Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed.

Some typographical errors have been corrected;

a list follows the text.

In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol  will bring up a larger version of the image.

will bring up a larger version of the image.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Appendix

(etext transcriber's note) |

THE

WALLS OF CONSTANTINOPLE

THE WALLS OF

CONSTANTINOPLE

BY

CAPTAIN B. GRANVILLE BAKER

LONDON: JOHN MILNE

1910

PREFACE

ROMANCE and the history of walled cities are inseparable. Who has not

felt this to be so at the sight of hoary ruins lichen-clad and

ivy-mantled, that proudly rear their battered crests despite the ravages

of time and man’s destructive instincts. It is within walled cities that

the life of civilized man began: the walls guarded him against barbarian

foes, behind their shelter he found the security necessary to his

cultural development, in their defence he showed his finest qualities.

And such a city—and such a history is that of Ancient Byzantium, the

City of Constantine, the Castle of Cæsar.

What wonder then that man should endeavour to express by pen and pencil

his sense of the greatness and beauty, the Romance of a Walled City such

as Constantinople. The more so that a movement is on foot to remove

these ancient landmarks of the history of Europe and Asia.

True there are other works on this same subject, works by men deeply

learned in the history of this fair city, works that bid fair to

outlive the city walls if the fell intent of destroying them is carried

into execution, and from these men and their works I derived inspiration

and information, and so wish to chronicle my gratitude to them—Sir

Edwin Pears and Professor van Millingen of Robert College,

Constantinople. There are many others too in Constantinople to whom my

thanks are due—His Majesty’s Vice-Consul, my host, his colleagues, now

my friends, and many others too numerous to mention. They all have

helped me in this work, and I am grateful for the opportunity offered me

of here recording my thankfulness for their kind offices.

B. Granville Baker.

Note.—As I have taken the historical events recorded in this book not

in chronological order, but as they occurred to me on a tour round the

walls of Constantinople, I have appended a brief chronological table,

for the guidance of my readers and for the elucidation of this work.

