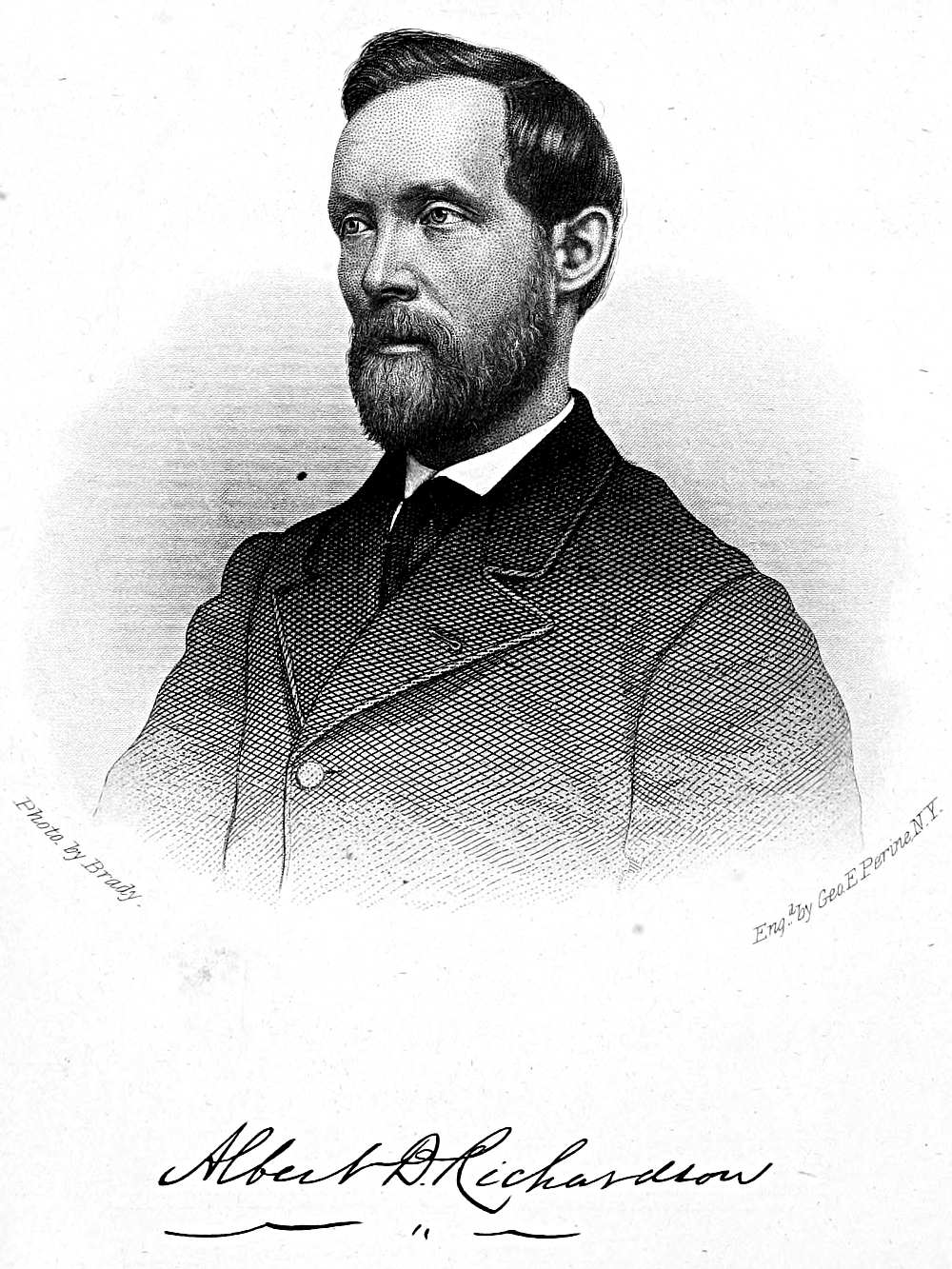

Photo by Brady.

Engd by Geo E Perine N.Y.

Albert D. Richardson

Title: The Secret Service, the Field, the Dungeon, and the Escape

Author: Albert D. Richardson

Release date: February 10, 2014 [eBook #44865]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Martin Mayer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

The transcribers' notes follow the text.

Othello.

BY

ALBERT D. RICHARDSON,

TRIBUNE CORRESPONDENT.

Hartford, Conn.,

AMERICAN PUBLISHING COMPANY.

JONES BROS. & CO., PHILADELPHIA, PA., AND CINCINNATI, OHIO.

R. C. TREAT, CHICAGO, ILL.

1865.

Entered according to an Act of Congress, in the year 1865,

Albert D. Richardson,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States

for the District

of Connecticut.

TO

Her Memory

WHO WAS NEAREST AND DEAREST,

WHOSE LIFE WAS FULL OF BEAUTY AND OF PROMISE,

THIS VOLUME

IS TENDERLY INSCRIBED.

17

Going South in the Secret Service.—Instructions from the Managing Editor.—A Visit to the Mammoth Cave of Kentucky.—Nashville, Tennessee.—Alabama Unionists.—How the State was Precipitated into the Rebellion.—Reaching Memphis.—Abolitionists Mobbed and Hanged.—Brutalities of Slavery.

31

In Memphis.—How the Secessionists Carried the Day.—Aims of the Leading Rebels.—On the Railroad.—A Northerner Warned.—An Amusing Dialogue.—Talk about Assassinating President Lincoln.—Arrival in New Orleans.—Hospitality from a Stranger.—An Ovation to General Twiggs.—Braxton Bragg.—The Rebels Anxious for War.—A Glance at the Louisiana Convention.

43

Association with Leading Secessionists.—Their Hatred of New England.—Admission to the Democratic Club.—Abuse of President Lincoln.—Sinking Buildings, Cellars and Walls Impossible.—Cemeteries above Ground.—Monument of a Pirate.—Canal Street.—The Great French Markets.—Dedication of a Secession Flag in the Catholic Church.—The Cotton Presses.—Visit to the Jackson Battle-ground.—The Creoles.—Jackson's Head-Quarters.—A Fire in the Rear.—A Life Saved by a Cigar.—A Black Republican Flag.—Vice-President Hamlin a Mulatto.—Northerners leaving the South.

57

How Letters were Written and Transmitted.—A System of Cipher.—A Philadelphian among the Rebels.—Probable fate of a Tribune Correspondent, if Discovered.—Southern Manufactures.—A Visit to a Southern Shoe Factory.—Where the Machinery and Workmen came from.—How Southern Shoes were Made.—Study of Southern Society.—Report of a Slave Auction.—Sale of a White Woman.—Girls on the Block.—Husbands and Wives Separated.—A most Revolting Spectacle.—The Delights of a Tropical Climate.

71

A Northerner among the Minute Men.—Louisiana Convention.—A Lively Discussion.—Boldness of the Union Members.—Another Exciting Discussion.—Secessionists Repudiate their Own Doctrines.—Despotic Rebel Theories.—The Northwest to Join the Rebels.—The Great Swamp.—A Trip through Louisiana.—The Tribune Correspondent Invited to a Seat in the Mississippi Convention.

81

The Mississippi State-House.—View of the Rebel Hall.—Its General Air of Dilapidation.—A Free-and-Easy Convention.—Southern Orators.—The Anglo-African Delegate.—A Speech Worth Preserving.—Familiar Conversation of Members.—New Orleans Again.—Reviewing Troops.—New Orleans Again.—Hatred of Southern Unionists.—Three Obnoxious Northerners.—The Attack on Sumter.—Rebel Bravado.

91

Abolition Tendencies of Kentuckians.—Fundamental Grievances of the Rebels.—Sudden Departure from New Orleans.—Mobile.—The War Spirit High.—An Awkward Encounter.—"Massa, Fort Sumter has gone Up."—Bells Ringing.—Cannon Booming.—Up the Alabama River.—A Dancing Little Darkey.—How to Escape Suspicion.—Southern Characteristics and Provincialism.—Visit to the Confederate Capital.—At Montgomery, Alabama.—Copperas Breeches vs. Black Breeches.—A Correspondent under Arrest.

105

A Journey Through Georgia.—Excitement of the People.—Washington to be Captured.—Apprehensions about Arming the Negroes.—A Fatal Question.—Charleston.—Looking at Fort Sumter.—A Short Stay in the City.—North Carolina.—The Country on Fire.—Submitting to Rebel Scrutiny.—The North Heard From.—Richmond, Virginia.—The Frenzy of the People.—Up the Potomac.—The Old Flag Once More.—An Hour with President Lincoln.—Washington in Panic.—A Regiment which Came Out to Fight.—Baltimore under Rebel Rule.—Pennsylvania.—The North fully Aroused.—Uprising of the whole People.—A Tribune Correspondent on Trial in Charleston.—He is Warned to Leave.—His Fortunate Escape

125

Sunday at Niagara Falls.—View from the Suspension Bridge.—The Palace of the Frost King.—Chicago, a City Rising from the Earth.—Mysteries of Western Currency.—A Horrible Spectacle in Arkansas.—Patriotism of the Northwest.—Missouri.—The Rebels bent on Revolution.—Nathaniel Lyon.—Camp Jackson.—Sterling Price Joins the Rebels.—His Quarrel with Frank Blair.—His Personal Character.—St. Louis in a Convulsion.—A Nashville Experience.—Bitterness of Old Neighbors.—Good Soldiers for Scaling Walls.—Wholesome Advice to Missouri Slaveholders

141

Cairo, Illinois.—A Visit from General McClellan.—A little Speech-making.—Penalty of Writing for The Tribune.—A Unionist Aided to Escape from Memphis by a Loyal Girl.—The Fascinations of Cairo.—The Death of Douglas.—A Clear-headed Contraband.—A Review of the Troops.—"Not a Fighting Nigger, but a Running Nigger."—Capture of a Rebel Flag

151

Missouri Again.—The Retributions of Time.—A Railroad Reminiscence.—Jefferson City.—A Fugitive Governor.—"Black Republicanism."—Belligerent Chaplain.—A Rebel Newspaper Converted by the Iowa Soldiers.—Two Camp Stories of the Marvelous

157

Chicago.—Corn, not Cotton, is King.—Curious Reminiscences of the City.—A Visit to the Grave of Douglas.—Patriotism of the Northwestern Germans.—Their Social Habits.—Cincinnati in the Early Days.—A City Founded by a Woman.—The Aspirations of the Cincinnatian.—Kentucky.—Treason and Loyalty in Louisville.—A Visit to George D. Prentice.—The first Union Troops of Kentucky.— Struggle in the Kentucky Legislature.—What the Rebel Leaders Want.—Rousseau's Visit to Washington.—His Interview with President Lincoln.—Timidity of the Kentucky Unionists.—Loyalty of Judge Lusk.

