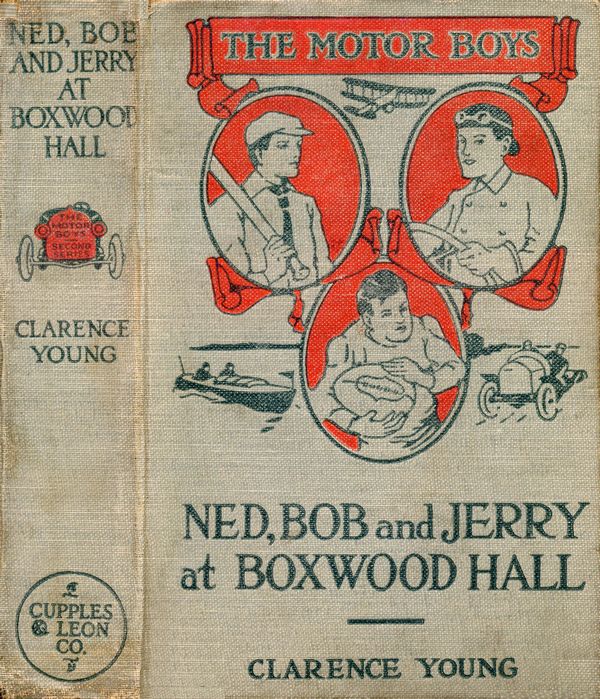

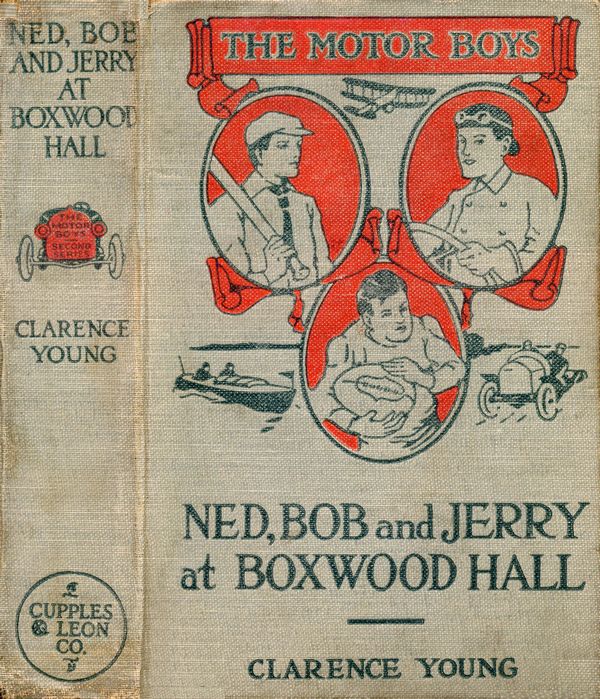

Title: Ned, Bob and Jerry at Boxwood Hall; Or, The Motor Boys as Freshmen

Author: Clarence Young

Release date: January 30, 2016 [eBook #51079]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

——The Motor Boys——

Or

The Motor Boys as Freshmen

BY

AUTHOR OF “THE MOTOR BOYS SERIES”

“THE RACER BOYS SERIES” “THE

JACK RANGER SERIES,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated.

Price, per volume, 60 cents, postpaid.

Copyright, 1916, by

Cupples & Leon Company

Ned, Bob and Jerry at Boxwood Hall

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | The Overturned Auto | 1 |

| II. | A Family Conference | 10 |

| III. | The Race | 20 |

| IV. | The Decision | 29 |

| V. | Good News | 37 |

| VI. | Boxwood Hall | 46 |

| VII. | Off to College | 53 |

| VIII. | Professor Snodgrass | 61 |

| IX. | The Professor’s Shoes | 70 |

| X. | A Cool Reception | 79 |

| XI. | The Professor’s Dilemma | 87 |

| XII. | In the Gymnasium | 97 |

| XIII. | The Bang-Ups | 105 |

| XIV. | The Initiation | 113 |

| XV. | Caught | 124 |

| XVI. | A Collision | 132 |

| XVII. | The Aeroplane | 140 |

| XVIII. | The Postponed Examination | 148 |

| XIX. | The Boxwood Picture | 160 |

| XX. | “Who Told?” | 167 |

| XXI. | The Coasting Race | 175 |

| XXII. | The Ice Boat | 183 |

| XXIII. | Spring Practice | 191 |

| XXIV. | A Scrub Game | 199 |

| XXV. | A Varsity Loss | 207 |

| XXVI. | Dissensions | 214 |

| XXVII. | The Rooters Insist | 220 |

| XXVIII. | In the Tenth | 228 |

| XXIX. | Mr. Hobson | 235 |

| XXX. | The Winning Game | 240 |

My Dear Boys:

With this volume begins a new series of adventures for the “Motor Boys.” Under the title “Ned, Bob and Jerry at Boxwood Hall; Or, The Motor Boys as Freshmen,” I have had the pleasure of writing for you the various happenings that took place when the three young men, whose activities you have followed for some time, entered a new field.

The fathers of Ned Slade and Bob Baker, and the mother of Jerry Hopkins, in consultation one day, decided that the young men were getting a bit too wild and frivolous.

“It is time they settled down,” said their parents, “and began to think of growing up. Let’s send them to college!”

And to the college of Boxwood Hall our heroes were sent. It was a surprise to them, but it turned out to be a delightful surprise, and one of the reasons was that their old friend, Professor Snodgrass, now an enthusiastic collector of butterflies, was an instructor at Boxwood.

Of what took place at the college, of the hazing, the initiation, the queer developments following an automobile rescue, of how the motor boys gradually overcame an unfair prejudice, and how they helped to win a baseball victory—for all this I refer you to the following pages. The titles of the second series will include the names Ned, Bob and Jerry, in various activities, and while they will still use their motors, in auto, boat or airship, those machines will be of secondary consideration.

And with this explanation, and with the hope that you will accord this book the same welcome you have given my other writings, I remain,

Sincerely yours,

Clarence Young.

NED, BOB AND JERRY AT BOXWOOD HALL

“What do you reckon it’s all about, Jerry?”

“Well, Bob, you’re as good a guesser as I am,” came the answer from the young man who was at the wheel of a touring car that was swinging down a pleasant country road, under arching trees. “What do you say it means?”

“I haven’t the least idea, unless it’s some business deal. Ned, why don’t you say something, instead of sitting there like a goldfish being admired by a tom-cat?” and Bob Baker, who sat beside Jerry Hopkins, the lad at the wheel, turned to his chum in the rear seat of the car.

“Say something!” exclaimed Ned Slade. “I’m as much up in the air about it as you fellows are. All I know is that my dad, and yours, and Jerry’s mother, are having a confab.”

“And a sort of serious confab at that,” added[2] Bob. “Look out there, Jerry!” he cried suddenly. “You nearly ran over that chicken,” and he involuntarily raised his hand toward the steering wheel as a frightened, squawking and cackling hen fluttered from under the front wheels of the automobile, shedding feathers on the way. Then Bob remembered one of the first ethics of automobiling, which is never to interfere with the steersman, and he drew back his hand.

“A miss is as good as a mile,” remarked Jerry coolly, as he brought the car back to a straight course, for he had swerved it to one side when he saw the chicken in the path. “But I agree with you, Bob, that the conference going on at my house, among our respected, and I might as well say respectable, parents does seem to be a serious one. However, as long as we can’t guess what it’s about there’s no use in worrying. We may as well have a good time this afternoon. Where shall we go?”

“Let’s go to Wallace’s and have a bite to eat,” put in Bob.

“Why, we only just had lunch!” exclaimed Ned, with a laugh.

“Maybe you fellows did, but I wouldn’t call it a lunch that I got outside of—not by a long shot! Mother isn’t at home, it was the girl’s day out and I had to forage for myself.”

“Heaven help the pantry, then!” exclaimed[3] Jerry. “I’ve seen Bob ‘forage,’ as he calls it, before; eh, Ned?”

“That’s right. He did it at our house once, and say! what mother said when she came home—whew!” and Ned whistled at the memory.

“I wasn’t a bit worse than you were!” cried Bob, trying to lean back and punch his chum, but the latter kept out of reach in the roomy tonneau. “Anyhow, what has that got to do with going to Wallace’s now? I’m hungry and I don’t care who knows it.”

“Well, don’t let that fat waiter at Wallace’s hear you say that, or he’ll double charge us in the bill,” cautioned Jerry. “They sure do stick on the prices at that joint.”

“Then you’ll go there?” asked Bob eagerly.

“Oh, I s’pose we might as well go there as anywhere. Does it suit you, Ned?”

“Sure. Only I can’t imagine where Bob puts it all. Tell us, Chunky, that’s a good chap,” and he patted the shoulder of the stout lad who sat in front of him.

“Tell you what?” asked Bob, responding to the nickname that had been bestowed on him because of his stoutness.

“Where you put all you eat,” went on Ned with a laugh. “You know it is impossible to make two objects occupy the same space at the same time. And if you’ve eaten one lunch to-day, and[4] not two hours ago, where are you going to put another?”

