Title: Slave Planet

Author: Laurence M. Janifer

Release date: April 24, 2016 [eBook #51855]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

A Science Fiction Novel by

LAURENCE JANIFER

PYRAMID BOOKS NEW YORK

SLAVE PLANET

A PYRAMID BOOK

First printing, March 1963

This book is fiction. No resemblance is intended between

any character herein and any person, living or dead,

any such resemblance it purely coincidental.

Copyright 1963, by Pyramid Publications, Inc.

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Pyramid Books are published by Pyramid Publications, Inc.

444 Madison Avenue, New York 22, New York, U.S.A.

[Transcriber's Note: Extensive research did not uncover any

evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

This moral tale is dedicated

To Philip Klass

Who will probably find it disagreeable

But who will think about it:

An occupation as cheering to the writer

As it is rare in the world.

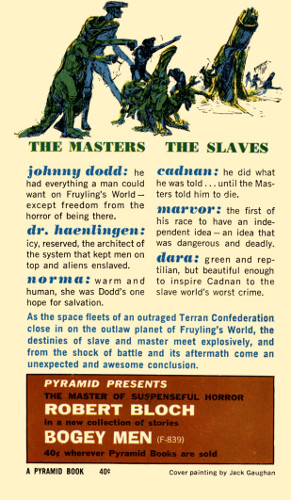

Fruyling's World

... rich in the metals that kept the Terran Confederation going—one vital link in a galaxy-wide civilization. But the men of Fruyling's World lived on borrowed time, knowing that slavery was outlawed throughout the Confederation—and that only the slave labor of the reptilian natives could produce the precious metals the Confederation needed!

As the first hints of the truth about Fruyling's World emerge, the tension becomes unbearable—to be resolved only in the shattering climax of this fast-paced, thought-provoking story of one of today's most original young writers.

"On Saturday, July 30, Dr. Johnson and I took a sculler at the Temple-stairs, and set out for Greenwich. I asked him if he really thought a knowledge of the Greek and Latin languages an essential requisite to a good education. JOHNSON. 'Most certainly, Sir; for those who know them have a very great advantage over those who do not. Nay, Sir, it is wonderful what a difference learning makes upon people even in the common intercourse of life, which does not appear to be much connected with it.' 'And yet, (said I) people go through the world very well, and carry on the business of life to good advantage, without learning.' JOHNSON. 'Why, Sir, that may be true in cases where learning cannot possibly be of any use; for instance, this boy rows us as well without learning, as if he could sing the song of Orpheus to the Argonauts, who were the first sailors.' He then called to the boy, 'What would you give my lad, to know about the Argonauts?' 'Sir, (said the boy) I would give what I have.' Johnson was much pleased with his answer, and we gave him a double fare. Dr. Johnson then turning to me, 'Sir, (said he) a desire of knowledge is the natural feeling of mankind; and every human being, whose mind is not debauched, will be willing to give all that he has, to get knowledge.'"

—James Boswell,

The Life of Samuel Johnson, L. L. D.

"It has become a common catchword that slavery is the product of an agricultural society and cannot exist in the contemporary, mechanized world. Like so many catchwords, this one is recognizable as nonsense as soon as it is closely examined. Given that the upkeep of the slaves is less than the price of full automation (and its upkeep), I do not think we shall prove ourselves morally so very superior to our grandfathers."

—H. D. Abel,

Essays in History and Causation

CONTENTS

PART ONE

"I would not repeat myself if it were not for the urgency of this matter." Dr. Haenlingen's voice hardly echoed in the square small room. She stood staring out at the forests below, the coiling gray-green trees, the plants and rough growth. A small woman whose carriage was always, publicly, stiff and erect, whose iron-gray eyes seemed as solid as ice, she might years before have trained her voice to sound improbably flat and formal. Now the formality was dissolving in anger. "As you know, the mass of citizens throughout the Confederation are a potential source of explosive difficulty, and our only safety against such an explosion lies in complete and continuing silence." Abruptly, she turned away from the window. "Have you got that, Norma?"

Norma Fredericks nodded, her trace poised over the waiting pad. "Yes, Dr. Haenlingen. Of course."

Dr. Haenlingen's laugh was a dry rustle. "Good Lord, girl," she said. "Are you afraid of me, too?"

Norma shook her head instantly, then stopped and almost smiled. "I suppose I am, Doctor," she said. "I don't quite know why—"

"Authority figure, parent-surrogate, phi factor—there's no mystery about the why, Norma. If you're content with jargon, and we know all the jargon, don't we?" Now instead of a laugh it was a smile, surprisingly warm but very brief. "We ought to, after all; we ladle it out often enough."

Norma said: "There's certainly no real reason for fear. I don't want you to think—"

"I don't think," Dr. Haenlingen said. "I never think. I reason when I must, react when I can." She paused. "Sometimes, Norma, it strikes me that the Psychological Division hasn't really kept track of its own occupational syndromes."

"Yes?" Norma waited, a study in polite attention. The trace fell slowly in her hand to the pad on her knees and rested there.

"I ask you if you're afraid of me and I get the beginnings of a self-analysis," Dr. Haenlingen said. She walked three steps to the desk and sat down behind it, her hands clasped on the surface, her eyes staring at the younger woman. "If I'd let you go on I suppose you could have given me a yard and a half of assorted psychiatric jargon, complete with suggestions for a change in your pattern."

"I only—"

"You only reacted the way a good Psychological Division worker is supposed to react, I imagine." The eyes closed for a second, opened again. "You know, Norma, I could have dictated this to a tape and had it sent out automatically. Did you stop to think why I wanted to talk it out to you?"

"It's a message to the Confederation," Norma said slowly. "I suppose it's important, and you wanted—"

"Importance demands accuracy," Dr. Haenlingen broke in. "Do you think you can be more accurate than a tape record?"

A second of silence went by. "I don't know, then," Norma said at last.

"I wanted reaction," Dr. Haenlingen said. "I wanted somebody's reaction. But I can't get yours. As far as I can see you're the white hope of the Psychological Division—but even you are afraid of me, even you are masking any reaction you might have for fear the terrifying Dr. Anna Haenlingen won't like it." She paused. "Good Lord, girl, I've got to know if I'm getting through!"

Norma took a deep breath. "I'm sorry," she said at last. "I'll try to give you what you want—"

"There you go again." Dr. Haenlingen shoved back her chair and stood up, marched to the window and stared out at the forest again. Below, the vegetation glowed in the daylight. She shook her head slowly. "How can you give me what I want when I don't know what I want? I need to know what you think, how you react. I'm not going to bite your head off if you do something wrong: there's nothing wrong that you can do. Except not react at all."

"I'm sorry," Norma said again.

Dr. Haenlingen's shoulders moved, up and down. It might have been a sigh. "Of course you are," she said in a gentler voice. "I'm sorry, too. It's just that matters aren't getting any better—and one false move could crack us wide open."

"I know," Norma said. "You'd think people would understand—"

"People," Dr. Haenlingen said, "understand very little. That's what we're here for, Norma: to make them understand a little more. To make them understand, in fact, what we want them to understand."

"The truth," Norma said.

"Of course," Dr. Haenlingen said, almost absently. "The truth."

This time there was a longer pause.

"Shall we get on with it, then?" Dr. Haenlingen said.

"I'm ready," Norma said. "'Complete and continuing silence.'"

Dr. Haenlingen paused. "What?... Oh. It should be perfectly obvious that the average Confederation citizen, regardless of his training or information, would not understand the project under development here no matter how carefully it was explained to him. The very concepts of freedom, justice, equality under the law, which form the cornerstone of Confederation law and, more importantly, Confederation societal patterns, will prevent him from judging with any real degree of objectivity our actions on Fruyling's World, or our motives."

"Actions," Norma muttered. "Motives." The trace flew busily over the pad, leaving its shorthand trail.

"It was agreed in the original formation of our project here that silence and secrecy were essential to the project's continuance. Now, in the third generation of that project, the wall of silence has been breached and I have received repeated reports of rumors regarding our relationship with the natives. The very fact that such rumors exist is indication enough that an explosive situation is developing. It is possible for the Confederation to be forced to the wall on this issue, and this issue alone: I cannot emphasize too strongly the fact that such a possibility exists. Therefore—"

"Doctor," Norma said.

