BIRDS.

ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR

PHOTOGRAPHY.

| Vol. III. |

JUNE, 1898. |

No. 6. |

JUNE.

"What is so rare as a day in June?

Then, if ever, come prefect days."

Y ES, Lowell, in a few words, describes

the month of June, or, at least, he indicates something of it. But, still, what are perfect days?

We look for them in April, when the birds, many of them, certainly the most attractive of them,

return from the south, and we find ourselves, when we visit the woods and parks, disappointed that

the sun does not shine, that the air is not soft and balmy, and that the grass and leaves and buds

do not show themselves in spring attire, for, on the contrary, we find winter lingering

distressingly near, that the merry Warblers are silent, and that the "greenery of young Nature" is

very slow to indicate her presence or even her early coming. We pull our wrappings about us and go

home. April past, we then fancy that her older sister, May, beautiful in literary

imagery—for do we not recall descriptive visions of May days of long ago, when the human

blossoms danced about the May pole, lolled luxuriantly in the soft, tender grass, hid themselves

in the deep-leaved trees, and at last gratified our imaginations with the belief that she is

altogether perfect? Unfortunately a chill takes possession of us and we return home disconsolate.

May also has disappointed us. We have had an experience which we shall not forget. We have seen

and recognized many birds, but they have not sung for us. They have been, as they almost always

are, influenced by the elements. And why should they not be? They have but one suit of clothes.

Have you observed the Robin in the early spring? He is worth watching. We watched a fine specimen

in south Washington Park in March last. It was a comparatively mild day for the windy month. He

perched on a lateral limb of a leafless tree a few yards from Sixtieth street. Whether he saw us

or not we could not be sure, as he took little notice beyond saying Toot-tut, toot-tut! He

ruffled his suit and seemed as fat as feathers could make him. They seemed as important to him as

were buffalo robes to the sleighing parties of {202}a

few days before. Still he was observant and seemed to be looking for stray food that would warm

him up. We had some fresh crackers in our pocket, which we broke into fine fragments, and

scattered, withdrawing several yards away. To our surprise, not only the Robin but several

Nuthatches, some Brown Creepers, a number of English Sparrows, three or four Bluejays, and a gray

Squirrel, (from whence he came I could not conceive, there being no large tree near in which he

might have had a winter home) came with great promptitude to feed on the unexpected offering.

Others, no doubt, have had this experience. Does it not suggest that the birds which remain with

us the whole year round—finding, of course, during the spring, summer, and fall, sufficient

for their wants,—should be looked after a little bit, if only that they may be permitted to

escape from the sometime unusually severe storms of winter? Nature has provided them with ample

feathery protection from her ordinary moods, but when she breaks out in icy blasts and snow that

covers the very face of her they suffer and they perish.

ES, Lowell, in a few words, describes

the month of June, or, at least, he indicates something of it. But, still, what are perfect days?

We look for them in April, when the birds, many of them, certainly the most attractive of them,

return from the south, and we find ourselves, when we visit the woods and parks, disappointed that

the sun does not shine, that the air is not soft and balmy, and that the grass and leaves and buds

do not show themselves in spring attire, for, on the contrary, we find winter lingering

distressingly near, that the merry Warblers are silent, and that the "greenery of young Nature" is

very slow to indicate her presence or even her early coming. We pull our wrappings about us and go

home. April past, we then fancy that her older sister, May, beautiful in literary

imagery—for do we not recall descriptive visions of May days of long ago, when the human

blossoms danced about the May pole, lolled luxuriantly in the soft, tender grass, hid themselves

in the deep-leaved trees, and at last gratified our imaginations with the belief that she is

altogether perfect? Unfortunately a chill takes possession of us and we return home disconsolate.

May also has disappointed us. We have had an experience which we shall not forget. We have seen

and recognized many birds, but they have not sung for us. They have been, as they almost always

are, influenced by the elements. And why should they not be? They have but one suit of clothes.

Have you observed the Robin in the early spring? He is worth watching. We watched a fine specimen

in south Washington Park in March last. It was a comparatively mild day for the windy month. He

perched on a lateral limb of a leafless tree a few yards from Sixtieth street. Whether he saw us

or not we could not be sure, as he took little notice beyond saying Toot-tut, toot-tut! He

ruffled his suit and seemed as fat as feathers could make him. They seemed as important to him as

were buffalo robes to the sleighing parties of {202}a

few days before. Still he was observant and seemed to be looking for stray food that would warm

him up. We had some fresh crackers in our pocket, which we broke into fine fragments, and

scattered, withdrawing several yards away. To our surprise, not only the Robin but several

Nuthatches, some Brown Creepers, a number of English Sparrows, three or four Bluejays, and a gray

Squirrel, (from whence he came I could not conceive, there being no large tree near in which he

might have had a winter home) came with great promptitude to feed on the unexpected offering.

Others, no doubt, have had this experience. Does it not suggest that the birds which remain with

us the whole year round—finding, of course, during the spring, summer, and fall, sufficient

for their wants,—should be looked after a little bit, if only that they may be permitted to

escape from the sometime unusually severe storms of winter? Nature has provided them with ample

feathery protection from her ordinary moods, but when she breaks out in icy blasts and snow that

covers the very face of her they suffer and they perish.

But April, with its weather uncertainties—although it has long been said and believed

that its showers bring May flowers—with its disappointments to all those who wish that the

balm of mild breezes would come—longed for by the invalid and the convalescent, the lover of

nature who would go forth to visit her and to court her, April seems a sort of humbug. And is May

much better? How many days, "so calm, so sweet, so bright, the bridal of the earth and sky," come

in May? A few do come, and we remember them. But, as Lowell says, perfect days are rare, even in

June, when, if ever, come "perfect days." We think that Lowell nevertheless lived a little too far

north to entitle him to state, even poetically, that perfect days are only to be enjoyed in June.

Had he, with the writer, lived in southern Ohio, on the Little Miami river, and gone fishing in

the month of May, he would, we think, have changed his mind. Or had he read the little less than

perfect poem of W. H. Venable, which, it may be, however, was written later than the verses of

our, many think, greatest poet, "June on the Miami," he might have put aside his books and his

criticisms and his philosophy, and sought out the beautiful river of western history—then

the sweetest stream that flowed in America, and even now, notwithstanding the giant sycamores have

largely disappeared and the waters of the river have greatly diminished in volume, leaving only

holes and ripples,—and modified his views of days perfect only in June. There were perfect

days in May on the Miami. There were perfect days on all the streams that made it. The birds were

multitudinous; they sang in chorus; they were, indeed, almost infinite in number—for the

naturalist and the collector were unknown—the birds were natural residents, without

fear of man, building their nests close to his habitations. A year or two ago we stopped off the

cars in May in order to recall, if possible, in the shadow of a few remaining trees at a familiar

place on the vanishing river, in the expected voices of the well known native birds, the

delightful far-gone years. Verily we had our reward, but it was not satisfactory. It seems to us

we should do our best, through legislation and personal influence to protect and multiply the

birds.

—C. C. Marble.

{203}

OUR NEIGHBOR.

We've a charming new neighbor moved in the next door;

He is hardly new either, he's lived there before;

I should think he had come here two summers or more;

His winters he spends far away.

He is handsome and stylish, most fine to behold,

In his glossy black coat and his vest of bright gold;

He is "proud of his feathers," so I have been told,

And I half believe what people say.

His wife is a beauty, he's fond of her, too;

He calls her his "Judy;" I like it, don't you?

And he sings every day all the long summer through,

Yet he is not a bit of a bore.

For he's a musician of wonderful power;

I could list to his beautiful voice by the hour,

As he sings to his wife in their green, shady bower

In the elm tree that shadows my door.

He's a sociable neighbor, we like him full well,

Although we've not called yet, and cannot quite tell

All he says, tho' his voice is as clear as a bell,

And as sweet as the notes of a psalm.

Do you ask what his name is? Our dear little Sue

Was anxious to know it, and asked him it, too,

And this was his answer, I'll tell it to you—

"My name is Sir Oriole, ma'am."

—L. A. P., in Our Dumb Animals.

{204}

BIRDS' NESTS.

T HE nest of the mourning

dove.—The nest of the Carolina or Mourning Dove, which authorities place on the horizontal

limb of a tree, is not always found in this situation, as I can testify. Last year, while

wandering in early May through a piece of low woodland in Amherst, Mass., my eye was caught by a

pair of well-grown youngsters covered with bluish pin feathers. The nest containing them—a

loose affair of small sticks and leaves—was placed on the ground, or rather on the decayed

base of a stump, surrounded by a ring of second-growth birches. Immediately suspecting their

identity, I merged myself in the landscape after the manner of bird-lovers, and was soon rewarded

by a sight of the parent Doves, who came sweeping down from a neighboring tree, uttering their

pensive call-note. The pair had been frequent visitors about the lawn and drive-way for a few

weeks previous.

HE nest of the mourning

dove.—The nest of the Carolina or Mourning Dove, which authorities place on the horizontal

limb of a tree, is not always found in this situation, as I can testify. Last year, while

wandering in early May through a piece of low woodland in Amherst, Mass., my eye was caught by a

pair of well-grown youngsters covered with bluish pin feathers. The nest containing them—a

loose affair of small sticks and leaves—was placed on the ground, or rather on the decayed

base of a stump, surrounded by a ring of second-growth birches. Immediately suspecting their

identity, I merged myself in the landscape after the manner of bird-lovers, and was soon rewarded

by a sight of the parent Doves, who came sweeping down from a neighboring tree, uttering their

pensive call-note. The pair had been frequent visitors about the lawn and drive-way for a few

weeks previous.

I have heard of another similar instance of ground-nesting on the part of Wild Doves.

—Dora Read Goodale.

Wrens—That clumsy little bunch of animated feathers, the Wren, is undoubtedly the most

contented of dwellers on the face of the earth. In country or city he is never homeless. Anything

hollow, with an aperture large enough to admit his jaunty little self is sufficient, and so long

as it remains undisturbed he is a happy tenant. The variety of sites selected by this agile little

creature, is greater than that of any other bird.

It has been said that "a Wren will build in anything from a bootleg to a bomb-shell." And this

seems to be so. Many an urchin can testify to having found the neat nest of the Wren in his

cast-off shoe or a tin can, and nests filled with Wren eggs are frequent finds in odd places

around the battle fields of the South.

The home of a Wren, a few miles from Petersburg, Va., furnishes the strangest case in the

matter of queer habitations yet discovered. This country is the site of one of the most dramatic

epochs of the civil war, and frequently the bones of unburied soldiers are picked up. Recently a

rusty old skull was found in which one of these Wrens chose a shelter. The skull, when found, was

hidden in a patch of shrubbery. The interior of the one-time pate was carefully cleaned out, and

nestled in the basin of the bony structure was the birth-place of many a baby Wren. The skull made

a perfect domicile. A bullet hole in the rear formed a window. An eyeless socket was the exit and

entrance to the grim home. It is easy to imagine that many a family feud had its origin in the

desire of others to possess so secure a home.

"I have myself," says A. W. Anthony, of San Diego, Cal., "watched Cactus Wrens in New Mexico

carrying grass and thickening the walls of their old nests in October, for winter use, and have

found them hidden in their nests during a snowstorm in November. But there is another trait in

bird nature that I have seen very little of in print—that of building nests before or after

the proper season, seemingly for the sole purpose of practice or pastime, the out-cropping of an

instinct that prompts ambitious birds to build out of season even though they know that their work

will be lost."

