Title: Some Distinguished Victims of the Scaffold

Author: Horace Bleackley

Release date: June 10, 2016 [eBook #52301]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, Wayne Hammond and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

i

iii

iv

The IDLE ‘PRENTICE Executed at Tyburn.

v

SOME

DISTINGUISHED VICTIMS

OF THE SCAFFOLD

BY

HORACE BLEACKLEY

WITH TWENTY-ONE ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRÜBNER, & CO., Ltd.

DRYDEN HOUSE, GERRARD STREET, W.

1905

vi

To

JOSEPH GREGO

WHOSE MEMORY IS STORED WITH

PICTURES OF THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

THESE MODERN IMPRESSIONS FROM

OLD PLATES ARE

OFFERED

vii

No apology is needed, save that which the consciousness of inadequate work may call forth, from him who writes a history of great criminals. Since the lives of so many whose crime is their only title to fame have been included in the Dictionary of National Biography, it is inevitable that some of these old stories shall be re-told. Already the books of Charles Whibley and J. B. Atlay, as well as the newspaper sketches of W. W. Hutchings, have advanced this portion of our bibliography to a large extent. By a judicious selection some rare human documents and many an entrancing tale may be found in the crimson pages of the Tyburn Chronicle. The dainty squeamishness that put Ainsworth into the pillory, not because he had written a clumsy novel, but because he had dared to weave a romance around the grisly walls of Newgate, would be out of place in an age that will listen to ballads of a drunken soldier, and reads our women’s stories of the boudoirs of Mayfair.

Without a knowledge of the Newgate Calendar it is impossible to be acquainted with the history of England in the eighteenth century. On the other hand, to him who knows these volumes, and who has verified his information in the pages of the Sessions papers and among the battles of the pamphleteers, the Georgian viii era is an open book. No old novel gives a more exact picture of a middle-class household than the trial of Mary Blandy, nor shows the inner life of those on the fringe of society more completely than the story of Robert Perreau. While following the fate of Henry Fauntleroy we enter the newspaper world of our great-grandfathers. And as we look upon these forgotten dramas, the most illustrious bear us company. For a time Wordsworth and Coleridge chat of nothing but the Beauty of Buttermere and rascally John Hadfield. Dr Johnson thinks wistfully of the charms of sweet Mrs Rudd. Boswell rides to Tyburn in the same coach as the Rev. Mr Hackman, or persuades Sir Joshua to witness an execution. Henry Fielding lashes the cowards who strive to condemn a prisoner unheard. To all who desire to understand the eighteenth century the Newgate Calendar is as essential as the Letters of Walpole.

In making a selection from the dozen or more causes célèbres that stand out in special prominence from the rebellion of ’45 to the death of George IV. the choice is not difficult. It is apparent that the stories of Eugene Aram, Dr Dodd, and John Thurtell must be omitted, for all have been told adequately in recent years. Little that is new or interesting can be found in the tale of mad Lord Ferrers, except that he was not hanged with a silken rope. Although the weird tragedy of the Rev. James Hackman sank more deeply into the popular mind than almost any other, the history of the brothers Perreau has been preferred, since Mrs Rudd appears a more attractive personage than the unfortunate Martha Ray. For similar reasons Wynne Ryland takes the place of Captain Donellan, and Eliza Fenning, naturally, has been excluded in favour of the Keswick Impostor. As to the rest, it is obvious—owing to the omission of the highwayman and ix those guilty of high treason such as Colonel Despard—that no more illustrious names can be found in the Newgate Calendar than Mary Blandy, Joseph Wall, and Henry Fauntleroy.

Each crime, moreover, bears the distinct impress of its epoch. None other but the dark night that separates a gorgeous sunset from the brilliant dawn could witness the sombre tragedy at Henley. While the nation begins its eager life as a young apprentice to trade, Tom Idle is found among the recreants, and many a sparkling macaroni like Daniel Perreau prefers to stake his all in Exchange Alley to pursuing laborious days. Wynne Ryland is dazzled by the birth of a most radiant springtide when the world becomes clothed in beauty, and man seems to have stolen the heavenly flame. Then comes the clash of arms and the strife of worlds, when the red giants are unchained, and the life of ten thousand men is naught in the policy of a statesman. With the story of the Maid of Buttermere we perceive again one of the spirits of the age—vain, ruthless Strephon in dandy attire pursuing his Phyllis, shallow-pated and simple. And last, the era of Henry Fauntleroy, when the nation has grown rich, and man must choose between the scarlet of the Corinthian, and the dull, sober garb of toil—a strange mingling of black and crimson.

In order to avoid an interruption of the narrative which a footnote must always cause, the editorial comments have been placed in the bibliography at the end of each monograph, to which those who differ from the author are requested to refer. Although the addition of the lists of authorities has robbed the book of due proportion, the fact that the useful adage “when found make a note of” has been observed will, it is hoped, cause the loss to be balanced by the gain.

The author wishes to acknowledge his obligations to x Mr John Arthur for his kindness in verifying references in the British Museum; to Mr Isaac Edwards of Bolton for similar help; to the editors of the Henley Advertiser, the Carlisle Journal, and the Tiverton Gazette for access to the files of their newspapers; to the rectors of Henley, Feltham, Mottram, St Sepulchre’s, Holborn, and St Martin’s, Ludgate, for permission to consult the church register; to Mr Richard Greenup of Caldbeck for information concerning the Beauty of Buttermere; and to Mrs Bleackley for the list of Wynne Ryland’s engravings. xi

| PAGE | |

| The Love Philtre. The Case of Mary Blandy, 1751-1752 | 1 |

| A Bibliography of the Blandy Case | 35 |

| The Unfortunate Brothers. The Case of Robert and Daniel Perreau and Margaret Caroline Rudd, 1775-1776 | 39 |

| A Bibliography of the Perreau Case | 70 |

| The King’s Engraver. The Case of William Wynne Ryland, 1783 | 74 |

| A Bibliography of the Ryland Case | 107 |

| A List of William Wynne Ryland’s Engravings | 110 |

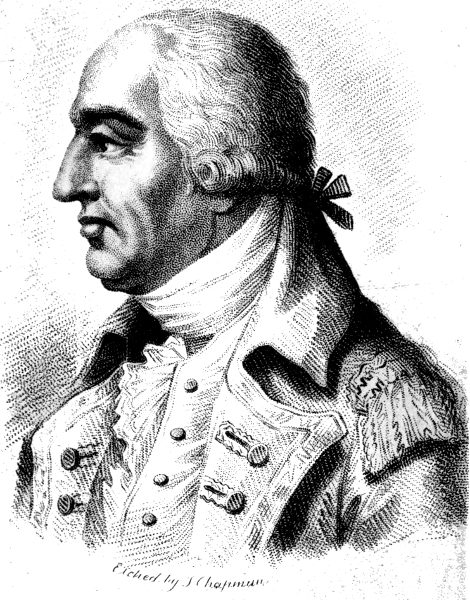

| A Sop to Cerberus. The Case of Governor Wall, 1782-1802 | 112 |

| A Bibliography of the Wall Case | 144 |

| The Keswick Impostor. The Case of John Hadfield, 1802-1803 | 146 |

| A Bibliography of the Hadfield Case | 175 |

| A Famous Forgery. The Case of Henry Fauntleroy, 1824— | |

| Part I. The Criminal and his Crime | 178 |

| Part II. Some Details of the Forgeries | 207 |

| Fauntleroy and the Newspapers | 220 |

| Notes on the Fauntleroy Case | 224 |

| Index | 227 |

xii

xiii

xv

xvi

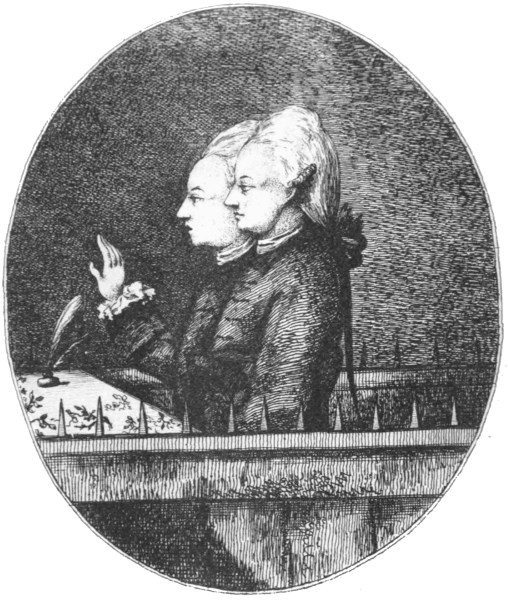

Miss Blandy

Now confined in Oxford Gaol on Suspicion of Poisoning her Father. 1

Some Distinguished Victims of the Scaffold

During the reign of George II.—when the gallant Young Pretender was leading Jenny Cameron toward Derby, and flabby, gin-besotted England, dismayed by a rabble of half-famished Highlanders, was ready to take its thrashing lying-down—a prosperous attorney, named Francis Blandy, was living at Henley-upon-Thames. For nine years he had held the post of town clerk, and was reckoned a person of skill in his profession. A dour, needle-witted man of law, whose social position was more considerable than his means or his lineage, old Mr Blandy, like others wiser than himself, had a foible. His pride was just great enough to make him a tuft-hunter. In those times, a solicitor in a country town had many chances of meeting his betters on equal terms, and when the attorney of Henley pretended that he had saved the large sum of ten thousand pounds, county society esteemed him at his supposed value. There lived with him—in an old-world 2 home surrounded by gardens and close to the bridge on the London road—his wife and daughter, an only child, who at this period was twenty-five years of age.

