Title: The Social Life of the Blackfoot Indians

Author: Clark Wissler

Release date: December 17, 2015 [eBook #50706]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Larry Harrison, Cindy Beyer, Ross Cooling and

the online Project Gutenberg team at

http://www.pgdpcanada.net with images provided by The

Internet Archives-US

ANTHROPOLOGICAL PAPERS

OF THE

American Museum of Natural

History.

Vol. VII, Part I.

THE SOCIAL LIFE OF THE BLACKFOOT INDIANS.

BY

CLARK WISSLER.

NEW YORK:

Published by Order of the Trustees.

1911.

ANTHROPOLOGICAL PAPERS

OF THE

American Museum of Natural History

Vol. VII, Part I.

THE SOCIAL LIFE OF THE BLACKFOOT INDIANS.

By Clark Wissler.

Text Figures.

| 1. | Section of a decorated Tipi |

| 2. | Selected Figures from a decorated Tipi |

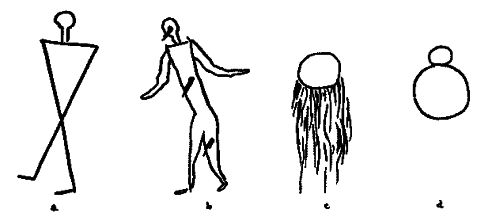

| 3. | Symbols used in War Records |

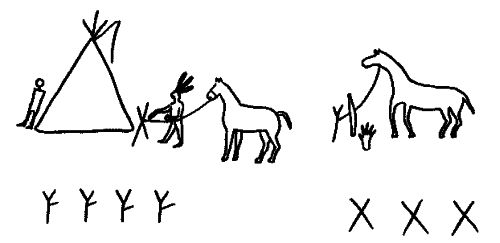

| 4. | Methods of recording the Capture of Horses |

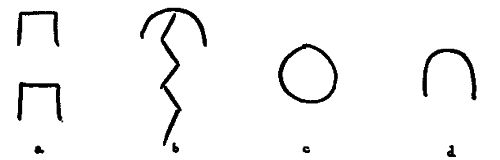

| 5. | Highly conventionalized Symbols |

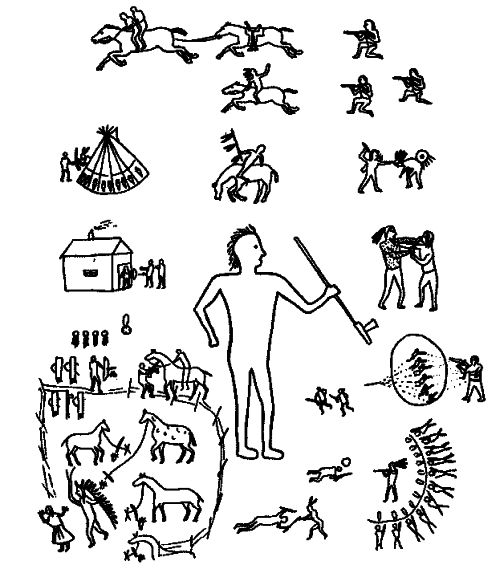

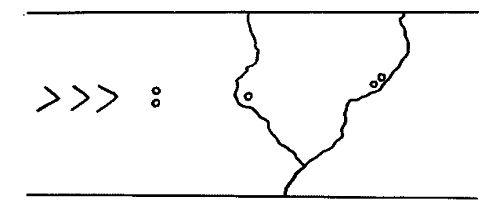

| 6. | A sand Map showing the Course of a War Party |

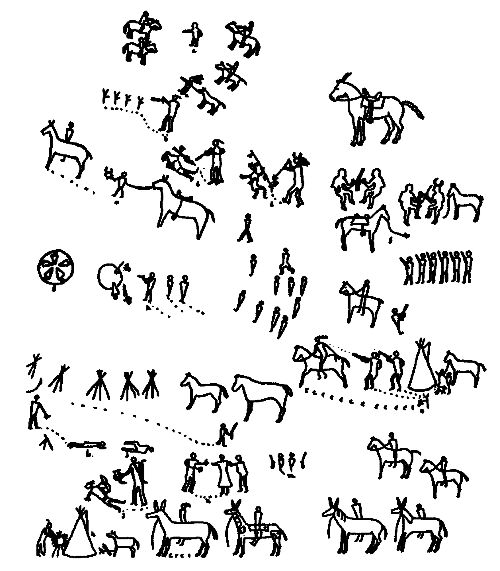

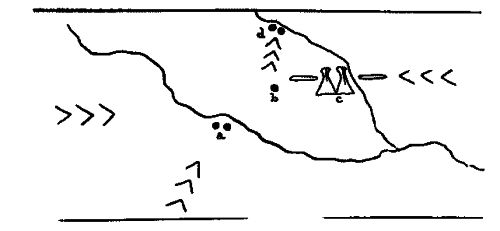

| 7. | Map recording a Battle |

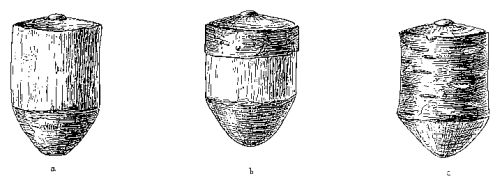

| 8. | Wooden Tops |

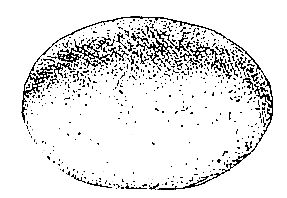

| 9. | A Stone Top |

| 10. | Top Whip with Lashes of Bark |

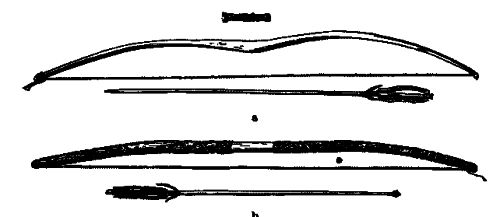

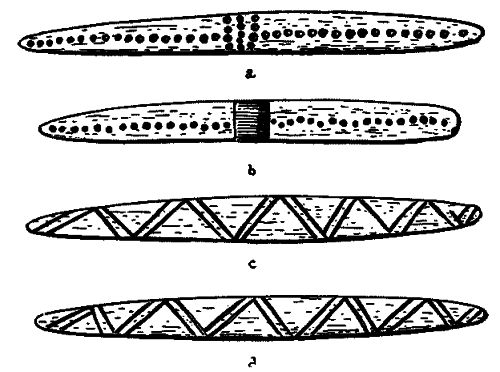

| 11. | Gaming Bows and Arrows |

| 12. | A Wooden Dart |

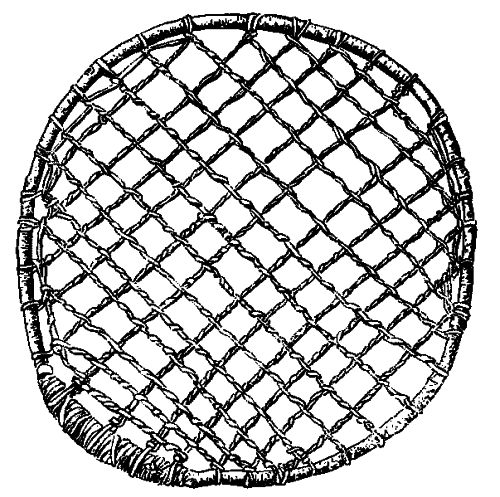

| 13. | The Wheel Game |

| 14. | A Shinny Stick |

| 15. | The Four-stick Game |

In this third paper on the ethnology of the Blackfoot Indians full recognition should again be given Mr. D. C. Duvall, with whose assistance the data were collected by the writer on a Museum expedition in 1906. Later, Mr. Duvall read the descriptive parts of the manuscript to well-informed Indians, recording their corrections and comments, the substance of which was incorporated in the final revision. Most of the data come from the Piegan division in Montana. For supplementary accounts of social customs the works of Henry, Maximilian, Grinnell, Maclean, and McClintock are especially worthy of consideration.