173

Western Virginia.—Campaigning in the Kanawha Valley.—A Bloodthirsty Female Rebel.—A Soldier Proves to be a Woman in Disguise.—Extravagant Joy of the Negroes.—How the Soldiers Foraged.—The Falls of the Kanawha.—A Tragedy of Slavery.—St. Louis.—The Future of the City.—A disgusted Rebel Editor.

181

The Battle of Wilson Creek.—Daring Exploit of a Kansas Officer.—Death of Lyon.—His Courage and Patriotism.—Arrival of General Fremont.—Union Families Driven Out.—An Involuntary Sojourn in Rebel Camps.—A Startling Confederate Atrocity.

189

Jefferson City, Missouri.—Fremont's Army.—Organization of the Bohemian Brigade.—An Amusing Inquiry.—Diversions of the Correspondents.—A Polite Army Chaplain.—Sights in Jefferson City.—"Fights mit Sigel."—Fremont's Head-Quarters.—Appearance of the General.—Mrs. Fremont.—Sigel, Hunter, Pope, Asboth, McKinstry.—Sigel's Transportation Train.—A Countryman's Estimate of Troops.

199

A Kid-gloved Corps.—Charge of Fremont's Body-guard.—Major White.—Turning the Tables.—Welcome from the Union Residents of Springfield.—Freaks of the Kansas Brigade.—A Visit to the Wilson-Creek Battle-Ground.—"Missing."—Graves Opened by Wolves.—Capture of a Female Spy.—Fremont's Farewell to His Army.—Dissatisfaction Among the Soldiers.—Spurious Missouri Unionists.—The Conduct of Secretary Cameron and Adjutant-General Thomas.

213

Rebel Guerrillas Outwitted.—Expedition to Fort Henry.—Scenes in the Captured Fort.—Commodore Foote in the Pulpit.—Capture of Fort Donelson.—Scenes in Columbus, Kentucky.—A Curious Anti-Climax.—Hospital Scenes.

225

Down the Mississippi.—Bombardment of Island Number Ten.—Sensations under Fire.—Flanking the Island.—Daily Life on a Gunboat.—Triumph of Engineering Skill.—The Surrender.

235

The Battle of Shiloh.—With the Sanitary Commission.—A Union Orator in Rebel Hands.—Grant and Sherman in Battle.—Hair-breadth 'Scapes.—General Sweeney.—Arrival of Buell's Army.—The Final Struggle.—Losses of the Two Armies.

243

Grant under a Cloud.—He Smokes and Waits.—Military Jealousies.—The Union and Rebel Wounded.

247

An Interview with General Sherman.—His Complaints about the Press.—Sherman's Personal Appearance.—Humors of the Telegraph.—Our Advance upon Corinth.—Weaknesses of Sundry Generals.—"Ten Thousand Prisoners Taken."—Halleck's Faux Pas at Corinth.—Out on the Front.—Among the Sharp-shooters.—Halleck and the War Correspondents.

259

Bloodthirstiness of Rebel Women.—The Battle of Memphis.—Gallant Exploit of the Rams.—A Sailor on a Lark.—Appearance of the Captured City.—The Jews in Memphis.—A Rebel Paper Supervised.—"A Dam Black-harted Ablichiness."—Challenge from a Southern Woman.—Valuable Currency.—A Rebel Trick.—One of Sherman's Jokes.—Fictitious Battle Reports.—Curtis's March through Arkansas.—The Siege of Cincinnati.

275

With the Army of the Potomac.—On the War-Path.—A Duel in Arizona.—How Correspondents Avoided Expulsion.—Shameful Surrender of Harper's Ferry.—General Hooker at Antietam.—"Stormed at with Shot and Shell."—A Night Among the Pickets.—The Battlefield.

287

The Day after the Battle.—Among the Dead.—Lee Permitted to Escape.—The John Brown Engine-House.—President Lincoln Reviewing the Army.—Dodging Cannon Balls.—"An Intelligent Contraband."—Harper's Ferry.—Curiosities of the Signal Corps.—View from Maryland Hights.

299

Marching Southward.—Rebel Girl with Sharp Tongue.—A Slight Mistake.—Removal of General McClellan.—Familiarity of the Pickets.—The Life of an Army Correspondent.—A Negro's Idea of Freedom.—The Battle of Fredericksburg.—A Telegraphic Blunder.—The Batteries at Fredericksburg.—A Disappointed Virginian.—The Spirit of the Army under Defeat.

311

Reminiscences of President Lincoln.—His Great Canvass with Douglas.—His Visit to Kansas.—His Manner of Public Speaking.—High Praise from an Opponent.—A Deed without a Name.—Sherman's Quarrel with the Press.—An Army Correspondent Court-Martialed.—A Visit to President Lincoln.—Two of his "Little Stories."—His familiar Conversation.—Opinions about McClellan and Vicksburg.—Our best Contribution to History.

327

Reminiscences of General Sumner.—His Conduct in Kansas.—A Thrilling Scene in Battle.—How Sumner Fought.—Ordered Back by McClellan.—Love for his Old Comrades.—Traveling Through the Northwest.—A Visit to Rosecrans's Army.—Rosecrans in a Great Battle.—A Scene in Memphis.

337

Running the Vicksburg Batteries.—Expedition Badly Fitted Out.—"Into the Jaws of Death."—A Moment of Suspense.—Disabled and Drifting Helplessly.—Bombarding, Scalding, Burning, Drowning.—Taking to a Hay Bale.—Overturned.—Rescued from the River.—The Killed, Wounded, and Missing.

347

Standing by Our Colors.—Confinement in the Vicksburg Jail.—Sympathizing Sambo.—Parolled to Return Home.—Turning the Tables.—Visit from Many Rebels.—Interview with Jacob Thompson.—Arrival in Jackson, Mississippi.—Kindness of Southern Rebels.—A Project for Escape.

357

A Word with a Union Woman.—Grierson's Great Raid.—Stumping the State.—An Enraged Texan Officer.—Waggery of a Captured Journalist.—The Alabama River.—Atlanta Editors Advocate Hanging the Prisoners.—Renegade Vermonters.

365

Arrival in Richmond.—Lodged in Libby Prison.—Sufferings from Vermin.—Prisoners Denounced as Blasphemous.—Thieving of a Virginia Gentleman.—Brutality of Captain Turner.—Prisoners Murdered by the Guards.—Fourth of July Celebration.—The Horrors of Belle Isle.

373

The Captains Ordered Below.—Two Selected for Execution.—The Gloomiest Night in Prison.—Glorious Revulsion of Feeling.—Exciting Discussion in Prison.—Stealing Money from the Captives.—Horrible Treatment of Northern Citizens.—Extravagant Rumors among the Prisoners.

381

Transferred to Castle Thunder.—Better than the Libby.—Determined Not to Die.—A Negro Cruelly Whipped.—The Execution of Spencer Kellogg.—Steadfastness of Southern Unionists.

387

A Waggish Journalist.—Proceedings of a Mock Court.—Escape by Killing a Guard.—Escape by Playing Negro.—Escape by Forging a Release.—Escaped Prisoner at Jeff Davis's Levee.

393

Assistance from a Negro Boy.—The Prison Officers Enraged.—Visit from a Friendly Woman.—Shut up in a Cell.—Stealing from Flag-of-Truce Letters.—Parols Repudiated by the Rebels.—Sentenced to the Salisbury Prison.—Abolitionists before the War.

401

The Open Air and Pure Water.—The Crushing Weight of Imprisonment.—Bad News from Home.—The Great Libby Tunnel.—Escape of Colonel Streight.—Horrible Sufferings of Union Officers.—A Cool Method of Escape.—Captured through the Obstinacy of a Mule.—Concealing Money when Searched.—Attempts to Escape Frustrated.—Yankee Deserters Whipped and Hanged.

411

Great Influx of Prisoners.—Starving in the Midst of Food.—Freezing in the Midst of Fuel.—Rebel Surgeons Generally Humane.—Terrible Scenes in the Hospitals.—The Rattling Dead-Cart.—Cruelty of our Government.—General Butler's Example of Retaliation.

419

Attempted Outbreak and Massacre.—Cold-blooded Murders Frequent.—Hostility to The Tribune Correspondents.—A Cruel Injustice.—Rebel Expectations of Peace.—The Prison Like the Tomb.—Something about Tunneling.—The Tunnelers Ingeniously Baffled.

427

Fifteen Months of Fruitless Endeavor.—A Fearful Journey in Prospect.—A Friendly Confederate Officer.—Effects of Hunger and Cold.—Another Plan in Reserve.—Passing the Sentinel.—"Beg Pardon, Sir."—Encountering Rebel Acquaintances.

435

"Out of the Jaws of Death."—Concealed in Sight of the Prison.—Certain to be Brought Back.—Commencing the Long Journey.—Too Weak for Traveling.—Severe March in the Rain.