Mrs Blandy, as consequential an old dame as ever flaunted sacque or nodded her little bugle over a dish of tea, seems to have spent a weary existence in wringing from her tight-fisted lord the funds to support the small frivolities which her social ambition deemed essential to their prestige. A feminine mind seldom appreciates the reputation without the utility of wealth, and the lawyer’s wife had strong opinions with regard to the propriety of living up to their ten-thousand-pound celebrity. While he was content with the barren honour that came to him by reason of the reputed dot which his daughter one day must enjoy—pluming himself, no doubt, that his Molly had as good a chance of winning a coronet as the penniless daughter of an Irish squireen—his lady, with more worldly wisdom, knew the value of an occasional jaunt to town, and was fully alive to the chances of rout or assembly hard-by at Reading. Thus in the pretty little home near the beautiful reach of river, domestic storms—sad object-lesson to an only child—raged frequently over the parental truck and barter at the booths of Vanity Fair.

Though not a beauty—for the smallpox, that stole the bloom from the cheeks of many a sparkling belle in hoop and brocade, had set its seal upon her face—the portrait of Mary Blandy shows that she was comely. Still, it is a picture in which there is a full contrast between the light and shadows. Those fine glistening black eyes of hers—like the beam of sunshine that illumines a sombre chamber—made one forget the absence of winsome charm in her features; yet their radiance appeared to come through dark unfathomable depths rather than as the reflection of an unclouded 3 soul. With warmth all blood may glow, with softness every heart can beat, but some, like hers, must be compelled by reciprocal power. Such, in her empty home, was not possible. Even the love and devotion of her parents gave merely a portion of their own essence. From a greedy father she acquired the sacred lust, and learnt from infancy to dream, with morbid longing, of her future dower; while her mother encouraged a hunger for vain and giddy pleasure, teaching unwittingly that these must be bought at the expense of peace, or by the sacrifice of truth. To a girl of wit and intelligence in whose heart nature had not sown the seeds of kindness, these lessons came as a crop of tares upon a fruitful soil. But, as in the case of all women, there was one hope of salvation. Indeed, since the passion of her soul cried out with imperious command that she should fulfil the destiny of her sex, the love of husband and children would have found her a strong but pliable material that could be fashioned into more gentle form. Without such influence she was one of those to whom womanhood was insufferable—a mortal shape where lay encaged one of the fiercest demons of discontent.

Molly Blandy did not lack admirers. Being pleasant and vivacious—while her powers of attraction were enhanced by the rumour of her fortune—not a few of the beaux in the fashionable world of Bath, and county society at Reading, gave homage and made her their toast. In the eyes of her parents it was imperative that a suitor should be able to offer to their daughter a station of life befitting an heiress. On this account two worthy swains, who were agreeable to the maiden but could not provide the expected dower, received a quick dismissal. Although there was nothing exorbitant in the ambition of the attorney and his dame, it is clear that the girl learnt an evil lesson from 4 these mercenary transactions. Still, her crosses in love do not seem to have sunk very deeply into her heart, but henceforth her conduct lost a little of its maidenly reserve. The freedom of the coquette took the place of the earnestness and sincerity that had been the mark of her ardent nature, and her conduct towards the officers of the regiment stationed at Henley was deemed too forward. However, the father, whose reception into military circles no doubt made the desired impression upon his mayor and aldermen, was well satisfied that his daughter should be on familiar terms with her soldier friends. Even when she became betrothed to a captain of no great fortune, he offered small objection on account of the position of the young man. Yet, although the prospect of a son-in-law who held the king’s commission had satisfied his vanity, the old lawyer, who foolishly had allowed the world to believe him richer than he was, could not, or (as he pretended) would not, provide a sufficient dowry. Thus the engagement promised to be a long one. Fate, however, decided otherwise. Very soon her suitor was ordered abroad on active service, and the hope of marriage faded away for the third time.

In the summer of 1746, while no doubt she was sighing for her soldier across the seas, the man destined to work the tragic mischief of her life appeared on the scene. William Henry Cranstoun, a younger son of the fifth Lord Cranstoun, a Scottish baron, was a lieutenant of marines, who, since his regiment had suffered severely during the late Jacobite rebellion, had come to Henley on a recruiting expedition. At first his attentions to Miss Blandy bore no fruit, but he returned the following summer, and while staying with his grand-uncle, General Lord Mark Kerr, who was an acquaintance of the lawyer and his family, he found that Mary was off with the old 5 love and willing to welcome him as the new. All were amazed that the fastidious girl should forsake her gallant captain for this little sprig from North Britain—an undersized spindleshanks, built after Beau Diddapper pattern—in whose weak eyes and pock-fretten features love must vainly seek her mirror. Still greater was the astonishment when ten-thousand-pound Blandy, swollen with importance, began to babble of “my Lord of Crailing,” and the little bugle cap of his dame quivered with pride as she told her gossips of “my Lady Cranstoun, my daughter’s new mamma.” For it was common knowledge that the small Scot was the fifth son of a needy house, with little more than his pay to support his many vicious and extravagant habits. Such details seem to have been overlooked by the vain parents in their delight at the honour and glory of an alliance with a family of title. In the late autumn of 1747 they invited their prospective son-in-law to their home, where, as no one was fonder of free quarters, he remained for six months. But the cruel fate that presided over the destinies of the unfortunate Mary intervened once more. Honest Lord Mark Kerr (whose prowess as a duellist is chronicled in many a page), perceiving the intentions of his unscrupulous relative, made haste to give his lawyer friend the startling news that Cranstoun was a married man.

This information was correct. Yet, although wedded since the year before the rebellion, the vicious little Scot was seeking to put away the charming lady who was his wife and the mother of his child. Plain enough were the motives. A visit to England had taught him that the title which courtesy permitted him to bear was a commercial asset that, south of the Tweed, would enable him to sell himself in a better market. As one of his biographers tells us, “he saw young sparklers every day running off with rich prizes,” for the chapels 6 of Wilkinson and Keith were always ready to assist the abductor of an heiress. Indeed, before his arrival at Henley, he had almost succeeded in capturing the daughter of a Leicestershire squire, when the father, who suddenly learnt his past history, sent him about his business. Still, he persisted in his attempts to get the Scotch marriage annulled, and his chances seemed favourable. Most of the relatives of his wife, who had espoused the losing side in the late rebellion, were fled in exile to France or Flanders. Moreover, she belonged to the Catholic Church, which at that time in stern Presbyterian Scotland had fallen upon evil days. Believing that she was alone and friendless, and relying, no doubt, upon the sectarian prejudices of the law courts, he set forth the base lie that he had promised to marry her only on condition she became Protestant. His explanation to the Blandys, in answer to Lord Mark’s imputation, was the same as his defence before the Scottish Commissaries. The lady was his mistress, not his wife!

Miss Blandy took the same view of the case that Sophy Western did under similar circumstances. Human nature was little different in those days, but men wore their hearts on their sleeve instead of exhibiting them only in the Courts, and women preferred to be deemed complacent rather than stupid. Doubtless old lawyer Blandy grunted many Saxon sarcasms at the expense of Scotch jurisprudence, and trembled lest son-in-law Diddapper had been entangled beyond redemption. Still, father, mother, and daughter believed the word of their guest, waiting anxiously for the result of the litigation that was to make him a free man. During the year 1748 the Commissaries at Edinburgh decided that Captain Cranstoun and the ill-used Miss Murray were man and wife. Then the latter, being aware of the flirtation at Henley, wrote to warn Miss Blandy, and 7 provided her with a copy of the Court’s decree. Great was the consternation at the house on the London road. Visions of tea-gossip over the best set of china in the long parlour at Crailing with my Lady Cranstoun vanished from the old mother’s eyes, while the town clerk forgot his dreams of the baby whose two grand-fathers were himself and a live lord. Nevertheless, the young Scotsman protested that the marriage was invalid, declared that he would appeal to the highest tribunal, and swore eternal fidelity to his Mary. Alas, she trusted him! Within the sombre depths of her soul there dwelt a fierce resolve to make this man her own. In her sight he was no graceless creature from the barrack-room, but with a great impersonal love she sought in him merely the fulfilment of her destiny.

At this time Cranstoun’s fortunes were in a parlous state. More than half of his slender patrimony had been sequestered for the maintenance of his wife and child, and shortly after the peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, his regiment being disbanded, he was left on half-pay. Still, he did not waver in his purpose to win the heiress of Henley.

