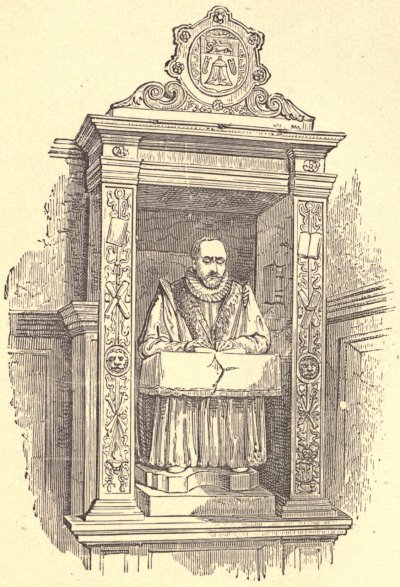

STOW'S MONUMENT, IN THE CHURCH OF ST. ANDREW UNDERSHAFT, LONDON.

Title: Bygone London

Author: Frederick Ross

Release date: December 28, 2014 [eBook #47796]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MWS and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Of this book 500 copies have been printed, and this is

No.......12

Bygone London.

BY

FREDERICK ROSS, F.R.H.S.,

AUTHOR OF

"LEGENDARY YORKSHIRE," "YORKSHIRE FAMILY

ROMANCE," ETC., ETC.

LONDON:

HUTCHINSON & CO., PATERNOSTER SQUARE.

1892.

Notwithstanding the multitude of books that have been written relating to its history and antiquities, the History of London still remains to be written, a work that cannot, from its ocean-like infinitude of matter, be accomplished by a single hand, but will require the combined action of a multiplicity of labourers.

By London is here meant, not the vast aggregation of buildings and population spreading into four or five counties but that small fraction lying north and south of the Thames, which is under the jurisdiction of the Lord Mayor of London—that portion which was a considerable emporium of trade under the Celtic Trinobantes; a military post and seat of commerce under the Romans, with roads, of which one still retains its name of Watling Street, in the centre of London, all radiating from a central miliarium, which may still be seen, a venerable relic of sixteen centuries of age, in the wall of St. Swithin's Church; which was a capital city and place of great mercantile importance under the Saxons and the Danes, and has in the subsequent thousand years, gradually expanded its limits, and gathered population, wealth, and commerce, until it has become the capital of the world, in magnitude and wealth unprecedented, to which the capitals of other nations are but as provincial cities: so vast and rich that Blucher might well exclaim, when shewn its banks and docks, its warehouses and shops—"Ye gods! what a place to sack."

Notwithstanding the many books in existence, descriptive of the various phases of London, it appeared to the publishers there was still room for a small, handy, and compact volume, of moderate price, which should give a clear and comprehensive view of some of the more salient features of the bygone history of the old city, which they presume to hope may be found in this volume.

| PAGE | |

| The Walls and Gates | 1 |

| Episodes in the Annals of Cheapside | 34 |

| Bishopsgate Street Within and Without | 76 |

| Aldersgate Street and St. Martin's-le-Grand | 118 |

| Old Broad Street | 142 |

| Chaucer and the Tabard | 165 |

| The Priory of the Holy Trinity, Aldgate | 178 |

| Convent of the Sisters Minoresses of the Order of St. Clare, Aldgate | 197 |

| The Abbey of St. Mary of Graces, or East Minster | 208 |

| The Barons Fitzwalter of Baynard's Castle | 219 |

| Sir Nicholas Brember, Knight, Lord Mayor of London | 239 |

| An Olden Time Bishop of London: Robert de Braybrooke | 249 |

| A Brave Old London Bishop: Fulco Basset | 262 |

| An Old London Diarist | 269 |

| Index | 291 |

BYGONE LONDON.

In prehistoric ages the valley of the Thames formed the bed of an estuary or arm of the sea, whose waters flowed over the low lands of Essex, and whose waves dashed against the sloping uplands of Middlesex and Surrey, on whose summits now stand the Crystal and Alexandra Palaces. In process of time, by the deposition of silt brought down from the west, and of sand brought up by the flow of the tide, the estuary was reduced to a river, afterwards still further reduced in width by the embankments made by the Romans along the coast of Essex; and the land intervening between the then and the former shores became a succession of fens and morasses, some of which remained to comparatively modern times, and have their localities indicated by such names as Moorfields, Fenchurch, Marsh-gate, Lambeth, etc.

Amongst these morasses were oases of high and firm land; and beyond, spreading up and over the slopes of the uplands, there grew a dense forest, the home of wolves, boars, and other wild animals. Upon one of these spots of dry land, at the time of the invasion of Cæsar, might be seen a village of wattled or mud-built and thatched huts, inhabited by the Celtic aborigines, with cattle and hogs feeding in the midst, a few patches of cultivated land, and beyond, the forest. This was the nucleus of the mighty London of the present, and is supposed to have occupied a space of some quarter of a mile along the river shore, with Dowgate for its centre, and stretching northward as far as Cheapside. In all probability it would be surrounded by earthworks, ditches, and stockades, for the purpose of defence, and would otherwise be protected by the broad stream of the Thames, and by the Fleet river on the west, and Walbrook on the east.

When the Romans completed the subjugation of the southern part of Britain and began to make settlements, their practical sagacity at once perceived the eligibility of this spot as a centre of commerce; and in a short time it put on the appearance of a Roman city, and gradually [3]became adorned with residential houses after the Roman fashion—whose tesselated pavements and other decorations are still often exhumed—with marts of commerce, temples of the gods, basilicæ, baths, amphitheatres, and other architectural appliances of an important city.

At what period the Romans substituted a wall of defence in place of the old earthworks is uncertain, but previous to its construction they appeared to have erected two forts on the north bank of the Thames—one at the eastern extremity of the City, where the tower now stands; the other at the western end, where the Fleet fell into the Thames. That it was an open town, or very imperfectly defended, in the middle of the first century, is evidenced by the facility with which Queen Boadicea, temp. Nero, entered it with her army, slaughtered the inhabitants, and most probably burnt it, as the charred remains of a great conflagration have been frequently found in making deep excavations. Henry of Huntingdon, and some other of the old chroniclers, tell us that it was first walled by Constantine the Great, at the request of his mother Helena, and that the materials he made use of were hewn stone and British bricks, and [4]that it was in compass about three miles. Camden seems to credit this statement, from the fact that coins of the Empress Helena have been found under the wall, but as these might have been in circulation long after her death, it only goes to prove that the wall was not built before her era. Constantine died in the year 337, and we find some twenty-five years afterwards London was entered and pillaged, and the inhabitants reduced to a state of great misery, by a combined army of Picts, Scots, Saxons, and Franks, which would scarcely have been possible if it had been walled, and defended by the disciplined soldiers of the empire. The probability seems to be that the walls were either built or commenced by Theodosius, the Roman general, afterwards emperor, who in the reign of Valentinian, came to Britain with an army, utterly routed the pirates and freebooters, and entered London in triumph, where he remained for a considerable period; and we are told by Ammianus Marcellinus that before he left the island he restored to their ancient sound condition both the towns and military strongholds throughout the country, and put everything in such a state of defence that peace was maintained until the reign of Honorius, [5]when Britain was abandoned by the Romans. Hence we may arrive at an approximate date for the building of the walls. Constantine came to the throne in 306, and Valentinian died 375: and it is almost certain that it took place some time within these 70 years, the balance of evidence seeming to refer it farther to the period of the sojourn of Theodosius in Britain, or about 368-70.