441

A Cabin of Friendly Negroes.—Southerners Unacquainted with Tea.—Walking Twelve Miles for Nothing.—Every Negro a Friend.—Touching Fidelity of the Slaves.—Pursued by a Home-Guard.—Help in the Last Extremity.—Carried Fifteen Miles by Friends

449

A Curious Dilemma.—Food, Shelter, and Friends.—Loyalty of the Mountaineers.—A Levee in a Barn.—Visited by an Old Friend.—A Day of Alarms.—A Woman's Ready Wit.—Danger of Detection from Snoring.—Promises to Aid Suffering Comrades.—A Repentant Rebel

461

Flanking a Rebel Camp.—Secreted among the Husks.—Wandering from the Road.—Crossing the Yadkin River.—Union Bushwhackers.—Union Soldiers "Lying Out."—An Energetic Invalid

469

Money Concealed in Clothing.—Peril of Union Citizens.—Fording Creeks at Midnight.—Climbing the Blue Ridge.—Crossing the New River at Midnight

477

Over Mountains and Through Ravines.—Mistaken for Confederate Guards.—A Rebel Guerrilla Killed.—Meeting a Former Fellow-Prisoner.—Alarm about Rebel Cavalry.—A Stanch old Unionist.—The Greatest Danger.—A Well Fortified Refuge

487

Dan Ellis, the Union Guide.—In Good Hands at Last.—Ellis's Bravery.—Lost! A Perilous Blunder.—A most Fortunate Encounter.—Rejoining Dan and His Party.—A Terrible March

495

Fording Creeks in the Darkness.—Prospect of a Dreary Night.—Sleeping among the Husks.—Turning Back in Discouragement.—An Alarm at Midnight.—A Young Lady for a Guide.—The Nameless Heroine.

503

Among the Delectable Mountains.—Separation from Friends.—Union Women Scrutinizing the Yankee.—"Slide Down off that Horse."—Friendly Words, but Hostile Eyes.—Hospitalities of a Loyal Patriarch.—"Out of the Mouth of Hell."

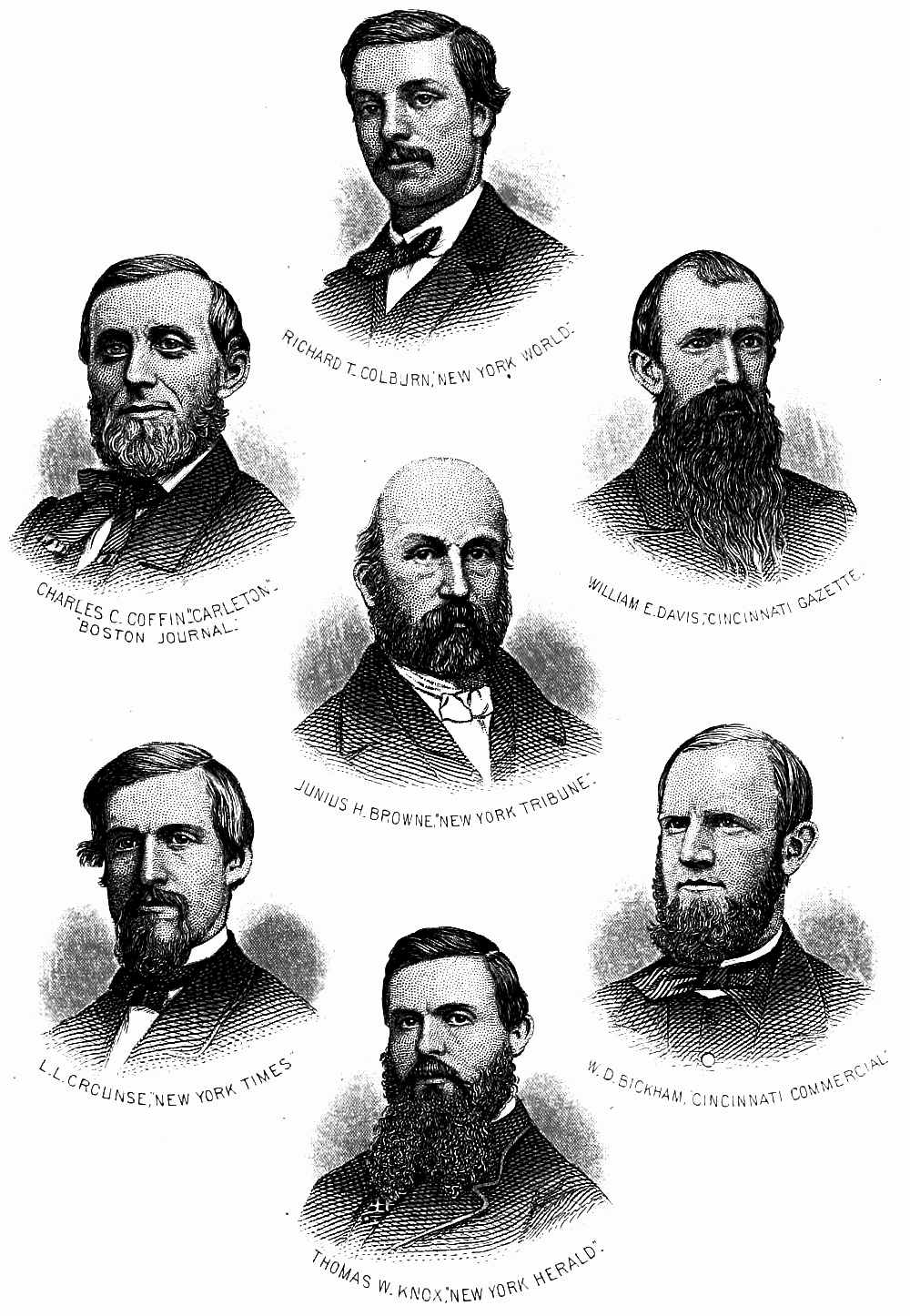

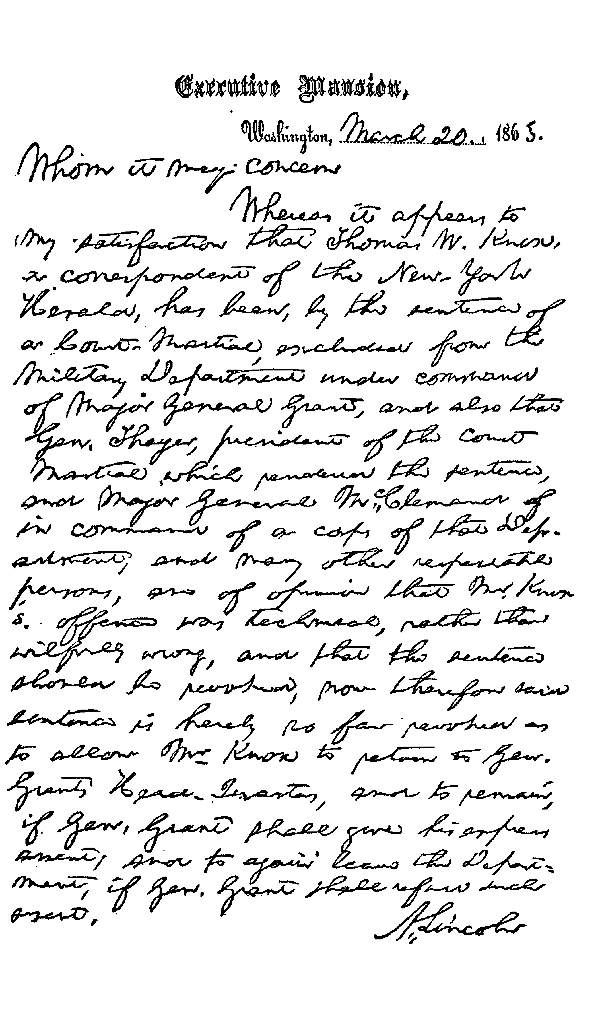

Engd. by Geo. E. Perine, N.Y.

RICHARD T. COLBURN, "NEW YORK WORLD". CHARLES C. COFFIN, "CARLETON" - "BOSTON JOURNAL". WILLIAM E. DAVIS, "CINCINNATI GAZETTE". JUNIUS H. BROWNE, "NEW YORK TRIBUNE". L. L. CROUNSE, "NEW YORK TIMES". W. D. BICKHAM, "CINCINNATI COMMERCIAL". THOMAS W. KNOX, "NEW YORK HERALD". A GROUP OF ARMY CORRESPONDENTS.

THE FIELD, THE DUNGEON, AND THE ESCAPE.

I will go on the slightest errand now to the antipodes that you can desire to send me on.

Much Ado about Nothing.

Early in 1861, I felt a strong desire to look at the Secession movement for myself; to learn, by personal observation, whether it sprang from the people or not; what the Revolutionists wanted, what they hoped, and what they feared.

But the southern climate, never propitious to the longevity of Abolitionists, was now unfavorable to the health of every northerner, no matter how strong his political constitution. I felt the danger of being recognized; for several years of roving journalism, and a good deal of political speaking on the frontier, had made my face familiar to persons whom I did not remember at all, and given me that large and motley acquaintance which every half-public life necessitates.

Moreover, I had passed through the Kansas struggle; and many former shining lights of Border Ruffianism were now, with perfect fitness, lurid torches in the early bonfires of Secession. I did not care to meet their eyes, for I could not remember a single man of them all who would be likely to love me, either wisely or too well. But the newspaper instinct was strong within me, and the journalist who deliberates is lost. My hesitancy resulted in writing for a roving commission to represent The Tribune in the Southwest.

A few days after, I found the Managing Editor in his office, going through the great pile of letters the morning mail had brought him, with the wonderful rapidity which quick intuition, long experience, and natural fitness for that most delicate and onerous position alone can give. For the modern newspaper is a sort of intellectual iron-clad, upon which, while the Editorial Captain makes out the reports to his chief, the public, and entertains the guests in his elegant cabin, the leading column, and receives the credit for every broadside of type and every paper bullet of the brain poured into the enemy,—back out of sight is an Executive Officer, with little popular fame, who keeps the ship all right from hold to maintop, looks to every detail with sleepless vigilance, and whose life is a daily miracle of hard work.