On the 30th of September 1749, the poor frivolous old head, which had sported its cap so bravely amidst the worries of pretentious poverty, lay still upon the pillow, and Mary Blandy looked upon the face of her dead mother. It was the turning-point in her career. While his wife was alive, the old lawyer had never lost all faith in his would-be son-in-law during the two years that he had been affianced to his daughter, in spite of the rude shocks which had staggered his credulity. Cranstoun had been allowed to sponge on him for another six months in the previous summer, and had pursued his 8 womenfolk when they paid a visit to Mary’s uncle, Serjeant Stevens, of Doctors’ Commons. However, soon after the death of his wife the patience of Mr Blandy, who must have perceived that the case of the pretender was hopeless, seems to have become worn out. All idea of the baron’s grandchild faded from his mind; the blear-eyed lover was forbidden the house, and for nearly twelve months did not meet his trusting sweetheart.

Although a woman of her intelligence must have perceived that, but for some untoward event, her relationship with her betrothed could never be one of honour, her fidelity remained unshaken. Having passed her thirtieth birthday, the dreadful stigma of spinsterhood was fast falling upon her. If the methods of analogy are of any avail, it is clear that she had become a creature of lust—not the lust of sensuality, but that far more insatiable greed, the craving for conquest, possession, the attainment of the unattainable, calling forth not one but all the emotions of body and soul. A sacrifice of honour—a paltry thing in the face of such mighty passion—would have been no victory, for such in itself was powerless to accomplish the essential metamorphosis of her life. In mutual existence with a lover and slave the destiny of this rare woman alone could be achieved. Thus came the harvest of the tempest. It was not the criminal negligence of the father in encouraging for nearly three years the pretensions of a suitor, who—so a trustworthy gentleman had told him—was a married man, that had planted the seeds of storm. Nor did the filial love of the daughter begin to fade and wither because she had been taught that the affections, like anything which has a price, should be subject to barter and exchange. Deeper far lay the roots of the malignant disease—growing as a portion of her being—a part and principle of life itself. Environment 9 and education merely had inclined into its stunted form the twig, which could never bear fruit unless grafted upon a new stalk! And while the sombre girl brooded over her strange impersonal passion, there rang in her ears the voice of demon-conscience, unceasingly—a taunting, frightful whisper, “When the old man is in his grave you shall be happy.”

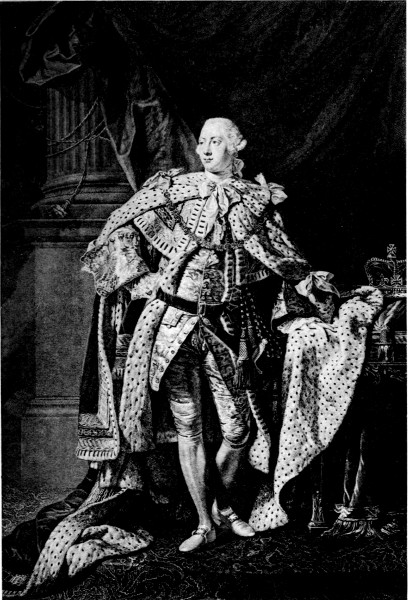

The esteem of posterity for the eighteenth century, to which belong so many noble lives and great minds, has been influenced by the well-deserved censure bestowed upon a particular epoch. The year 1750 marks a period of transition when all the worst characteristics of the Georgian era were predominant. For nearly a quarter of a century the scornful glance that the boorish little king threw at any book had been reflected in the national taste for literature. Art had hobbled along bravely on the crutches of caricature, tolerated on account of its deformity, and not for its worth. The drama, which had drifted to the lowest ebb in the days of Rich and Heidegger, was just rising from its mudbank, under the leadership of Garrick, with the turn of the tide. Religion, outside the pale of Methodism, was as dead as the influence of the Church of England and its plurality divines. The prostitution of the marriage laws in the Fleet and Savoy had grown to be a menace to the social fabric. London reeked of gin; and although the business of Jack Ketch has been seldom more flourishing, property, until magistrate Fielding came forward, was never less secure from the thief and highwayman. Our second George, who flaunted his mistresses before the public gaze, was a worthy leader of a coarse and vicious society. Female dress took its form from the vulgarity of the times, and was never uglier and more indecent simultaneously. Not only was the ‘modern fine lady,’ who wept when a handsome thief was hung, a common type, but the 10 Boobys and Bellastons were fashionable women of the day, quite as much alive as Elizabeth Chudleigh or Caroline Fitzroy. Such was the age of Miss Blandy, and she proved a worthy daughter of it.

In the late summer of 1750 the fickle attorney, who had become weary of opposition, consented to withdraw the sentence of banishment he had pronounced against his daughter’s lover. Possibly he fancied that there was a chance, after all, of the Scotch lieutenant’s success in the curious law-courts of the North, and perhaps a present of salmon, received from Lady Cranstoun, appeared to him as a favourable augury. Consequently the needy fortune-hunter, who was only too ready to return to his free quarters, paid another lengthy visit to Henley. As the weeks passed, it was evident that the temper of the host and father, whose senile humours were swayed by gravel and heartburn, could not support the new ménage. Fearful lest the devotion of his Molly had caused her to lose all regard for her fair fame, wroth that the clumsy little soldier should have disturbed the peace of his household, the old man received every mention of “the tiresome affair in Scotland” with sneers and gibes. Vanished was the flunkey-optimism that had led him to welcome once more the pertinacious slip of Scottish baronage. Naught would have appeased him but prompt evidence that the suitor was free to lead his daughter to the altar. Nothing could be plainer than that the querulous widower had lost all confidence in his unwelcome guest.

The faithful lovers were filled with dismay. A few strokes of the pen might rob them for ever of their ten thousand pounds. Their wishes were the same, their minds worked as one. A deep, cruel soul-blot, transmitted perhaps by some cut-throat borderer through the blood of generations, would have led William Cranstoun to commit, without scruple, the vilest of 11 crimes. Those base attempts to put away his wife, and to cast the stigma of bastardy upon his child, added to his endeavour to entrap one heiress after another into a bigamous marriage, make him guilty of offences less only than murder. In his present position he had cause for desperation. Yet, although utterly broken in fortune, there was a rich treasure at his hand if he dared to seize it. Were her father dead, Molly Blandy, whether as wife or mistress, would be his—body, soul, and wealth. Within the veins of the woman a like heart-stain spread its poison. All the lawless passion of her nature cried out against her parent’s rule, which, to her mind, was seeking to banish what had become more precious than her life. Knowing that her own fierce will had its mate in his, she believed that his obduracy could not be conquered, and she lived in dread lest she should be disinherited. And all this time, day after day, the demon-tempter whispered, “When the old man is in his grave you shall be happy.”

Which of the guilty pair was the first to suggest the heartless crime it is impossible to ascertain, but there is evidence, apart from Miss Blandy’s statement, that Cranstoun was the leading spirit. Possibly, nay probably, the deed was never mentioned in brutal plainness in so many words. The history of crime affords many indications that the blackest criminals are obliged to soothe a neurotic conscience with the anodyne of make-belief. It is quite credible that the two spoke of the projected murder from the first (as indeed Miss Blandy explained it later) as an attempt to conciliate the old lawyer by administering a supernatural love philtre, having magical qualities like Oberon’s flower in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which would make him consent to their marriage. Presently a reign of mystic terror seemed to invade the little house in the London road. With fear ever present in her eyes, the figure 12 of the sombre woman glided from room to room, whispering to the frightened servants ghostly tales of things supernatural—of unearthly music that she had heard during the misty autumn nights, of noises that had awakened her from sleep, of the ghastly apparitions that had appeared to her lover. And to all these stories she had but one dismal interpretation—saying it had come to her from a wizard-woman in Scotland—they were signs and tokens that her father would die within a year! Those who heard her listened and trembled, and the words sank deep into their memory. So the winter crept on; but while all slunk through the house with bated breath, shrinking at each mysterious sound, the old man, doomed by the sorceress, remained unsuspicious of what was going on around him.

Not long before Christmas, to the great relief of his churlish host, the little Scotsman’s clumsy legs passed through the front door for the last time, and he set out for his brother’s seat at Crailing in the shire of Roxburgh. Yet, though his lengthy visit had come to an end, his spirit remained to rule the brain of the woman who loved him. Early in the year 1751 she received a box, containing a present from Cranstoun, a set of table linen, and some ‘Scotch pebbles.’ Lawyer Blandy viewed the stones with suspicious eyes, for he hated all things beyond the Cheviot Hills, but did not make any comment. The relationship between father and daughter had become cold and distant. Quarrels were constant in the unhappy home. Often in the midst of her passion she was heard to mutter deep curses against the old man. Indeed, so banished was her love that she talked without emotion to the servants of the likelihood of his death, in fulfilment of the witch’s prophecy.

