Title: Artists and Arabs; Or, Sketching in Sunshine

Author: Henry Blackburn

Release date: April 14, 2014 [eBook #45380]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from page images generously

provided by the Internet Archive

CONTENTS

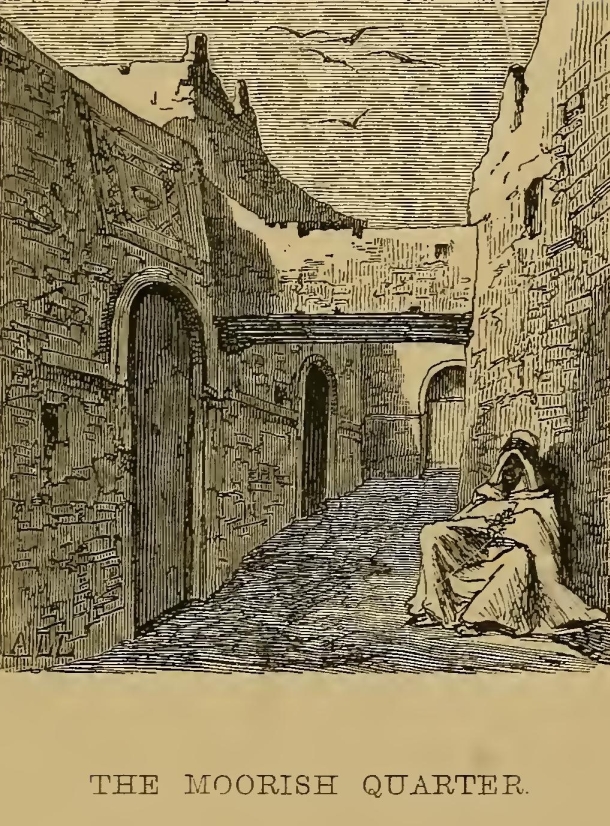

CHAPTER III. THE MOORISH QUARTER—OUR STUDIO.

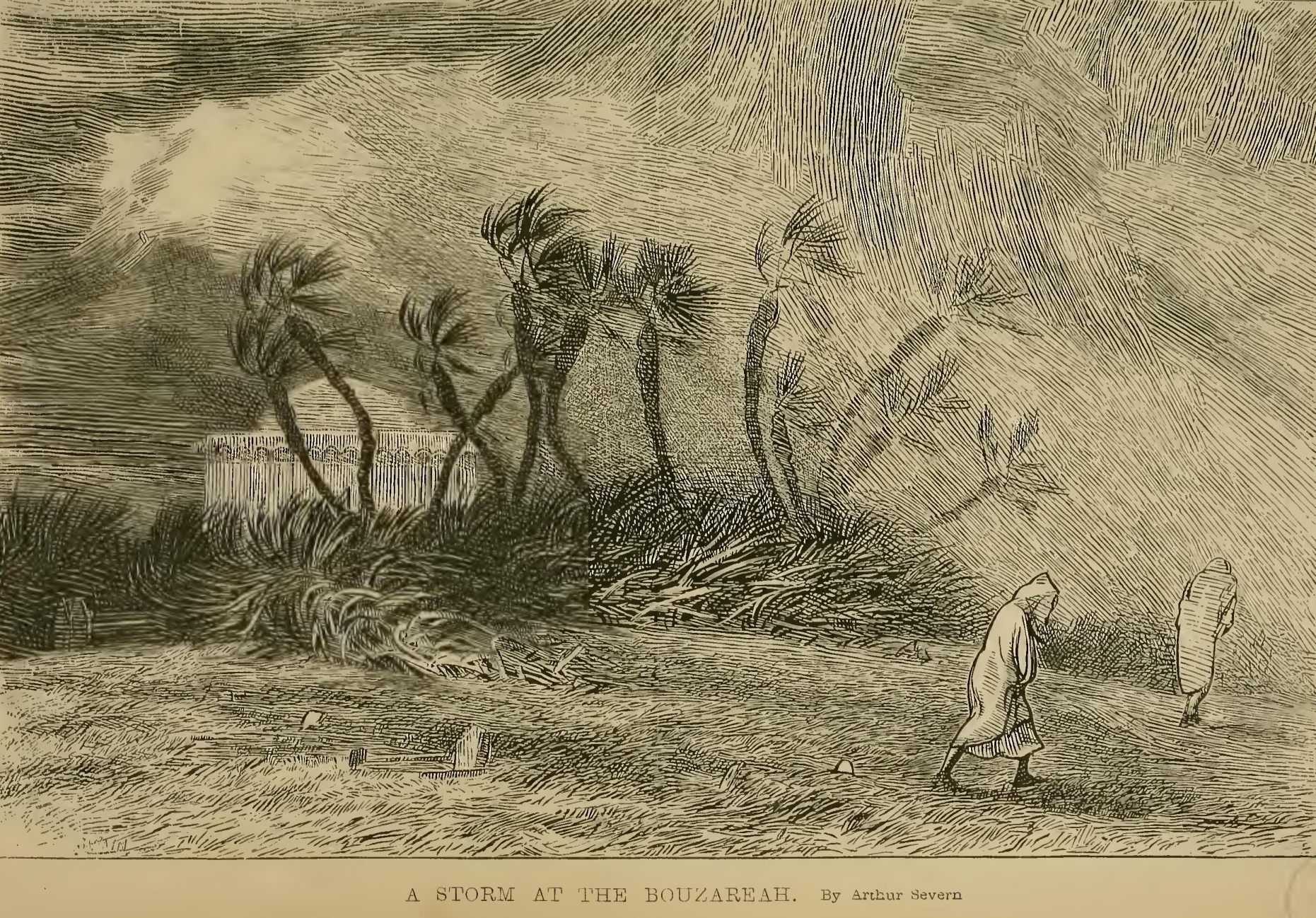

CHAPTER VI. THE BOUZAREAH—A STORM.

CHAPTER VII. BLIDAH—MEDEAH—THE ATLAS MOUNTAINS.

CHAPTER VIII. KAB YLIA—THE FORT NAPOLÉON.

CHAPTER IX. 'WINTER SWALLOWS.'

The advantage of winter studios abroad, and the value of sketching in the open air; especially in Algeria.

'The best thing the author of a book can do, is to tell the reader, on a piece of paper an inch square, what he means by it.'—Athenaeum.

Y the middle of the month of July, the Art season in London was on the wane, and by the end of August the great body of English artists had dispersed, some, the soundest workers perhaps, to the neighbourhood of Welsh mountains and English homesteads, to—'The silence of thatched cottages and the voices of blossoming fields.'

From the Tweed to the Shetland Isles, they were thick upon the hills; in every nook and corner of England, amongst the cornfields and upon the lakes; in the valleys and torrent beds of Wales, the cry was still 'they come.'

On the continent, both artists and amateurs were everywhere. Smith toiling across the Campagna with the thermometer at 95 (his reward a quiet pipe at the 'café Greco' when the sun goes down) is but a counterpart of a hundred other Smiths scattered abroad. In the galleries of Florence and Rome no more easels could be admitted, and in Switzerland and Savoy the little white tents and 'sun-umbrellas' glistened on the mountain side. Brown might be seen rattling down an arrête from the Flegére, with his matériel swung across his back, like a carpenter's basket, after a hard day's work sketching the Aiguilles that tower above the valley of Chamounix; and Jones, with his little wife beside him, sitting under the deep shade of the beech-trees in the valley of Sixt.

We were a sketching party, consisting of two, three or four, according to convenience or accident, wandering about and pitching our tent in various places away from the track of tourists; we had been spending most of the summer days in the beautiful Val d'Aosta (that school for realistic work that a great teacher once selected for his pupil, giving him three months to study its chesnut groves, 'to brace his mind to a comprehension of facts'); we had prolonged the summer far into autumn on the north shore of the Lago Maggiore, where from the heights above the old towns of Intra and Pallanza we had watched its banks turn from green to golden and from gold to russet brown. The mountains were no longer en toilette, as the French express it, and the vineyards were stripped of their purple bloom; the wind had come down from the Simplon in sudden and determined gusts, and Monte Rosa no longer stood alone in her robe of white; the last visitor had left the Hôtel de l'Univers at Pallanza, and our host was glad to entertain us at the rate of four francs a day 'tout compris'—when the question came to us, as it does to so many other wanderers in Europe towards the end of October, where to go for winter quarters, where to steal yet a further term of summer days.

Should we go again to Spain to study Velasquez and Murillo, should we go as usual to Rome; or should we strike out a new path altogether and go to Trebizond, Cairo, Tunis, or Algeria?

There was no agreeing on the matter, diversity of opinion was very great and discussion ran high (the majority we must own, having leanings towards Rome and chic; and also 'because there would be more fun'); so, like true Bohemians, we tossed for places and the lot fell upon Algeria.

The next morning we are on the way. Trusting ourselves and our baggage to one of those frail-looking little boats with white awnings, that form a feature in every picture of Italian lake scenery, and which, in their peculiar motion and method of propulsion (the rower standing at the stern and facing his work), bear just sufficient resemblance to the Venetian gondola to make us chafe a little at the slow progress we make through the smooth water, we sit and watch the receding towers of Pallanza, as it seems, for the livelong day. There is nothing to relieve the monotony of motion, and scarcely a sound to break the stillness, until we approach the southern shore, and it becomes a question of anxiety as to whether we shall really reach Arona before sundown. But the old boatman is not to be moved by any expostulation or entreaty, nor is he at all affected by the information that we run great risk of losing the last train from Arona; and so we are spooned across the great deep lake at the rate of two or three miles an hour, and glide into the harbour with six inches of water on the flat-bottom of the boat amongst our portmanteaus.

From Arona to Genoa by railway, and from Genoa to Nice by the Cornice road—that most beautiful of all drives, where every variety of grandeur and loveliness of view, both by sea and land, seems combined, and from the heights of which, if we look seaward and scan the southern horizon, we can sometimes trace an irregular dark line, which is Corsica—past Mentone and Nice, where the 'winter swallows' are arriving fast; making a wonderful flutter in their nests, all eagerness to obtain the most comfortable quarters, * and all anxiety to have none but 'desirable' swallows for neighbours. This last is a serious matter, this settling down for the winter at Nice, for it is here that the swallows choose their mates, pairing off wonderfully in the springtime, like grouse-shooting M.P.s in August.

