SPORTING DOGS

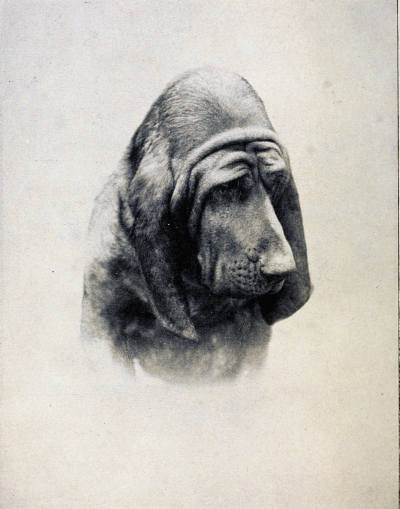

Photo by T. Fall, Baker St.]

[Frontispiece.

Head of Bloodhound Champion Sultan.

SPORTING DOGS

THEIR POINTS: AND MANAGEMENT;

IN HEALTH, AND DISEASE

BY

FRANK TOWNEND BARTON

M.R.C.V.S.

Veterinary Surgeon to the Gamekeepers' Kennel Association

Veterinary Adviser to the "Gamekeepers' Gazette"

AUTHOR OF

"NON-SPORTING DOGS," "TOY DOGS,"

"EVERYDAY AILMENTS AND ACCIDENTS TO THE DOG,"

"SOUND AND UNSOUND HORSES," "OUR FRIEND THE HORSE,"

"BREAKING AND TRAINING HORSES,"

"HOW TO CHOOSE A HORSE," "THE HORSE OWNER'S COMPANION,"

"THE VETERINARY MANUAL," "THE AGE OF THE HORSE,"

"DISEASES AND ACCIDENTS OF CATTLE,"

ETC., ETC.

COPIOUSLY ILLUSTRATED FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

London

R. A. EVERETT & CO., LTD.

1905

[All Rights Reserved]

Surely the lines—

"Trust, oh! trust me, I will be

Still true for ever, true to thee."

have never been more practically demonstrated, than in the following extract, from an account of a poaching affray, published in the Gamekeepers' Gazette.

"The dead gamekeeper's dog was to be seen by the roadside restlessly waiting for its master, while he lay in a cottage fatally riddled with shot."

TO

BREEDERS

Exhibitors, and Fanciers

OF

SPORTING DOGS

throughout the King's Dominions

PREFACE

This work—Sporting Dogs: Their Points and Management in Health and Disease—has been prepared as a companion volume to those already published, viz., Non-Sporting Dogs: Their Points, etc., and Toy Dogs, in response to numerous inquiries from readers of those volumes, asking for a work upon Sporting Dogs, to complete the series, at a proportionate price.

The Points of the various breeds used by Sportsmen have been freely discussed, supplemented by illustrations from photographs of the most celebrated animals known.

Kennel Management, The Management of Hounds, Diseases, Accidents and Simple Operations forms an important section of the work—features that should render the book of far greater practical utility than one dealing solely with the different varieties of dogs.

Both Author and Publisher, will be satisfied, if it meets with the hearty reception accorded to the companion publications.

In conclusion, the Author wishes to express most hearty thanks to all Breeders and Exhibitors who have so generously supplied him with Photographs: to Our Dogs Gazette; The Kennel Gazette; The Gamekeeper, etc.

CONTENTS

| SECTION A | |

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I | 3 |

| The Pointer | |

| Head—Colour—Eyes—Back—Hind-quarters—Faults—Value of Points. |

|

| Chapter II | 18 |

| The English Setter | |

| Laverack Setters—Coat—Colour—Skull—Ears—Eyes—Neck—Back-quarters—Tail—Fore-limbs—Weight—Faults. | |

| The Irish Setter | |

| Coat—Ears—Eyes—Neck—Forelegs—Loins. | |

| The Black=and=Tan Setter (Gordon Setter) | |

| Eyes—Ears—Head—Neck—Shoulders and Chest—Fore-limbs—Feet—Back—Loins—Stern—Value of Points. | |

| Chapter III | 32 |

| International Gundog League | |

| Pointer and Setter Society | |

| Rules—Rules for the Trial Meetings. | |

| [x] | |

| Chapter IV | 42 |

| Retrievers | |

| Flat-coated: Coat—Head—Ears—Eyes—Chest—

Neck—Back—Loins—Limbs—Faults. Curly-coated. |

|

| Labradors | |

| Rules of the Retriever Society | |

| Chapter V | 66 |

| Spaniels | |

| General Characteristics of the different Varieties—Temperament—Coat—Colour—Head—Ears—Fore-limbs—Body. | |

| The Clumber | |

| Weight—Head—Ears—Eyes—Coat—Neck—Club. | |

| The Sussex Spaniel | |

| Colour—Coat—Weight—Head—Eyes—Ears—Nose—Neck—Shoulders and Chest—Fore-limbs—Faults. | |

| Field Spaniels | |

| The Cocker Spaniel | |

| Head—Ears—Coat—Colour—Club Prices—Faults. | |

| The Irish Water Spaniel | |

| Colour—Nose—Skull—Ears—Neck—Coat—Height—General Appearances—Faults—Weight—Club. | |

| The English Water Spaniel | |

| Chapter VI | 94 |

| International Gundog League | |

| Rules—Regulations (subject to alteration). | |

| [xi] | |

| Chapter VII | 102 |

| Training Spaniels | |

| SECTION B | |

| HOUNDS | |

| Chapter VIII | 113 |

| The Foxhound | |

| Packs of Foxhounds. | |

| Harriers | |

| Loins—Back—Ribs—Chest—Fore-limbs—Coat. | |

| The Otterhound | |

| Colour—Height—Eyes—Ears—Skull—Neck. | |

| The Deerhound | |

| Head—Ears—Neck—Shoulders—Stern—Eyes—Body—Legs—Feet—Coat—Colour—Height—Weight—Points required. | |

| SECTION C | |

| HOUNDS | |

| Chapter IX | 141 |

| The Bloodhound | |

| Head—Eyes—Legs—Feet—Chest—Shoulder—Neck—Ribs—Back—Loins—Hind-quarters—Limbs—Tail—Coat—Colour—Height—Club—Association of Bloodhound Breeders. | |

| Irish Wolfhounds | |

| Weight—Height—Head—Ears—Neck—Fore-limbs—Hind-quarters | |

| [xii]The Greyhound | |

| Head—Eyes—Ears—Neck—Fore-quarters. | |

| The Whippet | |

| Coat—Constitution—Fore-limbs—Hind-quarters— Feet—Tail—General Appearance of the Whippet. | |

| SECTION D | |

| MIXED HOUNDS | |

| Chapter X | 179 |

| The Borzois or Russian Wolfhound | |

| Ears—Eyes—Chest—Neck—Fore-limbs—Colour—Coat—Height—Faults—Club. | |

| The Beagle | |

| English Beagle Club—Points—American Beagle Club—Points. | |

| Chapter XI | 194 |

| The Dachshund | |

| Coat—Head—Nose—Eyes—Ears—Neck—Chest—Shoulders—Legs—Feet—Toes—Hind-quarters. | |

| The Basset-hound | |

| Colour—Coat—Head—Fore-quarters—Chest—Club Rules of Basset Club—Points of Basset Hound (smooth)—General Appearance—Points of the Basset-hound (rough). | |

| SECTION E | |

| FOX TERRIERS | |

| Chapter XII | 239 |

| [xiii]The Fox Terrier | |

| Standard of Points recommended by the Fox Terrier Club. | |

| Rough Fox Terrier | |

| Scale of Points—Disqualifying Points. | |

| SECTION F | |

| TERRIERS | |

| Chapter XIII | 269 |

| The Skye Terrier | |

| Colour—Head—Body—Legs—Height—Faults—Club—Prices. | |

| The Bedlington Terrier | |

| History—Height—Weight—Colour—Nose—Coat—Skull—Body—Tail—Limbs and Quarters—Club. | |

| The Scottish Terrier | |

| Coat—Height—Colour—Body—Neck—Chest—Limbs and Feet—Ears—Eyes—Head—Hair—Muzzle—Height—Clubs. | |

| The Irish Terrier | |

| Coat—Colour—Neck—Body—Limbs and Feet—Weight—Club—Prices. | |

| The Airedale Terrier | |

| Standard of the Airedale Terrier Club—Points—Rules and Regulations. | |

| The White West Highland Terrier | |

| Description of. | |

| [xiv]The Welsh Terrier | |

| Head—Neck—Arms—Forearms—Back and Loins—Tail—First and Second Thighs—Feet—Club. | |

| The Dandie=Dinmont | |

| History—Head—Neck—Tail—Fore and Hind limbs—Colour—Society—Standard of Points of Dandie-Dinmont Terrier Club—Rules for Breeders' Challenge Cup—Rules for the Tiddeman Trophies—Rules for the Ringwood Club—Breeders' Cups, etc. | |

| SECTION G | |

| AFGHAN GREYHOUND-LURCHER | |

| Chapter XIV | 333 |

| The Afghan Greyhound | |

| Skull—Eyes—Ears—Neck—Colour—Weight—Height at Shoulder—Limbs. | |

| The Lurcher | |

| The Training, Use, and Abuse, of Night=Dogs | |

| Chapter XV | 351 |

| The Gamekeepers' Kennel Association | |

| Chapter XVI | 363 |

| Feeding Sporting Dogs | |

| Conditioning Dogs | |

| Chapter XVII | 369 |

| Specific Ailments | |

| Distemper—Rabies—Blood Poisoning—Rheumatism—Chest Founder or Kennel Lameness. | |