{206}

|

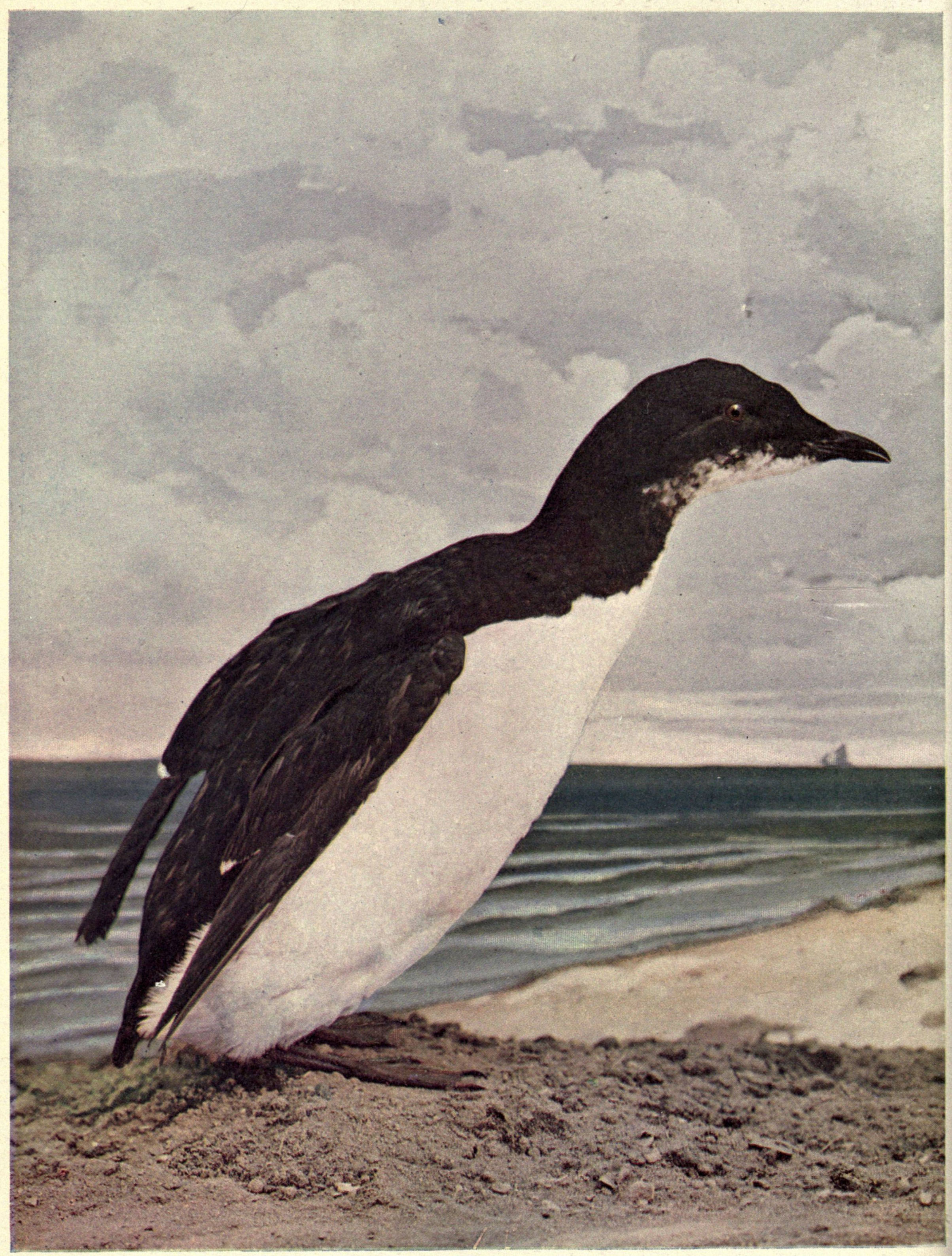

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

BRUNNICHS MURRE.

⅜ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{207}

BRÜNNICH'S MURRE.

T HIS species, which inhabits the

coasts and islands of the north Atlantic and eastern Arctic ocean, and the Atlantic coast south to

New Jersey, has the same general habits as the common Murre, which, like all the Auks, Murres and,

Puffins, is eminently gregarious, especially in the breeding season. Davie says that tens of

thousands of these birds congregate to make their nests on the rocky islands, laying single eggs

near one another on the shelves of the cliffs. The birds sit side by side, and although crowded

together never make the least attempt to quarrel. Clouds of birds may be seen circling in the air

over some huge, rugged bastion, "forming a picture which would seem to belong to the imaginary

rather than the realistic." They utter a syllable which sounds exactly like murre. The eggs

are so numerous as to have commercial value, and they are noted for their great variation in

markings and ground color. On the Farallones islands, where the eggs were until recently collected

for market purposes, the Murres nest chiefly in colonies, the largest rookery covering a hillside

and surrounding cliffs at West End, and being known as the Great Rookery. To observe the

egg-gatherers, says an eye-witness, is most interesting. "As an egger climbs his familiar trail

toward the birds a commotion becomes apparent among the Murres. They jostle their neighbors about

the uneven rocks and now and then with open bills utter a vain protest and crowd as far as

possible from the intruder without deserting their eggs. But they do not stay his progress and

soon a pair, then a group, and finally, as the fright spreads, the whole vast rookery take wing

toward the ocean. In the distance, perhaps, we see, suspended over a cliff by a slender rope, an

egger gathering the eggs from along the narrow shelves of rock, seeming indifferent to the danger

of the work." All this is now changed, the authorities having intervened to prevent the wholesale

destruction of the eggs. The Western Gull, however, is another enemy of the Murre (the California

species;) it carries off and devours both eggs and young. Mr. Bryant says the Gull picks up a

Murre's egg bodily and carries it away in his capacious mouth, but does not stick his bill into it

to get hold, as is stated by some writers, whose observations must have referred to the eggs

already broken by the Gulls or eggers.

HIS species, which inhabits the

coasts and islands of the north Atlantic and eastern Arctic ocean, and the Atlantic coast south to

New Jersey, has the same general habits as the common Murre, which, like all the Auks, Murres and,

Puffins, is eminently gregarious, especially in the breeding season. Davie says that tens of

thousands of these birds congregate to make their nests on the rocky islands, laying single eggs

near one another on the shelves of the cliffs. The birds sit side by side, and although crowded

together never make the least attempt to quarrel. Clouds of birds may be seen circling in the air

over some huge, rugged bastion, "forming a picture which would seem to belong to the imaginary

rather than the realistic." They utter a syllable which sounds exactly like murre. The eggs

are so numerous as to have commercial value, and they are noted for their great variation in

markings and ground color. On the Farallones islands, where the eggs were until recently collected

for market purposes, the Murres nest chiefly in colonies, the largest rookery covering a hillside

and surrounding cliffs at West End, and being known as the Great Rookery. To observe the

egg-gatherers, says an eye-witness, is most interesting. "As an egger climbs his familiar trail

toward the birds a commotion becomes apparent among the Murres. They jostle their neighbors about

the uneven rocks and now and then with open bills utter a vain protest and crowd as far as

possible from the intruder without deserting their eggs. But they do not stay his progress and

soon a pair, then a group, and finally, as the fright spreads, the whole vast rookery take wing

toward the ocean. In the distance, perhaps, we see, suspended over a cliff by a slender rope, an

egger gathering the eggs from along the narrow shelves of rock, seeming indifferent to the danger

of the work." All this is now changed, the authorities having intervened to prevent the wholesale

destruction of the eggs. The Western Gull, however, is another enemy of the Murre (the California

species;) it carries off and devours both eggs and young. Mr. Bryant says the Gull picks up a

Murre's egg bodily and carries it away in his capacious mouth, but does not stick his bill into it

to get hold, as is stated by some writers, whose observations must have referred to the eggs

already broken by the Gulls or eggers.

The eggs of Brunnich's Murre cannot be distinguished from those of the common

species. They show a wonderful diversity of color, varying from white to bluish or dark

emerald-green. Occasionally unmarked specimens are found, but they are usually handsomely spotted,

blotched, and lined in patterns of lilac, brown, and black over the surface.

{208}

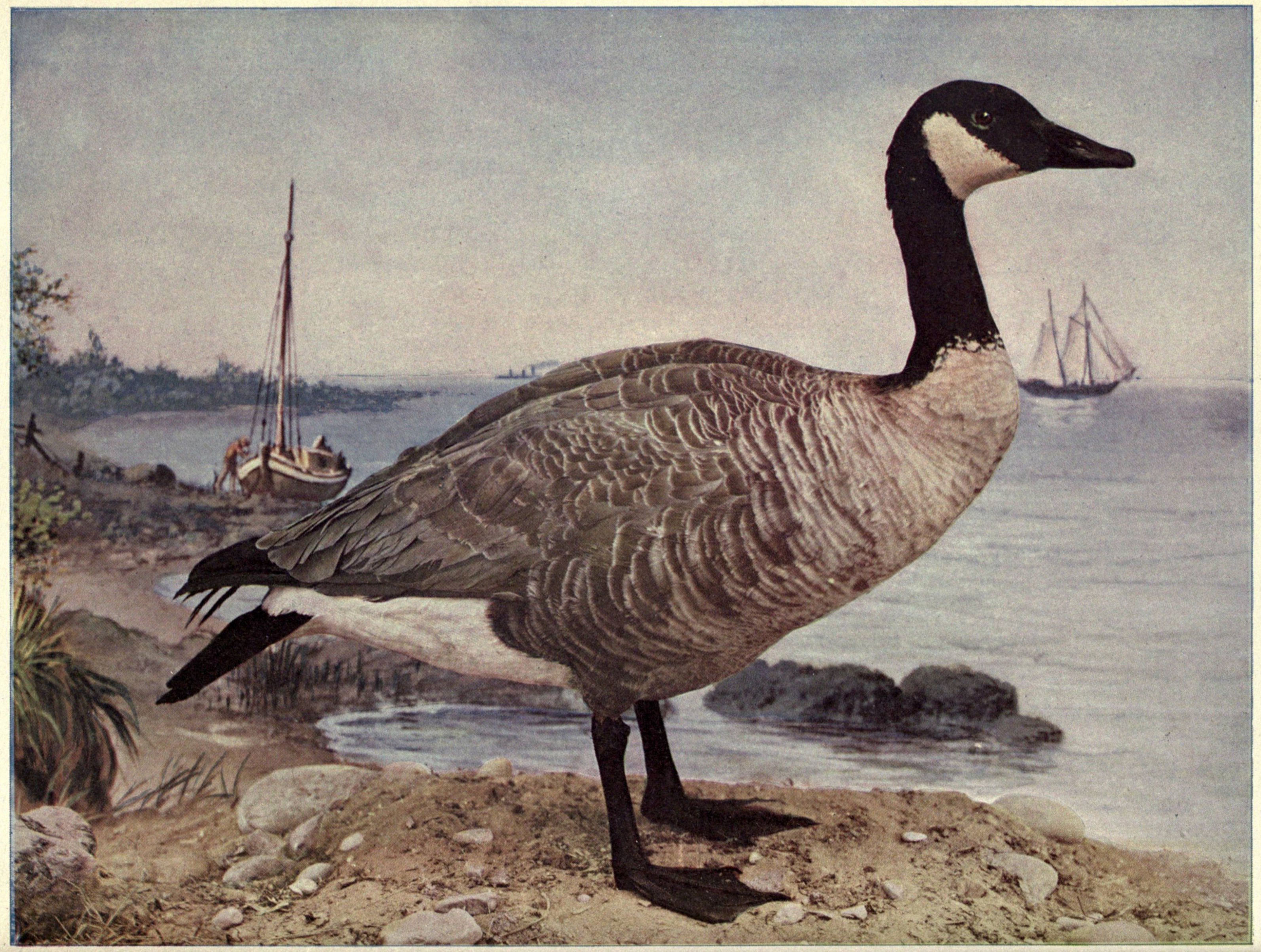

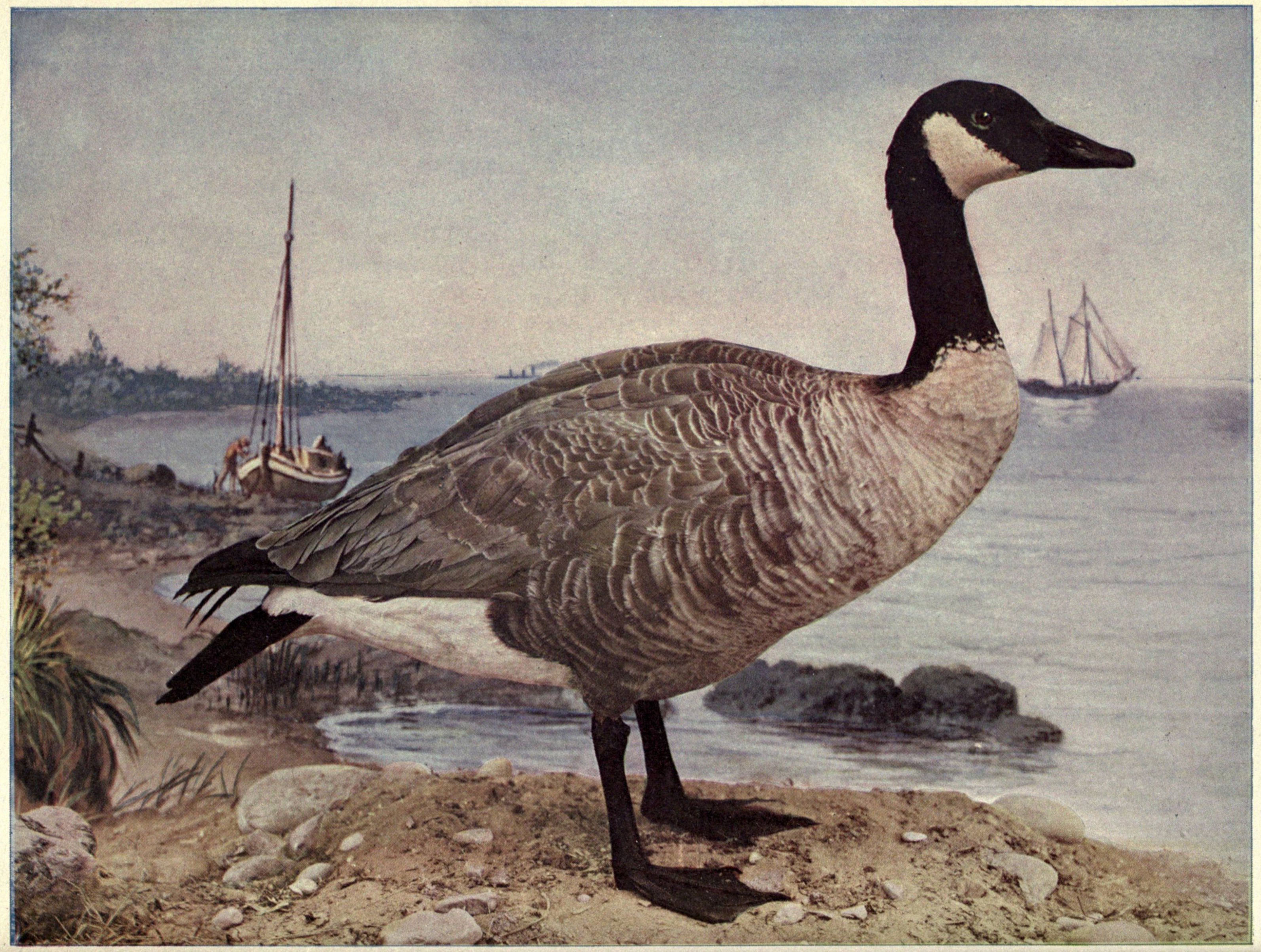

THE CANADA GOOSE.