CONTENTS

| CHAP. | |

PAGE |

| I | CONSTANTINOPLE | 13 |

| II | THE APPROACH TO THE CITY BY THE BOSPHORUS | 28 |

| III | SERAGLIO POINT | 54 |

| IV | SERAGLIO POINT (continued) | 84 |

| V | THE WALLS BY THE SEA OF MARMORA | 101 |

| VI | THE GOLDEN GATE | 124 |

| VII | THE GOLDEN GATE (continued) | 147 |

| VIII | THE WALLS OF THEODOSIUS TO THE GATE OF ST. ROMANUS | 172 |

| IX | THE VALLEY OF THE LYCUS | 198 |

| X | FROM THE GATE OF EDIRNÉ TO THE GOLDEN HORN | 225 |

| | ENVOI | 252 |

| | APPENDIX | 255 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

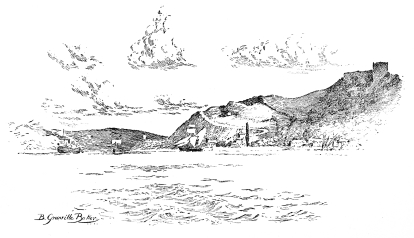

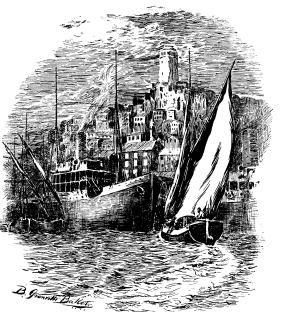

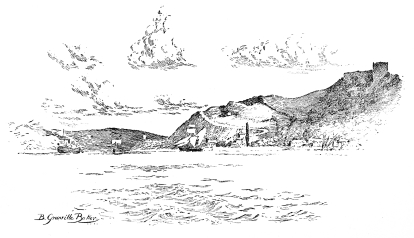

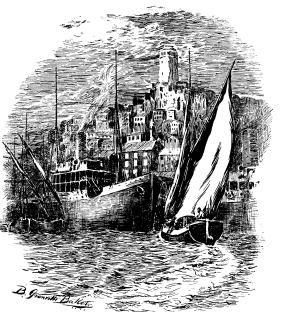

| CONSTANTINOPLE FROM THE SEA OF MARMORA |

Frontispiece |

| Facing page |

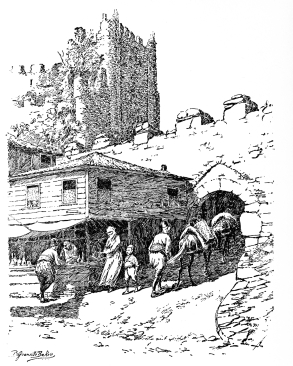

GENOESE CASTLE AT ENTRANCE TO BOSPHORUS FROM THE BLACK SEA | 31 |

ANATOLI HISSAR, OR THE CASTLE OF ASIA | 39 |

ROUMELI HISSAR, OR THE CASTLE OF EUROPE | 43 |

THE TOWER OF GALATA | 51 |

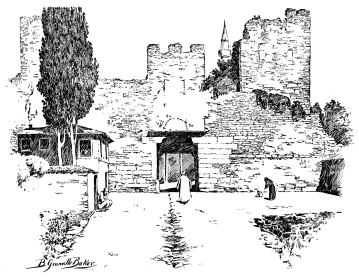

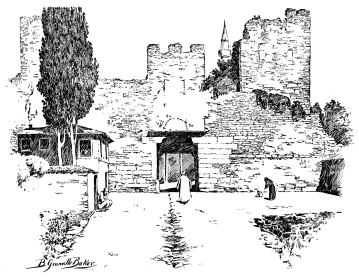

THE LANDWARD WALLS OF THE SERAGLIO | 58 |

THE PALACE OF HORMISDAS, OR JUSTINIAN | 101 |

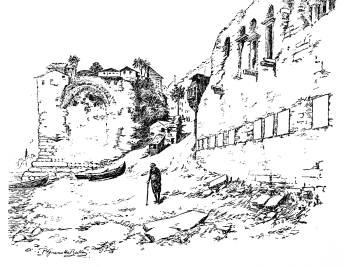

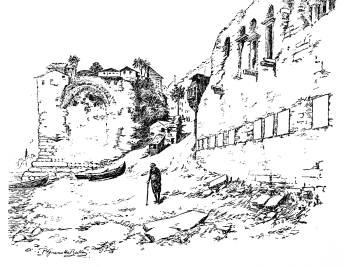

THE SEA-WALL | 117 |

THE MARBLE TOWER | 122 |

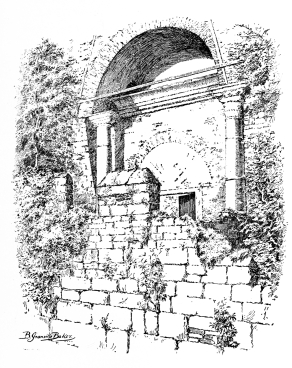

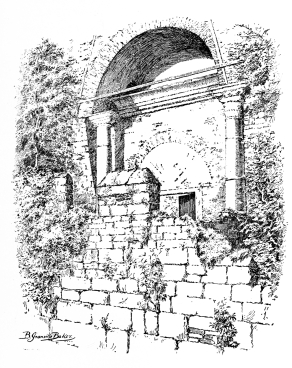

POSTERN WITH INSCRIPTIONS OF BASIL II AND CONSTANTINE IX | 124 |

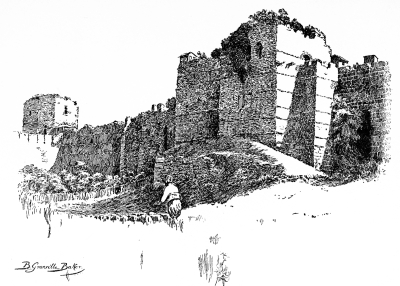

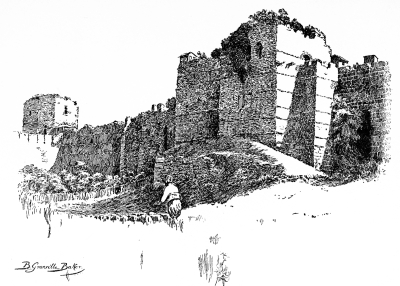

THE GOLDEN GATE FROM SOUTH-WEST | 126 |

THE APPROACH TO THE GOLDEN GATE FROM NORTH-WEST | 146 |

YEDI KOULÉ KAPOUSSI, OR GATE OF THE SEVEN TOWERS | 170 |

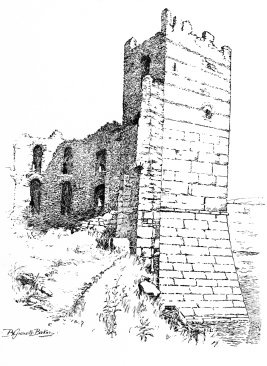

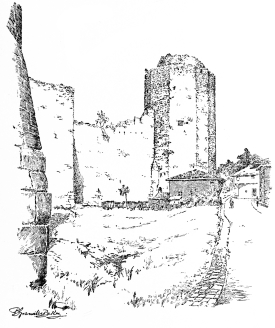

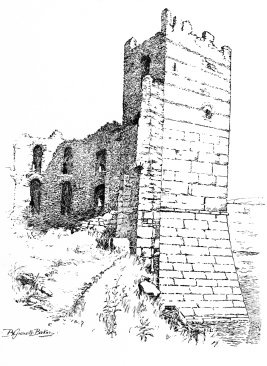

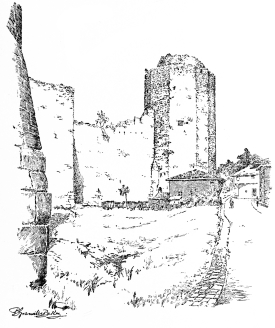

PART OF TURKISH FORTRESS OF YEDI KOULÉ | 172 |

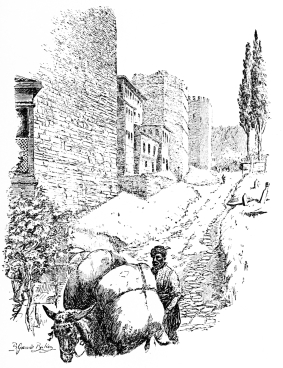

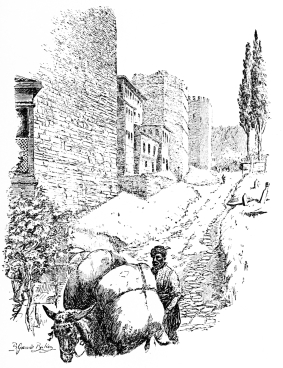

THEODOSIAN WALL AND APPROACH TO BELGRADE KAPOUSSI, SECOND MILITARY STATE | 183 |

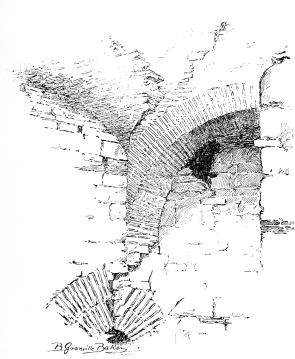

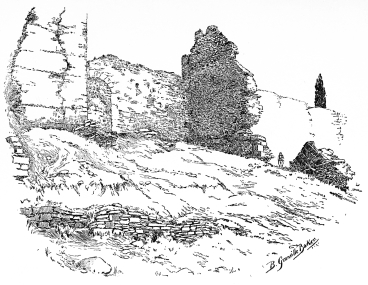

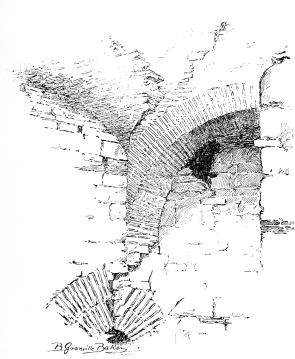

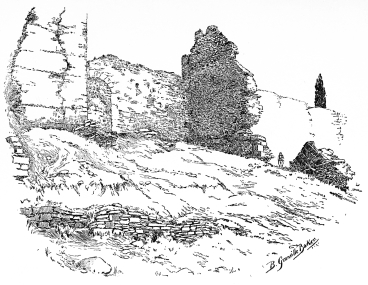

THEODOSIAN WALL—A BROKEN TOWER, OUTSIDE | 188 |

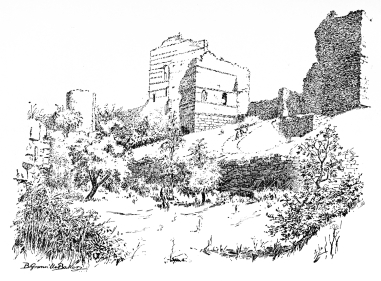

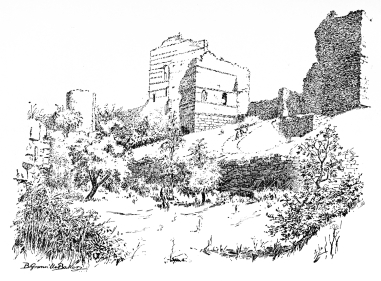

THEODOSIAN WALL—A BROKEN TOWER, INSIDE | 190 |

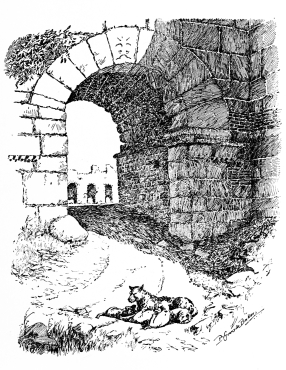

GATE OF RHEGIUM, OR YEDI MEVLEVI HANEH | 193 |

TOP KAPOUSSI, GATE OF ST. ROMANUS | 194 |

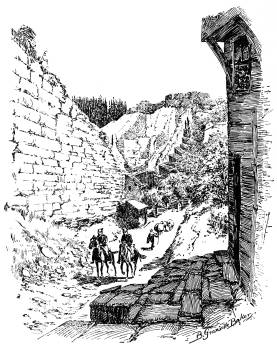

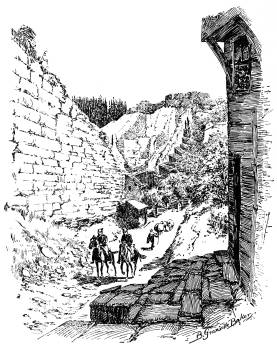

THIRD MILITARY GATE | 196 |

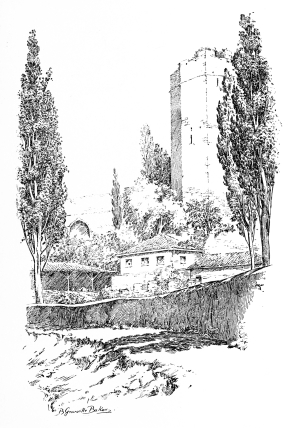

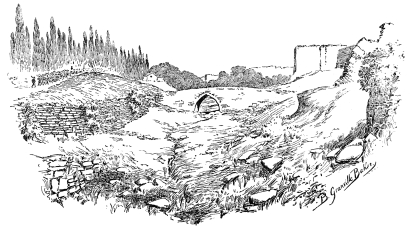

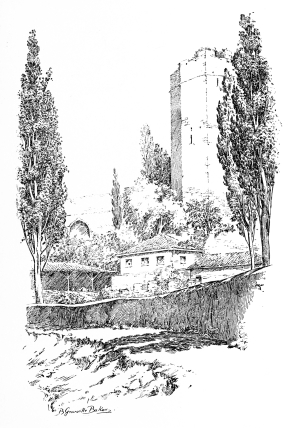

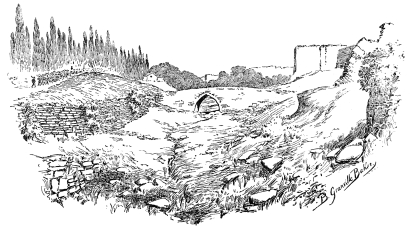

THE VALLEY OF THE LYCUS, LOOKING NORTH | 199 |

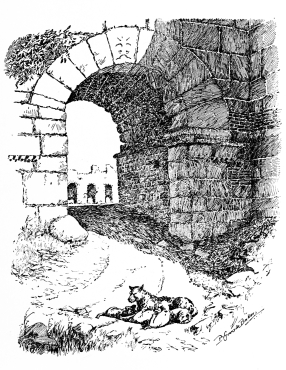

THE VALLEY OF THE LYCUS FROM INSIDE THE WALLS | 201 |

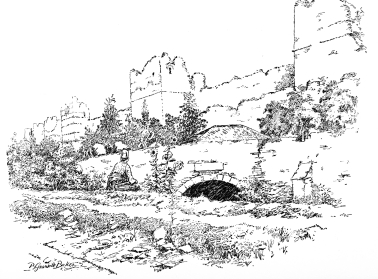

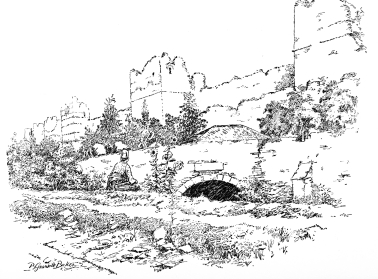

THE VALLEY OF THE LYCUS, SHOWING WHERE THE LAST EMPEROR FELL | 224 |

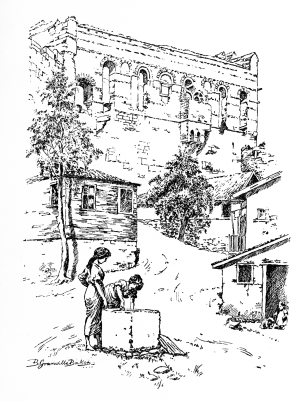

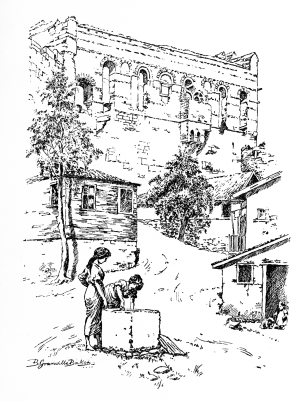

THE PALACE OF THE PORPHYROGENITUS FROM THE FOSSE | 226 |

THE PALACE OF THE PORPHYROGENITUS FROM WITHIN THE WALLS | 228 |

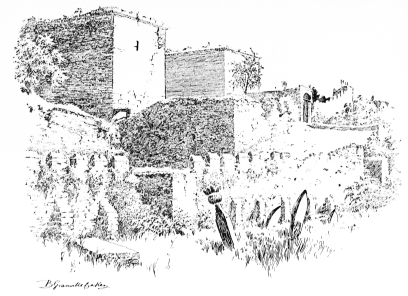

TOWER OF MANUEL COMNENUS | 232 |

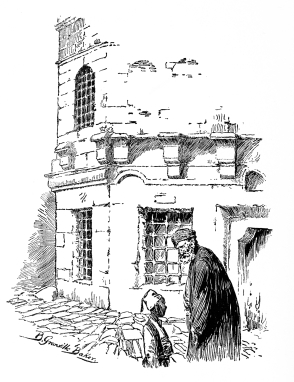

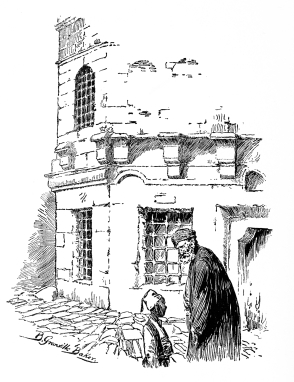

GATE OF THE BOOTMAKERS, OR THE CROOKED GATE | 241 |

WALL OF PALÆOLOGIAN REPAIR | 244 |

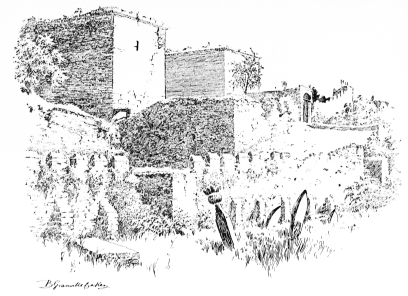

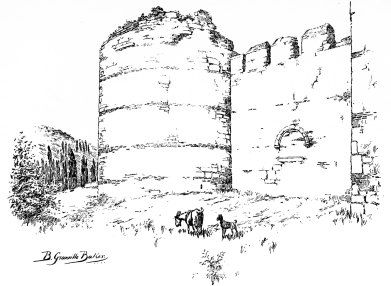

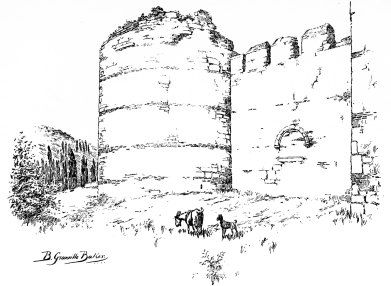

TOWERS OF ISAAC ANGELUS AND ANEMAS | 246 |

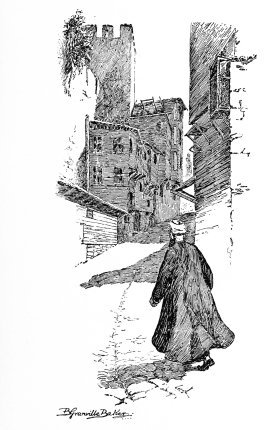

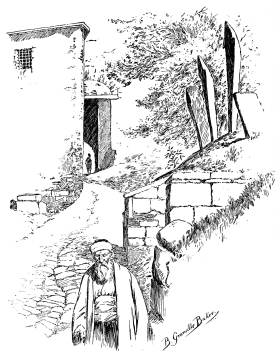

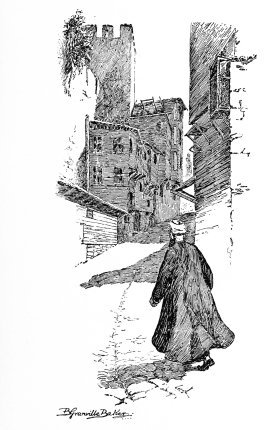

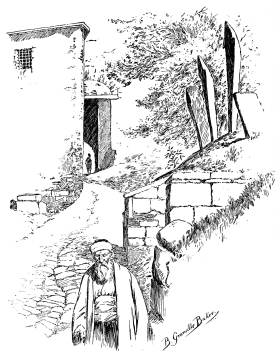

OLD HOUSE IN THE PHANAR | 249 |

THE

WALLS OF CONSTANTINOPLE

CHAPTER I

CONSTANTINOPLE

BYZAS the seafarer stood in the sacred copse, the copse of fir-trees

dedicated to his father Poseidon. His soul was filled with awe, for he

was listening for an answer to his prayer; he had prayed for help and

guidance in his next venture out upon the seas, and had brought rich

gifts with him.

Hush! the faint murmuring of the evening breeze—a sound—a whisper

only—it is the voice of the Oracle: “Build your city opposite the City

of the Blind, for there you shall prosper.” The voice died away in the

stillness of evening. Gently, with reverence, Byzas placed his offerings

upon the ground, turned and went his way without looking behind him.

Before the dawn arose, Byzas had joined his comrades. “To sea,” he

cried, “for the Oracle has spoken thus: ‘Go to the Country of the

Blind—there build you a city opposite their own—you shall prosper.’”

Silently the stout vessel that carried Byzas and his fortunes stood out

to sea as the rosy dawn touched the high peaks of the Peloponnese and

tinted with pale carmine and gold the unruffled water of the Ægean. And

ever bearing to the north, to that unknown region, with Byzas at the

helm, the ship held on. They sounded here and there, and asked of those

they met, “Is this the Country of the Blind?” Their question met with

little sympathy; the answers are nowhere recorded. After many vain

inquiries the adventurous crew drew out into the Sea of Marmora. Towards

evening they sighted land.

No doubt Byzas was drawn towards the Prince’s Islands ’twixt him and

Asia as he sailed northward up the quiet inland sea. But sternly he

resisted the temptation of these lovely isles, and held on his way. His

long craft pulled nearer in towards the narrow mouth, and through the

twilight a great city loomed up before him on his right—the city of

Chalcedon, better known by its modern name of Kadekeuy. Now in the days

of Byzas suspicious-looking craft of no ostensible occupation were not

encouraged, piracy was too common and, indeed, considered one of the few

occupations fit for a gentleman—night was falling; so we imagine Byzas

putting in to the spit of land that projects boldly into the sea as if

to meet the Asiatic shore and offer stepping-stones for any migrant

Titan that might pass that way. Rounding the point, he saw before him a

broad waterway winding inland till lost to sight behind the tree-clad

heights to northward. So Byzas steered towards this fairway, holding to

the southern bank, and then, some little distance from the point, his

comrades lowered the broad sails, dropped anchor and awaited the light

of day. Only when it dawned were they conscious that they had reached

their goal, the country mentioned by the whispering Oracle.

A fair sight that, by the first rays of the rising sun: the east aglow