The dictation stopped. Dr. Haenlingen turned slowly. "Yes?"

"You wanted reactions, didn't you?" Norma said.

"Well?" The word was not unfriendly.

Norma hesitated for a second. Then she burst out: "But they're so far away! I mean—there isn't any reason why they should really care. They're busy with their own lives, and I don't really see why whatever's done here should occupy them—"

"Because you're not seeing them," Dr. Haenlingen said. "Because you're thinking of the Confederation, not the people who compose the Confederation, all of the people on Mars, and Venus, the moons and Earth. The Confederation itself—the government—really doesn't care. Why should it? But the people do—or would."

"Oh," Norma said, and then: "Oh. Of course."

"That's right," Dr. Haenlingen said. "They hear about freedom, and all the rest, as soon as they're old enough to hear about anything. It's part of every subject they study in school, it's part of the world they live in, it's like the air they breathe. They can't question it: they can't even think about it."

"And, of course, if they hear about Fruyling's World—"

"There won't be any way to disguise the fact," Dr. Haenlingen said. "In the long run, there never is. And the fact will shock them into action. As long as they continue to live in that air of freedom and justice and equality under the law, they'll want to stop what we're doing here. They'll have to."

"I see," Nonna said. "Of course."

Dr. Haenlingen, still looking out at the world below, smiled faintly. "Slavery," she said, "is such an ugly word."

The Commons Room of the Third Building of City One was a large affair, whose three bare metal walls enclosed more space than any other single living-quarters room in the Building; but the presence of the fourth wall made it seem tiny. That wall was nearly all window, a non-shatterable clear plastic immensely superior to that laboratory material, glass. It displayed a single unbroken sweep of forty feet, and it looked down on the forests of Fruyling's World from a height of sixteen stories. Men new to the Third Building usually sat with their backs to that enormous window, and even the eldest inhabitants usually placed their chairs somehow out of line with it, and looked instead at the walls, at their companions, or at their own hands.

Fruyling's World was disturbing, and not only because of the choking profusion of forest that always seemed to threaten the isolated clusters of human residence. A man could get used to forests. But at any moment, looking down or out across the gray-green vegetation, that man might catch sight of a native—an Elder, perhaps heading slowly out toward the Birth Huts hidden in the lashing trees, or a group of Small Ones being herded into the Third Building itself for their training. It was hard, perhaps impossible, to get used to that: when you had to see the natives you steeled yourself for the job. When you didn't have to see them you counted yourself lucky and called yourself relaxed.

It wasn't that the natives were hideous, either. Their very name had been given to them by men in a kind of affectionate mockery, since they weren't advanced enough even to have such a group-name of their own as "the people." They were called Alberts, after a half-forgotten character in a mistily-remembered comic strip dating back before space travel, before the true beginnings of Confederation history. If you ignored the single, Cyclopean eye, the rather musty smell and a few other even more minor details, they looked rather like two-legged alligators four feet tall, green as jewels, with hopeful grins on their faces and an awkward, waddling walk like a penguin's. Seen without preconceptions they might have been called cute.

But no man on Fruyling's World could see the Alberts without preconceptions. They were not Alberts: they were slaves, as the men were masters. And slavery, named and accepted, has traditionally been harder on the master than the slave.

John Dodd, twenty-seven years old, master, part of the third generation, arranged his chair carefully so that it faced the door of the Commons Room, letting the light from the great window illumine the back of his head. He clasped his hands in his lap in a single, nervous gesture, never noticing that the light gave him a faint saintlike halo about his feathery hair. His companion took another chair, set it at right angles to Dodd's and gave it long and thoughtful consideration, as if the act of sitting down were something new and untried.

"It's good to be off-duty," Dodd said violently. "Good. Not to have to see them—not to have to think about them until tomorrow."

The standing man, shorter than Dodd and built heavily, actually turned and looked out at the window. "And then tomorrow what do you do?" he asked. "Give up your job? You're just letting the thing get you, Johnny."

"I'd give up my job in twenty seconds if I thought it would do any good," Dodd said. He shook his head. "I give up a job here in the Buildings, and then what do I do? Go out and starve in the jungle? Nobody's done it, nobody's ever done it."

"Well?" the squat man said. "Is that an excuse?"

Dodd sighed. "Those who work get fed," he said. "And housed. And clothed. And—God help us—entertained, by 3D tapes older than our fathers are. If a man didn't work he'd get—cast out. Cut off."

"There's more than 3D tapes," the squat man said, and grinned.

"Sure." Dodd's voice was tired. "But think about it for a minute, Albin. Do you know what we've got here?"

"We've got a nice, smooth setup," Albin said. "No worries, no fights, a job to do and a place to do it in, time to relax, time to have fun. It's okay."

There was a little silence. Dodd's voice seemed more distant. "Marxian economics," he said. "Perfect Marxian economics, on a world that would make old Karl spin in his grave like an electron."

"I guess so," Albin said. "History's not my field. But—given the setup, what else could there be? What other choice have you got?"

"I don't know." Again a silence. Dodd's hands unclasped: he made a gesture as if he were sweeping something away from his face. "There ought to be something else. Even on Earth, even before the Confederation, there were conscientious objectors."

"History again," Albin said. He walked a few steps toward the window. "Anyhow, that was for war."

"I don't know," Dodd said. His hands went back into his lap, and his eyes closed. He spoke, now, like a man in a dream. "There used to be all kinds of jobs. I guess there still are, in the Confederation. On Earth. Back home where none of us have ever been." He repeated the words like an echo: "Back home." In the silence nothing interrupted him: behind his head light poured in from the giant window. "A man could choose his own job," he went on, in the same tone. "He could be a factory-worker or a professor or a truck-driver or a musician or—a lot of jobs. A man didn't have to work at one, whether he wanted to or not."

"All right," Albin said. "Okay. So suppose you had your choice. Suppose every job in every damn history you've ever heard of was open to you. Just what would you pick? Make a choice. Go ahead, make—"

"It isn't funny, Albin," Dodd said woodenly. "It isn't a game."

"Okay, it isn't," Albin said. "So make it a game. Just for a minute. Think over all the jobs you can and make a choice. You don't like being here, do you? You don't like working with the Alberts. So where would you like to be? What would you like to do?" He came back to the chair, his eyes on Dodd, and sat suddenly down, his elbows on his knees and his chin cupped in his hands, facing Dodd like a gnome out of pre-history. "Go on," he said. "Make a choice."

"Okay," Dodd said without opening his eyes. His voice became more distant, dreamlike. "Okay," he said again. "I—there isn't one job, but maybe a kind of job. Something to do with growing things." There was a pause. "I'd like to work somewhere growing things. I'd like to work with plants. They're all right, plants. They don't make you feel anything." The voice stopped.

"Plants?" Albin hooted gigantically. "Good God, think about it! You're stuck on a planet that's over seventy per cent plant life—trees and weeds and jungles all over the land and even mats of green stuff covering the oceans and riding on the rivers—a planet that's just about nothing but plants, a king-sized hothouse for every kind of leaf and blade and flower and fruit you could ever dream up—"

"It's not the same," Dodd said.

"You," Albin said, "are out of your head. So if you're crazy for plants, so grow them in your spare time. If you've got a window in your room you can put up a window-box. If not, something else. Me, I think it's damn silly: with the plants all around here, what's the sense of growing more? But if you like it, God knows Fruyling's World is ready to provide it for you."

"As a hobby," Dodd said flatly.

"Well, then, a hobby," Albin said. "If you're interested in it."

"Interested." The word was like an echo. A silence fell. Albin's eyes studied Dodd, the thin face and the play of light on the hair. After a while he shrugged.

"So it isn't plants," he said. "It isn't any more than the Alberts and working with them. You want to do anything to get away from them—anything that won't remind you you have to go back."

"Sure," Dodd said. "Sure I do. So do all of us."

"Not me," Albin said instantly. "Not me, brother. I get my food and my clothing and my shelter, just like good old Marx, I guess, says I should. I'm a trainer for the Alberts, supportive work in the refining process, and some day I'll be a master trainer and get a little more pay, a little more status, you know?" He grinned and sat straight. "What the hell," he said "It's a job. It pays my way. And there's enough leisure time for fun—and when I say fun I don't mean 3D tapes, Dodd. I really don't."

