Title: Lochinvar: A Novel

Author: S. R. Crockett

Illustrator: Thure de Thulstrup

Release date: April 26, 2014 [eBook #45495]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by sp1nd, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

[Page 306

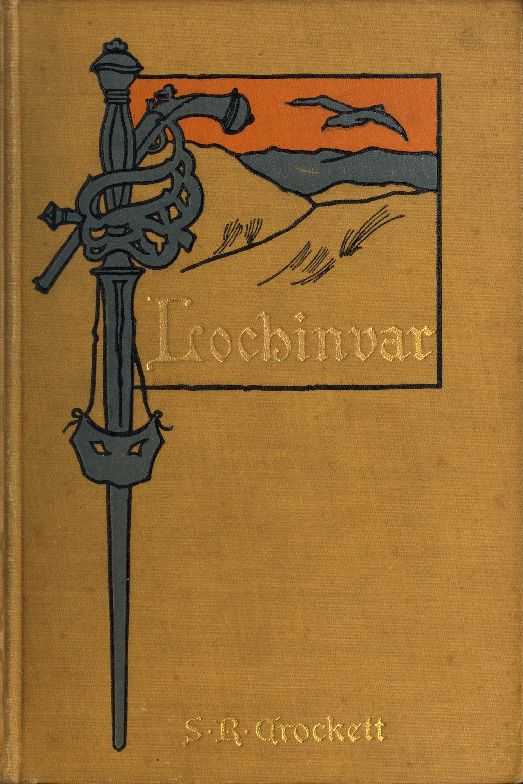

"WAT'S HAND MOSTLY ON HIS SWEETHEART'S SHOULDER"

A Novel

BY

S. R. CROCKETT

AUTHOR OF "THE GRAY MAN" ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

BY T. DE THULSTRUP

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

1898

By S. R. CROCKETT.

THE GRAY MAN. A Novel. Illustrated. Post 8vo,

Cloth, Ornamental, $1 50.

HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS,

NEW YORK AND LONDON.

Copyright, 1897, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Foreword to the Tale | 1 | |