* Necessary enough, to be protected from the cold blasts

that sweep down the valleys, as many invalids know to their

cost, who have taken houses or lodgings hastily at Nice.

A few hours' journey by railway and we are at Marseilles, where (especially at the 'Grand Hotel') it is an understood and settled thing that every Englishman is on his way, to or from Italy or India, and it requires considerable perseverance to impress upon the attendants that the steamer which sails at noon for Algiers is the one on which our baggage is to be placed, and it is almost impossible to persuade the driver of a fiacre that we do not want to go by the boat just starting for Civita Vecchia or Leghorn.

On stepping on board it almost seems as if there were some mistake, for we appear to be the only passengers on the after deck, and to be looked upon with some curiosity by the swarthy half-naked crew, who talk together in an unknown tongue; notwithstanding that at the packet office in the town we were informed that we could not secure berths for certain.

We have several hours to wait and to look about us, for the mail is not brought on board until three in the afternoon, and it is half-past, before the officials have kissed each other on both cheeks and we are really moving off—threading our way with difficulty through the mass of shipping which hems us in on all sides.

The foredeck of the Akhbar is one mass of confusion and crowding, but the eye soon detects the first blush of oriental colour and costume, and on nearer inspection it is easy to distinguish a few white bournouses moving through the crowd. There are plenty of Zouaves in undress uniforms, chiefly young men, with a superfluity of medals and the peculiar swagger which seems inseparable from this costume; others old and bronzed, who have been to Europe on leave and are returning to join their regiments. Some parting scenes we witness between families of the peasant order, of whom there appear to be a number on board, and their friends who leave in the last boat for the shore. These, one and all, take leave of each other with a significant 'au revoir,' which is the key-note to the whole business, and tells us (who are not studying politics and have no wish or intention, to trouble the reader with the history or prospects of the colony) the secret of its ill-success, viz.:—that these colonists intend to come back, and that they are much too near home in Algeria.

Looking down upon the fore-deck, as we leave the harbour of Marseilles, there seems scarcely an available inch of space that is not encumbered with bales and goods of all kinds; with heaps of rope and chain, military stores, piles of arms, cavalry-horses, sheep, pigs, and a prodigious number of live fowls.

On the after-deck there are but six passengers, there is a Moorish Jew talking fluently with a French commercial traveller, a sad and silent officer of Chasseurs with his young wife, and two lieutenants who chatter away with the captain; the latter, in consideration of his rank as an officer in the Imperial Marine, leaving the mate to take charge of the vessel during the entire voyage. This gentleman seems to the uninitiated to be a curious encumbrance, and to pass his time in conversation, in sleep, and in the consumption of bad cigars. He is 6 a disappointed man' of course, as all officers are, of whatever nation, age, or degree.

The voyage averages forty-eight hours, but is often accomplished in less time on the southward journey. It is an uncomfortable period even in fine weather, just too long for a pleasure trip, and just too short to settle down and make up one's mind to it, as in crossing the Atlantic. Our boat is an old Scotch screw, which has been lent to the Company of the Messageries Impériales for winter duty—the shaft hammering and vibrating through the saloon and after-cabins incessantly for the first twenty-four hours, whilst she labours against a cross sea in the Gulf of Lyons, indisposes' the majority of the company, and the captain dines by himself; but about noon on the next day it becomes calm, and the Akhbar steams quietly between the Balearic Islands, close enough for us to distinguish one or two churches and white houses, and a square erection that a fellow-traveller informs us is the work of the 'Majorca Land, Compagnie Anglaise.'

In the following little sketch we have indicated the appearance in outline of the two islands of Majorca and Minorca as we approach them going southward, passing at about equal distances between the islands.

The sea is calm and the sky is bright as we leave the islands behind us, and the Akhbar seems to skim more easily through the deep blue water, leaving a wake of at least a mile, and another wake in the sky of sea gulls, who follow us for the rest of the voyage in a graceful undulating line, sleeping on the rigging at night unmolested by the crew, who believe in their good omen.

On the second morning on coming on deck we find ourselves in the tropics, the sky is a deep azure, the heat is intense, and the brightness of everything is wonderful. The sun's rays pour down on the vessel, and their effect on the occupants of the fore-deck is curious to witness. The odd heaps of clothing that had lain almost unnoticed during the voyage suddenly come to life, and here and there a dark visage peeps from under a tarpaulin, from the inside of a coil of rope, or from a box of chain, and soon the whole vessel, both the fore and after-deck, is teeming with life, and we find at least double the number of human beings on board that we had had any idea of at starting.

But the interest of every one is now centred on a low dark line of coast, with a background of mountains, which every minute becomes more defined; and we watch it until we can discern one or two of the highest peaks, tipped with snow. Soon we can make out a bright green, or rather as it seems in the sunlight, a golden shore, set with a single gem that sparkles in the water. Again it changes into the aspect of a little white pyramid or triangle of chalk on a green shore shelving to the sea, next into an irregular mass of houses with flat roofs, and mosques with ornamented towers and cupolas, surrounded and surmounted by grim fortifications, which are not Moorish; and in a little while we can distinguish the French houses and hotels, a Place, a modern harbour and lighthouse, docks, and French shipping, and one piratical-looking craft that passes close under our bows, manned by dark sailors with bright red sashes and large earrings, dressed like the fishermen in the opera of Mas-aniello. And whilst we are watching and taking it all in, we have glided to our moorings, close under the walls of the great Mosque (part of which we have sketched from this very point of view); and are surrounded by a swarm of half-naked, half-wild and frantic figures, who rush into the water vociferating and imploring us in languages difficult to understand, to be permitted to carry the Franks' baggage to the shore.

Taking the first that comes, we are soon at the landing steps and beset by a crowd of beggars, touters, idlers and nondescripts of nearly every nation and creed under heaven.

'Ah oui, c'est qu'elle est belle avec ces châteaux forts,

Couchés dans les près verts, comme les géants morts!

C'est qu'elle est noble, Alger la fille du corsaire!

Un réseau de murs blancs la protège et l'enserre.'

HE first view of the town of Algiers, with its pretty clusters of white houses set in bright green hills, or as the French express it, 'like a diamond set in emeralds,' the range of the lesser Atlas forming a background of purple waves rising one above the other until they are lost in cloud—was perhaps the most beautiful sight we had witnessed, and it is as well to record it at once, lest the experience of the next few hours might banish it from memory.

It was a good beginning to have a stately barefooted Arab to shoulder our baggage from the port, and wonderful to see the load he carried unassisted. * As he winds his way through the narrow and steep slippery streets (whilst we who are shod by a Hoby and otherwise encumbered by broadcloth, have enough to do to keep pace with him, and indeed to keep our footing), it is good to see how nobly our Arab bears his load, how beautifully balanced is his lithe figure, and with what grace and ease he stalks along. As he slightly bows, when taking our three francs (his 'tariff' as he calls it), there is a dignity in his manner, and a composure about him that is almost embarrassing. How he came, in the course of circumstances, to be carrying our luggage instead of wandering with his tribe, perhaps civilization—French civilization—can answer.

* It is generally admitted, we believe, that a vegetable

diet will not produce heroes,' and there is certainly a

prejudice in England about the value of beef for navvies and

others who put muscular power into their work. It is an

interesting fact to note, and one which we think speaks

volumes for the climate of Algeria, that this gentleman

lives almost entirely on fruit, rice, and Indian corn.

The first hurried glance (as we followed our cicerone up the landing steps to the 'Hôtel de la Régence,' which faces the sea) at the dazzlingly white flat-roofed houses without windows, at the mosques with their gaily painted towers, at the palm-trees and orange-trees, and at the crowd of miscellaneous costumes in which colour preponderated everywhere, gave the impression of a thorough Mahommedan city; and now as we walk down to the Place and look about us at leisure, we find to our astonishment and delight that the Oriental element is still most prominent.

The most striking and bewildering thing is undoubtedly the medley that meets the eye everywhere: the conflict of races, the contrast of colours, the extraordinary brightness of everything, the glare, the strange sounds and scenes that cannot be easily taken in at a first visit; the variety of languages heard at the same time, and above all the striking beauty of some faces, and the luxurious richness of costume.

First in splendour come the Moors (traders looking like princes), promenading or lounging about under the trees, looking as important and as richly attired as was ever Caliph Haroun Alraschid.

They are generally fair and slight of figure, with false effeminate faces, closely-shaven heads covered with fez and turban, loose baggy trousers, jacket and vest of blue or crimson cloth, embroidered with gold; round their waists are rich silken sashes, and their fingers are covered with a profusion of rings. Their legs are often bare and their feet are enclosed in the usual Turkish slipper.

This is the prominent town type of Moor or Jew, the latter to be distinguished by wearing dark trousers, clean white stockings, French shoes, and a round cloth cap of European pattern. There are various grades, both of the Moors and Jews, some of course shabby and dirty enough; but the most dignified and picturesque figures are the tall dark Arabs and the Kabyles, with their flowing white bournouses, their turbans of camel's hair, and their independent noble bearing. Here we see them walking side by side with their conquerors in full military uniform and their conquerors' wives in the uniform of Le Follet, whilst white-robed female figures flit about closely veiled, and Marabouts (the Mahom-medan priests) also promenade in their flowing robes. Arab women and children lounge about selling fruit or begging furtively, and others hurry to and fro carrying burdens; and everywhere and ever present in this motley throng, the black frock-coat and chimney-pot hat assert themselves, to remind us of what we might otherwise soon be forgetting,—that we are but four days' journey from England.

There is noise enough altogether on the Place to bewilder any stranger; for besides the talking and singing, and the cries of vendors of fruit and wares, there is considerable traffic. Close to us as we sit under the trees, (so close as almost to upset the little tables in front of the cafés), without any warning, a huge diligence will come lunging on to the Place groaning under a pile of merchandise, with a bevy of Arabs on the roof, and a party of Moorish women in the 'rotonde'; presently there passes a company of Zouaves at quick step, looking hot and dusty enough, marching to their terrible tattoo; and next, by way of contrast again, come two Arab women with their children, mounted on camels, the beasts looking overworked and sulky; they edge their way through the crowd with the greatest nonchalance, and with an impatient croaking sound go shambling past.