"But you—"

"Look," Albin said. "That's what's wrong with you, kid. You talk as if we all had nothing to do but work and watch tapes. What you need is a little education—a little real education—and I'm the one to give it to you."

Dodd opened his eyes. They looked very large and flat, like the eyes of a jungle animal. "I don't need education," he said. "And I don't need hobbies. I need to get off this planet, that's all. I need to stop working with the Alberts. I need to stop being a master and start being a man again."

Albin sighed. "Slavery," he said. "You think of slavery and it all rises up in front of you—Greece, India, China, Rome, England, the United States—all the past before the Confederation, all the different slaves." He grinned again. "You think it's terrible, don't you?"

"It is terrible," Dodd said. "It's—they're people, just like us. They have a right to their own lives."

"Sure they do," Albin said. "They have the right to—oh, to starve and die in that forest out there, for instance. And work out a lot of primitive rituals, and go through all the Stone Age motions for thousands of years until they develop civilization like you and me. Instead of being kept nice and warm and comfortable and taken care of, and taught things, by the evil old bastards like—well, like you and me again. Right?"

"They have rights," Dodd said stubbornly. "They have rights of their own."

"Sure they do," Albin agreed with great cheerfulness. "How'd you like it if they got some of them? Dodd, maybe you'd like to see them starve? Because it's going to be a long, long time before they develop anything like a solid civilization, kiddo. And in the meantime a lot of them are going to die of things we can prevent. Right? And how'd you like that, Dodd? How would you like that?"

Dodd hesitated. "We ought to help them," he muttered.

"Well," Albin said cheerfully, "that's what we are doing. Keeping them alive, for instance. And teaching them."

"Teaching," Dodd said. Again his voice had the faintly mocking sound of an echo. "And what are we teaching them? Push this button for us. Watch this process for us. If anything changes push this button. Dig here. Carry there." He paused. "Wonderful—for us. But what good does it do them?"

"We've got to live, too," Albin said.

Dodd stared. "At their expense?"

"It's a living," Albin said casually, shrugging. Then: "But I'm serious. One good dose of real enjoyment will cure you, friend. One good dose of fun—by which, kiddo, I mean plain ordinary old sex, such as can be had any free evening around here—and you'll stop being depressed and worried. Uncle Albin Cendar's Priceless Old Recipe, kiddo, and don't argue with me: it works."

Dodd said nothing at all. After a few seconds his eyes slowly closed and he sat like a statue in the room.

Albin, watching him, whistled inaudibly under his breath. A minute went by silently. The light in the room began to diminish.

"Sun's going down," Albin offered.

There was no response. Albin got up again and went to the window.

"Maybe you're right," he said with his back to Dodd's still figure. "There ought to be some way of getting people off-planet, people who just don't want to stay here."

"Do you know why there isn't?" Dodd's voice was a shock, stronger than before.

"Sure I know," Albin said. "There's—"

"Slavery," Dodd said. "Oh, sure, maybe somebody knows about it, but it's got to be kept quiet. And if anybody got back—well, look."

"Don't bother me with it." Albin's voice was suddenly less sure.

"Look," Dodd said. "The Confederation needs the metal. It exists pure here, and in quantity. But if they knew, really knew, how we mined and smelted and purified it and got it ready for shipment...."

"So suppose somebody goes back," Albin said. "Suppose somebody talks. What difference does it make? It's just rumor, nothing official. No, the reason nobody goes back is cargo space, pure and simple. We need every inch of cargo space for the shipments."

"If somebody goes back," Dodd said, "the people will know. Not the government, not the businesses, the people. And the people don't like slavery, Albin. No matter how necessary a government finds it. No matter what kind of a jerry-built defense you can put up for it."

"Don't be silly," Albin said. There was less conviction in his voice; he looked out at the sunset as if he were trying to reassure himself.

"Nobody's allowed to leave," Dodd said, more quietly. "We're—they're taking every precaution they can. But some day—maybe some day, Albin—the people are going to find out in spite of every precaution." He sat straighter. "And then it'll all be over. Then they'll be wiped out, Albin. Wiped out."

"They need us," Albin said uncertainly. "They can't do without us."

Dodd swung round to face him. The sunset was a deepening blaze in the Commons Room. "Wait and find out," he said in a voice that suddenly rang on the metal walls. "Wait and find out."

After a long time Albin said. "Damn it, what you need is education. A cure. Fun. What I've been saying." He paused and took a breath. "How about it, Dodd?"

Dodd didn't move. Another second passed. "All right, Albin," he said slowly, at last. "I'll think about it. I'll think about it."

The sleeping room for the Small Ones was, by comparison with the great Commons Room only the masters inhabited, a tiny place. It had only the smallest of windows, so placed as to allow daylight without any sight of the outside; the windows were plastic-sheeted slits high up on the metal walls, no more. The room was, at best, dim, during the day, but that hardly mattered: during the day the room was empty. Only at night, when the soft artificial lights went on, shedding the glow from their wall-shielded tubes, was the room fit for normal vision. There were no decorations, of course, and no chairs: the Alberts had no use for chairs, and decorations were a refinement no master had yet bothered to think of. The Alberts were hardly taught to appreciate such things in any case: that was not what they had come to learn: it was not useful.

The floor of the room was covered with soft leaves striped a glossy brown over the pervasive gray-green of the planet's foliage. These served as a soft mat for sleeping, and were also the staple food of the Alberts. These were not disturbed to find their food strewn in such irregular heaps and drifts across the metal floor: in their birth sacs, they had lived by ingestion from the floor of the forest, and, later, they had been so fed in the Birth Huts to which the Elders had taken them, and where they had been cleaned and served and taught, among other matters, English.

What they had been taught was, at any rate, English of a sort, bearing within it the seeds of a more complex tongue, and having its roots far back in the pre-space centuries, when missionaries had first begun to visit strange lands. Men had called it pidgin and Beche-le-mer and a hundred different names in a hundred different variations. Here, the masters called it English. The Alberts called it words, and nothing more.

Now, after sunset, they filed in, thirty or so jewel-green cyclopean alligators at the end of their first day of training, waddling clumsily past the doorway and settled with a grateful, crouching squat on the leaves that served as bed and food. None were bothered by the act of sitting on the leaves: for one thing, they had no concept of dirt. In the second place, they were rather remarkably clean. They had neither sex organs, in any human sense of the word, or specific organs of evacuation: their entire elimination was gaseous. Air ducts in the room would draw off the waste products, and the Alberts never noticed them: they had, in fact, no conception of evacuation as a process, since to them the entire procedure was invisible and impalpable.

The last of them filed in, and the masters—two of them, carrying long metal tubes—shut the door. The Alberts were alone. The door's clang was followed by other sounds as the lock was thrown. The new noises, and the strangeness of bare metal walls and artificial light, still novel after only a single day's training, gave rise to something very like a panic, and a confused babble of voices arose from the crowd.

"What is this?"

"What place is this?"

"It is a training place."

"My name Hortat. My name Hortat."

"What is training?"

"There is food here."

"What place is this?"

"Where are elders?"

"Are masters here?"

"My food."

"Is this a place for sleeping?"

"Training is to do what a master says. Training—"

"There are no elders. My name Hortat."

"My place."

"My food."

"Where is this?"

"Where is this place?"

Like the stirring of a child in sleep, the panic lasted only a little while, and gave way to an apathetic peace. Here and there an Albert munched on a leaf, holding it up before his wide mouth in the pose of a giant squirrel. Others sat quietly looking at the walls or the door or the window, or at nothing. One, whose name was Cadnan, stirred briefly and dropped the leaf he was eating and turned to the Albert next to him.

"Marvor," he said. "Are you troubled?"

Marvor seemed slighter than Cadnan, and his single eye larger, but both looked very much alike to humans, as members of other races, and particularly such races as the human in question judges inferior, are prone to do. "I do not know what happens," he said in a flat tone. "I do not know what is this place, or what we do."

"This is the place of masters," Cadnan said. "We train here, and we work here, and live here. It is the rule of the masters."

"Yet I do not know," Marvor said. "This training is a hard thing, and the work is also hard when it comes."