| I. | From Liking to Love | 18 |

| II. | Why Kate Hated Lochinvar | 29 |

| III. | The Bull, the Calf, and the Killer | 38 |

| IV. | The Duel at the Inn of Brederode | 46 |

| V. | Haxo the Bull Interferes | 58 |

| VI. | The Prince of Orange | 68 |

| VII. | Mistress Maisie Lennox, Diplomatist | 74 |

| VIII. | The Street of the Butchery | 83 |

| IX. | My Lord of Barra | 90 |

| X. | The Descent of Avernus | 100 |

| XI. | The Hearts of Women | 114 |

| XII. | The Prison of Amersfort | 120 |

| XIII. | My Lord of Barra's Vow | 126 |

| XIV. | Maisie's Night Quest | 133 |

| XV. | A Night of Storm | 140 |

| XVI. | The Breaking of the Prison | 146 |

| XVII. | Jack Scarlett Calls Himself a Fool | 155 |

| XVIII. | A Perilous Meeting | 164 |

| XIX. | The Battle of the Dunes | 172 |

| XX. | Captain, My Captain | 179 |

| XXI. | The Good Ship Sea Unicorn | 187 |

| XXII. | Wise Jan Pettigrew | 192 |

| XXIII. | Wise Jan Waxes Wiser | 200 |

| XXIV. | Madcap Mehitabel | 206 |

| XXV. | True Love and Pignuts | 212 |

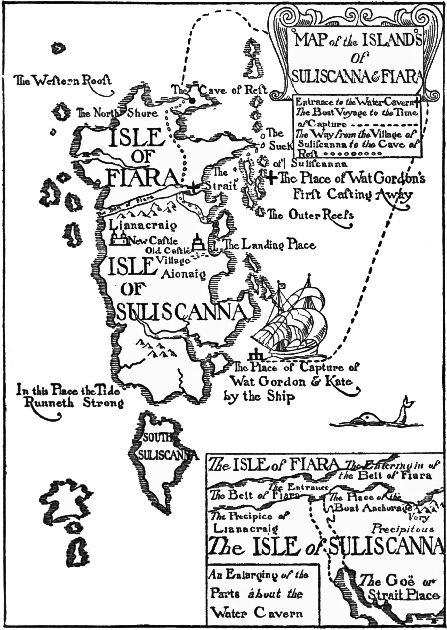

| XXVI. | A Boat in Sight at Suliscanna | 219 |

| XXVII. | The Tide-race of Suliscanna | 223 |

| XXVIII. | John Scarlett Comes Ashore | 230 |

| XXIX. | Wat's Isle of Refuge | 236 |

| XXX. | Wat Swims the Water Cavern | 243 |

| XXXI. | Bess Landsborough's Catechism | 249 |

| XXXII. | The Surrender of the Beloved | 256iv |

| XXXIII. | An Ancient Love Affair | 262 |

| XXXIV. | Captor and Captive | 270 |

| XXXV. | Skirting the Breakers | 279 |

| XXXVI. | Passage Perilous | 286 |

| XXXVII. | The Isle of Bliss | 292 |

| XXXVIII. | Misfortunate Colin | 302 |

| XXXIX. | Satan Spies out Paradise | 311 |

| XL. | Serpent's Eggs | 318 |

| XLI. | Love that Thinketh no Evil | 324 |

| XLII. | The Fiery Cross | 331 |

| XLIII. | Coll o' the Cows | 336 |

| XLIV. | Great Dundee | 343 |

| XLV. | Killiekrankie | 350 |

| XLVI. | The Leaguer of Dunkeld | 359 |

| XLVII. | The Golden Heart | 365 |

| XLVIII. | The Master Comes Home | 373 |

| XLIX. | The Curate of Dalry | 380 |

| L. | Lochinvar Keeps Tryst | 386 |

| LI. | The Bride's Loving-cup | 391 |

| LII. | Catch Them Who Can! | 397 |

| LIII. | Within the King's Mercy | 402 |

| Epilogue of Supererogation | 408 |

| "WAT'S HAND MOSTLY ON HIS SWEETHEART'S SHOULDER" | Frontispiece |

| Facing p. | |

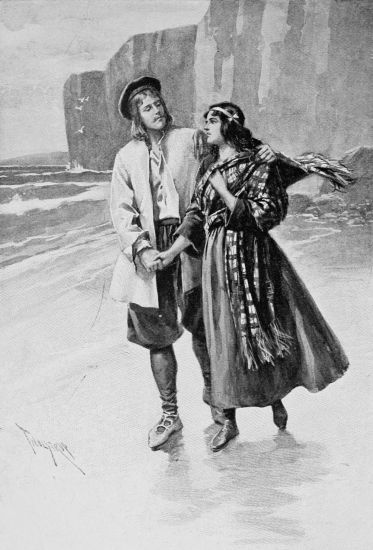

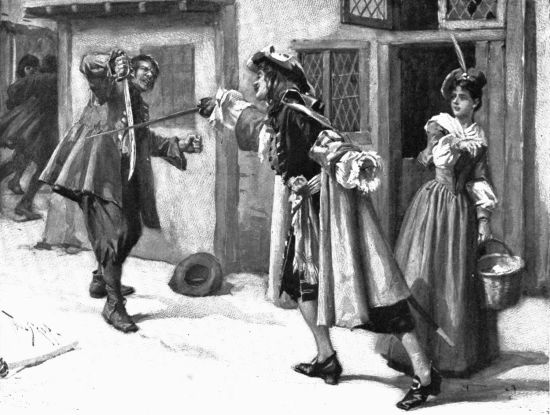

| "'I WILL TAKE MY OWN LOVE-TOKEN'" | 32 |

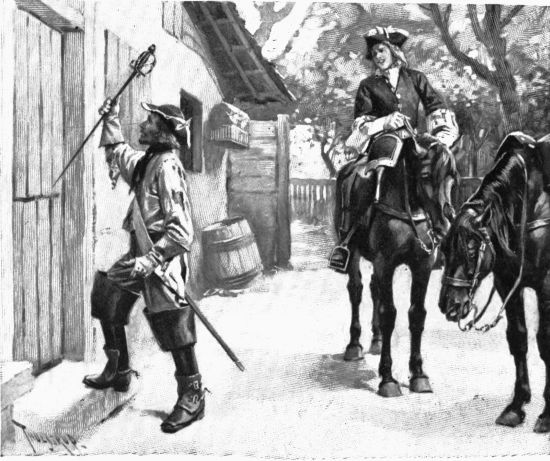

| "SCARLETT THUNDERED ON THE PANELS WITH THE HILT OF HIS SWORD" | 64 |

| "THE GENTLEMAN INSTANTLY ATTACKED THEM FURIOUSLY" | 90 |

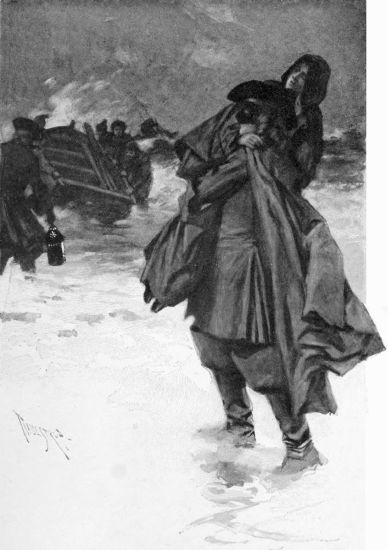

| "THE MAN CARRIED HER EASILY THROUGH THE SURF" | 144 |

| "A COUPLE OF PISTOL-SHOTS RANG OUT LOUDLY" | 176 |

| "THE SELF-SATISFACTION FLICKERED OUT OF HIS FACE" | 204 |

| "THEN THE SWIRLING TIDE-RACE TOOK HOLD OF HER" | 226 |

| "A GIGANTIC HIGHLANDER WITH A NAKED CLAYMORE BY HIS SIDE" | 250 |

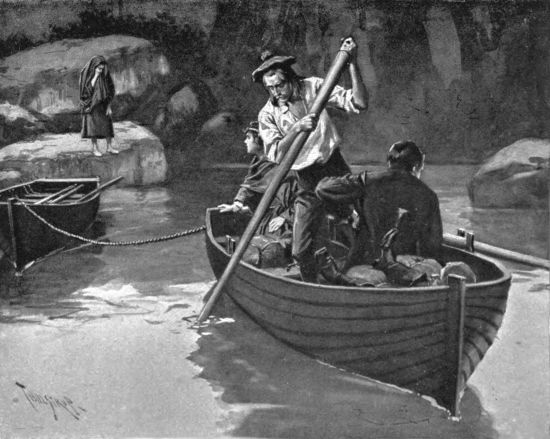

| "WAT PUSHED OFF IN THE SMALLER BOAT" | 284 |

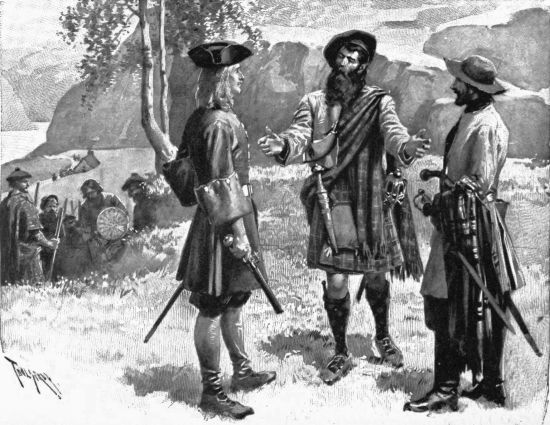

| "STRIDING FORWARD FRANKLY AND GIVING A HAND TO EACH" | 338 |

| "HE FELL INWARD AMONG THE WOUNDED" | 362 |

| "WITH HIS LOVE BETWEEN HIS ARMS" | 398 |

FOREWORD TO THE TALE, TELLING WHAT BEFELL AT THE HOUSE OF BALMAGHIE IN THE YEAR OF GRACE 1685, AND HOW MY LADY WELLWOOD PARTED TWO YOUNG LOVERS

"Aye," said Mistress Crombie, house-keeper to Roger McGhie, Laird of Balmaghie, a considerable house in the south-lying and better-cultivated part of the wild lands of Galloway—"aye, indeed, ye may well say it, Alisoun Begbie. It is a wondrous and most ungentle thing when the doe seeks the hart—panting and brayin' for a man, as the Guid Buik says. And saw ye ever sic feathers?—I declare they nearly soopit the floor. My Lady Wellwood, or no my Lady Wellwood, I trow she didna come ridin' by the hoose o' Balmaghie only to ask the time o' day, upsetting besom that she is!"

During this harangue Alisoun Begbie was clattering about among her bottles and dishes in the stone-flagged, slate-shelved still-room which constituted her pantry. A few minutes before she had cried mischievously out of the window to Lang Wat, the new under-gardener of Balmaghie, to the effect that "siccan a guid-lookin' chiel should be seen oftener about the house—but that she, Alisoun Begbie, was not wanting anything to do with the likes of him. She could get plenty of lads, and it was weel-kenned that the Glenkens' folk aye took up wi' their2 ain folk at ony rate." But as soon as the "bauchles"A of Mistress Crombie, the shrill-tempered house-keeper, were heard scuffling up the stairs, Alisoun made a pretty warning face of silence at Lang Wat, and tossed her head to intimate that some one approached from behind; so that, without making any verbal answer, the under-gardener resumed his occupation of the moment, which was the pruning and grafting of sundry rose-bushes—the pride and care of Mistress Kate McGhie, the "young leddy" of the great house of Balmaghie.

A Certain heelless and shapeless slippers, characteristic of the district.

"Na, 'deed, Alisoun Begbie," cried Mistress Crombie once more, from the cheek of the door, "believe me when I tell ye that sic a braw city madam—and a widow forbye—doesna bide about an auld disjaskit rickle o' stanes like the Hoose o' the Grenoch withoot haeing mair in her head than just sending warnings to Clavers aboot the puir muirland folk, that keep their misguided conventicles up ayont there, and pray a' nicht in the lirks o' the hills and the black hags o' the peat-mosses."

"Aye, ye may say so, 'deed, mistress," agreed Alisoun, keeping an eye upon the window of her pantry, through which she could see Lang Wat bending his back among the rose-bushes. Spite of his good looks, he had proved himself a singularly flinty-hearted fellow-servitor, and ill to set to the wooing. But Alisoun had still hopes of him. She had succeeded with some difficult—indeed, almost hopeless—cases in her time, and the very unresponsive nature of the young Glenkens' gardener stirred her ambition to brighter and more inviting glances, as well as to gayer and ever daintier ribbons.

But in spite of both loving looks and lovers' knots, Lang Wat neither succumbed nor yet appeared so much as conscious of her regard. Truly a marvellous young3 man—such as had never come within the sphere of the comely handmaiden's influence before.

"Weel, I'se warrant my lady needna set her cap at our maister," said Alisoun Begbie, willing to agree with the powerful and cantankerous house-keeper: "Na, Roger McGhie o' Balmaghie has his wits aboot him. Surely it is a terrible thing when a woman so far forgets hersel' as to set her cap for a man."

And pretty Alisoun glanced at the silver salver she was polishing, in order to be sure that her silken snood was in its proper place, and that the braids of her hair were drawn back smoothly and daintily from her brow. Being reassured on these points, she resumed the salver with renewed complaisance. Lang Wat was now standing meditatively outside, quite near the house, and with his face turned towards her window. He was leaning upon his spade; any moment he might look up. Pretty Alisoun Begbie breathed upon the silver with a certain seductive pouting of her lips, rubbed the place clear, breathed again upon it, and last of all frowned alluringly at it—for the very excellent reason that one of her former admirers had incautiously told her that such frowning became her mightily. But in spite of all, Lang Wat remained rapt in abstractest meditation. At which Alisoun Begbie tossed her head and frowned again—not this time for picturesque reasons, but in good earnest.

"He micht at least have kissed his hand, the silly cuif!" she said, half to herself, looking resentfully at the impervious under-gardener of Balmaghie.

"What!" cried Mistress Crombie, "kissed his hand, indeed, ye daft-speaking, licht-headed hizzie! I hope that my maister has something else to do than to gang kissin' his hand to a' the high-flyin' madams that likes to come aboot the hoose—wi' their auld guidmen hardly cauld in their coffins, and as much paint on their impudent faces as wad serve for the body o' a trail cart. Kiss4 his hand to her, indeed! Na, na, set her up; a deal less than that will serve her."

A stir was heard at the top of the stairs which led up from the still-room, among the cool recesses of which this conversation had been proceeding between Mistress Crombie and her favorite assistant.

"Dear sirs, that's the maister himsel', I declare," said the house-keeper, looking cautiously up, "and dressed in his Sunday breeks—mercy on us!—and his best coat wi' the new lace on the collar, and the cuffs that I laid aside for the next burial or siclike festivity. But—Lord preserve us!—here on a Wednesday he maun gang and put them on! The man's surely gane clean mad. He shall sup sorrow like sowens for this yet, and that will be seen."

"Maybe he has been kissin' mair than his ain hand," said Alisoun Begbie, slyly. She was still smarting from her rebuke by the house-keeper; besides which, Lang Wat would not look up.

Mistress Crombie started as if she had been stung.

"Save us!" she cried, "do ye think so? Then a' our good days aboot the hoose o' the Balmaghie are numbered! Oh, the bonny place, where I thocht to end my days wi' a guid maister and a kindly! Oh, women, women—what hae ye no to answer for, upsettin' a' plans, stirrin' up a' ill, pu'in' doon a' guid! Eh, Alisoun, but what a paradise the world wad be wi' only men in it, and no a woman frae end to end o't—forbye mysel'—whatna Gairden o' Eden wad that no make!"

But the eyes of Alisoun Begbie were fastened on a certain shaded nook among the rose-bushes, wherein a pretty enough comedy was being enacted; though, be it said, one little to the taste of the still-room maid. Mistress Crombie, had she been observant, might have discovered abundant cause to find fault with her maid's diligence and attention to the details of her duty during the5 next half-hour. But luckily for Alisoun Begbie, that good though suspicious lady had betaken herself indignantly up-stairs. There, with haughty head tossing in the air and a certain ominously aggrieved silence, she proceeded to meditate upon the other details of her master's attire—his Sunday shoes with silver buckles, his ribbons of pale blue at the knee, and especially the grand new wig of the latest court fashion, which Colonel John Graham of Claverhouse had brought all the way in his saddle-bag from Robin Rae's, the periwig-maker in the Lawnmarket, the last time he rode to Edinburgh to consult with the Lords of the Privy Council.