with many colours, repeated in the waters of the winding bay, henceforth

to be known as the Golden Horn; first touches of pink in the small

clouds over the rose-tipped mountain of the East; and, swimming in a

silvery haze, the islands they had passed.

Then the keenest and most fleet-footed of the crew betook themselves

ashore. They searched diligently everywhere, and brought back word that

all day long never a man had they seen of whom they could inquire, “Is

this the Country of the Blind?” So Byzas spoke: “This is the Country of

the Blind, for those are blind who could pass by this most favoured

spot, and build their city on the other side.”

So Byzas settled here and built a city and prospered—the Oracle had

spoken truly.

All this happened many centuries ago, when the world, at least the

Western World was young, and Rome—Imperial Rome, the eternal city, was

still wrapped in the legendary mysteries of her birth.

And so arose Constantinople,—a city known by many names, the one

familiar to the majority of those of Western race is that of the City of

Constantine, Constantinople, familiar but with subconscious charm of

strange remoteness: the Slavs still talk of Tsarigrad, the Castle of

Cæsar; to the Turk this is Stamboul, a corruption of εἱς τἡν πὁλιν—the phrase they must have so often heard on the lips of the

vanquished Greeks, but through all ages this is Byzantium in romance.

The first thing a man does when he comes into any kind of property, is

to safeguard it somehow. If this property be land, however acquired, the

natural thing is to build a wall around it, and this no doubt Byzas did

too. But of his walls nothing is left—the city grew and prospered, the

Oracle said it would, so the matter was in a sense already settled, and

new walls were thrown out further until Imperial Byzantium, like

Imperial Rome, stood on seven hills.

Behind these walls a busy populace increased the wealth and importance

of the place, and others who wanted wealth and importance flocked in

here for it. Byzant became a thoroughfare to all those of the West who

did business with the East, but was chary of being too much of a

thoroughfare for those who came from the East. For these latter had the

habit of coming in swarms and armed, otherwise empty-handed, but with a

sincere wish not to return in that condition. Against such as these the

walls were built, strong and cunningly planned. And so ancient Byzant

grew into the mart for those who traded from the West along the coasts

of the Mediterranean, away through Dardanelles and Bosphorus to the

Black Sea, to Trebizond, where the old Greek tongue yet lingers in its

purest form, the Crimea—even distant Persia. So also Byzant became the

bulwark that met, and broke, successive storm-waves of Asiatic attack,

until in due season a strong Asiatic race forced its way in, and has

stayed there, and still holds its hard-won stronghold.

It was this position that made Constantine, the man of genius, transfer

the capital of his empire from Rome to Byzant, after defeating his rival

Licinius at Chrysopolis (Scutari) opposite the mouth of the Golden Horn,

and henceforth to make the city known as his—Constantinople, the Castle

of Cæsar. This alone would justify his claim to be called Great, and, as

Dean Stanley remarked, of all the events of Constantine’s life, this

choice is the most convincing and enduring proof of his real genius.

It is to be doubted whether any city walls have such a stirring history

to relate as those of Constantinople, except perhaps the walls of Rome.

Of former, older fortifications traces have been found, and they reach

back to very ancient history.

Echoes come to us from those dim ages of history, shadowy forms of

warriors, seafarers, priests and sages pass by in pageant, with here and

there the bearer of some great name in bolder outline. Somebody has said

that the East is noteworthy as the grave of monarchs and reputations. Of

no spot is this truer than it is of Stamboul.

Chroseos, king of Persia, emerges from the gloom, and with him hordes of

warriors trained to ride, to shoot, to speak the truth. He is seen for a

brief space encamped before the walls to bring its citizens to

submission: he fades away with his phantom host. Then comes one better

known, and he stands out in bold relief, the light of history gives him

more definite outline,—Pausanias. He drove the Persians from the city

after defeating them in the field. His handiwork, ’tis said, can still

be traced in some gigantic blocks that went to fortify yet more the

walls that Byzas built. He was recalled in disgrace: well for him had he

never come. It needed but a little of the splendour and luxury of an

oriental court to corrode the old iron of the Spartan character. For him

the watery soup and black bread of the Eurotos valley could never have

quite the same flavour afterwards. He left the city a discredited

politician of more than doubtful loyalty to the land that reared him and

the great confederacy which had set him at its head.

Then follows an everchanging array of warriors of many nations, many

races. Seven times did the fierce sons of Arabia, fired by their

new-found faith, lay siege to old Byzantium, and seven times their

impetuous valour broke against these walls in vain. Albari, Bulgarians,

Sclavi, Russians, vainly spent their strength in trying to force an

entrance into the Castle of the Cæsars. Great bloodshed or great

treachery could alone serve as the key to what latter-day poets call

“the Gate of Happiness.” Crusaders too, men of the same faith, besieged

the city, and after one short period of success, they too vanished, to

leave the imperial city standing as before; to leave her, perhaps, a

little wickeder, perhaps a little more luxurious, but still as perennial

and unchanging as she is to-day.

Then came another, stronger race out of the East. They laid their plans

cunningly and boldly executed them, they hovered for years over the city

and around it, and for years their efforts proved abortive, until the

time had come when this bulwark of Europe, that had for centuries hurled

back the waves of warriors that dashed themselves against its ramparts,

had fulfilled its mission. Vain it was to cry for help to the Christ

whom they had persistently dishonoured, and to whom their very

existence, corrupt and luxurious, was a standing insult. No, they in

their turn were compelled to make way for the stern realities and honest

animalism over which the Crescent cast its protecting shadow. Then did

the conqueror Mohammed enter into possession, he and his people; here

they settled after centuries of storm and stress, and here they are

still, and they too are prospering—as said the Oracle in those dim

distant ages before the Greek seafarers landed here.

