Title: The Life of General Garibaldi

Author: Giuseppe Garibaldi

Translator: Theodore Dwight

Release date: November 24, 2015 [eBook #50544]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Carlo Traverso, readbueno and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

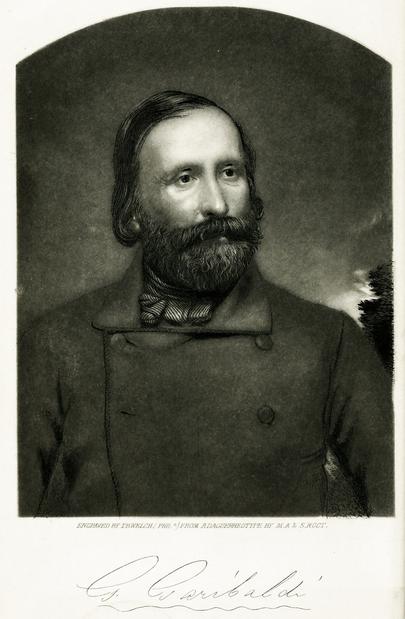

ENGRAVED BY T.B. WELCH, (PHILA) FROM A DAGUERROTYPE BY M.A. & S. ROOT.

G. Garibaldi

The following pages are principally written by the pen of the hero of our age, that pure-hearted man—that devoted patriot, and noble, generous, and disinterested philanthropist—that spirited, undaunted, and indomitable warrior, whose splendid deeds have dazzled the world, and whose career, according to his own recent declaration, will be brought to its close by a final triumph, for which he is now preparing, to be gained early in the present year.

While General Garibaldi resided in New York and its vicinity, in the years 1850 and '51, the author of this book enjoyed his acquaintance, and the favor of receiving from him his private memoirs, with permission to translate and publish them.[1] They had just been prepared for the press, when Garibaldi requested that they might be withholden from the public while he remained in this country, probably because he preferred to be unnoticed, being at that time employed in making candles on Staten Island, and naturally fond of retirement.

The first part of this volume, to page 210, contains a literal translation from his original private manuscripts, in which a clear, unadorned English style was adopted, as nearly corresponding, as the translator's abilities would allow, to the manly and pure Italian of the author. No attempt was made to change, by dilating or polishing, as the translator believed it to be almost as hopeless to improve his style as to rival him with the sword. That portion of the volume relates to his early life, and the fourteen years he spent in the service of the Republican cause in South America.

The succeeding pages are devoted to his services in Italy in the revolutions of 1849, 1859 and 1860; and a large proportion of their contents is occupied by his proclamations and other documents of his own, in translating which the same efforts have been made to render them correctly.

The author has received assistance from some of the countrymen of Garibaldi in New York, for information not otherwise to be obtained, several of whom have been his fellow-soldiers. Many extracts have been taken from the most authentic and interesting descriptions, by intelligent eye-witnesses, of scenes in the two last campaigns in Italy. A personal acquaintance with Italy and Italians has enabled the writer to select, arrange, and explain the vast amount of materials presented by those most extraordinary seasons, in a manner perhaps best adapted for his readers. Some omissions were necessary, in composing a work of this kind, but nothing of essential importance.

The reader can hardly fail to bear in mind, while here reviewing the life of this wonderful man, the most formidable of modern times, who is at the same time one of the most gentle and amiable at heart, that even now the present pause in his career is a solemn one, as it is speedily to be followed by a scene of excitement, conflict and consequences, perhaps unequalled by those which are past. The results none can foresee: but it is evident that they must be momentous and extensive, whether prosperous or adverse; and no intelligent American can anticipate them without deep emotion. Well may we look to heaven for the protection and success of the noble hero of Italian independence and liberty, the avowed enemy of the Papal Anti-Christ, whom he unmasks and denounces, and for the diffusion among his countrymen of that pure and undefiled Christianity, of which he declares himself a believer, and which he so earnestly claims for the religion of Italy.

The efforts, sacrifices, and sufferings of thousands of Italians for the independence, freedom, and happiness of their country, have been such, in past years, as to present pages worthy of record in history for the honor of mankind, and lessons for other nations. Many of the purest men have been suffering the pains and sorrows of exile in our own land, some of them after long and cruel punishment in the dungeons of Austria, those of the brutal kings of Naples, or of the Pope of Rome. With a patience and magnanimity astonishing to witness, they have justly excited the respect, love, and admiration of Americans who knew them, and ever showed themselves sincere and cordial friends of our country, our institutions, and state of society. Unlike too many other foreigners, they have been content with the protection which they enjoyed, and never sought for office or power, much less to act as the servants of European despots, to undermine American liberty. Some of these noble men, on returning to Italy, left with us records of their lives, which may, perhaps, hereafter be published, according to their desire, to promote a warm attachment between our countrymen and their own, for which those writings are admirably adapted.

The following pages contain the translation of one of the collections of manuscripts here referred to, and it is most gratifying to the translator to bring before the American public, at this time, so appropriate, interesting, and authentic a biography of the admired man of our age, under his own authority, and from his own pen.

Could there be a character better adapted as a model for American youth, in training them to just views of the value of what has been called the humble virtues of common life? The example of Garibaldi displays those virtues which adorn every pure, honest, and disinterested character, in happy contrast with the false and selfish principles which are too generally approved, admired, and recommended to the young. How much the world owes him, for his disinterested career, his devotion to the good of others, his refusal of rewards of every kind, and his preference of simple life in a lonely, rocky island, with only his son and daughter, and a few true friends, to all the honors, riches, and luxuries of the European capitals!

And how noble an example, also, have the Italians given us of union!

INTRODUCTION, 3

CHAPTER I.

My Father—My Mother—Her Influence on my Life—Incidents of my Childhood—My First Schoolmasters, 13

CHAPTER II.

First Impressions of a Young Sailor—My First Voyage—My Accomplished Captain—My Second Voyage—First Visit to Rome—Impressions—My Prayers—Join the Secret Society—Sentence of Death—Escape to France—Incidents at Marseilles, 17

CHAPTER III.

Voyage to Brazil—First Meeting with Rosetti—We Engage in Trade—Zambeccari's Arrival—The United Provinces—Engage in the Service of Rio Grande—Sail—My First Prize—Conduct of my Men—My Rule for Treating Prisoners—Reception at Maldonado—Sudden Departure, 23

CHAPTER IV.

Two Brazilian Vessels—My First Battle—My First Wound—Results—My own Condition—Burial of my Friend Fiorentino, 29

CHAPTER V.

Arrival at Gualaguay—Reception—My Wound Healed—My Sudden Departure and Return—Cruel Treatment—Señora Aleman—Tribute to that Noble Lady—Go to Bajada, 33

At Montevideo—Incognito—Departure for Rio Grande—March with the Army of the President, Bento Gonzalez—His Character, Family and Friends—Agreeable Society, 38

CHAPTER VII.

At the Galpon of Charginada, Repairing the Launches—My Friend, John Griggs—A Battle—Results—Tribute to a Fair Friend, 44

CHAPTER VIII.

Description of the Lake or Lagoon Dos Patos—The Enemy Command the Lake—Plan to Enter it—Transportation of Launches Over Land—Results of the Experiment—Breakers—Shipwreck—Sad Catastrophe, 50

CHAPTER IX.

Treatment Experienced by the Survivors of the Shipwreck—Expedition of Canabarro to Laguna—Results—Effects on my mind of the Loss of my Old Friends—My Resolution—Remarkable Meeting with Anna—Our Marriage—New Launches Built—Leave the Lagoon—Cruise at Sea—Prizes Taken—Fight with a Brazilian Ship of War—Results, 57

CHAPTER X.

Discontent of the People of St. Catharine's—Revolt at Jamaica—Attack on that town—Conduct of the Troops—Retreat to the Lagoon—Pursued—The Imperialists Gaining Strength—Col. Terceira's Expedition Against Mello—Our Disaster—Rally, 65

CHAPTER XI.

The Enemy still held in Check—Necessity of Retreat—Preparation—Commencement—Progress—Result—Arrival at the Town of Lages, 76

CHAPTER XII.

My High Estimate of the "Sons of the Continent"—Defects in Discipline—I Descend the Serra—Difficulties of the March—Reach Malacara—General Jorge—Gens. Netto and Canabarro—Two Large Armies Meet at Pineirino, on the Taguare—Patriotism of the Republicans—A wish for Italy—Result of the Expedition, 81

San Jose Del Norte—Its Capture—Ill Conduct—Its Results—Disasters of the Republicans—I go to San Simon—Birth of my First Child—My Solitary Journey to Procure Necessary Clothing for my Little Family—Trials and Oppressions—Sad Discovery on My Return, 92

CHAPTER XIV.

