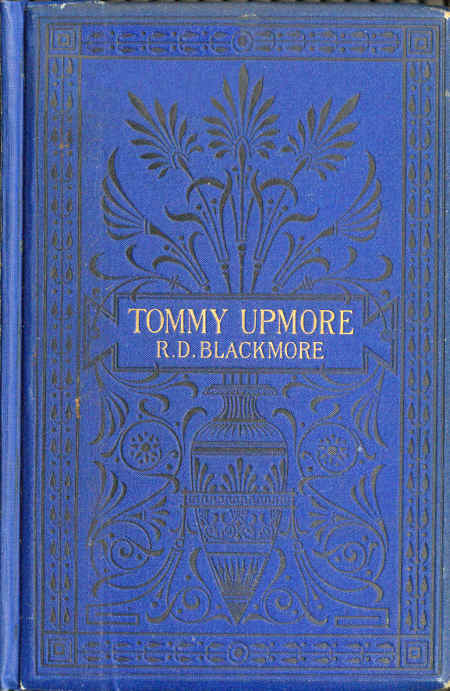

Title: The Remarkable History of Sir Thomas Upmore, bart., M.P., formerly known as "Tommy Upmore"

Author: R. D. Blackmore

Release date: August 1, 2014 [eBook #46467]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by sp1nd, Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

FORMERLY KNOWN AS

"TOMMY UPMORE."

A NEW EDITION.

LONDON:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE & RIVINGTON,

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188, FLEET

STREET.

1885.

(All rights reserved.)

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED.

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING-CROSS.

When Sir Thomas Upmore came, and asked me to write a short account of his strange adventures, I declined that honour; partly because I had never seen any of his memorable exploits. Perhaps that matters little, while his history so flourishes, by reason of being more creditable, as well as far more credible, than that of England, for the last few years.

Still, in such a case, the man who did the thing is the one to tell it. And his veracity has now become a proverb.

My refusal seemed to pain Sir Thomas, because he is so bashful; and no one can see him pained, without grieving for his own sake also, and trying to feel himself in the wrong.

This compelled me to find other arguments; which I did as follows:—

"First, my dear sir, in political matters, my humble view's are not strong, and trenchant—as yours are become by experience—but [Pg iv]exceedingly large, and lenient; because I have never had anything at all to do with politics.

"Again, of science,—the popular name for almost any speculation, bold enough,—I am in ignorance equally blissful, if it were not thrilled with fear. What power shall resist the wild valour of the man, who proves that his mind is a tadpole's spawn, and then claims for that mind supreme dominion, and inborn omniscience? Before his acephalous rush, down go piled wisdom of ages, and pinnacled faith, cloud-capped heights of immortal hope, and even the mansions everlasting, kept for those who live for them."

"All those he may upset," replied Sir Thomas, with that sweet and buoyant smile, which has saved even his supernatural powers, from the sneers of those below him; "or at least, he may fancy that he has done it. But to come to facts,—can he upset, or even make head, or tail, of such a little affair as I am? Not one of his countless theories about me has a grain of truth in it; though he sees me, and feels me, and pokes me in the side, and listens, as if I were a watch run down, to know whether I am going. I assure you, that to those who are not frightened by his audacity, and fame, his 'links of irrefragable proof' are but a baby's dandelion chain. In chemistry alone, and engineering, has science made much true advance. The main of the residue is arrogance."

"In that branch of science, we are all Professors," I answered, to disarm his wrath; knowing that, in these riper years, honest indignation wrought upon his system, as youthful exultation once had done; and I could not afford to have a hole made in my ceiling. "However, Sir Thomas, I shall stick to my resolve. Though your life—when its largeness is seen aright—will be an honour to the history of our race, justice comes before honour; and only you can do justice to it."

Humility, which competes with truth, for the foremost place in his character, compelled him to shake his head at this; and he began again, rather sadly.

"My purpose is a larger one, than merely to talk of my own doings. I want to put common sense into plain English, and to show—as our medical men show daily—that the body is beyond the comprehension of the mind. The mind commands the body to lie down, and be poked at, and probed, and pried into, with fifty subtle instruments, or even to be cut up, and analysed alive; and then understands never the more of it. If the mind can learn nothing of the body it lives in, grows, rejoices, and suffers with, how can it know all about it, for millions of years before either existed? How can it trace their joint lineage up to a thing, that had neither a head, nor a body?

"Go to; what I offer is not argument, but fact; and I care not the head of their ancestor for them.[Pg vi] But if I write it, will you remove whatever may offend a candid mind?"

"If you offend no mind but that," said I, being fresh from a sharp review of something I had written; "you will give small offence indeed; and to edit you will be a sinecure."

Both these predictions have proved correct; except indeed that a few kind readers of sadly unscientific mind have hankered for some explanation of parts which they failed to witness.

The reply is truly simple—"if you were not there the fault was yours; here are the facts as in evidence, better supported, and less strange, than those you accept without a wink; and perhaps your trouble in realising a case of specific levity proceeds from nothing but your own excessive specific gravity."

R. D. Blackmore.

1885.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Signs of Eminence | 1 |

| II. | Itur ad Astra | 10 |

| III. | The Dawn of Science | 16 |

| IV. | The Pursuit of Science | 25 |

| V. | "Grip" | 43 |

| VI. | True Science | 54 |

| VII. | The Great Washed | 65 |

| VIII. | For Change of Air | 75 |

| IX. | Thalatta! | 86 |

| X. | The New Admiral | 96 |

| XI. | Large Ideas | 106 |

| XII. | Twentifold Towers | 119 |

| XIII. | Whalebones | 131 |

| XIV. | A Silly Pair | 145 |

| XV. | Political Œconomy | 156 |

| XVI. | No Extras | 166 |

| XVII. | Self-defence | 178 |

| XVIII. | Ah Me! | 189 |

| XIX. | Comfort | 199 |

| XX. | Boil no more | 209 |

| XXI. | The Seat of Learning | 219 |

| XXII. | Hereditary Laws | 229 |

| [Pg viii]XXIII. | A County Meeting | 237 |

| XXIV. | Old Bones, and Young Ones | 247 |

| XXV. | On the Rocks | 256 |

| XXVI. | Beneath them | 266 |

| XXVII. | Pleasant, and Unpleasant Things | 277 |

| XXVIII. | The Welfare of the Family | 286 |

| XXIX. | Because he had no Pity | 295 |

| XXX. | Perfidy | 303 |

| XXXI. | Free Trade | 314 |

| XXXII. | A Pair of Blue Eyes | 326 |

| XXXIII. | Strong Intentions | 338 |

| XXXIV. | Fames Famæ | 350 |

| XXXV. | National Emergency | 362 |

| XXXVI. | Vote for Tommy! | 371 |

| XXXVII. | Sunny Bay | 379 |

| XXXVIII. | Prepare | 386 |

| XXXIX. | For Public and Private Benefit | 393 |

| XL. | Fair Counsel | 398 |

| XLI. | The Right Way to Surrender | 406 |

| XLII. | Spars | 415 |

| XLIII. | The Battle, and the Breeze | 421 |

| XLIV. | The English Lion | 435 |

TOMMY UPMORE.

If I know anything of mankind, one of them needs but speak the truth to secure the attention of the rest, amazed as they are at a feat so far beyond their own power and experience. And I would not have troubled any one's attention, if I could only have been let alone, and not ferreted as a phenomenon.

When the facts, which I shall now relate, were fresh and vivid in the public mind, it might have been worth twenty guineas to me to set them in order and publish them. Such curiosity, then, was felt, and so much of the purest science talked, about my "abnormal organism," that nine, or indeed I may say ten, of the leading British publishers went so far as to offer me £20,[1] with a chance of five dollars from America, if I would only write my history!

But when a man is in full swing of his doings and[Pg 2] his sufferings, how can he stop to set them down, for the pleasure of other people? And even now, when, if I only tried, I could do almost as much as ever, it is not with my own consent that you get this narrative out of me. How that comes to pass, you shall see hereafter.

Every one who knows me will believe that I have no desire to enlarge a fame, which already is too much for me. My desire is rather to slip away from the hooks and crooks of inquirers, by leaving them nothing to lay hold of, not even a fibre to retain a barb; myself remaining like an open jelly, clear, and fitter for a spoon than fork,—as there is said to be a fish in Oriental waters, which, being hooked, turns inside out, and saves both sides by candour.