“You watch and see,” was all the answer Bob made. “Hit her up a bit, Jerry. There’s a stiff hill just ahead.”

“That’s right. I forgot we were on this road. Well, then it’s settled. We’ll go to Wallace’s and let Bob eat,” and having ascended the hill, he turned off on a road that led to a summer resort not many miles from Cresville, the home town of the three lads.

“Aren’t you fellows going to have anything?” asked Bob. “You’ll eat; won’t you?”

“Oh, for cats’ sake, cut out the grub-talk for a while!” begged Ned. “Say, what about that conference, anyhow? Does any one know anything about it?”

“All I know,” said Jerry, “is that I asked mother to come out for an auto ride this afternoon, and she said she couldn’t because your dad, Ned, and Bob’s too, were coming over to call.”

“Did you ask her what for?”

“No, but I took it for granted it was something about business. You know mother owns some stock in your father’s department store, Ned.”

“Yes, and she deposits at dad’s bank,” added Bob, whose father, Andrew Baker, was the president of the most important bank in Cresville. “I guess it must be about some business affairs.”

“I don’t agree with you,” declared Ned.

“Why not?” Jerry demanded. “When mother said she couldn’t come out I hustled over and got you fellows, and here we are. But what’s your reason for thinking it isn’t business, Ned, that has brought our folks together at my house?”

“Because of some questions my father asked me this morning.”

“Serious questions?” Bob interrogated.

“Well, in a way, yes. He asked me what I’d been doing lately, what you fellows had been doing, and he wanted to know what my plans were for this winter.”

“What did you tell him?” inquired Jerry, slowing down as he came to the crest of another hill.

“Oh, I said we hadn’t decided yet. I didn’t tell him we had talked over making a tour of the South, for we hadn’t quite decided on it; had we?”

“Not exactly,” responded Jerry. “And yet the South is the place when winter comes. I guess we might do worse.”

“Well, I didn’t say anything about that,” went on Ned, “because, if I had, dad would have wanted to know all the particulars, and I wasn’t in a position to tell him.”

“Is that all he asked you that makes you think the conference may be about us, instead of business?” Bob inquired.

“No, that wasn’t quite all. He asked me about that trouble we got into last week.”

“Oh, do you mean about the time we were pulled in for speeding?” asked Jerry with a laugh.

“That’s it,” assented Ned. “Only it isn’t going to be anything to grin at if dad finds out all about it—that we nearly collided with the hay wagon while trying to pass that roadster. Say, but it was some going! We fractured the speed limits in half a dozen places.”

“But we beat the roadster!” exclaimed Jerry. “That fellow didn’t know how to drive a car.”

“You’re right there. And, for a second or two, I thought you were going to make a mess of it,” said Ned, referring to an incident that had happened about a week previously when the boys, out on the road in their car, had accepted an impromptu challenge to race, with what might have been disastrous results.

“It was a narrow squeak,” admitted Jerry.

“And the nerve of that farmer, setting the constable after us!” cried Bob. “Just because we wouldn’t let him rob us of ten dollars to make up for a scratch one of his horses got from our mud guard.”

“I sometimes think we might have come out of it better if we had given the hayseeder his ten,” said Jerry, reflectively. “It cost us fifteen for the speed-fine as it was. We’d have saved five.”

“And is that what your father was asking about?” asked Bob.

“Words to that effect—yes,” replied Ned.

“Wonder how he heard about it?”

“It wasn’t in the paper,” reflected Jerry. “I looked all over for an account of it, but didn’t see any.”

“No, it wasn’t in the paper,” said Ned, “but dad hears of more things than I think he does, I guess.”

“We have been speeding it up a bit lately,” observed Jerry in a reflective tone.

“Just a little,” admitted Ned, with a half smile.

The three chums were clean-cut, healthy-looking lads, and it needed but a glance into their clear faces to tell one that whatever “speeding” they had been doing was in a literal sense only, and was not in the way of dissipation. They were fun-loving youths, and, like all such, the excitement of the moment sometimes got the better of them.

“And so you think the conference may have something to do with us; is that it, Ned?” asked Jerry, after a moment or two of silence.

“I have an idea that way—yes, from what dad said, and from what he wanted to know about our future plans. We’re mixed up in it somehow, that’s as sure as turkey and cranberry sauce.”

“That sounds like Chunky!” laughed Jerry.

“Well, what’s the idea?” demanded the stout[8] youth. “I mean—what do you think will happen, Ned?”

“Well, you know we have been going a pretty lively gait lately, nothing wrong, of course, but a sort of butterfly existence, so to speak.”

“Butterfly is good!” exclaimed Jerry. “You’d think we were a trio of society girls.”

“Well, I mean we haven’t really done anything worth while,” went on Ned. “And it’s my idea that my dad, and yours, Bob, and Jerry’s mother, who is as good a dad as any fellow could want—I think they are going to put the brakes on us.”

“How do you mean?” Jerry demanded.

“Oh, make us cut out some of the gay and carefree life we’ve been living. Settle down and——”

“Get married?” laughed Jerry.

“Not much!” cried Bob. “Not if I can help it!”

“Of course not,” put in Ned. “I mean just settle down a bit, that’s all.”

They swung around a curve in the road, and as they did so they saw a powerful roadster coming toward them, driven by a man who was the sole occupant. He was speeding forward at a fast clip.

“That fellow had better settle down!” exclaimed Jerry. “He’s going too fast to make this turn, and this bank is one of the most dangerous around here.”

The boys themselves had safely taken the turn, and come past the steep embankment on which it bordered, but the man in the roadster was approaching it.

“He isn’t slowing down,” said Ned.

“Better yell at him,” suggested Bob. “Maybe he doesn’t know the road.”

“Look out for that turn!” cried Jerry, as the man passed them.

It is doubtful if he heard them. Certainly he did not heed, for he swung around the turn at full speed. A moment later the boys, who had drawn to one side of the road, in order to give the man plenty of room to pass, looked back.

They saw the speeding roadster leave the highway and plunge down the bank, turning over and pinning the driver underneath.

“There he goes!” cried Jerry, jamming on the brakes.

Jerry had put on the brakes so hard that the rear wheels were locked, and they slid along a foot or more, skidding until the automobile came to a stop on one side of the road. Then the three lads leaped out, and started back toward the scene of the accident.

“She’s on fire!” cried Bob, as he pointed to curling smoke arising from the overturned roadster.

“And the man’s under it!” yelled Ned.

“Keep moving!” shouted Jerry. “We’ve got to do something!”

Fortunately, the car was a light one, and it was tilted at such an angle that the combined strength of the three lads on the higher side served to turn it upright once more. The fire was under the bonnet, the covers of which were jammed and bent.

The boys had expected to find a very seriously injured man beneath the car, but, to their surprise, when they righted the machine, the driver,[11] somewhat dusty and dirty, crawled out and stood up, a few scratches on his hands and face alone showing where he was injured, though it was evident from the manner in which he rubbed one arm that it had been at least bruised.

There came a larger puff of smoke from beneath the car’s bonnet, and a flash of flame showed.

“Carburetor’s on fire!” cried Ned.

“Got an extinguisher?” asked Jerry of the man.

He shook his head, being either too much out of breath or too excited over his narrow escape to talk.

“I’ll get ours!” shouted Ned, as he raced back toward their machine, climbing up the bank, down which the boys had rushed to the rescue.

Jerry and Bob forced up the bent and jammed covers of the engine, and disclosed the fact that the fire, so far, was only in the carburetor, which had become flooded with gasoline when the car turned over.

In a few seconds Ned was back with the extinguisher, and when a generous supply of the chemicals it contained had been squirted on the blazing gasoline, the fire went out with a smudge of smoke.

“That was a narrow escape for me, boys,” said the man, and his voice shook a little. “I thought[12] sure I was done for when I felt the car leaving the road. I tried to bring it back, but the turn was too much for me, and over I went.”

“This is a dangerous turn,” commented Jerry. “There ought to be a warning sign put up here.”

“We called to you,” Bob told him.

“I didn’t hear you,” the man said. “Boys, I want to thank you!”

He seemed overcome for a moment. Then he went on.

“Mere thanks, of course, do not express what I mean. You saved my life. I don’t believe I could have gotten out of the car alone. My legs were held down, and so was one arm. I’d have burned to death if you hadn’t been here.”

“Well, we’re glad we were here,” Jerry said. “Are you much hurt?”

“Nothing worth speaking about. Some bruises and scratches. I certainly did have a lucky escape. My name is Hobson—Samuel Hobson,” and he drew a card from his pocket, handing it to Jerry. “I was driving a bit too fast, I guess, but I was in a hurry to get the express at Wrightville. I’m on my way West, on important business, and the only way to make connections is to go to Wrightville to get the fast train. So I started in my car, intending to leave it at the garage in Wrightville. I’m afraid I’ll miss the train now.”

“Oh, I guess you’ve got time to make it,” said Jerry, with a look at his watch. “Wrightville is only three miles from here. But I’m afraid you can’t make it in your car.”

