ELLEN TERRY

AND HER SISTERS.

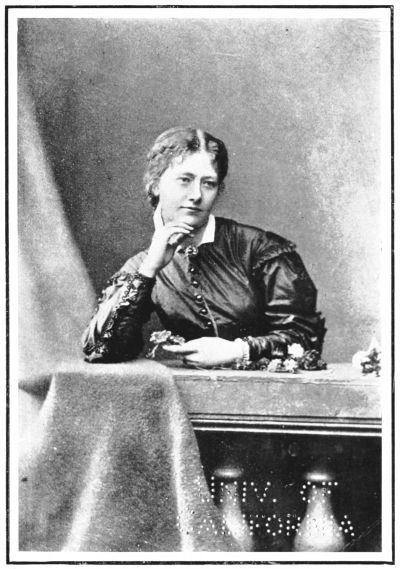

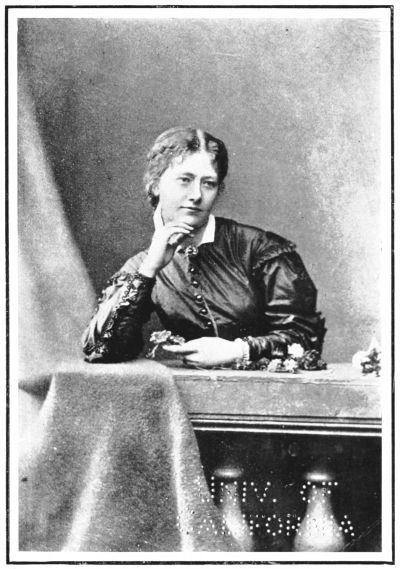

Photographed by Window & Grove.

