Title: Harper's Young People, February 15, 1881

Author: Various

Release date: February 15, 2014 [eBook #44925]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| A RIPPER. |

| CHATS ABOUT PHILATELY. |

| MY FIRST MUFF. |

| TOBY TYLER. |

| STANLEY'S GREAT JOURNEY. |

| A STRANGE VALENTINE. |

| PHIL'S FAIRIES. |

| THE END OF MY MONKEY. |

| OUR POST-OFFICE BOX. |

| Vol. II.—No. 68. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | Price Four Cents. |

| Tuesday, February 15, 1881. | Copyright, 1881, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

"It's nothing on earth but a pair of bobs. We've rigged that kind of thing lots of times over on our hill. All you need is a couple of sleds and a plank."

"Yes, Rod, and when you've done it, they won't steer worth a cent."

"Yes, they do. Dig your heels in."

"Stop your sled just so much every time you dig. A rudder's just as bad. We've tried 'em."

"So've we, Court Hoffman. I guess there wasn't ever anything much started on your hill till after we'd showed you how, over on ours."

"You never showed anybody how to make a ripper like this."

"Ripper? We'll see about that."

There they stood looking at Courtland Hoffman's new coasting machine. He was the undoubted leader of the West Hill coasters, as Rodney Sanderson was of the East Hill boys.

The new ripper was a beauty, and had cost some money. It was, as Rod said, a pair of bobs, with a plank on top to hold them together. There was room on it for half a dozen boys, and more if they packed, and it was handsomely finished. The one thing about it that no boy in Cuzco Centre really believed in, except Court Hoffman, was the steering gear.

This was a half-wheel, as wide as the sled, mounted on the front bob, on an axle that went down through the plank; and the idea that when you turned that wheel the front bob would turn too, and the ripper be steered by it, was too much for anything. Some of the oldest men in the village had shaken their heads at that sled, and Squire Sanderson himself had remarked to Deacon Rogers, "They didn't spile the boys with any sech nonsense in our day, Deacon."

Cuzco Centre had two hills, one on each side, and they were tremendous affairs. The older people believed they were put there so as to have a valley between them for the village to stand in, but the boys knew exactly what they were really for, especially in winter, and when the coasting was good.

The main street ran through the middle of the valley and the village; but it failed to make a fair division of things, for the river ran a crooked parallel with it a short distance eastward. It was the glory of the East Side boys that the river ran through their ground—fish, swimming-hole, ponds, skating, old bridge, and all—but it cut off the lower end of their long coast from the hill road. No sled in Cuzco had ever reached the bridge, however, so it was just as well; but the West Side boys told wonderful stories of the distances they had buzzed over on the half-mile level at the bottom of their hill. That was what Court Hoffman meant, too, when he said:

"You wouldn't have room for a ripper on your hill. If you want to see how one works, you'll have to come over and look on. Give you a ride, too, if you think you wouldn't be afraid. They go just like lightning."

Rod Sanderson did not say anything, but he looked up the road toward the East Hill, and the high, white, snow-covered ridge seemed to say:

"Look up here. There is as much of me as ever there was. You do your share, and we'll beat 'em."

Court Hoffman made two boys happy by letting them drag his ripper home for him, and Rod Sanderson walked off with an idea in his head.

"There'll be a moon to-night. Never was better coasting. I'll just try it on."

Part of that idea was now lying over in his father's barn-yard, in the shape of an old weather-beaten, worn-out double-seated sleigh, with a goose-neck front. It had been a handsome affair in its day, but it had not had any day to speak of since Rodney could remember. It was drifted under now, and it took a good hour to get it out, even with the help of Put Willoughby.

"Going to make a ripper of it?" said Put, doubtfully. "The runners are all right, but the box is on it yet, and the seats."

"We'll put in buffalo robes and blankets, and fix it fine."

"How on earth'll you steer? There isn't any boy in Cuzco with legs enough to heel it for a sleigh of that size."

"I'll show you. I'm going to rig a boom out astern for a rudder. Steer like a ship."

"You don't say!"

Put had a good deal to say, however, when he saw Rod cut a hole in the back of that sleigh box, and shove through it a long pole with a spike on the end.

"Steer? Of course it will. I could steer it myself. Only how on earth'll we ever get it up to the top of the East Hill?"

There might have been some difficulty about that, if all the boys on that side of the main street had not taken the matter in hand. They were a public-spirited lot, and they were all jealous of Court Hoffman's town-made, new-fangled, fancy-painted gimcrack. They knew it wouldn't work, and they said so, and they pulled and pushed at Rod's wonderful idea that evening until they got it up the hill. Then they all got in, or tried to, and the old ark looked more like a pyramid of boys than anything else.

It was a splendid moon-lit evening, and the West Hill boys were out, every soul of them, and the best friends Court Hoffman had were half afraid he wouldn't invite them to ride on his ripper the first time. Then they were more than half afraid he would, for they all knew Deacon Rogers had said there was no telling where that thing would go to if it once got well a-going.

The valley, and the village, and the river, and the East Hill would be in the way, to be sure, and that was something; but the hill road was as slippery as ice, and the new ripper looked more and more like a shark when Court Hoffman lifted it to show them how bright and smooth the runner irons were.

He showed them also how the wheel worked, and declared that he could steer that ripper all around a house. That was what made Jim Delany ask,

"Could ye stheer it round a wood-sleigh, wid three yoke of oxen, av ye met 'em in the sthrate yonder?"

"I'll show you. Now, boys, who's going with me? Hurrah! The more the merrier."

"I'm wid ye," shouted Jim Delany. "It'll be bad luck for any horned baste we run into."

One after another the larger boys followed Jim, and Court never stopped to count.

"Keep your feet on the foot-rests," he shouted. "Hold on hard. Hold steady as rocks. We'll be off in a minute. Ready, all? Go, then."

And go it was, with nearly a mile of sloping road before them, and beyond that the long glittering reach of the level.

There was time for a cheer or two, and they gave one, and nearly half of another; but that second cheer seemed to be cut in two by something.

Court Hoffman grasped his wheel tiller with all the strength he had in him, and looked straight ahead. He had ridden on that sort of machine before, and he knew what was coming the moment she got her speed on.

But the other boys?

Dan Varick's grip on Jim Delany would have brought a yell from him if he had dared to open his mouth. Jim was thinking, too, but he and all the rest were thinking the same thought.

"Fences? They're nothing but two black streaks at the side of the road. Oh dear! we'll go clean through the village. What if we should run into something!"

They held on like good fellows, and made that ripper-load[Pg 243] of boys as nearly as possible one solid mass, so that it was easier for Court Hoffman to steer. Even he, though, was beginning to have his doubts as to where they would bring up, and whether he could steer safely around the curve where the road from the West Hill crossed the main street, and met the road from the East that led over the bridge.

The speed was awful! No express train ever went faster, and a race-horse would have been passed as if he were standing still.

Danger in it? Of course there was, and the lives of all of them depended upon the nerve and pluck of Court Hoffman, and the skill he might show in getting around the curve. Yes, and on whether or not there should be a clear road, or a stray team or cow or human being to run against.

It was a terrible risk to run, and all the boys left on the hill were glad they had let somebody else try the first ride on the ripper.

Before the beginning of that swift, perilous dash, however, Rod Sanderson and the East Side boys had completed their preparations. Some of them had to get off and push to get the old sleigh started, and only one of these managed to get on again. Three more jumped off before the "whopper," as Rodney called her, had gone ten rods, and it may have been because they had doubts as to where she would fetch up.

"She just steers lovely," remarked Put Willoughby, as he noticed how Rod Sanderson was straining at the long handle of his rudder.

"She's beginning to go faster!"

"She's a-gaining!"

"Don't she go it!"

"Hurrah—ah—aw—aw!"

They all joined in that, but at just that moment the old sleigh shoved her goose-necks over the little roll at the edge of the first really steep slope of the East Hill road, and she seemed to give a great jump.

"Rod, where's your rudder?"

"Gone! I—"

There was no more to be said. It had been jerked from him, through the hole he had cut for it, the moment the bent spike caught in an icy place, and the old sleigh had things in her own hands from that moment.

She seemed to know it, and to be tickled half to death over the notion of doing her own running, without a span of horses in front of her. She was not a ripper, indeed, but she was a whopper, and she had weight enough on board to give her all the impetus she needed down that hill.