Just a common Wild Goose of North America. In the spring and fall you will see great flocks of

us flying overhead, an old Gander in the lead, crying honk, honk as loud as he can. Our

nests are only simple hollows in the sand, on the shores of lakes and rivers, around which are

placed a few sticks and twigs, the five eggs laid on a layer of gray down.

"You're a Goose."

That's a polite way some people have of calling another stupid, but there are Geese and Geese

as well as men and men. I am going to tell you about one Goose that dearly loved her master, and

considering the way he treated her you may conclude she was a stupid Goose after all.

Well, this particular Goose took such a fancy to her owner that she would follow him about like

a dog, even to the village, where she would wait outside the barber's or other shop which he might

enter.

People noticed this, and instead of calling the farmer by his proper name began to speak of him

as "Mr. Goosey." This angered the man and he ordered the poor loving Goose to be locked up in the

poultry-yard. Shortly after he went to an adjoining town to attend a meeting; in the midst of the

business he felt something warm and soft rubbing against his legs; he looked down and there stood

his Goose, with protruding neck and quivering wings, gazing up at him with pleasure and fondness

unutterable.

The people about shouted with laughter, which so enraged her master, that seizing his whip, he

twisted the thong of it about the poor bird's neck, swung her round and round, and supposing her

dead, angrily threw her body out of the window.

A few days after Mr. Goosey was seized with a severe illness, which brought him to the verge of

the grave. He recovered, however, and was able at length to sit beside the open window. There on

the grass sat the Goose gazing up at him with the same old look of affection in her eyes.

"Am I never to be rid of that stupid thing?" he cried, but when he was told that through all

his illness the faithful bird had sat there opposite his window, scarcely touching food, his hard

heart melted, and from thenceforth Mr. Goosey treated his feathered friend with the greatest

kindness.

{210}

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

CANADA GOOSE.

¼ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{211}

THE CANADA GOOSE.

"Steering north, with raucous cry,

Through tracts and provinces of sky,

Every night alighting down

In new landscapes of romance,

Where darkling feed the clamorous clans

By lonely lakes to men unknown."

N ORTH America at large is the range of

this magnificent bird. Common Wild Goose and Grey Goose are its other names, and by which it is

generally known. The Canada Goose is by far the most abundant and universally distributed of all

North American Geese, and in one or other of its varieties is found in all the states and

territories of our country except perhaps Florida and the Gulf States. In Texas, however, it is

plentiful during the winter months. According to Hallock, although by far the greater portion of

Wild Geese which pass the winter with us, go north to breed, still in suitable localities young

are reared all over the United States from North Carolina to Canada. They nest in the wilder parts

of Maine, and are especially numerous in Newfoundland near the secluded pools and streams so

abundant throughout that island. There, remote from man, they breed undisturbed on the edges and

islands of the ponds and lakes. The Geese moult soon after their arrival in the spring, and, says

Hallock, owing to the loss of their pinion feathers are unable to fly during the summer or

breeding seasons, but they can run faster than a man on the marshes, or if surprised at or near a

pond, they will plunge in and remain under water with their bills only above the surface to permit

breathing, until the enemy has passed by. They feed on berries and the seeds of grasses. Both the

old and young become enabled to fly in September, and as soon after that as the frost affects the

berries, and causes the seeds of the grasses on the marshes and savannas to fall to the earth, or

otherwise when the snow falls and covers the ground, they collect in flocks and fly off to the

southern shores of the island, and from thence to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where they remain

until December, and then assembled, take flight in immense flocks to the southern parts of

America, to return in the spring.

ORTH America at large is the range of

this magnificent bird. Common Wild Goose and Grey Goose are its other names, and by which it is

generally known. The Canada Goose is by far the most abundant and universally distributed of all

North American Geese, and in one or other of its varieties is found in all the states and

territories of our country except perhaps Florida and the Gulf States. In Texas, however, it is

plentiful during the winter months. According to Hallock, although by far the greater portion of

Wild Geese which pass the winter with us, go north to breed, still in suitable localities young

are reared all over the United States from North Carolina to Canada. They nest in the wilder parts

of Maine, and are especially numerous in Newfoundland near the secluded pools and streams so

abundant throughout that island. There, remote from man, they breed undisturbed on the edges and

islands of the ponds and lakes. The Geese moult soon after their arrival in the spring, and, says

Hallock, owing to the loss of their pinion feathers are unable to fly during the summer or

breeding seasons, but they can run faster than a man on the marshes, or if surprised at or near a

pond, they will plunge in and remain under water with their bills only above the surface to permit

breathing, until the enemy has passed by. They feed on berries and the seeds of grasses. Both the

old and young become enabled to fly in September, and as soon after that as the frost affects the

berries, and causes the seeds of the grasses on the marshes and savannas to fall to the earth, or

otherwise when the snow falls and covers the ground, they collect in flocks and fly off to the

southern shores of the island, and from thence to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where they remain

until December, and then assembled, take flight in immense flocks to the southern parts of

America, to return in the spring.

The Canada Goose also breeds in great numbers on the Mississipi river, in which region it often

places its nest in trees, choosing generally a cottonwood stub not more than thirty feet in

height. The young are said to be carried from the nest to the water in the mother's bill, as are

the young of the Wood Duck. (See Birds, vol. ii, p. 21).

The Wild Goose is often domesticated, and in many portions of the country they are

bred in considerable numbers. When these birds return south at the commencement of winter they are

generally very thin and poor, being quite worn out by their long journey. They soon recuperate,

however, and in a short time become fat and are delicious eating. A full and excellent account of

the method of capturing the Canada Goose may be found in Hallock's "Gazetteer."

{212}

THE BROWN CREEPER.

I'm not a showy looking bird like my friend the Woodpecker, but my habits are something like

his—and so is my tail. He uses his, you know, to aid him in climbing trees, and so do I.

They call me the Creeper because I am always creeping over the timber in search of insects.

If you ever see a brown-streaked little fellow, resembling a Wren, traveling up a tree in short

stages, now stopping to pick out an insect lurking in the crevices of the bark, or returning head

downwards to pounce on an unwary fly, that is your humble servant the Brown Creeper. Up

again, you will then see me creep, just like a little mouse, uttering now and then a low plaintive

note; clear to the top I go, exploring every nook and cranny, never using my wings once.

Last summer a little boy in the park wanted to get a good look at me, so he very slyly crept up

to the tree which I was exploring, thinking, perhaps, that I was too busy to notice that he was

there. But I did see him, for we little birds have to be always on the watch against our human, as

well as feathered enemies, so I just stood still and peeked out at him from the other side of the

tree. Very slily then he moved around to that side, and very slily did I move around to the other,

keeping the tree trunk all the time between me and his bright blue eyes.

"He's playing hide and seek with me, Mama," he shouted, and so pleased was the little fellow

that it was quite a while before I flew away.

Like the Woodpecker, I prefer a hole in a tree in which to build my nest, but instead of boring

I look for a tree that has some of its bark loose enough for me to squeeze in. I line it with dry

grass, moss, and feathers and see to it that the overhanging bark shelters me and my four, or six,

white, red-speckled eggs.

{214}

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

BROWN CREEPER.

Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{215}

THE BROWN CREEPER.

A LITTLE mite of a bird is this pretty

creature, which many observers claim is seldom seen, or, indeed, is known to few besides the

special student of ornithology and the collector. We venture to assert that any one with fairly

good eyes can see it almost any day creeping over the timber in search of its insect food. Besides

seeing it in the deepest woods, we often notice it in the open places in parks, and in gardens and

orchards it is quite common. It commences operations at the foot of a tree, and travels upwards in

short stages, "now stopping to pick out an insect lurking in the crevices of the bark with its

long, slender bill, or returning head downwards to pounce on an unwary fly. Up again it creeps,

more like a mouse than a bird, occasionally uttering a low and plaintive note; right to the top of

the tree it mounts, exploring every nook and cranny likely to reward its search as it goes. Now it

creeps on the under side of a projecting limb, then again on the top, and although it will explore

an entire tree, still it but rarely uses its wings to convey it from one part to another. You will

also find that it, like the Woodpecker, endeavors to be on the opposite side to you, and carry on

its explorations unseen." Curiosity, however, often seems to get the better of the Creeper, and

you will see its light colored breast and sharp little head peep trustfully at you and again

vanish from sight.

LITTLE mite of a bird is this pretty

creature, which many observers claim is seldom seen, or, indeed, is known to few besides the

special student of ornithology and the collector. We venture to assert that any one with fairly

good eyes can see it almost any day creeping over the timber in search of its insect food. Besides

seeing it in the deepest woods, we often notice it in the open places in parks, and in gardens and

orchards it is quite common. It commences operations at the foot of a tree, and travels upwards in

short stages, "now stopping to pick out an insect lurking in the crevices of the bark with its

long, slender bill, or returning head downwards to pounce on an unwary fly. Up again it creeps,

more like a mouse than a bird, occasionally uttering a low and plaintive note; right to the top of

the tree it mounts, exploring every nook and cranny likely to reward its search as it goes. Now it

creeps on the under side of a projecting limb, then again on the top, and although it will explore

an entire tree, still it but rarely uses its wings to convey it from one part to another. You will

also find that it, like the Woodpecker, endeavors to be on the opposite side to you, and carry on

its explorations unseen." Curiosity, however, often seems to get the better of the Creeper, and

you will see its light colored breast and sharp little head peep trustfully at you and again

vanish from sight.

The Creeper is admirably adapted to its ways of life. Its bill is formed for obtaining its

insect food, and its tail supports it while climbing.

The Brown Creeper nests in early summer, when insect life is most abundant, and,

like the Woodpecker, prefers a hole for the purpose. This it lines with dry grass, moss and

feathers, and makes a very warm and comfortable home. The eggs are from five to eight, white,

spotted and speckled with red. The Creeper is not migratory, and we see it in the woods throughout

the year. It is hardy and lives sumptuously the winter through. One who was very fond of the

little creatures said: "If the Swallow were to visit us at this time, it would undoubtedly perish,

for the air in winter is almost clear of insect life; but the little Creeper can live in ease when

the sun is at Capricorn, just because he can climb so dexterously, for the bark of trees abounds

with insects, and more particularly their eggs and larvae, which lie there torpid until called

into life by the genial presence of the vernal sun."

