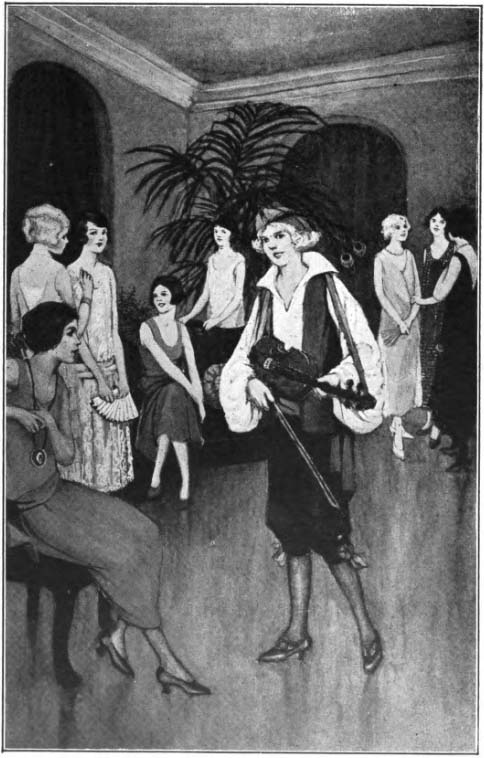

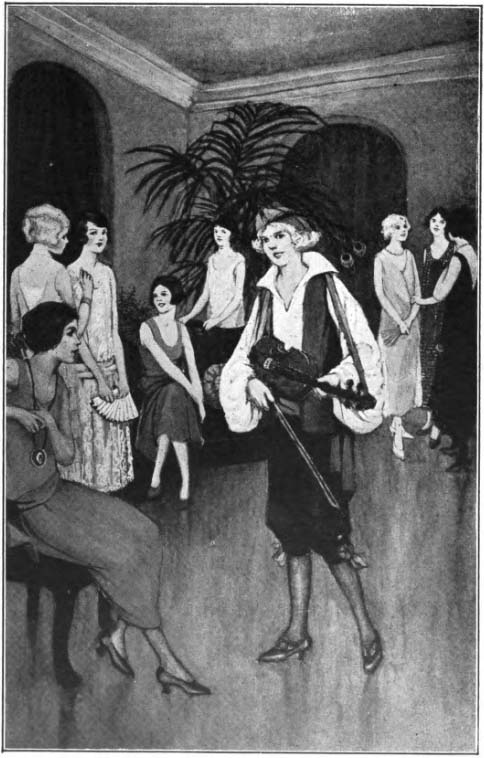

Phil, as the fiddler, presently came forward to play for the dance.

(Page 114) (Marjorie Dean at Hamilton Arms)

Title: Marjorie Dean at Hamilton Arms

Author: Josephine Chase

Release date: July 23, 2016 [eBook #52626]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from images made available by the HathiTrust

Digital Library.)

Phil, as the fiddler, presently came forward to play for the dance.

(Page 114) (Marjorie Dean at Hamilton Arms)

“They’ll be here before long.” Jerry Macy’s eyes calculatingly consulted the wall clock.

“And, oh, what a surprise!” Veronica Lynne spoke from the deeps of her own mischievous enjoyment.

“It’s going to be an occasion of surprises,” predicted Lucy Warner with the solemnity of a young owl. “Now why are you laughing, Muriel?” This very severely as she caught sight of Muriel Harding’s mirthful face and heard sound of her soft chuckle.

“Why am I laughing? You know better, Luciferous Warniferous, than ask me such a—well—such a leading question.” Muriel failed to make her laughing features match her reproving tones.

4“You’re both up to mischief. Think I don’t know the signs?” Jerry accused with a long-suffering air. “Luciferous looks too solemn to be true and your special variety of giggle is a dead give-away.”

“What special variety?” demanded Muriel with blank innocence.

“I wouldn’t attempt to classify it,” was Jerry’s withering retort. “I can only say, ‘it is.’”

“Of course it is.” Muriel light-heartedly furnished a rippling little sample. “Hark!” she held up an arresting hand. “Someone’s coming.”

Three energetic raps on the door followed her announcement. Then the door opened sufficiently to admit the laughing face of Leila Harper.

“Enter the Empress of Wayland Hall,” Leila heralded. She flung the door wide and bowed in Miss Remson. She and Vera Mason followed the little manager. Dressed in her best black satin gown, Miss Remson appeared signally amused at the honors done her. Leila was wearing an exquisite frock of orchid broadcloth. Vera, doll-like and dainty, looked like a cunning Dresden figure in a frock of gentian blue taffeta, the faint blue field scattered thickly with tiny pink rosebuds. Their light-hued dresses pointed to a celebration, as did 5those of the other girls gathered in ever-hospitable Room 15.

“The Empress of Wayland Hall.” Jerry bowed to the floor, pretended to lose her balance, but miraculously recovered it without accident. “Allow me to conduct you to the throne.” She offered her arm at a stiff angle. “Bow down, all the rest of you. Where are your court manners?” She briskly arraigned the smiling empress’s openly giggling subjects.

“Kindly give us a sample of court etiquette,” Ronny begged with mock humility.

“I thought I had.” Jerry exhibited deep surprise. “Am I crazy, or are you blind?”

“Ahem! My eye-sight is exceptionally keen,” Ronny said sweetly.

“I’ll have it out with you later,” promised Jerry. “Now don’t interrupt me again in the midst of my royal duties. Will your majesty please be seated?” She turned gallantly to the empress. “I would call your attention to the throne. Observe it closely. Would you even suspect it of having been ever anything but a throne?”

“Never,” Miss Remson made gratifying assurance. She feigned the most flattering admiration for the throne. It was composed of Jerry’s couch 6as a foundation, with all the bedding from Marjorie’s couch stacked upon it. Ronny had contributed a wonderful cloth of gold couch cover which her father had lately sent her from Lower California. Each one of the festive group had contributed her pet sofa pillows. Three fat velvet ones had been laid on the floor in front of the dais. The throne had blossomed into additional gorgeousness by the profusion of rich-hued pillows which graced it.

“It is a gorgeous and most imposing structure,” pronounced Miss Remson, her eyes dancing as she surveyed the metamorphized couch. She prodded its up-piled softness with an investigating hand, then raised herself with a nimble little spring to the place on the right to which Jerry had obsequiously bowed her.

“Thank you for them kind words. Praise is sweet, particularly when there are those about who are shy of proper appreciation. I won’t mention any names, your Majesty. I’m not speaking of myself, or you, either. I have too much delicacy to make disrespectful remarks about us.” Jerry peered knowingly at her majesty who nodded significant return.

“I trust your Majesty will not see fit to show partiality,” 7Ronny said very severely. “All here are entitled to your royal favor.”

“I see already the difficulties which attend royalty.” Miss Remson made a dismayed gesture.

“Don’t let it agitate you,” said Jerry. “Such—” She broke off to answer the door. Robin Page flitted across the threshold with a frisky little bounce. “Almost late! Not quite, thank fortune.” She glanced about the room with visible relief. “They haven’t come yet. I was so afraid I’d miss the fun. Two Craig Hall seniors called on me. They asked me to sing at a musicale they intend to give after the holidays. Miss French, one of them, has discovered a prodigy at Craig Hall. She’s a freshie named Miss Oliver. She can play divinely on the piano. But she is shy, and hangs backward when she should come forward. No one at Craig Hall suspected her of being a musical genius until one night last week.”

“Oh, I know her,” cried Muriel. “She’s a little girl with black straight hair and gray-blue eyes. I danced with her at the freshman frolic. She seemed to be rather timid, so I thought I’d encourage her by putting down my name on her card for three dances. I danced one with her then she suddenly disappeared and didn’t re-appear. I inquired for her. Some of the freshies said she was shy. Some 8said she was snippy. I didn’t think her the least bit snippy. I wrote a note to her on the strength of her being shy. She answered it in about two lines. That was rather snippy, I thought. Now I am all at sea about her. Is she shy, or is she snippy? That is the question.” Muriel ended with a laugh.

“She’s bashful,” Robin declared. “Wait until I salute the Empress of Wayland Hall, and I’ll tell you more of her.” Robin knelt on a plump blue velvet cushion at Miss Remson’s feet. The manager had thriftily set a small foot on each side of the cushion rather than use it as a foot rest. “Please pardon your admiring subject for being so neglectful.” She kissed the manager’s hand in approved gallant style. “Let me venture to remark, noble lady: Your throne is a daisy. Why oh, why, am I not of royalty?”

“Everyone can’t be. We’d not have thrones enough to accommodate the royal gang, if you all qualified,” Jerry pertinently reminded.

“Restrain your ambitions,” advised Lillian Wenderblatt cruelly.

“I’ll make a stagger at it,” sighed Robin. “Now let me finish telling you about my musical freshie before the rest of the royal party arrive. Where was I?”