Since this paper is an integral part of an ethnographic survey in the Missouri-Saskatchewan area some general statements seem permissible for there is even yet a deep interest in the order of social grouping in different parts of the world and its assumed relation with exogamy, to the current discussion of which our presentation of the Blackfoot band system may perhaps contribute. We believe the facts indicate these bands to be social groups, or units, frequently formed and even now taking shape by division, segregation and union, in the main a physical grouping of individuals in adjustment to sociological and economic conditions. The readiness with which a Blackfoot changes his band and the unstable character of the band name and above all the band’s obvious function as a social and political unit, make it appear that its somewhat uncertain exogamous character is a mere coincidence. A satisfactory comparative view of social organization in this area must await the accumulation of more detailed information than is now available. A brief résumé may, however, serve to define some of the problems. Dr. Lowie’s investigation of the Assiniboine reveals band characteristics similar to those of the Blackfoot in so far as his informants gave evidence of no precise conscious relation between band affiliation and restrictions to marriage.[1] The Gros Ventre, according to Kroeber, are composed of bands in which descent is paternal and marriage forbidden within the bands of one’s father and mother, which has the appearance of a mere blood restriction.[2] The Arapaho bands, on the other hand, were merely divisions in which membership was inherited but did not affect marriage in any way.[3] The Crow, however, have not only exogamous bands but phratries. The Teton-Dakota so far as our own information goes, are like the Assiniboine. For the Western Cree we lack definite information but such as we have indicates a simple family group and blood restrictions to marriage. The following statement by Henry may be noted: “A Cree often finds difficulty in tracing out his grandfather, as they do not possess totems—that ready expedient among the Saulteurs. They have a certain way of distinguishing their families and tribes, but it is not nearly so accurate as that of the Saulteurs, and the second or third generation back seems often lost in oblivion.”[4] On the west, the Nez Perce seem innocent of anything like clans or gentes.[5] The Northern Shoshone seem not to have the formal bands of the Blackfoot and other tribes but to have recognized simple family groups.[6] The clan-like organizations of the Ojibway, Winnebago and some other Siouan groups and also the Caddoan groups on the eastern and southern borders of our area serve to sharpen the differentiation.

The names of Blackfoot bands are not animal terms but characterizations in no wise different from tribal names. Those of the Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Teton-Dakota are, so far as reported, essentially of the same class. It seems then that the name system for these bands is the same among these neighboring tribes of the area and that it is an integral part of the whole system of nomenclature for groups of individuals. This may be of no particular significance, yet it is difficult to see in it the ear marks of a broken-down clan organization; it looks for all the world like an economic or physical grouping of a growing population.

We have seen in the Blackfoot system the suggestion that the band circle or camp circle organization is in function a political and ceremonial adjunct and that the exogamous aspects of these bands were accidental. So far as we know this holds to a degree for other tribes using the band circle.[7]

It seems probable that many discussions of social phenomena could be expedited if clear distinctions were established between what is conventional and what is the result of specific functions and adaptations. Unfortunately, our ignorance of the processes involved and their seeming illusiveness of apprehension make such a result well-nigh hopeless. By the large, conventional things, or customs, appear to be products of ideation or thinking. Now a band circle is clearly a scheme, a conception, that may well have originated within the mental activities of a single individual, a true psychic accident. Indeed this is precisely what conventions seem to be—customs, procedures or orders that happen to become fixed. A band, on the other hand, is not so easily disposed of. The name itself implies something instinctive or physical, as a flock, a grove, etc. Something like this is seen in the ethnic grouping of the Dakota since we have the main group composed of two large divisions in one of which is the Teton, this again sub-divided among which we find the Ogalalla, and this in turn divided into camps, etc. Though detected by conventionalities of language this dividing and diffusing is largely physical, or at least an organic adjustment to environment. Then among the Ojibway we have a population widely scattered in physical groups but over and above all, seemingly independent, a clan system; the latter is certainly conventional, but the former, not. Now the Blackfoot band seems in genesis very much of a combined instinctive and physical grouping, in so far as it is largely a sexual group and adapted to economic conditions. In its relation to the band system of government and its exogamous tendency it is clearly conventional. What may be termed the conventional band system consists in a scheme for the tribal group designated as a band circle. This scheme once in force would perpetuate the band names and distinctions in the face of re-groupings for physical and economic reasons. Something like this has been reported for the Cheyenne who have practically the same band scheme but live in camps or physical groups not coincident with the band grouping, hence, their band was predominatingly conventional. The following statement of the Arapaho, if we read correctly, is in line with this: “When the bands were separate, the people in each camped promiscuously and without order. When the whole tribe was together, it camped in a circle that had an opening to the east. The members of each band then camped in one place in a circle.”[8] All this in turn seems to support the interpretation that the band circle system is merely a conventionalized scheme of tribal government. We have noted that among the Blackfoot the tribal governments are so associated with the band circles that they exist only potentially until the camps are formed; at other times each band is a law unto itself. So far as our data go something like this holds in part at least, for the neighboring tribes. As a hypothesis, then, for further consideration we may state that the band circles and the bands are the objective forms of a type of tribal government almost peculiar to this area, an organization of units not to be confused with the more social clans and gentes of other tribes to which they bear a superficial resemblance. In closing, we may remark that exogamy is often but a rule for marriage respecting some conventional groupings. The Blackfoot appear to have paused at the very threshold of such a ruling for their bands.

December, 1910.

|

Lowie, (a), 34. |

|

Kroeber, (a), 147. |

|

Kroeber, (b), 8. |

|

Henry, 511. |

|

Spinden, 241. |

|

Lowie, (b), 206. |

|

See Mooney, 402; Swanton, 663; and Goldenweiser, 53. |

|

Kroeber, (b), 8. |

As previously stated, there are three political divisions of the Blackfoot Indians. These were definite when the tribes first came to our knowledge and their origins have long had a place in mythology. The genesis of these divisions must forever remain obscure, though there are a few suggestions as to what may have been the order of differentiation. While the term Blackfoot has been used by explorers from the very first, it seems also to have some general significance among the Indians themselves. Thus, a Piegan will tell you that he is a Piegan, but if asked who are the Piegan, will usually reply that they are Blackfoot Indians. Naturally, this may be due to foreign influence, the idea of subordination to the Blackfoot division having grown out of knowledge that such a classification was accepted by the dominant race.[9] In the sign language, there appears no distinct designation for the group as a whole. According to our information the signs are:—

Blackfoot. Pass the thumb and extended fingers down the side of the leg and supplement by pointing to black.

Blood. Crook the closed fingers and draw across the mouth, the teeth showing. The idea is that of picking clotted blood from the mouth.

Piegan. The closed fist, fingers down, rubbed on the cheek. The idea is “poorly dressed robes,” the sign signifying the rubbing of a skin.[10] One informant claims the name to have been given by the Crow because the first Piegan they killed wore a scabby robe.

To the many published stories accounting for the origin of the term Kainaw[11] (Blood) we add the following from the Piegan which is entirely consistent with the sign. A party of Piegan were found in the mountains frozen. They lay in a heap. Afterwards, the Blood taunted them by singing, “All in a pile.” Some time after this, some Blood were found in the same condition but with dried blood and froth smeared on their faces. Then the Piegan retorted by singing and making the sign. In daily speech, the significance of kai seems to be some dried effluvium from the body, hence, the name.

Henry gives a great deal of information as to the Blackfoot but is not quite consistent in his classification, for though he recognized the three historical divisions in his enumeration, he substituted two “bands” for the Blackfoot;[12] the Cold band and Painted Feather’s band, implying that these were distinct and strong divisions into which the Blackfoot were divided. This may have been a temporary segregation under two dominant leaders. Henry estimated the strength of the Piegan as equal to all the other divisions combined, an estimate consistent with all our information and with tradition.