Fitzstephen is the earliest writer who mentions the wall. He lived in the reign of Henry II., towards the end of the twelfth century, and describes the wall as high and thick, with seven double gates and many towers and turrets placed at proper distances. Originally there were only four exits from the City—by way of Aldgate on the east, Cripplegate on the north, Newgate on the west, and Dowgate on the south; the latter was the entrance to the "Trajectus," or ferry across the Thames, and derived its name from Dwr or Dour—water; or perhaps from Dwyr Dover, as leading to the Dover-road. Near to this gate was placed the Miliarium, a portion of which may still be seen in the wall of St. Swithin's Church, whence distances were measured along the roads, and from which [6]radiated four roads—one by Dowgate and across into Kent, and three others which passed respectively through Aldgate, Cripplegate, and Ludgate. The wall commenced at the eastern fort, and had a postern gate at its commencement which occupied the position of the row of posts in Postern-row, north of the Tower, whence it ran northward to Aldgate, the eastern exit (some portions of the old wall are still remaining at the back of the houses in America Crescent); from Aldgate it went in a north-western direction between Hounds-ditch and Camomile Street to Bishopgate, whence it proceeded directly west to Cripplegate. In the street called London-wall a fragment may be seen, and the remains of a bastion may be found between St. Giles's Church and the Barber Surgeons' Hall. From this point it turned southward for a short distance down Noble Street, and again deflected to the west, arriving at Aldersgate, after which it passed St. Botolph's Church and Christ's Hospital, then turned southward at a sharp angle, coming to Ludgate (which stood immediately to the west of St. Martin's Church), and hence to the Thames. In 1276 that portion south of Ludgate was taken down, and a new wall built from Ludgate to the [7]Fleet river, and hence south to the Thames, so as to enclose the new Blackfriars' Monastery. It has been doubted whether the wall was continued along the river bank, but Fitzstephen says:—"London once had its walls and towers on the south, but that vast river, the Thames, which abounds with fish, and enjoys the benefit of tides, and washes the City on this side, hath in a long track of time totally subverted and carried them away;" and adds, that in his day some relics might be seen. Salmon, in his Survey of England, vol. i., disputes this, chiefly on the ground that we have no historical account of any great inundation such as would be necessary to effect such a result; and Maitland combats his arguments at great length, contending that a period of 777 years was quite sufficient to account for their decay and disappearance; and Lord Lyttelton remarks that long previously it had not been necessary to repair the south wall, the Tower and the bridge being amply sufficient to prevent a hostile fleet approaching the City.

In the year 1707 considerable portions of the wall were laid bare in digging for the foundations of some houses near Bishopsgate, which Dr. Woodward carefully examined, and gave a [8]description of the materials and construction in "Remarks upon the Ancient and Present State of London: Occasioned by some Roman urns, etc., discovered near Bishopgate," originally published in the eighth volume of Leland's Itinerary, and afterwards separately. He says: "It was compiled alternately of layers of broad flat bricks and of ragstone. The bricks lay in double ranges, and each brick being but one inch and three tenths in thickness, the whole layer, with the mortar interposed, exceeded not three inches. The layers of stone were not quite two feet thick of our measure. To this height (eight feet) the workmanship was after the Roman manner, and these were the remains of the ancient wall. In this it was very observable that the mortar was, as usual in the Roman work, so very firm and hard that the stone itself was easily broke and gave way as that. It was thus far from the foundation nine feet in thickness. The broad thin bricks above mentioned were all of Roman make, and of the sort, as we learn from Pliny, that were in common use among the Romans, being in length one foot and a half of their standard, and in breadth one foot. The old wall having been demolished, was afterwards [9]repaired and carried up of the same thickness to eight or nine feet in height; or, if higher, there was no more of that work now standing. All this was apparently additional, and of a make later than the part underneath it. The outside, towards the suburbs, was faced with a coarse sort of stone, not compiled with care, nor disposed into a regular method; but on the inside there appeared more marks of workmanship and art. There was not one of the broad thin Roman bricks mentioned above in all this part, nor was the mortar near so hard as in that below; but from the description it may be easily collected that this part, when first made and entire, with so various and orderly a disposition of the materials—flint, stone, and bricks—could not but carry a very elegant and handsome aspect. Upon the additional work now described was raised a wall wholly of brick, only that it terminated in battlements topped with copings of stone. It was two feet four inches in thickness, and somewhat above eight feet in height.... This wall was strengthened and embellished with stately towers, which on the south, together with the wall, are long since become a prey to the tide and weather; but the remains of [10]those on the land side, being fifteen in number, are still to be seen: one thereof, about the middle of Houndsditch, is a Roman construction, composed of stone with layers of bricks. It is situated almost opposite the end of Gravel Lane, on the west of Houndsditch, and is still three stories high, but sorely decayed and rent from top to bottom in divers parts."

The height of the Roman wall is supposed to have been about twenty-two feet, and that of the towers about forty. Besides these towers there were bastions and other defensive works usual in fortifications. In Vineyard Street, on the south of Aldgate, the base of a tower about eight feet high was made use of for a new superstructure early in the last century, upon which had been fixed a stone with this inscription: —

"Glory be to God on high, who was graciously pleased in a wonderful manner to preserve the lives of all the people in this house, twelve in number, when the ould wall of this Bulwark fell down three stories high, and so broad as two cartes might enter a breast, and yet without any harm to their persones. The Lord sanctify this his great providence unto them. Amen and Amen. It was Tuesday, the 23rd September, 1651."

There is reason for believing that the first western wall ran southward, with a slight inclination to the west, from Cripplegate to the Thames, passing eastward of St. Paul's, as urns and other sepulchral remains have been found between this line and that indicated above. The Romans never buried their dead within the walls, consequently this locality must at some period have been extramural; and it would appear that as these remains have been found beneath pavements, as the City grew in population and required more space for the habitations of the living, the old graveyards were built over. Some forty years ago, in sinking a shaft in Paternoster Row, the excavators met, at a depth of eighteen feet, a stone wall of such intense hardness that it took the workmen three or four days to cut through it. This is supposed to have been a portion of the primitive wall, and is described by C. Roach Smith in the Archæologist, vol. xxvii., pp. 140-53.

After the departure of the Romans, the wall appears to have fallen to decay, and the City was easily taken by the Saxon pirates, who also neglected defences of this description to a great extent, trusting more to their own valour than in [12]bricks and mortar. It would no doubt suffer greatly in the destruction of its towers and bastions in the three great conflagrations which occurred in the years 764, 798, and 801, and consumed the greater part of the City. Such being the case, it fell an easy prey to the Danes, who in 851 sailed up the Thames with a fleet of 350 ships, speedily reduced it, and garrisoned it as a basis whence to attack Wessex. Alfred the Great succeeded to the throne of Wessex in 871, and from that period to 878 he fought no less than fifty-six battles with the invaders. In 884 he laid siege to London, drove out the Danes and compelled them to capitulate, after which he repaired the walls and forts, and appointed his son-in-law, Ethelred, governor. The repairs appear to have been of a substantial character, as when Anlaf and Swegen, or Sweyn, the kings of Norway and Denmark, attacked the City, with a fleet of 94 ships, in 994, the citizens were enabled to defy all their endeavours to enter within the walls, and compelled them to raise the siege with great loss, as happened again in 1013, when the city was defended by Ethelred II. But after some successes elsewhere, Sweyn returned, and again laid siege to the City; and again the [13]citizens might have closed their gates against him, but Ethelred, their king, pusillanimously fled to Normandy, and the citizens deemed it best to submit, whereupon the gates were thrown open, the Danes admitted, and Sweyn proclaimed King of England.

Sweyn did not long enjoy this dignity; he died the following spring, when the Londoners recalled Ethelred: and he also dying soon after. Edmund Ironsides, his son, was proclaimed king, and crowned in London. Canute, the son of Sweyn, however, claimed the crown won by the prowess of his father, and came with a large fleet up the Thames, but could not pass beyond the bridge, and finding he could make no impression on the eastern walls and forts, he cut a canal across Southwark and Lambeth, availing himself of certain watercourses, and conveyed his ships into the Thames somewhere about Vauxhall, whence he sailed downward, and attacked the western walls and towers; but the undaunted bravery of the citizens and the strength of their defences compelled him to raise the siege. Soon after, however, a treaty was entered into between Edmund and Canute for the division of the kingdom: and London falling to the share of the [14]latter, he took up his winter quarters there. By the death of Edmund a few months after, Canute became sole monarch of England.