9“Your last remark on the subject was that no one had suspected Miss Oliver of being a musical genius until one night last week,” repeated Katherine Langly in her quiet, accurate fashion. “See what splendid attention I was paying to you.”

“I’m charmed by it,” Robin gushed. “There are times, Kathie, when you are almost respectful to me. One might think, that, having gained such gratifying respect from a member of the faculty, I should be more than entitled to marks of respect from lesser college lights. Not so.” Robin looked vaguely about, not daring to allow her eyes to stop at any single member of the grinning group of girls.

“Another unhappy subject with a chip on her shoulder.” Jerry waved a hand toward Robin, thumb out.

“It behoves the lesser lights of college to be very careful upon whom they shine.” Lillian’s chin was raised to a painfully dignified angle.

“I wonder just who the lesser lights of college are?” Muriel said in a sweet child-like voice.

“As Empress it appears my duty to quell such disturbances as may lead to internal war in the kingdom,” put in the helpful Empress.

“Please, your Majesty, I want to keep on talking,” instantly petitioned Robin. “Kindly order this 10gang—pardon me, I mean your unruly subjects—to listen to me. Make them understand that if they don’t listen now, I sha’n’t tell them a single thing later.”

“We got that, your Majesty. Will you allow me to implore your miffed courtier to go right ahead. So pleased.” Jerry favored Robin with her far-fetched conception of a gracious smile.

“I can’t resist such a dazzling display of teeth and affability. May I ask what toothpaste you use?” Robin’s own pearl-white teeth showed themselves in an equally affable smile.

“Same as you do. Now proceed with your tale. The great moment is rapidly approaching.” Jerry indicated the clock. “Let us hear about this new musical wonder before the reception begins all over again.”

“One night last week,” Robin took up her narrative precisely where she had left off, “Miss French heard someone playing the living room piano. The Craig Hall girls had gone over to Hamilton Hall in a body to that illustrated lecture: ‘America South of Us.’ Miss French had stayed in her room. She had a severe headache.

“When she suddenly heard some one playing Chopin’s Second Nocturne on the piano in the most 11divine manner she slipped out of her room and downstairs to see who it might be. It surprised her even more to find there was no light in the living room. She was determined to find out who was in there in the dark, playing so entrancingly, so she sat down on the hall bench to wait for the unknown pianist to finish playing and come out.”

“And that odd little black-eyed freshie is a musician!” Muriel exclaimed. “I knew she had it in her to be something unusual. She is a dandy dancer. I suppose that is because of her well-developed sense of rhythm.”

“Yes, your black-eyed freshie is a musician. She’s more than that. She will be the greatest woman pianist in this country, I believe, before she is many years older,” Robin asserted with conviction. “She played that marvelous concert waltz by Wieniawski while Miss French was listening to her. Then she gave a little thing by Schumann, and then”—Robin paused—“she came out of the living room into the hall and Miss French simply grabbed her and shook hands with her and told her she was a genius.”

“What did she say?” came as a general breathless query.

“Oh, she was awfully confused. Miss French asked her to come to her and Miss Neff’s room and 12spend the evening. She went. Miss French made cocoa, and nobly drank some with Miss Oliver. She said she supposed it would give her the headache all over again. Her headache had stopped magically when she heard Miss Oliver playing. She surprised it out of her system, maybe,” Robin said, laughing. “Anyhow she didn’t have a new headache, which was a reward of virtue for being nice to Miss Oliver.”

“Has anyone at Craig Hall been mean to her?” Muriel inquired rather threateningly.

“No; only the house has so many more sophs and juniors than freshies,” Robin explained. “The juniors there are rather a smug self-satisfied lot, it seems, and Miss Oliver says she knows the Craig Hall sophs think her awfully stupid. She’s not used to being among a lot of girls. She hardly knows how to talk about the things that interest them. She was educated at home by her father and two older brothers. Her father is a noted ornithologist. One of her brothers is a geologist and the other is curator of a New York museum. Her father has given her the very best musical advantages, but he insists that she shall put college before even her music.”

“The Olivers must be a decidedly interesting family,” was Kathie’s opinion.

13“Miss Oliver’s mother died when Miss Oliver was a child. Her name is Candace Oliver. Isn’t that a nice name?” Robin asked animatedly.

There was a murmur of agreement.

“Have you heard her play, Robin?” asked Miss Remson from her throne. The manager of Wayland Hall was not a bit less interested in the “find” than were the others.

“Twice, Miss Remson. I can’t find words to describe her playing. You must hear her. She is so obliging about playing. She loves to please. She was too timid to touch the piano with a crowd of girls in the house. She stayed at home purposely the other night for the opportunity to play a little. I told her about my piano in my room, and advised her to have one put in hers. She has a single, second story back. She said, ‘no,’ her father would not like her to do so. That shows what an honorable little person she is,” Robin concluded with approval.

“To change the subject for only a minute, today is not the first time I have heard ‘smug’ and ‘self-satisfied’ applied to the junior class. Such conditions don’t help democracy along. I speak of it now because Robin has mentioned it, too. A crowd of “comfies,” who are either too lazy or else too well 14pleased with themselves to care what happens to the other Hamilton students are as detrimental to democracy as are snobs.” Leila advanced this opinion with considerable emphasis.

“The juniors were enthusiastic enough about the Beauty contest,” commented Muriel Harding. “I’m not disputing your opinion, Leila. They made a lot of fuss over it, I suppose, because it happened to appeal to them. If you consider the junies smug and self-satisfied, then they must be. I never knew you to make a mistake, Irish Oracle, in going straight to the root of a matter.”

“I am not making one this time, Matchless Muriel.” Leila’s blue eyes flashed Muriel a quick, bright glance. “This year’s junies are so complacent of their new, high estate. They are pleased as children with everything that happens so long as it suits their fancy. You may recall they were much the same in disposition when we did station duty and welcomed them to Hamilton as freshies.”

“I remember that of them,” declared Lillian Wenderblatt. “We thought them so amiable and easy-going. Later in the year they grew to have a kind of class stolidity that was positively exasperating at times.”

“I have watched them this year as junies. They 15have not changed. They are not interested in fighting for the right unless it might mean some gain for the class. They are partial to glory, but not to principle. It is a new weed patch in our democratic garden which we must root out.” Leila’s mobile face showed a hint of her mental resolution.

“Oh, what a job,” groaned Jerry. “Do you mean to tell me, Leila—”

“Sh-h-h-h! They’re coming down the hall.” Vera breathed a sibilant warning. “Ready, everyone with the new yell. Don’t one of you dare make a flivver of it.”

While Marjorie’s chums were buoyantly preparing a surprise tea for her she was seated beside Miss Susanna Hamilton in President Matthews’ office at Hamilton Hall. An expression of quiet happiness radiated from her lovely face as she listened to the heart-cheering words she had never expected to hear from the embittered grand-niece of Brooke Hamilton: “I have decided to give the world my great uncle’s biography.”

It had all happened so quickly, she was thinking. She was glad Miss Susanna had allowed her to tell her closest friends the good news. Though it had been near to ten o’clock she had gathered them into Room 15, and enthusiastically imparted it to them. Jerry had heard it with Marjorie’s first exclamatory utterance as she entered their room. It yet remained to tell Kathie and Lillian the next morning.

17While she made an early morning call on them, the following morning, her intimates gleefully arranged a tea for her. Into the midst of the preparations came a surprise for Jerry, who was heading the tea celebration. The welcome surprise was hastily bundled out of sight before Jerry had a suspicion of it. Such lecture periods as claimed the post graduates were, for once, to be ignored. Even Kathie had arranged with an obliging member of the faculty to take her last class for the afternoon.

Marjorie, sitting demurely beside Miss Susanna in the president’s office, a lovely symphony in warm brown velvet and furs, was wishing her intimates could be with her on the great occasion. They had overflowed with high spirits over this latest, greatest gift to Hamilton. Small wonder they were elated. They had fought loyally for true college spirit.

Regarding herself as Brooke Hamilton’s biographer, Marjorie’s emotions were jumbled. One moment she was exalted by Miss Hamilton’s steady assertion that Marjorie Dean was the one best equipped mentally to present her distinguished kinsman simply and truly to the world. Next moment a wave of utter panic would follow, sweeping away her newly-formed confidence in herself. She grew 18aghast at the bare idea of presuming to take upon herself so difficult a task. She had never done any notable theme work in college. How then could she hope to present the world with a finished biography to which the great man, Brooke Hamilton, was entitled?

“I am amazed, Miss Hamilton!” President Matthews’ eyes were riveted upon Miss Susanna’s face in polite bewilderment. They next strayed to Marjorie. His thought became self-evident. Marjorie turned very pink.

