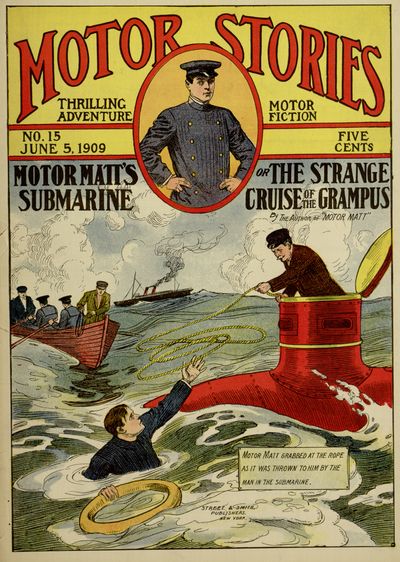

Title: Motor Matt's Submarine; or, The Strange Cruise of the Grampus

Author: Stanley R. Matthews

Release date: June 12, 2015 [eBook #49197]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Demian Katz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images

courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

|

THRILLING ADVENTURE |

MOTOR FICTION |

|

NO. 15 JUNE 5, 1909. |

FIVE CENTS |

|

MOTOR MATT'S SUBMARINE |

or THE STRANGE CRUISE of the GRAMPUS |

| By The Author of "MOTOR MATT" | |

|

STREET & SMITH, PUBLISHERS, NEW YORK. |

|

| MOTOR STORIES | |

| THRILLING ADVENTURE | MOTOR FICTION |

Issued Weekly. By subscription $2.50 per year. Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1909, in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, Washington, D. C., by Street & Smith, 79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York, N. Y.

| No. 15. | NEW YORK, June 5, 1909. | Price Five Cents. |

MOTOR MATT'S SUBMARINE;

OR,

THE STRANGE CRUISE OF THE GRAMPUS.

By the author of "MOTOR MATT."

CHAPTER I. A STARTLING REPORT.

CHAPTER II. MIXED MESSAGES.

CHAPTER III. HURRY-UP ORDERS.

CHAPTER IV. ACCIDENT OR DESIGN?

CHAPTER V. SIXTY SHOWS HIS HAND.

CHAPTER VI. AN UNEXPECTED RESCUE.

CHAPTER VII. A FRUITLESS SEARCH.

CHAPTER VIII. THE OVERTURNED BOAT.

CHAPTER IX. ADRIFT IN THE STORM.

CHAPTER X. THE DERELICT.

CHAPTER XI. THE SCHOONER.

CHAPTER XII. A STUNNING SURPRISE.

CHAPTER XIII. CLOSING IN.

CHAPTER XIV. THE "GRAMPUS" GETS A CLUE.

CHAPTER XV. AN ULTIMATUM.

CHAPTER XVI. "OFF WITH THE OLD, AND ON WITH THE NEW."

The Chicken-hearted Tenderfoot.

Motor Matt, a lad who is at home with every variety of motor, and whose never-failing nerve serves to carry him through difficulties that would daunt any ordinary young fellow. Because of his daring as a racer with bicycle, motor-cycle and automobile he is known as "Mile-a-minute Matt." Motor-boats, air ships and submarines come naturally in his line, and consequently he lives in an atmosphere of adventure in following up his "hobby."

Dick Ferral, a young sea dog from Canada, with all a sailor's superstitions, but in spite of all that a royal chum, ready to stand by the friend of his choice through thick and thin.

Carl Pretzel, a cheerful and rollicking German boy, stout of frame as well as of heart, who is led by a fortunate accident to link his fortunes with those of Motor Matt.

Captain Nemo, Jr., otherwise Archibald Townsend, a fast friend of the Motor Boys and skipper of the submarine, Grampus.

Cassidy, mate of the Grampus.

Gaines, Clackett and Speake, crew of the Grampus.

Captain Jim Sixty, a seaman of long experience who resorts to filibustering in order to gain big prizes in the lottery of Fortune. Master of the wrecked brig, Dolphin.

Ysabel Sixty, Captain Sixty's daughter, who plays an ignoble part, although against her better nature.

A STARTLING REPORT.

There is a speed limit for automobiles in the City of New Orleans, but a certain red touring car on this Wednesday morning gave little heed to the regulation. With two wheels in the air the car made a sharp turn into Prytania Street, slowed a little as it came within one of colliding with a two-wheeled milk wagon, swerved to one side and then leaped onward.

Besides the driver, the car contained only one man. This passenger sat in front, leaning eagerly forward and urging the driver constantly to a faster gait.

"That's the house," said the passenger finally, indicating a building with his stubby forefinger.

The car pulled up with a jerk and the passenger was out before the machine was fairly at a stop.

"Wait for me," he called as he rushed across the sidewalk, yanked the gate bell and then darted through and up the steps to the porch.

With savage impatience he jabbed at the push button beside the door and tramped fretfully until a colored servant answered his summons.

"Is Cap'n Nemo, Jr., in?" he flung at the darky.

"Dat's a new one on me, boss," was the puzzled answer. "Ah dunno no sich pusson. You-all must hab got de wrong——"

"Townsend, then?" broke in the caller. "Is he here?"

"Yassuh, Mistah Townsend is in his room, sah, but dat odder man——"

Without pausing further, the man pushed roughly past the darky, to that person's intense astonishment, and went up the hall stairs three steps at a time. A moment later he had flung open a door unceremoniously.

There were two men in the room, and they started up quickly as the newcomer hurled himself in on them.

"Clackett!" exclaimed one of the men who had been in the room, facing the other with a good deal of surprise. "What's all this hurry for?"

"Sixty has sailed, cap'n!" exclaimed Clackett, dropped into a chair.

"Great guns!" gasped the third man. "Must have been kind o' sudden."

"When did he sail, Clackett?"

"Ten o'clock this morning, steamer Santa Maria, a fruiter bound for British Honduras."

"He ain't goin' to British Honduras," burst from the third man, "and don't you think it."

"I don't think so either, Cassidy," replied the captain, "but he's the fellow we were to watch, and if he's gone we've got to put out after him."

The captain looked at his watch.

"Ten-twenty," he mused, slipping the watch back into his pocket. "How did you get here, Clackett?"

"In one of them automobiles, cap'n. Street cars was too bloomin' slow."

"You're positive there's no mistake?"

"I know Jim Sixty as well as I know you, cap'n, an' I'll take my solemn Alfred it was him standin' on the Santa Maria's deck when she steamed away from the dock."

"A mistake, you know," pursued the captain, "would put us on the wrong track and cause no end of trouble."

"There ain't no mistake—take it from me."

At this the captain became intensely alive. He whirled on Cassidy.

"You ride with Clackett in the automobile to Carrolton, Cassidy," said he briskly, "take the ferry to Westwego and bring the Grampus on the run to Stuyvesant Dock. Clackett and I will be there waiting for you."

"Tough luck," growled Cassidy, "we didn't know something about this move o' Sixty's, 'cause then we could have had the submarine handier by."

"We'll not lose much time," returned the captain. "The Grampus is all ready for a long cruise? That's the main thing."

"The boys was gettin' on the last of the stores over at Westwego," replied Cassidy.

The captain whirled on Clackett.

"The ferry from Carrolton runs on the half hour," said he, "and if you hit up that buzz-wagon you ought to get Cassidy on the ten-thirty boat. After that, rush back into town. The Snug Harbor Hotel is not far from Stuyvesant Dock. Go there, ask for Motor Matt, and bring him and his friends to the dock, prepared to make the run down the river and into the gulf with us. That will be all. Off with you, on the jump. I'll look after your luggage and mine, Cassidy."

If Cassidy was to catch the first boat from Carrolton landing there was no time for talk. With a hearty, "Ay, ay," the two men whirled from the room and rushed down the stairs. A moment later the captain, looking from a front window, saw them leap into the automobile and vanish up the street.

So far as the captain was concerned, he had plenty of time to make his preparations. It would be close to eleven o'clock before the Grampus could possibly get clear of Westwego, and possibly it would be eleven-fifteen before she would come alongside the Stuyvesant Dock.

For some time the captain had been lying ill in the Prytania Street house, but he was now rapidly recovering, and his restless, active nature welcomed this call to action. He felt that it was the one tonic he needed to bring him back to his usual form.

Cassidy was mate of the Grampus. Ever since the captain had been stricken down the mate had been with him as watcher and nurse.

Not much time was required to get Cassidy's property into his ditty-bag, and not much more time for the captain to pack his own satchel. The colored servant had telephoned for a carriage, and the vehicle came just as the captain had finished packing.