The Manager went through his mail, I think, at the rate of one letter per minute. He made final disposition of each when it came into his hand; acting upon the great truth, that if he laid one aside for future consideration, there would soon be a series of strata upon his groaning desk, which no mental geologist could fathom or classify. Some were ruthlessly thrown into the waste-basket. Others, with a lightning pencil-stroke, to indicate the type and style of printing, were placed on the pile for the composing-room. A few great packages of manuscript were re-enclosed in envelopes for the mail, with a three-line note, which, while I did not read, I knew must run like this:—

"My Dear Sir—Your article has unquestionable merit; but by the imperative pressure of important news upon our columns, we are very reluctantly compelled," etc.

There was that quick, educated instinct, which reads the whole from a very small part, taking in a line here and a key-word there. Two or three glances appeared to decide the fate of each; yet the reader was not wholly absorbed, for all the while he kept up a running conversation:

"I received your letter. Are you going to New Orleans?"

"Not unless you send me."

"I suppose you know it is rather precarious business?"

"O, yes."

"Two of our correspondents have come home within the last week, after narrow escapes. We have six still in the South; and it would not surprise me, this very hour, to receive a telegram announcing the imprisonment or death of any one of them."

"I have thought about all that, and decided."

"Then we shall be very glad to have you go."

"When may I start?"

"To-day, if you like."

"What field shall I occupy?"

"As large a one as you please. Go and remain just where you think best."

"How long shall I stay?"

"While the excitement lasts, if possible. Do you know how long you will stay? You will be back here some fine morning in just about two weeks."

"Wait and see."

Pondering upon the line of conduct best for the journey, I remembered the injunction of the immortal [Pg 20] Pickwick: "It is always best on these occasions to do what the mob do!" "But," suggested Mr. Snodgrass, "suppose there are two mobs?" "Shout with the largest," replied Mr. Pickwick. Volumes could not say more. Upon this plan I determined to act—concealing my occupation, political views, and place of residence. It is not pleasant to wear a padlock upon one's tongue, for weeks, nor to adopt a course of systematic duplicity; but personal convenience and safety rendered it an inexorable necessity.

On Tuesday, February 26th, I left Louisville, Kentucky, by the Nashville train. Public affairs were the only topic of conversation among the passengers. They were about equally divided into enthusiastic Secessionists, urging in favor of the new movement that negroes already commanded higher prices than ever before; and quasi Loyalists, reiterating, "We only want Kentucky to remain in the Union as long as she can do so honorably." Not a single man declared himself unqualifiedly for the Government.

A ride of five hours among blue, dreamy hills, feathered with timber; dense forests, with their drooping foliage and log dwellings, in the doors of which women and little girls were complacently smoking their pipes; great, hospitable farm-houses, in the midst of superb natural parks; tobacco plantations, upon which negroes of both sexes—the women in cowhide brogans, and faded frocks, with gaudy kerchiefs wrapped like turbans about their heads—were hoeing, and following the plow, brought us to Cave City.

I left the train for a stage-ride of ten miles to the Mammoth Cave Hotel. In the midst of a smooth lawn, shaded by stately oaks and slender pines, it looms up huge and white, with a long, low, one-story offshoot [Pg 21] fronted by a deep portico, and known as "the Cottages."

Several evening hours were spent pleasantly in White's Cave, where the formations, at first dull and leaden, turn to spotless white after one grows accustomed to the dim light of the torches. There are little lakes so utterly transparent that your eye fails to detect the presence of water; stone drapery, hanging in graceful folds, and forming an exquisitely beautiful chamber; petrified fountains, where the water still trickles down and hardens into stone; a honey-combed roof, which is a very perfect counterfeit of art; long rows of stalactites, symmetrically ribbed and fluted, which stretch off in a pleasing colonnade, and other rare specimens of Nature's handiwork in her fantastic moods. Many of them are vast in dimension, though the geologists declare that it requires thirty years to deposit a formation no thicker than a wafer! Well says the German proverb "God is patient because he is eternal."

With another visitor I passed the next day in the Mammoth Cave. "Mat," our sable cicerone, had been acting in the capacity of guide for twenty-five years, and it was estimated that he had walked more than fifty thousand miles under ground. The story is not so improbable when one remembers that the passages of the great cavern are, in the aggregate, upwards of one hundred and fifty miles in length, and that it has two hundred and twenty-six known chambers. The outfit consisted of two lamps for himself and one for each of us. Cans of oil are kept at several interior points; for it is of the last importance that visitors to this labyrinth of darkness should keep their lamps trimmed and burning.

The thermometer within stands constantly at fifty-nine Fahrenheit; and the cave "breathes just once a year." Through the winter it takes one long inspiration, and in summer the air rushes steadily outward. Its vast chambers are the lungs of the universe.

In 1845, a number of wood and stone cottages were erected in the cavern, and inhabited by consumptive patients, who believed that the dry atmosphere and equable temperature would prove beneficial. After three or four months their faces were bloodless; the pupils of their sunken eyes dilated until the iris became invisible and the organs appeared black, no matter what their original color. Three patients died in the cave; the others expired soon after leaving it.

Mat gave a vivid description of these invalids flitting about like ghosts—their hollow coughs echoing and reechoing through the cavernous chambers. It must have looked horrible—as if the tomb had oped its ponderous and marble jaws, that its victims might wander about in this subterranean Purgatory. A cemetery would seem cheerful in comparison with such a living entombment. Volunteer medical advice, like a motion to adjourn, is always in order. My own panacea for lung-complaints would be exactly the opposite. Mount a horse or take a carriage, and ride, by easy stages at first, across the great plains to the Rocky Mountains or California, eating and sleeping in the open air. Nature is very kind, if you will trust her fully; and in the atmosphere, which is so dry and pure that fresh meat, cut in strips and hung up, will cure without salting or smoking, and may be carried all over the world, her healing power seems almost boundless.

The walls and roof of the cave were darkened and often hidden by myriads of screeching bats, at this [Pg 23] season of the year all hanging torpid by the claws, with heads downward, and unable to fly away, even when subjected to the cruel experiment of being touched by the torches.

The Methodist Church is a semi-circular chamber, in which a ledge forms the natural pulpit; and logs, brought in when religious service was first performed, fifty years ago, in perfect preservation, yet serve for seats. Methodist itinerants and other clergymen still preach at long intervals. Worship, conducted by the "dim religious light" of tapers, and accompanied by the effect which music always produces in subterranean halls, must be peculiarly impressive. It suggests those early days in the Christian Church, when the hunted followers of Jesus met at midnight in mountain caverns, to blend in song their reverent voices; to hear anew the strange, sweet story of his teachings, his death, and his all-embracing love.

Upon one of the walls beyond, a figure of gypsum, in bass-relief, is called the American Eagle. The venerable bird, in consonance with the evil times upon which he had fallen, was in a sadly ragged and dilapidated condition. One leg and other portions of his body had seceded, leaving him in seeming doubt as to his own identity; but the beak was still perfect, as if he could send forth upon occasion his ancient notes of self-gratulation.

Minerva's Dome has fluted walls, and a concave roof, beautifully honey-combed; but no statue of its mistress. The oft-invoked goddess, wearied by the merciless orators who are always compelling her to leap anew from the brain of Jove, has doubtless, in some hidden nook, found seclusion and repose.

We toiled along the narrow, tortuous passage, chiseled [Pg 24] through the rock by some ancient stream of water, and appropriately named the Fat Man's Misery; wiped away the perspiration in the ample passage beyond, known as the Great Relief; glanced inside the Bacon Chamber, where the little masses of lime-rock pendent from the roof do look marvelously like esculent hams; peeped down into the cylindrical Bottomless Pit, which the reader shall be told, confidentially, has a bottom just one hundred and sixty feet below the surface; laughed at the roof-figures of the Giant, his Wife, and Child, which resemble a caricature from Punch; admired the delicate, exquisite flowers of white, fibrous gypsum, along the walls of Pensacola Avenue; stood beside the Dead Sea, a dark, gloomy body of water; crossed the Styx by the natural bridge which spans it, and halted upon the shore of Lethe.

Then, embarking in a little flat-boat, we slowly glided along the river of Oblivion. It was a strange, weird spectacle. The flickering torches dimly revealed the dark inclosing walls, which rise abruptly a hundred feet to the black roof. Our sable guide looked, in the ghastly light, like a recent importation from Pluto's domain; and stood in the bows, steering the little craft, which moved slowly down the winding, sluggish river. The deep silence was only broken by drops of water, which fell from the roof, striking the stream like the tick of a clock, and the sharp ylp of the paddle, as it was thrust into the wave to guide us. When my companion evoked from his flute strains of slow music, which resounded in hollow echoes through the long vault, it grew so demoniac, that I almost expected the walls to open and reveal a party of fiends, dancing to infernal music around a lurid fire. I never saw any stage effect or work of art that could compare with it. [Pg 25] If one would enjoy the most vivid sensations of the grand and gloomy, let him float down Lethe to the sound of a dirge.

We first saw the Star Chamber with the lights withdrawn. It revealed to us the meaning of "darkness visible." We seemed to feel the dense blackness against our eye-balls. An object within half an inch of them was not in the faintest degree perceptible. If one were left alone here, reason could not long sustain itself. Even a few hours, in the absence of light, would probably shake it. In numberless little spots, the dark gypsum has scaled off, laying bare minute sections of the white limestone roof, resembling stars. When the chamber was lighted the illusion became perfect. We seemed in a deep, rock-walled pit, gazing up at the starry firmament. The torch, slowly moved to throw a shadow along the roof, produced the effect of a cloud sailing over the sky; but the scene required no such aid to render it one of marvelous beauty. The Star Chamber is the most striking picture in all this great gallery of Nature.

