THE KACHÁRIS

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON . BOMBAY . CALCUTTA MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK . BOSTON . CHICAGO ATLANTA . SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON

1911

[iv]

N.B.—The Editorial Notes in this volume are from the pen of Colonel P. R. T. Gurdon, I.A., Director of Ethnology to the Government of Eastern Bengal and Assam. [vii]

CONTENTS

SECTION I PAGE

Characteristics, Physical and Moral; Origin, Distribution and Historic Summary, etc. 1

SECTION II

SECTION III

SECTION IV

Religion 33

SECTION V

Folk-lore, Traditions and Superstitions 54

SECTION VI

Appendix I. Tribes Closely Allied to Kacháris 81

Appendix II. Specimens of the Bodo Language 97 [ix]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

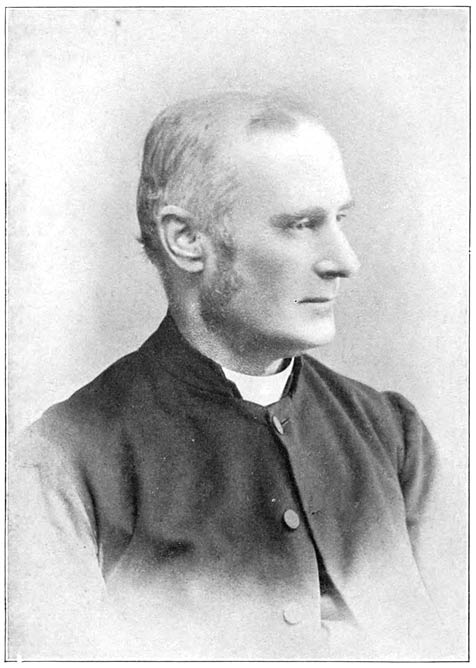

- S. Endle. From a Photograph by Messrs. Bourne & Shepherd Frontispiece

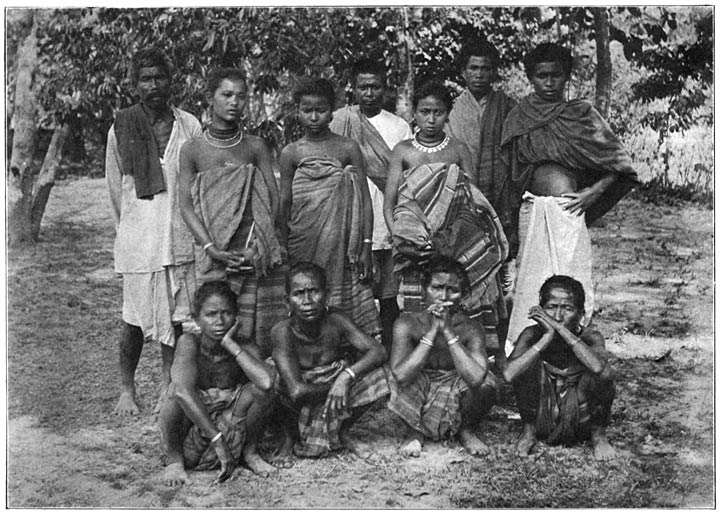

- Group of Meches (Goalpara District). From a Photograph by Mr. T. E. Emerson To face p. 5