There are some linguistic differences between the three tribes but these are chiefly in the choice of words and in current idioms. The Northern Blackfoot seem to differ more from the Piegan than the latter from the Blood.

|

“All these Indians [Piegan, Blood, Blackfoot] are comprehended, by the Whites, under the general name of Blackfeet, which they themselves do not, however, extend so far, but know each of the three tribes only by its own proper name.” Maximilian, Vol. 23, 96. |

|

Clark, 73, 74. |

|

See also Maclean, 44. |

|

Henry and Thompson, 530. |

It seems proper to begin the discussion of our subject with those conventions directly associated with sexual activities. Among the Blackfoot, as everywhere, the male is usually the aggressor. He lies in wait outside the tipi at night or along the paths to the water and wood-gathering places to force his attentions. This phase of sexual life is often expressed in myths and tales, intercepting the girl with her bundles of wood being the favorite.[13] Another manner of approach is by creeping under the tipi cover into the sleeping place of the girls. When countenanced by the girl’s family, attentions may be received by day in full view of all, the couple sitting together muffled in the same blanket, a familiar Dakota practice. Naturally, the girl may offer the first invitation. The most conventional way is for her to make moccasins secretly for the youth of her choice, this being regarded as the first proper step. Curiously enough, when married the young bride is expected to make a pair of moccasins for each of her husband’s male relatives. Then they will say, “Well, my female relative (nĭmps) is all right, she makes moccasins for us.” As the wife usually goes to live with her husband’s people, this is something of a formal demonstration of her worth to his family.

To all appearances, at least, virginity is held in very great esteem and extreme precaution is taken to guard the girls of the family. They are closely watched by their mothers and married off as soon as possible after puberty. For a girl to become pregnant is regarded as an extreme family disgrace. She will be scolded privately; but none of the family will speak of the matter in public if it can be avoided, they bearing their shame silently. No special demands are made of the co-partner in her shame, the girl alone being the one held responsible. Marriage may result, but the initiative is usually left to the man, since he is not regarded as having erred or fallen into disfavor. The formal virginity tests and puberty ceremonies practised among the Siouan tribes seem to have no place in Blackfoot society. The male lover enjoys unusual liberties. His efforts at debauchery are not only tolerated but encouraged by his family and should he lead a married woman astray is heralded as a person of promise. Thus, while great pains are taken to safeguard young girls, boys are, if anything, encouraged to break through the barriers.

While the flageolet is a favorite adjunct of courtship among many tribes of the area, its use in this connection seems to have been ignored by the Blackfoot. They did, however, resort to charms and formula known collectively as Cree medicine, a subject to be discussed in another paper. From what information we have, the pursuit of the female was much less in evidence than among the Dakota and other Siouan tribes.[14] We found no traces of conventional modes of registering conquests as among the young men of the Dakota and Village Indians.[15]

|

Vol. 2, 58, 109. |

|

Wissler, (b). |

|

Maximilian, Vol. 23, 282-283. |

Before proceeding, it should be noted that the courtship discussed in the preceding has no necessary relation to marriage, and may continue secretly after one or both are married. Proposals frequently come from the parents of either the girl or the man and often without the knowledge of one or both of the contracting parties. Mr. Grinnell has described in some detail what may be regarded as the most ostentatious form of proposal,[16] making it unnecessary to discuss the matter here. In general, it appears that the negotiations are carried on between the fathers of the couple or between the father and his prospective son-in-law. If successful, the next step is the exchange of presents. Grinnell denies that there is an idea of wife purchase in these transactions,[17] but when discussing divorce on the following page says the husband could “demand the price paid for her.” According to our information, the idea of purchase is still alive, though the woman herself may, as Grinnell claims, be regarded as more than a chattel. Even to-day, the bridegroom is expected to give a few horses and other property to the bride’s parents, and though presents are often sent with the bride, the bridegroom must return at least two-fold.[18] In former times, it is said, well-to-do families prepared the bride with an outfit of horses, clothing, etc., and paraded over toward the band of the bridegroom to be met in turn by a similar procession and outfit. The chief object here was a parade of wealth, that all the people might see the social excellence of the two families; for, as just stated, the bridegroom must in the end pay a price over and above the mere exchange of presents.

A Piegan to whom the text was read commented as follows:—They do pay for their women. When a man punishes his woman, he generally remarks that he paid enough for her, and, hence, can do with her as he will. On the other hand, if a man who gives few presents or pays nothing, becomes exacting, the woman’s relatives will remark that as he paid little or nothing he should desist; they may even take her away and find another husband for her.

There is a belief that the father-in-law was for a time entitled to part of the spoils of the chase and war, especially the latter. During the period between the proposal and the marriage, the hunt was delivered to the tipi of the prospective father-in-law and when cooked a portion was carried to the young man’s tipi by the girl.

The formal marriage ceremony was simple, the couple taking their proper places in the tipi and assuming at once their domestic responsibilities. The husband was expected to hunt and accumulate horses; the wife to prepare the food, make the clothing, etc. He had no great obligations to her in his associations with other women; but she, on the other hand, must strictly respect her compact. As the hour of marriage approached, the girl’s relatives gave her a forceful talk on her obligations and the shame of adultery. Her attention was called to the important part a virtuous married woman may take in the sun dance as well as her fitness to call upon the sun for aid in times of trial. She was threatened with death, if she yielded to temptation. Formerly, it is said, a wife was often executed for committing adultery. Should the husband fail to do this, her relatives would often carry it out to save the name of the family. Such executions are described as having been barbarous beyond belief. Later, the woman’s nose was cut off; several women now living bear these marks of shame.[19]

If the husband was a head man, he used his own judgment as to the woman’s guilt and it is believed that the penalty was often due more to his unreasonable jealousy than to real knowledge of his wife’s guilt. Yet, in any event, the disgrace and shame for the relatives of both husband and wife was so great that extreme penalties for mere suspicion were considered justifiable, if the interested parties were of some importance in social life. Another form of punishment was for the husband to call on the members of his society to deal with the woman, whom they debauched in the most shocking manner and turned out of doors to become a prostitute. Not many years ago, a young man called in all his friends, and delivered his faithless wife to them for such treatment.

The lending of wives was looked upon as a disgrace, or at least as irregular. A distinction should be made, however, between the favorite wife and other wives. These others were often captured women from other tribes, violated by a war party before becoming members of a household. Such were often loaned by their masters without exciting public dissent. It may have been such women that came to the notice of Henry and excited his extreme contempt.[20]

|

Grinnell, 211-216; see also McClintock, 185. |

|

Grinnell, 217. |

|

“There is no particular marriage ceremony among the Blackfeet; the man pays for the wife, and takes her to him; the purchase-price is announced to the father of the girl by a friend or some other man. If he accepts it, the girl is given up, and the marriage is concluded. If the wife behaves ill, or if her husband is tired of her, he sends her home without any ceremony, which does not give occasion to any dispute. She takes her property and retires: the children remain the property of the husband.” Maximilian, Vol. 23, 110. |

|

See Maximilian, Vol. 23, 110. |

|

Henry and Thompson, 526; also Maximilian, Vol. 23, 109. |

There were no restrictions as to the number of women taken to wife, but no woman could have more than one husband. Economic conditions, however, were unfavorable to a household of many wives, so that many men kept but a single wife and very few indeed ventured to support as many as five. On the other hand, a man of importance was expected to have two or more wives, suggesting wealth and resourcefulness. Plural wives speak of themselves as niskas (married to the same man) or, if of considerable difference in age, as elder and younger sisters. In the normal order of events, the first wife is the real, or head wife (she who sits beside him). A man may depose the head wife and confer the right upon another; but such was regarded as unusual, except where the provocation was great. When he went upon a journey, the head wife alone usually accompanied him. In the transfer of medicines, she took the woman’s part and afterwards cared for the bundle. It seems that in this function, at least, she was secure from the whims of her husband. Again, there is the belief that the marriage obligations demanded more of her; the other wives, especially if young, were generally assumed to have lovers among the young men even though such was formally forbidden.

It is said, that sometimes the intimate friends of a young man about to marry would ask for the loan of his wife after marrying, but that in such cases the wife rarely yielded to his requests as she was always upheld in an appeal to his or her relatives. In the absence of other data, it is not safe to consider this a survival of former practices. However, it should be considered a possible phase of the distant-wife relations.

The sisters of a wife are spoken of as “distant-wives” and may be, in a way, potential wives, though it is not clear that there was any obligation involved when plural marriages were permitted. If a man proved to be a good husband, it is said, he might be given the “distant-wives” in turn, but there was no compulsion. The marriage of sisters was justified on practical grounds, they being more likely to live together in harmony. If there was a twin brother, the distant-wife relationship applied to him also; if not an actual twin but an inseparable companion (nitâks ok kowŏmmaul) the same term would apply, though in these cases to a less degree.