After the battle of Hastings, William the Conqueror marched upon London, but was opposed by a body of the citizens in Southwark, whom he repulsed; but recognising their valour and perceiving the strength of the City's fortifications, he went to subdue the Western Counties, and his success in that direction showed the Londoners that the wisest and most politic course would be to submit; when the Norman duke entered the City, and was presented with the keys and acknowledged as King of England. He was no sooner in possession of the City than he caused three castles to be erected, ostensibly for the protection of the City, but really to overawe the inhabitants. These were the Tower at the eastern, and Baynard and Montfichet Castles at the western, extremity of the walls. The Tower became the residence of the Norman kings, and Baynard Castle that of the chatelain and standard-bearer of the City—offices held first by the Baynards, and afterwards by the Barons Fitzwalter. Montfichet Castle was destroyed by fire in the reign of William, and the Black Friars' [15]Monastery built on the site—the best of the stones being used in the re-edification of St. Paul's Cathedral, which had been destroyed by fire.

Fitzstephen speaks of the walls being "both high and thick, with seven double gates," which appear then to have been in good condition, although the south wall had been "subverted and carried away by the tide." But very soon after some portions seem to have fallen into a ruinous condition; as Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris tell us that the barons, when in arms against King John, in 1215, entered the City by Ealdgate, and demolished the houses of the Jews, to obtain materials wherewith to repair that gate and the adjoining walls. In 1257, also, it is stated, Henry III. "caused the walls, which were greatly decayed, and destitute of towers and turrets, to be repaired in a handsomer manner than before, at the common charge of the City."

King Edward I. granted permission to Kilwarby, Archbishop of Canterbury, to take down the wall, from Ludgate to the Thames, for the purpose of enlarging the Church of the Black Friars, and in 1282 granted a murage charter to the Corporation for levying certain tolls throughout [16]the kingdom, for making a new wall from Ludgate—westward to Fleet Bridge, along behind the houses and by the water of the Fleet to the Thames, "from the aforesaid day to the end of three years next following," from which none were exempt, saving the city of Winchester, and a few other cities, which, by composition, were to pay no Portage, Murage, or Pannage. After an enumeration of the articles to be subjected to toll, amongst which are: "Riges, Cetewal, Kanel, Frankincense, Cummin, Liquorish, Zuber, Cyromontani, Frails of Figs," etc., is added, "Whereas we have granted you for aid of the work of the walls of our City and the closure of the same, divers customs of vendible things, coming to the said City, to be taken for a certain time, we command you that you cause to be finished the wall of the said City now begun near the Friars-preachers, and a certain good and comely tower at the head of the said wall within the water of the Thames," etc. Similar letters were issued by Edward II. in the first, second, sixth, eighth, and twelfth years of his reign; but as it was found that levying a toll on retail commodities caused an insufficient supply, the patent ran in the latter year, that—"Victualia non adducuntur, in [17]detrimentum civitatis;" but that impositions should be levied in bulk on all merchandise brought by land or water. Richard II., in a letter to the Corporation, said in the preamble: "Know ye, that whereas the walls and forts of the City be old and weak, and for want of repair are fallen down in some places, as also the ditches of the said City are exceeding filled with dirt, dunghills, and other filth, not only to the evident danger of the said City and inhabitants thereof, but also to the manifest disgrace and scandal of the whole City," etc.; and granted to the Mayor and Corporation power to levy tolls for ten years for the purpose of placing the wall in a state of thorough repair. In order to enforce these murage tolls it was customary to have chains fixed across the entrances to the City, and no country people with provisions for sale were allowed to pass until they had paid the dues.

In the reign of Edward IV., Ralph Joscelyne, the mayor, repaired the wall from Aldgate to Aldersgate, for which purpose he caused bricks to be made in Moorfields, where also the lime brought from Kent was burnt for that purpose. This was in the year 1477, and several of the City companies—the Drapers (of which company [18]the mayor was a member), the Skinners, the Goldsmiths, and others—contributed to the work, and placed their arms on the portions they executed. The executors of Sir John Crosby also contributed freely out of the funds they held in trust towards the same object. By an order of the Common Council each parishioner also was directed to pay sixpence every Sunday at his Parish Church until the work was completed. After this the walls were neglected and suffered to fall in ruin. Camden, writing in 1607, says that the north wall "having been repaired by one Joscelin, who was mayor, it put on, as it were, a new face and freshness, but that towards the east and west, though the barons repaired it in their wars of the demolished houses of the Jews, is all ruinous and going to decay. For the Londoners, like the Lacedæmonians of old, do slight fenced cities, as fit for nothing but women to live in, and look upon their own City to be safe, not by the assistance of stones, but by the courage of its inhabitants." Nevertheless when the Civil Wars between Charles I. and his Parliament had fairly commenced, the citizens bethought them of their walls and forts as no contemptible means of defence. London had [19]declared most decisively for the Parliament; and in 1643, the Common Council gave directions that the ditches should be cleaned out of the accumulations of rubbish, all outside buildings cleared away, the bulwarks put in repair and mounted with cannon, and new works added to the weaker parts of the walls. The Parliament confirmed this resolution, and extended a plan of fortification, so as to include Southwark and Westminster. A chain of forts surrounding the whole, and lines of communication, were ordered to be erected. All the entrances to the City were closed excepting those at Charing Cross, St. Giles-in-the-Fields, St. John's Street, Shoreditch, and Whitechapel; and these were fortified with musket proof breastworks. To carry out these extensive works a levy was made of eight-fifteenths on all the wards of the City, which was cheerfully assented to by the citizens, and the works were commenced without delay, and carried on with such zeal and alacrity that the whole was completed in an incredibly short space of time. In the year 1647, when the dispute was raging between the Presbyterians and the Independents, the city was divided in opinion: but when the army under Fairfax advanced from Hounslow [20]upon London, the Mayor and Corporation met and saluted the general at Charing Cross; and by an ordnance of Parliament he was constituted Constable of the Tower, the army thus becoming masters of the City. The Parliament then demanded a loan of £50,000 from the City, which was not complied with and in consequence an Act was passed for demolishing the fortifications of London, Westminster, and Southwark.

Whether the Roman wall was protected by a ditch does not appear; probably not, as the first mention we have of one being made is by Dunthorn, who informs us that William, Bishop of Ely, Regent of England when Richard I. was absent in Palestine, made a ditch round the Tower as a defence against John, the King's brother, soon after which the citizens dug a ditch round the walls generally, which they commenced about 1190, but left it unfinished until 1213, as the register of Barmondsey states, when it was recommenced, and completed in two years. This ditch was 200 feet broad, but was afterwards neglected, and gardens planted and houses built upon it. In 1354, Edward III. caused it to be cleansed; and again in 1379, by direction of Lord Mayor Philpot, as also by Lord Mayor [21]Fawconer, in 1414, and Lord Mayor Joceline, in 1477. In 1519, 10th Henry VIII., it was "cleansed and scowered" between Aldgate and the Tower—the chief ditcher being paid 7d. per day, the second ditcher 6d., other ditchers 5d., and every "vagabond" (labourer) one penny and meat and drink at the charge of the City. It was cleansed out again in 1549 at the expense of the trade guilds, and twenty years after, temp. Elizabeth, at a cost of £814 15s. 8d., at which time "it had therein great store of good fish of divers sorts." After this the expense was defrayed by letting the banks and "the whole spoil of the ditch," excepting in 1595, when the Common Council granted two-fifteens for the purpose. In the following century the ditch was filled up, excepting Fleet Ditch on the west, which, after the Fire of 1666, was, by direction of the Mayor and Court of Aldermen, ordered to be cleansed, enlarged, and made navigable for barges up to Holborn-bridge. The sides were built of freestone, and it was arranged that its banks should be lined with warehouses and wharves, but this part of the project was not carried out in its integrity. "This ditch was built and made by Sir Thomas Fitch, bricklayer, who contracted [22]with the City for a very considerable sum, and enriched himself thereby." In 1723 the Corporation obtained an Act of Parliament for filling up the channel from Fleet-bridge to Holborn-bridge, which had become choked with mud and was no longer navigable, and to build thereon a new market in place of Stocks Market, near the Exchange, which it was proposed to dismarket and demolish, and erect on the site a Mansion House for the Lord Mayor.