{216}

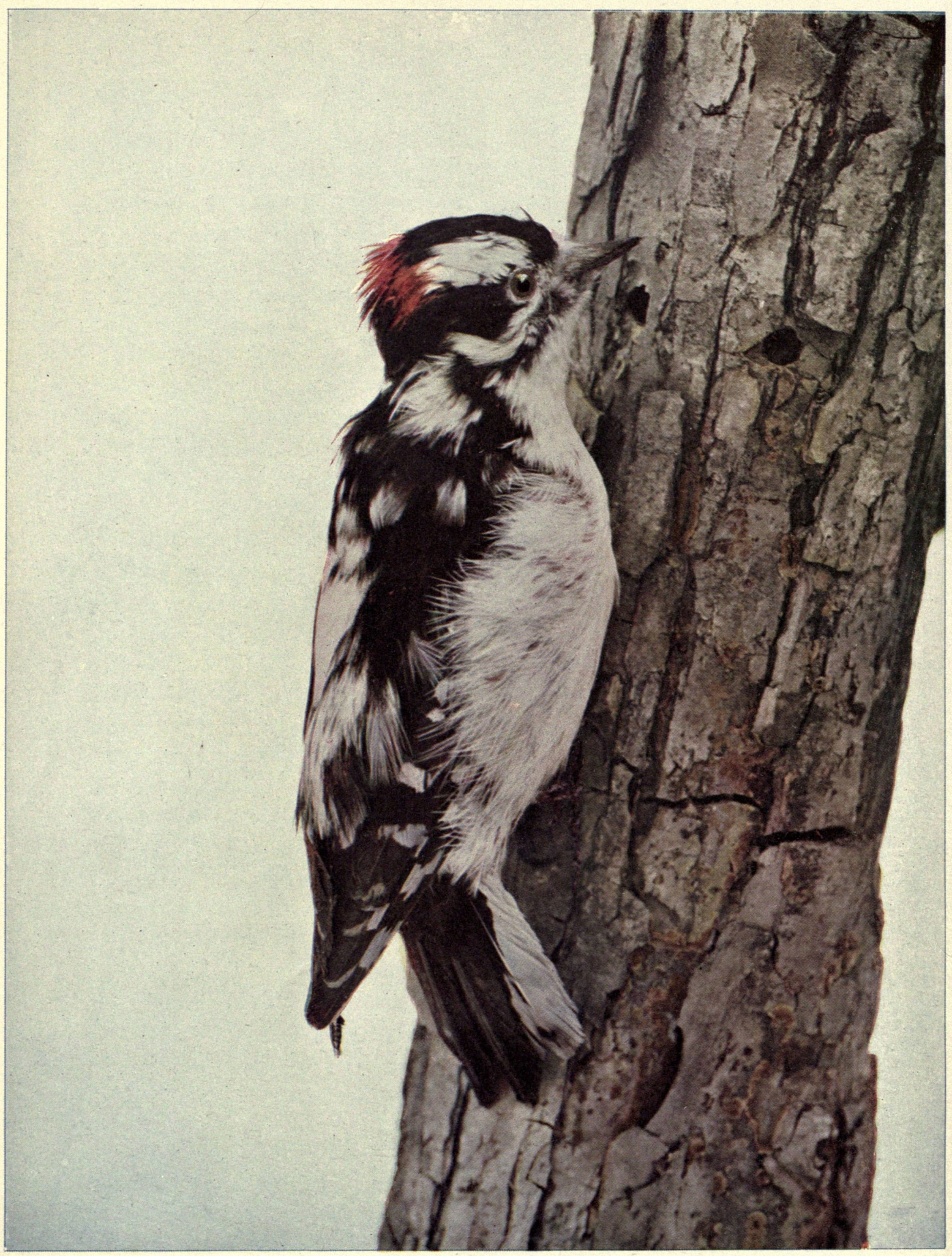

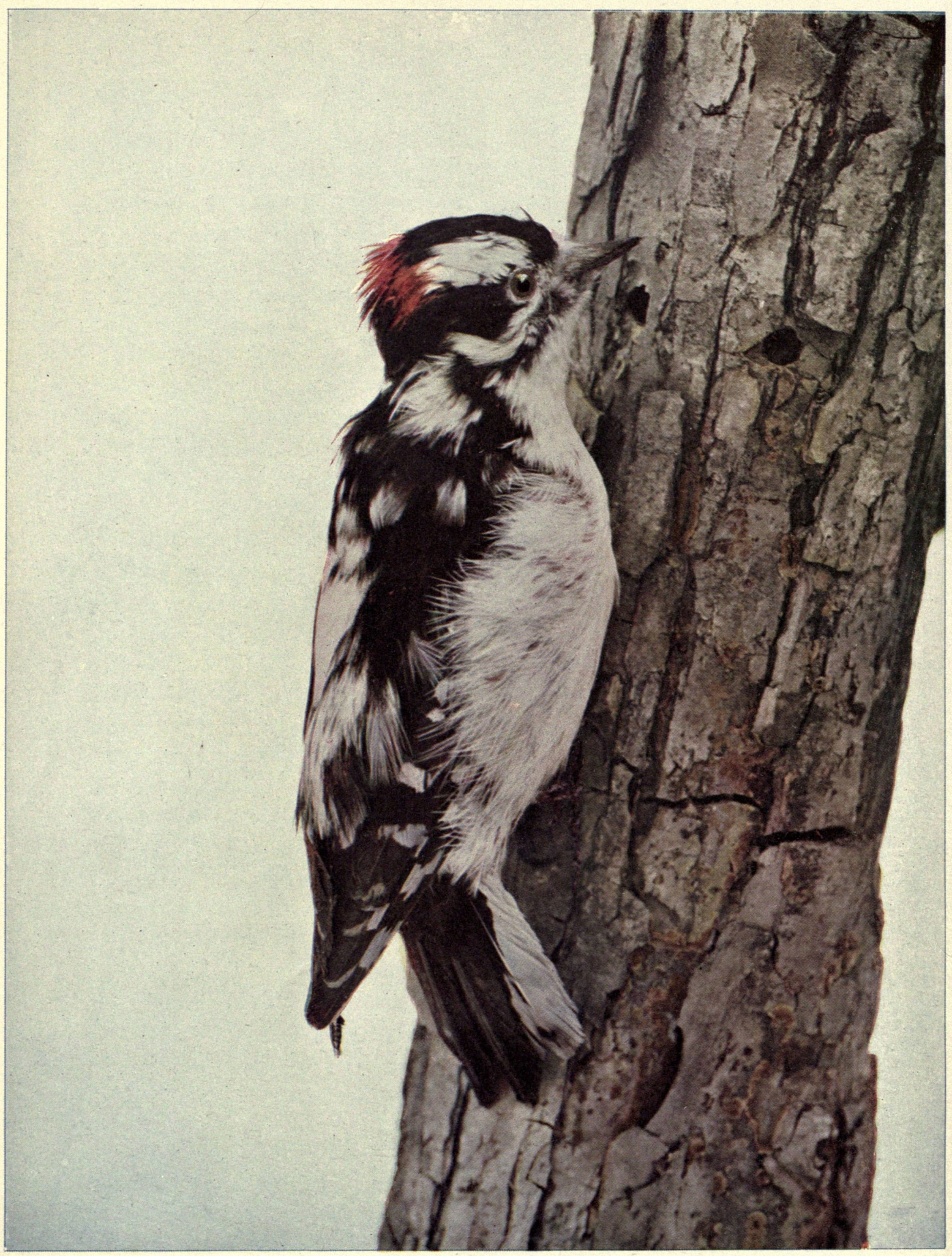

THE DOWNY WOODPECKER.

Another Woodpecker? Yes, there are such a tribe of us, you know; more than you can count on

your fingers and toes, as my cousin the Red-Bellied Woodpecker said in the February number of

Birds.

The word toes reminds me that I am not one of the three-toed fellows he was so anxious to tell

about. I have four, as you see, two before and two behind. So have most of the Woodpeckers. Should

you be looking out for me this summer you will recognize me by my four toes, the white band down

my back, and the two white stripes on the side of my head.

My tongue you can't see, but it is small, flat, short, and horny, armed along the edges with

hooks. When I catch an insect I do it by throwing my tongue forward, out of my mouth. I have an

idea the insects consider my treatment of them rather rough. If I didn't eat them, the wood-boring

ones, would destroy all the trees. My bill isn't strong enough to bore in the hard wood; I only

injure the bark, no matter what some people may say. The wood-eating beetles, caterpillars,

spiders, daddy longlegs, grass-hoppers, and flies, are all grist for my mill—or bill,

rather. I like beechnuts, too, when I can find them.

I'm the smallest of all the Woodpecker family, quiet and unobtrusive they say, in my manners. I

am sociable, however, and go about a great deal in the company of other birds. Mr. Nuthatch, Mr.

Brown Creeper, Mr. Titmouse, and Mr. and Mrs. Wren are my especial friends.

Can I drum?

Indeed, yes. I wouldn't belong to the Woodpecker family if I couldn't. All I need is the stub

of a dead limb whose center is hollow and whose shell is hard and resonant. I will drum on that

with my bill for an hour at a time, stopping now and then to listen for a response from my mate or

a rival.

Early in the spring we "Downies" pick a hole in a dead tree, or in a post or rail of a fence,

in which we lay four, five, or six glossy white eggs. Sometimes it takes us a whole week to chisel

out that hole, and we are so busy that a little boy or little girl can get very near without our

minding it.

{218}

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

DOWNY WOODPECKER.

Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{219}

THE DOWNY WOODPECKER

Every leaf was at rest, and I heard not a sound,

Save a Wood-drummer tapping on a hollow beech tree.

T HIS little Woodpecker is the smallest

of all those inhabiting the United States. In the shade trees about houses and parks, and

especially in orchards, he may be frequently seen tapping or scratching on the limb of a tree

within two or three yards' distance, where he has discovered a decayed spot inhabited by

wood-boring larvae or a colony of ants, his food consisting of ants, beetles, bugs, flies,

caterpillars, spiders, and grasshoppers. The late Dr. Glover of the Department of Agriculture,

states that on one occasion a Downy Woodpecker was observed by him making a number of small,

rough-edged perforations in the bark of a young ash tree, and upon examination of the tree when

the bird had flown, it was found that wherever the bark had been injured, the young larvae of a

wood-eating beetle had been snugly coiled underneath and had been destroyed by the bird. Beechnuts

also constitute a considerable portion of the food of this bird. Dr. Merriam says that in northern

New York they feed extensively on this nut, particularly in fall, winter, and early spring.

HIS little Woodpecker is the smallest

of all those inhabiting the United States. In the shade trees about houses and parks, and

especially in orchards, he may be frequently seen tapping or scratching on the limb of a tree

within two or three yards' distance, where he has discovered a decayed spot inhabited by

wood-boring larvae or a colony of ants, his food consisting of ants, beetles, bugs, flies,

caterpillars, spiders, and grasshoppers. The late Dr. Glover of the Department of Agriculture,

states that on one occasion a Downy Woodpecker was observed by him making a number of small,

rough-edged perforations in the bark of a young ash tree, and upon examination of the tree when

the bird had flown, it was found that wherever the bark had been injured, the young larvae of a

wood-eating beetle had been snugly coiled underneath and had been destroyed by the bird. Beechnuts

also constitute a considerable portion of the food of this bird. Dr. Merriam says that in northern

New York they feed extensively on this nut, particularly in fall, winter, and early spring.

This miniature Woodpecker is very social in its habits, far more so than other species, and is

often found associated with other birds, in the woods, the orchards, along fence rows, and not

infrequently in the cities. He is often seen in company with the White-breasted Nuthatch (See Vol.

II, p. 118) and the Brown Creeper (Vol. III, p. 214).

Early in the spring the "Downies" retire to the woods to make their nests, preferring the

vicinity of running water. The nest is begun about the second or third week in May, and consumes

from two days to a week in building. The holes are usually excavated in dead willow, poplar, or

oak trees, and the height varies from four to thirty feet, generally about fifteen feet. The

entrance to the nest is about two inches in diameter, and the depth of the nest hole varies from

eight to eighteen inches. The eggs are four or five, rarely six, and are pure glossy-white.

We know of no more interesting occupation than to observe this bird. It is fond of drumming on

the stub of a dead limb whose center is hollow, and whose shell is hard and resonant. Upon such

places it will drum for an hour at a time, now and then stopping to listen for a response from its

mate or of some rival. At all times it is unsuspicious of man, and when engaged in excavating the

receptacle for its nest it continues its busy chiseling, unheeding his near approach.

The Woodpecker is wrongfully accused of boring into the sound timber, and, by

letting in the water, hastening its decay. As Dixon says: "Alas! poor harmless, unoffending

Woodpecker, I fear that by thy visits to the trees thou art set down as the cause of their

premature decay. Full well I know thy beak, strong as it is, is totally incapable of boring into

the sound timber—full well do I know that, even if thou wert guilty of such offense, nothing

would reward thy labors, for thy prey does not lurk under the bark of a healthy tree. Insects

innumerable bore through its bark and hasten its doom, and it is thy duty in Nature's economy to

check them in their disastrous progress."

{220}

THE NEW TENANTS.

By Elanora Kinsley Marble.

And now the little Wrens are fledged

And strong enough to fly;

Wide their tiny wings they spread,

And bid the nest "good-bye."

Such a chattering as greeted Mrs. Wren when she returned with a fine black spider in her bill.

All the children talked at once. Bobbie alone never uttered a word.

"You naughty boy," exclaimed Mrs. Wren, turning to the crest-fallen Pierre, "did I not tell you

to take care of your brothers and little sister? The idea of trying to fly before you have had a

lesson! I have a good mind to whip every one of you," and the irate Mrs. Wren very unjustly did

indeed peck every little head sharply with her bill.

Bobbie cowered in the nest much too frightened to whimper or even mention the injury to one of

his legs which he had sustained in his fall.

Mr. and Mrs. Wren the next day proceeded to give the children a lesson or two in flying.

"My tail is so stubby," wailed Emmett at the first trial, "it brings me right down to the

ground."

"Tho doth mine," lisped little Dorothy, "dess wish I had no tail at all, so I do," at which the

others laughed very heartily.

Bobbie made a heroic effort to do as did the rest, but at the first movement sank back into the

nest with a cry of pain.

"Such fortitude!" exclaimed Mrs. Wren when it was found one of his legs was broken, "not a

whimper has the little fellow made since his fall. How heroic! How like my dear, dear papa!" and

Mrs. Wren laughed, and then cried, from mingled pity and joy.

"H'm," commented Mr. Wren, "if Bobbie had remembered the motto I gave them before I left

yesterday morning, this accident wouldn't have happened. Can you repeat it?" turning to the eldest

of the brood.

"Be sure you're right, then go ahead," shouted Pierre, totally forgetting he had not heeded the

rule any more than Bobbie.

"Yes, a safe rule to go by," said Mr. Wren, gravely stroking his chin with one claw. "Dear,

dear," ruefully examining the injured limb, "now the the child will go stumping through life like

his grandpa. I only hope," with a dry cough, "that he'll not turn out a rowdy and lose one eye,

too."