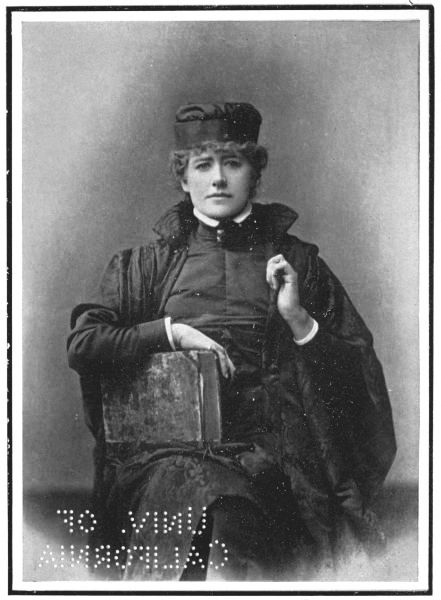

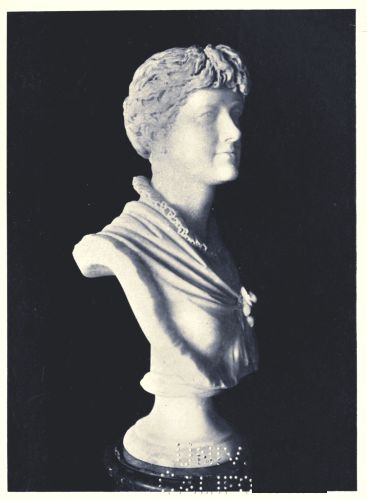

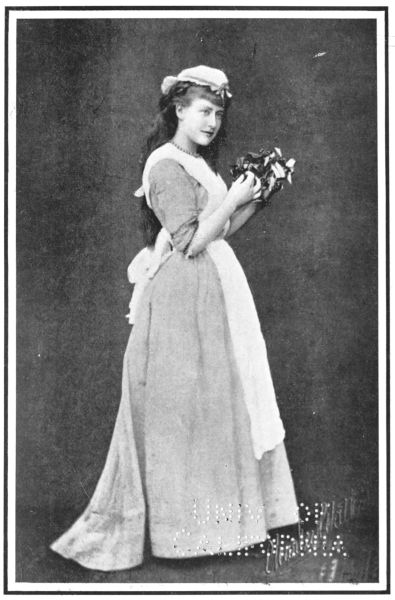

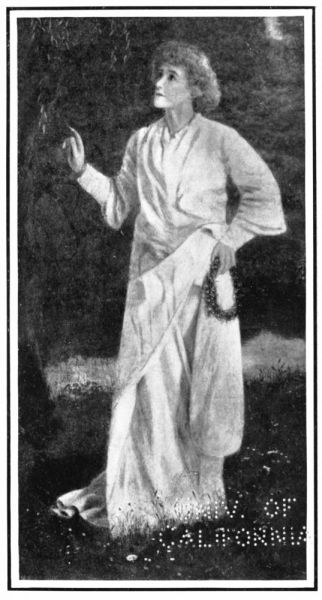

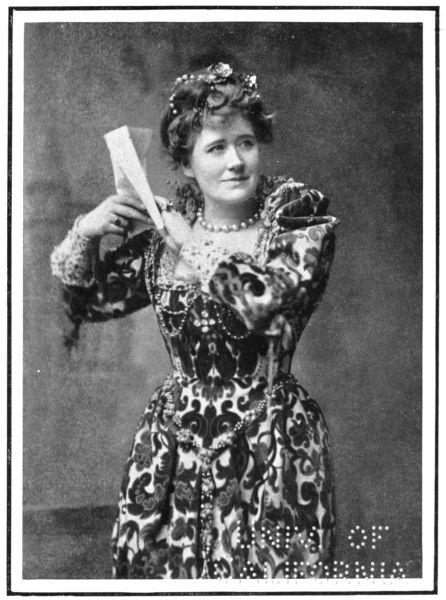

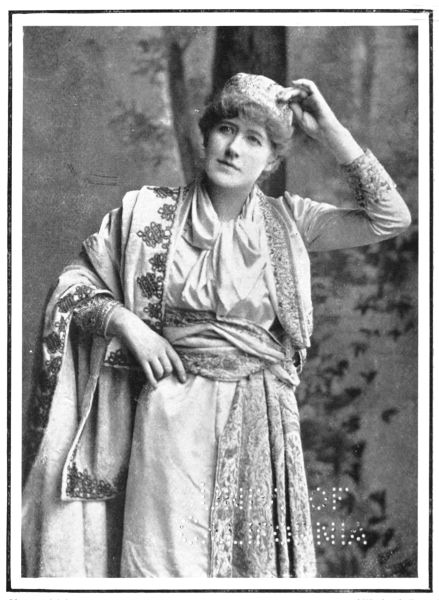

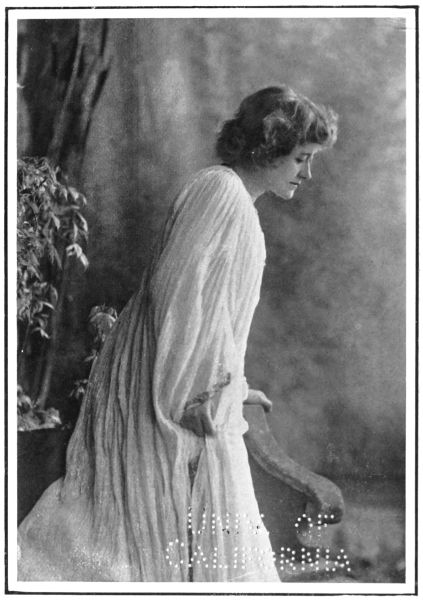

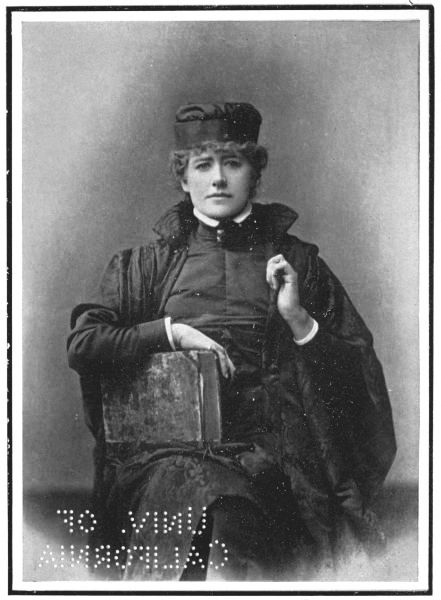

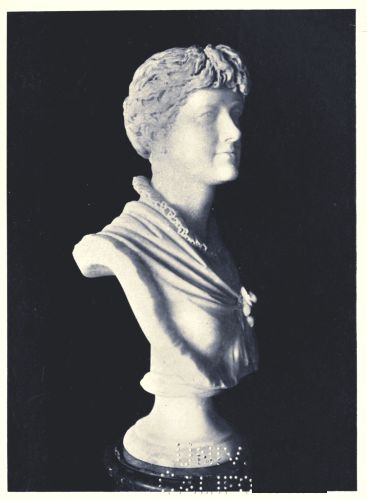

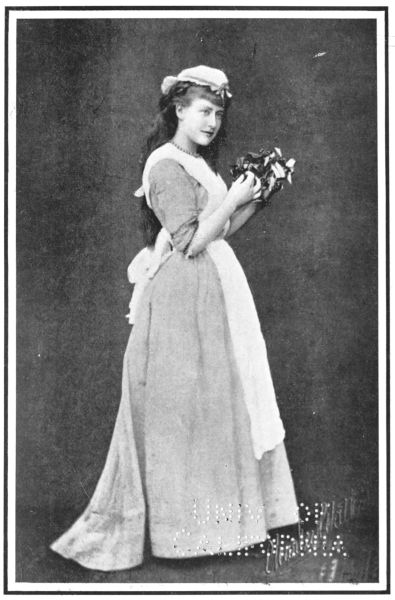

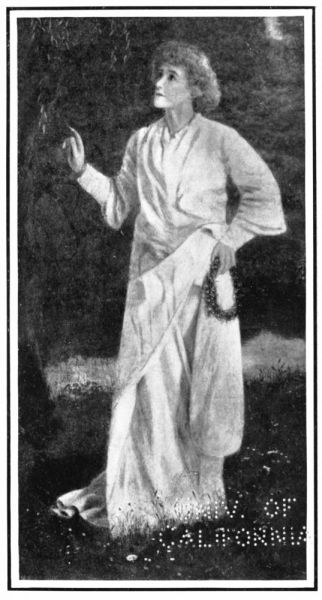

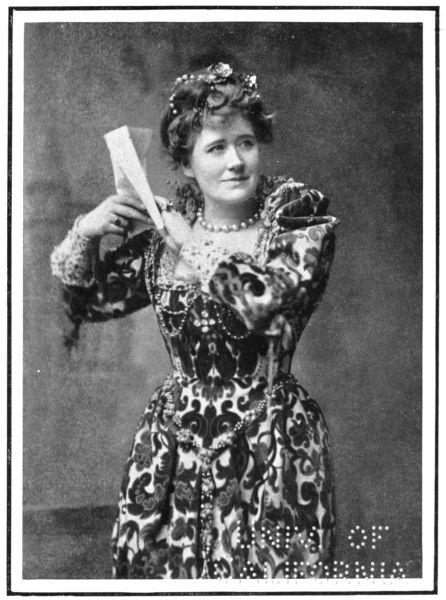

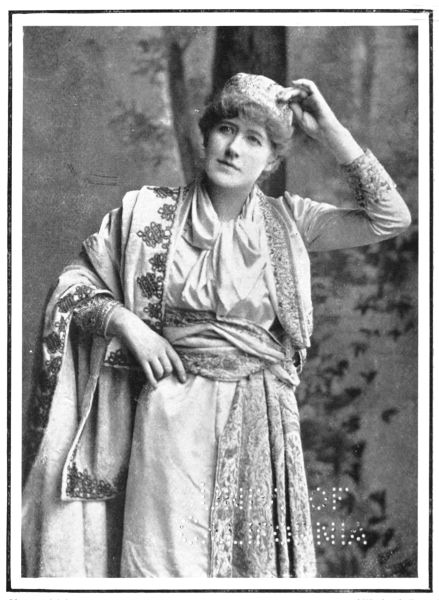

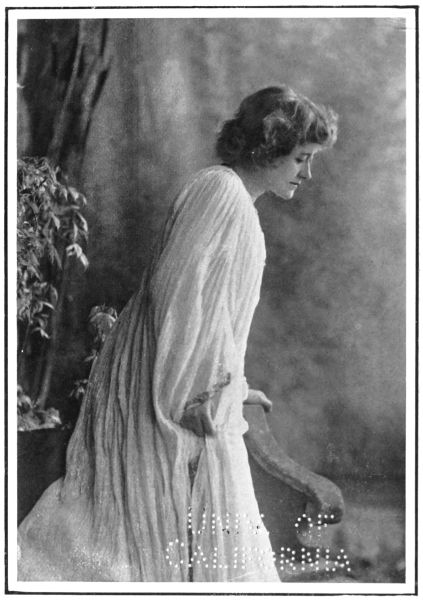

ELLEN TERRY AS PORTIA.

She first appeared in this part, one of the greatest of her Shakespearean creations, at the

old Prince of Wales's Theatre in 1875, and resumed it at the Lyceum in 1879.

Frontispiece.

ELLEN TERRY

AND HER SISTERS

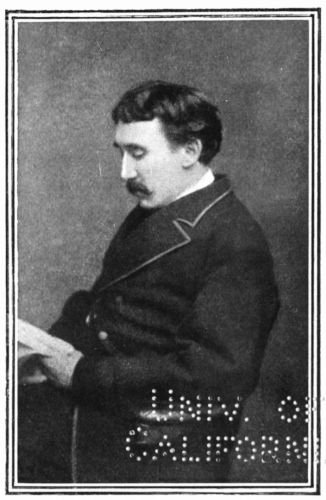

BY

T. EDGAR PEMBERTON

AUTHOR OF

"THE KENDALS;" "A MEMOIR OF E. A. SOTHERN;" "THE LIFE AND WRITINGS

OF T. W. ROBERTSON;" "CHARLES DICKENS AND THE STAGE;"

"JOHN HARE, COMEDIAN;" "BRET HARTE: A

TREATISE AND A TRIBUTE;"

ETC. ETC.

WITH TWENTY-FIVE ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

C. ARTHUR PEARSON, LIMITED

HENRIETTA STREET

1902

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

"THE KENDALS"

Demy 8vo, with Portraits and numerous Illustrations.

Price 16s.

"One of the most interesting theatrical records that

has been penned for some time."—Outlook.

"A charming work.... Pithy and well arranged.

Turned out with infinite credit to the publishers."—Morning

Advertiser.

"It leaves an impression like that of a piece in which the Kendals

have played, an impression of pleasure, refinement, refreshment, and of

the value of cherishing sweet and kindly feelings in art as in life.

Few books can do that, and so this work has every prospect of being

widely read."—Scotsman.

LONDON: C. ARTHUR PEARSON, LIMITED

April 11, 1901.

My dear Friend,—

You tell me that if I give you leave you can weave a

story about me that will interest your readers. If that be so, you have

my full permission to tell it, and it will please me to do anything in

my power to assist you in your work. Whilst writing about me you will,

I am sure, speak of those with whom I have been closely associated in

my acting life, and make mention of the affectionate regard in which I

hold them.

Your intimate knowledge of all that concerns the stage will at least

keep you right as to the facts of your pages.

I suppose I must leave the fancy of them in your

hands.

Yours cordially,

ELLEN TERRY.

Label designed for his sister by Gordon Craig

Ellen Terry's book-label designed by Gordon Craig

CONTENTS

| | PAGE |

| I. | BEGINNINGS | 1 |

| II. | FIRST APPEARANCES | 29 |

| III. | THE BRISTOL STOCK COMPANY | 57 |

| IV. | AT THE HAYMARKET THEATRE | 74 |

| V. | KATE TERRY | 91 |

| VI. | CHIEFLY AT THE QUEEN'S THEATRE | 132 |

| VII. | IN TOTTENHAM STREET | 142 |

| VIII. | IN SLOANE SQUARE | 156 |

| IX. | SOME SPLENDID STROLLING | 171 |

| X. | MARION AND FLORENCE TERRY | 192 |

| XI. | HENRY IRVING | 208 |

| XII. | AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE, 1878-1883 | 219 |

| XIII. | AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE, 1884-1901 | 252 |

| XIV. | ENDINGS | 296 |

| INDEX | 311 |

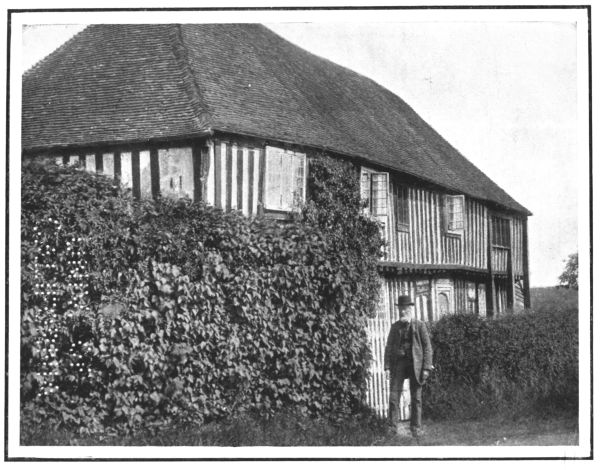

VINE COTTAGE,

KINGSTON VALE.

Ellen Terry's "Kingston Vale" letter-card heading designed by Gordon Craig

Ellen Terry's Monogram. Ellen Terry fecit

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

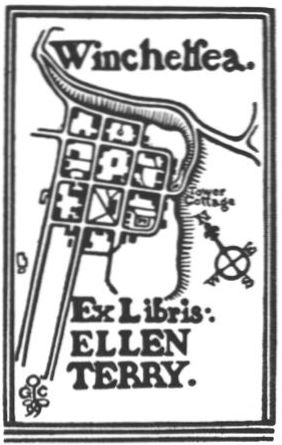

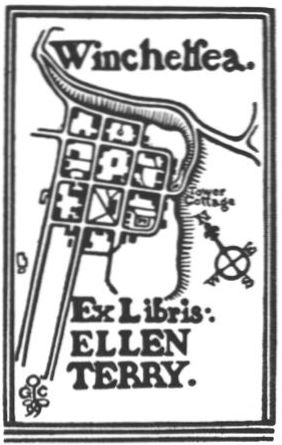

Ellen Terry's "Winchelsea" book-plate designed by Gordon Craig

[1]

ELLEN TERRY

AND HER SISTERS

CHAPTER I

BEGINNINGS

I know that to the majority of people who merely regard the theatre

as a place for occasional recreation, it is a subject for amazement

that others can exist who, not belonging to the theatrical profession,

take an absorbing and lasting interest in the stage, and in those

actors and actresses who have made its past history glorious, as well

as in the artists who adorn and make it a delight in the present. I

wonder how many of us truly realise the weight of Charles Dickens's

words: "If any man were to tell me that he denied his acknowledgments

to the stage, I would simply put to him one question—whether he

remembered his first play?"

Not only freely, but with gratitude, I acknowledge my indebtedness

to the theatre, and it is certain that from that magic night when for

the first time I saw the glitter of the footlights and watched the rise

of the curtain, I entered upon a[2]

new and most fascinating life. Of course I was called "stage struck,"

and those who controlled me shook their heads, thought it a great pity,

and did their best to thwart my inclinations. Concerning the stage and

its attractions the parents of the "fifties" were less liberal-minded

than those of to-day, and they had an unhappy knack of talking over

the tendencies of their children with uncles and aunts who, without

meaning to do the least kindly thing for them, seemed to regard their

nephews and nieces as so many ready-made reprobates open to their

interfering condemnation. Oh! those terrible uncles and aunts! In his

pages the grand old novelist, Richardson, reflecting the manners of his

time, made (apparently well meaning) ogres of them; the good and ever

interesting Jane Austen only contrived to soften them down; and I hope

my "fifties" saw the fag-end of them, for to-day they prove themselves

to be reasonable and generous beings.

But, as I say, I was set down as "stage struck," and I had to

grow accustomed to the shoulder-shrug greeting of relatives, and the

admonition that my first duty was to consider my father and mother.

Never was anything so unfair. I was not in the ordinary sense of the

word "stage struck." I was not fool enough to think that I could shine

either as tragedian or comedian. I knew that a more prosaic life had

been planned out for me, and I was prepared to enter into it; but,

for a lurking fear[3] that I should "take to the stage" (neither I nor

my parents, nor my uncles and aunts, knew how this was to be done), I

found myself compelled to read my beloved play-books and chronicles of

great actors in private. When it was accidentally discovered that I

had attempted to write a play there was real family trouble, and I am

afraid that some of those who pretended to take interest in me wrote me

down as "no good."

No! It never could be understood that I really wanted to make a

study of an art that appealed to me more strongly than its sisters,

music and painting. Yet the three are so closely allied that in

devotedly following my first love I learnt to appreciate her kith and

kin. I pen these lines because I am certain that many others must have

felt as I did, and do; and, while doing justice to other claims upon

their life energies, have taken their keenest delight in the story of

the stage.

Yes; I am sure that to many of us the theatre has formed a

little world of its own—a little world that we can enjoy and

grasp—while the great world outside it is so apt to torture us

with its perplexities, and half kill us with its seeming cruelties.

And I think that the little world in which I and my brother

enthusiasts delight is all the more appreciated when we understand that

it, too, is beset with its anxieties and grievous disappointments, and

is far from the dazzling, soul-soothing[4]

elysium we pictured in the halcyon days of our boyhood. Our hearts go

out all the more freely to the actors and actresses who warm them when

we realise that they, too, have their trials as well as their triumphs.

