|

Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed.

No attempt has been made to correct or normalize the

spelling of non-English words.

Some typographical errors have been corrected;

a list follows the text.

Some illustrations

have been moved from mid-paragraph for ease of reading.

In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol  will bring up a larger version of the image.

will bring up a larger version of the image.

Contents.

Appendix.

Index.

(etext transcriber's note) |

THE

B R I T I S H E X P E D I T I O N

TO THE

C R I M E A

BY

WILLIAM HOWARD RUSSELL, LL.D.

NEW AND REVISED EDITION

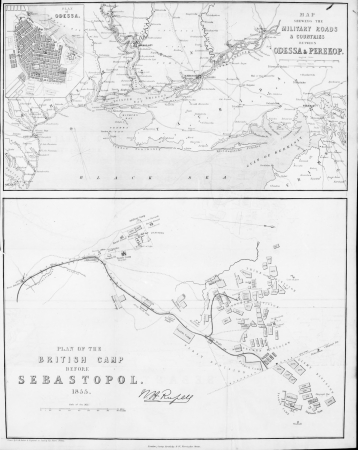

WITH MAPS AND PLANS

LONDON

G E O R G E R O U T L E D G E

A N D S O N S

THE BROADWAY, LUDGATE

NEW YORK: 416, BROOME STREET

1877

THE INDIAN MUTINY.

In crown 8vo, cloth, price 7s. 6d.

MY DIARY IN INDIA,

In the Year 1858-9.

BY

WILLIAM HOWARD RUSSELL, LL.D.

SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT OF "THE TIMES."

NOTICE TO THE READER.

EDITION OF 1858.

THE interest excited by the events of the Campaign in the Crimea has not

died away. Many years, indeed, must elapse ere the recital of the

details of that great struggle, its glories, and its disasters, cease to

revive the emotions of joy or grief with which a contemporary generation

regarded the sublime efforts of their countrymen. As records on which

the future history of the war must be founded, none can be more valuable

than letters written from the scene, read by the light documents, such

as those which will shortly be made public, can throw upon them.[1]

There may be misconception respecting the nature of the motives by which

statesmen and leaders of armies are governed, but there can be no

mistake as to what they do; and, although one cannot always ascertain

the reasons which determine their outward conduct, their acts are

recorded in historical memoranda not to be disputed or denied. For the

first time in modern days the commanders of armies have been compelled

to give to the world an exposition of the considerations by which they

were actuated during a war, in which much of the sufferings of our

troops was imputed to their ignorance, mismanagement, and apathy. They

were not obliged to adopt that course by the orders of their superiors,

but by the pressure of public opinion; and that pressure became so great

that each, as he felt himself subjected to its influence, endeavoured to

escape from it by throwing the blame on the shoulders of his

colleagues, or on a military scapegoat, known as "the system." As each

in self-defence flourished his pen or his tongue against his brother, he

made sad rents in the mantle of official responsibility and secrecy.

Even in Russia the press, to its own astonishment, was called on to

expound the merits of captains and explain grand strategical operations;

and the public there, read in the official organs of their Government

very much the same kind of matter as our British public in the evidence

given before the Chelsea Commissioners. Much of what was hidden has been

revealed. We know more than we did; but we never shall know all.

I avail myself of a brief leisure to revise, for the first time, letters

written under very difficult circumstances, and to re-write those

portions of them which relate to the most critical actions of the war.

From the day the Guards landed in Malta down to the fall of Sebastopol,

and the virtual conclusion of the war, I had but one short interval of

repose. I was with the first detachment of the British army which set

foot on Turkish soil, and it was my good fortune to land with the first

at Scutari, at Varna, and at Old Fort, to be present at Alma, Balaklava,

Inkerman, to accompany the Kertch and the Kinburn expeditions, and to

witness every great event of the siege—the assaults on Sebastopol, and

the battle of the Tchernaya. It was my still greater good fortune to be

able to leave the Crimea with the last detachment of our army. My

sincere desire is, to tell the truth, as far as I knew it, respecting

all I have witnessed. I had no alternative but to write fully, freely,

fearlessly, for that was my duty, and to the best of my knowledge and

ability it was fulfilled. There have been many emendations, and many

versions of incidents in the war, sent to me from various hands—many

now cold forever—of which I have made use, but the work is chiefly

based on the letters which, by permission of the proprietors of the

Times, I was allowed to place in a new form before the public.

W. H. RUSSELL.

July, 1858.

PREFACE TO THE EDITION OF 1876.

For several years the "History of the British Expedition to the Crimea,"

founded on the "Letters from the Crimea of the Times Correspondent,"

has been out of print, and the publishers have been unable to execute

orders continually arriving for copies of the work. At the present

moment the interest of the public in what is called the Eastern Question

has been revived very forcibly, and the policy of this country in

entering upon the war of 1854, has been much discussed in the Press and

in Parliament. "Bulgaria,"[2] in which the allied armies failed to

discover the misery or discontent which might, at the time, have been

found in Ireland or Italy, is now the scene of "atrocities," the

accounts of which are exercising a powerful influence on the passions

and the judgment of the country, and the balance of public opinion is

fast inclining against the Turk, for whom we made so many sacrifices,

and who proved that he was a valiant soldier and a faithful and patient

ally. The Treaty of Paris has been torn up, the pieces have been thrown

in our faces, and a powerful party in England is taking, in 1876,

energetic action to promote the objects which we so strenuously resisted

in 1854. "Qui facit per alium facit per se." Prince Gortschakoff must be

very grateful for effective help where Count Nesselrode encountered the

most intense hostility. He finds "sympathy" as strong as gunpowder, and

sees a chance of securing the spoils of war without the cost of fighting

for them. Since 1854-6 the map of Europe has undergone changes almost as

great as those temporary alterations which endured with the success of

the First French Empire, and these apparently are but the signs and

tokens of changes to come, of which no man can forecast the extent and

importance.

The British fleet is once more in Besika Bay, but there is now no allied

squadron by its side. No British minister ventures to say that our fleet

is stationed there to protect the integrity of Turkey. If the record of

what Great Britain did in her haste twenty-two years ago be of any use

in causing her to reflect on the consequences of a violent reaction now,

the publication of this revised edition of the "History of the

Expedition to the Crimea," may not be quite inopportune.

W. H. RUSSELL.

Temple, August, 1876.

Note.—In addition to the despatches relating to the landing in

the Crimea, the battles of the Alma, Balaklava, Inkerman, and the

Tchernaya, the assaults on the place, &c., there will be found in

the present edition the text of the most important clauses of the

Treaty of Paris in 1856, the correspondence between Prince

Gortschakoff and Lord Granville on the denunciation of the Treaty

in 1870, &c.

CONTENTS.