Now, what Alisoun Begbie watched behind the rosebushes was this:

She saw the under-gardener, "Lang Wat o' the Glenkens," as he was called about the house, in close and kindly converse with Mistress Kate McGhie, the only daughter of the house and heiress of her father's wide estates. She had come, a tall and graceful maid attired in white, lightfoot down a shady garden-path, the sunshine and the leaves together flecking her white dress with wavering shadows, her dark, shapely head thrown a little back, her chin tilted somewhat defiantly in the air, and her broad summer hat a-swing in her left hand. Fitfully she hummed a tune, but whenever she forgot the words (which was very often) the song dropped, and, without the least break of continuity, proceeded on its way as a whistle. And in either case the sounds proceeded, so thought the under-gardener, from the prettiest and most appetizing mouth in the world.

Indeed, as soon as Mistress Kate came within hearing distance of him, Lang Wat promptly swept his broad bonnet from his head in salute, and told her so. Which, when one thinks of it, was a considerable liberty for an under-gardener to take.

But the lady received the compliment not amiss, being6 to all appearance neither elated nor astonished. Was she not Kate McGhie of Balmaghie, and had she not been accustomed to be told that she was beautiful as long as she could remember? Consistent and continuous admiration had become familiar to her as the air she breathed, and had done her as little harm. It seemed to Kate as natural that she should be assured that she was winsome as to be told that she had a good appetite. And the information affected her equally in either case. Since her very tenderest years there had been but one dissentient voice in this chorus of universal love and admiration—a certain small boy from the Glenkens, a laird's son, one Walter Gordon of Lochinvar, who had come to the house of Balmaghie on a visit with his father, and had enshrined his dissent in a somewhat memorable form.

For, by the common bruit of the country-side, the girl had been denominated—while yet but a child with great hazel eyes that promised dangerous things, and a tossing fleece of curls—the Pride of Balmaghie. And the maid herself, when asked her name, was accustomed to reply frankly:

But this same Gordon lad from the Glenkens, scornful in the pride of half a dozen years of superior age, never heard the phrase without adding his own contemptuous disclaimer, "Little brute, I don't love her."

Nevertheless, the time came when the scorner recanted his renunciation. And that time was now, under the garden trees of the house of Balmaghie and the jealous eyes of Alisoun Begbie. For "Lang Wat o' the Glenkens," under-gardener to Roger McGhie of Balmaghie, was none other than Walter Gordon, the young laird of Lochinvar, fallen into ill-odor with the King's government—both7 in the matter of the wounding of my Lord of Wellwood, and as being suspected of companying and intercommuning with the wild Whigs of the hills. For the times bore hard on all such as were of doubtful loyalty, and fines and confiscations were the least those had to expect who refused to side openly with the blusterous riders and galloping compellers of the King's forces. The blaze of muskets in face of a stone wall, the ever-busy rope in the Grassmarket of Edinburgh (where during two brisk years of the "Killing Time" the hangman needed a new "tow" every month from the Town Council, and the pay of an additional assistant whenever "he was overthrong with the hanging of so many Westland men")—these and other symptoms of troublous times sent many well-disposed and innocent folk into hiding.

But it was not alone the superior advantages of Balmaghie as a hiding-place which had brought Wat Gordon of Lochinvar thither in search of shelter. It might rather be the sweeping, darksome under-curve of Kate McGhie's eyelashes, and the little specks of light which swam and sparkled in the depths of her hazel eyes, like the shredded gold in that rare liqueur which John Scarlett, the famous master-at-arms, had brought back with him last year from Dantzig.

Not that Wat Gordon was very deeply or seriously in love. He dallied and daintied with it rather. True—he thought about love and the making of it night and day, and (for the time being) his ideal and liege lady was the young mistress of the house of Balmaghie.

And Kate McGhie, knowing him for what he was, and being (unlike her father, but like most of the women-folk of Scotland) a sympathizer with the oppressed of the Covenant, showed no small kindness to the under-gardener.

She was a maiden left much alone. She was at the age when love is still an insubstantial, rosy dream, yet few8 youths of her own quality were ever encouraged to come about her father's house. So that her pity and her admiration were the more easily engaged on behalf of the handsome and unfortunate young laird who told her at least ten times a day (when he had the chance) that he was as willing as any Jacob to serve seven years, and seven to the back of that, in the hope of such a Rachel. For even before he began to do more than play with true love, Wat Gordon had a gift of love-making which might have wiled a bird off a tree.

Yet, for all that, when he came to practise on Kate McGhie, he wiled in vain. For the girl was buttressed and defended by a lifetime of admiration from all who came about her—by her father's adoration, the devotion of every man, woman, and child about the house of Balmaghie, and, above all, by the repute of reigning beauty athwart all the country-side. So, though she might think well enough of Wat Gordon, that handsome exile from his heritages and lordships now in picturesque hiding as her father's under-gardener, she was (so at least she told herself) in no danger of permitting that liking to develop into any feeling more dangerous or more exacting.

So these two fenced, each of them in their own way, right gallantly with lightsome love; while the love that is not lightsome, but strong as death, smiled out upon them from behind the rose-bushes, and lay in wait for one and the other.

Presently, while they were yet talking and Alisoun Begbie still carefully observant of them, the front door of the house of Balmaghie opened wide, and the laird himself came down the steps looking a little dashed and shamefaced, for Mistress Crombie had ushered him to the door with ironic state and ceremony.

"Dootless your honor is on his way to pay duty to the King's Commissioner at Kirkcudbright," she said,9 with pointed sarcasm which the shy laird did not know well how to parry. "But ye hae forgotten your pearl studs in your sark, and the wee hangie-swordie o' the court that will no draw oot o' its scabbard, nor so muckle as hurt a flea."

"I thank you, mistress," said Roger, not daring to look at his too faithful domestic, "but I go not so far afield as to see His Majesty's Commissioner. 'Tis but the matter of a visitor whom we must expect this forenoon. See that some collation is prepared for her."

"Her!" ejaculated Mistress Crombie, with an indescribable accent of surprise, not unmingled with scorn. "Her—we are to hae the company o' a great lady, nae doot. And this the first that your humble servant and house-keeper has heard o' the matter! 'Collation,' quo' he? Whatna dinner do ye think can be got ready between eleven and twa o' the clock on a Wednesday, wi' a' the lasses at the washin' except Alisoun Begbie, and nocht in the larder forbye twa pookit chuckie-hens, that came frae the Boat Craft less than half an hour since?"

"But, surely, these will do very well," said Roger McGhie, with increasing nervousness. "'Tis only my Lady of Wellwood, who rides over from the Grenoch."

For in truth he had been afraid to mention the matter to Mistress Crombie, and so had put off till it was too late—as the manner of men is.

"I forgot to acquaint you with the fact before; it—ah—it altogether escaped my memory," said he, beginning to pull his gloves on as he descended the steps.

"But ye didna forget to put on your Sunday claes, Laird Balmaghie," cried the privileged domestic after him, sarcastically; "nor did your best silken hose nor your silver buckles escape your memory! And ye minded brawly to scent your ruffles wi' cinnamon and rosemary. Ye dinna forget ony o' thae things—that were important, and maitters o' life and death, as one might10 say. It only escaped your memory to tell your puir feckless auld house-keeper to mak' ony provision for your dainty dames and court leddies. Ou aye, it maitters little for the like o' her—Marion Crombie, that has only served ye for forty year, and never wranged ye o' a fardin's-worth. Dinna waste a thought on her, puir auld woman, though she should die in a hedge-root, so long as ye can hae a great repair o' powdered weemen and galloping frisk-me-denties to come ridin' aboot your hoose."

But whatever else Mistress Crombie might have had to say to her master was lost in the clatter of hoofs and the stir and bustle of a new arrival.

Up the avenue came a bold horsewoman riding a spirited bay, reining it like a man as she stayed her course on the river gravel before the front door and sent the stones spraying from its fore-feet at the halt. The new-comer wore a plumed hat and the riding-dress of red, which, together with her warm sympathies with the "persecutors," caused my Lady Wellwood to be known in the country-side as "The Scarlet Woman." She was a handsome dame of forty, or mayhap a little more; but, save for the more pronounced arching of her haughty nose and the rounding curves of her figure, she might well have passed for ten or twelve years younger.

The Laird of Balmaghie went eagerly forward to meet his visitor. He took gratefully enough the hand which she reached to him a little indulgently, as one might give a sweetmeat to a child to occupy its attention. For even as he murmured his welcomes the lady's eyes were certainly not upon her host, but on the erect figure of his under-gardener, who stood staring and transfixed by the rose-bush which he had been pruning.

"My Lady Wellwood," said Roger McGhie, "this is indeed an honor and a privilege."

"Who may this youth be?" interrupted the lady, imperiously11 cutting short his sober courtesies and pointing to Lang Wat of the Glenkens.

"It is but one of my gardeners; he has lately come about the house," answered Roger McGhie, "a well-doing carle enough and a good worker. But hark ye, my lady, perhaps a wee overfond of Whiggery and such strait-lacedness, and so it may be as well to give his name the go-by when John Graham comes this way."

My Lady of Wellwood never took her eyes off the gardener's face.

"Come hither and help me to dismount," she said, beckoning with her finger.

