A Collection of Quipus

American Museum of Natural History, N. Y.

Nos. B 3453, 8704

Title: The Beginnings of Libraries

Author: Ernest Cushing Richardson

Release date: September 2, 2015 [eBook #49849]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

A Collection of Quipus

American Museum of Natural History, N. Y.

Nos. B 3453, 8704

A considerable mass of memoranda on the early history of libraries has been gathered by the author of this essay during the last twenty-five years, and out of this material various essays have been published from time to time on Antediluvian Libraries, Medieval Libraries, Some Old Egyptian Librarians, etc. The fact that the unworked mass of modern information through excavations is so great as to put off for a long time still a systematic treatise, has led to the plan of publishing these essays and addresses from time to time as completed and in uniform style. Although written for very different audiences and in various methods, each is an attempt to gather information not generally accessible and to be, so far as it goes, either a contribution to knowledge or to the method of knowledge, a sort of preliminary report or investigation in the field, pending full and systematic report. The nucleus of this essay on the Beginnings of Libraries was an address to the Library School of the New York Public Library at the beginning of the academic year 1912-13, and takes its color from this fact, but it has been freely enlarged. The writer owes special thanks to the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

| Preface | v | |

| Contents | vii | |

| List of illustrations | ix | |

| 1. | Introduction | 1 |

| 2. | The study of beginnings | 5 |

| 3. | Definition of the Library | 14 |

| 4. | Method | 22 |

| 5. | Antediluvian libraries. General | 25 |

| 6. | Libraries of the gods | 27 |

| 7. | Animal and plant libraries? | 34 |

| 8. | Preadamite libraries | 39 |

| 9. | Adamite and patriarchal libraries before the flood | 42 |

| 10. | Prehistoric and historic libraries | 50 |

| 11. | The evolution of record keeping | 54 |

| 12. | Memory libraries | 65 |

| 13. | Pictorial object libraries | 76 |

| 14. | Mnemonic object libraries | 91 |

| 15. | Picture book libraries | 100 |

| 16. | Ideographic records | 114 |

| 17. | Types of primitive libraries | 116 |

| 18. | Contents of primitive libraries | 132 |

| 19. | The administration of primitive libraries | 142 |

| 20. | The beginnings of library schools | 151 |

| 21. | The beginnings of library research | 156 |

| 22. | Bibliography | 159 |

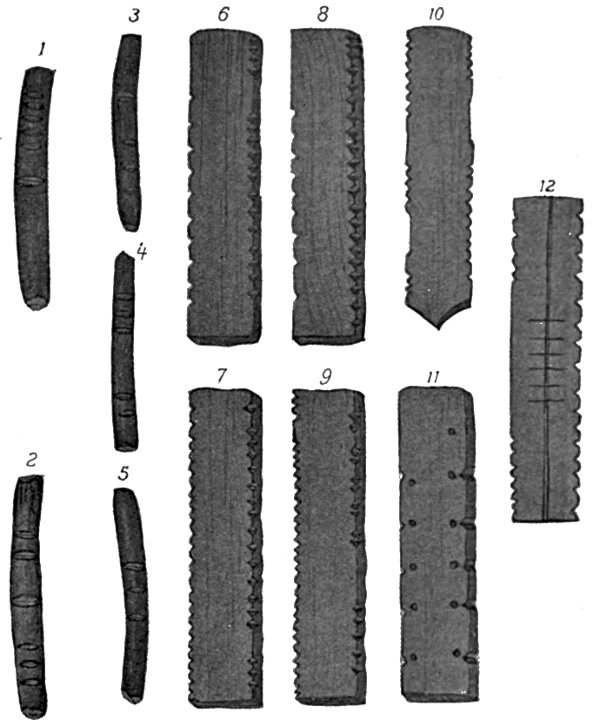

| 1. | A collection of quipus | Frontispiece. |

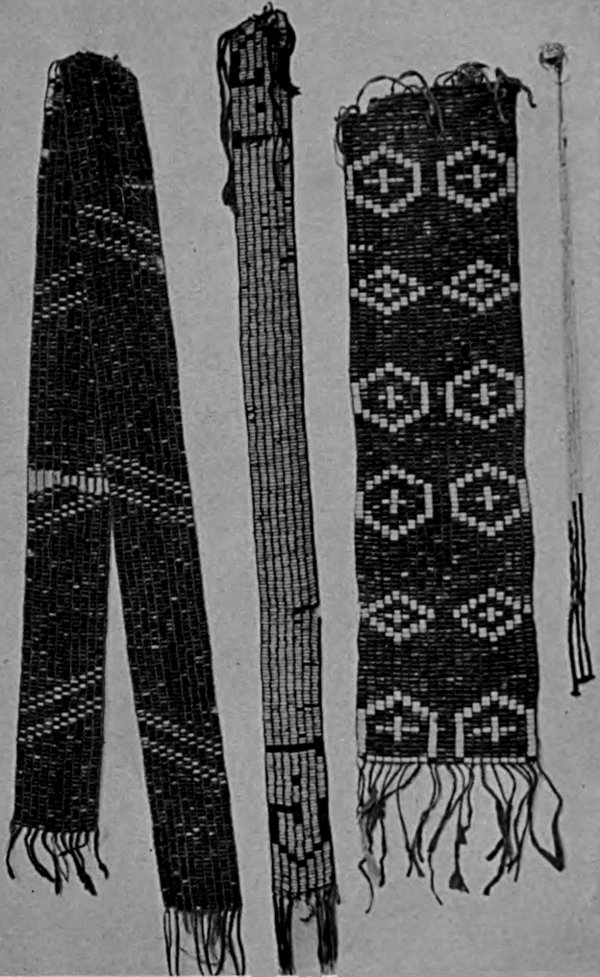

| 2. | A collection of message sticks | 94 |

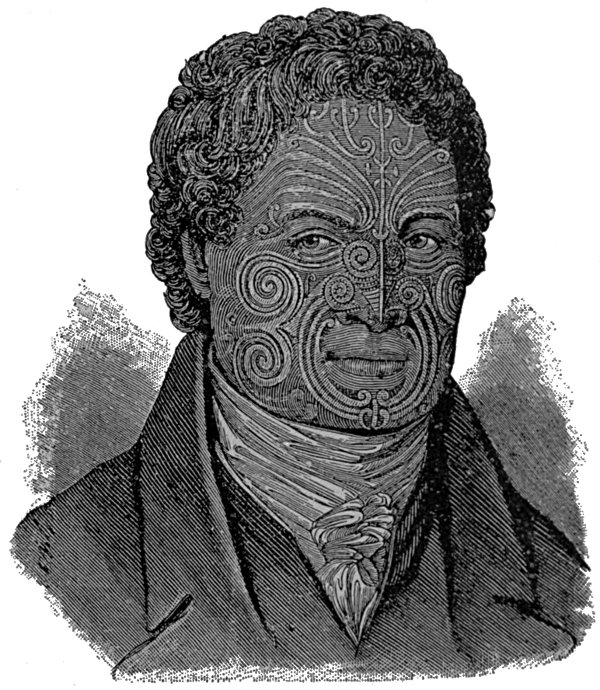

| 3. | A collection of wampum | 98 |

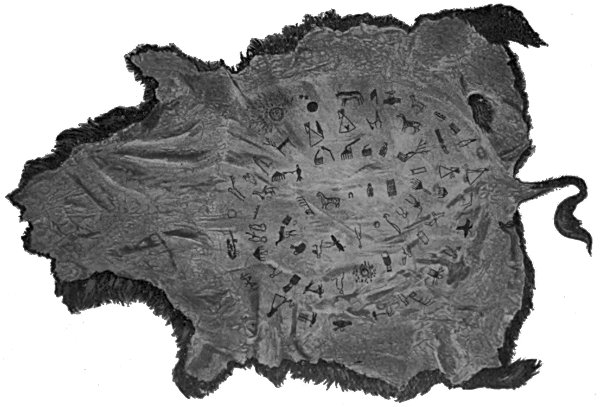

| 4. | A record ornament of leopard teeth | 102 |

| 5. | Tupai Cupa’s Tattoo Marks | 106 |

| 6. | Picture writing, Lone Dog’s Winter Count | 108 |

This talk is addressed to those beginning library work as a life work. This connects “library work” with two significant phrases, “those beginning” and “as a life work”.