“Yes, Doctor Matthews; you are right,” the old lady said with a fleeting smile. “I am here this afternoon because of Marjorie. Because of her, you and I have come to speaking terms. The years were going fast, and I was not growing less bitter against the college. Then I met this child. She has led me back to old Hamilton Hall. I’m here at last, but still selfish. I came here today to please myself, even more than her.” It was as though Miss Susanna had uttered a grim kind of confession.

“Miss Susanna is not selfish, Doctor Matthews,” Marjorie gently contradicted. “She’s unselfish, and altogether splendid. She came here to do honor to Mr. Brooke Hamilton’s memory, and give happiness to us all. It has not been easy for her to 19thrust away the barrier of years. Yet she has done it. She has been heroically unselfish.” Her voice rang triumphantly. Her fond smile at Miss Susanna brought unbidden tears to the old lady’s eyes.

“I am happy in agreeing with you, Miss Dean. Miss Susanna has today demonstrated her complete unselfishness.” The president bowed to Miss Susanna.

“I forbid you both to make any more personal remarks about me,” broke in Miss Susanna’s concise utterance. “I have been selfish and unfair to Uncle Brooke’s memory. It is time I did something to make up for it.” She wagged her head ruefully. “May I ask, Doctor Matthews, have you ever heard the story of my disagreement with the Board?”

“I have heard a story which had to do with your being rudely treated, a number of years ago, by a member of the Board whose estate adjoined yours. The churlish behavior of this member of the Board was the cause of your refusal to place in the hands of Dr. Burns, who had been selected to write Brooke Hamilton’s biography, the data for the biography,” the doctor stated in pleasant, impersonal tones.

“True enough so far as it goes,” Miss Susanna acknowledged tersely. “The member of the Board 20with whom I quarreled was Alec Carden. A greater scamp never lived. We quarreled over Uncle Brooke’s will. It seems a long long time ago.” She gave an impatient little sigh.

“It was before I accepted the presidency of Hamilton College. I have been informed by the two gentlemen, still serving on the Board, who were members then, that it was a deplorable period for the college during which the Board engaged in one wrangle after another. They frankly criticized Mr. Carden as having behaved more like an unscrupulous politician than as became a dignified member of a college board. I have never doubted but that your grievance against the Board was sound.” The doctor sat back in his chair and surveyed the little upright figure in gray opposite him with one of his encouraging, kindly smiles.

“Thank you, Doctor. The only way in which I may show proper appreciation of your confidence in me is to tell you the story from beginning to end.” Miss Susanna sat very still for a moment after her electrifying announcement. It was as though she were trying to choose her words for a beginning.

An anticipatory silence hung over the president’s office. Dr. Matthews awaited the revelation with 21profound relief. It would mark the laying of the unwelcome ghost which had walked the campus all these years. Marjorie found herself filled with an odd kind of astonishment. She was at last to hear the story which for years Miss Hamilton had stubbornly locked behind her lips.

“Alec Carden was a man of middle age when I was a young woman.” Miss Susanna’s characteristically brusque tones shattered the brief silence. “He had never liked Uncle Brooke, simply because Uncle Brooke was upright and he was not. Neither had my uncle liked him. As an older man of wide experience Uncle Brooke once or twice advised Alec Carden against certain enterprises in which he had engaged. Each time the advice was flouted. Carden chose to regard him as an interfering old meddler.

“Uncle Brooke made his will years before he died. He never changed it. From the time he built Hamilton College he knew precisely what was important to its welfare. He knew, too, what would be best for it in time to come. He went over the will with me, often and carefully. He was determined that I should thoroughly understand every clause of it.” Every sentence of the old lady’s narrative fell clear-cut from her lips.

23“He had divided his wealth, which was very great, equally between me and the college, aside from a few bequests to the servants and a special legacy to Jonas. He used to say to me whimsically, on occasion: ‘I’ve already given my college a large fortune, Susanna, and I’ve only given you a home and a little spending money. But you can get along with a little, and my college cannot. Besides, I’m here to look after you. When I’m gone, it’s you and my college; share and share alike.’”

“Miss Susanna,” Marjorie spoke as the old lady paused briefly, “may I please put that in the biography?” Forgotten for the moment were all her misgivings. She was not thinking of herself as biographer. She was desirous that such valuable matter should not be left out of the biography itself.

“So you’ve decided to make the best of it,” laughed the old lady. “Oh, I knew what I was doing when I chose you as his biographer. Since I’ve surrendered, I’ve surrendered unconditionally. I wish the world to know his little quirks and turns, his fancies and his whimsies.”

“It is indeed a pleasure to contemplate the thought of Miss Dean as Brooke Hamilton’s biographer,” gallantly supplemented President Matthews.

“I thank you both.” Marjorie’s sunshiny smile 24flashed briefly forth. It faded, leaving her beautiful features unusually grave. “Perhaps hearing these delightful personal memories of him will give me the inspiration to do him justice,” she said very humbly. “I can only try to write his story. If I fail—”

“You can’t fail,” broke in Miss Hamilton. “There is no such word as fail in your vocabulary.” She reached out and patted Marjorie’s arm. “Now you and the doctor are to listen to a letter of instruction which Uncle Brooke gave me, sealed, a year before he died.”

She took from a morocco handbag a letter, held it up and pointed to the superscription: “‘For Susanna. Not to be opened until after my death:’” she read. She drew the letter from its envelope. “I prefer to read it to you,” she explained. “You may examine it afterward as much as you like.” She began:

“Dear Susanna:

“I have just come from an afternoon spent with Mr. Walpole, my lawyer. I have arranged with him in a codicil certain matters pertaining to Hamilton College. I must now acquaint you with these. You must be fitly equipped to carry out my wishes in 25regard to my college when I have gone on to a world of blessed fulfillment, which can never be here.

“I love my college, Susanna. Because I love it I must leave nothing undone to safeguard its welfare. My ancestors left me the land. I gave the site, my money erected the buildings, endowed the college. My brain, heart and mind acted as one in bringing beauty to the campus. It is the child of my heart, Susanna. It must not, shall not depart from the near perfection to which I have raised it. I have gloried in the spirit of democracy that has developed among the students as a result of my own thoughtful planning. But the past three years have marked a change. A certain element of arrogance and false pride has stolen into the college with the enrollment of a few students who come from homes of affluence.

“The present Board are not in favor of conducting Hamilton College on the basis of nobility which I believe should be particularly the foundation of an institution of learning. They are desirous of commercializing the campus. They are possessed to ruin its natural beauty by dotting it thickly with ornate halls and houses. Such as these for the accommodation of a few students who can afford to pay extravagant prices for board and lodging. 26These sordid schemers are eager to take advantage of the fact that I have fitted and endowed Hamilton magnificently. They intend to put their stupid, ignoble ideas into force as soon as I am gone. I overheard one of them say to another at a Board meeting not long ago: ‘When he is out of the running we shall have a free sweep.’ They imagine that with my death Hamilton College will achieve freedom from the direction of a Hamilton, and with it a vast fortune. The board dreams of unlimited power to spend my money, and with no restraint.

“You are to assume my responsibility, Susanna. It is a great deal to ask of you. But to whom else can I turn? You know I have divided my wealth between you and the college. Its half of the inheritance may be distributed to the Board as a whole, or in payments; at your discretion. Nothing is to be either added or taken away from the campus without your consent. You are to retain the right to administrate my estate as you are convinced would be pleasing to me. The fees of the college are never to be increased. With Mr. Walpole you will find complete directions in regard to the offering of various scholarships which I have arranged to be offered in the course of time. I have also left, with him certain other welfare plans for the college. 27It will be your task to fulfill these for me should the Messenger come for me before I have had the time and opportunity to act.

“Never allow the Board to intimidate you or beat you down. It is the old story of the man who took home the frozen viper and warmed it, only to find that when life returned to it it had no will save to sting. So it is with the very men I have helped to present membership of the Board. There will one day be bitter resentment when these same men learn that I have protected Hamilton College against their vandalism. Remember, Susanna, resentment can break no bones; neither can it change that which was written to remain unchanged. I feel more at ease since I have written this to you. I rely upon your pride as a Hamilton, your loyalty and your good judgment to uphold the work of my hands.

“A letter in keeping with what we have known of Brooke Hamilton before today,” was the president’s thoughtful attribute to the founder of Hamilton College.

“It was his mind in the matter. By it you can understand the situation as it was then better than 28from an explanation of it on my part,” rejoined Miss Hamilton. “It remains for me to tell you what happened between the Board and me after Uncle Brooke had passed away. Mr. Walpole appointed a day and hour for the reading of the will at the Arms. The Board attended the reading to a member in the interest of Hamilton College. They raised a hub-hub immediately they learned that Uncle Brooke had secured the college against their commerciality.