Wat Gordon went reluctantly enough, dragging one foot after the other. He realized that the end had come to his residence among the flower-closes of Balmaghie, and that he must e'en bid farewell to these walks and glades as of Paradise, upon which, as upon his life, the hazel eyes of Kate McGhie had lately rained such sweet influences. Meanwhile the laird stood meekly by. The caprices of great court-ladies were not in his province, but, having set out to humor them, he was not to be offended by the favor shown his servitor. He had heard of such things at Whitehall, and the memory rather kindled him than otherwise. He felt all the new life and energy which comes of being transported into a new world of new customs, new ideas, and even of new laxities.

Wat gave my Lady Wellwood his hand in the courtliest manner. The habit and gait of the under-gardener seemed to fall from him in a moment at the sound of that voice, low and languorous, with a thrill in it of former days which it irked him to think had still power to affect him.

"You have not quite forgotten me, then, sweet lad of Lochinvar?" asked the Duchess of Wellwood softly in his ear. For so in the days of his sometime madness she had been wont to call him.

12 "No," answered Wat, sullenly enough, as he lifted her to the ground, not knowing what else to say.

"Then meet me at the head of the wood on my way home," whispered the lady, as she disengaged herself from his arm, and turned with a smiling face to Roger McGhie.

"And this is your sweet daughter," she murmured, caressingly, to Kate, who stood by with drooping eyelids, but who, nevertheless, had lost no shade of the colloquy between Wat Gordon and her father's guest.

The Lady Wellwood took the girl's hand, which lay cold and unresponsive in her plump white fingers. "A pretty maid—you will be a beauty one day, my dear," she added, with the condescension of one who knows she has as yet nothing to fear from younger rivals.

To this Kate answered nothing. For her flatterer was a woman. Had the Duchess of Wellwood been a man and condescended to this sort of left-handed praise, Kate would have flashed her eyes and said, "I have not seldom been told that I am one already." Whereupon he would have amended his sentence. As it was, Kate said nothing, but only hardened her heart and wondered what the great court lady had found to whisper to the man who, during these last months, had daily been avowing himself her lover. And though Kate was conscious that her heart sat secure and untouched on its virgin throne, it had, nevertheless, been not unpleasant to listen to the lad. For of a surety Wat Gordon told his tale wondrously well.

Roger McGhie conducted the lady gallantly through the garden walks towards the house. But she had not gone far when she professed herself overcome by the heat, and desired to be permitted to sit down on a rustic seat. She was faint, she said; yet, even as she said it, the keen eye of Kate McGhie noted that her color remained warm and high.

13 "A tass of water—nay, no wine," she called after the Laird of Balmaghie; "I thank you for your courtesy."

And Kate's father hastened away a little stiffly to bring it. She knew that his Sunday shoes irked him. It served him right, she thought. At his age he ought to know better—but there remained the more important matter of the under-gardener.

"Come and sit by me, pretty one," said the Lady Wellwood, cooingly, to Kate.

The "pretty one" would infinitely rather have set herself down by the side of an adder sunning itself on a bank than shared the woodland seat with the bold horsewoman of Grenoch.

"Ah! sly one," she said, "I warrant you knew that your under-gardener there, that handsome lad, was not the landward man he seemed."

She shook her finger reproachfully at her companion as she spoke.

Kate blushed hotly, and then straightway fell to despising herself for doing it almost as much as she hated my lady for making her. Lady Wellwood watched her covertly out of the corner of her eyes. She cultivated a droop of the left eyelid on purpose.

"I know that he is proscribed, and has a price set on his head," Kate said, quietly, looking after Wat with great indifference as he went down the avenue of trees.

"And do you know why?" asked the duchess, somewhat abruptly.

"No," answered Kate, wondering at her tone.

"It was for wounding my late husband within the precincts of Holyrood," said Lady Wellwood.

But Kate McGhie's anger was now fully roused, and her answer ran trippingly off her tongue.

"And was it for that service you spoke so kindly to him just now, and bade him meet you at the head of the wood as you went home?"

14 The duchess stared a little, but her well-bred calmness was not ruffled.

"Even so," she said, placidly, "and for the further reason that Walter Gordon was on his way to see me on the night when it was his ill fortune to meet with my husband instead."

"I do not believe it," cried the girl, lifting her head and looking Lady Wellwood straight in the eyes.

"Ask him, then!" answered the duchess, with the calm assurance of forty answering the chit of half her years. For at first sight my lady had envied and hated the clear, blushful ivory of the girl's cheek and the natural luxuriance of her close-tangled curls. And since all the art of St. James's could not match with these, she was now getting even with Kate in ways of her own.

The girl did not speak. Her heart only welled within her with contradiction and indignation.

"Or if you will not do that, sit down half an hour hence and read your book in the little arbor by the end of the avenue, and you will hear news. Whether you may like it or not is another question. But, at all events, you shall not have cause to say again that a Duchess of Wellwood lied."

Kate rose and walked away without answering a word. She cared no jot for Wat Gordon, so she told herself. He was nothing to her, save that she desired his safety and had risked much to give him shelter. Yet this Duchess of Wellwood—that woman of whom the gross popular tongue whispered commonly the most terrible things! Had Lochinvar made love to her? Was he to meet her at the end of the avenue? She could not believe it. It was, indeed, no matter if he did. What did she care? Go to the arbor, become an eavesdropper—not for any man alive, least of all for Wat Gordon! Thank God, she had a tongue in her head, and was not15 afraid to ask Wat Gordon, or any living soul, whatever she desired to know.

But after a little hesitation she went up-stairs to her chamber, and, denying herself the listening of the ear, she listened with her eyes instead. For she watched my Lady Wellwood being helped into her saddle right courteously by her father. She saw her looking down at him the while with a glance professionally tender—a glance that lingered in the memory by reason of the quiver of an eyelid and the pressure of a soft, reluctant hand. And Roger McGhie bowed over her plump fingers as though he had been bidding farewell to some angelic visitant.

For the first time in her life Kate McGhie despised her father. And, lo! to hurt her heart yet more, and to convince her of the ultimate falsity of all men, there was Wat, his tall figure overtopping the hawthorn hedge, walking briskly in the direction of the pinewood at the end of the avenue.

Kate went down-stairs with a set, still face. She would not cry. She did not care. She was only bitterly disappointed with the whole race of mankind, nothing more. They were all no better than so many blind fools, ready to be taken in by a plausible tongue and a rolling eye. A fine figure of a woman, and—Lord, where was the best of them?

But her Wat—and with the Duchess of Wellwood; she could not believe it! Why, she might be his—well, hardly that—but his mother at the very least.

Not that she cared; she had her work to think about; and Kate McGhie went down to the little suckling lamb she had fed daily with warm milk out of a wooden spoon, and which, though now almost of the greatness of a full-grown sheep, still leaped and fawned upon her. She fetched her pail and mixed pet Donald's mid-day meal.

Outside the garden wall the lamb was standing, bleating16 indignant petitions, and there Katie McGhie fed him with a gradually swelling heart. As the last drops disappeared into the moist black muzzle, Kate put her arms about the woolly neck and sobbed aloud.

"Oh, Donald, Donald, my lamb, you are the only friend I have! I do not love anybody else, and no one in the world loves me. But I am not sorry—I am glad, and I will not cry. It is not that I love him, Donald; but, oh! he might not have done it!"

That same evening Wat Gordon, as was his custom, came walking slowly through the garden pleasaunce. Kate McGhie met him by the rose-bush he had been pruning that morning.

"Is it true," she asked, looking at him bravely and directly, "that you are in hiding because, when going to visit the Duchess of Wellwood, you encountered her husband instead?"

"This much is true," answered Wat, promptly, "that while passing down the Canongate one snowy night, my cousin, Will Gordon of Earlstoun, and I were beset by a band of ruffians in the pay of the Duke of Wellwood, and that in defending ourselves the Duke himself was hurt."

"And when you went out of your lodging that night, was it to walk with your cousin or to visit my Lady of Wellwood in her boudoir?"

Wat Gordon took his breath hard. The manner of the question left him no escape with honor. But he could not lie. And he would offer no excuse.

"I went out to visit my Lady Wellwood!" he said, very shortly.

Kate McGhie held out her hand.

"I bid you good-bye," she said; "you will find your ancient friend and hostess at the Grenoch. There is nothing to detain you any longer about the poor house of Balmaghie."

17 And so saying the girl turned on her heel and walked slowly through the garden garth and past the pruned rose-bushes. She crossed the grassy slope to the door and there disappeared, leaving Wat Gordon standing silent, shamed, and amazed.

It was graying to the edge of dark upon one of the evenings towards the end of April, in the year 1688, when Walter Gordon, of Lochinvar in Galloway, and now for some time private in the Prince of Orange's Douglas regiment of dragoons, strode up the stairs of his cousin Will's lodging in the ancient Dutch city of Amersfort. The young man had come straight from duty at the palace, and his humor was not exactly gracious.

But Wat Gordon could not long remain vexed in spirit in the presence of his cousin Will's wife, Maisie Lennox. Her still, sweet smile killed enmity, even as spring sunshine kills the bite of frost. The little, low-roofed Dutch room, panelled with oak, had its windows open towards the sun-setting, and there in the glow of the west two girls were sitting. At sight of them Walter Gordon stopped suddenly in the doorway as he came bursting in. He had been expecting to see but one—his cousin's young wife, into whose pretty ear of patientest sympathy he might pour his fretful boyish disappointments and much-baffled aspirations.

