Title: How to Travel

Author: Thomas Wallace Knox

Release date: March 17, 2014 [eBook #45162]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

HINTS, ADVICE, AND SUGGESTIONS

TO TRAVELERS

BY

LAND AND SEA

ALL OVER THE GLOBE.

BY

THOMAS W. KNOX,

Author of "Camp-Fire and Cotton-Field," "Overland

Through Asia," "Underground," "Backsheesh,"

"John," "The Boy Travelers in the

Far East," Etc.

NEW YORK:

CHARLES T. DILLINGHAM.

BOSTON:

LEE AND SHEPARD.

LONDON AND GENEVA

THE AMERICAN EXCHANGE IN EUROPE.

1881.

Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1880, by

THOMAS W. KNOX,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

All rights of translation and foreign publication are reserved.

To all Travelers on Land and Sea,

this volume

is sympathetically inscribed.

In preparing this volume for the press the author of "How to Travel" has endeavored to supply a want whose existence has long been apparent to him. Having journeyed somewhat over the earth he is frequently consulted by friends and acquaintances who are about to travel, and wish to know what to do before setting out on their undertakings, and how to meet the various perplexities that are sure to arise. In preparing this book he has answered a great many interrogatories that have been addressed to him in person, and if the manner of his response should be considered didactic, he begs the reader to remember that the author is endeavoring to meet the questions of the would-be traveler, and, therefore, addresses him in the second person. As nearly as possible he has embodied in "How to Travel" as much information as could be wrung from him by a vigorous and thorough interrogation of a couple of long winter evenings, conducted by an inquisitive couple who were about starting on a journey around the world and up and down its surface.

With the changes that are constantly going on, some of the information here given may be found slightly inaccurate, but it is hoped that instances of this sort will be rare. Prices of hotels, steamships, railroads, and the like are subject to alteration, and consequently no absolute rule can be laid down. But the author believes that in the instances where his figures may be found astray they are so near the mark that they will prove of material assistance to the traveler.

As the author is neither a lady nor a lawyer, he has found it desirable to invoke the aid of those important members of society in the preparation of the book. A reference to the table of contents will show the assistance they have given him, the one in a chapter of "Special Advice to Ladies" and the other in "Legal Rights of Travelers." All other parts of the book are of his own production and the results of his experience in travel, covering a period of more than 20 years and embracing many lands and seas.

With this explanatory preface, and trusting that the volume will be a sufficient apology for its existence, the author delivers it to the hands of the traveling public, and hopes for a verdict in its favor.

T. W. K.

New York, February, 1881.

| CHAPTER. | PAGE. | ||

| I. | General Advice Applicable to all Kinds of Travel, | 9 | |

| II. | Railway Travel in the United States and Canadas, | 20 | |

| III. | American Steamboat Travel, | 28 | |

| IV. | Sea and Ocean Travel, | 37 | |

| V. | Sea Sickness and How to Avoid it, | 48 | |

| VI. | Special Advice to Ladies, by a Lady, | 55 | |

| VII. | Daily Life at Sea, | 64 | |

| VIII. | Going on Shore—Hotels, | 76 | |

| IX. | The System of Fees, | 87 | |

| X. | English and Continental Money, | 102 | |

| XI. | Languages and Couriers, | 108 | |

| XII. | Railway Traveling on the Continent, | 118 | |

| XIII. | Steamboat Traveling in Europe, | 133 | |

| XIV. | Sea-going Steamers in European Waters, | 139 | |

| XV. | Sea and Ocean Steamers in Various Parts of the World, | 147 | |

| XVI. | Travel by Stage-Coach, Diligence, and Post, | 155 | |

| XVII. | Traveling with Camels and Elephants, | 167 | |

| XVIII. | Traveling with Reindeer and Dogs, | 174 | |

| XIX. | Traveling with Man-power—Palankeens, Jinrikishas, and Sedan Chairs, | 179 | |

| XX. | Pedestrian Traveling—Mountain Climbing, | 186 | |

| XXI. | Traveling Without Money—Round the World for $50, | 193 | |

| XXII. | Skeleton Tours for America and Europe, | 201 | |

| XXIII. | } | General Directions for a Journey Round the World, with Routes, Distances, etc., etc., | 207 |

| XXIV. | } | ||

| XXV. | Legal Rights of Travelers, by a Lawyer, | 230 | |

| XXVI. | Wilderness and Frontier Travel, | 242 |

There is an old saying of unknown origin that a light heart and a thin pair of trowsers are the principal requisites for a journey. The proper texture of one's garments depends largely on his route of travel and the difficulties to be encountered; thin ones would be desirable in hot countries and for lounging on the deck of a ship in low latitudes, while they would be eminently out of place in the region of the north pole or in the rough traveling of the wilderness. But no one will deny that a light heart has much to do with the pleasure of travel, and the man who can be serene under all circumstances, who laughs at mishaps, and accepts every situation with a smile of content, or at least with a feeling of resignation, is the model voyager. For him the miles go by as on the wings of a bird, while to the grumbler and misanthrope they are weighted with lead. The former comes back from his wanderings refreshed and instructed while the latter is no better in mind and body than when setting out on his journey. For your own comfort and happiness, and your own mental and physical advantage, start on your journey with a determination to see the bright side of everything and to endure as cheerfully as possible the jolts and buffetings and petty disappointments that are sure to be your lot. And in the same proportion that a light heart makes you better for yourself it makes you better and more agreeable for those who may be traveling with you.

If you have been reared in the belief that your own country, or your own state, town, or hamlet, contains all that is good in the world, whether of moral excellence, mental development, or mechanical skill, you must prepare to eradicate that belief at an early date. That you and yours have the best and are the best we will not for a moment deny, but when you attempt to claim everything you claim too much. To an observant and thoughtful individual the invariable effect of travel is to teach respect for the opinions, the faith, or the ways of others, and to convince him that other civilizations than his own are worthy of consideration. At the same time he will find his love for his native land as strong as ever and his admiration for his own institutions as warm as on the day of his departure. An old traveler once said: "I have found good among every people, and even where there was much to condemn there was much to admire. I have never returned from a journey without an increased respect for the countries I have visited and a greater regard for my own land than ever before. The intelligent traveler will certainly be a true patriot."

So much for the mental conditions of travel. We will come now to the practical and tangible needs of locomotion.

Money is the first of these things. It is true that one can travel without money, and in a later chapter we will see how it may be accomplished; for the present we will look upon money as a requisite.

Never carry a large amount of cash about your person or in your baggage. A letter of credit, procurable at any banker's, is far better than ready money, as its loss causes nothing more than temporary inconvenience. It is best not to lose it at all; but, in case of its disappearance, payment may be stopped and the finder or thief can derive no benefit from its possession. The usual form of a letter of credit is about as follows:

"New York, 18 .

"To our correspondents:

"We have the pleasure of introducing to you * * * * * the bearer of this letter, whose signature you will find in the margin. We beg you to honor his drafts to the amount of * * * * * pounds sterling upon our London house. All deductions and commissions to be at the expense of the bearer.

"We have the honor to remain, gentlemen,

"Very truly yours,

"* * * * *"

Some banking-houses have their letters printed in French instead of English, but the substance is the same. The amount is usually expressed in pounds sterling, and drafts are made payable in London; but if the traveler is going directly to the continent of Europe, some of the bankers will give him, if he desires it, a letter on Paris and state the amount in francs. Sterling credits are generally the best to carry, no matter what country you may be visiting, as London is the money centre of the world, and there is never any difficulty in ascertaining the rate of exchange upon that great city. The traveling letter of credit is printed on the front of a four-page sheet, letter size; the second page is left blank for the endorsement of the amounts drawn, and the third and fourth pages contain a list of bankers in all the principal cities that the voyager is likely to visit. Any respectable banker, even if not named on the printed list, will generally cash a letter of credit; but it is advisable to adhere as much as possible to the correspondents of the establishment that issued the document.

