Title: Oxford

Author: Robert Peel

Harry Christopher Minchin

Release date: April 1, 2014 [eBook #45290]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: David Widger and Paul Flo Williams

THIS volume is not intended to compete with any existing guides to Oxford: it is not a guide-book in any formal or exhaustive sense. Its purpose is to shew forth the chief beauties of the University and City, as they have appeared to several artists; with such a running commentary as may explain the pictures, and may indicate whatever is most interesting in connection with the scenes which they represent. Slight as the notes are, there has been no sacrifice, it is believed, of accuracy. The principal facts have been derived from Alexander Chalmers' History of the Colleges, Halls, and Public Buildings of the University of Oxford, from Mr. Lang's Oxford, and from the Oxford and its Colleges of Mr. J. Wells.

The illustrations, with the exception of six only, which are derived from Ackermann's Oxford, are reproduced from the paintings of living artists, mostly by Mr. W. Matthison, the others by Mrs. C. R. Walton, Walter S. S. Tyrwhitt, Mr. Bayzant, and Miss E. S. Cheesewright.

CONTENTS

THE UNIVERSITY AND ITS BUILDINGS

OXFORD is so naturally associated with the idea of a University, and the Collegiate buildings which confront one at every turn have such an ancient appearance, that a stranger might be excused for thinking that the University is older than the town, and that the latter grew up as an adjunct to the former. Of course, the slightest examination of facts suffices to dissipate this notion. Oxford is a town of great antiquity, which may well have been in existence in Alfred the Great's time, though there is not a shred of documentary evidence to prove that he was, as tradition so long asserted, connected with the foundation of a university there: it certainly existed in the reign of his son and successor, Edward the Elder, because—and this is the earliest historical mention of the place—the English Chronicle tells us that Edward took "Lundenbyrg and Oxnaford and all the lands that were obedient thereto." That was in 912, a date which marks the first authenticated appearance of Oxford on the stage of English history. .

There is a passage in Domesday Book which gives us a fair idea of the size of the town in the Conqueror's day. It contained over seven hundred houses, but of these, so harshly had the Normans treated the place, two-thirds were ruined and unable to pay taxes. William made Robert D'Oily, one of his followers, governor of Oxford. D'Oily's is the earliest hand (a heavy one, by the way, as the townsfolk learnt to their cost) whose impress is visible on the Oxford of to-day. We may indeed, if we please, attribute a certain piece of wall in the Cathedral to a remoter date, but the grim old tower (which appears in the first illustration) is the first building in Oxford whose author can with certainty be named. It is all that remains of the Castle which Robert D'Oily built in order to control the surrounding country; and he built his stronghold by the riverside because he thereby dominated the waterway, along which enemies were apt to come, as well as wide tracts of land in every direction. No doubt the hands of the conquered English laboured at the massive structure which was to keep them in subjection.

A queen was once besieged in the castle, Matilda, Henry I.'s daughter. When food gave out she made her escape in a romantic manner, so the story tells. The river was frozen and the ground covered with snow. The queen was let down from the tower by night with ropes, clad in white, the better to escape observation. Three knights were with her, clad in white also, under whose guidance she reached Wallingford on foot, and so escaped King Stephen's clutches.

To the period of the Norman Conquest belongs also the tower of St. Michael's Church, in the Cornmarket. It has been usual to describe this edifice as Saxon; but antiquaries incline to think that if Robert D'Oily did not build St. Michael's tower, he at least repaired it. This tower formed a part of the city wall, and from its narrow windows arrows may have rained upon advancing foes. Adjoining it was Bocardo, the old north-gate of the city, whose upper chamber was long used as a prison. Nothing of Bocardo now remains; but Robert D'Oily's handiwork is traceable, as many think, in the crypt and chancel of St. Peter-in-the-East and in the chancel arch at Holywell.

In these buildings, then, the history of Norman Oxford is written, so far as history can be written in stone; yet here and there about the city are to be seen structures which, although two or three centuries younger, have an appearance hardly less venerable. Year after year the aged walls and portals are thronged with fresh generations of the youth of England; and it is in this combination of youth and age that no little of the charm of Oxford lies. We speak within the limitations of mortality: but, could we escape them for a moment, "immortal age beside immortal youth" might be her most appropriate description.

WHEN did the University come into existence? That is a question which many people would like to have answered, but which still, like Brutus, "pauses for a reply." It is to the last degree improbable that we shall ever know. There were teachers and learners in Oxford at an early date, but so there were in many other English towns; the plant struck deeper in Oxford than elsewhere, that is all that one can say. There are various indications that in the twelfth century the town had acquired a name for learning. In 1186, Giraldus Cambrensis, who had written a book about Ireland and wanted to get it known, came and read his manuscript aloud at Oxford, where, as he tells us, "the clergy in England chiefly flourished and excelled in clerkly lore." That was fifty years after the death of King Henry the Scholar, who—was it only a coincidence?—had a residence in Oxford. It is pleasant to find Oxford students, even in those early days, with ears attuned to hearing "some new thing."

"Doctors of the different faculties," we are told, were among Giraldus' auditors: a fact which shows that learning was already getting systematised. A little later it has clothed itself in corporate form, and possesses a Chancellor. That official (when, and by whom appointed, is the mystery) is first mentioned in 1214, and we can henceforth look upon the University as a living body. He is named in connection with the first recorded "town and gown" row, when the citizens of Oxford took two clerks and hung them. The papal Legate (this was in the evil days of King John) intervened, and the citizens were very properly rebuked and fined.

A century passed before "The Gown" had a building set specially apart for the transaction of their affairs. Then, in 1322, Bishop Cobham of Worcester added a chapel to the north-east corner of St. Mary's, and gave it to the University as a House of Congregation. The office of Proctor had already been instituted, and that functionary had plenty of students to employ his time—30,000 one writer assures us, but him we cannot credit. A fourth of that number is a liberal estimate. They lived in Halls and lodgings, a hard and an undisciplined life, preyed upon by the townsfolk and biting their thumbs at them in return (whence collisions frequently ensued) until Walter de Merton devised the College system, to the no small advantage of all concerned.

Benefactions poured in upon the several Colleges, but the greater institution was not forgotten. In the Divinity School, within whose walls Latimer and Ridley defended their opinions, and Charles II.'s Parliament debated, the University possesses, as is fit and proper, the most beautiful room in Oxford and one of the most beautiful in England. The style is Perpendicular and the ceiling is particularly admirable. Together with the fine room above it, in which Duke Humphrey's manuscripts were housed, the Divinity School was completed in 1480.

Those six hundred manuscripts of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, which he bestowed on the University, had a sad history. They were dispersed by Edward VI.'s Commissioners, who judged them to be popish in tendency, and only four of them were ever restored to their old home. Nevertheless, Duke Humphrey's gift was the origin of the Bodleian Library. One does not like to think what the Library was like in the days which followed, when its manuscripts were scattered abroad and its shelves sold; but in the last years of the sixteenth century there arose a man who took pity upon its desolation. This was Sir Thomas Bodley, Fellow of Merton, a man of travel and affairs, who devoted the last years of his life to the creation of what is now one of the most famous libraries in existence. It has ever been the delight of scholars since the days of James I., who wished he might be chained to the Library, as some of the books were.

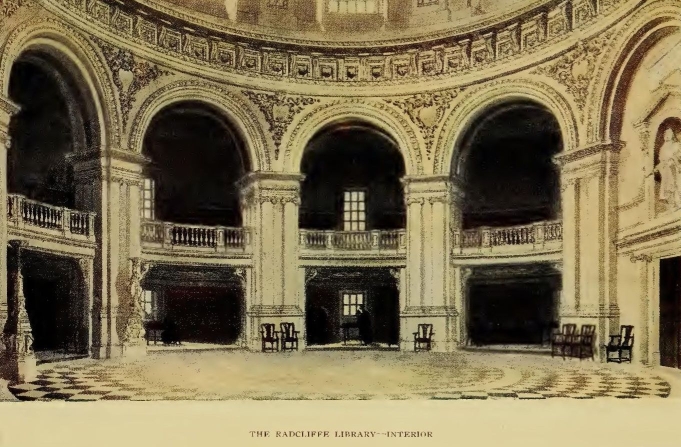

The original chamber did not long suffice to contain the volumes; an east and then a west wing were added, the latter over Archbishop Laud's Convocation House (1640) which superseded Cobham's Chapel. From these the books overflowed into various rooms in the Old Schools Quadrangle, which had been rebuilt in James I.'s reign. Further space was gained in 1860, when the Radcliffe, set free by the removal of its collection of scientific works to the New Museum, was lent to the Bodleian; and again in 1882, on the opening of the New Examination Schools (sketched by Mr. Matthison), when the Old Schools were rendered available for the uses of the Library.

The various public buildings belonging to the University erected during the nineteenth century, such as the Taylor Institution, the University Art Galleries, the New Museum, and the Indian Institute, can hardly escape attracting the attention of visitors to Oxford. It remains to say a word of two older structures, which appear side by side in Mr. Matthison's next drawing—the Clarendon Building and the Sheldonian Theatre.

The Clarendon Building was designed by Vanbrugh, and completed in 1713. It is named after the author of the History of the Rebellion, and was partially built out of the profits of the copyright of that work, which Clarendon's son presented to the University. It was the home of the University Press until 1830, and is now occupied by the offices of various University Boards.

