Title: Birds and All Nature, Vol. 4, No. 5, November 1898

Author: Various

Release date: December 8, 2014 [eBook #47603]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Christian Boissonnas, Joseph

Cooper and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY.

| Page | |

| NATURE'S ORCHESTRA. | 161 |

| A LITTLE BIRD. | 162 |

| THE TURKEY'S FAREWELL. | 162 |

| BIRDS. | 163 |

| BIRDS IN STORMS. | 163 |

| THE SLEEPING-PLACES OF BIRDS. | 164 |

| THE SHARP-TAILED GROUSE. | 167 |

| TAME BATS. | 168 |

| RED AND BLACK BATS. | 171 |

| THE OTTER. | 172 |

| THE AMERICAN OTTER. | 175 |

| THE SKYLARK. | 176 |

| NATURE STUDY AND NATURE'S RIGHT. | 176 |

| AMERICAN GOLDEN PLOVER. | 179 |

| CAN ANIMALS COUNT? | 180 |

| BUTTERFLIES LOVE TO DRINK. | 182 |

| THE ENVIOUS WREN. | 185 |

| THE CANADIAN PORCUPINE. | 186 |

| THE DEATH OF THE FLOWERS. | 189 |

| THE CASPIAN TERN. | 190 |

| COLOR PHOTOGRAPHS AND CONVERSATION LESSONS. | 194 |

| THE FLOWERING ALMOND. | 193 |

| SUMMARY. | 200 |

ALL nature is attuned to music. Man may seek the fields, the forests, the mountains, and the meadows, to escape from distracting noises of the city, but nowhere, not even in the depths of mountain forests, will he find absolute silence. And well for him that it is so, for should no noise, no vibration of the air greet his accustomed ear, so appalling would be the dead silence that he would flee from it as from the grave.

Even the Bugs make music. They may not be much as vocalists but they take part in nature's symphony with the brook, the Bird, and the deep diapason of the forest monarch swaying and humming to the gusts of the wayward wind. It is true that the great majority of our species of insects are silent, and those which do make sounds, have not true voices, breathing as they do through holes arranged along each side of their body, and not through their mouths, they naturally possess no such arrangement for making noises connected with breathing as we find in the human larynx.

The "buzzing Fly" and "droning Bee" are classed among nature's musicians, as well as the Cicadas, Grasshoppers, Crickets, Locusts, Katydids, and Beetles. Only the males are the musicians in the insect families—with the exception of the Mosquito, the lady being the musical member of that family—and the different kinds of Grasshoppers are provided with an elaborate musical apparatus by means of which they call their mates.

Chief among the insect performers is the Cicada, often confused with the Locust, though he does not belong to that family at all, who possesses a pair of complicated kettle-drums, which he plays with his muscles instead of sticks.

Directly behind the base of each hind leg is a circular plate of about one-quarter of an inch in diameter. Beneath each of these is a cavity across which is stretched a partition of three membranes. At the top is a stiff, folded membrane, which acts as a drum-head. Upon this he plays with his muscles, the vibrations being so rapid that to the ears of some listeners the noise, or music he engenders, sounds more like that of a mandolin than a drum. He is a black fellow with dull green scroll work over his thick body, lives in trees, and is generally invisible when he plays the drum.

The Grasshopper is the fiddler of the great orchestra, and the hotter the day the more energetically does he fiddle. The fellow with the short horns has a rough hind leg which he uses as a bow; this he draws across the wing cover, giving off the notes which he so dearly loves. Near the base of each fore wing is a peculiar arrangement of veins and cells. This arrangement differs in the different species, but in each it is such that by rubbing the fore wings together they are made to vibrate, and thus, some naturalists aver, they make the sounds which we hear.

The most easily observed of all insect musicians are the common Crickets. By placing a sod of growing grass in a cage with several male crickets, you can watch them play upon their fiddles. Upon the lower side of their wings you will see ridges like [Pg 162] those of a tiny file, and on the inner margin toward the base from the end of the principal vein, a hardened portion, which may be called the scraper. By using the files and scrapers of their fore wings the little musicians add their notes to the universal music of the world. Ellanora Kinsley Marble.

THE BIRD is little more than a drift of the air brought into form by plumes; the air is in all its quills, it breathes through its whole frame and flesh, and glows with air in its flying, like a blown flame; it rests upon the air, subdues it, surpasses it, outraces it—is the air, conscious of itself, conquering itself, ruling itself.

Also, into the throat of the Bird is given the voice of the air. All that in the wind itself is weak, wild, useless in sweetness, is knit together in its song. As we may imagine the wild form of the cloud closed into the perfect form of the Bird's wings, so the wild voice of the cloud into its ordered and commanded voice; unwearied, rippling through the clear heaven in its gladness, interpreting all intense passion through the soft spring nights, bursting into acclaim and rapture of choir at daybreak, or lisping and twittering among the boughs and hedges through heat of day, like little winds that only make the Cowslip bells shake, and ruffle the petals of the Wild Rose.

Also, upon the plumes of the Bird are put the colors of the air; on these the gold of the cloud, that cannot be gathered by any covetousness; the rubies of the clouds, the vermilion of the cloud-bar, and the flame of the cloud-crest, and the snow of the cloud, and its shadow, and the melted blue of the deep wells of the sky—all these, seized by the creating spirit, and woven into films and threads of plume; with wave on wave following and fading along breast and throat and opened wings, infinite as the dividing of the foam and the sifting of the sea-sand; even the white down of the cloud seeming to flutter up between the stronger plumes, seen, but too soft for touch.—Ruskin.

DURING windstorms birds may sometimes be seen flying overhead at a great height. When this is observable, it is said it may be taken for granted that the upper atmosphere is comparatively quiet, and the disturbance is confined chiefly to the lower regions. Many seabirds seek the upper air of comparative quietness during tropical hurricanes. A writer in the Boston Transcript says that when a heavy wind or gale springs up, the Gulls, Terns and Petrels will fly back and forth over the water's surface, rising and falling, and uttering their peculiar cries of warning. If the storm extends too high up they will drift gradually with the wind, or fly away on the edge of the hurricane. Very often they get caught unexpectedly in the gales of wind, and they find themselves in a dangerous position. Then they struggle with might and main against the powers of the air currents. Knowing that danger and death face them if they once come under the dominion of the wind, they use all the strength and tactics they are capable of to combat the elements. A young Herring Gull, a Petrel, or a Tern thus surprised will beat up against the wind with powerful flight. It will rise high in the air, facing the gale, and making a little progress forward as well as upward. Then it will suddenly descend with rapid flight toward one side of the storm-swept path, but falling off at the same time in the direction of the blowing wind. Once more it will sweep around and face the storm, ascending heavenwards and striking desperately out toward the direction of the storm. By pursuing these tactics, the bird will gradually work itself to one side of the storm centre.