All that remained was to settle with Mrs. Thomas, the landlady, to thank her for her kindness, and to leave for downtown.

Twenty minutes after the departure of Cassidy and Clackett the captain was speeding away in the direction of Canal Street. He halted at a bank, at the corner of Camp and Common, and drew five thousand dollars in gold. This money was given to him in a canvas bag, and, with that and his luggage, he was hurried on to Stuyvesant Dock.

As he had surmised would be the case, he was ahead of the Grampus. Gathering his goods about him, he sat down on a box near the edge of the dock and watched up stream for the first glimpse of the rounded deck, the conning tower, and the mast with the red periscope ball of the submarine.

Barely had he sighted her, cutting through the waves of the Lower Mississippi, when a quick step behind him caused him to look around.

Clackett, red-faced and perspiring, was hurrying toward him. There was a troubled, ominous look on Clackett's face.

"Where are Motor Matt and his two friends, Dick Ferral and Carl Pretzel?" cried the captain. "I need them on this cruise, and they understand the importance of their being here. Will they be along later, Clackett?"

"They'll not be along later, cap'n," answered Clackett. "You can wait for 'em as long as you please, an' the boys won't be showing up. Every minute you lose, too, the Santa Maria and Jim Sixty are gettin' farther and farther away from us."

A frown of heavy disappointment wrinkled the captain's brows.

"What's the matter?" he demanded. "Motor Matt's word is as good as his bond, and he told me he'd stay in New Orleans a week and wait for me to send word to him. Where is the boy?"

"He sailed on the Santa Maria this mornin'," was the startling announcement.

The captain jumped to his feet.

"Great Scott!" he exclaimed, staring at Clackett in blank amazement.

"It's a fact, cap'n," asserted Clackett. "I got it straight from the hotel feller that seen Matt and his friends aboard the boat. There's been queer doin's, somehow."

"What do you mean by queer doings?" asked the captain sharply.

"Well, cap'n, this is the way that hotel feller handed it out to me: Ysabel Sixty, the ole filibuster's gal, called at the Snug Harbor about nine-thirty, this mornin', and had a short talk with Motor Matt. When the girl went away, Motor Matt settled his hotel bill, rounded up his friends and they all stampeded upstairs to git their baggage together. Then they flocked down and hustled for the Santa Maria. The hotel feller went with 'em, helpin' tote their traps."

The captain stared in bewilderment, his amazement growing as he listened.

"There's underhand work of some kind here," he muttered. "Motor Matt would never have gone off like that without telling me something about it."

"He tried to git you over the telephone, but the line was busy and he didn't have no time to wait."

"You saw Sixty on the Santa Maria as she drew away from the Fruit Company's dock?"

"Ay, ay, sir, as plain as I see you, this blessed minute. The girl was with him, too."

"Did you see Motor Matt and his friends?"

"I wasn't lookin' for them, particular. They might have been on the deck, cap'n, but I wouldn't swear to it. I was so jolted up by seein' Sixty pull out when we wasn't expectin' it of him, yet a while, that mebby I was excited."

The captain, greatly perturbed, tramped back and forth across the dock. He was aroused from his unpleasant reflections by the voice of Cassidy.

"All aboard, cap'n! I reckon we pulled this off in short order, hey?"

The captain whirled around. Cassidy, standing in the top of the conning tower of the Grampus, was barely head and shoulders above the level of the dock. One of the hands, on the forward part of the rounded deck, had passed a rope through a ring and was holding the submarine steady.

"Pick up the luggage, Clackett," ordered the captain, himself taking charge of the bag of gold, "and we'll get aboard."

"What you goin' to do about Motor Matt?" queried Clackett as he picked up the luggage.

"He's aboard the Santa Maria, and I am convinced that, for some cause or other, he's there through some underhand work of Sixty's. Our orders call on us to follow the Santa Maria and keep watch of Sixty. By doing that, we shall also be trailing Motor Matt and his friends. Something is bound to happen that will give us a little light on this."

Fifteen minutes later the Grampus was hustling down the river, her screw racing under the terrific impulse of the gasolene motor, and a white line of foam surging across her low deck and breaking against the base of the conning tower.

MIXED MESSAGES.

"I tell you somet'ing," said Carl Pretzel gloomily, "I don'd like hanging aroundt mitoudt any pitzness. Id geds on my nerfs, yah, so helup me. For six tays, now, ve haf peen loafing in New Orleans, und eferyt'ing vas so keviet as some Quaker meedings. Nodding habbens. Vy don'd ve hear from Downsent mit a hurry-oop call to ged busy, eh?"

It was nine o'clock in the evening of the day preceding that on which the Grampus had got away in the wake of the Santa Maria, and Motor Matt, Dick and Carl were lounging in the small office of the Snug Harbor.

For two or three days Carl had been restless. He had visited all the five-cent shows on Canal Street, he had made a sight-seeing tour through the French Quarter, he had gone out to Lake Pontchartrain, and he had done various other things to pass away the time and make some excuse for his idleness, but his energetic spirit was not to be muzzled.

"Take it easy, old ship," said Dick; "I'm as anxious as you are to trip anchor and slant away for some port where we can do things, but there's a notion rattling around in my locker that it won't be long now before we run afoul of something real exciting. We were to wait a week on Townsend, and the week will be up to-morrow. We'll hear from him then, and I'll bank on it."

"So will I," spoke up Matt. "Don't be so impatient, Carl. Adventures are all right, but there are a few other things in life for fellows like us to think about."

"T'anks, brofessor," answered Carl, humbly. "Vat else vould you t'ink aboudt oof you vanted to be among der life vones?"

"An academy, for instance," said Matt with a far-away look in his gray eyes, "and a spell of grubbing at the stores of knowledge preparatory to a college course."

"Helup!" gasped Carl; "bolice! Matt is t'inking oof cutting himseluf oudt oof our herd, Tick, und going to school. Shpeaking for meinseluf, ven I go to school I don'd go, for I play vat you call hookey undt look for atvendures. All has got to go mit shnap und chincher for me, und vere iss lifeliness in pooks? Ach, donnervetter!"

"Avast, there, matey!" said Dick. "Matt is right. Adventures are all well enough in their place, but a cruise in the waters of learning is a main fine thing—for those who can afford it. Some day Matt will be in an academy, and some other day he will be in Harvard or Yale, and the King of the Motor Boys will be done with the buzz-engines for always."

Matt pulled himself together and laughed softly.

"Never, as long as I live," he declared, "will I be done with gasolene motors. Don't fool yourself on that for a minute. I may——"

"A message for you, Motor Matt. Just came off the wires."

A messenger boy pushed in among the three chums and handed a yellow envelope to Matt. All the messenger boys, together with nearly every one else in New Orleans, knew Motor Matt at least by sight. His work with the air ship, Hawk, which had recently been wrecked and destroyed, had kept him and his friends prominently in the public eye for some time.

"Sign the book, Dick," said Matt, tearing open the envelope.

"Vat you t'ink oof dot?" breathed Carl in a spasm of joyful excitement as the messenger boy went away. "Ve talk oof vanting t'ings to habben, und righdt off dey pegin. Ach, vat a luck! How easy id iss to be jeerful—somedimes!"

"Mayhap that message isn't anything to be cheerful about, Carl," said Dick. "I'll bet some one is asking to buy the Hawk, and her poor old bones are rusting in a live oak, down by Bayou Yamousa."

"Dot ain'd my guess, you bed you," palpitated Carl. "I t'ink id iss somepody asking vill ve go by der Spanish Main und hunt for birate shtuff. Vat a habbiness oof id iss!"

"You're both wrong," said Matt, a perplexed look on his face. "There has been some mistake in the telegraph office, and this message isn't for me."

"Not for you, mate?" queried Dick, picking the envelope off Matt's knee. "It's addressed plain enough—'Motor Matt, Care Snug Harbor Hotel, New Orleans.'"

"There's a different name inside," returned Matt.

"Vat id iss?" asked Carl, curiosity in a measure drawing the sting of disappointment.

"'Captain James Sixty,'" read off Matt, "'Snug Harbor Hotel, New Orleans, Louisiana.' The address is the same, but the name is different."

"Meppy der message iss for you, anyvay," persisted Carl. "Read him ofer und meppy you can dell."

"No, the message is part of the puzzle. Listen: 'In latitude twenty-eight degrees thirty minutes and twenty seconds north, longitude ninety-two degrees fourteen minutes and thirty-four seconds west two days ago. No wind and no drift since.' How could that possibly be for us, pards?"