The Sheldonian Theatre, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, is associated with less tranquil occupations. It is here that honorary degrees are conferred and the Encænia held; here the Terræ Filius, a licensed jester, used to hurl his witticisms at whomsoever he pleased; and here, in later times, the occupants of the Undergraduates' Gallery have endeavoured to keep up his tradition. Here, too, Convocation sometimes meets, when a burning question is to be discussed and Masters of Arts assemble in their hundreds. On such occasions the Sheldonian has been known to be as full of clamour as at the Encænia. It is perhaps pleasanter to view Wren's stately building when it is void alike of undergraduate merriment and of graduate contention.

ALTHOUGH St. Mary's, being a parish Church, cannot be numbered among the buildings which are University property, it has been almost as closely connected as any of them with the life and history of the University. Cobham's Chapel, as has been already said, was the first House of Congregation; and in the room above it the University kept its manuscripts, until Duke Humphrey's Library was built. The chancel and nave, moreover, were used by the gownsmen for both religious and secular purposes; and it is strange to reflect that consecrated walls heard not only sermons and disputations, but the jests of the Terræ Filius and the uproar which they excited. It was only when the Sheldonian was built (1669) that St. Mary's ceased to be the scene of the "Act"—the modern Encænia—and was restored to its original intention.

The porch, with its spiral columns and statue of the Virgin and Child, is much later than the rest of the building, being the work of Dr. Owen, Archbishop Laud's chaplain. Architecturally it is not in keeping with the nave and spire, but in itself, especially when the creeper which en-wreathes it takes on its autumnal colour, it is very beautiful. It was found necessary, in 1895, to restore the spire, which with the pinnacles at its base is the special glory of St. Mary's.

The Church is intimately connected with the religious history of the nation. Here Keble preached the famous Assize Sermon, which is regarded as the beginning of the Oxford Movement; here, too, Newman, before he withdrew to his retirement at Littlemore, preached those many sermons to whose spiritual force men of all schools of thought have borne witness. A later vicar was Dean Burgon, to whose memory the west window was put up in 1891.

But Cranmer's connection with St. Mary's transcends all its other associations. On September 12, 1555, he was here put on trial for his religious opinions, which he defended with as much ability as courage. He was then recommitted to his prison, and in December Rome pronounced him guilty. The hardships of his imprisonment told upon his resolution, and he was induced to write several letters of submission, in which his so-called errors were recanted. On March 21, 1556, he was once more brought to St. Mary's. His life was to be taken, but he was to crown his humiliation by a public confession. Placed upon a wooden stage over against the pulpit, he had to hear a sermon, at the close of which he was to speak. His fortitude returned, and to the amazement of all he recanted his recantation. "As for the Pope"—these were his memorable words—"I utterly refuse him, as Christ's enemy and Antichrist, with all his false doctrine; and as for the Sacrament, I believe as I have taught in my book against the Bishop of Winchester. And for as much as my hand offended, writing contrary to my heart, my hand shall first be punished therefore; for, may I come to the fire, it shall be first burned." He was hurried off to the stake, and there

"lifted his left hand to heaven,

And thrust his right into the bitter flame;

And crying in his deep voice, more than once,

'This hath offended—this unworthy hand!'

So held it till it was all burn'd, before

The flame had reach'd his body."

AT the east end of the choir aisle of the Cathedral there is a portion of the wall which is possibly the oldest piece of masonry in Oxford, for it is thought to be a part of the original Church of St. Frideswyde, on whose site the Cathedral Church of Christ (to give its full title) now stands. Even so it is not possible to speak with historical certainty of the saint or of the date of her Church, which was built for her by her father, so the legend says, when she took the veil; though the year 740 may be provisionally accepted as the last year of her life. St. Frideswyde's was a conventual Church, with a Priory attached, and both were burnt down in 1002, but rebuilt by Ethelred. How much of his handiwork survives in the present structure it is not easy to determine; but the Norman builders of the twelfth century effected, at any rate, such a transformation that no suggestion of Saxon architecture is obtruded. Their work went on for some twenty years, under the supervision of the then Prior, Robert of Cricklade, and the Church was consecrated anew in 1180. The main features of the interior—the massive pillars and arches—are substantially the same to-day as the builders left them then.

The Priory was surrendered to Henry VIII. in 1522, who made it over to Wolsey. That cardinal, in his zeal for the new College, which he now proceeded to found, shewed little respect for the old Church. He practically demolished its west end to make room for his building operations. The truncated Church was used as a chapel for his students, until the new and magnificent one which he had planned should be completed. That edifice was never built. Wolsey was disgraced, and the king took over St. Frideswyde's, to be the Cathedral Church of his newly created diocese of Oxford.

From this date, then, 1546, it is a Cathedral, but a College chapel also; for Henry was content that the one building should serve the two purposes. The Cathedral was restored in the seventeenth century and again in the nineteenth, with considerable alterations. It is hardly worth while here to enumerate these in their entirety; but when one sees in old engravings the beautiful east window, put up in the fourteenth century, which was removed at the time of Sir Gilbert Scott's restoration, it is impossible not to regret a change which appears to be quite unjustifiable. At the same time it may be readily admitted that the east end, designed on Norman lines, which the architect substituted, has considerable beauty, and harmonises with the general tone of the building. Regret is unavailing, and it is perhaps wiser to console oneself with the reflection that at any rate things might have been worse.

The Cathedral is so hemmed in by the various buildings of Christ Church that it is difficult to obtain a comprehensive view from the outside. Perhaps one sees it best from Merton Fields, with the beautiful Rose Window prominently visible. Even so the Cathedral is in part hidden by the ancient Refectory of St. Frideswyde's (long since converted into rooms). This is the view, sketched from the nearer foreground of the Canon's Garden, which appears in Mr. Matthison's drawing, only that the Rose Window is hidden by trees. The spire—or spire and tower combined—no longer holds the bells which chimed originally in Osney Abbey, on the river's farther side; they were removed to the new Belfry (completed in 1879), which appears to the left of the Refectory.

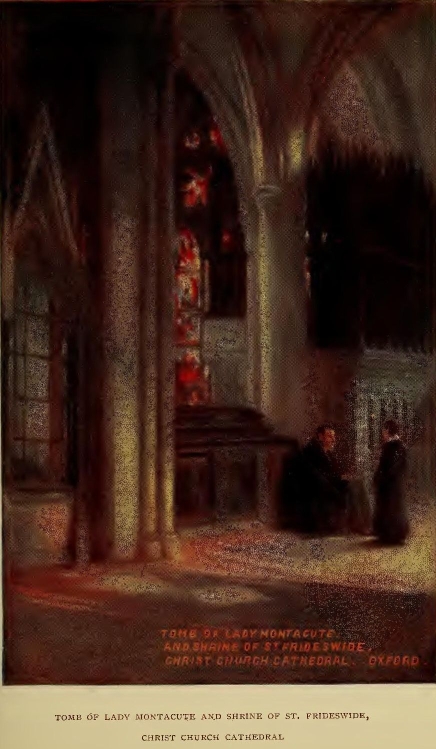

We are now to speak of the interior of the building. It is sketched from various points of view in the accompanying six illustrations: but twice as many would not suffice to exhaust its interest. At no time does the nave appear more impressive than when a shaft of sunlight strikes across the massive columns; and Miss Cheesewright has sought to fix upon her canvas the charm of such a moment. The Lady Chapel was added early in the thirteenth century; here are enshrined the remains of St. Frideswyde, which were moved several times before they reached their final resting-place. The Latin Chapel dates from the fourteenth century, and is full of interest. Some of its carved woodwork is to be referred to Wolsey's time, and it contains the tombs, among others, of Lady Elizabeth Montacute, the Chapel's reputed builder, and of Sir George Nowers, a comrade-in-arms of the Black Prince. Other notable tombs in various parts of the Cathedral are those of Robert Burton, author of the Anatomy of Melancholy; Bishop Berkeley, the metaphysician and upholder of the virtues of tar-water; Bishop King, last Abbot of Osney and first Bishop of Oxford; Dean Liddell and Dr. Pusey. A window in the south transept depicts the murder of Thomas à Becket, whose head has been obliterated, by the order, it is said, of Henry VIII. Another window in the same transept commemorates Canon Liddon. The art of Burne-Jones has contributed not a little to the Cathedral's beauty. In the east window of the Latin Chapel he has set forth the romantic story of St. Frideswyde. Another of the windows which he designed is at the east end of the Lady Chapel, and serves as a memorial of Mr. Vyner, who was murdered by Greek brigands in 1870; another, at the east end of the north aisle of the choir, commemorates St. Cecilia, with which corresponds a "St. Catherine of Alexandria" in the south aisle, put up in memory of Miss Edith Liddell, daughter of Dean Liddell. Lastly, at the west end of this aisle, the artist has chosen "Faith, Hope, and Charity" as his subject.

The Cloister and Chapter-House (thirteenth century) must not be overlooked. The entrance to the Chapter-House is by a singularly fine Norman doorway. The Cloister saw the unworthy degradation of Archbishop Cranmer, after the Pope had pronounced him guilty of heresy.

Enough has perhaps been said to shew intending visitors to Oxford that the interest of the Cathedral is both great and varied. To those who already know it, these hints will seem a poor and inadequate attempt to express its manifold charm, but the pictures may serve to emphasise their vivid recollections. Those who have yet to make acquaintance with it will perhaps exclaim, as the Queen of Sheba did of Solomon's wisdom and prosperity, "Behold, the half was not told me."