How she did plunge and slip! and how the loose snow and bits of ice did fly! Still, she had been over that road many a time, and seemed to know it like a book now; that is, the ruts were deep, and her runners kept in them as surely as the wheels of a street car keep in the grooves of the track. Faster and faster, with nobody to steer, and no earthly chance of stopping her! There never was such coasting, nor so many boys doing it on one big sled.

Rod Sanderson looked out ahead over his crouching load, and the wind cut by his face as if there had been a hurricane. A team on the bridge! What if it should come on into the road? What if the old sleigh should take a notion to go on over the bridge and into the village, or anywhere?

"Oh dear! she's going faster!"

The short stretch of level road at the bottom of the East Hill was reached like a flash, and it was now going by like another flash—a little slower, to be sure, but with no sign of stopping.

The driver of the team on the bridge had halted his oxen, and the boys in the sleigh seemed all at once to feel the same impulse to dodge. They leaned toward the right, and it may be some of them meant to jump; but the pressure helped a clog of wood the runners touched at that moment to turn the "whopper" out of the ruts of the road, and into the well-worn slide that led down the river-bank. It was her last plunge, and she was nearly out of breath when she took it, but it was well for those boys the ice was so thick. It bore them splendidly, sleigh and all, and away they went, until their ride used itself up, just half way over. Just as they were all drawing their breath for a grand hurrah, something black and long shot down from the western bank of the river, and out upon the very ice that belonged to them.

"Coming right for us!"

"Boys! boys! that's Court Hoffman's ripper!"

Court had done it. He had steered successfully around the curve, partly because some of his speed had gone when he reached it, and his remaining impetus had carried him on until he slipped into the gentle declivity toward the bridge and the river.

"I say," said Rod Sanderson, as the passengers of the ripper sprang to their feet, "how far did you have to haul that thing after you got down hill?"

"Ran all the way itself."

"Well, so did our whopper. Steered herself, too, and that's more'n yours can do."

"Well, yes, I should say so."

Court was looking and feeling a little thoughtful. The coasting on the West Hill was almost too good for his ripper, and he wanted to consider the matter before he tried it again.

As for the "whopper," there was no such thing as persuading the East Hill boys to haul her up the road for another free ride that evening.

In a previous chat with you I gave a few directions how to start properly in collecting stamps. You also got an inkling of the vast extent of Philately. While it embraces but two classes, stamps for postal purposes and stamps for revenue purposes, it has divided these two classes into several divisions, each of which has an equal importance, and each of which claims for itself all that can be given to it either of time or money. Jack of all trades, and master of none, can very truly be applied to stamp collecting. One who attempts to collect all kinds of stamps may, by the expenditure of a very large amount of money, succeed in accumulating a very great number of stamps; but one becomes merely an accumulator, and has ceased to be a Philatelist. The rule among collectors to-day is to take up some special portion of Philately, and to direct all their efforts to that portion.

Stamps for postal purposes include government adhesive stamps, local stamps recognized by several governments, private express stamps and private post-office stamps once prevalent in this country, stamped envelopes and stamped newspaper wrappers, postal cards, and proofs and essays. Stamps for revenue purposes include government adhesive stamps, municipal stamps, private die stamps of the United States, and proofs and essays. Here are divisions enough. To attain excellence, or even good results, in any one division, the others must be given up. One is just as fruitful of interest as another, but postage stamps of government issue are the most popular, being the easiest within reach.

Stamped envelopes and wrappers and postal cards should not be mutilated by having the design cut out. In the early days of collecting, attention was generally paid to the design only, which, whether in adhesive stamps or on envelopes, was trimmed up to the printed portion. The album-makers were responsible for this mutilation by marking off spaces in their albums. Collectors foolishly trimmed their stamps to fit into the prescribed spaces—a[Pg 244] course which they have since regretted; for these trimmed specimens, exceedingly valuable, and oftentimes priceless when not mutilated, would not now be admitted into any first-class collection. Even to this day the album-makers virtually compel the collector to cut the impression out of the envelope, or else have an album with unsightly pages here and there. But under no consideration should the envelope or postal card be mutilated. You may say that it is not practicable to keep the entire envelope in a book. But you do not keep butterflies or birds' eggs in a book. Keep the envelopes and cards in a box until you can devise a plan of your own for mounting them. I have a very excellent plan for mounting envelopes and cards, and one of these days I may explain it to you.

Government local stamps are privileges extended to individuals or localities for postal purposes within limits. The most important of these are the Russian local stamps. You are aware that Russia has a large extent of territory; the postal service of the Russian Empire is not yet adequate enough to cover properly this vast extent, and accordingly it has extended to all the governments or provinces of Russia local mail privileges. As a result of this, over a hundred and ten towns have their special postage stamps. These are the most interesting of all stamps, from the many historical or emblematical designs engraved on them. A full collection of these stamps would number between four and five hundred specimens.

With these government local stamps must not be confounded what are sometimes, but erroneously, called "United States locals," but which are in reality nothing more than private express stamps. Between thirty and forty years ago, private individuals, and sometimes express companies, carried letters between various cities, or most usually within the limits of certain cities or towns. Payment was indicated by stamps. The Post-office Department soon broke up these concerns, as interfering with the postal privileges of the government, and none are now in existence as letter-carrying concerns save a few firms in this city to whom the privilege is given by one of the old colonial charters, and with which the government can not interfere. I shall not discuss the admissibility of these stamps into a collection, although opinion is divided. But I would advise my young friends to give them a wide berth. Of the hundreds which are known, you can not possibly get together enough genuine specimens to fill up a page of your book. To supply the demand there is no lack of counterfeits, or concoctions, which will be represented to you as just as good as the stamps themselves.

But do not fill your albums with these vile forgeries. Many an album containing many fine stamps has been rendered almost worthless because page after page was plastered over with forgeries, reprints, and re-strikes of these private express stamps.

Among revenue stamps there are two most interesting classes—the municipal stamps of Italy and the private die or private proprietary stamps of this country. Revenue stamps are more in number than postage stamps, and, generally speaking, are more difficult to obtain, because of the higher values which the stamps represent. But the Italian municipal and the United States private die stamps will well repay the efforts of the young collector.

On one other point I wish to counsel you. Let there be consistency in your collection. By this I mean, let your stamps be all cancelled or all uncancelled!! Nothing looks so bad as to see part of a set bright and clean, and the rest all smudged with cancelling ink. Cancelled stamps are in the main much cheaper than uncancelled stamps, and the collector has less difficulty in procuring cancelled specimens than he has in procuring uncancelled specimens. In fact, one difficulty collectors of clean stamps have to contend against is that it is almost impossible to procure clean copies of some of the great rarities. But these will not trouble you for some time. Bear in mind what I said in a previous paper about putting in your collection none but perfect specimens. If you are careless on this point, you may be often imposed upon by many dealers, who will take particular pains to offer you their worst specimens.

Here's my little lady,

Dressed with thoughtful care,

Smiling at the sunlight,

Smiling at the air.

Whither, little lady,

Whither shall we go?

O'er the lofty hill-tops—

Through the winter's snow?

Will you with me wander

Through the copses bare,

Where the dead leaves linger?—

Autumn left them there.

No, my little lady;

Snows would damp your feet;

Thorns would tear your jacket,

Trimmed with ermine neat.

I will fetch a carriage,

Drawn by ponies fine,

Lined with silken cushions,

Fit for lady mine.

We will drive right swiftly

O'er the hill-tops then—

Drive as quick as lightning

Through the merry glen.

Then my little lady

Safe from harm will be,

And her rich soft ermine

From sharp thorns be free.

Toby was about to say that he did not intend to represent the matter other than it really was, when a voice from behind the canvas screen prevented further conversation.

"Sam-u-el, come an' help me carry these things in."

Something very like a smile of satisfaction passed over Signor Castro's face as he heard this, which told him that the time for the feast was very near at hand, and the snake-charmer, as well as the Albino Children, seemed quite as much pleased as did the sword-swallower.

"You will excuse me, ladies and gentlemen," said the skeleton, in an important tone; "I must help Lilly, and then I shall have the pleasure of helping you to some of her cooking, which, if I do say it, that oughtn't, is as good as can be found in this entire country."

Then he too disappeared behind the canvas screen.