"'He jests at scars who never felt a wound,'" loftily replied Mrs. Wren, who seemed never to

forget a quotation. "For my part I am proud that one of my boys should turn out to be such a

spirited little fellow. But there, Mr. Wren, the children are calling you from that bunch of weeds

over yonder. Go down to them, while I fetch a nice canker-worm for Bobbie."

After a few days the lame Bobbie was able to leave the nest and go hopping around with the

other children, adding his feeble chur chur to theirs. Mr. and Mrs. Wren led them from one

place to another, always among the weeds and shrubbery where they were soon taught to earn their

own livelihood.

"Moths, butterflies, gnats, flies, ants, beetles, and bugs constitute our bill of fare," said

Mrs. Wren as they went whisking along, "together with thousand-legs, spiders, and worms. If we

didn't eat them they would destroy the fruits in their seasons, so you see, my children, what

valuable citizens we are in the world."

At nightfall Mr. and Mrs. Wren, with their brood, flew to the crotch of {221}a tree, and in ten seconds every little head was under a wing, and every

little Wren sound asleep.

"Well," said Mr. Wren one day, "the children are old enough now to take care of themselves, and

we must begin, my dear, to build a nest in which once more to begin housekeeping."

"It will not be in an old tin pot this time," replied Mrs. Wren, with a toss of her head, "and

furthermore, Mr. Wren, I intend to have entirely new furniture."

"Of course, of course," assented her mate, "whoever heard of a Wren raising a second brood in

the same nest? We are much too neat and nice for that, my dear."

"We," sniffed Mrs. Wren, ever ready for quarrel. "I'd like to know, Mr. Wren, what you had to

do with building the nest, I would, really! Humph!" and Mrs. Wren flirted her tail over her head

and laughed shrilly.

"I brought the first sticks, my dear," he answered mildly, "and didn't I do all the house

hunting? Besides, I forgot to tell you, that when looking about in April, I found two other

apartments which, if the tin-pot had not appeared suitable, I intended to offer you. In order to

secure them I partly furnished each, so that other house hunters would know they were not 'to

let.'"

"Humph!" returned Mrs. Wren, though exceedingly well pleased, "I'll wager we'll find a Sparrow

family in each one of them."

"No we won't," chuckled Mr. Wren "for the houses I selected were much too small for Mr. and

Mrs. Sparrow to squeeze in."

"You clever fellow," exclaimed Mrs. Wren, pecking him gleefully with her bill. "I

am proud of my hubby, I am, indeed," and Mr. Wren laughed, and hopped about, never hinting to his

innocent spouse that all the gentlemen Wrens did the same thing every year.

The next day, while preening their feathers, and getting ready for a visit to the apartments

Mr. Wren had spoken of, a cry of distress smote upon their ears.

"That sounds like our Dorothy's voice," said Mrs. Wren, her little knees knocking together in

fright.

"It is Dorothy calling for help," assented Mr. Wren. "I left the children in the

orchard. Come, let us fly over there as quickly as we can."

On the ground, under some bushes, they found huddled their frightened group of little ones,

while above, on a limb of a tree, perched Mr. and Mrs. Jay, uttering at intervals their harsh cry

of jay, jay, jay.

"Its our Bobbie," cried Mrs. Wren, aghast, after she had counted her brood and found one of

them missing, "look at him fighting over there with that young Jay."

"That's it, give it to him," screamed the delighted Mr. Jay to his young son, "hit him in the

eye, my boy, hit him in the eye."

Mr. and Mrs. Wren flew about Bobbie uttering cries of distress.

"Fair play, fair play," cried papa Jay, flying down almost upon Mr. Wren's back. "Give the

young ones a chance, or——"

A loud, sharp twitter from the tree top caused Mr. Jay to glance up.

"My old enemy," he exclaimed, his crest falling at once, as a low crown encircling a pompon of

orange-red showed itself among the green branches. "That tyrant, Mr. Kingbird. He's always

meddling in other people's affairs, he is. I'd like to wring his neck. Come, Mrs. Jay; come, my

son," he screamed, and off they flew to boast of the victory among their neighbors.

"I hope your little boy is not much hurt," said Mr. Kingbird rather pompously, "I arrived just

in the nick of time, I think."

{222}

"Oh, my Bobby," wailed Mrs. Wren, wiping the blood from his face, "that dreadful Jay has

scratched out one of his eyes."

"How did it happen?" sternly inquired Mr. Wren, "tell me the truth or——"

Dorothy interrupted her father with loud sobbing.

"I—I was flirting," she stammered "just a little, with young Mr. Jay,

papa—you know how handsome he is, and bold—when Bobby steps up, and he says—he

says—"

"Well, go on, my little miss," said Mr. Kingbird, deeply interested, "what did your brother

say?"

"He said," wiping her eyes with a corner of her wing, "that 'birds of a feather flock

together,' and a girl with such a grandpa as I had should be ashamed to associate with the son of

a robber and coward like Mr. Bluejay, and so——"

"And so young Mr. Jay pitched into me," interrupted Bobbie, "and I pitched into him. I'd a

licked him, too, Pop," he added, flourishing his crippled leg, "if his old pa and ma hadn't come

up when they did and told him to hit me in the eye."

"A chip off the old block, ma'am," said Mr. Kingbird, who had heard of Mrs. Wren's fighting

papa, "a chip off the old block, I see. Well, good-day all, good-day. As your son wisely says

'birds of a feather flock together,' and it wouldn't look well, you know, for a person of my

aristocratic appearance to be seen in such humble company. So good-day, good-day," and off the

pompous fellow flew leaving Mr. and Mrs Wren decidedly angry though grateful.

Another week found the pair building a nest in the cavity of a maple tree near the study

window. To the sticks and straws which Mr. Wren had placed therein early in the season, Mrs. Wren

added spider webs and cocoons, lining the nest, or furnishing it as she called it, with horsehair

and the downiest goose and duck feathers she could procure.

"There!" said she, when all was completed and the first egg laid, "Mrs. John can't sneer at our

home now. No coarse chicken feathers, or stable straw this time, Mr. Wren. We will use the other

apartment you chose for the third brood, for three we are to have this summer as well as Mrs.

John. When we go south in November, our family I intend shall be as large as hers."

Mr. Wren made no answer, but, possibly being such an uncommonly wise bird, inwardly marveled

over that imperious force, that wonderful instinct which made it necessary for them and all the

feathered tribe to reproduce their kind.

Very carefully, one winter's day, Bridget removed the nest from the tin-pot and wreathing it in

ribbons, hung it above her chest of drawers in the the attic.

"It do same," said she to the children, who prided themselves upon their knowledge of the looks

and habits of the House Wren, "that in sthudoin the birds this summer I do be afther learnin' a

lesson I wasn't expectin' meself at all."

"A lesson?" said they curiously.

"Indade! Its young ye's aire, me darlint's, to be thinkin' of the same, but sure its not meself

that'll ever be forgetten the patience, ingenuity, industhry, and conjoogal love of the wee pair.

Faith but it was a purty sight. Dumb animals indade! Niver sphake to me of dumb animals,

for be St. Patrick, if them two blessed little crathers didn't talk, schold, make love, and sing

in a langwidge all their own, then me grandfather's name wasn't Dinnis, and I'm not Bridget

O'Flaherty, at all, at all."

[THE END.]

{223}

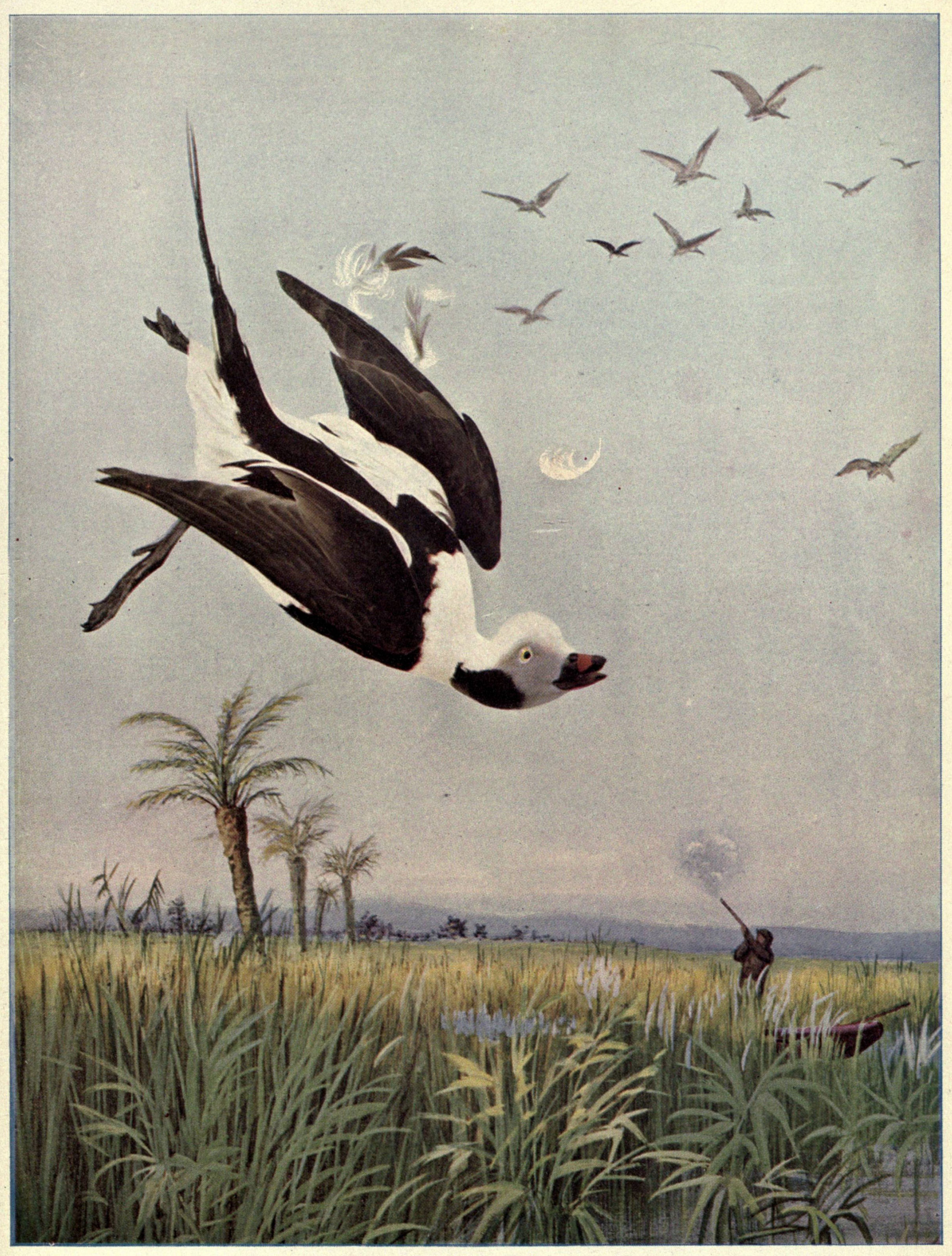

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

OLD SQUAW DUCK.

¼ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{225}

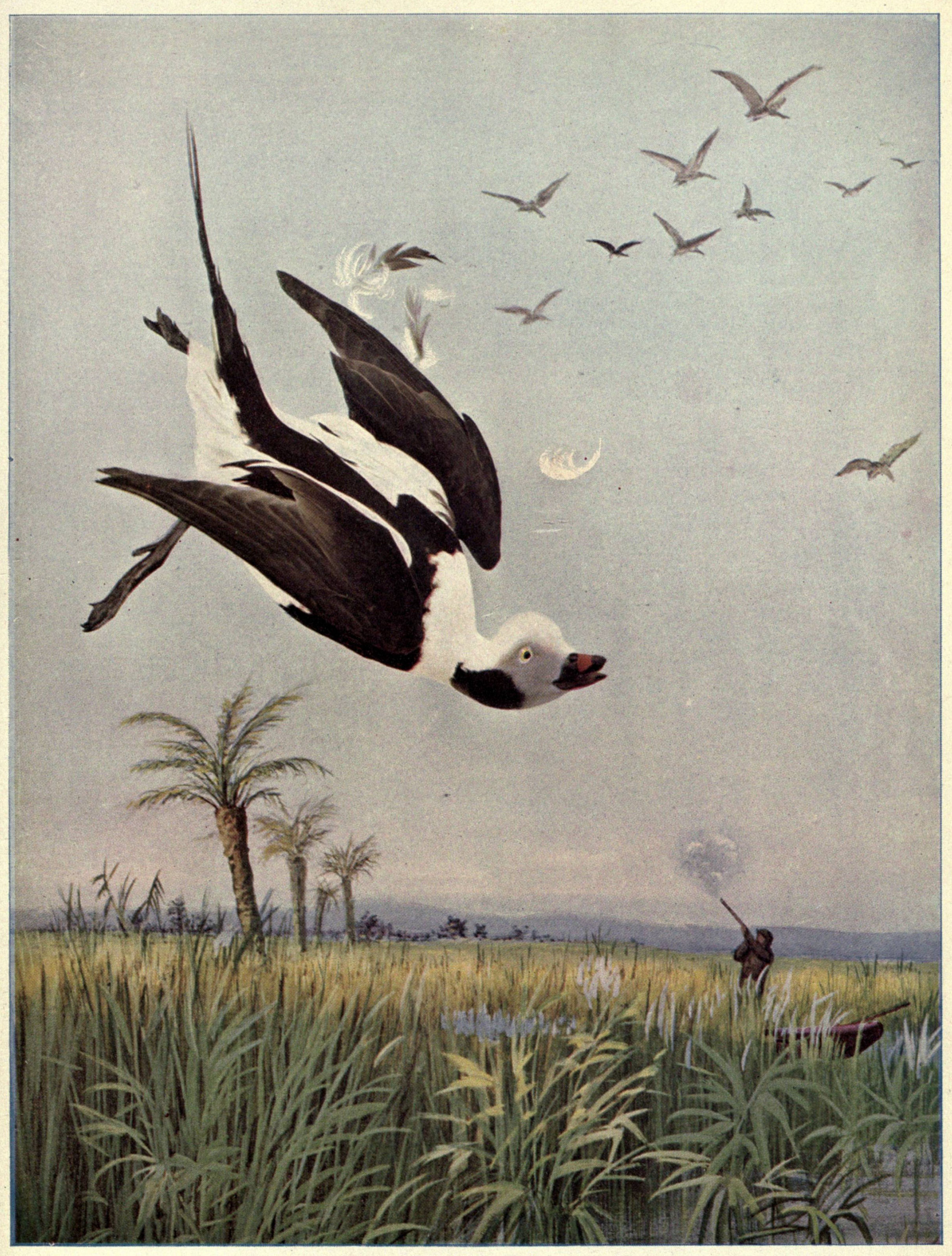

THE OLD SQUAW DUCK.