The traveler should only draw at one time sufficient money to last him for a few days, or till he reaches a convenient place for making another draft. A week's supply of cash is usually sufficient for a single draft; but, of course, no absolute rule can be laid down.

Another form of traveling credit is in the shape of circular notes, which are issued by some bankers, though not by all. They are for various amounts—five, ten, twenty, fifty, or a hundred pounds—and are accompanied by a letter of identification which bears the signature of the holder. The notes are useless without the letter, and the letter without the notes, and the traveler is advised to carry them apart from each other. The advantage of this kind of credit is that you can have the notes cashed at a hotel or at any large shop where you may be making purchases, and you may have remittances follow you from time to time in circular notes, the same letter of identification answering for all. The disadvantage is that they are bulky, and consequently inconvenient to carry, and the possession of two parcels in place of one, in different parts of your baggage, doubles the chances of loss. For a long journey where a considerable amount is to be carried, or where remittances are to follow, I would recommend that part of the funds should be in a letter of credit, and part in circular notes with an identification.

For domestic traveling, bankers' drafts and credits can always be procured; but American bankers are much more stringent about identifications than are those of Europe, and the traveler must be sure that he can be properly identified wherever he is going, or he may experience difficulty in obtaining his cash. An obliging banker has been known to pay a draft to an individual who had no other identification than his name written on his under-clothing or his initials tattooed on his arm. But such instances are rare, and the money-changer is very likely to be obdurate, though polite. It is said that a Boston banker once cashed a check payable to the order of Peter Bean, under the following circumstances:—The bearer said he knew nobody in the city, but he proved his identity by ripping open the lining of his coat-collar and revealing a pea and a bean, securely stowed away. "That's my name," said he, "P. Bean; and that's the way I mark my coats." But all names cannot be written with the products of the garden, and Mr. Bean is not likely to have many imitators.

Your letters can be sent to the care of any banker on whom your credits are drawn, and they will be forwarded by him as you may direct. This is the usual custom with European travelers, and there is rarely any cause for complaint.

When traveling, always be careful to have plenty of small change in your pockets, and be prepared to pay all obligations, especially the smallest, in their exact amount. The vast horde of cabmen, porters, guides, waiters, and all classes of people who render you services, or pretend to have done so, are proverbially without change, and if you cannot tender the exact sum due them you are pretty certain to overpay them. Even where they admit that they are possessed of small coin, they generally manage so as to mulct you in something by having their change give out before the proper return is reached. The New York hackman to whom you hand a five-dollar bill for him to deduct his fare of two dollars will usually discover that he has only two dollars, or perhaps two and a half, in his possession; and the London cabman will play the same trick when you ask him to take half a crown from a five-shilling piece. All over the world you will find it the same. There may be an occasional exception, but it only proves the rule. And when you enter the great field of gratuities, you will find that the absence of small change will cost you heavily. Many a man has given a shilling where a sixpence was quite sufficient, and all that was expected; but he did not have the sixpence in his pocket, and the shilling had to go.

Have as little baggage as the circumstances will justify. Don't carry anything on the principle of Mrs. Toodles, that it may come handy some time, but take only what you know to be absolutely necessary. No rule can be laid down, and each person must judge for himself. For a man, a suit of clothes in addition to the one he wears is sufficient for outward adornment, unless he is "in society," and expects to dine, attend parties, or make fashionable visits. In the latter case a dress-suit is indispensable, and in European travel it is generally well to have a dress-suit along, since there are many public ceremonies where the wearer of ordinary clothing is not admitted. For ladies, a traveling-dress, a walking-dress, and a black silk dress may be considered the minimum. The black silk garment corresponds to the masculine dress-suit, but it comes in use on many occasions where the latter is not demanded. The quantity of under-clothing will depend largely on personal habits. It should never be less than to cause no inconvenience in a week's absence of the laundress, and if a long voyage is to be made by steamship the supply should be proportionally increased. It is a good rule never to omit an opportunity of giving your soiled garments to be washed, even if only a day or two has elapsed since your last employment of the laundress. In all civilized parts of the world where there is an appreciable volume of travel, washing is done in from twenty-four to forty-eight hours, but away from the routes you must count on a week, or four or five days at least.

A single trunk of moderate size will contain all that is needed for the actual traveling wants of a reasonable being, of either sex, except on a long journey. To this add a hand-satchel to hold your toilet articles, and any little odds and ends of reading matter, or other personal comforts. Some travelers are content with such toilet materials as they find in hotels, and do not object to a public comb or hair-brush; but the majority of individuals are more fastidious. In most hotels in America, soap is supplied in private rooms; but in Europe the traveler must provide his own.

Endeavor as much as possible to avoid being in a hurry. Go to your train, boat, ship, diligence, or other conveyance, in ample season, so that all needed arrangements can be made without pressure for want of time. You will save money and temper by adopting this rule.

Respect the rights of other travelers, and by so doing you will lead them to respect yours. Keep your disposition as unruffled as possible at all times, and even when angry inside don't let the anger come to the surface. If you find yourself imposed upon by any official or employé of railway or steamer, state your views quietly but firmly, and, if he declines to redress the wrong, ask him to be kind enough to call his superior. If the latter is inaccessible, ask, in the same polite tone, for his address, and the chances are ten to one that your cause of complaint will be removed without more discussion.

Expenses may be roughly set down at five dollars a day, not including railway or other fares, and not including luxuries of any kind. Ordinary hotel expenses will be not far from three dollars a day, leaving two dollars for incidentals. Most persons would be likely to exceed rather than fall below this figure, and in the United States they will find that money melts away more rapidly than in Europe. England is at least twenty-five per cent. dearer than the continental countries, and only a trifle cheaper than America. The traveler who is not economical on the one hand and not wasteful on the other can get along very well on six dollars a day in England or America, and five dollars on the continent, with the exception of Spain and Russia, which are dearer than Germany, France, Italy, or Switzerland. The usual allowance to commercial travelers for their expenses, exclusive of railway fares, is one pound sterling daily in England, and twenty francs on the continent; and it is probable that the most of them manage to keep within their allowances.

A party of two or more will travel somewhat cheaper than the same number of individuals alone, for the reason that many items are no more for two than for one. Including all the expenses of travel—railways, steamships, hotels, carriages, fees, and the like—an extended journey may be made for ten dollars a day in England and Europe, and twelve dollars for the United States. This allows for first-class places on all conveyances, and good rooms at good hotels—requires no rigid economy, and permits no extravagance. For a journey around the world, to occupy ten or twelve months, and visiting Japan, China, Siam, Java, India, Egypt, Italy, France, and England, together with the run across the American continent, the cost will be about four or five thousand dollars. But, as before stated, there can be no fixed rule, and the amount of expenditure depends largely upon the tastes and habits of the traveler and the amount of money at his disposal. More will be said on this topic in subsequent pages.

Whenever you go out of your own country carry a passport. It may not be needed, as passports are now demanded in very few countries, but it is a good thing to have along, since it serves as an identification in case of trouble with the authorities, and is useful in civil actions or where the assistance of your consul may be required. In many countries the post-office employés refuse to deliver registered letters to a stranger except on presentation of his passport, and the document will occasionally be found useful at the banker's. An old frontiersman once said of the revolver which he habitually carried, "You don't need it often; perhaps may never need it at all, but when you do want it you want it awful bad, I tell you." The same may be said of the passport.