Meantime, behind those sheltering walls, Europe was working out its

destiny.

The Western Empire centred in Imperial Rome succumbed before the on-rush

of barbarians from the north, those warriors from primæval forests,

blue-eyed and strong, whose very aspect reduced the stout Roman

legionaries to tears of terror and despair, with fair hair floating in

the breeze as their long boats (sea-serpents they called them) bore them

from shore to shore, or as astride of their shaggy horses they crossed

the frontiers guarded by Roman legions, and conquered as they went. Then

these took root, the Langobards in northern Italy, Goths in the Iberian

Peninsula, Saxons and Angles in Britain, and, by degrees, became

conscious of political existence.

Some vanished before the fury of the Arab as did the Goths in Spain,

while others grew and prospered like the Franks. Races emerged from

darkness to add to the confusion of Europe’s seething mass of humanity.

Christianity shed its light upon them, and by degrees order appeared, to

make way again from time to time to wild disorder.

And all the time the walls of Constantine’s proud city prevented the

irruption of any Eastern foes whose advent would have made confusion

worse confounded.

So on the eastern frontier of the eastern empire a wonderful revival of

the power of Persia was held in check by those who held the fort of

Constantine, and a vigorous attempt to regain the possessions of

Hellas-hated Xerxes was frustrated.

Transient states arose and vanished—the republic of Rome, the exarchate

of Ravenna, mythical Celtic kingdoms like Armorica and Cornwall, and the

Vandal kingdom of Africa. Thereupon appeared the more lasting dominions

of the Moors at Cordova and Granada, and of the Normans in France and

Sicily, and the enduring Power of the Papal See.

Slowly, uncertainly, under the shelter of the walls of Constantinople,

Europe drew the first rough outline of her present political aspect, and

began to emerge from barbarism.

Ambitions and strange freaks of fanaticism flared up among young nations

and died away. Among the former the revival of the Roman Empire by

Germanic monarchs lingered longest. Conceived by Charlemagne with the

aid of the Roman pontiff and his own paladins, this dream lived on for

many centuries, caused endless bloodshed and such cruel deeds as the

murder of that hapless Conradin, the last of the Hohenstauffens, a race

of rulers that had given rise to many legends and heroic lays. Then the

Crusaders with all their fruitless sufferings, their lavish shedding of

blood and treasure, and the masses of private iniquity which they died

trusting to expiate by public sacrifice.

And yet Constantinople held the eastern foe at bay. The tradition of

Rome’s all-conquering legions lingered yet, and old Byzantium boasted of

a standing army, highly trained and disciplined through all these

centuries—those stormy times for Europe, when every man’s hand was

against his neighbours. Then bands of armed men roamed over Europe,

following this leader or the other, each bent only on his own

advancement.

Little by little degeneration set in within and without the walls of

Constantinople. One fair province after another was regained by those

barbarians from whom they had been conquered, and the mighty Eastern

Empire fell to pieces. The spirit of the people was no longer bent on

upholding the traditions of the past, or, mayhap, lived too much in

those traditions.

So when the nations had begun to settle, the day of Constantine’s city

was over and its task accomplished. The eastern foeman achieved the

oft-attempted end, and possessed himself of those ramparts which so long

had kept him at bay, and established a new empire in place of the

vanished power of Roman tradition. There is yet another aspect to the

history of Constantinople. It was here that its second founder embraced

Christianity. St. Sophia and St. Irene still stand as monuments to mark

that happening, albeit the crescent, not the cross, now glitters from

their pinnacles; although portly, bearded Imams now take the place of

the long-haired Greek priests, and the high altars have been turned

awry, so that the faithful may know that their gaze is fixed direct

towards Mecca.

Here much of St. Chrysostom’s life and energy was spent; here, since the

schism with the Church of Rome, has been the Seat of the Patriarch, head

and high priest of the Greek Church.

Rulers, dynasties, even governing races have replaced each other, yet

here the Patriarchate still maintains the dignity of the great Church it

represents. For the strong man who vanquished this proud city did not

seek to turn his new subjects to his faith, but rather gave them full

liberty to follow their own. And this has been the policy of his

successors; thus it is that a Greek patriarch, Joachim, third of that

name, this day watches over the interests of his flock. Adherents to

every creed, save that of the Armenians, have enjoyed complete religious

freedom, and Jews who were hounded out of Catholic Spain took refuge

under the Chalif of Islam.

The same policy is continued by those clear-headed men who have but

recently revived the Empire of the East, and trust in time to give it a

government conceived on modern lines. Romance! Are not the pages of

history, even the most recent, made glorious by it? So who will deny the

attribute of romance to the story of a walled city?

Think of the enterprise, the ingenuity, the steadfast endeavour that led

to the encircling of ever-increasing areas within the embrace of those

stout walls; of the life of the people who pressed onward out of

paganism to Christianity, from despotism to constitutional

government.—Romance!

In younger days wars were waged because some fair lady had been carried

off, some rich jewel stolen, and in order that black insults might be

wiped out. We live nowadays beneath a more sombre sky. From isolated

incidents our motives have crystallized into definite principles, and it

needs the delicate eye of the artist to see any of the old lustre in our

honest if humdrum efforts to defend them.

Constantinople—the name conjures up dreams of Eastern colour, Eastern

sights, and Eastern smells: visions of Turks in baggy breeches and

jaunty fez; visions of bearded elders in flowing robes and turbans,

white, green or multi-coloured according to the wearer’s calling,

descent, or personal taste, for only he who is learned in the Koran may

wear white. Those who claim descent from the Prophet bind their fez with

green, and divers colours are worn more by Ottoman subjects from over

the water. Then you dream of stalwart sunburnt Turkish soldiery whose

bearing speaks of Koran-bred discipline and stubborn fighting, and a

fanaticism which takes the place of imagination. Gorgeous cavasses,

frock-coated followers of Islam with unshaven jowls and green

umbrellas, smart Bedouins and copper-coloured eunuchs from Abyssinia,

immaculately-attired dragomans, veiled ladies, more mysterious even than

their Western sisters—in fact, splendour, squalor, light and life, and

all as picturesque and romantic as dreams can be. This is the vision,

and the reality to whosoever is fortunate enough to see Constantinople

is its fulfilment. All but the dragomans, perhaps, for you may pass one

by and not know he is that wonderful omniscient being—a dragoman. He

will hide his greatness under a straw hat, maybe, he may even affect an

air of Western hustle.

But every other effect makes up for any disappointment one may

experience over dragomans. In a golden haze kaleidoscopic changes, every

type of face a study, every street corner its own distinctive character,

even the spick and span liners that lie along the quays, or have their

station in the fairway of the Golden Horn, seem to adopt a catchet other

than their register provides for them. Over all, the domes of many

mosques with their attendant minarets, from which the call to prayer

goes forth, they point the way to the goal of all good Moslems, and few

there are who allow this world’s cares to interfere with their

devotions. Later in the day these mosques, silhouetted in the gold of a

Stamboul sunset along with the other tall columns “qui s’accusent”

against the sky, go to form, as Browning (who had never seen them)

suggests, a sort of giant scrip of ornamental Turkish handwriting.

So, having followed this sketch of Constantinople’s history from Byzas

to these days, in which an almost bloodless revolution has been

accomplished, let us approach the city, and mark the bulwarks that are

left, and hear what those massive towers and battlements have to tell

us.

CHAPTER II

THE APPROACH TO THE CITY BY THE BOSPHORUS

AUTHOR and Artist have, for the sake of compactness, been rolled into

one. This method leaves to both a free hand and ensures absolute

unanimity: their harmonious whole now proposes to the reader a

personally conducted tour around the walls of Constantinople, within and

without, stopping at frequent intervals to allow the Artist to ply his

pencil while the Author holds forth to an eager circle of intelligent

listeners.

Constantinople should not be approached by those who hail from the West

with any Western hustle—no charging to the agents or the booking-office

at the last moment to demand a return ticket by the quickest possible

route, to traverse all Europe, passing through many strange and

interesting countries with the determined tourist’s reckless haste, to

tumble out on to the platform of the German-looking Stamboul railway

station, worn out and wretched and wishing to be back at home again.

Rather should the traveller wean his mind from many Western notions.

Let him disabuse himself of the hackneyed superstition that time is of

any moment. In the East it is not. Men have all the time there is, and

plenty of that. In this respect it corresponds to the biblical

description of Heaven: “There is no time there.” Conscious of their

easily won eternity, trains, and more particularly boats, make no

attempt to start at the hour mentioned in the schedule, aware that by

doing so they would only cause inconvenience to the large majority of

their passengers. Any one who has had official relations with the Turk

knows that his most frequent exclamation is “Yarsah—yarsah”

(“Slowly—slowly”), but to most foreigners the system is, at first, a

little disconcerting. Again, the traveller should prepare his mind for

what he hopes to see—a walled city,—so should, ere starting, let his

mind’s eye travel beyond his garden wall, against which perchance he may

safely lean as aid to meditation, to what he has heard of walls, walls

that were built by many devoted generations and in return protected

their descendants from those hungry powers that seek to destroy whatever

prospers.

And travelling toward his Eastern goal the reader passes through many an

ancient city whose walls chronicle the history of its inhabitants. He

should take his journey easily, should move eastward with no undue

haste. Let him go down the Danube, that mighty river which arises from a

small opening in the courtyard of a German castle, flows majestically

through the lands of many nations, where before the days of history Saga

held her sway and gave birth to the Nibelungs. In its waters many ruined

castles are reflected, amongst others Dürnstein, where Blondel’s voice

at length brought hope of deliverance to his imprisoned liege, Richard

Cœur-de-Lion. He will pass many fair historic cities, Vienna,

Budapesth, Belgrade, the White Fortress, and so on through the Iron

Gates, whence the great stream swells with increasing volume through the

plains of Eastern Europe to throw out many arms to the Black Sea. It is

here that Author and Artist await you; for to worthily approach

Constantinople you should do so from the north, and by sea. And you are

in good company, for by this seaway came the Russians in their several

attempts on the Eastern capital. The Turks, too, the present masters of

the situation, found this way and followed it to victory. These, too,

overcame great difficulties—they sailed in small vessels and were much

at the mercy of wind and weather; in fact, the Russians found their

plans frustrated by the elements. They met with anything but a pleasant

reception, whereas the traveller nowadays steams in great comfort in a

racy-looking Roumanian

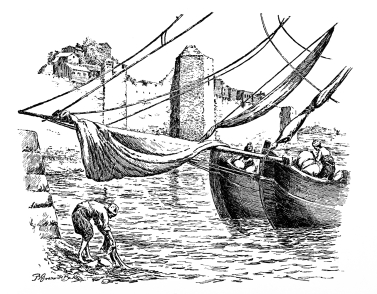

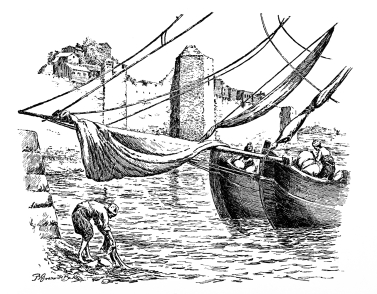

Genoese Castle at entrance to Bosphorus from the Black

Sea.