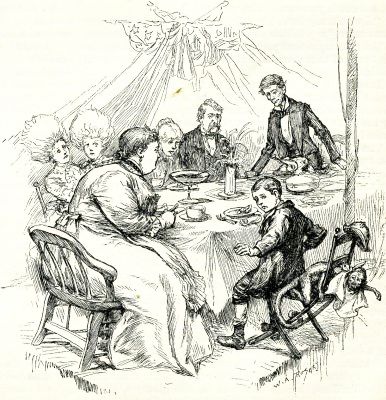

Left alone, Toby looked at the ladies, and the ladies looked at him, in perfect silence, while the sword-swallower grimly regarded all, until Mr. Treat appeared bearing on a platter an immense turkey, as nicely browned as any Thanksgiving turkey Toby ever saw. Behind him came his fat wife carrying several dishes, each one of which emitted a most fragrant odor; and as these were placed upon the table, the spirits of the sword-swallower seemed to revive, and he smiled pleasantly, while even the ladies appeared animated by the sight and odor of the good things which they were to be called upon so soon to pass judgment.

Several times did Mr. and Mrs. Treat bustle in and out from behind the screen, and each time they made some addition to that which was upon the table, until Toby began to fear that they would never finish, and the sword-swallower seemed unable to restrain his impatience.

At last the finishing touch had been put to the table, the last dish placed in position, and then, with a certain kind of grace, which no one but a man as thin as Mr. Treat could assume, he advanced to the edge of the platform, and said,

"Ladies and gentlemen, nothing gives me greater pleasure than to invite you all, including Mr. Tyler's friend Stubbs, to the bountiful repast which my Lilly has prepared for—"

At this point, Mr. Treat's speech—for it certainly seemed as if he had commenced to make one—was broken off in a most summary manner. His wife had come up behind him, and, with as much ease as if he had been a child, lifted him from off the floor, and placed him gently in the chair at the head of the table.

"Come right up and get dinner," she said to her guests; "if you had waited until Samuel had finished his speech, everything on the table would have been stone-cold."

The guests proceeded to obey her kindly command, and it is to be regretted that the sword-swallower had no better manners than to jump on to the platform with one bound, and seat himself at the table with the most unseemly haste. The others, and more especially Toby, proceeded in a leisurely and more dignified manner.

A seat had been placed by the side of the one intended for Toby for the accommodation of Mr. Stubbs, who suffered a napkin to be tied under his chin, and generally behaved in a manner that gladdened the heart of his young master.

Mr. Treat cut generous slices from the turkey for each guest, and Mrs. Treat piled their plates high with all sorts of vegetables, complaining, after the manner of housewives generally, that the food was not cooked as she would like to have had it, and declaring that she had had poor luck with everything that morning, when she firmly believed in her heart that her table had never looked better.

After the company had had the edge taken off their appetites, which effect was produced on the sword-swallower only after he had been helped three different times, the conversation began by the fat woman asking Toby how he got along with Mr. Lord.

Toby could not give a very good account of his employer, but he had the good sense not to cast a dampener on a party of pleasure by reciting his own troubles, and he said, evasively,

"I guess I shall get along pretty well, now that I have got so many friends."

Just as he had commenced to speak, the skeleton had put in his mouth a very large piece of turkey—very much larger in proportion than he was himself—and when Toby finished speaking, he started to say something evidently not very complimentary to Mr. Lord. But what it was the company never knew, for just as he opened his mouth to speak, the meat went down the wrong way, his face became a bright purple, and it was quite evident that he was choking.

Toby was alarmed, and sprang from his chair to assist his friend, upsetting Mr. Stubbs from his seat, causing him to scamper up the tent pole, with the napkin still tied[Pg 246] around his neck, and to scold in his most vehement manner. Before Toby could reach the skeleton, however, the fat woman had darted toward her lean husband, caught him by one arm, and was pounding his back, by the time Toby got there, so vigorously that the boy was afraid her enormous hand would go through his tissue-paper-like frame.

"I wouldn't," said Toby, in alarm; "you may break him."

"Don't you get frightened," said Mrs. Treat, turning her husband completely over, and still continuing the drumming process. "He's often taken this way; he's such a glutton that he'd try to swallow the turkey whole if he could get it in his mouth, an' he's so thin that 'most anything sticks in his throat."

"I should think you'd break him all up," said Toby, apologetically, as he resumed his seat at the table; "he don't look as if he could stand very much of that sort of thing."

But apparently Mr. Treat could stand very much more than Toby gave him credit for, because at this juncture he stopped coughing, and his face was fast assuming its natural hue.

His attentive wife, seeing that he had ceased struggling, pulled him up above the chair, and sat him down with a force that threatened to snap his very head off.

"There!" she said, as he wheezed a little from the effects of the shock; "now see if you can behave yourself, an' chew your meat as you ought to. One of these days when you're alone you'll try that game, and that'll be the last of you."

"If he'd try to do one of my tricks long enough, he'd get so that there wouldn't hardly anything choke him," the sword-swallower ventured to suggest, mildly, as he wiped a small stream of cranberry-sauce from his chin, and laid a well-polished turkey bone by the side of his plate.

"I'd like to see him try it!" said the fat lady, with just a shade of anger in her voice. Then turning toward her husband she said, emphatically, "Samuel, don't you ever let me catch you swallowing a sword!"

"I won't, my love, I won't; and I will try to chew my meat more," replied the very thin glutton, in a feeble tone.

Toby thought that perhaps the skeleton might keep the first part of that promise, but he was not quite sure about the last.

It required no little coaxing on the part of both Toby and Mrs. Treat to induce Mr. Stubbs to come down from his lofty perch; but the task was accomplished at last, and by the gift of a very large doughnut he was induced to resume his seat at the table.

The time had now come when the duties of a host, in his own peculiar way of viewing them, devolved upon Mr. Treat, and he said, as he pushed his chair back a short distance from the table, and tried to polish the front of his vest with his napkin:

"I don't want this fact lost sight of, because it is an important one. Every one must remember that we have gathered here to meet and become better acquainted with the latest and best addition to this circus, Mr. Toby Tyler."

Poor Toby! As the company all looked directly at him, and Mrs. Treat nodded her enormous head energetically, as if to say that she agreed exactly with her husband, the poor boy's face grew very red, and the squash pie lost its flavor.

"Although Mr. Tyler may not be exactly one of us, owing to the fact that he does not belong to the profession, but is only one of the adjuncts to it, so to speak," continued the skeleton, in a voice which was fast being raised to its highest pitch, "we feel proud, after his exploits at the time of the accident, to have him with us, and gladly welcome him now, through the medium of this little feast prepared by my Lilly."

Here the Albino Children nodded their heads in approval, the sword-swallower gave a little grunt of assent, and thus encouraged, the skeleton proceeded:

"I feel, when I say that we like and admire Mr. Tyler, all present will agree with me, and all would like to hear him say a word for himself."

The skeleton seemed to have expressed the views of all present remarkably well, judging from their expressions of pleasure and assent, and all waited for the honored guest to speak.

Toby knew that he must say something, but he couldn't think of a single thing; he tried over and over again to call to his mind something which he had read as to how people acted and what they said when they were expected to speak at a dinner table, but his thoughts refused to go back for him, and the silence was actually becoming painful. Finally, and by the greatest effort, he managed to say, with a very perceptible stammer, and while his face was growing very red:

"I know I ought to say something to pay for this big dinner that you said was gotten up for me, but I don't know what to say, unless to thank you for it. You see I hain't big enough to say much, as Uncle Dan'l says, I don't amount to very much 'cept for eatin', an' I guess he's right. You're all real good to me, an' when I get to be a man, I'll try to do as much for you."

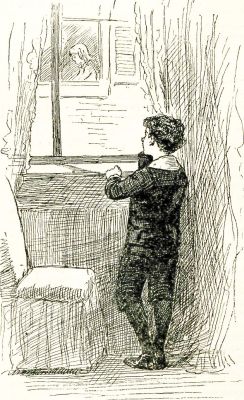

TOBY SITS DOWN ON MR. STUBBS.

TOBY SITS DOWN ON MR. STUBBS.

Toby had arisen to his feet when he began to make his speech, and while he was speaking, Mr. Stubbs had crawled over into his chair. When he finished, he sat down again without looking behind him, and of course sat plump on the monkey. There was a loud outcry from Mr. Stubbs, a little frightened noise from Toby, an instant's scrambling, and then boy, monkey, and chair tumbled off the platform, landing on the ground in an indescribable mass, from which the monkey extricated himself more quickly than Toby could, and again took refuge on the top of the tent pole.

Of course all the guests ran to Toby's assistance; and while the fat woman poked him all over to see that none of his bones were broken, the skeleton brushed the dirt from his clothes.

All this time the monkey screamed, yelled, and danced around on the tent pole and ropes as if his feelings had received a shock from which he could never recover.