Passports may be procured through a lawyer or notary public, and a single passport is sufficient for a family. They may also be obtained at any United States legation abroad on presentation of proofs of citizenship. The government fee for a passport is five dollars.

At the custom-house, whatever its nationality, be as civil as possible and anticipate the desires of the officials. They have a duty to perform, and if you facilitate their labors the chances are they will appreciate the politeness and let you off as easily as they can consistently. Unlock your trunk or valise, or offer to do so, before they ask you, and open the various compartments immediately. Declare anything that may be liable to duty and call attention to it, and conduct yourself generally as though it was one of the delights of your life to pass a custom-house examination. If you are inclined to defraud the revenue, do it gracefully and conceal your contraband articles so that it will not be easy to find them yourself after you are out of reach of the officials. Honesty is, however, the best policy in this business, and the smuggler is just as much a violator of the law as a burglar.

The ways of the custom-house may sometimes be smoothed by a numismatic application to the hand of the inspector, but it is not altogether a safe operation. In Turkey, Egypt, Syria, and other Moslem countries bribery is considered a legitimate and honorable transaction, and the customs officer looks at the outside of your trunk and extends his open hand for your money with as little attempt at concealment as does the cabman when he asks for your fare. At the Italian Dogana fees are taken on the sly, but you may sometimes make a mistake and hit the wrong man, and the same is the case in Spain and Russia. In the other continental countries generally, and in England and the United States, fee-taking at the custom-house is a pretty rare exception, and the traveler will do far better to avoid crooked ways than to attempt them. Instances have been known of American inspectors who went straight to the point and suggested that a five-dollar bill would make things easy, and when it was not forthcoming they gave all the trouble in their power. Happily such occurrences are rare, and if customs officials are occasionally dishonest it should be remembered that they are no worse than those who encourage them to be so. A bribe, like a bargain, requires two persons for its consummation, and of this twain the officer is but one.

Before starting on any journey buy a copy of "How to Travel," and if you find the book useful be kind enough to recommend it to your friends and acquaintances. Find the best guide-books for the region you are to visit and study them carefully; if you make a mistake and get hold of a poor one, remember that even a poor guide-book is better than none at all, and you will generally obtain the worth of your money from it.

For the United States Osgood's and Appleton's guides are to be recommended, though there are others that contain a great deal of information. The name of guide-books for the trans-continental journey is legion; all have their merits and their faults, and as they are to be found at all the news-stands on the great railway lines the tourist can choose for himself.

For Europe the principal guide-books are those of Murray and Baedeker. Baedeker's books are the most convenient, and contain more practical information than their English rival; and there are probably ten copies of Baedeker sold to one of Murray. Where a traveler wishes to learn about the hotels, railways, cabs, roads, and other things of every-day life, Baedeker is his friend, but where he desires a long historical sketch, or perhaps a dissertation on art, he will choose Murray. It is well to have both these guides, as the one supplies oftentimes what the other lacks. Harper's and Appleton's guide books to Europe and the East, each in three volumes, are popular with many Americans, on account of their compactness.

Syria, Palestine, and Egypt are also covered by both Baedeker and Murray, and the latter has a guide to India, but it has not been revised for a long time. There are no complete guide-books to China, Japan, and the Far East generally, and the tourist must rely on general works of history and travel. In this connection the writer respectfully calls attention to his volumes, named on the title-page of this work.

Travel in the United States and Canada virtually comprises but two kinds of conveyance, the railway and the steamboat. Once the stage-coach was an American feature, and it still remains in some parts of the country, but the rapid advance of the railway has almost swept it out of existence, and where it still lingers it is but the shadow of its former self. Long ago we had the canal-boat, a slow but remarkably safe mode of locomotion; it could not leave the track or be overturned, nor could it explode; The water beneath it was so shallow that it could not sink, and in case it took fire you had only to step ashore and be out of danger. But the canal-boat is a thing of the past, with here and there an exception still more rare than that of the stage-coach. We are a progressive people, and when the quicker mode of travel was developed the old was forgotten and sent into obscurity.

Until within the last fifteen or twenty years we had but a single class of passenger cars in America, as the emigrant trains on a few of the trunk lines were hardly to be considered by travelers, but the invention of the palace and sleeping-coaches (generally coupled with the name of Pullman, their inventor), has given us two classes which are virtually as distinct as are the first and second of a continental railway. Hardly a train runs on any road of consequence without a Pullman car attached, and a seat may be had in this vehicle on payment of an extra fee. There is the parlor car for day use only, but the "sleeper" is intended for both day and night. By the magic wand of a colored porter the seats are converted into comfortable beds, and the traveler may be whirled along at the rate of thirty miles an hour, and all the while he sleeps as calmly as at home. Toilet-rooms are at the ends of every carriage, one for gentlemen and the other for ladies, where you may perform your ablutions and put your hair in shape, so as to present as creditable an appearance as when starting on your journey. That "necessity is the mother of invention" is well exemplified in the history of the Pullman car. The great distances to be traveled in America called for something which should soften the asperities of sitting in an ordinary seat by night as well as by day. Step by step the work went on, till finally we have the perfection of railway travel.

The expense of a place in a parlor or sleeping-car on American railways varies from two to three dollars for twenty-four hours, with the addition of a fee to the porter of 25 cents a day. For this he looks after your personal needs, polishes your boots, and opens or closes your bed when you desire it. There has been considerable mystery relative to the sleeping hours of a porter in a palace car on long routes, as he appears to be on duty all the time from one day's beginning to another. It is suspected that he belongs to a race apart from the rest of humanity, and is so constituted that he never sleeps. The tickets for the palace car are not usually sold at the same place as the regular passenger tickets, but at a separate window or in an office by itself. It is well to secure your place in advance, as the cars are often crowded and you may arrive at a station to start on a long journey and find that every bed has been sold. Places may be secured hours and days ahead, and the earlier you take them the better choice do you have. The tickets for the car are collected by a conductor, and if any places are unsecured he can sell them to those who apply for them.

Never buy your tickets, either for passage or for a place in a palace car, of strangers in the street or of chance "runners." Such tickets may be good, but the probabilities are not in their favor, while there can be no doubt about the tickets at the regular offices. Where there are rival routes it is often difficult to get the exact facts concerning them, as the runners are apt to be inexact about the merits of their own lines or the demerits of others. They have been known to state that the track of a rival railway had been torn up and sold for old iron in order that a dividend might be declared to the stockholders, and the steamboat agent who told a timid old lady that his company had removed all the boilers from their boats, so as to destroy the possibility of an explosion, is not without imitators.

Beware of playing cards with strangers who wish to start a friendly game of euchre which is subsequently changed to draw-poker or some other seductive and costly amusement. This advice is superfluous in case you are in the gambling line yourself, and confident that you can "get away" with any adversary you may be pitted against. Be cautious, however, about "waking up the wrong passenger," as not unfrequently happens to skilled performers with cards.

On most of the railways each passenger has an allowance of 100 pounds of baggage, but it is never weighed unless the amount is greatly in excess. West of the Missouri river they are more particular, and all trunks must pass the scales. On the Pacific railways all extra baggage above the allowance is charged for at a certain rate per pound, but on the eastern roads the extra charge is generally for the trunk or box without much regard to its weight. On most of the eastern roads a passenger can take a single trunk without extra payment, even though it may rival a square piano in size. Sometimes a question about extra trunks may be settled by a fee to the man in charge of the baggage-room of the station or the baggage-car of the train. The passenger's ticket must be shown at the baggage-room, where a metal check will be given to the place of destination. The check secured, the traveler may proceed to the palace or other car of the train and give his trunk no farther consideration till he nears the place to which it is checked.

