RAMBLES ON RAILWAYS.

With Maps, Diagrams, and Appendices

BY

SIR CUSACK P. RONEY,

B.A. TRIN. COLL. DUB., L.R.C.S.I.

LONDON: EFFINGHAM WILSON.

1868.

All Rights Reserved.

PREFACE.

Just as the Author was completing the last of the following pages, he was seized with very serious illness. It has delayed their production two months beyond the time originally advertised. Meanwhile, several changes have taken place, which, though not of much importance, may be briefly referred to. Thus, Mr. Anthony Trollope, mentioned at page 104 as amongst the literary men connected with the Post Office, has, since that page was printed off, ceased to be an officer of the department.

Some trifling errors must also be mentioned; thus, at note of page 211, the length of Australian railways is stated at 480 miles, whereas it should have been 669, as set forth at page 307. Page 212; it is stated that the Euston portico is not used by anybody, whereas empty cabs, having set down their fares, go through it. Page 359; the name of the Secretary of the Palestine Fund is “Grove” not “Groves.” Page 390, line 27; the St. John’s Wood Railway terminates at 1 mile and 1,320 yards from Baker Street, and then the Hampstead Extension will commence with a gradient of 1 in 27. Page 423, line 11; for “Lowe” read “Love.”

The most important correction to be made has reference to pages 149 and 150, relating to the railway capital raised, traffic receipts, and net earnings for 1865. When the words in the text were written the complete returns of the Board of Trade had not been published, and the Author assumed that the debenture and preferential capital was greater in amount than it really[iv] is. The reader is, therefore, requested to take the subjoined analysis of the railway capital of the United Kingdom, extracted from the City article of the Times, of October 29th, 1867, as containing an exact statement of the several portions into which that capital was divided on the 31st of December, 1865, and to substitute it for the statements in the text as given in the before mentioned pages. If the traffic accounts, as published by the railway companies, be really correct, and that capital has not been improperly charged with items that should, in reality, be attributable to revenue, the dividends on unguaranteed capital are better, as a whole, than the Author assumed them to be.

“The complete railway returns of the Board of Trade for the year ended the 31st of December, 1865, have just been printed. They are full and elaborate, and would furnish excellent means for estimating the prospects of the enormous property involved, were it not for the drawback of their being issued so long after the period to which they refer. The leading features of the tables now presented may be summarised as follows:—At the end of 1865 the total ordinary capital of the railways of the United Kingdom was £219,598,196. Of this total £183,450,460 was represented by companies paying dividends, and £36,147,736, by companies (chiefly the Great Eastern and London and Chatham) not paying dividends, the latter including £12,849,590 for lines not yet opened. Setting aside the unopened lines, and reckoning only the capital of those at work—namely, £206,748,606—the average rate of distribution was £4. 11s. 5d. per cent., a satisfactory return could an assumption be safely made that it had not been in any degree paid out of capital. The result would have been still better but for the extent to which the average rate is reduced by the circumstance of the profits of the Scotch and Irish being below those of the English lines. The English rate was £4. 14s. 10d. per cent., while the Scotch was £4. 9s. 5d., and the Irish only £2. 16s. 8d. The lowest dividend disbursed by any of the English dividend-paying companies (57 in number) was by the Cromford and High Peak, which on an ordinary capital of £127,700 distributed 8s.[v] per cent. for the year, while the highest was £11. 2s. 6d., by the Lancaster and Carlisle on an ordinary capital of £2,420,300. The main cause of the respectable average of the English dividends is found, however, in the payment of £6. 12s. 6d. per cent. by the London and North-Western on an ordinary capital of £23,378,987; of £6. 15s. per cent. by the Midland, on £10,862,067; and of £7. 2s. 6d. per cent. by the Great Northern, on £6,455,584. At the same time there is an item which must now be regarded as fictitious, of £5. 15s. per cent., by the Brighton line, on an ordinary capital of £5,342,933. Of 19 dividend-paying lines in Scotland, the lowest was the Carlisle and Silloth Bay, 10s. per cent., and the highest was the Kilmarnock and Troon, £9. 5s. per cent., the ordinary capital of the latter being only £40,000. In this list the Caledonian figures for £7. 2s. 6d. on an ordinary capital of £4,141,254. Of 11 dividend-paying lines in Ireland, the lowest was the Waterford and Limerick, 15s. per cent., and the highest the Dublin and Kingstown, 9 per cent. The preferential capital of the railways of the United Kingdom was £124,263,475, and upon this the average rate paid (reckoning a sum of £8,455,279, on which the companies were unable to distribute anything) was £4. 7s. 9d. per cent. The total of the debenture stock, or funded debt of the railways in the United Kingdom, was only £13,795,375, and on this the average rate paid was £4. 2s. per cent., while the debenture loans, subject to renewal, and which in times of pressure must always be a cause of danger, amounted to £97,821,097, at an average rate of £4. 8s. 5d. per cent. The total paid-up capital of all kinds stood at £455,478,143.”

The Author had thought, that in tracing tunnels to the time of the erection of Babylon, he had gone as far backward as it was possible to extend research on this subject. It appears, however, that he was mistaken, for, during a visit that he paid to Paris just before his illness, he lighted, in Galignani, upon the following extraordinary paragraph, which is given in extenso, exactly as he found it.

“Antiquity of Man.—A most singular and unexpected discovery[vi] has just occurred at Chaguay, Department of the Soane et Loire, by some workmen. Engrossed in digging the foundations of a railway shed, at the depth of about ten yards, in a stratum of muddy clay and ferruginous oxides, remains of proboscians (elephants, rhinoceroses, &c.), were brought to light, comprising several back teeth and a formidable tusk, in large fragments, which, on being put together, constituted a length of seven feet. The depth at which this was found was more than six yards, higher than the level of the most considerable inundations of the Dheune, and in an undisturbed stratum. So far, there is nothing absolutely extraordinary, but who would have thought of finding, underneath the bed containing these fossils of the tertiary period, an aqueduct of the most primitive kind of human workmanship? Yet such is the case, and it is the only case of the kind on record. It is explained by M. Tremaux, who relates the circumstance, by the supposition—what seems indeed to have been the fact—that the tertiary fragments above alluded to had been pushed into the trench by a violent inundation, and thus filled up the aqueduct. The discovery of this aqueduct does not by any means authorise us to carry the antiquity of man as far back as the tertiary period, for, although the aqueduct lies under a stratum of tertiary formation, this stratum does not belong to the place, but was transported thither at a later period.”

One step from that period, whatever it was, to Anno Christi 1867. During the visit above referred to, the Author was afforded the opportunity, by M. Mouton, the eminent French contractor, of an inspection of the plans of the proposed Paris Underground Railway, which it is hoped will be commenced before the expiration of 1868. The course of the line is from Long Champs Race-course, beside the Seine, near Paris, underneath the Bois de Boulogne, thence to Arc de l’Etóile, from there almost in a straight line along the Champs Elysées, the Rue de Rivoli, the Rue St. Antoine, to the Chemins de Fer de Vincennes, thence to the Mazas Station of the Paris, Lyons, and Mediterranean Railway. Branches are given off from the main line just described, right and left, so as to form a complete underground connection between[vii] all the Railway Termini of Paris. There will be one bridge over the Seine, and one tunnel under it. The total length of the railway and branches will be 23 kilometres, of which about 18 will be in tunnel or covered way.

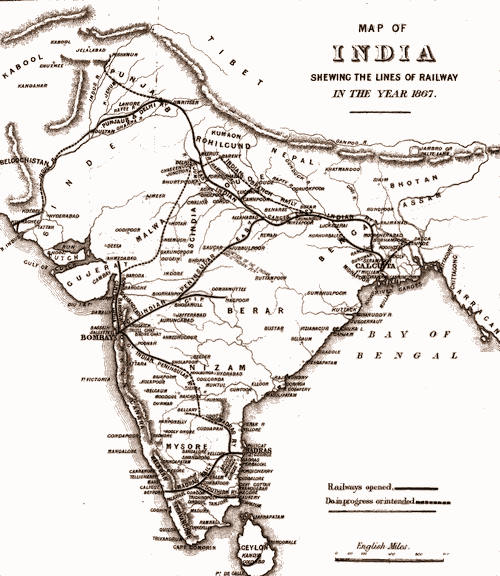

It only remains for the Author to express the sense of deep obligation which he feels to his numerous railway friends for the kindness and promptitude with which they have afforded him information upon every point upon which he sought it from them. It had been his wish to enumerate specially the names of all these gentlemen, and it is a source of much regret to him that the limited space allowed for the Preface prevents his performing this act of grateful recognition. To Mr. William Haywood, the Engineer of the Corporation of London; to Mr. John Fowler, President of the Institution of Civil Engineers; and to other members of the profession, he is also much indebted. He ventures likewise to tender his respectful thanks to George Graham, Esq., the Registrar-General, for the great kindness and courtesy with which he replied to several questions relating to populations; and the expression of the same feeling is due to Mr. Juland Danvers, the Government Director of Indian Railways, from whom information was sought on several occasions.

The Author has by him materials for another volume of “Rambles on Railways,” (relating principally to the railway networks of Foreign countries), which may probably be published in the course of the present year.