WHERE is the centre, the ὀμφαλὸς γῆς of Oxford? The average undergraduate will probably place it within the walls of his own College; but we, detached observers whose salad days, presumably, are over, look for a definition worthy of more catholic acceptance. To us Oxford is not a city of Colleges only, but of noble streets and wide spaces. Them it is our purpose to explore, not with the hasty stride of one bound for lecture-room, or cricket-ground, or river, but leisurely and with discrimination; we are ready to be chidden for curiosity, so we incur not the gravamen of indifference. Where, then, shall we start on our pilgrimage, and from what centre? If there be in any city a place where four principal roads meet, as at the Cross in Gloucester, we may listen there for the pulsations of that city's heart.

Such a place there is in Oxford, Carfax,—Quatre voies,—the spot where four ways meet. This, not too arbitrarily, we will name the centre of Oxford, and thence will wend upon our pilgrimage. But let us pause a moment, before we set out, at the parting of the ways.

The old Church of St. Martin's at Carfax was pulled down in 1896, and only the tower left. St. Martin's was the church of the city fathers, as St. Mary's was (and is) the church of the University. Nowadays the civic procession winds its way to All Saints, a nearer neighbour of St. Mary's. Such propinquity would have sorted ill with the manners of mediaeval Oxford, when the enmity of town and gown, at times quiescent, was never wholly quelled. In an age when the clerks, regular and secular, fell out among themselves in the precincts of St. Mary's, even to the shedding of blood, it is idle to look for a more civil temper in the burgesses: and the bells of Carfax and St. Mary's summoned those who frequented them to battle as well as to prayer. They rang out with the former intention on the feast of St. Scholastica in 1354. It is sad to record that the quarrel arose in a tavern, where two gownsmen abused the vintner for serving them with wine of wretched quality. The conflict which ensued was of a very deadly nature. The scholars held their own until evening, when the citizens called the neighbouring villagers of Cowley and Headington to their aid, and the Gown were routed. As many as forty students were slain, and twenty-three townsmen. Then Edward III. took steps to protect the men of learning, lowering, among other measures, the tower of Carfax, because they complained that in times of combat the townsmen retired thither as to a castle, and from its summit grievously annoyed and galled them with arrows and stones. The burgesses also were forced to attend annually at St. Mary's Church, when mass was offered for the souls of the slain, bearing on their persons sundry marks of degradation; and though these were subsequently done away, it was only in 1825 that they were excused the indignity of attending the commemorative service.

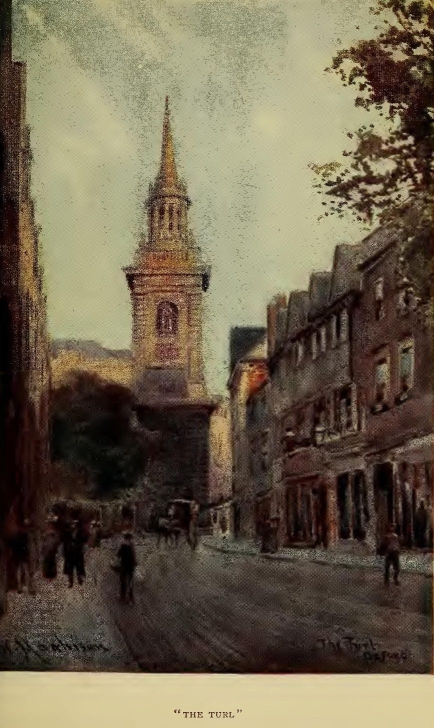

Such are some of the memories evoked by the Tower of Carfax, the best view of which is given in Mr. Matthison's first drawing. The second illustration is from a point rather farther to the eastward. Both give a glimpse of the Mitre Hotel, most picturesque of old Oxford hostelries, and the second a part of the front of All Saints. At this point we may for a moment leave the High Street (which we have begun to traverse, half insensibly, under the artist's guidance) and wander down "The Turl," as Turl Street is commonly called. "Turl" is said to be a corruption of Thorold, and Thorold to have been the name of a postern-gate in the old city walls. The quiet old street has Colleges on either hand, Lincoln, Exeter, and Jesus. Retracing our footsteps, we get the fine view of All Saints which is given in the third illustration. The history of this Church, known originally as All Hallows, goes back to the twelfth century, but the present building, designed by Dr. Aldrich, a former Dean of Christ Church, has only been in existence since 1708, the old one having been destroyed in 1699 by the fall of its spire. The present graceful tower and spire are a worthy memorial of Dean Aldrich's versatility.

We now return to our exploration of "The High," whose magnificence of outline become more and more apparent as one walks eastwards. It was a poet bred at Cambridge, no less a poet than Wordsworth, whom the manifold charm of Oxford tempted "to slight his own beloved Cam"; and he it is who has written the most quotable description of "The High" in brief. "The streamlike windings of that glorious street," he writes: and indeed its curve suggests nothing so much as the majestic bend of some noble river. We may cite, too, Sir Walter Scott's testimony, who claimed that the High Street of Edinburgh is the most magnificent in Great Britain, except the High Street of Oxford. It is not at all difficult to assent to this opinion. As the view gradually unfolds itself, we have on our left successively the new front of Brasenose, St. Mary's, All Souls, Queen's, and Magdalen; on our right the long, dark front of University, and many old dwelling-houses, whose architecture does not shame their situation. Looking backward for a moment at Queen's College (perhaps when the west is rosy, as in Mr. Matthison's drawing), one sees substantially the same view which delighted Wordsworth in 1820; and we, if we are wise, shall take as much delight in it as he. Many thousand times since then has the sun set behind the spires of St. Mary's and All Saints, but the unaltered prospect obliterates the intervening years, and we are at one with the great poet in his admiration.

Contrast is always pleasant, and one may reach Broad Street (which certainly must not be neglected) by several thoroughfares totally unlike "The High." We may traverse Long Wall Street, with Magdalen Grove on our right, a pleasance hidden from the wayfarer by a high wall, but visible to such as lodge in upper rooms on the other side of the way; thence along Holywell Street, with its queer medley of old houses, many of them pleasing to the eye. Or, still greater contrast, we may go by Queen's and New College Lanes, with their rectangular turns and severe masonry on either side. Or, again, we may go through the Radcliffe square with its massive buildings on every hand—the Radcliffe dome in the centre, girt about with St. Mary's, Brasenose, All Souls, and the Old Schools. In any case we find ourselves, at the last, in Broad Street.

It is a wide and quiet street, with comparatively little traffic, a street dear to meditation. Some such suggestion is conveyed by Mr. Matthison's sketch. He has not given us here the fronts of Balliol, Trinity, or Exeter,—views of the first two will be found later on,—but just the old houses (the one in dark relief is Kettell Hall, built by a President of Trinity in the seventeenth century) asleep in the sunshine, with the Sheldonian on the right, whose guardian figure-heads, traditionally said to represent the twelve Cæsars, seem by the expression of their stony countenances to be thinking hard of nothing in particular. At the other end of Broad Street, marked by a flat cross in the roadway, is the spot where tradition says the martyrs suffered for their faith.

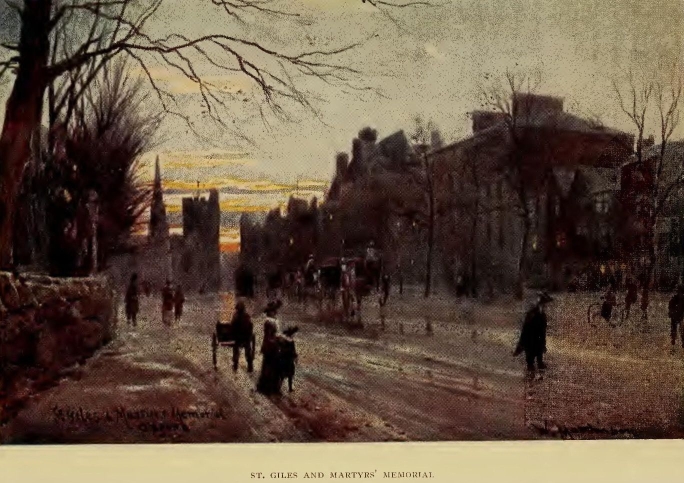

Their Memorial is a little distance off, in the neighbouring street of St. Giles'. It is an effective and graceful structure, with characteristic statues of Cranmer, Latimer, and Ridley, and an inscription stating the manner of their death and the reasons for their martyrdom. It was erected in 1841, by public subscription, when also the north aisle of the adjacent Church of St. Mary Magdalen was rebuilt out of the same fund. The Memorial appears twice in Mr. Matthison's drawings; once at the approach of evening, looking towards the city, and once as it is seen in full daylight, with the widening vista of St. Giles' Street in the background. St. Giles' is surely the widest street in the three kingdoms; Broad Street is narrow when compared with it. Each September it is the scene of what is said to be the largest and the oldest fair in England. But we have not chosen a fair-day for our pilgrimage.