The River Kapivari—My New Camp—Canoe Voyages to the Lake Dos Patos—State of the Republican Army Declining—Death of my Bosom Friend, Rosetti—Retreat—Difficulties and Sufferings—Anna's Exposure—Our Infant—Kindness of the soldiers, 97

CHAPTER XV.

Hunting Horses—Catching Wild Colts—Enter the Province of Missiones—Headquarters Established at San Gabriel—Love for my Parents—I turn Cattle-Drover—Results—Reach Montevideo—Teach Mathematics—Warlike Preparations—Join the Oriental Squadron, 104

CHAPTER XVI.

Origin of the War between Montevideo and Buenos Ayres—Character and Conduct of Rosas, Ouribes—The Centralists, called Unitarians, Opposed to the Republicans, 109

CHAPTER XVII.

Condition of the Italians at Montevideo, and elsewhere—My Wishes and Designs for their Benefit—In Command of the "Constitucion"—At Martin Garcia—A Battle with the Enemy—Providential Results—Proceed to Bajada—At Cerito—Another Fight—Cavallo-Quattia—Low Water—Join the Republican Flotilla—Labors and Difficulties, 114

CHAPTER XVIII.

The Enemy Appear under General Brown—We Fight—Labors and Fatigue by Night—Desertion—Preparations to Renew the Battle—Another Fight—Vessels Burned—Landing in Small Boats—Land Travel—Treatment by the Inhabitants—Traverse the Province of Corrientes—Reach San Francisco—Notice of the Battle of Arroyo Grande, Dec. 6, 1842—Sent by Gen. Aguyar to Versilles with the Vessels—Strange Presentiment—Catching Horses—Bad News, 122

Public Dismay—Enthusiasm of the People Rising—I Return to Montevideo—Ourives Coming to Besiege it—Preparations for Defence—General Paz—I am Ordered to Collect a Flotilla—A Fortunate Accident, 134

CHAPTER XX.

The Enemy reach Montevideo—Gen. Rivera's Movement on their Left Flank—Gen. Paz Commands in the City—Services by the French and Italian Corps—Treachery—Mismanagement—Gen. Pacheco Corrects it—Attack on the Besiegers—Italian Legion Distinguished—Anzani—Services of the Flotilla—A Providential Event—Commodore Purvis—British Intervention—Negotiation, 139

CHAPTER XXI.

Exploits of the Italian Legion during the Siege—Tres Cruces—The Pass of Bojada—The Quadrado—General Rivera Defeated at India Muerta, but without Discouraging Efforts, Intervention Continued—An Expedition in the Uruguay, the Flotilla being under my Command, 148

CHAPTER XXII.

The Expedition Proceeds for the Uruguay—Colonia Taken by It—Burned—Page, a Suspicious Frenchman—Martin Garcia Taken, 154

CHAPTER XXIII.

First Meeting with a "Martrero"—Description of his Habits and Character—Another Martrero, Juan de la Cruz—The Rio Negro—Joseph Mundell—The severity of the Enemy Drive the Martrero and People to us, 157

CHAPTER XXIV.

The Expedition Proceeds—Surprise Gualeguayechu—Reach the Hervidero—Accompanied by an English and a French Officer—A large Estancia, and its numerous Horses and other Animals—I leave the Vessels in Charge of Anzani—Go with the Martreros—La Cruz and Mundell—Attack on the Hervidero—Battle of Arroyo Grande, 163

CHAPTER XXV.

The Province of Corrientes calls General Paz from Montevideo—Alliance with Paraguay—I go to Salto with the Flotilla, to relieve it from a Siege—With La Cruz and Mundell attack Lavalleja—Return to Salto, 171

Urquiza Besieges us in Salto with all his Forces—Our Defences Incomplete—A sudden Attack—Repulsed Sorties—Bold Operation on the opposite Bank of the River—Surprising Feats of the Horsemen—Their Habits, 178

CHAPTER XXVII.

The Siege of Salto Continued—Night Attack on the Enemy's Camp—Successful—General Medina approaching—Send Gen. Baez and Anzani to Meet him—A Great Surprise—Almost Overwhelmed by the Enemy—Fight till Night—Retreat, 184

CHAPTER XXVIII.

Preparations for our Retreat—Attacked on the Way—Bravery of my Italians—I never Despaired of Italy—The noble Character of Anzani—Reach Salto—Kindness of French Physicians—Collect and Bury the Dead, 191

CHAPTER XXIX.

Effects of the Revolution in Montevideo—Change of Duties of the Italian Legion—No Important Military Movements—My Occupation with the Marine—Diplomatic Negotiations—The Temporizing Policy of Rosas—Change of English and French Agents and Admirals—Evil Consequences—Rivera in favor in Montevideo—My Operations at Salto Continued—Surprise Vergara's Camp—Leave it to Return, 196

CHAPTER XXX.

On the March Back to Salto—Sudden Attack—Desperate Defence—Flight and Pursuit—The "Bolla"—Excellence of the Horsemen—Incidents, 203

CHAPTER XXXI.

I Return to Montevideo, with the Flotilla—Rosas Gains Strength—The Army of Corrientes Destroyed by Urquiza—Rivera's Mismanagement—The Intervention Misdirected—Fall of Salto—Defence again reduced to Montevideo—High Deserts of its Defenders, Natives and Foreigners, not yet appreciated—An interval occurs, not marked by important events—The Revolutions in Europe, 208

OUTLINES OF GENERAL GARIBALDI'S CAREER IN ITALY DURING THE YEARS 1848 & 1849, 211

Principles of the Italian Republicans, in opposition to the claims of Popery, 213

The Condition of Rome, 216

Official Report of the Repulse of the French advance of 8,000 men, under General Oudinot, under the Walls of Rome—The First Battle: April 30th, 1849, 221

From an Account of the same Battle of April 30th, by Carlo Rusconi, 227

Spirited Proclamation to the People of Rome, by their Representatives, the day after the first Battle, 228

Proclamation by the Committee of the Barricades, two days after the first Battle, 229

The Neapolitan Invasion, 230

Proclamations of the Triumvirate, at the time of the Neapolitan Invasion, 231

The Battle of Palestrina, 232

General Garibaldi's Account of the Battles of Palestrina and Velletri, 234

The Battle of Velletri, 235

General Garibaldi's Account of the Action of June 3d, 1849, with the French, at Villas Corsini and Vascello, 238

Official Bulletin of events which took place on the 25th and 26th of June, 1849, 243

THE BATTLE OF JUNE 30TH, 249

The City to cease her resistance, 250

Roman Republic, 251

The Constitution of the Roman Republic adopted—The Constituent Assembly Dissolved, 253

Proclamation of the Minister of War, 255

Garibaldi's Departure from Rome with his remaining troops, and his Celebrated Retreat to the Adriatic, 255

CHAPTER I.

Garibaldi Waiting his Time—The Island of Caprera—His Confidence in the Approach of Italian Deliverance, expressed in his preceding Autobiography, and at New York—His Personal Appearance—Injustice Done to his Character and Style of Writing—M. Dumas' Book—Preparation of the Italian People for Union and Liberty, by Secret Societies—Changes Of Policy—The Principles of the Italian Patriots adopted by France and England—Consequences, 257

CHAPTER II.

Policy of Louis Napoleon since 1849—His Position in 1859—Causes of the War in Lombardy—Austrian Army Threatens Piedmont—French Troops sent to the Aid of Victor Emanuel—Garibaldi called into Service—Marches North—Apprehensions of his Friends—His Brilliant Successes at Varese and Como, 263

CHAPTER III.

Como—Approach of General Urban with 40,000 Austrians—Garibaldi Retires—Como Taken—Count Raimondi's Daughter—Garibaldi Returns and Expels the Austrians—The Battle of Camerlata—The Austrians Demand the Disbanding of Garibaldi's Troops—Refused—They Advance—The Canals Opened—They Retire—The Battles of Palestro, Montebello, and Magenta—The Mincio and its Banks—The Battle of Solferino, 270

CHAPTER IV.

The State of the Contending Parties—Specimen of the Barbarity of some of the Austrian Officers—The Armistice, 279

CHAPTER V.

The Character of Italian Patriots—How it has been Displayed by Exiles in the United States—Ignorance of Italy in America—Garibaldi's Appearance and Character—His Band—His "Englishman," Col. Peard, 287

Garibaldi with an Army at Rimini—General Lamoricière at Pesaro—Victor Emanuel Apprehends a Premature Collision—Garibaldi goes to Piedmont—Nice and Savoy Ceded to France—Garibaldi at Caprera—The Sicilian Revolution Commenced—Garibaldi's Expedition for Sicily—The Island—The People, 292

CHAPTER VII.