My companion had spent his whole life within a few miles of the cave, but now visited it for the first time. Thus it is always; objects which pilgrims come half across the world to see, we regard with indifference at our own doors. Persons have passed all their days in sight of Mount Washington, and yet never looked upon the grand panorama from its brow. Men have lived from childhood almost within sound of the roar of Niagara, without ever gazing on the vast fountain, where mother Earth, like Rachel, weeps for her children, and will not be comforted. We appreciate no enjoyment justly, until we see it through the charmed medium of magnificent distances.

Throughout Kentucky the pending troubles were uppermost in every heart and on every tongue. One gentleman, in conversation, thus epitomized the feeling of the State:—

"We have more wrongs to complain of than any other slave community, for Kentucky loses more negroes than all the cotton States combined. But Secession is no remedy. It would be jumping out of the frying-pan into the fire."

Another, whose head was silvered with age, said to me:—

"When I was a boy here in this county, some of our neighbors started for New Orleans on a flat-boat. As we bade them good-by, we never expected to see them again; we thought they were going out of the world. But, after several months, they returned, having come on foot all the way, through the Indian country, packing 1 their blankets and provisions. Now we come from New Orleans in five days. I thank God to have lived in this age—the age of the Railroad, the Telegraph, and the Printing Press. Ours was the greatest nation and the greatest era in history. But that is all past now. The Government is broken to pieces; the slave States can not obtain their rights; and those which have seceded will never come back."

An old farmer "reckoned," as I traveled a good deal, that I might know better than he whether there was any hope of a peaceable settlement. If the North, as he believed, was willing to be just, an overwhelming majority of Kentuckians would stand by the Union. "It is a great pity," he said, very earnestly, in a broken voice, "that we Americans could not live harmoniously, like [Pg 27] brethren, instead of always quarreling about a few niggers."

My recollections of Nashville, Tennessee, include only an unpalatable breakfast in one of its abominable hotels; a glimpse at some of its pleasant shaded streets and marble capitol, which, with the exception of that in Columbus, Ohio, is considered the finest State-house on the continent.

Continuing southward, I found the country already "appareled in the sweet livery of spring." The elm and gum trees wore their leafy glory; the grass and wheat carpeted the ground with swelling verdure, and field and forest glowed with the glossy green of the holly. The railway led through large cotton-fields, where many negroes, of both sexes, were plowing and hoeing, while overseers sat upon the high, zig-zag fences, armed with rifles or shot-guns. On the withered stalks snowy tufts of cotton were still protruding from the dull brown bolls—portions of the last year's crop, which had never been picked, and were disappearing under the plow.

A native Kentuckian, now a young merchant in Alabama, was one of my fellow-passengers. He pronounced the people aristocratic. They looked down upon every man who worked for his living—indeed, upon every one who did not own negroes. The ladies were pretty, and often accomplished, but, he mildly added, he would like them better if they did not "dip." He insisted that Alabama had been precipitated into the revolution.

"We were swindled out of our rights. In my own town, Jere Clemens—an ex-United States senator, and one of the ablest men in the State—was elected to the convention on the strongest public pledges of Unionism. When the convention met, he went completely over to the enemy. The leaders—a few heavy slaveholders, [Pg 28] aided by political demagogues—dared not submit the Secession ordinance to a popular vote; they knew the people would defeat them. They are determined on war; they will exasperate the ignorant masses to the last degree before they allow them to vote on any test question. I trust the Government will put them down by force of arms, no matter what the cost!"

The same evening, crossing the Alabama line, I was in the "Confederate States of America." At the little town of Athens, the Stars and Stripes were still floating; as the train left, I cast a longing look at the old flag, wondering when I should see it again.

The next person who took a seat beside me went through the formula of questions, usual between strangers in the South and the Far West, asking my name, residence, business, and destination. He was informed, in reply, that I lived in the Territory of New Mexico, and was now traveling leisurely to New Orleans, designing to visit Vera Cruz and the City of Mexico before returning home. This hypothesis, to which I afterward adhered, was rendered plausible by my knowledge of New Mexico, and gave me the advantage of not being deemed a partisan. Secessionists and Unionists alike, regarding me as a stranger with no particular sympathies, conversed freely. Aaron Burr asserts that "a lie well stuck to is good as the truth;" in my own case, it was decidedly better than the truth.

My querist was a cattle-drover, who spent most of his time in traveling through Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana. He declared emphatically that the people of those States had been placed in a false position; that their hearts were loyal to the Union, in spite of all the arts which had been used to deceive and exasperate them.

At Memphis was an old friend, whom I had not met [Pg 29] for many years, and who was now commercial editor of the leading Secession journal. I knew him to be perfectly trustworthy, and, at heart, a bitter opponent of Slavery. On the morning of my arrival, he called upon me at the Gayoso House. After his first cordial greeting, he asked, abruptly:

"What are you doing down here?"

"Corresponding for The Tribune."

"How far are you going?"

"Through all the Gulf States, if possible."

"My friend," said he, in his deep bass tones, "do you know that you

are on very perilous business?'"

"Possibly; but I shall be extremely prudent when I get into a hot climate."

"I do not know" (with a shrug of the shoulders) "what you call a hot climate. Last week, two northerners, who had been mobbed as Abolitionists, passed through here, with their heads shaved, going home, in charge of the Adams' Express. A few days before, a man was hung on that cottonwood tree which you see just across the river, upon the charge of tampering with slaves. Another person has just been driven out of the city, on suspicion of writing a letter for The Tribune. If the people in this house, and out on the street in front, knew you to be one of its correspondents, they would not leave you many minutes for saying your prayers."

After a long, minute conversation, in which my friend learned my plans and gave me some valuable hints, he remarked:

"My first impulse was to go down on my knees, and beg you, for God's sake, to turn back; but I rather think you may go on with comparative safety. You are the first man to whom I have opened my heart for years. [Pg 30] I wish some of my old northern friends, who think Slavery a good thing, could witness the scenes in the slave auctions, which have so often made my blood run cold. I knew two runaway negroes absolutely starve themselves to death in their hiding-places in this city, rather than make themselves known, and be sent back to their masters. I disliked Slavery before; now I hate it, down to the very bottom of my heart." His compressed lips and clinched fingers, driving their nails into his palms, attested the depth of his feeling.

Thus far into the bowels of the land

Have we marched on without impediment.

Richard III.

While I remained in Memphis, my friend, who was brought into familiar contact with leading Secessionists, gave me much valuable information. He insisted that they were in the minority, but carried the day because they were noisy and aggressive, overawing the Loyalists, who staid quietly at home. Before the recent city election, every one believed the Secessionists in a large majority; but, when a Union meeting was called, the people turned out surprisingly, and, as they saw the old flag, gave cheer after cheer, "with tears in their voices." Many, intimidated, staid away from the polls. The newspapers of the city, with a single exception, were disloyal, but the Union ticket was elected by a majority of more than three hundred.

"Tell me exactly what the 'wrongs' and 'grievances' are, of which I hear so much on every side."

"It is difficult to answer. The masses have been stirred into a vague, bitter, 'soreheaded' feeling that the South is wronged; but the leaders seldom descend to particulars. When they do, it is very ludicrous. They urge the marvelous growth of the North; the abrogation of the Missouri Compromise (done by southern votes!), and that Freedom has always distanced Slavery in the territories. Secession is no new or spontaneous uprising; every one of its leaders here has talked of it and planned it for years. Individual ambition, and wild dreams of a [Pg 32] great southern empire, which shall include Mexico, Central America, and Cuba, seem to be their leading incentives. But there is another, stronger still. You can hardly imagine how bitterly they hate the Democratic Idea—how they loathe the thought that the vote of any laboring man, with a rusty coat and soiled hands, may neutralize that of a wealthy, educated, slave-owning gentleman."

Thus Charles Mackay describes Memphis; but it impressed me as the pleasantest city of the South. Though its population was only thirty thousand, it had the air and promise of a great metropolis. The long steamboat landing was so completely covered with cotton that drays and carriages could hardly thread the few tortuous passages leading down to the water's edge. Bales of the same great staple were piled up to the ceiling in the roomy stores of the cotton factors; the hotels were crowded, and spacious and elegant blocks were being erected.

A few days earlier, in Cleveland, I had seen the ground covered with snow; but here I was in the midst of early summer. During the first week of March, the heat was so oppressive that umbrellas and fans were in general use upon the streets. The broad, shining leaves of the magnolia, and the delicate foliage of the weeping willow, were nodding adieu to winter; the air was sweet with cherry blossoms; with

On the evening of March 3d I left Memphis. A thin-visaged, sandy-haired, angular gentleman in spectacles, who occupied a car-seat near me, though of northern birth, had resided in the Gulf States for several years, as agent for an Albany manufactory of cotton-gins and agricultural implements. A broad-shouldered, roughly dressed, sun-browned young man, whose chin was hidden by a small forest of beard, accepted the proffer of a cigar, took a seat beside us, and introduced himself as Captain McIntire, of the United States Army, who had just resigned his commission, on account of the pending troubles, and was returning from the Texian frontier to his plantation in Mississippi. He was the first bitter Secessionist I had met, and I listened with attent ear to his complaints of northern aggression.

The Albanian was an advocate of Slavery and declared that, in the event of separation, his lot was with the South, for better or for worse; but he mildly urged that the Secession movement was hasty and ill advised; hoped the difficulty might be settled by compromise, and declared that, traveling through all the cotton States since Mr. Lincoln's election, he had found, everywhere outside the great cities, a strong love for the Union and a universal hope that the Republic might continue indivisible. He was very "conservative;" had always voted the Democratic ticket; was confident the northern people would not willingly wrong their southern brethren; and insisted that not more than twenty or thirty thousand persons in the State of New-York were, in any just sense, Abolitionists.

Captain McIntire silently heard him through, and then remarked:

"You seem to be a gentleman; you may be sincere in your opinions; but it won't do for you to express such [Pg 34] sentiments in the State of Mississippi. They will involve you in trouble and in danger!"