IT IS difficult to imagine a spot with fewer domestic features to adorn the home than a piece of the bare ceiling of a tropical veranda; but the attachment of animals to their chosen sleeping-places must rest on some preference quite clear to their own consciousness, though not evident to us. In some instances the ground of choice is intelligible. Many of the small blue British Butterflies have grayish spotted backs to their wings. At night they fly regularly to sheltered corners on the chalk downs where they live, alight head downwards on the tops of the grasses which there flourish, and closing and lowering their wings as far as possible, look exactly like seed-heads on the grasses. If the night is cold they creep down the stem and sleep in shelter among the thick lower growth of grass. The habits of birds in regard to sleep are very unlike, some being extremely solicitous to be in bed in good time, while others are awake and about all night. But among the former the sleeping-place is the true home, the domus et penetralia. It has nothing necessarily in common with the nest, and birds, like some other animals and many human beings, often prefer complete isolation at this time. They want a bedroom to themselves. Sparrows, which appear to go to roost in companies, and sometimes do so, after a vast amount of talk and fuss, do not rest cuddled up against one another, like Starlings or Chickens, but have private holes and corners to sleep in. They are fond of sleeping in the sides of straw-ricks, but each Sparrow has its own little hollow among the straws, just as each of a flock of sleeping Larks makes its own "cubicle" on the ground. A London Sparrow for two years occupied a sleeping-home almost as bare of furniture as the ceiling which the East Indian Butterfly frequented. It came every night in winter to sleep on a narrow ledge under the portico of a house in Onslow Square. Above was the bare white-washed top of the portico, there were no cosy corners, and at eighteen inches from the Sparrow was the gas-lit portico lamp. There every evening it slept, and guests leaving the house seldom failed to look up and see the little bird fast asleep in its enormous white bedroom. Its regular return during two winters is evidence that it regarded this as its home; but why did it choose this particular portico in place of a hundred others in the same square?—Spectator.

Bird Courtships.—When he (the Flicker) wishes to charm his sweetheart he mounts a very small twig near her, so that his foreparts shall not be hidden as he sits upright in regular Woodpecker attitude, and he lifts his wings, spreads his tail, and begins to nod right and left as he exhibits his mustache to his charmer, and sets his jet locket first on one side of the twig and then the other. He may even go so far as to turn his head half around to show her the pretty spot on his "back hair." In doing all this he performs the most ludicrous antics, and has the silliest of expressions of face and voice, as if in losing his heart, as some one phrases it, he has lost his head also. For days after she has evidently said yes, he keeps it up to assure her of his devotion, and, while sitting crosswise on a limb, a sudden movement of hers, or even a noise made by one passing, will set him to nodding from side to side. To all this she usually responds in kind.—Baskett.

|

||

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. | PRAIRIE SHARP-TAILED GROUSE. ⅓ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study Pub. Co., 1898, Chicago. |

A WELL-KNOWN observer, who has spent many years in the West, says that the Sharp-tailed Grouse, being a bird of the wild prairies and open woodlands, has gradually retreated westward as the settlements have advanced, and will soon be a rare bird, to be looked for only in the sand-hills and unsettled portions of the country.

During the summer months this bird inhabits the open prairies, retiring in winter to the ravines and wooded lands, and when the snow is deep and the weather severe often hides and roosts beneath the snow. This sometimes proves the destruction of the birds, the entrance to the roosting-place being filled by falling snow and frozen over.

The Sharp-tails feed chiefly on Grasshoppers, seeds, buds, blossoms, and berries.

"When walking about on the ground they stand high on their legs, with their sharp-pointed tails slightly elevated, and when flushed, rise with a whirring sound of the wings, uttering as they go a guttural kuk-kuk-kuk, and swiftly wing themselves away in a direct course. The birds have several cackling notes, and the males a peculiar crowing or low call, that in tone sounds somewhat like the call of the Turkey. In the early spring, as the love season approaches, they select a mound or slight elevation on the open prairies for a courtship ground, where they assemble at early dawn, the males dancing and running about in a circle before the females in a most ludicrous manner, facing each other with lowering head, raised feathers and defiant looks, crossing and recrossing each other's paths in a strutting, pompous way, seldom fighting, each acting as if confident of making the greatest display, and thus winning the admiration of and capturing the hen of his choice. These meetings and dances are kept up until the hens cease laying and begin to sit."

These Grouse place the nest in a tuft of grass or under a low, stunted bush. A hollow in the ground is worked out to fit the body and lined with a few blades of grass arranged in a circular form. The hens attend wholly to the hatching and rearing of the young and are attentive and watchful mothers.

The flesh of the Sharp-tail is lighter in color and more highly esteemed than that of the Prairie Hen, and the bird is therefore hunted more industriously.

THE Bat is a harmless little animal, but I doubt if many of us would care to have a number of them flying around. The hotter the climate the more Bats you will find. As evening draws nigh, even in Italy, Greece, and Spain, out of their nooks and corners thousands of them fly, fluttering over the fields, through the gardens and streets of the town, through houses and rooms.

People get used to them there, and when awakened by the noise of their wings will get up, chase them from the room with a stick, and though aware they will return again when all is quiet, lie down again and go to sleep.

You would scarcely think to look at these lively little animals that they could be tamed and become strongly attached to their masters, would you? But indeed they are very intelligent and many naturalists have made pets of them, training them to take food from their hands or search for it in a glass. They will follow the one they love all over the house, and show themselves very amiable and sensible, too.

One cold spring morning a lady with a sympathetic heart—a true Christian lady I should judge, since she loved all things "both great and small"—saw a boy tossing in the air a little animal which she took to be a Mouse. Even so insignificant a creature should not be needlessly tortured, so she went at once to its rescue. Instead of a Mouse she found it to be a Bat, half-dead from cold and fright. With tender hands she placed it upon some cotton in the bottom of a basket and set it near the fire. Many times she peeped into the basket and was at length delighted to see the little creature hanging bat-fashion on the side of the basket, its keen, bright eyes watching every movement. One of its feet she found was crushed. With trembling hands she severed the bit of skin by which it hung, and applied some healing salve to the wound. The poor little creature suffered too much to taste food, but after a few days accepted a Fly from her hands, then a bit of meat, after which it folded its wings to signify it had enough.

The Bat at length became as tame as a Mouse and would hang itself to any convenient portion of its mistress' dress; would eat whatever of animal food she gave it, and lick milk off her fingers. At night it would settle upon her hair, but never went near other members of the family; would fly about the room, and go out of the window in search of insects, returning in a couple of hours, and if the window was closed hang to the window-sill, or to the sash, until admitted. Thus it lived for two years, a happy, contented Bat, till one night it flew out and never returned—a prey probably to some White Owls who for years had made their home in an old belfry near by.

|

||

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. | BROWN AND RED BAT. ¾ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study Pub. Co., 1898, Chicago. |

BATS are so much alike, especially those common to this country, of which there are numerous species known to naturalists, that the description of one will serve for all, with the exception of the Vampire.