| BOOK I. |

THE CONCENTRATION OF THE BRITISH TROOPS IN TURKEY—THEIR

CAMPS AND CAMP-LIFE AT GALLIPOLI, SCUTARI, AND IN BULGARIA | 1 |

| BOOK II. |

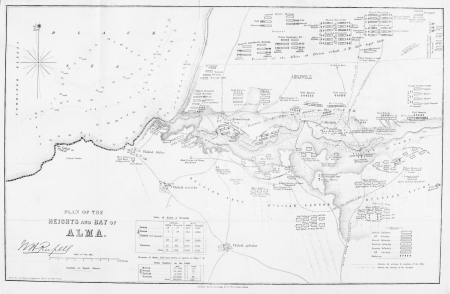

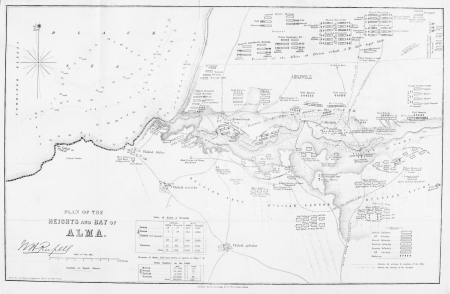

DEPARTURE OF THE EXPEDITION FOR THE CRIMEA—THE LANDING—THE

MARCH—THE AFFAIR OF BARLJANAK—THE BATTLE OF THE

ALMA—THE FLANK MARCH | 69 |

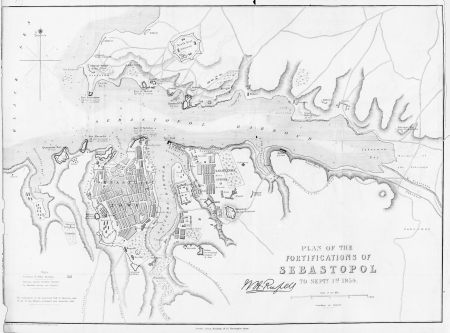

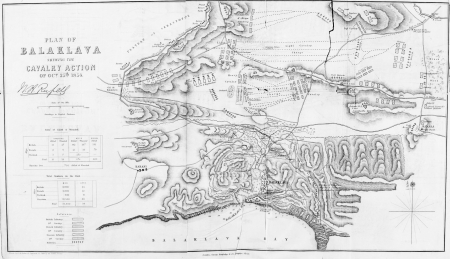

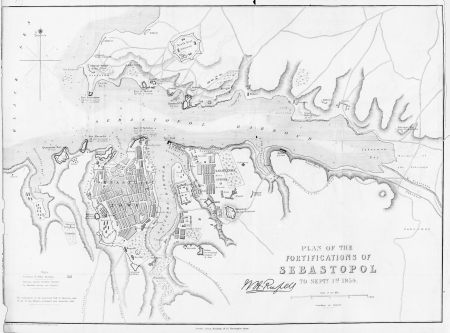

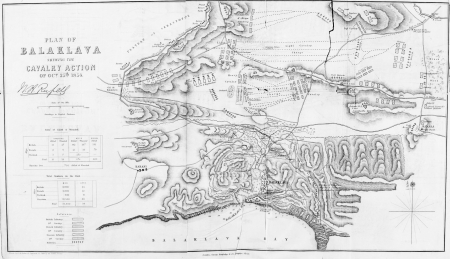

| BOOK III. |

THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE SIEGE—THE FIRST BOMBARDMENT—ITS

FAILURE—THE BATTLE OF BALAKLAVA—CAVALRY CHARGE—THE

BATTLE OF INKERMAN—ITS CONSEQUENCES | 140 |

| BOOK IV. |

PREPARATIONS FOR A WINTER CAMPAIGN—THE HURRICANE—THE

CONDITION OF THE ARMY—THE TRENCHES IN WINTER—BALAKLAVA—THE

COMMISSARIAT AND MEDICAL STAFF | 177 |

| BOOK V. |

THE COMMENCEMENT OF ACTIVE OPERATIONS—THE SPRING—REINFORCEMENTS—THE

SECOND BOMBARDMENT—ITS FAILURE—THIRD

BOMBARDMENT, AND FAILURE—PERIOD OF PREPARATION | 231 |

| BOOK VI. |

COMBINED ATTACKS ON THE ENEMY'S COUNTER APPROACHES—CAPTURE

OF THE QUARRIES AND MAMELON—THE ASSAULT OF THE

18TH OF JUNE—LORD RAGLAN'S DEATH | 282 |

| BOOK VII. |

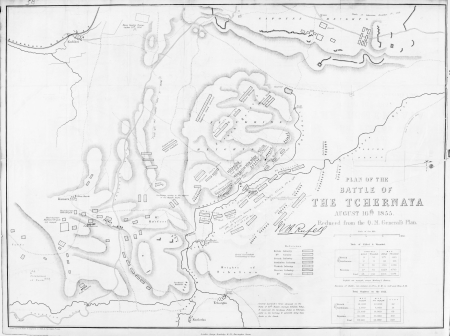

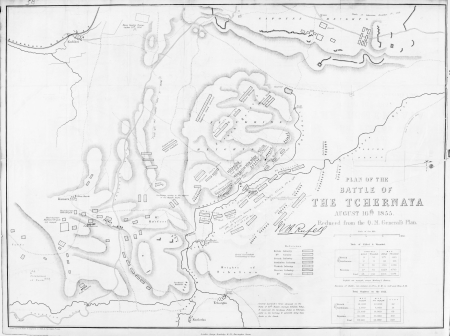

EFFORTS TO RAISE THE SIEGE—BATTLE OF THE TCHERNAYA—THE

SECOND ASSAULT—CAPTURE OF THE MALAKOFF—RETREAT OF THE

RUSSIANS TO THE NORTH SIDE | 303 |

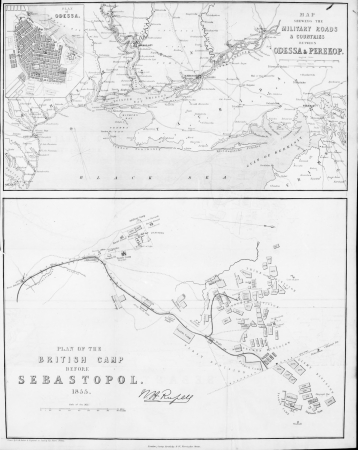

| BOOK VIII. |

THE ATTITUDE OF THE TWO ARMIES—THE DEMONSTRATIONS FROM

BAIDAR—THE RECONNAISSANCE—THE MARCH FROM EUPATORIA—ITS

FAILURE—THE EXPEDITION TO KINBURN AND ODESSA | 376 |

| BOOK IX. |

THE WINTER—POSITION OF THE FRENCH—THE TURKISH CONTINGENT—PREPARATIONS

FOR THE NEXT CAMPAIGN—THE ARMISTICE—THE

PEACE AND THE EVACUATION | 429 |

Appendix | 501 |

| Index:

A,

B,

C,

D,

E,

F,

G,

H,

I,

J,

K,

L,

M,

N,

O,

P,

Q,

R,

S,

T,

U,

V,

W,

Y,

Z |

{1}

THE BRITISH EXPEDITION TO THE

CRIMEA.

BOOK I.

CHAPTER I.

Causes of the quarrel—Influence of the

press—Preparations—Departure from England—Malta—Warnings.

THE causes of the last war with Russia, overwhelmed by verbiage, and

wrapped up in coatings of protocols and dispatches, at the time are now

patent to the world. The independence of Turkey was menaced by the Czar,

but France and England would have cared little if Turkey had been a

power whose fate could affect in no degree the commerce or the

reputation of the allies. France, ever jealous of her prestige, was

anxious to uphold the power of a nation and a name which, to the

oriental, represents the force, intelligence, and civilization of

Europe. England, with a growing commerce in the Levant, and with a

prodigious empire nearer to the rising sun, could not permit the one to

be absorbed and the other to be threatened by a most aggressive and

ambitious state. With Russia, and France by her side, she had not

hesitated to inflict a wound on the independence of Turkey which had

been growing deeper every day. But when insatiable Russia, impatient of

the slowness of the process, sought to rend the wounds of the dying man,

England felt bound to stay her hands, and to prop the falling throne of

the Sultan.

Although England had nothing to do with the quarrels of the Greek and

Latin Churches, she could not be indifferent to the results of the

struggle. If Russia had been permitted to exercise a protectorate over

the Greek subjects of the Porte, and to hold as material guarantee the

provinces of the Danube, she would be the mistress of the Bosphorus, the

Dardanelles, and even the Mediterranean. France would have seen her

moral weight in the East destroyed. England would have been severed from

her Indian Empire, and menaced in the outposts of her naval power. All

Christian{2} States have now a right to protect the Christian subjects of

the Porte; and in proportion as the latter increase in intelligence,

wealth, and numbers, the hold of the Osmanli on Europe will relax. The

sick man is not yet dead, but his heirs and administrators are counting

their share of his worldly goods, and are preparing for the suit which

must follow his demise. Whatever might have been the considerations and

pretences which actuated our statesmen, the people of England entered,

with honesty of purpose and singleness of heart, upon the conflict with

the sole object of averting a blow aimed at an old friend. To that end

they devoted their treasure, and in that cause they freely shed their

blood.

Conscious of their integrity, the nation began the war with as much

spirit and energy as they continued it with calm resolution and manly

self-reliance. Their rulers were lifted up by the popular wave, and

carried further than they listed. The vessel of the State was nearly

dashed to pieces by the great surge, and our dislocated battalions,

swept together and called an army, were suddenly plunged into the

realities of war. But the British soldier is ready to meet mortal foes.

What he cannot resist are the cruel strokes of neglect and

mal-administration. In the excitement caused by the news of victory the

heart's pulse of the nation was almost frozen by a bitter cry of

distress from the heights of Sebastopol. Then followed accounts of

horrors which revived the memories of the most disgraceful episodes in

our military history. Men who remembered Walcheren sought in vain for a

parallel to the wretchedness and mortality in our army. The press,

faithful to its mission, threw a full light on scenes three thousand

miles from our shores, and sustained the nation by its counsels. "Had it

not been for the English press," said an Austrian officer of high rank,

"I know not what would have become of the English army. Ministers in

Parliament denied that it suffered, and therefore Parliament would not

have helped it. The French papers represented it as suffering, but

neither hoping nor enduring. Europe heard that Marshal St. Arnaud won

the Alma, and that the English, aided by French guns, late in the day,

swarmed up the heights when their allies had won the battle. We should

have known only of Inkerman as a victory gained by the French coming to

the aid of surprised and discomfited Englishmen, and of the assaults on

Sebastopol as disgraceful and abortive, but your press, in a thousand

translations, told us the truth all over Europe, and enabled us to

appreciate your valour, your discipline, your élan, your courage and

patience, and taught us to feel that even in misfortune the English army

was noble and magnificent."