Mistress Maisie Lennox, now for half a year Will Gordon of Earlstoun's wife (for by her maiden name she was still used to be called, and so she signed herself, since it had not yet become the custom for a women to take among her intimates the style of her husband's surname), sat on a high-backed chair by the oriel window. She had the kind of sunny hair which it is a pleasure to look upon,19 and the ripples of it made crisp tendrils about her brow. Her face underneath was already sweetening and gaining in reposefulness, with that look of matronhood which comes early to patient, gracious women, who would yet venture much for the man they love. And not once nor yet twice had Maisie Lennox dared all for those whom she loved—as has, indeed, elsewhere been told.

But, all unexpected of the hasty visitor, there was yet another fair girl looking up at him there in that quaint, dusky-shadowed room. Seated upon a low chair, and half leaning across the knees of Mistress Maisie, set wide apart on purpose, there reclined a maiden of another temper and mould. Slender and supple she was as willow that sways by the water-edges, yet returning ever to slim, graceful erectness like a tempered blade of Damascus; above, the finest and daintiest head in the world, profiled like Apollo of the Bow, with great eyes that were full of alternate darkness and tenderness, of tears and fire; a perfectly chiselled mouth, a thing which is rarer and more excellent than the utmost beauty of splendid eyes—and sweeter also; a complexion not milk and rose like that of Maisie Lennox, but of ivory rather, with the dusky crimson of warm blood blushing up delicately through it. Such was Kate McGhie, called Kate of the Dark Lashes, the only daughter of Roger McGhie of Balmaghie, a well-reputed Galloway gentleman in the country of Scotland.

As Walter Gordon came bursting in his impetuous fashion into his cousin's room, his sword clashing about his feet and his cavalry spurs jingling against his boot-heels, he was stopped dead by this most pleasant sight. Yet all he saw was a girl with her head resting upon her own clasped hands and reclining on her friend's knee, with her elbows set wide apart behind her head—while Maisie's hand played, like a daring swimmer in breaking surf, out and in among the soft crisps of hair, which were20 too short to be waves and too long to be curls. And this hair was of several curious colors, ranging from black in the shadows through rich brown into dusky gold where the sun's light caught it lovingly, as though he had already begun to set over the sand-dunes into the Northern Sea. As Wat stood there, his fingers tingled to touch. It seemed somehow a squandering of human happiness that only a girl's hand should smooth that rich tangle and caress those clustering curls.

Walter Gordon of Lochinvar had flung himself into the little room in Zandpoort Street, ripe to pour his sorrows into the ear of Maisie Lennox. Nor was he at all forgetful of the fact that the ear was an exceedingly pretty one. Most devoutly he hoped that Will, his very excellent cousin and Maisie's good husband, might have been kept late at the religious exercises of the Regiment of the Covenant—as that portion of the Scotch-Dutch auxiliary force was called which had been mostly officered and recruited from among the more militant exiles and refugees of the Scottish persecution.

But as Lochinvar came forward somewhat more slowly after his involuntary start of surprise, his eyes continued to rest on those of the younger girl, who remained thus reclined on her gossip's lap. She had not moved at his entrance, but only looked at him very quietly from under those shadowy curtains which had gained her the name of Kate of the Dark Lashes. Then in a moment Wat set his hand to his breast suddenly, as if a bullet had struck him upon the field of battle.

"Kate!" he cried, in a quick, hoarse whisper, as though the word had been forced from him.

And for a long moment the young soldier stood still and speechless, with his eyes still fixed upon the girl.

"Walter, mind you not my dearest friend and gossip Kate, and how in old sad days in the dear far-away land we there underwent many things together?" asked Maisie21 Lennox, looking up somewhat doubtfully from her friend's face into that of Walter Gordon.

"I did not know—I had not heard—" were all the words that the young squire of dames could find to utter.

"Also there were, if I remember aright," the young matron went on, with that fatal blundering which sometimes comes to the kindest and most quick-witted of women, "certain passages between you—of mutual friendship and esteem, as it might be."

Then, with a single swift movement, lithe and instantaneous as that of a young wild animal which has never known restraint, Kate of the Dark Lashes rose to her feet.

"Walter Gordon of Lochinvar," she said, "is a Scottish gentleman. He will never be willing to remember that which a lady chooses to forget."

But Lochinvar himself, readiest tongue in wit-play as well as keenest blade when the steel clashed in sterner debate, on this occasion spake never a word. For in that moment in which he had looked upon Kate McGhie resting her beautiful head upon her clasped hands in her friend's lap he had fallen from the safe heights of admiration into the bottomless abysses of love.

While the pair were still standing thus face to face, and before Kate sat down again in a more restrained posture on the low-cushioned window-seat, Will Gordon strode in and set his musket in a corner. He was habited simply enough in the dark gray of the Hill Folks' regiment, with the cross of St. Andrew done in blue and white upon his breast. His wife rose to kiss him as he entered, and then, still holding her by the hand, he turned to the tall, slim girl by the window.

"Why, Kate, lass, how came the good winds to blow you hither from the lands of mist over the sea?" he asked.

22 "Blasts of ill winds in Scotland, well I wot," said Kate McGhie, smiling at him faintly and holding out her hand.

"Then the ill Scots winds have certainly blown us good here in Holland," he answered, deftly enough, in the words of the ancient Scottish proverb.

But the girl went on without giving heed to his kindly compliment.

"The persecution waxes ever hotter and hotter on the hills of the south," she said, "and what with the new sheriffs, and the raging of the red-wud Grier of Lag over all our country of Galloway, I saw that it could not be long before my doings and believings brought my easy-tempered father into trouble. So, as soon as I knew that, I mounted me and rode to Newcastle, keeping mostly to the hills, and avoiding the highways by which the king's soldiers come and go. There, after some wearisome and dangerous waiting, I got a ship to Rotterdam. And here I am to sorn upon you!"

She ended with a little gesture of opening her hands and flinging them from her, which Wat Gordon thought very pretty to behold.

"You are as welcome to our poor soldier's lodging as though it had been the palace of the stadtholder," answered William Gordon—with, nevertheless, a somewhat perplexed look, as he thought of another mouth to be fed upon the scanty and uncertain pay of a private in the Scottish regiments of the prince.

While his cousin was speaking Wat Gordon had made his way round the table to the corner of the latticed window farthest from Kate, where now he stood looking thoughtfully upon the broad canal and the twinkling lights which were beginning to mark out its banks.

"Why, Wat," cried his cousin Will, clapping him lovingly upon the shoulder as he went past him to hang up his blue sash on a hook by the window, "wherefore23 so sad-visaged, man? This whey face and dour speechlessness might befit an erewhile Whig gardener of Balmaghie, with his hod and mattock over his shoulder; but it sets ill with a gay rider in Douglas's dragoons, and one high in favor in the prince's service."

Lochinvar shook off his cousin's hand a little impatiently. He wanted nothing better than just to go on watching Kate McGhie's profile as it outlined itself against the broad, shining reach of water. He marvelled that he had been aforetime so blind to its beauty; but then these ancient admirations in Scotland had been only lightness of heart and a young man's natural love of love-making. But Walter Gordon knew that this which had stricken him to the heart, as he came suddenly upon the girl pillowing her head on her palms at Maisie's knee, was no mere love-making. It was love.

"Who were on duty to-day at headquarters?" Wat asked, gruffly enough.

"Who but Barra and his barbarians of the Isles!" William Gordon made answer.

Wat stamped his foot boyishly and impatiently.

"The prince shows these dogs overmuch of his favor," he said.

Will Gordon went to the chamber door and opened it. Then he looked back at his wife.

"Come hither, sweetheart," he said. "It is pay-day, and I must e'en give thee my wages, ere I be tempted to spend them with fly-by-night dragoons and riotous night-rakes like our cousin here. Also, I must consult thee concerning affairs of state—thy housewifery and the price of candles belike!"

Obediently Maisie rose and followed him out of the room, gliding, as was her manner, softly through the door like water that runs down a mill-lade. Kate of the Dark Lashes, on the contrary, moved with the flash and lightsome unexpectedness of a swallow in flight. Yet24 now she sat still enough by the dusky window, looking out upon the twinkling lights which, as they multiplied, began to be reflected on the waters of the long, straight canal.

For a while Wat Gordon was content silently to watch the changeful shapeliness of her head. He had never seen one set at just that angle upon so charming a neck. He wondered why this girl had so suddenly grown all wonderful to him. It was strange that hitherto he should have been so crassly blind. But now he was perfectly content only to watch and to be silent, so that it was Kate who first felt the necessity for speech.

"This is a strange new land," she said, thoughtfully, "and it is little wonder that to-night my heart is heavy, for I am yet a stranger in it."

"Kate," said Wat Gordon, in a low, earnest tone, leaning a little nearer to her as she sat on the window-seat, "Kate, is there not, then, all the more reason to remember old friends?"

"And have I not remembered?" answered the girl, swiftly, without looking at him. "I have come from my father's house straight to Maisie Lennox—I, a girl, and alone. She is my oldest friend."

"But are there, then, no others?" said the young man, jealously.

"None who have never forgotten, never slighted, never complained, never faltered in their love, save only my sweet Maisie Lennox," returned the girl, as she rose from her place and went towards the door, from behind which came the soft hum of voices in friendly conference.