"Id's some conuntrums, und dot's all aboudt id," grumbled Carl dejectedly. "Nodding habbens mit us more as you findt on a Suntay-school bicnic, und I'm going to ped mit meinseluf und hope for pedder t'ings in der morning. Good nighdt, bards."

With that Carl got up disgustedly and left the hotel office.

"How do you account for that, mate?" asked Dick.

"The messages got into the wrong envelopes," answered Matt. "Mr. James Sixty must be staying in this hotel. He's got my message and I've got his. That means we've got to find each other and exchange. Come on, Dick. We'll go over and talk with the clerk."

When they got to the desk they found a hulk of a man with a very red face talking with the night man in the office. The red-faced man seemed very much put out about something. He had a voice like a fog horn, and he was using it with a good deal of power. As Matt and Dick approached the desk the clerk suddenly put out his hand and stopped the flow of language.

"There's Motor Matt now," said he. "Here, Matt!" he called. "Have you got a telegram that don't belong to you? There's been a mix-up in messages, somehow, for Captain Sixty, here, has got one you ought to have. He was just asking me where you could be found."

"I was just coming to ask you about Captain Sixty," said Matt, holding out the message.

Sixty turned and snatched the message away.

"D'you read it?" he roared.

"Couldn't very well help it, captain," answered Matt. "If you'll look at the envelope you'll see it's addressed to me."

"I like some people's nerve," scowled the captain. "Here's your'n."

He flung a crumpled yellow sheet at Matt.

"It looks as though you'd read this," said Matt, "so I guess we're no more than even."

An angry gurgle came from Sixty's bull-like throat.

"I'll raise Cain if I find out this mix-up was done a-purpose," he growled.

"I don't see what anybody could want to do such a thing as that for," returned Matt.

The captain flung about and gave Matt an insolent up-and-down stare.

"Oh, you don't, huh?" he muttered. "Well, mebby it's well you don't."

The captain rolled away.

"The way to talk with him," said Dick resentfully, "is with a belaying pin. He looks like an old shellback, and I'll bet he's a bucko. But what's the message, mate?"

"A man in Boston wants to buy the Hawk," answered Matt, "and asks us to name our price. He says he knows Archibald Townsend, and refers us to him as to his financial standing."

"I could have kissed the book on that, Matt," said Dick soberly. "Keelhaul me if I don't wish we had that blessed little flying machine this minute."

"So do I. But there's no use crying about it, Dick. Maybe we'll build another, some time; just now, though, we ought to think more about bed than anything else."

"I'm ready to do a caulk, if you are."

"Come on, then."

As they were leaving the office to go upstairs to their room Matt took a look around. Captain Sixty was sitting in a chair in the corner, his message opened out on his knee. But his fishy little orbs were not on the message, but on Matt; and there was a glittering distrust in them which Matt could not fail to notice. However, he said nothing about it to Dick, and very soon forgot it himself.

Next morning the boys were hoping to hear from Townsend. Townsend, otherwise Captain Nemo, Jr., of the submarine Grampus, had some work in which he wanted Matt and his friends to assist him, and he had asked Matt, Dick and Carl to remain a week in New Orleans, at his expense, until he should be well enough to tell them about the work and get it under way.

The following day rounded out the period of time Townsend had asked for.

After breakfast the boys hung about the hotel waiting for some communication from Prythania Street. Toward the middle of the forenoon a bell boy ran into the office and hurried to the place where Matt was sitting with Dick and Carl.

"You're wanted in the parlor, Motor Matt," said the boy.

"Dere id vas!" exclaimed Carl delightedly. "Ve got id now, Tick."

"Who wants me?" asked Matt.

"A young woman—and she says she's in a hurry."

Matt was puzzled. He did not know any young ladies in New Orleans, and couldn't imagine why one should come to the hotel and ask for him.

"I'll go right up," said he—and immediately took the first step into a snare that had been laid for him.

HURRY-UP ORDERS.

When Matt entered the bare little room on the second floor which served as a public parlor for the hotel, a girl of sixteen or seventeen arose to meet him. She had black hair and eyes, was well dressed, and looked like a Spanish señorita.

"Motor Matt?" she asked, stepping toward him with an engaging smile.

"My name," he answered.

"I am——" She paused, and a frightened look came into her wide, dark eyes. For the first time Matt noticed that, in spite of her smile, she seemed to be ill at ease. "I am Miss Harris," she finally went on, "Miss Sadie Harris, a niece of your friend, Mr. Townsend. Perhaps you have heard my uncle speak of me?"

The girl's English was good, so Matt argued that she was not a Spaniard after all.

"No," he answered, "I did not know that Mr. Townsend had a niece."

"That's strange," murmured the girl, "for I was always a favorite of his. As soon as I learned that he was sick I came right on to New Orleans. When I arrived here, yesterday, I found my uncle nearly well again. All this, though, has nothing to do with my errand. Here are three tickets to British Honduras, good on the steamer Santa Maria, which sails at ten, this morning. There is not much time, Motor Matt, and it is my uncle's wish that you go on that boat."

To say that Matt was "stumped" would hardly do justice to his feelings.

"British Honduras?" he echoed.

"Yes; the boat sails from the Fruit Company's dock."

"But why am I and my friends to go to British Honduras?"

"I don't know. My uncle gave me the tickets and asked me to hand them to you and tell you to expect word from him at Belize. He said the work was very important, and that you must not say a word about it to anybody."

"I don't know anything about the work, Miss Harris," answered Matt, "so it won't be possible for me to say anything to any one."

"Your intention of leaving on the Santa Maria, too, ought to be kept a secret. At least, that's what my uncle says."

"This is mighty sudden," murmured Matt dazedly. "Why couldn't Mr. Townsend have called me out to the house and talked this over with me yesterday?"

"He didn't know anything about it yesterday, Motor Matt. In fact, the work only came to his knowledge an hour ago."

"Wasn't he well enough to come and tell me himself?"

"Well enough, yes, but he had not the time. The Grampus is over at Westwego, and he is very busy getting her ready for sea."

"Isn't he going to British Honduras on the Santa Maria?"

"No."

"How am I to hear from him in Belize?"

Miss Harris tossed her head petulantly.

"My uncle isn't telling all his plans, even to me. I've delivered his orders, and it's getting along toward ten o'clock and you haven't much time if you're to sail on the Santa Maria. I'm to go on the boat myself, and it isn't likely my uncle would leave me alone and unprotected in Central America. He thought you and your friends could look after me a little, both on the boat and until he was able to reach Honduras, but——"

Miss Harris used her lustrous Spanish eyes with telling effect.

"Certainly we will go," broke in Matt, "only it was such a hurry-up order that it rather floored me. I and my pards have been waiting to hear from Mr. Townsend about some work which he was going to do when he got well enough. Perhaps the work has something to do with you?"

Matt was clever at drawing inferences. There might be Spanish blood in Miss Harris' veins—British Honduras was partially peopled with men and women of Spanish descent—and here was a call to Belize. Then, again, Miss Harris had only recently arrived in New Orleans, and it required no great stretch of fancy to imagine that she had sprung, thus suddenly, some line of endeavor for which her uncle had been waiting.

"I am not at liberty to tell you anything more, Motor Matt," said Miss Harris, with another of her bright smiles. "Will you take the Santa Maria?"

"Yes."

A strange glow danced in the girl's expressive eyes.

"That is nice of you," said she. "Here are the tickets. My uncle was so sure you'd go that he got them and secured your stateroom reservations."

Matt took the envelope the girl handed to him and walked down the stairs with her. She bade him good-by at the ladies' entrance, and, as he turned to go back to the office he had a disturbing thought.

If there had been time to secure tickets and cabin reservations, there should have been time for Townsend to give Matt and his chums a little more notice of that trip to Honduras.

Matt, however, had abundant faith in Townsend. Undoubtedly he was proceeding in the manner that best suited his plans.

"Come on, boys," said the young motorist, hurrying up to Dick and Carl, "we've got to pack, and be in a rush about it."

"Hoop-a-la!" gloried Carl, catching the spirit of Matt's words, although he had not the remotest idea of the underlying cause. "Oof ve are going to pack oop, den id vas a skinch ve're going someveres; und oof ve vas going someveres, den der drouple-pot iss on, und vill pegin to poil righdt——"

"Ease up a bit on that jaw-tackle, mate," interrupted Dick, grabbing Carl's arm and hurrying him off after Matt. "It's as plain as the nose on your face that some kind of word has been received from Townsend, but it's just as plain that there's no time to talk about it. Matt's in a tearing hurry, and it's up to us to pull back into our shells, hustle the stuff into our dunnage-bags, and wait for him to tell us what we want to know."

