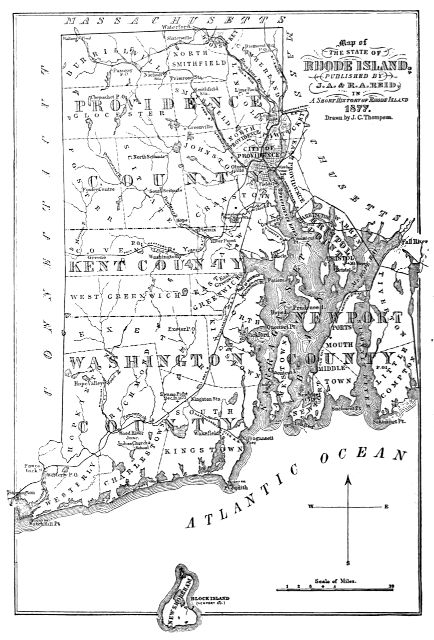

Title: A short history of Rhode Island

Author: George Washington Greene

Release date: February 18, 2014 [eBook #44955]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by KD Weeks, Charlene Taylor and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber’s Note

With one exception, footnotes were used only in the tables contained in the Appendix, and are kept in proximity of their references. They have been assigned sequential letters A-L, and hyperlinks are provided to facilitate inspection of the note.

Where a single note is referred to multiple times, the link from the note to its references will always return to the first instance.

The cover page was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Please consult the notes at the end of this text for a more detailed discussion of any other issues that were encountered during its preparation.

BY

George Washington Greene, LL.D.,

Late Non-Resident Professor of American History in Cornell University; Author of “The Life of Major-General Nathanael Greene;” “Historical View of the American Revolution,” etc., etc.

PROVIDENCE:

J. A. & R. A. Reid, Publishers,

1877.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1877, by

ANNA MARIA GREENE,

in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C.

TO

Anna Maria Greene,

My Dear Mother:

You bear your ninety-three years so lightly that i invite your attention to a new volume of mine with as much assurance of your sympathy as when i crowed and wondered over my first picture book an infant on your knee. For your sympathy is as quick and as warm as it was then, and your memory goes back with unerring certainty to the men and the scenes of almost a century ago. Your eyes have looked upon Washington, and your tenacious memory can still recall the outline of his majestic form.

The first time that i ventured to send forth a volume to the world, i set upon the dedication page the name of my father. He has been dead many years. You still linger behind, and long may you linger. Long may those fresh memories which give such a charm to your daily life continue to cheer you and instruct those who have the privilege of living with you. They have seen life imperfectly who have not seen what a charm it wears when the heart that has beat so long still lends its genial warmth to the still inquiring mind.

There are two classes of history, each of which has claims upon our attention peculiarly its own. One is a sober teacher, the other a pleasant companion. One opens new paths of thought, the other throws new light upon the old, and both agree in making man the chief object of their meditations.

Nearly two thousand years ago a Roman historian likened the life of his country to the life of man. Time has confirmed the parallel. Nations, like men, have their infancy and their youth, their robust manhood and their garrulous old age. Their lives like the lives of men are full of encouragement and of warning. Interpret them aright and they become trusty guides. Misapply their lessons and you grope in the dark and stumble at every step.

And both states and men have their special duties and were created for special ends. The God that made them assigned to each its problem, and to work this out is to work out His will. Of this problem history is the record and the interpreter. It tells us what man has been, and thereby aids us to divine what he yet may be.

If with the philosopher history reveals the laws of life, with the poet she recalls the past and stirs human sympathies in their profoundest depths. Man follows man on her checkered stage; nations rise and fall; mysteries enchain us; imagination controls us; reason guides us; conscience admonishes and warns; and first and foremost of all our stimulants to action is our sympathy with our fellow-man.

I have attempted in the following pages to tell what the part of Rhode Island has been in this great drama. A talent was entrusted to her. Did she wrap it in a napkin? To those who are familiar with the accurate and exhaustive work of Governor Arnold, it will be needless to say that but for the aid of his volumes, mine would never have been written.

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| CONDITION OF AFFAIRS IN MASSACHUSETTS BAY AND PLYMOUTH COLONIES.—ARRIVAL AND BANISHMENT OF ROGER WILLIAMS. | ||

| The religious sentiment connected with the foundation of states, | 1 | |

| Resistance to the doctrine of theocracy occasioned the settlement of Rhode Island, | 2 | |

| 1631. | Ship Lyon arrived at Boston, bringing Roger Williams, | 2 |

| Early life of Williams, | 2 | |

| Massachusetts in possession of two distinct colonies, | 3 | |

| In Massachusetts Colony the clergy were virtually rulers, and they were extremely rigid, | 3 | |

| Disputes between Williams and the authorities of Massachusetts Bay Colony, | 4 | |

| Removal of Williams to Plymouth, | 4 | |

| Williams makes friendship with Massasoit and Miantonomi, | 5 | |

| Learns the Indian language, | 5 | |

| Williams returns to Salem, | 5 | |

| 1635. | He is persecuted and finally banished, | 6 |

| Articles of banishment, | 6 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| SUFFERINGS OF ROGER WILLIAMS IN THE WILDERNESS.—FOUNDS A SETTLEMENT ON THE SEEKONK RIVER.—IS ADVISED TO DEPART.—SEEKS OUT A NEW PLACE WHICH HE CALLS PROVIDENCE. | ||

| Attempt to send Williams to England, | 7 | |

| His flight, | 8 | |

| He is fed by the Indians, | 8 | |

| He is given land on the Seekonk River by Massasoit and starts a settlement, | 8 | |

| He receives a friendly letter from the Governor of Plymouth asking him to remove, | 9 | |

| He starts with five companions in a canoe to find a place for a settlement, and finally lands at Providence, | 9 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| WILLIAMS OBTAINS A GRANT OF LAND AND FOUNDS A COLONY.—FORM OF GOVERNMENT IN THE COLONY.—WILLIAMS GOES TO ENGLAND TO OBTAIN A ROYAL CHARTER. | ||

| Early inhabitants of Rhode Island, | 11 | |

| Williams makes peace between Canonicus and Massasoit, | 12 | |

| He receives a grant of land from Canonicus and begins a settlement, | 12 | |

| Compact of the colonists at Providence, | 13 | |

| Experiment of separation of church from state tried in the new Colony, | 13 | |

| The right of suffrage not regarded as a natural right. Illustrated by Joshua Verin and his wife, | 14 | |

| 1639. | The first church founded in Providence, | 15 |

| Five select men appointed to govern the Colony, subject to the action of the Monthly Town Meeting, | 15 | |

| Massachusetts Colony applied for a new charter to cover the land occupied by Providence, | 15 | |

| 1643. | Providence in connection with Aquidneck and Warwick sent Williams to England to obtain a Royal charter, | 15 |

| 1644. | Williams returns in 1644 successful, and is received with exultation,, | 16 |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| SETTLEMENT OF AQUIDNECK AND WARWICK.—PEQUOT WAR.—DEATH OF MIANTONOMI. | ||

| 1637. | Anna Hutchinson arrived in Massachusetts and banished, | 17 |

| Nineteen of her followers under William Coddington and John Clarke, purchased the Island of Aquidneck and formed settlements at Pocasset and Newport, | 17 | |

| Roger Williams proclaimed the right of religious liberty to every human being, | 18 | |

| Samuel Gorton banished from Pocasset, | 19 | |

| He denied the authority of all government except that authorized by the King and Parliament, | 19 | |

| He, with eleven others, bought Shawomet and settled there, | 19 | |

| He is besieged by troops from Massachusetts, is captured, imprisoned, and afterwards released, | 19 | |

| He is appointed to a magistracy in Aquidneck, | 19 | |

| Roger Williams prevented the alliance of the Pequots and Narragansetts, and formed one between the English and the Narragansetts, | 21 | |

| Pequots rooted out and crushed, | 21 | |

| Miantonomi treacherously put to death, | 22 | |

| The Narragansetts put themselves under the protection of the English, | 22 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| CHARTER GRANTED TO PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS.—ORGANIZATION UNDER IT.—THE LAWS ADOPTED. | ||

| 1643. | The charter granted to Providence Plantations, | 23 |

| Provisions of the charter, | 23 | |

| 1647. | The corporators met at Portsmouth and in a general assembly accepted the charter, and proceeded to organize under it, | 24 |

| The government declared to be democratical, | 24 | |

| President and other officers chosen, | 25 | |

| Description of the code of laws, | 25 | |

| Design for a seal adopted, | 26 | |

| Roger Williams presented with one hundred pounds for services in obtaining the charter, | 26 | |

| Spirit of the law, | 27 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC TROUBLES.—UNSUCCESSFUL ATTEMPT AT USURPATION BY CODDINGTON. | ||