We have seen that in the old Roman walls there were four gates, the exits of four roads radiating from the "milliarum," now called London Stone. These gates were—Aldgate on the east, Aldersgate on the north, Ludgate on the west, and Dowgate on the south. What were the architectural features of these gates we know not, but undoubtedly they were similar to the usual Roman gateways, with round-arched openings and fortified upper chambers for the purpose of defence.

Aldgate, or Ealdgate, so called by the Saxons on account of its antiquity, was placed by King Eadger in the hands of the knights of the Knighten Guild, who held the soke, now called Potsoken Ward Without, by charter. Afterwards [23]it became part of the demesne of Maud, queen of Henry I., who bestowed it upon the prior and canons of her foundation, the Priory of the Holy Trinity, along with the soke and franchise of the ward. In 1215, the barons, in their war with King John, being favoured by the Londoners, entered the City by Aldgate, which was in a ruinous condition, and repaired, or rather rebuilt it, in the Norman style, with an arched opening built from the ruins of the Jews' houses, and bulwarks of Caen stone. In the 11th Edward IV., the Bastard of Fauconbridge sailed up the Thames with his fleet, he being the admiral, to attack London in the then hopeless interest of the Lancastrian ex-king, when the Londoners hastily fortified the river front, and he landed in Essex, marched to Aldgate, and forced an entrance; but the portcullis having been lowered, separated his forces, and they were defeated and driven back to Mile-end, many being slain and others dispersed. Having fallen to decay, the gate was taken down in 1606, and rebuilt, the finishing stone having been laid in 1609. It consisted of two three-storied square flanking towers, with a deep recessed centre, containing the archway and a room above, and a [24]footway postern in one of the towers. It was ornamented with two stone medallions, copies of two Roman coins found on digging the foundations, a figure of King James I., in gilt armour, over the arch, figures of two soldiers on the battlements, and a representation of Fortune standing on a globe. The rooms over the gate were appropriated to the Lord Mayor's carver as a residence.

Aldersgate, like Aldgate, was denominated Eldergate by the Saxons on account of its antiquity. It was at divers times enlarged, with additional buildings, and was rebuilt in 1617 by direction of the Corporation, William Parker, merchant tailor, contributing £1,000 towards that object. It was built with a recessed centre, and square flanking towers four stories in height. Over the arch was an equestrian figure of King James I., who entered London by this gate when he came from Scotland to succeed Elizabeth on the throne of England, and on the opposite or southern front were statues of the prophets Jeremiah and Samuel, and another representation of King James, seated in a chair of State, in his royal robes. The rooms over the postern were occupied by the Common Crier of the City. [25]This gate suffered great damage in the Fire of 1666, but was restored at the charge of the City, during the mayoralty of Sir Samuel Stirling.

Ludgate, Geoffry of Monmouth informs us, was built by King Lud, circa A.D. 66. It was repaired and partly reconstructed by the barons, in 1215, out of the materials of the Jews' houses, and was again rebuilt in 1586, when a stone was found in the old structure bearing an inscription in Hebrew characters, "This is the station of Rabbi Moses, the son of the honourable Rabbi Isaac." During some repairs in 1260, statues of Lud, and other ancient kings, were placed upon the gate; "but," as Stow says, "these had their heads smitten off in the reign of Edward the Sixth, by unadvised persons and such who judged every image to be an idol. In the reign of Queen Mary, they were again repaired, and had new heads set to their old bodies." In 1586, being much decayed, it was entirely rebuilt by the Corporation, at a cost of £1,500, with statues of Lud and other kings on the east, and of Queen Elizabeth on the west. From the year 1378, this gate was used as a prison for freemen of the City guilty of the crimes of "debt, trespasser, accompts and contempts." It was consumed in [26]the Fire of 1666, but substantially rebuilt, like an ordinary house, with central archway and side portions, and ornamented with statues of Queen Elizabeth, King Lud, etc.

The fourth ancient gate was the exit to the ferry across the Thames, called Dowgate, Downgate, or Dourgate, the great road to the Kentish sea-coast, running from the opposite bank. It seems to have disappeared, along with the ferry, when the bridge was built and the gateway transferred to that locality.

By the time of Henry II. the exigencies of commerce, and, as Maitland says, "the accommodation of the citizens in repairing to their gardens and fields," necessitated more exits through the walls; and thus we find, as Fitzstephen informs us, there were then seven double gates. These Maitland conjectures to have been Aldgate, Aldersgate, Cripplegate, Ludgate, Newgate, and the Tower Postern, but it seems more probable that instead of the last-mentioned, the seventh was Bridgegate which took the place of Dowgate.

Bishopgate was built by some bishop of London; Strype supposes Erkenwald, circa 675, but Maitland thinks it was William the Norman [27]in the reign of the Conqueror. There were effigies of two bishops on the gate, conjectured to have been Erkenwald and William, and the presumption is that the former was the original builder, and the latter the rebuilder; as, if Erkenwald were the founder, the old gate would be 400 years old in the time of William. In the reign of Henry III. it was placed under the charge of the Hanseatic Merchants of the Guildhalle Teutonicorum, who undertook to keep it in repair in consideration of certain privileges and immunities, but they neglected their duty, for which they were called to account in the reign of Edward I., upon which they paid 210 marks sterling to the Corporation for present repairs, and entered into a covenant to be less remiss in the future, and in the reign of Edward IV. they rebuilt it. In 1561 they had again made arrangements to rebuild it, but before the reconstruction was commenced they were deprived of their liberties, and the old gate remained until 1731, when it was taken down. It was a building of castellated character, with a pointed archway in the centre, and posterns in the two side towers, with statues over the central arch, and, high up in the towers, in niches.

Cripplegate dates from the Saxon era, and obtained its name from the circumstance that cripples there congregated to supplicate for alms. Maitland considers that it, and not Aldersgate, was one of the four original Roman gates. It is related that, in the year 1010, during an incursion of the Danes into East Anglia, the monks of Bury fled to London, carrying with them the sacred relics of St. Edmund, and entering by this gate, all the cripples crouching about it were miraculously healed. It was sometime a City prison for debtors and persons guilty of trespass, and was the residence of the water-bailiff of the City. In 1244, it was rebuilt by the Brewers' Company, and again in 1491, Edmund Shaa, goldsmith, and mayor in 1483, having left 400 marks for that purpose. It was repaired and beautified, and the foot postern new made, at the charge of the City of London, in 1663, during the mayoralty of Sir John Robinson, knight and baronet, and alderman of the ward. In its last aspect it was a castellated structure with battlements, two octangular turrets, a recessed centre with Tudor archway, and a side postern through one of the towers.

Newgate.—In the reign of William I., the church of St. Paul's was burnt, when Mauritius, [29]Bishop of London, commenced re-edification. In doing this he considerably enlarged the plan, and encroached so much upon the main street which ran through Cheapside, from Aldgate to Ludgate, that vehicles were compelled to take circuitous routes through narrow streets with dangerous angles, north or south of the cathedral, to reach Ludgate. The inconvenience became so great, that in the reign of Henry I., or Stephen, a new exit was made through the wall facing Holborn, to which there was better access from Cheapside, and was called Newgate, in contradistinction to the old gates. Howell, in his Londinopolis, says that it is a mistake to suppose that it was built so recently as the reign of Henry I., that it was of much older date, and was formerly called Chamberlaingate; and Maitland inclines to the opinion that it, and not Ludgate, was one of the four Roman gates, from the circumstance that there are vestiges of a Roman road leading in this direction. For 500 years the gate was the common prison for felons of London and Middlesex. In the year 1255, one John Offrem, a prisoner, who had killed a prior, made his escape, and Henry III. was so displeased that he committed the Sheriffs to the Tower, and inflicted [30]a fine upon the City of 3,000 marks. In 1422, the executors of Sir Richard Whittington, out of funds bequeathed for that purpose, "builded the Gate of London called Newgate," which Grafton says "before was a most ugly and loathsome prison." The east side was repaired in 1630, and the gate was entirely destroyed in the Great Fire of London; after which it was rebuilt "with greater magnificence than any of the gates of the City." The new building was a lofty structure, with battlemented roof, a recessed centre, with pointed archway, and two five-storied sexangular towers. It was ornamented on the west side with Tuscan pilasters, with niches holding statues in the inter-columniations, one of which was a figure of Liberty, with a cat crouching at her feet, emblematical of the career of Whittington; and on the east were three niches with figures of Justice, Truth, and Mercy.