One reason why I now must tell the simple truth, and be done with it, is that big rogues have begun to pile a pack of lies about me, for the sake of money. They are swearing one another down, and themselves up, for nothing else than to turn a few pounds out of me; while never a one of them knows as much as would lie on a sixpence about me. Such is the crop of crop-eared fame!

Now, if there is any man so eminent as to be made money of, surely he ought to be allowed to hold his own pocket open. Otherwise, how is he the wiser for all the wonder concerning him? And yet those fellows, I do assure you, were anxious to elevate me so high, that every sixpence pitched at me should jump down into their own hats. This is not to my liking; and I will do my utmost to prevent it. And when you know my peculiar case, you will say that I have cause for caution.

So fleeting is popularity, such a gossamer the clue of history, that within a few years of the time when I filled a very large portion of the public eye, and was kept in great type at every journal office, it may even be needful for me to remind a world, yet more volatile than myself, of the thrilling sensation I used to create, and the great amazement of mankind.

These were more natural than wise; for I never was a wonder to myself, and can only hope that a truthful account of my trouble will commend me, to all who have time enough to think, as a mortal selected by nature for an extremely cruel experiment, and a lesson to those who cannot enjoy her works, without poking sticks at them.

My father was the well-known Bucephalus Upmore—called by his best friends "Bubbly Upmore"—owner of those fine soap-boiling works, which used to be the glory of old Maiden Lane, St. Pancras. He was one of the best-hearted men that ever breathed, when things went according to his mind; blest with every social charm, genial wit, and the surprising products of a brisk and poetical memory. His figure was that of the broadest Briton, his weight eighteen stone and a half, his politics and manners Constitutional all over. At every step he crushed a flint, or split a contractor's paving-stone, and an asphalt walk was a quagmire to him.

My mother also was of solid substance, and very deep bodily thickness. She refused to be weighed, when philosophers proposed it; not only because of the bad luck that follows, but also because she was neither a bull, nor a pen of fat pigs, nor a ribboned turkey. But her husband vouched her to be sixteen[Pg 4] stone; and if she had felt herself to be much less, why should she have scorned to step into the scales, when she understood all the rights of women?

These particulars I set down, simply as a matter of self-defence, because men of science, who have never seen me, take my case to support their doctrine of "Hereditary Meiocatobarysm," as they are pleased to call it, presuming my father to have been a man of small specific gravity, and my mother a woman of levity. They are thoroughly welcome to the fact, out of which they have made so much, that the name of my mother's first husband was Lightbody—Thomas Lightbody, of Long Acre, a man who made springs for coaches. But he had been in St. Pancras churchyard, seven good years before I was born; and he never was mentioned, except as a saint, when my father did anything unsaintly.

But a truce to philosophy, none of which has ever yet bettered my condition. Let every tub stand, or if stand it cannot, let every tub fly on its own bottom. Better it is to have no attempt at explanation of my case, than a hundred that stultify one another. And a truly remarkable man has no desire to be explained away.

Like many other people, who have contrived to surprise the world before they stopped, I did not begin too early. As a child, I did what the other children did, and made no attempt to be a man too soon. Having plenty of time on my hands, I enjoyed it, and myself, without much thought. My mother alone perceived that nature intended me for greatness, because I was the only child she had. And when I began to be a boy, I took as kindly as any boy to[Pg 5] marbles, peg-top, tip-cat, toffy, lollipops, and fireworks, the pelting of frogs, and even of dogs, unless they retaliated, and all the other delights included in the education of the London boy; whose only remarkable exploit is to escape a good hiding every day of his life.

But as a straw shows the way of the wind, a trifle or two, in my very early years, gave token of future eminence. In the days of my youth, there was much more play than there ever has been since; and we little youngsters of Maiden Lane used to make fine running at the game of "I spy," and even in set races. At these, whenever there was no wind, I was about on a par with the rest of my age, or perhaps a little fleeter. But whenever a strong wind blew, if only it happened to be behind my jacket, Old Nick himself might run after me in vain; I seemed not to know that I touched the ground, and nothing but a wall could stop me. Whereas, if the wind were in front of my waistcoat, the flattest-footed girl, even Polly Windsor, could outstrip me.

Another thing that happened to me was this, and very unpleasant the effects were. My mother had a brother, who became my Uncle William, by coming home from sea, when everybody else believed him drowned and done for. Perhaps to prove himself alive, he made a tremendous noise in our house, and turned everything upside down, having a handful of money, and being in urgent need to spend it. There used to be a fine smell in our parlour, of lemons, and sugar, and a square black bottle; and Uncle William used to say, "Tommy, I am your Uncle Bill; come and drink my health, boy! Perhaps you will never[Pg 6] see me any more." And he always said this in such a melancholy tone, as if there was no other world to go to, and none to leave behind him.

A man of finer nature never lived, according to all I have heard of him. Wherever he might be, he regarded all the place as if it were made for his special use, and precisely adapted for his comfort; and yet as if something was always coming, to make him say "good-bye" to it. He had an extraordinary faith in luck, and when it turned against him, off he went.

One day, while he was with us, I came in with an appetite ready for dinner, and a tint of outer air upon me, from a wholesome play on the cinder-heaps. "Lord, bless this Tommy," cried Uncle William; "he looks as if he ought to go to heaven!" And without another word, being very tall and strong, he caught hold of me under the axle of my arms, to give me a little toss upward. But instead of coming down again, up I went, far beyond the swing of his long arms. My head must have gone into the ceiling of the passage, among the plaster and the laths; and there I stuck fast by the peak of my cap, which was strapped beneath my chin with Spanish leather. To see, or to cry, was alike beyond my power, eyes and mouth being choked with dust; and the report of those who came running below is that I could only kick. However, before I was wholly done for, somebody fetched the cellar-steps, and with very great difficulty pulled me down.

Uncle William was astonished more than anybody else, for everybody else put the blame upon him; but he was quite certain that it never could have happened, without some fault on my part. And this made a[Pg 7] soreness between him and my mother, which (in spite of his paying the doctor's bill for my repairs, as he called it) speedily launched him on the waves again, as soon as his money was got rid of.

This little incident confirmed my mother's already firm conviction that she had produced a remarkable child. "The Latin Pantheon is the place for Tommy," she said to my father, every breakfast time; "and to grudge the money, Bucephalus, is like flying in the face of Providence."

"With all my heart," father always answered, "if Providence will pay the ten guineas a quarter, and £2 15s. for extras."

"If you possessed any loftiness of mind," my mother used to say, while she made the toast, "you would never think twice of so low a thing as money, against the education of your only child; or at least you would get them to take it out in soap."

"How many times must I tell you, my dear, that every boy brings his own quarter of a pound? As for their monthly wash, John Windsor's boy, Jack, is there, and they get it out of him."

"That makes it so much the more disgraceful," my mother would answer, with tears in her eyes, "that Jack Windsor should be there, and no Tommy Upmore! We are all well aware that Mr. Windsor boils six vats for one of ours; and sixty, perhaps, if he likes to say it. But, on the other hand, he has six children against our one; and which is worth the most?"

My father used to get up nearly always, when it came to this, and take his last cup standing, as if his work could not wait for him. However, it was forced into his mind, more and more every morning, that my[Pg 8] learning must come to a question of hard cash, which he never did approve of parting with. And the more he had to think of it, the less he smiled about it. At last, after cold meat for dinner three days running, he put his best coat on and walked off straightway for the Partheneion, which is in Ball's Pond, Islington. He did not come home in at all a good temper, but boiled a good hour after boiling time, and would not let any one know, for several days, what had gone amiss with him.

For my part, having, as behoves a boy, no wild ambition to be educated, and hearing from Jack Windsor what a sad case he was in, I played in the roads, and upon the cinder-hills, and danced defiance at the classic pile, which could be seen afar sometimes, when the smoke was blowing the other way. But while I was playing, sad work went on, and everything was settled without my concurrence. Mrs. Rumbelow herself, the Doctor's wife, lady president of the college, although in a deeply interesting state—as dates will show hereafter—not only came in a cab to visit my mother, but brought with her on the dicky, as if he were nobody, the seventh nephew of the Lord Mayor of London, who could do a Greek tree, if it was pencilled out.