DEPARTURE OF THE GUARDS.

The press upheld the Ministry in its efforts to remedy the effects of an

unwise and unreasoning parsimony, prepared the public mind for the

subversion of an effete system, encouraged the nation in the moment of

depression by recitals of the deeds of our countrymen, elevated the

condition and self-respect of the soldiery, and whilst celebrating with

myriad tongues the feats of the combatants in the ranks, with all the

fire of Tyrtæus, but with greater power and happier results, denounced

the men responsible for huge disasters{3}—"told the truth and feared

not"—carried the people to the battlefield—placed them beside their

bleeding comrades—spoke of fame to the dying and of hope to those who

lived—and by its magic power spanned great seas and continents, and

bade England and her army in the Crimea endure, fight, and conquer

together.

The army saved, resuscitated, and raised to a place which it never

occupied till recently in the estimation of the country, has much for

which to thank the press. Had its deeds and sufferings never been known

except through the medium of frigid dispatches, it would have stood in a

very different position this day, not only abroad but at home. But

gratitude is not a virtue of corporations. It is rare enough to find it

in individuals; and, although the press has permission to exhaust

laudation and flattery, its censure is resented as impertinence. From

the departure of our first battalions till the close of the war, there

were occasions on which the shortcomings of great departments and the

inefficiency of extemporary arrangements were exposed beyond denial or

explanation; and if the optimist is satisfied they were the inevitable

consequences of all human organization, the mass of mankind will seek to

provide against their recurrence and to obviate their results. With all

their hopes, the people at the outset were little prepared for the costs

and disasters of war. They fondly believed they were a military power,

because they possessed invincible battalions of brave men, officered by

gallant, high-spirited gentlemen, who, for the most part, regarded with

dislike the calling, and disdained the knowledge, of the mere

"professional" soldier. There were no reserves to take the place of

those dauntless legions which melted in the crucible of battle, and left

a void which time alone could fill. When the Guards[3] left London, on

22nd February, 1854, those who saw them march off to the railway

station, unaccustomed to the sight of large bodies of men, and impressed

by the bearing of those stalwart soldiers, might be pardoned if they

supposed the household troops could encounter a world in arms. As they

were the first British regiments which left England for the East, as

they bore a grand part worthy of their name in the earlier, most trying,

and most glorious period of our struggles, their voyage possesses a

certain interest which entitles it to be retained in this revised

history; and with some few alterations, it is presented to the reader.

Their cheers—re-echoed from Alma and Inkerman—bear now a glorious

significance, the "morituri te salutant" of devoted soldiers addressed

to their sorrowing country.

"They will never go farther than Malta!"—Such was the general feeling

and expression at the time. It was supposed that the very news of their

arrival in Malta would check the hordes of Russia, and shake the iron

will which broke ere it would bend. To that march, in less than one

year, there was a terrible antithesis. A handful of weary men—wasted

and worn and ragged—crept slowly down from the plateau of Inkerman

where their comrades lay thick{4} in frequent graves, and sought the

cheerless shelter of the hills of Balaklava. They had fought and had

sickened and died till that proud brigade had nearly ceased to exist.

The swarm of red-coats which after a day of marching, of excitement, of

leave-taking, and cheering, buzzed over the Orinoco, Ripon,

Manilla, in Southampton Docks, was hived at last in hammock or

blanket, while the vessels rode quietly in the waters of the Solent.

Fourteen inches is man-of-war allowance, but eighteen inches were

allowed for the Guards. On the following morning, February 23rd, the

steamers weighed and sailed. The Ripon was off by 7 o'clock A.M.,

followed by the Manilla and the Orinoco. They were soon bowling

along with a fresh N.W. breeze in the channel.

Good domestic beef, sea-pudding, and excellent bread, with pea-soup

every second day, formed substantial pieces of resistance to the best

appetites. Half a gill of rum to two of water was served out once a day

to each man. On the first day Tom Firelock was rather too liberal to his

brother Jack Tar. On the next occasion, the ponderous Sergeant-Major of

the Grenadiers presided over the grog-tub, and delivered the order, "Men

served—two steps to the front, and swallow!" The men were not

insubordinate.

The second day the long swell of Biscay began to tell on the Guards. The

figure-heads of the ships plunged deep, and the heads of the soldiers

hung despondingly over gunwale, portsill, stay, and mess-tin, as their

bodies bobbed to and fro. At night they brightened up, and when the

bugle sounded at nine o'clock, nearly all were able to crawl into their

hammocks for sleep. On Saturday the speed of the vessels was increased

from nine-and-a-half to ten knots per hour; and the little Manilla was

left by the large paddle-wheel steamers far away. On Sunday all the men

had recovered; and when, at half-past ten, the ship's company and troops

were mustered for prayers, they looked as fresh as could be expected

under the circumstances;—in fact, as the day advanced, they became

lively, and the sense of joyfulness for release from the clutches of

their enemy was so strong that in reply to a stentorian demand for

"three cheers for the jolly old whale!" they cheered a grampus which

blew alongside.

ARRIVAL AT MALTA.

On Tuesday the Ripon passed Tarifa, at fifty minutes past five A.M.,

and anchored in the quarantine ground of Gibraltar to coal half-an-hour

afterwards. In consequence of the quarantine regulations there was no

communication with the shore, but the soldiers lined the walls, H.M.S.

Cruiser manned yards, and as the Ripon steamed off at half-past

three P.M., after taking on board coals, tents and tent-poles, they gave

three hearty cheers, which were replied to with goodwill. On Thursday a

target painted like a Russian soldier was run up for practice. The

Orinoco reached Malta on Sunday morning at ten A.M., and the Ripon

on Saturday night soon after twelve o'clock. The Coldstreams were

disembarked in the course of the day, and the Grenadiers were all ashore

ere Monday evening, to the delight of the Maltese, who made a harvest

from the excursions of the "plenty big men" to and from the town.{5}

The Manilla arrived at Malta on the morning of March 7th, after a run

of eighteen days from Southampton. The men left their floating prisons

only to relinquish comfort and to "rough it." One regiment was left

without coals, another had no lights or candles, another suffered from

cold under canvas, in some cases short commons tried the patience of the

men, and forage was not to be had for the officers' horses. Acting on

the old formula when transports took eight weeks to Malta, the Admiralty

supplied steamers which make the passage in as many days with eight

weeks' "medical comforts." By a rigid order, the officers were debarred

from bringing more than 90lb. weight of baggage. Many of them omitted

beds, canteen and mess traps, and were horror-stricken when they were

politely invited to pitch their tents and "make themselves comfortable"

on the ravelins, outside Valetta.

The arrival of the Himalaya before midnight on the same day, after a

run of seven days and three hours from Plymouth, with upwards of 1,500

men on board, afforded good proof of our transport resources. Ordinary

troop-ships would have taken at least six weeks, and of course it would

have cost the Government a proportionate sum for their maintenance,

while they were wasting precious moments, fighting against head winds.

The only inconvenience attendant on this great celerity is, that many

human creatures, with the usual appetites of the species, are rapidly

collected upon one spot, and supplies can scarcely be procured to meet

the demand. The increase of meat-consuming animals at Malta nearly

produced the effects of a famine; there were only four hundred head of

cattle left in the island and its dependencies, and with a population of

120,000—with the Brigade of Guards and 11 Regiments in garrison, and

three frigates to feed, it may easily be imagined that the Commissariat

were severely taxed to provide for this influx.

The Simoom, with the Scots Fusileer Guards, sixteen days from

Portsmouth, reached Malta on the 18th of March. The troops were

disembarked the following day, in excellent order. A pile of low

buildings running along the edge of the Quarantine Harbour, with

abundance of casements, sheltered terraces, piazzas, and large arched

rooms, was soon completely filled. The men in spite of the local

derangements caused on their arrival by "liberty" carousing in acid wine

and fiery brandy, enjoyed good health, though the average of disease was

rather augmented by the results of an imprudent use of the time allowed

to them in London, to bid good-bye to their friends.

