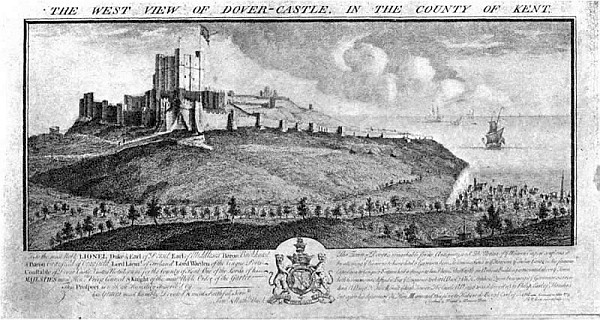

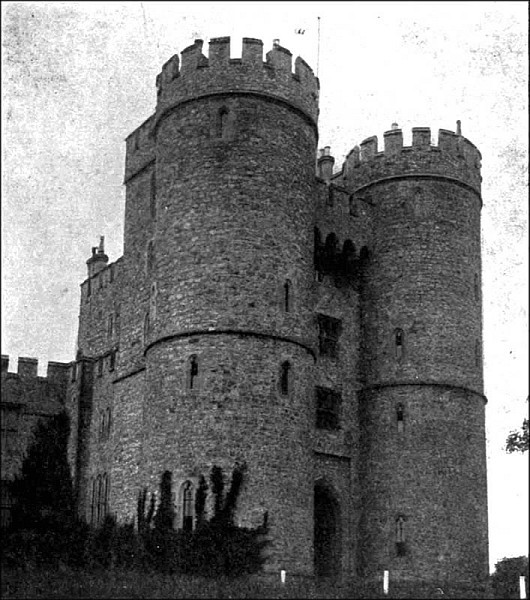

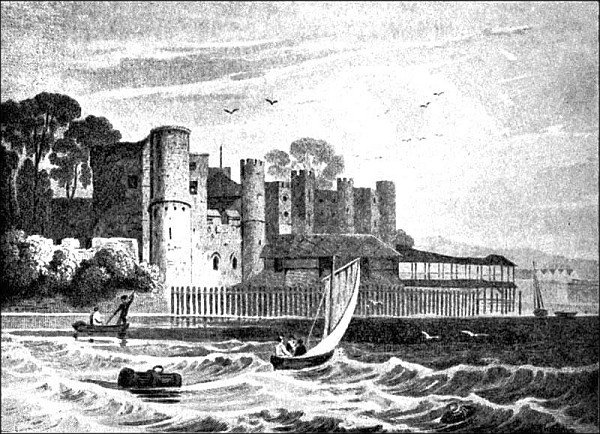

DOVER CASTLE, KENT

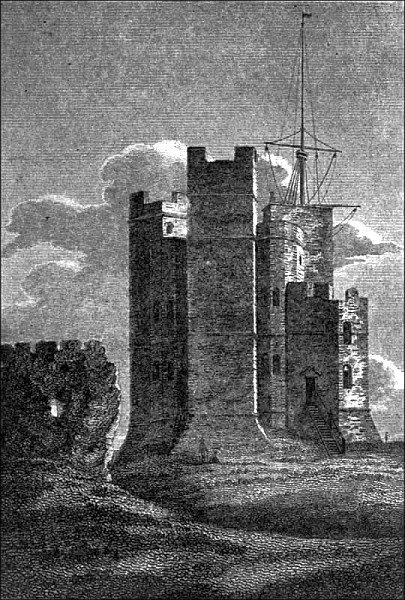

DOVER CASTLE, KENTFrom an engraving by S. and N. Buck

Title: English Coast Defences

Author: George Clinch

Release date: June 5, 2014 [eBook #45884]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

ENGLISH COAST DEFENCES

FROM ROMAN TIMES TO THE EARLY

YEARS OF THE NINETEENTH

CENTURY

BY

GEORGE CLINCH

LONDON

G. BELL AND SONS, LTD.

1915

CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

TO

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

ARTHUR JAMES BALFOUR, M.P.

FIRST LORD OF THE ADMIRALTY

THESE PAGES ARE

INSCRIBED

The intricate coast-line of England, so difficult for an enemy to blockade, so difficult at every point for combined naval and military forces to defend against raiders, presents to the student of history an extremely interesting subject. It is to its insularity that England owes something of its greatness, and to the great length of its coast-line that its vulnerability is due.

The present book represents the results of a study of the methods and means by which England, from Roman times down to the early years of the nineteenth century, has defended her shores against various over-sea enemies, who have attempted, sometimes successfully, to invade and conquer.

The author wishes to return thanks for the loan of blocks used in illustration of this volume, particularly to the Society of Antiquaries for Figs. 3, 10, 11, 29, 31, 32; the Royal Archaeological Institute for Figs. 1, 4, 7, 13, 18; the Kent Archaeological Society for Figs. 37, 38, 39, 40, 42, 43; the proprietors of the “Victoria History” and Professor Haverfield for Fig. 15; and the Technical Journals, Limited, and Mr. A. W. Clapham, F.S.A., for Fig. 24.

The corrected proof-sheets of the book have been submitted to the proper authorities at the War Office, and that Department has sanctioned the publication of the volume.