Our admiration is redoubled when it is leavened with sympathy. It is

all the more important, then, that our entertainers should know that

this feeling exists among those for whom they devote the work of their

lives.

The artistic temperament is always more or less self-tormenting, and

it is to be feared that my "little world," which shines so brightly

over our great one, where sorrow has daily to be met and borne, is in

itself a sorely troubled one.

In that strange French play which has our great English tragedian,

Edmund Kean, for its central figure, Alexandre Dumas, who knew

everything that could be known about the theatre, caused his actor-hero

to respond bitterly to the woman who loved him, and who opined that

all his troubles must vanish when he reflects that he is recognised

as the King of the Stage. "King! Yes, three times a week! King with

a tinselled sceptre, paste diamonds, and a pinchbeck crown. I rule a

kingdom of thirty-five feet, and subjects who are jealous of my power."

Then, when she asks, "Why do you not give it up?" he replies with

indignation, "Give up the stage? Ah! you don't realise that he who has

once donned the robe of Nessus cannot take it[5]

off without lacerating his flesh. I give up the

stage?—renounce its excitement?—its glitter?—its

triumphs? I give up my throne to another? Never! while I've

health and strength to walk the boards, and brains to interpret the

poetry I love. Remember, an actor cannot leave his work behind him.

He lives only in his own lifetime—his memory fades with the

generation to which he belongs, he must finish as he has begun, die

as he has lived—die, if fortune favours him, with the delicious

sound of applause in his ears. But those who have not set foot upon a

dangerous path do well to avoid it."

The actor's complaint that his fame, however great, cannot be

recollected many years beyond the time in which he lived is a very old

one, and it must have been with this mournful view in his mind that

David Garrick wrote:—

"The painter dead, yet still he charms the eye;

While England lives his fame can never die.

But he who struts his hour upon the stage

Can scarce extend his fame for half an age;

Nor pen nor pencil can the actor save,

The art and artist share one common grave."

The volumes of theatrical history and biography that have been

written and become popular since Garrick's day, prove that this is not

wholly true, that we are not ungrateful to those who have instructed

and amused us on the stage, and that we shall not willingly let their

honoured memories die.[6]

The fact that the depressing feeling that they and their work will

"soon be forgotten" still exists among members of the theatrical

profession is, I venture to believe, some excuse for records such as

this being issued during the lifetime of the artist, while memory is

green, and appreciation can be written at first hand. Even if such

works give little or no pleasure to their living subjects, it may be

borne in mind that they will probably be of service to those future

stage historians who will permanently inscribe their names on the

tablets of fame.

The passionate declaration of Dumas's Kean that, despite his

troubles and torments, he would never while life was in him leave the

stage, is an old tale. Actors, as a rule, love to die in harness, and

it was in the full knowledge of this that T. W. Robertson caused his

stage David Garrick to reply to Alderman Ingot, when he offered to

double or treble his income if he would abandon his profession, "Leave

the stage? Impossible!" Poor Sothern, who created the part, was staying

with me when his physician wrote saying that if he wished to prolong

his life he must give up all work. After a moment's depression the

actor with a sudden impulse snatched a portrait of himself as Garrick

from my wall, tore it from its frame, and in a large, firm hand, wrote

beneath it: "Leave the stage? Impossible!"

I have no doubt that Charles Wyndham, who, after Sothern's death,

took up the part, and made it[7]

one of the greatest successes of the modern stage, feels the full

import of the words every time he speaks them.

And if the actors suffer so do the dramatists, or at all events the

would-be dramatists. In an admirable little book called "Play Writing,"

the author gives sound advice to the ever-growing, ever-complaining

army of the unacted.

"Dramatic authorship," he says, "is to the profession of literature

as reversing is to waltzing—an agony within a misery. A man who

means to be a dramatist must be prepared for a life of never-ending

strife and fret—a brain and heart-exhausting struggle from

the hour when, full of hope, he starts off with his first farce in

his pocket to the days when, involuntarily taking the advice of one

of the early masters of his own craft—to wit, old rare Ben

Jonson—he leaves 'the loathed stage and the more loathsome

age.'"

And again, this anonymous but evidently experienced writer (I quote

from him freely) declares that any dramatist could tales unfold of

disappointments and delays, of hopes deferred, of chances dashed from

the grasp at the very moment they seemed clutched, of weary waitings

rewarded by failure, of enterprise and effort leading only to defeat,

of hard work winning only loss. It has been suggested, too, in this

connection, that any one sufficiently interested in such matters should

make a list of the plays that in[8]

"preliminary paragraphs" are spoken of as "about to be produced,"

and which are never heard of again,—and that it should then be

remembered that each of these unborn plays represents a very heavy

heart being carried about for many a long day under somebody or other's

waistcoat,—and means that somebody or other feels very sick and

hopeless as he moves about his little world, trying to appear careless

and to laugh it off,—that somebody or other grows very tired

and weary of the struggle, and almost wishes now and then that it was

over.

But to the young playgoer who sits in front these troubles are

unknown, and to him the theatre may well appear as the realisation of

Fairyland, and a veritable Palace of Fancy.

I believe there is another reason why men, if they would own it,

have come to be grateful to the stage. Has it not to many been the

scene in which they have first learned what it is to love? They may

never have spoken to the divinities who inspired their boyish ardour,

but they have been better and purer for it, and cherish the sweet

recollection of it to their old age.

Cannot we all enter into the feelings of young virgin-hearted Arthur

Pendennis when he first saw the lovely Miss Fotheringay on the boards?

Cannot we all understand how he followed the woman about and about, and

when she was off the stage the house became a blank? and how, when the

play was over,[9]

the curtain fell upon him like a pall? Poor Pendennis!

He hardly knew what he felt that night. "It was something overwhelming,

maddening, delicious; a fever of wild joy and undefined longing."

And then how he woke the next morning, when, at an early hour, the

rooks began to caw from the little wood beyond his bedroom windows;

and at that very instant, and as his eyes started open, the beloved

image was in his mind. "My dear boy," he heard her say, "you were in

a sound sleep, and I would not disturb you: but I have been close by

your pillow all this while; and I don't intend that you shall leave me.

I am Love! I bring with me fever and passion; wild longing, maddening

desire; restless craving and seeking. Many a long day ere this I heard

you calling out for me; and behold now I am come."

Yes, I am convinced that most of us have felt, rejoiced, and

suffered as Arthur Pendennis did, and that we first caught the fever

from the footlights. The attack may have been acute, and, in its

apparent hopelessness, painful. But recovery brought with it the sweet

knowledge that we had been permitted to understand the meaning of

Heaven's greatest gift to mankind—Love.

I know that there are many who only go to the theatre to carp and

cavil, and impotently point out that if the management of the playhouse

and the acting of all the parts had been placed in their hands[10]

a much better performance would have been provided; but I believe

that even these would love to recall the dreamy illusions of their

youth. Perhaps, in the hours of their solitude (and silence!), they do

so. Why, in their soured maturity, these unhappy, self-imposed, and

absolutely unconvincing critics go to the theatre to be (on their own

declaration) bored and disgusted is to me a mystery. It is all the more

a mystery when I know that they can thoroughly enjoy a variety hall.

Of course, everything depends on the spirit in which we go to the

theatre.

Do you remember the difference of opinion expressed between

Steerforth and David Copperfield on the night when they renewed the

acquaintance of their boyhood at the Golden Cross Hotel? David had been

to Covent Garden Theatre, and had there seen "Julius Cæsar." "To have,"

he says, "all those noble Romans alive before me, and walking in and

out for my entertainment, instead of being the stern task-masters they

had been at school, was a most novel and delightful effect. But the

mingled reality and mystery of the whole show, the influence upon me of

the poetry, the lights, the music, the company; the smooth, stupendous

changes of glittering and brilliant scenery were so dazzling, and

opened up such illimitable regions of delight, that when I came out

into the rainy street I felt as if I had come from the clouds, where I

had been leading a romantic[11]

life for ages, to a bawling, splashing, link-lighted,

umbrella-struggling, hackney-coach jostling, patten-clicking,

muddy, miserable world."

And when he told the superior Steerforth of his innocent enjoyment,

he had to listen to the laughing reply:—

"My dear young Davy—you are a very daisy. The daisy of the

field, at sunrise, is not fresher than you are! I have been at Covent

Garden, too, and there never was a more miserable business."

In my own mind I am convinced that if we will we can always, to

our great advantage and delight, keep up the enthusiasm of David

Copperfield;—that to some of us the theatre, even when we know

all about the fret and turmoil of the actor's life together with the

tricks of the stage, may from boyhood to old age remain a Palace of

Fancy.

And have we not in the heroine of these pages—Ellen

Terry—the very embodiment of Fancy,—the true Princess of

our Palace, one of the Queens of our little stage world? Other great

artists have delighted us with the perfection of their impersonations,

but there is in the method or inspiration of Ellen Terry something so

ethereal that in many of her characters she stands alone.

If the drama is indeed the Cinderella of the arts, then Ellen Terry

must have been touched by the magic wand of a Fairy Godmother so that

she might dazzle the Prince's ballroom with her beauty, radiance,[12]

and ever fragrant sweetness, and win the admiration of his guests.

But those who thoughtlessly and even contemptuously call the

drama "Cinderella" probably do not know the origin of the familiar

fairy-tale—how the little kitchen maid is Ushas, the Dawn Maiden

of the Aryans, and the Aurora of the Greeks; and how the Prince is

the Sun, ever seeking to make the Dawn his bride; and how the envious

stepmother and sisters are the Clouds and the Night, which vainly

strive to keep the Sun and the Dawn apart. It is pleasant to think

of Cinderella as the Dawn Maiden. Poor little lady! She has suffered

considerably in her transplantation to English soil.

To me the magic word "Fancy" has ever been associated with the pure

art of Ellen Terry, and whenever I see her on the stage the lines of

John Keats comes rippling through my mind:—

"Oh! sweet Fancy! let her loose;

Everything is spoilt by use;

Where's the cheek that doth not fade,

Too much gazed at? Where's the maid

Whose lip mature is ever new?

Where the eye, however blue,

Doth not weary? Where's the face

One would meet in every place?

Where's the voice, however soft,

One would hear so very oft?

At a touch sweet pleasure melteth

Like to bubbles when rain pelteth.

Let, then, winged Fancy find

Thee a mistress to her mind;

[13]

Dulcet-eyed as Ceres' daughter

Ere the god of Torment taught her

How to frown and how to chide;

With a waist and with a side

White as Hebe's, when her zone

Slipt its golden clasp, and down

Fell her kirtle to her feet,

While she held the goblet sweet,

And Jove grew languid. Break the mesh

Of the Fancy's silken leash;

Quickly break her prison string,

And such joys as these she'll bring—

Let the winged Fancy roam,

Pleasure never is at home."