This closed all discussion, and clenched my fate, and our tailor was ordered to come next morning. My father had striven his utmost to get me taken as a day-boy, or at any rate to be allowed to keep a book against the Muses. But Mrs. Rumbelow waved her hand, and enlarged upon liberal associations, and the higher walks of literature, to such an extent that my father could not put a business foot in anywhere. And[Pg 9] before I was sent to bed that night, when I went for my head to be patted, and to get a chuck below the chin, he used words which hung long in my memory.

"Poor Tommy, thy troubles are at hand;" he said, with a tender gaze at me beneath his pipe. "They can't make no profit from the victualling of thy mind; but they mean to have it out of thy body, little chap. 'Tis a woe as goes always to the making of a man. And the Lord have mercy on thee, my son Tommy!"

[1] Sir Thomas cannot be accepted here, without a good-sized grain of salt. Exciting as his adventures are, and sanguine as his nature is, what can he be thinking of, in the present distress of publisher, strict economy of libraries, and bankruptcy of the United States?

The grandest result of education is the revival of the human system, which ensues when it is over. If it be of all pangs the keenest to remember joy in woe, and of all pleasures the sweetest to observe another's travail, upon either principle, accommodated (as all principles are) to suit the purpose, how vast the delight of manhood in reflecting upon its boyhood!

Dr. Rumbelow, of the Partheneion, which is in Trotter's Lane, Ball's Pond, combined high gifts of nature with rich ornaments of learning. In virtue of all this, he strove against the tendency of the age towards flippancy, and self-indulgence, the absence of every high principle, and the presence of every low one. Having to fill both the heads and the stomachs of thirty-five highly respectable boys, he bestirred himself only in the mental part, and deputed to others the bodily—not from any greed, or want of feeling, but a high-minded hatred of business, and a lofty confidence in woman. So well grounded was this faith, that Mrs. Rumbelow never failed to provide us with fine appetites.

Here, and hence, I first astonished the weak minds of the public, and my own as much as anybody's.[Pg 11] Although we had several boys of birth, the boy of largest brains and body took the lead of all of us. And this was Bill Chumps, now Sir William Chumps, the well-known M.P. for St. Marylebone. His father was what was then called a "butcher," but now a "purveyor of animal provisions." He supplied under contract the whole Partheneion; and his meat was so good that we always wanted more.

Bill Chumps, being very quick at figures, had made bright hits about holidays impending, by noting the contents of the paternal cart, and blowing the Sibylline leaves of the meat-book, handed in by the foreman. But even Chumps was not prepared for a thing that happened one fine Friday.

We had been at work all the afternoon, or, at any rate, we had been in school; and a longing for something more solid than learning began to rise in our young breasts.

"Oh, shouldn't I like a good pig's fry?" the boy next to me was whispering.

"Or a big help out of a rump-steak pie?" said the fellow beyond him, with his slate-sponge to his mouth.

But Chumps said, "Bosh! What's the good of pigs and pastry? Kidneys, and mushrooms, is my ticket, Tommy. Give us the benefit of your opinion."

Chumps was always very good to me, although I was under his lowest waistcoat-button. For my father was a very good customer of that eminent butcher his father; not only when he wanted a choice bit of meat, but also as taking at a contract-price all bones that could not be sent out at a shilling a pound,[Pg 12] as well as all the refuse fat, which now makes the best fresh butter.

In reply to that important question, I looked up at Chumps, with a mixture of hesitation and gratitude. Being a sensitive boy, I found it so hard to give an opinion without offence to elder minds, yet so foolish to seem to have no opinion, and to spoil all the honour of being consulted. A sense of responsibility made me pause, and ponder, concerning the best of all the many good things there are to eat, and to lay "mechanically," as novelists express it, both hands upon a certain empty portion of my organization, when Dr. Rumbelow arose!

We did not expect him to get up yet for nearly three-quarters of an hour, unless any boy wanted caning; and at first a cold tremor ran through our inmost bones, because we respected him so deeply. But a glance at his countenance reassured us. The doctor stood up, with his college-cap on, a fine smile lifting his gabled eyebrows (as the evening sun lights up gray thatch), his tall frame thrown back, and his terrible right hand peacefully, under his waistcoat, loosening the button of didactic cincture. He spread forth the other hand, with no cane in it; and a yawn—such as we should have had a smack for—came to keep company with his smile.

"Boys!" he shouted, sternly at first, from the force of habit when we made a noise; "boys, Lacedæmonians, Partheneionidæ, hearken to the words which I, with friendly meaning, speak among you. It has been ordained by the powers above, holding Olympian mansions, that all things come in circling turn to mortal men who live on corn. Times there are for[Pg 13] the diligent study of the mighty minds of old, such as we, who now see light of sun, and walk the many-feeding earth, may never hope to equal. But again there are seasons, when the dies festi must be held, and the feriæ Latinæ, which a former pupil of mine translated 'a holiday from Latin.' Such a season now is with us. Once more it has pleased the good Lucina to visit our humble tugurium; and we are strictly called upon to observe the meditrinalia. Since which things are so, it behoves me to proclaim to all of you feriæ tridui imperativæ."

The doctor's speech had been so learned, that few of us were able to make out his meaning. But Chumps was a boy of vast understanding, and extraordinary culture.

"Three days' holiday. Holloa, boys, holloa!" cried Chumps, with his cap going up to the roof. "Three days' holiday! Rump-steak for breakfast, and lie a-bed up to nine o'clock. Hurrah, boys! holloa louder, louder, louder! Again, again, again! Why, you don't half holloa!"

To the ear of reason it would have been brought home, that the boys were holloaing quite loud enough; and of that opinion was our master, who laid his hands under his silvery locks, while the smile of good-will to us, whom he loved and chastened, came down substantially to the margin of his shave. But behold, to him thus beholding, a new and hitherto unheard-of prodigy, wonderful to be told, arose! He sought for his spectacles, and put them on; and then for his cane, and laid hold of it—because he beheld going up into the air, and likely to get out of his reach, a boy!

It is not for me to say how I did it. Nobody was more amazed than I was; although after all that had happened ere now to me, I might have been prepared for it. Much as I try to remember what my feelings were, all I can say is that I really know not; and perhaps the confusion produced by going round so (to which I was not yet accustomed), and of looking downward at the place I used to stand on, helped to make it hard for me to think what I was up to.

With no consideration, as to what I was about, and no sense of being out of ordinary ways, I found myself leaving all the ground, and its places, not with any jump, or other kind of rashness, but gently, equably, and in good balance, rising to the shoulders of the other little chaps, and then over the heads of the tallest ones. My sandals, because of the weather being warm, were tied with light-blue ribbon, according to the wishes of my mother; and these made a show which I looked down at, while everybody else stared up at them.

Chumps was a very tall boy for his age, by reason of all the marrow-bones he got; and the same thing had gifted him with high courage. So that while all the other boys could only stare, or run away, if their nerves were quick, he made a spring with both hands at my feet, to fetch me back to the earth again. And at the same instant he said, "Tommy!" in the very kindest tone of voice, entreating me to come down to him.

I do not exaggerate in saying that I strove with all my power to do this; and with his kind help I might have done it, if the string of my shoe had been sewed in. But unhappily, like most things now, it was made for ornament more than use; and so it[Pg 15] slipped out and was left in his hand; while, much against my will, I rose higher and higher. At the same time I found myself going round and round, so that I could not continue to observe the countenance of Dr. Rumbelow, gazing sternly, and with some surprise, at me. But I saw him put on his spectacles, which was always a bad sign for us.

"Capnobatæ is the true reading in Strabo, as I have so long contended. Fetch me a cane!—a long, long, cane!" the doctor shouted, as I still went up. "This is the spirit of the rising age! I have long expected something of this kind. I will quell it, if I have to tie three canes together. Thomas Upmore, come down, that I may cane you. Not upon my head, boy, or how can I do it?"

For no sooner had I heard what was likely to befall me, than my heart seemed to turn into a lump of cold lead. At once my airy revolutions ceased, my hands (which had been hovering like butterflies) stopped, and dropped, like beetles that have struck against a post, and down I came plump, with both feet upon the tassel of the trencher-cap upon the doctor's head.

This must have been a very trying moment, both for his patience and my courage, and it is not fair to expect me to remember everything that happened. However, I feel that if I had been caned, there would have been a mark upon my memory; even as boys bear the limits of the parish in their minds, through their physical geography. Likely enough my head was giddy, from so much revolving; and Chumps living near us marched me home, with a big lexicon strapped on my back, to prevent me from trying to fly again.