Accounts of the Expedition for Sicily—Voyage—Touch at Talamone, in Tuscany—Proceed to Marsala—Landing—March—Occurrences on the way to Palermo, 298

CHAPTER VIII.

Preparations to Attack Palermo—Night March—Attack—Battle—The Bombardment, 311

CHAPTER IX.

Journal of an Eye-witness Continued—Palermo after the Capture—Garibaldi in a Dangerous Crisis—The Archbishop of Palermo and many of the Heads of Convents with Garibaldi—Address of the Corporation—Incidents in Palermo—Garibaldi's Decree for Poor Soldiers and their Families, 319

CHAPTER X.

Garibaldi Solicited by the Sicilians to Accept the Dictatorship—Demand for Arms—Garibaldi's Proclamation Establishing a Government, etc.—His Different ways of Treating Good Priests and Jesuits—Reasons—The King of Naples' Liberal Decree—Rejected, 326

CHAPTER XI.

Medici's Expedition from Piedmont to Aid Garibaldi—Preparations, Departure, Voyage, Arrival, etc.—Capitulation of Messina, etc.—Garibaldi at Messina—His Reception, Manners, and Simple Habits—Difficulties in Arranging his Government—Letter from Victor Emanuel Forbidding him to Invade Naples—Garibaldi's Reply, 332

CHAPTER XII.

Garibaldi's Position—A Pause in Hostilities—A Period of Preparation—Public Anxiety—The Sicilian Fortresses—Catania—Milazzo —Boats, Men, and Arms Collected at Faro—Landing Attempted at Scylla—A Small Body Succeed, 340

The Uncertainty of the Prospect—Apprehensions—Garibaldi's Mysterious Disappearance—The Expedition Prepared in Sardinia—His Change of Plans—Sails from Giardini, and Lands at Reggio, 348

CHAPTER XIV.

The Condition of Naples in past Months—The Government Crisis Royal Decree—How it was Received—Cruelties Practised—First Movements of the People, 354

CHAPTER XV.

The Condition of Naples since the Reign of Terror in April—Agitation on Garibaldi's Approach, 368

CHAPTER XVI.

Garibaldi's Journey through Calabria—Reaches Palermo—Enters Naples—Enthusiasm and Good Order of the People—The New Government—The Army and Navy—Various Occurrences, 374

CHAPTER XVII.

The Good Order in Naples—Its Causes—Garibaldi Visits Palermo—Returns—The King and his Army at Gaeta and Capua—Description and History of Gaeta and Capua—Present Condition of Gaeta, 396

CHAPTER XVIII.

The Royal Palace and Gardens of Caserta—Change of Times—The River Volturno—Position of the King's Troops and Garibaldi's—The Battle of Volturno, 403

CHAPTER XIX.

The Pope urged by France and Sardinia to Dismiss his Foreign Troops—Inconsistencies of Louis Napoleon—Marked Changes of Times, Doctrines, and Measures—Victor Emanuel's Demands Pressed on the Pope—Conspiracies and Insurrections in the Pope's Remaining Dominions—The Ultimatum Refused—General Cialdini Marches—Battle of Castelfidaro—Capture of Spoleto, Ancona, Perugia, and other Places—Victor Enters the Kingdom of Naples, 416

The Present Position of Things—Doubts Respecting Garibaldi—Descriptions of the Camp at Capua—England Declares for Victor Emanuel—Garibaldi's Proclamations—Meeting of Garibaldi and Victor Emanuel, 431

CHAPTER XXI.

Garibaldi's Announcement of Victor Emanuel's Approach to Naples—They Enter Together—Garibaldi Resigns his Dictatorship—Capitulation and Surrender of Capua—His Address to the Hungarian Huzzars—His Farewell to his Troops—He Sails for Caprera—Unexpected Changes—Letters Describing them, 439

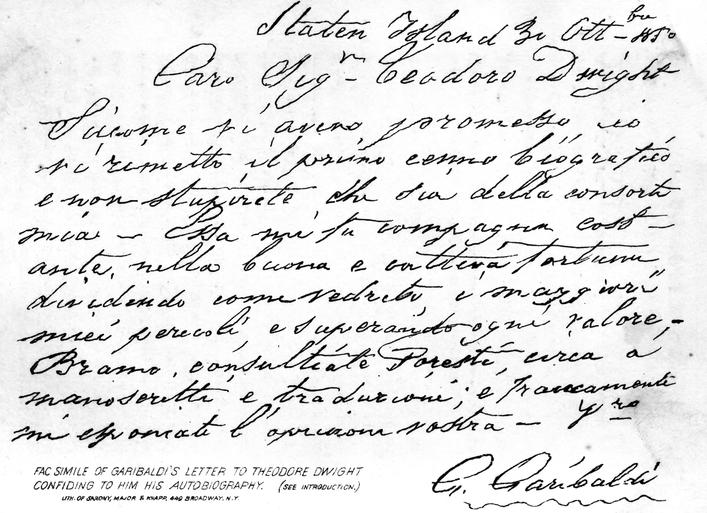

FAC SIMILE OF GARIBALDI'S LETTER TO THEODORE DWIGHT

CONFIDING TO HIM HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY. (SEE INTRODUCTION.)

LITH. OF SARONY, MAJOR & KNAPP, 449 BROADWAY. N. Y.]

1.

"Dear Mr. Theodore Dwight:

"According to what I have promised you, I send you the first biographical sketch; and do not be surprised that it is that of my wife. She was my constant companion, in good and bad fortune—sharing, as you will see, my greatest dangers, and surpassing the bravest men. I wish you to consult Foresti, respecting the manuscripts and translations, and frankly express to me your opinion.

MY FATHER—MY MOTHER—HER INFLUENCE ON MY LIFE—INCIDENTS OF MY CHILDHOOD—MY FIRST SCHOOLMASTERS.

In commencing an account of my life, it would be unpardonable in me to omit speaking of my kind parents. My father, a sailor, and the son of a sailor, educated me in the best manner he could in Nice, my native city, and afterwards trained me to the life of a seaman in a vessel with himself. He had navigated vessels of his own in his youth; but a change of fortune had compelled him afterwards to serve in those belonging to his father. He used often to tell his children that he would gladly have left them richer; but I am fully convinced that the course which he adopted in our education was the best he possibly could have taken, and that he procured for us the best instructors he was able, perhaps sometimes at the expense of his own convenience. If, therefore, I was not trained in a gymnasium, it was by no means owing to his want of desire.

In mentioning my mother—I speak it with pride—she was a model for mothers; and, in saying this, I have said all that can be said. One of the greatest sorrows of my life is, that I am not able to brighten the last days of my good parent, whose path I have strewed with so many sorrows by my adventurous career. Her tender affection for me has, perhaps, been excessive; but do I not owe to her love, to her angel-like character, the little good that belongs to mine? To the piety of my mother, to her beneficent and charitable nature, do I not, perhaps, owe that little love of country which has gained for me the sympathy and affection of my good, but unfortunate fellow-citizens? Although certainly not superstitious, often, amidst the most arduous scenes of my tumultuous life, when I have passed unharmed through the breakers of the ocean, or the hail-storms of battle, she has seemed present with me. I have in fancy seen her on her knees before the Most High—my dear mother!—imploring for the life of her son; and I have believed in the efficacy of her prayers.

I spent my childhood in the joys and sorrows familiar to children, without the occurrence of anything very remarkable. Being more fond of play than of study, I learned but little, and made but a poor return for the kind exertions of my parents for my education. A very simple accident made a deep impression on my memory. One day, when a very little boy, I caught a grasshopper, took it into the house, and, in handling it, broke its leg. Reflecting on the injury I had done to the harmless insect, I was so much affected with grief, that I retired to my chamber, mourned over the poor little creature, weeping bitterly for several hours. On another occasion, while accompanying my cousin in hunting, I was standing on the side of a deep ditch, by which the fields were irrigated, when I discovered that a poor woman, while washing clothes, had fallen from the bank, and was in imminent danger. Although I was quite young and small, I jumped down and saved her life; and my success afforded me the highest pleasure. On that occasion, and in various other circumstances of a similar kind, I never hesitated for a moment, or thought of my own safety.

Among my teachers, I retain a grateful recollection of Padre Gianone and Signor Arena. Under the former I made but very little progress, being bent more on play than on learning; but I have often regretted my loss in failing to learn English, whenever I have since been thrown in company with persons speaking that language. To the latter I consider myself greatly indebted for what little I know. The ignorance in which I was kept of the language of Italy, and of subjects connected with her condition and highest interests, was common among the young, and greatly to be lamented. The defect was especially great in Nice, where few men knew how to be Italians, in consequence of the vicinity and influence of France, and still more the neglect of the government to provide a proper education for the people. To the instructions of Padre Gianone, and the incitement given me by my elder brother Angelo, who wrote to me from America to study my native language, I acknowledge my obligations for what knowledge I possess of that most beautiful of languages. To my brother's influence, also, I owe it, that I then read Roman and Italian history with much interest.