“Alec Carden was infuriated. He lost his temper, shook a fist in Mr. Walpole’s and my face and shouted that no fool of a girl should stand between the college and its rights. He rushed from the house shouting: ‘I’ll find a way to break that fool will!’” Miss Susanna’s eyes flashed as she recalled the affront. “All but two of the Board members hurried after him. William Graves and Caleb Frazer had taken no part in the fuss. They had been true friends of Uncle Brooke’s. They assured Mr. Walpole and me of their regret in the matter.”

“Afterward, they refused to discuss the unfortunate incident with anyone,” commented Dr. Matthews. “This I learned from Doctor Burns. They were his staunch supporters during his long service 29as president of Hamilton College. The doctor had a great deal of trouble with Mr. Carden.”

“I am aware of that,” nodded Miss Susanna. “It was frequently remarked in the borough that how Alec Carden managed to keep himself on the college Board was a mystery. He was a violent man. He quarreled disgracefully with both of his sons. One of them stuck to him and inherited Carden Hedge when his father died. The other took a package of bonds which belonged to him from the family safe and ran off to California. He changed his name, so the story goes, engaged in a lucky speculation and grew rich. He never came back to Carden Hedge. His father never saw him again, though he wrote him repeatedly to come home. Alec died of apoplexy. Indulging in one of his fits of rage, he had a seizure. John Carden still lives at the Hedge, off and on. He turned out as disagreeable as was his father. Peter was a multimillionaire at last accounts of him.

“Alec Carden kept his word. He tried to break the will and have the codicil set aside. Just when I needed his help most Mr. Walpole died. Then I engaged Richard Garrett, a young lawyer, but very brilliant. He stood between me and Carden’s worst attacks. But I had plenty of disagreeable scenes 30with Alec Carden and his Board sympathizers. They got it through their scheming heads at last that Uncle Brooke had been too wise for them. Then they tried to patch up their quarrel with me and wheedle me into letting them have their own way about things. I soon sent them all about their business. From that time it was war to the knife between us. I refused ever to admit the belligerents to the Arms or to meet them elsewhere in the interests of college business. All checks for disbursements and papers were forwarded to me by Richard Garrett.

“At the beginning of my trouble with Carden I had talked with Doctor Burns about the writing of Uncle Brooke’s biography. Uncle Brooke had greatly liked the doctor. I wished him to undertake the biography. Before I had collected the data for it I got into the thick of the fight with Carden and the Board. Carden circulated calumnious reports about Uncle Brooke. Uncle Brooke had been a miser; he had made his fortune in slave trading in the South Seas. He had also been suspected of piracy on the high seas. He had commanded South American filibustering expeditions. It was grossly false; outrageous. And all because he had been in the exporting business in China.

31“Such reports reached the students of Hamilton College. I came in for very brutal criticism from the girls there. I could not go for a walk along the highway without meeting some of them and encountering everything from covert to open ridicule. So I came to despise those whom he had wished me to like. The story’s almost done.” Miss Susanna’s face, shadowed by the sorrow of the past, brightened beautifully.

“I still intended that Doctor Burns should begin the biography until one day Alec Carden and I met on the highway near the Arms. He stopped me and said I would be sorry if I attempted to publish a biography of Uncle Brooke. He threatened to follow it with what he declared would be a true story of ‘my sneak uncle’s pirate doings in the East.’ He said he had gathered enough information against him to make a most interesting pamphlet which he intended to have printed and published at his own expense to follow the biography. He was as explosive in his talk as usual. He declared that Doctor Burns was in sympathy with him, not me; that he had merely consented to write the biography to keep in my good graces. There was a chance that I might be flattered into turning over to the Board the authority they lacked.

32“I did not believe a word he said. I told him so. I went straight to the Arms and wrote to Doctor Burns.” The old lady paused. She brought one small hand down over the other with a sharp little smack. “I never received an answer to that letter. I wrote him two others. One I sent to him at this office.” She glanced about the large pleasant room. “The other I sent by Jonas to his campus residence. He was away at the time, but his secretary, a young man, promised to give it to him as soon as he returned.

“When I had been ignored by him a third time, I closed my heart against Hamilton College, forever, as I thought. I could not conceive of how a man like Doctor Burns could be in sympathy with Carden’s cheap villainy. Still, I had given him an opportunity to clear himself and he had made no sign. He was therefore not the one to write Uncle Brooke’s biography, and I knew no one else whom I considered qualified to do so. It was not until years afterward, quite by accident, that I learned that Alec Carden’s nephew was Doctor Burns’ secretary at that time. Then it was too late. The years had passed, and Doctor Burns with them. I believe now that he never received the letters I wrote him.”

33“I am sure he did not,” Doctor Matthews said quickly. “I am convinced that he had no knowledge of such a calumnious pamphlet as Mr. Carden threatened to have published. He attributed your failure to bring forward the data for the biography as the result of your having had an altercation with the Board. He was not in sympathy with the Board. You had asked him to write the biography of your great uncle. He preferred to await your pleasure.”

“He died not more than a year before Alec Carden.” Miss Susanna’s usually crisp tones were tinged with melancholy. “And he never knew!”

Marjorie had sat listening to the last of the Hamilton’s story, a lovely, absorbed figure. Her vivid imagination had visualized Miss Susanna as she had probably been in girlhood. Across her brain flashed the dramatic scenes which had occurred between Miss Susanna and the hated Alec Carden. Here was a real story infinitely more fascinating than one which was the product of imagination.

“I think I never knew of a more deplorable misunderstanding.” There was poignant regret in Doctor Matthews’ assertion. “We have, however one thing for which to give thanks. No calumnious word was ever published against the memory of Brooke Hamilton. Yet, if you had found the opportunity 34to talk with Doctor Burns, he would have advised you to go boldly ahead with the biography. I would say the same today in a similar situation.”

“Ah, that is precisely the point for which I blame myself!” the old lady cried out regretfully. “I should never have given up until I had seen the doctor. I have read Uncle Brooke’s letters and journals, over and over. They are the essence of truth. No slanderous reports could live beside them. I know that now. But I was young then, and alone in a great empty castle. I was more or less bewildered by the responsibility which had become mine. I despised Alec Carden, and I was full to the brim of Hamilton pride. I had never talked with Uncle Brooke about the biography. It was an issue that came to the fore after his passing. When I had been rebuffed, as I thought, three times, I retreated into my shell and stayed there.”

“But you are out of it, forever, and ever!” Marjorie exclaimed, her brown eyes beaming luminous warmth on the wistful old face of the mistress of the Arms. “You’ve been out of it a good many times in the past two years, too. All the years you were tucked away in it you were true to the trust Mr. Brooke Hamilton placed in you. You felt that you hated his college, but you guarded its welfare 35just as faithfully as though you had loved it. You are the most amazing person in the whole world, Miss Susanna. You’re the real guardian of Hamilton.”

“And now, Marvelous Manager, you and I will continue our walk on the campus.”

It was almost four by the chimes clock on Hamilton Hall when Marjorie and Miss Susanna issued from the president’s house, arm in arm. Neither would ever forget that wonderful afternoon. It marked for Miss Susanna the re-union with a valued friend of long ago—Hamilton College. For Marjorie it marked the answering of a most perplexing question. She believed buoyantly that with the answer was bound to come a new era of fellowship on the campus, far greater than had ever before manifested itself among the students.

“I can’t really believe it’s true, Miss Susanna,” she said happily; “that you and I are actually walking together across the campus. I feel as though, all of a sudden; whisk! there’d come a magic wind and you’d disappear and I’d wake up to find myself walking along alone.”

37“Not quite so bad as that. Let me tell you, I’m very real.” Miss Susanna gave Marjorie’s arm an only half gentle pinch. “There,” she said, “was that hard enough to convince you that I am not a campus sprite. I’m a crabbed old woman, ready to pinch if the occasion demands it.”

“I’m glad as can be you are real. I’m glad I know more now of how splendid you are than ever I knew before. I’m glad you’d rather have your own Marvelous Manager write the biography than even Prexy Matthews. I’m glad you have at last condescended to come and see me.” Marjorie had begun enthusiastically, gathering more enthusiasm as she rushed from one gladness on to another. She ended with a satisfied little exhalation of breath.

“You are a compendium of gladnesses, child.” Miss Hamilton smiled very tenderly at the glowing, graceful girl at her side. “Well, it is good to be here; to walk the old green again, even though it isn’t very green at present. I used to love the campus, Marjorie. I experienced a queer little thrill that day when you told me your best friend at Hamilton was the campus. I loved it in the same way when I was a student here.”

“And you never told me you were a graduate of Hamilton,” Marjorie lightly reproached. She stopped 38short on the campus. “I think you ought to be pinched on that account.”

“You never asked me where I was educated,” Miss Susanna replied, chuckling.