| PAGE | |

| Preface | vii |

| List of Illustrations | xi |

| Part I | |

| Prehistoric Camps | 3 |

| The Roman Invasion of Britain | 5 |

| The Count of the Saxon Shore | 13 |

| Roman Coast Fortresses | 16 |

| Part II | |

| The Saxon Settlement of England | 75 |

| Danish Incursions and Camps | 80 |

| The Norman Invasion of England | 86 |

| Norman Coast Castles | 87 |

| Part III | |

| Mediaeval Castles and Walled Towns on the Coast | 95 |

| Part IV | |

| Coast Defences under Henry VIII and Later | |

| On the East Coasts of Kent and Sussex | 159 |

| Of the Estuaries of the Thames, the Medway, etc. | 179 |

| Of the South Coast | 182 |

| Part V | |

| Miscellaneous Defences | |

| The Navy | 195 |

| The Cinque Ports | 196 |

| Defensive Chains, etc. | 204 |

| The Coastguard | 212 |

| Index | 219 |

| FIG. | PAGE | |

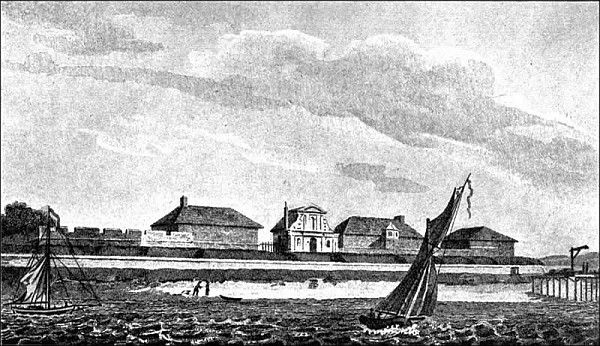

| Dover Castle. Buck’s engraving | Frontispiece | |

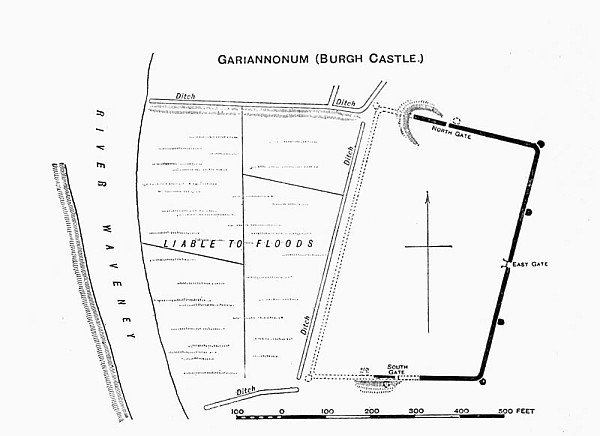

| 1. | Gariannonum (Burgh Castle). Plan | 22 |

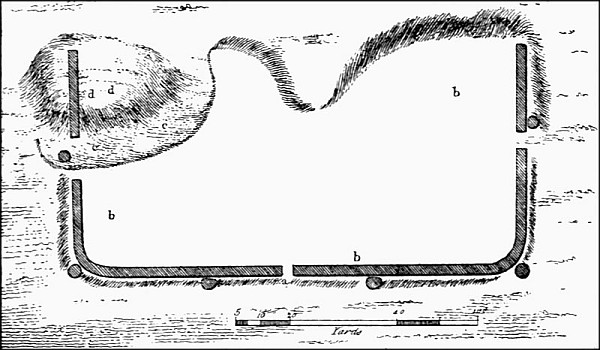

| 2. | Gariannonum (Burgh Castle). Plan published in 1776 | 23 |

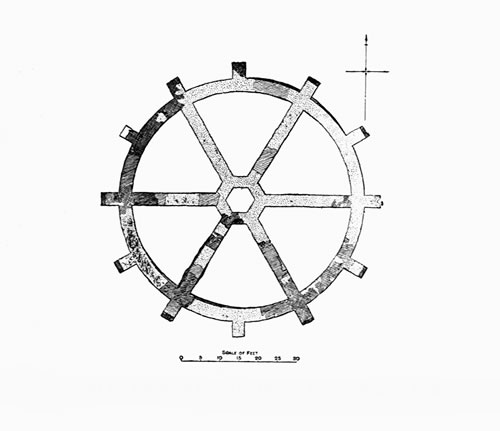

| 3. | West Mersea. Plan of Roman building | 27 |

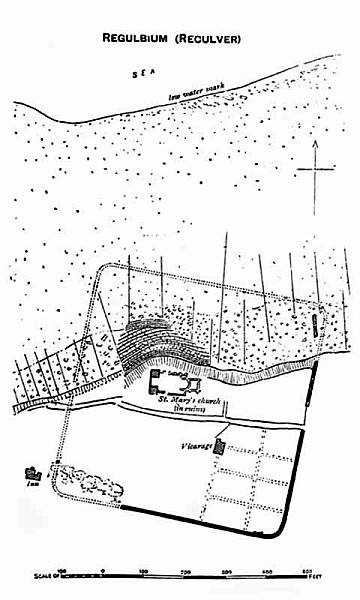

| 4. | Regulbium (Reculver). Plan | 29 |

| 5. | Regulbium (Reculver). Roman masonry | 31 |

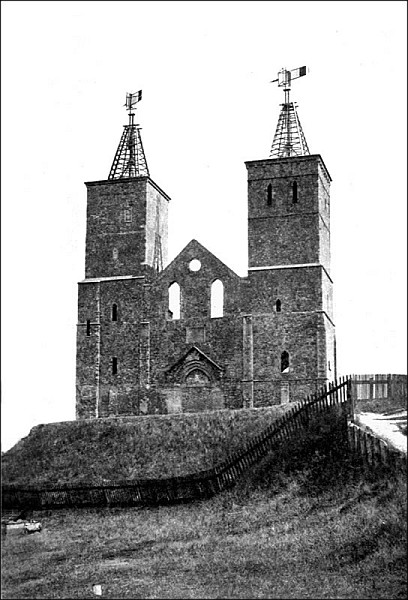

| 6. | Reculver. The ruins of the church | 33 |

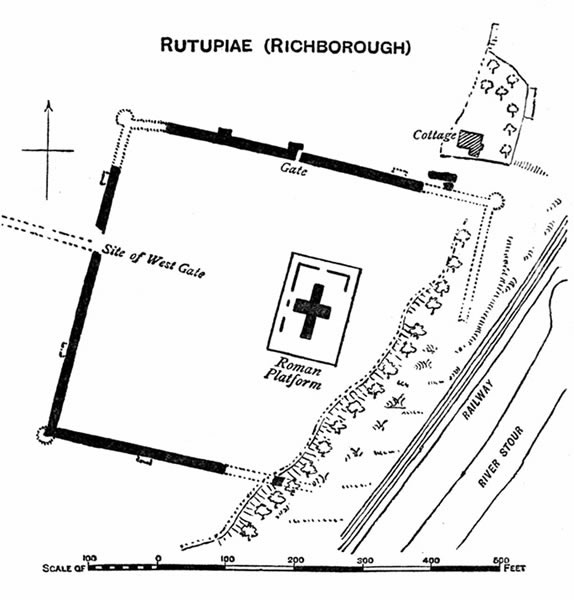

| 7. | Rutupiae (Richborough). Plan | 36 |

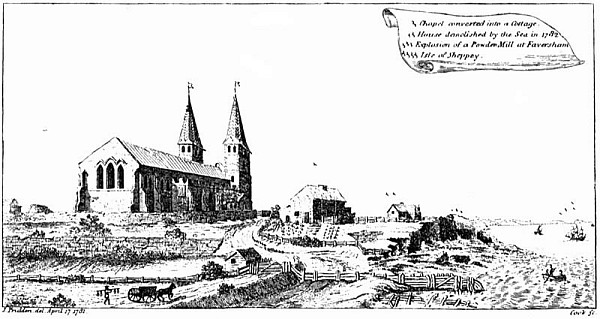

| 8. | Reculver. From a print published in 1781 | 39 |

| 9. | Richborough. Roman masonry of north wall | 43 |

| 10. | Dover, Roman Pharos. Elevation of north side | 47 |

| 11. | Dover, Roman Pharos. Section | 51 |

| 12. | Lymne. Roman walls | 54 |

| 13. | Lymne. Plan | 55 |

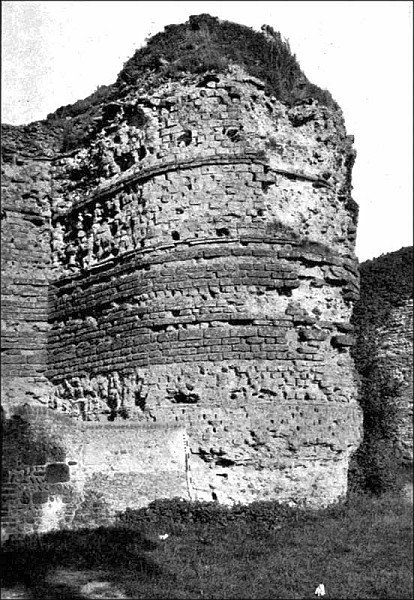

| 14. | Pevensey. Bastion | 59 |

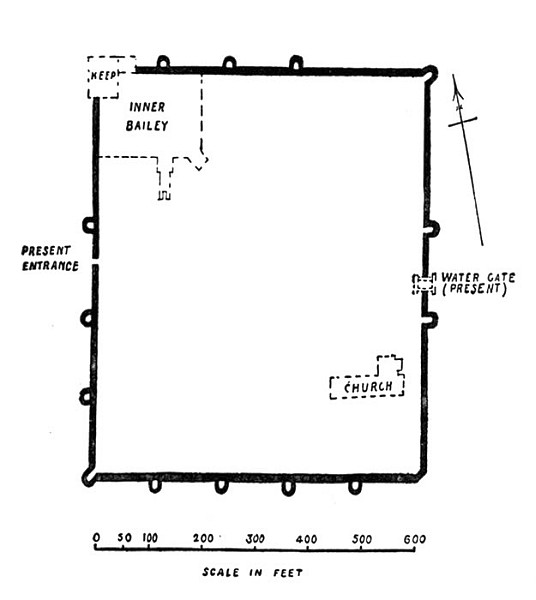

| 15. | Porchester. Plan | 63 |

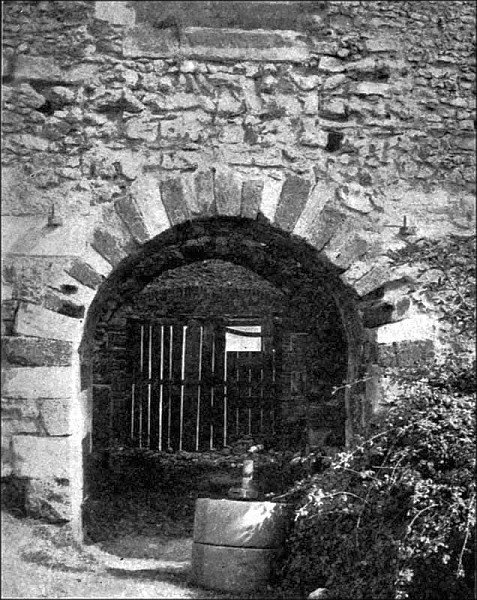

| 16. | Porchester. Water-gate | 65 |

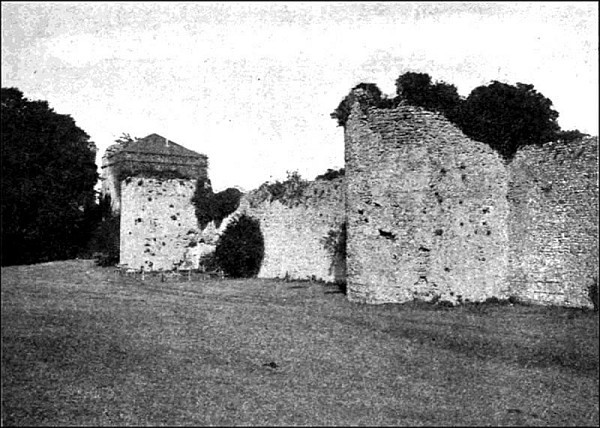

| 17. | Porchester. Exterior of west wall | 67 |

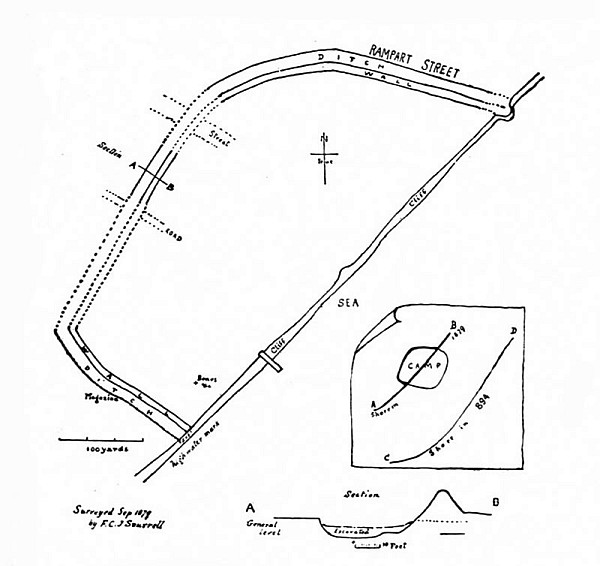

| 18. | Shoebury. Plan of Danish camp | 83 |

| 19. | Yarmouth. North Gate, 1807 | 104 |

| 20. | Yarmouth. South Gate, 1807 | 105 |

| 21. | Ipswich. St. Matthew’s Gate, 1785 | 107 |

| 22. | Orford Castle, Suffolk, 1810 | 109 |

| 23. | Cowling Castle, Kent, 1784 | 114 |

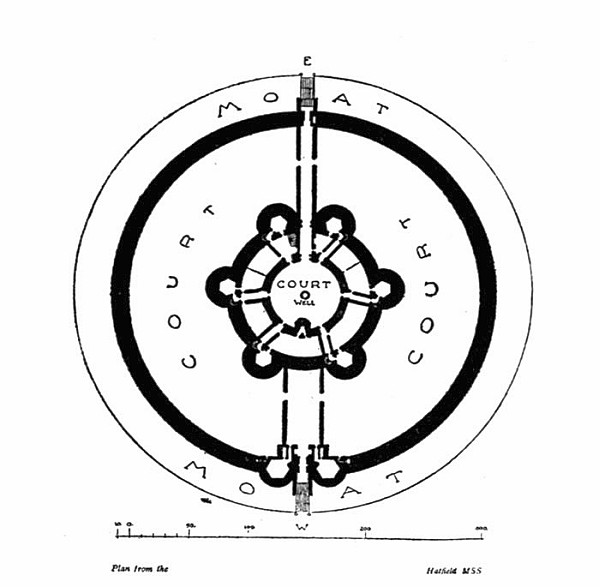

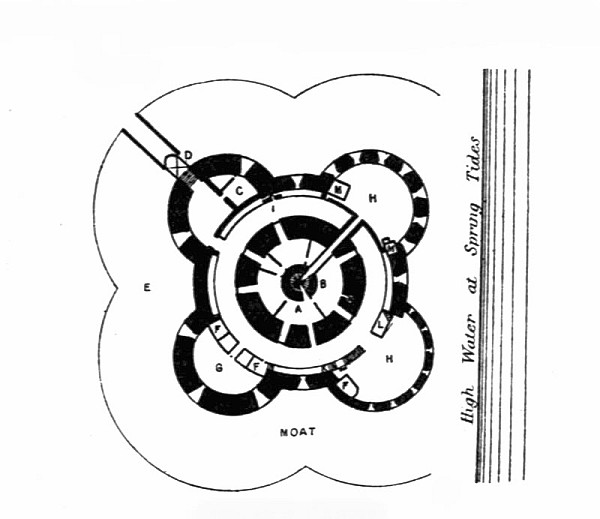

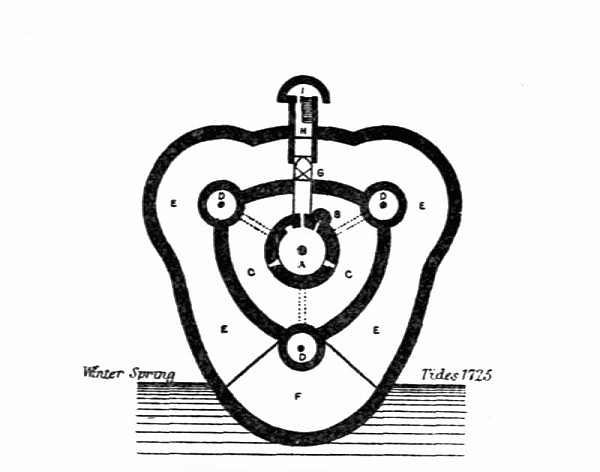

| 24. | Queenborough Castle, Kent. Plan | 118 |

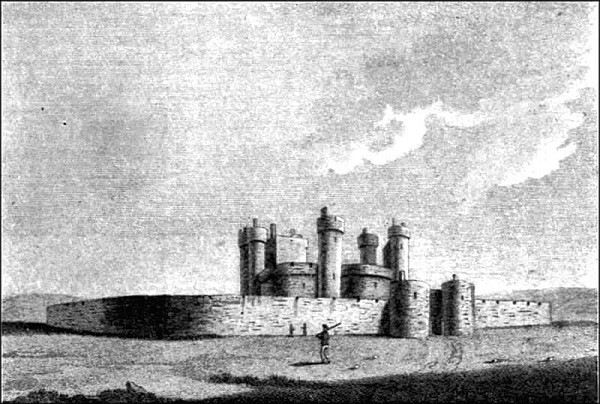

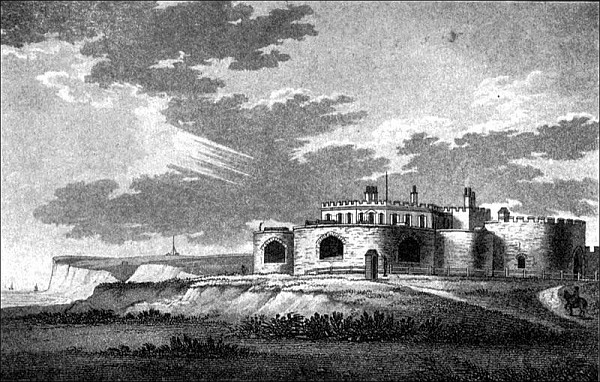

| 25. | Queenborough Castle, Kent. View in 1784 | 119 |

| 26. | Canterbury Castle in the Eighteenth Century | 121 |

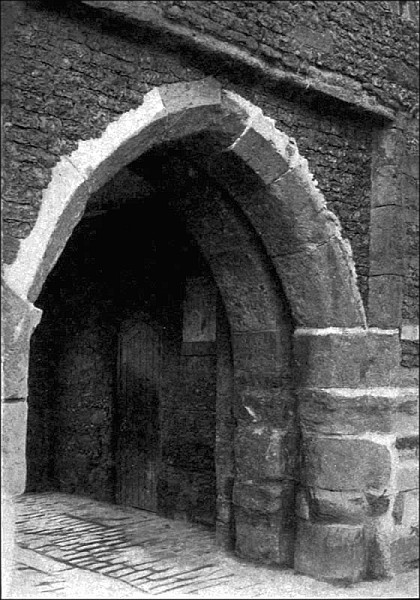

| 27. | Sandwich, Kent. Fisher Gate | 123 |

| 28. | Sandwich, Kent. Barbican | 126 |

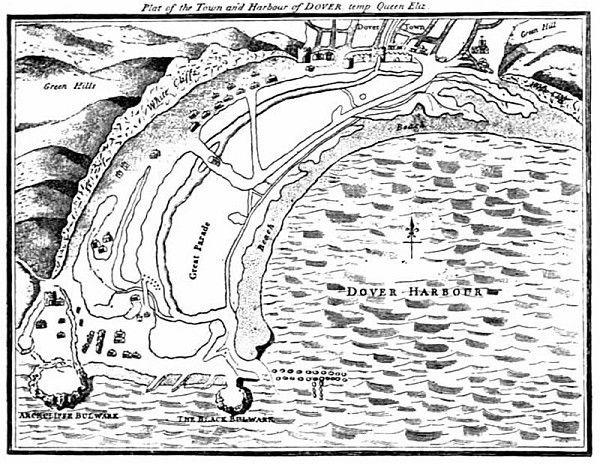

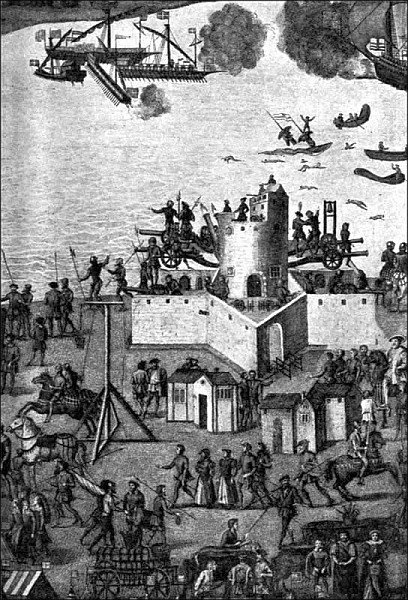

| 29. | Dover. Bird’s-eye view of town and harbour, temp. Queen Elizabeth | 131 |