| [xv] | |

| Chapter XVIII | 384 |

| Constitutional Skin Diseases | |

| Eczema—Boils—Herpes—Nettle Rash. | |

| Chapter XIX | 389 |

| External Parasites and Parasitic Skin Diseases | |

| Fleas—Pediculi or Lice—Ringworm—Sarcoptic Mange—Follicular Mange. | |

| Chapter XX | 394 |

| Diseases of the Gullet, Stomach, Bowels, and Digestive Glands | |

| Disease of the Gullet—Inflammation of the Stomach—Twist and Intussusception of the Bowels—Inflammation of the Bowels—Vomiting—Worms—Diarrhœa—Dysentery—Hæmorrhage—Hæmorrhoids—Dyspepsia—Jaundice—Ruptures. | |

| Chapter XXI | 413 |

| Poisons and their Remedies | |

| Poisoning by Arsenic—Antimony—Strychnine—Phosphorus—Rat and other Vermin Destroyers—By Lead—Mercury—Ptomaine Poisoning. | |

| Chapter XXII | 419 |

| Diseases of the Urinary Organs | |

| Disease of the Kidneys—Stone in the Bladder—Inflammation of the Bladder—Stricture of the Urethra. | |

| Chapter XXIII | 422 |

| Diseases of the Ear | |

| Dropsy of the Ear-flap—Otitis—Otorrhœa or Canker (internal)—Split Margin of Ear—(External Canker)—Eczema of Ears—Deafness—Morbid Growths in Passage—Concretions—Syringing ears. | |

| [xvi] | |

| Chapter XXIV | 428 |

| Diseases of the Eye | |

| Ophthalmia—Blindness—Inverted Eyelids—Everted Eyelids—Torn Eyelids—Foreign Bodies in Eyes—Bareness around Margins. | |

| Chapter XXV | 433 |

| Injuries and Minor Operations | |

| Wounds—Overgrown Claws—Fractures. | |

| Chapter XXVI | 438 |

| Minor Operations | |

| Docking—Setoning—Enemas—Fomentations—Blistering—Tumours and Warts. | |

| Appendix | 443 |

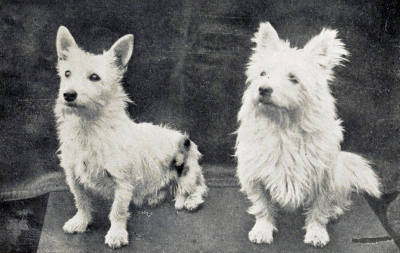

| White West Highland Terrier | |

| Club Standard of Points. | |

| Index | 447 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

| Head of Bloodhound Champion Sultan | Frontispiece |

| Pointers on Partridges | 5 |

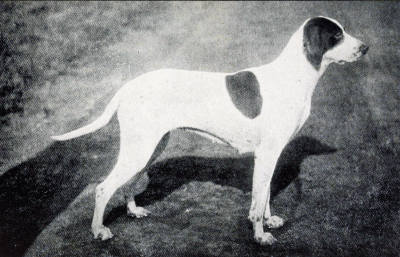

| Pointer Champion Faskally Brag | 7 |

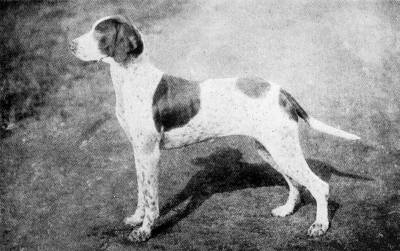

| Pointer Champion Coronation | 11 |

| Pointer Bitch Barton Beauty | 13 |

| Pointer Bitch Barton Blanche | 15 |

| A Brace of English Setters at Repose (Pride and Sally) | 19 |

| English Setter Romney Rock | 21 |

| Irish Setter Dog | 25 |

| Irish Setter Champion Florizel | 27 |

| Mr Cartwright's Flat-coated Retriever Champion Colwyn Clytie | 43 |

| Typical Flat-coated Retriever | 45 |

| Flat-coated Retriever Danehurst Rocket | 49 |

| Flat-coated Retriever Busy Marquis | 51 |

| Typical Flat-coated Retriever Dog | 53 |

| Curly-Coated Retriever Dog | 57 |

| [xviii]Clumber Spaniel Dog Bobs of Salop | 73 |

| Mr Newington's Sussex Spaniel Dog Rosehill Rock | 77 |

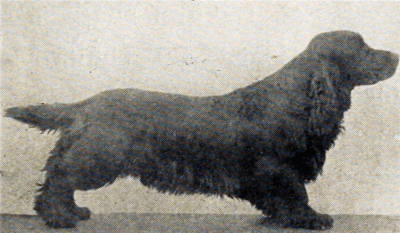

| Typical Cocker Spaniel | 85 |

| Irish Water Spaniel Pat O'Brien | 89 |

| Mr Walter Winans' Pack of Hounds and Master | 115 |

| Enemies at Peace—Foxhound Nameless and Tame Dog Fox | 117 |

| Lecturer—A Member of the Crickhowell Harriers | 123 |

| Deerhound Champion St Ronan's Rhyme | 131 |

| Deerhound Dog Champion Selwood Morven | 133 |

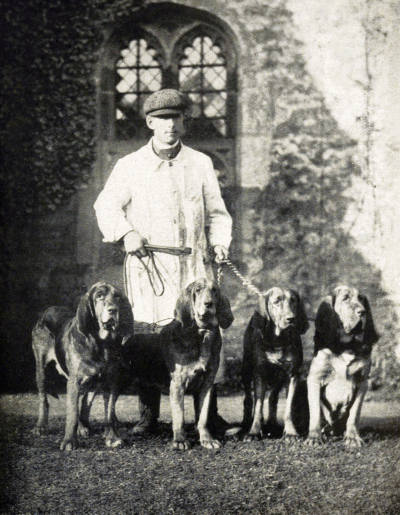

| A Quartet of Typical Bloodhounds | 143 |

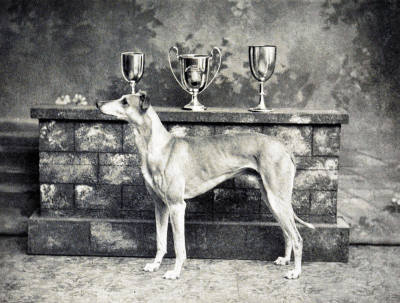

| Greyhound Bitch Lady Golightly | 159 |

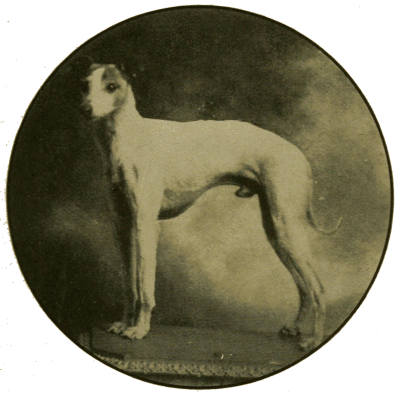

| Fawn Greyhound Dean Baden Powell | 161 |

| A Trio of Greyhounds, Duke o' Ringmer, Lady Golightly, Glory o' Ringmer | 163 |

| Greyhound Sussex Belle | 165 |

| Typical Whippet Dog Dandy Coon | 169 |

| Borzois Padiham Nordia | 175 |

| Borzois Dog | 177 |

| A Group of Leyswood Beagles | 183 |

| Pocket Beagle Cheerful of Rodnance | 185 |

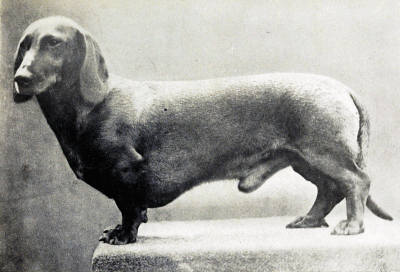

| Dachshund Champion Snakes Prince | 195 |

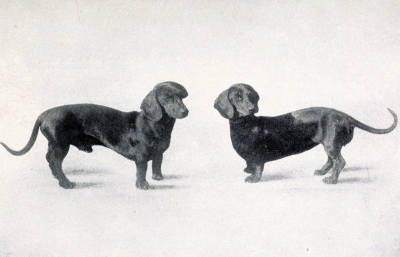

| A Brace of Typical Dachshunds | 197 |

| Dachshund Dog and Bitch | 199 |

| [xix]Red Dachshund Victoria Regina | 201 |

| Mr Proctor's Basset-hound Bitch Queen of the Geisha | 209 |

| A Brace of Typical Smooth-coated Basset-hounds | 211 |

| Smooth-coated Basset-hound Bitch and Her Puppies | 213 |

| Smooth Basset-hound Dog Champion Louis le Beau. A veritable pillar of the Stud Book | 215 |