This phrase “as a life work” suggests what is perhaps the chief value of a library school training. The distinction of and main justification for all kinds of higher education is that such education aims to put the student in position to view his work to be done as a whole, and life as a thing to be wrought out as a whole, not to be lived from hand to mouth. Presence at a library school means that the student has had foresight enough to be willing to spend energy, money, and a good bit of that most precious capital time, in sitting down to draw plans for his life building as a whole instead of starting in to build by rule of thumb.

There are however in this matter two factors—one’s self and the library. In order to sketch out one’s life work as librarian and live it, one must needs first know what libraries are, what they are capable of becoming and how one can best apply such knowledge and energy as one may have to making these libraries accomplish what they were intended to do for human society. This involves looking at libraries as a whole as well as at one’s life work as a whole, and the task of the library school is to give this view of the situation. In the last analysis this is the most important thing which any technical school does for one, this giving the vision of the whole of experience in one’s chosen field in order that one may draw his life plan in view of it. And for that matter, the task of technical education does not differ in this regard from the task of general education, which is simply the vision of the whole of human experience, as a whole, with reference to one’s own life among all kinds and conditions of men.

As therefore the field of science and general activities is the Universe, so the field of library science and education is libraries—libraries top and bottom, inside and out, beginning, middle and end and looked on as a whole.

On the other hand the phrase “those beginning” suggests the facts that you are yourselves at the beginning of a course of study, that the school year is at its beginning, that this New York Public Library school itself is still in its beginnings and that library schools in general are only in their beginnings. This in turn suggests as the topic of this talk three aspects of the matter of library beginnings: the beginnings of libraries themselves, the beginnings of library science and the beginnings of schools for library science. This talk will touch briefly, towards the end, on the two latter topics, but will have chiefly to do with the beginnings of libraries.

At the outset it should be said that the importance of this study of beginnings is in every science quite out of proportion to the importance of the objects studied. Beginnings are by nature small. The highest and best things are by nature the most complex and latest, but the study of the earliest and simplest libraries, like the study of the simplest cell life, is not only useful from several points of view but vital to a right understanding of the more complex. The great vice of technical education of all sorts is its tendency to fix attention on the latest and best only. It is true of course that man’s ideas and methods are an evolution—just as his body is. The fact of the accumulation of human experience is the central significant fact of human civilization. It is the glory of libraries that by reason of this fact they are an indispensable tool of progress in civilization. On the whole, by and large, the latest ideas are in fact best, for they tend to sum up in themselves the total of the useful variations of all preceding ideas, and the main time and attention of a course of education must of necessity therefore be given to the latest and best experience, because it does sum up all that has gone before. This does not, however, lessen the value of the study of earlier ideas on any subject back to the very beginnings, for at any given time and place, the latest idea or method in any field is not necessarily the best. It might be the best: it is in position to build on all previous experience and so become best. We all know, however, that the latest book on a subject is not always the best book. So it is, too, of individual ideas or methods.

This frequent failure of the latest to be best comes chiefly from lack of knowledge of previous experience. Every year sees library methods put in operation which were tried and found wholly wanting in the last century or it may be, two, three or even five thousand years ago. On the other hand again, every now and then we find that some method or idea, discovered long ago but neglected meantime, is far better than those in common use. This has often been true of great scientific ideas and we have in Mendelism a striking recent example. One must needs therefore study earlier ideas in any field, both in order to be sure that so-called new ideas are not exploded old ones and in order to find whether common practice in any field at a given time is not really the development of an inferior line of evolution.

And, again, from the point of view of science, this study of earlier stages is useful because the simple things are often the best interpreters of more complex, the early of the late, and it is the vision of the whole in perspective to the very beginning which gives the clue to the real meaning of the latest. “Students have come to realize,” says Professor Stewart Paton (in the Popular Science Magazine 8,1912,166), “that in the ... amoeba, jelly-fish, crab or fish, is to be found the key that will eventually open the book ... (of) the most complex psychic manifestations.” This is true also of libraries—the oldest, smallest and rudest give a clue to the more complex, and it may be added, parenthetically, the library is itself in fact the most complex psychic manifestation in the objective Universe.

Beginnings thus, though small, are the roots of the matter. This is so well recognized in the field of science as to have become an axiom, and in the study of any class of things nowadays the aim is to trace each kind of thing—plant, animal, idea or social institution back to its beginning. Evolution has taught us to expect a genealogical series back and back to very simple forms and the method of all science has become what is called historical or genetic. Natural science is not satisfied until the most complex animals and plants have been traced back through all their complexities to single cell origins, and, if Browning may be believed, the aim of humane and ethical science too does not rest short of the same effort “to trace love’s faint beginnings in mankind”.

This study of the beginnings is, moreover, not only at the bottom of the method of modern science but of the method of modern teaching. Every man, it is said, in his life history retraces the history of his race, and the race history of man is above all things a history of developing ideas. This has two aspects significant for the method of teaching. As investigating science must trace every complex idea back to its simplest beginnings, so teaching traces the idea forward from those beginnings to its latest form. The law by which man in his individual development of ideas must retrace the history of the race applies to every idea or group of ideas and it is doubtful therefore if any one ever learns anything rightly in life unless he patiently follows the idea of it from its simplest beginnings to its latest form—the path being sometimes a steady growth in value, sometimes a rise and fall again towards extinction. The historical method of teaching, therefore, is the only method which can be called natural.

The other teaching aspect of this matter is the very significant fact in child psychology that the general development of the child’s mind, like the development of its body, does in fact repeat the history of its ancestors as they passed from gestures and cries to articulate speech and writing and through these from the simplest knowledge to the most complex. The child must therefore, in short, be taken along “the paths upon which in a very real sense every human being has come in person” and the natural method of child teaching must consequently be deduced particularly from a study of the beginnings of speech and writing, books and book collections. In a sense, and in a very real sense, the key to the scientific pedagogy of the future lies in the group of studies summed up as library science, for the library is the late and complex object which sums up in itself the sciences of the book, the word, and all simpler elements of human expression and record, if there be any such. A fourth reason for the study of beginnings is, therefore, that it is the natural method of study and teaching.

Finally and closely connected with the preceding reasons is the fact that the purpose of all science is prophecy. We learn not so much that we may teach, as the motto says, but we learn that we may foretell. The object of all science is to understand from what has been the relation of cause and effect in the past, what is likely to be the result of any given set of circumstances in the future. Physics, e.g. has proved a very sure prophetic guide. An engineer can tell with precision that a bridge constructed in a certain way will break if loaded beyond a certain point. Load it to that point and his prophecy becomes true. In the same way, with somewhat less precision perhaps, the biologist can prophesy results in the breeding of plants and animals, the physician can prophesy that quinine will help malaria, the farmer that planted seed under certain conditions will or will not on the average produce certain results, and so on through every branch of human activity. We study in order that we may know the conditions which will be brought about in the future by one or another set of circumstances and so that we may be able to produce the circumstances if we wish the result. The preparation for foretelling may, therefore, be labeled the fifth reason for historical study.

In approaching the actual study of primitive libraries it is necessary to touch a little on definition and method. Both these matters, essential to the approach of any topic scientifically, doubly need some attention at this point, because library history has heretofore not troubled itself much about primitive libraries at all or indeed about libraries for the first two thousand years after they had left their more primitive stages. The very method, therefore, lies chiefly outside the experience of library history, being gathered mainly from primitive art and anthropology, and definition must needs consider what the essential nature of these primitive libraries is that links them with the great libraries of modern times. Discussion of definition is the more necessary in that the already contradictory usage has been still farther confused in the matter of the earlier historical libraries by those who, wishing to distinguish the collection of purely business records, public or private, from the collection of purely literary works by calling the former an archive, have yet applied the term archive, incorrectly, under their own definition, to mixed collections of business and other records.

