teacher noticed that one of the horns was broken off short.

Calling the school to order he asked who had broken the horn.

“I did it,” answered young Lincoln promptly. “I reached up and hung on the horn and it broke. I should not have done so if I had thought it would break.”

He did not wait until he was obliged to own up, but did so at once.

There were no libraries on the frontier in those early days. When the boy Lincoln heard of[25] anyone who had a book, he tried to borrow it, often walking many miles to do so. He said later that he had read through every book he had heard of within fifty miles of the place where he lived.

When living in Indiana he often worked as a hired boy for a well-to-do farmer named Josiah Crawford. Mr. Crawford owned a “Life of George Washington,” a very precious book at that time. The book-hungry boy borrowed it to read.

One night he lay by the wood fire reading until he could no longer see, and then he climbed the ladder into the attic and went to bed under the eaves. Before going to sleep he placed the book between two logs of the walls of the cabin for safe-keeping.

During the night a heavy rain-storm came up. When young Lincoln examined the book in the morning it was water soaked. The leaves were wet through and the binding warped.

He dried the book as best he could by the fire and then in fear and trembling took it home to Mr. Crawford. After telling the story he asked what he might do to make good the damaged property.

To his relief, Mr. Crawford replied: “Being[26] as it’s you, Abe, I won’t be hard on you. Come over and shuck corn for three days and the book is yours.”

Shuck corn for three days for such a book as that! It was nothing! He felt as if Mr. Crawford was making him a wonderful present.

After reading the book he often talked about what he was going to do when he grew up.

Mrs. Crawford, who was very fond of him, would ask, “Well, Abe, what do you want to be now?”

“I’ll be president,” he would declare.

She would laugh at him, and say, “You would make a pretty president with all your tricks and jokes, wouldn’t you?”

“Oh, I’ll study and get ready, then the chance will come,” he would reply.

At the age of twenty-one Abraham Lincoln became a store clerk for a short time. He was then six feet four inches tall and very strong. He could out-run, out-jump, out-wrestle, and[27] out-fight any man in the rough pioneer country where he lived.

While the people respected his great strength, they liked him still more for his honesty in little things.

One evening, on reckoning up his accounts, he found that in making change he had taken six cents too much from a customer. On closing the store he immediately walked three miles to the farmhouse where the customer lived and returned the six cents. Then he walked the three miles back.

On opening the store one morning, he discovered a four-ounce weight on the scales. He remembered that his last customer the evening before had purchased half a pound of tea. He saw at once that he had given her short weight. He measured out the four ounces still due, locked the store, took a long walk to the customer’s house, and explained the shortage.

These were little things, but Honest Abe could not rest until he had made them right.

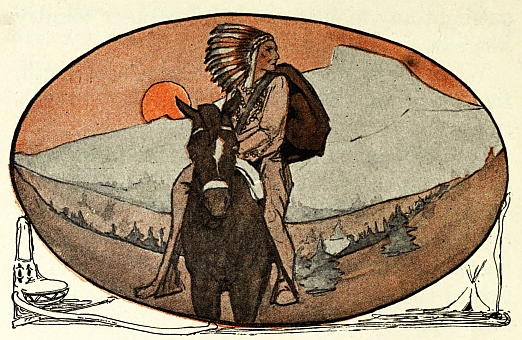

In the Indian country there was once a great drought. The land was very dry. No rain had fallen for many weeks. The crops and cattle were suffering from thirst.

Now, in one of the tribes there was a young Indian who had a very high opinion of himself. He pretended that he could foretell what was about to happen, long before it really did happen.

So he foretold that on a certain day a high wind would blow up, bringing with it a[29] great rain-storm with plenty of water for everybody.

The day came. Sure enough a high wind did blow up, but it brought only a violent sand-storm without a drop of rain, and it left the land drier than before.

So the Indians laughed at the young man who foretold before he knew and called him “Dry Rain.”

Although he afterwards became a noted chief, he never lost his name.

One day, when he was an old man, Dry Rain rode in from his village to the white man’s trading post.

The old chief purchased a number of articles, among them some jack-knives and six hatchets. The hatchets were for his six grandsons.

The trader packed all the purchases in a big bundle. Dry Rain paid for them, mounted his pony, and rode home to his village.

When he opened his package, he noticed that the trader by mistake had put in seven hatchets.

But Dry Rain said nothing. “That extra one will do for me,” he thought. “The white[30] men stole the Indian’s land and never gave it back; I will keep the hatchet.”

At the same time he did not feel that this would be doing just right.

In his wigwam that night he lay half-asleep and half-awake, thinking about the hatchet.

He seemed to hear two voices talking, in a tone so earnest that it sounded almost quarrelsome.

“Take back the hatchet,” said one voice. “It belongs to the white man.”

“No! do not take it back,” said the other voice. “It is right for you to keep it.”

Back and forth the voices argued and argued, for hours it seemed to the old chief.

“Take it back!” “Keep it!” “Take it back!” “Keep it!” “Take it back!”

At last he could stand the dispute no longer, and sat up in bed wide awake.

“Stop talking, both of you,” he commanded. “Dry Rain will take back the hatchet in the morning.”

Then he lay down again, pulled the blanket over his head, and was soon fast asleep.

At daylight he arose, mounted his pony, rode back to the trading post, and returned the hatchet to the trader.

“Why did you bring it back?” asked the[31] trader. “I had not missed it, and perhaps never should have known you had it.”