When Dick and Carl reached their room, Matt was already throwing his belongings into a grip. The sailor and the Dutch boy got busy.

"The girl is a Miss Sadie Harris," explained Matt as he worked, "and she's a niece of Townsend's."

"Vas she a pooty goot looker?" inquired Carl, rolling up his eyes.

"What's that got to do with it?" demanded Dick.

"Nodding, only id vas more romandick oof a pooty girl vas mixed oop in der pitzness."

"My eye!" exploded Dick. "Well, cut out the romance. Unless I'm wide of the course this is nothing but pure business. Eh, Matt?"

"Yes," answered Matt. "We're to sail at ten o'clock for Belize, in British Honduras."

Carl slumped into a chair with a gasp.

"Pridish Honturas!" he gurgled. "Vere iss dot? Ofer py China someveres?"

"It's in Central America, you saphead!" cried Dick. "I've been in those waters, and I'm a Feejee if they ever took much of my fancy."

"Miss Harris brought our tickets," proceeded Matt, "and she's going to sail on the same boat."

"Vat are ve to do ven ve ged dere?"

"Wait for instructions from Townsend."

"Then Townsend isn't sailing with us, mate?"

"No."

"Well, keelhaul me, it's a queer course that's been laid for us. What makes it queerer is, that in all the time we've been hooked up with Townsend he's never once mentioned his niece."

"Townsend is an odd chap, in some ways, but he's as straight as a string for all that," returned the young motorist. "This work in Honduras, I feel pretty sure, has something to do with the girl."

"I like dot," spoke up Carl, kneeling on his rusty old suit-case in order to make the cover go down. "Peauty in tisdress alvays cuts some ice mit me. Dere! I vas alretty for anyding vat comes my vay."

"I'm ready, too," added Dick.

"And I," said Matt, picking up his satchel.

They left the room hurriedly. At the bottom of the stairs Matt handed his grip to one of the porters.

"Carry that over to the Fruit Company's dock," said he. "Dick, you and Carl go on. I'll square up with the proprietor and trail along after you."

"Mind dot you don't get left," cautioned Carl.

"I've ten minutes," was the answer, "and I can get to the dock in half that time."

Dick, Carl and the porter hastened off, and Matt turned back into the office. He was only two or three minutes settling the bill, and as he started for the hotel door he passed a telephone booth and an idea came to him.

There could be no harm in calling up Mrs. Thomas' boarding-house in Prytania Street, telling Townsend they were off and saying good-by. A word of that kind with Townsend would prove reassuring.

The idea was no sooner conceived than it was carried out. But Matt was destined to disappointment. He was informed by "central" that the wire was busy, and, as it was already five minutes of ten, he had no time to wait.

Throwing the receiver back on the hooks, he left the hotel and ran toward the Fruit Company's dock. The warning bell of the Santa Maria was ringing, and deck hands were preparing to haul in the gang plank as he rushed across it.

"Py chiminy, aber dot vas some glose connections!" cried Carl, who, with Dick, was waiting and watching for Matt.

"A miss is as good as a mile," Matt replied. "Have you seen Miss Harris?"

"She's forward, matey," said Dick.

"We'll stow the luggage somewhere," went on Matt, "and then go forward ourselves and see the boat get away."

The baggage was piled in the cabin, and when the three boys reappeared and made their way toward the forward part of the main deck the Santa Maria was shivering from stem to stern under the impetus of her powerful engines and drawing away from the dock and into the channel.

There were a dozen or more people on the dock waving hats and handkerchiefs, while a dozen or more were clustered at the steamer's rail returning the parting salutes.

"Dere iss nopody dere to vave goot-py ad us," remarked Carl, "not efen Downsent!"

"We certainly couldn't expect Townsend, Carl," said Matt. "He has other matters to occupy his mind, I suppose."

"I shouldn't think he'd be too busy to come down and see his niece off on her voyage," put in Dick. "Still, as you say, mate, he may be——"

Dick suddenly broke off his words. His eyes had been roving over the passengers along the rail.

"Sink me!" he exclaimed, dropping a quick hand on Matt's arm. "Look over there—to the left."

Matt looked, and immediately experienced the same surprise that had laid hold of his chum.

The burly form of Captain Sixty was in plain view, and at the captain's elbow, and talking with him, was Miss Harris!

ACCIDENT OR DESIGN?

Motor Matt took Dick and Carl each by one arm and led them back into the cabin.

"We'd better talk a little, pards," said Matt, with a worried look.

"Vat's der madder?" inquired Carl.

He had not seen Captain Sixty, not having been in the office of the Snug Harbor Hotel at the time Dick and Matt had met Sixty and exchanged telegrams with him.

"The big fellow," explained Matt, "is the one who got my telegram last night. Why is he on this boat? That's the point that puzzles me."

"Maybe it's an accident, matey," returned Dick.

"Yes; and maybe it's design. I'd like to size this business up before we get clear of the river. If we don't like the looks of things, we can have the captain of the boat put us ashore."

"What's the trouble with the outlook, old ship?" queried Dick. "So far as I'm concerned, it was a shot between wind and water when I saw Sixty there at the rail; but I don't think that the fact of the old hunks being aboard the steamer is anything to worry us. He probably has business in Honduras as well as ourselves."

"I wish this boat was equipped with a wireless telegraph apparatus," muttered Matt. "There's a wireless station at Algiers, and we could flash a message to Townsend."

"What would be the use? We've got his orders."

"I'd like to have the orders confirmed," said Matt grimly. "I tried to get Townsend over the phone just before I left the hotel, but, as luck would have it, the wire was busy."

"You've been taken all aback, same as though you'd been struck by a white squall," muttered Dick perplexedly. "I don't think that old flatfoot bucko ought to put you in such a taking, Matt."

"It wasn't Sixty alone that took me aback, Dick," answered Matt. "Miss Harris had more to do with that than Sixty had."

"Dit you see der young laty, Matt?" asked Carl, brightening.

"I saw her, yes."

"You were expecting to see her," chimed in Dick. "You told us she was intending to sail on the Santa Maria."

"When we talked at the hotel," went on Matt, "Miss Harris gave me to understand that Townsend expected us to look after her during the trip to Belize, and after we reached that town."

"Vell," remarked Carl, dusting his coat with his hand and adjusting his necktie, "I guess ve can do dot as vell as anypody. You pedder indrotuce Tick und me, Matt."

"I don't believe our services will be needed," said Matt dryly. "Miss Harris was talking with Captain Sixty and seemed to be on familiar terms with him."

This startled Dick and Carl. It was a good deal of a coincidence, even if not alarming, to find Captain Sixty voyaging to Honduras on the Santa Maria; but to find him on friendly terms with Townsend's niece gave the captain's presence on the boat rather an odd look.

"All this," said Matt finally, "may be either the result of accident or design. I think it would be well for us to find out as much as we can before we get too far down the river."

"How'll you find out, mate?" queried Dick.

"By talking with the girl. Wait here for me. I'll go and have that talk with her now."

As Matt started away, the girl herself suddenly entered the cabin, and she was bringing Captain Sixty with her.

Matt halted and drew back to the side of his friends. The girl looked toward the boys, smiled, said something to her companion, and hurried him across the cabin.

"Hello, Motor Matt!" cried Miss Harris. "I was afraid you'd got left, and was just telling Uncle Jim here that I didn't know what Uncle Archie would say when he found you had not gone to Belize."

Uncle Jim! Miss Harris had called this Sixty person her Uncle Jim! While Matt was puzzling over this, the girl had drawn close and was introducing Captain Sixty.

"I'll be blowed, girl," bellowed Uncle Jim, "if I need any introduction to Motor Matt. We've met before, eh, messmate? Hand us your fist till I give it a friendly shake. Why, I hadn't the least idee you was mixed up in this affair of Townsend's! Ain't it astonishin' how things fall out, now and again?"

"I should say so," answered Matt. "This is your uncle, Miss Harris?" he added to the girl.

"Why, yes, of course!" she laughed.

"His name ought to be Townsend, hadn't it?"

"Not at all. Uncle Archie is my father's brother, while Uncle Jim is my mother's brother."

"Then your name ought to be Townsend instead of Harris."

"Ho, ho!" laughed Captain Sixty. "He's a keen one, girl, and no mistake!"

"Of course he's a keen one, Uncle Jim," replied the girl, "or Uncle Archie wouldn't have had him take a hand in this work. You see, Motor Matt," and here she turned to the youth, "Uncle Archie Townsend's real name is Harris, while my mother's maiden name was Sixty. So, you see——"

"Softly, girl, softly," breathed Captain Sixty. "We don't want to talk too much about our relatives in this public place. Walls have ears, you know."