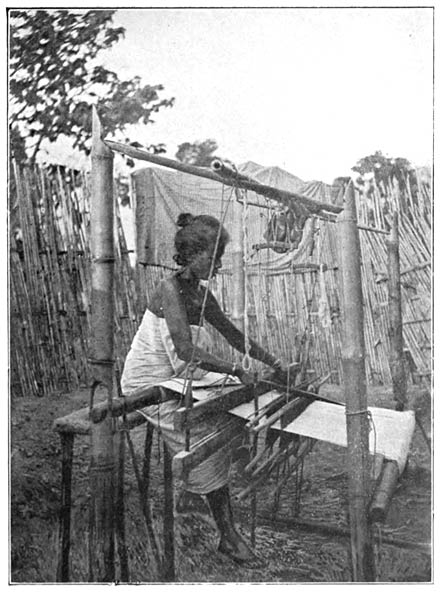

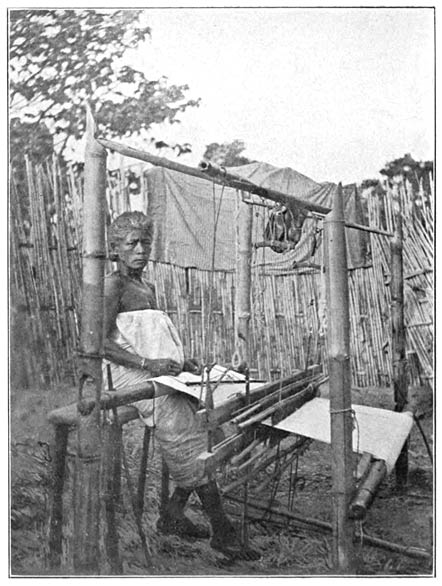

- Kachári Woman Weaving (Kamrup) 20

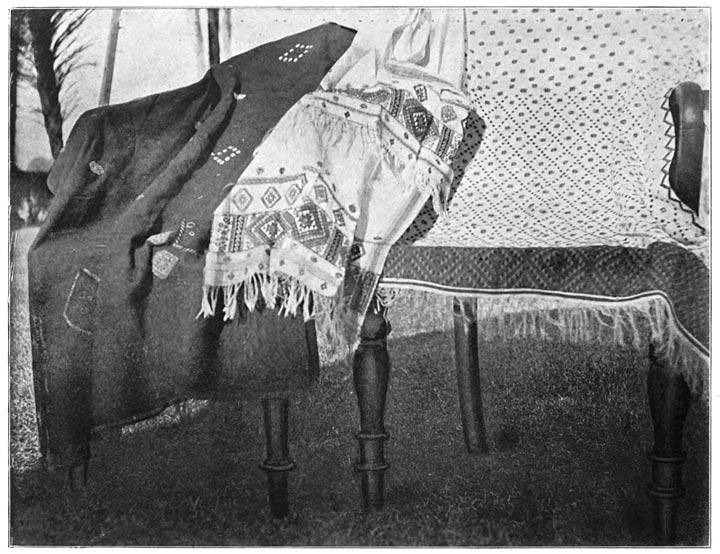

- Kachári Clothes 21

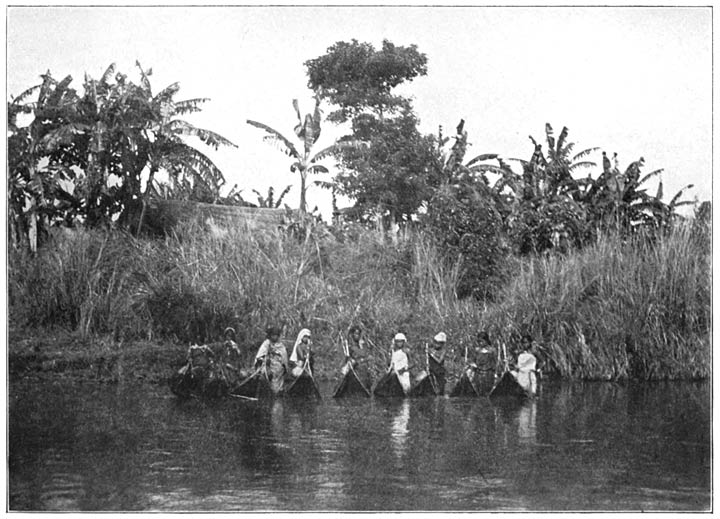

- Kachári Women Fishing (Kamrup). From a Photograph by Mrs. H. A. Colquhoun 22

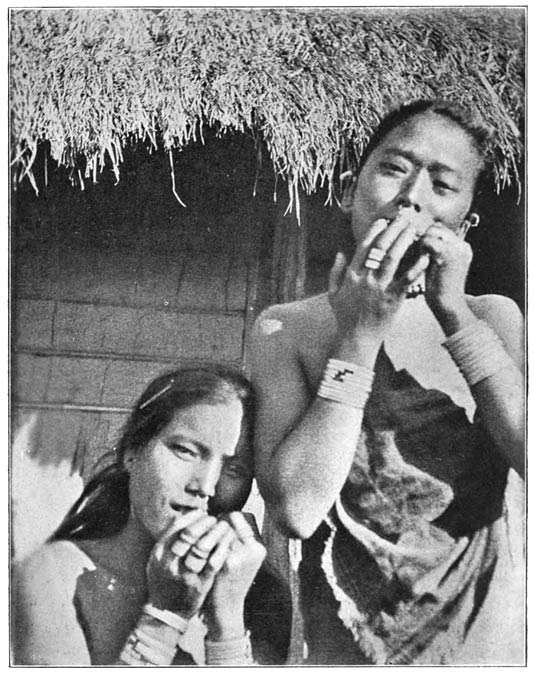

- Kachári Girls Playing Jew’s Harp (Gongina). From a Photograph by Mrs. H. A. Colquhoun 30