| Death of Canonicus, | 28 | |

| Possibility of the doctrine of soul liberty demonstrated, | 28 | |

| Dissensions among the colonists, | 29 | |

| Troubles with Massachusetts, | 29 | |

| Baptists persecuted in Massachusetts, | 30 | |

| 1651. | Coddington obtained a royal commission as Governor of Rhode Island and Connecticut for life, which virtually dissolved the first charter, | 30 |

| Roger Williams sent to England to ask for a confirmation of the charter, | 31 | |

| John Clarke, also, sent to ask for a revocation of Coddington’s commission, | 31 | |

| 1652. | Slaves not allowed to be held in bondage longer than ten years, | 32 |

| Commerce with the Dutch of Manhattan interrupted by war between England and Holland, | 32 | |

| Coddington’s commission revoked and the first charter restored, | 32 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| MORE FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC TROUBLES.—CIVIL AND CRIMINAL REGULATIONS OF THE COLONY.—ARRIVAL OF QUAKERS. | ||

| Conscience claimed as the rule of action in civil as well as religious matters, | 33 | |

| Contentions between the Island and the main-land towns, | 34 | |

| 1654. | Court of Commissioners met and effected a reunion in the Colony, | 34 |

| Attempts of the United Colonies to make war on the Narragansetts, but they failed, as Williams had influenced Massasoit not to sanction it, | 35 | |

| Qualification of citizenship, | 36 | |

| Duties of citizenship ascendant over dignity of office, | 37 | |

| Protection of marriage, | 38 | |

| The Pawtuxet controversy settled by acknowledgement of the claims of Rhode Island, | 38 | |

| Fort built for protection against Indians, | 39 | |

| Quakers arrived. Difference of treatment of them between Rhode Island and Massachusetts, | 39 | |

| 1663. | A new charter granted by Charles II. and accepted by the colonists, | 40 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| TROUBLES IN OBTAINING A NEW CHARTER.—PROVISIONS OF THE CHARTER.—DIFFICULTIES CONCERNING THE NARRAGANSETT PURCHASE.—CURRENCY.—SCHOOLS. | ||

| The new charter gave a democratic government, | 41 | |

| Some of its provisions, | 41 | |

| Religious liberty recognized by it, | 42 | |

| Assembly and courts reörganized, | 43 | |

| State magistrates chosen by the freemen, | 44 | |

| Jealousy of Massachusetts, | 44 | |

| Trouble concerning the ownership of Narragansett, | 45 | |

| Attempt to dispossess Rhode Island of part of her territory, | 46 | |

| The Narragansetts compelled to mortgage their lands to the United Colonies, | 47 | |

| New charter obtained by Connecticut extending its bounds to the Narragansett River, | 48 | |

| 1663. | The boundary line left to arbitrators who fix it at the Pawcatuck River, | 49 |

| The intrigues of John Scott for the purchase of the Narragansett tract, | 49 | |

| Letter obtained from the King, putting the Narragansett purchase under protection of Massachusetts and Connecticut, | 50 | |

| This was rendered null by the second charter of Rhode Island grant soon afterward, | 51 | |

| Wampum used as money in the Colony, | 52 | |

| Also used as an article of ornament by the natives, | 52 | |

| 1652. | Massachusetts began to coin silver in 1652, | 53 |

| Rhode Island abolished the use of wampum ten years later, | 53 | |

| 1662. | New England shilling made legal tender in Rhode Island, | 53 |

| 1640–1663. | First schools established at Providence and Newport, | 53 |

| Affirmation is declared to be equal to an oath, | 54 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| TERRITORY OF RHODE ISLAND IS INCREASED BY THE ADDITION OF BLOCK ISLAND.—DISPUTES BETWEEN RHODE ISLAND AND THE OTHER COLONIES SETTLED BY ROYAL COMMAND.—STATE OF AFFAIRS IN THE COLONY IN 1667. | ||

| 1663 | Block Island added to Rhode Island, | 55 |

| Regulations concerning its admission, | 56 | |

| It is incorporated under the name of New Shoreham, | 56 | |

| Four Commissioners sent to America to reduce the Dutch and settle all questions of appeal between the colonies, | 57 | |

| The vexed questions of boundary line between Rhode Island and Plymouth; the Narragansett question and Warwick difficulties referred to the Commissioners, who referred the first to the King and decided the second in favor of Rhode Island, | 57 | |

| The Indians removed from King’s Province, | 59 | |

| Five propositions submitted by the Commissioners to the Rhode Island Assembly, | 59 | |

| 1st. All householders should take the oath of allegiance to the King, | 59 | |

| 2d. Mode of admitting freemen, | 59 | |

| 3d. Admission to the sacrament open to all well disposed persons, | 60 | |

| 4th. All laws and resolves derogatory to the King repealed, | 60 | |

| 5th. Provisions for self-defence, | 60 | |

| 1672. | Trouble with John Paine concerning Prudence Island, | 62 |

| Members of the Assembly to be paid for their services, | 63 | |

| Financial difficulties in the Colony, | 64 | |

| 1667. | Preparations for defence against the French, | 64 |

| 1672. | Act passed to facilitate the collection of taxes, | 65 |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| KING PHILIP’S WAR. | ||

| Wamsutta summoned before the General Court at Plymouth, | 67 | |

| His death, | 67 | |

| Indignation of the Indians, especially King Philip, | 68 | |

| Condition of the Indians, | 68 | |

| Attack on Swanzey, | 69 | |

| The Indians pursued by the English, | 69 | |

| Philip and his allies besieged in a swamp at Pocasset, | 71 | |

| His escape, | 71 | |

| The Indian attack on Hadley, | 71 | |

| Goffe, the regicide, | 72 | |

| Philip joined the Narragansetts, | 72 | |

| Battle in the swamp, | 73 | |

| Indians defeated, and their village destroyed, | 74 | |

| Depredations in Rhode Island, | 75 | |

| Death of Canonchet, | 76 | |

| Death of Philip and end of the war, | 77 | |

| Condition of the country after the war, | 77 | |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| INDIANS STILL TROUBLESOME.—CONDITION OF THE PEOPLE.—TROUBLES CONCERNING THE BOUNDARY LINES. | ||

| Precautions against the Indians, | 78 | |

| Troubles with Connecticut concerning Narragansett, | 79 | |

| Two agents sent to England, | 80 | |

| War party obtains power, | 80 | |

| Foundation of East Greenwich, | 82 | |

| Bitter controversy concerning the limits and extent of the Providence and Pawtuxet purchase, | 82 | |

| 1696–1712. | Settled in 1696 and 1712, | 83 |

| CHAPTER XII. | ||

| DEATH OF SEVERAL OF THE MOST PROMINENT MEN.—CHANGES IN LEGISLATION. | ||

| The United Colonies still encroached upon Rhode Island, | 84 | |

| Deaths of John Clarke, Roger Williams, Samuel Gorton, William Harris, and William Coddington, | 85 | |

| 1678. | Financial condition of the Colony in 1678, | 88 |

| Changes in the usages of election, | 89 | |

| Bankrupt law passed and afterwards repealed, | 89 | |

| Law concerning disputed titles to lands, | 90 | |

| 1679. | Law for the protection of servants, | 91 |

| Law for the protection of sailors, | 91 | |

| John Clawson’s curse, | 92 | |

| CHAPTER XIII. | ||

| COURTS AND ARMY STRENGTHENED.—COMMISSIONERS SENT FROM ENGLAND.—CHARTER REVOKED. | ||

| Disputes concerning the title of Potowomut, | 93 | |

| 1680. | Power of the town to reject or accept new citizens, | 93 |

| Efficiency of the courts increased, | 94 | |

| English navigation act injures the commercial interests of the Colony, | 95 | |

| Commissioners appointed to settle the vexed question of the King’s Province, | 96 | |

| Rhode Island’s position in New England in regard to the other colonies, | 96 | |

| Trouble with the Commissioners, | 97 | |

| Charter revoked, | 98 | |

| Rhode Island returned to its original form of government, | 98 | |

| CHAPTER XIV. | ||

| CHANGES IN FORM OF GOVERNMENT.—SIR EDMOND ANDROS APPOINTED GOVERNOR.—HE OPPRESSES THE COLONISTS AND IS FINALLY DEPOSED. | ||

| John Greene sent to England with an address to the King for the preservation of the charter, | 100 | |

| Changes in the names and the boundaries of Kingston, Westerly and East Greenwich, | 101 | |

| 1687. | Arrival of Sir Edmond Andros, | 101 |

| Taxes farmed out, | 102 | |

| Marriages made illegal unless performed by the rites of the English Church, | 103 | |

