Title: The Mentor: Egypt, the Land of Mystery, Serial No. 42

Author: Dwight L. Elmendorf

Release date: November 4, 2015 [eBook #50384]

Most recently updated: October 22, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Tom Cosmas and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

EGYPT, THE LAND OF MYSTERY

By DWIGHT L. ELMENDORF

THE MENTOR · SERIAL NUMBER 42

DEPARTMENT OF TRAVEL

◆

MENTOR GRAVURES

| CAIRO | THE SPHINX | KARNAK |

| THE PYRAMIDS | LUXOR | THE DAM AT ASSOUAN |

It is no wonder that the Egyptians through all their history have worshiped the Nile; for that marvelous river is the spine, the marrow, and the life of Egypt. Indeed, it is Egypt; for living Egypt is only a narrow strip twelve or fifteen miles wide,—simply the banks of the Nile. Herodotus called Egypt "the gift of the Nile." The river nourishes and controls the land. All along that waterway are to be found wonders and mysteries of the past. The mind balks in contemplation of the monuments of Egypt. They whisper messages from so far distant a time that we stagger in trying to grasp their meaning.

A visit through Egypt usually begins with Cairo. And it is just as well that it is so; for in Cairo there is much that is modern and much that is familiar to the English traveler. It is, therefore, a good way for the visitor to break into ancient Egypt. In Cairo modern people mingle with the sons of ancient Egyptians. The English soldier is to be seen almost everywhere, and in front of Shepheard's Hotel you may at times almost forget that you are in Egypt.

That is because you are bound down in Cairo, mingling with your own fellow visitors and too close to hotel life. Get up early in the morning, and go to the top of the hill known as the Citadel, and there you will get an impression of an Egyptian city. Look at one of the greatest « 2 » buildings, the Mosque of Mehemet Ali. It is called the Alabaster Mosque. There is a great deal in modern Egypt that is imitation. That is the reason that this building of pure alabaster is to be valued. Its interior is rich and beautiful in design.

CAIRO AND ITS SURROUNDINGS

Stand on the parapet of the Citadel, and look over Cairo, and see the sun rise. Far in the distance is a sandstorm. Many people in the United States think that the weather in Egypt is as clear as crystal always. That is a great mistake. The days there are rarely as clear as American clear days. In January, February, and March you are likely to have sandstorms, or the sirocco, or wind from the desert, which almost obliterate the sun.

Down by the edge of the desert is the Dead City. The tombs there and their interiors are wonderful. The beautiful buildings have been allowed to decay. It is an oriental peculiarity not to repair anything.

On the other side of the Citadel are the tombs of the Mamelukes. I advise anyone going to Cairo to visit these tombs; for they contain very curious sarcophagi, and the tomb mosques are interesting, each of them being surmounted by a picturesque dome.

Our modern expositions and fair grounds would not be complete without "the streets of Cairo." As we know, a bit of street life is shown, more or less accurately—chiefly less. A fairly correct impression of Egyptian street life is, however, created by such artificial reproductions. One of our pictures will no doubt recall these exposition impressions. The genuine old streets of Cairo are fascinating. Some are so narrow that the traveler must go on foot, or on a donkey. The shops are almost within arm's reach on both sides, and many of them are temptingly attractive. « 3 » There on one side they make famous leather goods; on another they sell glassware. Be careful not to buy unless you know how to bargain.

THE STREETS OF CAIRO

You must go to these little streets to find the bazaars if you want to buy anything; for the great street of the Arab quarter, the famous Muski, is not any longer a thorough Cairo street. Big shops and department stores have crept into it.

Stand for a moment on the corner of this great street and see a little bit of the Arab life of old Cairo. It is a busy city. There goes a carryall (a camel), an entire family on its back, except the husband, who walks by the side. This man coming down with a strange sack on his back is a walking fountain. The sack is filled with something sweet and sticky which he calls "sweet water." It is not pleasant. The genuine water carrier of the old school goes to the river, fills his jar, and then goes through the streets shaking his cup in his hand with a chink. It is plain water that he peddles. I should not advise one to drink either of these beverages. Then there are the bread venders of Cairo, who walk the streets carrying bread on their heads and crying out their wares.