For the three last weeks in March, Valetta was like a fair. Money

circulated briskly. Every tradesman was busy, and the pressure of demand

raised the cost of supply. Saddlers, tinmen, outfitters, tailors,

shoemakers, cutlers, increased their charges till they attained the

West-End scale. Boatmen and the amphibious harpies who prey upon the

traveller reaped a copper and silver harvest of great weight. It must,

however, be said of Malta boatmen, that they are a hardworking, patient,

and honest race; the latter adjective is applied comparatively, and not{6}

absolutely. They would set our Portsmouth or Southampton boatmen an

example rather to be wondered at than followed. The vendors of oranges,

dates, olives, apples, and street luxuries of all kinds, enjoyed a full

share of public favour; and (a proof of the fine digestive apparatus of

our soldiery) their lavish enjoyment of these delicacies was unattended

by physical suffering. A thirsty private, after munching the ends of

Minié cartridges for an hour on the hot rocks at the seaside, would send

to the rear and buy four or five oranges for a penny. He ate them all,

trifled with an apple or two afterwards, and, duty over, rushed across

the harbour or strutted off to Valetta. A cool café, shining out on

the street with its tarnished gilding and mirrors more radiant than all

the taps of all our country inns put together, invited him to enter, and

a quantity of alcoholic stimulus was supplied, at the small charge of

one penny, quite sufficient to encourage him to spend two-pence more on

the same stuff, till he was rendered insensible to all sublunary cares,

and brought to a state which was certain to induce him to the attention

of the guard and to a raging headache. "I can live like a duke here—I

can smoke my cigar, and drink my glass of wine, and what could a duke do

more?" But the cigar made by very dirty manufacturers, who might be seen

sitting out in the streets compounding them of the leaves of plants and

saliva was villanous; and the wine endured much after it had left

Sicily. As to the brandy and spirits, they were simply abominable, but

the men were soon "choked off" when they found that indulgence in them

was followed by punishment worse than that of the black hole or barrack

confinement. The biscuit mills were baking 30,000lb. of biscuit per day.

Bills posted in every street for "parties desirous of joining the

commissariat department, under the orders of Commissary-General Filder,

about to proceed with the force to the East, as temporary clerks,

assistant store-keepers, interpreters," to "freely apply to Assistant

Commissary-General Strickland;" had this significant addition,—"those

conversant with English, Italian, modern Greek, and Turkish languages,

or the Lingua-Franca of the East will be preferred." Warlike mechanics,

armourers, farriers, wheelwrights, waggon-equipment and harness-makers,

were in request.

WARNINGS.

As might naturally be expected where so great a demand, horses were

scarcely to be obtained. To Tunis the contagion of high prices spread

from Malta, and the Moors asked £25 and £30 for the veriest bundles of

skin and bone that were ever fastened together by muscle and pluck. Our

allies began to show themselves. The Christophe Colomb, steam-sloop,

towing the Mistral, a small sailing transport, laden with 27 soldiers'

and 40 officers' horses arrived in Malta Harbour on the night of the

7th, and ran into the Grand Harbour at six A.M. the following morning.

On board were Lieutenant-General Canrobert, and his Chef d'État; Major

Lieutenant-General Martimprey, 45 officers, 800 soldiers, 150 horses.

Their reception was most enthusiastic. The French Generals were lodged

at the Palace, and their soldiers were fêted in every tavern. Reviews{7}

were held in their honour, and the air rang with the friendly shouts and

answering cheers of "natural enemies".

In a few days after the arrival of the Guards, it became plain that the

Allies were to proceed to Turkey, and that hostilities were inevitable.

On the 28th March war was declared, but the preparations for it showed

that the Government had looked upon war as certain some time previously.

Every exertion was made by the authorities to enable the expedition to

take the field. General Ferguson and Admiral Houston Stewart received

the expression of the Duke of Newcastle's satisfaction at the manner in

which they co-operated in making "the extensive preparations for the

reception of the expeditionary force, which could only have been

successfully carried on by the absence of needless departmental

etiquette,"—a virtue which has been expected to become more common

after this official laudation. This expression of satisfaction was well

deserved by both these gallant officers, and Sir W. Reid emulated them

in his exertions to secure the comfort of the troops. The Admiral early

and late worked with his usual energy. He had a modus operandi of

making the conditional mood mean the imperative. Soldiers were stowed

away in sailors' barracks and penned up in hammocks under its potent

influence; and ships were cleared of their freight, or laden with a

fresh one, with extraordinary facility.

It was at this time that in a letter to the Times I wrote as

follows:—"With our men well clothed, well fed, well housed (whether in

camp or town does not much matter), and well attended to, there is

little to fear. They were all in the best possible spirits, and fit to

go anywhere, and perhaps to do anything. But inaction might bring

listlessness and despondency, and in their train follows disease. What

is most to be feared in an encampment is an enemy that musket and

bayonet cannot meet or repel. Of this the records of the Russo-Turkish

campaign of 1828-9, in which 80,000 men perished by 'plague, pestilence,

and famine,' afford a fearful lesson, and let those who have the

interests of the army at heart just turn to Moltke's history of that

miserable invasion, and they will grudge no expense, and spare no

precaution, to avoid, as far as human skill can do it, a repetition of

such horrors. Let us have plenty of doctors. Let us have an overwhelming

army of medical men to combat disease. Let us have a staff—full and

strong—of young and active and experienced men. Do not suffer our

soldiers to be killed by antiquated imbecility. Do not hand them over to

the mercies of ignorant etiquette and effete seniority, but give the

sick every chance which skill, energy, and abundance of the best

specifics can afford them. The heads of departments may rest assured

that the country will grudge no expense on this point, nor on any other

connected with the interest and efficiency of the corps d'élite which

England has sent from her shores.[4] There were three first-class

staff-surgeons at Constantinople—Messrs. Dumbreck{8} Linton, and

Mitchell. At Malta there were—Dr. Burrell, at the head of the

department; Dr. Alexander, Dr. Tice, Mr. Smith, and a great accession

was expected every day."

The commissariat department appeared to be daily more efficient, and

every possible effort was made to secure proper supplies for the troops.

This, however, was a matter that could be best tested in the field.

On Tuesday, the 28th of March, the Montezuma, and the Albatross with

Chasseurs, Zouaves, and horses, arrived in the Great Harbour. The Zouave

was then an object of curiosity. The quarters of the men were not by any

means so good as our own. A considerable number had to sleep on deck,

and in rain or sea-way they must have been wet. Their kit seemed very

light. The officers did not carry many necessaries, and the average

weight of their luggage was not more than 50lb. They were all in the

highest spirits, and looked forward eagerly to their first brush in

company with the English.

Sir George Brown and staff arrived on the 29th in the Valetta. The 2nd

Battalion Rifle Brigade, the advance of the Light Division, which Sir

George Brown was to command, embarked on board the Golden Fleece. On

the 30th, Sir John Burgoyne arrived from Constantinople in the

Caradoc.

The Pluton and another vessel arrived with Zouaves and the usual

freight of horses the same day, and the streets were full of scarlet and

blue uniforms walking arm and arm together in uncommunicative

friendliness, their conversation being carried on by signs, such as

pointing to their throats and stomachs, to express the primitive

sensations of hunger and thirst. The French sailed the following day for

Gallipoli.

When the declaration of war reached Malta, the excitement was

indescribable. Crowds assembled on the shores of the harbours and lined

the quays and landing-places, the crash of music drowned in the

enthusiastic cheers of the soldiers cheering their comrades as the

vessels glided along, the cheers from one fort being taken up by the

troops in the others, and as joyously responded to from those on board.

CHAPTER II.

Departure of the first portion of the British Expedition from

Malta—Sea passage—Classical Antiquities—Caught in a

Levanter—The Dardanelles—Gallipoli—Gallipoli described—Turkish

Architecture—Superiority of the French arrangements—Close

shaving, tight stocking, and light marching.

DEPARTURE FROM MALTA.

Whilst the French were rapidly moving to Gallipoli, the English were

losing the prestige which might have been earned by a first appearance

on the stage, as well as the substantial advantages of an occupation of

the town. But on 30th March Sir George Brown and Staff, the 2nd

Battalion of the Rifle Brigade, under Lt. Colonel{9} Lawrence, Colonel

Victor, R.E., Captain Gibb, R.E., and two companies of Sappers, embarked

in the Golden Fleece, and a cabin having been placed at my disposal, I

embarked and sailed with them for Gallipoli, at five A.M. on 31st.