| Passport system introduced, | 103 | |

| Composition of the council, | 103 | |

| Andros’s commission enlarged, | 105 | |

| The press subjected to the will of the Governor, | 105 | |

| Title of Rhode Island to King’s Province again confirmed, | 106 | |

| Persecution of the Huguenots, | 107 | |

| Andros deposed, | 107 | |

| CHAPTER XV. | ||

| CHARTER GOVERNMENT AGAIN RESUMED.—FRENCH WAR.—INTERNAL IMPROVEMENTS.—CHARGES AGAINST THE COLONIES. | ||

| Chief-Justice Dudley attempted to open his court, he is seized and imprisoned, | 108 | |

| Return of the old form of government, | 108 | |

| Legality of resumption confirmed by the King, | 109 | |

| 1690. | The Assembly reorganized, | 110 |

| Town house built, | 111 | |

| The colonists taxed to sustain the French and Indian war, | 112 | |

| Coast invaded by French privateers, | 112 | |

| New taxes levied, | 113 | |

| Small-pox broke out in the Colony, | 113 | |

| 1691. | Sir William Phipps appointed Governor of Massachusetts with command over all the forces of New England, | 114 |

| This command over the forces of Rhode Island restricted to time of war, | 115 | |

| 1693. | First mail line established between Boston and Virginia, | 116 |

| State officers to be paid a regular salary, | 116 | |

| Assembly divided into two houses, | 116 | |

| Indians still troublesome, | 117 | |

| Courts of Admiralty established in the Colony, | 117 | |

| 1697–1698. | Trouble from enemies to the charter government, | 117 |

| Interests of trade fostered, | 118 | |

| Smuggling common, | 118 | |

| Charges made against the Colony by the Royal Governor, | 119 | |

| Captain Kidd, | 119 | |

| CHAPTER XVI. | ||

| COLONIAL PROSPERITY.—DIFFICULTIES OCCASIONED BY THE WAR WITH THE FRENCH.—DOMESTIC AFFAIRS OF THE COLONY. | ||

| 1702. | Prosperity of the Colony, | 120 |

| Providence the second town in the Colony, | 120 | |

| Religious freedom, | 120 | |

| Attempt to establish a Vice-Royalty over the Colonies, | 122 | |

| 1701. | Better Laws enacted, | 123 |

| 1702. | Preparations for defence, | 123 |

| 1703. | Boundary line between Rhode Island and Connecticut finally settled, | 124 |

| The character and interest of the Colony misunderstood by England, | 124 | |

| French privateer captured, | 125 | |

| Further acts of the Assembly, | 126 | |

| Slave trade, | 127 | |

| 1708. | First census taken, | 127 |

| Public auctions first held, | 128 | |

| Commercial and agricultural progress, | 128 | |

| 1709. | First printing press set up at Newport, | 129 |

| Internal improvements, | 130 | |

| CHAPTER XVII. | ||

| PAPER MONEY TROUBLES.—ESTABLISHMENT OF BANKS.—PROTECTION OF HOME INDUSTRIES.—PROPERTY QUALIFICATIONS FOR SUFFRAGE. | ||

| Issue of paper money, | 131 | |

| Clerk of the Assembly first elected from outside the House, | 131 | |

| Arts of peace resumed, | 132 | |

| New militia laws enacted, | 132 | |

| Laws concerning trade, | 133 | |

| Troubles occasioned by paper money, | 134 | |

| 1715. | Banks established in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, | 134 |

| Paper money question carried into election, | 134 | |

| Improvements in Newport, | 136 | |

| Criminal code, | 136 | |

| 1716. | School-houses built in Portsmouth, | 136 |

| Punishment of slander, | 137 | |

| Indian lands taken under the protection of the Colony, | 137 | |

| Law concerning intestates, | 137 | |

| 1719. | First edition of the laws printed, | 138 |

| Boundary troubles, | 138 | |

| Industry of the Colony protected by loans and bounties, | 138 | |

| 1724. | Freehold act passed, | 139 |

| 1723. | Pirate captured, | 139 |

| Evidences of the progress of the Colony, | 139 | |

| 1727. | Death of Governor Cranston, | 141 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | ||

| CHANGE OF THE EXECUTIVE.—ACTS OF THE ASSEMBLY.—GEORGE BERKELEY’S RESIDENCE IN NEWPORT.—FRIENDLY FEELING BETWEEN THE COLONISTS AND THE MOTHER COUNTRY. | ||

| New Governor elected, | 142 | |

| State of affairs in England, | 142 | |

| 1728. | Revision of the criminal code, | 143 |

| Laws for the encouragement and regulation of trade, | 144 | |

| 1727. | Earthquake, | 145 |

| 1723–1724. | Division of the Colony into counties, | 146 |

| George Berkeley, | 146 | |

| Establishment of Redwood Library, | 147 | |

| Laws concerning charitable institutions, Quakers and Indians, | 147 | |

| 1730. | New census taken, | 148 |

| 1731. | New bank voted, | 149 |

| Commercial prosperity, | 149 | |

| New edition of the laws published, | 149 | |

| Fisheries encouraged, | 150 | |

| Regulation concerning election, | 150 | |

| William Wanton chosen Governor, | 152 | |

| Depreciation of paper money, | 152 | |

| 1733. | Marriage laws, | 152 |

| John Wanton chosen Governor, | 153 | |

| Watchfulness of the Board of Trade, | 153 | |

| 1735–1736. | Throat distemper, | 154 |

| Law against bribery at elections, | 154 | |

| Arrival of his Majesty’s ship Tartar, | 155 | |

| Means of protection against fire, | 155 | |

| CHAPTER XIX. | ||

| WAR WITH SPAIN.—NEW TAXES LEVIED BY ENGLAND.—RELIGIOUS AWAKENING AMONG THE BAPTISTS. | ||

| Preparation for war against the Spaniards, | 156 | |

| Great expedition against the Spanish West Indies, | 157 | |

| New taxes levied on importations by England, | 157 | |

| Death of Governor Wanton, who is succeeded by Richard Ward, | 158 | |

| Arrival of Whitefield and Fothergill, | 159 | |

| Further provisions for the defence of the Colony, | 159 | |

| Report of the Governor concerning paper money, | 160 | |

| 1741. | Boundary line between Rhode Island and Massachusetts settled, | 161 |

| CHAPTER XX. | ||

| PROGRESS OF THE WAR WITH THE FRENCH.—CHANGE IN THE JURISDICTION OF THE COURTS.—SENSE OF COMMON INTEREST DEVELOPING AMONG THE COLONISTS.—LOUISBURG CAPTURED. | ||

| Privateers fitted out, | 162 | |

| 1741. | James Greene started an iron works, | 162 |

| Changes of the jurisdictions of the courts, | 163 | |

| Encroachments of Connecticut, | 163 | |

| 1741. | Newport Artillery chartered, | 165 |

| Counterfeit bills troublesome, | 164 | |

| 1744. | Lotteries legalized, | 165 |

| Rhode Island’s part in the capture of Louisburg, | 165 | |

| Death of Colonel John Cranston, | 166 | |

| Two privateers and two hundred men lost, | 166 | |

| Sense of common interest and mutual dependence gaining ground, | 166 | |

| Caution against fraudulent voting, | 167 | |

| Disaster to the French armada, | 168 | |

| 1746. | Close of the campaign, | 168 |

| Accession of territory, | 168 | |

| CHAPTER XXI. | ||

| ATTEMPT TO RETURN TO SPECIE PAYMENTS.—CHANGES IN THE REQUIREMENTS OF CITIZENSHIP.—NEW COUNTIES AND TOWNS FORMED.—FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR.—WARD AND HOPKINS CONTEST.—ESTABLISHMENT OF NEWSPAPERS. | ||

| 1748. | Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, | 170 |

| Hutchinson’s scheme for returning to specie payment rejected by Rhode Island, | 171 | |

| Act against swearing revised, | 172 | |

| Provisions concerning legal residence, | 172 | |

| New census taken, | 172 | |

| 1748–1749. | Death of John Callender, | 173 |

| Beaver Tail Light built, | 173 | |

| Troubles from depreciation of currency, | 173 | |

| 1754. | First divorce granted, | 174 |

| Kent County formed, | 174 | |

| 1752. | Gregorian calendar adopted, | 175 |

| Troubles concerning the Narragansett land settled, | 175 | |

| 1753. | First patent granted in the Colony for making potash, | 175 |

| Fellowship Club founded—afterwards the Newport Marine Society, | 176 | |

| 1754. | Commissioners sent to the Albany Congress, | 176 |

| French and Indian war, | 177 | |

| French settlers imprisoned, | 178 | |

| Ward and Hopkins contest, | 178 | |

| Providence court house and library burned, | 179 | |

| David Douglass built a theatre at Providence, | 180 | |

| 1758. | Newport Mercury established, | 180 |

| 1762. | Providence Gazette established, | 180 |

| Writs of assistance first called for, | 181 | |

| 1759. | Death of Richard Partridge, | 181 |

| Freemasonry first introduced into the Colony, | 181 | |

| Regulations concerning fires, | 181 | |

| Towns of Hopkinton and Johnston formed, | 182 | |

| CHAPTER XXII. | ||

| RETROSPECT.—ENCROACHMENTS OF ENGLAND.—RESISTANCE TO THE REVENUE LAWS.—STAMP ACT.—SECOND CONGRESS OF COLONIES MET AT NEW YORK.—EDUCATIONAL INTEREST. | ||