"I didn't mean to end it up that way, but it was Mr. Stubbs's fault," said Toby, as soon as quiet had been restored, and the guests, with the exception of the monkey, were seated at the table once more.

"Of course you didn't," said Mrs. Treat, in a kindly tone; "but don't you feel bad about it one bit, for you ought to thank your lucky stars that you didn't break any of your bones."

"I s'pose I had," said Toby, soberly, as he looked back at the scene of his disaster, and then up at the chattering monkey that had caused all the trouble.

Shortly after this, Mr. Stubbs having again been coaxed down from his lofty position, Toby took his departure, promising to call as often during the week as he could get away from his exacting employers.

Just outside the tent he met old Ben, who said, as he showed signs of indulging in another of his internal laughing spells,

"Hello! has the skeleton an' his lily of a wife been givin' a blow-out to you too?"

"They invited me in there to dinner," said Toby, modestly.

"Of course they did, of course they did," replied Ben, with a chuckle; "they carries a cookin'-stove along with 'em, so's they can give these little spreads whenever we stay over a day in a place. Oh, I've been there!"

"And did they ask you to make a speech?"

"Of course. Did they try it on you?"

"Yes," said Toby, mournfully, "an' I tumbled off the platform when I got through."

"I didn't do exactly that," replied Ben, thoughtfully; "but I s'pose you got too much steam on, seein' 's how it was likely your first speech. Now you'd better go into the tent an' try to get a little sleep, 'cause we've got a long ride to-night over a rough road, an' you won't get more'n a cat-nap all night."

"But where are you going?" asked Toby, as he shifted Mr. Stubbs over to his other shoulder, preparatory to following his friend's advice.

"I'm goin' to church," said Ben, and then Toby noticed for the first time that the old driver had made some attempt at dressing up. "I've been with the circus, man an' boy, for nigh to forty years, an' I allus go to meetin' once on Sunday. It's somethin' I promised my old mother I would do, an' I hain't broke my promise yet."

"Why don't you take me with you?" asked Toby, wistfully, as he thought of the little church on the hill at home, and wished—oh, so earnestly!—that he was there then, even at the risk of being thumped on the head with Uncle Daniel's book.

"If I'd seen you this mornin', I would," said Ben; "but now you must try to bottle up some sleep agin to-night, an' next Sunday I'll take you."

With these words old Ben started off, and Toby proceeded to carry out his wishes, although he rather doubted the possibility of "bottling up" any sleep that afternoon.

He lay down on the top of the wagon, after having put Mr. Stubbs inside with the others of his tribe, and in a very few moments the boy was sound asleep, dreaming of a dinner party at which Mr. Stubbs made a speech, and he scampered up and down the tent pole.

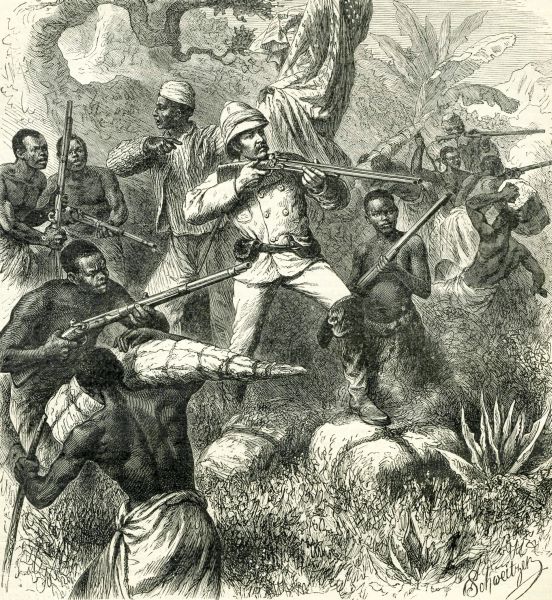

The great journey of Mr. Henry M. Stanley, in which he crossed the continent of Africa, was both the longest and the most important journey that any African traveller has made. Both Dr. Livingstone and Commander Cameron had already crossed Africa, but they crossed it by a more southerly and much shorter path than that taken by the American traveller. They suffered a great deal from fever and weariness and the terrible heat; but Mr. Stanley, in addition to these miseries, was compelled to fight his way through tribe after tribe of blood-thirsty cannibals, and to follow the course of a dangerous river, full of rapids, in a frail boat. It is almost a miracle that he ever lived to reach the civilized world; and had he not been as prudent and skillful as he was brave and persevering, he never would have finished his journey.

Mr. Stanley started from Zanzibar—a town on the east coast of Africa—in November, 1874, with three young Englishmen and three hundred and fifty-three native Africans. Only a few of these were armed with rifles, for most of them were porters. In Africa, calico and beads are used for money, and as a traveller must have plenty of these with him, he has to employ a great many porters. You will ask why he does not have horses or oxen to carry his goods. The reason is that there is an insect in Africa, called the tsetse, the bite of which kills all animals of burden, so that travellers have to hire natives to carry all their property on their heads.

Stanley marched first to Lake Victoria—a lake discovered by Captain Speke in 1858, and which is one of the sources of the Nile. After sailing all around this lake in a boat which was made for him in England, and was built so that it could be taken apart and carried by the porters, he went to another great lake, discovered by Captain Burton in 1856, and called Lake Tanganyika. This he also circumnavigated in his boat, and discovered that it had no outlet. West of Lake Tanganyika Dr. Livingstone had discovered a great river, which he thought might be the Congo. Commander Cameron had also seen this river, and both of them wanted to descend it to its mouth, but they thought it would be impossible to make their way through the fierce savages who live on its banks.

When Stanley reached this great river, two of the young Englishmen that had started with him, Fred Barton and Edward Pocock, had already died of the deadly African fever, and so many of his other men had died, or deserted, or been killed, that he had only one white man, Frank Pocock, and one hundred and forty-nine natives—some of whom were women—who were willing to join him in a voyage down the river. He bought a number of canoes, and with these and his English boat, the Lady Alice, began his voyage. He had to fight almost constant battles with the natives, and the great river, with its swift current, that swept many of his canoes over the rapids, was almost as dangerous as the savages. In one of these rapids poor Frank Pocock was drowned, and when, after suffering the most terrible hardships, Stanley reached the Portuguese settlement near the mouth of the Congo, he had only one hundred and fifteen followers left, and these, like himself, were nearly dead from starvation, disease, and hardship.

One day Mr. Stanley was sailing on Lake Victoria in the Lady Alice with eleven natives, and being out of provisions, and very hungry, they rowed toward the shore, intending to land and buy food. About two hundred savages, armed with spears and bows and arrows, gathered to meet them. Stanley's men called to them, and told them they were friends, and wanted to buy food. The savages seemed to be peaceful, but as soon as the boat touched the shore, they seized it, and dragged it twenty yards up the beach, with Mr. Stanley sitting in it.

Then they swarmed around him, yelling and flourishing their clubs and spears. Many of them took aim at Stanley with their arrows; but he told his men to speak gently to them, and to convince them that they were friends. They demanded calico and beads, and Stanley gave them all they asked. Then they seized the boat's oars, and carried them off; but still the traveller made no resistance. The crowd constantly increased, until there were at least three hundred of the savages, all armed and painted for battle. They abused Stanley and his men, telling them they were cowards, and that they were going to kill them, and twenty times Mr. Stanley thought his last moment had come. Finally he told one of his men to go a little distance away from the boat, and to engage the attention of the savages, while the rest of them should take hold of the boat on each side, and at the word of command try to launch it. They did so; but the savages saw the boat moving, and rushed to the water's edge just as she glided into the lake. The man who had tried to attract the attention of the wretches while the boat was launched sprang into the water after her, and a savage was just on the point of spearing him, when Stanley fired, and saved his follower's life by shooting the spear-man. The men now climbed into the boat, and tearing up the bottom boards, tried to paddle with them away from the shore, while Stanley threatened the savages with his gun, and for a few moments kept them at a distance. They soon plucked up courage, however, and springing into their canoes, paddled after the Lady Alice. There was no escape except by driving the enemy back, and Mr. Stanley, with four shots from his elephant rifle, loaded with explosive balls, sunk two of the canoes, and killed five men, after which the others retreated, and the Lady Alice, after paddling all night, and driving before a heavy gale all the next day and all the next night, in imminent peril of sinking, brought her exhausted crew to an uninhabited island, seventy-six hours after the fight. Instead of showing a hard-hearted readiness to fire on the poor Africans,[Pg 248] in this, as in all his other fights, Stanley showed the most wonderful self-control, and only used his rifle when he had to choose between being killed, together with his men, and firing on his brutal foes.