An early fisherman, a boatman in the Great Harbour, solitary sentinels

perched here and there on the long lines of white bastions, were the

only persons who saw the departure of the advanced guard of the only

British expedition that has ever sailed to the land of the Moslem since

the days of the great Plantagenet. The morning was dark and overcast.

The Mediterranean assumed an indigo colour, stippled with patches of

white foam, as heavy squalls of wind and drenching rain flew over its

surface. The showers were tropical in their vehemence and suddenness.

Nothing was visible except some wretched-looking gulls flapping in our

wake hour after hour in the hope of unintentional contributions from the

ship, and two or three dilapidated coasters running as hard as they

could for the dangerous shelter of the land. Jason himself and his crew

could scarcely have looked more uncomfortable than the men, though there

was small resemblance indeed between the cruiser in which he took his

passage and the Golden Fleece. "It all comes of sailing on a Friday,"

said a grumbling forecastle Jack.

The anticipations of the tarry prophet were not fully justified. Towards

evening the sky cleared, the fine sharp edge of the great circle of

waters of which we were the black murky centre, revealed itself, and the

sun rushed out of his coat of cumuli, all bright and fervent, and sank

to rest in a sea of fire. Even the gulls brightened up and began to look

comfortable, and the sails of the flying craft, far away on the verge of

the landscape, shone white. The soldiers dried their coats, and tried to

forget sloppy decks and limited exercise ground, and night closed round

the ship with peace and hilarity on her wings. As the moon rose a wonder

appeared in the heavens—"a blazing comet with a fiery tail," which

covered five or six degrees of the horizon, and shone through the deep

blue above. Here was the old world-known omen of war and troubles! Many

as they gazed felt the influence of ancient tales and associated the

lurid apparition with the convulsion impending over Europe, though Mr.

Hind and Professor Airy and Sir J. South might have proved to

demonstration that the comet aforesaid was born or baptized in space

hundreds of centuries before Prince Menschikoff was thought of.

At last the comet was lost in the moon's light, and the gazers put out

their cigars, forgot their philosophy and their fears, and went to bed.

The next day, Saturday (1st April), passed as most days do at sea in

smooth weather. The men ate and drank, and walked on deck till they were

able to eat and drink again, and so on till bed time. Curious little

brown owls, as if determined to keep up the traditions of the

neighbourhood, flew on board, and were caught in the rigging. They

seemed to come right from the land of Minerva. In the course of the day

small birds fluttered on the yards, masts, and bulwarks, plumed their

jaded wings, and after a short rest launched themselves once more

across{10} the bosom of the deep. Some were common titlarks, others greyish

buntings, others yellow and black fellows. Three of the owls and a

titlark were at once introduced to each other in a cage, and the ship's

cat was thrown in by way of making an impromptu "happy family." The

result rather increased one's admiration for the itinerant zoologist of

Trafalgar-square and Waterloo Bridge, inasmuch as pussy obstinately

refused to hold any communication with the owls—they seemed in turn to

hate each other—and all evinced determined animosity towards the

unfortunate titlark, which speedily languished and died.

This and the following day there was a head wind. No land appeared, and

the only object to be seen was a French paddle-wheel steamer with troops

on board and a transport in tow, which was conjectured to be one of

those that had left Malta some days previously. After dinner, when the

band had ceased playing, the Sappers assembled on the quarter-deck, and

sang glees excellently well, while the Rifles had a select band of vocal

performers of their own of comic and sentimental songs. Some of these,

à propos of the expedition, were rather hard on the Guards and their

bearskins. At daylight the coast was visible N. by E.—a heavy cloudlike

line resting on the grey water. It was the Morea—the old land of the

Messenians. If not greatly changed, it is wonderful what attractions it

could have had for the Spartans. A more barren-looking coast one need

not wish to see. It is like a section of the west coast of Sutherland in

winter. The mountains—cold, rocky, barren ridges of land—culminate in

snow-covered peaks, and the numerous villages of white cabins or houses

dotting the declivity towards the sea did not relieve the place of an

air of savage primitiveness, which little consorted with its ancient

fame. About 9.40 A.M. we passed Cape Matapan, which concentrated in

itself all the rude characteristics of the surrounding coast. We passed

between the Morea and Cerigo. One could not help wondering what on earth

could have possessed Venus to select such a wretched rock for her island

home. Verily the poets have much to answer for. Not the boldest would

have dared to fly into ecstasies about the terrestrial landing-place of

Venus had he once beheld the same. The fact is, the place is like

Ireland's Eye, pulled out and expanded. Although the whole reputation of

the Cape was not sustained by our annihilation, the sea showed every

inclination to be troublesome, and the wind began to rise.

After breakfast the men were mustered, and the captain read prayers.

When prayers were over, we had a proof that the Greeks were tolerably

right about the weather. Even bolder boatmen than the ancients might

fear the heavy squalls off these snowy headlands, which gave a bad idea

of sunny Greece in early spring. Their writers represented the

performance of a voyage round Capes Matapan and Malea as attended with

danger; and, if the best of triremes was caught in the breeze

encountered by the Golden Fleece hereabouts, the crew would never have

been troubled to hang up a votive tablet to their preserving deity.

CAUGHT IN A LEVANTER.

From 10 o'clock till 3.30 P.M. the ship ran along the diameter of{11} the

semicircle between the two Capes which mark the southern extremities of

Greece. Cape Malea, or St. Angelo, is just such another bluff,

mountainous, and desolate headland as Cape Matapan, and is not so

civilized-looking, for there are no villages visible near it. However,

in a hole on its south-east face resides a Greek hermit, who must have

enormous opportunities for improving his mind, if Zimmerman be at all

trustworthy. He is not quite lost to the calls of nature, and has a

great tenderness for ships' biscuit. He generally hoists a little flag

when a vessel passes near, and is often gratified by a supply of

hard-bake. Had we wished to administer to his luxuries we could not have

done so, for the wind off this angle rushed at us with fury, and the

instant we rounded it we saw the sea broken into crests of foam making

right at our bows. The old mariners were not without warranty when they

advised "him who doubled Cape Malea to forget his home." We had got

right into the Etesian wind—one of those violent Levanters which the

learned among us said ought to be the Euroclydon which drove St. Paul to

Malta. Sheltered as we were to eastward by clusters of little islands,

the sea got up and rolled in confused wedges towards the ship. She

behaved nobly, but with her small auxiliary steam power she could

scarcely hold her own. We were driven away to leeward, and did not make

much headway. The gusts came down furiously between all kinds of

classical islands, which we could not make out, for our Maltese pilot

got frightened, and revealed the important secret that he did not know

one of them from the other. The men bore up well against their

Euroclydon, and emulated the conduct of the ship. Night came upon us,

labouring in black jolting seas, dashing them into white spray, and

running away into dangerous unknown parts. It passed songless, dark, and

uncomfortable: much was the suffering in the hermetically sealed cells

in which our officers "reposed" and grumbled at fortune.

At daylight next morning, Falconero was north, and Milo south. The

clouds were black and low, the sea white and high, and the junction

between them on the far horizon of a broken and promiscuous character.

The good steamer had run thirty miles to leeward of her course, making

not the smallest progress. Grey islets with foam flying over them lay

around indistinctly seen through the driving vapour from the Ægean. To

mistrust of the pilot fear of accident was added, so the helm was put

up, and we wore ship at 6.30 A.M. in a heavy sea-way. A screw-steamer

was seen on our port quarter plunging through the heavy sea, and we made

her out to be the Cape of Good Hope. She followed our example. The

gale increased till 8 A.M.; the sailors considered it deserved to be

called "stormy, with heavy squalls." The heavy sea on our starboard

quarter, as we approached Malea, caused the ship to roll heavily; the

men could only hold on by tight grip, and they and their officers were

well drenched by great lumbering water louts, who tossed themselves in

over the bulwarks. At 3.30 P.M., the ship cast anchor in Vatika Bay, in

twenty fathoms. A French steamer and brig lay close in the shore. We

cheered them vigorously,{12} but the men could not hear us. Some time

afterwards the Cape of Good Hope and a French screw-steamer also ran

in and anchored near us. This little flotilla alarmed the inhabitants,

for the few who were fishing in boats fled to shore, and we saw a great

effervescence at a distant village. No doubt the apparition in the bay

of a force flying the tricolor and the union-jack frightened the people.

They could be seen running to and fro along the shore like ants when

their nest is stirred.