The New-Yorker was swift to explain that he was very "sound," favoring no compromise which would not give the slaveholders all they asked. Meanwhile, a taciturn but edified listener, I pondered upon the German proverb, that "speech is silver, while silence is golden." Something gave me a dim suspicion that our violent fire-eater was not of southern birth; and, after being plied industriously with indirect questions, he was reluctantly forced to acknowledge himself a native of the State of New Jersey. Soon after, at a little station, Captain McIntire, late of the Army of the United States, bade us adieu.

At Grand Junction, after I had assumed a recumbent position in the sleeping-car, two young women in a neighboring seat fell into conversation with a gentleman near them, when a droll colloquy ensued. Learning that he was a New Orleans merchant, one of them asked:—

"Do you know Mr. Powers, of New Orleans?"

"Powers—Powers," said the merchant; "what does he do?"

"Gambles," was the cool response.

"Bless me, no! What do you know about a gambler?"

"He is my husband," replied the woman, with ingenuous promptness.

"Your husband a gambler!" ejaculated the gentleman, with horror in every tone.

"Yes, sir," reiterated the undaunted female; "and gamblers are the best men in the world."

"I didn't know they ever married. I should like to see a gambler's wife."

"Well, sir, take a mighty good look, and you can see one now."

The merchant opened the curtains into their compartment, and scrutinized the speaker—a young, rosy, and rather comely woman, with blue eyes and brown hair, quietly and tastefully dressed.

"I should like to know your husband, madam."

"Well, sir; if you've got plenty of money, he will be glad to make your acquaintance."

"Does he ever go home?"

"Lord bless you, yes! He always comes home at one o'clock in the morning, after he gets through dealing faro. He has not missed a single night since we were married—going on five years. We own a farm in this vicinity, and if business continues good with him next year we shall retire to it, and never live in the city again."

All the following day I journeyed through deep forests of heavy drooping foliage, with pendent tufts of gray Spanish moss. The beautiful Cherokee rose everywhere trailed its long arms of vivid green; all the woods were decked with the yellow flowers of the sassafras and the white blossoms of the dogwood and the wild plum. Our road stretched out in long perspective through great Louisiana everglades, where the grass was four feet in hight and the water ten or twelve inches deep.

It was the day of Mr. Lincoln's inauguration. One of our passengers remarked:

"I hope to God he will be killed before he has time to take the oath!"

Another said:

"I have wagered a new hat that neither he nor Hamlin will ever live to be inaugurated."

An old Mississippian, a working man, though the owner [Pg 36] of a dozen slaves, assured me earnestly that the people did not desire war; but the North had cheated them in every compromise, and they were bound to regain their rights, even if they had to fight for them.

"We of the South," said he, "are the most independent people in the universe. We raise every thing we need; but the world can not do without cotton. If we have war, it will cause terrible suffering in the North. I pity the ignorant people of the manufacturing districts there, who have been deluded by the politicians; for they will be forced to endure many hardships, and perhaps starvation. After Southern trade is withdrawn, manufactures stopped, operatives starving, grass growing in the streets of New York, and crowds marching up Broadway crying 'Bread or Blood!' northern fanatics will see, too late, the results of their folly."

This was the uniform talk of Secessionists. That Cotton was not merely King, but absolute despot; that they could coerce the North by refusing to buy goods, and coerce the whole world by refusing to sell cotton, was their profound belief. This was always a favorite southern theory. Bancroft relates that as early as 1661, the colony of Virginia, suffering under commercial oppression, urged North Carolina and Maryland to join her for a year in refusing to raise tobacco, that they might compel Great Britain to grant certain desired privileges. Now the Rebels had no suspicion whatever that there was reciprocity in trade; that they needed to sell their great staple just as much as the world needed to buy it; that the South bought goods in New York simply because it was the cheapest and best market; that, were all the cotton-producing States instantly sunk in the ocean, in less than five years the world [Pg 37] would obtain their staple, or some adequate substitute, from other sources, and forget they ever existed.

"I spent six weeks last summer," said another planter, "in Wisconsin. It is a hot-bed of Abolitionism. The working-classes are astonishingly ignorant. They are honest and industrious, but they are not so intelligent as the nig-roes of the South. They suppose, if war comes, we shall have trouble with our slaves. That is utterly absurd. All my nig-roes would fight for me."

A Mississippian, whom his companions addressed as "Judge," denounced the Secession movement as a dream of noisy demagogues:

"Their whole policy has been one of precipitation. They declared: 'Let us rush the State out of the Union while Buchanan is President, and there will be no war.' From the outset, they have acted in defiance of the sober will of the masses; they have not dared to submit one of their acts to a popular vote!"

Another passenger, who concurred in these views, and intimated that he was a Union man, still imputed the troubles mainly to agitation of the Slavery question.

"The northern people," said he, "have been grossly deceived by their politicians, newspapers, and books like 'Uncle Tom's Cabin,' whose very first chapter describes a slave imprisoned and nearly starved to death in a cellar in New Orleans, when there is not a single cellar in the whole city!"

Midnight found us at the St. Charles Hotel, a five-story edifice, with granite basement and walls of stucco—that be-all and end-all of New Orleans architecture. The house has an imposing Corinthian portico, and in the [Pg 38] hot season its stone floors and tall columns are cool and inviting to the eye.

"You can not fail to like New Orleans," said a friend, before I left the North. "Its people are much more genial and cordial to strangers than ours." I took no letters of introduction, for introduction was just the thing I did not want. But on the cars, before reaching the city, I met a gentleman with whom I had a little conversation, and exchanged the ordinary civilities of traveling. When we parted, he handed me his card, saying:

"You are a stranger in New Orleans, and may desire some information or assistance. Call and see me, and command me, if I can be of service to you."

He proved to be the senior member of one of the heaviest wholesale houses in the city. Accepting the invitation, I found him in his counting-room, deeply engrossed in business; but he received me with great kindness, and gave me information about the leading features of the city which I wished to see. As I left, he promised to call on me, adding: "Come in often. By the way, to-morrow is Sunday; why can't you go home and take a quiet family dinner with me?"

I was curious to learn the social position of one who would invite a stranger, totally without indorsement, into his home-circle. The next day he called, and we took a two-story car of the Baronne street railway. It leads through the Fourth or Lafayette District—more like a garden than a city—containing the most delightful metropolitan residences in America. Far back from the street, they are deeply imbosomed in dense shrubbery and flowers. The tropical profusion of the foliage retains dampness and is unwholesome, but very delicious to the senses.

The houses are low—this latitude is unfavorable to climbing—and constructed of stucco, cooler than wood, and less damp than stone. They abound in verandas, balconies, and galleries, which give to New Orleans a peculiarly mellow and elastic look, much more alluring than the cold, naked architecture of northern cities.

My new friend lived in this district, as befits a merchant prince. His spacious grounds were rich in hawthorns, magnolias, arbor-vitæs, orange, olive, and fig trees, and sweet with the breath of multitudinous flowers. Though it was only the tenth of March, myriads of pinks and trailing roses were in full bloom; Japan plums hung ripe, while brilliant oranges of the previous year still glowed upon the trees. His ample residence, with its choice works of art, was quietly, unostentatiously elegant. There was no mistaking it for one of those gilt and gaudy palaces which seem to say: "Look at the state in which Crœsus, my master, lives. Lo, the pictures and statues, the Brussels and rosewood which his money has bought! Behold him clothed in purple and fine linen, faring sumptuously every day!"

Three other guests were present, including a young officer of the Louisiana troops stationed at Fort Pickens, and a lady whose husband and brother held each a high commission in the Rebel forces of Texas. All assumed to be Secessionists—as did nearly every person I met in New Orleans upon first acquaintance—but displayed none of the usual rancor and violence. In that well-poised, agreeable circle the evening passed quickly, and at parting, the host begged me to frequent his house. This was not distinctively southern hospitality, for he was born and bred at the North. But in our eastern cities, from a business man in his social position, it would [Pg 40] appear a little surprising. Had he been a Philadelphian or Bostonian, would not his friends have deemed him a candidate for a lunatic asylum?

New Orleans, March 6, 1861.

Taking my customary stroll last evening, I sauntered into Canal street, and suddenly found myself in a dense and expectant crowd. Several cheers being given upon my arrival, I naturally inferred that it was an ovation to The Tribune correspondent; but native modesty, and a desire to blush unseen, restrained me from any oral public acknowledgment.

Just then, an obliging by-stander corrected my misapprehension by assuring me that the demonstration was to welcome home General Daniel E. Twiggs—the gallant hero, you know, who, stationed in Texas to protect the Government property, recently betrayed it all into the hands of the Rebels, to "prevent bloodshed." His friends wince at the order striking his name from the army rolls as a coward and a traitor, and the universal execration heaped upon his treachery even in the border slave States.

They did their best to give him a flattering reception. The great thoroughfare was decked in its holiday attire. Flags were flying, and up and down, as far as the eye could reach, the balconies were crowded with spectators, and the arms of long files of soldiers glittered in the evening sunlight. One company bore a tattered and stained banner, which went through the Mexican war. Another carried richly ornamented colors, presented by the ladies of this city. There were Pelican flags, and Lone Star flags, and devices unlike any thing in the heavens above, the earth beneath, or the waters under the earth; but nowhere could I see the old National banner. [Pg 41] It was well; on such occasion the Stars and Stripes would be sadly out of place.

After a welcoming speech, pronouncing him "not only the soldier of courage, but the patriot of fidelity and honor," and his own response, declaring that here, at least, he would "never be branded as a coward and traitor," the ex-general rode through some of the principal streets in an open barouche, bareheaded, bowing to the spectators. He is a venerable-looking man, apparently of seventy. His large head is bald upon the top; but from the sides a few thin snow-white locks, utterly oblivious of the virtues of "the Twiggs Hair Dye,"2 streamed in the breeze. He was accompanied in the carriage by General Braxton Bragg—the "Little-more-grape-Captain-Bragg" of Mexican war memory. By the way, persons who ought to know declare that General Taylor never used the expression, his actual language being: "Captain Bragg, give them ----!"