But it must be recorded that Fancy, as let loose and impersonated

by Ellen Terry, is taken from the theatre in thousands of hearts, and

that it enters into many a home circle where the memory of it gives

unbounded and enduring pleasure. Into the simple homes of those who

elbow each other in the gallery, as well as into the luxurious mansions

of the wealthy folk who sit at their ease in the stalls. In many a

workman's dwelling I have come across a carefully framed photograph

of Ellen Terry, and a treasured play-bill kept in commemoration of a

never-to-be-forgotten evening enjoyed in her realms of Fancy.

But she did not drop from cloudland to delight us. Her great

achievements have been won—as all great achievements are

won—by early training, deep and constant study, hard work, and

possibly, above all, by family tradition.

In theatrical lore the name of Terry is, indeed, an[14]

old and honoured one. In Lockhart's beautiful biography of Sir Walter

Scott, and again in the happily published Diary of the Magician of the

North, we read much of the energetic Daniel Terry who was for many

years connected with the Edinburgh stage, and who subsequently joined

Yates in a memorable management of the Adelphi Theatre. Daniel Terry,

with the appreciative eye of the true actor, set his heart upon making

stage versions of the Waverley Novels, and though at first Scott (in

common with all great novelists) objected to this process, it was

subsequently allowed, and adapter and author became friends. It was

in the spring of 1816 that Terry produced a dramatic piece entitled

"Guy Mannering," which met with great success, and is still from time

to time seen. "What share," says Lockhart, "the novelist had in this

first specimen of what he used to call the art of 'Terryfying,' I

cannot exactly say; but his correspondence shows that the pretty song

of the Lullaby was not his only contribution to it; and I infer that

he had taken the trouble to modify the plot, and rearrange, for stage

purposes, a considerable part of the original dialogue."

Of the intimacy that commenced and grew between the poet and the

playwright, Lockhart records:—

"It was at a rehearsal of 'The Family Legend of Joanna Baillie'

that Scott was first introduced to another theatrical performer, who

ere long acquired a large share of his regard and confidence—Mr.[15]

Daniel Terry. He had received a good education, and been regularly

trained as an architect; but abandoned that profession at an early

period of life, and was now beginning to attract attention as a

valuable actor in Henry Siddons's company. Already he and the

Ballantynes were constant companions, and through his familiarity

with them Scott had abundant opportunities of appreciating his many

excellent and agreeable qualities. He had the manners and feelings

of a gentleman. Like John Kemble, he was deeply skilled in the old

literature of the drama, and he rivalled Scott's own enthusiasm for the

antiquities of vertu. Their epistolary correspondence in after days

was frequent, and none so well illustrates many of the poet's minor

tastes and habits. As their letters lie before me they appear as if

they had all been penned by the same hand. Terry's idolatry of his new

friend induced him to imitate his writing so zealously that Scott used

to say, if he were called upon to swear to any document, the utmost he

could venture to attest would be, that it was either in his own hand

or Terry's. The actor, perhaps unconsciously, mimicked him in other

matters with hardly inferior pertinacity. His small lively features had

acquired, before I knew him, a truly ludicrous cast of Scott's graver

expression; he had taught his tiny eyebrow the very trick of the poet's

meditative frown; and, to crown all, he so habitually affected his tone

and accent that, though a native of Bath, a stranger could hardly have[16]

doubted he must be a Scotchman. These things afforded all their

acquaintance much diversion; but perhaps no Stoic could have helped

being secretly gratified by seeing a clever and sensible man convert

himself into a living type and symbol of admiration."

In the pages of his fascinating Diary (or "Journal") Scott

records—

"October 20, 1826 (London).—At breakfast, Crofton

Croker, author of the 'Irish Fairy Tales.' Something like Tom Moore.

There were also Terry, Allan Cunningham, Newton, and others."

"October 21, 1826.—We returned to a hasty dinner in Pall

Mall, and then hurried away to see honest Dan Terry's house, called

the Adelphi Theatre, where we saw 'The Pilot,' from the American novel

of that name. It is extremely popular, the dramatist having seized on

the whole story, and turned the odious and ridiculous parts, assigned

by the original author to the British, against the Yankees themselves.

There is a quiet effrontery in this that is of a rare and peculiar

character. The Americans were so much displeased, that they attempted

a row—which rendered the piece doubly attractive to the seamen

at Wapping, who came up and crowded the house night after night to

support the honour of the British flag.... I was, however, glad to see

honest Dan's theatre as full seemingly as it could hold. The heat was

dreadful, and Anne was so very unwell that[17]

she was obliged to be carried into Terry's house—a curious

dwelling, no larger than a squirrel's cage, which he has contrived

to squeeze out of the vacant spaces of the theatre, and which is

accessible by a most complicated combination of staircases and small

passages. Here we had rare good porter and oysters after the play, and

found Anne much better. She had attempted too much; indeed, I myself

was much fatigued."

Later comes a sadder note:—

"February 3, 1827.—Terry has been pressed by

Gibson for my debt to him. That I may get

managed."

And again—

"April 15, 1828.—Got the lamentable news that

Terry is totally bankrupt. This is a most unexpected blow, though

his carelessness about money matters was very great. God help the

poor fellow! He has been ill-advised to go abroad, but now returns to

stand the storm—old debts, it seems, with principal and interest

accumulated, and all the items which load a falling man. And wife, such

a good and kind creature, and children. Alack! alack! I sought out his

solicitor. There are £7000 or more to pay, and the only fund his share

in the Adelphi Theatre, worth £5000 and upwards, and then so fine a

chance of independence lost. That comes of not being[18]

explicit with his affairs. The theatre was a most flourishing

concern. I looked at the books, and since have seen Yates. The ruin

is inevitable, but I think they will not keep him in prison, but let

him earn his bread by his very considerable talents. I shall lose the

whole or part of £5000, which I lent him, but that is the last of my

concern."

And then follow these interesting and touching entries:—

"May 8, 1828.—I have been of material assistance to

poor Terry in his affairs."

"June 18, 1829.—Poor Terry is totally prostrated by a

paralytic affection. Continuance of existence not to be wished for."

"July 9, 1829.—Many recollections die with poor

Terry."

Of his semi-partnership with his actor-friend, Sir Walter Scott, in

a humorous mood, wrote:—"I have been made a dramatist whether I

would or no. I believe my muse would be Terryfied into treading the

stage even if I should write a sermon."

Benjamin Terry, the father of the clever family who form the subject

of these pages, became in his time very popular in Edinburgh, and it

was there that he attracted the attention of Charles Kean, and obtained

his offer for the actor's Mecca—London. But his experience had

no doubt been earned in some of the old "circuits" that were the

theatrical schools of his early[19]

days, and turned out many a true artist. The actors and actresses who

thus served their apprenticeship to the stage assuredly had rough

times of it, but they had for the most part joined the profession

for the love of it—they adored Shakespeare and the authors of

the "legitimate drama,"—and, in spite of tedious journeys from

town to town, poor business, and bad theatrical accommodation at the

end of them, looked forward to and enjoyed the evening's performance.

Enthusiasm and hard work led to their reward, and many a poor

strolling-player became a shining light on the London stage.

When Ben Terry went on circuit, travelling actors were in better

plight than they were in the days of poor Roger Kemble and his devoted

wife, who travelled from town to town, and village to village, after

the manner and under the difficulties and disadvantages of the

time,—at some places being received with gracious favour, and at

others treated like lepers and threatened with the stocks and whipping

at the cart's tail, according as the great people were liberal minded

or puritanical. But this struggling, persecuted Roger Kemble lived to

see his daughter, Mrs. Siddons, and his son, John Philip, the stage

idols of their day; and if sometimes his perturbed spirit could revisit

Hereford (one of the cities of his early sorrows) he would realise the

happy fact that the portraits of his never-to-be-forgotten family hold

the places of honour on the Deanery walls.

[20]

Since to the often ridiculed circuits of a bygone day we can trace

such actors as the Kembles, the Robertsons, and the Terrys, surely we

should hold them in honoured memory?

Dickens turned them to comic account when he conceived the

impossible but immortal Crummles family; but he put the true ring into

the warm-hearted old manager's heart and voice when on bidding farewell

to Nicholas, he said, "We were a very happy little company. You and I

never had a word. I shall be very glad to-morrow morning to think that

I saw you again, but now I almost wish you hadn't come."

It is pleasant to think that in their own way the circuit players

all formed happy little companies. To enjoy the work of our choice is,

in spite of any drawbacks, one of the greatest sources of happiness.

My esteemed friend, John Coleman, whose memory carries him back to

the days of long ago, has told me that he met Mr. and Mrs. Ben Terry

on the Worcester Circuit. He remembers the former as a handsome,

fine-looking brown-haired man, and the wife as a tall, graceful

creature, with an abundance of fair hair, and with big blue eyes set

in a charming face. Years and years passed before he met his old-time

friend again; but at the memorable banquet given to Henry Irving on

the eve of his departure for his first tour in America, a grey-haired,

dignified old gentleman, who sat next to him, told him that he was the[21]

"Ben Terry" of the dead and gone Worcester Circuit, and introduced him

to his grandson, Gordon Craig.

On that evening the old actor had good reason to be proud, for he

could boast of being the father of one of the most gifted and cultured

of histrionic families. "Think of it," writes Mr. Clement Scott, "Kate,

with her lovely figure and comely features; Ellen, with her quite

indescribable charm; Marion, with a something in her deeper, more

tender, and more feminine than either of them; Florence, who became

lovelier as a woman than as a girl; and the brothers Fred and Charles,

both splendid specimens of the athletic Englishman."

It was while the parent Terrys were fulfilling an engagement at

Coventry—the interesting City of the Three Tall Spires—that

their daughter Ellen was born. This was in the February of 1848, and

quite a little feud has taken place between some of the good people

of Coventry as to the precise house in which the important event took

place. That it was on the 27th day of the second month of the year, and

that the street was Market Street, one and all seem agreed, but several

inhabitants of that thoroughfare have laid claim to be the occupiers,

if not the owners of the shrine. No. 5 and No. 26 are the chief

claimants of the honour (and in all seriousness it is no small honour),

but as an "old nurse," who should know something about such things, has

declared for No. 5, it stands first favourite; and a[22]

fact in its favour is that in the days of 1848 it was a popular

lodging-house for actors. One can sympathise with No. 26, but the

general vote must be given to No. 5. After all, it does not much

matter, for who knows what changes have taken place in the old street

during the last fifty years? Perhaps (but for pious pilgrims this is

a dreadful thought!) even the door numbers may have been changed!