“But Dry Rain would know,” replied the old chief. “The two men inside of him talked and quarreled about it all night! One said, ‘Take it back!’ the other said, ‘No, keep it.’ Now they will keep still and let him sleep.”

Do you think that most white men set the Indians a good example in being honest?

Dry Rain wanted very much to have the extra hatchet, didn’t he?

But was he comfortable when he decided to keep it?

Do you think the white trader would ever have found out?

But who would have known?

Did two voices inside of you ever talk when you were tempted to keep something which didn’t belong to you?

Truth will ever rise above falsehood, like oil above water.

Mr. Dingle was not looking toward Helen. He was busy grinding coffee in another part of the store.

How pretty the bright red cranberries looked! Helen wished she had some.

Her little hand crept over the edge of the barrel, and very quickly seven bright shining cranberries were in Helen’s pocket.

“What can I get for you, little girl?” asked the storekeeper.

“A pound of butter, please,” Helen answered. She did not look him in the eye; instead, she looked out of the window.

It took Helen but a short time to reach home.

She laid the butter on the table and put the seven cranberries in a cup.

“Aren’t they pretty!” she whispered. “I think I’ll play they are marbles.”

She found a piece of chalk and drew a circle on the floor. Then she began the game.

“What pretty bright cranberries!” exclaimed her mother coming into the room. “Where did you get them, dear?”

How Helen wished that her mother had not asked that question.

“Did Mr. Dingle give them to you?” her mother asked.

How Helen wished she could say yes! “But after all,” she thought, “that was not stealing, so I’ll just tell mother. She knows I would not steal.”

“No, mother,” she answered, shaking her head. “I took them out of the barrel.”

“You did!” exclaimed her mother. “Why, my dear, did you not know that was wrong?”

“I didn’t take many—only seven,” Helen said; “and Mr. Dingle had thousands and thousands of them!”

“Come here, dear, and sit on my knee,” said her mother. “I want to ask you something.”

When Helen came she asked, “When you took[34] the cranberries, was Mr. Dingle looking toward you?”

“No, he was busy,” answered Helen.

“Would you have taken them if he had been looking at you?”

Helen hung her head.

“I do not think you would, dear,” said her mother. “Of course, you did not think for a moment of stealing from Mr. Dingle.”

“I will never do such a thing again, mother,” promised the little girl. “I am sorry.”

“Are you sorry enough to take those berries back, and tell Mr. Dingle what you did?” asked her mother.

That was quite different from being sorry in their own kitchen.

“Oh, mother, I don’t want to do that!” said Helen, tears coming into her eyes.

“That is because you are ashamed, Helen,” said her mother; “but I hope you will always be brave enough to do the right thing.”

“Will you go with me to the store, mother?” asked Helen.

“No,” said her mother, “I want you to go by yourself. But I can help you this much: I can telephone Mr. Dingle that you are coming.”

Helen sighed. “I wish I had been, and was[35] back again,” she said, picking up the pretty berries.

“Well, well!” said Mr. Dingle, when Helen handed him the berries, “it takes a pretty brave girl to own up. If you were a boy, little girl, I would ask you to come and work for me this next vacation.”

Why do you think Helen felt so uncomfortable when she was asking for the butter, and later when her mother asked her where she got the cranberries?

Do you suppose Mr. Dingle would ever have known about the seven cranberries?

But who would always have known?

Why was it that Helen did not think taking the cranberries was really “stealing”?

What did Helen’s mother think about it?

What do you think about taking even the smallest thing that doesn’t belong to you?

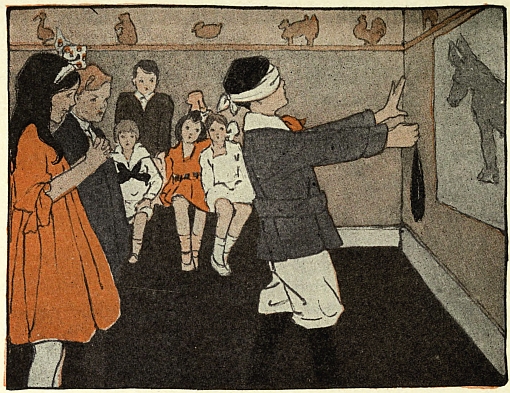

“Can you see?” asked Hilda Wells, as she tied the handkerchief over Fred Warren’s eyes.

“You might make it a little tighter,” answered Fred.

So Hilda tightened the blindfolder.

“Now, we’ll turn you around three times, start you straight,—and you pin the tail on the donkey,” she said.

The “donkey” was a large picture of that animal fastened to the wall at the opposite side[37] of the room. It was minus its paper tail, which Fred held in his hand.

“Don’t you peep!” cried all the children.

“We’ll see if he can do better than I did!” declared Frank Bennett. So far the prize belonged to Frank. Fred’s turn came last.

After being turned around three times, Fred walked straight up to the picture and pinned the tail exactly in place.

“Oh, Frank, that is better than you did by two inches!” said Hilda.

“Fred gets the prize!” cried the excited children, as Fred pulled off the handkerchief.

Then little Marie, Hilda’s sister, handed him a pearl-handled penknife.

Fred made little of his prize, and as soon as the children stopped examining it, slipped it into his pocket.

After that, Mrs. Wells served ice-cream and cakes.

Oh the way home Frank asked Fred to let him see the prize. “It is a beauty of a knife, Fred,” said he. “Until you tried, I thought I should be the winner.”

Fred muttered something about having too many knives already.

Frank opened his eyes wide in surprise. “Too[38] many!” he exclaimed. “I wish I had too many! I’ve never had more than one, and that was father’s when he was a boy.”