| Resumé of the progress of the Colony, | 183 | |

| Reason for the enactment of the laws, | 184 | |

| Rhode Island’s solution of the problem of self-government and soul-liberty, | 185 | |

| Encroachments of England on the liberties of the colonies, | 186 | |

| War had taught the colonies a much needed lesson, | 187 | |

| Harbor improvements, | 188 | |

| Parliament votes men and money for the defence of the American colonies, | 188 | |

| Restrictions of commerce, | 189 | |

| 1764. | Molasses and sugar act renewed and extended, | 189 |

| Resistance to the enforcement of the obnoxious revenue laws, | 190 | |

| Action of the colonies in regard to the stamp act, | 191 | |

| England is obliged to repeal the stamp act, | 193 | |

| Resistance to impressment, | 193 | |

| 1765. | Second Colonial Congress met at New York and issued addresses to the people, Parliament, and to the King, | 194 |

| New digest of the laws completed and printed, | 195 | |

| 1766. | Free schools established at Providence, | 196 |

| Brown University founded, | 196 | |

| Iron mine discovered, | 197 | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | ||

| TRANSIT OF VENUS.—A STRONG DISLIKE TO ENGLAND MORE OPENLY EXPRESSED.—NON-IMPORTATION AGREEMENT.—INTRODUCTION OF SLAVES PROHIBITED.—CAPTURE OF THE GASPEE. | ||

| Collision between British officers and citizens, | 199 | |

| Dedication of liberty trees, | 199 | |

| Laws concerning domestic interests, | 199 | |

| Transit of Venus, | 200 | |

| Armed resistance to England more openly talked of, | 201 | |

| Scuttling of the sloop-of-war Liberty, | 202 | |

| Non-importation of tea agreed to, | 203 | |

| Prosperity of Newport, | 203 | |

| First Commencement at Rhode Island College, | 204 | |

| 1770. | Further introduction of slaves prohibited, | 204 |

| Governor Hutchinson advanced a claim for the command of the Rhode Island militia, | 205 | |

| Evidence of justice in Rhode Island, | 206 | |

| Capture and destruction of the schooner Gaspee, | 207 | |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | ||

| PROPOSITION FOR THE UNION OF THE COLONIES.—ACTIVE MEASURES TAKEN LOOKING TOWARDS INDEPENDENCE.—DELEGATES ELECTED TO CONGRESS.—DESTRUCTION OF TEA AT PROVIDENCE.—TROOPS RAISED.—POSTAL SYSTEM ESTABLISHED.—DEPREDATIONS OF THE BRITISH.—“GOD SAVE THE UNITED COLONIES.” | ||

| 1774. | Limitation of negro slavery, | 210 |

| Resolution recommending the union of the colonies passed at Providence town meeting, | 210 | |

| 1774. | Boston port bill passed, | 211 |

| Small-pox at Newport, | 211 | |

| Indication of popular indignation, | 212 | |

| Activity of Committees of Correspondence, | 212 | |

| Publishment of the Hutchinson letters, | 213 | |

| Franklin removed from his position as superintendent of American post-offices, | 214 | |

| 1774. | General Gage entered Boston as Governor, | 215 |

| Sympathy of Rhode Island for Boston; East Greenwich the first to open a subscription, | 215 | |

| Hopkins and Ward elected delegates to Congress, | 216 | |

| 1774. | Congress met in Philadelphia; adopted a declaration of rights; recommended the formation of an American Association, | 217 |

| Distribution of arms, | 218 | |

| Exportation of sheep stopped; manufacture of fire-arms begun, | 219 | |

| Tea burnt at Providence, | 219 | |

| Troops started for Boston, | 219 | |

| Army of Observation formed with Nathanael Greene, commander, | 220 | |

| Rhode Island troops on Jamaica Plains, | 221 | |

| Articles of war passed, | 221 | |

| Capture of a British vessel by Captain Abraham Whipple, | 221 | |

| Rhode Island Navy founded, | 222 | |

| William Goddard’s postal system went into operation, | 222 | |

| Colony put upon a war footing, | 223 | |

| Bristol bombarded and the coast of Rhode Island plundered, | 224 | |

| Part of the debt of Rhode Island assumed by Congress as a war debt, | 225 | |

| Rhode Island in the expedition against Quebec, | 226 | |

| Depredation of the British squadron, | 226 | |

| Battle on Prudence Island, | 227 | |

| Evacuation of Boston, | 228 | |

| Death of Samuel Ward, | 228 | |

| The Assembly of Rhode Island renounced their allegiance to the British Crown, | 228 | |

| CHAPTER XXV. | ||

| RHODE ISLAND BLOCKADED.—DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE INDORSED BY THE ASSEMBLY.— NEW TROOPS RAISED.—FRENCH ALLIANCE.—UNSUCCESSFUL ATTEMPT TO DRIVE THE BRITISH FROM RHODE ISLAND. | ||

| Islands and waters of Rhode Island taken possession of by the British, | 229 | |

| Quota of Rhode Island, | 230 | |

| Inoculation introduced, | 231 | |

| Treatment of Tories, | 231 | |

| Declaration of Independence indorsed by the Assembly, | 232 | |

| Rhode Island’s part in the Continental Navy, | 232 | |

| Convention of Eastern States to form a concerted plan of action, | 233 | |

| Financial troubles, | 234 | |

| Regiment of negroes raised, | 234 | |

| 1778. | Tidings of the French alliance received, | 235 |

| Expedition against Bristol and Warren, | 235 | |

| Attempt to drive the British from Rhode Island rendered unsuccessful by a terrible storm, and jealousy among the officers of the French fleet, | 236 | |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | ||

| ACTS OF THE BRITISH TROOPS.—DISTRESS IN RHODE ISLAND.—EVACUATION OF NEWPORT.—REPUDIATION.—END OF THE WAR. | ||

| Disappointment of the Americans, | 241 | |

| Wanton destruction of life and property by the British, | 241 | |

| Pigot galley captured by Talbot, | 242 | |

| Scarcity of food in Rhode Island, | 242 | |

| Steuben’s tactics introduced into the army, | 244 | |

| Difficulty in raising money, | 244 | |

| British left Newport, | 245 | |

| Town records carried off by the British, | 246 | |

| Repudiation of debt, | 247 | |

| Rhode Island’s quota, | 248 | |

| Preparations for quartering and feeding the troops, | 249 | |

| An English fleet of sixteen ships menaced the Rhode Island coast, | 250 | |

| Assembly met at Newport; the first time in four years, | 250 | |

| 1781. | End of the war, | 251 |

| The federation completed, | 251 | |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | ||

| ARTS OF PEACE RESUMED.—DOCTRINE OF STATE RIGHTS. | ||

| Name of King’s County changed to Washington, | 252 | |

| New census taken, | 253 | |

| Question of State Rights raised, | 253 | |

| 1782. | Nicholas Cooke died, | 254 |

| Armed resistance to the collection of taxes, | 254 | |

| Troubles arising from financial embarrassment, | 255 | |

| 1783. | Acts of the Assembly, | 256 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | ||

| DEPRECIATION OF THE CURRENCY.—INTRODUCTION OF THE SPINNING-JENNY.—BITTER OPPOSITION TO THE FEDERAL UNION.—RHODE ISLAND FINALLY ACCEPTS THE CONSTITUTION. | ||

| Desperate attempt to float a new issue of paper money, | 257 | |

| Forcing acts declared unconstitutional, | 258 | |

| First spinning-jenny made in the United States, | 259 | |

| Bill passed to pay five shillings in the pound for paper money, | 260 | |

| Refusal of Rhode Island to send delegates to the Federal Convention, | 261 | |

| Proposed United States Constitution printed, | 261 | |

| Acceptance of the Constitution by various states, | 261 | |

| State of manufactures, | 262 | |

| 1790. | Rhode Island declared her adhesion to the Union, | 264 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | ||