Wat took two swift steps forward as if to forestall her, but she slipped past him, light as the shadow of a leaf windblown along the wall, and laid her hand on the latch.

"Will not you let me be your friend once again after these weary years?" he asked, eagerly.

25 The tall girl opened the door and stood a moment with the outline of her figure cut slimly against the light which flooded the passage—in which, as it grew dark, Maisie had lighted a tiny Dutch lamp.

"I love friends who never need to be friends again!" she said, in a low voice, and went out.

Left to himself, Wat Gordon clinched his hands in the swiftly darkening room. He strode back to the window pettishly, and hated the world. It was a bad world. Why, for no more than a hasty word, a breath of foolish speech, a vain and empty dame of wellnigh twice his age, should he lose the friendship of this one girl in all the world? That other to whom he had spoken a light word of passing admiration he had never seen again, nor indeed wished to see. And for no more than this, forsooth, he must be flouted by her whom his very soul loved! It was a hard world, a bad world—of which the grim law was that a man must pay good money, red and white, for that which he desires with his heart and reaches out his hand to possess himself of.

Just then the street door resounded with the clang of impetuous knocking. His cousin Will went down, and presently Wat heard the noise of opening bars, and then the sough of rude, soldier-like speech filled the stairway.

"Wat Gordon! Wat Gordon!" cried a voice which sounded familiar enough to him, "come down forthwith! Here! I have brought you a letter from your love!"

And Wat swore a vow beneath his breath to stop the mouth of the rascal who knew no better than to shout a message so false and inopportune in the ears of the girl of the dusky eyelashes. Nevertheless, he went quickly to the landing and looked down.

A burly figure stood blocking the stairway beneath, and a ruddy face gleamed upward like a moon out of a26 mist, as Maisie held the lamp aloft. A voice, somewhat husky with too recent good living, cried, "Lochinvar, here is a letter to you from the colonel. Great good may it do you, but may the last drop in the cogie of him that sent it be the sourest, for raising Davie Dunbar from the good company and the jolly pint-stoup, to be splattered at this time of night with the dirty suds of every greasy frow in all Amersfort!"

And the stout soldier dusted certain befouling drops from his military coat with a very indignant expression.

"Not that the company was over-choice or the wine fit to be called aught but poison. 'Mony littles mak' a mickle,' says the old Scots saw. But, my certes, of such a brew as yon it micht be said 'mony mickles make but little'! For an it were not for the filling up of your belly, ten pints of their Amersfort twopenny ale is no more kenned on a man than so much dishwashings!"

"Come your ways in and sit down, sergeant," said Mistress Maisie, hospitably. For her hand was somewhat weary with holding the lamp aloft, while Sergeant Davie Dunbar described the entertainment he had just left. Meanwhile Wat had opened his scrap of gray official letter, and appeared to stand fixed in thought upon the words which he found written therein.

"What may be the import of your message, since you are grown suddenly so solemn-jawed over it, Wat?" cried Davie Dunbar, going up to look over his shoulder, while Maisie and Kate McGhie stood talking quietly apart.

"I am bidden go on a quest into the wild country by the seashore, a mission that in itself I should like well enough were it not that it comes to me by the hand of Black Murdo of Barra."

Davie Dunbar whistled thoughtfully.

"When the corbie is from home, it's like to be an ill day for wee lame lammies!" he said, sententiously.27 Wat Gordon cocked his guardsman's cap at the words. He had set it on his head as he went down-stairs.

"I am Walter Gordon, of Lochinvar, and though that be for the nonce but a barren heritage, I am also a gentleman-private in the prince's Scots Dragoons, and I count not the Earl of Barra more than a buzzard-kite."

"I see well that ye are but a wee innocent lammie after all," retorted Sergeant Dunbar; "little ye ken about the regimen of war if at the outset of a campaign ye begin by belittling your enemy. I tell you, Murdo of Barra has more brains under his Highland bonnet than all your gay Douglas dragoons, from your swearing colonel to the suckling drummer-boy—who no sooner leaves his mother's breast than he learns to mouth curses and lisp strange oaths."

Wat Gordon shook his head with a certain unconvinced and dour determination.

"I have been in wild places and my sword has brought me through, but though I own that, I like not this commission—yet feared of Barra I am not."

And he handed Davie Dunbar the paper. The sergeant read it aloud:

"Walter Gordon, some time of Lochinvar, of the Prince's Scottish Dragoon Guards, you are ordered to obtain the true numeration of each regiment in the camp and city of Amersfort—their officering, the numbers of each company, and of those that cannot be passed by the muster officers, the tally of those sick with fever, and of those still recovering from it, the number of cannon on the works and where they are posted. These lists you are to transmit with your own hand to an officer appointed to receive them by His Highness the Prince at the Inn of Brederode by the Northern Sanddunes, who will furnish you with a receipt for them. This receipt you will preserve and return to me in token that you have fulfilled your mission. The officers of the regiments and the commanders of batteries have hereby orders to render you a correct and instant accompt.

"(Signed) For the Stadtholder and the States-General,

"Barra,

"Provost-Marshal of the City and Camp."

28 William Gordon had come into the room while the sergeant was reading the paper, and now stood looking at Walter's unusual commission.

"There will be murder done when you come to our colonel," he said, "and ask him to tell you that the most part of his regiment is already in hospital, and also how many of the rest are sickening for it."

But Wat Gordon stood up and tightened his sword-belt, hitching his sword forward so that the hilt fell easily under his hand. Then he flipped the mandate carelessly upon the widened fingers of his left hand before sticking it through his belt.

"It is, at least, an order," he said, grandly, "and so long as I am in the service of His Highness the Prince, my orders I will obey."

"And pray what else would you do, callant," interjected Sergeant David Dunbar, "but obey your orders—so long, at least, as ye are sure that the lad who bids ye has the richt to bid ye?"

It was the evening of the following day before Wat Gordon was ready to start. It had taken him so long to obtain all the invaluable information as to the strength of the armies of the States-General and of their allies, which were collected at Amersfort in order to roll back the threatened invasion of the King of France. Twice during the day had he rushed into his cousin's lodging for a brief moment in order to snatch a morsel of food, but on neither occasion had he been able to catch so much as a glimpse of Kate. It was now the gloaming, and the night promised to fall clear and chill. A low mist was collecting here and there behind the clumps of bushes, and crawling low along the surface of the canals. But all above was clear, and the stars were beginning to come out in familiar patterns.

For the third and last time Wat made an errand up to his cousin's rooms, even after his escort had arrived, and once more Maisie took him gently by the hand, bidding him good-speed on his quest perilous. But even while his cousin's wife was speaking the young man's eye continued to wander restlessly. He longed rather to listen to upbraiding from another voice, and, in place of Maisie's soft, willing kiss, to carry away the farewell touch of a more scornful hand.

"Cousin," he said at last, reluctantly and a little shyly, "I pray you say farewell for me to Mistress Kate, since30 she is not here to bid me farewell for herself. In what, think you, have I offended her?"

"Nay, Wat," answered the gentle Maisie, "concerning that you must e'en find means of judging for yourself on your return."

"But listen, Cousin Maisie, this venture that I go upon is a quest of life or death to me, and many are the chances that I may not return at all."

"I will even go speak with my gossip Kate, and see whether she will come to bid you good prospering on your adventure and a safe return from it."

And so saying Maisie passed from the room as silently as a white swan swims athwart the mere. In a little while she returned with Kate, who, beside her budding matronhood, seemed but a young lissom slip of willow-wand.

"Here, Kate," said Maisie, as she entered holding her friend by the hand, "is our cousin Wat, come in on us to bid farewell. He goes a far road and on a heavy adventure. He would say good-bye to the friends who are with him in this strange land before he departs, and of these you are one, are you not, my Kate?"

As soon as Mistress Maisie loosened her hand the girl went directly to the window-seat, where she stood leaning gracefully with her cheek laid softly against the shutter. She turned a little and shivered at her friend's pointed appeal.

"If Walter Gordon says it, it must be so," she answered, with certain quiet bitterness.

Lochinvar was deeply stung by her words. He came somewhat nearer to her, clasping his hands nervously before him, his face set and pale as it had never been in the presence of an enemy.

"Kate," he said, "I ask you again, wherein have I so grievously offended you that, on your coming to this land of exile, you should treat me like a dog—yes, worse than31 a wandering cur-dog. It is true that once long ago I was foolish—to blame, blackly and bitterly in the wrong, if you will. But now all humbly I ask you to forgive me ere I go, it may be to my death."

The girl looked at him with a strange light in her eyes—scorn, pity, and self-will struggling together for the mastery.

At last, in a hard, dry voice, she said, "There is nothing to forgive. If there had been I should have forgiven you. As it is, I have only forgotten."

Maisie had left the room and there was deep silence in it and about, save for the distant crying of the staid Dutch children late at their plays on the canal-sides of Amersfort, and the clatter of the home-returning wooden shoon on the pavemented streets. The young man drew himself up till his height towered above the girl like a watch-tower over a city wall. His eyes rested steadfastly on her the while. She had a feeling that a desperate kind of love was in the air, and that for aught she knew he might be about to clasp her fiercely in his arms. And it had, perhaps, been well for both if he had, for at that moment she raised her eyes and her heart wavered within her. He looked so tall and strong. She was sure that her head would come no higher upon his breast than the blue ribbon of his cavalry shoulder-knot. She wondered if his arms would prove as strong as they looked, if she suddenly were to find herself folded safe within them.