Most people, and more especially our writers of fiction, history, philosophy, and so forth, indulge in reflection, at those moments, when they are soaring above our heads; but I have always found myself so unlucky in this matter, as in many others, that nothing would ever come into my head, when aloft, to be any good when I came down. Or, at least only once, as will be shown hereafter; and that was the exception, which proves the rule.

Otherwise, I might now give many nice and precise descriptions of "variant motions and emotions, both somatic and psychical"—as Professor Brachipod expressed them—which must, according to his demonstration, have been inside me, at my first flight. Very likely they were; and even if they were not, it would never pay me to be positive—or negative perhaps is the proper word now—because ignorant science is remunerative, and nothing can be got by impugning it.

Yet that consideration, I assure you, has nothing to do with my present silence. I am silent, simply because I know nothing; and if all so placed would try my plan, how much less would be said and[Pg 17] written! Nevertheless all biologists, psychologists, anthropologists, and the rest of our race who make it their study (after proving it wholly below their heed) these men, if they deign to be called such, have a claim upon me for all my facts; which I will not grudge, when I know them.

From the very outset, they felt this; and my father and mother, who had not slept well, through talking so much of my above adventure—recounted perhaps with some embellishment by Chumps—hardly had got through their breakfast before some eminent "scientists" were at them. For my part, having made a hearty supper, (after long scarcity of butcher's meat,) or perhaps from having swallowed so much air, I had slept long and soundly, and was turning for another good sleep, when I heard great voices.

"Madam, allow me to express surprise," were the words which came up to me, through the ceiling, at the place where my head had made the hole, "extreme surprise at the narrowness of your views. Must I come to the conclusion, that you refuse to forward the interests of science?"

"Sir," replied mother, who was always polite, when she failed to make out what people meant, "science is what I don't know from the moon. But I do know what my Tommy is."

"My dear Mrs. Upmore," was the answer, in a soft sweet voice, which I found afterwards to be that of Professor Brachipod, "in consulting the interests of science, we shall consult those of the beloved Tommy. His existence is so interwoven with a newly formed theory of science"——

"You impudent hop'-my-thumb, what do you mean," broke in a deep sound, which I knew to be my father's, "by calling my wife your dear indeed? First time as ever you set eyes on her. Out you go, and no mistake."

Upon this ensued a heavy tread, and a little unscientific squeak; and out went Professor Brachipod, as lightly as if on the wings of his theory.

"Upmore, this violence is a mistake," another and larger voice broke in, as my father came back quietly; "the Professor's views may be erroneous; but to eliminate him, because of somatic inferiority, is counter to the tendency of the age. My theory differs from his, toto cœlo. But in the cause of pure reason, I protest against unmanly recourse to physics."

"You shall have the same physick, if you don't clear out;" said my father, as peaceable a man as need be, till his temper was put up; "an Englishman's house is his castle. No science have a right to come spoiling his breakfast. You call me unmanly, in your big words. You are a big man, and now I'll tackle you. Out goes Professor Jargoon."

There was some little scuffle, before this larger Professor was "eliminated," because he was a strong man, and did not like to go; but without much labour he was placed outside.

"Now, if either of you two chaps comes back," my father shouted from his threshold, "the science he gets will be my fist. And lucky for him, he haven't had it yet."

Running to the window of my room, I saw the professors, arm-in-arm, going sadly up the cinder-heaps; and glad as I was to be quit of them, I did not like[Pg 19] the way of it. However, I hoped for the best, and went down in my trousers and braces to breakfast. My father was gone to his boiling by this time, for nothing must ever interfere with that; but my mother would never give up her breakfast, till she saw the bottom of the teapot.

"Oh, Tommy darling," she cried, as she caught me, and kissed me quite into the china-cupboard, for we always had breakfast in the kitchen, when out of a maid-of-all-work: "my own little Tommy, do you know why you fly? All the greatest men in the kingdom have been here, to prove that you do it from reasons of Herod, Heroditical something—but he was a bad man, and murdered a million of little ones. They may prove what they like; and of course they know more about my own child, than I do. I don't care that for their science," said mother, snapping her thumb, which was large and very fat; "but tell me, Tommy, from your own dear feelings, what it was that made you fly so?"

"I didn't fly, mother; I only went up, because I could not help it. Because I was so empty, and felt certain of getting full again, quite early in the holidays."

"Begin at once, darling, and don't talk. Oh, it is a cruel, cruel thing, that you should leave the ground for want of victuals, when your father clears eight pounds a week. Deny it as he may, I can prove it to him. But I have found out what makes you fly. A flip for their science, and thundering words!"

"Well, mother, I don't want to do it again;" I answered as well as I could, with my mouth quite full of good bacon, and a baker's roll; "but do please tell me what made me do it."

"Tommy, the reason is out of the Bible. You cannot help flying, just because you are an angel."

"They never told me that at school," I said; "and old Rum would have caned me, if he could reach. But he never would have dared to cane an angel."

"Hush, Tommy, hush! How dare you call that learned old gentleman, with white hair, 'old Rum'? But never mind, darling. Whatever you do, don't leave off eating."

For this I might be trusted, after all I had been through; and so well did I spend my days at home (especially when Bill Chumps came to dine with us, upon his own stipulation what the dinner was to be), that instead of going up into the air at all, the stoutest lover of his native land could not have surpassed me in sticking to it.

Chumps, though the foremost of boys, was inclined to be shy with grown-up people, till mother emboldened him with ginger-wine, and then he gave such an account of my exploit, that my father, and mother, looked at him with faces as different as could be. My mother's face was all eyes and mouth, with admiration, delight, excitement, vigorous faith, and desire for more; my father's face was all eyebrows, nose, and lips; and he shook his big head, that neighbour Chumps should have such a liar for his eldest son. Nothing but the evidence of his own eyes would ever convince Bucephalus Upmore, that a son of his, or of any other Englishman, came out of an egg; without which there was no flying.

"Mr. Upmore, you should be ashamed of yourself," my mother broke in rather sharply, "to argue such[Pg 21] questions before young boys. But since you must edify us, out with your proof that the blessed angels were so born. Or will you deny them the power to fly?"

"Never did I claim," answered father, with a little wink at Chumps, "to know the ins and outs of angels, not having married one, as some folk do, until they discover the difference. Our Tommy is a good boy enough, in his way; but no angel, no more than his parents be. If ever I see him go up like a bubble, I'll fetch him down sharp with my clout-rake; but if I don't use my rake till then, it will last out my lifetime, I'll bet a guinea. Now, Tommy, feed, and don't talk or look about. You'll be sorry when you get back to school, for every moment that you have wasted."

"My mind is not altogether clear," said mother, "about letting him go back to the Latin Pantheon"—this was her name for the Partheneion; "he is welcome to have a gentle fly now and then, as Providence has so endowed him, and I am sure he would never fly away from his own mother; but as for his flying, because he is empty in his poor inside—I'll not hear of it. Bucephalus, how would you like it?"

"Can't say at all, mother, till I have tried it. Shall be glad to hear Tommy's next experience. Back he goes to-morrow morning; and by this day week, if they starve him well, he'll be fit to go sky-high again. A likely thing, indeed, that I should pay ten guineas beforehand, for a quarter's board, and tuition in classics and mathematics, all of the finest quality, and another ten guineas in lieu of notice, and get only three weeks for the whole of it! Come, Tommy, how much have you learned, my boy?"

"Oh, ever such a lot, father! I am sure I don't know what."

"Well, my son, give us a sample of it. Unless there's too much to break bulk at random. Tip us a bit of your learning, Tommy."

"Wait a bit, father, till I've got my fingers up. When they come right, I say hic, hæc, hoc, and the singular number of musa, a song. I have told mother every word of it."

"Out and out beautiful it sounds," said mother; "quite above business, and what goes on in the week. Dr. Rumbelow must be a wonderful man, to have made such great inventions."

"Well, it's very hard to pay for it, and leave it in the clouds," my father said, sniffing as if he smelled pudding. "Let's have some more of it, sky-high Tommy."

My mother looked at me, as much as to say, "Now, my dear son, astonish him"; and my conscience told me that I ought to do it; and I felt myself trying very hard indeed to think; but not a Latin word would come of it. Perhaps I might have done it, if it had not been for Chumps, who kept on putting up his mouth, to blow me some word, bigger than the one that I was after; while all that I wanted was a little one. And father leaned back, with a wink, to encourage me to take the shine out of himself, by my learning. But I could only lick my spoon.