| 30. | Saltwood Castle, Kent. The Gate House | 135 |

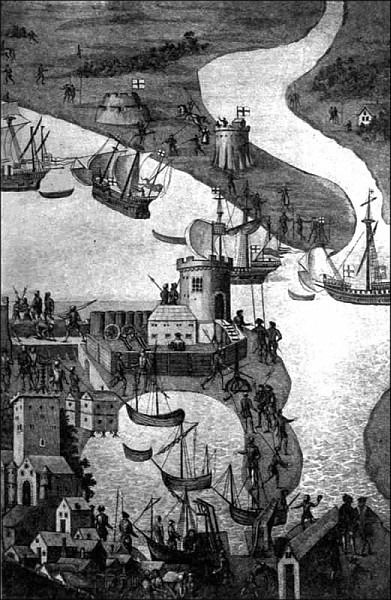

| 31. | Portsmouth Harbour, temp. King Henry VIII | 143 |

| 32. | Southsea Castle, temp. King Henry VIII | 147 |

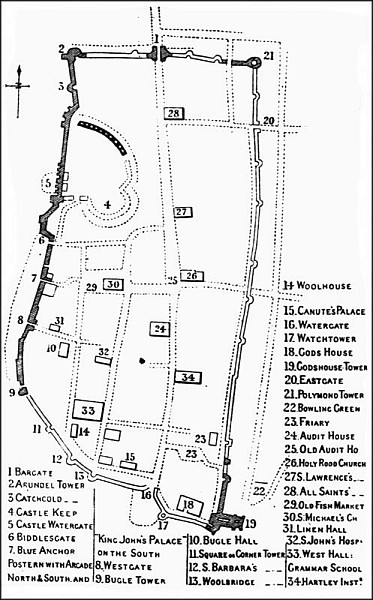

| 33. | Southampton. Plan | 150 |

| 34. | Deal Castle, Kent | 163 |

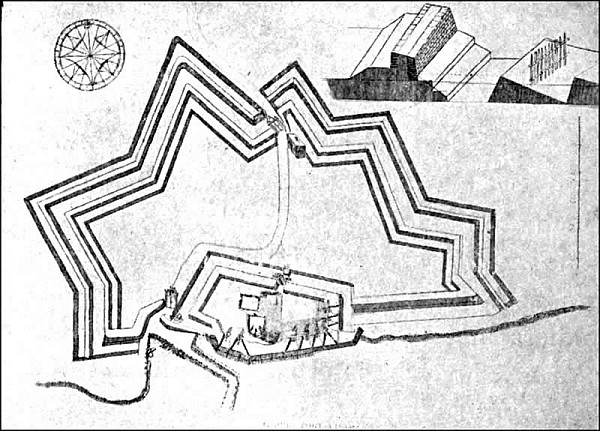

| 35. | Tilbury Fort in the Year 1588 | 166 |

| 36. | Tilbury Fort in the Year 1808 | 167 |

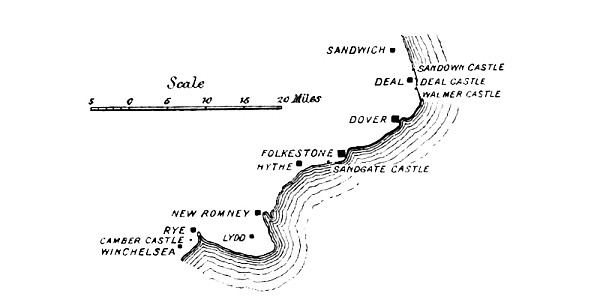

| 37. | General Plan of Henry VIII’s Blockhouses on Kent and Sussex Coasts | 170 |

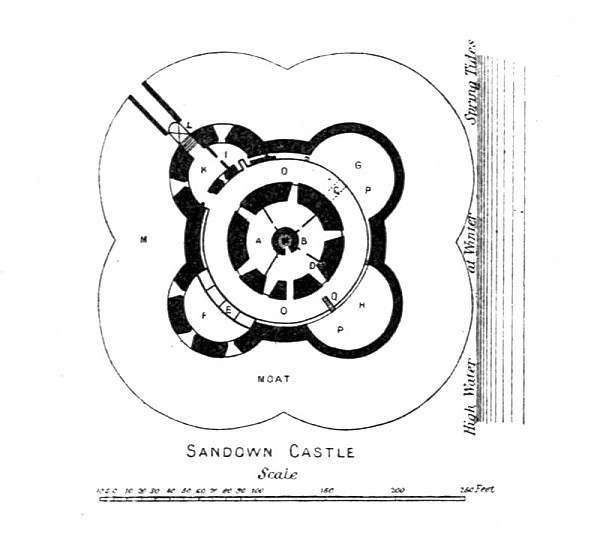

| 38. | Sandown Castle. Plan | 171 |

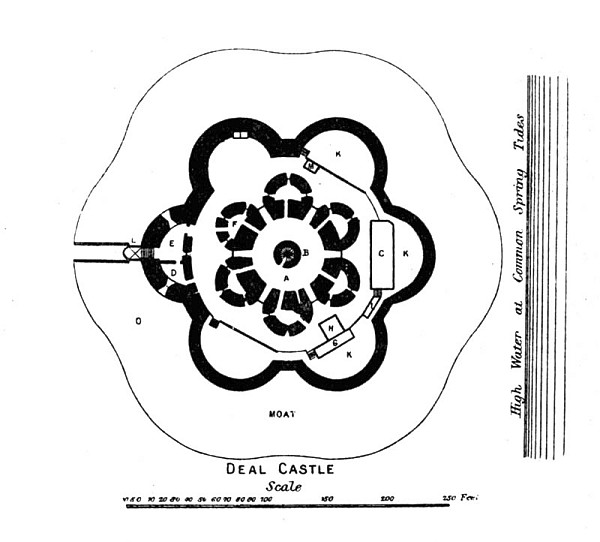

| 39. | Deal Castle. Plan | 172 |

| 40. | Walmer Castle. Plan | 173 |

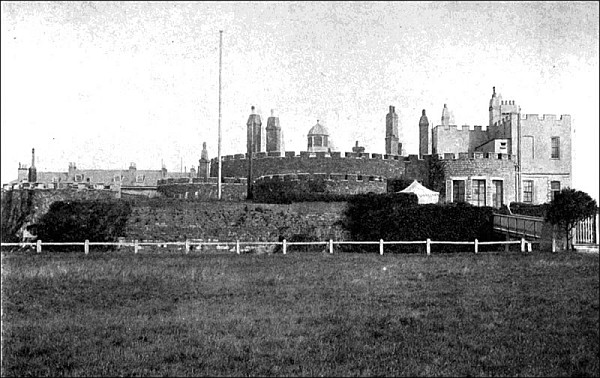

| 41. | Walmer Castle from the North | 175 |

| 42. | Sandgate Castle. Plan | 177 |

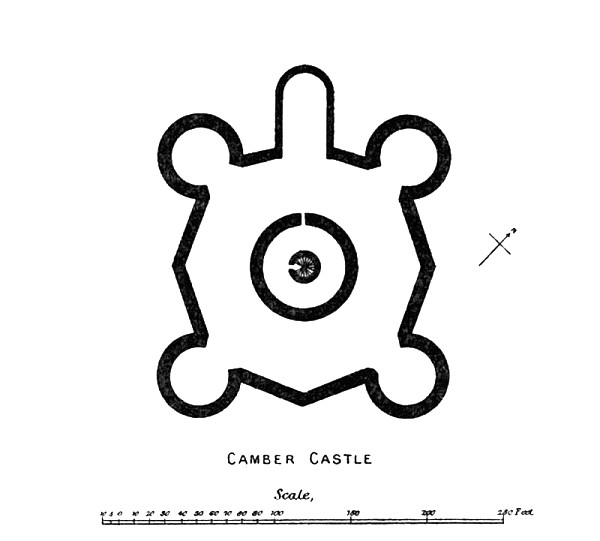

| 43. | Camber Castle. Plan | 178 |

| 44. | Upnor Castle, Kent | 180 |

| 45. | Hurst Castle, Hants | 183 |

| PREHISTORIC CAMPS |

| THE ROMAN INVASION OF BRITAIN |

| THE COUNT OF THE SAXON SHORE |

| ROMAN COAST FORTRESSES |

ENGLISH COAST DEFENCES

Round the coast of England there are many prehistoric earthworks of great extent and strength. These fall generally under the heads of hill-top fortresses and promontory camps. The works comprised under the former head are so arranged as to take the greatest possible advantage of natural hill-tops, often of large size. On the line where the comparatively level top developed into a more or less precipitous slope a deep ditch was dug, and the earth so removed was in most cases thrown outwards so as to form a rampart which increased the original difficulties of the sloping hill-side.

The latter type of earthwork, called promontory camps from their natural conformation, were strengthened by the digging of a[ 4] deep ditch, so as to cut off the promontory from the main table-land from which it projected, and in some cases the sides of the camp were made more precipitous by artificial scarping.

An examination of these types of earthworks leads to the conclusion that they were probably tribal enclosures for the safe-guarding of cattle, etc.; that, strictly speaking, they were not military works at all, and, in any case, had no relation to national defence against enemies coming over-sea.

One finds in different parts of the country a prevalent tradition that the Romans occupied the more ancient British hill-top strongholds, and the name “Caesar’s Camp” is popularly applied to many of them. If such an occupation really took place it was, in all probability, only of a temporary character. These fortifications were not suitable to the Roman method of military operations and encampment, and such archaeological evidences of Roman occupation as have been found point to the presence of domestic buildings, such as at Chanctonbury[ 5] Ring and Wolstanbury Camp (Sussex) rather than military works.

However, the question must not be dismissed as entirely without some foundation in fact, because it was only natural that the Roman invaders who dispossessed the Britons of their fastnesses should themselves have taken temporary possession of the works from which the Britons were driven out.

There is hardly a single detail of the first invasion of Britain by the Romans which has not been the subject of dispute or discussion among historians and antiquaries, but, briefly, it may be stated as highly probable that Caesar left Portus Itius (Boulogne) on 25 August 55 B.C., and landed at or near what is now Deal on the following day.

When Caesar found a convenient time for[ 6] the invasion of Britain, he got together about eighty transports, which he considered would be sufficient for carrying two legions across the channel. Those galleys which he had left he distributed to the questor, lieutenants, and officers of the cavalry. In addition to these ships there were eighteen transports, detained by contrary winds at a port about eight miles off, and these were appointed to carry over the cavalry.