STANLEY ATTACKED BY THE NATIVES.

STANLEY ATTACKED BY THE NATIVES.

The greater part of Stanley's battles were fought while descending the Congo. Sometimes the natives came out in canoes and attacked him on the river, and sometimes they attacked him while he was camping on the shore. Once fifty-four canoes, carrying at least two thousand men, were successfully beaten off in a sharp battle. At night the camp had to be protected by a stockade made of brush-wood; and often the tired explorer, after paddling all day, had to watch all night to repel the constant attacks of the enemy. Sometimes, when they were dragging the canoes through the forest around the rapids, the woods would suddenly be alive with cannibals who had been lying in ambush. Armed with clubs and spears and poisoned arrows, they would rush on Stanley and his handful of men, shouting that they would eat the strangers for dinner. But whether there were a hundred or a thousand of them, Stanley always managed to drive them back. It was his cool courage, quite as much as the rifles of his men, which gave him the victory. Had he not been a man born to command, he could never have inspired his men with courage to face such swarms of savages; and had he not been as brave a man as ever lived, he could never have fought hand to hand with a score of hungry cannibals all at once, and driven them back in terror of the dauntless white man.

Mr. Stanley has furnished a splendid example of what patience, perseverance, and courage can accomplish in the face of the most formidable obstacles, and he will always be celebrated as one of the greatest explorers the world has ever known.

"PERSEVERANCE."

"PERSEVERANCE."

"When will you be ready to go down street for our valentines, Lilla?" asked Margie Goold, as she stood listlessly at the window watching the passers-by. "You said you'd go half an hour ago, and I've been waiting ever since."

But Lilla was deep in her arithmetic, and apparently unconscious that Margie had asked any question, until suddenly she jumped up, and throwing some papers well covered with figures into the grate, exclaimed,

"I would have been ready long ago had it not been for that horrid D."

"Why, Lilla Goold, you ought to be ashamed to call D. horrid," cried little Fay, indignantly, from her seat on the rug, where she was giving Fido a lesson in making believe dead.

"Yes, indeed, you ought," seconded Margie. "Mamma was saying just a day or two ago that we must respect D., and remember what a faithful nurse she was to all of us. And you, of all others, to call her names, when she sat up night after night with you when you were so ill! And anyway she has only come to bring the clothes home, and will probably go right away again, as she always does."

Lilla interrupted Margie's praise of their old nurse by throwing herself on the sofa and laughing immoderately.

Margie looked indignant, Fay puzzled, while Fido came quickly to life and barked vociferously.

"There! even Fido resents having D. so talked about," cried Margie, triumphantly.

"I never meant Dinah at all," laughingly protested Lilla. "She is a dear old soul. I mean the D in my example, who is digging a ditch with A, B, and C, and I'm to find out how long it takes them, and then how much faster D works than A. I get along finely until D appears, and then I don't know how to go on."

"Oh," said Margie, in a relieved tone; "but wasn't it strange that just as you said something about D, old nurse D. came across the street with the washing, and of course I thought you meant her. Here she comes out again, and the poor thing can hardly stand, it is so slippery. Mamma"—as Mrs. Goold entered the room—"why does D. bring the clothes still? I should think Rosa would offer to come with them, instead of sending her old aunt out. Why, just see! she can scarcely stand."

"Rosa does not send her, dearie," said Mrs. Goold, joining her little girls at the window, "for she told me she thought it dangerous for Dinah to be out in the winter so unprepared as she is, but that Dinah persists in coming, no matter what the weather, that she may inquire herself about 'de chillen.'"

"Good old D.," said Fay, using the name that Lilla—the first baby—had given Dinah, and both the others had adopted in their turn. "Why, mamma," continued the little one, straining her eyes to catch a glimpse of Dinah's departing figure, "how will she ever get home? There! good! Rosa has met her. I'm so glad!"

"D. needs a pair of that new kind of rubbers that we stopped to look at to-day in Mr. Brooks's store window," said Lilla, putting away her books, "and then she could get along finely."

"Let's get her a pair," exclaimed the wide-awake Margie, "when we go for our valentines. Will you give us the money, mamma? I think the price is a dollar."

"I'll give twenty-five cents toward it," answered Mrs. Goold, as she laid some money on the table, and left the room.

"Of course mamma means by that that we ought to give the rest. What do you say to getting the rubbers, instead of valentines for Lou and Jess?" suggested Margie.

"Then they won't send us any. They never do, you know, until they get ours."

"That's so; and Madge Hammond proposed to-day that[Pg 250] all the girls bring their valentines to school Monday, and we want to have as many as we possibly can, and here"—spreading them out upon the table as she spoke—"so far I've got only three."

Fay's brown eyes were opening wider and wider as she listened. "Papa gave me a lot of pennies to send a vantaline to Cousin Daisy, but I'd rather send a rubber vantaline to Dinah."

"You little darling!" cried Lilla, kissing her, "you're a lesson to us." Then, turning to Margie: "I guess if baby can give her money, we can. Let's go right down for the rubbers, and send them in valentine style, as Fay proposes. Yes, of course Fay shall go too," she added, noticing the large eyes turned questioningly to hers.

About an hour later they rushed into the sitting-room, exclaiming, "We've got them, and they're beauties—lined throughout, and come over the ankles."

"How did you know the size?" inquired Mrs. Goold, after she had duly admired them.

"The most fortunate thing in the world," answered Margie, "was our meeting Rosa just as we were going into the store, and after she had promised not to breathe a syllable to D., we told her the plan, took her into the store with us, and she selected the rubbers."

And as Margie paused, Lilla went on: "Rosa says they're just the thing, and she's coming over to-night to tell us how D. likes them. Mr. Brooks waited on us himself at first, and looked crosser than a bear. He had his green glasses on, and stared at us so hard that I was glad when a gentleman came in to see him, and one of the clerks took his place."

"And the clerk," put in Margie, "kept telling us that the rubbers were the latest thing in the market, and I laughed right out at the thought of D.'s knowing or caring whether they were in style."

"Then," resumed Lilla, "as we were leaving the store, Mr. Brooks stepped forward, and said, in the sternest tone, to Rosa—you know she used to work at his house—'I wish you would wait a few moments, Rosa; I desire to speak to you;' so we left her there."

It was a picture not soon to be forgotten that met Mr. Goold's gaze as he came upon the little group in the cozy sitting-room, lighted only by the bright coals in the grate.

"Still talking valentines?" he asked, kissing mamma, and lifting Fay from her arms to his own. Then sitting down, and putting her on his knee, he questioned, "Well, how about them?"

Lilla and Margie then began an account of buying Dinah's rubber shoes, and when they were brought for his inspection, to their great delight he dropped a piece of money in each.

"Now Rosa will have a s'prise too," cried Fay, clapping her hands.

Supper over, the sleigh came round, and soon the package was left at Dinah's door, and the children were home again.

"Now I must try that example once more," announced Lilla, as she bent over her book. Then, after a few moments' study, "Oh! I see—I have it!" she cried, triumphantly: "D works just twice as fast as A."

"D must have worn a pair of stylish rubbers," laughed Margie. "Probably A couldn't stand as firmly in the ditch."

While they were laughing at Margie's explanation, Jane came to the door with some valentines, which excited the usual amount of wonderment.

"I had no idea we'd get so many," said Lilla, in a satisfied, tone; "I don't believe Madge can be ahead of us."

Another knock, and Rosa presented herself with a "Can I come in?" which showed all her beautiful teeth. The children made a rush for the young colored girl, and overwhelmed her with questions.

"Oh, chillen, she was so pleased, and so berry thankful! She wanted to come right over and show dem to you all, but I 'suaded her to wait till mornin'." And then Rosa went on to say what a perfect fit the rubbers were, and how Dinah was singing around, as happy as could be, and in a hurry for morning, that she might wear them.

"Does she s'pect who sent 'em?" asked Fay.

"I's 'fraid she does, honey, 'cause when she went to try dem on, some money fell out, an' I said: 'Dem careless chillen! I's feared Miss Goold's bringin' dem up to tink money grows on bushes'; an' Aunt Dinah said, 'Did dey gib 'em?' so I jest said, 'I'll take de money dar fust, anyway, an' see,'" and Rosa held up two silver pieces, saying, "Who lost, I's found?"

"Why, Rosa, it's your s'prise," explained Fay—"your vantaline," at which Rosa's astonishment and delight knew no bounds.