Cadnan closed his eye for a second, to relax, but he found he wanted to talk. His first day in the world of the masters had been too confusing for him to order it into any sensible structure. Conversation, of whatever kind, was a release, and might provide more facts. Cadnan was hungry for facts.

He opened his eye again.

"It is what the masters say," he told Marvor. "The masters say we do a thing, and we do it. This is right."

Marvor bent toward him. "Why is it right?" he asked.

"Because the masters say it is right," Cadnan told him, with the surprised air of a person explaining the obvious. "The elders, too, say it before we come to this place." He added the final sentence like a totally unnecessary clincher—unimportant by comparison with the first reason, but adding a little weight of its own, and making the whole story even more satisfying.

Marvor, however, didn't seem satisfied. "The masters always speak truth," he said. "Is this what you tell me?"

"It is true," Cadnan said flatly.

Marvor reflected for a second. "It may be," he said at last. He turned away, found a leaf and began to munch on it slowly. Cadnan picked up his own leaf quite automatically, and it was several seconds before he realized that Marvor had ended the conversation. He didn't want it to end. Talk, he told himself dimly, was a good thing.

"Marvor," he said, "do you question the masters?" It was a difficult sentence to frame: the idea itself would never have occurred to him without Marvor's prodding, and it seemed now no more than the wildest possible flight of fancy. But Marvor, turning, did not treat it fancifully at all.

"I question all," he said soberly. "It is good to question all."

"But the masters—" Cadnan said.

Marvor turned away again without answering.

Cadnan stared at his leaf for a time. His mind was troubled, and there were no ready solutions in it. He was not of the temperament to fasten himself to easy solutions. He had instead to hammer out his ideas slowly and carefully: then when he had reached a conclusion of some kind, he had confidence in it and knew it would last.

Marvor was just the same—but perhaps there had been something wrong with him from the beginning. Otherwise, Cadnan realized, he would never have questioned the masters. None of the Alberts questioned the masters, any more than they questioned their food or the air they breathed.

After a time Marvor spoke again. "I am different," he said, "I am not like others."

Cadnan thought this too obvious to be worth reply, and waited.

"The elders tell me in the hut I am different," Marvor went on. "When they come to bring food they tell me this."

Cadnan took a deep breath of the air. It was, of course, scented with the musk of the Alberts, but Cadnan could not recognize it: like his fellows, he had no sense of smell. "Different is not good," he said, perceiving a lesson.

"You find out how different I am." Marvor sat very still. His voice was still flat but the tone carried something very like a threat. Cadnan, involved in his own thinking, ignored it.

"The masters are big and we are small," he said slowly. "The masters know better than we know."

"That is silliness," Marvor said instantly. "I want things. They make me do training. Why can I not do what I want to do?"

"Maybe," Cadnan said with care, "it is bad."

Marvor made a hissing sound. "Maybe they are bad," he said. "Maybe the masters and the elders are bad."

Matters had gone so far that even this thought found a tentative lodgment in Cadnan's mind. But, almost at once, it was rejected as a serious concept. "They give us leaves to eat," he said. "They keep us here, warm and dry in this place. How is this bad?"

Marvor closed his eye and made the hissing sound again; it was equivalent to a laugh of rejection. He turned among the leaves and found enough room to lie down: in a few seconds he was either asleep or imitating sleep very well. Cadnan looked at him hopefully, and then turned away. A female was watching him from the other side, her eyes wide and unblinking.

"You ask many questions," the female said. "You speak much."

Cadnan blinked his eye at her. "I want to learn," he said.

"Is it good to learn?" the female asked. The question made Cadnan uncomfortable: who knew, for certain, what was good? He knew he would have to think it out for a long time. But the female wanted an answer.

"It is good," he said casually.

The female accepted that with quiet passivity. "My name is Dara," she said. "It is what I am called."

Cadnan said: "I am Cadnan." He found himself tired, and Dara apparently saw this and withdrew, leaving him to sleep.

But his sleep was troubled, and it seemed a long time before day came and the door opened again to show the masters with their strange metal tubes standing outside in the corridor.

"I'm not going to take no for an answer."

Albin stood in the doorway of his room, slouching against the metal lintel and looking even more like a gnome. Dodd sighed softly and got up from the single chair. "I'm not anxious for a party," he said. "All I want to do is go to sleep."

"At nine o'clock?" Albin shook his head.

"Maybe I'm tired."

"You're not tired," Albin said. "You're scared. You're scared of what you might find out there in the cold, cruel world, friend. You're scared of parties and strange people and noise. You want to be left alone to brood, right?"

"No, I—"

"But I'm not going to leave you alone to brood," Albin said. "Because I'm your friend. And brooding isn't good for you. It's brooding that's got you into such a state—where you worry about growing things, for God's sake, and about freedom and silly things like that." Albin grinned. "What you've got to do is stop worrying, and I know how to get you to do that, kiddo. I really do."

"Sure you do," Dodd said, and his voice began to rise. He went to the bed, walked along its length to the window, as he talked, never facing Albin. "You know how to make me feel just fine, no worries at all, no complications, just a nice, simple life. With nothing at all in it, Albin. Nothing at all."

"Now, come on—" Albin began.

"Nothing," Dodd said. "Go to parties, drink, meet a girl, forget, go right on forgetting, and then one day you wake up and it's over and what have you got?"

"Parties," Albin said. "Girls. Drinks. What else is there?"

"A lot," Dodd said. "I want—oh, God, I don't know what I want. Too much. Too many ideas ... trapped here being a master, and that's no good."

"Dodd," Albin said, in what was almost a worried tone, "what the hell are you talking about?"

"Being a master," Dodd said. "There shouldn't be masters. Or slaves. Just—beings, able to do what they want to do ... what makes me any better than the Alberts, anyhow?"

"The Belbis beam, for one thing," Albin said. "Position, power, protection, punishment. What makes anybody better than anybody else?"

"But that's the point—don't you see?"

Albin stood upright, massaging his arm. "What I see is a case of worry," he said, "and as a doctor I have certain responsibilities. I've got to take care of that case of worries, and I'm not going to take no for an answer."

"Leave me alone," Dodd said. "Just do me a favor. Leave me alone."

"Come with me," Albin said. "This once. Look—what can you lose? Just once can't hurt you—you can do all the brooding you want to do some other time. Give me a present. Come to the party with me."

"I don't like parties."

"And I don't like going alone," Albin said. "So do me a favor."

"Where is it?" Dodd asked after a second.

Albin beamed. "Psych division," he said. "Come on."

The metal door was festooned with paper drapery in red and blue. Dodd turned before they got to it, standing about five feet down the corridor. "How did you find out about a party in Psych division?" he asked.

Albin shrugged. "I'm an active type," he said. "I've got friends all over. You'd be surprised how many friends a man can have, Dodd, if he goes to parties. If he meets people instead of brooding."

"All right," Dodd said. "I'm here, aren't I? You've convinced me—stop the propaganda."

"Sure." Albin went up to the door and knocked. From inside they could hear a dim babel of voices. After a second he knocked again, more loudly.

A voice rose above the hum. "Who's there?"

"A friend," Albin said. "The password is Haenlingen-on-fire."

The voice broke into laughter. "Oh," it said. It was now distinguishingly a female voice. "It's you, Cendar. But hold it down on the Haenlingen stuff: she's supposed to be arriving."

"At a party?" Albin said. "She's a hundred and twelve—older than that. What does she want with parties? Don't be silly."

The door opened. A slim, blonde girl stood by it, her mouth still grinning. "Cendar, I mean it," she said. "You watch out. One of these days you're going to get into trouble."

Behind her the hum had risen to a chorus of mad clatter, conversation, laughter, song—the girl dragged Albin and Dodd inside and shut the door. "I'm always in trouble," Albin was saying. "It keeps life interesting." But it was hard to hear him, hard to hear any single voice in the swell of noise.

"Thank God for soundproofing," the girl said. "We can do whatever we like and there's no noise out there."

"The drapes give you away," Albin said.

"Let the drapes give us away," the girl said. "We're entitled to have quiet little gatherings, right? And who knows what goes on behind the drapes?"