London,

January 1868.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | PAGE |

| Travelling Two Hundred and One Hundred Years ago—The Liverpool and Manchester Railway—The First Locomotive, “Rocket”—The Grand Junction, London and Birmingham, and Birmingham and Manchester Railways—The Midland Railway—Early Gradients, Increase in their Steepness and in the Power of the Locomotive—The Carriage Road-way Passes of the Alps—Mountains of the World—The Sœmmering and Brenner Railways—The Route between London and Paris | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Union Pacific Railroad—South Austrian and Alta Italia—Paris, Lyons, and Mediterranean—Orleans—Mileage, Cost, and Receipts of French Railways—London Traffic—London and North-Western Railway | 17 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Railways of the United Kingdom—Coal and Iron | 40 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Railways and the Post Office—Speed on Railways | 73 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Railways and the Post Office—continued | 115 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Railway Receipts, Working Expenses, and Profits in the United Kingdom— Delays and Accidents | 147 |

| CHAPTER VII.[x] | |

| Horses and Engines—Crewe | 186 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| A Journey on the Locomotive | 210 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Indian Railways | 245 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Canadian and Australian Railways—The Railways of other British Colonies | 301 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

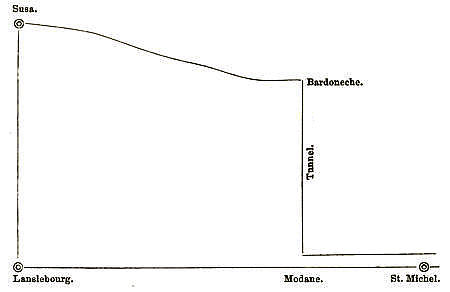

| Paris to St. Michel—“Above Sea-Level”—The Holborn Viaduct—The Mont Cenis Railway | 316 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Tunnels, Ancient and Modern | 358 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Great Tunnel of the Alps—Tunnel Ventilation—Ventilation in the Metropolitan Railway | 401 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Italy—The Eastern Mails—Sicily | 427 |

APPENDICES.

| APPENDIX, No. 1. | PAGE |

| Report by Mr. Edward Page, Inspector-General of Mails, on some points connected with the relations between the Post Office Department and Railway Companies | 439 |

| APPENDIX, No. 2. | |

| Reply of Robert Stephenson, Esq., M.P., President of the Institution of Civil Engineers, to Observations in the Second Report of the Postmaster-General. Delivered at the Meeting of May 20th, 1856 | 454 |

| APPENDIX, No. 3. | |

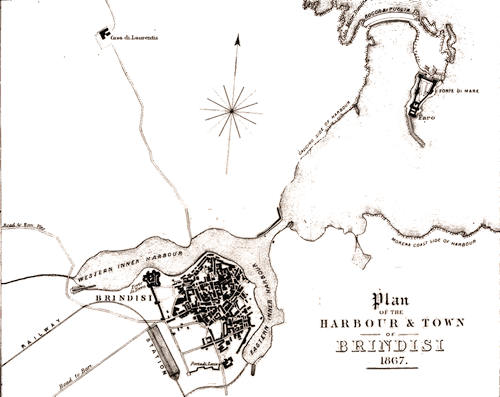

| Copy of Letter Addressed to a Member of the Italian Parliament upon the Importance of the Eastern Mails, now despatched viâ Marseilles and viâ Southampton, being transmitted viâ Brindisi | 482 |

| INDEX | 501 |

MAPS AND DIAGRAMS.

| PAGE | |

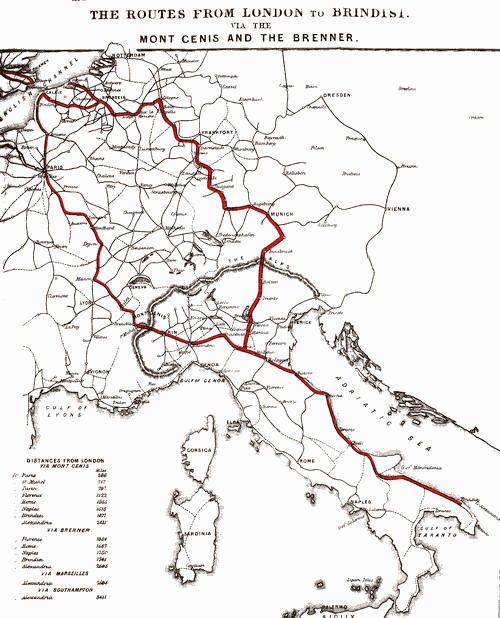

| Routes from London to Brindisi by the Mont Cenis and the Brenner | 14 |

| Plan of the Harbour and Town of Brindisi | 15 |

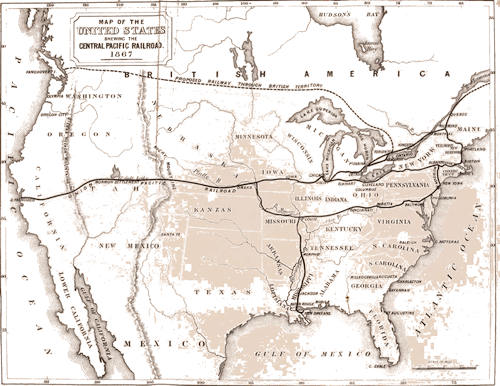

| Map of the United States and the Union Pacific Railroad | 17 |

| Map of India and of Indian Railways | 245 |

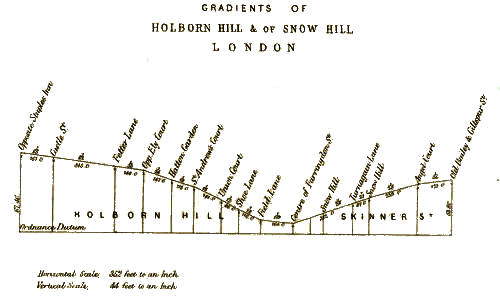

| Gradients of Holborn Hill and Snow Hill, London | 322 |

| A Centre-Rail Engine and Train ascending a steep Gradient and going round a sharp Curve | 334 |

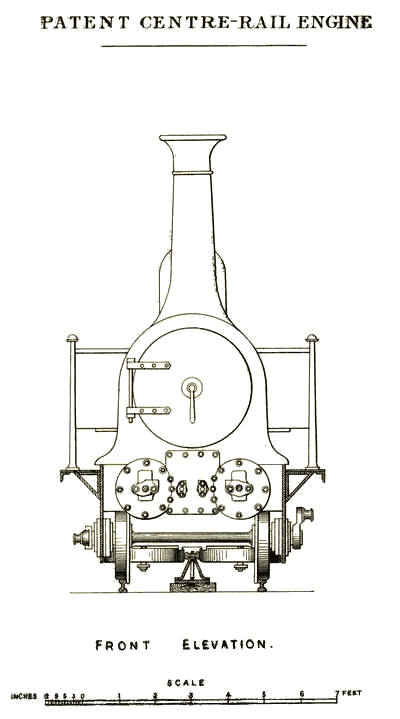

| Patent Centre-Rail Engine—Front Elevation | 337 |

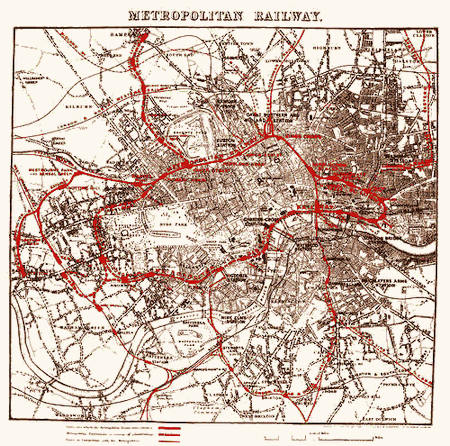

| Map of the Underground Metropolitan Railway, London | 387 |

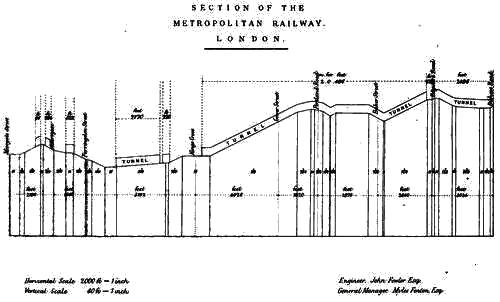

| Section of the Metropolitan Line | 388 |

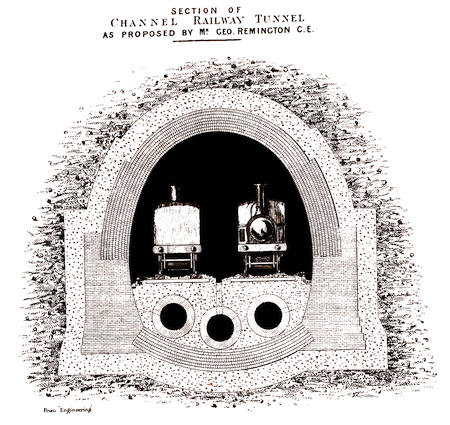

| Section of Mr. Remmington’s Proposed Tunnel between France and England | 399 |

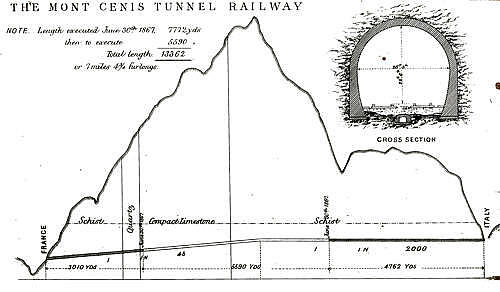

| The Great Tunnel of the Alps | 401 |

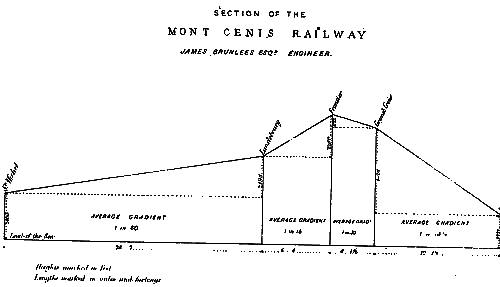

| Section of the Mont Cenis Railway | 401 |

RAMBLES ON RAILWAYS.