"Altogether it's been the nicest Valentine's Day we've ever had," Lilla and Margie agreed, as they were getting ready for bed, and Fay said, drowsily, from her crib, "I shouldn't think you'd care, now, if Madge Hammond"—and then the words came slower and slower, "should bring—twenty—rubbers—in—a—ditch."

Jane came into the nursery next morning, saying, "There is a valentine at each of your plates this morning;" but not another word would she say about them.

You may be sure no one was late to breakfast that morning, and I wish you could have seen how three expectant faces lit up as each spied a tiny basket of flowers at her plate.

"When did they come?" "Who could have sent them?" "Will they keep fresh till Monday?"

"Wait a minute," said papa, feeling for his pencil. "I must write down all these questions. Now I'm ready for number four."

"Don't tease us, papa," pleaded Margie. "Just answer what we've asked already."

"Agreed: firstly, they came last night, and mamma thought it best not to wake you; secondly, Mr. Brooks sent them."

"Mr. Brooks!" all in chorus.

"Yes, he's a kind of bear, I heard yesterday," said papa.

Lilla looked ashamed.

"Thirdly, they will keep till Monday, if good care is taken."

"Then we can carry them to school," joyfully exclaimed Lilla.

"And what do you think of Mr. Brooks now?" asked mamma.

"Why, I don't know what to think, I'm so surprised. Are you certain they're from him?"

"I judge so, from what Rosa told me last night. Mr. Brooks asked her who you were, and when she told him you were going to send the rubbers as a valentine to Dinah, he said, 'I believe I'll write down their names: "One good turn deserves another."' And more than that, Rosa says he is one of the kindest men she ever knew, and far from being as cross as he looks."

"I think," said Lilla, "I shall remember after this lesson to 'judge not by appearances.'"

"I guess I'll keep account of all the proverbs about Mr. Brooks," said Margie, and reaching mischievously for papa's pencil, she wrote:

"Before you say 'tis chill December,

Know all the signs of mild September."

Said Blackbird to Miss Yellow-Bird:

"How bright the sun does shine!

And you look sweet. Oh, pray consent

To be my Valentine!"

"I really can't," said Yellow-Bird;

"I don't to you incline;

I am too blonde—indeed, I am—

To be your Valentine."

Phil was alone, as indeed he was always, except on Sundays, or the few half-holidays that came to Lisa. Once in a while Lisa begged off, or paid another woman for doing an extra share of work in her place, if Phil was really too ill for her to leave him. The hot sun was pouring into the garret room, though a green paper shade made it less blinding, and Phil was lying back in a rocking-chair, wrapped in a shawl. On a small table beside him were some loose pictures from a newspaper, a pencil or two, and an old sketch-book, a pitcher of water, and an empty plate.

The boy opened his closed eyes as Joe came in, after knocking, and looked surprised.

"Why, Joe, what is the matter?" he asked. "You do not come twice a day very often."

"No," said Joe, "nor are you always a-sufferin' as you was this mornin'. I've come to know how you are, and to bring you that," said he, triumphantly putting the nosegay before the child's eyes.

The boy nearly snatched the flowers out of Joe's hand in his eagerness to get them, and putting them to his face, he kissed them in his delight.

"Oh, Joe dear, I am so much obliged! Oh, you darling, lovely flowers, how sweet you are! how delicious you smell! I never saw anything more beautiful. Where did they come from, Joe?"

"Ah, you can't guess, I reckon."

"No, of course not; they are so sweet, so perfect, they take all my pain away; and I have been nearly smothered with the heat to-day. Just see how cool they look, as if they had just been picked."

"It's a pity the one who sent 'em can't hear ye. Shall I bring her in?"

"Who, Joe—who do you mean?"

"Joe means me," said a soft voice; "I sent them to you, and I am Miss Rachel Schuyler, an old friend of Joe's. I want to know you, Phil, and see if I can not do something for that pain I hear you suffer so much with. Shall I put the flowers in water, so that they will last a little longer? Ah, no, you want to hold them, and breathe their sweet fragrance."

Miss Schuyler had opened the door so gently, and appeared so entirely at home, that Phil took her visit quite as a matter of course, and though astonished, was not at all flurried. He fastened his searching gaze upon her, over the flowers, which he held close to his lips, and made up his mind what to say. At last, after deliberating, he said, simply, "I thank you very much." His thoughts ran this way: "She is a real lady, a kind, lovely woman; she has on a nice dress—nicer than Lisa's; she has little hands, and what a soft, pleasant voice! I wonder if my mother looked like her?"

Miss Schuyler's thoughts were very pitiful. She was much moved by the pale little face and brilliant eyes, the pleased, shy expression, the air of refinement, and the very evident pain and poverty. She could not say much, and to hide her agitation, took up the sketch-book, saying, "May I look in this, please?"

Phil nodded, still over the flowers.

As the leaves were opened, one after the other, Miss Schuyler became still more interested. The sketches were simply rude copies of newspaper pictures, but there was no doubt of the taste and talent that had directed their pencilling.

"Have you ever had any teaching, Phil?" she asked.

"No, ma'am," answered Joe for Phil, thinking he might be bashful. "He hasn't had no larnin' nor teachin' of anythin'; but it is what he wants, poor chile, and he often asks me things I can't answer for want of not knowin' nuthin' myself."

"And what is this?" said Miss Schuyler, touching the box with violin strings across it, which was on a chair beside her.

"Please don't touch it," answered Phil, anxiously; then fearing he had been rude, added: "It is my harp, and I am so afraid, if it is handled, that the fairies will never dance on it again. You ought to hear what lovely music comes out of it when the wind blows."

Phil spoke as if fairies were his particular friends. Miss Schuyler looked at him pitifully, thinking him a little light-headed. Joe nodded, and looked wise, as much as to say, "I told you so."

Just then Phil's pain came on again, and it was as much as he could do not to scream; but Miss Rachel saw the pallor of his face, and turning to Joe, asked:

"Does he have a doctor? Is anything done for him?"

"Nuthin', Miss Rachel, that I knows of. I never knew of his havin' a doctor."

PHIL AND MISS SCHUYLER.

PHIL AND MISS SCHUYLER.

"Poor child!" said Miss Rachel, smoothing his forehead, and fanning him. Then she tucked a pillow behind him, and did all so gently that Phil took her hand and kissed it—it eased his pain so to have just these little things done for him. Then she poured a little of her cordial in a glass with some water, and he thought he had never tasted anything so refreshing. She sent Joe after some ice, and spreading her napkins out on Phil's table, set all her little store of dainties before him, tempting the child to eat in spite of his pain.

Phil thought it was all the fairies' doing and not Joe's—poor pleased Joe—who looked on with a radiant face of delight. Phil would not eat unless Joe took one of his cakes, so the old fellow munched one to please him.

Meanwhile Miss Schuyler gazed at the boy with more and more interest; a something she could hardly define attracted her. At first it had been his suffering and poverty, for her heart was tender, and she was always doing kind deeds; but now as she looked at him she saw in his face a likeness to some one she had loved, the look of an old and familiar friend, a look also of thought and ability which only needed fostering to make of Phil a person of great use in the world—one who might be a leader rather than a follower in the path of industry and usefulness. The grateful little kiss on her hand had gone deeply into her heart. Phil must no longer be left alone: he must have good food and medical care and fresh air, and Lisa must be consulted as to how these things should be gained. So while Phil nibbled at the good things, and Joe chuckled and talked, half to himself and half to Phil, Miss Schuyler wrote a note to Lisa, asking her to come and see her that evening, if convenient, explaining how her interest had been aroused in Phil, and that she wanted to know more about him, and wanted to help him, and was sure she could make his life more comfortable, and that Lisa must take her interference kindly, for it was offered in a loving spirit. Then she folded the note, and gave it to Phil for Lisa, and arranging all his little comforts about him, bade him good-by.

Phil thought her face like that of an angel's when she stooped to kiss him; and after Joe, too, had hobbled off, promising to come again soon with his violin, he took up his pencil, and tried to sketch Miss Schuyler. Face after face was drawn, but none to his taste: first the nose was crooked, then the eyes were too small, then the mouth would be twisted, and just as Lisa came in, with a tired and flushed face, he threw his pencil away, and began to sob.

"Why, my dear Phil," said Lisa, in surprise, "are you so very miserable to-night?"

"No, I am not miserable at all," said Phil, between his tears; "that is, I have had pain enough, but I have had such a lovely visitor!—Joe brought her—and I wanted to make a little picture of her, so that you could see what she looked like; and I can not. Oh dear! I wish I could ever do anything!"