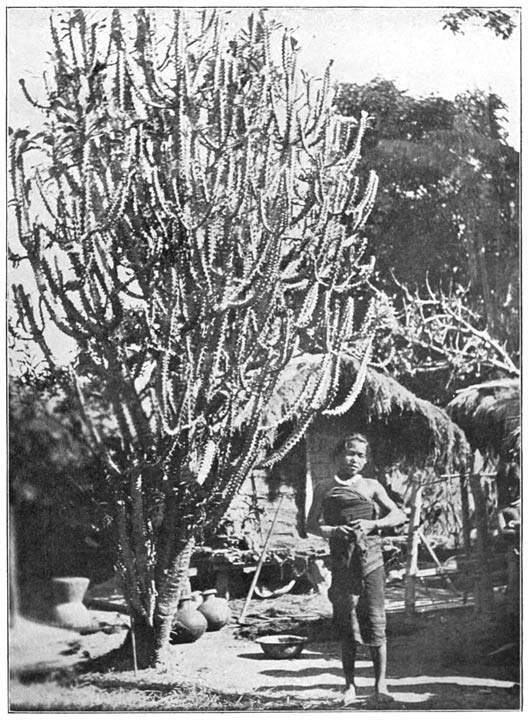

- Siju Tree (Euphorbia splendens). From a Photograph by Mrs. H. A. Colquhoun 36

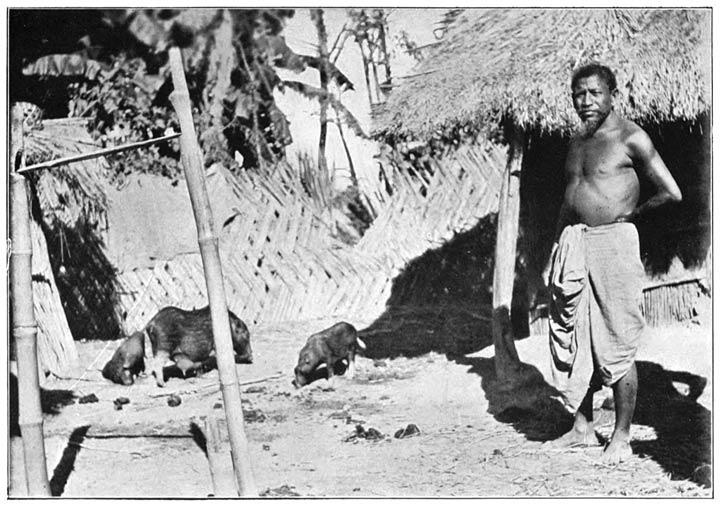

- Kachári Village Interior (Kamrup District). From a Photograph by Mrs. H. A. Colquhoun 56