| Typical Smooth-coated Basset Bitch | 217 |

| A Group of Champion Smooth-coated Bassets | 219 |

| Typical Rough Basset Bitch | 221 |

| Rough-coated Basset-Hound Dog Champion Puritan | 223 |

| Typical Rough-coated Basset Dog | 225 |

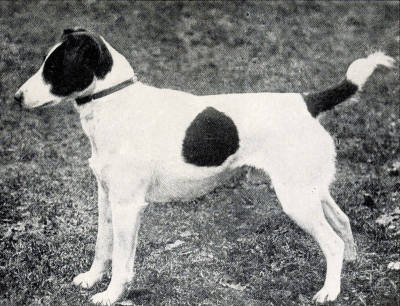

| Mr Scott's Smooth Fox Terrier Millgate Joe | 241 |

| Champion South Cave Leger | 243 |

| Smooth Fox Terrier Duke of Doncaster | 245 |

| Smooth Fox Terrier Champion Cymro Queen | 249 |

| Miss Lewis's Wire-haired Fox Terrier Champion Donington Venture | 251 |

| Mr Scott's Smooth Fox Terrier Millgate Bandit | 253 |

| Smooth Fox Terrier Dog Champion Dukedom | 257 |

| Smooth Fox Terrier Dog Darley Dale | 259 |

| Wire-haired Fox Terrier Dog Remus of Gaywood | 261 |

| Mr Scott's Wire-haired Fox Terrier Millgate Leader | 263 |

| Typical Prick-eared Skye Terrier Dog | 271 |

| [xx]Bedlington Terrier Dog | 275 |

| Scottish Terrier Dog Champion Hyndman Thistle | 279 |

| A Trio of Scottish Terriers | 281 |

| Group of Scottish Terriers | 285 |

| Irish Terrier Blackbrook Banker | 289 |

| Airedale Terrier Dog Barkerend Masterpiece | 291 |

| Airedale Terrier Dog Crompton Marvel | 295 |

| Airedale Terrier Dog Barkerend Victoria | 299 |

| Brace of White West Highland Terriers | 305 |

| Welsh Terrier | 309 |

| Dandie-Dinmont Terrier Dog Thistle Grove Ben | 311 |

| Afghan Greyhound | 335 |

| The Celebrated Keeper's Night-Dog Thorneywood Terror, said to be the most perfectly trained Night Dog ever bred | 339 |

SECTION A

CHAPTER I

Pointers

CHAPTER II

Setters

ENGLISH—IRISH—GORDON

CHAPTER III

International Gundog League

CHAPTER IV

Retrievers

FLAT-COATED—CURLY-COATED—LABRADOR

CHAPTER V

Spaniels

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DIFFERENT VARIETIES—CLUMBER—SUSSEX—FIELD—COCKER—IRISH WATER—ENGLISH SPRINGERS

SPORTING DOGS

CHAPTER I

The Pointer

Most authorities are in agreement that the English Pointer has been derived from a cross of the old Spanish Pointer and Southern Hound, or with the former and a Foxhound.

The old Spanish Pointer was a heavy, loose-made dog, had a large head, short and smooth coat, thin, loose ears and a thin tail.

In colour he was generally black, black and white, liver and white, red and white, dark brown, liver, etc. The breed, it is said, was first introduced into this country by a Portuguese merchant, living and shooting in Norfolk.

According to accounts, the Spanish Pointers had a remarkable degree of scenting power, never missing their game.

In Germany there are two varieties of Pointers—the[4] Rough-and the Smooth-coated. Like the old Spanish Pointer, these dogs are slow, but sure workers: they are heavily built, and frequently liver, or liver and white.

The chief drawback to the Spanish Pointer was his slowness, and indifferent temper. The French Pointer was probably superior, and may have had considerable influence towards making the many good qualities possessed by the English Pointer of to-day. A medium-sized dog is the most useful, the heavy being too slow and the light weights too fast, especially for aged shooters.

The Pointer may be described as fairly hardy; generally of good constitution, and when bred from working parents, puppies usually respond readily to the breaker's tuition.

A second-, or third-season dog, is preferable to a first-season one, so that, when purchasing, this should be borne in mind. Another matter worthy of attention, and that is, never to purchase a Pointer without having him for a week or two's trial on your own shoot.

The colour of a Pointer is more a matter for individual taste, though there is no doubt that one should choose such as can be the most readily discerned in the distance. Lemon and white, black and white, and liver and white ticked, especially the last-named, are the most general colours. Liver, and red and white are frequently seen, though the former is not so readily recognisable on ploughed land, etc.

[Photo by Horner.

Pointers on Partridges (Property of Mr F. R. Horner).

Pointer Champion Faskally Brag (Property of Mr H. Sawtell)

In action, these dogs ought to move with beauty and freedom, unobserved in any other breed. The movements alone ought to be sufficient to create admiration in the mind of the sportsman.

Head.—Should be of good size, wide in the dome, and wider between the eyes, with a long, broad, square nose and broad, well-dilated nostrils, giving the head a somewhat square conformation.

In colour, nose ought to be black, but in lemon and white dogs, flesh-coloured. Cartilages of ears, long and thin, covered by soft hair, and carried close to cheeks.

Eyes.—Of medium size.

Twenty-four per cent. of points are allowed for skull, nose, eyes, ears, lips, and six for the neck, which ought to be long, arched, and free from loose skin or dewlap. Long oblique shoulders and long arms are essentials of beauty in the Pointer. Forearms long, having plenty of bone and muscle. Pasterns of medium length, feet round (like those of the cat), and the soles hard. A good deal of attention is paid to the legs and feet, by Pointer judges. Some prefer the hare-foot. The elbow must stand well off the brisket and be low placed. Dog must not be "out" at elbow. Viewed from the front, the chest of[10] the Pointer, nevertheless, ought not to be broad, otherwise the beautiful elastic step is interfered with. The contour of the chest is round and deep. Back ribs must be deep, and flanks broad and thick, so as to give strength in these regions.

Back and Hind-quarters.—The back should be of good length but strongly built, and the loins broad and deep. First and second thighs well covered with muscle; hocks strong and good; stifles broad.

Too much importance cannot be attached to the stern of the Pointer, and judges are keen on quality in this region. First of all, it must be strong at its "set on," and gradually taper to a fine point.

If the tail is as thick at the end as it is at its "set on," or coarse in other respects, it indicates inferior breeding. Should be carried on a line with the back.

Faults.—Any approach to curl in tail, coarse coat, soft feet, short back ribs, wide chest, too heavy in head and facial expression, short on legs, under-or over-sized, presence of flews or big cheeks, undershot; too much of Hound character, bad temper, disobedience, bad constitution, etc.

Pointer Champion Coronation (Property of Mr H. Sawtell).

Pointer Bitch Barton Beauty (Property of Sir Humphry de Trafford, Bart.).

Pointer Bitch Barton Blanche (Property of Sir Humphry de Trafford, Bart.).

Value of Points

| Skull | 10 | |

| Ears | 5 | |

| Nose | 10 | |

| Neck | 5 | |

| —— | 30 | |

| Shoulders, chest, back and thighs, | 30 | |

| Colour and coat, | 10 | |

| Stern and general quality, | 10 | |

| Legs | 6 | |

| Feet | 6 | |

| Elbow | 4 | |

| Hocks | 2 | |

| Stifles | 2 | |

| —— | 20 | |

| —— | ||

| Total | 100 | |

CHAPTER II

The English Setter

Most authorities, or those who have made diligent inquiries into the history—if such it can be called—or origin, of the English Setter, are agreed that it has been derived from the Spaniel—Setting Spaniel—and Laverack, in his work on the Setter, says,—

"I am of the opinion that all Setters have more or less originally sprung from our various strains of Spaniels, and I believe most breeders of any note agree that the Setter is nothing more than a Setting Spaniel. How the Setter attained his sufficiency of point is difficult to account for, and I leave the question to wiser heads than mine to determine. The Setter is said and acknowledged by authorities of long standing, to be of greater antiquity than the Pointer. If this be true—and I believe it is—the Setter cannot at first have been crossed with the Pointer to render him what he is."

If the foregoing views be accepted, it follows that our lovely Setter is but an improved Spaniel.

A Brace of English Setters at Repose (Pride and Sally, Mr Stanhope Lovell).

An English Setter (Romney Rock).

The Laverack Setters—a strain preserved by the late Mr Laverack—has always played an important part in the more recent history of the Setter. The Llewellin Setter—a strain bred by Mr Llewellin—(a Laverack cross) stands out as being one of the best strains ever produced, both on the show bench and in the field.

A high-class English Setter should have a rich, glossy coat, and every movement should be one of elegance, dash, and beauty.

A high degree of intelligence and great power of physical endurance are a sine qua non.

Field trials have done more towards perfecting the working qualities of the Setter than could have been attained by any other means.

The breeding of stock from dogs coming out top at these trials affords the surest means of attaining the highest degree of working capacity.

The points of the English Setter are as follows:—

Coat.—To be soft, silky, and free from curl. There ought to be an abundance of soft feather on fore and hind legs.

Colour.—Not a great deal of importance is attached to this. The chief colours are:—Liver and white, lemon and white, black, black and white, red or yellow, orange Belton, black and white ticked, with splashes of black, or bluish tint—blue Belton, black, white and tan markings, &c. Black and white ticked are commonest.

Skull.—Long and narrow, with a well-developed occipital bone. Muzzle square, and lips full at their angles.

Ears and Eyes.—Ears set on low, thin and soft, carried close to the cheeks, and covered by silky hair about a couple of inches in length. Eyes of medium size, either brown or hazel.

Neck.—Slightly arched and covered by somewhat loose skin.

Back and Quarters.—Arched, and loins wide and strong. Hocks, strong.