Many answers have been given to this question: What is a library? All of these imply a book or books, a place of keeping and somebody to do the keeping—books, building and librarian—but some definitions emphasize the books, some the place and some the keeping. Far the commonest words used have been the Greek bibliotheke and the Latin libraria and their derivatives. The one rather emphasizes the place and the other the books but both were used sometimes for both library and bookshop. When modern languages succeeded to the Latin the Romance languages kept bibliotheca for library and libraria for bookshop. Germanic languages on the other hand kept both words for library, although in the course of time German has nearly dropped librerei for bibliothek, and English has quite deserted bibliotheke for library. Both English and German call “book shop”, or “book business”, what French, Italian and Spanish call “library”.

Library is thus the common modern word in English for a certain something which the German calls Bibliothek, the Frenchman bibliothèque and the Italian, Spaniard, Scandinavian and Slav call by some similar name. This something in its last analysis is a book or books kept for use rather than kept for sale or for the paper mill. A library is thus a book or books kept for use.

Among the many definitions of the library which do not recognize use as the library’s chief distinction, the commonest are perhaps those which adopt plurality or collection as the distinguishing factor. Many however adopt the building as chief factor. Typically, of course, the modern library does include many books, a whole separate building and a librarian, but even if the books are few, the place only a room, a chest, a bookcase, or a single shelf, and even if it is only the owner who is at the same time the keeper, it is still recognized to be a library if the books are kept for use and not for sale. Quantity does not matter: the point which divides is the matter of use or sale. Even a one book library is, in fact, a library just as much as a one cell plant is plant or a one cell animal is animal. A one book library is a very insignificant affair compared with the New York Public Library with its many books and many branches, but it is just as truly a library—or else you must find some other word. In point of fact “library” in English, or some derivative of bibliotheca in most other languages, is the word which in practice stands to the book-for-use as the word animal or plant does in biology for the living thing whether it is a single cell or a cell complex.

Some definitions again try to limit the library to printed books or bound books or literary works as distinguished from official or business documents, and these definitions have, as before said, sometimes led to a good deal of misunderstanding. Even if “archive” is assumed to be the right name for a collection of business documents, still such a collection is simply one kind of a library. Every one recognizes this when the collection of business documents is one of printed and bound public documents (U. S. public documents e.g.), and if the documents are tablets, rolls or folded documents, the case does not differ. If books are kept for use it makes no difference whether they are of wood, stone, metal, clay, vellum, or paper, whether they are folded documents, rolls or codexes, whether they are literary works, government or business documents: if intended for use they form a something for which some word must be found which will apply equally to all kinds of records for use and to a one-book-for-use library as well as to the New York Public Library. The right word in the English language seems to be this word “library”. The “business documents” in active current use in the registry or the counting house are perhaps the farthest away from the “library” of common speech but they are equally far from “archives” in the scientific sense, and curiously these have retained one of the very simplest and oldest names of the true library, “the books”, and of librarianship “book keeping”.

But the definition of a library as a book or books kept for use only brings us up against the farther question, What is a book? To this it may be answered that a book is any record of thought in words. Here again neither size, form, nor material matters; even a one word record may be a book and that book a library. This leads again however to still another question: What is a word? Without stopping to elaborate or to discuss definitions in detail, we may take the next step and define a word as “any sign for any thing”, and again explain the sign as anything which points to something other than itself. This is not an arbitrary definition but one founded in modern psychology and philology and to be found in sundry stout volumes by Marty, Leroy, Wundt, Dittrich, van Ginneken, Gabelentz, and others. The sign may be a sound, a color, a gesture, a mark or an object. In some stenographic systems a single dot stands for a whole word.

The most insignificant object, therefore, kept to suggest something not itself may be a library. A single word book is of course a very insignificant book indeed, and the single letter, single word, single book library a still more insignificant library, but, unless you invent other words for them, they are truly book and library, and there is no more reason to invent another word for book or library in this case, than another word for animal when it is intended to include both the amoeba and man. The very simplest library consists therefore of a single recorded sign kept for use. It is the feeble faint beginning of a library but just as much a library as the New York Public Library, the Library of Congress, the British Museum, or the Bibliothèque Nationale—and the beginning of library wisdom is to seek out diligently the nature of these rudimentary libraries.

So far for definition. Now a word or two as to method. In this search for the earliest history of the making and keeping of records, library science, like all the human sciences, has at least three ways of approach or sources. The first source is history. This includes the evidence from written documents (which is direct and is history proper) and the evidence from monuments (which is circumstantial and is archaeology proper).

The second source is the custom of primitive or uncivilized nations of recent times: this is comparative library science. The modern idea of evolution implies that these primitive peoples are simply cases of arrested or retarded development—they, having branched off from a common stock at an early stage of development or else having only slowly developed in parallel natural lines. Their customs therefore, it is alleged, truly represent early mankind when it was at a like stage of development. With this evidence belongs also the rich source of survivals in popular customs among civilized peoples and folklore generally; these are things which have kept on side by side with the things which have outgrown them.

The third source is the acts of children while they are developing from the speechless to the speaking stage and from the speaking to the writing stage;—the modern theory being, as has been said, that the child in developing repeats the experience of its ancestors, or, as it is said, “recapitulates the history of the race” in this regard. This is in the same sense perhaps that children’s games are supposed by some to reflect the hunting, the wars and the domestic life of their savage ancestors.

These three sources are supposed to cross-check one another and supply gaps in one another, and each might be followed out separately in detail, but for purposes of this talk it will be convenient rather to treat as one historical progress, illustrated from the customs and habits of modern savages, folk customs, and the psychology of children.

That part of methodology which has to do with the bibliography of the subject in its various aspects will be reserved for the end of the talk.

There are several classes of alleged libraries, which if they have real existence must necessarily precede all others. These include the libraries of the gods, animal or plant libraries, Preadamite and Coadamite libraries and the alleged libraries of the antediluvian patriarchs. All of these may be included under the term antediluvian and the period subdivided chronologically into Adamite or Patriarchal, Preadamite, Prehuman (plant and animal libraries) and Precosmic (libraries of the gods)!

There is a considerable literature on the subject of antediluvian libraries (cf. Schmidt, Bibliothekswissenschaft, 1840, p. 67; Richardson in Library Journal, 15, 1890, pp. 40-44), but this term has been, until recently, used to include mainly libraries which were alleged to have existed from Adam to Noah. Modern explorations in comparative psychology on the one hand and comparative mythology on the other have however now brought to light many potential or alleged libraries from before Adam—not forgetting that this first ancestor of ours has quite recently been dated some sixty million years before the Christian era!

The oldest of all alleged libraries are the libraries of the gods.

Almost all the great god families, Indian, Egyptian, Babylonian, Persian, Greek, and Scandinavian, had their own book-collections, so it is said. According to several religions there were book-collections before the creation of man; the Talmud has it that there was one before the creation of the world, the Vedas say that collections existed before even the Creator created himself, and the Koran maintains that such a collection co-existed from eternity with the uncreated God. It is obviously idle to try to trace libraries back farther than this.

Brahma, Odin, Thoth, and substantially all the creator gods who are described in terms of knowledge or words, are each sometimes in effect looked on by the mythologists as himself an incarnate library and sometimes even the books of which he is composed are specified.

On the other hand, by many all creation was looked on as a library. To the ancient Babylonians the stars of heaven were themselves books in which could be read the secrets of heaven and earth and the destiny of mankind. The whole firmament was thus a library of celestial tablets—tablets of destiny or tablets of wisdom from the “house of wisdom”, which was before creation, or carried upon the breast of the world ruler. “The Zodiac forms the Book of Revelation proper ... the fixed stars ... the commentary on the margin” (cf. Jeremias. Art. Book of Life, in: Hastings ERE.)

This belief, developed into the so-called science of astrology, had a prodigious influence even on the political history of mankind through its effect on the decisions and acts of kings. The conviction that the will of the gods as to future events was here written down, stored up and might be read, was at times the controlling factor in the shaping of human events.