"Right," Albin said. "You are right. You are absolutely, incredibly, stunningly right. And to prove how right you are I'm going to do you a favor."

"What kind of favor?" the girl said with mock suspicion.

"Greta," Albin said, "I'm going to introduce you to a nice young man."

"You don't know any nice young men."

"I know this one," Albin said. "Greta Forzane, Johnny Dodd. Take good care of him, kiddo—he needs it."

"What do you mean, good care of him?" she said. But Albin was gone, into the main body of the party, a melee confused enough so that he was lost in twenty steps. Greta turned back almost hopeless eyes.

A second passed.

"You a friend of Cendar's?" Greta asked.

Johnny blinked and came back to her. "Oh, Albin?" he said. "We're—acquaintances."

"Friends," Greta said firmly. "That's nice. He's such a nice guy—I bet you are, too." She smiled and took his arm. Her hand was slightly warm and very dry. Johnny took his first real look at her: she seemed shining, somehow, as if the hair had been lacquered, the face sprayed with a clear polish. The picture she made was vaguely unpleasant, and a little threatening.

"A nice guy?" he said. "I wouldn't know, Miss Forzane."

"Oh, come on, now," she said. "The name is Greta. And you're Johnny—right?"

" ... Right."

"You know," Greta said, "you're cute."

Behind her the party was still going on, but its volume seemed to have diminished a little. Or maybe, Johnny thought, he was getting used to it. "You're cute too," he said awkwardly, not knowing any more what he did want to do, or where he wanted to be. Her grasp on his arm was the main fact in the world.

"Thanks," she said. "Here."

And as suddenly as that she was in his arms, plastered up against him, pressed to him as tightly as he could imagine, her mouth on his, her hands locked behind his neck: he was choking, he couldn't breathe, he couldn't move....

The door behind him opened and shoved him gently across his back.

He fell, and he fell on top of her.

It seemed as if the entire party had stopped to watch him. There was no noise. There was no sound at all. He climbed to his feet to face the eyes and found they were not on him, but behind him.

A tiny white-haired woman stood there, her mouth one thin line of disapproval. "Well," she said. "Having a good time?"

In Dodd's mind, then and later, the sign began.

That was, as far as he could ever remember, the first second he had even seen it. It was there, behind his eyes, blinking on and off, like a neon sign. Sometimes he paid no attention to it, but it was always there, always telling him the same thing.

This is the end.

This is the end.

This is the end.

He looked into that ancient grim face and the sign began. And from then on it never stopped, never stopped at all—

Until, of course, the end.

PUBLIC OPINION ONE

Being an excerpt from a speech delivered by Grigor Pellasin (Citizen, white male, age forty-seven, two arrests for Disorderly Conduct, occupation variable, residence variable) in the district of Hyde Park, city of London, country of England, planet Earth of the Confederation, in the year of the Confederation two hundred and ten, on May fourteenth, from two-thirty-seven P. M. (Greenwich) until three-forty-six P. M. (Greenwich), no serious incidents reported.

They all talk about equality, friends, and you know what equality is? Equality is a license to rob you blind and steal you blind, to cut you up and leave the pieces for the garbage collector, to stuff what's left of you down an oubliette, friend, and forget about you. That's what equality is, friends, and don't you let them tell you any different.

Why, years ago there used to be servants, people who did what you told them. And the servants got liberated, friends, they all got freedom and equality so they were just like us. Maybe you can remember about those servants, because they're all in the history books, and the historical novels, and maybe you do a little light reading now and then, am I right about that?

Well, sir, those servants got themselves liberated, and do you think they liked it? Do you think they liked being free and equal?

Oh, don't ask the government, friends, because the government is going to tell you they liked it just fine, going to tell you they loved it being just like everybody else, free and equal and liberated at last.

The government's going to tell you a lot of things, and my advice is, friends, my advice is do some looking and listening for yourself and think it all out to the right conclusions. Otherwise you're just letting the government do all your thinking for you and that's something you don't want.

No, friends, you do your own thinking and you figure out whether they liked being free, these servants.

You know what being free meant for them?

It meant being out of work.

And how do you think they liked that?

Now, maybe here among us today, among you kind people listening to what I've got to say to you, maybe there are one or two who've been out of work during their lifetimes. Am I right? Well, friends, you tell the others here what it felt like.

It felt hopeless and dragged-out and like something you'd never want to go through again, am I right?

Of course I'm right, friends. But there was nothing you could do about being out of work. If you were out of work that was that, and you were through, no chance, no place to move.

These servants, friends, they liked being servants. I know that's hard to believe because everybody's been telling you different all your lives, but you just do a little independent thinking, the way I have, and you'll see. It was a good job, being a servant. It was steady and dependable and you knew where you stood.

Better than being out of work? You bet your last credit, you bet your very last ounce of bounce on that, friends.

And better than a lot of other things, too. They were safe and warm and happy, and they felt fine.

And then a lot of busybodies came along and liberated them.

Well, friends, some of them went right back and asked to be servants again—they did so. It's a historical fact. But that was no good: the machines had taken over and there was no room for them.

They were liberated for good.

And the lesson you learn from that, friends, is just this: don't go around liberating people until you know what they want. Maybe they're happier the way they are.

Now, out on a far planet there's a strange race. Maybe you've heard about them, because they work for us, they help get us the metals we need to keep going. They're part of the big line of supply that keeps us all alive, you and me both.

And there are some people talking about liberating those creatures, too, which aren't even human beings. They're green and they got one eye apiece, and they don't talk English except a little, or any Confederation tongue.

Yet even so there are people who want to liberate those creatures.

Now, you sit back and think a minute. Do those creatures want to be liberated? Is it like liberating you and me, who know what's what and can think and make decisions? Because being free and equal means voting and everything else. Do you want these green creatures voting in the same assemblies as yours?

If it were cruel to keep them the way they are, working on their own world and being fed and kept warm and safe, why, I'd say go ahead and liberate them. But what's cruel about it, friends?

They're safe—safer than they would be on their own.

They're fed well and kept warm.

And remember those servants, friends. Maybe the greenies like their life, too. It's their world and their metal—they have a right to help send it along.

You don't want to act hastily, friends, now do you?

My advice to you is this: just let the greenies alone. Just let them be, the way they want to be, and don't go messing around where there's no need to mess around. Because if anybody starts to do that, why, it can lead to trouble, friends, to a whole lot of unnecessary bother and trouble.

Am I right?

"I don't mind parties, Norma, not ordinary parties. But that one didn't look like an ordinary party."

Norma stood her ground in front of the desk. This, after all, was important "But, Dr. Haenlingen, we—"

"Don't try to persuade me," the little old woman said sharply. "Don't try to cozen me into something: I know all the tricks, Norma. I invented a good third of them, and it's been a long time since I had to use a textbook to remember the rest."

"I'm not trying to persuade you of anything." The woman wouldn't listen, that was the whole trouble: in the harsh bright light of morning she sat like a stone statue, casting a shadow of black on the polished desk. This was Dr. Haenlingen—and how did you talk to Dr. Haenlingen? But it was important, Norma reminded herself again: it was perfectly possible that the entire group of people at the party would be downgraded, or at the least get marked down on their records. "But we weren't doing anything harmful. If you have a party you've got to expect people to—oh, to get over-enthusiastic, maybe. But certainly there was nothing worth getting angry about. There was—"

"I'm sure you've thought all this out," Dr. Haenlingen said tightly. "You seem to have your case well prepared, and it would be a pleasure to listen to you."

"But—"

"Unfortunately," the woman continued in a voice like steel, "I have a great deal of work to do this morning."

"Dr. Haenlingen—"

"I'm sorry," she said, but she didn't sound sorry in the least. Her eyes went down to a pile of papers on the desk. A second passed.

"You've got to listen to me," Norma said. "What you're doing is unfair."

Dr. Haenlingen didn't look up. "Oh?"

"They were just—having fun," Norma said. "There was nothing wrong, nothing at all. You happened to come in at a bad moment, but it didn't mean anything, there wasn't anything going on that should have bothered you...."

"Perhaps not," Dr. Haenlingen said. "Unfortunately, what bothers me is not reducible to rule."

"But you're going to act on it," Norma said. "You're going to—"

"Yes?" Dr. Haenlingen said. "What am I going to do?"