There is, however, a curious social custom still in force by which a man and his distant-wives are expected, on meeting, to engage in bold and obscene jests concerning sexual matters. This is often carried to a degree beyond belief. Thus, there is not only the same freedom here as between man and wife, but the conventional necessity for license. As practically all other relatives by marriage are forbidden the least reference to such subjects, the force of the exception is greatly magnified. For example, a man will not even relate the obscene tales of the Old Man and other tales containing such reference in the presence of his brothers-in-law nor before their immediate relatives. If we add to this an equal prohibition against the presence of his sisters and female cousins, we have marked out the limits of this taboo. Thus, it appears that with respect to this taboo, the distant-wives are placed in an exaggerated sense in the category of real wives. Other familiarities of a man with his distant-wives are strictly improper.

The preceding may be a phase of the well-known mother-in-law taboo. Among the Blackfoot, still, a man should not speak to his mother-in-law, or even look at her. The taboo is equally binding upon her. If one is discovered about to enter the tipi where the other is present, someone gives warning in time to avoid the breach. Should the son-in-law enter, he must make her a present to mitigate her shame; should the mother-in-law offend, she must also make a small return. However, as usual with such taboos, there are ways of adjusting this restriction when necessary. If the son-in-law is ill, she may, in case of need, care for him and speak to him; upon his recovery the taboo is considered as permanently removed. Each may call on the other when in great danger, after which they need not be ashamed to meet. Sometimes when a man went out to war or was missing, his mother-in-law would register a vow that if he returned alive, she would shake hands with him and give him a horse and feel no more shame at meeting. The son-in-law may remove the taboo by presenting a few captured guns or horses. Some informants claim that four such presentations were necessary, after which his mother-in-law would take him by the hand and thus remove the taboo. She may receive support from her son-in-law but, even with the taboo removed, must not live in the same tipi with him, a small one being set up outside. It is observable that the presents for removing the taboo bear some analogy to those made the father-in-law during the first months of married life and may be genetically related to that practice.[21]

The counterpart of this taboo does not prevail, since a man need not avoid his daughter-in-law, his association with her being governed by the conventions applying to his own daughters. Yet, it is not looked upon as quite right for a man to spend too much time at the home of his son. On the other hand, for a man to live with his father-in-law, or spend a great deal of his time there, excites ridicule.

|

Among the Mandan, we are told, “the mother-in-law never speaks to her son-in-law; but if he comes home, and brings her the scalp of a slain enemy, and his gun, she is at liberty, from that moment, to converse with him.”—Maximilian, Vol. 23, 283. Among the Assiniboine the father-in-law taboo may be so removed.—Lowie, (a), 41. For the Cree we may add:—“Amongst our visitors was the son-in-law of the chief; and, according to Indian custom, he took his seat with his back towards his father and mother-in-law, never addressing them but through the medium of a third party, and they preserving the same etiquette towards him. This rule is not broken through until the son-in-law proves himself worthy of personally speaking to him, by having killed an enemy with white hairs; they then become entitled to wear a dress trimmed with human hair, taken from the scalps of their foes.” Kane, 393. |

The chief grounds for divorce from the man’s point of view, are laziness and adultery. For these or any other causes he may turn his wife out of doors. The woman then returns to her relatives where she is cared for and protected until another marriage can be arranged. The husband usually demands a return for the property he gave for her at marriage; he is sure to do this if she marries again. From the woman’s point of view, adultery does not justify divorce, but neglect and cruelty may result in abandonment. She flees to her relatives where she is safe from attack. The husband’s family then opens negotiations with her relatives and an attempt at adjustment is made. The woman’s family usually agrees to another trial, but may finally decide to find her another husband. Then her husband demands a settlement and is entitled to equivalent return for what he gave at marriage. Thus, formal divorce is really a restitution of the husband’s marriage gifts, or a refund of the purchase price.

In general, divorce seems not to have been common as it was looked upon as disgraceful under all circumstances and grievously expensive. The behavior of the husband was softened by his knowing that in case of continued discord his wife’s relatives were certain to interfere except she were charged with adultery and even in that event would retaliate if the accusation was manifestly unjust.

When the husband dies, the wife usually returns to her relatives who again arrange for her marriage.

The most important relationships in life are given in the accompanying table where the equivalents in our nomenclature are given for the Piegan terms: first, if the person considered is male, second, if female. In general, it appears that the terms as applied by males to males are more restricted and definite than those of males to females and females to persons of both sexes, though in function the terms are so used as to be equally intelligible. Thus, while a girl uses the term, father, in addressing men married to her mother’s sisters, she does not confuse this relation with the real one. On the other hand, it appears that the system as given in the table is ordered on the theory that sisters become the wives of the same man. This is also consistent with the distant-wife relationship previously discussed. Further, the system seems adapted to a gentile band organization in that the relationships of the women are more inclusive on the father’s side; this, however, is not entirely consistent.

Relationships.

| Terms | Significance as Applied to | Significance as Applied to |

| Males. | Females. | |

| nĭ′nna | my father | my father and husbands of my mother’s sisters. |

| niksŏ′stak | my mother and her sisters; wives of my elder brothers, brothers of my father and of my mother. | my mother and her sisters; wives of my father’s brothers. |

| nĭ′ssax | my elder brothers and all those of my mother; the elder (to me) sons of my father’s and mother’s brothers. | my elder brothers and all those of my father and mother; the elder sons of mother’s brothers and sisters. |

| nĭ′nst | my elder sisters and elder daughters of father’s and mother’s brothers. | |

| nĭ′nsta | my elder sisters and elder daughters of father’s brothers and sisters. | |

| nĭ′skŏn | my younger brothers and younger brothers of my father; all my younger first cousins by brothers of my parents. | |

| nĭssĭ′ssa | my younger brothers and sisters; all of my younger first cousins. | |

| nicĭnnauaxs | my father’s father, my mother’s father; also can be used for father-in-law. | |

| nitau′kaxs | the mothers of my father and mother and my father’s sister; also my mother-in-law. | |

| naa′xsa | all my paternal and maternal grandparents. Also my father’s sisters and their husbands. | |

| naa′xs | my father-in-law, mother-in-law; also may be used for grandparents. | |

| nĭmps | wives of my sons, younger brothers, and younger cousins. | wives of my cousins, of my brothers and of the brothers of my mother. |

| nĭstŏmmo′-wak | husbands of father’s and mother’s sisters; also my sister’s husband. | |

| nĭtaw′to-jombp | husbands of my sisters. |

There is a peculiar artificial relationship among boys that deserves attention. Many of them have a male companion from whom they are almost inseparable. The pairs are usually of the same age and grow up together as it were; they play together, they go to war together, they aid each other in courtship and in after life call on each other for help and advice. These bonds often last until death.[22] The terms of relationship for brothers are sometimes used by them and it is not unusual for them to assume the equality of twins. Thus, a twin will speak of his brother’s wife as his distant-wife, a term often used in the same way by men holding the relation alluded to above.

Persons of any age or nationality may be adopted into a family. Formerly a man losing a son might adopt a young man from his own or other bands, or even a captive, to fill the vacant place; an old woman might, on her own initiative, do the same thing. Very often the bosom companion of the deceased would be recognized as a son by adoption, but without obliterating his true family ties. In late years, a number of white men have been adopted as a mark of respect and in all cases of this kind, the Blackfoot expect the nominal support of a son to his parents. The ceremony of adoption is not as elaborate and fixed as among the Dakota and some other Siouan tribes, though a form of this ceremonial relation is used in the transfer of medicines.

|

Mooney finds something similar among the Cheyenne and makes a vague statement as to its wide distribution. Mooney, 416. However, it is difficult to eliminate the instinctive from the conventional in a comparative statement of this custom. |

Each individual has a name. The name is single in that there is neither family nor band name; though some persons, especially men, possess several names, these are co-ordinate and never used jointly. The right to name the child rests with the father; though he rarely confers it in person unless a man of great importance. He usually calls in a man of distinction who receives presents in return for his services. A woman may be called, but less often than a man, be the child male or female. There is no fixed time for this, but it is not considered right to defer it many weeks after birth. The namer asks to have a sweat house made which he enters, often in company with the father and other men he chances to invite. After the usual sweat house ceremonies, the namer suggests two or three names for consideration by the family. A selection is then made, the father, in any event, having the right of final approval. Prayers are usually offered by the namer. The conferring of the name is regarded as of very great importance since the manner of its doing is believed to influence the fate of the child during the entire span of life. The virtue of the naming is greatly enhanced, if the officiating person is one of great renown.