"Come, if that is ten guineas' worth of Latin," said my father, "I should like to know what sixpenn'orth is. Tell us the Latin for sixpence, Tommy."

It was natural that I should not know this; and I doubt whether even Chumps did, for he turned away,[Pg 23] lest I should ask him. But my mother never would have me trampled on.

"Mr. Upmore, you need not be vulgar," she said, "because you have had no advantages. Would you dare to speak so, before Latin scholars? Even Master Chumps is blushing for you; and his father a man of such fine common sense! No sensible person can doubt, for a moment, that Tommy knows a great many words of Latin, but is not to be persecuted out of them, in that very coarse manner, at dinner time. Tell me, my dear," she said, turning to me, for I was fit to cry almost, "what is the reason that you can't bring out your learning. I am sure that you have it, my chick; and there must be some very good reason for keeping it in."

"Then, I'll tell you what it is," I answered, looking at my father, more than her; "there is such a lot of it, it all sticks together."

"That's the best thing I ever heard in my life;" cried father, as soon as he could stop laughing, while Chumps was grinning wisely, with his mouth full of pudding. "What a glorious investment of my ten guineas, to have a son so learned, that he can't produce a word of it, because it all sticks together! To-morrow, my boy, you shall go back for the rest of it. Like a lump of grains it seems to be, that you can't get into with a mashing-stick. Ah, I shall tell that joke to-night!"

"So you may," said mother, "so you may, Bucephalus; but don't let us have any more of it. 'Tis enough to make any boy hate learning, to be blamed for it, so unjustly. Would he ever have flown, if it had not been for Latin? And that shows how[Pg 24] much he has got of it. Answer that, if you can, Mr. Upmore."

But my father was much too wise to try. "Sophy, you beat me there," he said; "I never was much of a hand at logic, as all the clever ladies are. Bill Chumps shall have a glass of wine after his pudding, and Tommy drink water like a flying fish; and you may pour me a drop from the black square bottle, as soon as you have filled my pipe, my dear."

"That I will, Bucephalus, with great pleasure; if you will promise me one little thing. If Tommy goes back to that Latin Pantheon, they must let him come home, every Sunday."

"Fly home to his nest, to prevent him from flying;" my father replied, with a smile of good humour, for he liked to see his pipe filled; "encourage his crop, and discourage his wings. 'Old Rum,' as they call him, wouldn't hear of that at first. But perhaps he will, now that he has turned out such a flyer."

Many people seem to find the world grow worse, the more they have of it; that they may be ready to go perhaps to a higher and better region. But never has this been the case with me, although I am a staunch Conservative. My settled opinion is that nature (bearing in her reticule the human atom) changes very slowly, so that boys are boys, through rolling ages; even as Adam must have been, if he had ever been a boy.

At any rate, the boys at Dr. Rumbelow's were not so much better than boys are now, as to be quoted against them. They certainly seem to have had more courage, more common-sense, and simplicity, together with less affectation, daintiness, vanity, and pretension. But, on the other hand, they were coarser, wilder, and more tyrannical, and rejoiced more freely than their sons do now, in bullying the little ones. The first thing a new boy had to settle was his exact position in the school; not in point of scholarship, or powers of the mind, but as to his accomplishments at fisticuff. His first duty was to arrange his schoolfellows in three definite classes—those who could whack him and he must abide it, those he would[Pg 26] hit again if they hit him, and those he could whack without any danger, whenever a big fellow had whacked him. Knowledge of the world, and of nature also, was needed for making this arrangement well: to over-esteem, or to undervalue self, brought black eyes perpetual, or universal scorn.

But to me, alas, no political study of this kind was presented. All the other boys could whack me, and expostulation led to more. Because I was the smallest, and most peaceful, among all the little ones, and the buoyancy of my nature made a heavy blow impossible. Yet upon the whole, the others were exceedingly kind and good to me, rejoicing to ply me with countless nicknames, of widely various grades of wit, suggested by my personal appearance, and the infirmity of lightness. Tom-tit, Butterfly-Upmore, Flying Tommy, and Skylark, were some of the names that I liked best, and answered to most freely; while I could not bear to be called Soap-suds, Bubbly, Blue-bottle, or Blow-me-tight. But whatever it was, it served its turn; and the boy, who had been witty at my expense, felt less disposed to knock me.

But, even as with the full-grown public, opinion once formed is loth to budge, so with these boys it was useless to argue, that having flown once, I could not again do it. If they would have allowed me simply to maintain the opposite, or to listen mutely to their proofs, it would have been all right for either side. But when they came pricking me up, with a pin in the end of a stick, or a two-pronged fork (such as used to satisfy a biped with his dinner, and a much better dinner then he gets now), endeavouring also to urge me on high, by an elevating grasp[Pg 27] of my hair and ears, you may well believe me, when I say how sadly I lamented my exploit above. I was ready to go up, I was eager to go up; not only to satisfy public demand, but also to get out of the way of it; and more than once I did go up, some few inches, in virtue of the tugs above, and pricks in lower parts of me. But no sooner did I begin to rise, with general expectation raised, and more forks ready to go into me, than down I always came again, calling in vain for my father and mother, because I could not help it.

Upon such occasions, no one had the fairness to allow for my circumstances. Every one vowed that I could fly as well as ever, if I tried in earnest; and I was too young to argue with them, and point out the real cause; to wit the large and substantial feeding, in which I employed my Sundays. By reason of this I returned to school, every Monday morning, with a body as heavy as my mind almost; and to stir up either of them was useless, for a long time afterwards.

As ill luck would have it, it was on a Monday, that science made her next attack on me. And now let me say, that if ever you find me (from your own point of view) uncandid, bigoted, narrow-minded, unsynthetical, unphilosophical, or anything else that is wicked and low, when it fails to square with theories,—in the spirit of fair play you must remember what a torment science has been to me.

Five of them came, on that Monday afternoon, four in a four-wheeler, and one on the dicky; and we had a boy who could see things crooked, through some peculiar cast of eye, and though the windows were[Pg 28] six feet over his head, he told us all about it, and we knew that he was right.

Presently in came the doctor's page (a boy who was dressed like Mercury, but never allowed in the schoolroom, unless he had urgent cause to show); his name was Bob Jackson, and we had rare larks with his clothes, whenever we got hold of him—and he waved above his head, as his orders were to do, a very big letter for the doctor. Every boy of us rushed into a certainty of joy—away with books, and away to play! But woe, instead of bliss, was the order of the day. Dr. Rumbelow never allowed himself to be hurried, or flurried, by anything, except the appearance of his babies; and when he was made, as he was by and by, a Bishop, for finding out something in Lycophron, that nobody else could make head or tail of, he is said to have taken his usual leisure, in loosing the button enforced by Mrs. Rumbelow, ere ever he broke the Prime Minister's seal.

"Boys," he said now, after looking at us well, to see if anybody wanted caning, "lads who combine the discipline of Sparta with the versatile grace of Athens, Mr. Smallbones will now attend to you. Under his diligent care, you will continue your studies eagerly. In these degenerate days, hard science tramples on the arts more elegant. Happy are ye, who can yet devote your hours to the lighter muses. At the stern call of science (who has no muse, but herself is an Erinnys), I leave you in the charge of Mr. Smallbones. Icarillus, you will follow me, and bring the light cane, with the ticket No. 7. A light cane is sweeter for very little boys."

My heart went down to my heels, while bearing my[Pg 29] fate in my hands, I followed him. Conscience had often reproached me, for not being able to fly, to please the boys. Universal consent had declared that it all was my fault, and I ought to pay out for it. What was the use of my trying to think that the world was all wrong, and myself alone right? Very great men, like Athanasius, might be able to believe it; but a poor little Tommy like me could not. But I tried hard to say to the doctor's coat-tails, "Oh, please not to do it, sir, if you can please to help it."

Dr. Rumbelow turned, as we crossed a stone passage (where my knees knocked together from the want of echo, and a cold shiver crept into my bones), and, seeing the state of my mind and body, and no boy anywhere near us, he could not help saying, "My poor Icarillus, cheer up, rouse up, tharsei! The Romans had no brief forms of encouragement, because they never required it. But the small and feeble progeny of this decadent country—Don't cry, brave Icarillus; don't cry, poor little fellow; none shall touch you but myself. What terror hath invaded you?"