This sketch of my early youth I must close, with the narration of a little expedition which I attempted to carry into effect—my first adventure. Becoming weary of school in Genoa, and disgusted with the confinement which I suffered at the desk, I one day proposed to several of my companions to make our escape, and seek our fortune. No sooner said than done. We got possession of a boat, put some provisions on board, with fishing tackle, and sailed for the Levant. But we had not gone as far as Monaco, when we were pursued and overtaken by a "corsair," commanded by good father. We were captured without bloodshed, and taken back to our homes, exceedingly mortified by the failure of our enterprise, and disgusted with an Abbé who had betrayed our flight. Two of my companions on that occasion were Cesare Tanoli and Raffaele Deandreis.

When I recur to the principles which were inculcated at school, and the motives used to encourage us to study, I am now able to understand their unsoundness and their evil tendency. We were in danger of growing up with only selfish and mercenary views: nothing was offered us as a reward for anything we could do, but money.

FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF A YOUNG SAILOR—MY FIRST VOYAGE—MY ACCOMPLISHED CAPTAIN—MY SECOND VOYAGE—FIRST VISIT TO ROME—IMPRESSIONS—MY PRAYERS—JOIN THE SECRET SOCIETY—SENTENCE OF DEATH—ESCAPE TO FRANCE—INCIDENTS AT MARSEILLES.

How everything is embellished by the feelings of youth, and how beautiful appeared, to my ardent eyes, the bark in which I was to navigate the Mediterranean, when I stepped on board as a sailor for the first time! Her lofty sides, her slender masts, rising so gracefully and so high above, and the bust of Our Lady which adorned the bow, all remain as distinctly painted on my memory at the present day, as on the happy hour when I became one of her crew. How gracefully moved the sailors, who were fine young men from San Remi, and true specimens of the intrepid Ligurians! With what pleasure I ventured into the forecastle, to listen to their popular songs, sung by harmonious choirs! They sang of love, until I was transported; and they endeavored to excite themselves to patriotism by singing of Italy! But who, in those days, had ever taught them how to be patriots and Italians? Who, indeed, had then ever said, on those shores, to those young men, that there was such a thing as Italy, or that they had a country to be ameliorated and redeemed?

The commander of the Costanza, the vessel in which I had embarked, was Angelo Pesante. He was the best sea-captain I ever knew, and ought to have the command of a ship of war of the first class, as soon as Italy shall have such a fleet as she deserves,—for a better commander could not be. He has, indeed, been captain of an armed vessel. Pesante was able to make or invent every thing that could be wanted in a vessel of any kind whatsoever, from a fishing-boat to a ship of the line; and, if he were in the service of the country, she would reap the advantage and the glory.

My second voyage was made to Rome, in a vessel of my father's. Rome, once the capital of the world, now the capital of a sect! The Rome which I had painted in my imagination, no longer existed. The future Rome, rising to regenerate the nation, has now long been a dominant idea in my mind, and inspired me with hope and energy. Thoughts, springing from the past, in short, have had a prevailing influence on me during my life. Rome, which I had before admired and thought of frequently, I ever since have loved. It has been dear to me beyond all things. I not only admired her for her former power and the remains of antiquity, but even the smallest thing connected with her was precious to me. Even in exile, these feelings were constantly cherished in my heart; and often, very often, have I prayed to the Almighty to permit me to see that city once more. I regarded Rome as the centre of Italy, for the union of which I ardently longed.

I made several voyages with my father, and afterwards one with Captain Guiseppe Gervino, to Caglieri, in a brig named the Emma, during which, on the return passage, I witnessed a melancholy shipwreck, at a distance, in such a storm that it was impossible to render any assistance. In that instance I witnessed, for the first time, that tender sympathy which sailors generally feel for others in distress. We saw Spaniards, in a Catalan felucca, struggling with the waves, who soon sank before our eyes, while my honest and warm-hearted shipmates shed tears over their hard fate. This disaster was caused by a sudden change of wind when the sea and wind were high. A Libaccio, a south-west wind, had been blowing furiously for several days, and a number of vessels were in sight, of all which the felucca seemed to make the best way. We were all steering for Vado, to make that port for shelter, until the storm should subside. A horrible surge unexpectedly broke over the Spanish vessel, and overset it in an instant. We saw the crew clinging to the side, and heard their cries to us for assistance, while we could perceive their signals, but could not launch a boat. They all soon disappeared in the foam of a second surge, more terrible than the first. We afterwards heard that the nine persons thus lost all belonged to one family.

From Vado I went to Genoa, and thence to Nice, whence I commenced a series of voyages to the Levant, in vessels belonging to the house of Givan. In one of these, in the brig Centesi, Captain Carlo Seneria, I was left sick in Constantinople. The vessel sailed; and, as my sickness continued, I found myself in somewhat straitened circumstances. In cases of difficulty or danger, I have never, in all my life, been disheartened. I then had the fortune to meet with persons kindly disposed to assist me, and, among others, I can never forget Signora Luigia Saiyuraiga, of Nice, whom I have ever since regarded as one of the most accomplished of women, in the virtues which distinguish the best and most admirable of her sex.

As mother and wife, she formed the happiness of her husband, who was an excellent man, and of their young and interesting children, whose education she conducted with the greatest care and skill. What contributed to prolong my abode in the capital of Turkey, was the war which at that time commenced between that power and Russia; and I then, for the first time, engaged as a teacher of children. That employment was offered me by Signor Diego, a doctor in medicine, who introduced me to the widow Temoin, who wanted an instructor for her family. I took up my residence in the house, and was placed in charge of her three sons, with a sufficient salary.

I afterwards resumed the nautical life, embarking in the brig Nostra Signora della Grazia, Captain Casabana; and that vessel was the first I ever commanded, being made Captain of it on a subsequent voyage to Mahon and Gibraltar, returning to Constantinople.

Being an ardent lover of Italy from my childhood, I felt a strong desire to become initiated in the mysteries of her restoration; and I sought everywhere for books and writings which might enlighten me on the subject, and for persons animated with feelings corresponding with my own. On a voyage which I made to Tagangog, in Russia, with a young Ligurian, I was first made acquainted with a few things connected with the intentions and plans of the Italian patriots; and surely Columbus did not enjoy so much satisfaction on the discovery of America, as I experienced on hearing that the redemption of our country was meditated. From that time I became entirely devoted to that object, which has since been appropriately my own element for so long a time.

The speedy consequence of my entire devotion to the cause of Italy was, that on the fifth of February, 1834, I was passing out of the gate of Linterna, of Genoa, at seven o'clock in the evening, in the disguise of a peasant—a proscript. At that time my public life commenced; and, a few days after, I saw my name, for the first time, in a newspaper: but it was in a sentence of death!

I remained in Marseilles, unoccupied, for several months; but at length embarked, as mate, in a vessel commanded by Captain Francesco Gazan. While standing on board, towards evening, one day, dressed in my best suit, and just ready to go on shore, I heard a noise in the water, and, looking below, discovered that some person had fallen into the sea, and was then under the stern of the vessel. Springing into the water, I had the satisfaction to save from drowning a French boy, in the presence of a large collection of people, who expressed their joy aloud, and warmly applauded the act. His name was Joseph Rasbaud, and he was fourteen years of age. His friends soon made their appearance; and I experienced very peculiar feelings excited in my heart, when the tears of his mother dropped, one after another, upon my cheek, while I heard the thanks of the whole family.

Some years before I had a similar good fortune, when I saved the life of my friend, Claudio Terese.

VOYAGE TO BRAZIL—FIRST MEETING WITH ROSETTI—WE ENGAGE IN TRADE—ZAMBECCARI'S ARRIVAL—THE UNITED PROVINCES—ENGAGE IN THE SERVICE OF RIO GRANDE—SAIL—MY FIRST PRIZE—CONDUCT OF MY MEN—MY RULE FOR TREATING PRISONERS—RECEPTION AT MALDONADO—SUDDEN DEPARTURE.

I made another voyage to the Black Sea, in the brig Unione, and afterwards one to Tunis, in a frigate, built at Merseilles for the Bey. From the latter port I next sailed for Rio Janeiro, in the Nautonier, a Nantes brig, Captain Beauregard.

While walking one day in a public place in Rio, I met a man whose appearance struck me in a very uncommon and very agreeable manner. He fixed his eyes on me at the same moment, smiled, stopped, and spoke. Although we found that we had never met before, our acquaintance immediately commenced, and we became unreserved and cordial friends for life. He was Rosetti, the most generous among the warm lovers of our poor country!