The sub-order of smooth-nosed Bats is represented in this country by several species peculiar to America. The most common in all the Atlantic coast states is the Red Bat, or New York Bat, which is a busy hunter of flying insects, which it follows so persistently that it frequently flies into rooms in pursuit of its favorite prey. It flies rather slowly, but it changes the direction of its flight very rapidly, and its movements in the air are very graceful. Besides this species is the Black Bat, and several others have been observed and described, but so far the descriptions, according to Brehm, have been principally technical, and little or nothing is known of their habits, except that no North American species seems to be harmful, but the contrary, as they are all insect-eaters.

The principal food of these Bats consists of Butterflies, Beetles, Mosquitoes, and the like.

All Bats sleep by day and fly about by night. Most of them make their appearance at dusk, and retire to their hiding-places long before dawn. Some species appear between three and five o'clock in the afternoon and flicker merrily about in the bright sunshine. Each species has its own hunting-grounds in forests, orchards, avenues, and streets, and over stagnant or slowly flowing water-surfaces. It is said to be rare that they fly over open fields, for the reason that there is no game for them. In the South they haunt the rice fields, where insects are numerous. Their hunting-ground is limited, although some large species will cover a mile in their flight, and the Bats of the tropics fly over much greater distances.

Bats are in general very much averse to the ground, and never voluntarily place themselves on a level surface. Their method of walking is very curious. First the forelegs or wings are thrust forward, hooking the claw at its extremity over any convenient projection, or burying it in the ground. By means of this hold the animals draw themselves forward, then raising their bodies partly off the earth advance the hind-leg, making at the same time a tumble forward. The process is then repeated on the opposite side, and thus they proceed in a strange and unearthly fashion, tumbling and staggering along as if their brains were reeling.

It has long been known that Bats are able to thread their way among boughs of trees and other impediments with an ease that seems almost beyond the power of sight. Even utter darkness does not apparently impede their progress, for when shut up in a darkened room, in which strings had been stretched in various directions, they still pursued their course through the air, avoiding every obstacle with precision. This faculty has been found not to result from any unusual keenness of sight, but from the exquisite nervous system of their wings.

NATURE, children, as you observe, gave my family a handsome coat. Now no bird can have fine feathers, nor beast a fine fur but men and women desire them for adornment, or possibly to keep themselves warm. So the hunters, finding it a paying business, shoot and trap us till places which once knew the Otter know us no more.

Such gentle animals as we are, too. No little girl or boy would care to have a more frolicsome playmate than a young cub Otter. He will romp with you, and play with Dog or Cat and sit up on his hindquarters, and whistle and do even many quaint tricks to make you laugh.

To make him happy you must have a little pond in the yard or a large tank, though he will run about the yard or house most of the time with the Dog. Feed him at first on bread and milk, then on fish, though you can train him to do without the latter and eat the "leavings" from the table.

Such fun as we Otters that live in the Northern part of the United States and Canada do have in winter. No school-boy enjoys coasting down hill more than we do. Though we live in the water, you may say, and are known as the fastest-swimming quadrupeds, yet, in spite of our short legs, we can run over land tolerably well, too. So we trudge along till we come to a high hill, well covered with snow; up we scramble to the top, lie down flat on our smooth jackets, bend our fore feet backward and, giving ourselves a shove with our hind legs, down we slide head-foremost. Such fun as it is! Not till we get hungry or too tired to jog up the hill any more do we give it up for that day.

In summer we enjoy the same sport, too. How? Oh, all we want is a clay-bank with a good muddy surface, and down we go to turn a somersault into the water of the creek below. "Shooting the chutes" you little people would call it, I suppose, though we call it our "slide."

Our homes are always on the banks of a stream. We begin to burrow three or four feet below the surface of the water, forming a tunnel which leads to a chamber in the bank high and dry. That is called our den and we line it with grass and live very comfortably.

Being a hunted animal our senses are very acute. When on land we are always on the alert and, at the approach of danger, down we go into the water and hide in our dens. After sunset we go out to fish. We beat the surface of the water with our tails and frighten the scaly fellows so that they seek refuge under stones or in holes in the bank. Then we catch our Fish. For a change we eat Crabs, Frogs, and sometimes small birds.

|

||

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. | AMERICAN OTTER. ¼ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study Pub. Co., 1898, Chicago. |

IN ALL parts of temperate North America this, the most interesting of the Otter family, makes its home on the banks of nearly all streams except those from which it has been driven by man. It is much larger than the European Otter, has a longer tail, and has a nasal pad between the nostrils which is larger than that of any other species. Though closely allied to the common species, it has distinctive differences which entitle it to be classed as a separate species. Its habits resemble those of its cousins, but it has one peculiarity that is noticed by naturalists who have studied this animal, which is the habit of sliding or coasting down hill, in which it displays a remarkable skill. In Canada, and other sections where the snow is plentiful, Otters indulge freely in this sport, and, says Godman, "they select in winter the highest ridge of snow they can find, scramble to the top of it, lie on their bellies with the forefeet bent backwards and then, giving themselves an impulse with their hindlegs, glide head-foremost down the declivity, sometimes for the distance of twenty yards. This sport they continue, apparently with the keenest enjoyment, until fatigue or hunger induces them to desist."

The young are born in April in the northern, and earlier in the southern part of the Otter's range, and a litter is composed of from one to three young ones.

Authorities agree that the number of the Otters is rapidly decreasing in America, because of the systematic way in which they are pursued by trappers for the value of their fur. The skin of the American Otter is in high reputation and general use with furriers, but those from Canada are said to be more valuable than those from the more southern sections.

The Otter, when taken young, is easily tamed. Audubon had several young Otters which he says "became as gentle as Puppies in two or three days. They preferred milk and boiled corn meal, refusing fish or meat till they were several months old." They became so tame that they would romp with their owner, and were very good-natured animals.

Rivers whose banks are thickly grown with forests are the favorite home of the Otter. There, says Brehm, it lives in subterraneous burrows, constructed in accordance with its tastes and mode of life. "The place of exit is always located below the surface of the water, usually at a depth of about eighteen inches; a tunnel about two yards long leads thence, slanting upwards into a spacious chamber, which is lined with grass and always kept dry. Another narrow tunnel runs from the central chamber to the surface and aids in ventilation. Under all circumstances the Otter has several retreats or homes." When the water rises, it has recourse to trees or hollow trunks.

The Otter is the fastest swimming quadruped known. In the water it exhibits an astonishing agility, swimming in a nearly horizontal position with the greatest ease, diving and darting along beneath the surface with a speed equal, if not superior, to that of many fishes.