The name chosen may have various origins. As a rule, it will be the name of some person long dead, if possible one of great distinction. Thus, the writer was in a way adopted by a Blood head man, who gave him choice of two names, one that of a distinguished warrior, the other of a great medicine man. If a person living is known to bear the preferred name, it may be slightly modified by the change or addition of attributes. Thus, Little Dog may become White Dog, or simply Dog, to distinguish the bearer from another of the same name. In all such cases, there is the feeling that the name itself carries with it some power to promote the well being of him upon whom it is conferred. Again, a father may name the child from deeds of his own, as Two-guns, Takes-the-shield, etc. As a rule, unless he has weighty deeds to his credit, the father will not himself venture to confer a name. As always, there is the feeling that unless the name is of great worth, the fates will be adverse to the named. Sometimes, one may have a dream or hear a voice that gives him power to confer a name; it goes without saying that such is considered highly efficacious.

Mothers usually give the baby a special name according to some characteristic habit or expression. This name is rarely used by others.

Women seldom change their names but men always do. When the youth goes on his first war party his companions give him a new name. This name often carries with it an element of ridicule and should the youth show reluctance at its proposal it will be changed to Not-want-to-be-called-etc. After the party has returned the family will say to the youth, “Well, I suppose you have a new name: I suppose it is the name of some old grandmother, etc.” Then the youth is forced to give his new name which is certain to excite great merriment and teasing. Later, when the youth performs some worthy deed, he will be given a new and more dignified name. This will be his name as a man, though subject to change at any time. Names are sometimes formally changed at the sun dance by the chief-weather-dancer who announces, “Now, if you wish this man to aid you, if you call upon him for help, etc., you must address him as ——. His other name is now left behind at this place.” At other times the change of names is less formal and may be at the sole initiative of the person concerned. In practice, it seems that a man never really abandons a name though always spoken of by the last conferred or current name since he will say that he has two, three, or any number, as the case may be, enumerating all those given him during his life. While to ask a man his name is very rude, he himself seems free to speak of it on his own initiative. The custom seems to rest upon ideas of politeness, since not to have heard a man’s name even before meeting him is said to reflect upon his good standing among the people.

Each of the three tribes is composed of bands, kaiyok′ kowŏmmostĭijaw, implying not only bonds of friendship but bonds of blood.[23] These bands have been discussed by Grinnell who considers them true gentes[24] though he states that in recent times, at least, the adherence to exogamy was not absolute. For our part, we have met with many contradictory statements and observations among the Indians now living, so that we can do no more than offer what seems to be the most consistent view of the data available.

In the first place, while the band is a definite group in the minds of the Indians and every individual knows to what band he belongs, they manifest uncertainty as to how membership is determined and as to its bearing upon marriage restrictions. There is, however, no evidence of a belief in a band ancestor, human or animal; and, hence, no band totem. The name of the band has no relation to a founder but is supposed to designate, in a way, some peculiarity common to the groups as a whole. Thus, the names are in theory and kind the same as tribe names—Blood, Piegan, etc.—originating normally after the manner of object names in general and apparently not in conformity to some system or belief concerning descent or relationship.

At marriage, the wife goes to her husband and is considered as belonging to his band. The general feeling seems to be that the children belong to the band of their father. Should the father die, the mother and children will go to their relatives best able and willing to care for them, but the children will always be called after their father’s band. Should the mother’s relatives in her own band be few and not as able to care for the children as the father’s people, they remain in the father’s band. These relatives may live in the same band, but in any event, the mother takes the dependent children with her. Should she marry in another band, as is frequent, her children may reside with her in their step-father’s band. There is no rule governing cases of this sort and it is said that the children usually go to the band in which they have the strongest ties. Yet, they are seldom really lost to the sight of the father’s band and are often reminded by them that they properly belong to their band. Thus, it seems that the bands are in part, at least, gentes. Yet a man may change his band even in middle life.[25]

For a man to join the band of his wife at marriage is not unusual. The reasons for such changes are usually selfish, in that greater material and social advantages are offered, but we have no suggestion of such transfers being made with the idea of recruiting a depleted band. A man who changes his band may become a head man or even a chief without hindrance, as in the case of a well-known Piegan chief now living. Thus, it appears that there is no absolute rule of descent in band membership and that what bonds exist are rather those of real blood relationship than of an artificial system. Further, it appears that continuous residence or association with a band is practically equivalent to membership therein. The individual seems free to select his band.

To marry within the band is not good form, but not criminal. Thus, when a proposal for marriage has been made, the relatives of the girl get together and have a talk, their first and chief concern being the question of blood relationship. Naturally, the band affiliations of the contracting parties cannot be taken as a criterion since both may have very near relatives in several bands and cousins of the first degree are ineligible. Should the contracting parties belong to the same band but be otherwise eligible, the marriage would be confirmed, though with some reluctance, because there is always a suspicion that some close blood relationship may have been overlooked. Thus, while this attitude is not quite consistent, it implies that the fundamental bar to marriage is relation by blood, or true descent, and that common membership in a band is socially undesirable rather than prohibitive. If we may now add our own interpretation, we should say that the close companionship of the members of the band leads to the feeling that all children are in a sense the children of all the adults and that all the children are brothers and sisters and to a natural repugnance to intermarriage. Further, since most of the men in a band are in theory, of common paternal descent, even the informal adoption of a stranger would tend to confer upon him the same inheritance which as time dulled the memory would become more and more of a reality. In any event, the attitude of the Blackfoot themselves seems to imply that the band system came into existence after the present marriage customs and adapted itself to them rather than they to it.

A woman is called nĭmps by all members of her husband’s band, not his actual relatives. She may speak of all male members of the band older than herself as grandfather while the younger males may in turn speak of her as mother. Sometimes men of the same age as her husband, speak of her as “distant-wife.” While this may be consistent with a theory of gentile band organization in opposition to other data secured by us, our opinion is that it is at least equally probable that these terms were originally applied as marks of respect and circumstantial association, and consequently of little value as indicating the genesis of the band relations.

We must not permit the question of exogamy to conceal the important political and social functions of the band system. As one informant says, “the members always hang together at all times.” In another place, we have noted how the responsibility for the acts of individuals is charged to the band as a whole and how all are bound to contribute to the payment of penalties and even risk life and limb in defense of a member guilty of murder. In such, we shall doubtless find the true function of the Blackfoot band. The confusion as to exogamy seems to arise from the fact that blood ties tend to hold the children to the band of the father.

The tendency is for each band to live apart. When a band becomes very weak in numbers or able-bodied men, it takes up its residence beside another band or scatters out among relatives in various bands, but this is from necessity rather than choice. At present, the Blackfoot reserves are dotted here and there by small clusters of cabins, the permanent or at least the winter homes of the respective bands. By tradition, this was always the custom, though tipis were used instead of cabins. When two or more bands choose to occupy immediate parts of the same valley, their camps are segregated and, if possible, separated by a brook, a point of highland, or other natural barrier. The scattering of bands during the winter was an economic necessity, a practice accentuated among the Thick-wood Cree and other similar tribes. Something was lost in defensive powers but this was doubtless fully offset by greater immunity from starvation. In summer, the bands tended to collect and move about, both for trade and for the hunt. From what information we could secure, this seemed to be a natural congregation under the leadership of some popular man, usually a head man in his band. While the tendency was for the bands as a whole to join such leaders, it often happened that part of a band cast its lot with one group and part with another; however, such unions were usually temporary, the whole band being ultimately re-united when the tribe finally came together, either to trade at a post or to perform a ceremony.