Some weeks later, when another consignment of the mysterious ‘Scotch pebbles’ had arrived for Miss 13 Blandy, it was noticed that her conduct became still more dark and strange. Slinking through the house with slow and stealthy tread, she appeared to shun all eyes, as though bent upon some hidden purpose. A glance within the box from the North would have revealed the secret. When the crafty accomplice found that she was unable to procure the means of taking her father’s life, he had been forced to supply her with the weapons. During the spring, the health of the old lawyer, who suffered more or less from chronic ailments, began to grow more feeble. His garments hung loosely upon his shrunken limbs, while the teeth dropped from his palsied jaws. The old witch’s curse seemed to have fallen upon the home, and, to those who looked with apprehension for every sign and portent, it was fulfilled in many direful ways. Early in June, Ann Emmet, an old charwoman employed about the house, was seized with a violent illness after drinking from a half-emptied cup left at Mr Blandy’s breakfast. A little later, Susan Gunnel, one of the maid-servants, was affected in a similar way through taking some tea prepared for her master. One August morning, in the secrecy of her own chamber, trembling at every footfall beyond the locked door, Mary Blandy gazed with eager, awestruck eyes upon a message sent by her lover.

“I am sorry there are such occasions to clean your pebbles,” wrote the murderous little Scotsman. “You must make use of the powder to them, by putting it into anything of substance, wherein it will not swim a-top of the water, of which I wrote to you in one of my last. I am afraid it will be too weak to take off their rust, or at least it will take too long a time.”

From the language of metaphor it is easy to translate the ghastly meaning. She must have told Cranstoun that the white arsenic, which he had sent to her under the pseudonym of ‘powder to clean the pebbles,’ 14 remained floating on the surface of the tea. Possibly her father had noticed this phenomenon, and, not caring to drink the liquid, had escaped the painful sickness which had attacked the less cautious servants. But now she had found a remedy—‘anything of substance!’—a safe and sure vehicle that could not fail. Louder still in the ears of the lost woman rang the mocking words, “When the old man is dead you shall be happy.”

During the forenoon of Monday, the 5th of August, Susan Gunnel, the maid, met her young mistress coming from the pantry.

“Oh, Susan,” she exclaimed, “I have been stirring my papa’s water gruel”; and then, perceiving other servants through the half-open door of the laundry, she added gaily, “If I was ever to take to eating anything in particular it would be oatmeal.”

No response came from the discreet Susan, but she marvelled, calling to mind that Miss Blandy had said to her some time previously, noticing that she appeared unwell:

“Have you been eating any water gruel? for I am told that water gruel hurts me, and it may hurt you.”

Later in the day, her wonder was increased when she saw her mistress stirring the gruel in a half-pint mug, putting her fingers into the spoon, and then rubbing them together. In the evening the same mug was taken as usual to the old man’s bedroom. On Tuesday night Miss Blandy sent down in haste to order gruel for her father, who had been indisposed all day, and such was her solicitude that she met the footman on the stairs, and taking the basin from his hands, carried it herself into the parlour. Early the next morning, while Ann Emmet, the old charwoman, was busy at her wash-tub, Susan Gunnel came from upstairs.

“Dame,” she observed, “you used to be fond of 15 water gruel. Here is a very fine mess my master left last night, and I believe it will do you good.”

Sitting down upon a bench, this most unfortunate old lady proceeded to consume the contents of the basin, and for a second time was seized with a strange and violent illness. Soon afterwards Miss Blandy came into the kitchen.

“Susan, as your master has taken physic, he may want some more water gruel,” said she. “As there is some in the house you need not make fresh, for you are ironing.”

“Madam, it will be stale,” replied the servant. “It will not hinder me much to make fresh.”

A little later, while tasting the stuff, Susan noticed a white sediment at the bottom of the pan. Greatly excited, she ran to show Betty Binfield, the cook, who bore no good-will towards her young mistress.

“What oatmeal is this?” asked Betty, significantly. “It looks like flour.”

“I have never seen oatmeal as white before,” said the maid.

Carefully and thoroughly the suspicious servants examined the contents of the saucepan, taking it out of doors to view it in the light. And while they looked at the white gritty sediment they told each other in low whispers that this must be poison. Locking up the pan, they showed it next day to the local apothecary, who, as usual in those times, was the sick man’s medical attendant.

Nothing occurred to alarm the guilty woman until Saturday. On that morning, in the homely fashion of middle-class manners, the lawyer, who wanted to shave, came into the kitchen, where hot water and a good fire were ready for him. Accustomed to his habits, the servants went about their work as usual. Some trouble seemed to be preying upon his mind. 16

“I was like to have been poisoned once,” piped the feeble old man, turning his bloodshot eyes upon his daughter, who was in the room.

“It was on this same day, the tenth of August,” he continued, in his weak, trembling voice, for his frame had become shattered during the last week. “It was at the coffee-house or at the Lyon, and two other gentlemen were like to have been poisoned by what they drank.”

“Sir, I remember it very well,” replied the imperturbable woman, and then fell to arguing with her querulous father at which tavern the adventure had taken place.

“One of the gentlemen died immediately,” he resumed, looking at her with a long, reproachful glance. “The other is dead now, and I have survived them both. But”—his piteous gaze grew more intense—“it is my fortune to be poisoned at last.”

A similar ordeal took place in a little while. At breakfast Mr Blandy seemed in great pain, making many complaints. As he sipped his tea, he declared that it had a gritty, bad taste, and would not drink it.

“Have you not put too much of the black stuff into it?” he demanded suddenly of his daughter, referring to the canister of Bohea.

This time she was unable to meet his searching eyes.

“It is as usual,” she stammered in confusion.

A moment later she rose, trembling and distressed, and hurriedly left the room.

There was reason for the old man’s suspicion. Before he had risen from his bed, the faithful Susan Gunnel told him of the discovery in the pan of water gruel, and both agreed that the mysterious powder had been sent by Cranstoun. Yet, beyond what he had said at breakfast, and in the kitchen, he questioned his daughter no 17 more! Still, although no direct charge had been made, alarmed by her father’s hints she hastened to destroy all evidence that could be used against her. During the afternoon, stealing into the kitchen under pretence of drying a letter before the fire, she crushed a paper among the coals. As soon as she was gone the watchful spies—servants Gunnel and Binfield—snatched it away before it had been destroyed by the flames. This paper contained a white substance, and on it was written ‘powder to clean the pebbles.’ Towards evening famous Dr Addington arrived from Reading, summoned by Miss Blandy, who was driven on account of her fears to show a great concern. After seeing his patient the shrewd old leech had no doubt as to the symptoms. With habitual directness he told the daughter that her father had been poisoned.

“It is impossible,” she replied.

On Sunday morning the doctor found the sick man a little better, but ordered him to keep his bed. Startling proofs of the accuracy of his diagnosis were forthcoming. One of the maids put into his hands the packet of arsenic found in the fire; while Norton the apothecary produced the powder from the pan of gruel. Addington at once took the guilty woman to task.

“If your father dies,” he told her sternly, “you will inevitably be ruined.”

Nevertheless she appears to have brazened the matter out, but desired the doctor to come again the next day. When she was alone, her first task was to scribble a note to Cranstoun, which she gave to her father’s clerk to “put into the post.” Having heard dark rumours whispered by the servants that Mr Blandy had been poisoned by his daughter, the man had no hesitation in opening the letter, which he handed over to the apothecary. It ran as follows:— 18

“Dear Willy,—My father is so bad that I have only time to tell you that if you do not hear from me soon again, don’t be frightened. I am better myself. Lest any accident should happen to your letters be careful what you write.

“My sincere compliments.—I am ever, yours.”

That evening Norton ordered Miss Blandy from her father’s room, telling Susan Gunnel to remain on the watch, and admit no one. At last the heartless daughter must have seen that some other defence was needed than blind denial. Still, the poor old sufferer persisted that Cranstoun was the sole author of the mischief. On Monday morning, although sick almost to death, he sent the maid with a message to his daughter.

“Tell her,” said he, “that I will forgive her if she will bring that villain to justice.”

In answer to his words, Miss Blandy came to her father’s bedroom in tears, and a suppliant. Susan Gunnel, who was present, thus reports the interview.

“Sir, how do you do?” said she.

“I am very ill,” he replied.

Falling upon her knees, she said to him:

“Banish me or send me to any remote part of the world. As to Mr Cranstoun, I will never see him, speak to him, as long as I live, so as you will forgive me.”

“I forgive thee, my dear,” he answered. “And I hope God will forgive thee, but thee should have considered better than to have attempted anything against thy father. Thee shouldst have considered I was thy own father.”

“Sir,” she protested, “as to your illness I am entirely innocent.”

“Madam,” interrupted old Susan Gunnel, “I believe you must not say you are entirely innocent, for the powder that was taken out of the water gruel, and the 19 paper of powder that was taken out of the fire, are now in such hands that they must be publicly produced. I believe I had one dose prepared for my master in a dish of tea about six weeks ago.”

“I have put no powder into tea,” replied Miss Blandy. “I have put powder into water gruel, and if you are injured,” she assured her father, “I am entirely innocent, for it was given me with another intent.”