The 'Place Royale' faces the north, and is enclosed on three sides with modern French houses with arcades and shops, and when we have time to examine their contents, we shall find them also principally French. Next door to a bonnet-shop there is certainly the name of Mustapha over the door, and in the window are pipes, coral, and filagree work exposed for sale; but most of the goods come from France. Next door again is a French café, where Arabs, who can afford it, delight in being waited upon by their conquerors with white aprons and neck-ties.

The background of all this is superb: a calm sunlit sea, white sails glittering and flashing, and far to the eastward a noble bay, with the Kabyle mountains stretching out their arms towards the north.

At four o'clock the band plays on the Place, and as we sit and watch the groups of Arabs and Moors listening attentively to the overture to 'William Tell,' or admiringly examining the gay uniforms and medals of the Chasseurs d'Afrique—as we see the children of both nations at high romps together—as the sweet sea-breeze that fans us so gently, bears into the newly constructed harbour together, a corvette of the Imperial Marine and a suspicious-looking raking craft with latteen sails—as Marochetti's equestrian statue of the Duke of Orleans, and a mosque, stand side by side before us—we have Algiers presented to us in the easiest way imaginable, and (without going through the ordeal of studying its history or statistics) obtain some idea of the general aspect of the place and of the people, and of the relative position of conquerors and conquered.

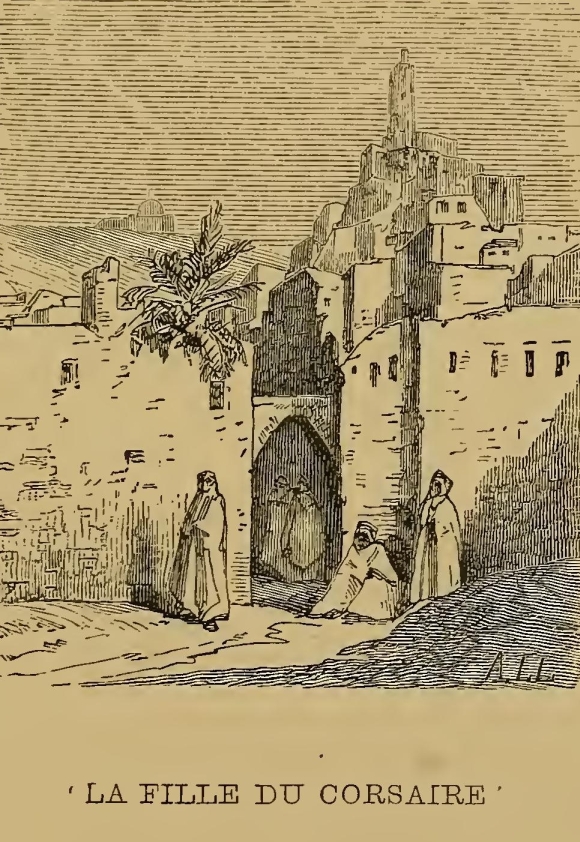

As our business is principally with the Moorish, or picturesque side of things, let us first look at the great Mosque which we glanced at as we entered the harbour, and part of which we have sketched for the reader.

Built close to the water's edge, so close that the Mediterranean waves are sapping its foundations—with plain white shining walls, nearly destitute of exterior ornament, it is perhaps 'the most perfect example of strength and beauty, and of fitness and grace of line, that we shall see in any building of this type. * It is thoroughly Moorish in style, although built by a Christian, if we may believe the story, of which there are several versions; how the Moors in old days took captive a Christian architect, and promised him his liberty on condition of his building them a mosque; how he, true to his own creed, dexterously introduced into the ground plan the form of a cross; and how the Moors, true also to their promise, gave him his liberty indeed, but at the cannon's mouth through a window, seaward.

* This beautiful architectural feature of the town has not

escaped the civilizing hand of the Frank; the last time we

visited Algiers we found the oval window in the tower gone,

and in its place an illuminated French clock!

The general outline of these mosques is familiar to most readers, the square white walls pierced at intervals with quaint-shaped little windows, the flat cupola or dome, and the square tower often standing apart from the rest of the structure as in the little vignette on our title-page, like an Italian campanile. Some of these towers are richly decorated with arabesque ornamentation,' and glitter in the sun with colour and gilding, but the majority of the mosques are as plain and simple in design as shown in our large sketch.

Here, if we take off our shoes, we may enter and hear the Koran read, and we may kneel down to pray with Arabs and Moors; religious tolerance is equally exercised by both creeds. Altogether the Mahommedan places of worship seem by far the most prominent, and although there is a Roman Catholic church and buildings held by other denominations of Christians, there is none of that predominant proselytizing aspect which we might have expected after thirty years' occupation by the French! At Tetuan, for instance, where the proportion of Christians to Mahommedans is certainly smaller, the 'Catholic church' rears its head much more conspicuously.

In Algiers the priestly element is undoubtedly active, and Soeurs de Charité are to be seen everywhere, but the buildings that first strike the eye are not churches but mosques; the sounds that become more familiar to the ear than peals of bells, are the Muezzin's morning and evening salutation from the tower of a mosque, calling upon all true believers to—

'Come to prayers, come to prayers,

It is better to pray than to sleep.'

The principal streets in Algiers lead east and west from the Place to the principal gates, the Bab-Azoun and the Bab-el-Oued. They are for the most part French, with arcades like the Rue de Rivoli in Paris; many of the houses are lofty and built in the style perhaps best known as the 'Haussman.' Nearly all the upper town is still Moorish, and is approached by narrow streets or lanes,—steep, slippery, and tortuous, * which we shall examine by-and-bye.

* It may be interesting to artists to learn that in this

present year 1868, most of the quaint old Moorish streets

and buildings are intact—neither disturbed by earthquakes

nor 'improved' out of sight.

The names of some of the streets are curious, and suggestive of change. Thus we see the 'Rue Royale,' the 'Rue Impériale there is, or was until lately, a 'Place Nationale,' and one street is still boldly proclaimed to be the 'Rue dé la Révolution'!

In passing through the French quarter, through the new wide streets, squares and inevitable boulevards, the number of shops for fancy goods and Parisian wares, especially those of hairdressers and modistes, seems rather extraordinary; remembering that the entire European population of Algeria, agricultural as well as urban, is not much more than that of Brighton. In a few shops there are tickets displayed in different languages, but linguists are rare, and where there are announcements of the labels have generally a perplexing, composite character, like the inscription on a statue at the Paris Exhibition of 1867, which ran thus 'Miss Ofelia dans Amlet.'

Before we proceed further, let us glance at the general mode of living in Algiers, speaking first of the traveller who goes to the hotels.

The ordinary visitor of a month or two will drop down pleasantly enough into the system of hotel life in Algiers; and even if staying for the winter he will probably find it more convenient and amusing to take his meals in French fashion at the hotels, ringing the changes between three or four of the best, and one or two well-known cafés, There is generally no table-d'hôte, but strangers can walk in and have breakfast or dine very comfortably at little tables 'a part,' at a fixed hour and at a moderate price. The rooms are pleasant, cool, and airy, with large windows open to the sea.

Everything is neatly and quietly served, the menu is varied enough, with good French dishes and game in abundance; the hosts being especially liberal in providing those delicious little birds that might be larks or quails,—which in Algiers we see so often on the table and so seldom on the wing.

Half the people that are dining at the 'Hôtel d'Orient' to-day are residents or habitués; they come in and take their accustomed places as cosily, and are almost as particular and fastidious, as if they were at their club.

There is the colonel of a cavalry regiment dining alone, and within joking distance, five young officers, whose various grades of rank are almost as evident from their manner as from the number of stripes on their bright red kepis ranged on the wall of the salon. A French doctor and his wife dine vis-à-vis, at one table, a lady solitaire at another; some gentlemen, whose minds are tuned to commerce, chatter in a corner by themselves; whilst a group of newly-arrived English people in the middle of the room, are busily engaged in putting down the various questions with which they intend to bore the viceconsul on the morrow, as if he were some good-natured house-agent, valet-de-place, and interpreter in one, placed here by Providence for their especial behoof. But it is all very orderly, sociable, and comfortable, and by no means an unpleasant method of living for a time.

There is the cercle, the club, at which we may dine sometimes; there are those pretty little villas amongst the orange-trees at Mustapha Supérieure, where we may spend the most delightful evenings of all; and there are also the Governor's weekly balls, soirées at the consulate, and other pleasant devices for turning night into day, in Algiers as everywhere else—which we shall be wise if we join in but sparingly. And there are public amusements, concerts, balls, and the theatre—the latter with a company of operatic singers with weak lungs, but voices as sweet as any heard in Italy; and there are the moonlight walks by the sea, to many the greatest delight of all.

The ordinary daily occupations are decidedly social and domestic; and it may be truly said that for a stranger, until he becomes accustomed to the place, there is very little going on.

You must not bathe, for instance, on this beautiful shelving shore. 'Nobody bathes, it gives fever,' was the invariable answer to enquiries on this subject, and though it is not absolutely forbidden by the faculty, there are so many restrictions imposed upon bathers that few attempt it; moreover, an Englishman is not likely to have brought an acrobatic suit with him, nor will he easily find a 'costume de bain' in Algiers.

There is very little to do besides wander about the town, or make excursions in the environs or into the interior (in which latter case it is as well to take a fowling-piece, as there is plenty of game to be met with); and altogether we may answer a question often asked about Algiers as to its attractions for visitors, that it has not many (so called), for the mere holiday lounger.

But for those who have resources of their own, for those who have work to do which they wish to do quietly, and who breathe more freely under a bright blue sky, Algiers seems to us to be the place to come to.

The 'bird of passage,' who has unfortunately missed an earthquake, often reports that Algiers is a little dull; but even he should not find it so, for beyond the 'distractions' we have hinted at, there is plenty to amuse him if he care little for what is picturesque. There are (or were when we were there), a troop of performing Arabs of the tribe of 'Beni Zouzoug,' who performed nightly the most hideous atrocities in the name of religious rites: wounding their wretched limbs with knives, eating glass, holding burning coals in their mouths, standing on hot iron until the feet frizzled and gave forth sickening odours, and doing other things in an ecstacy of religious frenzy which we could not print, and which would scarcely be believed in if we did. *

* Since writing the above, we observe that these Arabs (or a

band of mountebanks in their name), have been permitted to

perform their horrible orgies in Paris and London, and that

young ladies go in evening dress to the 'stalls' to witness

them.