Grinnell gives a list of the bands which he implies are to be taken as existing about 1860 and this agrees quite well with the information we secured. From the foregoing, it is natural to expect changes at any time. Since the names seem particularistic in their significance, we give only Mr. Duvall’s translations. For the Blood and North Blackfoot, our list is less complete.[26]

Piegan Bands.

| 1. Solid-Topknots | 12. Short-necks |

| 2. They-don’t-laugh | 13. Many-medicines |

| 3. Worm-people | 14. Small-robes |

| 4. Blood-people | 15. Red-round-robes |

| 5. Black-patched-moccasins | 16. Buffalo-dung |

| 6. Black-doors | 17. Small-brittle-fat |

| 7. Fat-roasters | 18. Undried-meat-in-parfleche |

| 8. Skunks | 19. Lone-fighters |

| 9. Sharp-whiskers | 20. No-parfleche |

| 10. Lone-eaters | 21. Seldom-lonesome |

| 11. White-breasts | 22. Early-finished-eating |

Blood Bands.

| 1. Fish-eaters | 5. Many-children |

| 2. Black-elks | 6. Many-lodge-poles |

| 3. Lone-fighters | 7. Short-bows |

| 4. Hair-shirts |

North Blackfoot Bands.

| 1. Many-medicines | 4. Biters |

| 2. Black-elks | 5. Skunks |

| 3. Liars | 6. Bad-guns |

These lists are doubtless far from being complete. Even among the Indians themselves confusion seems to exist as to some names since a band may be known by two or more names. Under these conditions we deemed the preceding data sufficient to our purpose. Mr. Grinnell explains the existence of bands of the same name among the various divisions as due to members of the bands leaving their own tribe to live with another. As we have no data on this point it must pass, though we see no reason why some of the band names may not be older than the tribal divisions. On the other hand, some of the translated names for Gros Ventre bands as stated by Kroeber are identical in meaning with some of those found among the several tribal divisions of the Blackfoot. Again, we are not ready to accept unconditionally the opinion of Grinnell that the disparity between band ties and blood ties is due to the gradual disintegration of tribal life, having previously stated our reasons for assuming the system of blood relationship the older form and pointed out that the band is rather political than otherwise.

|

As to the origin of the term band, used so generally by the older writers and traders of this area, we have a suggestion from Keating: “The term band, as applied to a herd of buffalo, has almost become technical, being the only one in use in the west. It is derived from the French term bande.” Keating, 379. We may venture that the use of this term for a head man and his following among the Indians of this same area was suggested by the analogy between the two kinds of groups, these old naïve observers not being blinded by sociological preconceptions. |

|

Grinnell, 223-224. |

|

On this point, the following statement of a Piegan informant may be worthy of note: A man may go into another band and live there if he choose, nothing much being said about it. Sometimes a man may not like the chief of his own band and so go to another. There is neither announcement nor formal adoption, he simply goes there to live. For a time, it may be thrown out to him that he belongs elsewhere but after a while he is always spoken of as a member. When a band begins, it may be a group of two or three brothers, fathers, and grandfather, or a small family band (which means the same thing); later, friends or admirers of the head man in this family may join them until the band becomes very large. Bands may split in dissention, one part joining another or forming a new one. A new group is soon given a name by other people according to some habit or peculiarity. They do not name themselves. |

|

For another list of Blood bands, see Maclean, (c), 255. For a Piegan list, see Uhlenbeck, (a). |

As among many tribes, there was a definite order of camping when the circle of tipis was formed. While Mooney may be correct in his claim that the circle of the Cheyenne is their fundamental social organization, it cannot be said that the circle of the Blackfoot holds a very close objective relation to their organization. In the first place, each division (Blackfoot, Blood and Piegan) had its own circle and there are no traditions that they were ever combined. When a circle is formed, all visitors from other divisions must, like those from strange tribes, camp outside and apart. Further, there is a firm belief among the Piegan that the circle was never formed except for the sun dance and certain related ceremonies connected with the beaver medicine. It seems likely that if the circle were fundamental and not of recent origin, there would be traces of a parent circle and vestiges of rules governing its formation. Further, as among the Cheyenne, there is no great unanimity of opinion as to the order of the various bands in the circle but at the sun dance the leading men decide arbitrarily any doubt that may exist as to the place of a particular band. The further discussion of this point may be deferred until we take up the sun dance and its problems.

The opening in the circle is to the east and the order of bands is enumerated from the south side of the opening, as in the characteristic ceremonial order of movement. The present order for the Piegan is as given in the list.

In a way, the band may be considered the social and political unit. There is, in a general sense, a band chief, but we have failed to find good grounds for assuming that he has any formal right to a title or an office. He is one of an indefinite number of men designated as head men. These head men may be considered as the social aristocracy, holding their place in society in the same indefinite and uncertain manner as the social leaders of our own communities. Thus, we hear that no Blackfoot can aspire to be looked upon as a head man unless he is able to entertain well, often invite others to his board, and make a practice of relieving the wants of his less fortunate band members. Such practices are sure to strain the aspirant’s resources and many sink under it; but he who can meet all such demands soon acquires a place in the social life of the band that is often proof against the ill fortunes of later years. This phase of their social life is very much alive, having survived not only the changes in economic conditions brought about by the reservation system but the direct opposition of its officers. This story is oft repeated: a young man takes to stock raising, accumulates cattle and horses, gradually taking into nominal employ all his less able relatives who thus come to depend upon him. Presently, he wakes up to the situation and entertains an ambition to become the leading head man of his band, or even of all bands. Then begins a campaign. He makes feasts, gives presents, buys medicines, and supports ceremonies; thus making his home the center of social and ceremonial activities, the leadership of which he assumes. His rivals are stirred to activity also and the contest goes on apace. From observation, we believe that bankruptcy is the usual result; but, unless this comes at the very beginning of the effort, the aspirant acquires enough prestige to give him some claim to being a head man for the rest of his days even though he becomes a hanger-on at the door of a younger aspirant.

Thus, the head men are those who are or have been social leaders. Naturally, individual worth counts in such contests and he who is born to lead will both in matters great and small. In former times, these rivalries often led to assassination and other dark deeds.

Before the reservation system came in, deeds of the warpath were also essential to the production of a head man, for in them was the place to demonstrate the power to lead. Great deeds in social and ceremonial life would alone elevate one to the status of a head man, though as a rule the warpath was the line of least resistance.

These head men of uncertain tenure come to regard one or two of their number as leaders, or chiefs. Such chiefs rarely venture to act without the advice of some head men, as to stand alone would be next to fatal. In tribal assemblies, the head men of the bands usually look to one of these as spokesman, and speak of him as their chief.

While the tenure and identity of a head man is thus somewhat vague, his functions are rather definite. He is the guardian and defender of the social order in its broadest sense. Of this, he is fully conscious; as, for example, no man of importance will accept an invitation to visit for a time in a distant band or tribe without calling a consultation. Should some head men of his band indicate disapproval, the invitations will be declined. The theory is that the welfare of his band is endangered by his absence. Above all, the head men are expected to preserve the peace. Should a dispute arise in which members of their band are concerned, one or more of them are expected to step in as arbitrators or even as police officials if the occasion demand. When it is suspicioned that a man contemplates a crime or the taking of personal vengeance some head men go to his tipi and talk with him, endeavoring to calm him, giving much kind advice as to the proper course for the good of all concerned. If he has been wronged, they often plead for mercy toward his enemy. Again, the head men may be appealed to for redress against a fellow member of the band. In the adjustment of such cases the head men proceed by tact, persuasion, and extreme deliberation. They restrain the young men, as much as possible, after the same method. In all such functions, they are expected to succeed without resort to violence.

For mild persistent misconduct, a method of formal ridicule is sometimes practised. When the offender has failed to take hints and suggestions, the head men may take formal notice and decide to resort to discipline. Some evening when all are in their tipis, a head man will call out to a neighbor asking if he has observed the conduct of Mr. A. This starts a general conversation between the many tipis, in which all the grotesque and hideous features of Mr. A’s acts are held up to general ridicule amid shrieks of laughter, the grilling continuing until far into the night. The mortification of the victim is extreme and usually drives him into temporary exile or, as formerly, upon the warpath to do desperate deeds.

When there is trouble between members of different bands, the head men of each endeavor to bring about a settlement. Thus, if one of the contending party is killed, the band of the deceased sends notice to the murderer’s band that a payment must be made. In the meantime, the murderer may have called upon a head man of his own band to explain the deed. The head men then discuss the matter and advise that horses and other property be sent over to the injured band at once. A crier goes about with the order and members of the band contribute.[27] This offer may be refused by the injured band and a demand made for the culprit’s life. No matter how revolting the offence, the band is reluctant to give up the accused without a fight. If no presents are sent in a reasonable time, the injured band assembles in force and marches out. A head man meets them for a conference, but a fight is likely. After a conflict of this kind, the band killing the greatest number moves to a distant part of the country and when the camp circle is formed keeps in sight but far out to one side. This separation may continue for a year or more. In all such disputes between bands, the head men of other bands may step in to preserve the peace; but, according to report, they seldom accomplish anything.