"I understand," said Matt. He had long known that Townsend, merely to save himself annoyance from newspaper reporters and other curious people, had one name ashore and another afloat, and used only his right name when at home in Philadelphia and among his friends. "Let me introduce both of you to my pards," Matt added, turning to Dick and Carl.

Sixty was more than agreeable to Dick and Carl, and Carl, on his part, tried to be more than agreeable to Miss Harris.

"Have we all got a part in this work of Mr. Townsend's?" asked Matt, feeling somewhat relieved, although still a little surprised over the way the matter had fallen out.

"Haven't you ever heard Uncle Archie speak of Captain Sixty?" inquired Miss Harris.

"Never."

"I wouldn't wonder at that none, girl," said Captain Sixty. "It's been some sort of a while, you know, since my course has crossed Townsend's; and then, too, Townsend is close-mouthed, and he wouldn't be apt to say anything about me when I've got such an important part to play in his present business."

The captain lowered his voice and took another cautious look around that part of the cabin.

"Was you boys told anythin' about the work?" he asked in a whisper.

Matt shook his head, and a glow of relief flashed for an instant from Sixty's fishy eyes.

"From that, my lad," went on Sixty, "you can figure out how mighty important is the work we're engaged in. I don't know much about it myself. That telegram I got at the hotel last night has somethin' to do with it, though blest if I know what. Cassidy came for it about midnight; and next morning, along comes the girl, here, with a ticket for Belize and orders to sail on the Santa Maria. Wished I'd have known who you boys were last night. I'd have hobnobbed with you some instead of bein' short-like as I was. No hard feelin's?"

"None at all," answered Matt.

"I used to be skipper of the brig Dolphin, a hooker as sailed from any place to any place wherever there was a cargo to be picked up and carried. That's how I got the name o' captain. I've had a master's ticket, though, ever since I was twenty. Ysabel here"—Matt caught a sharp look from the girl directed at Sixty—"which is my pet name for Sadie," continued the captain, "had as fine a father as ever walked. He married a Spanish lady in Belize, and that's how Sadie looks Spanish and talks American. I'm rough and ready, I am, and ain't got no time for these here parlor frills——"

"We'll have lots of time to talk, Uncle Jim," broke in the girl, "after we get settled in our staterooms and while we're crossing the gulf. Motor Matt and his friends, as well as ourselves, have got something else to do just now besides stand around and gossip. I don't think we'd better be seen talking together very much, anyhow."

"Right you are!" rumbled Captain Sixty. "See you again, messmates," and he lurched away with Miss Harris alongside him.

"Ach," muttered Carl, "dot leedle girl vas a peach, I bed you. Eferyt'ing iss all righdt, und ve all haf a finger in dot pie oof Downsent's."

"Wish I could smoke Townsend's weather roll a bit better than I do," said Dick. "I haven't any confidence in that man Sixty. From the cut of his jib, he's several kinds of a bear, bucko, bandicoot and crocodile. If we could, I think we ought to give him a good offing."

"We can't do that, Dick," answered Matt, "if Townsend's business throws us all together."

The boys fell into line at the purser's window, transacted their work there, and then picked up their luggage and went to their staterooms.

Each stateroom accommodated two passengers. Matt and Dick had one room to themselves, while Carl's room, which was next to theirs, would house a stranger in addition to the Dutch boy.

While Matt and Dick were stowing their traps and making themselves as comfortable as they could in their cramped quarters, Carl burst in on them.

"Vat you t'ink?" demanded Carl, closing the door securely behind him and dropping down on the lower berth.

"We're all ahoo and don't know what to think, matey," answered Dick, giving the Dutch boy a slow sizing. "Why? Have you anything in particular on your own mind?"

"I shouldt say! Dot Sixdy feller iss my roommate."

"You're welcome to him," said Dick. "I wouldn't take him for a roommate on a bet."

Matt turned from the washbowl, where he had been removing some of the grime from his hands, and reached for a towel.

"No accident about that," said he. "I'll bet Sixty fixed it up with the purser."

"Why?" demanded Dick.

"I don't know why, but I've got a hunch that that's the way of it." Matt finished with the towel, threw it back on the rack and sat down in a chair. "There are a few things connected with this situation that won't hold water. Listen, pards, and see if you don't agree with me."

SIXTY SHOWS HIS HAND.

"We'll suppose," proceeded Matt, "that Townsend has brought us all together on the Santa Maria for some work or other that's to be done in Belize. We'll suppose further that everything is all right and as it should be, and that Townsend had a niece whom he never mentioned to us, and a brother-in-law about whom he never said a word in all the time we have been with him. But why should the niece and the brother-in-law try to deceive us?"

"Der leedle girl vouldn't do dot, Matt," asserted Carl.

"I don't like to think that, Carl, any more than you do, but we're going it blind and ought to consider carefully anything we hear."

"Right-o, matey," said Dick. "What have you heard that makes you think the girl and her uncle are not dealing on the square with us?"

"Miss Harris said that her Uncle Archibald Townsend's real name is Harris, and——"

"Dot might be, Matt, for ve know dot Downsent uses odder names schust as he——"

"Wait a minute, Carl. Miss Harris also told us that her mother's maiden name was Sixty, and that Captain Sixty was her mother's brother."

"Also that Townsend was her father's brother," chimed in Dick. "I don't see anything wrong about that."

"Then," continued Matt, "Captain Sixty started to call Sadie Harris, Ysabel, but tried to explain away the break when the girl looked at him. The captain also said that Miss Harris' mother was of Spanish origin, and whoever heard of Spaniard by the name of Sixty? Furthermore, if the captain is a brother of Miss Harris' mother, then the captain ought to be a Spaniard himself."

It was hard for Carl to follow this line of reasoning, although Matt made it as clear as he could. Dick, however, grasped the point Matt had brought up.

"Shiver me!" he exclaimed. "It's a wonder I didn't see that myself. The old bucko stepped over his chalk mark, and the girl hustled him away before he could say anything more. Great kedge anchors! What sort of a deal are we in on, anyhow? The girl's yarn don't hold together, and it was Sixty himself who let the cat out of the bag. What's to be done? We could have the captain set us ashore, and then we could make our way back to New Orleans and have a talk with Townsend."

"No, I don't think we'd better do that. After all, Dick, it may be that Townsend has fixed this thing up, and that the girl and the captain are talking according to instructions."

"Townsend never told them to pull the wool over our eyes, mate. He's not that kind of a fellow."

"If it comes to that, he's not the kind of a chap, to my notion, to mix up with a man like Sixty. Still, everything may be all right. The girl knew that we were expecting word from Townsend; in fact, all her talk and actions prove that she knows more about Townsend's plans than she could possibly know if Townsend hadn't taken her into his confidence. At least, that's the way I look at it. If we had the captain of the Santa Maria put us ashore we might be spoiling Townsend's plans. For that reason I'm in favor of staying right where we are and waiting for developments. But we can be careful, pards, and keep our eyes open. If there is any crooked work on foot it will come to the surface in time."

"Aber ven id comes by der surface," spoke up Carl, with a good deal more wisdom than he generally showed, "meppy id vill be too lade to dodge drouple."

"If Miss Harris and Captain Sixty don't think we suspect anything underhand," answered Matt, "the advantage will be with us."

"Sure," averred Dick. "We can keep our own counsel and have a sharp eye to windward all the time."

"Oof Downsent vants us," continued Carl, "und oof dis ain'd vat he vants us for, den, py shinks, ve vas spoiling his blans vorse as ve vas by keeping on mit der poat."

"What's your idea, Dick?" asked Matt; "to keep on, or have the captain put us ashore and go back?"

"Our course is laid, matey," responded Dick, "so let's hang to it."

"There's no escaping Honduras after we once strike the gulf."

"Then we'll go to Honduras. It's a bally layout, any way you look at it, but the chances are that we're on the right tack."

"What have you to say, Carl?"

"I don'd t'ink der girl iss fooling us, und dot's all aboudt id. I say mit Tick dot ve keep on like ve're going, mit our vedder eyes shkinned bot' vays for preakers. Oof ve ged to Honturas, und Downsent don'd show oop, den ve can send him some caplegrams und say vere ve vas, und vy. Yah, ve hat pedder keep on."

"That's my idea. I can't see what motive any one would have for playing double with us. What enemies have we in New Orleans? And, if we had any there, why should they go to the trouble of buying tickets for us on the Santa Maria and sending us to Belize?"

"Right-o," agreed Dick. "We'll play a square game, and if any one tries to run afoul of us with anything different, why, we'll bring 'em up with a round turn. The outward trip to Honduras isn't costing us anything, anyhow."