Two of the most famous libraries of the gods are those of Brahma and of Odin. The books of Thoth, equally or more famous, belong to a somewhat different class. Brahma’s library contained or was the Vedas—themselves in fact a large collection of various works. These were, it is alleged, preserved in the memory of the omniscient Brahma and at the beginning of this present age they were, in the modern language of an ancient Sanskrit writer, Kalkuka Bhatta “drawn out”. Attention has been called to the fact that this library was represented as a classified library with notation founded on the points of the compass!

“From the eastern mouth of Brahma ... issued ... the rich verses.... From his southern mouth ... the yajash verses.... From the western mouth ... the saman verses and the metics.... From the northern mouth of Vedas (Brahma) was manifested the entire Atharvana” (Muir. 3:12). This library was, it should be noticed, quite up to date in having the special collections kept in separate rooms with separate exits. It was also, it appears, not a mere reference library but books were issued for outside use.

Brahma’s library was represented in various other forms e.g., as the milk of the cow goddess or the juice of the Soma plant, and in the same way Odin’s collection of words or knowledge is represented in various forms e.g., as the milk of the goat Heidrun, the water of the fountain of memory, the apples of Iduna, which were the fruit of the tree of knowledge and the blood of the wise Kvaser.

That which best identifies the mead, which is the source of the immortality of the gods themselves and without which they languish and die, with books, is the story of Kvaser. Kvaser was the wisest of all the gods (Fooling of Gylfe 54). The dwarfs put him to death and gave out that he had drowned himself in his own wisdom, but in fact they slew him for this wisdom, which was his blood. This was drawn off into a kettle called Odrörer (“that which moves the mind”) and mixed with honey was most carefully kept in jars. Drinking out of these jars makes an ordinary man “a poet and man of knowledge” but the mead is most jealously kept to renew the life of gods and poets (Brage’s talk 3 sq.) and grudged to mortals. Once Odin, hard pressed in flight, let fall a few drops of this essence of knowledge, and this scanty supply eagerly caught up by mortals produced the rabble of bad poets.

This collection of jar-fulls of knowledge was an obvious library and recalls the fact that almost all the mythologers represent books or knowledge as food or drink, kept in jars. It is not wholly excluded that this great series of myths came from the earliest practice of keeping clay tablets or papyrus rolls in clay jars, precisely similar to the jars in which wine, oil and grain were kept in some treasure houses. But however that may be the soma of India, the haoma of Persia, as well as the Scandinavian mead and the ambrosia and nectar of classical times, were all looked on as concrete knowledge and as such the food and drink of the spiritual or immortal life—a very reasonable philosophy.

These libraries of the gods should not be confused with real collections of books of alleged superhuman authorship like the books of the Old Testament, which are not claimed by any to have been written before 1200 or 1500 B.C., or the collections of actual oracles delivered at Delphis, Dodona or other shrines, or even with the forged oracles of Greece, or the apocryphal Jewish and Christian books. All these were actual historical book collections and the question whether authorship was really superhuman or not is indifferent at this point which has to do with the libraries which the gods are alleged to have had for themselves before man was.

The modern psychologists, by the science which they call comparative psychology, have gradually been robbing humanity of much that it used to plume itself upon as its own unique possession. Among the last strongholds to yield were reason and language, and the defenders of these, although retreating, are hardly yet put to rout. Even if the articulate speech of the parrot and the jackdaw is only “imitation”, and the alleged language of the apes a delusion, still it is something of an open question whether the sounds and gestures which animals use with one another are not really of the nature of language. The fox who doubles on his track in order to lead the dogs on a false scent is getting very close to language in a rudimentary sense, and the dog who sits up or barks for food or wags his tail to express good will, perhaps nearer still.

It is a long step, however, from even developed oral and gesture language to record, and it is still generally denied that among the traits of our kinship with the beasts any evidence has been discovered of what can be called record keeping. If this were true, then it would seem to follow that the animal ceased to be animal and became man precisely when he invented and began to practice record keeping—in short that libraries mark the very beginning of the human race!

On the other hand, however, it cannot be ignored that the psychologists are publishing monographs on the arithmetic of animals and the memory for facts among animals, and scores of other monographs on the minds of animals. There are those too who claim that the dog even marks the place where he caches his surplus of bones, and certainly the bringing home of a dead woodchuck, in order to show his master what he has done, comes very close to that keeping and exhibiting of human trophies which is recognized as among the beginnings of “handwriting”. If it is true that the animals do make conscious marks to guide them back to hidden objects, or even that they do have memory for facts, which is true memory, then possibly the beginnings at least of memory libraries and perhaps of external records must in the future be sought in the animal world. The ancient Egyptians, of course, found it there when they made the writing ape author, owner, and keeper of books. Perhaps after six thousand years modern psychology is about to catch up with this idea! Whether or not future psychology discovers anything like actual record collections and memory libraries among the animals, it remains true that the study of comparative psychology does lead into the beginnings of memory and helps therefore to the study of the real nature of human memory-books and memory libraries, while again it leads into the question of the nature of gesture language, and gesture is the own father of hand-written books. When true libraries have been discovered among animals it will be time enough to take up the question of plant libraries. Nevertheless it may be said that the question of “memory” among plants is seriously discussed and plants may perhaps receive impression as sensitively as animals. It is a little figurative to say that a tree which carries in itself a hundred annual records of its growth is a library in the sense of a public record office which keeps the annals of a nation’s growth for a like period. There is however a certain analogy which the discussions of natural records and object writing suggests may even have some slight germ of scientific interest. Of course where there is memory there may be groups of memorized records which would be collections of very rudimentary “Books”, but so far the weight of evidence seems to be against the existence even in animals, let alone plants, of that kind of memory which retains permanently fixed forms of expression. Sub-human libraries may therefore be for the present left to the fabulists and put with apocryphal, legendary and mythological libraries outside the pale of the real or historical libraries.

Whatever psychologists and mythologists may have to say about libraries before the existence of the human race, there seems to be a surprising consensus of opinion that book collections must have started at latest very soon after man himself. A great number of such libraries are claimed by the ancients for the period between Adam and Noah, and if there were human beings before Adam, as many say, it is likely that there were at least memory libraries, for, as will be seen later in discussing memory libraries, these are almost inseparable from human nature. And further than this it appears from those very same sources, which so fluently allege and describe the library of Adam, that the books of Adam’s library represent such an advanced stage in the evolution of handwritten records as to necessitate a long library history previous to his time. These books included e.g., it is said, inscriptions cut in stone, and such inscriptions imply centuries if not tens of centuries of knot and other mnemonic forms of writing, preceding. Therefore if Adam’s library was as described in its literature, there must have been, for a long time before, Preadamite libraries!

Moreover if those writers on the Preadamites are correct who hold that Adam was the father of the Caucasian race only, (M’Causland. Adam p. 282), and that Mongols and negroes at least (M’Causland. Babel p. 277) were already existing when Adam was created, then of course all negro or Mongol libraries are Preadamite survivals! It is true that such writers represent culture, and by implication libraries, to have been introduced to the Mongols from the Adamite line and by Cain, but if premises are granted, the inference is complete, that primitive libraries of all kinds at least up to the time of phonetic records were Preadamite in origin and were shared by Mongol and negro races as well as by the Caucasian Adamites! For that matter some of these ancient, if not veracious sources assert that Adam was the inventor of the alphabet, which makes the matter even clearer, throwing even syllabic written libraries, not to mention ideographic libraries, back into the Preadamite period!

For those who care to follow up this fruitful but not profitable subject, some guide to the extensive literature on the Preadamites will be given farther along.

The very considerable literature on Antediluvian libraries which has been already mentioned is, in general, confined chiefly to the line of the patriarchs, whom the various writers on the Preadamites often describe as Adamites to distinguish thus the patriarchal or Caucasian line from its Mongolian and negro contemporaries—Adam, Cain, Abel, Seth, Noah, Ham, etc.