The dying man did not wait for further explanation, but, turning in his bed, he cried:

“Oh, such a villain! To come to my house, eat of the best, drink of the best that my house could afford—to take away my life, and ruin my daughter! Oh, my dear,” he continued, “thee must hate that man, thee must hate the ground he treads on. Thee canst not help it.”

“Oh, sir, your tenderness towards me is like a sword to my heart,” she answered. “Every word you say is like swords piercing my heart—much worse than if you were to be ever so angry. I must down on my knees and beg you will not curse me.”

“I curse thee, my dear!” he replied. “How couldst thou think I could curse thee? I bless thee, and hope that God will bless thee and amend thy life. Go, my dear, go out of my room.... Say no more, lest thou shouldst say anything to thy own prejudice.... Go to thy uncle Stevens; take him for thy friend. Poor man,—I am sorry for him.”

The memory of the old servant, who repeated the above conversation in her evidence at Miss Blandy’s trial, would seem remarkable did we not bear in mind that she went through various rehearsals before the coroner and magistrates, and possibly with the lawyers for the prosecution. Some embellishments also must be credited to the taste and fancy of Mr Rivington’s reporters. Still, the gist must be true, and certainly has much pathos. Yet the father’s forgiveness of his 20 daughter, when he must have known that her conduct was wilful, although piteous and noble, may not have been the result of pure altruism. Naturally, the wish that Cranstoun alone was guilty was parent to the thought. Whether the approach of eternity brought a softening influence upon him, and he saw his follies and errors in the light of repentance, or whether the ruling passion strong in death made the vain old man struggle to avert the black disgrace that threatened his good name, and the keen legal intellect, which could counsel his daughter so well, foresaw the coming escheatment of his small estate to the lord of the manor, are problems for the student of psychology.

During the course of the day brother leech Lewis of Oxford—a master-builder of pharmacopœia—was summoned by the sturdy begetter of statesmen, and there was much bobbing of learned wigs and nice conduct of medical canes. Addington asked the dying man whom he suspected to be the giver of the poison.

“A poor love-sick girl,” murmured the old lawyer, smiling through his tears. “I forgive her—I always thought there was mischief in those cursed Scotch pebbles.”

In the evening a drastic step was taken. Acting on the principle of ‘thorough,’ which made his son’s occupancy of the Home Office so memorable at a later period, the stern doctor accused Miss Blandy of the crime, and secured her keys and papers. Conquered by fear, the stealthy woman for a while lost all self-possession. In an agony of shame and terror she sought to shield herself by the pretence of superstitious folly. Wringing her hands in a seeming agony of remorse, she declared that her lover had ruined her.

“I received the powder from Mr Cranstoun,” she cried, “with a present of Scotch pebbles. He had wrote on the paper that held it, ‘The powder to clean the 21 pebbles with.’ He assured me that it was harmless, and that if I would give my father some of it now and then, a little and a little at a time, in any liquid, it would make him kind to him and to me.”

In a few scathing questions the worldly-wise Addington cast ridicule upon this weird story of a love philtre. Taking the law into his own resolute hands, with the consent of colleague Lewis he locked the wretched woman in her room and placed a guard over her. Little could be done to relieve the sufferings of poor ten-thousand-pound Blandy—who proved to be a mere four-thousand-pound attorney when it came to the test—and on Wednesday afternoon, the 14th of August, he closed his proud old eyes for ever. In her desperation the guilty daughter could think of naught but escape. On the evening of her fathers death, impelled by an irresistible frenzy to flee from the scene of her butchery, she begged the footman in vain to assist her to get away. During Thursday morning—for it was not possible to keep her in custody without legal warrant—a little group of children saw a dishevelled figure coming swiftly along the High Street towards the river. At once there arose the cry of ‘Murderess!’ and, surrounded by an angry mob, she was driven to take refuge in a neighbouring inn. It was vain to battle against fate. That same afternoon the coroner’s inquest was held, and the verdict pronounced her a parricide. On the following Saturday, in charge of two constables, she was driven in her father’s carriage to Oxford Castle. An enraged populace, thinking that she was trying again to escape, surrounded the vehicle, and sought to prevent her from leaving the town.

Owing to the social position of the accused, and the enormity of her offence, the eyes of the whole nation were turned to the tragedy at Henley. Gossips of the day, such as Horace Walpole and Tate Wilkinson, tell us that the story of Miss Blandy was upon every lip. 22 In spite of the noble irony of ‘Drawcansir’ Fielding, journalists and pamphleteers had no scruple in referring to the prisoner as a wicked murderess or a cruel parricide. Yet the case of Henry Coleman, who, during the August of this year, had been proved innocent of a crime for which he had suffered death, should have warned the public against hasty assumption. For six months the dark woman was waiting for her trial. Although it was the custom for a jailor to make an exhibition of his captive to anyone who would pay the entrance fee, nobody was allowed to see Miss Blandy without her consent. Two comfortable rooms were set apart for her in the keeper’s house; she was free to take walks in the garden, and to have her own maid. At last, when stories of a premeditated escape were noised abroad, Secretary Newcastle, in a usual state of fuss, fearing that she might repeat the achievement of Queen Maud, gave orders that she must be put in irons. At first Thomas Newell, who had succeeded her father as town clerk of Henley four years previously, was employed in her defence, but he offended her by speaking of Cranstoun as “a mean-looking, little, ugly fellow,” and so she dismissed him in favour of Mr Rives, a lawyer from Woodstock. Her old invincible courage had returned, and only once—when she learnt the paltry value of her father’s fortune—did she lose self-possession. For a dismal echo must have come back in the mocking words, “When the old man is in his grave you shall be happy.”

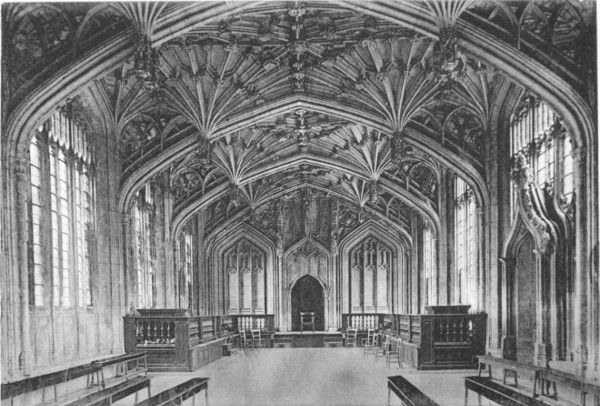

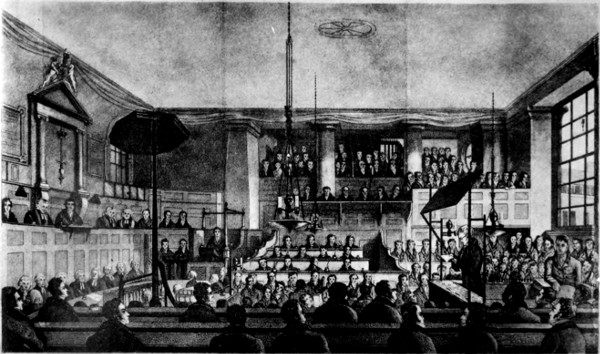

At last the magistrates—Lords Cadogan and ‘New-Style’ Macclesfield, who had undertaken duties which in later days Mr Newton or Mr Montagu Williams would have shared with Scotland Yard—finish their much-praised detective work, and on Tuesday, the 3rd of March 1752, Mary Blandy is brought to the bar. The Court meets in the divinity school, since the town-hall is in the hands of the British workman, and because the 23 University, so ‘Sir Alexander Drawcansir’ tells his readers, will not allow the use of the Sheldonian Theatre. Why the most beautiful room in Oxford should be deemed a fitter place of desecration than the archbishop’s monstrosity is not made clear. An accident delays the trial—this second ‘Great Oyer of Poisoning!’ There is a small stone or other obstruction in the lock—can some sentimental, wry-brained undergraduate think to aid the gallows-heroine of his fancy?—and while it is being removed, Judges Legge and Smythe return to their lodgings.

THE DIVINITY SCHOOL, OXFORD.

At eight o’clock, Mary Blandy, calm and stately, stands beneath the graceful fretted ceiling, facing the tribunal. From wall to wall an eager crowd has filled the long chamber, surging through the doorway, flowing in at the open windows, jostling even against the prisoner. A chair is placed for her in case of fatigue, and her maid is by her side. A plain and neat dress befits her serene manner—a black bombazine short sacque (the garb of mourning), white linen kerchief, and a thick crape shade and hood. From the memory of those present her countenance can never fade. A broad high forehead, above which her thick jet hair is smoothed under a cap; a pair of fine black sparkling eyes; the colouring almost of a gipsy; cheeks with scarce a curve; mouth full, but showing no softness; nose large, straight, determined—it is the face of one of those rare women who command, not the love, but the obedience of mankind. Still it is intelligent, not unseductive, compelling; and yet, in spite of the deep, flashing eyes, without radiance of soul—the face of a sombre-hearted woman.