“I guess you’ve said it,” admitted Mr. Hobson, after a quick inspection. “I can’t run my car until it’s been in the repair shop. It’ll be hard to get it back on the road, too,” he went on, as he looked at the steep bank down which he had rolled in the machine. “And I must get that train!” he exclaimed anxiously.

“I reckon we can get you to the train all right in our car,” said Bob. “We’re not in any special hurry—only out for a little ride. We’ll take you to the station.”

“Surely!” added Jerry. “If you feel well enough to take the ride.”

“Oh, I’m all right!” protested Mr. Hobson. “I had presence of mind enough to get out of the way of the steering wheel as I felt myself going over. I’ll be very much obliged if you will take me to the depot. It is extremely important that I get my train for the West. But about my car—I’ll have to leave it here, I guess.”

“Nobody can run it, that’s sure,” Ned remarked. “And if you were going to leave it at the garage in Wrightville you could tell the man there to come out here and get it, and tow it in for repairs.”

“That’s so, I could do that,” admitted Mr. Hobson. “I don’t know that I’ll have time, if I make my train, to tell the garage people, though.”

“We can do that for you,” offered Jerry. “We’ll tell the garage man after we leave you at the depot.”

“Will you, boys? I’ll be a thousand times obliged to you if you will! I wouldn’t miss that train for a good deal. Just tell the garage man to come and get my car. I’ll settle all expenses with him when I come back, which will be in a couple of weeks.

“And now, if you don’t mind, I’ll get in your car and let you take me to Wrightville. It’s very kind of you. I thought I was in for a streak of bad luck when my machine went over with me, but this seems to be a turn for the better.”

Leaving the wrecked car where it was, Jerry and his chums went back to their machine with Mr. Hobson, giving their names on the way. It was a short run to Wrightville, but Mr. Hobson, who did not have any too much time to begin with, only just made the train as it was.

“Good-bye, boys!” he called, as he swung aboard the express, waving his hand to them. “See you again some time, I hope.”

And it was under rather strange circumstances when Mr. Hobson once more confronted our heroes.

“Well, now to tell the garage man, and then for the eats!” exclaimed Bob as they rode away from the railroad station. “I’ve got more of an appetite than ever. That little excitement seemed to make me hungry.”

“It doesn’t take much to make you hungry,” commented Jerry. “But we might as well eat here as to go on to Wallace’s. That would take half an hour.”

“Yes, let’s eat here,” acquiesced Chunky, and Ned assenting, that plan was agreed upon.

“Mr. Hobson? Oh, yes, I know him,” the garage man said when the story of the wrecked car had been told. “He often passes through here. Just leave it to me. I’ll go out and get his machine, tow it in and fix it up. I know the place all right. That sure is a bad turn. I guess he never had been on that road before. But I’ll get his car right away.”

“Then we can eat,” said Bob, with a sigh of relief.

While the three boys were making for a restaurant, there was taking place back in Jerry’s home the family conference, the knowledge of which had, in a measure, rather disturbed the three chums. For though they knew that it was going on, they could only guess at the object, which seemed to be rather important.

And, in a sense, it was.

That morning Mr. Aaron Slade, the head of the largest department store in Cresville, a town not far from Boston, had called on Mr. Andrew Baker, the banker.

“Andrew,” Mr. Slade had said (for he and the banker were old friends), “what are we going to do with our boys?”

“That’s just the question which has been puzzling me,” said Mr. Baker.

“They are the finest fellows in the world,” went on Mr. Slade, “and so is their chum, Jerry Hopkins. But, to tell you the truth, Andrew, I’m a bit worried about Ned.”

“And I am about Bob. Not that he’s done anything wrong, but he is getting too wild. I’m afraid they’ve been allowed too much freedom, what with their auto, their motor boat, and airship. I thought, at the time, it was good for them to go off by themselves, and learn to depend on their own efforts, as they certainly did many times. But now I’m beginning to think differently.”

“So am I,” admitted his friend. “Take that little incident last week—I was telling you about it, I guess—how they raced with some fellow on the road, and nearly collided with a hay wagon.”

“Yes, I heard about it. Well, boys will be boys, I suppose, but I’ve made up my mind that mine will have to settle down a little more.”

“The same here. But how can we do it?”

For a moment the two business men remained in thought. Then Mr. Slade said:

“I’ll tell you what we’d better do, Andrew. Let’s go and have a talk with Mrs. Hopkins. She’s one of the most capable, efficient and level-headed women I know. That’s one reason why I sold her some stock in my store. Her son Jerry is such a chum of our boys that I’ve no doubt she feels about as we do, for Jerry is into the same scrapes and fun that our boys get into. Let’s go and have a talk with Mrs. Hopkins.”

“I’m with you!” the banker exclaimed. “I’ll call her on the ’phone and see if it’s convenient for us to run out there.”

A few moments’ talk over the wire apprised Mrs. Hopkins of what was in the air, and she invited the two gentlemen to call.

That is the reason Mrs. Hopkins did not go motoring with Jerry. So Jerry took his two chums, who were made aware of the family conference in that fashion.

“Well, gentlemen,” said Mrs. Hopkins, when the matter had been fully explained to her, and Mr. Slade and Mr. Baker had each expressed the idea that their sons were in need of a little taming down, “I feel about it as you do. I wish Jerry were not quite so lively and fond of such exciting adventures. But now we have arrived at that decision, what’s to be done?”

“The very question I asked!” exclaimed Mr. Slade.

“Send ’em to college!” proposed Mr. Baker, after a moment’s thought. “A good, strict, up-to-date college is the place for them. They’d have to buckle down to hard work, but there would be enough of athletic sport to give them an outlet for their energies. Send the boys to college! How does that idea strike you?”

“It might be the very thing,” answered Mrs. Hopkins thoughtfully. “The boys have a pretty good education as it is from the Academy and from their private studies, but of late they have been allowed to run a little too freely. I should say college would be the best thing in the world for them. Some difficult studies would give their too active brains something more than adventures to feed on, and I have faith enough in the boys to be sure they would strive to do well—to excel in their studies as they have excelled in quests, races and other things in which they have taken part.”

“I am glad you agree with me,” said Mr. Baker. “How about you, Aaron?” and he looked across at Ned’s father.

“I’m of the same opinion,” was the answer.

“Good!” exclaimed Mr. Baker. “Well, now that is settled, which college shall it be? There are several good ones in this section of New England,[19] but the question is whether they are just those best fitted for our boys.”

“How about a military academy?” asked Mr. Slade. “They’d get good discipline there.”

Mrs. Hopkins shook her head.

“I haven’t a word to say against militarism, except that I think war a terrible thing,” she said. “I believe in preparedness, too, but I don’t fancy a military school for Jerry. I’m afraid there would be a little too much discipline at first, when the boys have been used to so little.”

“Perhaps you are right,” said Mr. Slade. “I am not very much in favor of it myself.”

Several colleges were mentioned at the family conference, but nothing definite was decided on, and it was agreed to meet again in a day or so. Meanwhile the catalogues of several institutions could be sent for to judge which college would be best suited to the boys.

“A very capable woman,” commented Mr. Slade, as he and his friend left Mrs. Hopkins’s house.

“Very. And I am glad we have come to this decision about our boys.”

“So am I. I wonder how the boys will take it.”

“It’s hard to tell. We won’t say anything to them about it for a while.”

“No,” agreed Mr. Slade.

“Well, I feel better,” announced Bob Baker, with a satisfied sigh as he arose from the restaurant table.

“I should think you would!” commented Jerry. “You ate as much as the two of us,” and he nodded at Ned.

“I did not!” cried the indignant Chunky. “I’ll leave it to the waiter.”

“Oh, don’t call public attention to a thing like that,” put in Ned. “Let it go. Come on out and finish our ride. It’s too nice to be staying inside, even in a restaurant.”

It was a beautiful fall day. The fierceness of the summer heat had gone, but the tang of late fall had not yet come, and it was perfect weather for automobile riding.

Jerry and his chums were soon in the car once more, this time Ned taking the wheel. They drove out past the place where Mr. Hobson had met with his accident—an accident with a most fortunate outcome—and there the boys saw some[21] men from the garage engaged in pulling the disabled car up the bank.

“That was some tumble!” called one of the men, as the boys paused to look on.

“You’d have thought so if you’d seen it,” agreed Jerry.

It was just getting dusk when the three lads reached Jerry’s home.

“I’ll drive you chaps home, and put up the car,” he said, for the automobile, though owned jointly by the lads, was kept in a garage owned by Mrs. Hopkins.

“What are you going to do to-night?” asked Ned, as he was set down at his residence.

“Nothing special,” Jerry replied.

“Let’s go to the movies,” suggested Bob. “They’ve got some Southern travel scenes, according to the bills outside, and if we go down South this winter we may see some of the places where we expect to be thrown on the screen.”

“I’d just as soon,” agreed Jerry, and Ned nodded his assent.

“I’ll come over to your house, Ned, after supper,” Bob went on, “and Jerry can call there for us.”