The doctor stooped, and patted my head, which was covered with thick golden curls, and I raised my streaming eyes to him, and pointed with one hand at the cane, which was trembling in my other hand. My master indulged in some Latin quotation, or it may have been Greek for aught I know, and then translated, and amplified it, as his manner was with a junior pupil.

"Boys must weep. This has been ordained most wisely by the immortal gods, to teach them betimes the lesson needed in the human life, more often than[Pg 30] any other erudition. But, alas for thee, poor Icaridion! it seems, as from the eyes afar, a thing unjust, and full of thambos. For thou hast not aimed at, nor even desired, the things that are unlawful, but rather hast been ensnared therein, by means of some necessity hard to be avoided. Therefore I say again, cheer up, Tommy! Science may vaunt herself, as being the mistress of the now happening day, and of that which has been ordained to follow; but I am the master of my own cane. Thomas Upmore, none shall smite thee."

A glow of joy came into my heart, and dried up my tears in a wink or two, for we knew him to be a true man of his word, whether to cane, or to abstain; and if the professors had kept in the background, I might have soared up for them, then and there. But it never is their nature to do that; and before I had time to be really happy, four out of the five were upon me. Hearing the doctor's fine loud voice, they could no more contain themselves, but dashed out upon us, like so many dragons, on the back of their own eminence—Professors Brachipod, and Jargoon, Chocolous, and Mullicles; than whom are none more eminent on the roll of modern science. The fifth, and greatest of them all, whose name shall never be out-rubbed by time, but cut deeper every year, Professor Megalow, sat calmly on a three-legged stool, which he had found.

None of these learned gentlemen had seen my little self before; and an earnest desire arose in my mind, that not one of them ever should see me again. Their eyes were beaming with intellect, and their arms spread out like sign-posts; and I made off at[Pg 31] once, without waiting to think, till the doctor's deep voice stopped me.

"Icarillus," he said, and though he could not catch them, my legs could go no further, "Athena, the Muses, and Phœbus himself, command thee to face the enemy. This new, and prosaic, and uncouth power, which calls itself 'science,' as opposed to learning, wisdom, and large philosophy—excuse me, gentlemen, I am speaking in the abstract—this arrogant upstart is so rampant, because people run away from her. Tommy, come hither; these gentlemen are kind, very kind—don't be afraid, Tommy; you may stand in the folds of my gown, if you like. Answer any question they may ask, and fly again, if they can persuade you. Professors Brachipod, and Jargoon, Chocolous, and Mullicles, my little pupil is at your service."

Beginning to feel my own importance, I began to grow quite brave almost, and ventured to take down my hands from my face, and turn round a little, and peep from the corners of my eyes at these great magicians. And as soon as I saw, that the foremost of them had been carried out of our house by father, and sent away over the cinder-heaps, there came a sort of rising in my mind, which told me to try to stick up to them. And when they fell out one with another, as they lost no time in doing, they made me think somehow about the old women who came to pick over our ash-heaps—until through the doorway I saw another face, the kindest and grandest I ever had seen, the face of Professor Megalow.

Before I had time to get afraid again, there was no chance left to run away; for the four professors[Pg 32] had occupied all the four sides of my body. They poked me, and pulled me in every direction, and felt every tender part of me, and would have been glad to unbutton my raiment, if the master had allowed it. And they used such mighty words as nobody may reproduce correctly, unless he was born, or otherwise endowed, with a ten-chain tape at the back of his tongue. Every one talked, as fast as if the rest were listening eagerly; and every one listened, as much as if the rest had nought to say to him. For all worked different walks of science, and each was certain that the other's walk was crooked.

I assure you, that this was a very difficult thing for me to deal with, having so many tongues going on about me, and so many hands going into me, and a strong pull in one direction, crossed by a stronger push in the other. Moreover, two learned gentlemen wanted to throw me up perpendicular; while other two, of equal learning, would launch me on high horizontally. Between, and among, and amid them all, there was like to be nothing but specimens left of unfortunate Tommy Upmore.

"Gentlemen, gentlemen!" shouted Dr. Rumbelow; but they did not answer to that name. "Professors, professors, forbear, I beseech you. Is this scientific investigation? I will have no vivisection here"—for they hurt me so much, that I now screamed out—"I am sorry to lay hands upon you, but humanity compels me. Now, unless you all sit down, I shall send Argeiphontes for the police. I grieve that you drive me to such strong measures. But I cannot have my little Icarus treated like Orpheus, or Actæon."

Luckily for me the doctor's body might vie with[Pg 33] his mind in grasp of subject; and he soon had Professors Brachipod, Jargoon, and Mullicles seated in their chairs. But the fourth professor (whose name was Chocolous, and himself a foreigner of some kind) entreated that he might not be compelled to sit.

"Not for five, six, seven year, have I seet in ze shair," he cried, with his arms spread out, and his back in a shake against some degradation; "I must not, and I will not, seet. Herr Doctor, in many languages laboriously excellent, present not to me zis grade indignity. I vill keek, if you not leave off."

He was very angry, but his friends seemed to enjoy it.

"Oblige me, gentlemen," said Dr. Rumbelow, decorously quitting this excitement, "by telling me, why your learned friend resists my kindly efforts. When the body is seated, the mind is calm. What find we in Plato upon that subject? Not only once, but even thrice, in a single dialogue, we discover, directly and inferentially——"

"A flip for those old codgers, sir!" exclaimed Professor Brachipod. "Chocolous knows more than fifty Platos, though his leading idea is fundamentally erroneous"—("I say nah, I say non, I say bosh!" broke in Professor Chocolous)—"his leading idea that the human race may recover its primordial tail, by abstaining, for only a few generations——"

"Seven chenerations, first; and when he have attained one yoint, seven more. I am ze first. But in two, tree, four hundred year, continued in ze female line, wizout ever going upon ze shair——"

"Shut up, Chocolous!" broke in Professor Mullicles. "How can molecular accretion ever be affected[Pg 34] by human habitude? 'Tis a simple inversion of the fundamental process. Every schoolboy now is perfectly aware, that the protoplasmatic anthropomorphism was a single joint of tail. Molecular accretion immediately commenced; and the result—is such a fellow as you are."

"And such a fellow as Professor Megalow," the little German answered, with quiet self-respect; "if I vos one, he vos ze oder. Professor Megalow, vot for, you stay back so?"

"My reason for staying back so, as our learned friend expresses it," said the tall man, with the kind and noble face, at last advancing, "is that the matter now in hand, though deeply interesting, and (to judge by results) even highly exciting, is one that I have never dealt with. When I was kindly asked to come, I was very glad to do so. But with your good leave, I will form no opinion; until I find some grounds for it."

The four men of science were struck dumb, at the rashness of such a resolution; while Dr. Rumbelow took advantage of their amazement, to say a word.

"Professor Megalow, allow me the honour of shaking hands with you, sir. You speak like a genuine acolyte of that glorious sage, Pythagoras. The ereneuticon, in all truth, must precede the hermeneuticon. Whenever you like to examine Tommy, he shall be at your service."

This offer was highly disinterested; but I did not enjoy its magnanimity, especially as my protector now became so engrossed with the great professor, that he quite forgot poor little me.

"Now is your time, to go through with the [Pg 35]question," spake the arch-enemy, Brachipod, "which, beyond all doubt, is nothing more than a case of organic levigation——"

"Levigation be d—d!" cried Professor Jargoon. "Any fool can see, that it is gaseous expansion."

"Gaseous expansion is bosh, bosh, bosh," shouted Professor Chocolous; "ze babe, zat vos born a veek longer dis day, vill tell you—bacilli, bacilli!"

"How pleasant it would be, to hear all this nonsense," declared Professor Mullicles, "if ignorance were not so dogmatic! The merest neophyte would recognise, at once, this instance of histic fluxion."

Without any delay, a great uproar arose, and the four professors rushed at me, to save rushing at one another. My heart fell so low, that I could not run away, though extremely desirous of doing so; and the utmost I could manage was to get behind a chair, and sing out for my father and mother. This only redoubled their zeal, and I might not have been alive now to speak of it, had not Professor Brachipod pulled out an implement like a butcher's steelyard, and swung back the others, with a sweep of it.

"He belongs to me. It was I who found him out. I will have the very first turn at him," he cried. "I'll knock on the head any man, who presumes to prevent me from proving my theory. Just hold him tight, while I get this steel hook firmly into his collar. Now are you satisfied? This proves everything. Can this levigation be d—d, Jargoon? All his weight is a pound and five ounces!"