"Well, you—"

"Downgrade the persons who were there?" Dr. Haenlingen asked. "Enter remarks in the permanent records? Prevent promotion? Just what am I supposed to have in mind?"

"Well, I thought—I—"

"I plan," Dr. Haenlingen said, "nothing whatever. Not just at present. I want to think about what I saw, about the people I saw. At present, nothing more."

There was a little silence. Norma felt herself relax. Then she asked: "At present?"

Dr. Haenlingen looked up at her, the eyes ice-cold and direct. "What action I determine to take," she said, "will be my responsibility. Mine alone. I do not intend to discuss it, or to attempt to justify it, to you or to anyone."

"Yes, Dr. Haenlingen." Norma stood awkwardly. "Thank you—"

"Don't thank me—yet," Dr. Haenlingen said. "Go and do your own work. I've got quite a lot to oversee here." She went back to her papers. Norma turned, stopped and then walked to the door. At the door she turned again but Dr. Haenlingen was paying no visible attention to her. She opened the door, went out and closed it behind her.

In the corridor she took one deep breath and then another.

The trouble was, you couldn't depend on the woman to do anything. She meant exactly what she had said: "For the present." And who could tell what might happen later?

Norma headed for her own cubicle, where she ignored the papers and the telephone messages waiting for her and reached for the intercom button instead. She pushed it twice and a voice said:

"What happened?"

"It's not good, Greta," Norma said. "It's—well, undecided, anyhow: we've got that much going for us."

"Undecided?" the voice asked.

"She said she wouldn't do anything—yet. But she left it open."

"Oh. Lord. Oh, my."

Norma nodded at the intercom speaker. "That's right. Anything's possible—you know what she's like."

"Oh, Lord. Do I."

"And—Greta, why did you have to be there, right by the door, with that strange type—as if it had been set up for her? Right in front of her eyes...."

"An accident," Greta said. "A pure by-God accident. When she walked in, when I saw her, believe me, Norma, my blood ran absolutely cold. Temperature of ice, or something colder than ice."

"Just that one look, just that one long look around." Norma said, "and she was gone. As if she'd memorized us, every one of us, filed the whole thing away and didn't need to see any more."

"I would have explained. But there wasn't any time."

"I know," Norma said. "Greta, who was he, anyhow?"

"Him?" Greta said. "Who knows? A friend of Cendar's—you know Cendar, don't you?"

"Albin Cendar?"

"That's the one. He—"

"But he's not from Psych." Norma said.

"Neither is his friend, I guess," Greta said. "But they come over, you know that—Cendar's always around."

"And you had to invite them...."

"Invite?" Greta said. "I didn't invite anybody. They were there, that's all. Cendar always shows up. You know that."

"Great," Nonna said. "So last night he had to bring a friend and the friend got grabby—"

"No," Greta said. "He was—well, confused maybe. Never been to a party of ours before, or anyhow not that I remember. I was trying to—loosen him up."

"You loosened everybody up," Norma said.

There was a silence.

"I'm sorry," Norma said. "All right. You couldn't have known—"

"I didn't know anything," Greta's voice said. "She was there, that's all."

"I wonder whether Dr. Haenlingen knew him," Norma said. "The new one, I mean."

"His name was Johnny something," Greta said.

"We'll just have to wait and find out," Norma said. "Whatever she's going to do, there isn't any way to stop it. I did the best I could—"

"Sure you did," Greta said. "We know that. Sure."

"Cendar and his friends—" Norma began.

"Oh, forget about that," Greta said. "Who cares about them?"

The party had meant nothing, nothing at all, and Albin told himself he could forget all about it.

If Haenlingen wanted to take any action, he insisted, she'd take it against her own division. The Psych people would get most of it. Why, she probably didn't even know who Albin Cendar was....

But the Psych division knew a lot they weren't supposed to know. Maybe she would even....

Forget about it, Albin told himself. He closed his eyes for a second and concentrated on his work. That, at least, was something to keep him from worrying: the whole process of training was something he could use in forgetting all about the party, and Haenlingen, and possible consequences.... He took a few breaths and forced his mind away from all of that, back to the training.

Training was a dreary waste of time, as a matter of fact—except that it happened to be necessary. There was no doubt of that: without sufficient manual labor, the metal would not be dug, the smelters would not run, the purifying stages and the cooling stages and even the shipping itself would simply stop. Automation would have solved everything, but automation was expensive. The Alberts were cheap—so Fruyling's World used Alberts instead of transistors and cryogenic relays.

And if you were going to use Alberts at all, Albin thought, you sure as hell had to train them. God alone knew what harm they could do, left alone in a wilderness of delicate machinery without any instructions.

All the same, "dreary" was the word for it. (An image of Dr. Haenlingen's frozen face floated into his mind. He pushed it away. It was morning. It was time for work.)

He met Derban at the turn in the corridor, perhaps fifty feet before the Alberts' door. That wasn't strictly according to the rules, and Albin knew it: he had learned the code as early as anyone else. But the rules were for emergencies—and emergencies didn't happen any more. The Alberts weren't about to revolt.

He was carrying his Belbis beam, of course. The little metal tube didn't look like much, but it was guaranteed to stop anything short of a spaceship in its tracks, and by the very simple method of making holes. The Belbis beam would make holes in nearly anything: Alberts, people or most materials. It projected a quarter-inch beam of force in as near a straight line as Einsteinian physics would allow, and it was extremely efficient. Albin had been practicing with it for three years, twice a week.

Everybody did. Not that there's ever been a chance to use it.

And there wasn't going to be a chance, Albin decided. He exchanged a word or two absently with Derban and they went to the door together. Albin reached for the door but Derban's big brown hand was already on it. He grinned and swung the door open.

Air conditioning had done something to minimize the reek inside, but not much. Albin devoted most of his attention to keeping his face a complete mask. The last thing he wanted was to retch—not in front of the Alberts, who didn't really exist for him, but in front of Derban. And the party (which he wasn't going to think about) hadn't left his stomach in perfect shape.

The Alberts, seeing these masters enter stirred and rose. Albin barked at them in a voice that was only very slightly choked: "Form a line. Form a line."

The Alberts milled around, quite obviously uncertain what a line was. Albin gripped his beam tighter, not because it was a weapon but just because he needed something handy to take out his anger on.

"Damn it," he said tightly, "a line. Form a straight line."

"It's only their second day," Derban said in a low voice. "Give them time." Albin could barely hear him over the confused babble of the Alberts. He shook his head and felt a new stab of anger.

"One behind the other," he told the milling crowd. "A line, a straight line."

After a little more confusion, Albin was satisfied. He sighed heavily and beckoned with his beam: the Alberts started forward, through the door and out into the corridor.

Albin went before, Derban behind, falling naturally into step. They came to the great elevator and Albin pushed a stud. The door slid open.

The Alberts, though, didn't want to go in. They huddled, looking at the elevator with big round eyes, muttering to themselves and to each other. Derban spoke up calmly: "This is the same room you were in yesterday. It won't hurt you. Just go through the door. It's all right." But the words had very little effect. A few of the Alberts moved closer and then, discovering that they were alone, hurriedly moved back again. The elevator door remained open, waiting.

Albin, ready to shriek with rage by now, felt a touch at his arm. One of the Alberts was standing near him, looking up. Its eye blinked: it spoke. "Why does the room move?" The voice was not actually unpleasant, but its single eye stared at Albin, making him uncomfortable. He told himself not to blow up. Calm. Calm.

"The room moves because it moves," he said, a little too quickly. "Because the masters tell it to move. What do you want to know for?"

"I want to learn," the Albert said calmly.

"Well, don't ask questions," Albin said. He kept one eye on the shifting mob. "If there's anything good for you to know, you'll be told. Meanwhile, just don't ask any questions."

The Albert looked downcast. "Can I learn without questions?"

Albin's control snapped. "Damn it, you'll learn what you have to!" he yelled. "You don't have to ask questions—you're a slave. A slave! Get that through your green head and shut up!"

The tone had two effects. First, it made the Albert near him move back, staring at him still with that single bright eye. Second, the others started for the elevator, apparently pushed more by the tone than the words. A master was angry. That, they judged, meant trouble. Acceding to his wishes was the safest thing to do.