There are various Moorish ceremonies to be witnessed. There are the sacrifices at the time of the Ramadhan, when the negro priestesses go down to the water side and offer up beasts and birds; the victims, after prolonged agonies which crowds assemble to witness, being finally handed over to a French chef de cuisine.

There are the mosques to be entered barefoot, and the native courts of law to be seen. Then if possible, a Moor should be visited at home, and a glimpse obtained of his domestic economy, including a dinner without knives or forks.

An entertainment consisting entirely of Moorish dances and music is easily got up, and is one of the characteristic sights of Algiers. The young trained dancing girls, urged on to frenzy by the beating of the tom-tom, and falling exhausted at last into the arms of their masters; (dancing with that monotonous motion peculiar to the East, the body swaying to and fro without moving the feet); the uncouth wild airs they sing, their shrieks dying away into a sigh or moan, will not soon be forgotten, and many other scenes of a like nature, on which we must not dwell—for are they not written in twenty books on Algeria already?

But there are two sights which are seldom mentioned by other writers, which we must just allude to in passing.

The Arab races, which take place in the autumn on the French racecourse near the town, are very curious, and well worth seeing. Their peculiarity consists in about thirty Arabs starting off pell-mell, knocking each other over in their first great rush, their bournouses mingling together and flying in the wind, but arriving at the goal generally singly, and at a slow trot, in anything but racing fashion.

Another event is the annual gathering of the tribes, when representatives from the various provinces camp on the hills of the Sahel, and the European can wander from one tent to another and spend his day enjoying Arab hospitality, in sipping coffee and smoking everywhere the pipe of peace.

These things we only hint at as resources for visitors, if they are fortunate enough to be in Algiers at the right time; but there are one or two other things that they are not likely to miss, whether they wish to do so or not.

They will probably meet one day, in the 'Street of the Eastern Gate,' the Sirocco wind, and they will have to take shelter from a sudden fearful darkness and heat, a blinding choking dust, drying up as it were the very breath of life; penetrating every cavity, and into rooms closed as far as possible from the outer air. Man and beast lie down before it, and there is a sudden silence in the streets, as if they had been overwhelmed by the sea. For two or three hours this mysterious blight pours over the city, and its inhabitants hide their heads.

Another rather startling sensation for the first time is the 'morning gun.' In the consulate, which is in an old Moorish house in the upper town, the newly arrived visitor may have been shown imbedded in the wall a large round shot, which he is informed was a messenger from one of Lord Exmouth's three-deckers in the days before the French occupation; and not many yards from it, in another street, he may have had pointed out to him certain fissures or chasms in the walls of the houses, as the havoc made by earthquakes; he may also have experienced in his travels the sudden and severe effect of a tropical thunderstorm.

Let him retire to rest with a dreamy recollection of such events in his mind, and let him have his windows open towards the port just before sunrise,—when the earthquake, and the thunder, and the bombardment, will present themselves so suddenly and fearfully to his sleepy senses, that he will bear malice and hatred against the military governor for evermore.

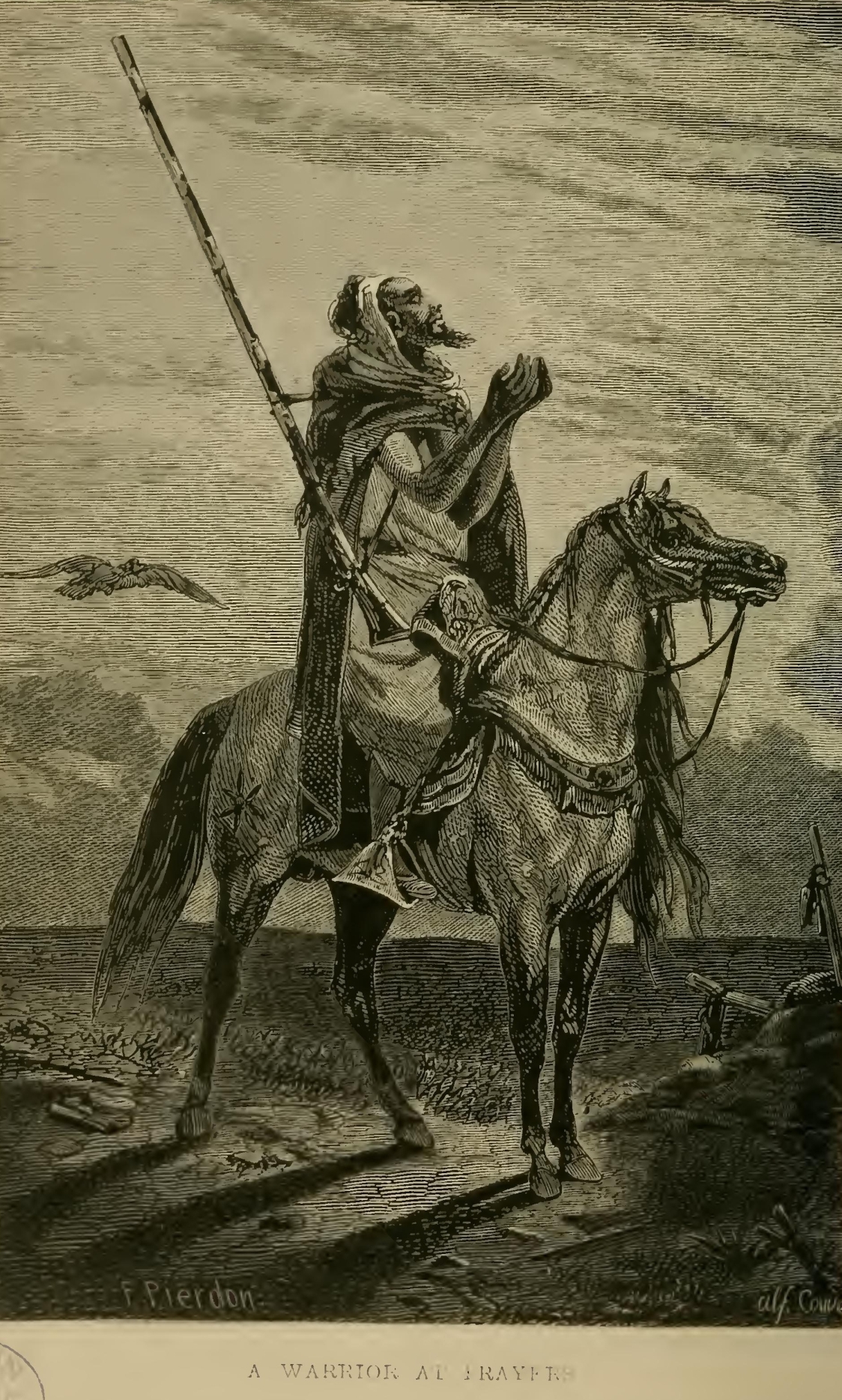

But it has roused him to see some of the sights of Algiers. Let him go out at once to the almost deserted Place, where a few tall figures wrapped in military cloaks are to be seen quietly sidling out of a door in the corner of a square under the arcades,—coming from the club where the gas is not quite extinguished, and where the little green baize tables are not yet put away for the night; * and then let him hurry out by the Bab-el-Oued and mount the fortifications, and he will see a number of poor Arabs shivering in their white bournouses, perched on the highest points of the rocks like eagles, watching with eager eyes and strained aspect for the rising of the sun, for the coming of the second Mahomet. Let him look in the same direction, eastward, over the town and over the bay to the mountains far beyond. The sparks from the chariot-wheels of fire just fringe the outline of the Kabyle Hills, and in another minute, before all the Arabs have clambered up and reached their vantage ground, the whole bay is in a flood of light. The Arabs prostrate themselves before the sun, and 'Allah il Allah' (God is great) is the burden of their psalm of praise.

* How often have we seen in the Tuileries gardens, the

bronzed heroes of Algerian wars, and perhaps have pitied

them for their worn appearance; but we shall begin to think

that something more than the African sun and long marches

have given them a prematurely aged appearance, and that

absinthe and late hours in a temperature of 90° Fahrenheit

may have something to do with it.

But Mahomet's coming is not yet, and so they return down the hill, and crowd together to a very different scene. The officers whom we saw just now leaving the Place, have arrived at the Champ de Mars, the drill-ground immediately below us, and here, in the cool morning air, they are exercising and manoeuvring troops. There are several companies going through their drill, and the bugle and the drum drown the Muezzins' voices, who, from almost every mosque and turret in the city, repeat their cry to the faithful to 'Come to prayers.'

E said, in the last chapter, that in Algiers there was very little going on for the visitor or idler; but if the traveller have anything of the artist in him, he will be delighted with the old town. If he is wise he will spend the first week in wandering about, and losing himself in the winding streets, going here, there, and everywhere on a picturesque tour of inspection. His artistic tendencies will probably lead him to spend much time in the Moorish cafés, where he may sit down unmolested (if unwelcomed) for hours on a mat, and drink his little saucer of thick, sweet coffee, for which he pays one sou, and smoke in the midst of a group of silent Moors, who may perchance acknowledge his presence by a slight gesture, and offer him their pipes, but who will more frequently affect not to see him, and sit still doing absolutely nothing, with that dignified solemnity peculiar to the East.

He will pass through narrow streets and between mysterious-looking old houses that meet over head and shut out the sky; he will jostle often in these narrow ways, soft plump objects in white gauze, whose eyes and ankles give the only visible signs of humanity; he may turn back to watch the wonderful dexterity with which a young Arab girl balances a load of fruit upon her head down to the market place; and he will, if he is not careful, be finally carried down himself by an avalanche of donkeys, driven by a negro gamin who sits on the tail of the last, threading their way noiselessly and swiftly, and carrying everything before them; * and he will probably take refuge under the ruined arch of some old mosque, whose graceful lines and rich decoration are still visible here and there, and he will in a few hours be enchanted with the place, and the more so for the reason that we have already hinted at, viz.:—that in Algiers he is let alone, that he is free to wander and 'moon' about at will, without custodian or commissionaire, or any of the tribe of 'valets de place.'

* How different from what we read of in Æothen. The cry is

not, 'Get out of the way, O old man! O virgin!—the

Englishman, he comes, he comes!' If we were to push an old

man out of the way, or, ever so little, to forget our duty

to a fair pedestrian, we should be brought up before the

Cadi, and fined and scorned, by a jury of unbelievers!