I spent several months in Rio, unoccupied and at ease, and then engaged in commerce, in company with Rosetti: but a short experience convinced us that neither of us was born for a merchant.

About this time Zambeccari arrived at Rio, having been sent as a prisoner from Rio Grande, when I became acquainted with the sentiments and situation of the people of that province. Arrangements were soon made for Rosetti and myself to proceed on an expedition for their aid, they having declared their independence. Having obtained the necessary papers, we engaged a small vessel for a crusier, which I named "The Mazzini." I soon after embarked in a garopera, with twenty companions, to aid a people in the south, oppressed by a proud and powerful enemy. The garope is a kind of Brazilian fish, of an exquisite flavor; and boats employed in taking it are called garoperas. My feelings, at that epoch of my life, were very peculiar. I was enlisted in a new and hazardous enterprize, and, for the first time, turned a helm for the ocean with a warlike flag flying over my head—the flag of a republic—the Republic of Rio Grande. I was at the head of a resolute band, but it was a mere handful, and my enemy was the empire of Brazil.

We sailed until we reached the latitude of Grand Island, off which we met a sumaca, or large coasting boat, named the Luisa, loaded with coffee. We captured her without opposition, and then resolved to take her instead of my own vessel, having no pilot for the high sea, and thinking it necessary to proceed along the coast. I therefore transferred everything from the Mazzini on board the sumaca, and then sunk the former. But I soon found that my crew were not all men like Rosetti, of noble and disinterested character and the purest morals; and, indeed, I had before felt some apprehensions, when I saw among them several physiognomies by no means prepossessing. I now found them, when on board the sumaca, affecting ferocity, to intimidate the poor Brazilian sailors, whom we had made prisoners. I took immediate steps to repress all such conduct, and to tranquilize the fears which they had excited, assuring the crew that they should be uninjured and kindly treated, and set on shore at the first convenient landing-place, with all their own personal property. A Brazilian, a passenger in the sumaca, took the first opportunity, after coming on board, to offer me a casket containing three valuable diamonds, in a supplicating manner, as if afraid for his life; but I refused to receive it, and gave peremptory orders that none of the effects of the crew or passengers should be taken from them, under any pretext whatever. And this course I pursued on all subsequent occasions, whenever I took any prizes from the enemy; and my orders were always strictly obeyed.

The passengers and crew were landed north of Itaparica, the launches of the Luisa being given to them, with all their movables, and as much brandy as they chose to take with them. I then went to the south, and soon arrived in the port of Maldonado, where the favorable reception given us by the authorities and the people, afforded us a very flattering prospect.

Rosetti set off for Montevideo, to arrange things connected with the expedition, leaving us to await his return; and during eight days we enjoyed one uninterrupted festival among the hospitable inhabitants. The close of that period of gayety would have been tragical, if the political chief of the town had been less friendly than he proved himself to be. I received unexpected notice, quite different from what I had been led to expect, that the flag of Rio Grande was not recognized, and that an order had arrived for our immediate arrest. Thus compelled to depart, although the weather was threatening, I hoisted sail without delay, and steered up the river Plata, with scarcely any plan or object, and almost without opportunity to communicate to any one that I should await, at the Point of Jesus Maria, news of the result of Rosetti's deliberations with his friends in Montevideo. After a wearisome navigation, I reached that place, having narrowly escaped shipwreck on the Point of Piedras Negras, in consequence of a variation of the compass caused by the muskets placed near it.

I found no news at that place; and our provisions were entirely consumed. We had no boat to land with: but it was indispensable to procure food for the men. At length, after some deliberation, having discovered a house about four miles distant from the shore, I determined to get to the land, by some means or other, and, at any cost, to procure provisions and bring them on board. The shore being very difficult of approach, because the wind was blowing from the pampas, the vast plains which extend far and wide, it was necessary to throw out two anchors to draw up a little nearer. I then embarked on the dining table, accompanied by one of my sailors, named Maurizio Garibaldi, and moved on towards the land, not navigating, but rolling through the breakers of that dangerous shore. In spite of the difficulty attending the enterprise we reached the river's bank in safety, and drew up our strange craft on the sand. Then, leaving my companion and namesake to refit, I set off for the house which I had seen from the vessel.

Walking up the bank I reached the level of the pampas, and then, for the first time in my life, caught a view of one of those vast South American plains. I was struck with admiration:—such a boundless scene of fertility, where wild horses and cattle were running free and unrestrained, feeding, resting, and racing at full speed, at will. My mind was filled with new, sublime and delightful emotions, as I passed on towards the solitary habitation to which I was bound. When I reached it I found a welcome, and easily obtained a promise of an abundant supply of food for my crew. The daughter of the proprietor of that vast estate was an educated, refined and agreeable young lady, and even a poetess; and I spent the remainder of the day very pleasantly, in company with her and the rest of the family.

The next day I returned to the shore, with the quarters of a fat bullock which had been killed for me out of the immense herd of cattle, at the order of the proprietor. Maurizio and I fastened the meat to the legs of the table, which were in the air, the table itself being placed upside down on the water, and then we launched out into the river to make our way to the vessel. But the weight of the cargo and crew proved entirely too great, and we immediately began to sink until we stood in the water; and on reaching the breakers, the agitation caused so much rocking that it was almost impossible to proceed, or even to keep our footing. Indeed, we were in actual danger of drowning. But, after great exertions, we reached the Luisa with our load of provisions, and were hailed by the shouts of our companions, whose only hope for subsistence depended on our success.

The next day, while passing a small vessel called a Balandra, we thought of purchasing her launch, which we saw on her deck. We therefore made sail, boarded her, and made the purchase for thirty dollars. That day also we spent in sight of Jesus Maria.

TWO BRAZILIAN VESSELS—MY FIRST BATTLE—MY FIRST WOUND—RESULTS—MY OWN CONDITION—BURIAL OF MY FRIEND FIORENTINO.

The day after, while lying a little south of Jesus Maria, two launches came in sight and approached us in a friendly manner, with nothing in their appearance to excite suspicion. I made a signal agreed on with friends, but it was not answered; and then I hoisted sail, had the arms taken from the chests, and prepared to meet them as enemies. The launches held on towards us: the larger showed only three men on deck: but, when she came nearer, called on us to surrender, in the name of the Oriental Government. The next instant thirty men suddenly rose, as if by a miracle, and she ran up on our larboard side. I immediately gave command to "brace the yards," and then to "fire." An active engagement then commenced. The launch being then alongside of us, several of the enemy attempted to board us, but were driven back by a few shots and sabre-cuts. All this passed in a few moments. But my order to brace the yards was not obeyed, for my men were new and in confusion, and the few who began to haul at the weather braces found they had not been let go to leeward, and were unable to move them. Fiorentino, one of the best of the crew, who was at the helm, sprang forward to cast them off, when a musket ball struck him in the head and laid him dead on deck. The helm was now abandoned; and, as I was standing near, firing at the enemy, I seized the tiller, but the next moment received a bullet in my neck, which threw me down senseless, and I knew nothing more until the action was over. When I came to myself I found that an hour had elapsed, a hard fight had been maintained against a superior force, and a victory won, chiefly by the bravery of the Italians, the mate, Luigi Carniglia, the second mate, Pasquale Lodola, and the sailors Giovanni Lamberti and Maurizio Garibaldi. Two Maltese and all the Italians, except a Venitian, fought bravely. The others, with two negroes, sheltered themselves under the ballast of the vessel.

I found that the enemy had hauled off out of gun-shot. I ordered that our vessel should proceed up the river, in search of a place of retreat. When I first began to recover consciousness, I lay helpless, apparently dead, but felt as if unable to die. I was the only man on board who had any knowledge of navigation; and, as none of the others had a single idea of geography, or knew where to go, they at length brought me the chart. None of us had been in the waters of the Plata before, except Maurizio, who had sailed on the Uruguay. When I turned my dying eyes on the chart, I was unable to see distinctly, but made out to perceive that one place on the river was printed in large letters, and at length discovered that it was Santa Fé, on the Paraná, and thought we might there make a temporary harbor. So, pointing at it with my finger, and signifying as well as I could the direction and distance, I left the helmsman to himself.