And so, in little, frightened bunches, they went in. When they were all clear of the door, Albin and Derban stepped in, too, and the doors slid shut. Derban took a second to mutter secretly: "You don't have to lose your temper. You're on a hell of a thin edge this morning."

Albin flicked his eyes over the brown face, the stocky, stolid figure. "So I'm on a thin edge," he said. "Aren't you?"

"Training is training," Derban said. "Got to put up with it, because what can you do about it?"

Albin grinned wryly. "I told somebody else that, last night," he said. "Man named Dodd—hell, you know Johnny Dodd. Told him he needed some fun. Holy jumping beavers—fun."

"Maybe you need some," Derban said.

"Not like last night, I don't," Albin said, and the elevator door opened.

Now others took over, guiding the Alberts to their individual places on the training floor. Each had a small room to himself, and each room had a spy-TV high up in a corner as a safeguard.

But the spy-eyes were just as much good as the beams, Albin thought. They were useless precautions: rebellion wasn't about to happen. It made more sense, if you thought about it, to worry the way Johnny Dodd worried, about the Confederation—against which spy-eyes and Belbis beams weren't going to do any good anyhow. (And nothing was going to happen. Nothing, he told himself firmly, was going to happen. Nothing.)

The Alberts were shunted off without trouble. Albin, heaving a small sigh, fixed the details of his next job in his mind: quality control in a smelting process. It took him a few seconds to calm down and get ready, and then he headed for room six, where one Albert waited for him, trying to think only of the job ahead, and not at all of the party, of Dr. Haenlingen, of Johnny Dodd, of rebellion and war.

He nearly succeeded.

When he opened the door the Albert inside turned, took a single look at him, and said: "I do not mean to make masters troubled."

Albin said: "What?"

"I do not ask questions now." Albin blinked, and then grinned.

"Oh," he said. "You're the one. Damn right you don't ask questions. You just listen to what I tell you—got that?"

"I listen," the Albert said.

Albin shut the door and leaned against it. "Okay," he said. "Now the first thing, you come over here and watch me." He went to the far side of the room, flicked on the remote set, and waited for it to warm up. In a few seconds it held a strong, steady picture: a single smelter, a ladle, an expanse of flooring.

"I see this when you teach me before," the Albert said in almost a disappointed tone.

"I know," Albin told it. Routine was taking over and he felt almost cheerful again. There was a woman working in the food labs in Building Two. He'd noticed her a few times in the past weeks. Now he thought of her again, happily. Maybe tonight "This time I'm going to show you what to do," he told the Albert, and swept a hand over a row of buttons. In the smelter, metal began to heat.

The job was simple enough: the metal, once heated, had to be poured out into the ladle, which acted as a carrier to take the stuff on to its next station. The only critical point was the color of the heated liquid, and the eyes of Alberts and humans saw the same spectrum, with perhaps a little more discrimination in the eyes of the Alberts. This Albert had to be taught to let the process go unless the color was wrong, when a series of buttons would stop everything and send a quality alarm into men's quarters.

A machine could have done the job very easily, but machines were expensive. An Albert could be taught in a week.

And this one seemed to learn more quickly than most. It grasped the idea of button-pushing before the end of the day, and Albin made a mental note to see if he could speed matters up, maybe by letting the Albert have a crack at actually doing the job on its own by day four or five instead of day six.

"You learn fast," he said, when work was finally over. He felt both tired and tense, but the thought of relaxation ahead kept him nearly genial.

"I want to learn," the Albert said.

"Good boy," Albin said absently. "What's your name?"

"Cadnan."

But Cadnan, he knew, was only a small name: it was not a great name. He knew now that he had a great name, and it made him proud because he was no longer only small Cadnan: he was a slave.

It was good, he knew, to be a slave. A slave worked and got food and shelter from the masters, and the masters told him what he could know without even the need of asking a question. The elders were only elders, but the masters were masters, and Cadnan was a slave. It made him feel great and wise when he thought of it.

That night he could hardly wait to tell his news to Marvor—but Marvor acted as if he knew it already and was even made angry by the idea. "What is a slave?" he asked, in a flat, bad tone.

Cadnan told him of the work, the food, the shelter....

"And what is a master?" Marvor asked.

"A master is a master," Cadnan said. "A master is the one who knows."

"A master tells you what to do," Marvor said. "I am training and there is more training to come and then work. This is because of the masters."

"It is good," Cadnan said. "It is important."

Marvor shook his head, looking very much like a master himself. "What is important?" he said.

Cadnan thought for a minute. "Important is what a master needs for life," he said at last. "The masters need a slave for life, because a slave must push the buttons. Without this work the masters do not live."

"Then why do the masters not push the buttons?" Marvor said.

"It is good they do not," Cadnan said stubbornly. "A slave is a big thing, and Cadnan is only a little thing. It is better to be big than little."

"It is better to be master than slave," Marvor said sullenly.

"But we are not masters," Cadnan said, with the air of a person trying to bring reason back to the discussion. "We do not look like masters, and we do not know what they know."

"You want to learn," Marvor said. "Then learn what they know."

"They teach me," Cadnan said. "But I am still a slave, because they teach me. I do not teach them."

Marvor hissed and at the same time shook his head like a master. The effect was not so much frightening as puzzling: he was a creature, suddenly, who belonged to both worlds, and to neither. "A master is one who does what he wants," he said. "If I do what I want, am I a master?"

"That is silliness," Cadnan said. Marvor seemed about to reply, but both were surprised instead by the opening of the door.

A master stood in the lighted entrance, holding to the sides with both hands.

Anyone with a thorough knowledge of men could have told that he was drunk. Any being with a sense of smell could have detected the odors of that drunkenness. But the Alberts knew only that a master had come to them during the time for eating and sleeping. They stirred, murmuring restlessly.

"It's all right," the master said, slurring his words only very slightly. "I wanted to come and talk. I wanted to talk to one of you."

Before anyone else could move, Cadnan was upright. "I will talk," he said in a loud voice. The others stared at him, including Marvor. Even Cadnan himself was a little surprised at his own speed and audacity.

"Come on over," the master said from the doorway. "Come on over." He made a beckoning motion.

Cadnan picked his way across the room over wakeful Alberts.

When he had reached the master, the master said: "Sit down." He looked strange, Cadnan realized, though he could not tell exactly how.

Cadnan sat and the master, closing the door, sat with his back against it. There was a second of silence, which the master broke abruptly.

"My name's Dodd," he said.

"I am called Cadnan," Cadnan said. He couldn't resist bringing out his latest bit of knowledge for display. "I am a slave."

"Sure," Dodd said dully. "I know. The rest of them say I shouldn't, but I think about you a lot. About all of you."

Cadnan, not knowing if this were good or bad, said nothing at all, but waited. Dodd sighed, shook his head and closed his eyes. After a second he went on.

"They tell me, let the slaves have their own life," he said. "But I don't see it that way. Do you see it that way? After all, you're people, aren't you? Just like us."

Cadnan tried to untangle the questions, and finally settled for a simple answer. "We are slaves," he said. "You are masters."

"Sure," Dodd said. "But I mean people. And you want the same things we do. You want a little comfort out of life, a little security—some food, say, and enough food for tomorrow. Right?"

"It is good to have," Cadnan said. He was determined to keep his end of the odd conversation up, even if it seemed to be leading nowhere.

"It isn't as if we've been here forever," Dodd said. "Only—well, a hundred or so of your years. Three generations, counting me. And here we are lording it over you, just because of an accident. We happen to be farther advanced than you, that's all."

"You are masters," Cadnan said. "You know everything."

"Not quite," Dodd said. "For instance, we don't know about you. You have—well, you have got mates, haven't you? Hell, of course you do. Male or female. Same as us. More or less."

"We have mates, when we are ready for mates," Cadnan said.

Dodd nodded precariously. "Uh-huh," he said. "Mates. They tell me I need mates, but I tried it and I got into trouble. Mates aren't the answer, kid. Cadnan. They simply aren't the answer."

Cadnan thought, suddenly, of Dara. He had not spoken to her again, but he was able to think of her. When the time of mating came, it was possible that she would be his mate....

But that was forbidden, he told himself. They came from the same tree in the same time. The rule forbade such matings.