He may go into the Grand Divan; or into the streets where the embroiderers are at work, sitting in front of their open shops, amongst heaps of silks, rich stuffs and every variety of material; or where the old merchant traders, whose occupation is nearly gone, sit smoking out their lazy uncommercial lives.

He may go to the old Moorish bath, in a building of curious pattern, which is as well worth seeing as anything in Algiers; and, if an Arabic scholar, he may pick up an acquaintance or two amongst the Moors, and visit their homes when their wives are away for the day, on some mourning expedition to a suburban cemetery. He may explore innumerable crooked, irregular streets, with low doorways and carved lattices, some painted, some gilt; the little narrow windows and the grilles, being as perfectly after the old type as when the Moors held undivided possession of the city.

One old street, now pulled down, we remember well; it was the one always chosen for an evening stroll because it faced the western sea, and caught and reflected from its pavement and from its white walls, the last rosy tints of sunset, long after the cobblers and the tinkers in the lower town had lighted their little lanterns, and the cafés were flaring in the French quarter. It was steep and narrow, so steep, in fact, that steps were made in the pavement to climb it, and at the upper end there was the dome of a mosque shining in the sun. It was like the child's picture of 'Jacob's ladder,' brighter and more resplendent at each step, and ending in a blaze of gold.

We are often reminded of Spain in these old streets; there are massive wooden doors studded with iron bosses or huge nails as we see them at Toledo, and there is sometimes to be seen over them, the emblem of the human hand pointing upwards, which recalls the Gate of Justice at the entrance to the Alhambra at Granada.

The Moors cling to their old traditions, and the belief that they will some day reconquer Spain is still an article of faith. But if ever the Moors are to regain their imaginary lost possessions in Spain, they must surely be made of sterner stuff than the present race, who, judging from appearances, are little likely to do anything great.

There are little shops and dark niches where the Moors sit cross-legged, with great gourds and festoons of dried fruits hanging above and around them; the piles of red morocco slippers, the oddshaped earthenware vessels, and the wonderful medley of form and colour, resembling in variety the bazaars at Constantinople, or carrying us in imagination still further East.

Other sights and sounds we might mention, some not quite so pleasant but peculiarly Eastern; and we should not forget to note the peculiar scent of herbs and stuffs, which, mingled with the aroma of coffee and tobacco, was sometimes almost overpowering in the little Covered streets; and one odour that went up regularly on Sunday mornings in the Moorish quarter that was not incense, and which it took us a long time to discover the origin of—an Arab branding his donkeys with his monogram!

Everything we purchase is odd and quaint, irregular or curious in some way. Every piece of embroidery, every remnant of old carpet, differs from another in pattern as the leaves on the trees. There is no repetition, and herein lies its charm and true value to us. Every fabric differs either in pattern or combination of colours—it is something, as we said, unique, something to treasure, something that will not remind us of the mill. *

* The little pattern at the head of this chapter was traced

from a piece of embroidered silk, worked by the Moors.

If we explore still further we shall come to the Arab quarter, where we also find characteristic things. Here we may purchase for about thirty francs a Kabyle match-lock rifle, or an old sabre with beautifully ornamented hilt; we may, if we please, ransack piles of primitive and rusty implements of all kinds, and pick up curious women's ornaments, beads, coral, and anklets of filagree work; and, if we are fortunate, meet with a complete set or suit of harness and trappings, once the property of some insolvent Arab chief, and of a pattern made familiar to us in the illustrated history of the Cid.

In the midst of the Moorish quarter, up a little narrow street (reached in five or six minutes from the centre of the town) passing under an archway and between white walls that nearly meet overhead, we come to a low dark door, with a heavy handle and latch which opens and shuts with a crashing sound; and if we enter the courtyard and ascend a narrow staircase in one corner, we come suddenly upon the interior view of the first or principal floor, of our Moorish home.

The house, as may be seen from the illustration, has two stories, and there is also an upper terrace from which we overlook the town. The arrangement of the rooms round the courtyard, all opening inwards, is excellent; they are cool in summer, and warm even on the coldest nights, and although we are in a noisy and thickly populated part of the town, we are ignorant of what goes on outside, the massive walls keeping out nearly all sound. The floors and walls are tiled, so that they can be cleansed and cooled by water being thrown over them; the carpets and cushions spread about invite one to the most luxurious repose, tables and chairs are unknown, there is nothing to offend the eye in shape or form, nothing to offend the ear—not even a door to slam.

Above, there is an open terrace, where we sit in the mornings and evenings, and can realise the system of life on the housetops of the East. Here we can cultivate the vine, grow roses and other flowers, build for ourselves extempore arbours, and live literally in the open air.

From this terrace we overlook the flat roofs of the houses of the Moorish part of the city, and if we peep over, down into the streets immediately below us, a curious hum of sounds comes up. Our neighbours are certainly industrious; they embroider, they make slippers, they hammer at metal work, they break earthenware and mend it, and appear to quarrel all day long, within a few feet of us; but as we sit in the room from which our sketch is taken, the sounds become mingled and subdued into a pleasant tinkle which is almost musical, and which we can, if we please, shut out entirely by dropping a curtain across the doorway.

Our attendants are Moorish, and consist of one old woman, whom we see by accident (closely veiled) about once a month, and a bare-legged, bare-footed Arab boy who waits upon us. There are pigeons on the roof, a French poodle that frequents the lower regions, and a guardian of our doorstep who haunts it day and night, whose portrait is given at Chapter V.

Here we work with the greatest freedom and comfort, without interruption or any drawbacks that we can think of. The climate is so equal, warm, and pleasant—even in December and January—that by preference we generally sit on the upper terrace, where we have the perfection of light, and are at the same time sufficiently protected from sun and wind.

At night we sleep almost in the open air, and need scarcely drop the curtains at the arched doorways of our rooms; there are no mosquitoes to trouble us, and there is certainly no fear of intrusion. There is also perfect stillness, for our neighbours are at rest soon after sundown.

Such is a general sketch of our dwelling in Algiers; let us for a moment, by way of contrast, return in imagination to London, and picture to ourselves our friends as they are working at home.

It is considered very desirable, if not essential, to an artist, that his immediate surroundings should be in some sort graceful and harmonious, and it is a lesson worth learning, to see what may be done, with ingenuity and taste, towards converting a single room, in a dingy street, into a fitting abode of the arts.

We know a certain painter well, one whose studio it is always a delight to enter, and whose devotion to Art (both music and painting) for its own sake has always stood in the way of his advancement and pecuniary success. He has converted a room in the neighbourhood of Gower Street into a charming nook where colour, form, and texture are all considered in the simplest details of decoration, where there is nothing inharmonious to eye or ear, but where perhaps the sound of the guitar may be heard a little too often. The walls of his studio are draped, the light falls softly from above, the doorway is arched, the seats are couches or carpets on a raised daïs, a Florentine lamp hangs from the ceiling, a medley of vases, costumes, old armour, &c, are grouped about in picturesque confusion, and our friend, in an easy undress of the last century, works away in the midst.

Not to particularize further, let the reader consider for a moment what one step beyond his own door brings about, on an average winter's day. A straight, ungraceful, colourless costume of the latter half of the nineteenth century which he must assume, a hat of the period, an umbrella raised to keep off sleet and rain, and for landscape a damp, dreary, muddy, blackened street, with a vista of areas and lamp-posts, and, if perchance he be going to the Academy, a walk through the parish of St. Giles!

Perhaps the most depressing prospect in the world, is that from a Gower Street doorstep on a November morning about nine o'clock; but of this enough. We think of our friend as we sit out here on our terrasse—sheltering ourselves on the same day, at the same hour, from the sun's rays—we think of him painting Italian scenes by the light of his gas 'sun-burner,' and wish he would come out to Algiers. 'Surely,' we would say to him, 'it is something gained, if we can, ever so little, harmonize the realities of life with our ideal world—if we can, without remark, dress ourselves more as we dress our models, and so live, that one step from the studio to the street shall not be the abomination of desolation.' *

* It would be obviously in bad taste for Europeans to walk

in the streets of Algiers, en costume Maure; but we may

make considerable modifications in our attire in an oriental

city, to our great comfort and peace of mind.

Let us turn again to Nature and to Light, and transport the reader to a little white house, overlooking a beautiful city, on the North African shore, where summer is perpetual and indoor life the exception; and draw a picture for him which should be fascinating and which certainly is true.

Algiers, Sunrise, December 10.

The mysterious, indefinable charm of the first break of day, is an old and favourite theme in all countries and climates, and one on which perhaps little that is new can be said. In the East it is always striking, but in Algiers it seems to us peculiarly so; for sleeping, or more often lying awake, with the clear crisp night air upon our faces, it comes to our couch in the dreamiest way imaginable—instead of being clothed (as poets express it) with the veil of night, a mantle seems rather to be spread over us in the morning; there is perfect quiet at this hour, and we seem to be almost under a spell not to disturb the stillness—the dawn whispers to us so softly and soothingly that we are powerless to do ought but watch or sleep.

The break of day is perhaps first announced to us by a faint stream of light across the courtyard, or the dim shadow of a marble pillar on the wall. In a few minutes, we hear the distant barking of a dog, a slight rustle in the pigeon-house above, or a solitary cry from a minaret which tells us that the city is awaking. We rouse ourselves and steal out quietly on to the upper terrace to see a sight of sights—one of those things that books tell us, rightly or wrongly, is alone worth coming from England to see.

The canopy of stars, that had encompassed us so closely during the night, as if to shut in the courtyard overhead, seems lifted again, and the stars themselves are disappearing fast in the grey expanse of sky; and as we endeavour to trace them, looking intently seaward, towards the North and East, we can just discern an horizon line and faint shadows of the 'sleeping giants,' that we know to be not far off. Soon—in about the same time that it takes to write these lines—they begin to take form and outline one by one, a tinge of delicate pearly pink is seen at intervals through their shadows, and before any nearer objects have come into view, the whole coast line and the mountains of Kabylia, stretching-far to the eastward, are flushed with rosy light, opposed to a veil of twilight grey which still hangs over the city.