"Kate," he said, wistfully, coming nearer to her.

Now Wat Gordon ought not to have spoken. The single word in the silence of the room brought the girl back to herself. Instinctively she put out her hand, as though to ward off something threatening or overpowering. The gulf yawned instantly between them, and the full flood-tide of Wat Gordon's opportunity ebbed away as rapidly as it had flowed.

Yet when a moment later the girl lifted her long, dark32 lashes and revealed her eyes shining shyly glorious beneath them, Wat Gordon gazed into their depths till his breath came quick and short through his nostrils, and a peal of bells seemed to jangle all out of tune in his heart. He stood like some shy woodland beast new taken in a trap.

"Well?" she said, inquiringly, yet somewhat more softly than she had yet spoken.

Wat clinched his fist. In that single syllable the girl seemed to lay all the burden of blame, proof, explanation of the past upon him alone, and the hopeless magnitude of the task cut him to the quick.

"Kate!" he cried, "I will not again ask you to forgive me; but if I do not come back, at least believe that I died more worthily than perhaps I have lived—though neither have I ever lived so as to shame you, even had you seen me at my worst. And, ere I go, give me at least a love-token that I may carry it with me till I die."

Kate's lips parted as though she had somewhat to answer if she would, but she kept a faintly smiling silence instead, and only looked casually about the room. A single worn glove lay on the top of a little cabinet of dark oak. She lifted it and handed it to Wat. The young man eagerly seized the glove, pressed it with quick passion to his lips, and then thrust it deep into the bosom of his military coat. He would have taken the hand which gave him the gift, but a certain malicious innocence in the girl's next words suddenly dammed his gratitude at the fountain-head.

"I have nothing of my own to give," she said, "for I have just newly come off the sea. But this glove of Maisie's will mayhap serve as well. Besides which, I heard her say yestreen that she had some time ago lost its marrow in the market-place of Amersfort."

With a fierce hand Wat Gordon tore the glove from his bosom and threw it impulsively out of the window into33 the canal. Then he squared his shoulders and turned him about in order to stride haughtily and indignantly from the room.

But even as he went he saw a quaintly subtle amusement shining in the girl's eyes—laughter made lovely by the possibility of indignant tears behind it, and on her perfectest lips that quick petulant pout which had seemed so adorable to him in the old days when he had laid so many ingenious snares to bring it out. Wat was intensely piqued—more piqued perhaps than angry. He who had wooed great ladies, and on whom in the ante-chambers of kings kind damsels all too beautiful had smiled till princes waxed jealous, was now made a mock of by a slim she-slip compact of mischievous devices. He looked again and yet more keenly at the girl by the window. Certainly it was so. Mischief lurked quaintly but unmistakably under the demure, upward curl of those eyelashes. A kind of still, calm fury took him, a set desperation like that of battle.

"I will take my own love-token," he cried, striding suddenly over to her.

And so, almost but not quite, ere Kate was aware, he had stooped and kissed her.

Then, in an instant, as soon indeed as he had realized his deed, all his courage went from him. His triumph of a moment became at once flat despair, and he stood before her ashamed, abject as a dog that is caught in a fault and trembles for the lash.

Without a word the girl pointed to the door. And such was the force of her white anger and scorn upon him that Wat Gordon, who was about to ride carelessly to face death as he had often done before, slunk through it cowering and speechless.

Maisie was coming along the little boarded passage as he passed out.

"Farewell, cousin," she said to him. "Will you not34 bid me good-bye again ere you go, if only for the old sake's sake?"

But Wat Gordon went past her as though he had not heard, trampling stupidly down the narrow stairs like a bullock in the market-place, the spring all gone out of his foot, the upstanding airy defiance fallen away from his carriage.

Then in a moment more there came up from the street front the sound of trampling horses and the ring of accoutrement, as three or four riders set spurs to their horses and rode clattering over the cobbles towards the city gates.

Maisie went quickly into the sitting-room to her friend.

"What have you been doing to my Wat?" she asked, grasping her tightly by the arm. "Have you quarrelled with him?"

Kate was standing behind the shutter, looking down the street along which the four riders were rapidly vanishing. At the corner where they turned one of the horses shied and reared, bringing down its iron-shod hoofs sharply on the pavement with a little jet of sparks, and almost throwing its rider. Instinctively the girl uttered a little cry, and set her hand against her side.

"What said Wat to you, dearest Kate," asked Maisie, again, altering the form of her question, "that you sent him thus speechless and dumfoundered away? He passed me at the stair-head as if he knew me not."

Finding Kate still absorbed and silent, Maisie sat down in her own chair and waited. Presently, with a long sigh, the girl sank on her knees beside her, and, taking her friend's hand, set it on her head. With sympathetic and well-accustomed fingers Maisie, as was her custom, softly smoothed and caressed the dark tangle of curls. She did not utter a word till she heard a quick sob catch at the bottom of Kate's throat. Then she spoke very35 low, leaning forward till she could lay her cheek against the girl's brow.

"What said he? Tell me, dearest, if you can; tell your gossip, Maisie," she whispered.

It was a voice that not many could resist when it pleaded thus—most like a dove cooing to its mate in the early summer mornings.

There fell a silence for a while in the little upper room; but Maisie the wise one did not again speak. She only waited.

"Oh, I hate him!" at last said Kate McGhie, lifting her head with centred intensity of expression.

Maisie smiled a little, indulgently, leaning back so that her friend's dark eyes should not notice it. She smiled as one who is in the things of love at least a thousand years older, and who in her day has seen and tasted bread sweet and bread bitter.

"And certainly you do well to hate him, my Kate," this cunning Mistress Maisie said, very gently, her hand continuing to run softly through the meshes of Kate's curls; "nevertheless, for all that you are glad that he kissed you."

The girl lifted her head as quickly from its resting-place as though a needle had pricked her unawares. She eyed her friend with a grave, shocked surprise.

"You were listening!" she said.

And the censure in her tone might have been that of a General Assembly of the Kirk, so full of weighty rebuke was it.

"No, Kate," said her friend, quietly. "I was in the kitchen all the time, putting the bone in the broth for William's supper. I heard no single word of your talk. But, Kate, my lassie, I am not so very ignorant concerning these things which you stand on the brink of. Come, what had you been saying to him to provoke him to kiss you?"

36 "He but asked me for a love-token to take with him to the wars—which I gave him, and how could I tell?" said the girl, a little plaintively. Things had not gone as they ought, and now her own familiar friend was about to blame her for it.

Maisie waited a moment discreetly, hoping that Kate would go on; but she appeared to consider that she had said enough. She only pillowed her head lower on her gossip's knee, and submitted contentedly to the loving hand which caressed her ringlets.

"And you gave him the love-token?" queried her friend, quietly.

"I told him that I had nothing of my own to give him, because my baggage had not yet arrived; and it chanced that I saw one of your old marrowless gloves lying there on the cabinet—so I gave him that. I thought," she added, plaintively, after a pause, "that it would do just as well."

At which conclusion Maisie laughed helplessly, rocking to and fro; then she checked herself, and began again. Kate raised her head and looked at her in new surprise.

"You are the strangest girl!" at last Maisie said. "You have sundry passages with a gallant youth. You smile not unkindly upon him. You quarrel and are separated. After years you meet in a distant land. He asks you for a gage to carry with him to the wars, a badge fragrant of his lady and his love, and you give him—an odd glove of his cousin's wife's. Truly an idea most quaint and meritorious!"

"And Maisie," said Kate, solemnly, looking up at her with her head still on her hands, "would you believe it? He stamped his foot and threw the glove out of the window there into the canal! He ought not to have done that, ought he?"

"My Kate," said her friend, "do not forget that I am no longer a girl, but a woman wedded—"

37 "Six months," interrupted Kate McGhie, a little mischievously.

"And when I see the brave lass with whom, in another and a dearer land, I came through so many perils, in danger of letting foolish anger wrong both herself and another, you will forgive me if I have a word to say. I speak because I have come in peace to the goal of my own loving. Wat loves you. I am sure of that. Can you not tell me what it is that you have against him? No great matter, surely; for, though reckless and headstrong beyond most, the lad is yet honest, up-standing, true."

Kate McGhie was silent for a while, only leaning her head a little harder against the caressing hand.

Then, with her face bent down, she spoke, softly:

"In Scotland he loved me not, but only the making of love. If so be that Wat Gordon will love me here in the Lowlands of Holland, he must do it like one that loves for death or life; not like a gay gallant that makes love to every maid in town, all for dalliance in a garden pleasaunce on a summer's day."

The girl drew herself up nearer to her friend's face. Maisie Lennox, on her part, quietly leaned over and laid her cheek against Kate's. It was damp where a cherry-great tear had rolled down it. Maisie understood, but said nothing. She only pressed her gossip a little closer and waited. In a while Kate's arms went gently round about her neck, and her face drew yet a little nearer to the listening ear.

"Once," she whispered, "I feared that I was in danger of loving him first and most—and that he but played with me. I feared it much," she went on, with a little return of the low sob, which caused her friend's arms to clasp themselves more tightly about her, "I feared that I might learn to love him too soon. So that is the reason—why—I hate him now!"