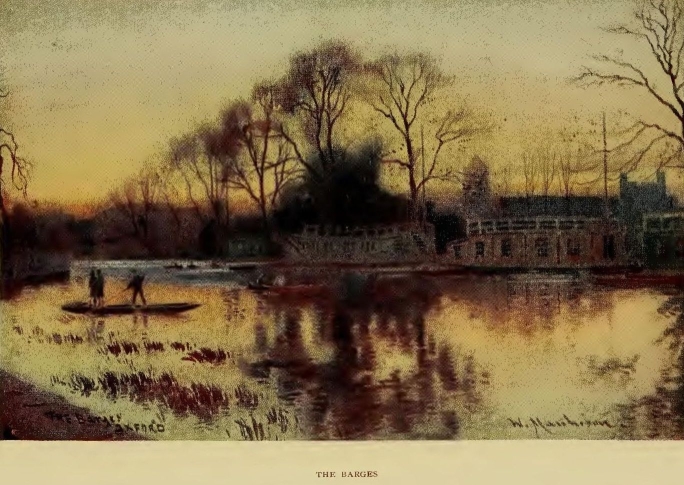

IF the "towers of Julius" are, as Gray called them, "London's lasting shame," the River is the lasting pride of Oxford. When does "The River" cease to be Isis and become Thames? One might as well ask when it ceases to be Thames and becomes Isis. The term is probably not used out of Oxford, and with much vagueness there. Matthew Arnold speaks of "the stripling Thames at Bablock-Hythe" (a very lovely ferry higher up than Oxford), and at Abingdon nobody talks about the Isis. The use of the name is one of the odd and pleasant conservatisms of Oxford.

Then, again, there are two rivers in Oxford, according to the map, Thames and Cherwell; but to the undergraduate there are three—"The River," "The Upper River," and "The Cher." For the sake of strangers it may be well to elucidate this enigma. "The River" is that part of the Thames which begins at Folly Bridge and ends at Sandford, except that on the occasion of "long courses" and Commemoration picnics it is prolonged as far as Nuneham. It is understood subsequently to pass through several counties and reach eventually the German Ocean. You do not go upon "The River" commonly for amusement, but for stern and serious work. You aspire to a thwart in your College "torpid" first, then in your College "eight," with the fantastic possibility of a place in the "Trials" or—crown of all—in the 'Varsity "Eight" on some distant and auspicious day! It is no child's-play that is involved, as every oarsman knows. "The River" is an admirable school of self-control and self-denial, and "training"—long may it flourish!—is one of the best of disciplines. It has been said, and with truth, that boating-men are the salt of undergraduate society.

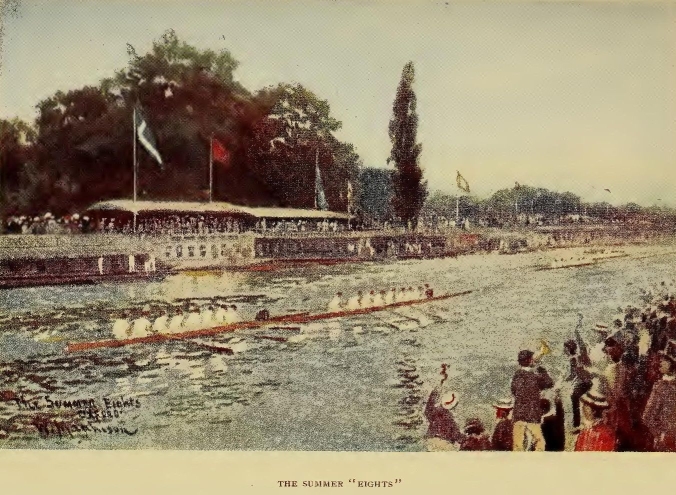

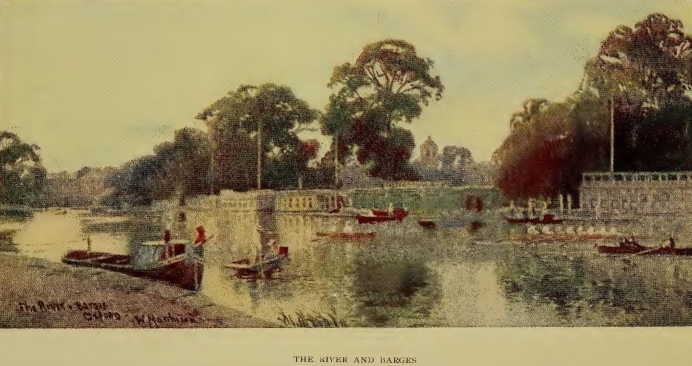

The "Torpids" are rowed in March—you will appreciate this fact if you are rowing "bow" and a hailstorm comes on—in eight-oared boats with fixed seats. The name bestowed on them seems a little unkind. The "Eights" come off in the summer term, when sliding seats are used—to the greater comfort of the oarsmen, and the greater gratification of the lookers-on, for this rowing is out of all comparison prettier, and of course the boats travel at a greater pace. Both "Eights" and "Torpids," as most people are aware, are bumping races; that is, the boats start each at a given distance from the one behind it, and the object is to bump the boat in front, and so bump one's way to that proudest of all positions, "the Head of the River." A bump in front of the Barges (which Mr. Matthison has sketched), following a long and stern chase from Iffley, is a thing to live for.

West of Folly Bridge "The River" might as well, for all the ordinary undergraduate knows of it, sink for some distance, like a certain classic stream, beneath the ground. Venturesome explorers tell of a tract of water put to base mechanical uses, flanked by dingy wharves and overlooked by attic windows.

But to most boating-men "The River" ends at Salter's, only to reappear in the modified form and style of "The Upper River" at Port Meadow. "The Upper River" is some distance from everything else, but it is well worth the journey to Port Meadow. There is nothing strenuous about "The Upper River." It always seems afternoon there, and a lazy afternoon. The standard of oarsmanship may not be very high, but no one is in a hurry and no one is censorious. To enjoy the Upper River as it deserves to be enjoyed, you should have laboured at the Torpid oar a Lent Term, and have found yourself not required (this year) for the Eight. You know quite enough of rowing, in such a case, to cut a figure on the Upper River; but you will not want to cut it. If you appreciate your surroundings properly, you will want to sit in the stern while somebody else does the rowing; or, if you take an oar, you will want to pull in leisurely fashion and to look about you as you please, in the blissful absence of raucous injunctions to "keep your eyes in the boat." There is much that is pleasant to look upon—the wide expanse of Port Meadow on the right, on the towpath willows waving in the wind, and on the water here and there the white sail of a centre-board. As you draw near Godstow, you may see cattle drinking, knee-deep in the stream; you may land and refresh yourself, if you will, at the "Trout" at Godstow; may visit the ruins of the nunnery, with their memories of "Fair Rosamond;" or, leaning on the bridge-rail over Godstow weir, lulled by the ceaseless murmur of the water, may muse upon the vanity of mere ambition and the servitude of such as row in College Eights. Then, if the day be young enough, you may go on to Eynsham or to Bablock-Hythe, and perhaps afoot to Stanton-Harcourt, a most lovely village; and returning at dusk, when the stream appears to widen indefinitely as the light fails, you will vow that for sheer peace and enjoyment there is nothing like the Upper River.

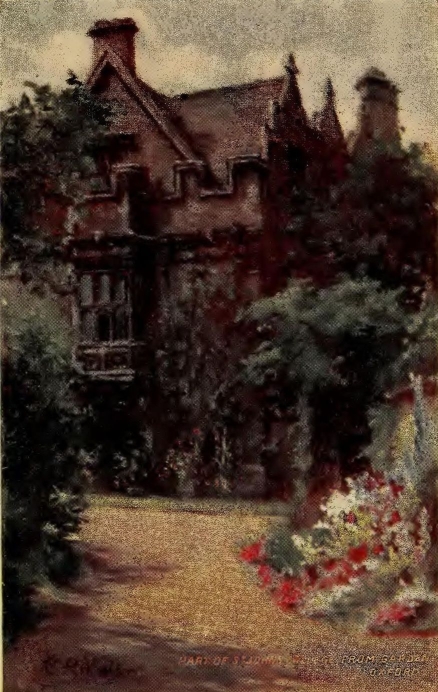

Unless, indeed, it be the Cherwell. This little stream, which flows into the Isis near the last of the Barges, while it winds about Christ Church Meadow, Magdalen, and Mesopotamia, is edged about, with shadowy walks; but once clear of the Parks, it is embedded in grassy and flower-laden banks, through which your boat passes with a lively sense of exploration. Presently, at a break in all this greenery, you come abreast of a grey stone building, with ancient gables and air of reposeful dignity. Instinctively your oar-blades rest upon the water, for so much beauty demands more than a moment's admiration. It is Water Eaton Hall, one of those smaller Elizabethan manor-houses which have survived the violence of the Rebellion and the neglect of impoverished owners. All about its aged masonry is the growth and freshness of the spring. Oxford is several miles away, but even so you are reminded of her special charm—the association of reverend age with youth's perennial renewal.

MERTON is in several respects the most interesting of the Colleges of Oxford. In the first place, it is the oldest; for though the original endowments of University and Balliol were bestowed a little earlier, Merton was the first College to have a corporate existence, regulated and defined by statute. With the granting of Merton's statutes in 1264, a new era of University life began. From being casual sojourners in lodgings and Halls, students from this date tended more and more to be gathered into organised, endowed, and dignified societies, where discipline was one of the factors of education.

Such is Oxford's debt to Walter de Merton, Chancellor of England and Bishop of Rochester, who died by a fall from his horse in fording a river in his diocese, and was buried in Rochester Cathedral. His tomb there has twice been renovated by the piety of the College which he founded.