Cairo is full of interesting mosques. The oldest and most celebrated is the Mosque of Omri. It is one of the earliest of Mohammedan temples in Egypt. They have a service there but once a year, when the khedive himself comes. The interior seems a veritable forest of pillars. One of these is a most remarkable pillar. I « 4 » will tell the story of it as my boy Mohammed Mousa told it to me: "This pillar very important one—very holy. This pillar sent by Mahomet here; for when Omri come to build this mosque Mahomet so pleased he sent pillar from Mecca. The pillar come here. He find no other pillar from Mecca here; so he get lonely and fly back. Mahomet very angry, and send pillar back. Second time he fly back. Mahomet then get very angry, draw his sword, and strike pillar, and tell Omri to put pillar in prison. So he put it in prison, and it stand there." That is the story that they all believe.

THE PYRAMIDS

The road leading down to the old Nile gate is a very beautiful one. Crossing the bridge there, we see the picturesque Nile boats, like the lateen boats of the Mediterranean. The avenue leads out to the pyramids, and there in the far distance you can see them,—those golden cones about which is wrapped so much of Egypt's history and mystery. The first sight of the pyramids naturally means much to any intelligent traveler. It makes no difference how much you have read, how much you have heard of them, you cannot be disappointed. It is said that the pyramids will last as long as the world, and they certainly look it. They represent to us the life of the world stretching back into the dim past; and, in their imposing solidity, they seem to give assurance of lasting to eternity. There are four of the pyramids in this group; though the mind naturally dwells on the largest,—the Pyramid of Khufu or Cheops. And to think that these are the works of man, and that they are tombs of the kings who lived and reigned somewhere « 5 » about fifty centuries ago! The Great Pyramid of Cheops is 480 feet high and covers an area of thirteen acres, each side being 755 feet. The dimensions of this astounding work are almost mathematically exact. It is built of over two million blocks of limestone, and they are fitted together with the nicety of mosaics. How could these wonderful structures have been erected?—that has been the question of modern engineers. It has been suggested that an inclined plane of earth was constructed, and that the blocks were dragged by men to the top, the inclined plane being added to and raised for each layer. Then, when the pyramid was complete, the inclined plane of earth might have been taken away. This, however, is only a theory. Nothing is known of the methods employed. Originally the sides of the pyramid were smooth, and a little of this outer facing is still in place. These prism-shaped blocks were taken away from time to time for building purposes in Cairo.

People climb the pyramid, and also go inside. In the very heart of the Great Pyramid is a tomb chamber, where we see the empty coffin of Cheops or Khufu. The tomb was rifled long ago, and no one knows where the king's ashes are.

Ascent to the summit of the Great Pyramid means arduous climbing; but it is worth while simply for the view it affords of the desert. Most of us imagine the desert as a level of white sand. I thought so until I saw it from the summit of this pyramid. The desert stretches off in long waves, and does not seem like a plain, but rather like the rolling ocean.

THE SPHINX

Not far from Cheops we see above the waves of sand a rough-hewn head that stirs us mightily. No one can forget the first impression of the Sphinx. It stands for something unique in history and in knowledge. No one with a spark of reverence in his nature can stand before that great stone face without a feeling of awe. There will be little that he can say—the most reverent ones say nothing. There before you is that half-buried, crouching figure of stone about which you have read and heard so « 6 » much. The paws are covered by sand. It is only by industrious shoveling and digging that the desert is prevented from rising on the wings of the wind and completely burying the great figure.

The Sphinx is the symbol of inscrutable wisdom, and its lips are supposed to be closed in mysterious silence,—knowing profoundly, but telling nothing. These are, however, mere impressions. Facts are the important things. No one knows how old the Sphinx is. It is supposed to have been made during the middle empire; but later investigations seem to prove that the Sphinx existed in the time of Cheops, which would mean that it is even older than the Great Pyramid. The Sphinx was made out of living rock, and the dimensions are as follows: Body, 150 feet long; paws, 50 feet long; head, 30 feet long; face, 14 feet wide; and the distance from top of head to base, 70 feet.

It must have been an imposing monument when constructed; for then it stood in position to guard the valley of the Nile, and about it was Memphis, the great city of Egypt—Memphis now past and gone. Memphis was once the capital city of the Pharaohs, and is said to have been founded by « 7 » Menes. In its day of glory it was a prosperous and well fortified city. About 1600 B. C. it was supplanted as capital by Thebes, and the glory of Pharaoh's court was transferred to the southern city.