President Lincoln's Inaugural, looked for with intense interest, has just arrived. All the papers denounce it bitterly. The Delta, which has advocated Secession these ten years, makes it a signal for the war-whoop:—

"War is a great calamity; but, with all its horrors, it is a blessing to the deep, dark, and damning infamy of such a submission, such surrenders, as the southern people are now called upon to make to a foreign invader. He who would counsel such— [Pg 42] he who would seek to dampen, discourage, or restrain the ardor and determination of the people to resist all such pretensions, is a traitor, who should be driven beyond our borders."

"Foreign invader," is supposed to mean the President of our common country! The "submission" denounced so terribly would be simply the giving up of the Government property lately stolen by the Rebels, and the paying of the usual duties on imports!

March 8.

The State convention which lately voted Louisiana out of the Union, sits daily in Lyceum Hall. The building fronts Lafayette Square—one of the admirable little parks which are the pride of New Orleans. Upon the first floor is the largest public library in the city, though it contains less than ten thousand volumes.

In the large hall above are the assembled delegates. Ex-Governor Mouton, their president, a portly old gentleman, of the heavy-father order, sits upon the platform. Below him, at a long desk, Mr. Wheat, the florid clerk, is reading a report in a voice like a cracked bugle. Behind the president is a life-size portrait of Washington; at his right, a likeness of Jefferson Davis, with thin, beardless face, and sad, hollow eyes. There is also a painting of the members, and a copy of the Secession ordinance, with lithographed fac similes of their signatures. The delegates, you perceive, have made all the preliminary arrangements for being immortalized. Physically, they are fine-looking men, with broad shoulders, deep chests, well-proportioned limbs, and stature decidedly above the northern standard.

I will be correspondent to command,

And do my spiriting gently.

Tempest.

The good fortune which in Memphis enabled me to learn so directly the plans and aims of the Secession leaders, did not desert me in New Orleans. For several years I had been personally acquainted with the editor of the leading daily journal—an accomplished writer, and an original Secessionist. Uncertain whether he knew positively my political views, and fearing to arouse suspicion by seeming to avoid him, I called on him the day after reaching the city.

He received me kindly, never surmising my errand; invited me into the State convention, of which he was a member; asked me to frequent his editorial rooms; and introduced me at the "Louisiana Democratic Club," which had now ripened into a Secession club. Among prominent Rebels belonging to it were John Slidell and Judah P. Benjamin, of Jewish descent, whom Senator Wade of Ohio characterized so aptly as "an Israelite with Egyptian principles."

Admission to that club was a final voucher for political soundness. The plans of the conspirators could hardly have been discussed with more freedom in the parlor of Jefferson Davis. Another friend introduced me at the Merchants' Reading-room, where were the same sentiments and the same frankness. The newspaper office also was a standing Secession caucus.

These associations gave me rare facilities for studying the aims and animus of the leading Revolutionists. I was [Pg 44] not compelled to ask questions, so constantly was information poured into my ears. I used no further deceit than to acquiesce quietly in the opinions everywhere heard. While I talked New Mexico and the Rocky Mountains, my companions talked Secession; and told me more, every day, of its secret workings, than as a mere stranger I could have learned in a month. Socially, they were genial and agreeable. Their hatred of New England, which they seemed to consider "the cruel cause of all our woes," was very intense. They were also wont to denounce The Tribune, and sometimes its unknown Southern correspondents, with peculiar bitterness. At first their maledictions fell with startling and unpleasant force upon my ears, though I always concurred. But in time I learned to hear them not only with serenity, but with a certain quiet enjoyment of the ludicrousness of the situation.

I had not a single acquaintance in the city, whom I knew to be a Union man, or to whom I could talk without reserve. This was very irksome—at times almost unbearable. How I longed to open my heart to somebody! Recently as I had left the North, and strongly as I was anchored in my own convictions, the pressure on every hand was so great, all intelligence came so distorted through Rebel mediums, that at times I was nearly swept from my moorings. I could fully understand how many strong Union men had at last been drawn into the almost irresistible tide. It was an inexpressible relief to read the northern newspapers at the Democratic Club. There, even The Tribune was on file. The club was so far above suspicion that it might have patronized with impunity the organ of William Lloyd Garrison or Frederick Douglass.

The vituperation which the southern journals heaped [Pg 45] upon Abraham Lincoln was something marvelous. The speeches of the newly elected President on his way to Washington, were somewhat rugged and uncouth; not equal to the reputation he won in the great senatorial canvass with Douglas, where debate and opposition developed his peculiar powers and stimulated his unrivaled logic. The Rebel papers drew daily contrasts between the two Presidents, pronouncing Mr. Davis a gentleman, scholar, statesman; and Mr. Lincoln a vulgarian, buffoon, demagogue. One of their favorite epithets was "idiot;" another, "baboon;" just as the Roman satirists, fifteen hundred years ago, were wont to ridicule the great Julian as an ape and a hairy savage.

The times have changed. While I write some of the same journals, not yet extinguished by the fortunes of war, denounce Jefferson Davis with equal coarseness and bitterness, as an elegant, vacillating sentimentalist; and mourn that he does not possess the rugged common sense and indomitable perseverance displayed by Abraham Lincoln!

While keeping up appearances on the Mexican question, by frequent inquiries about the semi-monthly steamers for Vera Cruz, I devoted myself ostensibly to the curious features of the city. Odd enough it sounded to hear persons say, "Let us go up to the river;" but the phrase is accurate. New Orleans is two feet lower than the Mississippi, and protected against overflow by a dike or levee. The city is quite narrow, and is drained into a great swamp in the rear. In front, new deposits of soil are constantly and rapidly made. Four of the leading business streets, nearest the levee, traverse what, a few years ago, was the bed of the river. Anywhere, by digging two feet below the surface, one comes to water.

The earth is peculiarly spongy and yielding. The unfinished Custom House, built of granite from Quincy, Massachusetts, has sunk about two feet since its commencement, in 1846. The same is true of other heavy buildings. Cellars and wells being impossible in the watery soil, refrigerators serve for the one, and cylindrical upright wooden cisterns, standing aboveground, like towers, for the other.

In the cemeteries the tombs are called "ovens." They are all built aboveground, of brick, stone, or stucco, closed up with mortar and cement. Sometimes the walls crack open, revealing the secrets of the charnel-house. Decaying coffins are visible within; and once I saw a human skull protruding from the fissure of a tomb. Here, indeed,

Despite this revolting feature, the Catholic cemeteries are especially interesting. About the humblest of the monuments, artificial wreaths, well-tended rose-beds, garlands of fresh flowers, changed daily, and vases inserted in the walls, to catch water and attract the birds, evince a tender, unforgetful attention to the resting-place of departed friends. More than half the inscriptions are French or Spanish. Very few make any allusion to a future life. One imposing column marks the grave of Dominique You, the pirate, whose single virtue of patriotism, exhibited under Jackson during the war of 1815, hardly justifies, upon his monument, the magnificent eulogy of Bayard: "The hero of a hundred battles,—a chevalier without fear and without reproach."

In New Orleans, grass growing upon the streets is no sign of decadence. Stimulated by the rich, moist soil, it [Pg 47] springs up in profusion, not only in the smaller thoroughfares, but among the bricks and paving-stones of the leading business avenues.

Canal street is perhaps the finest promenade on the continent. It is twice the width of Broadway, and in the middle has two lines of trees, with a narrow lawn between them, extending its entire length. At night, as the long parallel rows of gas-lights glimmer through the quivering foliage, growing narrower and narrower in perspective till they unite and blend into one, it is a striking spectacle—a gorgeous feast of the lanterns. On the lower side of it is the "French Quarter," more un-American even than the famous German portion of Cincinnati known as "Over the Rhine." Here you may stroll for hours, "a straggler from another civilization," hearing no word in your native tongue, seeing no object to remove the impression of an ancient French city. The dingy houses, "familiar with forgotten years," call up memories of old Mexican towns. They are grim, dusky relics of antiquity, usually but one story high, with steep projecting roofs, tiled or slated, wooden shutters over the doors, and multitudinous eruptions of queer old gables and dormer windows.

New Orleans is the most Parisian of American cities. Opera-houses, theaters, and all other places of amusement are open on Sunday nights. The great French market wears its crowning glory only on Sunday mornings. Then the venders occupy not only several spacious buildings, but adjacent streets and squares. Their wares seem boundless in variety. Any thing you please—edible, drinkable, wearable, ornamental, or serviceable—from Wenham ice to vernal flowers and tropical fruits—from Indian moccasins to a silk dress-pattern—from [Pg 48] ancient Chinese books to the freshest morning papers—ask, and it shall be given unto you.

Sit down in a stall, over your tiny cup of excellent coffee, and you are hobnobbing with the antipodes—your next neighbor may be from Greenland's icy mountains, or India's coral strand. Get up to resume your promenade, and you hear a dozen languages in as many steps; while every nation, and tribe, and people—French, English, Irish, German, Spanish, Creole, Chinese, African, Quadroon, Mulatto, American—jostles you in good-humored confusion.

Some gigantic negresses, with gaudy kerchiefs, like turbans, about their heads, are selling fruits, and sit erect as palm-trees. They look like African or Indian princesses, a little annoyed at being separated from their thrones and retinues, but none the less regal "for a' that." At every turn little girls, with rich Creole complexions and brilliant eyes, offer you aromatic bouquets of pinks, roses, verbenas, orange and olive blossoms, and other flowers to you unknown, unless, being a woman, you are a botanist by "gift of fortune," or, a man, that science has "come by nature."