“Good night, Frank,” said Fred, suddenly swinging into a side street. “I am going to take a short cut home.”

“Good night, Fred,” called Frank.

“That’s a queer way for a fellow to act,” he thought, as he walked on alone. “I wonder what is the matter with him.”

Suddenly he heard footsteps, and in a moment Fred had caught up with him. “Here, take it, I don’t want another knife,” he said, thrusting the prize into Frank’s hand.

“Oh—oh, I don’t want your knife!” exclaimed Frank.

“Well, I don’t want it, either!” said Fred. “It belongs to you, anyway; and I believe you know it! I am almost certain you could see me peeping from under that handkerchief!”

“I was not quite sure,” said Frank; “not sure enough to say anything about it, anyway.”

“Well, if you don’t keep the knife I’ll throw it into the river,” said Fred, running away as fast as he could.

This is the story of a boy who ruined a good book. A good book is always a good friend.

He did not mean to—oh, no! But what of that—he did it, as you may read.

His name was Max Green. One day Max borrowed a book from Tom Brown, a fine new book with a picture of a submarine on the cover. Tom had just received it as a birthday present from his uncle.

That night Max sat down in a corner to read it.[40] Soon he came to the place where the submarine was getting ready to fire a torpedo.

“Squeak!” went the book, as Max gave it a twist in his excitement. He did not hear the sound; he only saw the torpedo skimming through the water.

“Crack!” went the book, as Max gave it a heavier twist. He did not notice that he was bending the covers farther back. He only knew that the torpedo was striking the bow of a big man-of-war.

“Rip!” went the book down the middle, as Max gave it a harder twist with his hand.

But Max read right on, for just then the man-of-war lurched over on its side as if it was getting ready to sink.

In his excitement Max forgot all about what he was doing and twisted and bent the book back, cover to cover.

“Stop—quick—oh! oh! It hurts! You have broken my back—broken my back! Oh!—oh!” cried the book.

Suddenly Max woke up and saw what he had done—but it was too late. He had broken the glue and stitches apart and the covers hung limp.

Just then his mother came in.

“Look, mother—see what I have done to Tom[41] Brown’s book,” he confessed. “I am so sorry. It is such a good book. Can’t we glue it together again?”

“No,” said his mother, “it is ruined. Glue may help, but it will never be the same book.”

“Oh, I am so sorry!” said Max.

“Yes, Max, but being sorry will not make this book as good as it was when you borrowed it.”

“I will make it right with Tom, mother. I will take my birthday money to buy him a new one.”

“That is the right thing to do, Max,” answered his mother.

How is a good book a good friend?

Suppose it had been his own book that Max ruined, would he have been treating it fairly?

If you were a book, how would you want to be treated?

Do you know what holds a book together? Tell what you know about the way a book is made.

Why should we be so careful of books?

The little schoolhouse was painted white, with green shutters. Over the front gable was a little old-fashioned belfry. In it swung a little old-fashioned school bell, for this was a country district school, with scarcely a house in sight.

One bright September morning, the opening day of school, forty or fifty noisy children were drawn up in line, waiting for the bell to stop ringing.

When the bell stopped, the children marched[43] inside and took their seats facing the teacher’s desk.

“Order!” tapped the desk bell, and the room was suddenly still.

The pupils looked to see who had tapped the bell, for the teacher was nowhere to be seen.

They saw the new school-books piled on the platform and on the teacher’s desk—but where was the teacher?

“I am the new Spelling Book, full of hard words,” said the top book of the pile of spellers on the right-hand side of the platform.

“I am the new Reader, full of good stories,” announced the top one of a stack of readers on the left-hand side of the platform.

The pupils were startled. It was so quiet you could hear the clock tick.

“I am the new Arithmetic, full of problems harder to crack than the hickory nuts in the woods,” spoke up a book on the teacher’s desk; “but why don’t you find your teacher?”

No one answered. The children only sat half-frightened, wondering what would happen next.

“I am the new Language Book,” declared another book in the row on the teacher’s desk; “but who will teach you your mother tongue?”

Everyone was still. Only the clock ticked on.

“I am the Geography; in my pages are maps of all countries. Who will give you permission to look?” It was the largest book of all that asked this question.

The pupils stared opened-eyed over the desk at the teacher’s empty chair. They saw nothing but a sunbeam coming in through the window—full of particles of shining dust.

“There must be somebody hiding,” spoke up one boy who could stand the strain no longer.

“I am going to see,” said another boy braver than the rest.

Getting up, he looked behind the desk and in the closet, but nothing was to be seen, not even a mouse.

“Let us go out and look for the teacher,” he cried. With one accord they ran pell-mell out the door into the playground.

An automobile was coming up the road at top speed.

“Good morning, boys and girls,” the new teacher called, as the machine pulled up.

“Good morning, teacher,” they answered crowding about her.

“I am sorry to be late the first day of school. There was some trouble at Rockland and the train was delayed. Mr. Jones drove me over.”

“We are glad you are here,” said an older girl as the machine drove off. “We went in and took our seats at nine o’clock, thinking you would come at any minute. All at once something began to talk. ‘I am the Speller full of hard words; I am the Arithmetic; I am the Reader; I am the Geography; where is your teacher?’ the voices said. At first we thought somebody was hiding, but we could not find anyone. Then we got frightened and ran out.”

“Well, isn’t that strange?” said the teacher laughing. “We will go in and see.”

Together they trooped into the schoolroom. They looked everywhere; nothing had been moved; everything was just as usual.