THEBES

The most flourishing period in the history of Thebes was between 1600 and 1100 B. C. Thebes in turn fell into decay, and is now only a small place visited in the course of a trip to Luxor and Karnak. The situation of Thebes is interesting. It lies in the widest section of the Nile Valley, with a broad plain on the west stretching off to the Libyan Mountains. On this plain are the famous statues known as the Colossi of Memnon. Across the Nile, on the east bank, stand the ruins of Luxor and Karnak, and beyond them to the east are the Arabian hills.

Notable monuments on the west side are the temples of Seti I, Rameses II and III, which bear the names of El Kurna, the Ramesseum, and Medinet-Abu. Lying by the side of the Ramesseum is the fallen Colossus of Rameses II, the largest statue in Egypt. It is made of pink granite, and is about sixty feet in height—or length, we should now say, since the statue is prostrate.

LUXOR

Not far from Thebes is the village of Luxor: not much in « 8 » itself, but just a place to stay while visiting the temples. It is pleasing to note that they have done a good work there in raising the embankment in the hope of keeping the Nile water out of the temples. The bank is steep; for the Nile rises high every year. In olden times these temples were evidently protected from the water by some means; but now it rises half up over them. The Temple of Luxor is one of the most beautiful and interesting in Egypt; though not so imposing as the Temples of Karnak. As you approach you can only see a part of it; for there is a fence up there, and if you want to go through you have to show a ticket. A so-called "monument ticket" can be obtained from the government for about six dollars a year, and this will enable a visitor to see every monument in Egypt. The fund thus raised is used to save the monuments, and every penny of it goes to that work.

The beauty of the Temple of Luxor is in its splendid colonnade. It must have been superb when in good condition, with colors fresh and bright.

KARNAK

The Temple of Karnak, too, is a distinguished mass of columns, the most imposing structure of its kind in existence. It was erected by Seti I and his son, Rameses II. Amenophis also had a hand in the building of it. They were great builders in those days, and all their plans were conceived on a vast scale. The ruins of Karnak are magnificent. Some idea of the impressive character of their columns may be gathered from the following statement: There are 134 great columns forming the central aisle, 12 of these 62 feet high and 12 feet thick, the rest of them 42 feet high and 9 feet thick. You will notice traces of color, and can gather from that what the temple must have been in its full glory. On a recent trip I found some German artists at Karnak, and suggested that if they would get some water and throw it over the columns they would obtain the effect of the true coloring. A good color chart of these columns has now been secured, showing them as they were three thousand years ago. On its outside walls sculptures tell the history of the splendid conquests of the kings that erected the structure.

Egypt is a country of impressive temples and monuments, the interest of which has not been exhausted by a library of books on the subject. A trip through Egypt is not complete without a visit to the Ramesseum and that unique monument, the Temple of Denderah. The latter is a building set apart in architectural and in historic interest. It is not imposing; but it has an appeal that the other temples have not. It was a place of mystery. Its inner chamber, the sanctuary of Denderah, was sacred to Pharaoh himself.

THE GREAT DAM AT ASSOUAN

As one goes up the river visiting these strange monuments, he finds at the first cataract of the Nile an imposing object of modern interest. This is the dam at Assouan, one of the greatest feats of engineering in the world. The dam, which was completed in 1902, is a mile and a quarter long. It holds back the waters of the Nile, and supplies the reservoir, from which the waters are led into irrigation canals. The benefits of this great dam are felt from its location at the first cataract all through the farms and fields that skirt the Nile clear to the delta, six hundred miles below. It has made acres fertile that had been barren. It also, of course, has relieved the burden of the poor workmen at the shadoofs who dipped water for irrigation. Moreover, the dam has improved the conditions of transportation on the Nile; for it has disposed of the first cataract, where boats formerly had to be pulled through the rapids by men. Now the « 11 » vessels go into a canal, and are conveniently and promptly lifted up through four locks to the level of the upper Nile.