Another minute or two, and our shadows are thrown sharply on a glowing wall, towers and domes come distinctly into view, housetops innumerable range themselves in close array at our feet, and we, who but a few minutes ago, seemed to be standing as it were alone upon the top of a high mountain, are suddenly and closely beleaguered. A city of flat white roofs, towers, and cupolas, relieved here and there by coloured awnings, green shutters, and dark doorways, and by little courtyards blooming with orange and citron trees—intersected with innumerable winding ways (which look like streams forcing their way through a chalk cliff)—has all grown up before our eyes; and beyond it, seaward—a harbour, and a fleet of little vessels with their white sails, are seen shining in the sun.

Then come the hundred sounds of a waking city, mingling and increasing every moment; and the flat roofs (some so close that we can step upon them) are soon alive with those quaint white figures we meet in the streets, passing to and fro, from roof to roof, apparently without restraint or fear. There are numbers of children peeping out from odd corners and loopholes, and women with them, some dressed much less scrupulously than we see them in the market place, and some, to tell the truth, entirely without the white robes aforesaid. A few, a very few, are already winding their way through the streets to the nearest mosque, but the majority are collected in groups in conversation, enjoying the sweet sea breeze, which comes laden with the perfume of orange-trees, and a peculiar delicious scent as of violets.

The pigeons on the roof-tops now plume their gilded wings and soar—not upward but downward, far away into space; they scarcely break the silence in the air, or spread their wings as they speed along.

Oh, what a flight above the azure sea!

'Quis dabat mihi pennas sicut columbæ;

the very action of flying seems repose to them.

It is still barely sunrise on this soft December morning, the day's labour has scarcely begun, the calm is so perfect that existence alone seems a delight, and the Eastern aroma (if we may so express it) that pervades the air might almost lull us to sleep again, but Allah wills it otherwise.

Suddenly—-with terrible impulse and shrill accent impossible to describe—a hurricane of women's voices succeeds the calm. Is it treachery? Is it scandal? Has Hassan proved faithless, or has Fatima fled? Oh, the screeching and yelling that succeeded to the quiet beauty of the morning! Oh, the rushing about of veiled (now all closely veiled) figures on house-tops! Oh, the weeping and wailing, and literal, terrible, gnashing of teeth! 'Tell it not upon the house-tops', (shall we ever forget it being told on the housetops? ) 'let not a whole city know thy misdeeds,' is written in the Koran, 'it is better for the faithful to come to prayers!' Merciful powers, how the tempest raged until the sun was up and the city was alive again, and its sounds helped to drown the clamour.

Let us come down, for our Arab boy now claps his hands in sign, that (on a little low table or tray, six inches from the ground) coffee and pipes are provided for the unbelievers; and like the Calendar in Eastern Story, he proceeds to tell us the cause of the tumult—a trinket taken from one wife and given to another!

Oh, Islam! that a lost bracelet or a jealous wife, should make the earth tremble so!

ROM the roof-tops of our own and the neighbouring houses we have altogether many opportunities of sketching, and making studies from life. * By degrees, by fits and starts, and by most uncertain means (such as attracting curiosity, making little presents, &c.) we manage to scrape up a distant talking acquaintance with some of the mysterious wayward creatures we have spoken of, and in short, to become almost 'neighbourly.'

* In the Exhibition of the Royal Academy of 1867, there was

a picture by Alfred Elmore, R.A., taken almost from this

spot.

But we never get much nearer than talking distance, conversing from one roof to another with a narrow street like a river flowing between us; and only once or twice during our winter sojourn, did we succeed in enticing a veiled houri to venture on our terrace and shake hands with the 'Frank.' If we could manage to hold a young lady in conversation, and exhibit sufficient admiration of her to induce her, ever so slightly, to unveil whilst we made a hasty sketch, it was about all that we could fairly succeed in accomplishing, and 'the game was hardly worth the candle:' it took, perhaps, an hour to ensnare our bird, and in ten minutes or less, she would be again on the wing. Veiled beauties are interesting (sometimes much more interesting for being veiled); but it does not serve our artistic purposes much to see two splendid black eyes and a few white robes.

However models we must have, although the profession is almost unknown in Algiers. At Naples we have only to go down to the seashore, at Rome to the steps of St. Peter's, and we find 'subjects' enough, who will come for the asking; but here, where there is so much distinctive costume and variety of race, French artists seem to make little use of their opportunities.

It takes some days before we can hear of any one who will be willing to sit, for double the usual remuneration. But they come at last, and when it gets abroad that the Franks have money and 'mean business,' we have a number of applicants, some of whom are not very desirable, and none particularly attractive.

We select 'Fatima' first, because she is the youngest and has the best costume, and also because she comes with her father and appears tractable. She is engaged at two francs an hour, which she considers poor pay.

How shall we give the reader an idea of this little creature, when she comes next morning and coils herself up amongst the cushions in the corner of our room, like a young panther in the Jardin des Plantes? Her costume, when she throws off her haïk (and with it a tradition of the Mahommedan faith, that forbids her to show her face to an unbeliever) is a rich loose crimson, jacket embroidered with gold, a thin white bodice, loose silk trowsers reaching to the knee and fastened round the waist by a magnificent sash of various colours; red morroco slippers, a profusion of rings on her little fingers, and bracelets and anklets of gold filagree work. Through her waving black hair are twined strings of coins and the folds of a silk handkerchief, the hair falling at the back in plaits below the waist.

She is not beautiful, she is scarcely interesting in expression, and she is decidedly unsteady. She seems to have no more power of keeping herself in one position or of remaining in one part of the room, or even of being quiet, than a humming top. The whole thing is an unutterable bore to her, for she does not even reap the reward—her father or husband, or male attendant, always taking the money.

She is petite, constitutionally phlegmatic, and as fat as her parents can manage to make her; she has small hands and feet, large rolling eyes—the latter made to appear artificially large by the application of henna or antimony black; her attitudes are not ungraceful, but there is a want of character about her, and an utter abandonment to the situation, peculiar to all her race. In short her movements are more suggestive of a little caged animal that had better be petted and caressed, or kept at a safe distance, according to her humour. She does one thing, she smokes incessantly and makes us cigarettes with a skill and rapidity which are wonderful.

Her age is thirteen, and she has been married six months; * her ideas appear to be limited to three or four; and her pleasures, poor creature, are equally circumscribed. She had scarcely ever left her father's house, and had never spoken to a man until her marriage. No wonder we, in spite of a little Arabic on which we prided ourselves, could not make much way; no wonder that we came very rapidly to the conclusion that the houris of the Arabian Nights, must have been dull creatures, and their 'Entertainments' rather a failure, if there were no diviner fire than this. No wonder that the Moors advocate a plurality of wives, for if one represents an emotion, a harem would scarcely suffice!

* We hear much of the perils of living too fast, and of the

preternaturally aged, worn appearance, of English girls

after two or three London seasons. What would a British

matron say to a daughter—a woman at twelve, married at

thirteen, blasée directly, and old at twenty?

We get on but indifferently with our studies with this young lady, and, to tell the truth, not too well in Fatima's good graces. Our opportunities are not great, our command of Arabic is limited, and indeed, we do not feel particularly inspired.

We cannot tell her many love stories, or sing songs set to a 'tom-tom;' we can, indeed, offer 'backshish' in the shape of tobacco and sweetmeats, or some trifling European ornament or trinket; but it is clear that she would prefer a greater amount of familiarity, and more demonstrative tokens of esteem. However, she came several times, and we succeeded in obtaining some valuable studies of colour, and 'bits,' memoranda only; but very useful, from being taken down almost unconsciously, in such a luminous key, and with a variety of reflected light and pure shadow tone, that we find unapproachable in after work.

As for sketches of character, we obtained very few of Mauresques; our subjects were, as a rule, much too restless, and we had one or two 'scenes' before we parted. On one unfortunate occasion our model insisted upon examining our work before leaving, and the scorn and contempt with which it was regarded was anything but flattering.

It nearly caused a breach between us, for, as she observed, it was not only contrary to her creed to have her likeness taken, but it would be perdition to be thus represented amongst the Franks. * We promised to be as careful of this portrait as if it were the original, and, in fact, said anything to be polite and soothing.

* For fear of the 'evil eye.' There is a strong belief

amongst Mahommedans that portraits are part of their

identity; and that the original will suffer if the portrait

receive any indignity.

On another occasion, we had been working on rather more quietly than usual for half-an-hour, and were really getting a satisfactory study of a new position, when, without apparent cause or warning of any kind, the strange, pale, passionless face, which stared like a wooden marionette, suddenly suffused with crimson, the great eyes filled with tears, the whole frame throbbed convulsively, and the little creature fell into such a passion of crying that we were fain to put by our work and question ourselves whether we had been cruel or unkind. But it was nothing: the cup of boredom had been filled to the brim, all other artifices had failed her to obtain relief from restraint, and so this apparently lethargic little being, who had it seemed, both passion and grief at command, opened the flood-gates upon us, and of course gained her end. There was no more work that day, and she got off with a double allowance of bonbons, and something like a reconciliation. She gave us her little white hand at parting—the fingers and thumbs crowded with rings, and the nails stained black with henna—but the action meant nothing; we dare not press it, it was too soft and frail, and the rings would have cut her fingers, we could only hand it tenderly back again, and bid our 'model' farewell.

We got on better afterwards with a Moorish Jewess who, for a 'consideration,' unearthed her property, * including a tiara of gold and jewels, and a bodice of silver embroidery worked on crimson velvet; we purposely reverse the position and speak of the embroidery first, because the velvet was almost hidden. She came slouching in one morning, closely wrapped in a dirty shawl, her black hair all dishevelled and half covering her handsome face, her feet bare and her general appearance so much more suggestive of one of the 'finest pisantry in the world,' that we began to feel doubtful, and to think with Beau Brummel that this must be 'one of our failures.' But when her mother had arranged the tiara in her hair, when the curtain was drawn aside and the full splendour of the Jewish costume was displayed—when, in short, the dignity and grace of a queen were before us, we felt amply rewarded.

* Many of the poorest Jewesses possess gold ornaments as

heirlooms, burying them in the ground for security, when not

in use.

The Jewish dress differs from the Mauresque entirely; it is European in shape, with high waist and flowing robes without sleeves, a square cut bodice, often of the same material as the robe itself, and a profusion of gold ornaments, armlets, necklaces, and rings. A pair of tiny velvet slippers (also embroidered) on tiny feet, complete the costume, which varies in colour, but is generally of crimson or dark velvet.