“All right,” Jerry assented, and then he swung the car in the direction of his home.

“Did you have a nice ride?” his mother asked him.

“Fine!” he exclaimed. “Saved a man’s life, too!”

“More adventures!” Mrs. Hopkins exclaimed, thinking of the conference that afternoon.

“No, it was the other way around,” Jerry explained. “Mr. Hobson had the adventure, we just rescued him from it,” and he told of the overturned automobile.

“Such reckless driving!” his mother murmured. “I hope you boys don’t run your car so fast.”

“Oh, no!” exclaimed Jerry virtuously. “I wonder if she could have meant anything by that?” he asked himself as his mother went out of the room. “But I don’t believe she heard about that hay wagon. I hope not, anyhow.”

“Jerry! there’s a letter for you on the mantel,” his mother called back to him as she went upstairs.

“Wonder who it’s from,” mused the tall lad. It was in a long envelope, without any return designation, and Jerry’s name and address were typewritten, so he could not guess the sender, as he might have done had it been in script.

“Some advertisement,” the lad went on, somewhat disappointed, as he drew out a booklet. With it was a letter, and when Jerry had glanced at the signature, before reading the epistle, he cried in delight.

“Why, it’s from Professor Snodgrass! What in the world is he up to now?”

Readers of the former books of this series concerning Ned, Bob and Jerry (volumes which will be mentioned more at length later) will remember Professor Uriah Snodgrass, a most earnest scientist. His quest after rare bugs and queer animals furnished our heroes with more than one adventure, and took them into various queer places.

“Professor Snodgrass!” went on Jerry. “I haven’t heard from him in a long while. I wonder where he is now?”

A glance at the top of the letter showed him.

The epistle was dated from Fordham, a New England city, and at the top of the page, in embossed letters, was the name “Boxwood Hall.”

“Dear Jerry,” the letter read, “no doubt you will be surprised to hear that I have been appointed instructor of zoology, among other subjects, at Boxwood Hall.”

“Surprised is no name for it!” murmured Jerry, reading on.

“For some time the faculty has been trying to induce me to settle down here, but I have preferred to roam about, completing my collection of beetles. As that is about finished, I have decided to accept the chair here. It is an excellent college, and there are a number of fine students[24] here, but I shall miss the trips I used to take with you boys. Perhaps, though, during the vacations, I may be able to be with you for a time. I am making a collection of butterflies that are to be found in this section of New England. I have a number of fine specimens mounted, but as winter is approaching there will be little further chance to add to my collection until the spring.

“I am sending you one of the Boxwood Hall catalogues, thinking you may be interested in it. If you are ever in this neighborhood, please come to see me. I am sure you will like it here. I understand there are good football and baseball teams here, and if you get here this fall, on one of the many trips you take, you may see a good game. I don’t know much about such things myself. Please give my regards to your mother, and remember me to Ned and Bob.”

“Well, what do you know about that!” exclaimed Jerry. “Professor Snodgrass at Boxwood Hall! I’ve heard of that college, and it’s a good one. Well, I guess he’ll miss chasing around the country after bugs, but the college certainly has one good instructor! I must tell the boys.”

“Any news in your letter, Jerry?” asked Mrs. Hopkins at the supper table that evening.

“Professor Snodgrass has taken the chair of[25] zoology at Boxwood Hall,” he replied. And then Mrs. Hopkins was called to the telephone, so Jerry had no chance to mention the catalogue he had received.

A little later he went with his chums to the moving picture show, telling them the news of the professor. At Ned’s house, after the show, the boys looked at the catalogue, which contained many half-tone cuts of the college buildings and grounds.

“Seems to be a nice place all right,” commented Bob.

“Where is it?” asked Ned.

“It’s about a mile outside of Fordham,” said Jerry, who had glanced through the prospectus. “I didn’t know, before, what a large place Boxwood Hall was. See, it’s located right on Lake Carmona, and they have a boathouse on the college grounds. Lake Carmona is one of the prettiest in New England, they say, though I’ve never seen it.”

“I was at the upper end of it once,” Ned stated, “but I didn’t get near Boxwood. And so the dear old professor has settled down. Well, we sure did have good times with him!”

“That’s right!” agreed Jerry. “Maybe we’ll get a chance to run up and see him.”

“I hope so,” remarked Bob. “Look! Here’s the professor’s name in the list of the faculty,”[26] and he pointed it out in the catalogue. “He’s got half the letters of the alphabet after it, too.”

This was not strictly true, though Professor Snodgrass had received many degrees from prominent colleges for his scientific work. He had written several books, too, on various subjects connected with “bugology,” as the boys called it.

After some discussion of the new position which had been accepted by their friend, the professor, and some reminiscent talk of the times they had spent with him, Jerry and Bob went to their respective homes, agreeing to go for another automobile ride on the morrow.

“Well, what shall we do now?” asked Jerry of his chums one afternoon, several days after the receipt of the letter from Professor Snodgrass. “I don’t just fancy any more autoing for the present.”

“What’s the matter with a ride in the motor boat?” asked Bob, for the boys owned one. It was kept in the boathouse near the residence of Mrs. Hopkins.

“Suits me,” agreed Ned, while Bob began:

“We can drop down the river to Anderson’s place and——”

“Get something to eat,” cut in Jerry.

“I didn’t say so!” Bob cried.

“No, but you thought it all right. Come on.”

The boys started for Jerry’s home, and at the[27] foot of the long, green lawn that led up to the front porch Ned cried:

“I’ll race you to the front steps to see who pays for the ice cream sodas. Last man there pays!”

“All right!” assented Jerry.

“Give me a start,” begged Bob.

“Go on!” yelled Jerry. “You’re not so fat as all that. We start even.”

“I’m entitled to a handicap,” insisted Bob.

The boys were laughing and shouting, and making considerable noise.

Bob insisted that he would not race unless he was given the advantage he claimed because of his stoutness, and finally Ned and Jerry agreed, letting Bob have his “head start.”

“Are you ready?” yelled Jerry.

“Let her go!” shouted Ned.

“Go!” cried Bob, and the three lads raced toward the piazza.

Ned and Jerry cut down Bob’s lead in a short time, and Jerry, by reason of slightly longer legs, soon passed Ned. They all three approached the porch, Jerry and Bob reaching it at the same moment. They were both going so fast they could not stop, and a moment later Bob tripped and would have fallen had he not given a jump up in the air, and landed on the porch. Then he slipped, and fell with a bang, spinning along the[28] piazza floor, while Jerry and Ned, laughing and shouting, jumped up after him. Then, seizing him, one by each foot, they pulled him the length of the smooth porch, which had no railing.

“Whoop! That was some race!” yelled Ned.

“And I beat!” declared Bob.

“Go on! You did not! You were disqualified by falling!” declared Jerry. “I’m the champion!” and he executed a clog dance on the veranda.

At that moment the front door opened, and there stood Mrs. Hopkins, while behind her were Mr. Slade and Mr. Baker. Mrs. Hopkins did not smile, and there were rather serious expressions on the faces of the two gentlemen.

“Oh, was it you making all the noise, Jerry?” his mother asked.

“I guess we did our share,” admitted Ned, a little sheepishly.

“Come in, boys,” said Mr. Baker. “We have an announcement to make to you.”

“Looks as if something was up,” whispered Bob to Ned, as the three chums slid into the house.

“That’s what it does,” agreed Ned. “I guess Mrs. Hopkins thought we were making too much of a racket on her front stoop.”

“We did raise a sort of row,” commented Jerry, tossing his hat on a peg of the rack. “But mother doesn’t care an awful lot about that. She’s heard noise before. There’s something else in the wind, believe me!”

Mrs. Hopkins, with the fathers of Bob and Ned, had withdrawn from the hall into the library, where they could be heard in low-voiced conversation.

“I wonder what the game is,” came from Ned. “Another family conference! Did you know they were going to have it, Jerry?”

The tall lad shook his head.

“Unless it’s about us I can’t imagine what it’s for,” he said. “But I reckon it does concern us. Well, we’ll have to take our medicine, I suppose.”

“Come in, boys,” called Mrs. Hopkins. “What we have to say concerns you as much as it does us.”

Rather sheepishly Ned, Bob and Jerry filed into the library, and took seats. Mrs. Hopkins was seated at a table with her two guests, and on this there appeared to be a pile of books, over which a newspaper was thrown, as though to conceal them from view, temporarily at least.

“Seems to me you young men might be a little more quiet in approaching a lady’s house,” remarked Mr. Slade, looking at his son; and his voice was not as good-natured as usual.

“Oh, well, Dad,” came the response, “you see we just had a little race, to decide who’d buy the ice cream sodas, and we did make rather a strenuous finish of it, I guess.”

“I should say so!” exclaimed Mr. Baker, looking at his son. “I thought it was a mad-dog chase at least, banging up on the steps that way. But it only goes to show that it’s high time we took some action in your cases.”

“That’s right,” put in Mr. Slade, with a vigorous nod.

The three chums looked wonderingly at one another.