CHAPTER I.

TRAVELLING TWO HUNDRED AND ONE HUNDRED YEARS AGO—THE LIVERPOOL AND MANCHESTER RAILWAY—THE FIRST LOCOMOTIVE, “ROCKET”—THE GRAND JUNCTION, LONDON AND BIRMINGHAM, AND BIRMINGHAM AND MANCHESTER RAILWAYS—THE MIDLAND RAILWAY—EARLY GRADIENTS, INCREASE IN THEIR STEEPNESS AND IN THE POWER OF THE LOCOMOTIVE—THE CARRIAGE ROAD-WAY PASSES OF THE ALPS—MOUNTAINS OF THE WORLD—THE SŒMMERING AND BRENNER RAILWAYS—THE ROUTE BETWEEN LONDON AND PARIS.

When, in 1672, Madame de Sevigny wrote of a journey she had just made from Paris to Marseilles, she was able to inform her correspondent that she had completed it, with great satisfaction to herself, in a month. She travelled over 530 miles of ground; she was therefore able to get over some seventeen to eighteen miles a day. The courier that brought Madame de Sevigny’s letter from Marseilles to Paris travelled twice as fast as she had done. He was only a fortnight on the road. In that year the course of post[2] between London and Edinburgh—130 miles less distance than between Paris and Marseilles—was two months: one month going with a letter, and one month coming back with the answer. Ninety years afterwards the one stage-coach between London and Edinburgh started once a month from each city. But in nine-tenths of a century, speed had been accelerated. It only took a fortnight on the road in each direction. Seventy-five years afterwards—that is, in 1837—the year before any portion of railway between the two capitals was opened for traffic, the mail-coach completed its 400 miles in forty-two hours, or one day eighteen hours. Now-a-days, our limited mail (one of the few “limited” associations of very modern date that has not come to grief) is 7½ hours less time over the road than eighteen hours; and by the time the one day in addition has expired, a course of post from Edinburgh to London, and back again from London to Edinburgh, will have been nearly completed.

On the 14th of September, 1830, we opened our first passenger railway in England worked by the locomotive. The line, thirty-one miles long, was then called the Liverpool and Manchester, but it has long since become part and parcel of the London and North-Western Company. Although the railway between Birmingham and Liverpool was first projected so far back as 1824, its construction was not sanctioned by Parliament until 1833, and it was not completed for traffic until the 6th of July, 1837. The then London and Birmingham Company also got its act of incorporation in 1833, but, owing to the difficult nature of many of its works, and the time required for their construction, it was only on the 20th of September, 1838, that Liverpool, Manchester and Birmingham were completely connected with London by railway.

Several of the railways now constituting portions of the Midland Railway Company obtained their acts of incorporation in 1836. These lines, when amalgamated in 1844, comprised 181 miles. On the 1st of September, 1867, the mileage of the Midland Company was 695; and since the 1st of that month the important section between London and Bedford (forty-two miles long) was opened for goods traffic, thus making its present total working length, 737 miles.

By degrees, and notwithstanding the severe blow given to railway enterprise by the over-speculation of 1844-5, the net-work of British railways increased. On the 1st of January, 1843, there were 1,857 miles open for traffic; at the same date of 1849 they had increased to 5,007 miles; on the 1st of January, 1855, they were 8,054 miles; eight years afterwards, that is, on the 1st of January, 1863, they were 11,551; that day twelve months they were 12,322; on the 1st of January, 1865, they were 12,780; 1st January, 1866, 13,289; 1st of January, 1867, 13,882.[1]

We shall refer to the progress of the railway system on the continent of Europe and elsewhere hereafter.

Part of the heavy cost of the earlier railways was no doubt[4] due to the apprehension of engineers on the subject of gradients. And in the then state of our knowledge as regards the powers of the locomotive, this is not to be wondered at. Our first constructed lines had most favourable gradients. The rise from Camden Town to Tring, 1 in 200, or 26 feet in the mile for 31 miles, was considered by the late Mr. Robert Stephenson as the maximum gradient that ought to be ventured upon. Joseph Locke, more daring and venturous, and perhaps more prescient, ventured upon 1 in 100, or 52 feet in the mile for 10 miles; this is on what is known as the Whitmore incline, between Stafford and Crewe. Bucke, the engineer of the line from Crewe to Manchester, originally known as the Manchester and Birmingham, which obtained its act of incorporation in the same year as the Grand Junction, although it was five years later in its opening, determined upon a course the opposite of that which Locke had taken. Bucke therefore made his thirty-one miles nearly level, and no doubt (if we except the exceptional Great Western) there is not a line in England that comprises works better laid out as regards gradient, or more solidly finished than those we are now referring to.

There is a capital run of railway between York and Darlington, forty-four miles, almost level, and nearly straight. It was on this line that, just twenty years ago, most of the experiments and trials were made, instituted to vindicate the narrow gauge as the best for carrying on the traffic of the country. These trials formed one of the many phases of the great battle of the gauges, fought so vigorously by its champions on each side; yet, in the short space of the fifth of a century, how many of these then active and doughty men have passed away from us for ever.

By degrees, as the railway system progressed, we made[5] less flat gradients, and we made larger and more powerful locomotives. The result from the action of these two elements has been, that in present times we have got here and there to gradients of 1 in 45, 112 feet in the mile, more than four times as steep as Stephenson’s incline between Tring and Camden. It was on the 6th of October, 1829, that George Stephenson’s engine, “Rocket,” was first tried on a short length of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, in the presence of thousands, poured in from the adjacent country. Since then the weight of the engine has risen tenfold, from six tons to sixty; its speed not quite three-fold, from twenty miles an hour to something under sixty. Additional weight has been essentially used for overcoming stiff gradients. The stiffest, as has just been said, 1 in 45, with a moderate load; a Titanic locomotive, unfettered with any weights behind her, can go up 1 in 25, or 211 feet in the mile; no steeper.[2]

But this rate of inclination, of 1 in 45, acquired on some few elevated ridges, as will be seen presently, at an enormous cost, was incapable of general application. Nevertheless, railways had hardly been established on low lands before men’s minds ran upon constructing them over mountains. It is now fully twenty years since the first idea of placing an iron road upon the bed of one or more of the carriage roadway passes of the Alps was promulgated. Of course it found favour, and created interest. Nor can this be matter[6] of wonder when we remember that communication across them has, for centuries, been of world-wide importance. Even if we study the traces that still exist of man’s earliest history in mid and southern Europe, we find that the passage of the great barrier which for more than 500 miles separates north from south, had occupied men’s thoughts and actions from the remotest period. Etruscan tools, coins, and sacred images, have, as we learn from Dr. Ferdinand Keller’s recent work on the Lake Dwellings of Switzerland, been found frequently and in abundance, not only on the northern slopes of the actual Alps, but far northward beyond them. We know too, that the ancient Helvites and Gauls were ever seeking the traverse of the snow-capped mountains, that they might exchange their own cold and sterile plains for those on the sunny side, which gave them warmth and luxurious cultivation. By degrees, the early few, savage, daring, and intrepid, increased in numbers; they became masses,—they became colonies. They obtained possession of, and held the districts which in modern times we knew as Venetia, Lombardy, and Savoy; but now they form the northern boundaries of undivided Italy.

In the early Roman period, the northern limit of Roman territory extended to the Po, and no farther. Beyond was Cisalpeà, and so it continued until Augustus Cæsar Imperator finally subdued, some thirty years before the birth of Christ, the whole of the warlike tribes, and brought them under Roman subjection. History records but one solitary instance of the vanquished erecting a monument to do honour to their conqueror. This was at Susa, and the inscription on the Porta Cæsaris Augusti tells us why it was erected, and what deed it was intended to perpetuate.

Hannibal’s was the first army that made a passage across[7] the Alps, but the exact part at which he effected it is still matter of historic doubt. The balance of worthful opinion is however strongly in favour of its being by what we now call the Pass of the Little St. Bernard. The army would appear not to have been subjected to great difficulties in reaching its summit, notwithstanding that the 19th of October is believed to be the day on which the ascent was commenced, but the horrors to which his hourly thinned ranks were exposed, all occurred after they had attained the summit, and were within sight of the plains in which the autumnal foliage still spread a rich and glowing landscape before them. That some few of the army of ninety elephants with which Hannibal started from Spain completed the Alpine traverse is more than probable, but that one accomplished it is undoubted, for we have it on record that the Carthaginian General crossed the marshes of Clusium (which will be traversed by the railway train of the new and comparatively shorter line between Florence and Rome, to be opened for traffic a few months hence) upon the only elephant that was still spared to him.