Taking the Piegan, Blood, and Blackfoot as tribes, we may say that there was a head chief for each. His office was more definite than that of a band chief, though he was not formally elected. All the head men of the various tribes came by degrees to unanimity as to who would succeed the living chief, though the matter was rarely discussed in formal council. The main function of the tribal chief was to call councils, he having some discretion as to who should be invited. Some writers claim the Blackfoot appointed two chiefs, one for peace and one for war; but we could find no evidence for this, except that some band chiefs came to have special reputations for ability as war leaders and were likely to be called upon in time of need. They were not, however, regarded as head chiefs. While the office of head chief was not hereditary, there was a natural desire among the chief’s band to retain the office; thus it is said that among the Piegan most of them have been members of the Fat-roasters.

Everything of importance was settled in council. While each band was represented there was no fixed membership; yet the head chief usually invited those in excess of one member for each band. There seems to have been no formal legislation and no provisions for voting. In former times, the council was rarely convened except in summer. At the end of the fall hunt, the bands separated for the winter to assemble again in the spring at some appointed place. Even in summer they would often camp in two or three bodies, each one under the leadership of some able-bodied band chief, coming together for the sun dance at which time only the whole tribal government was in existence.

The organized men’s societies among the Blackfoot were, when in large camps, subject to the orders of the head chief or executive of the council and on such occasions seem to have exercised the functions of the head men of the respective bands. This subject will be taken up under another head, but it is a matter of some interest to note how, when such camps were formed, the head men of the bands were merged into a council for the whole and the men’s societies became their executive and police agents under the direction of the head chief. Thus, when there was danger, certain societies were detailed to guard duty, especially at night. As the chief aim of an organized summer camp was to hunt buffalo and the success of a general hunt depended upon successful co-operation, the discipline was devised to that end. The head chief gave out orders for making and breaking camp, and rules and punishments were announced. Thus, a man found running buffalo or riding about outside without orders might have his clothes torn off, be deprived of his arms, his horse’s ears and tail cropped. Should he resist, he might be quirted and his hair cropped. His tipi and personal property might be destroyed. However, these were extreme punishments, it being regarded as best to get along by persuading the would-be wrong-doer to desist. The punishment inflicted by the members of societies were not personally resented, as they were acting entirely within their rights. As to whether the men’s societies were police by virtue of their own membership, or whether they were individually called out to form an independent body is not certain, but will be discussed elsewhere.

A long time ago Nathaniel J. Wyeth[28] set down some interesting theories concerning the economic reasons for the unorganized state of the Shoshone in contrast to the buffalo-hunting horsemen of the Plains. He doubtless sensed a truth in so far as the camp organization of the Plains is considered as a type of government having for its chief function the supervision and conservation of their immediate resources. Perhaps of all cultural phases in this area, the one most often detailed in the older literature is the organization and control of the camp when pursuing buffalo. So far as we have read, the accounts for the different tribes are strikingly identical and agree with the data from the Blackfoot. In most every case, the horse, the tipi, the camp circle, and the soldier-band police were present, even though the participants, when at home lived in houses and cultivated corn. That the camp circle, or band circle, is a special type of tribal political organization in this area seems obvious. It would be suggestive to know just how some of the tribes having clan organizations adjusted themselves to this scheme when using the circle.[29]

|

One informant commented on this paragraph as follows: When the payment is made it is through the head men of the bands concerned. The head man of the band to which the wronged party belongs is given the offerings and he passes on them. When he judges them ample, he takes them to the wronged party and tells him to drop the case now since he has received full damages. |

|

Schoolcraft, 205-228. |

|

We have heard that the Winnebago used a provisional band scheme for the circle, entirely independent of their regular social organization and in conscious imitation of the Dakota. If this proves correct, it will throw some light on the whole problem of bands and camp circles. |

When a man dies his property is raided by the relatives. The older sons usually take the bulk but must make some concessions to all concerned. If the children are young, the father’s relatives take the property. In any event, nothing goes to the widow. She may, however, retain her own personal property to the extent of that brought with her at marriage. She may claim, though not always with success, the offspring of her own horses. These are horses given her by her relatives and friends. Though not clearly thought out, the feeling seems to be that as the widow returns to her band she is entitled to take only such property as she brought with her at marriage.

At the death of a wife, her personal property is regarded as due her relatives, and may go to her daughters, if grown, otherwise back to her band. Theoretically, at least, the woman owned the tipi, the travois, the horse she rode, her domestic implements and clothing. Even to-day, when the white conception of property tends to dominate, a man seldom speaks when his wife bargains away her own hand-work, bedding, and house furnishings.

Formerly, disputes concerning property were taken to the head men for adjustment: now the settlements of estates go to the authorized Indian court. Property was bequeathed by a verbal will. A man would state before witnesses and his relatives what horses and property were to go to the wife, to the children, etc. At present, written wills are sometimes executed to protect the family. Under the old régime, the relatives sometimes disregarded the wishes of the deceased and left nothing for the widow and children; but, if a woman of good character with many relatives, she was seldom imposed upon.

In the division of meat from a co-operative hunt, the best cuts went to the chief, the medicine men, and the owners of medicine pipes. This is somewhat at variance with the usual democratic way of doing things and bears a striking resemblance to a similar custom among the Western Cree. In an individual hunt anyone approaching a man engaged in butchering was given meat, sometimes even the last piece. However, he was certain of being invited later to eat.

The women dress the skins, make their own clothes and most of those used by men. They make most of their own utensils: the tipi, the travois, the riding-gear, prepare and cook the food, gather the vegetables and berries, and carry the wood and water. As the greater part of the baggage, when travelling, is their property, they bear the burden of its transportation. It is a disgrace both to himself and his women, for a man to carry wood or water, to put up a tipi, to use a travois, to cook food when at home and above all to own food or provisions.[30] While the men usually did the butchering, the meat on arriving at the tipi became the property of the women. A young man may cook food but in seclusion. There is a pretty tale of a young fellow surprised by his sweetheart while cooking meat. He threw the hot meat into the bed and lay upon it. The girl embraced him and fondled him while the meat burned deeply into his body; but he did not wince.

In the tipi, a man seldom rises to get a drink of water but calls on the women to hand it to him. The men often make their own ornaments and sometimes their leggings and coats. The painted designs upon men’s robes and upon tipis are made by men; those upon parfleche and bags are by women.

|

An informant states that this applies especially to married men: that in some cases a young single man is called upon to get water after dark, or at any time when it is very cold, a woman may call upon a young man to get wood. |

As the period of pregnancy nears its end the women discard their bracelets and most of their metal ornaments. They dress in old clothes and affect carelessness of person. Should a person look fixedly at one, she will say, “Don’t. My child will look like you; you are ugly,” etc. As the hour approaches, they retire to an isolated tipi where they are attended by other women, men not being admitted. A medicine woman may be called, who usually administers decoctions for internal use, supposed to facilitate delivery. For bearing down, the patient holds to a pole of the tipi, an attendant grasping her around the waist. When delivered she is laced up with a piece of skin or rawhide as a support. She is then required to walk or creep about in the tipi for a while instead of resting quietly, in the belief that recovery will be hastened thereby. The after-birth is thrown away and not placed in a tree as among the Dakota.

Men should not approach the birthplace for a period as their medicine and war powers would be weakened thereby. The father may enter but at some risk. It is bad luck for men to step upon the clothing of the newly born or touch those of the mother; lameness and other disorders of the feet and limbs will surely follow.

Birth marks are regarded as evidences of re-birth. Boys so marked are believed to be returned warriors bearing honorable scars. Twins are neither regarded with suspicion nor especially favored. What data we have seem to be against infanticide even in the case of great deformities. Tales emphasizing the enormity of the crime are told of mothers to whom suspicion attributed the death of such unfortunates. The still-born, it is believed, will be born again.

There is no special taboo upon a menstruating woman requiring her to live apart but she is not supposed to come near the sick. The belief is that in such a case something would strike the patient “like a bullet and make him worse.” Further, at this time, women are supposed to keep away from places where medicines are at work. These restrictions also apply to immediate associations with men and to women lax in virtue.