The Otter, said an eminent naturalist, is remarkable in every way; in its aquatic life, as well as in its movements; in its hunt for food and in its mental endowments. It belongs without question to the most attractive class of animals.

JOHN BURROUGHS relates that a number of years ago a friend in England sent him a score of Skylarks in a cage. He gave them their liberty in a field near where he lived. They drifted away, and he never heard or saw them again. But one Sunday a Scotchman from a neighboring city called on him and declared, with visible excitement, that on his way along the road he had heard a Skylark. He was not dreaming; he knew it was a Skylark, though he had not heard one since he had left the banks of the Doon, a quarter of a century or more before. The song had given him infinitely more pleasure than it would have given to the naturalist himself. Many years ago some Skylarks were liberated on Long Island, and they became established there, and may now occasionally be heard in certain localities. One summer day a lover of birds journeyed out from the city in order to observe them. A Lark was soaring and singing in the sky above him. An old Irishman came along and suddenly stopped as if transfixed to the spot. A look of mingled delight and incredulity came into his face. Was he indeed hearing the bird of his youth? He took off his hat, turning his face skyward, and with moving lips and streaming eyes stood a long time regarding the bird. "Ah," thought the student of nature, "if I could only hear the bird as he hears that song—with his ears!" To the man of science it was only a bird song to be critically compared to a score of others; but to the other it brought back his youth and all those long-gone days on his native hills!

There is another study which should go hand in hand with nature-work—nature's rights, people's rights. Too many little feet are learning to trespass; too many little hands are learning to steal, for that is what it really is. Children are young and thoughtless and love flowers. But does loving and wishing for things which are not ours make it right to take them? If the teacher can develop the love of nature, can she not develop the sense of honor also? Cannot the moral growth and the mental growth of the child develop together?

To love nature is not to ruthlessly rob her of her treasures. Therefore in collecting for the school-room teach the children to use thought and care in breaking the tender branches. They should remember that each flower on the fruit-tree will in time become fruit. Mother Nature has taken time and loving care to bring forth the leaves and flowers. The different parts of the flowers may be studied without sacrificing many blossoms.

And the birds, why rob them of nests or eggs? Many ways can be found for studying nests, eggs, and birds, without causing suffering. Nature and science study, taught by the thoughtless teacher, can do much harm.—A. G. Bullock in School Journal.

|

||

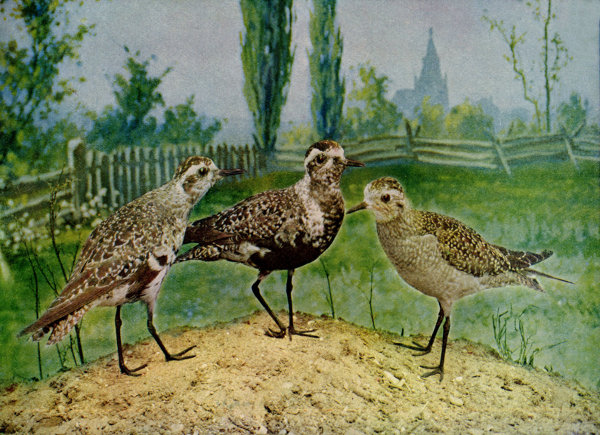

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. | AMERICAN GOLDEN PLOVER. ⅓ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study Pub. Co., 1898, Chicago. |

GOLDEN YELLOW RUMP Is one of the names often applied to this most beautiful member of the Plover family, which is thus made conspicuous and easily recognizable. It is found everywhere in the United States, from the Atlantic to the Rocky Mountains, but is rare on the Pacific coast south of Alaska. They are seldom found far inland, their natural home being on the seacoast, occasionally frequenting marshy or wet grounds, though as a rule they prefer the sandy beach and adjacent flats and uplands. During migration their flight, especially in the spring, is hurried, direct and in the night, only stopping to rest and feed during the day, returning, it is said, in a more leisurely manner and largely along the seashore. When on the ground these birds run about on unbended legs, the bodies in a horizontal position and heads drawn down. While sleeping or resting they usually sit or stand on one leg. Captain Houdlette of the Oceanic Steamship Company caught a Plover that came aboard his ship while on its way from Alaska to Hawaii. These birds are not web-footed, and the captain seems to have solved the problem as to whether they ever rest on the water during their long flights. He says they do. "It was during the run from San Francisco to Honolulu that I saw several Plovers in the water resting. When the steamer came too near they would rise with a few flaps of their wings, but, being very tired, they would soon settle back into the water again. In its efforts to get away one of them came on board and it lived for some time. I always thought the birds made a continuous flight of over 2,000 miles, but I am now satisfied that they rest on the waves when tired."

The flight of a flock of Golden Plovers is described by Goss as swift and strong, sweeping over the prairies in a compact, wavy form, at times skimming close to the ground, then high in the air; an everchanging, circling course, whistling as they go; and on alighting raising their wings until the tips nearly touch, then slowly folding them back, a habit which is quite common with them as they move about the ground.

Plovers eat Grasshoppers, Beetles, and many forms of insect life; small berries are also a part of their diet.

Mr. Nelson, in his "Report Upon Natural History Collections in Alaska," gives a full and interesting account of their nesting-habits. He says the courtship of this handsome bird is carried on very quietly, and there is no demonstration of anger or quarreling among the rivals. When two are satisfactorily mated they quietly go about their nesting, after which each pair limits its range to the immediate vicinity of its treasures. The eggs are deposited the latter part of May in a small depression among the moss and dried grass of a small knoll, and at times a slight structure is made of dried grass. Four eggs are laid, of a pale yellowish ground color, with very dark, well-defined umber brown spots scattered profusely over the shell.

MY LITTLE readers have heard their elders when speaking of the Horse, Dog, Cat, and other dumb creatures call them the "lower" animals. Well, so they are, but when you have grown to be men and women you may possibly prefer the faithful affection and good comradeship of one of these lower animals to the disagreeable society of a cold, mean, and selfish "higher" one. Indeed, to learn how near akin are man and beast, mentally, not physically, men and women of large and tender natures have given up the greater part of their lives. Many stories have been written concerning the faithful love of animals for their masters, big and little, of their marvelous instinct and almost human cunning, but when I tell you that animals can be taught to count—and birds are animals, too, you know—why, then, if you are bright children you will wonder, as your elders do, where instinct ends and reason begins. However, these animals, of which I am going to write, may have been more than usually intelligent and capable of learning where others would not.