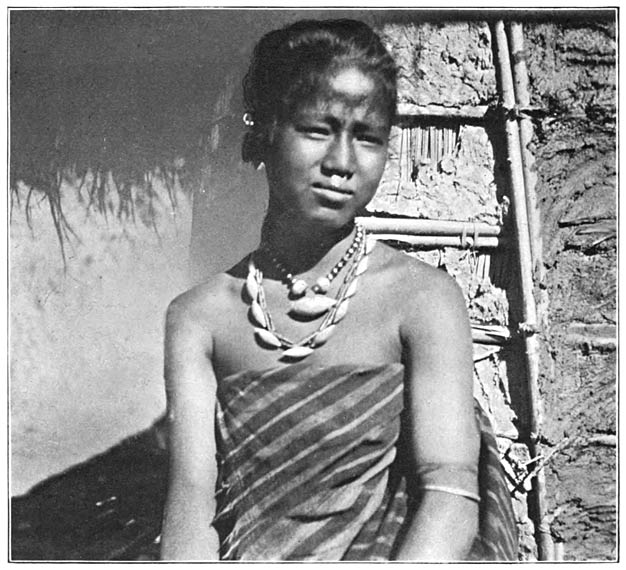

- Kachári Girl (Kamrup District). From a Photograph by Mrs. H. A. Colquhoun 67

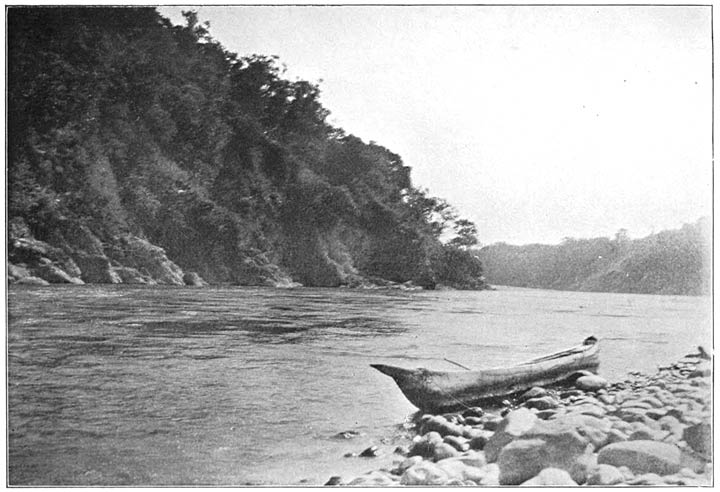

- Gorge of the River Manás. From a Photograph by Mrs. H. A. Colquhoun 96

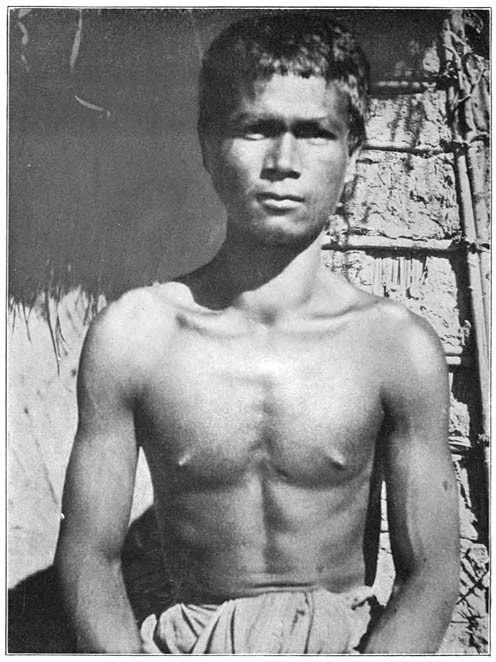

- Kachári Man (Kamrup District). From a Photograph by Mrs. H. A. Colquhoun 105

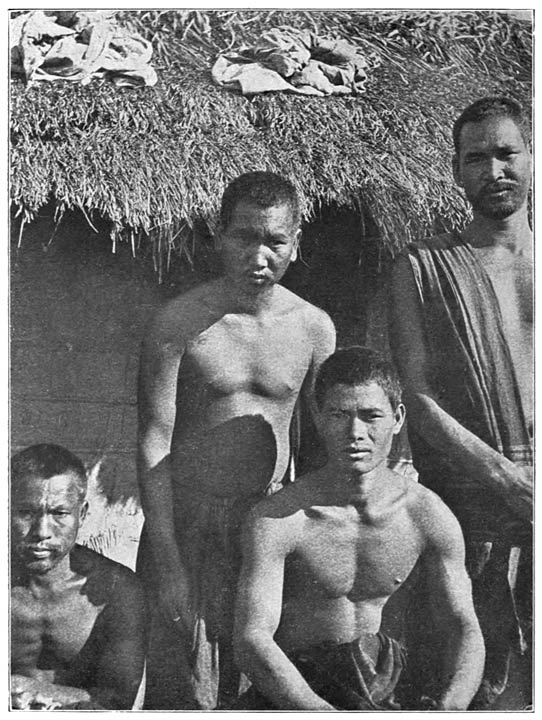

- Group of Kachári Men (Kamrup District). From a Photograph by Mrs. H. A. Colquhoun 113