His statutes are preserved at Merton, and were consulted as precedents when other Colleges were founded, at Cambridge as well as at Oxford. "By the example which he set," runs the inscription on his tomb, "he is the founder of all existing Colleges."

Another great distinction of Merton is its Library (whose interior appears in Mrs. Walton's sketch), which was built in 1377, by William Rede, Bishop of Chichester, and is the oldest Library in the kingdom. In monasteries and other houses where learning took refuge, books had hitherto been kept in chests, an arrangement which must have had its drawbacks, considering the weight of the volumes of those days.

Mr. Matthison's first drawing shews the College as seen from Merton Street, with the imposing tower of the Chapel in the background. A very fine view of the buildings of Merton, in their full extent, is obtained from Christ Church Meadow.

To speak of them in detail, the Muniment Room is the oldest collegiate structure in Oxford, and possibly dates from the lifetime of the Founder. The Hall gateway, with its ancient oak door and enormous iron hinges, is of the same epoch. Of the three Quadrangles the small one to the north (which contains the Library) is the oldest. The front Quadrangle opens by a magnificent archway into the Inner, or Fellows' Court, built in 1610 in the late Gothic style, its south gate surmounted with pillars of the several Greek orders. The Common Room (1661) was the first room of the kind to be opened in Oxford.

The beautiful Chapel has rather the appearance of a parish Church, which indeed it is. St. John the Baptist's parish, however, is so minute as hardly to need, in a city of many churches, a place of worship all to itself, and the building was assigned to Merton in the last decade of the thirteenth century, with the proviso that one of the chaplains should discharge such parochial duties as might arise. In the ante-chapel are the monuments of the famous Sir Thomas Bodley, Sir Henry Savile, once Master, and Antony Wood, greatest of Oxford antiquarians. Wood (who died in 1695) was associated with Merton all his life. He was born in the house opposite the College entrance, called Postmasters' Hall, and there he passed most of his days.

It is from him that we get a great deal of our information about early Oxford. Royalty has repeatedly enjoyed the hospitality of Merton, and here is Wood's account of a visit paid by Queen Catherine, wife of Henry VIII. "She vouchsafed to condescend so low as to dine with the Merton-ians, for the sake of the late Warden Rawlyns, at this time almoner to the king, notwithstanding she was expected by other Colleges." Elizabeth and her privy council were equally gracious, and were entertained after dinner with disputations performed by the Fellows. One would like to know what subjects were disputed, and what the queen thought of her entertainment. When Charles I.'s Court came to Oxford, Queen Henrietta Maria occupied the Warden's lodgings, which were again tenanted by Charles II.'s queen, when the Court fled from plague-stricken London.

Merton has had great men among her Fellows, but none greater than John Wycliffe; and among her postmasters (so the scholars are called here) no name captivates our sympathies more readily than that of Richard Steele, trooper and essayist, the friend of Addison and the husband of Prue.

IT was long and hotly maintained that University College was founded by Alfred the Great, and by celebrating its thousandth anniversary in 1872 the College would seem to have accepted this pious opinion. The claim was raised as far back as 1387, when the College, being engaged in a lawsuit about a part of its estates, tried to ingratiate itself with Richard II. by representing that its founder was his predecessor, Alfred, and that Bede and John of Beverley had been among its students. Now, Bede and John of Beverley died about a century before Alfred was born. Ex pede Herculem. The Alfred tradition need not keep us longer.

University College owes its existence to William of Durham, who, at his death in 1249, beqeathed to the University the sum of three hundred and ten marks for the use of ten or more Masters (at that time the highest academical title) to be natives of Durham or its vicinity. Certain tenements were purchased, one of them on a part of the site of Brasenose, and here, in 1253, Durham's scholars first assembled; but only in 1280 were they granted powers of self-government. The recent foundation of Merton no doubt suggested the idea of bestowing a corporate life on what had hitherto been known as "University Hall." Durham's scholars removed to their present locality in 1343.

One of the earliest benefactors whom "Univ." (as this College is familiarly termed in Oxford) is bound to remember is Walter Skirlaw, who became Bishop of Durham in 1403. He ran away from his home in youth in order to study at Oxford, and his parents heard no more of him (according to his biographer) till he arrived at the see of Durham. He then sought them out, and provided for their old age. Another benefactor (1566) was Joan Davys, wife of a citizen of Oxford, who gave estates for the support of two Logic lecturers, and for increasing the diet of the Master and Fellows. Had Mr. Cecil Rhodes heard of this lady? To touch on the Masters of "Univ.," a curious career was that of Obadiah Walker, who lost his Fellowship in Commonwealth times for adherence to the Church of England; later on was made Master and turned Roman Catholic; enjoyed the favour of James II.; and lost his Mastership at the Revolution for adherence to the Church of Rome.

Of the present buildings of the College none is of earlier date than the seventeenth century. The two Quadrangles form a grand front towards the High Street, with a tower over each gateway at equal distances from the extremities. Above the gateways are statues of Queen Anne and Queen Mary, on the outside; two more, within, represent James II. and Dr. Radcliffe. It was mainly at the cost of John Radcliffe, a member of the College, that the smaller Quadrangle was completed. Other famous members were the brothers Scott, afterwards Lords Stowell and Eldon; Sir William Jones, the great Oriental scholar; and Sir Roger Newdigate, responsible for so many thousand heroic couplets, who gave the handsome chimney-piece in the Hall. It is curious to notice, by the way, that the fireplace stood in the centre of this room until 1766. The Common Room contains two specimens of an out-of-the-way art, portraits of Henry IV. and Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, burnt in wood by Dr. Griffith, a former Master.

The beautiful monument to the poet Shelley, set up in the College in 1893, is the gift of Lady Shelley. Its honoured position within the walls of the Foundation which drove him out so hastily and harshly is indeed a fitting emblem of "the late remorse of love."

THIS College was originated about 1260 by John de Balliol, a baron of Durham, whose son for four years occupied the throne of Scotland. But inasmuch as John de Balliol only made provision for four students, and that as penance for an outrage, the greater credit attaches to his wife Dervorguilla, who endowed a dozen more and hired them a lodging close to St. Mary Magdalen Church, on the site where part of the present College stands. Devorguilla gave her scholars their first statutes in 1282. She bade them live temperately, and converse with one another in the Latin tongue.

Truth to tell, as the revenues at first yielded each scholar only eightpence a week, riotous living seemed hardly practicable. Benefactors, however, presently stepped in, notably Sir Philip Somervyle of Staffordshire, who in 1340 raised the weekly allowance to elevenpence, and to fifteenpence in case victuals were dear. The grateful College accepted from Sir Philip a new body of statutes, in which the now familiar title, "Master of Balliol," makes its first appearance, a title associated twenty years afterwards with the honoured name of John Wycliffe. Among later benefactors may be mentioned Peter Blundell, founder of the Devonshire school which bears his name; Lady Elizabeth Periam (a sister of Francis Bacon); and John Snell, a native of Ayrshire,—it is to his endowment that Balliol owes her most distinguished Scotsmen, such as Adam Smith, Lockhart (Sir Walter Scott's son-in-law and biographer), and Archbishop Tait.

Balliol was an early friend to the new learning, and fostered the scholarly tastes of Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, son of Henry IV., and Tiptoft, Earl of Worcester (to name but two of her most prominent humanists). Duke Humphrey left his books to the University, six hundred in number—a very large collection for those days, when as yet Caxton had not revolutionised the world. And in Reformation days, when the humanities were called to account, learning found a zealous supporter in Cuthbert Tunstall, Bishop of Durham, who had been bred at Balliol.

The annals of the College during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are not particularly distinguished. After the Restoration Balliol men seem to have been considerably addicted to malt liquors, and much ale does not conduce to profound study. But modern Balliol men might apply to their own use the words of Dr. Ingram's famous song, "Who fears to speak of '98?" for it was in 1798 that Dr. Parsons became Master of the College, and with his advent began the great days of Balliol.

Parsons, with two other heads of houses, established the Examination system, which has been so much belauded and so much abused. It was soon apparent that Balliol tutors had the knack of equipping men to face the ordeal of "the Schools"; the College speedily came to the front, and its intellectual pre-eminence in Oxford during the nineteenth century is now universally admitted. Men trained at Balliol during this period occupied and still occupy some of the very highest positions in the State. Not to mention the living, whose fame is in the mouths of all men, some of the most prominent names are those of Lords Coleridge, Bowen, and Peel (formerly Speaker of the House of Commons), Sir Robert Morier, and Archbishop Temple. Matthew Arnold and Clough were undergraduates at Balliol with Benjamin Jowett, afterwards its most famous Master; and, to balance the severity of these poets, the lighter Muse of Calverley sojourned for a time within its walls.

The buildings of Balliol, which Mr. Matthison has sketched from four points of view, are extensive, but not conspicuously beautiful. The front towards Broad Street was rebuilt in 1867 by Mr. Waterhouse. Old prints assure us that it had previously a forbidding and almost prison-like aspect. Mr. Matthison calls attention to the fact that this picture shows the spot where the martyrs were burned. The automobile in the foreground may suggest to the thoughtful reader that martyrdom is no longer by fire. The drawing from St. Giles' perhaps conveys a pleasanter impression. The third shews us that part of the College known as "Fisher's Buildings," erected at the cost of a former Fellow in 1769. The fourth drawing is of the Garden Quadrangle with the Chapel on the left (rebuilt in 1856); here the surroundings are more attractive; we are looking on "a grove of Academe," in which vigorous minds may still, as heretofore, grow happily towards their maturity.