He turned round in triumph, and a loud laugh met him. He was weighing my jacket, without me[Pg 36] inside it. For mother had told me, a hundred times, that a child had much better be killed, than weighed. At the fright of his touch, I slipped out of my sleeves, and set off at the top of my speed away. In the passage, I found a side door open, and without looking back dashed through it.

"Go it, little 'un!" a cabman cried, the very man who had brought mine enemies; and go it I did, like a bird on the wing, without any knowledge of the ground below. Some of our boys, looking out of a window, called out, "Well done, Tommy! You'll win the—" something, it may have been the Derby, I went too fast to hear what it was. Short as my legs were, they flew like the spokes of a wheel that can never be counted; and I left a mail-cart, and a butcher's cart too, out of sight, though they tried to keep up with me. Such was my speed, on the wings of the wind, with my linen inflated, and my hair blown out,—the nimblest professor, that ever yet rushed to a headlong conclusion, were slow to me. In a word, I should have distanced all those enemies, had I only taken the right road home.

But alas, when I came to the top of a rise, from which I expected to see my dear parents, or at any rate our cinder-heap, there was nothing of the kind in sight. The breeze had swept me up the Barnet road; and yonder was the smoke of our chimney, like a streak, a mile away down to the left of me. All the foot of the hill, which is now panelled out into walls, and streets, of the great cattle-market, remained to be crossed, without help of the wind, ere ever I was safe inside our door. And the worst of it was, that the ground had no cover,—not a house,[Pg 37] nor a tree, nor so much as a ditch, for a smallish boy to creep along; only piles of rubbish, here and there, and a few swampy places, where snipes sometimes pitched down, to have a taste of London.

Tired as I was, after that great run, and scant of breath, and faint-hearted—for the sun was gone down below Highgate Hill, and my spirits ever seem to sink with him—I started anew for my own sweet home, by the mark of the smoke of our boiling-house. I could hear my heart going pit-a-pat, faster than my weary feet went; for the place was as lonely as science could desire, for a snug job of vivisection. Of that grisly horror I knew not as yet the name, nor the meaning precisely; but a boy at our school, who was a surgeon's son, used to tell things, in bed, there was no sleeping after. And once he had said, "If they could catch you, Tommy, what a treat you would be, to be lectured on!"

As the dusk grew deeper in the hollow places, and the ribs of the naked hills paler, I began to get more and more afraid, and to start back, and listen at my own footstep. And before I could hear what I hoped to hear—the anvil of the blacksmith down our lane—the air began to thicken with the reeking of the earth, and the outline of everything in sight was blurred, and a very tired fellow could not tell, at any moment, what to run away from, without running into worse. At one time, I thought of sitting down, and hiding in a dip of the ground, till night came on, and my enemies could not see me; but although that might have been the safest plan, my courage would not hold out for it. So on I went, in fear and trembling,[Pg 38] peeping, and peering, both behind me and before, and longing with all my heart to see our own door.

But instead of that, oh, what a sight I saw—the most fearful that can be imagined! From the womb of the earth, those four professors (whose names are known all over it), Brachipod, Jargoon, Chocolous, and Mullicles, came forth, and joined hands in front of me. They laughed, with a low scientific laugh, like a surgical blade on the grindstone.

"Capital, capital!" Brachipod cried; "we have got him all snug to ourselves, at last. Let me get my hook into my pretty little eel."

"Famous, famous!" said the deep voice of Jargoon; "now you shall see, how I work my compressor."

"Hoch, hoch!" chuckled Chocolous; "ve have catch ze leetle baird at last. I vill demonstrate his bacilli."

But the one that terrified me most of all was Professor Mullicles; because he said nothing, but kept one hand, upon something, that shone from his long black cloak.

"Oh, gentlemen, kind gentle gentlemen," I sobbed, dropping down on my knees before them, "do please let me go to my father, and mother. They live close by, and they think so much of me, and I am sure they would pay you, for all your inventions, a great deal more than the Government. I only flew once, and I didn't mean to fly, and I am sure it must have been a mistake altogether; and I will promise, upon my Sammy, as Bill Chumps says, not to do it any more. Oh, please to let me go! It is so late; and I beg your pardon humbly."

"Eloquent, and aerial Tommy," replied that dreadful Brachipod, "this case is too momentous, in the interests of pure science, for selfish motives to be recognized. It will be your lofty privilege, to abstract yourself, to revert to the age of unbroken continuity, when that which is now called Tommy was an atom of protobioplasm——"

"Stow that rubbish," broke in Jargoon.

"Ach, ach, ach! All my yaw is on the edge!" screamed Chocolous, dancing with his hands up.

"Proto-potatoes!" spoke Mullicles sternly, advancing to support his view of me.

"D—n," exclaimed all of them, unanimous for once, when there was no view of me to be had; "was there ever such a little devil? After him, after him! He can't get away."

"Can't he?" thought I, though I did not dare to speak, having not a single pant of breath to spare. For, while I was down on my knees for mercy, through the tears in my eyes, I had seen a lamp lit. I knew where that lamp was, and all about it, having broken the glass of it, once or twice, and lamps were a rarity in Maiden Lane as yet. It was not a quarter of a mile away, and the light of it shone upon my own white pillow.

So when those philosophers parted hands, to shake fists at one another, out of the scientific ring I slipped, and made off, for the life of me. My foes were not very swift of foot, and none of them would let another get before him; so that, if I had been fresh and bold, even without any breeze to help me, I might have outstripped them easily. But my legs were tired, and my mind dismayed; and the scientific terms, in[Pg 40] which they called on me to stop, were enough to make any one stick fast. And the worst of it was, that having no coat on, I was very conspicuous in the dusk, and had no chance of dodging to the right or left. So that I could hear them gaining on me, and my lungs were too exhausted for me to scream out for father.

Thus, within an apple-toss of our back door, and with nothing but a down-hill slope, between me and our garden, those four ogres of grim science had me lapsing back into their grasp again. Their hands were stretched forth, in pursuit of my neck, and their breath was like flame at the tips of my ears—when a merciful Providence delivered me. I felt something quivering under my feet; over which I went lightly, with a puff of wind lifting the hollows of my hair, and shirt-sleeves. In an instant, I landed on a bank of slag; but behind me was a fearful four-fold splash!

So absorbing was my terror, and so scattered were my wits, that for ever so long I could not make out, what had happened betwixt me and my pursuers, except that I was safe, and they were not. There they were, struggling, and sputtering, and kicking—so much at least as could be seen of them—throwing up their elbows, or their heels, or heads, and execrating nature (when their mouths were clear to do it) in the very shortest language, that has ever been evolved. At the same time, a smell (even stronger than their words) arose, and grew so thick, that they could scarcely be seen through it.

This told me, at once, what had befallen them, or rather what they had fallen into,—videlicet, the[Pg 41] cleaning of our vats, together with Mr. John Windsor's; whose refuse and scouring is run away in trucks, upon the last Saturday of every other month. It would be hard to say, what variety of stench, and of glutinous garbage, is not richly present here; and the men from the sewers, who conduct it to the pit, require brandy, at short intervals. In the pit, which is not more than five feet deep, yet ought to be shunned by trespassers, the surface is covered with chloride of lime, and other materials, employed to kill smell, by outsmelling it; and so a short crust forms over it, until the contents become firm and slab, and can be cut out, for the good of the land, when the weather is cold, and the wind blows away.

Now certain it is, that all the science they were made of, could never have extricated those professors, without the strong arms of my father, and mother, and even small me at the end of the rope. The stuff they were in, being only half cooled (and their bodies grown sticky with running so), fastened heavily on them, like tallow on a wick, closing so completely both mouth and eyes, that instead of giving, they could only receive, a lesson in materialism. Professors Brachipod, and Chocolous, being scarcely five feet and a quarter in height, were in great danger of perishing; but Mullicles, and Jargoon, most kindly gave them a jump now and then, for breath. And, to be quit of an unfragrant matter, and tell it more rapidly than we did it,—with the aid of a blue-man from the Indigo works, and of two thickset waggoners, we rescued those four gentlemen from their sad situation, and condoled with them.[Pg 42]

Not for £5 per head, however, would any of our cabmen take them home; though a man out of work had been tempted by a guinea, to relieve them a little, with a long-handled broom, and to flush them with a bucket, afterwards. Under heavy discouragement, they set forth on their several ways, surveyed by the police at a respectful distance, on account of the danger to the public health.