Black, indeed, is the indictment that Bathurst, a venerable young barrister who represents the Crown, unfolds against her, but only once during his burst of carefully-matured eloquence is there any change in her serenity. When the future Lord Chancellor declares 24 that the base Cranstoun “had fallen in love, not with her, but with her fortune,” the woman’s instinct cannot tolerate the reflection upon her charms, and she darts a look of bitterest scorn upon the speaker. And only once does she show a trace of human softness. When her godmother, old Mrs Mountenay, is leaving the witness-box, she repeats the curtsey which the prisoner had previously disregarded, and then, in an impulse of pity, presses forward, and, seizing Miss Blandy’s hand, exclaims, “God bless you!” At last, and for the first time, the tears gather in the accused woman’s eyes.

Many abuses, handed down from a previous century, still render barbarous the procedure of criminal trials. The case is hurried over in one day; counsel for the prisoner can only examine witnesses, but not address the jury; the prosecution is accustomed to put forward evidence of which the defence has been kept in ignorance. Yet no injustice is done to Mary Blandy. Thirteen hours is enough to tear the veil from her sombre heart; the tongue of Nestor would fail to show her innocent; of all that her accusers can say of her she is well aware. Never for one moment is the issue in doubt. What can her scoffing, sceptic age, with its cold-blooded sentiment and tame romance, think of a credulity that employed a love-potion in the guise of affection but with the result of death! How is it possible to judge a daughter who persisted in her black art, although its dire effects were visible, not once, but many times! Her defence, when at last it comes, is spoken bravely, but better had been left unsaid.

“My lords,” she begins, “it is morally impossible for me to lay down the hardships I have received. I have been aspersed in my character. In the first place, it has been said that I have spoke ill of my father; that I have cursed him and wished him at hell; which is extremely false. Sometimes little family affairs 25 have happened, and he did not speak to me so kind as I could wish. I own I am passionate, my lords, and in those passions some hasty expressions might have dropt. But great care has been taken to recollect every word I have spoken at different times, and to apply them to such particular purposes as my enemies knew would do me the greatest injury. These are hardships, my lords, extreme hardships!—such as you yourselves must allow to be so. It was said, too, my lords, that I endeavoured to make my escape. Your lordships will judge from the difficulties I laboured under. I had lost my father—I was accused of being his murderer—I was not permitted to go near him—I was forsaken by my friends—affronted by the mob—insulted by my servants. Although I begged to have the liberty to listen at the door where he died, I was not allowed it. My keys were taken from me, my shoe-buckles and garters too—to prevent me from making away with myself, as though I was the most abandoned creature. What could I do, my lords? I verily believe I was out of my senses. When I heard my father was dead and the door open, I ran out of the house, and over the bridge, and had nothing on but a half sack and petticoat, without a hoop, my petticoats hanging about me. The mob gathered about me. Was this a condition, my lords, to make my escape in? A good woman beyond the bridge, seeing me in this distress, desired me to walk in till the mob was dispersed. The town sergeant was there. I begged he would take me under his protection to have me home. The woman said it was not proper, the mob was very great, and that I had better stay a little. When I came home they said I used the constable ill. I was locked up for fifteen hours, with only an old servant of the family to attend me. I was not allowed a maid for the common decencies of my sex. I was sent to gaol, and was in hopes, there, at least, this usage would have ended, but was told it 26 was reported I was frequently drunk—that I attempted to make my escape—that I never attended the chapel. A more abstemious woman, my lords, I believe, does not live.

“Upon the report of my making my escape, the gentleman who was High Sheriff last year (not the present) came and told me, by order of the higher powers, he must put an iron on me. I submitted, as I always do to the higher powers. Some time after, he came again, and said he must put a heavier upon me, which I have worn, my lords, till I came hither. I asked the Sheriff why I was so ironed? He said he did it by command of some noble peer, on his hearing that I intended to make my escape. I told them I never had such a thought, and I would bear it with the other cruel usage I had received on my character. The Rev. Mr. Swinton, the worthy clergyman who attended me in prison, can testify that I was very regular at the chapel when I was well. Sometimes I really was not able to come out, and then he attended me in my room. They likewise published papers and depositions which ought not to have been published, in order to represent me as the most abandoned of my sex, and to prejudice the world against me. I submit myself to your lordships, and to the worthy jury. I can assure your lordships, as I am to answer it before that Grand Tribunal where I must appear, I am as innocent as the child unborn of the death of my father. I would not endeavour to save my life at the expense of truth. I really thought the powder an innocent, inoffensive thing, and I gave it to procure his love. It was mentioned, I should say, I was ruined. My lords, when a young woman loses her character, is not that her ruin? Why, then, should this expression be construed in so wide a sense? Is it not ruining my character to have such a thing laid to my charge? And whatever may be the event of this trial, I am ruined most effectually.” 27

A strange apology—amazing in its effrontery!

Gentle Heneage Legge speaks long and tenderly, while the listeners shudder with horror as they hear the dismal history unfolded in all entirety for the first time. No innocent heart could have penned that last brief warning to her lover—none but an accomplice would have received his cryptic message. Every word in the testimony of the stern doctor seems to hail her parricide—every action of her stealthy career has been noted by the watchful eyes of her servants. And, as if in damning confirmation of her guilt, there is the black record of her flight from the scene of crime. Eight o’clock has sounded when the judge has finished. For a few moments the jury converse in hurried whispers. It is ominous that they make no attempt to leave the court, but merely draw closer together. Then, after the space of five minutes they turn, and the harsh tones of the clerk of arraigns sound through the chamber.

“Mary Blandy, hold up thy hand.... Gentlemen of the jury, look upon the prisoner. How say you: Is Mary Blandy guilty of the felony and murder whereof she stands indicted, or not guilty?”

“Guilty!” comes the low, reluctant answer.

Never has more piteous drama been played within the cold fair walls of the divinity school than that revealed by the guttering candles on this chill March night. Amidst the long black shadows, through which gleam countless rows of pallid faces, in the deep silence, broken at intervals by hushed sobs, the invincible woman stands with unruffled mien to receive her sentence. As the verdict is declared, a smile seems to play upon her lips. While the judge, with tearful eyes and broken voice, pronounces her doom, she listens without a sign of fear. There is a brief, breathless pause, while all wait with fierce-beating hearts for her 28 reply. No trace of terror impedes her utterance. Thanking the judge for his candour and impartiality, she turns to her counsel, among whom only Richard Aston rose to eminence, and, with a touch of pretty forethought, wishes them better success in their other causes. Then, and her voice grows more solemn, she begs for a little time to settle her affairs and to make her peace with God. To which his lordship replies with great emotion:

“To be sure, you shall have proper time allowed you.”

When she is conducted from the court she steps into her coach with the air of a belle whose chair is to take her to a fashionable rout. The fatal news has reached the prison before her arrival. As she enters the keeper’s house, which for so long has been her home, she finds the family overcome with grief and the children all in tears.

“Don’t mind it,” she cries, cheerfully. “What does it matter? I am very hungry. Pray let me have something for supper as soon as possible.”

That sombre heart of hers is a brave one also.

All this time William Cranstoun, worthy brother in all respects of Simon Tappertit, had been in hiding—in Scotland perhaps, or, as some say, in Northumberland—watching with fearful quakings for the result of the trial. Shortly after the conviction of his accomplice he managed to take ship to the Continent, and luckily for his country he never polluted its soil again. There are several contemporary accounts of his adventures in France and in the Netherlands, to which the curious may refer. All agree that he confessed his share in the murder when he was safe from justice. With unaccustomed propriety, our Lady Fate soon hastened to snap the thread of his existence, and on the 3rd of December of this same year, at the little town of Furnes in Flanders, 29 aged thirty-eight, he drew his last breath. A short time before, being seized with remorse for his sins, he had given the Catholic Church the honour of enrolling him a proselyte. Indeed the conversion of so great a ruffian was regarded as such a feather in their cap that the good monks and friars advertised the event by means of a sumptuous funeral.

Worthy Judge Legge fulfils his promise to the unhappy Miss Blandy, and she is given six weeks in which to prepare herself for death. Meek and more softened is the sombre woman, who, like a devoted penitent, submits herself day after day to the vulgar gaze of a hundred eyes, while she bows in all humility before the altar of her God. Yet her busy brain is aware that those to whom she looks for intercession are keeping a careful watch upon her demeanour. For she has begged her godmother Mrs Mountenay to ask one of the bishops to speak for her; she is said to entertain the hope that the recently-bereaved Princess will endeavour to obtain a reprieve. In the fierce war of pamphleteers, inevitable in those days, she takes her share, playing with incomparable tact to the folly of the credulous. Although the majority, perhaps, believe her guilty, she knows that a considerable party is in her favour. On the 20th of March is published “A Letter from a Clergyman to Miss Blandy, with her Answer,” in which she tells the story of her share in the tragedy. During the remainder of her imprisonment she extends this narrative into a long account of the whole case—assisted, it is believed, by her spiritual adviser, the Rev. John Swinton, who, afflicted possibly by one of his famous fits of woolgathering, seems convinced of her innocence. No human effort, however, is of any avail. Both the second and third George, knowing their duty as public entertainers, seldom cheated the gallows of a victim of distinction. 30

Originally the execution had been fixed for Saturday, the 4th of April, but is postponed until the following Monday, because the University authorities do not think it seemly that the sentence shall be carried out during Holy Week. A great crowd collects in the early morning outside the prison walls before the announcement of the short reprieve, and it speaks marvels for the discipline of the gaol that Miss Blandy is allowed to go up into rooms facing the Castle Green so that she can view the throng. Gazing upon the assembly without a tremor, she says merely that she will not balk their expectations much longer. On Sunday she takes sacrament for the last time, and signs a declaration in which she denies once more all knowledge that the powder was poisonous. In the evening, hearing that the Sheriff has arrived in the town, she sends a request that she may not be disturbed until eight o’clock the next morning.