The teacher tapped the bell and everyone took a seat.

“Well, children,” she said smiling, “we have already learned a very important lesson this morning, and that is that every school must have a teacher!”

| What should a school have?— | Teachers Pupils Books Schoolhouse |

What other persons or things should a school have?

Can you have a school without a teacher?

Why is the teacher so important?

| What should the pupils be?— | Obedient Clean Orderly Courteous Helpful Punctual Anxious to learn. |

| What else should the pupils be?— | Respectful to all connected with school. Respectful to principal, to teacher, to janitor, to other children. |

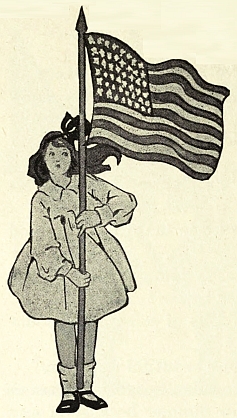

As you came to school this morning, did you look up at your flag floating from the top of the flag pole? Didn’t it look beautiful, waving and rippling in the sunshine against the blue sky? I wonder if you have ever thought about what it means?

You know flags are signs or emblems, and they all have a meaning.

There is no reading on our American flag, yet everyone knows what it means as certainly as if there were letters all over it.

Our flag means that the United States of America is the Land of the Free, and our government stands for:

That is the reason so many people come to this country from countries where they do not have such help from the government.

We Americans are very thankful for what our flag means.

If we are good Americans we shall live up to every one of the following duties:

I pledge allegiance to my flag and to the republic for which it stands; one nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

I give my head, my heart, my hand to God and my country; one country, one language, one flag.[A]

June 14 is the anniversary of the adoption of the flag, and that date is celebrated in many states as Flag Day.

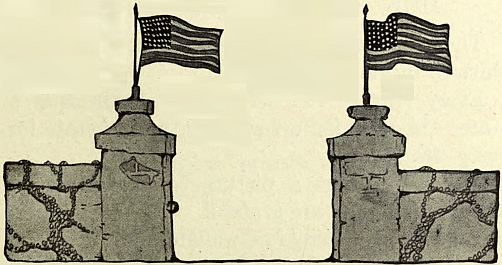

We can honor our flag

Our state has one star in the blue of the flag.

How shall we honor our star?

How shall we show respect for our country and our flag?

Since our flag means so much to us, we should respect it and love it with all our hearts.

When the flag passes in a parade, people should, if walking, halt; or if sitting, rise and stand at attention and uncover.

The flag should never be allowed to drag on the ground nor be left out after dark. Did you know that it must never be used as an old rag? You see no matter how old or torn a flag becomes, it is[51] still our flag and must be loved and honored always.

“America is another name for Opportunity.”

What do you understand by that?

The thirteen stripes in our flag represent the thirteen original colonies.

Every star in the field of blue represents a state—“A star for every state, and a state for every star.”

The flag brings a picture to our minds of all the things we are grateful for in our history, and of all the things we want our country and ourselves to be.

What does our flag mean?

Are you not glad that you live in a country where all the people rule, instead of any one person or just a few people?

Can you repeat the Scouts’ Pledge? (Standing.)

Who was Betsy Ross?

Can you form a tableau like the picture of Betsy Ross sewing the American Flag?

Isn’t it almost as brave to live up to the red, white, and blue as to die for our colors?

Why is our nation’s flag always hung higher in this country than the flag of any other nation?

Will you bring pictures of the flags of some other countries to class?

Do you think any other flag more beautiful than ours?

Will you try to do all you can to honor our flag, and never to let the star of your state grow dimmer because of any act of yours?

One snowy day shortly after Christmas, when carefully picking my way over the crossing at Market Street Ferry in Philadelphia, I almost ran into a big policeman.

Just back of the big policeman was a little dog, and just back of the little dog was a little dog-house, and just back of the dog-house was a beautiful Christmas tree.

Wouldn’t it have made you stop in surprise to see a dog-house in the middle of the busiest street in your city or town? Wouldn’t you have wondered why the big policeman had the little dog, and why the little dog had such a nice house there? And wouldn’t you have wondered and wondered whether the Christmas tree belonged to the dog or to the big policeman? It made me so curious that I did just as you would have liked to do—I asked the policeman to tell me the story.

“Good morning, Mr. Burke,” I said, for I knew the officer’s name. “Will you tell me about the little dog?”

“Why,” answered the policeman with a smile, “don’t you know about Cheesey? Come here, Cheesey, the lady wants to see you!”

Cheesey looked up at the speaker and wagged his tail.

“Cheesey was born on Race Street pier,” went on the policeman. “Nobody knows how he got his living after his mother died; but one thing is sure, he was not treated very kindly by the men who loaded the boats and swept the wharves. To this day Cheesey growls at the sight of one of those men.

“After a while Cheesey found a little playmate, but the playmate was run over by a fire engine. All night long Cheesey lay in the spot where his little mate had been killed.

“Weary and lonely and hungry, he crept back to the old cheerless corner of Race Street pier, which was the only place he knew as home.

“There he lay with his head on his paws, not noticing anything until one of the men kicked him out of the way.

“Cheesey ran out of the pier and down Delaware Avenue, not knowing where he was going; but he went just the right way, for he ran into Officer Weigner, one of the four of us who watch this crossing.

“He spoke kindly to the little fellow, and gave him something to eat.

“From that time, Cheesey seemed to think he belonged to the policemen on this crossing. Then we gave him his name.”