Baggage expresses exist in most of the large cities. They undertake to deliver your impedimenta on payment of a fee of from 25 to 50 cents for each parcel, at any hotel or private residence in the place, on the surrender of your check. If you are in a hurry and must have your trunk within a few hours after your arrival, it will be unsafe to trust to the baggage express; the agent who passes through the train to collect the checks will assure you that your baggage will be delivered within an hour of arrival, but if you ask a written guarantee to that effect he will be pretty sure to refuse it, and admit that he does not know when the delivery will take place. The writer speaks knowingly and feelingly of his experience with baggage expresses in New York; in only one instance in a period covering more than twenty years has a baggage express delivered his trunk or valise in the time promised by the agent, and he has been compelled to wait all the way from two to ten hours beyond the time stipulated. On one occasion a trunk that was promised for 7 A.M. was delivered at 8.30 P.M., and on another a valise promised for 2 P.M. did not reach its destination till 11 P.M. and the driver of the wagon demanded extra payment for night delivery.

Carriages from railway stations are always to be had, and in some of the cities, notably in Boston, the rates are reasonable and honestly stated, and the service is good and prompt. In New York very little can be said in praise of the carriage system, as the drivers are inclined to make as much as possible out of the stranger within the gates, and are more likely to overcharge him than to state the proper and legal fare. Most of the large hotels have their own coaches at the stations on arrival of the principal trains, not only in New York but in other cities, and by taking one of these coaches the traveler will greatly lessen the probabilities of being defrauded. If he intends to take a carriage from the station, and has only ordinary baggage, he will not give his checks to the express agent, but will hand them over to the driver whom he engages.

In the western cities there is an omnibus system of a very satisfactory character. As you approach a city, an agent of the omnibus company (generally called a Transfer Company) passes through the train, and interrogates each passenger. You state your destination—whether hotel, private house, or another railway station—surrender your baggage check, and with it your transfer ticket, if you have one; or if not, you pay a fee of from twenty-five to fifty cents. The agent tells you the number or letter of the omnibus you are to enter, and when you arrive at the station you find the vehicles drawn up in a row against the platform. Selecting the one that is to carry you, you enter it, and in a little while it moves off, followed by the wagon that holds your trunk. You are taken with reasonable directness to your destination, the omnibus sometimes making slight detours to drop passengers along its route. The same vehicles take passengers to the stations, and, by leaving notice at the company's office, you can be called for in any part of the city, at any hour you name.

Most of the American cities are well provided with street railways, or tramways, and with cheap omnibuses that ply along the principal streets. To make use of these to advantage, a knowledge of the city is necessary; but strangers will have little difficulty in securing the proper directions by applying to a policeman. Professional guides are unknown in American cities, but the services of a bootblack or other small and somewhat ragged boy can generally be secured to put the traveler on the right track.

On all the lines of railway there are eating-stations, where passengers may save themselves from starvation, and generally do a good deal more. The time allowed varies greatly, but the usual limit is twenty minutes; on some lines it is half an hour, while on others a quarter of an hour is deemed sufficient. The price of a "square meal" varies from fifty cents to a dollar, and there are a few places where it is a dollar and a quarter. The square meal is not, as might be supposed, a dinner, supper, or breakfast in the form of a cube; it includes the right of eating as much as one pleases from any or all the dishes on the bill of fare, and if the traveler chooses to repeat, again and again, any favorite article of food, the proprietor offers no objection. The service is generally good, and the supply of food palatable and bountiful. The majority of travelers, are apt to eat with considerable velocity at these stopping-places, and there are few spots in the world where one can witness greater dexterity with knife and fork than where a railway train halts "fifteen minutes for refreshments." The performances of the East Indian juggler are thrown in the shade, and the famous swordsman of Runjeet Singh, who could wield his weapon with such rapidity that it was altogether invisible while removing the head of an antagonist, might learn something if he would make a visit to the eating-house of an American railway.

Those who do not wish a full meal will generally find a counter at the eating-stations where coffee, tea, sandwiches, and cold meats may be bought cheaply, and on some roads there are stations where the trains stop for five or ten minutes only, to enable passengers to take a slight lunch, of a solid or liquid character. On many of the roads the sale of intoxicating liquors is forbidden; but these are not held to include beer, cider, and light wines.

It is a good rule for a traveler never to miss the opportunity of taking a meal. Sometimes the hours are a trifle inconvenient, and he may not feel hungry when an eating-station is reached; but if he allows it to pass he will find himself faint with hunger before he comes to the next. On long journeys it is well to carry a lunch-basket of such things as may strike the owner's fancy and palate, but care should be taken to avoid articles that give out disagreeable odors. Limburger cheese is not to be recommended—nor, in fact, cheese of any sort; cold tongue is another objectionable article, as it will not keep many hours, and has a way of smelling badly, or even worse. Crackers, English biscuit, and fruit, with a bottle of claret or some similar drink, are the best things for a railway lunch-basket, and sometimes they tend greatly to preserve the temper unruffled, by filling an aching void when the train is delayed and the square meal unattainable.

On several of the great lines running westward, dining and hotel cars have been established. The latter are both eating and sleeping-coaches in one, but they are not generally in favor, as it is found in actual practice that the smell of cookery is disagreeable to the slumberer, while that of the sleeping-room is not acceptable to the nostrils when one sits down to breakfast or dinner. The dining-car is kitchen and dining-room, and nothing more. It is attached to the train at a convenient time for a meal, and runs with it for a couple of hours or so, when it is turned to a side track and waits to serve the next banquet for a train going the other way. The dining-car is a most admirable institution, as it enables the traveler to take his meals leisurely while proceeding on his way. It is generally well-managed and liberally supplied, and one may be fed as bountifully, and on as well-cooked food, as in the majority of hotels. On some of these cars meals are served a la carte; but the most of them have the fixed-price system, at the same rates as the stations along the lines where they run.

In the parlor cars, your seat is designated on a ticket specially marked and numbered, and no one has any right to occupy it during your absence. On the ordinary cars, the seats are common property, and cannot be retained; though it is almost universally recognized that the deposit of an overcoat, shawl, bag, or some other article of the travelers equipment in a seat is prima facie evidence that it has been taken. Impudent persons will sometimes remove the property of one who is temporarily absent, and appropriate the seat to themselves; but they generally vacate it on being reasoned with. If they are obstinate, the conductor may be called, and sometimes the muscular persuasion of a strong brakeman or two is necessary to convince the intruder of his mistake.

The railway system of the United States had its beginning about fifty years ago, and is consequently a third of a century behind the adoption of the steamboat. According to the best authorities, the first American steamboat that carried passengers and made regular trips was built by John Fitch, at Philadelphia, and was the successor of two experimental boats by the same inventor. She ran on the Delaware river during the summer of 1790, and made altogether more than two thousand miles, at a maximum speed of seven and a half miles an hour. Fulton built the Clermont in 1806, and her regular trips began in 1807, seventeen years later than the achievement of Fitch. From this beginning, river-navigation by steam was spread through the United States till it reached every stream where boats could ply, and some where they were of no use. Of late years the steamboat interest has declined in some parts of the country, owing to the extension of the railway system; but it is still of great magnitude, and will doubtless so continue for many years to come.

American steamboats are undisputedly the finest in the world, and every foreigner who visits the United States looks with wonder at our floating palaces. Whether on eastern or western waters, the result is the same. The most ordinary boat surpasses the finest that English or European rivers or lakes can show.