It was half-past the hour she had named when the dismal procession reached the door of her chamber. The Under-Sheriff was accompanied by the Rev. John Swinton, and by her friend Mr Rives, the lawyer. Although her courage did not falter, she appeared meek and repentant, and spoke with anxiety of her future state, in doubt whether she would obtain pardon for her sins. This penitent mood encouraged the clergyman to beg her declare the whole truth, to which she replied that she must persist in asserting her innocence to the end. No entreaty would induce her to retract the solemn avowal.

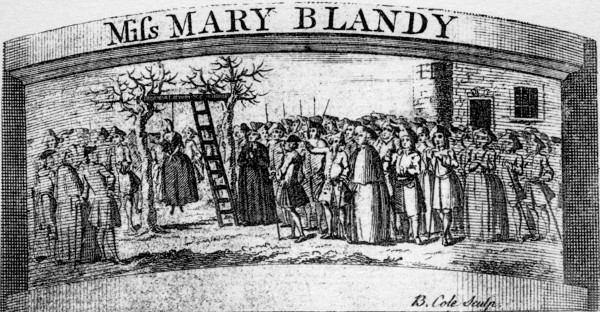

At nine o’clock she was conducted from her room, dressed in the same black gown that she had worn at the trial, with her hands and arms tied by strong black silk ribbons. A crowd of five thousand persons, hushed and expectant, was waiting on the Castle Green to witness her sufferings. Thirty yards from the door 31 of the gaol, whence she was led into the open air, stood the gallows—a beam placed across the arms of two trees. Against it lay a step-ladder covered with black cloth. The horror of her crime must have been forgotten by all who gazed upon the calm and brave woman. For truly she died like a queen. Serene and fearless she walked to the fatal spot, and joined most fervently with the clergyman in prayer. After this was ended they told her that if she wished she might speak to the spectators.

“Good people,” she cried, in a clear, audible voice, “give me leave to declare to you that I am perfectly innocent as to any intention to destroy or even hurt my dear father; that I did not know, or even suspect, that there was any poisonous quality in the fatal powder I gave him; though I can never be too much punished for being the innocent cause of his death. As to my mother’s and Mrs Pocock’s deaths, that have been unjustly laid to my charge, I am not even the innocent cause of them, nor did I in the least contribute to them. So help me, God, in these my last moments. And may I not meet with eternal salvation, nor be acquitted by Almighty God, in whose awful presence I am instantly to appear hereafter, if the whole of what is here asserted is not true. I from the bottom of my soul forgive all those concerned in my prosecution; and particularly the jury, notwithstanding their fatal verdict.”

Then, having ascended five steps of the ladder, she turned to the officials. “Gentlemen,” she requested, with a show of modesty, “do not hang me high.” The humanity of those whose task it was to put her to death, forced them to ask her to go a little higher. Climbing two steps more, she then looked round, and trembling, said, “I am afraid I shall fall.” Still, her invincible courage enabled her to address the crowd once again. “Good people,” she said, “take warning 32 by me to be on your guard against the sallies of any irregular passion, and pray for me that I may be accepted at the Throne of Grace.” While the rope was being placed around her neck it touched her face, and she gave a deep sigh. Then with her own fingers she moved it to one side. A white handkerchief had been bound across her forehead, and she drew it over her features. As it did not come low enough, a woman, who had attended her and who had fixed the noose around her throat, stepped up and pulled it down. For a while she stood in prayer, and then gave the signal by thrusting out a little book which she held in her hand. The ladder was moved from under her feet, and in obedience to the laws of her country she was suspended in the air, swaying and convulsed, until the grip of the rope choked the breath from her body.

Horrible! Yet only in degree are our own methods different from those employed a hundred and fifty years ago.

During the whole of the sad tragedy, the crowd, unlike the howling mob at Tyburn, maintained an awestruck silence. There were few dry eyes, though the sufferer did not shed a tear, and hundreds of those who witnessed her death went away convinced of her innocence. An elegant young man named Edward Gibbon, with brain wrapped in the mists of theology, who for three days had been gentleman commoner at Magdalen, does not appear to have been attracted to the scene. Surely George Selwyn must be maligned, else he would have posted to Oxford to witness this spectacle. It would have been his only opportunity of seeing a gentlewoman in the hands of the executioner.

After hanging for half an hour with the feet, in consequence of her request, almost touching the ground, the body was carried upon the shoulders of one of the sheriff’s men to a neighbouring house. At five o’clock 33 in the afternoon the coffin containing her remains was taken in a hearse to Henley, where, in the dead of night, amidst a vast concourse, it was interred in the chancel of the parish church between the graves of her father and mother.

So died ‘the unfortunate Miss Blandy’ in the thirty-second year of her age—with a grace and valour which no scene on the scaffold has ever excelled. If, as the authors of The Beggars Opera and The History of Jonathan Wild have sought to show, in playful irony, the greatness of the criminal is comparable with the greatness of the statesman, then she must rank with Mary of Scotland and Catherine of Russia among the queens of crime. Hers was the soul of steel, theirs also the opportunity.

In every period the enormity of a sin can be estimated only by its relation to the spirit of the age; and in spite of cant and sophistry, the contemporaries of Miss Blandy made no legal distinction between the crimes of parricide and petty larceny. Nay, the same rope that strangled the brutal cut-throat in a few moments might prolong the agony of a poor thief for a quarter of an hour. Had the doctors succeeded in saving the life of the old attorney, the strange law which in later times put to death Elizabeth Fenning would have been powerless to demand the life of Mary Blandy for a similar offence. The protests of Johnson and Fielding against the iniquity of the criminal code fell on idle ears.

Thus we may not judge Mary Blandy from the standpoint of our own moral grandeur, for she is a being of another world—one of the vain, wilful, selfish children to whom an early Guelph was king—merely one of the blackest sheep in a flock for the most part ill-favoured. As we gaze upon her portrait there comes a feeling that we do not know this sombre woman after all, for though the artist has produced a faithful resemblance, 34 we perceive there is something lacking. We look into part, not into her whole soul. None but one of the immortals—Rembrandt, or his peer—could have shown this queen among criminals as she was: an iron-hearted, remorseless, demon-woman, her fair, cruel visage raised mockingly amidst a chiaroscuro of crime and murkiness unspeakable.

In our own country the women of gentle birth who have been convicted of murder since the beginning of the eighteenth century may be counted on the fingers of one hand. Mary Blandy, Constance Kent, Florence Maybrick—for that unsavoury person, Elizabeth Jefferies, has no claim to be numbered in the roll, and the verdict against beautiful Madeleine Smith was ‘Not proven’—these names exhaust the list. And of them, the first alone paid the penalty at the gallows. The annals of crime contain the records of many parricides, some that have been premeditated with devilish art, but scarce one that a daughter has wrought by the most loathsome of coward’s weapons. In comparison with the murderess of Henley, even Frances Howard and Anne Turner were guilty of a venial crime. Mary Blandy stands alone and incomparable—pilloried to all ages among the basest of her sex.

Yet the world soon forgot her. “Since the two misses were hanged,” chats Horace Walpole on the 23rd of June, coupling irreverently the names of Blandy and Jefferies with the beautiful Gunnings—“since the two misses were hanged, and the two misses were married, there is nothing at all talked of.” Society, however, soon found a new thrill in the adventures of the young woman Elizabeth Canning. 35

Miss MARY BLANDY

Aged 33 and Executed at Oxford April 6, 1752, for poisoning her Father.

1. An Authentic Narrative of that Most Horrid Parricide. (Printed in the year 1751. Name of publisher in second edition, M. Cooper.)

2. A Genuine and Full Account of the Parricide committed by Mary Blandy, Oxford; Printed for, and sold by C. Goddard in the High St, and sold by R. Walker in the little Old Bailey, and by all booksellers and pamphlet Shops. (Published November 9, 1751.)

3. A Letter from a Clergyman to Miss Mary Blandy with her Answer thereto.... As also Miss Blandy’s Own Narrative. London; Printed for M. Cooper at the Globe in Paternoster Row. 1752. Price four pence. Brit. Mus. (March 20, 1752.)

4. An Answer to Miss Blandy’s Narrative. London; Printed for W. Owen, near Temple Bar. 1752. Price 3d. Brit. Mus. (March 27, 1752.)