Brockedon, whose illustrated work on Alpine Passes was published in 1828, states that there were ten passes traversable as carriage roads. The actual number has not been added to since then, but the trackway along many of the other passes has been greatly improved, and many, that at that period were only dangerous and very narrow mule paths, have now become available for chars, and possess other facilities and accommodation for traversing them that were quite unknown forty years ago. A very brief recapitulation of them may not be inappropriate. More full details of them can be obtained in The Alps and the Eastern Mails, a little work which we published a few months ago.

Commencing at the extreme west, we find the Col di Tenda, an easy pass for three-fourths of its ascent, when the mountain abruptly assumes a cone-like shape, and in a space of some two miles and a-half, rises on one side 1,200 feet. The descent on the other is of nearly equal length, and is nearly equally precipitous. Next comes Mont Genevre, the lowest of the Alpine passes that verge upon the Mediterranean. It is but a short giant’s step from Mont Genevre to the Mont Cenis. Next after, comes the Little St. Bernard, perhaps the easiest of all the passes over the Alps that connect important places together, for the construction of a carriage roadway. Napoleon, however, did not view it in this light, his great roads, being the Mont Cenis and the Simplon. Before we reach this last-named pass, we have that of the Great St. Bernard, one of the loftiest in the whole range, being in immediate proximity to the three highest mountains in Europe, Mont Blanc, 15,732 feet above the level of the sea, Mont Rosa, 15,130 feet, and Mont Cezvin, 14,835 feet.[3] It was by the Great St. Bernard that[9] Napoleon crossed with an army from Switzerland into Italy, in the winter of 1800, and, by a fall from his mule, narrowly escaped being hurled from the precipice of St. Pierre into the abyss beneath it.

Next after the Simplon comes the St. Gothard, and then[10] the Lukmanier, although this last can hardly be called a carriage roadway pass. Further east is the Bernardino. The easternmost pass between Switzerland and Italy, is the Splugen. There are as many as twenty passes available for mules and pedestrians between the Splugen and the next carriage road across the Alps, but they are only to be traversed by the knapsack tourist, who combines within himself vigorous health, activity, and endurance.

The Stelvio, the highest carriage road in Europe, 9,272 feet at its summit above the level of the sea, is, at that point, nearly 400 feet higher than the line of perpetual snow. It was constructed by the Austrians to give them direct access from Austria proper to Lombardy. The object in making it was political and military, not commercial; and now that not only Lombardy, but Venetia have become Italian, it is probable that a road, which in magnificence of conception and in grandeur of construction, exceeds even the Simplon, and which could only be maintained at great annual cost, will fall into decay.[4] For all the practical purposes of commerce it is useless, as within a short distance from it is the Brenner, the oldest, and at the same time the lowest carriage road across any of the Alpine passes. It has, in fact, been for centuries the trackway that has connected eastern and southern Germany with Lombardy and Venetia. It likewise can lay claim to the distinction of being the first pass that was made fit for the transport of carriages and of other vehicles, for it was certainly available for them, and was a good carriage road in the early part of the eighteenth[12] century. It was just one hundred years later, that is in 1809, that those deeds of daring and devotion were achieved in the defiles of the Brenner, which have rendered undying the name and fame of Andreas Hofer.

With all Austria’s arrierreism in politics, she is in the foremost rank of continental nations, as regards the world’s modern civiliser, the Railway. She was next after Belgium in determining upon their construction, and although Prussia anticipated her as regards actual opening, railway works have been accomplished within the Austrian dominions, the like of which cannot be seen within those of her great rival, no matter whether these dominions belong to her de jure divino, or by that of conquest.

To Austria, undoubtedly, belongs the honour of having constructed the first, which until the 18th of August, 1867, was the only iron road traversed by the locomotive through an Alpine pass. At a heavy expense it is true, for the cost of the double line over the Sœmmering was at the rate of £98,000 an English mile. The great line of railway which connects Vienna with its sea port Trieste, now more important and valuable to Austria than ever, is 362 miles long; and at Glognitz, exactly forty-seven miles from Vienna, the pass commences. Although the actual distance from one foot of the pass to the other is not more than sixteen miles, the length of the railway, owing to the numerous twists and zig-zags it was necessary to make to overcome the elevation with gradients that the engine could climb up, is twenty-six miles. Yet, in this short distance, there are no less than twelve tunnels and eleven vaulted galleries, the aggregate length of which is 14,867 feet, or nearly three miles. The longest tunnel—4,695 feet—is at the summit, which is 2,893 feet above the level of the sea. The gradients vary from 1 in[13] 40 for two miles and a-half to 1 in 54 for three miles and a-half. The average gradient is 1 in 47 on the north side, and 1 in 50 on the south. The foot of the mountain is 1,562 feet above the sea. The elevation to overcome was, therefore, only an average of 112 feet to the mile; nevertheless the difficulties in working the traffic have been very great. It was a considerable time before the present form of engine was adopted by M. Engerth, the locomotive engineer of the line. Its total heating surface is 1,660 square feet, its total weight, when filled with water and loaded with fuel, is fifty-five tons and a-half. This unfortunately is a weight most destructive both to rail and to roadway. The cost per train mile run averages 6s. 2d. the English mile down the pass as well as up it, whilst the average cost on the ordinary portions of the line is under 3s. per English mile. The time allowed for passenger trains is one hour and fifty minutes, being an average of fourteen miles an hour; for goods trains, two hours thirty minutes, or at the average rate of about ten miles an hour.

There was until just recently, a race running between the engineers at the Brenner and at the Mont Cenis, and it was, until the beginning of August, 1867, uncertain which of them would have the honour of being the second railway upon which the locomotive had crossed the Alps. But the Brenner has won by a length of eight days. The two lines differ in several respects, both as regard construction and working. The Brenner does not take a portion of the existing road for its road-bed. This is formed in the ordinary mode of construction; the company has made its own bridges, culverts, and viaducts, its own embankments and cuttings, its own tunnels and galleries, and in this way it has succeeded in constructing a railway of much less elevation at its summit[14] than the adjacent carriage roadway. It has done so, however, at great cost, but it is anticipated that the saving in working charges will more than compensate for the additional outlay which this species, as it were, of independent construction has rendered unavoidable. The line will be worked on the ordinary system, that is, with engines and other rolling stock similar to those on the plain, with the exception that the engines must and will be of great additional weight, to give them the power and adhesion required to overcome the very severe gradients they will have to contend against. “The opening of the Brenner Railway,” says the Times, “places not only Austria, but Bavaria and all Southern Germany, almost in contact with Lombardy, Venetia, and all Northern Italy. It recovers all the importance that the Brenner Pass possessed from the remotest Roman and Germanic ages, as the most direct and easy route across the main Alpine chain, as the natural highway from the Valley of the Inn, to that of the Adige, and which constituted it the key to the strong position of the March of Verona, which the Germans, from its erection into an imperial fief, under Otho I, in the 10th century, denominated ‘the Gate of Italy.’”[5]

Previous to describing the Mont Cenis Railway, we will ask the reader to place himself mentally with us in the train belonging to one or other of the two railway companies which, leaving the great British metropolis at four different points, Charing Cross or Cannon Street (South Eastern), Victoria or Ludgate Hill (London, Chatham and Dover), arrives by either route at a point common to both—the Admiralty Pier, Dover, in two hours and five minutes from the time of its departure. The South Eastern Company carries the land mails, both ordinary and extraordinary, as well as the bulk of the passengers; on the other hand, its rival carrying fewer passengers, and the distance being ten miles less, almost invariably arrives first at the Admiralty Pier, and thus enables those whom she (ships, trains, and locomotives are of the feminine gender) conveys, to secure some of the sofas, reclined upon which, the ceremony of seasickness can (as we know well, by great and varied experience) be performed with far greater ease, grace, precision, and satisfaction, than by him or her who is destined to perform it sitting or standing. At the time that the traveller touches terra firma at Calais, he has completed 110 miles of journeying, if he have travelled by the South Eastern Line, ten miles less, if he have committed himself to the London, Chatham and Dover. The original railway distance from Calais to Paris was 236 English miles, but thanks to two shortenings, the first between Creil and Paris, the second[16] between Hazebrouch and Arras, by which latter the detour to the neighbourhood of Lille was avoided, the length was diminished to 203 miles; and now, since the opening of the line between Calais and Boulogne, in April of the present year, the mail trains take this route to and from Paris, by which a further saving of seventeen miles is obtained, making the present distance between Calais and Paris 186 miles.

Our mental traveller having arrived at Paris, will need a pause, and whilst he is supposed to be refreshing himself, with a good dinner, at one of the innumerable restaurants to be met with at every corner, we will ask permission to occupy the time by giving, in the first instance, an epitome of the story of four great giants of modern times—the four longest and most important railways that science, practical skill, and money have as yet created on the European side of the Atlantic; and then we propose to show, by a general reference, how wonderfully and rapidly the railway system has already extended, and still continues to extend, in various parts of the globe. Eventually, most railways will have to yield the palm—at all events, as regards wonderful accomplishment—to the Great Pacific Railway, to which, therefore, we beg leave to accord precedence in our descriptions.

CHAPTER II.

UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD—SOUTH AUSTRIAN AND ALTA ITALIA—PARIS, LYONS, AND MEDITERRANEAN—ORLEANS—MILEAGE, COST, AND RECEIPTS OF FRENCH RAILWAYS—LONDON TRAFFIC—LONDON AND NORTH-WESTERN RAILWAY.