“Cheesey had no place to sleep,” went on the policeman after seeing some people safely across the street, “except on a pile of bags in the ferry house. He seemed so cold that I asked Charley, one of the workmen in the ferry, if he[59] could not knock together some packing boxes for the little fellow.

“Charley did the best he could, but I must say he made a sorry looking dog-house.

“One day, just before Christmas while I was on duty, Mr. Sheip, of the Sheip Box Factory, happened to notice the box Charley had knocked together.

“‘Well, well,’ he said, ‘is that the best you fellows can do?’

“‘Why, Mr. Sheip,’ I replied, ‘we are not box-makers, you know.’

“‘That’s so!’ he said. ‘I’ll have a dog-house made in the factory!’ and on Christmas day this beauty of a dog-house came. Have you noticed the label on it?”

I read the painted black letters on the large white label:

“It pleased us so,” went on the officer, “that we bought a Christmas tree and many people helped us trim it.

“A good many people brought presents for Cheesey. One lady from Camden brought a feather pillow; another lady brought a piece of meat. That dog could have seventeen meals a day if he could hold them—couldn’t you, Cheesey?”

The little dog wagged his tail, turned around twice, then went into his house. After thanking the officer I went on my way, made happier for all my life because of the true story of Cheesey.

Do you think the officers were repaid by knowing they had made Cheesey happy?

Does Cheesey remind you a little of Cinderella? Who were the fairies in Cheesey’s life?

What might have happened to Cheesey if the officers had not been kind?

Did you ever own a dog?

Can you tell some story showing your dog’s intelligence or bravery?

What is the kindest thing to do for an animal which is suffering if you cannot take care of it or feed it?

Do you know the address of the S. P. C. A. in your city?

Did you know that sometimes dogs are thought to be mad when they are only very thirsty?

Sometimes dogs have been treated unfairly and are cross; so it is best not to pat a strange dog’s head.

Do you realize that a dog is the only animal which makes people its companions and playmates?

How should we treat dogs?

What do you think of people who do not care for and feed the cats they own?

Do you know that a cat that is well cared for, and kept in the house at night is not likely to catch birds, because cats catch birds in the early morning and at twilight?

What do you think of people who move away from a place and leave their cats behind? What will become of the cats?

What should people do with cats they do not care to take away? Do you know where the nearest S. P. C. A. office is?

What good service does the cat do for people?

Why are rats and mice dangerous to our health?

How many toes has a cat on front paws? On back paws?

Which way does the fur lie on the under side of the legs?

If you cannot care for or feed a stray cat, what is the kindest thing to do?

How does it save the birds to see that stray cats either are given a home or are taken to a cat refuge?

On the porch of a comfortable old house, shaded by fine trees, a group of young girls were gathered around a small table, sewing.

Suddenly the harsh notes of a hand-organ came to their ears, disturbing the peaceful stillness of the summer afternoon.

Marion Johnson, who was visiting her cousins, laid aside her work and listened.

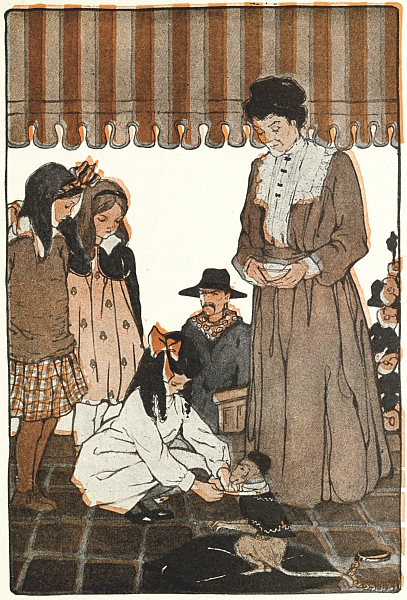

“Why, I do believe it is the very same man that came to our town a week ago,” she exclaimed. “He had with him a poor, miserable looking monkey, which he called Jocko.”

Just then they saw the organ-grinder, with the monkey perched on the, organ, coming up the village street. Seeing the girls on the porch, he turned up the walk.

“I think I shall call Aunt Kate,” remarked Marion, rising and going into the house.

Aunt Kate could always be depended upon to help any dumb creature needing a friend.

Aunt Kate’s face lost its usual look of quiet good humor, as she glanced over the porch railing and saw a tall swarthy man at the foot of the[70] steps, carelessly turning the handle of a small squeaky organ.

Keeping time to the music, a weak little monkey danced very wearily. When his steps dragged he was brought up quickly with a sharp jerking of the chain which was fastened to his collar.

A cap was held on his head by a tight rubber band which passed under the chin. His gaudy dress was heavy and warm and seemed to weigh down his tired limbs.

Now and then, when he dared, Jocko laid a tiny brown hand on the tugging chain in an effort to ease it. With an appealing look he glanced up at his master, as if trying to make him understand how painfully the collar was cutting his thin neck.

Aunt Kate’s mild blue eyes almost flashed as she motioned to the organ-grinder to stop playing.

“You no lika music?” he asked brokenly, glancing up at her in some surprise.

“Yes, that is right,” she answered, speaking very slowly and distinctly.

“We do not like the music; and we do not

like to see that poor monkey dance; and, above

[71]

[72]all, we do not like to see you hurting his neck by

pulling that chain.”

The look of sullen anger which came over the man’s face quickly disappeared when he saw the coin in Aunt Kate’s hand.

“I will give you this,” she said, holding up the piece of money, “if you will stay here and let Jocko rest for one hour.”