My mother was so frightened, at the fright I had been through, that she took it for an urgent sign from Heaven, that my education should be stopped at once. Having had as much of school as I desired, I heartily hoped, that her opinion would prevail; but father was as obstinate as ever, and after the usual argument—in which she had the best of the words perhaps, and he of the meaning—I was bound to the altar of the Muses once again, with a promise of stripes, if I should try to slip the cord. Dr. Rumbelow undertook, that no professor of anything harder than languages—unless it were Professor Megalow—should come in, at any door of the Partheneion, without having tallow poured over him, which he had found, from high Greek authority, to be the right ointment for Neo-sophistæ. And he said that my father must have been familiar with the passage he referred to, and had thus discomfited all the Pansophistæ, better than any modern Deipnosophist could have done. But my father said no; he had never even heard of the gentleman, with the hard name to crack; and as for them Prophesiers, they ought to have prophesied what his clots was, before tumbling into them. He[Pg 44] ought to have an action of trespass against them; and, but for the law, he would do so.

To make it quite certain, that no man of science should analyse, synthesise, generalise, or in any way scientise me, I was now provided with a guardian, intrepid of neologisms ten yards long. The father of our Bill Chumps, Mr. Chumps, the Purveyor of Meat, was the owner of a dog, who was the father of a pup, who was threatening, every day, to make mincemeat of the author of his existence. The old dog might have tackled him, Bill told me, or at any rate could have shown a good turn-up, but for having broken his best fighting-tooth, on the spiked collar of the last mastiff he had slain. Through this disability on the part of old Fangs, he found his son Grip too many for him; yet could not be brought to confess it, and abstain from a battle, at every opportunity. These encounters in no wise disturbed Mr. Chumps, but became inconvenient to Mrs. Chumps, when she heard the piano (which had cost £10, for her daughter, Belinda, to learn her scales) upset, and entirely demolished. If it had been possible to hang Grip, hanged he would have been that very day; for the mistress had nursed Fangs through his distemper, and never would listen to a word against him. Whereas the whole fault was upon the side of Fangs; of which I am quite certain, from the character of Grip, as it unfolded itself before me, when he became my own dear dog.

Providentially, their attempt to hang him had proved a miserable failure. Not that he resisted—he was too docile, and kind, and intelligent, to do that—but because his neck was much too thick, and[Pg 45] manifold, and his wind too good, for any rope to be of much account to him. And before they could try any other form of murder, his master came home, and made short work with them, knowing the superiority of the dog. Now, that same evening, the day being Monday, the very choice club, to which he, and my father, and Mr. John Windsor belonged, as well as the largest potato-man at King's Cross, and the owner of the Indigo-blue concern, and the most eminent merchant in the cat's meat line, and several other gentlemen of equal distinction, held their bi-daily congress at "The Best End of the Scrag," at the corner.

That night there was a very fine attendance; and my father, who had long been acknowledged to be the wittiest man on our side of the road—perhaps because he got no chance at home, to say what came inside him—upon this occasion was compelled, by the nature of some of the smells he had gone through, to be at his best, as he generally was, after not less than two glasses and a half. And he told the adventure, of the four professors, not as a sad and deplorable thing, but rather as matter for merriment. In such a light did he put it, that all the gentlemen laughed heartily, most of all Mr. John Windsor, who knew, even better than my father did, the variety of organic substance, active in that pit just then.

"There's things there," he said, "to my living knowledge, that'll never come out of their hair while they live. And those big Savage-Johns always have long hair, and as fuzzy as a cat stroked upward. Why, the very last Friday, when I was a-cooling, a pair of them comes with a brazen machine, and asked[Pg 46] me, as quiet as a statue, permission for to taste my follet oils. I up with the wooden spoon, and offered them a drop; but that was not their meaning. It was som'at about som'at we gives off, according to them philanderers. And I says—'Government inquiry, gents?' And they says—'No, sir; but for purposes of science.' 'Tell me,' says I, 'what the constitootion is of this here clot,' and they said 'Composite organic' something; while my composites all was upon the upper floor, and never a hurdy-gurdy allowed inside. 'So much for science!' says I; 'Jim, show these gentlemen out, by the back-alley door.' And now that you come to discourse of it, Bubbly, it strikes me they might have come very likely, smelling up a side-wind for your poor Tommy."

"I should hope they have had enough of that," said father; "if they come any more, I'll boil them down, and make 'Science-sauce for the million,' How would you like, John, to pay your money, and get no change out of it, along of such a lot?"

"You mean the missus," Mr. Windsor asked—"won't allow Thistledown, as my Jack calls him, to go to old Rum's any more, I suppose? Afraid of the ladies, Mr. Upmore is."

"I'll tell you what to do," Mr. Chumps broke in; "Upmore, you buy my young dog Grip. I'd give him to you with all my heart, if it wasn't for the bad luck of it; though he is worth ten guineas of anybody's money, for he comes of the best blood in England. Downright House of Lords bull-dog he is; same as should be chained to the pillars of the State, to keep them Glads, and Rads, away. Just you put[Pg 47] him in charge of Thistledown—or whatever you call that little yellow-haired chap, and I'll back Grip against all the Science, that ever made a pint contain a pot."

"What's the figure?" my father asked, knowing how generously all men talk, and that Mr. Chumps' bull-dogs were a fashionable race.

"If you was to offer me more than a crown," replied Mr. Chumps, with his fist on the table; "I should say, 'Bubbly, he's no dog of yours, because you desire to insult me.' But put you down a crown, as between old friends, and before this honourable company, I say, 'Bucephalus Upmore, Grip is your dog.' Why so? John Windsor here knows why, and so does Harry Peelings from King's Cross, and so does Bill Blewitt, and Sandy Mewliver, and all this honourable company. And so do you, Bubbly Upmore, if you are the man I have taken you for. Gentlemen, it is because Mr. Upmore has told the best story I have sat and listened to, ever since last election day; he digged a pit for his enemies in the gate, and they fell into it themselves; as well as because my son, Bill Chumps, who will make his mark, mind you, if you live to see it, has taken a liking to this gentleman's son—Thistledown, or Bubble-blow, or Up-goes-the-donkey—they've got at least fifty names for him—and, in my humble opinion, he must be protected from the outrages of all those fellows, philo-this, and anti-that,—my son Bill knows their names, and all about them—who have made the world a deal too clever for a quiet man's comfort."

These very simple and sensible words were received with much knocking on the table; and my[Pg 48] father put down his five-shilling piece, so that all the other gentlemen had time to see it, before they began talking, as the subject compelled them to do, of the merits of their children, respectively, severally, and all together. And they parted, in thorough good will, inasmuch as not anybody listened to anybody else.

My father's opinion, at the time, had been that the warmth of Mr. Chumps' political and social feelings (promoted by the comforts of the club) had hurried him into a disregard of money, which his friends should never lose a moment to improve. But when the journeyman came over in the morning, on his way to the Partheneion, with Grip trotting chained at the tail of the cart, my father cried—

"What! Has Chumps no more conscience, than to impose upon a friend like this? I, who have known him all these years, to pay as good a crown-piece as was ever coined, for a one-eyed, nick-eared, hare-lipped, broken-tailed son of a [female dog] like that! Gristles, you go back, and tell your master, that you saw me put an ounce of lead through him."

My father strode in, to fetch his gun, which he kept well-charged in the clock-case now, for the sake of so many Professors; and Grip, for a surety, would have been dead, and boiling, in less than five minutes, except for his luck. His luck was that I, being under debate between my two parents, had slipped out of doors, being old enough now by experience to know, that they took the kindest view of me, when I was out of sight. And coming round the corner, to peep in at the window, just to see whether they had settled my concerns, there I saw this poor dog[Pg 49]—hideous they might call him—doubtfully glancing in every direction, dimly aware that the world was against him, scenting the death of a dog in the air. One of his eyes was out of sight, and one of his ears was in need of a sling, his tail (which had lately been cracked by his father) hung limp in the dust with a pitiable wag, and every hair on his body was turned the wrong way. His self-respect had suffered a tremendous blow, by the effort of mankind to hang him yesterday, and by dragging at the tail of a cart to-day; and as sure as dogs are dogs, he was aware of the awful decision against him.