At dusk our bands played, and the mountains of the Morea, for the first

time since they rose from the sea, echoed the strains of "God save the

Queen." Our vocalists assembled, and sang glees or vigorous choruses,

and the night passed pleasantly in smooth water on an even keel. The

people lighted bonfires upon the hills, but the lights soon died out. At

six o'clock on Tuesday morning the Golden Fleece left Vatika Bay, and

passed Poulo Bello at 10.45 A.M. The Greek coast trending away to the

left, showed in rugged masses of mountains capped by snowy peaks, and

occasionally the towns—clusters of white specks on the dark purple of

the hills—were visible; and before evening, the ship having run safely

through all the terrors of the Ægean and its islands, bore away for the

entrance to the Dardanelles. At 2 A.M. on Wednesday morning, however, it

began to blow furiously again, the wind springing up as if "Æolus had

just opened and put on fresh hands at the bellows," to use the nautical

simile. The breeze, however, went down in a few hours, with the same

rapidity with which it rose. Smooth seas greeted the ship as she steamed

by Mitylene. On the left lay the entrance to the Gulf of

Athens—Eubœa was on our left hand—Tenedos was before us—on our

right rose the snowy heights of Mount Ida—and the Troad (atrociously

and unforgivably like the "Bog of Allen!") lay stretching its brown

folds, dotted with rare tumuli, from the sea to the mountain side for

leagues away. Athos (said to be ninety miles distant) stood between us

and the setting sun—a pyramid of purple cloud bathed in golden light;

and the Leander frigate showed her number and went right away in the

very waters that lay between Sestos and Abydos, past the shadow of the

giant mountain, stretching away on our port beam. As the vessel entered

the portals of the Dardanelles, and rushed swiftly up between its dark

banks, the sentinels on the forts and along the ridges challenged

loudly—shouting to each other to be on the alert—the band of the

Rifles all the while playing the latest fashionable polkas, or making

the rocks acquainted with "Rule Britannia," and "God save the Queen."

At 9.30 P.M., our ship passed the Castles of the Dardanelles. She was

not stopped nor fired at, but the sentinels screeched horribly and

showed lights, and seemed to execute a convulsive pas of fright or

valour on the rocks. The only reply was the calm sounding of second post

on the bugles—the first time that the blast of English light infantry

trumpets broke the silence of those antique shores.[5]

GALLIPOLI.

{13}

After midnight we arrived at Gallipoli, and anchored. No one took the

slightest notice of us, nor was any communication made with shore. When

the Golden Fleece arrived there was no pilot to show her where to

anchor, and it was nearly an hour ere she ran out her cable in nineteen

fathoms water. No one came off, for it was after midnight, and there was

something depressing in this silent reception of the first British army

that ever landed on the shores of these straits.

When morning came we only felt sorry that nature had made Gallipoli, a

desirable place for us to land at. The tricolor was floating right and

left, and the blue coats of the French were well marked on shore, the

long lines of bullock-carts stealing along the strand towards their camp

making it evident that they were taking care of themselves.

Take some hundreds of dilapidated farms, outhouses, a lot of rickety

tenements of Holywell-street, Wych-street, and the Borough—catch up,

wherever you can, any of the seedy, cracked, shutterless structures of

planks and tiles to be seen in our cathedral towns—carry off odd sheds

and stalls from Billingsgate, add to them a selection of the huts along

the Thames between London-bridge and Greenwich—bring them, then, all

together to the European side of the Straits of the Dardanelles, and

having pitched on a bare round hill sloping away to the water's edge, on

the most exposed portion of the coast, with scarcely tree or shrub,

tumble them "higgledy piggledy" on its declivity, in such wise that the

lines of the streets may follow on a large scale the lines of a bookworm

through some old tome—let the roadways be very narrow, of irregular

breadth, varying according to the bulgings and projections of the

houses, and paved with large round slippery stones, painful and

hazardous to walk upon—here and there borrow a dirty gutter from a back

street in Boulogne—let the houses lean across to each other so that the

tiles meet, or a plank thrown across forms a sort of "passage" or

arcade—steal some of the popular monuments of London, the shafts of

national testimonials, a half dozen of Irish Round Towers—surround

these with a light gallery about twelve feet from the top, put on a

large extinguisher-shaped roof, paint them white, and having thus made

them into minarets, clap them down into the maze of buildings—then let

fall big stones all over the place—plant little windmills with

odd-looking sails on the crests of the hill over the town—transport the

ruins of a feudal fortress from Northern Italy, and put it into the

centre of the town, with a flanking tower at the water's edge—erect a

few wooden cribs by the waterside to serve as café, custom-house, and

government stores—and, when you have done this, you have to all

appearance imitated the process by which Gallipoli was created. The

receipt, if tried, will be found to answer beyond belief.

To fill up the scene, however, you must catch a number of the biggest

breeched, longest bearded, dirtiest, and stateliest old Turks to be had

at any price in the Ottoman empire; provide them with pipes, keep them

smoking all day on wooden stages or platforms about two feet from the

ground, everywhere by the water's edge or up the main streets, in the

shops of the bazaar which is one of the "passages"{14} or arcades already

described; see that they have no slippers on, nothing but stout woollen

hose, their foot gear being left on the ground, shawl turbans (one or

two being green, for the real descendant of the Prophet), flowing

fur-lined coats, and bright-hued sashes, in which are to be stuck

silver-sheathed yataghans and ornamented Damascus pistols; don't let

them move more than their eyes, or express any emotion at the sight of

anything except an English lady; then gather a noisy crowd of fez-capped

Greeks in baggy blue breeches, smart jackets, sashes, and rich vests—of

soberly-dressed Armenians—of keen-looking Jews, with flashing eyes—of

Chasseurs de Vincennes, Zouaves, British riflemen, vivandières,

Sappers and Miners, Nubian slaves, Camel-drivers, Commissaries and

Sailors, and direct them in streams round the little islets on which the

smoking Turks are harboured, and you will populate the place.

It will be observed that women are not mentioned in this description,

but children were not by any means wanting—on the contrary, there was a

glut of them, in the Greek quarter particularly, and now and then a

bundle of clothes, in yellow leather boots, covered at the top with a

piece of white linen, might be seen moving about, which you will do well

to believe contained a woman neither young nor pretty. Dogs, so large,

savage, tailless, hairy, and curiously-shaped, that Wombwell could make

a fortune out of them if aided by any clever zoological nomenclator,

prowled along the shore and walked through the shallow water, in which

stood bullocks and buffaloes, French steamers and transports, with the

tricolor flying, and the paddlebox boats full of troops on their way to

land—a solitary English steamer, with the red ensign, at anchor in the

bay—and Greek polaccas, with their beautiful white sails and trim rig,

flying down the straits, which are here about three and a half miles

broad, so that the villages on the rich swelling hills of the Asia Minor

side are plainly visible,—must be added, and then the picture will be

tolerably complete.

In truth, Gallipoli is a wretched place—picturesque to a degree, but,

like all picturesque things or places, horribly uncomfortable. The

breadth of the Dardanelles is about five miles opposite the town, but

the Asiatic and the European coasts run towards each other just ere the

Straits expand into the Sea of Marmora. The country behind the town is

hilly, and at the time of our arrival had not recovered from the effects

of the late very severe weather, being covered with patches of snow.

Gallipoli is situated on the narrowest portion of the tongue of land or

peninsula which, running between the Gulf of Saros on the west and the

Dardanelles on the east, forms the western side of the strait. An army

encamped here commands the Ægean and the Sea of Marmora, and can be

marched northwards to the Balkan, or sent across to Asia or up to

Constantinople with equal facility.

SUPERIORITY OF FRENCH ARRANGEMENTS.

As the crow flies, it is about 120 miles from Constantinople across the

Sea of Marmora. If the capital were in danger, troops could be sent

there in a few days, and our army and fleet effectually commanded the

Dardanelles and the entrance to the Sea of Marmora,{15} and made it a mare

clausum. Enos, a small town, on a spit of land opposite the mouth of

the Maritza, on the coast of Turkey to the north-east of Samothrace, was

surveyed and examined for an encampment by French and English engineers.

It is obvious that if some daring Muscovite general forcing the passage

across the Danube were to beat the Turks and cross the western ridges of

the Balkans, he might advance southwards with very little hindrance to

the Ægean; and a dashing march to the south-east would bring his troops

to the western shore of the Dardanelles. An army at Gallipoli could

check such a movement, if it ever entered into the head of any one to

attempt to put it in practice.