A few years ago a confectioner bought a Parrot, and, though the bird talked very plainly and volubly, the man was not satisfied. He desired his bird to display more cleverness than the ordinary Parrot, so he conceived the idea of teaching her to count. Polly didn't take to figures at all; but, though she listened with a great deal of patience to what her teacher had to say she uttered never a word. When at length he turned away discouraged, Polly croaked, "Shut up," and turned a double somersault on her perch, evidently very glad indeed that school was over.

Day after day Polly had her lesson, but count aloud she would not. Still the confectioner didn't give up the idea, and one day, to the bird's amazement her teacher, at lesson time, stood before the cage with a pan of water and a whisk broom in his hand. Dipping the broom in the water and flirting the drops over her head the teacher said, "One." Giving her time to think the matter over, a few more drops were sprinkled upon her head, the teacher exclaiming, "Two," and so on in this way till he had reached ten. This method of instruction went on for some time; but, though Polly came near being drowned in several of the lessons, she stubbornly refused to repeat the figures after her teacher. Arithmetic was not her forte, and the confectioner at length gave up in despair, very much I fancy to Miss Polly's relief.

A month or more went by, when one day, as the bird in her cage was hanging out of doors, it suddenly began to rain. "One," the delighted confectioner heard Polly say, as the big drops fell upon her head, then "two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten," in rapid succession. But to the Parrot's vexation the rain did not cease as it was wont to do when taking her lesson, and every additional drop increased her anger. Finally she could stand it no longer, and in her shrillest tones shouted: "Stop it, stop it! That's all I know, hang it, that's all I know!"

The confectioner says no amount of money can buy that bird.

The Crow, an eminent doctor in [Pg 181] Russia says, can be taught, if you have the patience, to count up to ten, while a certain tribe of men in Polynesia, "higher" animals, you know, cannot be taught to count beyond five or six.

This same doctor had an intelligent Dog which was accustomed, like other Dogs, to bury his surplus bones in the garden. In order to test the mental powers of this animal the doctor one day gave him no less than twenty-six bones, every one of which he saw the Dog duly bury in separate places. The next day no food was given him at meal time, but he was commanded by his master to dig up the bones. This the intelligent fellow proceeded to do, but after uncovering ten came to a full stop. After whining and running about in great perplexity he finally succeeded in unearthing nine more. Still he seemed conscious that he had not found the full number and kept up the search till he had fetched to his master the other seven.

I think that was too much to ask of any Dog, don't you? Many a little boy or girl who goes to school couldn't count that number of bones, though you can, of course.

Well, the doctor then turned his attention to the Cat. When pussy was good and hungry a tempting morsel of meat was held under her nose, then withdrawn five times in succession; the sixth time she was permitted to secure it. This was repeated every day, till she got accustomed to waiting for the presentation of the meat five times; but upon the sixth Pussy never failed to spring forward and seize the meat. The doctor attempted the experiment with a higher number, but the Cat stuck to her first lesson and after counting one, two, three, four, five, six, would invariably make the spring. Had he begun with ten Pussy might have shown herself capable of counting that number as well as the Crow and the Parrot.

A farmer tells of a Horse which in plowing had acquired the habit of counting the furrows, stopping for a rest regularly at the twentieth row. The farmer at the end of the day used to estimate the amount of work done, not by counting the furrows but by remembering how many times the Horse had stopped to rest. The poor animal had never been taught his figures, and his mind did not say "one, two, three," and so on, but all the same he had his way of counting, and never failed to know when he had reached twenty.

Still another Horse was able to count the mile-posts and had been trained by its master to stop for feed when they had covered eighteen miles of a certain road. He always stopped after passing the eighteenth post. To test him they put up three false mile-posts between the real ones, and, sure enough, deceived by the trick, he stopped at the eighteenth post for his oats, unaware that he had not covered eighteen miles.

The doctor also observed another Horse which was accustomed to receiving his oats precisely at noon. Whenever the clock struck an hour the Horse pricked up his ears as if counting the strokes. If he heard twelve, off he would trot to be fed, but if a less number he would plod on resignedly at his work. The experiment was made of striking twelve strokes at the wrong time, whereupon the Horse started for his oats though he had been fed only an hour before.

All of which goes to prove that the capacity of an animal's mind is limited, and, so you may say, is that of the average man.

Mrs. E. K. Marble.

BUTTERFLIES have never had a character for wisdom or foresight. Indeed, they have been made a type of frivolity and now something worse is laid to their charge. In a paper published by the South London Entomological Society Mr. J. W. Tutt declares that some species are painfully addicted to drinking. This beverage, it may be pleaded, is only water, but it is possible to be over-absorptive of non-alcoholics. Excess in tea is not unknown—perhaps the great Dr. Johnson occasionally offended in that respect—and even the pump may be too often visited. But the accuser states that some Butterflies drink more than can be required by their tissues under any possible conditions. It would not have been surprising if, like some other insects, Butterflies had been almost total abstainers, at any rate, from water, and had contented themselves with an occasional sip of nectar from a flower.

MALES ARE THE SINNERS.

The excess in drinking seems to be almost a masculine characteristic, for the topers, he states, are the males. They imbibe while the females are busy laying eggs. This unequal division of pleasure and labor is not wholly unknown even among the highest of the vertebrates; we have heard of cases where the male was toping at the "public" while the female was nursing the children and doing the drudgery of the household. Mr. Tutt has called attention to a painful exhibition of depravity which can often be observed in an English country lane, where shallow puddles are common, but never so well as on one of the rough paths that wind over the upper pastures in the Alps. Butterflies are more abundant there than in England, and they may be seen in dozens absorbing the moisture from damp patches. Most species are not above taking a sip now and again, but the majority may be classed as "moderate drinkers." The greater sinners are the smaller ones, especially the blues, and the little Butterfly which, from its appearance, is called the "small copper." There they sit, glued as it were to the mud—so besotted, such victims to intemperance, that they will not rise till the last moment to get out of the way of horse or man. Some thirty years ago Prof. Bonney in his "Alpine Regions," described this peculiarity, saying that "they were apparently so stupefied that they could scarcely be induced to take wing—in fact, they were drunk."

OTHER LIQUIDS ARE LIKED.