Tail.—Should be carried in a straight line with the body, and the feather upon it to consist of straight, silky hairs, shortening towards the point. A beautiful flag is a great adornment to the Setter, especially when at work.

Fore-limbs.—Shoulders set well back. Forearms straight and strong, of medium length, and with a good fringe at the back. Pasterns short and nearly vertical. Feet well feathered below and cat-like.

Weight.—Dogs from 50 to 60 lbs. Bitches, 45 to 55 lbs. Club.—The English Setter.

Faults.—Curly coat, snipy head, bad carriage of stern, too light in bone, too short or too long in leg, out at elbows, too heavy in head, bad symmetry, disobedience, bad scenting power, indifferent at work, etc., etc.

The Irish Setter

The origin of these dogs, as in many other breeds, is enshrouded in mystery. The theory that they have been derived from Red Spaniels, crossed with the Bloodhound, is accepted by some breeders, the traces of Hound blood being observable in their method of working (scenting their game), so much objected to, by many sportsmen.

Irish Setter Dog.

In Ireland these Setters have been, and still are, greatly used for snipe shooting, being hardy, fast, and very keen-nosed—their ability to bear fatigue, and cold, being unequalled by any other variety of Setter.

It has been said that the finest and oldest strain of Irish Setters have a slight tinge of black on the tips of the ears and muzzle; others, again, regard the presence of black hairs as a sign of impurity of blood, agreeing that these dogs ought to be a very deep, rich red—a dark or blood red being preferred. White hairs ought not to be present anywhere, excepting on the forehead and chest, though many object to white in the situation last named.

The Coat should be close, of strong growth, and neither coarse nor silky in texture. Feather of a golden tinge, and of moderate amount.

Ears.—To be long, set low on the head, and have a medium degree of feathering.

Eyes.—A deep hazel or brown, and the nose dark or mahogany flesh. A black nose should disqualify.

Neck.—Of fair length, slightly arched, and body proportionately long; the chest deep, and ribs well sprung.

Forelegs.—Straight, not too much feathered, and the feet small, firm, and close, with well-arched toes.

Strong Loins, powerful thighs and hocks, and a horizontal carriage of the tail (not cocked) are excellences in this region.

Taken as a whole, the Irish Setter is built more after the type of a racer. Moreover, has a little wider skull than the English variety.

Irish Setter Champion Florizel (Property of Mrs Hamilton).

The Black-and-tan Setter (Gordon Setter)

This famous breed of Setters can be traced back for a hundred years to the castle of the Duke of Gordon, but whether this nobleman laid the foundation stone of the present breed of Black-and-tan Setter, becomes a matter of speculation.

It is not the least improbable that these Setters have been derived by crossing the English Setter with a Black-and-tan Collie, as certain Gordons exhibit more than a trace of the Collie element.

During the last few years the Black-and-tan Setter classes at the Kennel Club Shows in London have been very badly filled, and unless breeding this variety of dog becomes more popular, in England at least, it will soon deteriorate.

A well-broken Gordon is a most useful dog in the field, though certainly his luck at field trials has not been anything like that of the Englishman.

In colour he should be a glossy raven black, with rich mahogany tan markings, pencilling of the toes being allowable.

On the inside of the fore-limbs, tan ought to show nearly up to the elbows, and up to the hocks, on the inner sides of the hind ones.

There should be tan on the lips, cheeks, undersides of the ears; spots over eyes, on front of the chest, on the vent, and at the root of tail or flag.

Eyes.—To be of medium size and deep brown.

Ears.—The ears of the Gordon are longer than those of the Irish or English, are set on low and lie close to head.

Head.—There ought to be good evidence of "stop," rendering the occiput well-defined.

From eye to occiput, head should measure nearly 6 inches.

The old type of Gordon was much too clumsy in the head.

Neck.—Long, clean, and racey.

Shoulders and Chest.—Shoulders of good slope and chest deep. Ribs to be well sprung.

Fore-limbs and Feet.—To be of moderate length; strong in the forearms, and elbows well in. Feet arched and cat-like.

A strong back, loin, and well-bent stifles are qualifications of the Gordon.

Stern.—The tail carried as nearly in the same line as the body. Many Gordons have defective carriage of the caudal appendage.

The so-called "tea-pot" tail is the worst fault, and destroys a dog's chance of winning in the show ring.

Gordon Setter puppies are not difficult to rear, though good specimens are difficult to produce; still more so to purchase, when grown up, and thoroughly broken.

In America this variety of Setter is much thought[31] of, and in that country a great deal has been done towards the improvement of the breed, where the value of points is as follows:—

| Head, muzzle and nose | 15 |

| Shoulders and chest | 15 |

| Back, loins, thighs and stifles | 15 |

| Stern and flag | 8 |

| Fore-limbs | 15 |

| Colour and markings | 8 |

| Symmetry and quality | 8 |

| Neck | 5 |

| Eyes, ears and lips | 5 |

| Texture of coat and feather | 6 |

| —— | |

| 100 |

CHAPTER III

INTERNATIONAL GUNDOG LEAGUE

Pointer and Setter Society

Constitutional Rules

1. That the object of the Society be to promote the Breeding of pure Pointers and Setters, and to develop and bring to perfection their natural qualities. In order to carry out these purposes, an Autumn Trial—on grouse, if practicable—shall be annually held within the United Kingdom; and also Spring Trials on partridges shall be held (if possible), either on the Continent, or in the United Kingdom.

2. That the Society shall consist of a President, Vice-Presidents, a Central Committee, and an unlimited number of members, and that there may also be appointed triennially a Vice-President and Honorary Secretary for each separate Country or Colony. That these officers, after election, be empowered to call Sub-committees of their fellow-countrymen (being also members of the Pointer[33] and Setter Society), to advise and report to the Central Committee.

3. That one-third of the Central Committee (exclusive of the officers) shall be withdrawn by lot each year, at the Annual General Meeting for the first two years, and afterwards by rotation, and members shall be elected to fill their vacancies; the retiring members to be eligible for re-election. The President, Vice-Presidents, and Honorary Secretaries shall be ex-officio members of the Central Committee.

4. That the entire control and management of the Society shall be vested in the Central Committee (of which three shall form a quorum), who shall have power to make bye-laws and decide upon all matters in dispute not provided for by the Rules of the Society; and further that any member of the Central Committee, if unable to be present at a Central Committee Meeting, shall be permitted (upon application for same) to vote by proxy, duly signed, upon any resolution appearing upon the agenda paper, except as provided in Rule 8.

5. That each Candidate for admission shall be proposed and seconded by members of the Society. The Candidate's name, rank, residence and profession or occupation, if any, shall be sent to the Central Secretary a fortnight before the election[34] of Candidates at the Central Committee Meeting; and that each member of the Central Committee be advised, at least seven days beforehand, of the proposed election of a new member of the Society.

6. That the election of members shall be vested solely in the Central Committee, and be made by ballot, two black balls to exclude.

7. That for the present no entrance fee shall be charged, and that the annual subscription shall be two guineas, payable 1st January in advance; and that any member whose payments shall continue in arrear for six months shall (due notice of such arrear having previously been given in writing by the Central Secretary) have his name struck off the list, and shall cease to be a member of the Society. Any member joining the Society after the 31st of August in any year shall not be liable for an annual subscription for the current year. Life membership may be acquired upon payment in a lump sum of twenty guineas.

8. Any member of the Society who shall be proved to the satisfaction of the Central Committee to have in any way misconducted himself in connection with Dogs, Dog Shows, or Trials, or to have acted in any way which would make it undesirable that he should continue to be a member, shall be requested to retire from the Society; and if a resolution to[35] that effect shall be carried by three-fourths of the Central Committee (present and voting), duly summoned or warned to the consideration of the case, the member so requested to retire shall henceforth cease to be a member of the Society.

9. That subscriptions and donations, after payment of all liabilities, shall be applied in such a manner as the Central Committee may determine, for prizes at Trials or Workers' Classes, at not more than one Dog Show each year, or otherwise; and all balance shall be invested for the use of the Society, in such a manner as the Central Committee shall direct.

10. That Central Committee Meetings may be held at each Trial Meeting of the Society, or at such other times and places as the Central Committee may determine, notice thereof having been duly sent to each member of the Central Committee.

11. That the Annual General Meeting of the Society be held in May or June in London, and that a Special General Meeting may be called at any time, and at such place as may be agreed to by the Central Committee, on the requisition of six members.

12. At every meeting the President, or one of the Vice-Presidents, shall be chairman, or, failing these, a member of the Central Committee; such[36] chairman to have a casting vote at all meetings. And, further, the minutes of the preceding meeting shall be read, approved, confirmed, and signed by the chairman at the commencement of the next subsequent meeting.

13. Any member may withdraw from the Society on giving notice in writing to one of the Honorary Secretaries, or to the Central Secretary, provided always that such member shall be liable for his subscription to the Society for the current year in which he gives such notice.

14. That the Central Secretary shall enter the name and address of each member of the Society in a Book kept for that purpose.

A. E. Sansom,

Secretary,

12 and 13 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden,

London, W.C.