All the sailors, except the Italians, were frightened by seeing my situation, and the corpse of Fiorentino, and by the apprehension of being treated as pirates wherever they might go. Every countenance wore an expression of terror; and at the earliest opportunity they deserted. In every bird they observed on the water they imagined they saw an enemy's launch, sent to pursue them. The body of the unfortunate Fiorentino was buried the next day in the river, with the ceremonies usually practised by sailors, as we were unable to anchor anywhere near the land. I was perhaps affected the more by the sad scene, because I was in so feeble a condition. I had never thought much about death, although I knew I was liable to it every moment; but I mourned deeply at the funeral of my lost friend, who was very dear indeed to me. Among the numerous poetical lines which occurred to my mind, was that beautiful verse of Ugo Foscolo:

My friend had promised me never to bury me in the water: but who can tell whether he would have been able to keep his promise? I could never have felt sure that my corpse would not feed the sea-wolves and acaves of the great river Plata. If it were so, then I should never have seen Italy again; never fought for her—which was the great wish of my life: but then, too, I never should have seen her sink into ignominy. Who would have said to the amiable man that, within a year, Garibaldi would see him swallowed up in the surges of the ocean, and that he would search for his corpse, to bury it on a foreign shore, and to mark the spot with a stone, for the eyes of strangers? He deserved my kind regard; for he attended me, with the care of a mother, during the whole voyage from Mayaguay. During all my sufferings, which were very severe, I had no relief but what he afforded me, by his constant care and kind services. I wish to express my gratitude to God for sending me such a friend.

ARRIVAL AT GUALAGUAY—RECEPTION—MY WOUND HEALED—MY SUDDEN DEPARTURE AND RETURN—CRUEL TREATMENT—SEÑORA ALEMAN—TRIBUTE TO THAT NOBLE LADY—GO TO BAJADA.

Our vessel arrived at Gualaguay, where we were very cordially received and kindly treated by Captain Luca Tartabal, of the schooner Pintoresca, and his passengers, inhabitants of that town. That vessel had met ours in the neighborhood of Hiem, and, on being asked for provisions by Luigi, they had offered to keep company with us to their destination. They warmly recommended us to the governor of the province, Don Pasquale Echague, who was pleased, when going away, to leave his own surgeon with me, Dr. Ramon del Orco, a young Argentine. He soon extracted the ball from my neck and cured me. I resided in the house of Don Jacinto Andreas during the six months which I spent in that place, and was under great obligations to him for his kindness and courtesy, as well as for those which I received from his family.

But I was not free. With all the friendliness of Echague, and the sympathy shown me by the inhabitants of the town, I was not permitted to leave it without the permission of Rosas, the traitor of Buenos Ayres, who never acted for a good reason. My wound being healed, I was allowed to take rides on horseback, even to a distance of twelve miles, and was supplied with a dollar a day for my subsistence, which was a large sum for that country, where there is but little opportunity to spend money. But all this was not liberty. I was then given to understand by certain persons (whether friends or enemies), that it had been ascertained that the government would not wish to prevent my escape if I should attempt it. I therefore determined to gain my freedom, believing that it would be easier than it proved, and that the attempt would not be regarded as a serious offence.

The commandant of Gualaguay was named Millau. He had not treated me ill, but it was very doubtful what his feelings towards me really were, as he had never expressed any interest in me.

Having after a time formed my plan, I began to make preparations. One evening, while the weather was tempestuous, I left home and went in the direction of a good old man, whom I was accustomed to visit at his residence, three miles from Gualaguay. On arriving, I got him to describe with precision the way which I intended to take, and engaged him to find me a guide, with horses, to conduct me to Hueng, where I hoped to find vessels in which I might go, incognito, to Buenos Ayres and Montevideo. Horses and a guide were procured. I had fifty-four miles to travel, and that distance I devoured in less than half a night, going almost the whole way on the gallop. When day broke, we were at an estancia, within about half a mile of the town. My guide then told me to wait in the bushes where we were, while he went to inquire the news at the house. I complied, and he left me. I dismounted and tied my horse to a tree with the bridle, and waited a long time. At length, not seeing him return, I walked to the edge of the bushes, and looked about in search of him, when I heard behind me a trampling of horses; and, on turning round, discovered a band of horsemen, who were rushing upon me with their sabres drawn. They were already between me and my horse, and any attempt to escape would have been fruitless—still more any effort at resistance. I was immediately seized and bound, with my hands behind me, and then placed upon a miserable horse, and had my feet tied under him. In that condition I was taken back to Gualaguay, where still worse treatment awaited me.

Such were the impressions made upon my feelings by the barbarous usage which I received at that time, that I have never since been able to recall the circumstances without a peculiar agitation of mind; and I regard that period as the most painful of my life.

When brought into the presence of Millau, who was waiting for me at the door of the prison, he asked me who had furnished me with the means of escape. When he found that he could draw no information from me on that subject, he began to beat me most brutally with a club which he had in his hand. He then put a rope over a beam in the prison, and hung me up in the air by my hands, bound together as they were. For two hours the wretch kept me suspended in that manner. My whole body was thrown into a high, feverish heat. I felt as if burning in a furnace. I frequently swallowed water, which was allowed me, but without being able to quench my raging thirst. The sufferings which I endured after being unbound were indescribable: yet I did not complain. I lay like a dead man; and it is easy to believe that I must have suffered extremely. I had first travelled fifty-four miles through a marshy country, where the insects are insufferable at that season of the year, and then I had returned the same distance, with my hands and feet bound, and entirely exposed to the terrible stings of the zingara, or mosquito, which assailed me with vigor; and, after all this, I had to undergo the tortures of Millau, who had the heart of an assassin.

Andreas, the man who had assisted me, was put into prison; and all the inhabitants were terrified, so that, had it not been for the generous spirit of a lady, I probably should have lost my life. That lady was Señora Aleman, to whom I love to express my gratitude. She is worthy of the warmest terms of admiration, and deserves the title of "angelo generoso di bontà" (generous angel of goodness). Spurning every suggestion of fear, she came forward to the assistance of the tortured prisoner; and from that time I wanted nothing—thanks to my benefactress!

A few days after, I was removed to Bajada, the capital of the province, and I remained a prisoner in that city for two months. I was then informed, by Governor Echague, that I should be allowed to leave the province. Although I professed different principles from his, and had fought for a different cause, I have ever been ready to acknowledge my obligations to that officer, and always desired an opportunity to prove my gratitude to him for granting me everything that was in his power to give, and, most of all, my liberty.

I took passage in a Genoese brig, commanded by Captain Ventura, a man of such a character that he had risen superior to the principles inculcated in Italian youth by their priestly instructors. From him I received the most gentlemanly treatment on my passage to Guassu. There I embarked for Montevideo in a balandra, commanded by Pascuale Corbona, who likewise treated me with great kindness. Good fortune and misfortune thus often succeeded each other.

AT MONTEVIDEO—INCOGNITO—DEPARTURE FOR RIO GRANDE—MARCH WITH THE ARMY OF THE PRESIDENT, BENTO GONZALEZ—HIS CHARACTER, FAMILY, AND FRIENDS—AGREEABLE SOCIETY.

In Montevideo I found a collection of my friends, among whom the chief were Rosetti, Cuneo, and Castellani. The first was on his return from a journey to Rio Grande, where he had been received with the greatest favor by the proud Republicans inhabiting that region. In Montevideo I found myself still under proscription, on account of my affair with the launches of that state, and was obliged to remain in concealment in the house of my friend Pepante, where I spent a month. My retirement was relieved and enlightened by the company of many Italian acquaintances, who, at that time, when Montevideo was not suffering from the calamities it has too often known, and, as is always the case in time of peace, were distinguished by a refinement and hospitality worthy of all praise. The war, and chiefly the late siege, have since embittered the lives of those good-hearted men, and produced great changes in their condition.

After the expiration of a month, I set off for Rio Grande with Rosetti, on horseback; and that first long journey I ever made in that manner I highly enjoyed. On reaching Piratimin, we were cordially received by the Governor of the Republic; and the Minister of War, Almeida, treated us with great honor. The President, Bento Gonzalez, had marched at the head of a brigade to fight Silva Tavares, an imperial chief, who was infesting that part of the province. Piratimin, then the seat of the Republican government, is a small village, but a peaceful place, in a rural situation, and the chief town of the department of that name. It is surrounded by a warlike people, much devoted to the republic.

Being unoccupied in Piratimin, I requested permission to join the column of operations under S. Gonzalez, near the President, and it was granted. I was introduced to Bento Gonzalez, and well received; spent some time in his company, and thought him a man highly favored by nature with some desirable gifts. But fortune has been almost always favorable to the Brazilian Empire.

Bento Gonzalez was a specimen of a magnanimous soldier, though he was at that time nearly sixty years of age. Being tall and active, he rode a fiery horse with all the ease and dexterity of his young countrymen.