Moorgate was built in the year 1415, by Thomas Falconer, Lord Mayor. At that time the land outside the wall in this part was a marsh, or moor, whence the name. It was made for the easier access of the citizens to their gardens and the fields beyond the marsh; and a causeway, with dykes and bridges, was [31]constructed across the moor, which was improved by Roger Acheley, Lord Mayor in 1511. Afterwards, in the year 1606, in the mayoralty of Sir Leonard Halliday, "the moor, before an unhealthful place, was turned into pleasant walks set with trees, compassed with brick walls, and made convenient by sewers under ground for the conveyence of the water, which cost the City £5,000 or thereabouts." It was afterwards, during the mayoralty of John Baker, 1733, "new gravell'd and rail'd in a very strong and handsome manner." The old gate, having fallen to decay, was pulled down in 1672, and a new one of stone erected, with a central archway, and posterns with two stories above in the Italian style.

Bridgegate, which supplanted Dowgate, was constructed along with the bridge, in the ninth or tenth century, and was situated at the southern end. In 1436 it fell, along with the tower above it, and the two southernmost arches of the bridge; and in 1471 the new gate was burnt by the Bastard Fauconbridge. It was repaired at divers times, and was considerably damaged by fire in 1726, but was reinstated within two years. As it last appeared it had a central archway, [32]above which was one story ornamented with the City arms, and had two circular side towers, with posterns for foot passengers. This gate is historically memorable from the number of heads of traitors and victims of royal jealousy which have been placed upon it in terrorem. Besides these there were several posterns between the main gates, and many water gates, such as Billingsgate, Wolfsgate, Botolphsgate, etc., which, however, were only used for commercial purposes, as wharfs for the purpose of landing goods from ships and barges.

In the great Fire of London, Ludgate, Newgate, and Aldersgate were destroyed, and rebuilt. In 1760-1, eight gates being no longer necessary, and proving to be obstructions to the traffic, were sold for what the materials would fetch, and pulled down; Newgate was destroyed by the Lord George Gordon rioters in 1780. Temple Bar which was built by Sir Christopher Wren, 1670-2, has been removed to make way for the improvements about the new Law Courts; it had some historical associations connected with it, having succeeded the old gate on London Bridge for the ghastly display of traitors' heads. It has been carted away, very injudiciously, to be placed [33]in some private grounds, whilst there was one most suitable and alone proper place for it, where it would have retained its characteristic name, stood in a conspicuous position, and have become to a certain extent an ornament, and certainly an interesting memorial of the past history of London—that spot being on the Thames embankment, as the river-side entrance to the Temple Gardens.

There are many famous streets in the capitals of the world—the Rue de Rivoli, Paris; the Nevski Prospekt, St. Petersburg; the High Street, Edinburgh; the Broadway, New York; the Joseph Platz, Vienna; the High Street, Oxford; and the Via Sacra of Old Rome, with many others. All these are renowned for various characteristics of picturesque beauty, architectural grandeur, or as the scenes of important events in bygone times. In an æsthetic point of view, Cheapside is inferior to many of these, although architecturally it is now rapidly improving, and in a few years will be able to show ranges of buildings equal to those of any street in the world; but of all the streets mentioned above, excepting, perhaps, those of Edinburgh and Rome, there is not one that can compare with it for its historical associations, and for the grand series of events of national and world-wide importance which it has witnessed during the thousand years of its existence. We purpose to [35]bring before the reader a few of the more striking and picturesque of these events, which have occurred at different periods of its history, which will have a certain amount of value as serving to illustrate the modes of living, the customs and amusements, the fluctuations of opinion in politics and religion, the relations between king and people, and the ancient municipal glories of the citizens of London in bygone centuries.

Wondrously different was the Westchepen of the eleventh century when the Norman Conqueror granted his brief and pithy charter to the citizens of London, from that of the nineteenth, with its stately edifices, its asphalted pavement, and its rush and roar of never ceasing traffic. It was then somewhat like an ill-tended country road, in the summer rough and uneven and full of deep holes, and in winter a quagmire of mud and filth knee deep, with better beaten causeways at the sides for pedestrian traffic. It is recorded by Stow that in 1091, a terrible hurricane passed over London, when 600 houses were blown down, and the roof of the Church of St. Mary-le-Bow, erected a few years previously, was lifted off, carried some distance, and dashed into the street with such violence that four of the rafters, twenty-five [36]feet in length, were driven into the earth, "the ground being of a moorish nature," leaving only four feet exposed, "which were fain to be cut even with the ground, because they could not be plucked out." The houses stood apart from each other like cottages in a village, and were thatched with straw, which was the cause of many fires, one occurring two years after the great storm, in which nearly the whole of the remaining houses were consumed; and so did the citizens continue to rebuild their habitations after each successive fire, until 1245, when it was ordained that for the future they should be covered with tiles or slates, instead of straw, in the chief streets, "especially those close together, which were but few in number, for in Cheapside was a void place called Crown Field, from the Crown Inn which stood at the end of it." This field was at the end of Soper's Lane, by Bucklersbury, and upon it were erected stages for spectators of pageants. It was sold, 2 Ed. IV., to Sir Richard Cholmley, but does not appear to have been utilized immediately for building purposes, as we hear it spoken of in the time of Henry VII.

The curfew bell was tolled from the tower of [37]St. Mary, and on the top lanterns were suspended and lighted at night, "whereby travellers to the City might have the better sight thereof, and not miss their ways."

For the supply of water there was a great standard or conduit at the east end, where the Poultry commences, and a smaller one opposite Old Change, by Paul's Gate, and opposite Wood Street stood one of the Eleanor Crosses, erected in 1290, which having become decayed by time, was re-edified by John Hatherley, Lord Mayor, who added to it a fountain. These conduits were the frequent scenes of punishments for misdeeds and executions. Wat Tyler beheaded Sheriff Lyon at the western standard, and there Jack Cade chopped off the head of Lord Say; there also Stapleton, Bishop of Exeter, and treasurer to Edward II., was beheaded in 1326 "by the burgesses of London." In the same localities also was the pillory erected, where Prynne, Burton, and Bastwick, had their ears lopped off, and there Defoe and a multitude of other less known defenders of public rights and freedom of conscience have been exposed, sometimes to the derision, at others to the sympathy, of the mob.

In the Plantagenet and Tudor eras Cheapside [38]had assumed a different and more street-like aspect. Continuous lines of houses, with gables forming a vandyke sky line, with crossed timberings and latticed windows, ran down each side, with the steeple of St. Mary-le-Bow, which had fallen in 1271, and "slain many people, men, women, and children," and been restored gradually until the finishing stone was placed in 1469, standing proudly in the centre of the southern line. At the eastern end, between Laurence Lane and a house, called the "cage," was West Chepe Market, the goods being exposed for sale on stalls, which were let at 13s. 4d. the standing, causing much bickering between the street-sellers and the shopkeepers, in front of whose doors they stood, and whose goods were often seized and burnt at the standards for deficiencies in weight, or for inferiority in quality. The Eleanor Cross, which had been rebuilt in 1441, and the eastern and the western conduits still gave forth their supplies of water. The appearance of the cross is indicated in an old print of the procession of Edward VI. to his coronation in 1547; and again, with one of the conduits, in La Serre's view of Cheapside, with the procession of Catharine de Medicis, temp. [39]Charles I. The shops were open in front like modern butchers' shops, and the goods exposed for sale on bunks. Lydgate, in his "Lackpenny" ballad, thus speaks of them: —

The 'prentices of Cheapside were a conspicuous feature of the street at this period. During the day they paraded up and down in front of their masters' shop, crying "What d'ye lack; what d'ye lack?" followed by an enumeration and laudation of the articles within, and the wonderful bargains to be picked up; and in the evening listening eagerly for the sound of the curfew bell as the signal for shutting up shop. Stow tells us that in his time the bell-ringer was sometimes late, and that the 'prentices, precursors of the "Early Closing Movement" of our own time, addressed him as follows: —

The bell-ringer, knowing that they would be as [40]good as their word, and deeming "discretion to be the better part of valour," replies: —

These 'prentices were a pugnacious race of mortals, and were ever ready to issue forth at the cry of "Clubs! clubs! 'Prentices! 'Prentices!" leaving the shop to take care of itself, to join in any fray that was going on in the street, especially if it were a demonstration against a foreign interloper in trade. They waited upon their master and mistress at their meals, and on Sundays and saint-days followed them demurely to church, carrying hassocks for them to kneel upon. In the summer evenings, after the shops were shut and evening prayer over, as Stow tells us, they were wont "to exercise their wasters and bucklers, and the maidens, one of them playing upon a timbrel, in sight of their masters and dames, to dance for garlands hanged across the streets," and on holidays they went out to Finsbury Fields, and other open places, and exercised themselves in leaping, dancing, shooting, wrestling, casting the stone, etc., but especially in bow and arrow practice.