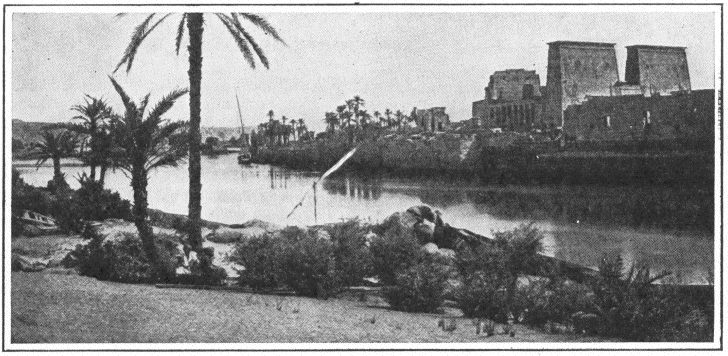

The visitor should not leave Egypt till he has seen Philæ, with its beautiful temples, ruined walls, and colonnades. It is a sight for artists to draw and for us to dream of,—Philæ apparently afloat; for now the Nile water has penetrated the halls of its temples and surrounded its beautiful columns.

On returning from the upper Nile a visitor should go to the new National Museum at Cairo. He may have visited this interesting place before he took the Nile trip; but he will know more on his return. The valuable collection of Egyptian antiquities there in the museum will mean more to him. Months could be spent with profit in this building. It contains one of the richest and most interesting collections of historic remains in the world—the result of years of exploration, excavation, and the intelligent study of eminent scholars. There before you are the relics of ancient Egypt. There are the statues, mummies, and other antiquities that the government has collected. In them you may read the history of ancient Egypt and learn to appreciate the life, literature, and art of Pharaoh's time.

SUPPLEMENTARY READING.—"Modern Egypt and Thebes," Sir Gardiner Wilkinson; "A Thousand Miles Up the Nile," A. B. Edwards; "Egypt," S. Lane-Poole; "A History of Egypt from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest," J. H. Breasted; "A Short History of Ancient Egypt," P. E. Newberry and J. Garstang; "The Empire of the Ptolemies," J. P. Mahaffy; "Egypt in the Nineteenth Century," D. A. Cameron; "Modern Egypt," Lord Cromer.

THE MENTOR

ISSUED SEMI-MONTHLY BY

The Mentor Association, Inc.

381 Fourth Ave., New York, N. Y.

Editorial

It was no easy matter for Mr. Elmendorf to present the subject of Egypt in an article of only 2,500 words. He has confined himself in his characteristic interesting manner to the impressions of a traveler. Of the great store of archæological treasures in Egypt, the monuments, statues, tablets, tombs, inscriptions—in fact all that is comprehended under the name Egyptology—Mr. Elmendorf could say nothing. These are subjects for the historical student rather than for the traveler. And they will be taken up in turn in The Mentor of some later date when we will approach the subject of Egypt from the standpoint of the historical student. There is, however, one question that readers of Mr. Elmendorf's article are apt to ask—in fact ordinary curiosity would prompt the inquiry. The monuments of Egypt are covered with historic records in the form of inscriptions. These records are hieroglyphic. They are what some people call "picture writings." The natural question is "How were these hieroglyphics deciphered." The answer is interesting, and it seems to us that both question and answer belong in the number of The Mentor with Mr. Elmendorf's article.

The River Nile separates at its delta into two branches. The eastern stream enters the Mediterranean at Damietta. The western stream enters the great sea at Rosetta. It was near this latter town that an officer in Napoleon's army discovered, in August, 1799, the key to Egyptian hieroglyphics. It is called the Rosetta Stone, and it is now in the British Museum.

For years the hieroglyphic was an unknown language, and the history of Egypt, except such as is contained in the Bible, was a blind book. The Rosetta Stone was found to contain an inscription in three different languages—the Hieroglyphic, the Demotic, which was the common language of the Egyptians, and the Greek. When these inscriptions were examined, it was discovered that they were each a translation of the other. There, then, was the clue which opened up the whole field of Egyptian history.

Dr. Young, in 1814, began the work of deciphering hieroglyphics by this clue. He worked on various inscriptions, especially the pictorial writings on the walls of Karnak. The value of this discovery may be appreciated when we consider that its discovery has enabled scholars to translate hieroglyphics almost as easily as they would any of the classic writings. The actual inscription on the Rosetta Stone is not so important in itself. It is a decree issued in honor of Ptolemy Epiphanes by the priests of Egypt assembled in a synod of Memphis on account of the remission of arrears on taxes and dues. It was put up in 195 B. C. Since the discovery of the Rosetta Stone other tablets containing more important inscriptions have been found, but the unique value of the Rosetta Stone lies in the fact that it contains a corresponding Greek inscription, thereby affording a clue to the meaning of the hieroglyphics.