IN COLOUR

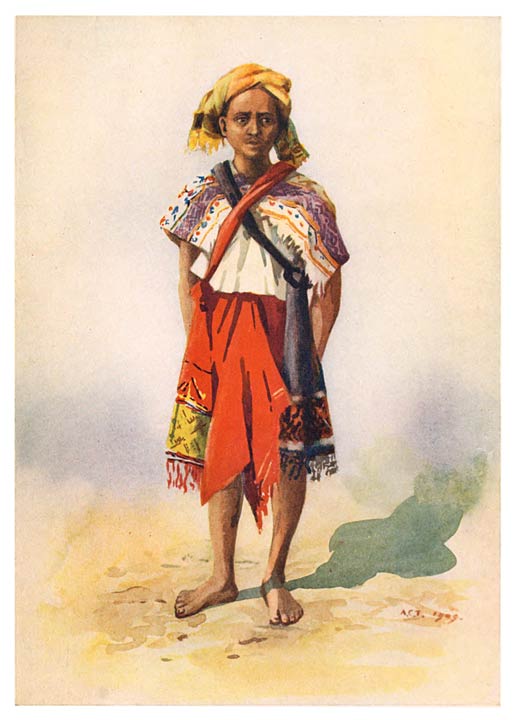

- Kachári Man To face p. 10

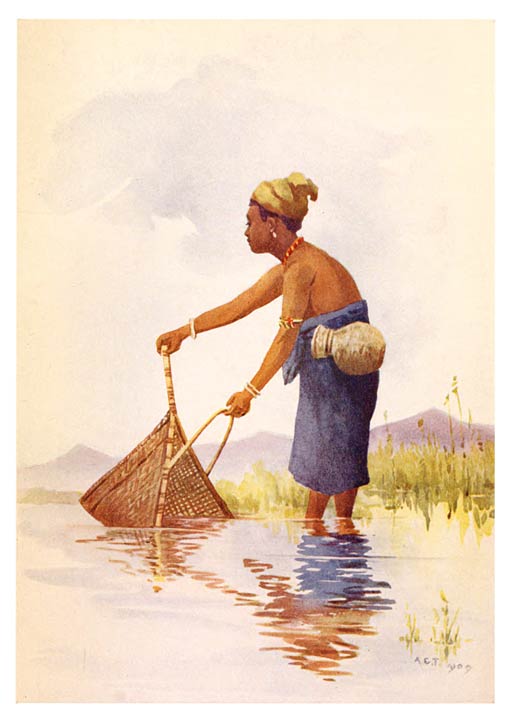

- Kachári Girl Fishing 16

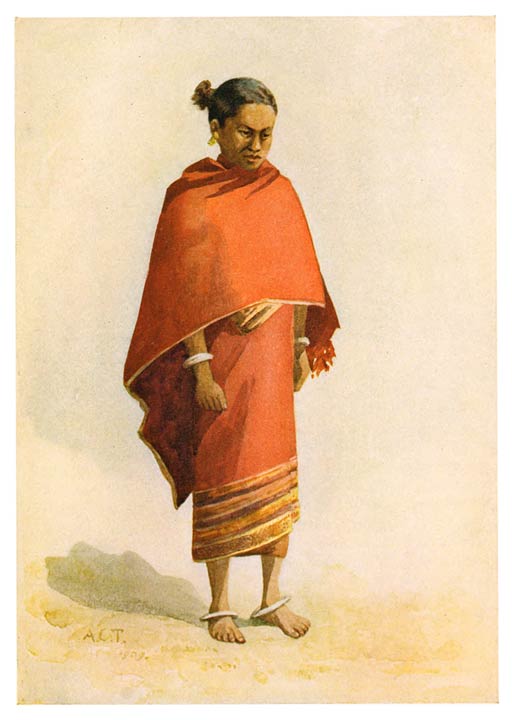

- Kachári Woman 60

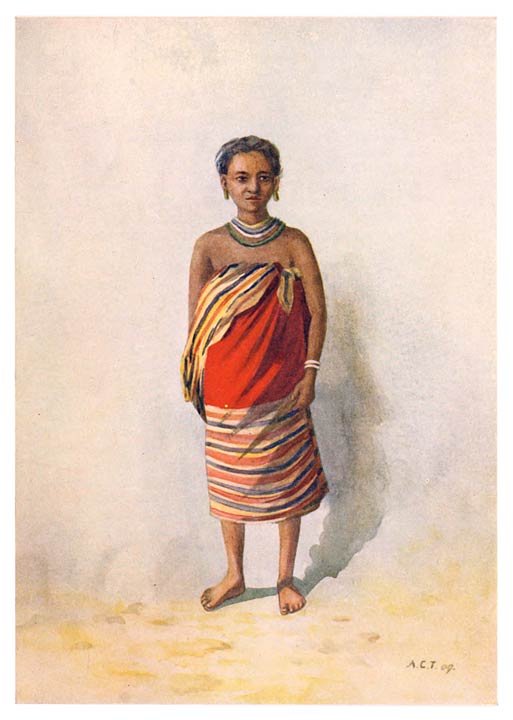

- Mech Girl 82

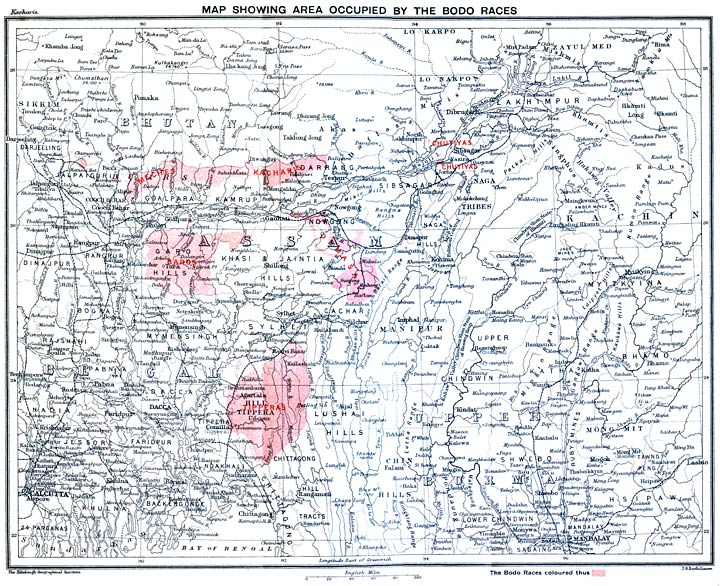

Map Showing Area Occupied by the Bodo Races At end of Volume [xi]

INTRODUCTION

It is with some diffidence that I comply with Colonel Gurdon’s request that I should add a few words of preface and explanation to the last literary work of an old friend and pastor, whose loss will long be lamented in the Assam Valley, where he laboured as a missionary and planter’s chaplain for upwards of forty years. Mr. Endle’s interest in his Kachári flock was that of an evangelist rather than that of a linguist or ethnologist, and this preoccupation has coloured his style and affected the matter of his book in a way that, however pleasant and natural it may seem to those who had the privilege of his acquaintance, may perhaps require a few words of explanation for the benefit of those who look for anthropology only, or linguistics, in his pages.