| MODE OF LIFE IN OUR FOREFATHERS’ DAYS. | ||

| Early condition of the land, | 265 | |

| Agriculture the principal pursuit of the early settlers, | 266 | |

| Early traveling, | 267 | |

| Early means of education, | 267 | |

| Amusements, | 268 | |

| CHAPTER XXX. | ||

| COMMERCIAL GROWTH AND PROSPERITY OF RHODE ISLAND. | ||

| Rhode Island wiser on account of her previous struggles for self-government, | 270 | |

| Commercial condition of Rhode Island, | 271 | |

| Trade with East Indies commenced, | 271 | |

| 1790. | First cotton factory went into operation, | 273 |

| 1799. | Free school system established, | 273 |

| 1819. | Providence Institution for Savings founded, | 274 |

| Canal from the Providence River to the north line of the state projected and failed, | 274 | |

| 1801. | Great fire in Providence, | 274 |

| Visit of Washington to Rhode Island, | 275 | |

| 1832. | Providence made a city, | 275 |

| Rhode Island in the War of 1812, | 276 | |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | ||

| THE DORR REBELLION. | ||

| The Right of Suffrage becomes the question of Rhode Island’s politics, | 277 | |

| Inequality of representation, | 278 | |

| No relief obtainable from the Assembly, | 278 | |

| Formation of Suffrage Associations, | 279 | |

| Peoples’ Constitution, so called, voted for, | 279 | |

| 1842. | Thomas Wilson Dorr elected Governor under it, | 280 |

| Conflict between the old and new government, | 280 | |

| Attempt of the Dorr government to organize and seize the arsenal both failures, | 281 | |

| End of the War, | 281 | |

| Dorr tried for treason and sentenced to imprisonment for life; afterwards restored to his political and civil rights, | 281 | |

| New Constitution adopted, | 282 | |

| Freedom of thought and speech the foundation of Rhode Island’s prosperity, | 282 | |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | ||

| LIFE UNDER THE CONSTITUTION.—THE WAR OF THE REBELLION.—THE CENTENARY. | ||

| Life under the Constitution, | 283 | |

| The War of the Rebellion, | 283 | |

| Rhode Island’s quota, | 284 | |

| The Centennial Exposition, | 285 | |

| APPENDIX. | ||

| King Charles’ Charter, | 291 | |

| Present State Constitution, | 301 | |

| Copy of the Dorr Constitution, | 317 | |

| State seal, | 333 | |

| Governors of Rhode Island, | 334 | |

| Deputy-Governors of Rhode Island, | 337 | |

| Members of the Continental Congress, | 339 | |

| Towns, date of incorporation, &c., | 340 | |

| Population from 1708 to 1875, | 345 | |

| State valuation, | 348 | |

| The Corliss Engine at the Centennial Exposition, | 349 | |

A Short History of Rhode Island.

CONDITION OF AFFAIRS IN MASSACHUSETTS BAY AND PLYMOUTH COLONIES.—ARRIVAL AND BANISHMENT OF ROGER WILLIAMS.

The nations of antiquity, unable to discover their real origin, found a secret gratification in tracing it to the Gods. Thus a religious sentiment was connected with the foundation of states, and the building of the city walls was consecrated by religious rites. The Christian middle ages preserved the spirit of Pagan antiquity, and every city celebrated with solemn rites the day of its patron saint. The colonies, which, in the natural progress of their development, became the United States of America, traced their history, by authentic documents, to the first Christian cultivators of the soil; and in New England the religious idea lay at the root of their foundation and development. In Plymouth it took the form of separatism, or a simple severance from the Church of England. In Massachusetts Bay it aimed at the establishment of a theocracy, and the enforcement of a rigorous uniformity of creed and discipline. From the resistance to this uniformity came Rhode Island and the doctrine of soul liberty.

On the 5th of February, 1631, the ship Lyon, with twenty passengers and a large cargo of provisions, came to anchor in Nantaskett roads. On the 8th she reached Boston, and the 9th, which had been set apart as a day of fasting and prayer for the little Colony, sorely stricken by famine, was made a day of thanksgiving and praise for its sudden deliverance. Among those who, on that day, first united their prayers with the prayers of the elder colonists, was the young colonist, Roger Williams.

Little is known of the early history of Roger Williams, except that he was born in Wales, about 1606; attracted, early in life, the attention of Sir Edward Coke by his skill in taking down in short hand, sermons, and speeches in the Star Chamber; was sent by the great lawyer to Sutton Hospital, now known as the Charter House, with its fresh memories of Coleridge and Charles Lamb; went thence in the regular time to Oxford; took orders in the Church of England, and finally embraced the doctrine of the Puritans. Besides Latin and Greek, which formed the principal objects of an University course, he acquired a competent knowledge of Hebrew and several modern languages, for the study of which he seemed to have had a peculiar facility. His industry and attainments soon won him a high place in the esteem of his religions brethren, and although described by one who knew him as “passionate and precipitate,” he gained and preserved the respect of some of the most eminent among his theological opponents. The key to his life may be found in the simple fact that he possessed an active and progressive mind in an age wherein thought instantly became profession, and profession passed promptly into action.

When this “godly and zealous young minister” landed in Boston, he found the territory which has long been known as Massachusetts in the possession of two distinct colonies, the Colony of Plymouth, founded in 1620, by the followers of John Robinson, of Leyden, and known as the colony of separatists, or men who had separated from the Church of England, but were willing to grant to others the same freedom of opinion which they claimed for themselves; and the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, founded ten years later by a band of intelligent Puritans, many of them men of position and fortune, who, alarmed by the variety of new opinions and doctrines which seemed to menace a total subversion of what they regarded as religion, had resolved to establish a new dwelling place in a new world, with the Old and New Testament for statute book and constitution. Building upon this foundation the clergy naturally became their guides and counselors in all things, and the control of the law, which was but another name for the control of the Bible, extended to all the acts of life, penetrating to the domestic fireside, and holding every member of the community to a rigid accountability for speech as well as action. Asking for no exemption from the rigorous application of Bible precept for themselves, they granted none to others, and looked upon the advocate of any interpretation but theirs as a rebel to God and an enemy to their peace.

It was to this iron-bound colony that Roger Williams brought his restless, vigorous and fearless spirit. Disagreements soon arose and suspicions were awakened. He claimed a freedom of speech irreconcilable with the fundamental principles of their government; and they a power over opinion irreconcilable with freedom of thought. Neither of them could look upon his own position from the other’s point of view. Both were equally sincere. And much as we may now condemn the treatment which Williams received at the hands of the colonial government of Massachusetts Bay, its charter and its religious tenets justified it in treating him as an intruder.

The first public expression of the hostility he was to encounter came from the magistrates of Boston within two months after his arrival, and, on the very day on which the church of Salem had installed him as assistant to their aged pastor, Mr. Skelton. The magistrates were a powerful body, and before autumn he found his situation so uncomfortable that he removed to Plymouth, where the rights of individual opinion were held in respect, if not fully acknowledged. Here, while assiduously engaged in the functions of his holy office, he was brought into direct contact with several of the most powerful chiefs of the neighboring tribes of Indians, and among them of Massasoit and Miantonomi, who were to exercise so controlling an influence over his fortunes. His fervent spirit caught eagerly at the prospect of bringing them under Christian influences, and his natural taste for the study of languages served to lighten the labor of preparation. “God was pleased,” he wrote many years afterwards, “to give me a painful, patient spirit to lodge with them in their filthy holes, even while I lived at Plymouth and Salem, to gain their tongue; my soul’s desire was to do the natives good.”

This was apparently the calmest period of his stormy career. It was at Plymouth that his first child, a daughter, was born. But although he soon made many friends, and had the satisfaction of knowing that his labors were successful, his thoughts still turned towards Salem, and, receiving an invitation to resume his place as assistant of Mr. Skelton, whose health was on the wane, he returned thither after an absence of two years. Some of the members of his church had become so attached to him that they followed him to the sister colony.

And now came suspicions which quickly ripened into controversies, and before another two years were over led to what he regarded as persecution, but what the rulers of the Bay Colony held to be the fulfillment of the obligation which they had assumed in adopting the whole Bible as their rule of life. In 1635 he was banished from the colony by a solemn sentence of the General Court, for teaching:

“1st. That we have not our land by Pattent from the King, but that the natives are the true owners of it, and that we ought to repent of such receiving it by Pattent.

2d. That it is not lawful to call a wicked person to swear, to pray, as being actions of God’s worship.

3d. That it is not lawful to heare any of the Ministers of the Parish Assemblies in England.

4th. That the civil magistrates power extends only to the Bodies and Goods and outward state of man.”

For us who read these charges with the light of two more centuries of progress upon them, it seems strange that neither the General Court nor Williams himself should have perceived that the only one wherein civilization was interested was that to which they have assigned the least conspicuous place.

SUFFERINGS OF ROGER WILLIAMS IN THE WILDERNESS.—FOUNDS A SETTLEMENT ON THE SEEKONK RIVER.—IS ADVISED TO DEPART.—SEEKS OUT A NEW PLACE, WHICH HE CALLS PROVIDENCE.