Chaucer, in the Cook's Tale, thus describes the 'prentice of Cheapside: —

Some of the more salient features in the past of Cheapside which present themselves to our view in the gradual unrolling of the panorama of the ten centuries are very varied in their character. We behold a strange intermingling of gorgeous processions in honour of the birth, marriage, and coronation of royal personages, with the pillory, the stocks, and the executioner's block, and the accompanying lopping-off of hands, ears, and heads, and whippings at the cart tail; Lord Mayors' shows, generally more grotesque than refined, and trade guild demonstrations of splendid liveries and floating banners; combined with 'prentices' club frays, and fights between rival trade companies, which seldom ended without bloodshed; tilting at the quintain; tournaments and joustings; alongside with [42]insurrectionary risings and outbursts of religious fanaticism.

A.D. 1196. At this period the rich and the noble of the land were chiefly of the Norman race, and the poor almost all Saxons, who were ground down to the earth by the tyranny and oppression of their masters, to which they submitted with a sullen dogged obedience, having still within them that spirit of freedom which animated the breasts of their ancestors previous to the Norman Conquest. Richard Cœur de Lion was king, and had just been liberated from his captivity. He ruled the kingdom with a high hand, and had said on one occasion, when remonstrated with for raising money by unconstitutional means, "Have I not a right to do what I like with my own? I would sell London itself if I could find a purchaser." At this juncture up rose a lawyer, one William Fitzosbert, otherwise called Longbeard, who seems to have been a designing character, and desirous of currying favour with the people, he proclaimed himself the advocate of the poor, the redresser of their wrongs, and the unflinching enemy of their oppressors. He soon had a gathering around him of the penniless and discontented serfs, [43]amounting eventually to 50,000 men, armed with bows and arrows, rudely fashioned pikes, clubs, axes, hedge stakes, and other similar weapons. This army—or rather mob—went about offering insults to the rich, breaking open their houses and plundering them in broad daylight. The Corporation had then but little authority and power, and were not able to cope with so formidable an insurrection; and Archbishop Hubert, the chief justiciary, summoned the leader to appear before him, who came, however, so numerously attended, that it was deemed wise to dismiss him with a rebuke. After this the outrages of the insurgents became more barefaced and open, as well as more numerous; whereupon more vigorous measures were taken, and after murdering an officer sent to apprehend him, Fitzosbert, with a concubine and a few followers, took refuge in the church of St. Mary-le-Bow, and fortified it against his pursuers, defying them for some time, many persons being killed in the assault, until at length a fire of damp straw was lighted beneath, the smoke of which compelled the garrison to issue forth, and after a fight in the street, they were captured and carried to the Tower, before the judges, who condemned them to [44]death. "And then," says Stow, "he (Fitzosbert) was by the heels drawn to the Elmes in Smithfield and there hanged with nine of his fellows, where because his favourers came not to deliver him, he forsook Mary's son (as he termed Christ our Saviour), and called upon the devil to help and deliver him. Such was the end of this deceiver, a filthy fornicator, a secret murderer, a pollutor of concubines, and (amongst his other detestable acts) a false accuser of his elder brother, who had brought him up in learning, and done many things for his preferment." The people, however, looked upon him as a martyr, secured his body, carried away the broken-up gibbet and the bloodstained earth as relics, and reports were afterwards spread abroad of sundry wonderful miracles which had been worked by their sacred influence.

A.D. 1236. An aspect of a very different and much more pleasing character was that which Cheapside assumed on one occasion in this year. King Henry III. had in January married with great magnificence at Canterbury, Eleanor, second daughter of Raymond, Earl of Provence, and it was when she passed through the City, on her way to Westminster to be crowned, that a [45]civic display was made in Cheapside, which surpassed in pomp and splendour everything which had preceded it, and which is the earliest of which we have any detailed account. The street was hung with arras, silk and cloth draperies of gay colours, and banners and pennons floating from the housetops and windows, accompanied by many strange devices, and pageants on scaffolds along the route. Andrew Bockrel, the mayor, with the sheriffs and aldermen, and a following of 360 citizens, rode forth to meet the king and queen, and escort them through the City to Westminster. They were all clad in long robes, lavishly embroidered with gold; their other garments were of silk, diversified in colour, and their horses were covered with trappings reaching to the ground, covered with embroidery and blazonry of arms. Each man carried in his hand a gold or silver cup, emblematic of the Lord Mayor's right to serve the office of chief butler at the coronation feast, and they were preceded by trumpeters. In the evening the city was illuminated with lamps, cressets, and other lights "without number," Cheapside presenting a most brilliant effect, with the bonfires blazing up from the [46]ground, lights of different kinds gleaming from the frontages of the houses, from end to end of the street, and multitudes of men, with lighted cressets on their shoulders, marching hither and thither, and mingling with others bearing torches, a scene infinitely more picturesque than the commonplace gas illuminations of the present.

A.D. 1249. In this year King Henry III. made a raid upon the shopkeepers of Cheapside, who, true to their instinctive abhorrence of regal interference with their liberties, presented so formidable an opposition to his demands that he was fain to give way. Stow thus narrates the occurrence: "This year the King kept his Christmas at London, with the meanness of spirit worthy of himself, for he begged, as it were, large new year's gifts of the citizens. But the money on that occasion not being deemed sufficient, Henry soon after sent and imperiously demanded much greater sums. This message occasioned a great alarm amongst the citizens, who justly complained that no regard was had to honour, justice, conscience, nor religion; and that their liberties, which they had so often dearly bought, and had so many times been confirmed and sworn [47]to, were not able to protect them from being treated as the worst of the slaves; yet, notwithstanding these great truths, they were compelled to pay the tyrant the sum of £2,000, a very great sum at that time. Nor did these wicked proceedings stop here, for many shopkeepers in the City were spoiled of their goods (especially those for the use of the kitchen) by the order of that iniquitous prince." We may fancy the commotion that would be excited in Cheapside when the king's officers appeared and seized the goods which were displayed on the bunks for sale, and can only wonder that the valorous 'prentices did not raise their usual war cry, seize their clubs, and drive the officers back with a sound thrashing to their master who sent them. Whether they did attempt to defend their master's property in this their usual fashion is not recorded, but Stow adds: "These diabolical oppressions caused many of the most eminent citizens to retire into the country, choosing rather to cohabit with brutes than to dwell in the capital of so wicked a tyrant.... Henry, being at last conscious of his having frequently and unjustly imposed upon the citizens of London by many heavy and intolerable exactions, resolved to reconcile [48]himself with them; and, in order thereunto, commanded them to attend him at Westminster, where, being assembled in the great hall, he, in the presence of his nobility, solemnly promised that for the future they should live happily under his government, and not be liable to such grievous taxations as formerly."

A.D. 1257. Sir Hugh Bigot, an itinerant judge, held a court in the City, although contrary to the ancient rights and liberties of the citizens, and made an example in Cheapside of certain bakers guilty of malpractices such as giving short weight and supplying an inferior article, "by setting them upon a tumbrell or dung-cart, wherein they were exposed in the streets as bawds usually were,"—a very wholesome punishment, which might be revived with advantage in the present day as an example to the adulterators of food.