“Surely they can’t be going to punish us just for a little prank like that,” thought Jerry. His mother looked at him and smiled.

“Well, I don’t mind a little noise,” she said. “But I really think it is time something was done to subdue the lads a little. They are getting a bit too much out of hand.”

“We haven’t acted a bit too soon,” murmured Mr. Slade.

“I only hope it isn’t too late,” added the banker.

Once more the chums looked wonderingly at one another, and then Ned, addressing his father, burst out with:

“Say, Dad, what’s it all about, anyhow? What’s up? Are we on trial just because we made a racket over a foot race?”

“We’ll apologize to Mrs. Hopkins, if you want us to,” Bob said.

“Oh, no, my dear boy, no apology is required!” Jerry’s mother made haste to say. “While you did make considerable noise, that isn’t the reason we called you in to hear our decision about a certain matter. Of course the way you all acted just now bears out what we have been fearful of for some time back, and that is—perhaps one of you gentlemen can explain better than I,” she finished with a nod toward Mr. Baker and Mr. Slade.

There was a momentary hesitation on the part of each of them, while the looks of wonder, not unmixed with apprehension, deepened on the faces of the chums. Then Mr. Slade said:

“Well, boys, it amounts to this. For some time[32] we have been noticing your conduct. Not that you have done anything wrong or improper, but you haven’t done exactly what is right, either. You are getting on in years, in fact you are young men now, and boys no longer, so it is time you acted like young men.”

“If that race just now——” broke in Ned.

“Oh, it isn’t altogether that!” his father made haste to say. “That is only one straw that shows which way the wind is blowing. You are entirely too frivolous, and when I say that I include you, Jerry, and you, Bob, with the permission of your parents.”

“Yes, I agreed with Mr. Slade,” murmured Mrs. Hopkins.

“And I,” added the banker.

“So we have called you in to acquaint you with our decision,” the department store proprietor went on. “And I want to say that we did not arrive at it hastily. We have had several conferences on the matter, as we wanted to be fair and just to all of you, and we wanted to do our duty. Now perhaps you have something to say, Mr. Baker, before we tell the boys what is in store for them.”

“Looks serious,” Jerry formed the words with his lips to Ned, but did not emit a whisper.

Ned nodded gloomily.

“Well, Aaron, you’ve said about all there is to[33] say on the subject,” began the banker slowly. “I might add that I think our boys have had plenty of good times and strenuous adventures. There can be no complaint on their part about that. And, boys, I want to say that you must now settle down and prepare to make real men of yourselves. You are boys no longer—you must prepare to accept the responsibilities of life. Have you anything to add, Mrs. Hopkins?”

“Nothing except that I fully agree with you gentlemen. And I think what we are about to do will be for the best interests of all of us, especially of our boys. We are proud of them in spite of the fact that they are sometimes a little too careless, and we want to continue to be proud of you, boys. Tell them what we have decided to do, Mr. Slade.”

“It is this,” said the department store keeper, as he removed the newspaper from the pile of books, or rather, pamphlets. “We are going to send you boys to some college or military academy, where, under stricter discipline than any to which you have hitherto been subjected, you will be able to develop your characters.”

“Sent away to college!” exclaimed Jerry.

“Military academy!” echoed Bob.

“Strict discipline!” murmured Ned.

There was silence for a moment, and then Mr. Baker went on:

“That is the conclusion we have arrived at after giving the matter serious thought. It will be the best thing in the world for you young men—boys no longer—to go away to some college. You will have regular hours and regular studies, which you have not had in the past two years. Not that you are backward, for you have kept yourselves well informed, and your travels have been helpful, in a measure. But you need regularity, and you are going to get it.

“Now we have here,” he went on, “catalogues from several institutions of learning. They are all good, as far as we can tell, and any one of them would suit me as a place for my boy. We have not quite made up our minds which one to choose. We want you all to go to the same one.”

“I should say, yes!” cried Jerry.

“We don’t want to be impertinent,” added Ned, “but we couldn’t think of going to separate colleges. We must be together.”

“Sure!” echoed Bob.

“Well, we are very glad we can give in to you on that point,” said Mr. Slade, smiling.

“Now we will proceed to the further discussion, which you interrupted with your strenuous foot race,” said Mr. Baker, “and we will let you help us decide which college you will attend. Now here is a catalogue that interests me,” and he held up one of a well-known college.

There was quite a lengthy discussion, in which the boys joined, telling what they knew, or had heard, of certain institutions. Some they flatly refused to consider at all. Toward others they were more favorably inclined.

“Now here is one I should like to see you attend,” said Mr. Slade, holding up another prospectus. “It is——”

He was interrupted by an exclamation from Jerry, who rushed from the room.

“Why! what in the world is the matter with him?” asked Mrs. Hopkins in surprise.

No one answered, and before they could indulge in any speculation Jerry was back again, waving over his head a catalogue similar to those on the table.

“If we have to go to college,” he said, “and I guess we do, this is the one we’d like you to pick out—Boxwood Hall! Let us go there! It’s a dandy place, according to the catalogue, and it has a good standing from a scholastic and athletic standpoint. Let us go to Boxwood Hall, where our old friend, Professor Snodgrass, is a teacher.”

“Boxwood Hall?” murmured Mr. Slade, questioningly.

“Professor Snodgrass,” said Mr. Baker, reflectively.

“He sent me this catalogue,” Jerry went on, “though when I got it I hadn’t the least notion in[36] the world that I would go there. Let me read you the professor’s letter”; and this he did.

Mr. Slade picked up the Boxwood Hall catalogue and glanced at the illustrations of the various buildings.

“It looks like a nice place,” he said.

“It sure does!” exclaimed his son, looking over his father’s shoulder. “We would like it there.”

“And there are some well known names on the faculty, aside from that of Professor Snodgrass,” went on Mr. Slade.

“Professor Snodgrass,” murmured Mr. Baker. “He’s the scientist who so often went with you boys on your trips, gathering queer bugs and so on.”

“He’s the one!” Jerry remarked. “Say, fellows, will you ever forget the time he saw a bug on the railroad track, and almost got under the locomotive to capture the insect.”

“That’s right,” chorused Ned and Bob.

“That’s the one objection to Boxwood Hall,” resumed Mr. Baker. “I’m afraid instead of studying, you boys will be going off on bug-hunting trips with Professor Snodgrass. I guess we’d better decide on some other college.”

Blank looks replaced those of pleasant anticipation on the faces of Ned, Bob and Jerry. Slowly they glanced at one another, then Ned burst out with:

“Say, Dad, that’s all wrong! Don’t be so hard on us. If we have to go to college the best one in the world for us will be Boxwood Hall, because we’ll have such a good friend in Professor Snodgrass.”

“And we won’t go off bug hunting with him—at least not very often,” said Jerry. “We won’t have time, nor will he. And you can see by his letter that he’s done with bugs. He’s making a collection of butterflies now.”

“That’s just as bad,” said Mrs. Hopkins, with a smile at her son. “Butterflies will lead you farther afield.”

“There won’t be many more butterflies this year,” Ned remarked. “Though I suppose there may be a few late ones up around Fordham that the professor will bag in his net. But, really, we[38] won’t waste any time on them. Let us go to Boxwood Hall, and we’ll buckle down to hard study.”

“We can go in for athletics though; can’t we?” asked Bob. “They have a swell football eleven and a dandy baseball nine at Boxwood Hall.”

“Oh, we haven’t any objections to sports, if you don’t go in for them too heavily,” said Mr. Baker. “What do you say?” and he glanced at the department store proprietor and at Mrs. Hopkins. “Shall we let the boys have their way?”

“Let’s consider it farther,” suggested Mr. Slade. “We’ll write to—let me see—Dr. Anderson Cole is the college president,” he went on, referring to the catalogue. “We’ll write to him and see what sort of arrangements can be made.”

“We could start in with the fall term,” observed Jerry. “Boxwood doesn’t open as early as some of the other colleges.”

“We’ll see about it,” said his mother.

“I’ll write the letters,” offered the banker. “My stenographer isn’t overworked, and I will get her at them the first thing in the morning. And I guess that ends the conference, for the time being,” he concluded.

“Then may we go?” asked his son. “We are going out in the motor boat.”

“Yes, run along,” said Mrs. Hopkins. “Jerry, let Mr. Baker have the catalogue the professor sent. He’ll need to refer to it for his letters.”

A little later the three chums were hastening toward the house where their motor boat was kept.

“Say! won’t it be great if we can go to Boxwood?” exclaimed Bob.

“The finest thing ever!” declared Jerry. “It will do us good to see the professor again.”

“So that’s what all this confabbing business on the part of our respected parents was about,” commented Ned. “I hadn’t any idea it would turn out this way.”

“Nor I,” admitted Jerry. “I thought something was in the wind along the line of making us settle down, but I was afraid mother might be going to make me go to work. Not that I would mind work,” he made haste to add, “but I’m not quite ready for it.”