The stone is black basalt, three feet seven inches in length, two feet six inches in width, and ten inches thick. After it was found by the French it was transferred to the British, and in 1802, it was brought to England, where it was mounted and placed in the British Museum.

The Rosetta Stone is a corner stone of Egyptology. And the revelations of early Egyptian history and life, brought to light by means of it, have cleared some of the mystery of Egypt and have made known much of its history.

Cairo is the capital of modern Egypt, and the most populous city in Africa. By the Arabs it is called Maçr-el-Qâhira or simply Maçr. It is situated on the Nile, extending along the east bank of that river for about five miles. Cairo itself is really the fourth Moslem capital of Egypt. The site of one of those which preceded it is partly included within its walls, while the other two were a little to the south. Jauhar or Gohar-el-Kaid, the conqueror of Egypt for the Fatimite calif El-Moizz, in 968 founded El-Qâhira, "The Victorious." This name was finally corrupted into Cairo.

The city was founded on the spot occupied by the camp of the conqueror. It grew larger and more important as the years went by. In 1175 the Crusaders attacked Cairo; but were repulsed. The town prospered; but in 1517 it was conquered by the Turks. Thereafter it declined. The French captured the city in 1798. The Turkish and English forces drove them out in 1801, and Cairo was then handed over to Turkey.

A few years later Mehemet Ali became the Turkish viceroy. This man was a bold and unscrupulous schemer. He was born in Macedonia, and became colonel of the troops of the Turkish sultan and was stationed in Egypt. In 1805 he was appointed governor. Two years later England tried to get possession of the country; but he foiled the British.

The Mamelukes, the former rulers of Egypt, had been conquered by Napoleon and were forced to acknowledge Mehemet Ali as master of Egypt. But they were still powerful, and their plots hindered the plans of the ambitious viceroy. So one day in 1811 Mehemet gave a great feast in the citadel in Cairo, to which the Mamelukes were all invited. Four hundred and fifty of them accepted and rode, a magnificent cavalcade, up to the citadel through a deep, steep passageway leading from the lower town.

The lower gates of the street were suddenly closed. Behind the walls were the armed men of Mehemet Ali. Point-blank they fired into the crowd of horsemen. The slaughter was kept up until all were dead. Tradition says that one man escaped by leaping his horse over a wall. Thus Mehemet became ruler indeed of Egypt.

Under his rule Cairo grew up. He is supposed to have watched over the welfare of his people; but, according to one historian, "they could not suffer more and live."

Ismail Pasha, the first of the khedives (keh-deeves') modernized Cairo. Coming from Paris filled with progressive but reckless ideas of civilization, he resolved to transform the ancient city by the Nile into an African metropolis. The festivities he organized on the occasion of the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 are said to have cost twenty million dollars. He built the opera house of Cairo, and had Verdi, the famous composer, write the opera "Aïda" especially to be produced there in 1871. His extravagances plunged Egypt into debt, but in 1882 Cairo was occupied by the British, and under their rule Egypt came gradually from under this heavy burden of indebtedness.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 42, SERIAL No. 42

COPYRIGHT, 1913. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

"All things fear Time; but Time fears the Pyramids," says the ancient proverb. The pyramids are for eternity. They alone of all man's works seem able to conquer time. They are mute witnesses to the greatness and majesty of Egypt five thousand years ago. The Egyptian pyramids are royal tombs, the burial vaults of kings. A pyramid was constructed of horizontal layers of rough-hewn blocks with a small amount of mortar. The outside casing was of massive blocks, usually greater in thickness than in height. Inside of each pyramid, always low down, and usually below the ground level, was built a sepulchral chamber. This room, which contained the body of the king, was always reached by a passage from the north, sometimes beginning in the pyramid face, sometimes descending into the rock on which the pyramid was built. To build but a single one of these huge tombs must have taken thousands of slaves many years, and there are seventy-six of them in existence today. What a record of toil and suffering for the vanity of kings!

The oldest of these pyramids is the Step Pyramid of Sakkara. It is supposed to be the oldest building of stone in the world. It lies near the vanished city of Memphis, the capital city of King Menes, the first Egyptian monarch whose name is known to history, and the founder of the earliest known dynasty, variously estimated to have been from 5702 to 2691 B. C.