From the day that the Americans became masters of California, they had always had it in their heads to join it by the best possible roadway to the old states of the Union; and it was a grand conception, for the distance between the railways of the valleys of the Mississippi and the Missouri, that here had stretched their arms outwards towards the West, were still separated from the Pacific by fully 2,000 miles—as near as can be the distance which intervenes between St. Petersburg and Lisbon. Fremont—then captain, now general—a few years back nearly President of the Republic—son-in-law of Benton, one of America’s most worthy sons—traversed, with a few companions, in 1847, the desert that led to the Rocky Mountains, found out the passes through them, as well as those of the Sierra Nevada (the Snowy Mountain), and arrived in California just as his countrymen were taking possession of its territory. It was at the same time that the first golden nugget was discovered. The news spread, and a party of emigrants followed Fremont’s footmarks. Those who arrived in California left the bones of many of their comrades to whiten and then to moulder in the desert, and it was nearly six months before the survivors reached the El dorado. Similar casualties beset the parties that followed the first gold-seeking pioneers, for the same spirit which makes every American believe that he[18] may be President of the United States (therefore no American ever commits suicide), made each survivor of each party, as its ranks were thinned by famine, fever, and the attacks of the Red Indians, believe that he, at all events, would be spared and arrive at last at his destination.

But some did arrive, and by degrees the perils of the route diminished, although they have never, even at this day, altogether ceased. In less than ten years from the date that Fremont first set out on his expedition, a regular Overland Mail had been established, which completed its journey between San Francisco and St. Joseph, both for passengers and despatches, in three weeks. A grand total distance of fully 2,000 miles, on the average 100 miles in each twenty-four hours, of course some days more some days less, for independent of nature’s road on the desert, no less than two mountain passes had to be surmounted, and on these there was not, in the first instance, even a bridle-way. This pace, however, was considered too slow, at all events as regards correspondence. The “Pony Express” was thereupon inaugurated in 1860, by which time the system of eastern railways had extended 400 miles more towards the west than what they were in 1858, consequently diminishing roadway distance to 1,600 miles. This ground was got over in the marvellously brief time of six days, or at the go-a-head, we might almost add “helter skelter,” rate of 265 miles a-day! The rider performed no greater journey each day than his horse. The latter set off on a gallop and never ceased his fifteen to twenty miles, except when, as occasionally, although not frequently, happened, Red Skin stopped the way, sent the rider to his long account, and then quietly rode off on the dead man’s horse, which he claimed as his trophy. On the 12th of November, 1860, the courier rode[19] into San Francisco with news from Europe of no longer date than the previous 21st of October. Even this speed did not satisfy; the telegraph was therefore laid the whole way across the American continent; and now, thanks to the Atlantic Cable, and to difference of longitude, the merchant of London can tell his correspondent at San Francisco, events that have happened twelve hours before the same hour has arrived in California. Unfortunately, however, for California, notwithstanding that the normal speed of electro-telegraphy is 280,000 miles a second, she is unable to let us know her news here in less than some twenty-four hours after its occurrence.

In 1862 President Lincoln signed the Act of Congress for “The Union Pacific Railroad Company.” Forthwith its works were commenced. Where? At two points:—The eastern, at Omaha, near the confluence of the Missouri River, with that of the Platte, or Nebraska, in the state of Nebraska, latitude 41° north, longitude 19° west, of Washington. The line follows the course of the river to the Rocky Mountains, which it climbs up until not far from the summit of the Bridger Pass, due west of Omaha. A tunnel not more than 500 yards in length carries the line into Utah. In this territory it passes by Salt Lake and Salt Lake City, head-quarters of Brigham Young and his Mormons; thence to the state of Nevada, as rich in silver-yielding mines as those in California are in supplying gold. No wonder, then, that its capital—Carson City—should now have a population of 15,000, although, seven years ago, there was not even one inhabitant to boast of. At the passage of the Sierra Nevada there will also be a tunnel 500 yards long. Thence to Sacramento, and from there, it will wend its way close to the river of the same name, and find itself at[20] San Francisco. This is not only its extreme western, but it is also its extreme southern point, for, in coming west from the Bridger Pass, the latitude changes from 41° to 38° 20″; and it is from San Francisco that the western works commence and proceed easterly to meet, at some point as yet uncertain, those advancing in the opposite direction. They are already at the eastern foot of the Rocky Mountains, 500 miles from Omaha; and on the Pacific side, they have reached the western slopes of the Sierra. Therefore, already more than a third of the whole line is accomplished. On the plain, progress is made at a rate that would astonish the European engineer, for the Americans are satisfied with the road bed such as nature has made it; and thus it is no uncommon thing to lay 2½ miles of the railway in a single day! As the road advances, so do the locomotive and the train, but not always with the most perfect safety, for the Indians have now learned to do wholesale what they only did isolately upon the riders of the Pony Expresses,—witness the following paragraph from the Times of no later date than August 31 of the present year:—

“A correspondent of the New York Tribune says that the Indians are out in strong force, and have begun the war in earnest. A strong force of savages laid ties on the track of the Union Pacific Railroad, six miles west of Plum Creek, and a valuable freight train was ambushed and upset. The engineer, fireman, two breakman, and three telegraph repairers were killed. The Indians burned eight cars, and completely destroyed a great deal of valuable merchandise, valued at 30,000 dollars. The savages burned the train, killed and scalped seven persons, and threw the slaughtered bodies into the flames of the burning cars. The conductor of the train narrowly escaped, and rushing back along the track, met another freight train, which he signalled. The train was stopped, and he was taken on board, after which the train returned to Plum Creek. The affair has created great excitement, and there is a general alarm along the line of the railroad, now that the Indians have discovered the means of arresting its traffic.”

No doubt the alarm is general along the line, but it will die out, for as a writer in the Revue des deux Mondes, to whom we are indebted for many of the facts we have just stated, says:—“En beaucoup d’endroits, le terrain a êté si bien nivelé par la nature, qu’ ou ne voit de quel coté il penche, et que les rails se posent sans aucune fouille sur le sol. Pas de grandes riviers a franchir, pas de torrens impetueux a dompter. Le seul enemi de la voie, est que sur quelques points, heureusement isolés, du desert, ou manquent l’eau et le bois, domine le peau-rouge, vagabond, et chasseur, adversaire-né du colon stable: mais le bois et l’eau, on les apporte, et quant a l’enfant des Prairies, il disparaitra et s’eteindra, bientot, devant l’homme civilisé. C’est la, une des lois fatales du progres; elle se verifie partout ou se presente l’Europeen.” Too true.

And who are making the railway? On the East they are all Irishmen. As each half-mile of it, or so, is made, they march along with it towards the West, with their wives, their children, their wooden houses rolled along on wheels, and their domestic animals—cats, dogs, goats—the more ambitious, have occasionally a cow, the richest of all can sport a little pony. When the day comes for the meeting of the two railway ends, the Irishmen will find that the fellow-labourers who have come to greet them are to a man “John Chinaman,” for none others work on the Pacific side of the railway.

Its total cost is to be £30,000,000 sterling—£16,000 a mile. Of the gross sum, one-third is guaranteed by the United States Government in money, in addition to the concession of immense tracts of land on each side of the railway. The state of Utah, or rather the individual Mormons, are good for £4,000,000, and private speculation furnishes the[22] remainder. Of the mighty company which carries out these works, General John A. Dix (now United States Minister in Paris) is president; and in Colonel Heine (an attaché of the Embassy) the Company has a warm, zealous, and active friend. We have said already that a third of the railway is already accomplished. By 1870, probably—by 1871, certainly—it will be finished in its entire length. New York will then certainly associate itself with Jeddo and Canton by this route; but not so London, Paris, and other parts of Europe. The writer in the Revue des Deux Mondes says, that, on the completion of the railway, Europe will only be one month from Canton. Let us see:—London to New York, ten days; New York to San Francisco, 3,000 miles, at 20 miles an hour (all stops and delays included), 150 hours—six days and a quarter; San Francisco is from Canton, even by great circle sailing, exactly 6,900 nautical miles. No paddle-wheel steamer could take coals for such a voyage; a screw vessel of very large size, but depending mainly upon her sails for her speed, might make twelve, but very probably would not average more than ten, knots an hour, yet, at the former rate, her passage would be twenty-five days—total, forty-one days and a quarter; at ten knots an hour, the passage would be nearly twenty-nine days, or a total of forty-five days. The Mail now goes from London to Canton in fifty-two days; in 1871 the journey will be six or seven days shorter. The route to Jeddo viâ San Francisco will be quicker than that viâ Suez by seven or eight days, even under circumstances the most favourable for the latter route. By great circle sailing, San Francisco is distant from Jeddo 5,600 knots, and it is also eleven degrees farther to the north than Canton. These eleven degrees of north add 600 miles more in favour of San Francisco.

The longest of all European railways is nearly half Italian, and a little more than half “South Austrian.” It is called in France “Sud, Autrichienne et Haute Italie.” In Italy the two last words are converted into “Alta Italia.” The total length is now 2,565 English miles, of which the South Austrian portion measures 1,349, and the Italian 1,216. The two next longest railways of Europe are French. The Paris, Lyons, and Mediterranean Company has a length of railway, in France, of 2,234 miles, and in 1864, it adopted a translitoral little son, which is known by the name of the “Algerian Railways.” At present the gentle youth is of modest proportions, only thirty-one miles open for traffic, eighty-one to be opened in the present year; and of the remaining 264 which are to constitute its full grown mileage (376 miles), little more work than “etudes preliminaries” has been bestowed upon them. At the period of the greatest growth of the Algerian railway, it will never be more than a pigmy as compared with its adopting parent.