“I thought maybe they were going to take the car, the boat and the airship away from us,” observed Bob, for our heroes, as their friends who have read about them in previous books know, did have a fine airship, in which they had gone through many adventures.

“That would be a hardship,” said Jerry. “But going to college isn’t half bad. I’m glad they decided on it. I guess a little discipline and settling down will be good for all of us. It’s a lucky thing Professor Snodgrass sent me that catalogue. If I hadn’t had that to spring on ’em they might[40] have packed us off to some place where we wouldn’t have a friend to our names.”

“They may yet,” suggested Bob half gloomily. “They may decide against Boxwood Hall.”

“I don’t believe so,” remarked Jerry. “I sort of think they’re favorably disposed toward it, for it is a first-class place. And say! why, we can take our motor boat there!” he cried. “There’s Lake Carmona—a dandy place for a boat.”

“But it will soon be winter,” objected Ned, “and the lake will freeze over.”

“That’s all right,” declared Jerry. “It will be some time before freezing weather sets in, and there’ll be lots of time to take trips on the lake. We’ll have to store the boat over winter, of course, but she’ll be there in the spring. We’ll take the Neboje with us.”

The Neboje (the name being made up of the first two letters of Ned, Bob and Jerry) was a new craft. It was smaller than the last boat the boys had bought, and they often preferred it, as it was easier to handle. It was so arranged that they could sleep and cook on board, and make short cruises on lake or river.

“Sure, take the boat!” exclaimed Bob. “And why can’t we take the auto too?”

“We could, I guess,” conceded Jerry. “The only thing is, though, that the fellows at Boxwood may think we’re putting it on rather thick.”

“I guess not,” said Ned. “If we took our airship they might. But some of them are sure to have cars themselves, and with the lake so near it would be a wonder if there wasn’t one or two motor boats owned by the students. We’ll take her along.”

“That is, if we go,” observed Jerry with a smile.

“Oh, we’ll go!” declared Bob, as they reached the boathouse.

“Got enough gasoline?” asked Jerry, as he took the tarpaulin cover off the Neboje.

“Plenty,” announced Bob, looking at the gauge. “We’ll only go for a little run, as I want to get back in time for——”

“Grub!” broke in Ned with a laugh, and then he had to dodge the bailing sponge which the stout youth threw at his head.

Ned caught the sponge and threw it back at Bob, but with such poor aim that it struck Jerry in the face, and, being wet, it was not the most desirable object in the world to receive in that fashion.

“Here! What are you doing?” roared Jerry, wiping his dripping face. “I’ve had my bath this week. Cut out the rough stuff!”

“I didn’t mean that,” came from Ned. “It was Bob’s fault.”

“It was not! You threw it!”

“You chucked it first.”

“Well, I wouldn’t have if you hadn’t ragged me about my eating. And I wasn’t going to say anything about grub, either. I meant I wanted to get home early so I could talk more to dad about Boxwood Hall.”

“Go on! You’re going to see a girl!” scoffed Jerry.

Bob flared up again, but quiet was finally restored and, the boathouse doors having been thrown open, Ned pressed the button of the self-starter and the Neboje swung out into the river which ran near the Hopkins’ house.

As the chums, comfortably seated in their craft, were getting under way, they heard a hail.

“Hold on, boys—wait a minute—got something to tell you—don’t go away without me—it’s great news—come on back—slow down—turn off the gasoline—shut off the spark—swing her around—whoop!”

“No need to look to tell who that is,” Jerry remarked.

“Yes, it’s Andy Rush,” said Bob, as he glanced at a small and very much excited boy who was dancing about on the dock.

“Come back and get me!” he begged.

“Shall we?” asked Ned, who was steering.

“Oh, yes, I guess so,” assented Jerry. “Andy’s all right if he does talk like a gasoline motor.”

“I wonder what news he has,” ventured Bob.

Ned swung the boat about, and Andy, whom my older readers will remember, got aboard. He was panting from his rapid-fire talk.

“What’s the news?” asked Bob.

“It’s about Noddy Nixon,” said Andy Rush, when he had gotten back his breath.

“Then it isn’t good news,” averred Jerry, for in the past Noddy had made much trouble for the three chums.

“No, it isn’t good news,” said Andy. “He’s hurt somewhere out West. He ran his automobile into another one, and now he’s in a hospital.”

“Well, I don’t wish Noddy any bad luck, for all he did us several mean turns,” remarked Jerry. “But he never did know how to handle a car—he was too reckless. Is he badly hurt, Andy?”

“Well, he won’t die, but it will be a good while before he’ll be well. A friend of my mother’s, who lives out West, wrote her about Noddy, knowing he used to live here.”

“I hope he never comes back here to live,” Ned remarked. “We can easily get along without him.”

“So say we all of us!” chimed in Bob.

The boys enjoyed the little motor boat trip, though Andy Rush, as usual, talked so much and so fast that Jerry said he gave him a headache.

“Here, earn your passage,” the tall youth finally[44] cried. “Polish some of the brass rail. That will give you a safety-valve,” and Andy, perforce, had to obey.

It was several days after this that Bob Baker came hurrying over to the Hopkins house.

“Good news!” cried the stout youth.

“What about?” asked Jerry.

“Dad has had a letter from President Cole, of Boxwood Hall, and everything is so satisfactory that dad has decided I am to go there. Hurrah!”

“Hurrah yourself!” retorted Jerry. “What about Ned and me?”

“It’s all right. I just left Ned, and his father says if Mr. Baker is satisfied he’ll be, so Ned can go. It rests with your mother whether you can, Jerry.”

“Oh, I’m sure mother will say yes! I’ll tell her! Say! this is great—all three of us to go to Boxwood Hall! Wow!” and Jerry did a clog dance that brought his mother to the door of her room to learn the cause of the excitement.

She readily gave her consent to the Boxwood Hall project for Jerry, and later that day there was another conference of the parents. There had been considerable correspondence between Mr. Baker and President Cole, and the banker was more than satisfied with the showing made by the college.

“I think it will be just the place for the boys,”[45] he declared, “and I will write to President Cole, informing him they will be on hand soon after, if not at, the opening of the fall term. We shall have to get them ready, I suppose.”

“That won’t take long,” Jerry said. “Now I’ll write to Professor Snodgrass, and tell him we’ll soon be with him.”

Thus the matter was decided. The names of Ned, Bob and Jerry were formally entered for admission to Boxwood Hall, and their standing in their studies was such that they had to take but few examinations.

In the letter to Professor Snodgrass Jerry explained how it had all come about, and he thanked the little scientist for having sent the catalogue.

“Only for that,” Jerry wrote, “we might have been packed off to some place where we wouldn’t have liked it at all. I’m afraid we won’t get a chance to go hunting butterflies with you, much as we would like it.”

In reply Jerry had another letter from the bug-collector. Professor Snodgrass wrote that there would be plenty of chance for him to have outings with the boys.

“That’s fine!” cried Jerry. “Hurrah for Boxwood Hall!”

And his chums echoed the exultant cry.

Imagine a great, green, grassy bowl, nestled snugly amid a succession of green hills, set, more or less regularly, in a circle. And at the bottom of the great, green, grassy bowl, which is miles across, imagine further a silvery sheet, irregular in outline and sparkling in the sun.

Up on one of the sides of the green, grassy bowl, where it leveled out into a sort of plateau, is a group of dull, red buildings, their maroon color contrasting pleasingly with the emerald tint of the surroundings. Across the tip of another hill lay a country town, and from a vantage point one could see a railroad, like a shiny snake, winding its way up to the town, stopping there, in the shape of a station, and then going on across the valley.

The town is that of Fordham—a city some called it. It was in New England, about half way between Boston and New York. The green bowl was Fordham valley, and the shining, glittering[47] bottom of it was Lake Carmona, a beautiful sheet of water, some miles in extent.

The group of red buildings was Boxwood Hall with which we shall soon concern ourselves, and which was very much in the minds of Ned, Bob and Jerry at this moment, as it had been for some time. The college buildings were about a mile, or, say a mile and a half to be exact, from the Fordham railroad station, and were practically on the shore of Lake Carmona, for the college owned the land running down to the lake, and had on it a boathouse and a dock. But the buildings themselves lay back a quarter of a mile from the water, and this quarter of a mile, somewhat less in width, formed the college campus—one not surpassed anywhere.

Upon this campus, strolling about here and there this fine fall day, was a group of lads attired in the more or less exaggerated costumes effected by college youth the world over.

“Say, fellows, I’ve got news for you!” cried Frank Watson, who, as one could tell by the manner he used toward some of the other students, was a sophomore. “Great news! Come here, Bill Hamilton—Bart Haley—you too, Sid Lenton and Jim Blake. Come here and listen to me.”

“What’s the matter now?” asked Bill Hamilton, a flashily dressed lad. “Has some one left you money?”

“I wish some one had,” remarked Frank.

“Same here,” drawled Bart Haley. “I never knew how much a fellow could spend until I came here. I’m up against it hard!”

“No, it isn’t money,” remarked Frank. “It’s worse than that. What do you know about this. There’s a bunch of new fellows coming here in a week or so, and they’re about the limit—or at least I think they’ll be that.”