A narrow entrance this—strongly fortified it was too, in olden times,

for on that height to the left stands a frowning ruin, a Genoese

Castle.

liner, and is sure of a courteous welcome from his hospitable host, the

Turk.

Along the coast of Bulgaria—that kingdom of strong men under a strong

ruler, whose history, with a long and melancholy hiatus, is taken up

again, is in the making, and bids fair to rival that of older nations as

a record of devotion and steadfastness of purpose. And so to the mouth

of the Bosphorus, a narrow entrance through which the strong current of

the Black Sea forces its way to join the warm waters of the

Mediterranean.

The Argonauts found their way through here, braved the crash of the

Symplegades, and sailed out into the unknown in search of the golden

apples of the Hesperides. Let no man say that these were simply oranges,

for these a man may cull in many a Greek garden to-day. No—it was an

ideal they sought, and, like true men, they found and followed it.

A narrow entrance this, and strongly held, as it deserves to be if

Nature be man’s handmaid. Strongly fortified it was, too, in olden

times, for on that height to the left stands a frowning ruin, a Genoese

castle, commanding the entrance for many miles round the open sea and

the rolling, wooded heights of Asia inland.

Intensely interesting are the naval exploits of the city republics of

Italy during the Middle Ages. It is not easy to realize the power

developed by such towns as Pisa, Genoa, and Venice, and the enormous

importance of the part they took in the development of Europe. Other

cities are so much overshadowed by Rome, that those who are not

historians hear only echoes of their greatness.

Primarily there seems to be a divergence in the origin of empire between

those gained by a northern or southerly race. Latin empires grew out of

cities—Rome and Constantinople, and Athens with her Delian Confederacy;

the States of Pisa which owned large oversea possessions, Genoa which to

a long strip of coast counted Corsica among her spoils, Venice which

with varying fortunes controlled Dalmatia and Istria and built the stout

fortress of Nauplia commanding the Gulf of Argolis. Whereas England,

France, Germany, in fact those empires founded by the men of a Northern

race, began, it appears, by the conquest of other people’s cities, and,

making themselves masters of a number of such towns, started states of

their own, drawing liberal and very elastic boundaries round them which

they could enlarge when strong enough by the simple expedient of picking

a quarrel with their neighbours. These depended for their defence more

on those who lived in fortified seclusion on the marches of their domain

than on the town-dwellers.

The Genoese navy, composed of ships fitted out alike for battle as well

as for commerce, was free to look further afield as soon as Pisa, their

whilom ally against the Saracens of Africa, Spain and the Mediterranean

islands (but a formidable rival at all other times), had been finally

crushed at Meloria. Opportunity soon offered, for trouble arose as usual

in the Eastern Empire. The Latin dynasty put into power by the crusaders

was sinking lower, and a feeling for the restitution of the Greek Empire

was growing. Also, the Venetians, new rivals, had assisted the Latins,

so there was every reason to interfere. The interference proved

successful, Michael Palæologus conceded the suburbs of Pera and Galata

to the Genoese. These places were fortified, and served as a base from

whence to push Genoese enterprise further into the Black Sea, and in the

Crimea a factory was established. From time to time the Genoese turned

against the Greeks, no doubt in order that their swords might not rust

for want of exercise during the piping times of that peace which in the

East was a seldom acquired taste. They stood by the Greeks, however,

when trouble came from elsewhere, and to the last upheld their high

reputation for bravery and devotion.

The Genoese tower of Galata still stands overlooking the Golden Horn. A

yet more notable monument to those gallant seafarers are the so-called

“Capitulations.” The Genoese colony was ruled by a magistrate sent from

home, and to this day that right is still granted to the Powers of

Europe, and can only be fully appreciated by those familiar with the

ordinary standards of Eastern justice.

On the next height the Giant’s Mountain, also on the left bank, is

another monument of yet greater antiquity, though perhaps its historical

value is less easily assessed—depending more than ever on personal

opinion and a romantic nature completely undisturbed by the galling

limitations of probability—the Tomb of Joshua. Its origin is shrouded

in mystery, as it well may be considering the countless ages that have

passed over it—there are so few records of Joshua’s travels that no

doubt that eminent warrior may have gone on leave to travel for the

improvement of his mind like his colleagues of the present day without

our hearing anything of his experiences in foreign parts. It is equally

possible that he may not have returned from furlough—owing to decease.

This is purely speculation—very real, however, is the tomb itself. A

long, narrow, walled-in space in connection with a small mosque and

under the care of the Hodja in charge contains this, his resting-place,

enclosed by iron rails and about 24 ft. long by 10. It also serves as

fruit garden, or orchard—for several fig-trees grow here, so we see

that, unless the legend lies, Joshua must have been a tall strapping

fellow and the sons of Anak can have caused him no real surprise or

alarm.

The correct thing to do is to walk round the tomb a great many times

(there is a fixed number, but it does not matter much), tie a bit of rag

to the railing and express a wish, keeping it strictly to yourself. The

next best thing to do is to forget the wish, pay two-pence in baksheesh

and ride away to get the most of a glorious view. Artist and Author

alike do so.

And a pleasant thing it is to ride on into Asia Minor on an alert,

sure-footed Arab; he need be sure-footed, for at one time your road

leads along the very edge of a steep decline, at another over the bed of

what is a rushing torrent in the rainy season. Everywhere a changing

vista, bold, rolling hills, now covered with short scrub and heather,

with black rocks peering through it—now under oak and beech, everywhere

the glorious bracing air of the uplands mingled with breezes from the

Northern Sea. Here and there you find patches of cultivation, the

patient team of oxen drawing the primitive plough, merely an iron-shod

staff at an angle to the shaft to which the team is yoked. Near by, a

village, small wooden houses sheltered by fig-trees, a little shady café

where of an evening the men smoke a solemn hubble-bubble and discuss

events in the measured sentences of a conversation which begins about

nothing in particular and ends in the same district.

What changes those fields have known! armies pouring into Asia full of

enterprise and the lust of conquest, returning to escort a victorious

emperor in triumph through the Golden Gate, or beaten remnants of a host

to seek refuge behind the city walls. And a plough of the same

construction, drawn by the same faithful servants, stopped its course a

while to watch, and then went on its way unchanging.

But the fairest road is still that glittering waterway with its

ever-increasing number of craft, so we pass on to Constantinople. With a

fair breeze from the Black Sea dead astern small sailing vessels hurry

on towards their goal—the Golden Horn. They are high in the bows,

higher still in the poop, with an elegant waist but withal a reasonable

breadth of beam, brightly painted too, with cunning devices on the prow

and sails that glisten white under the Ottoman ensign; they carry for a

flag a crescent argent in a field gules (the Artist insists on heraldic

terms, as they are so picturesque). These little ships have been busy

collecting many things for the Stamboul market along the Black Sea

Coast. Heavy-laden tramps thump onward to Odessa to return with corn or

wool. We overhaul a yacht-bowed Russian mail-boat and get a shrill

whinny of greeting from the stout little passenger steamers, Tyne-built,

that ply between the many landing-stages along the Bosphorus bringing

officials, business men and even artists back from the city to those

quiet, cosy little bungalows that hide among the trees on either side.

White-painted caiques flit across from side to side, one-oared and even

two-, some more pretentious ones with more oars still, the boatmen

dressed in becoming uniform, veiled ladies in the stern sheets. A

hustling steam-pinnace shoots by from one or the other “stationaires,”

for every larger Power keeps one here; and there on the right, that row

of gleaming palaces by the waterside is Therapia, those palaces the

different embassies in their summer quarters. Here homesick travellers

of many nations may feast their eyes on the war-flag of their country

and get up a thrill, if the scenery should have failed to cause one. It

certainly is a pleasant sight to see a sturdy British bluejacket again

or his smart colleague of the U.S. Navy in his jaunty white hat.

Therapia will tell you that this is the only place to live in during the

summer; other places along the road on either hand claim the same

advantage, and the claims must be allowed where the choice is so

difficult. For there is Candilli, and who that has spent some sunny

weeks under the trees of that favoured spot, has dived from the garden

wall (displacing volumes of water) into the evening phosphorescence of

the Bosphorus, but wishes to return and to repeat the performance? And

Arnoutkeni, where, on a hill-top, lives the most hospitable of

consuls-general.

The silvery way narrows and widens, and winds, though slightly, past

ever-increasing signs of human habitation. Wooden Turkish houses with

the jealously latticed windows of the harems dipping their stone

foundations in the sea, some with a little scala leading to a stoep,

where the veiled ladies of the house may take the air while children

play around them. Stately palaces walled off towards the land, the

sea-front open and mayhap the lordly owner’s steam-yacht moored just

opposite, barracks and cafés with vine-clad trellis-work, and behind the

narrow stone streets and little shops. Every now and then a mosque, its

dazzling minarets pointing to the sky, and also, too frequently, a very

modern residence in the very latest bad taste, which is saying a good

deal.