According to some of these veracious historians, on the seventh day of the first month of the first year Jehovah wrote a work on the creation in several volumes, primarily to teach Adam the alphabet, and secondarily, to preserve the record of the creation. This seems to have formed Adam’s entire library, until the fall. After this, however, Jehovah published a new edition of this work in one volume on stone, and added another work on another stone. These were placed by him in a “Beth” or “House” on a mount east of the Garden of Eden, where were also the Cherubim. This was according to them the first library building, and by inference the Cherubim were the first librarians. This library was bequeathed by Adam to Seth and by Seth to Enoch. It formed a part of the library of Noah, and was consulted by Moses, who incorporated, it is alleged, from it the Elohistic and Jehovistic documents into Genesis.

The libraries of Cain, Seth, Enoch and Ham were also famous among these old chroniclers—Seth’s for its astrological and astronomical works, and Ham’s for the heretical works, which he was not allowed to take into the ark with him.

Far the most famous however of all these libraries is the library of Noah. It contained that of Adam, with very many additions. At the time of the flood Noah was commanded to bury his books—“the earliest, middle, and recent”—in a pit dug at Sippara—and from this it appears that the library must have been very large since there was room in the ark for all kinds of animals, but not enough for the books.

After the flood this library was dug up by Noah, and preserved in his Beth at Nisibis, or, according to Berosus, was dug up by the sons of Noah, after their father had been translated, and formed the nucleus of the Babylonian libraries. A legend of the digging up of the library still exists, it is said, on the spot, where re-excavations are now going on.

The Hindu account of this library (Sir William Jones’ works. I, 288) has an interesting variation. It states that the flood came because, the sacred books having been stolen away, men had become wicked. After the deluge Vishnu slew the thief, and restored the books to Noah.

If Cassianus may be believed, however, these buried books were not all of Noah’s library since he took with him into the Ark at least a select collection, presumably for use on the voyage.

Nor were these the only libraries supposed to have been in existence when the flood came, for the Egyptian priests told Solon of many libraries which were destroyed by it. One rather wonders at this too, for in those days of course they were apt to make their books fire and water proof (rather than the buildings as now) and the flood should not have hurt them, but if they were in fact destroyed it simply shows that they were made of papyrus, leather or unbaked clay!

These writers not only tell us in detail about many of the books which Noah must have had in his library, but even in some cases give us a list of the books themselves. We find thus e.g. that the library must have contained the following works at least by Adam (a) “De nominibus animantium”, (b) a census report of the Garden of Eden, which included all living things, (c) The 92d psalm, (d) A poem on the creation of Eve, and various other works, all, it is to be presumed, written after the fall; for the very same authentic chroniclers who ascribe these works to Adam declare that he was born at three o’clock, sinned at eleven, was “damnatus” at twelve of one day and driven out of Eden early next morning—which left little time for literary work on his part, one may suppose, while in Eden.

The library must have contained also, if our sources are correct, works by Eve (“conversation with the serpent”), Cain, Seth, Enos, Enoch, Methuselah and others, and various works by Noah himself, including his history of the world to his own time, written before the flood and published in two editions, one on wood and one on stone.

The surviving samples of these alleged works are not calculated to make one regret anything about the deluge so much as its failure to be more thorough. Take e.g. Adam’s poems on the creation of Eve. Imagine Noah’s sons, “In the Springtime, when a young man’s fancy lightly turns to thought of love”, drawing out a tablet or two of this poem for inspiration and reading how calmly the new bride is invited by Adam to “shake hands and kiss him”!

The efforts to date the library of Adam have been various. A terminus ad quem is offered by Berosus, who asserts that the capital of the world before the Flood was named “The Library” or the “Book All”. He puts this at 250,000 years B.C., but this of course implies considerable development between Adam and the time when the world was populous enough to need a capital at all. There is, therefore, no necessary conflict between the veracious Berosus and the veracious modern historians of science, who place the terminus a quo at sixty million years ago. There is, however, considerable discrepancy between even the later of these two on the one hand and the very earliest of the one hundred and forty different dates between 3483 and 6984 B.C. actually assigned by more timid historians of the beginnings of Adamic civilization. As sober historians are bound to confess that at best the historical evidence for some 243,016 years on the one hand and 59,748,087 or so years on the other of Berosus’ date is not wholly continuous and 6984 B.C. may be regarded as about the earliest exact date known to have been ventured for Adamite libraries.

It hardly needs to be added that all these alleged patriarchal books and libraries are apocryphal although many of them have a respectable antiquity of more than two thousand years and most of them belong either to pre-Christian, early Christian or Mohammedan times. They have been by no means without their influence on human thought and on the actions of those who believed their statements to be historical truth. They are therefore not to be ignored in reckoning the influences which have shaped library development.

Leaving aside, however, all kinds of imaginary libraries, mythological, fabulous, legendary or apocryphal, we still have for real human libraries a very respectable historical and prehistorical antiquity.

This long period may be divided into prehistoric and historic or beginnings and later history—the prehistoric period or period of beginnings being understood to be the time before chronological record by years, or before the time of abundant and decipherable hand-written records.

On the whole, the term “beginnings”, is better for the early periods than the term “prehistoric period”. “Beginnings” in this point of view differs from “prehistoric period” simply in overlapping a very little the shifting and uncertain borderland between the old prehistoric and historic, carrying over just far enough onto the firm land of annual chronological history to insure a safe footing in the field where written records begin to abound.

In the case of books and libraries this line of division is most clearly made at the invention of phonetic writing, and this seems to correspond pretty well in time with the point of abundant written sources and of definite chronological data in the general history of mankind.

In terms of relative chronology this line corresponds fairly with the first dynasty of Egypt. No doubt in its real beginnings it shades back far beyond its distinguishable first appearance at this time, but in broad terms it begins for Egyptians and Sumerians about this time, and even if this was not the earliest point of its appearance, it is the point at which the earliest abundant well dated and understood phonetic records are found. What time we shall count this to be in terms of annual chronology depends altogether by about 1000 years on whether we accept the views of the school of chronology illustrated by Breasted’s History or that for which Flinders Petrie is champion and in the same way with the Sumerian where King stands for the reduced chronology. When doctors disagree, prudent conservatism suggests the acceptance of that minimum amount on which both agree, in this case about 3400 years of the pre-Christian era. Without prejudice, therefore, to the possibility that Flinders Petrie may be right in putting the first dynasty a thousand years or so earlier, and remembering that even Breasted accepts a predynastic historic period extending to 4500 B.C. with a strictly historic period from “the earliest fixed date in the history of the world” in 4241 B.C., the division between phonetic records and earlier forms of written documents may be taken as falling at about 3400 B.C. At this time the invention of alphabetic writing was still perhaps two thousand years in the future but writing of some kind, mnemonic and picture writing, had already been practised for perhaps two thousand years or even much more. The beginnings, or the prehistoric, prephonetic and predynastic period of libraries, lie therefore back of the phonetic writing of 3400 B.C.—in picture book libraries, mnemonic libraries, object and memory libraries.

These four classes of libraries, memory libraries, pictorial object libraries, “mnemonic” libraries, and picture book libraries, form thus the field. All of them existed before what may be called historical libraries; all are found among uncivilized peoples of all times; all have their faint remainders in popular custom among modern civilized nations, and suggestions of all may be found in child-study. Three of these classes, memory libraries, mnemonic libraries and picture book libraries, correspond to well recognized book forms. The term “mnemonic”, which is commonly used to include quipus, message sticks, wampum, and similar records, is itself not a very exact term, since all outward symbols, whether representative or conventional, are mnemonic. Moreover, what is generally meant by the term is the use as symbols of objects which do not represent or directly suggest their meaning—in short, of object signs with conventional rather than pictured meaning but as a matter of fact image signs with conventional meaning i.e. all ideograms or phonograms are equally “mnemonic” with conventional objects. A better distinction is therefore into the memory libraries, object libraries (including both representative, or pictorial, object sign collections and conventional object sign collections) and image libraries (including also both representative or pictorial images and arbitrary or conventional signs). For practical purposes, however, we may perhaps use the terms, memory, object, mnemonic, and picture, understanding by object, pictorial object, by mnemonic, mnemonic object and by picture, pictorial image, as distinguished from the mnemonic or conventionalized images known as ideograms and phonograms. To avoid confusion in this matter it must be kept clearly in mind that writing is not picture writing because its symbols are pictures, but because they picture something. If an ox’s head or its image (aleph or alpha) stands for an ox it is pictorial writing but if it stands for “divinity” it is ideographic and if, as it usually does, it stands for the sound “a” it is phonetic-alphabetic writing: It is pictorial writing only when it suggests its own meaning.