“What do you mean?” asked Bart, slightly interested.

“This. There are three fellows coming into the freshman class. And from what I hear they have been around pretty much, so they’ll probably be fresher than usual and will try to run things here to suit themselves. The know-it-all class, so to speak.”

“Who are they?” asked Bart.

“How’d you hear about this?” demanded Sid Lenton.

“They are—let me see. I jotted down their names so’s we’d have ’em handy to use in case we had to. Here they are—Jerry Hopkins, Bob Baker and Ned Slade. They’re from Cresville, and they’re going to bring their auto with them. Fawncy now!” and Frank assumed a mocking air and tone.

“I asked you how you heard it,” came from Sid again.

“Professor Snodgrass told me. He’s a friend of theirs, it seems, and he sent one of them a college catalogue. That’s how they came to be wished on to us. It seems that Professor Snodgrass, who isn’t a bad sort by the way, used to travel about with the Motor Boys, as their friends at home call them,” said Frank, sarcastically.

“Motor boys?” repeated Bart Haley.

“Yes, that’s what they used to call themselves. Think of that—motor boys!”

“Why was that?” asked Sid.

“Oh, because they did a lot of motoring. Had motor cycles first, it appears, then they got an auto, then a motor boat, and then they even had a submarine!”

“Get out! You’re stringing us!” cried several.

“No, it’s straight!” declared Frank. He sat down on the grass and continued: “Why, some fellow even wrote a book—two or three of them I guess—about these same motor boys. When Professor Snodgrass told me they were coming here I pumped him for all he was worth. Thinks I to myself, if we’re going to have fellows like that here, who sure will try to walk over us, the more I know about them the better.

“So he told me all he knew, which was a lot. It seems he used to go off on bug-hunting expeditions with them in the auto, the boat or the airship.”

“Airship!” cried Jim Blake. “You don’t mean to say they had an airship, do you?”

“That’s what the professor said.”

“Oh, he’s daffy! I’ll never believe that. They may have had an auto and a motor boat—I’ve got one of them myself,” said Bill Hamilton. “But an airship—never!”

“Well, we’ll find out about that later,” declared Frank. “Anyhow, some fellow did write about the motor boys. He made up a story of how they went overland, and even down into Mexico.”

“Mexico!” exclaimed Harry French.

“Yes, Mexico. And there they discovered a buried city, or something like that. The professor made a big find there—some new kind of bug I guess. And then there’s a book telling how these motor boys went across the plains, and how they first went cruising in their motor boat. They were on the Atlantic, on the Pacific, and in the strange waters of the Florida Everglades. Some trip, believe me!”

“Do you s’pose it’s all true?” some one asked.

“The professor says so, and you know what a stickler he is,” responded Frank.

“Well, if that’s the case, these fellows sure will try to put it all over us,” declared Sid.

“They may try, but they won’t succeed,” declared Frank, and there was a vindictive ring to his voice. “But this isn’t all. Ned, Bob and[51] Jerry—the motor boys—did go above the clouds in some sort of motor ship, according to the professor. They went across the Rockies, and out over the ocean. Then they went after some kind of a fortune, and even helped capture some Canadian smugglers up on the border. And it’s all in books, too.

“And, as I said, according to Mr. Snodgrass, these lads went down in a submarine. I didn’t believe that at first, but he told me of the things he saw and the specimens he caught, so I guess it’s true enough.

“Now they’re coming here. They got back from a long trip on road and river just before Professor Snodgrass came here to teach, and they had such lively times that their folks packed them here for us to look after,” and Frank grinned.

“Oh, we’ll look after ’em all right!” cried Sid.

“That’s what we will,” added Bart Haley.

“If they try to run things here they’ll find that they’re running themselves into the ground,” declared Jake Porter.

The group of students around Frank nodded assent. The boys were, as has been said, sophomores, and most of them were on the baseball nine.

“I wonder if they’ll go out for football?” asked Ted Newton, captain of the eleven. “We need some good material.”

“You wouldn’t have new fellows—butters-in like these three—on the team; would you?” asked Frank.

“Well, they’d be eligible for the varsity under the rules here, which are different from those of most colleges. I wouldn’t turn any fellow down just because he’d had some adventures. Cracky! I’d like a taste of them myself!”

“I tell you these motor boys will be impossible!” cried Frank. “You’ll see! They’ll think they’re the whole show, and that we don’t amount to anything. We can haze them and then we can sit on ’em good and proper, and that’s what I say let’s do!”

“I’m with you,” drawled Bill Hamilton.

“Are they rich?” asked Sid.

“I s’pose they are,” admitted Frank, “or they couldn’t afford to do all they have done. But that won’t make any difference to me. I’m going to snub ’em and sit on ’em, for they’ll be sure to try to run things.”

“That’s right!” agreed some of his cronies. “We’ll show these motor boys a thing or two at Boxwood!”

Thus, without having seen our heroes, the coterie led by Frank Watson decided on a verdict against them—a verdict that was destined to cause no end of trouble.

Ned, Bob and Jerry were not able to enter Boxwood Hall the first week of the fall term. They had expected to, and had begun to prepare for that. But some minor difficulties cropped up in regard to their entrance examinations, and they were obliged to pass certain tests which were arranged for by President Cole with the principal of the Cresville Academy, where the boys had been in attendance.

Finally, their previous work in their studies was found to be satisfactory, and, as Frank Watson informed his chums, the three chums were to enter the freshman class.

While the boys were busy with their examinations, their parents—the mothers especially—were busy preparing their sons’ outfits.

“It’s worse than when we went overland,” complained Ned, when he had been obliged to pass judgment on suits, caps, underwear and other wearing apparel—the outfit he was to take to college with him.

“Oh, well, it’ll soon be over,” was Jerry’s consoling suggestion.

“The worst of it is,” said Bob, “we may be all out of date with our clothes when we get to Boxwood and see what the fellows there are wearing. We may have to get a lot of new things.”

“Nothing more than a cap or two, I guess,” Jerry said. “We’ll wait about them until we get there, and find out what kind the fellows are sporting. We’ll wear our auto caps until then.”

“Auto caps!” cried Bob. “They won’t look good in the train.”

“Who said anything about a train?” asked Jerry.

“Why, aren’t we going to Fordham by train?”

“Didn’t you tell him about it?” asked the tall lad of Ned.

“No, Jerry, I forgot.”

“What’s the game?” inquired Bob.

“Why, Ned and I talked it over,” said Jerry, “and we decided it would be a good stunt, as long as we’re going to take our car to college with us, to motor down in it instead of going by train. I supposed he had told you, but I guess there was so much going on that he forgot about it.”

“That’s right,” affirmed Ned.

“Motor down!” Bob exclaimed. “That will be swell! We can do it easily in a day, and we can take along our——”

“Lunch!” cut in Ned, taking care to have Jerry between him and Bob.

“Oh, you make me tired!” exclaimed the stout lad. “I was going to say take our trunks along, and save a lot of bother with the expressman.”

“That’s so,” Jerry said. “Let Chunky alone, Ned. He’s all right, even if he does eat five times a day.”

“Now you’re picking on me!” laughed Bob. “Well, go as far as you like, I can stand it if you can.”

“Say, I’ll tell you what we might do,” cried Ned, as he and his chums got into their car for a spin out into the country, as it was a day or so yet before they would depart for Boxwood Hall.

“What?” asked Jerry.

“We might write to Professor Snodgrass, and ask him what sort of duds the fellows wear there. Then we’d know what to get and save doubling up.”

“Do you mean that?” asked Jerry, with a queer look at his chum.

“Of course I do. Why not?”

“You ought to know the professor by this time,” remarked the tall lad with a laugh. “He doesn’t know any more about clothes than a bat!”

“I should say not!” chimed in Bob, who was, as his friends said, “some nifty little dresser.” “The professor would get styles all mixed up with[56] his bugs and butterflies,” went on the stout lad. “He’d tell us that the fellows were wearing sweaters with double-jointed legs, and trousers with stripes running around them like that queer beetle he got when we were down in Mexico. He’d have just about that much idea of what we wanted to know.”

“I guess you’re right,” assented Ned. “I didn’t think about that. We’ll just settle the clothes question when we get there.”

They motored along a pleasant country road, talking of many things, but chiefly of their coming stay at Boxwood Hall, and what they would do when they got there.

“I hope we can room together,” said Ned.

“We’ll have connecting rooms,” Jerry said. “Mother wrote to the matron, a Mrs. Eastman, and she wrote back that there were three nice rooms in the main dormitory of Borton we could have. So mother clinched them for us. Mother’s a bit fussy about rooms, and I guess I’m glad she is.”

“Say, that will be swell all right!” exclaimed Bob.

“All to the merry!” chimed in Ned.

A little farther along they passed the place where they had put out the automobile fire some time previously.

“I wonder what ever became of Mr. Hobson—was[57] that his name, the fellow we saved?” asked Ned, musingly.

“That was it—Samuel Hobson,” affirmed Jerry. “Didn’t I tell you I had a card from him?”