With a few exceptions the birthplaces of celebrities are apt to be

disappointing. My enthusiasm for famous artists once took me to Brecon

so that I might visit the "Shoulder of Mutton" Inn, in which Sarah

Kemble was born, but, though it was properly inscribed, it was not

the interesting old tavern of my imagination, and manifest modern

"improvements" made me content with a brief gaze at its exterior. It

was at the beautiful Trinity Church at Coventry, on the 26th November

1773, that Sarah Kemble was married to Henry Siddons, the handsome

young actor from Birmingham; and this brings me back to "leafy

Warwickshire" (Warwickshire-men never forget that it is Shakespeare's

county), and the Coventry of Ellen Terry's birthday in 1848.

Now let me show how easily, by those who care about such things,

theatrical history may be traced.

Ellen Terry, as will soon be seen, was destined to make her earliest

(though childish) successes with Charles Kean. Charles Kean had acted

with his renowned father, Edmund Kean. Edmund Kean[23]

had in his childhood figured as one of the imps who danced around the

cauldron in John Philip Kemble's revival of "Macbeth." Roger Kemble,

the father of John Philip and Sarah Siddons, was the son of a Kemble

who had been engaged by and was associated with Betterton. After "the

King had got his own again" Betterton was acknowledged to be the

legitimate successor to Burbage. Burbage was the first of our great

tragic actors, and was the original performer of the greater number

of Shakespeare's heroes—of Coriolanus, Brutus, Romeo, Hamlet,

Othello, Lear, Shylock, Macbeth, Prince Hal, Henry V., and Richard III.

In "Hamlet" Shakespeare enacted the touching character of the Ghost to

the Prince created by Burbage; and so, in a rough and somewhat "House

that Jack Built" fashion, the connection of such famous histrionic

families as the Terrys can be traced back to the Elizabethan days, to

Shakespeare, and the actors of his period.

We may now follow the Ben Terrys and their pretty children to

the London Princess's Theatre, where the experienced actor not only

played many parts but became assistant stage-manager to Charles Kean.

Considering the magnitude of the productions aimed at, this must have

been a post of no small importance and responsibility. When the famous

series of Shakespearean revivals demanded the appearance of clever

children, what was more natural than a conference between Kean and his[24]

trusted lieutenant, and the recommendation by the fond father of the

engagement of his gifted little daughters, Kate and Ellen? Their

services were secured, and at a very early period of their lives they

began to make stage history. Their achievements in the once famous

Oxford Street playhouse will be recorded in the next chapter. In the

meantime it is pleasant to touch upon some of Ellen Terry's impressions

of her earliest childhood.

In a charming series of papers entitled "Stray Memories,"

contributed by her to the New Review about ten years ago, she thus

delightfully as well as dutifully recalls memories of her father

and mother. "It must be remembered," she says, "that my sister and

I had the advantage of exceedingly clever and conscientious parents

who spared no pains to bring out and perfect any talents that we

possessed. My father was a very charming elocutionist, and my mother

read Shakespeare beautifully, and then both were very fond of us and

saw our faults with eyes of love, though they were unsparing in their

corrections. And, indeed, they had need of all their patience, for, for

my own part, I know I was a most troublesome, wayward pupil. However,

'the labour we delight in physics pain,' and I hope, too, that my more

staid sister 'made it up to them.'"

Can anything be prettier than this daintily recorded, and no doubt

uncalled for admission?

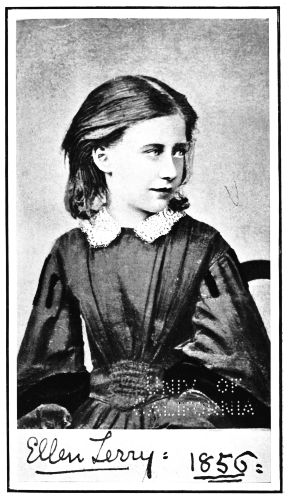

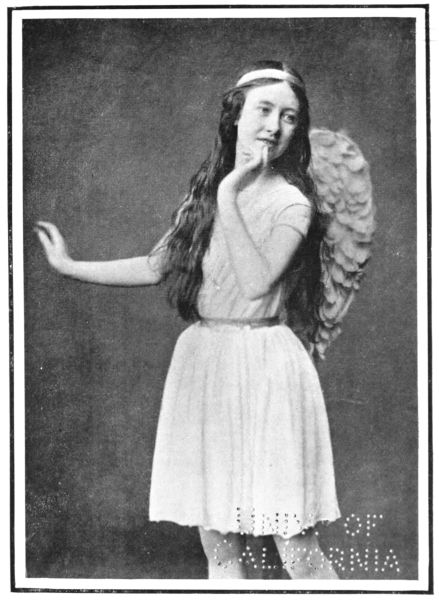

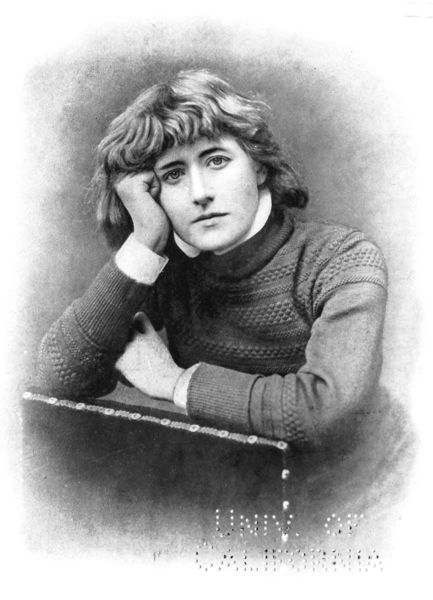

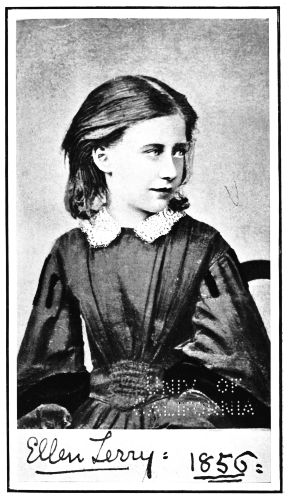

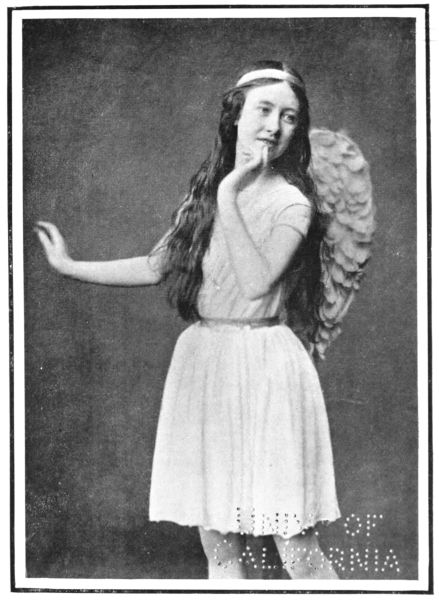

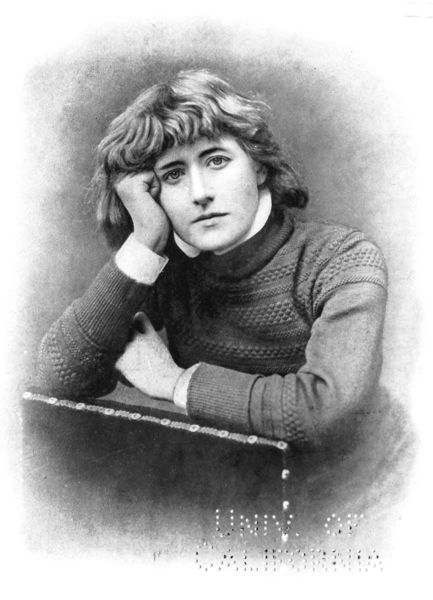

ELLEN TERRY WHEN EIGHT YEARS OF AGE.

The autograph shows her signature of to-day. [To face page 24.

With one more glimpse of her home-life in childhood[25]

I will bring this chapter of "Beginnings" to a close. Some time ago

it occurred to those who are responsible for that always sprightly

journal, The Referee, to ask some stage celebrities to contribute to

their Yule-tide number their impressions of Christmas in their early

days—of Christmas, the great and never-to-be-forgotten holiday of

little folk.

And this is what Ellen Terry conjured up:—

"Really," she said, "I have no Christmas experience worth

recounting. Ever since I can remember, Christmas Day has been for me at

first a day on which I received a good many keepsakes, and afterwards a

day on which I gave a good many little gifts.

"But well I remember one particular Christmas Day. I don't know that

the remembrance is worth the telling, but I'll tell it all the same,

because I was about seven years old, and went to 'a party.'

"I was much admired, and I in turn admired greatly a dark, thin

boy of about ten, who had recited 'The Burial of Sir John Moore' (so

jolly on a Christmas Day!). This thin boy was always going down to eat

something, and after the recitation he asked me to come down and have

an ice.

"You will, of course, understand that this was a real

party—a staying-up-late, low-necked dress, and fan sort of party.

When we had eaten the ices he suggested some lobster salad—which

I thought would be very nice. He went to fetch the salad and left me

dreaming of him and of his beautiful dark hair.

[26]

"Suddenly my dream was interrupted.

"A fat boy with stubbly light hair and freckles on his nose stood

grinning at me and asking me to have some lemonade. I didn't want any

lemonade, and told him so. Thereupon he produced a whole bough of

mistletoe from somewhere or another, and without more ado seized me by

my head and kissed me, and kissed me, and kissed me,—grinning all

the while.

"I was in a rage, and flew at him like a little cat. He fled out

of the room, up the stairs, I after him. I caught him on the landing,

clawed him by the hair, and banged him, and dared him to kiss me

again.

"He cried, the coward, though he was eight or nine years old. Adding

insult to injury, he said, 'He didn't want to,' and I was 'horrid.'

"I thought he was horrid, for my pretty white frock was torn, and

the thin dark boy, the boy I had fallen in love with, said I should not

have spoken with such a cur, and that it 'served me right.'

"My heart was broken for the first time, and that is why I remember,

and always shall, that miserable Christmas Day."

No doubt the impressionable and impulsive little lady has since

delighted in as many joyous Christmas Days as, in year succeeding

year, she has given happiness to the thousands and thousands who have

revelled in, and been made the better for, the display of her genius.

It is to be feared that the greatest of[27]

our stage artists never realise the amount of good that they do in the

world. If they did they would not only have their reward in applauding

audiences, but their re-reward in the knowledge that they have brought

light, understanding, and lasting pleasure into countless homes.