INTERNATIONAL GUNDOG LEAGUE

Pointer and Setter Society

Rules for the Trial Meetings

1. In Single Stakes the competing dogs shall be drawn into pairs by lot, dogs belonging to the same owner being guarded from each other as long as possible. The Judges having seen each pair run as drawn, if possible, will at the end of the first round[37] give to the Committee the names of those dogs which they consider have a chance of being placed. The Committee will then proceed to draw these dogs again, taking care that dogs which have met in the first round do not run together in the second. At the end of the second round the Judges will call up at their own discretion, any dogs they require further, and run them as they choose. If any dog would, by the withdrawal of his antagonist before running, be left untried, the Judge may order him to run with any dog similarly circumstanced in that round, or with the dog that has the bye. The dog that has drawn a bye, if not called for previously by the Judges, shall run as one of the first pair in the next round.

2. In Brace Stakes, the two dogs running together must belong to the same owner, and the order of running in the first round shall be decided by lot. No dog shall be allowed to form part of more than one brace at the same meeting, and only one man at a time shall work any brace.

3. In all Stakes the Judges will, except in cases of undoubted lack of merit, try each pair in the first round for at least fifteen minutes, and in Single Stakes the first and second prize dogs must have run together, likewise the second and third. In the Brace Stake, all prize-winning braces must have been down twice.

4. The Judges are requested not to award a Prize to any dog unless they are satisfied that he will back of his own accord.

5. The Judges will, in making their awards, give full consideration to the manner in which the ground is quartered and beaten, and are requested not to award a Prize to the dog of any owner or handler who does not beat his ground, and work exactly as he would do were he actually out shooting.

6. The Judges will avoid, if possible, holding a dog so long on his point, for the purpose of securing a back, as to cause the birds to run: but if the pointing dog be so held on a point by order of the Judge, he shall not incur any penalty for misbehaviour in reference to that particular point.

7. The Judges shall not decide the merit of a dog's running from the number of times he points game, backs, etc., but from the style and quality of his performance as a whole. Dogs are required to maintain a fast and killing range, wide or narrow, as the necessity of the case demands; to quarter the ground with judgment and regularity; to leave no birds behind them; and to be obedient, cheerful, and easily handled.

8. The Judges are requested and empowered by the Committee to first caution, and upon repetition of the offence, turn out of the Stake any breakers not beating the ground to their satisfaction; not[39] keeping together or out-walking their opponents; unduly whistling or shouting, or behaving in such a manner as, in the opinion of the Judges, is detrimental to the chances of success of their opponents. Any breaker or owner who feels that the behaviour of his opponent is unsettling his dog, may request the interference of the Judges.

9. A gun must have been fired over all aged dogs as well as puppies before they can be awarded either a Prize or a Certificate of Merit.

10. Certificates of Merit will be awarded with a view to the establishment of Workers' Classes at the Dog Shows, and as a guide to purchasers of dogs which, though not in the list of Prize Winners, give promise in their work of being valuable sporting dogs. In a Brace Stake this honour may be conferred on one dog without reference to the behaviour of his companion.

11. The Judges are empowered to withhold a Prize when, in their opinion, no merit is shown, and to exclude from competition bitches on heat, or any animals they may consider unfit to compete, and the entry fees of such dogs will be forfeited.

12. After the first round the Judges may order a flag to be hoisted at the end of each individual contest to indicate which of the two competitors has shown the greater merit in that particular trial. The hoisting of the "colour" of a dog whose performance[40] on that one occasion has been the more meritorious will not necessarily imply that his opponent is debarred from winning in the Stake. When a striking evenness of merit is shown, both flags will be hoisted simultaneously; and, conversely, when there is a total lack of good work, no flags will be displayed.

13. In the event of the weather being considered by the Committee unsuitable for holding trials, it shall be in their power to postpone the meeting from day to day until the Saturday following the first day of the trials, on which day either the stakes not already decided shall be abandoned and their entry fees returned, or a fresh draw for them shall take place, at the discretion of the Committee.

14. If, from unforeseen circumstances, the Committee deem it advisable to alter the date of the meeting after the closing of the entries, this may be done by sending formal notice to all competitors that they may recover their entry fees by exercising the option of cancelling their entries within four days from the date of such notice. All entries, however, about which no such application is made, within those four days will stand good for the meeting at its altered date.

The Committee also reserve to themselves the right to abandon the meeting at any time, on returning the entry monies to the competitors.

15. If any of the advertised Judges be prevented from fulfilling their engagement for either the whole or part of the Meeting, the Committee shall appoint any other person to judge, or shall make any other arrangement that to them seems desirable.

16. The Committee have the power—if they think fit—to refuse any entries for the Society's Trials, and if they consider that any persons by their conduct or otherwise, are undesirable visitants at the Society's Trials, they shall exclude such persons from the Trials, without being obliged to assign any reason for their action.

The disqualifications of any other recognised Trial Society—British, Continental or otherwise, shall be upheld by this Society.

17. An objection to a dog may be lodged with the Secretary at any time within seven days of the last day of any meeting, upon the objector depositing £5 with the Secretary, which shall be forfeited if the Committee deem such objection frivolous. All objections must be made in writing.

18. Upon any case arising not provided for in the above rules, the members of the Committee present shall decide, and their decision shall be final.

CHAPTER IV

Retrievers

(a) Flat-coated

There is good evidence to show that the Retriever is what may be termed a "made" breed, and that his present state of perfection is the outcome of careful selection during the last fifty years or thereabout, the latter thirty years of this time having been devoted by enthusiastic sportsmen to raise the standard of the Retriever to the highest standard of excellence, and no one did more in this respect than the lamented late President of the Kennel Club, S. E. Shirley, Esq., Ettington Park, Stratford-on-Avon.

Most of Mr Shirley's exhibits were an ornament to the show bench, and not only were they ornamental, but equally useful in the field, this gentleman being a keen sportsman and one of the most successful breeders and exhibitors of Flat-coats in the annals of this or any other time.

The Retriever is gradually coming more and more into favour, and will continue to do so when his usefulness becomes better known. It is a variety of dog that stands little chance of becoming spoiled by interbreeding, as in the case of so many Spaniels.

Mr Cartwright's Flat-coated Retriever Champion Colwyn Clytie.

Typical Flat-coated Retriever.

To the sportsman, the Retriever can claim advantages over the Pointer, Setter and Spaniel, but unless very thoroughly handled during his training, he is not of much service. A perfectly broken Retriever—more especially if rich in show-bench points—should readily bring sixty or seventy guineas at least, and cheap at that price.

Coat.—Should be perfectly flat—not wavy as formerly—of an intense raven blackness,[1] glossy, and the hair of good length and dense, more especially over the tops of the shoulders and along the back, but the contour ought not to be interfered with.

White hair upon any part of the body, head, tail, or extremities, is not desirable, and should, in the author's opinion, tell against the animal. We are aware that the presence of a few white hairs upon the chest is not regarded as being of much importance. Still, there is no gainsaying that to be perfect in all points, the Retriever must not have such.

Head.—Ought to possess the highest degree of intelligence. The occipital dome to be wide, of medium height, becoming much narrower as the nose is approached; the latter to be black.

Ears.—Small, carried close to cheeks, and thin cartilage covered with soft hair, yet free from feather at the margins.

Many Retrievers are very faulty here, a touch of the Spaniel element sometimes being in evidence.

Eyes.—To be of a deep hazel. Any tendency towards the so-called "snipy" nose is a defect.

Chest.—Deep, but not wide, and well covered with soft, black hair.

Neck.—Somewhat short, but thick.

Back and Loin.—A long, strong back and loin, slightly depressed about midway, with a beautiful rise towards the hind-quarters. These latter should be well muscled and covered by the same flatness of coat.

Limbs.—Shoulders, strong and oblique, and forearm big-boned and muscular; of medium length; pasterns short and strong; feet of proportionate size.

From the hinder face of the fore-limb there should be a sparing amount of feather, not of sufficiency to interfere with the dog when swimming.

When at rest the tail is carried down, but under excitement straight out, though slightly below the level of the back. Any tendency to curling of it, is very faulty.

Flat-coated Retriever Danehurst Rocket.

Flat-coated Retriever Busy Marquis (Property of Mr E. H. Blagg).

Flat-coated Retriever Dog.

Many capital working Retrievers carry their tails very badly, indicative of inferior breeding. What is equally important—no matter whether it be the Flat-, or Curly-coated variety—in a Retriever, is that of being good-tempered, obedient, persevering, quick to find, to remain at heel until given the word of command, and to have a very tender mouth.

If a dog is too headstrong, he will never make a good Retriever, running out directly a shot is fired. Must respond with alacrity to his master's word of command, in short, perfect obedience.

An "unstable" Retriever is not a useful dog; in fact, an annoyance. The chief faults of a Flat-coated Retriever are—too Setter-like in appearance, wavy coat, short coat, Spaniel-like ears, rusty tint, white hair, bad temper, disobedience, too long on the leg, too short on the leg, too much of the Newfoundland element, etc., etc.

(b) The Curly-coated

Of the two varieties, the Curly-coated can, we think, lay claim to have been the first established. In almost every particular, save that of coat, the Curly Retriever corresponds to the description given under the heading of (a)—the Flat-coat. Weight about 80 lbs. Particular attention is paid by judges to the coat. The dog must be covered all over with small tight curls, the tail to be the same. Any tendency towards slackness of curl or an open coat[56] necessarily handicaps the dog in the show ring. If black, should be free from any rusty tint, or from white. Face clean, neck long, and chest deep.

Liver Curly-coated specimens are nothing like so frequently met with as the black. Should be of an intense liver, free from white hairs and a nose of corresponding colour.