The organ-grinder smiled and sat down on the steps as a sign of agreement.

At first, Jocko could scarcely believe that he might rest his weary little legs and feet. After a while, however, he threw himself at full length upon the porch floor as some worn out child might have done.

Marion was left on guard to see that he was not disturbed when the others went to get food.

When they returned they found Jocko resting on a soft cushion, a comfort his little body had never known before.

Only after being promised more money did the organ-grinder permit Marion to take off Jocko’s hard leather collar, underneath which she had discovered sores.

She bandaged the tiny neck with soft linen spread with salve. She took off his cap, too, with its tight-cutting band.

When water was brought, Jocko drank with pitiful eagerness. Many hours had passed since he had had a drink, and his throat and lips were parched. He ate the food they offered him like a wild creature, for he was very hungry.

Every once in a while he would glance at the organ-grinder as though he feared punishment.

When the hour was up, the organ-grinder would stay no longer. As his master led him away, Jocko lifted his hat, just as if he wanted to thank Aunt Kate and the girls for their kindness.

“I never knew before,” said Marion, “how cruel it is to expect little monkeys to live such unnatural lives. I do hope the man will be more kind to Jocko after this.”

Why didn’t the girls and their aunt like to see the little monkey dance?

What did they enjoy seeing it do?

Have you ever been very, very tired?

Can you imagine how you would feel if some giant would not let you rest?

What kind of life is natural for monkeys?

Did you ever give a penny to an organ-grinder with a monkey?

If everyone stopped giving money to men who use monkeys for begging, how would it help the little monkeys?

“Cheer up! Cheer up!” sings Robin Redbreast every morning. “Listen to me! Listen to me! Oh, excuse me! I see, I see a feast!” and down he hops, hops, hops to the spot where he sees a nice fat worm wiggling out of the ground.

Perhaps it is an earthworm, perhaps it is a worse worm; but if it is an earthworm, you will have fun watching Robin.

He seizes the worm with his bill, then braces his feet against the earth, and pulls and pulls with all his might.

Out comes the worm with such a jerk that Robin almost topples over; but he doesn’t. He either eats the worm or flies away with it to his hungry little birdies.

Down he drops it into one of the wide open mouths in the nest.

Do you know how many earthworms one baby robin can eat in one day?

A man who loves birds once counted the worms that one pair of robins fed to their little ones, and found that each little robin ate sixty-eight earthworms in one day.

Sixty-eight earthworms if placed end to end would measure about fourteen feet. Just think[75] what busy lives Mr. and Mrs. Robin Redbreast live, and how they love their little ones.

Robins eat many other kinds of worms besides earthworms, and they eat insects, too. They work hard to feed their babies, and in this way they do a wonderful thing for us, for the insects they eat would destroy the plants which we need.

You know bread really grows on tall grasses called wheat and rye, and oatmeal grows on a grass called oats.

There are millions of insects which like wheat and rye and oats as much as we do, and they would eat up all the crops if it were not for the birds that eat the insects. Now you can see why we call the birds our friends.

Who killed Cock Robin?

No; it was not the sparrow with a bow and arrow. No—more likely a boy with an air rifle killed him, or a man with a gun who did not know what a wicked thing he was doing.

He did not know that he had killed one of his best friends.

He did not know that without the work of beautiful Robin Redbreast and other birds the world might go hungry.

What if robins do eat a few cherries? They like mulberries better. A wise farmer plants a Russian mulberry tree for the robins, and the mulberries save the cherries.

Do you know that millions of men and boys hunt and kill birds “for fun” every year?

Do you know that millions of birds are killed each year to be used in trimming women’s hats?

How many different birds can you name?

Can you tell the kinds of food each of them eats?

Do you know what kinds of nests they build?

What do you think of people who kill robins?

Have you ever placed food in a sheltered place for birds in winter when it is hard for them to find a living?

When I was only about six years of age, a Robin Redbreast that we used to feed got so tame that he would fly in through the window to our breakfast table.

In the spring he delighted us by bringing a small family of Roblings to the window sill of the room as if to introduce them to the people who had helped him through the hard winter!

Another special bird that I remember was a one-legged sparrow that used to be among the birds that came when we were living in Bucking-ham-shire. We always called him “Timber-toes.”

He came to us for two or three winters, so that, even with but one leg, he must have picked up a living somehow.

Did you ever make a house for a little house wren?

Little Jenny Wren is looking for a house every spring. She is a very friendly neighbor. Why not make her a house with a doorway too small for Mrs. Sparrow to squeeze through? Make the opening only one inch wide.

The meadow lark is one of our very helpful birds. Do you know the colors of the meadow lark’s feathers?

Now, I want to tell you something that is worth knowing. It is this. If all the birds in the world should die, all the boys and girls in the world would have to die also. There would not be one boy or girl left alive; they would all die of starvation.

And the reason is this. Most small birds live on insects; they eat millions and millions of insects. If there were no birds, the insects would increase so that they would eat up all vegetation. The cattle, and horses, and sheep, and swine, and poultry would all die, and we should have to die also.

Now, what I want all of you to remember, is that every time you kill one of these little insect-eating birds, it means that thousands of insects the bird would have eaten are going to[79] live to torment us; and every time you take an egg from one of these little birds’ nests, that means one less bird to eat the insects. I do not like mosquitoes and insects. I think it is better that the birds should live and eat the insects, than that the birds should die and the insects eat us.

If a bird in a cage could speak, what do you think it would say?

Can it tell you when it has no drinking water?