Wat Lochinvar rode out of the city of Amersfort with anger humming fierce in his heart, the Black Horseman riding pickaback behind him. He paid little attention to the three cutthroat-looking knaves who had been provided as his escort, till the outer port of the city gates had closed behind him and the chill airs of the outlands, unwarmed by friendly civic supper-fires, met him shrilly in the teeth.

He had been played with, tricked, betrayed, so he told himself. Never more would he think of her—the light trifler with men's hearts. She might gang her own wilful gait for him; but there was one thing he was well assured of—never more would Wat Gordon trust any woman born of woman, never speak a word of love to one of the fickle breed again. On this he was resolved like steel. For him, henceforth, only the stern elation of combat, the clatter of harness, the joy of the headlong charge—point to point, eye to eye, he would meet his man, when neither would be afraid of aught, save of yielding or craving a favor. From that day forth his sword should be his love, his regiment his married wife, his cause and king his family; while his faithful charger, nuzzling against his breast, would bestow on him the only passionate caresses he would ever know, until on some stricken field it was his fate to fill a soldier's grave.

Almost could Walter Gordon have wept in his saddle to think of his wrongs, and death seemed a sweet thing39 to him beside the fickle favors of any woman. He bethought him of his cousin Will with something of a pitying smile.

"Poor fool!" he said to himself; "he is married. He thinks himself happy. How much better had it been to live for glory!"

But even as he battered himself into a conviction of his own rooted indifference to the things of love, he began to wonder how long his present adventure would detain him. Could he be back in time on the morrow to hear the first trip of a light foot on the stairs in Zaandpoort Street, as she came from her sleeping-room, fresh as though God had made her all anew that morning?

For this is a quality of the wisdom of man, that thinking upon a maid ofttimes makes it vain—especially if the man be very brave or very wise, and the maid exceeding fair. Gradually, however, the changing clatter of the dozen hoofs behind Lochinvar forced itself upon his hearing, and he remembered that he was not alone.

He turned to his followers, and, curbing his horse a little, waited for them to come up. They ranged themselves two on one side of him and one on the other. Lochinvar eyed them with surprising disfavor.

"You are surely the last scourings of the camp," he said, brusquely, for it was too little his habit to beat about the bush; "what may you have been doing with yourselves? You could not all three have been made so unhallowedly ugly as that. After all, God is a good God, and kind to the evil and to the good."

The fellow on Lochinvar's left was a great red-faced man with an immense scar, where (as it appeared) one side of his face had been cut away wellnigh to the cheek-bone—a wound which had healed unevenly in ridges and weals, and now remained of a deep plum-color.

"What is your name?" said Lochinvar to this man.

40 "I am called Haxo the Bull," he answered, "and I am of the retinue of my Lord of Barra."

"And how came you by your English?" asked Lochinvar.

"My mother always declared that my father was of that nation," answered the man, readily enough.

"To conclude," continued Wat, who was impatient of further conference with such rank knaves, "what might be your distinguished rank in the service of my Lord of Barra?"

"I am his camp butcher," said the man, laying his hand on a long, keen knife which swung at his belt on the opposite side from his sword.

"And these other two gentlemen, your honorable companions?" queried Wat, indicating them over his shoulder with contemptuous thumb.

The hulking fellow of the scar made a gesture with his shoulders, which said as plain as might be, "They are of age; ask themselves."

But the nearer of the two did not wait to be asked. He was a hairless, flaccid-faced rogue of a pasty gray complexion, and even uglier than the plum-colored Bull, with a certain intact and virgin hideousness of his own.

"I, for my part, am called Haxo's Calf, and I am not ashamed of the name!" he said.

And, thinking this an excellent jest, he showed a row of teeth like those of a hungry dog when he snatches a bone from a comrade not his equal in the fray.

"And, I doubt not, a fit calf of such a sire," quoth Lochinvar, looking from one to the other.

"He is my apprentice, not my son—praise to the Virgin and all the saints!" said Haxo, looking at the Calf quite as scornfully as Wat himself.

Lochinvar now transferred his attention to the third. He wore a small round cap on the top of his head, and41 his narrow and meagre forehead ran back shining and polished to the nape of his neck. His lack-lustre eyes were set curiously at different angles in his head. He had thin lips, which parted nervously over black, gaping teeth, and his nose was broken as if with a blow of a hammer.

"And is this gentleman also of Monsieur Haxo's gallant company, and in the suite of his Excellency my Lord of Barra?"

Haxo nodded his head with some appreciation of Wat's penetration.

"He is, indeed," he said; "he is my chief slaughterman, and a prince at his business."

"He is called 'The Killer,'" interjected the Calf, smacking his lips with unction. "It is a good name for him."

Wat Gordon urged his horse onward with great and undisguised disgust. To be sent on a dangerous mission with three such arrant rascals told him the value that his employers set upon his life. And if he had chanced at that moment to turn him about in his saddle, the evil smile of triumph which passed simultaneously over the faces of his companions might have told him still more.

The small cavalcade of four went clattering on through the dusky coolness of night, across many small wooden bridges and over multitudinous canals. It passed through villages, in which the inhabitants were already snoring behind their green blinds the unanimous antiphonal bass of the rustic just—though, as yet, it was little past nine of the clock on the great kirk tower of Amersfort, and in the city streets and in the camp every one was at the height of merriment and enjoyment.

Wafts of balmy country scents blew across the by-ways along which they went; and through the limpid gray coolness where the young leaves of the sparse hedgerow42 trees brushed his face, Wat could see that he was passing countless squares of parti-colored bloom. Miles of hyacinth, crocus, and narcissus gardens stretched away on either hand beyond the low, carefully cut Dutch hedges. Haxo the Bull rode first, showing them the way to the inn of Brederode, silently, save that every now and then he would cry a word over his shoulder, either to one of his ill-favored retinue or to an unseen watcher at some lonely cross-road.

Wat followed sullenly and fiercely, without caring much about the direction in which he was being taken. His mind, however, was preternaturally busy, going carefully over all the points of his interview with Kate, and very soon from the heights of justified indignation he fell to accusing himself of rude stupidity.

"I fear she will never look kindly on me again," he said, aloud. "This time I have certainly offended her forever."

And the thought troubled him more than all the traitorous Barras and ill-conditioned Bull Haxos in the world.

A breath of perfume blew fresh across the way from a field of dark purple bloom, and with an overpowering rush there came back to him the sweet scent of Kate's hair as for a moment he had bent over her by the window. He let the reins fall on his horse's neck, and almost cried aloud in agony at the thought of losing so great a treasure.

"And shall I never see her more," he said, "never watch the responsive blood spring redly to her cheek, never see the anger flash proudly in her eye, never (were it but for once) touch the sweet tangle of her hair?"

Wat's love-lorn melancholy might have driven him to further and yet wilder utterance had he not been conscious of a slight metallic click behind him, which certainly did not come from the hoofs of the horses. He43 turned sharply at the sound and caught Haxo's Calf with a pistol in his right hand, and the Killer with his long butcher's knife bare and uplifted. Haxo himself was riding unconcernedly on in front. Wat quickened the pace of his horse, and rode alongside the Bull.

"Sir Butcher," he said, calmly, "do your men behind there wish to have their weapons ready in case of meeting the enemy, or do they perchance desire to flesh them in my back? It may seem a trifling matter to trouble you with, and of no great consequence, nevertheless I should somewhat like to ascertain their intentions."

Haxo glanced behind him. The Calf and the Killer were closing in upon Wat.

"Varlets," cried Haxo, in a terrible voice, "put your weapons in your belts, ride wide apart and far behind, or I will send you both quick to hell!"

The men fell asunder at the words, and for a mile or two only the sound of the horses' feet pounding the hard paven road came to Wat's ears. But he did not again return to that entrancing dream of Kate, her beauty, and her hard-heartedness which had so nearly led to his destruction. Yet, nevertheless, whatever he said or did, he remained through all that followed conscious of his love for her, and for the remainder of the night the desire of getting back to Amersfort in order to see her sharpened every faculty and kept every sense on the alert.

More than once during the night Haxo endeavored to enter into conversation, but Wat, indignant at the cowardly attempt on his life (for so he was bound to consider it), waved him peremptorily aside.

"Do your duty without further words," he said; "lead on directly to the inn of Brederode."

It was long past the gloaming, and already wearing nigh to the watershed of the night, before the perfectly flat country of marsh and polder through which they44 had been riding gave place to a district in which the undulations of the surface were distinctly felt beneath the horses' feet. Here, also, the hard-baked, dusty roads gave place to softer and more loosely knit tracks of sand, on which the iron-shod hoofs made no sound. They were, in fact, fast approaching that broad belt of dunes which shuts off the rich, flower-covered nurseries of Haarlem from the barren, heathy wastes along the borders of the Northern Sea.

On their right they passed the dark walls of the castle of Brederode, and pursued their way to the very edge of the lofty dunes, which at this point are every year encroaching upon the cultivated fields. Presently they came to a long, low, white building surrounded by dark hedges, which in the coolness of the night sent out a pleasant odor of young beech leaves. The court-yard was silent, the windows black. Not a ray of light was visible anywhere.

Walter Gordon rode directly up to the door. He felt with his hand that it stood open to the wall, and that a dark passage yawned before him. Instinctively he drew back a little way to decide what he should do. With an unknown house before him and a cut-throat crew behind, he judged that he would be wiser to proceed with extreme caution.