My first duty, then, is to say a few words about the author’s life and character. Sidney Endle was born about 1840 at Totnes in Devon, of sturdy yeoman parentage. His grandfather was, it seems, proud of being an armiger, and it is a family tradition that many Endles figured in the ranks of the Catholic clergy of the West country. Mr. Endle was educated at Totnes Grammar School, under the Rev. James Powney, and early conceived a wish to enter the ministry of the Church of England, and serve abroad as a missionary. With this view he entered St. Augustine’s College at Canterbury. Unfortunately the College seems to have kept no written record of the dates at which one of the most distinguished and devoted of its pupils entered and left its roof. It was in February, 1864, however, that he was sent by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel to Tezpur, in Assam, to be the assistant of Mr. Hesselmyer, then in charge of the Kachári mission at that place. In 1865 he was ordained deacon by the Bishop of [xii]Calcutta, and in the following year he was admitted to priest’s orders. Soon after he was transferred to the independent charge of the S.P.G. mission among the tea-garden coolies at Dibrugarh in Upper Assam. In 1869, on Mr. Hesselmyer’s death, Mr. Endle was made chaplain of the important tea-planting district of Darrang, with the charge of the Kachári mission in that district, having his head-quarters at Tezpur. His pastoral duties were thus two-fold. On the one hand, he became the pastor of an European community scattered over an area some 100 miles in length by 30 or 40 in breadth. It was his duty to gather his flock round him at some convenient tea-garden, or at the pretty little rustic church at Tezpur itself, where his congregation included the small band of officials. He was everywhere welcome, and it was not long before he was as popular as he was respected. One of the most unworldly and simple of men, almost an ascetic in his personal tastes and habits, he could sympathise with and understand men whose training and ideas were different from his. He had a native shrewdness and quiet sense of humour which stood him in good stead in his dealings with men probably as varied in their origins and temperament as are to be found in any collection of Englishmen beyond the seas. His sermons—and he could preach with equal ease and eloquence in English, Assamese, and Kachári—were ever those of a man who to shrewd observation of the various life about him, native and European, added an unwavering devotion to the responsibilities of his calling. Authoritative, and even stern, he could be when he thought it needful to assert his responsibility as a priest. But, somehow, the occasion rarely occurred, since his was not the disposition that demands impossible perfection of ordinary human nature. There was no touch of intolerance in his gentle and (there is no other word to describe him) saintly nature. I think he would have liked to have it said of him that, like Chaucer’s Parson,

He was a shepherd and no mercenerie,

And though he holy were and vertuous,

He was to simple men not dispitous,

Ne of his speech dangerous ne digne,

But in his teaching discrete and benigne.

[xiii]

Innumerable were the marriages and christenings he celebrated in all parts of Assam, and it was characteristic of the man that he regarded it as a duty to keep himself informed of the welfare, spiritual and physical, of the children he held at the font. During his rare visits to England he endeavoured when he was not busy preaching for his mission, to visit those whom in their infancy he had admitted to his Church. Few chaplains in India can have been so universally popular and respected as he was, and this without in any way relaxing from the dignity which, in his case, belonged rather to his sacred office than to any consideration for his own person.

But he made no secret of the fact that his heart was chiefly in his missionary work among his beloved Kacháris. The Bodos of the Kachári dwars (the dwars or “doors” of the Kachári plains are the passes that lead into the rough mountains of independent Bhutan) are, like most of the aboriginal races of Assam, cheery, good-natured, semi-savage folk; candid, simple, trustful, but incorrigibly disrespectful according to Indian notions of good manners. To a casual observer, they may well have seemed incapable of comprehending the gentle reserve and unaffected unselfishness of their pastor’s nature. Among them, however, it was his delight to unbend, and give way to the almost boyish simplicity and sense of fun which to the last were among his most engaging traits. When Mr. Endle approached a Kachári village during one of the prolonged preaching tours which were to him at once a duty and the keenest of pleasures, he was always greeted with a joyous and often noisy welcome. He travelled on foot, and the villagers would turn out to see the gāmi-nī-brai, the “old man of the village,” as they affectionately called him. He was often cordially invited to share in the village festivities, and it was an interesting sight to watch him seated in the midst of rough semi-savage folk, listening to the tale of their simple joys and sorrows, enjoying their primitive jokes, and, when occasion served, talking to them, as probably no one else will ever be able to talk to them again, of the matters nearest to the missionary’s heart.

In all parts of the Kachári country, Mr. Endle established many village schools, served by trusty converts. But his chief [xiv]pride was in the church he built at Bengbari, which, to his great joy, was consecrated by Bishop Milman in person. Under its thatched roof has now been placed a tablet to the memory of its founder.

No account of Mr. Endle’s life, however brief, would be complete without a mention of the fact that in 1875 he married Miss Sarah Ewbank Chambers, who for twenty years shared his pastoral anxieties. Mrs. Endle was much respected by the European community throughout Assam, and her sudden death in Calcutta in 1895 was universally regretted. How sorely her husband felt her loss, not even those who knew him best were allowed to guess, but it was plain that, from this time onwards, much of his old elasticity of mind and body deserted him, and though he continued his work with unabated industry the effects of age began for the first time to be apparent to his friends. In 1884 Mr. Endle compiled his well-known manual of the Kachári language, published by the Assam Secretariat Press. From time to time he contributed papers on the subject of the Bodo people to the Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. In 1891 he was elected an Honorary Fellow of St. Augustine’s College, in recognition of his linguistic studies and of his eminence as a worker in the mission field. In 1906 he was offered a canonry by the Bishop of Calcutta, but characteristically refused a dignity which might have involved absences from his missionary duties.