Again it must be said that pictorial writing is not confined to image writing as is usually implied by the phrase “picture writing” but applies just as well to objects. A real ox’s head and horns may mean “ox” or “divinity” or “a” just as well as a painting, drawing or sculpture of it.

Yet again it should be noted that the picture of an ox’s head is itself an object as truly as the head itself. The two kinds of objects might be called real or original objects and image objects but for short “objects” (originals) and “images” serve well enough. Again it should be remembered that an object is not a real object because it is in three dimensions or pictures necessarily drawings or paintings. A petroglyph is as suitable for “picture” writing as a painting (indeed most hieroglyphics are sculptured not drawn or painted). On the other hand a petroglyph is no more an “object” than a painting or drawing is.

With these distinctions in mind the following table of the kinds of symbols used in ancient records will make clear the kinds of primitive libraries.

For each of these kinds of “written” records there is a corresponding kind of library or record collection.

The question of the order of evolution among these various kinds of record collections is closely bound up with that of the evolution of language and handwriting, the very invention of handwriting probably implying a feeling of need for kept records.

The commonly recognized ways of human utterance are gesture and oral speech—the one appealing to the eye, the other to the ear, and each leaving its record probably at different points and in different molecular form in the brain. Hand gesture came in course of time to be the highest type of gesture language, evolving as it did into a highly complex and adaptable type of language, and modern hand writing is simply a form of hand gesture which, by means of ink or lead or chisel, or some other material or instrument, leaves a trail of the hand movement in permanent record.

The question whether gesture language preceded sound language may perhaps be settled by the answer to the question whether in the evolution of living beings the eye preceded the ear. If in the age of reptiles one saw the other glide or the grass move before he heard a swish or hiss, and if he himself first stayed still in order to escape being seen rather than heard, then doubtless gesture language began before sound language, and doubtless again also language began among men with simple gestures rather than simple cries. The biologists say in fact that reaction to light came earlier than reaction to sound, eye before ear, and if this is true, gesture language doubtless preceded oral speech. But, however it may be about simple utterance, when it comes to the matter of permanent external documentary record of utterance, it is clear enough that the records of gesture preceded the records of sound, and for some six thousand or eight thousand years, more or less up to yesterday, the only permanent records, or records in external material, were gesture records. Even phonetic writing, so called, is not sound record but a record of sounds translated into gestures; writing is a gesture sign which stands for a sound, not a record of sound. It is only within our own generation that, through the invention of the phonograph, oral or other sound utterance has been recorded in permanent material and libraries of sound records made possible.

The written recording of even signs for sounds did, however, in the evolution of record keeping mark a very decided advance over all previous methods. It was as great an advance perhaps as articulate speech itself is over gesture language or pantomime, and even greater than the next great step in human evolution, the invention of alphabetic writing. It was certainly a longer step in time from the very first beginnings up to this point than from here to the alphabet, perhaps longer than from 3400 B.C. to 1913 A.D., and the period of premnemonic record collections, therefore, it may be said in all seriousness, is perhaps longer than all later periods of library history put together.

The very first rudiments of record keeping were doubtless developed in the animal mind long before it learned expression to other animals and are to be found in the results recorded in its very structure, of its reactions to its environment. Certainly they began at the point where any experience, say of contact with an obstacle, left such record that on the next occasion action was taken in view of the previous experience.

The first attempt at expression or the effort of one individual to communicate an idea to another by signs may have been a mere movement to attract the attention of the other to the simple fact of its existence, and the first record of expression may have been the simple memory of this movement in the other’s mind.

However this may be, in the course of time and among human beings memory was the first record and as long as life was so simple that a man’s memory was sufficient for his own record uses and he felt no need of communicating to a distance, whether in space or time, the necessity of external records was not felt. As soon, however, as the number of a man’s cattle or cocoanut trees, or the contents of his hunting bag got beyond his count (perhaps beyond the number of his fingers and toes) or he felt the need of sending a message of defiance, peace, or ransom to a neighboring tribe, or from a hunting party back to the cave or wigwam, he began to make visible records—objects, specimens, images, and conventional signs of one sort or another. As the art progressed and became more and more complex, pictures of objects and pictures of gestures became the usual form of record until finally these pictures were recognized as standing for certain groups of sounds and phonetic writing had been invented.

Very soon after the introduction of phonetic writing documents began to abound and the chances of survival, therefore, to multiply. The Palermo stone seems to show that actual records by reign and by year of reign began in Egypt as early as the first king of the first dynasty. However that may be, within a few centuries of this time records and collections of records in Egypt had become abundant and varied, and these contained economic records, records of political and religious events, laws, censuses, etc., at least. In Babylonia too, long before 3200 B.C., there had been collections of laws, and a great variety of economic and religious documents.

In brief it may be said therefore that about 3400, or at least 3200 B.C., the vast number of documents, the firm establishment of phonetic record, the pains taken to insure permanence and the suggestions of methodical arrangement and custody point to the beginning of a strictly historic period.

The earliest form of library was, it is to be supposed, the memory library. This term is not fanciful and does not in any sense attempt figuratively to identify the human memory as such with the library. A few years ago this could have been done in an interesting way because a favorite analogy for conceiving the human brain was the system of pigeon-holes with different sorts of ideas classified and put away in their respective compartments furnishing a very exact analogy to a classified library. This analogy is now found less useful than terms of brain paths or other figures, although the actual geometrical location of each word in brain tissue in the case of memory is still not excluded and this possibility must have its bearing on the psychological study of memory libraries.

What is meant here by the memory library refers to the modern psychological study of inward speech and inward handwriting. This accounts for the existence of inward books and collections of books, and a collection of inward books is obviously a real library. It makes little difference where or how these are kept in the brain. They doubtless imply a library economy at least as different from that of printed and bound books as the books themselves are different from papyrus rolls, clay tablets, or phonographic records, but it is a real collection of books and the psychological study of the place and manner of their housing and the method of their arrangement and prompt service to the owner for his use is not a matter of analogy or figure of speech.

The essence of the book is a fixed form of words. The point is that a certain form of words worked into a unity is preserved in exactly that form. The author looks at it as a whole, prunes, corrects, substitutes better words for inferior ones, and generally works over it as a man works over a painting or statue. At the end of the process when the book is finished it is a fixed form of words, a new creation, an individuality. The ordinary habit of thought and conversation does not reach this point of fixed forms of words although in the case of very retentive memories, where the complete verbal form of conversation is remembered, it approaches it. In general men seldom remember the exact phraseology when they listen to a sermon or a story. On the other hand, however, the actor or the professional story teller can summon at will the exact verbal form of a great number of works and each of these works is properly a book. This permanent fixing of form undoubtedly implies some substance in which the words are recorded, but if that substance is the human brain the result is no less a book, a real record in the real substance, than if recorded in outward substance such as stone or ink.

The practice of keeping such inward records of exact fixed forms of words is not only the oldest form of record keeping and one extensively practised in illiterate periods, but it is commonly practised in modern life by orators who speak without notes, and as a method for the teaching of children before they learn to read (“memorizing”) as well as afterwards in the schools.