Early on the morning after the arrival of the Golden Fleece a boat

came off with two commissariat officers, Turner and Bartlett, and an

interpreter. The consul had gone up the Dardanelles to look for us. The

General desired to send for the Consul, but the only vessel available

was a small Turkish Imperial steamer. The Consul's dragoman, a

grand-looking Israelite, was ready to go, but the engineer had just

managed to break his leg. He requested the loan of our engineer, as no

one could be found to undertake the care of the steamer's engines.

After breakfast, Lieutenant-General Brown, Colonel Sullivan, Captain

Hallewell, and Captain Whitmore, started to visit the Pasha of

Adrianople (Rustum Pasha), who was sent here to facilitate the

arrangements and debarkation of the troops. On their return, about

half-past two o'clock, Lieutenant-General Canrobert came on board the

vessel, and was received by the Lieutenant-General. The visit lasted an

hour, and was marked at its close with greater cordiality, if possible,

than at the commencement.

In the evening the Consul, Mr. Calvert, came on board, when it turned

out that no instructions whatever had been sent to prepare for the

reception of the force, except that two commissariat officers, without

interpreters or staff, had been dispatched to the town a few days before

the troops landed. These officers could not speak the language. However,

the English Consul was a man of energy. Mr. Calvert went to the Turkish

Governor, and succeeded in having half of the quarters in the town

reserved. Next day he visited and marked off the houses; but the French

authorities said they had made a mistake as to the portion of the town

they had handed over to him. They had the Turkish part of the town close

to the water, with an honest and favourable population; the English had

the Greek quarter, further up the hill, and perhaps the healthier, and a

population which hated them bitterly.

Sir George Brown arrived on Wednesday, the 5th of April, but it was

midday on Saturday the 8th, ere the troops were landed and sent to their

quarters. The force consisted of only some thousand and odd men, and it

had to lie idle for two days and a half watching the seagulls, or with

half averted eye regarding the ceaseless activity of the French, the

daily arrival of their steamers, the rapid transmission of their men to

shore. On our side not a British pendant was afloat in the harbour! Well

might a Turkish boatman ask,{16} "Oh, why is this? Oh, why is this,

Chelebee? By the beard of the Prophet, for the sake of your father's

father, tell me, O English Lord, how is it? The French infidels have got

one, two, three, four, five, six, seven ships, with fierce little

soldiers; the English infidels, who say they can defile the graves of

these French (may Heaven avert it!), and who are big as the giants of

Asli, have only one big ship. Do they tell lies?" (Such was the

translation given to me of my interesting waterman's address.)

The troops were disembarked in the course of the day, and marched out to

encamp, eight miles and a half north of Gallipoli, at a place called

Bulair. The camp was occupied by the Rifles and Sappers and Miners,

within three miles of the village. It was seated on a gentle slope of

the ridge which runs along the isthmus, and commanded a view of the Gulf

of Saros, but the Sea of Marmora was not visible. Sanitary and certain

other considerations may have rendered it advisable not to select this

village itself, or some point closer to it, as the position for the

camp; but the isthmus was narrower at Bulair, could be more easily

defended, would not have required so much time or labour to put it into

a good state of defence, and appeared to be better adapted for an army

as regards shelter and water than the position chosen. Bulair is ten and

a half miles from Gallipoli, so the camp was about seven and a half from

the port at which its supplies were landed, and where its reinforcements

arrived.

SCARCITY OF PROVISIONS.

On Thursday there was a general hunt for quarters through the town. The

General got a very fine place in a beau quartier, with a view of an

old Turk on a counter looking at his toes in perpetual perspective. The

consul, attended by the dragoman and a train of lodging seekers, went

from house to house; but it was not till the eye had got accustomed to

the general style of the buildings and fittings that any of them seemed

willing to accept the places offered them. The hall door, which is an

antiquated concern—not affording any particular resistance to the air

to speak of—opens on an apartment with clay walls about ten feet high,

and of the length and breadth of the whole house. It is garnished with

the odds and ends of the domestic deity—empty barrels, casks of

home-made wine, buckets, baskets, &c. At one side a rough staircase,

creaking at every step, conducts one to a saloon on the first floor.

This is of the plainest possible appearance. On the sides are stuck

prints of the "Nicolaus ho basileus," of the Virgin and Child, and

engravings from Jerusalem. The Greeks are iconoclasts, and hate images,

but they adore pictures. A yellow Jonah in a crimson whale with fiery

entrails is a favourite subject, and doubtless bears some allegorical

meaning to their own position in Turkey. From this saloon open the two

or three rooms of the house—the kitchen, the divan, and the principal

bedroom. There is no furniture. The floors are covered with matting, but

with the exception of the cushions on the raised platform round the wall

of the room (about eighteen inches from the floor), there is nothing

else in the rooms offered for general competition to the public. Above

are dark attics. In such a lodging as this, in{17} the house of the widow

Papadoulos, was I at last established to do the best I could without

servant or equipment.

Water was some way off, and I might have been seen stalking up the

street with as much dignity as was compatible with carrying a sheep's

liver on a stick in one hand, some lard in the other, and a loaf of

black bread under my arm back from market. There was not a pound of

butter in the whole country, meat was very scarce, fowls impossible; but

the country wine was fair enough, and eggs were not so rare as might be

imagined from the want of poultry.

While our sick men had not a mattress to lie down upon, and were without

blankets, the French were well provided for. No medical comforts were

forwarded from Malta,—and so when a poor fellow was sinking the doctor

had to go to the General's and get a bottle of wine for him. The

hospital sergeant was sent out with a sovereign to buy coffee, sugar,

and other things of the kind for the sick, but he could not get them, as

no change was to be had in the place. In the French hospital everything

requisite was nicely made up in small packages and marked with labels,

so that what was wanted might be procured in a minute.

The French Commandant de Place posted a tariff of all articles which

the men were likely to want on the walls of the town, and regulated the

exchanges like a local Rothschild. A Zouave wanted a fowl; he saw one in

the hand of an itinerant poultry merchant, and he at once seized the

bird, and giving the proprietor a franc—the tariff price—walked off

with the prize. The Englishman, on the contrary, more considerate and

less protected, was left to make hard bargains, and generally paid

twenty or twenty-five per cent. more than his ally. These Zouaves were

first-rate foragers. They might be seen in all directions, laden with

eggs, meat, fish, vegetables (onions), and other good things, while our

fellows could get nothing. Sometimes a servant was sent out to cater for

breakfast or dinner: he returned with the usual "Me and the Colonel's

servant has been all over the town, and can get nothing but eggs and

onions, Sir;" and lo! round the corner appeared a red-breeched Zouave or

Chasseur, a bottle of wine under his left arm, half a lamb under the

other, and poultry, fish, and other luxuries dangling round him. "I'm

sure I don't know how these French manages it, Sir," said the

crestfallen Mercury, retiring to cook the eggs.

The French established a restaurant for their officers, and at the

"Auberge de l'Armée Expeditionnaire," close to General Bosquet's

quarters, one could get a dinner which, after the black bread and eggs

of the domestic hearth, appeared worthy of Philippe.

There seemed to be a general impression among the French soldiers that

it would be some time ere they left Gallipoli or the Chersonese. They

were in military occupation of the place. The tricolor floated from the

old tower of Gallipoli. The café had been turned into an

office—Direction du Port et Commissariat de la Marine. French

soldiers patrolled the town at night, and kept the soldiery of both

armies in order; of course, we sent out a patrol also, but the

regulations of the place were directly organized at the French

head-quarters, and even the miser{18}able house which served as our Trois

Frères, or London Tavern, and where one could get a morsel of meat and

a draught of country wine for dinner, was under their control. A notice

on the walls of this Restaurant de l'Armée Auxiliaire informed the

public that, par ordre de la police Française, no person would be

admitted after seven o'clock in the evening. In spite of their strict

regulations there was a good deal of drunkenness among the French

soldiery, though perhaps it was not in excess of our proportion,

considering the numbers of both armies. They had fourgons for the

commissariat, and all through their quarter of the town one might see

the best houses occupied by their officers. On one door was inscribed

Magasin des Liquides, on another Magasin des Distributions. M.

l'Aumonier de l'Armée Française resides on one side of the street;

l'Intendant Général, &c., on the other. Opposite the commissariat stores

a score or two of sturdy Turks worked away at neat little hand-mills

marked Moulin de Café—Subsistence Militaire. No. A., Compagnie

B., &c., and roasting the beans in large rotatory ovens; the place

selected for the operation being a burial-ground, the turbaned

tombstones of which seemed to frown severely on the degenerate posterity

of the Osmanli. In fact, the French appear to have acted uniformly on

the sentiment conveyed in the phrase of one of their officers, in reply

to a remark about the veneration in which the Turks hold the remains of

the dead—"Mais il faut rectifier tous ces préjuges et barbarismes!"