A favourable breeze sprang up, and anchor was weighed about one in the morning. The cavalry in the eighteen other transports embarked at the other port. It was ten o’clock when Caesar reached the coast of Britain, where he saw the cliffs covered with the enemy’s forces. He speaks of the place as being bounded by steep mountains in a way which clearly describes Dover and the eminences in its neighbourhood, comprising Shakespeare’s Cliff, the western and eastern heights, and all the magnificent cliff of precipitous chalk rock which extends to Kingsdown, near Walmer. On such a coast as this,[ 7] apart from the presence of the enemy, landing was impossible, and Caesar wisely determined to sail eight miles further on, where he found, probably at Deal, a plain and open shore. Caesar’s description is most interesting, and may be quoted:

“But the barbarians perceiving our design, sent their cavalry and chariots before, which they frequently make use of in battle, and following with the rest of their forces, endeavoured to oppose our landing: and indeed we found the difficulty very great on many accounts; for our ships being large, required a great depth of water; and the soldiers, who were wholly unacquainted with the places, and had their hands embarrassed and loaden with a weight of armour, were at the same time to leap from the ships, stand breast high against the waves, and encounter the enemy, while they, fighting upon dry ground, or advancing only a little way into the water, having the free use of all their limbs, and in places which they perfectly knew, could boldly cast their darts, and spur on their horses, well inured to that[ 8] kind of service. All these circumstances serving to spread a terror among our men, who were wholly strangers to this way of fighting, they pushed not the enemy with the same vigour and spirit as was usual for them in combats upon dry ground.

“Caesar, observing this, ordered some galleys, a kind of shipping less common with the barbarians, and more easily governed and put in motion, to advance a little from the transports towards the shore, in order to set upon the enemy in flank, and by means of their engines, slings, and arrows, drive them to some distance. This proved of considerable service to our men, for what with the surprise occasioned by the make of our galleys, the motion of the oars, and the playing of the engines, the enemy were forced to halt, and in a little time began to give back. But our men still demurring to leap into the sea, chiefly because of the depth of the water in those parts, the standard-bearer of the tenth legion, having first invoked the gods for success, cried out aloud: ‘Follow me, fellow-soldiers, unless[ 9] you will betray the Roman eagle into the hands of the enemy; for my part, I am resolved to discharge my duty to Caesar and the common-wealth.’ Upon this he jumped into the sea, and advanced with the eagle against the enemy: whereat, our men exhorted one another to prevent so signal a disgrace, all that were in the ship followed him, which being perceived by those in the nearest vessels, they also did the like, and boldly approached the enemy.

“The battle was obstinate on both sides; but our men, as being neither able to keep their ranks, nor get firm footing, nor follow their respective standards, because leaping promiscuously from their ships, every one joined the first ensign he met, were thereby thrown into great confusion. The enemy, on the other hand, being well acquainted with the shallows, when they saw our men advancing singly from the ships, spurred on their horses, and attacked them in that perplexity. In one place great numbers would gather round a handful of Romans; others falling[ 10] upon them in flank, galled them mightily with their darts, which Caesar observing, ordered some small boats to be manned, and ply about with recruits. By this means the foremost ranks of our men having got footing, were followed by all the rest, when falling upon the enemy briskly, they were soon put to the rout. But as the cavalry were not yet arrived, we could not pursue or advance far into the island, which was the only thing wanting to render the victory complete.”[1]

Sea-fighting was not unknown to the Romans, but as far as the invasion of Britain was concerned, Caesar’s fleet may be regarded as a collection of ships for transport purposes rather than a fighting naval force. The main object of Caesar was to land his soldiers so that they might encounter and vanquish the enemy on dry land. This, as the graphic words of the “Commentaries” clearly tell, was quickly accomplished. The British method of fighting, in which chariots were employed for[ 11] the attack, is described by Caesar,[2] who was evidently impressed by their skilful combination of rapid and awe-inspiring attack with the freedom and mobility of light infantry.

It is noteworthy that Caesar says nothing about coast defences in the form of earthworks, or indeed in any other form, and it is on other grounds improbable that the Britons possessed[ 12] any provision of that kind against invading enemies, although they themselves lived in stockaded enclosures.

The Romans were the first people to introduce anything like general coast defence in Britain, and in this, as in all other branches of their military enterprises, they displayed great skill, intelligence, and thoroughness. For the defence of the coast of the eastern and southern parts of Britain they erected a chain of castra or fortresses extending from Brancaster, on the north-west coast of Norfolk, to Porchester, situated on the extreme north-west shore of Portsmouth Harbour.

The position of the various fortresses shows that it was not necessary, according to the Roman plan of defence, that one fort should command views of its neighbours. Reculver and Richborough, Richborough and Dover, Dover and Lymne, Lymne and Pevensey, were in no case visible from each other, although the distance which separated them was not great in every case. Under these circumstances it is not remarkable to find evidences,[ 13] as will presently be explained, of special provision for signalling between the fortresses.

During the early part of the Roman occupation of Britain the chief mode of defence adopted against piratical incursions was the navy, classis Britannica. This, for the most part, moved in those waters which lay between the British and Gaulish coasts, answering to what we now know as the Straits of Dover and the southern part of the North Sea.

For a time the navy was able to keep the seas free from pirates, but towards the end of the third century the trouble became greater than ever. Raiders came in large numbers both to our own coasts and also to the Continental coasts opposite, to both of which the name of the Saxon Shore was given. The Romans decided to take strong measures to put an end to the trouble. For this purpose[ 14] they appointed a special officer, one Marcus Aurelius Valerius Carausius, commonly known by his last name.

The appearance of Carausius on the stage of history brings into prominence a man of strong but unscrupulous character. He is believed to have allowed the pirates to carry on their work of plunder at their pleasure, and then, having waited for the proper moment, he relieved them of their booty on the return journey. In this way he acquired great riches, and in due course he employed the fleet, not against the enemy of Rome, but against Rome, and in such a way as to render Britain independent. After several ineffectual attempts to break his power, Diocletian and Maximianus found it necessary to recognize him as their colleague in the empire, a triumph which Carausius commemorated by striking a medal bearing as a device three busts with appropriate emblems the legend:

| (ob.) | CARAVSIVS . ET . FRATRES . SVI |

| (rev.) | PAX AVGGG. |

Carausius was murdered by his chief official,[ 15] Allectus, in the year 293. Shortly after his death, and when the British province had ceased to be independent of Rome, an official was appointed called the Count of the Saxon Shore.

This officer, whose title was Comes Littoris Saxonici, was a high official whose duty it was to command the defensive forces and supervise the fortresses erected on the east, south-east, and south coasts of England against the piratical raids of the various tribes of Saxons and others during the latter part of the Roman occupation of Britain. The precise nature of his duties and the full extent of his authority are equally unknown, but they probably comprised the general oversight and command both of the fortresses on the British coast from the northern coast of Norfolk to a point near Portsmouth, and the navy which guarded our shores.

Opinions are divided on the question as to what was precisely meant by the phrase “the Saxon shore.” Was it, as some think, those parts of the shore of Britain and Gaul on which,[ 16] being specially subject to Saxon raiders, defences were erected or employed for repelling the invaders? Or was it, as others have supposed, perhaps with less probability, a strip of territory following the line of coast nearest the sea on which the Saxons were allowed to settle in late Roman times?

A careful examination of the fortresses which protected the line of coast to which reference has been made, is likely, we think, to afford some light upon the above-mentioned point.

If we pay attention to the plans of these fortresses, it will be obvious that at least two, Reculver and Brancaster, belong to a type of Roman fortress which is associated with a period much earlier than the time, as far as we know, when Saxon or other raiders began to molest the coasts of Britain and Gaul. Perhaps it is significant that these two castra command the entrance to two of the great water ways on[ 17] our east coast, the Thames and the Wash. The other seven fortresses, judging from their plans, belong to a later stage of development in Roman military architecture.

From this and other features already described we may infer that the whole series of fortresses was built at different periods, and probably in the following order:

| Reculver. | Richborough. |

| Brancaster. | Lymne. |

| Porchester. | Pevensey. |

Unfortunately, the architectural remains of the remaining castra are not sufficiently perfect to allow of classification.

One or two of the coast fortresses, such as Pevensey and Lymne, may well have been erected towards the close of the Roman occupation. It is significant that tiles bearing the impressed name of Honorius have been found built into the walls of Pevensey, pointing to the lateness of the building of at least some of the masonry at that castrum.[3]

At Lymne early inscriptions, etc. have been found built into the walls, indicating a period if not late in the Roman period, at least a considerable time after the date of the inscribed stones which were enclosed, as mere building material, in the walls. This is corroborated by indications of adhering barnacles, from which we may fairly conclude that there was a period of submergence between the time of the carving and the subsequent use as building material.

It seems probable, therefore, that although the earlier fortresses may have been intended to serve as centres for the Roman army, they may have been supplemented at a later period by other castra, forming altogether a chain of defences intended to protect the shores of Britain against Saxon invaders.

The late Mr. G. E. Fox, F.S.A., who made a special study of the subject, writes as follows:[4]

“By the last quarter of the third century the Romano-British fleet, on which no doubt[ 19] dependence had been placed for the protection of the east and south coasts from raids by plundering bands of rovers from over the seas, had evidently failed to afford that protection. Whether it was that the fleet was not numerous enough, or for whatever reason, the Roman government determined to supplement its first line of defence by a second, and this was achieved by the erection of forts capable of holding from 500 to 1,000 men each, on points of the coast-line extending from the mouth of the Wash to Pevensey on the coast of Sussex. The coast-line indicated received the name of Litus Saxonicum, and the nine fortresses which guarded it are called ‘the forts of the Saxon Shore.’”

The following were the nine fortresses referred to with the modern place-names:

| 1. | Branodunum. | Brancaster. | |

| 2. | Gariannonum. | Burgh Castle (near Yarmouth). | |

| 3. | Othona. | Bradwell-on-Sea. | |

| 4. | Regulbium. | Reculver. | [ 20] |

| 5. | Rutupiae. | Richborough. | |

| 6. | Dubris. | Dover. | |

| 7. | Portus Lemanus. | Lymne. | |

| 8. | Anderida. | Pevensey. | |

| 9. | Portus Magnus. | ? Porchester. |

It will be observed that the various fortresses in this chain of defensive works occur at irregular distances on or near the coast-line, and on examination it will be found that in most cases good reason exists for the selection of the various sites.

There is sufficient evidence to identify the Roman fort of Branodunum with some ruins lying to the east of Brancaster, a village situated near the north-western corner of Norfolk, on the shores of the Wash. The only early mention of the place is found in the “Notitia Imperii,” a catalogue of the distribution of the imperial military, naval, and civilian officers throughout the Roman world. From this remarkable work, a compilation which[ 21] has come down to us from a very early period, it appears that the “Comes Littoris Saxonici” (the Count of the Saxon Shore) had under him nine subordinate officers, called Praepositi, distributed round the coasts of Norfolk, Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Hampshire. The fortress at Brancaster is now in a very much ruined state, and but little can be gathered of its original form from a casual or superficial examination. Excavations and careful searches made about the middle of the nineteenth century brought to light many facts about its plan.[5] The fortress was a square of 190 yards and the angles were irregularly rounded. Exclusive of ashlar, the walls were found to be 10 feet thick, and bounded with large blocks of white sandstone. At one of the roughly rounded angles the ashlar facing remained intact. It consisted of blocks of sandstone firmly set in mortar with joints of three inches minimum thickness.

Traces were found within the walls of small[ 22] apartments adjoining the main walls into which the smaller walls were regularly bonded, pointing to contemporaneity of the work.

Two facts of some importance are proved by the excavations, viz. (1) the strength of the fortress as a defensive work, and (2) the simple and early character of the plan. Traces of gates were observed in the eastern and western walls.

FIG. 1. GARIANNONUM (BURGH CASTLE)

FIG. 1. GARIANNONUM (BURGH CASTLE) Now known as Burgh Castle, is situated in Suffolk near the point where the rivers Yare and Waveney fall into Breydon Water. The lines of its walls enclose a space, roughly speaking, 660 feet by 330 feet, over four acres. It is generally considered to be one of the most perfect Roman buildings remaining in the kingdom. The walls in places remain to[24] a height of 9 feet, and their foundations are no less than 12 feet in thickness. The bastions, or perhaps more correctly, towers, which flank the gates and support the rounded angles of the walls are of peculiar, pear-shaped plan. They are solid, and to the height of about 7 feet are not tied into the walls. Above that height, however, they are bonded into the walls with which, curious as it may appear, they are undoubtedly coeval. It is noteworthy that there are two bastions on the east side and one each on the north and south sides, and that they, six in all, are provided with a hole in the top, 2 feet wide and 2 feet deep, indicating in all probability that they once mounted turntables upon which ballistae were placed for the defence of the fortress.