Among savage peoples the medicine man is often a library of tribal tradition although the modern ethnologists agree that he was by no means the only professional repository of tribal records. The ancient Mexicans, for example, seem to have had special secular chroniclers whose business it was to memorize public events, and to be a sort of walking public records office, memorizing public accounts of all sorts as well as the story of events. According to many critics of the Old Testament this primitive method continued the chief or only method of transmitting records in Palestine for 2000 years after it had given place to writing in Egypt and Babylonia. They hold that the Pentateuch was formed and transmitted by such oral verbal tradition. The Vedic books were, it used to be alleged, gathered and handed down by a rigorous organized system of memorizing, and this has a certain counterpart in modern times in that memorizing of the Confucian books and of the Koran which forms a chief part of the system of education in the respective cases. The strictness with which this method of transmission of memory books has been carried out to the point of fixing every word and even letter is perhaps best illustrated from the Jewish oral tradition as to the sounds of the vowels which apparently continued oral for centuries before they were represented by the vowel point signs.

Whether blind Homer composed his songs and recited them throughout Greece without reducing to writing or not, he might have done so and would have done as many another before him in doing so. As a matter of fact the excavations of the last dozen years show pretty clearly a pre-Homeric Greek writing, and Homer himself indeed once refers to the written tablet. But however that may be, the race of minstrels began long before Homer and still exists. In the Middle Ages they were each a walking library, often with a very large repertory, and the same is often true to-day among their successors the actors, reciters and the lecturers. The learning of poems and declamations by school children often results in an inward collection of definite verbal forms in considerable numbers. A more complex form of memory library is that of certain ancients who are alleged to have organized their slaves into a system, each of the slaves being assigned a certain number of works in a certain class to learn by heart and kept ready on call to recite when any one of these should be desired.

These inward or memory libraries may be distinguished into two chief kinds. As a matter of fact there are almost as many different kinds of inward books as there are outward books, but as the two chief ways of expression are voice and gesture, so the records of oral speech and gesture language, received by eye, ear, or touch, and inwardly recorded, are the chief kinds of memory books. These are quite distinct as to their processes of reception and record, and very possibly occupy different areas of the brain. These differences may in part be realized from common observation, but one must take pains to guard against the assumption that the inward record is a photograph. It is entirely possible that the brain record of the sound “man” differs as much from a picture of a man as the thread of a phonographic record does. The same is true as to the inward record of a picture word or alphabetical handwritten word. The inward record may no more be a microscopic picture than the stenographic sign is. Nevertheless it is not hard to realize that there is somehow within a series of recorded impressions which may be called images, some of which recall sounds and others objects or gestures. The inward language may or may not have to do with sounds. Modern pantomime and the sign language of deaf-mutes and Indians are languages, and it is entirely possible to store in one’s mind an exact series of signs telling a story in gesture language, just as it is possible to store the symbols for sounds or oral speech.

One of the most interesting chapters in the antiquities of ancient nations and of modern savage tribes is the story of liturgical rites, sacred dances, symbolic processions, and the like. Savage dances e.g. sometimes rehearse events of the hunt or war or domestic scenes. In many of these cases what may be called historic events are represented and the whole ceremony is a rehearsal of these events, although wholly in gesture expression, with gesture or object symbols and without speech. It is the recital of visually memorized records in visual symbols, but the records are just as truly definite accounts of events, or records, or books if you like, as if they were oral words remembered and expressed by voice or in writing. In religious dances and dramatic religious ceremonies, the traditional representations were of ideas rather than events—the nature of the world and man, the future world and the means of attaining this,—and these formed groups and sequences of transmitted ideas quite as definite to the initiated as if expressed orally or in writing.

In the ceremonial processions of the Egyptians and in the Greek mysteries, these representations often become very elaborate and were, apparently, in the secret mysteries, often accompanied by oral explanations by the exegete. It is possible that in the case of both Greek and Egyptian mysteries the transmission had even ceased to be exclusive memory transmission, and that written records, or at least mnemonic tokens of some elaborateness, were preserved in the various chests or baskets carried in the ceremonies. However that may be, these were at least the more elaborate historical successors of symbolic dances and other ceremonies, transmitted among primitive men through visual and muscular sense memory, just as poems were preserved in auditory images and transmitted by oral utterance.

The significant point is that whether the ritual used in the mysteries was transmitted in auditory or visual images, and whether these symbols were external and kept in the basket or chest, which was carried about in the procession, or merely kept in memory, they were, so far as they were separate, complete and stable image-forms, real words, books, and libraries.

The simplest and presumably earliest form of outward record is the pictorial object record i.e. an object “in which a picture of the thing is given, whereby at a glance it tells its own story” as Clodd (p. 35) says of the corresponding image signs which form what is commonly thought of as “picture writing”. These pictorial objects are distinguished from mnemonic objects (quipu, abacus, etc.) as pictographic image writing is from ideographic and phonetic writing, by the fact that in themselves they suggest somehow the things meant while mnemonic objects or images require previous agreement or explanation.

The pictorial objects used for writing may be whole objects or parts of objects and they may stand for individuals or for classes of things, e.g. a goat’s head may stand for a certain wild goat killed on a certain hunting trip or, with numbers attached, it may stand for a herd of domestic goats.

The earliest records were no doubt whole object records of individuals. When the hunter first brought home his quarry this had in it most of the essential elements of handwriting (those left behind could read in it the record of the trip) and when he brought useless quarry, simply to show his prowess, it had in it all the elements of the record, as has in fact the bringing by a dog of a woodchuck to his master or the bringing home by a modern boy of a uneatable string of fish to “show”. The bringing home from war of living captives to be slain, or dead bodies to be hung from the ship’s prow or nailed on the city gates, has the same motive and the same record character. So too the hanging of criminals on gibbets has the character both of the record-book and the instruction book. In these cases the very object itself is kept and exhibited—the whole object (though without life). Perhaps the nearest approach to the whole object library, in the sense of a permanent collection of records, was when all the permanent spoils of a campaign were “devoted” or “laid up” and kept together for memorial rather than economic purposes in the treasury of the temple.

A strict modern illustration of this case is a collection of battle flags taken or carried in a certain war, campaign or battle. Or again if a modern hunter should have all the spoils of a certain hunt stuffed and mounted as a record of the hunt, this would be of the same nature—a whole object record collection with an object to stand for every individual.

The sample or specimen whole object record as distinguished from the individual record is in modern times extensively known and used in the sale of goods by travelling salesmen. In its rudiments as a means of visible communication of ideas it was doubtless as old and perhaps older even than the keeping of trophies for record. If e.g. man was herbivorous before he was carnivorous then doubtless primitive man scouting for food would bring back specimens for his family just as a modern boy may bring in specimens of the wild grapes or berries that he has found for information of the folks at home. The best modern illustration of the sample or specimen whole object is in museums, menageries, zoological and botanical gardens, and the like, where specimens of various kinds of objects are gathered to stand for classes, without any special regard to the number in the class.

Museums in general illustrate object record. The historical museums generally and collections of historical relics large and small, together with mineral, plant or animal collections of rare objects, otherwise unknown, or species otherwise extinct (e.g. the American bison) are of the nature of individual whole object records, while all museums come so close to the idea of the library, either in the matter of record or in the purpose of message or information, that one is tempted to describe museums as rudimentary libraries, and libraries as more complex museums. Art museums are in this aspect a sort of transition between the museum proper or whole object library and the library proper or the image-symbol-record collection.

Whole object record is, however, evidently cumbersome, and man, observing this, early learned a fact very significant for the history of handwriting i.e. that for record, reminder, or information, a part of an object may serve just as well as a whole object. This principle of the abbreviation of signs for the sake of economy is perhaps the most striking and consistent principle in the whole history of handwriting. It is the principle which led not only from the whole to the part and sample but from the part object to the mnemonic object, from object to image, from image to ideogram, and which prevails throughout the whole farther development of phonetic handwriting, during which picture phonetic signs became more and more conventionalized, through syllabic writing into alphabetic, and it is the law which has produced the numerous variations in the numberless historical alphabets, issuing also finally in numberless systems of stenography. This abbreviation is very early found in war trophies and in hunting trophies. In war it was found that the heads, hands, ears or scalps of enemies or even the left hand or right hand or ear, as conventionally agreed upon, was just as good an evidence of prowess and much more transportable than whole bodies—and Borneo and Filipino head hunters and American Indian scalpers have practised this discovery in very recent times.