Having arrived at this decision the boys left their stateroom and went down to their dinner.

The passenger business between New Orleans and Central America was not extensive, and there were no[Pg 9] more than twenty people seated around the two tables in the dining room.

Matt and his friends found themselves at the captain's table, with Sixty and Miss Harris directly opposite. Miss Harris greeted them with one of her engaging smiles, and Sixty grinned and nodded his bullet-like head. But there was no talk across the board, although Carl was visibly eager for a little conversation with the girl.

Following the meal the boys strolled about the deck, hoping that either Sixty or Miss Harris would come looking for them and engage in talk which might either confirm their suspicions or else set them at rest. But nothing of the sort happened.

"They're sheering off from us," commented Dick. "Probably that's in accordance with Townsend's plan, too. I wish I knew what our work is to be."

"I've puzzled my brain over it till I'm tired," said Matt. "We've been a long while getting at the work, and while we've been waiting Townsend hasn't dropped a hint about what it was. We're just as much in the dark now as ever."

During the afternoon the Santa Maria slipped through the lower end of South Pass into the gulf, and began to roll and wallow in the heavier swell.

Carl became indisposed. He declared that he wasn't seasick, but the motion of the boat annoyed him. He made for his stateroom with the announced intention of lying down and getting himself accustomed to the pitch and tumble. Dick, in the hope of discovering the whereabouts of Sixty and the girl, strolled forward. Matt was left alone on the stretch of deck aft of the bridge. An awning sheltered him from the sun, and the breeze that wafted itself across the broad reaches of the gulf was grateful and refreshing.

All the other passengers who had been occupying deck chairs in that part of the boat had gone away.

Matt, after half an hour's wait for Dick to return, got up with the idea of looking for him. As he passed a casual glance over the foamy trail left by the Santa Maria, his keen eye detected something appearing and disappearing in the tumbling waves that captured his immediate attention.

The object glistened in the rays of the afternoon sun and looked like a reddish ball. Sometimes he could see it quite plainly for a few moments, rolling and tumbling in the waters, and then a large wave would sweep past and blot it from his sight.

The ball seemed to be following the ship, maintaining at all times the same distance.

Was it some kind of a fish? Matt asked himself. If it was, then it was a variety of fish of which he had never heard or read.

He looked around to see if there were any of the officers or deck hands in his vicinity, but there were none, and he was obliged to watch and wrestle with his curiosity.

It might be a piece of wreckage, he told himself; yet, if it was, what kept it in the wake of the Santa Maria?

He continued to hang over the rail and watch the queer red object, waiting for some of the ship's officers or men to come to that part of the boat.

Presently he heard a muffled footfall close behind him. He turned his head and saw Captain Sixty at his side. Beyond Sixty, and gliding hastily in his direction, was Miss Harris.

There was a question on Matt's lips, but it died away quickly when the youth saw the diabolical expression on Captain Sixty's face.

"Here's where you go over!" said Sixty hoarsely.

Then, before Motor Matt could make a move to defend himself, the burly scoundrel seized him in a grip of iron, lifted him bodily and flung him from the rail.

A loud cry escaped Matt's lips. It was taken up by a shrill scream from the girl, and, the next moment, by a hoarse shout from the treacherous Sixty.

"Man overboard! Man overboard!"

As Matt dropped into the lashing waves that frantic yell of Sixty's smote on his ears. Even in that perilous moment the reason for the scoundrel's alarm flashed through his brain. Matt's yell and the girl's scream had aroused the officers and crew, and there was nothing else for Sixty to do but to give his alarm and hope that the speed of the ship would take her so far away from Matt that rescue would not be possible.

The first officer was on the bridge. Turning a look rearward he saw a dark object in the smother of foam, far astern, clinging to one of the ship's life-preservers.

It was the girl who had wrenched the life-preserver from the rail and flung it after Matt. She had succeeded in this before Sixty could reach her side and prevent the act.

Bells jingled in the engine room and the Santa Maria lessened speed quickly. Dick and Carl, hearing the loud yell of Captain Sixty, and the bustle on the deck, joined the other passengers who were hurrying from the cabin.

"Who was it?" cried Dick.

"Your friend, Motor Matt," answered Sixty, who was close to Dick and Carl.

Miss Harris, white as death and half fainting, was leaning against the deck-house. Sixty had his eyes on her, and their baleful influence held her silent.

"He was watching something astern," explained Sixty, "and went over the rail. I tried to get to him, but he slipped away from me."

"Matt!" whooped Carl, in a spasm of fear and apprehension. "It was our bard dot tumpled oferpoard!"

Dick rushed for the boat which the sailors, under an officer's direction, were getting ready to lower.

"We're going along!" shouted Dick wildly.

"Keep away!" ordered the officer.

"I'm a sailor," answered Dick, "and I can help! Motor Matt's my mate, and I'm going to help save him!"

Without waiting for permission, both Dick and Carl sprang into the boat. There was no time to lose making the boys get back on the deck, or arguing the question, and the officer yielded his place to Dick.

"Lower away!" he shouted, and the blocks rattled as the boat dropped from the davits.

AN UNEXPECTED RESCUE.

Sixty's unprovoked and murderous attack on Matt had been made with such brutal suddenness that the king of the motor boys had had no chance to defend himself. Before he fairly realized what had happened he was under the water and fighting his way upward to the surface.[Pg 10] Had he not been such a good swimmer the weight of his clothing would have dragged him down and rendered his case hopeless. He was seriously handicapped, as it was, and when he gained the top of the water he was thankful to find a life-preserver bobbing and ducking beside him.

How the life-preserver happened to be there he did not know, but he seized hold of it gratefully and allowed it to support him in the tumbling waves. By that time the Santa Maria was far in the distance, but there was a commotion on her decks which indicated that the cry of "Man overboard!" was receiving a prompt response. The sharp orders of the officer of the deck, the cries of excited passengers, and even the jingle of the engine-room bell came distinctly to the ears of the youth in the water.

Matt, although still bewildered, congratulated himself on escaping the swiftly-revolving screw. He had been thrown from the ship near the stern, and it was a piece of luck that the suction had not drawn him under the sharp propeller-blades.

Buffeted by the waves, Matt swung back and forth in the water and watched while the boat was lowered. Dick and Carl were in the boat, and there were two sailors at the oars. Dick, at the bow, was coiling a piece of rope in his hands, making ready for a cast as soon as the boat should come near enough.

Matt, his eyes fastened on the boat, gave no attention to the expanse of water in the other direction. Suddenly he heard a cry, coming from behind him, and turned his head. His amazement was complete when he saw a submarine rolling amid the waves. The mystery of the glistening red speck which had claimed his attention from the steamer was explained. It was the round periscope ball of the Grampus!

Some one—Matt could not see distinctly, for the spindrift was in his eyes—was half out of the conning tower of the submarine.

"Come aboard of us, Matt!" shouted the man, whirling a rope about his head and letting it fly.

The youth's ears were filled with the poppety-pop of the submarine's motor, but he heard the request. He could only guess how the submarine happened to be there, and guesses were useless, for he would soon be told everything about the queer situation.

Motor Matt grabbed at the rope as it was thrown to him by the man in the submarine.

As he hauled himself toward the Grampus, hand over hand, he saw that the man in the conning tower was Townsend, or Captain Nemo, Jr., as he preferred to be called when afloat.

Presently the young motorist was hauling himself up on the slippery deck of the submarine.

"Are you all right, Matt?" cried Captain Nemo, Jr.

"All right, captain," answered Matt, "except that I'm as wet as a drowned rat and can hardly understand why I was thrown from the steamer."

"You were thrown overboard?" demanded the captain.

"Yes; by your man, Sixty."

"My man? I don't understand you. But we'll let that go for now. Dick and Carl are in that boat yonder. Shall we take them aboard?"

"I'd like to, sir, but we have some luggage on the Santa Maria and the boys had better go back after it."

"Tell them to get the luggage and that we'll stand by to take them off." Nemo, Jr., threw a hasty look around at the sky, which was rapidly becoming overcast. "Ask them to hurry," he added, "for we'll be in for dirty weather before long and we must get them on the Grampus before the storm comes down on us."

The rowboat by then had drawn as close to the submarine as safety would permit. The two sailors were lying on their oars and gazing at the craft in astonishment, while the rail of the steamer was crowded with passengers and crew, all staring at the strange scene going forward there in the waters of the gulf.

"Ahoy, Dick!" shouted Matt.

"Ahoy, yourself, old ship!" roared Dick. "That's the Grampus, I take it?"