A.D. 1262 and 1264. At the eastern end of Cheapside is a street called the Old Jewry, a name formerly applied to a limited district westward of Lothbury, and so called from being the principal Jews' quarter of the early race of Jews, who were banished the kingdom temp. Edward I., and where they had a synagogue. Here they lived, as well as about Jewin Street, and in a Jewery near [49]the Tower, and then, as now, made great wealth by the practice of usury, and despoiling the Gentiles by means of hard bargains and crafty sharp practice in money dealings, which gave rise to a great deal of ill-will between the two races, much maltreatment, massacres, and unjust demands of money from the Jews, by the kings and other authorities, and the frequent pillaging of their houses by mobs.

In 1189, a general massacre of the Jews took place at the coronation of Richard I., the survivors living in constant peril of murder and confiscation, an instance of the latter occurring in 1241, when the Jews of London were fined 20,000 marks because the Jews of Norwich had circumcised a Christian child.

In 1262, a fierce quarrel broke out between a Christian and a Jew, in the Church of St. Mary Cole, in the Poultry, relative to some money transactions, which proceeded from words to blows, and the Jew, having dangerously wounded his adversary, fled into the Jewry for refuge, pursued by a mob of idlers who had witnessed the fray, and of 'prentices from the shops, nothing loth to join in a Jew-hunting frolic. The Jew was captured in his own house, dragged forth, and [50]bludgeoned to death. Not satisfied with that, the mob fell upon the inhabitants of the quarter and murdered them indiscriminately, afterwards plundering and burning their houses.

Two years afterwards the mob was again in arms, arising out of an attempt on the part of a Jew to extort more than the legal interest (twopence per week) for £20, which he had lent to a Christian. They attacked the "Jewery" in great force, destroyed the synagogue—the first erected in England—massacred 500, or according to another authority, 700 Jews, male and female, and "spoiled the residue of their property."

In the Westminster Parliament of 1273, laws were enacted to restrain their exorbitant rates of usury, and in 1290, by an Act of the Parliament assembled at Northampton, they were banished the realm, and all their immovable property confiscated. The number who were thus driven forth amounted, according to Matthew of Westminster, to 16,160, and thus ended the first race of Jews in England, from which period until the middle of the seventeenth century, although there might be individuals, there was no organised body of Jews in the land.

A.D. 1269. In this year, the 53rd of the [51]reign of Henry III., a great fight took place between the Goldsmiths and the Taylors Companies, which is thus graphically described by Fabyan: "In this lili. yere in ye moneth of November fyll a very aulnce atweene the felys-shyppes of Goldsmythes and Tayloures of London, whiche grewe to makynge of parties, so that with the Goldsmythes take partie the felyshep or craft of—and with the Tayloures held ye craft of Stayners; by meane of this moche people uyghtly gaderyd in the streetes in harneys, and at length as it were prouyded, the thirde nyght of the sayd parties mette upon the number of V. C. men on both sydes and ran togyder, with such vyolence, that some were slayne and many wounded. Then outcry was was made that ye shyreffes, with strengthe of other comers, came to the ryddynge of theym, and of theym toke certayne persones and sent them into dyvers prysons and upon the morrowe such serche was made, yt the moste of the chief causers of that fray were taken and put in warde. Then vpon the Fryday followynge Saynt Katteryn's daye, sessyons were kepte at Newgate by the Mayre and Lawrence de Broke, iustice, and others; where xxx. of the sayd persones [52]were arregned of felony, and xiii. of theym caste and hanged."

A.D. 1330. King Edward II. had been murdered in Berkeley Castle, and his son, Edward III., reigned in his stead, and now, five years after the decapitation of Bishop Stapleton, Cheapside was witness of a scene of a more joyous character. Unsuitable as it might be deemed nowadays, with its endless throng of cabs, omnibuses, and other vehicles, for such a display, it was then not unfrequently the chosen spot for tournaments and jousts. Two years before, the young King had married Philippa of Hainhault, and this year she had given birth to an infant, afterwards the famous Black Prince. In honour of this event, and to do honour to the visit of some French ambassadors, the King gave orders for a tournament to be held in Cheapside. The street was decorated with tapestries and silver draperies, pendant on the walls, and banners streaming from the roofs. The bright eyes of beauteous damsels glanced in the windows of the houses, and the street was filled with a crowd of gaily dressed holiday-makers. The lists were formed between Wood Street and Queen Street, and the ground bestrewn with sand to [53]prevent the horses slipping. There was seen all the glory and paraphernalia of heraldry. Kings-at-arms and pursuivants, decked in habits emblazoned with arms, trumpeters, and other officials; prancing steeds, bestridden by knights in full panoply, with their achievements blazoned on their shields, accompanied by their esquires bearing their arms. Across the street had been erected a scaffold, shaped like a tower, whereon sat Philippa and the ladies of her court, the great centre of attraction for the spectators in the street below. Thirteen knights entered the lists on each side; stalwart men and the flower of chivalry. Their esquires handed to them their lances, and making deep obeisance to the Queen, they ranged themselves at each end for the onset, when the trumpets sounded and they dashed forward. Scarcely, however, had they done so when the scaffold on which the Queen sat came down with a terrific crash, which stopped the jousters in midway. The King rushed to the spot, anxious for the safety of the Queen, but fortunately found that no one had been hurt beyond a few bruises and a terrible fright. Great confusion prevailed, and the King, in a tempest of rage, vowed that all the careless carpenters [54]who had constructed the stage should be put to death, but the Queen, says Stow, "took great care to save the carpenters from punishment, and through her prayers, which she made on her knees, she pacified the King and council, and thereby purchased great love of the people." After this the King caused a stone shed, called Sildham, to be built in front of Bow Church, "for himself, the Queen, and other estates to stand in, there to behold the joustings and other shows at their pleasure." It served this purpose until the year 1410, in the reign of Henry VI., when it was disposed of to Stephen Spilman, William Marchford, and John Wattel, mercers, for business purposes, with the condition that "The kings of England and other great estates, as well as those of foreign countries repairing to this realm, should be entitled to make use of it for witnessing the shows of the City, passing through Westchepe."

At the western standard by Paul's Gate, Jack Cade, the rebel leader, in 1450, caused Lord Say to be decapitated.

A.D. 1382-1445. In the interval between these dates, Cheapside was the scene of much royal pageantry of great splendour. When [55]Anne of Bohemia, the first Queen of Richard II., entered London after her marriage, in 1382, a castle, with towers, was erected in Cheapside, on whose battlements stood a bevy of fair maidens, who flung in their path counterfeit gold coins, and threw over them, as it were, showers of butterflies made of gold leaf; and when she and Richard passed in procession through Cheapside, afterwards, to celebrate his reconciliation with the City, after a fierce quarrel, a tower was erected, whence issued copious streams of red and white wine for all comers, the King and Queen quaffing draughts therefrom out of golden goblets, and an "angel descending from a cloud crowned them with golden circlets." In 1423 Katherine of Valois, widow of Henry V., after visiting St. Paul's Cathedral, passed through Cheapside, seated in a chair of state, with her infant king, Henry VI., in her lap, whence she proceeded to Newington Manor House. Henry VI. and his queen—the masculine and brave, but unfortunate, Margaret of Anjou—passed along Cheapside with much pageantry on the occasion of their marriage, in 1445, when they halted by the great conduit to witness a play called The Five Wise and the Five Foolish Virgins, who were [56]personated with great spirit by ten City maidens. Twenty-seven years after—in 1472—the corpse of the weak and unfortunate monarch, after his suspicious death in the Tower, and the fall of the Lancaster dynasty, passed along Cheapside in mournful funereal silence, by torchlight, and with the face exposed, that all might see that the last of the Lancasters was really dead, on its progress to St. Paul's, and hence to Windsor for burial.