FIG. 2. PLAN OF ROMAN WALLS, ETC., AT GARIANNONUM

(BURGH CASTLE)

FIG. 2. PLAN OF ROMAN WALLS, ETC., AT GARIANNONUM

(BURGH CASTLE)The masonry is of the kind which is usually found in Roman buildings, namely, a rubble core with courses of bonding tiles, and an outer facing of flints chipped to a flat surface.

Gariannonum was a place of great importance in Roman times. Here was stationed the captain of the Stablesian horse, styled Gariannonensis,[ 25] under the command of Comes littoris Saxonici.

Walton.—Near Felixstow, situated on what is now the fore-shore, but which originally was a cliff 100 feet high, and commanding extensive views of the surrounding country, are the ruins of what was an important Roman station. Although possibly not ranking as one of the nine great coast fortresses, it occupied a most important site for the defence of this part of the east coast of Britain, and commanded not only the entrance to the River Deben, but also all the adjacent coast to the south of it. Almost every trace of the station has now been obliterated by the waves, but from plans which have been preserved it appears that its plan was that of an oblong with towers or bastions at each angle.[6]

Or Ithanchester, near Bradwell-on-Sea, in Essex, was another important member of the[ 26] Roman coast defences of Britain. It commanded the entrances of the Rivers Blackwater and Colne. Little now remains of Othona, although it is on record that the fortress enclosed an area of 4 acres, and that its walls possessed foundations no less than 14 feet in thickness.

The defence of such a point as this against the incursions of foes was a matter of much importance, because this was a point on the coast of Britain specially susceptible to attack by marauders, and, as we shall see, special precautions were taken against attacks of this kind.

FIG. 3. PLAN OF

ROMAN BUILDING, WEST MERSEA, ESSEX

FIG. 3. PLAN OF

ROMAN BUILDING, WEST MERSEA, ESSEX At a distance of about four miles to the north of Othona, across the estuary of the River Blackwater, lies the island of Mersea. In the year 1896 some Roman foundations were accidentally discovered in the western part of the island which, upon examination, appear to have an important bearing on the Roman scheme of coast defence in this part of Britain. The foundations were circular, 65 feet in diameter, and closely resembling in gigantic[ 27] form the steering-wheel of a ship. The foundations were of Kentish rag and chalk lime mortar, and above this the low walling was almost entirely composed of Roman bricks set in red mortar. Dr. Henry Laver, F.S.A., who communicated the discovery to the Society of Antiquaries of London,[7] modestly abstains from giving any explanation or theory as to the purpose of the building which stood on this[ 28] site, but in the opinion of the present writer there seems to be little doubt that the foundations were intended to carry a lofty pharos, or perhaps signalling tower of timber by means of which messages might have been transmitted to Othona and Colchester.

FIG. 4. RECULVER, KENT

FIG. 4. RECULVER, KENT Now known as Reculver, is situated about three miles to the east of Herne Bay. The site, although originally some distance inland, is now, owing to the encroachment of the sea, quite close to the shore. Indeed, about half of its area has been destroyed by the waves, and is now covered at high water. Its area when complete was over seven acres, and its walls which, in the eighteenth century, stood 10 feet high, and still remain to a height of 8 feet in some places, are no less than 8 feet in thickness with two sets-off inside. It seems doubtful whether there was ever a ditch round the castrum. Owing to the ruinous condition of the main part of the masonry, and the [ 31] complete destruction which has overtaken the northern part of the foundations, it is impossible to ascertain any particulars as to the gates or internal arrangements.

FIG. 5. ROMAN MASONRY, RECULVER, KENT

FIG. 5. ROMAN MASONRY, RECULVER, KENTAs will be seen from the accompanying ground-plan the form of the castrum at Reculver was quadrangular. The angles were rounded, but there are no indications of towers[ 32] or bastions. These features are considered characteristic of Roman fortresses of early date. Another feature pointing to the same conclusion is the absence of tile courses in the walls.

The only recorded facts about this fortress is a mention in the “Notitia,” from which we learn that it was garrisoned by the first cohort of the Vetasians commanded by a tribune.

FIG. 6. RECULVER: THE RUINS OF THE CHURCH

FIG. 6. RECULVER: THE RUINS OF THE CHURCH At a comparatively early stage in the art of Roman masonry in Britain the idea was conceived of protecting the enclosing wall of the fortress by means of projecting bastions and towers. In an early type represented in the Romano-British coast fortresses, of which this of Reculver is an excellent illustration, there were, as we have seen, no projections whether of walls, bastions, towers, or gates. Reliance was placed in the strength and solidity of the walls themselves, which were 8 feet in thickness. But the desirability of having some points from which the enemy could be attacked in flank whilst battering the wall soon became evident, and in other cases such as Richborough, [ 35] Lymne, Pevensey, etc., we find that the fortress was furnished not only with massive walls, but also with strong angle-towers and bastions or towers at intervals by which the wall could be commanded and protected.

These various works furnish an interesting series of illustrations of the progress made in the military architecture of the period.

FIG. 7. RUTUPIAE (RICHBOROUGH)

FIG. 7. RUTUPIAE (RICHBOROUGH) Now known as Richborough, situated about two miles north-north-west of Sandwich, was a station of great importance in the Roman period, being then, as Sandwich was subsequently for many years, the chief British port for travellers and traffic to and from the Continent. In shape Rutupiae was a rectangular parallelogram, with the greater length from east to west. Its walls, which were lofty and massive, enclosed an area of somewhat less than 6 acres. At each angle is, or was, a circular bastion 18 feet 6 inches in diameter, and square towers or bastions at intervals[ 36] projected beyond the general face of the walls. A considerable part of the south-east corner, and the whole of the east wall have been destroyed by the falling of the cliff in the direction of the River Stour. The theory formerly propounded that the castrum had no eastern wall[ 37] has been disproved by the careful examinations of Mr. G. E. Fox and other eminent antiquaries. These examinations have definitely shown that large fragments of the east wall have fallen down the cliff. It is certain that the castrum of Rutupiae as also those of Regulbium and Portus Lemanis, in spite of the doubt which has been expressed in each instance, had four walls.

The chief peculiarity of Rutupiae is the presence of a solid mass of masonry underground, a little to the east rather than in the middle of the enclosed space. Many different theories have been put forward to account for its purpose, but it is now generally agreed that it was intended to serve as the foundation for a lofty structure, perhaps of timber, the purpose of which was for signalling between this station and that at Reculver, and possibly also answering to the pharos at Dover. It is not improbable that it also served as a lighthouse for ships entering the estuary of the Stour from the sea. If lights or signals could be seen as far as Dover they might from that[ 38] point be communicated easily to and fro from the coast of France from the high ground on which the pharos of Dover stands.

In order to understand the functions and relative positions of Regulbium and Rutupiae as coast fortresses during the Roman period, it is necessary to reconstruct the ancient geography of the north-eastern part of Kent. The small stream now falling into the sea near Reculver was at the period under consideration a river sufficiently broad and deep to afford a convenient channel for shipping. It was known as the Wantsum. Boats and ships voyaging from the French coast as well as from the British coast near Dover to London, usually took their course through the channel formed by the Stour and the Wantsum, thus avoiding the strong currents and tempestuous seas often raging off the North Foreland.

FIG. 8. RECULVER

FIG. 8. RECULVERIt will be seen, therefore, that a lofty tower or lighthouse at Rutupiae would have been of the greatest value both for the guidance of friendly shipping and as a means [ 41] of giving warning of the approach of the enemy.

The north wall of the castrum at Richborough is a remarkably perfect and interesting specimen of Roman masonry. It is noteworthy, too, as furnishing proof of the great care and thoroughness with which the Romans carried out their building works. At the base of the wall, on the outside, one sees four courses of flint in their natural form, and above them the following succession of materials, in ascending order: three courses of dressed flint; two courses of bonding tile; seven courses of ashlar and two of tile; seven courses of ashlar and two of tile; seven courses of ashlar and two of tile; seven courses of ashlar and two of tile; eight courses of ashlar and two of tile; nine courses of ashlar. The wall is 23 feet 2 inches high, and 10 feet 8 inches thick.

There is one aspect of some of the Roman coast fortresses which shows that their builders were not influenced entirely by utilitarian ideas. This is the methodical and tasteful use of[ 42] stones of different colours in such a way as to produce a pleasing species of colour decoration. The aim obviously was to break up the monotony of broad spaces of masonry, and possibly, also, to enhance their apparent size by multiplication of detail. The north wall of Richborough, although to some extent marred by rebuilding of some part of it, affords an illustration of this. Here we find dark brownish-red ironstone built into the wall in a way which reminds one of bands of chequer work. A Pevensey again, where the stones are cut with the regularity and precision of brickwork, large blocks of similar sandstone are employed in regular order at different heights in the walls and bastions. To the latter in addition to their decorative use they serve to tie in the outer skin of masonry to the inner rubble.

FIG. 9. RICHBOROUGH, KENT. EXTERIOR OF NORTH WALL

FIG. 9. RICHBOROUGH, KENT. EXTERIOR OF NORTH WALL A paper by Rev. Canon Puckle on Vestiges of Roman Dover was published some years ago in “Archaeologia Cantiana.”[8] It was [45] accompanied by a plan in which are set out the outlines of what are supposed to have been the limits of the Roman town or fortress of Dover. Although the outline is merely tentative and hypothetical, there is a certain plausibility about the suggested site and size of the castrum. It was situated, as is pointed out, quite away from the pharos, in the lowest part of the town, the present Market Square being approximately in the middle of the enclosure. The plan is roughly a parallelogram with certain irregularities on the north-west angle.

On the top of the eastern and western heights of Dover a lighthouse was erected by the Romans for the guidance of ships into the narrow mouth of the river. Traces of that on the western heights still remain, or remained recently: whilst that on the eastern heights stands intact, one of the most remarkable and interesting pieces of Roman architecture now remaining in the kingdom.

The Roman pharos at Dover consists of a strong and massive tower, hollow within,[46] which rises to a height of 42 feet, having walls whose thickness varies from 12 feet at the base to about 7 feet at the top. The structure is not entirely of Roman workmanship, because in the thirteenth century certain additions were made to its outer walls.

Doubtless its massive masonry was calculated to withstand the severe storms to which its exposed position on the lofty cliff subjected it. Whether employed for signalling purposes or as a lighthouse, this building was doubtless in such a position as to communicate with similar buildings on the coast of France, and with the lighthouse or signalling tower (it may have served in both capacities) at Richborough.

The pharos on the western heights of Dover, of which little now remains, must have formed an extremely valuable auxiliary to that on the eastern heights, affording a guide for ships making at night for the haven of Dover. It is not at all improbable that both structures combined the purposes of lighthouses at night with those of signalling stations in the daytime.

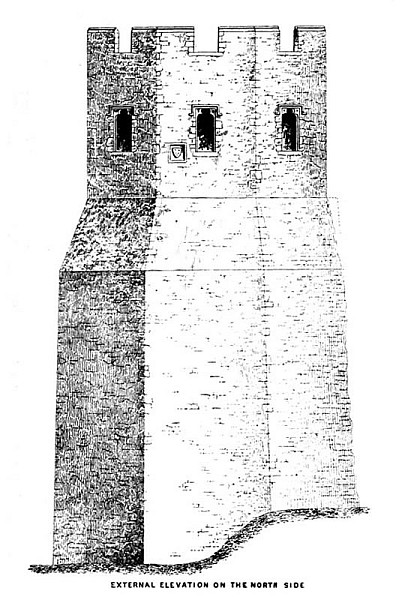

FIG. 10. PHAROS, DOVER

FIG. 10. PHAROS, DOVER The precise details of the existing pharos, although of the greatest interest from architectural and archaeological points of view, are not necessary to our present purpose, but a few facts are worthy of notice.

The masonry throughout is of tufa with the exception of two or three courses of Roman tiles at intervals of about 4 feet, and the foundations, which again consist of several courses of tiles arranged in three sets-off, and with an octagonal plan.

The tower is of octagonal plan externally, and square within, where each of the four walls measures about 14 feet. The structure is believed to have been repaired and cased with flint in the year 1259, when Richard de Codnore was Constable of Dover Castle. His arms, Barry of six, argent and azure, are carved in stone on the north side of the pharos. The octagonal chamber in the top story of the tower appears to have been restored or rebuilt in Tudor times.