“I always meant to. Somehow I never did.” Marjorie looked reflective. “You see, at first, I never felt you would like me to ask you any personal questions. After I came to know you well we had so many other things to talk about I never again thought of asking you. That must be the reason.” She gave a positive little nod.

“It must be,” the old lady agreed half jestingly. “I know that I used to be afraid you would say or do something, when first you came to the Arms to see me, that might cause me to dislike you. But you never did until the day we fell out about that snip of a girl who tried to run her car over me. I was a pig-headed, obstinate old chump that day, child.”

“Oh, no you weren’t. Now I shall pinch you for calling yourself names.” Marjorie affectionately made good her threat. “I’m going to keep on with these crab-like nips until you promise never to mention such ancient history again.”

“I had no idea you were such a bully. I’ll have to pretend good behavior. I never supposed anyone 39would care if I called myself disrespectful names,” giggled the amused old lady.

“You never know what may happen,” Marjorie blithely told her. “Look, Miss Susanna.” She pointed out a mammoth elm tree just ahead of them at their right. “That’s my favorite campus tree. During the spring and summer, until late in the fall, there are seats placed underneath it. Whenever I find a few minutes to relax and be downright lazy, I steer straight for that tree. Jerry calls it the Bean tree and the seats the Bean holders. She says all Bean supporters belong to the genus Bean. Hence the name Bean holders.”

Marjorie continued to entertain Miss Susanna in this gay strain as she proudly conducted her across the campus and toward Wayland Hall. On the stone walk leading up to the Hall the distinguished visitor halted for a prolonged look around.

“The same old Hall,” she half sighed. “I’ve lived for years almost in sight of it without having once seen it. I’ve cared for it more than the others because he liked it so well. And I never even suspected why he cared until I went over some of his papers after he died. You’ll read the story for yourself, Marjorie, when you come to the Arms to stay with me and write the biography. When 40do you think that will be, child?” she questioned, an eager, hungry light leaping into her eyes.

“I—I don’t know, Miss Susanna.” Marjorie looked concerned. “Not really to stay, perhaps, before spring. When we come back from Sanford after the holidays I’ll try to come almost every afternoon to the Arms. I’ll stay until about nine o’clock in the evening. Promise to give me my dinner, and plenty of it, O, Lady of the Arms? I’m always ravenous when dinner time comes.” She merrily endeavored to stave off disappointment from Miss Susanna.

“You may have a dozen dinners every night since that is all you demand,” the old lady assured with reckless hospitality. The slight shadow, called to her features by Marjorie’s first doubtful words of reply, faded instantly. “‘Half a loaf is better than no bread,’” she quoted with a kind of resigned content. “I hope you and Jerry will be able to settle down with me at the Arms by the first of March. I’d like you to see spring awaken at the old place. It is a memorable experience; to live and breathe with the return of spring in a beauty spot like Hamilton Arms. I look forward to and pass through it each year with wonder and gratitude toward my Creator,” she ended reverently.

41“I promise you, Jerry and I will surely be with you at the Arms to greet the spring,” Marjorie declared impulsively, imbued with the inspiration of her elderly friend’s deep sentiment. “It’s so comforting to know that Jerry is to come to the Arms with me. I’d hate so to leave her to room alone. The other girls would baby her and rush her if I were not at the Hall. She would miss me dreadfully, only she would try not to let me or anyone else know it.”

“Jerry can keep Jonas and me amused and in good humor,” Miss Susanna said humorously. “I expect to enjoy her company hugely while you are tucked demurely away in the study, living over life at Hamilton as Uncle Brooke found it. I shall make Jerry help me organize a grand social campaign. We’ll have the Travelers, old and new, here often to dinner and tea. And we’ll entertain the dormitory girls some fine spring afternoon and evening.”

Marjorie drew a long, ecstatic breath. “Oh, splendid!” she cried. “It’s simply one glorious good fortune piled on another for the Travelers, Miss Susanna.”

“You forget how much more it means to me. I am a greater gainer than the Travelers. I’m still 42looking strictly out for my own interest,” was the half joking reminder.

“Oh, you!” Marjorie gave the arm she held a playful shake. “I wish you felt it was strictly to your interest to go with me to Room 15, Wayland Hall, to visit Jeremiah and me this afternoon.”

Her inflection was wistfully coaxing. On the afternoon previous, Miss Susanna had announced, that, on the following afternoon she and Marjorie would together call upon President Matthews. Marjorie had then joyfully urged her to take tea afterward in Room 15, Wayland Hall, at a jollification in honor of her. The mistress of the Arms had refused, saying rather pessimistically that she doubted if she would be in the humor for a social tea after her interview with the president of Hamilton College. She promised instead to walk across the campus as far as Wayland Hall. She declared musingly that she would like to have a good look at the Hall again.

Now the momentous visit had been made and Miss Susanna was apparently in a very delightful humor. Marjorie could not resist the golden opportunity of making a last coaxing plea.

“I have changed my mind about not going to your room with you, Marvelous Manager,” the old 43lady announced, to Marjorie’s amazement. They were still standing on the stone walk in front of the Hall.

“I’m going to whisk you into the Hall before you have time to change it again.” Marjorie took resolute hold of the arm she had just gently shaken and began hurriedly marching the last of the Hamiltons up to the veranda.

Already she was planning an impromptu reception for her beloved guest. She hoped Miss Remson would not answer her ring of the bell. She frequently answered the bell if she chanced to be downstairs when it rang. To summon Miss Remson to Room 15, and have the manager and Miss Susanna meet there should be one feature of the reception. Tea should be another. She would levy upon Leila for maccaroons from the five pound box she had bought yesterday. Ronny still had plenty of Mexican candied fruit on hand. Jerry should be stripped of a precious glass jar of salted pecans. She would ruthlessly commandeer the jar of blackberry jam which Lucy had that morning received from home, provided it hadn’t been devoured already. There was always a supply of crackers, saltine and soda, on hand in 15, she reflected comfortably.

44Nellie, one of the maids, answered the bell. Marjorie stretched forth a hand and conducted Miss Susanna across the threshold in gallant fashion. An impulse to tears rose within her as she saw an unbidden sadness steal into her companion’s face the moment she stepped into the old-fashioned hall. It passed instantly. Miss Susanna poked her head into the living room and remarked on its tasteful furnishings in the most matter-of-fact tones.

“If I had dreamed that you would positively set your magnificent foot in my kingdom today I would have made elaborate preparations for you,” Marjorie presently apologized, her hand on the door knob of Room 15. “As it is, I’ll have to seat you in state in my best easy chair and rush Jerry out for Leila, Vera and the rest of the Sanfordites. There are certainly going to be some decidedly surprised Travelers.”

In the very next minute there was one decidedly surprised Traveler. As Marjorie stepped after Miss Susanna into her room a rising tide of jubilant sound assailed her ears.

Twice the merry company shouted out this welcome. Miss Susanna laughingly acknowledged the honor done her with a flourish of small hands and many bobbing bows. Far from showing surprise at the festal scene into which she and Marjorie had walked she irradiated only chuckling amusement.

“The Empress of Wayland Hall has already arrived and been conducted to her place on the throne.” 46Ronny tripped to the middle of the room with this announcement as soon as the hub-bub attending the new Hamilton yell had subsided. She was attired in a green velvet page’s costume which she had confiscated from a trunk in the attic. Her fair features were animated with mischievous light as she went through a kind of ceremonious dance before Miss Susanna. She gracefully beckoned the old lady to the throne and grandiosely pointed out the middle vacant place on it.

“What is all this about?” demanded Marjorie. She grandly waved Ronny off when the latter returned from escorting Miss Hamilton to the throne to perform the same kind office for her.

“Ask no questions, pretty maid, but gently follow your leader,” was Ronny’s lofty advice. “You are about to be ranked with royalty.”

“I shall remain a commoner all the rest of my life unless you explain some of this thusness,” defied Marjorie threateningly with an anything but threatening expression. “How did you know Miss Susanna was coming here today, when I didn’t? How does Miss Remson happen to be here to meet her? You never made up that dandy Hamilton yell on the spur of the moment. Look at this room! I know you’ve been fixing at it ever since I went 47out to meet Miss Susanna. You’re all conspirators, the dearest, bestest, dandiest old plotters under the sun.

“You’re as guilty as they are.” She leveled an accusing finger at Miss Hamilton. “You didn’t know a thing about it last night. I guess a flock of little birds flew over to the Arms this morning. That would account for why you changed your mind.”

“What a terrible tirade,” commented Ronny in a shocked tone.

“Why don’t you introduce us to the royal party you’ve just called down?” inquired Jerry, her cheerful smile in evidence.

“Judging from the preparations you’ve made for her, I’d say you know her better than I,” was Marjorie’s laughing rejoinder. “Now I’m going to do something I’ve longed to do for two years. I’m going to introduce the Empress of Wayland Hall to the Lady of Hamilton Arms.”