Such, briefly told, are the few outstanding events in a life wholly devoted to pastoral work, of which little was known outside his native flock. It was Mr. Endle’s repeatedly expressed wish that he might end his life and be laid to rest among his Kacháris. This wish was not fulfilled. Towards the end of 1905 it was evident that his persistent disregard of his personal comfort in an enervating climate had taxed a naturally robust constitution. He was induced with some difficulty to pay a brief visit to England for rest and change. He spent this holiday chiefly in preaching for his mission and visiting old friends. He was soon, perhaps too soon, back at his work. It could no longer be hidden from himself or others that he had overtaxed his strength. This, however, caused him no disquietude. He had done his day’s work, and was [xv]cheerfully ready to take his departure. In July 1907, he could struggle no longer against growing weakness, and was placed on one of the little mail steamers that ply up and down the Brahmaputra, in the hope that river breezes, rest, and change of scene might bring about some restoration to health. He himself, however, knew that his end was near, and he passed away, painlessly and peacefully, on the river bank at Dibrugarh, close to the scene of his first independent missionary charge, entrusted to him more than forty years before.

So much by way of biographical introduction seemed necessary, not only as an inadequate and too brief memorial of a singularly unselfish and blameless career, but also as an explanation of some features in Mr. Endle’s book not usually found in anthropological manuals. Of the subject of the book itself I may now be allowed to say a few words, if only to show that it has an interest and importance, from an ethnological point of view, which are perhaps disguised by the author’s characteristically modest estimate of his task and of his power of dealing with it. The book is, primarily, a monograph treating of that branch of the Kachári race which lives in scattered hamlets along the foot-hills of the Himalayas in Northern Bengal and Assam, intermixed now with Hindu people who have intruded into what was once their undisputed home. In Assam proper the Hindus call them Kacháris; in Bengal they are known as Meches.1 Their own name for their race is Boṛo or Boḍo (the o has the sound of the English o in “hot”). Among this northern branch of the race is embedded the tribe of the Koch, whose name is pronounced locally as if it were Koss, (to rhyme with our English “boss”). (Kachári, I may mention in passing, is also pronounced as Koss-āri.) The Koch have gradually become a semi-Hindu caste, most of whose members now talk the Indian Bengali or Assamese. It also contains the surviving remnants of the royal family of the great and powerful Koch empire, which, roughly, covered the same area as the present province of Eastern Bengal and Assam. It can be proved that the aboriginal members of the Koch caste within quite recent times spoke the Boṛo language. [xvi]In the East of the Assam Valley was another powerful kingdom, that of the Chutiyas, whose language was another branch of the speech described in this book. The river names of the whole Brahmaputra Valley are Boḍo names, and it is demonstrable that the Boḍos were the aborigines of the Valley. In the great mass of hills, an outlying spur of the mountains of Upper Burma, which divide the Brahmaputra Valley from that of the river Surma which runs parallel to it from east to west are two more Boḍo groups. The most eastern of these comprises the Di-mā-sā, Great-River-Folk (di- means “river” or “water,”) people who were driven out of the valley of the great river Brahmaputra in historical times, and finally became rulers of what is now the great tea-planting district of Cachar or Kāchār. They either gave its name to or perhaps derived their Hindu soubriquet of Kachāri from this district. Of this branch of the race an interesting description will be found in the supplement to this book. At the western extremity of the range of hills is another group, the Garos, of whom an excellent account has lately been published by Major A. Playfair, I.A. (London, David Nutt, 1909). The Garos are of peculiar interest as members of the Boḍo family, because they were head-hunters within the memory of men still living.

Finally in the range of hills in the south of the Surma Valley, there are the Tipperahs whose language is obviously a branch of the ancient Boḍo speech; quiet inoffensive people, ruled over by a semi-independent Raja who is also a great land-owner in the British districts of Tipperah and Sylhet.

Now, the anthropologists rightly caution us against rashly concluding that a common speech, where races are in contact, implies a common origin, since everywhere, and especially among people who use an unwritten language, nothing is more common than the borrowing of a neighbouring tongue. But where, as here, we have five absolutely separate communities of semi-savage people, who nowadays are not so much as aware of one another’s existence, and yet speak what is to all purposes the same language, it is plain that they must have been united at no very distant date by some common social bond. The date cannot have been very distant, because in the unwritten speech of semi-savage people phonetic decay acts very rapidly, and a [xvii]very few years may serve to disguise the relationships of adjacent and cognate tongues. No one who has heard members of the five branches of the Boḍo race speak their respective languages can fail to recognise that they belong to the same linguistic group. Moreover, this common Boḍo speech was, till within a few years ago, the language of the Koches, the dominant and ruling tribe in the great Koch kingdom, which survived, with something of its ancient prestige and power, long enough to be visited by an Englishman, Ralph Fitch, in Queen Elizabeth’s time. It would seem, then, that the language spoken in the ancient Koch kingdom, which extended from the Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal, was the Koch or Boḍo language, and the mass of the people must have been of Boḍo origin. In the Brahmaputra valley these Boḍos have survived in the midst of Hindu and Shan invaders and settlers, of whom those who are interested in the subject may read in Mr. E. A. Gait’s admirable History of Assam, (Calcutta, Thacker, Spink and Co., 1906). Here the anthropologist may come to the rescue of the historian. The Boḍo type of face and physical construction is, as Mr. Endle says, of an Indo-Chinese kind, easily distinguishable from the Arya-Dravidian type common in adjacent Bengal, and careful measurements in the Brahmaputra and Surma Valleys ought to show how far the old Koch element still persists, how far it has been obliterated by inter-marriage with Indian immigrants.