When the sentence of banishment was first pronounced against the future founder of Rhode Island, his health was so feeble that it was resolved to suspend the execution of it till spring. This, however, was soon found to be impracticable, for the affection and confidence which he had inspired presently found open expression, and friends began to gather around him in his own house to listen to his teaching. Lack of energy was not a defect of the government of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, and learning that rumors of a new colony to be founded on Narragansett Bay were already afloat, it resolved to send the supposed leader of the unwelcome enterprise back to England. A warrant, therefore, was given to Captain Underhill, a man of doubtful character in the employment of the Colony, with orders to proceed directly to Salem, put the offender on board his pinnace, and convey him to a ship that lay in Boston harbor ready to sail for England with the first fair wind. When the pinnace reached Salem, he found only the wife and infant children of the banished man, and a people deeply grieved for the loss of their pastor. Williams was gone, and whither no one could say.

And whither, indeed, could he go? The thin and scattered settlements of the northern colonies were bounded seaward by a tempestuous ocean, and inland by a thick belt of primeval forest, whose depths civilized man had never penetrated. If he escaped the wild beasts that prowled in their recesses, could he hope to escape the wilder savage, who claimed the forest for his hunting grounds? “I was sorely tossed,” Williams writes in after years, “for fourteen weeks in a bitter winter-season, not knowing what bread or bed did mean.” The brave man’s earnest mind bore up the frail and suffering body.

And now he began to reap the fruit of his kind treatment of the natives, and the pains which he had taken to learn their language. “These ravens fed me in the wilderness,” he wrote, with a touching application of Scripture narrative. They gave him the shelter of their squalid wigwams, and shared with him their winter store. The great chief Massasoit opened his door to him, and, when spring came, gave him a tract of land on the Seekonk River, where he “pitched and began to build and plant.” Here he was soon joined by some friends from Salem, who had resolved to cast in their lot with his. But the seed which they planted had already begun to send up its early shoots, when a letter from his “ancient friend, the Governor of Plymouth,” came, to “lovingly advise him” that he was “fallen into the edge of their bounds;” that they were “loth to displease the Bay,” and that if he would “remove but to the other side of the water,” he would have “the country before [him] and might be as free as themselves,” and they “should be loving neighbors together.” Williams accepted the friendly counsel, and, taking five companions with him, set out in a canoe to follow the downward course of the Seekonk and find a spot whereon he might plant and build in safety. As the little boat came under the shade of the western bank of the pleasant stream, a small party of Indians was seen watching them from a large flat rock that rose a few feet above the water’s edge. “Wha-cheer, netop?—Wha-cheer?—how are you, friend?” they cried; and Williams accepting the friendly salutation as a favorable omen, turned the prow of his canoe to the shore. Tradition calls the spot where he landed, Slate Rock, and the name of Wha-cheer square has been given in advance to the land around it. What was said or done at that first interview has not been recorded, but the parting was as friendly as the meeting, and Williams resuming his course, soon found himself at the junction of the Seekonk and Mooshausick. Two points mark the intermingling of the two streams, and in those days the waters must have spread their broad bosom like a lake, and gleamed and danced within their fringe of primeval forest. Williams, following, perhaps, the counsel of the Indians, turned northward and held his way between the narrowing banks of the Mooshausick, till he espied, at the foot of a hill which rose shaggy with trees and precipitate from its eastern shore, the flash and sparkling of a spring. Here he landed, and, recalling his trials and the mighty hand that had sustained him through them all, called the place Providence.

WILLIAMS OBTAINS A GRANT OF LAND AND FOUNDS A COLONY.—FORM OF GOVERNMENT IN THE COLONY.—WILLIAMS GOES TO ENGLAND TO OBTAIN A ROYAL CHARTER.

The territory which now forms the State of Rhode Island, with the exception of Bristol County, in which lay Mount Hope, the seat of Massasoit, chief of the Wamponoags, was held by the Narragansetts, a tribe skilled in the Indian art of making wampum, the Indian money, and the art common to most barbarous nations of making rude vessels in clay and stone. They had once been very powerful, and could still bring four or five thousand braves to the warpath. Their language was substantially the same with that of the other New England tribes, and was understood by the natives of New York, New Jersey and Delaware. With this language Roger Williams had early made himself familiar.

It was labor well bestowed, and he was to reap the reward of it in his day of tribulation. The chiefs of the Narragansetts when he came among them were Canonicus, an “old prince, most shy of the English to his latest breath,” and his nephew, Miantonomi. Their usual residence was on the beautiful Island of Conanicut; and when Williams first came he found them at feud with his other friend, Ossameguin, or Massasoit, Sachem of the Wamponoags. His first care was to reconcile these chiefs, “traveling between them three to pacify, to satisfy all these and their dependent spirits of (his) honest intention to live peaceably by them.” The well founded distrust of the English which Canonicus cherished to the end of his life did not extend to Williams, to whom he made a grant of land between the Mooshausick and the Wanasquatucket; confirming it two years later by a deed bearing the marks of the two Narragansett chiefs. This land Williams divided with twelve of his companions, reserving for them and himself the right of extending the grant “to such others as the major part of us shall admit to the same fellowship of vote with us.” It was a broad foundation, and he soon found himself in the midst of a flourishing colony.

The proprietors, dividing their lands into two parts, “the grand purchase of Providence,” and the “Pawtuxet purchase,” made an assignment of lots to other colonists, and entered resolutely upon the task of bringing the soil under cultivation. The possession of property naturally leads to the making of laws, and the new colonists had not been together long before they felt the want of a government. The form which it first assumed amongst them was that of a democratic municipality, wherein the “masters of families” incorporated themselves into a town, and transacted their public business in town meeting. The colonists of Plymouth had formed their social compact in the cabin of the Mayflower. The colonists of Providence formed theirs on the banks of the Mooshausick. “We, whose names are hereunder,” it reads, “desirous to inhabit in the town of Providence, do promise to subject ourselves in active or passive obedience to all such orders or agreements as shall be made for public good for the body, in an orderly way, by the major assent of the present inhabitants, masters of families, incorporated together into a town fellowship, and such others as they shall admit unto them only in civil things.”

Never before, since the establishment of Christianity, has the separation of Church from State been definitely marked out by this limitation of the authority of the magistrate to civil things; and never, perhaps, in the whole course of history, was a fundamental principle so vigorously observed. Massachusetts looked upon the experiment with jealousy and distrust, and when ignorant or restless men confounded the right of individual opinion in religious matters with a right of independent action in civil matters, those who had condemned Roger Williams to banishment, eagerly proclaimed that no well ordered government could exist in connection with liberty of conscience. Many grave discussions were held, and many curious questions arose before the distinction between liberty and license became thoroughly interwoven with daily life; but only one passage of this singular chapter has been preserved, and, as if to leave no doubt concerning the spirit which led to its preservation, the narrator begins with these ominous words: “At Providence, also, the Devil was not idle.”

The wife of Joshua Verin was a great admirer of Williams’s preaching, and claimed the right of going to hear him oftener than suited the wishes of her husband. Did she, in following the dictates of her conscience, which bade her go to a meeting which harmonized with her feelings, violate the injunction of Scripture which bids wives obey their husbands? Or did he, in exercising his acknowledged control as a husband, trench upon her right of conscience in religious concerns? It was a delicate question; but after long deliberation and many prayers, the claims of conscience prevailed, and “it was agreed that Joshua Verin, upon the breach of a covenant for restraining of the libertie of conscience, shall be withheld from the libertie of voting till he shall declare the contrarie”—a sentence from which it appears that the right of suffrage was regarded as a conceded privilege, not a natural right.

Questions of jurisdiction also arose. Massachusetts could not bring herself to look upon her sister with a friendly eye, and Plymouth was soon to be merged in Massachusetts. It was easy to foresee that there would be bickerings and jealousies, if not open contention between them. Still the little Colony grew apace. The first church was founded in 1639. To meet the wants of an increased population the government was changed, and five disposers or selectmen charged with the principal functions of administration, subject, however, to the superior authority of monthly town meetings; so early and so naturally did municipal institutions take root in English colonies. A vital point was yet untouched. Williams, indeed, held that the Indians, as original occupants of the soil, were the only legal owners of it, and carrying his principle into all his dealings with the natives, bought of them the land on which he planted his Colony. The Plymouth and Massachusetts colonists, also, bought their land of the natives, but in their intercourse with the whites founded their claim upon royal charter. They even went so far as to apply for a charter covering all the territory of the new Colony.