"What we ought to do," Dodd said abruptly, "is we ought to do a thorough anthropological—anthropological study on you people. A really big job. But that's uneconomic, see? Because we know what we have to know. Where to find you, what to feed you, how to get you to work. They don't care about the rest."

"The masters are good," Cadnan said stolidly into the silence. "They let me work."

"Sure," Dodd said, and shrugged, nearly losing his balance. He recovered, and went on as if nothing at all had happened. "They let you work for them," he said. "And what do you get out of it? Food and shelter and security, I guess. But how would you like to work for yourself instead?"

Cadnan stared. "I do not understand," he said slowly.

Dodd shook his head. "No," he said. "How would you like it if there were no masters? Only people, just you and your people, living your own lives and making your own decisions? How about that, kid?"

"We would be alone," Cadnan said simply. "No master would feed us. We would die."

"No," Dodd said again. "What did you do before we came?"

"It was different," Cadnan said. "It was not good. This is better." He tried to imagine a world without masters, but the picture would not come. Obviously, then, the world he lived in was better: it was better than nothing.

"Slaves," Dodd said to himself. "With a slave mentality." And then: "Tell me, Cadnan, do they all think like you?"

Cadnan didn't think of Marvor. By now he was so confused by this strange conversation that his answer was automatic. "We do not talk about it."

Dodd looked at him mistily. "I'm disturbing you for nothing," he said. "Nothing I can do but get killed trying to start up a slave revolt. Which might be okay, but I don't know. If you get me—I don't know about that, kid. Right?" He stood up, a little shakily, still leaning against the door. "And frankly," he said, "I don't want to get killed over a lot of alligators."

"No one wishes to die," Cadnan said.

"You'd be surprised," Dodd told him. He moved and opened the door. For a second he stood in the entrance. "People can wish for almost anything," he said. "You'd be surprised." The door banged shut and he was gone.

Cadnan sat staring at the door for a second, his mind a tangle of ideas and of new words for which he had no referents whatever. When he turned away at last his eye fell on Dara, curled in a far corner. She was looking at him but when he saw her he looked away. That disturbed him, too: the rules were very clear on matings.

Cadnan wanted to tell someone what he felt. He wanted information, and he wanted someone to follow. But the masters were masters: he could not be like them. And in the room where he slept there were no elders. The thought of speaking with an elder, in any case, gave him no satisfaction. He did not want an elder: he could not join the masters and ask questions.

Somewhere, he told himself, there would be someone....

Somewhere....

Of course, there was Marvor. Later in the night, while Cadnan still lay awake trying to put thoughts and words together in his mind, Marvor moved closer to him.

"I want you with me," he said.

But Marvor, Cadnan had decided, was bad. "I sleep here," Cadnan said, a trifle severely. "I do not move my place."

In the dimness Marvor shook his head no, like a master. "I want you with me in the plan I have," he said. "I want you to help me."

That was different. The rules of the elders covered such a request. "Does a brother refuse help to a brother?" Cadnan asked. "We are from the same tree and the same time. Tell me what I must do."

Marvor opened his mouth wide, wider, until Cadnan saw the flash of his many teeth, and a second passed in silence. Then Marvor snapped his jaws shut, hissing, and spoke. "The masters tell us what to do. They make our life for us."

"This is true," Cadnan muttered.

"It is evil," Marvor said. "It is bad. We must make our own lives. Every thing makes its own life."

"We are slaves," Cadnan said. "This is our life. It is our place."

Marvor sat up suddenly. Around them the others muttered and stirred. "Does the plant grow when a master tells it?" he asked. "Does the tree bud when a master tells it? So we must also grow in our own way."

"We are not plants or trees," Cadnan said.

"We are alive," Marvor said in a fierce, sudden whisper. "The masters, too, are alive. We are the same as they. Why do they tell us what to do?"

Cadnan was very patient. "Because they know, and we do not," he said. "Because they tell us, that is all. It is the way things are."

"I will change the way things are," Marvor said. He spoke now more softly still. "Do you want to be a master?"

"I am no master," Cadnan said wearily. "I am a slave."

"That is a bad thing." Cadnan tried to speak, but Marvor went on without stopping. "Dara is with me," he said, "and some of the others. There are not many. Most of the brothers and sisters are cowards."

Then he had to define "coward" for Cadnan—and from "coward" he progressed to another new word, "freedom." That was a big word but Cadnan approached it without fear, and without any preconception.

"It is not good to be free," he said at last, in a reasonable, weary tone. "In the cold there is a bad thing. In the rain there is a bad thing. To be free is to go to these bad things."

"To be free is to do what you want," Marvor said. "To be free is to be your own master."

After some thought Cadnan asked: "Who can be his own master? It is like being your own mate."

Marvor seemed to lose patience all at once. "Very well," he said. "But you will not tell the masters what I say?"

"Does a brother harm a brother?" Cadnan asked. That, too, was in the rules: even Marvor, he thought sleepily, had to accept the rules.

"It is good," Marvor said equably. "Soon, very soon, I will make you free."

"I do not want to be free."

"You will want it," Marvor said. "I tell you something you do not know. Far away from here there are free ones. Ones without masters. I hear of them in the Birth Huts: they are elders who bring up their own in hiding from the masters. They want to be free."

Cadnan felt a surge of hope. Marvor might leave, take away the disturbance he always carried with him. "You will go and join them?"

"No," Marvor said. "I will go to them and bring them back and kill all the masters. I will make the masters dead."

"You cannot do it," Cadnan said instantly, shocked.

"I can," Marvor said without raising his voice. "Wait and you will see. Soon we will be free. Very soon now."

This is the end.

Dodd woke with the words in his mind, flashing on and off like a lighted sign. Back in the Confederation (he had seen pictures) there were moving stair-belts, and at the exits, at turnoffs, there were flashing signs. The words in his mind were like that: if he ignored them he would be carried on past his destination, into darkness and strangeness.

But his destination was strange, too. His head pounded, his tongue was thick and cottony in a dry mouth: drinking had provided nothing of an escape and the price he had to pay was much too high.

This is the end.

There was no escape, he told himself dimly! The party had resulted only in that sudden appearance, the grim-mouthed old woman. Drinking had resulted in no more than this new sickness, and a cloudy memory of having talked to an Albert, some Albert, somewhere.... He opened his eyes, felt pain and closed them again. There was no escape: the party Albin had taken him to had led to trouble, his own drunkenness had led to trouble. He saw the days stretching out ahead of him and making years.

It was nearly time now to begin work. To begin the job of training, with the Alberts, the job he was going to do through all those days and years lying ahead.

This is the end.

He found himself rising, dressing, shaving off the stubble of beard. His head hurt, his eyes ached, his mouth was hardly improved by a gargle, but all that was far away, as distant as his own body and his own motions.

His head turned and looked at the clock set into his wall. The eyes noted a position of the hands and passed the information to the brain: 8:47. The brain decided that it was time to go on to work. The body moved itself in accustomed patterns, opening the door, passing through the opening, shutting the door again, walking down the hallway.

All that was very distant. Dodd, himself, was—somewhere else.

He met his partner standing before a group of the Alberts. Dodd's eyes noted the expression on his partner's face. The brain registered the information, interpreted it and predicted. Dodd knew he would hear, and did hear, sounds: "What's wrong with you this morning?"

The correct response was on file. "Drinking a little too much last night, I guess." It was all automatic: everything was automatic. The Alberts went into their elevator, and Dodd and his partner followed. Dodd's body did not stumble. But Dodd was somewhere else.

The elevator stopped, the Alberts went off to their sections, Dodd's partner went to his first assignment, Dodd found his body walking away down the hall, opening a door, going through the opening, shutting the door. The Albert inside looked up.

"Today we are going to do the work together." Dodd heard his own voice: it was all perfectly automatic, there were no mistakes. "Do you understand?"

"Understand," the Albert said.

This is the end.

At the end of the day he was back from wherever he had been, from the darkness that had wrapped his mind like cotton and removed him. There was no surprise now. There was no emotion at all: his work was over and he could be himself again. In the back of his mind the single phrase still flashed, but he had long since stopped paying attention to that.

He finished supper and went into the Commons Room, walking aimlessly.