H ERE is an instance where the female

is the head of the family indeed, for by common consent the name includes the male of this

species. It has numerous other names, however, as Old Wife, South-Southerly, Long-tailed Duck,

Swallow-tailed Duck, Old Injun (Massachusetts and Connecticut;) Old Molly, Old Billy, Scolder,

(New Hampshire and Massachusetts.)

ERE is an instance where the female

is the head of the family indeed, for by common consent the name includes the male of this

species. It has numerous other names, however, as Old Wife, South-Southerly, Long-tailed Duck,

Swallow-tailed Duck, Old Injun (Massachusetts and Connecticut;) Old Molly, Old Billy, Scolder,

(New Hampshire and Massachusetts.)

The habitat of the Old Squaw is the northern hemisphere; in America, south in winter to nearly

the southern border of the United States. It is distributed throughout the northern portions of

the globe, but makes its summer home in Arctic regions. George Harlow Clarke, Naturalist, Peary

Polar Expedition, in a recent article mentioned that, "in June the Old Squaw's clanging call

resounded everywhere along shore, and the birds themselves were often perceived gliding to and fro

amid the ice cakes drifting with the tide between the main ice-floe and the land." It is a

resident in Greenland and breeds in various places in Iceland. The nests are made on the margins

of lakes or ponds, among low bushes or tall grass, are constructed of grasses, and generally, but

not always, warmly lined with down and feathers. The eggs are from six to twelve in number. In the

United States the Long-tail is found only in winter. Mr. Nelson found it to be an abundant winter

resident on Lake Michigan, where the first stragglers arrived about the last of October, the main

body arriving about a month later and departing about the the first of April, a few lingering

until about the last of the month.

The words south—south—southerly, which some have fancied to resemble its

cry, and which have accordingly been used as one of its local names, did not, to the ear of Dr.

Brewer, in the least resemble the sounds which the bird makes; but he adds that the names "Old

Wives" and "Old Squaws" as applied to the species are not inappropriate, since when many are

assembled their notes resemble a confused gabble. Hallock says that most of the common names of

this Duck are taken from its noisy habits, for it is almost continually calling.

Mr. E. P. Jaques, asks, in Field and Stream, "What has become of our

Waterfowl?" assuming that their numbers have greatly diminished. "The answer is a simple one," he

goes on to say; "they have followed conditions. Take away their breeding and feeding grounds and

the birds follow. Bring back their breeding and feeding grounds and lo! the birds reappear. For

the past five years waterfowl have been about as scarce in the Dakotas as in Illinois or Indiana.

The lakes were dry and conditions were unfavorable for them. In the spring of 1897 the lakes

filled up once more. For the most part the bottoms of the lakes were wheat stubbles. This

furnished food for the spring flight and thousands of birds nested there. When the wheat was gone

the aquatic growth took its place and for every thousand Ducks that tarried there in the spring,

ten thousand appeared in the fall."

{226}

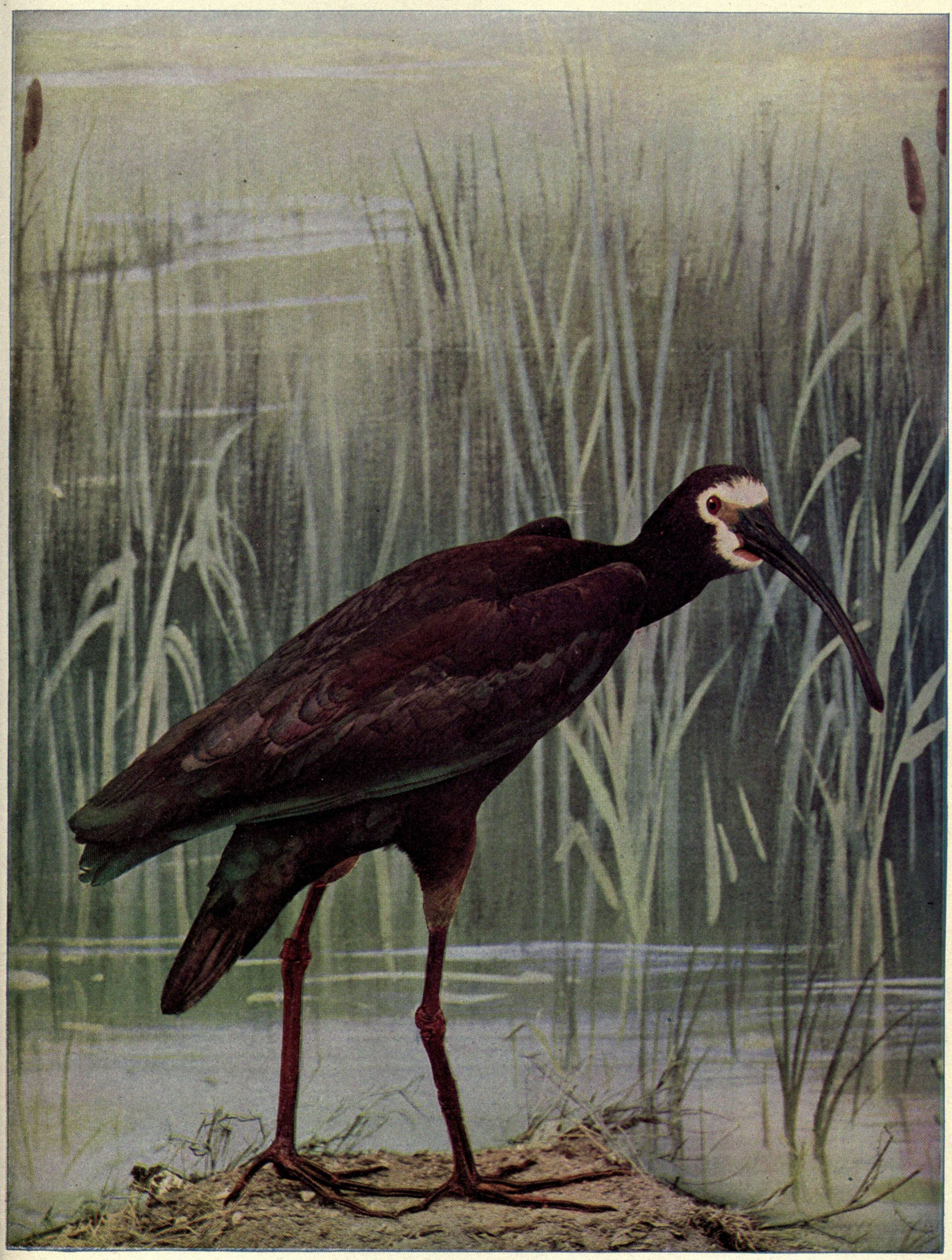

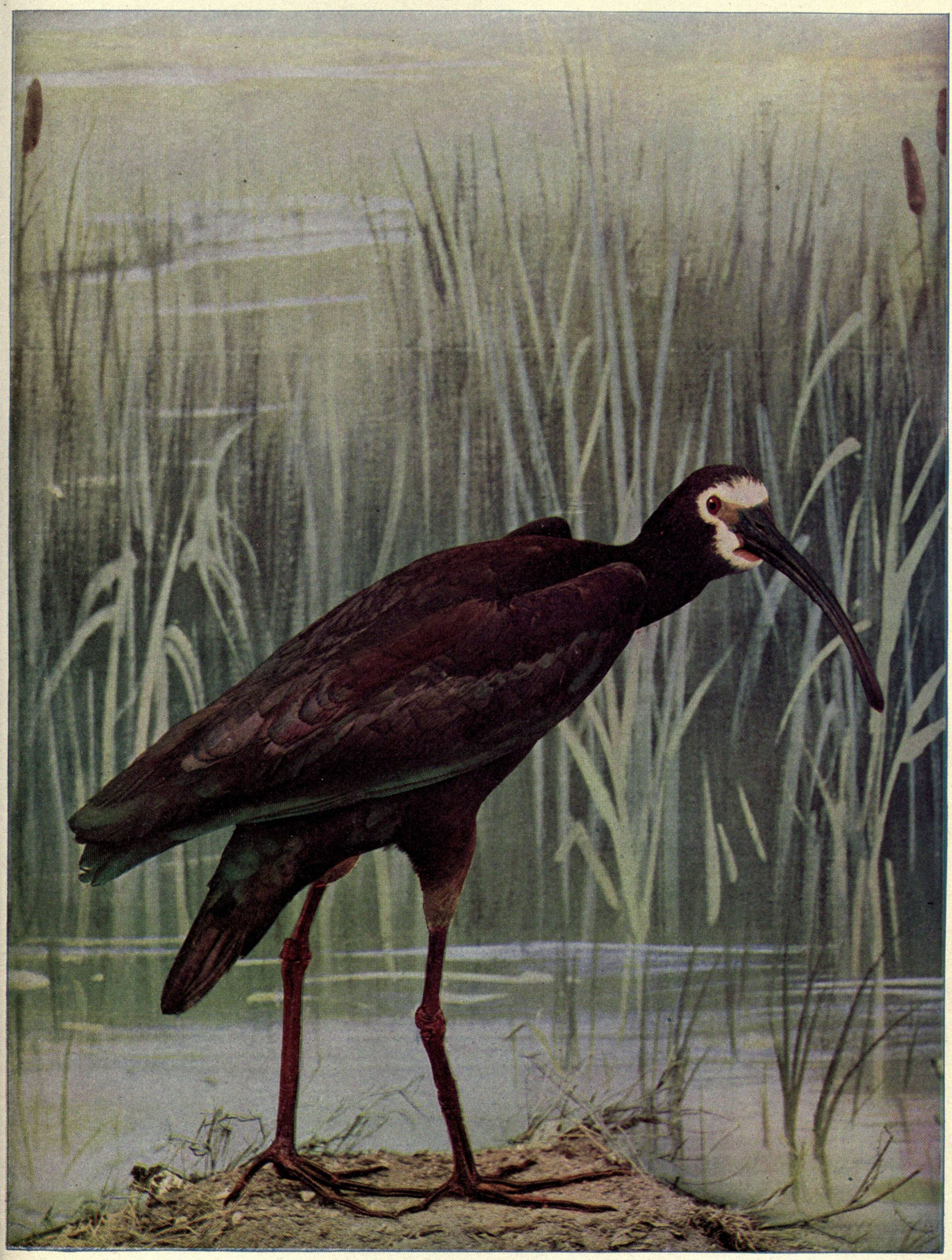

THE WHITE-FACED GLOSSY

IBIS.

Ibises, of which there are about thirty species, are distributed throughout the warmer parts of

the globe. Four species occur in North America. According to Chapman, they are silent birds, and

live in flocks during the entire year. They feed along the shores of lakes, bays, and salt-water

lagoons, and on mud flats over which the tide rises and falls.

The beautiful, lustrous White-faced Glossy Ibis inhabits the south-western United States and

tropical America. It is found as far north as Kansas, and west through New Mexico and Arizona to

California. In southern Texas it is very abundant, and in some localities along the banks of the

Rio Grande swarms by thousands. Dr. J. C. Merrill in May, visited a large patch of tule reeds,

growing in a shallow lagoon about ten miles from Fort Brown, in which large numbers of this Ibis

and several kinds of Herons were breeding. The reeds grew about six feet above the surface of the

water, and were either beaten down to form a support for the nests, or dead and partly floating

stalks of the previous year were used for that purpose. Dr. Merrill states that it was impossible

to estimate the number of Ibises and different Herons nesting here. "Both nests and eggs of the

Ibises were quite unlike those of any of the Herons, and could be distinguished at a glance. The

nests were made of broken bits of dead tules, supported by and attached to broken and upright

stalks of living ones. They were rather well and compactly built, quite unlike the clumsy

platforms of the Herons. The eggs were nearly always three in number, and at this date were far

advanced toward hatching; many of the nests contained young of all sizes."