To all this a background of trees, the warm depth of pines, the pleasant

green of oaks and beeches, the bright shining green of fig-tree, and

everywhere larger or smaller groups of slim cypresses, close-serried

beneath whose shade rest faithful sons of Islam—and

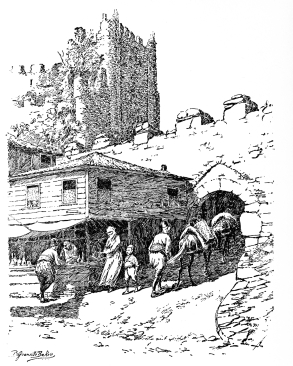

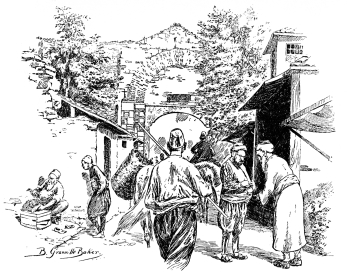

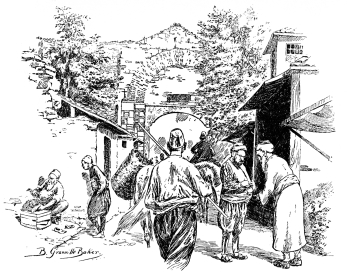

Anatoli Hissar, or the Castle of Asia.

Within the precincts of this castle, entered by narrow gates, are other

small houses, still smaller shops and cafés.

surely none of them might wish for a more lovely and decorous

burial-ground than here, looking out upon the narrow strait their

fathers won so dearly.

There are open spaces too, where groups of people, gay patches of bright

colours, disport themselves: a game of football is no unusual sight

here. Even a factory chimney stands out here and there, not emphatically

belching out defiant volumes of black smoke to insist on the power of

the main-d’œuvre, but in a gentler manner, as if rather apologizing

for this outrage upon nature and trying its best to adapt itself to its

surroundings by the kindly aid of quaint-looking craft, blackavised, but

free from any suggestion of machine-made regularity; these craft carry

the coal necessary to enterprise, just to oblige, they seem to say.

The Channel widens, then narrows again, and here stand two ancient

fortresses, one on either hand. Ancient, compared to Western notions,

though too recent to be mentioned by chroniclers of Old Byzant, for they

are of Turkish origin, and date back but a few odd centuries. On the

Asiatic side stands Anatoli Hissar, or the Castle of Asia. Wooden houses

of all ages cluster about it, the wood of some painted in bright

colours, pink or ochre, or others left to be coloured by time and

climate, ranging from warm purple greys to the strongest burnt Sienna.

Within the precincts of this castle, entered by narrow gates, are other

small houses, still smaller shops and cafés. To southward broad green

streams join the Bosphorus, the sweet waters of Asia, along the banks of

which are pleasant open spaces, a mass of colour on Friday afternoons;

for here the Moslem ladies take their leisurely walks abroad on that

day, and spend many pleasant hours chatting under the shady trees,

though what they find to talk about except their children, Allah alone

knows. The bridge leading over the northern arm of these waters in an

attractive spot: here the Artist put up his easel to sketch the

continuous stream of passers-by—grave merchants, portly of person on

small donkeys, small horses laden with baskets, pedestrians many and of

all manner of races, mostly Eastern, now and again a squad of cavalry on

active little Arabs, or a body of infantry with the fine decisive tramp

of a conquering race. At the foot of the rather high-arched wooden

bridge a number of caiques, white-painted with crimson cushions, their

oarsmen dozing in the sun, while heavier boats laden with fruit and

vegetables go out to market at Stamboul. Across the bridge quaint wooden

houses with the usual latticed windows, and, connecting them across the

narrow street, vine-covered trellis-work beneath the shade of which some

business is transacted, buying and selling conducted with all the

leisure and decorum of men for whom a year more or less means little.

Behind and crowning all, the frowning though dismantled fortress. Here

the Artist had an experience that struck him enormously. His morning

sketch was of the scene described above, his afternoon work was from

inside a boat-builder’s yard, looking over the sweet waters to some

Turkish houses, glorious in colour with quaint wood carving, each with

its tiny well-kept garden by the sea.

The second day while at work on the morning sketch, the genial

boat-builder approached and confided the key of his establishment to the

Artist, at the same time intimating that the yard would otherwise have

been found closed and thus the afternoon’s sketch delayed. Would this

have happened on Clyde or Tyne?

Over against Anatoli Hissar stands Roumeli Hissar, the Castle of Europe,

a yet more imposing mass of ruins. Its plan is said to be the cypher of

Mohammed. The whole fortress is said to have been built in two months by

the forced labour of Greeks, to each of whom was delegated a measured

area. The towers that command the upper part are of the construction

peculiar to the Turkish architecture of that period, a tower of smaller

dimension superimposed on the lower one is what it looks like, and we

shall see it again at Yedi Koulé. This castle encircling a picturesque

village is peculiarly beautiful in the spring, for then the flaming

colour of the Judas tree, swamping with its vivid tone the delicate pink

of almond sprays, lights up the deeper ochres and purples of the

surrounding masonry, and makes the dark cypresses that stand all about

strike even a yet deeper note than when the glamour of high summer

bathes all things in a golden haze and draws light even from these

sombre trees. And they are so beautiful, though perhaps a bit wistful

also—their slender shape, the warm grey and purple of their stems and

branches and the cool depth of their foliage.

Close by this castle stands Robert College.

Further south, obliquely opposite is Candilli, a place where it is good

to be. At first glance, but for its prominent situation, it may appear

to be much like other places along the banks of the Bosphorus. A short

bit of narrow street, stone-paved and very bad to walk on, leads to a

cross-road, the cord that connects all these little villages. It is

equally badly paved, but as many of the blocks of stone that once served

as pavement have vanished, there are quite a number of softer spots

wherein a man may set his feet when walking. There is a café by the

waterside, where Turks, Armenians, Greeks and others take their

Roumeli Hissar, or the Castle of Europe.

Over against Anatoli Hissar stands Roumeli Hissar, the castle of Europe.

Its plan is said to be the cypher of Mohammed.

leisure, drink endless cups of coffee and gaze into the water.

The gentleman who sells tickets to those who leave by boat, and collects

them from those who land here, may generally be seen fishing from the

landing-stage. He is a philosopher; it is but little that he wants, and

he takes a long time getting it. There is a mosque close by whose Hodja

is counted among the Artist’s personal friends. He is a busy man, as

Turks go: he sweeps out his mosque, trims and lights the candles that

adorn it by night, and fulfils all the Koran’s requirements in daily

prayer, encouraging others in the same commendable practice. He also

possesses a magnificent tenor voice which is heard to best advantage

rising up from his minaret to the hill overlooking Candilli, when

exactly one hour and a half after sunset he announces to the world that

“Allah is Great. There is no God but Allah, and Mohammed is His

Prophet.” He has a son who is learning to chant the same refrain and to

quote the Koran. Like most of the early apostles, he is a fisherman.

All around by the seaport, on the hillside, in garden and under trees,

stand the houses of those who live in Candilli, either permanently or as

summer tenants only. Should the reader ever visit here, let him turn

sharp to his right and keep along the sea-front, a stone-paved terrace

about 8 feet broad occasionally broken to admit boats into the

boathouses, caverns in the stone foundations of the houses that stand

here. These breaks are planked over for the convenience of

foot-passengers; and so we keep on till a sharp turn to the left takes

us to a flight of steep steps. We ascend and join the high-road, the

cord referred to above. You are welcomed there by a sportive litter of

pariah pups who have an al fresco lodging here on a luxurious bed of

melon-skins, which provide food and bedding at the same time, and quite

a plentiful supply of each during the season. The neighbourhood for

miles round, city and suburbs, is full of little corners convenient for

receiving things that you no longer want. A few hundred yards along the

high-road another sharp turn to the left, another litter of pariah pups

and their white mother, generally called the “old lady,” all most

pleased to see you; another ascent, short but sharp with holes torn out

of the pavement as if the shell of a cow-gun had struck it, and you

arrive at a doorway in the wall. It is quite unpretentious, in fact its

modesty is carried so far that a piece of string that dangles out of a

hole will, when you pull it, lift the latch and so give you admittance.

You enter an unpaved yard, in fact after a few days’ rain you may call

it a garden, for grass grows up without any other encouragement, just

as it does in all Eastern gardens. Before you stands a wooden house,

shrouded with vine and overshadowed by a fig-tree; there is yet another

fig-tree in the garden, and a walnut-tree and another sitting-out-under

tree, which finds that sufficient avocation, and therefore yields no

fruit of any kind.

Entering the house, the first thing that meets your eye and holds it is

a row of boots on the left-hand side of a stone-flagged apartment called

the hall. Your eyes rest on the boots, for you know at a glance that

they are British made—they are, for Englishmen live here. A doorway

opposite the entrance leads to the kitchen; here the Greek cook, Aleko,

reigns supreme, and with him the butler, Kotcho, which being interpreted

means Alexander and Constantine. A wooden staircase leads to upper

regions, to a spacious sitting-room, where no one ever sits save in wet

weather. But why this lengthy description of an ordinary English

bachelor abode? the reader asks of the Author. He gets behind his

collaborator—the Artist lived here, and thus history is made.

The Artist lived here as the guest of those whose work lies in

Constantinople. There were several, their numbers had frequent additions

towards the weekend, and the assembly went by different names, the most

common being the “Y.M.C.A.,” because one of the number nearly lunched in

the company of a bishop one day, and a bishop in the Levant is rare

enough for comment.

They lived in great contentment, did these Britons abroad; at work

during the day, they foregathered at dinner in the variegated garb that

betokens ease and talked of many things between the peals of the pianola

wafted from a villa higher up on the hillside. They listened to the

Eastern sounds that came to them from afar, to the warning hum of the

mosquito, the distant barking of a dog, the tapping of the watchman’s

iron-shod staff on the pavement outside. One night they heard his cry of

“Yungdin Var” (“There is a fire”), as in accordance with time-honoured

custom he proclaimed some distant conflagration, while his colleagues

all along the coast on either side gave the same warning. This call

sounded in the lane below the bungalow, and was vigorously repeated from

within. The watchman answered, “Pecci, pecci, effendi” (“All very fine,

gentle sirs”—or words to that effect), but tell me where it is? and

then himself announced the place and went on his way rejoicing in a

“score.”

Now and then these men would sally forth of an evening to one or the

other hospitable house, to dance or dine, a solid phalanx of dazzling

shirt-fronts.