Through simple and cheerful paths the good Ben Terrys conducted their

youthful daughters into the profession that Mrs. Kendal has humorously

summed up as follows:—

So many, she declares, have wrong impressions of the stage. Some

think they can jump into fame, and that there is no hard work; others

think it is all hard work, and there is no reward. But, of course,

there are many drawbacks, and people who only sit in the front of

the theatre cannot possibly comprehend what it is until they have

been behind the scenes and worked at it from childhood, as she has

done. Every day, people write to her and ask the qualifications of an

actress. Well, she should have the face of a goddess, the strength

of a lion, the figure of a Venus, the voice of a dove, the temper of

an angel, the grace of a swan, the agility of an antelope, and the

skin of a rhinoceros; great imagination, concentration, an exquisite

enunciation, a generous spirit, a loyal disposition, plenty of courage,

a keen sense of humour, a high ideal of morality, a sensitive mind, and

an original treatment of everything. She must be capable of being a

kind sister, a good daughter, and an excellent wife; a judicious[28]

mother, an encouraging friend, and an enterprising grandmother! These,

according to an undeniable authority, are the only qualities that are

required for the stage!

Mrs. Kendal's dictum reminds me of what her brother, T. W.

Robertson—one of the best and most popular dramatists of his

age—who had gone through a perfect torture of disappointment

before the production of "Society" by the Bancrofts made his name

famous and his path easy, caused one of his characters in a later play

from his pen to say—

"Yes, I want to write a comedy."

And when the answer came—"Well, write one; I should think it

is easy enough—you've only got to be amusing, spirited, bright,

and life-like. That's all!"

"Oh, that's all, is it?" ruefully responded the would-be comedy

writer.

[29]

CHAPTER II

FIRST APPEARANCES

The first appearances on the stage of Kate and Ellen Terry were

in every respect triumphant, and in theatrical history will always

be held worthy of record. A time-worn adage tells us not to judge by

first appearances, but those experts who discerned the extraordinary

promise of these children in the opportunities afforded them under the

memorable Charles Kean régime, at the Princess's Theatre, proved

themselves to be true dramatic critics.

As to the very first public appearance of the heroine of these pages

there has been much discussion. When any one deserts an avocation to

"take to the stage," as the phrase goes, a first performance is a

milestone on the road of life and is never forgotten. With children

who, coming from a theatrical family, are, as it were, born to the

stage, it is almost a matter of indifference, and is apt to become

nebulous. Mrs. Kendal, for example, once frankly stated that she

remembered little or nothing of her initial professional efforts until

she was reminded of them by some of the mature actors who[30]

had appeared in the same pieces on those destined to be interesting

occasions.

There was a general feeling that Ellen Terry's first appearance was

as Mamillius, the little son of King Leontes of Sicilia, in Kean's

elaborate revival of "The Winter's Tale," until in the June of 1880

the eminent dramatic critic and stage historian, Mr. Dutton Cook,

contributed an article to the unhappily defunct Theatre Magazine, in

which he said:—

"Some four-and-twenty years ago, when the Princess's Theatre was

under the direction of the late Charles Kean, there were included

in his company two little girls, who lent valuable support to the

management, and whose young efforts the playgoers of the time watched

with kindly and sympathetic interest. Shakespearean revivals,

prodigiously embellished, were much in vogue; and Shakespeare, it

may be noted by the way, has testified his regard for children by

providing quite a repertory of parts well suited to the means of

juvenile performers. Lady Macduff's son has appeared too seldom on the

scene, perhaps, to be counted; but Fleance, Mamillius, Prince Arthur,

Falstaff's boy, Moth (Don Armado's page), King Edward V., and his

brother, the Duke of York, Puck, and the other fairies of 'A Midsummer

Night's Dream,' and even Ariel—these are characters specially

designed for infantile players; and these, or the majority of these,

were sustained at the Princess's Theatre, now by Miss Kate, and now by

Miss Ellen[31]

Terry, who were wont to appear, moreover, in such other plays, serious

or comic, poetic or pantomimic, as needed the presence and assistance

of the pretty, sprightly, clever children. Out of Shakespeare,

opportunities for Miss Kate Terry were found in the melodramas of 'The

Courier of Lyons' (Sir Henry Irving's 'The Lyons Mail' of to-day),

'Faust and Marguerite,' and the comedy of 'Every One has his Fault.'

The sisters figured together as the Princes murdered in the Tower,

by Mr. Charles Kean as Richard III. What miniature Hamlets they

looked in their bugled black velvet trunks, silken hose, and ostrich

feathers! They were in mourning, of course, for their departed father,

King Edward IV. My recollection of Miss Ellen Terry dates from her

impersonation of the little Duke of York. She was a child of six, or

thereabout, slim and dainty of form, with profuse flaxen curls, and

delicately-featured face, curiously bright and arch of expression; and

she won, as I remember, her first applause when, in clear resonant

tones, she delivered the lines:—

'Uncle, my brother mocks both you and me;

Because that I am little, like an ape,

He thinks that you should bear me on his shoulders.'

Richard's representative meanwhile scowling wickedly and tugging

at his gloves desperately, pursuant to paternal example and stage

tradition. A year or two later and the baby actress was representing

now Mamillius, and now Puck."

[32]

Now, when he arrived at this point, Mr. Dutton Cook raised a

hornet's nest about his ears. In the mind of playgoers it had been

long decided that this all-important first appearance had been in

the character of Mamillius. Where, then, did Mr. Dutton Cook's

picturesquely described Duke of York come in? Mr. George Tawse, who

modestly described himself as a "play-bill-worm," took great interest

in the matter, and having carefully consulted the happily preserved

documents in the British Museum, wrote many letters on the subject to

Mr. Clement Scott, who was then the erudite editor of The Theatre.

These communications attracting some notice (Mr. Tawse, be it noted,

being all in favour of Mamillius), Mr. Scott appealed to headquarters,

and Ellen Terry characteristically wrote to him:—"The very

first time I ever appeared on any stage was on the first night of

'The Winter's Tale,' at the Princess's Theatre, with dear Charles

Kean. As for the young Princes, them unfortunate little men, I never

played—not neither of them—there! What a cry about a little

wool! P.S.—I was born in Coventry, 1848, and was, I think,

about seven when I played in 'The Winter's Tale.'"

Following up his careful researches, Mr. Tawse ultimately came to

the conclusion that on April 28, 1856, Ellen Terry appeared at the

Princess's as Mamillius in "The Winter's Tale"; on October 15, 1856, as

Puck in "A Midsummer Night's Dream";[33]

on December 26, 1857, as the Fairy "Golden Star" in "The White Cat"

pantomime; on April 5, 1858, as Karl in "Faust and Marguerite"; on

October 18, as Prince Arthur in "King John"; on November 17, as Fleance

in "Macbeth"; and on December 28, of the same busy year, as "The Genius

of the Jewels," in the pantomime of "The King of the Castle."

As the lady has so strongly declared for Mamillius, and as Mr. Tawse

thus champions her, I suppose the verdict must be accepted; and yet it

seems very unlikely that such an accurate writer as Mr. Dutton Cook

could have been mistaken concerning that impersonation of the little

Duke of York. Can Ellen Terry have forgotten it? Knowing that she does

not set sufficient value on her work, or the impression it makes on

others, I think it very probable. Indeed, in all due deference to her

and Mr. Tawse (for even play-bills will sometimes unwittingly lie),

I like to give credit to Mr. Dutton Cook's miniature sister Hamlets

in their bugled black velvet trunks, their silken hose, and ostrich

feathers!

As poor little Mamillius, cursed with a jealous yet respected

father, and wondering what the troubles could be that existed between

him and his unhappy, deeply-wronged mother, she must have been very

sweet, and one can fancy what Charles Kean felt when he cried to his

"boy"—

"Come, Sir Page,

Look on me with your welkin eye."

[34]

We have only to realise that in using the word "welkin" Shakespeare

meant "heavenly," to get the expression of the anxious but inspired

little Terry girl.

And if this was indeed her first appearance, her dismissal by

Leontes with the words, "Go play, Mamillius," was almost prophetic.

But if Mr. Dutton Cook chanced to err on the much discussed first

appearance question, he was certainly correct in his critical estimate

of the two remarkable child actresses.

"The public applauded these Terry sisters," he wrote, "not simply

because of their cleverness and prettiness, their graces of aspect, the

careful training they evidenced, and the pains they took to discharge

the histrionic duties entrusted to them, but because of the leaven

of genius discernible in all their performances—they were born

actresses.

"Children educated to appear becomingly upon the scene have always

been obtainable, and upon easy terms; but here were little players who

could not merely repeat accurately the words they had learnt by rote,

but could impart sentiment to their speeches, could identify themselves

with the characters they played, could personate and portray, could

weep themselves that they might surely make others weep, could sway

the emotions of crowded audiences. They possessed in full that power

of abandonment to scenic excitement which is rare even among the most

consummate[35]

of mature performers. They were carried away by the force of their

own acting; there were tears not only in their voices but in their

eyes; their mobile faces were quick to reflect the significance of the

drama's events; they could listen, their looks the while annotating,

as it were, the discourse they heard; singular animation and alertness

distinguished all their movements, attitudes, and gestures. There was

special pathos in the involuntary trembling of their baby fingers,

and the unconscious wringing of their tiny hands; their voices were

particularly endowed with musically thrilling qualities. I have never

seen audiences so agitated and distressed, even to the point of

anguish, as were the patrons of the Princess's Theatre on those bygone

nights when little Prince Arthur, personated by either of the Terry

sisters, clung to Hubert's knees as the heated iron cooled in his

hands, pleading passionately for sight, touchingly eloquent of voice

and action; a childish simplicity attendant ever upon all the frenzy,

the terror, the vehemence, and the despair of the speeches and the

situation.

"Assuredly Nature had been very kind to the young actresses, and

without certain natural graces, gifts, and qualifications, there can

scarcely be satisfactory acting. All Romeo's passion may pervade

you, but unless you can look like Romeo—or something like

him—if your voice be weak or cracked, your mouth awry or your

legs askew—it is vain to feel like him;[36]

you will not convince your audience of your sincerity, or induce them

to sympathise in the least with your actions or sufferings; still less

will you stir them to transports. Of course Genius makes laws unto

itself, and there have been actors who have triumphed over very serious

obstacles; but, as Mr. G. H. Lewes has observed, 'a harsh, inflexible

voice, a rigid or heavy face, would prevent even a Shakespeare from

being impressive and affecting on the stage.' The player is greatly

dependent upon his personality. At the same time, mental qualities must

accompany physical advantages. The constitutionally cold and torpid

cannot hope to represent successfully excitement or passion. The actor

must be en rapport with the character he sustains, must sympathise

with the emotions he depicts. A peculiar dramatic sensitiveness and

susceptibility from the first characterised the sisters Terry; their

nervous organisation, their mental impressibility and vivaciousness,

not less than their personal charms and attractions, may be said to

have ordained and determined their success upon the stage."

Coming from this high source such trustworthy and carefully analysed

appreciation is invaluable; but the criticism that I love best to

preserve in connection with the early appearances of the little Terrys

at the Princess's Theatre is that of John William Cole, the biographer

of Charles Kean. Writing for a book (published in 1859), long before

the girls had established their names, he said:—

[37]

"Before quitting the subject of 'King John' (1852) at the Princess's

Theatre, it would be unjust not to name in a special sentence of

approval the impressive acting of Miss Kate Terry, then a child of ten

years of age, as Prince Arthur, and of Mr. Ryder as Hubert."