The largest and most elaborate of the eastern boats are on the Hudson river and Long Island sound; the finest of the western boats are on the Mississippi. Some of those that connect New York and Albany and New York and Boston are capable of carrying six hundred first cabin passengers with comfort, and they have been known to transport as many as a thousand. On the night-boats there is a general sleeping-room below deck, and a bed in this locality is included in the ticket. Separate rooms on the upper deck must be paid for extra; but they are worth their cost in the privacy, better ventilation, and superior accommodations that they afford, besides being easier to escape from in case of accidents. The saloons are large, and elaborately furnished; and, if the boat is crowded to repletion, the sofas are used as sleeping-places by those who were not lucky enough to obtain rooms or beds below. Sometimes extra beds are put up in the saloon and lower cabin, so that the place looks not unlike a hospital, or the dormitory of a charity school.

A crowded steamboat at night is the paradise of the pickpocket, who frequently manages to reap a rich harvest from the unprotected slumberers. Even the private rooms are not safe from thieves, as their occupants are frequently robbed. On one occasion, some thirty or more rooms on a sound steamer were entered in a single night. The scoundrels had obtained access to the rooms in the day-time, and arranged the locks on the doors so that they could not be properly fastened. The night traveler on the steamboats plying in eastern waters should be very particular to fasten his door securely, and if he finds the lock has been tampered with he should report the circumstance to an officer or to one of the stewards. The windows should be looked after as well as the doors, and the rules that apply on railways to social games of cards with polite strangers should be remembered on steamboats.

Where steamboats are in competition with railways their fares are generally much cheaper, owing to the longer time consumed on the route. Where time is not an object the steamboat is the preferable conveyance, as the traveler is not inconvenienced by dust, the ventilation is better, means of circulation are far superior, and on river routes there is a better opportunity to study the scenery. Tickets may be bought and rooms secured at the offices at the terminal points in advance, and they may also be had on board the boats at the time of departure. It is needless to add that the earlier they are taken the better is the choice of rooms.

Meals are not included in the price of the ticket. They are served on nearly all boats, sometimes at a fixed price, as at the railway stations, and sometimes a la carte. The latter system appears to be gaining in popularity, as it is now adopted on many lines that formerly adhered to the old method.

On the great lakes there are propellors on the general model of the ocean steamer, and in summer they ply to all the principal ports. Interesting excursions may be made on these steamers, provided the traveler is not disturbed by a little roughness of the water now and then; of late years the voyage around the lakes has become highly popular, and is very pleasurable in Summer. Paddle steamers also abound on the lakes, but they do not equal those of the Hudson and Long Island sound, either in size or in the splendor of their accommodations.

On the Western rivers the model of the boat differs materially from the Eastern one. The main saloon is quite above the engine-room, which is on the lower deck, where the freight is piled and the steerage passengers are congregated. The Eastern and lake boats are propelled by low-pressure engines, while the craft of the Mississippi and its tributaries are generally high-pressure, and sometimes work a hundred and thirty pounds to the square inch. Explosions are less frequent now than formerly, but there are still enough of them to make traveling a trifle hazardous. Not infrequently fifty or a hundred lives will be lost by a steamboat explosion, and on one occasion the number of deaths by the blowing up of a steamboat and her consequent destruction by fire exceeded fifteen hundred.

Steamboat racing was once one of the amusements of the Mississippi and is not altogether unknown at present, though it has greatly declined. In the annals of the West there are many famous races recorded, where large sums of money were risked on the result, and where the passengers were as much excited over the event as the owners of the boats. In 1853 there was a race from New Orleans to Louisville, between the steamers Eclipse and Shotwell, on which seventy thousand dollars were staked by the owners of the rival craft, and probably the private bets were fully equal to that amount. The two boats were literally "stripped for the race;" they were loaded to the depth that would give them the greatest speed, and their arrangements for taking fuel were as complete as possible. Barges were filled with wood at stated points on the river and dropped out to mid-stream as the boats approached; they were taken alongside and their cargoes of wood transferred without any stoppage of the steamer's engines. At the end of the first twenty-four hours the Eclipse and Shotwell were side by side, 360 miles from New Orleans. They continued in almost this way to Louisville, and, though the race was supposed to have been won by the Eclipse, there was so much dispute about it that the wager was never paid.

Passenger travel on the Western rivers has been greatly reduced in the last twenty years, owing to the creation of lines of railway parallel to the rivers, and the majority of the boats now running are far behind those of the palmy days between 1850 and 1860. Fares are lower than on the railways, and they include rooms and meals as of old, but the table is less bountifully supplied than formerly, and the number of servants is not so large. There is less competition, and the schedule of fares is generally adhered to. In the old days there was comparatively little regularity, and the clerk or captain of each boat could do pretty much as he liked about terms to passengers. On the Red river the clerks were accustomed to graduate the fare according to the locality where the passenger came on board. The more fertile and wealthy the region, the higher was the price of passage. Travelers from the cotton districts paid more than those from where tobacco was the staple product, and those from the sugar country paid more than any other class. With few exceptions there was no ticket system, every man paying his fare when it best suited him to do so. At present on a changé tout cela.

The departure of a steamboat from one of the great landings is a matter of some uncertainty. If she is advertised to leave at a certain time, those familiar with the business will understand that she will not leave before that hour, and her departure after it will be guided by circumstances. She will go when her freight and passenger-list are sufficiently full to make the trip a profitable one, unless she belongs to a line performing a regular service, in which case she is held to her schedule. The writer once took passage on a Mississippi steamer that remained at the wharf twenty-nine hours after her advertised time, and all the while she had steam up and her whistle was blown every half hour or so to indicate that she was "just going." And a friend of his once took passage on a steamboat from St. Louis to Cincinnati before the days of the railway. He lived on board for nearly a week with the boat tied up to the landing. At the end of that time the trip was abandoned, as the boat could not obtain a cargo for Cincinnati, and the passage-money was refunded in full.

When you go on board a Western steamboat proceed at once to the office and pay your fare. The clerk will hand you the key to your room or assign you to a berth in one that already contains a passenger, and then you can make yourself at home. You will find the manners of the Western waters more free than those of the East, and it is quite possible that your room-mate, if you have one, will commence the cultivation of your acquaintance with an invitation to drink; the custom of shooting a man who declines this politeness does not prevail at present, and the records of its having ever occurred are shrouded in obscurity. Western and Southwestern passengers are often rude and uncouth, but the rudeness is almost always unintentional, and the coarse exterior is very apt to cover a warm heart. The stranger will find much to amuse and interest him, and there are few places where human nature can be studied to better advantage than in the saloon of a Western steamboat.

The gambler once flourished on the Mississippi. He is less abundant than of yore, but the supply is still quite equal to the demand. He is generally not so polished as his confrere of the eastern boats and railway trains, but his ways are no less winning, so far as the taking of money is concerned, and he goes much further in the science of cheating. The unsophisticated stranger who takes a fourth hand with a trio of the light-fingered fraternity, "just to make up a game," might as well hand over his pocket-book at the start, unless he prefers going through the form of losing his cash.

Never be in a hurry on a western boat, as the time of arrival at your destination is a matter of more or less uncertainty. Delays at the landings, to take or discharge freight, are sometimes vexatious, and the journey may require double the time that was expected at the start. In the season of low water the boat is liable to get aground, and may lie there for hours, days, or even for weeks, before she is again afloat.