In Camarino, where we had our arsenal, and whence the Republican flotilla went out, resided the families of Bento Gonzalez; and his brothers and numerous relations inhabited most of the extensive tracts of country lying along both sides of the river. And on these beautiful pastures were fed immense herds of cattle, which had been left undisturbed by the war, because they were out of the reach of the troops. The products of agriculture were very abundant; and surely nowhere, in any country on earth, is found more kind and cordial hospitality than among the inhabitants of that part of the Province of Rio Grande. In their houses, in which the beneficent character of the patriarchal system is everywhere perceived in every family, and where the greatest sympathy prevails, in consequence of a general uniformity of opinions, I and my band were received with the warmest welcome. The estancias, to which we chiefly resorted, on account of their proximity to the Lagoon, as well as for the conveniences which it offered us, and the kind reception which always awaited us, were those of Donna Antonia and Donna Anna, sisters of Bento Gonzalez. The former was situated on the Camones, and the latter on the Arroyo Grande.

Whether I was under the influence of my imagination, which at that early age may have been peculiarly sensitive, and inclined me, with my little knowledge of the world, to receive strong impressions from every thing agreeable, or whatever else may have affected me, there is no part of my life on which I look back with greater pleasure, as a period of enjoyment, than that which I spent in that most agreeable society of sincere friends. In the house of Donna Anna, especially, I took peculiar interest. That lady was advanced in years, but possessed a most amiable disposition, and was a very attractive acquaintance. She had with her a family which had migrated from Pilotos, the head of which was Don Paolo Ferreira. Three young ladies, all of them agreeable, formed the ornaments of that happy home. One of these, named Manuela, I most highly admired, regarding her with that pleasure which is natural to a young man, who goes into the world with such a pure and exalted estimate of female excellence as I had imbibed from my mother, and who, after enduring great reverses, meets the sympathy of such a person in a remote land of exile. Signora Manuela, as I well knew, was betrothed to a son of the President. In a scene of danger that young lover displayed his attachment to her, in a manner which convinced me of the sincerity of the love which he professed; and I witnessed it with as much satisfaction as if I had been her brother. I thenceforth regarded the President's son as worthy of Manuela, and rejoiced in the conviction that her happiness was in no danger, in being entrusted to such faithful hands. The people of that district are distinguished for beauty; and even the slaves seem to partake of the same characteristic.

It may be supposed that an occasional contrary wind, a storm, or an expedition, whatever else it might produce, if it threw our vessel on that friendly shore long enough to allow opportunity to visit their friendly inhabitants, was not altogether disagreeable. Such an occasion was always a festival. The Grove of Teviva, (a kind of palm growing on the Arroyo Grande,) which was the landmark for the entrance of the stream, was always discovered with lively pleasure, and saluted with redoubled enthusiasm and the loudest acclamations. When the gentle hosts, to whose kindness we felt so much indebted, wished to go to Camacuan to visit Don Antonio and his amiable family, I seized the opportunity with great pleasure, as it afforded me a way to make some return for the many kindnesses they had shown us, while it gave new occasions for the display of their amiable character and refined and pleasing manners, amidst the varying scenes of the little voyage.

Between Arroyo Grande and Camacuan are several sand-banks, called Tuntal, which extend from the west shore of the Lagoon, almost at right angles and nearly across, touching the opposite side, except only the narrow space occupied by the boat channel, called Dos Barcos. To go round these bars would greatly prolong the time necessary for the voyage: but that might be avoided, with some trouble. By throwing themselves into the water and pushing the launches along by main force, with their shoulders, the men could get them over the bars, and then keep along the western side of the Lagoon. This expedient was almost always adopted by us, and especially on the occasions referred to, when the boats were honored with the presence of our welcome guests—that precious freight! Whatever might be the wind, I was usually sure of getting the launches over the bars; and, so accustomed were my men to the task, and so prompt in the performance of that laborious service, that the order to take to the water ["Al aqua, Tatos!"] was scarcely pronounced before they were overboard and at their posts. And so, on all occasions, the task was performed with alacrity and success, as if the crews had been engaged in some favorite amusement on a day of jubilee, whatever might be the hour or the weather. But when pursued by the enemy in superior force, and suffering in a storm, we were obliged to pass that way, sometimes in the water a whole night, and without protection from the waves, which would break over us, while the temperature of the Lagoon was cooled by the rain, and we were far from land, the exposure, the labor and the sufferings were sometimes very great, and all the fervor of youth was necessary to enable us to endure them.

AT THE GALPON OF CHARGINADA, REPAIRING THE LAUNCHES—MY FRIEND, JOHN GRIGGS—A SURPRISE—A BATTLE—RESULTS—TRIBUTE TO A FAIR FRIEND.

After the capture of the Sumaca, the imperial merchant vessels no longer set sail without a convoy, but were always accompanied by vessels of war; and it became a difficult thing to capture them. The expeditions of the launches were, therefore, limited to a few cruises in the Lagoon, and with little success, as we were watched by the Imperialists, both by land and by water. In a surprise made by the chief, Francisco de Abrea, the whole of my band was near being cut off with its leader.

We were at the mouth of the Camacua, with the launches drawn up on land, opposite the Galpon of Charginada,—that is, the magazine or depôt of the estancia, or large estate of that name. We were engaged in salting meat and collecting Yerba Matté, a species of tea, which grows in those parts of South America, and is used as their daily beverage by the inhabitants. The estate belonged to Donna Antonia, sister of the President. In consequence of the war, meat was not then salted there; and the Galpon was occupied only with Yerba Matté. We used the spacious establishment as our arsenal, and had drawn up our launches some distance from the water, between the magazine and the bank of the river, in order to repair them. At that spot were the shops of the smiths and laborers of the establishment, and there was a plentiful supply of charcoal; for although not then in use, the place retained something of its former condition and appearance. There were not wanting pieces of iron and steel, fit for different purposes in our little vessels. We could easily visit the distant estancias by a galloping ride, where we were most cheerfully supplied with whatever we found deficient in the arsenal.

With courage, cheerfulness, and perseverance, no enterprise is impossible; and, for these I must do justice to my favorite companion and usual forerunner, John Griggs, who surmounted numerous difficulties, and patiently endured many disappointments, in the work of building two new launches.

He was a young man of excellent disposition, unquestionable courage, and inexhaustible perseverance. Though he belonged to a rich family, he had devoted himself disinterestedly to the young Republic; and, when letters from his friends in North America invited him to return home, and offered him a very large capital, he refused, and remained until he sacrificed his life for an unhappy, but brave and generous, people. I had afterwards to contemplate the sad and impressive spectacle, presented by his death, when the body of my friend was suddenly cut down by my side.

While the launches were lying drawn up, as before mentioned, and the repairs were busily going on, some of the sailors were engaged with the sails, and some at other occupations, near them, while several were employed in making charcoal, or keeping watch as sentinels, every one being busy about something,—by some unexpected chance, Francisco de Albera, commonly called Moringue, determined to surprise us; and, although he did not succeed in his design, he gave us not a little trouble. A surprise certainly was effected on that occasion, and in a masterly manner.

We had been on patrols all night, and all the men had been, a short time before, assembled in the Galpon, where the arms were loaded and deposited. It was a beautiful morning, though cloudy; and nothing seemed to be stirring, but all around was silent and apparently lonely. Observations, however, were made around the camp, with the greatest care, without discovering a trace of anything new. About nine o'clock, most of the people were set at work, in cutting wood; and for this purpose were scattered about at considerable distances. I had then about fifty men for the two launches; and it happened that day, by a singular concurrence of circumstances, our wants being peculiar, that only a very few remained near the boats. I was sitting by the fire, where breakfast was cooking, and was just then taking some Matté. Near by was the cook, and no other person.

All on a sudden, and as if just over my head, I heard a tremendous volley of firearms, accompanied by a yell, and saw a company of the enemy's horsemen marching on. I had hardly time to rise and take my stand at the door of the Galpon, for at that instant one of the enemy's lances made a hole through my poncho. It was our good fortune to have our arms all loaded, as I have before mentioned, and placed in the Galpon, in consequence of our having been in a state of alarm all night. They were placed inside of the building, against the wall, ready and convenient for use. I immediately began to seize the muskets and discharge them in turn, and shot down many of the enemy. Ignacio Bilbao, a brave Biscayan, and Lorenzo N., a courageous Genoese, were at my side in a moment; and then Eduardo Mutru, a native of the country, Rafaele and Procopio, one a mulatto and the other a black, and Francisco. I wish I could remember the names of all my bold companions, who, to the number of thirteen, assembled around me, and fought a hundred and fifty enemies, from nine in the morning until three in the afternoon, killing and wounding many of them, and finally forcing them to retreat.