If we remember rightly, the female occasionally is overcome by the temptation to which her mate so readily falls a victim. But we are by no means sure that Butterflies are drinkers of water only. Certainly they are not particular about its purity; they will swallow it in a condition which would make a sanitarian shudder; nay, we fear that a not inconsiderable admixture of ammoniacal salts increases the attraction of the beverage. It is admitted that both Moths and Butterflies visit sugar, overripe fruit, and the like, but it is pleaded that they do this for food. Perhaps; but we fear this is not the whole truth. The apologist has forgotten that practice of entomologists called "sugaring," which is daubing trunks of trees and other suitable places with a mixture of which, no doubt, sugar is the main ingredient, but of which the attraction is enhanced by a little rum. Every collector knows what a deadly lure this is, and what treasures the dark-lantern reveals as he goes his rounds. True, this snare is fatal only to the Moth, because at night the Butterfly is asleep. If he once adopted nocturnal habits we know where he would be found, for he is not insensible by day to the charms of this mixture.

|

||

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. | MOTHS.—15/16 Life-size. | |

| Phylampelus Achemon. | Phylampelus pandorus. | |

| Smerinthus exaecatus. | ||

| Triptagon Modesta. | ||

| Sphinx chersis. | Choerocampa tersa. | Coratomia amynton. |

FORMERLY plentiful in the northern United States, but now quite rare in this country, although not so scarce in Canada, is the Urson, otherwise called the Canadian Porcupine. It is the tree or climbing species and is distinguished from other members of the family by its slender body and tail of greater or less length. The Urson attains a length of thirty-two inches, seven and one-half of which are included in the tail. A thick set fur, which attains a length of four and one-half inches on the nape of the neck and changes into sharp spines on the under parts of the body and the tip of the tail, clothes the animal.

The Canadian Porcupine is a native of the forests of North America, ranging as far south as Virginia and Kentucky and as far west as the Rocky Mountains. "The Urson," says Cartwright, "is an accomplished climber and probably never descends a tree in winter, before it has entirely denuded the upper branches of bark. It is most partial to the tenderest roots or seedling trees. A single Urson may ruin hundreds of them during one winter." Audubon states that he passed through woods, in which all the trees had been stripped by this animal, producing an appearance similar to that induced when a forest has been devastated by fire. Elms, Poplars, and Firs furnish its favorite food, and therefore usually suffer more than other trees from its destructiveness.

The nest of this Porcupine is generally found in holes in trees or rocky hollows, and in it the young, usually two, more rarely three or four in number, are born in April or May. The young are easily tamed. Audubon says that one which he possessed never exhibited anger, except when some one tried to remove it from a tree which it was in the habit of mounting. It had gradually become very tame and seldom made any use of its nails, so that he would open its cage and afford it a free walk in the garden. When he called it, tempting it with a sweet potato or an apple, it turned its head toward him, gave him a gentle, friendly look and then slowly hobbled up to him, took the fruit out of his hand, sat down on its hind legs and raised the food to its mouth with its fore-paws. Frequently when it would find the door of the family room open it would enter, approach and rub itself against a member of the family looking up pleadingly as if asking for some dainty. Audubon tried in vain to arouse it to an exhibition of anger. When a Dog came in view matters were different. Then it instantly assumed the defensive. With its nose lowered, all its quills erect, and its tail moving back and forth, it was ready for the fray. The Dog sprang upon the Porcupine with open mouth. That animal seemed to swell up in an instant to nearly double its size, sharply watched the Dog and at the right moment dealt it such a well-aimed blow with its tail that the Mastiff lost courage and set up a loud howl of pain. His mouth, tongue, and nose were full of Porcupine quills. He could not close his jaws, but hurried open-mouthed off the premises. Although the spines were immediately extracted, the Dog's head was terribly swollen for several weeks afterward, and it was months before he entirely recovered.

|

||

| From col. Chi. Acad. Sciences. | CANADIAN PORCUPINE. ¼ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study Pub. Co., 1898, Chicago. |

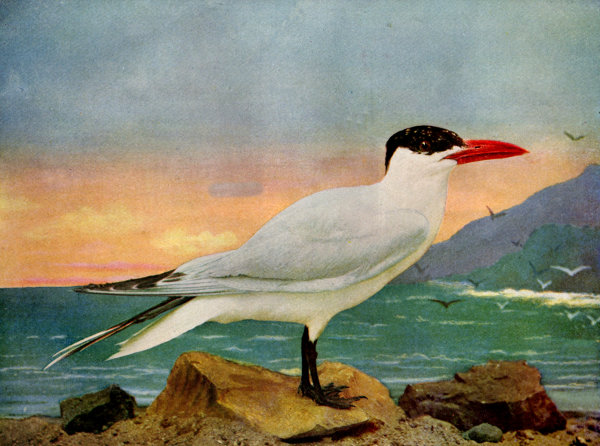

THE great Caspian Tern is the largest of the family, its wings, when extended, measuring from fifty to fifty-five inches in length. It is a bird of very irregular distribution, breeding in Labrador, along the Arctic coast, on islands in Lake Michigan, on the coasts of Virginia, Texas, and California, and is numerous in Australia. Forbes found it to be more or less common about Washoe Lake and the Humboldt Marshes, Nevada, and the Great Salt Lake, Utah, where it was no doubt breeding. He says that unlike most other Terns, particularly unlike the almost equally large Royal Tern, the Caspian appears to breed in isolated pairs instead of large colonies, its nest being found far removed from that of any other bird, and consisting merely of a shallow depression scooped in the sand, in which its two eggs are laid, with little if any lining, though a few grass or sedge blades or other vegetable substance are sometimes added. It is very bold in defense of its eggs or young, darting impetuously at the intruder, uttering meanwhile hoarse barking or snarling cries.

This elegant and graceful bird is also known as the Imperial Tern. At a distance it is often mistaken for the Royal Tern, but may be distinguished from the latter by its more robust form and less deeply forked tail. Eggs and young have been taken on Cobb's Island, Virginia, in July. Dr. Merrill observed it breeding on Padre Island, near Fort Brown, Texas, in May. Large numbers of this species are said to breed on Pelican Island in the Gulf of Mexico. The eggs vary from white to greenish-buff, spotted and blotched with brown and lilac of different shades.

The Terns furnish abundant interest while flying. They seem always to be on the wing, and always hungry. Like the Gulls, they seize their food by darting upon it, tossing it into the air and catching it again, without alighting. They pick up from the surface of the water floating objects. They swim on the surface, rarely diving deep. They dart also upon fish from above, and "one plows the water in flight with a knifelike beak in hopes of running through a shoal of fishes."

|

||

| From col. F. M. Woodruff. | CASPIAN TERN. ⅓ Life-size. |

Copyright by Nature Study Pub. Co., 1898, Chicago. |

| CHICAGO COLORTYPE CO., CHIC. & NEW YORK. | ||

By Emily C. Thompson.

THE Sweet, the Bitter, and the Flowering Almond are all of a kin and in this kinship many include also the Peach and the Nectarine. The Flowering Almond or the dwarf Almond is a shrub which early in the spring, in March or April, sends forth its fair rosy blossoms before its leaves are sprouted. The shrub seldom exceeds three feet in height. The leaves are like those of the willow, only darker and of a more shining green. It is really a native of Calmuck Tartary but now is used extensively in gardens because it blooms so early and can easily be cultivated in any dry soil.