The greatest and most famous pyramid is the Pyramid of Khufu (Cheops) at Gizeh. It was originally four hundred and eighty feet high; its base covers an area of thirteen acres; and each side is seven hundred and fifty-five feet long. The ancient builders were so accurate in their work that modern engineers have discovered an error of only sixty-five one-hundredths of an inch in the length of the sides of the base, and of one-three-hundredth of a degree in angle at the corners. The base is practically a perfect square.

The Pyramid of Khufu is the only surviving wonder of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. One hundred thousand men worked for twenty years to build this tomb, which contains two million three hundred thousand limestone blocks, of an average weight of two and a half tons. How the tremendous undertaking was ever accomplished is one of the mysteries of the world. But even this huge tomb was no protection against robbers. The body of King Khufu has disappeared, stolen from its famous resting place centuries ago.

To ascend the pyramid one has to climb steps, narrow and about three feet apart. For a small fee the Arabs help the tourist to the top, from where the view is well worth the trouble. The blocks that formed the point of the pyramid have been removed, and the summit is a level platform thirty-six feet square.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 42, SERIAL No. 42

COPYRIGHT, 1913. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

Battered and broken by the attacks of time and man, buffeted by the desert winds, flat faced, and almost featureless, the Sphinx is still the possessor of its mighty secret—the mystery of the ages. "It is still able to express by the smile of those closed lips the inanity of our most profound human conjectures."

Everyone knows about the Sphinx at Gizeh near the Great Pyramids. This is proved by the common use of the word "sphinxlike," applied to that which holds, but will not disclose, mystery. But not everyone knows the reason for the form of the Sphinx, half human and half beast.

Sphinx is the Greek name for a compound creature with a lion's body and a human head. The Greek sphinx had male wings and a female bust. The sphinx of Egypt was wingless, and was called "Androsphinx" by Herodotus. In Egypt the sphinx was usually designed as lying down. The heads of the Egyptian sphinxes are royal portraits, apparently intended to represent the power of the reigning Pharaoh.

The most famous sphinx is the great Sphinx of Gizeh. No one knows who formed this gigantic figure of mystery nor when it was made. It was cut from a ridge of natural rock, with patches of masonry here and there to carry out the effect. The body is one hundred and forty feet long, and it faces eastward, looking out over the valley of the Nile. It has been said that the Sphinx was probably intended to be the guardian of the entrance to the Nile Valley.

The name of the Sphinx in Egyptian was "Hu." The inscriptions in the shrine between its paws say that it represented the sun god Hormakhu.

In the long past days of Egypt's grandeur the Sphinx was a central feature of the grandest cemetery the world has ever seen. This was the cemetery of Memphis, the metropolis of Egypt. The city of Memphis was the chief city of King Menes, who founded the earliest known dynasty. Now the only things that mark the site of the vanished metropolis are two colossal but fallen statues of Egypt's vainest king, Rameses II, the Great.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 42, SERIAL No. 42

COPYRIGHT, 1913. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

The ancient Egyptians had a great many gods; but the greatest of all was the Sun God. His name was Amun, and this meant "the hidden or veiled one." All worship of this god was mysterious and shrouded in darkness. In that way the priests held their power over the people. It was at old Thebes that the greatest temples of the Sun God were built. For about two thousand years Thebes was the capital of the powerful Egyptian Pharaohs. It was called Weset and Nut, which means "The City." The Greeks gave it the name of Thebai. Now this once great and important city has disappeared except for its ruins.

The little village of Luxor occupies the southern part of ancient Thebes. It is on the east bank of the Nile, four hundred and fifty miles from Cairo. Its name, Luxor, is a corruption of the Arabic El-Kusur, meaning "The Castles," and referring to the many-columned courts of the abandoned temples.

The great king of Egypt, Amenophis III, built the temple of Amun about which Luxor has grown up. He did not finish it, and Rameses II added to it a huge columned court. But this temple was never altogether completed. Still, it measures almost 900 feet from front to rear.

Rameses II also erected outside some colossal statues and a pair of obelisks. One of these obelisks now stands in the Place de la Concorde in Paris. It was taken there in 1831.

The chief religious festival of Thebes was that of "Southern Opi," the ancient name of Luxor. The sacred ships of the gods, which were kept in the temple of Karnak, were then taken in procession to Luxor and back.

Most of the old village of Luxor lay inside the courts of the temple. The Christians built churches within the temple. Luxor was also called Abul Haggag, from a Moslem saint of the seventh century. His tomb stands on a high heap of debris in the court of Rameses.