It is interesting and instructive to compare the Dover lighthouses in their relation to the[ 50] French coast and Richborough, with the signalling tower or lighthouse of West Mersea, by means of which communications were kept up with the sea-coast station and castrum of Othona.

Bearing in mind the defensive character of the forts with which the lighthouses were associated, it seems probable that their purpose had a close relation to the work of watching the coast, and obtaining early information of the approach of invaders.

There is a strong probability that more of such buildings for observing the approach of enemies once existed, traces of which have now perished.

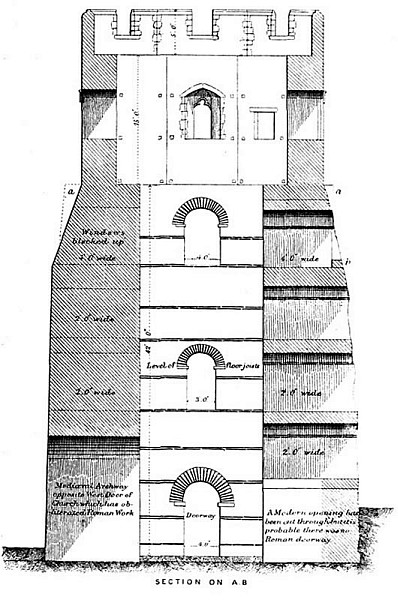

FIG. 11. PHAROS, DOVER

FIG. 11. PHAROS, DOVER Situated originally on the side of a spur of high ground at Lymne, near Hythe, and overlooking the flat ground of Romney Marsh, was a fortified station of sufficient importance to rank as a town. Its distance from Dover, and its situation on the south coast, suggest [ 53] that it cannot have formed a part of the group of contemporary fortresses which defended the east coast of Kent.

Owing to a landslip on a large scale, which happened possibly before the Norman Conquest, the whole of the site upon which this town stood slipped downwards towards Romney Marsh, and the massive walls and towers by which it was once encompassed were disturbed, shattered, and overturned.

The form, as far as can be gathered from the disturbed foundations, was somewhat irregular. The east and west walls were parallel, and the south wall ran at right angles with them, but the north wall had an outward bow-like projection. The walls, when the place was intact, enclosed a space of about 11 acres, and were from 12 feet to 14 feet thick, whilst the height of both walls and mural towers was somewhat more than 20 feet.

The purpose of placing a strongly fortified town at this place was partly in order to command a view over the surrounding country, and partly to defend the Roman port which[ 54] was situated on a branch of the River Limene,[9] or rather, just at the foot of the hill on the side of which it stood.

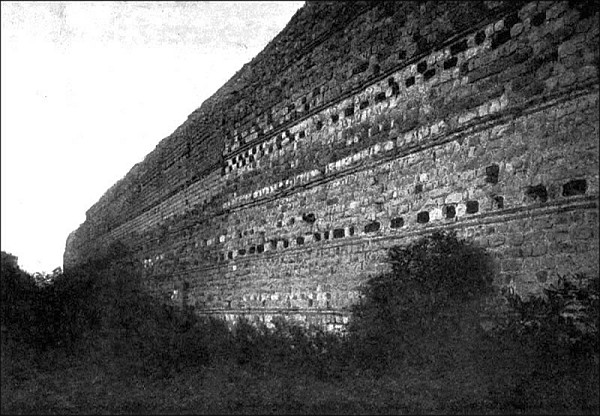

FIG. 12. ROMAN WALLS, LYMNE, KENT

FIG. 12. ROMAN WALLS, LYMNE, KENT Among the discoveries made at Portus Lemanis there were two of remarkable and significant character. The first consisted of a mutilated altar-stone, bearing a much-worn inscription indicating the dedication of the altar by a praefect of the British fleet, named Aufidius Pantera, probably to Neptune. The stone [ 57] was found built into the masonry of the principal gate, and from its worn condition, and the remains of barnacles which it still bore when found, it was justly inferred that it belonged to an earlier period than that of the building of the gate. The second discovery, of quite equal interest with the first, was that of a number of broken roof and other tiles, inscribed CLBR, which has been read Classiarii Britannici, Marines of the British fleet.

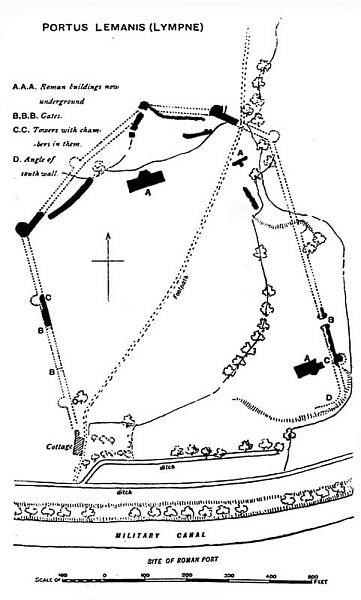

FIG. 13. PORTUS LEMANIS (LYMPNE)

FIG. 13. PORTUS LEMANIS (LYMPNE) From these discoveries one may gather that at some period, probably before that of Constantine, a division of the British fleet was situated at Portus Lemanis, and that some of the buildings there were erected by the crew from the fleet.

The principal gate, which may have been battered down during a siege, and required rebuilding, was evidently the work of a late date in the Roman period. This view is supported by a comparison of the whole building with the work at Anderida (Pevensey). The general arrangement of the walls, the disposition of the mural towers, or bastions, and the facing[ 58] of regularly cut limestone blocks present points of very considerable similarity.

It will be observed from a comparison of Portus Lemanis with Anderida (about to be described) that there is reason to think that both works belong to a date somewhat late in the Roman period.

The castrum at Pevensey retains so much of its enclosing walls and bastions that it is particularly worthy of study if one would learn, by direct observation, what splendid specimens of architecture the Romans erected in this country. Although a mediaeval castle has been built within the boundary of the Roman castrum, the walls of the latter may be traced for almost the whole of the circuit, and on the north, east, and west sides they stand to a considerable height. At the south-western extremity is the main gateway, its two flanking towers forming perhaps the most prominent features. Proceeding to the north of this gate [ 61] we find three good specimens of bastions of somewhat horse-shoe form on plan. A series of six similarly planned bastions remain at the opposite side of the fortress, the general plan of which may be said to be elliptical.

FIG. 14. BASTION ON SOUTH-WESTERN WALL, PEVENSEY

FIG. 14. BASTION ON SOUTH-WESTERN WALL, PEVENSEY The character of the facing masonry, especially on the south-west side, is quite remarkable. The facing consists of carefully squared blocks of limestone laid with the regularity and precision of brickwork.

Two characteristics stand out prominently in comparing this with other Roman castra on the coast of Britain. One is the irregularity of plan, the other is the presence of numerous projecting bastions. Both point to the lateness of the work, and some valuable evidence, confirming this view, has been brought to light in recent years. In 1907 Mr. Charles Dawson, F.S.A., communicated to the Society of Antiquaries[10] some notes on tiles found here bearing the stamp

HON AUG

ANDRIA

The first line apparently refers to the Emperor Honorius (395-423), whilst the second may be regarded as indicating with somewhat less certainty the name Anderida.

This remarkably fine castrum, which stands on the edge of the most northern creek forming a part of Portsmouth Harbour, consists of a square enclosure containing a space of about 9 acres. Its walls, 10 feet in thickness, are constructed of flint rubble with courses of bonding-tiles. Originally each angle was furnished with a hollow bastion, or tower, and similar bastions, hollow within, were placed along the walls at intervals of from 100 feet to 200 feet. Some of these bastions have been destroyed, but fourteen examples, in a more or less perfect condition, remain. The water-gate, on the eastern side, still survives in a peculiarly perfect state. It is remarkable from the fact that the blocks of stone forming its semicircular arch are of light and dark colour,[ 63] and are arranged alternately, so as to impart a picturesque and decorative effect.

FIG. 15. PLAN OF

PORCHESTER ROMAN CASTRUM

FIG. 15. PLAN OF

PORCHESTER ROMAN CASTRUM The identification of Porchester with the Portus Magnus of the Romans has been questioned by Professor Haverfield, and there can be no doubt that it rests upon insufficient evidence. Conceivably it may be the Portus[64] Adurni of the Romans: but this is not certain.

A Norman castle, with remarkably fine keep, still practically intact, was built in the north-west corner, and the parish church, also of Norman architecture, was constructed near the south-east angle, within the walls of the castrum.

Clausentum, an important Roman station, now known as Bitterne, is situated a little to the north of Southampton, on the banks of the tidal estuary of the River Itchen. Practically nothing in the shape of architectural traces now remain, but from accounts written before their complete destruction we know that it was enclosed with walls 9 feet thick, and constructed of flint bonded with large flat tiles and roughly faced with small square stones. It has been supposed that the outer defences when perfect measured 500 yards in length. The station was three-sided, the walls each having an outward curve. The outer defences are believed to have enclosed an area of 20 acres: the inner defences, 10 acres.

FIG. 16. THE WATER-GATE, PORCHESTER

FIG. 16. THE WATER-GATE, PORCHESTER Cardiff.—Although not situated near the Continent, it is probable that Cardiff took its part in the defence of our coast during the Roman period. Whether the Roman fortress at this point formed part of the defences which were placed under the control of the Count of the Saxon Shore may be doubted, but in size and general plan it certainly resembled the coast fortresses of the south-eastern shores.

FIG. 17. PORCHESTER. EXTERIOR OF WEST WALL

FIG. 17. PORCHESTER. EXTERIOR OF WEST WALL In the course of recent excavations in and near Cardiff Castle the nearly complete ground-plan of this castrum was found. Its form was nearly quadrangular, the only irregularity being in the western wall, which was inclined eastward at its southern end. Gates were situated about the middle of the northern and southern walls, whilst semicircular bastions were placed along the walls at intervals, roughly, of about 120 feet. At the angles were built towers of irregular form and of somewhat unusual interest, from the fact that they were obviously additions to the original work. The area enclosed by the walls was roughly a square of 600 feet.

The question of angle towers or bastions is one of considerable importance. Their presence in a Roman castrum may generally be taken as evidence of late date; but it is necessary to bear in mind that in some cases they have certainly been added to give strength to fortresses of early type, which, as we have seen in the cases of Reculver and Brancaster, were furnished with rounded angles, without[ 69] any such projecting features as angle-towers or bastions. At Cardiff[11] it is perfectly clear that the original building had rounded angles against which towers of irregularly circular plan were subsequently built.

As at Pevensey and Porchester, a Norman castle was ingeniously constructed within this castrum by placing the mound towards the north-western corner. Two walls thrown out from this, one towards the western wall and the other to about the middle of the southern wall, enclosed practically a quarter of the whole area in the south-western angle, and formed the inner court, whilst the whole of the rest of the area of the castrum formed the outer court. It is obvious that at the period when this Norman castle was built the Roman walls were sufficiently perfect to afford an effective barrier of defence.

The coast to the north of Brancaster, the most northern of the nine regular Roman coast castra, is provided in certain places with defences of Roman date, either in the form of watch-houses, or lighthouses, or fortresses.

Professor Haverfield, in a recent lecture on the subject,[12] suggests that such structures once existed at (1) Huntcliffe (near Saltburn); (2) at a point near Staithes; (3) on the high promontory of Peak, near Robin Hood Bay; and (4) on another high headland, called Carrnase, to the north of Filey Bay. Generally speaking, the altitude of the sites of these works suggests their use for watching or lighting purposes rather than for purely military defence.

To a certain extent the Roman walled towns of Canterbury, Rochester, Chichester, Colchester, and London, must be regarded as[ 71] having exercised a share in the coast defence of England, because they were situated on rivers now or formerly navigable, and not too far from the sea-coast to be absolutely without value in repelling invaders.

The fact that they were constructed specially for defensive purposes, not only against near neighbours, but also against those unwelcome visitors who, from the remote past, and all through the middle ages, have been attracted by the wealth of England, brings them within the scope of the present essay. For obvious reasons, however, and mainly because of the question of space, it is unnecessary to describe in detail every defensive work which was partially available for English coast defence.

| THE SAXON SETTLEMENT OF ENGLAND |

| DANISH INCURSIONS AND CAMPS |

| THE NORMAN INVASION OF ENGLAND |

| NORMAN COAST CASTLES |

With the settlement of the Saxons, the Angles, and the Jutes in England, this book has no immediate concern, but it is worthy of note that having driven the British people westward into Wales and south-westward into Cornwall, they quickly spread over the greater part of England. Their weapons, their costumes, their jewellery, and, indeed, their general standard of civilization, are clearly reflected and illustrated by the contents of numerous cemeteries, which have been scientifically explored and examined. We know little of their houses or other buildings until the eleventh century, when we are aided by the actual remains of churches, the evidence of illuminated manuscripts and the “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.”