The dangers of the western waters are greater than those of the east. The boats are more liable to take fire, owing to their form of construction, and, as their engines are on the high-pressure principle, the chance of explosion of the boilers is much greater. The navigation of the rivers is hazardous, as the sand-banks are constantly shifting, and the course to be followed by the pilots is rarely the same for three months at a time. Snags and sawyers present dangers quite unknown to eastern waters, and in the Missouri river especially they are very numerous. A snag is a log or tree-trunk imbedded in the bottom of a river, with one end at or near the surface. The current causes it to incline down stream, and it is more dangerous to an ascending boat than to a descending one. The flat bottom of the boat is pierced by it, and sometimes the craft is impaled as one might impale a fly with a pin. On one occasion, on the Missouri river, some twenty years ago, a snag pierced the hull of a steamer, passed through the deck and cabin, and actually killed the pilot in the wheel-house. The sawyer is a tree that is loosely held by the roots at the bottom of the river, while its branches are on the surface; the current causes it to assume a sort of sawing motion, and hence its name. It is nearly if not quite as dangerous as the snag, and some of the pilots hold it in greater dread, for the reason that sawyers frequently change their position, while the snags, being more firmly imbedded, are less likely to drift away.

The current of the lower Mississippi is very strong, and it is a common remark that when a man falls into that stream his chances of escape are small. Many good swimmers have been drowned in it, and the great majority of those who dwell on its banks have a wholesome dread of attempting to bathe in its waters.

When we go westward beyond the valley of the Mississippi we find very few inland lakes and streams that are navigable. Great Salt Lake maintains a steamer or two for excursion purposes, and the waters of California had at one time a fair-sized fleet of boats that navigated San Francisco bay and the streams flowing into it. Their importance has diminished since the construction of the railway, and at present the steamboats of the Golden State are of no great consequence. Those that exist are managed more on the eastern than on the Mississippi system, but the rates are generally higher than on the Atlantic coast.

The Columbia river and its navigable tributaries have some thirty odd boats, most of them of small size, and intended to run where there is little water. The models in use are a modification of those of the Hudson and Long Island sound, and the rooms on the boats intended for night travel are generally large and comfortable. In going up the river from Portland, Oregon, the regular boats leave at five o'clock in the morning, and travelers making that journey will find it to their advantage to sleep on board instead of spending the night at the hotel and rising at an unseasonable hour in the morning.

On all the river steamers of America it is advisable to get a forward room rather than one near the stern. There is less jarring of the machinery, less heat from the engines, and, when the water is rough, there is less "pitching." On the other hand, there is more danger from collisions, and, on the Mississippi boats, a greater chance of being blown up. You pay your money, and you take your choice. But don't trouble yourself about accidents; don't put on your life-preserver before you go to sleep, as timid persons have been known to do; and if anything should happen try to face the danger coolly, and do the best you can. If you have occasion to don a life-preserver, be sure to fasten it well up under the arms, and not around the waist. In the proper position it will support the head above water, while, if fastened around the waist, it is apt to sustain the lower part of the body and submerge the head. If compelled to take to the water, divest yourself of the greater part of your clothing, and have your feet bare, or, at best, only stockinged. Ladies should reject their corsets under such circumstances, as they are serious hindrances to breathing in the water, and it is hardly necessary to say that long skirts are great impediments to swimming, or even to floating. Some persons have recommended their retention, on account of their buoyancy; but this only lasts for a few moments. As soon as they become soaked with water they become heavy, and have a tendency to drag the wearer down, rather than to support her.

The landsman who has never been on a sea-voyage looks with more or less hesitation at the prospect of making one. His thoughts are occupied with what he has heard or read of the perils of the great deep, and he regards with a feeling akin to veneration the bronzed sailor who has plowed every ocean on the globe, and tasted the delights of every climate. He questions his friends who have been to sea before him, and from their varied experience lays up a store of knowledge more or less useful. He wonders how he will enjoy sailing over the blue waters, how the spectacle will impress him, and more than all else he wonders whether or no he will be sea-sick. He busies himself with procuring a suitable outfit for his nautical journeys, and in nine cases out of ten selects a quantity of articles he never uses, and which it is not always easy to give away.

Before the days of steamships a sea voyage was an affair of considerable moment, as it implied an uncertain period on the waters, and the passenger was obliged to take along a good many articles of necessity or comfort, or go without them altogether. Nowadays the principal preparation is to secure your place and pay for your ticket, and, unless you are very eccentric in your wishes and desires, you will find everything you want to eat or drink on board the ship that is to carry you. In selecting your place, if you are inexperienced in sea travel, try and get as near the middle of the ship as you possibly can, and if you are forward of "amidships" you are better off than if the same distance "aft." In the middle of the ship there is less motion than elsewhere in a pitching sea, and the further you can get from the screw the less do you feel the jarring of the machinery. The rolling is the same all over the craft, and there is no position that will rid you of it. Several devices in the shape of swinging-berths have been tried, for the benefit of persons with tender heads and stomachs, and some of them have been quite successful in smoothing the rough ways of the ocean, but the steamship companies have been slow to adopt them, and the old salts do not regard them with a friendly eye.

Close all your business and have everything ready the day before your departure. It is better to sit around and be idle for a few hours than to have the worry of a lot of things that have been deferred till the last.

If you are going on a long voyage by sailing ship and expect to pass through the torrid and both temperate zones, you should provide yourself with thick and thin clothing suitable to all latitudes. If you are a society man of course you will carry your dress suit and a goodly stock of fine linen to match, but if you are "roughing it," and have no letters of introduction nor social designs, the dress suit will be superfluous. Take three or four suits of linen for wearing on shore in hot countries, a medium suit of woolen for temperate lands and a thick suit of the same material for high latitudes north or south. The roughest clothing procurable is what you need for wearing on shipboard, thin for the torrid zone and thicker for the temperate. Woolen or "hickory" shirts are the proper things for sea wear, and the only occasion when you need a white shirt is when you go on shore. Your own judgment must be your guide as to the proper supply of collars, handkerchiefs, and the like; don't forget to be well provided with underclothing, and remember that wool is a much safer article to wear against the skin than cotton or linen. Take plenty of woolen undershirts of the lightest texture for hot climates, and of course you will have thick ones for the cold regions. An umbrella and a cane are desirable for protection against sun and rain, or dogs and beggars, when going on shore. A sun hat, or sola topee, as it is called in India, is desirable in the tropics, but there is no need of taking it along at the start. It can be bought in the first tropical port you visit, and will be found there at a lower price than where it is not in regular use.

If you are going to China or India from an American port you need take only enough shore clothing to last you till you arrive there, as the tailors in those countries can outfit you very expeditiously, and at lower prices than you have at home. Of course you should have something to wear during the day or two it will require them to make up the goods after taking your measure. They will not give you a very snug fit, and quite possibly your garments may look as if they had been made on another man's measure, but if they are comfortable and succeed in touching you here and there they are about all you can expect. The Chinese tailor generally suggests "no fittee no takee" when he measures you, but his ideas of a fit are different from those of the fashionable clothiers of New York and London.

If you carry gloves through the tropics be sure to wrap them well in oiled silk before starting. It is well to observe this rule with gloves on all sea voyages, as the marine atmosphere is very injurious to them.

If you are a smoker carry your own cigars and tobacco. Fine cigars should be put up in tin or glass, as they are apt to suffer from the sea air; it is the opinion of many travelers that it is not worth the trouble to carry good cigars on an ocean voyage, as they are quickly spoiled, and soon taste no better than common ones. A fine cigar may be desirable after each meal, but for other times and for "smoking between smokes" an ordinary one is just as well. The author has tried all kinds of cigars at sea, and gives his verdict in favor of the manilla cigar of the quality called "seconds" (understand that the manilla cheroot is not intended, but only the cigar). Seconds are preferable to firsts, as they are lighter in size and quality; the firsts make a very fair after-dinner cigar, and in the Far East many persons prefer them to choice Havanas. If you smoke a pipe be sure and have a supply of pipes with perforated covers for use on deck when the wind is blowing.