The walk of the Ibis is quiet and deliberate, though it can move over the ground with

considerable speed whenever it chooses. Its flight is lofty and strong, and the bird has a habit

of uttering a loud and peculiar cry as it passes through the air.

The Ibis was formerly invested with sacerdotal honors by the ancient Egyptians, and embalmed

and honored after death with a consecrated tomb, in common with the bull and the cat. The bird

probably owes its sacred character to the fact that its appearance denotes the rising of the Nile,

an annual phenomenon on which depends the prosperity of the whole country.

The food of the Ibis consists mostly of mollusks, both terrestrial and aquatic, but it will eat

worms, insects, and probably the smaller reptiles.

The sexes have similar plumage, but the female is smaller than her mate.

{227}

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

WHITE-FACED GLOSSY IBIS.

3⁄7 Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{229}

SOME LOVERS OF

NATURE.

Our Music's in the Hills.—Emerson.

The groves were God's first temples.—Bryant.

Nature, the vicar of the Almighty Lord.—Chaucer.

The liquid notes that close the eye of day, (the Nightingale).—Milton.

When spring unlocks the flowers to paint the laughing soil.—Bishop

Heber.

O, for a seat in some poetic nook,

Just hid with trees and sparkling with a brook.—Leigh Hunt.

By shallow rivers, to whose falls

Melodious birds sing madrigals.—Christopher Marlowe.

To me the meanest flower that blows can give

Thoughts that do often lie too deep for tears.—Wordsworth.

To him who in the love of nature holds

Communion with her visible forms, she speaks

A various language.—Bryant.

And this one life, exempt from public haunt,

Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything.—Shakespeare.

And now 'twas like all instruments,

Now like a lonely flute;

And now it is an angel's song,

That makes the heavens be mute.—Coleridge.

There is a pleasure in the pathless woods,

There is a rapture in the lonely shore,

There is society, where none intrudes,

By the deep sea, and music in its roar;

I love not Man the less, but Nature more.—Byron.

In June 'tis good to be beneath a tree

While the blithe season comforts every sense;

Steeps all the brain in rest, and heals the heart,

Brimming it o'er with sweetness unawares,

Fragrant and silent as that rosy snow

Wherewith the pitying apple-tree fills up

And tenderly lines some last-year's Robin's nest.—Lowell.

{230}

THE ARKANSAS

KINGBIRD.

O NE of the difficulties of the

scientific ornithologist is to differentiate species. This bird is often confounded with the

Flycatchers, and for a very good reason, its habits being similar to those of that family. It is

almost a counterpart of the Kingbird, (See Birds, vol. ii, p. 157)

possessing a harsher voice, a stronger flight, and, if possible, a more combative, pugnacious

spirit. It is a summer resident, is common in the western United States, and occasionally a

straggler far eastward, migrating southward in winter to Guatemala.

NE of the difficulties of the

scientific ornithologist is to differentiate species. This bird is often confounded with the

Flycatchers, and for a very good reason, its habits being similar to those of that family. It is

almost a counterpart of the Kingbird, (See Birds, vol. ii, p. 157)

possessing a harsher voice, a stronger flight, and, if possible, a more combative, pugnacious

spirit. It is a summer resident, is common in the western United States, and occasionally a

straggler far eastward, migrating southward in winter to Guatemala.

Col. Goss, in his history of the birds of Kansas, one of the most comprehensive and valuable

books ever published on ornithology, says that the nesting places and eggs of this species are

essentially the same as those of the Kingbird. They are brave and audacious in their attacks upon

the birds of prey and others intruding upon their nesting grounds. Their combative spirit,

however, does not continue beyond the breeding season. They arrive about the first of May, begin

laying about the middle of that month, and return south in September. The female is smaller than

the male and her plumage is much plainer.

Mr. Keyser "In Birdland" tells an interesting story which illustrates one of the well known

characteristics of the Kingbird. "One day in spring," he says, "I was witness to a curious

incident. A Red-headed Woodpecker had been flying several times in and out of a hole in a tree

where he (or she) had a nest. At length, when he remained within the cavity for some minutes, I

stepped to the tree and rapped on the trunk with my cane. The bird bolted like a small cannon ball

from the orifice, wheeled around the tree with a swiftness that the eye could scarcely follow, and

then dashed up the lane to an orchard a short distance away. But he had only leaped out of the

frying-pan into the fire. In the orchard he had unconsciously got too near a Kingbird's nest. The

Kingbird swooped toward him and alighted on his back. The next moment the two birds, the Kingbird

on the Woodpecker's back, went racing across the meadow like a streak of zigzag lightning, making

a clatter that frightened every echo from its hiding place. That gamy Flycatcher actually clung to

the Woodpecker's back until he reached the other end of the meadow. I cannot be sure, but he

seemed to be holding to the Woodpecker's dorsal feathers with his bill. Then, bantam fellow that

he was, he dashed back to the orchard with a loud chippering of exultation. 'Ah, ha!' he flung

across to the blushing Woodpecker, 'stay away the next time, if you don't fancy being converted

into a beast of burden?'"

Eggs three to six, usually four, white to creamy white, thinly spotted with purple to dark

reddish brown, varying greatly in size.

{231}

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

ARKANSAS KING-BIRD.

¾ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

{233}

QUEER RELATIONS.

A N English terrier, despoiled of her

litter of puppies, wandered around quite inconsolable. A brood of ducklings one day attracted her

attention. Notwithstanding their quacks of protest, she seized them in her mouth, bore them to her

kennel, and with the most affectionate anxiety followed them about, giving them, in her own

fashion, a mother's care.

N English terrier, despoiled of her

litter of puppies, wandered around quite inconsolable. A brood of ducklings one day attracted her

attention. Notwithstanding their quacks of protest, she seized them in her mouth, bore them to her

kennel, and with the most affectionate anxiety followed them about, giving them, in her own

fashion, a mother's care.

When the ducklings at length took to water, her alarm knew no bounds. "You dreadful children,"

her sharp barks seemed to say when they returned to land, and taking them in her mouth bore them

one by one back to safety, as she thought, to the kennel.

The year following, when again deprived of her puppies, she adopted two cock-chickens, rearing

them with the same care she had bestowed upon the ducklings. Their voices, however, when they grew

older, greatly annoyed her, and by various means their foster-mother endeavored to stifle their

crowing.

A hen that had selected an unused manger in which to lay her eggs, and rear her brood, found

that the barn cat had also selected the same place in which to pass her hours of repose. The hen

made no objection to the presence of Mrs. Tabby, and vice-verse, so that a strong frendship

in time grew up between the two.

Things went on very smoothly, the hen placidly sitting on her eggs, while Mrs. Tabby came and

went at will, spending at least half her time beside her companion as friendly as though she were

a sister cat.

Vainly did the hen sit, vainly did she turn her eggs. All the warmth in the world would not

have hatched a chick from the stale eggs beneath her.

Mrs. Tabby, however, had better luck. To the hen's amazement she found beneath her very nose

one morning five squirming furry little creatures which might have been chicks but were not.

Certainly they were young of some sort, she reflected, and with true motherly instinct she lent

her aid to their proper bringing up.

The kittens thrived, but unfortunately, when still of tender age were deprived, by death of

their mother. All but one of her offspring found comfortable homes elsewhere, and that one

received the devoted attention of the hen during the whole of that summer.

"To see it going between the house and barn clucking for the kitten," says Dr.

Beadner in Our Animal Friends, "was indeed a funny sight, and quite as remarkable to see

the kitten run to her when she made the peculiar call that chickens understand means something to

eat. At night and during the resting hours of the daytime, kittie would crawl under the warm wings

of her foster mother; and the brooding hen and her nestling kitten were happy and contented,

little dreaming and caring less that they were so far from being related to each other."

{234}

ONE AUDUBON SOCIETY.

F IVE hundred invitations were sent out

for a novel reception by the Wisconsin Audubon Society a while ago. One of the directors lent a

large, handsome house, and six milliners were invited to send hats unadorned with aigrettes or

birds. Ostrich plumes, quills and cock's-tails were not disbarred. Twenty-five other milliners

applied for space, "everybody" went, and a great many tastefully trimmed hats were sold. People

who had never before heard of the Audubon Society became, through the newspaper reports of the

affair, greatly interested in its object, and the society itself greatly encouraged through the

fact that by their hats and bonnets many of the "best" people of Milwaukee were ready to proclaim

it no longer good form to wear the plumes or bodies of wild birds.

IVE hundred invitations were sent out

for a novel reception by the Wisconsin Audubon Society a while ago. One of the directors lent a

large, handsome house, and six milliners were invited to send hats unadorned with aigrettes or

birds. Ostrich plumes, quills and cock's-tails were not disbarred. Twenty-five other milliners

applied for space, "everybody" went, and a great many tastefully trimmed hats were sold. People

who had never before heard of the Audubon Society became, through the newspaper reports of the

affair, greatly interested in its object, and the society itself greatly encouraged through the

fact that by their hats and bonnets many of the "best" people of Milwaukee were ready to proclaim

it no longer good form to wear the plumes or bodies of wild birds.

"Certificates of heartlessness," a writer in Our Dumb Animals calls them and we know of

no better appellation to apply. Women of fashion, says the same writer, have been urged to use the

power which they possess—and it is a power greater than that of law—to bring this

inhumanity to an instant stop. The appeals for the most part were in vain. Birds continue to be

slaughtered by millions upon millions, simply for the gratification of a silly vanity of which

intelligent women should be ashamed. Whole species of the most beautiful denizens of field and

forest, woodland and shore, have been almost or quite exterminated. Song birds have been driven

further and further from the dwellings of men; our country is stripped of one of its least costly

and most charming delights and all that women may deck themselves in conformity with a fad.

A bill for the protection of birds was passed on March 24, by the Senate of the United States,

introduced into the House of Representatives on March 25, and referred to the Committee on

Agriculture. It is entitled "An Act for the Protection of Song Birds."

We confess, says the same writer, to a feeling of humiliation when reading this bill, because

it seems a just indictment of the women of America on a charge of willful, wanton, reckless

inhumanity. That such legislation should be made necessary, through vanity alone, ought in our

estimation, to bring the blush of shame to every good woman's cheek.

"I didn't think," is the usual reply of the fair sex, when approached on the subject. "I didn't

think." Aye you didn't think, but that plea can no longer avail when press and pulpit, in the name

of humanity, so earnestly and eloquently plead with you to spare the birds.

If compassion for the little creature whose life went out in agony, to supply that ornament

above your brow does not move you to abstain from wearing such in the future, then the knowledge

that some of the "best" people in the country consider it "bad form," perhaps will.

—E. K. M.

The lady has surely a beautiful face,

She has surely a queenly air;

The bonnet had flowers and ribbon and lace;

But the bird has added the crowning grace—

It is really a charming affair.

Is the love of a bonnet supreme over all,

In a lady so faultlessly fair?

The Father takes heed when the Sparrows fall,

He hears when the starving nestlings call—

Can a tender woman not care?

—Susan E. Gammons, Our Dumb

Animals.