The railway that in mileage comes next in succession, is the Orleans Company. Its length is 2,052 miles. The last of the four railway giants, is our own English giant, the London and North-Western. Now, although the length of our countryman is the least of all—only 1,320 miles—it will nevertheless be seen hereafter, that in its other dimensions it is in most respects superior, in none inferior, to its continental brethren, just as the late Mr. Thomas Sayers was less in height and length of arm than Heenan, nevertheless, in the long run, he managed to beat him.

The two extreme western points of the mighty system of the South Austrian and Alta Italia are at Susa, at the foot of the Mont Cenis Pass of the Alps, and Cuneo at the foot of that of the Col di Tenda. Its two eastern are Vienna,[24] and still farther (by means of its Hungarian net-work to the southward of Vienna), Pesth. Its northern is Kutzen, about a hundred miles to the south-east of Munich. Its southern, Pistoja, is twenty-two miles to the north-east of Florence. It possesses railways across two of the passes of the Alps, the Sœmmering and the Brenner. Its stations are at Genoa, Turin, Milan, Innspruch, capital of the Tyrol, Verona and Venice, Trieste, Vienna, and Pesth. It is equally fitted (as it has proved itself to be) for a great military railway, and for one to be devoted only to commercial and industrial development, but it has its skeleton in its closet,—it is not at Florence, capital of United Italy, nor is there prospect of its being there, except by a combination which shall unite with it the whole of the Strade Ferrate Romane, of which some particulars will be given hereafter.

The course and direction of the Paris, Lyons, and Mediterranean, of the Orleans, and of the London and North-Western Companies, are, as there can be no doubt, sufficiently known to our readers to render description of them unnecessary. The great port of the Paris, Lyons, and Mediterranean is Marseilles, the Liverpool of the Mediterranean, 537 miles from Paris, and 833 from London. The chief port of the Orleans Company is Bordeaux, 366 miles from Paris, 662 from London.

Before proceeding farther, let us refer, very briefly, to the early history of railways in France.

Neither the French Government nor the French people seemed to feel much interest about their construction until long subsequent to the opening of several hundred miles of them, both in Belgium and in Germany. The nation, was not, however, altogether ignorant of their existence, for tramways had been used in the Mineral Districts of St.[25] Etienne, and near to the Banks of the Loire, for many years previously. They were, for the most part, worked by horses, but in some few cases by locomotives of the rudest construction, just as happened in our own coal districts in the North of England, previous to the epoch of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Dr. Lardner, in his Railway Economy, says that “to M. Emile Pereire is due the honour of having first impressed upon his countrymen the advantages which must arise from the adoption of this mode of transport.” With much difficulty he succeeded in forming a Company for making the short line between Paris and St. Germain. The Act for its construction was obtained in July 1835, and it was opened for traffic in December 1837. It was originally, in part, worked as a locomotive line, and partly on what was known as the atmospheric system, but for the last five or six years the traffic is carried exclusively by means of the locomotive. Its length is thirteen miles, and it now forms one of the “Lignes de Banlieue,” of the Western of France Railway Company. (Chemin de Fer de l’Ouest.)

But it was not until 1837 that the importance of France having a net-work throughout the Kingdom was appreciated. In that year a Royal Commission Avas appointed, which made its report in 1838, but owing to internal jealousies and other causes, the recommendations of the report were not adopted, and the Government of the day had to submit to defeat upon them.

In 1838, what is now the Great Orleans Company obtained its first concession, which was for a Railway to extend from Paris to Orleans. Powerful and elongated as the Company now is, it had, in its early career, to undergo much financial difficulty and embarrassment, and it was only owing to the Government coming to its aid, by guaranteeing four per[26] cent. on its capital, that the Company was able to complete and to open the railway for traffic.

A concession was given to the Paris and Rouen Company in 1841. The line was opened for traffic on the 9th of May, 1843.

The Fundamental Law for the construction of French Railways, and for the subsequent administrative surveillance of them by the Government, was passed on the 11th of June, 1842.

By this law France was to possess seven main arterial lines of railway, all of which were to start from Paris as the concentric point. The first was to take the direction towards Belgium, so as to meet the railways then opened in that kingdom, approaching the French frontier. The second, part of which was to be in common with the first, was to proceed towards Calais or Dunkirk; Calais was selected as the most convenient for traffic with England, and the line to Dunkirk, twenty-five miles long, which branches off at Hazebrouck, was not constructed for several years after the main line had been completed. We remember Hazebrouck, a mere road-side stopping place, but it has of late become a first-class junction station, for in addition to the Dunkirk line diverging here, it is also the junction (bifurcation) at which the line leading to Lille, and to Brussels separates from those that run to Amiens, one viâ Douai (the old road), and the other, viâ Bethune, constructed to shorten the distance between Paris and Calais by twenty miles, and also to give railway access to the recently-opened collieries in the vicinity of Bethune, Nœux, Chocques, &c.

The third arterial line was to run towards the ports on the Bay of Biscay, from the Loire to the Gironde. The fourth was to extend to Bayonne and thence, eventually, to the[27] Spanish frontier. The fifth was to be common to the fourth, and then to follow a course tending towards the Mediterranean, passing through Toulouse and finally arriving at Perpignan, close to the Spanish frontier, and at the foot of the Pyrenees, not much farther removed from the Mediterranean than Bayonne is from the Bay of Biscay. It is but within the last few months that this line has been completed in its entire extent; the line to Perpignan having only been opened for traffic in September last.

The sixth was the great and important arterial line from Paris through Dijon, Chalons, Macon, Lyons, and Avignon, to Marseilles. The seventh, or last, was the important strategic and commercial line that was to connect Paris with Strasburg and the Rhine.

Of course, since the first conception of these seven arterial lines, modifications in the exact direction of several of them have taken place, but in the main they follow the courses originally proposed and afterwards decided upon. It will be unnecessary to record the various difficulties, financial and administrative, which attended the construction of the first net-work of French railways. Suffice it, therefore, to say, that by the end of 1847, 1,750 miles had been completed, and that by 1853, the essential parts of the whole system were finished. These have been followed by the “new” net-work, and the total mileage of French railways at present is 14,382 kilometres, or, 8,989 English miles.

This digression finished, we proceed to state the cost at which each of the four European leviathans of the railway world have been constructed. The capital expenditure of the South Austrian and Alta Italia, up to the 31st December, 1866, was £41,763,301, or at the rate of £18,200 a mile. Capital expenditure on the Paris, Lyons, and Mediterranean Company is nearly double that of the South[28] Austrian and Alta Italia, being £80,922,000, which brings the cost per mile to £36,218. This expenditure is exclusive of £1,740,202, upon the Algerian lines, making the company’s total capital expenditure to the 31st December, 1866, £82,662,202.

As the total length of French railways was, on the 31st December, 1866, 14,382 kilometres, or 8,989 miles, and the total capital expenditure upon them to that date was £306,089,000, it follows that the Paris, Lyons, and Mediterranean Company is one-fourth in length, all but twenty-eight miles, of the total railway mileage of France, but its gross cost has exceeded one-fourth of the total cost of French railways by £4,399,500, and its cost per mile, being £36,218, it has exceeded their average cost per mile (£34,051) by £2,167.

The capital expenditure of the Orleans Company has been £42,944,862, or at the rate of £20,928 a mile, which is £13,123 per mile below the average cost per mile of French railways. In addition, the company is proprietor of the coal and iron mines, and the Iron Works of Aubin, at a cost of £671,216. 194,694 tons of coal were raised there in 1866, of which 43,200 were used by the company’s locomotives, 16,000 were sold to the public, and the balance was consumed in the iron works, which manufactured 22,021 of rails during the year.

The total expenditure on capital account of all the railways of the United Kingdom up to the 1st January, 1866, was £455,478,143.

On the London and North-Western the expenditure on capital account has been £45,576,361, but a subdivision of this capital by the mileage worked by the company would not represent the cost per mile of the railway as the company is subscriber to the capital of other companies[29] (some of which are worked by it and some are not) for £3,556,969, but this amount hardly represents a tenth of the capital expended by those companies. There is no doubt however that the cost per mile of those lines for which the capital was exclusively provided by the London and North-Western Company exceeds £50,000 a mile.

The gross receipts from traffic for the year were, South Austrian, £2,957,713, Alta Italia, £1,738,202, total of the Company, £4,695,915; average weekly receipts, £90,306; per mile per annum £1,932. Paris, Lyons, and Mediterranean, total traffic £8,105,776; average weekly receipts, £155,691; per mile per annum, £3,640. As the total traffic receipts of French railways was, approximately (but the figures are very nearly exact) £24,140,000, it follows that the receipts of this company exceeded one-third of the total railway receipts of the empire by £101,110, and that its average weekly receipts per mile exceed the average weekly receipts per mile of all France (£2,865) by £955.

The traffic receipts of the Orleans Company, for 1866, were £4,401,894; average weekly receipts, £94,267; per mile per annum, £2,189, or £496 per mile per week below the receipts per mile per week of the total French railway system. London and North-Western, £6,312,056; average weekly receipts, £120,400; per mile per annum, £4,782.