For the trans-Atlantic voyage, between America and Europe, there is very little need of preparation, beyond getting your ticket and putting affairs in shape for your absence. Take plenty of thick underclothing, your roughest suit of clothes for wearing on the voyage, the roughest and heaviest overcoat that you possess for wet weather, and an equally rough rug or other wrap for keeping you warm on deck when the north wind blows merrily. If you are of a sedentary habit buy a steamer chair, and when you buy it make up your mind that you will occupy it when you want to. A great number of people who say they "don't want the bother of a chair," or "didn't think to get one," are in the habit of helping themselves to the chairs of others without the least compunction of conscience and without caring a straw as to the desires of the owners for their property. Women are worse offenders than men in this matter, and the young and pretty are worse than the older and plainer. If you have a stony heart you will turn an intruder out of your chair without ceremony, whatever the age or sex, but if you cannot muster the courage to do so your best plan is to send the deck steward to bring the chair, and while he is getting it you can remain quietly out of sight. When you buy the chair have it marked with your name or initials, so that it can be easily distinguished from others of the same shape and color.

You are expected to come to the dinner-table in a black coat on most of the steamship lines. The rule is not imperative, however, but it is well to comply with it, as you will encounter many people whose notions about dressing for dinner are rigid, and, besides, the half hour spent in arranging the toilet before the bell calls you to the table is a variation of the monotony of the voyage.

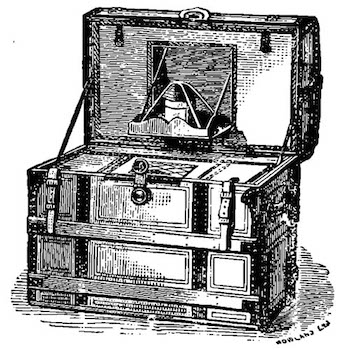

Everything needed for the voyage may be contained in a valise or "steamer trunk," with a toilet satchel, and all heavy luggage should be sent below at the dock. A steamer trunk is designed to be stowed under the berth out of the way; its proper dimensions are 30 inches long, 15 or 16 wide, and 12 high. Its length or width may be greater, but its height should not exceed 12 or at most 13 inches, or it will be often found too large for the space where it is intended to go.

An old valise or sack should be taken along for containing the rough sea-clothing which may be left with the steamer-chair at the company's office in Liverpool or whatever port the passenger may land at. There they remain till his return, in a storeroom specially provided for them. They should be properly marked, so that the storekeeper will have no difficulty in selecting them when wanted.

The servants who wait upon you will expect a reward for their attentions, and you will be flying in the face of a long-established custom if you fail to give it. On the English steamers half a sovereign (ten shillings English) is the proper fee for the room-steward on the voyage either way, and the same to the table-steward. You will not diminish the attention upon you if you say to these men at starting that you will remember each of them with a ten-shilling piece, provided you are satisfied with them; they know what to expect and will act accordingly. On the French and German steamers a ten-franc piece is the usual fee to each of the servants above mentioned. The "boots" expects a five-shilling or a five-franc piece, according as the steamer is English or French, provided he polishes your boots during the voyage, and the man in charge of the bath comes along for a similar amount if you make regular use of his services. If you frequent the smoking-room the steward in charge of it expects to be remembered with a half crown, and a similar coin will not be refused by the deck-steward who looks after your chair. None of these fees should be paid until the last day of the voyage and the service of the men has ended. It often happens that the room-steward is very attentive through the voyage and in every way satisfactory; he answers your bell promptly and you consider him a model servant, but if you give him his fee before he has carried your impedimenta on deck it is quite possible that you will carry them yourself or hire another man to do it. His interest in you has ceased and he is looking after somebody who hasn't yet rewarded him. The same thing may happen with the table-steward, and he cannot hear your summons after he has been paid off, though before that event he was the very beau ideal of all you could wish.

It is always well to provide yourself with the money of the country you are going to, or with that of the nationality of the steamer. On an English ship, take ten pounds or so of English money, to cover all your fees and extras, and to have a supply on landing until a visit can be made to the banker. On the French steamers, take a proportionate amount in francs, and on the German steamers, a supply of marks will be quite in order. You can get this cash at a money-changer's without as much trouble as you will have in case you find no one on the steamer to make change for you, and the discount will be less.

The perils of the transatlantic voyage are now practically reduced to the dangers resulting from fog on and near the banks of Newfoundland. The ships performing the service of the best of the lines are built so strong that no wind to which the North Atlantic is accustomed can injure them, and the captains are men of experience and ability. But the fog is an evil which will not disappear at our bidding; the most intelligent commander is helpless in the fog, and he cannot be sure at any moment that he is not rushing to destruction upon a pitiless iceberg, or dashing forward to collide with another ship, in which one or both of the unlucky vessels may be lost. The ice is probably the greater of the dangers, as the steamers give warning of their presence to each other by the sound of whistles or fog-horns, and of late years there has been an attempt to establish steam lanes across the Atlantic, so that steamers going eastward should be several miles from the track of those that are westward-bound. The iceberg hangs out no lights and blows no whistle, and the first warning the captain can have of its presence is when its white outline looms through the fog less than a ship's length ahead. Many a steamer has had a narrow escape from destruction, and not a few have been lost by encounters with the ice. Of those that have never been heard from it is conjectured that the majority were lost by collisions with the ice, as in most instances it was abundant at the time of their disappearance.

The ingenuity of man has been taxed to avert the dangers from the ice and fog, but thus far comparatively little has been accomplished. At times the density of the fog is so great that the eye cannot penetrate it more than twenty yards; experiments have been made with the electric light, but the result has not been favorable to its general adoption. A careful observation of the thermometer will sometimes show the proximity of a berg, as the melting ice causes a fall in the temperature of the water, frequently amounting to ten or twelve degrees, and sometimes there will be a chilly blast of air, that says very plainly there is ice in the vicinity. The early summer months are the most dangerous on the score of ice, but the bergs abound till late in autumn; they come from the west coast of Greenland, where they are broken off from the immense glaciers that flow down from the interior and push out into the sea. The great polar current carries them southward, past Labrador and Newfoundland, till they are thrown into the warm waters of the Gulf-stream and there melted away. They rarely go further south than to the fortieth parallel, but are sometimes drifted as far east as the Azores.

By taking a course that will carry them to the south of the Grand Banks the steamers might avoid the fog and its consequent dangers; some of them do so, and others advertise that they will. After they get at sea the mind of the captain sometimes undergoes a change, and the ship is headed so that she passes near Cape Race. The more to the south a ship is kept the longer will be her course, and in these days of keen competition to make the shortest passages the temptation is great to run away to the northward as far as possible. The author was once a passenger on a steamer that laid her course within fifty miles of Cape Race, although he had been assured at the office of the company that she would "take an extreme southerly course," and the promise to do so had been inserted in the advertisements. A passenger ventured to say as much to one of the officers and to ask if the managers of the company had not ordered the southerly route. "The captain commands here," was the reply, "and the managers have nothing to do with his course; he can run wherever he pleases, and trust to Providence for the result."

It is to be hoped that the great companies will some day make an agreement, and keep it, that they will all take the southerly course and make an end of a competition that is dangerous in a certain degree. They would be greatly aided to such an arrangement if the American government would withdraw its offer to give the carrying of the mails to the company making the shortest average of passages across the Atlantic. Public opinion might also do something in this way, but, unfortunately, public opinion happens to be in favor of the most rapid transit, and looks upon safety as a minor consideration. Whenever the majority of travelers shall think more of the pleasure of staying longer on the earth than of going over its surface at the greatest speed there will be a move in the right direction.