Marjorie walked up to the make-shift throne and salaamed profoundly before it to its two occupants. Then she lifted one of Miss Remson’s hands and placed it in one of Miss Susanna’s. The crowd of laughing girls had drawn close to the trio as she did thus. “We love you both so much,” she said 48in her clear enunciation. “I know you are friends already.”

Approving applause went up from the more humble subjects. Their compact movement toward the throne had not been without an object. Marjorie felt herself suddenly seized and shoved into the throne’s vacant left-hand place before she could make the least resistance.

“Now will you be good?” Muriel Harding threatened the flushed giggling addition to royalty. “Don’t fail to notice that I am hanging over you with my most menacing air.”

“You look about as menacing as a peaceful sheep,” Lillian Wenderblatt promptly criticized.

“If you had said a lamb I shouldn’t have minded. I’m very certain I do not look like a sheep, peaceful or ferocious,” Muriel asserted with vast dignity.

“A ferocious sheep,” pleasantly repeated Vera. “How very entertaining; the idea, I mean.”

“Oh, start on someone else. If you don’t treat me with more respect I shall tell the royal party what the throne’s made of,” warned Muriel.

“I could do that, but I won’t.” Marjorie beamed knowingly at Jerry. “How you must have hustled, Jeremiah Macy, to do all this.” A comprehensive sweep of an arm not only included the throne, but 49also the study table, flower-trimmed and set out with a tea service. There were two gorgeous bunches of roses, one on each chiffonier. Scattered about the room was the pick of decorative treasures from each Travelers’ room.

“Oh, I hustled a little bit. The girls did a lot, too. After Leila and I called up Miss—” She clapped her hand to her mouth in merry dismay.

“So it wasn’t a flock of birds that told you.” Marjorie bent a gaily disapproving glance upon Miss Hamilton. “And I was the only one surprised of all this crowd. I’m still more surprised at being royalty. Would you mind mentioning my royal title.”

“The Royal Countess of Bean,” Jerry instantly supplied. “I hope you like and appreciate it.”

“I’ll try to,” Marjorie promised with a plaintive meekness which produced a gale of ready laughter in which she joined.

Miss Remson and Miss Susanna had clasped hands and taken but one straight survey, each of the other, before knowing that they were destined to pass quickly from acquaintanceship to the estate of friendship. “My girls,” as the old lady loved to call the special little coterie to which Marjorie belonged, 50would be the fragrant, youthful bond between these two elder sisters of Hamilton.

While royalty took its ease on a plumped-up throne the hard working subjects of the imperial trio prepared the feast. Leila made the tea, boastfully asserting that no such tea had ever been made before in the history of the world.

“My, such an equivocal statement! It might mean either the best or the worst tea that was ever made,” Kathie pointed out, grave as a judge.

“Rather sweeping, I should say,” was Vera’s ironical opinion.

“I am not sorry I praised my own tea. Now I know that nobody else would have done it,” Leila remarked loudly to the teapot as she set it on the table. “Even Midget has a grudge against my sayings.”

“Oh, never mind about Midget. I approve of you and your sayings, Leila Greatheart,” consoled Jerry. “Do say something to me now.”

“That I will.” Leila dropped into a brogue. “I’ll be askin’ a favor of you, Jeremiah.” There was a mirthful gleam in Leila’s blue eyes which Jerry happened to miss. “Go to Marjorie’s closet and bring out of it the box of maccaroons I placed there a while ago.”

51Jerry obediently started for the closet. Her progress was followed by several pairs of laughing eyes. Leila watched her with an amused show of white teeth.

“Aa-h-h-h!” Jerry emitted a sharp yell and made a headlong dive into the closet. She kicked the box of maccaroons, which reposed on the closet floor at her feet, nearly overturning it. She had forgotten everything except the tall slender girl stowed away in the closet whose unexpected appearance in such a place had given her a startling surprise. Both plump arms wound around Helen Trent. Jerry was now giving a bear-like demonstration of affection.

“Helen; good old Helen Trent!” she was crying out in delight. “How long have you been lurking in that closet? Come out of it, this instant. Leila Harper put you there, of course. That’s why she sent me for the maccaroons.”

Fondly escorted by Jerry, Helen emerged from Marjorie’s dress closet to become the center of attraction in the room for the time being.

“So glad to get out of that stuffy old closet,” she sighed, with her ever attractive display of dimples. “Leila told me to stay in there until she sent Jerry to let me out. I could hear all of you talking. How 52I wanted to butt in. For Jeremiah’s sake I was noble and silent.”

“Cut out being noble and silent. Talk,” urged Jerry. She was bubbling over with good cheer at sight of pretty, easy-going Helen whose cheery disposition was always toward the funny side of life.

“I will. First let me hug Marjorie and Miss Susanna. I haven’t hugged them yet. Then do give me some tea and a chair over which to drape my weary frame.” Helen grew ridiculously pleading.

“You talk like a one-piece dress,” Jerry snickered.

“Well?” Helen lazily opened her limpid blue eyes. “You know you didn’t specify as to the kind of talk, Jeremiah. You simply said: ‘Talk.’ It’s werry fatiguing, Jeremiah, to stand up indefinitely in a dress closet. I don’t aspire to a seat on the throne. I am too modest. I think your arm chair might be nice.” Helen sent an ingratiating smile to Muriel who was complacently occupying the coveted arm chair.

“I’ll tip Muriel out immediately.” Jerry swaggered over to the grinning occupant. “Vacate gracefully, or be tipped out bodily?” she asked with dangerous suavity.

“You can’t tip me out of what I’m not in.” Muriel 53made an agile bound from the chair and dodged Jerry’s reaching hands.

“Let Muriel have the chair. Take my place on the throne, Helen. Miss Susanna wants to monopolize you.” Marjorie came forward and escorted Helen to the dais. Muriel instantly retrieved the chair and jeered at Jerry.

“It’s a wonder you didn’t see me when I came in this morning,” Helen laughingly told Marjorie. “I dodged into Miss Remson’s office just as you came downstairs to go to the laboratory.”

“I was too obliging to see what I wasn’t supposed to,” Marjorie made jesting return. With her usual love of action she began helping Leila serve the tea. The spread was a lap collation with the guests informally occupying, for the most part, cushions on the floor. Paper napkins, paper plates and tea cups balanced on knees were leading features. But Leila’s tea was above reproach. The tiny toothsome sandwiches made by Ronny and Vera disappeared like magic. Ellen’s famous caramel cake was delicious as ever and the salted nuts, olives and cheese straws appetizing relishes.

None of the effervescently gay company in 15 was enjoying the party more hugely than Miss Susanna. She ate the delectable fare offered her with hungry 54heartiness, drank two cups of tea; laughed and chatted with the happy abandon of girlhood.

Because she loved these girls who had loved her and revered the memory of her kinsman, the once-prejudiced, only living representative of a grand old colonial family, suddenly experienced a new and overwhelming sympathy toward all girlhood. Little by little the rusting bars of prejudice had worn away against the friendly assaults of “her girls.” For that she owed girlhood a debt which she purposed to pay.

More than once as her eyes strayed to Marjorie, to rest with content on the young girl’s glowing, sunshiny face she was reminded of the lines of a favorite old song. She found exquisite happiness in fitting the worshipping words to Marjorie.

“Yes, Bean, there is nothing like efficiency. And I am so efficient. I didn’t hear you say a thing.” Jerry cupped a hand to an ear and eyed Marjorie hopefully. Marjorie was frowningly occupied with a page of maddeningly abstruse French. “I certainly have worked hard at this schedule.” Jerry continued her self-laudatory remarks. “But the results are celostrous, Bean; simply celostrous! Ha! I thought my new word would prove irresistible!” she exclaimed in triumph as Marjorie looked up in mild surprise at Jerry’s latest coining.

“Something sounded new and queer,” Marjorie averred with the gurgling little laugh Jerry liked to hear.

“Now that I have your attention, never mind about my new descriptive adjective. I’ve been frisking gaily about the room, dropping things on the floor, growling as I picked them up. And why? 56On purpose to be noticed by you. Seeing you’re now seeing me, may I venture to ask if you know the reason for my nice new adjective?” Jerry pursued blandly.

“I never heard you frisk a single frisk, Jeremiah, or drop a single drop, or growl a single growl. This page of French is awful! It’s an odd old religious argument between two Norman priests. I’d say it couldn’t be lucidly translated into English, but it can, or we wouldn’t be stuck with it for a study.”

“Go and ask her frozenness, the Ice Queen, to give you a lift,” innocently proposed Jerry. “Muriel says she is a wonder in French. Due to having had a French governess ever since she could hot-foot it around the nursery.”

“I’d like to ask her about this very thing,” sighed Marjorie. “If I wanted to know about it for someone else I suppose I might. I don’t feel inclined to go to her on my own account.”