Today Luxor is a tourist center, and several fine hotels have been erected to accommodate the many visitors to the famous ruins. Nearly all the debris has been cleared away by the Service des Antiquités, which took up this work in 1885. Most of the natives thereabout are engaged in the manufacture of forged antiques, which they sell to the unwary traveler.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 42, SERIAL No. 42

COPYRIGHT, 1913. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

A little village with a big ruin,—that is Karnak. Karnak itself is a town of only twelve thousand people in upper Egypt, which has given its name to the northern half of the ruins of ancient Thebes. The most important of these ruins are the ruins of the temple of Amun. These are to other ruins what the Grand Canyon of the Colorado is to other gorges.

Many of Egypt's kings contributed to build the temple of Amun at Karnak.

Karnak represents colossal antiquity. Here are to be found the highest columns on earth. They are one hundred and thirty-four in number; but many have crumbled and fallen to earth. The large columns were nearly twelve feet thick and sixty-two feet high. On top of each a hundred men could have stood. Each column was made up of many half-drums put together, and on them are raised reliefs, once painted with bright colors, picturing the events in the reigns of the various kings of Egypt. But now their glory has departed. The walls of the temple have fallen, and all that we can see is a mass of ruins, resembling the litter of an avalanche.

Tribute from all the world once poured into the coffers of the priests of Amun. The Egyptian kings gave them a great share of the spoils of their conquering raids, and Rameses III gave ninety thousand of his prisoners of war to them for slaves. Finally these priests became so rich and powerful that the high priest of Amun took the throne and became ruler of the Egyptians.

In 1899 a great calamity came upon the ruins of the temple. Eleven of the standing columns fell. These were all restored by 1908, and the work of excavation, strengthening, and reconstruction is still going on.

Beside the temple of Amun at Karnak there are two other ruins of importance. A temple of the god Mut, built by Amenophis III, and restored by Rameses II and the Ptolemys, has almost disappeared, except for a well preserved gateway and the plan of the foundations. The other ruin, the temple of Khuns, was built by Rameses II and his successors.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 42, SERIAL No. 42

COPYRIGHT, 1913. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

There are many ancient and awe-inspiring monuments in Egypt; but one work of modern times there does not suffer in comparison with the greatest things that the Pharaohs have left us. The tombs, the pyramids, and the obelisks were built at the cost of terrible suffering, merely to satisfy the vanity of selfish kings; but this great work has given life to the land, enriched the population, and made their labor far lighter. It is the dam at Assouan.

Assouan, or Aswan, is a town of upper Egypt on the east bank of the River Nile below the first cataract. It has of late grown very popular as a winter health resort, and many large modern hotels are now situated there.

At the beginning of the cataract, three and a half miles above the town, is the dam of Assouan. This is a mile and a quarter long from shore to shore. It was finished in December, 1902. This dam controls the water of the Nile, and makes possible the irrigation of vast areas of land that had hitherto been dead and unproductive. Water is very valuable in Egypt.

Before the dam was built a boat had to be hauled up the rapids of the first cataract by hundreds of natives. It was an all-day task. Now a canal with four locks quietly and quickly takes vessels to the upper level of the Nile.

The dam has transformed the river above it into a huge lake. Many former islands have been wholly or partly submerged. The Isle of Philæ is the most important of these. The goddess Isis was worshiped there, and there were temples erected to her. One rocky point of the island is still above water. The rest of Philæ is an Egyptian Venice. Water paves the courts of the temples and gives added beauty to the relics of the past.

Opposite Philæ, on the east bank of the Nile, is the village of Shellal. This town is the southern terminus of the Egyptian railway, and the starting point of steamers for the Sudan.

Near Assouan are the quarries from which the old Egyptians took granite for their obelisks. There is still one obelisk all carved and shaped, ready to be taken from the rock. When an obelisk was shaped, holes were bored in the rock all along the line of separation. Wedges of wood were driven into these holes and soaked with water. The wet wood expanded, and the great obelisk was broken from the mother rock. It was then ready to be shipped to its destination.

PREPARED BY THE EDITORIAL STAFF OF THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION

ILLUSTRATION FOR THE MENTOR, VOL. 1, No. 42, SERIAL No. 42

COPYRIGHT, 1913. BY THE MENTOR ASSOCIATION, INC.

Transcriber Notes

The cover image was derived from an image made available on The Internet Archive and is placed in the Public Domain.