Do you know that thirst is worse than hunger?

Do you know that a person can do without food much longer than without water?

What do birds do for farmers?

What do they do for you? Don’t you think it would be foolish to destroy them?

Do you think it right to keep wild birds in cages? Why not?

Did you ever notice the beautiful doves or pigeons in the city?

Why are they so tame?

My house is in a little grove of oak trees.

Every winter I feed several gray squirrels with nuts.

Every day about noon a big father squirrel comes and scratches on my kitchen window.

There he sits on the sill, watching with bright eyes until I open the window and throw out some nuts.

The more timid squirrels are seated on the ground looking up at the window. They catch the nuts and scamper away with them up to the tops of the trees. But not Furry. He takes nuts from my hands, and holding them in his little finger-claws, gnaws away the shell faster[81] than I can count ten. He acts quite like a little pig sometimes, for he asks for more than he needs.

What do you think he does with them?

He jumps down with one in his mouth and starts to dig. As soon as the hole is deep enough to suit him he buries the nut, packing the earth carefully over it to make it look as though the ground had not been disturbed.

Then back he comes for another nut.

If all the nuts he plants were acorns and he should forget to come and find half of them when he is hungry—how big my oak forest would be!

Have you ever fed a squirrel?

Where have you seen the largest number together?

Why were they not afraid?

How do mother squirrels carry their babies from one place to another?

How do mother cats carry their babies?

If mothers did not love their babies so much, what would happen to all animals and people?

Do we have to thank squirrels for some of our trees? Why?

Did you ever wish your doll or rocking horse were alive?

Could anyone make them live?

Isn’t being alive the most wonderful thing you can think of?

Doesn’t it make you glad to think of the little wild things living in the out-of-doors?

Name some of the animals living in the woods.

Would the country be as pleasant without them?

Why should you dislike to hurt any of them?

Do you know that if people do not stop hunting wild ducks, mountain sheep, deer, and other animals they may all be killed?

Did you ever see a reindeer?

Did you notice its beautiful eyes?

Would it be fun to fight a baby?

Are not many animals as helpless as babies when they are hunted?

Don’t you think it is cowardly to shoot little helpless animals “for fun”?

It was the week before Christmas. Everybody was ordering all sorts of good things to be sent home “just as soon as possible.”

The grocer’s boy, John, was on duty early. Soon many baskets were filled with orders to be delivered.

The horse was hurried out of the stable before he had quite finished his breakfast, and John soon had the baskets piled into the wagon.

“Be lively, now,” the grocer said. “Get back as soon as you can.”

John jumped on the wagon, seized the whip and gave the horse a sharp cut to begin the day with.

John kept the whip in his hand. If the horse held up his pace a minute to give himself a chance to breathe, another snap of the whip kept him on the run.

At the different houses where he left the groceries John rushed in and out as quickly as possible. In several places he was given fresh orders for articles that were needed.

So the morning passed, and dinner time arrived. As John put the horse in the stable he could not help seeing that his breath came hard and fast, and that he was wet with sweat.

“I guess it won’t do to give him any water, he is so hot,” John said, as he hurriedly put a scanty allowance of dry feed into the manger.

The worn-out horse, trembling in every nerve with the fatigue of going hard all the morning, was almost choking with thirst.

When John hurried in to his dinner, the first thing he asked for was something warm to drink. His mother gave him a cup of hot cocoa, and a good dinner, which he ate rapidly. Then off he started for the afternoon’s work.

“Hurry up,” said the grocer as soon as John appeared. “Get out the horse and take these baskets; they are all rush orders.”

“I went to Mrs. Bell’s twice this morning,”[85] said John. “I should think she might give all her order at one time and not keep us running there all day.”

“I can’t help it. She is a good customer. Hurry up,” answered the grocer.

John ran out to the barn. He certainly had meant to give the horse water before he started out again, but being hurried, he forgot it. In a few minutes, whip in hand, he was urging the tired, thirsty horse again over the road.

Toward the close of the afternoon the horse began to hang his head. When John touched him up with the whip he did not go any faster. When he stopped for the third time at Mrs. Bell’s house his legs were trembling and he closed his eyes as if he were going to sleep.

Mrs. Bell looked out of the window and said to her Aunt Sarah, who was visiting her, “I think it is a shame for Mr. Rush to let that boy race his horse so all day. Every time he comes here the horse is in a sweat, and now he looks as if he would drop. It is wicked to work a horse so!”

Her aunt replied, “Yes, the horses have to suffer for man’s thoughtlessness, and woman’s, too. He’s been here three times to-day, hasn’t he?” But Mrs. Bell did not see the point of the reply.

It was seven o’clock before John put the horse in the stable. He remembered then that he had given him no water all day. As he did not want to be obliged to go out to the barn again he gave him a pail of ice-cold water, which the horse drank greedily. Then he put his supper before him and left him.

He did not stop to rub down the aching legs or to give the faithful, exhausted creature any further attention. He just threw a blanket over him and closed the barn for the night.

When John came to the store the next morning a very angry looking grocer met him at the door. “You can go home as soon as you like. I won’t have a boy that drives my horse to death,” he said.

“Is the horse dead?” asked John, turning pale.

“It is not your fault if he is not dead. I have been up nearly all night with him, and I must get another horse to take his place until he is well.”

“You told me to hurry every time I went out,” answered John.

“Well, if you had any sense, you would know when a horse is used up and rest him,” replied the grocer.

The horse died that day; and the grocer, the boy driver, and Mrs. Bell were all to blame.