{235}

|

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. |

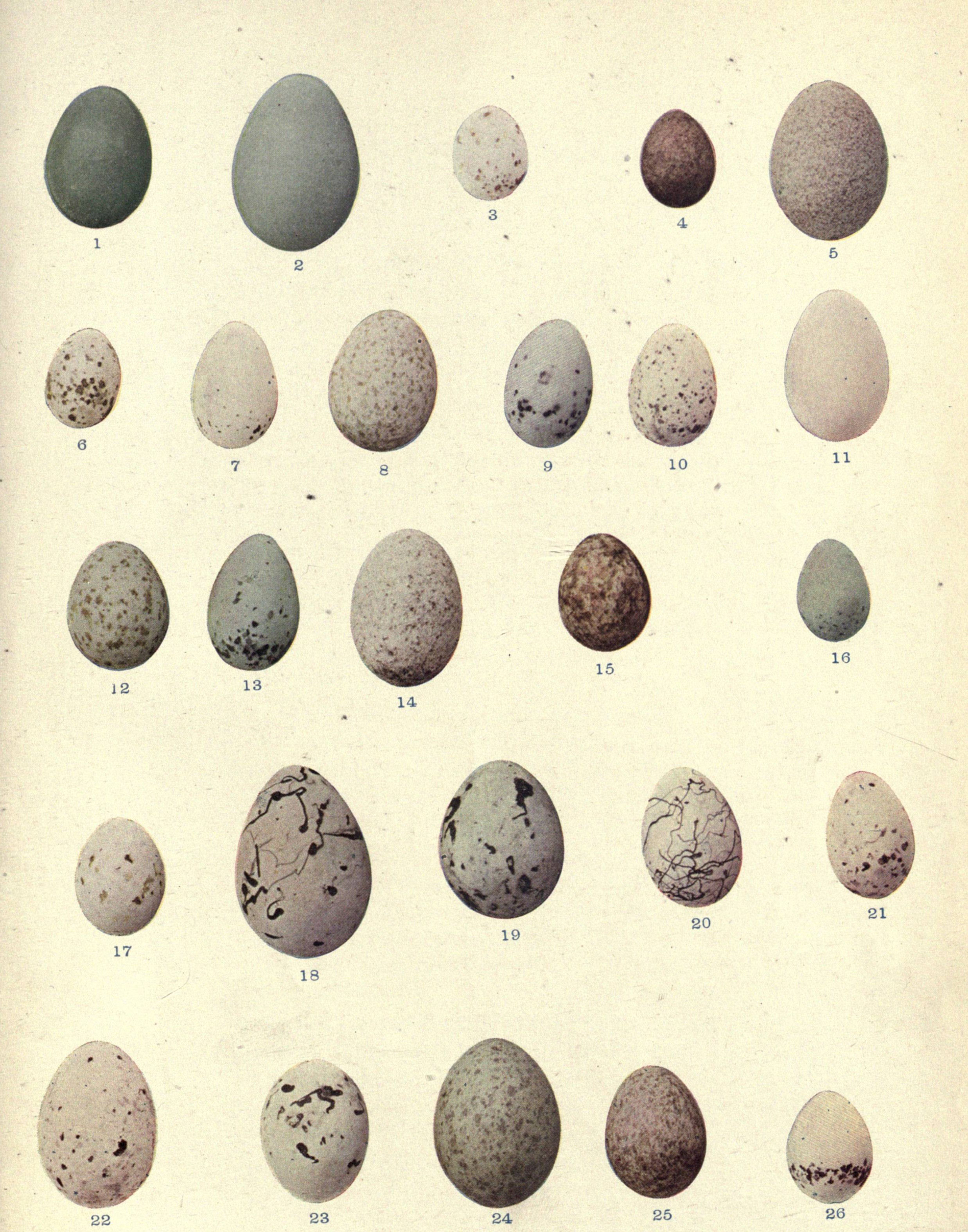

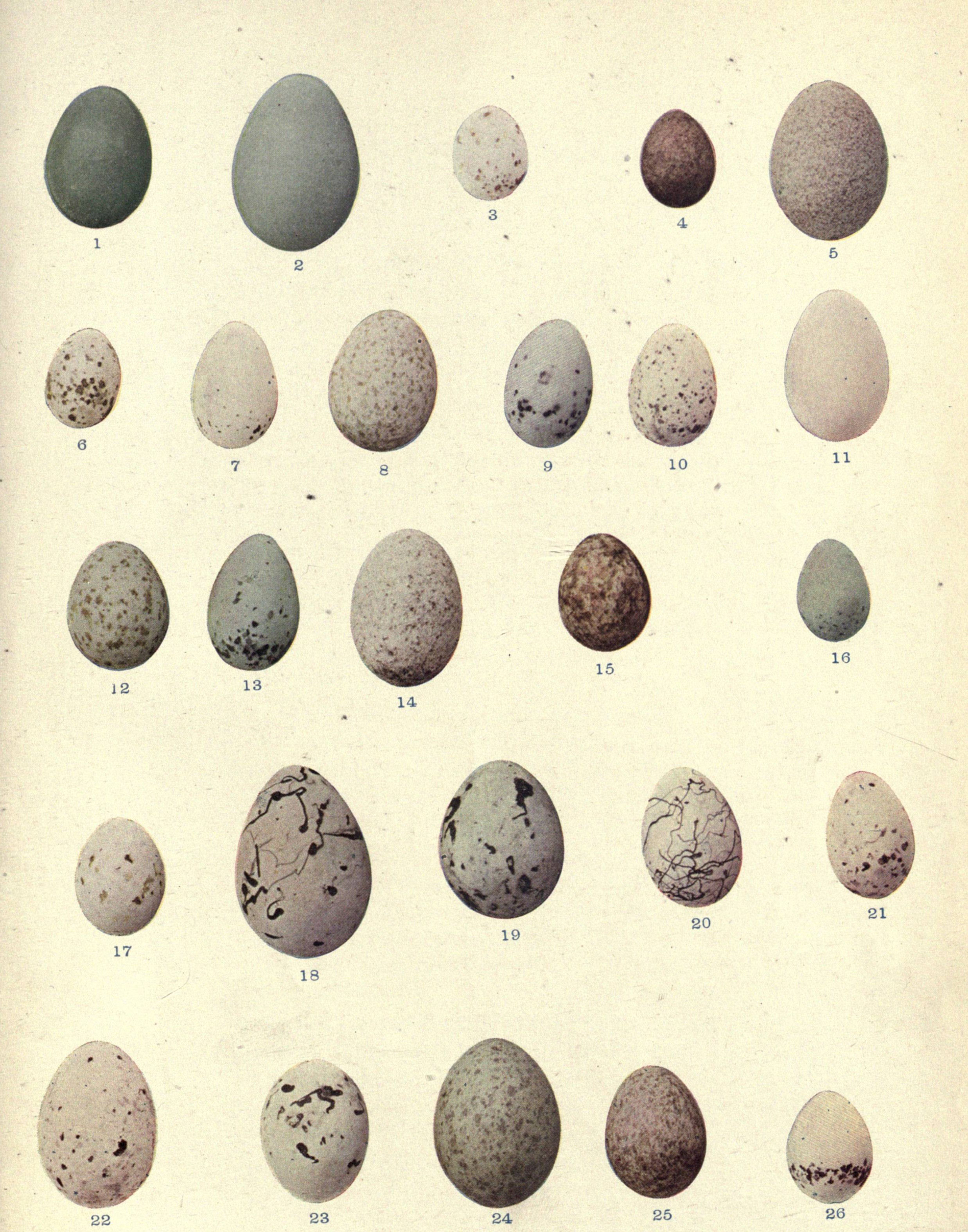

EGGS.

Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study

Pub. Co., 1898. Chicago. |

1. Cat Bird.

2. Robin.

3. Chickadee.

4. Long-billed Marsh Wren.

5. Brown Thrasher.

6. Yellow Warbler.

7. Red-eyed Vireo.

8. Loggerhead Shrike.

9. Cedar Waxwing.

10. Cliff Swallow.

11. Martin.

12. Rose-breasted Grosbeak.

13. Scarlet Tanager.

14. Towhee.

15. Song Sparrow.

16. Chipping Sparrow.

17. Vesper Sparrow.

18. Great-tailed Grackle.

19. Bronzed Grackle.

20. Baltimore Oriole.

21. Orchard Oriole.

22. Meadow Lark.

23. Red-winged Blackbird.

24. Blue Jay.

25. Prairie Horned Lark.

26. Wood Pewee.

{237}

THE YOUTH OF BUDDHA.

From "The Light of Asia."

... In mid-play the boy would oft-times pause,

Letting the deer pass free; would oft-times yield

His half-won race because the laboring steeds

Fetched painful breath; or if his princely mates

Saddened to lose, or if some wistful dream

Swept o'er his thoughts. And ever with the years

Waxed this compassionateness of our Lord,

Even as a great tree grows from two soft leaves

To spread its shades afar; but hardly yet

Knew the young child of sorrow, pain, or tears,

Save as strange names for things not felt by kings,

Nor ever to be felt. But it befell

In the royal garden on a day of spring,

A flock of wild Swans passed, voyaging north

To their nest-places on Himâla's breast.

Calling in love-notes down their snowy line

The bright birds flew, by fond love piloted;

And Devadatta, cousin of the prince,

Pointed his bow, and loosed a willful shaft

Which found the wide wing of the foremost Swan

Broad-spread to glide upon the free blue road,

So that it fell, the bitter arrow fixed,

Bright scarlet blood-gouts staining the pure plumes.

Which seeing, Prince Siddârtha took the bird

Tenderly up, rested it in his lap—

Sitting with knees crossed, as Lord Buddha sits—

And, soothing with a touch the wild thing's fright,

Composed its ruffled vans, calmed its quick heart,

Caressed it into peace with light kind palms

As soft as plantain leaves an hour unrolled;

And while the left hand held, the right hand drew

The cruel steel forth from the wound, and laid

Cool leaves and healing honey on the smart.

{238}

SUMMARY.

Page 206.

BRUNNICH'S MURRE.—Uria lomvia.

Range—Coasts and islands of the north Atlantic and eastern Arctic

oceans, south on the Atlantic coast of North America to New Jersey.

Nest—On the bare rock, often on the narrow shelves of cliffs.

Eggs—One.

Page 210.

CANADA GOOSE.—Branta canadensis. Other names: "Common Wild Goose," "Grey

Goose," "Honker."

Range—North America at large.

Nest—Of dried grasses, raised about twelve inches from the

ground; has been found in trees.

Eggs—Generally five, of a pale dull greenish color.

Page 214.

BROWN CREEPER.—Certhia familiaris americana.

Range—Eastern North America, breeding from northern border of

United States northward.

Nest—In holes of trees lined with dry grass, moss, and

feathers.

Eggs—Five to eight.

Page 218.

DOWNY WOODPECKER.—Dryobates pubescens. Other name: "Little or Lesser

Sapsucker." This, however, is a misnomer.

Range—Northern and eastern North America, and sporadically the

western portions—Colorado, Utah, Nevada, California, etc.

Nest—In an excavation in a tree.

Eggs—Four or five, rarely six, pure glossy white.

Page 223.

OLD SQUAW DUCK.—Clangula hyemalis. Other names: South Southerly;

Long-tailed Duck; Swallow-tailed Duck; Old Injun (Mass. and Conn.) Old Molly; Old Billy; Scolder

(New Hampshire and Massachusetts.)

Range—Northern hemisphere; south in winter to nearly the southern

border of the United States.

Nest—On the margins of lakes and ponds, among low bushes or low

grass, warmly lined with down and feathers.

Eggs—From six to twelve, of pale, dull grayish pea-green.

Page 227.

WHITE-FACED GLOSSY IBIS.—Plegadis autumnalis.

Range—Tropical and sub-tropical regions generally; rare and of

local distribution in the southeastern United States and West Indies.

Nest—Of rushes, plant stems, etc., in reedy swamps on low

bushes.

Eggs—Three, rather deep, dull blue.

Page 231.

ARKANSAS KINGBIRD.—Tyrannus verticalis. Other name: Arkansas

Flycatcher.

Range—Western United States from the plains to the Pacific, and

from British Columbia south through Lower California and western Mexico to Guatemala.

Nest—On branches of trees, in open and exposed situations, six to

twenty feet from the ground; built of stems of weeds and grasses.

Eggs—Three to six, white, thinly spotted with purple

to dark redish-brown.

{239}

VOLUME III. JANUARY TO JUNE,

1898.

INDEX.

| Apple Blossom Time |

pages |

153 |

| Audubon Society, One |

" |

234 |

| Aviaries |

" |

121-2 |

| Birds, Foreign Song Birds in Oregon |

" |

123 |

| Birds, in the Schools |

" |

20 |

| Birds, Hints on the Study of Winter |

" |

109 |

| Birds, Interesting Facts About |

" |

100 |

| Birds' Answer, The |

" |

83 |

| Bird Study, The Fascinations of |

" |

164 |

| Birds, Let Us All Protect the Eggs of the |

" |

154 |

| Birds, Pairing in Spring |

" |

189 |

| Bird, Only a |

" |

73 |

| Bird Superstitions and Winged Portents |

" |

172 |

| Bird Day |

" |

82 |

| Birds, a Friend of |

" |

43 |

| Bird, The Mound |

" |

114 |

| Bird Lovers, Some |

" |

81 |

| Bittern, Least, Botaurus exilis |

" |

46-47 |

| Bob White, Colinus virginianus |

" |

16-18-19-34 |

| Buddha, The Youth of |

" |

237 |

| Christmas, Where Missouri Birds Spend |

" |

84 |

| Cockatoo, Rose, Cacatua leadbeateri |

" |

29-30-31 |

| Coot, American, Fulica americana |

" |

96-98-99 |

| Contentment |

" |

163 |

| Crane, Queer doings of a |

" |

44 |

| Creeper, Brown, Certhia familiaris americana |

" |

212-214-215 |

| Dickcissel, Spiza americana |

" |

146-147-149 |

| Duck, Bald Pate, Anas americana |

" |

48-50-51 |

| Duck, Black, Anas obscura |

" |

86-87 |

| Duck, Pintail, Dafila acuta |

" |

176-8-9 |

| Duck, Old Squaw, Clangula hyemalis |

" |

223-5 |

| Duck Farms, Eider |

" |

113 |

| Egg, What is An |

" |

60 |

| Eggs |

" |

155-195-235 |

| Feathers or Flowers? |

" |

180 |

| Finch, Purple, Carpodacus purpureus |

" |

54-55 |

| Flycatcher, Arkansas, Tyrannus verticalis |

" |

230-231 |

| Gnat-catcher, Blue-gray, Polioptila caerulea |

" |

94-95 |

| Goose, Canada, Branta canadensis |

" |

208-210-211 |

| Goose That Takes a Hen Sailing |

" |

194 |

| Grouse, Dusky, Dendragapus obscurus |

" |

150-151 |

| Hawk, Sparrow, Falco sparverius |

" |

105-6-7 |

| Heron, Great Blue, Ardea herodias |

" |

190-1-3 |

| Ibis, White-Faced Glossy, Plegadis guarauna |

" |