The Curly-coated Retriever Club has done much towards encouraging breeding typical specimens. Although very useful, we fancy that the Flat-coats are in more demand, probably because really A1 Curly-coats are not so readily obtainable at a moderate price, and an indifferent one, has not as good an appearance as an indifferent specimen of the Flat-coats.

At the recent Kennel Club Shows in London, etc., the proportion of Flat-coats to Curly was as three to one—the best evidence as to which is the most popular variety.

Labradors

At the Kennel Club Show there are classes for this variety of Retriever, and, in our opinion, the Labrador will, in course of time, become very popular amongst sportsmen, as they are excellent retrievers, when properly broken. They are wavy-coated dogs, either black, fawn, or yellow in colour, and, what is remarkable, these coloured dogs often appear in a litter belonging to a black sire and dam.

Curly-coated Retriever Dog.

White specimens have been produced, and it seems likely enough that a race of white Retrievers will, in course of time, become established, though, from a sportsman's view, they will not be as serviceable as their black or darker-coloured brethren.

The author remembers several fawn-coloured Labradors on an estate in Scotland, and the gamekeeper spoke most highly of the breed for work, though, constitutionally, somewhat delicate.

Constitutional Rules of the Retriever Society

1. That the object of the Society be to promote the breeding of pure Retrievers, and to develop and bring to perfection their natural qualities. In order to carry out these purposes, a working trial, if practicable, shall be annually held.

2. That the Society shall consist of a President, Vice-Presidents, a Committee, and an unlimited number of members.

3. That one-third of the Committee (exclusive of officers) shall be withdrawn by lot each year, at the Annual General Meeting for the first two years, and afterwards by rotation, and members shall be elected to fill their vacancies; the retiring members to be[60] eligible for re-election. The President, Vice-Presidents, and Honorary Secretaries shall be ex-officio members of the Committee, and shall be elected annually.

4. That the entire control and management of the Society shall be vested in the Committee (of which three shall form a quorum), who shall have power to make bye-laws, and decide upon all matters in dispute not provided for by the rules of the Society; and, further, that any member of the Committee, if unable to be present at a Committee Meeting, shall be permitted (upon application for same) to vote by proxy, duly signed, upon any resolution appearing upon the agenda paper, except as provided in Rule 8.

5. That each candidate for admission shall be proposed and seconded by members of the Society. The candidate's name, rank, residence, and profession or occupation, if any, shall be sent to the Secretary a fortnight before the election of candidates at the Committee Meeting; and that each member of the Committee be advised, at least seven days beforehand, of the proposed election of a new member of the Society.

6. That the election of members shall be vested solely in the Committee, and be made by ballot, two black balls to exclude.

7. That for the present no entrance fee shall be charged, and that the annual subscription shall be[61] one guinea, payable 1st January in advance; and that any member whose payments shall continue in arrear for six months shall (due notice of such arrear having previously been given in writing by the Secretary) have his name struck off the list, and shall cease to be a member of the Society. Any member joining the Society after the 31st October in any year shall not be liable for an annual subscription for the current year. Life membership may be acquired upon payment in a lump sum of ten guineas.

8. Any member of the Society who shall be proved to the satisfaction of the Committee to have in any way misconducted himself in connection with Dogs, Dog Shows, or Trials, or to have acted in any way which would make it undesirable that he should continue to be a member, shall be requested to retire from the Society; and if a resolution to that effect shall be carried by three-fourths of the Committee (present and voting), duly summoned or warned to the consideration of the case, the member so requested to retire shall henceforth cease to be a member of the Society.

9. That subscriptions and donations, after payment of all liabilities, shall be applied in such a manner as the Committee shall determine, for prizes at Trials or Workers' Classes at Dog Shows, or otherwise; and all balance shall be invested for the use of the Society, in such manner as the Committee shall direct.

10. That Committee Meetings may be held at each Trial Meeting of the Society, or at such other times and places as the Committee may determine, notice thereof having been duly sent to each member of the Committee.

11. That the Annual General Meeting of the Society be held in May or June, in London, and that a Special General Meeting may be called at any time, at such place as may be agreed to by the Committee, on the requisition of six members.

12. At every meeting the President, or one of the Vice-Presidents, shall be chairman, or failing these, a member of the Committee, such chairman to have a casting vote at all meetings. And, further, the minutes of the preceding meeting shall be read, approved, confirmed, and signed by the Chairman at the commencement of the next subsequent meeting.

13. Any member may withdraw from the Society on giving notice in writing to the Secretary, provided always that such member shall be liable for his subscription to the Society for the current year in which he gives such notice.

14. That the Secretary shall enter the name and address of each member of the Society in a book kept for that purpose.

A. E. Sansom,

Secretary,

12 and 13 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden.

Rules Adopted at the Retriever Society

(Subject to Alteration)

1. Before the Trials a number will be drawn by lot for each competing dog, and the dogs will be tried by batches accordingly during the first round. The handler of the dog must shoot with ammunition supplied by the Committee, and he will not be allowed to carry in his hand anything besides his gun. After all the competing dogs have been tried, the Judges will call up, at their own discretion, any dogs they require further, and try them again. No dog can win a prize which has not been subjected to both tests of "walking up" and "driving."

2. All aged dogs will be expected to retrieve fur as well as feather, if ordered to do so, but no handler must send his dog after any game until bidden by a Judge to do so. The Judges have power to order any handler to set his dog to retrieve game not shot by him personally.

3. The principal points considered by the Judges are sagacity, steadiness, nose, dash, perseverance, obedience, and retrieving. This last should be done quickly, with a tender and dry mouth, and right up to the hand.

4. Any dog not present to be tried in its turn, the Committee reserve the right of disqualifying at the expiration of fifteen minutes.

5. The Judges are empowered to turn out of the Stake the dog of any person who does not obey them or who wilfully interferes with another competitor or his dog, and to withhold a prize when, in their opinion, no merit is shown; and to exclude from competition bitches on heat, or any animals they may consider unfit to compete. The entry fees of all such dogs will be forfeited.

6. Certificates of merit will be awarded with a view to the establishment of Workers' Classes at the Dog Shows, and as a guide to purchasers of dogs which, though not in the list of prize-winners, give promise in their work of being valuable Sporting Dogs.

7. An objection to a dog may be lodged with the Secretary at any time within seven days of a meeting, upon the objector depositing with the Secretary the sum of £2, which shall be forfeited if the Committee deem such objection frivolous. All objections must be made in writing.

8. The Committee have the power, if they think fit, to refuse any entries for the Society's Trials, without assigning any reason for their action.

9. In the event of the weather being considered by the Committee unsuitable for holding the Trials, it shall be in their power to postpone the Meeting from day to day until the Saturday following the first day of the Trials, on which day the Stakes not already[65] decided shall be abandoned and their entry fees returned.

10. The Committee reserve to themselves the right to abandon the Meeting at any time, on returning their entry monies to the competitors, and if, from unforeseen circumstances, they deem it advisable to alter the date of the meeting, after the closing of the entries, this may be done by sending formal notice to all competitors that they may recover their entry fees by exercising the option of cancelling their entries within four days from the date of such notice. All entries, however, about which no such application is made within those four days, will stand good for the Meeting at its altered date.

11. If an advertised Judge be prevented from filling his engagement for either the whole or part of the Meeting, the Committee shall appoint any other person to judge, or shall make any other arrangements that to them seem desirable.

12. Upon any case arising not provided for in the above Rules, the Members of the Committee present shall decide, and their decision shall be final.

CHAPTER V

Spaniels

General Characteristics of the Different Varieties

Regarding the word "Spaniel" as a generic title, and the different varieties (Toys excepted) as "species" belonging to this genera, the author purposes taking a brief survey of certain features characteristic of Spaniels, leaving distinctive features for discussion under the various titles of classification as adopted by the Kennel Club. Judging from the literature at our disposal upon the subject, it is at once evident that the Spaniel of to-day—no matter how changed by selection—is of very ancient lineage, having existed as the Springing Spaniel and Cocking, for upwards of 600 years, and his uses were[67] then, as they are—or rather ought to be—now: to range well within gunshot, chase neither fur nor feather; never give tongue; find quickly, and retrieve tenderly on either land, or water.

All these excellences are revealed in many of the beautiful old coloured sporting prints, now so highly priced and prized, and so difficult to obtain, though when obtained are a joy for ever, gladdening the hearts of lovers of the old forms of such sport.

It is, we believe, universally accepted that the Spaniel originally came from Spain, but during what period, there is no reliable data to go upon. The departure, from what we may conveniently speak of as the normal type of Spaniel, is most marked in that of the Irish Water Spaniel, more especially in those coming from the north of Ireland.

Adhering to our original intention of general comparison, the author will first of all consider—

Temperament.—Most Spaniels are of a quick, inoffensive disposition, a sour temper being oftener the results of bad training than any inherent vice.

As with all other breeds, quarrels frequently arise over canine love affairs, etc. Few, we think, can speak of the Spaniel as a quarrelsome dog.

The sportsman's Spaniel—which is not commonly the show-bench animal—is of hardy constitution, taking the water in the coldest of weather, doing his[68] eight or ten hours' work in a day, and roughing it in the matter of food and kennelling.

The progeny of the working dog are not any more trouble to rear than those of a rough-and-tumble Terrier.

The "soft" constitution of so many black and Sussex Spaniels is due to that foolish system (in breeding) having been carried beyond all sense of reason.

All are water-loving dogs, and, when properly trained, retrieve their game tenderly.