There is, however, one fact which stands[ 76] out quite clearly in an age which is remarkable for the obscurity of its historical evidence. This is that the Saxons, as a general rule, did not immediately occupy the ruins of Romano-British towns or houses. On the contrary, they seem to have avoided them, even to the extent of diverting the roads which originally passed through the towns. This is so marked that we can only infer that it was due to a superstitious dread of sites which had once been inhabited by the Romans. The site of the important Romano-British town of Silchester, although full of evidences of Roman occupation, and of intercourse with contemporary British population, has furnished absolutely no trace of Saxon habitation.

What was true of cities and towns and houses, was probably true of the coast fortresses upon which the Romans, particularly in the latter part of their occupation of Britain, had expended so much time and labour.

It is extremely doubtful whether the Saxons ever garrisoned the coast fortresses abandoned when the Roman legions were withdrawn from[ 77] Britain. Numismatic evidence shows that there was an Anglo-Saxon mint at Lymne, the Portus Lemanus of the Romans, and possessing an important harbour. The coins minted there range from King Edgar’s time to that of Edward the Confessor, but there is reason to believe that the Roman site was deserted at an early period in the Saxon occupation, the neighbouring town of Hythe taking its place. Certain Saxon coins bearing the legend RIC, have been attributed to a mint at Richborough, but there is a good deal of doubt as to this identification. Coins of middle and late Saxon kings, as we might have expected, were minted at Canterbury, Rochester, Sandwich, and Dover, but generally speaking the evidence of Saxon coinage does not support the view that the purely coast fortresses of the Romans were ever used to any great extent by the Saxons.

The Saxons built burhs, or towns fortified with earthen ramparts, probably palisaded, in many parts of the kingdom, and the evidence for them will be found in the “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,” but they were not castle-builders.[ 78] They were a people with tribal instincts and traditions. They did not construct defensive dwellings for a single lord and his family and retainers; they expended their efforts rather on fortified towns for the protection of all their people.

Wareham, in Dorset, is generally believed to be an example of the fortified towns of the Anglo-Saxons. Sandwich, again, which retains considerable traces of mediaeval earthern ramparts, and was a port of great consequence in early times, was also probably fortified by the Anglo-Saxons. It is impossible to say whether any part of its earthwork defences are of that early period. Dover, Canterbury, Rochester, Chichester, Colchester, and some other walled towns of Roman origin, appear, from archaeological evidence, to have had Anglo-Saxon populations, possibly of late date, when the Roman houses had disappeared and the dread of the Romans had become forgotten. It may be doubted whether the Saxons took advantage of the Roman walled defences.

As we have already pointed out, there are very few remains of purely defensive works belonging to the Anglo-Saxon period. For this reason the quadrangular moated site at Bayford, near Sittingbourne, in Kent, is of peculiar interest, because as Mr. Harold Sands, F.S.A.,[13] has pointed out, the “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle” mentions that King Alfred here threw up a “geweorc” in 893 in order to repel the inroads of the Danes under Bjorn-laernside, who had formed an encampment at a place called Milton, in Kemsley Downs on the opposite side of Milton Creek, a mile and a half north of Bayford Castle.

The incursions of the Danes and other raiders provided the Saxons with excellent opportunities for displaying their skill in defensive warfare, and brought into prominence a great man whose name must ever be held in honour as one of the bravest and most enlightened defenders of our shores. To King Alfred, commonly known in recent years as Alfred the Great, belongs the credit of having[ 80] conceived the idea of destroying the enemy’s power at sea in order to secure the safety of our shores. He seems to have been the first man in our history to have grasped this great principle. He led this navy to action in person and so acquired the epithet of “the first English admiral.”

Early in his reign, King Alfred devoted his attention to the important question of his navy, and he brought it to such a condition of strength and proficiency as to defeat the Danish raiders, one of the greatest pests by which our shores were ever troubled.

The coast-line of England is of curious complexity, and is long out of all proportion to that of any other great European nation, perhaps not even excepting Norway. Consequently its defence presents and always has presented problems of great difficulty. Much of the coast-line is rocky and dangerous even[ 81] for friendly shipping. In other places, where cliffs are absent, shoals and sand-banks make navigation and landing difficult and dangerous. In looking back to the days when there were no artificial harbours and landing-places, one sees quite clearly that estuaries of rivers would have afforded the safest and most convenient places for landing. That such spots were selected is abundantly proved by tradition, history, and actual contemporary remains.

The Danes were quick to seize upon such favourable landing-places. They were provided with boats of great length and slight draught, and their operations were not limited, therefore, to the deeper rivers. During the latter years of the eighth century, and practically throughout the tenth, the Danish raids on Britain were numerous. In due course they established themselves on river-banks, and built permanent camps. According to the “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,” Hasting constructed and occupied a camp at Shoebury for a short period in the year 894. The camp,[ 82] or such part of it as now exists, has been described by Mr. Spurrell[14] as a Danish work. The place has been much destroyed by the inroads of the sea and the building of various military works, such as barracks, etc., but the plan can be made out, and as restored by Mr. Spurrell, may be described as an irregular quadrangle with rounded corners, and containing an area of about one third part of a square mile.

Another Danish camp was constructed the same year at Appledore, the Danes sailing or rowing up the river Rother. According to Somner[15] they discovered at Appledore a half-built fortress, but finding it insufficient for their needs they built a larger entrenchment on the same site.

FIG. 18. PLAN OF DANISH CAMP, SHOEBURY, ESSEX

FIG. 18. PLAN OF DANISH CAMP, SHOEBURY, ESSEX Other places where the Danes settled were Benfleet, probably Swanscombe (although the existing remains of the camp belong probably to the Norman period); Bramber, Sussex; an earthwork surrounding East Mersea Church,[ 83] Essex; and many other places. Here they constructed their camps and established their forces for long periods, using the adjacent rivers as channels for quickly putting to sea in their swiftly-moving boats when embarking[ 84] on raiding excursions to the neighbouring coasts.

They raided Sheppey in 832, Kent, Canterbury and London in 851. In 876 they took Wareham, where are interesting earthen town-walls, perhaps of Saxon origin. During one or more of their raids in the Medway they penetrated as far as Rochester, which they pillaged. Sandwich and Canterbury suffered much from their visits in the eleventh century.

It may be noted that the favourite methods of the Danes when invading England was to enter the rivers so as to reach by that means populous towns and districts where they could seize valuable possessions. The monastic houses were their favourite prey, and few in England escaped injury or pillage at their hands.

The following extract from the “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle” gives a vivid picture of the doings of the Danes at the end of the tenth century:

“A.D. 999. In this year the army again came about into the Thames, and then went[ 85] up along the Medway, and to Rochester. And then the Kentish force came against them, and they stoutly engaged together, but alas! that they too quickly gave way and fled; because they had not the support which they should have had. And the Danish had possession of the place of carnage; and then took horses and rode whithersoever they themselves would, and ruined and plundered almost all the West Kentish. Then the king with his ‘witan’ resolved that they should be opposed with a naval force, and also with a land force. But when the ships were ready, then they delayed from day to day, and harassed the poor people who lay in the ships; and ever as it should be forwarder, so was it later, from one time to another: and ever they let their foes’ army increase, and ever they receded from the sea, and ever they went forth after them. And then in the end neither the naval force nor the land force was productive of anything but the people’s distress, and a waste of money, and the emboldening of their foes.”

It is a remarkable fact that the greatest event in the whole history of foreign attack upon England, namely, the invasion under the leadership of William, Duke of Normandy, in 1066, excited less interest, and provoked less effective opposition than many other incidents of infinitely minor importance.

The invasion was not unexpected by any means. When tidings of the projected invasion reached England, the largest fleet and army ever seen in this country were being mobilized at Sandwich. Yet, when the Norman invaders actually arrived the English made practically no opposition at all. It appears that the crews of the navy were tired of being under arms so long, and went home; whilst the king was bound to go northward to put down the troubles in Yorkshire. Nothing was ready.

The Norman fleet consisted, according to various accounts, of from 696 to 1,000 vessels. It can hardly be described as a navy, because the ships were too small to carry much more than the men and their arms: there was no room for provisions, and when on the 28 September 1066, the invaders landed in Pevensey Bay they encountered no opposition. In the Battle of Hastings the English forces were protected within palisaded entrenchments, but the result of the conflict was a decisive defeat.

The Normans having secured a foot-hold in the country, commenced at once to make their tenure secure, and to establish their power. This they accomplished with wonderful skill and success.

The castles first built in England by the Normans consisted of palisaded earthworks, the main feature being a lofty but truncated mound encircled by a deep ditch, and closely[ 88] related to it were generally two courts or baileys. They were built in such situations as would command rivers and important roads, and so dominate the English people. Usually the castles of this period were built just within the boundaries of walled towns. The relation of the Tower to the City of London affords an excellent example of this arrangement.

Primarily the purpose of the Norman castle was to complete the work begun at the Battle of Hastings of subjugating the native population of England, and it is believed that castles of this type were employed for this purpose, because of the ease and rapidity with which they could be thrown up. Castles of this type were erected in England, not only after the Norman Conquest but also before it, and at one time the idea was generally held that they represented the usual and normal species of defence employed in Saxon times. The late G. T. Clark, who was a pioneer in the scientific study of English and Welsh castles, considered that these works were the actual burhs of the Anglo-Saxons, so often mentioned in[89] the “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.” The theory was generally accepted for some years, but in due course doubts were cast upon it by the researches of Dr. J. Horace Round, Mrs. E. S. Armitage and others. It is now generally held that those examples of this type of defence which are known to have been constructed before the Conquest were built under the influence of Edward the Confessor’s Norman friends. England at that time was following the fashions of Normandy; but the great majority of defences of this type were built, probably, very soon after the Norman Conquest, and under the direct influence of the Norman Conquerors. It is worthy of note that numerous examples exist to this day in Normandy, and some, with the characteristic palisaded mound, are represented in the Bayeux tapestry.

In many cases the earthwork castles as first built were, in due course, rebuilt in stone, the top of the mound being capped by a shell-keep and the other eminences being surmounted and reinforced by walls. Another type of keep,[ 90] generally square in plan and of great strength and size, was built, as at Dover, Rochester, Canterbury, London, etc.; but such massive structures required firm foundations, and they were always built on undisturbed sites. These two kinds of keeps practically determine the two types into which the Norman castles built in England naturally fall.

A fairly large proportion of those Norman castles which may be considered to have been built for coast defence, have been constructed in such a way as to take advantage of pre-existing Roman castra. Porchester is an admirable specimen. Here the north-western portion of the Roman enclosure has been cut off by Norman walls so as to form the inner bailey, whilst the remainder has been converted into the outer bailey. Pevensey, London, Rochester, Colchester, Cardiff and Lancaster are other excellent examples.

In passing, it may be noted, that at Reculver and Porchester, the parish church has been built, doubtless for safety, within the walls of the castrum; whilst at Pevensey two parish[ 91] churches have been erected sufficiently near the castrum to suggest that the sites were selected with a view to securing protection.

The regular castles of masonry erected during the reign of Henry II, a great castle-building period, although very important as military works, were not in the main built for the defence of the coast. But it is necessary to bear in mind that in ancient times river-courses, even far from the sea-coast, were subject in a peculiar degree to the incursions of the enemy, and the great Norman keeps of Canterbury, Rochester, and the White Tower of London, although situated far from the sea-coast, played an important part in the defence of the coast. At Porchester, Pevensey, Hastings, Folkestone and Dover, the relation between the Norman castles and the coast defences was much more intimate.

| MEDIAEVAL CASTLES AND WALLED TOWNS ON THE COAST |

In the following account of the more important of the castles which in mediaeval times guarded the coast, it has been found convenient to include a notice of those walled towns with which, in many cases, they were closely associated. The mediaeval castle, generally speaking, represents an effort to maintain the power of the feudal lord, and, in a lesser and secondary degree, provision for resisting raids and invasion by foreign enemies. Walled towns, on the other hand, when situated on or near the coasts, or on navigable rivers, were primarily designed for coast defence. The mediaeval castles which were built in situations remote from the coast were the fastnesses and strongholds of nobles fighting amongst themselves or against the king.