THIS College," wrote Fuller the historian, in words which Exeter men will approve, "consisteth chiefly of Cornish and Devonshire men, the gentry of which latter, Queen Elizabeth used to say, were courtiers by their birth. And as these western men do bear away the bell for might and sleight in wrestling, so the scholars here have always acquitted themselves with credit in Palæstra literaria!'

The western College was founded in 1314 by Walter de Stapledon, Bishop of Exeter, who twelve years later met his death as a supporter of Edward II., when that king was overthrown and murdered. A later and liberal patron was Sir William Petre, father of Dorothy Wadham, a statesman of the Tudor period. Of the ancient buildings of Exeter hardly anything remains. The Hall dates from the seventeenth century, the fronts to the Turl and Broad Streets from the nineteenth. The present Chapel is the third in which Exeter men have worshipped. Designed by Sir Gilbert Scott on the model of the Sainte Chapelle in Paris, it is certainly the most attractive of the College buildings. Its interior is richly decorated, and contains a tapestry representing "The Visit of the Magi," the work of Burne-Jones and William Morris, formerly undergraduates of Exeter.

Among interesting members of this Foundation may be cited Dr. Prideaux, Rector from 1612 to 1642, who began residence at Exeter as a kitchen-knave, and lived to be a Bishop; the first Lord Shaftesbury, Dryden's "Achitophel"; the Marquis of Winchester, a loyal Cavalier, whose epitaph by the same poet may be read in Englefield Church, Berkshire; William Browne, author of Britannia's Pastorals; and Sir Simon Baskerville (ob. 1641), an eminent physician, who would take no fee from any clergyman under the rank of dean. The Fellows' Gardens, a secluded and beautiful spot, contains two noted trees, a large chestnut known as "Heber's Tree," from the fact that it overshadowed his rooms in Brasenose, and "Dr. Kennicott's Fig Tree." Dr. Kennicott, the great Hebrew scholar, regarded this tree as peculiarly his own. During his proctorate, some irreverent undergraduates stole its fruit, upon which Dr. Kennicott caused a board to be hung upon it, inscribed "The Proctor's Fig." Next morning it was discovered that someone had substituted the audacious legend, "A fig for the Proctor."

ORIEL COLLEGE was founded by Adam de Brome, almoner to King Edward II., in 1324. He was Rector of St. Mary's, whose spire forms with the dome of the Radcliffe a background to the view of Oriel Street, and obtained leave from the king to transfer the Church and its revenues to his College. The College originally had the same title as the Church, but five years after its foundation it received from King Edward III. a messuage known as La Oriole (a title of disputed meaning), and from this date was renamed "Oriel College."

The Front Quadrangle, whose exterior and interior are here depicted, was erected in the first half of the seventeenth century. Viewed from without, it has an air of quiet dignity; but the visitor will be even better pleased when he has passed the Porter's Lodge. A striking feature is the central flight of steps, with a portico, by which the Hall is reached. On either side of the statues of the two kings (Edward II. and Charles I.) stretches a trio of finely moulded windows, flanked by an oriel to right and left. Mr. Matthison clearly made his drawing when the "Quad." was gay with flowers and Eights-week visitors, but at no season is it anything but beautiful. The Garden Quadrangle, which lies to the north and includes the Library, was built during the eighteenth century. The adjacent St. Mary Hall, with its buildings, was recently incorporated with Oriel, on the death of its last Principal, Dr. Chase.

Among famous men nurtured at this College were Raleigh, Prynne, Bishop Butler, and Gilbert White, the naturalist; but it was in the first half of the nineteenth century that Oriel's intellectual renown was at its highest. To recall the names of Pusey, Keble, Newman, Whately, and Thomas Arnold suffices to indicate the subject which most preoccupied the Oxford of that epoch. Oriel seemed fated to be the seat of religious controversy, from the seventeenth century days of Provost Walter Hodges, whose Elihu, a treatise on the Book of Job, brought him into suspicion of favouring the sect of Hutchinsonians. Happily there was some tincture of humour in the differences of those days. When this Provost resented the imputation, his detractors told him that a writer on the Book of Job should take everything with patience. Controversy apart, any College might be proud of a group of Fellows of whom one became an archbishop, another a really great headmaster, and a third a cardinal. Oriel has had poets, too, within her gates, for in a later day Clough and Matthew Arnold won fellowships here.

But Oriel has had no more dutiful son, if liberality is any measure of dutifulness, than Cecil Rhodes. It is too soon to appraise the value of his scholarship scheme, which provides an Oxford education for numerous colonial and foreign students; but his old College, which benefited so largely by the provisions of his will, can have no hesitation in including him among its benefactors.

OPINIONS will differ as to whether the Italian style, of which this College is a fine example, is as suitable for collegiate buildings as the Gothic, and whether the contrast which Queen's presents to its neighbour, University, is not more striking than pleasing; but the intrinsic splendour of its façade, as viewed from "The High," is indisputable. "No spectacle," said Dr. Johnson, "is nobler than a blaze"; and those who saw the west wing of the Front Quadrangle of Queen's in flames, one summer night in 1886, must have felt their regrets tempered by admiration, so imposing was the sight. Happily the damage was mainly confined to the interior of the building. A fire had already devastated the same wing in 1778. On that occasion, as Mr. Wells narrates in Oxford and its Colleges, the Provost of the day "nearly lost his life for the sake of decorum. He was sought for in vain, and had been given up, when he suddenly emerged from the burning pile, full dressed as usual, in wig, gown, and bands." This recalls Cowley's story of a gentleman in the Civil Wars, who might have escaped from his captors had he not stayed to adjust his perriwig. Less fortunate than the Provost, his sense of ceremony cost him his life.

Queen's College was founded by Robert Eglesfield of Cumberland, Confessor to Philippa, Edward III.'s queen. Impressed with the lack of facilities for education among Englishmen of the North, he practically restricted the benefits of his Foundation to students from the north country, and Queen's is still intimately connected with that part of England. Philippa did her best for her Confessor's institution, and later queens have shewn a similar interest. The statue under the cupola, above the gateway, represents Queen Caroline.

With the exception of the Library (1696) and the east side of the Inner Quadrangle, all the present buildings were erected in the eighteenth century. The Library, a handsome room in the classical style, was decorated by Grinling Gibbons, and contains, as well as a very valuable collection of books, ancient portraits on glass of Henry V. and Cardinal Beaufort. The Chapel (1714) was designed by Wren, and the Front Quadrangle by his pupil Hawksmoor.

Queen's is tenacious of her old customs. Still the trumpet calls the Fellows to dinner; still, on Christmas day, the boar's head is brought in

bedecked with bays and rosemary;

a survival, possibly, of the pagan custom by which at Yule-tide a boar was sacrificed to Freyr, god of peace and plenty.

Peace and plenty, at any rate, have characterised the annals of Queen's; and among those who have enjoyed these good things within her walls may be mentioned "Prince Hal," Addison (before his migration to Magdalen), Tickell, Wycherley, Bentham, Jeffrey of the Edinburgh Review, and Dr. Thomson, late Archbishop of York.

HALLS for the accommodation of students existed in Oxford before Colleges were founded, and a few were established subsequently; of these St. Edmund Hall is the only one which retains its independence. The quaintness and irregular beauty of its buildings may plead with stern reformers for its continued survival.

Opposite to the side entrance of Queen's, St. Edmund Hall is in another respect under the wing of that College; for Queen's has the right of nominating its Principal.

The origin of St. Edmund Hall is uncertain, but it is commonly supposed to derive its name from Edmund Rich, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1234 to 1240. Its buildings, grouped round three sides of an oblong quadrangle, date from the middle of the seventeenth century.

The first view shews the entrance to the Hall, with the interesting old Church of St. Peter-in-the-East in the background. The crypt and chancel of this Church take us back to the times of the Conqueror, and may have been the work of Robert D'Oily, one of William's Norman followers, who is known to have built Oxford Castle.

In the view of the interior of the Quadrangle the building at the back is the Library; the abundance of creepers on the left hand adds to the idea of comfort suggested by the homeliness of the architecture.

The third illustration shews the Hall as seen from St. Peter's Churchyard. The vicinity of the monuments may serve to remind members of the Hall of their mortality.

Hearne, the antiquary, was a member of St. Edmund Hall; so also was Sir Richard Blackmore, who was in residence for thirteen years. It was his lot, says Johnson, "to be much oftener mentioned by enemies than by friends"; but this is hardly surprising, in view of the interminable epics which he inflicted upon his contemporaries.

THIS College, in respect of its buildings and its endowments, is one of the most splendid in the University. Its founder, William of Wykeham, rose through the favour of Edward III. to high positions in Church and State, being made Bishop of Winchester in 1366 and Chancellor of England in the following year. He was a man of affairs, liberal and tolerant, who took delight in building, and had himself great skill in architecture. He had already, before he designed New College, as Clerk of the Works to Edward III., rebuilt Windsor Castle. Doubtless, zeal for education was one of his incentives; but he must have known a deep gratification, as the work went on, in the growth of the stately buildings which were to perpetuate his name. Richard II.'s sanction was given in 1379, and Wykeham's Society took possession of its completed home in 1386. During the six years which followed, its founder was occupied with the building of Winchester College, the other great institution connected with his name. He died in 1404, in his eightieth year, and was buried in Winchester Cathedral, having lived long enough to see his two Foundations prosperously started upon their several careers.