Coat.—Either flat, wavy, or curly, a flat coat being typical of the up-to-date Spaniel. Many of the older type have a strong tendency to show a "top-knot," and even now and again (Water Spaniels excepted), in a litter of well-bred ones there is a reversion towards this type. All have an abundance of feather on both fore and hind limbs, Irish Water breed excepted.

Colour

| Irish Water Spaniel | Liver. | |

| English Water Spaniel | Liver and white, black and white, black, or black, white, and tan. | |

| The Clumber Spaniel | White, with red, lemon, or orange patches. | |

| The Sussex Spaniel | Golden liver. | |

| Field Spaniels(?) | Black or tri-coloured, also liver and white, or tan. | |

| [69]Cocker Spaniels | Black, black, white and tan, liver, roan, liver and white, black and white, red and white, etc., etc. | |

| English Springers | Variously coloured. | |

| Welsh Springers | Do. do. |

Liver, liver and white, black, and black and white, are by far the most frequent colours of the Spaniel. Tan markings are very common in Welsh Springers.

The Irish Water and the Clumber Spaniel are really the only two varieties free from the introduction of blood from other varieties of the breed.

Except in rare instances, the show-bench Sussex contains a lot of Field Spaniel blood, the result of crossing a typical Sussex Spaniel with a black bitch, over twenty years since, and its perpetuation until the present day.

Head and Ears.—They all agree in the anatomical outlines of their skulls, the greatest breadth being in the head of the Clumber.

Heavy facial expressions are characteristic of the pure Sussex, the half-bred, or Jacobs' strain of Sussex, and the Jacobs' strain of Black Spaniels. Many Cockers also show it.

Long ears, not only long in the cartilage, but heavily feathered—excepting the Northern Irish[70] Water—are very characteristic of Spaniels, but this large amount of hair in this region can hardly be a recommendation for work, knowing that it is very liable to become entangled in brambles, etc.

The occipital dome is well marked, and in some there is evidence of "stop," as in Toys. Muzzles generally broad; nose broad, and cheeks full.

Fore-limbs.—With the exception previously alluded to, Spaniels all agree in having a short arm and short forearm, largely augmented in the Spaniels of to-day (excepting Clumbers, etc.) through the introduction of Sussex blood.

From a sportman's point of view, this has been a detrimental influence, short legs greatly interfering with retrieving of hares, etc., although there may be what can be described as compensatory advantages, such as getting under the low runs of brushwood, etc.

The older type of Field Spaniel was vastly superior for work to many of the lethargical, long-bodied, low-legged, semi-intelligent specimens on the show benches at the present time.

Body.—Mostly of medium length, with well-sprung ribs, strong back and loins.

Tail carried on a level with the back. In all, the feet are full, and toes prominent, well feathered in the interspaces.

Length of body has always been a marked feature[71] of the Sussex, and "massiveness" characteristic of body, head and limbs in the Clumber.

From the foregoing outlines, it must be allowed that conformity of type throughout the whole of the Spaniels is general.

The points, etc., of the different varieties are as follows:—

The Clumber

Very early on, these Spaniels were bred at Clumber House, the seat of the Duke of Newcastle, one William Mansell having had the care of them under the Duke for a great number of years, and much was done to improve the beauty and utility of this handsome variety of Spaniel.

It is, in the author's opinion, the one variety of Spaniel that has suffered the least in the way of introducing the blood of other species. To attempt to cross the Clumber, with the object of making some improvement, is defeating the first principles of the Clumber exhibitor, purity of breed being the aim of his affection.

On the other hand, the introduction of Clumber blood into other strains of Spaniels, for working purposes at least, is rather beneficial than otherwise, and it is a cross frequently employed.

At one time the Duke of Portland had a very fine kennel of Clumbers, and when these dogs appeared[72] at the Palace or other Kennel Club Shows, they simply swept the boards.

Mr Holmes of Lancaster had also a strong team, though I did not like the appearance of his Clumbers anything akin to those shown by the Duke.

Probably the handsomest—we will not say the most typical—Clumber that ever adorned the show bench was Mr Parkinson's Champion "Trusty," though, for some unknown reason, this exhibitor quietly dropped from the show ring, and "Trusty" sank into insignificance.

My dog, Champion "Psycho," was one of the most typical Clumbers going the rounds, and deserved a much more successful career than he had. He was about as sweet-tempered a dog as it was possible to have, and formed a most devoted attachment to my mother, under whose care he chiefly was.

At one time the classes for Clumber Spaniels were well filled, though in recent years they have declined considerably.

Lately His Most Gracious Majesty the King, and the Duchess of Newcastle, have shown Clumbers, and this alone should give a fresh impetus towards the popularity of the breed. At anyrate, we hope it will have this effect.

When carefully broken, Clumbers make excellent workers, and can stand a lot of heavy work.

Clumber Spaniel Dog (Bobs of Salop).

A typical Clumber must be long, low and heavy. The author does not like a Clumber to be so short on the leg that the belly nearly sweeps the ground, and considers extreme lowness ought not to be encouraged. The Americans bred their Clumbers for use more than show bench, consequently kept up a good useful sort. Of course, any tendency to legginess is fatal to type.

Weight, about 55 lbs.; bitches a trifle less, and big in bone.

The Head of a Clumber is very characteristic. It must be "massive" in every sense of the word, or wide in all proportions, and the nose broad, full and flesh-coloured—a Dudley nose.

Ears.—Long, carried close to head and "set on" low with feathering on front edge, not elsewhere. [2] Eyes.—Deeply set in orbits, and rather large.

Coat.—Soft, silky, shining, straight, dense, and feather long and profuse.

For colour markings, we prefer orange ears, with an evenly marked head and ticked legs. Orange is a common marking. Less marking on the body the better.

Powerful loins; a long and straight back, and a[76] nicely rounded croup are essentials of beauty. A deep chest, well-rounded ribs, and powerfully-built fore-quarters are equally important.

A good Clumber must have staying power, and if he has not a well-developed muscular system, he cannot have this requisite.

Neck.—To be of medium length and stoutly built.

The head, body and hind-quarters constitute fifty per cent. of the total value of points, and the neck and shoulders fifteen per cent., hence the significance of being well done up in these regions.

Stout arms and forearms, with an abundance of feather, are necessary.

A good deal of brushing and combing, together with washing before showing, are needful to make the Clumber look fit. His heavy appearance can be increased by keeping him a bit above average condition.

One should be able to purchase a good pup—one likely to make a winner—for, say, ten guineas.

Club.—Clumber Spaniel.

The Sussex Spaniel

This is a very old variety of Spaniel, said to have originated in the county of Sussex, in the locality of Rosehill.

Mr Newington's Sussex Spaniel Dog Rosehill Rock.

Five-and-twenty years ago, typical specimens of the Rosehill strain were scarce, and since that time not a great deal has been done towards maintaining the purity of breed.

Very few Spaniels shown in the Sussex classes can claim purity of breeding, the introduction of black blood by mating Champion Bachelor to Negress, being the cause of this. Jacobs Bachelor was by Buckingham ex Peggie and own brother to Rover III.—though very different types of Spaniels.

The author was personally acquainted with these and many other old Sussex Spaniels.

I always took Buckingham to be a very typical Sussex and Rover III. was much of the same stamp as his sire; whereas Bachelor was more akin to the Dam Peggie—of course much her superior, though quite unlike his brother, Rover III.

At one time the judges would not look at Champion Bachelor, Messrs Willet then preferring Rover III.

Later on the order was reversed, and we believe—though cannot be certain—at the London Kennel Club Show. Champion Lawyer—at one time in my possession—was a heavily built type of Sussex. The Rev. Mr Shields, Mr Fuller, and Mr Newington, all had some of the pure Rosehills, and I also bought a good bitch from Mr Henry Hawkins by Rover III. ex Duchess. The last time that old Buckingham ever appeared on the show bench—and then not for[80] competition—was at the Royal Lancashire Agricultural Society's Show, held at Preston about 1880.

Although the litter out of which I bought Countess was an exceptionally good one—and Countess very typical—Messrs Willet would not award them prizes, owing, they said, to the faintest evidence of tan markings, observed with difficulty.

The typical colour for the Sussex is a light golden liver, and this Bachelor certainly was, Rover being darker.

Poor old Bachelor had a violent death through fighting with a kennel companion—a Gordon Setter.

Champion Rover III. was withdrawn from the show ring for some reason.

Even in those days animated discussion went on in the Press as to what was and what was not typical of the Sussex. There is no gainsaying one fact, and that is that the Sussex of twenty years ago existed in a different state of purity to what he does in the present day.

In casually looking over recent entries at the Kennel Club Show of Sussex Spaniels, it is questionable whether there is a single animal so entered that can justly claim the title of Sussex.

When Mr Jacobs had old Champion Bachelor in his possession, he had not more than one Sussex bitch to mate him with, to my recollection. There can be no doubt that the great improvement—for[81] the show bench—of the modern Spaniels began when Jacobs crossed Bachelor with old Negress, a black Field Spaniel bitch. It destroyed the purity of the Sussex, but if it had not been indulged in, there would, in all probability, have been no class for the breed now. Blacks, livers, and liver and tan, all used to come in the same litter out of Negress, who certainly constituted the nucleus of a fortune to her owner.

The points of the Sussex are as follows:—

Colour.—Deep golden liver.

Coat.—Flat, and slightly wavy, but absolutely free from any tendency to curl. Soft and abundant.