Owing to the war in Italy in 1866, the tables connected with the passenger traffic of the Alta Italia are defective, but of the 7,858,893 passengers carried on the South Austrian in 1866, 1 per cent. only were first class, but they yielded 5 per cent. of the passenger receipts; 12 per cent. in number were of the second class, they yielded 19 per cent. of the receipts; the third class were 87 per cent. in number and 76 per cent. in receipts.

The number of passengers carried on the Paris, Lyons, and[30] Mediterranean was 18,443,597, of which about 6 per cent. in number were first class, 13½ second, and 80½ third.

This total number represents between a fourth and a fifth of the gross number carried in France during 1866—about eighty-four millions—and is in no way in accordance with its proportion, either as regards its gross receipts or its gross mileage, the former being, as just stated, more than a third, and the latter one-fourth of the total railway receipts and mileage of the empire; thus showing that the principal traffic of the Paris, Lyons and Mediterranean Company is long traffic; in this respect very strikingly resembling the traffic of the London and North-Western Railway Company. According to the testimony of M. Charles La Vollée, furnished in his very interesting work, “Les Chemins de Fer en France,” Paris, 1866, the average distance travelled by each passenger on French railways in 1865, was 40 kilometres (25 miles); average distance of a ton of merchandise, 140 kilometres (87½ miles); but as the average price of passenger travelling of all classes in France is only 5½ centimes per kilometre, equal to 9½ centimes per mile: of goods per ton, 6½ centimes per kilometre, equal to 10½ centimes per mile, it follows that each passenger and each ton of goods travels on the Paris, Lyons and Mediterranean Railway nearly double the average distance on all French railways. According to the investigations of M. La Vollée, the average cost of all three classes of passengers in England is 14½ centimes, or 1⅜d. per mile; goods precisely the same per ton. This gentleman makes the following calculation with regard to the saving effected in consequence of the substitution of railways for diligences in travelling. The latter, he says, sped their way at the rate of 6¼ miles an hour. Railways go at the rate of 25. For each of the 80,000,000 who were carried on French railways in 1865, there is a saving of 10[31] sous an hour, equal to 112,500,000 francs, or £4,500,000, and upon the transport of goods there would he a saving of ten millions sterling, supposing that all goods now carried by railway were to be carried by road.

The construction of railways cheaply in France is now occupying attention. A railway on this system was opened on the 25th of August last—the line from Fougères to Vitré, on the Chemin de Fer de l’Ouest. Its length is 23 miles, and it has been constructed for £100,000, or at the rate of £4,348 a mile, notwithstanding the fact that it is carried through a difficult country, necessitating numerous heavy works, the greatest of which is a viaduct constructed of granite 120 yards long, and 22 yards high. The rails are Vignoles pattern, 60 lbs. to the yard. The above price includes rolling stock, shops, and their equipment, &c. But everybody received “argent sonnant” as the works progressed, and the line was not opened until everything had been settled up and paid for. This is one of the secrets appertaining to the economic construction of railways.

On the Orleans Railway, 9,630,460 passengers were conveyed in 1866: of which 7½ per cent. in number were first class, 14½ per cent. second, and 78 third.

Before quitting the subject of French traffic receipts, a word must be said about a little railway which appertains to the most stately city in France—Lyons—until a few years ago, when Marseilles superseded it,[6] the second in commercial[32] importance, the second also, not long back, in revolutionary susceptibility, yielding only in this respect to the once great head quarters of rebellion, barricades, and insurrection, Paris. As it is some years since our last visit to Lyons, an accident alone put us upon the track of this railway. We looked for some account of it in that great compendium of hotel-keepers’ advertisements, Bradshaw’s Continental Guide, (lucus, &c.), but, of course, not a word is said about it, and we are bound to record the same omission in the (with this exception) admirable “Indicateur des Chemins de Fer, et de la Navigation”, published weekly by Messrs. Chaix & Co., of Paris. Thanks, however, to “my Murray,” we discover the “Lyons-Croix Rousse” runs from the heart of the city to the Croix Rousse, the former hotbed of insurrection, and “inhabited principally by silk-weavers who live in densely crowded narrow streets, where twelve to twenty families are piled, one above the other, in the lofty houses.” But these revolutionary silk-weavers must be a grand moving population, for although the line is stated in the Moniteur des Interets Materiels, a weekly journal which treats, according to the words of its title, upon “tout ce qui a rapport au bien-être general, hormis la politique,” to be only 587 yards long, it had a daily traffic in 1866 of 666 francs, equal to 243,093 francs, or £9,723 per annum! The company has paid off all its debenture debt, and its modest share capital receives the benefit of all profits. What they are, however, is a mystery, for the directors have, in their wisdom and discretion, never thought fit to publish them.

Our Gallic neighbours lodge their Sovereign, his Empress, and his suite, in palaces replete with magnificence and luxury, and when he travels, they are equally mindful of his dignity[33] and of his comfort. Witness the following description of the imperial train in which the Emperor and the Empress went from Paris to Salzburg to visit the Emperor and Empress of Austria, in August last. It may well he said that it exceeds in comfort and elegance any previous equipment of a similar nature. It consists of nine carriages, communicating with each other by tastefully decorated bridges. In the middle is a handsome sitting-room, furnished with chairs, ottomans, pictures, clocks, and chandeliers. On one side of this room is the dining-room, and on the other the Emperor’s study. In the middle of the dining-room there is a table capable of being extended or contracted at pleasure, with easy chairs placed parallel to the sides of the carriage. The Emperor’s study contains an elegant writing-table, a clock in the style of the renaissance, a thermometer, a barometer, and a telegraphic apparatus, by means of which telegraphic communication is established with the several apartments of the various court officials travelling with His Majesty. Next to the study is the bed-room of the Emperor and Empress, with two beds placed transversely against the sides of the carriage. Two dressing-rooms are attached to the bed-room. The remaining carriages consist of a kitchen, wine cellar, and the apartments of the imperial suite. There is also a conservatory for the choicest flowers.

Our own gracious Sovereign travels in her journeys to and from Scotland with great comfort, but without the extent of magnificence above depicted.

Proportioned to the passenger traffic of other English railways, the London and North-Western Company is deficient as regards numbers, for although it has on its system Birmingham, Wolverhampton, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, and almost all the leading manufacturing bee-hives in the[34] north of England, it is the sole railway having its terminus in London, that does not encourage short local and Sunday traffic. Nevertheless the number of passengers carried on the London and North-Western in 1866 was 20,811,173, which however is less than a tenth (excluding the holders of 97,147 periodical tickets) of the total number (251,862,715) conveyed on all the railways of the United Kingdom in 1865. The returns before us do not enable us to state the relative proportions of classes of passengers carried by the London and North-Western, but, at all events, we know that they exceed two-thirds of the population of Great Britain and Ireland, which, according to the estimate of the Registrar-General, published a few days ago, was 30,157,239 in June, 1867. The estimated population of London and of its suburbs, comprised within a circle of twelve miles from the General Post Office, St. Martin’s-le-Grand, is, at present, 3,521,267, which is more than the population of half-a-dozen German Principalities;[7] more than half that of Ireland,[8] and equal to that of all Scotland. Those desirous of knowing the component parts of the metropolitan population, and how it is distributed over its area of 687 square miles, are[35] referred to the recently published vigorous and able statistical vindication of the City of London,[9] by its distinguished and learned Chamberlain, Mr. Benjamin Scott.

Here let us indicate a few facts illustrating the motive habits of the immense London population. In the twelve months ending the 30th of June, 1867, the number of passengers conveyed on the Metropolitan Railway—4½ miles in length—were 22,458,067, or 1,646,894 more than on the whole system of the London and North-Western Railway in 1866. In the same twelve months, the London General Omnibus Company, which owns about seven-eighths of those vehicles that ply in the metropolis, carried 42,995,910. These, independent of steam-boat passengers, the number of which we are not able to state, our application to the secretary of one of the companies for information not having been replied to; independent also of the persons who travelled in the 6,000 cabs that are licensed for London, and independent, finally, of the persons conveyed in the innumerable vehicles which are unceasingly circulating[36] during about sixteen hours every day through every portion of the great metropolis.[10]

Mr. Watkin, M.P., the chairman of the South-Eastern Railway, gave, at the recent meeting of the shareholders of[37] that company, a very striking illustration of the motive habits of the metropolitan population. During the half-year ending the 30th June, 1867, the total number of passengers conveyed on the South-Eastern Railway was 9,700,000, but of these 7,200,000 came into or went out of its three London stations (Charing Cross, Cannon Street, and London Bridge—the traffic of the last immensely diminished since the opening of the two first), yet the total length of the South-Eastern is 330 miles, and in the usual proportion of stations to mileage on English railways (one for each 3¼ miles) the number of stations is 101. Although we have not the exact figures before us, we believe the same proportions, as regards passenger traffic, holds good on the London, Brighton and South Coast, the South-Western and the Great Western Railways, and nearly so on the Great Eastern and the Great Northern.