The nights on the shores of the Bosphorus are very fair. Quite still,

the lights of Stamboul and Pera gleaming in the distance, the swish of

passing steamers whose searchlights flash unbidden through your windows,

and the moonlight reflected in their wash in myriads of sparkling

facets. And then the rosy dawn dispelling the faint haze upon the

waters, when the tall trees that are silhouetted black against the clear

nocturnal sky, lose their sharply-defined shape as they resume their

colours and merge with the glorious scheme of awakening chiaroscuro.

And for many ages night on the Bosphorus has enjoyed this deep repose,

making an occasional disturbance such as happens where men inhabit seem

incongruous. Imagine the deep stillness when Byzas first settled in his

City, set out in early morning to search out the land on his own side of

this broad waterway, that led to lands remotely known to him through

legend only. His constant pleased surprise at finding more and more

treasure beautiful and material in the wooded bays where safe anchorage

offered. And his return at nightfall in the stillness till he saw the

ramparts of his City purple against the evening sky, faint lights

twinkling and fainter sounds reaching him across the water betokening

the activity of his settlers.

These peaceful waters have known much strife and turmoil, the valleys on

either hand, the hills of Europe and Asia have echoed back the sounds of

battle. Fast sailing ships brought swarms of adventurers down time after

time to try their fortunes before the walls of Cæsar’s Castle. From

Roumeli Hissar, the fortress built by Mahomed the Conqueror, right down

beyond Seraglio Point and into the Sea of Marmora stretched that

monarch’s fleet. But it was of no avail against the seaward walls.

Entrance to the harbour was impossible, as a chain had been stretched

across the mouth of the Golden Horn, and behind it the larger vessels of

the Genoese and Venetians rode at anchor. So Mahomed conceived a plan

bold and in keeping with his character and ability. He decided to convey

a portion of his fleet across country to the upper reaches of the Golden

Horn and to attack the walls that guarded the upper harbour.

There appears to be some doubt still as to the exact spot where these

galleys were beached and as to the route they took. Galata, the Genoese

fortress, must be avoided, and at the same time the shortest route must

be taken. Galata stands in a position somewhat similar to

Constantinople, on a promontory formed by the Hellespont on one side and

on the other by the Golden Horn, which bends slightly to the north

after passing west of where the land-wall of Theodosius joined the

sea-wall of the Bosphorus, towards the sweet waters of Europe. At any

rate we pass the place where this great feat was accomplished, and this

is how it was done. Mahomed made a road of smooth planks covered with

grease, and along this road a host of men pulled eighty galleys in the

night. The next morning these ships were riding at anchor in the upper,

shallower part of the harbour beyond reach of the larger vessels of the

Genoese and Venetians. According to the Byzantine chronicler Ducas,

every galley had a pilot at her prow and another at her poop, with the

rudder in his hand, one moved the sails while a fourth beat the drum and

sang a sailor’s song. And thus the whole fleet passed along as though it

had been carried by a stream of water, sailing, as it were, over the

land.

Certainly a most remarkable feat carried out to the sound of the drum.

The drum an instrument, some say of torture during the month of Ramazan,

for it serves to arouse the faithful Moslem an hour before sunrise that

he may eat—for he may touch neither meat nor drink between sunrise and

sunset during this fast, and it cannot fail to wake others in the

neighbourhood. Entirely oriental in its origin—no doubt an ancient, its

enthusiasts think venerable means of producing sound—its appearance in

Europe is of comparatively recent date; in fact, not till after West and

East met in the Crusades did the drum become part of a European army’s

outfit, and to this we may directly trace the creation of military

bands, for where would any band, save a German one performing in

England, be without a drum? We may conclude that in all probability it

served a double purpose, the uncanny noise both struck terror into the

heart of the enemy and cheered on “the Faithful” to battle. The Roman

armies sounded the tuba, Frank or Teuton put his soul into a bullock’s

horn, which a later period imitated in brass, and that so successfully

that not even the best of modern composers can altogether do without it.

The Crusaders rallied their bands by means of horns, each in a different

key, no doubt; the Saracens beat drums to draw their followers to the

Crescent standard, and a happy blending of these two, with the addition

of some attempts at harmony, now brighten the soldier’s life when

marching to church in sections, or returning heavy footed from a field

day.

The traveller is at liberty to choose any spot he likes, given that it

be on our right, to settle where Mahomed’s galleys left the waters; that

safely accomplished, he should look before him. We have passed many

charming little villages quaintly named—Beylerbey,

The Tower of Galata.

Galata’s proud Tower comes into view, and right at its feet the Golden

Horn, all life and bustle and glittering harmonies of colour.

the Bay of the Beys; Tshengelkeui; Beshiktache; Kabatache. On the

heights above palaces, palaces on the sea-front, as we sail on towards

Constantinople, and there it is before us.

We see Seraglio Point, and then the view increases, showing a glorious

vista of mosques, gleaming domes and tapering minarets. We pass on our

right a couple of steam-yachts, bright and trim, moored opposite a

splendid palace. H.M. the Sultan’s yachts lie here, and his residence is

the Palace of Dolma Bagche. On the heights above Pera, the city of

Italian origin, now inhabited by those Western by birth or inclination,

and standing some distance away from it, is Yildiz Kiosk, the deserted

haunt of baleful associations.

Galata’s proud tower comes into view, and right at its feet the Golden

Horn, all life and bustle and glittering harmonies of colour. The very

smoke rising from the tall funnels of tramps and ocean liners catches

the light, reflects it, and add another beauty to the aspect.

Over our port bow we look down the smooth, shining expanse of the Sea of

Marmora, in which the Prince’s Islands seem to float as in a sunny haze.

These have their history, and sad it is for the greater part, and

reference will be made to that later, when the Artist has finished

talking about the scenery, and has returned to his legitimate

occupation. Behind these islands are faintly seen the mountains of the

Asiatic mainland, then the coast draws in towards the Golden Horn, and

here are Modar and Kadikeui, villages so called, though perhaps more

truly suburbs, wherein you may find many hospitable houses. One of them

gave shelter to a Turkish gentleman, a high-placed personage whom an

angry soldiery were in search of during the last counter-revolution, the

last dying effort of reaction. And here below Modar lie many yachts, for

it is a fair sea for yachting is the Sea of Marmora, and the coast and

the islands offer ever-varying change of scene. Then close to Kadikeui

and north of it is Haidar Pasha, with its blot upon the landscape, the

terminus of the Bagdad railway, an edifice German in construction and of

consummate ugliness. Close under this eyesore is a peaceful spot where

many tombstones and a monument bear record of the deeds of the English

soldiers, victims of the Crimean War. A peaceful spot, and oh! so

beautiful. Above it stands a large yellow building many storied, with a

background of tall cypresses in thousands that shade the Turkish

cemeteries, where many lie who fought side by side with Britons and our

gallant friends the French against their old northern enemy, Russia.

This building may fall to ruin and perish, the dead that lie about here

and their deeds may be forgotten by all but the straight-stemmed

cypress-trees, but the memory that lives about this place will never

die, for it tells the glorious story of a noble woman’s work—this

building was Florence Nightingale’s hospital.

And near here another work by women is in progress, work devoted to

rising generations at the American Girls’ College.

The traveller may cast a glance backward to the way he came and see a

small tower standing in the sea—this is a trim-looking tower and shows

a light o’ nights—this is called the tower of Leander.

But no more looking back. We have arrived opposite Seraglio Point, and

our goal is before us; for here is the starting-point of the strange and

glorious history of the City of Constantine, here the foundations of the

city of Byzas were laid—here is Constantinople.

CHAPTER III

SERAGLIO POINT

PERSONS of importance like our travellers land at Seraglio Point instead

of travelling round to the bridge of Galata. Byzas did so, we have it in

black and white a few pages back, so it must be true. We can without

much fear of contradiction suppose that Constantine the Great landed

here also, though perhaps he went to one of the harbours on the Sea of

Marmora. Indeed, he is more likely to have done so, for the current runs

pretty strongly and the sea is more than a little choppy at this point.

Byzas had no harbour to turn into except the Golden Horn, and he must

have been too eager to land and survey his new property to have followed

that waterway any considerable distance. Just a little west of the point

is perhaps the best place to land, somewhere near the Turkish Custom

House.

It is, of course, very interesting to land at the bridge of Galata,

passing through crowded shipping on the way up the Golden Horn. On one

hand, to the south, one sees the irregular mass of buildings, mosques,

and public offices which go to form Stamboul. You may descry that vast

square of solid ugliness owned by the international creditors of the

Ottoman Empire and known as the Public Debt. Close by you catch sight of

the head-quarters of Government—the Sublime Porte. Drowsy fox-hunting

squires, to whom their wives read the paper of an evening, must often

have started at the reiteration of this familiar phrase, and wondered to

what year the marvellous Eastern vintage belonged.

Opposite the business quarter of Galata, crowned by its tower. The life,

the colour ever changing, on the highway across the Golden Horn is

extraordinarily fascinating. Sons of every race and nation upon earth

are freely mingled here. The Western official or the business man, whose

garb is allowed to betray no ease or originality, here brave the fierce

suns of summer clad in the drab discomfort of business attire, with the

Perote or native of Pera and Levantines of European origin who have

imbibed some longing for oriental display without the requisite taste.

Western ladies unveiled, Eastern ladies veiled, the latter in many cases

beautifully shod and gloved. Also the Artist raves about a little hand

he has seen ungloved, such a dainty, beautiful hand, and according to

his own estimate he is an expert in such matters. Then there are Turks,

Western Turks, whose costume is also Western, the fez and seldom-shaven

cheeks being the only things in which they differ from others, for many

are fair and most are fine, handsome men with every sign of the

self-control good breeding gives. Hamals, the porters, push their way

with backs bent double and their packs joined upon the leather rests

provided for that purpose. Great men in carriages drawn by dashing,

spirited Arab steeds roll by you, a servant in gorgeous livery beside

the driver on the box. Asiatics of all kinds and colours, fantastically

yet harmoniously clad, move past with silent, unhurried footsteps. And

then a batch of soldiers, fine, upstanding fellows in business-like

khaki, march past on their way to embark for the Yemen, the Sierra Leone

of the Turkish Empire, for which men even volunteer nowadays, since the

bad old order changed.