As a 'model,' although almost her first appearance in that character, this Jewish woman was very valuable, and we had little trouble after the first interview, in making her understand our wishes. But we had to pay more than in England; there were many drawbacks, and of course much waste of time. On some holydays and on all Jewish festivals, she did not make her appearance, and seemed to think nothing of it when some feast that lasted a week, left us stranded with half-done work.

Without being learned in costumes des dames, we believe, we may say, that the shape and cut of some of these dresses, and the patterns of the embroidery (old as they are) might be copied with advantage by Parisian modistes; the more we study these old patterns, the more we cannot cease to regret that the Deae ex machina, the arbiters of fashion in the city where Fashion is Queen, have not managed to infuse into the costume of the time more character and purity of design—conditions not inconsistent with splendour, and affording scope, if need be, for any amount of extravagance.

We are led irresistibly into this digression, if it be a digression, because the statuesque figure before us displays so many lines of grace and beauty that have the additional charm of novelty. We know, for instance, that the pattern of this embroidery is unique, that the artificer of that curiously twined chain of gold has been dead perhaps for ages, that the rings on her fingers and the coins suspended from her hair are many of them real art treasures. *

* The 'jewels turned out to be paste on close inspection,

but the gold filagree work, and the other ornaments, were

old, and some very valuable and rare.

The result of our studies, as far as regards Moorish women, we must admit to have been after all, rather limited and unsatisfactory. We never once lighted upon a Moorish face that moved us much by its beauty, for the simple reason that it nearly always lacked expression; anything like emotion seemed inharmonious and out of place, and to disturb the uniformity of its lines. Even those dark lustrous eyes, when lighted by passion, had more of the tiger in them, than the tragedy queen.

The perfection of beauty, according to the Moorish ideal, seems to depend principally upon symmetry of feature, and is nothing without roundness of limb and a certain flabbiness of texture. It is an ideal of repose, not to say of dulness and insipidity; a heavy type of beauty of which we obtain some idea in the illustration before us, of a young girl, about thirteen years old, of one of the tribes from the interior. The drawing is by a Frenchman, and pretends to no particular artistic excellence, but it attempts to render (and we think succeeds in rendering) the style of a Mahommedan beauty in bridal array; one who is about to fulfil her destiny, and who appears to have as little animation or intelligence as the Prophet ordained for her, being perfectly fitted (according to the Koran) to fill her place in this world or in the next. *

* It detracts a little from the romance of these things to

learn from Mrs. Evans (who witnessed, what only ladies, of

course, could witness, the robing and decorating of the

bride before marriage) the manner in which the face of a

Moorish lady is prepared on the day of marriage:

'An old woman having carefully washed the bride's face with

water, proceeded to whiten it all over with a milky-looking

preparation, and after touching up the cheeks with rouge

(and, her eyes with antimony black), bound an amulet round

the head; then with a fine camel-hair pencil, she passed a

line of liquid glue over the eyebrows, and taking from a

folded paper a strip of gold-leaf fixed it across them both,

forming one long gilt bar, and then proceeded to give a few

finishing touches to the poor lay figure before her, by

fastening two or three tiny gold spangles on the forehead!'

We cannot help thinking that this might have been an

exceptional case, especially in the matter of gilding, but

we have seen both patches and paint on Moorish features—as

indeed we have seen them in England.

Thus decked with her brightest jewels and adorned with a crown of gold, she waits to meet her lord, to be his 'light of the harem,' his 'sun and moon.' What if we, with our refined aesthetic tastes, what if disinterested spectators, vote her altogether the dullest and most uninteresting of beings? what if she seem to us more like some young animal, magnificently harnessed, waiting to be trotted out to the highest bidder? She shakes the coins and beads on her head sometimes, with a slight impatient gesture, and takes chocolate from her little sister, and is petted and pacified just as we should soothe and pacify an impatient steed; there is clearly no other way to treat her, it is the will of Allah that she should be so debased! *

* We have before spoken of the influence of beautiful forms

and harmony in colour, in our homes and surroundings; and we

feel acutely, that the picture of this Moorish woman,

intellectually, does not prove our case; but Mahomet decreed

that women should endeavour to be beautiful rather than

understand, or enjoy it.

One day we had up a tinker, an old brown grizzled Maltese, who with his implements of trade, his patchwork garments and his dirt, had a tone about him, like a figure from one of the old Dutch masters. He sat down in the corner of our courtyard against a marble pillar, and made himself quite at home; he worked with his feet as well as his hands at his grinding, he chattered, he sang, and altogether made such a clatter that we shall not be likely to forget him.

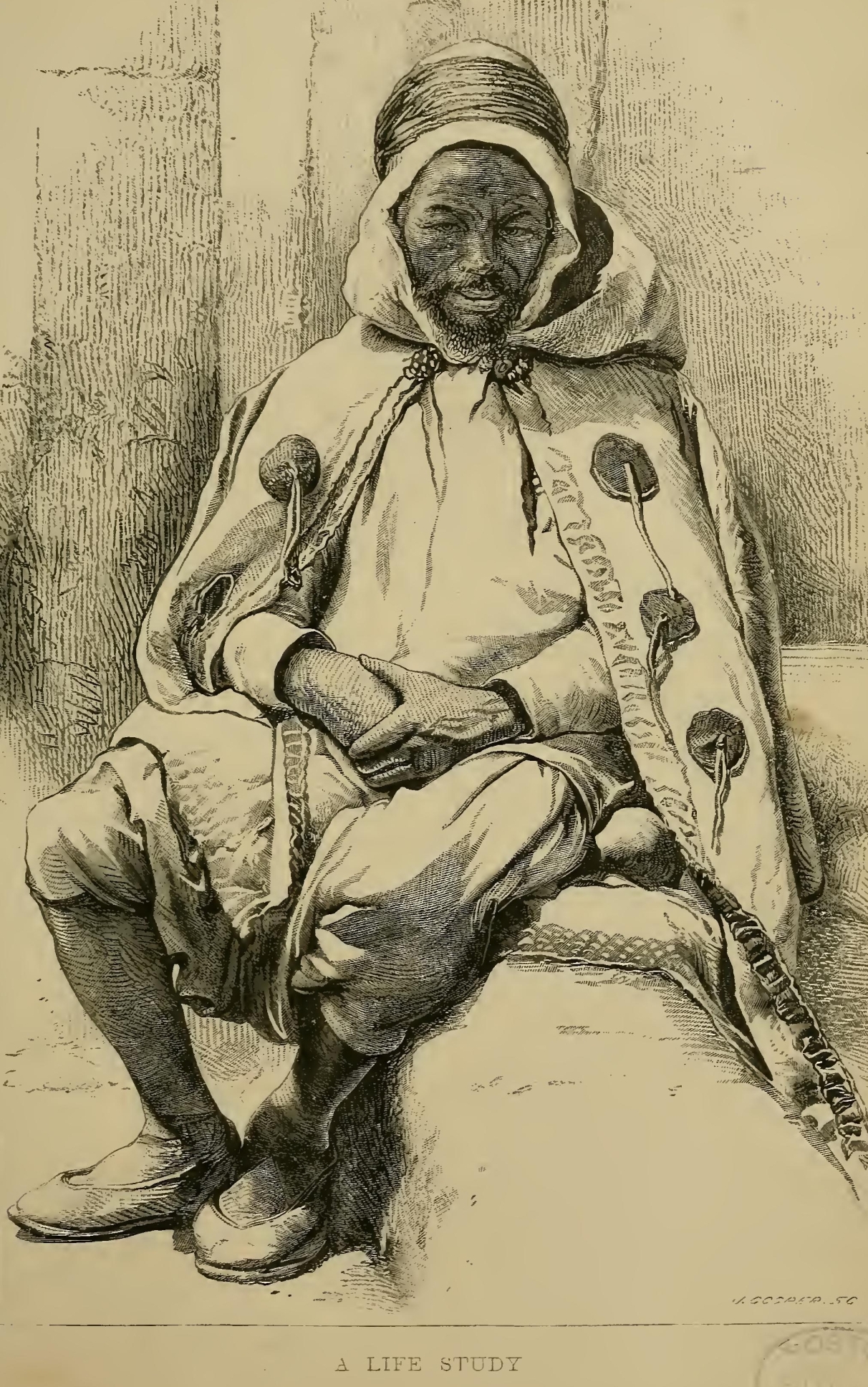

This gentleman, and the old negro that lived upon our doorstep, were almost the only subjects that we succeeded in inducing to come within doors; our other life studies were made under less favourable circumstances.

From the roof of our own house, it is true, we obtained a variety of sketches, not (as might be supposed from the illustrations and pictures with which we are all familiar) of young ladies attired as scantily as the nymphs at the Theâtre du Chatelet, standing in pensive attitudes on their housetops, but generally of groups of veiled women—old, ugly, haggard, shrill of voice, and sometimes rather fierce of aspect, performing various household duties on the roof-tops, including the beating of carpets and of children, the carrying of water-pots and the saying of prayers.