Among our assailants were eighty Germans, in the infantry, who were accustomed to accompany Maringue in such expeditions, and were skilful soldiers, both on foot and on horseback. When they had reached the spot, they had dismounted and surrounded the house, taking advantage of the ground, and of some rough places, from which they poured upon us a terrible fire from different sides. But, as often happens in surprises, by not completing their operations and closing, men ordinarily act as they please. If, instead of taking positions, the enemy had advanced upon the Galpon, and attacked us resolutely, we should have been entirely lost, without the power to resist their first attack. And we were more exposed than we might ordinarily have been in any other building, because, to allow the frequent passage of carts, the sides of the magazine were left open.

In vain did they attempt to press us more closely, and assemble against the end walls. In vain did they get upon the roofs, break them up and throw upon our heads the fragments and burning thatch. They were driven away by our muskets and lances. Through loop-holes, which I made through the walls, many were killed and many wounded. Then, pretending to be a numerous body in the building, we sang the republican hymn of Rio Grande, raising our voices as loud as possible, and appeared at the doors, flourishing our lances, and by every device endeavoring to make our numbers appear multiplied.

About three o'clock in the afternoon the enemy retired, having many wounded, among whom was their chief. They left six dead near the Galpon, and several others at some distance. We had eight wounded, out of fourteen. Rosetti, and our other comrades, who were separated from us, had not been able to join us. Some of them were obliged to cross the river by swimming; others ran into the forest; and one only, found by the enemy, was killed. That battle, with so many dangers, and with so brilliant a result, gave much confidence to our troops, and to the inhabitants of that coast, who had been for a long time exposed to the inroads of that adroit and enterprising enemy, Maringue.

We celebrated the victory, rejoicing at our deliverance from a tempest of no small severity. At an estancia, twelve miles distant, when the news of the engagement was received, a young lady inquired, with a pallid cheek and evident anxiety, whether Garibaldi was alive. When I was informed of this, I rejoiced at it more than at the victory itself. Yes! Beautiful daughter of America! (for she was a native of the Province of Rio Grande,) I was proud and happy to enjoy your friendship, though the destined bride of another. Fate reserved for me another Brazilian female—to me the only one in the world whom I now lament, and for whom I shall weep all my days. She knew me when I was in misfortune; and her interest in me, stronger than any merit of my own, conquered her for me, and united us for ever.

DESCRIPTION OF THE LAKE OR LAGOON DOS PATOS—THE ENEMY COMMAND THE LAKE—PLAN TO ENTER IT—TRANSPORTATION OF LAUNCHES OVER LAND—RESULTS OF THE EXPERIMENT —BREAKERS—SHIPWRECK—SAD CATASTROPHE.

The Lake or Lagoon Dos Patos is about 45 leagues in length, or 135 miles, and from eleven to twenty miles in medium width. Near its mouth, on the right shore, stands a strong place, called Southern Rio Grande, while Northern Rio Grande is on the opposite side. Both are fortified towns, and were then in possession of the Imperialists, as well as Porto Alegre. The enemy were therefore masters of the lake by water. It was thought impossible for the Republicans to pass through the outlet which leads from the lake to the sea, and as that was the only water passage, we were obliged to prepare to effect a way of communication by land. This could be done only by transporting the launches on carts over the intermediate country. In the northern part of the lake is a deep bay, called Cassibani, which takes its name from a small river that empties in at its further side. That bay was chosen as the place for landing the launches; and the operation was performed on the right bank. An inhabitant of that part of the province, named De Abrea, had prepared wheels of great solidity, connected two and two by axles, proportioned to the weight of the vessels. About two hundred domestic oxen were then collected, with the assistance of the neighboring inhabitants, and, by their labor, the launches were drawn to the shore and got into the water, being carried on wheels, placed at proportionate distances from each other. Care, however, was taken to keep them in such positions that the centre of gravity should be preserved, by supporting the vessels laterally, without disturbing the free action of the wheels. Very strong ropes were, of course, provided, to attach the oxen to the wheels.

Thus the vessels of the Republican squadron started off, navigating across the fields. The oxen worked well, they being well placed and prepared for drawing freely in the most convenient manner. They travelled a distance of fifty-four miles without any difficulty, presenting a curious and unprecedented spectacle in those regions. On the shore of Lake Tramandai the launches were taken from the carts and put into the water, and then loaded with necessaries and rigged for sailing.

Lake Tramandai, which is formed by the streams falling from the chain of Espenasso, empties into the Atlantic, but is very shallow, having only about four feet of water at high tide; besides, on that coast, which is very open and all alluvial, the sea is never tranquil, even in the most favorable weather: but the numerous breakers incessantly stun the ear, and from a distance of many miles their roar sounds like peals of thunder.

Being ready to sail, we awaited the hour of the tide and then ventured out, about four o'clock in the afternoon. In those circumstances, practical skill in guiding vessels among breakers was of great value, and without it it is hard to say how we could ever have succeeded in getting through them, for the propitious hour of the tide was passed, and the water was not deep enough. However, notwithstanding this, at the beginning of the night our exertions were crowned with entire success, and we cast anchor in the open sea, outside of the furious breakers. It should be known here, and borne in mind, that no vessel of any kind had ever before passed out from the mouth of the Tramandai. At about eight in the evening we departed from that place, and at three in the afternoon of the following day were wrecked at the mouth of the Arevingua, with the loss of sixteen of the company in the Atlantic, and with the destruction of the launch Rio Pardo, which was under my command, in the terrible breakers of that coast. The particulars of that sad disaster were as follows:

Early in the evening the wind threatened from the south, preparing for a storm, and beginning to blow with violence. We followed the coast. The launch Rio Pardo, with thirty men on board, a twelve pounder on a pivot, and some extra rigging, taken for precaution, as I was unacquainted with that navigation, seemed strong and well-prepared for us to sail towards the enemy's country. But our vessels lay deep in the water, and sometimes sank so low into the sea, that they were in danger of foundering. They would occasionally remain several minutes under the waves. I determined to approach the land and find out where we were; but, the winds and waves increasing, we had no choice, and were compelled to stand off again, and were soon involved in the frightful breakers. I was at that moment on the top of the mast, hoping to discover some point of the coast less dangerous to approach. By a sudden turn the vessel was rolled violently to starboard, and I was thrown some distance overboard. Although in such a perilous situation, I did not even think of death; but, knowing I had many companions who were not seamen and were suffering from sea sickness, I endeavored to collect as many oars and other buoyant objects as possible, and brought them near the vessel, advising each man to take one to assist him in reaching the shore.

The first one who came near to me, holding to a shroud, was Eduardo Mutru; and to him I gave a dead-light, recommending to him not to let go of it on any account. Carniglia, the courageous man who was at the helm at the moment of the catastrophe, remained confined to the vessel on the windward side, being held down in such a manner, by a Calmuc jacket which confined his limbs, that he could not free himself. He made me a sign that he wanted my assistance, and I sprang forward to relieve my dear friend. I had in the pocket of my trowsers a small knife with a handle; this I took, and with all the strength I was master of, began to cut the collar, which was made of velvet. I had just divided it when the miserable instrument broke,—a surge came over us, and sunk the vessel and all that it contained.

I struck the bottom of the sea, like a shot; and the waters, which washed violently around me like whirlpools, half-suffocated me. I rose again: but my unfortunate friend was gone for ever! A portion of the crew I found dispersed, and making every exertion to gain the coast by swimming. I succeeded among the first; and the next thing, after setting my feet upon the land, was to turn and discover the situation of my comrades. Eduardo appeared, at a short distance. He had left the dead-light which I had given him, or, as is more probable, the violence of the waves had torn it from his grasp, and was struggling alone, with an appearance that indicated that he was reduced to an extremity. I loved Eduardo like a brother, and was affected beyond measure at his condition. Ah! I was sensitive in those days! My heart had never been hardened; and I was generous. I rushed towards my dear friend, reaching out to him the piece of wood which had saved me on my way to the shore. I had got very near him; and, excited by the importance of the undertaking, should, have saved him: but a surge rolled over us both; and I was under water for a moment. I rallied, and called out, not seeing him appear; I called in desperation,—but in vain. The friend dear to my heart was sunk in the waves of that ocean which he had not feared, in his desire to join with me in serving the cause of mankind. Another martyr to Italian liberty, without a stone, in a foreign land!

The bodies of sixteen of my companions, drowned in the sea, were transported a distance of thirty miles, to the northern coast, and buried in its immense sands. Several of the remainder were brought to land. There were seven Italians. I can mention Luigi Carniglia, Eduardo Mutru, Luigi Stadirini, Giovanni D.,—but three other names I do not remember. Some were good swimmers. In vain I looked among those who were saved, to discover any Italian faces. All my countrymen were dead. My feelings overpowered me. The world appeared to me like a desert. Many of the company who were neither seamen nor swimmers were saved.