In the case of hunting trophies the history was the same. Actual bodies brought back from a hunting trip were not altogether a permanent record, but after the tribal feast or sacrifice (commonly perhaps in earliest times both in one) the head and skin remained and formed a potentially more permanent record. Even in modern times such skins may be kept as wholes—stuffed for museum purposes or as hunting trophies, and they are, indeed, often mounted as rugs with both head and tail attached. In this stage they form what may be still counted as whole object records but from this stage object abbreviation followed as rapidly as in war trophies. If the skin was separated from head and horns for economic reasons, either was found to serve the purposes of record. A man’s collection of pelts e.g. is obviously a collection of hunting records as well as a collection of wealth. The Egyptian determinative for quadruped is, as a matter of fact, the picture not of a whole animal but of a skin with tail and without head. On the other hand, head and horns served equally as well for record as skin and tail, whether the purpose was a mere record of exploits or a record of sacrifices. This precise stage is amply represented in the modern hunting lodge with its heads of moose or other animals, and it is possible that the expression so many “head of cattle” is a relic of this stage.

In each of these cases the principle of the characteristic part obtains i.e. the abbreviation is not beyond the point where the object can be recognized at sight as standing for a certain animal.

The principle of the characteristic part once established, the tendency to abbreviation for the sake of economy in transportation, storage, or exhibition, led rapidly to the use of the very simplest unmistakable part showing the individual and then to the simplest unmistakable part showing kind. In the case of war-trophies head was reduced to scalp, and this was conventionalized again so that the trophy scalp consisted of a very small portion from a particular point on the head. In the case of hunting trophies, the head was reduced to perhaps ears or horns, tusks or teeth. The process is found definitely illustrated in the Cretan history in the reduction of the ox’s head to simple horns in ritual use, and vestiges of this are probably also to be found in the symbolic use of horns on altars, horns on men as a symbol of power, and the like. On the other hand the skin and tail separated from the horns followed the same law of progressive economy and was reduced perhaps to the tail only (the fox’s brush) or the claws (the primitive claw necklaces).

The modern bounty on wolf scalps contains the whole principle of characteristic part abbreviation up to this point in a nutshell. It is the smallest unmistakable readily recognized and nonduplicable part. It is important for individual record that it should not be possible to collect two bounties on one wolf or to boast of two fish caught or two dead enemies, where there has been but one.

It is thus not fancy or jest to say the scalp belt of an American Indian chief (albeit this did not play such a part in the Indian world as is commonly imagined), or the tiger-tooth necklace of the African chief, is a collection of records representing a rather advanced stage of evolution.

Abbreviations in the case of sample records may be carried one step farther still, for a single eagle’s feather or a very small piece of fur shows kind just as well as a head or tail or a whole skin.

Perhaps the best examples of collections of record objects in the most abbreviated forms are, for individual records, the collections of trophies worn on the person, and for specimen records the medicine bag of West Africa.

Individual trophy collections are common to all primitive peoples and everywhere tended towards abbreviated trophies which could be worn. It would be more than rash to trace the use of clothing and all personal adornment to the wearing of trophies as there is some slight temptation to do, but trophy necklaces, feather bonnets, and the like, were certainly worn in many tribes and without very much other clothing, either of protective or ornamental character. The leopard’s tooth necklace of the African chief, recording the number of leopards slain by his tribe, and the feather bonnet of the American Indian, are true record collections. In general all objects of personal adornment among primitive peoples are symbolic, that is, they have meaning and are of the nature of writing. They are kept for record rather than as objects of beauty or for the enhancement of personal beauty. Labrets, for example, are a sign of aristocratic birth, and even if the objects worn are ritual rather than trophy in character, still each one has its symbolic meaning, and the expert may read in each collection a tale of events or of specific religious ideas almost as clearly as in the phonetic words of a printed book.

The West African medicine bag, like other medicine bags, contained a collection of so called fetish objects of all sorts—bits of fur, feathers, claws, hair, twigs, bark, etc., etc.—but the use of these objects was not for medicine or magical purposes as commonly understood. They formed obviously an object record collection quite in the nature of a collection of books. As each object was drawn out of the bag, the keeper of the bag recited some appropriate tale or formula for which the object stood.

This probably casts light on many other so-called fetish collections of primitive people, as for example those of the North American Indians. “Mooney says, in describing the fetish, that it may be a bone, a feather, a carved or painted stick, a stone arrowhead, a curious fossil or concretion, a tuft of hair, a necklace of red berries, the stuffed skin of a lizard, the dried hand of an enemy, a small bag of pounded charcoal mixed with human blood—anything, in fact ... no matter how uncouth or unaccountable, provided it be easily portable and attachable. The fetish might be ... even a trophy taken from a slain enemy, or a bird, animal, or reptile.” (Hodge. HandbAmInd 1:458.)

These fetishes might be kept in the medicine sack (the Chippewa pindikosan) or “It might be fastened to the scalp-lock as a pendant, attached to some part of the dress, hung from the bridle bit, concealed between the covers of a shield, or guarded in a special repository in the dwelling. Mothers sometimes tied the fetish to the child’s cradle.” (Hodge. HandbAmInd 1:458.)

These fetishes represent not only events but ideas (a vision, a dream, a thought, or an action). They represent not only religious and mythological ideas and tribal records, but individual exploits in war or hunting and other individual records. In short, the medicine bag the world over is a collection of recorded ideas, both of historical and mythological character if not also of an economic character.

So far as the “fetish” objects are not trophy objects, but stand for ideas, they form a transition to the mnemonic object, but so long as the object is such as to suggest to the keeper and expounder the idea of the particular form of words or ideas which he relates, it is still to be counted as object rather than mnemonic writing e.g. if a bit of fox fur suggests a story of a fox, it is still to be counted a pictorial object rather than a mnemonic object.

If twenty eagle feathers, e.g. stand for twenty eagles, or twenty small bits of fur for twenty reindeer, these sample objects are still used pictorially, but if a feather head-dress is made of eagle’s feathers, each feather symbolizing some particular exploit, the matter has passed over from the pictorial to the mnemonic stage.

Mnemonic writing, as it is generally treated in the textbooks, includes all sorts of simple memory aids, and is generally, and probably rightly, regarded by writers of palaeography as preceding picture writing, although there is an element of abstractness even in the tally or knotted cord or pebble as compared with the actual imitation or representation of the picture, and in the evolution of human thinking, other things being equal, the abstract necessarily follows the concrete in time and in the order of evolution.

The most familiar examples of mnemonic books are the quipus or knotted cord books, the notch books, which include tallies and message sticks, the wampum belts of American Indians, and the abacus. Collections of any of these kept in the medicine tent or temple, or even the counting house, are, of course, true libraries, or at least true collections of written documents as generally understood by the historians of writing.

The knotted cord is best known under the name of quipu, which was the name for the Peruvian knot record. At bottom the idea does not differ from the simple tying of knots in a handkerchief as a reminder, or the sailor’s log line. It has been most commonly used for numerical records, but in many cases it preserved and transmitted very extensive historical records. One very simple use was the noting on different colored cords by knots the number of the different animals taken to market for sale, and again the price received for these at market.

It is still used among the Indians of Peru and some North American Indians, also in Hawaii and among various African tribes, and all over Eastern Asia and the Pacific.

It was the traditional method in China before the use of written characters, and the written characters themselves were, it is alleged, made up out of these combined with the pictures of bird tracks.

Among the ancient civilizations there are many remains or reminiscences of these knot books. They are found among the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics (as in the sign for amulet and perhaps in several other signs); they appear also in the mnemonic knotted fringes to garments in the Jewish antiquities and, as Herodotus tells us, Darius made use of such knots to guide certain Ionians who remained behind to guard a bridge as to when it should be time for them to sail away. In 1680 the Pueblo Indians of North America marked the days to their uprising in the same way.

This use of the knotted cord for amulets is among the most widespread of uses, being found among the medicine men of nearly all primitive peoples. Juno wore such an amulet, and Ulysses carried one.