Meanwhile two other colonies had been planted on the shores of Narragansett Bay: the Colony of Aquidnick, on the Island of Rhode Island, and the Colony of Warwick. The sense of a common danger united them, and, in 1643, they appointed Roger Williams their agent to repair to England and apply for a royal charter. It has been treasured up as a bitter memory that he was compelled to seek a conveyance in New York, for Massachusetts would not allow him to pass through her territories. His negotiations were crowned with full success. In 1644 he was again in the colonies, and the inhabitants of Providence, advised of his success, met him at Seekonk and escorted him across the river with an exultant procession of fourteen canoes.

To defray the expenses of his mission he taught Latin, Greek and Hebrew—counting “two sons of Parliament men” among his pupils—and read Dutch to Milton.

SETTLEMENT OF AQUIDNECK AND WARWICK.—PEQUOT WAR.—DEATH OF MIANTONOMI.

I have said that two other colonies had been founded in Rhode Island. Like Providence, they both had their origin in religious controversy. Not long after the return of Roger Williams there came to Boston a woman of high and subtle spirit, deeply imbued with the controversial temper of her age. Her name was Anna Hutchinson, and she taught that salvation was the fruit of grace, not of works. It is easy to conceive how such a doctrine might be perverted by logical interpretation, and religious standing made independent of moral character. This was presently done, and Massachusetts, true to her theoretic system, banished Anna Hutchinson and her followers as she had banished Roger Williams. In the autumn of 1637, nineteen of these Antinomians, as they were called to distinguish them from the legalists or adherents of the law, took refuge in Rhode Island, where they were kindly welcomed; and, soon after, purchasing the Island of Aquidneck, through the intervention of Williams and Sir Henry Vane, laid the foundation of a new town at Pocasset, near the north end of the Island. Their leaders were William Coddington and John Clarke, under whose wise guidance the little Colony made rapid progress, and soon began another settlement at Newport, in the southern part of the island. Here, breaking roads, clearing up woods, exterminating wolves and foxes, opening a trade in lumber, engaging boldly in building ships, and above all forming a free and simple government, with careful regard to religion and education, they soon found themselves in advance of their elder sister, Providence. In both colonies the principle of religious liberty formed the basis of civil organization. On Rhode Island, however, it was confined to Christians—a step greatly in advance of the general intelligence of the age. But in Providence Roger Williams went still further, and, meeting the wants of all future ages, proclaimed it the right of every human being.

The other Colony, as if to illustrate the varieties of human opinion, was founded by Samuel Gorton, one of those bold but restless men who leave doubtful names in history because few see their character from the same point of view. In Gorton’s religious sentiments there seems to have been a large leaven of mysticism, and the writings that he has left us are not pleasant reading. But the practical danger of his teaching lay in his denial of all government not founded upon the authority of the King or of Parliament. Massachusetts was a legitimate government within her own bounds. But unchartered Rhode Island had no legal existence. At Pocasset Gorton soon came into collision with the civil authorities and was banished. In Providence he presently raised such dissensions that Williams almost lost heart, and began to think seriously of withdrawing to his little Island of Patience, in Narragansett Bay. At last Gorton with eleven companions bought Shawomet of its Indian owners and established himself there. This brought him into open hostility with Massachusetts, which having already cast longing eyes upon the commercial advantages of Narragansett Bay, was secretly endeavoring to establish a claim to all the land on its shores.

Hostile words were soon followed by hostile acts. Gorton and his companions were besieged in their house by an armed band, compelled to surrender, carried by force to Massachusetts, tried for heresy, and barely escaping the gibbet, condemned to imprisonment and irons. A reaction soon followed. Public sentiment came to their relief. They were banished indeed from Massachusetts, but they were set at liberty and allowed to return to Rhode Island. At Aquidneck they were received with the sympathy which generous natures ever feel for the victims of persecution, and Gorton was raised to an honorable magistracy in the very colony wherein he had been openly whipped as a disturber of the public peace. It was not till the claims of Massachusetts had been virtually set aside by the charter which Roger Williams obtained for his Colony that Gorton returned to Shawomet, and set himself to rebuild the Colony of Warwick.

Meanwhile great changes had taken place in the relations of the white man to the red. I have told how kindly the natives received Roger Williams, and how justly he dealt by them. I will now tell, though briefly, with what a Christian spirit he used the influence over the Indians, which his justice had won for him, to protect the white men who had driven him from amongst them. On the western border of the territory of the Massachusetts dwelt the fierce and powerful Pequots. No Indian had ever hated the whites with a hatred more intense than they, or watched the growth of the white settlements with a truer perception of the danger with which they menaced the original owners of the soil. They resolved upon war, and to make their triumph sure, resolved also to win over the Narragansetts as active allies. Tidings of the danger soon reached the Bay Colony, and Governor Vane appealed to Roger Williams to interpose and prevent the fatal alliance. Not a moment was to be lost. The Pequot embassadors were already in conference with Canonicus and Miantonomi on Conanicut. Forgetting his personal wrongs, and barely taking time to tell his wife whither he was going, he set forth alone in his canoe, “cutting through a stormy wind and great seas, every minute in hazard of life.”

Greater hazard awaited him on shore. English blood had already been shed by the Pequots, and knowing their fierce nature, he “nightly looked for their bloody knives at his own throat also.” For three days and three nights he confronted them face to face, and so great was the control which he had gained over the Narragansett chiefs that he succeeded in “breaking in pieces the Pequot negotiation and design, and made and finished by many travels and charges the English league with the Narragansetts and Mohegans against the Pequots.” The war came. The Narragansetts were on the side of the English; fearful massacres were committed; the Pequots were rooted out from their native soil forever; Massachusetts was saved; but the Christian, forgetting of injuries wherewith Williams had come to her aid in the critical moment of her fortunes, was not deemed of sufficient virtue to wash out the stain of heresy, and the sentence of banishment was left unrepealed on the darker page of her colonial records.

The Pequots were crushed. The turn of the Narragansetts came next. It was the fate of the red man to everywhere give way as a civilization irreconcilable with his habits and his beliefs advanced, and it is for the good of humanity that it is so. But it is sad to remember that the Christian, with the Bible in his hand, should have sought his examples in the stern denunciations of the Old Testament, rather than in the injunctions to love and mercy of the New. Six years after the formation of the league against the Pequots, a war broke out between Sequasson, an ally of Miantonomi and the Mohegans. The Narragansett Sachem, trusting to the good faith of his adversary, the powerful Uncas, was betrayed in a conference, and his followers, taken by surprise in open violation of the laws of even Indian warfare, were put to flight. The unfortunate chief fell into the hands of his enemy, who, fearing the English too much to put an ally of theirs to death, referred the question of his fate to the Commissioners of the United Colonies—Massachusetts, Plymouth, Connecticut and New Haven—who were about to hold a conference in Boston. Rhode Island, which had been excluded from the league, had no voice in this outrage, and Williams, whose remonstrances might have been of some avail, was in England. To give greater solemnity to their deliberations the Commissioners called to their aid “five of the most judicious elders,” and by their united voices Miantonomi was condemned to die. The execution of the sentence was entrusted to Uncas, and the only condition attached to the shameful act was that the generous friend of the white man should not be tortured. His people never recovered from the blow. In the very next year they placed themselves by a solemn resolution under the protection of the King, and appointed four commissioners, one of whom was Gorton, to carry their submission to England.

CHARTER GRANTED TO PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS.—ORGANIZATION UNDER IT.—THE LAWS ADOPTED.

We have seen that in 1643 Roger Williams had been sent to England as agent to solicit a charter for the three colonies of Narragansett Bay. He found the King at open war with the Parliament, and the administration of the colonies entrusted to the Earl of Warwick and a joint committee of the two Houses. Of the details of the negotiation little is known, but on the 14th of March of the following year, a “free and absolute charter was granted as the Incorporation of Providence Plantations in Narragansett Bay in New England.” It was not such as Charles would have given. But one fetter was placed upon the free action of the people—“that the laws, constitutions, punishments for the civil government of the said plantation be conformable to the laws of England”—and that was made powerless by the qualifying condition that the conformity should extend only “so far as the nature and constitution of that place will admit.” Civil government and civil laws were the only government and laws which it recognized; and the absence of any allusion to religious freedom in it shows how firmly and wisely Williams avoided every form of expression which might seem to recognize the power to grant or to deny that inalienable right. The regulation of the “general government” in its “relation to the rest of the plantations in America,” was reserved “to the Earl and Commissioners.”

Yet more than three years were allowed to pass before it went into full force as a bond of union for the four towns. Then, in May, 1647, the corporators met at Portsmouth in General Court of Election, and, accepting the charter, proceeded to organize a government in harmony with its provisions. Warwick, although not named in the charter, was admitted to the same privileges with her larger and more flourishing sisters.