"Ah, you are tired; drink this nice milk, and you will be better."

"I have had delicious things to eat, and I saved some for you, Lisa. Look;" and he showed her the little parcel of cakes Miss Schuyler had left. "And see the big piece of ice in my glass."

"Some one has been kind to my boy."

"Yes; and here is a note for you; and you must dress up, Lisa, when you go to see our new friend."

Lisa looked down at her shabby garments; they were all she had, but she did not tell Phil that her only black silk had been sold long ago. She read the note, and her face brightened. There seemed a chance of better things for Phil.

"I will go to-night, if you can spare me."

"Not till you have rested, Lisa; and you must drink all that milk your own self. Did you ever hear of Miss Schuyler?"

"I don't know," said Lisa, meditating; "the name is not strange to me. But there used to be so many visitors at your father's house, Phil dear, that I can not be sure."

"She is so nice and tender and kind— Have you had a tiresome day, Lisa?" added Phil, quickly, fearing Lisa might think herself neglected in his eager praise of the new friend.

"Yes, rather; but I can go. So Joe brought her here?"

"Yes; and see these flowers—yes, you must have some. Put them in your belt, Lisa."

"Oh, flowers don't suit my old clothes, child; keep them yourself, dear. Well, it is a long lane that has no turning," she said, half to herself and half to Phil. "Perhaps God has sent us Miss Schuyler to do for you what I have not been able to; but I have tried—he knows I have."

"And I know it too, dear Lisa," said Phil, pulling her down to him, and throwing both arms around her. "No one could be kinder, Lisa; and I love this old garret room, just because it is your home and mine. Now get me my harp, and when you have put it in the window, you can go; and I will try not to have any pain, so that you won't have to rub me to-night."

"Dear child!" was all Lisa could say, as she did what he asked her to do, and then left him alone.

I haven't any monkey now, and I don't care what becomes of me. His loss was an awful blow, and I never expect to recover from it. I am a crushed boy, and when the grown folks find what their conduct has done to me, they will wish they had done differently.

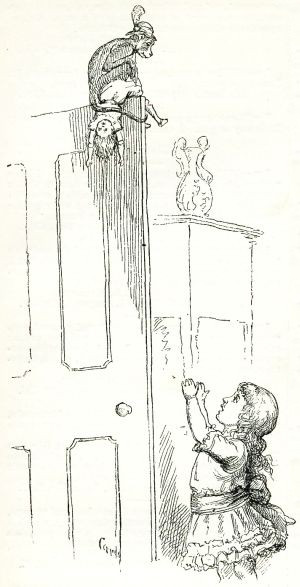

It was on a Tuesday that I got the monkey, and by Thursday everybody began to treat him coldly. It began with my littlest sister. Jocko took her doll away, and climbed up to the top of the door with it, where he sat and pulled it to pieces, and tried its clothes on, only they wouldn't fit him, while sister, who is nothing but a little girl, stood and howled as if she was being killed. This made mother begin to dislike the monkey, and she said that if his conduct was such, he couldn't stay in her house. I call this unkind, for the monkey was invited into the house, and I've been told we must bear with visitors.

A little while afterward, while mother was talking to Susan on the front piazza, she heard the sewing-machine up stairs, and said, "Well I never that cook has the impudence to be sewing on my machine without ever asking leave." So she ran up stairs, and found that Jocko was working the machine like mad. He'd taken Sue's nightgown and father's black coat and a lot of stockings, and shoved them all under the needle, and was sewing them all together. Mother boxed his ears, and then she and Sue sat down and worked all the morning trying to unsew the things with the scissors.

They had to give it up after a while, and the things are sewed together yet, like a man and wife, which no man can put asunder. All this made my mother more cool toward the monkey than ever, and I heard her call him a nasty little beast.

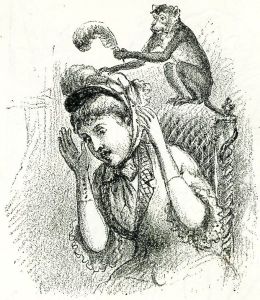

The next day was Sunday, and as Sue was sitting in the hall waiting for mother to go to church with her, Jocko gets up on her chair, and pulls the feathers out of her bonnet. He thought he was doing right, for he had seen the cook pulling the feathers off of the chickens, but Sue called him dreadful names, and said that when father came home, either she or that monkey would leave the house.

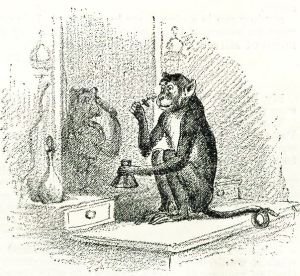

Father came home early Monday, and seemed quite pleased with the monkey. He said it was an interesting study, and he told Susan that he hoped that she would be contented with fewer beaux, now that there was a monkey constantly in the house. In a little while father caught Jocko lathering himself with the mucilage brush, and with a kitchen knife all ready to shave himself. He just laughed at the monkey, and told me to take good care of him, and not let him hurt himself. Of course I was dreadfully pleased to find that father liked Jocko, and I knew it was because he was a man, and had more sense than girls. But I was only deceiving myself and leaning on a broken weed. That very evening when father went into his study after supper he found Jocko on his desk. He had torn all his papers to pieces, except a splendid new map, and that he was covering with ink, and making believe that he was writing a President's Message about the Panama Canal. Father was just raging. He took Jocko by the scruff of the neck, locked him in the closet, and sent him away by express the next morning to a man in the city, with orders to sell him.

The express-man afterward told Mr. Travers that the monkey pretty nearly killed everybody on the train, for he got hold of the signal cord and pulled it, and the engineer thought it was the conductor, and stopped the train, and another train just behind it came within an inch of running into it and smashing it to pieces. Jocko did the same thing three times before they found out what was the matter, and tied him up so that he couldn't reach the cord. Oh, he was just beautiful! But I shall never see him again, and Mr. Travers says that it's all right, and that I'm monkey enough for one house. That's because Sue has been saying things against the monkey to him; but never mind.

First my dog went, and now my monkey has gone. It seems as if everything that is beautiful must disappear. Very likely I shall go next, and when I am gone, let them find the dog and the monkey, and bury us together.

Roma, on the Rio Grande, Texas,

December 31, 1880.

Early this morning, just as we were all dressed, a great noise was heard on the stairs; it was Morton, who was shouting, "Oh, papa, the ground is all over white, and the orange-tree has a great white cap on its head!"

We all knew at once that it was snow, which we children had heard and read so much about, but had never seen.

We all rushed out, and found the air full of little feathers, and everything dazzling white. We went wild over it. Papa chased our two little brothers, washed their faces with snow, and showed them how to make snow-balls, and after doing so, got pelted by his boys, and girls too, for that matter, for we all took part. Two inches of snow had fallen. The air was still and calm. And at last we thought of the snow crystals we had read about in Harper's Young People, and asked papa to show them to us. He got a piece of black cloth, and we spread it on the top of a box in the yard, and recognized nearly all of the forms we had seen in the illustration. Little Northern readers will say, "Why such a fuss about two inches of snow?" But they must remember we had never seen it before, and I do not believe they ever saw an orange-tree loaded with snow, and its golden fruit shining out from a setting of frosted silver and deep green leaves. I know they never saw anything so beautiful in their lives.

But I forgot—I must tell you who I am, or rather who we are. We are seven sisters and brothers. Our two elder sisters are married, and have homes of their own. I am the youngest of the girls, and the two boys are the youngest of the family. My mother is a Mexican lady, and father is an American from Ohio. He has lived in this country thirty years. One sister, one brother, and myself were born in Mexico, and Spanish is our mother-tongue, but we read and understand Young People.

Clotilde C.

Thyatira, Mississippi.

I have six goats. Two of them I work in a little wagon. When I can get some little boys to help me, it is royal fun to drive them.

I do not go to school, as we have none near by, and I have no one to go with me. I had three sweet little sisters and one little brother, but they all died. I would love to tell you a great deal about them, but this is my first letter to the Post-office Box, and I am afraid it will be too long, and go into that much-dreaded waste basket. I will be nine years old the 17th of February.

It is awfully cold here this winter.

Jack C.

Hoboken, New Jersey.

I thought I would write to say how much I like the stories of "Toby Tyler" and "Mildred's Bargain." They are so nice I can not help writing to tell you.

I am glad to hear from so many little girls who have seen blossoms and fruit as late in the season as I have.

Reba H.

Sheboygan, Wisconsin.