But do not disturb yourself with unpleasant thoughts of what may happen in the fog. Remember, rather, that of the thousands of voyages that have been made across the Atlantic only a few dozens have been unfortunate, and of all the steamers that have plowed these waters only the President, City of Glasgow, Pacific, Tempest, United Kingdom, City of Boston, and Ismailia—seven in all—are unheard from. The chances are thousands to one in your favor, and if this does not satisfy you, try and recall the philosophy of the man who said it was none of his business whether the ship was in danger, as he had paid his fare to the company and they were under obligations to carry him safely to the other side. If the wind rises to a gale, don't worry in the least, and if you have any doubt about the matter ask your room-steward what the appearances of things are to a sea-faring man like himself. Quite possibly his answer may be in the substance, if not in the words, of the mariner's song:—

When a steamer is in a rough sea, especially if she is lightly laden, the screw is frequently out of water for several seconds at a time. Relieved from the resistance of the water, the screw whirls with the rapidity of lightning and gives the stern of the ship a very lively shaking. This is called "racing," and it is anything but pleasant, but there is a comforting assurance when you hear it that everything is all right and the machinery in order. Whenever you hear the racing of the screw in rough weather you will hear a welcome sound. If a wave seems to hit the ship a staggering blow, and send her half over, do not listen for a commotion and spring from your berth, but bend your ears to catch the sound of the engine, and when you hear its "choog! choog!" you may make yourself easy. In rough weather or in smooth, the first thing to listen for on awaking is the engine, and when you hear its steady breathing and feel its great heart pulsating, as if it were the vital force of an animate being, you may turn and sleep again, satisfied that the ship which carries you "walks the water like a thing of life" and is bearing you safely onward to your destination.

Inventors have busied themselves to devise something that should put a stop to the racing of the screw, with its liability to derange the machinery and its certainty of disturbing the nerves of excitable passengers. Several plans have been tried, but, up to the date of writing this volume, none of them have proved successful. Somebody will doubtless accomplish the desired result before the end of another decade, and when this is done he should give attention to the jar caused by the machinery. It is hardly reasonable to expect that a fast steamer will ever go over the water with the steadiness of a sailing-ship, and with no perceptible jarring, but so much has been done in the last twenty-five years in smoothing the ways of the ocean, and the vessels that plow it, that the scheme here suggested is by no means impossible.

While sitting on deck some afternoon you may be at a loss for a subject to think about. Busy yourself with imagining what will be the style, model, speed, and propelling force of the transatlantic ship of twenty, fifty, a hundred, and five hundred years hence! Here is enough to occupy you for many hours, and perhaps you may devise something that will benefit the human race, and, also, not the least consideration, put money in your pocket.

We come now to the momentous question of mal de mer. It is a question that has puzzled the scientific men of all ages since the departure of the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece on the first ship that ever sailed the sea, and, from present appearances, it will continue to be a puzzle as long as the waves of the ocean continue to roll. By some it is claimed to be a nervous disturbance, others contend that it is purely a stomachic affair and the nerves have nothing to do with it, and there are others who argue that the brain is the seat of the disorder and disturbs the stomach by sympathetic action. There are wise men who charge sea-sickness to the spleen, the liver, or other internal organs, and it is not impossible that we may yet hear of a savant who attributes it to corns on the toes. Sea-sickness is a mystery, and the more we study it the more are we at sea as to its exact operation.

Some people, who are bundles of nerves, are not affected by the motion of a ship, while others, who are nerveless as a paper-weight, are disturbed with the least movement. Weak stomachs escape while strong ones are upset, and there seems to be no rule that can be laid down with exactness or anything that approaches it. But on one point there can be no two opinions, that sea-sickness is a most disagreeable malady, even in its mildest form, and that any means of relieving it, or even of mitigating it in a small degree, will be hailed with delight by all who suffer from it. It will also be a boon to those who are never sea-sick, as it will relieve them from a companionship that is not always the most agreeable in the world.

For some persons there is no escape, and they will be prostrate in their berths during the whole voyage of the ship, or just able to get around. But, in the majority of cases, sea-sickness may be wholly prevented by a free use of cathartics or anti-bilious remedies a day or two before departure on a voyage. In America, the pills of Ayer, Brandreth, or Wright will serve the purpose; in England, the famous "Cockle's pills," and in France the Pilules Duhaut. The relaxation of the system should be sustained during the voyage by the same means or by the use of Seidlitz powders, or similar effervescent substances; this simple precaution will save most persons from being disturbed by sea-sickness, no matter how wildly the ship may toss, provided they combine with it an abundance of air and exercise. As before stated, there is no relief known at present for the other fourth of humanity, except to stay at home.

Dr. Fordyce Barker, an eminent physician who has made a careful study of sea-sickness, opposes the previous use of cathartics, and advises that a hearty meal be eaten a short time before going on board. Those who are subject to sea-sickness he enjoins to undress and go to bed before the vessel moves from her dock or anchorage. He says they should eat regularly and heartily without raising the head for at least one or two days, and in this way they will accustom the digestive organs to the performance of their functions. He advises the use of laxative pills the first night out and, if necessary, during the entire voyage. The following is his prescription:—

LAXATIVE PILLS.

| ℞. | Pulv. Rhei. (Turk.), | ʒss. |

| Ext. Hyoscyami, | ℈j. | |

| Pulv. Aloes Soc., | ||

| Sapo Cast., | āā gr. xv. | |

| Ext. Nux Vomicæ Alchoh., | gr. x. | |

| Podophyllin p., | gr. v. | |

| Ipecac., | gr. ij. | |

| M. | ft. pil, (argent) No. 20. | |

| S. | Dose—one, two, or three. |

Where there is a tendency to diarrhœa, which sometimes happens at sea, he recommends the following, and he also advises the traveler to carry it in his journeys over the Continent to counteract the effects that occasionally come from drinking bad water. The dose is, for an adult,

| ℞. | Tinct. Camphoræ, | ℈vj. |

| Tinct. Capsici, | ℈ij. | |

| Spts. Lavendul. Comp., | ||

| Tinct. Opii, | āā ℥ss. | |

| Syr. Simp., | ℥ij. |

M.S. A small teaspoonful in a wineglass of water after each movement.

Dr. Barker says that in cases where the victim has suffered several days from sea-sickness, with constant nausea, nervous depression, and sleeplessness, he has found great benefit in the use of bromide of potassium. The powders are to be taken in a half-tumbler of plain soda-water, and, if this cannot be obtained, in cold water sweetened with sugar. It is to be sipped slowly, so that the stomach may be persuaded to retain and absorb it. The powders should be kept in a wide-mouthed vial, or in a tin box, so as to protect them from the effects of the sea-air. The following is the prescription:

| ℞. | Potass. Bromide, | ℥j. |

| Div. in Chart No. 20. | ||

| S. | One, two, or three times a day. |

He also recommends a person about making a sea-voyage to take a supply of "mustard leaves," which can be had at the druggist's. They are useful in allaying the nausea and vomiting by getting up a counter irritation, and should be applied over the pit of the stomach.

Many individuals, especially those inclined to corpulency, find relief in wearing a tight belt around the waist. This is so well understood that some of the makers of surgical appliances advertise "belts for sea-sickness" as part of their stock in trade. Some persons recommend a tight-fitting undergarment of strong silk, but, in order to be of use, it must be altogether too close for comfort, and the wearer is quite likely to say that he considers it the greater of the evils.