The greatest cordiality existed between the chiefs of the armies. Sir

George Brown and some of his staff dined one day with General Canrobert;

another day with General Martimprey; another day the drowsy shores of

the Dardanelles were awakened by the thunders of the French cannon

saluting him as he went on board Admiral Bruat's flagship to accept the

hospitalities of the naval commander; and then on alternate days the

dull old alleys of Gallipoli were brightened up by an apparition of

these officers and their staffs in full uniform, clanking their spurs

and jingling their sabres over the excruciating rocks which form the

pavement as they proceeded on their way to the humble quarters of "Sir

Brown," to sit at return banquets.

The natives preferred the French uniform to ours. In their sight there

can be no more effeminate object than a warrior in a shell jacket, with

closely-shaven chin and lip and cropped whiskers. He looks, in fact,

like one of their dancing troops, and cuts a sorry figure beside a great

Gaul in his blazing red pantaloons and padded frock, epaulettes, beard

d'Afrique, and well-twisted moustache. The pashas think much of our

men, but they are not struck with our officers. The French made an

impression quite the reverse. The Turks could see nothing in the men,

except that they thought the Zouaves and Chasseurs Indigènes

dashing-looking fellows; but they considered their officers superior to

ours in all but exact discipline. One day, as a man of the 4th was

standing quietly before the door of the English Consulate, with a horse

belonging to an officer of his regiment, some drunken French soldiers

came reeling up the street; one of them kicked the horse, and caused it

to rear violently; and,{19} not content with doing so, struck it on the

head as he passed. Several French officers witnessed this scene, and one

of them exclaimed, "Why did not you cut the brigand over the head with

your whip when he struck the horse?" The Englishman was not a master of

languages, and did not understand the question. When it was explained to

him, he said with the most sovereign contempt, "Lord forbid I'd touch

sich a poor drunken little baste of a crayture as that!"

TROUBLES OF THE TURKISH COMMISSION.

The Turkish Commission had a troublesome time of it. All kinds of

impossible requisitions were made to them every moment. Osman Bey, Eman

Bey, and Kabouli Effendi, formed the martyred triumvirate, who were kept

in a state of unnatural activity and excitement by the constant demands

of the officers of the allied armies for all conceivable stores,

luxuries, and necessaries for the troops, as well as for other things

over which they had no control. One man had a complaint against an

unknown Frenchman for beating his servant—another wanted them to get

lodgings for him—a third wished them to send a cavass with self and

friends on a shooting excursion—in fact, very unreasonable and absurd

requests were made to these poor gentlemen, who could scarcely get

through their legitimate work, in spite of the aid of numberless pipes

and cups of coffee. One of the medical officers went to make a

requisition for hospital accommodation, and got through the business

very well. When it was over, the President descended from the divan. In

the height of his delusions respecting Oriental magnificence and

splendour, led away by reminiscences of "Tales of the Genii" and the

"Arabian Nights," the reader must not imagine that this divan was

covered with cloth of gold, or glittering with precious stones. It was

clad in a garb of honest Manchester print, with those remarkable birds

of prey or pleasure, in green and yellow plumage, depicted thereupon,

familiar to us from our earliest days. The council chamber was a room of

lath and plaster, with whitewashed walls; its sole furniture a carpet in

the centre, the raised platform or divan round its sides, and a few

chairs for the Franks. The President advanced gravely to the great

Hakim, and through the interpreter made him acquainted with particulars

of a toothache, for which he desired a remedy. The doctor insinuated

that His Highness must have had a cold in the head, from which the

symptoms had arisen, and the diagnosis was thought so wonderful it was

communicated to the other members of the Council, and produced a marked

sensation. When he had ordered a simple prescription he was consulted by

the other members in turn: one had a sore chin, the other had weak eyes;

and the knowledge evinced by the doctor of these complaints excited

great admiration and confidence, so that he departed, after giving some

simple prescriptions, amid marks of much esteem and respect.

Djemel Pasha, who commanded the pashalic of the Dardanelles, was a very

enlightened Turk, and possessed a fund of information and a grasp of

intellect not at all common among his countrymen, even in the most

exalted stations. He was busily engaged on a work on the constitution of

Turkey, in which he proposed to{20} remodel the existing state of things

completely. He had been much struck by the notion of an hereditary

aristocracy, which he considered very suitable for Turkey, and was

fascinated by our armorial bearings and mottoes, as he thought them

calculated to make members of a family act in such a way as to sustain

the reputation of their ancestors. Talking of the intended visit of the

Sultan to Adrianople, he said, one day, that it was mere folly. If the

Sultan went as his martial ancestors—surrounded by his generals—to

take the command of his armies and share the privations of his soldiers,

he granted it would be productive of good, and inflame the ardour of his

soldiery; but it would produce no beneficial result to visit Adrianople

with a crowded Court, and would only lead to a vast outlay of money in

repairing the old palace for his reception, and in conveying his

officers of State, his harem, and his horses and carriages to a city

which had ceased to be fit for an imperial residence. He was very much

of the opinion of General Canrobert, who, at the close of a splendid

reception by the pashas, at Constantinople, in which pipes mounted with

diamonds and begemmed coffee-cups were handed about by a numerous

retinue, said, "I am much obliged by your attention, but you will

forgive me for saying I should be much better pleased if all these

diamonds and gold were turned into money to pay your troops, and if you

sent away all these servants of yours, except two or three, to fight

against your enemy!" Djemel Pasha declared there could be no good in

tanzimats or in new laws, unless steps were taken to carry them out and

administer them. The pashas in distant provinces would never give them

effect until they were forced to do so, and therefore it will be

necessary, in his opinion, to have the ambassadors of the great Powers

admitted as members of the Turkish Council of State for some years, in

order that these reforms may be productive of good. The Koran he

considered as little suitable to be the basis and textbook of civil law

now in Turkey, as the Old Testament would be in England. It will be long

indeed ere the doctrines of this enlightened Turk prevail among his

countrymen, and when they do the Osmanlis will have ceased to be a

nation. The prejudices of the true believers were but little shaken by

these events. The genuine old green-turbaned Turk viewed our

intervention with suspicion, and attributed our polluting presence on

his soil to interested motives, which aim at the overthrow of the Faith.

This was seen in their leaden eyes as they fell on one through the

clouds of tobacco-smoke from the khans or cafés. You are still a

giaour, whom Mahomet has forced into his service, but care must be taken

that you do not gain any advantage at the hands of the faithful.

In the English general orders the greatest stress was laid on treating

the Turks with proper respect, and both officers and men were strictly

enjoined to pay every deference to "the most ancient and faithful of our

allies." The soldiers appeared to act in strict conformity with the

spirit of these instructions. They bought everything they wanted, but on

going for a walk into the country one might see the fields dotted by

stragglers from the French camp, tearing up hedgestakes, vines, and

sticks for fuel, and looking out generally with eyes wide open for the

pot à feu.{21}

CHASSEURS INDIGÈNES.

With the exception of the vivandières, the French brought no women

whatever with them. The Malta authorities had the egregious folly to

send out ninety-seven women in the "Georgiana" to this desolate and

miserable place, where men were hard set to live. This indiscretion was

not repeated.

The camps in the neighbourhood of Gallipoli extended every day, and with

the augmentation of the allied forces, the privations to which the men

were exposed became greater, the inefficiency of our arrangements more

evident, and the comparative excellence of the French commissariat

administration more striking. Amid the multitude of complaints which met

the ear from every side, the most prominent were charges against the

British commissariat; but the officers at Gallipoli were not to blame.

The persons really culpable were those who sent them out without a

proper staff, and without the smallest foresight. Early and late these

officers might be seen toiling amid a set of apathetic Turks and stupid

araba drivers, trying in vain to make bargains and give orders in the

language of signs, or aided by interpreters who understood neither the

language of the contractor nor contractee. And then the officers of a

newly-arrived regiment rushed on shore, demanded bullock-carts for the

luggage, guides, interpreters, rations, &c., till the unfortunate

commissary became quite bewildered. There were only four commissary

officers, Turner, Bartlett, Thompson, and Smith, and they were obliged

to get on as well as they could with the natives.

The worst thing was the want of comforts for the sick. Many of the men

labouring under diseases contracted at Malta were obliged to camp in the

cold, with only one blanket, as there was no provision for them at the

temporary hospital. Mr. Alexander succeeded in getting hold of some

hundreds of blankets by taking on himself the responsibility of giving a