In the revival of "King John" in 1858, Ellen Terry was the Prince

Arthur, that sound actor, John Ryder (he had been one of the mainstays

of Macready), again playing Hubert.

Concerning the production of "A Midsummer Night's Dream" in 1856,

Mr. Cole says: "Another remarkable evidence of the excellent training

of the Princess's Theatre presented itself in the precocious talent of

Miss Ellen Terry, a child of eight years of age, who played the merry

goblin Puck, a part that requires an old head on young shoulders,

with restless elfish animation, and an evident enjoyment of her own

mischievous pranks."

It is because Mr. Cole wrote and published, as it were, "upon the

spot," that I consider his criticism not only discerning, but beyond

all price. We all know how easy it is to prophesy after the event!

Ellen Terry's recollections of her appearance as the infant

Mamillius in "The Winter's Tale" are very vivid, as, indeed, they may

be. In more ways than one it was a notable first night for the little

maid. Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and the Princess Royal were

present, and the next morning she woke to find[38]

herself with her foot on the first step of the steep stairs that lead

to fame. No less an authority than the Times declared that she had

played her part with a vivacious precocity that proved her a worthy

relation of her sister. No doubt there were that day rejoicings in the

Terry family, and the sensitive child must have been rewarded for her

own passing tribulations. "My young heart swelled with pride—I

can recall the sensation now," she has declared, "when I was told what

I had to do,"—and then comes the sad confession that she wept

bitter and prolonged tears when the audience laughed when she fell over

the rather ridiculous toy-cart with which Mamillius was ordered to

"go play." She calls it her "first dramatic failure," and felt at the

moment that her "career as an actress was ruined for ever."

I wonder if that untoward episode of the toy-cart had anything to

do with the extreme nervousness that, according to her own confession,

the actress always suffers from on "first nights"? Probably not; for I

believe all true stage artists are continually nervous—nervous

for themselves, nervous for their audiences. She says to this day that

she is so "high strung" on a first night that if she realised that

there was an audience in front staring at her, she would fly away from

the theatre and be far off "in two-twos."

Yes, I fear that all of them, or, at all events, the best of them,

undergo the enduring agonies of nervousness. Once Sothern and Toole

were dining[39]

with me in Birmingham. In the evening the one had to play Lord

Dundreary at the Theatre Royal, and the other Caleb Plummer at the

Prince of Wales Theatre. They had acted these parts for many, many

hundreds of times, and I had imagined that their approaching work would

be mere pastime to them. But Sothern, speaking to his brother comedian,

said, "I don't know how you feel, John, but I'm as nervous to-night as

I was on my first appearance on the stage."

To my amazement, Toole, who always seemed so at home with his

audiences as to become one amongst them, confessed that he had the same

feeling; and they agreed in saying that when an aspiring young actor

conceitedly set forth as one of his qualifications for the profession

the fact that "he did not know what nervousness meant," he was certain

to do no good. "If you are not always anxious about your work," said

Sothern, "always painfully desirous to be doing your best, you will

soon lose whatever hold you may have on the public." And so said every

one's friend—the genial John Toole.

Surely this applies to other pursuits besides the art of acting?

Ellen Terry has happier recollections of Puck than of Mamillius, and

no wonder, for the part, although trying, is a delightful one. During

the two hundred and fifty nights of the performance of "A Midsummer

Night's Dream" at the Princess's (a marvellous run[40]

for those days) she "revelled in the impish unreason of 'the sprite,'"

and since then she has ever felt the charm of parts "where imagination

can have free play, and there is no occasion to observe too closely the

cold, hard rules of conventionality, and the fetters of dry-as-dust

realism."

Of her performances in the pantomimes, with which, at Christmas

time, Charles Kean found it necessary to supplement his elaborate

productions, we can only imagine (and that is easily done) that she was

a very fascinating little fairy; and it seems equally certain that when

she was called upon to appear in two lengthy entertainments on the same

night, she must often have been a very tired little fairy.

Concerning her representation of Prince Arthur in "King John," a

pathetic little story is extant. At the point where she left the stage

in the full and terrible knowledge that her eyes were to be burnt

out, she at first (presumably at rehearsal) made her exit with such

composure that she received a strong reprimand from Mrs. Kean, who told

her that she must give expression to the anguish of the situation. This

little scolding caused the easily affected child to shed such earnest

tears that her monitress cried out, "Oh, if you can only do that on the

stage, what a Prince Arthur you will be!" The hint was taken to heart

and adopted, and the success of the impersonation was assured.

[41]

The new Prince Arthur was honoured with a special call, and the

critics were loud and unanimous in their praises, freely acknowledging

the dramatic force of the performance, together with its delightful

simplicity, tenderness, and truth to nature.

No doubt her position in the theatre compelled Mrs. Kean to be

from time to time an apparently harsh task-mistress, but little Ellen

learnt to love her, and has always remembered with generously expressed

gratitude the benefit she derived from her suggestions and lessons.

But in spite of the hard work and childish troubles that she must

have undergone, she speaks brightly of every one she met in that very

early engagement at the Princess's. In his old age and infirmities she

sympathetically recalls Harley, the eminent comedian for whom Charles

Dickens was induced to write some of those ephemeral farces that in

earlier days had fitfully flourished at the St. James's Theatre; she

remembers affectionately her earnest but exacting dancing-master, Mr.

Oscar Byrn, and the tiring hours that she spent under his determined

rule; she conjures up with pride her first and only meeting with

Macready, and how, when she apologised for accidentally jostling him

while running to her dressing-room, he smiled, laughed, and then said,

"Never mind, you are a very polite little girl, and you act very

earnestly and speak very nicely;" and she is warm in the praises of

Charles Kean, and lastingly appreciative of the strong impression made

upon[42]

her by his vivid personality. But I fancy that the sunny nature of

Ellen Terry has found good in everything, and, throughout her stage

career, has shed brightness and warmth on the somewhat dingy world

behind the scenes.

My friend, Geneviève Ward, who has taken part with her in several

of her memorable Lyceum triumphs, tells me that it is delightful to

bear witness to her sweet disposition—a cultivated charm that

prompts her to be generous, thoughtful, kind, and considerate to every

one, and to make her genuinely anxious that the humblest actresses

in the company, as well as the principals, should appear to the best

advantage. Thus lovingly thinking of others, Ellen Terry makes herself

loved, and by her radiant presence lightens many a weary heart.

In her own gossamer-like and gem-bespangled "Stray Memories," she

has written: "Why is it, I wonder, that pain is so deeply felt at the

time, and that its memory fades so quickly, while joy flits by almost

unperceived, and yet leaves such deep traces behind? At least, this is

my experience. It may not be so with most people. They may, perhaps,

suffer deeply and remember lightly; enjoy strongly and forget quickly.

If so, I pity them with all my heart. When I sit down to write it is

not the sad recollections that come crowding before me; it is the

bright joyous moments which shape themselves most distinctly in my

mind. 'Oh, what a light, frivolous nature you must have, then!' I hear

some grave and[43]

reverend signior remark, if any such person ever deigns to read this

flimsy chatter. Well, I am ready to plead guilty to the charge. I was

made like that, and so Nature is to blame, and not I."

Ours would be a gayer and happier world if Nature had cast more of

us in the same mould.

Another Princess's experience was her appearance as a diminutive

"Tiger" page-boy in a farce by Edmund Yates, entitled "If the Cap

Fits," and she confesses to the infinite pride she took in her pair of

miniature and rather tight-fitting top-boots. Here again, though in a

different way to her Shakespearean representations, genuine success was

secured. In his interesting volumes of "Reminiscences" Edmund Yates

records the production, saying, that "'If the Cap Fits' was admirably

acted by, amongst others, Mr. Frank Mathews, Mr. Walter Lacy, and Miss

Ellen Terry ... who played a juvenile groom, a 'tiger,' with great

spirit and vivacity." And, much later on, he says: "In the present

days of genuine heroine-worship, with recollections full upon us of

Beatrice, Viola, Olivia, and Camma, it seems odd to read, in connection

with this slight comedietta, that Miss Ellen Terry is worthy of praise

for the spirit and point with which she played the part of a youthful

groom."

Evidently she believed in the same doctrine as, in his early days,

Colley Cibber did. Weary of being told that the parts he wanted to

attempt were "not in his way," he protested: "I think anything, naturally[44]

written, ought to be in everybody's way that pretends to be an

actor."

Ellen Terry could not agree with those critics who declared

that Charles Kean went too far in the mounting of his plays. The

theatre-goers of those days had not been taught to expect beautiful

and correct scenery, and exact accuracy in costume; and some of them

actually resented it, leaning to the view held by Kean's contemporary

and friend, Dr. Westland Marston, who considered that in some of the

spectacular revivals at the Princess's, unnecessary pageantry was not

only introduced but absolutely obtruded. For example, he said that

in the beautiful production of Richard II. a display of too minute

correctness in armorial bearings, weapons and household vessels made

the stage an auxiliary to the museum, and forced it to combine lessons

on archæology with the display of character and passion.

Such were the thanks that Charles Kean received for his

indefatigable and scholarly research, and lavish expenditure! How he

would have loved to hear his little Mamillius and winsome Puck declare

in the days of her fame, and when hers had become a voice in the land

greater than his own, that with rare perception he had opened his eyes

to the absurd anachronisms in costume and accessories which prevailed

at that period, and that he established a system which has been

perfected by Sir Henry Irving and his contemporaries. To have been a

pioneer in good work eventually means fame, but[45]

pioneers are apt to be distrusted by those who have not the courage to

accompany them on their explorations.

She also draws an apt comparison between the remuneration and work

of the actors of the Charles Kean days and now.

"Very young actors," she says (I again venture to quote from her

"Stray Memories"), "sometimes complain of low salaries and long hours.

I wish they could see Mr. Kean's salary-list—they would soon

cease to grumble. Why, a young man to-day gets as much for carrying

on a coal-box as an experienced actor then received for playing an

important part. Then, how different the hours are! If a company now has

to rehearse for four hours in the day it is thought a great hardship.

But when I was a child rehearsals often used to last until four or five

in the morning. What weary work it was to be sure! My poor little legs

used to ache, and sometimes I could hardly keep my eyes open when I was

on the stage. Often I used to creep into the green-room, which every

one acquainted with the old Princess's will remember well; and there,

curled up in the deep recess of the window, forget myself, my troubles,

and my art—if you can talk of art in connection with a child of

eight—in a delicious sleep."

It is a pathetic little portrait, but the hard work,

the early training and the weary hours resulted in

well won, nay almost unique success, and an artistic[46]

career that has rejoiced the hearts of her fellow creatures, and will

for ever live in the history of the stage.