New College, as left by William of Wykeham, consisted of the chief Quadrangle (which includes the Chapel, Hall, and Library), the Cloisters with their tower, and the gardens. It is this Quadrangle (shewing the Chapel) which appears in Mr. Matthison's first drawing; but it is not quite as Wykeham saw it, for the third storey was added, as at Brasenose, in the seventeenth century, when the windows also were modernised.

Passing through this Quadrangle, the visitor reaches the Garden Court, which is also the creation of the seventeenth century, and was built in imitation of the Palace of Versailles. Seen from the garden (as in the second illustration) it certainly has, with its fivefold frontage and its extensive iron palisade, a most imposing appearance.

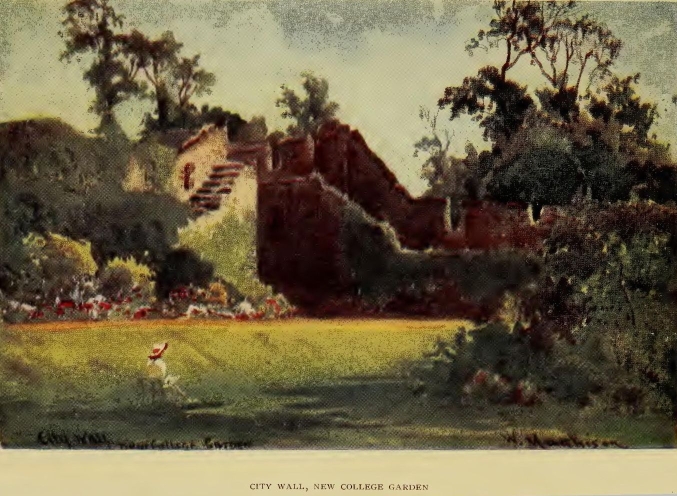

The garden contains a structure older by several centuries than any of the Colleges—that fragment of the old City Wall which is shewn in Mr. Matthison's third drawing. Its reverse side is visible from the back of Long Wall Street, and another fragment now acts as the wall of Merton garden. The city wall existed in its entirety in Wykeham's time, though already falling into decay: there is a brief of Richard II., issued to the then mayor and burgesses of Oxford, wherein the king complains of the ruinous state of the fortifications, and demands that they be at once repaired. He thought of taking refuge in Oxford, it appears, if his enemies in France should invade the country. He was soon to learn, at Flint Castle, how impotent is any masonry to protect a sovereign against subjects whose affections he has estranged. One may climb the old wall in New College garden and think of the days when it was a real defence, when the occupants of the "mural houses" at its base were exempted from all imposts, with the reservation that they should defend the wall with their bodies, in the event of an enemy's assault. On some part of the ground now occupied by the College and its garden stood several of those Halls where students lodged in the pre-collegiate days; but the greater part was waste land, strewn with rubbish and haunted by all sorts of bad characters. Certainly the whole community benefited, and not Wykeham's scholars only, when king and pope sanctioned his undertaking.

The Cloisters, of which two views are given, are singularly beautiful. They were designed, together with the area which they enclose, as a burial-ground for the College. It is unfortunate that many of the brass tablets were removed during the Civil War, when the College was used as a garrison. Royalist pikes, in those days, were trailed in the Quadrangle, and ammunition was stored in Cloisters and Tower. Later on the College was tenanted by soldiers of the Commonwealth, who in course of fortifying it did some damage to the buildings.

The Chapel is perhaps the finest extant specimen of the Perpendicular style. It suffered severely during the Reformation, when the niches of the reredos were denuded and filled up with stone and mortar, with a coat of plaster over all. In course of time the original east end was rediscovered, and the reredos renewed. By 1894 statues were erected in the niches; and as the open timber roof had been replaced in 1880, the whole may now be considered to have been restored, as far as is possible, to its original appearance. The west window (in the ante-chapel) is famous as having been designed by Reynolds. An illustration of it is here given. The beauty of the figures and of the colouring is universally admitted.

The last illustration shews the New Buildings, through which is a back entrance to the College, as seen from Holywell Street. Of these it must be said that they are far less interesting than the quaint old street in which they are situated. The best of them is the most recent addition, a fine tower put up in 1880 to the memory of a former Bursar, Mr. Robinson.

The Hall is a fine building, though its original proportions have been altered, not for the better. Here on August 29, 1605, King James I. with his queen and the Prince of Wales were entertained to dinner; and here on festival days the scholars were bidden by their Founder to amuse themselves after supper with singing and with recitations, whose themes were to be "the chronicles of the realm and the wonders of the world." On the walls are portraits of Chichele and William of Waynflete, members of the College, who were presently to rival, as Founders, the munificence of William of Wykeham himself; of Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury, friend of Erasmus and promoter of humanism; and of Sydney Smith.

The exclusive connection between Winchester and New College, which the Founder planned, proved in course of time a disadvantage. In 1857 half the fellowships and a few scholarships were thrown open to public competition. Since then the College has largely increased its numbers, and representatives of all the great schools of England are sojourners within its walls. The Founder's motto, "Manners Makyth Man," is of too wide an application to be limited to the members of any one school; and it is permissible to think that William of Wykeham, shrewd and liberal-minded as he was, would approve the change. An earlier alteration he would certainly have endorsed. He secured as a special privilege to the Fellows of his Foundation, that they should be admitted to all degrees in the University without asking any grace of congregation, provided they passed a satisfactory examination in their own College. His object was to impose a severer educational test than that which the University then afforded; when, however, University examinations became a reality, his good intention was nullified. Wykehamists pleaded their privilege, and so evaded the ordeal which members of other Colleges must undergo. Thus was an originally good custom corrupted. The College, to its credit, voluntarily abjured this questionable privilege in 1834; and is now second only to Balliol in the intellectual race.

JOHN FLEMMYNGE, Bishop of Lincoln, was for the greater part of his life a sympathiser with the Lollards; but on changing his opinions—for what reason is not known—he founded a College for the express purpose of training divines who should confute their doctrines. Such was the origin of Lincoln College, in the year 1429.

Mr. Matthison's first picture shews the entrance to the College, as seen from Turl Street. Farther on is a part of the front of Exeter, and the spire of its Chapel, with Trinity in the background. Lincoln's entrance-tower dates from the Founder's time.

The second gives the interior of the Front Quadrangle. Reference to old engravings, such as that given in Chalmers' History of the Colleges, Halls, and Public Buildings of the University of Oxford (1810), shews the battlements to be a modern addition, and anything but an improvement.

The Chapel, which stands in the inner court, was built at the expense of Dr. John Williams, Bishop of Lincoln and afterwards Archbishop of York, and was consecrated on September 15, 1631. Its roof and wainscoting are of cedar, the roof in particular being richly ornamented. The painted windows are also noteworthy. Tradition says that they were bought by Dr. Williams in Italy. That at the east end represents six principal events of the gospel narrative, with their corresponding types in the Old Testament. The following is the complete list:—The Creation of Man—the Nativity of Christ; the Passage through the Red Sea—the Baptism of Christ; the Jewish Passover—the Lord's Supper; the Brazen Serpent in the Wilderness—the Crucifixion; Jonah delivered from the Whale—the Resurrection; the Ascent of Elijah in the Chariot of Fire—the Ascension.

John Wesley spent nine years in Lincoln College, being elected Fellow in 1726. Among its members may be named Sir William Davenant, Poet Laureate; and Dr. Robert Sanderson, Bishop of Lincoln, a man of great piety, learning, and amiability, who forms the theme of one of Izaak Walton's Lives. It is to him that our English Liturgy owes the beautiful "Prayer for all Conditions of Men" and "General Thanksgiving." A recent Rector of Lincoln was Mark Pattison, B.D., who might rival Sanderson in learning, though not in the quality of forbearance. His Memoirs, posthumously published, contained, with much that was of interest, some unusually outspoken judgments upon his contemporaries in Oxford.

COLLEGIUM Omnium Animarum Fidelium defunctorum de Oxon.

This title expresses one of the purposes for which All Souls was founded. It was a Chantry first, a home of learning afterwards. An obligation was imposed upon the Society to pray for the good estate of the Founders, during their lives, and for their souls after their decease; also for the souls of Henry V. and the Duke of Clarence, together with those of all the dukes, earls, barons, knights, esquires, and other subjects of the Crown of England who had fallen in the French War; and for the souls of all the faithful departed. To think of All Souls is to think of Agincourt.

As to learning, sixteen of the Fellows were directed to study civil and canon law, the rest philosophy, theology, and the arts.

The Founders were Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury, and King Henry VI. Chichele is the Archbishop who in Shakespeare's King Henry V. urges the king (quite in accordance with history) to vindicate his claims to the crown of France. Educated in all the prejudices of his age, he set his face against the followers of Wyckliffe; at the same time he protested against the encroachments of Rome, and was spoken of in Oxford as "the darling of the people, and the foster-parent of the clergy." He was deeply read in the law, and All Souls still bears the impress of his legal tastes.

The buildings are very extensive, and are grouped around three quadrangles. The first view (which gives also a glimpse of the Radcliffe and the Old Schools) shews the front of the North Quadrangle, as seen from St. Catherine Street, with the windows of the magnificent Codrington Library.