"Yes. Captain Nemo, Jr., is going to take you and Carl aboard. Go back to the Santa Maria and get our traps. Be quick about it, for the weather is threatening."

"Ay, ay," cried Dick heartily, "and it's glad I am to leave the old hooker."

Dick dropped down in the boat and the sailors fell-to on the oars.

"Come inside, Matt," called Captain Nemo, Jr. "I'll get out of the way and make room for you."

The captain disappeared downward, and Matt climbed over the rim of the conning tower and quickly descended the iron ladder.

In a square chamber called the periscope room, at the foot of the ladder, Matt found the captain and Cassidy waiting for him. Each grasped his hand. There was only a moment for congratulations.

"Up into the tower with you, Cassidy," called the captain, "and keep watch for Dick and Carl. We're going to take them on as soon as they pick up their belongings."

"Ay, ay, sir," answered Cassidy, "I heard your talk with Matt, and Matt's talk with the fellows in the boat."

Cassidy disappeared up the ladder and Matt dropped down on a locker and began pulling off his water-logged shoes.

"I've got a dry suit in my grip," said he, "and when the boys get here I'll slide into a more comfortable rig."

"And Sixty threw you overboard!" muttered Nemo, Jr., a black frown crossing his face. "The murderous scoundrel! I have long known him as a desperate man, but I would hardly have believed him capable of such a move as that! What was his reason?"

"That's more than I know."

"You mean to say that you don't know what his motive was for attempting such a high-handed piece of work?"

"That's exactly what I mean, captain."

"Did any one see him?"

"Only his niece—and yours."

Captain Nemo, Jr.'s, amazement increased.

"My niece?" he echoed. "I have no niece."

"Is your real name Harris, Captain?"

"No, certainly not."

"And Sixty isn't your brother-in-law?"

The captain flung up his hands.

"I should hope not! Where did you get all this queer misinformation?"

"From the girl who called herself Sadie Harris, and who said she was a niece of yours."

"You and your friends have been badly fooled, Matt," said the captain. "We must probe to the bottom of this and——"

Just at that moment the Grampus gave a wild roll, nearly upsetting Captain Nemo, Jr., and almost throwing[Pg 11] Matt from the locker. A bucket of water came sloshing down the conning-tower hatch.

"The squall's hit us!" roared Cassidy. "The weather's so thick with rain and flying scud I can't see the steamer."

"Did the boys get aboard?"

"Yes, and they've had time to get back into the whaleboat again, but there's been some sort of a hitch."

The Grampus was rolling and wallowing frightfully, and it seemed at times as though she must surely turn turtle. The slap of waves on her steel sides and against the conning tower caused a thunderous noise to echo through the boat.

"Close the hatch, and come down, Cassidy!" shouted the captain. "We'll have to submerge her, and try to pick up the steamer with the periscope."

Cassidy could be heard clamping down the hatch. While he was coming down the ladder, the captain turned to one of the speaking tubes that entered the periscope room.

"Let the water into the ballast tanks, Clackett!" he called. "A ten-foot submergence. Slow speed ahead, Gaines," he added through another tube. "Keep her south by west, Cassidy," said he to the mate.

"South by west it is, sir," answered Cassidy, posing himself by a small binnacle and laying hands on a steering wheel.

From a distance Matt heard the old familiar rhythm of the gasoline cylinders. There was a splashing as water poured into the ballast tanks, followed by a very perceptible sinking motion. The frightful wallowing and pitching ceased to a great extent, and the Grampus hung on a fairly even keel.

"Ten feet of submergence, cap'n!" came from a speaking tube so distinctly that it almost seemed as though the speaker was in the periscope room.

"Very good, Clackett," replied the captain. "Hold her so. Now, Matt," the captain went on, "we'll see what the periscope has to show us."

The hollow steel mast of the periscope, contrived with powerful reflectors, terminated in a hood that swung above a table.

Captain Nemo, Jr., pushed aside a fold of the hood and he and Matt looked down on the highly-polished mirror that formed the top of the table.

A stormy scene lay under their eyes. Their horizon was narrowed to only a few yards by rain and spray, but within this brief radius they got a sight of raging waves and a fierce tumult of waters. Now and again the scene was blotted out for a moment as the periscope ball was drenched by a comber.

"We can't take the boys off now, captain," said Matt.

"It would be impossible in this sea," answered the captain. "I was not looking for the squall to hit us so soon. We'll try and follow the Santa Maria, however, and take them off later."

"How can you follow her when you can't see her?"

"We know her track, and we'll follow her by compass."

The wild roaring of wind and sea came to those in the Grampus like a dull murmur, and the submarine's rocking, at a ten-foot submergence, was proof of the power the elements must be showing on the surface.

Both Matt and the captain kept their eyes constantly on the table top, then, abruptly, Matt gave a gasp and caught at the table to support himself.

"Look!" he cried. "Captain—the boat——"

But Captain Nemo, Jr.'s, startled eyes had already seen what Matt had beheld. This was a whaleboat tossed wildly on the crest of a huge wave adrift, and with Carl and Dick clinging desperately to the oars.

Only Matt's two chums were in the boat. The captain whirled to one of the tubes.

"Turbines at work, Clackett!" he shouted; "quick, on your life. Empty the tanks and get us back to the surface! Reverse your engine, Gaines," he added through another tube.

Matt, still clinging to the table, stared down on its polished top. The drifting whaleboat, with his two chums, had vanished as quickly as it had appeared.

A FRUITLESS SEARCH.

"That boat was adrift!" cried Matt, as soon as he could find his tongue.

"Yes," answered the captain in a tense voice, "and only Dick and Carl were aboard of her."

"How could that have happened?"

"When the boys got back to the ship, the boat must have been left at the steamer's side while the luggage was being secured. The boys had time to get down into the boat, and before the sailors could follow the squall came rushing down and tore the boat away from the Santa Maria. Hard luck, Matt! Still, the case isn't hopeless by any manner of means. The whaleboat has an air chamber at each end and can't be sunk. If the boys can stay in her, and keep her right side up, we'll be able to rescue them."

The fierce pitching and plunging of the submarine told Matt that she was again battling with the elements on the surface. A look into the periscope also laid bare the heaving and churning waters within a narrow zone of observation, but nowhere could the whaleboat be seen.

"Follow the wind, cap'n," said Cassidy. "By doin' that we ought to be able to find the boat."

"That's my intention, Cassidy," returned the captain. "Take the waist-tarp and go up into the conning tower. Carry a rope with you, and be ready to throw it the moment we sight the boat."

"Let me go, captain!" requested Matt. "I'm already as wet as I can possibly be, and I should like to do my part."

"Very well, Matt," replied the captain. "Put the tarp around him, Cassidy."

Cassidy lifted the lid of the locker and took a circular oilskin from inside. There was a round hole in the centre of the oilskin, and around the outside edge were eyelets.

The mate pulled the tarp over Matt's head and tied it about his waist.

"There's a ring of hooks around the rim of the tower, Matt," he explained, "and by fitting the edge of the tarp over them you'll keep us from being drowned out down here."

"I understand," answered Matt.

That was not his first voyage in the Grampus, and he was fairly familiar with the boat's equipment.

When he was ready, Cassidy handed him the coil of wet rope recently used by the captain to get Matt aboard.

"When you get tired, Matt," said the captain, "come down and Cassidy will relieve you."

"I hope we'll find the boys before then," answered Matt hopefully. "They were drifting, and if we go with the wind we ought to overhaul them."

"We'll keep track of operations through the periscope and do all we can to lay you alongside the boat if we sight her."

Matt climbed the ladder, pushed back the lever that held the air-tight hatch in place, and threw over the cover just in time to get a barrel of water over his head and shoulders.

Quickly as he could he pushed on until his body, from the waist upward, was over the top of the conning tower. Then, with deft fingers, he made the circular tarp fast along the edge of the hatch. A minute more, when he had leisure to look around over the riotous waters, the novelty of his position caused his pulses to leap.

Forward and aft the water creamed over the steel deck of the Grampus, hiding the hull and leaving only the upper part of the conning tower and the steel periscope mast exposed. It seemed to Matt as though he was afloat in nothing more substantial than a barrel, with the clamoring, rushing waves all around him.

Forward, backward and sideways the submarine rolled through a terrific arc, and an occasional wave charged over him, leaving his dripping hair tumbled about his eyes.

For a brief space only did the awful spectacle claim his attention, and then he turned his eyes over the roaring waves in an attempt to locate the whaleboat. The Grampus was now racing with the wind, and the stinging lines of rain struck against the young motorist's back. Again and again he brushed the water from his eyes and continued to peer eagerly ahead.