Large families seem not to have been unusual though I have never seen many children with one woman. Some old men now living claim to be fathers of more than twenty children each, though not by a single mother.[31] The young children, at least, receive considerable attention and some discipline. They are sometimes punished by a dash of cold water or a forced plunge. In former times, some old men were charged with responsibility for each boy’s morning bath in the stream regardless of temperature; hence, children were admonished that these men would get them. Striking a child is not regarded as proper. The favorite boggie is the coyote, or the wolf. Women will say, “Now, there is a coyote around: he will get you.” Sometimes they say, “Come on wolf and bite this baby.” Such words often compose lullabies, a favorite one being, “Come, old woman, with your meat pounder smash this baby’s head.” After the use of intoxicants became general, children were threatened with a drunken man.

From the first, children are taught to respect all the taboos of the medicine bundles owned by the family and those of their relations and guests. Girls are taught to be kind and helpful, to be always willing to lend a hand, to be virtuous and later, to respect their marriage vows. Special stress is laid upon virtue as a “fast” girl is a disgrace to all her relatives. All children are expected to retire early and rise early. They must respect the words and acts of the aged and not talk back to elderly people. They are taught to take “joking” gracefully and without show of temper. All “tongue-lashing” is to be taken quietly, without retort. Should a child be struck by his equal, to retaliate in kind is proper. All requests for service or errands made by elders, are to be rendered at once and in silence. The ideal is the child that starts to perform the service before it is asked; or, if asked, before the last word of the speaker is uttered. Talkativeness is almost a crime in the presence of elders. The ideal is he who sits quietly while the adults talk. If he is teased, he may smile but not speak. Above all, when grown up, he should be self-controlled as well as firm and brave.

Boys were taught to care for the horses and to herd them by day: girls to carry wood and water and to assist with other children and household duties. Before marriage, girls must be proficient in the dressing of skins, the making of garments, and the preparation of food. About the time of puberty, boys are expected to go to war. Singly or in pairs they may get permission to accompany a war party, provided they have shown efficiency in hunting. At such times, they receive new names, as previously stated. While the boy is expected to go to war, his family not only uses persuasion to keep him at home, but often forbids his going. In any event, he gets permission or goes secretly. It is said, that in this way the virtue of both parents and sons is shown.

We failed to find definite evidences of puberty ceremonies aside from the boy’s change of name. Certain other small ceremonies may be noted. Often when a child takes its first step or speaks its first word, the parents are adroitly reminded that it is their duty to do something. Then they give out presents or make a feast to which all the relatives contribute. Ear-piercing is also somewhat of a ceremony and may be accompanied by a display of wealth, except when performed at the sun dance. An old woman is called for this service and, in imitation of a warrior counting coup, calls out just before piercing an ear, “I have made a tipi, worked a robe, etc., with these hands.”

|

“These Indians often have many children, who generally run and play about quite naked, and swim in the river like ducks. The boys go naked till they are thirteen or fourteen years old, but the girls have a leather dress at an early age.” Maximilian, Vol. 23, 110. |

When one is taken ill the family sends for a medicine man, promising him a horse. If the family is of some importance they may call in a number of such men, to each of whom a horse is promised. They sit around the tipi and work their magic powers in turn while their women assist with the songs. Food and other comforts must be provided for them and their enthusiasm stimulated by gifts of additional horses. A long acute illness will deprive the family of its accumulated property. Often a man will tell you that he is very poor now since he or some of his relatives have been ill for a time. Medicine men usually permit the family to keep the gift horses until needed and often transfer, or sell, their claims to a third party. Should the patient die, they leave at once, often taking with them all the loose property of the family.

If a person dies in a house it is abandoned, or afterwards torn down and erected elsewhere, as the Blackfoot believe the ghost of the deceased haunts the spot. Should a young child die, the house will be abandoned for a time only. In former times, the tipi was abandoned or used as a burial-tipi.

When all hope for the patient is abandoned, he is painted and dressed in his best costume and, at present, often taken out of the house to a tipi so that it may not be necessary to tear down the building. After death the body is wrapped in a blanket, formerly in a robe, and buried within a few hours.[32]

In recent years, the Indians have been forced to use coffins and to practise interment. These are placed upon high hills and barely covered with earth and stones. No effort is made to mark the spot and fear keeps all the mourners far from the place. Indeed, it is difficult to persuade any one to go near a known burial site. Some distinguished chiefs rest in houses built on lonely hills. In former times, tree burial was common but now rare, only one example having come under our observation. A person of some importance was placed in a tipi on some high place. The edges of the tipi cover were often weighted down with stones, circles of which are often met with on elevated positions. Persons usually make requests of their families that certain personal belongings are to be buried with them. Sometimes the request is for a horse; in this event, one will be killed at the burial place. It was quite usual for the tail and mane of a man’s favorite horse to be cut at his death.

At death, or its announcement, there is great wailing among the women, who gash their legs and often their arms. Their hair is cut short, a practice often followed by the men. Such hair should be thrown away and not handled or used for any practical purpose. Women may wear a single bead over one ankle for a time. In former times, a man would take to the warpath and go along indifferently, neither seeking enemies nor avoiding them if encountered. At present, they go on a long visit to some distant relative. If a man owning an important medicine bundle loses a dear relative he may be moved to cast it into the fire or otherwise desecrate it because of its failure to prevent death; hence, a person once owning such a bundle takes it away at once. After a time, medicine men approach the mourner with suggestions that it is well to take up the care of his bundle now. When he consents, a sweat house is made and after the ceremony, the mourner is painted and newly dressed. The medicine bundle is then brought into his tipi and he resumes his former functions. While the preceding is the normal order of events, men have been known to destroy medicine bundles in the face of great opposition.

During the mourning period—an indefinite time—the man may dress in the meanest possible clothes, neglect his hair and person, and live in a small dilapidated tipi. However, there seems to be less formality in this than among the Dakota, and the spectacular abandonment of the mourning state often observed among the Teton is wanting.

In this connection, may be mentioned a practice not unlike “running a-mok,” though apparently without mania. A man realizing that he is the victim of an incurable disease may with more or less deliberation arm himself and attempt the life of all persons he may meet. He will announce that as he must die, he expects to take as many with him as possible. The records of the reservations will show a number of killings brought about in this way. Thus, a man took his wife out to a small hill, shot her and took his stand against his pursuers, whom he held at bay to his last cartridge with which he, though badly wounded, took his own life. An attempt of this kind came under the observation of the writer while camping with a Blood band. A young man suffering from consumption, slightly intoxicated and threatened with arrest for disorderly conduct, announced to his family one night that he expected to kill all of them and as many of the camp as possible. Fortunately, while he attacked his wife with a knife, his rifle was spirited away and the camp aroused; yet, as he kept out of reach, it was necessary to hold him off with guns until dawn, when he fled in terror of capture alive. Many officials attribute such outbreaks entirely to intoxication, but the evidence we have gathered indicates that there is a conventional side to the practice and a strong probability that it is a variant, and in some respects a survival, of taking to the warpath. Officials and many Indians, respect the convention to such an extent that every effort is made to prevent persons fatally afflicted becoming aware of the fact until near the hour of death. The writer found a similar practice among the Teton, though it seemed that one life is regarded as sufficient, the doomed man usually taking his own life after a short interval.

|

See Maximilian, Vol. 23, 121. |

Many Blackfoot men now but a half-century old took part in raids and fights, or went on the warpath, so that now, as of old, deeds of war are important social assets. In former times, only men of great deeds were called upon to perform certain public and ceremonial functions, a custom still in force but naturally less binding. While there are other social ideals, such as owning important medicines, becoming a head man and possessing wealth, that of being a successful warrior can scarcely be over-estimated. The tale of adventure as told by the chief actor is the delight of the fireside and entrances old and young alike when delivered by a skilful narrator. Other tales, those of tradition and hearsay, are seldom offered as it is the custom for one to narrate his own experiences, a rather high ideal of truthfulness being entertained. Of course, there are historical traditions, but they are usually given in brief without much life. Adventures with animals and of the hunt have a place, but are of far less social significance. The following is offered as a type of war narrative and also because it gives a very clear picture of just how an expedition for plunder was conducted. It was narrated by Strangle Wolf, a very old man, and recorded by Mr. Duvall.