The rolling stock of the South Austrian and Alta Italia consists of 963 locomotives, 2,663 passenger carriages, in which are included 11 for the exclusive use of royal personages, 19,182 waggons, in which are included 57 for the service of the Post. Its total mileage of train engines 10,451,870. The amount of rolling stock of the Paris, Lyons, and of the Orleans Companies is not stated in their reports, but the total engine mileage of the former company in 1866 was 17,271,502 miles, of which 9,656,690 were for passenger trains, and 7,614,812 were for goods, cattle, and coal trains; of the Orleans Company 10,715,458, of which 5,878,010 miles were for passenger trains, and 4,837,448 for goods, cattle, and coal trains.

We are not able to state the total mileage of the trains of French railways, but it will be seen by reference to the Annuaire des Postes de l’Empire Francais, published on the 1st of January, 1867, a work analagous in its character to[38] the Annual Reports of the Postmaster-General of England, that the postal service of France upon railways was, in 1865, 27,730,000 kilometres, equal to 17,331,250 miles. The British Post Office does not avail itself of all the railways of the United Kingdom for the transmission of mails. Thus the total mileage of British railways on the 1st of January, 1866, was 13,289 miles, but the Post Office only sent mail bags over about 12,000 of them. The Post Office Railway Service is 60,000 miles a day, equal (deducting for Sundays) to 18,780,000 per annum, or about 1,450,000 per annum more than the postal mileage on French railways.

Before proceeding to describe the present position of the London and North-Western Company as regards locomotive and rolling stock, a short epitome of what it was twenty years ago, may not prove uninteresting.

On the 30th June, 1847, the total length of railway worked by the company was 670 miles. The number of its locomotive engines was 504, or an engine for about each three-quarters of a mile of railway. The engine mileage was—

| For passenger trains | 4,649,556 |

| For goods trains | 2,882,674 |

| ———— | |

| Total | 7,532,230 |

On the 30th of June, 1847, there were 1,018 passenger carriages, and so little encouragement was given by the company at that time to travellers of the humbler classes, that out of the 1,018 only 75 were third class. The Company had also 8 travelling post offices, and 13 post office tenders, 210 horse boxes, 183 guards’ break and parcels vans, 4,874 goods waggons, 612 cattle and sheep trucks, 653 coal and coke waggons. The total number of passengers conveyed in the year 1848, was 6,001,576. Tons of goods conveyed[39] (estimated) 1,811,000. At that period the conveyance of coal by railway was in its infancy.

On the 31st December, 1866, the London and North-Western Company possessed 1,347 locomotive engines, which is rather more than an engine a mile, the average for the whole kingdom being just over one-half of one per mile. It had 2,237 passenger carriages, 46 travelling post offices and post office tenders, 408 horse boxes, 418 guards’ break and parcel vans, 22,483 goods waggons, 1,703 cattle and sheep trucks, 2,069 coal and coke waggons, and for shunting carriages and waggons, and other work at stations, no less than 619 horses, all of good breeds, well-fed, intelligent, and well-tutored.

Its engines ran, in 1866, 21,637,163 miles, of which 10,613,324 were for passenger trains, and 11,023,839 for goods and minerals: average mileage of each engine for the year, 16,063; per day, of 365 to the year, 44, but, as the average number of working days of an engine in a year is about 250, the average mileage of the year, so divided, is 64. This seems an extremely low average. Besides the passengers already referred to, the company conveyed 15,425,119 tons of goods and minerals. These exceed the amount carried on the Paris, Lyons and Mediterranean by 1,803,405 tons, and they are very nearly three times as much as those conveyed by the Orleans Company (5,216,879 tons). Although the length of the London and North-Western system is not at present more than a tenth of the total mileage length of the United Kingdom, its receipts are a little more than a sixth of those earned by all British and Irish railways. Its income, in fact, is just three times what Lord Macaulay tells us, in the fourth volume of his History of England, was the total national revenue at the time that William III. ascended the English throne.

CHAPTER III.

RAILWAYS OF THE UNITED KINGDOM—COAL AND IRON.

Thanks to the very valuable tables of railway statistics prepared by Mr. John Cleghorn, the secretary of the North-Eastern Railway, and compiled from the returns of the Board of Trade for the years from 1859 to 1865, both inclusive, we are able to present to our readers, in an abbreviated shape, a number of details respecting the railways of the United Kingdom, of a very interesting and instructive character.

Prefacing them with the remark that on the 31st December, 1852, the capital invested in British railways was £264,165,672, yielding a gross revenue of £15,710,554, we proceed to state that on the 31st of December, 1859, the amount of capital paid up was £334,362,928, and that there were then 10,002 miles opened for traffic. The number of passengers carried in 1859, exclusive of journeys made by 49,856 holders of periodical tickets, were 149,757,294, of whom 19,204,151 were first class, 44,351,903 were second, and 86,201,240 were third. The receipts from passengers, luggage, parcels, horses, carriages, dogs, and mails, were £12,537,493. Merchandise, 22,005,737 tons; minerals, 51,756,782 tons; live stock, 12,805,613 head. Receipts from these sources, £13,206,009. Total receipts, £25,743,502. The number of miles run by passenger trains was 49,753,344; by those for goods, minerals, and cattle, 43,762,452; total, 93,516,796. The Board of Trade did not furnish returns of working expenses for 1863, but we know that their proportions to receipts were about 45 per cent.

On the 31st of December, 1860, the capital paid up was £348,130,327. Miles opened for traffic, 10,433. Passengers conveyed in 1860 (exclusive of 47,894 holders of periodical tickets), 163,435,678, of whom 20,625,851 were first class, 49,041,814 were second, and 93,768,013 were third. Receipts from passenger traffic, &c., £13,085,756. Merchandise, 29,470,931 tons; minerals, 60,386,788 tons; live stock, 12,083,503 head. Receipts from these sources, £14,680,966. Total receipts, £27,766,622. The miles run by passenger trains were 52,816,579; by those for goods, minerals, and cattle, 49,427,113; total, 102,243,692. The total working expenses were £13,196,368; their proportion to receipts, 47 per cent.

On the 31st December, 1861, the capital paid up was £362,327,338. Miles opened for traffic, 10,869. Passengers conveyed in 1861 (exclusive of 52,079 holders of periodical tickets), 173,721,139, of whom 21,917,936 were first class, 51,146,672 second, and 100,656,531 third. Receipts from passenger traffic, &c., £13,326,475. Merchandise, 30,638,893 tons; minerals, 63,604,434 tons; live stock, 12,870,683 head. Receipts from these sources, £15,238,880. Total receipts, £28,565,355. The miles run by passenger trains were 54,055,476; by those for goods, minerals, and cattle, 51,085,964; total, 105,141,440. Total working expenses, £13,843,337; their proportion to receipts, 48½ per cent.

On the 31st December, 1862, the capital paid up was £385,218,438. Miles opened for traffic, 11,551. Passengers conveyed in 1862 (exclusive of 56,656 holders of periodical tickets), 180,429,071, of whom 23,105,351 were first class, 51,869,239 second, and 105,454,481 third. Receipts from passenger traffic, &c., £13,911,985. Merchandise, 30,256,913 tons; minerals, 63,405,864 tons; live stock,[42] 12,885,003 head. Receipts from these sources, £15,216,573. Total receipts, £29,128,558. The miles run by passenger trains were 57,542,831; by those for goods, minerals and cattle, 50,518,966; total, 108,061,797. Total working expenses, £14,268,409; their proportion to receipts 49 per cent.

On the 31st December, 1863, the capital paid up was £404,215,802. Miles opened for traffic, 12,322. Passengers conveyed in 1863 (exclusive of 64,391 holders of periodical tickets), 204,635,075, of whom 26,086,008 were first class, 57,476,669 second, and 121,072,398 third. Receipts from passenger traffic, &c., £14,521,528. Merchandise, 32,517,247 tons; minerals, 68,043,154 tons; live stock, 13,029,675 head. Receipts from these sources, £16,663,869. Total receipts, £31,156,397. The miles run by passenger trains were 61,032,143; by those for goods, minerals and cattle, &c., 55,560,018; total, 116,592,161. Total working expenses, £15,027,234; their proportion to receipts 48·23 per cent.

On the 31st December, 1864, the capital paid up was £425,719,613. Miles opened for traffic, 12,789. Passengers in 1864 (exclusive of 76,499 holders of periodical tickets), 229,272,165, of whom 27,701,415 were first class, 65,269,169 second, and 136,301,581 third. Receipts from passenger traffic, &c., £15,684,040. Merchandise, 34,914,913 tons; minerals, 75,445,781 tons; live stock, 13,673,786 head. Receipts from these sources, £18,331,524. Total receipts, £34,015,564. The miles run by passenger trains were 66,555,219; by those for goods, minerals and cattle, 62,575,724; total, 129,130,943. Total working expenses, £16,000,308; their proportion to receipts, 47·03 per cent.

On the 31st December, 1865, the capital paid up was[43] £455,478,143. Miles opened for traffic, 13,289. Passengers conveyed in 1865 (exclusive of 97,147 holders of periodical tickets), 251,862,715, of whom 29,663,205 were first class, 70,783,241 second, and 151,416,269 third. Receipts from passenger traffic, &c., £16,572,051. Merchandise, 36,787,638 tons; minerals, 77,805,786 tons; live stock, 14,530,937 head. Receipts from these sources, £19,317,475. Total receipts, £35,890,073. The miles run by passenger trains were 71,206,818; by those for goods, minerals and cattle, 68,320,309; total, 139,527,127. Total working expenses, £17,149,073; their proportion to receipts, 48 per cent.