5. The Case of Miss Blandy considered as a Daughter, as a Gentlewoman, and as a Christian. Oxford; Printed for R. Baldwin, at the Rose in Paternoster Row. Brit. Mus. (April 6, 1752.)

6. Original Letters to and from Miss Blandy and C—— C——, London. Printed for S. Johnson, near the Haymarket, Charing Cross. 1752. Brit. Mus. (April 8, 1752.)

7. A Genuine and Impartial Account of the Life of Miss M. Blandy. W. Jackson and R. Walker. (April 9, 1752.)

8. Miss Mary Blandy’s Own Account. London; Printed for A. Millar in the Strand. 1752 (price one shilling and sixpence). N.B. The Original Account authenticated by Miss Blandy in a proper manner may be seen at the above A. Millar’s. Brit. Mus. (April 10, 1752. The most famous apologia in criminal literature.)

9. A Candid Appeal to the Public, by a Gentleman of Oxford. London. Printed for J. Clifford in the Old Bailey, and sold at the Pamphleteer Shops. 1752. Price 6d. Brit. Mus. (April 15, 1752.) 36

10. The Tryal of Mary Blandy. Published by Permission of the Judges. London. Printed for John and James Rivington at the Bible and Crown and in St Paul’s Churchyard. 1752. In folio price two shillings. 8vo. one shilling. Brit. Mus. (April 24, 1752.)

11. The Genuine Histories of the Life and Transactions of John Swan and Eliz. Jeffries, ... and Miss Mary Blandy, London. Printed and sold by T. Bailey opposite the Pewter-Pot-Inn in Leadenhall Street. (Published after April 10, 1752.)

12. An Authentic and full History of all the Circumstances of the Cruel Poisoning of Mr. Francis Blandy, printed only for Mr. Wm. Owen, Bookseller at Temple Bar, London, and R. Goadby in Sherborne. Brit. Mus. (Without date. From pp. 113-132 the pamphlet resembles the “Answer to Miss Blandy’s Narrative,” published also by Wm. Owen.)

13. The Authentic Tryals of John Swan and Elizabeth Jeffryes.... With the Tryal of Miss Mary Blandy, London. Printed by R. Walker for W. Richards, near the East Gate, Oxford. 1752. Brit. Mus. (Published later than the “Candid Appeal.”)

14. The Fair Parricide. A Tragedy in three acts. Founded on a late melancholy event. London. Printed for T. Waller, opp. Fetter Lane. Fleet Street (price 1/). Brit. Mus. (May 5, 1752.)

15. The Genuine Speech of the Hon. Mr ——, at the late Trial of Miss Blandy, London; Printed for J. Roberts in Warwick Lane. 1752. (Price sixpence.) Brit. Mus. (May 15, 1752.)

16. The x x x x Packet Broke Open, or a letter from Miss Blandy in the Shades below to Capt. Cranstoun in his exile above. London. Printed for M. Cooper at the Globe in Paternoster Row. 1752. Price 6d. Brit. Mus. (May 16, 1752.)

17. The Secret History of Miss Blandy. London. Printed for Henry Williams, and sold by the booksellers at the Exchange, in Ludgate St, at Charing Cross, and St. James. Price 1s. 6d. Brit. Mus. (June 11, 1752. A sane and well-written account of the whole story.)

18. Memoires of the Life of Wm. Henry Cranstoun Esqre. London. Printed for J. Bouquet, at the White Hart, in Paternoster Row; 1752. Price one shilling. Brit. Mus. (June 18, 1752.)

19. The Genuine Lives of Capt. Cranstoun and Miss Mary Blandy. London. Printed for M. Cooper, Paternoster Row, and C. Sympson at the Bible Warehouse, Chancery Lane. 1753. Price one shilling. Brit. Mus.

20. Capt. Cranstoun’s Account of the poisoning of the Late Mr. Francis Blandy. London. Printed for R. Richards, the Corner of Bernard’s-Inn, near the Black Swan, Holborn. Brit. Mus. (March 1-3, 1753.)

21. Memories of the life and most remarkable transactions of Capt. William Henry Cranstoun. Containing an account of his conduct in his younger years. His letter to his wife to persuade her to disown him as her husband. His trial in Scotland, and the Court’s decree thereto. His courtship of Miss Blandy; his success therein, and the tragical issue of that affair. His voluntary exile abroad with the several accidents that befel him from his flight to his death. His reconciliation to the Church of Rome, with the Conversation he had with a Rev. Father of the Church at the time of his conversion. His miserable death, and pompous funeral. Printed for M. Cooper in Paternoster Row; W. Reeve in Fleet Street; and C. Sympson in Chancery Lane. Price 6d. With a curious print of Capt. Cranstoun. Brit. Mus. (March 10-13, 1753. As the title-page of this pamphlet is torn out of the copy in the Brit. Mus., it is given in full. From pp. 3-21 the tract is identical with “The Genuine Lives,” also published by M. Cooper.)

22. Parricides! The trial of Philip Stansfield, Gt, for the murder of his father in Scotland, 1688. Also the trial of Miss Mary Blandy, for the murder of her Father, at Oxford 1752. London (1810). Printed by J. Dean, 57 Wardour St, Soho for T. Brown, 154 Drury Lane and W. Evans, 14 Market St, St James’s. Brit. Mus. 37

23. The Female Parricide, or the History of Mary-Margaret d’Aubray, Marchioness of Brinvillier.... In which a parallel is drawn between the Marchioness and Miss Blandy. C. Micklewright, Reading. Sold by J. Newbery. Price 1/. (March 5, 1752.)

Lowndes mentions also:—

24. An Impartial Inquiry into the Case of Miss Blandy. With reflections on her Trial, Defence, Repentance, Denial, Death. 1753. 8vo.

25. The Female Parricide. A Tragedy, by Edward Crane, of Manchester. 1761. 8vo.

26. A Letter from a Gentleman to Miss Blandy with her answer thereto. 1752. 8vo. (Possibly the same as “A Letter from a Clergyman.”)

The two following are advertised in the newspapers of the day:—

27. Case of Miss Blandy and Miss Jeffreys fairly stated, and compared.... R. Robinson, Golden Lion, Ludgate Street. (March 26, 1752.)

28. Genuine Letters between Miss Blandy and Miss Jeffries before and after their Conviction. J. Scott Exchange Alley; W. Owen, Temple Bar; G. Woodfall, Charing Cross. (April 21, 1752.)

29. Broadside. Execution of Miss Blandy. Pitts, Printer, Toy and Marble Warehouse, 6 Great St. Andrew’s St. Seven Dials. Brit. Mus.

30. The Addl. MSS., 15930. Manuscript Department in the Brit. Mus.

1. Read’s Weekly Journal, March and April (1752), February 3 (1753).

2. The General Advertiser, August-November (1751), March and April (1752).

3. The London Evening Post, March and April (1752).

4. The Covent Garden Journal (Sir Alexander Drawcansir), February, March, and April (1752).

5. The London Morning Penny Post, August and September (1751).

6. Gentleman’s Magazine, pp. 376, 486-88 (1751), pp. 108-17, 152, 188, 195 (1752), pp. 47, 151 (1753), p. 803, pt. II. (1783).

7. Universal Magazine, pp. 114-124, 187, 281 (1752).

8. London Magazine, pp. 379, 475, 512(1751), pp. 127, 180, 189(1752), p. 89 (1753).

Note I.—In recent years the guilt of Cranstoun has been questioned. Yet a supposition that does not explain two damning circumstances must be baseless:

(a) In the first place, one of his letters to Miss Blandy, dated July 18, 1751, was read by Bathurst in his opening speech. Although the reports of the trial do not tell us that the note was produced in court, or that the handwriting was verified, it cannot be presumed that the Crown lawyers were guilty of wilful fabrication. However strange it may appear that this letter alone escaped destruction, it is improbable that Miss Blandy invented it. Had she done so its contents would have been more consistent with her defence. As it stands it is most unfavourable to her. Therefore, in the absence of further evidence, we must conclude that the letter is genuine, and if genuine Cranstoun was an accomplice.

(b) In the second place, the paper containing the poison which was rescued from the fire, is said by the prosecution to have borne the inscription in Cranstoun’s 38 handwriting, ‘Powder to clean the pebbles’ If this had been counterfeit, Miss Blandy would have had no object in destroying it, but would have kept it for her purpose.

At any cost Lord Cranstoun must have been anxious to remove the black stain from his scutcheon. That this was impossible the fact that it was not done seems to prove. Indeed, if Captain Cranstoun had been ignorant of the crime, he could have proved his innocence as soon as Miss Blandy was arrested by producing her letters, which, granting this hypothesis, would have contained no reference that would have incriminated him. That she had written a great deal to him was shown in evidence at the trial by the clerk Lyttleton.

For these reasons it is impossible to accept the conclusion of the writer of Cranstoun’s life in the Dic. Nat. Biog. (who has adopted the assertion in Anderson’s Scottish Nation, vol. i. p. 698), that “apart from Miss Blandy’s statement there is nothing to convict him of the murder.”