It may, however, be assumed that the population of the Koch kingdom, and therefore of its predecessor, the famous classical empire of Kāma-rūpa, of which Sanskrit scholars may read in the Mahābhārata (perhaps in a late interpolation in the epic) was chiefly Boḍo, of the same type as the humble folk who are the subject of Mr. Endle’s book. Kāma-rūpa was visited in the first half of the seventh century of our era by the famous Chinese traveller Hiuen Tsiang, whose interesting account of the land and people may be found at page 22 of Mr. Gait’s History. “They adore and sacrifice,” says the Chinese explorer, “to the Devas and have no faith in Buddha.”

It was apparently in the kingdom of Kāma-rūpa that there came into being that form of Hinduism whose scriptures are the later Purāṇas and the Tantras, the worship of Śiva and his [xviii]Sakti, that form of the Hindu cult which, to this day and even in the temple of Kāli-ghāṭ in Calcutta itself, is distinguished by sacrifice by decapitation. In the earlier times of British rule, as readers of Mr. Gait’s book may find for themselves, the Hindus of Assam were much addicted to human sacrifice by beheading, and, to this day, the appropriate method of propitiating the terrible goddess Kāli, the “dark one” (who is also Dur-gā, “hard of approach”), is by bloody sacrifices. The Śaiva or Śāktā form of Hinduism would therefore seem to be due to an engrafting of Koch superstitions on the purer and humaner religious ideas imported into India by the Aryan settlers to whom we owe the Vedas and the religious literature based on those early pastoral hymns. From this point of view, it is important to bear in mind that the Garos were till lately headhunters, and that the Chutiyas were conspicuous, even in North-Eastern India, for their addiction to human sacrifices.

How does it happen then, it may be asked, that the Boḍos described in this book are among the most innocent and kindly of semi-savage people? The answer seems to be that the bulk of the inhabitants of North-Eastern India were always simple inoffensive folk, and that it was only the ruling tribes and families that were addicted to war, rapine, torture, cruelty, and the religious developments that go with these. If Assam is undoubtedly still the home of the Tantrik beliefs which have their centre at the famous shrine of Kāmākṣā at the old capital of the Koch monarchs (now known as Guā-hāṭi or Gauhati), Assam is also the home of the Viṣṇu-ite reform, an attractive and learned account of which will be found in a paper by Sir Charles N. E. Eliot, published in the “Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society” for October, 1910. The common people in Assam, the rustic Hindus of the Brahmaputra Valley, are in temperament and habits very like the cheerful and smiling Boḍo folk among whom Mr. Endle laboured, and of whom he writes with such frank regard and appreciation. The climate of the valley is enervating and soft, and any traveller in Assam can see for himself how the once fierce and warlike Ahom invaders, who gave its name to the country of Assam, have become as soft and kindly in disposition as the Kacháris themselves. No more remarkable instance of the effect of environment on national [xix]temperament could be found anywhere, and the anthropological theories of Dr. Ridgeway could hardly have a more remarkable support than he might find by contrasting the semi-savage inhabitants of the Brahmaputra Valley with the bloodthirsty and warlike tribes in the surrounding mountains, their neighbours and relatives.

I have only to say, finally, that I have added, as an Appendix to my old friend’s book, a literal interlinear translation of three stories from my little Collection of Kachári Folk-tales. In adding these I have followed the example set by Sir Charles Lyall in his monograph on the Mikirs. By means of this interlinear and word-for-word translation, the comparative linguist may see for himself how far Kachári is still a monosyllabic agglutinative language, and how far it has borrowed the inflectional mechanism of Assamese and Bengali. There has, of course, been mutual borrowing, and I, for one, do not doubt that the syntactical peculiarities of Assamese are largely due to the fact that it is a speech with an Aryan vocabulary spoken by a people who are largely non-Aryan. Any careful reader of the stories in this book can see for himself that the Boḍo spoken in the Kachári dwars is the language of a biglot people. Their picturesque agglutinative verb is plainly a survival of days when the language was as monosyllabic as Chinese. But the general structure of the language is now governed by inflections obviously borrowed from Bengali and Assamese.

J. D. Anderson.

Cambridge,

December, 1910. [1]