I want to tell the boys and girls what we do away out here in Sheboygan. This winter has been very cold, and it has been thirty degrees below zero part of the time. A good deal of snow has fallen, and yesterday the pupils of my school took a sleigh-ride. We were in a large sleigh drawn by four horses. We went to Sheboygan Falls, and on the way we saw farm-houses, forests, and fields all covered with deep snow.

Sheboygan is a nice place in summer. It is on the western shore of Lake Michigan, about sixty miles north of Milwaukee. I am eleven years old.

Erwin B.

Bridgewater, New York.

My brother takes Young People, and we like it ever so much.

We have the dearest little three-year-old colt. Papa broke him to the harness last fall, and he seems to enjoy taking us out to ride. Papa is going to have him trained to the saddle for my use.

I have to walk three-quarters of a mile to school. The snow has drifted nearly level with the fences, and now the crust has formed, so that we enjoy skimming over it.

May R.

Washington, D. C.

I think Young People is just splendid, and only wish it would come every day. I could never get tired of reading it. Toby Tyler's life with the circus is delightful. I would like to have such a friend as "Mr. Stubbs."

We are having the coldest winter known in this city for years. My little sister, my brother, and myself have elegant times coasting down the streets.

Emma H. T.

Gilroy, California.

I have received so many answers to my request for exchange, which was printed in Young People, that my stock of duplicate eggs is exhausted. I will keep the addresses, and in the spring, when I can get a new supply of eggs, will try to answer all letters which I can not answer now.

Fannie W. Rogers.

Owing to the severe weather, I have been unable to collect enough arrow-heads to supply all my correspondents, but I will send them as soon as possible. If those who have offered me coins and other things in exchange will wait until I can get some more arrow-heads, which will be before long, I will be very glad.

Isobel L. Jacobs,

Darlington Heights, Prince Edward County, Va.

I am very much interested in the Post-office Box. I like Young People very much.

I live beside the beautiful Geneva Lake, which is a great summer resort. In warm weather we have great sport fishing, but now it is all ice-boating and skating.

We raised five Bramah chickens last summer. They were very tame. One went to sleep with its head on my aunt's shoulder, and they were capital pickpockets. They were in such demand that we had to part with all but one. She is named Pulleta, and is so tame I can pick her up anywhere.

I would like to exchange postmarks, for foreign stamps, or shells from the Gulf of Mexico or Atlantic coast.

Hubert C. Scofield,

P. O. Box 207, Geneva, Wis.

I would like to exchange pieces of bass-wood, red and white oak, bird's-eye and hard and soft maple, iron-wood, red and yellow birch, elm, ash, and butternut, for specimens of other kinds of woods. Correspondents will please mark specimens.

George Empey,

Hersey, St. Croix County, Wis.

I would like to exchange postmarks, for sea-shells. I am nine years old.

Reynolds White,

132 East Forty-fifth Street, New York City.

I will exchange postmarks, for stamps, with any little boy or girl. I am nine years old.

Percy G. Lapey,

62 Clinton Street, Buffalo, N. Y.

I would like to exchange postage stamps. I have a Swedish, a Canadian, and a New South Wales stamp, two Italian, some French, English, and old issues of United States stamps, which I will give for others.

A Subscriber to "Young People,"

141 Fifth Avenue, New York City.

I wish to notify correspondents that I do not wish to exchange for postage stamps any longer, but I will exchange stamps, curiosities, shells, and minerals, for curiosities, shells, and minerals.

V. L. Kellogg,

P. O. Box 411, Emporia, Kansas.

I would like to exchange shells and pressed sea-weeds, for other shells, Lake Superior agates, ore, or other small specimens of minerals. I would like everything sent me to be clearly marked, and I, in return, will name and classify the shells.

Miss May Hart,

Soquel, Santa Cruz County, Cal.

I live only eighteen miles from King's Mountain, where a great battle of the Revolutionary war was fought.

I have a little rat terrier I have named Rip Van Winkle, because he sleeps so much. I would like to exchange birds' eggs with readers of Harper's Young People. I am twelve years old.

Willie F. Robertson, Yorkville, S. C.

I have a collection of about fifteen hundred stamps, and I have about five hundred duplicates, which I would like to exchange for others. Correspondents will please send a list of those they desire.

Hiram H. Bice,

39 Second Street, Utica, N. Y.

The following exchanges are also offered by correspondents:

Coins or specimens of woods, for Indian relics, curiosities, fossils, or minerals.

Alfred S. Kellogg,

P. O. Box 103, Westport, Fairfield County, Conn.

Postage stamps.

J. Clarke Burrell,

307 East Eighty-sixth Street, New York City.

Postage stamps, for Indian relics, or anything suitable for a museum.

George Lunham,

147 Skillman Street, Brooklyn, L. I.

Foreign postage stamps.

Lionel W. Crompton,

Care of Mr. Clifton, 104 Sixth St., Hoboken, N. J.

Foreign postage stamps, for old issues of United States postage stamps, or for any Department stamps.

Frank Bang,

271 Avenue B, New York City.

Postmarks, for stamps.

Jay Hollis Gibson,

Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, N. Y.

A silver Japanese coin and a piece of prehistoric pottery, for a genuine Indian bow and arrow.

David M. Gregg,

404 Penn Street, Reading, Penn.

Ocean curiosities, for a guinea-hen's egg or other eggs; or twenty-five postmarks, for a Chinese stamp and nine other foreign stamps.

Helen S. Lovejoy,

39 Munjoy Street, Portland, Maine.

Cotton and rice as they grow, Spanish moss, arrow-heads, Southern insects, or pressed flowers, for stamps.

John J. Hawkins,

Prosperity, S. C.

An ancient Spanish coin to exchange for some curiosity.

Thomas Ewing,

Osceola, Clark County, Iowa.

Persian, Japanese, and other stamps, for Turkish or South American stamps or minerals.

Theodore Morrison,

3262 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Penn.

Teasels, which are pretty for bouquets and decorating, for coins, curiosities, or minerals.

J. E. Garbutt,

Garbutt, Monroe County, N. Y.

A stone from Delaware or Pennsylvania, for one from any other State; or shells, postmarks, or June beetles, for ore of any kind, or for curiosities.

S. Stinson,

1705 Oxford Street, Philadelphia, Penn.

Sea-shells or minerals, for minerals.

John D. Brown,

P. O. Box 171, Newton Centre, Mass.

Pressed sea-weeds from Santa Cruz, on Monterey Bay, for ferns or sea-weeds from other localities.

Nellie Hyde,

162 Third Street, Oakland, Cal.

Postmarks.

Henry F. Steele,

63 East Fifty-fifth Street, New York City.

Soil from Illinois, for that of any other State.

Arthur Davenport,

34 Ogden Avenue, Chicago, Ill.

An Italian stamp, for one of any other foreign country.

Giorgino Chapman,

Everett House, Union Square, New York City.

A ten-cent United States stamp, War Department stamps, or a Cuban, Spanish, or Netherlands stamp, for a Brazilian ten-reis.

Fred McGahie,

78 Second Place, Brooklyn, L. I.

Twenty-five postmarks, for a Japanese, Chinese, or East Indian stamp, or twelve other foreign stamps.

Annie Dryden,

Care of John Dryden, Brooklin, Ontario, Canada.

Buttons, or California postmarks, for postage stamps.

Floy Moody,

Care of Charles Moody,

San José, Santa Clara County, Cal.

Postmarks and postage stamps, for Indian relics and ocean curiosities.

Charles B. Bartlett,

92 Franklin Avenue, Brooklyn, N. Y.

Postage stamps, minerals, fossils, coins, ocean curiosities, and Indian relics.

S. G. Guerrier,

Emporia, Kansas.

Stamps from Peru, United States official stamps, and others, in exchange for rare stamps.

Allen R. Baker,

P. O. Box 1275, Bay City, Mich.

Copper ore from the Eli Copper Mines, New Hampshire, specimens of meteoric rock, and stone from the Hoosac Tunnel, for Indian relics, ocean curiosities, fossils, or minerals.

Fred W. Glasier,

P. O. Box 235, Adams, Berkshire County, Mass.

Ocean curiosities, for turtles not more than three inches long, newts, or lizards. Correspondents will please write before sending any of these creatures.

Daniel D. Lee, 14 Myrtle Street,

Jamaica Plains, Suffolk County, Mass.

Postmarks, for postmarks; or twice the number of postmarks, for any number of postage stamps.

Ralph D. Clearwater,

Care of A. T. Clearwater, Kingston, N. Y.