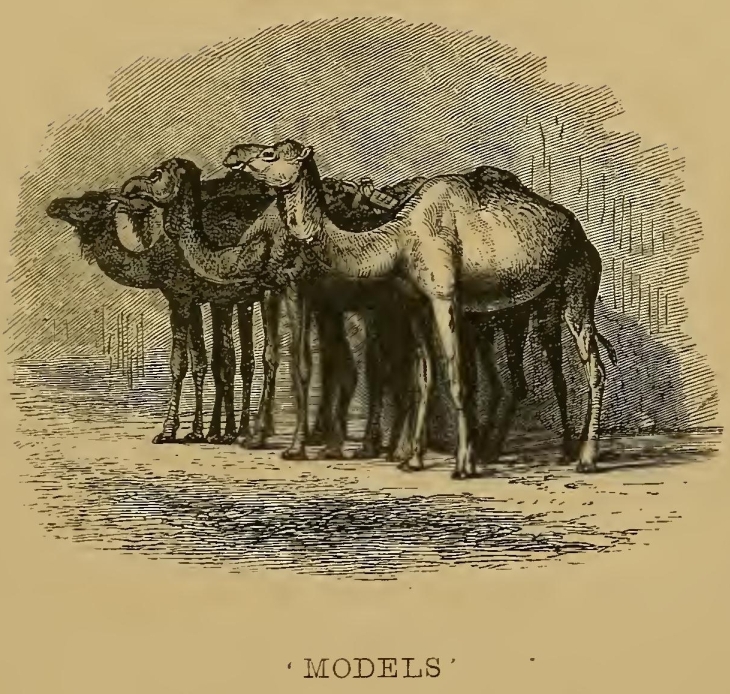

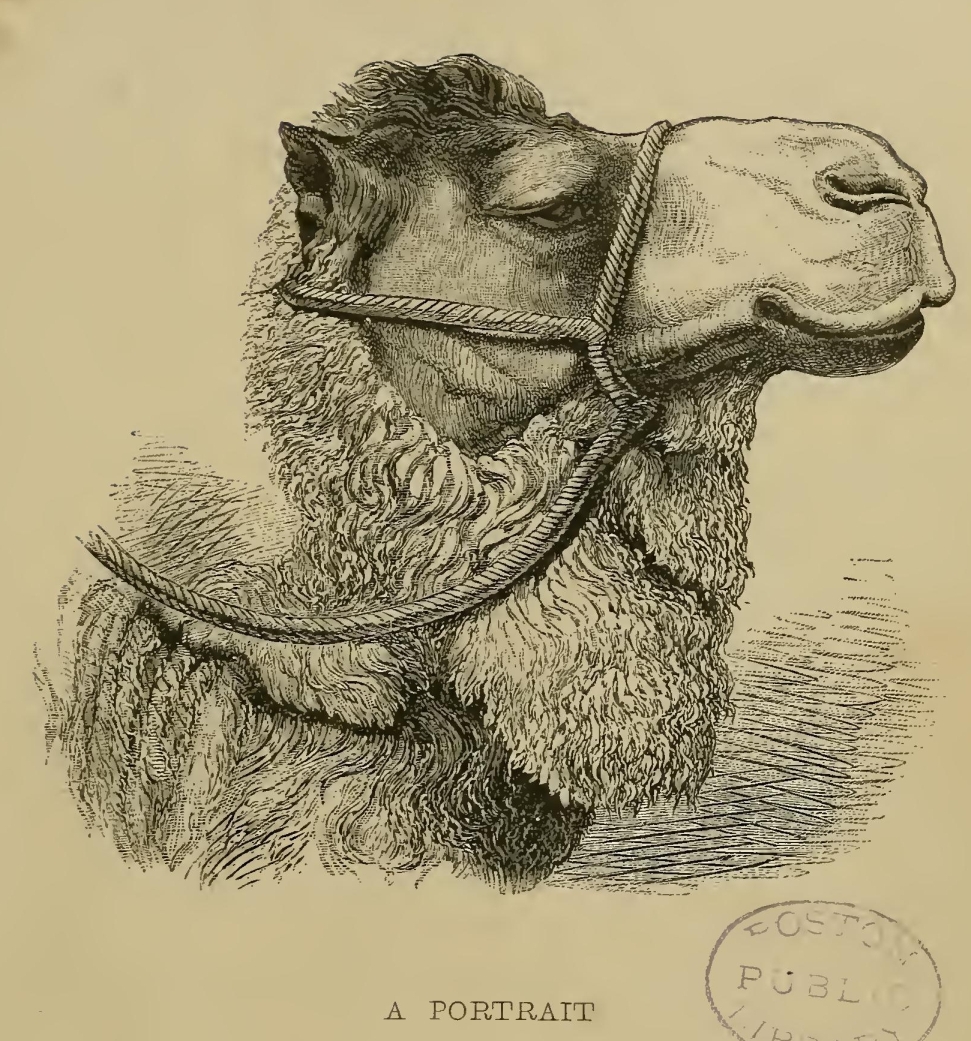

A chapter on 'Models' would not be complete without some mention of the camels, of which there are numbers to be found in the Arab quarter of the town. Some of them are splendid creatures, and as different from any exotic specimens that we can see in this country as an acclimatised palm-tree from its wild growth.

Some one tells us that these Algerian 'ships of the desert' have not the same sailing qualities, nor the same breadth of beam, as those at Cairo. But (if true) we should have to go to Cairo to study them, so let us be content. We should like to see one or two of our popular artists, who persist in painting camels and desert scenes without ever having been to the East, just sit down here quietly for one day and paint a camel's head; not flinching from the work, but mastering the wonderful texture and shagginess of his thick coat or mane, its massive beauty, and its infinite gradations of colour. Such a sitter no portrait painter ever had in England. Feed him up first, get a boy to keep the flies from him, and he will sit almost immoveably through the day. He will put on a sad expression in the morning, which will not change; he will give no trouble whatever, he will but sit still and croak.

Do we seem to exaggerate the value of such studies? We cannot exaggerate, if we take into full account, the vigorous quality which we impart into our work. And we cannot, perhaps, better illustrate our argument in favour of drawing from, what we should call, natural models, than by comparing the merits of two of the most popular pictures of our time, viz.:—Frith's 'Derby Day,' and Rosa Bonheur's 'Horse Fair?' The former pleasing the eye by its cleverness and prettiness; the latter impressing the spectator by its power, and its truthful rendering of animal life.

The difference between the two painters is probably, one, more of education than of natural gifts. But whilst the style of the former is grafted on a fashion, the latter is founded on a rock—the result of a close study of nature, chastened by classic feeling, and a remembrance it may be, of the friezes of the Parthenon.

F the various studies to be made in Algiers, there are none at the same time so quaint and characteristic, as the Moors in their own homes, seated at their own doors or benches at work, or at the numerous cafés and bazaars; and nothing seems to harmonize so well in these Moorish streets as the groups of natives (both Moors and negroes) with their bright costumes, and 'wares for sale. Colour and contrast of colour, seem to be considered, or felt, everywhere. Thus for instance, no two Orientals will walk down a street side by side, unless the colours of their costume harmonize or blend together (they seem to know it instinctively), and then there is always grey or some quiet contrasting tone for a background, and a sky of deep, deep blue. A negress will generally be found selling oranges or citrons; an Arab boy with a red fez and white turban, carrying purple fruit in a basket of leaves; and so on. The reader will think this fanciful, but it is truer than he imagines; let him come and see.

It was not at all times easy to sketch in the open street on account of the curiosity it excited; a crowd sometimes collecting until it became almost impossible to breathe. The plan was to go as often as possible to the cafés and divans, and by degrees to make friends with the Moors.

There was one café, in a street that we have been to so often, that it is as familiar to us as any in the western world; and where by dint of a little tact and a small outlay of tobacco, we managed to make ourselves quite at home, and were permitted to work away all day, comparatively unmolested. It was a narrow and steep overhanging street, crowded at all times with Moors on one side embroidering, or pretending to sell goods of various kinds; and on the opposite side there was a café, not four feet distant, where a row of about eighteen others sat and smoked, and contemplated their brethren at work. The street was always full of traffic, being an important thoroughfare from the upper to the lower town, and there were perpetually passing up and down, droves of laden donkeys; men with burdens carried on poles between them; vendors of fruit, bread, and live fowls, and crowds of people of every denomination.

In a little corner out of sight, where we were certainly rather closely packed, we used to install ourselves continually and sketch the people passing to and fro. The Moors in the café used to sit beside us all day and watch, and wait; they gave us a grave silent salutation when we took our places, and another when we left, but we never got much further with our unknown neighbours. If we can imagine a coterie in a small political club, where the open discussion of politics is, with one consent, tabooed for fear of a disturbance, and where the most frolicsome of its members play at chess for relaxation, we shall get some notion of the state of absolute decorum which existed in our little café maure.

It was very quaint. The memory of the grave quiet faces of these most polite Moorish gentlemen, looking so smooth and clean in their white bournouses, seated solemnly doing nothing, haunts us to this day. Years elapsed between our first and last visit to our favourite street, yet there they were when we came again, still doing nothing in a row; and opposite to them, the merchants who do no trade, also sitting in their * accustomed places, surrounded with the same old wares.

There was the same old negro in a dark corner making coffee, and handing it to the same customers, sitting in the same places, in the same dream.

There is certainly both art and mystery in doing nothing well which these men achieve in their peculiar lives; here they sit for years together, silently waiting, without a trace of boredom on their faces, and without exhibiting a gesture of impatience. They—the 'gentlemen' in the café on the right hand—have saved up money enough to keep life together, they have for ever renounced work, and can look on with complacency at their poorer brethren. They have their traditions, their faith, their romance of life, and the curious belief before alluded to, that if they fear God and Mahomet, and sit here long enough, they will one day be sent for to Spain, to repeople the houses where their fathers dwelt.

This corner is the one par excellence, where the Moors sit and wait. There is the 'wall of wailing' at Jerusalem; there is the 'street of waiting' in Algiers, where the Moors sit clothed in white, dreaming of heaven—with an aspect of more than content, in a state of dreamy delight achieved, apparently, more by habit of mind than any opiates—the realisation of 'Keyf'.

Not far from this street, but still in the Moorish quarter, we may witness a much more animated scene, and obtain in some respects a still better study of character and costume—at a clothes auction in the neighbourhood of the principal bazaar. If we go in the afternoon, we shall probably find a crowd collected in a courtyard, round a number of Jews who are selling clothes, silks, and stuffs, and so intent are they all on the business that is going forward, that we are able to take up a good position to watch the proceedings.

We arrived one day at this spot, just as a terrible scuffle or wrangle, was going forward, between ten or a dozen old men (surrounded by at least a hundred spectators) about the quality or ownership of some garment. The merits of the discussion were of little interest to us and were probably of little importance to anybody, but the result was in its way as interesting a spectacle as ever greeted the eye and ear, something that we could never have imagined, and certainly could never have seen, in any other land.

This old garment had magical powers, and was a treasure to us at least. It attracted the old and young, the wise and foolish, the excited combatant and the calm and dignified spectator; it collected them all in a large square courtyard with plain whitewashed walls and Moorish arcades. On one side a palm-tree drooped its gigantic leaves, and cast broad shadows on the ground, which in some places, was almost of the brightness of orange; on the other side, half in sunlight, half in shadow, a heavy awning was spread over a raised daïs or stage, and through its tatters and through the deep arcades, the sky appeared in patches of the deepest blue—blue of a depth and brilliancy that few painters have ever succeeded in depicting. It gave in a wider and truer sense, just that quality to our picture—if we may be excused a little technicality and a familiar illustration—that a broad red sash thrown across the bed of a sleeping child in Millais' picture in the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1867, gave to his composition, as many readers may remember.