This new government was in reality a government of the people, to whose final decision in their General Assembly all questions were submitted. “And now,” says the preamble to the code, “sith our charter gives us powere to governe ourselves and such other as come among us, and by such a forme of Civill Government as by the voluntairie consent, &c., shall be found most suitable to our estate and condition:

“It is agreed by this present Assembly thus incorporate and by this present act declared, that the form of Government established in Providence Plantations, is Democratical; that is to say, a Government held by ye free and voluntairie consent of all or the greater part of the free Inhabitants.”

In accordance with this fundamental principle all laws were first discussed in Town Meeting, then submitted to the General Court, a committee of six men from each town freely chosen, and finally referred to the General Assembly. The General Court possessed, also, the power of originating laws, by recommending a draft of law to the towns, upon whose approval the draft obtained the force of law till the next meeting of the General Assembly.

The first act of this first Colonial Assembly was to organize by electing John Coggeshall Moderator, and secure an acting quorum by fixing it at forty. It was next “agreed that all should set their hands to an engagement to the Charter.” Then, after some provision for the union of the towns, the formation of the General Court and the adoption of the laws “as they are contracted in the bulk,” Mr. John Coggeshall was chosen “President of this Province or Colonie; Wm. Dyer, General Recorder; Mr. Jeremy Clarke, Treasurer, and Mr. Roger Williams, Mr. John Sanford, Mr. Wm. Coddington and Mr. Randall Holden, Assistants for Providence, Portsmouth, Newport and Warwick” respectively. Then, entering boldly upon its independent existence, the little Colony—a State in all but the name—proceeded to examine the body of laws which had been prepared for its acceptance. One of the most significant of them, as indicating their commercial aspirations, was their adoption of the laws of Oleron for a maritime code; and another, as illustrating their consciousness of their perilous position in the midst of savages, still able to strike sudden blows, though no longer strong enough to wage long wars, the revival and extension of “the Statute touching Archerie,” and the enactment of a stringent militia law. The laws against parricide, murder, arson, robbery and stealing, show that there were men in the community who were believed to be capable of these crimes. The law against suicide, and still more the law against witchcraft, are too much in harmony with the general spirit of the age to warrant a severe condemnation. The punishment provided against drunkenness reads as though it were not an infrequent offence. Marriage was regarded as a civil contract. The law of debt was wise and humane, forbidding the sending of the debtor to prison, “there,” it says with simplicity and force, “to lie languishing to no man’s advantage, unless he refuse to stand to their order.” The character of the whole code was just and benevolent, breathing a gentle spirit of practical Christianity and a calm consciousness of high destinies. “These,” it says, “are the laws that concern all men, and these are the Penalties for the transgression thereof; which by common consent are Ratified and Established throughout this whole Colonie; and otherwise than thus what is herein forbidden, all men may walk as their consciences persuade them, every one in the name of his God.”

By the same Assembly it was ordered, “that the seale of the Providence shall be an anchor.” A free gift, also, of one hundred pounds was made to Roger Williams, “in regarde to his so great travaile, charges, and good endeavors in the obtaining of the Charter for this Province.” This sum was “to be levied out of the three towns;” and how far the island was in advance of the main-land may be seen by the distribution of the levy which assigns fifty pounds to Newport and thirty to Portsmouth, while Providence was held at twenty. Of Warwick, still poor and weak, nothing was asked.

The spirit of this first legislation may be comprised in four articles: the first of which provides for the protection of the citizen against the government by guaranteeing liberty of property and person, and restricting criminal suits to the violation of the letter of the law. The second forbids the assumption of office by any who are not legally chosen, and the extension of official action beyond its prescribed bounds. The third by making the charter and acts of the Assembly the sources of law, secures the rights of minorities. And the fourth, displaying a comprehension of the true principles of public service which succeeding generations would do well to study, required that every citizen should serve when chosen to office or pay a fine, and that his service should receive an adequate compensation. The engagement of state and officer was reciprocal—the officer binding himself to serve the state faithfully, and the state to stand by her officers in the legitimate exercise of their functions.

FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC TROUBLES.—UNSUCCESSFUL ATTEMPT AT USURPATION BY CODDINGTON.

And now, just as the new Province was entering upon that chartered existence which was to lead to such brilliant results, the wise and peaceable Canonicus died, closing in humiliation and sorrow a life which had begun in strength and hope. He had seen the first foot-prints of the stranger; had aided him in his weakness; had resisted him in his strength; had lived to see his destined successor fall victim to an unholy policy, and his people, impoverished and enfeebled, vainly strive to avenge the murder on their adversaries; and thus with a heavy heart he passed away from the scene of his early glory and his long humiliation. We shall see bye and bye the miserable end of the great Narragansetts.

The new Colony entered upon its career with two great problems before it. The first was almost solved. An experience of eleven years had demonstrated the possibility of soul liberty, which had taken a hold upon the hearts of the colonists too strong to be shaken. But did it leave the needed strength in the civil organization to bear “a government held by the free and voluntary consent of all, or the greater part, of the free inhabitants?” Thus the reconciliation of liberty and law formed from the beginning the fundamental problem of Rhode Island history.

At first there were great and frequent dissensions. There were dissensions between Newport and Portsmouth. There were still greater dissensions in Providence. Enemies exulted, foretelling an early dissolution of the feeble bands which held the dangerous Colony together. Friends trembled lest their last hope of the reconciliation of liberty and law should fail them. But still the great work of solution went on, each new dissension revealing some new error, or aiding in the demonstration of some new truth. It would take us far beyond our limits were we to attempt to follow up the history of these dissensions in detail, even if the materials for a full narrative of them had been preserved. There were other difficulties, also, which demand more than a passing allusion.

Massachusetts had not yet renounced her designs upon the territories of the heretical Colony. A party in Pawtuxet which had put itself under the protection of the Bay Colony had opened the way for action, and the dispute with Shawomet had enlarged it. Gorton was in England in 1647, exerting himself to answer the assertions of the Massachusetts agent, Winslow. Three years later the question became so complicated and the danger so imminent that Roger Williams was asked to go again to England on behalf of the Colony. Meanwhile there were menacing indications of an Indian war, and a serious effort was made on the part of the Island towns to obtain admission to the New England confederation. The application was refused unless on terms equivalent to the surrender of all right to independent existence. The time for justice and a clear comprehension of the common interest was not yet come. Especially strong was Massachusetts’ dread of the Baptists, who were becoming a powerful body in Rhode Island, and three of the prominent members of that communion, among whom was John Clarke, one of the most illustrious of the colonists, were seized at Lynn—whither they had been summoned to give comfort and counsel to an aged brother—cast into prison, fined, and one of their number, Obadiah Holmes, cruelly scourged with a three-corded whip.

Another danger menaced the Colony. William Coddington, who had been chosen President, but had never taken the legal engagement, had gone to England, and, as was soon ascertained, with the design of applying for a commission as Governor of the Island. For two years he was unable to obtain a hearing. The new government of England was too busy with its own concerns to lend an ear to the agent of a distant and humble Colony. At last the favorable moment came, and, on the 3d of April, 1651, he received a commission from the Council of State, appointing him Governor for life of Rhode Island and Connecticut. By what representations or misrepresentations he obtained the object of his ambition, history does not tell us. A council of six, nominated by the people and approved by him, were to assist him in the government. The charter government was apparently dissolved.

But the men of Providence and Warwick did not lose heart. Roger Williams, who had already given proof of his diplomatic skill at home by his successful negotiations with the native chiefs, and in England by obtaining a charter, was still with them, and to him all turned their eyes in this hour of supreme danger. It was resolved that he should repair to England without delay, and ask for a confirmation of the charter in the name of Providence and Warwick. To provide money for the support of his family during his absence he sold his trading-house in Narragansett, and, obtaining a hard-wrung leave to embark at Boston, set forth in October, 1651, upon his memorable mission. In the same ship went John Clarke, as agent for the Island towns, to ask for the revocation of Coddington’s commission. On the success of their application hung the fate of the Colony. Meanwhile the Island towns submitted silently to Coddington’s usurpation, and the main-land towns continued to govern themselves by their old laws, and meet and deliberate as they had done before in their General Assembly.

It was in the midst of these dangers and dissensions that on the 19th of May, in the session of 1652, it was “enacted and ordered ... that no black mankind or white being forced by covenant, bond or other wise shall be held to service longer than ten years,” and that “that man that will not let them go free, or shall sell them any else where to that end that they may be enslaved to others for a longer time, hee or they shall forfeit to the Colonie forty pounds.” This was the first legislation concerning slavery on this continent. If forty pounds should seem a small penalty, let us remember that the price of a slave was but twenty. If it should be objected that the act was imperfectly enforced, let us remember how honorable a thing it is to have been the first to solemnly recognize a great principle. Soul liberty had borne her first fruits.