But we have landed our travellers on the northern extremity of the

promontory on which stands Constantine’s ancient city. This part serves

as a public promenade, and here people take the air, admire the glorious

view, and generally behave like people do everywhere else, when they

find time for a leisurely stroll, the only difference being that here

men find time for one more often. The point is open to the sea, for

there is no further occasion for the walls and towers that encircled

this the starting-point of Byzantine history. Here was the first

settlement of Byzas that grew into an Acropolis, walled, and strongly

held, the heart of a growing empire. So we go inland, crossing by a

bridge the railway that discreetly hides its unloveliness in a cutting

before running into a terminus that might have been picked up from one

of the Hanseatic towns and planted here by some malignant fairy.

The road leads upwards to the Seraglio buildings, and here is much of

interest. There is the Museum containing many treasures, among them two

of wondrous beauty—two sarcophagi, one of which claims to have held the

remains of Alexander the Great, the other is presumed to be the last

resting-place of one of Alexander’s higher officers, and is known as

“Les Pleureuses,” from the beautifully-sculptured female figures in

mourning garb that adorn it. Within these precincts is the School of

Art, where much good, earnest work is being done under the guidance of

Humdi Bey, to whose efforts the recovery of the sarcophagi and other

monuments is due as the result of excavations in Asia Minor.

A broad road leads us with park-like plantations on either hand up from

the sea towards the Seraglio buildings. These buildings stand on a

height, the first of the seven hills that form the immovable

foundations of the city.

The Seraglio no longer serves its original purpose, the Imperial Museums

and School of Art have taken up a considerable portion of them, and

others find accommodation for troops. Here you may see the stalwart

Anatolian peasant being made into a soldier after the German pattern,

and a very good pattern too. Bugle-calls, reminiscent of those heard in

Germany, tells the Turkish soldier the time for all the many duties he

should attend to. Sergeants in manner emphatic and teutonesque impart

the mysteries of that solemn, high-stepping march which takes the place

of route marching in an army that has to train its men to reach

perfection in two years’ time. Slim-waisted subalterns, whose moustaches

follow Imperial precept, superintend these operations, and an anxious

company commander may be seen in conference with his colour-sergeant.

It would sound invidious, it would savour of interference, to wonder

which is the better use for the Seraglio buildings, that of the present

or the past. The Artist doth profess loudly on this point, that no

building can serve a higher purpose than that of housing in comfort

those who are taken from their homes to learn how to defend the honour

of their

The Landward Walls of the Seraglio.

Romance and mystery cling to the place and live in the name Seraglio. It

is jealously walled in, the wall being of Turkish construction and

comparatively recent, and to it may be seen clinging quaint wooden

houses.

country, and that again the honour and glory of a community is well

served by making ample provisions for the encouragement of art. Both

Author and Artist wish these Seraglio buildings a glorious future in

their present warlike and peaceful missions.

But romance and mystery cling to the place and live in the name

Seraglio. It is jealously walled in, the wall being of Turkish

construction and comparatively recent, and to it may be seen clinging

quaint wooden houses.

No doubt Byzas dwelt somewhere about here, though the exact spot is

possibly beyond the ken of the keenest archæologist. Remains of solid

masonry, huge blocks of stone, have been discovered near the Seraglio

kitchens, of which a fine view is offered from the railway, peeps of the

massive, high-standing building through the ranks of its solemn escort

of cypress-trees.

When Byzantium became the City of Constantine it was found necessary to

extend the enceinte of the older fortifications, as the number of

inhabitants had grown prodigiously, and this first rampart was of

greater extent than the present Seraglio walls. The many improvements

made by Constantine, the palace he built unto himself, the Forum and

Hippodrome he laid out, and the churches he erected, are nearly all

within the immediate neighbourhood of the Seraglio, if not inside its

precincts. So here again was the centre of the civic and religious life

of the city, rising rapidly to the zenith of its power, and here it has

remained until most recent times.

There were walls and towers round the point to guard the city both

against her enemies and the violence of the elements, and, sooth to say,

it was the latter caused more damage than the former. These had need to

be constantly repaired. Of the very earliest walls no trace remains, yet

they too had their page in history. Not far from where our distinguished

travellers landed, just round the eastern point and looking east, is Top

Kapoussi, which means cannon-gate, for here stood a gate dedicated to

St. Barbara, who is the patron saint of gunners. But a more likely

reason for the Turks to retain the memory of the original name is that

close by stood a magazine or military arsenal when they conquered the

city, and may have stood for years after. It seems that there was a yet

older gate at this spot, a gate through which the Spartan admiral

Anaxibius entered the Acropolis when he escaped from the city by boat

along the Golden Horn, what time Xenophon and his truculent Greeks were

in possession.

After Constantine had led his people, or at least those under his

immediate influence, into the fold of the Christian community, many

churches sprang up about this northern extremity of the promontory.

(There are, no doubt, those who will differ from the Author on the

subject of Constantine’s conversion, who may say that his people led

Constantine to adopt Christianity, and that reasons of policy rather

than the conviction born of a sudden inspiration guided him, but the

Artist will on no account allow such a prosaic version.) Five churches

stood about here, one dedicated to St. Barbara, as we have seen, another

to St. Demetrius, a third to St. Saviour, yet another to St. Lazarus,

and a fifth one built to St. George on the highest ground available just

there, according to custom, for in former times all churches dedicated

to the warrior’s patron saint were built on higher ground, as if to give

the saint an opportunity of keeping a good look-out from his sanctuary.

This church gave to the Sea of Marmora its mediæval name of Braz St.

George.

There were evidently other buildings in connection with St. George’s

Church, a monastic institution most probably, for here under the name of

Joasaph the Emperor John Cantacuzene dwelt in seclusion after his

abdication until he withdrew altogether from among his former subjects

to a monastery on Mount Athos. Another great feature of this

neighbourhood was its holy well, which may be springing still, though

for this the Author cannot vouch, as he has not seen it. The Church of

St. Saviour guarded this holy spring—its water had healing qualities,

and pilgrimages were made to it on the Festival of the Transfiguration.

The life of the capital of an empire stirred the precinct of what is now

the Seraglio enclosure and the vicinity outside it for close on twenty

centuries. We have seen the city rise under the fostering care of Byzas

its founder, and followed those dim paths of remotest history when the

world was young, though no doubt the sad young cynics of the period

thought it as old and foredone as they do to-day. Then came the glorious

epoch of Constantine and his successors—glorious indeed in the new

light of Christianity, but in that name much evil was done, and by it

murder and violence and civil war were held to be excused. But through

it all the city, this seat of empire, exhibited a most astounding

elasticity and power of recovery. True the Palace of Cæsar built by

Constantine was not within the precincts enclosed by the Seraglio walls

of to-day, but the brain of the empire held its sway hard by here, and

its tumultuous heart beat everywhere among the ruins and decay that now

mark the site of palaces.

Constantine in his glory and genius passes, and others follow him in an

unbroken sequence, some good, many bad, all human, and thus surrounded

by the romance that envelops those that played their part in history

and did their share in making it. A noble sequence taking them all in

all from Constantine, who reigned from 306 to 337, then his successors

down to the last emperor, another Constantine of the house of

Palæologus, twelfth of the name who fell before his city walls to be

succeeded by a conqueror of the house of Ottoman, the house that has

filled the throne of the Eastern Empire until to-day.

If we take but a few of this unbroken line of sovereigns, more than one

hundred altogether, such names stand out in the world’s history as

Valens, whose aqueduct still stands as a monument to perpetuate his

name. Then Theodosius II, whose master mind gave to the city its

furthest limit in those proud walls that have encircled it since the

beginning of his reign, and still stand as testimony to the genius of

man. Justinian the Great, too, first of that name of whom we must say

more when we come to the ruins of the lordly palace he inhabited. Leo V

the Armenian who entered the city as a poor groom, they say, but served

his Imperial master, Michael I the Drunkard, so well that he then

ascended his throne and restored the expelled Government of the Empire.

And there are many others of whom mention will be made elsewhere in

connection with fortifications and palaces that were erected far beyond

the first narrow limits of the city that Byzas had founded and the great

Constantine made his own.

About this neighbourhood centred the life of the city; there was a broad

esplanade near where the Church of St. Lazarus stood, down by the Sea of

Marmora, its site probably not far from the foot of the Seraglio

kitchens. This esplanade was called the Atrium of Justinian the Great,

for it was his creation. And a fair place it was, all built of white

marble. Here the good citizens might walk and breathe the soft air,

looking out towards the Prince’s Islands and the coast of Asia, across

the Sea of Marmora, reflecting in its translucent depths the glorious

colours of an Eastern sunset. And here they walked and talked, and no

doubt discussed all subjects upon earth, religion, politics, those chief

incentives to resultless argument, and the news, with all its

variations, which were nothing uncommon even in the days before a daily

paper first appeared. How portly burghers must have smiled with

satisfaction at the sight of bellying sails that drove their galleys

back from the shores of many countries to the great market.

Or a racing craft under full sail with all its rows of glittering oars

rising and dipping in strict accord would round the point into the

Golden Horn, leaving the gazers in the Atrium the prey to many

conjectures, until a gentle sound coming from the north, round by the

Senate, growing to a roar conveyed the news of some great victory.

Perhaps an anxious heart of mother, wife or sister would beat against

the coping of the Atrium, as tearful eyes followed the swift sails of

departing war fleets that pressed onward into the morning. And the sun

would rise to arouse the golden glories of the city, and yet leave that

heart unlightened.

Here, too, good folk would meet to discuss the pomp and splendour of the

escort that had brought the Emperor’s bride-elect to the sea-gate of

Eugenius down by the Golden Horn. How Cæsar there had met her with great

pomp and ceremony, and had himself invested her with the insignia of her

exalted rank. The talk would then go on to the high doings at the

palace, and all those good things that had been brought together from

every quarter of the earth for the delectation of the wedding guests.

When lowering clouds obscured the brightness of the sun of Cæsar what

whisperings, what anxious glances out to sea! Yes, and perhaps what

black looks when an alliance was proposed, and indeed consummated,

between a princess of their royal house and the polygamist ruler of

their enemies the Turks, Amurath I.

What troublous times and discontents when every messenger brought news

of fresh disaster, of yet another portion of the Empire torn from its

enfeebled grasp. What grumbling at the supineness of the Christian world

that looked on with apathy when it could find the time to spare from its