But the Library is eclipsed, in general opinion, by the Chapel. "It is usually observed," says Chalmers, "that whatever visitor remembers anything of Oxford, remembers the beautiful Chapel of All Souls, and joins in its praises." It is characterised by dignity and simplicity, and its great reredos has a remarkable history. The Chapel was wrecked in Reformation days, and the remains of the reredos were covered with plaster in the reign of Charles II. In 1870 some workmen accidentally discovered, on removing some of the plaster, the ruins of the now forgotten reredos. It was then reconstructed, and the empty niches refilled with statues of Chichele, Henry VI., and the great ones of their time. The College also owns a fine sundial, the work of Sir Christopher Wren, who was one of its Fellows.

The four Bible-clerks, as is well known, are the only undergraduates. An All Souls' Fellowship is now what an Oriel Fellowship was in the early part of the nineteenth century, the blue ribbon of Oxford. Since its foundation in 1437 the following are a few of the eminent men who have been members of this Society:—Linacre, Sheldon, Jeremy Taylor, the poet Young, Blackstone, and Bishop Heber.

WILLIAM OF WAYNFLETE, who founded this College, was brought up in the traditions of William of Wykeham, and maintained them most worthily. A member of Wykeham's school, and perhaps of New College, he became Headmaster of Winchester, only leaving it to act as first Headmaster of Eton, on the foundation of that College by Henry VI. Like Wykeham he lived through troubled times, and like him occupied the see of Winchester and was Chancellor of England. The latter post he resigned in the last year of Henry VI., but remained Bishop of Winchester until his death in 1486. He was buried in Winchester Cathedral, where eighty-two years earlier Wykeham had been laid to rest.

On the present site of Magdalen College stood an old hospital, named after St. John the Baptist. This hospital, with its grounds, was made over to William of Waynflete in 1457; some remains of its buildings still survive in what is known as the Chaplains' Quadrangle; and in this hospital the new society found temporary shelter. Waynflete did not proceed at once to build his new College; the times were disturbed, and with the victory of the Yorkist faction he found himself in some peril. Pardoned, however, by Edward IV., he was at liberty to carry out his designs. If not his own architect, he certainly superintended the building; and with the exception of the famous Tower, the work was completed before his death.

In the result, taste has generally decided, what most visitors feel instinctively at first sight, that Magdalen is the most beautiful College in Oxford. This distinction it owes partly to the perfect proportions of its buildings, and partly to the loveliness of its surroundings. To assure oneself of this, one may take a boat up the Cherwell (as the people in Mr. Matthison's first drawing have done), and, while the sculls rest idly on the water's surface, drink deeply of the beauty of the scene.

The foundation stone of the famous Tower (which from different points of view appears in three more of the illustrations) was laid in 1492. Tradition says that it was designed by Wolsey, who was about that time Bursar of Magdalen; and also asserts that a mass for the soul of Henry VII. used, before the Reformation, to be performed upon the top of the Tower on every May-day at early morning. It is certain that a hymn is still sung there annually at that season, as those who are up early enough may hear for themselves.

Whether one approaches Magdalen by the water-way or by "The High"—as in the second illustration—the Tower is still the dominant feature of the view. On the left are seen St. Swithun's Buildings, designed in happy harmony with the older structure. When the Lodge is passed, one is confronted with the old stone pulpit (sketched by Mrs. Walton), from which an open-air sermon was formerly preached on St. John the Baptist's day. * The court on that occasion used to be fenced round with green boughs, in allusion to St. John's preaching in the wilderness.

* This custom has recently been revived.

The Cloisters are next entered, from which is obtained a splendid view of Waynflete's Quadrangle and Tower (the "Founder's Tower" of the next illustration). The perfect grace of Magdalen is here revealed, and praise becomes superfluous. The Chapel, Hall, and Library open out of this Quadrangle. The College choir is among the best in the three kingdoms.

Many theories have been suggested in explanation of the curious stone figures in the Quadrangle, which were put up after Waynflete's day. The most reasonable appears to be that which makes them represent the several virtues and vices which members of the College should follow after and eschew. But even so that interpretation seems a little forced which makes the hippopotamus, carrying his young one on his shoulder, emblematic of "a good tutor, or Fellow of a College, who is set to watch over the youth of the society, and by whose prudence they are to be led through the dangers of their first entrance into the world." *

* Oedipus Magdalensis, in the College Library.

To speak now of the three remaining illustrations, the first shews the garden, reached from the Quadrangle, the exterior of which forms the background of the picture. From here a good view is obtained of the new buildings, a stately eighteenth-century pile, which adjoin the deer park; a part of them, as well as of the deer park, is seen in Mr. Matthison's sketch. Finally, he gives his impression of the College as seen at evening from the entrance of Addison's Walk, with the Tower blue-grey against a paling sky.

That walk, which commemorates "the famous Mr. Joseph Addison," as Esmond called him, was in part, at any rate, laid out in Queen Elizabeth's day; and here the future essayist may have often strolled and meditated, in the exercise of that gift of "a most profound silence" with which, half in jest, he credited himself. There stood in his time at the entrance of the water-walk an oak, which for centuries had been, according to Chalmers, "the admiration of many generations." Evelyn, the diarist, commemorates its huge proportions. It was overthrown by a storm in 1789, and a chair made of its wood is preserved in the President's lodgings.

Magdalen in its time has welcomed many royal visitors, among them Edward IV. in 1481, and Richard III. in 1483. Richard was so pleased with the disputations provided for his entertainment that he presented the two protagonists (one of them was Grocyn, the Greek scholar) with a buck apiece and money as well. Other guests were Arthur, Prince of Wales, elder son of Henry VII., and Henry, son of James I., whose great promise was cut short by an early death. Cromwell and Fairfax dined at Magdalen, when they received the degree of D.C.L. in 1649, and, instead of hearing the usual disputations, played at bowls upon the College green.

Meanwhile the College had educated its fair share of prominent men: Wolsey; Colet, afterwards Dean of St. Paul's; Cardinal Pole; William Tyndale, translator of the Bible; Lyly, whose Euphues gave a name to a certain style of writing; and John Hampden. A notable President (1561) was Dr. Laurence Humphrey, who was among the Genevan exiles in Queen Mary's time. On his return he retained the Genevan dislike for ecclesiastical vestments, but was persuaded to wear them on the occasion of Queen Elizabeth's visit to Oxford. "Mr. Doctor," said the queen, who was aware of his usual practice, "that loose gown becomes you mighty well. I wonder your notions should be so narrow."

The life of a College is in general self-contained, but in the last year of James II.'s reign Magdalen becomes for a time the centre of a constitutional struggle. There is no more glorious page in her annals. James II. had done his best to turn University College into a Roman Catholic seminary, and had made a professor of that religion Dean of Christ Church. He now sought to impose upon the Fellows of Magdalen a President of his own choosing, one Farmer, a papist, and a man of known bad character. The Fellows replied by electing one of their own number, John Hough, upon which they were cited before the Court of High Commission and bullied by Judge Jeffreys, while Hough's election was declared invalid. Farmer was so generally discredited that the king did not press his claims, but shortly afterwards nominated in his stead Dr. Parker, Bishop of Oxford. When the Fellows respectfully refused to accept him, Hough and twenty-six Fellows were forcibly ejected, as well as many of the "demies" (or scholars) who sympathised with their action. Parker died after a few months' tenure of office, when James named Gifford, a Roman Catholic, as his successor. It was only in October 1688, when moved to terror by the Declaration of William of Orange, that the king, among other concessions, cancelled Gifford's appointment and restored Dr. Hough and the ejected Fellows. But then, as we know, all concessions were too late. Hough remained President until 1701.

During the eighteenth century Magdalen was not exempt from the general somnolence which pervaded the University. Gibbon's residence there was cut short by his becoming a Roman Catholic. His harsh judgment of the College, warped as it was, cannot be entirely refuted. Famous nineteenth-century members of Magdalen were Robert Lowe, Lord Selborne, Charles Reade, and Professor Mozley. At present it does not look as if the charge of inactivity could ever again be preferred against Waynflete's Foundation.

THE first thing about this College to excite a stranger's curiosity is its name. The explanation is trivial enough. Brasenose Hall (which was in existence in the thirteenth century and became Brasenose College in 1509) was so called from the brass knocker—the head of a lion with a very prominent nose—which adorned its gateway. In 1334 the members of the Hall, from whatever reason, migrated into Lincolnshire, taking the knocker with them, and set up their rest at Stamford. "There is in Stamford," wrote Antony Wood, "a building in St. Paul's parish, near to one of the tower gates, called Brazenose to this day, and has a great gate, and a wicket, upon which wicket is a head or face of old cast brass, with a ring through the nose thereof. It had also a fair refectory within, and is at this time written in leases and deeds Brazen Nose." This building was bought by "B. N. C." (to adopt Oxford phraseology) in 1890, and the knocker brought back to Oxford, none the worse for its prolonged rustication.

The College named after this venerable relic owes its foundation to a pair of friends, William Smyth, Bishop of Lincoln, and Sir Richard Sutton of Sutton, in the county of Cheshire, an ecclesiastically-minded layman, who became Steward of the monastery of Sion, near Brentford. "Unmarried himself," the knight's biographer informs us, "and not anxious to aggrandize his family, Sir Richard Sutton bestowed handsome benefactions and kind remembrances among his kinsmen; but he wedded the public, and made posterity his heir."