Charles Kean's memorable management of the Princess's Theatre came

to an end in 1859, and with it terminated the engagement of the Terry

family.

In thinking of Charles Kean I always conjure up three pictures.

The first one represents the dingy lodging in the now demolished

Cecil Street, Strand, where his father, Edmund Kean, is staying with

his devoted wife and three-year-old boy. The struggling strolling

player has got his chance at last. He is to appear to-night as Shylock

at Drury Lane. It is the night of January 14, 1814, and in theatrical

lore is for ever memorable. "I must dine to-day," the nervous actor

said—and for the first time in many days he indulged in the

luxury of meat. "My God!" he exclaimed to his wife, "if I succeed I

shall go mad!" As the church clocks were striking six he sallied forth

from his meagre apartment with the parting words: "I wish I was going

to be shot." In his hand he carried a small bundle—containing

shoes, stockings, wig, and other trifles of costume, and so he trudged

through the cold and foggy streets, and the thick slush of thawing snow

that penetrated his worn boots and chilled him to the bone. And then

the exultant return home after the curtain had fallen upon the wild

enthusiasm of an electrified audience! Nearly mad with delight, and

with half-frenzied[47]

incoherency he poured forth the story of his triumph. "Mary!" he cried

to his wife, "you shall ride in your carriage yet! Charles," lifting

the boy from his bed, "shall go to Eton!"

Then followed his career of unexampled success and prosperity

continually marred and at last ruined by the dissipated habits to

which this giant among tragic actors allowed himself to become the

unhappy victim—habits that wrecked his home and well-nigh ruined

his reputation. Between 1814 and 1827 his earnings had amounted to

£200,000, and yet when he died in 1833 everything he left behind him,

all his presents and mementos, had to be sent to the hammer to pay his

debts.

The 25th March 1833 (here is my second picture) saw the end of his

stage career. For the first and only time Edmund the father and Charles

the son (who had been sent to Eton, but who had taken to the stage as

most of the sons of true actors will) stood upon the London boards

together, the one playing Othello, the other Iago.

The event caused great excitement among playgoers, and the house was

crammed to suffocation. But Edmund Kean went through his part "dying

as he went," until he came to the "Farewell,"—and the strangely

appropriate words—"Othello's occupation's gone."

Then he gasped for breath, and, falling upon his son's shoulder, moaned,

"I am dying, speak to them for me." Within a few months the restless spirit of[48]

Edmund Kean was at peace in the quiet churchyard at Richmond.

The third picture has been limned by Dr. Westland Marston, and shows

a sad little episode in the declining years of Charles Kean, a man

who, devoid of the genius of his erring father, had ever attempted to

promote the highest interests of his calling, and to do good in the

world.

"In the autumn of 1866," says my vivid word painter, "I chanced to

be at Scarborough. The evening before leaving, when passing by one of

the hotels—I think the Prince of Wales's—there appeared,

framed in one of the windows, a worn, pallid face, with a look of

deep melancholy abstraction. 'Charles Kean!' I exclaimed to myself,

and prepared to retrace my way and call. But, having heard already

that he had been seriously unwell while playing a round of provincial

engagements, I thought it better not to disturb him or to bring home to

him a grave impression as to his health, even by a card of enquiry. In

little more than a year after this his death took place. It occurred

in January 1868, when he had reached his fifty-seventh year.... His

friends who are still amongst us will cherish the recollection of

a high-principled gentleman, warm in his attachments, generous in

extending to others the appreciation he coveted for himself, and

gifted with a charm of simple candour that made even his weaknesses

endearing."

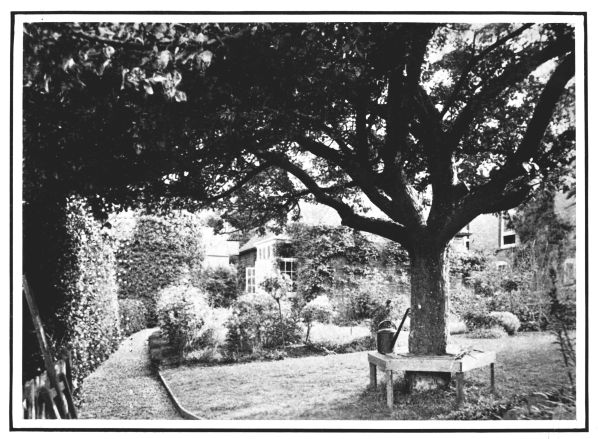

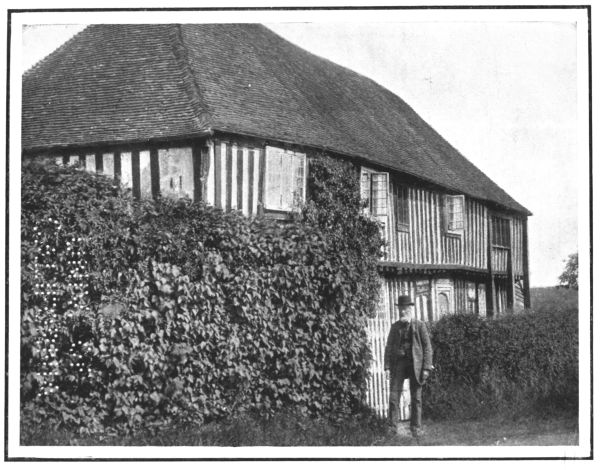

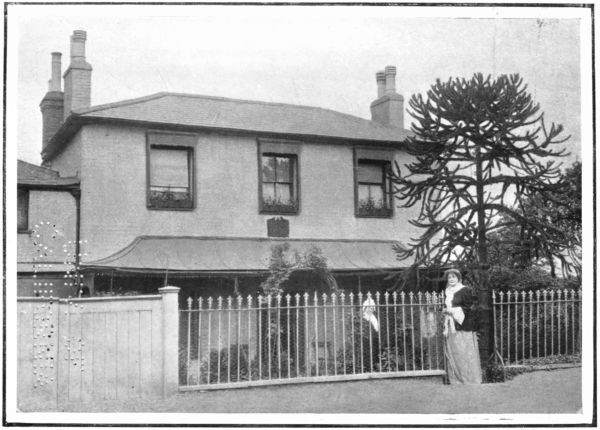

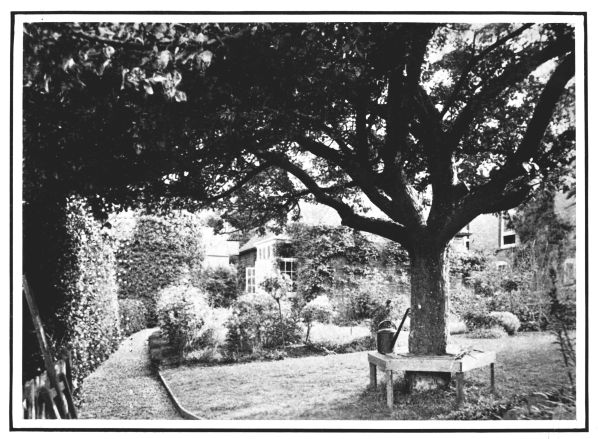

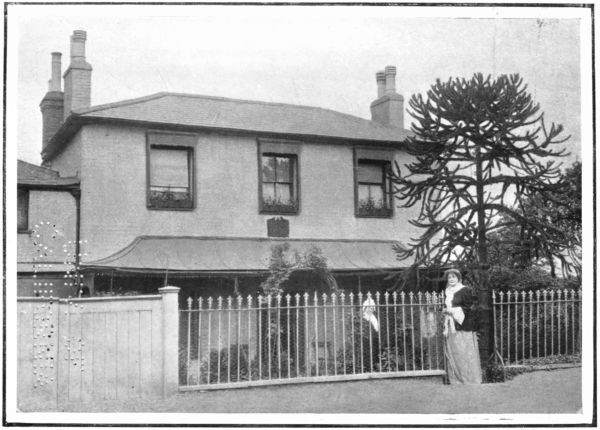

TOWER COTTAGE, WINCHELSEA.

Ellen Terry's country home. [To face page 48.

It is to be feared that in the theatrical career on[49]

which he started with so much energy and confidence Charles Kean met

with lack of appreciation and much disappointment.

I wonder what would have been the effect if the consoling words of

George William Curtis (one of the most beautiful of American writers)

had been wafted to him across the Atlantic?

"Success," says Curtis, "is a delusion. It is an

attainment—but who attains? It is the horizon, always bounding

our path and therefore never gained. The Pope, triple-crowned, and

borne with flabella through St. Peter's, is not successful—for he

might be canonised into a saint. Pygmalion, before his perfect statue,

is not successful,—for it might live. Raphael, finishing the

Sistine Madonna, is not successful,—for her beauty has revealed

to him a finer and an unattainable beauty."

To the true artist such truths as these strike home, and I fear

they often throw their cloud over the apparently ever sunny-minded

Ellen Terry. It is a fact that she often feels she has failed where

enthusiastic audiences, and even the most captious critics, testify to

the fact that she has triumphed. But she knows that any seeming victory

in human life is not final achievement, but a spur (often a cruel one)

to endless endeavour. The artistic temperament must be more or less

self-tormenting, and those who desire mere personal comfort should

never attempt to cultivate it. Devoid of it they can smugly criticise,

and with intense self-satisfaction condemn, the life[50]

work of those who well nigh exhaust their energies in order to provide

them with entertainment.

At the conclusion of the Princess's engagement Mr. Ben Terry seems

to have been inspired by a happy thought. Probably he knew that in 1859

there were thousands of goody-goody people who did not like to be seen

in a real theatre, but who would flock to see theatricals under the

guise of "A Drawing-Room Entertainment." Possibly he was aware that

the congregations of goody-goodies, who still had an idea that Mawworm

was right when he declared that the playhouse was the devil's hot-bed,

took an eager interest in reading anything that appeared concerning the

stage. The youthful fame of Kate and Ellen Terry was well established.

Their stars were in the ascendant, everybody (including the useful army

of goody-goodies) wanted to see them;—why not let them appear in

a "Drawing-Room Entertainment"?

Perhaps I am wrong in hinting at such things as these in

connection with the business arrangements of Mr. Ben Terry. Anyway, a

"Drawing-Room Entertainment" was devised for the attractive sisters,

and it became exceedingly popular.

It was first brought out at the Royal Colosseum, Regent's Park,

in those days a favourite place for amusements of this description.

It proved so attractive that it ran for thirty consecutive nights,

during which more than thirty thousand people paid for admission, and

expressed their delight in the entertainment.[51]

Thus encouraged, it was taken on tour to the leading as well as the

smaller provincial towns.

Those who, like myself, remember the Colosseum as it used to be, and

were in their juvenile days taken there as to one of the "Sights of

London," will remember the weird, imitation stalactite caverns. Ellen

Terry has confessed that it was amid the artificial gloom of these

shams that she first studied Juliet. At least they served one good