But his heart was steadily sinking. Dick was a sailor, but what skill could keep the whaleboat right side up in such a tempest? The waves drove past the Grampus at racehorse speed, flinging their foamy arms high in the air. Matt shouted at the top of his lungs, but his voice was puny and ineffective. The gale caught it, feathered it out into a thousand wisps of sound and scattered it into the roar and crash of the waves.

From below him came the notes of a Gabriel horn, but these were little more effective than Matt's voice had been. The minutes passed, and Matt's hopes declined steadily. After a time, he knew not how long, he felt a hand tugging at his feet. Quickly unhooking the edges of the tarp, he descended.

"You've been up there an hour, Matt," said Captain Nemo, Jr., "and Cassidy will relieve you."

"I don't think there's much hope," returned Matt heavily, removing the waist-tarp and handing it to the mate. "I don't see how Dick and Carl could possibly stay in the boat in such a frightful sea."

"We never can tell what we're able to do in this world," said the captain hopefully, "until we're called upon to put forth our best powers. Dick is a cool one, and he knows the sea. If any one could pull through that storm and bring Carl along with him, it's Dick Ferral. We may not find them while the gale is on, but afterward we can cruise about and perhaps be able to pick them up. That is my hope, at all events."

Cassidy, rope in hand, was already on his way up the ladder. When he had taken up his position, the captain turned to Matt.

"That locker is our slop chest," said he, "and in it you will find some dry clothes. Better make a change, Matt, and be as comfortable as possible."

This was good advice, and Matt proceeded to carry it out.

"I had thought of taking Cassidy's place again in an hour," he observed.

"No use," was the answer. "If we don't sight the boat within an hour, then the chances are that we have gone wide of her—perhaps left her behind. We'll sink into quieter waters and come up again when the storm has abated. Then we'll cruise around and do everything possible to locate Dick and Carl."

The captain drew up a chair and braced himself at the periscope table.

At the end of an hour night had fallen, closed in with the Stygian gloom of the clouds and tempest. From that on the periscope was useless, and even a lookout from the top of the conning tower was of no avail.

Cassidy descended, closing the hatch behind him. His face was long and ominous.

"This ends it till mornin', cap'n," said he.

"Exactly so, Cassidy," replied the captain; "but the case isn't hopeless, by any means." He whirled to a speaking tube. "Fill the tanks, Clackett," he ordered, "and descend to twenty yards. Shut off your engine, Gaines," he added through another tube; "we'll pass the night where we are, sixty feet down."

The orders were repeated back, and the Grampus began to sink. When the periscope ball was submerged an automatic valve closed the hollow mast against an inrush of water.

Down and down they went, slipping noiselessly into great depths. Cassidy turned on a light from the storage batteries and an incandescent bulb flooded the periscope room.

Climbing the ladder into the conning tower, Matt stole a look through the lunettes. To see under water, contrary to the usual fiction on the subject, is impossible. Only a sombre void met Matt's eyes. By means of electric light and powerful reflectors Captain Nemo, Jr., could throw a gleam several yards through the lunettes; but this was a drain on the storage batteries, and for use only in case of emergency.

At sixty feet down the Grampus lay as easily under the enormous water pressure as a man in a hammock. At the captain's suggestion, Matt stretched himself out on a blanket on the floor of the periscope room and, in spite of his worry, was soon asleep.

When he was aroused by Cassidy a gleam of day was shining down the conning-tower hatch.

"Speake is getting breakfast, Matt," said Cassidy, "and we're up at the surface again. The storm is over, and the cap'n is on deck, calling for you. Better go up."

Matt jumped to his feet and raced up the ladder. The sea was still a bit rough, although part of the submarine's deck was high and dry. Captain Nemo, Jr., was on the deck, clinging to one of the wire guys that supported the periscope mast.

"Do you see anything of the whaleboat, captain?" were Matt's first words.

"Not a sign," answered the captain, handing Matt a pair of binoculars. "Take a look for yourself."

Bracing himself in the top of the tower Matt swept the glasses over the vast expanse of sunlit, heaving water.

There was nothing to be seen. From horizon to horizon the gulf held only the dancing, gleaming waves.

THE OVERTURNED BOAT.

Matt's heaviness of spirit was reflected in his face.

"Don't be discouraged," said the captain. "We'll cruise around in this part of the gulf and I feel pretty sure we'll find your friends. It would have been difficult to locate them during the storm, and the Grampus might have passed within a cable's length of the whaleboat without seeing it or being seen; but, on a day like this, we've got the range of the ocean for miles, and the whaleboat can't get away from us!"

"Providing it's afloat," replied Matt apprehensively.

"Breakfast!" yelled Cassidy from the periscope room.

"That means us," said Captain Nemo, Jr.

The present complement of the submarine consisted of the captain, mate and three men. The duties of the captain and mate kept them constantly in the periscope room and conning tower. Gaines had charge of the hundred and twenty horse-power gasoline motor, Clackett looked after the trimming tanks, and Speake was general utility, taking care of the electric supply and compressed air and preparing the meals. Each had his particular station, and when the boat was running the officers rarely saw any of the crew.

Gaines' room was aft, Clackett's was nearer the waist of the boat, and Speake was forward in the torpedo room.

There being no use for the torpedo room during peaceable cruising, it was transformed into a galley, and here Speake prepared the meals on an electric range.

During breakfast Speake relieved Gaines at the motor, and Cassidy took the lookout. Gaines, Clackett, Captain Nemo, Jr., and Matt crowded into the little messroom, dropped down on low stools and drank their hot coffee and ate their crackers and boiled eggs.

When Matt and the captain had finished they went up and relieved Cassidy and sent him down. Matt seated himself on the deck at the base of the conning tower, the captain taking the elevated position in the top of the tower.

"While I'm using the glasses, and you're using your eyes, Matt," said the captain, "we might as well talk and try to understand the causes that brought you and your chums into this situation. I was curious on that point last night, but didn't want to bother you when you were so tired and worried."

"If you were surprised to see me, captain," returned Matt, "you can imagine how astounded I was to find you and the Grampus."

"The wind was taken out of my sails completely when I learned that you and your friends had sailed on the Santa Maria."

"Then you didn't send us three tickets and ask us to sail on the steamer for British Honduras?"

"Certainly not! That was part of the plan for getting you away. Sixty must have laid the plan and trusted to his daughter to carry it out."

"His daughter?"

"Yes. She was the girl who called on you at the hotel shortly before the steamer sailed—Ysabel Sixty. Captain Sixty married a Spanish woman in Cuba, and the girl was their only child."

"She used pretty good English when she talked with me."

"That's because she has passed most of her life in the United States, while her father has been engaged in questionable work all over the high seas."

"She said she was your niece, that her mamma was Sadie Harris, and that she had come to New Orleans as soon as she heard that you were sick."

The captain smiled grimly.

"Sixty told her what to say," he answered.

"But," and Matt's surprise took another tack, "how do you happen to know that she called on me at the hotel?"

"Clackett found that out. I sent him to the hotel to ask you and your chums to come to Stuyvesant Dock and board the Grampus. Cassidy was to bring the submarine down from Westwego. But let's begin at the beginning and get at this thing with some sort of system."

Matt led off with an account of the mixed messages, following this with a description of the girl and of what had transpired during their interview, and then finishing with what had taken place on the steamer.

The captain, although he kept the binoculars sweeping the sea, was absorbed in the recital.

"What name was signed to that message that fell into your hands by mistake?" he asked.

"I didn't pay any attention to the name," Matt replied. "I read the message to make sure it wasn't for me, but I didn't read the signature."

"What was the message?"

"It merely gave a position by latitude and longitude with the added words, 'two days ago—no wind and no drift since.'"

The captain showed signs of suppressed excitement.

"What was the latitude and longitude?" he asked. "Can you remember it?"

"No," said Matt. "I knew it did not concern me, so I failed to charge my mind with it."

"It concerned you more than you know. I am positive that Sixty lured you aboard the steamer because he feared you had learned something from the telegram which you could use to his disadvantage. What was your message—the one that Sixty got and read?"

"It was from a man who didn't know our air ship had been wrecked and destroyed. He wanted to buy her, and referred us to you, saying that he knew you."

"My name was mentioned in the telegram?"

"The name of Townsend was mentioned."

"Ah! The cause of Sixty's work is becoming clearer and clearer. He knew I was a friend of yours, that the government had asked me to watch him, and that you had had a chance to secure some important information from the telegram. It was enough to make a man like Sixty try something desperate!"

"You were watching him?" queried Matt, "and for the government?"