A.D. 1510. Perhaps the most splendid of the sights of Cheapside was the setting of the Marching Watch on the Vigil of St. John the Baptist, in June, and on that of Saints Peter and Paul in July. The City Watch was instituted in the year 1253 by Henry III., and consisted of a body of substantial citizens, with an alderman or magistrate at their head, for each ward, to protect the houses from robbery and the streets from outrages by night—crimes which had hitherto been very rife; and it was ordained that if anyone suffered loss or violence whilst the guard was on duty he should receive compensation from the ward. The Marching Watch was a grand processional display of fire and light, banners and music, glittering armour and flashing weapons, bonfires in the streets, and numberless cressets [57]borne aloft. The citizens' wives and daughters, apparelled in their most fascinating costumes, occupied the windows; men and boys clambered on the gabled roofs; whilst in the street below tables were spread with viands and provided by the citizens, which were presided over by their 'prentices, attired in their blue gowns and yellow hosen, like the Christ's Hospital boys of our time, who invited the passers-by—more especially if they were young and pretty and of the other sex—to partake of their masters' cheer.

On the Vigil of St. John in 1510, Henry VIII., then a frolicsome young man of nineteen, who had only been a year on the throne, with a companion or two, perhaps Charles Brandon, came from Westminster, disguised as a yeomen of the guard, to see this setting of the Watch, of which he had heard so much. He came from Westminster in a public wherry, and landing at Bridewell Stairs, proceeded on foot, like a modern Haroun al Raschid, mingling with the people and cracking jests with them as he went along. He stationed himself at the cross in West Cheap, where he saw the proceedings admirably, and after partaking, most probably, of a cake and a flagon [58]of ale at some hospitable citizen's door, he returned, so much struck with the splendour of the festival that he vowed he would bring the Queen (Catherine of Arragon, whom he had married the previous year) to see it on the next occasion, in July.

The Vigil of Saints Peter and Paul arrived, and the gay monarch, faithful to his promise, and wishing to give pleasure to his queen, dreaming not then of divorces and the headman's axe, with which he became so familiar in after life, brought her in regal state and pomp, accompanied by a crowd of nobles and court ladies, to see the civic spectacle, which they witnessed from the hall of the Mercers' Company in Cheapside. The street itself, before the procession was arranged, was a sight worth seeing, and one to be remembered for many a long day. Huge bonfires were blazing up in different parts; the houses were hung with tapestry, and were lighted up with oil lamps and "branches of iron curiously wrought, containing hundreds of lamps, lighted at once, which made a great show;" timber stages, hung with variously coloured stuffs, and the latticed windows were filled with elegantly-dressed ladies, whose diamonds flashed in the light; banners [59]and pennons floated in the evening breeze; "every man's door was shadowed with green birch, long fennel, St. John's-wort, and such like, garnished upon with beautiful flowers;" whilst prancing steeds in gay trappings, armed men with plumed casques, city and guild officials in gay liveries and a crowd of citizens, male and female, in the quaint costume of the period, mingled in picturesque groups below. After sunset the procession was arranged, and set out. First came a band of music, followed by the officials of the Corporation in parti-coloured liveries, and the sword-bearer mounted on a gaily-trapped steed, and in armour. Then came the Mayor on a magnificent horse with housings reaching to the earth, accompanied by a giant; two pages, mounted; a band of morris dancers, footmen, and three pageants. After him came the sheriffs, similarly attended with giants, morris dancers, and torchbearers, but with only two pageants. Then followed a cloud of demi-lancers, in armour, with the City arms emblazoned on their backs and breasts; a company of archers with their bows bent; pikemen and halberdiers, in corslets and helmets; and billmen, with helmets and aprons of mail. [60]The whole body consisted of about 2,000 men, and between the divisions were bands of drummers, fifers, and whifflers, and standard and ensign bearers. Interspersed amongst them were 940 men bearing lighted cressets—iron frames filled with pitched rope, which blazed up and sent forth volumes of black smoke, "which showed at a distance like the light of a burning city," and the same number of men to supply the cressets with fresh supplies of fuel. Two hundred of these were supplied by the City; 500 were supplied at the expense of the City companies, and the remainder were the ordinary watchmen.

The midsummer watch was kept up until 1539, when Henry VIII., considering the great expense it was to the City, caused it to be abolished. It was revived, however, in 1548, and continued until 1569, when in consequence of its bringing together "abundance of rogues, pickpockets, quarrellers, whoremongers, and drunkards," it was again abolished, and although some attempts were made afterwards to restore it, they were not successful.

A.D. 1485-1610. In the interval between these dates, Cheapside was the scene of many a grand spectacle, and it may be added of many a [61]so-called vindication of justice in a way of barbarous mutilations and inhuman executions.

A.D. 1513. The Cheapsides 'prentices, of whom we have spoken, were a turbulent and unmanageable element of the community, keeping their clubs at hand in the shops, to be ready at any moment to rush out and join a fray, and many a broken head they gave and got in these fights, which generally arose, not so much out of malice as from pure love of contention for mastery, which then developed itself in this rough way as it now displays itself in games of cricket and athletic sports. There was one class of persons, however, against whom they had a special hatred, and nothing pleased them better than to insult them with vile speeches, drag them in the gutter or belabour them with their clubs. These were the foreign merchants, importers of silks, wine, and other commodities; the Lombard money-lenders and stranger craftsmen and citizens, who, they said, impoverished the English traders and carried away the English gold. This jealousy continued to grow, and was brought to a crisis by a Lombard seducing a citizen's wife, and obtaining through her, his plate chest, and afterwards causing the citizen to [62]be arrested for a debt for his wife's board and lodging during the time she was at his house. A rumour got abroad that on the ensuing May Day a sort of Bartholomew's massacre should take place, and that all foreigners found in London then would be put to death. The 'prentices now began to insult and ill-treat them as they passed along the street, and several fled from the city. A report of these proceedings reached the king, and Wolsey sent for the mayor and charged him to see that the peace was kept in the city, which he assured the cardinal he was quite capable of maintaining, and departed. This was about four o'clock on the eve of May Day, and on his return to the city he assembled the magistrates and council, amongst whom was Sir Thomas More, ex-under-sheriff, when, after some discussion, it was decided to issue an order to the citizens to have their doors closed at nine o'clock, and to keep all their 'prentices and servants within until nine the following morning, and the aldermen went to their respective wards to see that this mandate, which had been confirmed by the king and council, was obeyed.

After the issuing of this order, which only [63]took place about half-an-hour before nine, Alderman Sir John Munday, on going down Cheapside found two young fellows playing at bucklers in the middle of the street, and a number of other young men looking on. He ordered them to desist and go within doors, and upon their asking him why, instead of explaining the order, which they had no knowledge of, he threatened to send them to the compter, and after a little altercation, seized one of the youths to commit him to prison. "But," says Stow, "the 'prentices resisted the alderman, taking the young man from him, and cried, ''Prentices! 'prentices! clubs! clubs!' Then out of every door came clubs and other weapons, so that the alderman was put to flight. Then more people arose out of every quarter, and forth came serving-men, watermen, courtiers, and others, so that by eleven o'clock there were in Cheap 600 or 700, and out of St. Paul's Churchyard came about 300. From all places they gathered together and broke open the compters, took out the prisoners committed thither for hurting the strangers. They went also to Newgate and took out Studley and Bets, committed for the like cause. The mayor and sheriffs were present and [64]made proclamation in the king's name, but were not obeyed." After this they went in separate bands, breaking open and plundering the houses of the foreigners, until about three in the morning, when they began to disperse, and being thus disunited, the authorities were enabled to capture about 300 of the rioters and place them in prison. Sir Roger Cholmley, lieutenant of the Tower, had come forth with a military force, "and shot off certain pieces of ordnance against the City, but did no great hurt." About five o'clock the Earl of Shrewsbury and other nobles, and the prior of St. John's, Clerkenwell, came with what forces they could get together, as did the Inns of Court, "but before they came the business was over."

A special commission of oyer and terminer was issued to the Duke of Norfolk and other lords, with the Lord Mayor, aldermen, and justices, to try the prisoners. The court was held in the Guildhall, on the 2nd of May, whither the delinquents, to the number of 278 persons, were brought, tied together with ropes, and escorted by 1,300 men. On the 4th, thirteen of them were condemned to be hanged, drawn, and quartered, in divers parts of the City; which sentence was [65]carried out with great barbarity, in the presence of Lord Edward Howard, "a knight marshal, who shewed no mercie, but extreme crueltie to the poore younglings in their execution."