The Almond tree figures in history, mythology and poetry. In the Bible we find four references to it: Exodus 25:33, 34; 37:19, 20; Num. 17:8; Ecc. 12:5. In this connection it is interesting to note that Aaron's famous rod was the shoot of an Almond tree. Theophrastus mentions the Almond as flourishing in Greece. Cato also tells us that it was grown, but as a luxury, in Italy. The rest of its history is obscure and all we know about its cultivation in England is that it was introduced during the reign of Henry VIII. Virgil in the Georgics welcomes the Almond when covered with blossoms as the sign of a fruitful season.

In ancient times everything that was considered of any importance to the Greeks had some connection with the siege of Troy. The Almond tree here fared especially well, for two stories have come down to us in mythology relating its connection with that wonderful event. Demophon returning from Troy suffered the fate of many another Greek worthy. He was ship-wrecked on the shores of Thrace. He was befriended by the king and received as a guest. While at the court he met the beautiful daughter of his host. Immediately he fell in love with the charming princess, gained her love in return, and made arrangements for the marriage. But Demophon was obliged to return home to settle up his affairs before he could take upon himself these new ties. So the youth sailed away, but never to return. The princess, faithful Phyllis, watched and waited, hoping in vain for the return of her promised lord. Her constancy was noted even by the gods who, when she was gradually pining away, turned her into an Almond tree. Since then this tree has been a sign of constancy and hope.

Another version of the same story relieves Demophon of such gross inconstancy. It is reported by some that the marriage took place and not until after the couple were happily wedded was the hero called to Athens by the death of his father. Day by day the young wife watched for his return on the shore, but he was detained until the winter passed away and with it his faithful bride. In the spring he returned to find only an Almond tree awaiting his coming. He realized what had happened and in his despair clasped the tree in his arms when it burst forth into blossoms although it was bare of leaves.

|

||

| From Nature, by Chicago Colortype Co. | FLOWERING ALMOND. Life-size. |

|

SINCE Nature Study Publishing Company, in January, 1897, put before the teaching world the first accurately beautiful representations, not only of the forms of nature but of the tints and colors also, the brightest minds have been active in noting the effectiveness of the color photograph in school. Thousands of teachers have vied with each other in applying them in nature study with most gratifying results.

An important discovery has been made almost at the same time by many of them. The lively interest aroused by the bird presented, the agreeable sensations the child experiences in relating incidents and hearing from his mates and teacher about its habits, and the reminiscences of delightful outdoor experiences, all tend to warm the child to enthusiasm.

This point of warmth is the supreme opportunity of the teacher. Instruction given under such a glow is intensely educative. A few minutes of such work is worth hours of effort where the child is but indifferently aroused.

Many of the best first primary teachers do not begin to teach reading during the first few weeks of the child in school. They aim, first, to establish a bond of sympathy between themselves and their pupils, to extend their range of ideas, and to expand their powers of expression. Expression is induced and encouraged along all lines, by words, music, drawing, color work, and physical motions.

The common things of life are discussed, experiences related, and the imagination brought strongly into play. Songs and recitations are given with the actions of birds, animals, persons, or machines, imitated joyously by groups of children. Games calculated to train the senses and the memory are indulged in. The whole nature of the child is called into play, and perfect freedom of expression is sought.

Experience shows that intelligent training along these lines is profitable. The time of learning reading and spelling is somewhat deferred, and number work is delayed, but the children who are skilfully trained in this way outstrip the others rapidly when they bring their trained powers to bear upon the things that are popularly supposed to be the business of a school. Superintendent Speer has shown that pupils whose technical instruction has been deferred for several months in this way are found at the end of the second year far superior to others of equal promise, who have been put at reading, spelling, and number work directly.

To conduct a conversation lesson requires some tact. Not tact in asking questions, nor in "talking down" to the level of the children. Direct questions are of doubtful value in the first grade. In fact, the value of the lesson may sometimes be judged by the absence of such questions put by the teacher. The question mark and the pump handle resemble each other, and often force up perfunctory contributions, and sometimes they merely produce a dry sound. Children do not care to be pumped.

Here are a few questions that give the children little pleasure and less opportunity for expression: Isn't this a very pretty bird? Do you see what a bright eye it has? How many [Pg 197] of you have seen a bird like this? How would you like to own him, and have him at your house? Don't you think, dear children, God is very good to us to let us have such beautiful birds in the world?

Any one of these questions by itself is not harmful, but an exercise made up of such material merely gives the class a chance to say, "Yes, ma'am," and raise their hands. All talk by the teacher and no activity by the class. With a bright smile and a winning voice, the teacher may conduct what appears to be a pleasant exercise with such material, but there is little real value in it under the best circumstances and it should be avoided systematically. It is unskilful, and a waste of time and opportunity.

Attempts to lower one's conversation to the level of little children are often equally unsatisfactory. Too much use of "Mamma bird," "baby birdies," "clothes," "sweet," "lovely," "tootsy-wootsy," and "Oh, my!" is disappointing.

Ordinary conversation opened with a class in much the same style and language as used by one adult in talking with another is found to be the most profitable. Introductory remarks are generally bad, though some otherwise excellent teachers do run on interminably with them. To begin directly with a common-sense statement of real interest is best.

Here are a few profitable opening statements for different exercises: One day I found a dead mouse hanging upon a thorn in a field. Mr. Smith told me he heard a Flicker say, "Wake up! Wake up! Wake up!" Willie says his bird is fond of fruit, and I notice that most birds that eat fruit have beautiful, bright feathers. This bird likes the cows, and I once saw him light on a cow's horn.

Such statements open the minds of young people where many times direct questions close them. Questions and regular contributions to the conversation flow readily from members of the class when the right opening has been made. Do not let the class feel that your purpose is to get language from them. Mere talk does not educate. Animated expression alone is valuable.

Have plenty of material to use if the class seem slow to respond, and have patience when they have more to offer than the time will admit. Bear in mind that a conversation lesson on some nature subject is not a nature lesson, but is given to induce correct thinking, which shall come out in good language. It may incidentally be such a nature lesson as to satisfy the requirements of your course of study in that line, but if you give it as a conversation lesson, let conversation be the exercise.

Where a few in the class tend to monopolize the time you may frequently bring a diffident one into the exercise by casually looking at him as if you felt his right to be heard. It is better not to ask him to talk, but to make it easy for him to come into the conversation by referring to something he has previously done or said, or by going near him while others talk. A hand on his shoulder while you are conversing with others, will sometimes open him to expression. Sometimes you need to refer to what Willie's father said, or what you saw at his house, or to something that Willie owns and is pleased with. Many expedients should be tried and some time consumed in endeavoring to get such a pupil into the conversation instead of saying point blank, "Now, Willie, what do you think?"

The matter of spoken language is words largely. The thinking of children is always done in words, as far as school matters go. The thoughts of [Pg 198] the average child are correct enough from his standpoint, and when the teacher represses him on his first attempt to carry his part in the exercise, he is hurt to such an extent that he may never recover from it, and he may always believe himself peculiarly unfortunate in that he is incapable of speaking as others do.