In the following accounts of the more important examples of castles and walled towns[ 96] wholly or partially designed for the defence of the coast, occasion will be taken to point out the interesting series of developments through which these mediaeval fortifications passed as time went on. For example:

The massive keep of the Norman castles was able to resist fire and battering-ram when the besieging force came near enough to apply them. Its strength consisted in its thick walls, its height, and its massive masonry. The Edwardian castle, on the other hand, presents certain structural improvements which mark a great advance in military construction. The walls, gates, and towers are so built as to present curved surfaces to the engines of the enemy, with the result that missiles hurled against them would glance off at various angles according to the direction of the curve at the point of impact. The extent to which this development of the curve is carried in the walls of many of the Edwardian castles is quite remarkable and instructive. It shows that mere weight and bulk were no longer relied upon, but constructive skill and the judicious[ 97] use of materials were guiding principles in the military architecture of the period.

The following list does not include the sixteenth century blockhouses and other fortifications erected by Henry VIII, and in subsequent years.

The defences on the eastern coast of England consist of an extremely interesting and important series of fortresses. In the extreme north is—

Berwick-upon-Tweed, a town which, from its position on the English and Scottish border, has always been a place of strategic moment, and which Queen Elizabeth spoke of as “the chief key of the realm.” In the time of Edward I (1272-1307) it was encompassed by a great moat, or ditch, 80 feet wide and 40 feet deep. A crenelated wall from 15 to 22 feet high, with 19 towers at intervals, was constructed during the reign of Edward II (1307-1327). A castle had been erected at Berwick during the reign of Henry II, and together with the Edwardian wall and ditch must have formed an extremely formidable defence.

The mediaeval fortifications included a large area, and in the time of Elizabeth a portion within this area was enclosed and strengthened by works of more modern character, the main features of which comprised five examples of the orillon type of bastion. The orillon was an enclosure of flattened triangular form, projecting beyond the curtain. The middle angle was obtuse, and the passage from the opening in the curtain into the bastion was somewhat restricted. It is obvious that such a bastion as this, which was introduced into England in the latter half of the sixteenth century, would give the maximum range for defensive fire, whilst affording most valuable means of protecting the flanks.

The fortifications of Berwick-upon-Tweed were primarily intended for defence against the Scottish Border raiders and incursions coming overland, but they also served to protect the town against the enemy approaching by sea.

Bamborough.—The site of this castle must have been a place of great natural strength, and probably a fortress, from prehistoric times[99] downwards. It would not be inaccurate to describe it as one of the important and historic spots in the kingdom. The castle dates from a period before the Norman Conquest. Here the Danish raiders were successfully repelled in 912. The castle was maintained in a good state of defence under Henry I, and the keep is of the twelfth century. Structural repairs were made at frequent intervals, viz., in 1183, 1197, 1198, 1201, and 1202. A new gate-house was built here in consequence of the invasions of the Scots in 1383-4.

On several occasions Bamborough Castle has served as a prison, and it was brought into considerable prominence during the Wars of the Roses. The part it played in the various wars between England and Scotland must have been important.[16]

Dunstanburgh.—Situated on a bold, rugged headland, this fine castle reminds one of such great fortresses on the east coast as Scarborough and Tynemouth. Its share in the Border troubles was perhaps less than that of[100] Bamborough. Dunstanburgh is the largest castle in Northumberland, is built on a remarkable plan, and comprises an area of ten acres, the main part of which was occupied by the outer bailey. Its history is associated with Simon de Montfort and Thomas of Lancaster.

The castle was mainly erected in 1313-14. The great gate-house of the latter part of the fourteenth century, was planned and built on a colossal scale, and still forms a striking object, even in its ruin. By the sixteenth century the place had fallen into ruin.[17]

Warkworth.—This castle, remarkable for its eccentric plan, was built about the middle of the twelfth century.

Tynemouth.—The priory and castle of Tynemouth (for it was a combination of both) occupied a prominent position among the mediaeval coast defences of England. The office of Prior of Tynemouth was one of great importance. The person who held it was possessed of vast spiritual and worldly influence. He maintained his own armed force, just as the[ 101] Bishop of Durham did, and the gate-house[18] of the priory was in reality a military fortress, a building of great solidity and strength. It was approached by a barbican, the passage-way being vaulted and furnished with a gate at each end.[19]

Scarborough.—This place was defended by walls or earthworks and a fosse before the time of Henry III. Its castle was built as early as the time of Stephen, and rebuilt or enlarged in the reign of Henry II. During the Civil War Scarborough Castle was besieged. It was surrendered in 1645, and has long been in ruins. It enclosed nineteen acres of land and occupied a romantic site 300 feet above sea-level.

Hull.—From an early period this seaport has been defended by fortifications. In the seventeenth century these comprised a moat and a complete system of walls, fortified gates, and drawbridges. It possessed five gates,[ 102] called Hessle Gate, Myton Gate, Beverley Gate, Low Gate, and North Gate, and two sally-ports. The whole fortified walls were 2,610 yards, or slightly less than one-and-a-half miles in circuit. In front of the principal gates were drawbridges and half-moon shaped batteries. In the year 1540 the eastern side of the town was defended by two blockhouses, erected by Henry VIII. These were known as the North Blockhouse and the South Blockhouse, and both mounted guns when the town was besieged during the Civil War. A castle was also built on the eastern side of the town by Henry VIII.

King’s Lynn.—The eastern side of this important town was in former times defended by a wall strengthened by nine bastions, and by a broad and deep fosse over which were three drawbridges leading to the principal gates. One of the latter and fragments of the wall remain. From the statement of Stow in his “Chronicle,” and from certain illustrations of the walls as they existed in 1800, we may infer that the walls at any rate belonged to the first[ 103] half of the thirteenth century. The East Gate and the West Gate were rebuilt on the sites of earlier gates in the fifteenth century.

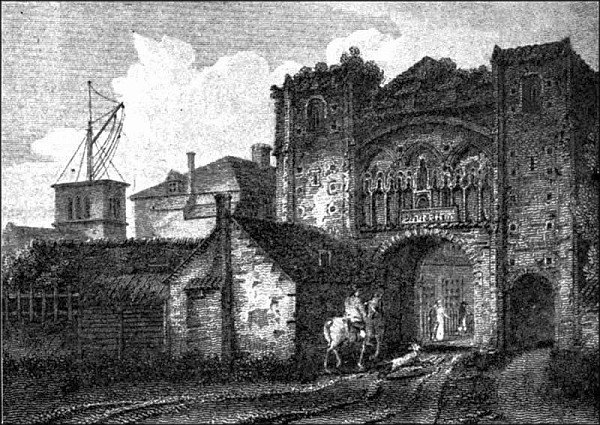

FIG. 19. NORTH GATE, YARMOUTH, 1807

FIG. 19. NORTH GATE, YARMOUTH, 1807 Yarmouth.—The town-wall, of which some traces remain, measured between six and seven thousand feet in compass, and possessed ten gates and sixteen towers. Swinden,[20] the historian of Yarmouth, states that the building of the wall

“was begun on the east side, and very probably at the north-east tower in St. Nicholas’s churchyard, and so proceeded southward: for in the 11th of Edward III we find them at work at the Black Friars, at the south end of the town; and afterwards we trace them to the north end, which, I presume, was the last part that was finished.

“And there is a tradition, that the north gate was built by the person or persons who had amassed considerable sums of money by being employed in burying the dead in the time of the plague.

“As soon as the walls were finished, there[ 104] was made a moat or ditch round the town, with bridges at each gate: the whole so complete that boats could pass with their lading to any part of the town, for the conveniency of trade and commerce. And so careful were the magistrates to preserve the said moat from being filled or stopped with earth, rubbish, stones, etc., that in the rolls of the leets, there appear several fines, levied on different persons for offending in that behalf. Thus the tower[ 105] being fortified with a wall and moat, towers, gates, and bars, was deemed a sufficient defence against all assailants with bows and arrows, slings, battering-rams, and all other missive engines of those times. But afterwards, when great guns of various denominations were employed in sieges, the aforesaid fortification, it was adjudged, would make but little resistance against them, without several additional works, as mounts, ravelins, etc.”

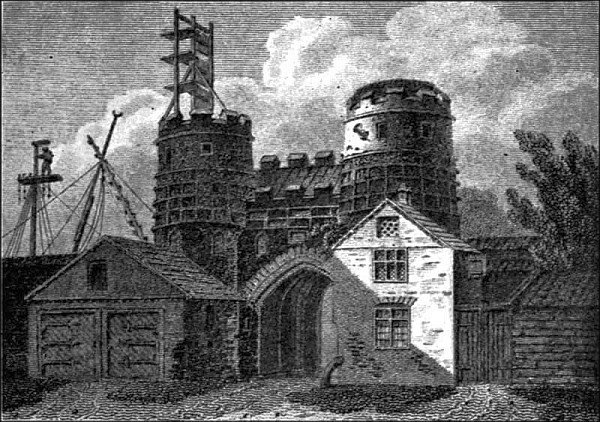

FIG. 20. SOUTH GATE, YARMOUTH, 1807

FIG. 20. SOUTH GATE, YARMOUTH, 1807 In the 36th year of Henry VIII the fortifications of Yarmouth were strengthened by rampiring, or backing up the walls by earthwork mounds. Additional works were constructed by Queen Mary in 1557, and by Queen Elizabeth, the complete process of rampiring not having been finished until 1587, the year before the coming of the Spanish armada. In the following year it was considered desirable to secure the haven against any sudden attacks of the enemy, and it was accordingly decided to construct jetties of timber on either side of the entrance, whilst across the actual entrance was placed a boom of massive timbers furnished with iron spikes, and this was so constructed that it could be opened or closed at pleasure. This work, including probably the two jetties and the boom, cost £120.

Traces of the wall of Yarmouth and its towers still remain, whilst other evidence of the wall is the extraordinary way in which the houses are crowded together, leaving only narrow alleys, or “rows,” for the traffic. A plan of Yarmouth in 1819, published as a frontispiece[ 107] to John Preston’s “Picture of Yarmouth,” shows in an admirable way the congested state of the buildings within the walls.

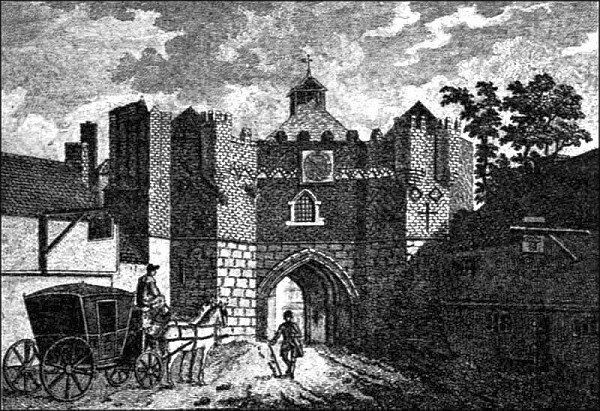

FIG. 21. ST. MATTHEW’S GATE, IPSWICH

FIG. 21. ST. MATTHEW’S GATE, IPSWICHIpswich.—There is a tradition that Ipswich was defended by a wall and fortified gates soon after the time of the Norman Conquest, but unfortunately no traces of either remain. Westgate Street preserves the memory of the picturesque West Gate. The interesting old[ 108] engraving shows St. Matthew’s Gate, now demolished. There appears to have been a castle at Ipswich built by William the Conqueror, and Roger Bigot, one of the Conqueror’s powerful nobles, held it. With the exception of certain earthworks all traces of the castle have perished. The form of the town in mediaeval times has been made out by John Wodderspoon in his “Memorials of Ipswich,” 1850.

Orford.—This castle, situated half a mile from the River Ore, in Suffolk (hence its name), commands a view of the sea, two miles distant, owing to the fact that it is built on a mound partly natural and partly artificial. All round is swampy ground.

FIG. 22. ORFORD CASTLE, SUFFOLK, 1810

FIG. 22. ORFORD CASTLE, SUFFOLK, 1810 The building of Orford Castle was begun in 1166. Strictly speaking, perhaps, it should not be called a castle: it was essentially a keep, and its purpose primarily was to serve as an outpost for observation and for the protection of the coast. The plan of the actual keep, if so we may term it, was peculiar, being circular within, and so much modified by the buttresses [111] without as to present the appearance of a large number of angles.