“I get you, Bean. Don’t take my advice. I wouldn’t take it myself. You could ask Muriel to ask her about it. That ain’t no way to do, either.” She shook a reproving head at herself in her dressing table mirror in front of which she had paused to fluff and pat her hair.

“This translation would really be a good excuse 57for going to see Miss Monroe,” Marjorie reflected aloud. “I wonder what she will do during the holidays? She told Muriel she had no friends in the United States besides the Hamilton girls she knows.”

“I suppose she includes Leslie Hob-goblin Cairns among the Hamilton aggregation.” Jerry swung disdainfully around from the mirror.

“Um-m; probably.” Marjorie sat chin in hand, staring ruminatively at Jerry. “Leslie Cairns may ask Miss Monroe to spend Christmas with her,” she advanced after a moment’s silence. “I don’t mean in the town of Hamilton, at the Hamilton Hotel. I mean away from there; New York or Philadelphia, or even Chicago.”

“She may have asked her long before this.” Jerry spoke rather impatiently. “Suppose she hasn’t, Marvelous Manager?”

“Then some of us should take her home with us,” Marjorie said with conviction.

“Uh-h-h-h. I knew it,” Jerry groaned. “But it can’t be you, and it won’t be me. At least I hope it won’t. You ought not attempt to entertain Miss Susanna at Castle Dean and run a welfare bureau there at the same time.”

“You’re positively outrageous, Jeremiah, but there’s fatal truth in what you say,” Marjorie smiled 58at Jerry’s humorous injunction. “It would complicate things to have Miss Monroe visit me while Miss Susanna is at the castle. I am so anxious, for Miss Susanna’s sake, to have the perfect spirit of Christmas in the house. Leila, Vera and Robin will help it along, but Miss Monroe wouldn’t. There’d be a strain on everything that would spoil all the joy and dearness of Yuletide. It would worry General and Captain. I—I couldn’t do it and be fair to them.” The laughter had died out of her face.

“How do you know she’d come if you asked her?” quizzed Jerry. “It’s only recently that she’s discovered you are on the college map. She hasn’t discovered me yet. Can you blame me for not being crazy to welcome her to the Macy’s humble hut? Suppose I did, and she fell in love with Hal? I’d have put myself in line for the lasting reproach of an injured brother.”

“You’re a nonsensical goose.” Marjorie felt her face grow rosy at mention of Hal Macy. She was provoked with herself for blushing.

“I suspect it, but you’ve said it. Nothing can be done about it either.” Jerry drew a chair up to the study table. She sat down opposite Marjorie, leaned her elbows on it in imitation of her chum and stared at Marjorie with a refulgent smile. She 59drew from a pocket of her serge dress a little blue book. “Every blessed thing we have to do, person we have to see, or place we have to go on the campus within the next ten days is down in this book,” she said with satisfaction.

“Oh, let me see it!” Marjorie reached out eagerly for the book. She examined it with growing enthusiasm. “It’s a treasure, Jerry. How did you happen to think of doing it?”

“Past sad experience, my child. I’m growing old.” Jerry gave a muffled sob. “I can’t rush around and do ten days pre-Christmas celebrating, shopping, calling, and get away with it, all within three hours before train time. This lovely schedule includes everything and everybody who it is up to us to include on the campus.”

“It’s—” Marjorie paused: “celostrous,” she said with a laugh. “There, Jeremiah, I remembered your new adjective. If we stick to that program we’ll be wonders. If we half stick to it we’ll avoid a rush at the last minute. I’m so glad the dormitory girls are beautifully taken care of. That was another of your inspirations.”

On the evening following Miss Susanna’s visit to Wayland Hall the original Travelers had held a meeting in Leila’s and Vera’s room. Its purpose 60was to discuss what should be done in the way of Christmas entertainment on the campus for the students who expected to remain in college during holidays. Persistent scouting for two weeks previous among the students, by both chapters of the Travelers, had established the fact that not more than a dozen girls on the campus would spend the holidays at Hamilton College. Again the dormitory girls became the main problem for consideration.

Jerry had solved the problem by proposing that each Traveler should make herself responsible for the holiday amusement of two dormitory girls. “Find out what they’d like to do over the holidays and then help them do it,” she had advised. “Some will want to spend Christmas in the city. Others would probably love to be invited to spend the holidays in the kind of homes we have, where there is lots of Christmas cheer. I’ll take four dorms home with me. Let me hear from the rest of you.”

Hailing Jerry’s suggestion with the good will attending the season, Page and Dean, the dormitory girls’ main stand-bys, called a meeting of the “dorms” in Greek Hall and electrified the off-campus girls with their unexpected proposal. Before the favored company of students left Greek Hall each had confided either to Robin or Marjorie her choice 61in regard to how she would prefer to spend the Christmas vacation. Fifteen of the dormitory girls had already made plans to spend the holidays at their own homes or those of friends. Forty of them wistfully declared for the joy of a family Christmas, but demurred in the same breath as being “afraid of causing too much work and trouble for others.” The comparatively small remainder consisted of the more independent and adventurous contingent of “dorms” who welcomed the experience of seeing New York, Philadelphia or Washington, D. C., the three cities among which they were given choice.

Leila, Vera, Kathie, Helen, Robin, Phil Moore and Barbara Severn were among the Travelers Sanford bound. Leila, Vera and Robin were to be Marjorie’s guests as well as Miss Susanna. Kathie was to be Lucy’s company. Helen fell to Jerry, who would also entertain the four dorms. Ronny had arranged to go to Miss Archer. Phil and Barbara would share her hospitality. So would two of the dormitory girls. Lucy had also invited Anna Towne and Verna Burkett. She was highly edified at the prospect of entertaining three girls instead of one.

Jerry’s whole-souled proposal had now been successfully carried out so far as the preliminaries of 62choice went. It now remained to the Travelers, original and of the new branch of the sorority, to look out for the off-campus girls who longed for a home-like Christmas. As seven of the Travelers themselves were to be guests of the Sanford girls they could not be counted upon, therefore, to furnish the holiday pleasures of home to the dormitory girls. They did their part by taking upon themselves the financing of the modest city expeditions planned by the off-campus girls. Nor would they allow their chums to contribute a penny toward it.

“You heard what I said, Jerry Macy.” Marjorie suddenly bounced up from her chair and made one of her funny, little-girl rushes at Jerry. “Don’t pretend you didn’t.” She pounced upon Jerry, threatening: “I’m going to muss up your hair, since you took so much trouble to fix it. The only way you can save your nice fluffy coiffure is to say: ‘Yes, Marjorie, it was another of my inspirations.’ You may notice I don’t refer to my precious self as ‘Bean,’ either.”

“Sorry, but I never could talk like you, Bean.” To complete her defiance up went Jerry’s hands in a backward reach. She caught Marjorie wrists. The two girls were engaged in a friendly grapple when the door opened and Muriel Harding came in, her 63arms piled high with packages, her smart little hat set far back on her head, two or three loosened curling locks of hair hanging over her face.

“What have we here?” Jerry demanded pleasantly. “Just what one might expect would drift in without knocking.”

“You’re doing the knocking now; why worry,” chuckled Muriel. She walked over to Jerry’s couch bed; dumped her packages upon it with a great sigh of relief. “I made port at the front door with my cargo beautifully, but I fell up two steps of the stairs. You can see what a wreck it made of me.” She sat down on the couch beside her bundles, whipped off her hat and began tucking up her unruly locks of bright hair. “Every last present that I intend to buy for campus dwellers is in this heap,” she declared with stress.

“Is there anything for me there?” Jerry showed sudden flattering interest in Muriel. “If so, let me see it.”

“No, there’s nothing for you,” mimicked Muriel. “I’m going to buy your Christmas present at home, in the Sanford ten-cent store.”

“Perhaps we’ll meet there.” Jerry arched significant brows. “I had thought of some nice little ten-cent token for—” She made an effective pause.

64“I didn’t come here to talk to you.” Muriel tossed her head. “I came to see Marjorie. I’ve had bad luck about my two Christmas dorms, Marvelous Manager. The same nice thing has happened to them both. Their families have sent them the money to go home for the holidays. Neither of them had expected any such good fortune. The rest of the dorms have their plans all made. Not a single, double, triple or quadruple dorm will grace the would-be hospitable hearth of Harding. I’ll bet you couldn’t make up a sentiment as effective as that, Jeremiah.”

“A double dorm would be twins. A triple dorm would be a freak. A quadruple dorm would constitute material for a side-show,” was Jerry’s reflectively satirical observation. “Oh, I forgot. Kindly confine your conversation to Bean.”