Weight.—About 40 lbs.

Head.—Heavy, though smaller and lighter than that of the Clumber.

Eyes.—Rather deeply set, giving the dog a very thoughtful expression.

Ears.—These should be long and well clothed with long, silky hair. Above, the ears ought to be rather narrow, but broad below, set on low down, and carried close to sides of head.

Nose.—Broad and liver-coloured, open nostrils.

Neck.—Short and strong, and the back long, strong, and level.

Shoulders and Chest.—A fairly deep chest, oblique shoulders, and well-sprung ribs are necessary.

Flat-sidedness, and "tucked up under" are decidedly faulty.

Fore-limbs.—Must be short on the leg. Arms and forearms short but well boned. Crooked fore-limbs are objectionable; turned out at elbows equally bad. There should be an abundance of feather springing from the backs of the fore-limbs, and down to the hocks, in the hind ones.

For the show bench the more feather the better.

Feet also well feathered, round and strong. The chief faults of the Sussex are: white hairs on any portion, tan markings, curly coat, too leggy, light in body, snipy head, short ears, want of feather, bad constitution, and Bloodhound expression on face.

Field Spaniels

To attempt to define the term "Field Spaniel" so as to be free from objection, would be, indeed, a difficult problem.

Unquestionably it is a very ambiguous term, and capable of wide interpretation. The mere fact of the Kennel Club and other shows having a class or classes for Field Spaniels, does not satisfy (though it simplifies classification) the mind of the thoughtful observer.

Anything from a half-bred Clumber, or Irish Water Spaniel may constitute a Field Spaniel, and rightly so, in the eyes of a sportsman.

That such dogs would win—say at a Kennel Club[83] Show—could not be entertained for a moment. It is the cross-bred Sussex that generally comes out top, and the longer and lower and more Sussex-like in character, the better the chances of success on the show bench. These are the author's views, though they may not coincide with those of others.

Some twenty-five years ago the "modern" Field Spaniel was as yet unknown. Jacobs' Champion Kaffir and Royle's Champion Zulu, and my dog Negro (by Kaffir ex Negress) were all black Field Spaniels of the Sussex type.

Zulu, with his Bloodhound-like eyes, had a remarkable show career, so had Kaffir, but they were not Field Spaniels from a sportsman's point of view, more especially Zulu. I had the two best pups[A]—one whole black and the other liver and tan—though, unfortunately for me, they both died from distemper before they were three months old. The black puppy I remember in particular. He was a facsimile of his dad, old Champion Bachelor, and had he lived, might have proved to be a little gold mine. Like his brother, nothing would ever have persuaded me that he was a "Field Spaniel," accepting that term as did the sportsman of days gone by.

My black Spaniel, Negro, though a big winner, was about as stupid a sportsman's dog or companion as ever saw daylight. The author's opinion is that[84] a Field Spaniel should have a fair length of leg, be of good size, have short, thick ears, and not much feather on them, or yet on the legs. Should be stoutly built, have a good tight jacket, be big-boned, have nice full eyes, well-rounded ribs, and, above all, quick hearing and a sound constitution. Colour unimportant, but black and white, black, or black, white and tan, or liver and white, for preference. Weight 40 to 50 lbs. There is no doubt that in course of time the Field Spaniel Trials will do much towards building up a proper type of field dog. A flat coat, of silky texture, and very glossy: long, heavily-feathered ears, short, strong, straight, cull-feathered fore-limbs, long body, and well-sprung ribs, long, graceful neck, and a long, moderately-wide head, with level carriage of the tail, are points of the Show Field Spaniel. Black (no white) or particolours (also liver) are preferred.

The Cocker Spaniel

This is a pretty type of small Spaniel, and one that has been in existence from a very early date.

Modern Cockers have been bred in all sorts of ways, though lately it has become a fairly general rule to breed only Cocker with Cocker, not necessarily of the same colour. A typical Cocker should weigh between 20 and 25 lbs., and be of smart, active appearance.

Typical Cocker Spaniel.

Probably two of the most successful black Cocker Spaniels ever adorning the show bench were Obo and Miss Obo. My (formerly Mr Easton's) Champion Bess was a very typical variety Cocker.

The American clubs' standard for Cockers is not quite the same as the English, the weight there being from 18 to 28 lbs.

Head.—Ought to be of medium length, and the muzzle square cut off, tapering from the eye, though there must be no appearance of the so-called "snipy" head.

There is a marked "stop," and from it there is a groove running up the skull, gradually fading away.

Ears.—Set on low, covered with long, silky, straight or wavy hairs, and reaching at least to the tip of nose.

Coat.—To be free from any sign of curl, plentiful, straight, or wavy and silky. Body of medium length, with well-sprung ribs, fairly deep chest, and full in the flanks. Many Cockers are very defective here, being what is called "tucked up."

Short fore-legs, strong, straight, well feathered, and well-placed, good-sized, feet. The tail should be carried on a level with back when dog is at ease, but lower under excitement.

Colour.—Unimportant; regularity and beauty of markings (if any) being qualifications.

Clubs.—The English Cocker Spaniel; the American Cocker Spaniel.

Prices.—Very typical puppies can be bought for three or four guineas shortly after weaning.

Faults.—Top-knot, out at elbows, light in bone, too leggy, and, from a sportsman's view, too short on leg. In whole-coloured specimens white is objectionable; shallow flanks, high carriage of tail, deafness, and bad constitution. Narrowness of chest, flat-sidedness, and a narrow flank constitutes faulty conformation.

The Irish Water Spaniel

There are said to be two distinct types of Irish Water Spaniels, one coming from the South and the other from the North of Ireland. The former is usually pure liver-coloured, with long and well-feathered ears, whereas the latter has short ears, and the liver colour mixed with considerable white.

One of the most characteristic features of the Irish Water Spaniel is his "top-knot," consisting of a crown of hair from the occiput to between the eyes, leaving the temples free. These Spaniels, to a sportsman of but slender means, in particular, cannot be over-valued. They are, so to speak, born to water, and in their element when retrieving wild-duck in the depth of winter, requiring very little tuition.

Irish Water Spaniel Pat O'Brien (Property of Major Birkbeck).

A famous dog of this variety, and one that had a wonderful show-bench career, was Mr Skidmore's Larry Doolan. The writer remembers this dog very well, as he was shown from north to south, east to west.

In Colour, these Irishmen should be a dark liver, free from any white hairs, unless it be a very small patch on the breast, or toes. A boiled liver (sandy) colour is objectionable.

Nose.—Large, of the same colour, and the Eyes a deep amber.

Skull.—High in the occipital dome, and of good width. A good top-knot essential.

Ears.—Set on low, having long cartilage (15 to 20 inches), and well feathered, the hair in this region being wavy and profuse.

Hair on tail short, and straight, blending the curls, towards its set-on , with those on the stern. Tail, whip-like.

Neck.—Long and well set up, blending below with strong shoulders.

A deep chest, strong back and loins, are necessary for the working capacity of the breed.

Coat.—Very important. To consist of tight, crisp curls all over body, and limbs. Fifteen per cent. of points go to the coat.

Height (shoulder measurement).—Not more than 24 inches, or less than 20 inches.

General Appearances.—To win, the Irish Water[92] Spaniel must look proportionate all over, be active, have a tight curly coat and a good top-knot, carry the head well up, be keen in facial expression, have a cat-like tail, and look as though he would be ready to dive at the word of command—in fact a workman from top-knot to tail.

Faults.—Total absence of top-knot, a fully feathered tail and much white hair will disqualify. An open woolly coat, light in colour, cording of hair, Setter feathering on legs, and a moustache, are objectionable, and should tell heavily against an Irishman in the show-ring.

Weight.—55 to 65 lbs.

Club.—The Irish Water Spaniel Society.

The English Water Spaniel

Bewick gives an excellent figure of a large Water Spaniel. It is generally liver-coloured and white, with the hair on the body in little curls. The dog is of medium size, strong, active and intelligent, and used by the water-fowl shooter.

In the Gentleman's Recreation and in the Sportman's Cabinet, this variety of dog is also described.

In the writer's opinion, there are plenty of these dogs to be seen about at the present time. They are larger than the Field Spaniel, and stronger built[93] altogether, looking as though they had both the blood of Retriever and Irish Water Spaniel in them.

The English Water Spaniel Club looks after the interests of this breed, and the Kennel Club provides a class for them.

A narrow head, small eyes, large nose, straight neck, strong back, rather narrow, deep chest, long strong legs, large feet, a six-inch dock, with a coat of ringlets or curls (no top-knot), and good general appearance, are the chief points.

Black, liver, liver and white, black and white, black and liver, are the accepted colours, but pied is most admired.

In addition to this breed of Spaniel, the Kennel Club also provides classes for English Springers and Welsh Springers.

CHAPTER VI

INTERNATIONAL GUNDOG LEAGUE

The Sporting Spaniel Society

Constitutional Rules

1. The name of the Society shall be "The Sporting Spaniel Society," its objects being to encourage the working qualities of Spaniels in every possible way, the breeding of them upon working lines, and the judging of them at shows from a working standpoint. All varieties of Sporting Spaniels, English and Irish Water, Norfolk, Clumber, Sussex, Black Springer, and Cocker Spaniels, and any other varieties of Spaniels used with the gun, shall be fostered and encouraged by this Society. It shall, if possible, hold a series of working Trials.