The grocer ought not to have trusted a boy who had no sympathy for animals. Such a boy is not fit to drive and care for a horse.

John was too selfish to give the horse time to breathe or to eat, and he did not care whether he was made comfortable in the stable or not.

Mrs. Bell was thoughtless in giving her orders; so she made the horse take many unnecessary trips to her house.

So a willing, patient animal was neglected and worked to death, when with good care he might have lived many years and done faithful work. This all happened because the man, the boy, and the woman had never learned to be thoughtful and kind.

What do you think of a man who is cruel to horses?

Do you think people respect such a person?

Did you ever hear that “cruelty is the meanest crime”?

How would you treat a pony? A horse?

Did you ever read “Black Beauty”?

Which should you like better for a friend—a man who is kind to animals or a man who does not care how they are treated, just so that he gets his work done?

When you are hurt, or sick, what do you do?

Can a horse or any animal tell a friend when he is sick?

To the Lady of the House:

Please order your supplies for the day early in the morning and all in one order. One daily trip to your door is enough. Two trips will wear me out twice as fast.

Telephoning in an extra order doubles the work for the sales clerk and bookkeeper as well as for the driver and horse. This adds to the cost of all you buy.

Hurry up orders make whippings for me.

Please think of those who serve you, both people and horses.

P. S. Some boys play with a whip over my back, not meaning to hurt me, but I cannot see the fun. It makes me nervous, and I get so tired by night from being worried that I tremble all over. I know boys do not think about that part.

Every horse will work longer and better if given three ample meals daily; plenty of clean, fresh water; proper shoes, sharpened in slippery weather; a blanket in cold weather; a stall six feet by nine feet or room enough to lie down; a fly net in summer and two weeks’ vacation each year. Do not use the cruel, tight check rein, or closely fitting blinders which cause blindness.

Wouldn’t you have much more work to do if there were no horses?

Have you ever been very tired?

Have you ever been very thirsty?

Could you ask for a drink of water?

Can a horse ask?

Don’t you suppose animals suffer terribly with thirst?

What would a horse say if he could talk?

Can you drive?

Did you ever stop to think that it is because a horse’s mouth is so tender that the great strong animal does what the driver wishes?

What do you think about jerking the reins?

Should we have as nice and comfortable houses or food or clothing if we had no horses?

Is the horse a laborer?

Has he a right to wages? What should they be?

How many meals a day should a horse have?

Can you imagine how it would seem if you were very, very hungry to be taken into a place where tables were spread with tempting food, and be driven past them without a bite?

How do hungry horses feel when they see and smell apples and grass?

Can you run as fast when you carry a heavy load as you can with a light load?

Can a horse?

Did you ever burn your mouth?

Did you know that the steel bit, if put very cold in the horse’s mouth, will burn off the skin of the tongue and make the mouth sore—and perhaps prevent the horse from eating?

Could the bit be easily warmed by dipping it into hot water, or breathing on it to take out the frost?

Did you ever stop to think that every creature that is alive can suffer?

Did you ever see a driver stop on a cold day and go into a restaurant for a bowl of warm soup or a cup of coffee?

Did he put a blanket on the horse?

Did you ever see a horse taken into a stable and given a warm meal on a cold day?

Did you ever see non-skid chain-shoes for horses?

Do you know that burlap tied on the horses’ hoofs answers the same purpose, and costs only a little time and forethought?

The driver can best help this horse to get up by spreading a blanket or carpet over the icy roadway under his feet.

These stories develop very simply, the fundamental ideas of service, dependence and interdependence, and reciprocal duties. They also teach incidentally the civic virtues of thoroughness, honesty, respect, etc., which form the subject matter of Part I of this book.

“Good morning, children,” said Mrs. Duwell, with a bright smile—so bright that it seemed as if the oatmeal she was stirring smiled too.

“Good morning, mother,” said Ruth. “My, but we are early this morning; it is only seven o’clock.”

“Good morning, mother,” said Wallace, sleepily. “May I go back to bed again?”

“Yes—after supper to-night,” replied his mother. “But I am glad you are up, for I am expecting a caller to knock at the door any moment.”

“Who is it?” asked Ruth.

“Oh, he is a very important man,” said her mother. “The strange part of it is that he never rings the front door bell, but always comes to the kitchen door and knocks.”

“Please tell us who he is!” cried both the children.

“Yes,” went on Mrs. Duwell, “he is going to bring us the most useful and wonderful article sold in any store in this city.”

“Oh, mother, tell us what it is,” begged the children.

Just then there came a heavy knock at the kitchen door.

“There he comes with it now, I believe,” whispered Mrs. Duwell. “Wallace, you may open the door.”

Wallace ran quickly to the door and opened it, and there stood—the bread man.

“Oh, mother,” exclaimed Wallace, “it’s only the bread man!”

“Wallace,” said his mother, “speak more politely. Say ‘good morning,’ and take a loaf of bread and a dozen rolls.”

“Now, mother, tell us who it is you expect, and what he is going to bring,” coaxed Ruth as soon as the door was closed.

“Sit down and eat your breakfast, children, and I will tell you all about it.”

When the children had been served, she went on: “The man I spoke about has just gone—he is the bread man. Isn’t a loaf of bread the most useful and wonderful article sold in any store in the city?”

“Why, mother, you are joking!” exclaimed Wallace.

“No, indeed, I am not. Tell me, children, what must you have in order to live?”

“Food,” replied Ruth.

“Correct; and what article of food do we most need?”

“Bread,” replied Ruth.