“Go away, Jeremiah,” Muriel firmly requested. “Go and see Ronny. A big box for her from California is downstairs in the hall. Tell her I saw it first and politely sent you to hand her the news. It will show Ronny how helpful my disposition is. You can square yourself with me at the same time.” Muriel opened her eyes, showed her teeth and bobbed her head at Jerry in what she termed her “delighted” expression.

65“Tell her yourself; I’m no news herald.” Jerry made no move to perform the squaring act Muriel had suggested. In the next two minutes she changed her mind and hustled to tell Ronny of the box.

“I happen to remember that you are just the person I want to talk to, Muriel,” Marjorie said. “Jerry and I have been wondering what Miss Monroe is going to do over the holidays. Last time I asked you about her you hadn’t been able to find out her plans. What do you know about them now?”

“Not a blessed thing except this. She said yesterday she might spend Christmas in New York. I had asked her outright what she was going to do over the holidays. It was inquisitive; maybe.” Muriel shrugged her shoulders. “I knew you were anxious to know.”

“If she is going to New York, it means Leslie Cairns has invited her. That’s too bad; after the encouraging signs she’s shown lately of thawing toward us.” Marjorie’s tone was rather gloomy. “It will quash everything we’ve tried to do to draw her away from Leslie Cairns. I’d invite her to go home with me for the holidays, but I have Miss Susanna to consider first of all. If I hadn’t, Miss Monroe wouldn’t accept a Christmas invitation from me,” Marjorie ended with a trace of self-mockery.

66“To hear you talk one might think you were a tabooed character.” Muriel’s gurgle of laughter brought a smile to Marjorie’s troubled features.

“I feel so cross sometimes when I think about that aggravating girl.” Marjorie’s answer rang with vexation. “I’ve not been in your room since you came back to Hamilton. Neither has Ronny, Jerry nor Lucy. She snubbed the four of us thoroughly in the beginning. Now proper pride won’t allow us to put ourselves in direct line for further snubs. She’s been fairly nice to Robin. Yet Robin hasn’t cared to try calling on Miss Monroe yet. She doesn’t wish to risk a snubbing, now that she’s made a little headway with our enchanted princess.”

“I could like her if she’d let me,” Muriel said bluntly. “We don’t meet often in the room except just before old ten-thirty, and in the morning. We’re both out a good deal. She is brilliant or she couldn’t cut study the way she does and not be conditioned.” There was a hint of admiration in Muriel’s observation.

“Oh-h!” Marjorie swung round in her chair until she was facing Muriel. “Why couldn’t—I wonder if you—It doesn’t seem fair to ask you, Muriel, but, since both the dorms have gone back on you, 67would you care to ask Miss Monroe to go home with you for Christmas?”

Marjorie fairly held her breath as she finished asking the question. This splendid way of helping the strange, beautiful girl in whom she had become so thoroughly interested she was inclined to regard as a positive dispensation of a kindly Providence.

“I might.” Muriel stared contemplatively at the anxious questioner. “I was so disappointed when my two dorms flivvered and renounced me I never thought of my old friend the Ice Queen.” She looked rather sheepish then smirked at Marjorie and said: “‘Charity begins at home.’ If I mentioned Charity in my invitation to the Ice Queen, br-r-r, she’d freeze Matchless Muriel solid at one glance. Then I couldn’t go home for Christmas. Neither could she go with me. Think how sad it would be! Two cold, shiny, slippery, glittery Ice Queens, friz solid over the holidays.”

Giggling at her own weird fancy, Muriel rose and began gathering up her packages. “I’ll ask her directly, if she’s home, dear Bean. I’ll let you know as soon as I can escape from her royal presence to tell you.”

“You’re a darling, and the most obliging person 68in the universe. If you’d said you’d rather not ask her, I shouldn’t have blamed you in the least. I thought, after the idea popped into my head, that I ought to ask you for Miss Monroe’s sake,” was Marjorie’s honest avowal. “Let me give you a basket to put your stuff in. Here’s the laundry basket.”

Marjorie proceeded to stack the piles of clean laundry on the couch and place Muriel’s packages in the basket instead. The two girls performed the little task with the usual amount of light talk and laughter. After Muriel had gone Marjorie sat down again at the table to indulge in a kindly little daydream which had to do with helping Muriel entertain Doris Monroe should she become Muriel’s Christmas guest.

Jerry presently drifted into the room to announce that Ronny had cruelly refused to unpack the box from California before her and Lucy. “She made us help her upstairs with it, then she coldly turned us out.” Jerry complained plaintively. “I’d have raged like a gale at such treatment only she gave me some Mexican candied fruit. It was very celostrous. My new adjective just describes the candied banana I had. What became of Matchless Muriel? I see she’s beaten it.”

69“She’ll return presently,” Marjorie made mysterious answer.

But it was fully an hour afterward before Muriel suddenly popped into the room, closing the door quickly but soundlessly after her.

“Excuse my conspirator entrance,” she began just above a whisper. “I didn’t care to have the Ice Queen know where I went. I ducked out of our room without saying a word. I promised to tell you what she said, Marjorie, to our plan.” Muriel’s eyes were bright with the importance of her information. “Don’t turn all colors with surprise. She says she’ll go to Sanford with me for Christmas.”

While Marjorie Dean and Muriel Harding had been earnestly discussing a welfare invitation for difficult Doris Monroe, the latter had been spending a couple of very disagreeable hours with Leslie Cairns. Leslie had seen fit to assume the particularly dictatorial air which of all her category of unpleasant moods Doris most thoroughly detested.

To begin with Leslie had come to meet Doris at the Colonial fresh from a hot argument with the Italian, Sabatini, whom she had seen fit to call on at his garage and scathingly upbraid for being a “cheating dago quitter.” Leslie argued that, for the amount of money she had paid Sabatini he should have stood out against the threats of Signor Baretti and declined to put the busses back into service.

“You are no lady, but the creza girl; thick head you have,” Sabatini had finally shouted at Leslie when his temper broke all bounds. “You are the foolish. I don’ run the busses when Baretti say I 71must, I get my franchisa take from me. Then don’ run, anyhow. You get that through your head, you can.”

“Then give back part of that money, and cut out the pet names,” Leslie had blazed back at him. “You’ll find out who you’re talking to, you thieving dago, before you are many weeks older. I’ll break you. Put you out of business. Just like that!” Leslie had given her usual imitation of what she fondly believed would have been her father’s way of dealing with the situation.

As a matter of fact her father, Peter Cairns, would never have figured personally in any such affair. He would have placed it in the hands of a subordinate below his rank as financier, who would have in turn detailed his subordinate to act and so on down until one competent to deal with the Italian had been secured.

Leslie was not ignorant of her father’s methods of procedure but she was ambitious to prove her own power over people and circumstances. She was determined to prove to her father that she could bring about any consummation she desired either by her own clever maneuvering or by force of will. Her idea of will power was—“make other people do as you say.”

72Sabatini’s parting, furious speech had been: “You try make troubla I make you the troubla, too. You see. I tell about you to the paper man. Everabuddy read ’bout you in the paper.” He had already refused to return a penny of the money she had given him. Leslie’s humor as she lounged out of the garage with an air of lofty indifference was ferocious.

This had been her third and most trying interview with the Italian, Sabatini, since the busses had again begun to run. She reflected morosely as she drove her car along Hamilton Pike to keep her engagement with Doris that not a single thing she had planned since first she had come to Hamilton College as a student had ever turned out advantageously to her. She did not in the least blame herself or her methods. She was conceitedly sure of herself. Someone or something had always “butted in” at the wrong time. Or else the persons on whom she depended to do their parts in her various schemes had failed her.

She wondered if her father had received the letter she had written him. She was confident that it would be forwarded to him if he were not in New York. She was particularly anxious to know where he was. She hoped he was not in New York. For weeks, a scheme, the most ambitious plan to make 73trouble which Leslie had yet concocted, had been foremost in her thoughts. It had kept her busy ever since Thanksgiving, daily visiting her garage property and prowling in the immediate neighborhood of the dormitory building. The gray stone walls of the dormitory were well started and steadily reaching upward, a fact which seemed to furnish Leslie with deep though frowning interest.

Coming within sight of the dormitory that afternoon she had glanced toward it and given a short angry laugh. She had then stopped her car for a moment to compare the activities on the dormitory lot with those going on at her garage site. The operation of tearing down the old houses in the block she had purchased, and afterward clearing the ground, had gone very slowly. The contractor who had charge of that part of the work had dragged it, so as to benefit himself. Under honest management the operation should have been far enough advanced at least to show the garage cellar dug. As it was the ground she owned was yet partially littered with the debris of demolishment.

When she had finally arrived at the Colonial there to find Doris waiting for her at one of the tables she had reached a point where nothing could please her. On the way from the dormitory site to the 74Colonial she had decided to go to New York alone over the holidays. She had important work to do. She did not propose to allow entertaining Doris to interfere with it.