The truth is that all children are eloquent. They talk easily, very easily, in comparison with adults who have been frightened out of their natural tongues, and are forever trying to say what they think in terms that they do not think it in.

All children are sensitive concerning their speech. Some of the keenest hurts children experience are inflicted by those who notice patronizingly or critically the language they use. Mothers are in a hurry to have them learn English at once, and so correct them instantly when such mistakes as "runned," "mouses," and "me wants" occur. The child allowed to think in his own terms overcomes his verbal difficulties in a short time if associated at home with those who speak correctly, and he is perfectly excusable for using what we call incorrect forms until he has acquired the so-called correct ones.

There are times when the child's mind is open to acquisition of formal expertness in language. He will find these times for himself and exercise himself in forms without being driven to it at the very times when his mind is most active with other things which he tries to express to us in his moments of overflowing enthusiasm. In these moments he should not be bothered and confused by formal quibbling. In his most active states intellectually he ought not to be repressed. This applies to the child who hears good English at home. It also applies, with slight modifications, to the child who hears imperfect language at home. The child who will eventually prove capable of correct speech will learn to speak the best language he hears without direct instruction if encouraged in it and given the respect a growing child is entitled to receive.

Children learn to speak while at play. They are active and much interested when they are acquiring a natural vocabulary. Much of the vocabulary is wrong from the standpoint of the grammar and dictionary, and they have to unlearn it. They have to unlearn it at school and from the lips of pains-taking parents. One reason it is so hard for them to learn the correct forms is this unintelligent way of teaching. Another is that the incorrect conversation is heard under circumstances favorable to retention and reproduction; that is, when the child is much interested and happy; while the correct forms are given him when he is but half aroused, or when he is somewhat intense over another matter, and many times the intended instruction goes in at one ear and out at the other. When the skill of the teacher and the things of the school room become so powerfully attractive to the pupil that once hearing a new word will fix it, once seeing a word will make him master of it in all its forms, then the language lesson will not need to be given; for language, which is as natural to man as breathing, will flow in correct forms trippingly from the tongue, being so fixed in the pupil's mind from the first that he will have nothing to unlearn.

Conversation lessons are intended to take care of some of the crudest errors in speech before the child has committed the indiscretion of putting them in writing. It can be done with so much less severity in conversation than in a written lesson. Notice [Pg 199] silently the peculiarly bad expressions and forms of statements of the whole class, then plan your talking lesson in which those who are not guilty of those errors are allowed to lead. Then let the child whom you consider most likely to profit by hearing correct expression from his mates give you the necessary statement. If he use correct forms, let another try.

For instance, suppose you have a number of pupils who are inclined to say "The robin isn't so purty as the bluejay." The reason for this is that the parents of nearly all these pupils will make the same error. If early in their experience with you you are shocked by their speech and let them know it, you either lose their respect or make them feel that they and their parents are inferior beings with no right to speak.

It will take a few minutes to speak of something else that is pretty, and let several of your pupils who speak the word correctly give some statements concerning pretty things. Then call upon one of the offenders, without his suspecting himself to be such, and the probability is that he will say "pretty," as you wish. But suppose he fail, you must not think he does so because of dullness, for he may say "purty" for the sole reason that his mates are listening and he fears they may think he is trying to "put on style." If you pass the matter in silence that day you will find him bolder or more acute the next day, and he will speak the word correctly. In this way he will seem to himself to be teaching himself. Self-culture will begin in him and the credit will be yours. Another teacher would suppress that sort of language and compel the boy to say the word right instanter. But her pupils speak one language in school and a different one in places where they are more comfortable.

Aim to set the child to correcting his own speech by his own apparent choice. A single error is easily repressed, but the habit of looking after one's own speech is not easily acquired. It is easy to make a child feel his inferiority to you, but it is a great thing to inspire him to do the good and wise and elegant things which you are capable of doing in his presence.

The process of unlearning words has always been a failure with the majority of pupils, and most of the English speaking race are ashamed of their inability to speak. Men most eloquent and successful in business conversation, who were by nature fitted to thrill the world with tongue and pen, have been confused and repressed by this process till they believe themselves vastly inferior to others because they cannot translate their thoughts out of the terms of the street or counting room into the language of the grammar school, and so they never try to fill the large places that would have been open to them if they could but have learned to think in terms which may be spoken right out without fear of opprobrium.

Now since so much of our teaching psychology and common sense have shown to be radically wrong, let us build up our language work on the high plane of interest in real things, expressing thought directly without translation into fitter terms. Let the thinking be done in terms suitable for life. And use the color photograph to insure that enthusiasm necessary to good thinking; be guarded as to how you deal with thoughts that come hot from growing minds, repress never, advise kindly, and know that by following the natural method in language you are not ruining the speech powers of your best pupils, as has been done heretofore.

Page 166.

SHARP-TAILED GROUSE—Pediocœtes phasianellus campestris. Other names: Sprig-Tail, Pin-Tail, White Belly.

Range—Plains and prairies east of the Rocky Mountains; east to Wisconsin, north to Manitoba, south to New Mexico.

NEST—In a tuft of grass or under a low bush.

Eggs—Six to thirteen.

Page 170.

RED BAT—Atalapha noveboracensis. Other name: "New York Bat."

Range—Throughout all the Atlantic coast states.

Page 170.

BLACK BAT—Scotophilus carolinensis. Other name: "Carolina Bat."

Range—Common throughout North America.

Page 174.

AMERICAN OTTER—Lutra canadensis.

Range—All parts of temperate North America, encroaching closely on the Arctic region.

Page 178.

GOLDEN PLOVER—Charadrius dominicus. Other names: Frost Bird, Bull Head.

Range—Nearly the whole of North America, breeding in the Arctic regions; south in winter to Patagonia.

Nest—In a small depression among the moss and dried grass of a small knoll.

Eggs—Four, of a pale yellowish ground color, with dark umber-brown spots scattered over the shell.

Page 187.

CANADIAN PORCUPINE—Erethizon dorsatus.

Range—A native of the forests of North America, from the sixty-seventh parallel of north latitude south to Virginia and Kentucky, the eastern and western boundaries being Labrador and the Rocky Mountains.

Page 191.

CASPIAN TERN—Sterna tschograva.

Range—Nearly cosmopolitan; in North America, breeding southward to Virginia, Lake Michigan, Texas, Nevada, and California.

Nest—A mere hollow scooped in the dry sand.

Eggs—Two or three, varying from white to greenish-buff, spotted with brown and lilac of different shades.

Page 193.

FLOWERING ALMOND—Amygdalus communis. Native of Calmuck, Tartary.