Upon Jackson Square, a delicious bit of verdure fronting the river, gloom antique public buildings, which were the seat of government in the days of the old Spanish régime. Near them stands the equally ancient cathedral, richly decorated within, where devout Catholics still worship. Its great congregations are mosaics of all hues and nationalities, mingling for the moment in the democratic equality of the Roman Church.

Attending service in the cathedral one Sunday morning, I found the aisles crowded with volunteers who, on the eve of departure for the debatable ground of Fort Pickens, had assembled to witness the consecration of [Pg 49] their Secession flag, a ceremonial conducted with great pomp and solemnity by the French priests.

In the First Presbyterian Church, the Rev. Dr. Palmer, a divine of talent and local reputation, might be heard advocating the extremest Rebel views. The southerners had formerly been very bitter in their denunciation of political preaching; but now the pulpit, as usual, made obeisance to the pews, and the pews beamed encouragement on the pulpit.

If I may go abruptly from church to cotton—and they were not far apart in New Orleans—a visit to one of the great cotton-presses was worthy of note. It is a low building, occupying an entire square, with a hollow court in the center. It was filled with heaped-up cotton-bales, which overran their limits and covered the adjacent sidewalks. Negroes stood all day at the doors receiving and discharging cotton. The bales are compressed by heavy machinery, driven by steam, that they may occupy the least space in shipping. They are first condensed on the plantations by screw-presses; the cotton is compact upon arrival here; but this great iron machine, which embraces the bales in a hug of two hundred tons, diminishes them one-third more. The laborers are negroes and Frenchmen, who chant a strange, mournful refrain in time with their movements.

The ropes of a bale are cut; it is thrown under the press; the

great iron jaws of the monster close convulsively, rolling it under

the tongue as a sweet morsel. The ropes are tightened and again

tied, the cover stitched up, and the bale rolled out to make room

for another—all in about fifty seconds. It weighs five hundred

pounds, but the workmen siezeseize it on all

sides with their iron hooks, and toss it about like a schoolboy's

ball. The superintendent informed me that they pressed,

[Pg 50]

during the previous winter, more than forty thousand bales.

The Rebels, with their early penchant for capturing empty

forts and full treasuries, had seized the United States Branch Mint,

containing three hundred thousand dollars, and the National barracks,

garrisoned at the time by a single sergeant. Visiting, with a party

of gentlemangentlemen, the historic Jackson

battle-ground, four miles below the city, I obtained a glimpse of

the tall, gloomy Mint, and spent an hour in the long, low, white,

deep-balconied barracks beside the river.

The Lone Star flag of Louisiana was flying from the staff. A hundred and twenty freshly enlisted men of the State troops composed the garrison. Three of the officers, recent seceders from the Federal army, invited us into their quarters, to discuss political affairs over their Bourbon and cigars. As all present assumed to be sanguine and uncompromising Rebels, the conversation was one-sided and uninteresting.

We drove down the river-bank along the almost endless rows of ships and steamboats. The commerce of New Orleans, was more imposing than that of any other American city except New York. It seemed to warrant the picture painted by the unrivaled orator, Prentiss, of the future years, "when this Crescent City shall have filled her golden horn." The long landing was now covered with western produce, cotton, and sugar, and fenced with the masts of hundreds of vessels. Some displayed the three-striped and seven-starred flag of the "Southern Confederacy," many the ensigns of foreign nations, and a few the Stars and Stripes.

We were soon among the old houses of the Creoles.3 [Pg 51] These anomalous people—a very large element of the population—properly belong to a past age or another land, and find themselves sadly at variance with America in the nineteenth century. They seldom improve or sell their property; permit the old fences and palings to remain around their antique houses; are content to live upon small incomes, and rarely enter the modern districts. It is even asserted that old men among them have spent their whole lives in New Orleans without ever going above Canal street! Many have visited Paris, but are profoundly ignorant of Washington, New York, Philadelphia, and other northern cities. They are devout Catholics, sudden and quick in quarrel, and duelling continues one of their favorite recreations.

We stopped at the old Spanish house—deeply embowered in trees—occupied as head-quarters by General Jackson, and saw the upper window from which, glass in hand, he witnessed the approach of the enemy. The dwelling is inhabited, and bears marks of the cannon-balls fired to dislodge him. Like his city quarters—a plain brick edifice, at one hundred and six, Royal-street, New Orleans—it is unchanged in appearance since that historic Eighth of January.

A few hundred yards from the river, we reached the battle-ground where, in 1815, four thousand motley, undisciplined, half-armed recruits defeated twelve thousand veterans—the Americans losing but five men, the British seven hundred. This enormous disparity is explained by the sheltered position of one party behind a breastwork, and the terrible exposure of the other in its march, by solid columns, of half a mile over an open field, without protection of hillock or tree. A horrible field, whence the Great Reaper gathered a bloody harvest!

The swamp here is a mile from the river. Jackson dug a canal between them, throwing up the earth on one side for a breastwork, and turning a stream of water from the Mississippi through the trench. The British had an extravagant fear of the swamp, and believed that, attempting to penetrate it, they would be ingulfed in treacherous depths. So they marched up, with unflinching Saxon courage, in the teeth of that terrible fire from the Americans, ranged four deep, behind the fortification; and the affair became a massacre rather than a battle.

The spongy soil of the breastwork (the tradition that bales of cotton were used is a fiction) absorbed the balls without any damage. It first proved what has since been abundantly demonstrated in the Crimean war, and the American Rebellion—the superiority of earthworks over brick and stone. The most solid masonry will be broken and battered down sooner or later, but shells and solid shot can do little harm to earthworks.

Jackson's army was a reproduction of Falstaff's ragamuffins. It was made up of Kentucky backwoodsmen, New Orleans clergymen, lawyers, merchants and clerks; pirates and ruffians just released from the calaboose to aid in the defense; many negroes, free and slave, with a liberal infusion of nondescript city vagabonds, noticeable chiefly for their tatters, and seeming, from their "looped and windowed raggedness," to hang out perpetual flags of truce to the enemy.

Judah Trouro, a leading merchant, while carrying ammunition, was struck in the rear by a cannon-ball, which cut and bore away a large slice of his body; but, in spite of the awkward loss, he lived many years, to leave an enviable memory for philanthropy and public [Pg 53] spirit. Parton tells of a young American who, during the battle, stooped forward to light a cigar; and when he recovered his position saw that a man exactly behind him was blown to pieces, and his brains scattered over the parapet, by an exploding shell.

More than half of Jackson's command was composed of negroes, who were principally employed with the spade, but several battalions of them were armed, and in the presence of the whole army received the thanks of General Jackson for their gallantry. On each anniversary the negro survivors of the battle always turned out in large numbers—so large, indeed, as to excite the suspicion that they were not genuine.

The free colored population, at the time of my visit, was a very peculiar feature of New Orleans. Its members were chiefly of San Domingo origin; held themselves altogether aloof from the other blacks, owned numerous slaves, and were the most rigorous of masters. Frequently their daughters were educated in Paris, married whites, and in some cases the traces of their negro origin were almost entirely obliterated. This, however, is not peculiar to that class. It is very unusual anywhere in the South to find persons of pure African lineage. A tinge of white blood is almost always detected.

Our company had an invaluable cicerone in the person of Judge Alexander Walker, author of "Jackson and New Orleans," the most clear and entertaining work upon the battle, its causes and results, yet contributed to American history. He had toiled unweariedly through all the official records, and often visited the ground with men who participated in the engagement. He pointed out positions, indicated the spot where Packenham fell, and drew largely upon his rich fund of anecdote, tradition, and biography.

A plain, unfinished shaft of Missouri limestone, upon a rough brick foundation, now marks the battle-field. It was commenced by a legislative appropriation; but the fund became exhausted and the work ceased. The level cotton plantation, ditched for draining, now shows no evidence of the conflict, except the still traceable line of the old canal, with detached pools of stagnant water in a fringe of reeds, willows, and live oaks.

A negro patriarch, with silvery hair, and legs infirm of purpose, hobbled up, to exhibit some balls collected on the ground. The bullets, which were flattened, he assured us, had "hit somebody." No doubt they were spurious; but we purchased a few buckshots and fragments of shell from the ancient Ethiop, and rode back to the city along avenues lined with flowers and shrubbery. Here grew the palm—the characteristic tree of the South. It is neither graceful nor beautiful; but looks like an inverted umbrella upon a long, slender staff. Ordinary pictures very faithfully represent it.

New Orleans, March 11, 1861.

We are a good deal exercised, just now, about a new grievance. The papers charged, a day or two since, that the ship Adelaide Bell, from New Hampshire, had flung defiant to the breeze a Black Republican flag, and that her captain vowed he would shoot anybody attempting to cut it down. As one of the journals remarked, "his audacity was outrageous." En passant, do you know what a Black Republican flag is? I have never encountered that mythical entity in my travels; but 'tis a fearful thing to think of—is it not?

The reporter of The Crescent, with charming ingenuousness, describes it as "so much like the flag of the late United States, that few would notice the difference." [Pg 55] In fact, he adds, it is the old Stars and Stripes, with a red stripe instead of a white one immediately below the union. Of course, we are greatly incensed. It is flat burglary, you know, to love the Star Spangled Banner itself; and as for a Black Republican flag—why, that is most tolerable and not to be endured.

Captain Robertson, the "audacious," has been compelled, publicly, to deny the imputation. He asserts that, in the simplicity of his heart, he has been using it for years as a United States flag. But the newspapers adhere stoutly to the charge; so the presumption is that the captain is playing some infernal Yankee trick. Who shall deliver us from the body of this Black Republican flag?

If it were possible, I would like to see the "Southern Confederacy" work out its own destiny; to see how Slavery would flourish, isolated from free States; how the securities of a government, founded on the right of any of its members to break it up at pleasure, would stand in the markets of the world; how the principle of Democracy would sustain itself in a confederation whose corner-stones are aristocracy, oligarchy, despotism. This is the government which, in the language of one of its admirers, shall be "stronger than the bonds of Orion, and benigner than the sweet influences of the Pleiades."