“No,” replied his chums.

“Well, I had. A souvenir card from San Francisco. He’s out there on business, but expects to come East again. He said he’d write a letter when he had time. Sent his regards to all of you.”

“It’s a wonder he wouldn’t drop us a line,” grumbled Bob.

“He apologized for that,” explained Jerry. “Said he’d lost your addresses, and asked me to send them on.”

“Well, make mine Boxwood Hall,” said Ned.

“Same here,” came from Bob.

Several busy days followed in which last preparations were made. The boys’ plan to motor to Boxwood Hall was agreed to by the parents. As the car was a roomy one there was space in it for their trunks, as well as for themselves, and, thus taking their baggage, they would save themselves considerable trouble.

The boys had looked up the best route to take, and though the trip was something over a hundred and fifty miles, they figured that by making an early start they could reach the college in the late afternoon.

“And it’ll be a whole lot better than traveling in a stuffy train, fellows,” said Bob.

Professor Snodgrass had been written to again by the boys, who told of their automobile trip, and they mentioned the time they expected to arrive. In reply the little scientist said he would be on the lookout for them, and he again expressed his pleasure that they were going to be near him.

“He’s as jolly as a young fellow himself,” declared Jerry.

The morning for the start came, and after a substantial breakfast, at least on the part of Bob, our heroes took their places in the big touring car.

“Now boys,” said Mr. Slade, who, with Mr. Baker, had come to the home of Mrs. Hopkins to see the three off, “remember that you are not going to college for fun.”

“But we can have a little; can’t we, Dad?” asked Ned.

“Yes, of course. I want you all to have a good time within reason. But you must all buckle down to hard work too. As we said before, you’ve had more than your share of strenuous adventures. Leave some for the other fellows. You must prepare to take your places as men in the world soon, and a good education is the best preparation.”

“I agree with what Mr. Slade says,” added the banker. “We don’t want to be too preachy, but,[59] boys, dig in hard now, and let us all be proud of you.”

“I’m sure we shall be,” said Mrs. Hopkins, and there was a smile on her face, though she found it rather hard to let Jerry go for such a long time. Still he was used to being away from home, and his mother knew he could take care of himself, as could his chums.

Good-byes echoed and re-echoed as Jerry started the motor and, throwing in the gears, let the clutch slip into place. Hands were waved, and then our three heroes swung down the road on their way to college. It was a momentous occasion for them.

“Good-bye, fellows—wish I were going—don’t forget to write—send me tickets—football game—maybe I can come—it’ll be great—hope you play and win every game—good-bye!”

It was Andy Rush, of course, and the little chap ran alongside the automobile for a few feet as he delivered his rapid-fire remarks.

“I wonder what will happen to him when he goes to college,” mused Bob.

“He’ll have to dictate his recitations into a phonograph,” said Jerry, “and when the prof wants to listen he’ll have to run it at half speed, or he wouldn’t catch a word.”

“Oh well, Andy’s all right. He’s done us lots of good turns,” declared Ned.

“That’s right,” agreed his chums.

Little of incident marked their morning trip, save that Ned and Bob had a discussion as to which was the best place to eat, a dispute that ended when Jerry picked out an altogether different restaurant, and stopped the car in front of it.

After a brief rest they were on their way again. Now they were in unfamiliar country, and several times they had to stop to ask which road to take, as the road map seemed faulty.

“We’re not going to get there before dark at this rate,” said Bob, as he looked at his watch, and noted a sign-board which stated that Fordham was still many miles away.

“Oh, well, we’ve got good headlights,” Jerry said.

It clouded up about four o’clock, and at five was so dark that the headlights had to be set aglow. At a cross-road Jerry stopped the car.

“Hop out, Ned, and see which turn to take,” he said.

Ned, with a pocket flashlight, examined the board.

“Say, this is queer!” he exclaimed.

“What is?” asked Bob.

“Why, one of these roads goes to Lawrenceville and the other to Ogdenburg. We’ve come the wrong way, fellows. Fordham isn’t anywhere around here!”

Momentary silence followed the rather disconcerting remark made by Ned after his discovery. Then Jerry asked:

“Are you sure about that? Look around. Maybe there’s another sign-board somewhere else that gives information about Fordham.”

“This is the only one there is,” declared Ned, flashing his light about, “and it doesn’t intimate that such a place as Fordham even exists.”

“Then we must have come the wrong road!” exclaimed Bob.

“Oh, fine! How’d you guess it? That’s a brilliant head you have!” said Ned, rather sarcastically.

“Well, it isn’t my fault,” observed Bob. “I wasn’t guiding the car.”

“No, I s’pose it’s up to me,” admitted Jerry. “Though I’m sure I took the turn that last fellow we asked told us to take.”

“Yes, you did all right,” agreed Ned. “It was that farmer who misdirected us. I beg your pardon,[62] Bob, for jumping at you that way. But it makes me mad to think we’ve gotten on the wrong road, and we won’t get to Boxwood until after supper.”

“Getting hungry?” asked Jerry. “That’s Chunky’s role, you know.”

“Roll or bread—I’d be glad of either,” said Ned. “Yes, I am hungry. I didn’t eat as much lunch as you fellows did. Now go ahead, Bob, and lay it into me. I deserve it.”

Bob reached under the rear seat and held up a package.

“I’ll lay this into you, Ned,” he laughed.

“What is it?” asked the complaining one.

“Grub! Sandwiches, cake and so on.”

“Grub!” Jerry exclaimed. “Where’d you get it?”

“Oh, I had the waiter in the restaurant put it up for me. I thought we might get hungry before supper, but I didn’t think we would get lost. It’ll come in handy, won’t it?”

“It’ll come in stomachicly, to coin a new word,” declared Ned. “Chunky, if ever I say anything again about your eats, just you remind me of this occasion.”

“All right,” agreed the stout youth.

“Well, we won’t starve, that’s sure,” Jerry said. “But the question is which road are we to take?”

“Neither one of these, I vote,” said Bob. “They don’t go where we want to go. I say, let’s go back until we get to another cross highway, and that may have a sign on that we didn’t notice before which will direct us to Fordham.”

“I guess Bob’s right,” conceded Jerry. “Back we go.”

“And we can eat on the way,” Bob went on; and neither of his chums joked him this time.

Somewhat disappointed and chagrined at the outcome of their automobile trip, or rather, at the prospective outcome, the boys put back. They had counted on arriving at Boxwood Hall in some “style” with their big car. Not that the three chums cared so much about showing off, but they felt they had a right to make a certain impression, since, according to present plans, they were to remain at the college for some time.

But now they would arrive after dark, and they would be met by strange professors and college officials (all save Professor Snodgrass), they would be late for supper, and would have no chance to view the college until morning.

“Hang that farmer, anyhow!” murmured Jerry.

“I wish he had to go without his suppers for a week,” added Ned.

“Oh, we’re not so badly off,” declared Bob, as he was munching a sandwich.

“Bob wouldn’t want any one condemned to go without food,” said Jerry. “Well, I suppose it was my own fault in a way. I should have consulted the map after that fellow told us which turn to take. We’ll know better next time.”

“There’s a house,” remarked Ned. “Suppose we inquire there.”

“No!” decided Jerry. “That’s a farmer’s house, and I won’t trust any more farmers. I’ll go on back to the last turn we made. There’s a garage not far from there, and they’ll know the road, that’s sure.”

It was not a long ride back to the place where Jerry felt they had made the wrong turn, and a few minutes more took them to the garage. But it was now quite dark.

“Fordham—um, yes,” said the garage man, reflectively. “I should say you did take the wrong turn!”

“Well, please tell us how to take the right one,” begged Jerry.

“The right one happens to be a left one,” said the man with a laugh. Then he gave them the proper directions, and said they ought to be at Boxwood Hall in about an hour.

“Come on!” cried Ned, as they started away once more. “On with the dance!”

“Speaking of dances, I wonder if they ever have any at the college?” asked Bob, reflectively.

“Sure they do!” exclaimed Ned, who of late had taken up fox-trotting. “Didn’t the catalogue say that all proper facilities were given for the best social life. And what is social life, I’d like to know, without a dance now and then?”

“I guess you’ll get your share of it,” remarked Jerry, his eyes on the road ahead, for it was an unfamiliar one to him, and, though the garage man had said it was a fine, straight highway, Jerry was taking no chances. The powerful electric lights made a fine illumination far ahead.

Now it might have been reasonably expected that Fate, if you choose to call it such, having dealt our heroes one blow, would refrain from giving them another, at least for a while. But it was not to be.

About a half hour after having left the garage they came to an obstruction across the road. It was in the form of a big sawhorse such as is used in cities to block streets when repair work is being done. From the barrier hung a red lantern.

“Hello! What does this mean?” asked Jerry, bringing the car up with a screeching of brakes.

“Looks like danger,” observed Bob.

“There’s some kind of a sign,” said Ned. “I’ll get out and read it.”

With his pocket flashlight he inspected a placard that was tacked on the big sawhorse.